Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Ionic Electroactive Polymers as Renewable Materials and Their Actuators: A Review

1 Institute for Bionic Technologies and Engineering, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street 2-4, Moscow, 119991, Russia

2 Department of Physical Chemistry, National University of Science and Technology “MISIS”, Moscow, 119049, Russia

3 Institute of Biomedical Systems, National Research University of Electronic Technology, Zelenograd, Moscow, 124498, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Tarek Dayyoub. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1267-1292. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0022

Received 21 October 2024; Accepted 05 February 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

The development of actuators based on ionic polymers as soft robotics, artificial muscles, and sensors is currently considered one of the most urgent topics. They are lightweight materials, in addition to their high efficiency, and they can be controlled by a low power source. Nevertheless, the most popular ionic polymers are derived from fossil-based resources. Hence, it is now deemed crucial to produce these actuators using sustainable materials. In this review, the use of ionic polymeric materials as actuators is reviewed through the emphasis on their role in the domain of renewable materials. The review encompasses recent advancements in material formulation and performance enhancement, alongside a comparative analysis with conventional actuator systems. It was found that renewable polymeric actuators based on ionic gels and conductive polymers are easier to prepare compared to ionic polymer-metal composites. In addition, the proportion of actuator manufacturing utilizing renewable materials rose to 90%, particularly for ion gel actuators, which was related to the possibility of using renewable polymers as ionic or conductive substances. Moreover, the possible improvements in biopolymeric actuators will experience an annual rise of at least 10% over the next decade, correlating with the growth of their market, which aligns with the worldwide goal of reducing global warming. Additionally, compared to fossil-derived polymers, the decomposition rate of renewable materials reaches 100%, while biodegradable fossil-based substances can exceed 60% within several weeks. Ultimately, this review aims to elucidate the potential of ionic polymeric materials as a viable and sustainable solution for future actuator technologies.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

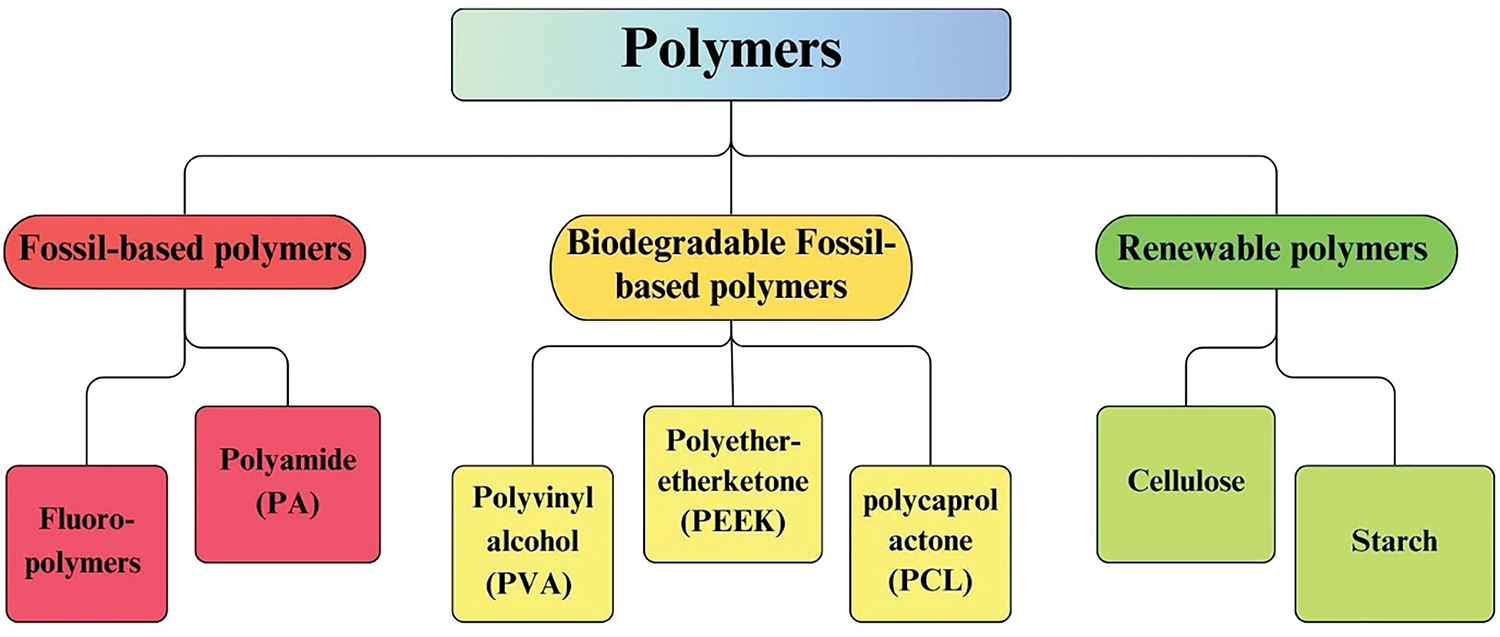

Because of the desired properties of polymers, such as lightweight, design flexibility, and good mechanical properties, they have inspired a broad range of applications in medicine, industry, aerospace, energy storage, and robotics [1–3]. Generally, polymers can be divided regarding their base into fossil-based, biodegradable fossil-based, and renewable polymers (Fig. 1). However, many known polymers are synthesized from fossil fuel sources, leading to serious environmental pollution [4,5]. Over the past twenty years, renewable polymers have gained attention as a viable solution because of their beneficial environmental properties as renewable biomaterials and a sustainable resource for materials [6,7]. The effect of conventional fossil polymers begins with the extraction and refining of fossil fuels, which emit significant levels of carbon dioxide and methane. The manufacturing process of fossil-based plastics requires a lot of energy and usually depends on fossil fuels, leading to extra emissions of greenhouse gases. In addition, conventional polymers derived from fossil resources also play a role in the accumulation of pollution and waste that endure for hundreds of years. The increasing issue of plastic waste can be seen in oceans, landscapes, and the food chain, leading to a pressing demand for sustainable solutions [8]. Biopolymers, as renewable materials, are seen as another option and are being researched further in order to find the most effective solutions, with the goal of reducing impact on the environment as much as possible. Biopolymers are derived from renewable biological resources, providing a sustainable alternative to traditional fossil-based plastics. Biopolymers are made from plant materials like corn starch, sugarcane, flax, hemp, and wood fibers instead of non-renewable petroleum used in traditional plastics. The transition to plant-based sources greatly decreases the environmental impact linked to plastic production [9]. Furthermore, typically, biopolymers are biodegradable under specific conditions, leading to a decrease in ongoing pollution and aiding in the prevention of plastic waste buildup in nature. Nevertheless, it is crucial to mention that this is true only when appropriate waste disposal facilities exist. By improving recycling systems, both traditional and biodegradable polymers can be recycled into new products instead of ending up in landfills. On the other hand, over 380 million tons of plastic are produced each year, with a yearly growth rate of 4%, resulting in the generation of 6300 million tons of plastic waste since 1950 [9–11]. Currently, approximately 2 million tons of biopolymers that are completely bio-based are being produced annually, with the aims of moving away from fossil resources, implementing new recycling or degradation methods, and utilizing fewer harmful reagents and solvents during production [8–10]. In addition, the estimated value of the biopolymers market worldwide in 2023 was USD 17.54 billion and is expected to increase by 10.4% annually from 2024 to 2030 [12]. Thanks to their biocompatibility, biopolymers are widely utilized in the medical field, and they can be engineered to decompose naturally over time, eliminating the necessity for follow-up surgery to extract the implants. This feature is advantageous in cases where controlled drug release or temporary support is necessary. This indicates that the utilization of biopolymers matches the increasing focus on environmentally friendly, efficient, and secure materials [12]. However, one of the major obstacles for biopolymers is their price competitiveness in comparison with conventional fossil-based plastics. Frequently, their production costs are higher, which can make them less economically viable for certain uses. Overcoming the challenge of reaching the same cost as traditional plastics is still a struggle. Companies that utilize these polymers could be at a competitive disadvantage when compared to competitors using traditional plastics. Their widespread use may be restricted until they are able to compete in terms of price without sacrificing performance and quality. Increased production expenses could restrict the use of these polymers to specialized markets or high-end product categories [13]. The biopolymer market is categorized into films, bottles, fibers, seed coating, vehicle components, medical implants, actuators, sensors, artificial muscles, soft robotics, and others [13]. Biopolymer films are commonly utilized in the packaging sector as eco-friendly substitutes for traditional plastic films. Consumer demand for eco-friendly and biodegradable packaging materials has led to the use of biopolymer films in food packaging, bags, wraps, and labels. The natural flexibility of these materials allows them to be used in a variety of packaging applications, meeting the diverse requirements of industries such as food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics [14].

Figure 1: Division of polymers regarding their base

Soft robotics is regarded as a novel and intriguing branch of robotics. Such robots must be made from soft, flexible, and compliant materials to execute tasks that adapt to their surroundings [15]. Additionally, soft robots are more versatile and safer for human interaction, more resilient and dependable, and could be less expensive than conventional robots [16]. Soft robotics could embody a technology that benefits humanity and the Earth by tackling global issues and environmental deterioration via specific productive uses. Firstly, in terms of urban agriculture, soft robots can enhance food security and alleviate poverty through precise planting and harvesting of crops in cities, encouraging sustainable consumption, monitoring crop health, and ensuring food safety, and they can also minimize the carbon footprint associated with the food system and farming practices [17,18]. Secondly, regarding ocean conservation, soft robotics can play a crucial role in cleaning, safeguarding, conserving, and restoring marine biodiversity and ocean health, encouraging sustainable exploitation of ocean resources, and comprehending the effects of climate change on marine environments [19]. Third, in the context of disaster response, soft robots can assist in search and rescue operations following natural disasters, enhancing safety and mitigating the effects of such events, delivering prompt aid to impacted communities, restoring and fixing infrastructure, and enhancing transportation and communication systems [20]. Additionally, the energy production sector is regarded as a significant area for utilizing soft robotics. For instance, incorporating renewable energy sources into soft robotics structures could transform energy production into a clean, adaptable, and easily accessible process [21]. Ultimately, healthcare applications are regarded as the most significant area of soft robotics. Soft robotic exosuits, wearables, and manipulators can assist in physical therapy and minimally invasive surgery, thereby enhancing mobility capabilities, fostering independence for individuals with disabilities, and shortening patients’ recovery periods [22,23].

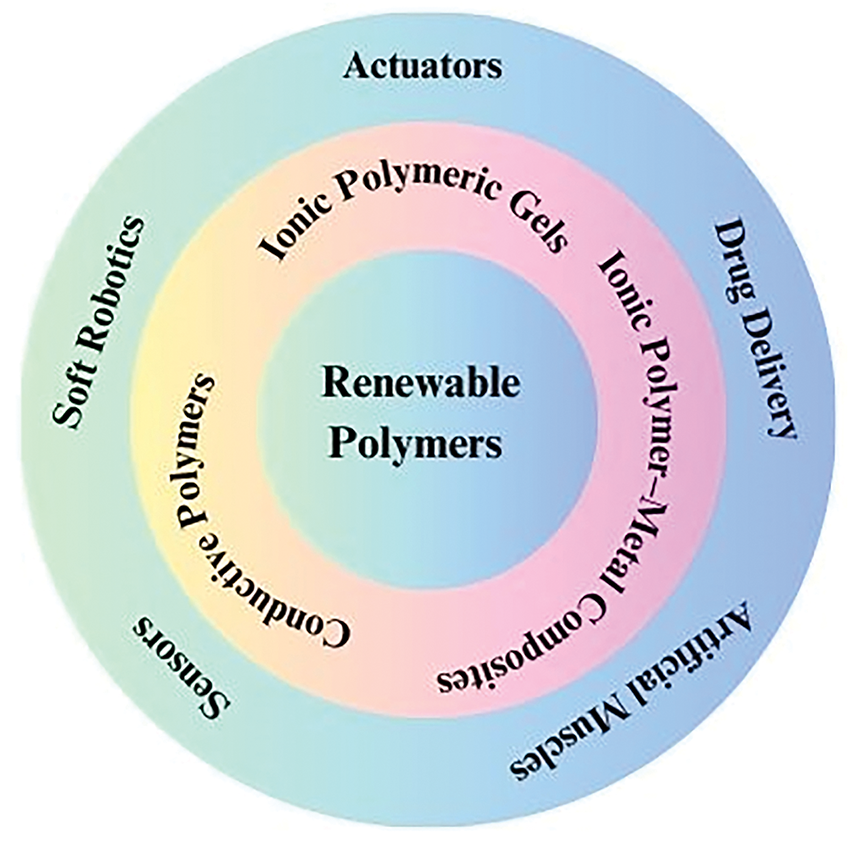

Eco-friendly materials, including recyclables, renewables, and biodegradable substances, are particularly appealing for application in soft robotics [24]. Soft actuators are essential components of all soft robotic systems. This thus necessitates a strong emphasis on the advancement of sustainable soft actuator technologies and, more broadly, for researchers to adopt sustainability as a primary design objective for soft robotic systems [25,26]. Nevertheless, as polymeric actuators are made up of various components, including a polymer matrix and electrodes, which necessitate distinct materials to obtain desired characteristics, fully biodegradable material systems for these actuators have not yet been manufactured [27]. The most important applications of the biopolymers are considered medical and soft robotics ones that will be reviewed in this work (Fig. 2). In addition, cellulose, starch, and gelatin are considered the most used materials as renewable ones. For example, Lihui Chen et al., in their work [28], prepared a cellulose-based soft robot that had a dual-layer structure, which consists of cellulose nanofibers as an upper layer and a hydrophobic biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP) membrane as a bottom layer. The authors presented that this prepared soft robot can be actuated by only 67 mW cm−2 of light or a 2.8 V power source, accomplishing a 360° bending range with a bending curvature of 2.67 cm−1. In the work [29], biocompatible soft robotics were prepared based on pure cassava-starch-based film that can be activated for over 60 min with a continuous supply of water vapor and can generate a force of 4.2 mN. Also, using gelatin in manufacturing soft robotics is considered an interesting direction. For example, in the work [30], a miniature soft robot was created using a magnetic gelatin hydrogel with mechanical characteristics that can be adjusted easily using a Hofmeister effect-assisted reaction in a single step. Additionally, the authors reported that this robot was created with legs that resemble insect claws, enabling it to carry out gripping and transporting tasks like its biodegradable counterparts.

Figure 2: Types and applications of renewable polymers

2 Ionic-Based Actuators Based on Renewable Polymers

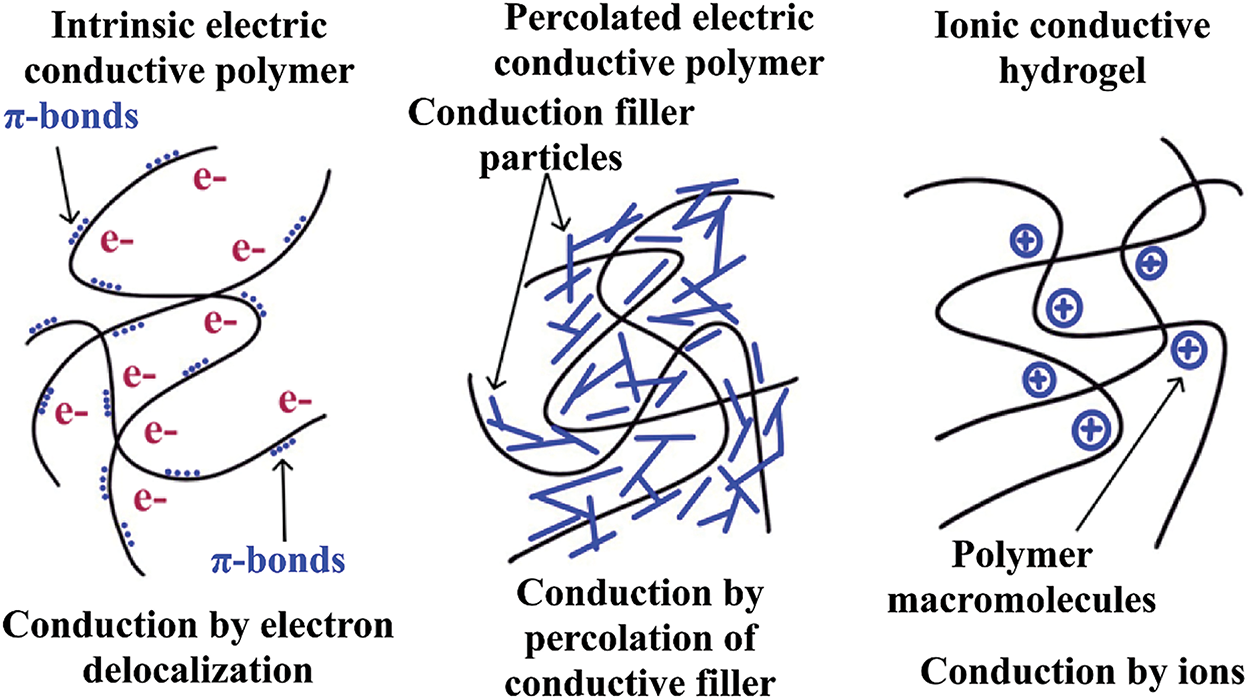

Actuators are commonly devices that transform supplied energy into movement. Due to their distinctive qualities as environmentally friendly biomaterials, polymer actuators are now receiving greater interest compared to conventional actuators such as piezoelectric metal-ceramic actuators [31,32]. These polymers can react to different external stimuli like pH changes, electric current, humidity variations, light, temperature changes, magnetic fields, etc., altering their size or form, and they can return to their initial shape once the external stimulus is gone [1,2]. One of the most important and interesting types of polymers is electroactive polymers (EAPs), which can be deformed under the influence of an external electric field. Their characteristics, such as lightweight, noiselessness, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and good mechanical properties, especially under high load, make them attractive for use as actuators, sensors, and artificial muscles [31]. EAPs are an excellent choice for a wide range of applications as electromechanical actuators since they are materials that, when exposed to an electric current, modify their mechanical or optical characteristics with exact control of the energy transfer from electrical to mechanical and vice versa [32]. Electroactive polymers can be divided into two main groups: dielectric and ionic EAPs, depending on their conductivity mechanism [33–35]. In other words, EAPs can be categorized based on their conduction mechanism into intrinsic types, which achieve electric conductivity through electron mobility or conductive particles dispersed in a polymer matrix, and extrinsic types, which exhibit ionic conductivity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Conduction mechanisms of electroactive polymers

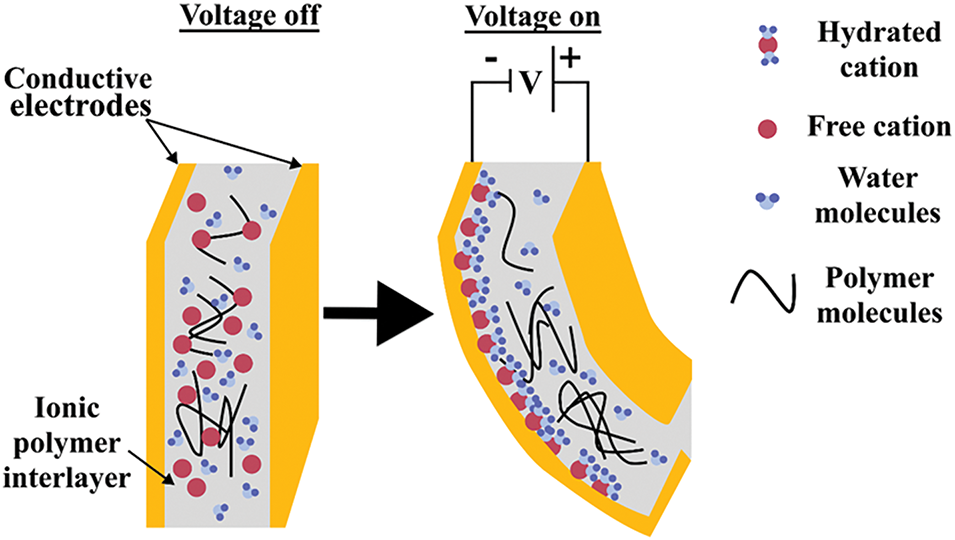

Ionic electroactive polymers (IEAPs) are operated by the diffusion of ions within the electrolyte’s ionic liquids, affecting the actuator’s transformation in size and shape through the movement and dispersion of ions. Anions move towards the cathode and cations move towards the anode when a steady electric field is present. This results in the actuator expanding/contracting and bending [31,36]. Ionic EAPs have two stable equilibrium states and require lower actuation electrical current compared to dielectric EAPs. Ionic EAPs have several disadvantages, like slow activation, low strength, the need for constant humidity when water is utilized as an ionic liquid, and the risk of electrolysis above a certain voltage, resulting in irreversible damage to the material; furthermore, maintaining constant deformation can be difficult when a constant voltage is applied [37]. Fig. 4 presents the activation mechanism of IEAPs, which generally consists of a polymeric conductive interlayer located between two conductive electrodes. When the electric field is applied, the hydrated cations in the ionic EAP move towards the negatively charged electrode, causing a change in volume in a specific area (Fig. 4), which means that the ionic EAPs exhibit a distinct bending motion due to the volume change [38]. The actuators based on ionic EAPs can be divided into ionic polymeric gels, conductive polymers, and ionic polymer–metal composites.

Figure 4: Principle of operation of ionic EAPs

This review, illustrated in Fig. 5, will examine actuators derived from sustainable ionic EAPs and their actuation mechanisms, focusing on recent progress in developing ionic EAP actuators. It will discuss the potential for incorporating renewable materials as the polymer matrix in actuators, the role of renewable polymers in enhancing actuator characteristics or lowering costs, and applications in diverse areas, particularly in medicine.

Figure 5: A diagram depicting the organization of the review

2.1 Ionic Polymeric Gels and their Actuators

Ionogels, also known as ionic polymer gels, are a unique subset of polyelectrolytes distinguished by the existence of ionic linkages along their polymer chains. Usually, these gels are formed by polymerizing monomers sourced from ionic liquids or by altering neutral polymers post-polymerization [39]. Recently, there has been an increasing fascination with ionic polymer gels, especially in fields like soft robotics, biomedicine, and biotechnology. Ionogels are typically classified as hydrogels, comprising polymer networks that can absorb and expand in water [40]. Additionally, non-aqueous ionic gels are formed by stretching polymer frameworks with organic electrolyte solutions, demonstrating physical interactions within the polymer structures [41].

Hydrogels consist of two phases, porous and permeable solids with a minimum of 10% interstitial fluid, mainly water. Different substances, such as inorganic materials, organic molecules, and polymers, can be used as these solids. Lately, there has been an increase in the creation of functionalized hydrogels, which not only create a three-dimensional hydrophilic structure but also have improved features. These improved properties include abilities like in-place solidification, sticking power, regulated medication delivery, slickness, cellular protection, and pH control. Additionally, hydrogels are capable of responding to chemical stimuli such as changes in molecular composition, pH levels, redox potential, or ionic strength, as well as physical stimuli like fluctuations in temperature, pressure, magnetic and electric fields, sound waves, or exposure to light [42]. Actuators made from hydrogels are flexible components that can act as pliable actuators, versatile sensors, multi-functional logic switches, and devices for medical uses [43].

Cellulose is a polymer that is green, sustainable, biodegradable, and found in abundance. These distinctive qualities of cellulose make it a practical polymer for creating bio-based hydrogels or soft materials for multiple uses [44]. Cellulose is not just seen as a renewable substance but also possesses important features like biodegradability, biocompatibility, and insolubility in most solvents, making it a highly sought-after option in forming hydrogels [45]. Furthermore, due to cellulose’s non-toxicity to humans, its hydrogels have the potential to be utilized for applications such as actuators, wound healing, wound dressings, and drug delivery. In Reference [46], an actuator based on 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO)-oxidized cellulose nanofiber (TOCN)/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(4-styrenesulfonate)/ionic liquid (PEDOT:PSS/IL) gel electrode with a TOCN/IL or poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVdF(HFP)/IL) gel electrolyte was prepared (Fig. 6). The authors reported that OCN/PEDOT:PSS/IL gel electrode actuators exhibited high strain performance and excellent electrical and ionic conductivity. The ionic conductivity of the TOCN/IL gel electrolytes ranged from 0.49 to 1.33 mS.cm−1. The maximum strain value of 1.11% was observed for TOCN/PEDOT:PSS/IL (50/200/200), which was thought to be influenced by capacitance, ionic conductivity, electrical conductivity, and Young’s modulus. Additionally, the hydrogel had a cycle life of at least 10,000 cycles under conditions of ±1 V, 1 Hz, indicating prolonged functionality in air.

Figure 6: Ionic hydrogel actuators based on TOCN/PEDOT:PSS/IL. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [46]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier

In Reference [47], a highly electro-responsive ionic actuator based on functional carboxylated cellulose nanofibers (CCNF) by doping with ionic liquid (IL) and graphene nanoplatelets (GN) was developed (Fig. 7). The researchers demonstrated that the suggested actuator achieved a significant 15.71 mm tip displacement at 2.0 V and 0.1 Hz, with a quicker rise time of 2.9 s, and maintained 98.6% retention for 3 h without any distortion in actuation response.

Figure 7: Highly electro-responsive ionic actuator based on CCNF-IL-GN. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [47]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier

In Reference [48], the authors prepared electro-actuators based on cationic cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) and studied the impact of the type of electrolytes and their anions on the actuation performance (Fig. 8). The authors presented that by using two types of electrolytes, which were lithium-based salts and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride (EMIM)-based ionic liquids, the prepared actuators can be activated by low DC voltage up to 5.0 V with a bending strain value up to 0.15%.

Figure 8: Fabrication steps of CNFs actuators. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [48]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier

In Reference [49], the authors prepared an electro-active actuator based on cellulose nanocrystals (CNC)–polyacrylamide nanocomposite hydrogels (Fig. 9). They reported that the prepared actuators showed greater field-induced bending responses and longer lifetimes because of the incorporation of CNCs into non-electroresponsive polyacrylamide. These actuators had a high bending speed of up to 9° s–1.

Figure 9: Electro-active actuator based on CNC–polyacrylamide nanocomposite hydrogels. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [49]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society

Nonetheless, it was observed that preparing complete actuators using cellulose hydrogels is deemed quite challenging. The primary issue in this case is that the remaining parts of actuators also need particular characteristics, notably the excellent electrical conductivity regarding actuator electrodes. This ensures that creating actuators from ionic polymeric gels with solely renewable materials remains challenging yet feasible in the coming years.

Polyacrylic acid, a polymer that is biocompatible and biodegradable, has been extensively researched for its potential applications in drug delivery. It has several properties that make polyacrylic acid a promising material for various applications, including the ability to form hydrogels, mucoadhesive properties, and stimuli-responsive behavior. Polyacrylic acid-based hydrogels could transport medications to a range of tissues and organs [50]. In addition, hydrogels based on polyacrylic acid are widely used in actuator manufacturing. The study [43] investigated how different types and amounts of electrolyte salts affect the water retention and electrical conductivity of polyacrylamide (PAM) hydrogels (Fig. 10). As seen in Fig. 10, the flexible actuator consists of highly stretchable PAM conductive hydrogel electrodes along with an Ecoflex dielectric elastomer layer. In this case, the way it works is that when a direct current “DC source” is connected, electrodes that are compatible get charged with opposite charges. As a result, these opposite charges on the electrodes are drawn towards each other due to the Coulomb force, resulting in the creation of electrostatic pressure (P). This pressure then causes the elastomer film to easily deform in the plane. Both LiCl and CaCl2 were highly effective in improving water retention, with the ability to hold water increasing as the concentration of the salts increased. The hydrogel made with PAM and LiCl showed noteworthy electrical conductivity. By adding electronic conductors such as SWCNTs, MWCNTs, and GO, composite conductive hydrogels demonstrated enhanced electrical conductivity properties. Significantly, the electrical conductivity of PAM-LiCl was increased from 8 to 10 S/m with the addition of SWCNTs. The conductive hydrogels, which have both strong electrical conductivity and high water retention, were used to create a flexible actuator that responds to electricity. This actuator demonstrated remarkable flexibility, reaching a peak area strain of 18% when exposed to a 10 kV external voltage.

Figure 10: Flexible actuator based on electrically conductive PAM hydrogel electrodes. (a–d) The area of the flexible actuator increases with time when a triangular external voltage with a period of 40 s was applied. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [43]. Copyright 2022, MDPI

2.2 Conductive Polymers and Their Actuators

Conductive polymers (CPs) have been widely recognized for their potential in actuator technologies because of their unique electrochemical properties [51–53]. Conductive polymers are organic substances that can conduct electricity, and their conductivity can come from either being inherent or being induced through doping. Conductive polymers are substances that expand/contract when a voltage is applied. Nevertheless, as of now, there are no actuators made from renewable conductive polymers, although many are thought to be biodegradable. Hydrogels composed of conductive polymers provide several advantages [54–56]. They need very little voltage to function, possess great conductivity, contain a significant amount of water, and have a structured system that facilitates effective interactions between various components, and they are biocompatible. Another significant factor in the advancement of conductive actuators is the impact of the structural design, as the size of the actuators also contributes to their performance. Actuators that are wider can show more torsional deformation due to stress distribution, whereas shorter lengths result in increased curvature and induced strain [57]. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy indicates that ion penetration depth is greater in shorter actuators, enhancing their responsiveness [58].

A fascinating example of how conductive polymers are activated is through the oxidation or reduction processes based on their polarity. In Fig. 11, oxidation causes electrons to be removed and anions to be introduced, creating crosslinking between polarons and dopant anions, leading to the actuator expanding. During the recovery period, applying negative voltage influences the compression-stretching reaction, which is influenced by the size and movement of the neutralized anions [59,60]. When the dopant anion is small and highly mobile, it displaces anions and solvent molecules from the polymer to keep it neutral, causing the polymer to compress. If the dopant anion is large and unable to move, as shown in Fig. 11b, the anions are trapped within the polymer during reduction. This causes the cations in solution to migrate towards the polymer to maintain charge balance, leading to increased polymer expansion to counteract the trapped anions, ultimately resulting in further expansion of the polymer matrix [61].

Figure 11: Ionic actuation mechanisms of conductive polymer actuators depending on the anion size and mobility: (a) small anion mobile, (b) large and immobile anion

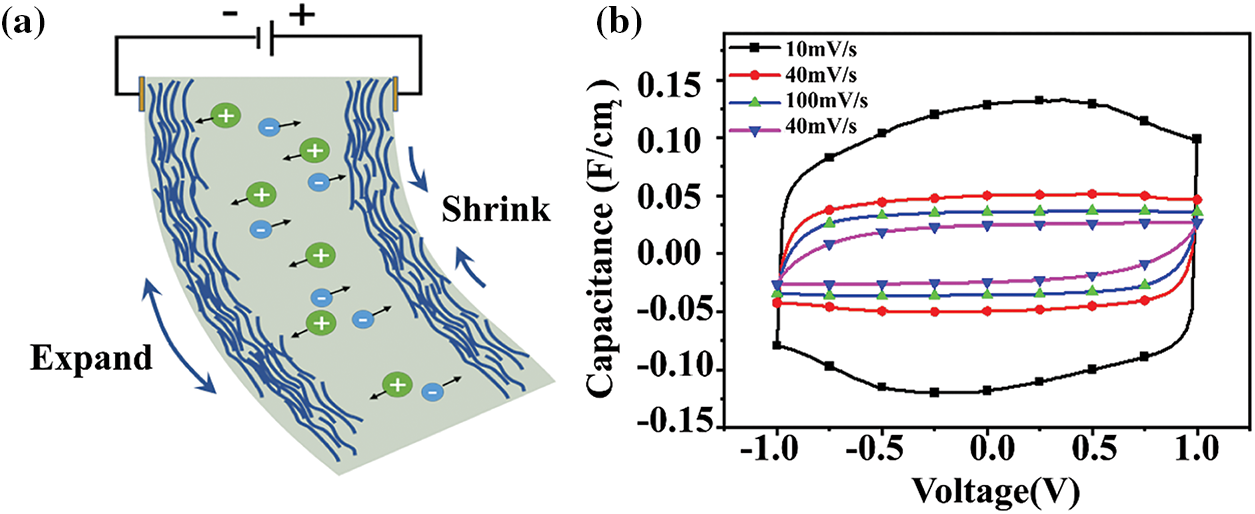

In Reference [62], the researchers presented a new electrochemical actuator that relies on ionic liquids, including EMIMTFSI (1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluorome- thylsulfonyl)imide, BMImOTs 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate, and PEDOT:PSS aqueous solution that utilizes conductive polymer ionogel as active electrodes. This ionogel showed outstanding characteristics, such as excellent conductivity, flexibility, and electrochemical activity. Their electrochemical actuators displayed impressive bending strain capabilities and quick response times, reaching frequencies of up to 10 Hz with a low voltage of 1 V. This highly flexible actuator surpasses other materials like graphene in terms of conductivity, flexibility, and electrochemical activity. The researchers demonstrated that the main factor driving the principle of work is the movement of cations. In Fig. 12a, it was apparent that cations cause the film to swell on the negative side, while the removal of cations leads to the film shrinking on the positive side. The researchers analyzed the actuator’s cyclic voltametric features at various scan rates, as shown in Fig. 12b. They determined that the cyclic voltammetry curve appears to be roughly rectangular.

Figure 12: Actuation performance of the CP ionogel actuator. (a) Illustration of the actuation mechanism of CP ionogel actuator; (b) CV curves of the actuator at different scan rates. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [62]. Copyright 2023, MDPI

In Reference [63], a conducting polymer actuator was modified with enantiomers of a naturally chiral oligomer to create a bipolar valve for sealing a tube filled with dye in a solution with chiral analytes. Upon the application of an electric field, the actuator that was specifically created exhibited a reversible deflection in a cantilever-like manner, enabling the dye to be discharged from the reservoir. Changing the polarity of the system allows for the opening and closing of the tube. The operational principle relied on applying an external electrical field. Chiral bipolar enantioselective valve (BPE) becomes polarized in the solution, leading to the preferential oxidation of one enantiomer. Hence, in order to observe the electromechanical distortion of polypyrrole (Ppy), it is crucial for the chiral oligomer to have a compatible configuration to interact with the appropriate molecular probe in the solution. Fig. 13 displays the typical experimental arrangement. The oligomer having the correct configuration was important because Fig. 13 showed that electromechanical changes had not taken place. Nevertheless, the primary benefit of these actuators lies in their wireless capabilities and ability to directly translate molecular chirality into the discharge of specific compounds. Therefore, these valves could be valuable in the realm of microfluidics for wireless drug delivery, among other applications.

Figure 13: (a) Schematic illustration of the bipolar set-up used for the wireless enantioselective valve with a representation of the chemical reactions, the electromechanical activation and the release of the dye; Bipolar enantioselective valve (1.5 cm long) operating with a Ppy actuator functionalized with (R)-oligo-BT2T4 dipping in an aqueous 0.2 M LiClO4 solution of (b) 5 mM D-DOPA and (c) 5 mM LDOPA. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [63]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons

In Reference [64], a novel conductive hydrogel based on gelatin methacrylate (GelMA), collagen, and silver nanowires (AgNW) was developed (Fig. 14). The inclusion of silver nanowire (AgNW) resulted in a significant rise in storage modulus, boosting it from 2.2 to 13.77 kPa, underscoring the essential impact of AgNW on improving both the electrical conductivity and mechanical strength of the gel. Furthermore, the researchers showed that they could selectively release fluorescent molecules from the conductive gel mixture by applying electrical stimulation. This means that the GelMA-Collagen-AgNW conductive hydrogels could be used as accurate actuators to facilitate the controlled discharge of molecules.

Figure 14: Schematic of the conductive gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)–collagen–silver nanowire (AgNW) blended hydrogel: (a) The protocol for generating the conductive GelMA–collagen–AgNW blended hydrogel; (b) electrical stimuli-mediated molecule release from the conductive GelMA–collagen–AgNW blended hydrogel in the microfluidic device. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [64] Copyright 2021, MPDI

In Reference [65], the authors utilized electrochemical polymerization to cover the electrospun polyurethane (PU) nanofibers with conductive polypyrrole (PPy), aiming to create bending actuators. The basic principle that guides how these devices work is illustrated in Fig. 15. In Fig. 15, it is visible that in the oxidation of the actuators, electrons are removed from the PPy structure, while in the reduction phase, electrons are reintroduced into the structure. This event causes a shift in volume, resulting in a change in the bending angle of the actuator being produced because of the mechanical restrictions imposed by the inactive adhesive tape.

Figure 15: The schematic representation of bending actuation mechanism of the PU/PPy nanofibrous actuators during oxidation and reduction processes. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [65]. Copyright 2020, IOP Publishing Ltd.

The positions of various actuators after oxidation and reduction are shown in Fig. 16. As can be seen in Fig. 16, the introduction of perchlorate ions from the electrolytic solution into the structure of the actuator during oxidation is accompanied by an increase in volume of the actuators, resulting in their counterclockwise rotation and vice versa. The authors presented that the angular displacement in the potential cycle can reach 225° [65].

Figure 16: Position of PU/PPy nanofibrous actuators produced using total consumed charges of (a) 2 C, (b) 3 C, (c) 4 C and (d) 5 C in reduced and oxidized states. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [65]. Copyright 2020, IOP Publishing Ltd.

2.3 Ionic Polymer–Metal Composites

Ionic polymer-metal composites (IPMCs) are one of the prospective types of actuators, which are composed of a single ionic polymer layer, functioning as an electrolyte with conductive electrode layers. A fundamental key characteristic of IPMCs is that their deformation results from the transport and redistribution of ions within the internal structure of the actuator [66]. IPMCs are advanced materials with considerable promise for diverse applications, especially in the fields of robotics and bioengineering. Structurally, they comprise a polymer electrolyte core encapsulated by metal electrode layers, facilitating their operation as flexible actuators and sensors. By the type of polymer matrix, IPMCs can be classified into several groups, such as fluoropolymers, liquid crystal polymers (LCPs), and biopolymer-based IPMCs, including cellulose and chitosan [67]. This classification reflects the variety of materials used to create the polymer matrix, each offering distinct properties such as ionic conductivity, flexibility, and biocompatibility.

Fluoropolymers are polymers that are based on fluorocarbons and contain numerous carbon–fluorine bonds. They play a crucial role in renewable energy sources [68]. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) are considered well-known fluoropolymers. Copolymerizing PVDF with hexafluoropropylene (HFP) is a common method to boost the strength of ionic polymer matrices during preparation. Ionic membranes based on PVDF have a greater ion-exchange capacity and lower elastic modulus compared to PTFE, which makes them ideal for creating very effective IPMC actuators. Nonetheless, PVDF generally exhibits strong resistance to internal ionic migration, which leads to a slower response time and diminished sensitivity as a sensor in comparison to PTFE-based IPMCs [67]. Liquid crystal polymers (LCPs) are commonly created by orienting liquid crystal mesogens in a polymer matrix. Because of the loose arrangement of these mesogens, there are nanoscale channels present in LCPs, and the introduction of ionic liquids into these channels can lead to the synthesis of ionic LCPs. The way the liquid crystals are oriented, whether planar, hybrid, or homeotropic, affects the electromechanical deformation of ionic LCPs in IPMCs. Columnar liquid crystals are frequently employed in ionic liquid crystalline polymers for ionic polymer-metal composites. It is possible to alter the properties of the matrix by efficiently creating 1D and 3D ionic channels through different self-assembly methods. Stretchable membranes composed of ionic LCPs enhance the compatibility and adaptability of IPMCs with various interfaces, thereby assisting in the advancement of high-performance IPMC sensors. Nevertheless, the majority of ionic LCP-based IPMCs are used as actuators. LCP actuators have programmable features and operate at low voltage, but they show restricted deformation [67]. Research is currently concentrating on biodegradable IPMCs within the realm of rapid advancements in zero-carbon flexible bioelectronics. Cellulose, the most plentiful natural polymer, is an ideal material for those purposes. Cellulose’s porous structure and high number of hydroxyl (-OH) groups make it a potential option for creating biodegradable IPMC actuators. Utilizing cellulose as the base for actuators is hindered by its limited conductivity. Nevertheless, it provides benefits as a biodegradable substance with a notable ion-exchange capacity (IEC) [67].

Fig. 17 illustrates the operational concept of ionic polymer–metal composites. When a voltage is applied to these IPMCs, the charged cation in the hydrated state starts to move easily towards the cathode via the polymer membrane, which acts as pathways for their motion; consequently, the cation gathers at the cathode, leading to the actuator’s expansion and bending [69–71]. In more detail, the actuation mechanism of IPMCs in the presence of an electric field likely comprises an ion cluster movement and electro-osmotic water flow that travels from the anode to the cathode through hydrophilic and ionic pathways, causing the IPMCs to bend [72]. Furthermore, the movement of the ion-water clusters within the IPMC leads to the contraction of one side while the opposite side expands. When an electric voltage is applied, the movement of charges in an IPMC membrane results in alterations in the electrostatic, osmotic, and elastic interaction forces both within and outside the clusters. This leads to localized changes in volume within the clusters, which, along with variations in water content, results in either stretching or relaxation of the polymer chains. These effects are common in generating the quick bending response of the IPMC, which is then succeeded by gradual relaxation [38]. Furthermore, the direction of back relaxation is influenced by the makeup of the backbone ionomers and the characteristics of the counter-ions. On the anode side, the decrease in cation concentration lowers the osmotic pressure within the clusters. Additionally, the rearrangement of the leftover water molecules in the clusters generally boosts the effective electric permittivity of the clusters, thereby diminishing the electrostatic repulsive forces between the fixed charges inside the clusters. Owing to the cation deficiency, a repulsive electrostatic force is generated in the clusters close to the anode. This generally raises the average size of the clusters, which in turn prompts the accumulation of water molecules on the anode side. On the cathode side of an IPMC, clusters hold surplus cations because of the voltage-induced cation flow. The elevated cation concentration decreases the effective electric permittivity of the clusters, leading to an enhancement of the electrostatic forces between cations and the stationary anions [71,73].

Figure 17: Work principle of ionic polymer–metal composites

Nafion, a brand name for a sulfonated tetrafluoroethylene-based fluoropolymer-copolymer, was created in 1962 by Dr. Donald J. Connolly at the DuPont Experimental Station in Wilmington, DE, USA [74]. It shows adequate biocompatibility, and in order to improve its biodegradability, it can be blended with eco-friendly materials, such as chitosan or vegetable cellulose [74,75]. For example, in Reference [76], the authors prepared IPMC actuators mixed with cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) to partly replace Nafion to cut production costs, improve mechanical/thermal characteristics, and increase biodegradability. The authors found that including CNF resulted in a notable improvement in the actuator’s mechanical characteristics. Furthermore, they noted that elevated levels of mild acids like phosphoric and phytic acid were found to enhance the ion conductivity of bacterial cellulose, offering the potential to increase ionic conductivity in CNF and utilize higher CNF levels in CNF-Nafion composite membranes. The authors proposed that these CNF-Nafion hybrid membranes have the potential to function as synthetic muscles and sensors and actuators in low temperatures.

In Reference [76], researchers developed an IPMC actuator based on a multilayer multiwalled carbon nanotube/Nafion macroporous membrane. The authors reported that a structured arrangement of silica spheres was used to incorporate macropores and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MCNTs) into multilayered IPMC actuators for improved performance, as shown in Fig. 18. The addition of both MCNTs and macroporous multilayered MCNTs/Nafion membranes greatly enhanced the mechanical characteristics of the membranes that were prepared. Specifically, the Young’s modulus of the macroporous multilayered MCNTs/Nafion membrane increases by a factor of 3.3 (from 262.6 to 858.1 MPa), while the hardness increases by a factor of 4.4 (from 28.2 to 123.9 MPa). Electromechanical performance of the IPMC actuator improves by 1.41 times in displacement (33.5 mm) and 2.2 times in force (19.2 mN) when operated in air with a 5 V DC voltage, compared to standard IPMC actuators (Fig. 18).

Figure 18: IPMC actuator based on multilayer multi-walled carbon nanotubes/Nafion macroporous membrane: (a) schematic representation of bending actuation; (b) photo of prepared actuators. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [76]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier

In Reference [77], a square rod-shaped IPMC based on perfluorinated sulfonic acid resin with multi-degree-of-freedom motion was prepared. According to the authors, when the actuator was subjected to an 8 V DC voltage, the highest bending angles recorded were 48.50°, 44.70°, and 43.07°, and the maximum blocking forces at the end were 116.33, 117.90, and 99.70 mN, respectively. They demonstrated that a functional interventional catheter with active guidance can be developed, and a human aortic vascular model can be constructed to conduct in vitro interventional simulation experiments (Fig. 19).

Figure 19: The human aortic vascular model. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [77]. Copyright 2020, Taylor & Francis

The authors in Reference [78] prepared a high-performance sandwich-structure low-voltage ionic electroactive actuator based on Nafion membranes and conductive PEDOT:PSS electrodes by the hot-pressing technique, which can be used as actuators in biosensor microrobots and biomedical microdevices. They reported that the prepared actuator can be used with alternating sine-wave voltages in the range of 0.25–3 V and frequencies of 0.1–0.5 Hz. The actuator showed a large bending displacement of 5.7 mm with four sets of measurements without degradation, a long-term cyclic stability of 98% up to 300 cycles at the conditions of 1.0 V and 0.1 Hz; in addition, they had a high bending strain of 0.25% with low applied voltages of 0.25 to 3 V.

In Reference [79], eco-friendly actuators driven by moisture were developed using Nafion™ membrane and polyimide tape. The researchers showed that the actuator they made performed well in terms of both bending curvature (ranging from −0.98 to 5.34 cm−1) and response speed (0.29 cm−1/s). Programmable structure design enabled the creation of various functional structures that can undergo complex deformations such as torsion and bending (Fig. 20).

Figure 20: Actuators based on commercial Nafion™ membrane and polyimide tape. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [79]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier

3 Hydrogel-Based Actuators Activated by AC Voltage as a Novel Activation Method

As mentioned in the section of “ionic polymeric gels and their actuators”, the actuation process of actuators that rely on electroactive gels is triggered by DC voltage. Nevertheless, these actuators exhibit sluggish response times for activation and restoration, as well as subpar mechanical properties, necessitating the need to uphold a consistent level of humidity [80]. Furthermore, electrolysis may occur at a specific DC voltage level, potentially causing permanent harm to the material [36,39]. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a non-toxic and biodegradable material, which makes it an eco-friendly choice for many applications. An important advantage of PVA is its ability to break down by natural processes and dissolve in water. When in contact with water and tiny organisms, PVA decomposes into safe substances, making it a greener option compared to regular plastics [81].

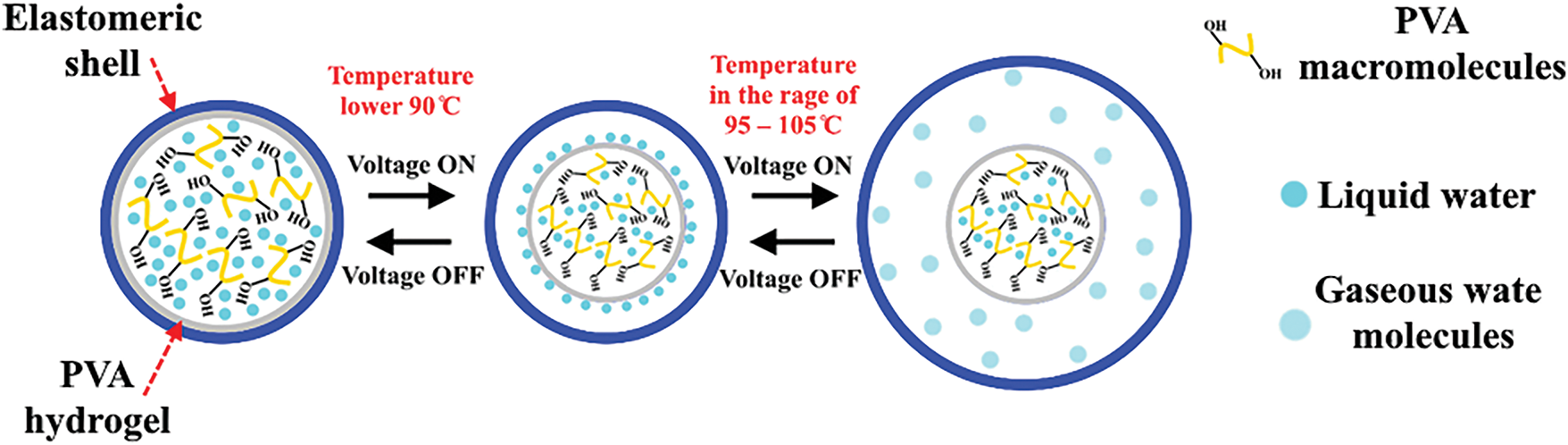

In References [82,83], a novel method for activating hydrogel actuators was suggested that involves using AC voltage in place of DC power. This mechanism operates by alternating between extension and contraction for actuating the actuator. Under AC voltage, the localized vibration of ions without movement towards the electrodes heats the hydrogel, causing water molecules to evaporate and resulting in actuator swelling. In other words, the network structure of the hydrogel is compressed by hydrogen bonds at room temperature, and when AC current is applied, the hydrogel warms up, leading to a weakening of hydrogen bonds and the elongation of twisted polymer molecular chains. When the hydrogel temperature exceeds 95°C, the actuator will expand due to the breaking of hydrogen bonds within the hydrogel network and the subsequent vaporization of water molecules. Once the voltage is turned off, the vaporized water reverts to liquid and is absorbed by the hydrogel, causing the actuator to go back to its original shape as shown in Fig. 21. The primary factor in this activation process is the Joule heating effect, as the electrolyte heats up in AC systems because of Ohmic current, which is generated by the vibration of ions in the electrolyte, even when electrodes are blocked [84,85]. Furthermore, Joule heating causes the density of the electrolyte to change, generates an AC electro-thermal flow, and leads to the boiling of the electrolyte [86,87].

Figure 21: Diagram of activation mechanism for hydrogel actuators using AC power. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [67]. Copyright 2024, MDPI

In these works [82,83], two linear actuators utilizing polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogels were developed by placing the hydrogels inside latex balloons with elastic shells and incorporating spiral weave and braided mesh fabric as external reinforcements, as shown in Fig. 22. It was reported that PVA hydrogel actuators, when exposed to an AC voltage of 200 V, a frequency of 500 Hz, and a load of ~20 kPa, can achieve over 60% extension with an activation time of ~3 s when reinforced with a spiral weave. On the other hand, actuators reinforced with fabric-woven braided mesh can achieve over 20% contraction with the same activation time of ~3 s. In addition, the activation force of the actuators based on PVA hydrogels can reach up to 297 kPa. The authors tried to decrease the required actuation voltage by adding conductive salt of lithium chloride (LiCl) to the PVA hydrogels [82], and it was discovered that at a LiCl content of 100 wt. % of PVA mass, the minimum actuation AC power required was 20 V. Moreover, the highest deformation achieved in extension mode was 52% with an activation time of approximately 2.5 s using an AC voltage of 110 V and a 50 Hz frequency when the LiCl content was 10 wt.%. On the other hand, the maximum deformation in contraction mode was 20% with an activation time of around 2.2 s by using an AC voltage of 90 V and a 50 Hz frequency when the LiCl content was 30 wt.%. These hydrogel actuators had an activation force exceeding 0.5 MPa when exposed to an AC current of 110 V.

Figure 22: (a) Actuators based on PVA hydrogel: (a) effect of AC-voltage, frequency and polymer content on overall extension/contraction and activation time of actuators; (b) types and activation forms of linear actuators based on PVA hydrogels. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [83]. Copyright 2023, MDPI

These hydrogel actuators can be used in a wide range of applications, such as soft robotics, artificial muscles, and aerospace (Fig. 23).

Figure 23: Application of linear hydrogel actuator as an artificial muscle. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [82]. Copyright 2024, MDPI

4 Renewable Polymers in Actuators

In the past two decades, there has been a growing emphasis on creating polymeric actuators using renewable polymers as a possible solution because of their eco-friendly qualities as renewable biomaterials and as sustainable alternative to metallic materials and fossil fuel-based polymers. Nevertheless, as illustrated in Table 1, cellulose-based actuators are presently regarded as the leading type of ionic EAPs, primarily utilized as ionic polymeric gels [34–36]. Additionally, cellulose may serve as a co-material in the creation of ionic polymer–metal composites to decrease actuator costs and enhance biodegradability [76]. Moreover, gelatin and collagen may be utilized as conductive polymers for the creation of renewable-based actuators [64]. Furthermore, to this day, fossil-based and biodegradable fossil-based polymers are regarded as the primary materials for all types of actuators.

This review discussed the recent research on ionic electroactive polymer-based actuators and their operational principles. These materials are currently popular in fields like soft robotics, sensors, and actuators for medical uses like artificial muscles and drug delivery. In order to use ionic EAPs derived from renewable materials in various fields like soft robotics and aerospace technology, it is important to enhance their unique characteristics such as mechanical properties, conductivity, porosity, viscosity, hydrophobicity, etc. [9,10]. Comprehension of the ionic EAP functioning principles is crucial for their application, involving enhancing the polymer structure through necessary modifications and optimizing the processing and programming technology of the ionic EAP. The key limitations for utilizing renewable materials in different applications are the necessary structural properties and achieving the specific mechanical properties required for a long-lasting application with quick cycle activation. It is important to mention that the decomposition rate of polymers utilized in actuator production is regarded as one of the most crucial factors. For instance, cellulose, as a renewable resource, breaks down in soil with microbial enzymes in a span of weeks to months [88]. In contrast, PVA, a biodegradable material derived from fossils, is challenging to decompose under natural conditions, initiating at a temperature of 240°C [89]. However, in aquatic environments, PVA can achieve up to 60% degradation in 32 days [90]. Conversely, materials derived from fossils do not decompose. For instance, fluoropolymers like Teflon require approximately 4.4 million years to degrade, and they start to decompose at around 260°C [91]. This indicates that actuators made from renewable materials offer the primary benefit to the environment.

Over the next decade, there will be an increased focus on studying new renewable polymers that can be utilized as ionic hydrogels and membranes for ionic EAPs, concerning the necessary structural, physical, and mechanical properties, as well as in terms of lowering material costs. A key focus for the next generation of actuators is bioinspired soft robotics, which can be utilized in scenarios where rigid-body robots are ineffective, particularly in biomedical fields, surgical procedures, drug delivery systems, aerospace tools, crop harvesting in agriculture, underwater exploration, and interactive wearables. Nevertheless, the primary constraint that necessitates further research soon is the flexibility and continuous nature of soft robots, which in turn demands enhancements in their modeling and control. To advance toward soft robots lacking rigid parts, it is crucial to explore innovative renewable materials, as integrating sensors, power systems, or control circuits might present challenges. Renewable energy sources like solar, wind, vibrations, and microbial fuel cells can be utilized to energize soft robots. A move toward a more environmentally sustainable approach will occur by integrating biodegradable materials with renewable energy sources. The possibility of preserving and reapplying these actuators is seen as another major challenge. As actuators can be reused several times, using renewable materials for their production could offer a practical and cost-effective solution to this problem. This will facilitate the creation of tech products that use less energy and have more straightforward recycling initiatives. Achieving this, however, will require extensive research focused on closing the gap to high-performance solutions or providing entirely new opportunities, with robotics acting as the main driver of continuous technological advancement.

Acknowledgement: Our sincere gratitude goes out to Ms. Crystal Feng, Managing Editor of the Journal of Renewable Materials, for providing us with the opportunity to publish our work.

Funding Statement: The research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), grant No. 24-23-00558, https://rscf.ru/en/project/24-23-00558/ (accessed on 04 February 2025).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tarek Dayyoub, Aleksey Maksimkin; data collection: Emil Askerov, Ksenia V. Filippova, Lidiia D. Iudina, Elizaveta Iushina; analysis and interpretation of results: Tarek Dayyoub, Mikhail Zadorozhnyy, Dmitriy G. Ladokhin, Dmitry V. Telyshev; draft manuscript preparation: Tarek Dayyoub. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ozsecen MY, Mavroidis C. Nonlinear force control of dielectric electroactive polymer actuators. Electroactive Polym Actuators Devices (EAPAD). 2010;7642:76422C. doi:10.1117/12.847240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Brighenti R, Li Y, Vernerey FJ. Smart polymers for advanced applications: a mechanical perspective review. Front Mater. 2020;7:196. doi:10.3389/fmats.2020.00196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Naseri M, Fotouhi L, Ehsani A. Recent progress in the development of conducting polymer-based nanocomposites for electrochemical biosensors applications: a mini-review. The Chemical Record. 2018;18(6):599–618. doi:10.1002/tcr.201700101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Omer AM. Energy, environment and sustainable development. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2008;12(9):2265–300. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2007.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chu S, Majumdar A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature. 2012;488:294–303. doi:10.1038/nature11475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yamaguchi S, Tanha M, Hult A, Okuda T, Ohara H, Kobayashi S. Green polymer chemistry: lipase-catalyzed synthesis of bio-based reactive polyesters employing itaconic anhydride as a renewable monomer. Polym J. 2014;46:2–13. doi:10.1038/pj.2013.62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Satoh K. Controlled/living polymerization of renewable vinyl monomers into bio-based polymers. Polym J. 2015;47(8):527–36. doi:10.1038/pj.2015.31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rosenboom JG, Langer R, Traverso G. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat Rev Mater. 2022;7(2):117–37. doi:10.1038/s41578-021-00407-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Pellis A, Malinconico M, Guarneri A, Gardossi L. Renewable polymers and plastics: performance beyond the green. New Biotechnol. 2021;60(11):146–58. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2020.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ali SS, Abdelkarim EA, Elsamahy T, Al-Tohamy R, Li F, Kornaros M, et al. Bioplastic production in terms of life cycle assessment: a state-of-the-art review. Environ Sci Ecotech. 2023;15:100254. doi:10.1016/j.ese.2023.100254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017;3(7):1700782. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Biopolymers Market Report 2024. The Business Research Company. 2024 Nov [cited 2024 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/6027116/biopolymers-market-report#rela0-5935393. [Google Scholar]

13. Global Biopolymers Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By End-useBy Application, By Product (Biodegradable Polyesters, Bio-PE, Bio-PET, Polylactic Acid (PLAPolyhydroxyalkanoate (PHAand OthersBy Regional Outlook and Forecast, 2023–2030. KBV research. Report ID: KBV-19744. 2024 Jan [cited 2024 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.kbvresearch.com/biopolymers-market/. [Google Scholar]

14. Luo T, Hu Y, Zhang M, Jia P, Zhou Y. Recent advances of sustainable and recyclable polymer materials from renewable resources. Resour Chem Mater. 2024;7(2):83. doi:10.1016/j.recm.2024.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jumet B, Bell MD, Sanchez V, Preston DJ. A data-driven review of soft robotics. Adv Intell Syst. 2022;4(4):2100163. doi:10.1002/aisy.202100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dzedzickis A, Subačiūtė-Žemaitienė J, Šutinys E, Samukaitė-Bubnienė U, Bučinskas V. Advanced applications of industrial robotics: new trends and possibilities. Appl Sci. 2022;12(1):135. doi:10.3390/app12010135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cacucciolo V, Shea H, Carbone G. Peeling in electroadhesion soft grippers. Extreme Mech Lett. 2022;50(2):101529. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2021.101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Junge K, Hughes J. Soft sensorized physical twin for harvesting raspberries. In: 2022 IEEE 5th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft); 2022 Apr 4–8; Edinburgh, UK. p. 601–6. doi:10.1109/RoboSoft54090.2022.9762135 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Aracri S, Giorgio-Serchi F, Suaria G, Sayed ME, Nemitz MP, Mahon S, et al. Soft robots for ocean exploration and offshore operations: a perspective. Soft Robot. 2021;8(6):625–39. doi:10.1089/soro.2020.0011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Luo M, Wan Z, Sun Y, Skorina EH, Tao W, Chen F, et al. Motion planning and iterative learning control of a modular soft robotic snake. Front Robot AI. 2020;7:599242. doi:10.3389/frobt.2020.599242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Laschi C, Mazzolai B. Bioinspired materials and approaches for soft robotics. MRS Bull. 2021;46(4):345–9. doi:10.1557/s43577-021-00075-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lin Z, Shao Q, Liu X-J, Zhao H. An anthropomorphic musculoskeletal system with soft joint and multifilament pneumatic artificial muscles. Adv Intell Syst. 2022;4(10):2200126. doi:10.1002/aisy.202200126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Giordano G, Murali Babu SP, Mazzolai B. Soft robotics towards sustainable development goals and climate actions. Front Robot AI. 2022;10:1116005. doi:10.3389/frobt.2023.1116005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Trivedi D, Rahn CD, Kier WM, Walker ID. Soft robotics: biological inspiration, state of the art, and future research. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2008;5(3):99–117. doi:10.1080/11762320802557865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rothemund P, Kim Y, Heisser RH, Zhao X, Shepherd RF, Keplinger C. Shaping the future of robotics through materials innovation. Nat Mater. 2021;20(12):1582–7. doi:10.1038/s41563-021-01158-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li M, Pal A, Aghakhani A, Pena-Francesch A, Sitti M. Soft actuators for real-world applications. Nat Rev Mater. 2022;7(3):235–49. doi:10.1038/s41578-021-00389-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rumley EH, Preninger D, Shomron AS, Rothemund P, Baumgartner M, Kellaris N, et al. Biodegradable electrohydraulic actuators for sustainable soft robots. Sci Adv. 2023;9(12):eadf5551. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf5551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li Y, Fu C, Huang L, Chen L, Ni Y, Zheng Q. Cellulose-based multi-responsive soft robots for programmable smart devices. Chem Eng J. 2024;498(6299):155099. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.155099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kumar V, Siraj SA, Satapathy DK. Multivapor-responsive controlled actuation of starch-based soft actuators. ACS Appl Mater & Interfaces. 2024;16(3):3966–77. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c15065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yang L, Miao J, Li G, Ren Y, Zhang T, Guo D, et al. Soft tunable gelatin robot with insect-like claw for grasping, transportation, and delivery. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2022;4(8):5431–40. doi:10.1021/acsapm.2c00522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rahman MH, Werth H, Goldman A, Hida Y, Diesner C, Lane L, et al. Recent progress on electroactive polymers: synthesis, properties and applications. Ceramics. 2021;4:516–41. doi:10.3390/ceramics4030038;. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cardoso VF, Ribeiro C, Lanceros-Mendez S. Metamorphic biomaterials. Bioinspired Mater Med Appl. 2017;126:69–99. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100741-9.00003-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ohm C, Brehmer M, Zentel R. Liquid crystalline elastomers as actuators and sensors. Adv Mater Deerfield. 2010;22(31):3366–87. doi:10.1002/adma.200904059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Sappati K, Bhadra S. Piezoelectric polymer and paper substrates: a review. Sensors. 2018;18(11):3605. doi:10.3390/s18113605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Nelson J. Polymer: fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. Mater Today. 2011;14(10):462–70. doi:10.1016/S1369-7021(11)70210-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Liu Y, Lu C, Twigg S, Lin J-H, Hatipoglu G, Liu S, et al. Ion distribution in ionic electroactive polymer actuators. In: Proceedings of the Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD); 2011. Vol. 7976. doi:10.1117/12.880528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Biddiss E, Chau T. Electroactive polymeric sensors in hand prostheses: bending response of an ionic polymer metal composite. Med Eng Phys. 2006;28(6):568–78. doi:10.1016/j.medengphy.2005.09.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Jo C, Pugal D, Oh I-K, Kim KJ, Asaka K. Recent advances in ionic polymer-metal composite actuators and their modeling and applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38(7):1037–66. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Dakova I, Karadjova I. Ionic liquid modified polymer gel for arsenic speciation. Molecules. 2024;29(4):898. doi:10.3390/molecules29040898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Cao H, Duan L, Zhang Y, Cao J, Zhang K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 16;6(1):426. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00830-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wang H, Wang Z, Yang J, Xu C, Zhang Q, Peng Z. Ionic gels and their applications in stretchable electronics. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2018;39(16):e1800246. doi:10.1002/marc.201800246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zöller K, To D, Bernkop-Schnürch A. Biomedical applications of functional hydrogels: innovative developments, relevant clinical trials and advanced products. Biomaterials. 2025;312(30):122718. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hong Y, Lin Z, Yang Y, Jiang T, Shang J, Luo Z. Flexible actuator based on conductive PAM hydrogel electrodes with enhanced water retention capacity and conductivity. Micromachines. 2022;13(11):1951. doi:10.3390/mi13111951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Kundu R, Mahada P, Chhirang B, Das B. Cellulose hydrogels: green and sustainable soft biomaterials. Curr Res Green Sustain Chem. 2022;5(1):100252. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Athar S, Bushra R, Arfin T. Cellulose nanocrystals and PEO/PET hydrogel material in biotechnology and biomedicine: current status and future prospects. In: Jawaid M, Mohammad F, editors. Nanocellulose and nanohydrogel matrices: biotechnological and biomedical applications. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2017. doi:10.1002/9783527803835.ch7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Terasawa N. High-performance TEMPO-oxidised cellulose nanofibre/PEDOT: PSS/ionic liquid gel actuators. Sens Actuat B: Chem. 2021;343(1–6):130105. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2021.130105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang F, Huang D, Li Q, Wu Y, Yan B, Wu Z, et al. Highly electro-responsive ionic soft actuator based on graphene nanoplatelets-mediated functional carboxylated cellulose nanofibers. Compos Sci Technol. 2023;231(1):109845. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Héraly F, Pang B, Yuan J. Cationic cellulose Nanofibrils-based electro-actuators: the effects of counteranion and electrolyte. Sens Actuators Rep. 2023;5:100142. doi:10.1016/j.snr.2023.100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Reid L, Hamad WY. Electro-osmotic actuators from cellulose nanocrystals and nanocomposite hydrogels. CS Appl Polym Mater. 2022;4(1):598–606. doi:10.1021/acsapm.1c01530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Eslami H, Ansari M, Darvishi A, Pisheh HR, Shami M, Kazemi F. Polyacrylic acid: a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer for controlled drug delivery. Polym Sci Ser A. 2023;65(6):702–13. doi:10.1134/S0965545X2460011X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Abel SB, Frontera E, Acevedo D, Barbero CA. Functionalization of conductive polymers through covalent postmodification. Polymers. 2022;15(1):205. doi:10.3390/polym15010205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Huo B, Guo CY. Advances in thermoelectric composites consisting of conductive polymers and fillers with different architectures. Molecules. 2022;27(20):6932. doi:10.3390/molecules27206932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Paramshetti S, Angolkar M, Al Fatease A, Alshahrani SM, Hani U, Garg A, et al. Revolutionizing drug delivery and therapeutics: the biomedical applications of conductive polymers and composites-based systems. Pharmaceutics. 2023;1 5(4):1204. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15041204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Liu C, Li Y, Zhuang J, Xiang Z, Jiang W, He S, et al. Conductive hydrogels based on industrial lignin: opportunities and challenges. Polymers. 2022;14(18):3739. doi:10.3390/polym14183739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Barbero CA. Functional materials made by combining hydrogels (cross-linked polyacrylamides) and conducting polymers (polyanilines)—a critical review. Polymers. 2023;15(10):2240. doi:10.3390/polym15102240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Hasan N, Bhuyan MM, Jeong JH. Single/multi-network conductive hydrogels—a review. Polymers. 2024;16(14):2030. doi:10.3390/polym16142030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Nada AA, Eckstein Andicsová A, Mosnáček J. Irreversible and self-healing electrically conductive hydrogels made of bio-based polymers. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):842. doi:10.3390/ijms23020842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wang S, Zhang J, Gharbi O, Vivier V, Gao M, Orazem ME. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1(1):41. doi:10.1038/s43586-021-00039-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Liu C, Yoshio M. Ionic liquid crystal-polymer composite electromechanical actuators: design of two-dimensional molecular assemblies for efficient ion transport and effect of electrodes on actuator performance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(21):27750–60. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c03821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Nazrin A, Kuan TM, Mansour DA, Farade RA, Ariffin AM, Rahman MSA, et al. Innovative approaches for augmenting dielectric properties in cross-linked polyethylene (XLPEa review. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e34737. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Chakraborty D, Chattaraj PK. Conceptual density functional theory based electronic structure principles. Chem Sci. 2021;12(18):6264–79. doi:10.1039/D0SC07017C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Xu J, Hu H, Zhang S, Cheng G, Ding J. Flexible actuators based on conductive polymer ionogels and their electromechanical modeling. Polymers. 2023;15(23):4482. doi:10.3390/polym15234482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Salinas G, Malacarne F, Bonetti G, Cirilli R, Benincori T, Arnaboldi S, et al. Wireless electromechanical enantio-responsive valves. Chirality. 2023;35(2):110–7. doi:10.1002/chir.23521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Ha JH, Lim JH, Kim JW, Cho H-Y, Jo SG, Lee SH, et al. Conductive GelMA–collagen–AgNW blended hydrogel for smart actuator. Polymers. 2021;13(8):1217. doi:10.3390/polym13081217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ebadi SV, Fashandi H, Semnani D, Rezaei B, Fakhrali A. Electroactive actuator based on polyurethane nanofibers coated with polypyrrole through electrochemical polymerization: a competent method for developing artificial muscles. Smart Mater Struct. 2020;29(4):045008. doi:10.1088/1361-665X/ab73e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Lu C, Zhang X. Ionic polymer-metal composites: from material engineering to flexible applications. Acc Chem Res. 2024;57(1):131–9. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.3c00591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Tang G, Zhao X, Mei D, Zhao C, Wang Y. Perspective on the development and application of ionic polymer metal composites: from actuators to multifunctional sensors. RSC Appl Polym. 2024;2(5):795. doi:10.1039/D4LP00084F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Peer K. Modern fluoroorganic chemistry: synthesis, reactivity, applications. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. p. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

69. Osada Y, Hasebe M. Electrically activated mechanochemical devices using polyelectrolyte gels. Chem Lett. 1985;9(9):1285–8. doi:10.1246/cl.1985.1285 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Zhao D, Ru J, Wang T, Wang Y, Chang L. Performance enhancement of ionic polymer-metal composite actuators with polyethylene oxide. Polymers. 2022;14(1):80. doi:10.3390/polym14010080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Yang L, Wang H. High-performance electrically responsive artificial muscle materials for soft robot actuation. Acta Biomater. 2024;185:24–40. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2024.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Lee JH, Lee JH, Nam JD, Choi H, Jung K, Jeon JW, et al. Water uptake and migration effects of electroactive ion-exchange polymer metal composite (IPMC) actuator. Sens Actuators A. 2005;118(1):98–106. doi:10.1016/j.sna.2004.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Nemat-Nasser S, Wu Y. Comparative experimental study of ionic polymer-metal composites with different backbone ionomers and in various cation forms. J Appl Phys. 2003;93:5255–67. doi:10.1063/1.1563300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Kusoglu A, Weber AZ. New insights into perfluorinated sulfonic-acid ionomers. Chem Rev. 2017;117(3):987–1104. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Noonan C, Tajvidi M, Tayeb AH, Shahinpoor M, Tabatabaie SE. Structure-property relationships in hybrid cellulose nanofibrils/nafion-based ionic polymer-metal composites. Materials. 2019;12(8):1269. doi:10.3390/ma12081269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Zhang X, Yu S, Li M, Zhang M, Zhang C, Wang M. Enhanced performance of IPMC actuator based on macroporous multilayer MCNTs/Nafion polymer. Sens Actuators A: Phys. 2022;339:113489. doi:10.1016/j.sna.2022.113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. He Q, Huo K, Xu X, Yue Y, Yin G, Yu M. The square rod-shaped ionic polymer-metal composite and its application in interventional surgical guide device. Int J Smart Nano Mater. 2020;11(2):159–72. doi:10.1080/19475411.2020.1783020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Wu Y, Xia H, Wang F. High-performance hot-pressed ionic soft actuator based on ultrathin self-standing PEDOT: PSS electrodes and Nafion membrane. MRS Commun. 2023;13(6):1441–8. doi:10.1557/s43579-023-00486-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Tang G, Zhao C, Zhao X, Mei D, Pan Y, Li B, et al. Nafion/polyimide based programmable moisture-driven actuators for functional structures and robots. Sens Actuators B: Chem. 2023;393(16):134152. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2023.134152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Maksimkin AV, Dayyoub T, Telyshev DV, Gerasimenko AY. Electroactive polymer-based composites for artificial muscle-like actuators: a review. Nanomater. 2022;12(13):2272. doi:10.3390/nano12132272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Ghosh P, Roy S, Banik A. Usage of microbes for the degradation of paint contaminated soil and water. In: Microbes and microbial biotechnology for green remediation. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Inc.; 2022. p. 601–17. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90452-0.00041-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Dayyoub T, Zadorozhnyy M, Filippova KV, Iudina LD, Telyshev DV, Zhemchugov PV, et al. Linear actuators based on polyvinyl alcohol/lithium chloride hydrogels activated by low AC voltage. Journal of Composites Science. 2024;8(8):323. doi:10.3390/jcs8080323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Dayyoub T, Maksimkin A, Larionov DI, Filippova OV, Telyshev DV, Gerasimenko AY. Preparation of linear actuators based on polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels activated by AC voltage. Polymers. 2023;15(12):2739. doi:10.3390/polym15122739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Han ZJ, Morrow R, Tay BK, McKenzie D. Time-dependent electrical double layer with blocking electrode. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;94(4):043118. doi:10.1063/1.3077605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Hossain R, Adamiak K. Dynamic properties of the electric double layer in electrolytes. J Electrost. 2013;71(5):829–38. doi:10.1016/j.elstat.2013.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Hong F, Cao J, Cheng P. A parametric study of AC electrothermal flow in microchannels with asymmetrical interdigitated electrodes. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2011;38(3):275–9. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2010.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Lian M, Wu J. Microfluidic flow reversal at low frequency by AC electrothermal effect. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2009;7(6):757–65. doi:10.1007/s10404-009-0433-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Chmolowska D, Hamda N, Laskowski R. Cellulose decomposed faster in fallow soil than in meadow soil due to a shorter lag time. J Soils Sediments. 2017;17(2):299–305. doi:10.1007/s11368-016-1536-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Yang H, Xu S, Jiang L, Dan Y. Thermal decomposition behavior of poly (vinyl alcohol) with different hydroxyl content. J Macromol Sci Part B Phy. 2012;51(3):464–80. doi:10.1080/00222348.2011.597687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Alonso-López O, López-Ibáñez S, Beiras R. Assessment of toxicity and biodegradability of poly(vinyl alcohol)-based materials in marine water. Polymers. 2021;13(21):3742. doi:10.3390/polym13213742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Gehrmann H, Taylor P, Aleksandrov K, Bergdolt P, Bologa A, Blye D, et al. Mineralization of fluoropolymers from combustion in a pilot plant under representative european municipal and hazardous waste combustor conditions. Chemosphere. 2024;365:143403. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools