Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

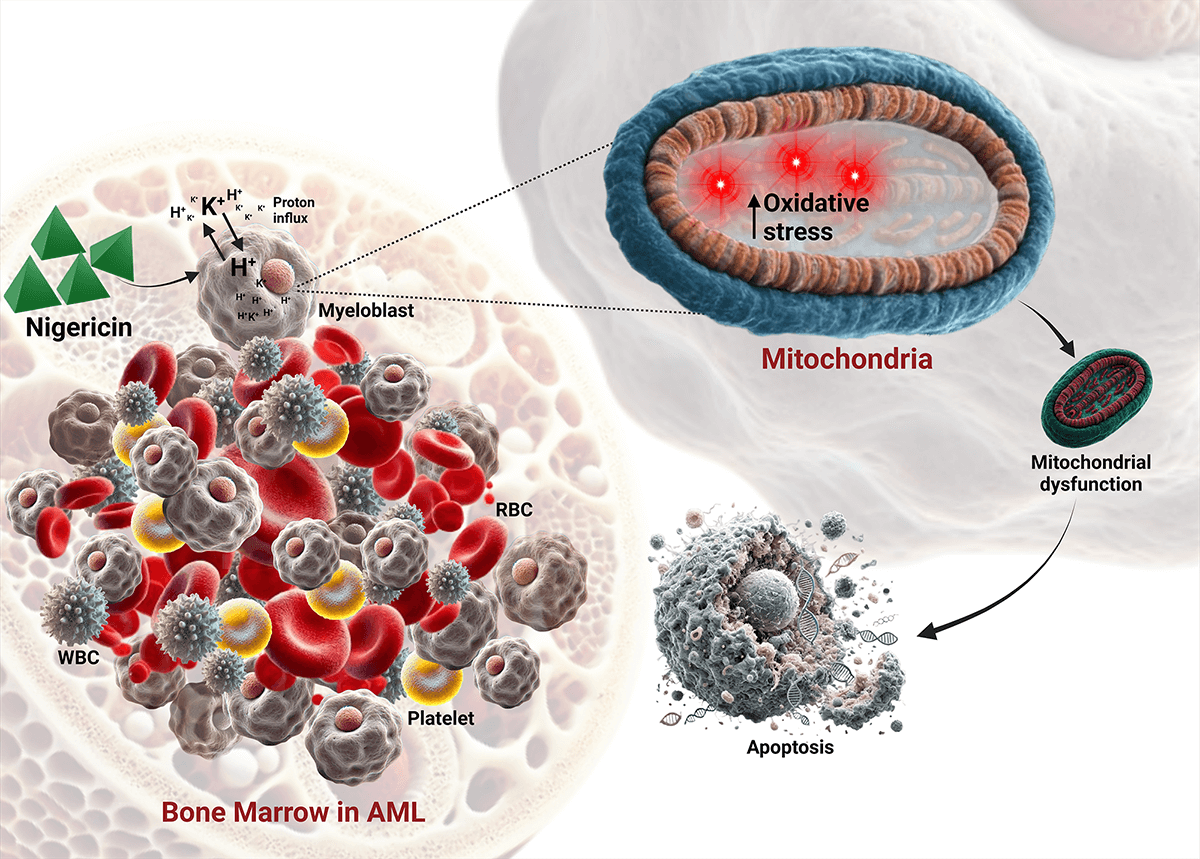

Nigericin-induced apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia via mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress

1 Hasan Lab, Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC), Tata Memorial Centre, Navi, Mumbai, 410210, India

2 Department of Biotechnology, Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT Madras), Chennai, 600036, India

3 Homi Bhabha National Institute (HBNI), Anushaktinagar, Mumbai, 400094, India

4 National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms (NCIM), CSIR National Chemical Laboratory, Pune, 411008, India

* Corresponding Authors: SYED G DASTAGER. Email: ; SYED K HASAN. Email:

# Joint first author

Oncology Research 2025, 33(8), 2161-2174. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.062951

Received 31 December 2024; Accepted 19 May 2025; Issue published 18 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is a highly aggressive clonal hematological malignancy with limited treatment options. This study aimed to evaluate the therapeutic potential of nigericin, a polyether ionophore derived from Streptomyces DASNCL-29, as a mitochondrial-targeted agent for AML treatment. Methods: Nigericin was isolated from Streptomyces DASNCL-29 and characterized via chromatography and NMR. Its cytotoxicity was tested in MOLM13 (sensitive and venetoclax-resistant) and HL60 (sensitive and cytarabine-resistant) cells using the MTT assay. Mitochondrial dysfunction was assessed by measuring reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), and mitochondrial mass. Apoptosis was evaluated with Annexin V/PI assays and immunoblotting, while proteomic analysis was conducted using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify differentially regulated proteins. Results: Nigericin demonstrated potent cytotoxicity with IC50 values of 57.02 nM in MOLM13-sensitive, 35.29 nM in MOLM13-resistant, 20.49 nM in HL60-sensitive, and 1.197 nM in HL60-cytarabine-resistant cells. Apoptosis was confirmed by Annexin V/PI staining and caspase-3/PARP cleavage, along with MCL-1 downregulation. Mitochondrial dysfunction was evident from increased ROS, reduced Δψm, and decreased mitochondrial mass. Proteomic profiling identified 264 dysregulated proteins, including a 3.8-fold upregulation of Succinate Dehydrogenase [Ubiquinone] Flavoprotein Subunit A (SDHA). Conclusion: Nigericin induces apoptosis in AML cells by disrupting mitochondrial function and enhancing oxidative stress. Its nanomolar potency highlights the need for further mechanistic studies and in vivo evaluations to explore its potential in AML treatment.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is a rapidly progressing myeloid neoplasm that originates in the bone marrow, characterized by the clonal expansion of immature myeloid-derived cells known as blasts [1,2]. Recent advancements have significantly improved the efficacy of mitochondrial-targeted therapies in treating AML [3,4]. AML cells are characterized by excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to increased oxidative stress and weakened antioxidant defenses [5,6]. A hallmark of AML, particularly in relapsed/refractory cases, is its metabolic dependency on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for survival, a feature that distinguishes it from many other cancers and amplifies its sensitivity to mitochondrial perturbations [7,8]. This OXPHOS-driven redox imbalance not only promotes genomic instability but also creates a therapeutic vulnerability, where further ROS elevation can overwhelm AML’s antioxidant buffering capacity, selectively triggering apoptosis in leukemic cells while sparing normal hematopoietic cells with lower baseline ROS [9,10]. This strategy is particularly relevant for eliminating leukemic stem cells (LSCs), which, although inherently resistant to standard therapies due to their quiescent nature, remain vulnerable to disruptions in redox homeostasis [11–13]. Critically, LSCs in refractory AML retain OXPHOS dependency, as demonstrated by the persistence of oxidative metabolism in venetoclax-resistant clones [14,15]. This metabolic reliance renders them susceptible to mitochondrial-targeted agents, bypassing resistance mechanisms to conventional therapies [16–18]. Furthermore, the inherent heterogeneity of AML complicates the identification of universally effective therapies, as different genetic mutations and resistance mechanisms can lead to varied responses among patients [19–21]. In light of these challenges, drug repurposing has emerged as a promising strategy for developing new treatments for AML [22].

Nigericin is a polyether ionophore originally discovered as an antibiotic derived from the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus [23]. It possesses unique chemical properties that enable it to facilitate the transport of cations, particularly potassium (K+), hydrogen (H+), across cellular membranes, thereby influencing ion homeostasis and pH regulation within cells [24]. By collapsing mitochondrial ion gradients, nigericin disrupts OXPHOS, exacerbates ROS accumulation, and impairs pH-dependent antioxidant defences [25,26]. Therefore, the study hypothesizes that AML’s OXPHOS addiction lowers the threshold for ionophore-mediated cytotoxicity compared to non-malignant cells, as shown by the selective targeting of LSCs by other ionophores like salinomycin in preclinical models [27]. This mechanism is uniquely suited to target AML’s metabolic vulnerabilities [28–30]. The study proposes that nigericin, like salinomycin in AML [31] and UM4118 in SF3B1-mutant leukemia [32] could exploit ionophoric properties to target AML. Specifically, it has the ability to modulate ion flux, inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin and SRC/STAT3 pathways, and induce pyroptosis [24,33,34]. Combined with mitochondrial destabilization, it may eradicate apoptosis-resistant clones.

This study explored the effects of nigericin, a compound derived from a novel Streptomyces strain DASNCL-29, on MOLM13 Parental and MOLM13 Venetoclax-resistant cells. The venetoclax-resistant model was chosen since resistance to BCL-2 inhibition is mechanistically linked to retained OXPHOS dependency, providing a rationale for nigericin’s efficacy in this context [14,15]. This study’s findings suggest that nigericin induces apoptosis by disrupting mitochondrial dynamics, warranting further investigation to establish its potential as a therapeutic candidate for AML.

Isolation and characterisation of nigericin from a novel Streptomyces strain

This study used an earlier characterized nigericin metabolite from a novel indigenous species of Streptomyces strain DASNCL-29, which was isolated from a plant-associated soil sample collected from Unkeshwar, Maharashtra, India. A seven-day log-phase culture of DASNCL-29 was used for fermentation to produce the bioactive compound nigericin. The fermentation was carried out in a 10-L lab-scale fermenter (Eppendorf BioFlow® CelliGen® 115, Hamburg, Germany). The harvested fermentation broth was used to extract the metabolite, and purification was carried out by gradient column chromatography and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC, UltiMate 3000, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Further, structural elucidation was done with standard Nuclear Magnetic Resonance techniques (NMR) (Bruker Avance III HD 400 MHz spectrometer, Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Silberstreifen 4, 76287, Rheinstetten, Germany). The structural characteristics of purified nigericin were analyzed using spectral techniques, including Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC), Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (NOESY), and Correlation Spectroscopy (COSY) [35].

Anticancer potential of nigericin

The anticancer effects of nigericin were evaluated against 17 cancer cell lines including U-937 (human myeloid leukemia), MDA-MB-468 (human breast cancer), HOP-62 (human lung cancer), SCC-40 (human oral squamous cell carcinoma), HL-60 (human leukemia), HT-29 (human colon cancer), COLO-205 (human colon cancer), HeLa (human cervical cancer), JURKAT (human T-cell leukemia), SiHa (human cervical cancer), DU-145 (human prostate cancer), Hep-G2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma), K-562 (human chronic myelogenous leukemia), MCF-7 (human breast cancer), A-549 (human lung carcinoma), PC-3 (human prostate cancer), and MDA-MB-231 (human breast cancer) with Vero cell line as a control. (Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC), Mumbai, India) using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) (0.4 % (w/v) in 1 % acetic acid) (Cat No. 230162, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) assay. All the cell lines used in this experiment were authenticated using short tandem repeat (STR) profiling, and their mycoplasma contamination status was routinely monitored to ensure experimental validity. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5000 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM L-glutamine (SLM-240, Sigma-Aldrich), followed by 24 h incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2. Nigericin and Doxorubicin, dissolved in DMSO (10−2 M stock), were serially diluted to final concentrations of 100, 10, 1.0, 0.10 µM. After 48 h of treatment, cell viability was assessed using the SRB.

Percentage Growth was calculated using the equation

where C represents the control absorbance, Ti the test sample absorbance, and Tz the baseline (time zero) absorbance.

Synthetic compounds showing Growth inhibition of 50% (GI50) (calculated from [(Ti-Tz)/(C-Tz)] × 100 = 50) ≤10 μg/mL were considered to be exhibiting significant anticancer activity.

AML cells and culture conditions

The MOLM13 paired sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cell lines were procured from the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy, and HL60 paired sensitive and Cytarabine-resistant cells from the University Hospital, Leipzig, Germany. The authentication of cell lines was confirmed through STR profiling in February 2024, with concurrent verification of mycoplasma contamination-free status. The procured cells were maintained in RPMI medium (Gibco, Grand Island, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and penicillin-streptomycin (Himedia, Mumbai, India). The cultures were incubated under standard conditions, and subculturing was performed every three to five days once the cells reached 60%–80% confluency.

1 × 104 MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant and 1 × 104 HL60 sensitive and cytarabine-resistant cells were seeded per well in a 96-well plate, with different concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 nM) of nigericin. The plates were incubated for 48 h under standard conditions. After the incubation period, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent (Himedia) at 1 mg/mL. The plates were further incubated for an additional 5 h to allow formazan crystal formation. The crystals were solubilized using a solubilizing buffer (Isopropanol, Triton X-100, and concentrated HCl), and the plate was left overnight at 37°C to ensure complete solubilization of the crystals. Absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, Cytation 5, Winooski, VT, USA). The absorbance readings in each treatment group were normalized to the untreated group to acquire percentage viabilities. The concentrations were transformed into a logarithmic scale, and a non-linear regression curve for log (inhibitor) vs. normalized response-variable slope was used to calculate the IC50.

MOLM13 sensitive cells were labelled with the membrane-permeable fluorescent dye Carboxyfluorescein Diacetate Succinimidyl Ester (CFSE) (Cat No. C34554, Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific) prior to nigericin treatment. CFSE (2 µM in DMSO) was freshly diluted 100-fold in 1× PBS (pH 7.4), and the cells were incubated with the dye for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. Complete RPMI medium was added to terminate the reaction, followed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min. Afterward, 1.0 × 106 cells/mL in fresh RPMI medium were harvested and seeded. After a 24-h incubation, the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended, and analysed by flow cytometry using the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Assessment of apoptosis by flow cytometry

1 × 106 MOLM13 sensitive (with or without 5 µM. MitoTempo (MedChemExpress, Cat No. HY-112879, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) pretreatment) and MOLM13 and venetoclax-resistant cells were seeded in a 6-well plate with 5 mL of complete RPMI and treated with different concentrations of nigericin. After a 24-h incubation, the cells were harvested, washed with 1× PBS (pH 7.4) and resuspended in 1X annexin binding buffer and stained with Annexin V conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 and Propidium Iodide (Cat No. V13241, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and acquired on an Attune NxT Flow Cytometer.

MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cells were treated with nigericin (20, 40, and 80 nM) for 24 h, then harvested and lysed using RIPA buffer (Cat No. R0278, Sigma-Aldrich) on ice for 45 min. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford reagent (Himedia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 40 µg of protein was loaded onto 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels, resolved, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk (Himedia) or BSA (Himedia), incubated overnight with primary antibodies including Succinate Dehydrogenase [Ubiquinone] Flavoprotein Subunit A (SDHA) (Cat No. PA5-27482, dilution 1:1000, ThermoFisher Scientific), Full length PARP (Cat No. 9532, dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), Cleaved PARP (Cat No. 32563, dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), Cleaved Caspase-3 (Cat No. 9664, dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), γH2AX (Cat No. 2577, dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), MCL-1 (Cat No. 94296, dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4°C overnight, and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Cat No. 7074, dilution 1:3000, Cell Signaling Technology) at room temperature for 1 h. Unbound primary and secondary antibodies were washed with TBS-T buffer (1M Tris pH 8, 2.5M NaCl, Tween 20, and double-distilled water) thrice for 15 min. After washing, protein bands were visualized using Cytiva ECL select™ western blotting detection reagent (Cat. No. RPN2235) and Bio-Rad Chemidoc system, California, USA (12003153).

Approximately 2 × 106 MOLM13 sensitive cells, both untreated and 100 nM nigericin-treated, were used for protein isolation. The cells were lysed in a native buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% NP-40, adjusted to pH 7.5. Following lysis, proteins were subjected to reduction with 10 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylation using 20 mM iodoacetamide (IAA). Subsequent to reduction and alkylation, the proteins were digested overnight with trypsin at 37°C. The completeness of digestion was verified by SDS-PAGE. The digested samples were then cleaned using C18 ZipTips (Cat No. ZTC18S096, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) prior to analysis by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (nLc-ESI-Q-TOF, Triple TOF 5600 plus, SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA).

Measurement of mitochondrial ROS

Mitochondrial ROS levels were quantified using the MitoSOX™ Red probe (Cat No. M36008 ThermoFisher Scientific). MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were treated with 20, 40, and 80 nM concentrations of nigericin or left untreated as a control, in a 6-well plate. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were harvested, washed with PBS and stained with 5 μM of MitoSOX Red for 15 min in the dark. The cells were then washed with PBS and analysed using flow cytometry.

Evaluation of mitochondrial membrane potential

1 × 106 MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cells were seeded in a 6-well plate. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were harvested, washed with 1× PBS (pH 7.4), and stained with JC-1 probe (Cat No. HY-15534, MedChemExpress) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were then washed with 1× PBS (pH 7.4) and analysed using an Attune NxT flow cytometer.

Quantification of mitochondrial mass

1 × 106 MOLM13 sensitive cells were seeded and treated with nigericin for 24 h. Post-treatment, the cells were collected and washed with 1× PBS (pH 7.4). Subsequently, the cells were incubated with 50 nM Mitotracker Green (Cat No. M6514, Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific) at 37°C for 30 min. Following this staining, the cells were washed with PBS and then stained with Hoechst 33342 (Cat No. 62249, Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific) for 10 min at 37°C. Finally, the cells were transferred to poly-L-lysine-coated glass-bottom dishes and visualized using a Nikon AX Eclipse Ti2 confocal microscope (New York, NY, USA). The mean fluorescence intensity of at least 30 cells per concentration was measured using the Image J version 1.54 g software, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA).

The data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 8.4.2 (679), 8 April 2020, San Diego, CA, USA). An unpaired Student’s t-test was employed to evaluate differences in cell apoptosis, proliferation, mitochondrial ROS production, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondrial mass. For cell viability assessments, non-linear regression analysis was applied, while simple linear regression was used for the Bradford assay. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Isolation and structural analysis of bioactive metabolites produced by streptomyces DASNCL-29

Submerged fermentation of Streptomyces strain DASNCL-29 yielded 25.0 g of a pure white crystalline compound from 75.0 g of crude extract, which translates to a 33% (w/w) yield. Further, the structural characteristics analysis via the mass spectrum of nigericin from strain DASNCL-29 supported its structural integrity, in comparison with the standard nigericin.

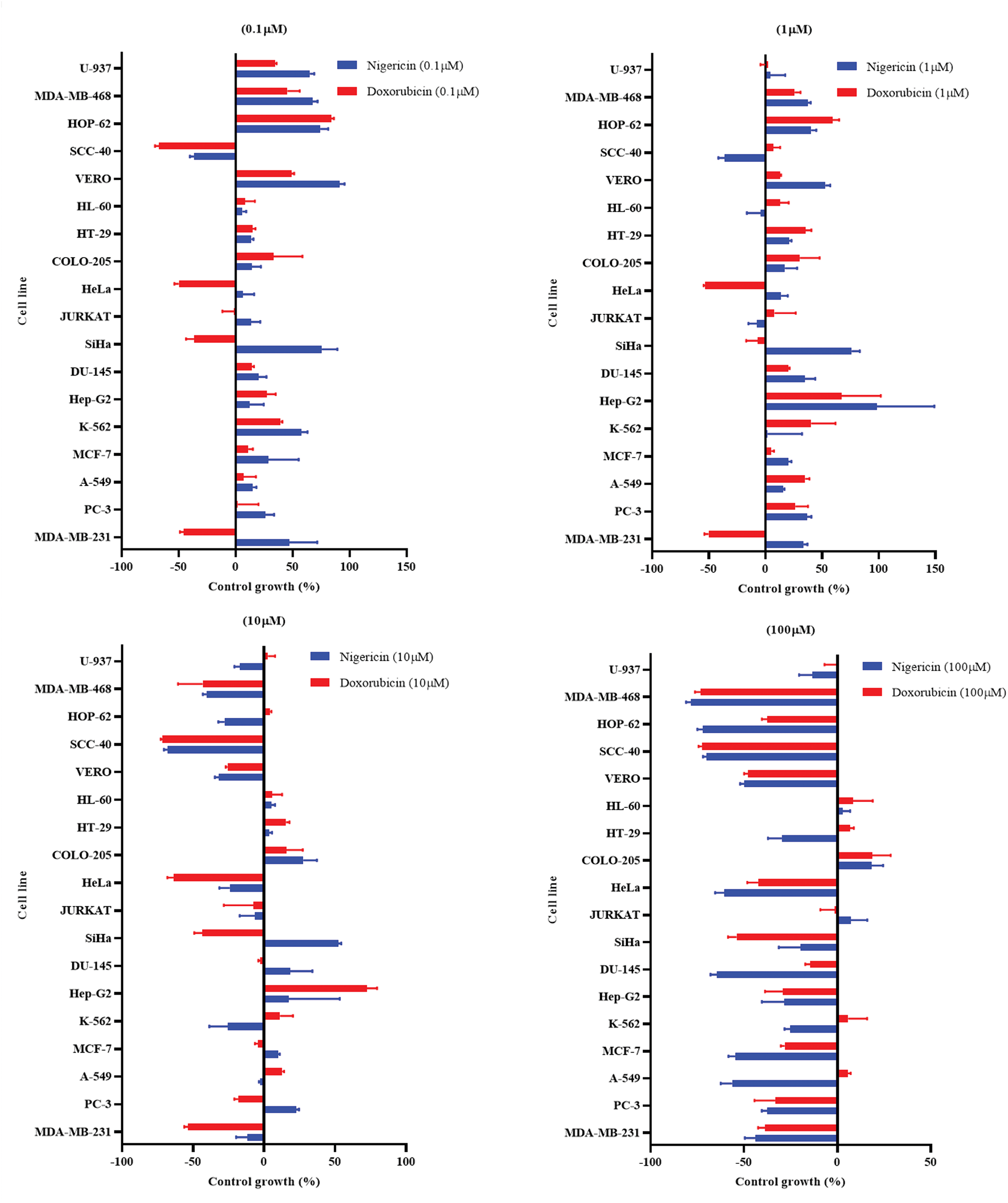

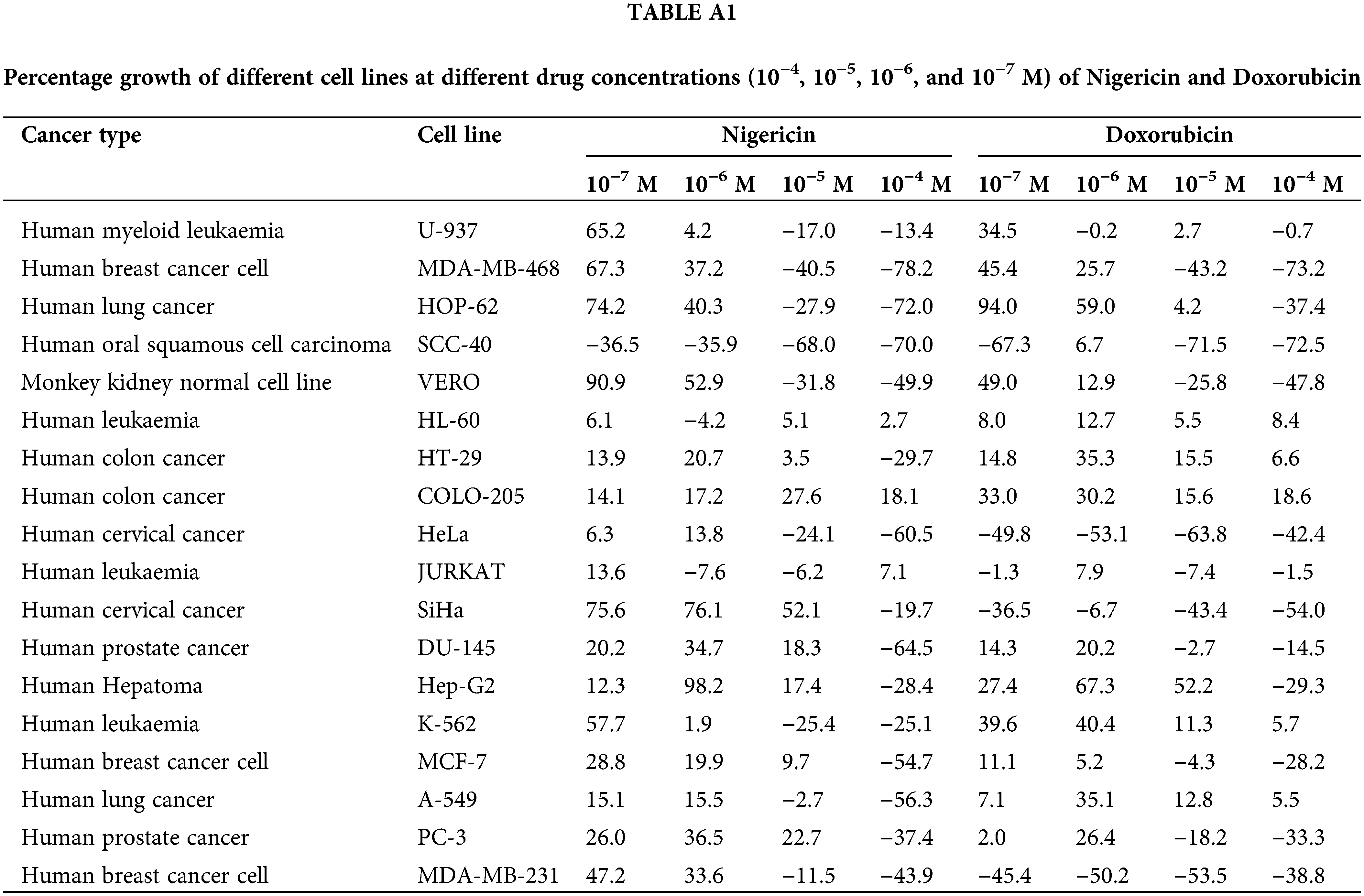

Anticancer potential of nigericin

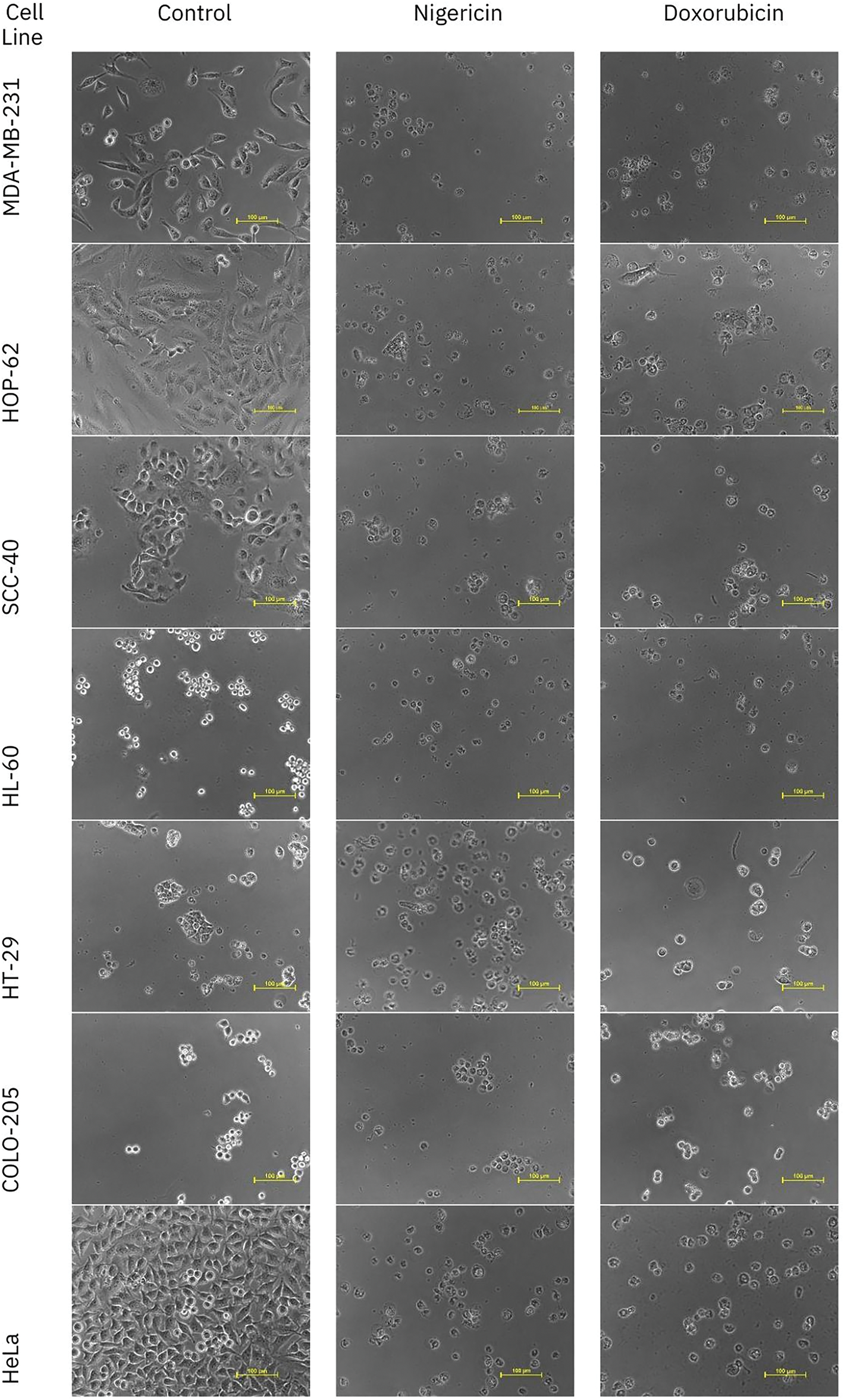

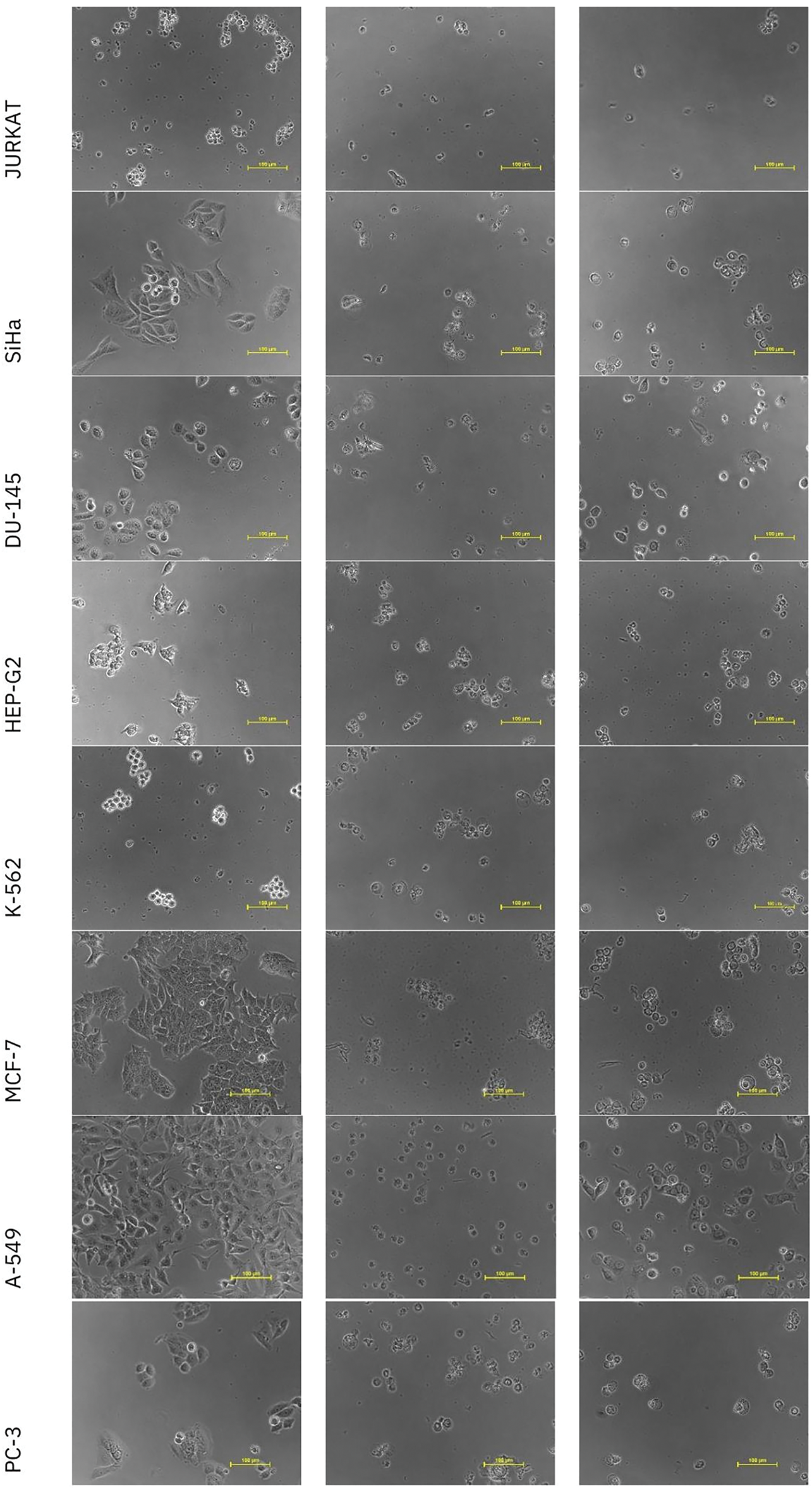

The in vitro cytotoxicity of nigericin was evaluated using the sulforhodamine B assay across seventeen human cancer cell lines representing various histological origins. Comprehensive anticancer screening data are presented in Fig. A1. The anticancer potential of nigericin, including its effects on AML cells, was investigated (Table A1). Notably, nigericin induced morphological changes, including cell shrinkage and detachment, as illustrated in Fig. A2, indicative of cell death. These findings emphasize nigericin’s ability to disrupt cellular viability in AML.

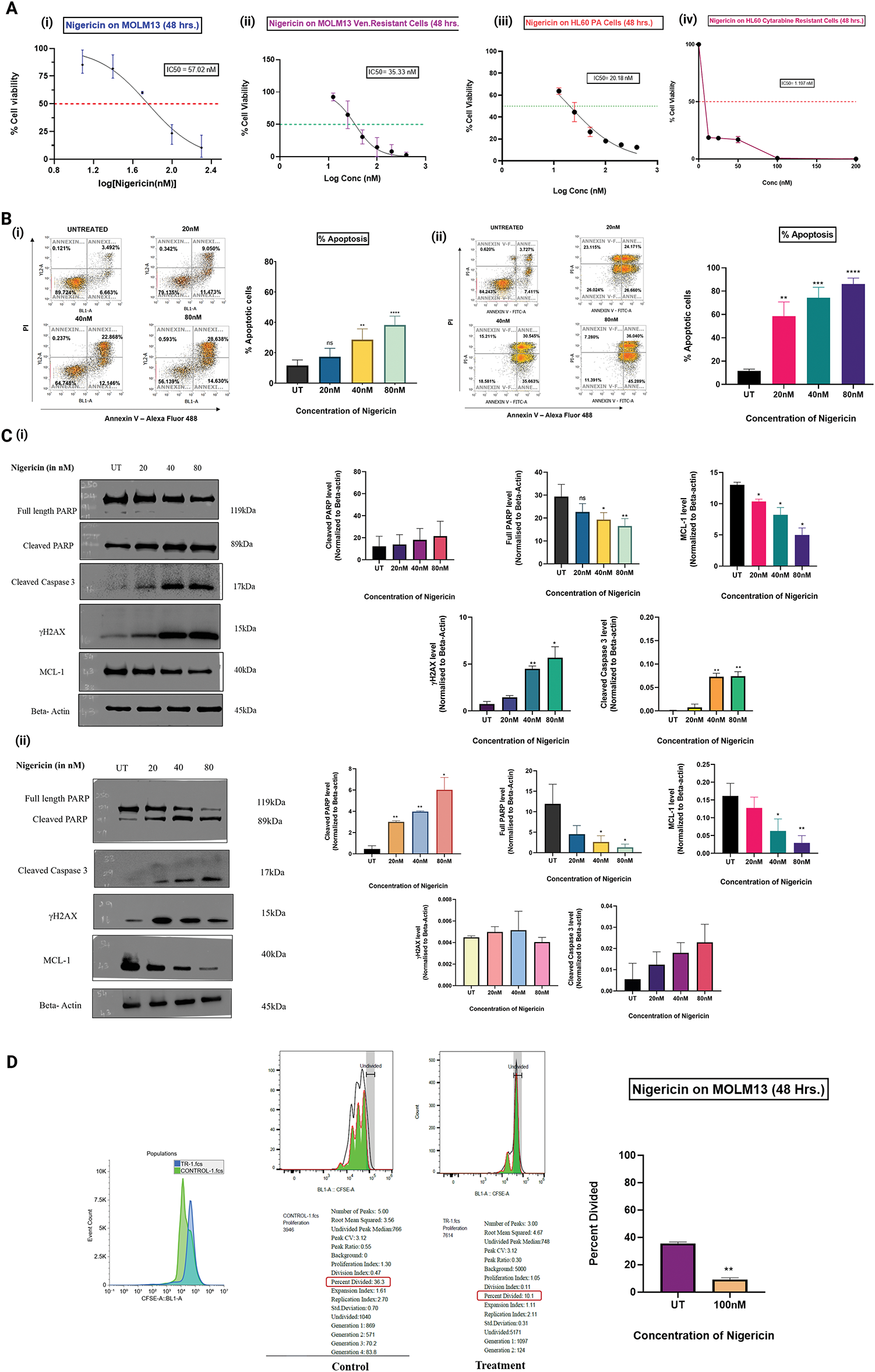

Nigericin inhibits AML cell survival and proliferation in vitro

MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cells, and HL60 sensitive cells and cytarabine-resistant cells were treated with increasing concentrations of nigericin (12.5–200 nM) for 48 h, and an MTT assay was performed. The results indicated that nigericin reduced the viability of the treated AML cells in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 57.02 and 35.29 nM in MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cells and 20.49 and 1.197 nM in HL60 sensitive cells and cytarabine-resistant cells (Fig. 1A). Further, MOLM13-sensitive and Venetoclax-resistant cells were incubated with different concentrations of nigericin for 24 h, and an Annexin V/PI assay was done. Nigericin was found to significantly increase the percentage of apoptotic cells (early and late) in a dose-dependent manner, whereas the percentage of necrotic cells was not significantly altered (Fig. 1B). Additionally, immunoblotting was performed to validate the induction of apoptosis. Upregulation of apoptotic markers, including cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3, and subsequent downregulation of full-length PARP and pro-survival protein MCL-1, was observed. Also, DNA double-strand breakage was confirmed by the upregulation of the protein γH2AX with increasing concentrations of nigericin (Fig. 1C). Next, the CFSE assay was done to check the effect of nigericin on AML cell proliferation. MOLM13 sensitive cells were stained with CFSE dye and treated with or without nigericin for 48 h. The results indicated a reduction in the percentage of cells divided in the 100nM nigericin-treated group, and a peak shift was observed in the control group, compared to nigericin-treated MOLM13 sensitive cells, reflecting the reduced proliferation of treated cells (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1: Nigericin decreases cell viability, inhibits proliferation, and induces apoptosis in AML cells. (A) Dose-response curves show the effect of nigericin on cell viability after 48 h in MOLM13 sensitive (IC50 = 57.02 nM), venetoclax-resistant MOLM13 (IC50 = 35.33 nM), HL60 sensitive (IC50 = 20.18 nM), and cytarabine-resistant HL60 (IC50 = 1.197 nM) cells. Data represents Mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) The apoptotic levels of nigericin-treated (i) MOLM13 sensitive cells and (ii) MOLM13 venetoclax-resistant cells were evaluated using the Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488/Propidium Iodide assay. The values were analysed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns, not significant) (n = 3). (C) Immunoblotting of apoptosis-related proteins and γH2AX, using actin as the loading control in (i) MOLM13 sensitive cells and (ii) MOLM13 venetoclax-resistant cells (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (n = 3). (D) Proliferation of MOLM13-sensitive cells measured by CFSE dilution assay, comparing control and 100 nM nigericin-treated groups. Data represents Mean ± SD (**p < 0.01) (n = 2).

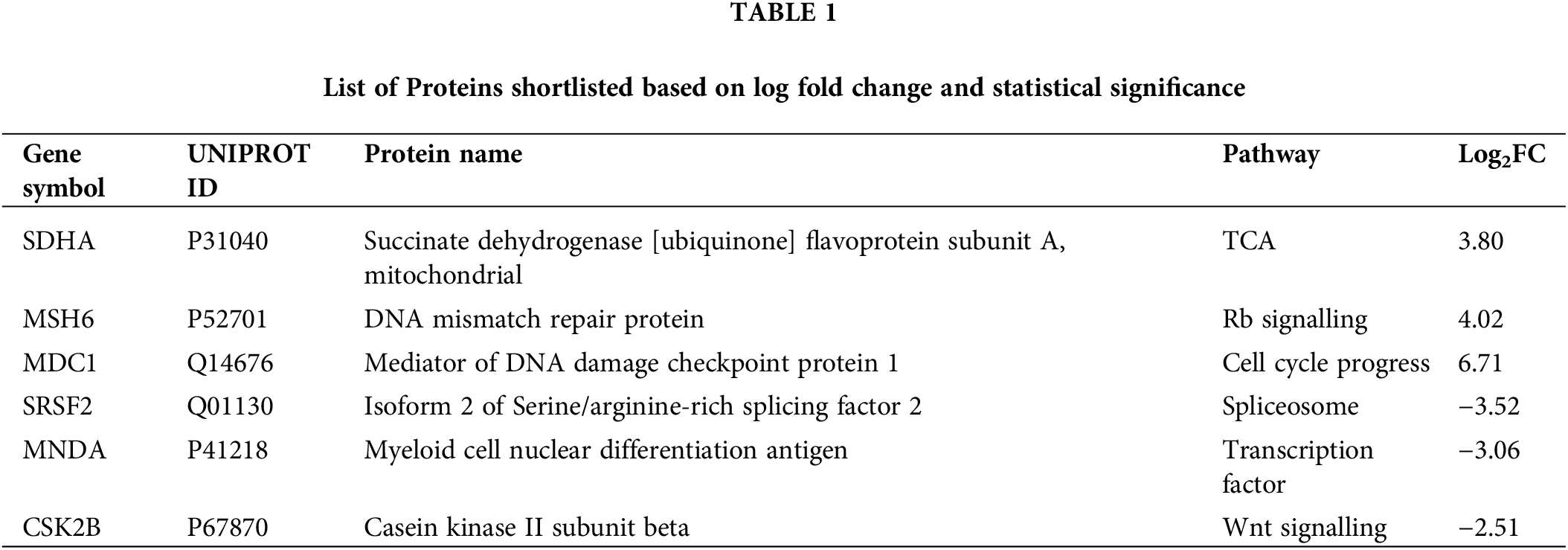

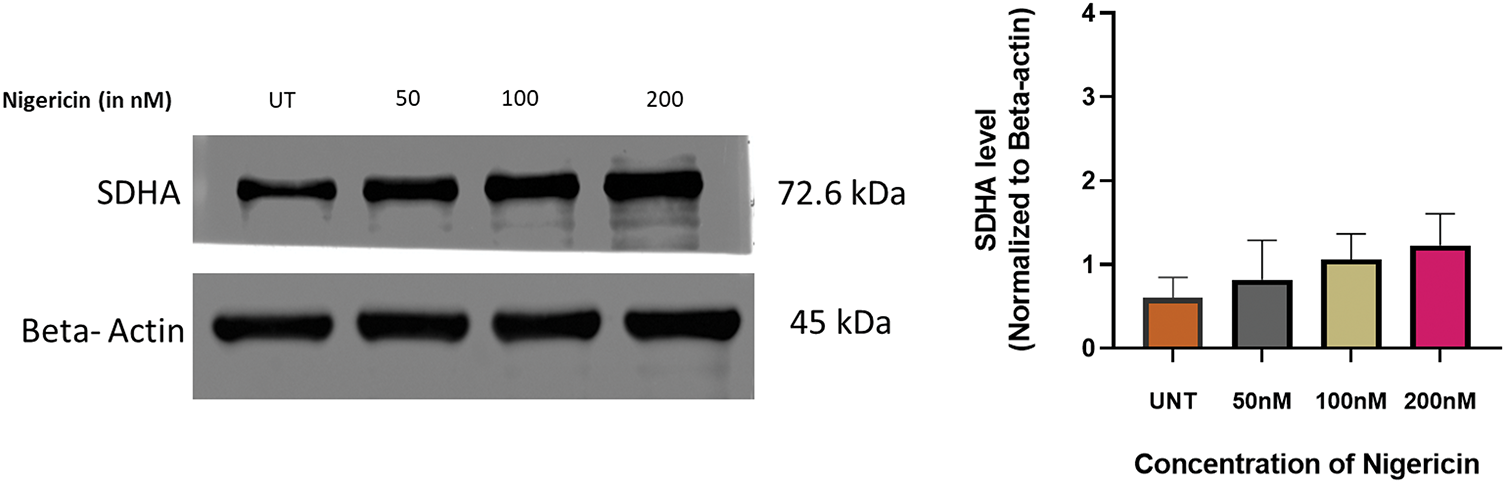

Nigericin induces differential protein expression profiles

Proteomic profiling of MOLM13 sensitive cells treated with 100 nM nigericin identified 785 proteins, of which 264 were significantly dysregulated (p < 0.05) compared to controls. Among these, 115 proteins were upregulated, with 45 showing a fold change greater than 5.0, while 149 proteins were downregulated, with 39 exhibiting a fold change less than 0.2. Six proteins were further selected based on log-fold changes and statistical significance (Table 1). Among these, Succinate Dehydrogenase [Ubiquinone] Flavoprotein Subunit A (SDHA), an essential enzyme in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, was found to be upregulated and stood out as the protein of interest due to the previously reported role of nigericin to induce mitochondrial dysfunction in breast cancer cells. Further, immunoblotting revealed an upward trend in SDHA expression in nigericin-treated cells, though the increase did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Regulation of SDHA by nigericin. Western blot to detect the expression of SDHA upon nigericin treatment, with β-actin as the internal reference (n = 3).

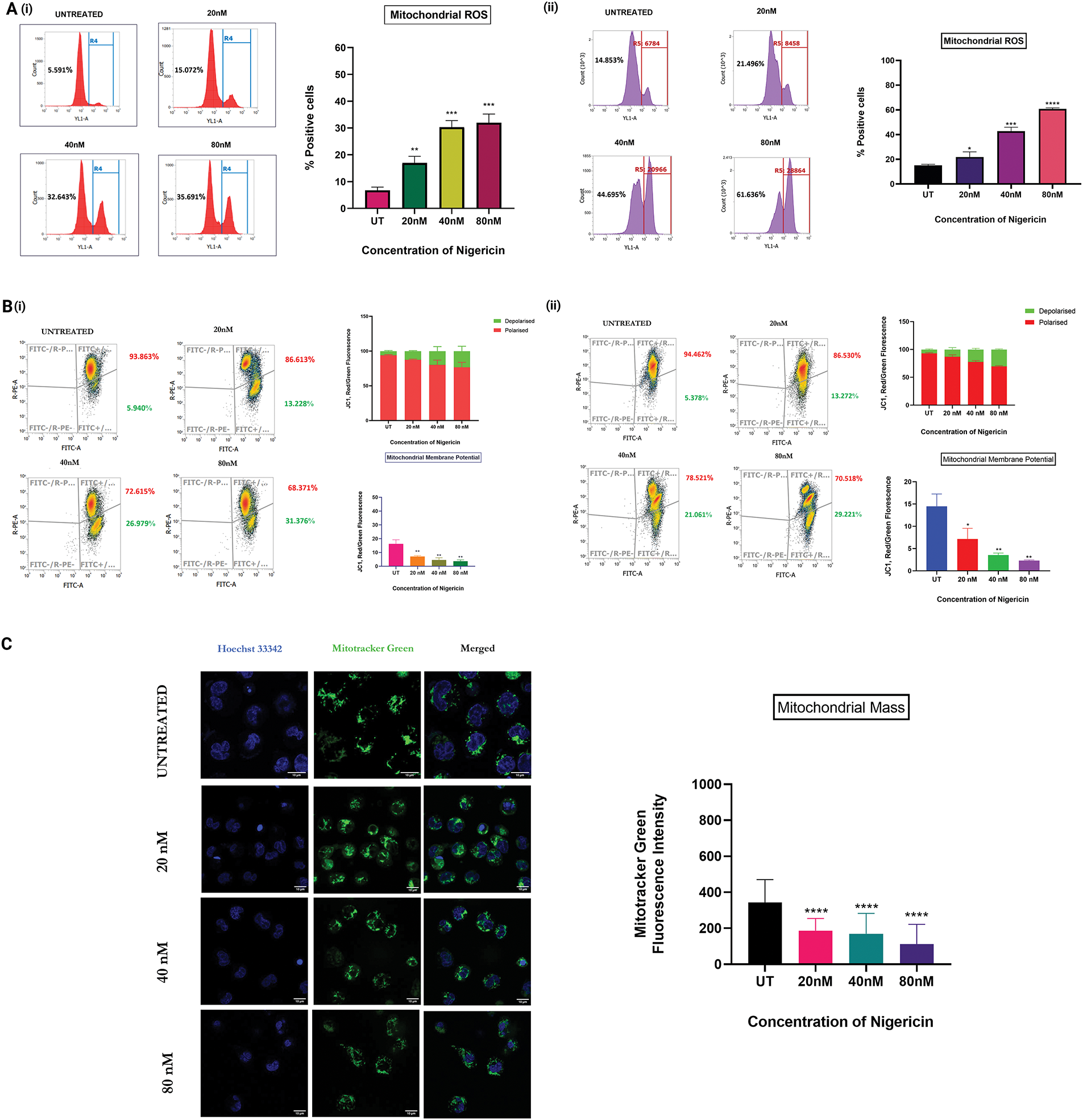

Nigericin significantly alters mitochondrial ROS, mass, and membrane potential

Mitochondrial ROS levels were quantified in MOLM13 sensitive and venetoclax-resistant cells treated with nigericin for 24 h using the MitoSOX Red probe, which selectively detects mitochondrial superoxide production. The results demonstrated a significant increase in mitochondrial ROS, indicating elevated oxidative stress with increasing nigericin concentrations (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was assessed in both MOLM13-sensitive and Venetoclax-resistant cells using the JC-1 probe. Under normal conditions, JC-1 accumulates within mitochondria and forms red-fluorescent J-aggregates, indicative of an intact membrane potential. In contrast, a shift to green fluorescence occurs when Δψm is disrupted, as JC-1 remains in its monomeric form. Our findings revealed a concentration-dependent shift from red to green fluorescence, confirming that nigericin progressively decreases mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 3B). Finally, mitochondrial mass was evaluated in MOLM13 sensitive cells via confocal microscopy using the MitoTracker Green probe. A substantial reduction in mitochondrial mass was observed with increasing nigericin concentrations, further supporting the evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction at higher nigericin concentrations (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: Nigericin alters mitochondrial homeostasis and induces apoptosis via mitochondrial ROS. (A) Increase in mitochondrial ROS levels in a concentration-dependent manner in (i) MOLM13 sensitive cells and (ii) MOLM13 venetoclax-resistant cells (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001) (n = 3). (B) Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) measured by JC-1 staining after 24 h nigericin treatment in (i) MOLM13-sensitive and (ii) MOLM13 venetoclax-resistant cells. Data represents Mean ± SD (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (n = 3). (C) A concentration-dependent decrease in mitochondrial mass was observed with increasing nigericin doses in MOLM13 sensitive cells. Statistical significance is indicated as ****p < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2).

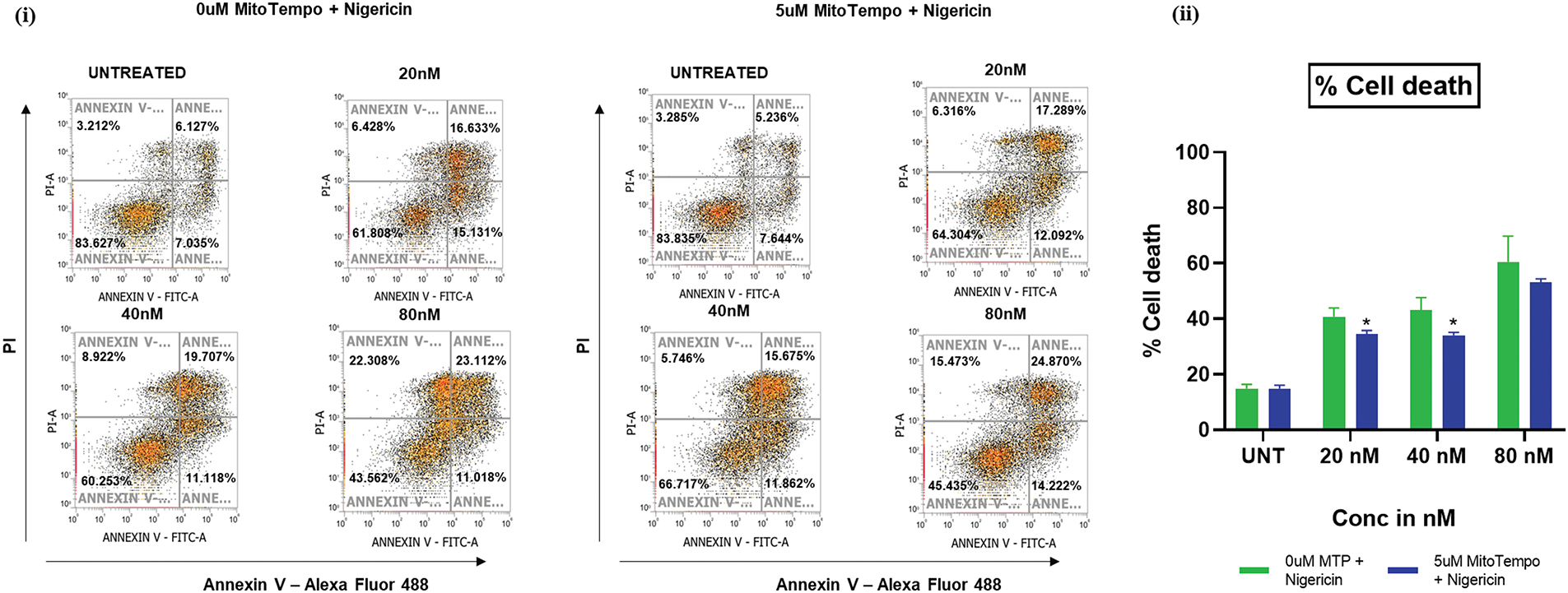

Mitochondrial ROS mediates nigericin-induced apoptosis in MOLM13 cells

An apoptosis assay was performed using Annexin V/PI staining in MOLM13 sensitive cells. They were pretreated with or without 5 µM MitoTempo, a mitochondria-targeted ROS scavenger, followed by treatment with different concentrations of nigericin. Pretreatment with MitoTempo was found to attenuate nigericin-induced cell death, with a marked reduction in the percentage of dead cells compared to cells treated with nigericin alone. This functional linkage demonstrates that mitochondrial ROS elevation is one of the mechanistic drivers of apoptosis induction by nigericin in AML (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Nigericin induces apoptosis via mitochondrial ROS. Apoptosis analysis by Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488/PI staining in nigericin-treated MOLM13-sensitive cells ± 5 µM MitoTEMPO pretreatment (*p < 0.05) (n = 3).

Nigericin’s anticancer effects have been documented in several solid tumors, including lung, breast, and colorectal cancers, where it inhibits key signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt, and MAPK/ERK [22,36]. Our study extends these findings to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a hematological malignancy characterized by treatment resistance and relapse. Recent studies have highlighted the role of mitochondrial metabolism and oxidative stress in sustaining AML cell survival, particularly in relapsed/refractory cases [8]. Building on this foundation, our findings demonstrate that nigericin, a polyether ionophore derived from Streptomyces DASNCL-29, induces apoptosis in AML cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

Nigericin’s mechanism aligns with emerging strategies targeting mitochondrial vulnerabilities in AML [3,37,38]. This is consistent with studies showing that LSCs and resistant clones remain dependent on OXPHOS for survival, rendering them susceptible to mitochondrial stressors [13]. For instance, venetoclax-resistant AML cells retain OXPHOS dependency, making them vulnerable to agents that disturb redox balance. The study’s observations that nigericin downregulates MCL-1 and activates caspase-3/PARP cleavage in AML cells further support its role in overcoming apoptosis resistance, a hallmark of refractory AML. Additionally, nigericin may enhance its therapeutic efficacy against AML by potentially lowering intracellular pH and inducing apoptosis through a mechanism similar to that of Sodium-Hydrogen Exchanger 1 (NHE1) inhibitors [39].

Proteomic analysis revealed that nigericin upregulated SDHA, a succinate dehydrogenase (Complex II) subunit, in AML cells (Fig. 2). While SDHA is typically associated with mitochondrial respiration, its overexpression under stress conditions has been linked to ROS amplification and apoptosis in cancer cells [40]. This paradoxical response, an attempt to compensate and restore energy production, may exacerbate oxidative damage, as observed with other ionophores like salinomycin [31]. Salinomycin and other ionophores have shown efficacy in drug-resistant cancers by exploiting metabolic vulnerabilities [27]. Prior work on ionophores in cancer provides a roadmap for optimizing these properties through structural modifications or combination regimens [35]. For example, combining nigericin with BCL-2 inhibitors could synergistically target mitochondrial apoptosis pathways, as suggested by recent preclinical studies in SF3B1-mutant AML [32].

While this study establishes the anti-leukemic potential of nigericin in AML, it has certain limitations. The lack of in vivo validation restricts the translational relevance of the findings. Additionally, validation using primary blasts from FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients is necessary to support results obtained from the MOLM-13 cellular model. Future studies should also investigate nigericin in combination with standard-of-care therapies to evaluate its potential clinical applicability.

This study demonstrates that nigericin induces apoptosis in AML cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. These findings contribute to the exploration of mitochondrial-targeted strategies in AML and support further preclinical studies to evaluate the broader applicability and safety profile of nigericin in diverse models of the disease

Acknowledgement: None to declare.

Funding Statement: None to declare.

Author Contributions: Syed G Dastager isolated, characterised, and provided the compound; Syed K Hasan and Bhavyadharshini Arun designed the experiments; Bhavyadharshini Arun, Prarthana Gopinath, Anup Jha and Nishtha Tripathi performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Syed K Hasan and Bhavyadharshini Arun wrote the manuscript. Syed K Hasan supervised the research. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The authors have confirmed that the ethical approval statement is not needed for this submission.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kantarjian H, Kadia T, DiNardo C, Daver N, Borthakur G, Jabbour E, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia: current progress and future directions. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(2):41. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00425-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Emadi A, Law JY. Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/hematology-and-oncology/leukemias/acute-myeloid-leukemia-aml. [Google Scholar]

3. Sheth AI, Althoff MJ, Tolison H, Engel K, Amaya ML, Krug AE, et al. Targeting acute myeloid leukemia stem cells through perturbation of mitochondrial calcium. Cancer Discovery. 2024;14(10):1922–39. doi:10.1101/2023.10.02.560330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tjahjono E, Daneman MR, Meika B, Revtovich AV, Kirienko NV. Mitochondrial abnormalities as a target of intervention in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol. 2025;14:1532857. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1532857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Khorashad JS, Rizzo S, Tonks A. Reactive oxygen species and its role in pathogenesis and resistance to therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024;7:5. doi:10.20517/cdr.2023.125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hole PS, Zabkiewicz J, Munje C, Newton Z, Pearn L, White P, et al. Overproduction of NOX-derived ROS in AML promotes proliferation and is associated with defective oxidative stress signaling. Blood. 2013;122(19):3322–30. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-04-491944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lagadinou ED, Sach A, Callahan K, Rossi RM, Neering SJ, Minhajuddin M, et al. BCL-2 Inhibition targets oxidative phosphorylation and selectively eradicates quiescent human leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(3):329–41. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lee JB, Khan DH, Hurren R, Xu M, Na Y, Kang H, et al. Venetoclax enhances T cell-mediated antileukemic activity by increasing ROS production. Blood. 2021;138(3):234–45. doi:10.1182/blood.2023019985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Hole PS, Pearn L, Tonks AJ, James PE, Burnett AK, Darley RL, et al. Ras-induced reactive oxygen species promote growth factor-independent proliferation in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2010;115(6):1238–46. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-06-222869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Trachootham D, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Demizu Y, Chen Z, Pelicano H, et al. Selective killing of oncogenically transformed cells through a ROS-mediated mechanism by β-phenylethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(3):241–52. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Huang D, Zhang C, Xiao M, Li X, Chen W, Jiang Y, et al. Redox metabolism maintains the leukemogenic capacity and drug resistance of AML cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(13):e2210796120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2210796120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Trombetti S, Cesaro E, Catapano R, Sessa R, Lo Bianco A, Izzo P, et al. Oxidative stress and ROS-mediated signaling in leukemia: novel promising perspectives to eradicate chemoresistant cells in myeloid leukemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):2470. doi:10.3390/ijms22052470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Chen Y, Liang Y, Luo X, Hu Q. Oxidative resistance of leukemic stem cells and oxidative damage to hematopoietic stem cells under pro-oxidative therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(4):291. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2488-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Pollyea DA, Stevens BM, Jones CL, Winters A, Pei S, Minhajuddin M, et al. Venetoclax with azacitidine disrupts energy metabolism and targets leukemia stem cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Nature Medicine. 2018;24(12):1859–66. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0233-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Pei S, Pollyea DA, Gustafson A, Stevens BM, Minhajuddin M, Fu R, et al. Monocytic subclones confer resistance to venetoclax-based therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(4):536–51. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-19-0710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Farge T, Saland E, De Toni F, Aroua N, Hosseini M, Perry R, et al. Chemotherapy-resistant human acute myeloid leukemia cells are not enriched for leukemic stem cells but require oxidative metabolism. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(7):716–35. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Walter RB, Appelbaum FR, Tallman MS, Weiss NS, Larson RA, Estey EH. Shortcomings in the clinical evaluation of new drugs: acute myeloid leukemia as paradigm. Blood. 2010;116(14):2420–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-05-285387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Panina SB, Pei J, Kirienko NV. Mitochondrial metabolism as a target for acute myeloid leukemia treatment. Cancer Metab. 2021;9(1):17. doi:10.1186/s40170-021-00253-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Short NJ, Konopleva M, Kadia TM, Borthakur G, Ravandi F, Dinardo CD, et al. Advances in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: new drugs and new challenges. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(4):506–25. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-19-1011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Romer-Seibert JS, Meyer SE. Genetic heterogeneity and clonal evolution in acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2021;28(1):64–70. doi:10.1097/MOH.0000000000000626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Arnone M, Konantz M, Hanns P, Paczulla Stanger AM, Bertels S, Godavarthy PS, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia stem cells: the challenges of phenotypic heterogeneity. Cancers. 2020;12(12):3742. doi:10.3390/cancers12123742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Gao G, Liu F, Xu Z, Wan D, Han Y, Kuang Y, et al. Evidence of nigericin as a potential therapeutic candidate for cancers: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;137:111262. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Deryabin PI, Shatrova AN, Borodkina AV. Targeting multiple homeostasis-maintaining systems by ionophore nigericin is a novel approach for senolysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):14251. doi:10.3390/ijms232214251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Xu Z, Gao G, Liu F, Han Y, Dai C, Wang S, et al. Molecular screening for Nigericin treatment in pancreatic cancer by high-throughput RNA sequencing. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1282. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.01282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Järås M, Benjamin. Power cut: inhibiting mitochondrial translation to target leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):555–6. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Birsoy K, Wang T, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Abu-Remaileh M, Sabatini DM. An essential role of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in cell proliferation is to enable aspartate synthesis. Cell. 2015;162(3):540–51. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Fuchs D, Heinold A, Opelz G, Daniel V, Naujokat C. Salinomycin induces apoptosis and overcomes apoptosis resistance in human cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390(3):743–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Kaushik V, Yakisich JS, Kumar A, Azad N, Iyer AKV. Ionophores: potential use as anticancer drugs and chemosensitizers. Cancers. 2018;10(10):360. doi:10.3390/cancers10100360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Yakisich JS, Azad N, Kaushik V, O’Doherty GA, Iyer AKV. Nigericin decreases the viability of multidrug-resistant cancer cells and lung tumorspheres and potentiates the effects of cardiac glycosides. Tumour Biol. 2017 Mar;39(3):101042831769431. doi:10.1177/1010428317694310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Goel Y, Yadav S, Pandey SK, Temre MK, Singh VK, Kumar A, et al. Methyl jasmonate cytotoxicity and chemosensitization of t cell lymphoma in vitro is facilitated by HK 2, HIF-1α, and Hsp70: implication of altered regulation of cell survival, pH homeostasis, mitochondrial functions. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:628329. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.628329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Roulston GDR, Burt CL, Kettyle LMJ, Matchett KB, Keenan HL, Mulgrew NM, et al. Low-dose salinomycin induces anti-leukemic responses in AML and MLL. Oncotarget. 2016;7(45):73448–61. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.11866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Moison C, Gracias D, Schmitt J, Girard S, Spinella J-F, Fortier S, et al. SF3B1 mutations provide genetic vulnerability to copper ionophores in human acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Adv. 2024;10(12):eadl4018. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adl4018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhou B, Wang C, Liu X, Wu B, Li J, Yao S, et al. Combination of nigericin with cisplatin enhances the inhibitory effect of cisplatin on epithelial ovarian cancer metastasis by inhibiting slug expression via the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2021;22(4):700. doi:10.3892/ol.2021.12961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Wu L, Bai S, Huang J, Cui G, Li Q, Wang J, et al. Nigericin boosts anti-tumor immune response via inducing pyroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers. 2023;15(12):3221. doi:10.3390/cancers15123221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sahu AK, Said MS, Hingamire T, Gaur M, Khan A, Shanmugam D, et al. Approach to nigericin derivatives and their therapeutic potential. RSC Advances. 2020;10(70):43085–91. doi:10.1039/d0ra05137c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yang Z, Xie J, Fang J, Lv M, Yang M, Deng Z, et al. Nigericin exerts anticancer effects through inhibition of the SRC/STAT3/BCL-2 in osteosarcoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;198:114938. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2022.114938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Panina SB, Baran N, Brasil Da Costa FH, Konopleva M, Kirienko NV. A mechanism for increased sensitivity of acute myeloid leukemia to mitotoxic drugs. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(8):617. doi:10.1038/s41419-019-1851-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chen X, Glytsou C, Zhou H, Narang S, Reyna DE, Lopez A, et al. Targeting mitochondrial structure sensitizes acute myeloid leukemia to venetoclax treatment. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(7):890–909. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rich IN, Worthington-White D, Garden OA, Musk P. Apoptosis of leukemic cells accompanies reduction in intracellular pH after targeted inhibition of the Na+/H+exchanger. Blood. 2000;95(4):1427–34. doi:10.1182/blood.v95.4.1427.004k48_1427_1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yang Y, An Y, Ren M, Wang H, Bai J, Du W, et al. The mechanisms of action of mitochondrial targeting agents in cancer: inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation and inducing apoptosis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1243613. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1243613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Appendix A

Figure A1: Percentage growth of different cell lines at different drug concentrations (100, 10, 1, and 0.1 µM) of Nigericin and Doxorubicin.

Figure A2: Representative images of in vitro anticancer activity of Nigericin and Doxorubicin against different cell lines.

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools