Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Acetylation of Corn Stalk (Zea mays) for Its Valorization

Department of Chemical Processes, Food and Biotechnology, Chemical Engineering Career, Faculty of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Universidad Técnica de Manabí, Portoviejo, 130101, Ecuador

* Corresponding Author: María Antonieta Riera. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellulose and Nanocellulose in Polymer Composites: Sustainable Engineering Approach)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 837-851. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.067277

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 14 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Agricultural waste is a potentially interesting resource due to the compounds present. In this study, cellulose was extracted from corn stalks (Zea mays) and subsequently converted into cellulose acetate (CA). Before the extraction process, the waste sample was characterized by pH, moisture, ash, protein content, total reducing sugars (TRS), carbohydrates, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Acid and alkaline hydrolysis were performed with different reagents, concentrations, and extraction times. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and acetic acid (CH3COOH) were used in the acid hydrolysis, while sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was used in the alkaline hydrolysis. Three concentrations (0.62, 1.25, 2.5)% and two reaction times (60, 120) min were established. An ANOVA was performed on the hydrolysis results to determine the existence of significant differences. The extracted cellulose was revalued by acetylation, and finally, the CA was characterized by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectroscopy. The highest cellulose extraction yield was obtained by alkaline hydrolysis, with an extraction time of 120 min and a yield of 65%. The statistical analysis indicated that the reagent used, its concentration, reaction time, and their interaction significantly affect the process yield. After obtaining CA and performing an infrared analysis of the compound’s structure, it was determined that the byproduct corresponds to CA, demonstrating the possibility of revaluing the waste through the studied process. Future studies could improve the results obtained here to promote the development of biobased products within a circular economy framework.Keywords

CA is the first organic ester of the cellulose family, discovered by Schutzenberger in 1865 and developed by Franchimont and Miles in 1879 and 1903. It is synthesized industrially by mixing cellulose with acetic anhydride and CH3COOH as solvent in the presence of H2SO4 as a catalyst [1,2]. Depending on its characteristics, it can be used as a film, membrane, or fiber [3]. It is used as a film for food packaging since it is considered a safe material. However, it is mixed with plasticizers or some polymers to improve its physical and mechanical characteristics related to rigidity, elasticity, stability, brightness, permeability, and barrier properties [4].

CA is a cellulose derivative and a long-chain linear biopolymer formed by β-d-glucopyranose molecules linked by β (1→4) glycosidic bonds. It is a polysaccharide of the cellular structure of plants, mycelium, and some animals. It is a widely available material, constituting the most abundant biopolymer on earth [5–7]. The cellulose used at an industrial level comes from two primary sources: cotton fibers and wood pulp [8,9]. The overexploitation of wood for use as a raw material at an industrial level has contributed to the current deforestation problems. The incorporation of substitutes from non-wood sources to obtain cellulose could represent a relief to the existing environmental problem [10].

Different types of cellulose can be obtained from agricultural by-products or residues, biomass waste, and some bacteria [9]. Agricultural waste is a lignocellulosic material composed mainly of cellulose and lignin. Being widely available, especially in countries with agricultural activity, they represent an excellent source for extracting cellulose [11]. Among the types of wastes with cellulose in their composition are those from corn, sugarcane, rice, wheat, pineapple, and others [8,10].

Corn is one of the most consumed cereals in the world, with production exceeding 1.2 billion tons by 2023 [12]. During the harvest and industrialization of crops, a large amount of waste. It is estimated that only 20% of the total weight of the plant corresponds to the edible part of the cereal [13]. The stubble consisting of the stem, leaf, ears, and bracts of the cob are generated in the field after the harvest. The husk that covers the grain and the cob, also known as corn or cob, are obtained during corn processing [14–17].

Corn residues are generally used for animal feed, as a cover for arable land, or are discarded. Occasionally, they are disposed of in the open air and eliminated by open-air incineration, impacting the environment by affecting the soil and generating greenhouse gases [13,18]. Corn cobs are one of the most frequently studied corn residues for revaluation [19], although the rest of the residues from the cultivation or processing of this product can also be used.

An alternative to revalue these residues is the removal of hemicellulosic sugars to obtain CA [20]. One method used for this purpose consists of extracting cellulose by alkaline hydrolysis and subsequent acetylation with glacial CH3COOH and a mixture of (CH3CO)2 and H2SO4 [21]. This procedure is applied to obtain CH3COOH from other agricultural waste [22,23].

The use of corn waste appears to be a sustainable and effective alternative from an environmental and economic perspective [24]. Corn residues can be used to produce carbohydrate and lignin platforms for biofuels and bio-based chemicals production. Optimizing the production of these bioproducts is possible by establishing the techno-economic prospects for biorefineries based on these types of residues [25]. In this research, CA was obtained from corn stalks, thereby providing an environmental solution to the problems caused by the accumulation of these residues at the generation site, proposing an alternative for the recovery of a little-used agricultural residue.

This research is integrated with the green economy by using a low-value residue to obtain a product of industrial and commercial interest, enhancing the possibilities of using specifically the corn stalk generated in the crops while seeking to promote economic development sustainably, in addition to ensuring the efficient use of resources [26]. It is linked to Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 9 and 12 by promoting innovation and responsible production through the production of a biobased product capable of competing with or replacing synthetic products.

2.1 Selection and Pretreatment of Biomass

Corn stalks (Zea Mays) were used as biomass from crop waste from a farm located in Bejuco town, Manabí province, Ecuador. The biomass was cut into sections of approximately 10 cm and washed to remove impurities that could affect cellulose extraction. It was placed on trays and dried in an oven at 70°C for 24 h. The dried biomass was ground in an IKA cutting mill to obtain a particle size of 1 mm [27].

The biomass was characterized by pH, moisture, ash, total carbohydrates, cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and total reducing sugars. A 3:1 ratio between distilled water and residue was used for the pH of the sample. It was determined using a potentiometer by diluting the 0.05 g sample in 30 mL of distilled water [28].

Moisture content was determined gravimetrically using a BOECO Germany thermobalance, series 392292, model BMA-150. The 0.070 g sample was placed in the equipment at a predetermined temperature and reached the final constant weight after 7 h. Moisture content is expressed as a percentage according to Eq. (1):

The amount of protein was known by the Kjeldahl method [29], using Eqs. (2) and (3). Where P is the weight in grams of the sample, V1 is the volume of HCl consumed in the titration (mL), V0 is the volume of HCl consumed in the titration of a blank (mL), N is the normality of the HCl and F is the conversion factor, set as 6.25.

The ash content was determined by calcination. A 2 g sample was placed in two crucibles and placed in a muffle furnace at a temperature of 600°C–700°C for 2 h [30]. The samples were cooled to room temperature, weighed, and the % ash was calculated using Eq. (4):

Total carbohydrates were determined using the phenol-sulfuric acid method [31]. A solution was prepared with 40 mL of distilled water and 1 g of sample, homogenized, and placed in three test tubes. 2 mL of the resulting solution was placed in each tube, along with 0.5 mL of 5% phenol and 2.5 mL of H2SO4, and then taken to a UV-VIS Genesys 180 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) to take the reading at a wavelength of 540 nm.

The ether extract was made by a Soxhlet extractor using hexane as solvent [32]. The corresponding percentage was calculated using Eq. (5):

The cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content were determined using the Van Soest method [33], which allows the LDA (Lignin), NDF (Neutral Detergent Fiber), and ADF (Acid Detergent Fiber) values to be determined from the crude fiber. The corresponding calculations were performed according to the Eqs. (6)–(8):

Total reducing sugars were determined by the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method. For that, a solution was prepared with 40 mL of distilled water and 1 g of sample. 2 mL of the solution was placed in a test tube with 1 mL of DNS. The remaining solution was subjected to a thermostatic bath at 80°C–90°C for 15 min. It was cooled at room temperature and diluted with distilled water. The dilution was 99 mL of distilled water with 1 mL of the prepared solution. Part of the sample was extracted and read on the spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 540 nm [34].

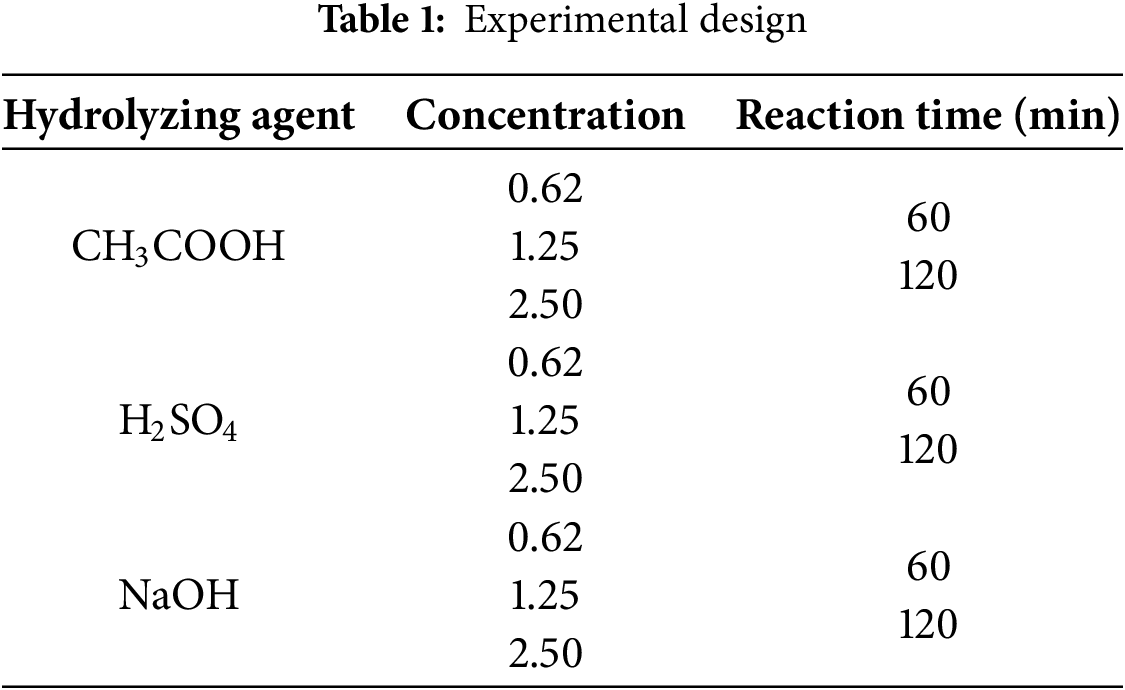

Cellulose extraction (pulping) was carried out by hydrolysis, for which a mixed experimental design was proposed (Table 1), with three factors: hydrolyzing agent (3 levels), concentration (3 levels), and reaction time (2 levels) [27]. Acid hydrolysis was carried out at atmospheric pressure and 100°C without variation. The procedure was carried out in a graduated flask using distilled water and the necessary hydrolyzing agent content to reach the mentioned concentration. 1 g of the crushed sample was placed in small, pre-weighed wool bags and taken to an ANKOM A200 crude fiber digester. Once the reaction time was over, the sample was removed from the digester and cooled to room temperature. The sample was taken to the oven at 105°C for 2 h to ensure the drying. The sample was then transferred to a desiccator to cool, and finally, the weight of the extracted cellulose was recorded.

To determine the cellulose yield, Eq. (9) was used based on the weight difference between the extracted cellulose mass and the initial corn stalk sample [35]:

The obtained cellulose was washed with distilled water until reaching a neutral pH. Cellulose was bleached with a 10% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution poured into a 100 mL solution. The resulting solution was heated in an oven for 2 h until reaching a temperature of 70°C. Once the cooking time was over, the sample was washed with distilled water, and the pH was measured. Finally, it was filtered and dried for 24 h in the oven at a temperature of 35°C [36].

CA was obtained by acetylation of cellulose from corn waste. In the synthesis, the main chemicals involved were glacial CH3COOH, H2SO4 at 99% (v/v), and (CH3CO)2, reagent grade. It was subjected to a homogeneous acetylation treatment, which resulted in hydrolysis of the acetyl group. A sample of 2.8 g of cellulose was dissolved in 24 mL of glacial CH3COOH. The mixture was kept under constant stirring for 1 h in an oven at 37°C. 20 mL of glacial CH3COOH and 0.04 mL of H2SO4 were added to the mixer and stirred for 45 min. After the stirring time, the mixture was cooled to room temperature 18°C using an ice bath. 14 mL of (CH3CO)2 and 0.3 mL of H2SO4 were added, and the mixture was heated to 32°C with stirring for 1.5 h. Finally, 5 mL of distilled water and 10 mL of glacial CH3COOH were added with stirring [36,37].

CA was characterized using infrared spectroscopy (IR) to determine the functional groups present in the extracted cellulose and in the CA. The procedure was carried out on an Infrared Thermo Scientific™ Nicolet™ Summit™ PRO FTIR Spectrometer from USA and consisted of inciting a spectrum of infrared light on the material at a wavelength of 4000 to 500 cm−1. A comparison was made between the cellulose pulp extracted before and after acetylation in order to differentiate the modifications that have occurred [38].

All experiments, except for chemical hydrolysis, were performed in triplicate. The results are reported as the mean value with its corresponding standard deviation. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed on the results obtained for cellulose extraction to determine the impact of the variables on the process studied. R Studio version 4.3.1 software was used for this purpose.

3.1 Characterization of the Waste

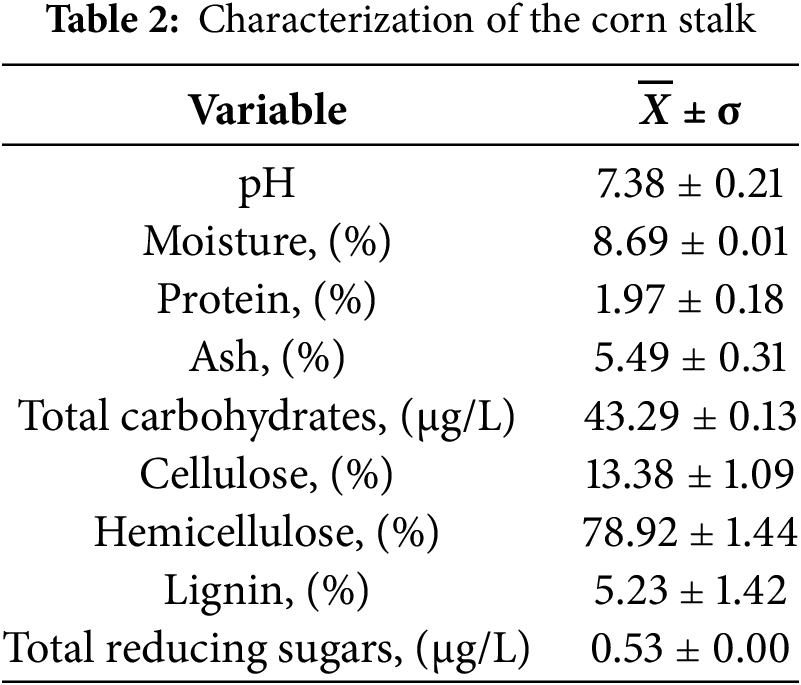

The results obtained for each variable analyzed in the characterization of the corn stalk are presented in Table 2.

The pH of the corn stalk was 7.38, close to neutral. pH is highly dependent on pre-harvest soil treatment, as it influences the availability of plant nutrients. The optimal pH for high yields should range between 6.5 and 7.0 [39]. The origin of the biomass and the pH are values that can subsequently affect the cellulose extraction process [40].

The moisture content of the corn stalk was 8.69%, lower than the 10.50% reported for this agricultural residue in another study [38]. There may be variations in this variable, depending on the maturity at which the stalk is extracted. Likewise, the amount of water in the raw material to be used can affect the hydrolysis processes, generating unwanted exothermic reactions and interfering with cellulose extraction [41].

The protein percentage was 1.97%, and as reported in previous research, the crude protein content in the stem is 18% in the first 50 days, decreases to 11% at 80 days, and in the remaining days remains around 6.5% or lower value [42]. Based on the above, it can be inferred that the stem used in this research has an average age of 3 months.

The ash content in the corn stalk was 5.49%, lower than the 6.74% reported in another study. The difference may be due to the conditions under which the stalks were dried since temperature and drying time are determining variables. The drying time in that study was 4 h at 550°C, while in this study, a drying time of 2 h at 650°C was used [43].

The total carbohydrate concentration was 43.29 μg/L, while a previous study that characterized stem, leaves, and roots from native corn recorded a content of 65.28, 20.5, and 237.99 mg/kg. Carbohydrates, specifically sugars and polysaccharides, are an important component of plants. According to previous reports, residual biomass from native corn showed a lower monosaccharide content than that recorded after hydrolysis [44].

The cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin percentages in this research differ from those reported in other investigations, with values of lignin 11.58%, hemicellulose 20%, and cellulose 50%. The state of maturity from which the raw material is extracted determines the content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [43,45]. Wood is the raw material par excellence from which cellulose is extracted. The hemicellulose and α-cellulose content in the wood forms the majority of its composition (on average 65%–75%) [46]. In this research, the hemicellulose and cellulose content exceeds 70% between both, representing a possibility of use as raw material. Corn stalks have a chemical composition different from conventional sources used for cellulose production. Concert to cellulose content (the component of interest in this research) is lower compared to softwoods, hardwoods, cotton, almond trees, and olive trees, with a value close to 40% [47,48]. It is also lower compared to the amount of cellulose present in native or silane-treated isinglass palm fibers, which report values greater than 60% and less than 70% [49].

The total reducing sugars for this research were 0.53 μg/L. This result is lower than that reported in studies where wheat straw was hydrolyzed with 2% H2SO4, obtaining 2.0 g/L of reducing sugars [45] and when applying different hydrolysis methods with corn stalk where 7 g/L of total reducing sugars were obtained. These differences may be due to the concentrations of the reagent used, reaction times and temperatures, as well as the maturation state of the raw material used [50]. Total reducing sugars are an indicator used to analyze the subsequent conversion of biomass into biofuels and value-added chemicals [51].

Among the variables analyzed in corn stalks, moisture content, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin are key components prior to cellulose extraction. Lignocellulosic biomass tends to absorb moisture, and at the industrial level, high moisture contents indicate a high presence of water, which can influence waste deterioration [13,41]. The properties of cellulose are closely linked to its molecular structure, which is affected by water. Its interaction with moisture is a complex process that depends on the highly differentiated structure of cellulose. Moisture in contact with cellulose causes water molecules to diffuse into non-crystalline domains, swelling the structure and forming new hydrogen bonds. Water bridges can also be created in place of the hydrogen bonds present in dry cellulose. Greater water mobility facilitates the reorganization of amorphous cellulose into a more ordered alignment. In the crystalline structure, water adsorption indirectly causes lateral contraction of cellulose crystals [52,53].

Moisture content influences process performance, reagent dosage, and extraction efficiency. Moisture concentrations above 15% could increase the concentration of the reagent used in subsequent hydrolysis. In related research, biomass moisture is maintained at around 10% (BS) when subjected to chemical cellulose extraction processes and subsequent characterization applications [54,55].

The cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content are crucial for process efficiency. The higher the native cellulose content relative to the other components, the greater the expected amount of cellulose recovered. During the extraction of cellulose from any plant biomass, delignification and the removal of hemicellulose are required. The complex composition of biomass, especially the binding of lignin to other cell wall components, is an obstacle to efficient conversion. Biomass composition directs pretreatment efforts to optimize separation and conversion processes. Based on this, the type of pretreatment to be used (acid-alkaline, salts, ionic liquids, enzymatic, integrated strategies) can be established for effective lignin removal, efficient cellulose recovery, and viable optimization of biomass conversion processes into specific products [56,57].

3.2 Cellulose Extraction Yield

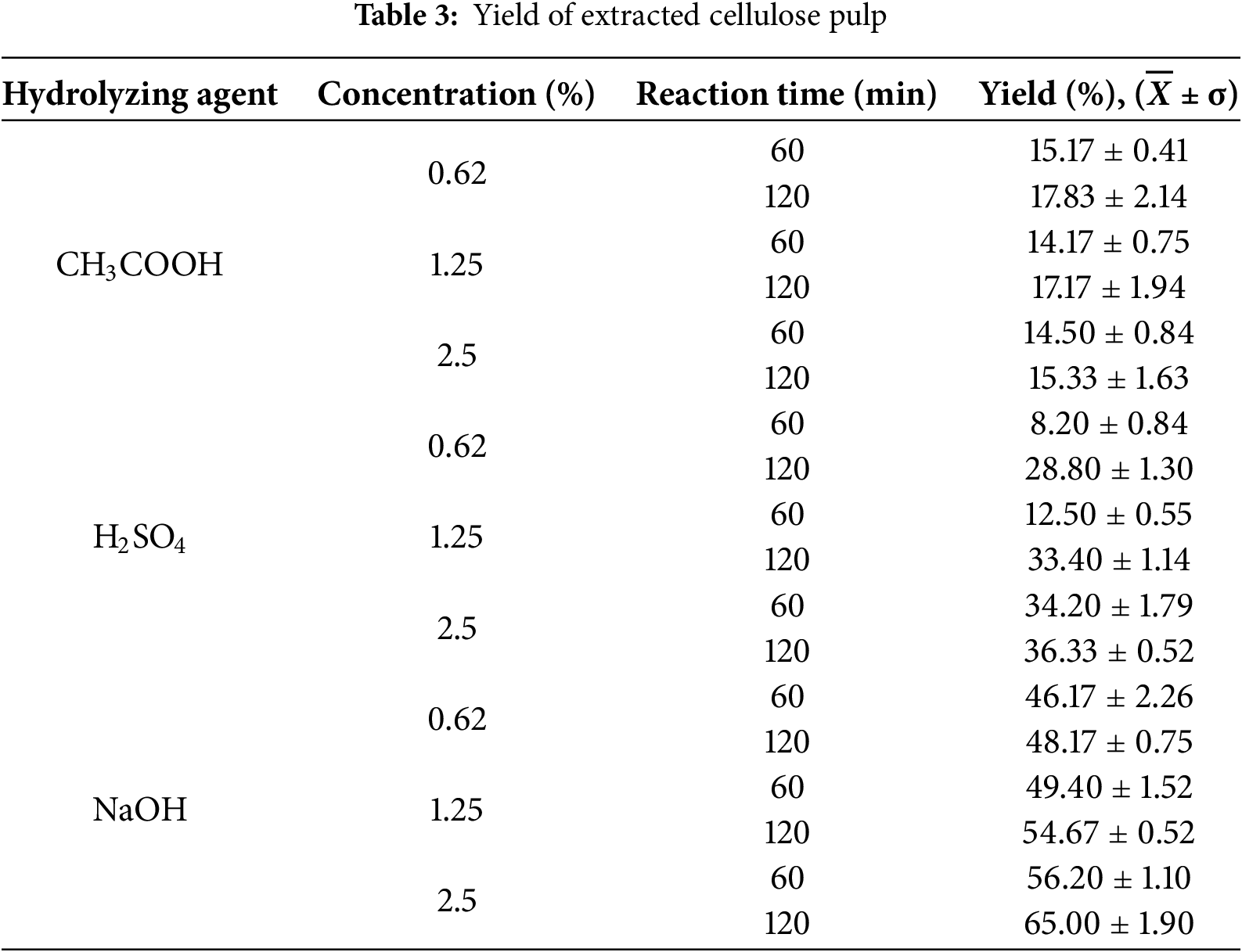

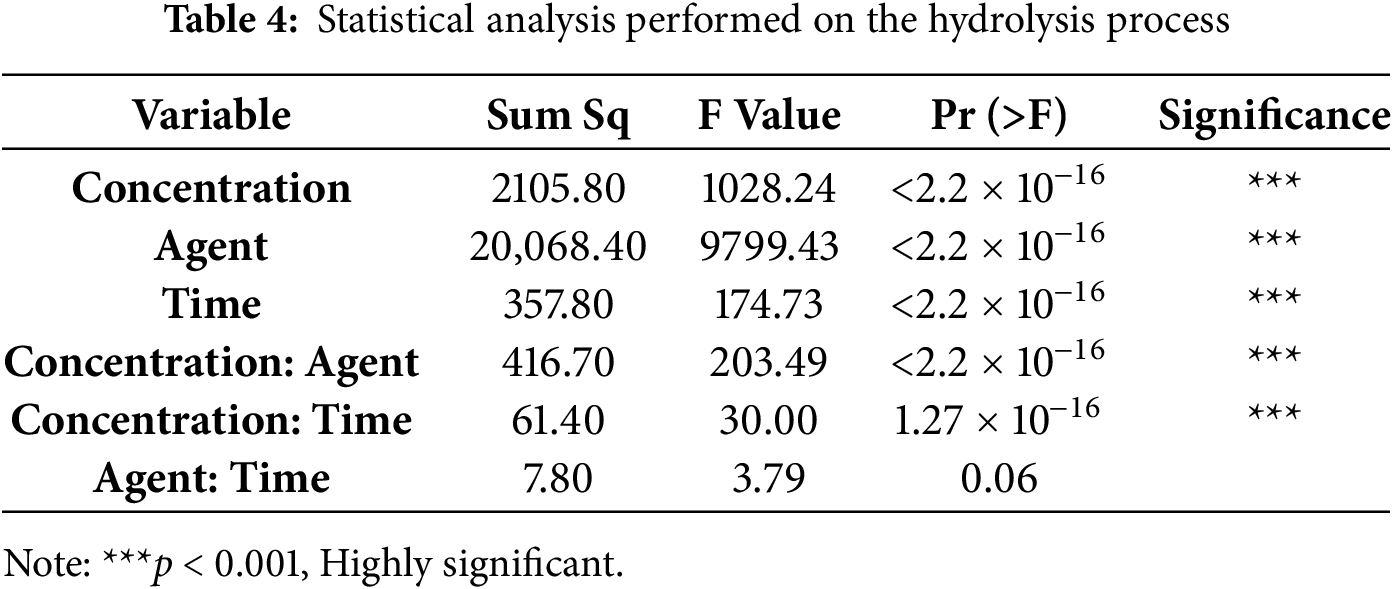

Table 3 presents the yield obtained for cellulose extraction after hydrolysis of the residue. Table 4 shows the statistical analysis performed on the experimental design proposed for hydrolysis.

The highest cellulose extraction yield was obtained with alkaline hydrolysis, reaching 65% at a concentration of 2.5% in a reaction time of 120 min. In acid hydrolysis, the highest yields reported were 17.83% and 36.33%, working with CH3COOH and H2SO4 at concentrations of 0.62% and 2.50%, respectively, both in a reaction time of 120 min.

In an investigation where alkaline hydrolysis was performed on corn cob waste, yields from 52.19% to 78.185% were reached when working with NaOH from 0.50% to 4.00%, with reaction times of 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, autoclaving at 121°C [58]. In contrast, acid hydrolysis gave better results when working with H2SO4 instead of CH3COOH. H2SO4 has advantages over other acids because the reaction rate is higher, providing solubility in cellulose and other sugars more quickly and effectively [59]. The yield results in acid hydrolysis with H2SO4 are compared with studies where cellulose was extracted from corn stalk with acid hydrolysis, in which using a concentration of 2% and 5%, a yield of 30.07% and 34.19% was obtained, respectively [60].

Acid-base hydrolysis is the most widely used method to extract cellulose from corn stalks, as it is a simple extraction process, highly efficient, with good thermal stability, good crystallinity, easy control of reaction conditions, and low cost. These advantages facilitate large-scale industrial production with a wide range of development [61]. Alkaline hydrolysis increases the porosity and accessibility of cellulose by removing lignin through the cleavage of ether bonds and solubilizing hemicellulose by saponifying the intermolecular ester bonds between hemicellulose and lignin [62]. Alkalization with NaOH is one of the chemical treatments commonly used to remove amorphous portions or modify the surface of natural fibers in biomass. The effectiveness of alkaline hydrolysis may have been due to the elimination of the amorphous portion of the fibers present in biomass, enabling its use [63].

In general, it was observed that all three variables analyzed in hydrolysis influenced the cellulose yield. In all cases, regardless of the type of hydrolyzing agent, higher yields were obtained with increasing reaction time. In acid hydrolysis with CH3COOH, although higher yields were achieved with longer reaction times, the yield trend was downward with an increase in the concentration of the hydrolyzing agent. This also occurred when using H2SO4, where the highest yields were reported for longer reaction times. When using CH3COOH, the yield increased with increasing acid concentration. In alkaline hydrolysis, the extraction yield was directly proportional to both the concentration of the agent and the reaction time.

The yield obtained in cellulose and nanocellulose crystal extraction processes depends on factors such as time, concentration, and the isolation method used. Depending on the operating parameters established for the hydrolysis process used, it is possible to control the yield, among other aspects, which allows obtaining materials with properties for several applications [64]. The reaction time affects the elimination of hemicellulose. Longer reaction times and higher alkali concentrations increase the yield of cellulose extraction [65]. The hydrolyzing agent used also influences the pH of the extraction process. pH adjustment in an alkaline medium is usually carried out with NaOH, and increasing its concentration along with temperature can favor the optimization of yield [66]. Cellulose is more stable at neutral to slightly alkaline pH, and its degradation is accelerated under acidic or highly alkaline conditions. Lignin and hemicelluloses are solubilized in alkaline solutions, but under strong alkaline conditions, the degree of cellulose removal can be significantly lower [67]. At acidic pH < 4, lignin dissolution and degradation also occur. In the acid hydrolysis of cellulose, the glycosidic bonds of hemicellulose are broken in an acidic medium, leading to the degradation of hemicellulose [68].

Statistical analysis indicated that Concentration, Agent, Reaction Time, and the Concentration-Agent and Concentration-Time interactions, with p-values < 0.05, had a significant impact on hydrolysis yield. To determine the normality of the data, the normality test Shapiro-Wilk was performed, with a p-value of 0.3871 > 0.05, thus failing to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the data analyzed exhibited normal or parametric behavior. De Medeiros Souza et al. [65], when studying the influence of KOH concentration as alkali and reaction time on the extraction of cellulose from plant fibers, determined that time was the factor with the greatest impact on alpha-cellulose yield compared to others evaluated. The effect of concentration was significant, being equally important in the studied response, while the concentration-time interaction was not significant.

In this regard, the conditions under which alkaline hydrolysis is carried out, such as alkali concentration, treatment time, and temperature, affect subsequent yields, which are also influenced by biomass composition. In the statistical analysis of a previous study where cellulose was extracted from corn cobs, it was found that NaOH concentration is the most significant factor in the entire reaction, playing a fundamental role in removing impurities from the corn cob to isolate cellulose. The removal of these impurities increases with increasing alkali concentration and reaction time. Hydrolysis may even require a longer reaction time to allow for the cleavage of the α-ether bonds of hemicelluloses and lignin by NaOH [19].

The physical appearance of the extracted cellulose was light brown with a soft texture. There was no variation in its appearance concerning the extraction variables. The shade of the extracted cellulose depends on the raw material used and the pH at which the hydrolysis was performed [69]. Although bleaching time was not considered a variable of interest, the findings of other researchers reported that H2O2 concentration and bleaching time were substantial factors when the biomass was bleached without alkaline treatment [19].

The yield of extracted cellulose can also vary depending on the reagent used during the bleaching process. A reduction in cellulose yield of 5%–7% can occur when hydrogen peroxide is used instead of sodium hypochlorite. Likewise, the concentrations of these reagents can influence the final quality [70].

Wet crystalline cellulose was obtained after the acetylation process. The mass yield of CA relative to the initial cellulose mass varies depending on the degree of substitution and the process efficiency. Without biomass pretreatment, CA conversions from corn fiber are typically low compared to other starting materials since the amount of cellulose present is less than 15%. In acetylation of untreated corn fibers, a yield of 1.8% was obtained by acetylating the cellulose, and after chemical hydrolysis pretreatment, the conversion rate increased to about 24% by weight [20].

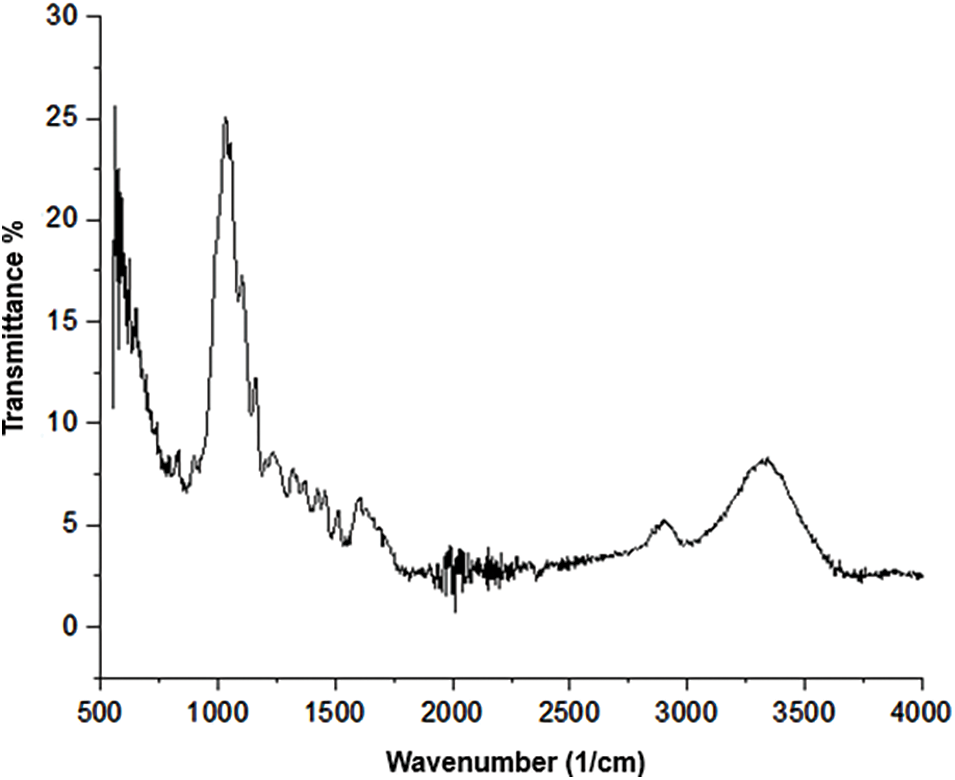

Fig. 1 shows the IR spectrum of untreated corn stalk cellulose, showing some characteristic groups of cellulose before the acetylation process. The band recorded at 3400 cm−1 indicates the presence of hydroxyl groups linked by hydrogen bonds with intermolecular bonds in its structure, and a wide signal is maintained due to the tension produced. The signal recorded at 2900 cm−1 is related to the C-H group, saturated in cellulose and hemicellulose. The typical bands of pure cellulose are those recorded at 1050, 1160 and 1320 cm−1. There are also several bands with symmetric and asymmetric stretching due to the presence of the bonds C-H [19,71].

Figure 1: Infrared IR spectrum of cellulose

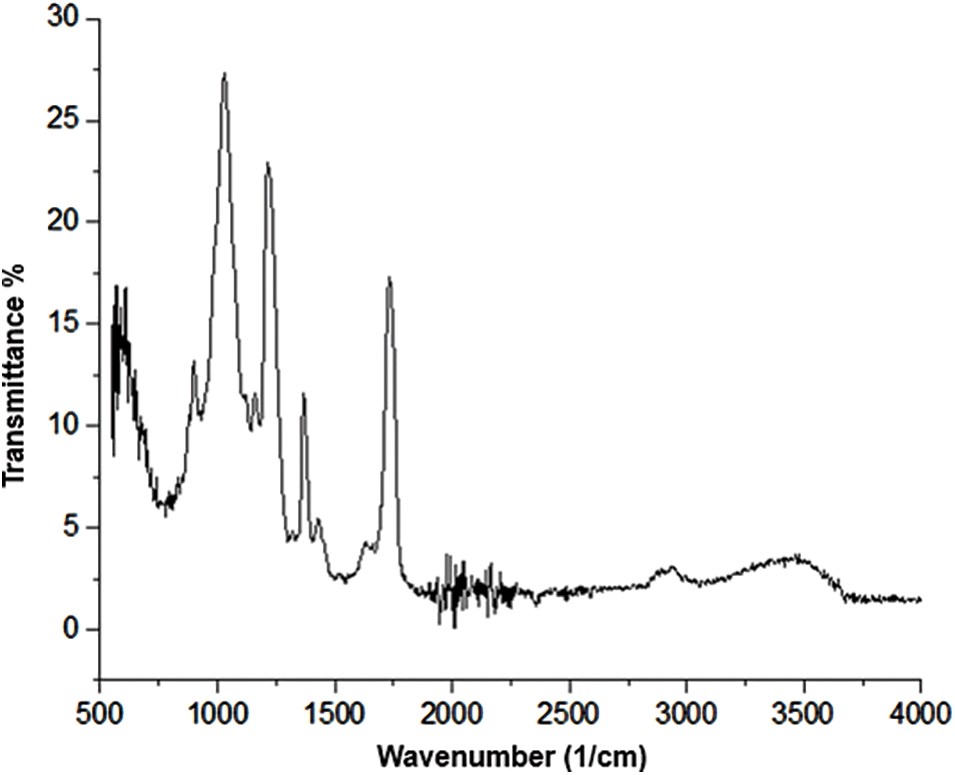

Fig. 2 shows the IR spectrum of the obtained CA. It shows the presence of the acetate functional group (C=O) in the band near 1700 cm−1 corresponds to the presence of the carboxylic group. The bands at 1400, 1050, and 1600 cm−1 are attributed to CH2, CO stretching, and the C=C group. The band near 3450 cm−1 represents the formation of CA. The results indicate that the substitution of the OH group by the acetate group has occurred correctly.

Figure 2: Infrared IR spectrum of CA

When comparing the FTIR of cellulose with CA, the structural transformation is evident. In cellulose-to-CA, the intense bands at 3400 and 1050 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching of –OH and the activity of C–O–C in anhydroglucose units. In comparison, the spectrum of acetylated cellulose (Fig. 1) shows the presence of three vibrations of the acetyl group at 1700, 1400 and 1050 cm−1 attributable to the species (nC]O), (n–CH3) and (nC–O), respectively. Furthermore, the reduced intensity of the hydroxyls (–OH) at 3450 cm1 is characteristic of acetylation. Another observable difference between the spectra is the slight shift towards the hydroxyl groups of cellulose about CA, which can be attributed to the large number of hydrogen bonds present in cellulose that are destroyed by the acetylation reaction [72].

The cellulose acetylation process presented the desired results, by what is observed in the compounds reported in the infrared and what has been reported in other investigations, where it shows the acetate group in the 1715 cm−1 signal [73], also coinciding with the characteristic signal of the acetate group in the 1753 cm−1 band [74].

Plant cellulose was obtained from corn stalk residue by acid-base hydrolysis, with higher cellulose yields achieved with alkaline hydrolysis. This cellulose pulp was revalued into CA and characterized by infrared spectroscopy, which displayed similar behavior to commercial cellulose about spectral signals and compound structures. Although the primary raw material for obtaining cellulose is wood, the use of agricultural waste represents a potential option for exploitation under a biorefinery approach to produce various products. Cellulose is a platform molecule that can be transformed into diverse bioproducts, including CA. The obtained AC can be used as a raw material for the chemical industry in the manufacture of paints, textiles, or packaging materials. The results obtained are a precedent for the development of research focused on the design of biorefineries under a cascade economy model, which allows the use not only of cellulose but also of other compounds present in biomass, such as xylose and arabinose, which are high-value pentoses used in the production of products such as xylitol and furfural.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, María Antonieta Riera; methodology, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales; software, María Antonieta Riera; validation, María Antonieta Riera; formal analysis, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales; investigation, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales; resources, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales; data curation, María Antonieta Riera; writing—original draft preparation, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales; writing—review and editing, María Antonieta Riera; visualization, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales; supervision, María Antonieta Riera; project administration, María Antonieta Riera; funding acquisition, Jhony César Muñoz Zambrano and Douglas Alexander Bermúdez Parrales. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ali Ashter S. Chemistry of cellulosic polymers. In: Technology and applications of polymers derived from biomass. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2018. p. 57–74. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-51115-5.00004-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ganster J, Fink HP. Cellulose and cellulose acetate. In: Kabasci S, editor. Bio-based plastics. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013. p. 35–62. doi:10.1002/9781118676646.ch3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Fischer S, Thümmler K, Volkert B, Hettrich K, Schmidt I, Fischer K. Properties and applications of cellulose acetate. Macromol Symp. 2008;262(1):89–96. doi:10.1002/masy.200850210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tyagi P, Rumjit NP, Garg S, Ahmed S, Lai CW. Biobased materials for increasing the shelf life of food products. In: Ahmed S, Annu, editors. Advanced applications of biobased materials. Cambridge, MA, USA: Elsevier; 2023. p. 231–43. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-91677-6.00031-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Vega-Baudrit J, Sibaja BM, Nikolaeva NS, Rivera AA. Síntesis y caracterización de celulosa amorfa a partir de triacetato de celulos. Rev Soc Quím Perú. 2020;80(1):45–50. (In Spanish). doi:10.37761/rsqp.v80i1.211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Etale A, Onyianta AJ, Turner SR, Eichhorn SJ. Cellulose: a review of water interactions, applications in composites, and water treatment. Chem Rev. 2023;123(5):2016–48. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Worku LA, Bachheti A, Bachheti RK, Rodrigues Reis CE, Chandel AK. Agricultural residues as raw materials for pulp and paper production: overview and applications on membrane fabrication. Membranes. 2023;13(2):228. doi:10.3390/membranes13020228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. García JIB, Ramos MMF, Alemán LSEA, López EV. El experimento formativo en la obtención de celulosa microcristalina a partir del pennisetum purpureum. Univ y Soc. 2023;15:389–99. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

9. Bonifacio A, Bonetti L, Piantanida E, De Nardo L. Plasticizer design strategies enabling advanced applications of cellulose acetate. Eur Polym J. 2023;197(10):112360. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2023.112360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. López-Martínez A, Bolio-López GI, Veleva L, Solórzano-Valencia M, Acosta-Tejada G, Hernández-Villegas MM, et al. Obtención de celulosa a partir de bagazo de caña de azúcar (Saccharum spp.). Agro Product. 2016;9(7):41–5. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

11. Riseh RS, Vazvani MG, Hassanisaadi M, Thakur VK. Agricultural wastes: a practical and potential source for the isolation and preparation of cellulose and application in agriculture and different industries. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;208(8):117904. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Faostat F. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Crops and livestock products. Production quantities of corn by country 2023 [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL/visualize. [Google Scholar]

13. Mayta-Paucara S, Norabuena-Meza E, Tello-Sánchez A, Quintana-Cáceda ME. Extracción y caracterización de celulosa a partir de residuos de hojas de maíz. Tecnia. 2023;33(2):53–61. (In Spanish). doi:10.21754/tecnia.v33i2.1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Grande Tovar CD, Orozco Colonia BS. Producción y procesamiento del maíz en Colombia. Rev Guillermo Ockham. 2013;11(1):97. doi:10.21500/22563202.604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Muñoz-Tlahuiz F, Guerrero-Rodríguez JDD, López PA, Gil-Muñoz A, López-Sánchez H, Ortiz-Torres E, et al. Producción de rastrojo y grano de variedades locales de maíz en condiciones de temporal en los valles altos de Libres-Serdán, Puebla, México. Rev Mex De Cienc Pecuarias. 2013;4(4):515–30. (In Spanish). doi:10.29312/remexca.v14i29.3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lesme Jaén R, Martillo Aseffe JA, Oliva Ruiz LO. Estudio de la gasificación de la tusa del maíz para la generación de electricidad. Ing Mec. 2020;23(3):e613. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

17. Bioenergía y seguridad alimentaria. Evaluación rápida. BEFS RA [Internet]; 2014 [cited 2025 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/bp843s/bp843s.pdf. [Google Scholar]

18. Riera M, Palma R. Obtención de bioplásticos a partir de desechos agrícolas. Una revisión de Las potencialidades en Ecuador. Avanquim. 2019;13(3):69–78. doi:10.53766/avanquim/2018.13.03.04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ng YS, Ooi ZX, Teoh YP, Ooi M, Hoo PY. Optimization of purified cellulose extraction from corn cob and characterization of the isolated product. Cellulose Chem Tech. 2024;58(5–6):467–79. doi:10.35812/cellulosechemtechnol.2024.58.44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Biswas A, Saha BC, Lawton JW, Shogren RL, Willett JL. Process for obtaining cellulose acetate from agricultural by-products. Carbohydr Polym. 2006;64(1):134–7. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Azubuike CP, Mgboko MS, Ologunagba MO, Oseni BA, Madu SJ, Igwilo CI. Preparation and characterization of corn cob cellulose acetate for potential industrial applications. Niger J Pharm. 2023;57(2):709–18. doi:10.51412/psnnjp.2023.31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hossain ME. Preparation and characterization of cellulose derivatives from agricultural wastes. Sch J Agric Vet Sci. 2024;11(2):11–5. doi:10.36347/sjavs.2024.v11i02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fernandes MAM, Nörnberg LV, Acosta AP, Barbosa KT, Cardoso GV. Green chemistry in the production of cellulose acetate: the use of a new low-cost, highly available waste product. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2025;15(8):12515–23. doi:10.1007/s13399-024-06016-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ariyanti D, Rimantho D, Leonardus M, Ardyani T, Fiviyanti S, Sarwana W. Valorization of corn cob waste for furfural production: a circular economy approach. Biomass Bioenergy. 2025;194(6):107665. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2025.107665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zabed HM, Akter S, Yun J, Zhang G, Zhao M, Mofijur M, et al. Towards the sustainable conversion of corn stover into bioenergy and bioproducts through biochemical route: technical, economic and strategic perspectives. J Clean Prod. 2023;400(2):136699. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Loiseau E, Saikku L, Antikainen R, Droste N, Hansjürgens B, Pitkänen K, et al. Green economy and related concepts: an overview. J Clean Prod. 2016;139(1/2):361–71. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.08.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. American Oil Chemists’ Society. Crude Fiber in Feeds, Filter Bag Technique (AOCS Ba 6a-05). [cited 2025 Mar 19]. Available from: https://7157e75ac0509b6a8f5c-5b19c577d01b9ccfe75d2f9e4b17ab55.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/JFCSWRAG-PDF-1-422536-4428457257.pdf. [Google Scholar]

28. De Carvalho Mendes CA, De Oliveira Adnet FA, Moreira Leite MCA, Guimarães Furtado CR, Furtado De Sousa AM. Chemical, physical, mechanical, thermal and morphological characterization of corn husk residue. Cellul Chem Technol. 2014;49(4):727–35. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2015.02.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Licon C. Proximate and other chemical analyses. In: McSweeney PLH, McNamara JP, editors. Encyclopedia of dairy sciences. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2022. p. 521–9. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818766-1.00344-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Vega M. Uso de residuos celulósicos de la agroindustria para la producción de bioetanol [dissertation]. Quito, Ecuador: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; 2010. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

31. López-Legarda X, Taramuel-Gallardo A, Arboleda-Echavarría C, Segura-Sánchez F, Restrepo-Betancur LF. Comparación de métodos que utilizan ácido sulfúrico para la determinación de azúcares totales. Rev Cubana Quím. 2017;29(2):180–98. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

32. AOAC International. Official methods of analysis. 22nd ed. Washington, DC, USA: AOAC International; 2023. [Google Scholar]

33. Torres Jaramillo D, Morales Vélez SP, Quintero Díaz JC. Evaluación de pretratamientos químicos sobre materiales lignocelulósicos. Ingeniare Rev Chil Ing. 2017;25(4):733–43. doi:10.4067/s0718-33052017000400733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Vegas Niño RM, Acosta Arteaga Y, Fernández Segura C. Obtención, purificación y aprovechamiento de azúcares reductores a partir de materiales lignocelulósicos. Rev Bol Quim. 2024;41(2):10–27. (In Spanish). doi:10.34098/2078-3949.41.2.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sommano SR, Ounamornmas P, Nisoa M, Sriwattana S, Page P, Colelli G. Characterization and physiochemical properties of mango peel pectin extracted by conventional and phase control microwave-assisted extractions. Inter Food Res Jour. 2018;25(6):2657–65. [Google Scholar]

36. Candido RG, Gonçalves AR. Synthesis of cellulose acetate and carboxymethylcellulose from sugarcane straw. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;152:679–86. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chun KS, Husseinsyah S, Yeng CM. Effect of green coupling agent from waste oil fatty acid on the properties of polypropylene/cocoa pod husk composites. Polym Bull. 2016;73(12):3465–84. doi:10.1007/s00289-016-1682-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. López Sardi EM. Fabricación de pasta de celulosa: aspectos técnicos y contaminación ambiental. Rev C T. 2018;6:37–46. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

39. Ibarra Castillo D, Ruiz Corral JA, González Eguiarte DR, Flores Garnica JG, Díaz Padilla G. Distribución espacial del pH de los suelos agrícolas de Zapopan, Jalisco, México. Agric Téc Mex. 2009;35(3):267–76. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

40. Abolore RS, Jaiswal S, Jaiswal AK. Green and sustainable pretreatment methods for cellulose extraction from lignocellulosic biomass and its applications: a review. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2024;7(29):100396. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. González-Velandia KD, Daza-Rey D, Caballero-Amado PA, Martínez-González C. Evaluación de las propiedades físicas y químicas de residuos sólidos orgánicos a emplearse en la elaboración de papel. Luaz. 2016;43:499–517. (In Spanish). doi:10.17151/luaz.2016.43.21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Amador RAL, Boschini FC. Fenología productiva y nutricional de maíz para la producción de forraje. Agron Mesoam. 2000;11(1):171–7. (In Spanish). doi:10.15517/am.v11i1.17362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Huatatoca S. Elaboración de papel artesanal a base de los residuos vegetales de los tallos de maíz (Zea mays L.) y cáscara de plátano (Musa paradisiaca L.) utilizando los métodos químicos de Jayme-Wise, Kurshner y Hoffner [dissertation]. Riobamba, Ecuador: Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo; 2020. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

44. Karpiuk U, Kyslychenko V, Hnoievyі I, Buhay T, Abudayeh ZH, Fedosov A. The study of carbohydrates of corn raw materials. Sci Pharm Sci. 2023;44(1):32–40. doi:10.15587/2519-4852.2023.274698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. González G, López-Santín J, Caminal G, Solà C. Dilute acid hydrolysis of wheat straw hemicellulose at moderate temperature: a simplified kinetic model. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1986;28(2):288–93. doi:10.1002/bit.260280219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Helle G, Pauly M, Heinrich I, Schollän K, Balanzategui D, Schürheck L. Stable isotope signatures of wood, its constituents and methods of cellulose extraction. In: Siegwolf RTW, Brooks JR, Roden J, Saurer M, editors. Stable isotopes in tree rings. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2022. p. 135–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-92698-4_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Baeza J, Freer J. Chemical characterization of wood and its components. In: Hon DNS, Shiraishi N, editors. Wood and cellulosic chemistry. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 1997. p. 275–384. [Google Scholar]

48. Ververis C, Georghiou K, Christodoulakis N, Santas P, Santas R. Fiber dimensions, lignin and cellulose content of various plant materials and their suitability for paper production. Ind Crops Prod. 2004;19(3):245–54. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2003.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sabarinathan P, Rajkumar K, Annamalai VE, Vishal K. Characterization on chemical and mechanical properties of silane treated fish tail palm fibres. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163(6):2457–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Bardales Vásquez CB, León Torres CA, Mostacero León J, Arellano Barragán J, Nomberto Rodríguez C, Salazar Castillo M, et al. Producción de bioetanol del desecho lignocelulósico “peladilla” de Asparagus officinalis L. “espárrago” por Candida utilis var. Major. CECT 1430. Julio-Diciembre. 2011;3(2):205–13. (In Spanish). doi:10.18050/revucv-scientia.v3i2.919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Tesfaw AA, Tizazu BZ. Reducing sugar production from Teff straw biomass using dilute sulfuric acid hydrolysis: characterization and optimization using response surface methodology. Int J Biomater. 2021;2021(2):2857764. doi:10.1155/2021/2857764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Xu J, Li J, Wan C, Ma E. Water variation and its induced structural changes in cellulose extracted from wood. Cellulose. 2025;32(8):4689–703. doi:10.1007/s10570-025-06552-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Hofstetter K, Hinterstoisser B, Salmén L. Moisture uptake in native cellulose—the roles of different hydrogen bonds: a dynamic FT-IR study using Deuterium exchange. Cellulose. 2006;13(2):131–45. doi:10.1007/s10570-006-9055-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Melesse GT, Hone FG, Mekonnen MA. Extraction of cellulose from sugarcane bagasse optimization and characterization. Adv Mat Sci Eng. 2022;2022(3–4):1712207. doi:10.1155/2022/1712207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Haro D, Marquina-Barrios S, Fuentes-Olivera A, Quezada A, Cruz-Monzón J, Cueva-Almendras L, et al. Caracterización composicional y estructural de once tipos de biomasa lignocelulósica y su potencial aplicación en la obtención de nanopolisacáridos y producción de polihidroxialcanoatos. Sci Agropecu. 2024;15(4):513–23. (In Spanish). doi:10.17268/sci.agropecu.2024.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chopra L. Extraction of cellulosic fibers from the natural resources: a short review. Mater Today Proc. 2022;48(17):1265–70. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Wang L, Li G, Chen X, Yang Y, Liew RK, Abo-Dief HM, et al. Extraction strategies for lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose to obtain valuable products from biomass. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2024;7(6):219. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-01009-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Mensah MB, Jumpah H, Boadi NO, Awudza JAM. Assessment of quantities and composition of corn stover in Ghana and their conversion into bioethanol. Sci Afr. 2021;12(13):e00731. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Castillo Saldarriaga CR, Velasquez Lozano ME. Efecto del pretratamiento con ácido sulfúrico diluido sobre la hidrólisis enzimática del Panicum maximum. Rev Bio Agro. 2018;16(1):68. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

60. Sanaguano S. Obtención de nanocelulosa a partir de la hoja de mazorca de maíz (Zea mays L.) Mediante el proceso de hidrólisis ácida [dissertation]. Riobamba, Ecuador: Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo; 2021. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

61. Lou C, Zhou Y, Yan A, Liu Y. Extraction cellulose from corn-stalk taking advantage of pretreatment technology with immobilized enzyme. RSC Adv. 2022;12(2):1208–15. doi:10.1039/d1ra07513f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Vele Salto AM, Abril González MF, Zalamea Piedra TS, Pinos Vélez VP. Mini-Revisión: aplicación de líquidos iónicos en hidrólisis ácida de material lignocelulósico Para la obtención de azúcares. Cienc En Desarro. 2021;12(1):55–67. (In Spanish). doi:10.19053/01217488.v12.n1.2021.12477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Vishal K, Rajkumar K, Nitin MS, Sabarinathan P. Kigelia africana fruit biofibre polysaccharide extraction and biofibre development by silane chemical treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;209(Pt A):1248–59. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.04.137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Mohomane SM, Motloung SV, Koao LF, Motaung TE. Effects of acid hydrolysis on the extraction of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCsa review. Cellulose Chem Technol. 2022;56(7–8):691–703. doi:10.35812/cellulosechemtechnol.2022.56.61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. de Medeiros Souza KLF, Hidalgo Falla MDP, Da Luz SM. The influence of potassium hydroxide concentration and reaction time on the extraction cellulosic jute fibers. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(13):6889–901. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.1934934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Doner LW, Hicks KB. Isolation of hemicellulose from corn fiber by alkaline hydrogen peroxide extraction. Cereal Chem. 1997;74(2):176–81. doi:10.1094/cchem.1997.74.2.176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Chen Y, Wen Y, Zhou J, Xu C, Zhou Q. Effects of pH on the hydrolysis of lignocellulosic wastes and volatile fatty acids accumulation: the contribution of biotic and abiotic factors. Bioresour Technol. 2012;110(3):321–9. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Yang Z, Cao L, Li Y, Zhang M, Zeng F, Yao S. Effect of pH on hemicellulose extraction and physicochemical characteristics of solids during hydrothermal pretreatment of Eucalyptus. BioResources. 2020;15(3):6627–35. doi:10.15376/biores.15.3.6627-6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Contreras QHJ, Trujillo PHA, Arias OG, Pérez CJL, Delgado FE. Espectroscopia ATR-FTIR de celulosa: aspecto instrumental y tratamiento matemático de espectros. e-Gnosis. 2010;8:1–13. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

70. García-Alcocer SK, Salgado-García S, Córdova-Sánchez S, Rincón-Ramírez JA, Bolio-López GI, Castañeda Ceja R, et al. Blanqueo de la fibra de celulosa de paja de caña de azúcar (Saccharum spp.) con peróxido de hidrógeno. Agro Product. 2019;12(7):11–7. (In Spanish). doi:10.32854/agrop.v0i0.1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Romero Viloria P, Marfisi S, Oliveros Rondón P, Rojas de Gáscue B, Peña G. Obtención de celulosa microcristalina a partir de desechos agrícolas del cambur (Musa sapientum) síntesis de la celulosa microcristalina. Rev Iber Polímeros. 2014;15:286–300. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

72. Fei P, Liao L, Cheng B, Song J. Quantitative analysis of cellulose acetate with a high degree of substitution by FTIR and its application. Anal Methods. 2017;9(43):6194–201. doi:10.1039/c7ay02165h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Pinos A, Braulio J. Modificación de la celulosa obtenida de la fibra de banano para el uso de polímeros biodegradables. Afinidad. 2018;76(585):45–51. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

74. Ibrahim MM, Fahmy TYA, Salaheldin EI, Mobarak F, Youssef MA, Mabrook MR. Role of tosyl cellulose acetate as potential carrier for controlled drug release. Life Sci J. 2015;12(10):127–33. doi:10.7537/marslsj121015.16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools