Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Organoid Technology in Precision Medicine for Head and Neck Cancer

1 Beijing Tongren Hospital, Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Capital Medical University, Beijing, 100730, China

2 Key Laboratory of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (Capital Medical University), Ministry of Education, Beijing, 100005, China

3 Translational Radiation Oncology Research Laboratory, Department of Radiooncology and Radiotherapy, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin), Berlin, 10117, Germany

4 Experimental Surgery, Department of Surgery, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Campus Charité Mitte Campus Virchow-Klinikum, Affiliated with Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin), Berlin, 13353, Germany

* Corresponding Author: Yang Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancing Cellular Therapeutics in Oncology: Innovations, Challenges, and Clinical Translation)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(12), 3633-3656. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.071296

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 04 October 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Organoid technology, characterized by high fidelity in mimicking the in vivo microenvironment, preservation of tumor heterogeneity, and capacity for high-throughput operations, has emerged as a critical tool in head and neck cancer research. To address clinical challenges in head and neck cancer management—including marked tumor heterogeneity, therapeutic resistance, and significant prognostic variability—this review focuses on four key translational applications of organoid technology: In mechanistic studies, organoid models provide a reliable platform for investigating tumorigenesis, progression, and drug resistance mechanisms. In personalized therapy, organoid-based drug sensitivity testing enables data-driven clinical decision-making. For biomarker discovery, organoids facilitate the identification of novel diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets. With ongoing improvements and standardization of organoid culture systems, this technology holds substantial promise for advancing precision medicine in head and neck cancer, bridging the gap between basic research and clinical practice.Keywords

Head and neck cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies globally, with over 900,000 new cases diagnosed annually and a five-year survival rate below 50%. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) accounts for the majority of these cases [1]. While combined modalities of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy have improved patient outcomes to some extent, clinical management remains challenged by several critical issues. First, chemoradiotherapy resistance is widespread: approximately 60% of patients with locally advanced disease (Stage III/IV) develop resistance to cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy, leading to treatment failure [2]. Second, pronounced tumor heterogeneity exists, whereby cells from distinct regions of the same tumor exhibit marked variations in genomic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental characteristics, hindering precision therapy. Additionally, the lack of reliable individualized efficacy prediction models impedes clinicians from tailoring optimal treatment strategies for specific patients. These challenges underscore the urgent need for innovative research models and precision therapeutic approaches [3,4].

Traditional research models, such as cell lines and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), have contributed to head and neck cancer research but possess inherent limitations. Cell lines lose primary tumor heterogeneity due to long-term in vitro passaging, while PDX models are time-consuming, costly, and fail to preserve the human immune microenvironment, and involve animal ethical restrictions due to reliance on immunodeficient animals for tumor transplantation [5]. Organoids, defined as three-dimensional (3D) in vitro culture systems derived from stem or progenitor cells (adult or pluripotent), exhibit self-organization capacity to recapitulate the structural architecture, cellular composition, and partial physiological functions of their corresponding in vivo organs [6]. For normal organoids across different tissues, they maintain tissue-specific differentiation characteristics: for example, normal salivary gland organoids form acinar-like and duct-like structures that can secrete amylase [7], while normal thyroid organoids retain follicular structures and iodine uptake ability [8]. In contrast, pathologic organoids (especially cancer organoids) are established from tumor tissues or cancer stem cells, and they preserve key malignant features of the original tumor, including histological heterogeneity, patient-specific genetic mutations, and responsiveness to therapeutic agents [5]. Notably, cancer organoids differ from normal organoids in their uncontrolled proliferation, disrupted tissue polarity, and ability to simulate tumor-stromal interactions within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [7]. Furthermore, organoids support high-throughput drug screening and real-time dynamic monitoring, providing a unique platform for studying tumor biology and developing personalized treatment strategies [9–11]. Fine-needle aspiration has been proposed as a minimally invasive method to establish organoids directly from patient tumors, preserving native tissue growth patterns and immune cell infiltration, thereby offering more physiologically relevant models for high-throughput drug screening and immunotherapy evaluation [12].

To date, various head and neck cancer organoid models have been successfully developed. Taking the establishment of organoids for three common types of head and neck tumors as examples, the establishment of these three head and neck cancer organoids all uses Matrigel as the matrix, contains Y-27632 (a Rho-Associated Protein Kinase [ROCK] inhibitor) in the culture medium, and requires cryopreservation and verification of consistency between the organoids and the original tumor. However, their key differences are as follows: In terms of dissociation, papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) uses collagenase type II combined with DNase I [13]; salivary gland cancer employs Liberase TM (research grade) and hyaluronidase [14]; HNSCC adopts enzymatic dissociation combined with mechanical dissociation [9]. Regarding the culture medium, PTC uses AdDMEM/F12 as the basal medium, supplemented with N-acetyl-L-cysteine, fibroblast growth factor-7/10 (FGF-7/10), SB202190 (a p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase [MAPK] inhibitor), and other relevant components; salivary gland cancer uses complete medium (with Y-27632 supplemented during passage); HNSCC uses Advanced DMEM as the basal medium, containing B27 cell supplement, FGF-b, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and Forskolin. In addition, the HNSCC medium requires the additional addition of 50% L-WRN conditioned medium (containing Wnt Family Member 3a [Wnt3a], R-Spondin 3 [RSPO3], and Noggin proteins), 10% R-Spondin 1 [RSPO1] conditioned medium, and 100 μg/mL Primocin (for contamination prevention). Scheemaeker et al. developed the first canine medullary thyroid carcinoma organoid model, with Single-nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) genotyping validating its homology to the primary tumor [15]. Millen et al. established the largest head and neck cancer organoid biobank, comprising over 100 organoids from distinct patients—each linked to patients by tumor type (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma), TNM stage (e.g., T2N0M0), and location (e.g., oral cavity)—with a 71% recovery and expansion rate post-cryopreservation [16]. They also generated organoid models for two rare head and neck cancers and four salivary gland subtypes, validated via SNP genotyping (genetic homology), Whole-Exome Sequencing/Next-Generation Sequencing (WES/NGS) (molecular features), and retention of subtype-specific histology (e.g., salivary duct carcinoma’s cribriform structures). By comparing responses of 31 organoids to six targeted drugs, they observed marked inter-donor variability even with known actionable mutations, highlighting the potential of organoid cohorts in identifying drug-specific responders. Notably, radiosensitive organoids from 15 patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy exhibited a significant correlation with longer recurrence-free survival [17]. Yang et al. demonstrated that papillary thyroid carcinoma organoids retain features of the original tumors, providing a novel preclinical model for research [13]. Mouse embryonic stem cell-derived salivary gland organoids, resembling embryonic salivary glands, serve as valuable tools for studying gland development and diseases [18]. Aizawa et al. established organoid models for multiple histological subtypes of human salivary gland cancers, including salivary duct carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and myoepithelial carcinoma; these models preserved original tumor histological features (e.g., cribriform structures in salivary duct carcinoma and cystic patterns in mucoepidermoid carcinoma) during passaging [14]. Tran et al. demonstrated that salivary gland-specific extracellular matrix-induced bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressed various epithelial markers and exhibited morphology and ultrastructure similar to those of salivary glands. When implanted under the renal capsule of immunodeficient mice for 30 days, these aggregates formed functional salivary gland organoids expressing tissue-specific markers [19]. Zhang et al. successfully generated esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) patient-derived xenografts and their corresponding organoids [20], while Takada et al. developed patient-derived adenoid cystic carcinoma organoids [21].

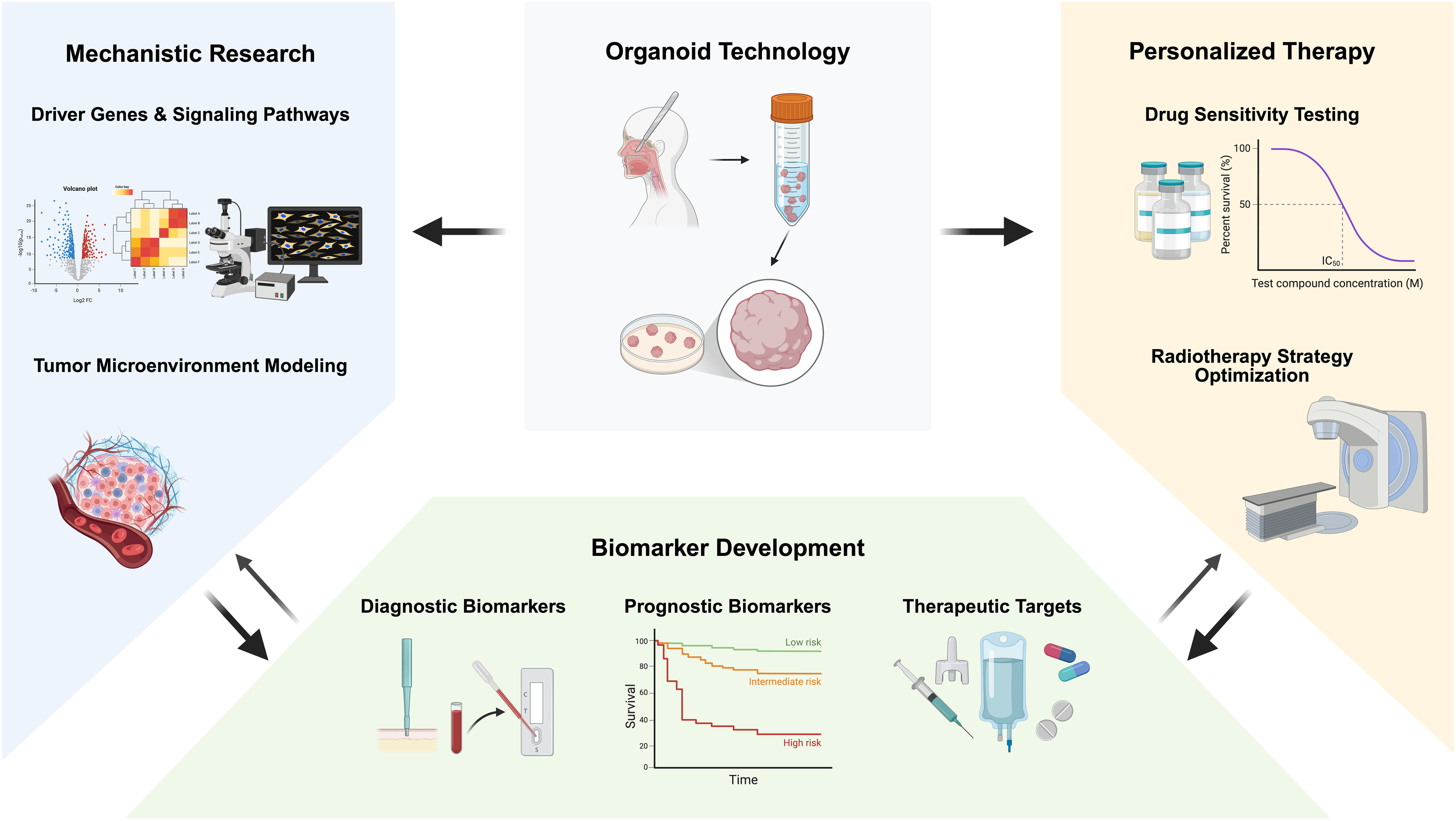

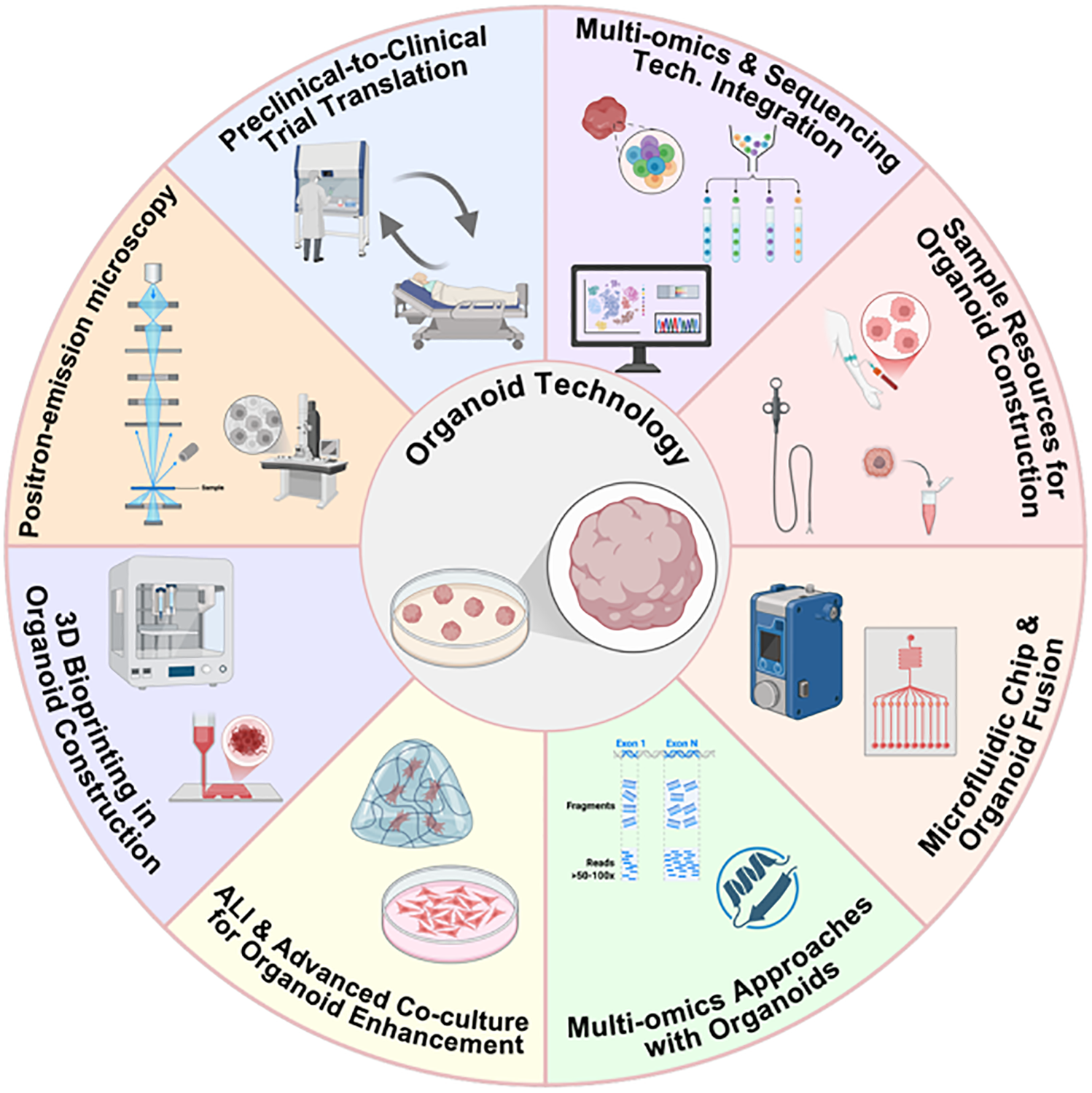

This review systematically analyzes the translational value of organoid technology in head and neck cancer research, focusing on applications in mechanistic studies, personalized treatment decisions, and biomarker development. It also discusses current challenges in standardized culturing, genetic stability, and clinical translation, while envisioning integration of organoids with cutting-edge technologies such as single-cell sequencing and microfluidic chips. The overall framework of this review, encompassing its key focuses and aims, is summarized in Fig. 1; specifically, the framework centers on three core application directions of organoids and two key thematic discussions. The three application directions include: 1) the use of organoids in head and neck cancer pathogenesis research (covering functional validation of driver genes and tumor microenvironment simulation); 2) the enabling role of organoids in personalized therapy (including drug sensitivity testing and chemoradiotherapy sensitization/protection); 3) the promotional value of organoids in biomarker discovery (involving diagnostic biomarkers, prognostic biomarkers, and therapeutic targets). The two key thematic discussions refer to the existing challenges of organoid technology (standardized culturing, genetic stability, clinical translation) and future integration directions (combination with cutting-edge technologies like single-cell sequencing and microfluidic chips). Its aim is to provide theoretical foundations and practical guidance for advancing precision medicine paradigms in head and neck cancer.

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of applications of organoids in translational medicine for head and neck cancer (This figure was created using BioRender, available at https://biorender.com/; developed by BioRender Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada)

2 Role of Organoids in Exploring the Pathogenesis of Head and Neck Tumors

2.1 Functional Validation of Driver Genes

Organoid models serve as an optimal research platform for functional validation of driver genes in head and neck cancers. By precisely simulating the tumor microenvironment and preserving the molecular features of primary tumors, organoid technology allows researchers to dissect the mechanisms of key oncogenes under near-physiological conditions. In recent years, multiple studies using this model have systematically validated the functions of various driver genes in head and neck carcinogenesis, yielding critical insights into tumor pathogenesis.

In esophageal cancer research, Klf5 has been shown to promote ESCC transformation by regulating Sox2 binding sites—specifically, it physically interacts with Sox2, guides Sox2 to newly opened chromatin regions and de novo super-enhancers (which drive the expression of oncogenes such as STAT3), stabilizes Sox2’s binding to these de novo sites, and forms a positive feedback loop with Sox2 (where Sox2 activates Klf5 transcription, and Klf5 in turn reinforces Sox2’s oncogenic binding activity). When combined with Trp53/Cdkn2a deletion, Sox2 can induce tumor formation from mouse esophageal organoids in vivo [22,23]. Ko et al. further employed Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 technology to demonstrate that dual knockout of Trp53 and Notch1 alone induces esophageal neoplasia, characterized by increased proliferation and loss of differentiation. Notably, simultaneous knockout of Trp53, Cdkn2a, and Notch1 yielded more aggressive tumors that recruited myeloid cells via Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand 2 (CCL2) secretion to form an immunosuppressive microenvironment, facilitating immune evasion [24]. Sun et al. elucidated the synergistic oncogenic interaction between CDKN2A-p16 deletion and KRASG12D activation, which significantly accelerates the progression from Barrett’s esophagus to dysplasia and activates multiple oncogenic pathways, including MAPK [25].

In salivary gland tumor research, Agaimy et al. identified a distinct KRAS codon 12 mutation subgroup in metaplastic Warthin tumors. Through systematic analysis of 22 cases, the researchers proposed reclassifying these tumors as “de novo proliferative Warthin tumors” with distinct neoplastic features, rather than traditional metaplastic lesions [26]. This discovery not only refined the molecular classification of the disease but also provided novel theoretical bases for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Notable advances have also been achieved in thyroid cancer research. The BrafV637E mutation has been confirmed to rapidly activate MAPK signaling, leading to cell dedifferentiation and disruption of follicular structures. This mutation induces downregulation of thyroid differentiation markers and enhanced proliferation, ultimately generating organoid models with characteristic thyroid cancer features [27]. Additionally, analysis of malignant teratoid tumors of the thyroid identified DICER1 “hotspot” mutations and TP53 missense variants, supporting the redefinition of these tumors as “thyroblastomas” [28]. Chen et al. further validated BRAFV600E’s role in 9 patient-derived PTC organoids (5 with BRAFV600E, PTC’s most common driver mutation), which stably cultured for >3 months and recapitulated parental tumors’ histology and mutations—confirming organoid BRAF mutations mirror clinical PTC characteristics. Clinically, this has translational value: for the 20% of PTC patients with recurrence/metastasis post-conventional therapy, BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) alone showed mild efficacy in organoids (consistent with clinical observations), while combining them with MEK/RTK inhibitors or chemotherapeutics improved efficacy, providing preclinical evidence for guiding clinical targeted combinations [29].

These studies have systematically elucidated the functions of multiple key driver genes in head and neck carcinogenesis via organoid models. Across esophageal, salivary gland, and thyroid cancers, research teams have utilized organoid technology to reveal how driver gene mutations regulate tumor biology through specific signaling pathways. These findings not only deepen our understanding of head and neck cancer pathogenesis but also establish theoretical foundations for designing targeted therapeutic strategies. With ongoing advancements in organoid technology, its application potential in driver gene functional studies and personalized medicine is poised to expand further.

2.2 Tumor Microenvironment Modeling

Research on tumor microenvironment simulation has made groundbreaking advancements in head and neck cancer organoid models, offering novel insights into the complex interaction mechanisms between tumor cells and microenvironmental components. Through innovative organoid culture techniques, researchers can accurately recapitulate the dynamic characteristics of the tumor microenvironment, encompassing the regulatory roles of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune microenvironment features, signaling pathways, and other critical biological processes. These studies not only enhance the understanding of head and neck cancer pathogenesis but also establish a critical foundation for developing targeted therapeutic strategies targeting the tumor microenvironment.

As a key metabolite in tumor metabolism, lactate exerts intricate regulatory effects in the head and neck cancer microenvironment. Sharpe et al. obtained tumor tissues and CAFs from surgical resection specimens of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) patients, subsequently culturing the tumor tissues into organoids. Through co-culturing CAFs and tumor organoids at a 2:1 ratio to form assembloids, RNA sequencing analysis revealed high expression of hypoxia markers in these constructs [30]. Zhao et al. validated the role of CAFs-lactate crosstalk in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC): they isolated patient-derived OSCC organoid CD44+ cancer stem cells (via flow sorting) and co-cultured them with autologous CAFs in Matrigel, showing CAFs enhance CD44+ cell organoid-forming ability and upregulate stemness markers (CD44, OCT-4) via lactate—effects blocked by inhibiting lactate production/uptake. Key precautions include using patient-matched CAFs (to avoid heterogeneity) and ensuring CD44+ cell purity; clinically, this model recapitulates CAFs-driven OSCC recurrence-related stemness, supporting screening of lactate axis-targeted drugs [31]. Su et al. identified that lactate exerts a dual regulatory effect on EAC organoid growth: while reducing average organoid area and expression of proliferation marker Ki67, it enhances cellular heterogeneity. Mechanistic studies demonstrated that lactate inhibits glycolysis by altering the Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (Reduced Form, NADH)/Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (Oxidized Form, NAD+) redox state and may influence immune and metabolic pathways through regulation of ID1 and RSAD2 genes. Notably, pharmacological inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) reversed lactate’s suppressive effect on EAC organoid growth [32]. These findings elucidate the intricate regulatory network of lactate metabolism in head and neck cancer progression, providing novel perspectives for metabolism-targeted therapies.

Organoid technology facilitates the elucidation of immune microenvironment characteristics in head and neck cancer. Liao et al. identified unique immune features in esophageal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia via single-cell transcriptomics, including elevated Regulatory T Cells (Treg) cell counts and impaired CD8+ T cell function, which potentially facilitate immune evasion [33]. Baregamian et al. reported that co-culturing thyroid cancer organoids with T lymphocytes enhances immune cell cytokine secretion, while irradiation induces Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses [34]. Shin et al. employed organoid technology to validate trogocytosis—a process where cancer cells acquire immune cell surface markers (e.g., CD4) from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes—in PDX models of head and neck cancer [35].

Organoid technology deciphers the mechanisms by which signaling pathways within the TME regulate cancer progression. Murakami et al. compared metabolic profiles of tongue cancer cells across culture conditions and found that 3D organoid cultures better recapitulate in vivo metabolic characteristics, including enhanced glycolysis and Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle (TCA) cycle activity [36]. Zhao et al. characterized the Nicotinamide N-Methyltransferase (NNMT)-Lysyl Oxidase (LOX)-Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) regulatory axis in the OSCC microenvironment via organoid models. NNMT was significantly upregulated in OSCC-associated CAFs, with fibroblast-attached organoids partially recapitulating this phenotype. NNMT inhibition reduced CAF activation and organoid regenerative capacity, whereas its overexpression promoted regeneration. Mechanistically, NNMT facilitated tumor initiation and growth by increasing type I collagen deposition and sustaining FAK signaling to preserve cancer stemness. Epigenetically, NNMT enhanced LOX transcription through reduced histone methylation, further driving collagen deposition in the TME [37]. Zhang et al. established an organoid model demonstrating that acidic bile salts induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), potentially contributing to esophageal intestinal metaplasia [38]. Anand et al. co-cultured Barrett’s esophagus organoids with fibroblasts, showing that Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells (NF-κB) β CCL5/CCL20 levels and prevented dysplasia development [39]. Diaz et al. demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor pyrvinium markedly suppressed anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) cell lines and patient-derived ATC organoids, with enhanced efficacy in BRAFV600E-mutated organoids when used in combination with standard therapy [40]. Czerwonka et al. validated the anticancer activity of Notch modulator RIN-1 in HNSCC organoids [41].

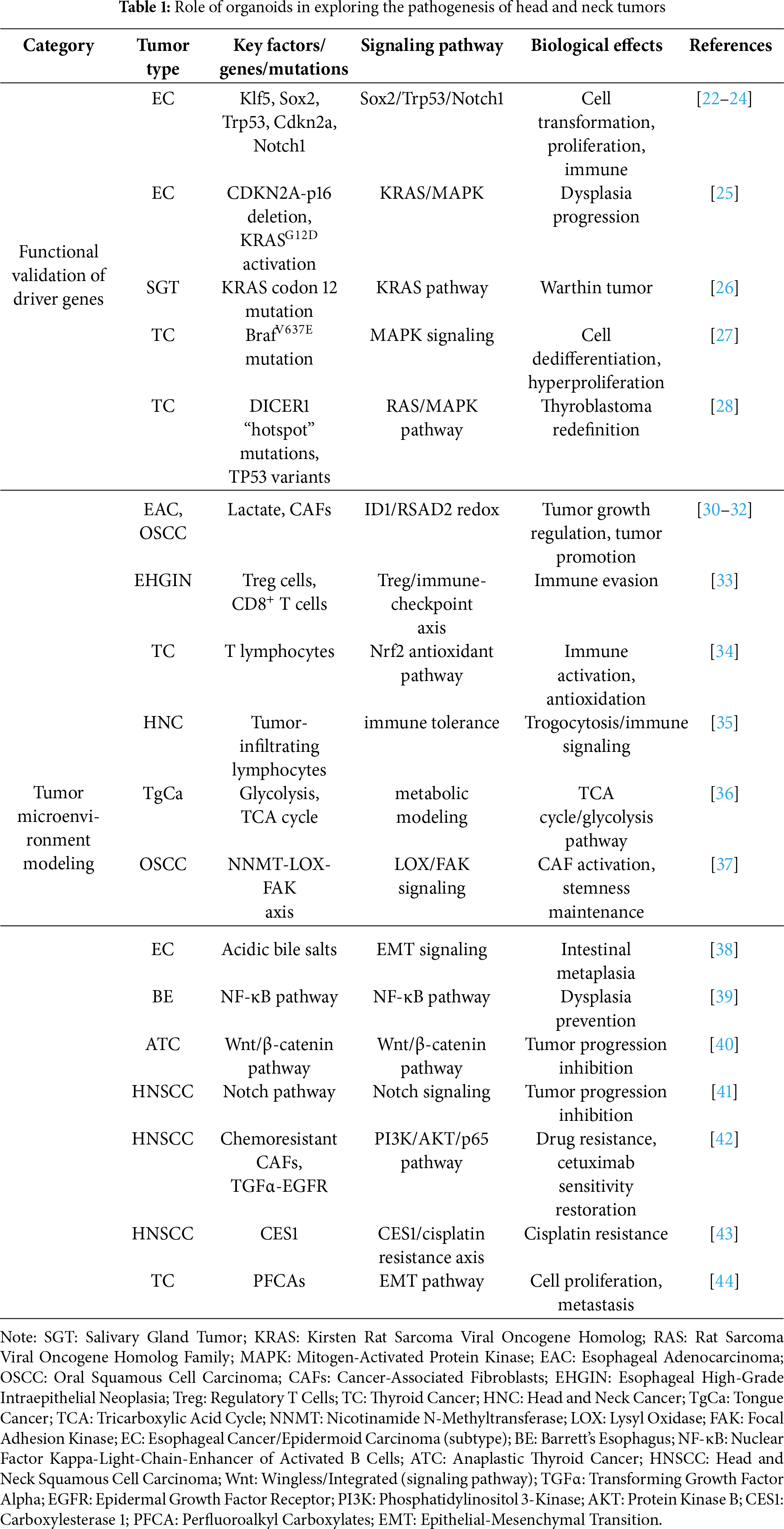

In summary, organoids are invaluable for validating driver genes and tumor-microenvironment interactions in head and neck cancer. They also facilitate deciphering chemotherapy resistance mechanisms. These roles of organoids in exploring the pathogenesis of head and neck tumors are summarized in Table 1. Su et al. employed HNSCC patient-derived organoids to demonstrate that chemotherapy-resistant CAFs promote drug resistance via Transforming Growth Factor Alpha (TGFα)-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) paracrine signaling, thereby activating Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)/Protein Kinase B (AKT)/p65 to suppress p53/caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. Cetuximab restored chemosensitivity by blocking TGFα in CAFs [42]. Jiang et al. identified carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) as a mediator of cisplatin resistance in HNSCC organoids [43]. Organoid models also enable assessment of environmental carcinogens: Yoo et al. exposed thyroid cancer organoids to perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFCAs, 10 μM) and observed decreased Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Receptor (TSHR) expression, elevated Thyroglobulin (Tg) levels, cytoplasmic relocalization of E-cadherin, upregulation of vimentin, and increased Ki-67+ cells—findings suggesting PFCAs promote proliferation and metastasis via EMT [44].

3 Role of Organoids in Establishing Therapeutic Platforms for Head and Neck Cancer

Organoid technology has demonstrated significant clinical utility in drug sensitivity testing for head and neck cancers, providing a novel research tool for developing personalized treatment strategies [45]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that head and neck cancer-derived organoids can highly recapitulate the histological characteristics and molecular profiles of primary tumors while retaining differential sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents [45,46]. For example, head and neck cancer organoids not only serve as preclinical models for predicting chemotherapy responses but also exhibit significant correlations between their drug sensitivity parameters (e.g., Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration [IC50], Half-Maximal Effective Concentration [EC50], and Area Under the Curve [AUC]) and clinical outcomes. This finding has been validated in studies employing patient-derived organoids (PDOs) of EAC treated with cisplatin and paclitaxel [46].

In the field of targeted therapy, organoid models exhibit unique heterogeneity in drug response patterns [45,47]. Although the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib has been approved for the treatment of PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer [47], studies on head and neck cancer organoids demonstrate that its efficacy does not significantly correlate with PIK3CA mutation status, suggesting that tumor type may influence targeted drug sensitivity patterns [45]. Notably, organoids with specific genetic alterations, such as CDKN2A deletion, exhibit marked sensitivity to Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) inhibitors [16], highlighting the value of organoids in identifying biomarker-drug associations. Significant progress has also been made in research on different tumor subtypes. For example, patient-derived organoid models of salivary gland carcinoma not only retain 97.6% of Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC)-annotated variants and critical gene rearrangements but also accurately reflect subtype-specific differential responses to agents such as erlotinib in adenoid cystic carcinoma [48].

Organoid research in thyroid cancer has further extended the utility of this technology in precision medicine [49]. Papillary thyroid carcinoma organoids harboring the BRAFV600E mutation not only exhibit long-term culture stability but also effectively predict the superior efficacy of BRAF/MEK inhibitor dual therapy, whereas wild-type organoids display the expected resistance profile [49]. Similarly, studies of esophageal cancer organoids have confirmed that their response patterns to cisplatin, paclitaxel, and proton beam therapy closely correlate with patient clinical outcomes. RNA sequencing has revealed gene expression heterogeneity, offering novel insights into treatment resistance mechanisms [50]. Driehuis et al. validated the utility of 31 patient-derived HNSCC organoids—recapitulating genetic and molecular traits of primary tumors (e.g., 69% TP53 mutation rate)—in drug sensitivity testing for HNSCC. Notably, in 7 patients receiving radiotherapy, organoid radiosensitivity (quantified by AUC) correlated with clinical outcomes: organoids from 3 patients with disease recurrence were among the most resistant, while radiosensitive organoids matched those from patients with sustained remission. Key strategies included covering standard HNSCC therapies (cisplatin, carboplatin, cetuximab, radiotherapy) with a significant correlation between cisplatin and carboplatin sensitivity (r = 0.64, p < 0.05), screening non-standard targeted agents (e.g., alpelisib, vemurafenib) to identify subtype-specific responses (e.g., BRAFV600E-mutant organoid T9 exhibited higher sensitivity to vemurafenib), and evaluating chemoradiation combinations (cisplatin enhanced radiotherapy efficacy in 6/10 organoid lines). For clinical translation, an HNSCC organoid biobank was established (accessible via www.hub4organoids.eu), and the observational trial ONCODE-P2018-0003 was initiated to link organoid drug/radiotherapy responses to patient outcomes, aiming to standardize the “biopsy-organoid testing-therapy selection” workflow for HNSCC [51]. Notably, a longitudinal study of salivary gland secretory carcinoma found that organoids generated pre- and post-treatment can dynamically capture acquired resistance mutations. However, discrepancies between predicted sensitivity to repotrectinib and clinical outcomes highlight the necessity of optimizing culture systems to enhance predictive accuracy [52].

Overall, organoid models exhibit substantial potential and unique technical advantages in drug testing for head and neck cancers [16,45,46,48]. From predicting chemotherapy sensitivity and screening targeted drugs to optimizing combination therapies, organoid technology provides reliable experimental evidence for clinical decision-making [49,50]. However, current studies also highlight technical challenges, including inconsistencies in predictive accuracy and variable culture success rates [52]. Future efforts should focus on optimizing microenvironmental simulation and establishing standardized protocols to enhance translational value. With the accumulation of additional clinical validation data, organoid technology is poised to become a critical decision-supportive tool for personalized treatment in head and neck cancers [45,48].

3.2 Radiosensitization and Radioprotection

Organoid models exhibit unique value in head and neck cancer radiotherapy research, serving as a critical platform for investigating radiosensitization mechanisms and developing radioprotection strategies [53]. Studies have shown that HNSCC PDOs not only retain histopathological and genomic characteristics of primary tumors but also display variations in radiation sensitivity that correlate with patient prognosis. The overall culture success rate of 35% increases to 77% in samples with ≥30% tumor cellularity, supporting the feasibility of personalized radiotherapy planning [53]. In radiosensitization research, cisplatin and carboplatin significantly augment radiotherapy efficacy, whereas cetuximab exhibits radioprotective properties—and these drug-radiation interactions are precisely quantified in organoid models [16]. Notably, AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) pathway activation diminishes radiosensitivity in EAC cells and organoids, and pharmacological inhibition of this pathway markedly enhances radiation-induced cytotoxicity, thereby identifying a molecular target for novel radiosensitizers [54].

Salivary gland radioprotection studies utilizing organoid models have yielded groundbreaking findings [10,55,56]. Compared to traditional Two-Dimensional (2D) cultures, 3D organoid systems better recapitulate the complex architecture of salivary glands, preserving cell-cell interactions and extracellular matrix synthesis, thereby providing a physiologically relevant experimental platform for investigating radiation-induced damage [55,57,58]. Radiation induces mitochondrial dysfunction in salivary gland stem/progenitor cells, characterized by reduced membrane potential, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) accumulation, and aberrant mitochondrial networks, while pharmacological activation of mitophagy markedly enhances organoid self-renewal capacity [10]. Senescent cell clearance strategies exhibit therapeutic potential: ganciclovir and ABT263 administration effectively eliminate radiation-induced senescent cells, restoring both organoid formation efficiency and secretory function [56]. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) promotes salivary gland stem cell proliferation via the mesenchymal-epithelial Transition Factor (cMET) receptor, mitigating premature senescence caused by low-dose radiation (3–7 Gy), though its reparative effects are limited in high-dose radiation-induced injury [59]. Murine parotid organoid studies further confirm the multipotent differentiation potential of acinar stem cells, whose radiosensitivity parallels that of submandibular glands, with Wingless/Integrated (Wnt) signaling exerting a key regulatory role in post-radiation tissue regeneration [60].

Organoid models offer novel insights into refining radiotherapy approaches [61–63]. Canine follicular thyroid cancer organoids maintain expression of iodine uptake-related proteins (e.g., thyroglobulin and sodium-iodide symporter [NIS]), providing an ideal in vitro platform for optimizing radioactive iodine therapy [61]. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma organoid studies demonstrate subtype-specific differences in chemoradiation sensitivity: the epidermoid carcinoma (EC) subtype exhibits a synergistic response to EGFR inhibitors in combination with radiotherapy, while squamous cell carcinoma (SC) and mixed squamous cell and epidermoid carcinoma (MSEC) subtypes show greater sensitivity to microtubule inhibitors—findings that inform precision combination therapy [62]. Mouse esophageal organoid experiments reveal that high-Linear Energy Transfer (LET) iron ion radiation induces more severe DNA damage and differentiation abnormalities than low-LET cesium radiation, with even low doses inducing sustained stress responses, which inform clinical radioprotection strategies [63].

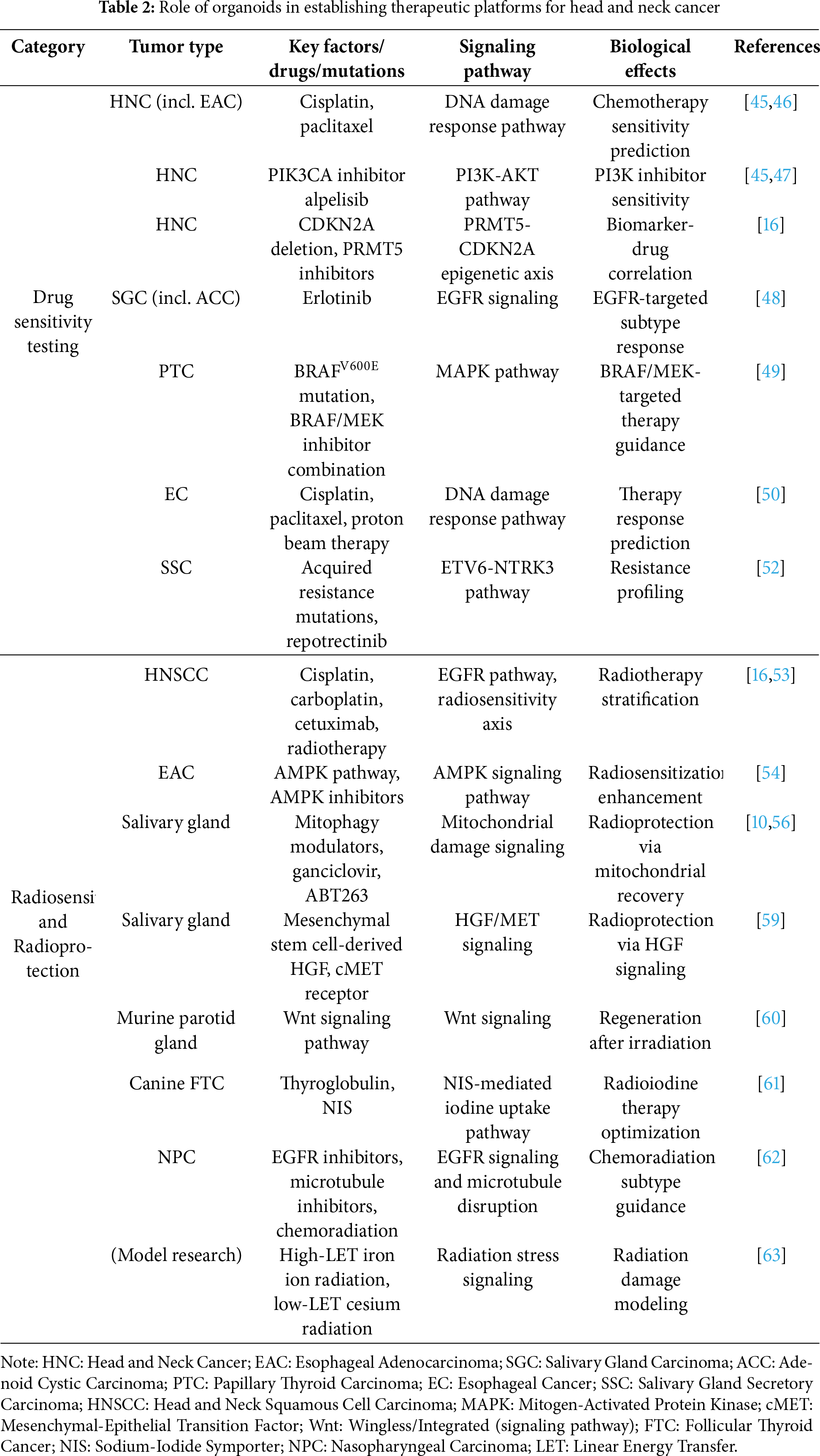

Organoid technology has been revolutionizing head and neck cancer radiotherapy research [16,53,54]. From elucidating radiosensitivity mechanisms to validating combination therapies, and from exploring radioprotection strategies to optimizing dose parameters, organoid models demonstrate multifaceted applications. Current studies not only confirm their reliability in predicting radiotherapy responses [53,62] but also identify potential therapeutic targets, including the AMPK pathway and mitophagy [10,54]. However, challenges remain, such as variable culture success rates [53] and limited repair capacity for high-dose radiation-induced damage [59]. Future research should prioritize culture system optimization, microenvironment integration, and large-scale clinical validation to translate organoid technology into clinically actionable tools for enhancing radiotherapy outcomes [55,60]. These roles of organoids in establishing therapeutic platforms for head and neck cancer are summarized in Table 2.

4 Role of Organoids in the Discovery of Biomarkers for Head and Neck Cancer

Organoid models have emerged as a pivotal tool for biomarker development in head and neck cancers, providing a novel platform for identifying diagnostic markers, prognostic indicators, and therapeutic targets [64,65]. Studies demonstrate that head and neck cancer organoids retain high fidelity to the molecular features and heterogeneity of primary tumors, thereby enhancing the clinical relevance of organoid-based biomarker screening [64,66]. For instance, through the establishment of a biobank comprising 45 salivary gland tumor organoids, researchers successfully identified subtype-specific biomarkers such as protein tyrosine phosphatase 4A1 (PTP4A1), offering new diagnostic criteria for mucoepidermoid carcinoma [64]. Similarly, single-cell RNA sequencing of adenoid cystic carcinoma organoids revealed PRMT5 upregulation correlated with MYB/MYC genes—a finding that not only uncovered novel biomarkers but also validated PRMT5 inhibitors as a viable therapeutic strategy currently in phase I clinical trials [67].

Organoid models demonstrate distinct advantages in prognostic biomarker development [68,69]. Research on HNSCC organoids demonstrated that collective invasion patterns correlate strongly with YAP signaling activation, facilitating the establishment of a gene signature predictive of poor patient outcomes [68]. Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-negative HNSCC organoids further confirmed that high p-mTOR/p-ERK expression correlates with worse survival and predicts therapeutic resistance to mTOR inhibitor everolimus [69]. EAC studies integrated organoid models with long-read sequencing to resolve complex genomic amplification events, revealing potential early-diagnostic biomarkers [70]. Notably, cancer-fibroblast interaction-based organoid models accurately predict immunotherapy responses in HNSCC patients, with high interaction gene scores correlating strongly with immunosuppressive microenvironments and therapeutic resistance [65].

Organoids serve as a critical tool in therapeutic target discovery [71–73]. CRISPR-mediated SIRT7 knockout in HNSCC organoids validated its oncogenic role while demonstrating enhanced 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) chemosensitivity following deletion [73]. RNA Interference (RNAi) screening coupled with organoid models identified Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 (FGFR4) as a key target in HPV-negative HNSCC, inhibition of which reverses EMT—specifically, in sensitive cells, it leads to significant downregulation of mesenchymal markers such as Vimentin and upregulation of epithelial markers—and improves radiosensitivity [71]. In immunotherapy, ESCC organoids validated CD276 as an ideal Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Natural Killer (CAR-NK) target, with patient-derived organoid results showing perfect alignment with humanized mouse models [72]. Adenoid cystic carcinoma organoid studies revealed the superior efficacy of proteolysis-targeting chimera dBET6 (targeting Bromodomain-Containing Protein 4 [BRD4]) when compared to conventional inhibitor JQ1, particularly in myoepithelial-rich tumors [66].

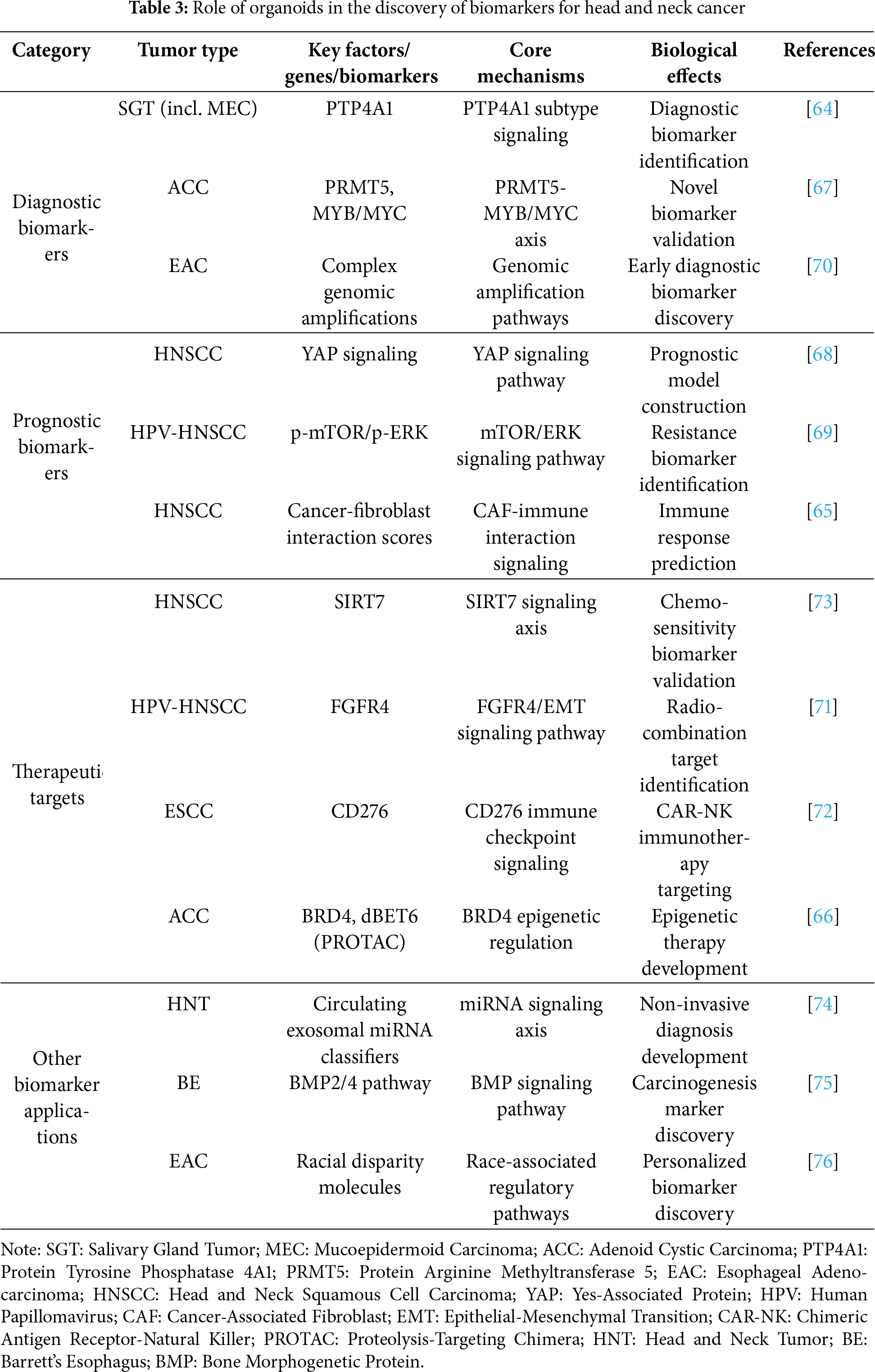

Organoid technology is ushering in a new era in head and neck cancer biomarker research [74–76]. From circulating small extracellular vesicle miRNA classifiers to Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 2/4 pathway validation in Barrett’s esophagus carcinogenesis [74,75], to molecular dissection of racial disparities in EAC [76], organoids provide a robust translational platform. These roles of organoids in the discovery of biomarkers for head and neck cancer are summarized in Table 3. Current studies not only confirm their efficacy in biomarker discovery [64,67] but also highlight their clinical decision-guiding potential [65,69]. However, challenges such as standardization and heterogeneity preservation persist [68]. Future efforts should integrate multi-omics data, optimize co-culture systems, and perform prospective clinical trials to accelerate clinical translation [70,72]. With technological refinement, organoid models are poised to become the cornerstone of biomarker development for precision medicine in head and neck cancers [66,71].

The application of organoid technology in head and neck cancer research marks a groundbreaking advancement in tumor modeling. Its unique advantage resides in its capacity to faithfully preserve cancer stem cells and differentiated cell lineages while accurately recapitulating dynamic tumor–stromal interactions within the TME [45]. For instance, via co-culture systems integrating CAFs and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), organoids successfully recapitulate the features of an immunosuppressive TME, thereby providing a powerful tool for investigating tumor-stroma interactions and therapy resistance mechanisms [31]. Additionally, patient-derived organoids (PDOs) exhibit high concordance with clinical therapeutic outcomes in drug sensitivity assays, offering reliable evidence for personalized treatment decisions [22,77]. Such technological advancements have not only enhanced our understanding of head and neck cancer pathogenesis but also significantly accelerated the clinical translation of precision medicine [55].

Despite its potential, the widespread application of organoid technology remains limited by several unresolved challenges. A key limitation lies in the fact that conventional PDO systems often fail to replicate the spatial architecture and immune complexity of native tumor microenvironments, thereby constraining their physiological relevance [78]. Compounding this issue is the lack of standardized culture protocols, which contributes to substantial inter-laboratory variability and undermines the reproducibility of experimental results [79]. Moreover, current models struggle to maintain appropriate stromal-to-epithelial cell ratios; the overgrowth of cancer-associated fibroblasts, for instance, can obscure tumor-specific characteristics and confound data interpretation. The genetic integrity of organoids also poses a concern, as extended in vitro expansion has been associated with clonal drift and the gradual loss of driver gene mutations, ultimately diminishing the representativeness of long-term cultures [19]. In addition, microbial contamination—particularly with fungi such as yeast and pseudohyphae—can interfere with organoid viability and formation during passaging procedures [80]. Finally, the efficiency of tumor tissue sampling remains a critical determinant of PDO establishment success, with variable yields depending on biopsy quality and cellular composition [81]. To overcome these limitations, future research must focus on refining organoid culture media [8,82], engineering more sophisticated co-culture systems that preserve cellular diversity and spatial structure [83,84], and implementing rigorous quality control strategies to maintain genomic fidelity over prolonged cultivation periods [85–87].

The integration of organoid technology with other advanced methods will open up new avenues for its applications. For instance, the integration of spatial omics technologies (e.g., Deterministic Barcoding in Tissue for Spatial Omics Sequencing [DBiT-seq]) enables simultaneous mapping of RNA and protein expression profiles in the tissue context, thereby providing a means to evaluate whether PDOs can accurately recapitulate the native spatial cellular organization and biomarker localization [26,28]. The integration of single-cell sequencing technology facilitates precise analysis of cellular heterogeneity and dynamic evolutionary patterns within organoids [22,88]. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) derived from liquid biopsies and isolated from peripheral blood can serve as the basis for constructing three-dimensional organoid models, which are applicable for drug screening and disease modeling [89,90]. Endoscopic biopsy specimens have shown significant potential in establishing EAC organoids [86]. Tumor organoid-on-a-chip platforms, which combine PDOs with microfluidic chips, can precisely simulate physiological factors such as nutrient gradients, fluid shear stress, and immune cell perfusion. Meanwhile, microfluidic chip technology itself enables high-throughput simulation and real-time monitoring of the TME, providing a dynamic platform for studying tumor-immune interactions. These systems exhibit superior dynamic modeling capabilities and enhance the translational relevance of in vitro assays [25,27,91]. Furthermore, multi-omics approaches integrating single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial proteomics, and exome sequencing help dissect cellular heterogeneity and clonal dynamics within organoids, thereby uncovering drug resistance mechanisms and tumor evolution [13,17,30]. The incorporation of the air-liquid interface (ALI) and advanced co-culture systems containing immune cells, endothelial cells, and matched stromal components further enhances the ability of organoids to simulate interactions in the complex TME, such as lymphangiogenesis and crosstalk between CAFs and immune cells [5,19,21].

Moreover, the adoption of 3D bioprinting technology offers a new solution to improve the structural complexity of organoids and overcome the limitations of traditional extracellular matrices (e.g., Matrigel); its introduction may further enhance organoid function, making them more similar to in vivo tumor states [92–94]. Similarly, the use of synthetic hydrogels provides a new solution to improve structural complexity and address the limitations of traditional extracellular matrices like Matrigel. As alternatives to Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels show great promise and offer new strategies for cell repopulation and tissue regeneration in cancer therapy [93–95]. Positron emission microscopy (PEM) is an emerging tool that can be used for metabolic imaging, functional evaluation, and high-resolution detection of metabolic activity of tumor organoids in response to treatment, serving as a powerful tool for personalized therapy and drug screening [96].

Beyond these technical integrations, a seamless “preclinical-to-clinical trial” model based on organoids is currently under exploration; notably, among the various areas summarized in Fig. 2, this translational model stands out as the most promising, as it directly addresses the core bottleneck of organoid technology by bridging preclinical research and clinical practice. This approach directly translates organoid drug sensitivity results into clinical trial design, potentially shortening drug development timelines and improving treatment success rates. Currently, two relevant clinical trials targeting head and neck cancer and its subtypes have been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov to advance this translational application: 1) NCT06686342 (titled “PDO Based Drug Sensitive Test in R/M HNSCC”), a prospective multicenter observational study that aims to evaluate the consistency of drug efficacy between clinical systemic treatment and patient-derived organoid (PDO)-based drug sensitivity testing in patients with recurrent/metastatic (R/M) HNSCC, with the design of multicenter observation to increase the generalizability and reliability of research conclusions; 2) NCT06482086 (titled “Efficacy of Organoid-Based Drug Screening to Guide Treatment for Locally Advanced Thyroid Cancer”), which focuses on exploring the potential advantages of anti-cancer therapy implemented based on organoid-derived drug sensitivity testing, enrolling individuals with locally advanced thyroid cancer who have undergone conventional therapy in the past or have unresectable tumors. It is expected to accelerate the development of therapeutic strategies, shorten the drug development cycle, and concurrently improve both the accuracy of response prediction and the success rate of treatments [19,25,97]. These innovations—encompassing the aforementioned technical integrations and the clinical translation model (summarized in Fig. 2)—reflect the evolving trend of integration between organoid platforms and advanced methods, with an overview of these technical and translational integrations also presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Schematic illustration of the integration of organoid technology with advanced methodologies (This figure was created using BioRender, available at https://biorender.com/; developed by BioRender Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada)

Head and neck cancer organoids hold notable strengths, such as recapitulating tumor heterogeneity, enabling high-throughput drug screening, and being derivable from minimally invasive samples (e.g., endoscopic biopsies). However, they face limitations including incomplete TME simulation, reliance on animal-derived Matrigel, and lack of standardized protocols. Future efforts should focus on addressing these issues: using co-culture or organoid-on-chip systems to optimize TME mimicry, developing synthetic hydrogels as Matrigel alternatives, and establishing consensus protocols for different subtypes.

In conclusion, as technological advancements continue to progress, organoids will play an increasingly vital role in precision medicine for head and neck cancer. By integrating spatial biology validation, organoid-on-chip systems, multi-omics analytics, and standardized co-culture strategies—along with long-term genomic fidelity assurance and clinical trial pipelines—organoid models are positioned to evolve from descriptive systems to predictive platforms, thereby offering renewed hope for patients.

Acknowledgement: We wish to acknowledge the foundational contributions of all researchers in the field of head and neck cancer organoids, whose seminal work has laid the critical foundation for the synthesis and discussion presented in this review. Additionally, we express our gratitude to the AI tool “Doubao” for providing non-core auxiliary support during manuscript preparation, including optimizing English academic expressions, standardizing the formatting of tables and abbreviation lists, and assisting in collating and verifying abbreviation definitions from the literature—all core academic content (e.g., research framework design, data analysis, conclusion derivation) remains the original work of the authors.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82072997), the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z221100007422045), and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (Code: ZLRK202304).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Boxuan Han, Shaokun Liu; formal analysis, Boxuan Han, Shaokun Liu; data curation, Ridhima Das; visualization, Boxuan Han; writing—original draft preparation, Boxuan Han, Shaokun Liu; writing—review and editing, Shiqian Liu, Yang Zhang; supervision, Yang Zhang; funding acquisition, Yang Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviation

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| ATC | Anaplastic thyroid cancer |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| BRD | Bromodomain-Containing Protein |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblast |

| CAR-NK | Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer |

| CCL | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand |

| CES1 | Carboxylesterase 1 |

| COSMIC | Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| cMET | Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition Factor |

| EC | Esophageal Cancer/Epidermoid Carcinoma (subtype) |

| EC50 | Half-maximal effective concentration |

| EAC | Esophageal adenocarcinoma |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| ESCC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| FGFR | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LET | Linear energy transfer |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MSE C | Mixed squamous cell, epidermoid carcinoma (subtype) |

| NADH/NAD+ | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (Reduced Form/Oxidized Form) |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NIS | Sodium-iodide symporter |

| NNMT-LOX-FAK | Nicotinamide N-Methyltransferase—Lysyl Oxidase—Focal Adhesion Kinase |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| PDX | Patient-derived xenograft |

| PFCA | Perfluoroalkyl carboxylate |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PRMT5 | Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 |

| PTC | Papillary thyroid carcinoma |

| PTP | Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase |

| ROCK | Rho-Associated Protein Kinase |

| RSPO | R-spondin |

| RNAi | RNA Interference |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SC | Squamous cell carcinoma (subtype) |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| SSC | Salivary Gland Secretory Carcinoma |

| Tg | Thyroglobulin |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TSHR | Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Receptor |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cells |

| WES | Whole-Exome Sequencing |

| Wnt3a | Wingless/Integrated 3a |

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Uppaluri R, Haddad RI, Tao Y, Le Tourneau C, Lee NY, Westra W, et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab in locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(1):37–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2415434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Qi H, Tan X, Zhang W, Zhou Y, Chen S, Zha D, et al. The applications and techniques of organoids in head and neck cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1191614. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1191614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wong M, Vasani S, Breik O, Zhang X, Kenny L, Punyadeera C. The potential of hydrogel-free tumoroids in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2024;13(16):e70129. doi:10.1002/cam4.70129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lee TW, Lai A, Harms JK, Singleton DC, Dickson BD, Macann AMJ, et al. Patient-derived xenograft and organoid models for precision medicine targeting of the tumour microenvironment in head and neck cancer. Cancers. 2020;12(12):3743. doi:10.3390/cancers12123743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Corrò C, Novellasdemunt L, Li VSW. A brief history of organoids. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2020;319(1):C151–65. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00120.2020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yoon YJ, Kim D, Tak KY, Hwang S, Kim J, Sim NS, et al. Salivary gland organoid culture maintains distinct glandular properties of murine and human major salivary glands. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3291. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30934-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhao J, Ren Y, Ge Z, Zhao X, Li W, Wang H, et al. Thyroid organoids: advances and applications. Endokrynol Pol. 2023;74(2):121–7. doi:10.5603/EP.a2023.0019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Perréard M, Florent R, Divoux J, Grellard JM, Lequesne J, Briand M, et al. ORGAVADS: establishment of tumor organoids from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma to assess their response to innovative therapies. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):223. doi:10.1186/s12885-023-10692-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cinat D, De Souza AL, Soto-Gamez A, Jellema-de Bruin AL, Coppes RP, Barazzuol L. Mitophagy induction improves salivary gland stem/progenitor cell function by reducing senescence after irradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2024;190:110028. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2023.110028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wakai E, Suzumura Y, Ikemura K, Mizuno T, Watanabe M, Takeuchi K, et al. An integrated in silico and in vivo approach to identify protective effects of palonosetron in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13(12):480. doi:10.3390/ph13120480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Abd El-Salam MA, Troulis MJ, Pan CX, Rao RA. Unlocking the potential of organoids in cancer treatment and translational research: an application of cytologic techniques. Cancer Cytopathol. 2024;132(2):96–102. doi:10.1002/cncy.22769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yang H, Liang Q, Zhang J, Liu J, Wei H, Chen H, et al. Establishment of papillary thyroid cancer organoid lines from clinical specimens. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1140888. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1140888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Aizawa Y, Takada K, Aoyama J, Sano D, Yamanaka S, Seki M, et al. Establishment of experimental salivary gland cancer models using organoid culture and patient-derived xenografting. Cell Oncol. 2023;46(2):409–21. doi:10.1007/s13402-022-00758-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Scheemaeker S, Inglebert M, Daminet S, Dettwiler M, Letko A, Drögemüller C, et al. Organoids of patient-derived medullary thyroid carcinoma: the first milestone towards a new in vitro model in dogs. Vet Comp Oncol. 2023;21(1):111–22. doi:10.1111/vco.12872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Millen R, De Kort WWB, Koomen M, Van Son GJF, Gobits R, Penning de Vries B, et al. Patient-derived head and neck cancer organoids allow treatment stratification and serve as a tool for biomarker validation and identification. Med. 2023;4(5):290–310.e12. doi:10.1016/j.medj.2023.04.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Done AJ, Birkeland AC. Organoids as a tool in drug discovery and patient-specific therapy for head and neck cancer. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4(6):101087. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Tanaka J, Mishima K. In vitro three-dimensional culture systems of salivary glands. Pathol Int. 2020;70(8):493–501. doi:10.1111/pin.12947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Tran ON, Wang H, Li S, Malakhov A, Sun Y, Abdul Azees PA, et al. Organ-specific extracellular matrix directs trans-differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and formation of salivary gland-like organoids in vivo. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):306. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02993-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang S, Wang C. Protocol to establish patient-derived xenograft and organoid for radiosensitivity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. STAR Protoc. 2024;5(4):103273. doi:10.1016/j.xpro.2024.103273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Takada K, Aizawa Y, Sano D, Okuda R, Sekine K, Ueno Y, et al. Establishment of PDX-derived salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma cell lines using organoid culture method. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(1):193–202. doi:10.1002/ijc.33315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wu Z, Zhou J, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Xie Y, Liu JB, et al. Reprogramming of the esophageal squamous carcinoma epigenome by SOX2 promotes ADAR1 dependence. Nat Genet. 2021;53(6):881–94. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00859-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Diao FY. Organoid models combined with genome engineering and epigenome studies to define SOX2 function evolution in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12(20):2635–6. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.14118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ko KP, Huang Y, Zhang S, Zou G, Kim B, Zhang J, et al. Key genetic determinants driving esophageal squamous cell carcinoma initiation and immune evasion. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(3):613–28.e20. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sun J, Sepulveda JL, Komissarova EV, Hills C, Seckar TD, LeFevre NM, et al. CDKN2A-p16 deletion and activated KRASG12D drive barrett’s-like gland hyperplasia-metaplasia and synergize in the development of dysplasia precancer lesions. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;17(5):769–84. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2024.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Agaimy A, Mantsopoulos K, Iro H, Stoehr R. KRAS codon 12 mutations characterize a subset of de novo proliferating “metaplastic” Warthin tumors. Virchows Arch. 2023;482(5):839–48. doi:10.1007/s00428-023-03504-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lasolle H, Schiavo A, Tourneur A, Gillotay P, de Faria da Fonseca B, Ceolin L, et al. Dual targeting of MAPK and PI3K pathways unlocks redifferentiation of Braf-mutated thyroid cancer organoids. Oncogene. 2024;43(3):155–70. doi:10.1038/s41388-023-02889-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Agaimy A, Witkowski L, Stoehr R, Cuenca JCC, González-Muller CA, Brütting A, et al. Malignant teratoid tumor of the thyroid gland: an aggressive primitive multiphenotypic malignancy showing organotypical elements and frequent DICER1 alterations-is the term thyroblastoma more appropriate? Virchows Arch. 2020;477(6):787–98. doi:10.1007/s00428-020-02853-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Chen D, Su X, Zhu L, Jia H, Han B, Chen H, et al. Papillary thyroid cancer organoids harboring BRAFV600E mutation reveal potentially beneficial effects of BRAF inhibitor-based combination therapies. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12967-022-03848-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Sharpe BP, Nazlamova LA, Tse C, Johnston DA, Thomas J, Blyth R, et al. Patient-derived tumor organoid and fibroblast assembloid models for interrogation of the tumor microenvironment in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep Methods. 2024;4(12):100909. doi:10.1016/j.crmeth.2024.100909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao H, Jiang E, Shang Z. 3D co-culture of cancer-associated fibroblast with oral cancer organoids. J Dent Res. 2021;100(2):201–8. doi:10.1177/0022034520956614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Su SH, Mitani Y, Li T, Sachdeva U, Flashner S, Klein-Szanto A, et al. Lactate suppresses growth of esophageal adenocarcinoma patient-derived organoids through alterations in tumor NADH/NAD+ redox state. Biomolecules. 2024;14(9):1195. doi:10.3390/biom14091195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Liao G, Dai N, Xiong T, Wang L, Diao X, Xu Z, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics provides insights into the origin and microenvironment of human oesophageal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(5):e874. doi:10.1002/ctm2.874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Baregamian N, Sekhar KR, Krystofiak ES, Vinogradova M, Thomas G, Mannoh E, et al. Engineering functional 3-dimensional patient-derived endocrine organoids for broad multiplatform applications. Surgery. 2023;173(1):67–75. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2022.09.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Shin JH, Jeong J, Maher SE, Lee HW, Lim J, Bothwell ALM. Colon cancer cells acquire immune regulatory molecules from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes by trogocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(48). doi:10.1073/pnas.2110241118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Murakami S, Tanaka H, Nakayama T, Taniura N, Miyake T, Tani M, et al. Similarities and differences in metabolites of tongue cancer cells among two- and three-dimensional cultures and xenografts. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(2):918–31. doi:10.1111/cas.14749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zhao H, Li R, Chen Y, Yang X, Shang Z. Stromal nicotinamide N-methyltransferase orchestrates the crosstalk between fibroblasts and tumour cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma: evidence from patient-derived assembled organoids. Oncogene. 2023;42(15):1166–80. doi:10.1038/s41388-023-02642-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang Q, Bansal A, Dunbar KB, Chang Y, Zhang J, Balaji U, et al. A human Barrett’s esophagus organoid system reveals epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity induced by acid and bile salts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2022;322(6):G598–614. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00017.2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Anand A, Fang HY, Mohammad-Shahi D, Ingermann J, Baumeister T, Strangmann J, et al. Elimination of NF-κB signaling in Vimentin+ stromal cells attenuates tumorigenesis in a mouse model of Barrett’s Esophagus. Carcinogenesis. 2021;42(3):405–13. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgaa109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Diaz D, Bergdorf K, Loberg MA, Phifer CJ, Xu GJ, Sheng Q, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a therapeutic target in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine. 2024;86(1):114–8. doi:10.1007/s12020-024-03887-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Czerwonka A, Kałafut J, Wang S, Anameric A, Przybyszewska-Podstawka A, Mattsson J, et al. Evaluation of the anticancer activity of RIN-1, a Notch signaling modulator, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13700. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-39472-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Su L, Wu S, Huang C, Zhuo X, Chen J, Jiang X, et al. Chemoresistant fibroblasts dictate neoadjuvant chemotherapeutic response of head and neck cancer via TGFα-EGFR paracrine signaling. npj Precis Oncol. 2023;7(1):102. doi:10.1038/s41698-023-00460-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Jiang C, Liu C, Yao XI, Su J, Lu W, Wei Z, et al. CES1 is associated with cisplatin resistance and poor prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Res. 2024;32(12):1935–48. doi:10.32604/or.2024.052244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Yoo MH, Kim Y, Lee BS. Thyroid cancer risk associated with perfluoroalkyl carboxylate exposure: assessment using a human dermal fibroblast-derived extracellular matrix-based thyroid cancer organoid. J Hazard Mater. 2024;479:135771. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.135771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Mohtasham N, Mohajer Tehran F, Abbaszadeh H. Head and neck cancer organoids as a promising tool for personalized cancer therapy: a literature review. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5(3):e580. doi:10.1002/hsr2.580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Bolger JC, Allen J, Radulovich N, Ng C, Derouet M, Shathasivam P, et al. Patient-derived organoids for prediction of treatment response in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2024;111(1):335. doi:10.1093/bjs/znad408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, Campone M, Loibl S, Rugo HS, et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(20):1929–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1813904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lassche G, Van Boxtel W, Aalders TW, Van Hooij O, Van Engen-van Grunsven ACH, Verhaegh GW, et al. Development and characterization of patient-derived salivary gland cancer organoid cultures. Oral Oncol. 2022;135:106186. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.106186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Chen D, Tan Y, Li Z, Li W, Yu L, Chen W, et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(5):1410–26. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Karakasheva TA, Gabre JT, Sachdeva UM, Cruz-Acuña R, Lin EW, DeMarshall M, et al. Patient-derived organoids as a platform for modeling a patient’s response to chemoradiotherapy in esophageal cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21304. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00706-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Driehuis E, Kolders S, Spelier S, Lõhmussaar K, Willems SM, Devriese LA, et al. Oral mucosal organoids as a potential platform for personalized cancer therapy. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(7):852–71. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Lassche G, Van Engen-van Grunsven ACH, Van Hooij O, Aalders TW, Am Weijers J, Cocco E, et al. Precision oncology using organoids of a secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland treated with TRK-inhibitors. Oral Oncol. 2023;137:106297. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.106297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Fisch AS, Pestana A, Sachse V, Doll C, Hofmann E, Heiland M, et al. Feasibility analysis of using patient-derived tumour organoids for treatment decision guidance in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2024;213:115100. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2024.115100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. McNamee N, Rajagopalan P, Tal-Mason A, Roytburd S, Sachdeva UM. AMPK activation serves as a common pro-survival pathway in esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. Biomolecules. 2024;14(9):1115. doi:10.3390/biom14091115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Tanaka J, Mishima K. Application of regenerative medicine to salivary gland hypofunction. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2021;57:54–9. doi:10.1016/j.jdsr.2021.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Peng X, Wu Y, Brouwer U, Van Vliet T, Wang B, Demaria M, et al. Cellular senescence contributes to radiation-induced hyposalivation by affecting the stem/progenitor cell niche. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(10):854. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-03074-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Klangprapan J, Souza GR, Ferreira JN. Bioprinting salivary gland models and their regenerative applications. Br Dent J Open. 2024;10(1):39. doi:10.1038/s41405-024-00219-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Chansaenroj A, Yodmuang S, Ferreira JN. Trends in salivary gland tissue engineering: from stem cells to secretome and organoid bioprinting. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2021;27(2):155–65. doi:10.1089/ten.TEB.2020.0149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Soto-Gamez A, Van Es M, Hageman E, Serna-Salas SA, Moshage H, Demaria M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived HGF attenuates radiation-induced senescence in salivary glands via compensatory proliferation. Radiother Oncol. 2024;190:109984. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Serrano Martinez P, Cinat D, Van Luijk P, Baanstra M, de Haan G, Pringle S, et al. Mouse parotid salivary gland organoids for the in vitro study of stem cell radiation response. Oral Dis. 2021;27(1):52–63. doi:10.1111/odi.13475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Jankovic J, Dettwiler M, Fernández MG, Tièche E, Hahn K, April-Monn S, et al. Validation of immunohistochemistry for canine proteins involved in thyroid iodine uptake and their expression in canine follicular cell thyroid carcinomas (FTCs) and FTC-derived organoids. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(6):1172–80. doi:10.1177/03009858211018813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Ding RB, Chen P, Rajendran BK, Lyu X, Wang H, Bao J, et al. Molecular landscape and subtype-specific therapeutic response of nasopharyngeal carcinoma revealed by integrative pharmacogenomics. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3046. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23379-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Carswell L, Sridharan DM, Chien LC, Hirose W, Giroux V, Nakagawa H, et al. Modeling radiation-induced epithelial cell injury in murine three-dimensional esophageal organoids. Biomolecules. 2024;14(5):519. doi:10.3390/biom14050519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Wang B, Gan J, Liu Z, Hui Z, Wei J, Gu X, et al. An organoid library of salivary gland tumors reveals subtype-specific characteristics and biomarkers. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):350. doi:10.1186/s13046-022-02561-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Xu Y, Li J, Wang J, Deng F. A novel CAF-cancer cell crosstalk-related gene prognostic index based on machine learning: prognostic significance and prediction of therapeutic response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):645. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05447-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Rose AJ, Fleming MM, Francis JC, Ning J, Patrikeev A, Chauhan R, et al. Cell-type-specific tumour sensitivity identified with a bromodomain targeting PROTAC in adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Pathol. 2024;262(1):37–49. doi:10.1002/path.6209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Mishra V, Singh A, Korzinkin M, Cheng X, Wing C, Sarkisova V, et al. PRMT5 inhibition has a potent anti-tumor activity against adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13046-024-03270-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Haughton PD, Haakma W, Chalkiadakis T, Breimer GE, Driehuis E, Clevers H, et al. Differential transcriptional invasion signatures from patient derived organoid models define a functional prognostic tool for head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2024;43(32):2463–74. doi:10.1038/s41388-024-03091-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. de Kort WWB, de Ruiter EJ, Haakma WE, Driehuis E, Devriese LA, Van Es RJJ, et al. P-mTOR, p-ERK and PTEN expression in tumor biopsies and organoids as predictive biomarkers for patients with HPV negative head and neck cancer. Head Neck Pathol. 2023;17(3):697–707. doi:10.1007/s12105-023-01576-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Ng AWT, McClurg DP, Wesley B, Zamani SA, Black E, Miremadi A, et al. Disentangling oncogenic amplicons in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4074. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47619-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Broghammer F, Korovina I, Gouda M, Celotti M, Van Es J, Lange I, et al. Resistance of HNSCC cell models to pan-FGFR inhibition depends on the EMT phenotype associating with clinical outcome. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):39. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-01954-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Lin X, Guan T, Xu Y, Li Y, Lin Y, Chen S, et al. Efficacy of the induced pluripotent stem cell derived and engineered CD276-targeted CAR-NK cells against human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1337489. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1337489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Halasa M, Afshan S, Wawruszak A, Borkowska A, Brodaczewska K, Przybyszewska-Podstawka A, et al. Loss of Sirtuin 7 impairs cell motility and proliferation and enhances S-phase cell arrest after 5-fluorouracil treatment in head and neck cancer. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):2123. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-83349-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Li G, Wang H, Zhong J, Bai Y, Chen W, Jiang K, et al. Circulating small extracellular vesicle-based miRNA classifier for follicular thyroid carcinoma: a diagnostic study. Br J Cancer. 2024;130(6):925–33. doi:10.1038/s41416-024-02575-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Correia ACP, Straub D, Read M, Hoefnagel SJM, Romero-Pinedo S, Abadía-Molina AC, et al. Inhibition of BMP2 and BMP4 represses barrett’s esophagus while enhancing the regeneration of squamous epithelium in preclinical models. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;15(5):1199–217. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Ghosh P, Campos VJ, Vo DT, Guccione C, Goheen-Holland V, Tindle C, et al. AI-assisted discovery of an ethnicity-influenced driver of cell transformation in esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas. JCI Insight. 2022;7(18). doi:10.1172/jci.insight.161334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Shen S, Liu B, Guan W, Liu Z, Han Y, Hu Y, et al. Advancing precision medicine in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using patient-derived organoids. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):1168. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05967-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Demers I, Donkers J, Kremer B, Speel EJ. Ex vivo culture models to indicate therapy response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cells. 2020;9(11):2527. doi:10.3390/cells9112527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Seliger B, Al-Samadi A, Yang B, Salo T, Wickenhauser C. In vitro models as tools for screening treatment options of head and neck cancer. Front Med. 2022;9:971726. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.971726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Nam SY, Lee SJ, Lim HJ, Park JY, Jeon SW. Clinical risk factors and pattern of initial fungal contamination in endoscopic biopsy-derived gastrointestinal cancer organoid culture. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36(4):878–87. doi:10.3904/kjim.2020.474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. de Kort WWB, Millen R, Driehuis E, Devriese LA, Van Es RJJ, Willems SM. Clinicopathological factors as predictors for establishment of patient derived head and neck squamous cell carcinoma organoids. Head Neck Pathol. 2024;18(1):59. doi:10.1007/s12105-024-01658-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Parikh AS, Yu VX, Flashner S, Okolo OB, Lu C, Henick BS, et al. Patient-derived three-dimensional culture techniques model tumor heterogeneity in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2023;138:106330. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2023.106330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Pecce V, Sponziello M, Bini S, Grani G, Durante C, Verrienti A. Establishment and maintenance of thyroid organoids from human cancer cells. STAR Protoc. 2022;3(2):101393. doi:10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Gao J, Lan J, Liao H, Yang F, Qiu P, Jin F, et al. Promising preclinical patient-derived organoid (PDO) and xenograft (PDX) models in upper gastrointestinal cancers: progress and challenges. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):1205. doi:10.1186/s12885-023-11434-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Van Zanten J, Jorritsma-Smit A, Westra H, Baanstra M, de Bruin-Jellema A, Allersma D, et al. Optimization of the production process of clinical-grade human salivary gland organoid-derived cell therapy for the treatment of radiation-induced xerostomia in head and neck cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(3):435. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16030435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Skardal A, Sivakumar H, Rodriguez MA, Popova LV, Dedhia PH. Bioengineered in vitro three-dimensional tumor models in endocrine cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2024;31(4):936. doi:10.1530/ERC-23-0344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Zhang S, Cheng G, Zhu S, Lin D, Wu C. Protocol for the generation, characterization, and functional assays of organoid cultures from normal and cancer-prone human esophageal tissues. STAR Protoc. 2024;5(4):103316. doi:10.1016/j.xpro.2024.103316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Jawa Y, Yadav P, Gupta S, Mathan SV, Pandey J, Saxena AK, et al. Current insights and advancements in head and neck cancer: emerging biomarkers and therapeutics with cues from single cell and 3D model omics profiling. Front Oncol. 2021;11:676948. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.676948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Yang WY, Feng LF, Meng X, Chen R, Xu WH, Hou J, et al. Liquid biopsy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor DNA, and exosomes. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20(12):1213–27. doi:10.1080/14737159.2020.1855977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Ghiyasimoghaddam N, Shayan N, Mirkatuli HA, Baghbani M, Ameli N, Ashari Z, et al. Does circulating tumor DNA apply as a reliable biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma? Discov Oncol. 2024;15(1):427. doi:10.1007/s12672-024-01308-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Lugo-Cintrón KM, Ayuso JM, Humayun M, Gong MM, Kerr SC, Ponik SM, et al. Primary head and neck tumour-derived fibroblasts promote lymphangiogenesis in a lymphatic organotypic co-culture model. eBioMedicine. 2021;73:103634. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Derouet MF, Allen J, Wilson GW, Ng C, Radulovich N, Kalimuthu S, et al. Towards personalized induction therapy for esophageal adenocarcinoma: organoids derived from endoscopic biopsy recapitulate the pre-treatment tumor. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14514. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71589-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Sachdeva UM, Shimonosono M, Flashner S, Cruz-Acuña R, Gabre JT, Nakagawa H. Understanding the cellular origin and progression of esophageal cancer using esophageal organoids. Cancer Lett. 2021;509:39–52. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2021.03.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Schaafsma P, Kracht L, Baanstra M, Jellema-de Bruin AL, Coppes RP. Role of immediate early genes in the development of salivary gland organoids in polyisocyanopeptide hydrogels. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1100541. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2023.1100541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Chitturi Suryaprakash RT, Kujan O, Shearston K, Farah CS. Three-dimensional cell culture models to investigate oral carcinogenesis: a scoping review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24). doi:10.3390/ijms21249520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Khan S, Shin JH, Ferri V, Cheng N, Noel JE, Kuo C, et al. High-resolution positron emission microscopy of patient-derived tumor organoids. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5883. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26081-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Li J, Dong Z, Ren W, Sibo S, Gao T, Zhou J. Global research status and hotspots of squamous cell carcinoma endothelial cells in the last 20 years: a bibliometric analysis research article. Life Conflux. 2024;1(1):e114. doi:10.71321/m8qh8d83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue