Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Biomass-Derived Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: Current Research, Trends, and Challenges

1 Department of Chemistry, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville, 7535, South Africa

2 Energy Centre, Smart Places Cluster, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Pretoria, 0001, South Africa

* Corresponding Authors: Ntalane Sello Seroka. Email: ; Lindiwe Khotseng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Biochar Based Materials for a Green Future)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1935-1977. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0026

Received 05 February 2025; Accepted 20 May 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

The review investigates the use of biomass-derived carbon as precursors for nanomaterials, acknowledging their sustainability and eco-friendliness. It examines various types of biomasses, such as agricultural residues and food byproducts, focussing on their transformation via environmentally friendly methods such as pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonisation. Innovations in creating porous carbon nanostructures and heteroatom surface functionalisation are identified, enhancing catalytic performance. The study also explores the integration of biomass-derived carbon with nanomaterials for energy storage, catalysis, and other applications, noting the economic and environmental benefits. Despite these advantages, challenges persist in optimising synthesis methods and scaling production. The study also highlights existing research gaps, forms a basis for future studies, and underscores the role of biomass-derived nanomaterials in promoting a circular economy and sustainability.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The pressing requirement for sustainable and eco-friendly technologies has led to considerable interest in nanomaterials. Of the different methods, the use of carbon obtained from biomass for the environmentally friendly synthesis of nanomaterials emerges as a notable tactic. The synthesis, characteristics, and uses of materials, particularly nanomaterials, derived from biomass, highlight their potential role in promoting sustainable development and protecting the environment. Nanomaterials have significantly impacted fields such as electronics, medicine, energy storage, and catalysis because of their distinctive physical and chemical characteristics. Conventional methods for synthesising these materials often rely on hazardous chemicals and high energy consumption, raising environmental concerns. Therefore, the pursuit of environmentally friendly synthesis techniques has accelerated in line with the broader objectives of sustainable development and the principles of green chemistry. Biomass carbon, obtained from agricultural waste, forest residues, and other organic resources, offers a renewable and abundant avenue for the sustainable production of nanomaterials [1–3].

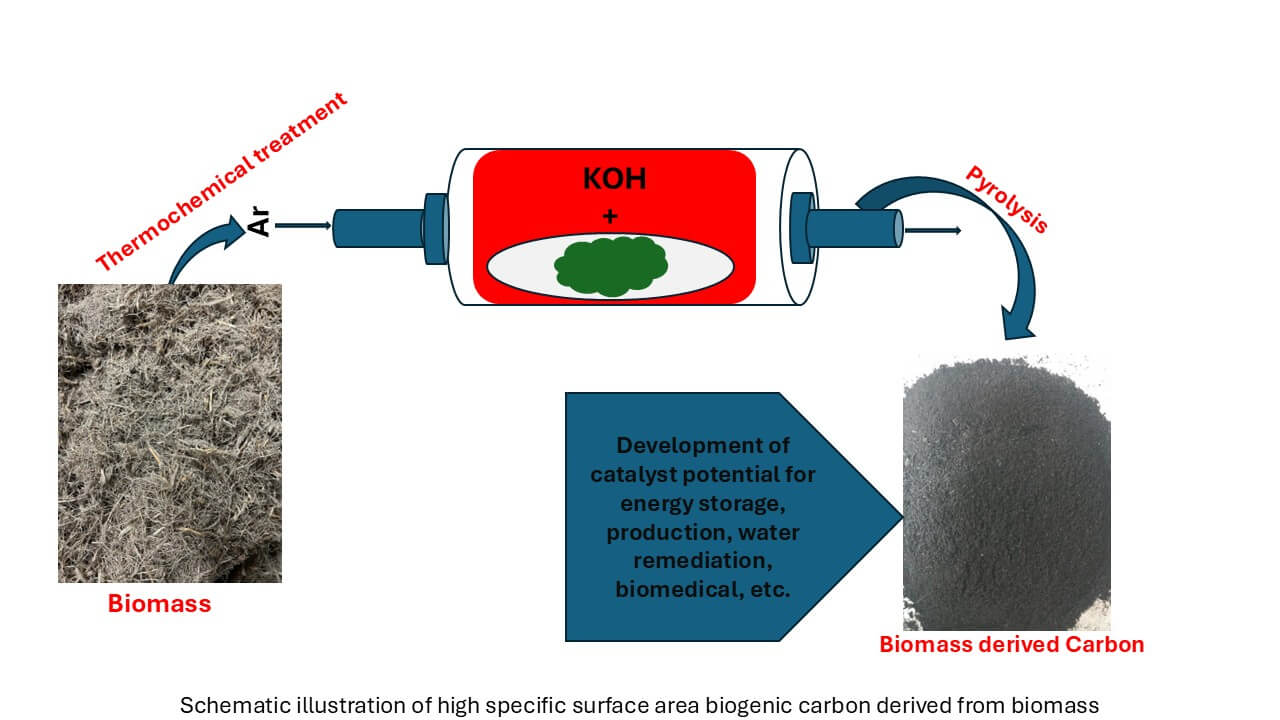

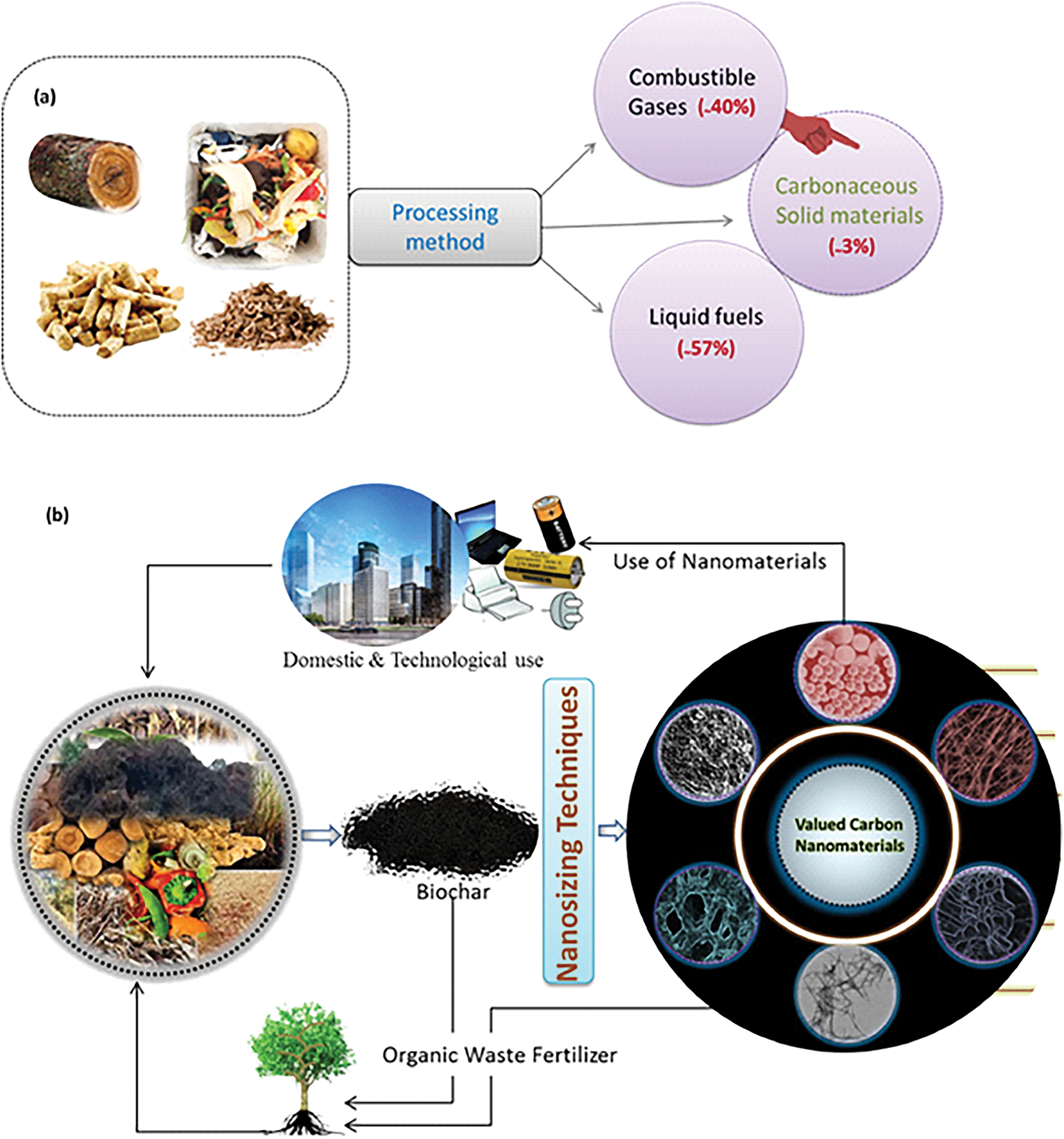

The transformation of biomass waste into value-added products involves gases, oil and carbonaceous materials, with carbon micro/nano materials comprising only a minor portion, as shown in Fig. 1a. Technological progress and the circular economy have propelled interest in biochar and carbon nanomaterials, which have impacted the commercial scene for biomass waste. Nations like China and India have achieved significant advances in the use of biomass to produce renewable energy and carbon materials, approximately 3%–5%, as shown in Fig. 1b. Initially focused on hygiene and environmental cleanliness, the focus of biomass waste management has shifted to sustainable energy and materials. Since the 1970s, there has been an increasing interest in converting waste into valuable products, with great technological progress in biomass conversion from 1980 to 2008 and a focus on nanosystems for energy and sensing applications from 2008 to 2017 [4].

Figure 1: (a) The possible applications and high-value products emerging from biomass waste, especially biochar. (b) Functionalised carbon nanomaterials find uses in renewable energy, catalysis, and oxygen reduction reactions, with pure biochar acting as a carrier for carbon storage [4]. Copyright © 2025 Elsevier B.V

Graphene is an exceptionally promising functional nanomaterial, characterised by its exceptional attributes such as outstanding tensile strength, excellent electrical and thermal conductivity, high carrier mobility, elasticity, and impressive optical transparency of roughly 97%. Composed of a single layer of carbon atoms in a hexagonal arrangement, graphene is lightweight, transparent, and flexible. It is known as the strongest material globally, being approximately 200 times stronger than steel and capable of conducting electricity at speeds surpassing most materials. No other material matches the extent of graphene’s impressive qualities, making it suitable for a multitude of applications. However, despite its vast potential, graphene has not yet become more integrated into everyday use primarily because its production remains costly due to underdeveloped methods and issues with scalability. Presently, existing manufacturing techniques yield either low-quality graphene or only limited amounts of high-quality graphene. However, it is established that any solid carbon-based material, including mixed plastic waste and rubber tyres, can be transformed into graphene [5,6].

Biomass utilisation not only addresses waste management issues, but also reduces reliance on fossil fuels, thus reducing carbon emissions. Converting waste into useful products embodies the principles of circular economy and resource efficiency. Biomass valorisation has brought about innovative technological advancements due to its excellent application-specific characteristics, such as a high specific surface area, high porosity, and low density. These traits have been applied in various domains, including portable electronics like TNGs, water purification, and energy storage. A report highlights the development of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) negative friction film with pore features, enhanced with 2D hexagonal boron nitride (100% h-BN) and defective h-BN (50%), serving as an efficient dielectric material to improve the electrical performance of TENGs. The TENG device, which incorporates carbon nanotubes, showed exceptional energy harvesting capabilities, generating a 60 V output voltage, a current of 1805 nA and a power density of 110.6 mW/m2 under a force of 10 N. The energy captured by the device can effectively light up 50 green LEDs and power a portable timer clock’s LCD. Nanocomposites based on 2D MXenes were evaluated for their performance, sensing capabilities, and various electroanalytical properties in an electrochemical sensor to detect phenolic pollutants [7,8].

This review employs a systematic approach to analyse existing research on b-d CMs for the green synthesis of nanomaterials. The methodology consists of four (4) main steps as described in the infographic below Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Flow chart explaining the methodology of this review

The eco-friendly synthesis of nanomaterials using carbon sourced from biomass serves as a prime example of integrating nanotechnology with sustainability, offering a means to address pressing environmental and resource challenges. This project seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research, highlighting the potential and limitations of this methodology. By examining existing knowledge and identifying gaps, this review sets the stage for future research aimed at optimising sustainable synthesis methods, expanding applications, and improving the environmental and economic viability of biomass-derived carbon materials (b-d CMs). The analysis meticulously investigates various biomass sources for suitability in producing carbon nanomaterials through green and sustainable processes. By exploring a variety of biomasses, from microorganisms to organic waste, the review illustrates how these can be transformed into valuable carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, and carbon dots. The applications of these b-d CMs in several domains include energy storage, environmental remediation, biomedical uses, water purification, agriculture, and catalysis. The study underscores the versatility and efficiency of b-d CMs in addressing contemporary issues such as clean energy generation and pollution control [9,10].

As this domain evolves, cross-disciplinary cooperation and innovation will play a vital role in addressing technical obstacles and improving production scalability. Incorporating sophisticated characterisation methods, computational modelling, and life cycle analysis can further enhance understanding and utilisation of biomass-derived carbon within sustainable nanotechnology. In the end, this research supports the larger goal of a circular economy and a more sustainable future. Sugarcane serves as the main source of sugar and juice and is also used as a raw material in various industries to produce sugar, jaggery, and syrups. However, these industrial processes generate a significant amount of leftover bagasse, which is typically used to produce thermal energy through burning. Interestingly, approximately 25–30 weight percent of residual lignocellulosic bagasse (RSB) is produced for each kilogramme of sugarcane processed in sugar mills. Recently, research has increasingly focused on industrial agricultural waste to address the growing issues associated with the improper disposal of agricultural waste residues. As a result, there has been the development of hybrid composites through reinforcement in polymer science. The adoption of alternative materials like sugarcane bagasse as fillers in rubber and cement applications has become a global concern, with the aim of reducing waste disposal, particularly for non-biodegradable materials that threaten ecosystems. Therefore, recycling and reusing these industry-derived residues has proven to be an effective strategy to reduce the disposal of harmful environmental waste [11].

The review investigates the state of research on the green synthesis of biogenic carbon from biomass, highlighting advances, methodologies, and applications related to biomass-derived precursors in biogenic carbon synthesis. It focusses on the characterisation techniques, properties, and environmental impacts of graphene-like materials from biomass, focussing on their industrial and technological applications. The aim of this review is to improve the understanding of biomass utilisation in graphene synthesis and to suggest future research directions.

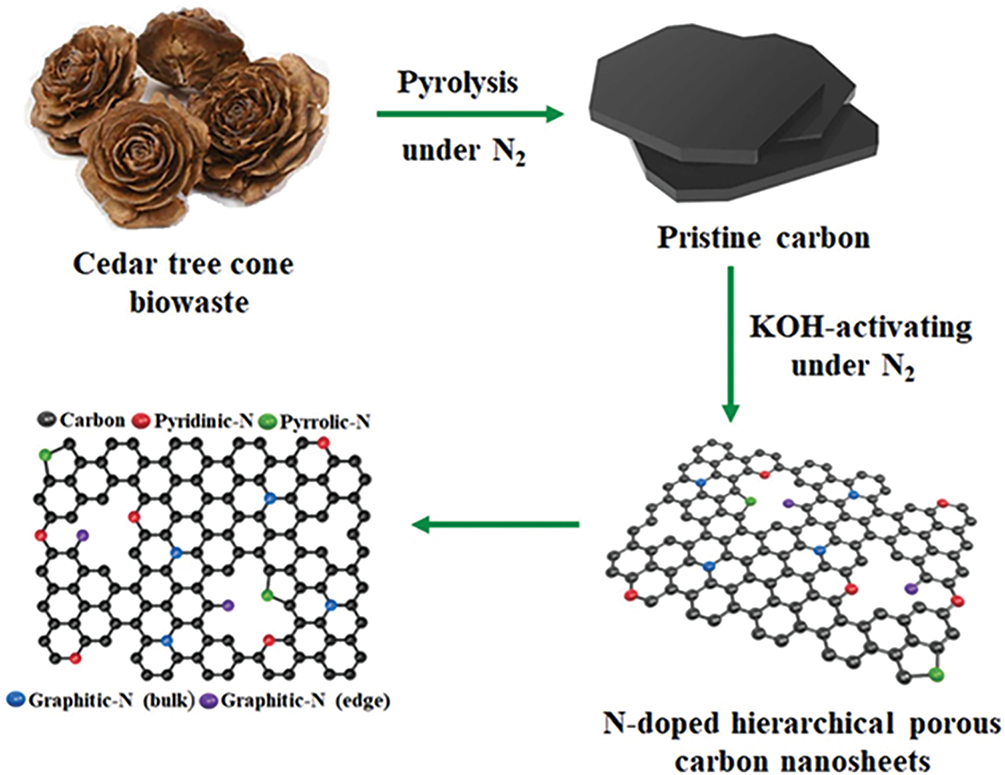

2 Current Trends and Innovations

The use of biomass precursors in material synthesis, particularly for nanomaterials, is experiencing noteworthy advancements. Recent research has explored a variety of biomass sources, such as agricultural residues such as rice husks and corn stover, forest waste including sawdust and bark, and even food waste such as fruit peels and coffee grounds, as sources of carbon. These biomass sources undergo different carbonisation techniques, illustrated in Fig. 3, such as pyrolysis, hydrothermal carbonisation, and chemical activation, to produce carbon-rich materials with desirable properties for material synthesis. In practice, biowaste is thermally treated in a nitrogen atmosphere, as depicted in Fig. 3, to obtain pure carbon, followed by chemical activation with KOH. A notable trend is the development of hierarchical and porous nanostructures from carbon derived from biomass. These nanostructures possess a high surface area, adjustable pore sizes, and excellent electrical conductivity, making them ideal for energy storage applications such as supercapacitors and batteries. Furthermore, surface modification of carbon with heteroatoms has been proven to enhance the catalytic activity and stability of nanomaterials, thus creating opportunities in catalysis and environmental remediation [12–14].

Figure 3: Schematic of the synthesis of hierarchical porous carbon from cedar tree cones. Reproduced with permission from [14], Copyright © 2022 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved

A new frontier in research is the combination of carbon derived from biomass with other nanomaterials, such as metal nanoparticles and metal oxides, to form hybrid nanocomposites. Recently, biogenic carbon has shown exceptional uses in energy storage, serving as a catalyst in anode materials for electrodes and in supercapacitors. The widely accessible renewable biomass resource has transformed the energy sector by serving as a feedstock for biochar, providing desirable physical and chemical characteristics, such as high specific surface area, porosity, altered electrical properties through foreign atom doping, and a variety of structural phase transformations. These composites utilise the combined properties of their components, leading to improved performance in a wide range of applications, notably in sensors, drug delivery systems, photocatalysis, and water purification [15].

2.1 Environmental and Economic Implications

The environmental and economic ramifications associated with the use of biomass-derived carbon for material synthesis are considerable. Environmentally, this strategy encourages the conversion of waste materials into valuable products, thus lessening landfill strain and alleviating pollution. The environmentally friendly synthesis techniques frequently function at reduced temperatures and strive to minimise the use of harmful reagents, consequently reducing the ecological impact. Economically, taking advantage of abundant and low-cost biomass resources can reduce production expenses, improving the affordability of sustainable (nano)materials for a variety of uses [16].

Biomass is defined as organic matter, predominantly originating from plants or substances based on plants, which can be produced via biological photosynthesis. This definition can be broadened to encompass materials or by-products from both animals and plants that serve as prospective energy sources. Interest in carbon derived from biomass has grown under the Waste-to-Way principle, which emphasises prioritising prevention and considering disposal as a last resort; it advocates exploring multiple avenues for waste reduction, reuse, reprocessing, recycling, and recovery. As biomass waste is abundant, environmentally friendly and cost-effective, it has been recognised as a promising precursor for sustainable production of carbon nanostructures/materials, highlighting its significant potential for utilisation [17,18].

Carbon materials exhibit a range of traits that make them suitable for a variety of applications. The properties of biomass-derived carbon materials (b-d-CM) are specifically shaped for their intended use. Multiple methods have been established to produce and alter these materials. Carbon, which is an easily accessible resource, has been used by humans for many years. Conventional carbon materials such as graphite, carbon black (CB) and activated carbon (AC) have been in use for even longer. Furthermore, the last century saw the advent of novel carbon materials with customised features, focussing primarily on substances such as graphite and carbon fibres. In recent times, even more advanced nanosized and nanostructured carbon materials have been developed. These carbon materials have been extensively researched, particularly the latest nanocarbons, although the study also extends to macroscopic carbons, such as carbon fibres [19].

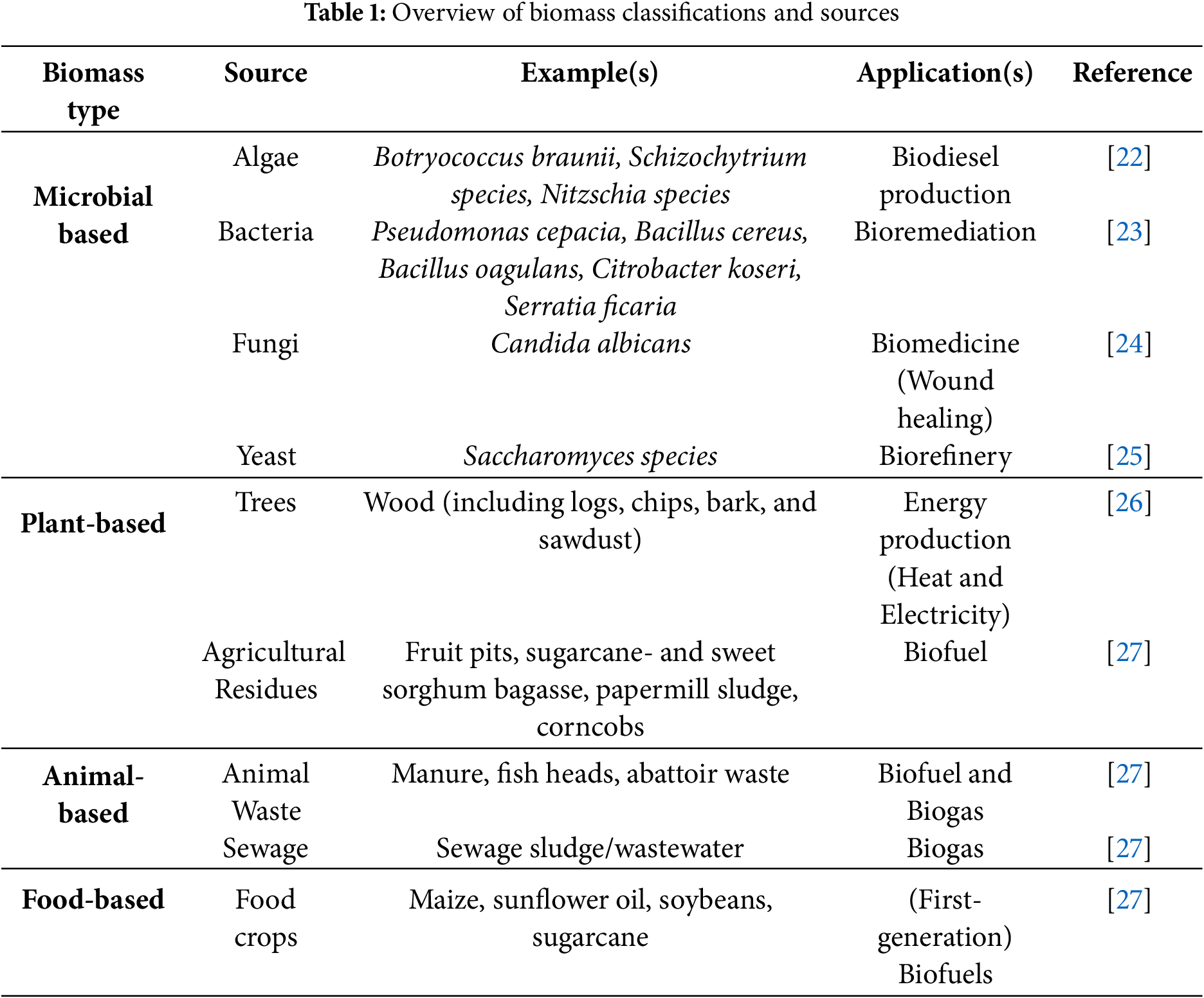

Biomass encompasses a variety of organic substances that originate from living organisms. It can be classified into four (4) principal categories based on the primary source of the organisms. These categories are identified as microbial, animal, plant and food-based biomasses. By categorising biomass in this way, we establish a structure for understanding the diverse origins and possible uses of organic materials derived from these living sources [20,21].

Table 1 offers an in-depth overview of the distinct categories of biomass, detailing their sources and industrial uses. Each category is exemplified with typical biomass sources that fall under it. This table facilitates an understanding of the diverse range of biomass resources accessible for various industrial purposes, including energy and biofuel production, biorefinery processes, and bioremediation. Biomass, which is a versatile group of organic materials sourced from living organisms, covers a wide array of carbon-based resources, with each type presenting unique characteristics for different potential applications. From conventional agricultural residues to new sources such as algae and organic waste, these unique attributes provide promising opportunities for sustainable solutions. The suitability of biomass types for specific applications varies, influenced by factors such as chemical composition, structural properties, accessibility, availability, cost effectiveness, and others, which guide their suitability for different end-use requirements [22–26].

An in-depth understanding of the reasons behind the selection of different biomass types for varying purposes is crucial to advance sustainable methodologies and address a range of social demands. Through meticulous assessment of these variables, stakeholders including researchers, policymakers, and industry executives can make well-informed choices about biomass use and process optimisation to improve environmental sustainability and economic feasibility. This strategy encourages innovation and the proactive pursuit of a more sustainable future, a future that, with ongoing research and the successful execution of thoughtfully considered decisions, has the potential to improve resilience, sustainability, and environmental management in biomass use practices in various industrial fields [27–31].

2.3 Considerations in Biomass Selection

The diverse range of available biomasses presents a wealth of possibilities for researchers and industry professionals engaged in sustainable projects. However, choosing the optimal biomass requires a thorough assessment of several key factors, including chemical composition, energy value, availability, cost efficiency, and environmental impact. These crucial criteria inform the selection of biomass, illuminating the complex relationship between the biomass attributes and the goals of synthesis processes. By thoughtfully and strategically considering these critical factors, stakeholders can improve biomass utilisation routes, thereby concentrating on innovative and resilient solutions. With precision and foresight, these strategies can lead to environmentally sustainable and economically feasible approaches for biomass-related applications [32–36].

2.3.1 Chemical Composition of Biomass

Biomass, whether lignocellulosic or herbaceous, is fundamentally composed of five main components: cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, extractives/volatiles, and ash. The chemical composition of biomass differs due to varying growth and harvesting conditions, and this variation complicates conversion processes. Conversion processes typically require materials that are uniform both physically and chemically. Consequently, these compositional differences affect how each type of biomass is appropriate for conversion methods such as combustion, fermentation, or thermochemical conversion [36–40].

Carbon Content

An important consideration for biomass to function as a precursor for the synthesis of graphene-like materials is its carbon content. The high carbon content and the possibility of a crystalline structure make the use of biomass as a precursor more suitable for the development of graphitic carbon. Nature adds interesting, complex, and varying microstructures to biomass and, as a result, the biomass-derived carbon generated from said biomass also displays natural structural diversity such as 0-dimensional (0D) spherical, 1D fibrous, 2D lamellar, and 3D spatial structures. These variations are considered potential crystalline structures. Several researchers have previously shown that an increase in carbon content in a selected precursor tends to produce higher quality graphene-like structures in the final synthesised product [40–44].

Microbial biomass, consisting primarily of fungi, bacteria, yeast, and algae and their derivatives, has shown great promise for creating new materials because nature contains a wide range of biopolymer sources that may be able to function as novel materials that are currently underutilized. Dried microbial biomass usually consists of between 45%–58% carbon. There are diverse applications for microbial biomasses in various industries due to their rich carbon content. These applications include the production of biofuels, such as ethanol and biodiesel, where microbial biomass serves as a feedstock for fermentation processes. In addition, microbial biomass is used in bioremediation efforts to degrade organic pollutants and contaminants in soil and water environments, using its carbon-rich composition to fuel metabolic activities that break down harmful substances. Furthermore, microbial biomass, such as fungi, is instrumental in the production of commercially value-added products such as enzymes and metabolites, organic acids, and biopolymers through microbial fermentation processes, with its carbon content serving as a crucial precursor for the synthesis of these bioproducts. The carbon content of microbial biomass supports their versatile applications in areas such as bioenergy, environmental remediation, and bioprocessing industries, which drives innovation and sustainability in these sectors [45,46].

Animals consume plants, and their digestive systems generate waste, manifested as manure or sewage, categorized as animal biomass. The meat industry adds to this biomass through by-products like fish heads and slaughterhouse waste. The carbon content in animal biomass varies, influenced by factors like the species, its diet, and its health state, but generally comprises about 50% carbon weight. This diverse and plentiful biomass has numerous applications across different sectors. A significant use is in bioenergy production, where carbon-rich animal waste, such as manure and agriculture remnants, are critical feedstocks for anaerobic digestion and thermal processes, yielding biofuels like biogas and bio-oil. It also plays an essential role in creating organic fertilizers, utilizing its carbon-rich content to enhance soil fertility and structure via composting and vermicomposting. Additionally, sustainable management of animal biomass aids in carbon sequestration, with practices such as rotational grazing and silvopasture enhancing soil carbon storage and reducing atmospheric CO2 levels. Outside agriculture, animal biomass is used to produce valuable bioproducts like bioplastics and biobased chemicals, leveraging its carbon-rich materials from meat and dairy by-products. Furthermore, the carbon content in animal biomass is beneficial for soil amendments, where substances like bone and blood meal improve nutrient supply and soil vitality. Biomaterials sourced from animal biomass, such as collagen and gelatin, are also applied in biomedical fields due to their structural and functional qualities, showcasing the versatile role of carbon-rich animal biomass in bioenergy, agriculture, environmental sustainability, biotechnology, and healthcare sectors [47].

2.3.4 Plant- and Food-Based Biomass

In plant and food biomass, the carbon content is typically quite high, ranging from 40%–60%, and can reach as high as 90% of their elemental makeup. However, the actual carbon output is significantly influenced by the chemical composition, notably the mass fractions of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose. Lignin stands out as the most thermally stable compound among them. Therefore, its proportion in the resulting biochar is a key determinant of carbon content, as it primarily impacts the measurement. The vast availability of rapidly growing lignocellulosic (nonedible) biomass positions it as a promising carbon source, free from the Food vs. Fuel conflict, wherein edible biomass like sugars, starches, and vegetable oils used for vast fuel production have resulted in food supply issues. Nevertheless, the global increase in various waste biomasses presents a disposal challenge. Consequently, such biomasses show potential as sustainable feedstocks for crafting graphene-like materials in various applications to produce carbon from biomass [48].

3 Proximate, Ultimate, and Energy Values Analysis Considerations of Biomass

Proximate, ultimate, and energy values analysis of biomasses are essential techniques used to characterise and evaluate biomass materials for various application. Proximate analysis provides a quick assessment of a biomass’s composition and suitability for various energy conversion processes. This type of analysis involves determining the moisture, ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon content of the biomass source. Ultimate analysis delves deeper by quantifying the elemental composition of the biomass—including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur, and oxygen. The detailed chemical profile it provides is crucial to understand the combustion behaviour and potential environmental impacts of the precursor. Energy values analysis focuses on the calorific value—or heating-value of biomass, as this indicates the amount of energy that can be derived from it. The energy content is measured in terms of higher heating value (HHV) and lower heating value (LHV), reflecting the total energy potential and the net energy available after accounting for water vaporisation, respectively. These analyses provide comprehensive data that help optimise biomass utilisation for various commercial purposes as further described [49].

Research indicates that lowering the moisture content of biomass materials is often necessary for energy-related objectives, and it can also affect biomass transport and storage. There is a clear link between the dryness of biomass fuel and its energy content. Most biomass gasifiers are optimized for feedstock with very low moisture content, typically between 10%–20%. Conversely, some biomass combustion systems are capable of handling fuel with much higher moisture levels, utilizing the combustion heat to dry the fuel as it nears the combustion area. Meanwhile, technologies like anaerobic digestion, fermentation, hydrothermal upgrading, and supercritical gasification operate with feedstock in water-rich environments and are ideal for biomass with extremely high moisture content, where drying isn’t required. High moisture biomass possesses significantly lower net energy density by both mass and volume, largely due to the presence of water that demands energy for evaporation. Hence, transporting such biomass becomes inefficient as a substantial amount of the load is essentially water. Storage is also inefficient due to reduced net energy, compounded by risks such as composting, heat-induced fires, and mold growth. While ventilation and airflow can mitigate these issues, they may involve high costs. The moisture content of biomass critically affects its appropriateness for varied applications. Careful evaluation of biomass moisture levels enables stakeholders to tailor biomass choice for specific purposes, aiding in the development of high-quality products designed to fulfil diverse end-use needs [50].

3.2 Energy Content (In Terms of Caloric Value) of Biomass Source

The energy content of biomass plays a crucial role in determining its suitability for different industrial processes and end uses. Biomass types with high heating value (HHV), such as woody biomass or agricultural residues rich in cellulose, lignin, or hemicellulose, are typically employed for energy production. For instance, sawdust, wood chips, and forest residues are commonly used as primary feedstocks in biomass power plants, where they can be transformed into heat, electricity, or biofuels through techniques like combustion, gasification, or pyrolysis. Additionally, high-energy biomass sources, such as sugarcane bagasse and corn stover, are utilized in the manufacture of biofuels, within biorefineries, or for co-firing with coal in power plants, aiding in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing energy efficiency. On the other hand, biomass with lower energy content, like herbaceous crops or grasses, is often employed for non-energy purposes, such as creating biobased materials, biochemicals, or bio-composites. For example, fibrous biomass like hemp or flax is used to produce biobased textiles, biodegradable plastics, and construction materials, owing to their structural integrity and renewable characteristics. By considering the energy content of biomass sources, industries and researchers can determine the most appropriate biomass feedstocks for specific applications, thereby optimizing resource use, promoting environmental sustainability, and enhancing economic viability across various sectors [51].

4 Preparation Methods and Their Impact on End-Use Requirements

How specific biomass feedstocks are prepared is vital in determining their appropriateness for various applications. This is because the preparation method impacts the chemical makeup, physical attributes, and structural features of the resultant materials. Various techniques, including mechanical grinding, chemical extraction, or thermal treatment, significantly affect the functionality and performance of biomass feedstocks for specific uses. For instance, woody biomass materials like sawdust or wood chips are subjected to mechanical milling or size reduction to increase their surface area, which aids in downstream processes such as bioenergy production or biochemical conversion. In the case of lignocellulosic biomass sources like sugarcane bagasse, chemical pretreatments such as acid hydrolysis or steam explosion are employed to eliminate lignin, hemicellulose, and other non-cellulosic elements, thus enhancing enzymatic digestibility and boosting bioethanol yields in biofuel production. Moreover, the technique for preparing biomass feedstocks determines their applicability beyond energy-related industries. For example, fibrous biomass like cotton or hemp undergoes mechanical or chemical processing to extract cellulose fibers, which are then used to make paper, textiles, or bio-composites due to their excellent tensile strength and biodegradability. Adapting the preparation methods to meet specific application needs allows for optimization of biomass feedstocks across a broad spectrum of uses [52].

Various methods exist for synthesizing biochar, each resulting in biochar with unique features despite coming from the same feedstock. These production techniques influence aspects such as total surface area, porosity, pore distribution, functionalization, and elemental composition. Biochar is generated through biological, thermochemical, and hybrid conversion methods, as illustrated in Fig. 4 of biomass. A comprehensive overview of the three conversion methods is provided. The mixed conversion (hybrid) process employs thermal decomposition of biomass to create substrates, which are then utilized in making fuels, chemicals, and other valuable mixtures or composites after the metabolic processes of microorganisms. It involves two pathways for fuel production: syngas and bio-oil fermentation. Converting lignocellulosic biomass using pyrolysis (a type of thermochemical conversion) is a notably sustainable approach, as it efficiently tackles the resistant and fibrous nature of the biomass. The biological use of the pyrolysate allows for high selectivity in products, especially since it shows strong potential for producing cost-effective fermentation substrates compared to enzymatic hydrolysis, which needs costlier enzymatic mixtures [52].

Figure 4: An illustration of biomass preparation techniques. Reproduced with permission from [52] Copyright © 2025 Oxford University Press

5 Availability and Accessibility of the Biomass Source

The availability and accessibility of biomass sources are critical factors shaping potential applications in various industries, Fig. 5. Biomass materials that are locally abundant and readily accessible offer advantages in terms of transportation costs, logistic ease, and overall economic feasibility [53].

Figure 5: Graph showing the global abundance of different types of biomasses [53]. Copyright © 2025 National Academy of Sciences

Graph 1 illustrates the various categories of biomass along with their respective quantities, offering valuable insights into the worldwide distribution and availability of biomass resources by displaying the global prevalence of different biomass types (see Fig. 5). Examples of commonly available and easily accessible biomasses include agricultural residues like wheat straw, rice husks, or corn stover, which are prevalent in agricultural regions and can be conveniently sourced from nearby farms or processing facilities. These biomass types are frequently utilized in bioenergy production, being converted into biofuels, biogas, or heat through processes such as combustion, anaerobic digestion, or thermal treatments. Similarly, industrial by-products like sugarcane bagasse or wood chips are easily accessible from nearby manufacturing or processing industries, making them appealing for biomass-based materials, biochemicals, or bioenergy applications. Utilizing locally available biomass resources optimizes resource use, reduces environmental impacts, and may enhance economic competitiveness across various sectors while contributing to sustainable development and resource stewardship [54,55].

6 Environmental Impact, End-Use Requirements/Predetermined Application

Renewable and eco-friendly biomass materials bring benefits like lowering the carbon footprint, reducing environmental harm, and encouraging sustainable management of resources. Industrial by-products serve as sustainable biomass sources that minimize waste and align with circular economy principles. These materials are used to create biobased materials, biochemicals, or bio-composites, providing greener alternatives to products derived from fossil fuels. Emphasizing sustainable biomass sources lessens environmental impact, conserves resources, and aids in the shift towards a more sustainable and resilient bioeconomy. Different biomass sources have unique chemical, physical, and structural characteristics, making them suitable for specific applications. Woody biomass, for example, is often favored for bioenergy due to its high energy content and effective conversion into biofuels or heat, whereas lignocellulosic biomass is preferred for biochemical conversions, where it is enzymatically broken down into fermentable sugars that can be transformed into bioethanol or other biochemicals. Choosing the appropriate biomass based on specific end-use ensures optimal resource use, product quality, and process efficiency across various sectors, supporting sustainable development. In conclusion, such analyses are essential as they facilitate the selection of suitable biomass types for specific uses and technologies, guaranteeing efficiency and sustainability. Moreover, understanding these biomass properties aids in designing systems that minimize environmental impacts, thus enhancing economic feasibility [56,57].

Biomass-derived carbon is a type of carbon material that is man-made and differs significantly from naturally occurring carbons such as charcoal, diamond, and graphite. These biomass-derived carbon products are usually generated by converting natural products like plant and/or animal waste using processes such as thermal carbonisation or activation. The application of such materials has and continues to attract much attention due to their ease of production, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability. There are many crucial advantages associated with biomass-derived carbon, such as cheap and plentiful supply, environmental safety, establishment of nanoporous structures in situ and elasticity of the processing. Since the source of the biomass affects the finish carbon return and its structural features, which are important characteristics in various applications, the correct selection of a biomass precursor is crucial [58].

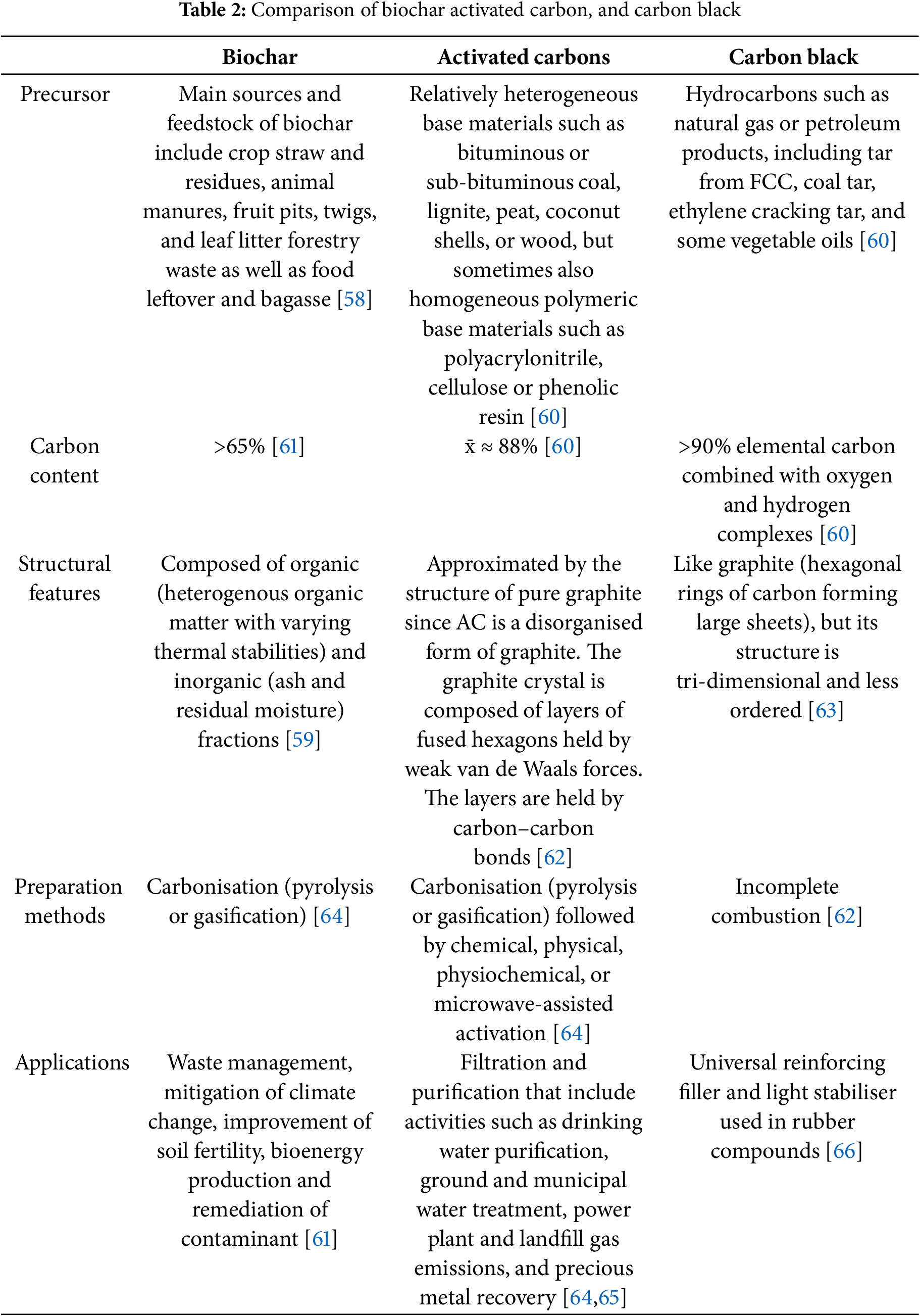

Carbons derived from biomass rely on precursors that are by-products of fossil fuels and involve energy-intensive synthetic techniques such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD), electric arc discharge, and laser ablation, among others. Table 2 outlines these methods, their various precursors, and the resulting types of carbon products. These processes are not only costly but also harmful to the environment, exacerbating climate change issues. While these synthesis techniques are advanced at the laboratory scale, their complex processes are not yet suitable for commercialization on an industrial scale. Therefore, there is a need to develop more efficient,eco-friendly, and cost-effective strategies for carbon material processing [59].

Table 2 provides a comprehensive analysis of biochar, activated carbon, and carbon black—three commonly utilized carbon-based materials with unique features and applications. It examines essential aspects such as common precursors, typical carbon content, structural properties, preparation techniques, and general uses for each material. By showcasing the distinctions among these carbonaceous materials, the table underscores their unique properties and potential applications across various sectors. Repurposing agricultural and other waste into biomass emerges as a promising strategy for creating more sustainable precursors. This conversion of biomass into useful products offers a better alternative to waste management than open burning, which releases greenhouse gases contributing to global warming [67].

Agricultural by-products such as corn stover, wheat straw, and rice husks are repurposed as animal bedding, soil amendments, or feedstock for bioenergy via anaerobic digestion or thermochemical processes. Likewise, food waste from homes, restaurants, and food industries can be turned into nutrient-rich soil amendments through composting or used in anaerobic digestion to generate biogas. Forestry by-products—like wood chips, sawdust, and bark—are utilized in pulp and paper production, heating wood pellets, or converted into value-added products such as biochar for soil enhancement. Municipal solid waste can be recycled, composted, or processed for energy recovery, diverting recyclables from landfills and converting organic waste into compost or biogas. These biomass repurposing methods are often more economically advantageous owing to their lower costs, offering potential savings for industries producing carbon materials. Evidently, the economic advantages of converting biomass extend beyond mere cost savings for industries. As industries look for sustainable replacements for traditional carbon materials, biomass-derived solutions show substantial promise [68].

7 Leveraging Biomasses for Sustainable Nanomaterial Synthesis

The investigation of biomass as a precursor for graphene synthesis stresses a paradigm shift towards sustainable and environmentally conscious material production. Repurposing industrial wastes into high-value products, like carbonaceous materials, allows stakeholders to not only address the growing demand for advanced carbon materials but also noticeably contribute decent solutions to the consistent issues of waste reduction and environmental sustainability. As the search for innovative graphene synthesis methods continues, biomass utilisation is at the forefront of sustainable materials research, offering promising avenues for both scientific advancement and environmental stewardship.

7.1 (Green) Nanomaterial Synthesis

Nanomaterials are defined as materials with at least one dimension in the nanoscale range smaller than 100 nm. These materials have garnered significant attention due to their unique properties that differ distinctly from their bulk counterparts. They exhibit outstanding electrical, thermal, and mechanical characteristics, making them invaluable in various applications, including electronics, medicine, energy storage, and environmental remediation. The nanoscale dimensions of these materials lead to a high surface area-to-volume ratio, quantum confinement effects, and enhanced surface reactivity, which all contribute to their exceptional performance. Despite their incredible benefits, the conventional synthesis of nanomaterials often involves environmentally detrimental processes, characterised by high energy consumption and the use of toxic chemicals. These methods can lead to significant ecological and health hazards such as the generation of hazardous waste and the release of greenhouse gases. As global awareness of environmental issues grows, there is an increasing demand for sustainable alternatives in (nano)material synthesis that better align with the principles of green chemistry. Sustainable synthesis aims to minimise environmental impact by utilising renewable resources, reducing energy consumption, and minimising or even eliminating hazardous substances. The concept of green chemistry emphasises the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances. In the context of nanomaterials, this translates into developing synthesis methods that are efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally benign [69].

A promising approach to sustainable nanomaterial synthesis is using biomass as the precursor for synthesising carbon materials since biomass is a renewable and abundant resource that can be converted into carbon materials. The transformation of biomass into carbonous nanomaterials addresses waste management issues and reduces dependency on fossil fuels which contribute to a circular economy. The synthesis of b-d CM involves processes such as pyrolysis, hydrothermal carbonisation, and chemical activation. These methods yield carbon structures with high surface area, tunable pore size, and functional groups that enhance their performance in various applications. Currently, the sustainable and eco-friendly synthesis of high-quality nanomaterials, like graphene, is one of the most popular topics in the field of material science because graphene is one of the most attractive functional nanomaterials in the world with its excellent and unique properties. This interest has led researchers to look for different and more environmentally friendly methods of production, since sustainable and environmentally friendly approaches to the production of materials as monumentally important as these would benefit not only industry, but society at large in terms of resource efficiency, environmental protection, and technological innovation [70].

7.2 Traditional Methods for Nanomaterial Synthesis

Nanomaterials, famous for their distinct properties and varied applications, have been created using numerous techniques throughout the years. Classic synthesis methods have significantly propelled the progress of nanotechnology. Techniques like Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD), the Sol-gel Process, and Hydrothermal Synthesis offer exact control over the dimensions, form, and composition of the nanomaterials. Each technique presents unique advantages and obstacles impacting the development and utilization of these substances. CVD is preferred for its capability to generate high-purity materials with controlled shapes, crucial for industrial usage. Nonetheless, it generally necessitates high temperatures and can involve toxic precursors, prompting environmental concerns. The Sol-gel Process is celebrated for its adaptability and ability to synthesize at low temperatures, yielding uniformly pure nanomaterials but demands precise reaction parameter control to avoid defects which could affect material performance. Hydrothermal Synthesis, which uses water as a solvent in high-pressure and high-temperature settings, is an eco-friendly choice that results in highly crystalline materials, although its application can be hampered by the need for specialized equipment. Grasping these traditional techniques lays the groundwork for the development of more environmentally conscious synthesis methods, ensuring the alignment of future nanotechnological innovations with sustainability objectives [71–73].

7.2.1 Chemical Vapour Deposition

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) is a key method for creating high-grade thin films and nanomaterials, as depicted in Fig. 6. This technique involves the deposition of a solid material from gaseous precursors onto a substrate via chemical reactions, making it essential across sectors like electronics, optics, and materials science. CVD is extensively employed for producing materials such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, and diverse metal oxides, given its precision in controlling material properties. The procedure commences with the introduction of gaseous precursors into a reaction chamber holding the substrate, which is usually heated to facilitate the necessary chemical reactions. As the gases mix, they undergo decomposition or reactions in the gas phase, producing reactive species that travel to the substrate surface. Upon reaching the surface, these species adsorb and engage in further reactions that result in a solid film deposition. Reaction by-products are released from the surface and expelled from the chamber. There are several CVD variations, each designed for material needs. Thermal CVD relies on high temperatures to drive reactions, whereas Plasma-Enhanced CVD (PECVD) uses plasma to accelerate reaction rates, permitting lower processing temperatures. Metal-Organic CVD (MOCVD) uses metal-organic compounds as its precursors, allowing for the deposition of complex materials. CVD is vital for the creation of nanomaterials since it can generate high-quality, defect-free structures with exact control over their attributes. A key benefit of CVD is its capability to yield high-purity materials, crucial in applications like electronics and optics. The process permits precise regulation of film thickness, composition, and morphology, allowing customization of material properties to fulfil specific needs. Additionally, the process is highly scalable, suitable for industrial applications, as it can evenly coat large areas [74,75].

Figure 6: Schematic diagram of the general elementary steps of a typical CVD process. In step (a) the reactant gases (blue circles) are transported into the reactor. Then, in step (b) there are two possible routes for the reactant gases: directly diffusing through the boundary layer and adsorbing onto the substrate—as seen in step (c); or forming intermediate reactants (green circles) and by-products (red circles) via the gas-phase reaction—illustrated as step (d) and being deposited onto the substrate by diffusion—step (b) and adsorption step (c). Surface diffusion and heterogeneous reactions—shown as step (e) take place on the surface of substrate before the formation of thin films or coatings. Finally, in step (f), the by-products and unreacted species are desorbed from the surface and forced out of the reactor as exhausts [79]. Copyright © 2025 Springer Nature Limited

Moreover, CVD’s adaptability enables the deposition of various materials like metals, semiconductors, and insulators. However, CVD does come with certain drawbacks. It often demands high temperatures, limiting substrate options, especially those sensitive to heat. The technology used in CVD can be intricate and costly, hindering its accessibility for certain applications. Additionally, some CVD methods utilize toxic or dangerous precursors, raising safety and environmental concerns. Its high energy consumption also adds to the environmental impact, highlighting the need for more eco-friendly approaches. In the realm of nanomaterials, CVD stands as a crucial technique, providing unparalleled control over material properties and allowing for the creation of high-performance materials for diverse advanced applications. Despite the obstacles, advancements in CVD technology are continually expanding its capabilities, solidifying its role as an essential tool in nanotechnology [76–78].

The Sol-gel process is a versatile and widely used method for synthesising nanomaterials, particularly metal oxides and ceramics. This wet chemical technique, Fig. 7, involves the transition of a solution, or sol, into a solid gel phase. The method is renowned for its ability to produce materials with high purity and uniformity, making it essential in fields such as electronics, optics, and catalysis. This process begins with the preparation of a colloidal solution (or sol) which contains metal alkoxides or metal salts as precursors. These precursors undergo hydrolysis and polymerisation reactions, forming a network of metal-oxo or metal-hydroxo species. As the reaction progresses, the sol gradually transforms into a gel—a three-dimensional network of interconnected particles. This gel is then dried and calcined to remove any remaining solvents and organic components which results in a solid material. The Sol-gel process is crucial for the synthesis of nanomaterials because it can produce materials with finely controlled microstructures and morphologies. Nanoparticles, thin films, and porous structures synthesised through this process find applications in a wide range of fields because the process can be tailored to produce a variety of structures, from dense monoliths to porous aerogels, by adjusting parameters such as pH, temperature, and precursor concentration. It is this flexibility that allows for the precise control over the synthesised material’s properties, including porosity, surface area, and particle size. This synthesis technique offers several advantages including operating at relatively low temperatures compared to CVD thereby reducing energy consumption and making it suitable for substrates sensitive to heat. The So-gel Process allows for the incorporation of dopants and the synthesis of complex compositions, enabling the production of materials with tailored properties. Additionally, it produces materials with high purity and homogeneity, which is crucial for many applications [80–83].

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of different sol-gel process steps to control the final morphology of the desired material synthesised [86]. Copyright © 2021 JCC Research Group

The process is also relatively simple and cost-effective, making it accessible for various research and industrial applications. Even with its many benefits, the Sol-gel process has certain limitations. The reactions involved are sensitive to various parameters, requiring precise control to prevent aggregation and ensure reproducibility. During the drying phase, the gel may undergo shrinkage and cracking, which can affect the final material’s properties. Furthermore, some precursors used in the process may be expensive or environmentally hazardous, necessitating careful handling and disposal. These factors can pose challenges in scaling up the process for industrial production. The Sol-gel process is a vital tool in the synthesis of nanomaterials, offering a combination of versatility, precision, and relative simplicity. While there are challenges to address, particularly in terms of scalability and environmental impact, its ability to produce high-purity, finely tailored materials ensure its continued importance in nanotechnology and materials science. As research progresses, innovations in Sol-gel techniques will likely expand its applications and improve its sustainability, reinforcing its role in the development of advanced materials [84,85].

Fig. 8 illustrates hydrothermal synthesis, a valuable technique for crafting nanomaterials, especially crystalline structures, using aqueous solutions at elevated temperatures and pressures. This method emulates natural geological formation and is essential for creating a variety of materials like metal oxides, zeolites, and diverse nanocomposites. The process involves dissolving precursor substances in water, which is then secured in an autoclave. The autoclave is heated to temperatures exceeding 100°C, often between 120°C and 220°C, with pressures ranging from 1 to several hundred bars. In this environment, water functions both as a solvent and a reactant, promoting the crystallisation of materials. The elevated temperature enhances precursor solubility, while the pressure prevents boiling, enabling the development of well-defined crystals. The reaction duration can range from hours to days, depending on the material characteristics desired. Hydrothermal synthesis is vital in nanomaterial production for yielding high-quality materials with specific attributes, making it especially beneficial for catalytic, energy storage, and environmental remediation applications [87,88].

Figure 8: Schematic diagram of the hydrothermal synthesis process. Reproduced with permission from [89]. Copyright © 2025 Springer Nature

The capability to manipulate the shape and crystal structure of nanomaterials boosts their catalytic effectiveness and durability. Furthermore, the method’s increased eco-friendliness, by using water as a solvent and reactant, aligns with green chemistry principles, fostering sustainable progression in nanotechnology. Through hydrothermal synthesis, the adjustment of parameters like temperature, pressure, reaction time, and precursor concentration allow precise control over particle size, shape, and crystallinity, which is crucial for customizing nanomaterial properties for uses. This technique also provides important advantages, such as producing highly crystalline materials with specific morphologies without needing high-temperature calcination that could lead to particle clumping or phase alterations. It further facilitates the incorporation of dopants and the creation of complex materials that might be challenging to generate through other methods. The process can form distinctive nanostructures, including rods, wires, and tubes, which are beneficial in various applications. Despite its significant benefits, hydrothermal synthesis comes with some drawbacks. The necessity for high-pressure equipment, like autoclaves, can be expensive and restrict its use to smaller-scale manufacturing. It can also be time-intensive, with material crystallization taking hours to days. Moreover, meticulous control over reaction conditions is essential to attain the desired material features, presenting a challenge. Safety concerns related to high pressure and temperature also demand careful operation and expertise. Hydrothermal synthesis remains crucial in nanotechnology, offering a unique set of advantages that make it suitable for producing various nanomaterials. Despite its limitations, its ability to generate highly crystalline, well-defined structures with relatively few harmful effects ensures its ongoing relevance [86].

7.3 Limitations of Conventional Methods

The shift towards sustainable nanomaterial synthesis offers significant environmental and economic benefits. Environmentally, the use of biomass-derived carbon promotes the valorisation of waste materials, reducing landfill burden and pollution. The green synthesis methods employed often operate under mild conditions and minimise the use of toxic chemicals, further reducing the environmental footprint. Economically, the utilisation of low-cost and abundant biomass resources can lower production costs, making sustainable nanomaterials more accessible and appealing for widespread use [90].

Conventional nanomaterial synthesis methods, while integral to advancements in technology and materials science, have significant environmental impacts that present notable limitations. These methods contribute to environmental degradation in several ways, raising concerns about their long-term sustainability. One major issue is the high energy consumption associated with many of these techniques. Processes like CVD and hydrothermal synthesis often require extreme temperatures and prolonged reaction times, which lead to substantial energy use. This high energy demand not only increases operational costs but also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, as many energy sources are still fossil fuel based. The carbon footprint of these methods is a critical concern, as it exacerbates climate change and undermines efforts to reduce global emissions. The energy-intensive nature of these processes highlights the need for more energy-efficient alternatives that can produce nanomaterials with lower environmental costs. The energy requirements of these processes not only elevate operational costs but also contribute significantly to the carbon footprint of nanomaterial production. High energy consumption also poses challenges for scalability and sustainability, as the carbon emissions associated with electricity generation offset the potential benefits of the nanomaterials produced. The cumulative energy consumption of these processes has broader implications for resource use and environmental impact [79,89].

According to some studies, the energy required for nanomaterial production can be several times higher than that for bulk materials, highlighting the inefficiency of conventional methods. For instance, producing carbon nanotubes via CVD may require energy inputs ranging from 100 to 500 kWh per kilogram, depending on the specific conditions and scale. This level of energy use is unsustainable in the long term, especially as the demand for nanomaterials continues to grow across various industries. Additionally, the reliance on high energy inputs raises concerns about the lifecycle sustainability of nanomaterials. The energy-intensive nature of their production offsets some of the potential environmental benefits these materials offer, such as enhanced efficiency in catalysis or energy storage. For example, while nanomaterials can improve the efficiency of solar cells or batteries, the energy and emissions associated with their production may negate some of these benefits, calling into question the overall sustainability of their use. Efforts to reduce energy consumption in nanomaterial synthesis are crucial for advancing sustainable nanotechnology [91–93].

Another significant environmental concern is the use of toxic precursors and solvents. Many conventional synthesis methods employ hazardous chemicals that pose risks to both human health and the environment. For instance, CVD often uses gaseous precursors that can be toxic or corrosive, requiring careful handling and containment to prevent exposure and environmental release. Similarly, the Sol-gel process can involve solvents and metal alkoxides that are harmful if not properly managed. The potential for accidental releases or improper disposal of these substances poses serious risks of soil and water contamination, which can have far-reaching ecological consequences. Moreover, the stringent safety measures required to handle these materials safely add to the complexity and cost of these processes, making them less appealing from a sustainability perspective. The generation of hazardous waste and by-products is another limitation of conventional nanomaterial synthesis methods. The production of nanomaterials can result in the accumulation of waste materials that are toxic or difficult to dispose of safely. For example, the by-products of certain chemical reactions may require specialised treatment before disposal to prevent environmental contamination. This waste management process is resource-intensive and can significantly increase the environmental footprint of nanomaterial production [94].

Inadequate handling or disposal of waste can lead to pollution of air, water, and soil, posing risks to ecosystems and human populations. These challenges highlight the importance of developing synthesis methods that minimise waste generation and enhance the recyclability of materials. Resource depletion is also a critical issue associated with conventional synthesis methods. Many of these processes rely on non-renewable or scarce raw materials, which raises concerns about the long-term viability of these resources. The extraction and processing of raw materials often result in habitat destruction, soil erosion, and loss of biodiversity, further exacerbating environmental degradation. As the demand for nanomaterials continues to grow, the pressure on these finite resources will increase, leading to potential supply shortages and increased costs. This scenario underscores the need for alternative synthesis methods that use abundant or renewable resources and promote the sustainable use of materials. Water pollution is another environmental impact of conventional nanomaterial synthesis methods. Many processes involve the use of solvents or other chemicals that can contaminate water sources if not properly managed. Wastewater from synthesis processes may contain residual chemicals that can be harmful to aquatic life and ecosystems. The release of these contaminants into water bodies can lead to eutrophication, disruption of aquatic ecosystems, and contamination of drinking water supplies. This pollution not only poses risks to environmental health but also has implications for human health and well-being [95].

Furthermore, while nanomaterials can theoretically be reused, the limited focus on recyclability and reusability in conventional synthesis methods results in increased waste and further resource depletion. Many traditional methods do not prioritise the design of materials for recyclability, leading to challenges in reusing or recycling nanomaterials at the end of their life cycle. This lack of circularity contributes to waste accumulation and the loss of valuable resources, undermining efforts to promote sustainable materials management. Incorporating more principles of green chemistry and sustainable design into nanomaterial synthesis can help address these challenges and promote more environmentally friendly practices. Overall, the environmental impact of conventional nanomaterial synthesis methods presents significant limitations that need to be addressed to ensure the sustainable development of nanotechnology. High energy consumption, the use of toxic precursors, hazardous waste generation, resource depletion, water pollution, and limited recyclability are all critical concerns that highlight the need for more sustainable approaches. Transitioning to greener synthesis methods that prioritise energy efficiency, non-toxic precursors, waste minimisation, and resource sustainability is essential to mitigate the environmental impact of nanomaterial production. By embracing sustainable practices, the field of nanotechnology can continue to advance while minimising its ecological footprint and contributing to broader environmental sustainability goals [96–98].

Traditional nanomaterial synthesis methods, while effective in producing high-quality materials, often face significant limitations in terms of cost-effectiveness. Techniques such as CVD, Sol-gel processes, and hydrothermal synthesis typically involve substantial expenses related to equipment, raw materials, and operational requirements, which can hinder their scalability and broader application. CVD, for example, requires specialised reactors and equipment capable of withstanding high temperatures and corrosive gases. The initial capital investment for such equipment is considerable, often running into millions of dollars, making it accessible primarily to well-funded research institutions or industrial laboratories. Moreover, the maintenance and operational costs of these systems add to the overall expense. The need for high-purity precursors and gases further increases the cost, as these materials are not only expensive but also require stringent handling and storage conditions. This financial burden limits the widespread adoption of CVD in industries where cost competitiveness is crucial. Similarly, the Sol-gel process, while versatile and capable of producing a variety of nanomaterials, is also cost-prohibitive in many cases. The method involves the use of metal alkoxides or salts as precursors, which can be costly, especially when high purity is required. The process itself, involving multiple steps such as hydrolysis, gelation, drying, and calcination, is labour-intensive and time-consuming. Each step requires careful control of parameters to ensure the desired material properties, which adds to the operational complexity and cost. Additionally, the energy requirements for drying and calcination are significant, contributing to the overall expense of the process [99–101].

The combination of costly precursors and high operational costs often makes the Sol-gel process economically challenging, particularly for large-scale production. Hydrothermal synthesis, known for its ability to produce well-defined crystalline nanomaterials, also encounters cost-related limitations. The requirement for high-pressure autoclaves and the energy-intensive nature of the process contribute to high operational costs. The equipment needed to withstand the high-pressure and temperature conditions of hydrothermal synthesis is expensive, and the prolonged reaction times further exacerbate energy consumption. Moreover, the scalability of hydrothermal synthesis is often limited by the size of the autoclaves, making it difficult to produce large quantities of nanomaterials economically. These factors collectively impact the cost-effectiveness of the process, limiting its application to niche markets or specialised research settings [102].

The reliance on high-purity raw materials and the generation of waste products also contribute to the cost limitations of conventional synthesis methods. Many processes generate hazardous waste that requires proper disposal, incurring additional costs. Waste management not only increases the financial burden but also poses environmental concerns, making these methods less attractive from a sustainability standpoint. The need for stringent safety protocols and waste handling further complicates the economic feasibility of these synthesis techniques. Additionally, the lack of scalability and reproducibility in conventional methods adds to their cost limitations. Achieving consistent results across different batches can be challenging due to the sensitivity of the processes to various parameters. This variability often leads to increased material costs, as additional resources are needed to optimise and standardise production. The trial-and-error nature of achieving the desired material properties further increases expenses, making the process less viable for large-scale or commercial applications. Besides direct costs, the opportunity costs associated with conventional synthesis methods are significant. The time and resources spent on optimising processes and ensuring quality control divert attention from other potentially more cost-effective or sustainable approaches. This focus on traditional methods may inhibit innovation and the development of alternative synthesis routes that could offer better cost-effectiveness and environmental benefits. Overall, the cost-effectiveness of conventional nanomaterial synthesis methods is limited by high equipment and operational costs, expensive precursors, energy-intensive processes, and waste management requirements [103–105].

These factors collectively hinder the scalability and broader adoption of these techniques in commercial applications where economic viability is crucial. As the demand for nanomaterials continues to grow, addressing these cost limitations is essential for the sustainable development of nanotechnology. Developing more economical synthesis methods that reduce reliance on expensive raw materials, minimise energy consumption, and enhance scalability will be critical in making nanomaterials more accessible and economically viable for a wider range of industries. Advances in green synthesis techniques and alternative approaches hold promise for overcoming these limitations, potentially leading to more sustainable and cost-effective solutions in nanomaterial production [106].

‘Green’ synthesis can be considered an environmentally friendly method that presents an improved way of thinking in chemical sciences that aims to eliminate toxic waste, reduce energy consumption, use ecological solvents such as water, ethanol, ethyl acetate, etc., increase efficacy and lower economic cost. Green synthesis methods represent ecofriendly and economical approaches to otherwise environmentally and monetarily taxing processes. The fundamental principles of ‘green synthesis’ are waste prevention/minimisation, reduction of derivatives/pollution, and the use of safer/ecological (or non-toxic) solvents/accessories, as well as renewable feedstock. Techniques considered ‘green’ attempt to avoid the production of unwanted or harmful by-products by building reliable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly synthesis procedures. Using ideal solvent systems and natural resources (such as organic systems) is essential to achieve the goals of, while adhering to the principles of, green synthesis. Thus, green synthesis is deemed an important step towards reducing the destructive effects of conventional synthesis methods such as those commonly used in laboratories and industry. This plays a vital role in advancing sustainable development goals by promoting environmentally friendly, socially responsible, and economically viable approaches to chemical synthesis and manufacturing. Green synthesis is widely recognised in material science as a reliable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly protocol for the synthesis of a broad variety of materials (and nanomaterials), including metal/metal oxide, hybrid and even bioinspired nanomaterials [107].

7.3.4 Hierarchical and Porous Nanostructures

The development of hierarchical and porous nanostructures from biomass-derived carbon represents a significant trend in sustainable nanomaterial synthesis. These structures, characterised by their complex architecture and high porosity, offer advantages in catalysis, adsorption, and energy storage. The interconnected pore networks facilitate rapid ion transport, making them suitable for applications in supercapacitors and batteries. Additionally, their high surface area and active sites enhance their catalytic efficiency in environmental and industrial processes. The synthesis of hierarchical and porous nanostructures typically involves environmentally friendly methods that utilise relatively low temperatures and renewable precursors. For instance, hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass in the presence of mild acids can produce carbon materials with tunable porosity and surface chemistry. These methods align with the principles of green chemistry, as they minimise energy consumption and tend to avoid the use of toxic reagents [108].

Characteristics and Importance

Following the thermal treatment, the precursor template fully decomposed into a hierarchical porous nanocomposite, as depicted in Fig. 9A. Hierarchical and porous nanostructures lead the way in nanotechnology due to their distinct features and broad applications shown in Fig. 9B. These structures are identified by their multiscale architecture, which integrates various levels of structural organization, typically containing pores ranging in size from nanometres to micrometres, as clearly illustrated in Fig. 9C. This complexity results in a high surface area and a variety of pore sizes, offering numerous functional advantages that are critical in fields such as catalysis, energy storage, environmental remediation, and biomedical applications. The high surface area of hierarchical porous nanostructures is one of their most significant characteristics. This feature maximises the number of active sites available for chemical reactions, making them highly efficient in catalytic applications. For example, in catalysis, the increased surface area allows for more reactants to interact with the catalyst simultaneously, enhancing reaction rates and improving the overall efficiency of the catalytic process. This is particularly beneficial in heterogeneous catalysis, where the performance of the catalyst depends significantly on the availability of active sites. The presence of multiple levels of porosity also facilitates enhanced mass transport within the structures. The network of interconnected pores, from micropores to macropores, facilitates the effective diffusion of molecules, as shown in Fig. 8b. This characteristic is vital in applications requiring swift ion or molecule transport, like fuel cells and batteries. In these energy storage systems, the hierarchical porosity enables rapid and efficient ion and electron movement, thereby enhancing charge and discharge rates. This results in higher power densities and better overall performance, which are vital for applications requiring fast energy delivery, such as in electric vehicles and portable electronics [109,110].

Figure 9: Hierarchical porous structure of a nanocomposite material—(A) schematic diagram and the corresponding SEM images of the hierarchical porous nanocomposite, indicating the differences in surface and internal pore characteristics, (B) cross-section SEM images of prepared hierarchical porous nanocomposite. The dense accumulation layer on the surface is approximately 100–200 μm, displaying a completely different morphology from the internal macropores, (C) pore size distribution of prepared hierarchical porous composite materials [109].

Additionally, the tunable porosity of these nanostructures allows for selective adsorption and separation of molecules based on their size and shape, Fig. 8c. This characteristic is particularly important in environmental remediation and adsorption processes. For instance, hierarchical porous materials can effectively adsorb pollutants, heavy metals, or organic contaminants from water, thereby purifying it. The ability to customise pore sizes enables selective adsorption of specific molecules, enhancing the efficiency of water treatment processes. Moreover, this selectivity is advantageous in gas separation and storage, where specific gases can be captured or stored more efficiently due to the tailored pore structures. The mechanical stability of hierarchical porous nanostructures is another crucial characteristic. The interconnected frameworks provide structural integrity, ensuring that the materials maintain their shape and functionality under various conditions. This is particularly important in applications like catalysis and energy storage, where the materials undergo repeated use and are subjected to harsh environments. The robustness of these structures helps prevent collapse or degradation, thus extending their operational lifespan and maintaining performance over time. In supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries, for example, this stability is critical for long-term cycling and durability, as the materials must withstand numerous charge-discharge cycles without significant loss of capacity. In biomedical applications, hierarchical and porous nanostructures play a vital role in drug delivery systems. The high surface area and porosity allow for the loading of substantial amounts of therapeutic agents. Additionally, the pore sizes can be tailored to control the release kinetics of the drugs, enabling sustained or targeted delivery. This capability is crucial for enhancing the efficacy of treatments while minimising side effects. Furthermore, the biocompatibility of certain hierarchical porous materials makes them suitable for use in-vivo, broadening their potential in medical applications [111–113].

The importance of hierarchical and porous nanostructures is further underscored by their role in enhancing the efficiency of renewable energy technologies. In photocatalysis, for example, these structures can improve the absorption of light and the separation of charge carriers, leading to higher catalytic activity in processes like water splitting or pollutant degradation. The increased surface area and tailored porosity facilitate better interaction between the photocatalyst and the reactants, improving overall performance. Similarly, in solar cells, hierarchical structures can enhance light absorption and charge transport, leading to improved energy conversion efficiencies. Moreover, the environmental benefits of hierarchical and porous nanostructures cannot be overstated. Their ability to adsorb and degrade environmental pollutants makes them invaluable in addressing pollution and contributing to cleaner environments. For instance, in wastewater treatment, these materials can efficiently remove contaminants, offering a sustainable solution to water pollution. Their reusability and potential for regeneration further enhance their environmental appeal, reducing the need for constant replacement and minimising waste. In short: hierarchical and porous nanostructures possess unique characteristics that make them indispensable in a wide range of applications. Their high surface area, enhanced mass transport capabilities, tunable porosity, and mechanical stability provide significant advantages in catalysis, energy storage, environmental remediation, and biomedical applications. By improving reaction rates, enhancing ion and molecule diffusion, and enabling selective adsorption, these structures contribute to more efficient and sustainable technological solutions. As research in nanotechnology continues to advance, the development of innovative hierarchical and porous materials will play a critical role in addressing global challenges in energy, environment, and health, underscoring their importance in promoting sustainable development and technological innovation [113–115].

8 Synthesis Methods of Hierarchical and Porous Nanostructures

Hierarchical and porous nanostructures are synthesised through various methods that enable precise control over their properties and applications. These methods are essential for developing materials with tailored porosity and high surface areas, critical for applications in catalysis, energy storage, and environmental remediation. Three of the most noteworthy techniques used in the synthesis of these structures include pyrolysis, hydrothermal carbonisation, and chemical activation. Each method offers unique advantages in controlling the morphology and pore size distribution of the resulting materials. Fig. 10 demonstrates that recognizing the application-specific properties stemming from the synergy between pore size, scale levels, and geometric configuration is vital for leveraging the structural, geometric, and organizational characteristics of pores across different length scales, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of hierarchically structured porous materials [116].

Figure 10: A schematic representation of hierarchically structured porous materials. Reproduced with permission from [115]. Copyright © 2020 Oxford University Press