Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Characteristics of Bioplastics Based on Chitosan and Kraft Lignin Derived from Acacia mangium

1 Department of Agricultural Industry Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Lampung University, Bandar Lampung, 35145, Indonesia

2 Department of Forestry, Faculty of Agriculture, Lampung University, Bandar Lampung, 35145, Indonesia

3 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, Research Organization for Life Sciences and Environment, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Jl. Raya Bogor KM 46, Cibinong Bogor, 16911, Indonesia

4 Department of Fisheries Processing Technology, Faculty of Fishery and Marine Science, Padjadjaran University, Jatinangor, 45363, Indonesia

5 Research Collaboration Center for Marine Biomaterials, Jl. Ir. Sukarno, Jatinangor, 45360, Indonesia

6 Department of Wood Industry, Faculty of Applied Sciences, University Technology MARA Pahang Branch Jengka Campus, Bandar Tun Razak, 26400, Malaysia

7 Research School of Chemistry & Applied Biomedical Sciences, Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, 634000, Russian

8 Department of Forest Products, Faculty of Forestry, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Kampus USU Padang Bulan, Medan, 20155, Indonesia

* Corresponding Authors: Sri Hidayati. Email: ; Widya Fatriasari. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1367-1388. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0006

Received 04 January 2025; Accepted 11 March 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

Biodegradable plastics are types of plastics that can decompose into water and carbon dioxide the actions of living organisms, mostly by bacteria. Generally, biodegradable plastics are obtained from renewable raw materials, microorganisms, petrochemicals, or a combination of all three. This study aims to develop an innovative bioplastic by combining chitosan and lignin. Bioplastic was prepared by casting method and characterized by measuring the mechanical properties like tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break. The chemical structure, together with the interactions among chitosan and lignin and the presence of new chemical bonds, were evaluated by FTIR, while the thermal properties were assessed by thermogravimetric analysis. The water vapor permeability, tests and transparency as well as biodegradability, were also carried out. The results show a tensile strength value of 34.82 MPa, Young’s modulus of 18.54 MPa, and elongation at a break of 2.74%. Moreover, the interaction between chitosan and lignin affects the intensity of the absorption peak, leading to reduced transparency and increased thermal stability. The chitosan/lignin interactions also influence the crystalline size, making it easier to degrade and more flexible rather than rigid. The contact angle shows the bioplastic’s ability to resist water absorption for 4 minutes. In the biodegradation test, the sample began to degrade after 30 days of soil burial test observation.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Environmental health plays a crucial role in enhancing human life, as the cleanliness of our surroundings directly influences our quality of life. One of the causes of environmental pollution is the large amount of accumulated plastic waste, which is difficult to decompose [1]. The use of plastic in daily life is very widespread, such as in the production of various soft or hard materials, including household appliances, and food packaging. Plastic waste is a serious and complex environmental problem that requires cooperation between various parties to address and resolve it. However, owing to their chemical stability and inability to break down naturally in the environment, plastic materials derived from petroleum-based products have severely contaminated the environment when utilized on a large scale [2]. In response to the yearly increase in plastic waste, alternative packaging materials made from renewable sources that decompose naturally (biodegradable) are receiving increasing interest. Biopolymers can provide a sustainable substitute for nonbiodegradable plastics in the development of natural and eco-friendly materials [2]. Examples of biodegradable biopolymers as substitutes for synthetic polymers include polysaccharides such as cellulose, chitosan, starch, and agar; proteins such as casein; and complex organic polymers such as lignin [3–7].

Chitin is a primary component of cell walls in fungi and in the exoskeletons of arthropods, such as crustaceans and insects [8]. Commercially, chitin is extracted from the shells of crabs, shrimp, shellfish, and lobsters, which are all byproducts of the seafood industry [8]. Chitosan is obtained by the deacetylation of chitin, which is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (after cellulose), with a global production of approximately 1010−1012 tons per year [8]. Chitosan has several qualities, including film formation, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antibacterial and antioxidant properties [9–11]. Owing to the presence of amino groups, chitosan may be easily chemically modified to obtain various derivatives. In addition, it combines well with other biopolymers, including lignin, providing a substitute to replace synthetic polymers, especially in the food packaging industry [9,12]. In fact, it can appropriately generate strong oxygen barriers and translucent, resilient films [13].

Chitosan-based bioplastics are promising sustainable alternatives to current food packaging methods [12]. Chitosan has been utilized to enhance the bioactive and barrier characteristics of films or polymers [14]. However, bioplastics based on chitosan alone have low mechanical properties and thermal stability [15]. To obtain more favorable physicochemical qualities, chitosan is frequently blended with starch [16]. For example, Albar et al. [17] integrated chitosan into Malaysian cassava (Manihot esculenta) starch, resulting in a bioplastic with enhanced compressive and tensile strength, along with better water resistance. In addition, chitosan alone cannot be heat-sealed or extruded like conventional packaging materials, which limits its workability and scaling production potential [18]. Therefore, blending of chitosan and thermoplastic starch is vital for improving the workability of chitosan-based plastics, allowing for thermocompression, blown extrusion, and melt extrusion, thus promoting scaling production potential for food packaging [19].

However, despite offering several advantages, chitosan-starch-based bioplastics have several drawbacks, such as poor mechanical strength and water vapor permeability [20,21]. Both of these drawbacks limit its effectiveness in certain applications, particularly food packaging. Therefore, other biodegradable materials, such as lignocellulosic materials, can be blended with chitosan to overcome the abovementioned limitations. Lignocellulosic materials have been used as feedstocks for bioplastic preparation [22]. Lignin is the second most abundant aromatic biopolymer in the cell walls of lignocellulosic biomass (15%–35%). It can be produced in large quantities as a byproduct in the biorefinery and pulp and paper industries through various processes [23,24]. Indonesia is the world’s largest supplier of Acacia fibers, and the majority of the country’s pulp and paper sector uses this wood as a feedstock for short fibers. This species produces a significant amount of wood due to its rapid growth and status as a nitrogen-fixing tree [1]. Black liquor is also produced because of a lignin-rich pulping process [22]. Therefore, effectively utilizing these resources would be beneficial for a sustainable future.

Lignin has a complex chemical structure with methoxyl, carbonyl, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups, which are responsible for some of the main properties of lignin, such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, and UV barriers [10,11,25,26]. Lignin can act as a green filler to improve the mechanical properties of a polymer [24]. However, research on chitosan-lignin-based bioplastics is rather limited. Rosova et al. [9] mixed chitosan dissolved in acetic acid with lignin, producing bioplastics with better thermal stability and tensile strength than those based only on chitosan. Similarly, Agustiany et al. [27] blended lignin from oil palm empty fruit bunches (OPEFBs) with chitosan dissolved in acetic acid. This produced a biofilm with improved mechanical and antioxidant properties that completely decomposed in the soil in just seven days.

In addition to blending between chitosan and lignin, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) can also be added to improve the physiochemical properties of bioplastics. By improving the matrix properties of the composite system, PVA and chitosan may be combined to generate a matrix. Integration with PVA can improve the drawbacks of chitosan, including its restricted surface area, poor thermal and mechanical capabilities, ability to dissolve in acidic conditions, and increased price. PVA is a water-soluble semicrystalline synthetic polymer with hydrophilic properties that are similar to those of chitosan because of the presence of OH groups, chemical resistance, good mechanical properties, high biocompatibility, biodegradability, nontoxicity, water solubility, and effective film-forming capabilities with notable mechanical strength [28]. Among the chitosan-PVA films, PVA is responsible for good flexibility, and the films have outstanding UV resistance, high thermal stability, and unique shapes [29–31]. In this research, we developed chitosan/PVA/lignin bioplastics, taking into account the benefits of integrating PVA into chitosan as a matrix through polymer blending [30] and using lignin as a filler to add active properties such as UV shielding and to improve the hydrophobicity of bioplastics. The dissolution of chitosan in various types of acids, such as acetic acid, lactic acid, and citric acid, has shown great potential in the development of bioplastics [32]. Therefore, in this study, various types of solvents for dissolving chitosan were evaluated. The chitosan/PVA/lignin biofilms were characterized in terms of their mechanical, physical, and biodegradability properties as well as their UV shielding ability and water vapor transmission rate, and the results were compared with those of pure chitosan bioplastics to demonstrate the advantages reported for lignin and PVA.

Chitosan from shrimp shells with an 80% degree of deacetylation was obtained from the University of Padjajaran, Bandung, Indonesia. The Acacia mangium black liquor used for lignin extraction was obtained from the pulp and paper industry (PT TELPP) in Palembang, South Sumatera Province, Indonesia. Acacia mangium kraft lignin with a purity of 82.66% (isolated by hydrochloric acid precipitation as reported by Falah et al. 2022 [33]), acetic acid, polyvinyl alcohol, and ethanol were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). All the chemicals were of analytical grade and were used without any refinement.

2.2 Preparation of Chitosan/Lignin Bioplastics

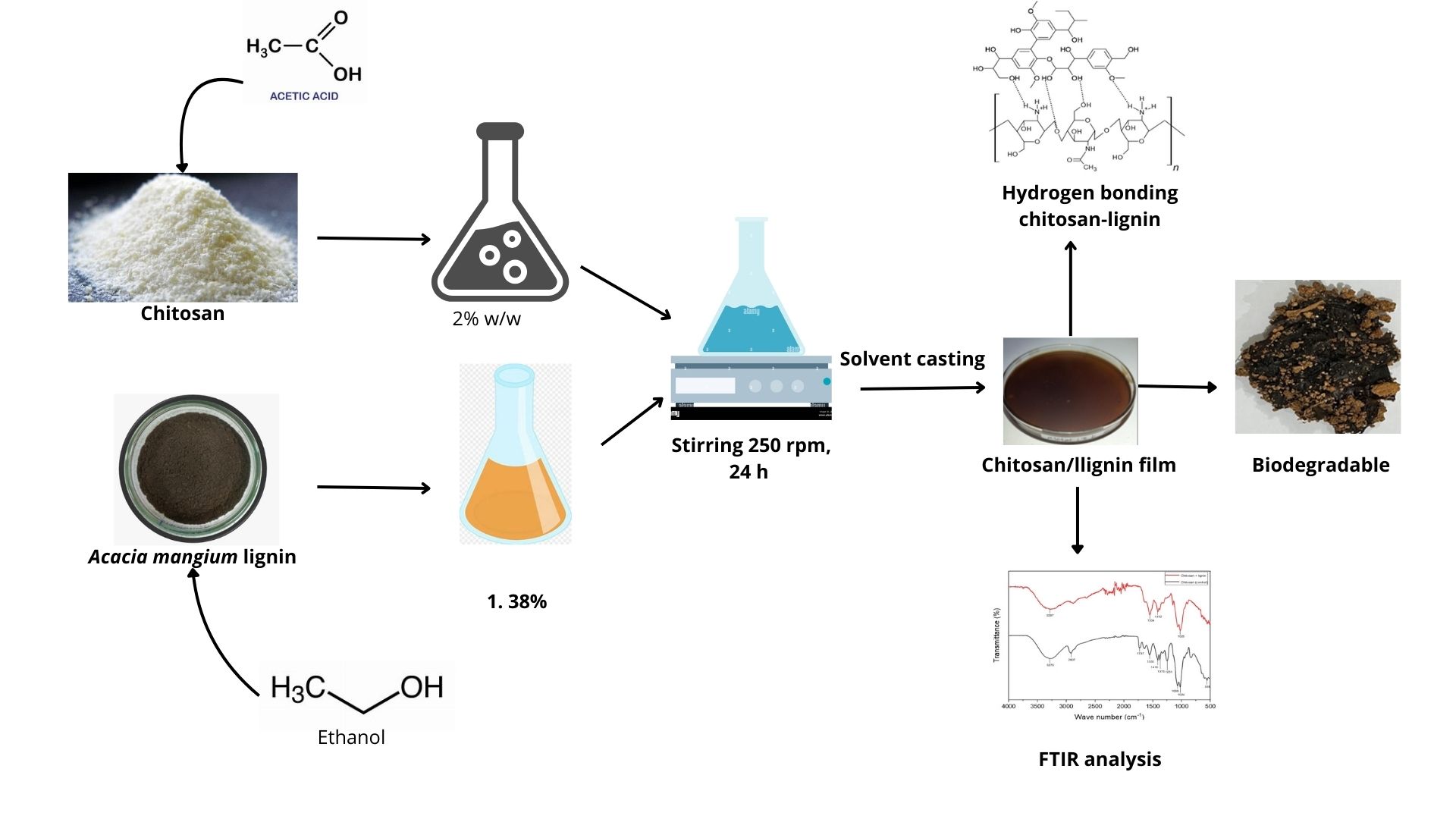

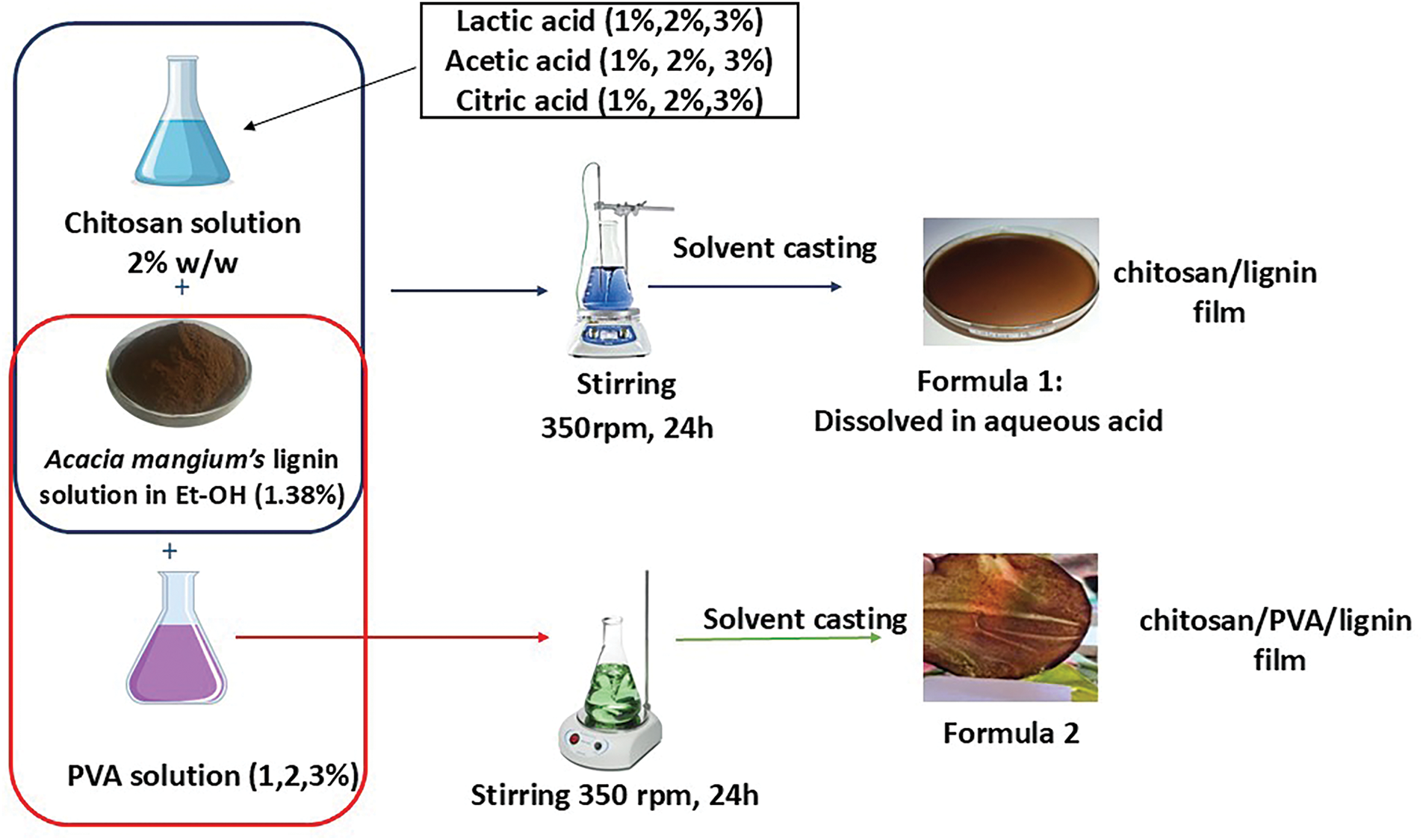

The bioplastics were prepared following the method reported by Crouvisier-Urion et al. [13], with modifications related to the matrix and lignin types. Each treatment was assigned a code: chitosan with an acidic aqueous solution called formula 1 with lactic acid concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%; acetic acid concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%; citric acid concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%; and PVA with concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%. The preparation for making the casting films was as follows: a chitosan film was formed by dispersing 2% (w/w) chitosan in an aqueous solution (28 mL) of lactic acid at concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%; acetic acid at concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%; citric acid at concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%; and stirring at 350 rpm for 24 h. For PVA solution film preparation (28 mL), 2% chitosan in aqueous solution was prepared and then mixed with a (1%, 2%, 3%) PVA aqueous solution and left under magnetic stirring at 350 rpm for 24 h. The lignin solution (12 mL) was prepared by dispersing lignin in ethanol (1.38% w/w) with stirring at 350 rpm for 24 h. Afterward, the composite film-forming solution, made from these two dispersions (chitosan/PVA solution and lignin dispersion), was obtained by mixing them to reach a water/ethanol ratio of 70:30 (w/w). Then, 40 mL of this final forming solution was poured into a polystyrene Petri dish with a diameter of 13.5 cm and dried at room temperature. The film is then peeled off from the Petri dish and stored at room temperature (~25°C–27°C) for further analysis. A flow diagram of the preparation of the bioplastic casting film is shown in Fig. 1. The pH of the formed solution was analyzed with a pH meter, and the values are recorded in Table 1.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for the preparation of chitosan-lignin bioplastic

The resulting film was selected on the basis of its pH range of 4–6 [32,34] and physical appearance, including elastic, unbroken, nonsticky, and compact [9], and then its mechanical strength was tested via tensile tests, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break. The film has the most favorable result from the tensile test, which was chosen for additional examination. To investigate and define the impact of lignin addition on the characteristics and qualities of the bioplastic, the results were compared with those related to a pure chitosan film.

2.3 Characterization of Chitosan/Lignin-Based Bioplastics

2.3.1 Mechanical Tests of Bioplastics

The tensile strength test of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic was conducted according to ASTM D 882–02 [35]. The sample, in the form of a sheet with a width of 2.5 cm, was tested via a universal testing machine (AGS-X 10 kN, Shimadzu, Japan) and stretched at a speed of 30 mm/min at a pressure of 5 kN until the film broke. The tensile strength and percentage of elongation (% E) were determined via Eqs. (1) and (2):

where σ is the tensile strength (MPa), F is the tensile force (N), A is the cross-sectional area (mm2), %E is the percentage of elongation (%), ΔL is the elongation (mm), and L1 is the initial length (mm).

For the calculation of the Young’s modulus, the following equation was used:

where ΔL (mm) was obtained from the tensile test.

2.3.2 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis of Bioplastics

The functional groups on the bioplastics were evaluated via FTIR (Perkin Elmer, USA) with the universal attenuated total reflectance (UATR) technique. The IR spectrum was recorded in adsorption mode with 16 scans, a spectral resolution of 4.0 cm-1, and a wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm-1 at room temperature via Spectrum software (Perkin Elmer, USA).

2.3.3 Thermogravimetric Analysis of Bioplastics

In accordance with Suryanegara et al. [36], the chitosan/PVA/lignin film was subjected to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA 4000 Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) in accordance with ASTM E1131, which measured the thermal weight loss of the bioplastic. The temperature ranged from 20°C to 600°C with a heating rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen flow. The weight loss percentage was calculated via the following formula:

where Winitial = the initial weight (mg) and Wfinal = the weight (mg) at a certain temperature.

2.3.4 Water Vapor Transmission Rate and Water Vapor Permeability Analysis of Bioplastics

The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) and water vapor permeability (WVP) were calculated via the cup method, which is based on ASTM E 95-96 1995, as reported by Suryanegara et al. [36]. The WVTR and WVP for each sample were measured in triplicate, and the water mass loss was evaluated at 5-min intervals until a steady state was reached, which occurred after 24 h. The WVTR and WVP values can be calculated via Eqs. (4) and (5) as follows:

where WVTR is the water vapor transmission rate (gs−1m−2), WVP is the water vapor permeability (gs−1m−1Pa−1), the flux is the slope of the linear regression, d is the film thickness (m), S is the saturated air pressure at 37°C (6266.134 Pa), R1 is the relative humidity (RH) in the Petri dish (100%), and R2 is the RH at 37°C (81%).

2.3.5 Spectrophotometer Ultraviolet–Visible (UV–Vis) Analysis of the Bioplastic Films

Analysis was performed via a UV/Vis spectrophotometer model UV–1800 (SHIMADZU Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) according to ASTM E169, with the wavelength set in the range of 200–800 nm. The sample was in the form of a thin sheet measuring 10 mm × 10 mm.

2.3.6 X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of the Bioplastic Films

The analysis was performed via an XRD SmartLab Rigaku instrument with a Cu source. The X-ray source was used with an angle range of 10° to 80° and a scan speed of 2°/min. The crystallite size in the crystalline phase can be calculated via the Scherrer equation, whereas the degree of crystallinity (Xc) was calculated on the basis of the ratio of the crystalline fraction to the crystalline and amorphous fractions (Eq. (8)) via the Lorentz fitting curve with Origin Pro 8.5.1 software (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

where D = the crystallite size (nm); K = the Scherrer constant (0.9); and λ = the X-ray wavelength (1.54 Å). β = full width at half maximum (FWHM) in radians; θ = Bragg angle (half of the 2θ value).

2.3.7 Contact Angle Analysis of Bioplastics

Contact angle analysis was performed according to ASTM D7334 by depositing deionized water (200 µL) onto the surface of the bioplastic film. A Dino-Lite Pro Digital Microscope (AnMo Electronics Corporation, Taiwan) and Dino-Lite Capture application (Version 2.0) were used over a period of 180 s, and the droplets were recorded. The recorded video was cut into 3-s intervals, and from each frame, the contact angle was measured via ImageJ with the Drop Snake analysis plugin.

2.3.8 Color Transparent Analysis of Bioplastic Films

Transparency was measured via UV–Vis spectrophotometry. The color transparency of the bioplastic was reported as transparency or % transmittance. The transparency (% transmittance) is calculated via the Beer–Lambert law as follows:

where A is the absorbance. It is then derived as %T = T × 100, where %T is the percentage transmittance and T is the transmittance value obtained from the spectrophotometer.

2.3.9 Biodegradability Analysis of Bioplastic Films

The biodegradability of the film was studied via a soil burial test, where the samples were buried in clay soil at daily temperatures ranging from 27°C (night) to −35°C (day). The soil remained dry without any watering. At a depth of 10 cm, observations were made every 10 days. The burial test was conducted during the El Niño phenomenon. The observations included physical changes (such as color, shape, and texture) as well as changes in the weight of the bioplastic samples.

The data obtained were averaged, and Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test was performed to further separate the means of each group.

3.1 pH and Physical Properties of the Bioplastics

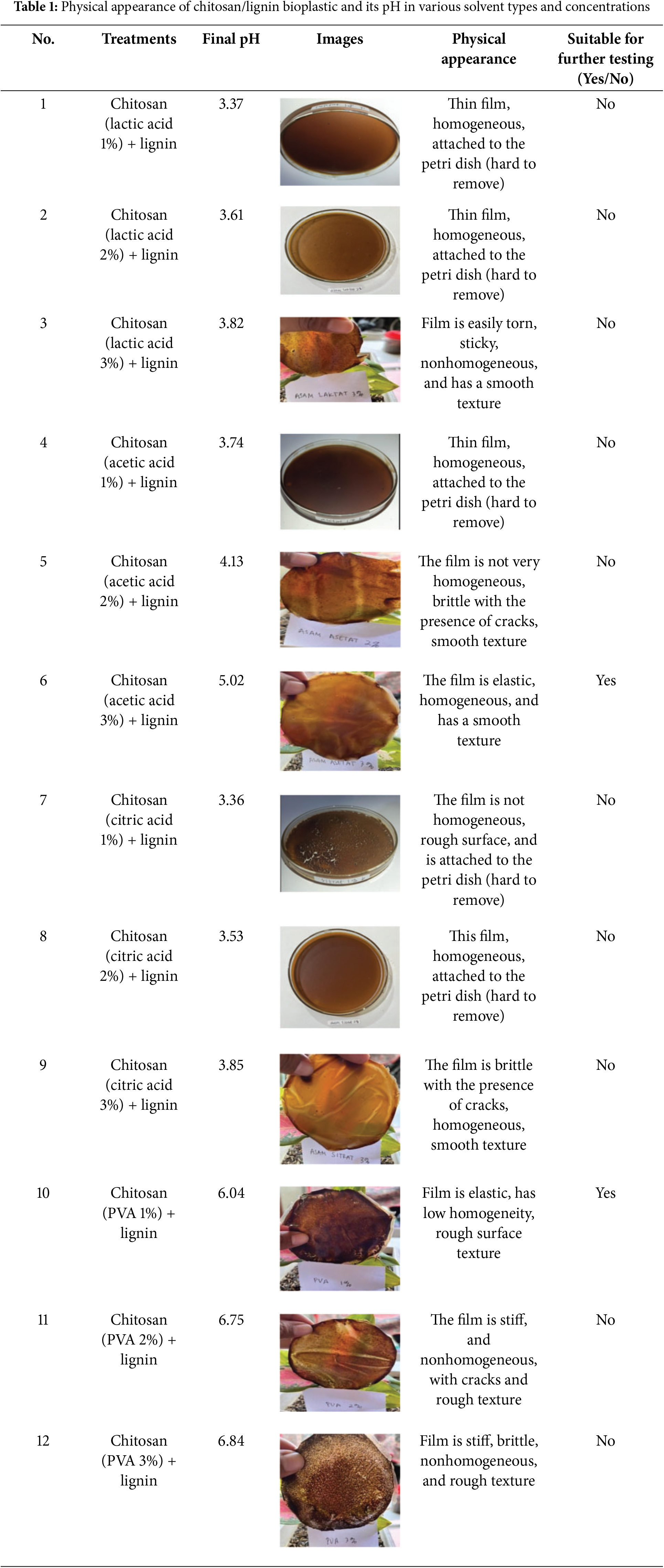

The different acid types used as solvents for chitosan and PVA at three concentrations were mixed with lignin to produce bioplastics with different pH values and physical appearances, as shown in Table 1.

For the sample where chitosan was dissolved in 1% and 2% lactic acid (pH 3.6), the dried bioplastic film was very thin, stuck to a Petri dish, and very difficult to remove without damage. When the lactic acid concentration was increased to 3%, the bioplastic film could be removed but presented a nonhomogeneous distribution of the components, a rough texture, and was sticky. This is probably due to the interactions among the amine groups of chitosan, the carboxyl groups of lactic acid, and the hydroxyl groups of lignin, making the bioplastic film matrix softer, with a sticky surface layer. This stickiness arises from the polar nature of lactic acid, which tends to attract water molecules from the environment [37].

The sample containing chitosan dissolved in a 1% acetic acid solution produced a bioplastic film that was difficult to remove from the mold. When the acetic acid concentration was increased to 2% acetic acid, the bioplastic film was easily removed from the mold, but this resulted in low homogeneity, brittleness in the presence of cracks, and a smooth texture. When a 3% acetic acid solution was used to dissolve the chitosan, the bioplastic film was elastic and homogeneous, with a smooth texture. The interaction between chitosan (in an acetic acid solution) and lignin in the bioplastic occurred through the hydroxyl groups (-OH) of lignin, forming hydrogen bonds with the amino groups (-NH2) of chitosan as well as the hydroxyl groups (-OH) in acetic acid. Acetic acid helps improve the mixing of lignin and chitosan by reducing the polarity difference [37]. At pH 5, chitosan and lignin can disperse well, resulting in a more stable and homogeneous solution [34].

On the basis of these results, mixing chitosan with a 1% citric acid concentration and lignin, as well as a 2% citric acid concentration, produced dried bioplastic films that could hardly be removed from the mold without damaging them. Moreover, treatment at a 3% concentration produced a bioplastic film that was brittle and homogeneous but contained cracks. Lignin is poorly soluble under highly acidic conditions, and at a pH below 4, it starts to agglomerate and precipitate, affecting the properties of the film, resulting in low homogeneity and flexibility.

The results revealed that mixing chitosan with PVA (2% and 3% concentrations) and lignin produced rigid, nonhomogeneous, cracked, and rough texture bioplastic formulations. Moreover, the mixing of chitosan with PVA (1% concentration) and lignin resulted in films that were slightly rigid but elastic, less homogeneous, and had a rough texture. On the basis of these results, bioplastics made from a mixture of chitosan with 3% acetic acid and lignin, as well as chitosan with 1% PVA and lignin, are elastic, nonfragile, nonsticky, and compact [9], which make them suitable for tensile strength testing. The tensile strength test results of these two formulations of bioplastics were then used to determine the best formulation for further analysis.

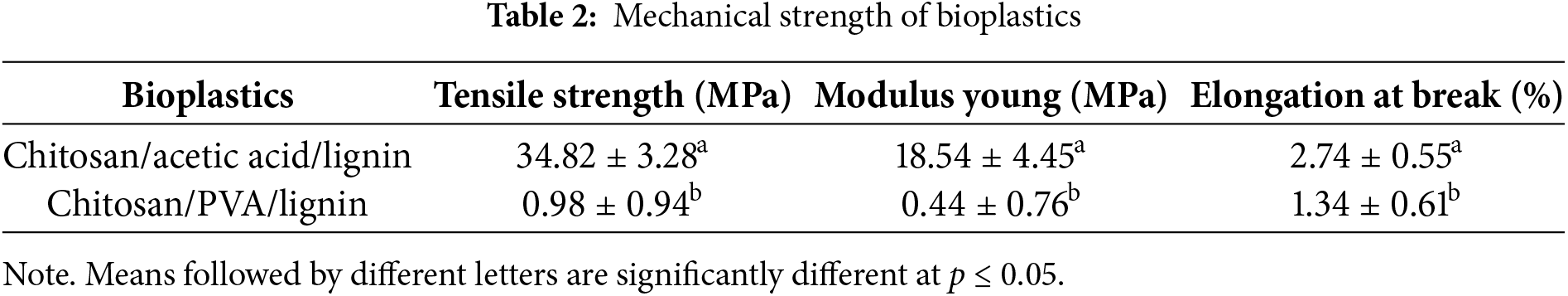

3.2 Mechanical Properties of Chitosan/Lignin Bioplastics

The mechanical properties of the bioplastics, tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break, are shown in Table 2.

The mechanical characteristics of the bioplastics in Table 2 show that the chitosan/acetic acid/lignin (Formula (1)) bioplastic film has a higher tensile strength than the chitosan/PVA/lignin (Formula (2)) does. This finding indicates the effect of the composition on the strength of the film. The chitosan/PVA/lignin bioplastic mixture has a lower tensile strength because of the presence of PVA, which acts as a plasticizer, making the film more flexible and consequently reducing the tensile strength. PVA is hydrophilic, which could lead to moisture absorption, weakening the mechanical strength of the bioplastic. Even though PVA can form hydrogen bonds with lignin, excessive water uptake can disrupt these interactions and reduce overall cohesion. Chitosan and PVA can form hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions, but these interactions might not be strong enough to significantly enhance the mechanical strength unless properly optimized. The hydrophobic-aromatic character of lignin may cause partial phase separation with the more hydrophilic PVA and chitosan, resulting in weak interfacial adhesion. Moreover, the insolubility of chitosan in water and the formation of lignin aggregates also affect the film strength. Furthermore, the absence of a crosslinking agent may also contribute to the poor mechanical strength of the material.

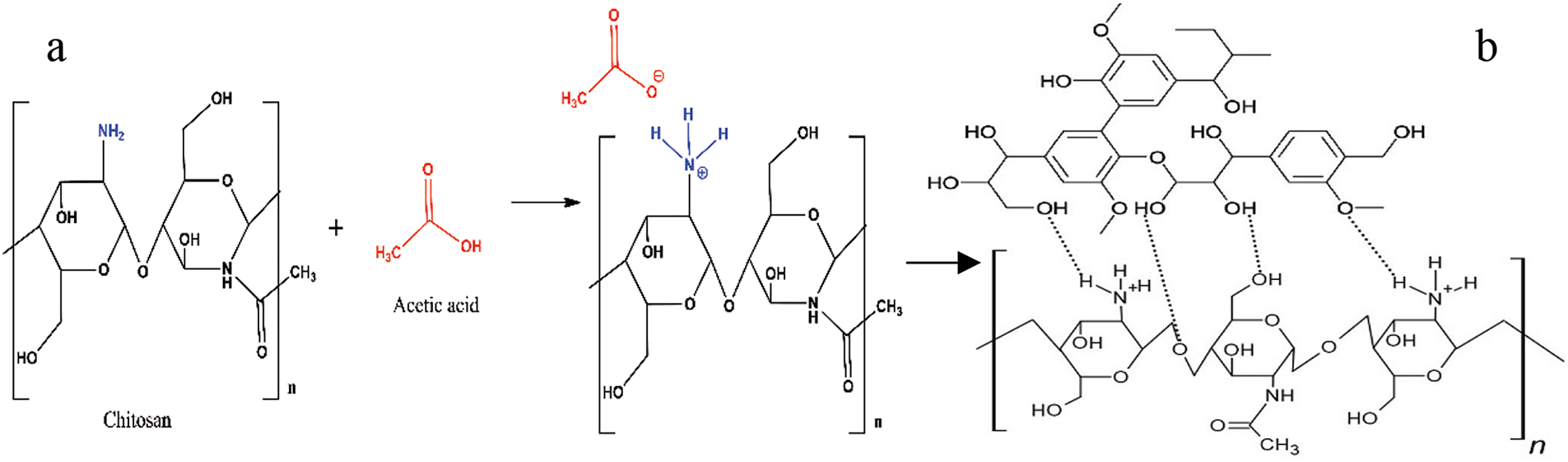

On the other hand, when acetic acid is used, chitosan dissolves because of the protonation of the amino groups [38], as presented in Fig. 2a. Furthermore, polycationic chitosan can create hydrogen bonds with the OH groups of lignin (Fig. 2b). The use of acetic acid in a mixture of chitosan and lignin effectively optimizes the formation of crosslinks and molecular interactions, resulting in a material with better mechanical properties than those of the chitosan/PVA-lignin mixture [38]. When lignin is integrated into chitosan matrices, composite systems with strong mechanical strength and elasticity may be created. These systems are necessary for handling, sterilizing, and cell development and can operate in wet or dry forms [9].

Figure 2: Possible hydrogen bonding between chitosan and lignin

The strength of a bioplastic material increases with its tensile strength [13]. According to ASTM D882 (Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting), the tensile strength for chitosan-based bioplastics is 10–50 MPa; therefore, the bioplastic with Formula (1) is suitable for additional study on the basis of the findings of the tensile strength test. To evaluate the impact of lignin addition on the properties of the final bioplastic, bioplastic Formula (1) was compared with pure chitosan bioplastic for further investigation.

3.3 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

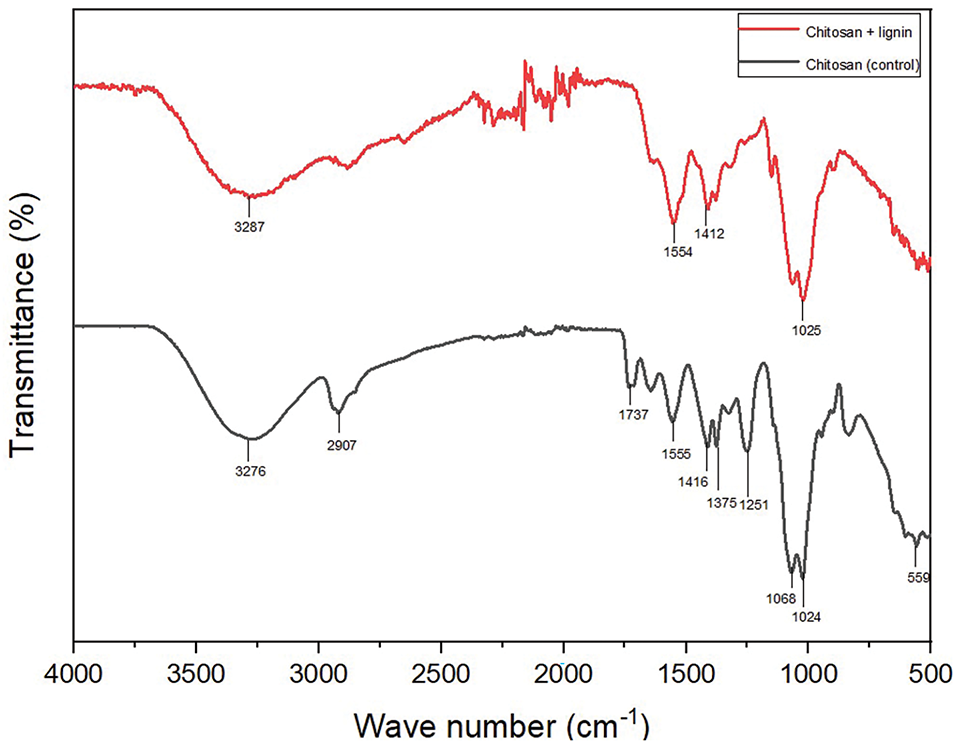

FTIR analysis was applied to identify the functional groups of chitosan and lignin and their interactions with the chitosan/lignin bioplastics (with acetic acid as a solvent for dissolving chitosan) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: FTIR spectra of the chitosan/lignin and pure chitosan bioplastics

Fig. 3 shows the characteristic peaks of chitosan and lignin in the track of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic film. The peaks at 1554 and 1412 cm−1 are associated with vibrations in the phenylpropane aromatic ring derived from lignin. At 1554 cm−1, a sharp peak, which is characteristic of the amide II band in chitosan, is observable [39]. Compared with those of the pure chitosan bioplastic, shifts in the peaks at 1555 and 1416 cm−1, indicating N-H and C-O stretching from the amide groups, are observed. This shift is likely related to the interaction between chitosan and lignin. The broad adsorption band at 3287 cm−1 corresponds to the O-H groups and the presence of hydrogen bonds between chitosan and lignin (Fig. 2b). For the chitosan bioplastic, the absorption peak at 3276 cm−1 indicates the presence of O-H and N-H groups, whereas the absorption peak at 1737 cm−1 refers to the carbonyl group [39]. In contrast, for the chitosan/lignin bioplastic, the absorption peaks are not detected because of the interaction between chitosan and lignin, which affects the intensity of these peaks. The FTIR analysis results in Fig. 3 show that the transmittance of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic is lower than that of the pure chitosan bioplastic, indicating that lignin reduces the transparency of the bioplastic because of light scattering by lignin particles. This result aligns with previous studies [39,40], where the mechanical properties of chitosan fibers were evaluated in accordance with the lignin type and concentration [40]. Crouvisier-Urion et al. [11] demonstrated that the addition of lignin to chitosan bioplastics reduces transparency and improves thermal stability.

3.4 Thermogravimetric Analysis/TGA

The TGA results shown in Fig. 4 reveal that the main decomposition phase for both bioplastic samples occurred in the range of 200°C–400°C, with the chitosan/lignin bioplastic film experiencing a lower mass loss than the pure chitosan film. The decomposed weight percentage was 55.77% for the pure chitosan bioplastics and 41.41% for the chitosan-lignin bioplastics. These findings indicate that the inclusion of lignin enhances the thermal stability of the bioplastic. Mass loss is related to a series of breakdown processes, with the formation of low-molecular-weight compounds [36]. In the early stages of decomposition (up to 200°C), the mass reduction is related to the evaporation of moisture and volatile residues present in the sample, as shown in the thermogram (Fig. 4), which was also described in a previous study [37]. Both samples showed similar initial weight losses up to 200°C.

Figure 4: TGA curves of the chitosan/lignin and pure chitosan bioplastics

The major decomposition of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic began at 200°C, but overall, the weight loss during this phase was significantly lower than that of the chitosan film, confirming the ability of lignin to increase the thermal stability. At this stage, mass loss may occur due to dehydration of the saccharide ring complex, chitosan depolymerization, disintegration of the acetate polymer unit, and its deacetylation [41,42]. In the temperature range of 400°C–600°C, the mass loss is due to the cleavage of the bonds between the carbon atoms in the benzene rings of lignin and those in the chitosan chains. At a final temperature of 600°C, the residual weight of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic sample was significantly greater (28.23%) than that of the pure chitosan bioplastic sample (14.61%). The findings of this study align with those reported by Ji et al. [2] and Rosova et al. [9]. The inclusion of lignin improved the thermal stability of the bioplastics.

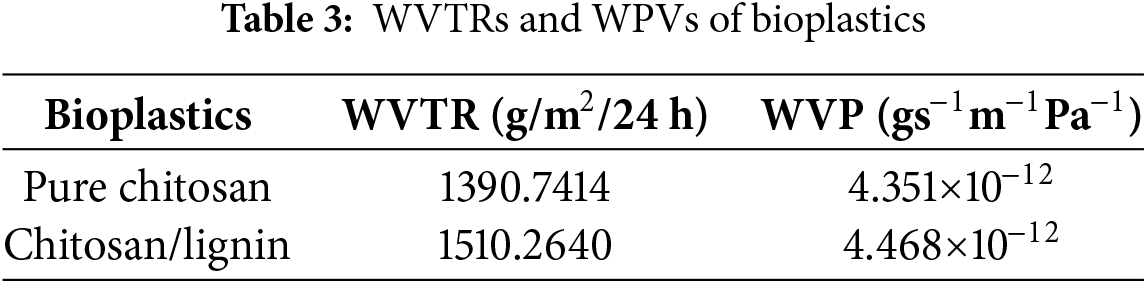

3.5 Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) and Water Vapor Permeability (WVP) Analysis

WVTR denotes a material’s capacity to retain water vapor. The transmission value influences the WVP, which denotes a material’s capacity to transmit water vapor per unit area. This value is influenced by the pore size and hydrophilicity of the bioplastic components [36]. The values of WVT and WVP are presented in Table 3. The WVP of chitosan/lignin is slightly greater than that of pure chitosan. Water adsorption increases with the addition of lignin. This difference might be related to the better dispersion of a mono-component (only chitosan) than a multiple-component (chitosan and lignin) in solution. Moreover, the intermolecular interaction between chitosan and lignin molecules can also lead to WVP and water adsorption [43].

The WVP values of the chitosan/lignin-based bioplastics were greater than those of commercial polyethylene (PE) plastic, which ranges from (7.3–9.7) × 10−13 (gs−1m−1Pa−1) [9], but lower than those of PLA, which has a WVP of 2.47 × 10−11 (gs−1m−1Pa−1) [44]. Compared with the WVP values of chitosan-ZnO and chitosan-TiO2 bioplastics [36], this value is also lower, indicating that they are more hard and brittle; thus, water vapor will easily pass through bioplastics. The elevated WVTR score for bioplastics combined with chitosan and lignin may result from weak interactions between chitosan and lignin, hence compromising barrier characteristics. The created water barrier is not as successful as anticipated in forming a robust barrier against water vapor. A higher WVP bioplastic signifies a diminished capacity to impede water vapor transmission [36]. The results suggest that the prepared bioplastics have unique applications in food packaging, particularly for those products that require moisture exchange to preserve freshness and all nutritional and organoleptic qualities.

3.6 Absorbance Capacity via UV–Vis Spectroscopy Analysis

The UV–Vis absorbance spectra of the pure chitosan bioplastic and the chitosan/lignin bioplastic are shown in Fig. 5. The absorbance of the pure chitosan bioplastic gradually increased from approximately 550 nm to 800 nm, reaching a peak (λmax) at 800 nm, with a value of 9.5495. In the case of chitosan/lignin bioplastics, light absorption increases sharply from a wavelength of 200 to 550 nm and then stabilizes at 800 nm. The maximum absorbance (λmax) for the chitosan/lignin bioplastic occurred at 800 nm, with a value of 46.5585. The UV–Vis spectra indicate that the addition of lignin to chitosan significantly enhances the absorbance, particularly in the UV range up to near the visible segment. The functional groups of lignin have the ability to block strong UV rays. Lignin chromophore functional groups have the ability to absorb UV light at wavelengths between 250 and 400 nm [45]. The absorption of UV-B (280–320 nm) may act as a natural UV protector to protect the products from degradation and variation in chemical composition, leading to alterations in color and nutritional and organoleptic properties [46]. The high UV absorbance of chitosan/lignin bioplastic indicates its potential for packaging, ensuring that the amount of UV radiation reaching the products remains low or minimal to avoid their alteration [47].

Figure 5: Absorbance capacity of pure chitosan and chitosan/lignin bioplastics

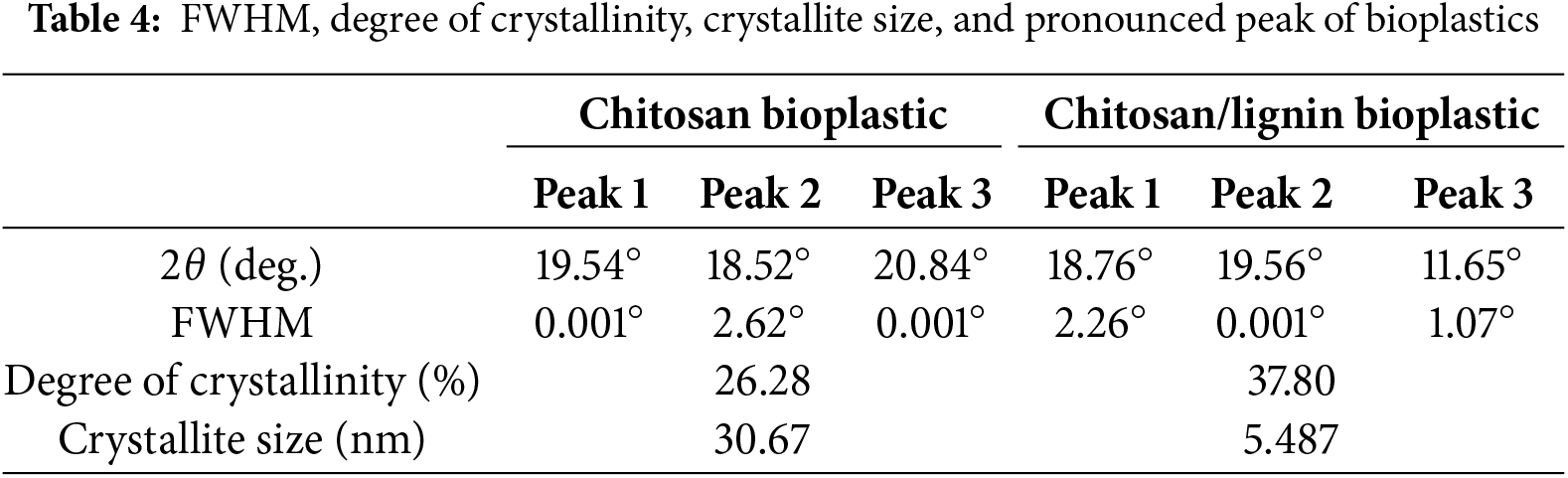

3.7 X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

XRD analysis is important for determining the potency of bioplastics for packaging applications. From the data in Table 3, the main peak of pure chitosan bioplastic occurs at 2θ values of 10°, 19.54°, 18.52°, and 20.84°, whereas the most prominent peak of chitosan/lignin bioplastics is observed at 2θ values of 18.76°, 19.56°, and 11.65°.

The chitosan bioplastic exhibited two peaks at 2θ values of approximately 10° and 20°, associated with the (101) and (020) planes, indicating an organized crystalline structure of chitosan, which is consistent with prior reports [45,48]. The presence of –OH and –NH2 groups in the chitosan structure facilitates the formation of strong inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds, and the structural regularity of chitosan enables the molecules to form crystalline areas. The diffraction pattern of pure chitosan bioplastic shows sharper peaks due to its semicrystalline structure with the presence of crystalline and amorphous regions [49]. On the other hand, the diffraction pattern of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic does not show sharp peaks, which aligns with the amorphous nature of lignin [50]. Table 4 shows the degree of crystallinity and crystallite size of the bioplastics.

The FWHM of the pure chitosan bioplastic exhibited a maximum value of 2.62° at the second peak, indicating a strain in that region, which corresponds to a decreased crystal size relative to the surrounding area. Peaks 1 and 3 exhibit FWHM values approaching 0, indicating a more uniform crystal morphology. Similarly, for chitosan and lignin bioplastics, the highest FWHM value occurred at peak 1, measuring 2.26°, followed by peak 3, which had a value of 1.07°. The FWHM value is employed to evaluate crystallite size; a smaller FWHM value in bioplastics indicates a greater crystal size, which influences the orderliness of the material’s crystal structure [51]. According to the Scherrer equation (described in the methods section), the crystal sizes of the pure chitosan bioplastics are greater than those of the chitosan/lignin bioplastics. The decreased crystal size in the pure chitosan bioplastics yields wider, sharper diffraction peaks than the smaller crystal sizes observed in the chitosan/lignin bioplastics. This is because the widening of the peak decreases with increasing crystal size, as evidenced by the Scherrer equation.

Table 4 shows the degree of crystallinity expressed as a percentage (%). Pure chitosan bioplastic has a crystallinity degree of 26.28%, whereas chitosan/lignin bioplastic has a crystallinity degree of 37.80%. In pure chitosan bioplastic, the molecular chains formed are less ordered than those in chitosan/lignin bioplastic. However, in its pure form, the interaction between chitosan chains is limited to intramolecular hydrogen bonds, resulting in lower crystallinity. In contrast, in chitosan/lignin bioplastics, lignin acts as a filler that modifies the structure and enhances intermolecular interactions. The incorporation of lignin into chitosan can form hydrogen bonds or van der Waals interactions with chitosan chains [39], which strengthen intermolecular bonding in the blend, contributing to the formation of crystalline domains.

The degree of deacetylation (DD) of chitosan influences its crystallinity; a higher DD leads to a more ordered structure, hence enhancing its crystallinity [49]. This work utilized chitosan with a DD of 80%, which is characterized by a more amorphous structure than chitosan with a greater DD (>85%) [52]. Chitosan with a DD of 80% has good solubility in aqueous acidic media due to the presence of free amino groups [53]. The incorporation of lignin additionally influences the crystal dimension, as lignin is amorphous in nature. This state leads to a reduced crystal size of the bioplastic, as the amorphous lignin particles act as a physical barrier that restricts the mobility of the polymer chains [39]. The XRD pattern demonstrated that the crystal peaks were broader and less defined than those of the pure chitosan bioplastics (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: XRD patterns of pure chitosan and the chitosan-lignin bioplastic

The addition of lignin to chitosan bioplastic induces amorphization in the resulting film [9]. As shown in the graph, the peak at 2θ = 19.54° for the pure chitosan film appears sharper than the peak at 2θ = 18.76° for the chitosan/lignin bioplastic. Since lignin is amorphous, the diffraction pattern shows weak and diffuse signals, commonly referred to as a diffraction halo [51]. This further confirms that lignin lacks an orderly crystalline structure. The incorporation of lignin into the bioplastic increases the hydrated form, enhancing the ability of the bioplastic to retain or absorb water while reducing the anhydrous form [9]. The degree of deacetylation (DD) of chitosan influences its crystallinity; a higher DD results in a more ordered structure, hence enhancing its crystallinity [49]. This work utilized chitosan with a DD of 80%, which is characterized by a more amorphous structure than chitosan with a greater DD (>85%) [52].

Contact angle studies evaluate the capacity of a bioplastic surface to repel or absorb liquids, providing information about the hydrophobicity/hydrophilic balance [54]. The results of the contact angle analysis are shown in Fig. 7. Using ImageJ, the initial contact angle value of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic was 98.5 ± 3°, which remained constant for up to 4 min. Afterwards, a decrease was observed, dropping to 88 ± 1°, and this trend continued until the 13th min. For the pure chitosan bioplastics, the initial contact angle was 91.6 ± 1°. The contact angle measured at the first minute significantly decreased to 84.3 ± 4° and 49.8 ± 2° 2 min and 30 s after contact, respectively. The contact angle is in the range of the contact angle measured in chitosan/lignin bioplastics of 85°–95°, as lignin can slightly increase the surface hydrophobicity of the film [13]. This phenomenon has also been reported in other polysaccharide and lignosulfonate films [55].

Figure 7: Changes in the contact angle of the chitosan and chitosan/lignin bioplastics based on the water absorption time

Compared with the chitosan bioplastic, glycerol was added as a plasticizer, as reported by Agustiany et al. [27]. The contact angle is also greater. The contact angle of 90°–150° indicates the hydrophobic properties of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic surface [56]. According to the theory of contact angle analysis, a contact angle of less than 90° indicates that a solid surface is hydrophilic, whereas a contact angle greater than 90° indicates that the surface is not “wetted” or is hydrophobic [57]. Furthermore, superhydrophobic surfaces emulate the water-repellent characteristics found in nature, exhibiting significant resistance to water with contact angles above 150° [58].

3.9 Color and Transparency Analysis

On the basis of the results of UV–Vis spectrophotometry, the transmittance (%T) value for pure chitosan bioplastic at 600 nm was 1.54%, whereas that for chitosan/lignin was 5.16 × 10−45%. A %T value approaching 0 indicates that almost no light is transmitted through the bioplastic, demonstrating that the presence of lignin makes the bioplastic highly opaque at a wavelength of 600 nm.

The dark color of lignin, which is complex aromatic and results from the acid isolation and drying process, has a structure that absorbs more light, which results in reduced transparency of the bioplastic [47]. This finding is in agreement with a previous study in which the color of lignin fluctuated significantly throughout the separation and purification process. In the isolation of lignin, condensation might occur, which contributes to conjugation and saturation, and then dark lignin is obtained at a high pH [59]. The transparencies of the two bioplastic types are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Comparison of color transparency between chitosan (a) and chitosan/lignin bioplastics (b)

3.10 Biodegradability Analysis

The biodegradability test (soil burial test) was conducted from September 2023 to March 2024. The climatic circumstances for the biodegradability test included average daily temperatures ranging from 33°C to 35°C during the day and 27°C to 32°C at night. The soil utilized for biodegradability assessment is sourced from the local environment and is devoid of any compost or decomposer, including EM4. The average initial weight of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic was 0.4144 g.

To evaluate the biodegradability of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic in this study, a soil burial test was conducted from September 2023 to March 2024. The average initial weight of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic was 0.4144 g (0 days). As presented in Fig. 9, after 10 days of burial, no obvious deformation or physical changes occurred, and there was no color change. The sample adheres to the soil surface but remains readily removable; its weight is somewhat diminished, measuring 0.407 g, indicating a 1.8% loss. On day 20, the chitosan/lignin bioplastic lost its stiffness, became brittle, and exhibited difficulty in removing soil residues from its surface. Owing to a segment of the dirt being adhered to and unable to be extricated, the sample weight increased to 0.5441 g. The chitosan/lignin bioplastic samples exhibited no discoloration on day 20. On day 30, the bioplastic began degrading, resulting in significant soil adhesion; consequently, the weights of the chitosan and lignin bioplastics were accurately determined. The mass of the bioplastic sample combined with chitosan and lignin was 0.9069 g. Moreover, the chitosan/lignin bioplastic exhibited holes characterized by a brittle texture.

Figure 9: Physical changes in bioplastics via the soil burial test method

By day 40, the chitosan/lignin bioplastic exhibited significant brittleness, and an increased amount of dirt had adhered to its surface. Consequently, measuring the weight of microplastics is a challenge because of their delicacy and the deposition of soil on their surface. The weights of the chitosan and lignin bioplastics were measured, and the samples were subsequently retrieved after 180 days. The soil burial test results indicated that the degradation of chitosan/lignin bioplastics occurred over 180 days, resulting in a final weight of 0.3047 g, indicating a 26% reduction. On the 180th day, the chitosan/lignin bioplastic exhibited fragmentation without any alteration in color, retaining the soil residues on its surface. Fig. 9 summarizes the physical changes that transpired in the bioplastics over a period of 180 days. As both lignin and chitosan are biodegradable, plastic can be degraded through microbial colonization and enzymatic breakdown during soil burial tests. Chitosan enhances the water absorption of bioplastics, promoting microbial accessibility and enzymatic activity and resulting in accelerated breakdown rates [60]. Moreover, the intricate structure of lignin, formed by related complexes, engages with microbial enzymes that degrade lignin components and facilitate mineralization [61]. As a result, owing to their biodegradability, the lignin-chitosan bioplastic was reduced to fragments on day 180, as shown in Fig. 9.

In the present work, bioplastic films based on the combination of chitosan and lignin were developed with properties suitable for future applications in food packaging to replace fossil-based plastics. Compared with the traditional fillers used in food packaging, the advantages of using lignin to improve some key properties of bioplastics have been defined. The results indicate that dissolving chitosan in a 3% acetic acid solution and then combining it with lignin leads to the formation of a bioplastic film with better properties than those obtained at lower concentrations of acetic acid or when other largely used organic acids, such as lactic acid and citric acid, are used. The FTIR analysis confirmed the interactions between the chitosan matrix and lignin, which led to an increase in the tensile strength (34.82 MPa), Young’s modulus (18.54 MPa), and elongation at break (2.74%) of the bioplastic. Thermal analysis revealed thermal stability of the composite film due to the presence of lignin. Moreover, UV–Vis analysis elucidates the role of lignin in improving the UV absorption capacity of the film. The WVP resulted in a relatively high value, indicating that improvement in the blending of chitosan and lignin should be considered to ensure a homogeneous distribution of lignin within the film matrix. The presence of lignin increases the hydrophobicity of the chitosan film and decreases the transparency of the lignin/chitosan bioplastic because of its dark color. The biodegradation study revealed slow degradation of the chitosan/lignin bioplastic in the soil, with an onset after 30 days and a loss of 26% of the weight after 180 days. The reported results reveal the potential of using bioplastics made of chitosan and lignin as fillers as single-use packaging for fresh products, shopping bags, or agricultural mulch, considering the environmental aspects that they offer. Despite the obvious advantages of chitosan-based bioplastics, issues persist in scaling production and maintaining uniform quality across various chitosan and lignin sources. Additional research is needed to refine formulations and improve the market potential of these sustainable materials.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to convey their appreciation to the Laboratory of Agro-industrial waste processing, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Lampung, and the Integrated Laboratory of Bioproduct BRIN for supporting the facilities and resources required to conduct this research. Gratitude is expressed to colleagues and collaborators who provided essential input and help during the manuscript’s preparation.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the joint research collaboration of the Research Organization of Agriculture and Food National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) FY 2024 (Grant number: 6/III.11/HK/2024), with Widya Fatriasari as the Principal Investigator.

Author Contributions: Conceptual, writing—original draft, writing—review editing: Widya Fatriasari, Pelita Ningrum, Samsul Rizal, Antonio Di Martino, Wahyu Hidayat, and Lee Seng Hua; Methodology and validation: Wahyu Hidayat, Widya Fatriasari, Sri Hidayati, Lee Seng Hua, Antonio Di Martino, Pelita Ningrum, Apri Heri Iswanto, and Erika Ayu Agustiany; Resources and project administration: Widya Fatriasari, Emma Rochima, and Apri Heri Iswanto; Investigation: Widya Fatriasari, Sri Hidayati, and Wahyu Hidayat; Visualization: Widya Fatriasari, Pelita Ningrum, and Atonio Di Martino. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are contained within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships, which may be considered potential competing interests: Widya Fatriasari reports financial support provided by the National Research and Innovation Agency. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

1. Wang X, Pang Z, Chen C, Xia Q, Zhou Y, Jing S, et al. All-Natural Degradable, rolled-up straws based on cellulose micro and nano-hybrid fibers. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(22):1910417. doi:10.1002/adfm.201910417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ji M, Li J, Li F, Wang X, Man J, Li J, et al. A biodegradable chitosan-based composite film reinforced by ramie fibre and lignin for food packaging. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;281:119078. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.119078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Fabra MJ, López-Rubio A, Lagaron JM. 15—Biopolymers for food packaging applications. In: Aguilar MR, San Románs J, editors. Smart polymers and their applications. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

4. Thakur VK, Thakur MK. Recent advances in graft copolymerization and applications of chitosan: a review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2014;2(12):2637–52. doi:10.1021/sc500634p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mousavi SN, Nazarnezhad N, Asadpour G, Ramamoorthy SK, Zamani A. Ultrafine friction grinding of lignin for development of starch biocomposite films. Polymers. 2021;13(12):2024. doi:10.3390/polym13122024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ghozali M, Meliana Y, Fatriasari W, Antov P, Chalid M. Preparation and characterization of thermoplastic starch from sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) by extrusion method. J Renew Mater . 2023;11(4):1963–76. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.026060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xie F, Luckman P, Milne J, McDonald L, Young C, Tu CY, et al. Thermoplastic starch: current development and future trends. J Renew Mater . 2014;2(2):95–106. doi:10.7569/JRM.2014.634104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ravi Kumar MNV. A review of chitin and chitosan applications. React Funct Polym. 2000;46(1):1–27. doi:10.1016/S1381-5148(00)00038-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rosova E, Smirnova N, Dresvyanina E, Smirnova V, Vlasova E, Ivan’kova E, et al. Biocomposite materials based on chitosan and lignin: preparation and characterization. Cosmetics. 2021;8(1):24. doi:10.3390/cosmetics8010024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Solihat NN, Hidayat AF, Ilyas RA, Thiagamani SMK, Azeele NIW, Sari FP, et al. Recent antibacterial agents from biomass derivatives: characteristics and applications. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2024;9(3):283–309. doi:10.1016/j.jobab.2024.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Crouvisier-Urion K, Regina da Silva Farias F, Arunatat S, Griffin D, Gerometta M, Rocca-Smith JR, et al. Functionalization of chitosan with lignin to produce active materials by waste valorization. Green Chem. 2019;21:4633–41. doi:10.1039/C9GC01372E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Priyadarshi R, Rhim J-W. Chitosan-based biodegradable functional films for food packaging applications. Innovat Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2020;62(2):102346. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Crouvisier Urion K, Bodart P, Winckler P, Raya J, Gougeon R, Cayot P, et al. Biobased composite films from chitosan and lignin: antioxidant activity related to structure and moisture. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4(12):6371–81. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fiallos-Núñez J, Cardero Y, Cabrera-Barjas G, García-Herrera CM, Inostroza M, Estevez M, et al. Eco-friendly design of chitosan-based films with biodegradable properties as an alternative to low-density polyethylene packaging. Polymers. 2024;16(17):2471. doi:10.3390/polym16172471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jin J, Luo B, Xuan S, Shen P, Jin P, Wu Z, et al. Degradable chitosan-based bioplastic packaging: design, preparation and applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;266:131253. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Nguyen M, Marc E, Hessel V, Coad B. A review of the current and future prospects for producing bioplastic films made from starch and chitosan. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2024;12(5):1750–68. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c06094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Albar N, Anuar S, Azmi A, Che Soh S, Bhubalan K, Ibrahim Y, et al. Mechanical, and wettability properties of bioplastic material from Manihot esculenta cassava-chitosan blends as plastic alternative. Starch-Stärke. 2024;77(1):2300278. doi:10.1002/star.202300278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nair S, Trafiałek J, Kolanowski W. Edible packaging: a technological update for the sustainable future of the food industry. Appl Sci. 2023;13(14):8234. doi:10.3390/app13148234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Souza VGL, Pires JRA, Rodrigues C, Coelhoso IM, Fernando AL. Chitosan composites in packaging industry—current trends and future challenges. Polymers. 2020;12(2):417. doi:10.3390/polym12020417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hao Y, Cheng L, Song X, Gao Q. Functional properties and characterization of maize starch films blended with chitosan. J Thermoplastic Compos Mater. 2023;36(12):4977–96. doi:10.1177/08927057221142228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hafizulhaq F, Zainal P, Abdullah S. The potential of chitosan-starch blend polymers as edible coatings for the preservation of fruits and vegetables: a mini-review. J Fibers Polymer Compos. 2023;2(2):157–67. doi:10.55043/jfpc.v2i2.126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ahmed MJ, Ashfaq J, Sohail Z, Channa IA, Sánchez-Ferrer A, Ali SN, et al. Lignocellulosic bioplastics in sustainable packaging—Recent developments in materials design and processing: a comprehensive review. Sustain Mater Technol. 2024;41(4):e01077. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2024.e01077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bajwa DS, Pourhashem G, Ullah AH, Bajwa SG. A concise review of current lignin production, applications, products and their environmental impact. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;139(9):111526. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ridho MR, Agustiany EA, Rahmi Dn M, Madyaratri EW, Ghozali M, Restu WK, et al. Lignin as green filler in polymer composites: development methods, characteristics, and potential applications. In: Advances in materials science and engineering. London, UK: Hindawi Limited; 2022. p. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

25. Li K, Zhong W, Li P, Ren J, Jiang K, Wu W. Recent advances in lignin antioxidant: antioxidant mechanism, evaluation methods, influence factors and various applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;251(11):125992. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Naebe M. Lignin: a review on structure, properties, and applications as a light-colored UV absorber. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021;9(4):1427–42. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c06998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Agustiany EA, Nawawi DS, Di Martino A, Sari FP, Fatriasari W. Lignin-chitosan-based bioplastics from oil palm empty fruit bunches for seed coating. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2024;62(5):103435. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jufri M, Lusiana RA, Prasetya NBA. Effects of additional polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) on the physiochemical properties of chitosan-glutaraldehyde-gelatine bioplastic. Jurnal Kimia Sains dan Aplikasi. 2022;25(3):7. doi:10.14710/jksa.25.3.130-136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Patiparn B, Piyachat W. Effects of chemical compositions of chitosan-based hydrogel on properties and collagen release. ASEAN Eng J. 2021;11(2):85–100. doi:10.11113/aej.v11.16684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Janik W, Wojtala A, Pietruszka A, Dudek G, Sabura E. Environmentally friendly melt-processed chitosan/starch composites modified with PVA and lignin. Polymers. 2021;13(16):2685. doi:10.3390/polym13162685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kanikireddy V, Yallapu M, Varaprasad K, Nagireddy N, Ravindra S, Neppalli S, et al. Fabrication of curcumin encapsulated chitosan-PVA silver nanocomposite films for improved antimicrobial activity. J Biomater Nanobiotechnol. 2011;2:55–64. doi:10.4236/jbnb.2011.21008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Roy J, Salaün F, Giraud S, Ferri A, Guan J, Chen G. Solubility of chitin: solvents, solution behaviors and their related mechanisms. In: Solubility of chitin: solvents, solution behaviors and their related mechanisms; Amsterdam, Netherland: Elsevier Ltd.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

33. Falah F, Salsabila RN, Pradiani W, Karimah A, Lubis MAR, Prianto AH, et al. Pengaruh lama penyimpanan dan pengenceran lindi hitam terhadap karakteristik lignin kraft Acacia mangium. Jurnal Riset Kimia. 2022;13(2):138–51. doi:10.25077/jrk.v13i2.506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Vernaez O, Neubert KJ, Kopitzky R, Kabasci S. Compatibility of chitosan in polymer blends by chemical modification of bio-based polyesters. Polymers. 2019;11(12):1939. doi:10.3390/polym11121939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. International A. Standard test method for tensile properties of thin plastic sheeting. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM. 2002. 2002 p. [Google Scholar]

36. Suryanegara L, Fatriasari W, Zulfiana D, Anita SH, Masruchin N, Gutari S, et al. Novel antimicrobial bioplastic based on PLA-chitosan by addition of TiO2 and ZnO. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2021;19(1):415–25. doi:10.1007/s40201-021-00614-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Silvestre J, Delattre C, Michaud P, de Baynast H. Optimization of chitosan properties with the aim of a water resistant adhesive development. Polymers. 2021;13(22):4031. doi:10.3390/polym13224031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chan MY, Husseinsyah S, Sam ST. Corn cob filled chitosan biocomposite films. Adv Mater Res. 2013;747:649–52. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.747.649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen L, Tang C-Y, Ning N-Y, Wang C-Y, Fu Q, Zhang Q. Preparation and properties of chitosan/lignin composite films. Chin J Polym Sci. 2009;27(5):739–46. doi:10.1142/S0256767909004448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang K, Loo LS, Goh K-L. A facile method for processing lignin reinforced chitosan biopolymer microfibres: optimising the fibre mechanical properties through lignin type and concentration. Mater Res Express. 2016;3:035301. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/3/3/035301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Haldorai Y, Shim J-J. Novel chitosan-TiO2 nanohybrid: preparation, characterization, antibacterial, and photocatalytic properties. Polym Compos. 2014;35(2):327–33. doi:10.1002/pc.22665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Aradmehr A, Javanbakht V. A novel biofilm based on lignocellulosic compounds and chitosan modified with silver nanoparticles with multifunctional properties: synthesis and characterization. Coll Surf A: Physicochem Eng Aspe. 2020;600(1):124952. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.124952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Debeaufort F, Voilley A, Meares P. Water vapor permeability and diffusivity through methylcellulose edible films. J Membr Sci. 1994;91(1):125–33. doi:10.1016/0376-7388(94)00024-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li W, Zhang C, Chi H, Li L, Lan T, Han P, et al. Development of antimicrobial packaging film made from Poly(Lactic Acid) incorporating titanium dioxide and silver nanoparticles. Molecules. 2017;22(7):1170. doi:10.3390/molecules22071170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Morsy M, Khaled M, Amyn H, El Ebissy A, Salah A, Youssef M. Synthesis and characterization of freeze dryer chitosan nano particles as multi functional eco-friendly finish for fabricating easy care and antibacterial cotton textiles. Egyptian J Chem. 2019;62(7):1277–93. [Google Scholar]

46. Kaur R, Bhardwaj SK, Chandna S, Kim K-H, Bhaumik J. Lignin-based metal oxide nanocomposites for UV protection applications: a review. J Clean Prod. 2021;317(4):128300. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sadeghifar H, Venditti R, Jur J, Gorga R, Pawlak J. Cellulose-lignin biodegradable and flexible UV protection film. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;5(1):625–31. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Tripathi S, Mehrotra G, Dutta P. Physicochemical and bioactivity of cross-linked chitosan-PVA film for food packaging applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2009;45(4):372–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Hilya Nur I, Ruri Agung W, Silfiana Nisa P. Biopolimer Kitosan dan Penggunaanya dalam Formulasi Obat penerbitgraniti Location: penerbitgraniti; 2020. (In Indonesian). [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Available from: http://repository.akfarsurabaya.ac.id. [Google Scholar]

50. Erfani Jazi M, Narayanan G, Aghabozorgi F, Farajidizaji B, Aghaei A, Kamyabi MA, et al. Structure, chemistry and physicochemistry of lignin for material functionalization. SN Appl Sci. 2019;1(9):1094. doi:10.1007/s42452-019-1126-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Warren B. X-ray diffraction. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.; 1969. [Google Scholar]

52. Khaled A. A review on natural biodegradable materials: chitin and chitosan. React Funct Polymrs. 2021;6:2021–2. [Google Scholar]

53. Sikorski D, Gzyra-Jagieła K, Draczyński Z. The kinetics of chitosan degradation in organic acid solutions. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(5):236. doi:10.3390/md19050236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Pavoni JMF, Luchese CL, Tessaro IC. Impact of acid type for chitosan dissolution on the characteristics and biodegradability of cornstarch/chitosan based films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;138(3):693–703. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Baumberger S, Lapierre C, Monties B, Lourdin D, Colonna P. Preparation and properties of thermally moulded and cast lignosulfonates-starch blends. Ind Crops Prod. 1997;6(3):253–8. doi:10.1016/S0926-6690(97)00015-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Parvate S, Dixit P, Chattopadhyay S. Superhydrophobic surfaces: insights from theory and experiment. J Phys Chem B. 2020;124(8):1323–60. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b08567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Deng Y, Peng C, Dai M, Lin D, Ali I, Alhewairini SS, et al. Recent development of super-wettable materials and their applications in oil-water separation. J Clean Prod. 2020;266(3):121624. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Fatriasari W, Daulay IRS, Fitria, Syahidah, Rajamanickam R, Selvasembian R, et al. Recent advances in superhydrophobic paper derived from nonwood fibers. Biores Technol Rep. 2024;27:101900. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2024.101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Zhang H, Fu S, Chen Y. Basic understanding of the color distinction of lignin and the proper selection of lignin in color-depended utilizations. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;147(2):607–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Alam M, Halid T, Illing I. Efek penambahan kitosan terhadap karakteristik fisika kimia bioplastik pati batang kelapa sawit. Indonesian J Fundam Sci. 2018;4(1):39–44. (In Indonesian). doi:10.26858/ijfs.v4i1.6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Raychaudhuri A, Behera M. Chapter 9—Microbial degradation of lignin: conversion, application, and challenges. In: Shah MP, Rodriguez-Couto S, Kapoors RT, editors. Development in wastewater treatment research and processes. Amsterdam, Netherland: Elsevier; 2022. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools