Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Comprehensive Study on Application and Prospect of Hydrogel Detection Methods

1 Guobiao (Beijing) Testing & Certification Co., Ltd., Beijing, 101400, China

2 School of Mechanical Engineering, University of South China, Hengyang, 421001, China

* Corresponding Authors: Wei Wang. Email: ; Xiaomin Kang. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 621-660. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.068852

Received 08 June 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Due to their high water content, stimulus responsiveness, and biocompatibility, hydrogels, which are functional materials with a three-dimensional network structure, are widely applied in fields such as biomedicine, environmental monitoring, and flexible electronics. This paper provides a systematic review of hydrogel characterization methods and their applications, focusing on primary evaluation techniques for physical properties (e.g., mechanical strength, swelling behavior, and pore structure), chemical properties (e.g., composition, crosslink density, and degradation behavior), biocompatibility, and functional properties (e.g., drug release, environmental stimulus response, and conductivity). It analyzes the challenges currently faced by characterization methods, such as a lack of standardization, difficulties in dynamic monitoring, an insufficient micro-macro correlation, and poor adaptability to complex environments. It proposes solutions, such as a hierarchical standardization system, in situ imaging technology, cross-scale characterization, and biomimetic testing platforms. Looking ahead, hydrogel characterization techniques will evolve toward intelligent, real-time, multimodal coupling and standardized approaches. These techniques will provide superior technical support for precision medicine, environmental restoration, and flexible electronics. They will also offer systematic methodological guidance for the performance optimization and practical application of hydrogel materials.Keywords

Hydrogel is a kind of three-dimensional network structure material formed by physical or chemical crosslinking of hydrophilic polymers, which can absorb and retain a large amount of water without dissolving. Its basic characteristic is that it swells significantly in water, and the water content can usually reach more than 90% of its own weight, while still maintaining the mechanical properties of solid materials. The hydrogel may be composed of natural polymers (such as gelatin, sodium alginate, chitosan, hyaluronic acid, etc.), synthetic polymers (such as polyacrylamide (PAAm), polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly N-isopropyl acrylamide (PNIPAM), etc.), or a composite system of the two. The stability and response behavior of hydrogels are determined by the crosslinking mode.

Significant advances have been made in hydrogel research in recent years, particularly in the rational design of material architectures and functional diversification.

In regard to material structure design, performance is enhanced through composite modification and structural optimization. For instance, metal-organic framework (MOF)-doped hydrogel composites have been shown to exhibit enhanced adsorption and detection capabilities for pollutants [1]. Additionally, molecularly imprinted hydrogels incorporating aggregation-induced emission (AIE) monomers have demonstrated specific optical recognition of lysozyme [2]. Furthermore, core-shell structured hydrogel beads have been developed, which integrate pre-enrichment with functionalized cores and signal amplification by engineered bacteria, resulting in a substantial enhancement in detection sensitivity [3].

These developments have yielded transformative applications across multiple domains, including biomedical engineering [4–8], environmental surveillance [9–13], and flexible electronic systems [14–16]. The field is currently undergoing a paradigm shift toward multifunctional integrated platforms. Concomitant with advancements in characterization methodologies (e.g., super-resolution microscopic techniques, in situ spectroscopic analyses), exhaustive investigations of structure-property interrelationships in hydrogels have provided fundamental insights, catalyzing innovative implementations in intelligent sensing modalities [17–19] and precisely controlled therapeutic delivery platforms [20–24] with unprecedented potential.

1.1 Basic Properties of Hydrogels

The basic properties of hydrogel are mainly determined by its high water content and crosslinked network structure, which not only endow it with mechanical properties similar to biological soft tissue, but also make it have unique advantages such as stimulation response, biocompatibility and porous structure. Hydrogel has both solid mechanical properties and liquid transport properties, which makes it a bridge between material science and life science. Hydrogels have been widely used in biomedical, environmental monitoring, flexible electronics and other fields due to their unique properties.

1.1.1 High Water Content and Swelling Behavior

The most notable feature of hydrogels is their high water content after reaching swelling equilibrium, typically exceeding 70% of their wet weight in water, with superabsorbent hydrogels reaching over 95%. This property is attributable to the strong interactions between hydrophilic groups on the polymer chains (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amide groups) and water molecules. The water content of hydrogels exerts a dual influence on their mechanical properties and their biocompatibility. It also affects their material transport capabilities. Research findings indicate that HA hydrogels can achieve a swelling ratio of 8:1 (wet weight:dry weight) in physiological saline, providing ideal conditions for their use as drug carriers. Swelling behavior constitutes a fundamental functional characteristic of hydrogels, and its quantitative assessment can be facilitated by the implementation of the swelling ratio.

According to the standards for evaluating the swelling performance of hydrogels (e.g., ASTM F2258 or the modified ASTM D570 method), there is significant variation in the mass swelling rate (Qm) of different types of hydrogels. Specifically, physically crosslinked types exhibit a range of 200% to 500%, while chemically crosslinked superabsorbent hydrogels can reach levels exceeding 1000%. The initial kinetics can be analyzed using the Peppas power-law model (limited to Mt/M∞ ≤ 0.6), while equilibrium swelling rates require integration with Flory-Huggins thermodynamic theory.

Lin proposed that by preparing polyacrylamide/chitosan (PAAM/CS) hydrogel, its excellent swelling property and adsorption performance make this material not only able to efficiently adsorb xylenol orange (XO), but also realize dual signal detection of Fe3+ and Al3+ in water through XO loading, thus providing a multifunctional solution for water environmental pollutant treatment and monitoring [25]. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel significantly improved the fluorescence detection efficiency of mold and yeast by virtue of its high water holding capacity (71.7%), and the detection time was shortened from ≥5 d of national standard to 36 h [26].

Intelligent hydrogels can produce reversible physical or chemical responses to environmental stimuli, which makes them unique advantages in the field of sensing and controlled release. According to the different stimulation signals, they can be divided into the following categories:

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) is a prototypical temperature-sensitive hydrogel with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) ranging from 30 to 35°C (typically around 32°C). When the temperature exceeds the LCST, PNIPAM undergoes a hydrophilic-hydrophobic transition, causing the hydrogel to rapidly dehydrate and shrink (with a volume shrinkage rate of up to 90%) [27]. This property has been used to develop temperature-controlled drug delivery systems, such as the EV71 virus detection sensor [5]. Temperature-sensitive hydrogel (PNIPAM) can realize SERS detection of protein at single molecule level by adjusting the spacing of gold nano-triangular plate array dynamically through temperature-regulated volume phase transition [28].

pH responsiveness: Hydrogels containing weak acid/base groups (such as carboxyl and amino groups) will undergo protonation/deprotonation with pH changes, resulting in changes in network charge and swelling degree. Zhang et al. achieved multi-mode detection of pH (6.0–11.0) and trace water (minimum detection limit 0.0060%) based on deprotonation and aggregation mechanisms, and successfully applied to the fields of biological imaging and information encryption [29]. pH-responsive hydrogels (such as polyacrylic acid/chitosan) produce reversible deformation through coordination between carboxyl groups and metal ions to achieve visual detection of Fe3+ [30].

Photoresponsiveness: Photosensitive groups (such as azobenzene and spiropyran) can be introduced into the hydrogel network to achieve photo-controlled deformation. The hydrogel modified by upconversion nanoparticles is excited by near-infrared light to achieve high-sensitivity dual-mode detection of formaldehyde (fluorescence/colorimetric detection limits of 10 and 25 nM, respectively), providing a new strategy for high-precision portable detection for food safety monitoring [31].

Biomolecular responsiveness: aptamer-functionalized hydrogels can specifically recognize target molecules (such as ATP, miRNA, etc.) and trigger changes in network structure. For example, DNA hydrogels achieve highly specific detection of miRNA-21 (detection limit 27.8 pM) by hybridization chain reaction (HCR), significantly reducing detection time and simplifying the procedure [29,32]. Table 1 summarizes the response mechanism, response time, typical materials and application cases of temperature, pH, light and biomolecule stimulus-responsive hydrogels.

In recent years, the research of stimulus-responsive hydrogel has been further extended to the development of multi-responsive materials. Zhao proposed a device-free, label-free paper-based flow sensor based on enzyme-induced stimulus-responsive polymer solution viscosity change. This technology realizes high-sensitivity detection of hyaluronidase (HAase) by increasing the water flow distance on pH test paper (detection limit up to 0.2 U/mL). This method has important application value in clinical instant detection field [30,33]. In addition, the application of photoresponsive hydrogel in macromolecular detection has also attracted much attention, such as the photoresponsive hydrogel particle sensor developed by Wang, which generates fluorescence and structural color dual optical signal output by triggering phase transition, so that the quantitative detection of alkaline phosphatase has high accuracy and reliability [34].

1.1.3 Biocompatibility and Degradability

In biomedical applications, hydrogels need to have good biocompatibility and controlled degradation to ensure their safety and functionality. Medical grade hydrogels must meet stringent biocompatibility standards (e.g., ISO 10993). Sodium alginate and galactosidase modified gold nanoparticle composite hydrogel has excellent biocompatibility, detection limit up to 100–1000 CFU/mL, used for wound bacterial infection monitoring [35].

Degradation performance is another key indicator. Methods to regulate degradation behavior include changing crosslinking density (covalent crosslinking degrades slower than ionic crosslinking), introducing enzyme-sensitive bonds (e.g., matrix metalloproteinase substrate peptides), and adjusting hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance. Optimization of biocompatibility and degradability is the key to clinical transformation of hydrogels. Future research could further enhance its performance through material modification (e.g., introduction of bioactive peptides) or composite design (e.g., nanomaterial enhancement). For example, poly (1-pyrenebutyric acid)/sodium alginate hydrogel developed by Li et al. can degrade 72.4% within 24 h, effectively avoiding secondary pollution and providing a new idea for the design of green sustainable fluorescence sensors [36]. In addition, biosafety assessment of degradation products has also received increasing attention. For example, Zhang et al. confirmed the low toxicity of DNA hydrogel degradation products by mass spectrometry analysis [37].

1.1.4 Porous Structure and Permeability

The porous structure of hydrogels plays an important role in their mechanical properties and material transport. The porous structure of hydrogel (pore size 10–500 μm) directly affects substance transport (such as oxygen, nutrients, drug diffusion) and cell migration, which is an important basis for its function realization. Material transport: porous structure provides efficient diffusion channels for hydrogels, suitable for drug delivery or cell culture. Cell migration: large pore size hydrogel (>100 μm) is more conducive to cell migration and tissue ingrowth.

Permeability depends on pore connectivity and surface chemistry. Hydrogels with hierarchical pore structure can be prepared by freeze-thaw method, which can significantly improve the diffusion coefficient of small molecules such as drugs. For example, the unique pore structure of DNA-functionalized cryogels enables rapid detection of aflatoxin B1 within 45 min [30].

In recent years, important progress has been made in the precise regulation of porous structures. For example, Gao et al. achieved SERS detection of proteins at the single molecule level by dynamically adjusting the spacing of plasma nanostructures through gold nanotriangular plate arrays (AuTAG) constructed on the surface of thermally responsive hydrogels [28]. Three-dimensional porous polyacrylamide hydrogel embedded with upconversion optical probe to construct intelligent nanosensor, its porous structure enhances formaldehyde diffusion efficiency, detection limit as low as 10 nM [31].

β-cyclodextrin/carbon dot-loaded cellulose nanofiber/MIL-100 (Fe) hydrogel (βCCM) improves malachite green adsorption performance (1789 mg/g) and fluorescence detection sensitivity (LOD = 0.09 μg/L) through three-dimensional porous structure [38]. In addition, the introduction of microfluidic technology also provides a new method for the controllable preparation of hydrogel porous structure, such as the microfluidic chip developed by Liu et al. can prepare hydrogel microspheres with uniform pore size distribution [39].

The application of hydrogel in biomedicine mainly includes three aspects:

Drug delivery system: The three-dimensional network of hydrogels effectively embeds and protects drug molecules. Gelatin hydrogel patch loaded with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) can significantly reduce the expression of inflammatory factors, increase SOD activity and effectively improve oxidative stress [40]. Intelligent responsive hydrogels are more able to achieve space-time controlled release, such as pH-sensitive chitosan hydrogels for stomach targeted drug delivery.

Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: Hydrogels mimic the microenvironment of the extracellular matrix (ECM). After wrapping tendon stem cells with chitosan/β-glycerophosphate/collagen composite hydrogel, it can significantly increase the deposition of type I collagen, up-regulate the expression of genes related to tendon differentiation, and promote the repair of Achilles tendon injury in rats [41].

Diagnostic sensing: The high throughput modification properties of hydrogels make them ideal sensing platforms. DNA hydrogels incorporating the CRISPR/Cas12a system achieved ultrasensitive detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (10 copies/μL) [37]. Additionally, hydrogels can be administered via local injection into tumor tissue and, when combined with near-infrared irradiation, provide support for tumor treatment and related monitoring [42].

In recent years, the application of hydrogel in biomedical field has been further extended to personalized medicine and precise diagnosis. For example, Yang et al. developed a cascade signal amplification system based on DNA hydrogel microneedle array, which achieved high sensitivity detection of microRNA in interstitial fluid (detection limit 241.56 pM), providing a new tool for minimally invasive personalized diagnosis [43]. Aptamer-based portable biosensors enable specific in situ detection of cytochromes at the biomembrane-material interface by integrating DNA aptamers and fluorescence detection technology [44]. Wearable europium metal-organic frame microneedle patch achieves high sensitivity detection of cortisol (detection limit up to 10−9 M) by fluorescence quenching sensing technology [45].

In addition, important breakthroughs have also been made in the application of hydrogel in organ chip and organoid culture. For example, Duan et al. integrated oxygen gradient and hydrogel sensor through multi-layer microfluidic technology to realize in situ spatiotemporal detection of pancreatic beta cell function [46].

1.2.2 Environmental Monitoring and Food Safety

Hydrogel sensors show significant advantages in detecting environmental contaminants:

Heavy metal detection: functional hydrogels based on specific recognition enable highly selective detection. Carboxylated agarose hydrogel binds to X-ray fluorescence nanoparticles and increases protein detection sensitivity to 2 μg/mL through dehydration condensation effect [47]. Biomimetic chromotropic hydrogels (Cys-BCH) achieve a detection limit of 0.3 nM through specific binding of sulfhydryl groups to mercury ions [48].

Antibiotic residue analysis: molecular imprinting technology endows hydrogels with specific recognition capabilities. The wood-derived fluorescent molecularly imprinted hydrogel (FMIH) has a maximum adsorption capacity of 544.4 mg/g for tetracycline, a detection limit as low as 0.11 μg/L, and a cost that is only 1/34 of that of commercial activated carbon [49].

Food Freshness Monitoring: Smart color hydrogels can indicate food quality in real time. Alizarin Red S-based hydrogel sensor platform improves freshness detection accuracy of aquatic products to 84% [50]. A fluorescence-visualization dual function sensor based on CRISPR/Cas 12a system and DNA hydrogel achieves a detection limit of Salmonella typhimurium as low as 150 CFU/mL [51].

Hydrogels also show great potential for integrating environmental remediation and monitoring. For example, SCDs-KTOCS gel developed by Wang et al. realizes simultaneous detection and removal of Hg(II) pollutants in water through a dual mechanism of fluorescence emission and efficient adsorption [52]. It plays a role in the rapid transport of water and self-purification [53].

The anti-interference ability of hydrogel in complex environment is continuously improved, such as CS/CN/Ag flexible substrate developed by Luo et al., which can simultaneously realize surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy detection and photocatalytic degradation of sulfonamide pollutants (efficiency up to 99.22%) [54].

In addition, conductive hydrogels have also demonstrated excellent performance in the field of acoustic sensing. As shown in Fig. 1, by comparing the output voltage (A), sound pressure sensitivity (B), and signal-to-noise ratio (C) of the traditional hydrogel (RHC-14) with the new conductive hydrogel (CH), it is demonstrated that the latter exhibits higher detection sensitivity and directionality (D,E) across a wide frequency range (20–800 Hz). This technology offers a new strategy for monitoring low-frequency signals in complex environments [55].

Figure 1: CH of performance testing. (A) Output voltages of CH and RHC-14 in the frequency range (20–800 Hz). (B) Measured sound pressure sensitivity of CH and RHS-14 at different frequencies. (C) SNR comparison between CH and RHC-14. (D) Schematic diagram of the directionality test. (E) Pattern of CH at 100 Hz (i) and 700 Hz (ii). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [55]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society

1.2.3 Flexible Bioelectronics, Neural Interfaces, and Wearable Sensors

Conductive hydrogel materials possess a unique combination of flexibility and electrical activity, rendering them highly promising for applications in flexible bioelectronics, neural interfaces, and wearable sensors.

Advances in the Application of Conductive Hydrogels in Flexible Bioelectronics

Conductive hydrogels, characterized by their distinctive flexibility and electrical activity, have emerged as pivotal materials within the domain of flexible bioelectronics. Researchers have continuously refined their performance through composite modification and structural design, thereby establishing a significant foundation for related applications.

Cui et al. [56] developed a composite hydrogel composed of phytic acid-chitosan/ polyethyleneimine/gold nanoparticles (PA-CS/AuNPs/PEI), which exhibited a 23% increase in triboelectric power output compared to traditional chitosan-based materials. This advancement provides a novel perspective on energy supply in wearable devices. Zhang et al. [57] elucidated the self-adhesive mechanism of the PEDOT:PSS/WPU/SOR ternary blend, thereby providing theoretical underpinnings for the stable application of stretchable conductive polymer materials in flexible electronic devices. Wang et al. designed a photosensitive biphasic structure conductive polymer hydrogel (PB-CH) that achieved 5-μm high-resolution patterning while maintaining high conductivity of approximately 30 S cm−¹ at 50% strain, thereby meeting the requirements for the fabrication of precision devices [58].

Advancements in flexible electronics have led to significant expansions in the application scope of hydrogels [59]. For instance, Shi et al. enhanced the resolution of epidermal electrical signal detection arrays by reducing the interface gap between the hydrogel and the skin and enhancing adhesion [60]. Similarly, Sun et al. developed a composite conductive hydrogel medium for self-powered real-time lactate monitoring with a detection limit as low as 4.38 nM [61]. Ullah et al. noted that hydrogels play a key role in enhancing human-machine interface applications. However, challenges remain to be overcome regarding stability, biocompatibility, and scalability [62].

Applications of Conductive Hydrogels in Neural Interface Technology

Conductive hydrogels have been instrumental in propelling the advancement of neural modulation and brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies, thereby achieving substantial progress in the realm of precise monitoring and prosthetic control.

The optimization of neural interface materials and systems is a subject of significant interest in contemporary research.

PEDOT:PSS hydrogels have emerged as pivotal materials for neural interfaces, with Li et al. demonstrating their capacity to markedly enhance the monitoring accuracy and control capabilities of neural interfaces [63]. Shi et al. investigated the issue of photonic artifacts in ultra-soft electrode photonic neural interfaces based on conical optical fibers, thereby establishing the foundation for the development of high-precision implantable multimodal neural interfaces [64]. The Smart Wireless Artificial Neural System (SWANS) was developed by and transmits signals through human tissue, achieving energy efficiency 15 times that of Bluetooth and near-field communication [65]. Yang et al. integrated triboelectric sensing with pneumatic feedback technology into the TSPF-Ring system, achieving over 99% tactile classification accuracy and significantly activating the sensorimotor cortex in stroke patients [66].

Multimodal sensing has been demonstrated to enhance neural prosthesis control.

Multimodal sensing systems have been shown to enhance the precision of prosthesis control. For instance, Yin et al. [67] integrated A-mode ultrasound, surface electromyography, and inertial measurement units, achieving a prosthetic gesture recognition accuracy of 96.9% ± 1.3%. Similarly, Mongardi et al. developed a direction correction algorithm that is both fast and low-power, requiring only two gesture calibrations to real-time correct sensor displacement. This algorithm achieved an average recognition accuracy of 93.36% for nine gestures [68].

Notwithstanding the substantial progress that has been made, the field continues to grapple with several challenges, including inadequate material stability [56,58,62], limited device durability [69,70], and unresolved signal interference [71]. Future efforts should prioritize the optimization of material design and fabrication processes, the development of novel anti-interference algorithms, and the conduction of clinical translation studies to advance the large-scale application of conductive hydrogels in neural interfaces.

Applications of Conductive Hydrogels in Wearable Sensor Technology

The flexibility and electrical activity of conductive hydrogels make them a core material for wearable devices, enabling multi-dimensional applications in physiological monitoring, human-machine interaction, and energy harvesting.

The objective of this study is to develop a high-precision monitoring system for physiological signals.

PEDOT:PSS hydrogels have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in the field of sweat analysis, with sensors developed based on these hydrogels exhibiting the capability to detect metabolites such as glucose (1–800 μM) [72] and uric acid (0.42 μmol/L) [73] in sweat samples collected in real-time. A self-healing nanocomposite hydrogel inspired by mussels, composed of polyvinyl alcohol/gold nanoparticles @polydopamine (PVA/AuNPs@PDA), integrates human motion monitoring (response time 122.9 ms) with sweat glucose detection functionality [74], further expanding the scope of physiological monitoring applications.

The objective of this study is to optimize human-machine interfaces.

The viscoelastic nature of hydrogels guarantees the reliable transmission of mechanical signals. For instance, the PVA/CNCs@PDA-Au nanocomposite hydrogel exhibits a deformation capacity of 508.6% and a strength of 2.9 MPa, facilitating precise capture of human motion [75]. Following optimization of the formulation, the response time can be further diminished [73]. Furthermore, the integration of carbon nanotube topological networks with hydrogels, as demonstrated in the capacitive hydrophone, has been shown to enhance low-frequency acoustic signal detection sensitivity to −159.7 dB. This significant improvement over traditional hydrophones (RHC-14) in the low-frequency range is a testament to the stability advantages of structural reinforcement [55].

The present study explores the relationship between energy harvesting and the development of new sensors.

Ion-conductive hydrogels have been utilized in conjunction with triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs), resulting in the development of a TENG system that facilitates battery-free human motion detection and real-time fall detection through artificial intelligence. This innovation offers a novel power supply solution for wearable devices [76].

Other novel sensors include: Zhang et al. developed bioelectronic sensors that can be directly printed onto the skin [77]. This was accomplished using freeze-drying and thermal annealing of PEDOT:PSS/PVA composite bioink combined with in situ DIW 3D biomanufacturing technology. This resulted in a dry-state conductivity of approximately 6 S/m and a maximum strain of 170%. Guo et al. developed a flexible fiber optic sensor with a sensitivity of 5.85 V/kPa in the low-pressure range of 0–0.15 N, which enables precise monitoring of pulse waveforms and heart rate [78]; Dong et al. developed a wearable gas sensor that achieves highly selective detection of exhaled NH3 through the heterojunction effect and protonation mechanism [79]; Huang et al. prepared flexible electronic devices using a dynamic hydrogen bond interface in-situ self-welding strategy, with interface toughness ≈ 700 Jm−2, enabling reliable collection of joint rehabilitation pressure signals [70].

Machine learning has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on the performance of devices.

The integration of machine learning technology has been demonstrated to significantly enhance device functionality. Jiang et al. combined a multi-layer microstructure composite thin-film piezoresistive sensor array with deep learning, achieving a gesture recognition accuracy of 97.5% [80]. Similarly, Wang et al. combined an arched structure self-powered triboelectric sensor with an LSTM network, achieving a sign language recognition accuracy of 96. Fifteen percent [81]. Ren et al. developed a near-field sensing edge computing system, achieving a gesture recognition accuracy of 96.77%, gait classification accuracy of 98.31%, latency of less than 10 nanoseconds, and energy consumption of less than 0.34 pJ [82].

1.3 Significance of Study on Hydrogel Detection Method

Performance testing of hydrogels is not only the core of quality control, but also the cornerstone to promote their application innovation.

1.3.1 Performance Evaluation and Optimization

Standardized testing methods are the basis for material development. Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) can characterize the viscoelasticity of materials and guide the optimization of crosslinking networks. The swelling method combined with Flory-Rehner theory can accurately calculate the crosslinking density, which provides a basis for material modification. Microstructural characterization is equally important. Micro-CT imaging can reconstruct pore network of hydrogel in 3D and quantify porosity, connectivity and other parameters. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) can detect surface nanoscale morphologies, such as the layered structure of graphene oxide self-assembled hydrogels [83]. In addition, hydrogel crosslinking density is optimized by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), such as acrylamide hydrogel, which achieves label-free detection of antibodies by adjusting the degree of crosslinking, with sensitivity of submilligrams per liter [61].

In recent years, hydrogel performance evaluation technology has been developing towards high-precision and multi-scale. For example, Luo et al. developed laser cavitation rheology technology to minimally invasively detect the internal elastic modulus of hydrogels at high strain rates, achieving micron-level resolution [84]. In addition, the progress of in-situ characterization technology also provides a new perspective for the study of hydrogel properties. For example, Liu et al. revealed the dynamic bond change of hydrogel under strain through in-situ Raman spectroscopy [85].

1.3.2 Application Scenario Adaptability

Detection methods need to be customized for specific application scenarios. Clinical diagnosis requires high sensitivity and specificity, and CRISPR/Cas12a hydrogel increases the sensitivity of MRSA detection to 10 copies/μL through cascade signal amplification [37]. Smartphone-based fluorescence detection platforms (such as βCCM hydrogel) are more suitable for primary care, with Cr(VI) detection limits of 0.09 μg/L [38]. Environmental monitoring emphasizes anti-interference ability. The aptamer sensor protected by agarose hydrogel (HP-EAB) can effectively block the interference of biological macromolecules in whole blood and realize high selective detection of doxorubicin [86]. Development of pH-responsive hydrogel sensors adapted to complex biological samples, such as loach mucus-inspired guanosine hydrogels to break through non-specific adsorption interference in blood and detect tau protein, a marker of Alzheimer’s disease [85].

Industrial quality inspection is fast and simple, and the distance readout microfluidic chip (DPMC) realizes the naked eye quantification of aflatoxin B1 through the change of capillary flow velocity, and the detection time is less than 30 min [86]. Similarly, hydrogel-assisted paper-based sensors perform trypsin detection without specialized equipment [87].

With the diversification of application scenarios, hydrogel detection technology also presents a personalized development trend. For example, pH-responsive hydrogel sensors have been developed to adapt complex biological samples, such as loach mucus-inspired guanosine hydrogels, to break through non-specific adsorption interference in blood and detect tau protein, a marker of Alzheimer’s disease [85].

For extreme environmental monitoring, the Ag/SA SMH membrane developed by Gai et al. enables highly sensitive detection of trace uranyl (detection limit 6.7 × 10−9 mol/L) under strongly acidic conditions (pH 1.0) [88]. In the field of home medicine, the paper-based water flow distance sensor developed by Tai et al. realizes visual quantitative detection without instrument through viscosity change caused by alkaline phosphatase degradation [89].

2 Classification of Key Techniques for Hydrogel Detection Methods

Hydrogels have shown promising applications in biomedicine, environmental monitoring, flexible electronics and other fields due to their excellent hydrophilicity, biocompatibility and stimulus response characteristics. Accurate characterization of hydrogel properties is very important for its application development. Based on four aspects of physical properties, chemical properties, biocompatibility and functionality, this chapter systematically combs the key technologies of hydrogel detection methods to provide methodological guidance for R&D and quality control of hydrogel materials.

2.1 Characterization of Physical Properties

Physical properties are the basis for hydrogel applications. The physical properties of hydrogels directly affect their key characteristics such as mechanical strength, swelling behavior and microstructure, and are the basic indicators for evaluating the applicability of materials. Physical properties testing mainly includes mechanical properties, swelling behavior, pore structure and morphology.

2.1.1 Mechanical Property Test: Tensile/Compression Test, Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Principles and Methodology:

Tensile/compression testing: Uniaxial loads are applied using a universal testing machine and stress-strain curves are recorded in order to calculate the modulus, strength and ductility (ISO 37/ASTM D638).

DMA: Oscillatory stress is applied to measure the storage modulus (G’), the loss modulus (G”) and tan δ to characterise viscoelasticity (ASTM D4065).

Key Parameters:

Tensile strength (≥50 kPa medical threshold), compressive modulus, fracture strain and the G’/G” ratio (which indicates whether the material is elastic or viscous).

Method Evaluation:

Advantages of tensile/compression testing: It directly quantifies load-bearing capacity and is suitable for rigid materials.

Limitations: It cannot characterise frequency-dependent behaviour.

DMA advantages: reveals molecular chain motion (nano-filler dimensions influence viscoelasticity); suitable for dynamic applications (e.g., wearable sensors). Limitations: expensive equipment; high sample preparation requirements.

Selection logic: Static mechanics selects tensile/compression testing. For studying cell-matrix interactions in tissue engineering or dynamic responses in flexible electronic devices, DMA is mandatory.

The mechanical properties of hydrogels are usually quantified by tensile strength, compressive modulus and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA). Fig. 2 shows the stress-strain curves of original and self-healing hydrogels with different concentrations of CNCs@PDA-Au added. The curves show the relationship between the ultimate fracture stress and fracture strain of the hydrogels and the concentrations of different nanomaterials [73]. According to ISO 37 standard, the tensile strength of medical grade hydrogel should be ≥50 kPa. For example, mussel-inspired nanocomposite hydrogel (MPS@PDA-Au) developed by Wang et al. shows strength of 2.9 MPa and deformability of 508.6%, which is significantly better than traditional materials [74]. Compressive modulus testing is often performed using a universal testing machine (ASTM D575) with a strain rate setting of 1 mm/min. DMA technique is used to characterize the frequency-dependent storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”), as Xu et al. found that nanofiller dimensions significantly affect the viscoelasticity of hydrogels [90]. MPS@PDA-Au nanocomposite hydrogel was tested for mechanical properties (508.6% deformability, 2.9 MPa strength) by tensile/compressive testing for human motion monitoring [74]. Polyvinyl borate (PVB) hydrogels detect glucose by electrical resistance change, combined with DMA analysis of mechanical-chemical coupling properties [91].

Figure 2: (A) Effect of nanomaterials on self-healing and mechanical properties of hydrogels. (B) Stress-strain curves of hydrogels with 3 mg/mL nanomaterials at 1, 2, 3 h healing. (C) Cyclic stretch curves of original and self-healing hydrogels. (D) Conductivity of hydrogels and self-healing hydrogels with different nanomaterial concentrations. (E) Conductivity at different healing times. (F) Light microscopy images of hydrogels at 0, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3 h healing: (a) 0 h, (b) 1 h, (c) 1.5 h, (d) 2 h, (e) 2.5 h, (f) 3 h. (G) Physical images of stained hydrogel self-healing process and load-bearing test: (a) Uncut dual-colour hydrogel, (b) Cut into two pieces, (c) Reassembled for self-healing, (d) After complete self-healing, (e) Load-bearing test. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [73]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society

The mechanical properties of hydrogels are an important basis for their practical application, and the mechanical properties of different types of hydrogels vary significantly, as shown in Table 2. The table compares the tensile strength and compressive modulus of polyacrylamide/chitosan, hyaluronic acid and MPS@PDA-Au nanocomposite hydrogel. The data show that the mechanical strength of synthetic polymer-based hydrogel (such as MPS@PDA-Au) is significantly better than that of natural polymer hydrogel. The accurate test results of mechanical properties provide key data support for the mechanism analysis and application optimization of nanomaterial modification to improve the mechanical properties of hydrogel.

In recent years, the study of mechanical properties of hydrogels has been extended to the characterization of dynamic mechanical behavior. For example, Chen et al. revealed changes in molecular chain orientation of P(AA-co-N-MA)/PEDOT:PSS hydrogels under strain by in situ Raman spectroscopy [92].

2.1.2 Evaluation of Swelling Behavior: Swelling Ratio Measurement, Swelling Kinetic Model

Principles and Methodology:

Determination of swelling rate: Calculated based on mass change, using the formula SR = (Ws − Wd)/Wd × 100% (ASTM D570).

Kinetic models: Fickian diffusion model (diffusion-controlled) vs Schott’s second-order model (swelling rate-controlled).

Key Parameters:

Equilibrium swelling rate (200%–1000% in the medical range), diffusion index (determination of the n value), swelling rate constant.

Method Evaluation:

Advantages of swelling rate determination: simple operation (e.g., temperature-responsive PNIPAM hydrogel optimisation); limitations: only endpoint data is provided.

Advantages of kinetic models: Predicting complex environmental behaviour (e.g., a formaldehyde-responsive hydrogel exhibiting a 160 nm blue shift in reflectance spectroscopy).

Limitations: Model assumptions may introduce errors (e.g., non-homogeneous structures deviating from Fickian diffusion).

Selection logic: Rapid screening of materials based on swelling rate.

Designing drug-controlled release systems requires the combination of kinetic models to predict release behaviour.

Swelling behavior is the most remarkable characteristic of hydrogel, which directly affects its drug-carrying capacity, response speed and service life. Swelling ratio measurement is usually carried out according to ASTM D570 standard: first weigh the mass of xerogel (Wd), then soak it in deionized water or simulated body fluid until swelling equilibrium (Ws), calculate swelling ratio (SR) = (Ws − Wd)/Wd × 100%. The swelling ratio of medical grade hydrogels is typically in the range of 200–1000%, depending on the material composition and crosslinking density.

For swelling kinetics, mathematical models (such as Fickian diffusion model, Schott second-order kinetic model, etc.) were established to analyze the swelling mechanism and rate-controlling steps of hydrogel. These models can predict the swelling behavior of hydrogels under different environmental conditions and provide theoretical guidance for material design and application. Temperature-sensitive hydrogels (PNIPAM) optimize temperature response characteristics by swelling ratio measurement and are used to regulate the spacing of plasmonic nanostructures [28]. Formaldehyde-responsive photonic hydrogels were analyzed by swelling kinetics model to achieve a blue shift of reflection spectrum exceeding 160 nm [93].

The swelling behavior of hydrogel is closely related to its functionality. The swelling characteristics under different conditions can be visually displayed through experiments. As shown in Fig. 3, the structural evolution and performance difference between pCBMA-Al³+ and pCBMA hydrogel during swelling process are revealed through Raman spectra, swelling size change, conductivity and SEM images, which provides experimental basis for regulating swelling kinetics and functional optimization of hydrogel through ion coordination. In recent years, important progress has been made in dynamic monitoring techniques of swelling behavior. For example, the photonic crystal-based swelling sensor developed by Sun et al. enables real-time monitoring of hydrogel swelling process through reflection spectral shift [95]. In addition, machine learning has also been applied to the prediction of swelling behavior, such as Wang et al. successfully predicted the swelling rate change of hydrogel under different environmental conditions by using neural network model [96].

Figure 3: Schematic illustration of the swelling behavior of hydrogels. (A) Raman spectra analysis of the pCBMA-Al3+ and pCBMAhydrogels. Swelling size (cm) of the pCBMA-Al3+ (B) and pCBMA (C) at different times. (D) Conductivity of the pCBMA-Al3+ and pCBMA (inset shows the resistance values of the pCBMA-Al3+ and pCBMA). Cross-sectional SEM images of freeze-dried hydrogels: pCBMA (E), pCBMA-Al3+ (F). (G) The pore size distribution curves of the pCBMA and pCBMA-Al3+ hydrogels. Copyright 2024, Springer-Verlag GmbH, DE. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [94]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier

2.1.3 Pore Structure and Morphology Characterization: SEM, AFM, Micro-CT Imaging

Principles and Methodology:

SEM: A scanning electron beam is passed over the surface with a resolution of up to 1 nm (e.g., Gao observed an AuTAG array with pores ranging from 50 to 200 nm).

AFM: Probe scanning over the surface to quantify roughness (e.g., Liu discovered that Zn2+ triggers nanotopography in hydrogels).

Micro-CT: Three-dimensional X-ray reconstruction for analysing pore connectivity (e.g., Wang’s evaluation of the ‘liver lobule’ microstructure).

Key Parameters:

Pore size distribution (SEM/AFM), surface roughness (AFM) and porosity/connectivity (micro-CT).

Method evaluation:

SEM Advantages: high-resolution morphological observation. Limitations: requires vacuum drying, which may damage natural structures; provides only surface information.

Advantages of AFM: in situ liquid-phase detection. Limitations of AFM: small scanning range (<100 μm).

MicroCT advantages: non-destructive three-dimensional structural analysis. Limitations: limited resolution (~0.5 μm); metal fillers interfere with imaging.

The selection logic is as follows: surface morphology is selected using SEM/AFM (with AFM being mandatory in liquid environments), and micro-CT is required for evaluating pore connectivity in tissue engineering scaffold development.

The pore structure and surface morphology of hydrogels have a decisive influence on their biocompatibility, material transport and mechanical properties. The microstructure, surface morphology and three-dimensional spatial distribution of hydrogel were characterized by scanning electron microscope (SEM), atomic force microscope (AFM) and micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), which provided basis for material performance optimization. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is the most commonly used morphology observation technique, which can visually display the microstructure and pore size distribution of hydrogels, which shows SEM images of silver nanoparticles assembled microcavity array hydrogel at different growth times, revealing the effect of nanoparticle deposition time on the regulation of hydrogel pore structure, providing morphological basis for hydrogel sensor design based on pore engineering [39]. Gao et al. confirmed by SEM that the pore size of AuTAG array hydrogel is 50–200 nm [28]. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) can quantify the surface roughness. Micro-CT imaging is used for 3D pore network reconstruction, and Wang et al. analyzed pore connectivity of “hepatic lobules” micro-tissue through micro-CT [96].

The precise regulation of pore structure is the key to the optimization of hydrogel properties. For example, graded porous DNA hydrogel prepared by freeze-drying method by Lu et al. significantly improved the detection sensitivity of aflatoxin B1 [30]. In addition, the development of new imaging technology also provides new means for the study of hydrogel microstructure, such as super-resolution optical microscope developed by Zhang et al. to realize the visualization of hydrogel nano-scale pore structure [97]. SEM was used to observe the pore structure of photonic crystals assembled by mesoporous silica particles, and it was found that solute preferentially occupied mesopores, which could lead to an increase in reflection index, thus solving the detection failure problem caused by the decrease of refractive index contrast of traditional colloidal photonic crystals [98].

The chemical properties of hydrogels determine their stability, functional properties and biocompatibility, and are the basis of material design and application. Chemical properties testing mainly includes component analysis, crosslinking density determination and degradation behavior research.

2.2.1 Composition Analysis: FTIR, XPS, NMR

Principles and Methodology:

FTIR: functional group vibration spectrum (COOH peak at 1700 cm−1).

XPS: elemental composition and valence (e.g., Zhang confirmed the dispersion of single Pt atoms).

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR): Molecular structure analysis (e.g., Chen analysed the PEG-DA cross-linked network).

Key Parameters:

- Characteristic peak positions (FTIR)

- Elemental binding energies (XPS)

- Chemical shifts (NMR)

Method Evaluation:

FTIR

Advantages: Rapid functional group screening.

Limitations: Low sensitivity (>1% component).

XPS advantages:

- High sensitivity

- Low sensitivity

XPS advantages: Quantitative surface element analysis (depth < 10 nm).

Limitations: Requires a vacuum environment and cannot detect H/He.

NMR advantages: Non-destructive structural analysis.

Limitations: Samples must be soluble and there is low sensitivity.

Selection logic: Choose XPS for analysing surface modifications; choose solid-state NMR for characterising cross-linked networks; choose FTIR for rapid quality control.

Component analysis is an important means to confirm the chemical structure and functional groups of hydrogel. as shown in Fig. 4. It shows the preparation process and FT-IR characterization results of PPNAH biosensor. Through the change of characteristic functional groups in infrared spectrum (such as the appearance of amide bond absorption peak at 1600 cm), the successful coupling of penicillin enzyme and hydrogel matrix is confirmed, which provides chemical structure evidence for the specific recognition of penicillin G by this sensor [97]. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is used to identify functional groups such as the-COOH peak (1700 cm−1) in polyacrylic acid. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can quantify the elemental composition, Zhang et al. confirmed the atomic dispersion of Pt in Co3O4/Pt monoatomic catalyst by XPS [72]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was used to analyze the crosslinking network, and Chen et al. used 1 H-NMR to determine unreacted monomer residues in polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEG-DA) [99].

Figure 4: Fabrication and characterization of PPNAH biosensors. (A) Schematic manufacturing diagram (A1→A4), PG identification (A4 →A5) and recycling (A5 →A6). SEM images of (B) PNAH, (C) penicillinase-modified PNAH (PPNAH), (D) and PG-recognized PPNAH (PPNAH@PG). (E,F) SEM/EDS images of PPNAH and scale bars are 15 μm in Fig. 1, such as FT-IR spectra of (G) PNAH, PPNAH, and PPNAH@PG. (H) Reflectance spectra and digital photographs (inset) of PPNAH before (red line) and after (blue line) in response to PG. PG = 1000 U/mL ≈ 2.8 mM. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [97]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier

The sensitivity and resolution of compositional analysis techniques continue to improve. For example, synchrotron radiation XPS technology developed by Wang et al. realized nano-resolution imaging of element distribution on hydrogel surface [100], and characterized the structure of synthesized 3-QW-NiFe metal hydrogel by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [100]. In addition, the development of in-situ characterization technology also provides a new perspective for the study of hydrogel chemical properties, such as Liu et al. monitoring the dynamic process of hydrogel crosslinking reaction through in-situ FTIR [85]. To further elucidate the intricate composition and chemical states within advanced hydrogel composites, comprehensive spectroscopic characterization is indispensable. As shown in Fig. 5, the elemental mapping (Panel A) of the 3-QW-NiFe xerogel confirms the homo-geneous distribution of C, N, O, Fe, and Ni, indicating a well-integrated metallic hydrogel network. The FTIR spectra (Panel B) and XRD patterns (Panel C) provide evidence for successful composite formation and crystallographic structure. Furthermore, the full XPS survey spectra (Panel D) and the high-resolution scans of Ni 2p (Panel E) and Fe 2p (Panel F) offer critical insights into the elemental composition and valence states, revealing the synergistic interactions between the metal ions and the organic matrix that are pivotal for the hydrogel’s enhanced functional properties [100].

Figure 5: (A) Elemental mapping of C, N, O, Fe, and Ni of 3-QW-NiFe xerogel. (B) IR spectra. (C) XRD pattern of 3-QW powder and 3-QW-NiFe xerogel. Full XPS survey spectra of 3-QW powder and 3-QW-NiFe xerogel (D), high resolution spectra of Ni 2p (E) and Fe 2p (F), respectively. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [100]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier

2.2.2 Determination of Crosslinking Density: Swelling Method, Mechanical Modulus Back Extrapolation

Method Principle:

Swelling Method: Based on the Flory-Rehner theory, the modulus (G) is calculated using the equation: G = (RT ∗ φ^(1/3)) / (V_r ∗ (φ^(1/3) − φ/2)).

Modulus Back-Calculation Method: ν_e = G/(RT) (rubber elasticity theory).

Key Parameters:

Crosslink density (mol/m3) and swelling equilibrium parameter (φ).

Method Evaluation:

Advantages of the Swelling Method: Broad applicability (e.g., adjusting Mg2+ concentration in DNA hydrogels)

Limitations: It assumes an idealized network structure and ignores entanglement.

Modulus inversion advantages: Direct correlation with mechanical properties

Limitations: Only applicable in the elastic dominance region (fails when G’ > G).

Selection logic: Swelling method for soft gels with high water content and modulus inversion for highly crosslinked elastomers.

Crosslinking density is a key parameter affecting the mechanical properties, swelling behavior and stability of hydrogels. The swelling method is the most commonly used method for determining the crosslinking density. Based on Flory-Rehner theory, the crosslinking density is calculated by equilibrium swelling ratio. Mechanical Modulus Backward Method By measuring the elastic modulus of hydrogels, the crosslinking density is estimated by the elastic theory of rubber. DNA hydrogel can adjust the crosslinking density by adjusting Mg2+ concentration. The swelling ratio measurement shows that the swelling ratio decreases by 30% and the mechanical modulus increases to 120 kPa at high crosslinking density (Mg2+ concentration 10 mM) [101].

Accurate determination of crosslinking density is crucial to the regulation of hydrogel properties. For example, Cao et al. significantly improved the sensitivity of alginate hydrogels to putrescine (detection limit 10−9–10−10 mol/L) by optimizing the crosslinking density [102].

2.2.3 Degradation Behavior: In Vitro Simulated Degradation Experiment, Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Principles and Methodology:

In Vitro Degradation: Monitor mass loss in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/enzyme solution. For example, Li’s polybutyrate hydrogel degraded by 72.4% over 28 days.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Identify the molecular weights of degradation fragments (e.g., no degradation fragments were detected in the chitosan hydrogel).

Key Parameters:

Mass loss rate, fragment molecular weight distribution, and enzymatic degradation rate constant.

Method Evaluation:

Advantages of in vitro degradation: low cost and high throughput (ISO 10993 standard process). Limitations: cannot simulate in vivo dynamic environments.

Advantages of mass spectrometry: precise fragment analysis. Limitations: cannot distinguish between fragment sources (material vs. metabolic products).

Selection logic: Use in vitro degradation for initial screening and combine mass spectrometry for biosafety verification in preclinical studies.

The study of degradation behavior is particularly important for the application of hydrogels in biomedical field. In vitro simulated degradation experiments are usually carried out in PBS solution (pH 7.4) or solutions containing enzymes (such as lysozyme and collagenase) at 37°C. The degradation performance was evaluated by periodically measuring the mass loss, mechanical property change and degradation product release of the samples. Mass spectrometry can identify the molecular structure and composition of degradation products and assess their biological safety. For example, poly (1-pyrenebutyric acid)/sodium alginate hydrogel developed by Li et al. degraded 72.4% in 28 days [36]. After incubation in phosphate buffer at pH 6.8 for 7 days, weighing method showed mass loss < 5%, confirming its chemical stability; mass spectrometry analysis did not detect chitosan degradation fragments, indicating that the ion-imprinted layer inhibited matrix decomposition, and the stable degradation behavior ensured the reusability of IICA in Cd (II) adsorption and detection [103].

Precise regulation of degradation behavior is the key to clinical application of hydrogel. For example, Yang et al. developed enzyme-sensitive peptide-modified hydrogels whose degradation rate can be precisely controlled by enzyme concentration [43]. In addition, breakthroughs have been made in real-time monitoring technology of degradation products, such as microdialysis coupled with mass spectrometry system developed by Liu et al., which realizes online analysis of hydrogel degradation products [85].

2.3 Biocompatibility Characterization

The application of hydrogel in biomedical field must meet strict biocompatibility requirements, including cell compatibility, histocompatibility and degradation safety. Biocompatibility testing is a key step in evaluating the clinical potential of hydrogels.

2.3.1 Cytocompatibility Characterization: Cell Proliferation/Toxicity Test (MTT, Live and Dead Staining)

Method Principle:

MTT Assay: Mitochondrial dehydrogenase reduces MTT to purple formazan, and the OD value quantifies the survival rate.

Live/Dead Staining: Dual staining with calcein-AM (green) and iodopurine (red) is observed under fluorescence microscopy.

Key Parameters:

Cell survival rate (≥70% is the medical threshold) and the proportion of live and dead cells.

Method Evaluation:

MTT

Advantages: Quantitative and efficient (e.g., verifying low toxicity in cellulose hydrogel).

Limitations: It indirectly reflects metabolic activity rather than directly measuring survival rate.

Live/dead staining advantages: It directly assesses single-cell status (e.g., gelatin patch wound healing studies).

Limitations: Semi-quantitative and low throughput.

Selection logic: Use MTT for high-throughput screening and live/dead staining for 3D cultures or complex microenvironments.

Cellular compatibility is the primary indicator for evaluating the biological safety of hydrogels. MTT assay is the most commonly used method to detect cytotoxicity, which reflects cell survival rate by measuring mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. According to ISO 10993-5 and GB/T 16886.5 standards, the cell survival rate of medical materials should be ≥70% (L929 fibroblasts as the model). The method of living and dead staining shows the living state of cells visually by double staining with calcein AM (live cells) and propidium iodide (dead cells). Nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots prepared from cellulose hydrogel were verified to have low toxicity by MTT and used for Hg² detection [104]; gelatin hydrogel patches were evaluated for cell compatibility by live and dead staining and used for wound repair research [40] The cell compatibility evaluation system was continuously improved. For example, Debnath et al.’s photopatterned hydrogel microwell array combined with a deep learning algorithm enables high-throughput biocompatibility assessment (mAP up to 0.989) at the single cell level [105]. In addition, the development of 3D cell culture model also provides an evaluation platform closer to in vivo environment for hydrogel biocompatibility research, such as pancreatic β cell microtissue model constructed by Duan et al. [46].

2.3.2 In Vivo Biodegradation Characterization: Animal Model Tracking, Tissue Section Analysis

Principles and Methodology:

Animal Model: Tissue samples were taken after implantation and stained with H&E to observe inflammation. This was confirmed by Chen, who found that the P(AA-co-N-MA) hydrogel does not cause inflammation.

Tissue sections: Masson staining to assess collagen deposition and immunohistochemistry to detect specific proteins.

Key Parameters:

Inflammation score (ISO 10993-6), neovascularization density, and collagen area ratio.

Method Evaluation:

Advantages of Animal Models: Evaluation in a real physiological environment

Limitations: High ethical costs and significant species differences.

Advantages of tissue sections: Analysis of pathological mechanisms

Limitations: Endpoint analysis lacks dynamic processes.

Selection logic: Animal experiments are mandatory according to regulations, and mechanistic studies require the use of multi-staining techniques.

In vivo biodegradation study the degradation behavior and host response of hydrogels were evaluated by animal models. Common methods include subcutaneous implantation, muscle implantation or implantation in specific sites (such as bone defect area), and periodic sampling for histological analysis. H&E staining was used to observe inflammatory reaction, Masson staining to evaluate collagen deposition, and immunohistochemistry to analyze specific protein expression. According to ISO 10993-6 standard, the degree of inflammatory cell infiltration after implantation for 28 days is an important indicator for evaluating the histocompatibility of materials. Chen et al. demonstrated that P(AA-co-N-MA)/PEDOT:PSS hydrogel had no significant inflammatory response within 28 days by mouse model [92].

Precision and non-invasiveness of in vivo evaluation technology is an important development trend. For example, Liu et al. developed fluorescence-NMR dual-mode probe, which realized real-time non-invasive monitoring of hydrogel degradation process [45]. In addition, the application of large animal models also provides more reliable data support for clinical transformation of hydrogels, such as Yang et al. assessing the biocompatibility of DNA hydrogel microneedles [43]. The stability of agarose hydrogel sensors has been confirmed by animal models, blocking the adsorption of biological macromolecules in whole blood [86].

2.4 Functional Characterization

Functional testing is aimed at optimizing the performance of hydrogels in specific application scenarios, covering drug release, environmental response and electrochemical characteristics, etc., and is a bridge connecting basic research and practical application of materials.

2.4.1 Evaluation of Drug Release Performance: HPLC, Fluorescent Label Tracking

Principles and Methodology:

HPLC: Chromatographic separation and quantification of drug concentration (e.g., 40% doxycycline release from lanthanum ion hydrogel over 24 h).

Fluorescent labeling: Labeling drug molecules to monitor release kinetics in real time (e.g., tracking formaldehyde diffusion as done by Liu).

Key Parameters:

Cumulative release rate, burst release effect, and release rate constant.

Method Evaluation:

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Advantages: Precise quantification of multiple components (e.g., sustained-release data from ZIF-8@hydrogel).

Limitations: Sample destruction and inability to monitor in situ.

Fluorescent labeling advantages: Real-time, in situ tracking (e.g., bFGF gelatin hydrogel).

Limitations: Labeling may alter drug properties.

Selection logic: Choose HPLC for quantitative release curve analysis and choose fluorescent labeling to study release mechanisms or spatial distribution.

Drug release performance is the core evaluation index of drug-loaded hydrogels. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is the mainstream technique for drug release analysis. Mei et al. confirmed the sustained release efficiency of lutetium ion hydrogel to doxycycline by HPLC (40% release in 24 h) [106]. Fluorescence labeling method is used for real-time tracking, such as Liu et al. using near-infrared probes to monitor formaldehyde diffusion in hydrogel [31]. Release kinetics optimize treatment effectiveness. Gelatin hydrogels loaded with bFGF were used in wound healing studies to track drug release by fluorescent labeling [40]. The drug loading and release efficiency of different hydrogels vary significantly, as shown in Table 3. Table 3 compares the drug loading, 24-h release rate and detection technology of different hydrogels, showing that intelligent responsive hydrogels (such as lutetium ion hydrogel) can realize controlled release of drugs through structural design, providing data reference for optimization of targeted drug delivery system.

Drug release monitoring technology is constantly developing towards real-time and accurate. For example, temperature-sensitive hydrogels can be used to determine drug release efficiency by HPLC, which can be combined with temperature trigger mechanism to improve targeting [28]. In addition, important progress has also been made in the research of stimulus-responsive release systems, such as the near-infrared light-controlled hydrogel developed by Zhao et al., which realizes the time-space accurate release of drugs [42].

2.4.2 Characterization of Environmental Responsiveness: Real-Time Monitoring of Temperature/pH/Light Responsiveness

Method Principle:

Real-time monitoring: Spectroscopy (wavelength shift, reflection, or absorption) or electrical signals (resistance or capacitance) in response to stimuli.

Key Parameters:

Response time (seconds), sensitivity (e.g., pH hydrogel detection of Fe3+ with a limit of 0.58 μmol/L), and cyclic stability.

Method Evaluation:

Spectroscopy

Advantages: Non-contact detection (e.g., photonic crystal hydrogel detection of penicillin G).

Limitations: Optical interferences may affect accuracy.

Advantages of the electrical signal method: easy integration with electronic devices (e.g., PEDOT:PSS hydrogel Fe3+ detection). Limitations: requires conductive materials.

Selection logic: Choose the spectroscopic method for high biocompatibility requirements and the electrical signal method for wearable device integration.

Environmental responsiveness is an important characteristic of intelligent hydrogels. Stimulus-responsive hydrogels can be dynamically monitored by changes in spectra or electrical signals. For example, temperature-sensitive hydrogels developed by Gong et al. release EV71 virus at 45°C [5], while photonic crystal hydrogels detect penicillin G by reflection wavelength shift [97]. pH responsive hydrogels detect Fe3+ by color change (detection limit 0.58 μmol/L) [107].

Environmental response monitoring technologies are becoming increasingly sensitive and responsive. For example, the high-frequency ultrasonic imaging system developed by Shi et al. has achieved millisecond resolution observation of hydrogel phase transition process [60]. In addition, breakthroughs have also been made in the study of multi-response hydrogels, such as the temperature-pH dual-response hydrogel designed by Chen et al., which can simultaneously indicate two environmental parameters through color changes [92].

2.4.3 Electrochemical Performance Measurement: Impedance Spectrum, Conductivity Test

Method Principle:

Impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measures impedance at different frequencies and fits an equivalent circuit (e.g., MXene sensors for hydrogen peroxide detection).

Conductivity testing: The four-probe method eliminates contact resistance (e.g., changes in the conductivity of PEDOT:PSS hydrogels).

Key Parameters:

Conductivity (≥1 S/m is the threshold for flexible electronics), charge transfer resistance (R_(ct)), and double-layer capacitance.

Method Evaluation:

EIS advantages:

- Analyze interface reaction mechanisms (e.g., the linear relationship between Fe3+ concentration and conductivity);

- Limitations: Data analysis is complex.

Four-probe method advantages: Accurate bulk conductivity. Limitations: Not suitable for anisotropic materials.

Selection logic: Choose EIS for sensor interface optimization and the four-probe method for screening conductive materials.

Electrochemical properties are critical to the application of conductive hydrogels. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyzes charge transfer and substance transport processes by measuring impedance response at different frequencies. Chen et al. confirmed that Fe3+ concentration is linearly related to P(AA-co-N-MA)/PEDOT:PSS conductivity through EIS [92]. The conductivity of conductive hydrogels (such as polyaniline/polyvinyl alcohol system) is usually required to be ≥1 S/m to meet the requirements of flexible electronic devices. Electrochemical technology improves detection accuracy. The MXene-based sensor monitors H2O2 through impedance spectroscopy, with a detection limit of 1.08 × 10−3 mM [108]; the conductive PEDOT:PSS hydrogel detects Fe3+ through changes in conductivity, and integrates electronic equipment to achieve health warning [92].

Conductivity, as a core performance index, directly affects signal conduction and sensing accuracy in flexible electronic devices. Performance optimization and function expansion of conductive hydrogels are research hotspots. For example, the conductivity peaks with the CNCs@PDA-Au nanomaterial concentration of 3 mg/mL, revealing the intrinsic correlation between the nanomaterial loading and the hydrogel conductive network construction efficiency, providing a key basis for optimizing the functional design of conductive hydrogels through conductivity testing [73]. The PDEA-HRP/MXene/PG composite hydrogel electrochemical biosensor developed by Ma et al. not only realizes high sensitivity detection of H2O2 in a wide linear range of 0.04–1.80 mM (detection limit up to 1.08 × 10−3 mM), but also successfully constructs a variety of biomolecular electrocatalytic logic gate systems including 5-input/5-output logic gate networks, which provides a new detection platform for disease prevention and diagnosis and biomolecular calculation [108].

3 Challenges Faced by Existing Detection Methods

Although significant progress has been made in the detection technology of hydrogel, there are still many challenges in standardization, dynamic monitoring, micro-macro correlation and complex environmental adaptability. This chapter systematically analyzes the core limitations of the existing detection methods, and combined with typical cases and cutting-edge research, reveals the technical bottlenecks and improvement directions.

3.1.1 Problem: Lack of Standardization

The rapid development of hydrogel detection techniques has been accompanied by significant material preparation diversity and methodological confusion. Material preparation and testing procedures vary significantly between laboratories, resulting in results that are not comparable. For example, when silver nanoparticles modify hydrogel substrates, the reducing agent (e.g., sodium borohydride vs. ascorbic acid) or crosslinking method (photoinitiation vs. ionic crosslinking) used in different laboratories leads to differences in nanoparticle size distribution (10–100 nm), which directly affects SERS signal intensity and reproducibility [109,110]. In terms of detection process, there is no uniform specification for key steps such as background subtraction and calibration curve establishment in fluorescence detection, which makes the detection limit of similar sensors in literature fluctuate by 1–3 orders of magnitude (e.g., Hg2+ detection limit varies from 0.2 μM to 15 nM [104,111]). In addition, the absence of quality control indicators (such as industry standard values for crosslinking density and minimum requirements for degradation rates) makes it difficult to compare test methods developed by different teams horizontally, hindering the process of technical standardization.

This challenge directly impacts the characterization of hydrogels’ chemical properties (such as compositional analysis and crosslinking density measurement) and functional performance (such as drug release evaluation). For instance, the lack of standardized methods for determining crosslinking density leads to incomparable mechanical test results across different research teams, thereby hindering material optimization and application suitability assessment.

3.1.2 Solution: Establishment of Grading Standard System

The standardization of hydrogel testing technology is the key to promote the comparability of material properties and industry standardization. The establishment of grading standard system can effectively solve the problems of chaotic testing process and incomparable results. Hierarchical standardization: Develop subdivision standards by material type (e.g., synthetic gel, natural gel, intelligent response gel); Cross-platform calibration: Establish reference sample libraries (e.g., NIST standard hydrogel) for data calibration between devices; Open source algorithm sharing: Develop uniform data processing software (e.g., Python script) to reduce human interpretation bias.

This solution addresses the standardization requirements for characterizing the chemical properties (e.g., Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)) and physical properties (e.g., mechanical testing, swelling behavior) of hydrogels. For instance, the establishment of a unified FTIR testing process and data analysis algorithm would ensure the comparability of analysis results for hydrogel functional groups across different laboratories, thereby providing a reliable basis for material design.

3.2 Dynamic Process Monitoring

3.2.1 Problems: Dynamic Transient Changes Are Difficult to Capture

The dynamic characteristics of hydrogels make real-time monitoring of their rapid gelation and degradation process a major challenge. Although traditional methods such as rheometer can characterize gelation time, it is difficult to capture the dynamic crosslinking process at molecular level. Although the Glu-MIPH sensor developed by Sun et al. can monitor the molecular recognition process through Debye diffraction ring change, its time resolution (≥10 s) is still insufficient to reveal the rapid conformation change of sub-second level, which reveals the bottleneck of traditional detection technology in tracking sub-second dynamic events and provides an improvement direction for developing high time resolution in-situ monitoring technology [112]. To further illustrate the challenges in capturing rapid dynamic responses, Fig. 6 presents the selectivity, response time, and sensitivity of a typical molecularly imprinted photonic hydrogel sensor (Glu-MIPH) for L-glutamic acid detection. As shown in Fig. 6A, the sensor exhibits excellent selectivity against interfering compounds. Fig. 6B demonstrates its rapid response within seconds, yet even such advanced systems struggle to resolve sub-second conformational changes, highlighting the limitations of current technologies in monitoring ultrafast hydrogel dynamics. The linear detection ranges in Fig. 6C,D further underscore the need for higher temporal resolution in real-time sensing applications.

Figure 6: (A) Detection selectivity and immunity to interference. The concentration of each compound is 10 mM, regardless of the pure and mixed solutions (Mix-1 and Mix-2). (B) Response time (in 10 mM L-Glu solution). (C) Detection sensitivity. Image: Linear correlation of L-Glu concentrations in the range of 1–10 μM. (D) Linear correlation of L-Glu concentrations in the range of 20–100 μM. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [112]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier

The crosslinking process of DNA hydrogels depends on Mg2+ concentration, but its gelation time (from seconds to hours) and network structure evolution lack dynamic characterization means, and can only be indirectly inferred from ex post swelling ratio or mechanical modulus [101]. In terms of degradation behavior, in vitro simulation experiments (such as phosphate buffer incubation) cannot completely reproduce the complex environment in vivo (such as enzyme concentration gradient, pH microenvironment), resulting in the degradation rate of chitosan hydrogel in animal models faster than in vitro by 30%–50% [8]. Such differences may trigger bias in drug release kinetics predictions or distortions in biocompatibility assessments, limiting clinical translation. In addition, the lack of real-time monitoring technology makes it difficult to accurately obtain the dynamic changes of key parameters such as local pH value and mechanical properties during degradation, which restricts the design optimization of controllable degradation hydrogel.

This challenge imposes elevated demands on testing methodologies, such as dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) and swelling kinetics modeling of hydrogels. For instance, while traditional DMA can adequately characterize the viscoelasticity of hydrogels, it lacks the capability to capture the instantaneous response of the cross-linked network in dynamic environments (e.g., temperature changes) in real time. This limitation restricts the optimization of the application of smart hydrogels.

3.2.2 Solution: Dynamic Monitoring of New Technologies

Emerging technologies offer the possibility of solving the dilemma of capturing dynamic transients. Miniaturized sensing technology: develop fiber optic probes or nano-electrodes implanted in hydrogel to monitor parameters such as pH and ion concentration in real time; non-invasive imaging: use optical coherence tomography (OCT) or Raman spectroscopy to achieve nondestructive dynamic imaging; computational simulation assistance: combine finite element analysis (FEA) to predict dynamic processes and reduce experimental blind spots.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is another promising technique, and Sun et al. successfully tracked the dynamic evolution of pore structure in hydrogels using OCT [95]. In addition, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation can assist in predicting substance transport behavior, for example, Wang et al. established a “liver lobe” model to accurately predict drug diffusion system [96].

These novel technologies complement the dynamic mechanical analysis and swelling behavior evaluation methods of hydrogels. For instance, OCT technology can be utilized in conjunction with DMA to observe the microscopic structural changes of hydrogels under mechanical loading in real time, thereby establishing a more accurate dynamic performance model.

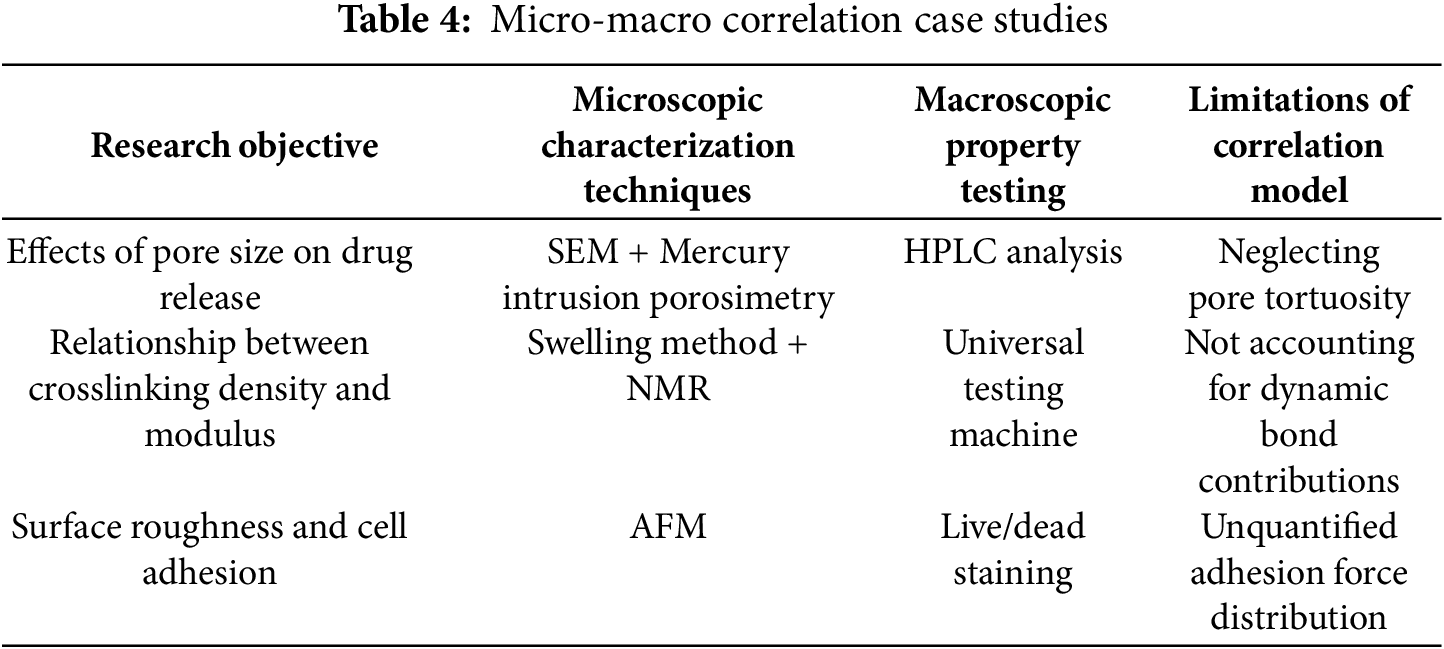

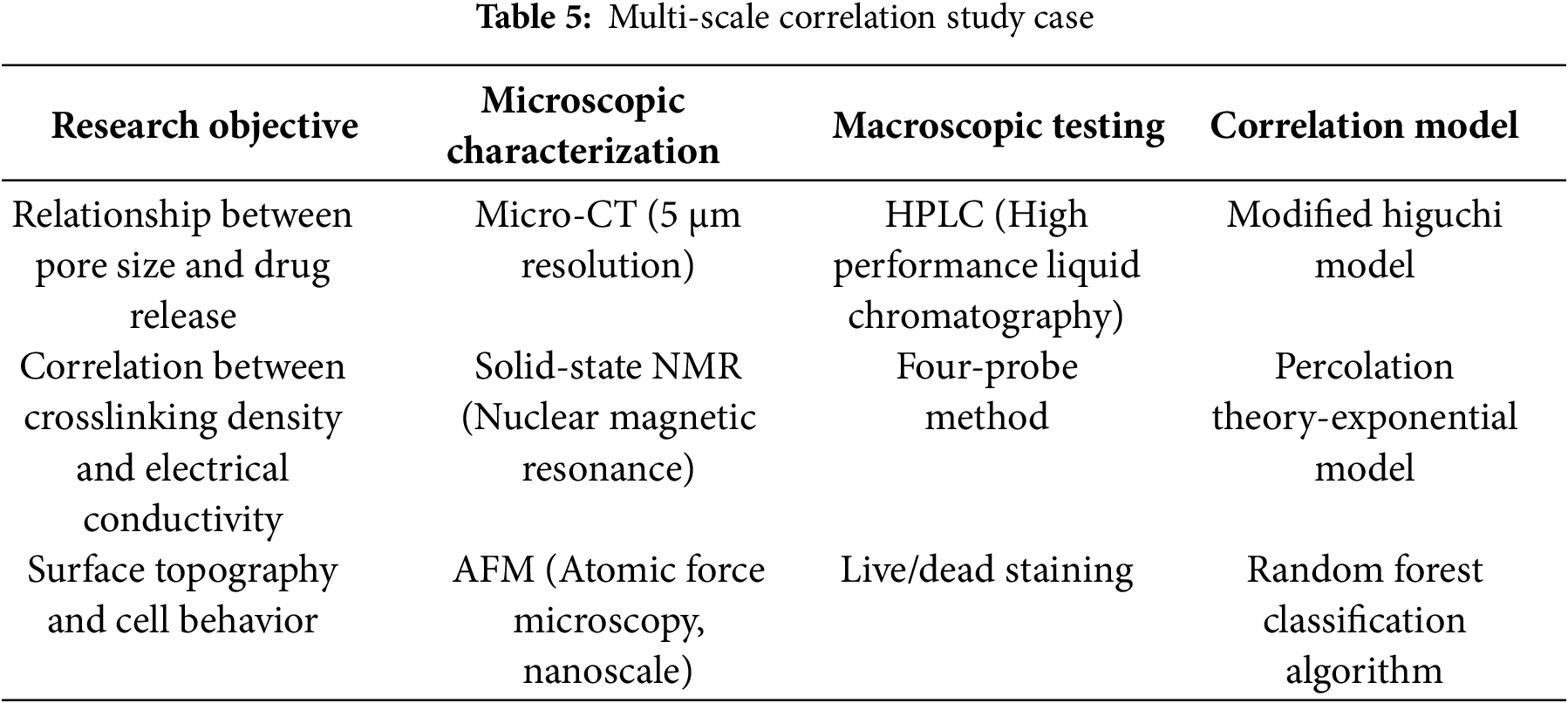

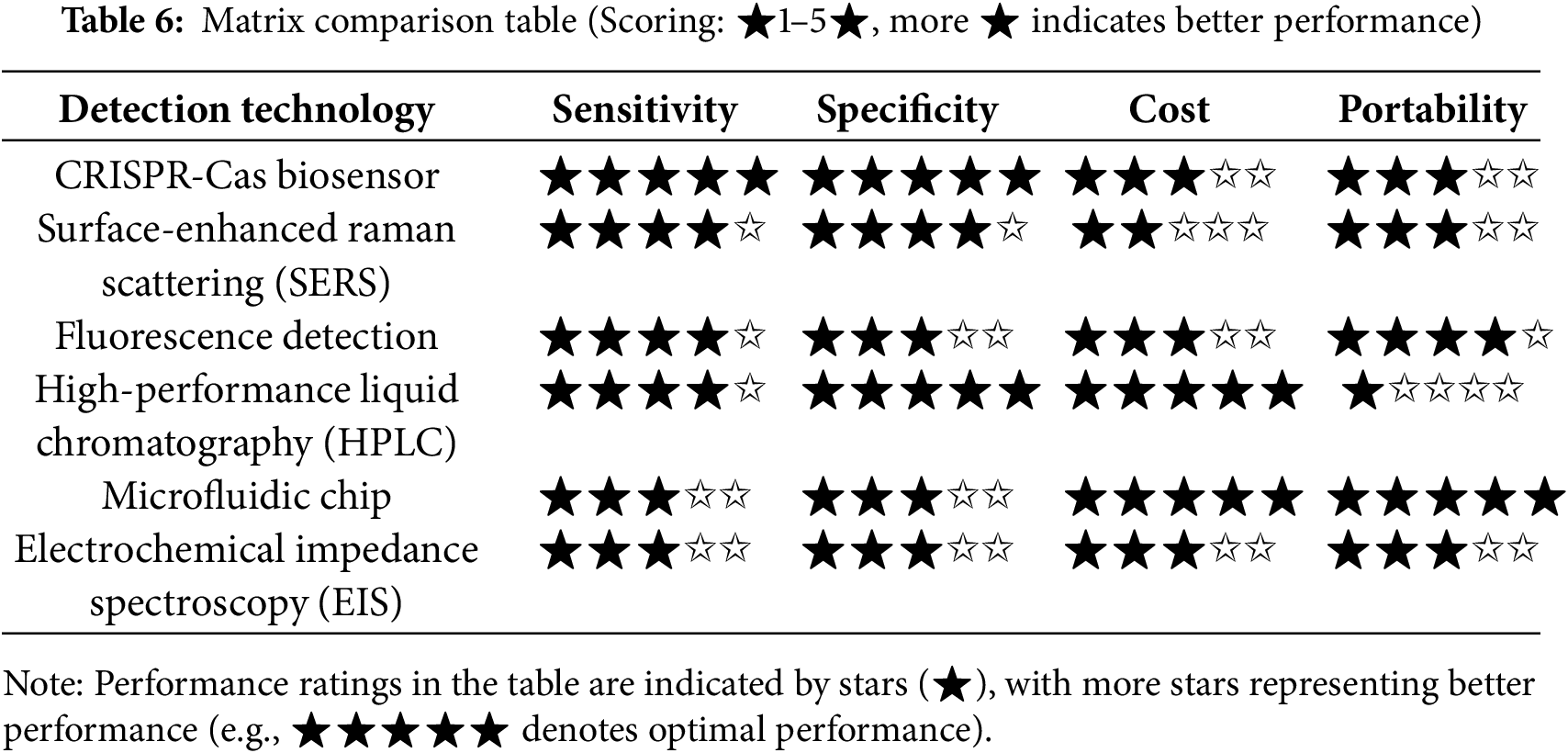

3.3 Micro-Macro Performance Correlation Detection

3.3.1 Problem: Multiscale Modeling Challenges