Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Plywood Bio-Adhesives by Oxidized Lignin Urea Bridged with Oxidized Starch

1 Department of Wood and Paper Sciences, Faculty of Natural Resources, Semnan University, Semnan, 35131-19111, Iran

2 LERMAB-ENSTIB, University of Lorraine, 27 rue Philippe Seguin, Epinal, 88000, France

* Corresponding Authors: Hamed Younesi-Kordkheili. Email: ; Antonio Pizzi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Renewable and Biosourced Adhesives-2023)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0179

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

The aim of this research was to synthesize a new totally bio wood adhesive entailing the use of oxidized starch (OST), urea, and oxidized lignin (OL). For this reason, non-modified (L) and oxidized lignin (OL) at different contents (20%, 30%, and 40%) were used to prepare the starch-urea-lignin (SUL) and starch-urea-oxidized lignin (SUOL) resin. Sodium persulfate (SPS) as oxidizer was employed to oxidize both starch and lignin. Urea was just used as a low cost and effective crosslinker in the resin composition. The properties of the synthesized resins and the plywood panels bonded with them were measured according to relevant standards. The viscosity and gel time of the SUOL resins containing oxidized lignin are respectively higher and faster than for non-modified lignin (SUL). The lignin phenolic hydroxyl groups (-OH) proportion was markedly increased by oxidation as shown by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometry. The molecular mass and the polydispersity of the lignin did also decrease by its oxidization pretreatment. DSC analysis showed a decrease of the glass transition temperature of the lignin (Tg) due to its oxidation. The thermal analysis of the oxidized lignin SUOL resin also showed that it had a lower peak temperature than the SUL equivalent non-modified lignin resin. The plywood panels bonded with oxidized lignin gave acceptable bending modulus, bending strength, peak temperature by thermal analysis and dry shear strength as well as a better plywood dimensional stability when used in the SUOL formulation. The synthesized SUOL adhesive is a lignin-derived, totally bio, no-aldehyde added, inexpensive resin applicable to bond plywood.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Due to the enhanced public awareness of to-day environment constraints and the increasing cost and availability oil reserves the biomass uses in wood adhesive preparation are growing [1,2]. For this reason, bio-based wood adhesives have attracted increasing attention. Lignin, as being the second largest and one of the most important biomass sources, can be used for wood adhesives. Its industrial yearly production from the pulp and paper industry as the main source of lignin can reach 6 × 1010 t [3]. Although lignin-based wood adhesives have several advantages, due to lignin’s complex structures, broad chemical differences, and low reactivity, they haven’t been used widely in the wood adhesive industry. To overcome these problems, to chemically modifying lignin is needed before using it for wood adhesives [4]. A number of different approaches to modify lignin have so far been taken. Among these, phenolation, hydroxymethylation and others, have been tried and are on record with some success in improving lignin reactivity [5,6]. Oxidation as a green method is one of the best proposed methods used for lignin modification. Oxidation is a modification which under certain conditions changes lignin superficial structure and degrades its original arrangement, increases the types and quantities of oxygen-containing functional groups, and increases the active sites on the surface of the material. Oxidation of lignin can be carried out with several different oxidizing agents. Oxidative pre-treatment of lignin has been described as a way to weaken the lignin structure, making it more susceptible to depolymerisation, and created aldehyde groups that can further cross-link the lignin by itself or with other materials [7]. Previous research has shown that sodium persulfates (SPS) yielded the best results among the all lignin oxidizing agents tried [8]. To use sodium persulfate Na2S2O8 (SPS) is much cheaper and easier than systems using ionic liquids or deep eutectic solvents for lignin modification. The hydroxyl groups from primary and secondary carbons of the lignin aliphatic chains can be oxidized by SPS. Chen et al. [7] have shown that the oxidation results of lignin resulted in depolymerisation, achieving higher reaction rates under milder conditions.

Conversely, the use of nontoxic aldehyde instead of formaldehyde (as a very toxic aldehyde) to obtain bio-adhesive based on lignin is necessary. Previous work has shown that oxidizing starch and other polymeric carbohydrates can yield non-volatile bio-aldehydes on the starch structure itself [9–15]. Different types of strong and mild oxidizing agent can be used to reach this purpose. Compared to strong oxidizing agents which can cause significant structural damage to the starch, SPS is a relatively mild and inexpensive oxidizing agent and it has been recently used as the most apt oxidizing agent for carbohydrate adhesives for wood [8]. Previous work has shown that SPS does cleave the C–C bonds in monomeric and polymeric carbohydrates in which the two carbons present vicinal –OH groups oxidizing them to two aldehydes, this also being valid for starch [16–23]. Therefore, in the work presented here, SPS was the choice of preference to be used to yield aldehyde groups as well as for the chemical modification of the lignin structure. The aldehyde groups generated in oxidized starch are capable of reacting with the aromatic rings of oxidized lignin to yield cross-linked networks usable as adhesives for wood, and moreover with the participation of the aldehydes formed on lignin by its specific oxidation [7]. However, previous work has shown that to obtain just oxidized either oxidized starch alone or lignin/oxidized starch adhesives with good physical and mechanical properties, the use of a cross-linking modifiers is necessary [17–22]. As in previous works on oxidized biomaterials urea as a low cost, nontoxic and effective material was used to ease and increase cross-linking between oxidized lignin and oxidized starch. Hence, this current research was aimed to achieve the synthesis of bio-adhesives for wood panels by oxidized starch, urea and oxidized lignin along with the investigation of the performance and properties of the plywood bonded with them.

Bagasse Soda black liquor with pH = 13% and 40% solid content as source of lignin.

For that purpose, Soda lignin was extracted from black liquor by sulfuric acid method. The chemical materials used in this research such as urea, sodium persulfate (SPS) and soluble starch were purchased from the Sigma Aldrich chemical company. In this research, soluble amylose-rich type of starch as bio-aldehydes was used to preparation of lignin-based adhesives.

Starch was oxidized according to a method reported by Liu et al. [23]. At a temperature of 60°C, a certain mass ratio of starch (ST) was added into a three-neck flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer to prepare a 50 wt% aqueous solution of starch. After the starch was fully and evenly homogenized, a certain amount of sodium persulfate (Na2S2O8) as oxidizing agent was charged and stirred for a certain period of time. After the reaction is complete, filter a portion was exposed to freeze-drying to obtain the oxidized starch (OST).

At a temperature of 50°C, lignin was blended with 25 wt% sodium persulfate (with 30% concentration) based on the lignin dry weight. They were mixed together rapidly under stirring (400 rpm) for 60 min at temperature of 50°C. Finally, the re-action mixture was then cooled to room temperature to obtain OL. The prepared OT was vacuum dried.

2.2.3 Preparation of Starch-Urea-Lignin (SUL) Wood Adhesives

To prepare the SUL adhesive, 20%, 30% and 40% unmodified/oxidized lignin (based on the dry starch mass) were added to the prepared oxidized starch (OST) solution (50%) and stirred for 60 min. In the next step, 20 wt% urea (based on the starch mass) as a cross-linking agent was added to mixing by vigorously stirring with a magnet rotor for 90 min at room temperature. Then, the temperature of the water bath was raised to 90°C and the reaction continued for 100 min. Finally, the reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature to obtain the SUL and SUOL adhesives.

2.2.4 Physicochemical Properties of the Synthesized Resin

Physicochemical properties (gelation time, viscosity and Specific Gravity (SPG)) of the prepared resins were measured according to related standard methods. The percent non-volatile content (solid content) of the adhesives was determined as per China National Standard GB/T 14074-2017 [24]. The specific gravity of resin solution was obtained by hydrometer and the viscosity was measured using hydrometer.

2.2.5 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FTIR)

The changes in the chemical structure of lignin after oxidation have been analyzed by Fourier Transform Infrared spectrometry (FTIR) (Shimadzu FTIR 8400S, Kyoto, Japan). FTIR spectra were obtained from KBr pellets with 1 wt% of the powdered resin at wave numbers in the 400 and 4000 cm−1 range. The obtained spectra were normalized by a constant peak.

2.2.6 Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

The changes in curing temperature of the adhesive containing oxidized lignin compared to the resin with unmodified lignin were determined by a NETZSCH DSC 200 F3Model thermal analyzer. To determine the curing temperature of the resins, about 5 mg of freeze-dried sample was added to the aluminum pan. The samples were then heated from ambient temperature (25°C) to 250°C under a nitrogen atmosphere. The DSC scans were recorded at a heating rate of 10°C/min under nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 60 mL/min.

2.2.7 Gel Permeation Chromatography

The molecular weight and dispersion of lignin samples before and after oxidation were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (LC-20A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Acetylation of lignin was done before molecular weight testing. The concentration of lignin in tetrahydrofuran (THF) was about 5 mg/mL. The column temperature was 40°C, THF was the eluent, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min. The average molecular weight of virgin and oxidized lignin was measured by an external standard method, in which monodisperse polystyrene was applied as the standard compound.

The manufacturing of the plywood was performed according to the method of Younesi-Kordkheili et al. (2017) [2]. Resins obtained above were used to prepare plywood panels. Standard single layer sheets of beech (Fagus orientalis) of dimensions 400 mm × 400 mm × 2 mm were dried to lower than 6 wt% moisture content, coated with 310 gm2 adhesive to prepare three-layer plywood, and then hot pressed. The hot press temperature was 180°C, the maximum pressure was 6 MPa, and the hot-pressing time was 7 min. The plywood samples were kept indoors for 24 h and then sawn to test the shear strength. Three samples of each adhesive and were selected randomly and tested for dry strength.

Shear specimens were prepared from each board to examine dry according to ASTM D 906-98 [25]. The samples were conditioned at a temperature of 23 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 60 ± 5% for two weeks. Five specimens were tested for each resin. Water absorption tests were performed according to ASTM D4442-07 [26]. Five specimens for each resin were taken from the panels and dried in an oven for 24 h at a temperature of 100 ± 3°C. The weight of the dried specimens (W0) was determined at an accuracy of 0.001 g. The specimens were then immersed in distilled water for 24 h at a temperature of 23 ± 2°C, and weight was again measured (W24). Weight of the specimens was measured after a 24 h immersion. The values of the water absorption (WA24) in percentage were calculated using Eq. (1).

where WA24 is the water absorption (%) at time 24 h, W0 is the oven dried weight and W24 is the weight of specimen at a given immersion time 24 h.

The value of the thickness swelling in percentage was calculated using Eq. (2).

where TS24 is the thickness swelling (%) at time 24 h, T0 is the initial thickness of specimens, and T24 is the thickness at time t.

2.2.10 Measure of Bending Strength and Modulus of Elasticity in Bending

Bending Modulus and Bending Strength were calculated with the formulas:

• Where F2 − F1 is the gradual increase of load on the straight-line portion of the load deflection curve and is measured in Newtons; N. F1 is approximately 10% of the maximum load while F2 is approximately 40%.

• Fmax is the maximum load measured in Newtons.

• b is the breadth of the specimen, measured in millimeters, mm.

• t is the thickness of the specimen, measured in mm.

• l is the distance between the centers of the support which is also measured in mm.

• a2 − a1 is the deflection of the specimen at mid span, corresponding to F2 − F1 and is also in mm.

The effects of the unmodified and oxidized lignin content on the plywood panels’ properties were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance (Two-way ANOVA) at 95% confidence level by SPSS software.

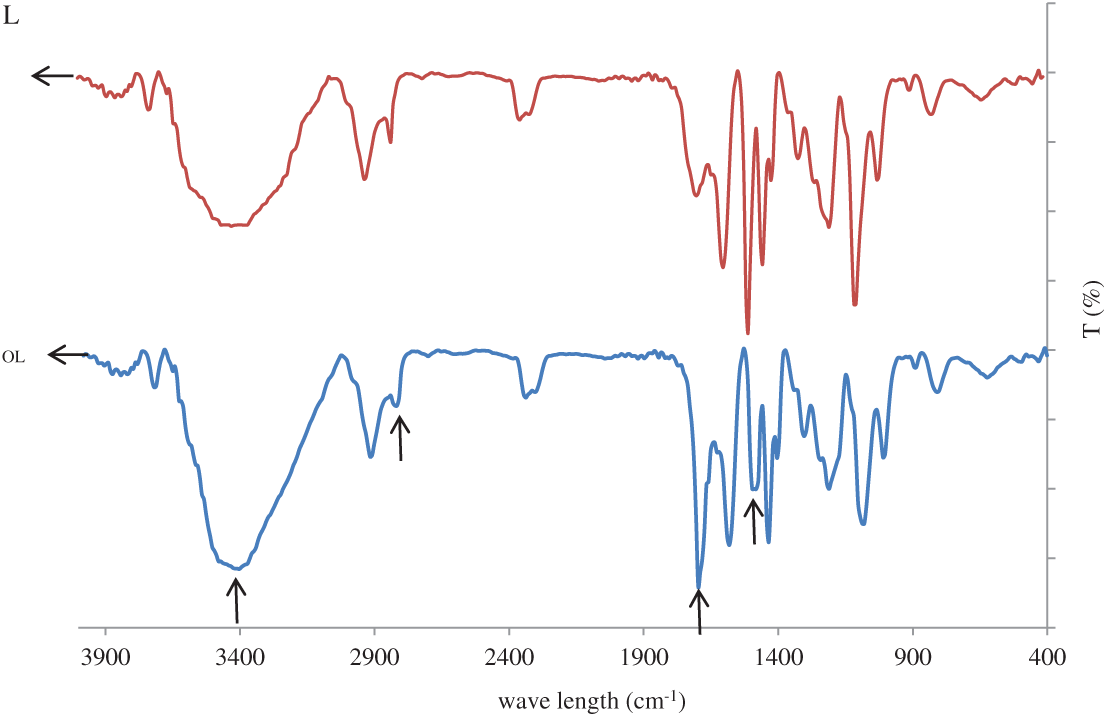

The infrared spectrum of the virgin lignin (L) and oxidized lignin (OL) are shown in Fig. 1. The FTIR assignments for lignin are reported in Table 1. Comparing the spectra of the two, oxidized lignin appears to clearly have a higher proportion of hydroxyl groups at the 3420–3440 cm−1 wave length peak. Moreover, the FTIR spectrum of oxidized lignin (OL) exhibits a sharper peak at 1685 cm−1 characteristic of the stretch of the carbonyl groups (–C=O) generated by oxidation.

Figure 1: Lignin (L) (red trace) and oxidized lignin (OL) (blue trace) FTIR spectra

Additionally, Fig. 1 also shows that the intensity of transmittance in the 955–1211 cm−1 band range in OL decreased compared to virgin lignin. This indicates that most probably molecular chain fragmentation and depolymerization of the lignin during its oxidation has occurred. The 2811 and 1470 cm−1 peaks appear to belong to the –O–CH3 moieties on the lignin units [27] which in OL are lower than in pure lignin (L). In fact, the greater proportion of hydroxyl groups in OL derives from the oxidation of the –OCH3 groups. It confirms that lignin’s oxidation occurred successfully. Ye et al. (2024) [28] have shown that the methoxy groups and the molecular weight of lignin were decreased by oxidation. They also showed that with oxidation a marked increase of the proportion of phenolic –OHs and carboxyls occurs [29].

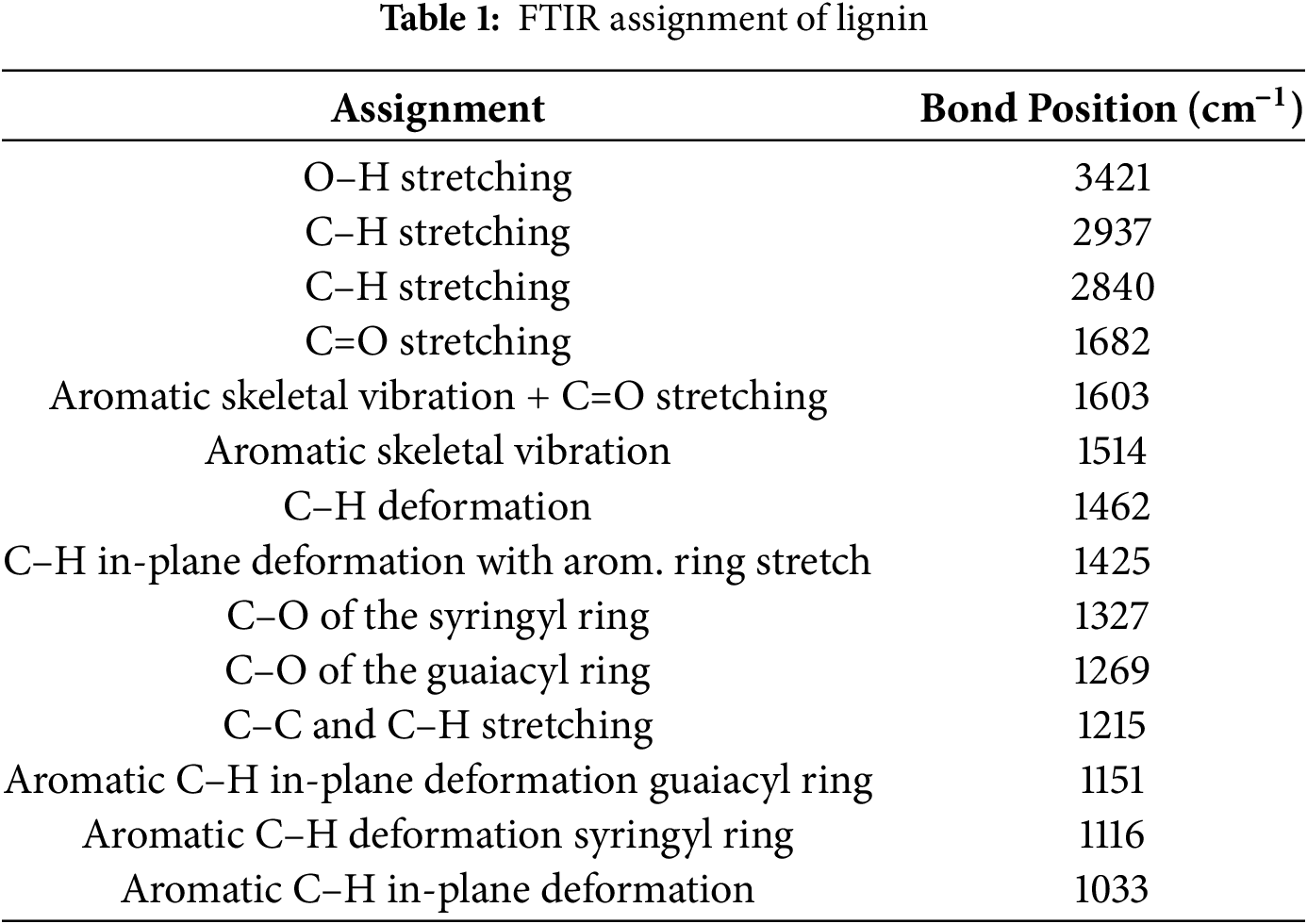

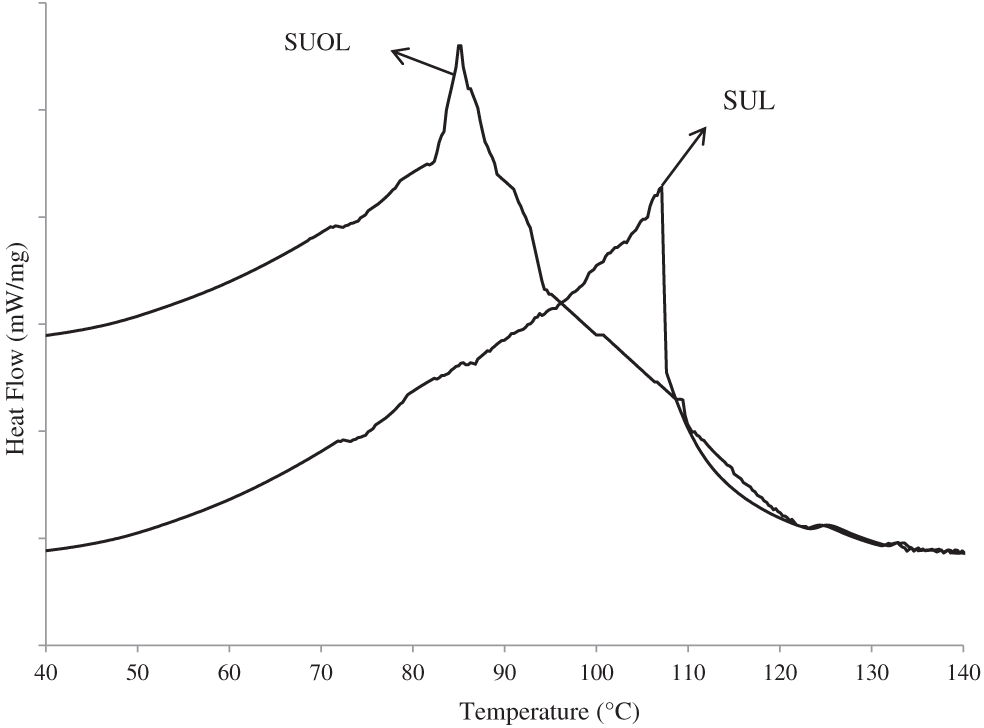

The heat flow changes for oxidized and non-modified lignins are shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 2 shows that the Tg of oxidized lignin is lower at 76°C than that at 92°C for the non-modified one.

Figure 2: DSC of lignin (L) (green trace) and oxidized lignin (OL) (blue trace)

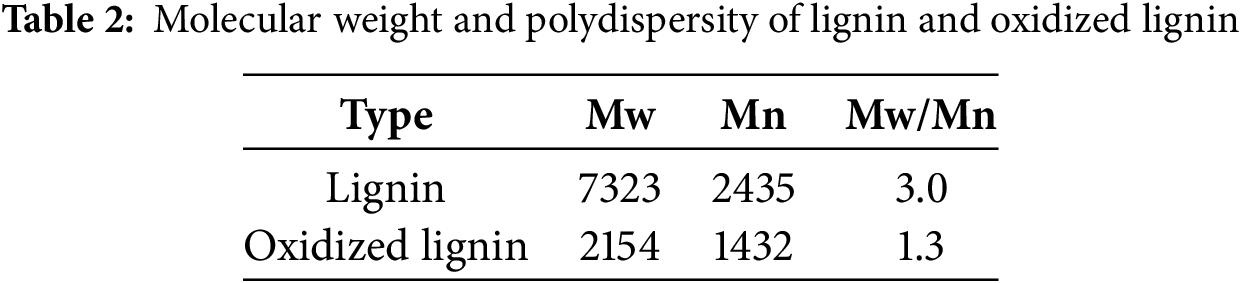

Molecular mass and extent of cross-linking have been shown previously to be the predominant parameters of having a marked effect on lignin’s Tg. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) was used to determine the oxidation influence by SPS on lignins as well as acetylated lignin molecular masses when treated and untreated. The values of weight-average molecular weights (Mw), number average molecular weights (Mn), and polydispersity index (Mw/Mn) of oxidized lignin and virgin lignin have been reported in Table 2.

Comparing the two lignins in Table 2 indicates that oxidation has caused a lowering of the Mw and Mn average molecular weights. The polydispersity coefficient of oxidized lignin (1.3) was lower than that of the control sample (3.0). It indicates that the homogeneity of lignin was improved after oxidation. Lower molecular weight and polydispersity values can significantly influence the improvement of the chemical re-activity of oxidized lignin. DSC analysis confirms the FTIR analysis results that, the reaction of SPS with lignin decreases its methoxy group content and cleaves part of the chemical bridges between lignin units.

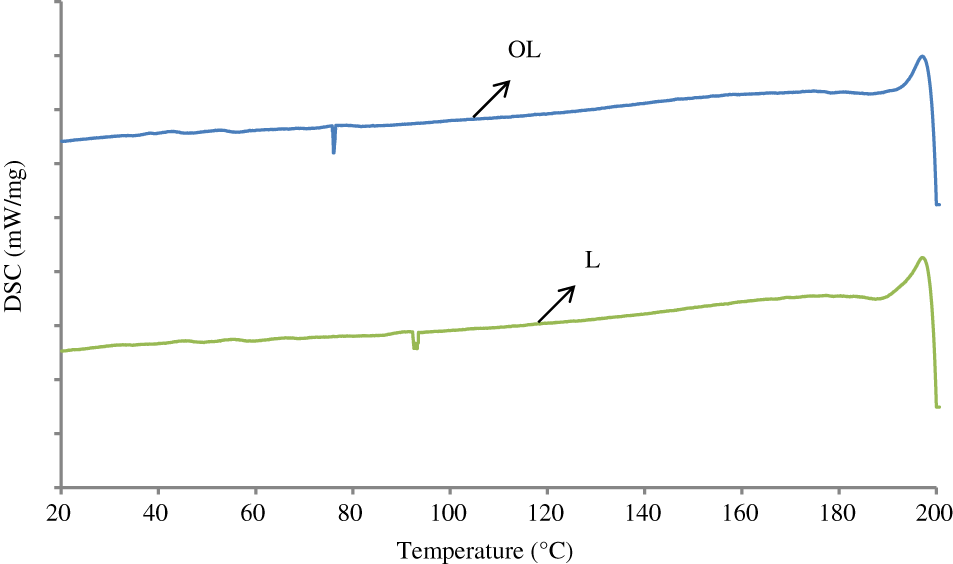

The DSC analysis of synthesized SUL resins containing 40% virgin and oxidized lignin has been shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: DSC analysis of the oxidized starch-urea-non-modified lignin resin (SUL) and of the oxidized starch-urea-oxidized lignin resin (SUOL)

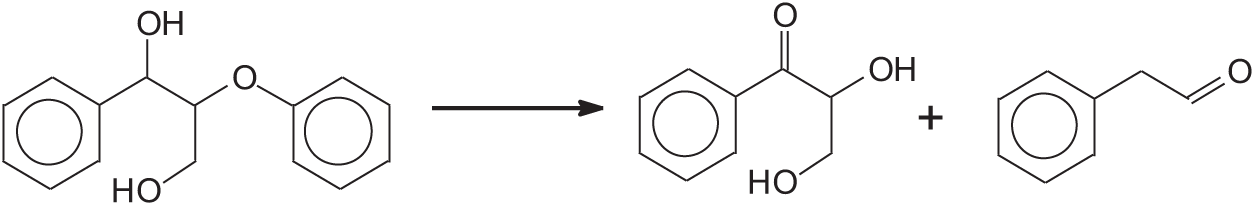

The SUL resin containing virgin lignin exhibits a distinct exothermic peak at about 107°C. However, the adhesive sample with oxidized lignin had its peak at 85°C. This infers that the pretreatment of lignin by SPS has a significant influence on the adhesive curing. The oxidation results in a higher susceptibility of lignin to depolymerisation, achieving higher reaction rates under milder conditions. The mild conditions employed can be an advantage for industrial application. The good performance of oxidized lignin can also be attributed to its higher proportion of phenolic hydroxyl groups on the chains of the lignin molecules. This higher proportion of hydroxyl groups was generated by β-O-4 bridges between lignin units being cleaved (Fig. 4) and the consequent decrease of the lignin molecular mass according to the study of Chen et al. using lignin model compounds [30].

Figure 4: Example of cleavage of β-O-4 linkages between lignin units by oxidation

Cleavage of the β-O-4 ether bridges was also found to occur with relative ease as a consequence of the oxidizing treatment and this even when the oxidation was mild [7]. This was also one cause of the increase in the proportions of –OH groups as well as of the presence of generated aldehyde groups [31]. Furthermore, it can be noted that, the oxidation of lignin by SPS can achieve a SUOL resin with good curing temperature, a point valuable from an economic perspective for industry.

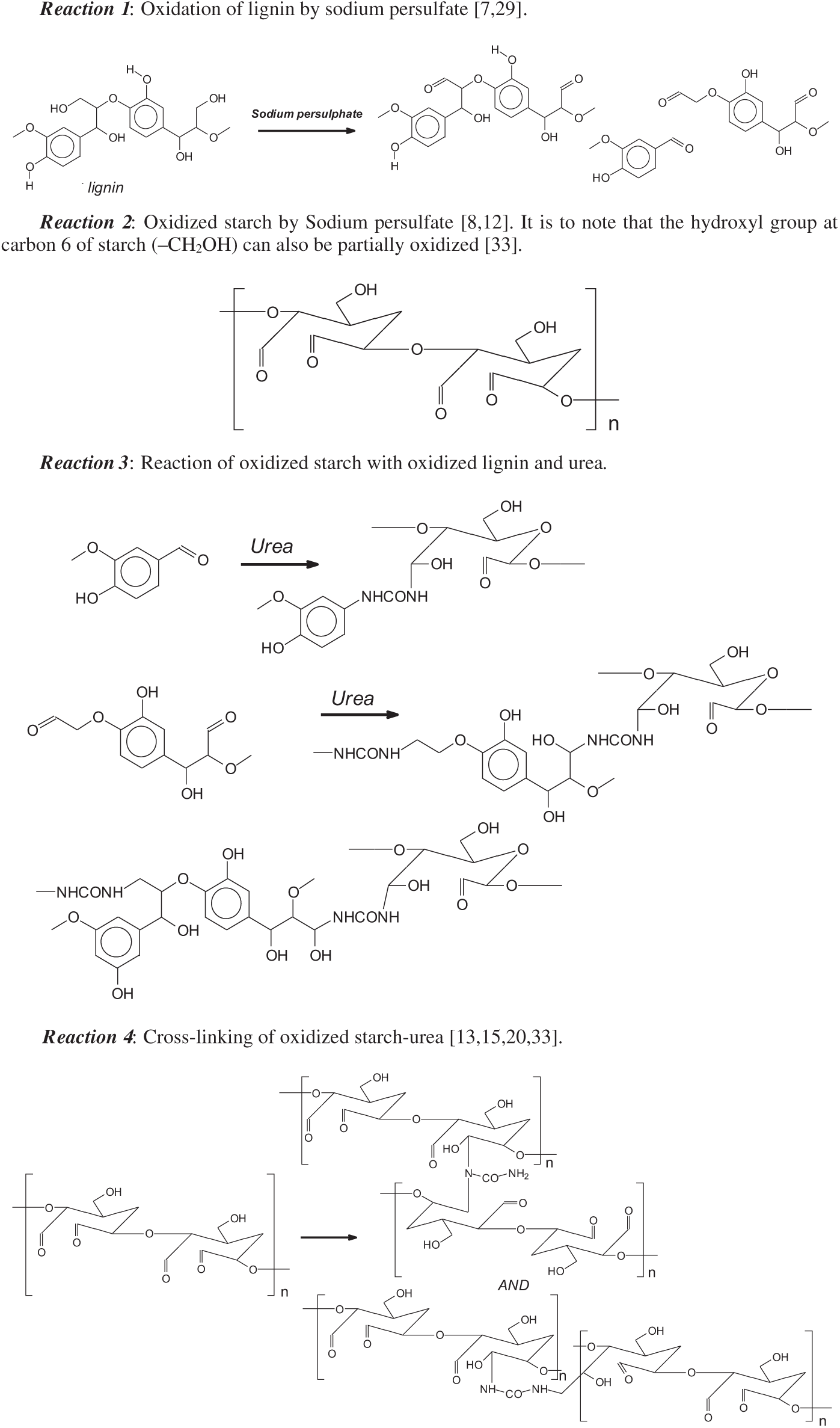

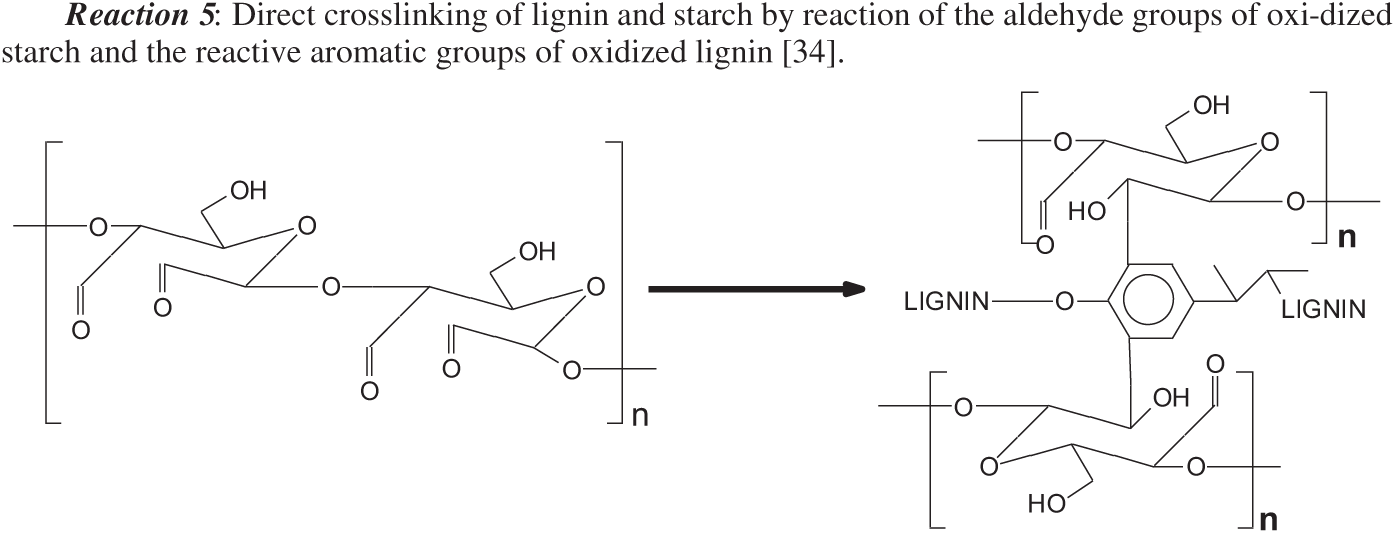

All the possible reactions in the SUOL resin preparation are shown in Fig. 5. The reaction of oxidized lignin with oxidized starch can occur to different extents with (i) the addition of urea working as a cross-linker by reaction with the aldehyde groups generated by oxidation on both the lignin and the starch, hence linking the two [13,32], (ii) the cross-linking of oxidized starch itself by reaction of urea with some of the aldehyde groups on oxidized starch chains [20], (iii) the direct cross-linking of oxidized starch just with oxidized lignin by reaction of the generated aldehyde groups on the starch with the reactive aromatic sites of lignin [32], (iv) by urea cross-linking just the oxidized lignin chains by reacting with the aldehyde groups generated by lignin oxidation, (v) by continuous increase of the oxidation by cross-linking of the oxidized starch chains without any other addition [12]. Finally, (vi) depending on the severity and extent of the oxidation of lignin that has occurred, the oxidation does even cleave the C–C bond of some of the aliphatic chains linking lignin units. Cleavage then occurs between the alpha and beta carbons of the aliphatic chains generating different fragments all carrying further aldehyde groups. These may also be able to participate in the cross-linking reaction involving the lignin as described above [7]. It must be noted that other reactions also occur, and have been determined, namely quinones being formed from the lignin’s aromatic –OHs [31] as well as the β-O-4 links connecting lignin units being cleaved at higher oxidation levels as already found (Fig. 4).

Figure 5: All the possible reactions in the oxidized starch-urea-oxidized lignin (SUOL) resin preparation [7,8,12,13,15,20,29,33,34]

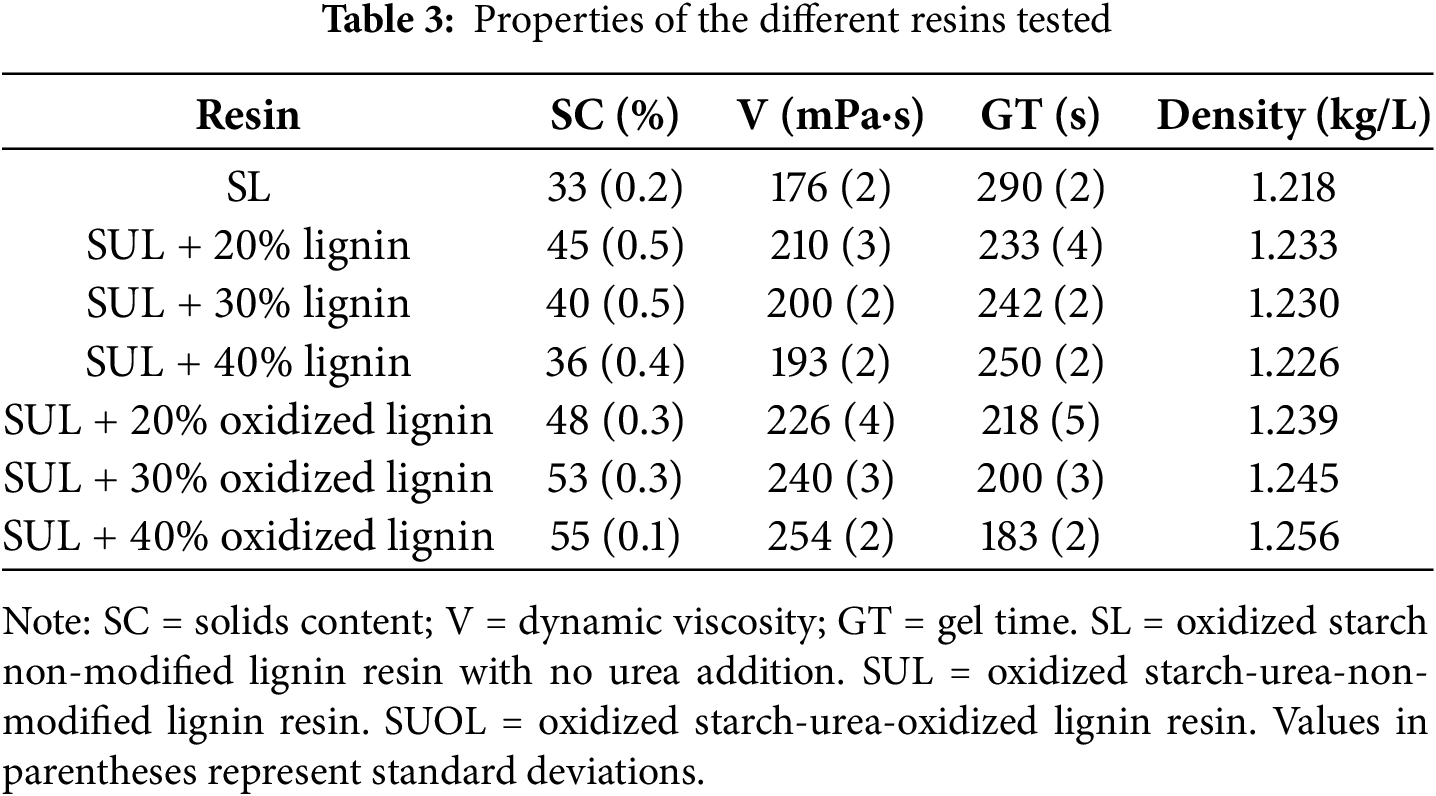

3.3 Physicochemical Properties

Table 3 shows the SUL and SUOL resins properties. It can be observed that after addition of 20% urea as cross-linker the solid content and the viscosity of the resins significantly increased and the gel time shortened, respectively. Physical effects like an increased percentage of resin solids as well as chemical effects appear to be responsible for the higher viscosity of the SUOL and SUL resin compared to the simple oxidized starch non-modified lignin resin with no urea added (SL). In other words, the high chemical reactivity of urea increases the proportion of crosslinks between lignin and starch thus influencing the viscosity and gel time of the resins pre-pared. The higher level of cross-linking in the wood adhesive by urea being added is on record by a number of research groups [35,36].

Table 3 also shows that the SUOL resins with oxidized lignin have higher solids content, viscosity and a shorter gel time compared to those with unmodified lignin (SUL and SL). Adding oxidized lignin to the SUL adhesives to form the SUOL one leads to their increased viscosity and their shorter gel times caused by the inherently higher reactivity of the oxidized rather than of the non-modified lignin. Oxidized lignin can form numerous chemical bonds with starch and urea, which hinders the mobility resulting in higher viscosity of the resin. The very active oxide groups on the surface of modified lignin can further increase the level of cross-linking. The increase in the addition of oxidized lignin from 20 to 40 wt% also continuously increased the solids content and viscosity as well as accelerating the gelation time of the SUOL resins. The SUOL resin containing 40% OL had the highest sol-ids content (55%), viscosity (254 mPa·s) and the shortest gel time (183 s) among all the resins prepared. Zhu et al. (2025) [37] indicated that addition of oxidized lignin to the resin can improve the physicochemical properties of synthetic resins. Conversely, Table 3 also shows that the progressively larger increases in the SUOL adhesive of added oxidized lignin progressively induce SUOL density increases. Among all the resins the lowest density at 1.218 kg/L is recorded by the SL resin control and at 1.256 kg/L the highest is presented by the resin at 40% oxidized lignin.

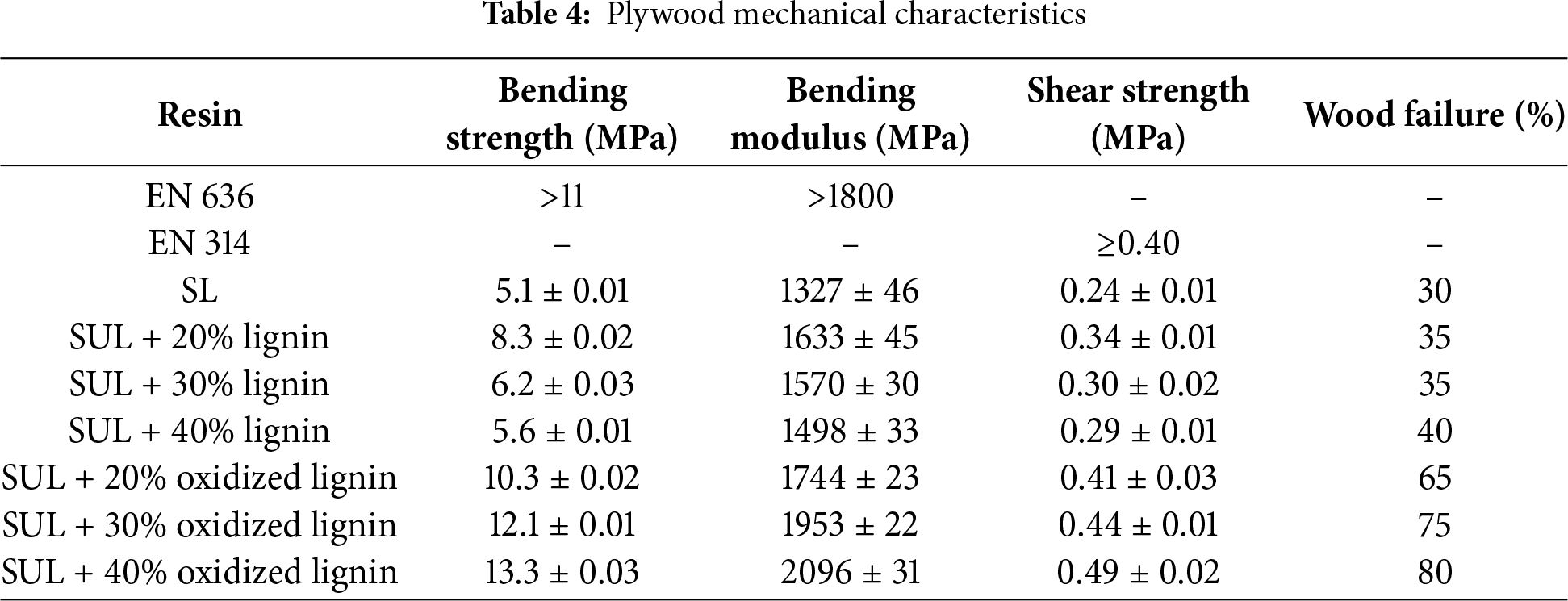

3.4 Mechanical Properties of the Plywood Prepared

Table 4 shows the mechanical properties (shear strength, bending modulus, and bending strength) of the plywood panels prepared in this research work. It can be seen that urea addition was a critical factor in the preparation of SUL adhesive as the addition of urea as a cross-linker significantly improves the mechanical strength of the plywood panels bonded with oxidized starch-oxidized lignin resin. The amino groups (–NH2) of urea can easily react with the functional groups of both oxidized lignin and oxidized starch to enhance the cohesive bond strength of the adhesive. So far several researchers used urea to improve the mechanical strength of the bio-wood adhesives [38]. Zhao et al. (2018) [13] synthesized urea-oxidized starch (UOSt) adhesive with high quality and zero formaldehyde-emission by polycondensation reaction of urea and oxidized starch. The majority of the oxidized starch-generated aldehydes reacted with urea, while hydrogen bonds formed between the –OH groups still present on starch with the unreacted C=O groups. With non-modified lignin increasing from 20% to 40% this does progressively induce a shear and bending strength decrease of the plywood panels prepared (Table 4). However, conversely, different results are obtained for plywood bonded using oxidized lignin. The highest shear strength at 0.49 MPa coupled with the highest wood failure percentage at 80% was presented by the resins with 40% oxidized lignin. Conversely, the lowest values of these two parameters, namely at 0.29 MPa and wood failure percentage (40%), were recorded for the plywood bonded with the resin containing 40% by weight of unmodified lignin. Chen et al. (2021) [7] have already shown that the plywood panels bonded with oxidized demethylated lignin give acceptable shear strength.

Conversely, Table 4 shows clearly that the plywood panels prepared from SUOL resins with oxidized lignin have better shear strength and higher wood failure percentages than when non-modified lignin is used. The panels with 20, 30 and 40 wt% SUOL containing oxidized lignin had 20%, 46% and 68% stronger shear strength than the SUL resin containing unmodified lignin, respectively. This can be attributed to the differences in physicochemical properties of the SUOL resins with oxidized lignin compared to those with unmodified lignin (Table 3). Moreover, the improvement in the chemical reactivity of the lignin using sodium persulfate (Na2S2O8) can increase the level of cross-linking between the lignin and starch resulting in improving the dry shear strength of the associated plywood panels.

The bending properties of the plywood panels prepared are also reported in Table 4. The panels containing SUOL resins with oxidized lignin had 7, 24 and 40 wt% higher bending modulus and 24, 95 and 130 wt% bending strength than the plywood panels with unmodified lignin, respectively. Oxidation modification improves the surface properties and reactivity of lignin by introducing oxygen-containing functional groups. Oxidized lignin can also increase the surface polarity and enhance its adsorption capacities. Improved bending characteristics of the plywood prepared with the SUOL resin with oxidized lignin are due to the higher level of reactivity of this type of lignin. The sodium persulfate as oxidizing agent is able to increase the amount of phenolic hydroxyl groups of lignin. Previous researchers confirmed that the amount of phenolic hydroxyl groups, as the highest reactive functional groups in the lignin structure, has markedly positive influence on the bending properties of the wood-based panels [39]. Generally, based on the results reported in Table 4, the measured mechanical properties of the wood-based panels containing SUL resin with oxidized lignin by sodium persulfate were higher than the values required by the relevant standards (EN 636 for bending strength and bending modulus, and EN 314 for shear strength) [40,41]. The lowest shear strength, bending modulus and bending strength were shown by the oxidized starch-non-modified lignin resin (SL) used as a control sample among all resins prepared.

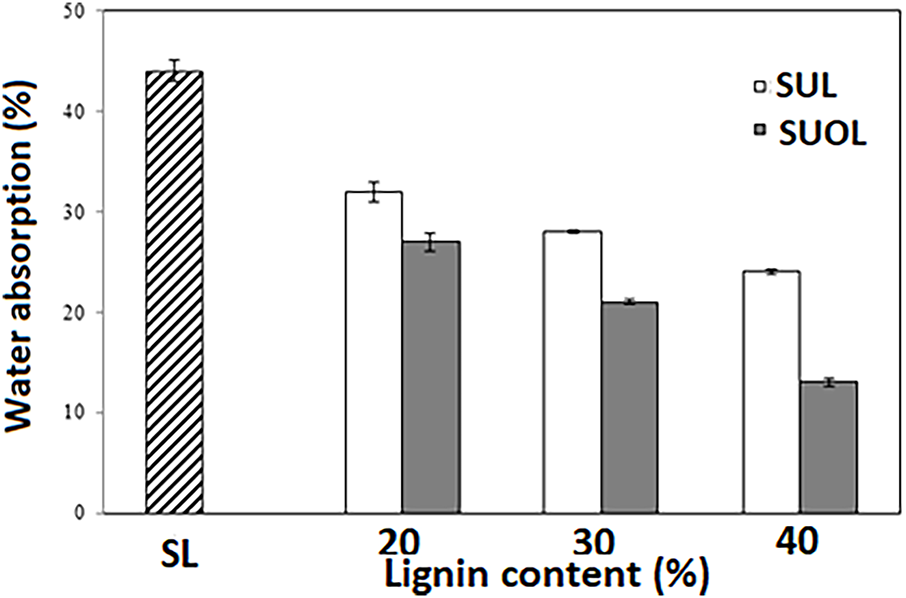

3.5 Physical Properties of the Plywood Prepared

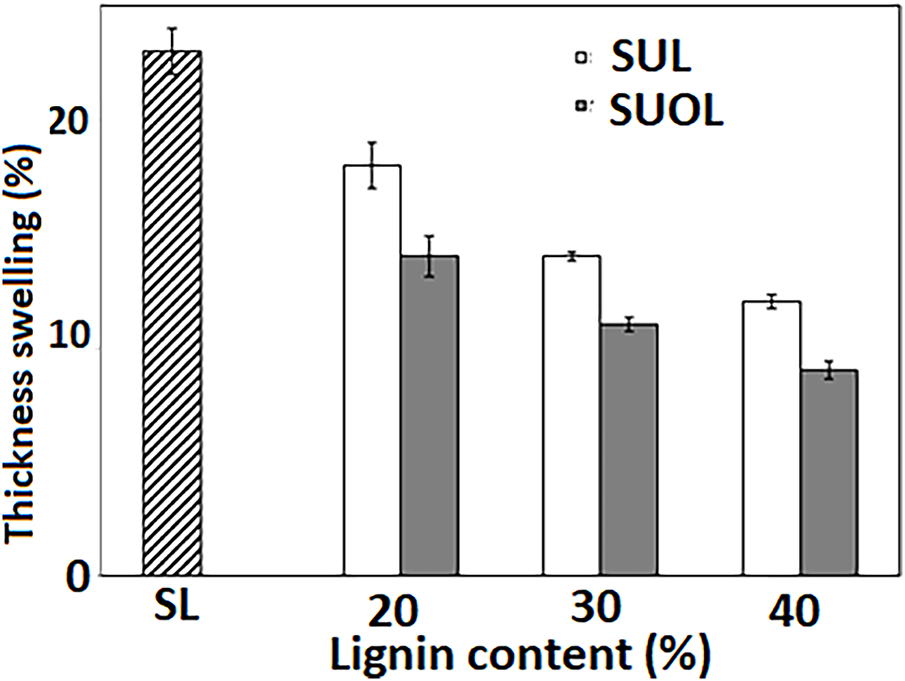

One of the main disadvantages of the wood-based panels bonded with bio-adhesives is their poor dimensional stability. Hence, to overcome this important defect many efforts have been made. Water absorption and thickness swelling of the manufactured plywood panels are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. These figures show that increasing the amount of unmodified/oxidized lignin from 20% to 40% in the SUL and SUOL resins decreases the thickness swelling and water absorption percentages of the panels. The sensitivity to water in the SUL and SUOL resin is mainly due to the presence of the starch and urea, and the plywood panels swelling decreases in the SUOL resins, thus on the addition of oxidized lignin as the residual –OHs of the starch can be consumed. The hydrophobic nature of the lignin is the other parameter which can influence this reduction. Thus, Figs. 6 and 7 also show that the addition of urea to the oxidized lignin/oxidized starch mixture induces in plywood a marked decrease in thickness swelling and its concomitant water absorption. The number of cross-linking reactions is multiple involving (i) oxidized starch generated aldehydes reacting with amide moieties of urea, and (ii) oxidized starch carboxyl groups from its C6 site hydrogen-bonding the starch residual –OHs [21]. All this occurs as the carbonyl and aldehyde groups generated in oxidized lignin, the urea amide moieties and the oxidized starch generated aldehydes can react together, cross-link and form a hardened network practically water insoluble. Moreover, by increasing the amount of crosslinking between lignin and starch by addition of urea appears to positively affect the level of water absorption.

Figure 6: Water absorption of the plywood panels prepared

Figure 7: Thickness swelling of the plywood panels prepared

Water absorption analysis also shows that a 40 wt% modification with oxidized lignin of the resin prepared does yield plywood of low thickness swelling at 9% and low water absorption at 13%. Conversely, the 20% non-modified lignin adhesive showed at 18% the worst thickness swelling and the worst water absorption at 32%. This can be ascribed to an increased proportion of phenolic hydroxyl groups on lignin induced by the Na2S2O8 pretreatment. Furthermore, by adding the oxidized lignin to the SUOL adhesives induces a decrease in the starch bridges more prone to be hydrolysis sensitive. It has already been shown that adding oxidized lignin significantly improves the dimensional stability of the panels bonded with synthetic resins.

Finally, it is to note that several issues have been resolved by this adhesive system: no formaldehyde emission as none of it was added, the poor water resistance of starch-based adhesives, and poor mechanical strength of lignin-based adhesives can be solved by synthesizing SUL resins. In fact, this new synthesized resin opens a new window for development of bio-adhesives.

In the research work presented here, the characteristics of the plywood panels bonded with oxidized starch/urea/oxidized lignin(SUOL) as a new bio-adhesive have been investigated. The following conclusions could be drawn from the experimental results obtained:

• The SUOL resins containing oxidized lignin have higher solids content and viscosity as well as shorter gelation times than with non-modified lignin (SUL).

• Weight average and number average molecular masses (Mw and Mn) and polydispersity coefficient of lignin have been decreased by the oxidation pretreatment.

• The lignin chain is fragmented and partially depolymerized by oxidation, as shown by the FTIR analysis.

• DSC analysis indicated that the Tg of lignin was decreased by oxidation. Moreover, the SUOL resin with oxidized lignin presented a curing temperature lower than the SUL one with non-modified lignin.

• SUOL-bonded plywood acquired improved mechanical strength and dimensional stability when lignin oxidized with sodium persulfate was used in the formulation.

• Greater mechanical strength and higher dimensional stability could be achieved by increasing the amount of oxidized lignin in SUOL adhesive from 20 to 40 wt%.

• The functional groups of lignin, even those generated by its oxidation, the oxidized starch-generated aldehydes and the urea amide moieties all reacted together to yield a SUOL wood adhesive with excellent performance and water resistance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research has been funded by Semnan University, research grant No. 226/1403/T140211.

Author Contributions: Hamed Younesi-Kordkheili, Antonio Pizzi: concepcion, validation; Hamed Younesi-Kordkheili: experiments, data interpretation, first draft; Antonio Pizzi: reactions interpretation, data interpretations, editing, final version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All contained in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zeng H, Bi W, Yang Y, Liu L, Guo H, Xie L, et al. Biomass-based adhesives prepared with cellulose and branched polyamines. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2024;686(1):133414. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.133414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Younesi-Kordkheili H, Kazemi Najafi S, Behrooz R. Influence of nanoclay on urea-glyoxalated lignin-formaldehyde resins for wood adhesive. J Adhes. 2017;93(6):431–43. doi:10.1080/00218464.2015.1079521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Balk M, Sofia P, Neffe AT, Tirelli N. Lignin, the lignification process, and advanced, lignin-based materials. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11668. doi:10.3390/ijms241411668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Younesi-Kordkheili H. Reduction of formaldehyde emission from urea-formaldehyde resin by maleated nanolignin. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2024;132:103677. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2024.103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gonçalves AR, Benar P. Hydroxymethylation and oxidation of organosolv lignins and utilization of the products. Bioresour Technol. 2001;79(2):103–11. doi:10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00056-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hu L, Pan H, Zhou Y, Zhang M. Methods to improve lignin’s reactivity as a phenol substitute and as replacement for other phenolic compounds: a brief review. BioResources. 2011;6(3):3515–25. doi:10.15376/biores.6.3.3515-3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen X, Xi X, Pizzi A, Fredon E, Du G, Gerardin C, et al. Oxidized demethylated lignin as a bio-based adhesive for wood bonding. J Adhes. 2021;97(9):873–90. doi:10.1080/00218464.2019.1710830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Song J, Chen S, Zhang Q, Lei H, Xi X, Du G, et al. Developing on the well performance and eco-friendly sucrose-based wood adhesive. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;194:116298. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yong H, Liu J. Recent advances on the preparation conditions, structural characteristics, physicochemical properties, functional properties and potential applications of dialdehyde starch: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;259(1):129261. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yu J, Chang PR, Ma X. The preparation and properties of dialdehyde starch and thermoplastic dialdehyde starch. Carbohydr Polym. 2010;79(2):296–300. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Frihart CR, Pizzi A, Xi X, Lorenz LF. Reactions of soy flour and soy protein by non-volatile aldehydes generation by specific oxidation. Polymers. 2019;11(9):1478. doi:10.3390/polym11091478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Codou A, Guigo N, Heux L, Sbirrazzuoli N. Partial periodate oxidation and thermal cross-linking for the processing of thermoset all-cellulose composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2015;117:54–61. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.05.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao XF, Peng LQ, Wang HL, Wang YB, Zhang H. Environment-friendly urea-oxidized starch adhesive with zero formaldehyde-emission. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;181:1112–8. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.11.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xi X, Pizzi A, Frihart CR, Lorenz L, Gerardin C. Tannin plywood bioadhesives with non-volatile aldehydes generation by specific oxidation of mono- and disaccharides. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2020;98:102499. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2019.102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Oktay S, Kızılcan N, Bengü B. Development of bio-based cornstarch-Mimosa tannin-sugar adhesive for interior particleboard production. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;170:113689. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Diaz-Baca JA, Fatehi P. Production and characterization of starch-lignin based materials: a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2024;70:108281. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bobbitt JM. Periodate oxidation of carbohydrates. In: Advances in carbohydrate chemistry. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1956. p. 1–41. doi:10.1016/s0096-5332(08)60115-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hoda S, Kakehi K, Takiura K. Periodate oxidation analysis of carbohydrates part IV. Simultaneous determination of aldehydes in di-aldehyde fragments as 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazones by thin-layer or liquid chromatography. Anal Chim Acta. 1975;77:125–31. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(01)95163-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Dimri S, Aditi, Bist Y, Singh S. Oxidation of starch. In: Starch: advances in modifications, technologies and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 55–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-35843-2_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fiedorowicz M, Para A. Structural and molecular properties of dialdehyde starch. Carbohydr Polym. 2006;63(3):360–6. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.08.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhao X, Guo X, Wang Y, Su Q, Wang H, Li Z, et al. Composite modified starch-based adhesive with high adhesion and zero aldehyde. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;206:117566. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen X, Pizzi A, Zhang B, Zhou X, Fredon E, Gerardin C, et al. Particleboard bio-adhesive by glyoxalated lignin and oxidized dialdehyde starch crosslinked by urea. Wood Sci Technol. 2022;56(1):63–85. doi:10.1007/s00226-021-01344-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu C, Lin H, Zhang S, Essawy H, Wang H, Wu L, et al. Characterization of water-resistant adhesive prepared by cross-linking reaction of oxidized starch with lignin. Polymers. 2025;17(11):1545. doi:10.3390/polym17111545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. GB/T 14074-2017. Testing methods for wood adhesives and their resins. Beijing, China: AQSIQ and SAC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

25. ASTM D906-98(2017). Standard test method for strength properties of adhesives in plywood type construction in shear by tension loading. West Conshohoken, PA, USA: American Society of Testing Materials; 2017. [Google Scholar]

26. ASTM D4442-07. Standard test methods for direct moisture measurement of wood and wood base materials. West Conshohoken, PA, USA: American Society of Testing Materials; 2007. [Google Scholar]

27. Li J, Zhang J, Zhang S, Gao Q, Li J, Zhang W. Fast curing bio-based phenolic resins via lignin demethylated under mild reaction condition. Polymers. 2017;9(9):428. doi:10.3390/polym9090428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Lin Y, Qin LQ, Liang CM, Xian XQ. Effect of ultrasound assisted Fenton oxidation modified lignin on HDPE based composites. Plast Sci Technol. 2024;52(5):13–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.15925/j.cnki.issn1005-3360.2024.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lei H, Zhou X, Xi X, Du G, Pizzi A. Recent developments in bioadhesives and binders. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(2):199–249. doi:10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen J, Yang H, Fu H, He H, Zeng Q, Li X. Electrochemical oxidation mechanisms for selective products due to C-O and C-C cleavages of β-O-4 linkages in lignin model compounds. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2020;22(20):11508–18. doi:10.1039/d0cp01091j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shi M, Wang S, Xi Y, Yang W, Lin X, Qiu X, et al. Preparation of chemically modified lignin and its application in advanced functional materials. Resour Chem Mater. 2025;4(3):100104. doi:10.1016/j.recm.2025.100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang Y, Wu H, Zhang J, Wen T, Du G, Charrier B, et al. Soybean protein wood adhesive with enhanced water resistance and low environmental impact through lignin-protein hybridization. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;234:121571. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.121571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Oktay S, Kızılcan N, Bengu B. Oxidized cornstarch–urea wood adhesive for interior particleboard production. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2021;110:102947. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2021.102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Younesi-Kordkheili H, Pizzi A. The synthesis of bio-based wood adhesive by oxidized starch and deep eutectic solvent-modified lignin. Intern J Adhes Adhes. 2025. [Google Scholar]

35. Tene Tayo L, Cárdenas-Oscanoa AJ, Beulshausen A, Chen L, Euring M. Optimizing a canola-gelatine-urea bio-adhesive: effects of crosslinker and incubation time on the bonding performance. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2024;82(5):1449–64. doi:10.1007/s00107-024-02098-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xu Y, Zhang Q, Lei H, Zhou X, Zhao D, Du G, et al. A formaldehyde-free amino resin alternative to urea-formaldehyde adhesives: a bio-based oxidized glucose–urea resin. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;218:119037. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhu Z, Yang P, Huang W, Zhou X. Photocatalytic oxidation of technical lignin to potent modifiers for improving the performance of urea-formaldehyde resin. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2025;7(11):7575–88. doi:10.1021/acsapm.5c01279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Jiang K, Lei Z, Yi M, Lv W, Jing M, Feng Q, et al. Improved performance of soy protein adhesive with melamine-urea-formaldehyde prepolymer. RSC Adv. 2021;11(44):27126–34. doi:10.1039/d1ra00850a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Younesi-Kordkheili H, Pizzi A, Chenaghchi F. Modified lignin by deep eutectic solvent as a novel coupling agent for wood-plastic composites. J Mol Liq. 2024;413:125959. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. EN 636:2012. Plywood-specifications. Bruxelles, Belgium: European Standard Committee; 2012. [Google Scholar]

41. EN 314-2:1993. Plywood-bond quality-requirements. Bruxelles, Belgium: European Standardization Committee; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools