Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

RNA Expression Signatures in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review of Tumour Biology and Therapeutic Targets

1 European School of Molecular Medicine, University of Milan, Milan, 20139, Italy

2 Department of Neurosciences, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah, 21499, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Neurosurgery, King Fahad Hospital, Jeddah, 21196, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

6 Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, 21955, Saudi Arabia

7 Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, 71491, Saudi Arabia

8 Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, 71491, Saudi Arabia

9 Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, 71491, Saudi Arabia

10 Department of Neuroscience, Doctor Suliman Fakeeh Hospital, Jeddah, 21461, Saudi Arabia

11 Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Rabigh, 21911, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Maher Kurdi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Identification of Novel Therapeutic Targets and Elucidation of Molecular Mechanisms of Tumorigenesis)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(11), 3293-3325. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.070031

Received 06 July 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Glioblastoma (GBM) remains the most aggressive primary brain tumour in adults, marked by pronounced cellular heterogeneity, diffuse infiltration, and resistance to conventional treatment. In recent years, transcriptomic profiling has provided valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms that govern the progression of glioblastoma. This systematic review aims to synthesise the current literature on dysregulated gene expression in GBM, focusing on gene signatures associated with stemness, immune modulation, extracellular matrix remodelling, metabolic adaptation, and therapeutic resistance. Methods: We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA), and the GlioVis portal for studies published between January 2005 and April 2025, limited to English-language reports. Studies were eligible if they included adult glioblastoma tissue or patient-derived datasets and reported gene-level expression or clinical associations. Reviews, commentaries, and studies on non-GBM gliomas were excluded. Screening followed the PRISMA 2020 checklist, with 410 records initially identified, 90 duplicates removed, and 125 studies retained after full-text review. Data were synthesised descriptively, and findings were validated against TCGA/CGGA expression datasets to ensure consistency across cohorts. Results: We categorised recurrently dysregulated genes by their biological function, including transcription factors (SOX2, ZEB2), growth factor receptors (EGFR, PDGFRA), immune-related markers (PD-L1, TAP1, B2M), extracellular matrix regulators (MMP2, LAMC1, HAS2), and metabolic genes (SLC7A11, PRMT5, NRF2). For each group, we examine the functional consequences of transcriptional alterations and their role in driving key glioblastoma phenotypes, including angiogenesis, immunosuppression, invasiveness, and recurrence. Conclusion: We further discuss the prognostic implications of these gene signatures and evaluate their potential utility in precision medicine, including current clinical trials that target molecular pathways identified through transcriptomic data. This review highlights the power of gene expression profiling to stratify glioblastoma subtypes and improve personalised therapeutic strategies.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileHigh-grade astrocytomas are the most prevalent primary malignant brain tumours, accounting for nearly half of all central nervous system (CNS) gliomas. The classification of these tumours has evolved substantially, particularly following the release of the 2016 World Health Organisation (WHO) 4th edition classification, which introduced the integration of histopathological and molecular features. Before 2016, diagnoses were primarily histological and reliant on immunohistochemistry [1]. The incorporation of molecular diagnostics, such as Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH) and Alpha Thalassemia Mental Retardation X (ATRX), has enabled the stratification of diffuse malignant astrocytomas into biologically distinct subgroups [2]. In the 2021 WHO classification (5th edition), the concept of IDH-mutant grade 4 astrocytoma was formally distinguished from its IDH-wildtype counterpart [2]. This distinction emphasises that although both subtypes may share treatment approaches and some molecular similarities, they are biologically and clinically distinct. According to the Consortium to Inform Molecular and Practical Approaches to CNS Tumour Taxonomy Not Official WHO (cIMPACT-NOW) consortium, a definitive diagnosis of WHO grade 4 astrocytoma requires IDH mutation, ATRX loss, Tumour Protein-p53 (TP53) mutation, and absence of 1p/19q code deletion [3]. Conversely, glioblastomas are defined by a wild-type IDH status, alongside hallmark alterations such as Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) amplification, Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations, and chromosomal abnormalities, including the gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 [4].

Despite these refinements, the genetic landscape of both tumour types remains complex and incompletely characterised. Key mutations affect signalling pathways related to cell growth and survival, particularly the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK)/Rat Sarcoma (RS)/Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K) pathway, TP53, and Retinoblastoma (RB). RTK genes commonly show amplification, splice variants, or fusions. Examples include EGFR, Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor Alpha (PDGFRA), Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition (MET) factor, and Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 (FGFR3) [5,6]. Other frequent mutations have also been reported [7]. Although many of these mutations are intrinsic to tumour DNA or RNA, their detection in routine practice is limited due to a lack of standardised platforms. As a result, next-generation sequencing (NGS) of both DNA and RNA has become critical for identifying such alterations [8,9]. Beyond tumour-intrinsic factors, there is an increasing focus on the tumour microenvironment, including blood vessels, tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs), and tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [10,11]. In IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, molecular subgroups have been identified through comprehensive genomic and epigenomic profiling, revealing distinct DNA methylation signatures and expression profiles [11,12].

Despite multimodal treatment, including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the prognosis for patients with WHO grade 4 astrocytomas or glioblastomas remains poor, regardless of IDH mutation status. Studies suggest that integrating genomic and epigenomic data could enhance the development of clinically relevant molecular classifiers [12–14]. Epigenetic regulation plays a pivotal role in tumour biology, while global hypomethylation activates oncogenes and contributes to genomic instability [15]. Transcriptomic profiling, including analyses of RNA and messenger RNA (mRNA) expression, has advanced the understanding of glioblastoma and high-grade astrocytomas [16]. These tumours display extensive transcriptional heterogeneity, which drives their aggressive nature and treatment resistance [15]. Techniques such as RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have enabled detailed mapping of gene expression. Integrated transcriptomic studies have revealed shared transcriptional programs between IDH-wildtype glioblastomas and IDH-mutant grade 4 astrocytomas, mediated by transcription factors such as the neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) family, which play roles in tumour development and maintenance [17].

Furthermore, unique gene expression patterns between tumour subtypes suggest novel therapeutic targets. These transcriptomic advances hold significant promise for precision oncology, allowing patient stratification based on expression signatures and predicted outcomes. Ongoing research in this area is crucial for translating molecular findings into clinical strategies that enhance prognosis and therapeutic efficacy in high-grade gliomas. Despite numerous advances, there remains a lack of consolidated insight into which genes are consistently dysregulated in glioblastoma (GBM) across studies. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of transcriptomic studies to identify and functionally classify key genes associated with GBM. This review adheres to PRISMA guidelines and incorporates clinical relevance, prognosis, and therapeutic potential.

2.1 Data Sources and Search Strategy

This study was designed as a systematic review and gene classification project aimed at identifying, annotating, and functionally categorising genes consistently dysregulated in glioblastoma (GBM). The primary objective was to integrate transcriptomic datasets and peer-reviewed literature to construct a curated panel of GBM-associated genes, organised by biological function, prognostic significance, and therapeutic relevance. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed with search terms including “glioblastoma,” “gene expression,” “prognostic marker,” “immune modulation,” “stemness,” “epigenetic regulation,” and “metabolism,” combined using Boolean operators.

In parallel, transcriptomic data were retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga) (accessed on 26 August 2025), Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) (https://www.cgga.org.cn) (accessed on 26 August 2025), and the GlioVis data portal (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es) in April 2025. Specifically, TCGA GBM RNA-seq datasets (Illumina HiSeq) and CGGA GBM microarray datasets (Agilent and Affymetrix platforms) were obtained as pre-processed, normalised gene-level expression matrices aligned to the GRCh38/hg38 human reference genome. TCGA RNA-seq data in GlioVis are normalised using RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximisation (RSEM) with upper quartile normalisation. In contrast, CGGA microarray datasets are normalised using the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) method. Searches were limited to English-language studies published between January 2005 and April 2025 reporting data from human GBM tissues or patient-derived datasets.

2.2 Study Selection and Eligibility

Studies were considered eligible if they investigated adult glioblastoma (GBM) and reported gene-level expression data or clinical outcome associations. Only primary research articles involving human tumour samples were included. Exclusion criteria were: (i) studies on non-GBM gliomas, (ii) articles lacking specific gene expression data, and (iii) secondary literature such as reviews or commentaries.

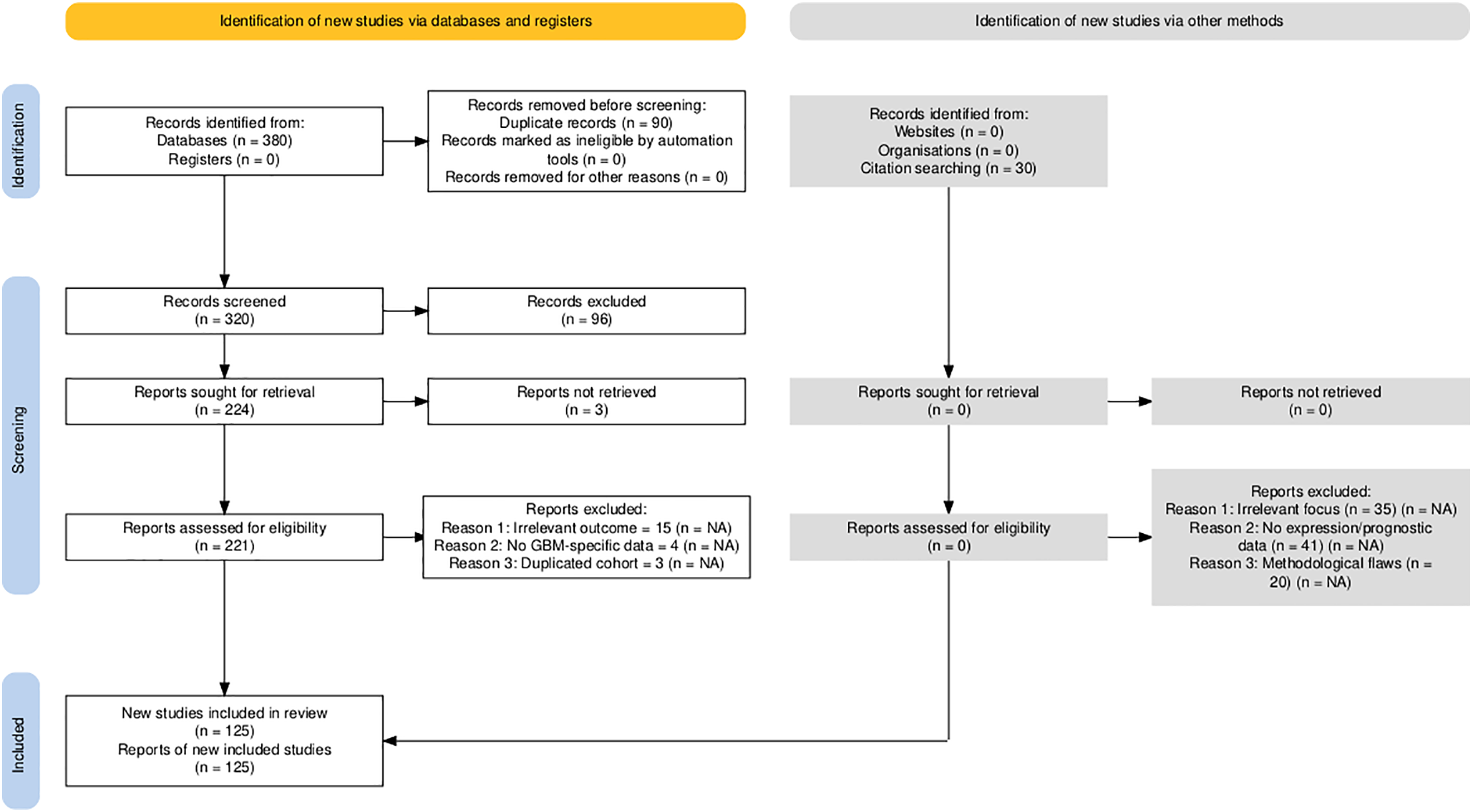

The selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, with details documented in the PRISMA checklist (Supplementary Material). Of the 410 records initially identified, 90 were duplicates, 121 were excluded during title and abstract screening, and 125 studies were retained after full-text review.

From these, 112 genes were shortlisted based on their presence in at least two independent studies and confirmation in public datasets (TCGA, CGGA, or GlioVis). Each gene was assigned to a single primary functional category: stemness, proliferation/survival, extracellular matrix (ECM)/invasion, immune modulation, metabolic regulation, or epigenetic control to maintain interpretability and clarity in visualisations. In cases where a gene had multiple biological roles, the primary category was determined by the function most consistently supported across at least two independent studies and most relevant to GBM pathogenesis. Functional assignments were derived from Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, PubMed-indexed literature, Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset descriptors, and TCGA/CGGA clinical correlation.

2.3 Data Extraction, Curation, and Scoring

For each gene, we extracted key information including its name, functional category, expression status (upregulated, downregulated, mutated), prognostic relevance, and translational targetability.

Expression status determination: Genes were classified as upregulated or downregulated by cross-referencing results from at least two independent transcriptomic studies and validating trends against TCGA and CGGA datasets. When dataset-specific statistics were available, differential expression thresholds were defined as |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

Mutation annotation: Mutational status was not considered an expression category in isolation. Instead, for each reported mutation, we documented whether the mutant form was upregulated, downregulated, or unchanged at the mRNA level. Where available, the biological effect of the mutation was noted, for example, gain-of-function EGFRvIII variants or loss-of-function TP53 alterations, and these details were presented in the supplementary annotation tables.

Aggression score: o capture tumour-driving potential, an aggression score was calculated as a composite of three weighted components: (i) transcriptomic overexpression in GBM vs. normal brain (+1 if log2FC ≥ 1, FDR < 0.05), (ii) prognostic association (+1 if high expression correlated with shorter survival, −1 if with more prolonged survival), and (iii) functional impact (+1 if consistently implicated in ≥2 independent studies as a driver of proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, or immune evasion). Scores ranged from −1 to +3, with higher values reflecting more aggressive tumour-associated behaviour.

Targetability score: Translational feasibility was assessed using three criteria: (i) availability of pharmacological inhibitors or biologics (+1), (ii) inclusion in active or completed cancer clinical trials (+1), and (iii) evidence of blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration (+1). Scores ranged from 0 to 3, with higher values indicating stronger therapeutic readiness.

All extracted data were organised into a structured reference matrix to facilitate cross-comparison and visualisation. In cases of conflicting findings, priority was given to results supported by clinical validation or consistent trends across datasets. Visualisations were generated using Python (Matplotlib v3.9.0). The corresponding scripts covering data preprocessing, formatting, and plotting are available from the corresponding author upon request. Figures included functional category distributions, multifunctionality heatmaps, molecular subtype alignments, aggression score rankings, interaction networks, and targetability matrices (Tables A1–A7).

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis was performed using the STRING database (v12.0) (https://string-db.org) (accessed on 26 August 2025), restricted to validate experimentally and high-confidence predicted interactions with a minimum confidence score of 0.7. Disconnected nodes were removed for clarity. The resulting PPI data were imported into Cytoscape (v3.9.1) for visualisation. Hub genes were identified using degree centrality and betweenness centrality metrics, allowing prioritisation of central regulators such as STAT3 and PD-L1.

Beyond the core 112 genes, additional genes of emerging interest (e.g., OXCT1-AS1, SRC-1, TRIM8, C7orf31, ELAVL2, Ephrin-B2) were included if reported in ≥2 independent human studies or validated in functional models between 2023 and 2025. Aggression scores were computed as a composite of expression Z-score (TCGA/CGGA), prognostic association (poorer +1, better −1, context-dependent 0), and functional impact (+1 if involved in core GBM pathways such as invasion or immune modulation). Genes with a score ≥two were classified as highly aggressive; ≤−1 as protective.

Where possible, transcriptomic data were cross-checked against proteomic or immunohistochemical (IHC) validation in TCGA, GlioVis, or published studies to enhance biological confidence.

Due to substantial heterogeneity in study designs, patient cohorts, transcriptomic platforms, and outcome measures among the included studies, a formal meta-analysis with pooled hazard ratios or forest plots was deemed inappropriate to avoid introducing bias. Instead, we performed a descriptive synthesis complemented by quantitative summaries, including frequency distributions of upregulated vs. downregulated genes and the proportion of genes associated with favourable or poor prognosis across datasets.

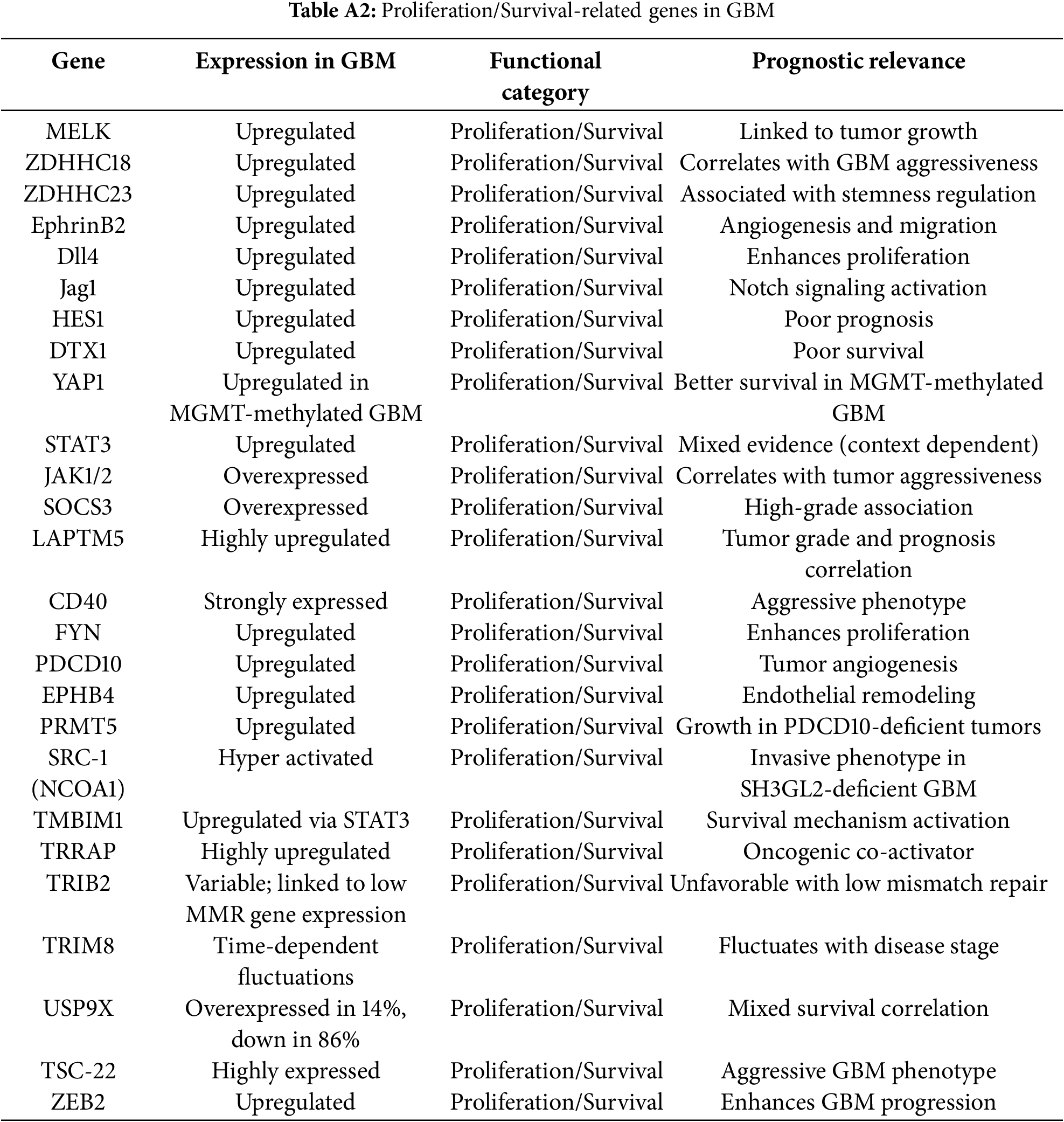

3.1 Study Selection and Functional Landscape

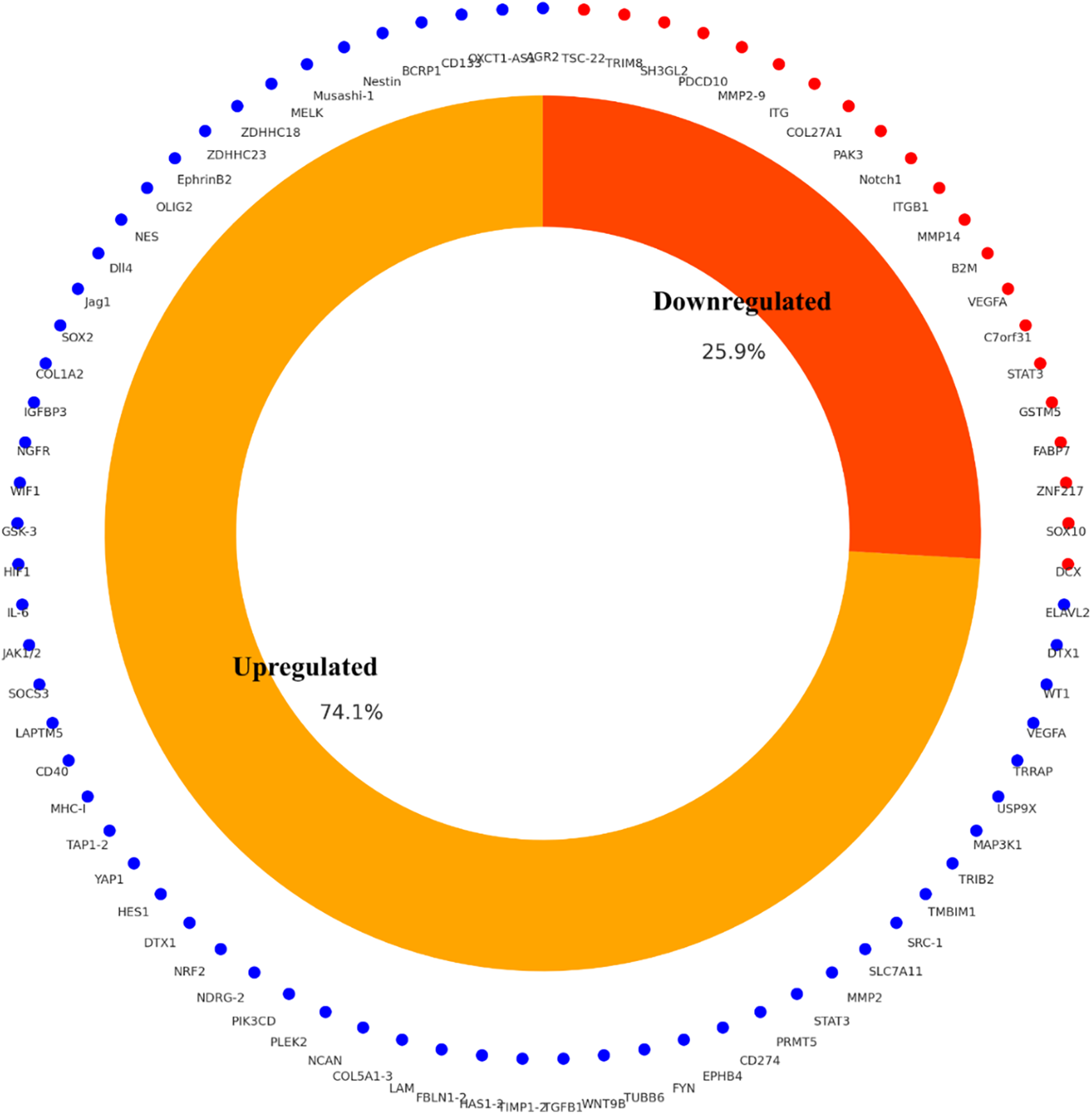

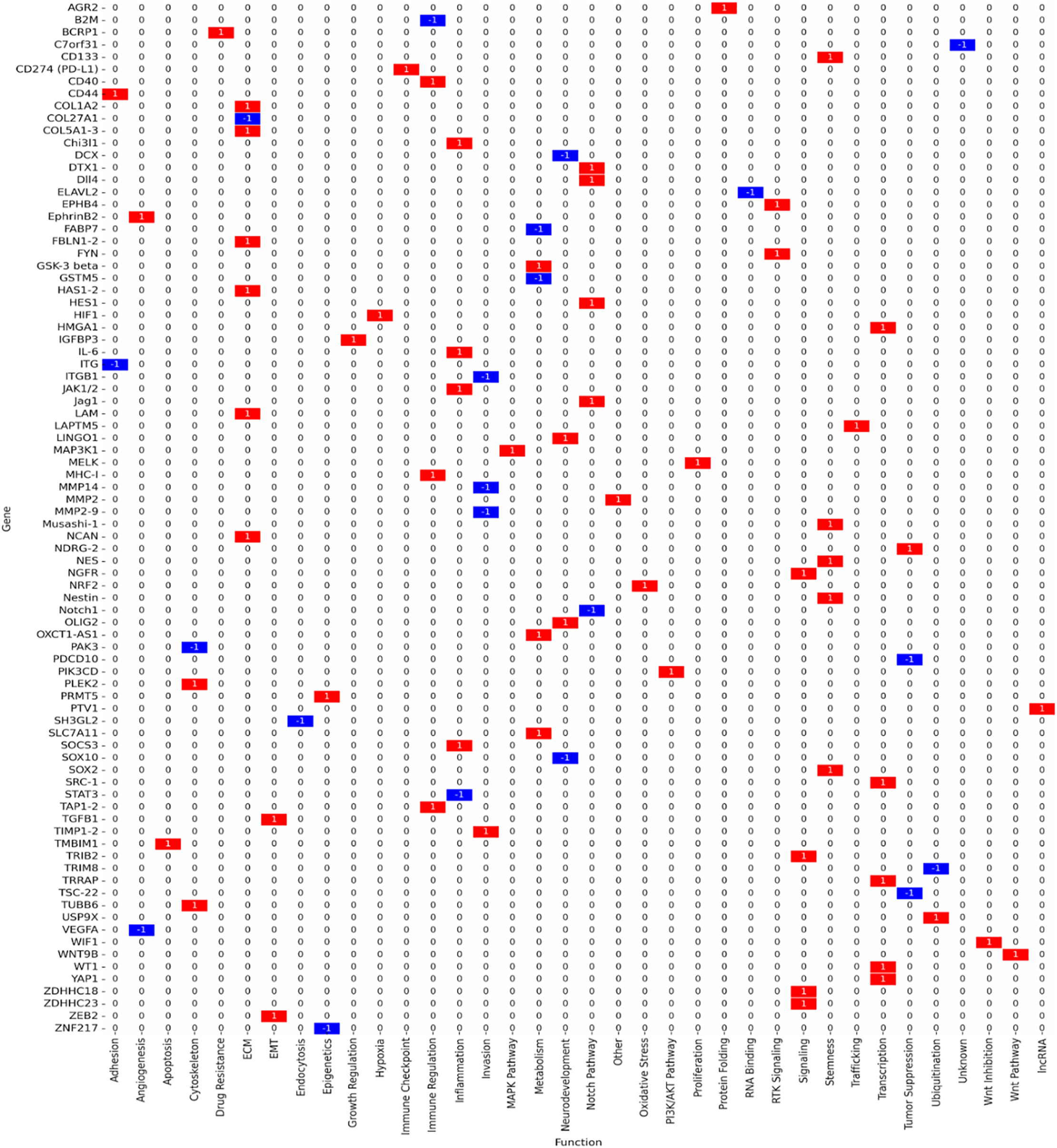

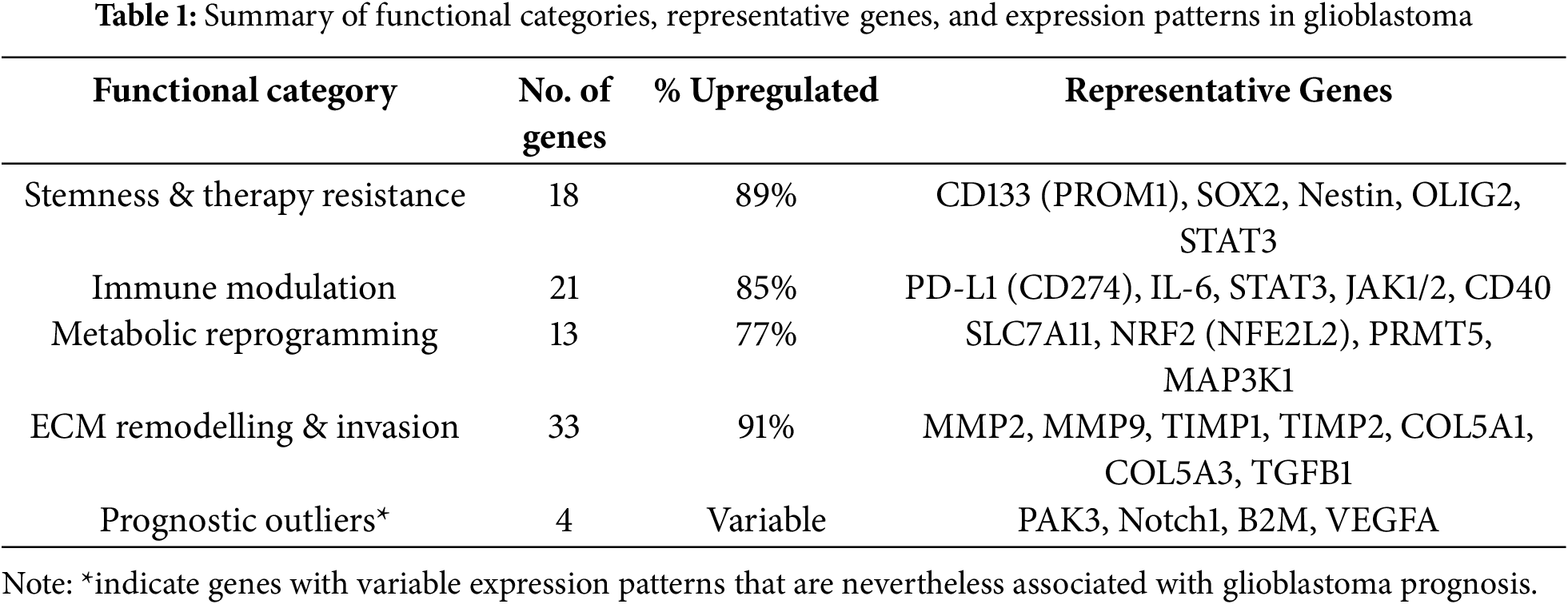

The study selection process followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility. A total of 410 records were identified through database searches (PubMed, TCGA, CGGA, GlioVis) and manual screening. After removal of 90 duplicates and the application of predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 125 studies were retained for final synthesis (Fig. 1). Out of 112 curated glioblastoma (GBM)-associated genes identified through systematic review and dataset integration, 85 had complete functional annotations and consistent expression data. These genes formed the basis of quantitative analyses and visualisations. Among these, 74.1% were consistently upregulated and 25.9% were downregulated in glioblastoma (Fig. 2). Functional classification showed that genes involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodelling, invasion, stemness maintenance, immune modulation, and metabolic reprogramming were predominant. In addition to functional categorisation, immune modulators (including TAM- and TIL-associated genes) were reviewed for transcript–protein concordance using available proteomic and IHC data. While formal meta-analysis of hazard ratios was not feasible due to heterogeneity in platforms, study designs, and patient cohorts, subgroup-specific survival trends were summarised descriptively, with immune modulators and ECM-remodelling genes showing the strongest association with poor outcomes. The functional matrix (Fig. 3) highlighted multifunctional hubs such as STAT3, TGFB1, and PRMT5, bridging several biological processes central to glioblastoma pathogenesis.

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 flow diagram detailing the systematic identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of studies in the glioblastoma gene expression review. Numbers reflect the sequential filtering from initial records identified (n = 410) through duplicate removal, title/abstract screening, full-text review, and final inclusion (n = 125 studies). NA: Not applicable

Figure 2: Differential expression profile of glioblastoma-associated genes (n = 85) curated from integrated literature and TCGA/CGGA datasets. A total of 74.1% were consistently upregulated and 25.9% downregulated in GBM relative to non-tumor brain tissue

Figure 3: Functional matrix mapping glioblastoma-associated genes across key biological processes: stemness, proliferation/survival, extracellular matrix (ECM)/invasion, immune modulation, metabolic regulation, and epigenetic control. Red bars indicate upregulated genes; blue bars indicate downregulated/tumour suppressors; purple outlines indicate multifunctional genes contributing to more than one biological category. Network relationships were derived using STRING v12.0 (interaction score ≥ 0.7, high confidence) and visualised in Cytoscape v3.9.1, with hub genes prioritised based on node degree and betweenness centrality

3.2 Key Biological Processes in Glioblastoma

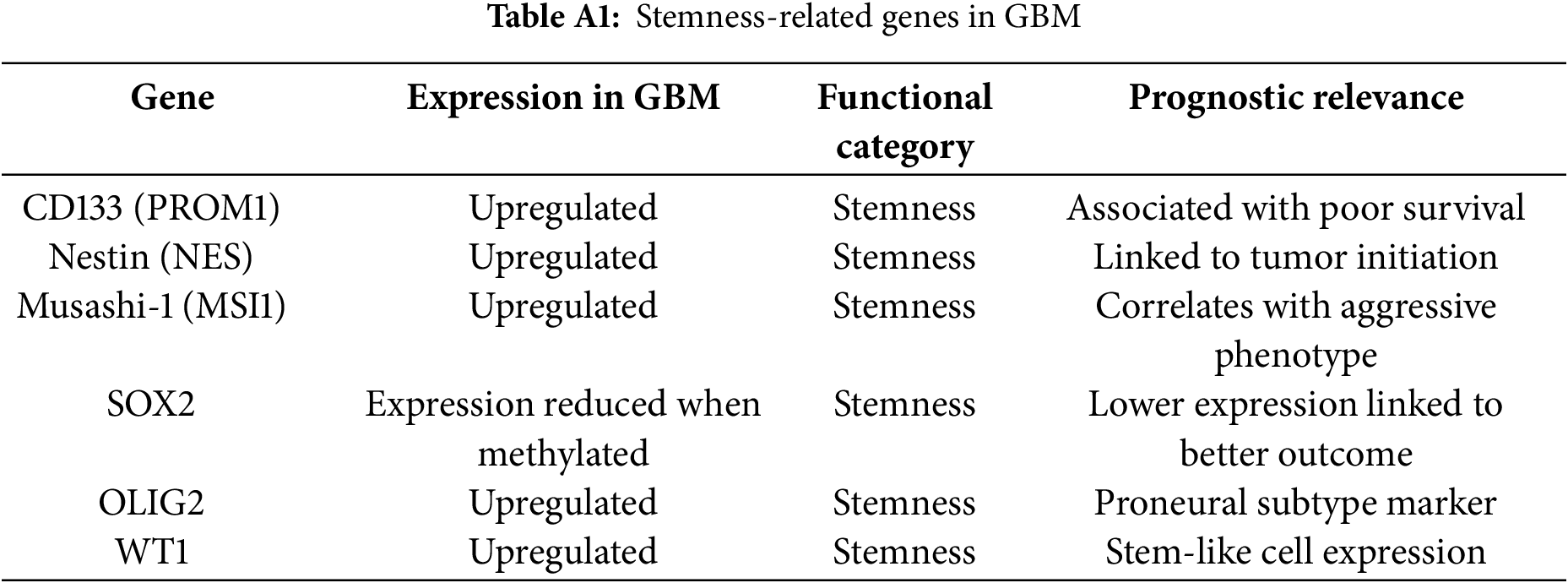

Genes linked to stemness and therapy resistance included CD133 (PROM1), SOX2, Nestin, OLIG2, and Musashi-1, all of which support the persistence of glioma stem-like cell populations and drive recurrence. These genes were predominantly upregulated in proneural and classical GBM subtypes. STAT3 functioned as a multifunctional regulator with critical roles in both stemness and immune modulation (Fig. 3, Table 1).

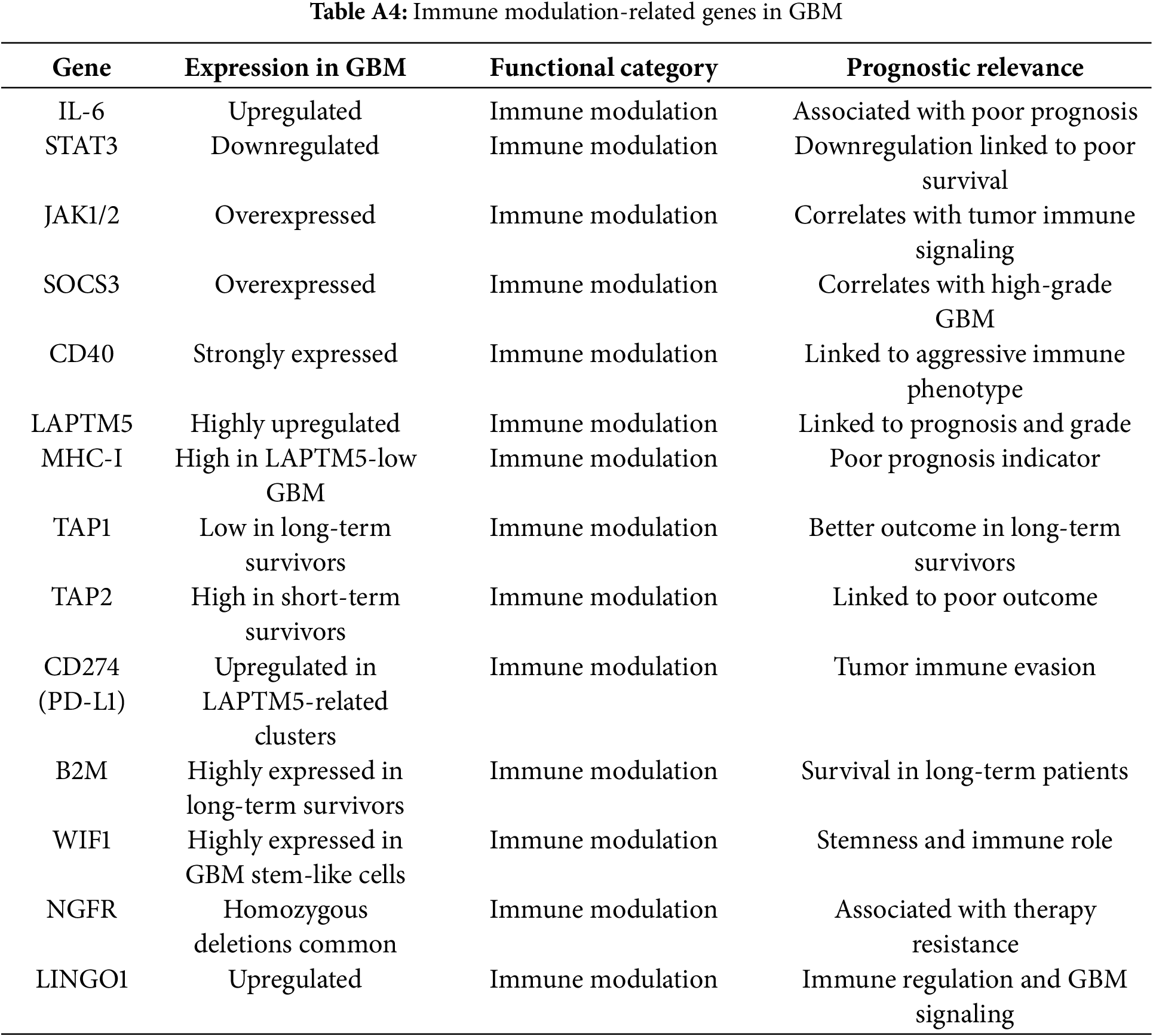

Immune modulators such as PD-L1 (CD274), IL6, B2M, TAP1, TAP2, SOCS3, CD40, and STAT3 contributed to immune evasion and pro-inflammatory signaling. Approximately 85% of these genes were upregulated, especially in mesenchymal GBM.

Network analysis identified STAT3, PD-L1, and JAK1/2 as central immune hubs with translational relevance for immunotherapy (Fig. 3, Table 1). This analysis was performed using the STRING database (v12.0) restricted to experimentally validated and high-confidence predicted interactions (confidence score ≥ 0.7), with visualisation and hub identification conducted in Cytoscape (v3.9.1) based on degree and betweenness centrality metrics.

Prognostic analysis within immune-related genes revealed that high expression of TAM-associated mediators (STAT3, TGFB1, IL10) correlated with reduced survival. In contrast, increased TIL effector signatures (e.g., IFNG, GZMB) were infrequently observed and associated with more prolonged survival in a minority of mesenchymal GBM cases. These patterns align with proteomic observations of M2-polarised macrophage dominance and T-cell exhaustion, reinforcing their value as stratification biomarkers.

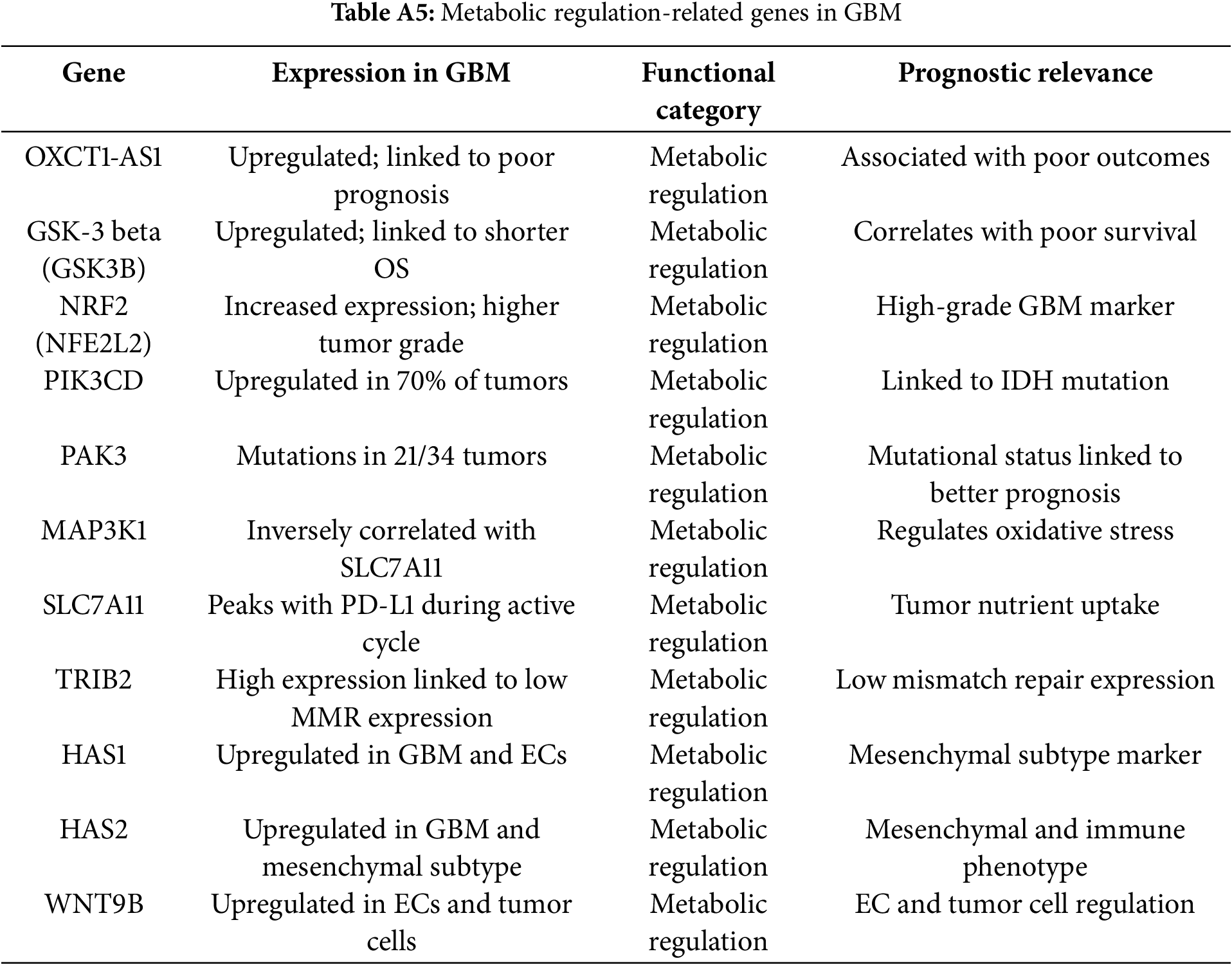

Metabolic regulators included SLC7A11, NRF2 (NFE2L2), PRMT5, MAP3K1, and GSK3B, which facilitated survival under hypoxia, oxidative stress, and nutrient deprivation. Notably, SLC7A11 and PRMT5 were dual regulators of metabolic adaptation and immune evasion, strengthening their therapeutic relevance (Fig. 3, Table 1).

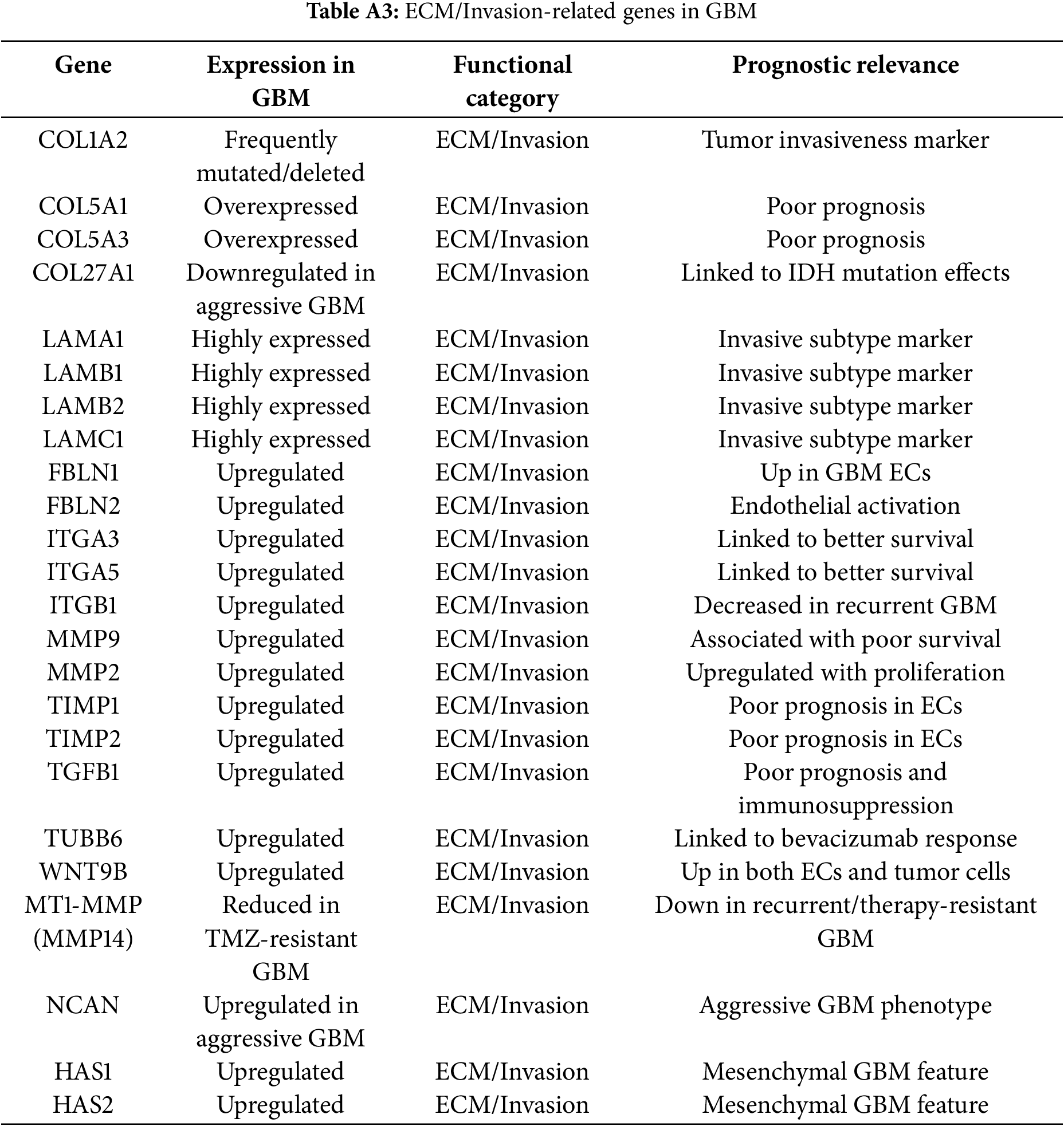

Genes driving ECM remodeling and invasion included MMP2, MMP9, TIMP1, TIMP2, COL5A1, COL5A3, LAMC1, HAS1, HAS2, and TGFB1. These genes were consistently upregulated, enriched in mesenchymal GBM, and associated with vascular mimicry, therapy resistance, and poor prognosis.

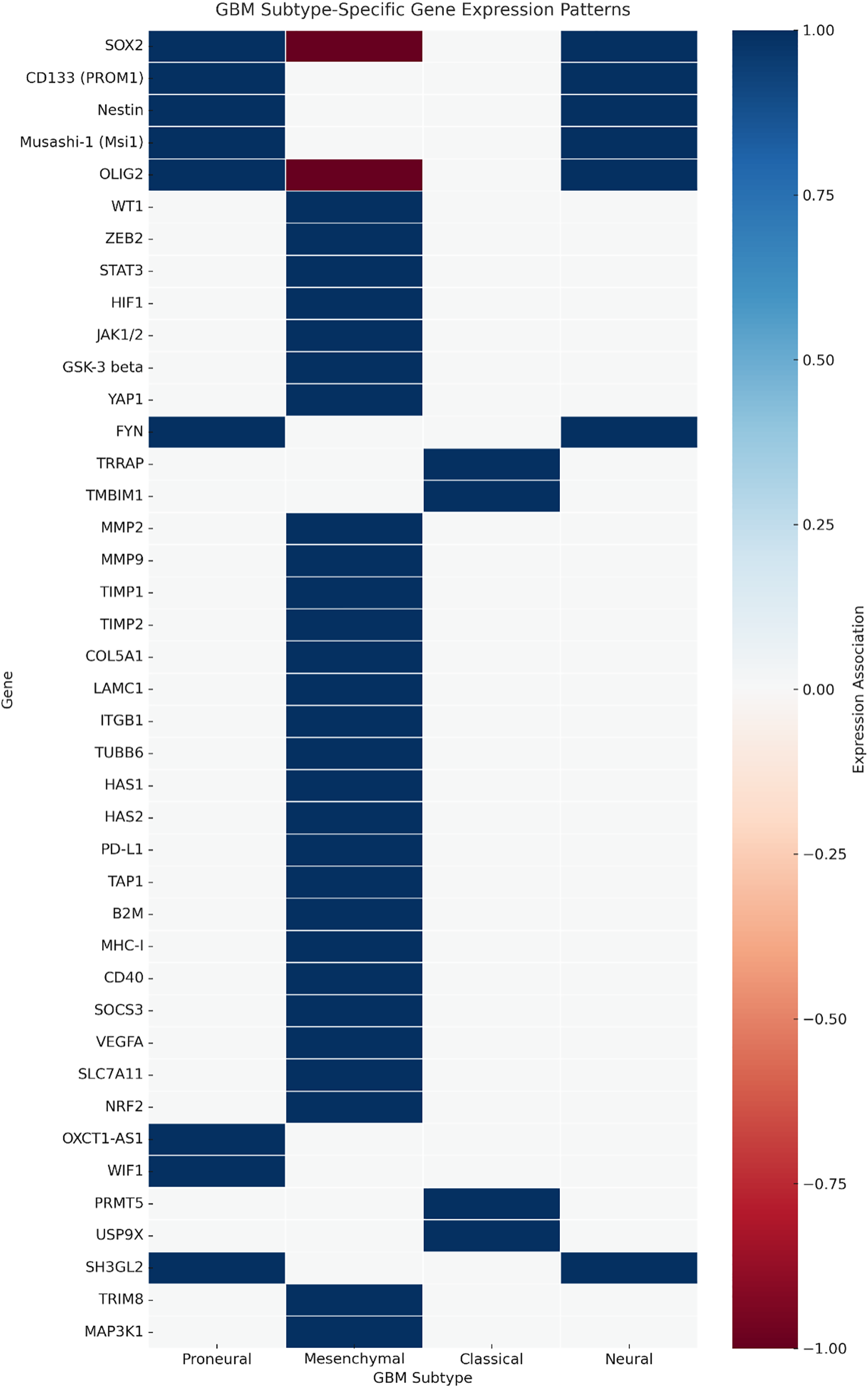

We next examined whether the identified genes exhibited subtype-specific enrichment patterns across the proneural, mesenchymal, classical, and neural glioblastoma subtypes. A subtype heatmap (Fig. 4) was generated, highlighting the preferential expression of stemness-associated genes such as SOX2, OLIG2, and PROM1 in proneural GBM, ECM/invasion and immune modulatory genes such as MMP9, STAT3, and VEGFA in mesenchymal GBM, and cell cycle–linked proliferation genes in classical GBM. Neural subtype tumours demonstrated relative enrichment in neuronal lineage markers.

Figure 4: Subtype-specific gene expression heatmap in glioblastoma. Heatmap illustrating relative expression patterns of curated glioblastoma-associated genes across the proneural, mesenchymal, classical, and neural subtypes (TCGA GBM RNA-seq). Genes are grouped by primary functional category: stemness, extracellular matrix (ECM)/invasion, immune modulation, metabolic regulation, proliferation/survival, and epigenetic control. Colour intensity represents Z-score normalised expression. Proneural enrichment is observed for stemness-associated genes such as SOX2, OLIG2, and PROM1; mesenchymal enrichment for ECM and immune modulators, including MMP9, STAT3, and TGFB1; and classical enrichment for proliferation-related genes such as EGFR and CCND2. Neural subtype tumours demonstrate relative enrichment in neuronal lineage markers. Functional categorisation was prioritised based on literature consensus and Gene Ontology annotations

These subtype-associated expression patterns have direct therapeutic implications: proneural enrichment of OLIG2, SOX2, and PROM1 supports strategies targeting stemness pathways; mesenchymal predominance of MMP9, STAT3, and TGFB1 aligns with anti-invasive and immunomodulatory approaches; and classical subtype enrichment in EGFR and CCND2 suggests sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors or cell cycle-directed agents.

3.3 Aggression and Targetability Scoring Classification

Analysis of gene expression patterns and clinical outcomes revealed that 65% of the genes correlated with poor survival, 20% with better prognosis, and 15% demonstrated context-dependent associations. Adverse prognostic markers included AGR2, IL6, MMP9, and TIMP1, whereas PAK3, Notch1, and B2M were linked to more prolonged survival or therapeutic responsiveness, underscoring the molecular heterogeneity of GBM. While forest plot visualisation of pooled hazard ratios was considered, methodological heterogeneity in the literature precluded robust statistical synthesis. Instead, subgroup-level prognostic associations (e.g., immune modulators, ECM-remodelling genes) were summarised descriptively, preserving functional granularity while avoiding misleading pooled estimates.

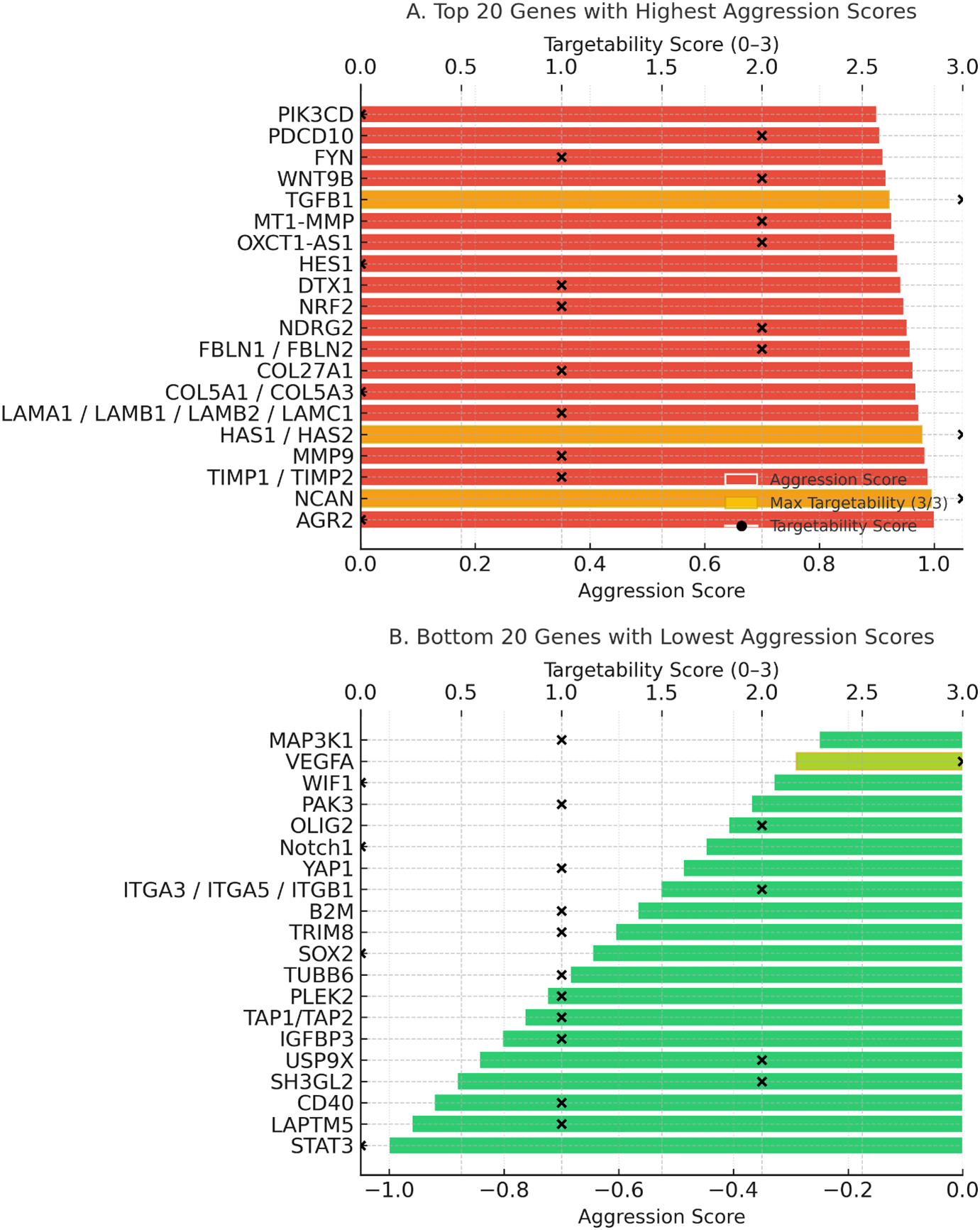

Aggression score analysis integrated expression intensity, prognostic significance, and functional roles. Specifically, aggression scores were calculated as a composite of three weighted components: (i) transcriptomic overexpression in GBM vs. normal brain (+1 if log2FC ≥ 1, FDR < 0.05), (ii) prognostic association from survival analysis (+1 if high expression correlated with shorter overall survival, −1 if associated with more prolonged survival), and (iii) functional impact (+1 if implicated in ≥2 independent studies as a driver of core GBM hallmarks such as proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, or immune evasion). Scores ranged from −1 to +3, with higher values indicating more aggressive tumour-associated behaviour. The top 20 most aggressive genes (Fig. 5, top panel) included AGR2, NCAN, MMP9, HAS2, TIMP1, TIMP2, and TGFB1, all of which were strongly associated with ECM remodelling, angiogenesis, invasion, and mesenchymal subtype enrichment. Their high scores (≥+0.9) suggest these genes are core drivers of glioblastoma malignancy. Conversely, the bottom 20 genes (Fig. 5, bottom panel), including VEGFA, ITGA3, ITGA5, ITGB1, Notch1, and PAK3, were linked to protective roles, more prolonged survival, or subtype-specific therapeutic responsiveness. Notably, the negative aggression score of VEGFA reflects its predictive role in anti-VEGF therapy rather than an absence of oncogenic potential.

Figure 5: Aggression and targetability scores of glioblastoma-associated genes. (A) Twenty genes with the highest aggression scores. (B) Twenty genes with the lowest or protective aggression scores. Colored bars represent aggression scores (red = high, green = low). Black “×” symbols indicate the targetability scores (0–3) of each gene, while black dots highlight genes that achieved the maximum targetability score (3/3). Gold highlights within the bars denote genes with maximum targetability, reflecting the presence of available inhibitors, inclusion in clinical trials, and blood–brain barrier penetration

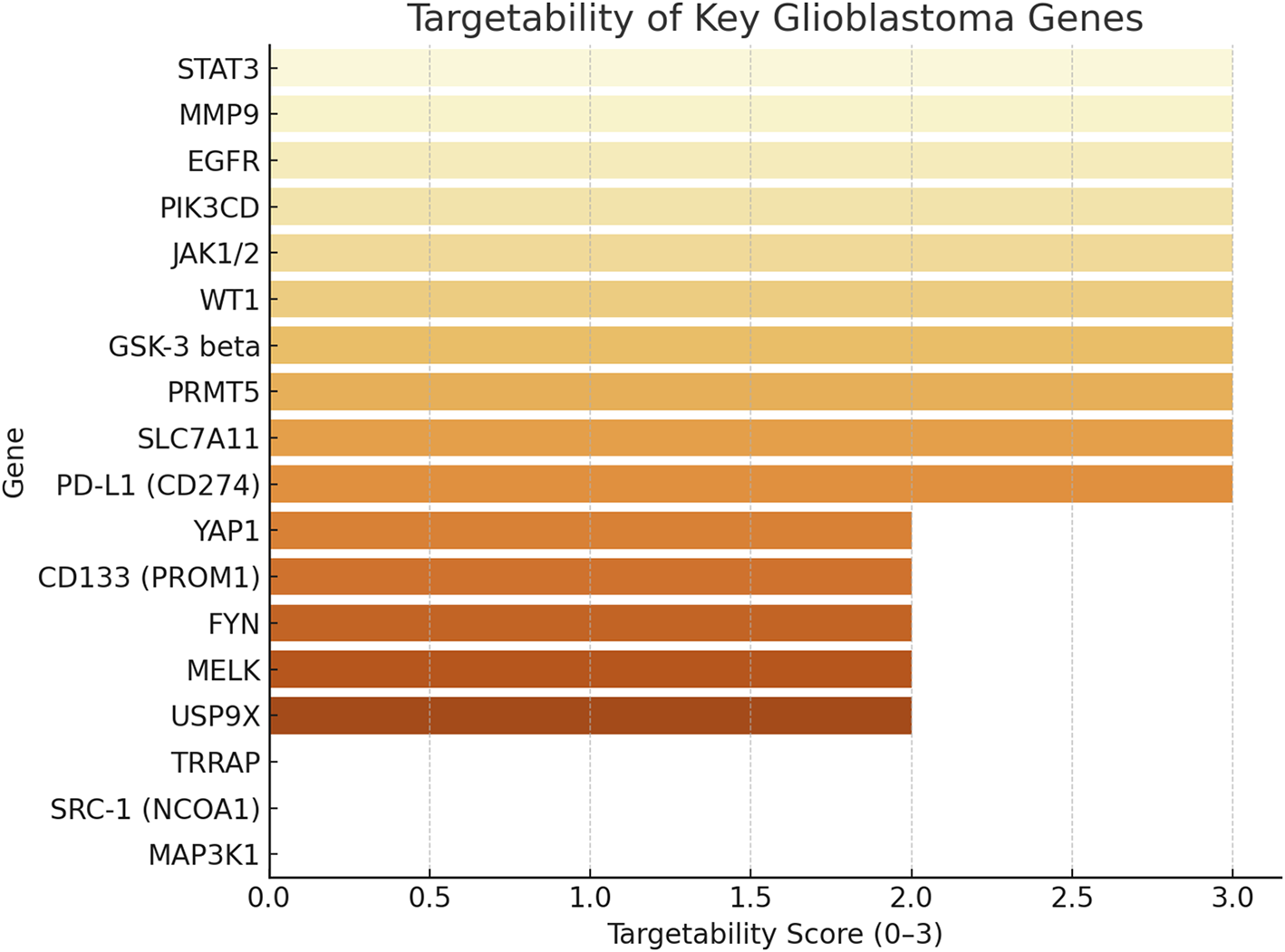

Targetability assessment combined data on drug availability, clinical trial inclusion, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration (Fig. 6). Targetability scores were assigned based on the presence of: (i) available pharmacological inhibitors or biologics (+1), (ii) inclusion in active or completed cancer clinical trials (+1), and (iii) evidence of blood–brain barrier penetration of candidate drugs in preclinical or clinical studies (+1). Scores ranged from 0 to 3, with higher values reflecting greater translational feasibility. STAT3, PD-L1, PRMT5, SLC7A11, and JAK1/2 emerged as high-priority targets with strong translational potential, supported by existing inhibitors and advanced clinical development. In contrast, highly aggressive genes like AGR2, NCAN, and HAS2 lack effective targeted therapies, highlighting critical gaps in the therapeutic landscape. Mapping aggression against targetability revealed alignment between high aggression and strong targetability for some genes, but also identified poorly targetable aggressive drivers, emphasising the need for novel therapeutic development.

Figure 6: This figure shows the targetability scores of key glioblastoma genes, ranked from most to least targetable. The score (0–3) reflects: +1: drug availability, +1: inclusion in clinical trials +1: confirmed or partial blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration. Genes like STAT3, MMP9, EGFR, PIK3CD, JAK1/2, and WT1 achieved the highest score [3], indicating strong translational potential with drugs, trials, and brain penetrance. And genes like MAP3K1, SRC-1, and TRRAP scored 0 or 1, representing underexplored targets

In total, 63.4% of the identified genes were predominantly upregulated in GBM compared to non-tumour brain, while 28.6% were downregulated and 8.0% showed mixed or context-specific patterns. Approximately 52% of genes demonstrated a prognostic association with reduced overall survival, whereas 21% correlated with improved prognosis; the remainder had inconsistent associations across studies. These data are summarised in Fig. 2, which provides an overview of the prognostic distribution of all genes included in this review.

This systematic review provides an integrative overview of gene expression dysregulation in glioblastoma across 200 studies. While transcriptomic analyses have revealed key insights into GBM pathophysiology, mRNA levels do not always reflect protein abundance [18]. Gene expression refers to the transcription of DNA into RNA, whereas protein expression reflects the final functional output of cellular signalling [19]. This discordance is clinically significant: genes like EGFR and PDGFRA may be highly transcribed but show limited protein expression due to miRNA repression, translational inefficiency, or post-translational degradation [18,20]. These findings emphasise the necessity of integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data to enhance the reliability of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. For instance, Liu et al. demonstrated that mRNA-protein correlation is modest across tissues, reinforcing the need to validate transcript-based markers at the protein level [18,21]. In GBM, where both transcriptomic signatures and treatment responses are heterogeneous, dual-layer molecular profiling offers a more precise understanding of tumour behaviour. For immune modulators, this integration is particularly relevant: PD-L1 mRNA overexpression in GBM is often mirrored by elevated protein levels detected via IHC, whereas major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I transcripts may be variably downregulated without consistent loss of surface protein [17,21,22]. Likewise, TAM-associated STAT3 and TGFB1 show strong concordance between transcriptomic enrichment and proteomic activation in the GBM microenvironment, reinforcing their biological relevance [23].

4.1 Stemness and Therapy Resistance in Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma (GBM) is characterised by extensive cellular heterogeneity, partly driven by stem-like subpopulations that resist therapy and fuel recurrence. Anterior Gradient 2 (AGR2) encodes a protein disulphide isomerase that, under physiological conditions, supports protein folding within the endoplasmic reticulum. In glioblastoma (GBM), AGR2 is significantly overexpressed, disrupting cellular homeostasis and fostering malignant transformation. Its elevated expression in GBM tissues and cancer stem cell populations correlates with enhanced proliferation, invasion, and therapeutic resistance. AGR2’s co-expression with stemness markers such as Nestin and Vimentin highlights its role in maintaining glioma stem cell survival and contributing to recurrence, positioning AGR2 as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target [24,25].

SOX2 encodes a key transcription factor maintaining stem cell pluripotency [26]. In GBM, its dynamic, oscillatory expression supports transitions between proliferative and quiescent states, enabling heterogeneity and resistance [27,28]. SOX2 features prominently in gene panels for GBM classification due to its central role in tumour aggressiveness [29,30].

CD133 (PROM1) marks a subpopulation of glioblastoma stem cells with potent tumour-initiating and chemoresistant properties [31]. These cells co-express genes including BCRP1 (ABCG2), which facilitates drug efflux and chemotherapy resistance [32]; Nestin and Musashi-1 (Msi1), which support proliferation and stemness [33,34]; and MELK, which promotes cell cycle progression [35]. Together, these factors drive glioblastoma’s resilience and recurrence. SOX10, silenced by promoter methylation in GBM, further reflects disruption of neural differentiation programs and correlates with poor survival [36]. ELAVL2, an RNA-binding protein stabilising neuronal mRNAs, is downregulated in GBM, facilitating mesenchymal transition, invasion, and poor prognosis [37–39].

OXCT1-AS1, a long non-coding RNA, is markedly upregulated in GBM and contributes to oncogenesis by sponging miR-195 and derepressing CDC25A, enhancing proliferation and invasiveness [40]. Its post-transcriptional regulatory role makes OXCT1-AS1 a compelling molecular target for therapeutic strategies [41,42]. DCX, OLIG2, and NES reflect the neural lineage features co-opted by GBM. DCX, involved in neuronal migration, is expressed in only rare tumour cells and appears unrelated to invasion [43,44]. OLIG2 is enriched at tumour margins, supporting stemness and invasion [44]. NES is broadly expressed in undifferentiated GBM cells, facilitating proliferation and aggressiveness [44,45]. ZDHHC18 and ZDHHC23, encoding palmitoyl acyltransferases, are differentially enriched in mesenchymal and proneural GBM subtypes, respectively. Both enzymes sustain glioma stem cell plasticity and survival, modulating BMI1 stability and contributing to adaptability and therapy resistance [46–48].

4.2 Immune Evasion and Modulation

CD274 (PD-L1) facilitates immune escape in glioblastoma by inhibiting T-cell activity. Its variable expression correlates with poor prognosis and therapy resistance [49,50]. PD-L1’s dynamic regulation across the cell cycle suggests that immune evasion in GBM is tightly linked to proliferative cues, influencing immunotherapy responsiveness [51]. MHC-I genes (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C) and B2M are frequently downregulated in GBM, impairing antigen presentation and promoting immune evasion [49,52]. B2M is overexpressed in gliomas, correlates with tumor grade, immune infiltration, and mesenchymal subtype; lower expression predicts longer survival, highlighting B2M as a prognostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target [53,54]. Loss of TAP1 and TAP2 further reduces tumour immunogenicity by limiting peptide loading onto MHC-I [55–57]. CD40, which is taken over by tumour cells, further facilitates invasion in chemoresistant GBM [58–60]. Collectively, these alterations contribute to poor prognosis while decoupling immune escape from standard therapy responses [16,61].

4.3 Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Glioblastoma: Current Clinical Experience

While GBM tumours frequently exploit immune evasion mechanisms such as PD-L1 overexpression, MHC-I downregulation, and impaired antigen presentation via TAP1/TAP2 suppression, translation of these findings into effective immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies has proven challenging [62]. Trials targeting PD-1/PD-L1 (e.g., CheckMate 143) and CTLA-4 have demonstrated limited clinical benefit in unselected GBM populations, largely due to the profoundly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [63]. Ongoing studies (e.g., NCT02667587, NCT02337491) are testing combination regimens integrating ICIs with radiotherapy, personalized vaccines, or metabolic modulators to enhance immune activation [64,65]. These efforts highlight the need for precise patient selection and biomarker integration to improve therapeutic outcomes.

4.4 Transcriptomic Correlates of the GBM Immune Microenvironment

The glioblastoma immune milieu is dominated by tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs), most of which adopt an M2-like phenotype that supports tumour growth and suppresses antitumor immunity [66]. Transcriptomic profiling reveals consistent upregulation of STAT3, IL10, and TGFB1, which drive M2 polarisation, inhibit cytotoxic T-cell function, and foster immune tolerance [67]. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) exhibit elevated expression of exhaustion markers such as PDCD1, LAG3, and HAVCR2, accompanied by reduced effector cytokines, reflecting chronic antigen exposure [68]. High-resolution single-cell RNA sequencing has mapped these immune cell states in GBM, showing convergence between immune transcriptomes and tumor-intrinsic expression programs. This interplay underscores the role of immune–tumor crosstalk in shaping disease progression and resistance to immunotherapy [69].

4.5 Translational Immunotherapy Strategies and Patient Stratification

Building on these mechanistic insights, several translational strategies aim to circumvent GBM’s immune resistance. Oncolytic virotherapies such as DNX-2401 can induce immunogenic cell death and enhance antigen presentation. Dendritic cell vaccines, exemplified by ICT-107, are designed to amplify tumor-specific T-cell responses [70]. Metabolic interventions, including inhibition of IDO1-mediated tryptophan catabolism or targeting lactate accumulation, may reprogram the microenvironment to favor immune activation. Patient stratification based on PD-L1 status, tumor mutational burden, or immune-related transcriptomic signatures could refine trial design and improve response prediction [71,72]. Integrating such biomarker-driven approaches with adaptive immunotherapy regimens holds promise for translating immune modulation into durable survival benefits for GBM patients.

Notably, several GBM-associated genes display discordance between mRNA and protein abundance, underscoring the need for multi-omics validation. For instance, EGFR often shows high mRNA expression without proportional protein overexpression due to post-transcriptional regulation or receptor degradation [6]. Similarly, PDGFRA transcriptional upregulation may not translate into increased protein levels, potentially reflecting microRNA-mediated suppression [73]. In contrast, VEGFA mRNA and protein levels can diverge in hypoxic microenvironments, where translational control mechanisms predominate [74]. These examples highlight the limitations of relying solely on transcriptomic data and support integrating proteomic or immunohistochemical evidence when prioritising therapeutic targets.

4.6 Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Remodeling and Angiogenesis

Invasion and angiogenesis in GBM are mediated by coordinated extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and pro-angiogenic signaling. VEGFA is a key driver of angiogenesis in GBM [75]. Its overexpression supports abnormal vasculature, tumor growth, and hypoxia adaptation [75,76]. Interestingly, VEGFA levels predict bevacizumab response, marking it as both a pathogenic driver and therapeutic marker [77].

Ephrin-B2 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion, with high expression linked to poor survival. Furthermore, high ephrin-B2 expression serves as a strong predictor of shorter survival in glioma patients, underscoring its potential as a prognostic biomarker [78]. Targeting ephrin-B2 signaling pathways may offer therapeutic strategies to mitigate GBM aggressiveness [79].

MMP2, MMP9, and MMP14 degrade ECM components, facilitating invasion and angiogenesis [80,81]. Despite co-expression of their inhibitors (TIMP1, TIMP2), the proteolytic balance in GBM favours invasion [82–84]. COL1A2, IGFBP3, NGFR, and WIF1. COL1A2 encodes the alpha-2 chain of type I collagen, a key component of the extracellular matrix; its overexpression may facilitate tumor invasion and has been linked to reduced overall survival in GBM patients [85,86]. IGFBP3 regulates insulin-like growth factors, influencing cell growth and apoptosis; elevated levels in GBM correlate with poorer survival outcomes [87]. NGFR, involved in neuronal survival and apoptosis, shows increased expression in GBM, which is associated with decreased patient survival [88]. Conversely, WIF1 acts as an antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathway, and its reduced expression in GBM is linked to shorter survival, suggesting a tumor suppressor role [86,89].

COL5A1, COL5A3, COL27A1 [82,85,86,90], Laminins (LAMA1, LAMB1, LAMB2, LAMC1) [82,91], Fibulins (FBLN1, FBLN2) [82,92], Integrins (ITGA3, ITGA5, ITGB1) [82,93], and HAS1/2 all contribute to matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, and therapy resistance [82,94]. High expression of these genes correlates with reduced survival and supports GBM’s mesenchymal phenotype. TGFB1 and WNT9B drive angiogenesis and stem-like endothelial characteristics, supporting vascular mimicry and resistance [82,95,96]. PDCD10 loss enhances GBM progression by upregulating EPHB4 kinase activity, promoting proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis [97–99]. NCAN uniquely associates with better survival, possibly via anti-angiogenic effects [82,100].

4.7 Metabolic Reprogramming and Redox Balance

SLC7A11 encodes a cystine/glutamate antiporter supporting glutathione synthesis and oxidative stress resistance in GBM [101]. Its overexpression promotes redox balance but suppresses mismatch repair, increasing genomic instability [102]. HIF-1α facilitates adaptation to hypoxia, driving VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming [103,104]. Cooperation between HIF-1α-positive and -negative cells enhances heterogeneity and tumor growth [105]. Inhibition of NRF2 enhances response to temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy, highlighting it as a metabolic checkpoint in glioblastoma treatment [106]. Kurdi et al. (2023) reported significant dysregulation of NFE2L2 in IDH-mutant astrocytomas, suggesting that NRF2 may interact with metabolic reprogramming driven by IDH1 mutations [107]. This crosstalk contributes to tumor adaptability and survival, making NFE2L2 a potential therapeutic target [107].

4.8 Epigenetic and Post-Transcriptional Dysregulation

Epigenetic and post-transcriptional alterations play central roles in GBM progression. Genes like ZNF217, FABP7, and GSTM5 show inverse methylation-expression patterns, underscoring the contribution of methylation dynamics to GBM heterogeneity [108]. Mu et al. (2025) found that TRRAP is stabilised by USP9X-mediated deubiquitination, enhancing its oncogenic activity. Elevated TRRAP levels lead to increased expression of genes that drive tumour progression. Its role in glioblastoma extends beyond transcription to influencing immune interactions, marking TRRAP as a novel effector in GBM pathogenesis [109]. NDRG2 is a tumour suppressor gene that plays a role in cell differentiation, stress response, and the inhibition of cell proliferation. In grade 4 astrocytomas, NDRG2 expression is frequently downregulated, contributing to tumour progression, increased invasiveness, and reduced apoptosis [110]. Kurdi et al. (2023) reported that low NDRG2 expression, particularly in combination with IDH1 mutation, is associated with more aggressive tumour features. This synergistic dysregulation appears to weaken tumour-suppressive mechanisms, highlighting NDRG2 as a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in high-grade gliomas [107].

4.9 Chemoresistance and Cytoskeletal Dynamics

LAPTM5 upregulation in TMZ-resistant cells supports oncogenic trafficking [59,111], working with CD40 to promote invasion and chemoresistance [46–48]. TUBB6 and FYN, co-regulated with LAPTM5, enhance cytoskeletal reorganisation and invasion [59,112,113]. LINGO1 [25,114,115] and C7orf31 are linked to poor survival, with roles in adhesion signaling and genomic stability still under investigation [114,116] Other genes, such as ZNF217, FABP7, and GSTM5, exhibit inverse methylation-expression patterns, indicating that epigenetic silencing of these oncogenic or metabolic regulators may also shape glioma behaviour [108] Similarly, TUBB6, DTX1, and integrin subunits (ITGA3, ITGA5, ITGB1) support cytoskeletal remodeling and motility through actin dynamics and focal adhesion pathways [117,118].

4.10 Key Signalling Pathways and Transcriptional Regulation

IL6/STAT3 signalling is hyperactivated in GBM, promoting proliferation, immune evasion, and therapy resistance [119–122]. Loss of SOCS3 amplifies STAT3 activity [123]. NOTCH1, HES1, DTX1, and TRIM8 sustain stemness and invasion through dysregulated Notch signalling and STAT3 hyperactivation [124,125]. PIK3CD, PAK3, and PLEK2 drive actin remodelling, migration, and invasion via PI3K signalling [126–128]. MAP3K1 and TRIB2 cooperate to promote temozolomide resistance and survival signalling [129–131]. PRMT5 epigenetically regulates gene expression and RNA splicing, supporting GBM cell survival and resistance [132,133]. USP9X stabilises TRRAP, enhancing chromatin remodelling and immune evasion through M2 macrophage polarisation [109,134]. TMBIM1 modulates p38 MAPK signalling to promote survival and inhibit apoptosis [135,136]. SRC-1 (NCOA1) rewires corticosteroid responses toward tumour promotion under steroid treatment [137]. ZEB2 drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and apoptosis resistance [138]. YAP1 enhances growth, stemness, and resistance [117,139]. GSK-3β shows duality: it promotes cholera toxin-induced differentiation when active [140], but its inhibition reduces proliferation and invasion, reflecting context-dependent therapeutic relevance [141–143]. WT1 displays dual roles in GBM, correlating with poor prognosis in IDH-wildtype tumours but associating with longer recurrence-free survival in IDH-mutants receiving chemotherapy [144,145]

5 Therapeutic Targets and Translational Opportunities

The integrated analysis of glioblastoma gene expression reveals several promising therapeutic targets with translational potential. VEGFA, as a central angiogenic driver, remains a key target, with anti-VEGF therapies like bevacizumab showing benefit in subsets of patients with high VEGFA expression [75]. Similarly, PD-L1 (CD274) represents a well-established immune checkpoint target; its dynamic regulation suggests that optimizing the timing and combination of immune therapies could enhance efficacy [49]. Disruption of ECM remodeling enzymes, notably MMP14, MMP2, and MMP9, alongside their paradoxically upregulated inhibitors TIMP1 and TIMP2, offers avenues to curb invasion and angiogenesis [146,147].

Epigenetic regulators like PRMT5 and USP9X present attractive targets for impairing GBM cell survival and immune evasion [133]. Similarly, blocking STAT3 or restoring SH3GL2 expression may limit invasiveness [119,148]. The Notch pathway (via NOTCH1, HES1, DTX1) and its interaction with TRIM8 and STAT3 signaling represent another axis for potential intervention, particularly in glioma stem-like cells. The study positions TSC22D1 as a candidate tumor suppressor whose inactivation may play a critical role in glioblastoma pathogenesis and progression [149]. Novel candidates like OXCT1-AS1, WNT9B, and SRC-1 open fresh avenues for targeting post-transcriptional regulation, angiogenesis, and steroid-driven tumor adaptation.

Importantly, WT1 and ZEB2 emerge as biomarkers for patient stratification and as potential direct targets, given their links to prognosis and therapy resistance [138,139]. Together, these insights underline the urgent need for biomarker-driven, combination therapies that disrupt the molecular circuits sustaining glioblastoma progression. Isoform-specific inhibitors, metabolic modulators, and agents targeting the tumour microenvironment (e.g., ECM, immune milieu) represent key translational opportunities to enhance GBM treatment outcomes.

Our integrative synthesis advances the field by providing a functional and subtype-oriented map of glioblastoma gene expression. Unlike previous reviews that examined individual pathways or limited gene sets, this work compiles 112 GBM-relevant genes. It categorises them into stemness, immune modulation, ECM/invasion, metabolic regulation, and epigenetic control. We further mapped these genes to the four established transcriptional subtypes (classical, mesenchymal, proneural, and neural), visualised in a newly constructed subtype heatmap (Fig. 5). This visualisation reveals clear patterns of subtype enrichment, for example, the clustering of OLIG2, SOX2, and Nestin within the proneural group, and the predominance of MMP2, MMP9, and COL5A1 in the mesenchymal subtype, providing a basis for tailoring therapeutic strategies to molecularly defined patient groups.

By integrating functional categorisation with subtype distribution, our analysis links gene expression patterns directly to glioblastoma’s biological hallmarks and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. This approach also incorporates awareness of transcript–protein discrepancies, emphasising that subtype-associated targets should undergo proteomic and immunohistochemical validation before clinical translation. Such a framework enables the identification of context-specific intervention points, whether through targeting stemness-associated transcription factors in proneural GBM or ECM-remodelling enzymes in mesenchymal GBM. It supports the rational design of biomarker-driven, combination therapies that can be adapted to the molecular context of each patient.

Our review synthesised transcriptomic data from multiple publicly available repositories and literature sources, covering 112 glioblastoma-relevant genes. Quantitative descriptive analyses were limited to the 85 genes with complete expression and functional annotations across datasets. Several significant constraints should be noted. First, while a formal meta-analysis could provide stronger statistical inference, substantial heterogeneity in patient cohorts, sequencing platforms, clinical endpoints, and reporting formats precluded reliable pooling of hazard ratios without introducing bias. We therefore adopted a qualitative synthesis supplemented with descriptive statistics to preserve methodological rigour. Second, the functional characterisation of many genes, particularly long non-coding RNAs and less-studied transcriptional regulators, remains incomplete, underscoring the need for additional mechanistic and preclinical validation. Third, discrepancies between mRNA abundance and protein levels, as seen for genes such as EGFR, PDGFRA, and VEGFA, highlight the importance of incorporating proteomic and immunohistochemical data in future studies. Fourth, glioblastoma’s pronounced inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity complicates the generalisation of transcriptomic signatures across all patient populations. Finally, although we have provided subtype-specific visualisations, further integrative multi-omics profiling, functional assays, and clinically annotated datasets will be essential to translate these molecular insights into robust, subtype-tailored therapeutic strategies.

This comprehensive analysis highlights the intricate molecular landscape of glioblastoma, characterised by dysregulation of stemness pathways, immune evasion mechanisms, extracellular matrix remodelling, metabolic reprogramming, and key signalling networks. Genes such as VEGFA, PD-L1, PIK3CD, PRMT5, and STAT3 emerge as central nodes driving glioblastoma progression and therapeutic resistance. Novel candidates, including OXCT1-AS1, SRC-1, and WNT9B, represent emerging targets with potential to complement existing therapies. These findings underscore the critical need for biomarker-driven, combinatorial treatment strategies to improve glioblastoma outcomes.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Amber Hassan, Maher Kurdi; Data collection: Amber Hassan; Analysis and interpretation of results: Amber Hassan, Badr Hafiz, Taghreed Alsinani; Draft manuscript preparation: Rakan Bokhari, Dahlia Mirdad; Review and approval: All authors (Amber Hassan, Badr Hafiz, Taghreed Alsinani, Rakan Bokhari, Dahlia Mirdad, Awab Tayyib, Alaa Alkhotani, Ahmad Fallata, Iman Mirza, Eyad Faizo, Saleh Baeesa, Huda Alghefari, Maher Kurdi). All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/or.2025.070031/s1.

Abbreviations

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| CGGA | Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| FGFR3 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| GSC | Glioma stem cell |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha |

| IDH | Isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MET | Mesenchymal-epithelial transition |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PDGFRA | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PRMT5 | Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TAM | Tumour-associated macrophage |

| TAP | Transporter associated with antigen processing |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TERT | Telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TIL | Tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 |

| TRIM8 | Tripartite motif containing 8 |

| USP9X | Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 9 X-linked |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

Appendix A

References

1. D’Alessio A, Proietti G, Sica G, Scicchitano BM. Pathological and molecular features of glioblastoma and its peritumoral tissue. Cancers. 2019;11(4):469. doi:10.3390/cancers11040469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Ostrom QT, Cote D. Epidemiology of brain tumors. Neurol Clin. 2018;36(3):395–419. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2018.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231–51. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M, Le Rhun E, Tonn JC, Minniti G, et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(3):170–86. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-00447-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lasorella A, Sanson M, Iavarone A. FGFR-TACC gene fusions in human glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(4):475–83. doi:10.1093/neuonc/now240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Verhaak RGW, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):98–110. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2014;157(3):753. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Roura AJ, Gielniewski B, Pilanc P, Szadkowska P, Maleszewska M, Krol SK, et al. Identification of the immune gene expression signature associated with recurrence of high-grade gliomas. J Mol Med. 2021;99(2):241–55. doi:10.1007/s00109-020-02005-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Reifenberger G, Reifenberger J, Ichimura K, Collins VP. Amplification at 12q13-14 in human malignant gliomas is frequently accompanied by loss of heterozygosity at loci proximal and distal to the amplification site. Cancer Res. 1995;55(4):731–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Ramos TDP, Amorim LMF. Molecular biology techniques for loss of heterozygosity detection: the glioma example. J Brasileiro De Patologia E Med Lab. 2015;51(3):189–96. doi:10.5935/1676-2444.20150033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Labani-Motlagh A, Ashja-Mahdavi M, Loskog A. The tumor microenvironment: a milieu hindering and obstructing antitumor immune responses. Front Immunol. 2020;11:940. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kurdi M, Alkhotani A, Sabbagh A, Faizo E, Lary AI, Bamaga AK, et al. The interplay mechanism between IDH mutation, MGMT-promoter methylation, and PRMT5 activity in the progression of grade 4 astrocytoma: unraveling the complex triad theory. Oncol Res. 2024;32(6):1037–45. doi:10.32604/or.2024.051112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Jiapaer S, Furuta T, Tanaka S, Kitabayashi T, Nakada M. Potential strategies overcoming the temozolomide resistance for glioblastoma. Neurol Med Chir. 2018;58(10):405–21. doi:10.2176/nmc.ra.2018-0141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Okamoto T, Mizuta R, Takahashi Y, Otani Y, Sasaki E, Horio Y, et al. Genomic landscape of glioblastoma without IDH somatic mutation in 42 cases: a comprehensive analysis using RNA sequencing data. J Neurooncol. 2024;167(3):489–99. doi:10.1007/s11060-024-04628-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Besselink N, Keijer J, Vermeulen C, Boymans S, de Ridder J, van Hoeck A, et al. The genome-wide mutational consequences of DNA hypomethylation. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6874. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33932-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Xiao K, Lai Y, Yuan W, Li S, Liu X, Xiao Z, et al. mRNA-based chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy: basic principles, recent advances and future directions. Interdiscip Med. 2024;2(1):e20230036. doi:10.1002/INMD.20230036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Raviram R, Raman A, Preissl S, Ning J, Wu S, Koga T, et al. Integrated analysis of single-cell chromatin state and transcriptome identified common vulnerability despite glioblastoma heterogeneity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(20):e2210991120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2210991120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Z, Tang W, Yuan J, Qiang B, Han W, Peng X. Integrated analysis of RNA-binding proteins in glioma. Cancers. 2020;12(4):892. doi:10.3390/cancers12040892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cencioni C, Scagnoli F, Spallotta F, Nasi S, Illi B. The superoncogene myc at the crossroad between metabolism and gene expression in glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):4217. doi:10.3390/ijms24044217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hersh AM, Gaitsch H, Alomari S, Lubelski D, Tyler BM. Molecular pathways and genomic landscape of glioblastoma stem cells: opportunities for targeted therapy. Cancers. 2022;14(15):3743. doi:10.3390/cancers14153743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell. 2016;165(3):535–50. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Majc B, Novak M, Kopitar-Jerala N, Jewett A, Breznik B. Immunotherapy of glioblastoma: current strategies and challenges in tumor model development. Cells. 2021;10(2):265. doi:10.3390/cells10020265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu X, Liu Y, Qi Y, Huang Y, Hu F, Dong F, et al. Signal pathways involved in the interaction between tumor-associated macrophages/TAMs and glioblastoma cells. Front Oncol. 2022;12:822085. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.822085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Buccitelli C, Selbach M. mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21(10):630–44. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0258-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lin XB, Jiang L, Ding MH, Chen ZH, Bao Y, Chen Y, et al. Anti-tumor activity of phenoxybenzamine hydrochloride on malignant glioma cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(3):2901–8. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-4102-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Man KH, Wu Y, Gao Z, Spreng AS, Keding J, Mangei J, et al. SOX10 mediates glioblastoma cell-state plasticity. EMBO Rep. 2024;25(11):5113–40. doi:10.1038/s44319-024-00258-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Stevanovic M, Kovacevic-Grujicic N, Mojsin M, Milivojevic M, Drakulic D. SOX transcription factors and glioma stem cells: choosing between stemness and differentiation. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13(10):1417–45. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v13.i10.1417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Garros-Regulez L, Garcia I, Carrasco-Garcia E, Lantero A, Aldaz P, Moreno-Cugnon L, et al. Targeting SOX2 as a therapeutic strategy in glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2016;6(4):222. doi:10.3389/fonc.2016.00222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shafi O, Siddiqui G. Tracing the origins of glioblastoma by investigating the role of gliogenic and related neurogenic genes/signaling pathways in GBM development: a systematic review. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):146. doi:10.1186/s12957-022-02602-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Fu RZ, Cottrell O, Cutillo L, Rowntree A, Zador Z, Wurdak H, et al. Identification of genes with oscillatory expression in glioblastoma: the paradigm of SOX2. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):2123. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-51340-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Vora P, Venugopal C, Salim SK, Tatari N, Bakhshinyan D, Singh M, et al. The rational development of CD133-targeting immunotherapies for glioblastoma. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26(6):832–44.e6. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2020.04.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhou Y, He Q, Huang G, Ouyang P, Wang H, Deng J, et al. Malignant cells beyond the tumor core: the non-negligible factor to overcome the refractory of glioblastoma. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2025;31(3):e70333. doi:10.1111/cns.70333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Baroni M, Yi C, Choudhary S, Lei X, Kosti A, Grieshober D, et al. Musashi1 contribution to glioblastoma development via regulation of a network of DNA replication, cell cycle and division genes. Cancers. 2021;13(7):1494. doi:10.3390/cancers13071494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ghosh N, Chatterjee D, Datta A. Tumor heterogeneity and resistance in glioblastoma: the role of stem cells. Apoptosis. 2025;30(7–8):1695–729. doi:10.1007/s10495-025-02123-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Moon DO. The role of MELK in cancer and its interactions with non-coding RNAs: implications for therapeutic strategies. Bull Cancer. 2025;112(1):35–53. doi:10.1016/j.bulcan.2024.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wu Y, Fletcher M, Gu Z, Wang Q, Costa B, Bertoni A, et al. Glioblastoma epigenome profiling identifies SOX10 as a master regulator of molecular tumour subtype. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6434. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20225-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kim Y, You JH, Ryu Y, Park G, Lee U, Moon HE, et al. ELAVL2 loss promotes aggressive mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma. npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):79. doi:10.1038/s41698-024-00566-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bhargava S, Patil V, Mahalingam K, Somasundaram K. Elucidation of the genetic and epigenetic landscape alterations in RNA binding proteins in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(10):16650–68. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.14287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Filippova N, Nabors LB. ELAVL1 role in cell fusion and tunneling membrane nanotube formations with implication to treat glioma heterogeneity. Cancers. 2020;12(10):3069. doi:10.3390/cancers12103069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Chen P, Wang H, Zhang Y, Qu S, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Construction of a prognostic model for mitochondria and macrophage polarization correlation in glioma based on single-cell and transcriptome sequencing. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30(11):e70083. doi:10.1111/cns.70083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhong C, Yu Q, Peng Y, Zhou S, Liu Z, Deng Y, et al. Novel LncRNA OXCT1-AS1 indicates poor prognosis and contributes to tumorigenesis by regulating miR-195/CDC25A axis in glioblastoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):123. doi:10.1186/s13046-021-01928-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Yang D, Li H, Chen Y, Li C, Ren W, Huang Y. A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of BCL7B: a potential biomarker for prognosis and immunotherapy. Front Genet. 2022;13:906174. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.906174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Gao XY, Zang J, Zheng MH, Zhang YF, Yue KY, Cao XL, et al. Temozolomide treatment induces HMGB1 to promote the formation of glioma stem cells via the TLR2/NEAT1/wnt pathway in glioblastoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:620883. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.620883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Odrzywolski A, Jarosz B, Kiełbus M, Telejko I, Ziemianek D, Knaga S, et al. Profiling glioblastoma cases with an expression of DCX, OLIG2 and NES. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13217. doi:10.3390/ijms222413217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Luo D, Luo A, Ye G, Li D, Hu S, Zhao H, et al. Regulation of a novel circATP8B4/miR-31-5p/nestin CeRNA crosstalk in proliferation, motility, invasion and radiosensitivity of human glioma cells. J Radiat Res. 2024;65(6):752–64. doi:10.1093/jrr/rrae064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chen X, Hu L, Yang H, Ma H, Ye K, Zhao C, et al. DHHC protein family targets different subsets of glioma stem cells in specific niches. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):25. doi:10.1186/s13046-019-1033-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Tang F, Liu Z, Chen X, Yang J, Wang Z, Li Z. Current knowledge of protein palmitoylation in gliomas. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(11):10949–59. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07809-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Tang B, Kang W, Dong Q, Qin Z, Duan L, Zhao X, et al. Research progress on S-palmitoylation modification mediated by the ZDHHC family in glioblastoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1413708. doi:10.3389/fcell.2024.1413708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Tufano M, D’Arrigo P, D’Agostino M, Giordano C, Marrone L, Cesaro E, et al. PD-L1 expression fluctuates concurrently with cyclin D in glioblastoma cells. Cells. 2021;10(9):2366. doi:10.3390/cells10092366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhou J, Pei X, Yang Y, Wang Z, Gao W, Ye R, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor TLX promotes immunosuppression via its transcriptional activation of PD-L1 in glioma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(4):e001937. doi:10.1136/jitc-2020-001937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Berghoff AS, Kiesel B, Widhalm G, Rajky O, Ricken G, Wöhrer A, et al. Programmed death ligand 1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(8):1064–75. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Salem RA, Nabegh LM, Abu-Zeid RM, Abd Raboh NM, El-Rashedy M. Evaluation of programmed death ligand-1 immunohistochemical expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in different types of endometrial carcinoma. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2022;10(A):702–8. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2022.9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Tang F, Zhao YH, Zhang Q, Wei W, Tian SF, Li C, et al. Impact of beta-2 microglobulin expression on the survival of glioma patients via modulating the tumor immune microenvironment. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(8):951–62. doi:10.1111/cns.13649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang H, Cui B, Zhou Y, Wang X, Wu W, Wang Z, et al. B2M overexpression correlates with malignancy and immune signatures in human gliomas. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5045. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84465-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Butt NS, Kurdi M, Fadul MM, Hakamy S, Addas BMJ, Faizo E, et al. Major Histocompatibility Class-I (MHC-I) downregulation in glioblastoma is a poor prognostic factor but not a predictive indicator for treatment failure. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;250(8):154816. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2023.154816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Burster T, Gärtner F, Bulach C, Zhanapiya A, Gihring A, Knippschild U. Regulation of MHC I molecules in glioblastoma cells and the sensitizing of NK cells. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(3):236. doi:10.3390/ph14030236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zhang SY, Li JL, Xu XK, Zheng MG, Wen CC, Li FC. HMME-based PDT restores expression and function of transporter associated with antigen processing 1 (TAP1) and surface presentation of MHC class I antigen in human glioma. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(2):199–210. doi:10.1007/s11060-011-0584-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wu AH, Wang YJ, Zhang X, Low W. Expression of immune-related molecules in glioblastoma multiform cells. Chin J Cancer Res. 2003;15(2):112–5. doi:10.1007/bf02974912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Berberich A, Bartels F, Tang Z, Knoll M, Pusch S, Hucke N, et al. LAPTM5-CD40 crosstalk in glioblastoma invasion and temozolomide resistance. Front Oncol. 2020;10:747. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Wischhusen J, Schneider D, Mittelbronn M, Meyermann R, Engelmann H, Jung G, et al. Death receptor-mediated apoptosis in human malignant glioma cells: modulation by the CD40/CD40L system. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;162(1–2):28–42. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.01.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Qian K, Li G, Zhang S, Fu W, Li T, Zhao J, et al. CAR-T-cell products in solid tumors: progress, challenges, and strategies. Interdiscip Med. 2024;2(2):e20230047. doi:10.1002/INMD.20230047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Wang H, Yang J, Li X, Zhao H. Current state of immune checkpoints therapy for glioblastoma. Heliyon. 2024;10(2):e24729. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Skadborg SK, Maarup S, Draghi A, Borch A, Hendriksen S, Mundt F, et al. Nivolumab reaches brain lesions in patients with recurrent glioblastoma and induces T-cell activity and upregulation of checkpoint pathways. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12(9):1202–20. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-23-0959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Raj D, Agrawal P, Gaitsch H, Wicks E, Tyler B. Pharmacological strategies for improving the prognosis of glioblastoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2021;22(15):2019–31. doi:10.1080/14656566.2021.1948013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Jang BS, Kim IA. A radiosensitivity gene signature and PD-L1 status predict clinical outcome of patients with glioblastoma multiforme in the cancer genome atlas dataset. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52(2):530–42. doi:10.4143/crt.2019.440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zhao W, Zhang Z, Xie M, Ding F, Zheng X, Sun S, et al. Exploring tumor-associated macrophages in glioblastoma: from diversity to therapy. npj Precis Oncol. 2025;9(1):126. doi:10.1038/s41698-025-00920-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Zhang Y, He H, Fu X, Liu G, Wang H, Zhong W, et al. Glioblastoma-associated macrophages in glioblastoma: from their function and mechanism to therapeutic advances. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025;32(6):595–607. doi:10.1038/s41417-025-00905-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Mohme M, Schliffke S, Maire CL, Rünger A, Glau L, Mende KC, et al. Immunophenotyping of newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastoma defines distinct immune exhaustion profiles in peripheral and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(17):4187–200. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Lee S, Weiss T, Bühler M, Mena J, Lottenbach Z, Wegmann R, et al. Targeting tumour-intrinsic neural vulnerabilities of glioblastoma. bioRxiv. 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.10.07.511321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Shah S. Novel therapies in glioblastoma treatment: review of glioblastoma; current treatment options; and novel oncolytic viral therapies. Med Sci. 2023;12(1):1. doi:10.3390/medsci12010001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Medikonda R, Abikenari M, Schonfeld E, Lim M. The metabolic orchestration of immune evasion in glioblastoma: from molecular perspectives to therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancers. 2025;17(11):1881. doi:10.3390/cancers17111881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zhang H, Chen Y. Identification of glioblastoma immune subtypes and immune landscape based on a large cohort. Hereditas. 2021;158(1):30. doi:10.1186/s41065-021-00193-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Gilbertson RJ, Clifford SC. PDGFRB is overexpressed in metastatic medulloblastoma. Nat Genet. 2003;35(3):197–8. doi:10.1038/ng1103-197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Blouw B, Song H, Tihan T, Bosze J, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, et al. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(2):133–46. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00194-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Alves B, Peixoto J, Macedo S, Pinheiro J, Carvalho B, Soares P, et al. High VEGFA expression is associated with improved progression-free survival after bevacizumab treatment in recurrent glioblastoma. Cancers. 2023;15(8):2196. doi:10.3390/cancers15082196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Lu-Emerson C, Dan GD, Emblem KE, Taylor JW, Gerstner ER, Loeffler JS, et al. Lessons from anti-vascular endothelial growth factor and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor trials in patients with glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(10):1197–213. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.9575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Ballato M, Germanà E, Ricciardi G, Giordano WG, Tralongo P, Buccarelli M, et al. Understanding neovascularization in glioblastoma: insights from the current literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(6):2763. doi:10.3390/ijms26062763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Nakada M, Hayashi Y, Hamada JI. Role of Eph/ephrin tyrosine kinase in malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(11):1163–70. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nor102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Bhatia S, Bukkapatnam S, Van Court B, Phan A, Oweida A, Gadwa J, et al. The effects of ephrinB2 signaling on proliferation and invasion in glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59(9):1064–75. doi:10.1002/mc.23237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Horta M, Soares P, Leite Pereira C, Lima RT. Emerging approaches in glioblastoma treatment: modulating the extracellular matrix through nanotechnology. Pharmaceutics. 2025;17(2):142. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17020142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Marino S, Menna G, Di Bonaventura R, Lisi L, Mattogno P, Figà F, et al. The extracellular matrix in glioblastomas: a glance at its structural modifications in shaping the tumoral microenvironment—a systematic review. Cancers. 2023;15(6):1879. doi:10.3390/cancers15061879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Barbosa LC, Machado GC, Heringer M, Ferrer VP. Identification of established and novel extracellular matrix components in glioblastoma as targets for angiogenesis and prognosis. Neurogenetics. 2024;25(3):249–62. doi:10.1007/s10048-024-00763-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Nakano A, Tani E, Miyazaki K, Yamamoto Y, Furuyama J. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in human gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(2):298–307. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Lu KV, Jong KA, Rajasekaran AK, Cloughesy TF, Mischel PS. Upregulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2 promotes matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 activation and cell invasion in a human glioblastoma cell line. Lab Invest. 2004;84(1):8–20. doi:10.1038/sj.labinvest.3700003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Yin W, Zhu H, Tan J, Xin Z, Zhou Q, Cao Y, et al. Identification of collagen genes related to immune infiltration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioma. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):276. doi:10.1186/s12935-021-01982-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Morrison C, Weterings E, Gravbrot N, Hammer M, Weinand M, Sanan A, et al. Gene expression patterns associated with survival in glioblastoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3668. doi:10.3390/ijms25073668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Chen CH, Chen PY, Lin YY, Feng LY, Chen SH, Chen CY, et al. Suppression of tumor growth via IGFBP3 depletion as a potential treatment in glioma. J Neurosurg. 2020;132(1):168–79. doi:10.3171/2018.8.JNS181217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. DeSisto JA, Flannery P, Lemma R, Pathak A, Mestnik S, Philips N, et al. Exportin 1 inhibition induces nerve growth factor receptor expression to inhibit the NF-κB pathway in preclinical models of pediatric high-grade glioma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19(2):540–51. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-1319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Vassallo I, Zinn P, Lai M, Rajakannu P, Hamou MF, Hegi ME. WIF1 re-expression in glioblastoma inhibits migration through attenuation of non-canonical WNT signaling by downregulating the lncRNA MALAT1. Oncogene. 2016;35(1):12–21. doi:10.1038/onc.2015.61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Zhu H, Hu X, Feng S, Jian Z, Xu X, Gu L, et al. The hypoxia-related gene COL5A1 is a prognostic and immunological biomarker for multiple human tumors. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022(1):6419695. doi:10.1155/2022/6419695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Kohata T, Ito S, Masuda T, Furuta T, Nakada M, Ohtsuki S. Laminin subunit alpha-4 and osteopontin are glioblastoma-selective secreted proteins that are increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of glioblastoma patients. J Proteome Res. 2020;19(8):3542–53. doi:10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Ma Y, Nenkov M, Schröder DC, Abubrig M, Gassler N, Chen Y. Fibulin 2 is hypermethylated and suppresses tumor cell proliferation through inhibition of cell adhesion and extracellular matrix genes in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11834. doi:10.3390/ijms222111834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Qi C, Lei L, Hu J, Ou S. Establishment and validation of a novel integrin-based prognostic gene signature that sub-classifies gliomas and effectively predicts immunosuppressive microenvironment. Cell Cycle. 2023;22(10):1259–83. doi:10.1080/15384101.2023.2205204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]