Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

RAPD Marker Associations and Antioxidant Enzyme Responses of Houttuynia cordata Germplasms under Lead Stress

1 Vegetable Industry Research Institute, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550000, China

2 Agricultural College, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550000, China

3 Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Guizhou Province, Guiyang, 550000, China

4 Fruit and Vegetable Technical Guidance Station, Wusheng County, Wusheng, 638499, China

5 Agricultural and Rural Bureau, Qiannan Buyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Duyun, 558000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jingwei Li. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Plant Breeding and Genetic Improvement: Leveraging Molecular Markers and Novel Genetic Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3003-3021. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069166

Received 16 June 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Houttuynia cordata, a characteristic edible and medicinal plant in southwestern China, is prone to absorbing lead (Pb2+). Excessive consumption may lead to Pb2+ accumulation in the human body, which has been linked to serious health risks such as neurotoxicity, kidney damage, anemia, and developmental disorders, particularly in children. Therefore, the development of molecular markers associated with Pb2+ uptake and the investigation of the plant’s physiological responses to Pb2+ pollution are of great significance. In this study, 72 H. cordata germplasms were evaluated for Pb2+ accumulation after exogenous Pb2+ treatment. A significant variation in Pb2+ content was observed among the germplasms, indicating rich genetic diversity. Using RAPD markers, seven loci were identified to be significantly associated with Pb2+ uptake, with locus 43 (R2 = 6.72%) and locus 53 (R2 = 5.39%) showing the strongest correlations. Marker validation was performed using five low- and five high-accumulating accessions. Two representative germplasms were further subjected to 0, 500 and 1000 mg/kg Pb2+ treatments for 40 days. Pb2+ content, membrane lipid peroxidation, and redox enzyme activities (SOD, POD and CAT) were measured across different organs. Organs with greater soil contact (roots) exhibited higher Pb2+ accumulation and oxidative damage. POD and CAT activities were markedly induced by Pb2+ stress, while SOD response was limited. This study provides a theoretical foundation for breeding low Pb2+-accumulating H. cordata varieties through marker-assisted selection (MAS) and supports their safe use and application in phytoremediation.Keywords

Houttuynia cordata, a highly popular vegetable in Southwest China, belongs to the Saururaceae family. This versatile plant serves dual purposes as both a vegetable crop and a medicinal herb. Studies have demonstrated its potent inhibitory effects on viral infections [1,2]. Furthermore, H. cordata boasts antibacterial, antioxidant, and antitumor properties [3–5], making it a valuable asset in alleviating inflammation. China is endowed with abundant germplasm resources of H. cordata, and its utilization spans a lengthy historical period [4]. Beyond its medicinal and edible worth, this plant finds applications in the production of fermented beverages, health supplements, and cosmetics, further underscoring its multifaceted utility [6].

Pb2+ contamination poses a worldwide challenge [7], manifesting in diverse forms in the natural environment. This contamination can lead to varying degrees of environmental pollution, impacting soil, plants, water, air, and other vital components closely intertwined with human life [8–11]. Exposure to Pb2+-contaminated environments may result in different levels of Pb2+ poisoning towards humans [12]. Excessive intake of lead can easily lead to the accumulation of lead ions (Pb2+) in the human body. Its harm not only involves serious health risks such as neurotoxicity, kidney damage, anemia and developmental disorders, but also has a particularly significant impact on children. Furthermore, crops cultivated in Pb2+-contaminated soil pose significant safety risks to agricultural produce [13], thereby elevating the likelihood of Pb2+ poisoning in human tissues and organs [14–17].

H. cordata has a propensity for absorbing heavy metals. In China, numerous studies have demonstrated its strong ability to absorb Pb2+. Wang et al. [18] employed Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to confirm the robust absorption capacity of H. cordata for lead (Pb2+). Li [19] found that H. cordata has a certain absorption capacity for Cd2+, As3+/As5+, and Pb2+, with the strongest absorption for Pb2+, aligning with the results of the study of Zhao et al. [20]. The rhizomes, serving as the primary edible portion, exhibit a remarkable tolerance for Pb2+ concentrations as high as 1000 mg/kg [21]. In light of H. cordata’s strong absorption capacity for Pb2+, concerns arise regarding the safety of its consumption and use.

Molecular markers refer to DNA sequences located at specific positions within the genome, which, due to their polymorphic characteristics, can reveal genetic variations among different individuals. Association analysis between heavy metal absorption and molecular markers facilitates molecular breeding for plant resistance to heavy metal stress. Nie et al. [22] conducted measurements of Cr6+ content in Liriodendron chinense treated with 200 mg/L Cr6+ and subsequently performed a general linear model Generalized linear model (GLM) analysis with Expressed sequence tags-simple sequence repeat (EST-SSR) markers. At a significance level of p < 0.05, 46 loci were found to be associated. Huang et al. [23] employed QTL mapping and identified molecular marker loci associated with the absorption of Cd2+, Zn2+, or selenium (Se4+/Se6+) on chromosomes 5, 7 and 11, respectively, with molecular marker loci related to Pb2+ absorption present on all three of these chromosomes. Williams et al. [24] were the first to discover and report the Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) technique for molecular markers. The principle of this technique involves using random primers of 8–10 base pairs in length to amplify DNA fragments at non-specific loci through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions [25]. RAPD offers advantages such as ease of operation, low cost, minimal requirements for DNA quality, and no prior knowledge of DNA sequence information being necessary [26].

Pb2+ contamination induces profound physiological effects on plants. A comparative analysis of Zea mays planted in soil with or without high Pb2+ contamination revealed that plants subjected to Pb2+ stress exhibited significantly elevated levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), and stimulated activities of redox enzymes, for instance, activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT), compared to their non-stressed counterparts [27]. In contrast, research on Picea asperata seedlings under Pb2+ stress observed a notable decline in their antioxidant enzyme activities [28]. When Alnus cremastogyne trees were cultivated in soil with varying Pb2+ concentrations (ranging from 0 to 400 mg/kg), the findings indicated that as Pb2+ concentrations increased, the activities of antioxidant enzymes and the content of osmolytes initially rose but eventually declined [29]. In living organisms, redox enzymes work in tandem to scavenge oxygen radicals and peroxides, effectively inhibiting membrane lipid peroxidation and protecting cellular membranes from damage or destruction. Under adverse environmental conditions, such as heavy metal contamination, the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants surges considerably. These excessive ROS can directly or indirectly initiate peroxidation of membrane lipids, a process that, akin to a chain reaction, irreversibly generates additional radicals, thereby exacerbating damage to cellular structure and function.

In this study, we assessed the Pb2+ absorption capacity of 72 H. cordata samples under high Pb2+ contamination conditions. DNA was extracted from each germplasm, and RAPD molecular marker analysis was conducted. By analyzing the patterns of PCR products, combined with the Pb2+ absorption characteristics of the germplasms, correlation analysis was performed to identify potential molecular markers or loci indicative of Pb2+ absorption capacity in H. cordata. A pair of H. cordata materials with extremely high and low Pb2+ absorption capacities were selected and planted in substrates with varying Pb2+ concentrations. By examining Pb2+ content, MDA content, and activities of SOD, POD, and CAT enzymes in different organs of this pair, the spatial distribution pattern of Pb2+ within H. cordata and the physiological impact mode of Pb2+ on the plant were analyzed. The research data provide a foundational dataset for molecular-assisted breeding of H. cordata with low Pb2+ absorption capacity.

In this study, 72 accessions of H. cordata germplasms served as the plant materials. In order to investigate their ability to absorb Pb2+, The rhizomes of H. cordata were cultivated in a Pb2+-contaminated substrate composed of equal parts (1:1:1) of peat, vermiculite, and perlite. A 500 mg/kg Pb2+ solution was added to 3 kg of dry substrate, mixed thoroughly, and then filled into pots. Following 40 d of repeated watering and air-drying cycles, a naturally passivated Pb2+-contaminated substrate was obtained. The reagent used for preparing the Pb2+-contaminated substrate was analytical-grade lead nitrate solution (Pb(NO3)2, TMRM, Beijing, China). The rhizomes of H. cordata, each consisting of three nodes, were planted in the Pb2+-contaminated and uncontaminated substrate. For each treatment, 30 g of stem segments were planted at a depth of 5 cm. The plants were uniformly managed with water and fertilizer according to standard cultivation practices for a period of 180 days, with no additional fertilizers, growth regulators, or other agents applied throughout this duration.

2.2 Determination of Pb2+ Content in the Rhizomes of H. cordata

The content of Pb2+ in H. cordata was determined by ICP-MS according to Paul et al. [30] with some mofidication. The Pb2+ content in H. cordata was determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Fresh samples were first rinsed with tap water and ultrapure water, oven-dried at 60°C, and ground into a fine powder. Powder of 0.3 g was weighed into microwave digestion vessels and digested with 5 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO3, 65%) and 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) using a microwave digestion system. The digested solution was evaporated to near dryness at 140°C, diluted to 50 mL with 2% HNO3, and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane. Pb2+ concentrations were measured using a Thermo Fisher iCAP Qc ICP-MS. Standard solutions (0–10 μg/L) were prepared using 2% HNO3, with a 10 μg/L internal standard solution added for calibration. The absorptivity of Pb2+ is determined as the difference value of Pb2+ content of 500 mg/kg Pb2+ treated samples minus Pb2+ content of 0 mg/kg Pb2+ treated samples. The external standard method was used to calculate Pb2+ content based on the following equation:

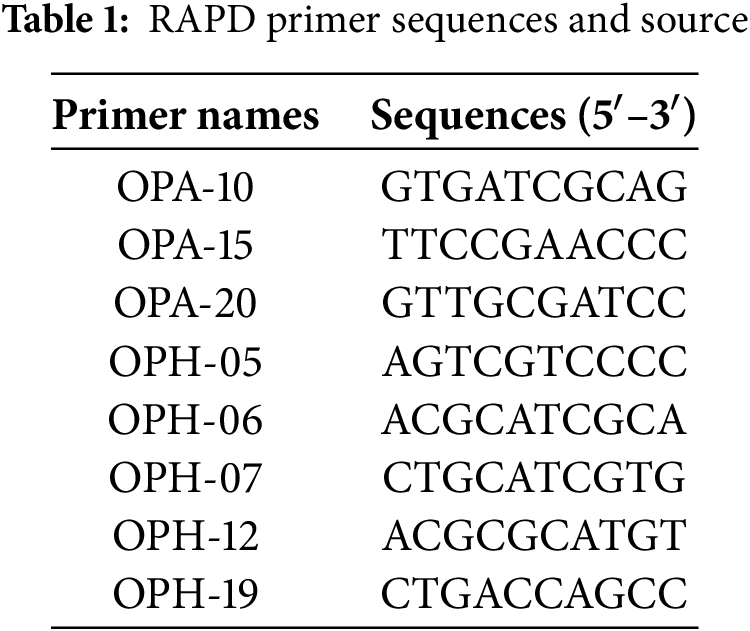

DNA extraction was conducted according to Zhu et al. [31]. The 34 RAPD primer sequences used in this experiment were sourced from Wu et al. [32], and the synthesis of the primers was commissioned to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd. A total of 8 primers producing clear polymorphic bands were screened out for experimental and statistical analysis (Table 1). The PCR mix system was 20 μL, containing 2 μL of template DNA, 1 μL of primer, 10 μL of 2× Taq enzyme, and 7 μL of ddH2O. The PCR program was as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 53°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. After the last cycle, the mixture was kept at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel. The results were observed and photographed on a ChampChemi610 (Beijing Sai zhi, Beijing, China).

2.4 Correlation Analysis of RAPD Molecular Markers and Pb2+ Content

To assess the relationship between RAPD molecular markers and Pb2+ content in H. cordata, we conducted an association analysis using a GLM implemented in TASSEL 5.2 software. In this model, the Pb2+ content for each accession (log-transformed to approximate normal distribution) was used as the dependent variable, and the presence/absence (1/0) of each RAPD locus was treated as an independent predictor. For each RAPD locus, the model calculated the F-statistic to test the significance of its effect on Pb2+ content, along with the corresponding p-value derived from the F-distribution. To assess the robustness of the observed associations, a permutation test (1000 permutations of genotype-phenotype assignments) was performed to calculate empirical permutation p-values (Perm p). Additionally, the phenotypic variation explained by each marker was reported as the coefficient of determination (R2), representing the proportion of total variance in Pb2+ content attributable to each marker. Significance was determined at the nominal level of p < 0.05. Although permutation p-values were not significant for individual loci, further validation was conducted using five accessions with the highest and five with the lowest Pb2+ content, to confirm the consistency of marker-locus patterns.

2.5 Detection of Pb2+ Content in Different Organs of H. cordata

Due to the low reproduction rate of GZZZ (the lowest Pb2+ absorbent germplasm) and the insufficient sample amount to be tested, H. cordata GZNJ1 and GZSCP were used as experimental materials. GZNJ1 and GZSCP were the Pb2+ second-lowest and the highest absorption germplasms, respectively. The rhizomes of two germplasms were planted on Pb2+-contaminated cultivation substrate (Pb2+ concentrations of 0, 500 and 1000 mg/kg, respectively). These three levels were chosen to establish a dose response range from moderate to high Pb stress in pots; the 1000 mg/kg level was included to elicit clear phenotypic and physiological differences among germplasms under controlled conditions. Each rhizome carried 3 internodes, and each treatment cultivated a total of 30 g stem segments. The planting depth of the stem segments was 5 cm, and each experimental treatment was repeated 3 times. After 40 d of treatment, H. cordata fibrous roots, rhizomes, stems and leaves were taken and washed with tap water, washed with deionized water 3 times, and then dried with absorbent paper to remove excess water. ICP-MS was used to determine the Pb2+ content in each organ.

2.6 Determination of MDA Content of Different Organs of H. cordata

Forty-day-old adventitious roots, rhizomes, stems, and leaves of 0, 500 and 1000 mg/kg Pb2+ treated H. cordata were collected. The samples were washed with tap water, followed by 3 rinses with deionized water, and then dried with absorbent paper to remove excess water. The samples were then ground into a homogenate. The content of MDA was determined according to the instructions provided by MDA assay kit (TBA method) (A003-1-2, Nanjing Jiancheng, Nanjing, China).

2.7 Determination of Activities of Redox Enzymes in Different Organs of H. cordata

After 0, 500 and 1000 mg/kg Pb2+ treatment, 40 d adventitious roots, rhizomes, stems, and leaves of H. cordata were collected. The samples were washed as described above and then ground into a homogenate. The activities of SOD, POD, and CAT were determined according to the instructions provided by SOD Activity Assay Kit (BC0175, Solarbio, Beijing, China), POD Activity Assay Kit (BC0090, Solarbio) and CAT Activity Assay Kit (BC0205, Solarbio), respectively.

All experiments were repeated at least three times, with each replicate containing no fewer than 30 biological samples. The data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

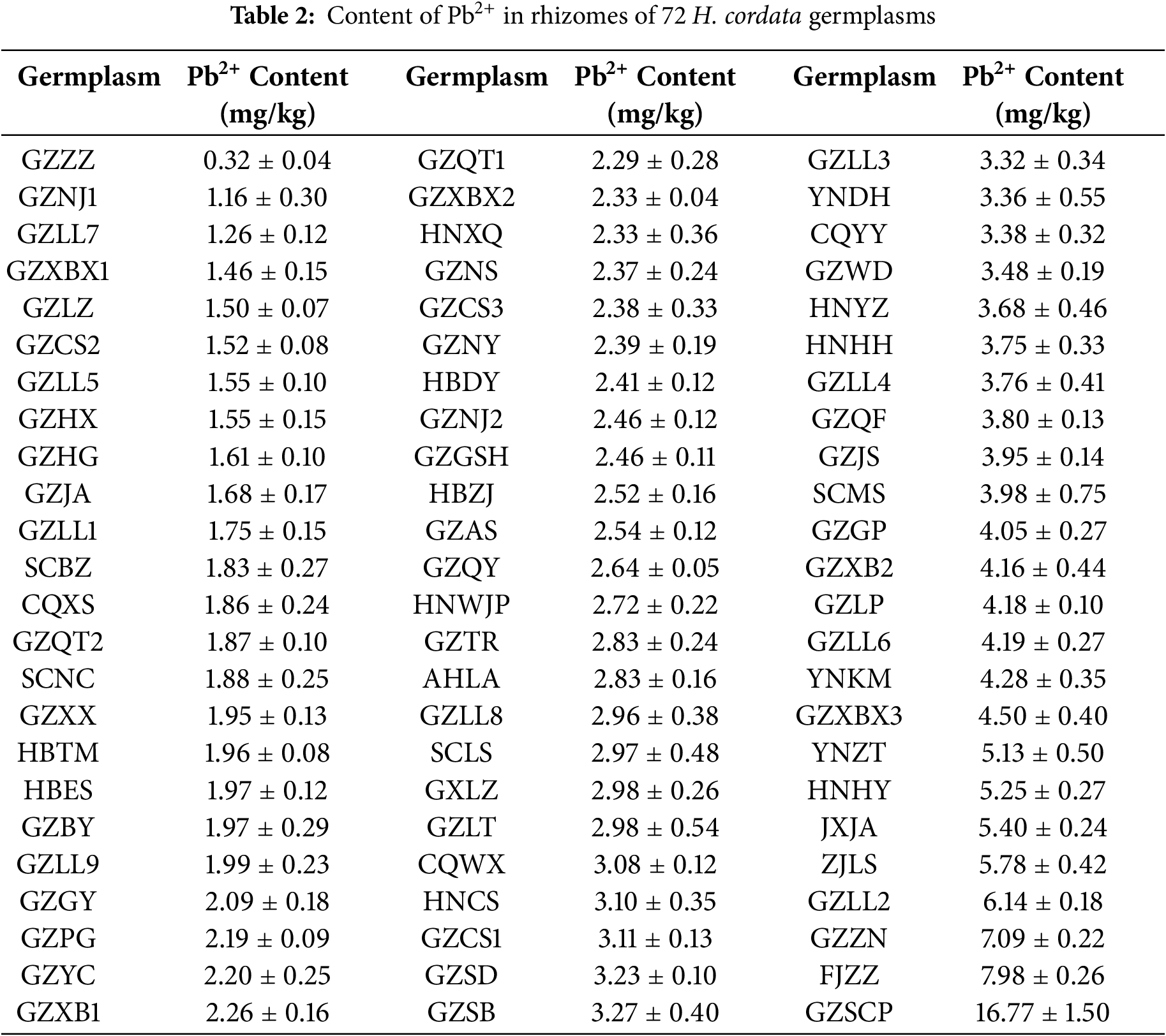

3.1 The Pb2+ Content in the Rhizomes of H. cordata

Among the 72 accessions of H. cordata, one accession had a Pb2+ content below 1.00 mg/kg, which was GZZZ (at 0.32 mg/kg). There were 19 accessions with Pb2+ content ranging from 1.00 to 2.00 mg/kg. Among these, the accession with the lowest Pb2+ content was GZNJ1, at 1.16 mg/kg, followed by GZZZ. The accession with the highest Pb2+ content in this range was GZLL9, at 1.99 mg/kg. There were 23 accessions with Pb2+ content ranging from 2.00 to 3.00 mg/kg. The lowest in this range was GZGY, with a Pb2+ content of 1.97 mg/kg, while the highest was GZLT, with a Pb2+ content of 2.98 mg/kg. Fifteen accessions had Pb2+ content ranging from 3.00 to 4.00 mg/kg. The lowest in this range was CQWX, with a Pb2+ content of 3.08 mg/kg, and the highest was SCMS, with a Pb2+ content of 3.98 mg/kg. Six accessions had Pb2+ content ranging from 4.00 to 5.00 mg/kg. The lowest in this range was GZGP, with a Pb2+ content of 4.05 mg/kg, and the highest was GZXBX3, with a Pb2+ content of 4.50 mg/kg. Four accessions, YNZT, HNHY, JXJA, and ZJLS, had Pb2+ content ranging from 5.00 to 6.00 mg/kg. Only GZLL2 had a Pb2+ content between 5.00 and 6.00 mg/kg. There were two accessions with Pb2+ content ranging from 7.00 to 8.00 mg/kg, which were FJZZ and GZZN. Among the 72 accessions, the one with the highest Pb2+ content was GZSCP, with a Pb2+ content of 16.77 mg/kg (Table 2).

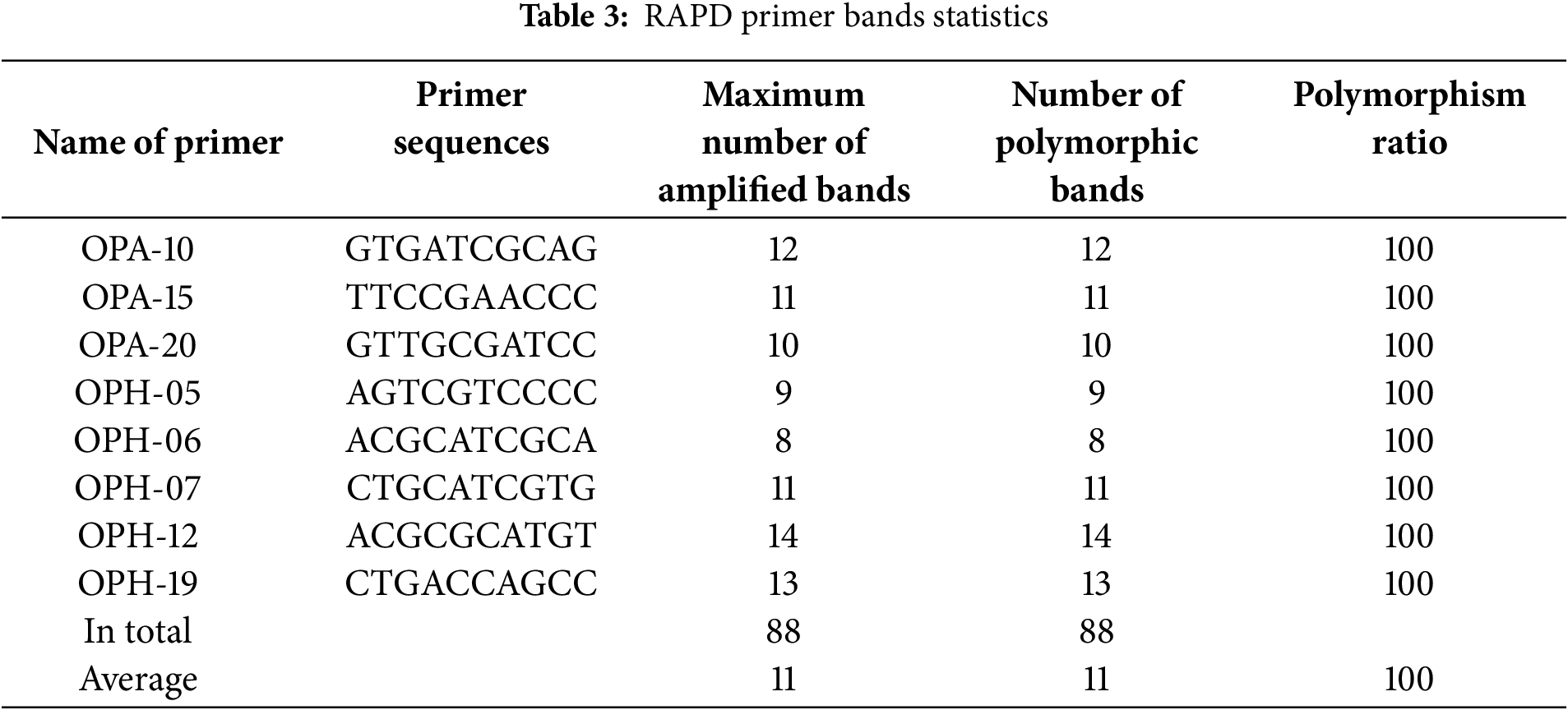

3.2 RAPD Polymorphic Marker Amplification

Eight RAPD primers were used, resulting in a total of 88 bands, with an average of 11 bands per primer. All 88 bands were polymorphic. The number of bands amplified by each of the primers ranged from 8 to 14. Specifically, the primers produced the following number of bands: OPH-06 amplified 8 bands; OPH-05 amplified 9 bands; OPA-20 amplified 10 bands; OPA-15 and OPH-07 both amplified 11 bands; OPA-10 amplified 12 bands; OPH-19 amplified 13 bands; and the primer with the highest number of bands was OPH-12, which amplified 14 bands (Table 3).

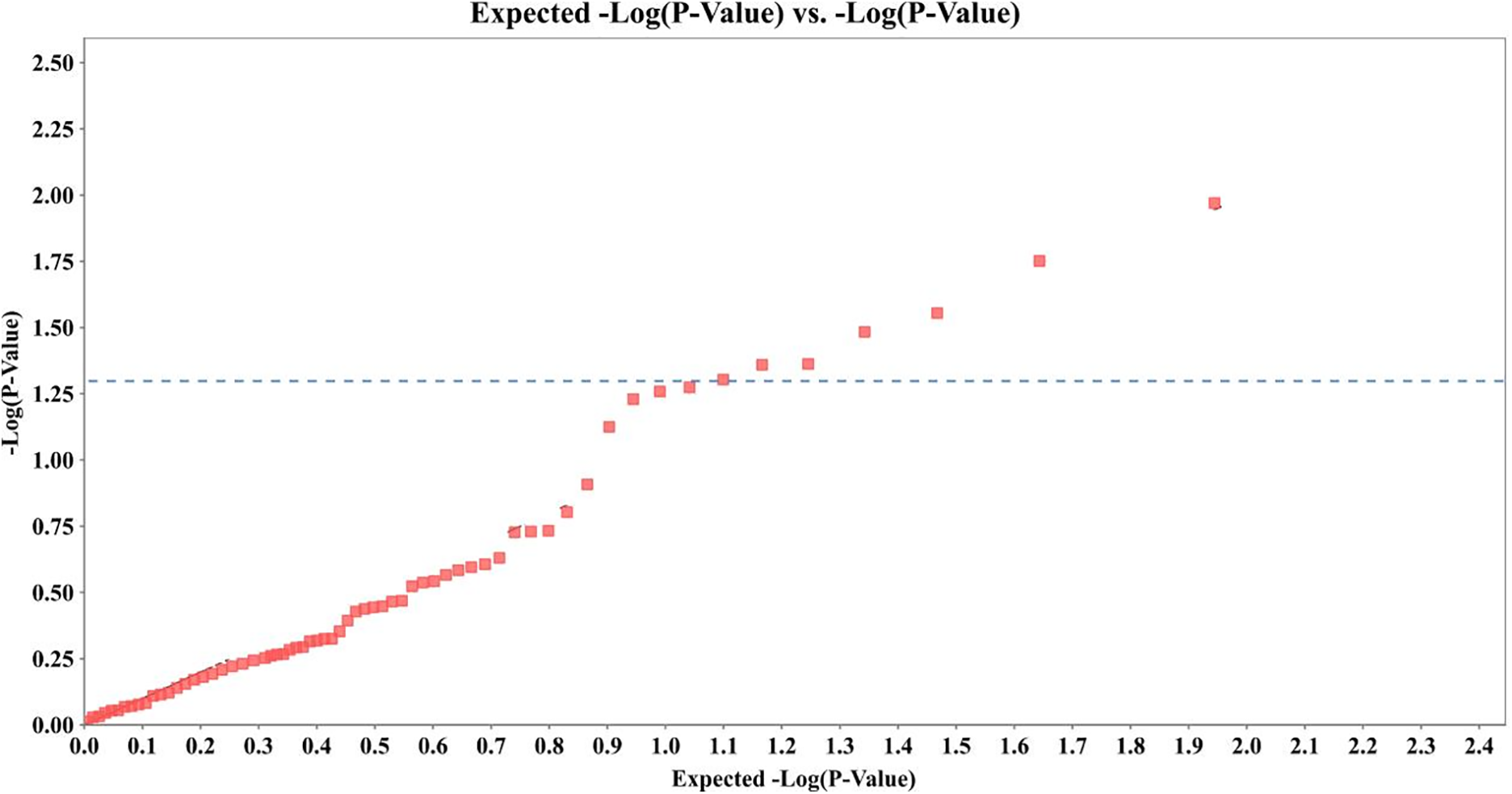

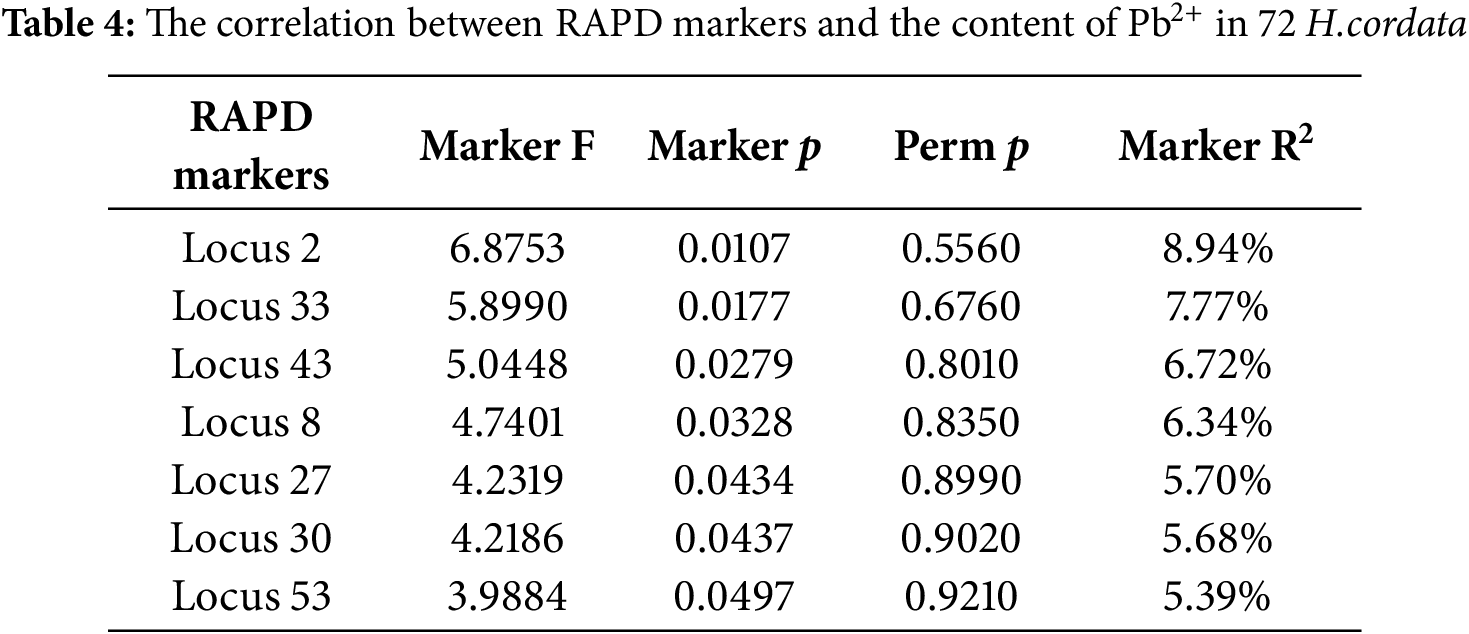

3.3 Correlation Analysis of Pb2+ Content and RAPD Markers

Association analysis using a GLM in TASSEL 5.2 revealed seven RAPD loci significantly associated with Pb2+ (Fig. 1) content at the nominal level (p < 0.05; Table 4), Among them, locus 2 exhibited the highest explanatory power with F = 6.88 and R2 = 8.94%, followed by locus 33 (R2 = 7.77%) and locus 43 (R2 = 6.72%). However, the permutation p-values for all loci exceeded 0.5, indicating that none of the associations remained significant under random phenotype-genotype reshuffling. This suggests that the observed associations may be sensitive to sampling structure, limited sample size, or false positives due to multiple testing.

Figure 1: Correlation analysis of Pb2+ content and RAPD markers in 72 samples of H. cordata. Blue line indicates p = 0.05

Despite this limitation, locus 43 stands out as a candidate marker due to its consistent amplification in high-Pb2+-absorbing accessions (see Table 5), combined with moderate effect size and statistical support (p = 0.0279, R2 = 6.72%). Locus 53, though less significant (p = 0.0497), also showed promising group-specific patterns, present in 60% of high absorbers but absent in all low absorbers. These loci are thus prioritized for further validation in larger populations and potential use in marker-assisted selection (MAS).

The relatively low R2 values (5.39%–8.94%) across all loci suggest that Pb2+ accumulation in H. cordata is a polygenic trait, likely controlled by multiple small-effect loci rather than a single dominant gene. Further work involving multi-locus models and genome-wide approaches may help uncover additional genetic factors contributing to lead uptake.

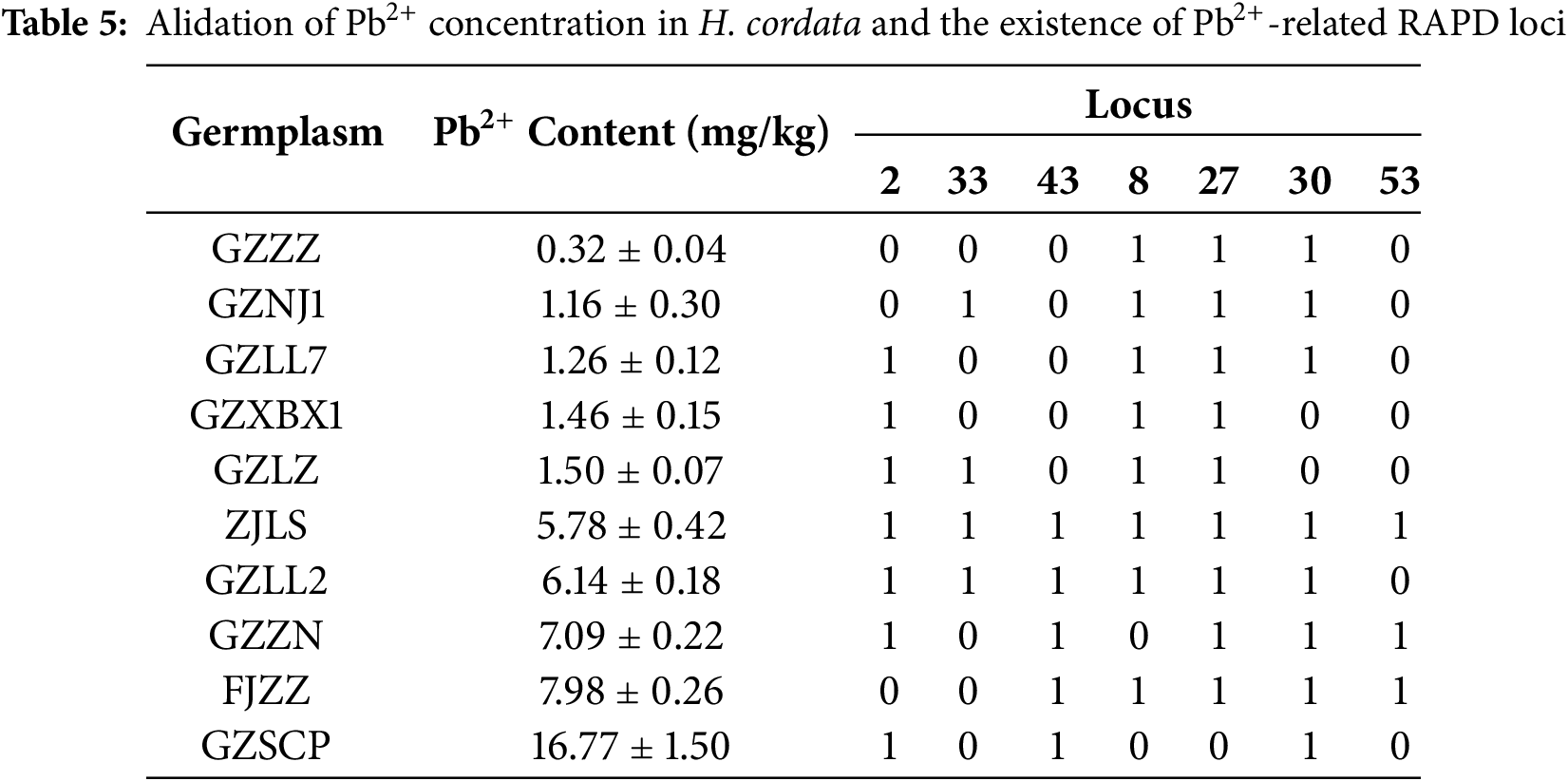

3.4 Verification of the Correlation between Pb2+ Content and RAPD Markers

To verify the discriminative power of the seven candidate loci, five accessions with the lowest and five with the highest Pb2+ content were selected as an independent panel (Table 5). Locus 43 segregated perfectly between the two groups: it was present in all five high-Pb2+ accessions and absent from all five low-Pb2+ accessions (sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 100%; two-tailed Fisher’s exact p = 0.008). This indicates that locus 43 can serve as a diagnostic marker for high Pb2+ absorption. Locus 53 was detected in 3/5 high absorbers but in none of the low absorbers (sensitivity = 60%, specificity = 100%; p = 0.17), suggesting moderate screening value that needs confirmation in larger populations.Locus 30 showed high sensitivity (100%) but low specificity (40%), while loci 2, 8 and 27 displayed inconsistent patterns and therefore limited predictive value. Collectively, the validation highlights locus 43—and, to a lesser extent, locus 53—as the most reliable markers for distinguishing Pb2+-high from Pb2+-low germplasms. These loci will be prioritised in subsequent MAS programs aimed at breeding low-Pb2+ cultivars of H. cordata.

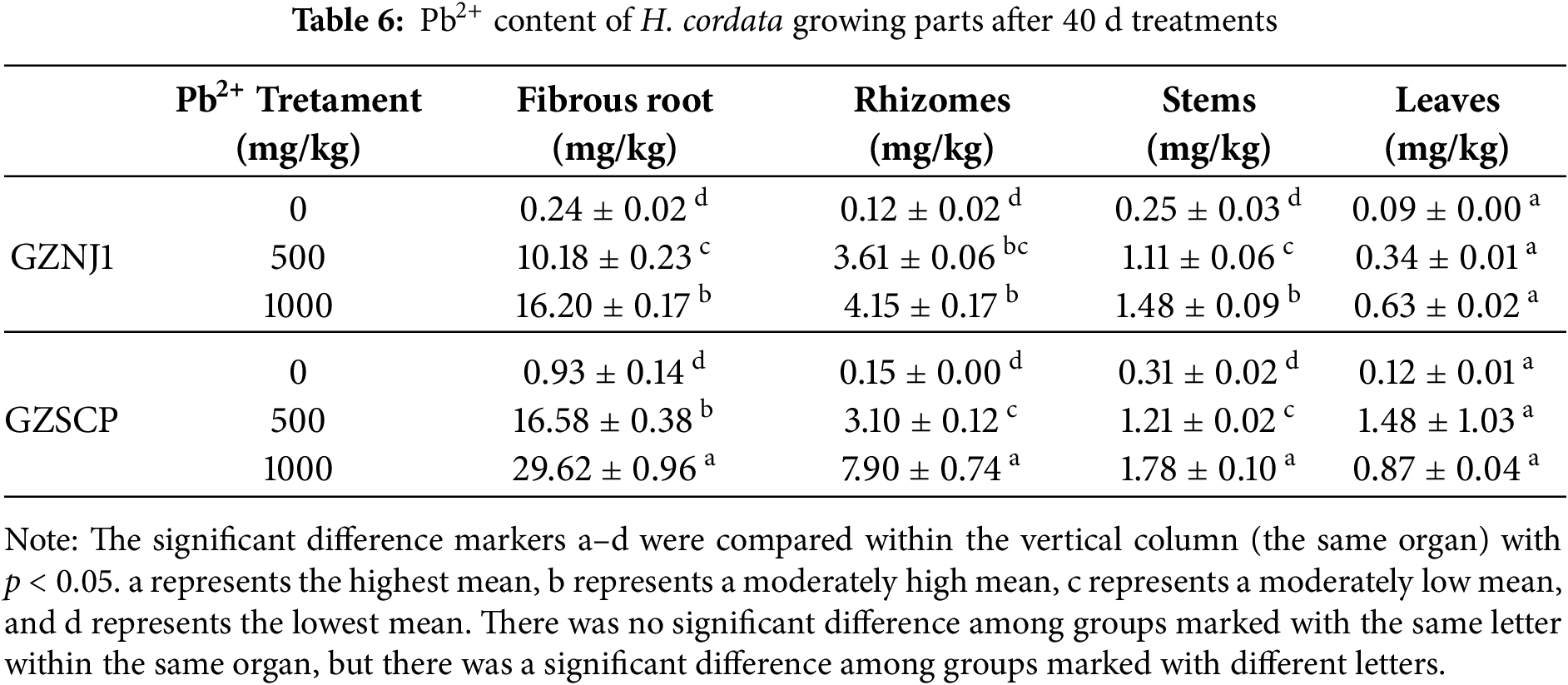

3.5 Patterns of Pb2+ Uptake in Different Organs of High/Low Pb2+-Absorbing H. cordata

After validating the relationship between Pb2+ absorption and key loci of RAPD molecular markers, we selected two germplasms exhibiting extreme differences in lead absorption capacity-specifically, high and low-to conduct a study on the spatial distribution patterns of endogenous lead in H. cordata. After 40 days of post Pb2+ treatment, as the concentration of Pb2+ increased from 0 to 1000 mg/kg in planting substrate, the Pb2+ content in all parts of the two materials, GZNJ1 and GZSCP, increased generally (Table 6). The organ with the highest Pb2+ content was the fibrous root, followed by the rhizomes. The Pb2+ content in the stem was lower than that in the rhizomes, and the Pb2+ content in the leaves was the lowest among the four types of organs. Pb2+ content was higher in GZSCP than in GZNJ1 regardless of organ types. The highest Pb2+ content was found in the fibrous root of GZSCP at a Pb2+ concentration of 1000 mg/kg, which was 29.62 mg/kg, while the lowest content was in the leaves of GZNJ1 at a Pb2+ concentration of 0 mg/kg, which was 0.09 mg/kg (Table 6). According to the Chinese National Food Safety Standard (GB 2762-2022), the maximum allowable Pb2+ content in vegetables ranges from 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg (fresh weight), depending on the vegetable type. In this study, the Pb2+ concentrations measured in the stems and leaves of the low-absorbing germplasm GZNJ1 under 1000 mg/kg treatment remained relatively low, suggesting a potential for edibility of aerial parts, though further assessment under fresh weight conditions is needed.

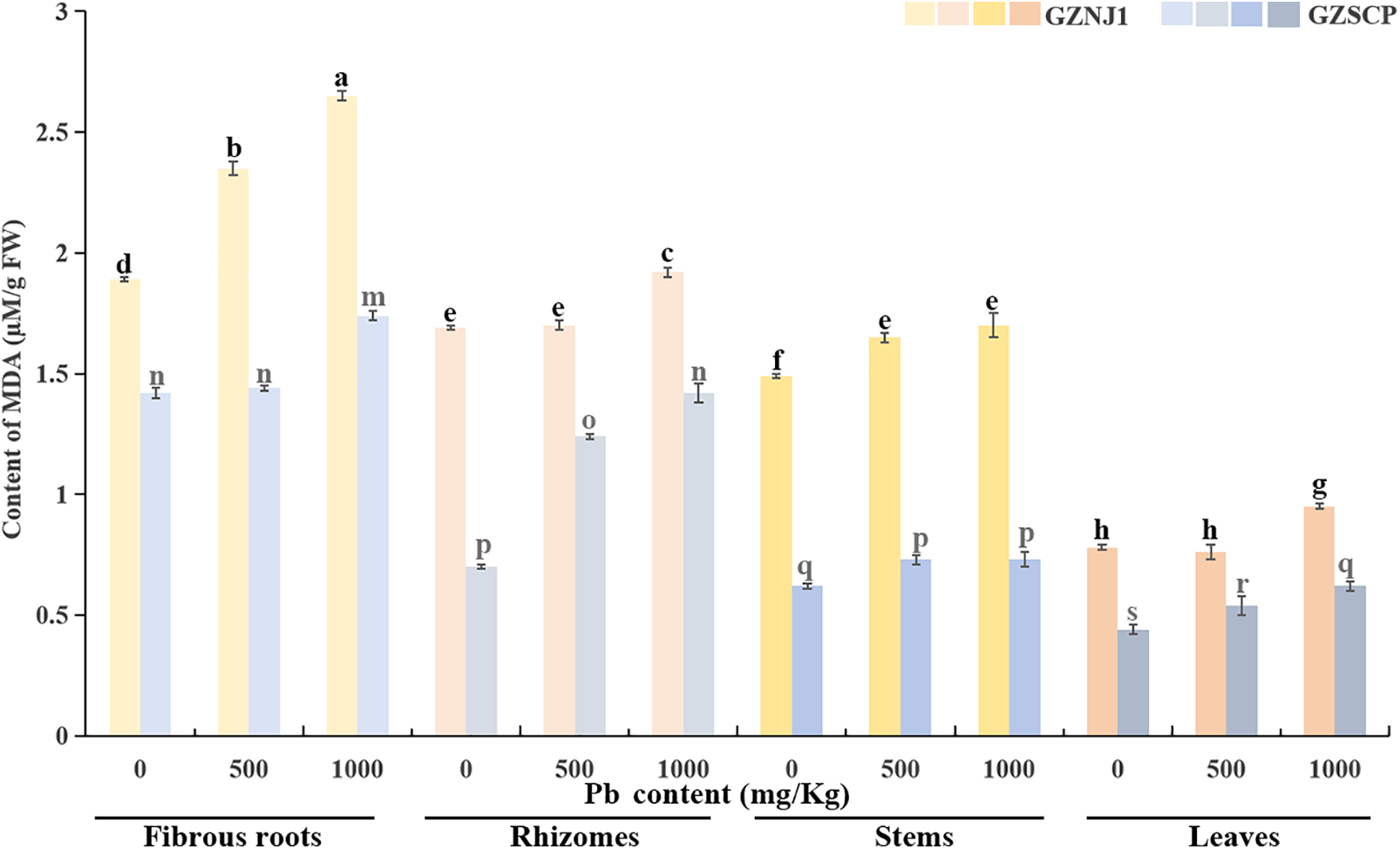

3.6 Changes of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation in Different Pb2+ Treated H. cordata Organs

In the absence of exogenous Pb2+ stress, the MDA content in the fibrous roots was higher than that in the other three organs. The MDA content in the rhizomes was the second highest, followed by that in the stems, and the leaves had the lowest MDA content. Moreover, the MDA level in the low Pb2+-absorbing germplasm (GZNJ1) was higher than that in the high Pb2+-absorbing germplasm (GZSCP), indicating that the biomembrane homeostasis of GZSCP may be higher than that of GZNJ1. When the two H. cordata germplasms with high and low Pb2+ absorption were subjected to different concentrations of exogenous Pb2+ stress, the MDA concentrations in the fibrous roots, rhizomes, stems, and leaves showed an increasing trend with the increase of Pb2+ stress intensity. That is, the degree of membrane lipid peroxidation in H. cordata is positively correlated with the degree of exogenous Pb2+ stress (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Content of MDA in different Pb2+ treated H. cordata organs. Data were present by average value ± stand error. The significant differences in data are compared within the same germplasm. The data were analyzed for significant differences at p < 0.05

3.7 Changes of Redox Enzyme Activities in Different Pb2+ Treated H. cordata Organs

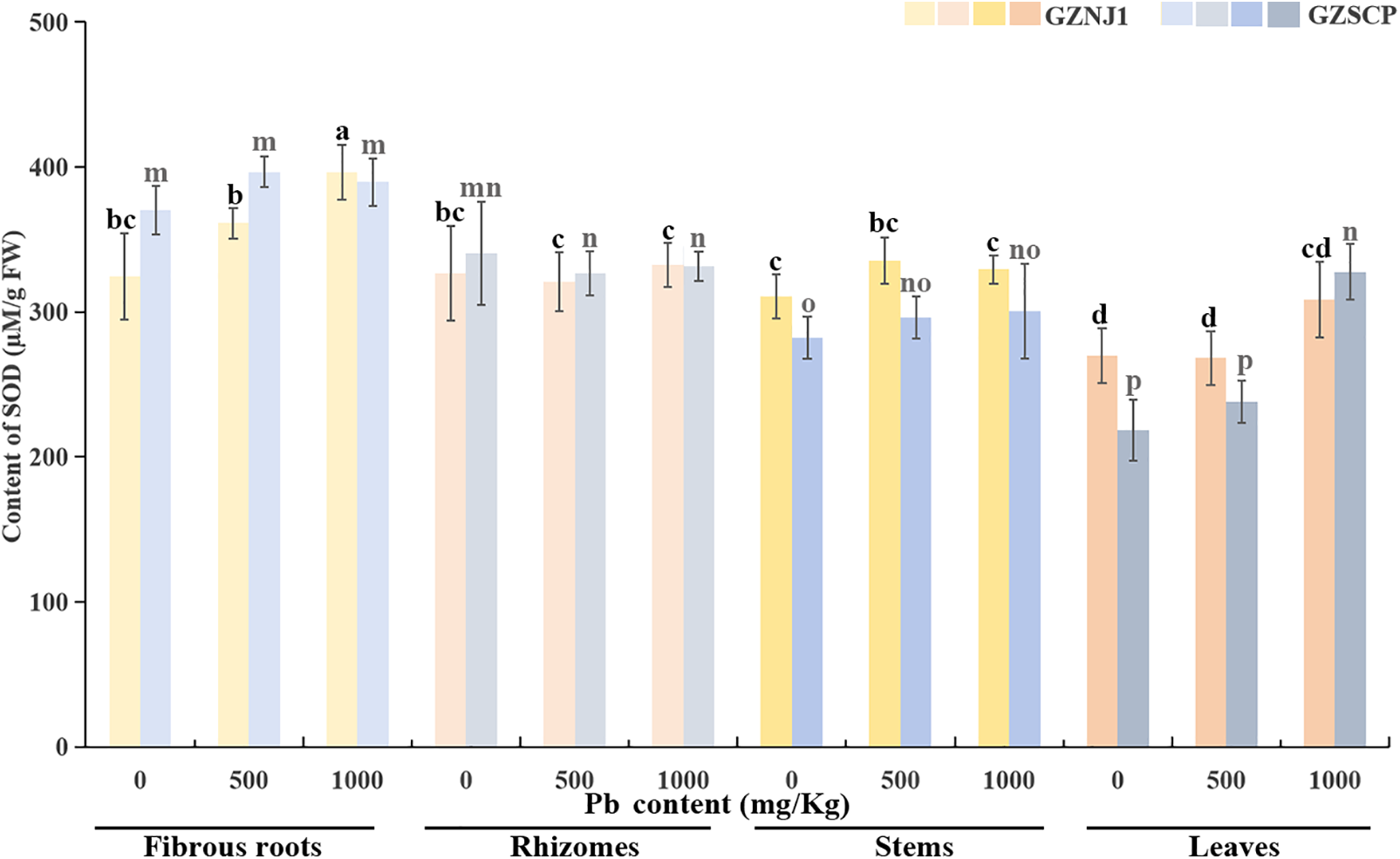

Compared to POD and CAT, the changes in SOD activity across various organs of two H. cordata germplasms, exhibited minor variations under exogenous Pb2+ stress. Notably, a significant increase in SOD activity was only observed in the fibrous roots of the GZNJ1 germplasm treated with 1000 mg/kg Pb2+, with insignificant changes in SOD activity in organs from other treatments. Similarly, a marked uptrend in SOD activity was evident in the leaves of the GZSCP subjected to 1000 mg/kg Pb2+ treatment, whereas minimal alterations were detected in SOD activity among organs from the remaining treatments (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Activities of SOD in different Pb2+ treated H. cordata organs. Data were present by average value ± stand error. The significant differences in data are compared within the same germplasm. The data were analyzed for significant differences at p < 0.05

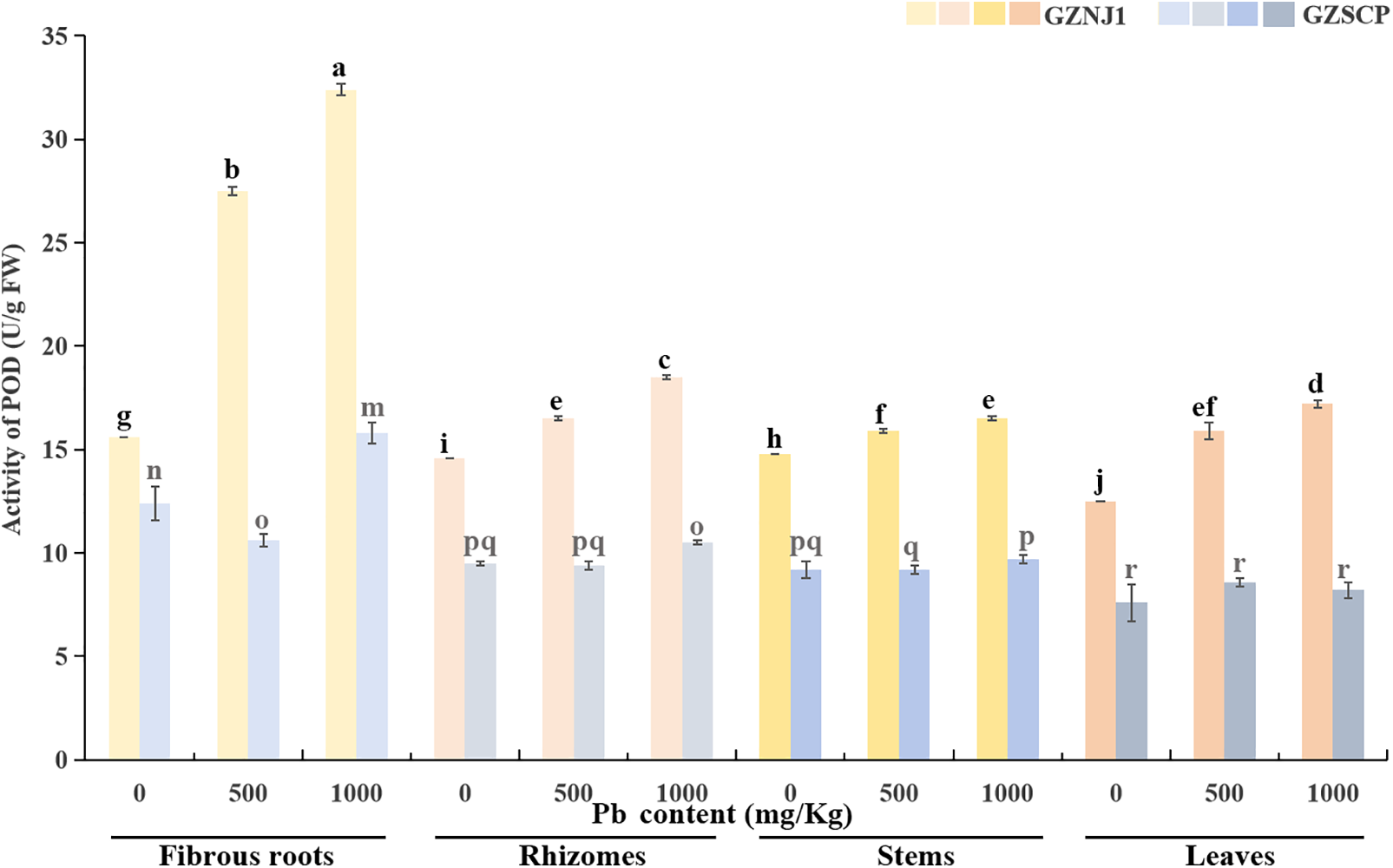

The POD activity in the various organs of the Pb2+-low-absorbing germplasm (GZNJ1) exhibited a significant upward trend as exogenous Pb2+ stress intensified. Among these organs, the POD activity was strongest in the fibrous roots, followed by the rhizomes, then the stems, and finally the leaves, which showed the lowest POD activity. In contrast, within the Pb2+-high-absorbing germplasm (GZSCP), the POD activity was notably altered only in the fibrous roots in response to exogenous Pb2+ stress (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Activities of POD in different Pb2+ treated H. cordata organs. Data were present by average value ± stand error. The significant differences in data are compared within the same germplasm. The data were analyzed for significant differences at p < 0.05

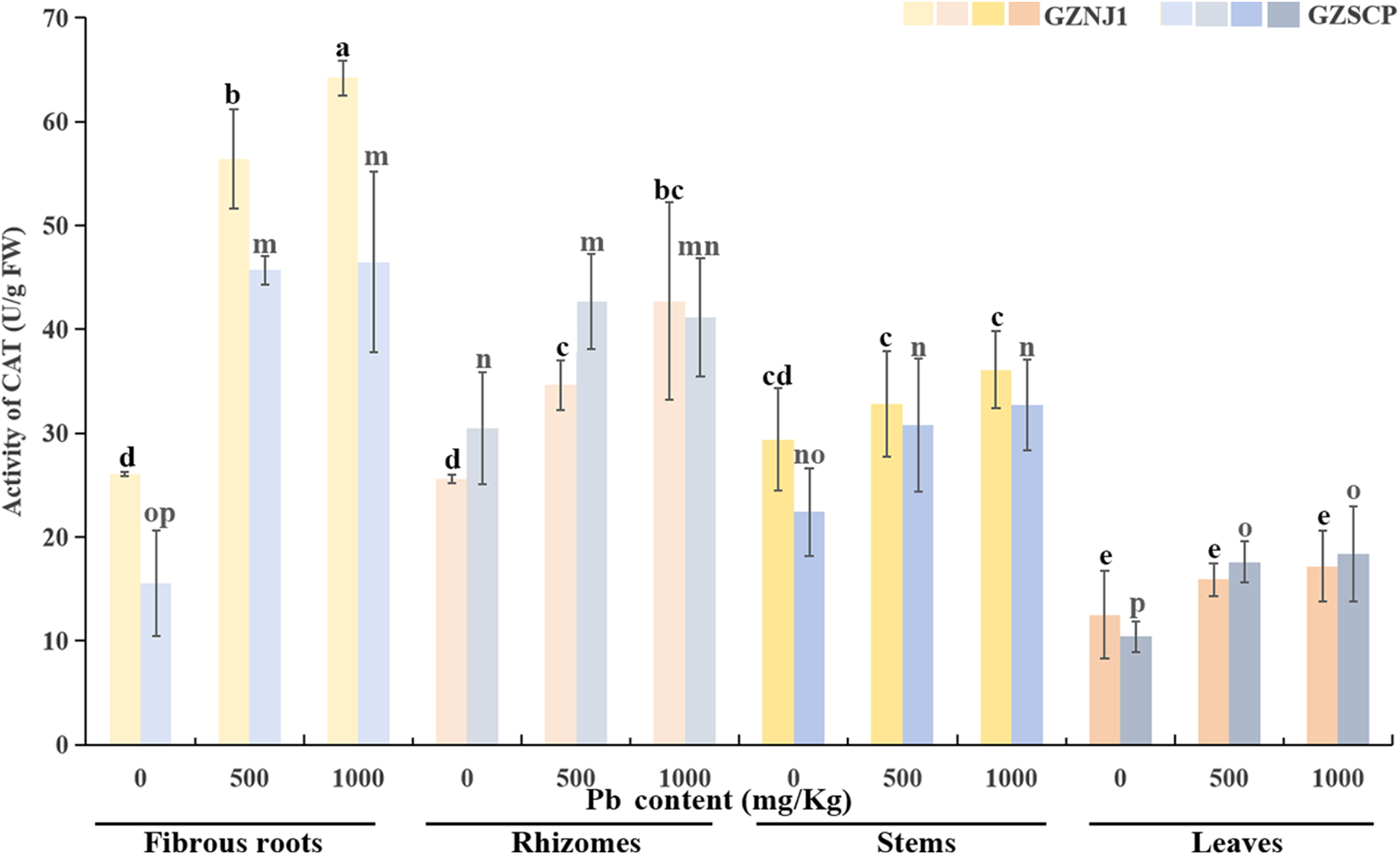

Among the 3 redox enzymes, the CAT activity in various organs of both H. cordata germplasms exhibited a significant upward trend with increasing exogenous Pb2+ stress, generally. Notably, exposure to 500 and 100 mg/kg of exogenous Pb2+ stress significantly induced an enhancement in CAT activity in the fibrous roots and rhizomes. However, in the stems and leaves of the Pb2+-low-absorbing germplasm (GZNJ1), the CAT activity was not markedly induced by exogenous Pb2+ stress. Conversely, in the stems and leaves of the Pb2+-high-absorbing germplasm (GZSCP), the CAT activity showed a significant increase in response to exogenous Pb2+ stress (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Activities of CAT in different Pb2+ treated H. cordata organs. Data were present by average value ± stand error. The significant differences in data are compared within the same germplasm. The data were analyzed for significant differences at p < 0.05

The H. cordata investigated in this research was primarily collected from southwestern China, where the germplasm exhibited considerable variation in Pb2+ absorption capacity, indicating a rich diversity of H. cordata germplasm resources in this region. A substantial proportion of the collected H. cordata samples exhibited robust Pb2+ absorption capabilities, with only a solitary sample recording a concentration below 1 mg/kg (Table 2). The identification of H. cordata varieties with low Pb2+ absorption holds immense promise for biotechnology-driven breeding programs and the cultivation of low Pb2+ absorption varieties. Furthermore, the striking disparities in Pb2+ absorption between high and low absorbers offer valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms governing Pb2+ absorption in H. cordata. By integrating studies on Pb2+ absorption in H. cordata with RAPD molecular markers, we can pinpoint RAPD loci that are associated with Pb2+ absorption. This will enable the efficient screening of H. cordata germplasm resources with either high or low Pb2+ absorption abilities, thereby furnishing technical support for the molecular-assisted breeding of low Pb2+ absorption varieties.

In this study, 500 and 1000 mg/kg Pb2+ treatments were chosen to establish a clear physiological response range under pot conditions, based on both preliminary observations and literature on H. cordata Pb tolerance. Prior studies have shown that 500–1000 mg/kg often induces marked phenotypic and biochemical changes within short experimental windows, whereas ≥2000 mg/kg typically causes severe growth inhibition or mortality [33–35]. The inclusion of 1000 mg/kg was therefore intended to maximize the detection of genotype- and organ-specific differences—patterns that were indeed most evident at this higher level—while 500 mg/kg served as a moderate stress reference. We acknowledge that these concentrations exceed typical agricultural contamination scenarios (<100 mg/kg in most polluted farmlands), and that direct extrapolation of absolute values from high-dose pot experiments to field conditions must be made with caution. Environmental factors such as soil pH, organic matter content, and nutrient status can markedly affect Pb bioavailability and plant uptake; therefore, follow-up trials under field-relevant Pb levels and varied soil chemistries are planned to test the stability of the marker–phenotype associations reported here.

In our study, loci 43 and 53 were consistently associated with high Pb2+ accumulation, suggesting that these RAPD markers may be linked to genes with known roles in heavy-metal tolerance. First, a likely candidate class is ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Recent work in the hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii identified an ABCC-type transporter (Sa14F190) whose heterologous expression in yeast enhanced vacuolar sequestration and accumulation of Cd2+, thereby reducing cytosolic toxicity [36]. Second, another plausible candidate is phytochelatin synthase (PCS), which catalyzes the synthesis of thiol-rich peptides that chelate heavy metals. For example, heterologous expression of NtPCS1 from Nicotiana tabacum increased phytochelatin production and altered Cd2+ distribution in host plants, directly impacting metal tolerance [37]. Third, based on these well-documented mechanisms, it is reasonable to hypothesize that loci 43 and 53 in H. cordata could tag genomic regions harboring ABC transporter or PCS genes that influence Pb2+ uptake and detoxification. We will next validate this linkage by sequencing the RAPD fragments and performing co-segregation analysis in mapping populations, enabling the deployment of these markers in breeding programs for low-Pb cultivars.

RAPD molecular markers require no prior knowledge of DNA sequences, are cost-effective, and offer rapid and effective results [38]. This technology has been successfully applied in the identification of genetic resources of H. cordata [32,39]. However, to date, there have been no studies or reports on the use of RAPD molecular markers for identifying the lead adsorption characteristics of H. cordata. In this study, a correlation analysis was conducted between the Pb2+ absorption capacity and RAPD markers of 72 samples of H. cordata. The findings revealed multiple loci associated with Pb2+ absorption traits, indicating that Pb2+ absorption is not controlled by a single gene but is likely the result of the combined action of multiple genes. Associating Pb2+ content with molecular markers facilitates the identification of loci related to Pb2+ absorption, providing a theoretical basis for the molecular breeding of H. cordata varieties with low Pb2+ absorption.

The results of this experiment demonstrate that regardless of the Pb2+ absorption property of H. cordata, organs with a larger contact area with the cultivation substrate contaminated with Pb2+ exhibit stronger Pb2+ absorption capacity, leading to higher Pb2+ concentrations within those organs. This finding aligns with previous researches. When Lactuca sativa was subjected to Pb2+ treatment, the Pb2+ content in both the roots and stems of the samples increased with the Pb2+ content in the cultivation substrate, with the roots containing higher Pb2+ levels than the shoots [40]. Studies on the adaptability of three ornamental plants—Tagetes erecta, Solanum nigrum, and Mirabilis jalapa—to Pb2+ stress revealed that the growth of their branches and root systems was inhibited to varying degrees under different Pb2+ stress conditions, with Pb2+ primarily accumulating in the roots [41]. These findings may serve as a preliminary reference for assessing whether the Pb2+ content in H. cordata grown under polluted conditions approaches or exceeds the permissible lead limits for vegetables established in the Chinese National Food Safety Standard (GB 2762-2022), and may inform future evaluations of its edibility and safety.

Similarly, when 3 varieties of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) were planted in Pb2+-contaminated cultivation substrates with concentrations of 0, 100, 200, 400 and 800 mg/kg, Pb2+ was predominantly concentrated in the sorghum roots and increased with the treatment concentration [42]. The consistency between the findings of this study and previous research indicates that Pb2+ transport efficiency in plants is relatively low, with metabolism mainly occurring in the underground parts. Strategies such as immobilizing Pb2+ in the soil into forms that are not absorbable by plant roots or utilizing molecular biology techniques to study and modify root Pb2+ absorption properties could contribute to the development of commercial varieties with reduced Pb2+ adsorption. Furthermore, the results of this study indicate that the aerial parts of H. cordata, including the stems and leaves, are safer for consumption or medicinal use compared to its edible rhizomes. In situations where consumers cannot purchase commercial varieties with low Pb2+ absorption, they should prioritize purchasing products derived from the aerial stems and leaves to ensure safety in use.

As the exogenous Pb2+ concentration increased, so did the MDA content in fibrous roots, rhizomes, stems and leaves, indicating an elevated degree of membrane lipid peroxidation in the whole plants of two H. cordata germplasms. Notably, this trend was consistent across germplasms exhibiting extreme differences in Pb2+ absorption capacity (Fig. 1). This suggests that Pb2+ can induce certain oxidative damage in various aerial and subterranean organs. The highest accumulation of MDA was observed in the fibrous roots, followed by the rhizomes, then the stems, with the leaves exhibiting the lowest MDA content (Fig. 2). This distribution pattern mirrors the internal spatial distribution of Pb2+ within H. cordata, implying a direct correlation between the degree of membrane lipid peroxidation and endogenous Pb2+ accumulation (Table 4; Fig. 1). In other words, Pb2+ accumulation directly contributes to membrane lipid peroxidation damage in H. cordata. Among the germplasms with extreme differences in Pb2+ absorption capacity, GZSCP cells demonstrated higher tolerance to Pb2+ in their biomembranes, with lower MDA levels compared to GZNJ1, which exhibits lower Pb2+ absorption capacity. This could be one of the reasons why GZSCP has a greater capacity to accommodate Pb2+ compared to GZNJ1.

The differential responses of redox enzyme activities in various organs of the GZNJ1 and GZSCP to exogenous Pb2+ stress provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying their Pb2+ absorption and tolerance at the level of oxidative stress and reductive remediation. SOD is a primary antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, thereby protecting cells from oxidative damage [43]. POD is generally involved in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide and the reinforcement of cell walls, contributing to plant stress tolerance [44]. CAT is another important antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, reducing oxidative stress [45]. SOD can catalyze the conversion of O2− into O2 and H2O2, and CAT and POD can further catalyze H2O2 into H2O [46]. In this study, the relatively minor variations in SOD activity across most organs under Pb2+ stress suggest that SOD may not serve as the dominant antioxidant mechanism in H. cordata’s defense system. However, increases in SOD activity were observed in the fibrous roots of GZNJ1 and the leaves of GZSCP under 1000 mg/kg Pb2+ treatment (Fig. 3). This organ and germplasm specific upregulation implies that SOD may play a localized and conditional role in Pb2+ stress response—being more active where oxidative damage is most acute or persistent. Together, these findings imply that SOD activity in H. cordata is spatially regulated and genetically dependent, which is consistent with the notion that SOD acts as the first line of antioxidant defense, followed by more pronounced downstream detoxification via POD and CAT enzymes [27,43]. This may also be due to the relatively late sampling time in this study, by which SOD may have already completed its initial response phase.

The pronounced increase in fibrous roots of GZNJ1 can be attributed to direct exposure to Pb2+, as root tissues are the primary site of heavy metal uptake and accumulation. Meanwhile, the elevated SOD activity in the leaves of GZSCP suggests a systemic oxidative response, potentially due to long-distance translocation of Pb2+ and secondary ROS production in photosynthetically active tissues. The limited SOD activity observed in other tissues may indicate a reliance on downstream H2O2 scavenging systems, such as POD and CAT, to complete the detoxification cascade. And our results are consistent with the explanations of Li et al. [47] and Mubeen et al. [48]. The differential responses of SOD, POD, and CAT activities in various organs of the two H. cordata germplasms to exogenous Pb2+ stress highlight the complexity of plant stress responses. The organ-specific and germplasm-dependent responses suggest that different organs and germplasms have evolved distinct mechanisms to cope with Pb2+ stress. Understanding these mechanisms can provide a basis for developing strategies to enhance the tolerance of H. cordata to Pb2+ pollution, potentially improving its use in phytoremediation efforts [21].

This study investigated the Pb2+-absorption capacity of H. cordata germplasm collected from southwestern China, revealing considerable variation and thus rich genetic diversity in the region. RAPD analysis identified seven loci associated with Pb2+-absorption traits, laying a theoretical foundation for MAS. A preliminary “extreme-phenotype” validation—comparing five high- and five low-absorbing accessions—showed that loci 43 and 53 consistently distinguished the two groups, suggesting good diagnostic potential. Nevertheless, broader cross-validation in genetically diverse populations and under multiple environmental conditions is under way to confirm the stability and applicability of these markers.

Our results also showed that organs with larger contact areas with the contaminated substrate (especially fibrous roots) accumulated more Pb2+, whereas aerial parts were comparatively safer for consumption. While the present work centred on Pb2+ concentration gradients, we recognise that environmental factors such as soil pH and nutrient availability can markedly influence metal bioavailability, root activity and antioxidant-enzyme expression. To clarify these interactions, we also have launched a follow-up factorial experiment that systematically varies soil pH (5.5, 6.5, 7.5) and macronutrient levels under constant Pb2+ exposure. This study will pinpoint the individual and combined contributions of soil chemistry and heavy-metal stress to Pb2+ uptake and oxidative responses in H. cordata.

The identification of RAPD loci significantly associated with Pb2+ accumulation, especially loci 43 and 53, provides a foundation for MAS in breeding H. cordata. MAS has been widely employed to accelerate genetic improvements—such as disease resistance or abiotic stress tolerance—by selecting individuals based on linked molecular markers rather than phenotypes [49,50]. In our study, the consistent absence of loci 43 and 53 in low-Pb2+ accessions suggests they could act as negative selection markers in MAS pipelines: individuals lacking these bands would be prioritized as candidate low-accumulating germplasms. This strategy would significantly reduce reliance on labor-intensive Pb2+ assays and expedite early-generation screening.

Similar RAPD-based MAS approaches have proven effective in developing low heavy-metal accumulating crops. For instance, RAPD markers tightly linked to a cadmium uptake gene were successfully used to screen durum wheat across diverse genotypes [51,52]. In durum wheat, molecular markers such as usw47, Cad-5B and KASP achieved accurate classification of low-Cd accessions (96.2%) from large germplasm pools, significantly improving selection efficiency and reducing phenotyping costs [52].

Based on these precedents, we propose that loci 43 and 53 in H. cordata could be incorporated into a two-step MAS framework: first screen seedlings via RAPD-PCR for absence of these markers, then validate Pb2+ accumulation in the subset that passes marker screening. Ongoing validation trials across diverse genetic backgrounds and field conditions aim to confirm marker robustness and pave the way for developing Pb2+-safe cultivars.

This study reveals the genetic diversity and physiological response mechanisms of lead absorption in H. cordata: seven RAPD markers associated with lead absorption were identified, underground organs were found to accumulate significantly higher lead than aerial parts, and antioxidant enzymes (POD, CAT) respond to lead stress by mitigating membrane lipid peroxidation. The findings provide a theoretical basis for molecular breeding of low-lead varieties and environmental remediation applications of high-lead-accumulating germplasms. Furthermore, different germplasms and organs showed varied responses in antioxidant enzyme activities under Pb2+ stress, highlighting the complex mechanisms of plant stress responses. These findings offer important insights for developing H. cordata varieties with low Pb2+ absorption, enhancing their application in phytoremediation, and ensuring consumer safety.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the Guizhou Highland Specialty Vegetable Green Production Science, Technology Innovation Talent Team (Qiankehe Platform Talent-CXTD [2022] 003), Guizhou Mountain Agriculture Key Core Technology Research Project (GZNYGJHX-2023013), Platform construction project of Engineering Research Center for Protected Vegetable Crops in Higher Learning Institutions of Guizhou Province (Qian Jiao Ji [2022] No. 040), for their self-help on this project.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the Guizhou Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the Guizhou Provincial Department of Science and Technology, and the Guizhou Provincial Department of Education. Funding Project are Guizhou Highland Specialty Vegetable Green Production Science, Technology Innovation Talent Team (Qiankehe Platform Talent-CXTD [2022] 003), Guizhou Mountain Agriculture Key Core Technology Research Project (GZNYGJHX-2023013) and Platform construction project of Engineering Research Center for Protected Vegetable Crops in Higher Learning Institutions of Guizhou Province (Qian Jiao Ji [2022] No. 040).

Author Contributions: Yi Yan: Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation and Writing—original draft; Min He: Methodology and Validation; Feifeng Mao: Methodology and Investigation; Xinyu Zhang: Resources and Supervision; Liyu Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology and Project administration; Jingwei Li: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Resources and Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All raw data and associated materials are publicly available at Figshare via http://10.6084/m9.figshare.29910008 (accessed on 03 September 2025). This includes Pb accumulation data, RAPD band patterns, physiological measurements, primer sequences, and germplasm accession details.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Adhikari B, Marasini BP, Rayamajhee B, Bhattarai BR, Lamichhane G, Khadayat K, et al. Potential roles of medicinal plants for the treatment of viral diseases focusing on COVID-19: a review. Phytother Res. 2021;35(3):1298–312. doi:10.1002/ptr.6893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Du H, Ding J, Wang P, Zhang G, Wang D, Ma Q, et al. Anti-respiratory syncytial virus mechanism of Houttuynia cordata Thunb exploration based on network pharmacology. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2021;24(8):1137–50. doi:10.2174/1386207324666210303162016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wu Z, Deng X, Hu Q, Xiao X, Jiang J, Ma X, et al. Houttuynia cordata Thunb: an ethnopharmacological review. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:714694. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.714694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rafiq S, Hao H, Ijaz M, Raza A. Pharmacological effects of Houttuynia cordata Thunb (H. cordataa comprehensive review. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(9):1079. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wang S, Li L, Chen Y, Liu Q, Zhou S, Li N, et al. Houttuynia cordata Thunb. alleviates inflammatory bowel disease by modulating intestinal microenvironment: a research review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1306375. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1306375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wei P, Luo Q, Hou Y, Zhao F, Li F, Meng Q. Houttuynia cordata Thunb.: a comprehensive review of traditional applications, phytochemistry, pharmacology and safety. Phytomedicine. 2024;123:155195. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Plaza P, Uhart M, Caselli A, Wiemeyer G, Lambertucci S. A review of lead contamination in South American birds: the need for more research and policy changes. Perspect Ecol Conserv. 2018;16(4):201–7. doi:10.1016/j.pecon.2018.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Vasudevan S, Oturan MA. Electrochemistry: as cause and cure in water pollution-an overview. Environ Chem Lett. 2014;12(1):97–108. doi:10.1007/s10311-013-0434-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kushwaha A, Hans N, Kumar S, Rani R. A critical review on speciation, mobilization and toxicity of lead in soil-microbe-plant system and bioremediation strategies. Ecotoxicol Env Saf. 2018;147:1035–45. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.09.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Alsafran M, Usman K, Ahmed B, Rizwan M, Saleem M, Al Jabri H. Understanding the phytoremediation mechanisms of potentially toxic elements: a proteomic overview of recent advances. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:881242. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.881242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Fuller R, Landrigan PJ, Balakrishnan K, Bathan G, Bose-O’Reilly S, Brauer M, et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6:e535–47. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00090-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Balali-Mood M, Naseri K, Tahergorabi Z, Khazdair MR, Sadeghi M. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:643972. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.643972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bouida L, Rafatullah M, Kerrouche A, Qutob M, Alosaimi AM, Alorfi HS, et al. A review on cadmium and lead contamination: sources, fate, mechanism, health effects and remediation methods. Water. 2022;14(21):3432. doi:10.3390/w14213432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. García-Niño WR, Pedraza-Chaverrí J. Protective effect of curcumin against heavy metals induced liver damage. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;69:182–201. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2014.04.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Matović V, Buha A, Ðukić-Ćosić D, Bulat Z. Insight into the oxidative stress induced by lead and/or cadmium in blood, liver and kidneys. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;78:130–40. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2015.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Renu K, Chakraborty R, Myakala H, Koti R, Famurewa AC, Madhyastha H, et al. Molecular mechanism of heavy metals (Lead, Chromium, Arsenic, Mercury, Nickel and Cadmium)-induced hepatotoxicity—a review. Chemosphere. 2021;271:129735. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Parida L, Patel TN. Systemic impact of heavy metals and their role in cancer development: a review. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195(6):766. doi:10.1007/s10661-023-11399-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Q, Li Z, Feng X, Li X, Wang D, Sun G, et al. Vegetable Houttuynia cordata Thunb. as an important human mercury exposure route in Kaiyang county, Guizhou province, SW China. Ecotoxicol Env Saf. 2020;197:110575. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li Y. Study on the accumulation characteristics of Uranium (UCadmium (CdArsenic (As) and Lead (Pb) by hydrophytes Alisma orientale and Houttuynia cordata [master’s thesis]. Mianyang, China: Southwest University of Science and Technology; 2020. (In Chinese). doi:10.27415/d.cnki.gxngc.2020.000841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhao M, Yue J, Zhou X, Liang Y. Effects of cadmium and lead stress on antioxidant enzyme system in Houttuynia cordata leaves. Sichuan Environ. 2021;40(4):199–204. doi:10.14034/j.cnki.schj.2021.04.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Z, Cai J, Wang T, Wu L, Chen C, Jiang L, et al. Houttuynia cordata hyperaccumulates lead (Pb) and its combination with bacillus subtilis wb600 improves shoot transportation. Int J Agric Biol. 2018;20:621–7. doi:10.17957/IJAB/15.0532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nie G, Liu A, Ghanizadeh H, Wang Y, Tang M, He J, et al. Natural variation in chromium accumulation and the development of related EST-SSR molecular markers in miscanthus sinensis. Agronomy. 2024;14(7):1458. doi:10.3390/agronomy14071458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Huang Y, Sun C, Min J, Chen Y, Tong C, Bao J. Association mapping of quantitative trait loci for mineral element contents in whole grain rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(50):10885–92. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Williams JG, Kubelik AR, Livak KJ, Rafalski JA, Tingey SV. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(22):6531–5. doi:10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lynch MMBG, Milligan BG. Analysis of population genetic structure with RAPD markers. Mol Ecol. 1994;3(2):91–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.1994.tb00109.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu L, Zhang Y, Jiang X, Du B, Wang Q, Ma Y, et al. Uncovering nutritional metabolites and candidate genes involved in flavonoid metabolism in Houttuynia cordata through combined metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;203:108059. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.108059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Alhammad BA, Ahmad A, Seleiman MF. Nano-hydroxyapatite and ZnO-NPs mitigate Pb stress in maize. Agronomy. 2023;13(4):1174. doi:10.3390/agronomy13041174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Du L, Yang H, Xie J, Han L, Liu Z, Liu ZM, et al. The potential of Paulownia fortunei Hemsl for the phytoremediation of Pb. Forests. 2023;14(6):1245. doi:10.3390/f14061245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao J, Hu H, Gao S, Chen G, Zhang C, Deng W, et al. Pb pollution stress in Alnus cremastogyne monitored by antioxidant enzymes. Forests. 2024;15(7):1100. doi:10.3390/f15071100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Paul V, Sankar MS, Vattikuti S, Dash P, Arslan Z. Pollution assessment and land use land cover influence on trace metal distribution in sediments from five aquatic systems in southern USA. Chemosphere. 2021;263:128243. (In Chinese). doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhu D, Dong Y, Zhou L, Hua G. Comparison of total RNA isolation methods for folium Houttuyniae. J Guangzhou Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2012;29(3):300–4. (In Chinese). doi:10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2012.03.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu W, Zheng Y, Chen L, Wei Y, Yan Z, Yang R. RAPD analysis of Houttuynia cordata germplasm resources. Acta Pharm Sin. 2002;12:986–92. (In Chinese). doi:10.16438/j.0513-4870.2002.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Z. Response of Houttuynia cordata. to combined Pb-Zn contamination and its metal accumulation characteristics [master’s thesis]. Chengdu, China: Sichuan Agricultural University; 2007. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

34. Li H. Effects of Pb and As stress on the growth and Pb, as enrichment characteristics of Houttuynia cordata [master’s thesis]. Chengdu, China: Sichuan Agricultural University; 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

35. Zeng Z. Effects of Pb and Cd stress on the physiological characteristics and accumulation effects of Houttuynia cordata [master’s thesis]. Chengdu, China: Sichuan Agricultural University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

36. Feng T, He X, Zhuo R, Qiao G, Han X, Qiu W, et al. Identification and functional characterization of ABCC transporters for Cd tolerance and accumulation in Sedum alfredii Hance. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20928. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-78018-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wu C, Zhang J, Chen M, Liu J, Tang Y. Characterization of a Nicotiana tabacum phytochelatin synthase 1 and its response to cadmium stress. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1418762. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1418762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Khabiya R, Choudhary GP, Sairkar P, Silawat N, Jnanesha AC, Kumar A, et al. Unraveling genetic diversity analysis of Indian ginseng (Withania somnifera (Linn.) Dunal) insight from RAPD and ISSR markers and implications for crop improvement vital for pharmacological and industrial potential. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;210:118124. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lan Y, Wu L, Qiu B, Gao Y, Shi J. Polymorphisms of RAPD molecular markers in Houttuynia cordata. J Zhejiang Univ. 2008;25(3):309–13. [Google Scholar]

40. Ikkonen E, Kaznina N. Physiological responses of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) to soil contamination with Pb. Horticulturae. 2022;8(10):951. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8100951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shao Z, Li M, Zheng J, Zhang J, Lu W. Lead tolerance and enrichment characteristics of three hydroponically grown ornamental plants. Appl Sci. 2023;13(20):11208. doi:10.3390/app132011208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Osman HE, Fadhlallah RS, Alamoudi WM, Eid EM, Abdelhafez AA. Phytoremediation potential of sorghum as a bioenergy crop in Pb-amendment soil. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):2178. doi:10.3390/su15032178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Islam MN, Rauf A, Fahad FI, Emran TB, Mitra S, Olatunde A, et al. Superoxide dismutase: an updated review on its health benefits and industrial applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(26):7282–300. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1913400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Liu X, Lu X, Yang S, Liu Y, Wang W, Wei X, et al. Role of exogenous abscisic acid in freezing tolerance of mangrove Kandelia obovata under natural frost condition at near 32° N. BMC Plant Biol. 2022;22(1):593. doi:10.1186/s12870-022-03990-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li Y, Zhao X, Jiang X, Chen L, Hong L, Zhuo Y, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation with exogenous catalase on growth performance, oxidative stress, and hepatic apoptosis in weaned piglets challenged with lipopolysaccharide. J Anim Sci. 2020;98(3):skaa067. doi:10.1093/jas/skaa067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Yang F, Zhang H, Wang Y, He G, Wang J, Guo D, et al. The role of antioxidant mechanism in photosynthesis under heavy metals Cd or Zn exposure in tobacco leaves. J Plant Interact. 2021;16(1):354–66. doi:10.1080/17429145.2021.1961886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Li Y, Cheng X, Feng C, Huang X. Interaction of lead and cadmium reduced cadmium toxicity in Ficus parvifolia seedlings. Toxics. 2023;11(3):271. doi:10.3390/toxics11030271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Mubeen S, Pan J, Saeed W, Luo D, Rehman M, Hui Z, et al. Exogenous methyl jasmonate enhanced kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) tolerance against lead (Pb) toxicity by improving antioxidant capacity and osmoregulators. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31(21):30806–18. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-33189-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Collard BCY, Mackill DJ. Marker-assisted selection: an approach for precision plant breeding in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1491):557–72. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Song L, Wang R, Yang X, Zhang A, Liu D. Molecular markers and their applications in marker-assisted selection (MAS) in Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agriculture. 2023;13(3):642. doi:10.3390/agriculture13030642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Penner GA, Bezte LJ, Leisle D, Clarke J. Identification of RAPD markers linked to a gene governing cadmium uptake in durum wheat. Genome. 1995;38(3):543–7. doi:10.1139/g95-070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Alsaleh A, Baloch FS, Sesiz U, Nadeem MA, Hatipoğlu R, Erbakan M, et al. Marker-assisted selection and validation of DNA markers associated with cadmium content in durum wheat germplasm. Crop Pasture Sci. 2022;73(1):66–75. doi:10.1071/CP21317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools