Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mechanisms and Mitigation of Heavy Oil Invasion into Drilling Fluids in Carbonate Reservoirs

1 Sinopec Group Northwest Petroleum Branch, Urumqi, 650100, China

2 Key Laboratory of SINOPEC Ultra Deep Well Drilling Engineering Technology, Beijing, 102206, China

3 National Engineering Research Center for Oil & Gas Drilling and Completion Technology, School of Petroleum Engineering, Yangtze University, Wuhan, 430100, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jingwei Liu. Email: ; Peng Xu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fluid and Thermal Dynamics in the Development of Unconventional Resources III)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(8), 1875-1894. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.066404

Received 08 April 2025; Accepted 23 June 2025; Issue published 12 September 2025

Abstract

Drilling operations in carbonate rock heavy oil blocks (e.g., in the Tahe Oilfield) are challenged by the intrusion of high-viscosity, temperature-sensitive formation heavy oil into the drilling fluid. This phenomenon often results in wellbore blockage, reduced penetration rates, and compromised well control, thereby significantly limiting drilling efficiency and operational safety. To address this issue, this study conducts a comprehensive investigation into the mechanisms governing heavy oil invasion using a combination of laboratory experiments and field data analysis. Findings indicate that the reservoir exhibits strong heterogeneity and that the heavy oil possesses distinctive physical properties. The intrusion process is governed by multiple interrelated factors, including pressure differentials, pore structure, and the rheological behavior of the heavy oil. Experimental results reveal that the invasion of heavy oil occurs in distinct phases, with temperature playing a critical role in altering its viscosity. Specifically, as temperature increases, the apparent viscosity of the drilling fluid decreases; however, elevated pressures induce a nonlinear increase in viscosity. Furthermore, the compatibility between the drilling fluid and the intruding heavy oil declines markedly with increasing oil concentration, substantially raising the risk of wellbore obstruction. Simulation experiments further confirm that at temperatures exceeding 40°C and injection rates of ≥0.4 L/min, the likelihood of wellbore blockage significantly increases due to heavy oil infiltration. Based on these insights, a suite of targeted mitigation strategies is proposed. These include the formulation of specialized chemical additives, such as viscosity reducers, dispersants, and plugging removal agents, the real-time adjustment of drilling fluid density, and the implementation of advanced monitoring and early-warning systems.Keywords

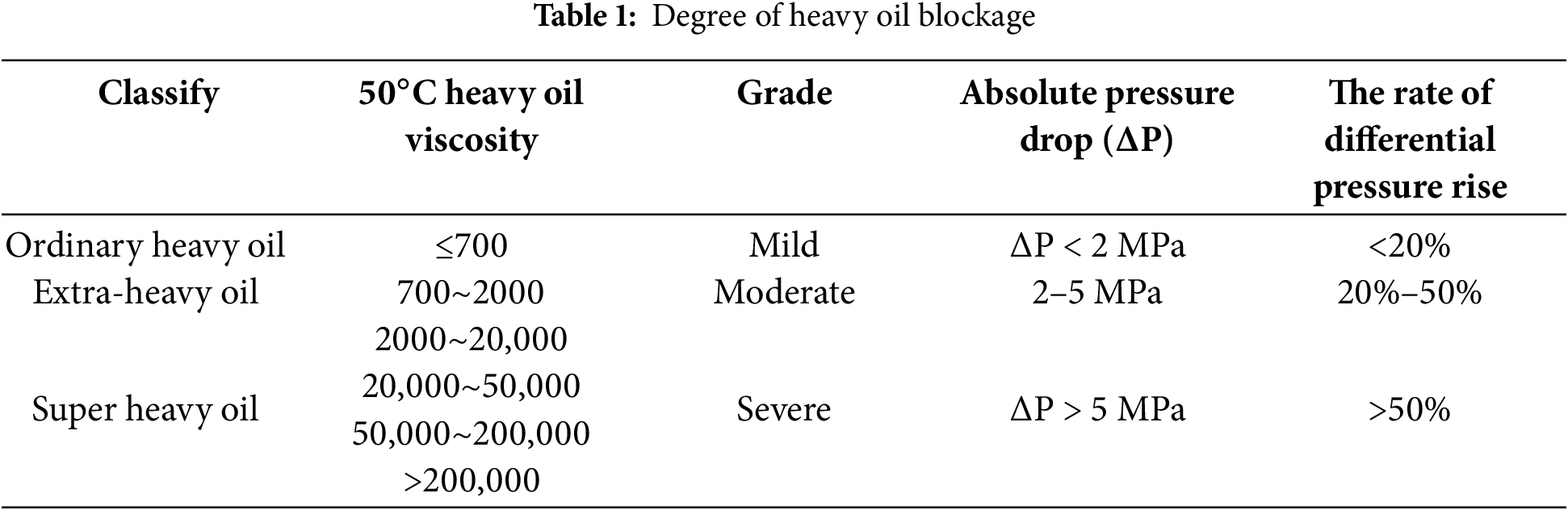

Tahe Oilfield serves as a crucial production hub for ultra-deep and ultra-heavy oil. Its fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoirs are characterized by highly complex properties, encapsulated by the term “two ultra-deep and three high”—referring to the ultra-deep reservoir depth, ultra-heavy oil, as well as the high temperature, high pressure, and high hydrogen sulfide content within the reservoir [1]. In the process of drilling in the carbonate formations of Tahe, the intrusion of heavy oil into drilling fluids is a persistent and formidable challenge. The degree of heavy oil blockage is shown in Table 1. The in-situ heavy oil is characterized by high viscosity and significant temperature sensitivity. As the heavy oil is carried upward by the drilling fluids during circulation, it experiences a rapid decline in temperature and pressure. This rapid change triggers wax precipitation and asphaltene coagulation. Consequently, issues such as the “solidified pipe” phenomenon, wellbore blockage, decreased drilling rates, and heightened well-control risks emerge [2]. These challenges not only extend drilling cycles but also increase costs owing to frequent plug removal operations. Furthermore, in Tahe’s ultra-deep wells (with depths exceeding 7000 m and bottomhole temperatures surpassing 150°C), the extreme high-temperature and high-pressure (HTHP) environments intensify the phase transformations between drilling fluids and heavy oil, rendering conventional technologies inadequate [3,4].

The case investigation of Yada Oilfield provides significant insights for tackling heavy oil intrusion in complex carbonate reservoirs [5]. In the Yadavaran Oilfield, the Kazhdumi Formation harbors asphalt-laden heavy oil. Within this formation, the combined high-pressure and high-H2S environment gives rise to critical challenges, including contamination of drilling fluids, deterioration of their rheological properties, and failures of liner hangers [6,7]. During initial operational phases, three wells had to be abandoned as a result of asphalt invasion, with conventional plugging methodologies—such as the use of inert materials and sodium silicate consolidation—demonstrating insufficient efficacy in addressing the issue [8–10]. As a result, the research team formulated comprehensive solutions through mechanistic analysis and technological innovation. These include optimized drilling fluid systems, the use of diesel blended with emulsifiers to decrease the interfacial tension between oil and fluids in the Kazhdumi asphalt-bearing formation, implementation of managed pressure drilling (MPD), and application of specialized curing agents for chemical consolidation of microfractures. These measures shortened drilling cycles by 15 days and reduced fluid-related costs by USD 260,000.

For Tahe Oilfield, two treatment systems—composite viscosity reduction and dispersive viscosity reduction—have been developed to mitigate heavy oil invasion [11]. The composite formulation integrates oil-soluble viscosity reducers, which aid in the dilution of heavy crude, and water-soluble emulsifiers to generate stable oil-in-water emulsions, resulting in a substantial 98% viscosity reduction under laboratory conditions. In field trials conducted across six wells, a 5% concentration effectively mitigated the risk of pipe solidification. However, several operational challenges remain, including elevated additive consumption, an increase in hazardous waste with oil content reaching up to 4%, and significant rubber swelling in downhole motors, ranging from 38.5% to 44.8%. The dispersive formulation utilizes dispersants that adsorb onto the oil surface, forming molecular films that break the heavy oil into smaller droplets (with a 2%–3% dosage), thereby preventing re-agglomeration. Deployed in over 10 wells, this system reduced tripping friction, although it required the addition of defoamers to manage excessive foaming at ambient temperatures. Future improvements should focus on refining additive dosages, formulating cost-effective agents, reducing hazardous waste production, and developing motor materials with enhanced resistance to swelling.

The fluidity of heavy oil in carbonate rock fractures is significantly influenced by temperature variations. Temperature fluctuations directly impact the viscosity of heavy oil, which serves as a critical determinant of fluid mobility. As temperature decreases, the molecular motion of heavy oil slows down, leading to an increase in viscosity and a substantial reduction in fluidity. Specifically, a 20°C drop in ambient temperature can cause the flow rate of heavy oil to decrease by up to 40%. This phenomenon highlights that temperature is not only a major factor affecting heavy oil fluidity but also a key variable governing whether heavy oil can penetrate fractures smoothly.

In actual drilling operations, temperature changes—particularly in deep oil and gas reservoirs or low-temperature zones—may significantly affect heavy oil fluidity, making its invasion into fractures more challenging and thus impacting the smooth progression of drilling activities. Under such circumstances, the performance of drilling fluids becomes of utmost importance. Drilling fluids must not only effectively maintain the smooth execution of drilling operations but also counteract the adverse effects induced by temperature changes.

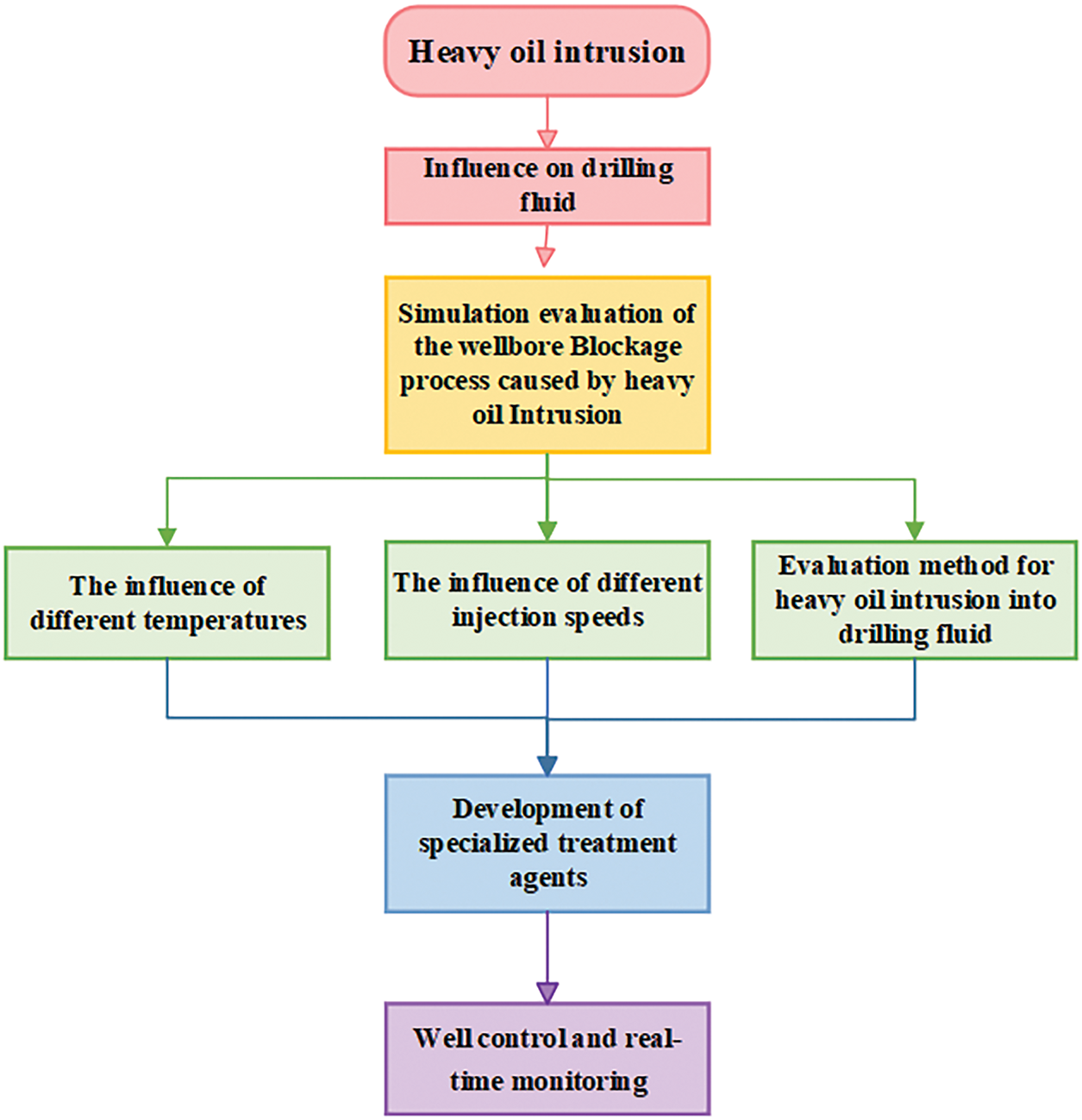

Additionally, traditional polymer-based drilling fluids tend to form a rigid liquid-rock interfacial film upon contact with heavy oil. This film arises from the interaction between polymer molecules and heavy oil components, increasing the interfacial film’s rigidity and exacerbating adhesion between the fluid and fracture walls. As the interfacial film thickens, heavy oil flow within fractures encounters significant resistance, potentially leading to fracture blockage and reducing oil-gas extraction efficiency. In high-temperature, high-pressure (HTHP) environments, polymer molecules may undergo chemical reactions such as aggregation and cross-linking, further enhancing film rigidity and imposing more severe restrictions on fluid mobility. Under these conditions, drilling fluid performance may be drastically degraded, potentially causing system failure and increasing operational risks and costs. The technical roadmap is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Technology road map

Thus, traditional drilling fluid formulations often prove inadequate when confronting these challenges. To effectively address this issue, optimizing drilling fluids and adopting new materials better adapted to complex subsurface environments are imperative. Introducing nanocomposites with high-temperature stability and superior rheological properties—or employing more flexible, temperature-responsive polymers—can enhance fluidity and sealing performance under high-temperature conditions.

This study systematically tackles heavy oil invasion in Tahe’s carbonate reservoirs by first analyzing reservoir characteristics and invasion mechanisms. Experimental investigations characterize the invasion process, interfacial interactions, and impacts on drilling fluid performance. Simulation-based evaluations further clarify wellbore plugging dynamics. Leveraging these insights, targeted countermeasures are proposed, including drilling fluid optimization, development of specialized additives, operational process enhancements, and real-time well control monitoring. These strategies establish a theoretical and technical foundation for resolving heavy oil invasion challenges in Tahe Oilfield.

2 Characteristics of Carbonate Heavy Oil Reservoir and Potential Intrusion Mechanism of Drilling Fluid

2.1 Characteristics of Heavy Oil Reservoir of Tahe Carbonate Rock

The heavy oil carbonate reservoirs in Tahe Oilfield exhibit unique geological characteristics. These reservoirs primarily developed in Ordovician strata through multiple phases of tectonic movements and karstification, resulting in complex and diverse reservoir morphologies. The reservoirs are predominantly fracture-vuggy types, where interconnected fractures and dissolution cavities form a complex network of storage spaces. These fractures and cavities vary significantly in size, shape, and connectivity, leading to extreme reservoir heterogeneity. In some areas, well-developed fractures act as conduits for heavy oil migration and accumulation, while dissolution cavities serve as storage compartments, creating highly irregular and complex oil-water distribution patterns within the reservoirs.

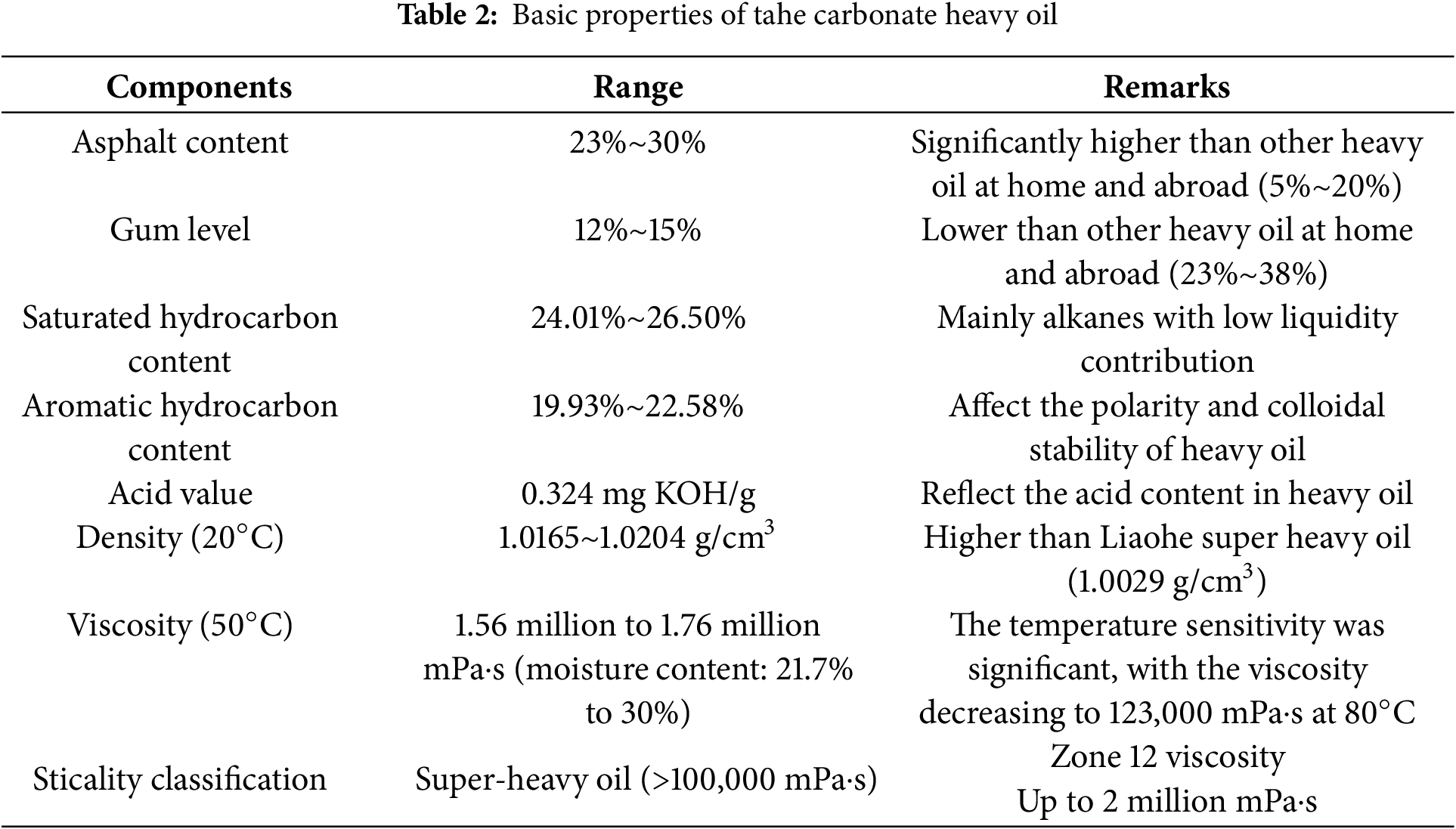

In terms of heavy oil properties, Tahe’s carbonate heavy oil is characterized by high density and viscosity (as shown in Table 2). The reservoirs, classified as fracture-vuggy carbonate systems, exhibit strong spatial heterogeneity and intricate fracture-cavity structures [12]. Development targets have shifted from early-stage large fractures and cavities to medium-small ones, with effective reservoir volumes reduced to 1/3~1/2 of previous scales. The reservoirs are deeply buried (5400~7000 m), with high temperatures (130~155°C) and salinity (200,000~240,000 ppm) [13]. Heavy oil invasion types are categorized as constant-volume and non-constant-volume, with the former posing the highest risk of pipe solidification. Over the past two years, 53 wells encountered heavy oil, averaging 2.54 days of non-productive time (NPT) per well, with a maximum of 32 days. Tahe’s heavy oil is classified as ultra-heavy oil, with viscosities typically exceeding 100,000 mPa·s (reaching up to 2000,000 mPa·s). It contains high asphaltene content (23%~30%), moderate resin content (12%~15%), and shows a propensity for C7-asphaltene deposition. The acid number is 0.324 mg KOH/g, and the density (20°C) ranges from 1.0165 to 1.0204 g/cm3. Significant temperature-dependent viscosity reduction is observed, with viscosity decreasing to 123,000 mPa·s at 80°C.

2.2 The Basic Process of Heavy Oil Invasion

2.2.1 Dynamic Characteristics of Heavy Oil Intrusion

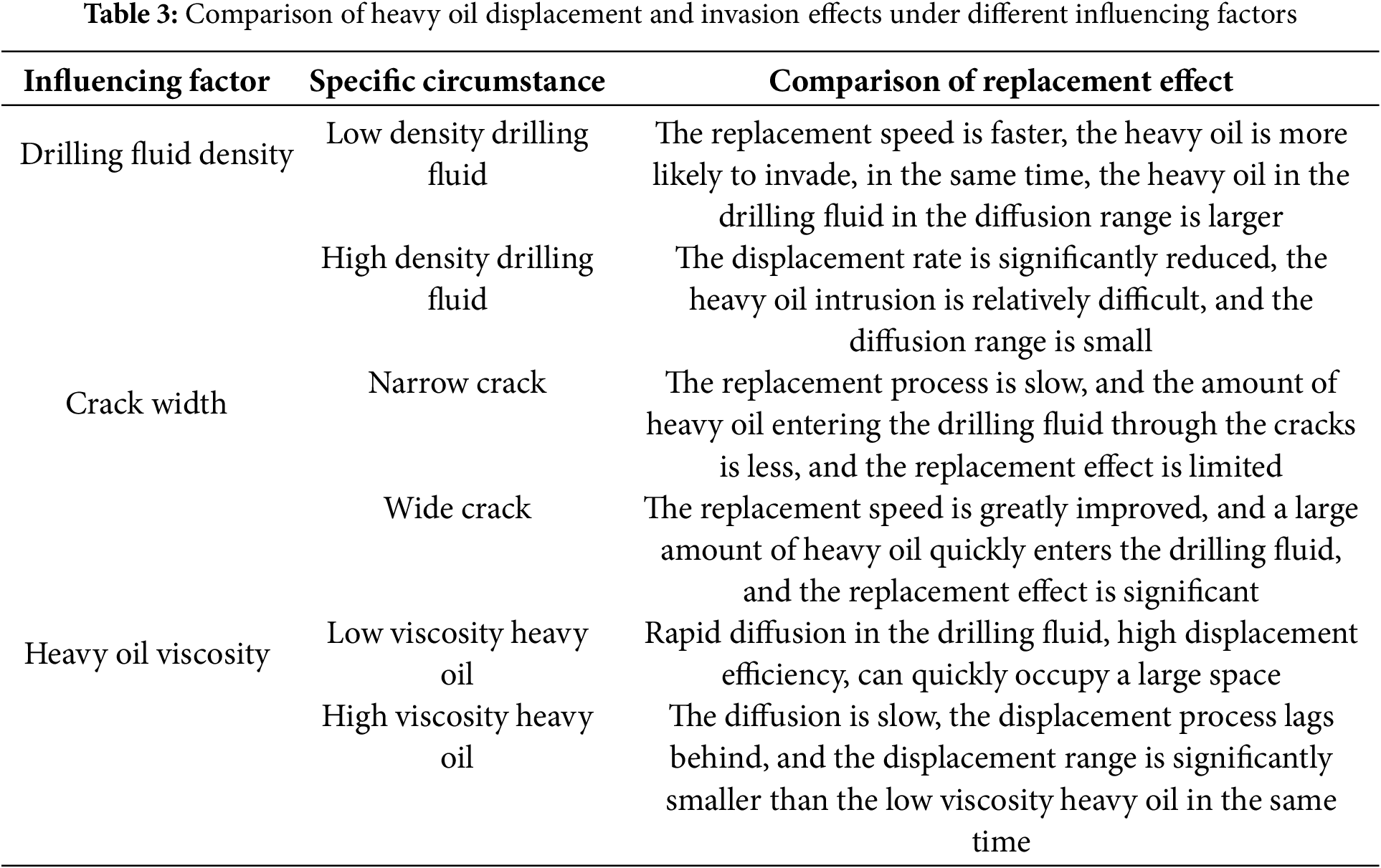

During drilling operations, the pressure differential between the drilling fluid in the wellbore and the heavy oil within the reservoir acts as the primary driving force for the displacement of oil by water [14]. When the wellbore penetrates the reservoir, the heavy oil attempts to flow into the wellbore under this pressure differential, triggering oil-water displacement. From a microscopic perspective, the pore structure of the reservoir provides pathways for heavy oil migration, while the imbalance between the hydrostatic column pressure of the drilling fluid and the reservoir pressure drives the oil to overcome pore resistance and invade the wellbore. The invasion dynamics process is complex, influenced by multiple factors. A larger pressure differential accelerates the invasion rate. The size and connectivity of pore structures are critical-larger, well-connected pores facilitate smoother invasion. Additionally, the viscosity of the heavy oil itself is a key factor: higher viscosity increases invasion resistance, thereby slowing the invasion rate. The comparison of heavy oil displacement and intrusion effects under different influencing factors is shown in Table 3.

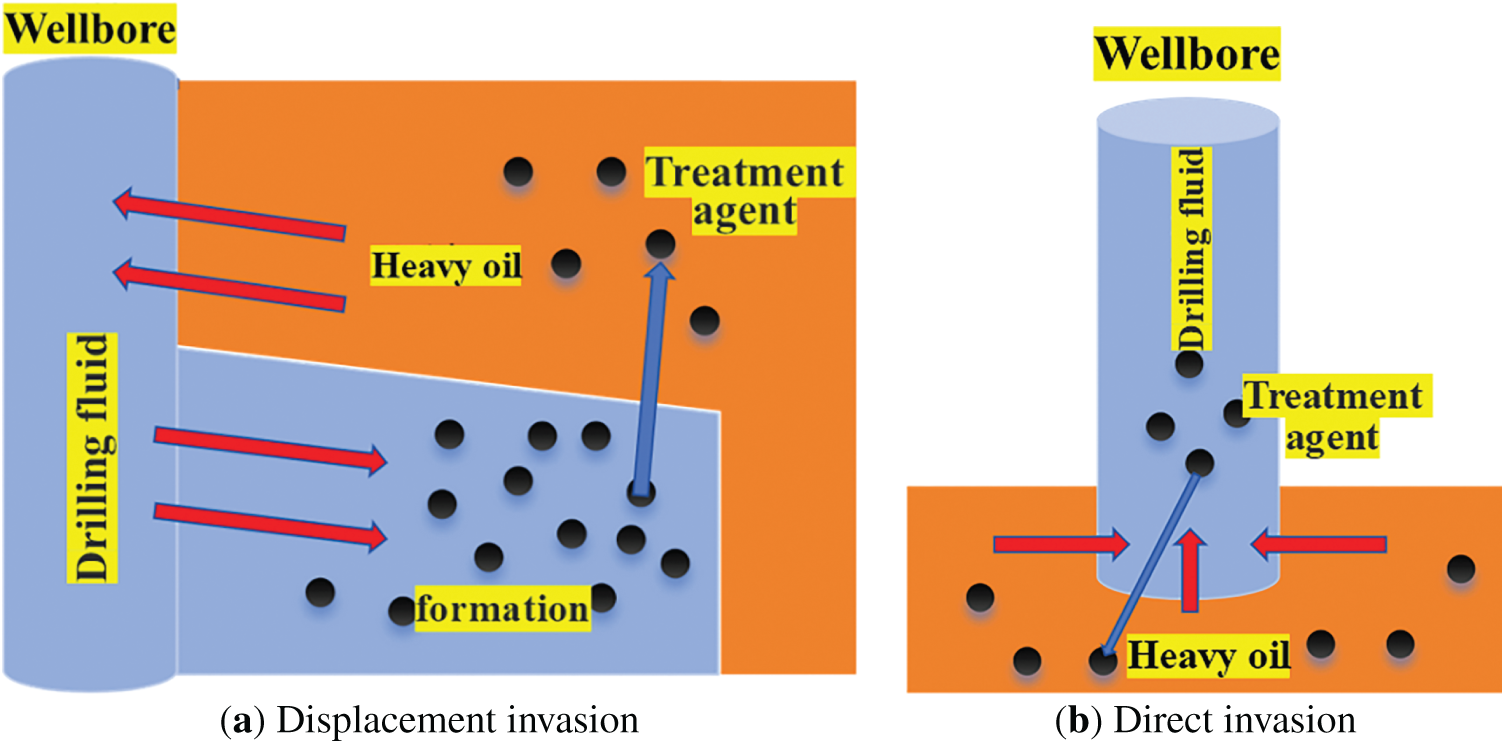

In the dynamic process of heavy oil invading the drilling fluid, in the initial stage, when the heavy oil contacts with the drilling fluid, the concentration gradient starts to slowly spread the heavy oil molecules to the drilling fluid [15]. At this time, the diffusion speed is relatively slow, and the diffusion range of the heavy oil in the drilling fluid is small. With the advance of time, the intrusion rate of heavy oil is gradually accelerated under the dual action of pressure difference and concentration difference. The pressure differential accelerates the ingress of heavy oil into the drilling fluid, while the concentration gradient further facilitates the diffusion of heavy oil molecules. During the intermediate phase, the diffusion range of heavy oil within the drilling fluid significantly expands, exhibiting an irregular distribution pattern. As the process progresses into the later stage, both the concentration gradient and pressure differential gradually diminish, leading to a reduction in the rate of heavy oil intrusion. Eventually, a relatively stable equilibrium state is reached. At this time, the distribution of heavy oil in the drilling fluid is basically stable, and the final distribution form of heavy oil in the drilling fluid is formed. The process of heavy oil invasion into drilling fluid is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Process of heavy oil invasion into drilling fluid

2.2.2 Dynamic Process of Heavy Oil Invasion into Drilling Fluids

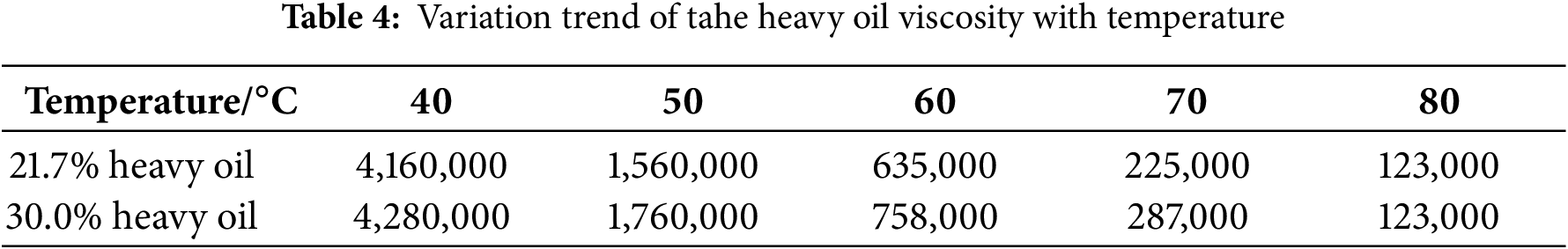

During the initial stage of heavy oil invasion into drilling fluids, when heavy oil comes into contact with the drilling fluid, heavy oil molecules begin to slowly diffuse into the fluid under the driving force of the concentration gradient [16]. At this phase, the diffusion rate is relatively low, and the spatial extent of heavy oil dispersion within the drilling fluid remains limited. As time progresses, the invasion rate gradually accelerates under the combined effects of the pressure differential and concentration gradient. The pressure differential forces the heavy oil to penetrate the drilling fluid more rapidly, while the concentration gradient continues to drive molecular diffusion. The variation trend of tahe heavy oil viscosity with temperature is shown in Table 4.

In the intermediate stage, the spatial dispersion of heavy oil within the drilling fluid undergoes substantial expansion, manifesting as irregular morphological patterns. As the process advances to the later stage, with the gradual attenuation of the concentration gradient and stabilization of the pressure differential, the invasion rate progressively decelerates, ultimately achieving a state of dynamic equilibrium. At this equilibrium condition, the distribution of heavy oil in the drilling fluid stabilizes, forming a final dispersed configuration.

2.3 Interfacial Interaction between Drilling Fluid and Heavy Oil

(1) Surface interactions

When the drilling fluid is in contact with the heavy oil, the surface tension leads to the interaction between the two to achieve energy balance [17]. The complex surface properties of drilling fluid and the high surface energy of heavy oil can affect the dispersion of heavy oil. When the surface tension difference is large, the heavy oil is not easy to disperse evenly, which may form large oil droplets and affect the performance of drilling fluid. Surface action may also alter interfacial properties, influence subsequent processes.

(2) Dispersion effects

The dispersion of heavy oil into drilling fluids involves components such as surfactants that reduce interfacial tension, enabling heavy oil to break into smaller droplets. These droplets diffuse during fluid circulation, with agitation enhancing dispersion efficiency. However, the high viscosity and aggregation tendency of heavy oil may impede dispersion, leading to droplet coalescence. The rheological properties of the drilling fluid are critical: appropriate rheological parameters create a stable environment, ensuring uniform dispersion and minimizing agglomeration.

(3) Bridging blockage by cuttings-heavy oil mixtures

During drilling operations, the interaction between cuttings and heavy oil can give rise to mixed bridging blockages. The irregular geometries and large specific surface areas of cuttings serve as adhesion sites for heavy oil, whose high viscosity promotes adsorption onto the surfaces of cuttings. As cuttings and heavy oil accumulate and interconnect, they form bridging structures that impede the flow of drilling fluid, thereby compromising operational efficiency. In severe scenarios, such blockages may escalate to pipe sticking incidents, posing significant risks to drilling safety and productivity.

3 Mechanisms of Heavy Oil Invasion Impact on Drilling Fluid Performance

3.1 Evaluation Method for Heavy Oil Intrusion into Drilling Fluid

The experiments systematically evaluated the impact of heavy oil invasion on drilling fluids using a high-temperature/high-pressure (HTHP) simulation system and multi-parameter testing methods. The study employed an HTHP rheometer (temperature range: 40~150°C, pressure: 0~20 MPa) and a high-precision interfacial tensiometer (resolution: 0.1 mN/m), combined with operational parameters from the Tahe Oilfield, to simulate real-world conditions. The focus was on analyzing the dynamic effects of heavy oil invasion on the rheological properties and compatibility of drilling fluids.

A typical drilling fluid system from the Tahe Oilfield served as the base fluid. By stepwise addition of heavy oil at varying volume fractions (0%~30%), scenarios representing different invasion severities during drilling were simulated. Real-time monitoring tracked changes in rheological parameters, including apparent viscosity, plastic viscosity, and yield point. Concurrently, compatibility between heavy oil and the drilling fluid was assessed through interfacial tension measurements, emulsification stability observations, and corrosion product analysis.

3.2 Viscosity Variation under High Temperature and High Pressure

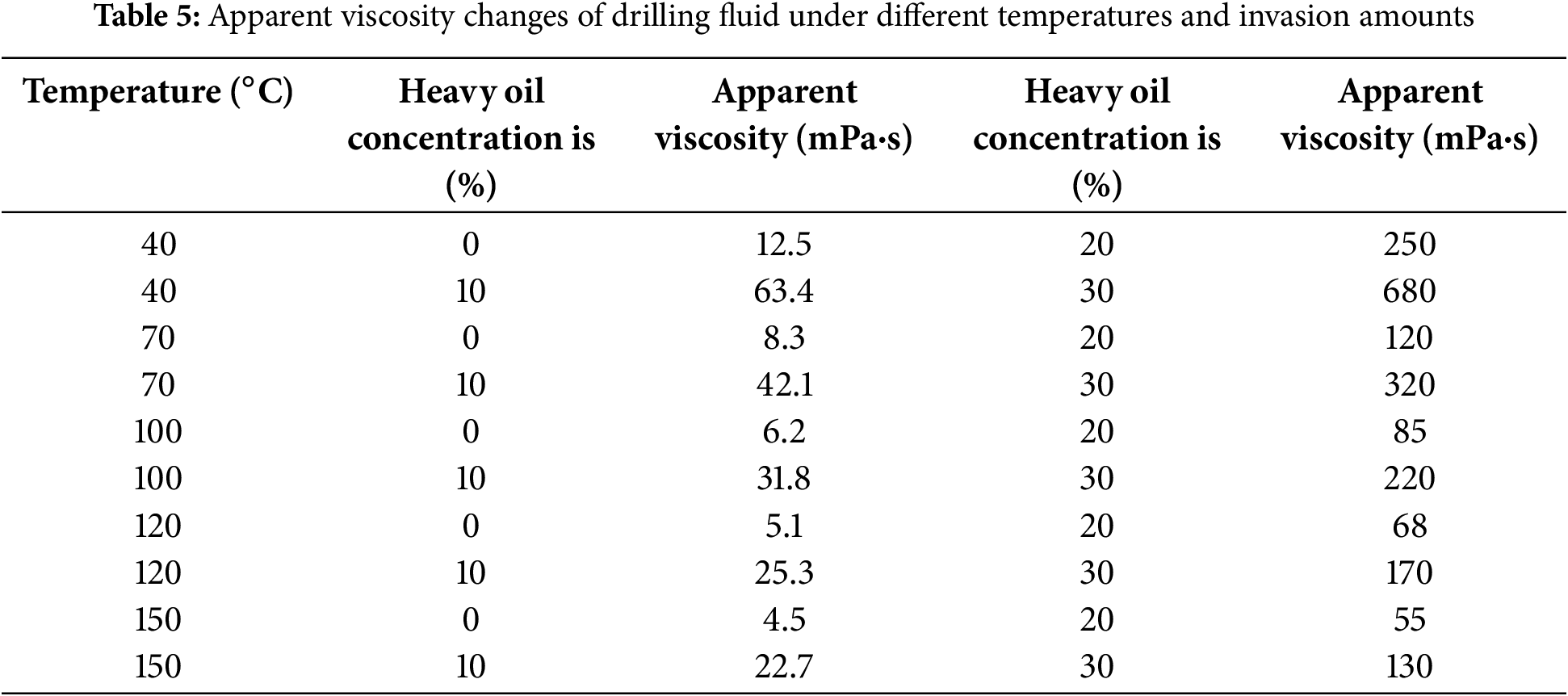

3.2.1 Apparent Viscosity Changes of Drilling Fluid under Different Temperatures and Invasion Amounts

The experiments were conducted within a high-temperature range of 40~150°C to simulate deep well drilling conditions in the Tahe Oilfield. A low-solid aqueous drilling fluid served as the base fluid, with heavy oil invasion concentrations incrementally added from 0% to 30%. Apparent viscosity measurements at varying temperatures were performed using a high-temperature/high-pressure (HTHP) rotational viscometer, ensuring temperature control accuracy within ±0.5°C, to quantify the temperature-dependent viscosity behavior of the drilling fluid.

Experimental results revealed a monotonic decline in the apparent viscosity of the drilling fluid with increasing temperature. For instance, at 30% heavy oil invasion, the viscosity measured 680 mPa·s at 40°C but dropped to 130 mPa·s at 150°C, representing an 81% reduction. This trend aligns with the physical mechanism of enhanced molecular thermal motion and weakened intermolecular forces at elevated temperatures. However, in the high-temperature range (>100°C), the viscosity reduction rate significantly slowed (merely a 30% decrease from 100°C to 150°C), indicating reduced sensitivity of viscosity to temperature variations in this regime. The apparent viscosity changes of drilling fluid under different temperatures and invasion amounts are shown in Table 5.

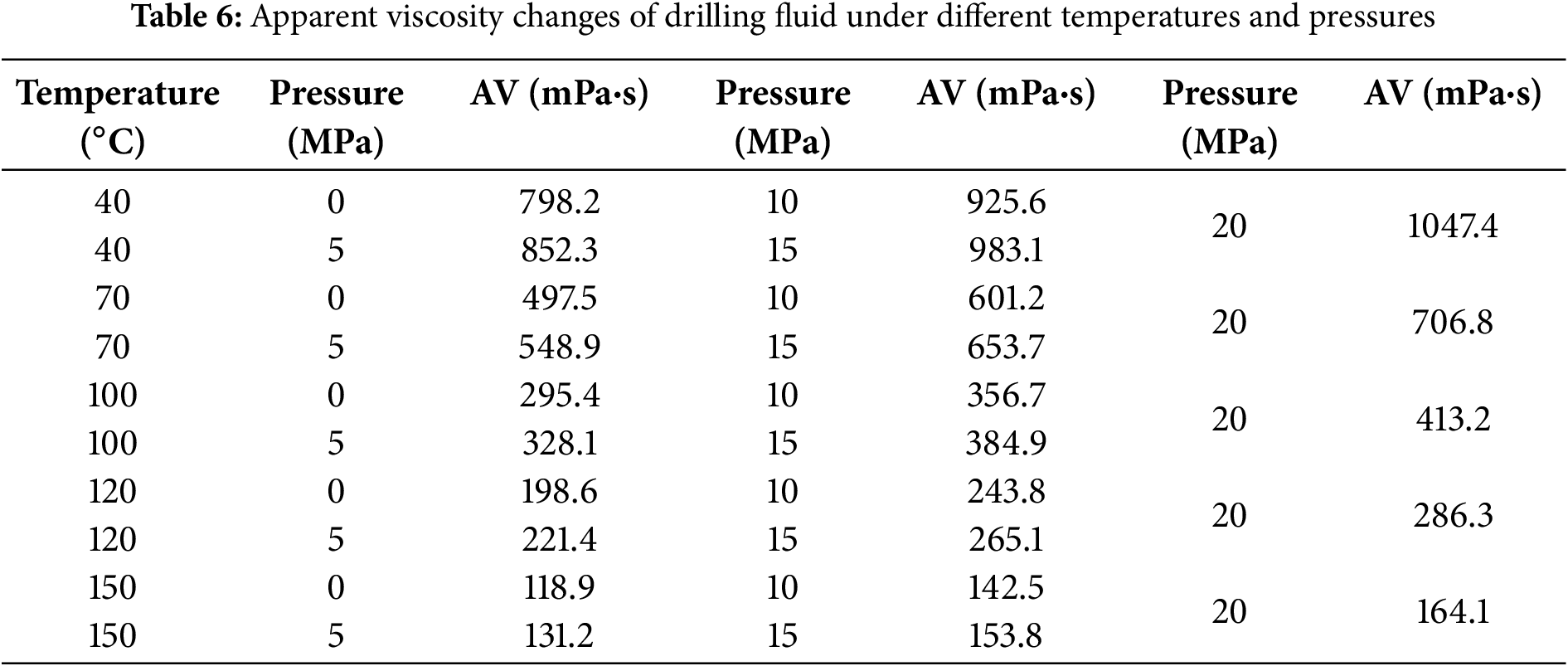

3.2.2 Apparent Viscosity Changes of Drilling Fluid under Different Temperatures and Pressures

The experiments were carried out under temperature (40~150°C) and pressure (0~20 MPa) conditions to explore the temperature-pressure coupled variation patterns of viscosity in a drilling fluid system with 30% heavy oil invasion under deep drilling environments. Apparent viscosity measurements under combined temperature-pressure conditions were conducted using a high-temperature/high-pressure (HTHP) rotational viscometer.

As temperature increased from 40°C to 150°C, the apparent viscosity plummeted from 1047.4 mPa·s (at 20 MPa) to 164.1 mPa·s (at 20 MPa), representing an 84% reduction. Pressure exhibited a nonlinear viscosity-enhancing effect: at constant temperatures, viscosity increased with rising pressure, but the magnitude of this increase decayed significantly at higher temperatures. For instance, at 40°C, the viscosity at 20 MPa was 25% higher than that at 0 MPa, whereas at 150°C, the enhancement diminished to only 38%. Additionally, increased data variability was observed at elevated temperatures, indicating reduced changes in heavy oil molecular dispersion and diminished sensitivity of viscosity to pressure under high-temperature conditions. Apparent viscosity changes of drilling fluid under different temperatures and pressures are shown in Table 6.

3.3 Compatibility between Heavy Oil and Drilling Fluid

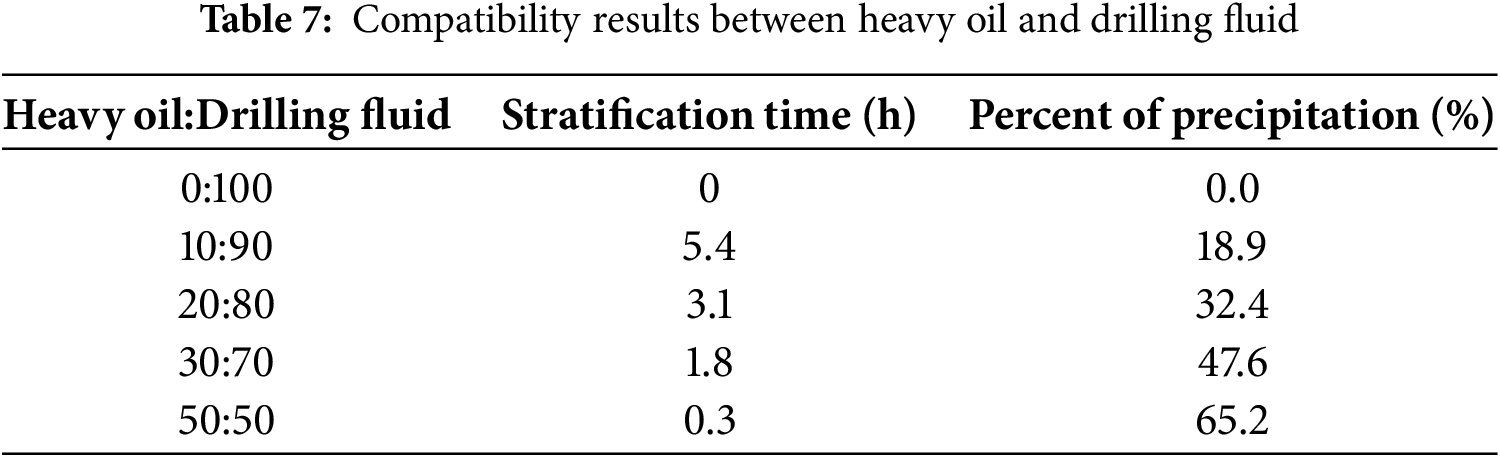

The experiments were conducted under standard conditions (25°C, atmospheric pressure) by blending low-solid aqueous drilling fluid with heavy oil sourced from the Tahe Oilfield at varying mass ratios of heavy oil to drilling fluid: 0:100, 10:90, 20:80, 30:70, and 50:50. Static settling tests were carried out to determine the time required for the mixtures to transition from a homogeneous dispersion to observable phase separation. After complete stratification, centrifugation (3000 rpm, 15 min) was employed to measure the sediment mass percentage relative to the total mixture mass. The compatibility results between heavy oil and drilling fluid are shown in Table 7.

Compatibility between heavy oil and the drilling fluid deteriorated sharply with increasing heavy oil content. At a 10:90 ratio, the phase separation time remained 5.4 h with a sediment percentage of 18.9%. However, when the ratio increased to 20:80, the separation time plummeted to 3.1 h, accompanied by a sediment percentage surge to 32.4%, indicating that heavy components such as colloids and asphaltenes in the heavy oil began to dominate system stability, leading to rapid breakdown of the emulsified structure. Further increasing the heavy oil ratio to 30:70 and 50:50 reduced separation times to 1.8 and 0.3 h, respectively, with sediment percentages reaching 47.6% and 65.2%. At these ratios, the mixtures exhibited complete incompatibility, characterized by immediate phase separation and massive sediment formation, significantly elevating the risk of wellbore blockage.

4 Simulation and Evaluation of Heavy Oil Invasion-Induced Wellbore Blockage Processes

4.1 Evaluation Method for Heavy Oil Intrusion into Drilling Fluid

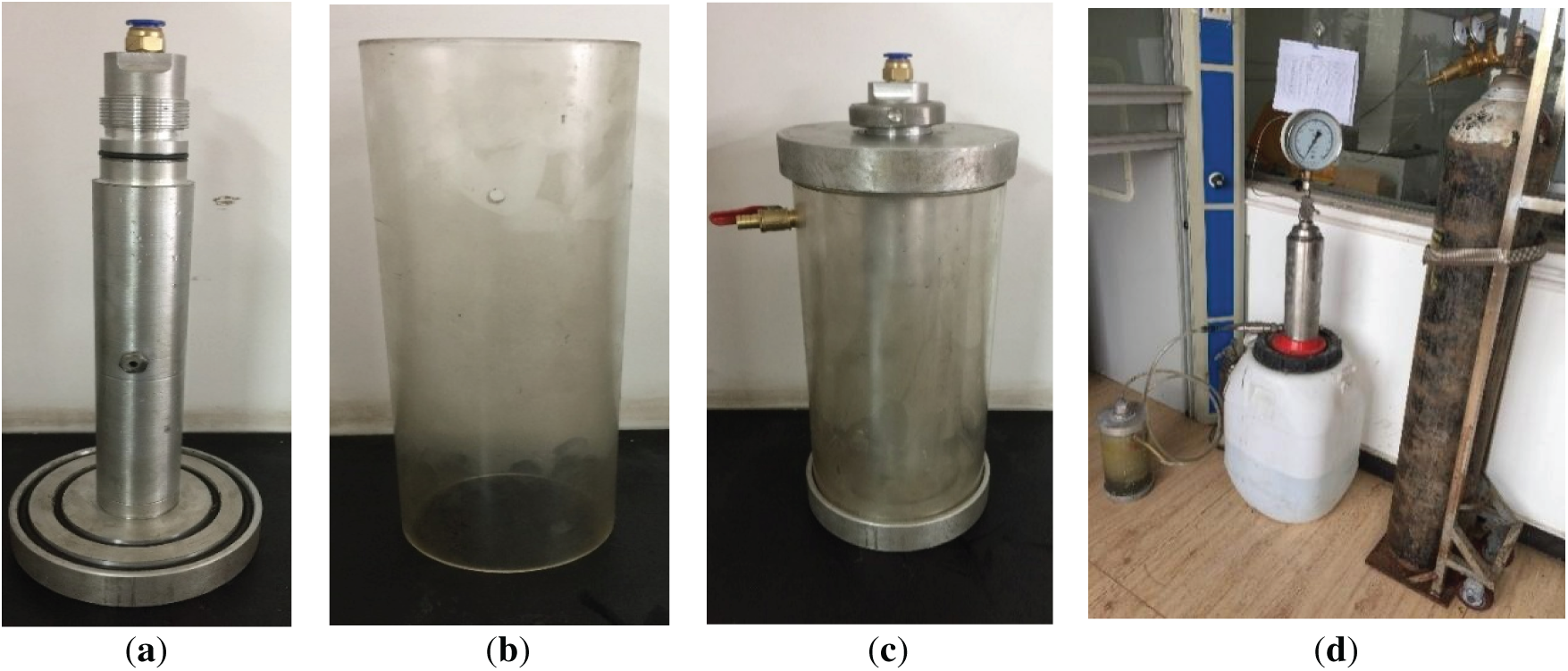

According to the process of heavy oil invading drilling fluid, a simple visual simulation evaluation device of heavy oil blockage is established, which is mainly composed of three parts: simulation shaft and formation ring air, intermediate liquid storage device and squeezing heavy oil (as shown in Fig. 3). The main body of the device is a transparent glass shaft model, whose size and structure refer to the actual shaft design, which can intuitively observe the internal blockage. Use the standby constant pressure pump to accurately control the injection pressure to simulate the intrusion of heavy oil under different reservoir pressure conditions; use the temperature control system to create different temperature environment in the wellbore model.

Figure 3: Visual simulation evaluation device for heavy oil blockage. (a) Simulated casing; (b) Simulated formation; (c) Simulation wellbore and formation ring space; (d) Simulation extrusion injection process

A simplified visual simulation apparatus was developed to assess the blockage of heavy oil during its intrusion into drilling fluids. The system consists of three primary components: a simulated wellbore and formation annulus, an intermediate fluid storage unit, and a heavy oil injection system. The central element is a transparent acrylic wellbore model, scaled according to the actual dimensions and structures of a wellbore, allowing for direct observation of internal blockage phenomena. A constant-pressure pump is employed to precisely regulate the injection pressure, thereby simulating the intrusion of heavy oil under varying reservoir pressure conditions. Additionally, a temperature control system is incorporated to create different thermal environments within the wellbore model.

Multiple experimental scenarios were designed with temperatures spanning 30°C to 80°C to investigate thermal effects on heavy oil invasion and blockage patterns. Injection speeds were tested at multiple levels (0.1 to 1 L/min) to assess intrusion dynamics and blockage severity under different flow regimes.

4.2 Impact of Different Temperatures on Heavy Oil Invasion and Blockage

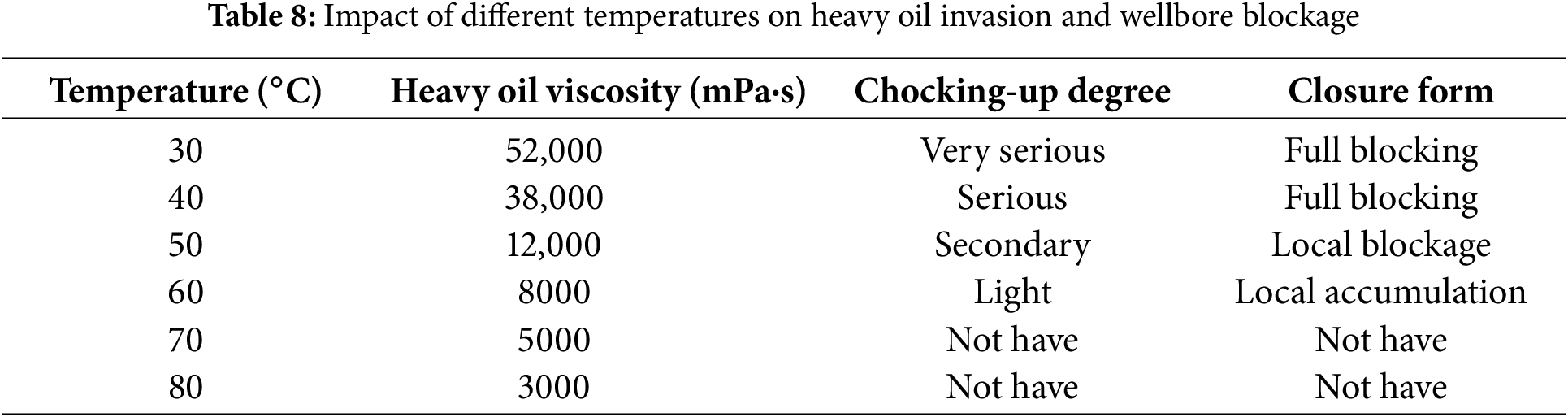

Indoor experiments simulating the process of heavy oil intrusion into drilling fluids were conducted using a visual simulation device designed for evaluating heavy oil blockage. The temperature range was maintained between 30°C and 80°C to replicate the drilling conditions of carbonate heavy oil reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield. A field-formulated water-based drilling fluid was utilized in the experiments. By varying the temperature conditions, the extent of heavy oil blockage was monitored. Heavy oil viscosity was measured with a Brookfield viscometer, and blockage morphology was thoroughly analyzed through imaging techniques and pressure gradient measurements (as shown in Table 8).

Experimental results showed that in the low-temperature range (30°C~40°C), heavy oil viscosity reached 38,000~52,000 mPa·s, with extremely poor fluidity, leading to complete blockage. This was mainly due to the high-viscosity heavy oil and drill cuttings retaining in the annulus and adhering to the wellbore wall. In the mid-temperature range (50°C), viscosity decreased to 12,000 mPa·s, and fluidity improved, but partial blockage still occurred due to interactions between heavy oil and cuttings. In the high-temperature range (≥60°C), viscosity dropped below 8000 mPa·s, and fluidity recovered. The drilling fluid effectively carried the heavy oil upward, with only minor accumulation in localized low-flow zones and no systemic blockage risks. The results indicate that 40°C is the critical threshold between complete and partial blockage, while 50°C marks a significant turning point for blockage mitigation. This highlights the necessity of prioritizing anti-blockage measures in low-temperature sections (<40°C) during drilling operations.

4.3 Impact of Different Injection Rates on Heavy Oil Invasion and Blockage

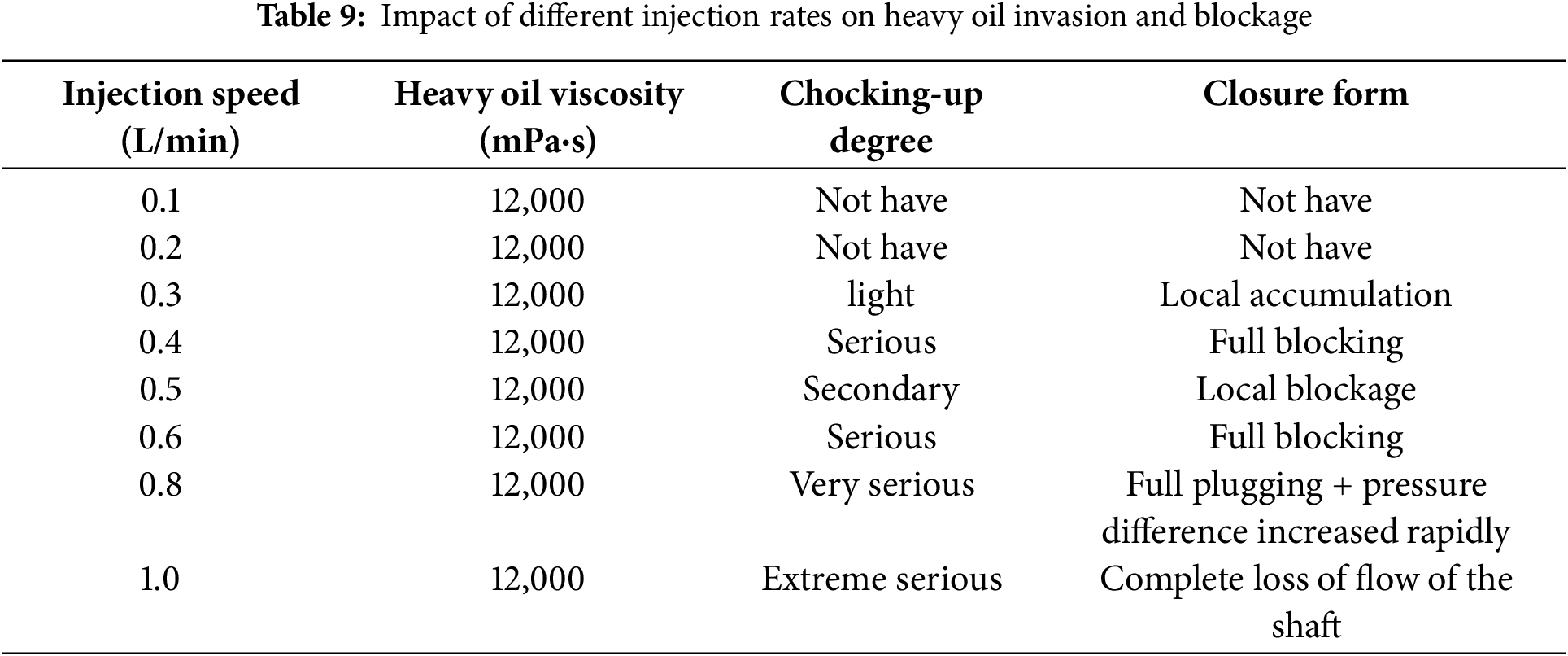

Based on the impact of temperature on heavy oil blockage, local blockage was observed at 50°C, which aligns with the experimental conditions. Therefore, the experiment was conducted at a constant temperature of 50°C. To simulate the drilling conditions of the carbonate heavy oil block in the Tahe Oilfield, a heavy oil blockage simulation evaluation device was utilized [18]. The effect of the field water-based drilling fluid system was studied by controlling the heavy oil injection rate of 0.1~1.0 L/min. In the experiment, the viscosity of heavy oil was maintained at 12,000 mPa·s, and the degree and form of blockage were determined by the pressure gradient mutation, the state of annular fluid flow and camera observation (as shown in Table 9).

Experimental results indicate that injection speed is a critical factor influencing heavy oil blockage in the wellbore at 50°C. When the injection speed was ≤0.3 L/min, the heavy oil exhibited good compatibility with the drilling fluid system, with no blockage or only minor localized accumulation. However, when the injection speed reached 0.4 L/min, severe blockage occurred, forming complete plugging. This suggests that the speed exceeded the annular fluid’s carrying capacity for heavy oil, leading to rapid adsorption of heavy oil mixed with drill cuttings in the annulus and the formation of a continuous blockage layer. Further increasing the injection speed to 0.5 L/min slightly alleviated blockage severity (moderate), but heavy oil still bridged with cuttings in low-flow annular zones, causing partial blockage. When the injection speed exceeded 0.6 L/min, blockage intensified again, with complete plugging reoccurring and sudden pressure differential spikes. This demonstrates that excessively high injection speeds disrupt the dynamic equilibrium between heavy oil and drilling fluid, preventing effective upward transport of heavy oil and ultimately triggering extreme blockage risks.

5 Prevention and Control Strategies for Heavy Oil Invasion into Drilling Fluid

To address the issue of heavy oil invasion into drilling fluids, comprehensive prevention and control measures can be implemented, including drilling fluid system optimization, development of specialized additives, improvement of construction techniques, and well control with real-time monitoring. Drilling fluid optimization primarily focuses on enhancing its capacity to carry dispersed heavy oil and its resistance to contamination by heavy oil. Improvements in construction techniques involve dividing the drilling process into multiple stages based on temperature variations at different wellbore depths and the rheological properties of heavy oil, implementing precise temperature control for each stage, and adopting methods such as thermal washing or ultrasonic blockage removal.

5.1 Development of Specialized Additives

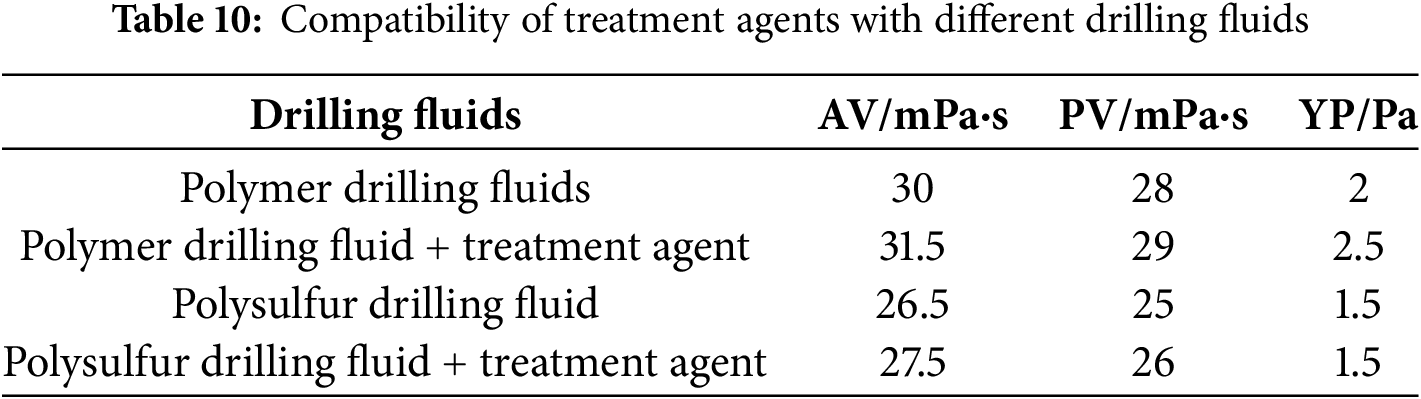

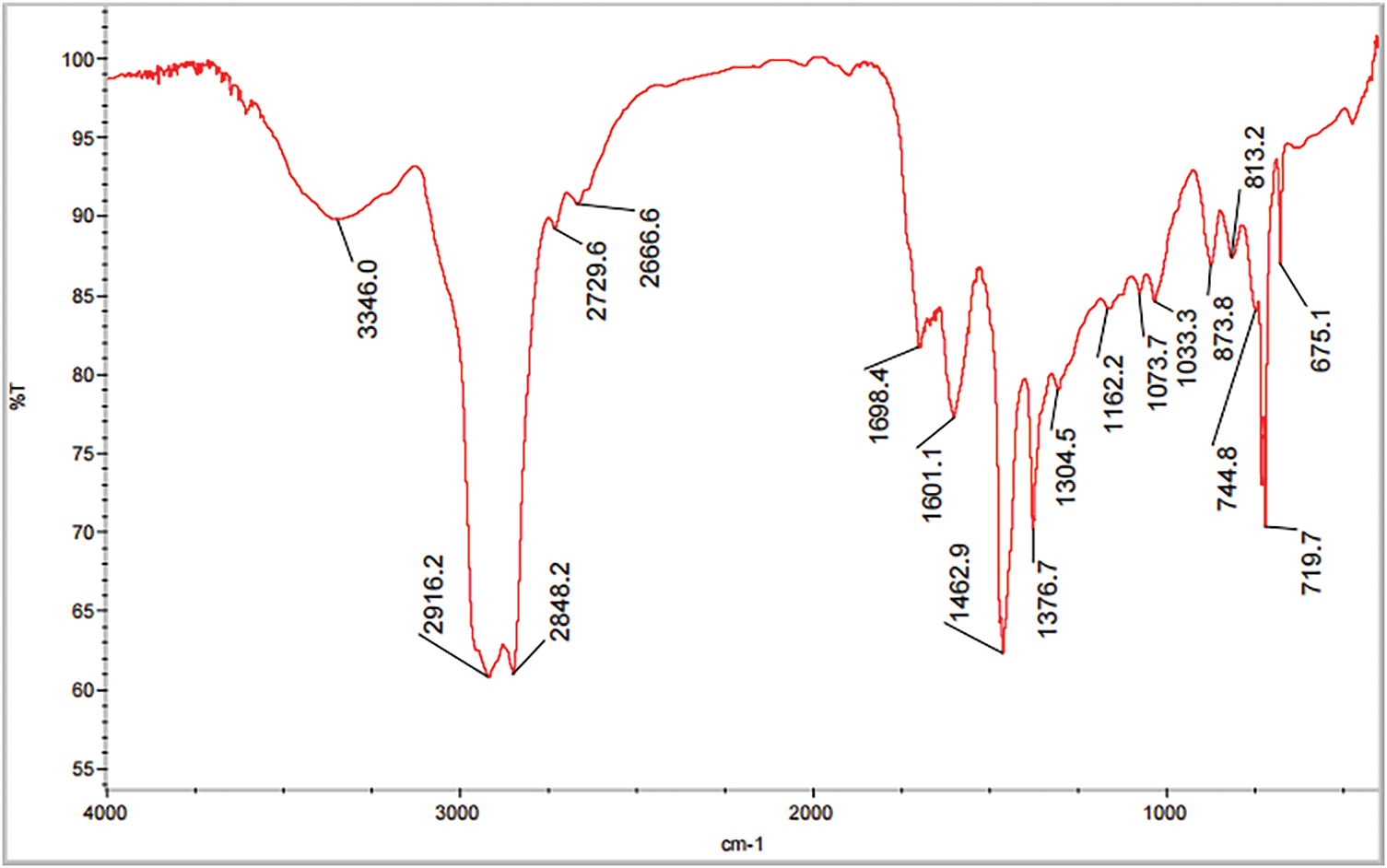

In addressing the issue of heavy oil invasion into drilling fluids, viscosity reducers, dispersants, and blockage removers are crucial components. The primary objective of viscosity reducers is to lower the viscosity of heavy oil, thereby improving its flow properties. Given the substantial influence of large molecules, such as asphaltenes, within the complex composition of heavy oil on its viscosity, specially formulated surfactant blends are employed. These surfactants, with their distinctive molecular structures, adsorb onto heavy oil molecules, weakening intermolecular forces, disrupting aggregation patterns, and promoting the dispersion of heavy oil into smaller particles. The addition of 1% to 2% of these viscosity reducers significantly reduces the viscosity of heavy oil under varying temperature and pressure conditions, facilitating its dispersion post-invasion and improving the mobility of the drilling fluid (as shown in Table 10). The infrared spectrum of the treatment agent is shown in Fig. 4. The function of specialized additives is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 4: Infrared spectrum of the treatment agent

Figure 5: Function of specialized additives

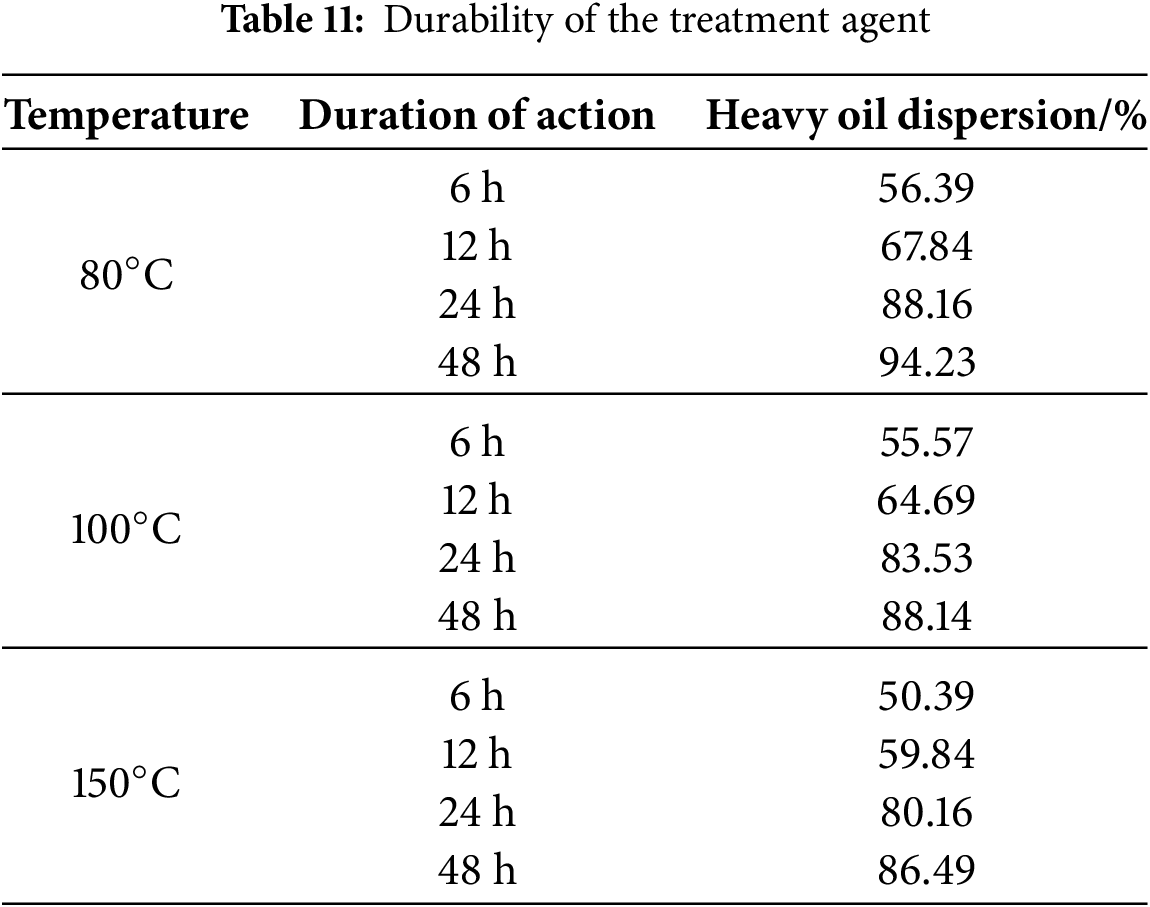

Dispersants utilize amphiphilic polymers, with one end interacting with heavy oil molecules and the other with water molecules, significantly reducing the oil-water interfacial tension and enhancing emulsification and dispersion capabilities. The addition of 2% to 3% dispersants ensures the uniform dispersion of heavy oil in drilling fluids, preventing aggregation-induced performance degradation and wellbore deposition. The development of blockage removers focuses on disrupting heavy oil blockage structures within the wellbore. By targeting the composition of the blockages, chemical agents interact with heavy oil components to reduce viscosity and adhesion, while physical agents penetrate the blockage to destabilize its structure (as shown in Table 11). This combined chemical-physical approach effectively disperses and dissolves the blockages, restoring wellbore integrity, ensuring the normal circulation of drilling fluid, and facilitating smooth drilling operations [19].

5.2 Well Control and Real-Time Monitoring

Dynamic Adjustment of Drilling Fluid Density: To ensure drilling safety and efficiency, drilling fluid density must be dynamically adjusted in real time based on heavy oil invasion. By analyzing parameters such as the appearance, density, and viscosity of returned drilling fluid, the degree of heavy oil invasion is assessed. If heavy oil invasion reduces drilling fluid density, weighting materials like barite powder should be added to increase density and balance reservoir pressure. If heavy oil invasion decreases and drilling fluid density becomes excessively high, low-density additives or water are introduced to reduce density and maintain fluidity. This dynamic adjustment ensures that drilling fluid density aligns with reservoir pressure, effectively controls heavy oil invasion, stabilizes wellbore pressure, and provides favorable conditions for drilling operations [20].

Real-time monitoring and early warning systems are essential for preventing the escalation of heavy oil invasion during drilling operations. Pressure, temperature, and flow sensors are strategically placed to continuously collect and transmit wellbore parameters. Data analysis software processes this real-time data to identify anomalies and trigger alerts. Additionally, machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms analyze the data to predict potential risks and recommend proactive mitigation strategies, ensuring both the safety and efficiency of drilling operations [21].

(1) Economic impact

The economic impact of heavy oil invading drilling fluid in drilling operations is substantial. Firstly, the processing costs of drilling fluid rise dramatically. Drilling fluid is a critical operational material, and its stability is directly linked to drilling efficiency and the smooth progression of operations. When heavy oil infiltrates, it increases the viscosity of the fluid, making it more difficult to handle. As a result, more chemical additives are required, or more frequent replacements and cleanings must be performed, significantly raising the cost of drilling fluid.

Furthermore, the infiltration of heavy oil can lead to increased wear on drilling equipment, causing more frequent maintenance and replacement. These additional maintenance costs, along with the need for specialized equipment handling the more viscous fluid, further contribute to the financial strain. In total, the presence of heavy oil in drilling fluids can significantly increase operational costs, impacting both the efficiency of the drilling process and the bottom line.

(2) Environmental impact

Heavy oil contamination of drilling fluid not only poses challenges to the drilling operation itself, but also may pose a potential threat to the environment. Traditional drilling fluids usually contain a variety of chemical additives. After heavy oil invades, these additives may undergo chemical reactions to produce harmful substances, thereby increasing the pollution level of the waste drilling fluid. Dealing with waste drilling fluid is itself an extremely complex and resource-intensive task. Especially when the drilling fluid contains a large amount of heavy oil, the difficulty of recovering and treating the waste liquid will increase significantly, and more expensive equipment and processes may be required to achieve the separation and purification of pollutants.

If these waste drilling fluids are not properly treated or disposed of, they may have a serious impact on soil, water sources and air quality. For instance, if discarded drilling fluids are directly discharged into the environment without treatment, they may cause soil pollution, water pollution, and even affect the local ecosystem, thereby posing a threat to the survival of surrounding organisms. Therefore, the development of environmentally friendly drilling fluids and effective waste liquid treatment technologies is not only necessary for improving operational efficiency, but also essential measures to reduce environmental pollution and ensure the sustainable utilization of resources.

(3) Engineering optimization

The optimization of drilling engineering plays a crucial role in the development of heavy oil reservoirs. By precisely controlling the properties of drilling fluids, drilling technologies, and downhole operations, the risk of heavy oil infiltration can be significantly minimized, leading to enhanced drilling efficiency and operational stability. In the selection and formulation of drilling fluids, specialized fluid systems tailored to the characteristics of heavy oil reservoirs can be employed, such as high-viscosity or low-viscosity fluids, and oil-based or water-based fluids. By adjusting the rheological properties of these fluids, their adaptability is improved, thereby reducing the interaction between heavy oil and drilling fluids, which in turn decreases the risk of contamination.

During underground operations, a refined process design and optimization can significantly mitigate issues encountered during the drilling process. For example, precise control of temperature and pressure can prevent changes in the viscosity of heavy oil caused by extreme temperature variations, thus minimizing the likelihood of its intrusion into the drilling fluid. Additionally, the implementation of advanced shielding layer technologies and real-time monitoring systems enables the effective detection and management of heavy oil contamination in drilling fluids. This allows for the prompt implementation of corrective measures to prevent the escalation of contamination issues.

Engineering optimization not only enhances the efficiency of drilling operations but also reduces the occurrence of complex procedures and minimizes the wastage of additional resources. In the development of heavy oil reservoirs, minimizing the contamination of drilling fluids by heavy oil helps reduce production losses due to equipment failures or operational stoppages, thereby boosting oil and gas output and improving the economic viability of the entire project.

In the drilling of carbonate rock heavy oil reservoirs, the infiltration of heavy oil into the drilling fluid is a prevalent issue that negatively impacts drilling efficiency, reservoir protection, and subsequent exploitation activities. Investigating the mechanisms of heavy oil intrusion into drilling fluids, along with the development of effective prevention and control strategies, is crucial for advancing drilling technology, reducing operational costs, and improving oil and gas recovery rates. However, this line of research does present certain limitations.

(1) Limitations of mechanism research

Laboratory simulations of the process in which heavy oil infiltrates drilling fluids often fail to fully replicate the complex conditions present in actual oil reservoirs. The real reservoir environment typically involves higher temperatures, pressures, and more intricate reservoir structures, factors that are challenging to precisely simulate in experimental setups. Consequently, the experimental outcomes may not accurately reflect the actual conditions encountered during the drilling process.

The physical and chemical properties of heavy oil, such as viscosity, specific gravity, and composition, exhibit significant variability. This variation, along with the differing characteristics of heavy oil across various reservoirs, can lead to distinct mechanisms of heavy oil intrusion into drilling fluids during drilling operations. As a result, relying on a single research methodology and experimental data may be insufficient to comprehensively address the complexities of all types of heavy oil reservoirs. Additionally, the composition and performance of drilling fluids are intimately linked to the extent of heavy oil intrusion. Changes in the rheological properties, viscosity, density, and formulation of drilling fluids can directly influence the behavior of heavy oil infiltration. Given the complexity of drilling fluid formulations and the variability of environmental conditions, it is challenging to identify a universally optimal drilling fluid design capable of preventing the intrusion of all types of heavy oil.

(2) Limitations of research on prevention and control countermeasures

Although numerous prevention and control strategies have been proposed, including the application of high-efficiency chemical additives such as demulsifiers and thickeners, or the mitigation of heavy oil intrusion by regulating drilling fluid temperature and pH, these measures are often effective only under specific conditions. Variations in the properties, temperature, and pressure of heavy oil across different reservoirs can result in the limited applicability of these prevention and control methods.

Some strategies may also incur significant costs, particularly when utilizing chemical additives or high-performance drilling fluid formulations. This can lead to elevated operational costs, especially in large-scale oilfield developments or when drilling in low-yield reservoirs. While most research on preventive measures emphasizes short-term effects—such as minimizing heavy oil intrusion and enhancing drilling efficiency—there is insufficient focus on evaluating the long-term impacts on oil reservoirs, such as potential reservoir damage and production decline. Therefore, long-term monitoring and the comprehensive assessment of these effects remain unresolved challenges.

To address the limitations of current research, more comprehensive and systematic studies should be conducted through enhanced interdisciplinary collaboration among fields such as geology, reservoir engineering, drilling technology, and chemical engineering. For instance, by integrating data from numerical simulations, field experiments, and long-term oilfield testing, a better understanding of the mechanisms of heavy oil intrusion and the effectiveness of prevention and control measures can be achieved, leading to improved prediction and evaluation capabilities.

In actual drilling operations, it is crucial to strengthen the application of preventive and control measures on-site, as well as to implement an effective feedback mechanism. Real-time monitoring of drilling fluid performance and heavy oil intrusion, among other factors, will enable timely adjustments to prevention and control strategies, allowing for better adaptability to varying oil reservoirs and reservoir conditions. The accumulation and analysis of on-site data will facilitate the optimization of these strategies, enhancing their effectiveness and adaptability.

(1) The Tahe carbonate heavy oil reservoir exhibits pronounced heterogeneity and distinct heavy oil characteristics. The intrusion of heavy oil into the drilling fluid is influenced by factors such as pressure differentials, pore structure, and the viscosity of the heavy oil. The invasion process progresses in distinct stages, with temperature playing a crucial role in altering the viscosity of the heavy oil.

(2) As the temperature increases, the apparent viscosity of the drilling fluid is reduced due to heavy oil invasion, while pressure exerts a nonlinear effect, causing viscosity to increase. The compatibility between heavy oil and drilling fluid deteriorates significantly as the proportion of heavy oil increases, leading to an elevated risk of wellbore blockage.

(3) Simulation studies indicate that heavy oil is more prone to causing wellbore blockage at lower temperatures (30°C to 40°C) and higher injection rates (≥0.4 L/min). Drilling operations should prioritize anti-blockage strategies under these conditions to prevent operational disruptions.

(4) The development of specialized additives, dynamic adjustments to drilling fluid density, and the implementation of real-time monitoring and early warning systems are effective strategies for mitigating heavy oil invasion into the drilling fluid, thereby ensuring safe and efficient drilling operations in the Tahe Oilfield.

Acknowledgement: The authors are sincerely grateful for the support of the following funds: Hubei Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Engineering (Yangtze University), China; Hubei Province Science and Technology Plan Project (Key R&D Special Project), China; Key R&D Program Project in Xinjiang, China; Guiding Project of Scientific Research Program of Education Department of Hubei Province, China; Open Fund of National Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Reservoir Geology and Exploitation (Southwest Petroleum University).

Funding Statement: (1) Hubei Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Engineering (Yangtze University), China (Grant No. YQZC202415). (2) Hubei Province Science and Technology Plan Project (Key R&D Special Project), China (Grant No. 2023BCB070). (3) Key R&D Program Project in Xinjiang, China, Grant No. 2022B01042. (4) Guiding Project of Scientific Research Program of Education Department of Hubei Province, China (Grant No. B2023024). (5) Open Fund of National Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Reservoir Geology and Exploitation (Southwest Petroleum University), Grant No. PLN2023-03.

Author Contributions: Yang Yu: Visualization, Validation. Sheng Fan: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft. Zhonglin Li: Supervision, Formal analysis. Zhong He: Investigation. Jingwei Liu: Resources, Methodology. Peng Xu: Validation, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

List of Acronyms

| AV | Apparent Viscosity |

| CoF | Coefficient of Friction |

| FL | Filtration Loss |

| GS | Gel Strength |

| HPHT | High-Pressure/High-Temperature |

| HGS | High-Specific-Gravity |

| LPLT | Low-Pressure/Low-Temperature |

| LGS | Low-Specific-Gravity |

| PV | Plastic Viscosity |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| YP | Yield Points |

References

1. Li Y, Kang Z, Xue Z, Zheng S. Theories and practices of carbonate reservoirs development in China. Petrol Explor Dev. 2018;45(4):712–22. doi:10.1016/s1876-3804(18)30074-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ma X, Li H, Luo H, Nie S, Gao S, Zhang Q, et al. Research on well selection method for high-pressure water injection in fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoirs in Tahe oilfield. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2022;214(1):110477. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Abhishek R, Hamouda AA, Murzin I. Adsorption of silica nanoparticles and its synergistic effect on fluid/rock interactions during low salinity flooding in sandstones. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2018;555(04):397–406. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Muatasim A, Bahlani A, Babadagli T. Steam-over-solvent injection in fractured reservoirs (SOS-FR) for heavy-oil recovery: experimental analysis of the mechanism. In: Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference & Exhibition; 2009 Aug 4–6; Jakarta, Indonesia. doi:10.2118/123568-ms. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bai M, Zhang Z, Cui X, Song K. Studies of injection parameters for chemical flooding in carbonate reservoirs. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;75(1):1464–71. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kang WL, Zhou BB, Issakhov M, Gabdullin M. Advances in enhanced oil recovery technologies for low permeability reservoirs. Petrol Sci. 2022;19(4):1622–40. doi:10.1016/j.petsci.2022.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. He D, Jia C, Zhao W, Xu F, Luo X, Liu W, et al. Research progress and key issues of ultra-deep oil and gas exploration in China. Pet Explor Dev. 2023;50(6):1333–44. doi:10.1016/S1876-3804(24)60470-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Agi A, Junin R, Jaafar MZ, Majid ZA, Amin NAS, Sidek MA, et al. Dynamic stabilization of formation fines to enhance oil recovery of a medium permeability sandstone core at reservoir conditions. J Mol Liq. 2023;371(15):121107. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2022.121107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Asl HF, Zargar G, Manshad AK, Ali Takassi M, Ali JA, Keshavarz A. Effect of SiO2 nanoparticles on the performance of L-Arg and L-Cys surfactants for enhanced oil recovery in carbonate porous media. J Mol Liq. 2020;300(4):112290. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bianco LC, Gabrysch AD, Montagna JN. Challenges on completion for productivity for deepwater heavy oil. In: SPE International Symposium and Exhibition on Formation Damage Control; 2006 Feb 15–17; Lafayette, LA, USA. p. SPE-98342. doi:10.2118/98342-ms. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zargar G, Arabpour T, Khaksar Manshad A, Ali JA, Mohammad Sajadi S, Keshavarz A, et al. Experimental investigation of the effect of green TiO2/Quartz nanocomposite on interfacial tension reduction, wettability alteration, and oil recovery improvement. Fuel. 2020;263(6):116599. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zheng SQ, Yang M, Kang ZJ, Liu ZC, Long XB, Liu KY, et al. Controlling factors of remaining oil distribution after water flooding and enhanced oil recovery methods for fracture-cavity carbonate reservoirs in Tahe Oilfield. Petrol Explor Dev. 2019;46(4):746–54. doi:10.1016/S1876-3804(19)60236-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ali JA, Kolo K, Manshad AK, Stephen KD. Potential application of low-salinity polymeric-nanofluid in carbonate oil reservoirs: IFT reduction, wettability alteration, rheology and emulsification characteristics. J Mol Liq. 2019;284:735–47. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2019.04.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zou H, Wang Y, Xu Y, Li J, Wu L, Su G, et al. Synthesis and performance study of self-degradable gel plugging agents suitable for medium- and low-temperature reservoirs. ACS Omega. 2024;9(31):33702–9. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c02410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Cheng H. The enhanced oil recovery effect of nitrogen-assisted gravity drainage in karst reservoirs with different genesis: a case study of the Tahe oilfield. Processes. 2023;11(8):2316. doi:10.3390/pr11082316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sen S, Abioui M, Ganguli SS, Elsheikh A, Debnath A, Benssaou M, et al. Petrophysical heterogeneity of the Early Cretaceous Alamein dolomite reservoir from North Razzak oil field, Egypt integrating well logs, core measurements, and machine learning approach. Fuel. 2021;306(1):121698. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu G, Zhao K, Qu H, Scarselli N, Zhang Y, Han J, et al. Permeability distribution and scaling in multi-stages carbonate damage zones: insight from strike-slip fault zones in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Mar Pet Geol. 2020;114:104208. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang R, Zhang D, Kang Z, Zhou R, Hui G. Study on deep reinforcement learning-based multi-objective path planning algorithm for inter-well connected-channels. Appl Soft Comput. 2023;147(4):110761. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Al-Shargabi M, Davoodi S, Wood DA, Ali M, Rukavishnikov VS, Minaev KM. A critical review of self-diverting acid treatments applied to carbonate oil and gas reservoirs. Petrol Sci. 2023;20(2):922–50. doi:10.1016/j.petsci.2022.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Briggs PJ, Baron PR, Fulleylove RJ, Wright MS. Development of heavy-oil reservoirs. J Petrol Technol. 1988;40(2):206–14. doi:10.2118/15748-pa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rahimi PM, Gentzis T. The chemistry of bitumen and heavy oil processing. In: Practical advances in petroleum processing. New York, NY, USA: Springer New York; 2007. p. 597–634. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-25789-1_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools