Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Finger-Joint Lumber: A Systematic Literature Review and a Global Industry Survey on this Ecofriendly Structural Building Material

1 Post-Graduation Program in Civil Engineering, São Paulo State University, Ilha Solteira, 15385-007, Brazil

2 Development of Lignocellulosic Products Research Group, São Paulo State University, Itapeva, 18409-010, Brazil

3 Post-Graduation Program in Civil Engineering, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, 13565-905, Brazil

4 Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Rondônia, Porto Velho, 76801-974, Brazil

5 Post-Graduation Program in Agricultural Engineering, São Paulo State University, Botucatu, 18610-034, Brazil

6 Undergraduation Program in Civil Engineering, Federal University of Western Pará, Itaituba, 68183-300, Brazil

7 Post-Graduation Program in Forest Resources, University of São Paulo, Piracicaba, 13418-900, Brazil

8 Department of Construction Technology, Economy and Management, Technical University of Košice, Košice, 042-00, Slovakia

* Corresponding Authors: Victor De Araujo. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Eco-friendly Wood-Based Composites: Design, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications – Ⅱ)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(12), 2479-2524. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0127

Received 23 July 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Finger-joint lumber is a sustainable building product commercialized as a structural solution for beams, pillars and other thin flat load-bearing elements. This study aims to study finger-joint lumber and its industry to promote this engineered wood product. The first research stage assessed the collection of publications on finger-joint lumber available globally, in which a structured protocol was developed to prospect studies based on two complementary methodologies: PRISMA 2020 using Scopus and Web of Science databases, and Snowball using both forward and backward models to complete with additional literature. The second research stage assessed finger-joint lumber manufacturers, in which companies were globally prospected using Google search engine and their corporate websites were profoundly analyzed using a structured script to collect information. Literary approaches have provided structural performance and bonding quality of finger-jointing. In the review, we provide a global overview and data regarding the current stage and future directions of finger-joint lumber for industrialized construction. Regarding this structural product, we review the main resources, material preparation and processing, and automated production. Mainly active in Europe and already present in 38 nations across five continents, we survey a finger-joint lumber industry comprising 186 producers controlling 214 manufacturing operations worldwide. The vast majority of this industry has exported linear engineered solutions in different dimensions, certified as to compliance with the origins of their bioresources and the European Union requirements, to markets exposed to 24 languages in order to meet commercial applications such as single-story houses, townhouses, roof structures, and hangars.Keywords

Structural timber is a versatile building product with different shapes and compositions, including linear, curved and planar solutions manufactured from fitting, gluing, doweling, nailing or screwing, as defined in different literatures [1–7].

Added to this is the use in different building systems (e.g., half-timbered frame, log-home, light-woodframe, post-and-beam, modular, etc.) and application types (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial, infrastructural, etc.), reinforcing the multiplicity and applicability of wood in civil construction [8]. This use is reinforced by the advantages of embodied carbon, resource renewability, and material rationalization, which ensure efficient results in environmental-social-economic analyses aligned to a more sustainable life cycle as observed by many authors [2,5,9–20].

Given the different shapes in simple beams and columns or complex and sophisticated structures, Bier [1] stated that there was already space for innovation in construction from engineered wood in the late 20th Century, especially in commercial and industrial fields, as these industrialized products can provide greater levels in production efficiency, construction simplicity, and economic feasibility. In that period, Ketchum [21] confirmed the usability of engineered wood as a prefabricated construction material. Their advantages become possible due to the use of computer-integrated manufacturing and flexible production systems [22]. Over time, some expressions such as “massive timber” and “mass timber” began to be used to define engineered solutions with more robust dimensions than the reconstituted boards [23,24]. Whether as beams or large panels, especially in terms of thickness, mass timber products have become valuable structural options due to more standardized and homogenized qualities ensured by prefabrication processes. Although Smith et al. [25] confirmed only 9 mass timber products, De Araujo [7] identified 20 different types of commercial panels and beams, which are classified as mass timber products, including finger-joint lumber. Mass timber is produced in manufacturing plants, using processes with union by fittings among parts, insertion of additional elements (e.g., metals, woods, etc.) or adhesion of structural adhesives (polyurethanes, phenolics, polyvinyls, epoxies, etc.), offering a complete range of solutions [7].

Given the applicability of these products in different building systems, with different uses and sizes [7–8], more complex structural systems are built connecting beams and pillars while the modernization process of construction facilitates the creation of lighter structures both from lightweight materials and from the edification of central cores and stabilizing tubes, as addressed by several authors [26–31]. This evolution has been encouraged by the inclusion and consideration of massive timber products in standard codes that have become strict and specific to regulate the structural performance [32]. Some massive timber products—such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels and laminated-veneer timber (LVL) and glued laminated timber (GLT) beams—are receiving greater attention from the market [7,33], to the detriment of other commercial options. This is also confirmed by specific codes available worldwide [32]. Recent approaches follow the popular solutions and, therefore, other massive options still require further examination—this includes finger-joint lumber. Given this gap and the authors’ motivations for more sustainable building materials, this hybrid study was started with a systematic literature review on structural finger-joint lumber beams and completed with an industry survey on the global perspective to raise unknown data and foster discussion to promote this solution and respective manufacturers.

This hybrid study was designed using two stages: a systematic literature review with snowballing and a global sectoral survey to address finger-joint lumber products and industry.

2.1 Stage 1: Systematic Literature Review with Snowballing

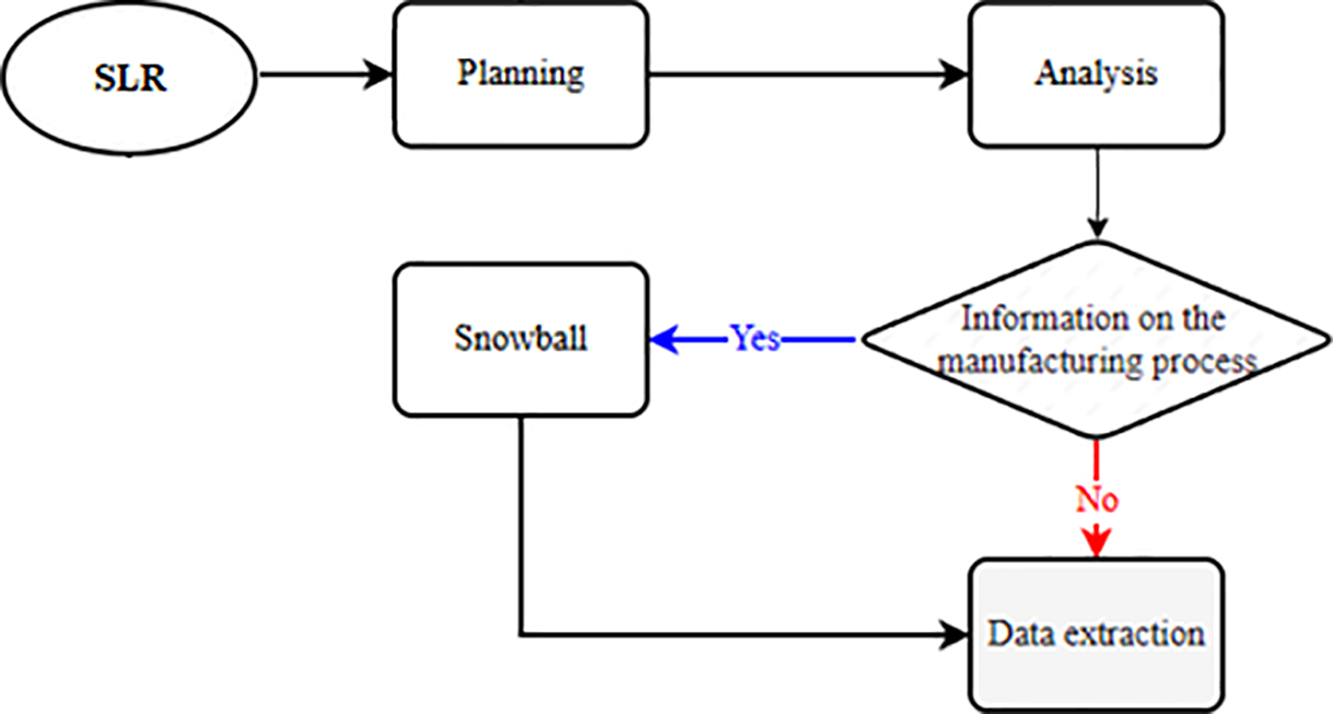

Systematic literature review (SLR) followed the stages according to PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses), to map and discuss the perspectives on finger-joint lumber, including performance, configuration and manufacture and other topics (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Procedures and methodologies of the Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

In the planning stage (Fig. 1), Scopus and Web of Science databases were defined for prospecting studies and a search string was developed to systematically ensure a comprehensive search. Other databases and strings were tested, including in other languages but their results were similar and, therefore, not duly considered. Thus, the following search string used was:

• (“finger-joint” OR “fingerjoint” OR “finger-jointed”) AND (“timber” OR “lumber”)

The sample analysis included three successive filters of eligibility:

• Filter 1: primary reading (title, abstract and keywords) to eliminate publications outside the SLR scope, carried out in the first quarter of 2025;

• Filter 2: secondary reading (introduction and conclusion sections) to verify the alignment of objectives and contributions related to the SLR, carried out in the first quarter of 2025;

• Filter 3: tertiary reading (full text) of pre-screened publications to confirm the relevance and adequacy to compose the final sample, carried out in the second quarter of 2025.

Additionally, snowballing methodology was applied to identify other publications with relevant data and information on finger-joint lumber. This stage was carried out from the direct assessment of literature referenced and cited by publications screened in filter 3 and from indirect evaluation of recent publications which cited the publications identified in filter 3. This strategy was used to verify opportune publications that had not been retrieved initially. In the data extraction stage, screened publications were organized in spreadsheets using Microsoft Excel 2021 with main parameters of interest: wood, adhesive, joint, and processes of manufacturing (Fig. 1).

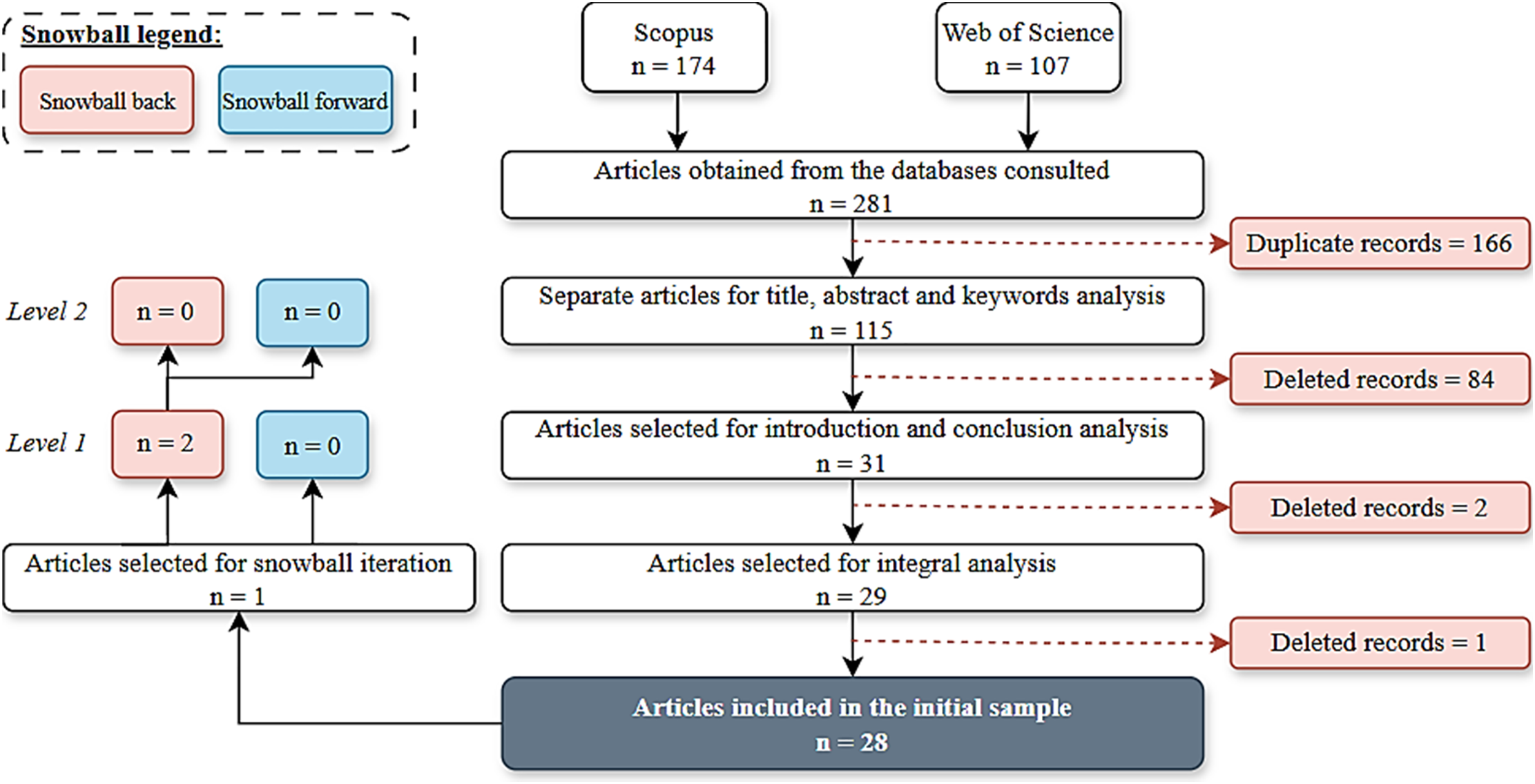

The complete process of systematic literature review using PRISMA 2020 protocol is presented in Fig. 2, in which the sample selection stages were identified according to level/function and number of publications. The development time of this SLR lasted the entire first half of 2025.

Figure 2: Framework and stages of this Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

Initially, 28 papers were screened after three filters, excluding repeated and insufficient works on finger-joint lumber. In sequence, two studies were identified by snowballing methodology from direct evaluation (backward) and indirect evaluation (forward) and, therefore, included in the final sample. In total, 30 studies formed the collection of screened publications, among which only three studies addressed manufacturing scopes (Fig. 2). Due to the broad perspective, every information was read and relevant data regarding finger-joint lumber was registered.

Bibliographic and bibliometric data were registered and quantified using Microsoft Excel 2021, as well as VOSviewer were used to visually display results.

2.2 Stage 2: Global Sectoral Survey

Whether in a regional, national or global context, population surveys involving industry sectors are efficient methodologies to prospect and characterize individuals and stakeholders, respectively.

In this way, global sectoral surveys (GSS) become instruments to identify and demonstrate the corporate perspective from different regionalities, showing similarities, evincing contrasts, understanding challenges, and identifying the potential of a certain population.

For example, two studies [7,34] were successful in their analyses on mass timber and cross-laminated timber products, which allowed the characterization of a broad audience in the context of the wood industry focused on the producing of sustainable prefabricated engineered material for structural applications in industrialized buildings.

The systematic literature review developed in the first stage (Fig. 2) confirmed the lack of research on the finger-joint lumber industry. Given the gaps that justify the development of this present research, this study seeks to raise and characterize all manufacturers of finger-joint lumber products for structural applications in construction currently active around the world.

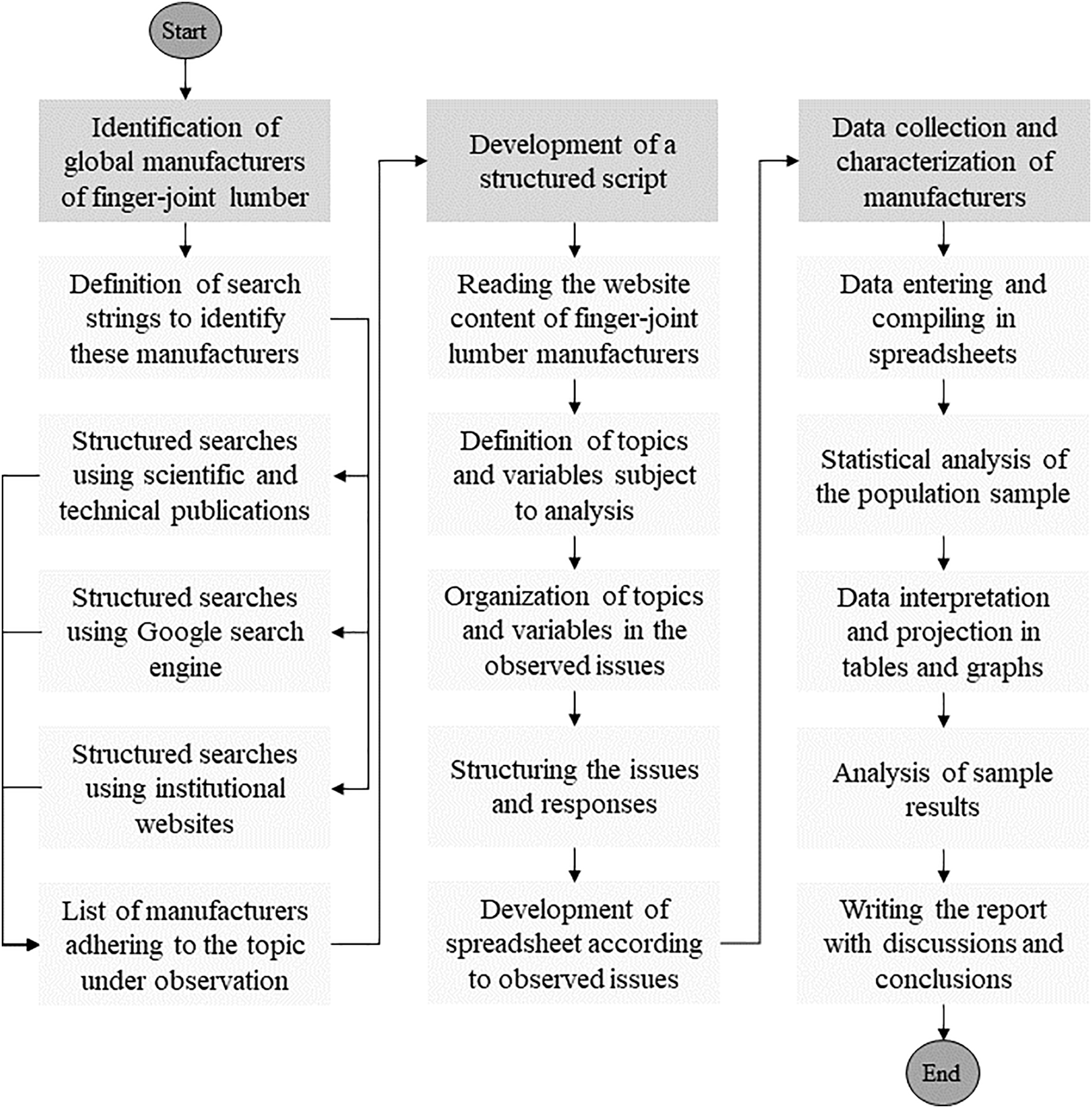

The script of this global sectoral survey is illustrated by Fig. 3 according to the steps of the main stages, which were inspired in the protocol prescribed by a study [7], and adjusted and completed for the new observation on structural finger-joint lumber producers.

Figure 3: Flowchart of this Global Sectoral Survey (GSS)

2.2.1 Identification of Finger-Joint Lumber Manufacturers

Due to the unavailability of lists in scientific and technical publications with the names and respective websites of structural finger-joint lumber manufacturers, this primary stage focused on a structured process for identifying individuals adhering to the goals of this survey (Fig. 3). Taking into account the major objective on this global industry, this stage included the definition of strings for supporting the prospecting and listing steps.

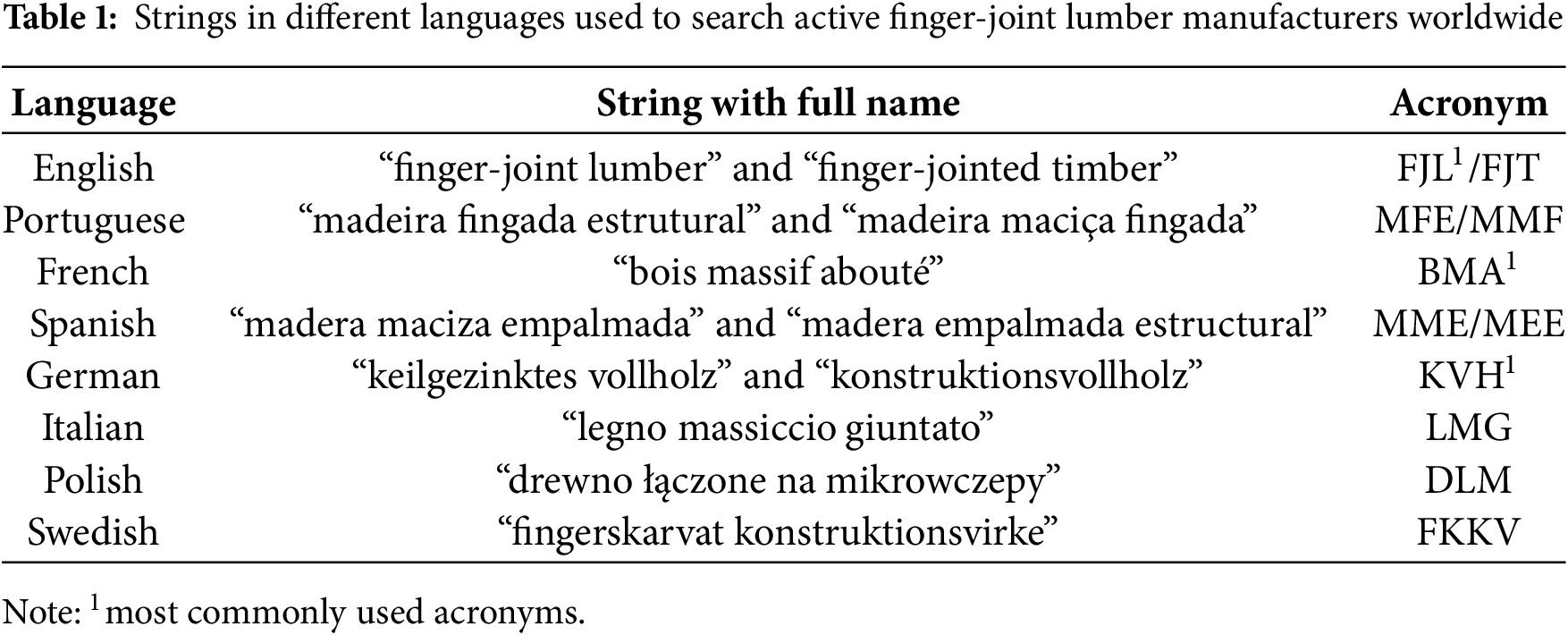

By checking information from different leading manufacturers, nomenclatures and abbreviations written in eight different languages were considered, according to Table 1.

From Google Search Engine, a prolonged routine of prospections of structural finger-joint lumber manufacturers was carried out using this series of strings written in different languages (Table 1) to obtain a broad coverage of results and, therefore, identify a greater number of individuals to be sampled (Fig. 3).

Prospections were individually sought, analyzing the last entry registered in each searching proof. After, the process was re-started with a string formed by the full name with the insertion of respective acronym (Table 1), as well as each full term was sought with the German acronym—we considered this alternative prospection due to the popularity of finger-joint lumber in Germany.

Evidence was sought based on graphic-textual statements publicly available on each corporate website, which allowed researchers to identify each individual and confirm its compliance with the objectives. Therefore, producers of other structural massive products were not considered as they are not classified as a finger-joint lumber producer.

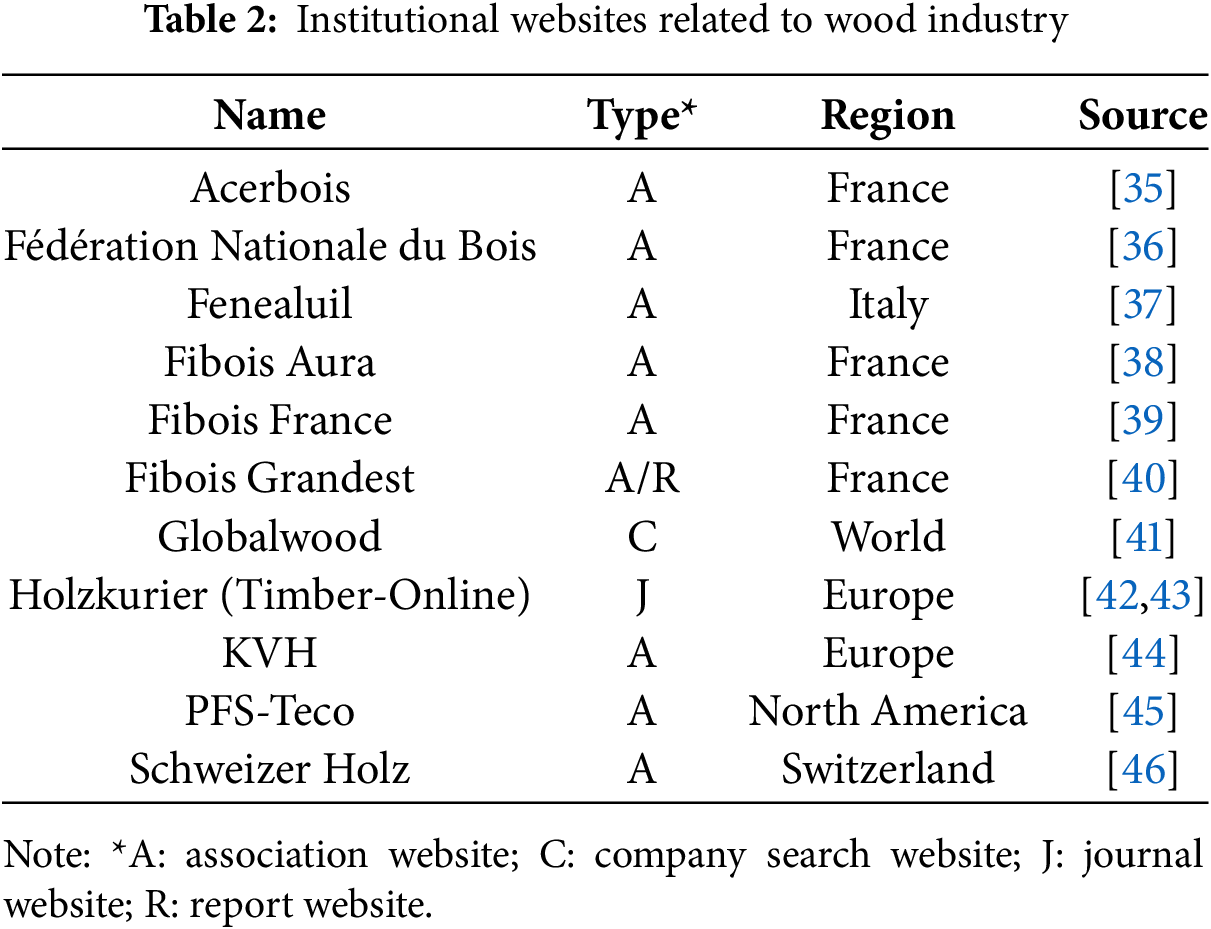

Despite the prolonged searches that presented consistent results, this prospective stage was extended to identify and validate the manufacturers publicly declared on some institutional websites, which are identified in Table 2.

Although more laborious, the multi-level prospecting process using multi-language terms (Table 2), used by the authors in other studies, allowed the identification of a greater number of manufacturers as well as the validation of these individuals.

For each company identified, its name, territorial origin and website address were recorded in spreadsheets using Excel software (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA, version 2021), and organized by location.

All respondents were not identified from their respective results for purposes of confidentiality and sample impartiality. The results of the information and characteristics identified were counted individually for each company, although the study was designed to present the general panorama of the global finger-joint lumber industry for each category and respective variables to be observed, as detailed in the following items on the structured script and data collection.

2.2.2 Development of the Structured Script

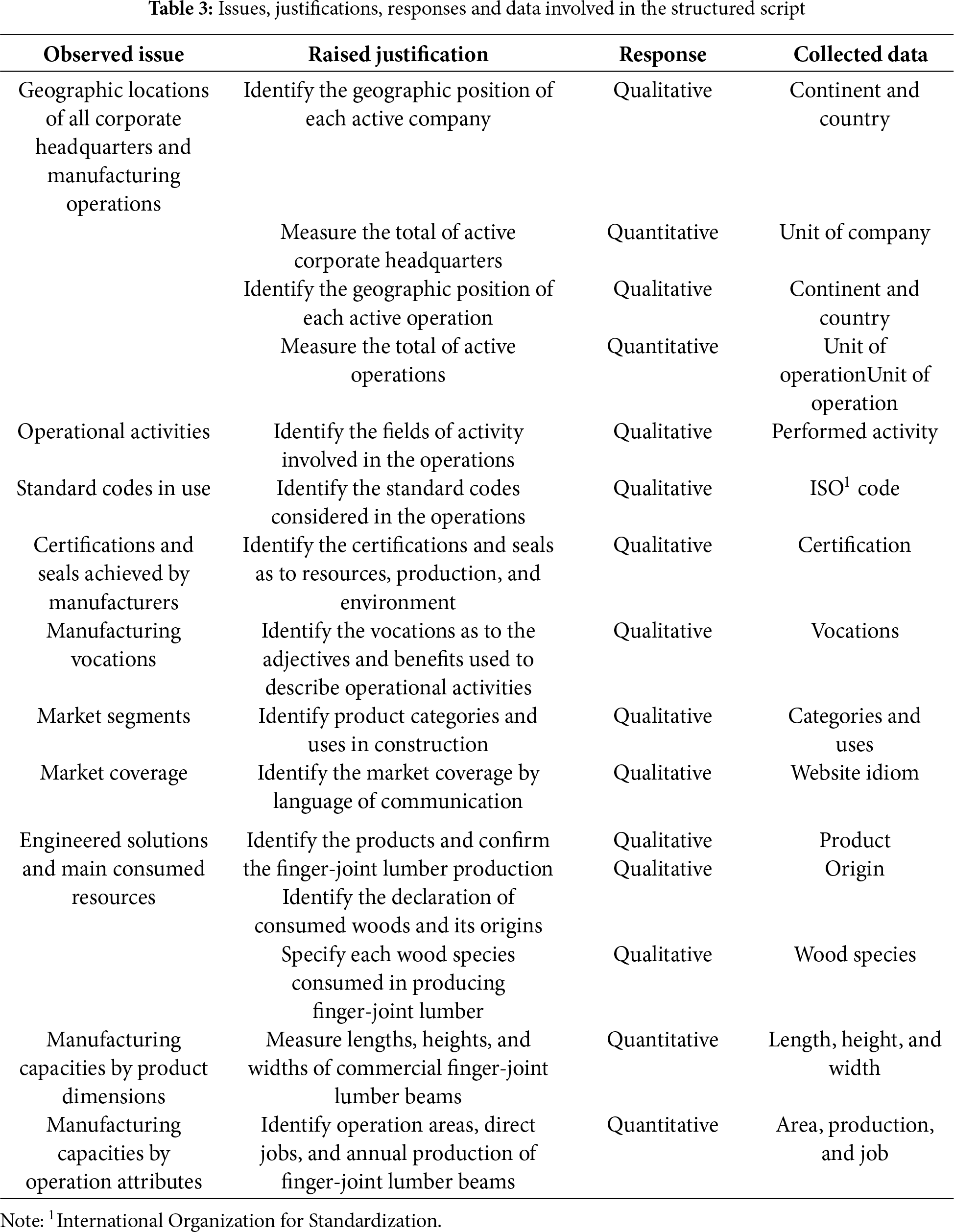

A script of questions and variables was structured in the second stage to evaluate the sample (Fig. 3). Table 3 details the script standardized for the data collection to characterize the studied industry and thus compare responses.

During the confirmation of the adherence of each manufacturer to the major objective of this survey, every graphic and textual content publicly disclosed on the websites was assessed at this research stage.

It was possible to identify several issues and their categories and possible variables subject to be observed, as seen in Table 3, enabling comparisons and evaluations of all sampled individuals. Geographic locations, numbers of companies and operations, activities, markets, standards and certifications, and manufacturing capacities were the main conditions observed in this global sectoral survey.

The initial stage prospected and discussed selected scientific publications to contextualize finger-joint lumber from bibliometric and bibliographic analyses, and the subsequent stage identified and sampled active manufacturers of structural finger-joint lumber from a sectoral survey to characterize its industry.

3.1 Stage 1: Systematic Literature Review with Snowballing

3.1.1 Bibliometric Analysis on Finger-Joint Lumber Studies

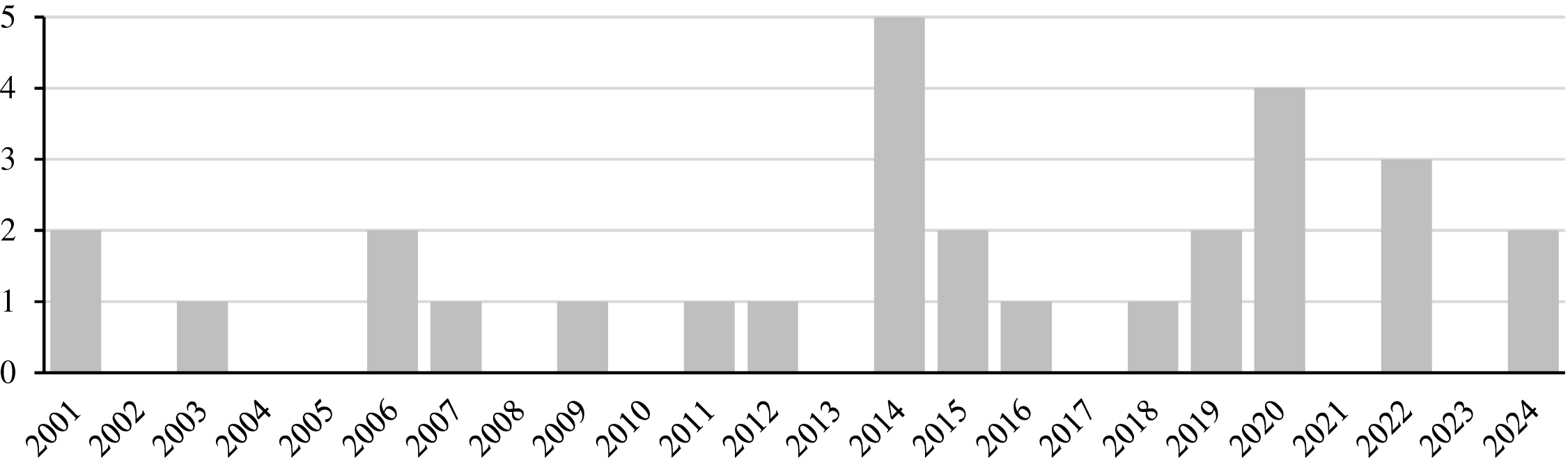

A sample of 30 studies was obtained, including 28 from Systematic Literature Review and 2 from Snowballing. The number of publications on this scope has been reduced and dispersed over the last two decades. The largest number of articles published occurred in 2014 with five studies, right after no study published in 2013 and before only two studies in 2015—this reinforces the limitation and discontinuity of scientific production regarding this structural massive beam (Fig. 4) and, therefore, a challenge to be overcome by the scientific community with further research for the coming years.

Figure 4: Number of publications per year

In the final sample represented in Fig. 4, 88 different authors were identified, none of whom had published more than two papers on the finger-joint lumber scope, which indicates the absence of a recurring reference or consolidated author in this field of study.

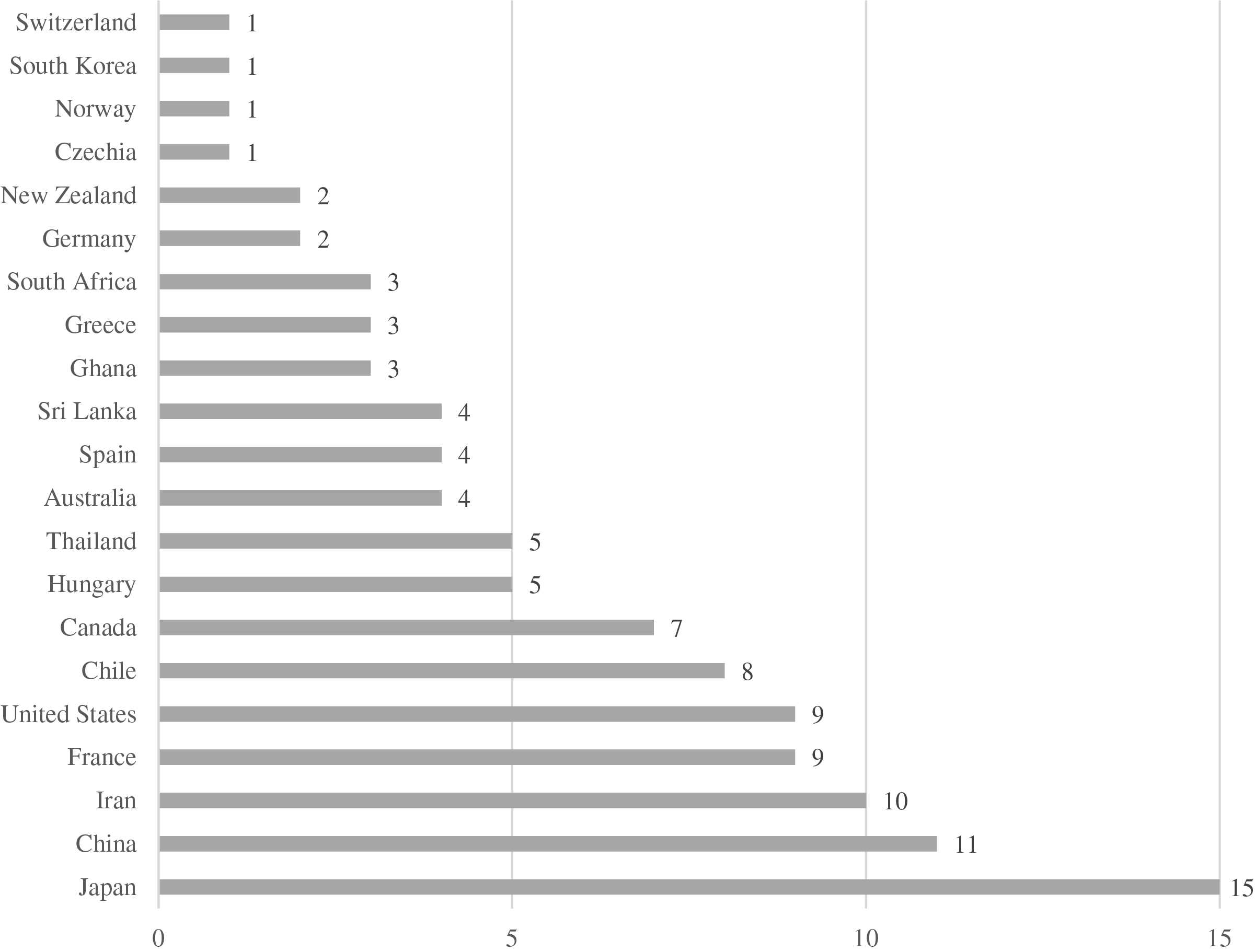

Regarding the institutional affiliation of the literature authors, a broad geographic distribution was identified in the global perspective, with research representation from all continents (Fig. 5). There are authors from nations located in both hemispheres.

Figure 5: Countries according to affiliation of authors

This geographic scenario is considered positive, as it allows us to observe, for example, regional practices under different regulatory conditions, climatic conditions and wood species. From Fig. 5, it is possible to confirm that the countries with the largest numbers of affiliated authors were Japan (15 authors), China (11), and Iran (10)—all of them located in Asia. Also, it is important to highlight that the specific three studies that address the manufacturing process of finger-joint lumber beams come from Japanese institutions.

The predominance of Asian studies, especially from Japan and China (Fig. 5), denotes the perceptible level of industrialization and cultural tradition of these countries in wood engineering, while the scarcity of research in the Latin-American region can be a future opportunity for the development of local technology.

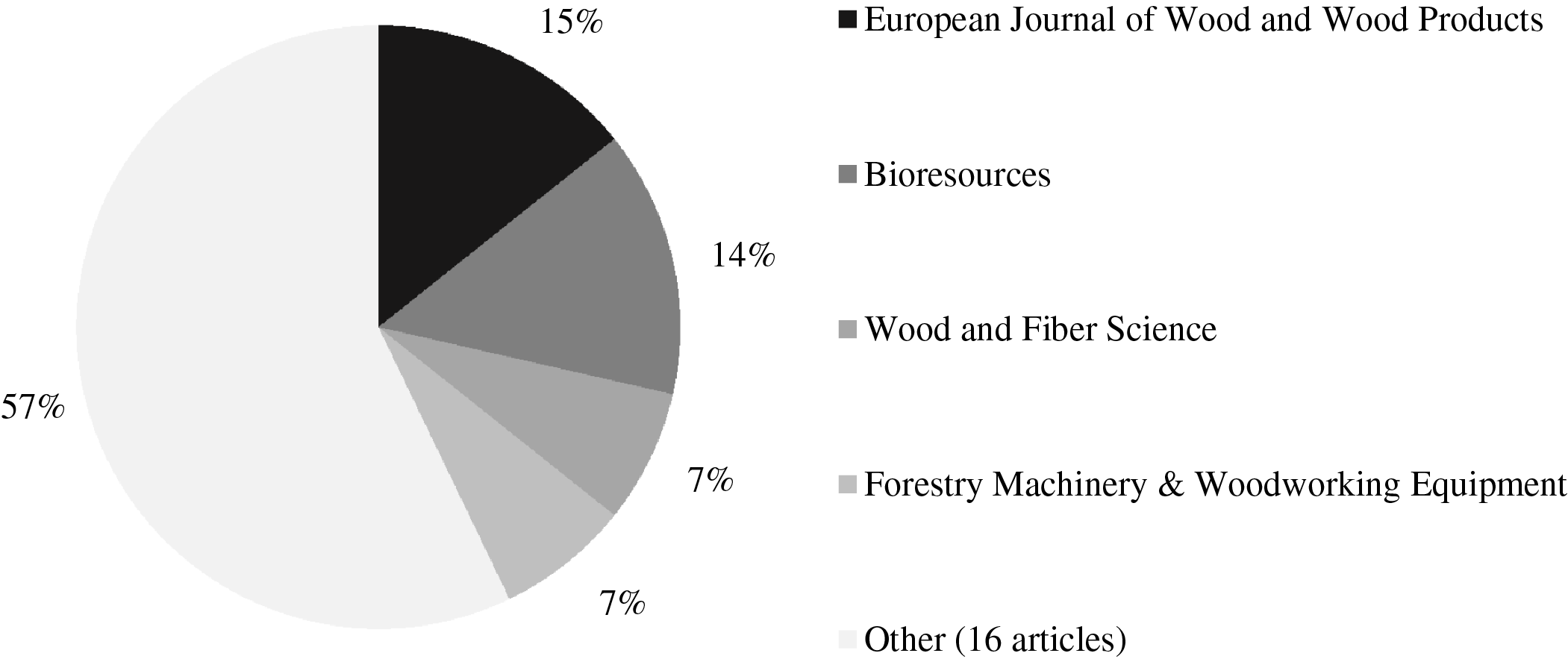

In Fig. 6, the scientific journals in which screened studies were published are presented. The following journals with greater numbers of publications are European Journal of Wood and Wood Products (Springer-Nature) and BioResources (North Carolina State University) with four publications each, as well as Wood and Fiber Science (Society of Wood Science and Technology) and Forestry Machinery & Woodworking Equipment (China Forestry Publishing House) with two studies each. Other 16 journals (1 per publication) were also identified.

Figure 6: Main scientific journals used in publications on finger-joint lumber

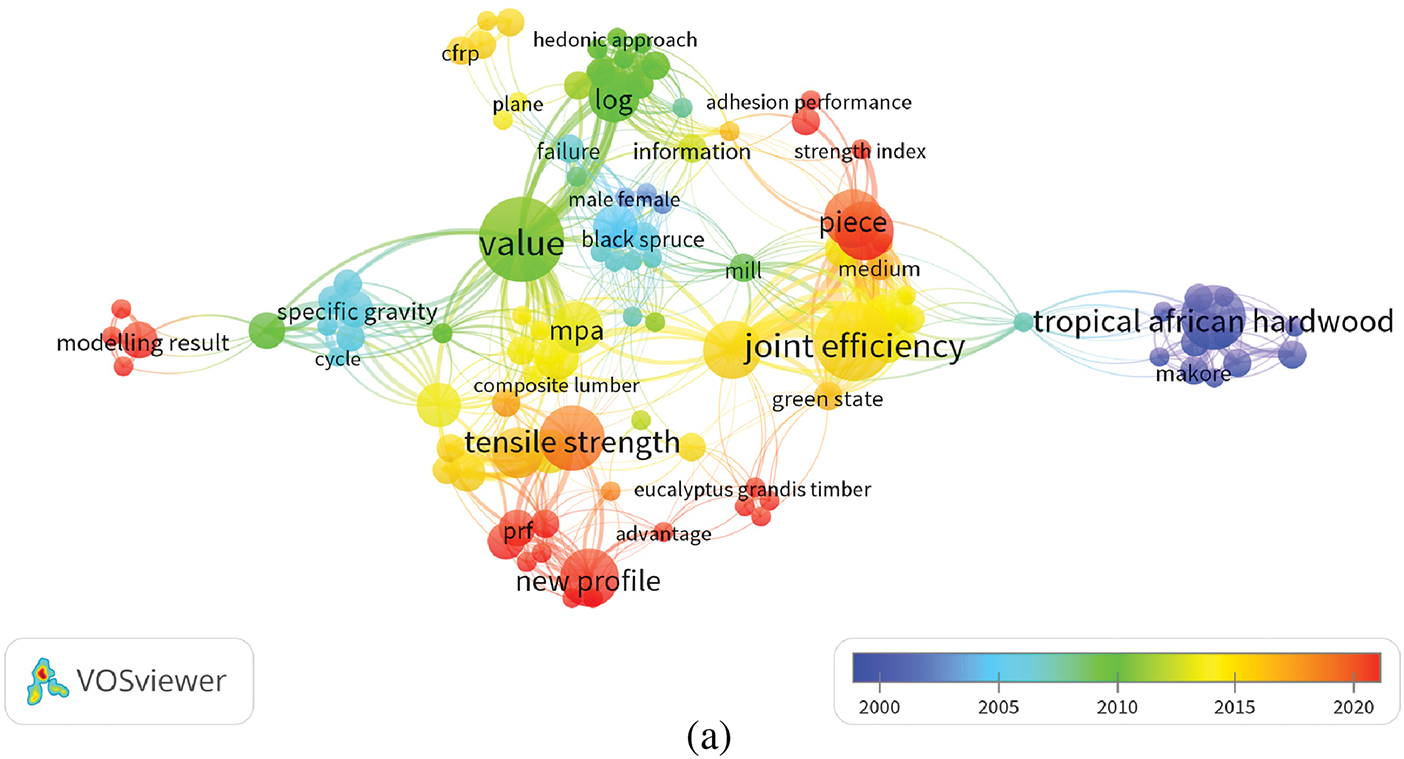

Regarding the terminology used in prospective stage of systematic literature review, it was also possible to analyze the relation and intensity of words for keywords and titles with abstracts. By observing all words present in the titles and abstracts (Fig. 7a), 24 clusters were obtained. For all keywords (Fig. 7b), 19 clusters were found.

Figure 7: Relationship map between terminologies of: (a) titles and abstracts and (b) keywords used in the analyzed publications

In titles and abstracts (Fig. 7a), joint efficiency, value, piece, tropical African hardwoods, tensile strength, new profile and log were the most frequent terminologies, while finger joint, bending test, CFRP (carbon fiber–reinforced polymer), adhesive, density, and finger-jointing were the most used terms as keywords (Fig. 7b).

In general, the main terms refer to the analysis of structural performance and bonding quality, indicating these topics as those of greatest interest in the literature.

In both analyses (Fig. 7a,b), the lack of terms about the manufacturing process of these elements stands out. Furthermore, there is also the lack of terms referring to (finger-joint lumber product) industry and sector, which demonstrates a potential scientific gap.

3.1.2 Bibliographic Analysis on Finger-Joint Lumber Studies

Wood Species and Material Characterization

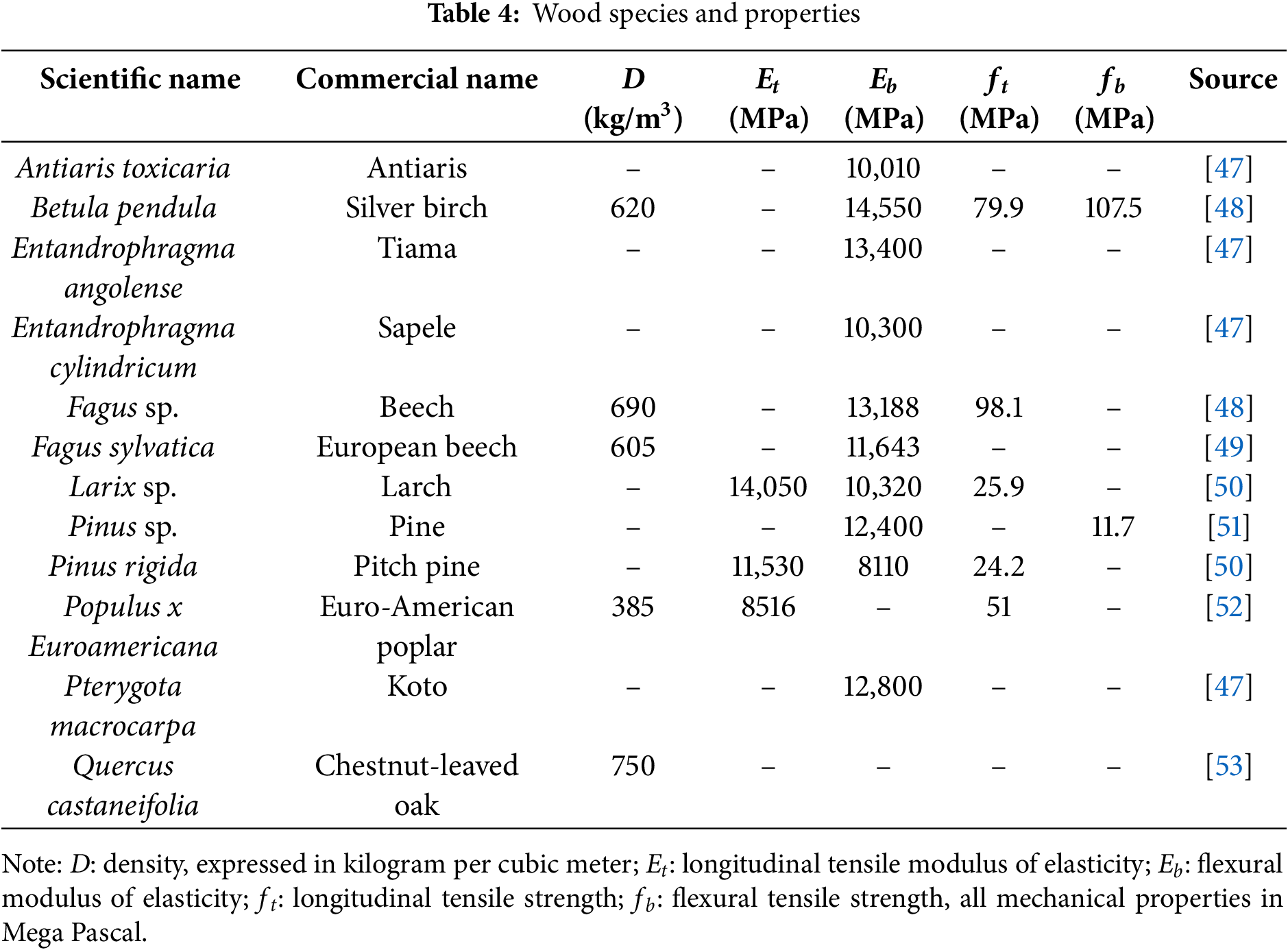

From the sample of screened publications, it was possible to identify the wood species and respective characteristics addressed by scientific studies in the development of finger-joint lumber. 18 species were identified as bioresources utilized as raw material, including Antiaris toxicaria, Baillonella toxisperma, Betula pendula, Entandrophragma angolense, Entandrophragma cylindricum, Eucalyptus sp., Fagus sp., Fagus sylvatica, Larix sp., Picea spp., Picea mariana, Pinus sp., Pinus rigida, Populus x Euroamericana, Pterygota macrocarpa, Quercus castaneifolia, Tieghemella heckelii, and Triplochiton scleroxylon. 12 species were characterized (Table 4), although no study fully assessed the main properties.

Baillonella toxisperma, Picea mariana, Picea spp., Pinus sp., Tieghemella heckelii and Triplochiton scleroxylon were characterized in two studies each. From these wood species, there was a predominance of hardwoods with emphasis on African tropical woods and commercial species such as Pinus sp. and Eucalyptus sp., as well as an absence of native species from South American region, especially from the Brazilian Amazon, which indicates a research gap with a visible potential for further studies.

By observing data from Table 4, few studies carried out wood property characterization, as only seven publications have some characterization. This illustrates the complexity in carrying out tests and also indicates the importance in adopting main properties for dimensioning large wooden beams. In general, flexural modulus of elasticity was the most studied property in the screened studies. It is worth noting the lack of information on the shear strength of these linear elements. Simultaneously, most screened studies did not provide the density values for their products.

Among these characterized species, there is a predominance of wood with higher density and stiffness, which is very desirable due to the nature of typical efforts in structural beams. Denser woods usually have a better flexural strength and a greater capacity to withstand the typical stresses associated with variable loads, as can be seen in Table 4. In contrast, the gluing performance in high-density woods, with consequent low porosity due to greater mass of bio-based material per volume, tends to be less efficient, as confirmed by Marra [54], Silva et al. [55] and others.

According to Amin et al. [56], the glue line can undergo accelerated degradation in dense woods, increasing the stresses concentrated in the joint. When observing the publication sample of this review (Table 4), no studies evaluated this condition in solid wood beams glued with finger-jointing. This fact is worrying because the lack of information on long-term performance can negatively impact the performance of current built structures. In other words, this gap is an essential topic to be studied. This can be filled by studies involving other alternative wood technologies.

For example, the consideration of superficial incisions on the glue face in glued-laminated timber using high-density conifers was studied by Vella et al. [57], where these authors observed a visible reduction in glue line stresses. Atmospheric pressure rotating plasma jet used by Yáñez-Pacios and Martín-Martinez [58] to treat wood-plastic composites can be considered.

Furthermore, no correlation was observed between wood density and the reduction in the modulus of elasticity (MOE) and modulus of rupture (MOR) of finger-joint lumber beams compared to continuous solid wood beams. The reduction in MOR is more pronounced than that recorded in other studies [59,60] that analyzed usual species such as pine and eucalypt in glued-laminated timber beams, which demonstrated average reductions of around 34%.

However, the MOE observed by Işleyen and Peker [60] increased with the use of finger joints (mean value of 21%); this was not observed in the publications analyzed by this review. This demonstrates that—although high-density woods are desirable in terms of mechanical performance—the impact of finger joints on their structural performance is still not fully understood.

When assessing the impact of scientific data for the timber industry and construction sectors, the high taxonomic heterogeneity and the low incidence of repeated studies with the same species make it difficult to implement best practices, making each research little transferable to the market. Thus, there is an evident space for further studies on finger-joint lumber characterization regarding physical and mechanical properties using available standard documents for structural elements based on timber to intensify global markets of this massive timber of linear element category.

Finger-Joints and Geometries

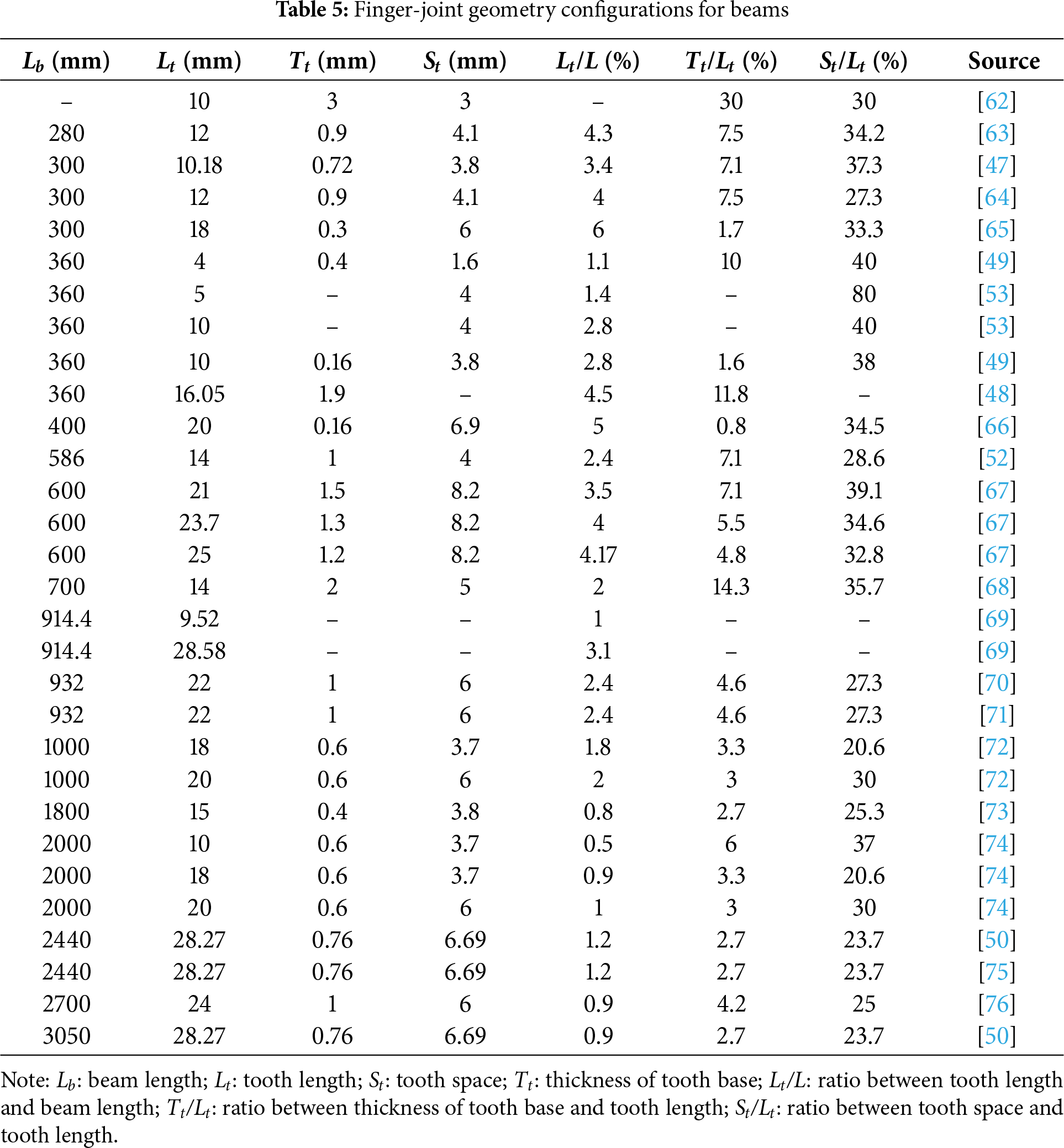

By analyzing screened publications, it was possible to verify different geometric configurations of finger-jointing. As there is no standard recommended in international normative codes, this section provides the dimensions adopted by publications, numerically expressed in millimeters (mm) in Table 5, for beam length (Lb) as well as for tooth length (Lt), tooth space (St), and thickness of tooth base (Tt) and relationships among these dimensions for prototypes and products.

By analyzing relationships (Table 5), the Tt/Lt ratio was the one that presented the greatest consistency as it varied between 20.6% and 80%, with an average of 32.82% and a coefficient of variation of 33.92%. From Table 5, the Lt/L ratio provided values between 0.5% and 6%, with an average of 2.42% and a coefficient of variation of 59.44%, with an intermediate dispersion. In turn, the St/Lt ratio was the most dispersed, oscillating between 0.8% and 30%, with an average of 6.13% and a coefficient of variation of 95.24%. The results reveal a lack of standardization with respect to the minimum dimensions adopted in the screened studies, which may make it difficult to define optimal parameters for the industrial finger-jointing production for finger-jointed lumber beams.

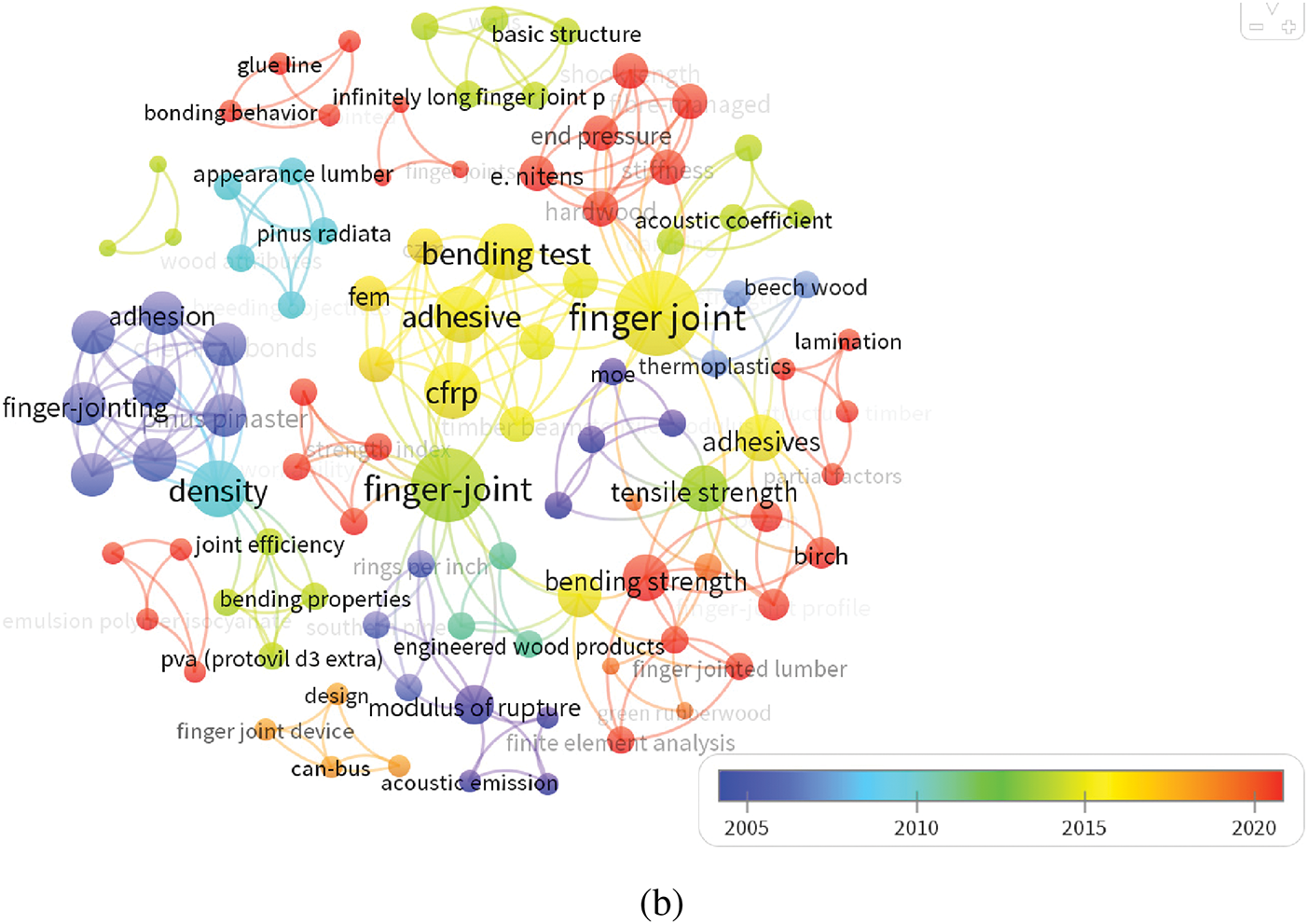

Fig. 8 presents a correlation analysis of the finger-joint measurements and their studied geometric relationships (Table 5) with the variation of the MOE (ΔMOE) and MOR (ΔMOR) of the beams that had revealed this information. When evaluating the effect of the geometric variables of the finger-joint “teeth” (Lt, Tt and St) on the ΔMOE of the beams (Fig. 8a), Spearman correlations (rs) were observed that varied between rs = −0.31 (St) and rs = −0.34 (Lt). These values indicate a weak negative correlation between the analyzed variables, as suggested by Montgomery and Runger [61].

Figure 8: Correlations of finger-joint lumber geometry with the variation of ΔMOE and ΔMOR for dimensions of: (a) Lt, (b) Tt, (c) St, (d) Lt/L, (e) Tt/Lt, and (f) St/Lt

The effect of the geometric variables on ΔMOR was lower than that observed on ΔMOE, with no significant correlations between these variables and ΔMOR. As shown in Fig. 8a,b weak positive correlation (rs = 0.46) was identified between the St/Lt ratio and ΔMOE. A weak negative correlation (rs = −0.45) was also found between the Lt/L ratio and ΔMOE, following the consideration of [61].

As in the previous analyses, no relevant correlations were observed between the finger-joint ratios and ΔMOR, which evinces a gap to be observed. It is important to emphasize that the analysis was performed with a limited number of data (n = 38 beams analyzed in the literature), which may limit the generalizability of the conclusions. Future studies are essential to deepen this analysis and better understand the impacts of geometric variables on the mechanical performance of beams.

Le et al. [77] led a study focused on optimizing finger joints, aiming to improve MOR while minimizing production costs. These authors also found that the number of finger joints (e.g., number of “teeth”) and the tooth length (Lt) were the most significant parameters for mechanical performance. The observation corroborates, even if discreetly, the results presented in Fig. 8a.

Therefore, it is strongly recommended by the authors of the present review to expand the studies on the influence of the geometric configuration of finger-joints on the mechanical performance of beams, in order to better understand the interrelations and influences between these variables and the mechanical properties of materials.

Adhesives for Finger-Joint Lumber

The development of structural finger-joint lumber beams has scientifically considered the utilization of different commercial resins, including polyurethane (PUR), polyvinyl acetate (PVA), melamine-urea-formaldehyde (MUF), emulsion polymeric isocyanate (EPI), phenol-resorcinol-formaldehyde (PRF) and resorcinol-formaldehyde (RF) were the main examples. Nine studies considered PUR for the development and analysis of finger-joint lumber, followed by six studies based on PVA, five with MUF, three with EPI and PRF each, and two with RF. Five studies did not specify the adhesive used. Specifically, five studies performed direct comparisons between the performance of different adhesives applied to finger-joints.

Liu et al. [65] evaluated melamine-based UF (urea-formaldehyde) and phenol-based RF (resorcinol-formaldehyde) resins at different wood moisture contents, finding that pressing time affected tensile and shear strength more significantly when MUF was used and they verified that no significant differences were detected in flexural strength. Hemmasi et al. [53] observed that both PVA and PUR reduced the dynamic modulus of elasticity and the acoustic coefficient of beams in relation to solid wood elements, but without relevant distinction in performance between the adhesives for 10 mm joints. Srivaro et al. [64] compared PUR and EPI, reporting that the MOR (modulus of rupture) of joints bonded with EPI was slightly lower, while the MOE (modulus of elasticity) was slightly higher, but without statistically significant impacts.

The study by Pommier and Elbez [78] highlighted the superiority of a new PUR developed specifically for wood with higher moisture contents, whose application resulted in the highest average flexural strength values when compared to both commercial PUR and PRF for dried woods. Furthermore, the type of adhesive influenced the failure mechanism: the use of PRF and commercial polyurethane (PU) resins in dry wood presented failures typically initiated in the finger joint regions, while the innovative PU resins applied to green wood provided failures outside the bond line, indicating a more efficient adhesive-wood interface.

In summary, the experimental results of Table 5 show the decisive influence of the type of adhesive, especially in interaction with the hygroscopic state of the wood and the manufacturing parameters, on the structural performance of the finger-joints. This way, innovations can be reached by developments using bio-adhesives—which have non-toxic and renewable features for industry, as stated by Lei et al. [79] and Watumlawar et al. [80], due to the use of biosourced raw materials in more sustainable formulations.

It is noteworthy that the adhesives found in the publications sample are commonly used in the gluing of wood elements. Although they are widely known and globally adopted, these adhesives have limitations and disadvantages that were not properly evaluated in finger-joints of structural lumber beams.

For example, polyurethane resins (PUR) may develop bubbles on the glue line due to the reaction of isocyanate with moisture, resulting in the generation of carbon dioxide. This can implicate the transmission of efforts to the joints, negatively affecting the mechanical performance of the elements and their durability [57,81–83]. Additionally, structural resins containing formaldehyde—e.g., melamine-urea-formaldehyde (MUF), phenol-resorcinol-formaldehyde (PRF), and resorcinol-formaldehyde (RF)—have the sanitary disadvantage of being confirmed carcinogenic to humans [84]. The use of resorcinol substantially increases the cost of formulations, which has motivated investigations dedicated to mitigating the use of this chemical compound, for example, reducing it to a lower resorcinol content or even replacing it with tannins [85–87].

Alternatively, the use of bio-based adhesives (lignin, tannin, protein, cellulose, starch, etc.) has been increasingly studied due to more sustainable features, especially in glued-laminated timber elements. The adoption of bio-adhesives can promote technological advances in structural finger-joint lumber, improving not only mechanical performance and durability, but also reducing the environmental impact. Although they still face limitations, bio-adhesives based on lignin, tannins, cellulose, starch and vegetable proteins appear to be promising alternatives to replacing petroleum-based adhesives in wooden elements, as studied by some authors [88–90]. The use of natural components as additives or replacements in commercial adhesives has also been the subject of research for decades, with promising results [87,91–93]. However, water resistance, cure behavior and time, and adhesive capacity still represent some of the significant challenges [88,94,95]. Studies as Yang and Kosentrater [96] demonstrate that the use of bio-based adhesives is economically feasible, potentially compatible with the traditional market, although the volatility of raw material can directly impact; this way, studies on this use in finger-joint are still required.

Oliveira et al. [97] evaluated a PUR based on castor oil (Ricinus communis), verifying the absence of air bubbles in the glue line and obtaining results similar to those obtained with RF-based adhesives. Other alternatives are being studied, as cited by Islam et al. [90], who suggest that the use of dispersing agents and hydrophobic chemicals can improve the adhesive properties and water resistance in wood composites. Research on milling techniques has shown improvements in the properties of protein-based bio-adhesives.

Industrial fast-cure systems such as “honeymoon” type (PRF/PRF, PRF/tannin, and tannin/tannin variants) have demonstrated, since the early 1980s, the ability to substantially reduce the curing time and increase productivity in finger-joint lumber and glued-laminated timber [85,87,98,99].

The impact of the type of adhesive on the manufacturing of finger-joint lumber is a missing topic in the scientific literature. On the other hand, studies on the gluing of laminated beams indicate that the fast-cure adhesives can reduce the bonding time to two hours with the use of MUF [99,100] and fast-fixation PRF [85]. Studies regarding fast-fixation bio-adhesives are available, including PRF with the addition of flavonoid tannin extract in this main component, and the addition of up to 65% preserves long-term performance and does not affect the speed of resin curing [101].

A lack of systematic experimental studies that correlate adhesive type, industrial processes (productivity rates) and long-term performance in finger-joint lumber is a literature gap. Although bio-adhesives were not observed in publications analyzed by this review, the introduction of modern and technological adhesives could significantly contribute to the advancement of greener finger-joint lumber. It is imperative to align with more sustainable global ambitions so that future studies can be carried out to explore this potential involving the sustainability of innovative solutions in wood gluing of joints.

Material Preparation and Gluing: Steps and Parameters for Finger-Joint Lumber

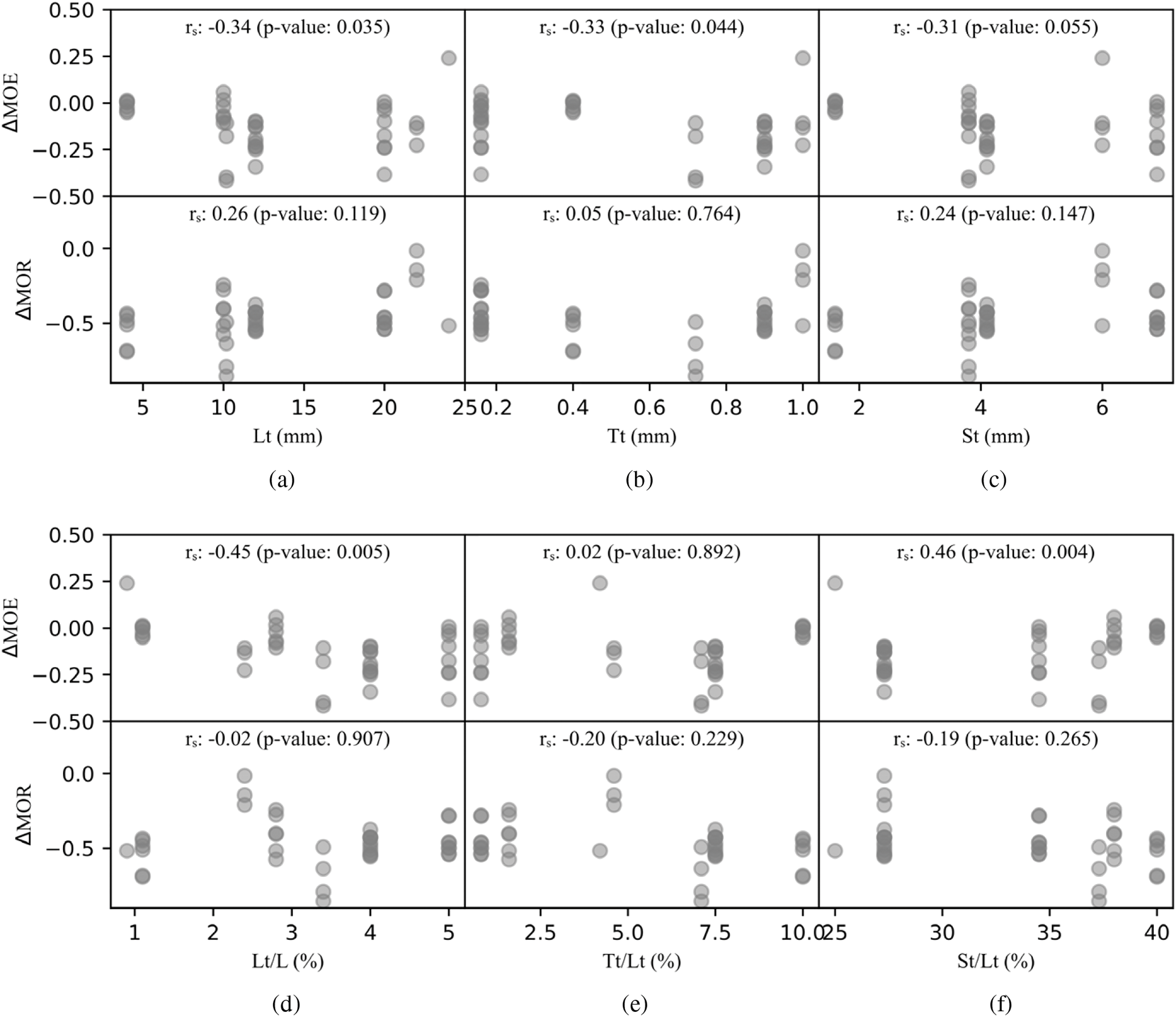

A conventional finger-joint factory usually includes a manufacturing process formed by: a tilt hoist to load lumber onto the infeed system, a sizer to plan edges and faces, a shaper table to load the lugs and trims the trailing end for grading, an oven to dry random length pieces on the slow-moving oven chains, glue spread to apply glue to lugs and trims using an automatic feeder, a crowder to apply the necessary pressure to squeeze out excess glue and lock the joint, a flying cut-off saw to trim pieces according to expected length, and a final dressing to plan pieces for compliance with final stud grade [102]. This way, a standard production flow of finger-joint lumber with respective stages and processes with machinery can be understood through Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Finger-joint lumber production flow

Among the screened papers that detailed the wood preparation for subsequent gluing of finger joints (Fig. 9), the procedures adopted were somewhat similar, differing from each other in the use of equipment to speed the process compared to artisanal technique (which is notably slower). In general, the wood was dried at 12% moisture content. Although the literature specifies the use of kilns or laboratory driers (e.g., furnaces, ovens, etc.), few studies described the procedure adopted in detail.

For example, Pommier and Elbez [78] reported that drying was carried out for 24 h (hour) at 60°C (Celsius degree), while Rodríguez-Grau et al. [68] experimentally maintained the wood for nine days at 40°C, followed by a week in a controlled environment at 20°C (±3°C) and 60% (±5%) relative humidity. This still obtained 6% to 8% moisture content with minimal cracking [68]. In a conditioning room at 20°C and 65% relative humidity, while Srivaro et al. [63] dried wood at 12% moisture during three months. The analysis of the bonding procedures used in the different studies demonstrates a significant variation in the steps and parameters adopted, reflecting the diversity of experimental contexts and objectives evaluated.

In general, the studies describe the conditions of adhesive application and curing, but important differences are observed with respect to the application method, pressing pressure, curing time and environmental control. Among the application methods, manual applications [47–49,66] using a brush or a spreader as well as industrial techniques [63,64] were found.

The pressure on the joints during gluing varied considerably among the studies analyzed. The final pressures ranged from relatively low values, such as 0.5 MPa [63] to very high pressures, reaching 18 MPa [72]. Pressure times also varied widely: while some studies maintained the pressure for only a few seconds, such as a study [68] who applied 6 MPa for a few seconds and another [48] who applied 11 and 15 MPa for 5 s, in woods of different densities, Ayarkwa et al. [72] contrastingly adopted the pressure time on the joints as 48 h. In some cases [47,52,68], the samples were subsequently kept in climate-controlled chambers or controlled environments, with 20°C and 65% moisture. Despite the impact on the performance of structural elements [103,104], no studies were found that compare the intensity or time of pressure application on the joint, which becomes a lack in the literature.

The variations reflect distinct experimental approaches and specific requirements of each research, and they can impact the quality of adhesion and the structural performance of finger joints.

No comprehensive studies were found specifically evaluating the impact of preparation and bonding procedures on the performance of solid beams glued with finger joints. For an efficient gluing, Udvardy [105] prescribes different considerations such as wettable and solidification conditions of adhesive, uniform and sufficient conditions of glue spreading, clean and flat conditions of surfaces, and sufficient and uniform conditions of pressure.

It has been observed that the type of bonding surface treatment can impact the interface [97]. Adam et al. [106] compared the bonding performance of sanded and milled surfaces, obtaining better behavior on the milled surfaces. In addition to investigations such as those based on the study by Vella et al. [57] on the use of incisions on the bonding surface, the level of sanding of this interface can also be evaluated to improve adhesion at the interface.

Furthermore, there are modern technologies that can be more intensely utilized and tested to optimize the adhesive curing process, and they were not observed in our sample. For example, radiofrequency and microwave energies have been used in some industrial processes to accelerate the curing of adhesives, and both technologies have been adapted to press some engineered products such as cross-laminated timber, glued-laminated timber, and parallel strand lumber [107].

Safin et al. [108] investigate the effect of radiofrequency plasma on increasing the resin adhesion to wood. In tests with three types of adhesives (PVA, PU, and UF), plasma pretreatment improved surface adhesion, with the effects being more evident for PVA. Radiofrequency-treated laminated beams showed increased strength, which was attributed to the improved adhesive-substrate interaction after treatment.

The application of radiofrequency to cure adhesives in finger-joints thus emerges as a promising technological alternative, as its curing can significantly reduce polymerization times, making production cycles shorter and curing more uniform throughout the adhesive line. Furthermore, surface treatments can increase the surface energy of the wood and, consequently, the adhesive strength, acting not only as a curing catalyst, but also enhancing the adhesive-substrate interaction. Thus, radiofrequency could play an additional role in improving adhesion. Wood surface treatment with radiofrequency plasma could be effective in increasing the adhesive strength and performance of laminated beams [108].

Potentially relevant for finger-joints, Trosa and Pizzi [109] highlight that some innovative hardeners, such as tris(hydroxymethyl)nitromethane, can achieve adequate levels of structural performance when the same is subjected to thermal activation or radiofrequency curing. For certain adhesive systems, the use of this technology is not only an advantage, but a necessary condition for their practical application.

Therefore, there is an existing gap in studies on the integration of radiofrequency curing into industrial finger-joint production lines. Targeted research evaluating operational parameters, process economics, scalability, and long-term structural performance would be relevant to assess the potential for industrial diffusion of this technology and its compatibility with next-generation adhesives.

Processing and Automated Production of Finger-Joint Lumber

Those screened publications that address solutions for the automation of the finger-jointing production converge in the diagnosis of traditional problems: low efficiency, high non-conformity rates and strong dependence on the manual skills of operators. Different automated processes of finger-joints were found.

In a work [110], a production line is outlined for the production of finger-joint beams of “practically infinite” lengths, with a special focus on their application for structural elements. The structure of their equipment comprises integrated modules such as combing, feeding, pre-joining, CNC (computer-controlled cutting machine) feeding by double roller, execution of the finger-jointing itself and automatic stacking. It is worth noting the adoption of a servomotor feeding system, which ensures precision in the longitudinal feeding of the parts, contributing decisively to the quality of the final product.

The operational flow is fully sequential and automated, from loading the workpiece and its correct positioning, through the stages of machining of the fingers, automated application of the adhesive and joining of the elements, to the final stacking, all under programmable logic control, touch-sensitive interface and speed adjustments via frequency inverter. With this, the system offers high adaptability, operational stability, precision and efficiency, surpassing previous generation equipment and increasing productivity in high-performance industrial lines [110].

Another study [111] focuses on the development of a fully automatic intelligent device for finger-jointing wood panels, outlining both the mechanical architecture and the hardware and software configurations, showing the use of the CAN (controller area network) bus to orchestrate the multiple functions of the system. The equipment also integrates specialized modules for combing, gluing, joining and sawing panels, in addition to allowing, through a human-machine interface, flexible parameterization of the process and adjustment to the specificities of each production batch. The device operates from the automated stacking and transfer of short pieces of wood, execution of different finger-joint geometries with automated tool change, controlled application of the adhesive, handling of the part between the machining areas, pre-tightening and joining of the finger joints, until the final production of solid panels with variable width and length. The use of distributed control via CAN bus, combined with hydraulic mechanisms for joining and comprehensive automation of each stage, stands out for solving problems of operational coordination, configuration flexibility and robustness of the production process.

Yang et al. [112] presented the industrial application of a specific equipment for automatic application of adhesive in finger joints using sawn wood. Unlike the others, the focus is on the optimization and validation of the gluing stage, recognized as one of the biggest bottlenecks in uniformity, yield and quality of finger-joints. The equipment adopts a modular architecture, based on programmable logic controllers, automatic detection sensors, pneumatic actuators and aligned part feeding system.

Industrial tests achieved approval rates above 97% (single cycle) and 98% (double cycle), in addition to high operational consistency, even in intensive production, far surpassing both manual methods and semi-automated configurations. This approach highlights how dedicated automation and factory-scale validation can make a decisive contribution to efficiency gains, waste reduction and improved quality [112].

From the sample of publications, most studies on finger joints in structural parts focus on aspects such as comparing wood species, adhesive type, tooth geometry and configuration, and, in some cases, the pressure used in bonding. However, adhesive drying is generally performed in climate-controlled chambers or other controlled environments in laboratory infrastructures. Despite the importance of drying and curing processes in the final performance of finger joints, no studies were found in the literature discussing innovations specifically applied to this stage under large-scale production.

Available studies generally focus on conventional drying methods, such as oven drying and natural drying of the adhesive over time. These technologies, while effective in certain situations, do not constitute recent or disruptive innovations.

However, Troughton [113] confirmed that finger-joint lumber could be dried using three different ways such as impression finger jointing, preheating, and radio-frequency heating. Impression method is a stop- and-go process, in which glue is applied to the fingers and the profiled pieces are compressed into a heated die [114]. Preheating is a method used to manufacture parts from variable moisture content, in which finger-joint lumber is pre-heated in a kiln with a time-temperature schedule just before glue application [115–118]. Radio-frequency is a high cycle or frequency process in which the equipment transmits energy or electrical impulses [113,119].

The heat buildup within the glue line depends on moisture content and wood species [120]. Radio-frequency has some advantages over heat pressing such as high energy transfer efficiency, uniform heating, short process time, and equipment with reduced size [119]. In contrast, considerable thermal degradation and checking can occur due to rapid escape of formaldehyde and steam vapors [113]. Due to this fact, further research is necessary to improve the finger-jointing quality using fast curing and drying.

Thus, there is a visible gap in finger-joint manufacturing processes, especially regarding the research and development of faster, more efficient drying technologies adapted to the specific needs of the production of defect-free products. Therefore, it is important that future research explore this manufacturing stage, experimentally evaluating the performance of alternative drying and curing methods in terms of efficiency, contribution, quality, and industrial viability.

For professionals, producers and researchers, some factors contribute to a profitable operation with product quality such as the proper selection of equipment to meet sizes and production rates, condition of material (surface, defects, squareness, moisture, etc.), maximum dimensions (length, width and thickness), length and type of joint and tooth, type of glue, end products, and factory service and assistance [121]. This author still explains that proper installation should consider extraction, compressed air (amount and dryness), electrical supply, space, temperature, handling and grinding equipment, maintenance and cleaning.

Lastly, it is worth noting that no research screened in this first stage sought to assess the commercial structural finger-joint lumber beams as well as characterize respective global industry, which reinforces the novelty to be presented in the second stage of this study.

3.2 Stage 2: Global Sectoral Survey

3.2.1 Prospection, Identification and Data Collection of Finger-Joint Lumber Manufacturers

After a long prospective process during the first semester of 2024, a perceptible population of finger-joint lumber manufacturers was identified using their respective official websites. In total, 186 companies were prospected and, from this sum that composed the final list, all individuals were duly validated based on information of institutions and associations listed in Table 2 during the second semester of 2024 and, therefore, sampled in data collection and analyzed in 2025. This way, the response rate was well-tried, as it notably surpassed the minimum prescription of 20% by Yu and Cooper [122].

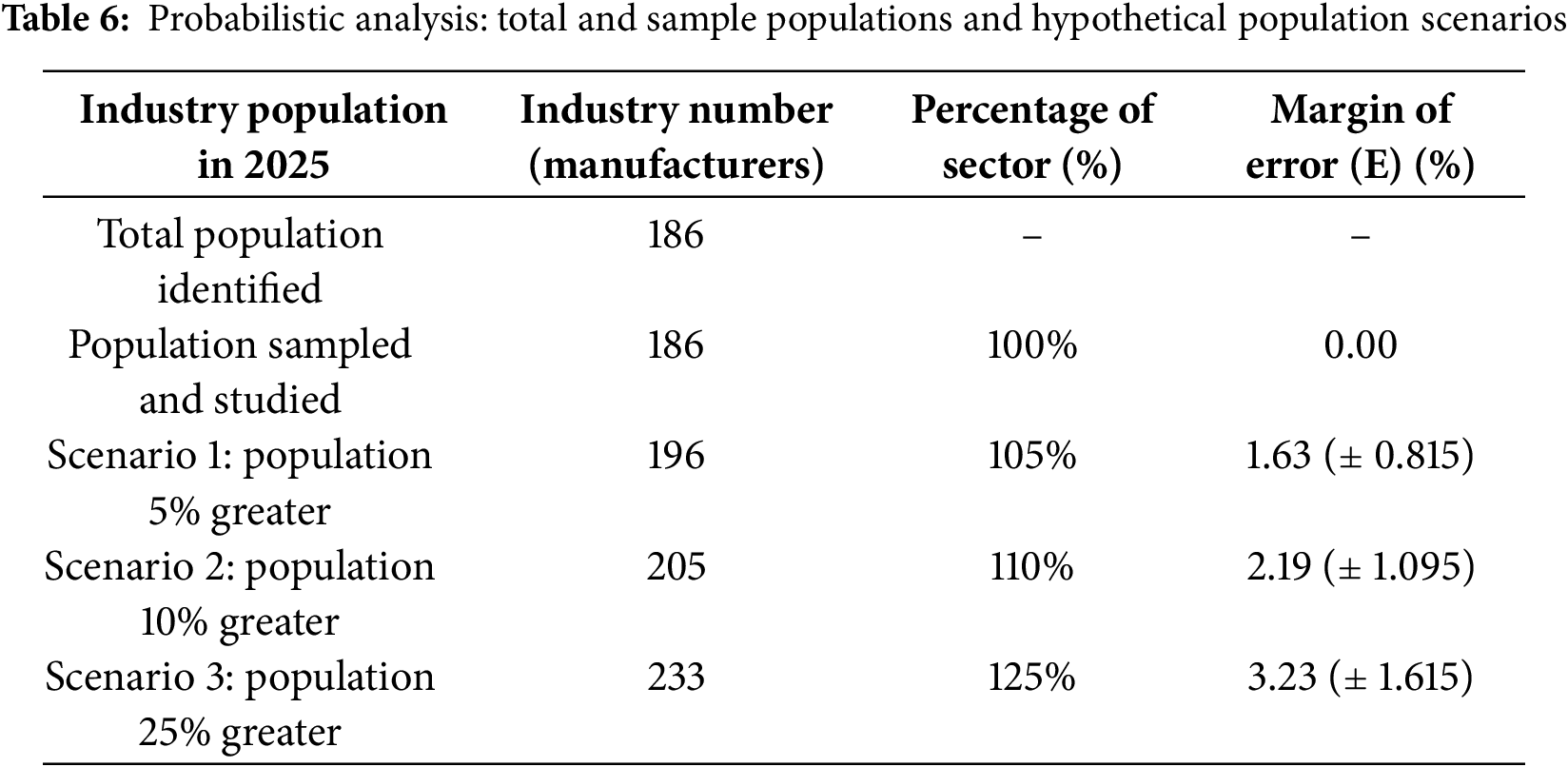

Although each company is expected to have its own official website to promote its brands and products, this survey considered three hypothetical scenarios for populations larger than the sum found here with respective margins of error, both due to the possibility of disseminating outdated data and the impossibility of confirming an exact total of individuals. The projections allowed us to identify margins of error for each hypothetical scenario (Table 6), which were statistically low given the high number of individuals sampled. This is confirmed by the fact that all hypothetical population scenarios (even the atypical supposed condition for a global population 25% larger) had margins of error smaller than the ideal significance level of 5% (±2.50%), which is widely used by the scientific community and prescribed, for example, both by two publications [123,124] and two statistical tools [125,126].

For a greater analytical certainty, the most atypical hypothetical scenario (Scenario 3, Table 6) was inferred from the results of the studied sample (being the number of individuals: n = 186).

3.2.2 Characterization of Finger-Joint Lumber Manufacturers

Considering the novelty of the topic represented by the need to identify and assess structural finger-joint lumber manufacturers, this study achieved its main objective and, above all, exceeded expectations regarding the size of the total and sample populations (Table 6) and the collection of unprecedented information in different categories observed in the following subitems. It was possible to analyze different issues of this industry (Table 3), involving the geographic locations of corporate headquarters and manufacturing operations, operational activities, standard codes, certifications, manufacturing vocations, market segments, market coverage, solutions and resources consumed, and manufacturing capacities by product dimensions and by operational attributes.

Geographic Locations of Corporate Headquarters and Manufacturing Operations

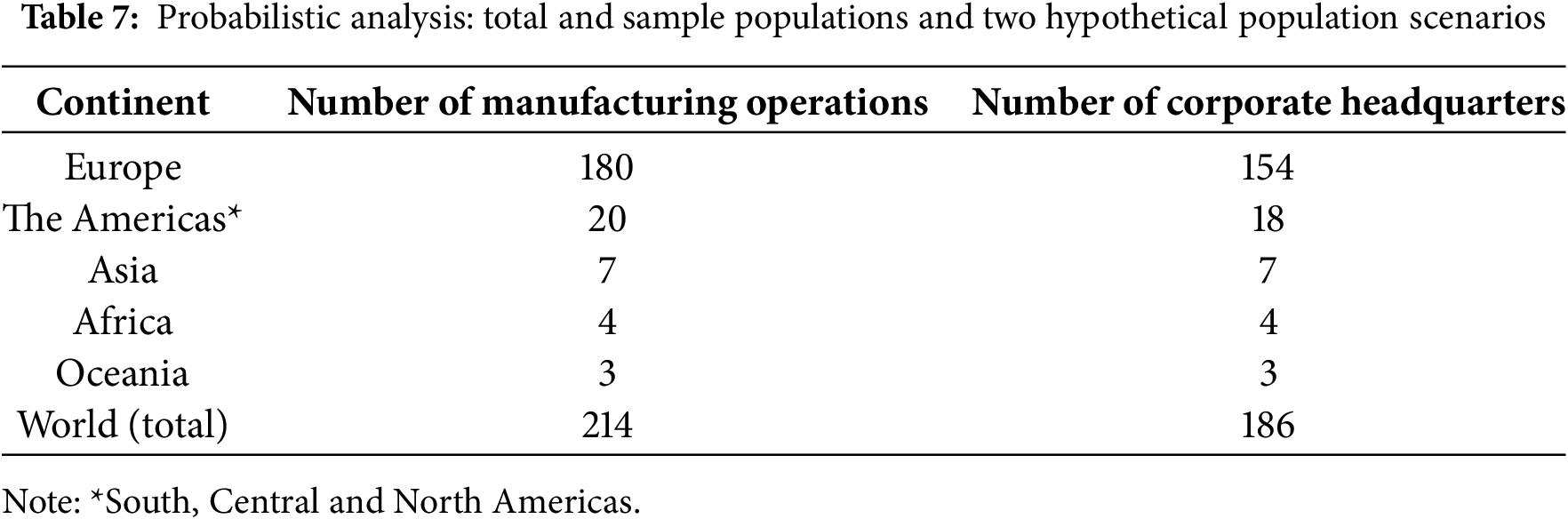

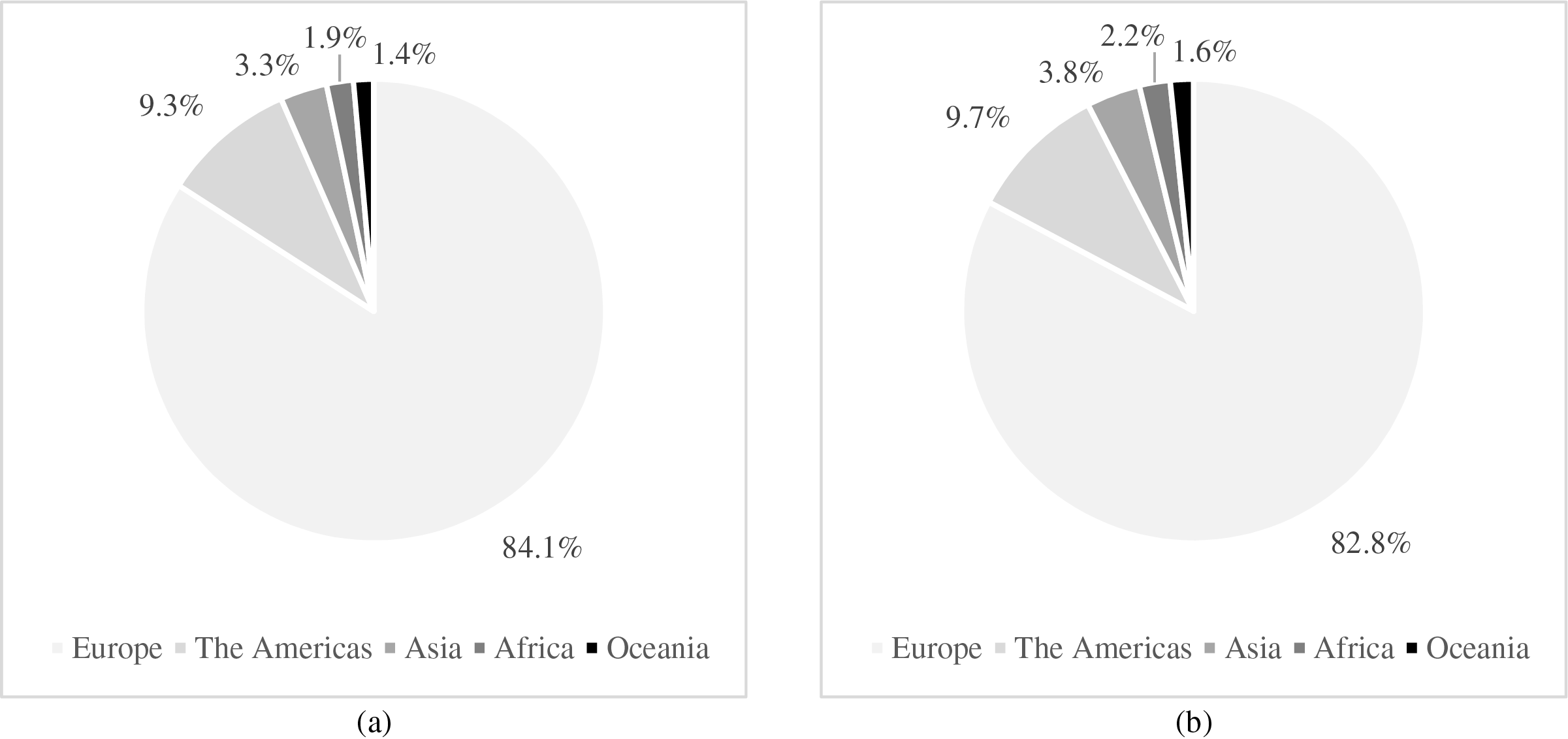

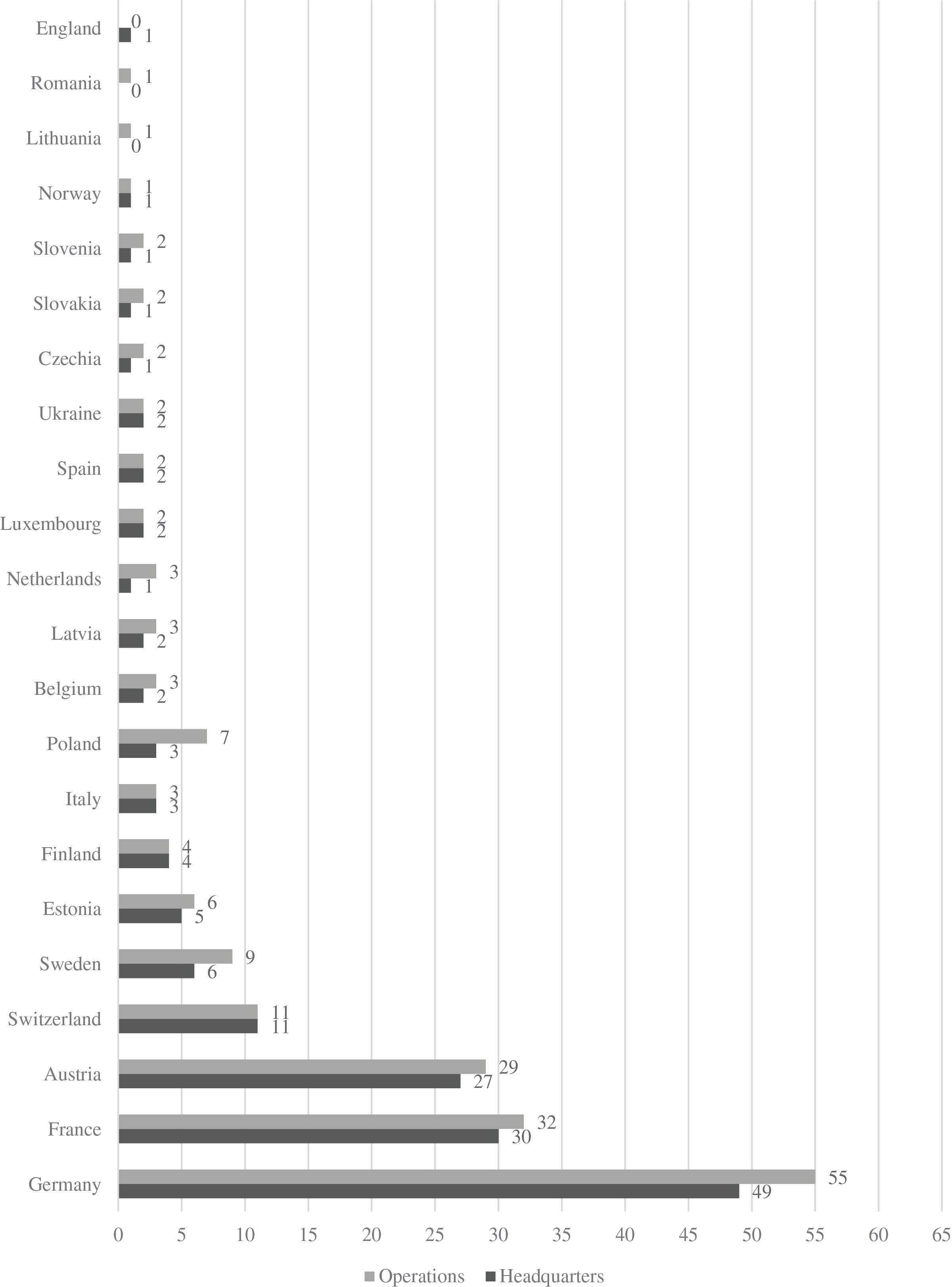

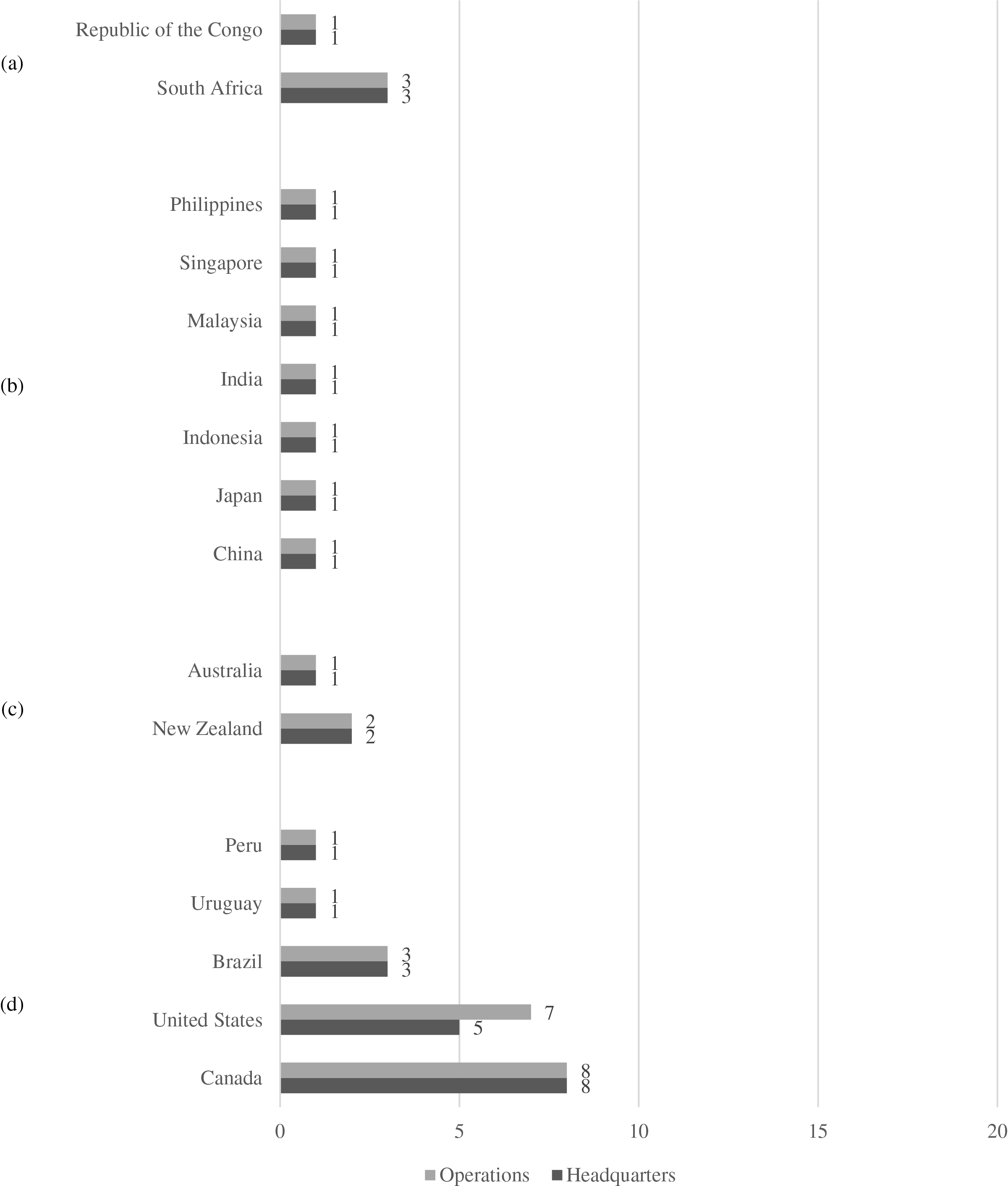

In early 2025, the global industry of structural finger-joint lumber is operating on five continents (Table 7), being actively present in 38 countries through 186 controlling companies of 214 manufacturing operations. Regionally, Europe has the largest numbers of headquarters (82.8% of the entire sector, E = ± 1.615%) and operations (84.1% of the total), followed by the Americas (9.7% and 9.3%), Asia (3.8% and 3.3%), Africa (2.2% and 1.9%), and Oceania (1.6% and 1.4%). Applying the positive and negative variations provided by the margin of error for a population 25% larger than that found (Scenario 3; Table 6), it is possible to confirm a regional similarity in the distributions of headquarters and operations for each region (Fig. 10), despite the predominance of this industry in Europe.

Figure 10: Continental distribution of finger-joint lumber industry according to: (a) manufacturing operation and (b) corporate headquarters (n = 186; E = 3.23% or ± 1.615%)

The significant presence of active manufacturers located in European countries was already expected (Fig. 10a,b), based on research predominance also confirmed in Fig. 5 and facts reported in previous studies; whether on the production sector of cross-laminated laminated timber panels [34] or the general mass timber product industry [7], this outcome agrees with the significant presence of engineered wood product manufacturers in Europe.

Following previous studies [7,34], the secondary participation of The Americas was also expected and, therefore, similarly confirmed by Fig. 10. Despite the little information on structural finger-joint lumber beams in the literature, especially about producers and their locations, this global sectoral survey confirms the presence of this solution on other three habitable continents.

Individually, Germany, France, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Estonia, Finland, Poland and Italy have the largest number of operations and companies in Europe (Fig. 11). It is possible to confirm the greater production engagement on the part of European countries located in the central, eastern and northern regions. The top five countries in terms of the number of companies and manufacturing operations are leaders not only in Europe (Fig. 11), but throughout the world in The Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania (Fig. 12). The greater availability of manufacturing facilities in Western Europe (such as Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland; Fig. 11) is consistent with the genesis and greater patenting of engineered wood in this region, as highlighted by Rug [127–129].

Figure 11: Number of headquarters and operations of manufacturers in Europe (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

Figure 12: Number of headquarters and operations of manufacturers in the following territories: (a) Africa, (b) Asia, (c) Oceania and (d) The Americas (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

Formed by Germany, Austria and Switzerland, the DACH region has 87 producers, which represents 46.77% of the global industry and 56.49% of the European stratum (Figs. 11 and 12). Despite the existence of an organization that represents finger-joint lumber manufacturers in Europe since 1995, namely KVH reported in Table 2 as the information source used in this study, this association primarily brings together companies from DACH region, especially from Germany and Austria. Specifically, KVH lists 35 European manufacturers [44]. Based on this single piece of information with a supposed factory population, it was possible to determine that the global finger-joint lumber industry is 81.18% larger than this KVH’s sum. Taking into account only the trait of European producers (Fig. 11), the KVH’s list represents only 22.73% of producers from that continent. The Benelux countries, Spain, Czechia, Slovakia and Slovenia, which are still emerging in the culture of production and use of massive timber, are emerging as new producers of finger-joint lumber beams (Fig. 11). Contrary to the growing interest and use of engineered wood in the United Kingdom reported by [130], England already has a company (Fig. 11), but still lacks the installation of manufacturing operations.

Contrary to the European predominance (Fig. 11), the other continents hold 17.2% of the companies and 15.9% of the manufacturing operations of finger-joint lumber beams, in which Canada, the United States, Brazil, South Africa and New Zealand stand out as the nations with more numerous sums in non-European regions (Fig. 12a,c,d). In sequence, Uruguay and Peru (Fig. 12d), the Republic of Congo (Fig. 12a), Australia (Fig. 12c), as well as China, Japan, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and India (Fig. 12b), have only one corporate-production representation each.

It was expected that this industry would have greater representation from China due to the growing use of wood in construction [131], from Japan and Australia due to current engagements in establishing standard codes for wood buildings [32], and from Canada due to academic efforts confirmed both in Fig. 5 and some studies presented in a local finger-jointing conference [102,105,113,121]. The perceptible interest in finger-joint lumber in Europe, The Americas and Asia was confirmed by greater numbers of manufacturers (Figs. 11 and 12) and research studies (Fig. 5) in these continents. Considering the size and complexity of manufacturing larger products such as structural beams, this presence of manufacturers on five continents (Figs. 11 and 12) demonstrates a more globalized capillarity of the timber industry to supply civil construction in a manufacturing development process that aligns with the needs mentioned by [2] regarding the increase in training and education aimed at qualification in the field of Timber Engineering and public policies to enhance the use of wood as a construction material.

Operational Activities

Following the protocol previously tested by another study [7], six fields of activity were proposed to comprehend the coverage of operational activities of samples.

According to Fig. 13, all fields were available in this studied industry. In view of the requirement of this global sectoral survey with finger-joint lumber manufacturers, the unanimous result for the “product manufacturing” field was already expected, with the participation of all samples (n = 186) as this was the minimum requirement for this analysis.

Figure 13: Fields of activity of manufacturers (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

Of this total, 69.9% of global manufacturers already operate in the “product exportation” (Fig. 13), suggesting a visible sectoral engagement in the destination of manufactured goods to other international territories, as well as the existence of distribution networks focused on supplying different regions, as raised in Figs. 11 and 12.

Concern for customers is present in 59.1% of this global sector (Fig. 13), because the “product support” represents a formal service that aims at closer technical contacts with potential customers (professionals, prefabricated building factories, suppliers, contractors, etc.), offering better levels of quality and safety. In the construction context, 61.8% of this studied sector already works directly with “off-site building manufacturing” activities (37.6%), followed by 36.6% with “building project”, and 34.9% with “on-site building assembly” using their own products, that is, finger-joint lumber beams.

By analyzing the raw data on fields of activity showed in Fig. 13, it is possible to confirm that only 20 companies (or 10.8%) of the individuals sampled operate exclusively in the manufacturing of linear finger-joint lumber, 63 companies (33.9%) have another secondary activity given mainly by the product exportation, and 33 companies (17.7%) operate in three fields, including exportation and product support. About activities directly related to construction (off-site manufacturing, design and on-site assembly), four, five and six trades are present in 4 (2.2%), 28 (15.1%) and 38 producers (20.4%) of this sector, respectively; that is, again reinforcing the proximity among manufacturers and product applications.

This proximity to the applications of their industrialized products, while evidencing a certain vertical integration already detailed by Krippaehne et al. [132], also confirms a “multitasking capacity” of a visible number of companies sampled in this global survey.

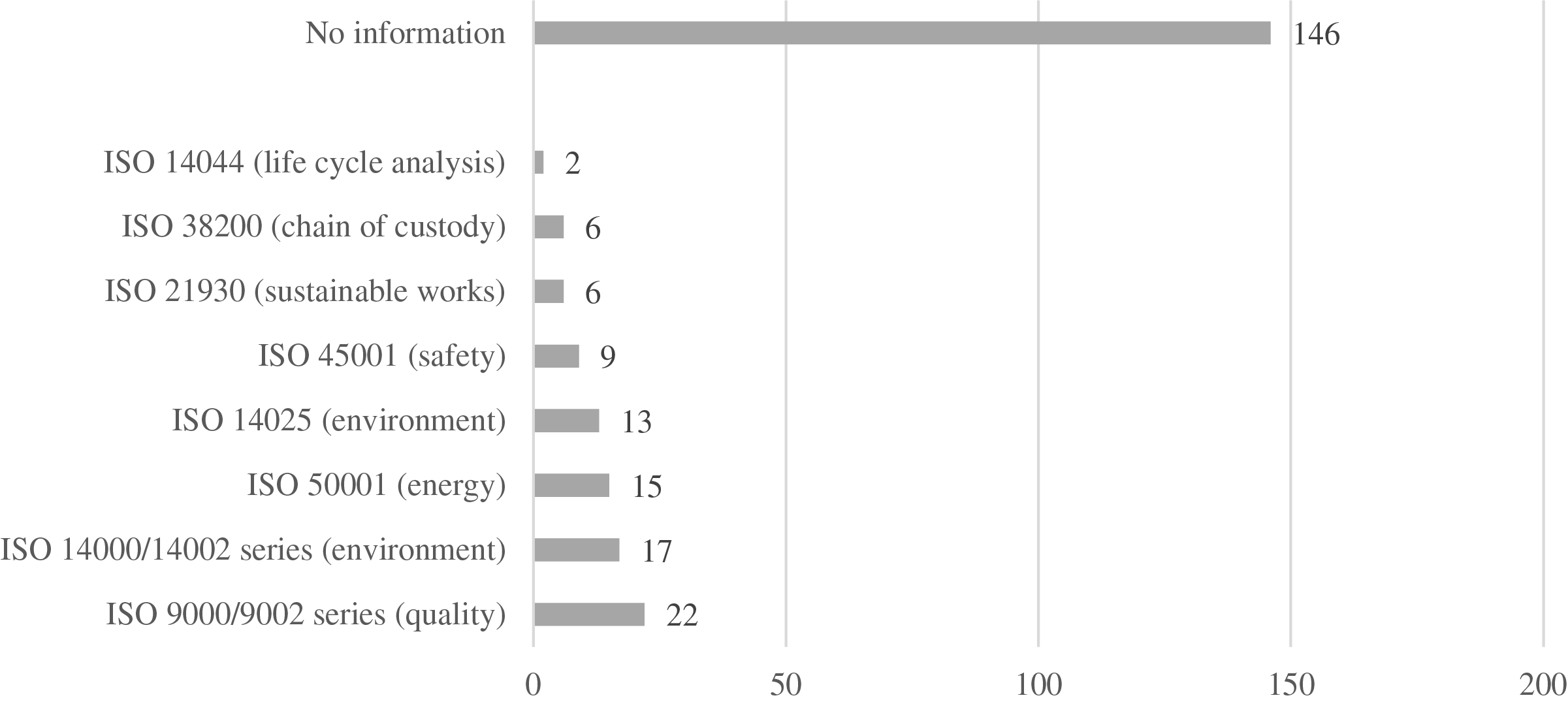

Standard Codes

In the context of manufacturing practices, the utilization of codes from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) applied to procedures and systems was investigated. According to Fig. 14, 78.5% of manufacturers do not formally declare the consideration of standard codes in their processes and internal programs, suggesting a certain disconnection in the use and explicit declaration on the strict following of standards; of this global stratum, 65.1% refers exclusively to producers from Europe.

Figure 14: Standard codes followed by manufacturers (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

This low declaration disagrees with the condition in Fig. 13, which confirms a visible global engagement in the exportation of products—this contrast suggests an oversight on the part of many companies, as the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) [133] establishes that all international exchange of goods and services must follow standards and codes.

Regarding the declarants of the standard codes of principles and management of the ISO collection [134], 11.8% of global manufacturers (10.8% represented exclusively by European industry) apply the ISO9000 series for quality procedures, while 8.1% (all from Europe) consider the ISO50001 for energy performance, and 4.8% (4.3% from Europe) rely on the ISO45001 for occupational health and safety.

Specifically on environmental issues, 9.1% (7.5% from Europe) utilize the ISO14000 series on environment requirements and guidelines, 3.2% (2.7% from Europe) take advantage of the ISO21930 for the environmental declaration of the construction product and other 3.2% (1.6% from Europe) of ISO38200 for chain of custody and resources supply and, finally, 1.1% (all from Europe) already utilize the life cycle analysis prescribed by the ISO14044 (Fig. 14). These results show the need to increase the use of these and other ISO codes present in its catalogue. According to UNIDO [133], the consideration of standards is important due to the greater control and efficiency of resources in order to increase the compatibility of solutions.

From the raw data used in Fig. 14, it can also be confirmed that 17 sampled individuals (9.1% of the global industry, E = ± 1.615%) use only one code from the aforementioned options, while 11 (5.9%), 6 (3.2%) and 3 (1.6%) producers use 2, 3 and 4 codes, respectively. The use of more documents (6, 7 and 8) is recorded by a single company each. All companies could benefit from intensifying codes in their processes. For example, Elwardi et al. [135] stated that industrial performance (especially regarding delay, quality and cost) can be improved using standard codes as a part of solution to obtain a leaner production.

According to KVH [136], Western European manufacturers have agreed to use different Eurocodes—EN15497 on finger-joint lumber for structures, as well as EN14081, EN1912 and DIN4074 on structurally classified rectangular timber for load-bearing applications in the development of finger-joint lumber in Europe.

Taking into account the observation focused on the international codes established by ISO (Fig. 14), it was also possible to confirm that, despite this convention institutionalized by the KVH entity, none of its associated companies formally expressed the application of these technical standards in the development of their products. In this way, making this information explicit and declaring the level of compliance regarding local and international regulations can bring more industry transparency and product quality.

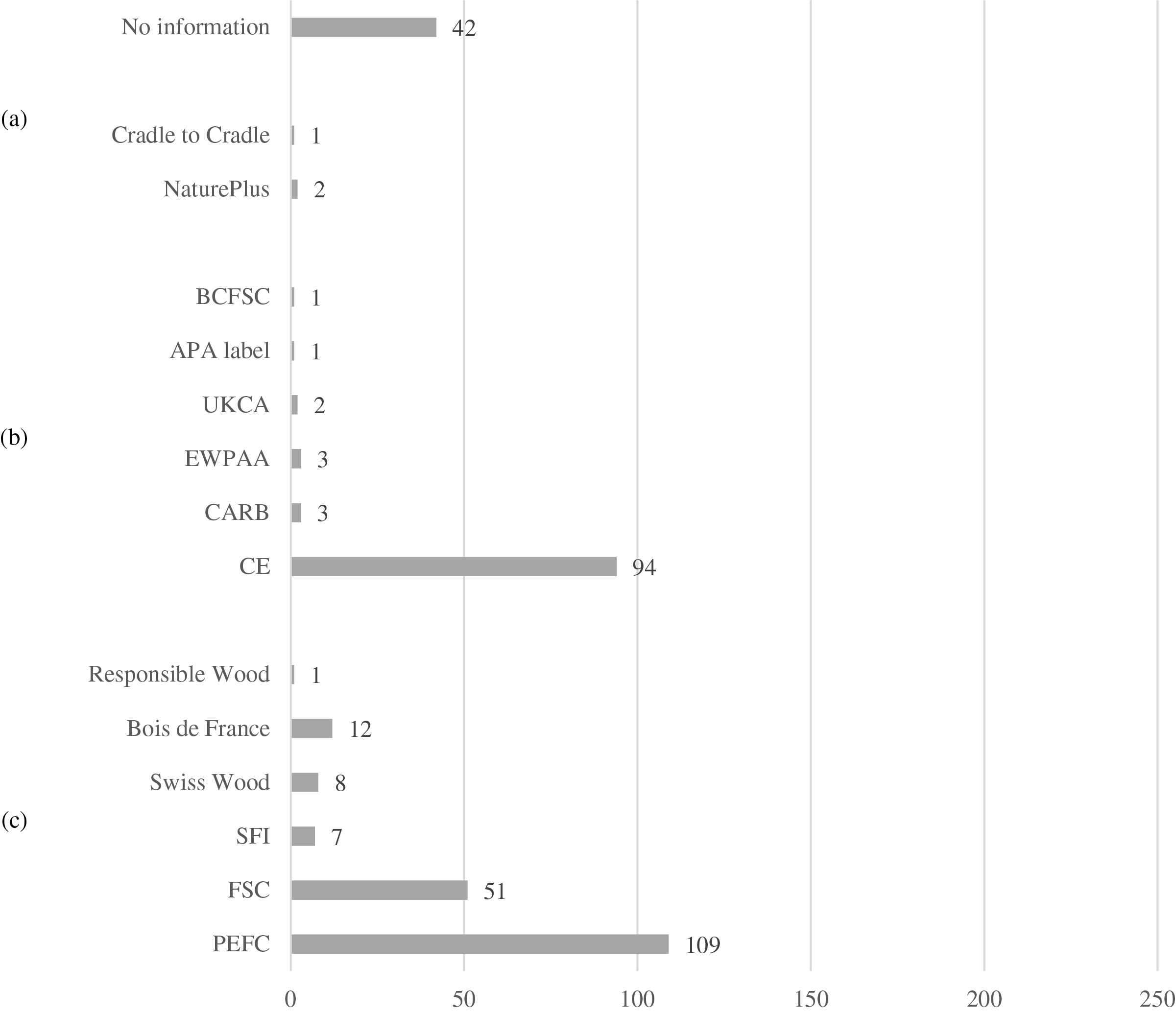

Certifications

Given the consideration of procedures to standardize programs and systems as verified in the previous section, it was possible to verify the access and declaration of certifications and seals as to manufacturing practices. Only 22.6% of manufacturers do not show any certification or seal, which results in an intense sectoral engagement regarding this topic. Therefore, 77.4% of manufacturers are already certified (Fig. 15), in which 67.7% are exclusively composed of individuals from the European industry.

Figure 15: Certifications obtained by manufacturers: (a) circularity, (b) quality, and (c) resources (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

Two environmental and sustainability compliance certifications are available in 1.6% of this sector in order to ensure circularity, being 1.1% with the NaturePlus and 0.5% with Cradle-to-Cradle seal (Fig. 15a). Although part of this sector is already engaged in the circular certification, the current scenario is incipient considering the environmental advantages of wood processing into prefabricated engineered parts.

Six certifications for quality and manufacturing management were also identified by this survey for 53.8% of this sector (Fig. 15b): the European Conformity (CE), California Air Resources Board (CARB), Engineered Wood Products Association of Australasia (EWPAA), British Conformity (UKCA), Engineered Wood Association (APA) and British Columbia Forest Safety Council (BCFSC) marks are already available, respectively, in 50.5%, 1.6%, 1.6%, 1.1%, 0.5% and 0.5% of all producers assessed.

Six certifications regarding the efficient management and production of forest resources and materials were confirmed in 70.4% of this global industry (Fig. 15c), where: the Program for the Recognition of Forest Certification Schemes (PEFC) and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) are present in 58.6% and 27.4% of this global industry, while the regionalized certifications such as French Wood (Bois de France), Swiss Wood (Swiss Wood), Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) from North America and Responsible Wood (Responsible Wood) from Australia is present, respectively, in 6.5%, 4.3%, 3.8% and 0.5%. Although forest certifications incur investment and operating costs, Deniz [137] suggests that the contribution to sustainable forestry is greater than its costs, whether by improving the image in the environmental context or favoring access to more demanding international markets. Although more than half of individuals have some type of manufacturing certification (Fig. 15), there is still space for improvements and, therefore, this also includes European producers.

Observing the raw data used in Fig. 15, it was found that 40 manufacturers (21.5% of global industry) have only one certification seal, while 64 (34.4%) individuals already have two certifications, 35 of them (18.8%) have three seals, 3 (1.6%) have four certifications, and 2 (1.1%) have five certifications.

Manufacturing Vocations

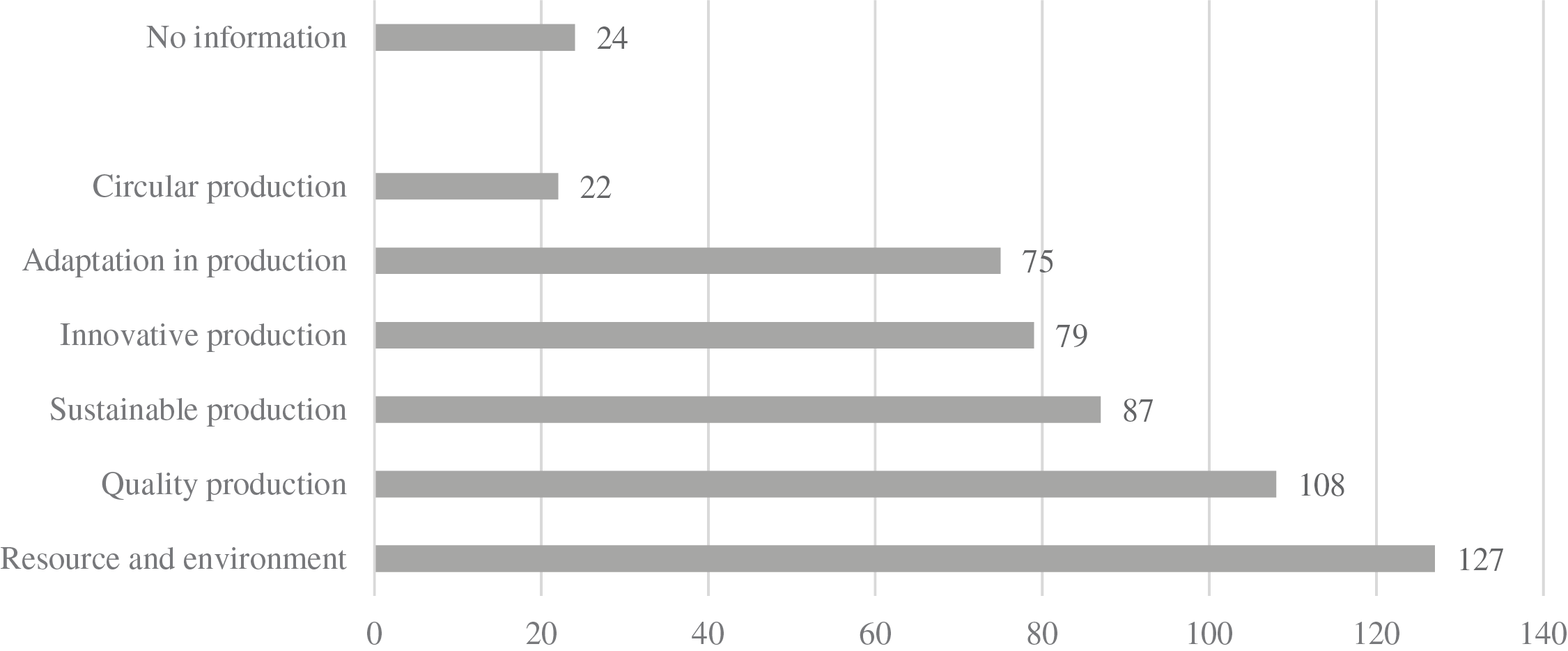

Regarding aptitudes of manufacturers, only 12.9% of these sampled individuals do not clarify industry features and advantages (Fig. 16) and, therefore, 87.1% of this sector evinced its potential of which 75.3% is only given by European producers. Vocations from the context of manufacturing sustainability include resources and the environment present in 68.3% of this global industry (being 60.2% in European industry), followed by 46.8% sustainable production (39.8% in EU), and 11.8% circular production (11.3% in EU).

Figure 16: Vocations of manufacturers (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

The global results differ when compared to statements on the use of codes on environmental management and life cycle analysis (ISO14000 series), sustainable production (ISO21930), and circularity and chain of custody (ISO38200) already confirmed by Fig. 15. The sums recorded in Fig. 16 on the circular production differ from the low sectoral participation confirmed by Fig. 15a with respect to companies certified in terms of life cycle by the Nature Plus and Cradle-to-Cradle seals. This suggests an increased interest by companies in adjusting their activities and objectives to obtain such seals; the development of global policies on the use of wood, as raised by [2], must be considered by future actions in industry and science.

The manufacturers’ vocations involved production quality (58.1% of global industry, in which 53.2% refers to European producers), production innovation (42.5% in global scenario and 37.6% only in Europe) and production adaptation (40.3% worldwide and 38.2% in EU) in the context of manufacturing (Fig. 16). However, the global records differ significantly from the declarants who use the ISO9000 collection with respect to standards (Fig. 14). In contrast, innovation and adaptation coincide with the engagement in the use of their products in sequential activities of design, manufacturing and assembly of buildings (Fig. 13).

From results (Fig. 16), it can be confirmed that this industry is aligned with sustainable development—agreeing with Yang et al. [138], which identified technological innovation and intelligent transformation as essential factors for an industry to be considered modern, efficient, and sustainable—although there is still a space for advancing and promoting sustainability in the global industry of finger-joint lumber.

Based on the raw data in Fig. 16, the presence of a vocation is confirmed in 27 manufacturers (14.5%), as well as two vocations in 43 producers (23.1%), three in 32 of them (17.2%), four in 20 (10.8%), five in 31 (16.7%) and six in 9 of them (4.8%). No declaration was observed in 12.9% of this sector.

Market Segments

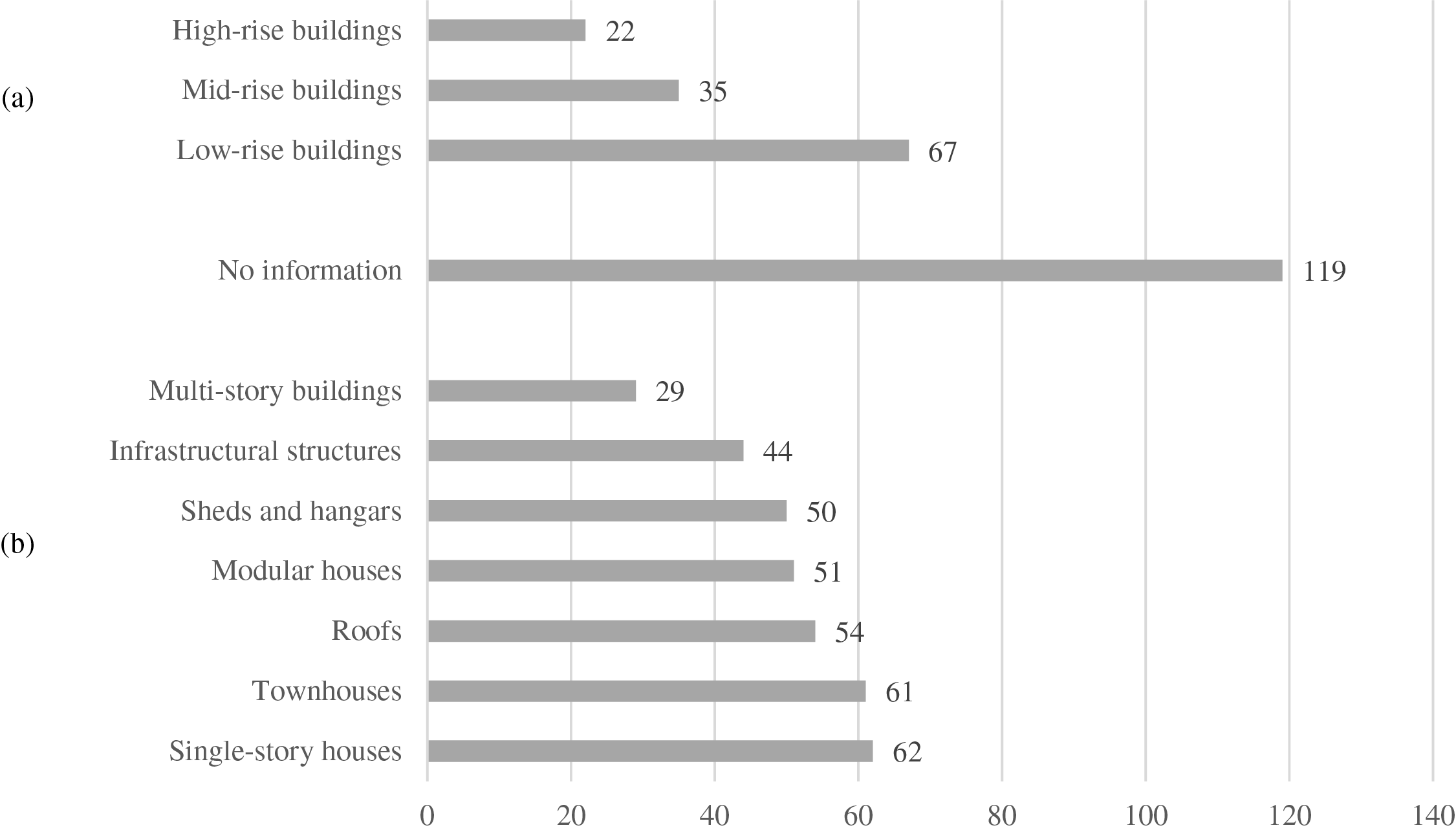

Analyzing all manufacturers, structural finger-joint lumber is commercially sold to be used in posts, beams for buildings of different sizes and purposes, and linear elements for structures and substructures for roofing, drywall, garage, and gazebo; this way, it is already present in practically all market segments of construction. Only 67 producers (36% of the global industry, being 30.7% exclusively formed by the European industry) have explicitly suggested possible construction applications (Fig. 17; E = ± 1.615%). This more limited engagement regarding the possible categories and uses suggests an amateur attitude on the part of some companies towards advertising and marketing practices.

Figure 17: Market segments by construction application suggested by manufacturers according to: (a) categories and (b) uses (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

Regarding the construction categories (Fig. 17a), finger-joint lumber has been produced and marketed as a suitable structural solution for high-rise buildings (11.8% worldwide and 11.3% only in Europe), mid-rise buildings (18.8% worldwide and 17.7% in Europe) and low-rise buildings (36% worldwide and 30.7% in Europe). Considering the complexity of building the larger categories, the greater frequency of the shorter height was expected. Specifically, seven uses were confirmed (Fig. 17b): single-story houses (33.3% worldwide and 28% in Europe), townhouses (32.8% worldwide and 28% in Europe), roofs (29.0% worldwide and 25.8% in Europe), modular houses (27.4% worldwide and 25.3% in Europe), sheds and hangars (26.9% worldwide and 24.2% in Europe), infrastructural structures for common uses (23.7% worldwide and 21.5% in Europe), and multi-story buildings (15.6% worldwide and 14.5% in Europe).

A greater dissemination in the uses of roofs, warehouses and hangars was expected (Fig. 17b), which are designed to be applied to linear elements of wood-based structures. Considering a greater use of planar elements for modular houses and multi-story buildings, a lower use of linear solutions from finger-joint lumber was expected for these applications. However, both uses reached visible participations, possibly affected by new hybrid systems as addressed by a recent study [8].

In general, this application plurality, as demonstrated by Fig. 17, may facilitates the insertion of finger-joint lumber as a potential material to be more explicitly explored. For example, this structural product can be inserted globally in future promotion campaigns, studied by the scientific community, clarified in education and professional formation, and included in inclusive policies, as discussed by [2], with respect to current and future initiatives focused on the greater use of wood products in the civil construction.

From the raw data used in Fig. 17, it can still be confirmed that seven uses were disseminated by 24 manufacturers (12.9% of global industry), six and three uses (6.5% each) were declared by 12 companies, four uses in 11 of them (5.9%), five uses in 5 of them (2.7%), and two uses in 3 of them (1.6%). No producer declared the single application condition, and 119 companies do not declare or suggest any type of construction application for their finger-joint lumber solutions.

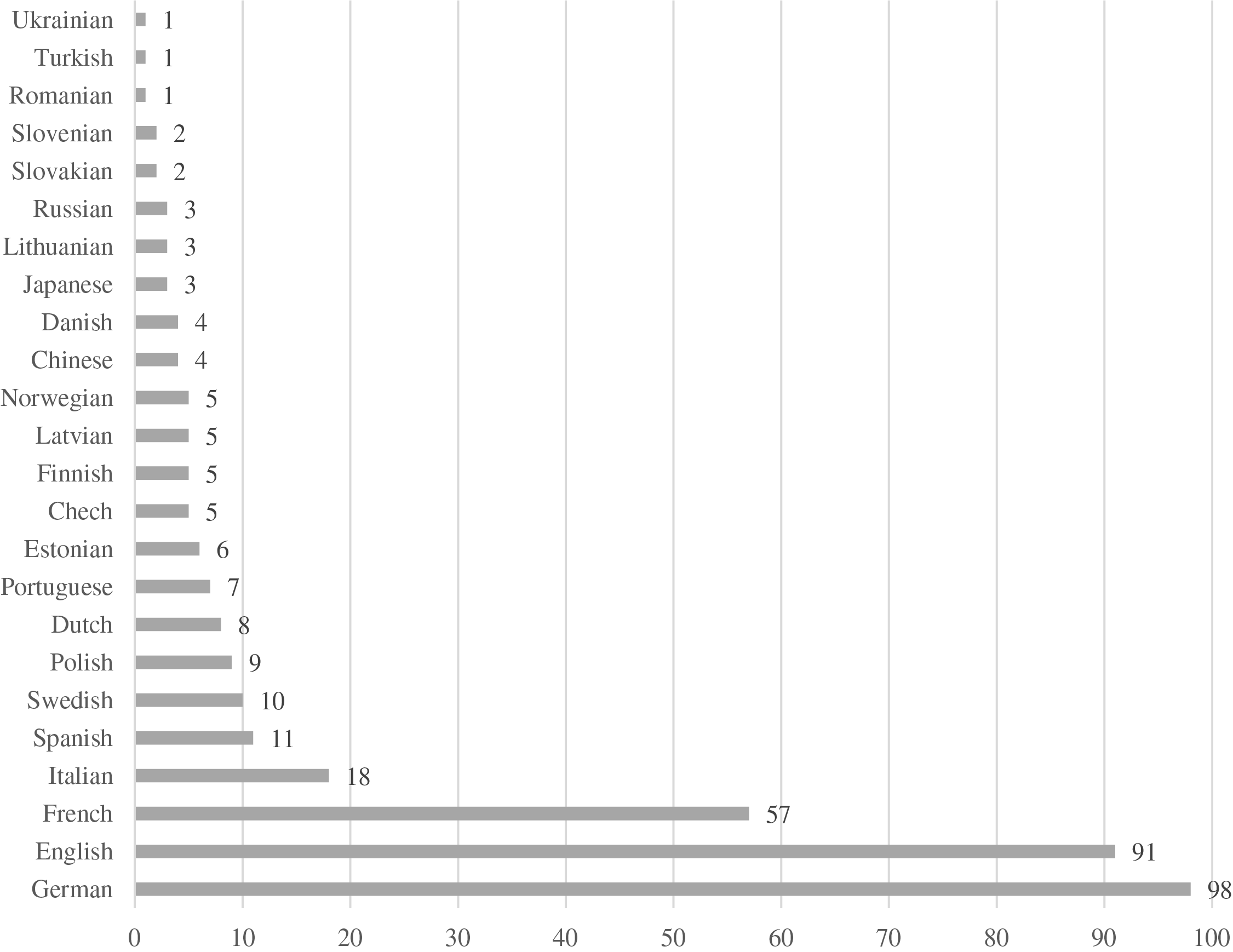

Market Coverage

Due to limitations regarding the identification of consumers through the corporate websites of sampled individuals, the market coverage of finger-joint lumber was measured by the surveying the number of languages made available by manufacturers as the mean of communication to their consumers (Fig. 18).

Figure 18: Frequencies of main languages used by manufacturers in their websites (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

From a view on languages used by the manufacturers’ websites as a mean of communication (Fig. 18), it was possible to identify the regions most exposed to the production and market of finger-joint lumber, which include fluent populations in German (52.7%), English (48.9%), French (30.6%), Italian (9.7%), Spanish (5.9%), Swedish (5.4%), Polish (4.8%), Dutch (4.3%), Portuguese (3.8%), and Estonian (3.2%), considering the 10 main regionalities. All of the most used languages have European origins (Fig. 18), which was expected due to the strong corporate presence as identified by Table 7. More 14 different languages are already available, contributing to expanding the visibility and market of finger-joint lumber in other parts of the world.

In the context of the numbers of manufacturing operations identified per continent (Table 7; Fig. 10) and country (Figs. 11 and 12), the scope of main markets was mapped, where European nations have concentrated the largest portion of manufacturing operations and, therefore, the intensification of supply and sale of finger-joint lumber. This predominance is in line with the records of Rougieux et al. [139], in which Europe is among the largest global consumers of bioresources and their derived products.

Despite the industry predominance in Europe (Fig. 10a), the “rest of the world” is already present in the finger-joint lumber market. Future expectations are promising worldwide, because programs and policies on timber are being established both in Europe and in emerging nations [2]. It should be noted that assertive actions need to clarify and promote the sustainability potential of finger-joint lumber in these initiatives.

In an analysis of raw data on manufacturing operations (Figs. 11 and 12) according to subdivisions prescribed by the United Nations for European subregions, 63.1% of the global market is present in Western Europe, while 11.2% is in Northern, 5.6% in Eastern, and 4.2% in Southern Europe. The western popularity was expected, as Germany, Austria and Switzerland are visibly engaged in the production of finger-joint lumber to the point that these nations have created an association to represent local manufacturers [44].

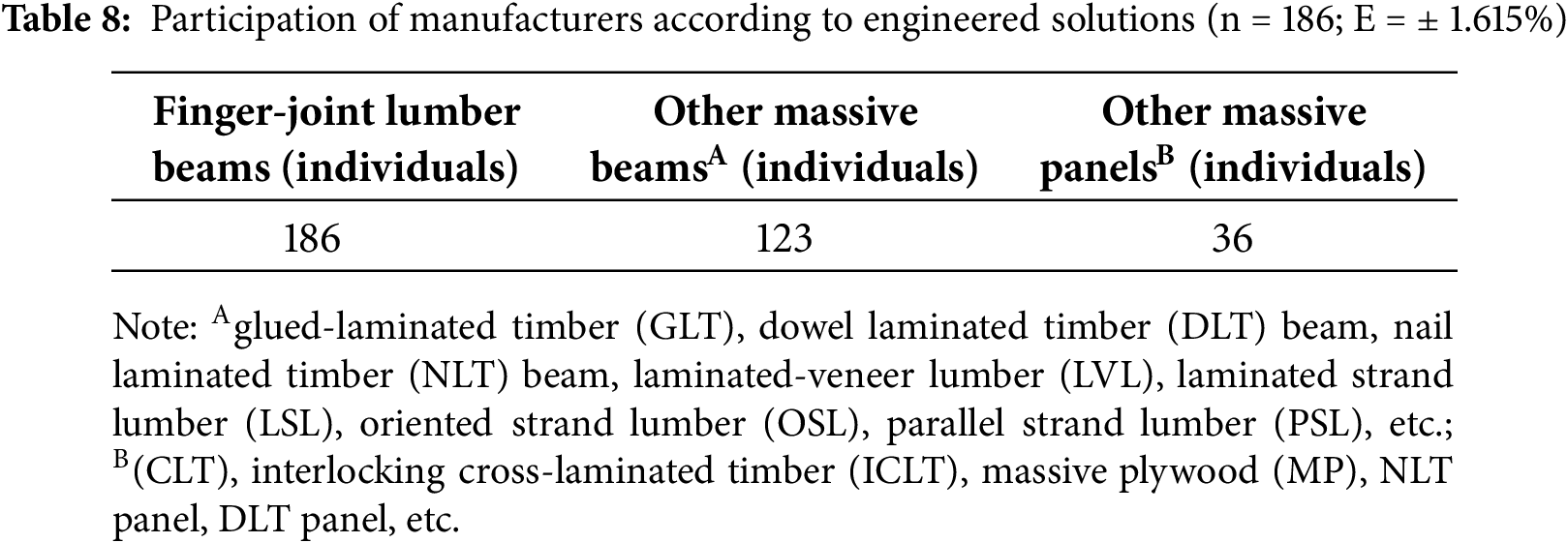

Commercial Solutions and Main Bio-Based Resources

Graphic and textual information declared on the websites confirmed the production engagement of 100% of the studied sample (n = 186; E = ±1.615%) in the production of finger-joint lumber (Table 8), of which 66.1% of the global industry makes other linear elements using engineered wood and 19.4% already produces massive planar solutions. Analyzing the raw data, it is confirmed that 61 (32.8%) companies exclusively manufacture structural finger-joint lumber, while 125 (67.2%) individuals offer a commercial line of structural engineered products formed by this and other massive solutions (Table 8).

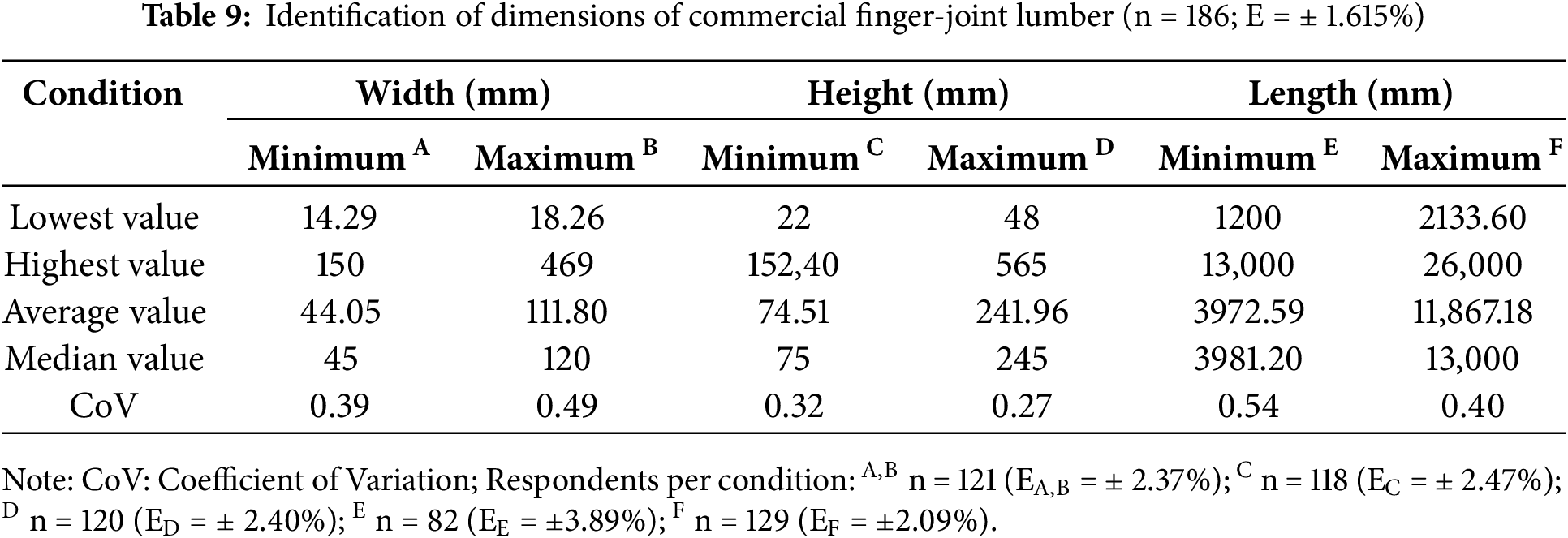

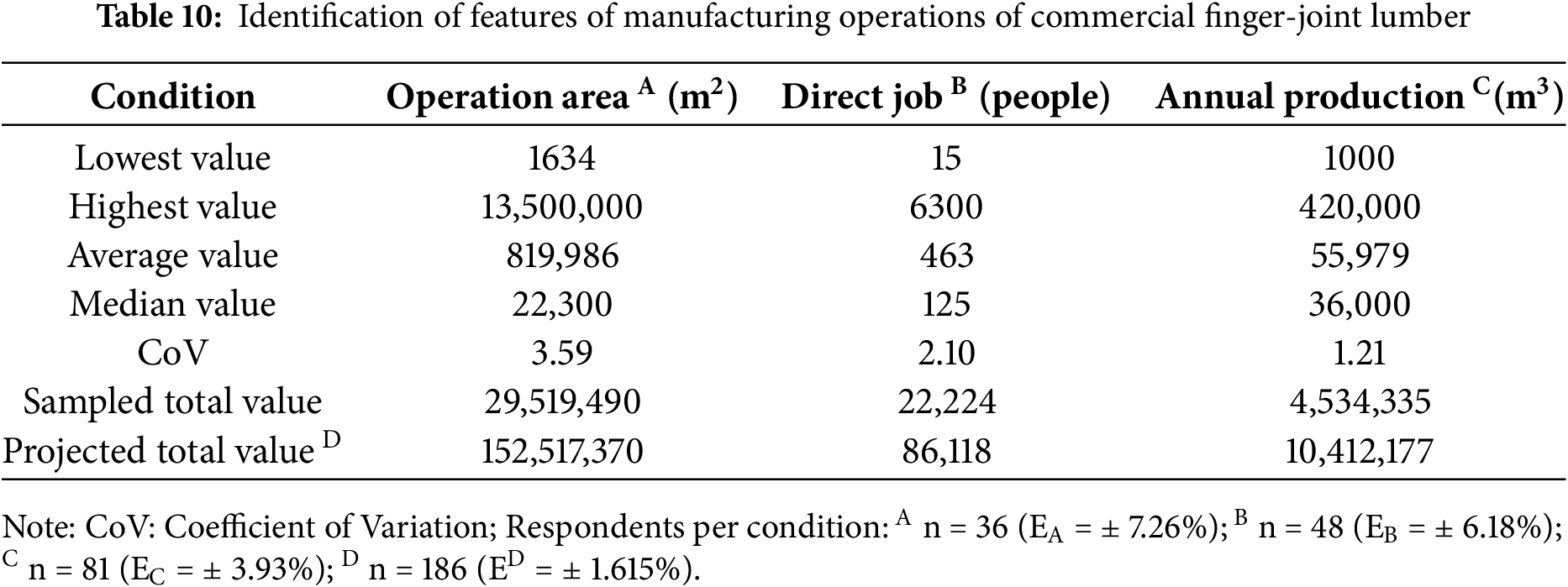

During the identification of the products manufactured by sampled individuals, it was also possible to verify some defining characteristics of production aspects such as the wood materials and sizes of solutions offered by the global industry.

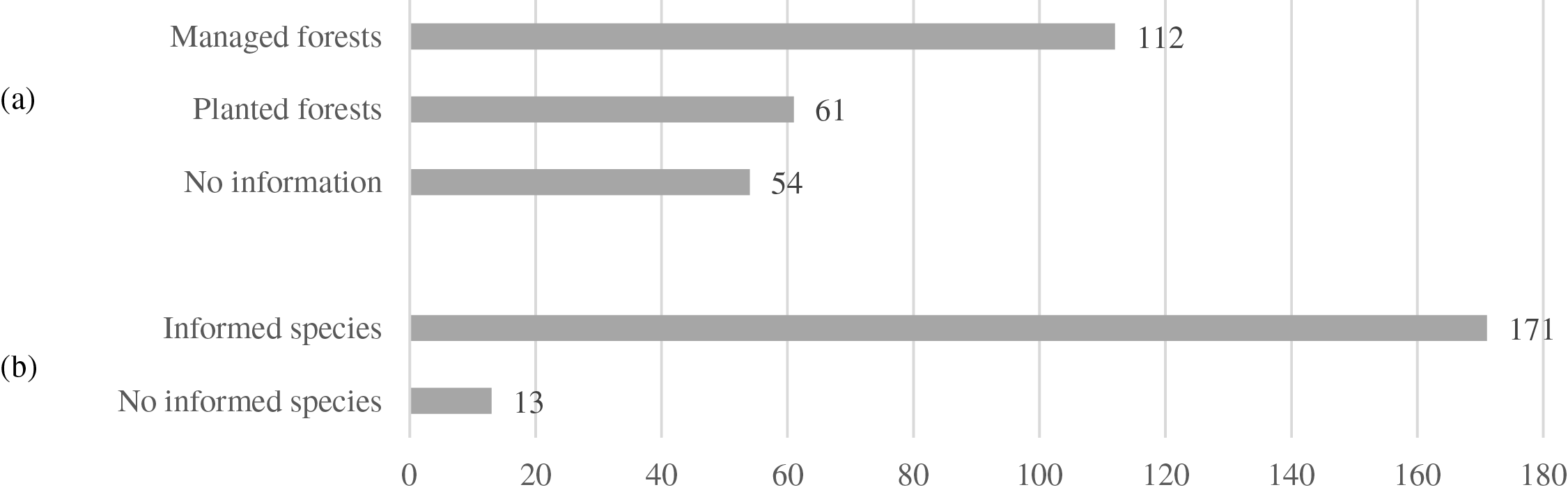

In terms of the forest species used to produce finger-joint lumber, it was confirmed that 29.0% of producers do not declare wood origins (Fig. 19a) and 7.0% do not specify species (Fig. 19b). Today, 60.2% of this global industry declares the production and procurement of forest resources from managed areas and 32.8% already produces and purchase wood from reforestation areas (Fig. 19).

Figure 19: Forest resource declaration regarding: (a) origin and (b) species consumed for the production of finger-joint lumber beams (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

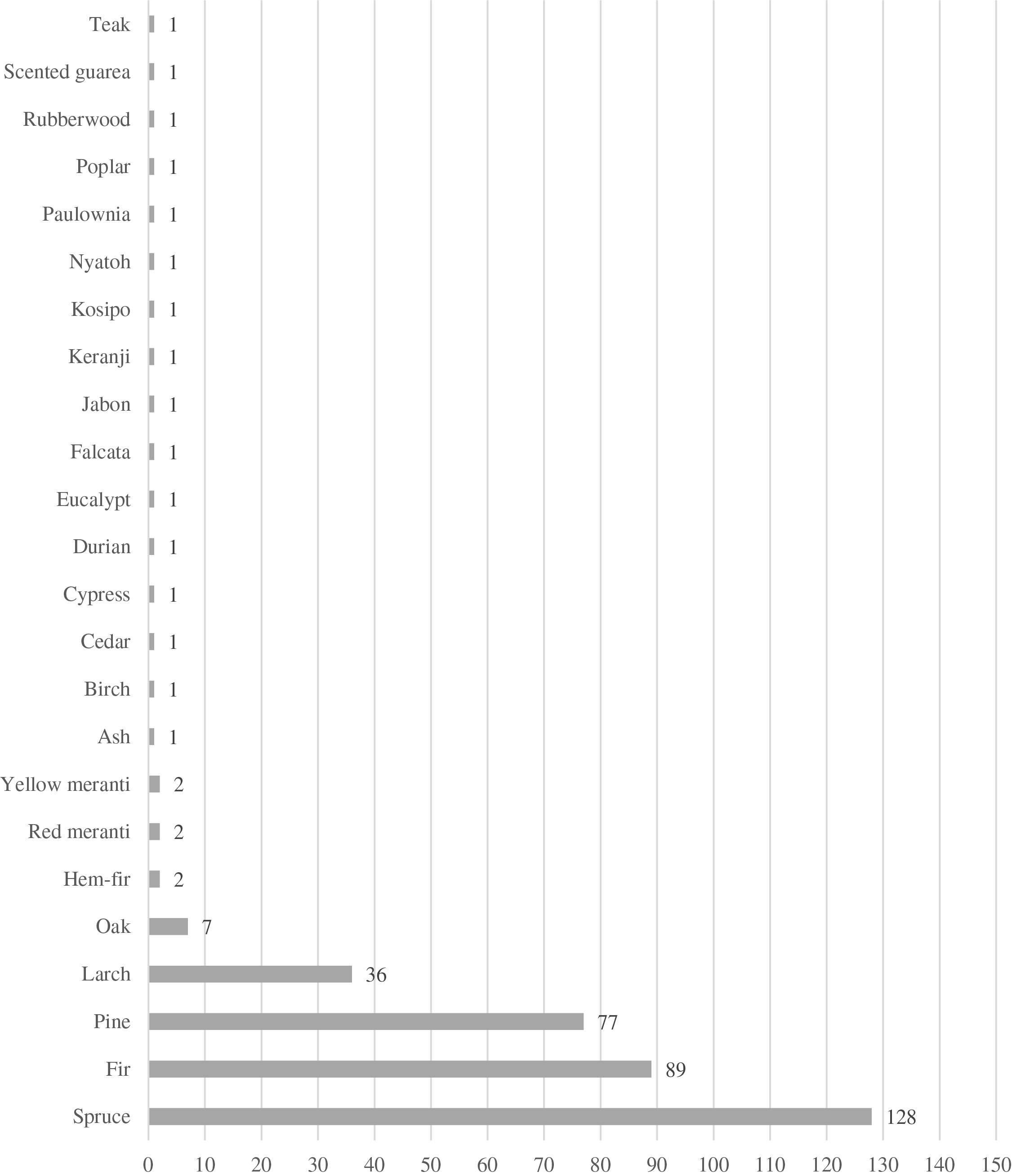

This survey indicates the use of 24 different species in the manufacture of finger-joint lumber (Fig. 20), of which 17 species are hardwoods (angiosperms) and the other 7 are conifers (gymnosperms). Despite the variety of hardwoods, several companies prioritize coniferous species, as spruce (68.8%), fir (47.8%), pine (41.4%) and larch (19.4%) predominate as the raw materials proportionally most used in terms of the number of consumer companies. The only hardwood species that is more evident is oak, used by 3.8% of the sector (Fig. 20).

Figure 20: Identification of wood species consumed by manufacturers (n = 186; E = ± 1.615%)

Only birch, beech, larch, pine, poplar and oak were simultaneously identified both as woods commercially used by this industry (Fig. 20) and species characterized by studies on finger-jointing ends (Table 4). Despite the use of woods with regional importance (e.g., nyatoh, kosipo, keranji, jabon, falcata, durian, meranti, etc.) confirmed in Fig. 20, none of these species were identified by previous research analyzed in Table 4. Thus, they can be further studied. However, other non-conventional species were tested for the development and innovation of finger-jointing for prototypes and alternative products for construction.

Analyzing the raw data of Fig. 20, 51 manufacturers (30.4%) consume only one species and the remaining majority use two or more, which can suggest a certain flexible consumption of wood species for commercial operations.