Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Characterization, In Vitro Dissolution, and Drug Release Kinetics in Hard Capsule Shells Made from Hydrolyzed κ-Carrageenan and Xanthan Gum

1 Halal Research Center, Airlangga University, Surabaya, 60286, Indonesia

2 Departement of Chemistry, Faculty of Science dan Technology, Airlangga University, Surabaya, 60115, Indonesia

3 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, Airlangga University, Surabaya, 60115, Indonesia

4 Departement Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, Brawijaya University, Malang, 65145, Indonesia

5 Department of Bioprocess & Polymer Engineering, Faculty of Chemical & Energy Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310, Skudai, Johor, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Pratiwi Pudjiastuti. Email: ; Siti Wafiroh. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(9), 1841-1857. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0084

Received 31 December 2024; Accepted 22 May 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

This study aims to enhance the mechanical properties, disintegration, and dissolution rates of cross-linked carrageenan (CRG) capsule shells by shortening the long chains of CRG through a hydrolysis reaction with citric acid (CA). The hydrolysis of CRG was carried out using varying concentrations of CA, resulting in hydrolyzed CRG (HCRG). This was followed by cross-linking with xanthan gum (XG) and the addition of sorbitol (SOR) as a plasticizer. The results indicated that the optimal swelling capacity of HCRG-XG/SOR hard-shell capsules occurred at a CA concentration of 0.5%, achieving a maximum swelling rate of 445.39% after 15 min. Additionally, the best capsule hardness was also measured at this CA concentration, reaching a hardness level of 480.157 g (F = 4.67 N). FTIR analysis demonstrated that the presence of the acid group from CA altered the composition of the CRG chains. Furthermore, SEM-EDX mapping analysis revealed that the surface morphology of the synthesized capsules exhibited a relatively smooth texture with a limited number and size of pores, resulting in good capsule stability for drug delivery. The in vitro disintegration and dissolution rates of the HCRG-XG/SOR capsules were observed to be the fastest and highest at pH 1.2, respectively. The disintegration time was recorded at 20 min and 46 s, while the dissolution test indicated a drug release of 78.08% after 5 min and 100% after 120 min. The drug delivery kinetics of HCRG-XG/SOR followed the Ritger-Peppas model, indicating a complex release mechanism that involved swelling, diffusion, erosion, and capsule disintegration.Keywords

Capsules are a popular form of medication because they mask unpleasant tastes and odors of the active ingredients, are easy to swallow, and provide good flexibility and biocompatibility [1]. The most commonly used material for making both soft and hard-shelled capsules is gelatin, a pure protein obtained from the partial hydrolysis of collagen, which is sourced from animals [2]. Gelatin is favored for several reasons: it is tasteless, non-toxic, has excellent gelling strength, and disintegrates rapidly within the body [3]. However, gelatin has some drawbacks, including being sensitive to temperature, gradually degrading in low-acid environments, and being derived from animal sources, primarily pigs, cows, and fish [4]. Most of the gelatin produced in Europe, and subsequently exported globally, comes from pig skin (80%), with 15% derived from a split source, which is a thin collagen-containing layer from the bovine dermis, situated between the epidermis and subcutaneous layers. The remaining 5% of gelatin comes from the bones of pigs, cows, and fish [5]. This means that Muslims, Hindus, vegetarians, and individuals with allergies to animal products cannot consume it. Consequently, there is a need for plant-based alternatives for capsule materials.

Currently, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) is the most widely used alternative in capsule manufacturing. However, it tends to be more fragile and susceptible to breakage compared to gelatin [6]. Although HPMC is derived from renewable wood or cotton cellulose, its production does have limitations. As a result, seaweed-based materials are gaining attention for their cost-effective and simpler production processes.

Indonesia, being one of the largest producers of seaweed, is considering it as a plant-based alternative to gelatin. Several studies have explored the use of carrageenan for capsules [7], xanthan gum for microcapsules [8], and alginate-based hard capsules [9]. Characterization from these studies indicates that these materials have the potential to replace HPMC; however, they also have weaknesses, including rigidity, susceptibility to cracking, slow disintegration times, and poor drug dissolution rates across different pH levels (stomach pH of 1.2, duodenum pH of 4.5, and small intestine pH of 6.8). Therefore, modifications are needed to enhance the mechanical properties of these hard-shell capsule materials and improve their disintegration times and drug dissolution rates.

To strengthen the capsules, this research introduces cross-linking between carrageenan and xanthan gum, aiming to enhance the viscosity and mechanical properties [10]. Additionally, sorbitol is used as a plasticizer to increase flexibility and elasticity, reducing the risk of cracking [10,11]. An acid hydrolysis process is applied to break down the long chains of carrageenan, which improves the capsule’s disintegration time and dissolutin rate [12].

This study also evaluates the mechanical properties of the capsules, including swelling degree, hardness, disintegration, and drug dissolution analysis. The release kinetics of the drug are examined to determine which model best describes the drug release profile from the capsules. Statistical analysis of the models is conducted using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). This research has the potential to promote health and well-being in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals by offering an alternative material for producing commercial capsules.

The edible kappa carrageenan (ĸ-CRG) used in the study was purchased from PT. Kapsulindo Nusantara, while the xanthan gum was obtained from PT. Rumah Organik 88. The plasticizer, 70% sorbitol (food-grade), was purchased from PT. Brataco Chemika in Surabaya. Diclofenac acid is obtained from PT. Dexa Medika in Indonesia. For the drug release kinetics analysis, distilled water and concentrated HCl (36.5%), citric acid, sodium citrate, sodium dihydrogen sulfate, and disodium phosphate were used. The swelling analysis was conducted using distilled water.

2.2 Preparation of CRG-XG/SOR and (H)CRG-XG/SOR

ĸ-CRG powder (4 g) was first mixed with citric acid at different concentrations of 0.5%, 1.0% and 1.5% by using a mortar and pestle or a dry mixer to ensure a uniform distribution. Then, 2 g of xanthan gum (XG) was added followed by blending thoroughly until a homogeneous dry mixture was obtained. Separately, 0.5 mL of sorbitol (SOR) was gradually dissolved in distilled water while stirred continuously by using a glass rod or magnetic stirrer until fully dissolved at room temperature.

Subsequently, the dry powder mixture of ĸ-CRG, citric acid, and XG was added slowly into the sorbitol solution while stirring constantly to prevent clumping. The mixture was further stirred manually by using a glass rod or a mechanical stirrer for approximately 5 min until a colloidal mixture was formed. The mixture was then heated in a water bath at 70°C–80°C for approximately 2 h to form a gel without trapped air bubbles. The dipping bath which is the container holding the molding material was heated simultaneously with the heating process of the dry mixture to avoid temperature differences between the capsule material and the dipping bath [13].

For the molding process, dipping pens were first coated evenly with lecithin, which served as a lubricant. The lubricated dipping pens were then quickly immersed in a preheated dipping bath containing gel. To ensure uniform coating and prevent excessive thickening on one side, the dipping bath was rotated at a constant speed. This dipping process was repeated twice to achieve the desired thickness. For drying, the coated dipping pens were placed in an air-drying chamber or in a clean, dust-free environment at room temperature. The capsules were left to dry undisturbed for 24 h until they were fully hardened. Once dried, the capsules were carefully removed from the dipping pens and inspected for uniformity. To identify the best formula, the physical properties of the capsules—such as uniformity, hardness, and integrity—were assessed. The preparation process was replicated at least three consecutive times under identical conditions to ensure repeatability. The results were then compared for consistency across the batches [13].

2.3 Molecular Weight Determination of the ĸ-CRG, (H)CRG, and XG

The molecular weight determination of the ĸ-CRG, (H)CRG, and XG material samples was performed using the viscometry method. A total of 0.5 g of the sample was dissolved in 500 mL of distilled water. The Brookfield viscometer was used with spindle number one, operated at room temperature (25°C) and a speed of 60 rpm. The intrinsic viscosity data obtained after the test was then analyzed using the Mark-Houwink-Sakurada equation to calculate the average molecular weight.

2.4 Swelling Degree Analysis of (H)CRG-XG/SOR Hard Capsules

Tunneling The swelling test was conducted by first drying the hard-shell capsules in an oven and weighing them to obtain the dry weight (W0). Next, the dried capsules were immersed in distilled water, and their mass was measured again to determine the wet weight (Wt). The degree of swelling (Q) was then calculated using the following formula:

where Q = swelling degree; W0 = dry weight; and Wt = wet weight [14,15].

2.5 Hardness Test of CRG-XG/SOR and (H)CRG-XG/SOR Hard Capsules

The hardness test for the capsules was conducted using a CT3 Texture Analyzer from Brookfield. Each capsule formulation was tested with a minimum of three repetitions. A flat-ended probe (TA-10) with a diameter of 12.7 mm was used for this assessment. The hard capsule was placed on the texture analyzer’s platform and centered directly beneath the probe. The test was performed in ‘compression’ mode with a target compression distance of approximately 4.0 mm and a compression speed of 1.0 mm/s. The breaking force, also known as fracture strength, of the compressed capsule was recorded. This force serves as an indicator of the capsule’s hardness and structural integrity [16].

2.6 FTIR Analysis of (H)CRG-XG/SOR Hard Capsules

The identification of functional groups within the material of the capsule shell was performed using FTIR (Fourier-transform infrared) analysis. To prepare the sample, 2 mg of the capsule was homogenized with 200 mg of KBr. This mixture was then shaped into a pellet by vacuuming and applying pressure with a hydraulic press at 10,000–15,000 psi to form a thin disc. The transmittance of the sample pellet was recorded using FTIR spectroscopy over a wavenumber range of 400 to 4000 cm−1 [17].

2.7 SEM-EDX Mapping Analysis of the Surface of (H)CRG-XG/SOR Hard Capsules

The hard capsules of CRG-XG/SOR and (H)CRG-XG/SOR, which exhibited the most optimal mechanical test results, were analyzed for their morphological structure using Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX) mapping. The samples were coated with either gold or palladium at a maximum pressure of 0.06 mBar. Subsequently, the samples were placed on a brass stub holder for observation with the SEM-EDX mapping instrument [18].

2.8 In-Vitro Disintegration Analysis of (H)CRG-XG/SOR Hard Capsules

The disintegration test was conducted to determine the time required for a drug to break down. The test was performed using a disintegration test apparatus in accordance with USP 8.0 (2020). Three samples of hard-shell capsules were immersed in 900 mL of medium under three different pH conditions (pH 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8) at a temperature of 37°C ± 0.5°C. The apparatus was operated until all the hard-shell capsules had completely dissolved. A sample was considered to have undergone 100% disintegration when no core mass remained. The medium solutions (10 L total) with different pH levels were prepared as follows: For the pH 1.2 medium, which simulates conditions in the human stomach, 52 mL of hydrochloric acid (36.5%) was used. The standard pH 4.5 solution, representing the pH of cellular fluids, was prepared by mixing 1.212 g of citric acid and 29.41 g of trisodium citrate dihydrate. Lastly, the standard pH 6.8 solution, which mimics the pH in the small intestine, was prepared by dissolving 2.844 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) and 17.42 g of dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4). The total volume of all solutions was adjusted to 10 L with distilled water [19].

2.9 Dissolution Profile and Release Kinetics of Natrium Diklofenac from (H)CRG-XG/SOR Hard Capsules

The dissolution test was performed to measure the time required for drug release from the synthesized hard-shell capsule. Water was chosen as the dissolution medium since it constitutes the largest part of the human body. However, adjustments to the acidity of the dissolution medium were necessary because different parts of the human body have varying acidity levels. In this study, the recommended pH values were: stomach acid at pH 1.2 [20], average body tissue pH at 4.5 [21], and saliva pH at 6.8 [22]. pH adjustments were achieved using buffer solutions. The dissolution test was conducted at pH levels of 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8 to simulate key physiological conditions in the gastrointestinal tract where the capsule is expected to dissolve. Since the formulation is designed for release in the stomach or small intestine, testing at pH 7.4, which represents the colon or plasma, was deemed irrelevant. The selected pH values align with pharmacopeial standards, and additional testing at pH 7.4 could be considered in future studies if necessary. The experiment utilized a basket-type dissolution apparatus, which included a 1000 mL glass vessel, a motor, a metal shaft driven by the motor, and a basket. The glass vessel was filled with 900 mL of buffer solution at 37°C, and the drug-filled capsules were placed inside the basket. The baskets were then immersed in the different dissolution media and rotated at 60 rpm. Samples were taken at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min and subsequently analyzed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. The drug release kinetics were analyzed by plotting the concentration of the samples over time and fitting the data to various models, including the zero-order equation, first-order equation, Higuchi model, Korsmeyer-Peppas model, and Peppas-Sahlin model [23,24].

3.1 Preparation of (H)CRG-XG/SOR

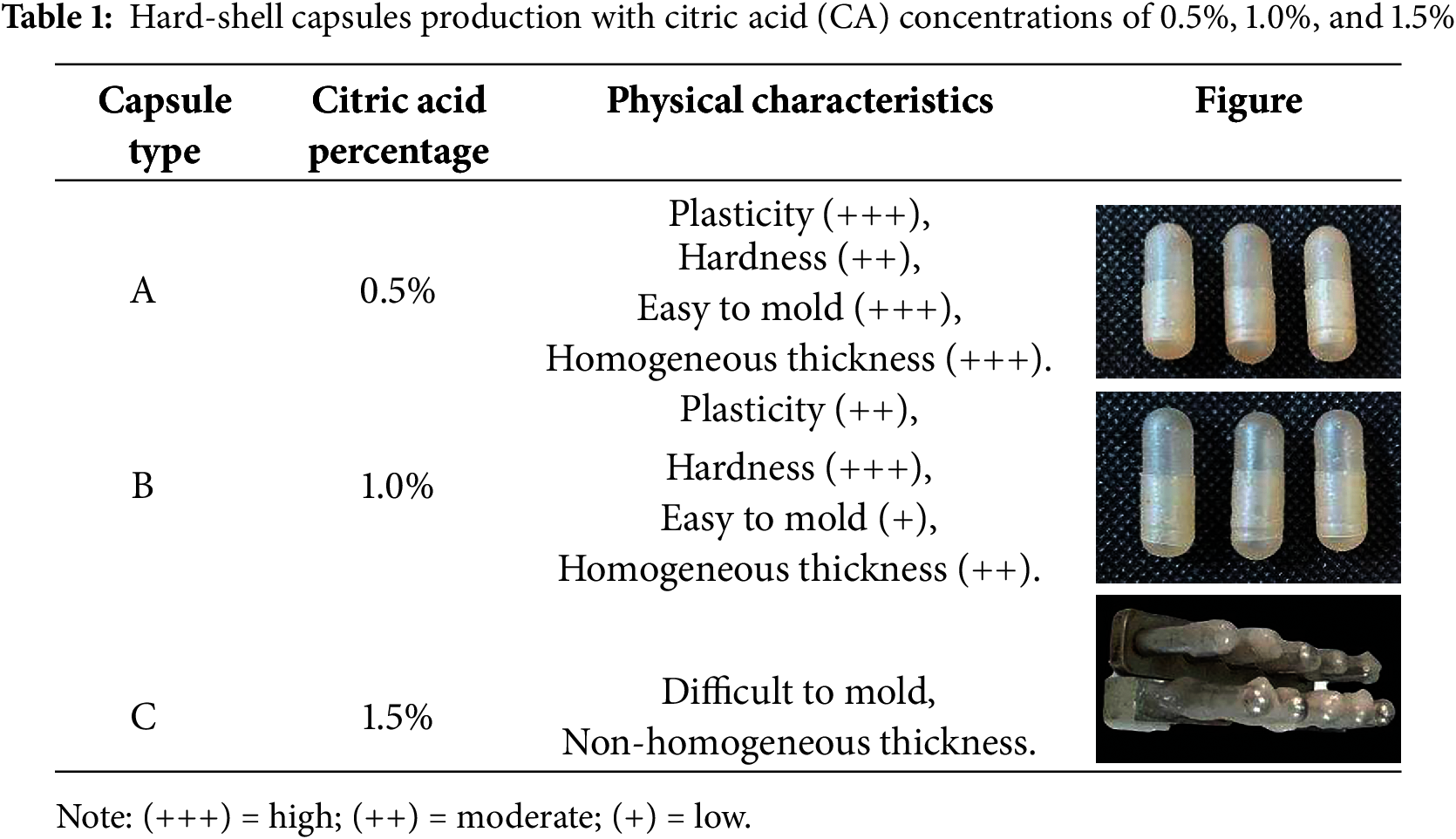

The results of capsule production with various concentrations of citric acid (CA) 0.5%, 1.0%, and 1.5% are presented in Table 1. According to the table, Capsule A, which was produced using 0.5% CA, exhibited better physical characteristics compared to Capsules B and C. Capsule A was easier to mold and demonstrated optimal plasticity and hardness. In contrast, Capsule B displayed lower plasticity and higher hardness, indicating that it was more brittle, fragile, and less well-gelated, which made it difficult to mold uniformly. Capsule C was challenging to mold and showed inconsistency in thickness; therefore, no further analysis was performed on it.

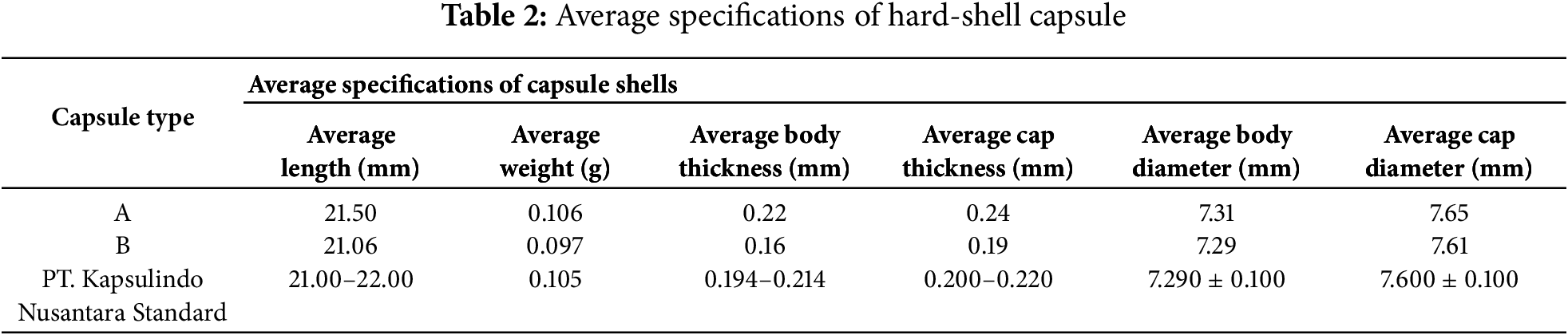

The subsequently, the average specifications of Capsules A and B were compared to a commercial hard-shell capsule from PT Kapsulindo Nusantara, as detailed in Table 2. The addition of 0.5% CA in Capsule A matched the specification standards of the hard-shell capsules from PT Kapsulindo Nusantara. However, with 1.0% CA in Capsule B, some specifications, including average weight and average capsule thickness, fell below the required standards. Thus, this study concluded that the most physically optimal capsule was Capsule (H)CRG-XG/SOR with the addition of 0.5% CA.

3.2 Molecular Weight Determination of the CRG, (H)CRG, and XG

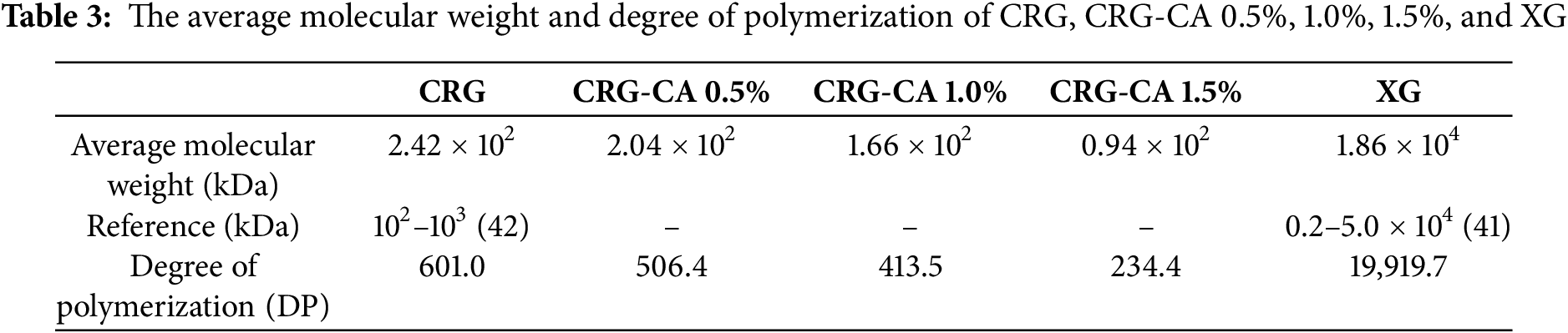

Citric acid (CA) is an organic acid that can act as a catalyst in hydrolysis reactions under specific conditions, such as low pH and high temperature. When CA is added to a solution of CRG, the hydrogen ions (H+) from the acid attack the glycosidic bonds (C-O-C bonds) along the CRG chain, causing the polymer chain to break. This process results in the fragmentation of the CRG polymer into smaller fragments with lower molecular weights, as shown in Table 3. The average molecular weight of CRG decreases from 2.42 × 102 to 0.94 × 102 kDa with increasing CA concentrations, confirming that CA can cleave the polysaccharide bonds in CRG through hydrolysis Table 3. In contrast, XG has an average molecular weight of 1.86 × 104 kDa, which contributes to the mixture’s strong mechanical properties. The degree of polymerization (DP) data in Table 3 indicates a decrease in DP for CRG when hydrolyzed with higher concentrations of CA. However, even at the tested CA concentrations, the reduced DP of hydrolyzed CRG remains in the oligomeric form, consisting of 3 to 8 monomer units. Further hydrolysis of CRG to create its oligomers increases the difficulty of molding capsules due to the significantly reduced gel strength. Additionally, elasticity diminishes when CRG is hydrolyzed into its oligomeric form; in higher molecular weight polymers, elasticity arises from the polymer chains’ ability to stretch and return to their original shape. Shorter chains lose this ability, making the capsules less flexible and more prone to breaking under external mechanical pressure [25]. This observation is supported by the data in Table 2, which shows that with 1.0% CA concentration, the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules became more difficult to mold compared to (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules produced with 0.5% CA. Moreover, capsules formed with 1.5% CA concentration did not meet the required standards.

3.3 Hardness Test of (H)CRG-XG/SOR Capsules

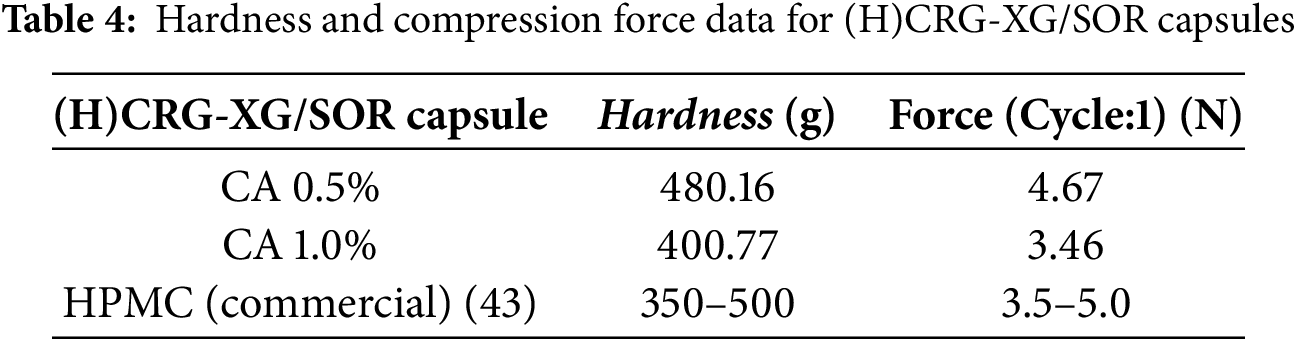

In real-world applications of hard-shell capsules, sufficient strength is crucial to prevent cracking during the filling and packaging processes. The hardness of the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules was measured, and the results are presented in Table 4. According to the table, the (H)CRG-XG/SOR hard-shell capsules containing 0.5% of CA exhibited the highest hardness at 480.16 g. In contrast, the hardness decreased to 400.77 g when the CA concentration was increased to 1.0%. Additionally, the higher compression force observed at 0.5% CA (4.67 N) indicates that capsules with lower CA concentration are more resistant to mechanical stress. On the other hand, the reduction in hardness and compression force at 1.0% CA suggests that these capsules are more susceptible to cracking and have reduced elasticity. When compared to commercial HPMC capsules, which have a compression force range of 3.5 to 5.0 N, the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules with 0.5% CA fall within the acceptable range. This makes them a viable alternative to HPMC capsules for accommodating various active ingredients.

3.4 Hardness Test of (H)CRG-XG/SOR Capsules

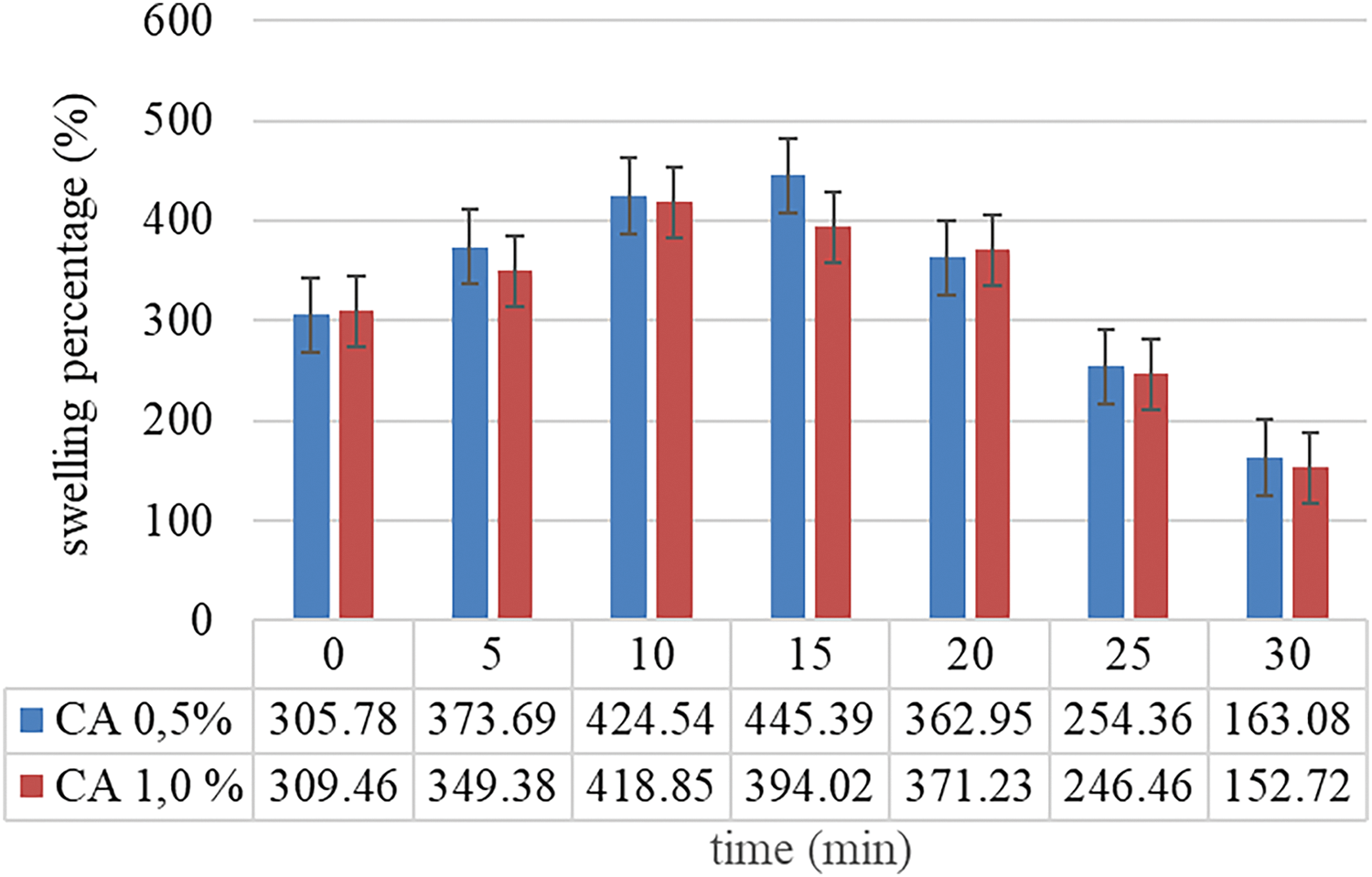

The swelling degree is crucial for determining a capsule’s capacity to absorb water, which is directly related to the drug release mechanism. The swelling degree of (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules with different concentrations of CA was tested for 30 min, and the results were illustrated in Fig. 1. From the figure, it was observed that when 0.5% of CA was used, the maximum swelling degree of the synthesized capsule occurred at 15 min reaching 445.39%. In contrast, the highest swelling degree of the capsule with 1.0% of CA was achieved at an earlier time, which was at 10 min, with a value of 418.85%. This suggested that a capsule with 0.5% CA was more stable and able to withstand higher mechanical stress for a longer duration.

Figure 1: Swelling degree percentage

Fig. 1 showed that (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules with 0.5% CA exhibit a greater swelling degree compared to those with 1.0% CA, susceptible to a more plastic material that can resist the internal pressure caused by swelling. On the other hand, capsules with 1.0% CA showed to disintegrate more quickly due to a higher brittle structure, leading to uncontrolled release of active ingredients.

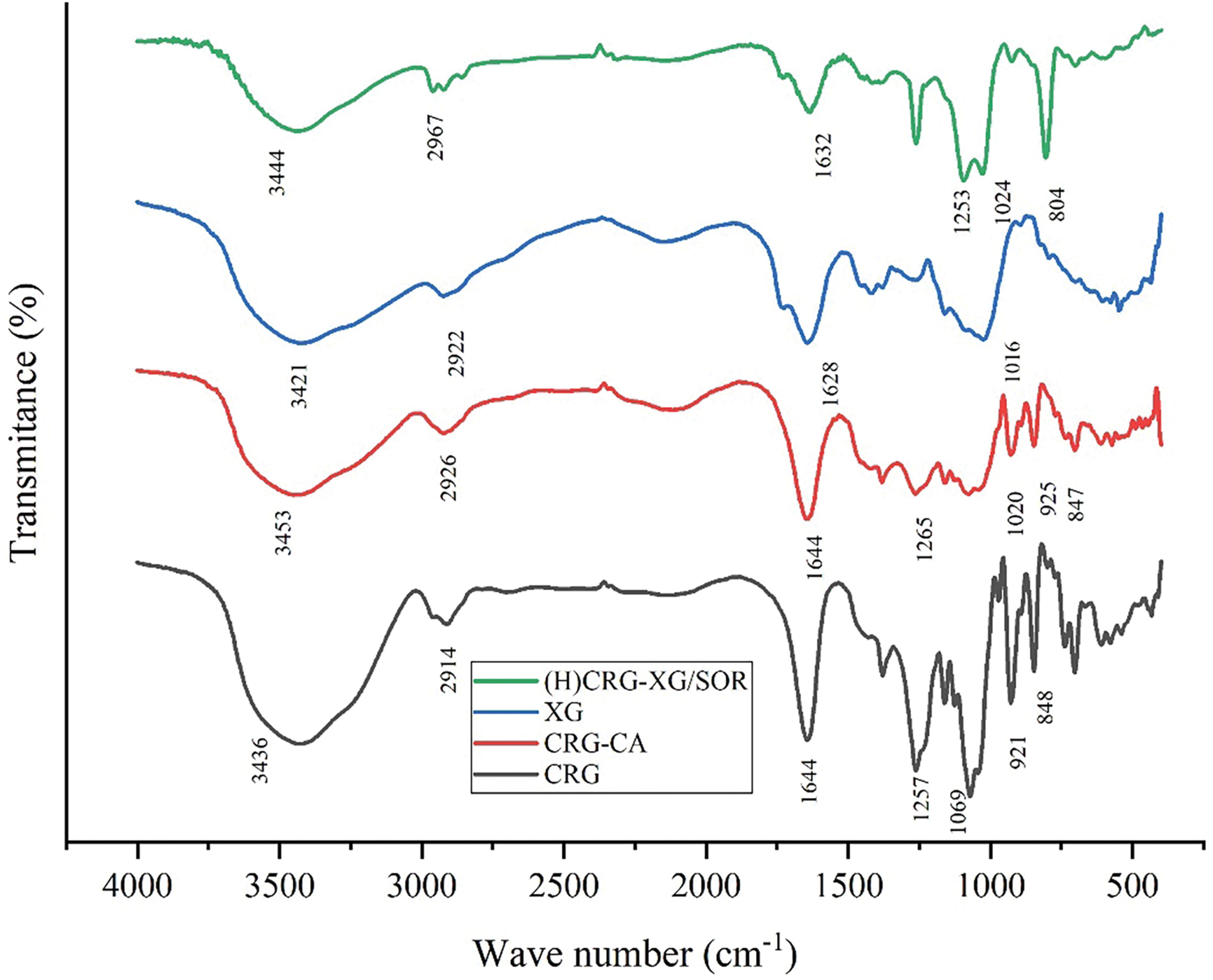

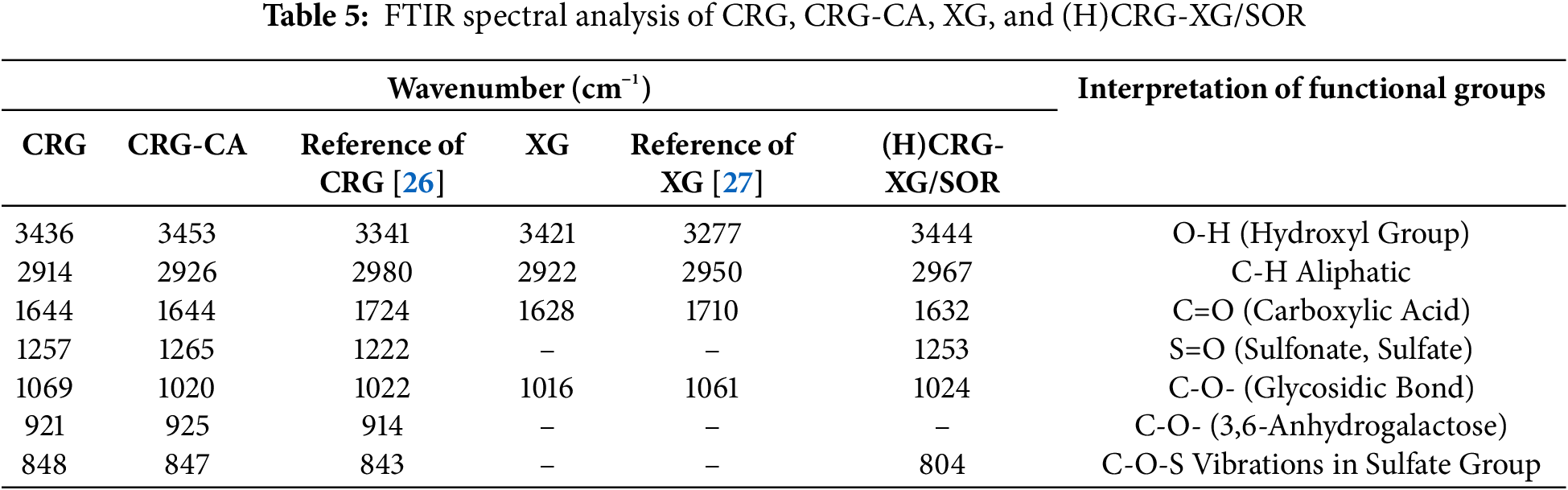

FTIR analysis was conducted to identify the functional groups present in the materials used for capsule formation, specifically CRG, CRG-CA, XG, and the printed capsule material (H)CRG-XG/SOR. The FTIR spectra of these samples are presented in Fig. 2, and the interpretation of the peaks is summarized in Table 5. The analysis revealed several key functional groups within the capsule base materials. In the wavenumber range of 3436–3453 cm−1, a broad peak was observed, indicating the presence of hydroxyl groups (O-H stretching) in all four samples (CRG, CRG-CA, XG, and (H)CRG-XG/SOR). This suggests a strong hydrogen bonding within the material system. In the spectrum of (H)CRG-XG/SOR, the hydroxyl peak appeared broader and less intense compared to that of pure CRG, indicating stronger interactions among the components in the system. Additionally, aliphatic C-H peaks were noted in the wavenumber range of 2914–2967 cm−1, reflecting the stable aliphatic bonds within the capsule structure.

Figure 2: FTIR spectra of CRG, CRG-CA, XG, and (H)CRG-XG/SOR

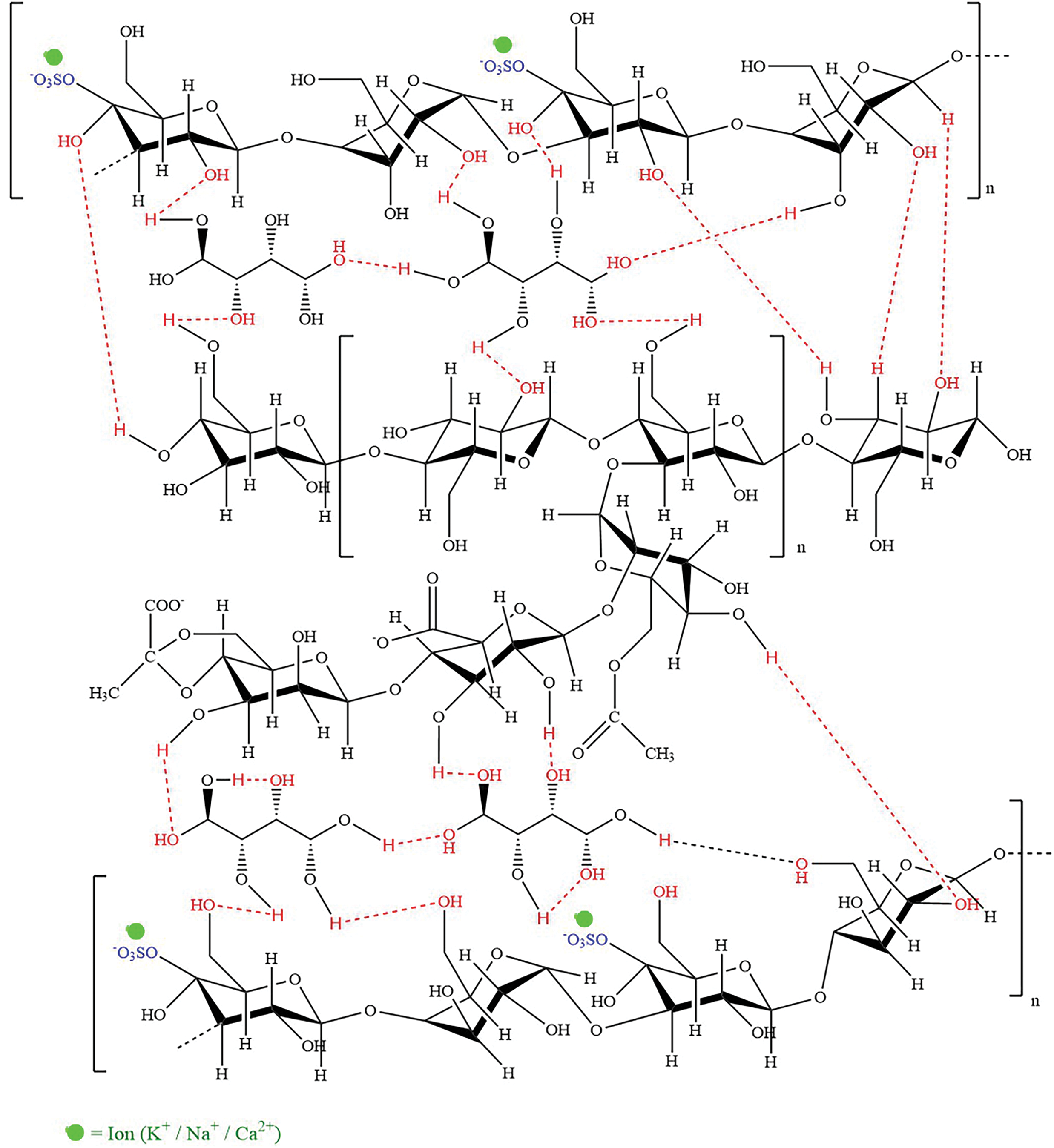

In addition, the C=O peak detected in the range of 1628–1644 cm−1 indicates a more complex interaction among CRG, XG, and SOR in the (H)CRG-XG/SOR system, causing slight shifts in peak intensity and position. The interaction of the C=O group in (H)CRG-XG/SOR material also reveals the formation of hydrogen and electrostatic bonds between the components. The S=O group observed at wavenumbers 1253–1265 cm−1 demonstrates the presence of sulfonate or sulfate structures in the capsules, while the C-O vibrations at wavenumbers 921–925 cm−1 confirm the presence of glycosidic bonds in CRG, which contributes to the formation of the gel network within the capsule (Table 5). The overall spectra indicate that the hard-shell capsules possessed stable bonds and interactions between components, supporting the formation of a solid hard-shell capsule structure. Fig. 3 showed the hypothesis of chemical bonds occurring in the formation of the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsule.

Figure 3: Hypothesis of chemical bonds occurring in the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsule

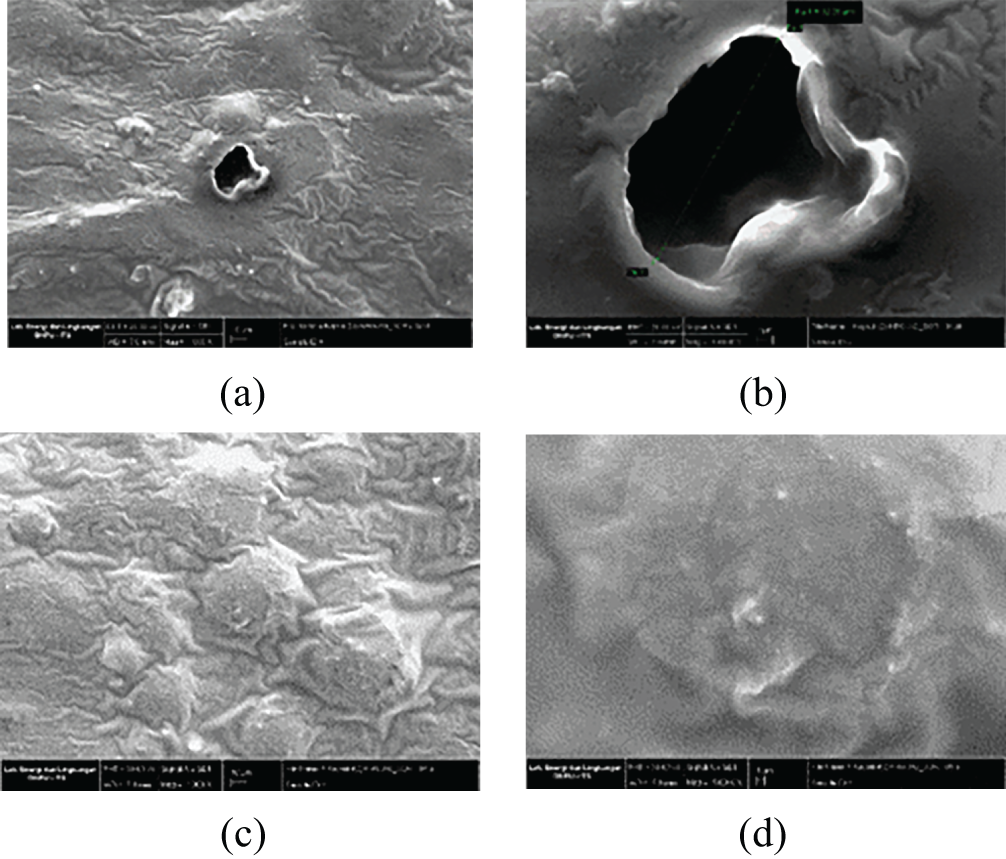

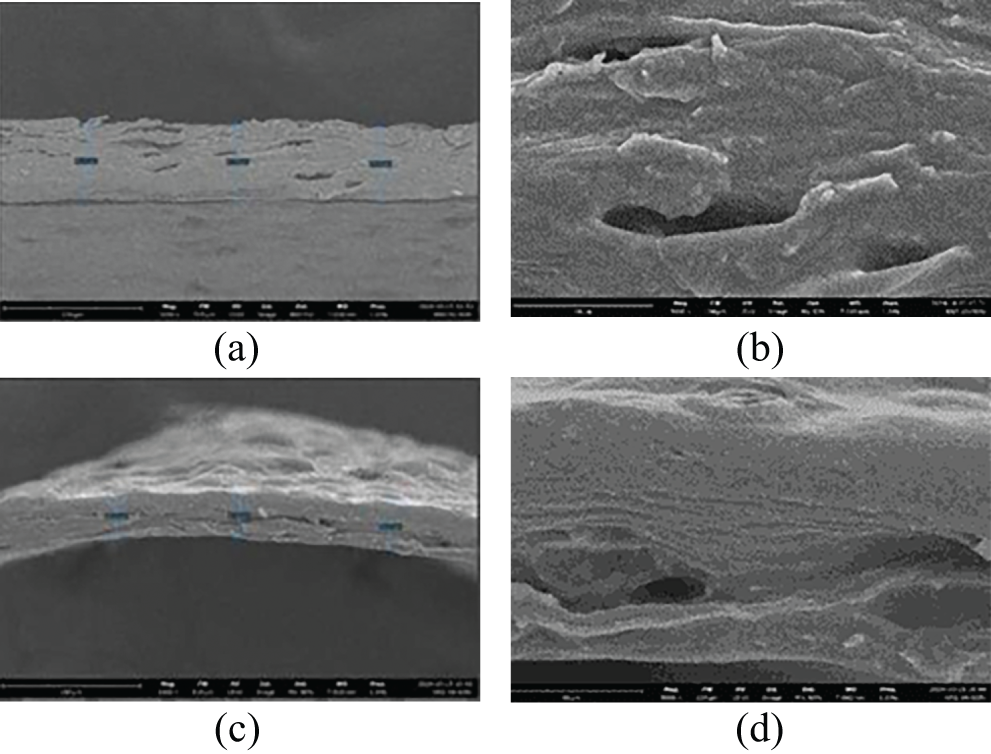

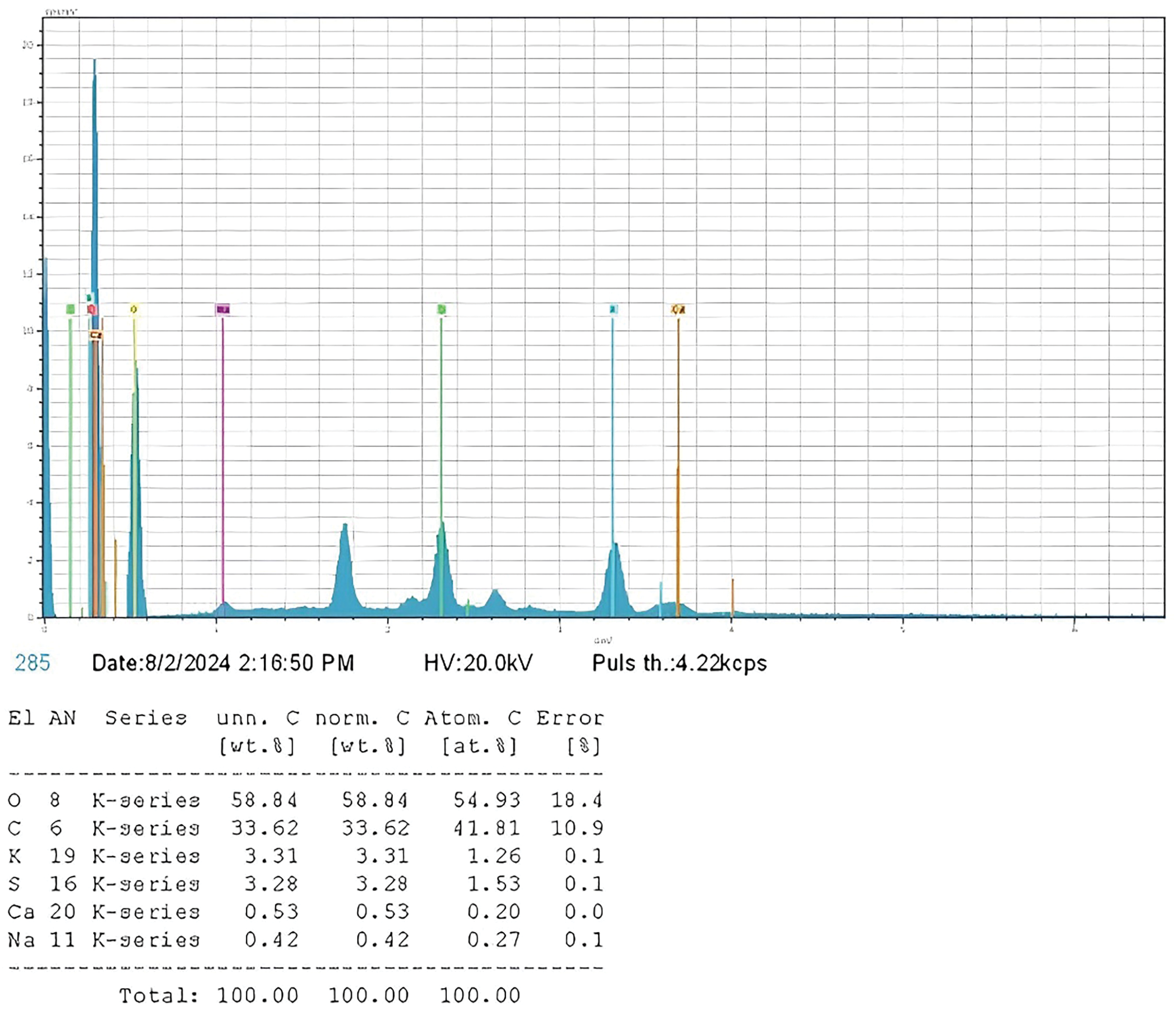

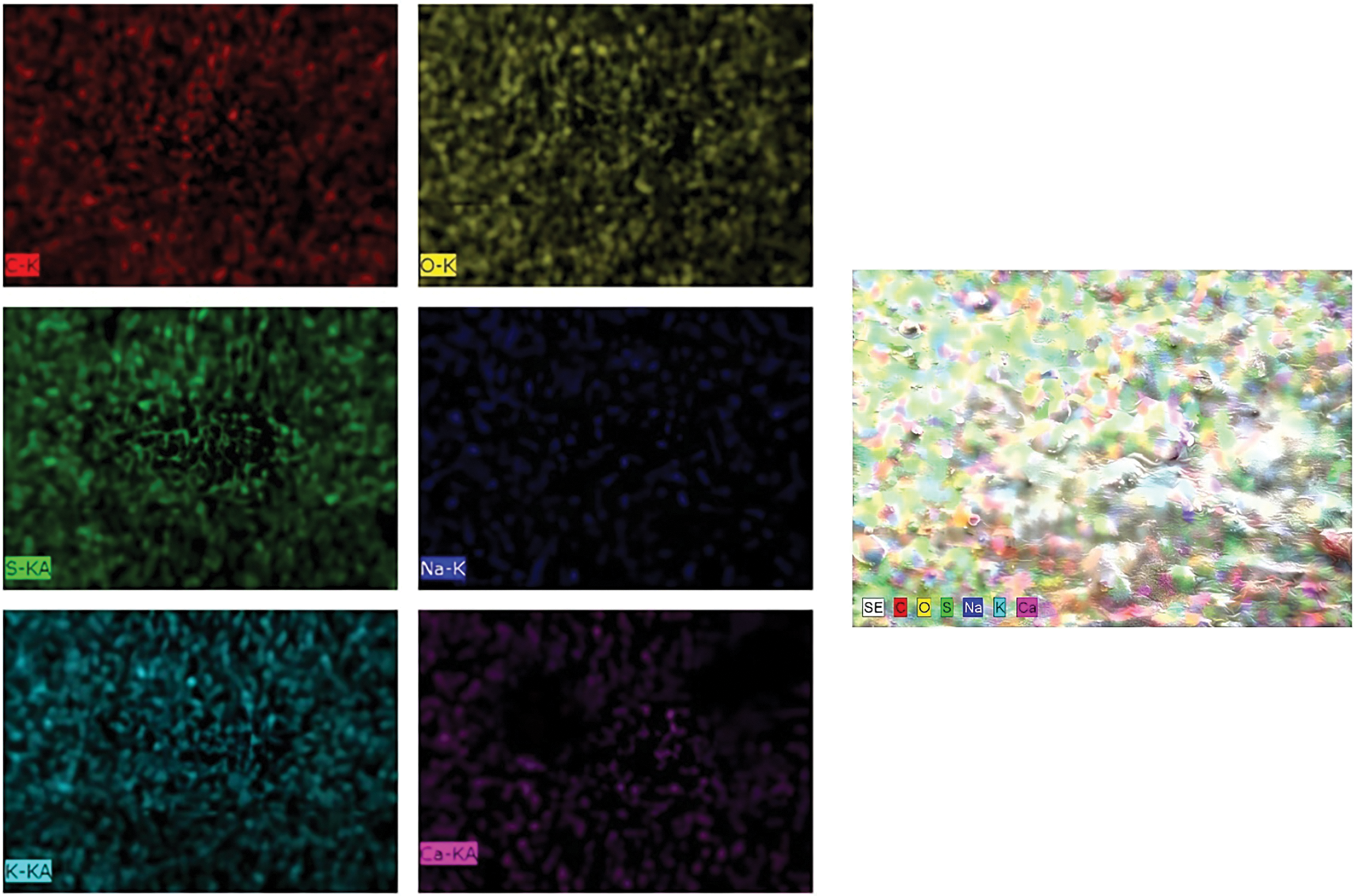

3.6 Analysis of Capsules Using SEM-EDX Mapping

The morphology and element distributions of the synthesized capsules were characterized using SEM-EDX mapping. The surface and cross-sectional images of the capsules are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively, while the EDX analysis is presented in Fig. 6. Fig. 4 shows that the SEM images reveal the surface morphology of the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules, which exhibit small pores with an average diameter of 32.35 μm. The relatively low number of pores indicates good mechanical stability of the capsules and resistance to oxidation, providing protection to the encapsulated active ingredients against degradation. The cross-sectional view of the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules, presented in Fig. 5, demonstrates the overall structure of the capsule wall at 1000 times magnification (Fig. 5c), revealing an average thickness of 64.69 μm. The surface of the capsule appears uneven, with visible porous regions likely due to the presence of porosity. At 5000 times magnification (Fig. 5d), the cross-sectional details become more pronounced, uncovering microstructural features such as cracks, cavities, or small channels. These features may act as pathways for material diffusion and contribute to faster capsule degradation.

Figure 4: SEM surface morphology images of the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules at (a) point I with a 1000× magnification; (b) point I with a 5000× magnification; (c) point II with a 1000× magnification; and (d) point II with a 5000× magnification

Figure 5: SEM cross-sectional images of the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules at (a) point I with a 1000× magnification; (b) point I with a 5000× magnification; (c) point II with a 1000× magnification; and (d) point II with a 5000× magnification

Figure 6: Percentage composition of elements in the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsule as determined by EDX analysis

Eventually, the EDX analysis shown in Fig. 6 indicates that the primary elements in the capsules were oxygen and carbon, followed by smaller amounts of other elements such as potassium, sulfur, calcium, and sodium. Subsequently, the uniform and homogeneous distributions of these elements in the mapping image were depicted in Fig. 7 where the result illustrates that the capsule’s base materials were well-mixed, resulting in stable capsules with an element distribution that supports their chemical and physical stability.

Figure 7: Atomic distribution of (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsule

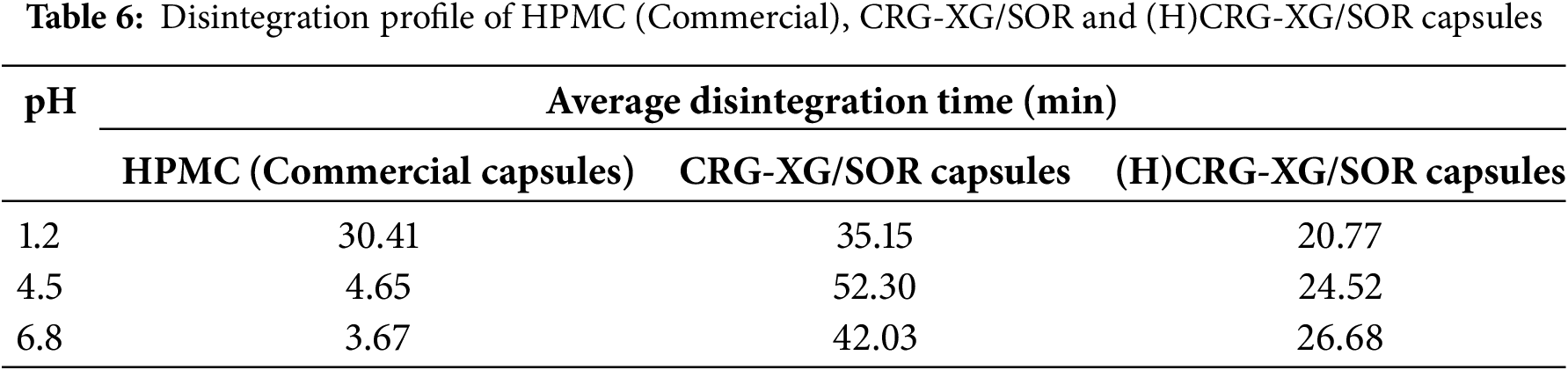

According to Table 6, the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules disintegrated at pH 1.2 in 20 min and 46 s, which is faster than the unhydrolyzed CRG-XG/SOR capsules, which took 35 min and 9 s to disintegrate. This difference is attributed to citric acid, which breaks the CRG chains into shorter fragments, thereby accelerating the disintegration process. A similar pattern was observed at pH 4.5 and pH 6.8, where the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules also disintegrated more rapidly than the CRG-XG/SOR capsules. Overall, the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules demonstrated the fastest disintegration time at pH 1.2, as carrageenan tends to degrade more readily in acidic conditions. While (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules exhibited faster disintegration at pH 1.2, they disintegrated more slowly at pH 4.5 and pH 6.8 compared to commercial HPMC capsules. This suggests that (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules are better suited for rapid drug release in acidic environments, such as the stomach.

3.8 Analysis of Dissolution Profile and Drug Release Kinetics

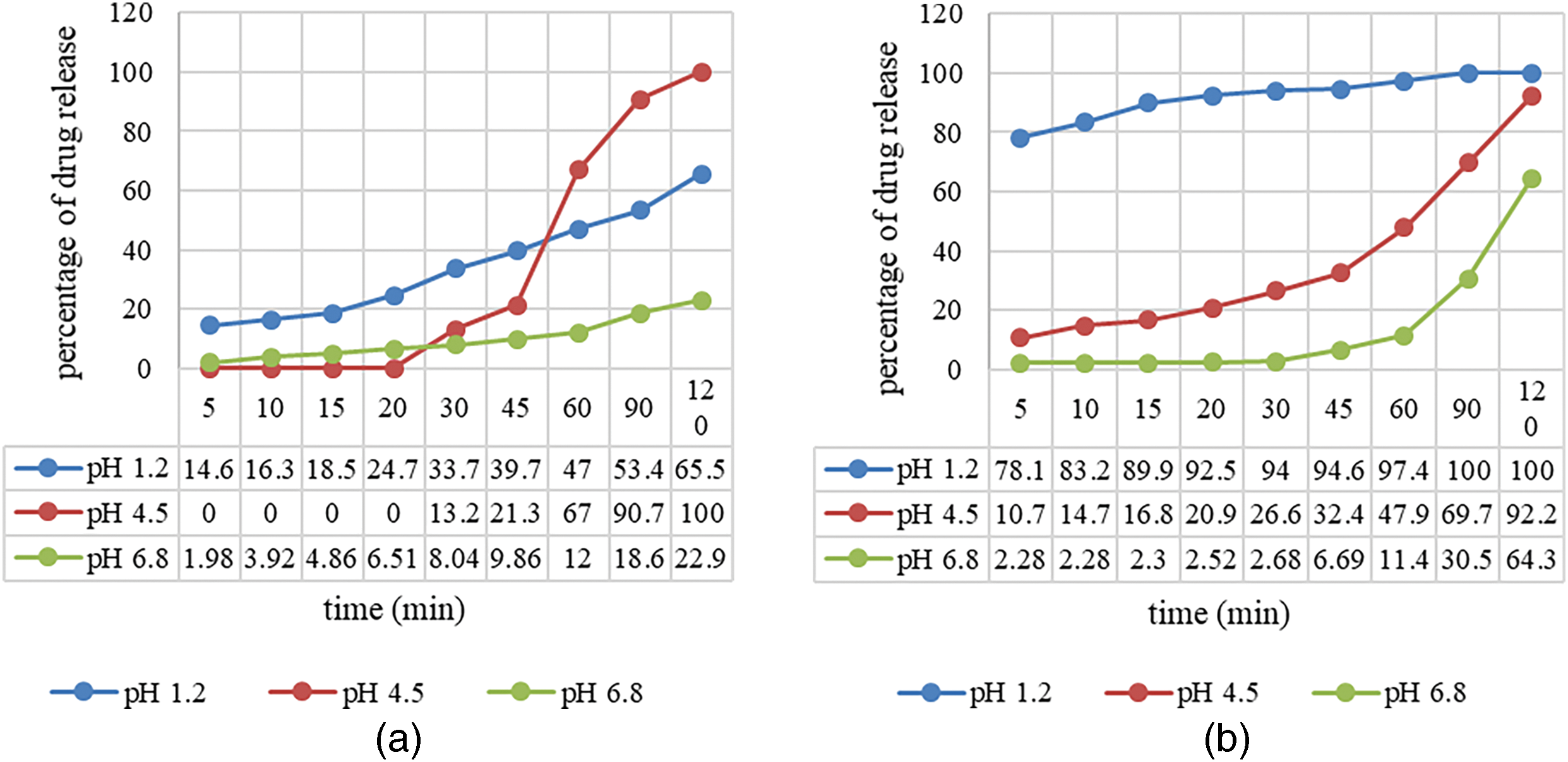

The dissolution profile analysis was performed to measure the release rate of sodium diclofenac from commercial HPMC capsules and (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules under three different pH conditions: pH 1.2 (stomach), pH 4.5 (duodenum), and pH 6.8 (small intestine). The results are illustrated in Fig. 8. From Fig. 8, we observe that the initial drug release from commercial HPMC capsules at pH 1.2 reached 14.61% within 5 min and increased to 65.54% after 120 min. Significant drug release from the HPMC capsules at this pH began after 20 min, with an accelerated release phase occurring between 60 and 120 min. At pH 4.5, the drug release from HPMC capsules was very slow during the first 15 min; however, it increased exponentially to achieve a complete release of 100% by 120 min. In contrast, at pH 6.8, the drug release was even slower, only reaching 22.86% within the same period, indicating suboptimal sodium diclofenac release from HPMC capsules under neutral conditions.

Figure 8: Dissolution rate of sodium diclofenac in (a) HPMC capsules and (b) (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules

Overall, the HPMC capsules exhibited the most optimal drug release at pH 4.5, with 100% of the drug released within 120 min. At pH 1.2, drug release was efficient but did not achieve complete release by the 120-min mark, as seen at pH 4.5. At pH 6.8, the release was significantly lower than at pH 1.2, indicating that neutral pH conditions were less suitable for rapid sodium diclofenac release from HPMC capsules. According to Fig. 8, the release of sodium diclofenac from (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules at pH 1.2 was notably rapid, reaching 78.08% within 5 min and achieving complete release within 90 min, demonstrating the capsule’s effectiveness for rapid release under acidic conditions. At pH 4.5, the release was slower, reaching 92.17% after 120 min, indicating a gradual drug release profile. At pH 6.8, the initial drug release was minimal (2.28% within 5 min) and reached only 64.25% within 120 min, suggesting that the capsules are less effective for rapid release in neutral pH conditions.

In summary, the synthesized (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules exhibited the fastest drug release at pH 1.2, with complete release occurring within 90 min, making these capsules suitable for gastric drug delivery applications. At pH 4.5, the drug release was gradual but nearly reached 100% by 120 min. The slowest release occurred at pH 6.8, with only 64.25% of the drug released within 120 min. These findings correlate with the disintegration rate of (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules (Table 6), where the fastest disintegration occurred under acidic conditions due to the high solubility of carrageenan in such environments.

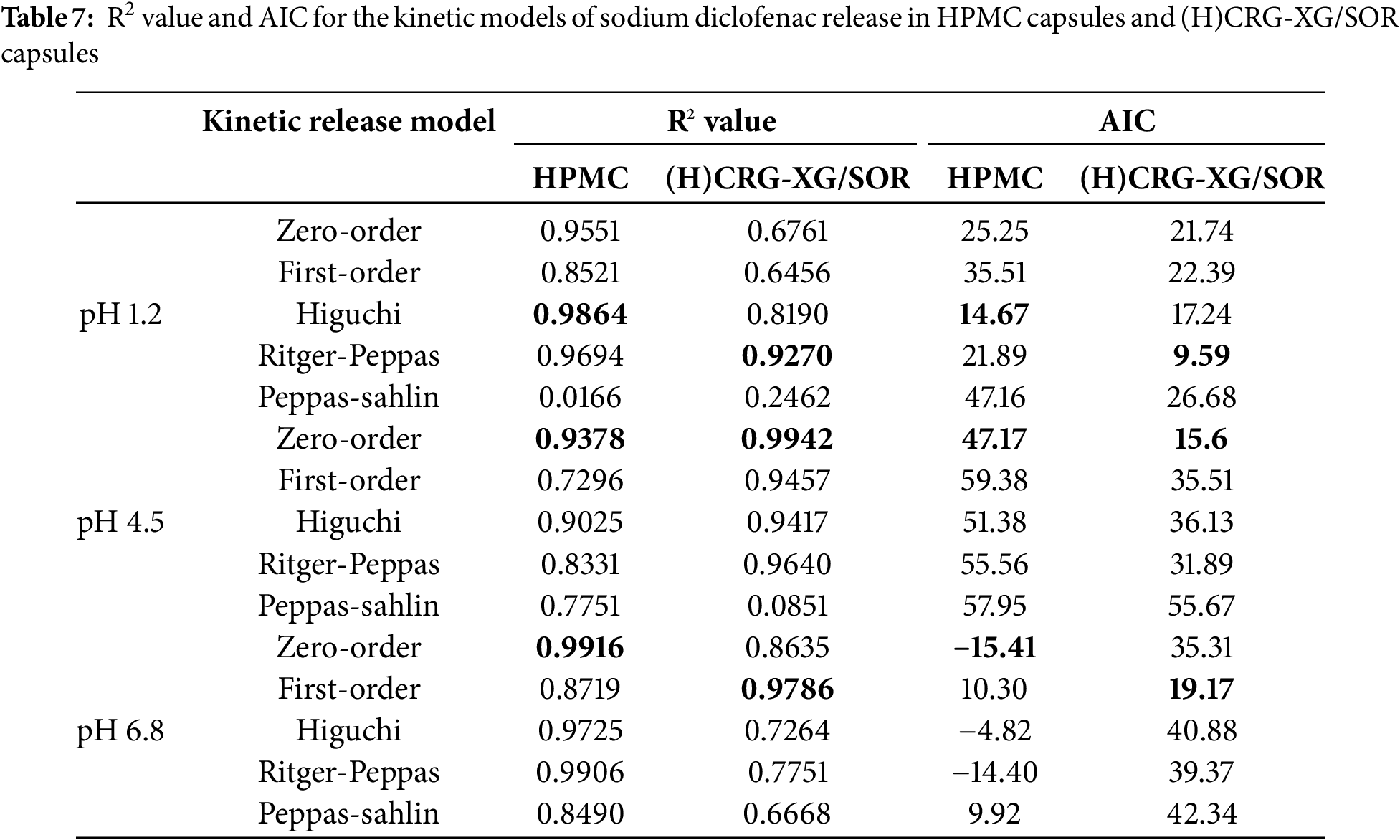

According to Table 7, the Higuchi model is the most suitable for describing the release kinetics of sodium diclofenac from HPMC capsules at pH 1.2. HPMC capsules are hydrophilic polymer matrices, and the drug release mechanism is primarily controlled by diffusion through the hydrated matrix. The Higuchi model is most appropriate for release systems where the matrix maintains its physical integrity and does not undergo erosion or disintegration, allowing the drug to diffuse out. At acidic pH levels, HPMC retains its structural integrity because the polymer does not dissolve quickly at pH 1.2. As a result, drug release is entirely controlled by diffusion through the hydrated matrix [28]. This behavior is further supported by the disintegration time of HPMC capsules, which is ten times longer at pH 1.2 compared to their disintegration times at pH 4.5 and 6.8, as shown in Table 6. At pH 4.5 and pH 6.8, the release of sodium diclofenac from HPMC capsules follows a zero-order model. This model describes the release of the drug at a constant rate that is independent of the remaining drug concentration in the capsule.

A constant release rate occurs when the drug release is controlled by the properties of the matrix or polymer, rather than by the drug concentration. At pH 4.5 and pH 6.8, HPMC forms a stable gel matrix, allowing the drug to be released at a steady rate, consistent with the characteristics of zero-order kinetics. The near-neutral pH conditions facilitate polymer-water interactions that create an environment where the drug is released at a constant rate, as the polymer forms a stable gel barrier [29]. For (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules, the sodium diclofenac release kinetics at pH 1.2 followed the Ritger-Peppas model.

This model is particularly suitable for (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules under acidic conditions because it accounts for complex drug release mechanisms, including swelling, polymer erosion, and non-Fickian diffusion [30]. In the acidic environment of pH 1.2, the properties of the polymers in the capsules change, making the Ritger-Peppas model a better fit for describing the drug release patterns.

Polymers like carrageenan (CRG) and xanthan gum (XG) tend to swell rapidly in acidic environments, leading the capsules to absorb water quickly, which opens the matrix and accelerates diffusion and erosion [31]. This results in a faster drug release rate at pH 1.2, and gastric acid may further enhance the degradation or erosion of the polymers, contributing to the accelerated release. At pH 4.5, the release kinetics of sodium diclofenac from (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules adhered to a zero-order model with an R2 value of 0.9942. This model represents a constant drug release over time, where the amount of drug released per unit of time remains steady and is unaffected by the remaining drug concentration. At this pH, the (H)CRG-XG/SOR polymers form a stable structure, enabling a consistent drug release rate. Polymer swelling and erosion are likely slower at pH 4.5 compared to pH 1.2 but balanced enough to ensure that the drug release rate is not significantly influenced by the remaining drug concentration. As a result, the drug is released in a more controlled and gradual manner. Finally, the first-order model was determined to be the most appropriate for the drug release kinetics in (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules at pH 6.8, with an R2 value of 0.9786. This model describes the drug release as being proportional to the remaining drug concentration in the system. As the amount of drug decreases in the matrix, the release rate also slows. At this higher pH of 6.8, the initial drug release occurs at a slower rate because the (H)CRG-XG/SOR polymers are not fully hydrated. Furthermore, the polymer composite forms a more stable structure in the (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules, resulting in a gradual drug release that depends on the amount of drug remaining in the polymer matrix. As the drug concentration decreases, the rate of drug release progressively slows [12].

The data on drug release kinetics indicate that (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules are most effective under acidic conditions (pH 1.2), achieving rapid and complete drug release within 90 min. This environment is ideal for drugs designed to be released in the stomach. In contrast, under neutral pH conditions (pH 6.8), the drug release occurs more slowly and in a controlled manner. This suggests that these capsules could also be used for gradual drug release in the intestinal environment.

The research results indicated that hard-shell capsules made from carrageenan (CRG), which were hydrolyzed with citric acid (CA), crosslinked with xanthan gum (XG), and plasticized with sorbitol (SOR), referred to as (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules, have been successfully developed. The optimal formula was determined to have a CA concentration of 0.5%, which meets the standards of PT. Kapsulindo Nusantara. The characteristics and mechanical properties of the capsules displayed a hardness of 720.945 g, a compression force of 7.12 N, and a swelling degree of 445.39% after 20 min. These properties suggest better-controlled drug release compared to the formula with 1.0% CA. In vitro disintegration tests demonstrated faster disintegration times of 20 min and 46 s at pH 1.2, 24 min and 31 s at pH 4.5, and 26 min and 41 s at pH 6.8, compared to capsules without CA. The in vitro dissolution profile of diclofenac sodium showed that 100%, 92.17%, and 64.25% of the drug were released within 90 min at pH 1.2, 120 min at pH 4.5, and 120 min at pH 6.8, respectively. The drug release kinetics followed the Ritger-Peppas model at pH 1.2 (R2 = 0.9270), exhibited zero-order kinetics at pH 4.5 (R2 = 0.9942), and first-order kinetics at pH 6.8 (R2 = 0.9786). This indicates the potential of (H)CRG-XG/SOR capsules as a controlled and pH-dependent drug delivery system.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Science and Technology, Airlangga University for the permission to use the laboratory and all of the science officers for their kind assistance.

Funding Statement: This study is funded through the Penelitian Unggulan Halal, Airlangga University FY 2024 grant number: 987/UN3/2024.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Tri Susanti: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; Syahnur Haqiqoh: Formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation; Pratiwi Pudjiastuti: Conceptual, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, validation and writing—review and editing; Siti Wafiroh: Conceptual, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, validation and writing—review and editing; Esti Hendradi: Data curation, methodology and validation; Oktavia Eka Puspita: Data curation, methodology and validation and Nashriq Jailani: Writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study. This paper is a part of master’s degree thesis.

References

1. Roy S, Upadhyay R, Vyas J, Upadhyay U. Taste masking of oral pharmaceutics: a review. Res Rev Pharm Pharm Sci. 2023;12(2):001. [Google Scholar]

2. Wang D, Zhang A, Guo W, Zhu B, Yu H, Chen Y. Identification of residues in ethylene oxide sterilized hard gelatin capsule shells by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and development of a simple gas chromatography-flame ionization detector method for the determination of residues. J Chromatogr Open. 2022;2:100061. doi:10.1016/j.jcoa.2022.100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Fauzi MARD. Pengembangan Kapsul Cangkang Keras Berbasis Karagenan yang Berpotensi sebagai Alternatif Kapsul Konvensional dengan Proses Oligomerisasi [dissertation]. Surabaya, Indonesia: Fakultas Sains dan Teknologi, Universitas Airlangga; 2022. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

4. Damian F, Harati M, Schwartzenhauer J, Van Cauwenberghe O, Wettig SD. Challenges of dissolution methods development for soft gelatin capsules. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(2):214. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13020214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Gelatine Manufacturers of Europe. Premium raw materials and state-of-the-art industrial facilities deliver a pure/high-grade protein [Internet]. Gelatine.org. [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.gelatine.org/en/gelatine/manufacturing.html. [Google Scholar]

6. Guarve K, Kriplani P. HPMC-A marvel polymer for pharmaceutical industry-patent review. Recent Adv Drug Deliv Formul. 2021;15(1):46–58. doi:10.2174/1872211314666210604120619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pudjiastuti P. Carrageenan-based hard capsules. Int J Appl Pharm. 2017;9(5):5–9. [Google Scholar]

8. Hassanisaadi M, Vatankhah M, Kennedy JF, Rabiei A, Saberi Riseh R. Advancements in xanthan gum: a macromolecule for encapsulating plant probiotic bacteria with enhanced properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;348(5):122801. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Abbasiliasi S, Shun TJ, Tengku Ibrahim TA, Ismail N, Ariff AB, Mokhtar NK, et al. Use of sodium alginate in the preparation of gelatin-based hard capsule shells and their evaluation in vitro. RSC Adv. 2019;9(28):16147–57. doi:10.1039/c9ra01791g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Susanti T. Effect of plasticizer on carrageenan-based capsules. Asian J Pharm. 2018;12(4):255–61. [Google Scholar]

11. Fauzi MA. Pengembangan drug delivery system berbasis rumput laut. J Farm Ind. 2019;15(3):78–89. [Google Scholar]

12. Fauzi MA. Development of oligomerized carrageenan capsules. Int J Pharm. 2022;624:121890. [Google Scholar]

13. Kohrs NJ. Drug delivery system evaluation methods. J Control Release. 2019;289:123–35. [Google Scholar]

14. Fauzi MA. Kinetic models in drug delivery systems. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(8):2445–56. doi:10.5336/pharmsci.2019-65857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ulfa M, Azzahra F. Physical characterization methods for DDS. J Pharm Anal. 2018;8(4):187–98. [Google Scholar]

16. Sami F. Swelling behavior of polymeric systems. Int J Pharm. 2018;545(1–2):437–47. [Google Scholar]

17. Hussain AL-M, Hameed IH. Drug release kinetics models. Int J Pharm Res. 2023;15(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

18. Smith BC. Fundamentals of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

19. Kustomo J. SEM-EDX applications in pharmaceutical analysis. Microsc Res Tech. 2020;83(10):1195–206. [Google Scholar]

20. Eradiri O. Recommended in vitro studies. SBIA 2022: an in-depth look at the April 2022 final FDA Guidance: bioavailability studies submitted in NDAs or INDs–general considerations. Silver Spring, MD, USA: US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2022 [cited 2025 May 21]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/167019/download. [Google Scholar]

21. Ali SM, Yosipovitch G. Skin pH: from basic science to basic skin care. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(3):261–7. doi:10.2340/00015555-1531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Pudjiastuti P, Wafiroh S, Hendradi E, Darmokoesoemo H, Harsini M, Fauzi MARD, et al. Disintegration, in vitro dissolution, and drug release kinetics profiles of k-carrageenan-based nutraceutical hard-shell capsules containing salicylamide. Open Chem. 2020;18(1):226–31. doi:10.1515/chem-2020-0028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Erdem V, Yildiz M, Erdem T. The evaluation of saliva flow rate, pH, buffer capacity, microbiological content, and indice of decayed, missing and filled teeth in Behçet’s patients. Balk Med J. 2013;30(2):211–4. doi:10.5152/balkanmedj.2013.7932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Kapoor DN. Drug release mechanisms and modeling. Int J Pharm. 2020;585:119464. [Google Scholar]

25. Unagolla JM, Jayasuriya AC. Polyelectrolyte microparticles for controlled drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2018;114:199–209. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2017.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. He Y. Effects of hydrolysis on carrageenan. J Pharm Sci. 2017;121:54–64. [Google Scholar]

27. Said M, Haq B, Al Shehri D, Rahman MM, Muhammed NS, Mahmoud M. Modification of xanthan gum for a high-temperature and high-salinity reservoir. Polymers. 2021;13(23):4212. doi:10.3390/polym13234212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Song C, You Y, Wen C, Fu Y, Yang J, Zhao J, et al. Characterization and gel properties of low-molecular-weight carrageenans prepared by photocatalytic degradation. Polymers. 2023;15(3):602. doi:10.3390/polym15030602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Park J. HPMC and its applications in drug delivery. Polymers. 2022;15(3):602. [Google Scholar]

30. Kang CYX, Chow KT, Lui YS, Salome A, Boit B, Lefevre P, et al. Mannitol-coated hydroxypropyl methylcellulose as a directly compressible controlled release excipient for moisture-sensitive drugs: a stability perspective. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(9):1167. doi:10.3390/ph17091167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Talevi A, Ruiz ME. Korsmeyer-Peppas, Peppas-Sahlin, and Brazel-Peppas: models of drug release. In: Talevi A, editor. The ADME encyclopedia. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2022. p. 613–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-84860-6_35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools