Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Two Different Methods of Impregnation of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles in Wood Composites of Three Tropical Species in Costa Rica

1 Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, Escuela de Ingeniería Forestal, Apartado, 159-7050, Cartago, Costa Rica

2 BCMaterials, Basque Center for Materials, Applications and Nanostructures, UPV/EHU Science Park, Leioa, 48940, Spain

3 Materials Science and Engineering Research Center (CICIMA), University of Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060, Costa Rica

4 School of Physics, University of Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060, Costa Rica

5 SINTEF Helgeland AS, Halvor Heyerdahls vei 33, Mo i Rana, 8626, Norway

* Corresponding Author: Róger Moya. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Modification and Functionalization of Wood)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(4), 799-816. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.058755

Received 20 September 2024; Accepted 15 January 2025; Issue published 21 April 2025

Abstract

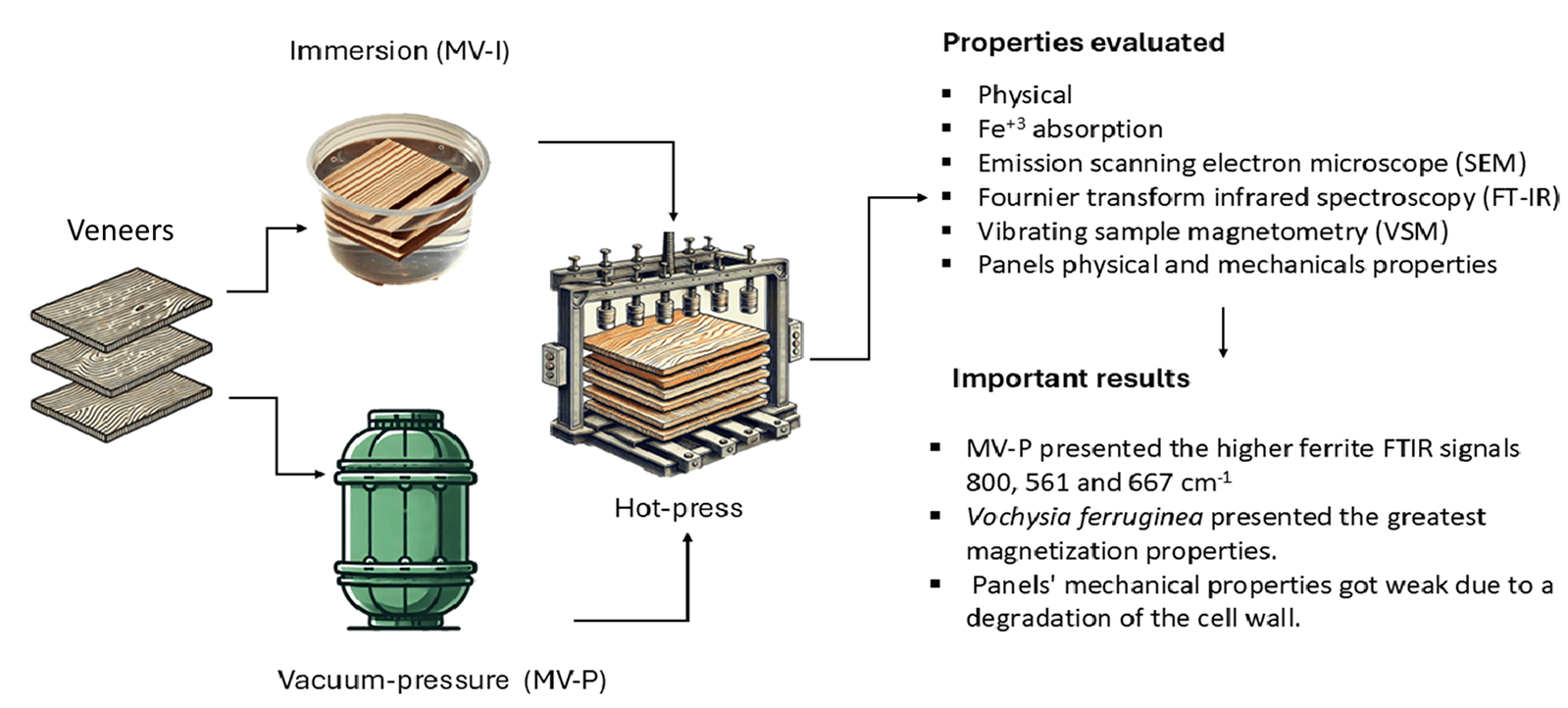

The impregnation of nanoparticles magnetified into wood had been developed by different methods, like surface chemical coprecipitation and vacuum-pressure coprecipitation of magnetic nanoparticles (NPs). However, there is a lack of information on the best method to coprecipitation NPs. Then, the present study has the objective to measure the effects of the impregnation process of wood veneers through two in situ processes (immersion and vacuum-pressure) using a solution of FeCl3·6H2O, FeCl2·4H2O and ammonia in three tropical species (Pinus oocarpa, Vochysia ferruginea and Vochysia guatemalensis). It was measured the degree of synthesis of iron NPs using weight and density gains, Fe+3 absorption, emission scanning electron microscope (SEM), Fournier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and for magnetic properties were measured using vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM). After 5-layer veneer panels were fabricated, we evaluated their physical and mechanical properties. Wood samples impregnated by vacuum-pressure methods showed the higher amount of Fe3O4 NPs formation, which was observed in the SEM, X-ray diffraction (XDR), FT-IR and VSM. Vacuum-pressure on treatment presented higher ferrite signals and better magnetic properties. Vochysia ferruginea presented the greatest magnetization properties. The magnetization treated causes probably a degradation of the cell wall, which weakens its mechanical properties, especially internal bonding.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The proliferation of electronic appliances has resulted in an unprecedented surge in wireless devices (such as mobile phones, wireless networks, and home robots), which have generated increased electromagnetic waves that may impact human health [1,2]. Consequently, it is imperative to mitigate radiation sources and thereby reduce their effect on human life [3]. Recent investigations [2,4,5] have focused on developing and studying lightweight materials capable of attenuating or blocking these electromagnetic waves.

In this context, researchers have investigated the combination of magnetic materials (both renewable and non-renewable) with lightweight dielectric properties, leveraging their synergistic effects [2,6,7]. Among renewable materials, wood and its composites have shown potential as magnetic wave-blocking materials while also offering the unique advantages of being renewable, biodegradable, and decorative [8–10]. Initial studies on wood as a magnetic material focused on impregnating magnetic powder into the wood structure [11,12]. More recently, with advancements in nanoparticle (NP) technology, ferrite-based nanoparticles have gained attention, including Fe3O4 [13,14], CoFe2O4 [15,16], and MFe2O4 [17].

To impregnate the wood with these NPs, three methods have been evaluated: (i) immersion of the wood in solvents containing a mixture of NPs for 30 to 120 min [18], (ii) impregnation of wood with magnetic NPS and resins, where wood is placed in a press tank, followed by the application of vacuum and pressure for 15 min and 1–2 h, respectively [8], and (iii) application of wood surface coatings with magnetic substances using manual tools [19].

The most prominent method is the impregnation with a mixture of NPs such as Fe3O4, CoFe2O4, and MnFe2O4 [2,13–15,17]. The synthesis of the magnetic material occurs through in situ co-precipitation of ferric NPs using a chemical reaction of two aqueous solutions of Fe3+ and Fe2+, followed by ammonia impregnation via immersion or vacuum-pressure processes [4,5,20]. Sudirman [1] and Lou et al. [5] described various methods of in situ impregnation by immersion of solid and veneer wood without producing superficial impregnation. Oka et al. [8] reported low coercivity (Hc), retentivity (Mr), and saturation magnetization (Ms) values in wood and veneers and attributed these features to the inability to control the shape and size of the surface. They concluded that the impregnation process was not feasible and magnetized NPs were not deposited correctly. Foroutan et al. [21] and Jirouš-Rajković et al. [22] corroborated the lower magnetic properties obtained with the immersion method of impregnating wood, but they employed TiO2 NPs layer-by-layer using two media with opposite electric charges applied instead of a noncovalent attachment of amine-containing water and soluble polyelectrolytes. They [21,22] concluded that this method provided a means to activate wooden surfaces in a controlled manner for surface impregnation.

Additionally, several studies [23,24] have explored methods to enhance magnetic properties through various techniques and processes. For instance, Geeri et al. [23] employed an immersion impregnation technique involving Fe3+ and Fe2+ solutions with ammonia and extended immersion periods. Their findings indicated that electromagnetic (EM) wave absorption increased with the duration of wood submersion (24–72 h). In a separate study, Cheng et al. [24] proposed a two-step strategy for synthesizing functional magnetic wood. This process initially involved removing the lignin polymer, followed by immersing the wood in alternating incubation cycles with FeSO4 and Na2CO3. This approach facilitated the transport of the ferric salt precursor into the mesoporous wood substrate, resulting in the creation of magnetic wood.

Several challenges have been identified when impregnating wood via an immersion process. Tang et al. [25] noted that the abundant hydroxyl groups on the wood surface made the assembly of NP layers unattractive under aqueous conditions. Furthermore, Gao et al. and Lou et al. [26,27] reported that in superficially impregnated particles, dipolar forces caused the formation of clusters, affecting the uniformity of particle deposition across different parts of the magnetic wood. These authors also highlighted that large quantities of magnetic particles mixed with wood composites and polymers resulted in brittle compounds, limiting the adequate impregnation of magnetic NPs through the immersion process. The impregnation based on immersion methods relies on the wood’s capillary pressure, which is lower in magnitude and rate compared to methods employing additional pressure [28].

To enhance impregnation through the immersion process, vacuum pressure methods were implemented. The application of vacuum pressure for impregnation expands the air trapped within wooden vessels, forcing some out of the wood [29]. This creates a pressure differential between the external fluid and the wooden vessels upon returning the system to atmospheric pressure. This process alters the wood’s temperature without modifying its chemical structures, resulting in physical property changes attributed to the loss of volatile extractives and water [30]. Moreover, the increased vacuum level removes more air from the sample’s pores, creating a vacuum that can be filled by substances once the system returns to atmospheric pressure [31].

Fadia et al. [32] utilized this method to synthesize magnetic NPs in wood through a co-precipitation vacuum-pressure process and concluded that the addition of a second solvent, such as furfuryl alcohol, enhanced the penetration of magnetite NPs. Similarly, Wahyuningtyas et al. [33] employed a vacuum-pressure process for magnetic NPs and confirmed the efficacy of these processes in creating magnetic wood with favorable physical properties. Laksono et al. [34] produced soft magnetic wood with superparamagnetic properties using a vacuum-pressure process and magnetite solvents at varying concentrations. The researchers determined this procedure to be an effective method for synthesizing magnetic wood.

Recently, Moya et al. [35,36] conducted pioneering research on magnetic wood using tropical species. They employed the in situ method with an immersion process for both solid and particulate wood. Their findings revealed low levels of Hc, Mr, and Ms in three tropical wood species. Moya et al. [35,36] subsequently demonstrated that in situ synthesis methods utilizing vacuum pressure were suitable for tropical wood. However, when wood particles were subjected to an immersion in situ process, the quantity of nanoparticles was insufficient to achieve high values of Hc, Mr, and Ms. This limitation is attributed to the immersion process itself, which adversely affects the magnetic properties of the samples [36].

Considering the context and disparities between surface chemical coprecipitation and vacuum-pressure coprecipitation of magnetic NPs, this study aims to evaluate the impregnation process of wood veneers through two in situ methods (immersion and vacuum-pressure) using a solution of FeCl3·6H2O, FeCl2·4H2O and ammonia, in three tropical species (Pinus oocarpa, Vochysia ferruginea and Vochysia guatemalensis). The degree of iron NPs synthesis within the wood was assessed through weight and density gains, Fe3+ absorption, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and magnetic properties measurement via vibrating-sample magnetometry (VSM) in veneers treated with both methods. Subsequently, five-layer veneer panels were fabricated, and their physical and mechanical properties were evaluated.

The chemical reagents utilized in this study were distributed by Casjim Costa Rica. They included iron (III) hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) with ≥98% purity from (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) (https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/OrderCenterView?storeId=11001) (accessed on 14 January 2025), iron (II) chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O) with ≥98% purity from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) (https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/OrderCenterView?storeId=11001) (accessed on 14 January 2025), 30% pure ammonium hydroxide solution from LABQUIMAR (San José, Costa Rica) (http://www.labquimar.com/) (accessed on 14 January 2025), and absolute ethyl alcohol and toluene from J.T. Baker brand (Madrid, Spain) (https://www.fishersci.es/es/es/brands/IPF8MGDA/jt-baker.html) (accessed on 14 January 2025). The adhesive employed was Grip Bond from the LANCO brand (San José, Costa Rica), a precatalyzed vinyl acetate resin glue. This adhesive was a copolymer of vinyl acetate and ethylene, and it comprised high-performance emulsions with enhanced flexibility, moisture resistance, and adhesion under low temperature and high humidity conditions. These copolymers are used in various industrial and consumer products, including waterproofing coatings, carpet backings, engineered fabrics, paints and coatings, woodworking adhesives, laminating applications, and others.

Sapwood from Gmelina arborea, Vochysia ferruginea, and Pinus oocarpa was utilized in this study. The wood was sourced from Maderas SyQ in Perez Zeledon, San Jose, Costa Rica, and it originated from fast-growth plantations in Costa Rica’s Pacific Zone, with tree ages of 8–12 years. These species have been previously investigated and demonstrated to possess good permeability [37,38] and excellent absorption characteristics for enhancing wood properties. Moreover, prior research has established the feasibility of impregnating these species with magnetic NPs [35,36].

Twelve logs, each with an average diameter of 25 cm and length of 1.3 m, were selected from each species. The logs underwent industrial rotary peeling at the Fabrica de Palillos Continental S.A. (FAPACO) in Heredia, Costa Rica, and 3 mm-thick veneers were obtained. These veneers were then dried in a solar kiln [39] until they reached a moisture content of 6%–8%. Subsequently, 50 dried veneers per species, measuring 28 cm in length and 28 cm in height, were prepared. The veneers were categorized into two types: (i) surface veneers, which were free of defects, and (ii) inner veneers, which permitted a limited quantity of knots and cracks.

Twelve veneers from a total of 50 were selected for treatment: six for immersion impregnation and six for vacuum-pressure impregnation. The remaining veneers served as untreated samples. The selected veneers underwent a pre-treatment process, involving multiple washes with hot distilled water until the water became clear. Subsequently, the wood samples were dried at 105°C for 24 h. The 12 selected veneers were then immersed in an alcohol/toluene solution (1:2, V/V) overnight to remove wood extractives such as fatty acids, fats, tropolones, and gums, thereby improving the wood surface’s affinity for iron salts [20]. Finally, the wood samples were dried until they reached 4% moisture content.

Magnetization of veneers through in situ precipitation was conducted using the method described by Rahayu et al. [40]. This process involved in situ precipitation based on two distinct solutions: the first comprising FeCl3·6H2O and the second FeCl2·4H2O, with a molar ratio of 2:1 (Fe3+:Fe2+). Each solution was dissolved in diluted water at a concentration of 0.45 mL/L ferric chloride. Two impregnation methods were evaluated and compared with an untreated control, resulting in the establishment of three distinct treatments:

Immersion process treatment (MV-I): Six veneers underwent immersion in Fe3+:Fe2+ solutions at atmospheric pressure for 12 h. Subsequently, the wood veneers were rinsed multiple times with distilled water to remove surface iron salts. The veneer samples were then dried for 12 h at 65°C, followed by immersion in a 25% ammonia solution for an additional 12 h. Afterward, they were washed repeatedly with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved. Finally, the treated veneers were dried at 65°C for 24 h.

Vacuum-pressure process treatment (MV-P): Veneers of all species underwent a multi-step treatment process. First, they were subjected to an absolute vacuum for 30 min in a tank. Subsequently, Ferrum solutions were introduced, and a pressure of 690 kPa was applied for 2 h. The veneers were removed from the tank and thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to eliminate residual Ferrum salt from the surface. The samples were then dried at 65°C for 12 h. Afterward, they were immersed in a 25% ammonia solution for an additional 12 h, followed by multiple rinses with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved. Finally, the treated veneers were dried at 65°C for 24 h.

Untreated treatment (UMT): This treatment refers to veneers that were not subjected to any magnetic substance application.

2.4 Characterization of Wood Veneers

The veneers treated with MV-I and MV-P were characterized to assess the efficacy and properties of wood magnetized through the impregnation process. Additionally, both treated and untreated veneers were evaluated for these properties. Initially, the percentage of ash and iron was determined. For each species with three treatments, three samples were milled between 40 and 60 mesh (420 and 250 µm, respectively), and ash content was measured using ASTM-D-1102-84 standards [41]. Subsequently, the ash content values were utilized to determine the Fe3O4 content through metal determination using an atomic absorption spectrometer model AAnalyst 800 (Thermo Scientific, Mundelein, IL, USA), in accordance with the APHA-AWWWA-WEF standard [42]. The quantity of Fe3O4 in magnetic wood was obtained using the following equations: Eq. (1) for Fe3O4 content measured by wood weight, and Eq. (2) for Fe3O4 content measured by veneer volume.

where Ash contentsample: ash content measured in the laboratory and Fe3O4 contentsample represents the Fe3O4 value measured in the atomic absorption.

2.5 Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM)

For each treated species (MV-I, MV-P) and the untreated species (UMT), three samples from different locations in the veneers were analyzed via SEM. This analysis was conducted using a TM 3000 microscope. The samples were not coated with gold or carbon film. A working distance of 3.8 to 5.8 mm was employed, with a voltage of 7.5 kV and 400× magnification. The formation of magnetite and the deposition of Ferrum in various anatomical structures were observed.

2.6 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Three samples were extracted for each species for the evaluated treatments (MV-I, MV-P, and UMT), and these were milled to a size between 420 and 250 µm (40 and 60 mesh, respectively). The milled samples were dried to 0% moisture content. These samples were subjected to FTIR analysis using a Nicolet 380 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Mundelein, IL, USA) equipped with a single reflective cell (containing a diamond crystal). The equipment was configured to accumulate 32 scans with a resolution of 1 cm−1, and a background correction was performed before each measurement. The obtained FTIR spectra were processed using Spotlight 1.5.1, HyperView 3.2, and Spectrum 6.2.0 software developed by Perkin Elmer, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). The following main vibrations were identified: (i) 1251 cm−1 peak related to C-O stretching vibration, (ii) 1505 cm−1 lignin present in the cell wall, (iii) 1601 cm−1 cellulose in the cell wall, (iv) 1739 cm−1 assigned to C=O stretching in unconjugated ketones and ester groups, (v) 2901 cm−1 corresponding to asymmetric -CH3, and (vi) 3340 cm−1 absorption band assigned to O-H stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups [15,20,36].

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted on each species subjected to the three treatments using a PANanalytical Empyrcan Series 2 diffractometer (Cu-Kα, 6°—40° 20) and PANanalytical High Score Plus software (Cambridge, UK) for data management. Sawdust samples from the treated specimens (MV-I and MV-P) and UMT were placed on a neoprene rectangle atop a glass plate for measurement. The parameters employed were as follows: Cu-Ka radiation with a graphite monochromator, voltage of 40 kV, electric current of 40 mA, and a 2θ scanning range from 5° to 90° with a scanning speed of 2°/min. The average diameter of Fe3O4 (D) crystalline nanoparticles in magnetic wood was calculated from its XRD pattern using the Scherrer Eq. (3) [40].

where D represents average diameter of Fe3O4, K is 0.15418 which represents ray wavelength, λ is the Scherrer constant (0.89), β is the peak full width at half maximum (FWHM) and θs the Bragg diffraction angle.

2.8 Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM)

The magnetic hysteresis loops (magnetization vs. applied magnetic field) of sawdust samples treated (MV-I and MV-P) and UMT were analyzed using a MicroSense EZ7 vibrating-sample magnetometer at room temperature. The experimental conditions included an external magnetic field ranging from −20 to 20 kOe, with 2 Oe and 10 Oe steps at low magnetic fields, and 100 and 500 Oe steps at higher fields, with a measurement time of 100 ms. The Ms, Hc, and remanence (Mr) were extracted from the hysteresis loops. The stability of the magnetic properties was evaluated in an acidic environment. Acid resistance tests were conducted by immersing the samples in a 4% hydrochloric acid solution for 7 days, after which the magnetic properties were reassessed using VSM. The samples used for magnetic testing measured 3 mm × 3 mm × 7 mm (tangential × radial × longitudinal).

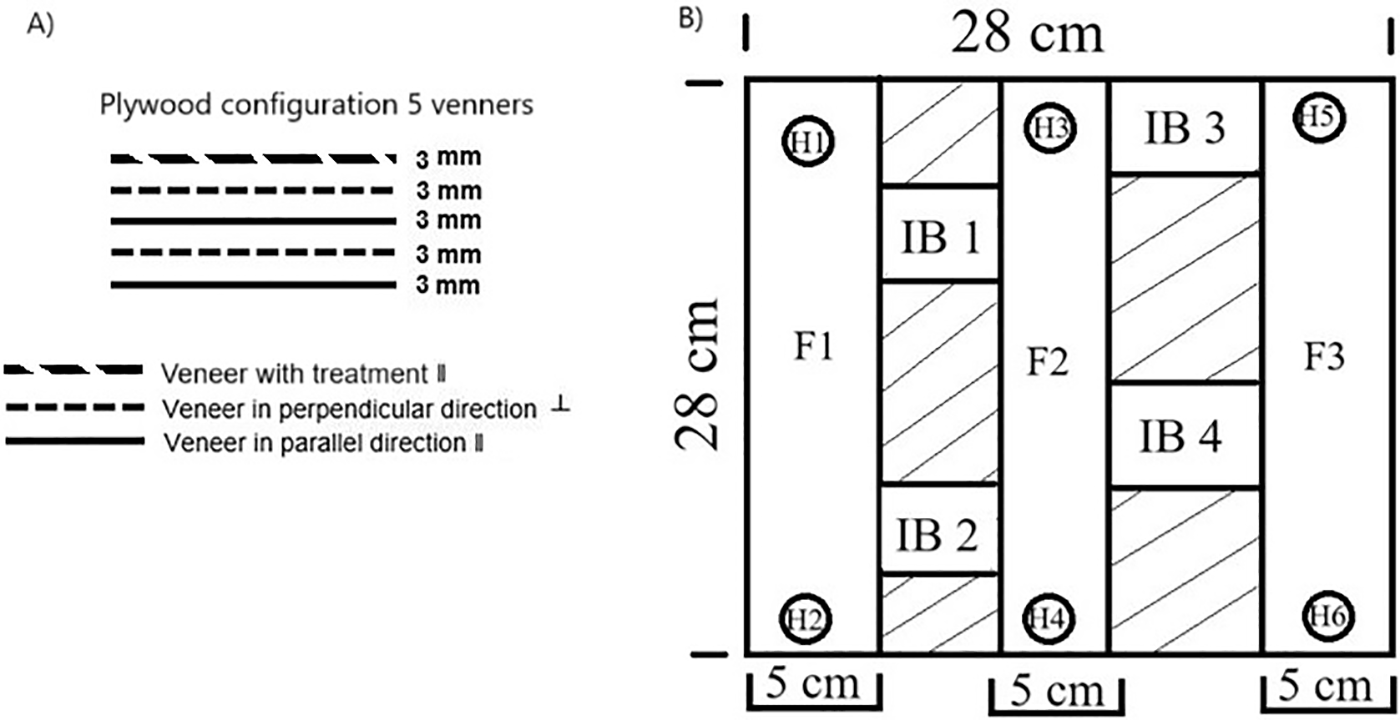

A total of 27 panels of five-layer veneers (3 species × 3 treatments × 3 panels) were fabricated, measuring 12 mm in thickness, 28 cm in width, and 28 cm in length. The layers were arranged with two outer layers, one containing the treatment (MV-I, MV-P, and UMT), and four inner layers without any treatment, each layer being 3 mm thick (Fig. 1A). Grip Bond from LANCO brand (San Jose, Costa Rica), a pre-catalyzed vinyl acetate resin glue, was applied as an adhesive at a dose of 10 L/m2 for each layer. According to the area (g/cm2) of the layer, 0.45 g/cm2 was adopted per veneer. The preformed board was pressed in a hydraulic press at a temperature of 120°C for 30 min using a pressure of 3 MPa. The panels were then conditioned in an environmental control chamber until they achieved 12% equilibrium moisture content. Subsequently, samples for mechanical properties testing were cut.

Figure 1: Veneer manufacturing configuration (A) and sampling for mechanical properties (B) Legend: F: flexion specimens, H: hardness specimens, IB: internal bonding specimens

The mechanical properties analyzed included flexion, Janka hardness, and internal bonding. Janka hardness was measured at six distinct points on each panel (Fig. 1B), using a universal testing machine (Instruments J BOT S.A. model mod853, Barcelona, Spain), consistent with ASTM D143-14 [43]. For the flexion test, three samples measuring 28 cm × 5 cm were obtained from each treated (MV-I and MV-P) and untreated (UMT) panel (Fig. 1B) and tested according to ASTM D143-14 [43] using a Tinius Olsen H10KT universal testing machine (Canterbury, UK). Internal bond testing involved eight 5 cm × 5 cm samples cut for each treatment (MV-I and MV-P) and untreated condition, following ASTM D143-14 [43] procedures, using an Instruments J BOT S.A. model mod853 universal testing machine (Barcelona, Spain).

Prior to the statistical analysis, the data were verified for homogeneity and normality, and the presence of outliers was examined in the evaluated variables. A descriptive analysis was conducted, and the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation were determined. One-way variance analysis (ANOVA) was applied with a statistical significance level of p < 0.05 to assess the effect of the impregnation method (independent variable) on the evaluated properties (response variables). The Tukey test was employed to determine the statistical significance of the differences between means.

Table 1 presents the percentages of ash and iron content, as well as the retention values. V. ferruginea exhibited the highest ash content and retention values in both MVI-I and MVI-P treatments (Table 1). Conversely, UMT samples demonstrated the lowest values across all three species, with the exception of G. arborea, which showed comparable values to the VI-I treatment (Table 1). The VI-P treatment consistently yielded the highest percentage of ash in all three species studied (Table 1). Regarding Fe3O4 content, the VI-I treatment produced results similar to untreated wood in all three species, while the VI-P treatment resulted in the highest percentages and retention values across all species (Table 1). V. ferruginea displayed significantly higher values, followed by G. arborea, and lastly P. oocarpa (Table 1).

The observed increase in ash content aligns with findings from studies on other species [4,20,44], attributable to the augmented presence of inorganic material in wood resulting from the in situ deposition of iron. Notably, the highest ash content values were recorded in the VI-P treatment (Table 1), and this value was associated with the maximum Fe3O4 content across all species. For instance, in G. arborea, the ash content reached 4.96%, while the Fe3O4 content was 418.67%. This indicates that vacuum-pressure treatment methods achieved the highest rates of in situ Fe3+ precipitation. Konopka et al. [45] noted that vacuum-pressure preservation techniques facilitated the saturation of specimens with various Ferrum sources, leading to extensive precipitation throughout the wood samples’ cross-sections.

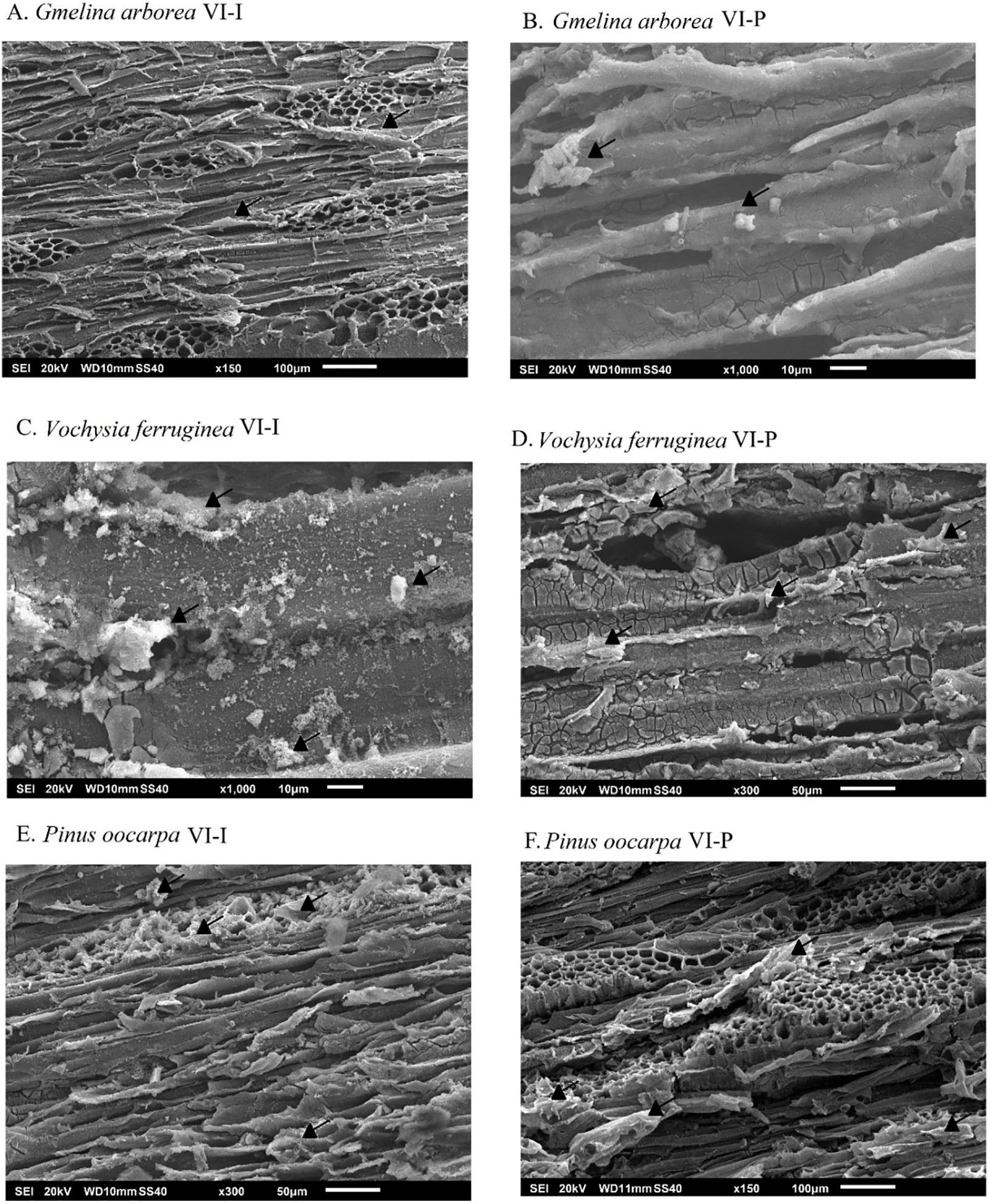

3.1 Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM)

SEM imaging revealed magnetite formation on the veneer surfaces, particularly in the VI-P treatment (Fig. 2A–C). The largest deposits of material were observed around wood cavities and vessel lumens, as illustrated in Fig. 2A–C. Visual inspection suggests that V. ferruginea contained the highest concentration of magnetic material among the three species examined (Fig. 2B). This observation can be attributed to the primary role of vessels in fluid flow within hardwood anatomy [46]. Consequently, the in situ formation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles predominantly occurred within wood cavities, specifically vessel lumens. Ray lumens represent the secondary anatomical feature facilitating fluid flow within the wood, particularly in radial tissue [38].

Figure 2: SEM images of magnetic wood veneers of G. arborea (A, B), V. guatemalensis (C, D) and P. oocarpa (E, F)

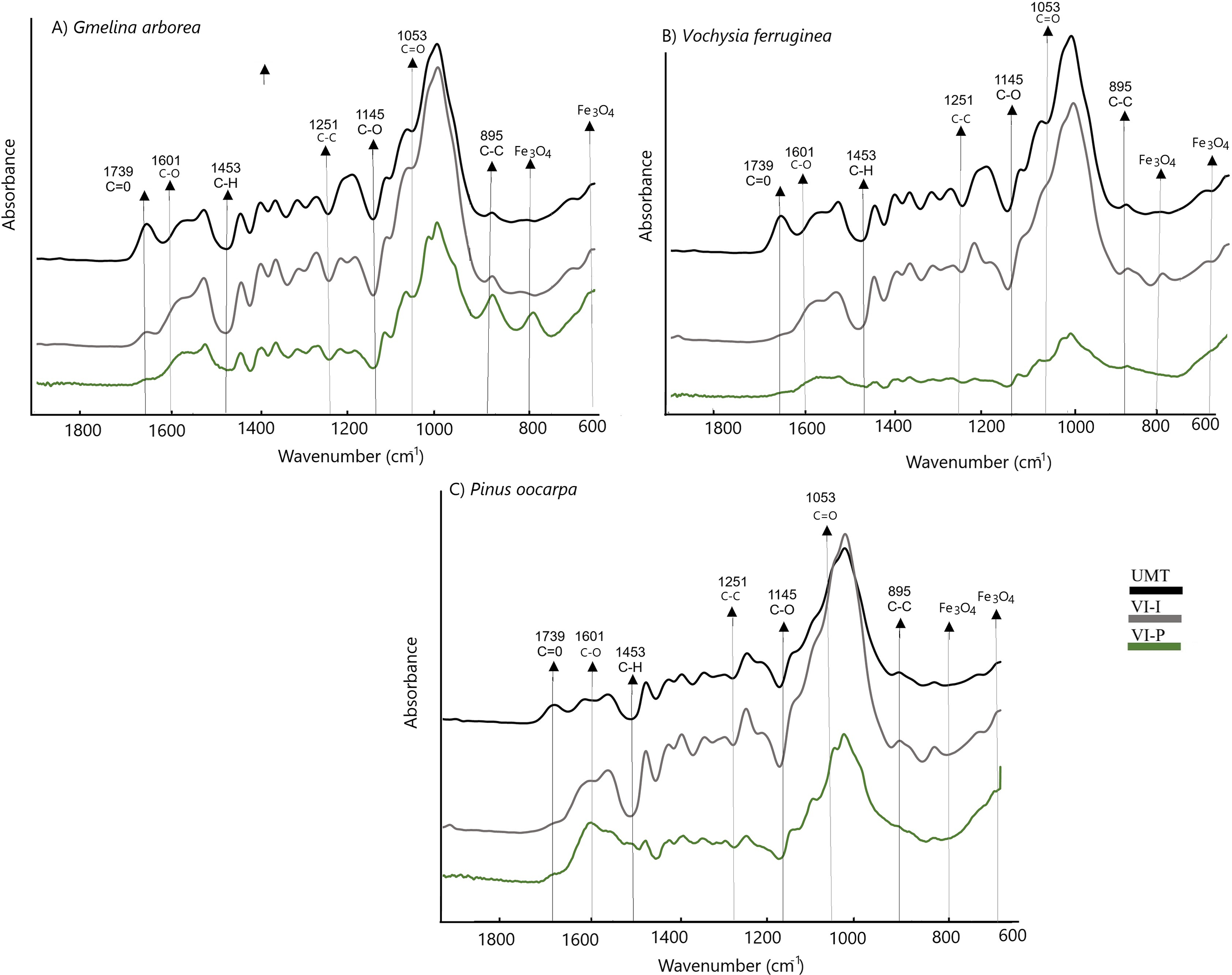

3.2 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The infrared spectra presented in Fig. 3 illustrate the alterations in the chemical composition of the material following magnetization. The figure demonstrates changes primarily in the attenuation of signals at 1739 and 1053 cm−1, corresponding to the absorption peak of the C-O stretching vibration of hemicellulose and cellulose [44], observed in all three species. This attenuation aligns with studies by Gao et al. [27], Dong et al. [20], Gan et al. [47], Wang et al. [17], Lou et al. [48], Yang et al. [44], and Garskaite et al. [49], who attributed this behavior to hemicellulose degradation resulting from ammonia treatment. Regarding cellulose structure, a decrease in peak intensity at 1145 and 1453 cm−1 occurred owing to magnetization. The peaks at 1145 and 1453 cm−1 corresponded to the C-O stretching vibration and C-H deformation, asymmetry in CH3 and CH2, respectively, in cellulose glucose [40], which these peaks appeared similar in treated and untreated wood (Fig. 3A–C). For lignin, the most significant signal attenuation occurred in the 1601 cm−1 band (C-C aromatic skeletal vibrations) [49] and 1251 cm−1 (the ester bond of carboxylic groups in all three wood species [5]), indicating substantial degradation in this structure with treatment. The 895 cm−1 peak, representing CH stretching vibrations and CO stretching of cellulose, showed differences between species: G. arborea remained unaffected (Fig. 3A), while V. guatemalensis and P. oocarpa exhibited changes (Fig. 3B,C). These results suggest that cellulose (with weakened signals at 1739, 1453, 1251, 1145, and 895 cm−1) and lignin (with weakened signals at 1601 and 1251 cm−1) were hydrolyzed and dissolved owing to magnetization treatment, or the total biomass content was reduced owing to magnetic particle formation [44]. However, the degradation of G. arborea wood was less pronounced than that of the other two species, suggesting it was less affected by the magnetization treatment. Additionally, VI-P demonstrated a greater decrease than VI-I, indicating that VP-P was a more invasive treatment for the various wood polymers.

Figure 3: FTIR spectrum of magnetic wood veneers of three tropical species (A–C) from fast growth plantations in Costa Rica

The formation of Fe3O4 in the wood samples was evident in the lower bands at 800 cm−1, and around 561 and 667 cm−1, particularly in the VI-P treatment. The signal at 800 cm−1 corresponded to the tetrahedral sites of the crystal lattice, resulting from the oxidation of Fe2+ and Fe3+ cleavages [49]. This signal was more pronounced in G. arborea wood, followed by V. ferruginea (Fig. 3B,C). In P. oocarpa wood spectra, there was minimal evidence of this peak (Fig. 3A), corroborating the low measurement of Fe3O4 content (Fig. 2A). The decrease at 800, 561, and 667 cm−1 in VI-P indicated greater Fe3O4 formation, suggesting that this treatment resulted in higher magnetization.

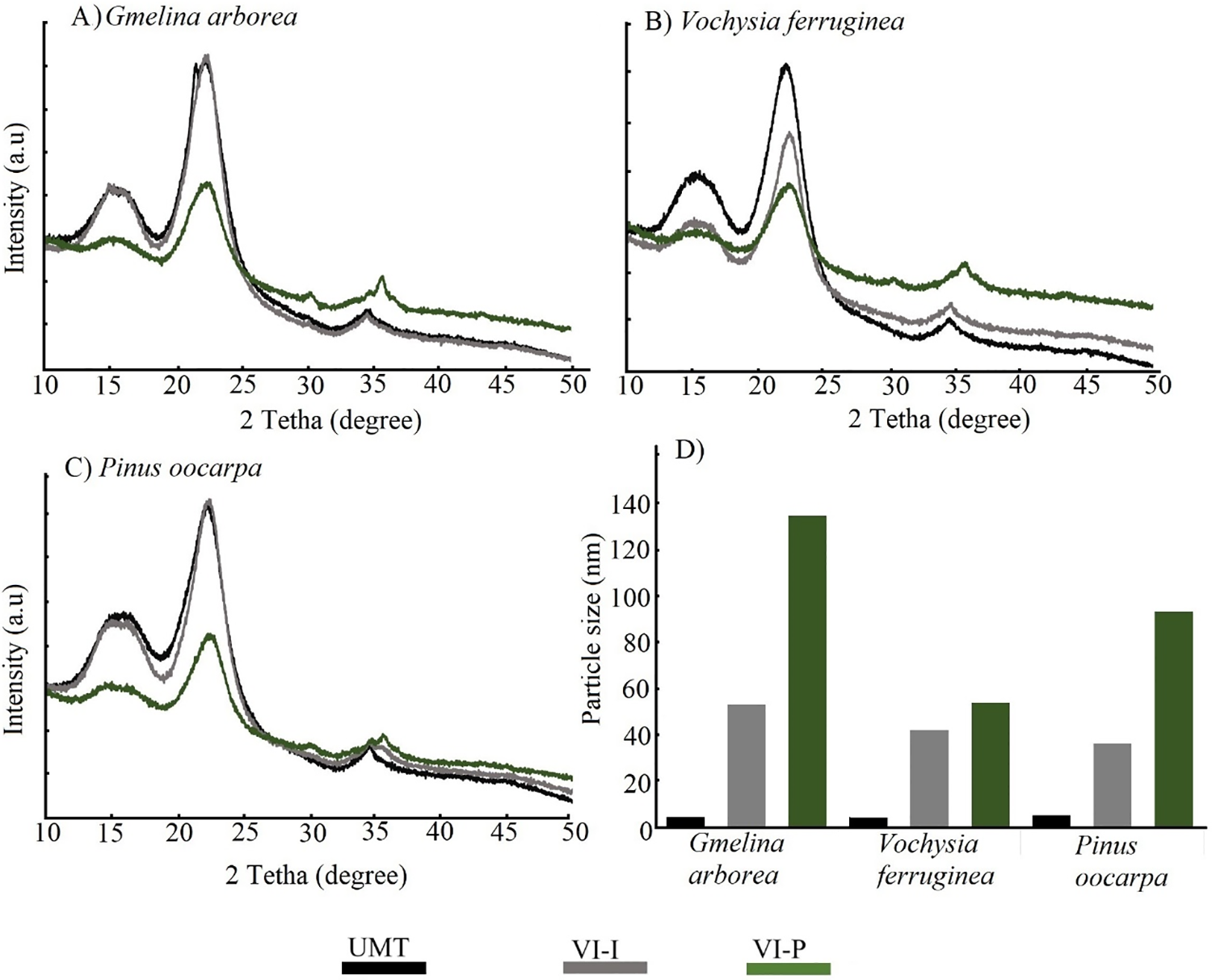

The characterization of crystalline structures using XRD revealed that treated samples exhibited more pronounced peaks than untreated samples, particularly at angles of 16° and 22.5°. The VI-P treatment demonstrated greater peak intensity (Fig. 4A–C) at angles of 30° and 35°, while the VI-I treatment resulted in decreased intensity across all species. According to the Segal empirical formula, which measures the crystallinity index (CI) by relating the total intensity value at 22.7° 2θ to the minimum intensity value at 18° 2θ, it can be inferred that VI-P treatment decreased the CI value, whereas VI-I treatment yielded values similar to untreated wood. XRD diffraction confirmed that magnetization treatment reduced the crystallinity of different species [40].

Figure 4: XDR diffraction of magnetic wood veneers of three tropical species (A–C) and particle size of Ferrum particle (D) for different treatment

An increase in particle size was observed following magnetic treatments (Fig. 4d). The VI-P treatment yielded the largest particle sizes, particularly in G. arborea, followed by P. oocarpa, and lastly V. ferruginea (Fig. 4D). For the latter two species, minimal differences were noted compared with the VI-I treatment.

The magnetized wood exhibited pronounced diffraction peaks at 2θ angles of 19°, 30°, 35° and 44° corresponding to the (111), (220), (311), and (400) planes of magnetite, respectively (JCDS number 19-0629) (Fig. 4A,B). These peaks aligned with the cubic phase structure with Fd3–m spacing [48]. In the Gmelina arborea spectrum, the most intense diffraction occurred at 34° (311), particularly in the VI-P treatment (Fig. 4A). For V. ferruginea, the strongest peak appeared at 35° (Fig. 4B). For P. oocarpa, the most prominent diffractions occurred at 30°, 35°, and 44°, especially in the VI-P treatment (Fig. 4C). The variations in diffraction patterns and particle size calculations based on Scherrer’s Eq. (3) [40] indicated that Fe3O4 nanoparticle deposition differed among species. G. arborea displayed the largest particle size, followed by P. oocarpa, and V. ferruginea exhibited the smallest particle size (Fig. 4D). The observed particle sizes aligned with findings reported by Mashkour et al. [4], Lou et al. [5], and Gao et al. [27] for the VI-P treatment, where the magnetic properties remained comparable to those of untreated wood.

3.4 Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM)

VSM curves of different treatments indicated that UMT curves approached a nearly straight line close to zero in all three species (Fig. 5). The values of Hc, Mr, and Ms derived from these curves were zero (Table 2), demonstrating the non-magnetic property of untreated wood. In contrast, all specimens of magnetic wood veneers exhibited distinct hysteretic and ferromagnetic behavior, particularly in the VI-P treatment (Fig. 5A–C). Nevertheless, differences among species were observed; the Ms value was lowest (ranging from 1.0 to 1.5 emu) in G. arborea (Fig. 5A) and highest in V. ferruginea (Fig. 5C), suggesting that V. ferruginea responded most effectively to the treatments. This trend is corroborated by the magnetism parameters (Hc, Mr, Ms), which were low in G. arborea and high in V. guatemalensis (Table 2). This distinction was particularly evident in the VI-P treatment, as the VI-I treatment showed no statistically significant differences from the untreated condition (Fig. 5 and Table 2).

Figure 5: Hysteresis curves of magnetic wood of three tropical species (A–C) from fast growth plantations of Costa Rica

The magnetic properties of species studied confirmed by Tang et al.’s [25] results showed that wood hysteresis curves consistently exhibited paramagnetic characteristics. However, magnetic wood samples displayed magnetic behavior, characterized by low values of Mr and Hc [50,51] (Fig. 5A–C, Table 2). This behavior was also reflected in the magnetic material’s particle size; the VI-P treatment yielded higher particle size values than other treatments (Fig. 4D). Moreover, Bukit et al. [52] asserted that larger magnetite particle sizes resulted in a greater number of magnetic domains and increased magnetic domain boundaries, leading to enhanced Ms values. This effect was particularly evident in the VI-P treatment, especially for V. ferruginea (Fig. 5 and Table 2), indicating that this species exhibited the most favorable magnetic properties.

Fadia et al. [32] explained that vacuum-pressure treatment enhanced impregnation depth by removing air from porous lumina and wood spaces. However, the effectiveness of this process is contingent upon the wood’s structural anatomy. In the present study, V. ferruginous exhibited the highest magnetite content (Table 1) [53]. According to Gaitán-Alvarez et al. [37], this species possesses favorable anatomical features, including vessel diameters exceeding 120 μm, ray widths ranging from 2 to 10 cell series, and a ray frequency surpassing 5 ray/mm2. Additionally, various types of cell parenchyma facilitate solution flow, promoting greater magnetite formation. In the present study, although G. arborea also demonstrated advantageous anatomical characteristics, the presence of tyloses in its vessels reduced permeability, consequently impeding impregnation.

The VI-P treatment resulted in the highest MOR for V. ferruginea and G. arborea, while no statistical differences existed between VI-I and UTM (Table 3). Module elasticity (MOE) in P. oocarpa showed no statistical differences among treatments, whereas the highest values were observed in VI-P for G. arborea and V. ferruginea, which were statistically different from VI-I and UMT (Table 3). Janka hardness exhibited no statistical differences across the three treatments or species studied (Table 3). Regarding internal bond resistance, the highest value was observed in UMT for Gmelina arborea, followed by VI-I and VI-P (Table 3). For V. ferruginea, no statistical differences were observed; however, in P. oocarpa, the VI-P treatment presented the highest value, which was statistically different from the values obtained via the other treatments (Table 3).

The alterations in mechanical properties of the treated and untreated wood are primarily attributed to changes in the hierarchical structure and interactions among cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin [54], resulting from the in situ precipitation of magnetic NPs during wood treatment. The FTIR spectrum (Fig. 3) revealed degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, particularly in VI-P. The increase in MOE is attributable to the softening of the cellulose’s crystalline zone during treatment, especially in VI-P, as confirmed by the XRD spectrum (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the incorporation of NPs into the wood matrix can reinforce the structure, acting as an additional support that absorbs and distributes stress; this dispersion within wood fibers may enhance flexure strength by increasing stress resistance when a load is applied in this direction [55]. The decreases in MOR values for G. arborea and P. oocarpa (Table 3) subjected to VI-I treatment are attributable to the agglomeration of magnetic NPs in the veneer matrix without proper coupling, leading to a reduction in the wood mechanical properties (Table 3) [56]. Conversely, in the vacuum pressure treatment, mechanical properties improved, particularly in V. ferruginea (Table 3).

The decrease in internal bond (IB) values can be attributed to the interaction between chemical treatments and wood veneers. As observed in the FTIR analysis (Fig. 3A–C), the application of ammonia solution led to hemicellulose degradation [27]. According to Wibowo et al. [56], hemicellulose plays a crucial role in adhesion, as this biopolymer directly interfaces with the adhesive. A reduction in hemicellulose resulted in fewer exposed OH groups available for bonding with the adhesive. Furthermore, the incorporation of inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) such as Fe3O4 into the wood matrix can disrupt the natural hydrogen bonds between fibers, potentially leading to a decrease in the IB strength of the boards [57].

The synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the three tropical species (Gmelina arborea, Vochysia ferruginea and Pinus oocarpa) was possible by in situ Fe3+ and Fe2+ impregnation and ammonium immersion. However, the impregnation method (immersion or vacuum-pressure) affected the effective synthesis of the nanoparticles. Vacuum-pressure impregnation was the method that presented the highest amount of Fe3O4 formation, obtaining a concentration from 24.25 to 34.36 g/kg of veneers. A decrease of the signal at 1739, 1453, 12,51, 1145 and 895 cm-1 for cellulose and at 1601 and 1251 cm−1 for lignin in the FT-IT spectrum showed that cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin were hydrolyzed and dissolved due to magnetization treatment and the other is that total content of biomass is reduced due to the formation of magnetic particles. Meanwhile, XDR analysis evidenced changes in the hierarchical structure and the interactions among cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. Both techniques evidenced higher ferrite signals in the vacuum pressure treatment. According to the parameters of the analysis of magnetic properties (Ms, Hc, and Mr), the vacuum pressure method presented higher values of ferromagnetic behavior. Besides, SEM observations showed that the largest amount of material was deposited around the wood cavities or vessel lumen and in minor quantities in other anatomical structures. According to the above magnetic values, SEM observations and spectrum analysis, the best impregnation method was the vacuum pressure treatment. However, this treatment produced a reduction in internal bonding due to the agglomeration of the magnetic NPs in the veneers matrix, without proper coupling and the use of ammonia solution causes degradation to polymers of wood mainly due to the affinity of the hydroxyl group with adhesive specifically the adherence force. However, contradiction is presented in the bending test, where plywood increases the flexure resistance due to ammonium treatment increasing the crystals area of cellulose. Vochysia ferruginea presented the highest level of magnetization, therefore this species can be considered as potential for wood panel fabrication, and then several products can be fabricated with the species with the capacity to reduce or block electromagnetic waves. And so, the development of sustainable materials helps human health. However, further research is necessary to develop the capacity to absorb electromagnetic waves of these materials, which is not well-known.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to thank Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Extensión of the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica (ITCR, Cartago, Costa Rica) for the project financial support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Róger Moya, Alexander Berrocal. Data collection: Johanna Gaitán-Alvarez, Róger Moya, Alexander Berrocal. Analysis and interpretation of results: Johanna Gaitán-Alvarez, Róger Moya, Alexander Berrocal, Karla J. Merazzo. Draft manuscript preparation: Johanna Gaitán-Alvarez, Alexander Berrocal, Róger Moya. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data presented in this article were deposited in https://doi.org/10.18845/RDA/U3YLCS (accessed on 14 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sudirman AW. Effect of cellphone electromagnetic wave radiation on the development of sperm. JIKSH. 2020;9(2):708–12. doi:10.35816/jiskh.v12i2.385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang J, Wang B, Wang Z, Chen L, Gao C, Xu B, et al. Synthesis of 3D flower-like ZnO/ZnCO2O4 composites with the heterogeneous interface for excellent electromagnetic wave absorption properties. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;586(12):479–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2020.10.111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lv H, Yang Z, Wang PL, Ji G, Song J, Zheng L, et al. A voltage-boosting strategy enabling a low-frequency, flexible electromagnetic wave absorption device. Adv Mater. 2018;30(15):1706343. doi:10.1002/adma.201706343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mashkour M, Ranjbar Y. Superparamagnetic Fe3O4@wood flour/polypropylene nanocomposites: physical and mechanical properties. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;111:4 7–54. [Google Scholar]

5. Lou Z, Zhang Y, Zhou M, Han H, Cai J, Yang L, et al. Synthesis of magnetic wood fiber board and corresponding multi-layer magnetic composite board, with electromagnetic wave absorbing properties. Nanomater. 2018;8(6):441. doi:10.3390/nano8060441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Manna R, Srivastava SK. Reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4/polyaniline ternary composites as a superior microwave absorber in the shielding of electromagnetic pollution. ACS Omega. 2021;6(13):9164–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Liu J, Che R, Chen H, Zhang F, Xia F, Wu Q, et al. Microwave absorption enhancement of multifunctional composite microspheres with spinel Fe3O4 cores and anatase TiO2 shells. Small. 2012;8(8):1214–21. doi:10.1002/smll.201102245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Oka H, Kataoka Y, Osada H, Aruga Y, Izumida F. Experimental study on electromagnetic wave absorbing control of coating-type magnetic wood using a grooving process. J Magn Magn Mater. 2007;310–e1029. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.11.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ahmed A, Abu Bakar MS, Azad AK, Sukri R, Phusunti N. Intermediate pyrolysis of Acacia cincinnata and Acacia holosericea species for bio-oil and biochar production. Energy Convers Manag. 2018;176:393–408. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.09.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu TT, Cao MQ, Fang YS, Zhu YH, Cao MS. Green building materials lit up by electromagnetic absorption function: a review. J Mater Sci Technol. 2022;112(25):329–44. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2021.10.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Oka H, Narita K, Osada H, Seki K. Experimental results on indoor electromagnetic wave absorber using magnetic wood. J Appl Phys. 2002;91(10):7008–10. doi:10.1063/1.1448796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Oka H, Hamano H, Chiba S. Experimental study on actuation functions of coating-type magnetic wood. J Magn Magn Mater. 2004;272–276:E1693–4. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2003.12.977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gan W, Gao L, Liu Y, Zhan X, Li J. The magnetic, mechanical, thermal properties and UV resistance of CoFe2O4/SiO2-coated film on wood. J Wood Chem Technol. 2016;36(2):94–104. doi:10.1080/02773813.2015.1074247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lou Z, Han X, Liu J, Ma Q, Yan H, Yuan C, et al. Nano-Fe3O4/bamboo bundles/phenolic resin oriented recombination ternary composite with enhanced multiple functions. Compos Part B-Eng. 2021;226:109335. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gan W, Gao L, Xiao S, Zhang W, Zhan X, Li J. Transparent magnetic wood composites based on immobilizing Fe3O4 nanoparticles into a delignified wood template. J Mater Sci. 2017;52(6):3321–9. doi:10.1007/s10853-016-0619-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xuan CTA, Tho PT, Xuan ND, Ho TA, Ha PTV, Trang LTQ, et al. Microwave absorption properties for composites of CoFe2O4/carbonaceous-based materials: a comprehensive review. J Alloys Compd. 2024;174429. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.174429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang S, Ashfaq MZ, Gong H, Zhang Y, Lin X, Feng Y, et al. Electromagnetic wave absorption properties of magnetic particle-doped SiCN (C) composite ceramics. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2021;32(4):4529–43. doi:10.1007/s10854-020-05195-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Oka H, Tanaka K, Osada H, Kubota K, Dawson FP. Study of electromagnetic wave absorption characteristics and component parameters of laminated-type magnetic wood with stainless steel and ferrite powder for use as building materials. J Appl Phys. 2009;105(7):07E701. doi:10.1063/1.3056403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Oka H, Hojo A, Osada H, Osada H, Namizaki Y, Taniuchi H. Manufacturing methods and magnetic characteristics of magnetic wood. J Magn Magn Mater. 2004;2332–4. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2003.12.1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dong Y, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Li J. Combined treatment for conversion of fast-growing poplar wood to magnetic wood with high dimensional stability. Wood Sci Technol. 2016;50(3):503–17. doi:10.1007/s00226-015-0789-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Foroutan R, Mohammadi R, Ahmadi A, Bikhabar G, Babaei F, Ramavandi B. Impact of ZnO and Fe3O4 magnetic nanoscale on the methyl violet 2B removal efficiency of the activated carbon oak wood. Chemosphere. 2022;286:131632. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jirouš-Rajković V, Miklečić J. Enhancing weathering resistance of wood—a review. Polymers. 2021;13(12):1980. doi:10.3390/polym13121980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Geeri S, Murthy BK, Kolakoti A, Murugan M, Elumalai PV, Dhineshbabu NR, et al. Influence of magnetic wood on mechanical and electromagnetic wave-absorbing properties of polymer composites. Int J Polym Sci. 2023;2023(1):1142654. doi:10.1155/2023/1142654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Cheng Z, Wei Y, Liu C, Chen Y, Ma Y, Chen H, et al. Lightweight and construable magnetic wood for electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22(10):2000257. doi:10.1002/adem.202000257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Tang T, Fu Y. Formation of chitosan/sodium phytate/nano-Fe3O4 magnetic coatings on wood surfaces via layer-by-layer self-assembly. Coatings. 2020;10(1):51. doi:10.3390/coatings10010051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lou Z, Wang W, Yuan C, Zhang Y, Li Y, Yang L. Fabrication of Fe/C composites as effective electromagnetic wave absorber by carbonization of pre-magnetized natural wood fibers. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2019;4(1):43–50. doi:10.21967/jbb.v4i1.185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gao Y, Yang X, Garemark J, Olsson RT, Dai H, Ram F, et al. Gradience free nanoinsertion of Fe3O4 into wood for enhanced hydrovoltaic energy harvesting. ACS Sustain Chemist Eng. 2023;11(30):11099–109. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c01649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Liu J, Kong X, Wang C, Yang X. Permeability of wood impregnated with polyethylene wax emulsion in vacuum. Polymer. 2023;281:126123. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Popham N. Resin infusion for the manufacture of large composite structures. In: Pemberton R, Summerscales J, Graham-Jones J, editors. Marine composites: design and performance. 1st ed. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. 227–68. [Google Scholar]

30. Tarmian A, Zahedi Tajrishi I, Oladi R, Efhamisisi D. Treatability of wood for pressure treatment processes: a literature review. Eur J Wood Prod. 2020;78:635–60. doi:10.1007/s00107-020-01541-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Frias M, Blanchet P, Bégin-Drolet A, Triquet J, Landry V. Parametric study of a yellow birch surface impregnation process. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2021;79(4):897–906. doi:10.1007/s00107-020-01532-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fadia SL, Rahayu I, Nawawi DS, Ismail R, Prihatini E, Laksono GD, et al. Magnetic characteristics of sengon wood-impregnated magnetite nanoparticles synthesized by the co-precipitation method. AIMS Mater Sci. 2024;11(1):1–27. doi:10.3934/matersci.2024.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wahyuningtyas I, Rahayu I, Maddu A, Prihatini E. Magnetic properties of wood treated with nano-magnetite and furfuryl alcohol impregnation. BioResources. 2022;17(4):6496. doi:10.15376/biores.17.4.6496-6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Laksono GD, Rahayu IS, Karlinasari L, Darmawan W, Prihatini E. Characteristics of magnetic sengon wood impregnated with nano Fe3O4 and furfuryl alcohol. J Korean Wood Sci Technol. 2023;51(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

35. Moya R, Gaitán-Álvarez J, Berrocal A, Merazzo KJ. In situ synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles and wood composite properties of three tropical species. Materials. 2022;15(9):3394. doi:10.3390/ma15093394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Moya R, Gaitán-Álvarez J, Berrocal A, Merazzo KJ. Magnetic and physical-mechanical properties of wood particleboards composite (MWPC) fabricated with Fe3O4 nanoparticles and three plantation wood. Wood Fiber Sci. 2023;55(3/4):211–27. doi:10.22382/wfs-2023-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Gaitán-Alvarez J, Berrocal A, Mantanis GI, Moya R, Araya F. Acetylation of tropical hardwood species from forest plantations in Costa Rica: an FTIR spectroscopic analysis. J Wood Sci. 2020;66(1):49. doi:10.1186/s10086-020-01898-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gaitán-Álvarez J, Moya R, Berrocal A, Araya F. In-situ mineralization of calcium carbonate of tropical hardwood species from fast-grown plantations in Costa Rica. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2020;29(10):9184–94. [Google Scholar]

39. Moya R, Tenorio C, Torres JDC. Steaming and heating Dipteryx panamensis logs from fast-grown plantations: reduction of growth strain and effects on quality. For Prod J. 2021;71(1):3–10. doi:10.13073/FPJ-D-20-00041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Rahayu I, Prihatini E, Ismail R, Darmawan W, Karlinasari L, Laksono GD. Fast-growing magnetic wood synthesis by an in-situ method. Polymers. 2022;14(11):2137. doi:10.3390/polym14112137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. ASTM. Standard test method for ash in wood. D-1102-84(2021). West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2021. doi:10.1520/D1102-84R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. APHA-AWWA-WEF. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 20th ed. Washington, DC, USA: American Public Health Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

43. ASTM. Standard test methods for small clear specimens of timber. D-143(2023). ASTM D143-23. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2023. [Google Scholar]

44. Yang L, Lou Z, Han X, Liu J, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Fabrication of a novel magnetic reconstituted bamboo with mildew resistance properties. Mater Today Commun. 2020;23:101086. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Konopka A, Barański J, Orłowski K, Szymanowski K. The effect of full-cell impregnation of pine wood (Pinus sylvestris L.) on changes in electrical resistance and on the accuracy of moisture content measurement using resistance meters. BioResources. 2018;13(1):1360–71. doi:10.15376/biores.13.1.1360-1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Acosta AP, de Avila Delucis R, Santos OL, Amico SC. A review on wood permeability: influential factors and measurement technologies. J Indian Acad Wood Sci. 2024;21(1):175–91. [Google Scholar]

47. Gan W, Liu Y, Gao L, Zhan Z, Li J. Magnetic property, thermal stability, UV-resistance, and moisture absorption behavior of magnetic wood composites. Polym Compos. 2017;38(8):1646–54. doi:10.1002/pc.23733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Lou Z, Yuan C, Zhang Y, Li Y, Cai J, Yang L, et al. Synthesis of porous carbon matrix with inlaid Fe3C/Fe3O4 micro-particles as an effective electromagnetic wave absorber from natural wood shavings. J Alloys Compd. 2019;775:800–9. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.10.213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Garskaite E, Stoll SL, Forsberg F, Lycksam H, Stankeviciute Z, Kareiva A, et al. The accessibility of the cell wall in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) sapwood to colloidal Fe3O4 nanoparticles. ACS Omega. 2021;6(33):21719–29. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c03204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Sumadiyasa M, Manuaba IBS. Determining crystallite size using Scherrer formula, Williamson-Hull plot, and particle size with SEM. Bul Fis. 2018;19(1):28–35. doi:10.24843/BF.2018.v19.i01.p06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Tebriani S. Analysis of the vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) on the electrodeposition results of a thin magnetite layer using a continuous direct current. Nat Sci J. 2019;5:722–30. doi:10.15548/nsc.v5i1.892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bukit N, Frida E, Simamora P, Sinaga T. Synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles of iron sand coprecipitation method with polyethylene glycol 6000. J Chem Mater Res. 2015;7(7):110–5. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2018.04.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Fan S, Gao X, Pang J, Liu G, Li X. Enhanced preservative performance of pine wood through nano-xylan treatment assisted by high-temperature steam and vacuum impregnation. Materials. 2023;16(11):3976. doi:10.3390/ma16113976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Rahayu IS, Ismail R, Darmawan W, Wahyuningtyas I, Prihatini E, Laksono GD, et al. Impregnation effect of synthesized Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the jabon wood’s physical properties. Int J Recent Technol Appl Sci. 2024;6(2):87–100. doi:10.36079/lamintang.ijortas-0602.701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Przystupa K, Pieniak D, Samociuk W, Walczak A, Bartnik G, Kamocka-Bronisz R, et al. Mechanical properties and strength reliability of impregnated wood after high temperature conditions. Materials. 2020;13(23):5521. doi:10.3390/ma13235521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Wibowo ES, Park BD. Effect of hemicellulose molecular structure on wettability and surface adhesion to urea-formaldehyde resin adhesives. Wood Sci Technol. 2022;56(4):1047–70. doi:10.1007/s00226-022-01397-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Nagraik P, Shukla SR, Kelkar BU. Enhancing poplar-wood properties through nano-silica fortified polyvinyl-acetate impregnation. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2024;1-14(3):1–14. doi:10.1080/17480272.2024.2337150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools