Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Extraction, Utilization, Functional Modification, and Application of Cellulose and Its Derivatives

Department of Polymer Material and Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology (GDUT), Guangzhou, 510006, China

* Corresponding Author: Haoqun Hong. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(9), 1707-1763. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0005

Received 04 January 2025; Accepted 18 March 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

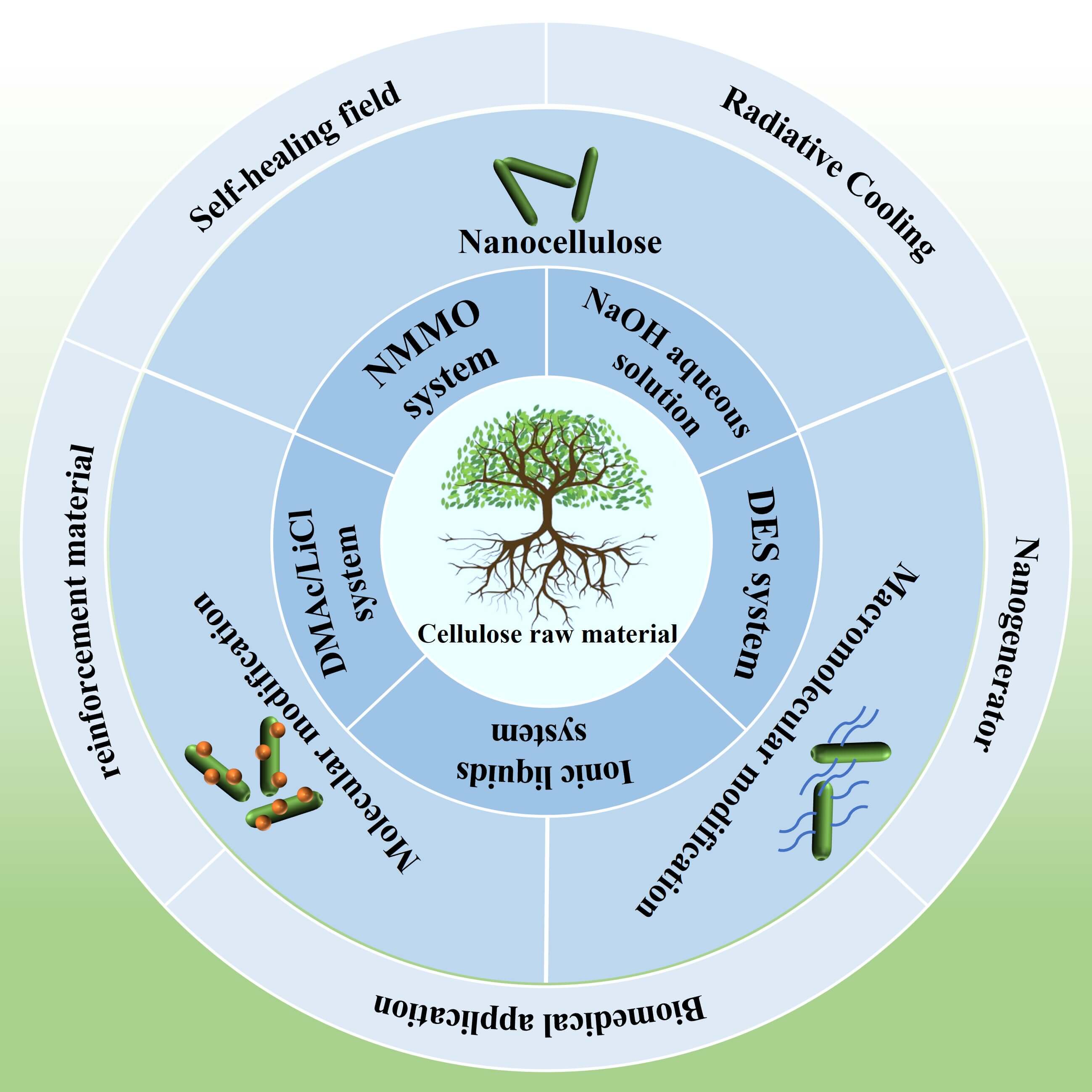

Under the background of the current energy crisis and environmental pollution, the development of green and sustainable materials has become particularly urgent. As one of the most abundant natural polymers on earth, cellulose has attracted wide attention due to its green recycling, sustainable development, degradability, and low cost. Therefore, cellulose and its derivatives were used as the starting point for comprehensive analysis. First, the basic structural properties of cellulose were discussed, and then the extraction and utilization methods of cellulose were reviewed, including Sodium Hydroxide based solvent system, N, N-Dimethylacetamide/Lithium Chloride System, N-Methylmorpholine-N-Oxide (NMMO) system, ionic liquids (ILs) system, and deep eutectic solvent (DES) system. Then, the functional modification techniques of cellulose are introduced, including nano-modification, small molecule modification, and macromolecular modification. Finally, the potential applications of cellulose in the fields of reinforcement materials, self-healing materials, radioactive cooling, nanogenerators, and biomedicine were discussed. At the end of this paper, the challenges and future development direction of cellulose materials are prospectively analyzed, aiming at providing guidance and inspiration for the research and application in related fields.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Nowadays, in this challenging era, environmental issues and energy crisis have increasingly become the focus of global attention, and it is urgent for us to find new solutions to deal with these challenges. Compared with traditional petroleum-based materials, bio-based materials have attracted much attention due to their degradability, renewability, and environmental friendliness. Among the many bio-based materials, cellulosic materials have attracted much attention due to their abundant sources, excellent biodegradability, contribution to sustainable development, excellent mechanical strength, excellent biocompatibility, and relatively low cost. These characteristics make cellulosic materials of great significance in resource recycling.

Among various biomass-derived materials, cellulose-based materials have garnered considerable attention in the scientific community. Primarily, this preference stems from two critical advantages: First, compared with protein-based materials, cellulose is a kind of green natural polymer material with the most abundant reserves on the earth, which makes its raw material supply sufficient. Secondly, cellulose and its derivatives exhibit superior physical and mechanical properties relative to starch-based materials, including exceptional tensile strength, enhanced toughness, and remarkable thermal stability [1]. In addition, cellulose material contains active hydroxyl groups on its surface, which enables us to endow cellulose with new functions through chemical modification (such as molecule modification and large molecule modification), and then develop diversified cellulose derivatives. Nanocellulose, as a refined cellulose material, has injected new impetus to the development of cellulose materials because of its high specific surface area, excellent heat resistance and excellent mechanical properties.

Currently, the mainstream products of cellulose materials include cellulose films, cellulose elastomers, cellulose hydrogels, and cellulose microspheres. Through functional modification or combination with other materials, these cellulose materials are widely used in several fields such as energy, biomedicine, and intelligent manufacturing, promoting green transformation in these fields. This review focuses on cellulose materials, discusses their structure and properties, summarizes the extraction and utilization methods of cellulose, combs the ways of cellulose functionalization and modification, and summarizes its application in different fields. Finally, the advantages and challenges of cellulosic materials are summarized, and their future development prospects are prospected.

2 Cellulose Structure and Properties

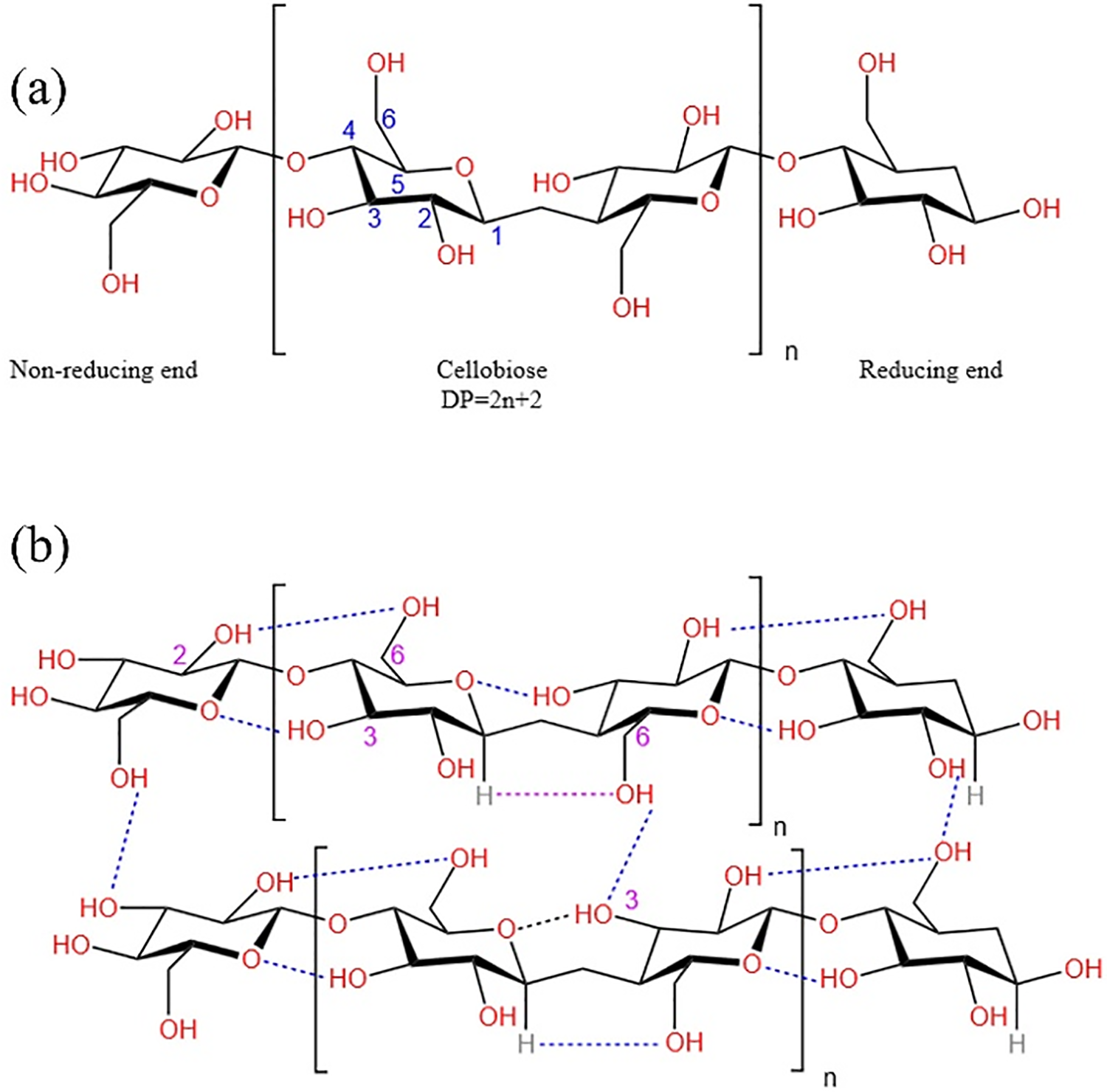

The chemical structural formula of cellulose is (C6H10O5)n, and its basic chemical structure is D-Galactose. The specific structure as shown in Fig. 1a. The bond between the structures is formed by the condensation reaction between the hydroxyl group on C-1 of the glucose unit and the hydroxyl group on C-4 of the adjacent glucose unit to form 1-4 glycosidic bond, that is, β-(1→4)-glycosidic bond to form a natural linear polymer [2]. In general, the repeating unit of cellulose polymers is cellobiose (a dimer of glucose), because in space two adjacent glucose units rotate 180 degrees with each other along the fiber axis in the polymer chain.

Figure 1: (a) Structure of cellulose. (b) Hydrogen bond network of cellulose

Cellulose has abundant hydroxyl groups, with each glucose unit containing three hydroxyls, which are located in carbon atoms C-2, C-3, and C-6, thus contributing to the establishment of an extensive hydrogen bond network. The specific hydrogen bond network is shown in Fig. 1b. In the molecular chain, because the H on O-3(oxygen at C-3) on the glucose unit forms a stable hydrogen bond (O(3)-H······O) with the epoxy on another glucose or the H on O-2(oxygen at C-2) with O-6(oxygen at C-6) (O (2)-H······O (6)), make the structure of cellulose molecular chain rigid. As for the molecular chains, the hydrogen bonds formed between the H on the O-3 of the glucose units and the O-6, as well as between the H on the unconventional C and the O (O(3)-H······O(6) and C-H······O), lead to close packing of the cellulose molecular chains, which contributes to the development of crystallization. The specific structure and hydrogen bond interaction of cellulose is shown in Fig. 1.

The different positions of the H atom and hydroxy -OH at the two ends of the C atom endow cellulose with different physicochemical properties. The hydroxyl group on the chain unit of dehydrated glucose was located at C-2, C-3, and C-6, respectively. The reaction activity was also different according to the different structural positions. Among them, the most representative reaction is the reaction of primary and secondary alcohols, and the adjacent primary hydroxyl group shows a typical diol structure [3]. In addition, the hydroxyl group at the end of the cellulose chain also has different behaviors: the hydroxyl group at the C-1 end is reducing, while the hydroxyl group at the C-4 end is oxidizing.

3 Utilization and Extraction of Cellulose

The primary source of cellulose is plants, with a smaller portion derived from microorganisms. Compared to plant cellulose, bacterial cellulose exhibits superior mechanical properties, polymerization rates, and crystallinity [4]. Natural plant fibers consist of multiple fiber bundles, which are adhered together by adhesives. The main chemical components of natural plant fibers are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, along with trace amounts of waxes and lipids [5]. Cellulose, as the primary component, reinforces the material, while hemicellulose and lignin act as fillers and binders. Although these components protect the cell walls, they are not conducive to the utilization of cellulose materials. Additionally, within the cellulose microfibrils, there are variations in the degree of molecular chain packing, which leads to the classification of “crystalline regions” and “amorphous regions.” This alternating arrangement endows cellulose with unique properties: good flexibility, high thermal stability, and excellent mechanical strength [6,7]. However, it also makes it difficult for solvents to penetrate the crystalline regions, resulting in poor solubility of cellulose. The degree of reaction, reaction rate, and reaction uniformity are all adversely affected. Therefore, to utilize cellulose as a material, it must undergo treatment beforehand.

To effectively utilize cellulose, it typically needs to be dissolved. Therefore, breaking the tightly packed molecular structure is required to separate the cellulose chain. In general, it is necessary to destroy its hydrogen bond network, thus destroying its crystalline regions, and achieving the dissolution of cellulose. Generally, cellulose can be swollen by water, acid, alkali or salt solution can be used to enter the crystallization zone of fiber by osmosis, so that cellulose can be swelled infinitely and further dissolved. It is worth noting that cellulose exhibits different reactions under various conditions. When exposed to a high concentration of inorganic acid, cellulose undergoes hydrolysis to produce glucose. In contrast, when it encounters a high concentration of caustic soda solution, it forms alkali cellulose. Furthermore, in the presence of a strong oxidizing agent, cellulose is oxidized to produce oxidized cellulose.

Generally, the factors affecting cellulose dissolution are mainly divided into molecular weight, crystallinity, and hydrophobic interaction [2]:

(1) The effect of molecular weight:

Molecular weight is a key factor affecting the physical properties of polymers, and this value is inversely proportional to the entropy of dissolution [2]. In general, cellulose is insoluble in water, whereas its hydrolysate glucose, cellobiose (the basic unit of cellulose), and cellulose oligomers with a degree of polymerization (DP) less than 10 all appear water-soluble. Therefore, reducing the molecular weight of cellulose may be an effective strategy to achieve its enhanced dissolution [8–10]. The DP of cellulose depends on the extraction process and source of cellulose. Normally, the change of DP can be affected by adjusting reaction time, controlling temperature, changing pressure, and adding polar aprotic cosolvent [11]. In addition, in strong polar solvents (such as highly acidic or basic environments), the degradation of the cellulose chain due to environmental influences leads to a decrease in DP, which increases its solubility. If the product does not require high mechanical properties, reducing the molecular weight is an effective strategy to achieve the dissolution and utilization of cellulose [12–14].

(2) The effect of crystallinity:

Since cellulose is a highly crystalline polymer, its amorphous region is easily permeated by solvents, whereas parts of its crystalline region are difficult to dissolve, which makes it difficult for solvents to enter cellulose. Therefore, selecting an appropriate solvent is crucial. Usually, cellulose dissolution includes crystal removal and molecular chain unwinding [15]. If crystallization removal is the decisive step, reducing crystallinity facilitates the dissolution of cellulose fibers. On the other hand, if the unwinding of the molecular chain is the decisive step, then the diameter of the fiber is more important than the crystallinity [16]. Ghasemi et al. [15] showed that both crystallization removal and chain untangling play an important role in the dissolution process of cellulose. They pointed out that during the dissolution process of cellulose, only crystal detachment occurred, with no chain untangling taking place. Although it can reduce the crystallinity of cellulose, it does not dissolve well. In contrast, if there is only disentanglement and no crystal removal occurs, only the amorphous region of cellulose dissolves. Therefore, for cellulose to dissolve fully, the solvent system must be equipped with the ability to remove the crystallization of cellulose and untangle the molecular chains.

(3) The effects of hydrophobic effect:

Research has shown that the solubility of cellulose is related to the hydrophobic interaction [17]. It has been found that the accumulation of cellulose tends to form crystalline structures under hydrophobic action, and the contribution of hydrophobic interaction is about 8 times that of hydrogen bonding [18]. Medronho et al. [17,19,20] improved the solubility of cellulose in ILs and NaOH/ urea/water systems by reducing its hydrophobic interaction. This is because, in ILs, amphiphilic cations in the system will change the hydrophobic interaction between cellulose. In the NaOH/H2O solution system, the polarity of the solvent system can be reduced by adding urea, and the hydrophobic effect can be weakened, to improve the solubility of cellulose.

In addition, to make cellulose dissolve well, it is necessary to equip the corresponding solvent system. In general, cellulose solvents can be divided into two categories: cellulose-derived solvent system and non-derived solvent system [2]. The so-called derived solvent system refers to the chemical reaction between the solvent and the OH group on the cellulose chain to destroy the strong interaction between the molecular chains, especially the crystalline part of the cellulose [21]. However, the non-derived solvent system can dissolve cellulose by breaking the strong interaction force between the OH groups of cellulose and establishing a new interaction relationship [22]. In addition to the above two solvent systems, researchers have also found that some metal salt hydrates can affect the interaction between cellulose chains, establishing a new interaction between the OH group of cellulose and the cations and anions of metal salts [11], thereby replacing the original hydrogen bond network and realizing the dissolution of cellulose.

3.1 Extraction of Cellulose Based on NaOH Aqueous Solution by Alkali Method

The solvent system using NaOH to dissolve cellulose has developed rapidly due to its low cost and easy recovery. Early studies found that NaOH concentration between 7% and 10% was associated with lower temperature (<10°C), and cellulose can show good dissolution [23]. Since the solubility of cellulose is affected by molecular weight, crystallinity, and hydrophobic interaction, only the oligosaccharides with DP less than 250 can be dissolved, and the solubility is limited to 5% in the case of high crystallinity cellulose. Therefore, to improve the dissolution ability of cellulose in NaOH, people changed the composition of the original system to improve the dissolution ability. However, the aqueous solution of NaOH has a major disadvantage as a solvent. This system can only dissolve cellulose at low temperatures and within a limited concentration range of NaOH [24]. Moreover, the solubility of cellulose in this system and the stability of the solution obtained is low. With the development of time, people have a deeper understanding of the dissolution of cellulose by NaOH. He et al. [25] conducted a systematic study on the dissolution performance of cellulose based on the three parameters of NaOH concentration, temperature, and pretreatment. They found that the purity of cellulose was higher after drying and crushing pretreatment. In addition, they found that high temperature and high concentration of NaOH had more advantages in the dissolution and purification of cellulose than low temperature and low concentration of NaOH solvent. This is because the high temperature and high concentration conditions help to loosen the surface structure of cellulose, so that the solution can penetrate its interior, dissolve impurities and achieve the purpose of purification. Moreover, they also found that the yield of cellulose extracted at 30°C alkaline solution temperature was higher than that at 90°C alkaline solution temperature, indicating that high temperature had a slight degradation effect on cellulose.

As for the dissolution mechanism of NaOH on cellulose, it is generally believed that NaOH molecules in aqueous solution system form sodium hydroxide hydrate at low temperature. These hydrates can dissolve cellulose by forming a new interaction force with the hydroxyl group on the cellulose chain unit, thus replacing the hydrogen bond between the original molecular chains [19,26]. Xiong et al. [27] pointed out that OH−, as a strong hydrogen bond receptor, replaced the intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds of cellulose by forming a new hydrogen bond force with the hydroxyl group in cellulose. Meanwhile Na+ ions played a role in preventing cellulose chains from being close to each other to achieve stability in aqueous solution. The reason for the poor water solubility of cellulose at low concentration of NaOH can be explained as that the hydrodynamic radius of sodium hydroxide hydrate is too large in the environment of low concentration of NaOH so that the hydrate cannot penetrate the hydrogen bond network of cellulose, thus replacing the corresponding force. When urea is added to the system, the solubility of cellulose will be improved, due to the urea hydrate occurring in NaOH and cellulose of complex surface form clathrate self-assembly behavior. Urea, as a hydrogen bond donor, can prevent cellulose chains from trying to get close, thereby improving the stability of the aqueous solution [28]. Peng et al. [29] systematically summarized the mechanism and influence of an alkaline solution system to dissolve cellulose through designed experiments. Through polarizing microscopy, they found that as the concentration of NaOH increased, the spots gradually decreased, because the volume of hydrate molecules formed was smaller when the concentration of NaOH was higher. However, smaller molecules can better penetrate the internal structure of cellulose molecules and form new hydrogen bonds with cellulose molecular chains, thus destroying the original hydrogen bond interaction and affecting the optical properties. They then carried out a systematic analysis of the sediment and found that the sediment decreased as the concentration of NaOH increased, and the mass of the sediment decreased significantly at a NaOH concentration of 7%. They concluded that the hydrate network was the smallest and most likely to penetrate the cellulose. In addition, they also analyzed the samples by FTIR and found that the change in NaOH concentration did not affect the intrinsic structure of cellulose. However, they found that the peak intensity of 3350 cm−1(-OH) increased when the concentration of NaOH increased. Combined with the previous polarizing microscope pictures, it was proved that the size of the crystal structure of cellulose would gradually decrease during the dissolution process. This indicates that the cellulose structure is opened. The reduction of the size means that the increase of the specific surface area of cellulose easily exposes more hydroxyl groups, thus enhancing the strength of the tensile vibration absorption peak of -OH. In addition, they concluded by XRD tests that when NaOH concentration was low, the volume of the solvent hydration network was large, and difficult to penetrate the tight crystalline region. On the contrary, these solvents are more likely to enter the loose amorphous region and form hydrogen bonds with the cellulose molecular chains, resulting in the preferential dissolution of the amorphous region of cellulose and an increase in the proportion of crystalline regions, thereby improving the crystallinity of cellulose. However, as the concentration of NaOH increases, the crystalline region is dissolved, resulting in a decrease in the crystallinity of the cellulose.

To improve the solubility of cellulose in NaOH, new variant systems have been developed, such as adding different hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (such as urea, thiourea, zinc oxide (ZnO), and polyethylene glycol with different molecular weights) to the original system or pretreating the raw material before adding NaOH aqueous solution. These pretreatment techniques include mechanical pretreatment (e.g., steam blasting and ultrasonic treatment), chemical pretreatment (e.g., ethanol and hydrochloric acid treatment), and enzymatic pretreatment (e.g., cellulase) [30].

3.2 Extraction of Cellulose Based on N, N-Dimethylacetamide (DMAc)/Lithium Chloride (LiCl) System

Initially, Dawsey et al. [31] found that the mixed solvent system of DMAc/LiCl could dissolve cellulose. Although the solvent system has good solubility, DMAc is physiologically toxic and does not have the characteristics of environmental friendliness. People conducted a series of gradient experiments on this system and found that 8%(w:v) LiCl was the most suitable and commonly used in DMAc [32]. It was also found that the system not only has a good ability to dissolve cellulose but also can derivate cellulose. Due to the good solubility of this system, it is often used to measure the molecular weight of cellulose in GPC.

Although this system has good solubility, there are two points to pay attention to: one is high moisture absorption, because DMAc and LiCl components are easy to absorb moisture. Hence, the solvent solubility will be seriously reduced in the presence of water [33]; The other is the formation of keteniminium ion, which forms an active intermediate in a two-component solvent system under high-temperature conditions, resulting in the induced degradation of cellulose [34].

For cellulose to exist stably in DMAc, the following factors should be considered: the amount of LiCl, the content of cellulose, the storage time, and the presence of water [33], among which the presence of water and the content of LiCl are the key parameters affecting the dissolution stability of cellulose. From the mechanism, the solvation shell of Li+ absorbs the water in the system [34], which leads to the hydrolysis of DMAc, and the additional water also enters DMAc. This accumulation of water limits the complexation of the Li+ solvated shell with cellulose [34]. Therefore, it is necessary to dry the cellulose and solvent system before dissolving the cellulose. For example, flame drying can be used for LiCl, and distillation and water catcher can be used together for DMAc to keep the system dry [33].

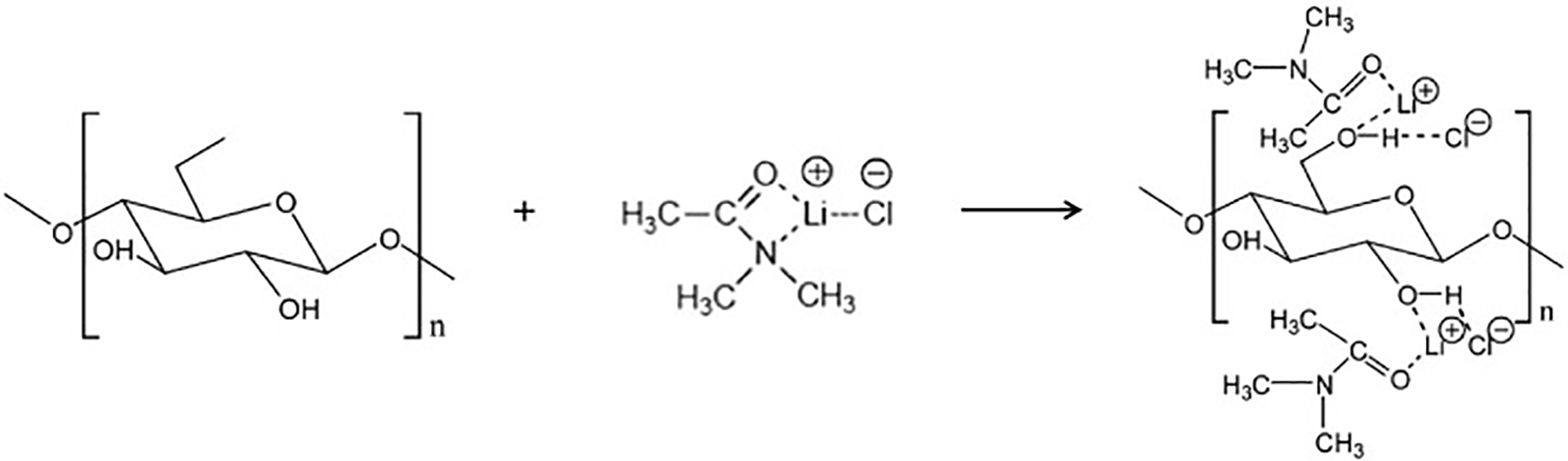

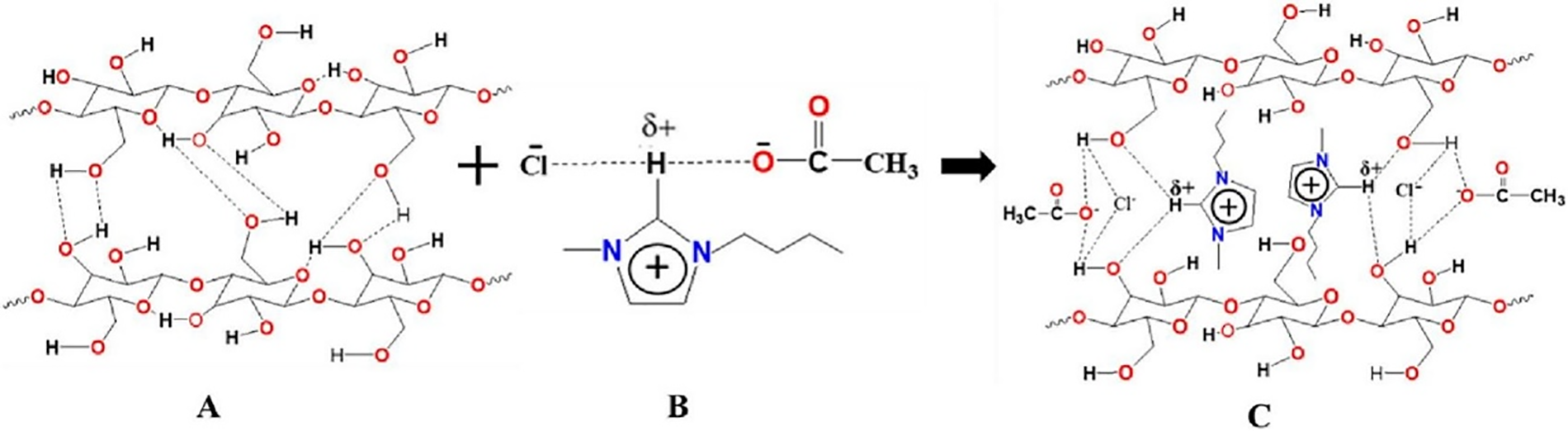

As for the dissolution mechanism of cellulose by the DMAc/LiCl system, it is speculated that a new interaction relationship is established between Cl− and cellulose, thus replacing the original hydrogen bond network, as shown in Fig. 2. It has been reported that about 80% of the dipole-dipole interaction between DMAc and cellulose is due to the Cl-cellulose interaction. In addition, due to the solvation of Li+ by DMAc molecules, a large cationic complex ([Li−(DMAc) x]) is formed, which forms new interactions with cellulose, accounting for 10% of the total dipole interactions [35]. Sen et al. [36] added through the study that the strong hydrogen bond formed between the hydroxyl proton and the Cl− of the salt caused the original hydrogen bond to break, thus allowing cellulose to dissolve, and pointed out that the hydroxyl proton of cellulose did not form a new interaction relationship with the carbonyl group in DMAc molecule.

Figure 2: Diagram of hydrogen bond fracture mechanism of cellulose dissolved in LiCl/dimethylacetamide (LiCl/DMAc) solvent system. Adapted with permission from Reference [19], Copyright © 2015, Elsevier

Ma et al. [37] found that LiCl was the most important for cellulose dissolution in the LiCl/DMAc system through a series of characterization methods. Their analysis showed that the Li bond plays a major role in the formation of the Lix (DMAc)yClz complex. They found through FMO analysis that the splitting of Li+-Cl− ion pairs increases the HOMO energy level, which facilitates the insertion of the [Li (DMAc)4] Cl complex into the cellulose chain and facilitates the transfer of Cl− ion electrons to unoccupied orbitals of the cellulose molecule. In addition, by combining the DFT calculation results with the nuclear magnetic test, they found that when the [Li (DMAc)4] Cl complex is inserted into the cellulose dimer, it can effectively weaken the hydrogen bond interaction and promote the separation of the two cellulose dimers. Based on these results, they deduced that the two cellulose chains are separated at the non-reducing end by the combination of the Cl− ion and the steric hindrance of the [Li (DMAc)] + unit. The hydrogen proton is terminated by the Cl− ion and blocked by the steric hindrance of the tetrahedron-arranged [Li (DMAc)4] + unit, effectively preventing the hydrogen bond recombination of the two cellulose chains. Therefore, the Li bond plays an important role in DMAc solvent.

To enhance the dissolution of cellulose in the DMAc/LiCl system, the general treatment method is to pretreat the raw material to activate the cellulose. By pretreatment, the structure and properties of cellulose can be changed, so that it is more conducive to dissolution in solvents. One of the methods is the solvent exchange method, by adding a polar solvent (such as water) to make the cellulose swell, remove the original solvent, dry, and then adding to the DMAc/LiCl system, this method can improve the solubility of cellulose in the solvent system. Another method is to expand in water and then freeze dry. The result of this method is to increase the porosity, voidness, and surface area of cellulose [38]. These structures facilitate the rapid diffusion of solvent into cellulose to achieve dissolution. Another common method is the high temperature activated cellulose method. At high temperatures, the solvent diffuses into the fiber, and the solvent vapor causes the fiber to expand. Although this method can process a large amount of cellulose, high temperatures may lead to cellulose degradation [34].

Although the DMAc/LiCl system has good solubility, DMAc is physiologically toxic and not environmentally friendly. In addition, the combination of DMAc and LiCl is highly toxic, corrosive, and volatile, leading to a higher degree of health and safety-related issues. Therefore, the technology has yet to achieve successful commercialization [39].

3.3 Extraction of Cellulose Based on N-Methylmorpholine-N-Oxide (NMMO)

The NMMO solvent system belongs to the non-derived solvent system of cellulose solvent. Cellulose can be directly dissolved in 13% NMMO aqueous solution at 80°C~120°C, and the cellulose concentration in its aqueous solution can reach 23% [40]. The Lyocell process is an important process for cellulose production in the industry, which uses an NMMO solvent system to dissolve cellulose. It does not need to be pre-treated or derivatized in advance to dissolve well like the above solution system, so it can shorten the process route in industrial production and improve production efficiency thanks to its unique advantages. Compared with the viscose method for obtaining cellulose, the lyocell method is considered an environmentally friendly process in the fiber production route because it is environmentally friendly and does not release toxic gases [41]. It is worth noting that the maximum recovery rate of NMMO solvent in this process can reach 99% [42].

Generally, the cellulose needs to be swelled before dissolving, so the cellulose needs to be put into a dilute solution of NMMO (60% NMMO and 20%–30% water) [43]. However, when the water content is high (>15%), NMMO will not dissolve cellulose [41], so to achieve the dissolution of cellulose, the process needs to use the vacuum heating evaporation method to remove water, which leads to the shortcoming of high energy consumption of this process. In addition, the process also causes oxidation of solvents and polymers [39].

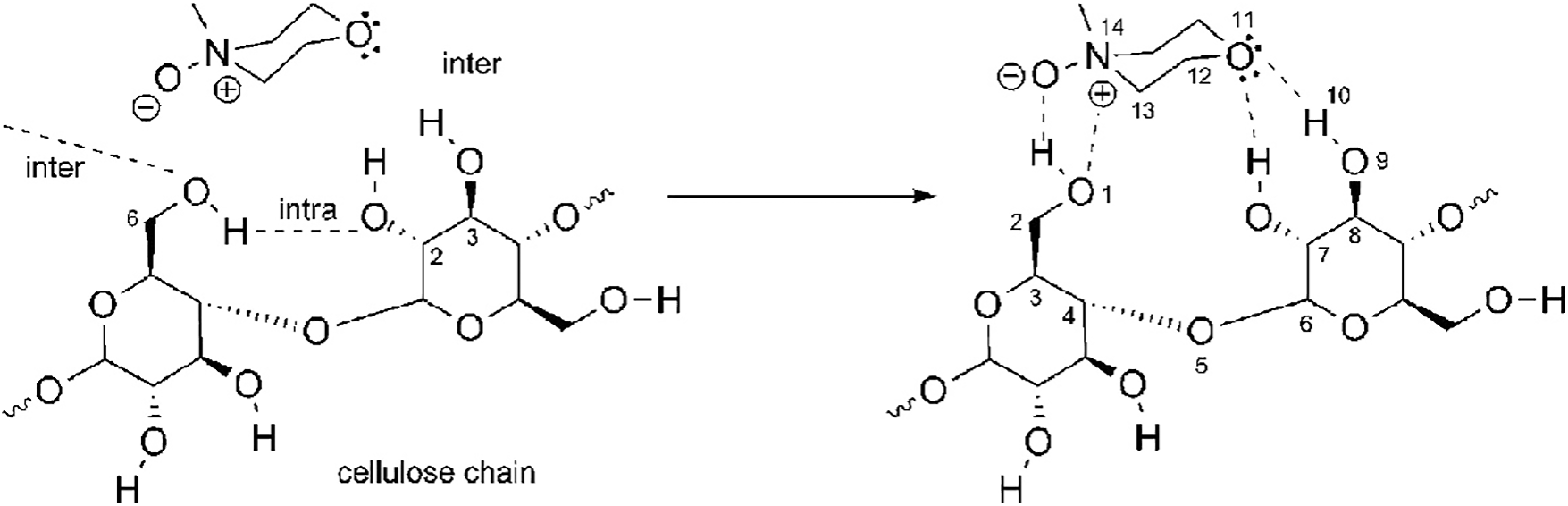

So why does NMMO dissolve cellulose? From the perspective of the dissolution mechanism, due to the strong dipolar nature of the active NO part in NMMO, its oxygen atoms form a new hydrogen bond force with cellulose, thus replacing the original hydrogen bond network. Finally, water-soluble cellulose-NMMO hydrogen bonding complexes are formed [44]. The reason why cellulose is difficult to dissolve when the water content exceeds 15% can be explained by the coordination between water and the O atom of NMMO, which hinders the formation of the interaction between cellulose and NMMO [45]. Fig. 3 shows the corresponding mechanism of cellulose dissolution in NMMO:

Figure 3: Possible hydrogen bond interaction between NMMO and cellulose. Adapted with permission from Reference [46], Copyright © 2010, American Chemistry Society

However, in actual production, NMMO is prone to degradation and oxidation side reactions due to its poor thermal stability and high N-O bond energy, which will lead to degradation and color change of the obtained cellulose products. Therefore, it is necessary to add stabilizer in the production to prevent the impact of side reactions. N-Methylmorpholine (NMM) and morpholine are common by-products of NMMO degradation. The main degradation mechanisms of NMMO are free radical reaction (main) and two heterodegradation processes (including Polonowski-type reaction and autocatalytic decomposition of NMMO catalyzed by Mannich intermediates). To prevent these side reactions, it is necessary to add the corresponding stabilizer. For the type of free radical reaction stabilizer, it is crucial to play the role of free radical scavenger and stabilize the subsequent products by forming stable free radicals, to achieve the blocking effect. For the heterodegradation reaction, the stabilizer needs to be captured after the formation of N-(methylene)morpholinium ions to remove the degradation catalyst, or by consuming formaldehyde so that the degradation catalyst cannot be formed [47]. Therefore, to eliminate the above three side reactions, the optimal stabilizer must be able to well capture the three reactive substances in the system: free radicals, formaldehyde, and N-(methylene)iminium ions.

3.4 Extraction of Cellulose Based on Ionic Liquid (ILs)

Ionic liquids are defined as molten salts that remain liquid at or below 100°C [48]. These ionic liquids have good thermal stability and do not release toxic gases. Therefore, ILs can be used not only for the design and synthesis of novel polymer ionic liquid-based biomaterials [49] but also for the extraction of cellulosic materials. However, ILs are highly absorbent when dissolving cellulose, so this solvent is difficult to recycle [50].

At present, ILs can be used to dissolve and deconstruct cellulose. The dissolution of cellulose is achieved through the interaction of anion and cation with cellulose. In terms of mechanism study, Swatloski et al. first proposed that the anions in ILs interact with the hydroxyl group of cellulose molecules, destroying the original hydrogen bond network [51], and the solubility of cellulose seems to follow its alkalinity [52]. Zhao et al. found that when the anions in ILs have the following characteristics: hydrogen bond acceptor with higher electron density (the order of interaction strength is Cl−> [CH3COO]− > [(CH3O)2PO2]− > [SCN]− > [PF6]−), shorter alkyl chain and no electron-withdrawing group, the dissolution capacity of ionic liquids will increase [53].

For cation, its role after anion. Zhang et al. [54] pointed out that cations can also form hydrogen bonds with cellulose, while Li et al. [55] believe that the van der Waals forces between cations and cellulose contribute to the formation of hydrogen bonds. In conclusion, the type of anion (such as imidazolyl or pyridyl) and the length of the alkyl chain have an important impact on the dissolution of cellulose by ILs [53]. Rahman et al. [56] used imidazolyl double salt ionic liquid (DSIL) to dissolve and extract cellulose. The relevant mechanism of dissolving cellulose is shown in Fig. 4 below.

Figure 4: Mechanism diagram of cellulose dissolution by imidazole-based double salt ionic liquid (A–C). Adapted with permission from Reference [56], Copyright © 2023 Elsevier

Although ILs have good solubility, their high-water absorption has seriously affected its application in cellulose. This is because the presence of water competes with ILs and prevents cellulose from forming hydrogen bonds with ILs [51]. Therefore, dehydration is required when using the ILs system to dissolve cellulose. To make this technology widely used in the industrial production of cellulose, appropriate heating can be used to increase the dissolution rate [57]. However, when the method of heating is used to improve the dissolution rate, it is inevitable to consider the influence of excessive temperature on cellulose, and excessive heating will induce cellulose degradation [58]. Therefore, new methods are needed to improve the dissolution rate. It has been found that the addition of aprotic cosolvent to the system can help improve the dissolution ability of ILs. As for the dissolution mechanism, some researchers believe that the addition of cosolvent to the system can promote the solvation of cations in ILs, thereby releasing anions, to improve the interaction between anions and cellulose [57]. Other studies have shown that the main function of cosolvents is to promote the better dispersion and dissolution of cellulose in solvents by changing the mass transfer characteristics of the solution (such as ionic conductivity or viscosity) [59].

To reduce the cost of ionic liquids and minimize their impact on the environment, several technologies have been proposed to recover ionic liquids from different solutions. These methods include distillation, extraction, adsorption, membrane separation, aqueous two-phase extraction, crystallization, and external force field separation [50]. Although some single methods can achieve good recovery of ionic liquids, the efficiency of most methods is limited, which leads to low product purity and high cost and energy consumption. Therefore, in terms of recycling, how to optimize the recycling process is the focus of future research. The existing separation technology needs to be studied more deeply and comprehensively. It is also necessary to summarize and evaluate the selection and design of the recycling process.

3.5 Extraction of Cellulose by Deep Eutectic Solvent Method (DES)

Although ionic liquids have a stable chemical system, due to various factors such as high cost and negative environmental impacts, the new ionic liquid DES has a great advantage over ionic liquids in these aspects [60]. DES is mainly composed of hydrogen bond donor (HBD) and hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), which can be prepared by mixing by simple heating [61]. DES is utilized to extract cellulose mainly based on the DES system’s difficult solubility of cellulose [62] and the priority of lignin dissolved [63]. In this case, the dense hydrogen bond network of DES only led to the swelling between hydrogen bonds of cellulose, keeping the relatively complete structure of cellulose. At the same time, DES dissolves lignin, separating cellulose from lignin and degumming the original biomass [64]. In addition to being used to extract cellulose, DES can also be used to adjust the thermal behavior of heat-responsive polymer [65].

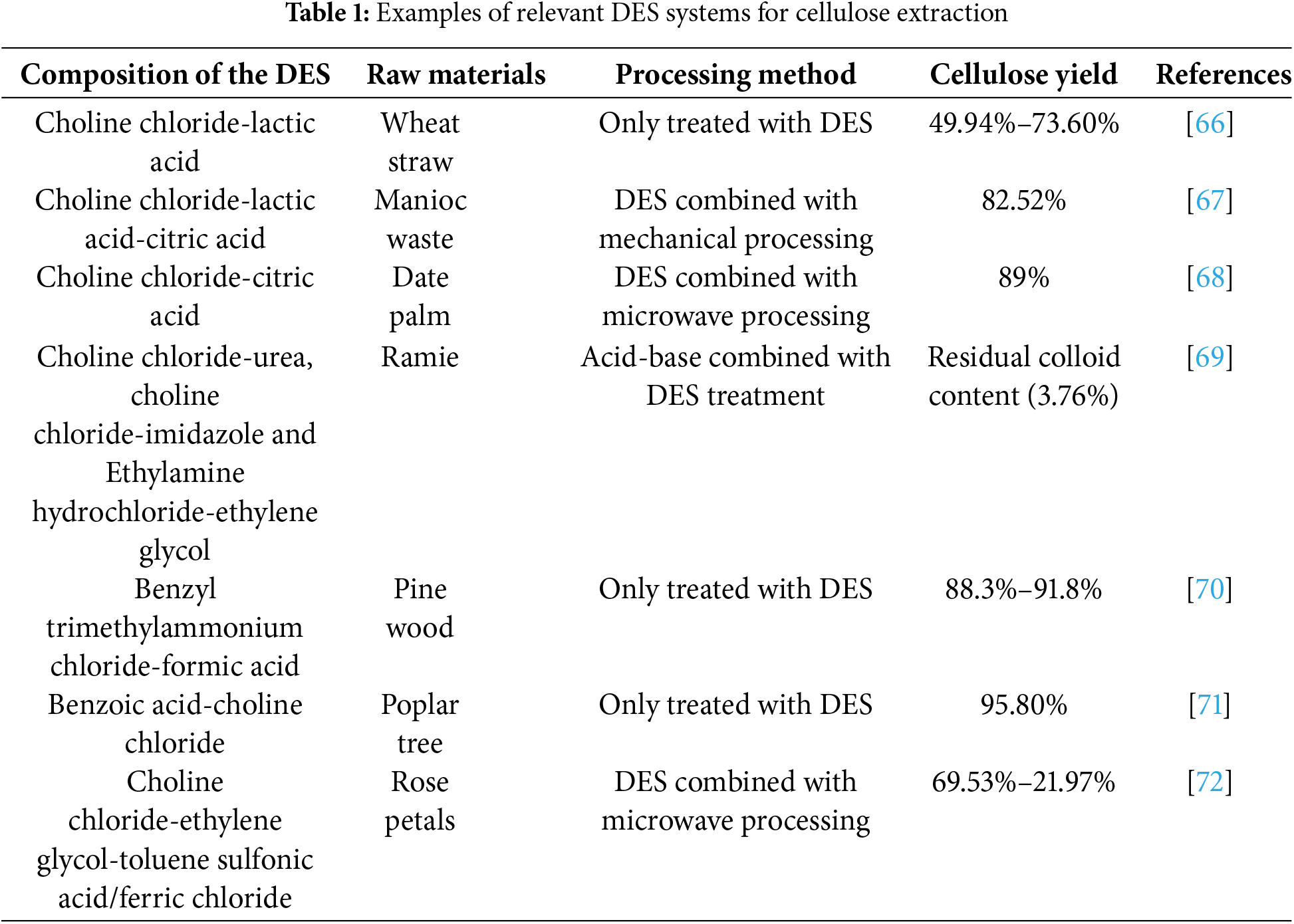

At present, there have been quite a lot of studies on the extraction of cellulose by DES, and most of the studies have focused on changing the composition of DES, adopting more efficient mechanical combined DES treatment to improve the treatment effect, and expanding the source of cellulose. In Table 1, the research achievements in this field in recent years are listed. Surprisingly, this carboxylic acid type of DES seems to have become the focus of current research.

This is because, in all kinds of DES, carboxylic acids DES promote further hydrolysis and carboxylation between cellulose due to the existence of active hydrogen ions [73]. Compared with other DES, carboxylate DES can pretreat cellulose more efficiently [74]. Liu et al. [75] applied different carboxylic acids DES to prepare CNF from pretreatment cellulose raw materials, combined with spiral extrusion and colloidal grinding and carried out esterification modification of cellulose nanofibers (CNF) at the same time. The results show that the combination of DES pretreatment with mechanical treatment can swell and esterify the cellulose material to produce CNF with a width of less than 100 nm.

In addition, DES pretreatment temperature plays an important role in the esterification modification and nano-fibrillation of cellulose. The esterification modification of cellulose prevented excessive hydrolysis and dissolution of cellulose during DES pretreatment, ensuring a high CNF yield of 72% to 88% and maintaining the cellulose I crystal structure. Ma et al. [76] explored a ternary DES system composed of chloroacetic acid, urea, and choline chloride to pretreat bamboo fiber and then grind it to prepare carboxymethylated modified cellulose nanofibers. This ternary DES pretreatment was modified while maintaining the crystal structure of cellulose. In addition, it also has a wetting and swelling effect on the fibers, resulting in the successful destruction of strong hydrogen bonds during mechanical treatment and the rapid production of cellulose nanofibril. Carboxymethylation enhanced the dispersion of CNF and increased the stability of the suspension. In addition, prolonging the duration of DES pretreatment can enhance the fibril fabrication process and reduce fibril polymerization. The produced CMCNF exhibits a high aspect ratio, with diameters ranging from 10 to 50 nm and lengths extending to several microns.

In addition, due to the stable physical and chemical characteristics of DES, DES has good recycling characteristics. By separating and purifying DES after pretreatment, it can be recycled and reused many times. Usually, the pretreated plant residue can be filtered to remove impurities such as lignin from the DES solvent using the antisolvent method or acid gradient method. Then the reaction system was purified by rotating evaporation [77], freeze-drying [78], electrodialysis [79], and membrane separation [80], and the obtained DES solvent could be recycled continuously. In a word, the main separation and purification ideas of DES can be divided into two categories, one is to remove impurities from the solvent, and the other is to transfer the solvent. At present, the evaluation of DES process performance is mainly based on recovery times and pretreatment efficiency. However, it is worth noting that the pretreatment efficiency of DES decreases with the increase in the number of recoveries because some plant fibers will be dissolved in DES during the reaction, occupying a part of the solvent space. In addition, these impurities also affect the hydrogen bond network of DES. As a result, its processing efficiency decreases [81].

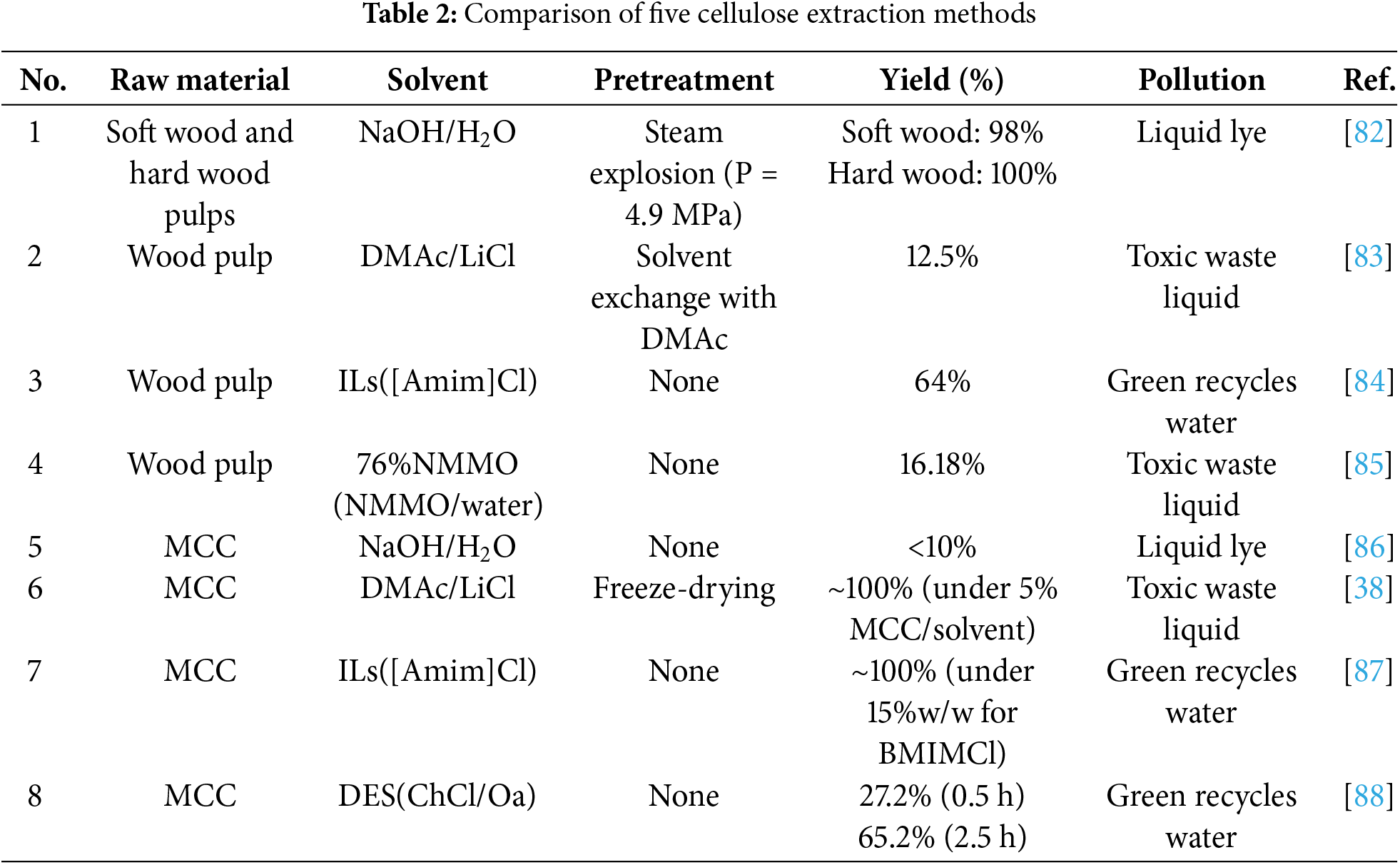

3.6 Comparison of Solvent Systems

There are many methods to extract cellulose, and the yield of cellulose obtained by different extraction methods will also be affected. Therefore, to make a reasonable comparison, this paper tries to unify the raw materials and summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of five cellulose extraction methods by comparing them. As shown in Table 2.

The first four items are derived from wood pulp, and the last four are sourced from MCC. From example 1, it can be seen that different materials will lead to changes in cellulose yield. Compared with 1 and 5 in Table 2, the same NaOH system has a relatively large impact on cellulose yield with or without pretreatment. Based on the above examples, it can be roughly concluded that the ionic liquid system and DES system have more advantages in the extraction of cellulose. The traditional NaOH system requires material pretreatment to achieve good extraction efficiency. The dissolution capacity of the DMAc/LiCl system is limited, which is easily affected by the content of raw materials in the system. In addition, in terms of environmental problems, NaOH is easy to affect the environment due to the need for a large amount of alkali solution, while DMAc/LiCl system and NMMO system have certain impacts on human health and the environment due to toxic organic solvents. As for the ionic liquid and DES system, their solvents can be recycled and reused repeatedly, which has a good circular economic effect. It is worth noting that DES solvents are generally green and low toxic solvents, which are environmentally friendly and pollution-free.

In addition, by comparing the five systems, it can be found that there are some potential obstacles in the field of cellulose extraction, which will affect the promotion and application of cellulose materials. The main reason for these obstacles is that the sources of raw materials are different, and the content of cellulose contained in different raw materials will be different, which will more or less affect the extraction efficiency of cellulose. The different structures of raw materials (such as soft and hard plants) will lead to changes in process conditions, which will affect the cost. In addition, cellulose extracted from different plants using the same process will have certain differences in structure, size, surface topography, and other aspects, which will directly affect the performance of cellulose products. Therefore, it is critical to solve the batch stability problem of cellulose or bio-based materials.

4 Modification of Cellulose and the Derivatives

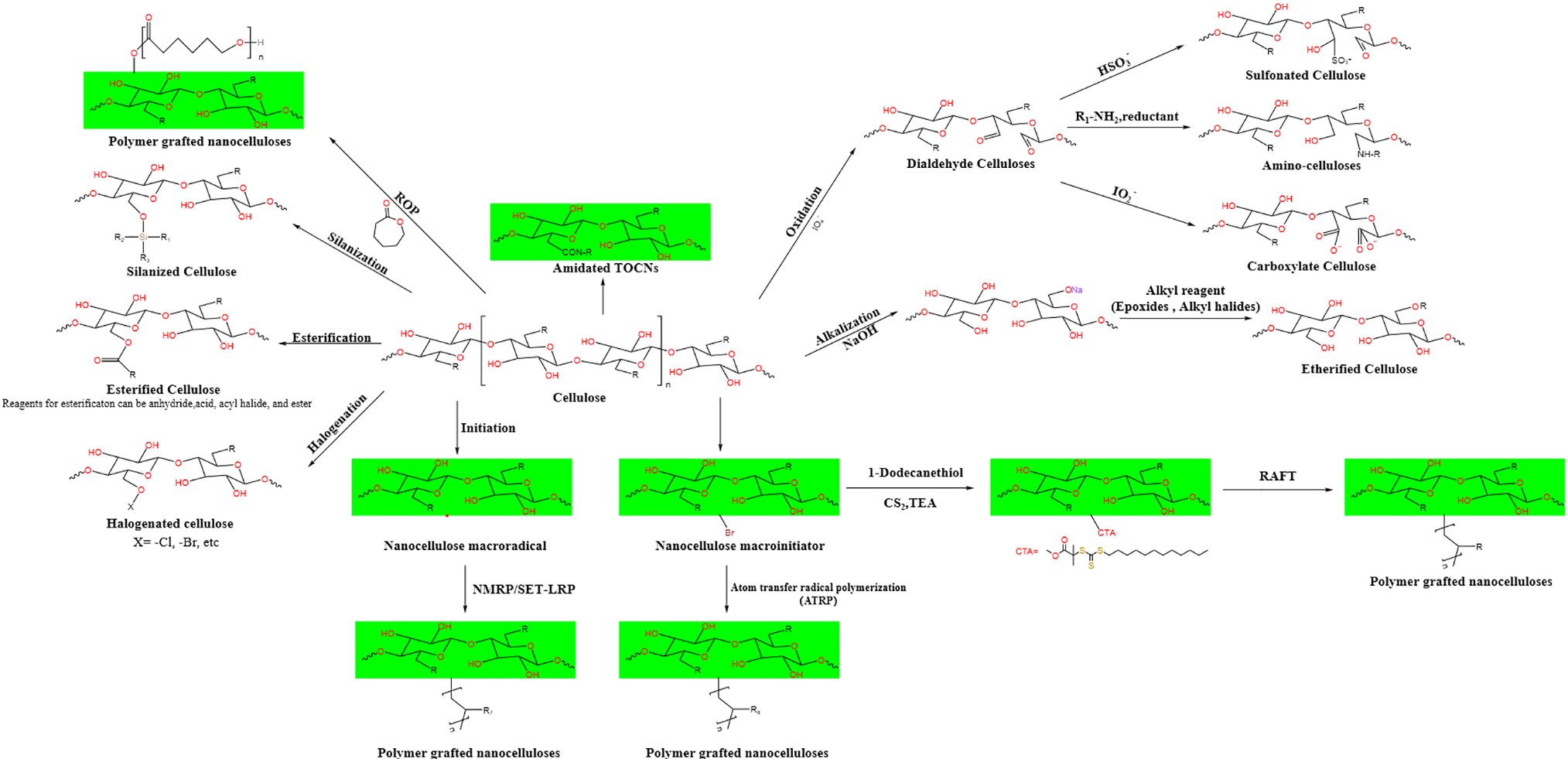

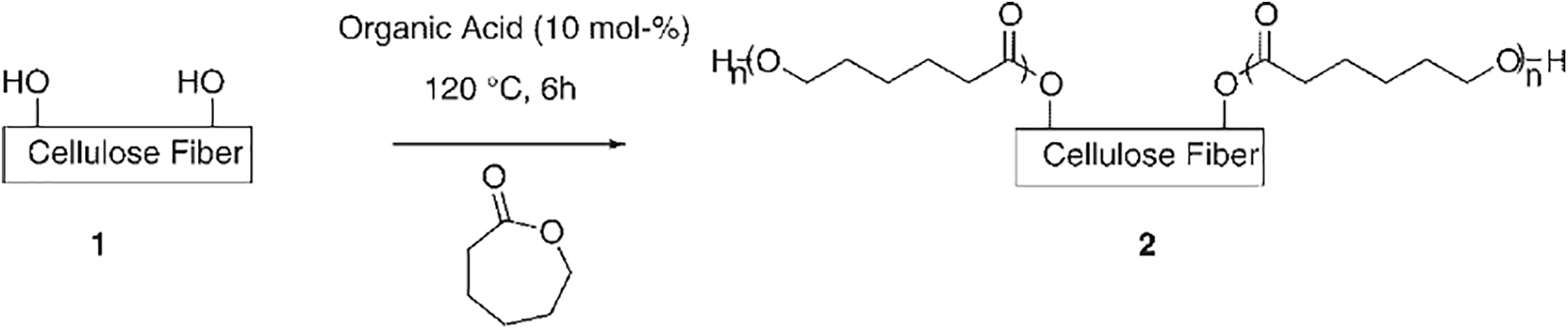

Due to the presence of a large number of free active hydroxyl groups at C-2, C-3, and C-6 on the surface cellulose structural units, strong hydrogen bonding exists between linear cellulose molecular chains. To make cellulose can be used efficiently, people have modified its structure to expand its application range. Since cellulose is composed of linear chains and has abundant reactive sites, it can be transformed into many cellulose derivatives, such as cellulose acetate, carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, etc., by surface modification with small or large molecular reagents. Cellulose nanofibers (CNF) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) with smaller structural scales can be obtained by mechanical treatment or chemical acid and enzyme treatment, which can meet the application of cellulose in various related fields. The cellulose-related modification process is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Modification process of cellulose (including molecule modification and macromolecule modification)

Regardless of the source of cellulose, only two forms of nanoscale cellulose exist after the cellulose is dissolved and extracted. The first is a semi-crystalline type of fiber with a high aspect ratio and flexibility, known as cellulose nanofibers or nanofibril (CNF). The other is the rigid fibril with high crystallization and low aspect ratio, which is obtained by destroying the amorphous region of cellulose, and is called cellulose nanocrystalline whiskers or nanorods or nanocrystals (CNC). In general, the composition of fibrils includes crystalline regions and amorphous regions. The fibrils and fibril bundles extracted by solvent are collectively called CNF. The crystalline part extracted from the fiber is called CNC [89].

4.1.1 Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF)

The so-called cellulose nanofibers (CNF) are materials with a semi-crystalline structure, usually with a diameter of 1 to 100 nm and a length of approximately 500 nm or more. Generally, CNF can be obtained in two approaches: the physical method and the chemical method.

Physical Method

The physical method generally allows CNF to be extracted longitudinally from the pretreated fibers through mechanical shear forces. The common physical methods for extracting CNF include steam blasting [90], high-pressure homogenization [91], microfluidization [92], ball milling [93], grinding [94], etc. These processes have in common the use of strong mechanical forces, such as shear forces, to break the hydrogen bond network and hydrolyze the glycosidic bonds in cellulose to produce CNF materials. To obtain CNF more efficiently, chemical or biological enzyme pretreatment can be carried out before mechanical treatment, which makes the structure of cellulose loose and reduces the hydrogen bond force, which is helpful for further treatment to obtain CNF. Liu et al. [95] combined a high-pressure homogenization method with ultrasonic assistance to obtain CNF from potato residue. According to the experiment, the yield of CNF is the highest (19.81%) when the ultrasonic power is 125 W for 15 min and the high-pressure homogenization treatment is 40 MPa for 4 times. However, the shortcoming of this method is that the crystallinity of CNF will be reduced.

Chemical Method

In the chemical treatment of cellulose to obtain CNF, the most common methods are TEMPO(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpethidine-1-oxyradical) reagent guided oxidation, and carboxymethyl method [96]. By modifying the surface of cellulose, this method brings charge, which helps the cellulose to undergo electrostatic repulsion and realize the expansion of the cell wall, thus promoting the generation of CNF. In general, CNF oxidized by TEMPO can be written as TOCNs for distinction. Huang et al. [97] used office waste paper as raw material and adopted the TEMPO oxidation method to prepare CNF materials. Before preparation, three different pretreatment methods (low acid treatment, alkali treatment, and bleaching treatment) were used to treat raw materials to explore the influence of different pretreatment methods on the preparation of CNF. The experimental results show that: (1) Using low acid treatment (1% sulfuric acid solution) to treat the office wastepaper can remove part of the hemicellulose and lignin, to expose more cellulose. This process will help to follow up the TEMPO oxidation process, making cellulose more effective in the preparation of nanofibers (CNF). In addition, the crystallinity of CNFs (WCNF1) treated with low acid was increased, which helped to improve the mechanical properties and tensile strength of CNFs. (2) The alkali treatment is by using a 12% sodium hydroxide solution to deal with office wastepaper, the purpose is to further remove impurities such as lignin and ink so that more pure cellulose. After alkali treatment, CNFs (WCNF2) showed a relatively concentrated size distribution in particle size distribution, which helped improve the uniformity and dispersion stability of CNF. (3) Bleaching was performed by using the D0(EP)D1 bleaching sequence (where D represents the chlorine dioxide stage and (EP) represents the hydrogen peroxide enhanced alkali extraction stage) to selectively remove lignin and improve the purity of cellulose. The bleaching treatment of CNF showed higher crystallinity, which in turn enhanced the optical properties of CNF and increased its transmission in the visible light range.

Besides the TEMPO oxidation process for CNF, a deep eutectic solvent system (DES) is also available on CNF. Due to the dense hydrogen bond network of DES, the long chain of cellulose will expand, and the hydrogen bond within the amorphous regions of cellulose will be destroyed to promote fiber liberation [98]. This results in DES still needing mechanical treatment, such as ultrasonic crushing, high-pressure homogenization, ball milling, extruder extrusion, etc., to further refine the cellulose after the treatment of cellulose. Yu et al. [99] prepared CNF by treating ramie fiber (RF) with a choline chlorine-urea (CU)DES system and ball milling technology. The CNF yield reached 94.06%, the crystallinity reached 66.51%, and the thermal stability was

4.1.2 Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC)

Cellulose nanocrystalline (CNC), a rod-like nanomaterial, can be extracted from lignocellulose. By removing the amorphous areas in the CNC, the degree of crystallinity can be enhanced. In general, the diameter of CNC is 3 to 50 nm, and the length is 50 to 500 nm. Compared with CNF, CNC has a lower aspect ratio and a higher crystallinity. To be able to prepare CNC, it is generally necessary to remove lignin and hemicellulose in cellulose to obtain CNC with high cellulose content. The usual pretreatment methods mainly include physical, chemical, and biological pretreatment.

Physical Method

The first physical pretreatment method involves the use of mechanical shearing forces to disrupt the cellulose cell walls, thereby transforming cellulose from its fibrillar state to a nano-structured form. Wet disk milling (WDM) can refine biomass into bent microfibers through high-speed rotation, and then obtain CNC materials through hydrolysis [100]. Another common method is the ultrasonic method, which uses high-frequency oscillations to separate cellulose fibers. Generally, ultrasonic (>20 kHz) acting under the liquid, using the alternating change of low pressure and high-pressure waves to achieve the generation and rupture of small vacuum bubbles. With powerful mechanical oscillation power, high-intensity waves are generated, which contribute to the formation, expansion, and implosion of microscopic bubbles as molecules absorb ultrasonic energy. This treatment will produce a strong hydrodynamic shear force, which can destroy the hydrogen bond force between cellulose molecules, thus achieving the destruction of the fiber cell wall. Under the action of low-concentration acid, the destruction and hydrolysis of amorphous region can be realized, to prepare CNC. Gui et al. [101] successfully produced CNC with microcrystalline cellulose as the basic raw material under the combined action of ultrasonic and phosphotungstic acid (PTA). Compared with the traditional sulfuric acid method, the crystallinity of the CNC prepared by this method can reach 86.93% under the condition of 20°C, and the required acid concentration is lower (13.7%), which has little damage to the CNC. Zianor Azrina et al. [102] used empty fruit bunch pulp (EFBP) as raw material to obtain CNC through ultrasonic-assisted acid hydrolysis. It is worth noting that, compared with the raw empty fruit bunch fiber (REFB), the CNC prepared from EFBP as raw material has a spherical structure, and the spherical CNC has higher crystallinity and better thermal stability.

Chemical Method

Acid hydrolysis is generally used to prepare cellulose nanocrystals by chemical methods. In the process of acid hydrolysis, the surface properties of CNC are also different according to the types of inorganic acids. By hydrochloric acid hydrolysis method of CNC surface contains a small amount of negative charge, so prone to reunite phenomenon between CNC particles [103]. However, the surface of CNC prepared by hydrolysis with sulfuric acid will react with sulfuric acid to modify the sulfate group, thus providing a large amount of negative charge on the surface of CNC [104]. Due to the strong mutual repulsion between the charges, the CNC suspension prepared by the sulfuric acid method has strong colloidal stability.

Unfortunately, the use of large amounts of acid can lead to inevitable damage to the environment. In recent years, researchers have also tried to use DES to prepare nanocellulose. As with the preparation of CNF, this mild treatment method cannot directly prepare CNC but requires a combination of different mechanical or chemical treatments. Zhang et al. [88] proposed and evaluated a method for preparing CNC by combining hydrated DES with a mechanical high-shear force method. When the processing time was increased, the CNC output increased from 27.2% (0.5 h) to 65.2% (2.5 h). The average diameter of the CNC is 25.1–33.3 nm, and the length ranges from 281.3 to 404.2 nm. Wang et al. [105] reported the preparation of CNC from cotton and other biomass feedstocks using DES and high-pressure homogenization (HPH). The diameter range of the CNC is 50–100 nm and the length range is 500–800 nm. The obtained CNC remained stable even after one month of storage. It is a good choice to use carboxylic acid DES to prepare CNC, and the processed cellulose can directly obtain CNC without post-processing [106]. Zhu et al. [107] prepared CNC by using purple potato peel as raw material by ultrasound-assisted maleic acid hydrolysis of cellulose. After acid hydrolysis, the CNC retains the cellulose type I structure and carries out esterification modification on the CNC surface.

Biological Method

Biological methods generally involve the separation of cellulose structures using cellulase. This method mainly involves the conversion of the carbonyl group to the carboxyl group and the subsequent modification by the sulfate group in the hydrolysis process with the acid. This helps to increase the charge density of the CNC surface, thus achieving a stable dispersion of the CNC suspension. The combination of biological methods with chemical methods can reduce the acid concentration required for the hydrolysis of CNC in subsequent chemical methods. In addition, biological methods can be combined with physical methods and chemical methods to achieve efficient preparation of CNC materials. Cui et al. [108] used wheat microcrystalline cellulose as raw material to prepare CNC by combining ultrasonic-assisted and enzymatic hydrolysis. Under the condition of 120 h of enzymatic hydrolysis and 10 times of ultrasonic treatment for 1 h, the maximum yield of CNC can reach 22.57%. In addition, without ultrasonic treatment, the yield of the CNC was reduced by 6.81%. Ren et al. [109] used MCC as raw material and carried out enzymatic hydrolysis in the way of complex enzymes to prepare spherical CNC. Spherical CNC with a particle size of 24~76 nm can be extracted under the condition of lye (pH = 9) and centrifugation speed of 3000 rpm, and then washed and purified three times under the condition of pH = 4 acid, pure spherical CNC materials can be obtained. The crystal structure of the spherical CNC material is cellulose Iβ type, but the degree of crystallization is low.

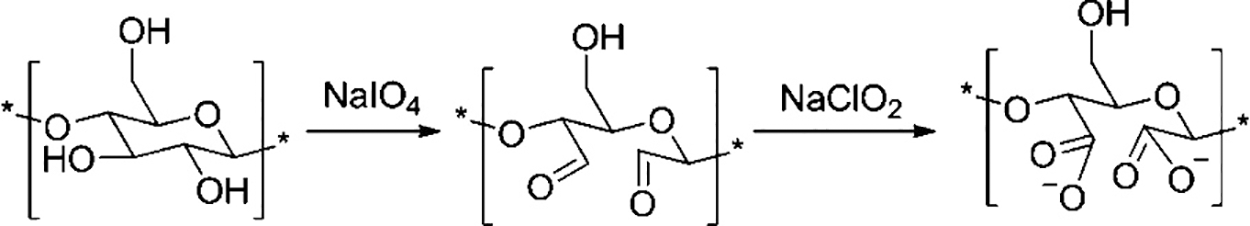

Hydrophilic modification:

2,2,6,6-tetramethylpethidine-1-oxyradical (TEMPO) is a good agent for promoting the separation of nanocelluloses, which selectively introduces carboxyl groups at the glucose unit C-6. In this process, an additional catalyst (NaBr), and an initial oxidizer (NaClO) are generally added at a PH of 9 to 11. In addition to the carboxylation modification of cellulose by the TEMPO oxidation method, the carboxylation treatment of cellulose can also be realized by using a periodate-sodium chlorite system to oxidize cellulose, and the conversion of cellulose secondary alcohol to carboxyl group can be realized [110]. Liimatainen et al. [110] used a periodate-sodium chlorite system to oxidize cellulose. In this process, secondary alcohol was first oxidized to the aldehyde group by periodate and then oxidized to the carboxyl group by sodium chlorite, and the oxidation process is shown in Fig. 6. The degree of nano fibrillation of hardwood cellulosic pulp was enhanced by applying a periodate-chlorite system for region-selective oxidation, coupled with mechanical homogenization treatment.

Figure 6: Oxidation of cellulose with periodate and chlorite. Adapted with permission from References [110], Copyright © 2012 American Chemistry Society

Zhou et al. [111] prepared carboxylate cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs-COOH) using potassium permanganate and oxalic acid as oxidant and reducing agent, respectively, with the reaction temperature of 50°C and the concentration of sulfuric acid of 1wt% from paper pulp. Compared with Tempo oxidation, the amount of oxidant is greatly reduced, and the yield can reach 68.0%. Ammonium persulfate (APS) can also carboxylate cellulose materials, but the yield of this method is low in industry. Therefore, Liu et al. [112] improved the APS method. In this paper, a method was proposed to optimize the preparation process of cellulose carboxylate nanocrystals by APS using the activation of N, N, N’, N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) and ultrasonic assistance. The yield of carboxylate cellulose nanocrystals prepared by this method can reach 62.5%, and the crystallinity of carboxylate cellulose nanocrystals prepared by this method is high (93%), and the content of carboxylic acid groups is also high (1.45 mmol/g).

The sulfonation reaction is one of the methods to attach negative groups to the surface of cellulose. The sulfonation reagent is combined with the hydroxyl group on the surface of cellulose to achieve surface sulfonation modification. Thiangtham et al. [113] first oxidized MCC with sodium periodate to obtain dialdehyde cellulose, and then sulfonated dialdehyde cellulose with K2S2O5 to prepare sulfonated cellulose (SC). Through the experimental characterization test, it was found that when the content of the sulfonic acid group was 528~689 μmol/g, the water solubility of SC was improved, and the transmittance of SC could reach 80% in the wavelength range of 400~800 nm. Mayer et al. [114] to create sodium 4-((4,6-dichloro-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)amino)benzenesulfonate (SDTAB). The reagent was mixed with sodium sulfate and the target cellulose for 30 min, and then sodium carbonate was added for one hour. Finally, the cellulose with the sulfonic acid group was prepared by rotating under the shaker for 30 min at a speed of 80 revolutions per minute, which established the basis for subsequent conductive modification through interface interaction between ionic bonds and conductive polymers. After extracting MCC from bagasse, Kanbua et al. [115] carried out sulfonation modification of cellulose by gamma-ray and potassium sulfite successively. The increase of γ radiation will increase the oxidation degree of cellulose. The prepared sulfonated cellulose (SC) can be used as filler to fill the polyether block amide/polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEBAX/PEGDA) polymer matrix, thereby improving the electrolyte affinity and thermal stability of the composite film.

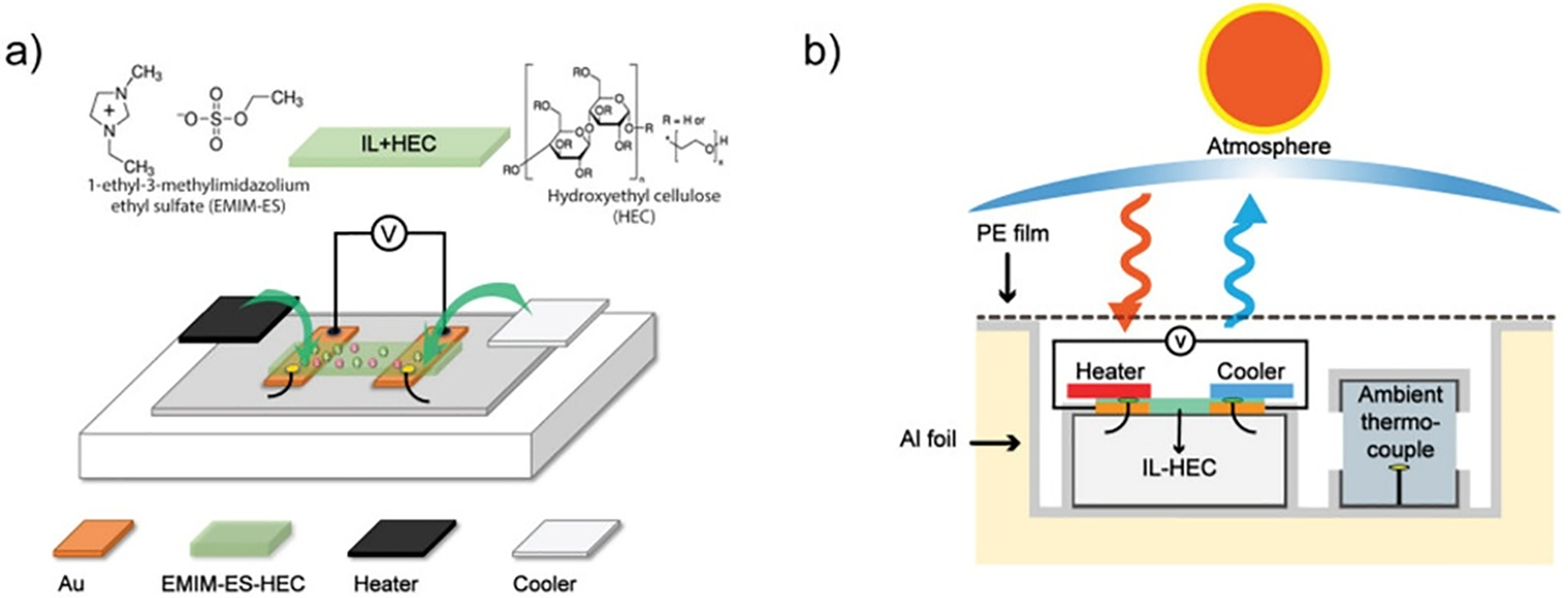

Etherified cellulose is prepared by homogeneous reaction with alkyl reagents such as epoxides and alkyl halides under alkaline conditions [116]. At present, ether cellulose such as methylcellulose (MC), carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPC), and carboxyethyl cellulose (CEC) have been developed.

Etherified cellulose can be classified as single ether and mixed ether according to the substitution situation. The single ether can be subdivided into alkyl ether (such as ethyl cellulose, propyl cellulose, etc.), hydroxyalkyl ether (such as hydroxymethyl cellulose, hydroxyethyl cellulose, etc.), and carboxyalkyl ether (such as carboxymethyl cellulose, carboxyethyl cellulose, etc.) three large pieces.

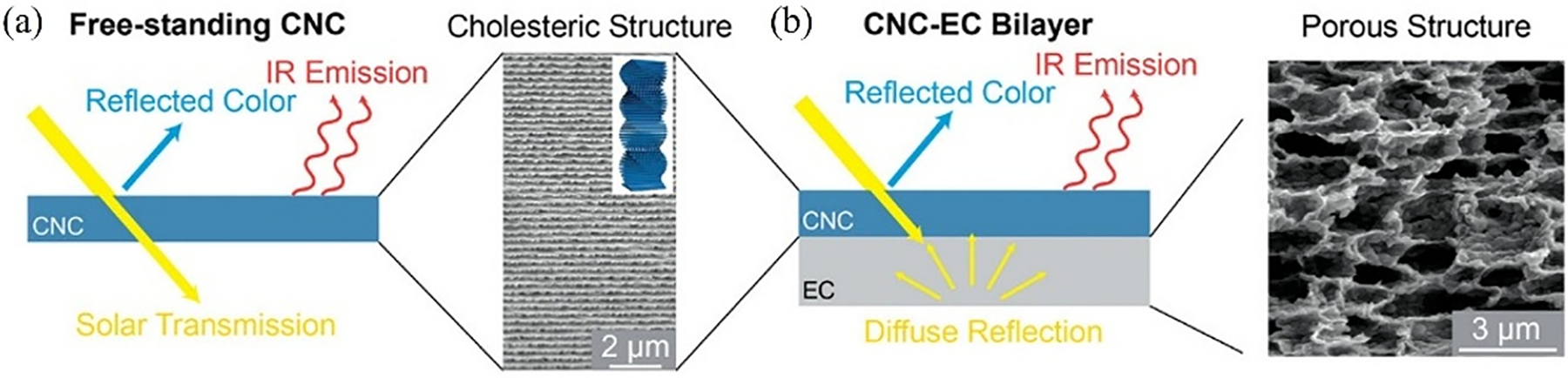

In addition, it can be divided into four categories according to the types of substituted ionic groups: non-ionic cellulose ethers, anionic cellulose ethers, cationic cellulose ethers, and amphoteric cellulose ethers (that is, both cationic and anionic groups). Among them, cellulose ether with quaternary ammonium cationic group has good flocculation and decolorization efficiency and has been widely used. Aguado et al. [117] prepared water-soluble cationic cellulose derivatives (WSCC) by cationizing cellulose with (3-chloro-2-hydroxypropyl) trimethyl ammonium chloride. This material is usually used as a dynamic coating material for capillary, which can effectively inhibit the adsorption of basic protein on the tube wall and improve the separation efficiency of basic protein. Matsumoto et al. [118] introduced amyl ether on the side chain of ethyl cellulose (EC). The degree of substitution of amyl ether is affected by the concentration of solvent and base in the process. The EC modified by side chain etherification can be dissolved in methacrylic acid (MAA), and liquid crystal with cholesteric photonic crystal structure (CLC) can be prepared.

In addition, under alkaline conditions, due to the different positions of the three hydroxyl groups of cellulose in the glucose group, they are affected by the neighboring substituents and the spatial obstruction. The dissociation degree of the three hydroxyl groups is C-2 > C-3 > C-6. Therefore, when etherification is carried out under alkaline conditions, the reaction order is that the hydroxyl group on C-2 is the first reaction, followed by C-3, and finally C-6, while esterification under acidic conditions is the opposite.

Hydrophobic modification:

Esterification of hydroxyl groups on cellulose chains with acids, acyl halides, and anhydrides is used to make esters, including aliphatic and aromatic [119]. Generally, this type of cellulose can be divided into inorganic and organic acid esters. The so-called inorganic acid ester refers to the product obtained by esterification of the hydroxyl group in the cellulose molecular chain with the inorganic acid. Among them, cellulose nitrate and cellulose sulfate are widely used. By adjusting the proportion of the mixture of sulfuric acid and nitric acid cellulose nitrate processing.

Among the inorganic ester types, cellulose nitrate esters can be divided into fire cotton and gum cotton based on the amount of nitrogen content. Because of its high nitrogen content, fire cotton is usually used to make smokeless gunpowder, while rubber cotton is low in nitrogen content and is usually used in artificial leather, etc. As for sulfate, because of its low price and degradable, it is widely used as a drilling fluid treatment agent in the petrochemical field. In the field of industrial coatings, it can be used as a thickening agent in the preparation process.

In organic acid esters, the preparation idea is to generate the hydroxyl group in the cellulose molecular chain by reacting with organic acids, acyl halides, or acid anhydrides, mainly including cellulose formats, acetic esters, and so on. For example, the traditional transesterification reaction occurs under heterogeneous conditions, when the catalyst is an inorganic base, it needs to react at high temperatures for a long time, and the reaction is insufficient. Therefore, preprocessing is required to solve the problem. Chen et al. [120] pretreated cellulose with CO2/DBU/DMSO to induce transesterification between cellulose and vinyl ester, increasing the degree of substitution of cellulose to 0.58~3.0. The transesterification reaction conditions are relatively mild, without adding a catalyst, the reaction degree is relatively sufficient, and the steps are simple, clean, and pollution-free. It is worth noting that the physical and chemical properties of organic acid esters will be changed by the degree of substitution. Physical properties such as strength, melting point, density, and hygroscopic properties decrease as the molecular weight of the substituent increases. In addition, organic acid groups also have great effects on its performance characteristics. The esterified cellulose derivatives produced by esterification reactions can be used in the chemical industry and other fields.

Using different types of reagents (such as acetyl chloride, acetic anhydride, and vinyl acetate) can realize the acetylation of cellulose. These reagents have solubilization effects on cellulose and can even be used as organic catalysts for the reaction. Gao et al. [121] used

Besides cellulose can react with isocyanate and can achieve ammonia formylation, preparation of ammonia by formylation cellulose can be expected to replace traditional esterification agents. Siqueira et al. [122] used octadecyl isocyanate to modify the surface of CNC and CNF and then compared the effects of the two modified cellulose on the thermal and mechanical properties of polycaprolactone composites. The results showed that the substitution degree of carbamylated CNC and CNF reached 0.07 and 0.09, respectively. Since the incorporation of isocyanate improves the dispersion of CNC and CNF in organic solvents, the final properties of the composites are enhanced. The study by Beaumont [123] studied the solid-phase reaction between cellulose and N-acetylimidazole under different moisture conditions (anhydrous, 7%, 20%, and 30%). When the water content of cellulose is 7%, the acetylation reaction is the most active. They believed that the presence of water promoted the diffusion of reactants through the hydration layer of cellulose, and the imidazole generated during the reaction played the role of an alkaline catalyst, realizing the autocatalytic effect. By using nuclear magnetic resonance technology, they explored the effect of confined water on the chemical activity of hydroxyl groups on cellulose surface, revealing that changes in water content can regulate the reactivity of different hydroxyl groups, and then control the regional selectivity of acetylation on cellulose surface. The team hypothesized that the localized water facilitates the cellulose surface acetylation because it facilitates the proton transfer process from the cellulose acyl imidazolium intermediate to the imidazole base catalyst. In addition, the surface wettability of cellulose after acetylation changed significantly, and the contact Angle of water increased from 12° to 134°, indicating that its hydrophobicity was significantly enhanced.

The so-called amino cellulose (AC) is a chemical reaction that converts the hydroxyl group on cellulose into a derivative of the amino group. The replacement of the hydroxyl group on the molecular chain with amino groups results in the destruction of the inherent crystalline structure of cellulose. Consequently, amino cellulose exhibits enhanced water solubility, biocompatibility, and degradability. In the actual production situation, the hydroxyl group on cellulose is difficult to directly ammoniate, so the common way to produce amino cellulose is to synthesize active intermediates to prepare amino cellulose. There are four methods to synthesize amino cellulose by active intermediate: p-toluene sulfonic acid method, halogenated cellulose method, cyanoethyl cellulose method, and oxidized cellulose method.

(1) P-toluene sulfonic acid method:

The active intermediate was obtained by the reaction of p-toluenesulfonyl chloride with cellulose. Then, with the p-toluenesulfonic acid group as the leaving group, a suitable nucleophilic reagent was selected to carry out the substitution reaction, and the amino group was attached to the cellulose to obtain 6-deoxyaminocellulose. Heinze et al. [124] synthesized cellulose p-toluene sulfonyl chloride by esterifying cellulose with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride in the DMAc/LiCl system. The resulting intermediates are dispersed in ethylenediamine and heated to dissolve gradually, resulting in 6-deoxy-6 -(2-amino-alkyl) amino cellulose derivatives. The method has good solvent recovery ability and is environmentally friendly and harmless. This method involves the direct reaction of amino compounds with p-toluenesulfonate, which is simple and convenient. However, it is challenging to achieve complete replacement of the p-toluenesulfonate group. Zarth et al. [125] prepared amino cellulose hydrochloride in the presence of human p-toluenesulfonic acid chloride, using lactam as a nucleophile. By changing the reaction solvent conditions, the degree of substitution of amino cellulose can be controlled (between 0.24 and 1.17).

The preparation of amino cellulose by using p-toluenesulfonate as an intermediate is the most common method at present, which has the advantage of a quick and convenient reaction. However, when the intermediate is replaced, many p-toluenesulfonate ions are produced, which will be combined with the amino group, so the resulting product is generally amino-cellulose p-toluenesulfonate.

(2) Halogenated cellulose method:

The halogenated cellulose method is to synthesize halogenated cellulose intermediates and then convert them into amino cellulose. Deng et al. [126] prepared chlorinated cellulose intermediates by reacting cellulose with sulfoxide chloride. Amino-cellulose (ADC) was prepared by dissolving the intermediate in DMSO and adding ethylenediamine for an amination reaction. Gao et al. [127] prepared 6-amino-6-deoxy cellulose by using cellulose bromide as the base material through an aside reduction reaction. The results showed that the azide group was almost completely reduced and the degree of amino substitution reached 0.97 when DMSO was used as the solvent and reacted with 20 times excessive NaBH4 at 115°C for 7 h.

The halogenated cellulose method uses sulfoxide chloride to activate the C-6 position on cellulose, which makes the reaction selective. At the same time, the chlorine atom has a good departure, so that the intermediate can be replaced by an amino group so that the amino cellulose derivatives with relatively high purity can be obtained. However, sulfoxide chloride is toxic and easily decomposed, so the development of the chlorinated cellulose method is limited.

(3) Cyanoethyl cellulose method:

In the early stage, it was proposed that cyanoethyl cellulose could be prepared by reacting cellulose with acrylonitrile under alkaline conditions. Hassan et al. [128] pointed out that cyanoethyl cellulose was reduced by BH3 to the amino group and p-aminopropyl cellulose was prepared. It was found that the nitrogen content of aminopropyl cellulose was 12.43%, indicating that the hydroxyl group on cellulose was almost completely replaced. However, this method can only synthesize aminopropyl cellulose, resulting in a relatively simple type of amino cellulose synthesized.

(4) Oxidized cellulose method:

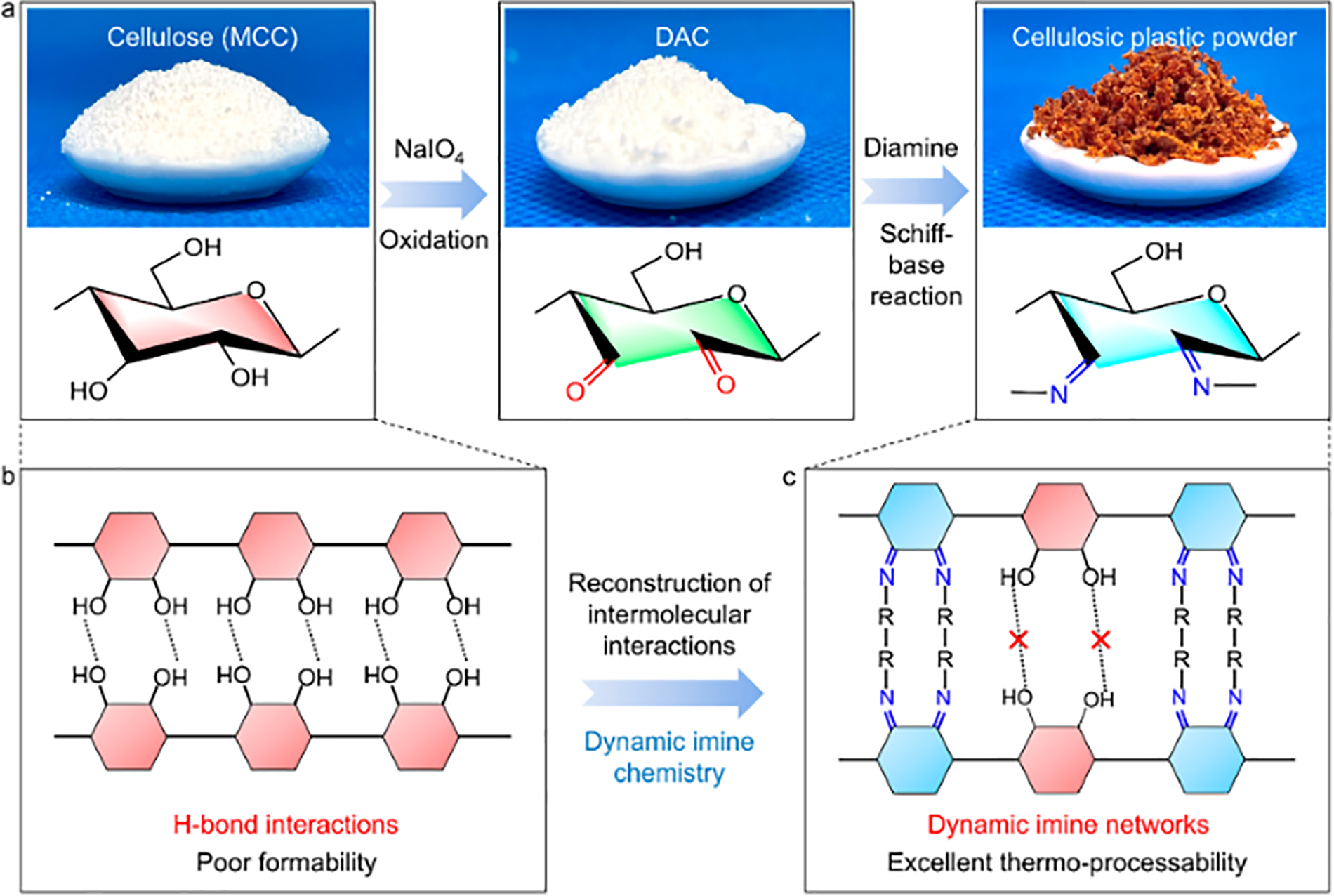

The main idea of this method is that aldehyde cellulose is used as an intermediate, and ethylene diamine is added to react with the intermediate to obtain the Schiff base. On this basis, it is further reduced with sodium borohydride to obtain amino ethylamine deoxy cellulose. The synthesis of aldehyde cellulose intermediates is based on the ring-opening reaction of periodate salts (such as sodium periodate NaIO4) on cellulose, which oxidizes C-2 and C-3 on glucose units to aldehyde groups, thus obtaining dialdehyde cellulose intermediates [129]. Dash et al. [130] used sodium periodate to oxidize cellulose to dialdehyde cellulose, and then grafted methylamine and butylamine on dialdehyde cellulose by Schiff base reaction to prepare amino cellulose derivatives. Su et al. [131] firstly oxidized cellulose with sodium periodate to obtain dialdehyde cellulose by using the above ideas. Subsequently, the DAC undergoes dynamic crosslinking with long-chain vegetable oil diamine (Schiff base reaction) at ambient temperature. This process entails partial replacement of the hydrogen bond network within the cellulose with a dynamic imine crosslinking network. This method significantly improves the stress relaxation ability and free movement ability of cellulose molecular chains and produces cellulose-based plastics with excellent thermoplastic processing. Its mechanism is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: (a) Flow chart of cellulose plastic powder preparation; (b) and (c) Diagrams of reconstructing cellulose hydrogen bond networks using dynamic imine covalent bonds. Adapted with permission from Reference [131], Copyright © 2023 American Chemistry Society

Lasseuguette [132] used Tempo, sodium hypochlorite, and sodium bromide to selectively oxidize primary alcohols on cellulose into carboxyl groups under the condition of water as a solvent. Amino cellulose derivatives were then prepared by coupling the amine derivatives with oxidized cellulose by adding carbodiimide (catalyst) and hydroxysuccimide (amidation agent).

Silanization modification of cellulose is a method of surface hydrophobic modification. Generally, Si-OR does not react with the cellulose hydroxyl group but can react with the lignin hydroxyl group at high temperatures without water. Under high temperatures, when water is introduced into the system, it can trigger a reaction between the silanol and hydroxyl groups that promote cellulose. By adding a silane coupling agent to cellulose suspension for mixing reaction, silyl groups can be introduced on cellulose surfaces.

The commonly used silane coupling agents are alkyl alkyloxysilane, vinyltriethoxysilane, etc. The reason for choosing this type of coupling agent is that the presence of hydrocarbon chains in silane enhances the wettability of the fiber, which can pave the way for subsequent chemical reactions. The reason for choosing this type of coupling agent is that the presence of hydrocarbon chains in the silane enhances the wettability of the fibers, paving the way for subsequent chemical reactions. Wang et al. [133] used two different organ silane coupling agents to functionalize and modify the CNF suspension before spray drying and applied 1 wt.%, 3 wt.%, and 5 wt.% organ silane solutions according to the gradient design and the solid content of CNF, respectively. After modification, Wang et al. determined the surface morphology and properties of the modified CNF. The experimental results show that there is agglomeration behavior between large particles and small rectangular particles in the system, and there is a local difference in CNF before and after treatment. By connecting different functional groups on the surface of CNF, not only can the acid-base properties be changed, but also the surface energy of CNF can be reduced. Pacaphol et al. [134] studied the effects of different silyl groups (amino group, epoxy group, and methacryloxy group) on the adhesion properties of nanocellulose films on glass and aluminum substrates. The experimental results show that amino silanized nanocellulose is better in bonding properties. In terms of elasticity, the performance of epoxy silanized nanocellulose is more significant. Amino silanized cellulose showed the worst performance in elongation and crack resistance. In the transmission of light, all below the glass, the aspect of hydrophobicity is slightly higher than that of pure aluminum.

Halogenated cellulose refers to the halogenated modification of cellulose by reacting with hydroxyl groups on the surface of cellulose. Chlorine stands as the most prevalent halogen in polymers, with the option to introduce halogen atoms through the selection of distinct chemical feedstocks as precursors. Due to the reactivity between hydroxyl groups and the diversity of commonly used chlorinating agents, the chlorination selectivity of cellulose regions is affected. Moreover, the halogenation of cellulose provides a precursor for subsequent nucleophilic substitution reactions, so that cellulose can be incorporated into new functional groups. Gao et al. [135] prepared 6-chloro-6-deoxycellulose ester and its derivatives by halogenation reaction. The primary alcohol group of cellulose acetate with a substitution degree of 1.75 was selected to react with methylsulfonyl chloride for quantitative chlorination to prepare 6-chloro-6 deoxy cellulose acetate. The experimental results show that chemical and regionally selective chlorination occurs at C-6. In addition, the study also showed that cellulose chloride acetate is a useful intermediate for the preparation of functional cellulose ester derivatives by substitution reaction with nucleophiles such as sodium azide, amine, and mercaptan. Du et al. [136] developed a new type of cellulose paper by impregnating nanocellulose paper (CNP) in CS and then impregnating CNP/CS in 0.6 wt% NaClO aqueous solution to achieve simple acyl chlorination modification to obtain CNP/CS-Cl. The CNP/CS-Cl had a good bactericidal effect on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (bactericidal rate reached 100% within 10 min). Therefore, the new material has potential application value in food packaging.

In addition to chlorine, the modification of cellulose by fluorine has also attracted attention. Khanjani et al. [137] used 2H,2H,3H,3H-perfluorononanoyl chloride and 2H,2H,3H,3H-perfluorodecanoyl chloride to perform regional fluorine-containing modification of CNC. Then nano spherical cellulose fluoride ester dispersion was prepared by nanoprecipitation method. Finally, the superhydrophobic paper is prepared by coating the dispersion in the paper by the spinning coating method. The superhydrophobic paper has good hydrophobic properties, which the contact angles are all greater than 150°. Therefore, it has potential application value in the field of packaging.

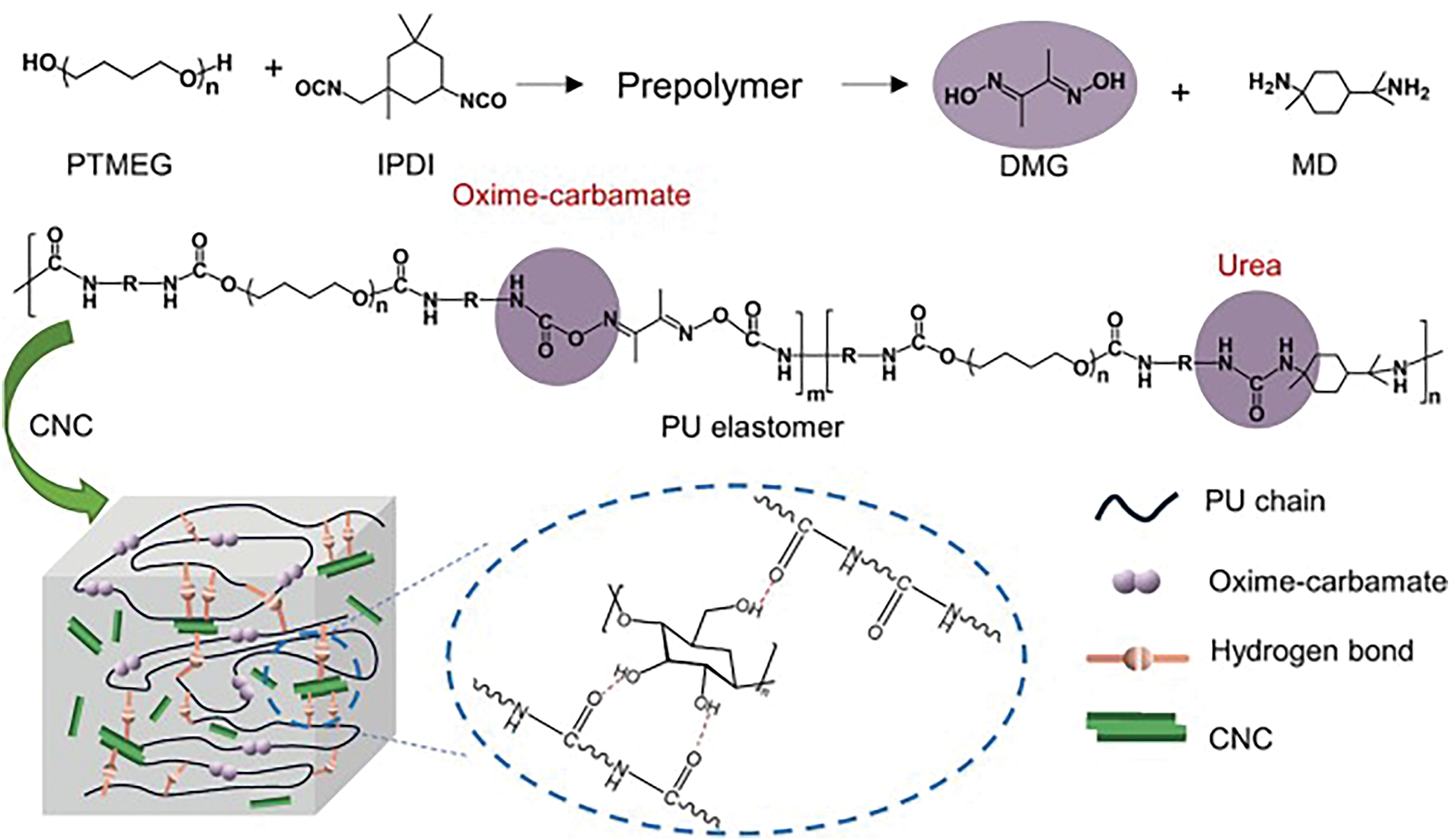

4.3 Macromolecular Modification

Although the surface structure and properties of cellulose can be well changed by molecule modification, the molecular weight and structure on the main chain do not change much. Therefore, molecule modification has little effect on other properties of cellulose, such as mechanical properties. Macromolecular modification is a new method to change the physical and chemical properties of cellulose. Under the premise of maintaining the original properties of cellulose, the introduction of macromolecules can give cellulose new and unique properties. In the modification of macromolecules, grafting copolymerization is the most used method. By grafting other designed polymers on cellulose macromolecules, unique properties can be conferred to form functionalized cellulose materials.

Three methods are commonly used to synthesize grafted cellulose, namely “grafting from”, “grafting onto” and “grafting through” [138]. “Grafting from” refers to the polymerization and growth of other monomers on the active site of the polymer backbone by the initiator according to its own active reaction point, to form a new graft polymer. “Grafting onto” means that the active groups are present on the two different polymers. When the third substance is added, a new covalent bond can be formed with the active groups on the other two polymers to form a new grafting polymer. “Grafting through” means because the owner chain polymerization is available for reaction activity of double bond. Consequently, it can act as a polymerization monomer, facilitating copolymerization.

In the “grafting from” method, the reaction site on the backbone can be directly initiated by chemical treatment or irradiation, and then the monomer is added to generate the graft copolymer. Although the grafting density of this method is high, there are also many shortcomings, such as the molecular weight of the graft polymer cannot be determined, the molecular weight of the graft polymer is low, and the homopolymer exists in the polymerization system. Therefore, the above shortcomings can be overcome by the mechanism of reversible chain termination and reversible chain transfer through active polymerization.

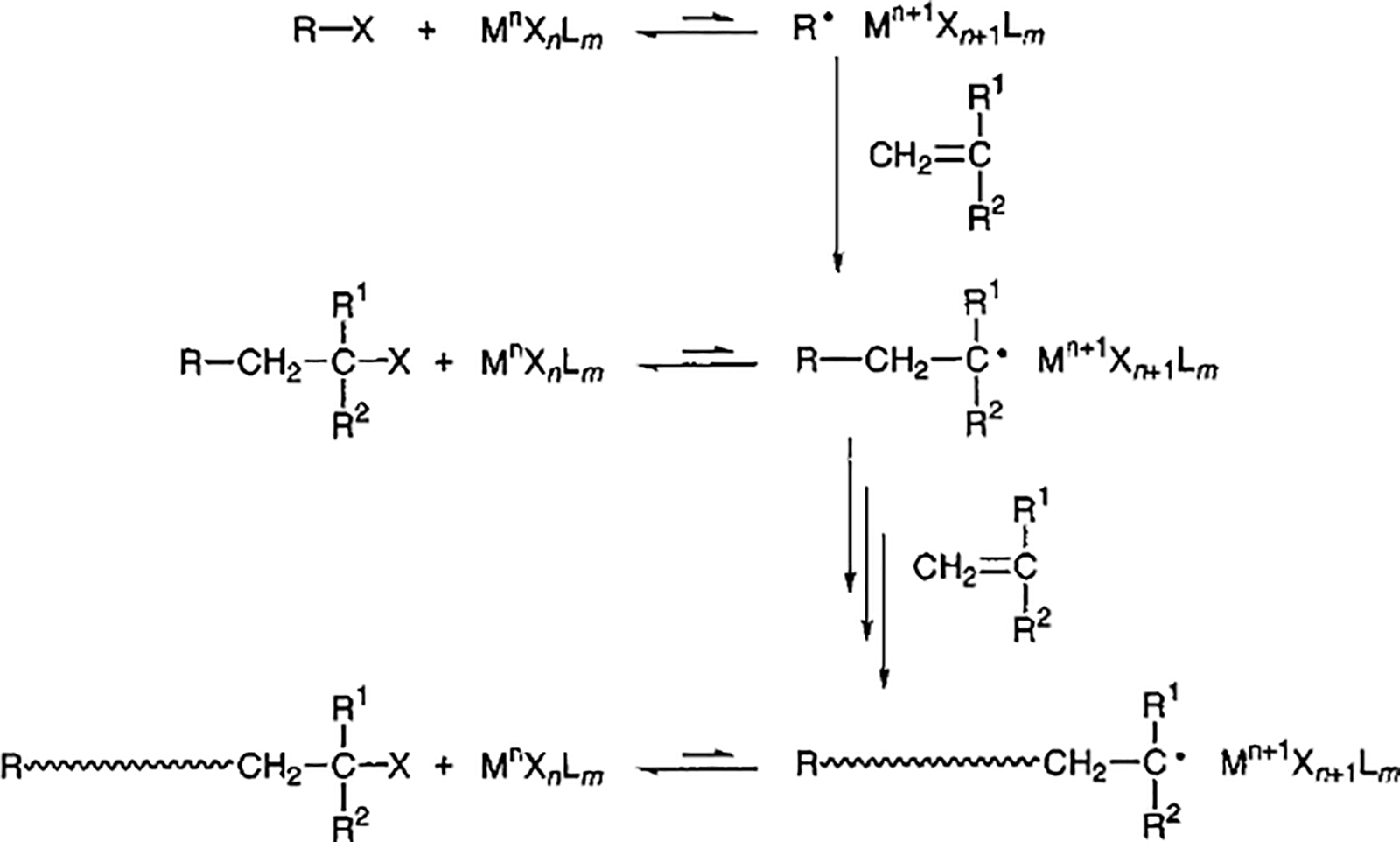

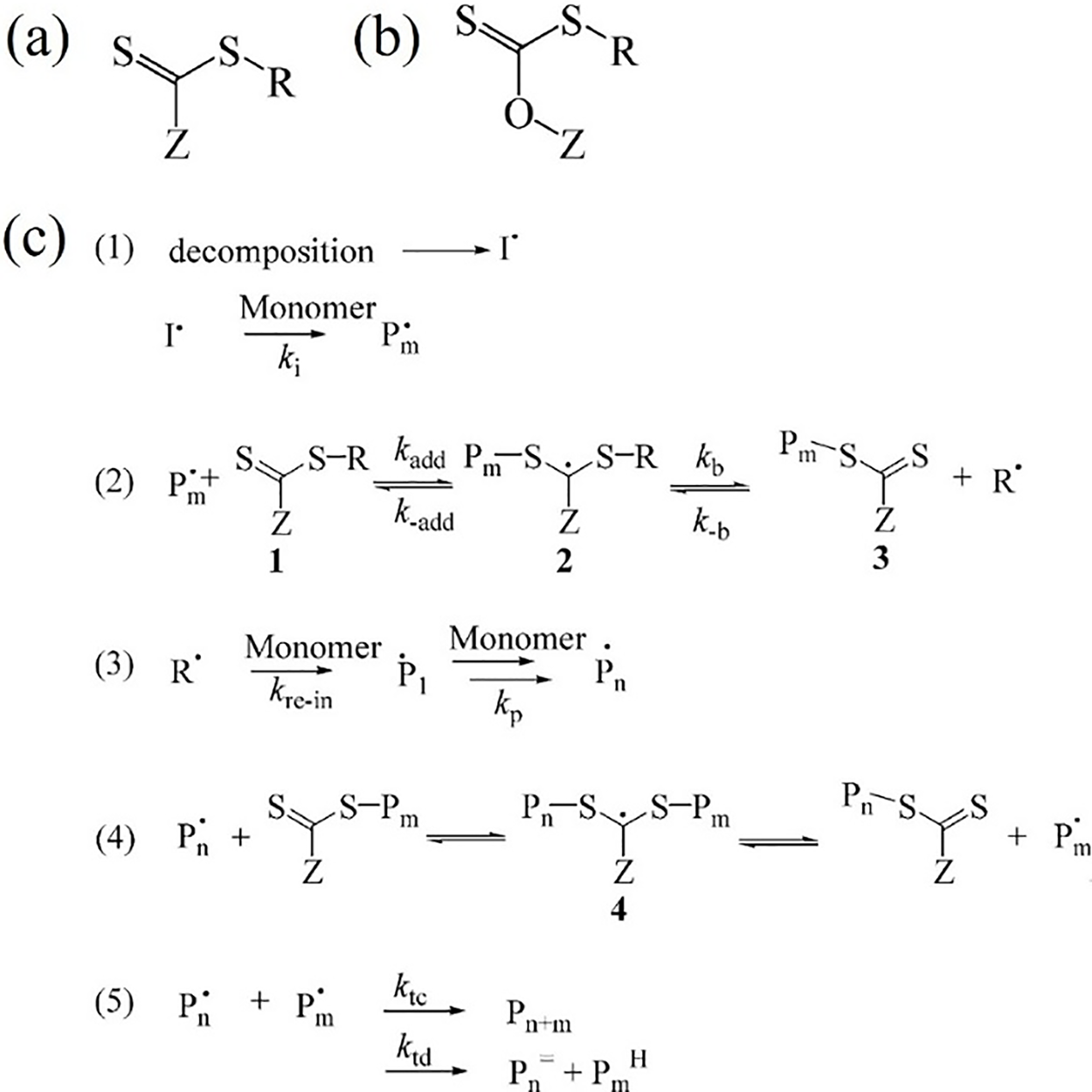

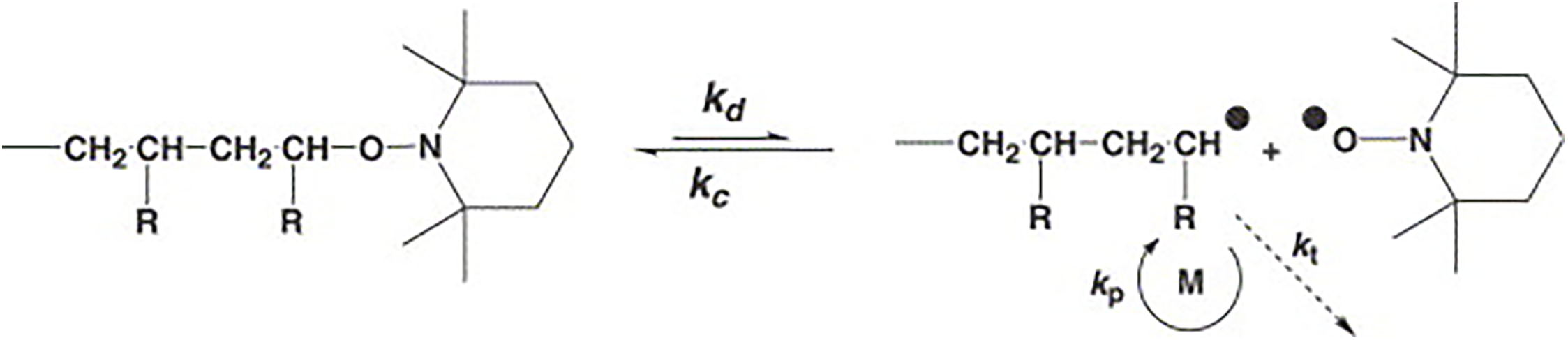

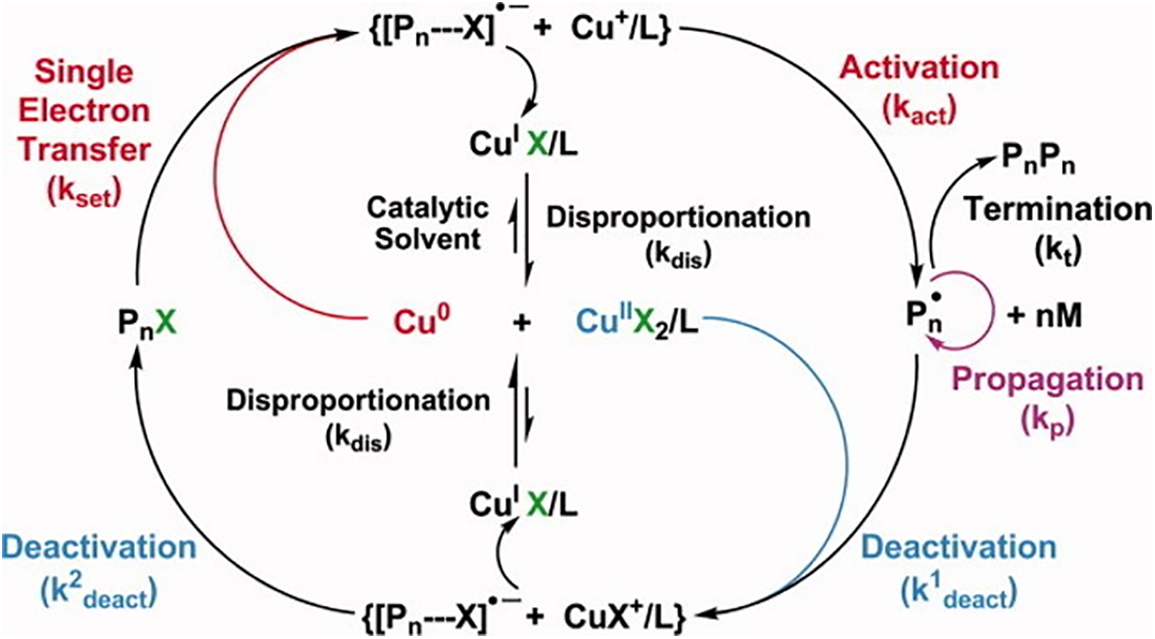

(1) ATRP

The initiation system of ATRP is mainly composed of halides, metal catalysts, and ligands. The polymerization mechanism is the formation of the complex by free radicals through a reversible REDOX reaction. This complex first undergoes oxidation to lose electrons while capturing halogen atoms from halides of dormant species [139]. The reaction mechanism is shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Mechanism of metal-catalyzed active radical polymerization. Adapted with permission from Reference [139], Copyright © 2001 American Chemistry Society