Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Study of Biosynthesis and Biodegradation by Microorganisms from Plastic-Contaminated Soil of Polyhydroxybutyrate Based Composites

1 Department of Physical Chemistry of Fossil Fuels of the Institute of Physical-Organic Chemistry and Coal Chemistry Named after L. M. Lytvynenko of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Lviv, 79060, Ukraine

2 Department of Chemical Technology and Plastic Processing, Lviv Polytechnic National University, Lviv, 79013, Ukraine

3 Institute of Chemical Engineering, Polish Academy of Sciences, Gliwice, 44-100, Poland

4 Department of Chemical Technology of Oil and Gas Processing, Lviv Polytechnic National University, Lviv, 79013, Ukraine

* Corresponding Author: Serhiy Pyshyev. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1439-1458. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0030

Received 03 February 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

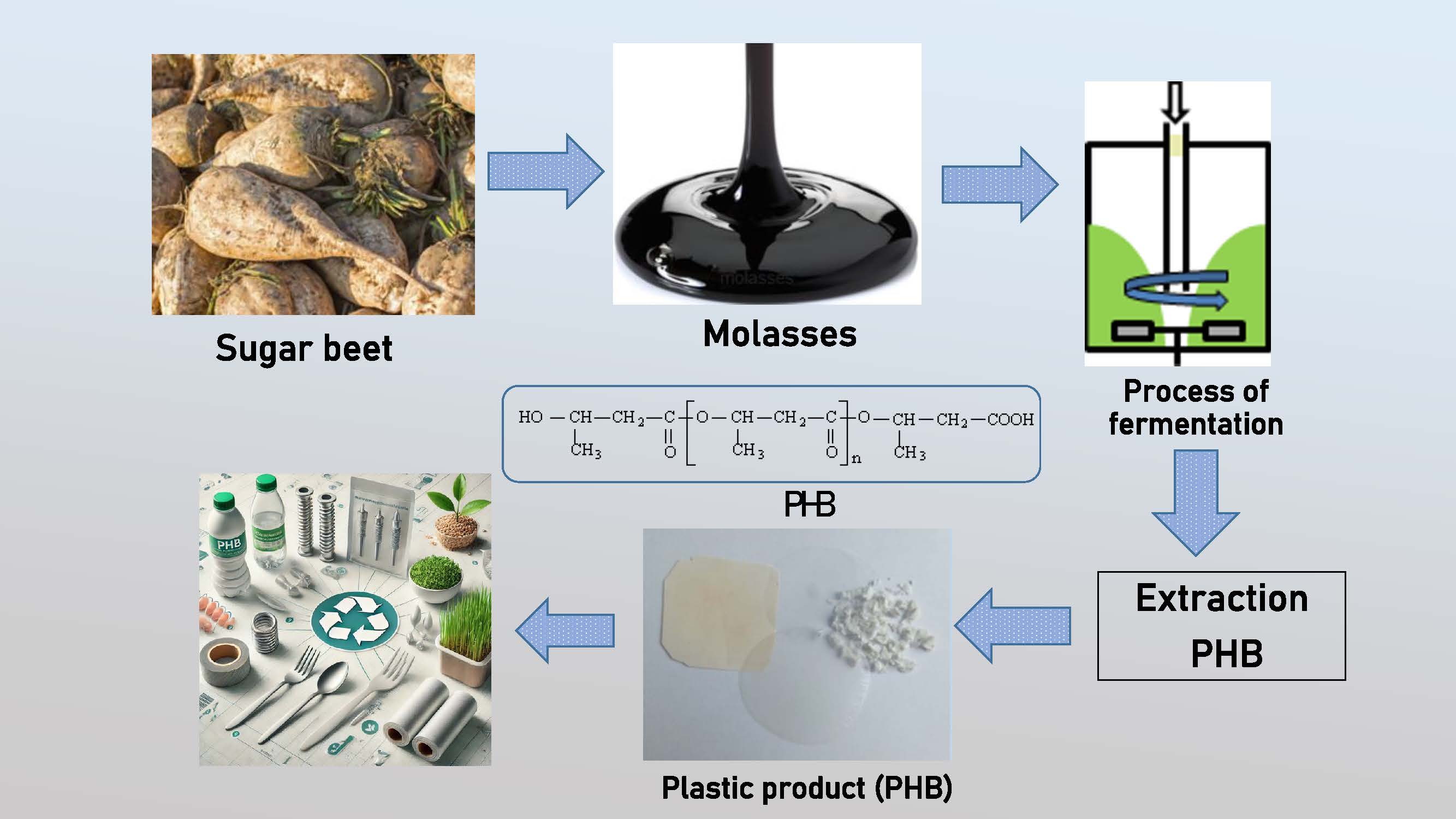

The selection of carbon sources and the biosynthesis of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) by the Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 strain using renewable raw materials were investigated. Among the tested substrates (starch, sucrose, molasses, bran), molasses as the carbon source yielded the highest PHB production. The maximum polymer yield (26% of dry biomass) was achieved at a molasses concentration of 40 g/L. PHB formation was confirmed via thin-layer chromatography, gas chromatography and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Composite films based on PHB, polylactic acid (PLA), and their blends were fabricated using the solvent casting. The biodegradation of these films was studied with bacteria isolated from plastic-contaminated soil. These bacteria utilized the biopolymers as their sole carbon source, with the biodegradation process lasting three months. Structural and chemical changes in the films were analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry, and thermogravimetry. Among the microorganisms used to study the biodegradation of PHB, PLA, and their blends, Streptomyces sp. K2 and Streptomyces sp. K4 exhibited the highest biodegradation efficiency. PHB-containing films demonstrated significant advantages over other biodegradable polymers, as they degrade under aerobic conditions via enzymatic hydrolysis using microbial depolymerases.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Plastics are durable, chemically and biologically inert polymers widely used in construction, packaging, and medicine [1–3]. Derived from petrochemical feedstocks, they have become an essential part of modern life due to their low cost, durability, and excellent mechanical and thermal properties [4]. Global plastic production is around 140 million tons annually. However, their resistance to biodegradation has led to severe environmental concerns, as plastics persist in ecosystems for decades.

The accumulation of plastic waste poses significant ecological and health risks. Plastic pollution affects water resources and threatens marine and avian life [5,6]. Over the past decade, global plastic production has increased by 1.5 times, with the United Nations’ estimates predicting an annual output of 1.2 billion tons by 2060. Despite efforts to recycle certain plastics, substantial amounts of plastic waste still end up in landfills, contaminating soil and ecosystems. Packaging materials, including plastic bags and single-use items, constitute approximately 40% of total plastic waste. Given the inevitable depletion of petroleum reserves, developing sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics is imperative.

Thus, biodegradable polymers and polymeric materials, which remain durable during use but can degrade under environmental influences, have recently garnered significant attention [7,8]. Among them, biodegradable materials based on biopolymers offer a promising alternative to traditional plastics. These polymers, produced by various microorganisms, share similar properties with conventional plastics but can degrade under aerobic or anaerobic conditions [9]. Two of the most widely used biopolymers are polylactic acid (PLA) and polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB).

PLA ([CH(CH3)COO]n) is a synthetic, biocompatible, and biodegradable aliphatic polyester with excellent barrier properties. It is a viable alternative to polystyrene, polypropylene, and acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene plastics in various applications [10]. PLA is a transparent, colorless, and rigid thermoplastic derived from renewable resources via lactic acid fermentation. However, PLA is less susceptible to biodegradation than other aliphatic polyesters, such as PHB, and decomposes more slowly only under specific conditions [11,12].

The degradation rate of PLA depends on factors such as surface area and susceptibility to soil microorganisms. PLA primarily degrades through chemical hydrolysis of the ester bonds into shorter oligomers, dimers, and monomers. Under severe composting conditions (60°C, high humidity), PLA decomposes within 30 days [13]. However, the process is significantly slower in natural environments such as soil and water. Most PLA-degrading microorganisms belong to the Pseudonocardiaceae family, including genera such as Amycolatopsis, Lentzea, Kibdelosporangium, Streptoalloteichus, and Saccharothrix [14]. UV irradiation is often used to accelerate PLA degradation.

PHB ([CH(CH3)CH2COO]n) is the most common polymer in the polyhydroxyalkanoate family. It is hydrophobic, highly crystalline, and has a high melting point. PHB is synthesized by bacteria under conditions of limited oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, or trace element concentrations, combined with an excess of carbon sources. Typically, the nutrients in the growth medium are the same as those used for protein synthesis. However, protein synthesis ceases under nitrogen-limited conditions, and PHB production is triggered instead [15].

The increasing interest in polyhydroxyalkanoates, along with polymeric materials and items based thereon with enhanced biodegradability and biocompatibility, is driven by their potential to be produced from renewable resources, industrial organic waste, and agricultural residues. Therefore, research efforts focus on developing new and modifying known biodegradable polymers and thermoplastic composites with high manufacturability and desirable properties, including controlled biodegradability. These features make them suitable for packaging (including food and medicines), osteoplastic materials for bone tissue repair, single-use items, etc. Understanding the biodegradation mechanisms of PHB and its blends with PLA is crucial for developing effective packaging materials and short-lifespan products to replace conventional petrochemical plastics.

Previous research [16–18] conducted at the Department of Physical Chemistry of Fossil Fuels at the Institute of Physical-Organic Chemistry and Coal Chemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine demonstrated that among the bacterial strains studied—Azotobacter vinelandii N-15, Pseudomonas sp. PS-17 and Rhodococcus erythropolis Au-1—the first strain, exhibited the highest PHB bioproduction efficiency.

This study aims to investigate PHB production from renewable feedstocks, its blends with PLA, and the biodegradation of films based on these polymers using bacteria isolated from plastic-contaminated soil.

The Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 strain was obtained from the “Enzyme” collection (Vinnytsia, Ukraine). PHB was extracted from the biomass of Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 at the Department of Physical Chemistry of Fossil Fuels at the InPOCC, named after L. M. Lytvynenko of the NAS of Ukraine. Bacteria were isolated from biofilms on polyethylene degraded in compost (K2, K4, K5, K6) and soil (U1, U2, U3, U3.1, U4, U5). PLA granules were provided by Damas-beta (China) (CAS 26100-51-6). Salts, nutrient media, and solvents were purchased from Merck Chemical Company.

Polymer-degrading bacteria were isolated as described in [19]. Polyethylene samples were buried in soil mixed with biodegradable waste (vegetable and fruit peels, tea leaves, shredded leaves, and grass) at a depth of 30 cm. After one year, the polyethylene was carefully removed and washed with a sterile PBS buffer (pH 7). Bacterial isolation was performed using serial dilution and spread plate techniques on agar plates. Following incubation on agar plates supplemented with LDPE powder as a carbon source, morphologically and biochemically distinct isolates were obtained. All pure isolates were characterized for their physiological and biochemical properties according to [20].

The Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 strain was cultivated in a nutrient medium with the following composition (g/L): molasses—30; KH2PO4—0.2; K2HPO4—0.8; CaSO4—0.13; trace elements—1 mL; distilled water—to 1 L; pH—7 ± 0.2; temperature—31 ± 0.5°C. The inoculum was a 24-h culture in the exponential growth phase, grown on Ashby medium with 3% (w/w) mannitol, with a cell titer of 2 × 108 CFU/mL. The trace element solution contained (g/L): ZnSO4·7H2O—0.2; H3BO3—0.6; MnCl2·4H2O—0.06; CoCl2·6H2O—0.4; CuSO4·4H2O—0.02; NaMoO4·2H2O—0.06. Cultivation was carried out for 72 h.

2.2.3 Biomass and PHB Content Analysis

To assess strain growth dynamics and biopolymer accumulation, 3 mL of culture fluid was sampled at 4, 7, 24, 30, 48, 54, and 72 h, and optical density (OD) was measured at a wavelength of λ = 590 nm (Shimadzu UVmini-1240). PHB was extracted by centrifuging the bacterial biomass, washing it twice with purified water, and disintegrating it using ethanol (100 rpm, 2 h, 35°C). After centrifugation (15 min, 6000 rpm), the precipitate was transferred to a Soxhlet apparatus for chloroform extraction over five cycles. The solvent was evaporated under a vacuum. For polymer purification, PHB was dissolved in chloroform and precipitated with ethanol (chloroform-ethanol 1:5). The resulting PHB precipitate was decanted and dried to a constant weight.

The purity of PHB synthesized by A. vinelandii N-15 was determined using gas chromatography [21] with a Thermo Trace 1300 Series Gas Chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific S.p.A., Milan, Italy) equipped with an FID detector and a WM-FFAR capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 mm), with a maximum temperature of 240°C.

Chromatographic separation of polyhydroxybutyrate was performed under the following conditions: evaporator temperature—230°C, initial column temperature—60°C (held for 5 min), then increased at 10°C/min to 220°C, detector (FID) temperature—275°C. Standardization was performed using analytical PHB (BIOMER) under identical conditions.

PHBs were also identified by gas chromatography. The analysis was performed by injecting 1 μL of the resulting solution in a Thermo Trace 1300 Series Gas Chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific S.p.A. Milan, Italy) equipped with a FID detector and a WM-FFAR capillary column.

2.2.4 Preparation of Polymer Films

Films were prepared by casting from a 4% polymer solution in chloroform. PHB, PLA, and PHB/PLA blends (50/50 wt.%) were dissolved in chloroform at its boiling temperature until completely dissolved. The polymer solution was poured onto degreased glass Petri dishes and dried at room temperature for 24 h in the air, followed by vacuum drying at 40°C and 400 mm Hg until a constant weight was achieved. The films were stored in a desiccator at +4°C in darkness. Before experiments, circular samples (20 mm diameter, 50 μm thickness) were cut from the prepared films and weighed using an analytical balance (KERN ADB 100-4 WEIGHING SCALE, ANALYTICAL, 120G/0.0001G).

2.2.5 Medium and Conditions for Cultivating Microorganisms

Three sets of bioplastic samples were prepared as 30 mm × 30 mm films. Before use, the plastics were disinfected with 75% ethanol for 1 h, washed three times with sterilized distilled water, and dried in an oven at 60°C overnight. The films were disinfected and weighed (±0.02 mg) before being placed in culture flasks containing sterile mineral salts medium (MSM). MSM was prepared using (per 1000 mL of sterilized water): 0.7 g of KH2PO4, 0.7 g of K2HPO4, 0.7 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 1.0 g of NH4NO3, 0.005 g of NaCl, 0.002 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.002 g of ZnSO4·7H2O, and 0.001 g of MnSO4·H2O. The medium was autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. Culture flasks were incubated at 30°C with rotation at 130 rpm for 1 and 3 months. Bacteria were inoculated onto Petri dishes with oatmeal agar for 7 days. Four 5 mm diameter disks were excised from Petri dishes under aseptic conditions and used as inoculants for biodegradation. Control samples consisted of bioplastics placed in flasks with MSM but without bacteria grown under identical conditions. All experiments were performed in duplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Bioplastic film weight loss was assessed by removing, gently washing (three times with 75% ethanol and sterilized water), and immersing the films in 30 mL of 10% SDS solution for 24 h. The films were then oven-dried at 65°C for 24 h, and their weight was measured using a six-digit balance. Weight loss was calculated as: (initial weight − final weight)/initial weight × 100.

2.2.6 Determination of Weight Loss

Degree of destruction (N), %

where Δm is the change in polymer film weight after the cultivation of microorganisms under certain conditions (or in the control samples under identical conditions); minitial is the initial film weight before the cultivation of microorganisms.

Degree of destruction relative to the control samples (n), fold change:

where Nexp is the destruction degree of a polymer film after cultivation of microorganisms under certain conditions; Nc is the destruction degree of a polymer film in the control samples under identical conditions.

2.2.7 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis (FTIR)

The chemical transformations of bioplastic samples were examined using an ATR-FTIR technique (PerkinElmer, USA). Clean, disinfected plastic films were scanned on both sides eight times at a resolution of 4 cm−1 over a spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1.

2.2.8 Thermal Analysis (DSC, TG, DTG)

The thermophysical properties before and after microbial degradation were analyzed using a PerkinElmer DSC 4000 (Shelton, Connecticut, USA) instrument under a nitrogen atmosphere in the temperature range of −50 to +200°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min, followed by isothermal heating for 5 min. The first cooling and second heating procedures were performed at 10°C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. Thermal degradation temperatures were determined using a NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter (Jülich, Germany) under a nitrogen atmosphere from 25 to 800°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min, with an average sample mass of 5 mg.

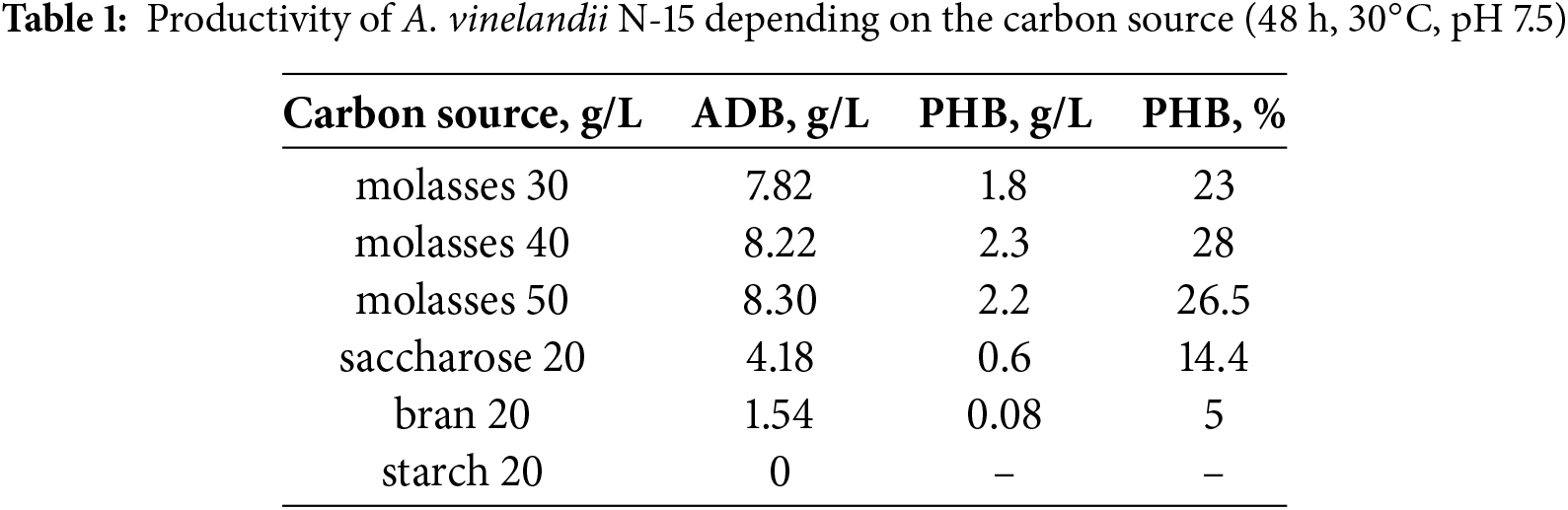

3.1 Selection of Optimal Nutrient Medium Composition for PHB Synthesis by Azotobacter Vinelandii N-15 and Biopolymer Identification

The selection of an optimal carbon source for PHB synthesis by A. vinelandii N-15 was conducted. Among the tested substrates (starch, sucrose, molasses, and bran), molasses yielded the highest PHB production, reaching up to 28% of absolutely dry biomass (ADB) (Table 1).

The nature of the obtained polymer was confirmed via thin-layer chromatography (TLC) [22]. Yellowish spots, characteristic of PHB, appeared on the plate when visualized in an iodine chamber. The retention factor (Rf = 0.8) confirmed that the sample was PHB.

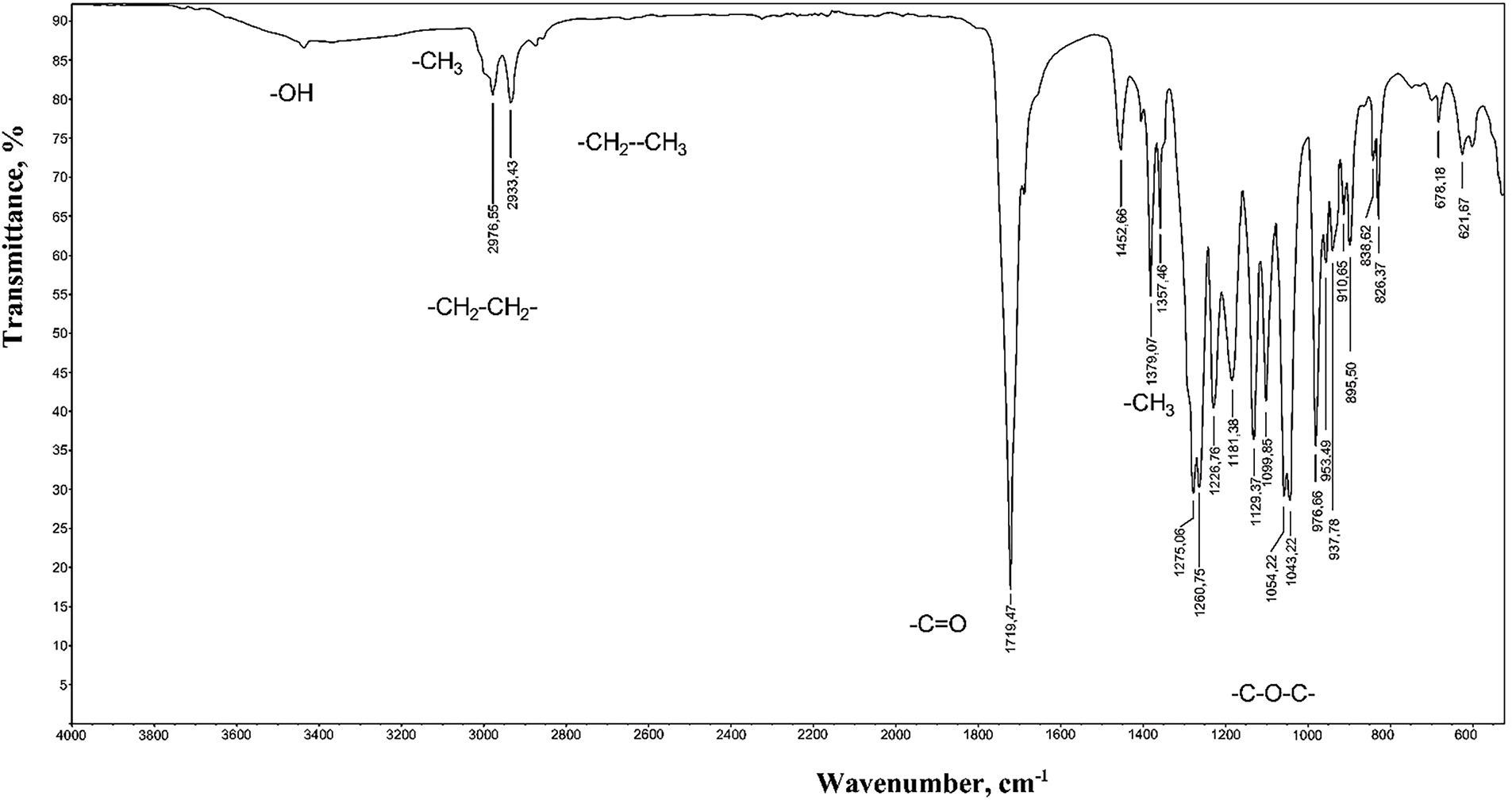

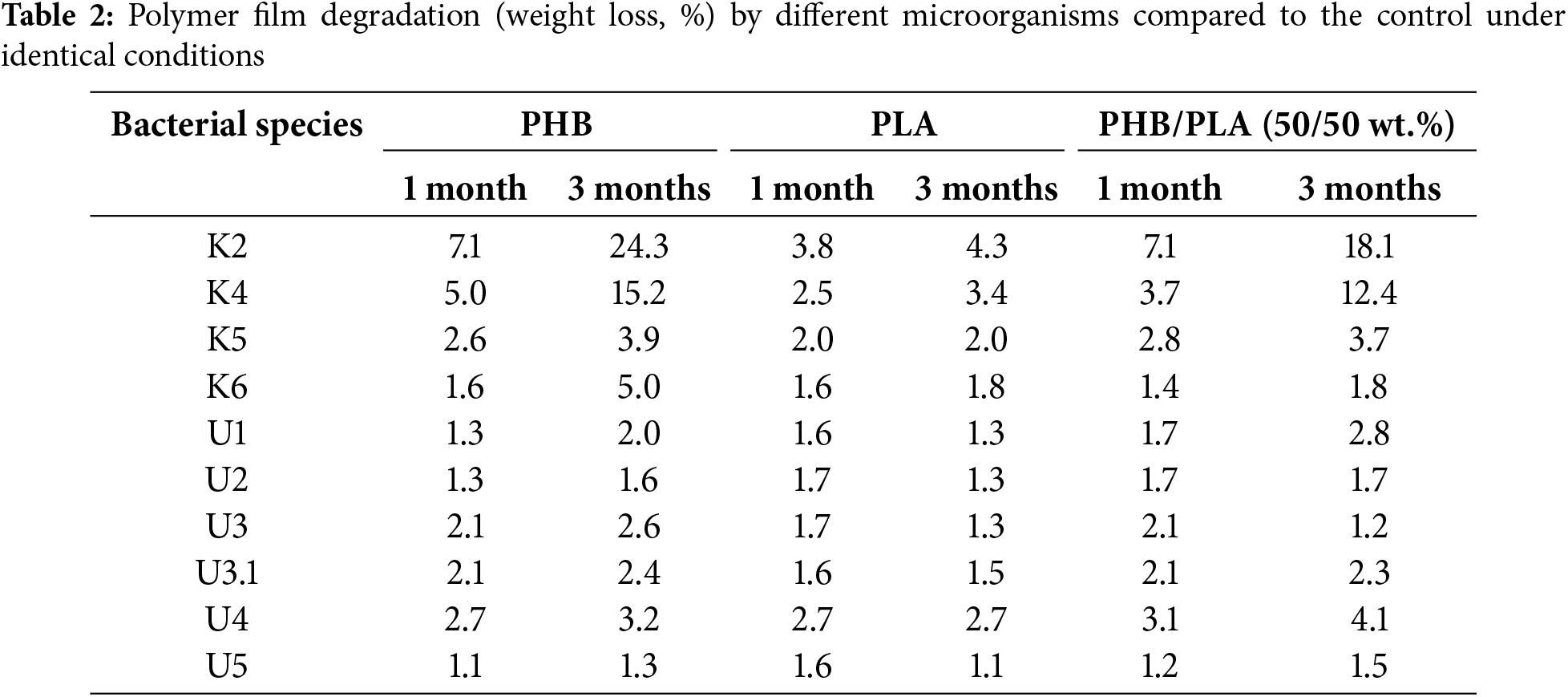

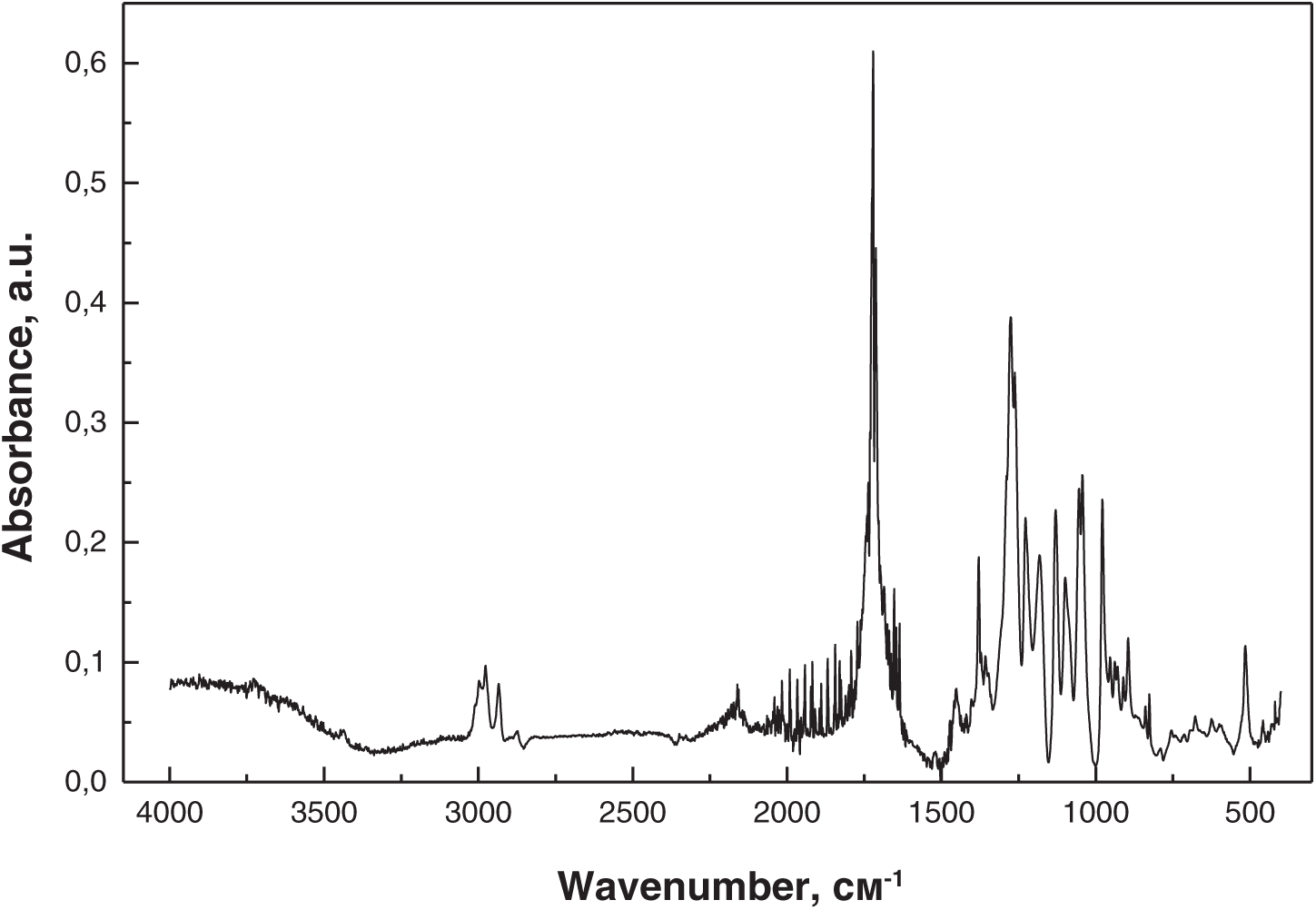

FTIR analysis of the samples revealed a broad band at 3600–3100 cm−1 (Fig. 1), corresponding to the stretching vibrations of terminal groups (-OH) of both alcoholic and acidic nature. The band at 1226 cm−1 corresponds to asymmetric stretching vibrations νa (C-O-C), confirming the presence of PHB functional bonds. The band at 1712 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the carbonyl group ν (C=O). Bands at νa 2976 cm−1 and νs 2933 cm−1 correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the (CH2) group. Other absorption bands appear at νa 2990 cm−1 and νs 2860 cm−1 for (CH3) groups, while the bands at 1452 and 1300 cm−1 correspond to the deformation CH vibrations of (CH3) and (CH2) groups, respectively. These results align with the literature data [23].

Figure 1: FTIR spectrum of PHB produced by the Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 strain

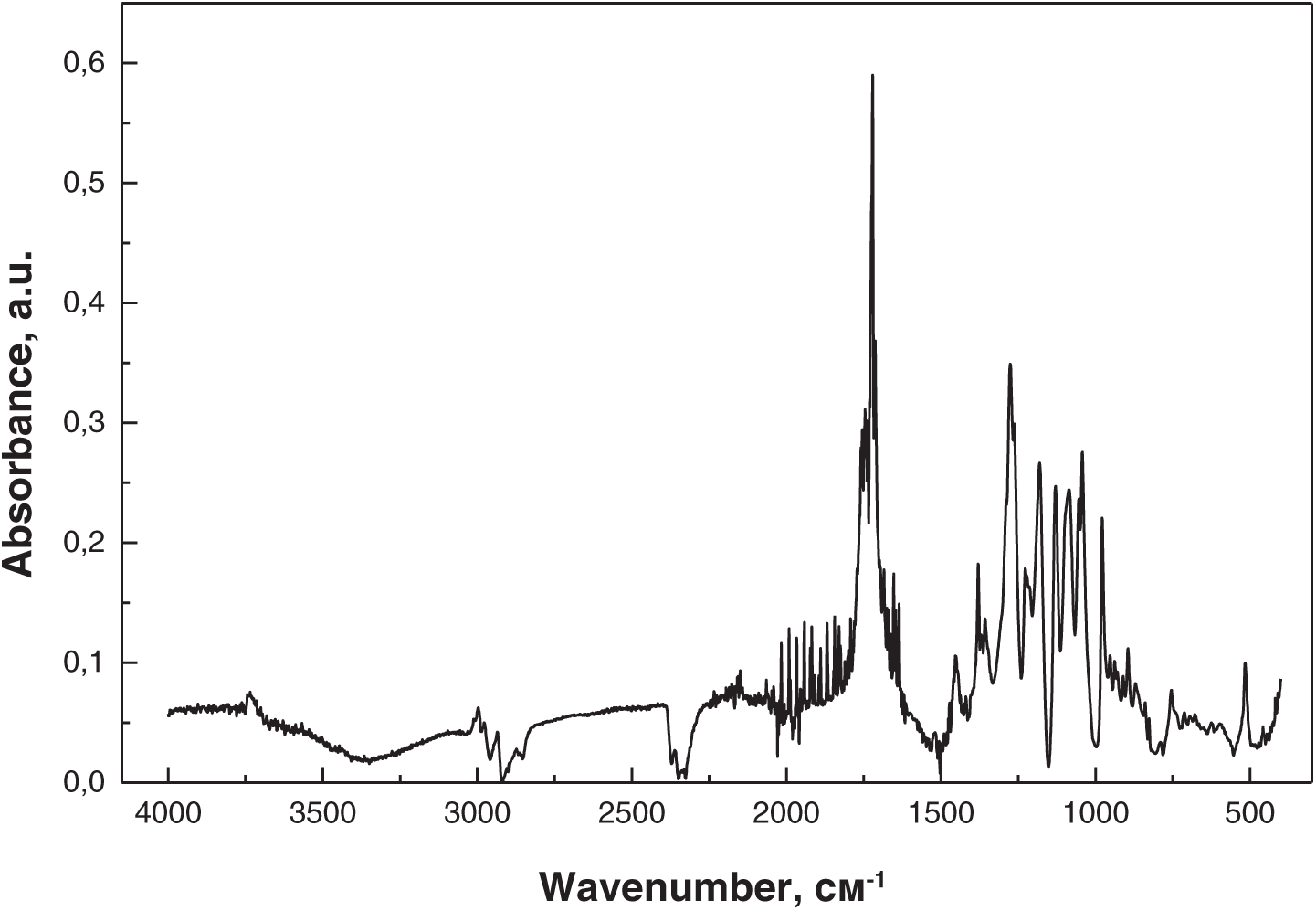

3.2 Study of Polymer Weight Loss during Microorganism Cultivation

The degradation of PHB, PLA, and PHB/PLA blends (50/50 wt.%) by Streptomyces sp. K2, Streptomyces sp. K4, Kitasatospora sp. K5, Kitasatospora sp. K6, Streptomyces sp. U1, Streptomyces sp. U2, Streptomyces sp. U3, Streptomyces sp. U3.1, Streptomyces sp. U4, and Streptomyces sp. U5 was studied in MSM medium at 30°C under rotation at 130 rpm for 1 and 3 months.

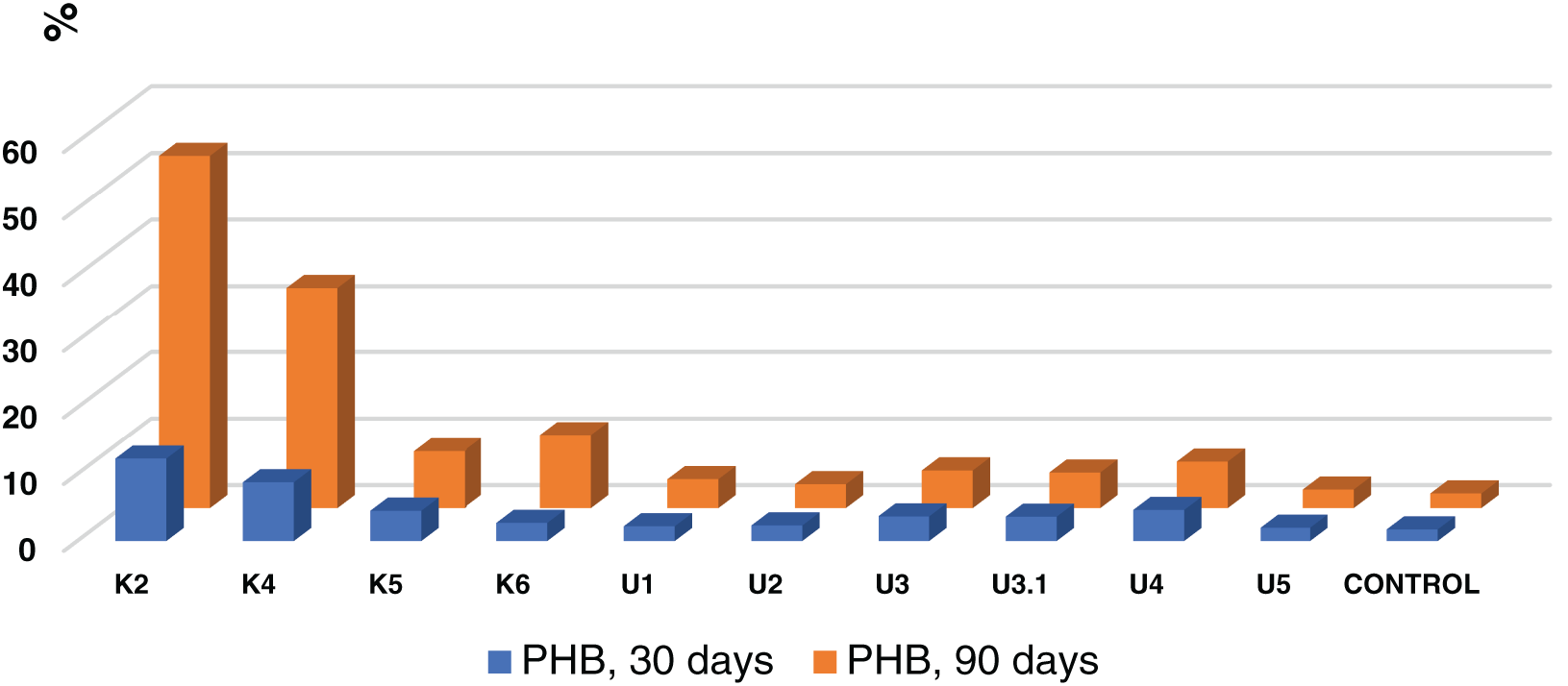

3.2.1 Effect of Microorganism Cultivation on PHB Degradation

Among the studied bacterial strains, Streptomyces sp. K2 and Streptomyces sp. K4 exhibited the highest PHB degradation degrees. Notably, Streptomyces sp. K2 was the most effective, degrading PHB films by 12.3% after 1 month of cultivation, which is 7.1 times higher than the control. After 3 months, the PHB degradation rate reached 53.03%, which is 24.3 times higher than the control (Fig. 2, Table 2). Additionally, the Kitasatospora sp. K5, Kitasatospora sp. K6, Streptomyces sp. U3, Streptomyces sp. U3.1, and Streptomyces sp. U4 strains demonstrated significant degradation activity, ranging from 5.3% to 10.9% after three months of cultivation, which is 2.4 to 5.0 times higher than the control (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Figure 2: Degree of PHB film degradation (%) by bacteria over 1 and 3 months

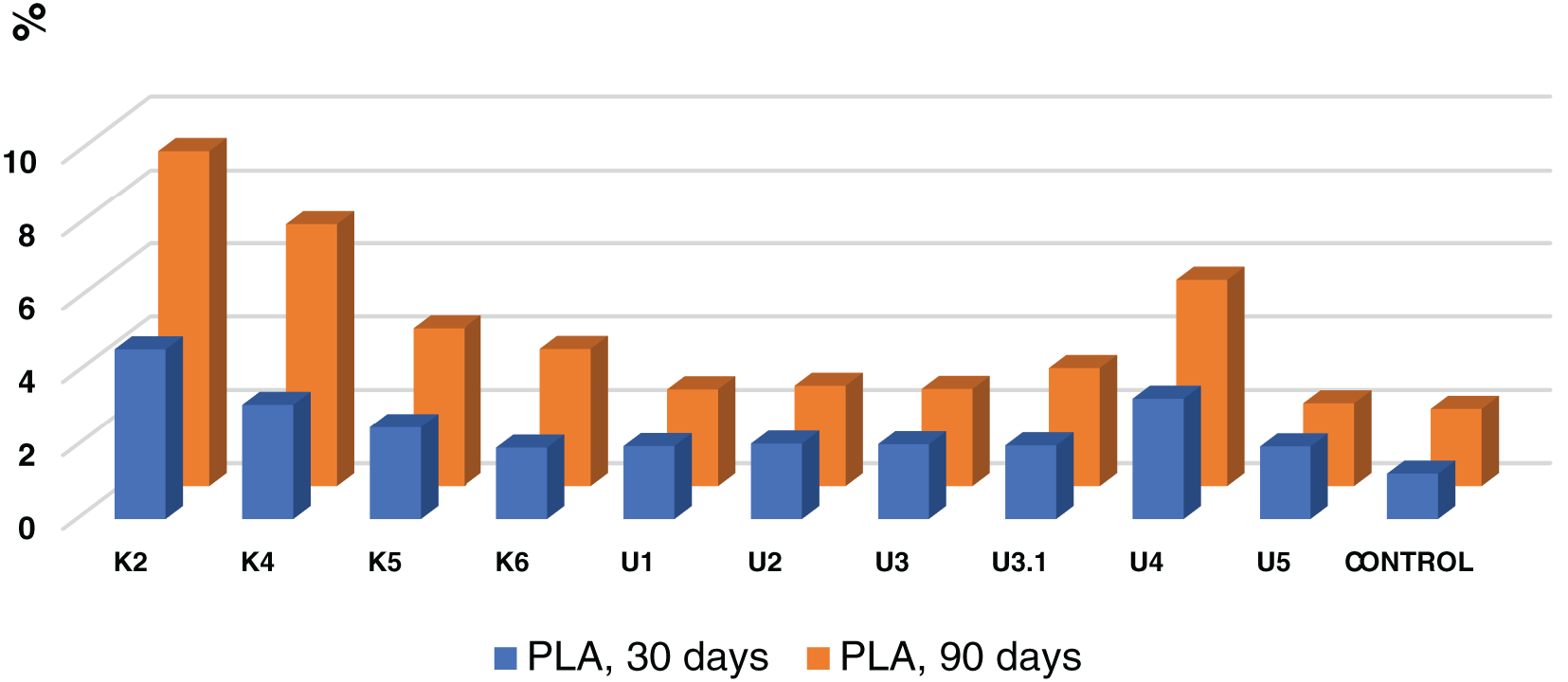

3.2.2 Effect of Microorganism Cultivation on PLA Degradation

All the studied bacteria demonstrated significantly lower degradation rates of PLA films compared to PHB films (Fig. 3). The highest degradation degree (4.6%) after 1 month of cultivation was observed with Streptomyces sp. K2. After 3 months, Streptomyces sp. K2, Streptomyces sp. K4, and Streptomyces sp. U4 exhibited the most efficient PLA degradation rates at 9.2%, 7.1%, and 5.6%, respectively. Compared to the control, PLA degradation rates after 3 months ranged from 1.1 to 4.3 times, depending on the microorganism (Table 2).

Figure 3: Degree of PLA film degradation (%) by bacteria over 1 and 3 months

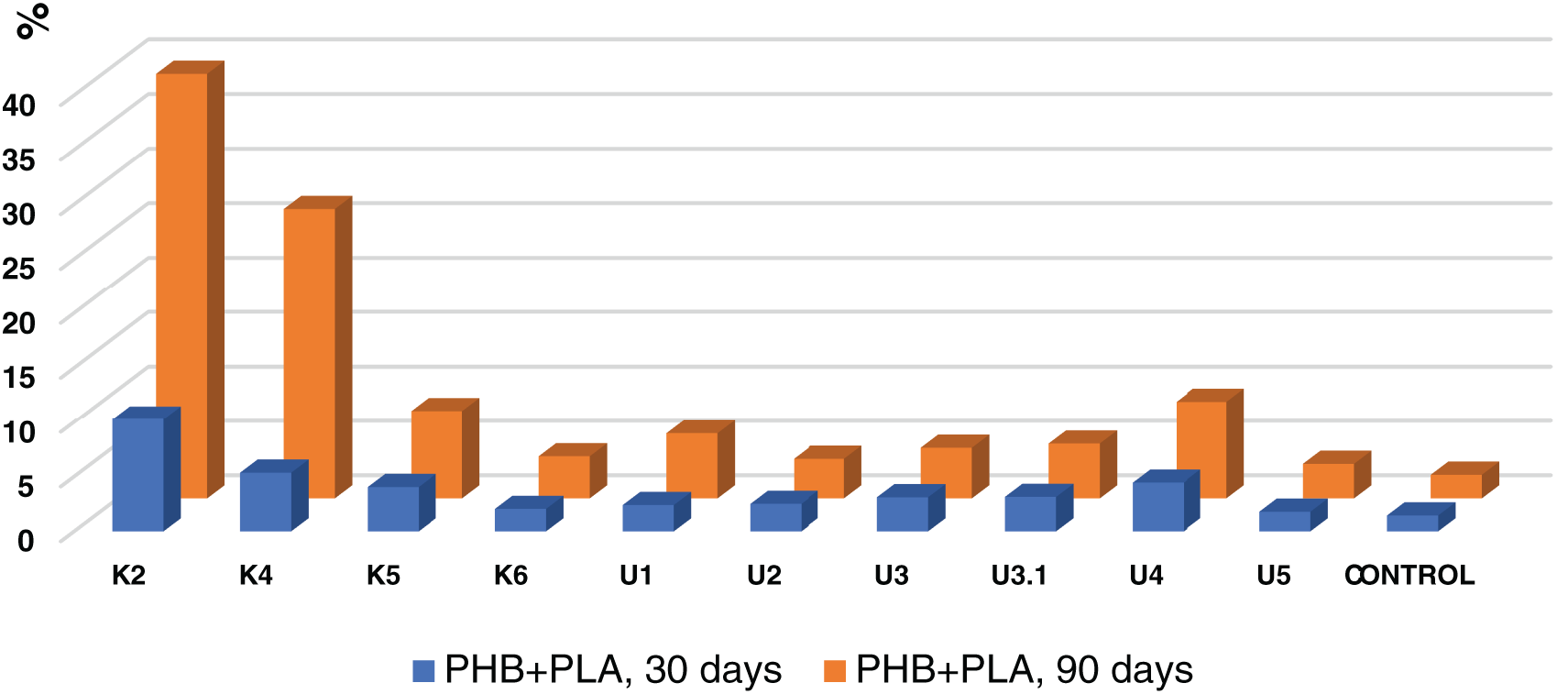

3.2.3 Influence of Microorganism Cultivation on the Degradation of PHB/PLA Blend

Blends of PHB and PLA have garnered significant interest due to their ability to form new biomaterials with enhanced properties—compared to both PHB and PLA alone—while maintaining environmental sustainability. The addition of PHB to PLA has been shown to improve stiffness [24], plasticity [25], and barrier properties [26], which are critical characteristics for food packaging materials.

All the tested bacterial species exhibited degradation activity on PHB/PLA films after 3 months of cultivation (Fig. 4). The Streptomyces sp. K2 and Streptomyces sp. K4 strains demonstrated the highest degradation rates at 38.9% and 26.6%, respectively, which were 18.1 and 12.4 times higher than the control. Additionally, Kitasatospora sp. K5 and Streptomyces sp. U4 showed notable degradation capabilities, 3.7 and 4.1 times higher than the control medium, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 4: Degree of PHB/PLA film degradation (%) by bacteria over 1 and 3 months

3.3 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis (FTIR)

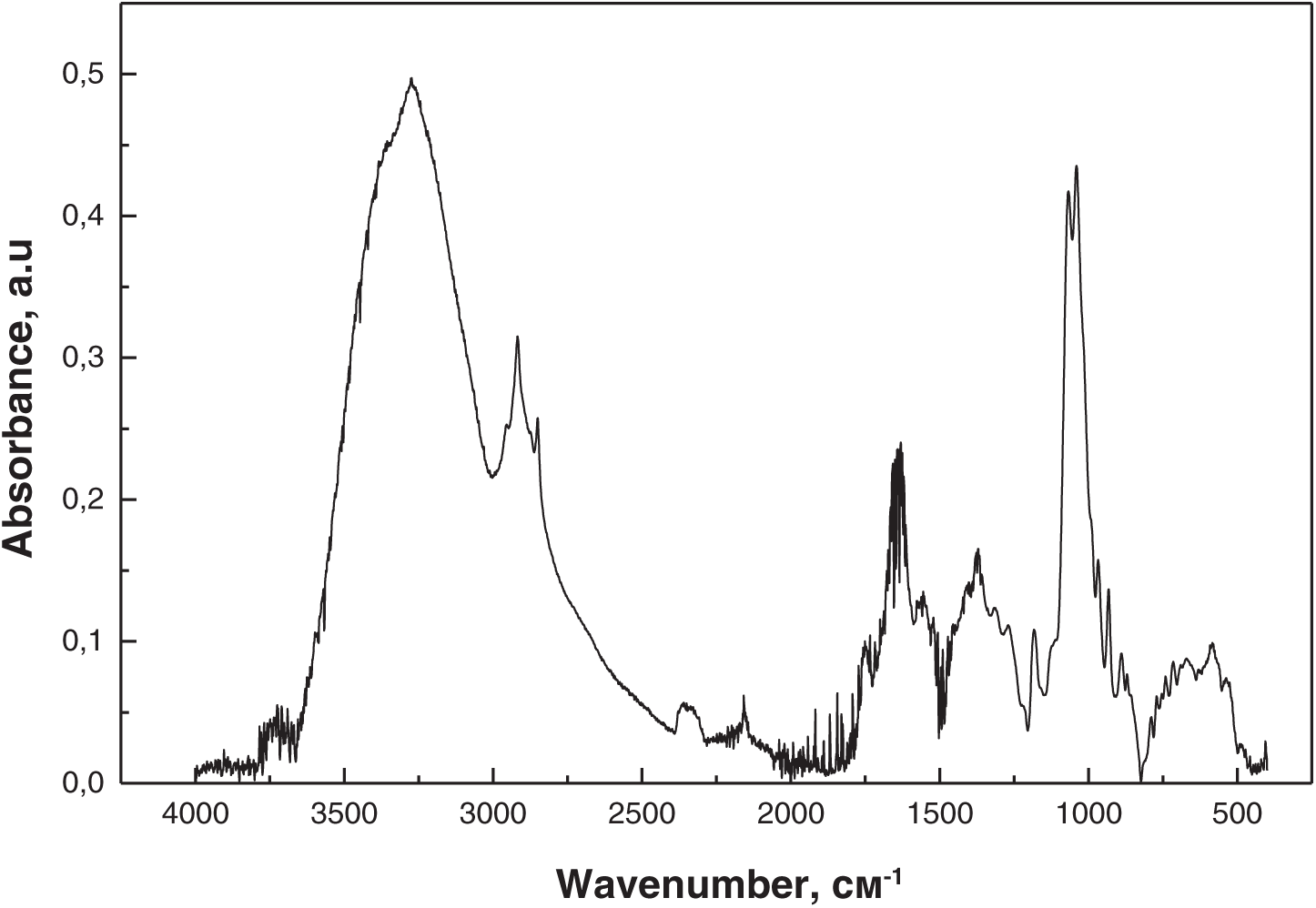

FTIR spectroscopy was used to study the degradation of PHB, PLA, and PHB/PLA (50/50 wt.%) films under the cultivation conditions using microorganisms isolated from plastic-contaminated soil. Figs. 5–7 present the FTIR spectra of PHB/PLA (50/50 wt.%) films before the experiment (Fig. 5), after thermostatting in an MSM solution (Fig. 6), and after cultivation in a medium containing Streptomyces sp. U1 bacteria for 30 days (Fig. 7).

Figure 5: FTIR spectrum of initial PHB/PLA

Figure 6: FTIR spectrum of PHB/PLA after thermostatting in an MSM solution

Figure 7: FTIR spectrum of PHB/PLA after cultivation in a medium with Streptomyces sp. U1

No changes in the original absorption bands or new peaks were observed in the spectra of the PHB/PLA films before and after thermostatting in an MSM solution. However, after cultivation with Streptomyces sp. U1 bacteria, noticeable changes in peak intensity were observed, increasing over time. After three months of cultivation, significant structural changes were detected in the PHB/PLA samples, with a marked increase in the intensity of the hydroxyl O-H group (3100–3600 cm−1), indicating polymer degradation. The strong peak at 1725 cm−1, characteristic of carbonyl group stretching, significantly decreased in the degraded sample, suggesting the breakdown of ester bonds (C-O-C) and the formation of terminal carboxyl groups. Primary alcohol groups may have also formed, indicating the microbial decomposition of the PHB/PLA blend and an increase in hydroxyl groups at both alcohol and carboxyl chain ends. No similar changes were observed in the PHB and PLA films.

Therefore, judging by the weight loss of the films, the decrease in molecular weight and the analysis of the FTIR spectra, the strains take a rather active part in biodegradation. No changes in molecular weight or FTIR spectrum were recorded for the films that were in abiotic conditions (films in saline solution without bacteria).

3.4 Thermal Analysis of Polymer Biodegradation

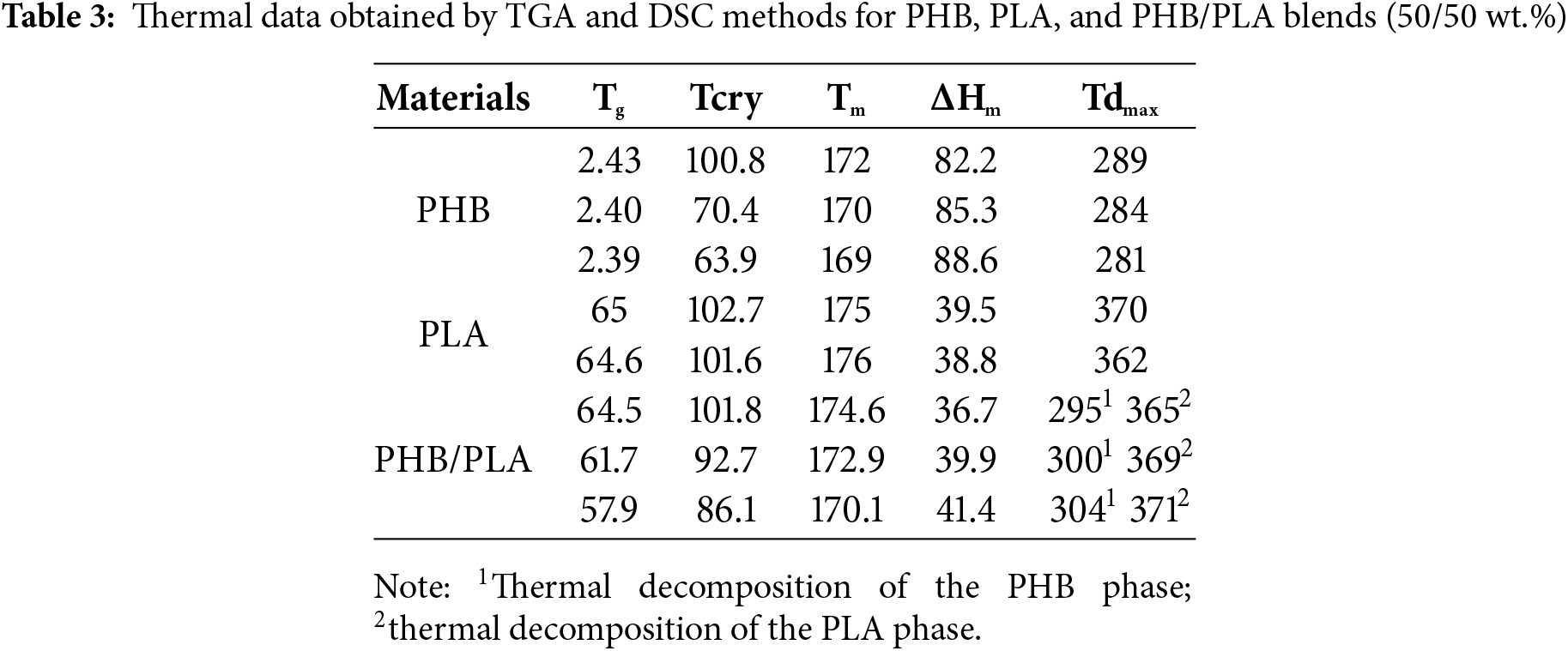

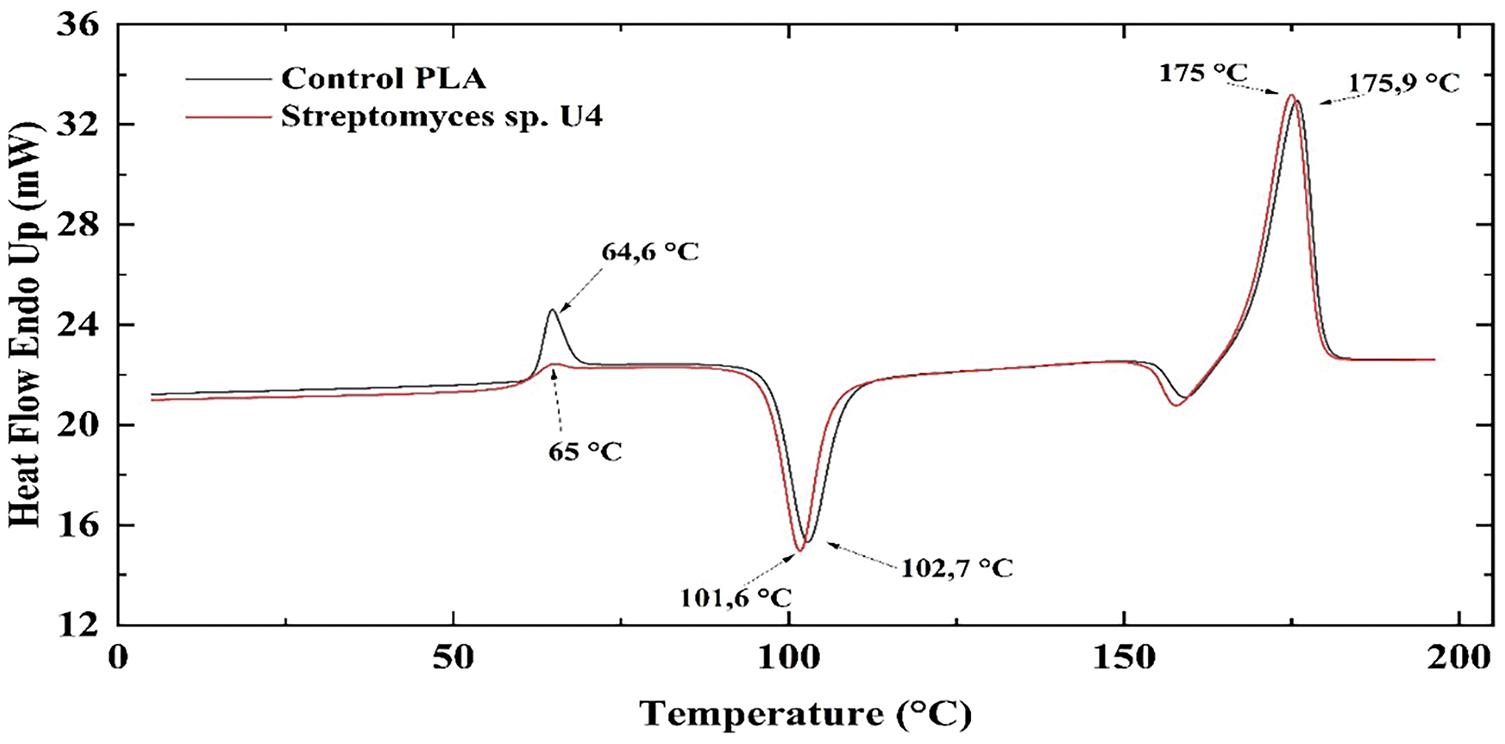

Thermal analysis was conducted to determine the average crystallization temperature (Tcry), melting temperature (Tm), thermal degradation temperature (Td), and specific heat of melting (ΔHm) of the PHB, PLA, and PHB/PLA (50/50 wt.%) films prepared as described in Section 2.2.2. These parameters were measured after three months of thermostatting in an aqueous MSM solution without bacteria (control films) and incubation in media containing ten bacterial species (Streptomyces sp. K2, Streptomyces sp. K4, Kitasatospora sp. K5, Kitasatospora sp. K6, Streptomyces sp. U1, Streptomyces sp. U2, Streptomyces sp. U3, Streptomyces sp. U3.1, Streptomyces sp. U4, and Streptomyces sp. U5) maintained in the microorganism collection of the Department of Physical Chemistry of Fossil Fuels at the InPOCC, named after L.M. Lytvynenko of the NAS of Ukraine. The melting and thermal degradation temperatures were determined from exothermic peaks, while the crystallization temperature was determined from endothermic peaks in thermograms.

3.4.1 Thermal Analysis of PHB Biodegradation

Among the studied microbial species, Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2 exhibited the highest PHB degradation rates after three months, at 33.2% and 53.0%, respectively, compared to 3.1% in control samples incubated in MSM without microorganisms. Consequently, thermal properties were compared between PHB samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2 and control samples.

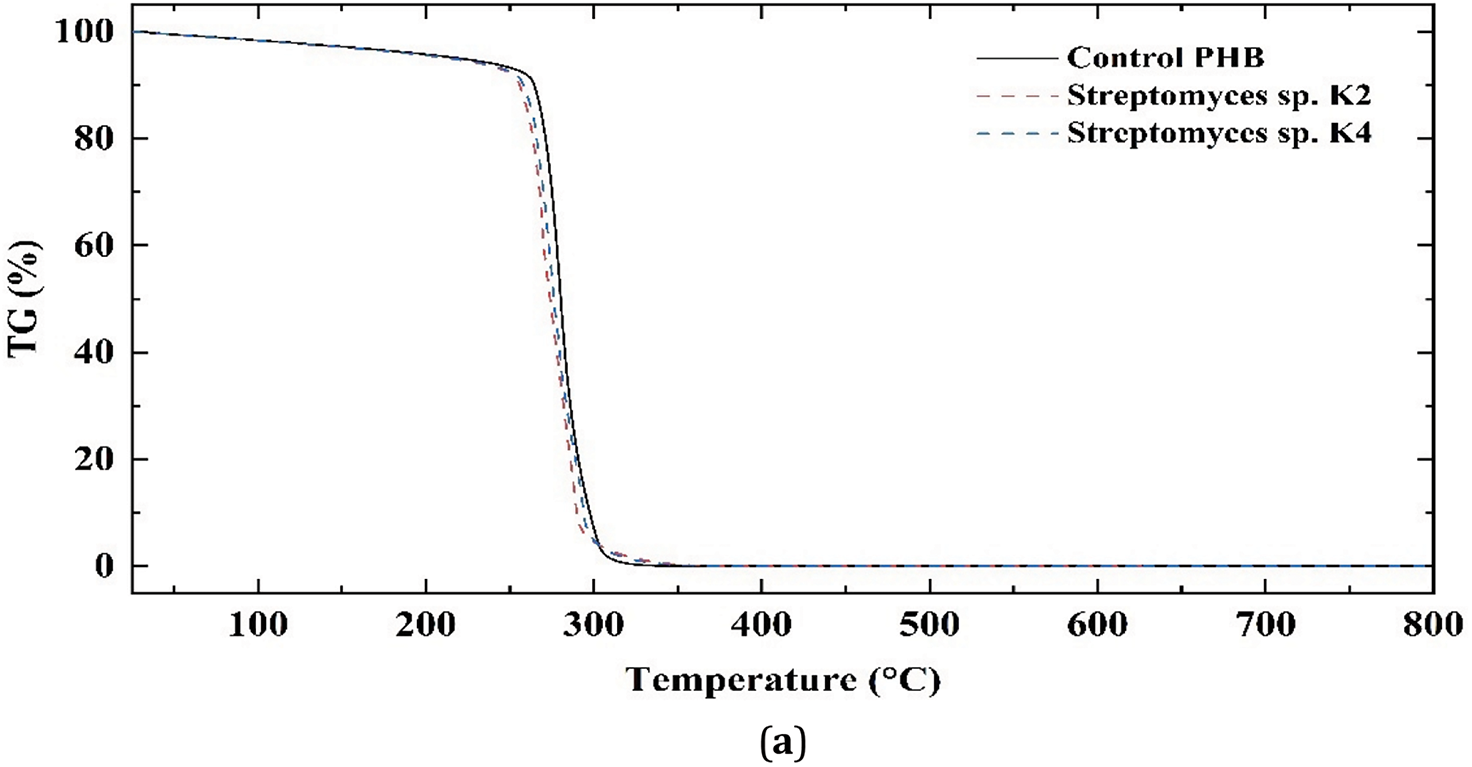

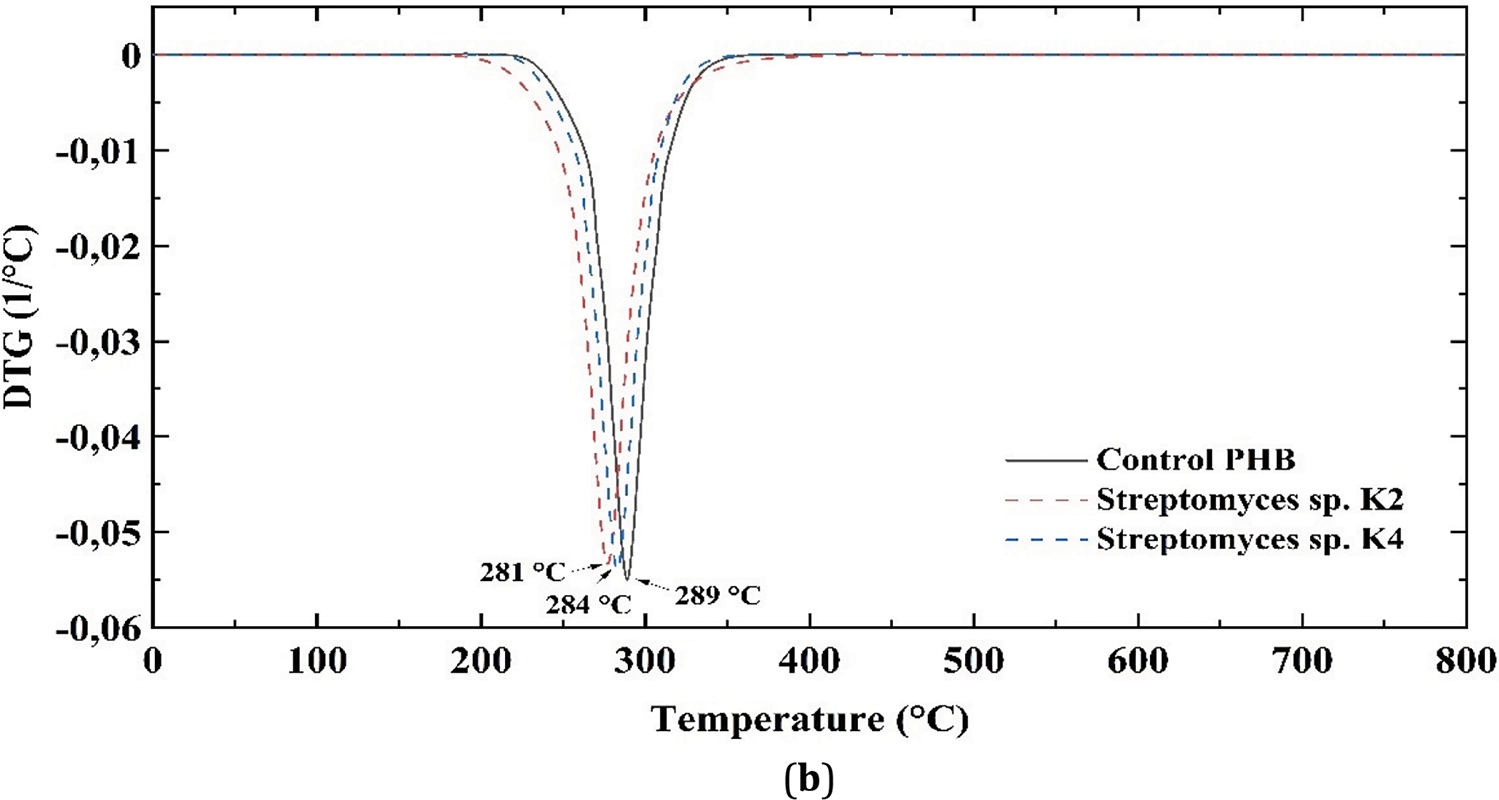

Fig. 8 presents the TG and DTG curves of PHB samples incubated in MSM and exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2. The average temperatures at 5% decomposition of PHB (Td5%) were recorded as the onset of thermal degradation. For the control PHB sample, Td5% was 258°C whereas for samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, it was slightly lower (252°C and 250°C, respectively). The average temperature at 55% decomposition of PHB for the control sample was 279°C, while for the samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, it was 275°C and 272°C, respectively. The bacterially degraded PHB samples demonstrated lower thermal stability compared to the control sample, as evidenced by an earlier decomposition onset and a downward shift in the DTG curve. The extremum describing the maximum decomposition rate (Tdmax) was observed at 289°C for the control sample, compared to 284°C and 281°C for samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively (Table 3). The decrease in thermal stability in degraded samples is a positive point (e.g., from the point of view of further pyrolysis of polymers). This decrease can be explained by the fact that, perhaps, during biodegradation, thermally stable functional groups are removed from the polymers and/or the biodegradation products are catalysts for further thermal decomposition.

Figure 8: TG (a) and DTG (b) curves of the PHB samples

The endothermic melting peak of the PHB sample cultured on MSM without microorganisms appeared at 172°C (Fig. 9), while samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2 showed the peaks at 170°C and 169°C, respectively. The specific heat of melting (ΔHm) of the control PHB sample (82.2 J/g) increased to 85.3 and 88.6 J/g after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively.

Figure 9: DSC thermograms of PHB: (a) melting temperature changes, (b) glass transition temperature changes

The degree of crystallinity (Xc, %) of the PHB samples was calculated using the equation:

where ΔHm is the enthalpy of melting of the studied samples, ΔH0 is the enthalpy of melting for 100% crystalline PHB (146 J/g), w is the sample weight.

The crystallinity degree of PHB increased from 56.3% in the control sample to 66.5% and 72.4% in samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively. This increase is attributed to the preferential degradation of the polymer’s amorphous regions at the onset of thermal degradation. The crystallization temperature of the PHB samples shifted from 100.84°C in the control to 70.41°C and 63.91°C after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, while specific heat of crystallization (ΔHcry) increased from −66.3 to −49.5 J/g and −43.5 J/g, respectively.

The primary degradation mechanism of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) involves temperature-catalyzed hydrolysis followed by bacterial attack on fragmented residues [27].

According to the literature [28–30], abiotic hydrolysis of PHB under environmentally relevant conditions (typically below 30°C) is an extremely slow process, taking several months. Therefore, we consider that microbial degradation is the dominant pathway for PHB degradation in soil environments, as it occurs much faster than hydrolytic degradation.

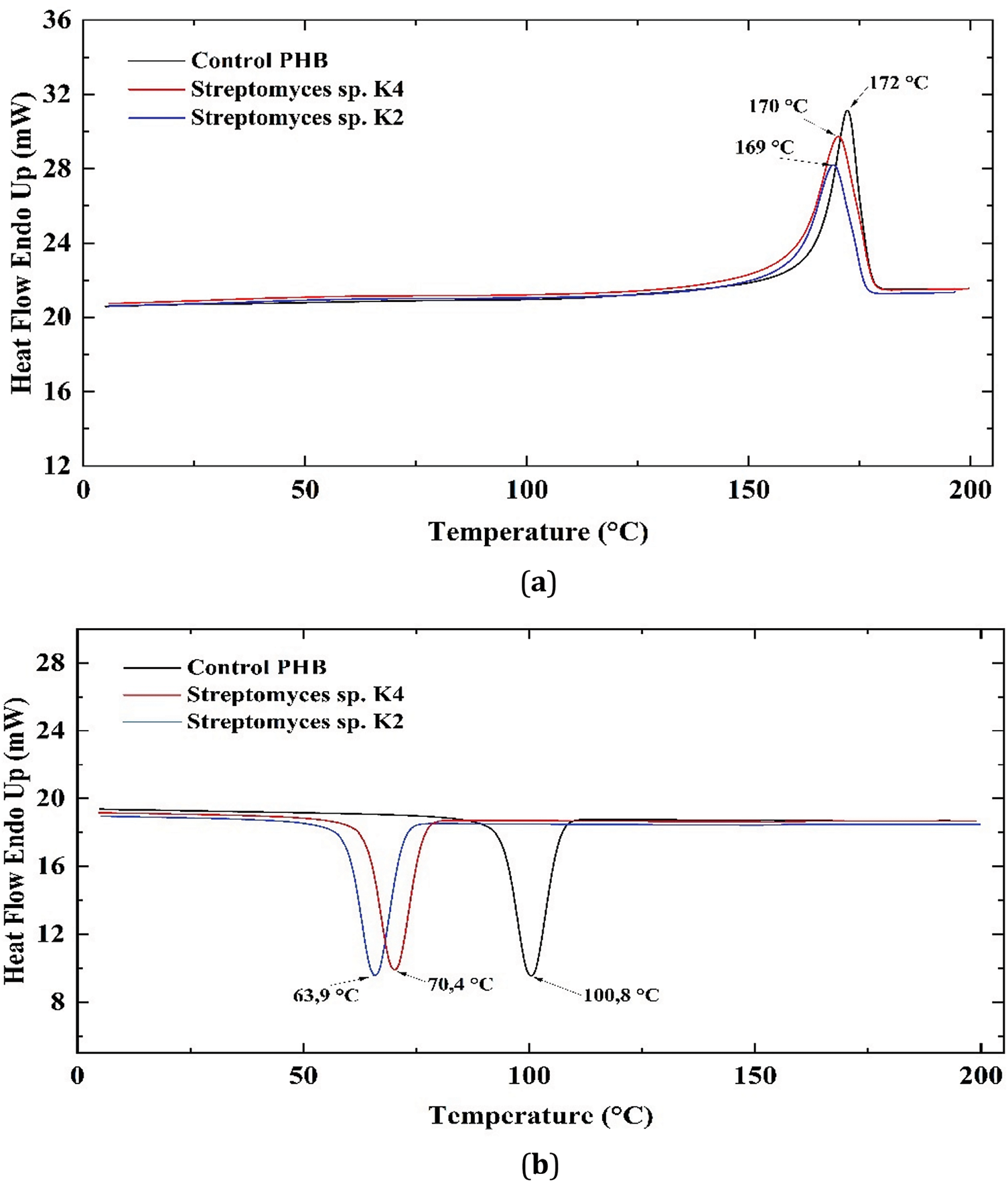

3.4.2 Thermal Analysis of PLA Biodegradation

After three months of cultivation, the control PLA sample exhibited minimal degradation, with a decomposition rate of 4.5% in MSM without microorganisms. However, the highest biodegradation rate (8.3%) was observed in PLA samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. U4, surpassing those exposed to other microorganisms.

TG and DTG analysis (Fig. 10) showed no significant changes in average decomposition temperatures (Td5% and Td55%) and extremes of the maximum decomposition rate (Tdmax) for the PLA sample exposed to Streptomyces sp. U4 compared to the control cultivated in MSM—325°C, 360°C, and 370°C, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 10: TG (a) and DTG (b) curves of the PLA samples

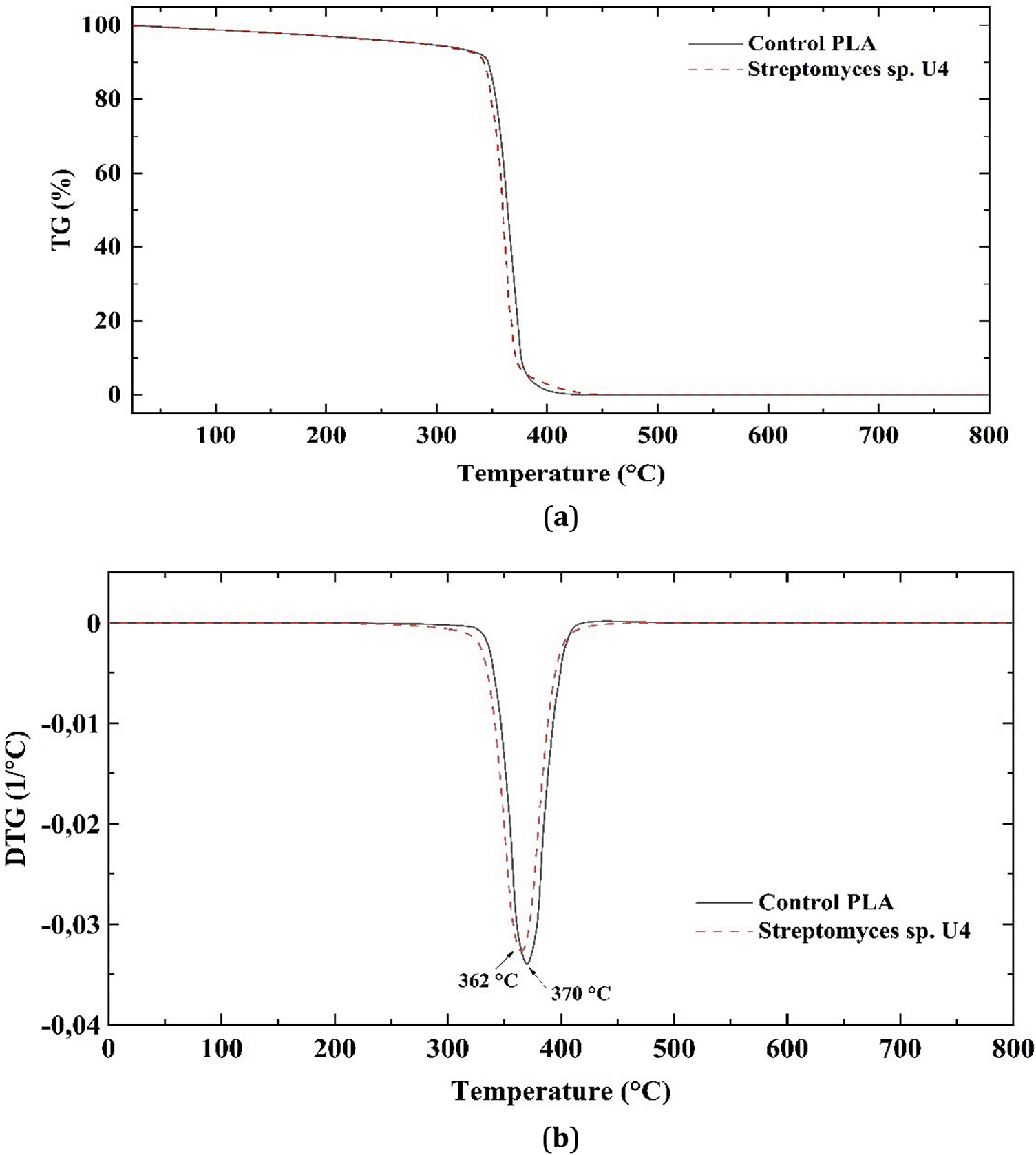

Fig. 11 illustrates the endothermic melting peaks for the control PLA sample and the sample exposed to Streptomyces sp. U4 bacteria, both of which remain within the range of 175°C–176°C. The specific enthalpy of melting (ΔHm) decreases slightly from 39.5 to 38.8 J/g.

Figure 11: DSC thermograms of PLA

The crystallization temperature of the PLA sample after cultivation in MSM under the influence of Streptomyces sp. U4, determined by DSC, shifts slightly from 102.7°C to 101.6°C, while its ΔHcry increases from −29.3 to −26.8 J/g. The glass transition temperature of the PLA samples remains nearly unchanged, staying within the range of 65°C–64.6°C.

These results indicate that, compared to PHB, PLA degrades more slowly under the studied conditions of microbial cultivation.

3.4.3 Thermal Analysis of the Biodegradation of PHB/PLA Blend (50/50 wt.%)

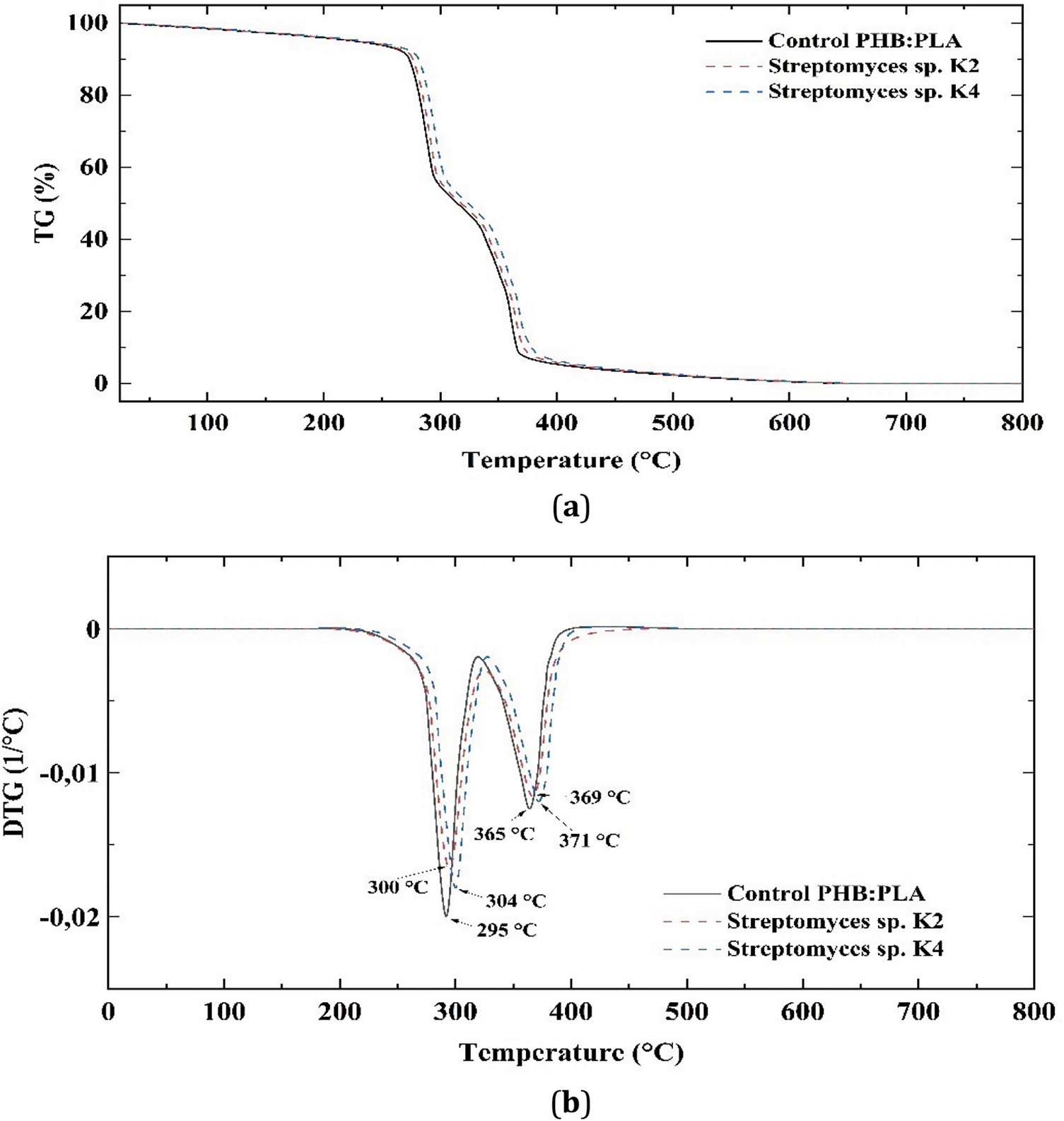

The thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves for the PHB/PLA blend (50/50 wt.%) are shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: TG (a) and DTG (b) curves of the PHB/PLA blend (50/50 wt.%)

The TG curves reveal a two-stage degradation process for the PHB/PLA blend: the first stage of weight loss corresponds to PHB degradation, while the second stage corresponds to PLA degradation. The temperatures Td5% PHB and Tdmax PHB are associated with the PHB phase, whereas Td5% PLA and Tdmax PLA correspond to the PLA phase. Considering separate thermal decomposition of the PHB and PLA phases, a slight increase in the thermal stability of both phases within the blend was observed. Specifically, the initial degradation temperature Td5% PHB (266°C) shifted to higher temperatures after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, reaching 268°C and 270°C, respectively. Similarly, the maximum weight loss temperature Tdmax PHB increased from 295°C in the control sample to 300°C and 304°C after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively.

For the PLA phase, Td5% PLA (320°C) shifted to higher temperatures after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, reaching 323°C and 325°C, respectively. Likewise, the maximum weight loss temperature Tdmax PLA increased from 365°C to 369°C and 371°C after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively.

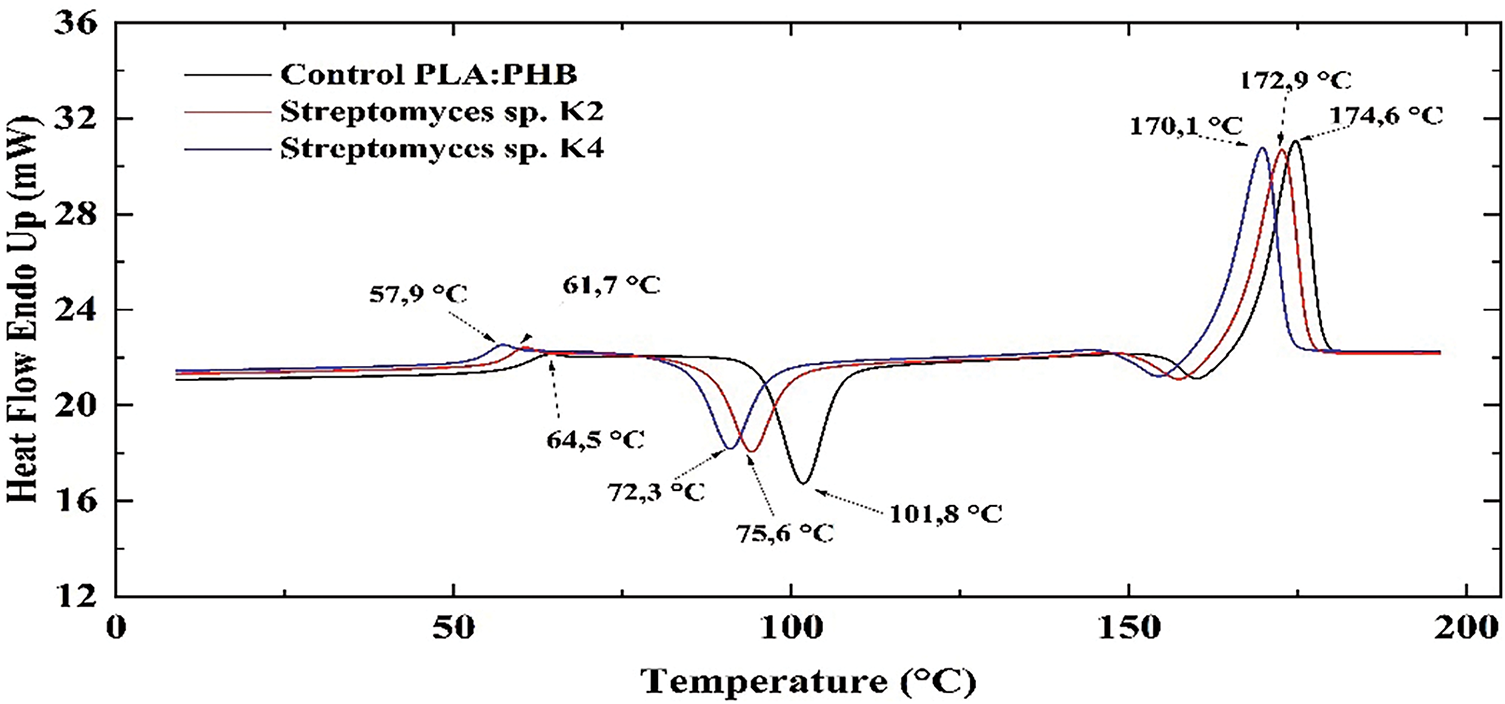

The PHB/PLA blend (50/50 wt.%) exhibits a glass transition temperature of the PLA component at −64.6°C (Fig. 11), which decreases slightly with the addition of PHB, reaching −61.7°C (Fig. 13). This suggests good compatibility between the two polymers.

Figure 13: DSC thermogram of the PHB/PLA blend (50/50 wt.%)

As shown in Fig. 13, the peak of the endothermic melting effect for the control PHB/PLA blend is observed at 174.6°C. However, after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, this peak shifts to 172.9°C and 170.1°C, respectively. The specific enthalpy of melting (ΔHm) of the PHB/PLA blend, cultured in MSM without microorganisms (36.69 J/g), slightly increases to 39.90 and 41.44 J/g after exposure to Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively. The increase in ΔHm after three months of microbial cultivation suggests an increase in the degree of crystallinity of the blend. The crystallization peak of the PLA component within the PHB/PLA blend is lower than that of pure PLA, indicating that PHB enhances PLA crystallization. The crystallization temperature of the PHB/PLA blend (50/50 wt.%) decreases from 101.8°C in the control sample to 92.7°C and 86.13°C after degradation in the presence of Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively. Concurrently, ΔHcry increases from −25.48 to −23.4 J/g and −22.8 J/g, respectively. The glass transition temperature decreases slightly from 64.5°C to 61.7°C and 57.9°C after three months of cultivation with Streptomyces sp. K4 and Streptomyces sp. K2, respectively.

Finally, it should be noted that the results of studies of the behavior in soils of similar materials based on polyhydroxybutyrate, obtained by other methods, have proven the possibility of reasonably rapid biodegradation [31], which significantly depends on the soil type. Therefore, it can be assumed that the biodegradation of the polyhydroxybutyrate obtained by the authors will occur intensively.

The study confirmed the effectiveness of molasses, a by-product of sugar production, as a carbon source for the biosynthesis of the cell polymer of Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 culture.

The highest yield of Azotobacter vinelandii N-15 polymer—25.8% from the cell mass—was achieved when the bacteria were cultivated in a nutrient medium containing 40 g/L of molasses for 48 h at 30°C and pH 7.5.

The obtained product was identified as polyhydroxybutyrate using thin-layer chromatography, gas chromatography, and infrared spectroscopy.

All tested polymer samples exhibited varying degrees of degradation when cultivated in an MSM medium. Among the microorganisms studied, Streptomyces sp. K2 and Streptomyces sp. K4 demonstrated the highest degradation efficiency for PHB, PLA, and their blend. However, PLA degradation was only slightly higher than that of the control samples, while PHB/PLA films exhibited an intermediate degradation rate between PHB and PLA.

Thermal analysis of PHB and PLA samples exposed to Streptomyces sp. K2 and Streptomyces sp. K4 revealed a slight reduction in thermal stability and melting point compared to the control samples. In contrast, the PHB/PLA blend exhibited greater thermal stability when subjected to the same microbial activity.

FTIR spectroscopy of PHB/PLA (50/50 wt.%) films showed noticeable changes in the peak intensities of OH, C=O, and C-O-C functional groups, indicating microbial decomposition of the polymer blend.

The combined findings from weight loss measurements, FTIR, DSC, TG, and DTG analyses suggest that the degradation of PHB, PLA, and their blend by microorganisms occurred enzymatically from the surface of the films. One of the key advantages of PHB and PLA over other biodegradable polymers is their ability to degrade under aerobic conditions via enzymatic hydrolysis using microbial depolymerases.

Therefore, the polymers developed by the authors are biodegradable and aim to address a significant issue that humanity faces today: the challenge of recycling used plastics. Additionally, if we consider that the nutrient medium for synthesizing these polymers can come from waste generated in the production of organic products and the industry-waste that also requires considerable resources for recycling—it becomes evident that producing polyhydroxyalkanoates will be a profitable venture for potential manufacturers.

The authors plan to use the results of this research to create a database on the biodegradation times of bioplastics in the environment.

Given the possible differences in the biodegradation of polyhydroxybutyrate in different soils, the study of the decomposition of the obtained biopolymers in Ukrainian soils is the main task of further experiments. It is also planned to expand the information on determining the type of microorganism present.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors acknowledge the financial support of this paper by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine under grant (Biotherm/0124U000789).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Tetyana Pokynbroda, and Ihor Semeniuk; data curation: Nataliya Semenyuk, Volodymyr Skorokhoda and Serhiy Pyshyev; formal analysis: Tetyana Pokynbroda, Ihor Semeniuk, Agnieszka Gąszczak, Elżbieta Szczyrba, Nataliya Semenyuk, Volodymyr Skorokhoda and Serhiy Pyshyev; investigation: Ihor Semeniuk, Agnieszka Gąszczak, Elżbieta Szczyrba and Nataliya Semenyuk; methodology: Ihor Semeniuk and Nataliya Semenyuk; project administration: Volodymyr Skorokhoda and Serhiy Pyshyev; resources: Ihor Semeniuk and Volodymyr Skorokhoda; software: Agnieszka Gąszczak and Elżbieta Szczyrba; supervision: Volodymyr Skorokhoda; validation: Tetyana Pokynbroda, Nataliya Semenyuk and Serhiy Pyshyev; visualization: Tetyana Pokynbroda, Nataliya Semenyuk and Serhiy Pyshyev; writing—original draft preparation: Tetyana Pokynbroda, Ihor Semeniuk, Nataliya Semenyuk and Volodymyr Skorokhoda; writing—review and editing: Nataliya Semenyuk and Serhiy Pyshyev. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pilapitiya PGC, Ratnayake AS. The world of plastic waste: a review. Clean Mater. 2024;11:100220. doi:10.1016/j.clema.2024.100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Boey JY, Mohamad L, Khok YS, Tay GS, Baidurah S. A review of the applications and biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates and poly(lactic acid) and its composites. Polymers. 2021;13(10):1544. doi:10.3390/polym13101544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Semenyuk N, Dudok G, Skorokhoda V. Hydrogels in biomedicine: granular controlled release systems based on 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate copolymers. A review. Chemistry. 2024;18(2):143–56. doi:10.23939/chcht18.02.143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dokl M, Copot A, Krajnc D, van Fan Y, Vujanović A, Aviso KB, et al. Global projections of plastic use, end-of-life fate and potential changes in consumption, reduction, recycling and replacement with bioplastics to 2050. Sustain Prod Consum. 2024;51(1):498–518. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2024.09.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang L, Nabi G, Yin L, Wang Y, Li S, Hao Z, et al. Birds and plastic pollution: recent advances. Avian Res. 2021;12(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s40657-021-00293-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tariq A, Qadir A, Ahmad SR. Consequences of plastic trash on behavior and ecology of birds. In: Microplastic pollution: environmental occurrence and treatment technologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 347–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-89220-3_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lebedev V, Miroshnichenko D, Pyshyev S, Kohut A. Study of hybrid humic acids modification of environmentally safe biodegradable films based on hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose. Chem Chem Technol. 2023;17(2):357–64. doi:10.23939/chcht17.02.357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fedoryshyn O, Chervetsova V, Yaremkevych O, Skril Y, Khomyak S, Kohut A. Physico-chemical and microbiological characterization of starch-based biodegradable films. Chem Chem Technol. 2024;18(3):417–25. doi:10.23939/chcht18.03.417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sintim HY, Bary AI, Hayes DG, Wadsworth LC, Anunciado MB, English ME, et al. In situ degradation of biodegradable plastic mulch films in compost and agricultural soils. Sci Total Environ. 2020;727:138668. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kosmalska D, Janczak K, Raszkowska-Kaczor A, Stasiek A, Ligor T. Polylactide as a substitute for conventional polymers-Biopolymer processing under varying extrusion conditions. Environments. 2022;9(5):57. doi:10.3390/environments9050057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Swetha TA, Bora A, Mohanrasu K, Balaji P, Raja R, Ponnuchamy K, et al. A comprehensive review on polylactic acid (PLA)–synthesis, processing and application in food packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;234:123715. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Naser AZ, Deiab I, Darras BM. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAsgreen alternatives to petroleum-based plastics: a review. RSC Adv. 2021;11(28):17151–96. doi:10.1039/D1RA02390J. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. McKeown P, Jones MD. The chemical recycling of PLA: a review. Sustain Chem. 2020;1(1):1–22. doi:10.3390/suschem1010001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Richert A, Dąbrowska GB. Enzymatic degradation and biofilm formation during biodegradation of polylactide and polycaprolactone polymers in various environments. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;176(8):226–32. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.01.202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Kopperi H, Amulya K, Mohan SV. Simultaneous biosynthesis of bacterial polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and extracellular polymeric substances (EPSprocess optimization and scale-up. Bioresour Technol. 2021;341(6):125735. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Semeniuk I, Kochubei V, Skorokhoda V, Pokynbroda T, Midyana H, Karpenko E. Biosynthesis products of Pseudomonas sp.-PS-17 strain metabo-lites. 1. Obtaining and thermal characteristics. Chem Chem Technol. 2020;14(1):26–31. doi:10.23939/chcht14.01.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Semeniuk I, Pokynbroda T, Kochubei V, Midyana H, Karpenko O, Skorokhoda V. Biosynthesis and characteristics of polyhydroxyalkanoates. 1. Polyhydroxybutyrates of Azotobacter vinelandii N-15. Chem Chem Technol. 2020;14(4):463–7. doi:10.23939/chcht14.04.463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Semeniuk I, Koretska N, Kochubei V, Lysyak V, Pokynbroda T, Karpenko E, et al. Biosynthesis and characteristics of metabolites of Rhodococcus erythropolis AU-1 strain. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2022;11(4):1–5. doi:10.55251/jmbfs.4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Szczyrba E, Pokynbroda T, Koretska N, Gąszczak A. Isolation and characterization of new bacterial 1 strains degrading low-density polyethylene. Chem Process Eng New Front. 2024;45(2):60–72. doi:10.24425/cpe.2024.148554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Holt JG, Krieg NR, Sneath PHA. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 8th ed. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1997. ISBN: 978-0-387-95042-6. [Google Scholar]

21. Juengert JR, Bresan S, Jendrossek D. Determination of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) content in Ralstonia eutropha using gas chromatography and Nile red staining. Bio Protoc. 2018;8(5):e2748. doi:10.21769/BioProtoc.2748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Panda B, Sharma L, Singh A, Mallick N. Thin layer chromatographic detection of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) and poly-β-hydroxyvalerate (PHV) in cyanobacteria. Biotechnol. 2008;7(2):230–4. [Google Scholar]

23. Ramezani M, Amoozegar MA, Ventosa A. Screening and comparative assay of poly-hydroxyalkanoates produced by bacteria isolated from the Gavkhooni Wetland in Iran and evaluation of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate production by halotolerant bacterium Oceanimonas sp. GK1 Ann Microbiol. 2015;65(1):517–26. doi:10.1007/s13213-014-0887-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Arrieta MP, Samper MD, López J, Jiménez A. Combined effect of poly(hydroxybutyrate) and plasticizers on polylactic acid properties for film intended for food packaging. J Polym Environ. 2014;22(4):460–70. doi:10.1007/s10924-014-0654-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang M, Thomas NL. Blending polylactic acid with polyhydroxybutyrate: the effect on thermal, mechanical, and biodegradation properties. Adv Polym Technol. 2011;30(2):67–79. doi:10.1002/adv.20235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Burgos N, Armentano I, Fortunati E, Dominic F, Luz F, Fiori S, et al. Functional properties of plasticized bio-based Poly(Lactic Acid)_Poly(Hydroxybutyrate) (PLA_PHB) films for active food packaging. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017;10(4):770–80. doi:10.1007/s11947-016-1846-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Iglesias-Montes ML, Soccio M, Luzi F, Puglia D, Gazzano M, Lotti N, et al. Evaluation of the factors affecting the disintegration under a composting process of poly(lactic acid)/poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PLA/PHB) blends. Polymers. 2021;13(18):3171. doi:10.3390/polym13183171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Tarazona NA, Machatschek R, Lendlein A. Unraveling the interplay between abiotic hydrolytic degradation and crystallization of bacterial polyesters comprising short and medium side-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biomacromolecules. 2020;21(2):761–71. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.9b01458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bonartsev AP, Boskhomodgiev AP, Iordanskii AL, Bonartseva GA, Rebrov AV, Makhina TK, et al. Hydrolytic degradation of poly(3-hydroxybutyratepolylactide and their derivatives: kinetics, crystallinity, and surface morphology. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 2012;556(1):288–300. doi:10.1080/15421406.2012.635982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pei R, Tarek-Bahgat N, van Loosdrecht MCM, Kleerebezem R, Werker AG. Influence of environmental conditions on accumulated polyhydroxybutyrate in municipal activated sludge. Water Res. 2023;232(14):119653. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2023.119653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kim J, Gupta NS, Bezek LB, Linn J, Bejagam KK, Banerjee S, et al. Biodegradation studies of polyhydroxybutyrate and polyhydroxybutyrate-co-polyhydroxyvalerate films in soil. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7638. doi:10.3390/ijms24087638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools