Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GC-MS Analysis and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Potential of Pimenta dioica Flower Essential Oil

1 Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Ain Shams University, Abbassia, Cairo, 11566, Egypt

2 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Gulf Medical University, Ajman, 4184, United Arab Emirates

3 Department of Pharmaceutical Organic Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, Cairo, 11562, Egypt

4 Laboratory of Plant Biotechnology, Ecology and Ecosystem Valorization, URL—CNRST n° 10, Faculty of Sciences, ChouaiDoukkali University, P.O. Box 20, El Jadida, 24000, Morocco

5 Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0002, South Africa

6 School of Natural Resources, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

7 College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Bonne Terre, Vacoas-Phoenix, 73304, Mauritius

8 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Dubai Medical University, Dubai, 19996, United Arab Emirates

* Corresponding Authors: Heba A. S. El-Nashar. Email: ; Ahmed T. Negmeldin. Email:

; Naglaa S. Ashmawy. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Approaches in Experimental Botany: Essential Oils as Natural Therapeutics)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3269-3281. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067998

Received 19 May 2025; Accepted 01 August 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Pimenta dioica is a tropical Caribbean tree belonging to the family Myrtaceae, widely used in various human activities, including perfume production, food flavoring, natural pesticides, and medicine. This study aimed to explore the chemical composition of Pimenta dioica flower essential oil obtained via hydrodistillation using GC-MS analysis. Additionally, the oil’s tyrosinase inhibitory activity was investigated. The effectiveness of the oil’s major constituents in binding to tyrosinase was also evaluated through molecular docking simulations. GC-MS analysis identified fifteen compounds, with eugenol (70.59%) as the major component, followed by β-myrcene (10.54%), limonene (8.55%), β-ocimene (4.92%), α-phellandrene (1.39%), and linalool (1.46%). The oil exhibited tyrosinase inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 28.65 ± 0.77 μg/mL, compared to kojic acid (IC50 = 1.94 ± 0.53 μg/mL). It also showed moderate antioxidant activity with an IC50 of 5.41 ± 0.68 μg/mL, relative to quercitrin (0.78 ± 0.37 μg/mL). Molecular docking studies revealed that the six identified constituents exhibited good binding affinity and fitting to the tyrosinase active site, as indicated by docking scores and specific interactions. These interactions likely contribute to the overall inhibitory effect through multiple binding modes. The findings suggest that the monoterpene content plays a crucial role in the observed inhibitory activity and enhance our understanding of natural compounds as potential therapeutics for tyrosinase-related disorders. Therefore, P. dioica flower essential oil may represent a safe and effective natural source of skin-whitening agents for cosmetic and pharmaceutical applications. Further investigations, including in vivo studies, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicity profiling, are recommended.Keywords

Skin color is distinguished according to the type of melanin pigments found in skin and their quantity [1]. Melanocytes are epidermal cells responsible for Melanin synthesis, then these pigments are transferred via dendrites to keratinocytes to provide the color of the skin [2]. This process is defined as melanogenesis, which occurs in melanocytes that contain different primordial enzymes [3]. Among these enzymes, tyrosinase is the predominant enzyme that initiates the hydroxylation of L-tyrosine into β-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) and then catalyzes the oxidation of DOPA into DOPAquinone, which is converted to melanin pigments (eumelanin and pheomelanin) [4]. Skin hyperpigmentation and age spotting represent societal disorders and widespread cultural oppression in many countries [5]. Many intrinsic and extrinsic considerations can badly affect the normal process of skin pigmentation [6]. Skin hyperpigmentation is activated by the malfunction of melanocytes and keratinocytes, hormonal disturbance, inflammatory conditions, aging, injuries, scars, and surgeries [7,8]. Further, permanent exposure to sunlight intensifies the number of melanocytes in the epidermal cells, stimulating the formation of melanocyte clusters [9]. Additionally, excessive UV radiation causes an imbalance in the melanocytes and melanin overproduction, leading to spotty pigmentation [10].

Topical cosmetic skin lighteners experience a large and fast-growing market share worldwide, particularly Middle East and Asia [11]. These products can act through different modules like blockage of UV radiation, inhibition of melanogenesis, hindering melanin transfer, and epidermal renewal stimulation [12]. Recently, there has been a great interest in searching for new active and efficient lightning products directly linked to antiaging facial treatments and body products [9]. The current topical lighting therapies contain hydroquinone, kojic acid, azelaic acid, glycolic acid, retinol, salicylic acid, and niacinamide. Unfortunately, many of these mentioned products are highly expensive and suffer from adverse reactions as well as some ingredients are banned or limited in some countries [13]. Formerly, personal care was moving away from commercially available undesired ingredients towards plant-based ingredients [14]. Plant products are being increasingly explored worldwide for many biological activities [15–17], and consumers are pursuing plant-derived mixtures for skin hyperpigmentation complications [18]. Among these plant-derived agents, essential oils are gaining increasing attention due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and skin-lightening properties. Essential oils contain a wide range of chemical constituents, including both phenolic and non-phenolic compounds, which differ in their mechanisms of antioxidant activity. Phenolic components, such as eugenol and thymol, often act as chain-breaking antioxidants that directly scavenge free radicals, while non-phenolic compounds may exert termination-enhancing effects by stabilizing radical intermediates. These complementary mechanisms contribute to the overall bioactivity and efficacy of essential oils in dermatological applications [19].

Genus Pimenta is one of the evergreen flowering plants that incorporates about fifteen species and belongs to the family Myrtaceae. Pimenta plants are distributed in the West Indies and Central America and are mostly copious in Jamaica [20]. In traditional medicine, various organs of the Pimenta species were employed for the treatment of common cold, viral infections, bronchitis, dental and muscle aches, rheumatic pains, and arthritis [21]. Moreover, the essential oils of Pimenta species are associated with the traditional treatment of microbial infections and exert antimicrobial, antiseptic, anesthetic, and analgesic effects [20]. The isolated essential oils of Pimenta plants are characterized by the abundance of eugenol, methyl eugenol, β-caryophyllene, and myrcene [22]. Whereas limonene, 1,8-cineole, terpinolene, β-selinene, and methyl eugenol were reported to be the predominant components in some studies [23]. Pimenta dioica (PD) is a Caribbean tropical tree belonging to the family Myrtaceae, cultivated in the West Indies, Mexico, and South America [24]. It is widely cultivated in tropical regions, particularly in Central America and the Caribbean, for commercial use. The plant is suitable for industrial cultivation due to its high demand and adaptability, although wild harvesting may still occur in some regions. It has many traditional names like allspice, Pimenta, pimento, clove pepper, and Jamaica pepper [24]. It is widely utilized in a variety of human endeavors, including perfume manufacturing, food spice, a natural pesticide, and medicine [25]. In folk medicine, P. dioica was used for different disorders like colds, dysmenorrhea, dyspepsia, diabetes, bruises, viral infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, depression sore joints, and myalgia [26]. It was reported for the treatment of indigestion, inflammation, and fatigue in Cuban medicine [25,27]. Further, it was incorporated into Indian traditional medicine to relieve respiratory congestion and assorted odontalgia [25]. In Egypt, it is known as “fulful afrangi” and used as a spice, condiment, and appetizer [24]. From the pharmacological point of view, Pimenta dioica demonstrated antioxidant [28], hypotensive [29], estrogenic [30], and cytotoxic activities [24]. Regarding phytochemical constituents, several classes of active components were reported, like phenylpropanoids, phenolic acids, essential oils, flavonoids, galloyl glycosides, catechins, and diterpenes [31,32].

In this study, we planned to explore the chemical composition of Pimenta dioica flowers essential oil isolated by hydrodistillation using GC-MS analysis. Further, we aimed to investigate the ability of the tested oil to inhibit the tyrosinase enzyme. Additionally, we focused on discovering the effectiveness of oil components to fit with the tyrosinase enzyme using molecular docking studies.

Pimenta dioica flowers were collected in April 2023 from Zohrya garden (30°2.75′ N, 31°13.4666′ E), Giza, Egypt. The plant was botanically identified by Mrs. Therease Labib, the taxonomy specialist at the herbarium of the El-Orman Botanical Garden, Giza, Egypt. Voucher specimens with a code of PHG-P-PD-478 were deposited at the Department of Pharmacognosy herbarium, Faculty of Pharmacy, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

2.2 Isolation of the Essential Oil by Hydrodistillation

250 g of fresh Pimenta dioica flowers were hydrodistilled for four hours in a Clevenger-type glass apparatus. The isolated oil was collected and weighed, then preserved in sealed vials at 4°C for further analysis. The experiment was performed three times.

2.3 GC/MS Analysis of Essential Oils

The chemical composition of the essential oils obtained through isolation was assessed using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Analysis was performed on a Shimadzu GC/MS-QP 2010 system (Kyoto, Japan), linked to a Thermo-Finnigan SSQ 7000 quadrupole mass spectrometer (Bremen, Germany). A Restek Rtx-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness; USA) was employed. The oven temperature was initially held at 45°C for 2 min, then ramped to 300°C at a rate of 5°C/min, and held for 5 min. Injector and detector temperatures were maintained at 250°C and 280°C, respectively. Essential oil samples were diluted in n-hexane to a 1% (v/v) concentration prior to analysis. Automatic injections of 1 μL were performed using a split ratio of 1:15. Helium served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.41 mL/min. The mass spectrometer was operated under the following conditions: a scan range of 35–500 amu, ion source temperature of 200°C, and an electron ionization voltage of 70 eV.

2.4 Identification of the Oil Components

The identification of the GC peaks in the mass spectra was done by searching the commercial libraries (WILEY, NIST), and the identification of the compounds was then confirmed by matching with the published data as well as by calculating the retention indices (RI) of the peaks compared to (C6-C22) n-alkanes. Peak area percentage was used for quantification and reported as an average of the three measurements.

2.5 Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

To evaluate the anti-tyrosinase potential of the essential oils isolated from Pimenta dioica (PD), a similar method to Mérida-Reyes et al. (2020) [33] was used with slight modifications. A stock concentration of 40 mg/mL in DMSO was prepared for PD, while 20 mg/mL was prepared for the positive control, kojic acid. Thereafter, the stock concentrations were serially diluted to achieve a final concentration of 400–3.12 μg/mL for PD and 200–1.56 μg/mL for kojic acid. The enzyme used was mushroom tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and L-DOPA (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the substrate. A 1% DMSO vehicle control was prepared in the same manner, along with a 0% control consisting of phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). Using a BIO-Tek Power-Wave XS plate reader (Analytical and Diagnostic Products CC, Roodepoort, South Africa) the absorbance values were determined at a wavelength of OD 492 nm for 30 min. To calculate the percentage inhibition, the following equation was used. All samples were tested in triplicate. GraphPad Prism 4 software was used to calculate the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of PD.

% Inhibition = 100 − ((“Absorbance sample at 30 min” − “Absorbance sample at 0 min”)/(“Absorbance control at 30 min” − “Absorbance control at 0 min”)) × 100.

2.6 1,1-Diphenyl-2-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Activity

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of PD was evaluated using a method described by [1,34]. A stock concentration of PD (10 mg/mL) and the positive control, quercitrin (2 mg/mL), were prepared in ethanol. Thereafter, in a 96-well plate, 20 μL of either PD or quercitrin was added to 200 μL of ethanol in triplicate. The samples were serially diluted two-fold to obtain a final concentration of 500–7.81 μg/mL for PD and 100–1.56 μg/mL for the positive control. Thereafter, 90 μL of DPPH (0.04 M) ethanolic solution was added to each well. The DPPH solution was freshly prepared before each assay using analytical grade ethanol, and all experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. A vehicle control consisting of ethanol was prepared similarly, while the 0% control did not contain DPPH solution. Ascorbic acid was also included as a standard antioxidant reference in a separate parallel run for comparative purposes. The plates were developed at room temperature in the dark for 30 min before the absorbance was measured at 515 nm using a BIO-Tek Power-Wave XS plate reader. A similar equation as Section 2.5 was used, while GraphPad Prism 4 software was utilized to calculate the IC50 values.

2.7 Molecular Docking Studies of the Identified Compounds

Molecular Operating Environment (MOE program 2020.09; Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) was used to perform the molecular docking study. The crystal structure of the tyrosinase enzyme (PDB: 6EI4) was downloaded from the protein databank (rcsb.org). The downloaded crystal structures were prepared for docking by adding the missing protons and deleting one of the chains, the co-crystallized ligand, and water molecules using MOE software. All the docked compounds were prepared in the MOE program by adding hydrogen, calculating charges, and performing energy minimization. The docking placement methodology used was a triangle matcher with London dG as the initial scoring methodology. 30 poses were set as the number of placement poses that were passed to the refinement step. The rigid receptor was utilized as the post-placement refinement method with GBVI/WSA dG as the final scoring methodology, and 5 poses were retained after the final refinement. The best poses in terms of binding interactions, proper placement in the active site of the enzyme, and docking scores are discussed in the text.

3.1 Essential Oil Yield and Composition

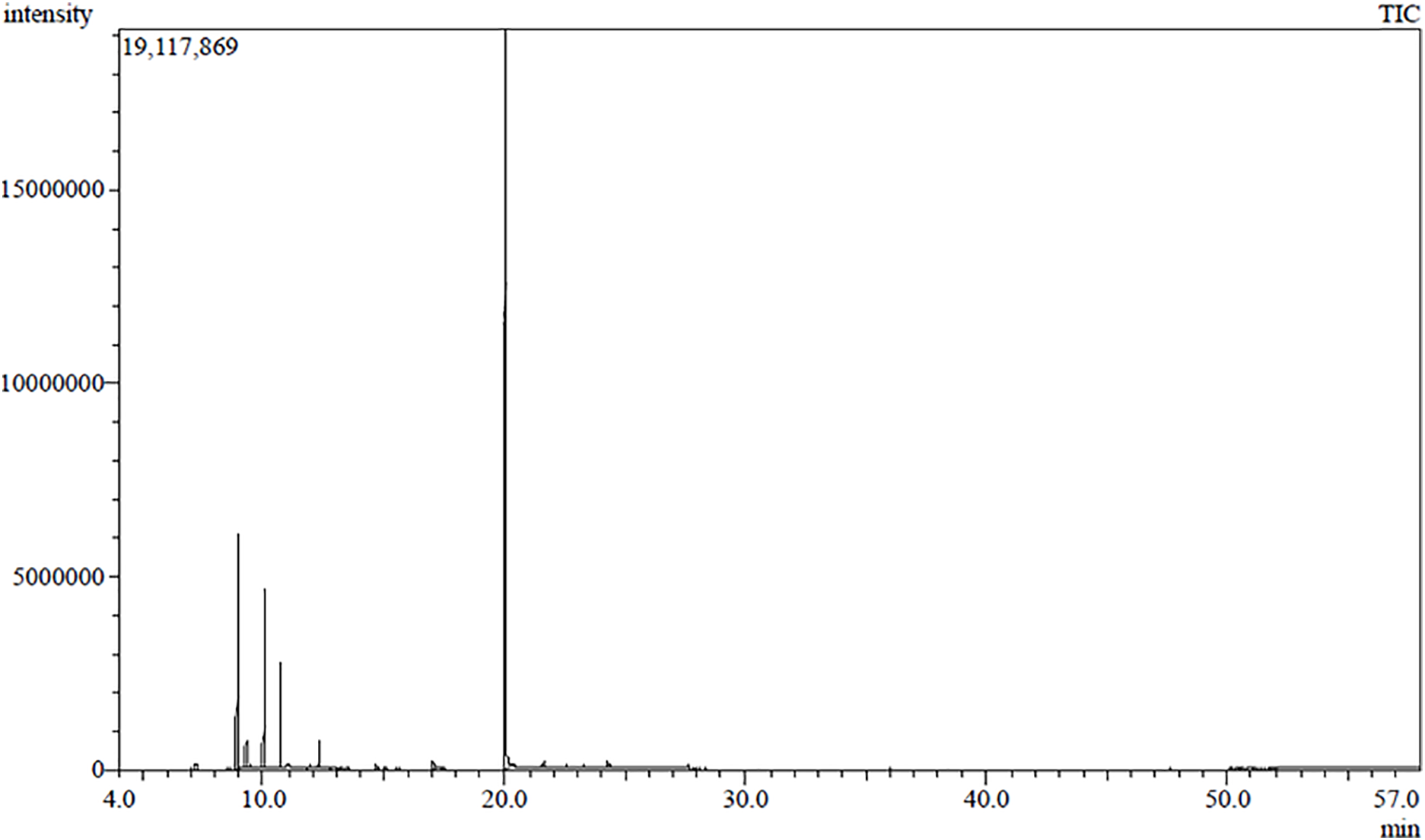

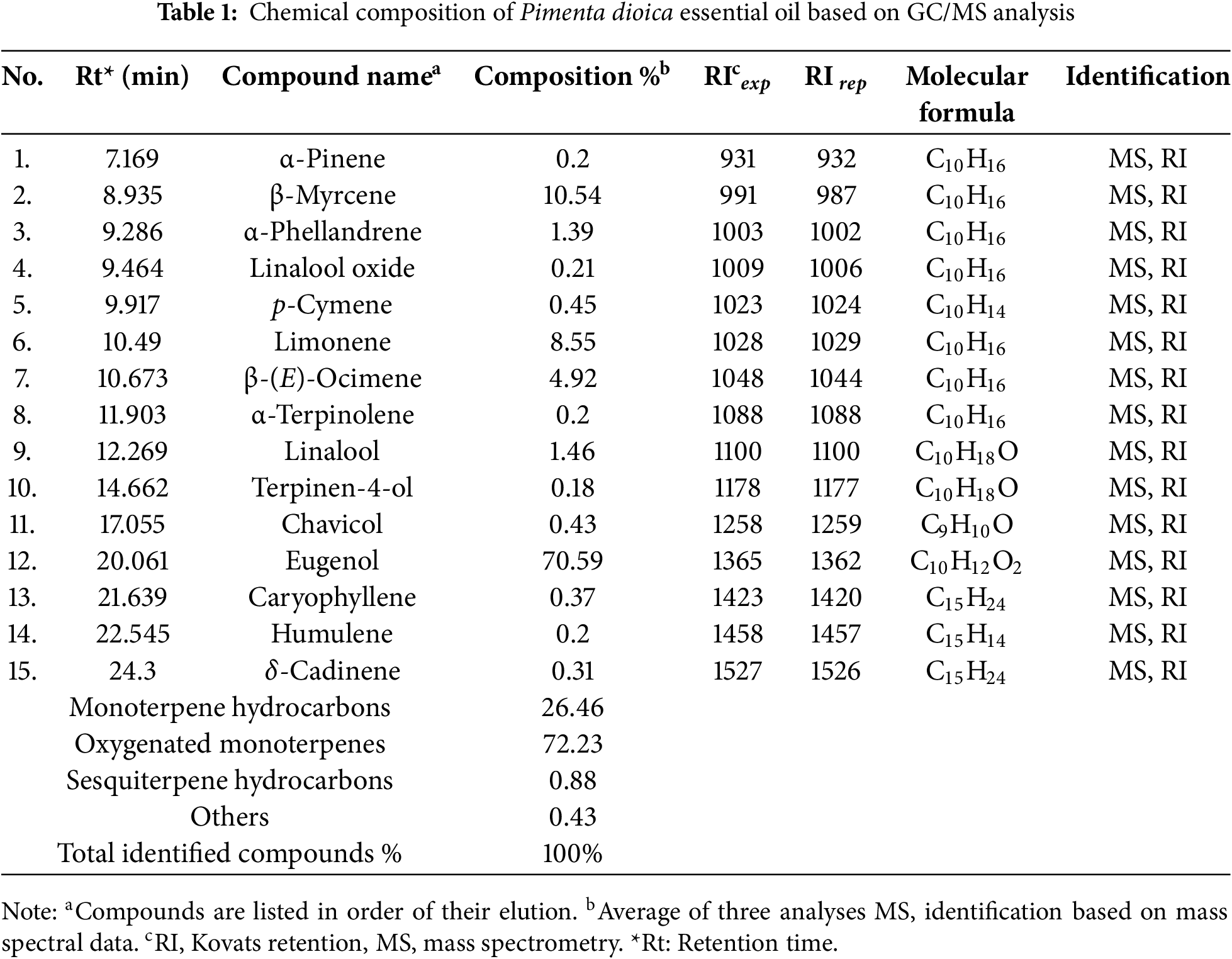

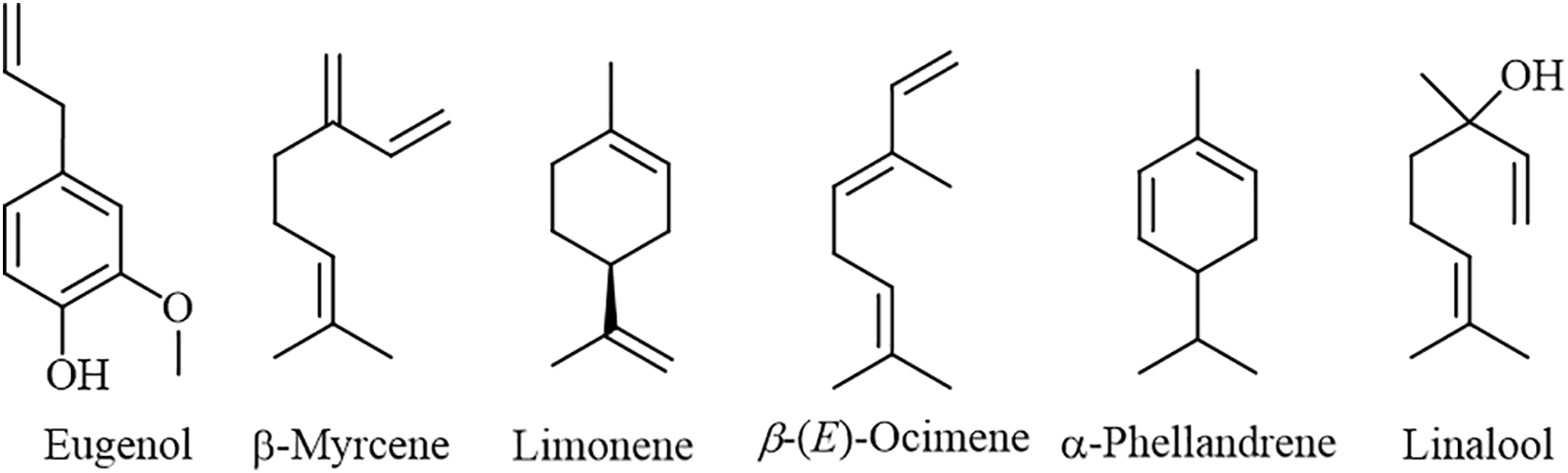

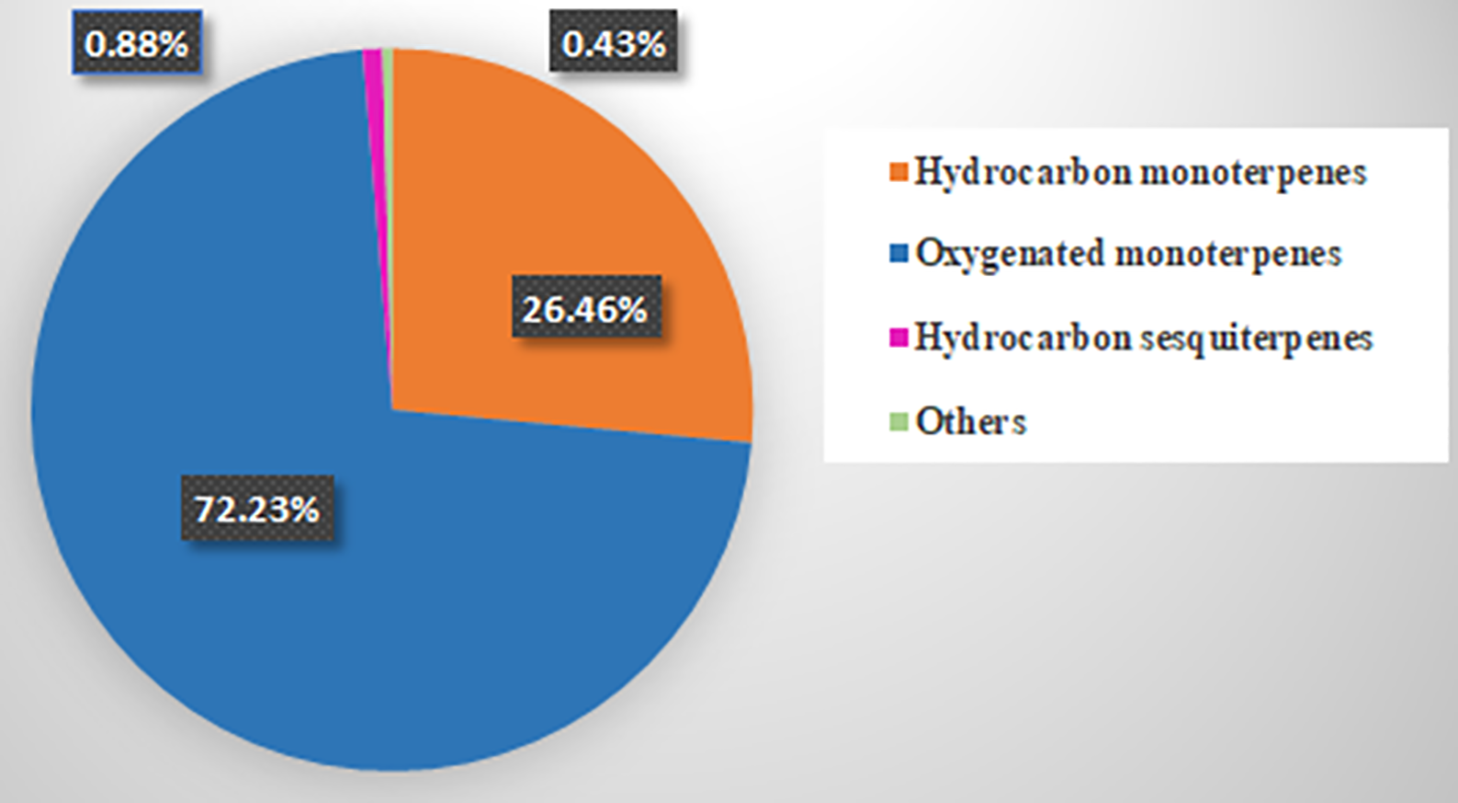

The essential oil of Pimenta dioica flowers was isolated by the hydrodistillation method, and the chemical constituents of the oil were analyzed using GC-MS. The GC-MS chromatogram of the essential oil is shown in Fig. 1. This resulted in the identification of a total of fifteen different compounds, as listed in Table 1. Eugenol (70.59%), β-Myrcene (10.54%), Limonene (8.55%), and β-Ocimene (4.92%) represent the main identified components isolated from P. dioica essential oil. The chemical structures of the main volatile components are shown in Fig. 2. Oxygenated monoterpenes represent the main class of compounds in the essential oil of Pimenta dioica, accounting for 72.23%. The distribution of the identified compound classes is illustrated in Fig. 3. Eugenol and β-Myrcene have been also reported as the main components of P. dioica leave oil collected from Guatemala with a percent composition of 71.4%, and 10.1%, respectively [33], together with caryophyllene, another study has reported the essential oil composition of the P. dioica leaves collected from the Essential Oil University, USA, where eugenol, methyl eugenol and caryophyllene comprised the main components of the oil USA with percent composition of 64.29%, 20.55% and 5.53%, respectively [34]. The essential oil isolated from the P. dioica leaves collected from Jamaica has shown a similar composition to this study, with eugenol, methyl eugenol, and caryophyllene being the major components at 73.35%, 9.54%, and 3.30%, respectively [21]. In our study, caryophyllene has been identified and detected, but with lower concentrations of 0.37%, while methyl eugenol was not detected. On the other hand, although limonene has been identified in our study in high concentrations of 8.55%, it was reported as a minor component in the other reports in the literature with a % composition of 0.5% [35] and 0.46% [36].

Figure 1: GC-MS chromatogram of the essential oil isolated from Pimenta dioica flowers

Figure 2: The chemical structures of the volatile components detected in the essential oil isolated from Pimenta dioica flowers

Figure 3: Pie charts display the distribution of different classes of components (%) identified in the essential oil isolated from Pimenta dioica flowers

These differences between the essential oil composition reported in the literature from the leaves of P. dioica, may be due to several variables that may influence the composition of essential oils, including the source, the harvesting time, oil isolation technique, the environment, and growing circumstances [37,38].

3.2 Tyrosinase Inhibition Activity of the Isolated Essential Oil

The anti-tyrosinase activity of PD was evaluated, and an IC50 of 28.65 ± 0.77 μg/mL was obtained with kojic acid (positive control), showing a value of 1.94 ± 0.53 μg/mL. Similar values were observed by Aumeeruddy-Elalfi et al. [39], who found that PD displayed an IC50 of 22.33 ± 0.13 μg/mL in comparison to kojic acid (2.28 ± 0.05 μg/mL). This could be due to the similar hydrodistillation method that was used, as well as the same plant parts that were harvested.

The anti-tyrosinase activity of PD oil may be attributed to its monoterpene composition represented mainly in eugenol (70.59%), β-Myrcene (10.54%), Limonene (8.55%), and β-Ocimene (4.92%), moreover, other minor monoterpenes like α-Phellandrene (1.39%) and Linalool (1.46%) may also be contributing to the inhibitory activity of the oil under study.

Although the major component of the oil, eugenol, has been previously reported for its tyrosine inhibition activity with IC50 906.54 μg/mL [40], the PD oil showed a higher potency toward tyrosinase enzyme inhibition. This suggests that the inhibitory activity of the oil is attributed to the collective effects of the components. This is supported by the fact that the anti-tyrosinase activity of some monoterpenes found in the oil has been reported previously [41–43]. In our current study, a molecular docking study has been conducted in order to explore the compounds responsible for the inhibitory activity of the PD oil.

3.3 Antioxidant Activity of the Isolated Essential oil

A DPPH method was used to quantify the antioxidant potential of PD, and it was discovered that the essential oil displayed an IC50 of 5.41 ± 0.68 μg/mL and while quercitrin showed a value of 0.78 ± 0.37 μg/mL. A study conducted by Sarathambal et al. (2021) [44] found that PD displayed an IC50 of 19.40 μg/mL and noted that their values were higher than previously reported. In a separate study authored by Salem et al. (2014) [45], the authors found the half-maximal scavenging concentration (SC50) of an extract prepared from PD to be 1.42 ± 0.24 μM. This change in antioxidant potential could be due to the different extraction methods used by the various authors, indicating that the essential oil may be a more potent free radical scavenger than the extract.

3.4 Molecular Docking Studies with Tyrosinase Enzyme

Molecular docking studies were conducted to assess the binding interactions and affinities of the four major isolated compounds, Eugenol, β-Myrcene, Limonene, and β-(E)-Ocimene, in addition to the two minor compounds, Linalool, and α-Phellandrene. The crystal structure of the tyrosinase enzyme (PDB: 6EI4) [46] was utilized in this work to simulate the binding of the isolated compounds with the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme. The reference tyrosinase inhibitor, kojic acid, was also included in the docking study simulation.

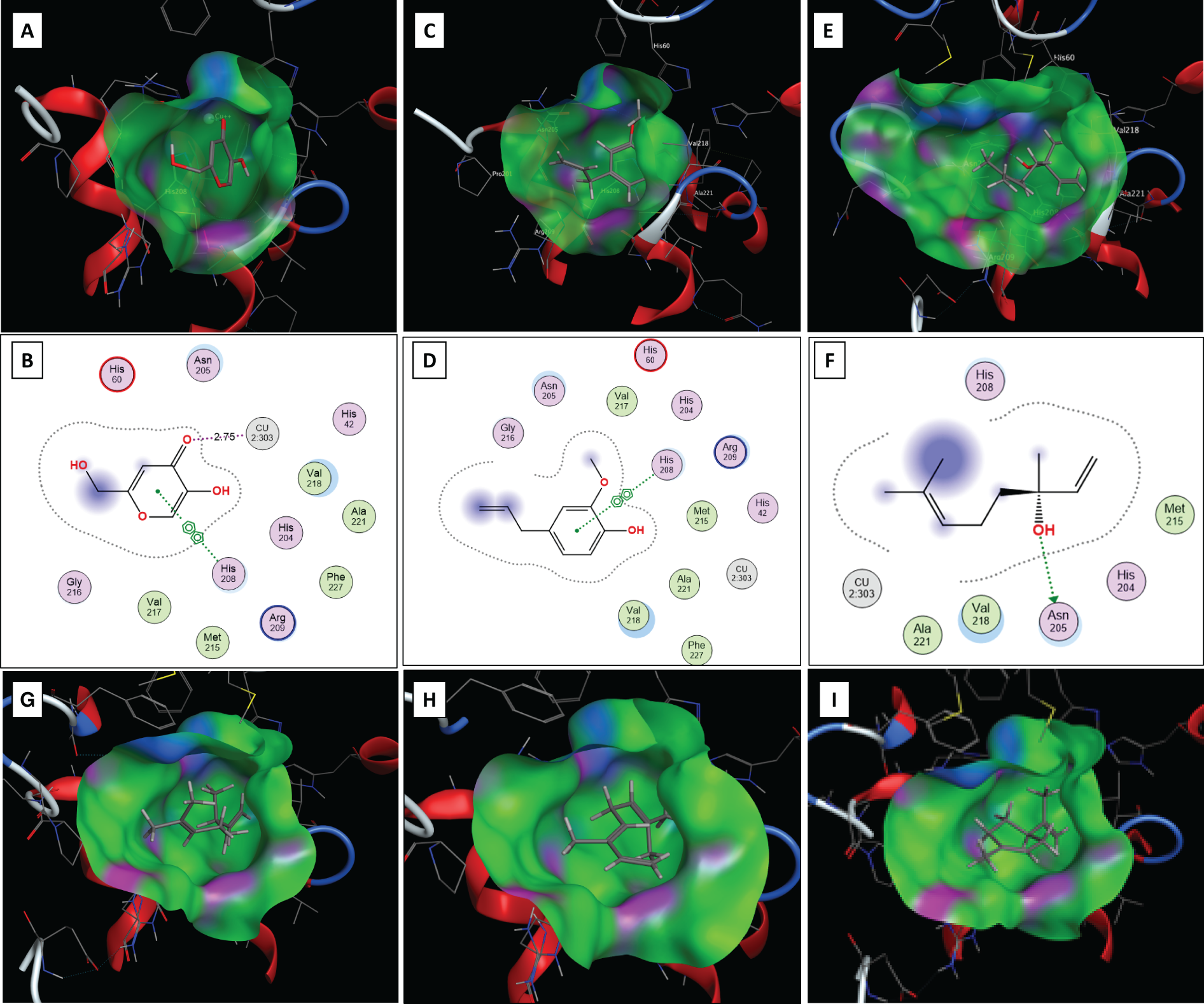

To validate the molecular docking procedure, the known tyrosinase inhibitor kojic acid was docked into the active site of the enzyme (Fig. 4A,B). As expected, kojic acid bound well into the pocket of the tyrosinase enzyme and displayed two main interactions with the active site of the enzyme with a docking score of −5.1940 kcal/mol. The first observed interaction was a metal coordination between the carbonyl oxygen of kojic acid with the metal cofactor of the active site, the copper ion. The second interaction was between the aromatic ring of kojic acid and His 208-imidazole ring through an arene-arene interaction (Fig. 4A,B) [47–49].

Figure 4: Molecular docking studies output poses of kojic acid, eugenol, Linalool, β-Myrcene, β-(E)-Ocimene, and Limonene with the active site of tyrosinase enzyme. The 3D binding of the docked kojic acid (A), eugenol (C), Linalool (E), β-Myrcene (G), β-(E)-Ocimene (H), and Limonene (I) are shown as grey molecules. Green = hydrophobic surface, purple = hydrogen bonding site, and blue = mild polar. Atoms colour code: grey = carbon, red = oxygen, blue = nitrogen, Cu2 + metal ion = light blue sphere. The 2D interactions of kojic acid (B), eugenol (D), and of Linalool (F) with different amino acids in the binding site. Metal coordination is shown as purple dotted lines. Arene-arene interactions are represented as green dotted lines. Amino acids spheres: pink circled in blue = basic, pink circled in black = polar, green circled in black = greasy

The six isolated compounds in the current study were then docked into the active site of the enzyme. The docking procedure was identical to the procedure used in the validation step done with kojic acid. All six docked compounds fit well into the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme (Fig. 4C–I). The docking scores observed for all six main compounds ranged from −5.2436 to −4.8719 kcal/mol. The observed docking scores of the six compounds indicate that they bind with high affinities to the tyrosinase active site, with comparable scores to kojic acid, which showed a docking score of −5.1940 kcal/mol. Upon docking eugenol, it showed good fitting into the binding site of the enzyme similar to kojic acid with a docking score of −5.2436 kcal/mol (Fig. 4C). In terms of binding interactions, eugenol had an arene-arene interaction as one of the major interactions of its aromatic ring and the imidazole ring of His 208 (Fig. 4C,D). 4,5 In addition, it was observed that the enzyme’s active site is predominantly hydrophobic, as indicated by the green regions within the binding pocket (Fig. 4C). This would further enhance the binding affinity and the inhibitory potency of eugenol through hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 4C). The presence of the allyl, and methyl groups in its chemical structure in addition to the central aromatic ring, contribute to the hydrophobic interactions mediated through the hydrophobic amino acids Ala 221, Val 218, His 60, His 208, Arg 209, Pro 201, and Asn 205 (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, one of the minor compounds, Linalool, exhibited a high docking score of −5.1440 kcal/mol and formed one key hydrogen bonding interaction with Asn 205 (Fig. 4E,F). Similarly, several additional hydrophobic interactions were observed with the aforementioned hydrophobic amino acids, including Ala 221, Val 218, His 60, His 208, Arg 209, and the carbon backbone of Asn 205 (Fig. 4E).

Molecular docking of the other three major compounds, β-Myrcene, β-Ocimene, and Limonene, demonstrated good fitting into the active site of the tyrosinase (Fig. 4G–I). The observed docking scores for the three compounds were −5.1286, −4.9454, and −4.8868 kcal/mol, which indicate that they have good affinity to the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme and contribute to the inhibitory effect on the isolated oil. All three compounds, due to their hydrocarbon nature, exhibited several interactions with the hydrophobic amino acids (green surfaces in Fig. 4G–I) in the tyrosinase active site, leading to good binding affinity and inhibitory effects as indicated by the docking scores of the three compounds. Docking of the second minor compound, α-Phellandrene, showed a good fitting into the binding site with a docking score of −4.8719 kcal/mol and similar interactions with the hydrophobic amino acids side chains and backbones lining the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme. Notably, compounds such as eugenol and linalool, which possess hydroxyl groups, particularly with phenolic characteristics, demonstrated stronger binding affinities to tyrosinase compared to non-phenolic hydrocarbons like β-myrcene, β-ocimene, and limonene. This may be attributed to the ability of hydroxyl groups to form hydrogen bonds and participate in metal coordination with the enzyme’s active site, thus enhancing binding stability and inhibitory potential.

The molecular docking studies highlight the possible binding interactions and the potential abilities of the six isolated compounds to bind to and inhibit the tyrosinase enzyme with different binding abilities. Moreover, the docking studies suggest that all the isolated compounds in the current work maintain good affinity with various docking scores, leading to a collective inhibitory effect of the enzyme. This collective inhibitory effect occurs as a result of various binding modes and interactions with the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme and is suggested to result from the six compounds identified in the oil.

While the molecular docking results provide valuable insight into the potential binding interactions and inhibitory effects of the major and minor compounds identified in Pimenta dioica essential oil, it is important to recognize the limitations of this in silico approach. Docking simulations are based on static protein structures and do not fully account for the dynamic behavior of proteins, solvation effects, or metabolic transformations that may occur in biological systems. Furthermore, binding affinity predictions alone cannot confirm functional inhibition in vivo. Therefore, although the docking data support the likelihood of tyrosinase inhibition by these compounds, further validation through enzyme kinetics, cell-based assays, and ultimately in vivo or clinical studies is essential to confirm their efficacy and safety in biological contexts.

Our findings revealed that the essential oil extracted from Pimenta dioica flowers comprises fifteen constituents, predominantly eugenol, β-myrcene, limonene, β-(E)-ocimene, linalool, and α-phellandrene. The oil exhibited significant tyrosinase inhibitory activity and remarkable antioxidant potential. Molecular docking analysis assessed the binding interactions of six major compounds with the tyrosinase enzyme, all of which demonstrated favorable docking scores (ranging from −5.2436 to −4.8719 kcal/mol), comparable to that of kojic acid (−5.1940 kcal/mol). These compounds showed diverse interaction modes within the enzyme’s active site, indicating their collective contribution to the oil’s inhibitory action. The results suggest that the anti-tyrosinase effect of the essential oil may be attributed not solely to eugenol but also to the synergistic role of other monoterpenes. Notably, the essential oil displayed stronger activity than previously reported for pure eugenol alone, highlighting the importance of its compositional complexity.

Therefore, the essential oil of P. dioica flowers presents promising potential as a natural, safe source of skin-depigmenting agents for use in pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. However, to validate its efficacy and safety, further investigations, including in vivo studies as well as pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and toxicity assessments, are warranted.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Ain Shams University, and the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa, for providing laboratory facilities and technical support essential to this study. Special thanks are also extended to Therease Labib, taxonomy specialist at the El-Orman Botanical Garden, Giza, Egypt, for her valuable assistance in plant identification.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Heba A. S. El-Nashar; data collection, analysis and interpretation of results: Ahmed T. Negmeldin, Aziza El Baz, Marizé Cuyler, Brandon Alston, Naglaa S. Ashmawy; draft manuscript preparation: Heba A. S. El-Nashar, Ahmed T. Negmeldin, Aziza El Baz, Marizé Cuyler, Brandon Alston, Namrita Lall, Naglaa S. Ashmawy. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are available upon request from the corresponding authors: Heba A. S. El-Nashar: heba_pharma@pharma.asu.edu.eg, Ahmed T. Negmeldin: dr.ahmedthabet@gmu.ac.ae, and Naglaa S. Ashmawy: naglaa.saad@pharma.asu.edu.eg.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| MS | M spectrometry |

| OD | Optical density |

| PD | Pimenta dioica |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| RI | Retention index |

| GBVI/WSA dG | Generalized Born Volume Integral/Weighted Surface Area docking score |

References

1. Wakamatsu K, Kavanagh R, Kadekaro AL, Terzieva S, Sturm RA, Leachman S, et al. Diversity of pigmentation in cultured human melanocytes is due to differences in the type as well as quantity of melanin. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19(2):154–62. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00293.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yamaguchi Y, Brenner M, Hearing VJ. The regulation of skin pigmentation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(38):27557–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.r700026200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Slominski RM, Sarna T, Plonka PM, Raman C, Brozyna AA, Slominski AT. Melanoma, melanin, and melanogenesis: the Yin and Yang relationship. Front Oncol. 2022;12:842496. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.842496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Oh KE, Shin H, Lee MK, Park B, Lee KY. Characterization and optimization of the tyrosinase inhibitory activity of Vitis amurensis root using LC-Q-TOF-MS coupled with a bioassay and response surface methodology. Molecules. 2021;26(2):446. doi:10.3390/molecules26020446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. El-Nashar HA, El-Labbad EM, Al-Azzawi MA, Ashmawy NS. A new xanthone glycoside from Mangifera indica L.: physicochemical properties and in vitro anti-skin aging activities. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2609. doi:10.3390/molecules27092609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Rabie O, El-Nashar HA, Majrashi TA, Al-Warhi T, El Hassab MA, Eldehna WM, et al. Chemical composition, seasonal variation and antiaging activities of essential oil from Callistemon subulatus leaves growing in Egypt. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2023;38(1):2224944. doi:10.1080/14756366.2023.2224944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yamaguchi Y, Hearing VJ. Physiological factors that regulate skin pigmentation. Biofactors. 2009;35(2):193–9. doi:10.1002/biof.29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. El Khoury R, Michael Jubeli R, El Beyrouthy M, Baillet Guffroy A, Rizk T, Tfayli A, et al. Phytochemical screening and antityrosinase activity of carvacrol, thymoquinone, and four essential oils of Lebanese plants. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(3):944–52. doi:10.1111/jocd.12754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yardman-Frank JM, Fisher DE. Skin pigmentation and its control: from ultraviolet radiation to stem cells. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(4):560–71. doi:10.1111/exd.14260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Sena LM, Zappelli C, Apone F, Barbulova A, Tito A, Leone A, et al. Brassica rapa hairy root extracts promote skin depigmentation by modulating melanin production and distribution. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(2):246–57. doi:10.1111/jocd.12368 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Burger P, Landreau A, Azoulay S, Michel T, Fernandez X. Skin whitening cosmetics: feedback and challenges in the development of natural skin lighteners. Cosmetics. 2016;3(4):36. doi:10.3390/cosmetics3040036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ali SA, Choudhary RK, Naaz I, Ali AS. Understanding the challenges of melanogenesis: key role of bioactive compounds in the treatment of hyperpigmentory disorders. J Pigment Dis. 2015;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

13. Hu S, Laughter MR, Anderson JB, Sadeghpour M. Emerging topical therapies to treat pigmentary disorders: an evidence-based approach. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33(4):1931–7. doi:10.1080/09546634.2021.1940811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sasounian R, Martinez RM, Lopes AM, Giarolla J, Rosado C, Magalhães WV, et al. Innovative approaches to an eco-friendly cosmetic industry: a review of sustainable ingredients. Clean Technol. 2024;6(1):176–98. doi:10.3390/cleantechnol6010011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ashmawy NS, Nilofar N, Zengin G, Eldahshan OA. Metabolic profiling and enzyme inhibitory activity of the essential oil of Citrus aurantium fruit peel. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024;24(1):262. doi:10.1186/s12906-024-04505-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Al-Mijalli SH, Mrabti HN, Elbouzidi A, Ashmawy NS, Batbat A, Abdallah EM, et al. Thymus serpyllum L. essential oil: phytochemistry and in vitro and in silico screening of its antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(1):1. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.060438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abd Algaffar SO, Satyal P, Ashmawy NS, Verbon A, van de Sande WW, Khalid SA. In vitro and in vivo wide-spectrum dual antimycetomal activity of eight essential oils coupled with chemical composition and metabolomic profiling. Microbiol Res. 2024;15(3):1280–97. doi:10.3390/microbiolres15030086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Insaf A, Parveen R, Gautam G, Samal M, Zahiruddin S, Ahmad S. A comprehensive study to explore tyrosinase inhibitory medicinal plants and respective phytochemicals for hyperpigmentation; molecular approach and future perspectives. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2023;24(6):780–813. doi:10.2174/1389201023666220823144242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. López PL, Enemark GKG, Grosso NR, Olmedo RH. Antioxidant effectiveness between mechanisms of “chain breaking antioxidant” and “termination enhancing antioxidant” in a lipid model with essential oils. Food Biosci. 2024;57(6):103498. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2023.103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ismail MM, Samir R, Saber FR, Ahmed SR, Farag MA. Pimenta oil as a potential treatment for Acinetobacter baumannii wound infection: in vitro and in vivo bioassays in relation to its chemical composition. Antibiotics. 2020;9(10):679. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9100679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Padmakumari KP, Sasidharan I, Sreekumar MM. Composition and antioxidant activity of essential oil of pimento (Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr.) from Jamaica. Nat Prod Res. 2011;25(2):152–60. doi:10.1080/14786419.2010.526606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Prasad MA, Zolnik CP, Molina J. Leveraging phytochemicals: the plant phylogeny predicts sources of novel antibacterial compounds. Future Sci OA. 2019;5(7):FSO407. doi:10.2144/fsoa-2018-0124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Tucker AO, Maciarello MJ, Landrum LR. Volatile leaf oils of Caribbean Myrtaceae. II. Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr. of Jamaica. J Essent Oil Res. 1991;3(3):195–6. doi:10.1080/10412905.1991.9700504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Marzouk MS, Moharram FA, Mohamed MA, Gamal-Eldeen AM, Aboutabl EA. Anticancer and antioxidant tannins from Pimenta dioica leaves. Z Für Naturforschung C. 2007;62(7–8):526–36. doi:10.1515/znc-2007-7-811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang L, Lokeshwar BL. Medicinal properties of the Jamaican pepper plant Pimenta dioica and allspice. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13(14):1900–6. doi:10.2174/138945012804545641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kamatou GP, Vermaak I, Viljoen AM. Eugenol—from the remote Maluku Islands to the international market place: a review of a remarkable and versatile molecule. Molecules. 2012;17(6):6953–81. doi:10.3390/molecules17066953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. García MD, Fernández MA, Alvarez A, Saenz MT. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effect of the aqueous extract from leaves of Pimenta racemosa var. ozua (Myrtaceae). J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91(1):69–73. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2003.11.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ramos A, Visozo A, Piloto J, García A, Rodríguez CA, Rivero R. Screening of antimutagenicity via antioxidant activity in Cuban medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87(2–3):241–6. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00156-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Suárez A, Ulate G, Ciccio JF. Cardiovascular effects of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Pimenta dioica in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55(2):107–11. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01485-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Doyle BJ, Frasor J, Bellows LE, Locklear TD, Perez A, Gomez-Laurito J, et al. Estrogenic effects of herbal medicines from Costa Rica used for the management of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16(4):748–55. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a4c76a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Miyajima Y, Kikuzaki H, Hisamoto M, Nikatani N. Antioxidative polyphenols from berries of Pimenta dioica. Biofactors. 2004;22(1–4):301–3. doi:10.1002/biof.5520220159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hussein SAM, Hashim ANM, El-Sharawy RT, Seliem MA, Linscheid M, Lindequist U, et al. Ericifolin: an eugenol 5-O-galloylglucoside and other phenolics from Melaleuca ericifolia. Phytochemistry. 2007;68(10):1464–70. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mérida-Reyes MS, Muñoz-Wug MA, Oliva-Hernández BE, Gaitán-Fernández IC, Simas DLR, Ribeiro da Silva AJ, et al. Composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr. from Guatemala. Medicines. 2020;7(10):59. doi:10.3390/medicines7100059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Nel M, van Staden AB, Twilley D, Oosthuizen CB, Meyer D, Kumar S, et al. Potential of succulents for eczema-associated symptoms. S Afr J Bot. 2022;147(3):1105–11. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2022.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Berrington D, Lall N. Anticancer activity of certain herbs and spices on the cervical epithelial carcinoma (HeLa) cell line. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012(1):564927. doi:10.1155/2012/564927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zabka M, Pavela R, Slezakova L. Antifungal effect of Pimenta dioica essential oil against dangerous pathogenic and toxinogenic fungi. Ind Crops Prod. 2009;30(2):250–3. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2009.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bakkali F, Averbeck S, Averbeck D, Idaomar M. Biological effects of essential oils—a review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(2):446–75. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Dodoš T, Rajčević N, Janaćković P, Vujisić L, Marin PD. Essential oil profile in relation to geographic origin and plant organ of Satureja kitaibelii Wierzb. ex Heuff. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;139:111549. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Aumeeruddy-Elalfi Z, Gurib-Fakim A, Mahomoodally MF. Kinetic studies of tyrosinase inhibitory activity of 19 essential oils extracted from endemic and exotic medicinal plants. S Afr J Bot. 2016;103(6):89–94. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2015.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li J, Min X, Zheng X, Wang S, Xu X, Peng J. Synthesis, anti-tyrosinase activity, and spectroscopic inhibition mechanism of cinnamic acid—eugenol esters. Molecules. 2023;28(16):5969. doi:10.3390/molecules28165969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. El Omari N, Mrabti HN, Benali T, Ullah R, Alotaibi A, Abdullah ADI, et al. Expediting multiple biological properties of limonene and α-pinene: main bioactive compounds of Pistacia lentiscus L. essential oils. Front Biosci Landmark. 2023;28(9):229. doi:10.31083/j.fbl2809229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Capetti F, Tacchini M, Marengo A, Cagliero C, Bicchi C, Rubiolo P, et al. Citral-containing essential oils as potential tyrosinase inhibitors: a bio-guided fractionation approach. Plants. 2021;10(5):969. doi:10.3390/plants10050969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Touhtouh J, Laghmari M, Benali T, Aanniz T, Lemhadri A, Akhazzane M, et al. Determination of the antioxidant and enzyme-inhibiting activities and evaluation of selected terpenes’ ADMET properties: in vitro and in silico approaches. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2023;111(5):104733. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2023.104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sarathambal C, Rajagopal S, Viswanathan R. Mechanism of antioxidant and antifungal properties of Pimenta dioica (L.) leaf essential oil on Aspergillus flavus. J Food Sci Technol. 2021;58(7):2497–506. doi:10.1007/s13197-020-04756-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Salem MA, Marzouk MI, El-Kazak AM. Synthesis and characterization of some new coumarins with in vitro antitumor and antioxidant activity and high protective effects against DNA damage. Molecules. 2016;21(2):249. doi:10.3390/molecules21020249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Ferro S, Deri B, Germanò MP, Gitto R, Ielo L, Buemi MR, et al. Targeting tyrosinase: development and structural insights of novel inhibitors bearing arylpiperidine and arylpiperazine fragments. J Med Chem. 2018;61(9):3908–17. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Lai X, Wichers HJ, Soler-Lopez M, Dijkstra BW. Structure of human tyrosinase related protein 1 reveals a binuclear zinc active site important for melanogenesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(33):9812–5. doi:10.1002/anie.201704616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Noh JM, Kwak SY, Seo HS, Seo JH, Kim BG, Lee YS. Kojic acid—amino acid conjugates as tyrosinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(19):5586–9. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.08.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Deri B, Kanteev M, Goldfeder M, Lecina D, Guallar V, Adir N, et al. The unravelling of the complex pattern of tyrosinase inhibition. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):34993. doi:10.1038/srep34993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools