Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Long-Term Synergistic Antimicrobial Tannic Acid-Silver Nanoparticles Coating

1 Institute of Chemistry, Far East Department, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, 690022, Russia

2 Institute of High Technologies and Advanced Materials, Far-Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, 690922, Russia

3 G. B. Elyakov Pacific Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, Far East Department, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, 690022, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Yury Shchipunov. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1293-1313. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0032

Received 08 November 2024; Accepted 15 January 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

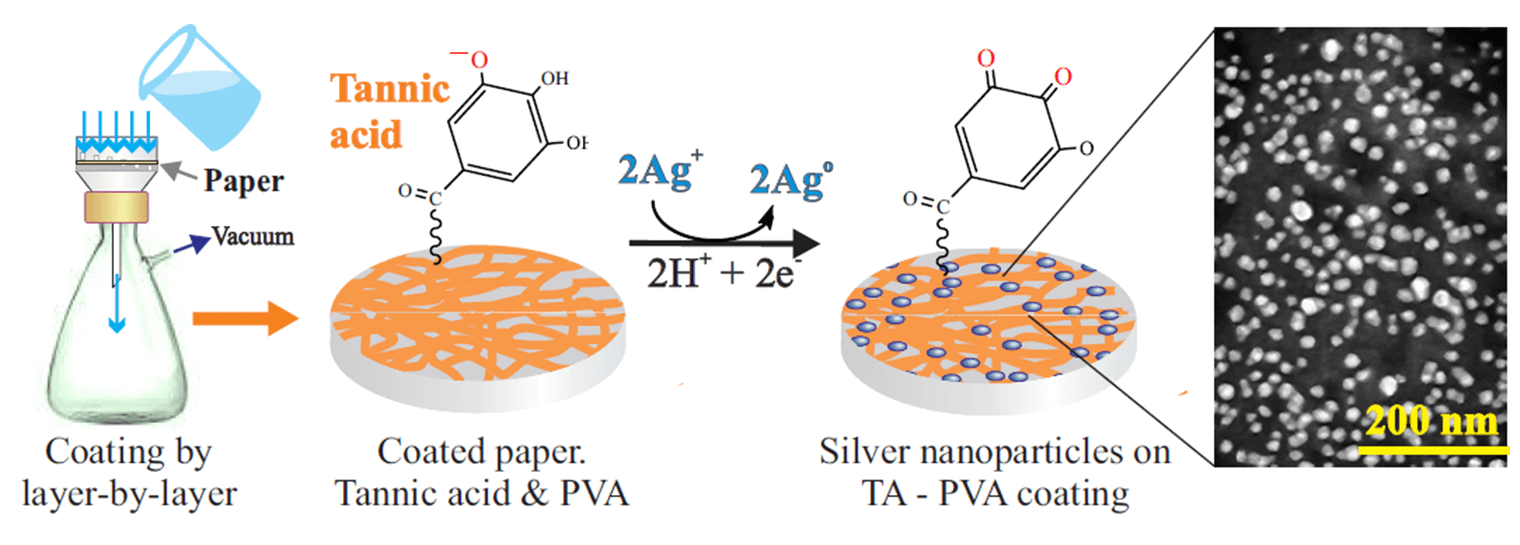

The main objective of the study was to prepare a highly active antimicrobial remedy by combining active agents such as tannic acid and silver nanoparticles, which are usually used separately. This was achieved by applying a coating of 11 alternating layers of an insoluble complex of tannic acid with polyvinyl alcohol on paper by the layer-by-layer approach, on the surface of which uniformly distributed spherical silver nanoparticles of uniform size, mainly 20–30 nm, were synthesized by in situ reduction using tannic acid, which also acts as a stabilizer, or an external reducing agent, which prevented polyphenol oxidation. This gave an insight into which form-oxidized or reduced-is more active against microorganisms. It was shown that sterilization was not required after the coating of the paper with tannic acid and silver nanoparticles. When combined, their activity against the studied bacteria-gram-negative Escherichia coli and gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, as well as yeast Candida albicans was higher and lasting up to 7 days than when tannic acid and silver nanoparticles were used separately, indicating possible synergism in their action.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The main antimicrobial drugs in medical practice are antibiotics, which after the beginning of industrial production began to be widely used since the 40s of the last century [1], practically displacing traditional remedies used for centuries [2,3]. As they were used, more and more factual evidence emerged indicating that microorganisms adapt to them after some time, bringing into existence multidrug-resistant bacterial strains [4–7]. As a result of antimicrobial resistance, the number of deaths is growing, the increase in which by 2050 may reach 10 million [4]. The constant decrease in the effectiveness of the drugs employed as they are used forces researchers to seek new types of remedies to prevent and improve the treatment of bacterial infections, which turns into a race without a visible successful outcome [1,4,6].

Nowadays, there is a strong trend towards antimicrobial agents that were widely used before the antibiotic era. These include silver and polyphenols.

The antiseptic and biocidal properties of silver have been known since ancient times [8,9], as indicated by one of the first documented sources from 702–705 [10]. It was used in the form of salts, as shown in an appropriate historical review [8], but a survey of the literature was performed in Ref. [11] revealed that silver began to be used in nanosized form as early as 130 years ago in the form of preparations such as Collargol and Colloidal Silver, which are still being produced today [9,12]. They have become quite widespread in medical practice along with AgNO3 [13] after the development of a synthesis procedure proposed in 1889 [14]. It included Ag nanoparticles, which will be further designated as AgNPs, ranging in size from 3.7 to 4.5 nm [15]. Currently, antimicrobial agents based on nanosized Ag are preferred because of their greater activity than silver salts [16,17]. Moreover, the effect increases as the size of the nanoparticles decreases [18,19].

An important advantage of silver, which distinguishes it from antibiotics, is the lack of adaptation of microorganisms to Ag [9,20,21]. This is evidenced by its constant use over centuries. In addition, silver agents are characterized by a wide spectrum of action against some 650 different pathogens, demonstrating bacteriostatic, antifungal, antiviral, anticancer and antiinflammatory activities [22–24], while antibiotics have a very limited spectrum. To extend the range of action, it is necessary to combine at least 3 antibiotics, but the effectiveness comparable to silver is not always achieved [25]. Moreover, it decreases over time due to the adaptation of microorganisms. The difference is explained by the fact that silver does not act by one mechanism, like antibiotics, but by several simultaneously [23,26,27]. The multiple effects do not allow pathogens to adapt to silver [21,24]. It is also important that AgNPs do not suppress the immune system, whereas antibiotics do, and they also cause allergic reactions [4,6,28].

The antimicrobial action of AgNPs is caused by partial dissolution. Owing to the huge surface area, the concentration of silver ions quickly reaches the level of 50–100 ppm, remaining nearly constant for 3 to 9 days [3,23,25,29]. Silver salts allow for a higher concentration of highly active Ag+ cations, but as a result of their binding with Cl− anions, leading to the formation of an insoluble precipitate, it quickly drops to trace amounts after a couple of hours [3]. This requires frequent changes of dressings [25]. The long-term action of AgNPs is associated with the dissolution of silver in the elemental form of Ag°, in which an insoluble compound with chlorine anions is not formed [3]. Although the solubility, according to estimates made in [30], is less than 0.5%, the level of dissolved Ag is maintained over a long period of time, which determines the long-term antimicrobial action of AgNPs [29].

A number of studies have mentioned that the activity of AgNPs against pathogens is caused not only by the ionic form formed by partial dissolution, but is supplemented by their direct contact with microbial cells [16,17,31]. A possible action may consist of pitting the cell membrane and its subsequent destruction, which leads to cytoplasm leakage and cell death [17,23].

Among natural antimicrobial organic compounds that exhibit pronounced activity against a wide variety of pathogens, polyphenols stand out [32–34]. They were used by the ancient Egyptians and Greeks of the archaic period (ca. 800–500 BC) to prevent the rotting of leather and its tanning, in traditional Chinese medicine to control infections, and in herbal medicine in Europe to treat wounds and suppress inflammatory processes [34–37]. A distinctive chemical feature of this class of numerous chemically diverse compounds is the presence of a varying number of phenolic groups in the form of dihydroxyphenyl and trihydroxphenyl, represented by catechol and gallic acid residues [37–39]. They demonstrate various types of biological activity, which is directly related to their biological function in the plant kingdom. Plants produce secondary metabolites to protect themselves from attacks by bacteria, fungi, viruses and insects, as well as protect against UV radiation and oxidants, an important component of which are polyphenols [40]. The development of a protective response to them in microorganisms is not observed, which is explained by a set of different mechanisms of antimicrobial action [33,37,38].

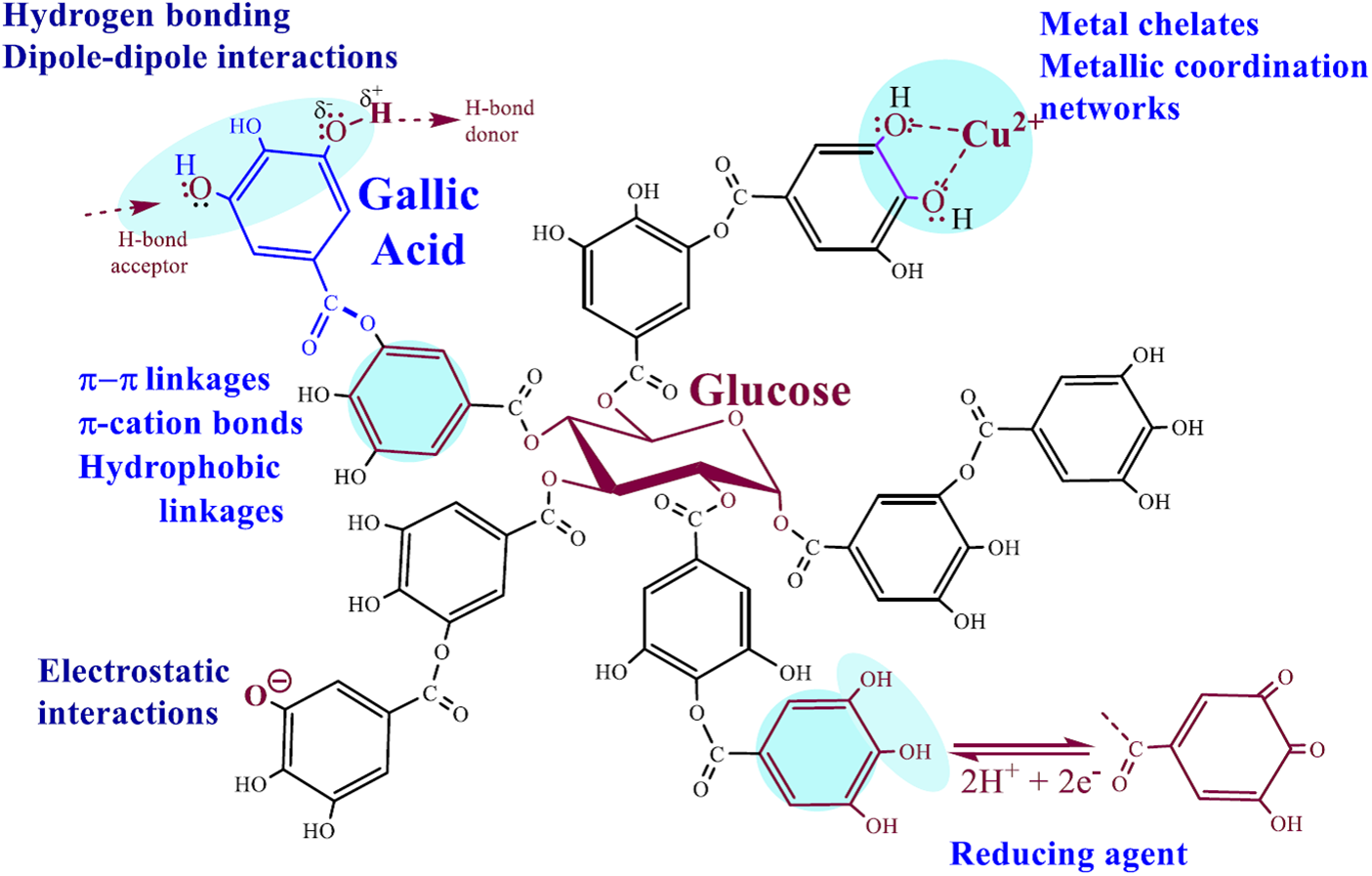

One of the best known and commercially available polyphenols is tannic acid (TA), which is isolated efficiently from a variety of readily available herbaceous and woody plants [36,41–43]. Among its advantages, which have been known since antiquity [44], is the combination of a wide range of biological activity with a unique set of various physicochemical properties. TA exhibits antimicrobial, antiviral, antiinflammatory, antihelminthic, antitumor, antimutagenic, antioxidant and homeostatic effects [42,45–48]. It is an ester of glucose and gallic acids, which are attached in pairs to all five hydroxyl groups of the sugar (Fig. 1). The residue of the latter is in the center of the macromolecule, and on its periphery, there are numerous hydroxyl groups, since each residue of gallic acid contains three hydroxyls. Due to its unique structure, TA is well soluble in water and, as shown schematically in Fig. 1, is capable of entering into electrostatic interactions, forming hydrogen and π-π bonds, acting as a chelating agent with respect to metal cations, exhibiting hydrophobic properties and serving as a reducing and cross-linking agent [26,38,49,50]. This allows much room for the chemical engineering of various functional materials for emergency technology and biomedicine [34,47,51–53].

Figure 1: The chemical formula of commercial TA is considered to be C76H52O46, which includes a glucose residue and 10 gallic acid residues attached to all OH groups of the sugar. The bonds and interactions in which the phenolic groups participate and which determine the reactivity, the formation of complexes with substances of different nature and the biological activity of TA are shown schematically

Participation of TA in almost all types of physical interactions with the formation of non-covalent bonds-electrostatic, hydrogen, ionic, π-π and coordination-leads to the association and complexation with organic and inorganic compounds, with hydrophilic and hydrophobic polymers and biopolymers, adsorption on the surface of materials of different polarity. Polyphenol has been used for centuries for leather tanning, which is based on the formation of hydrogen bonds between TA hydroxyls, acting as H-bond donors (Fig. 1), with H-bond accepting amino groups and carbonyl groups of protein peptide bonds, as well as hydrophobic binding to hydrophobic cores of proteins [32,36,44,53,54]. Stable complexes are formed with the amine-containing polysaccharide chitosan and its mixtures with collagen [42,47,55–57]. A well-known example is hydrogels and films with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), the association with which occurs due to hydrogen bonds with numerous hydroxyl groups in the polymer macromolecule [41,58–60]. In the case of poly(ethylene glycol), polyvinylpyrrolidone and poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate), gelation of solutions was noted only after the addition of iron salt. Coordinate bonds (Fig. 1) with Fe3+ cations complemented the binding of TA to polymers through H-bonds [61].

Complexes of TA with cellulose are of considerable interest. Polyphenol is traditionally used as a mordant in the dyeing of cotton with basic dyes, which it binds while in an adsorbed state on the surface of the fibers due to hydrogen bonds with the OH groups of the polysaccharide [62,63]. This was the basis of a hydrogel of hydroxyethyl cellulose with polyacrylic acid that was used as an adsorbent for methylene blue. TA has been employed by many authors for the sorption of dyes, as well as heavy metals [64–67]. In this case, cellulose is taken in both traditional fibrous and nanosized forms [41,47,64,67,68].

Among the various properties of TA, the reduction of noble metal salts to the metallic state is of particular practical utility (Fig. 1) [46,50–52,69]. One of the first articles devoted to the preparation of silver was published by Lea in 1891 [70]. He described the formation of apparently nanosized silver, called allotropic, which after the reduction of silver nitrate remained in the solution, coloring it, but did not precipitate. This indicated the stabilizing effect of polyphenol, preventing the aggregation of nanoparticles. Currently, TA as a reducing and stabilizing agent has been used by many research groups to obtain hybrid structures with AgNPs [41,52,71–73].

Silver reduction using TA is related to green chemistry methods, since polyphenol is a natural substance without pronounced toxicity [37,42,47,48,74]. It was shown in Ref. [75] that the complex of TA with AgNPs is also not toxic, but their combination allows for obtaining highly effective bactericidal agents. Most authors associated the antimicrobial activity of the polyphenol-nanosized silver complex with the AgNPs [66,73,76–78]. In some studies, such as [79], it was noted that both TA and AgNPs had an effect on microorganisms. An assumption was made about possible synergism in their antimicrobial action [80,81], which, however, requires additional confirmation.

The aim of this article is to create a highly active antimicrobial coating on paper by combining TA with silver nanoparticles, which are usually used separately, and to perform a thorough study of their properties and structure by means of various methods. To achieve this, a layer-by-layer method is used for the first time to form an insoluble film of alternating layers of polyphenol and PVA, on the surface of which silver nanoparticles are synthesized in situ. It is shown that the combination of TA with Ag NPs leads to synergism in antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and yeast for 6–7 days. The proposed approach is universal and can be used to form an antimicrobial coating on various cellulose materials for biomedical purposes.

TA, PVA and silver nitrate (99.9%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, 2 M sodium borohydride solution in triethyleneglycol dimethyl ether was purchased from Acros. Hydrazine was of chemical pure grade (Reakhim, Russia). General purpose filter paper (Russia) served as a cellulose base for the antimicrobial coating. Deionized water obtained from Rios-Di Clinical water purification system (Millipore) was applied to prepare aqueous solutions with pH between 5.6 and 6.5.

For microbiological studies, typical strains of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli VKPM B-7335, gram-positive-Staphylococcus aureus subsp. Aureus VKPM B-6646, as well as yeast Candida albicans KMM 455 from the Collection of Marine Microorganism Cultures of the Pacific G. B. Elyakov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, Far East Department of the Russian Academy of Sciences were taken.

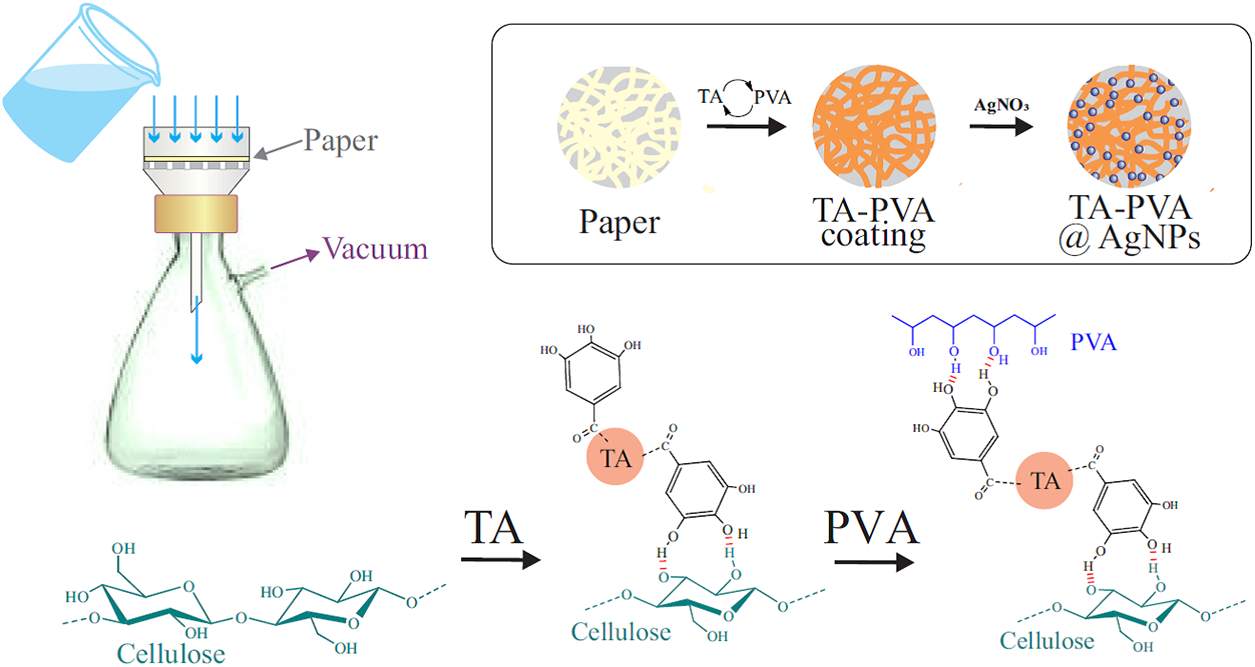

Layer-by-layer technique was applied for coating the paper using a filtration setup including a plastic Buchner funnel, a glass Bunsen flask and a laboratory vacuum station (Fig. 2). Filter paper was placed on the perforated bottom of a 50 mm diameter funnel, moistened with a small amount of water and then soaked with ~3.5 mL of a 1 wt.% tannic acid solution, evenly distributed over the surface. The excess was carefully removed by suction under vacuum. The initial coating was not washed. A solution with 1 wt.% PVA was used to obtain the second layer. Approximately 3.5 mL of the solution was applied to the TA-coated filter paper and then a vacuum was turned on to remove its excess. When the first drops flowed into the Bunsen flask with the previously filtered TA solution, a suspension was immediately formed, indicating the formation of an insoluble polyphenol complex with PVA. Vacuuming continued until the filter appeared dry. After the vacuum was turned off, the filter was completely wetted with water, after which, continuing to add H2O, the vacuum station was turned on again. About 5 mL of water was used for washing. The third layer was applied by passing a TA solution. As in the previous case, the vacuum was turned off, ~3.5 mL of TA solution was evenly distributed over the paper surface, the station was turned on and at least 5 mL of water was passed through at the final stage. In this way, a coating of 11 layers was formed, consisting of alternating TA and PVA. The final layer was represented by polyphenol.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the formation of a multilayered coating of alternating layers of TA and PVA on a cellulose base (paper)

The filter with the applied TA-PVA coating was kept in a silver nitrate solution for 30 min. It was taken out and after the solution drained, it was transferred to a Buchner funnel for washing. For this, a small amount of water was added, a vacuum was turned on and up to 5 mL of H2O was passed through. The concentrations of AgNO3 in the preliminary experiment were 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1 mM. After the synthesis of metallic silver, it was found that a rather uniform coating with reproducible properties was formed from a solution with a concentration of 1 mM AgNO3. Hereafter, only this solution was used for the synthesis of AgNPs.

Silver reduction was performed by:

- TA, located in the coating. The filter was placed in a drying cabinet with a temperature of 70°C for 60 min.

- Sodium borohydride or hydrazine. The concentration of the reducing agent was taken equal to 4 mM in accordance with the previous study [82]. NaBH4 is a highly active reducing agent. The process proceeded at a high rate and was poorly controlled. Therefore, it was later abandoned in favor of hydrazine.

To identify the reduced or oxidized TA exhibits greater activity against microorganisms, coated filters that do not contain silver were treated with hydrazine or kept at 70°C for 60 min. In the first case, the polyphenol was completely converted to the reduced form, in the second, to the oxidized form.

As the control samples, the non-treated filter paper and the paper impregnated with 1 mM AgNO3 solution were used. In the latter case, no washing was performed after the impregnation. In addition, samples were prepared for the study by single impregnation in the TA solution, as well as by impregnation in the TA solution and then in the AgNO3 solution. In both cases, treatment with hydrazine was carried out to convert the oxidized polyphenol to the reduced form and obtain AgNPs.

2.3 Scanning Electron Microscopy

Images of samples were obtained using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) SIGMA VP (Carl Zeiss, Germany) operating in a deep vacuum. No sputtering was applied. The optimal value of accelerating voltage was matched by varying it in the range of 1–15 kV. Elemental analysis was performed using Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

Spectra were recorded on an IR Tracer-100 (Shimadzu) spectrometer in the wavelength range of 350–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 at room temperature. The final version had an average of 64 scans.

The antimicrobial action of the prepared samples was studied using the most common disk diffusion method [83]. A 200 μL suspension of daily cultures of microorganisms (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL) was applied to the surface of agarized Mueller-Hinton medium (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Limited, Mumbai, India) in Petri dishes, then samples were placed in the form of disks with a diameter of 8 mM. Incubation was carried out at a temperature of 37°C. The testing duration was 7 days. A minimum of 3 replicates were made. Sterilization, where indicated, was performed in an autoclave at 120°C for 20 min.

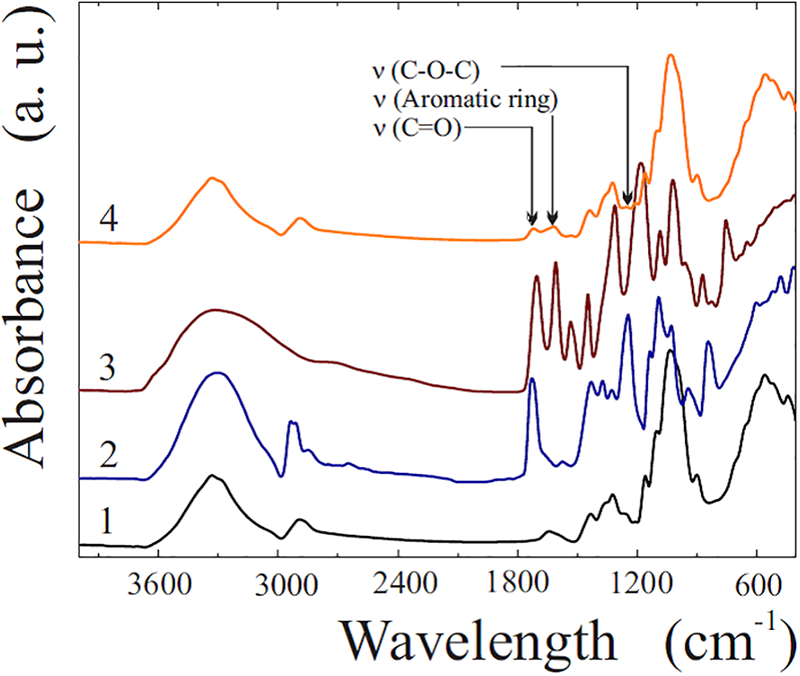

The proposed method for applying an antimicrobial coating to paper was based on the properties of TA to be attached to the surface of cellulose fibers [62,63] and to form a poorly soluble complex (associate) with PVA [46,58,59,84,85] (Fig. 2). In the latter case, evidence of its formation was the almost instantaneous appearance of a suspension in a solution with polyphenol when PVA got into it and vice versa. Confirmation of TA binding to cellulose and formation of a coating on a paper filter was coloring caused by polyphenol. It gradually increased with an increase in the number of TA coating cycles. Its presence on the paper surface was confirmed by the analysis of the spectral data presented in Fig. 3. There are the FTIR spectra of paper, PVA, TA and a bionanocomposite consisting of a multilayer coating of TA and PVA with AgNPs on its surface.

Figure 3: FTIR spectra of paper filter (1), PVA (2), TA (3) and bionanocomposite (4), which is a multilayer coating of TA-PVA@AgNPs on cellulose fibers

The spectrum of the paper (curve 1) includes characteristic bands, on the basis of which and in accordance with literature data [86–90] it can be reasonably attributed to cellulose. The strong broad band at 3339 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl group, at 1432 and 1315 cm−1 is due to the scissor and bending vibrations of the bonds of the CH2, CH and C-O groups, and at 1158 and 1024 cm−1, respectively, refers to the pendulum vibrations of the C-O-C bond and the bending vibrations of the C-O bond in the glucoside ring.

The spectral characteristics of PVA and TA are also in agreement with the literature data. In the first case (curve 2), bands at 3298 and 2924 cm−1 should be noted, which are due to stretching vibrations O–H and C–H, as well as at 1376, 1328 and 1027 cm−1, which can be associated with-CH2-wagging, -O-H and C-H bending, respectively. Bands at 1725, 1437 and 1097 cm−1 should be noted, apparently related to C=O, C–O–C and C-O stretching of the vinyl acetate group, which remained after incomplete hydrolysis of polyvinyl acetate [58,91,92].

In the case of TA (curve 3) there is also a broad intense peak at ~3300 cm−1, due to O–H stretching, but hydroxyls are located in phenolic groups. The hydroxyl group also manifests itself at 1313 and 1178 cm−1. The peak at 1702 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching mode of C=O in the ester group, at 1606, 1532 and 1445 cm−1, to the skeletal vibration of the benzene ring [93,94].

The spectrum of the bionanocomposite (curve 4), with a few exceptions, is practically a copy of that for cellulose (curve 1). This is explained by the fact that the TA-PVA coating consists of small amounts of polyphenol and polymer, the contribution of which to the spectral characteristics of the sample is not so significant. Among the differences, it is worth highlighting the band at 1617 cm−1, which is absent in the cellulose spectrum. Its presence is due to aromatic ring stretching vibrations observed in the range of 1625–1590 cm−1 [95]. Its presence is unambiguous evidence of the presence of TA in the coating. There is also a band at 1711 cm−1, which is absent in the spectrum of cellulose. It can be attributed to the C=O group [95]. The carbonyl group occurs in TA, which contains residues of gallic acids linked by an ester bond to a glucose residue (Fig. 1). It is also present in PVA, which contains vinyl acetate residues due to incomplete hydrolysis of the initial poly(vinyl acetate) [91]. The presence of this band in the spectrum indicates the availability of both polyphenol and polymer in the coating. This is also evidenced by the characteristic band at 1205 cm−1, which is due to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the C–O–C ester group in the range of 1275–1185 cm−1 [95]. The presence of the above both bands in the spectrum (curve 4) allows us to state that using the proposed method, it is possible to apply a stable coating to cellulose fibers (paper), consisting of a complex of TA with PVA.

The next step after coating formation was to form nanoscale silver by reducing Ag+ according to the reaction:

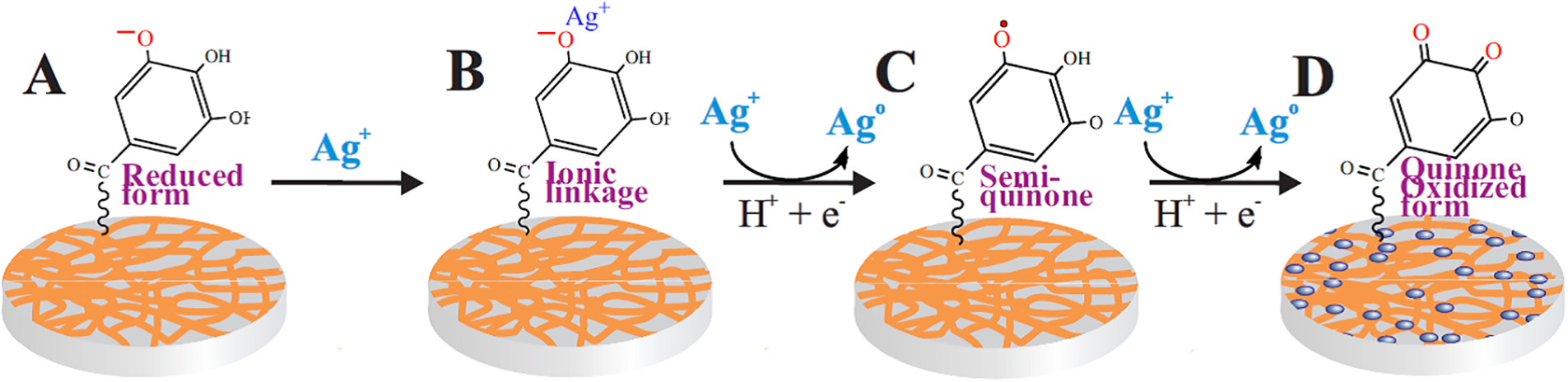

The TA, which was in the coating, acted as a reducing agent. Polyphenol is widely used for the synthesis of noble metal nanoparticles [46,52,71,75,81]. According to the suggested mechanism, the process occurs in several stages [26,41,71,81,96] schematically shown in Fig. 4. Silver ions initially bind to the reduced form of the gallic acid residue (A) due to electrostatic interactions (B) and are then reduced to the atomic state. The gallic acid residue is converted into the semiquinone form (C), which is an active reducing agent, reducing the next silver ion in the adjacent layers of the aqueous solution. In this case, it is oxidized to quinone (D), transferring to an oxidized state. As a result of the reduction of Ag+, numerous silver atoms are formed, which coalesce with each other into clusters. The latter merge further into AgNPs, filling the surface of the paper (D). At this stage, TA also plays an important role, acting as a capping agent, preventing the merging of clusters and nanoparticles into large agglomerates.

Figure 4: Schematic representation of the process of in situ silver reduction on the surface of paper (cellulose fibers) coated with a TA-PVA complex. For simplicity, only the gallic acid residue is shown. A–initial stage, the polyphenol is in the reducing form; B–electrostatic binding of silver ions from the solution by the gallic acid residue; C–reduction of bound silver with the transition of gallic acid to the semiquinone form; D–reduction of Ag+ by active semiquinone with the transition of TA to the quinone (oxidized) form

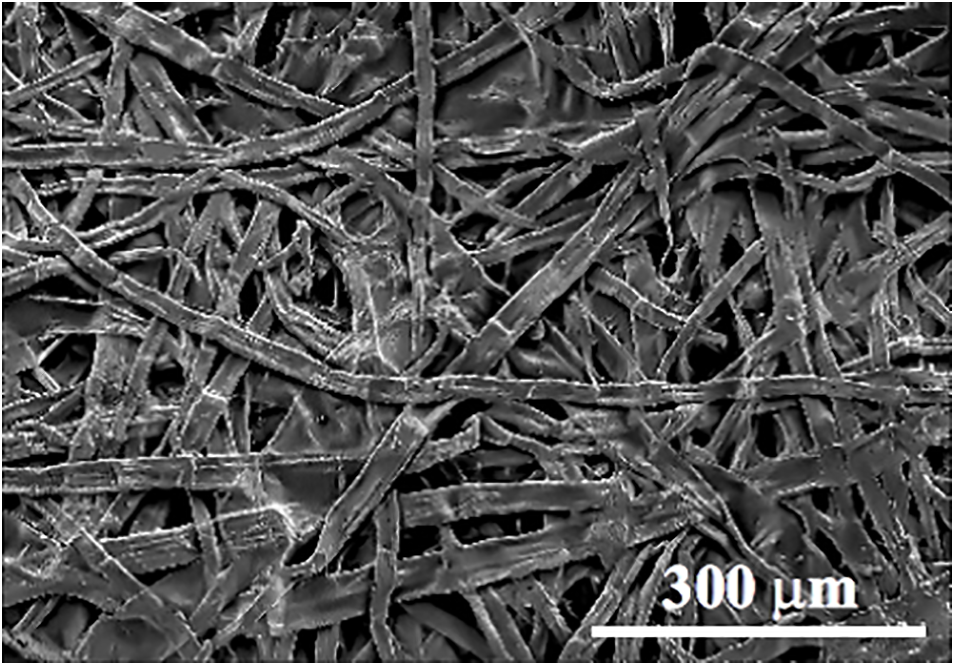

The presence of AgNPs on the surface of the TA-PVA coating was confirmed by means of SEM. The image in Fig. 5 shows a snapshot of the paper surface. It was taken at a small magnification. One can clearly see the remains of cellulosic fibers, randomly located at different angles.

Figure 5: SEM image of filter paper used as a substrate for forming the antimicrobial coating

A series of pictures of the surface of paper coated with alternating layers of PVA and TA with nanosized silver particles synthesized under different conditions are shown in images A–D in Fig. 6. Each sample is represented by two pictures taken at two different magnifications to provide a more comprehensive idea of the structure at different dimensional levels. In addition, images E and F (Fig. 6) show pictures of nanoparticles that were synthesized on the paper surface in the absence of TA-PVA coating.

Figure 6: SEM images of AgNPs on the surface of TA-PVA coated filter paper (A–D) and directly on cellulose fibers (E, F). The nanoparticles were synthesized by the reduction of Ag+ ions by polyphenol (A, B) and hydrazine (C–F)

A comparison of the presented images in Fig. 6 reveals noticeable differences in the sizes and shapes, as well as the packing density of AgNPs. The most uniform coating of silver nanoparticles with a small spread in sizes was formed upon reduction of Ag+ with TA (Fig. 6A and B). Most of the synthesized AgNPs are much like spherical in shape, and their diameter varies in the range of 20–30 nm. They are fairly uniformly distributed over the surface. There are individual pairs of contacting nanoparticles, and merged ones are practically absent. This indicates that TA is an effective reducing agent for silver and also a stabilizer for the synthesized AgNPs, preventing their merging into agglomerates. Our conclusion is consistent with numerous results of other authors (see, for example, [71,96–98]).

The pair of images C and D in Fig. 6 shows nanosized silver synthesized with the help of hydrazine. It is widely applied to reduce noble metals [99–102]. From a comparison of photographs C and A (Fig. 6), it follows that in the first case, there are noticeably less nanoparticles on the surface than in the second, but if we turn to picture D, taken with better resolution, we can see, along with them, smaller AgNPs, which, due to their size, are practically not visible at low magnification. This leads us to conclude that spherical nanoparticles of two sizes were formed during reduction with hydrazine. The diameter of some does not exceed 20 nm, while others are 30–40 nm. AgNPs obtained by reduction of TA occupy an intermediate position (Fig. 6B). The presence of silver nanoparticles of two sizes is evidence of more complex reduction processes. It can be assumed that the main reducing agent for Ag+ was the more active hydrazine, but the formation of AgNPs also occurred with the participation of the less active TA. This could lead to the formation of nanosized silver of varying sizes.

It should be noted that the synthesized nanoparticles (pictures C and D, Fig. 6) do not contact each other and are distributed fairly evenly over the surface. This can be explained by the fact that TA, which is in the coating, can act as a stabilizer, preventing their merging. Apparently, polyphenol takes part in the formation of AgNPs along with hydrazine, being an active participant in the process.

The third alternative synthesis of silver nanoparticle is shown by images E and F in Fig. 6. It consisted of the reduction of silver ions with hydrazine in the absence of TA-PVA coating on the paper. As can be seen from the comparison with the previous images A–D, there are significant differences between the synthesized AgNPs. First, their number in the same area is very limited, and second, agglomerates are found, which are absent in the two previous samples. Agglomerates are usually formed in the absence of a capping agent that prevents the merging of nanoparticles [103]. This once again points to the important role and deep involvement of TA in the synthesis of silver nanoparticles, which can act as both a reducing agent and a stabilizer.

The formation of AgNPs on the surface of TA-PVA coated paper was confirmed by EDS. The initial surface before silver synthesis consisted (pictures not shown) of 53.7 wt.% carbon and 46.2 wt.% oxygen. In addition, up to 0.2 wt.% aluminum was found. Its presence is probably due to contamination by TA, which forms a strong complex with this metal.

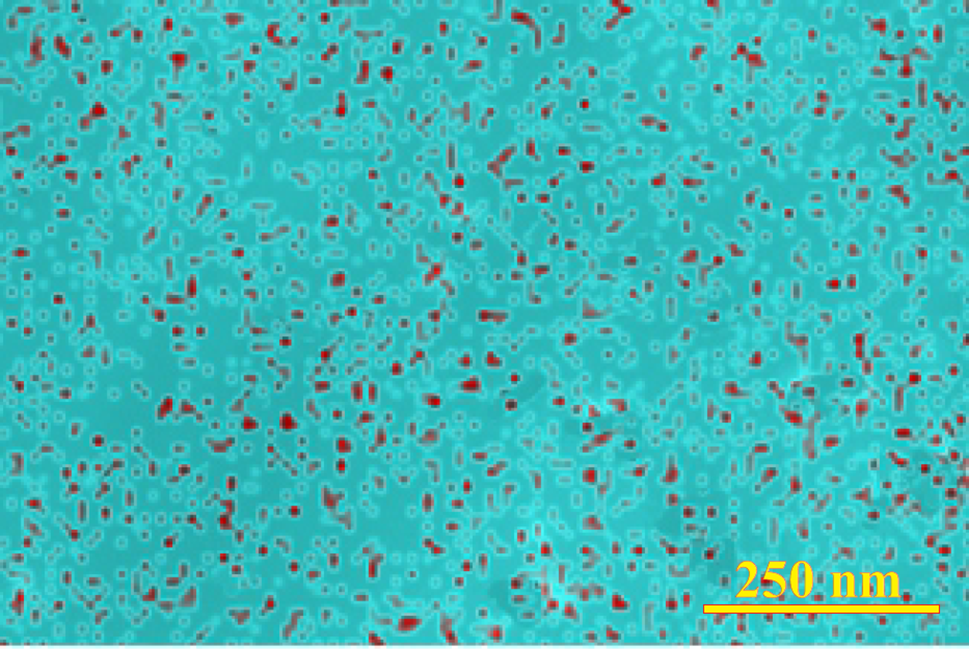

Fig. 7 shows an EDS image of the sample surface with AgNPs. They were synthesized by the action of hydrazine. The greenish-blue background shows the distribution of carbon. Numerous dark red dots, fairly uniformly distributed over the surface, are AgNPs. Their content is about 1.5 wt.%. Thus, EDS analysis allowed us to independently confirm the in situ formation of silver nanoparticles on the surface of the TA-PVA coating in the course of the reduction of Ag+ cations.

Figure 7: The corresponding element map of the surface showing the distribution of AgNPs as red dots on a solid greenish-blue carbon background

The test cultures were strains of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, and yeast Candida albicans. Traditional sample preparation included a sterilization stage. In our work, standard autoclave treatment at 120°C for 20 min was used. In a number of cases, noticeable changes in the color of the coating on the paper were observed. They were possibly caused by oxidation of TA, which could change its state and, accordingly, differ from that planned in the experiment. Furthermore, in the control experiment with AgNO3, which impregnated the paper, silver was not in the ionic form, but partially in the nanosized state, since it was reduced by cellulose, which is an active reducing agent with respect to Ag+ [104–108]. Therefore, a decision was made to abandon sterilization. Trial testing of antimicrobial activity of non-sterilized samples showed fairly good agreement with the results obtained with sterilized analogs. Moreover, when samples were placed on the surface of the agar layer with the tested culture, no foreign microorganisms were introduced to it. This was evidenced by the presence of only one, tested culture throughout the entire experiment, which lasted up to 7 days. This fact indicates that when the studied antimicrobial coatings-TA and AgNPs-are applied to paper, apparently, no microorganisms are introduced and its effective disinfection occurs as well.

Fig. 8 shows pictures of the surface of Petri dishes with two parallel series of samples-sterilized and non-sterilized. In both cases, after applying the antimicrobial coating, the prepared samples were left overnight, and then half of them was put through standard sterilization in an autoclave, and the other half were not sterilized, after which both were placed on the surface of different Petri dishes with test cultures on an agar coating. The experiment lasted for seven days. The samples showed comparable antimicrobial activity. On this basis, it was decided to continue the study with non-sterilized samples. Hereafter, the results obtained only with them are considered.

Figure 8: Pictures of the surface of Petri dishes with test samples in the form of 8 mm diameter disks placed on an agar layer. The numbers in the top row indicate the composition of coatings on the paper: 1-disk impregnated with TA and then treated with hydrazine to reduce polyphenol; 2-disk with TA-PVA coating; 3-TA-PVA@AgNPs obtained by reducing Ag+ with hydrazine; 4-TA-PVA@AgNPs synthesized by reducing Ag+ with polyphenol; 5-AgNPs on paper obtained by reducing Ag+ with hydrazine. The filter paper disk is designated as the control, and the disk impregnated with AgNO3 is designated as Ag+. The samples on Petri dishes in the second and third rows are arranged in a similar manner

Microbiological activity testing showed that the zone of growth inhibition was absent in most cases. In addition, there was usually no growth of colonies of microorganisms on the surface of the samples. The result with the control sample, which was sterilized filter paper, is a good example. The appearance of colonies of microorganisms on its surface was not observed for seven days. This behavior can be explained by the fact that cellulose is not a nutrient medium for the tested cultures. When the disk was picked up, microorganism colonies that had developed on the nutrient medium were found underneath it. Similar situations were observed with samples containing an antimicrobial coating. As an illustration, a photo of a disk (sample 1, Fig. 8) impregnated with TA (photo A, Fig. 9), which was taken 4 days after the start of the experiment, is provided. There are no E. coli colonies on its surface. However, when the disc was removed (bottom image), it was discovered that most of the surface of the resulting cavity had been colonized, i.e., bacteria were able to penetrate and growth due to the presence of a nutrients and a decrease in antimicrobial activity of coating with time. In further experiments, it was decided to examine not only the surface, but also the areas under the disks, beginning from the first day after the start of testing, to establish the dynamics of the processes.

Figure 9: Pictures of individual discs on the surface of an agar layer with E. coli (A–C) and S. aureus (D–G) on the second (B–E), fourth (A) and sixth (F, G) days after the beginning of the experiments. A, B, D-disc impregnated with TA and then treated with hydrazine to reduce polyphenol; C, E-disc with TA-PVA coating; F-TA-PVA@AgNPs obtained by reducing Ag+ with hydrazine; G-TA-PVA@AgNPs synthesized by reducing Ag+ with polyphenol. Each sample is presented in two images located one below the other; the upper one shows the disc on the surface of the agar layer, the lower one, the cavity left after its displacement and a part of the displaced disc, as can be seen from the explanatory notes in A. In the image E, the arrow indicates the colonies of microorganisms grown under the disc

It was of interest to correlate the antimicrobial action of TA with the TA-PVA complex, which was used for the first time here for this purpose as a coating on paper. This can be done by comparing images B–E in Fig. 9, taken on the second day after the beginning of the experiment. The testing was carried out with E. coli (B, C) and S. aureus (D, E) cultures. It should be noted that there were no colonies on the surface of the samples. The inhibition zone was absent in the case of E. coli (B, C), but was present in the case of S. aureus (D, E), although the release of TA from the coated paper, revealing from the brown halo around the disks, took place in both instances. The coloring was spread wider when the paper was impregnated with TA only (B, D). In the case of the TA-PVA complex (B, E), a thin brown ring can be seen, indicating its sufficiently strong adsorption on the cellulose matrix and poor solubility.

A number of differences are also revealed when examining the cavity exposed after removing the disks. On the agar layer with E. coli, the colonies of microorganisms occupy a larger area under a disk impregnated with TA (B, Fig. 9) than with the TA-PVA complex (C). In the case of S. aureus (E), the gram-positive bacterium growth was limited to a small area marked with an arrow, while in D most of the cavity is filled with colonies. In addition, the inhibition zone boundary is more diffuse and less distinct (D) than in the case of the TA-PVA complex (E). The mentioned difference may be explained not by the fact that the polyphenol is differently active, but by its surface concentration. It is lower in the experiment with the paper impregnated with TA, since, judging from the wide brown halo, the polyphenol was released in greater quantities and distributed over a larger area (B, D). Activity TA against bacteria depends on its concentration [42].

Correlation of the antimicrobial action of TA and TA-PVA against E. coli and S. aureus, comparing, respectively, images B and C with D and E in Fig. 9, shows that bacterial growth is suppressed to a greater extent in the latter case, i.e., S. aureus. This follows from the presence of the inhibition zone and noticeably less overgrowing of the areas under the disks. The noted difference allows us to make a conclusion that the antimicrobial action of TA is expressed to a greater extent against the gram-positive bacterium S. aureus than against the gram-negative bacteria E. coli. Our finding is in line with recent results published in [42,109,110]. However, there is an observation that the inhibition of E. coli growth was more pronounced than in the case of S. aureus in experiments with films consisting of tannic acid and hyaluronan [111].

The combination of TA-PVA complex with AgNPs, each of which is an antimicrobial agent, brings up the question of the peculiarities of their combined action on microorganisms and possible synergism. It is also important to note that during the synthesis of nanosized silver, significant changes in the state of the polyphenol occurred. In particular, when the polyphenol acted as a reducing agent, it was converted to the oxidized (quinone) state (Fig. 4D). When hydrazine was applied as a reducing agent, it eliminated the oxidation of TA or even converted most of the polyphenol to the reduced form. The reduced/oxidized forms may have different antimicrobial activities, which may also have effect when TA combined with AgNPs. It was inferred that a comparison of the studied samples should lead to clarification of the issues raised.

The corresponding results with S. aureus obtained on the sixth day are shown in images F and G in Fig. 9. In both cases, narrow inhibition zones are present. They are colored brown, indicating the presence of TA or, more likely, the TA-PVA complex, possibly together with AgNPs. Outside the zones, the color is weak, pointing to a limited extension beyond their boundaries due to the poor solubility of the complex. A comparison of the images shows that in F, which corresponds to the sample exposed to hydrazine, the inhibition zone has become overgrown, while in G, which represents the sample with AgNPs reduced by TA, no bacterial colonies are visible in the inhibition zone. This difference allows us to suggest, which requires further confirmation, that the polyphenol may exhibit higher antimicrobial activity in the oxidized state than in the reduced one. This is also noted in [45,112].

It was also of interest to consider the antimicrobial action of AgNPs in comparison with the ionic form of silver. Their comparison has been repeatedly performed in the literature (see, for example, [16,20]). In the case of the ionic form, the paper disk was impregnated with AgNO3. Silver salt is widely used as an antiseptic. The antimicrobial activity of Ag+ was fully confirmed in our study. The effect of AgNO3 was short-lived as well. The day after beginning, a wide inhibition zone (up to 5–8 mm) was found on the surface of the agar layer with the studied strains of microorganisms, but after some time its colonization began, which was completed in 2–3 days. In the case of AgNPs, the presence of narrow inhibition zones (F and G, Fig. 9) was found, but judging by them and the cavity, the antimicrobial activity was maintained for a longer time. In particular, after 6–7 days, colonization by E. coli and S. aureus bacteria under the disks was only partial, and at the initial stage, it was practically absent. In the case of C. albicans yeast, for example, small colonies were detected only on the third day.

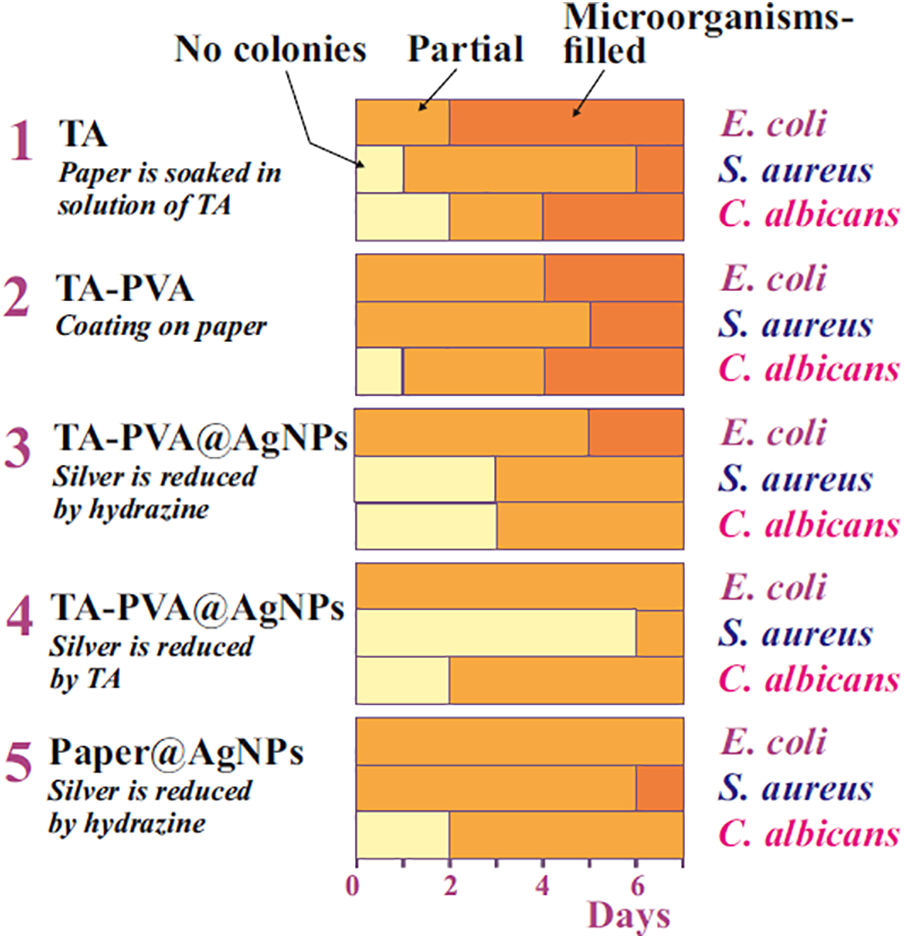

All the results obtained from daily testing of five samples of different compositions in relation to the three studied strains of microorganisms are summarized in Fig. 10 as a 3-color diagram representing the state of the areas under the disks-the absence of microorganism colonies, the presence of partial and complete colonization. Partial colonization included the emergence of even small areas (~10%), as shown by the arrow in picture E (Fig. 9), as well as the overgrowth of the areas under the disks with colonies by 80%–90%. No distinction was made between them.

Figure 10: Diagram characterizing the state of the cavities after the disks were removed for five test samples by testing days. The colors corresponding to the absence of microorganisms, partial and complete overgrowth of the cavities by the test strains are marked with arrows with corresponding notices at the top

A quick glance at the diagram shows that there are noticeable differences in the color gamma, both among individual samples and among strains, pointing to differences in the antimicrobial activity of the compositions studied. The following main conclusions can be drawn from the analysis of the diagram.

- All the studied coating compositions applied to paper showed high antimicrobial activity against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, represented by strains of E. coli and S. aureus, as well as yeast C. albicans. The conclusion reached is in full agreement with the results of the study of TA and AgNPs by other authors (see, for example, [12,23,42,55]).

- The new coating in the form of an insoluble TA-PVA complex had an antimicrobial effect comparable to TA. Unlike the latter, it is less soluble in water and better bound to the cellulose matrix, reducing the release and staining of the surface of the agar layer.

- Comparison of the TA-PVA complex with AgNPs showed that the latter had a longer lasting effect and were somewhat more effective in suppressing the growth of microorganisms.

- The combination of TA-PVA with AgNPs in the coating resulted in some increase in antimicrobial activity compared to that which they showed separately. This allows us to assume that the combination led to the synergism in their action against the studied microorganism strains.

- Correlation of the effect of the studied substances and compositions-TA-PVA and TA-PVA@AgNPs-on the growth of E. coli and S. aureus, showed its more pronounced suppression in the case of gram-positive bacteria than gram-negative ones. The trend was rather the opposite when studying only AgNPs.

- The effects of the above samples on C. albicans yeast and bacteria did not differ significantly, which did not allow us to come to an unambiguous conclusion about the differences in their action.

It should be emphasized that the conclusions made are preliminary. They require additional confirmation, for which a detailed study is needed.

In closing, it is important to note the high efficiency and duration of the antimicrobial action of the TA-PVA coating with AgNPs (Fig. 10). It reached 6–7 days, despite the fact that standard sterilization of the samples before testing was not carried out. In most studies, the experiments were limited to several days. In the article [113], the paper was coated only with TA and AgNPs without using a complex with PVA, the antimicrobial activity was observed for up to 96 h, i.e., 4 days. The authors noted that this result was achieved only with a high content of nanoparticles in the sample, which was 15%. When a smaller amount was examined, the duration did not exceed 24 h. In our experiments, a thin coating with an extremely low content of antimicrobial components was applied to paper. According to EDS analysis data, there was only about 1.5 wt.% AgNPs (Fig. 7), which is 10 times less than in [113].

Nanosized silver, as noted in [23], is a “double-edged sword” that kills and inhibits the growth of pathogenic microorganisms, but also turns out to be cytotoxic to several human cell lines, i.e., it kills microorganisms, but it can be toxic to the body. Combination with TA, which has almost the entire set of biological activities, exerting a beneficial effect on the body as a whole [35–38,42,47,48] gives hope for partial neutralization of the negative action of AgNPs. This seems very important since there is an urgent need for effective bacteriostatic agents due to the rapid adaptation and resistance of microorganisms to antibiotics. Silver has proven itself as an effective antiseptic for centuries, to which adaptive mechanisms have not been developed. Therefore, its use is in demand and will remain so in the future. At the same time, reduction or compensation of the negative effect on the human body remains highly desirable. The use of TA for these purposes can be quite successful. Moreover, polyphenol itself has an antimicrobial effect, which is synergistically enhanced when combined with AgNPs. This allows reducing the content of nanosized silver in preparations, thereby reducing its negative impact. Further research is needed to fully elucidate this effect and use it in the development of antimicrobial remedies.

Acknowledgement: Evgenii Gerasimov from Boreskov Institute of Catalysis, Siberian Department of Russian Academy of Sciences is acknowledged for the FE-SEM images and Oleg Khlebnikov from Institute of Chemistry, Far East Department, Russian Academy of Sciences for the FTIR spectra.

Funding Statement: IP and YS were funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant 22-13-00337.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Valeria Kurilenko, Yury Shchipunov; data collection: Irina Postnova, Valeria Kurilenko, Yury Shchipunov; analysis and interpretation of results: Irina Postnova, Valeria Kurilenko, Yury Shchipunov; draft manuscript preparation: Yury Shchipunov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AgNPs | Silver nanoparticles |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| TA | Tannic acid |

References

1. Podolsky SH. The antibiotic era: reform, resistance, and the pursuit of a rational therapeutics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

2. Burrell R. A scientific perspective on the use of topical silver preparations. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2003;49(Suppl. 5A):19–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Dunn K, Edwards-Jones V. The role of Acticoat with nanocrystalline silver in the management of burns. Burns. 2004;30(Supplement 1):S1–9. doi:10.1016/s0305-4179(04)90000-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cattoir V, Felden B. Future antibacterial strategies: from basic concepts to clinical challenges. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(4):350–60. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Church N, Mckillip J. Antibiotic resistance crisis: challenges and imperatives. Biologia. 2021;76(2):1535–50. doi:10.1007/s11756-021-00697-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Van den Brink R. The end of an atibiotic era: Bacteria’s triumph over a universal remedy. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. Akram F, Imtiaz M, Haq IU. Emergent crisis of antibiotic resistance: a silent pandemic threat to 21st century. Microb Pathogen. 2023;174:e105923. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Klasen HJ. Historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. I. Early uses. Burns. 2000;26(2):117–30. doi:10.1016/S0305-4179(99)00108-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Uthaman A, Lal HM, Thomas S. Fundamentals of silver nanoparticles and their toxicological aspects. In: Lal HM, Thomas S, Li T, Maria HJ, editors. Polymer nanocomposites based on silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2021. p. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

10. Alexander JW. History of the medical use of silver. Surg Infect. 2009;10(3):289–92. doi:10.1089/sur.2008.9941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Nowack B, Krug HF, Height M. 120 Years of nanosilver history: implications for policy makers. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(4):1177–83. doi:10.1021/es103316q. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kühni W, Holst W. Colloidal silver: the natural antibiotic. Rochester: Healing Arts Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

13. Duhamel BG. Electric metallic colloids and their therapeutical applications. The Lancet. 1912;179(4611):89–90. doi:10.2174/1381612054065738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lea MC. On allotropic forms of silver. Am J Sci. 1889;37(6):476–91. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-37.222.476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Frens G, Overbeek JT. Carey Lea’s colloidal silver. Kolloid-Z U Z Polymere. 1969;233(1–2):922–9. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bondarenko O, Ivask A, Kakinen A, Kurvet I, Kahru A. Particle-cell contact enhances antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64060. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Choi O, Deng KK, Kim NJ, Ross L, Surampalli RY, Hu Z. The inhibitory effects of silver nanoparticles, silver ions, and silver chloride colloids on microbial growth. Water Res. 2008;42(12):3066–74. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2008.02.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Park J, Lim DH, Lim HJ, Kwon T, Choi JS, Jeong S, et al. Size dependent macrophage responses and toxicological effects of Ag nanoparticles. Chem Commun. 2011;47(15):4382–4. doi:10.1039/c1cc10357a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Jung R, Kim Y, Kim H, Jin HJ. Antimicrobial properties of hydrated cellulose membranes with silver nanoparticles. J Biomater Sci Polymer Edn. 2009;20(3):311–24. doi:10.1163/156856209X412182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Patel M. Antimicrobial paper embedded with nanoparticles as spread breaker for corona virus. Am J Nanotechnol Nanomed. 2020;3(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

21. Lal HM, Uthaman A, Thomas S. Silver nanoparticle as an effective antiviral agent. In: Lal HM, Thomas S, Li T, Maria HJ, editors. Polymer nanocomposites based on silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. Cham: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 247–65. [Google Scholar]

22. Coburn DL, Dignan PD. The wonders of colloidal silver: nature’s super antibiotic. Epub: Moonfeather Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

23. Liao C, Li Y, Tjong S. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Int J Molec Sci. 2019;20:e449. doi:10.3390/ijms20020449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Oves M, Rauf MA, Qari HA. Therapeutic applications of biogenic silver nanomaterial synthesized from the paper flower of Bougainvillea glabra (Miami, Pink). Nanomaterials. 2023;13:615. doi:10.3390/nano13030615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Leaper DJ. Silver dressings: their role in wound management. Int Wound J. 2006;3(4):282–94. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2006.00265.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kim J, Lee K, Nam YS. Metal-polyphenol complexes as versatile building blocks for functional biomaterials. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng. 2021;26(5):689–707. doi:10.1007/s12257-021-0022-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jahed FS, Hamidi S, Zamani-Kalajahi M, Siahi-Shadbad M. Biomedical applications of silica-based aerogels: a comprehensive review. Macromol Res. 2023;31(6):519–38. doi:10.1007/s13233-023-00142-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Percival SL, Slone W, Linton S, Okel T, Corum L, Thomas JG. The antimicrobial efficacy of a silver alginate dressing against a broad spectrum of clinically relevant wound isolates. Int Wound J. 2011;8(3):237–43. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00774.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Cavanagh MH, Burrell RE, Nadworny PL. Evaluating antimicrobial efficacy of new commercially available silver dressings. Int Wound J. 2010;7(5):394–405. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00705.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang HY, Smith JA, Oyanedel-Craver V. The effect of natural water conditions on the anti-bacterial performance and stability of silver nanoparticles capped with different polymers. Water Res. 2012;46(3):691–9. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ravikovitch PI, Neimark AV. Characterization of micro-and mesoporosity in SBA-15 materials from adsorption data by the NLDFT method. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105(29):6817–23. doi:10.1021/jp010621u. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tannins PA. Major sources, properties and applications. In: Belgacem MN, Gandini A, editors. Monomers, polymers and composites from renewable resources. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. p. 179–99. [Google Scholar]

33. Martinengo P, Arunachalam K, Shi C. Polyphenolic antibacterials for food preservation: review, challenges, and current applications. Food. 2021;10:e2469. doi:10.3390/foods10102469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Salman M, Farooq MU, Rahman AU, Yaseen M. Polyphenols for wastewater and industrial influents’ treatment. In: Verma C, editor. Science and engineering of polyphenols: fundamentals and industrial scale applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2024. p. 107–33. [Google Scholar]

35. Haslam E, Lilley TH, Cai Y, Martin R, Magnolato D. Traditional herbal medicines—The role of polyphenols. Planta Med. 1989;55(1):1–8. doi:10.1055/s-2006-961764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Quideau S, Deffieux D, Douat-Casassus C, Pouysegu L. Plant polyphenols: chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(3):586–621. doi:10.1002/anie.201000044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Subhan S, Zeeshan M, Rahman AU, Yaseen M. Fundamentals of polyphenols: nomenclature, classification and properties. In: Verma C, editor. Science and engineering of polyphenols: fundamentals and industrial scale applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2024. p. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

38. Belscak-Cvitanovic A, Durgo K, Hudek A, Bacun-Druzina V, Komes D. Overview of polyphenols and their properties. In: Galanakis CM, editor. Polyphenols: properties, recovery and applications. Cambridge: Elsevier; 2018. p. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

39. Qin J, Guo N, Yang J, Chen Y. Recent advances of metal-polyphenol coordination polymers for biomedical applications. Biosensors. 2023;13:e776. doi:10.3390/bios13080776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Lattanzio V, Kroon PA, Quideau S, Treutter D. Plant phenolics-Secondary metabolites with diverse functions. In: Daayf F, Lattanzio V, editors. Recent advances in polyphenol research. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

41. Koopmann AK, Schuster C, Torres-Rodriguez J, Kain S, Pertl-Obermeyer H, Petutschnigg A, et al. Tannin-based hybrid materials and their applications: a review. Molecules. 2020;25:e4910. doi:10.3390/molecules25214910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kaczmarek B. Tannic acid with antiviral and antibacterial activity as a promising component of biomaterials—A minireview. Materials. 2020;13(14):e3224. doi:10.3390/ma13143224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Maharani F, Hartati I, Paramita V. Review on tannic acid: potential sources, isolation methods, aplication and bibliometric analysis. Res Chem Eng. 2022;1(1):46–52. doi:10.30595/rice.v1i2.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chaplin AJ. Tannic acid in histology: an historical perspective. Stain Technol. 1985;60(4):219–31. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Cowan MM. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clinical Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(4):564–82. doi:10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Xu LQ, Neoh KG, Kang ET. Natural polyphenols as versatile platforms for material engineering and surface functionalization. Prog Polym Sci. 2018;87(2):165–96. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Jafari H, Ghaffari-Bohlouli P, Niknezhad SV, Abedi A, Izadifar Z, Mohammadinejad R, et al. Tannic acid: a versatile polyphenol for design of biomedical hydrogels. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10(31):5873–912. doi:10.1039/D2TB01056A. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Jing W, Xiaolan C, Yu C, Feng Q, Haifeng Y. Pharmacological effects and mechanisms of tannic acid. Biomed Pharmacotherapy. 2022;154:e113561. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Guo JL, Suma T, Richardson JJ, Ejima H. Modular assembly of biomaterials using polyphenols as building blocks. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2019;5(11):5578–96. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b01507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhou J, Lin Z, Ju Y, Rahim MA, Richardson JJ, Caruso F. Polyphenol-mediated assembly for particle engineering. Acc Chem Res. 2020;53(7):1269–78. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Guo J, Ping Y, Ejima H, Alt K, Meissner M, Richardson JJ, et al. Engineering multifunctional capsules through the assembly of metal-phenolic networks. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;53(2):5546–51. doi:10.1002/anie.201311136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Postnova I, Shchipunov Y. Tannic acid as a versatile template for silica monoliths engineering with catalytic gold and silver nanoparticles. Nanomater. 2022;12:e4320. doi:10.3390/nano12234320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Wu M, Liu J, Wang X, Zeng H. Recent advances in antimicrobial surfaces via tunable molecular interactions: nanoarchitectonics and bioengineering applications. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;66:e101707. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2023.101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Abdel-Aty AM, Barakat AZ, Abdel-Mageed HM, Mohamed. Development of bovine elastin/tannic acid bioactive conjugate: physicochemical, morphological, and wound healing properties. Polym Bull. 2023;81(14):2069–89. doi:10.1089/wound.2018.0853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Sathishkumar G, Gopinath K, Zhang K, Kang ET, Xu L, Yu Y. Recent progress in tannic acid-driven antibacterial/antifouling surface coating strategies. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10(14):2296–315. doi:10.1039/D1TB02073K. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Rahim MA, Kristufek SL, Pan SJ, Richardson JJ, Caruso F. Phenolic building blocks for the assembly of functional materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58(7):1904–27. doi:10.1002/anie.201807804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Valentino C, Vigani B, Zucca G, Ruggeri M, Boselli C, Cornaglia AI, et al. Formulation development of collagen/chitosan-based porous scaffolds for skin wounds repair and regeneration. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242:e125000. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Dai HJ, Huang Y, Huang HH. Enhanced performances of polyvinyl alcohol films by introducing tannic acid and pineapple peel-derived cellulose nanocrystals. Cellulose. 2018;25(8):4623–37. doi:10.1007/s10570-018-1873-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Chen YN, Jiao C, Zhao YX, Zhang JA, Wang HL. Self-assembled polyvinyl alcohol tannic acid hydrogels with diverse microstructures and good mechanical properties. ACS Omega. 2018;3(9):11788–95. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b02041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Ge WJ, Cao S, Shen F, Wang YY, Ren JL, Wang XH. Rapid self-healing, stretchable, moldable, antioxidant and antibacterial tannic acid-cellulose nanofibril composite hydrogels. Carbohyd Polym. 2019;224:e115147. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Fan HL, Wang L, Feng XD, Bu YZ, Wu DC, Jin ZX. Supramolecular hydrogel formation based on tannic acid. Macromolecules. 2017;50(2):666–76. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Chakraborty JN. Fundamentals and practices in colouration of textiles. Delhi: Woodhead; 2014. [Google Scholar]

63. Ning F, Zhang J, Kang M, Ma C, Li H, Qiu Z. Hydroxyethyl cellulose hydrogel modified with tannic acid as methylene blue adsorbent. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138:e49880. doi:10.1002/app.49880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Santos SC, Bacelo HA, Boaventura RA, Botelho CM. Tannin-adsorbents for water decontamination and for the recovery of critical metals: current state and future perspectives. Biotechnol J. 2019;14:e1900060. doi:10.1002/biot.201900060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ji Y, Wen Y, Wang Z, Zhang S, Guo M. Eco-friendly fabrication of a cost-effective cellulose nanofiber-based aerogel for multifunctional applications in Cu(II) and organic pollutants removal. J Cleaner Prod. 2020;255:e120276. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Shang QQ, Cheng JW, Hu LH, Bo CY, Yang XH, Hu Y, et al. Bio-inspired castor oil modified cellulose aerogels for oil recovery and emulsion separation. Colloid Surf A. 2022;636:e128043. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.128043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Syed HI, Yap PS. A review on three-dimensional cellulose-based aerogels for the removal of heavy metals from water. Sci Total Environ. 2022;807:e150606. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Yang XP, Biswas SK, Han JQ, Tanpichai S, Li MC, Chen CC, et al. Surface and interface engineering for nanocellulosic advanced materials. Adv Mater. 2021;33:e2002264. doi:10.1002/adma.202002264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Postnova IV, Sarin SA, Karpenko TY, Shchipunov YA. Formation of photocatalytically active titania on mesoporous silica with silver nanoparticles synthesized using tannin as a template and a reductant. Doklady Chem. 2020;495(2):191–4. doi:10.1134/S0012500820120022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Lea MCLXI. Allotropic silver. Part III. Blue silver, soluble and insoluble forms. Phil Mag Ser. 1891;31(193):497–504. [Google Scholar]

71. Kaabipour S, Hemmati S. Green, sustainable, and room-temperature synthesis of silver nanowires using tannic acid-Kinetic and parametric study. Colloid Surf A. 2022;641:e128495. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.128495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Xia M, Jiang W, Wu C, Wang C, Yoo CG, Liu Y, et al. Tannin-assisted synthesis of nanocomposites loaded with silver nanoparticles and their multifunctional applications. Biomacromolecules. 2023;24(11):5194–206. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Ounkaew A, Jarensungnen C, Jaroenthai N, Boonmars T, Artchayasawat A, Narain R, et al. Fabrication of hydrogel-nano silver based on Aloe vera/carboxymethyl cellulose/tannic acid for antibacterial and pH-responsive applications. J Polym Environm. 2023;31(1):50–63. doi:10.1007/s10924-022-02611-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Moghaddam SYZ, Biazar E, Esmaeili J, Kheilnezhad B, Goleij F, Heidari S. Tannic acid as a green cross-linker for biomaterial applications. Mini-Reviews Medic Chem. 2022;22:e1330. doi:10.2174/1389557522666220622112959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Szaleniec J, Gibala A, Stalinska J, Ocwieja M, Zeliszewska P, Drukala J, et al. Biocidal activity of tannic acid-prepared silver nanoparticles towards pathogens isolated from patients with exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis. Int J Molec Sci. 2022;23:e15411. doi:10.3390/ijms232315411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Wang B, Moon JR, Ryu S, Park KD, Kim JH. Antibacterial 3D graphene composite gel with polyaspartamide and tannic acid containing in situ generated Ag nanoparticle. Polym Compos. 2020;41(7):2578–87. doi:10.1002/pc.25556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Zhang X, Sun D, Cai J, Liu W, Yan N, Qiu X. Robust conductive hydrogel with antibacterial activity and UV-shielding performance. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2020;59(40):17867–75. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.787886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. He X, Gopinath K, Sathishkumar G, Guo L, Zhang K, Lu Z, et al. UV-assisted deposition of antibacterial Ag-tannic acid nanocomposite coating. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(17):20708–17. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c03566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Kim T, Cha SH, Cho S, Park Y. Tannic acid-mediated green synthesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39(3):465–73. doi:10.1007/s12272-016-0718-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Wu Y, Yang S, Fu F, Zhang J, Li J, Ma T, et al. Amino acid-mediated loading of Ag NPs and tannic acid onto cotton fabrics: increased antibacterial activity and decreased cytotoxicity. Appl Surf Sci. 2022;576:e151821. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.151821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Li Q, Ai R, Fan J, Fu X, Zhu L, Zhou Q, et al. AgNPs-loaded chitosan/sodium alginate hydrogel film by in-situ green reduction with tannins for enhancing antibacterial activity. Mater Today Commun. 2024;38:e107927. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Burkova Y, Beleneva I, Shchipunov Y. Bactericidal sodium alginate films containing nanosized silver particles. Colloid J. 2015;77(6):707–14. doi:10.1134/s1061933x15060058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Barry AL, Thornsberry C. Susceptibility tests: diffusion test procedures. In: Balows A, Hausler WJ, Herrmann KL, Isenberg HD, Shadomy HJ, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. Washington: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. p. 1117–25. [Google Scholar]

84. Cheng ZH, DeGracia K, Schiraldi DA. Sustainable, low flammability, mechanically-strong poly(vinyl alcohol) aerogels. Polymers. 2018;10:e10101102. doi:10.3390/polym10101102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Fan HL, Wang JH, Jin ZX. Tough, swelling-resistant, self-healing, and adhesive dual-cross-linked hydrogels based on polymer-tannic acid multiple hydrogen bonds. Macromolecules. 2018;51(5):1696–705. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Mathlouthi M, Koenig JL. Vibrational spectra of carbohydrates. Adv Carbohyd Chem Biochem. 1986;44(1):7–89. doi:10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60077-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Klemm D, Philipp B, Heinze T, Heinze U, Wagenknecht W. Comprehensive cellulose chemistry: fundamentals and analytical methods. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 1998. [Google Scholar]

88. Poletto M, Pistor V, Zattera AJ. Structural characteristics and thermal properties of native cellulose. In: Van de Ven T, Godbout L, editors. Cellulose–fundamental aspects. Rijeka: InTech; 2013. p. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

89. Khlebnikov ON, Postnova IV, Chen LJ, Shchipunov YA. Silication of dimensionally stable cellulose aerogels for improving their mechanical properties. Colloid J. 2020;82(4):448–59. doi:10.1134/S1061933X20040043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Abidi N. FTIR microspectroscopy: selected emerging applications. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2021. [Google Scholar]

91. Patachia S, Valente AJM, Papancea A, Lobo VMM. Poly(vinyl alcohol) [PVA]-based polymer membranes. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

92. Gohil JM, Bhattacharya A, Ray P. Studies on the crosslinking of poly(vinyl alcohol). J Polym Res. 2006;13(2):161–9. doi:10.1007/s10965-005-9023-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Kozlovskaya V, Kharlampieva E, Drachuk I, Cheng D, Tsukruk VV. Responsive microcapsule reactors based on hydrogen-bonded tannic acid layer-by-layer assemblies. Soft Matter. 2010;6(15):3596–608. doi:10.1039/b927369g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Park JJ, Choi YH, Sim EJ, Lee E, Yoon KC, Park WH. Biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) films coated with tannic acid as an active food packaging material. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2023;35:e101009. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Socrates G. Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies: tables and charts. Chicheste: Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

96. Bulut E, Ozacar M. Rapid, facile synthesis of silver nanostructure using hydrolyzable tannin. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2009;48(12):5686–90. doi:10.1021/ie801779f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Tian X, Wang W, Cao G. A facile aqueous-phase route for the synthesis of silver nanoplates. Mater Lett. 2007;61(1):130–3. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2006.04.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Ali A, Hussain F, Attacha S, Kalsoom A, Qureshi WA, Shakeel M, et al. Development of novel antimicrobial and antiviral green synthesized silver nanocomposites for the visual detection of Fe3+ Ions. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:e2076. doi:10.3390/nano11082076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Nickel U, Mansyreff K, Schneider S. Production of monodisperse silver colloids by reduction with hydrazine: the effect of chloride and aggregation on SER(R)S signal intensity. J Raman Spectrosc. 2004;35(2):101–10. doi:10.1002/jrs.1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Tan KS, Cheong KY. Advances of Ag, Cu, and Ag-Cu alloy nanoparticles synthesized via chemical reduction route. J Nanoparticle Res. 2013;15:e1537. doi:10.1007/s11051-013-1537-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Pacioni NL, Borsarelli CD, Rey V, Veglia AV. Synthetic routes for the preparation of silver nanoparticles. A mechanistic perspective, Silver nanoparticle applications. In: Alarcon EI, Griffith M, Udekwu KI, editors. Silver nanoparticle applications. In the fabrication and design of medical and biosensing devices. Cham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2015. p. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

102. Mukherji S, Bharti S, Shukla G, Mukherji S. Synthesis and characterization of size- and shape-controlled silver nanoparticles. Phys Sci Rev. 2019;4:e20170082. doi:10.1515/psr-2017-0082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Kang H, Buchman JT, Rodriguez RS, Ring HL, He JY, Bantz KC, et al. Stabilization of silver and gold nanoparticles: preservation and improvement of plasmonic functionalities. Chem Rev. 2019;119(1):664–99. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Klemm D, Schumann D, Kramer F, Hessler N, Hornung M, Schmauder HP, et al. Nanocelluloses as innovative polymers in research and application. Adv Polym Sci. 2006;205(1):49–96. doi:10.1007/12_097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Emam HE, Saleh NH, Nagy KS, Zahran MK. Functionalization of medical cotton by direct incorporation of silver nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;78(1):249–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.04.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Foresti ML, Vazquez A, Boury B. Applications of bacterial cellulose as precursor of carbon and composites with metal oxide, metal sulfide and metal nanoparticles: a review of recent advances. Carbohyd Polym. 2017;157(2):447–67. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Shchipunov Y, Postnova I. Cellulose mineralization as a route for novel functional materials. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;26:e1705042. doi:10.1002/adfm.201705042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Skatova AV, Sarin SA, Shchipunov YA. Linear assemblies of monodisperse silver nanoparticles on micro/nanofibrillar cellulose. Colloid J. 2020;82(3):324–32. doi:10.3390/biom11111684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Liu R, Ge H, Wang X, Luo J, Li Z, Liu X. Three-dimensional Ag-tannic acid-graphene as an antibacterial material. New J Chem. 2016;40(7):6332–9. doi:10.1039/C6NJ00185H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Zhang ZY, Sun Y, Zheng YD, He W, Yang YY, Xie YJ, et al. A biocompatible bacterial cellulose/tannic acid composite with antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities for biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng C. 2020;106:e110249. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.110249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Wekwejt M, Malek M, Ronowska A, Michno A, Palubicka A, Zasada L, et al. Hyaluronic acid/tannic acid films for wound healing application. Intern J Biol Macromol. 2024;254:e128101. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Scalbert A. Antimicrobial properties of tannins. Phytochem. 1991;30(12):3875–83. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(91)83426-L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

113. Hanif Z, Khan ZA, Siddiqui MF, Tariq MZ, Park S, Park SJ. Tannic acid-mediated rapid layer-by-layer deposited non-leaching silver nanoparticles hybridized cellulose membranes for point-of-use water disinfection. Carbohyd Polym. 2020;231:e115746. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools