Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Melatonin Biosynthesis, Growth Regulation, and Adaptability to Environmental Stress in Plants

1 College of Biological and Pharmaceutical Engineering, West Anhui University, Lu’an, 237012, China

2 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Sakarya University of Applied Sciences, Arifiye, 54580, Sakarya, Turkey

3 National Key Laboratory for Tropical Crop Breeding, School of Breeding and Multiplication (Sanya Institute of Breeding and Multiplication), Hainan University, Sanya, 572025, China

* Corresponding Authors: Muhammad Aamir Manzoor. Email: ; Cheng Song. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants: Physio-biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 2985-3002. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070697

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Melatonin is a multifunctional molecule found in all organisms that has been shown to play a crucial role in plant growth, development, and stress response. Plant melatonin is typically synthesized in organelles termed chloroplasts, and the mechanisms of its synthesis and metabolic pathways have been extensively studied. Melatonin serves a significant regulatory function in plant growth and development, influencing the morphological and physiological characteristics of plants by modulating biological processes. While studies on plant melatonin receptors are in their early stages compared to studies in animal receptors, the binding mechanism with melatonin is now recognized as the key initiating step that triggers a series of downstream protective effects. This suggests that melatonin in plants may exert its effects through two main modes of target binding. The CAND2/PMTR1 protein binds to melatonin with a high degree of affinity. This binding activates downstream heterotrimeric G proteins, which trigger rapid intracellular signaling cascades. These cascades include activating the MAPK pathway and modulating ion channel activity. This action swiftly regulates stomatal closure in response to physiological processes such as drought stress. Additionally, melatonin has been demonstrated to regulate the plant stress response through two main mechanisms. First, it directly inhibits the accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Second, it indirectly influences the stress response pathways. This paper examines plant melatonin from three perspectives: the synthesis pathways of melatonin, its effects on plant growth, and its applications in plants under stress. Finally, the prospects for melatonin study and its applications in plants are discussed.Keywords

Melatonin is a small molecule belonging to the class of indole heterocyclic compounds. Its chemical designation of the substance is N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine. It was first discovered in the pineal gland of cattle in 1958, and it quickly became apparent in a number of other animals [1]. However, plant-related research did not begin to emerge until the 1980s. Although plant melatonin and animal melatonin have the same chemical structure, their functions differ significantly. In animals, melatonin primarily regulates circadian rhythms and sleep, modulates seasonal reproduction, and provides potent antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects. In contrast, the main role of plant melatonin, aside from regulating circadian rhythms, is to combat oxidative stress. This protects plants from environmental challenges, such as ultraviolet radiation, drought, and pests and diseases [2,3]. Melatonin plays an important role in plant growth and development. It regulates seed germination, root growth and development, leaf senescence, circadian rhythms, and postharvest fruit ripening. Melatonin is also implicated in the process of plant hormone-mediated signal transduction. By interacting with these pathways, melatonin contributes to the regulation of plant development and growth [4]. Recent studies have made significant progress in understanding melatonin’s role in plant responses to abiotic stresses. Melatonin has been demonstrated to enhance the plant’s capacity to withstand abiotic stresses, such as drought, salt, cold, and heat, by modulating the expression of genes involved in DREB/CBF, HSF, SOS, and ABA pathways [5].

Although the biosynthesis and signaling pathways of melatonin in plants are well understood, the interaction mechanism between melatonin and other hormones under abiotic stress remains unclear. This paper summarizes the synthesis and metabolic pathways of melatonin in plants to establish a foundation for future research on its regulatory mechanisms. The text delineates how melatonin promotes plant growth and development while simultaneously outlining its interactions with plant hormones (e.g., IAA, CTK, and ABA) in regulating plant growth and development. This facilitates a more profound understanding of the combined effects of these hormones on plant growth and development. Despite numerous studies examining the biosynthesis and regulation of melatonin in plants, the connection between melatonin and abiotic stress remains unclear. This review provides an in-depth overview of the crucial role of melatonin in plant growth and its response to abiotic stresses. Additionally, we discuss the effect and related applications of melatonin in response to various abiotic stresses and present the prospects for plant melatonin in agriculture. As a green, highly efficient biostimulant, melatonin offers potential solutions for addressing global food security, reducing chemical pesticide use, and coping with stresses caused by climate change. Melatonin significantly enhances plants’ tolerance to various environmental stresses. Spraying melatonin can improve fruit set rates in certain fruits and vegetables, increase individual fruit weight, and thereby boost yields. When pathogenic microorganisms invade, melatonin treatment alerts plants to preemptively accumulate defense compounds and synthesize pathogen-associated proteins. The agricultural value of melatonin lies in its multifunctionality, natural origin, and safety profile. Unlike traditional chemical pesticides or fertilizers, it functions by regulating the plant’s own physiological and defense systems, representing an empowering rather than coercive strategy.

2 Biosynthetic and Metabolic Pathways of Plant Melatonin

2.1 Biosynthetic Pathway of Melatonin

Melatonin has a low molecular weight and a stable chemical structure. It occurs naturally in a variety of plants. When 14C-labeled tryptophan was introduced into plants such as Hypericum perforatum, it was found that they contained indoleacetic acid, tryptamine, 5-hydroxytryptophan, and 5-hydroxytryptamine, which are intermediates of the melatonin synthesis pathway. It has also been established that the presence of these substances is an inherent feature of the melatonin synthesis process in animals [6]. The evidence also indirectly shows that the melatonin synthesis pathway of plants is similar to that of animals. However, the synthesis pathways are still different between the two. Animals cannot synthesize the melatonin precursor substance, tryptophan, by themselves, but plants can. We speculate that the synthesis of plant melatonin may be more complex.

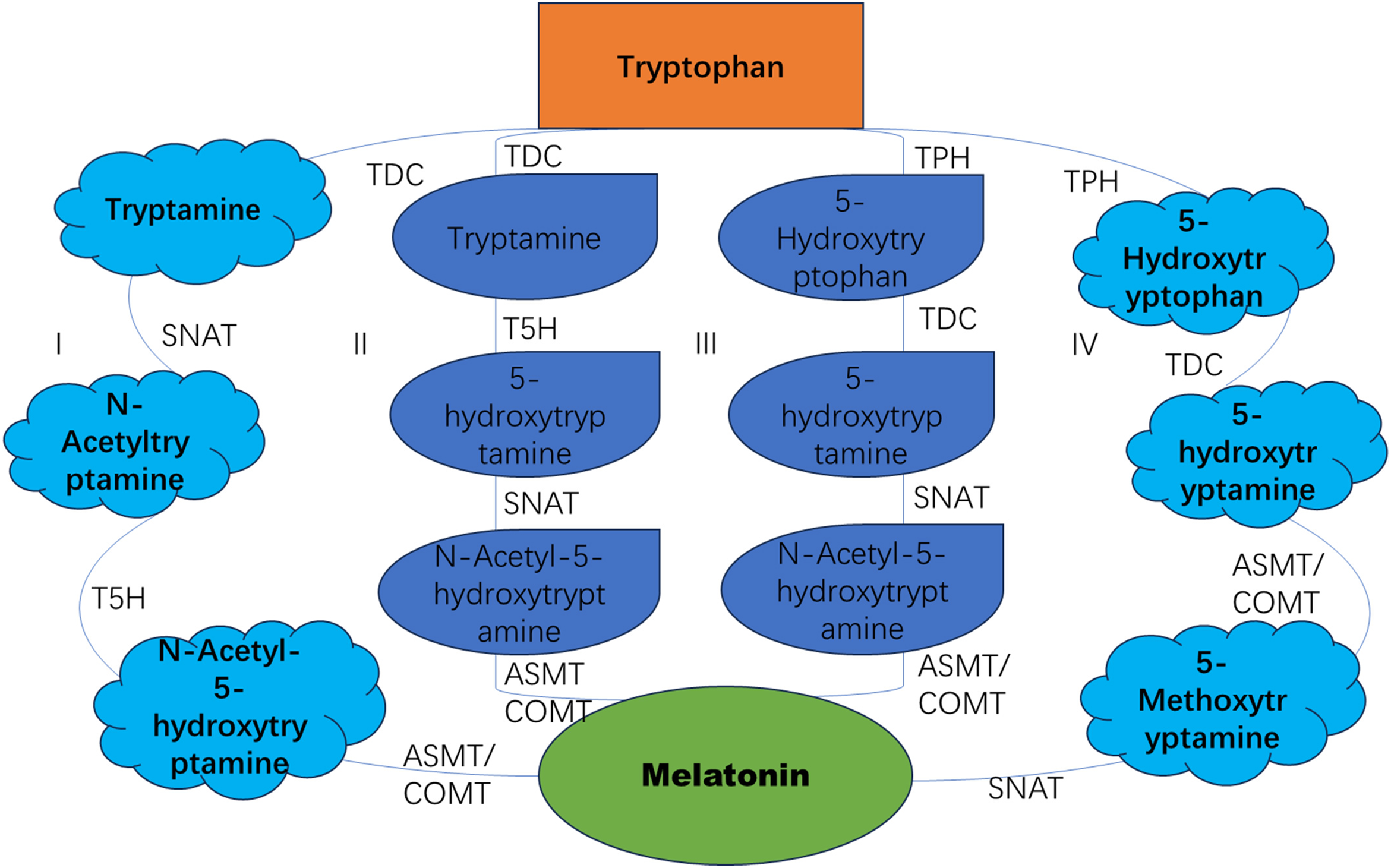

Many studies have indicated that there are multiple pathways for plant melatonin biosynthesis. As a general rule, the process of melatonin synthesis can be considered to follow four primary pathways, all of which necessitate the participation of more than six enzymes. These include tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC), tryptamine 5-hydroxylase (TPH), tryptamine 5-hydroxylase (T5H), 5-hydroxytryptamine-N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine methyltransferase (ASMT), and caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) [7]. In all four pathways, there is an important intermediate product, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin). The production of 5-hydroxytryptamine requires two-step enzymatic reactions. Firstly, the decarboxylation of tryptophan is initiated by the enzyme tryptophan decarboxylase, resulting in the formation of tryptamine. Subsequently, the subsequent synthesis of 5-hydroxytryptamine is catalysed by the action of tryptophan-5-hydroxylase. An alternative synthetic pathway involves the hydroxylation of tryptophan by tryptamine 5-hydroxylase, followed by decarboxylation by tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC) to produce 5-hydroxytryptamine [4]. In the first and second biosynthetic pathways, 5-hydroxytryptamine is synthesised in the endoplasmic reticulum. In contrast, in the third and fourth biosynthetic pathways, the same process occurs in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). Studies have also indicated that tryptophan hydroxylase is a copper-dependent enzyme that can catalyze the conversion of tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan. Additionally, 5-hydroxytryptophan in cells is primarily transported to the cytoplasm via plasma membrane transporters and is subsequently catalyzed by decarboxylase to produce 5-hydroxytryptamine. Therefore, in different melatonin biosynthetic pathways, the variance in the synthesis site of 5-hydroxytryptamine—whether in the endoplasmic reticulum or the cytoplasm—may be associated with the localization of tryptophan hydroxylase and tryptophan decarboxylase [8]. The synthesis of plant melatonin is relatively complex, and its crosstalk with other hormones requires further validation.

Figure 1: The biosynthesis pathway of melatonin in plants

This is a classic melatonin biosynthesis pathway. TDC (tryptophan decarboxylase), TPH (tryptophan hydroxylase), T5H (tryptophan-5-hydroxylase), SNAT (serotonin N-acetyltransferase), ASMT (N-acetylserotonin methyltransferase), COMT (caffeic acid O-methyltransferase), and ASDAC (N-acetylserotonin deacetylase).

2.2 Metabolic Pathway of Melatonin

Melatonin, as an important bioactive molecule, can be degraded through enzymatic conversion pathways. In plants, melatonin degradation is primarily catalyzed by melatonin N-acetyltransferase (NAT), which converts it into N-acetylmelatonin, and by melatonin-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT), which further catalyzes the production of 6-hydroxymelatonin. This compound is subsequently metabolized and degraded by chloroplast esterase. A similar degradation pathway is present in vertebrates and other eukaryotic organisms; NAT and HIOMT also play crucial roles in melatonin metabolism in mammals [9]. The metabolic pathway of melatonin is subject to influence by many factors, including oxidative stress, the endocrine system, and environmental changes. Studies have confirmed that the metabolite of melatonin in water hyacinth, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK), has a high antioxidant effect and found that the content of AFMK and melatonin is high under strong light, which is believed to be related to plant photosynthesis or light protection [10]. AFMK has shown distinct rhythms in water hyacinth, with peaks occurring during the photophase. As light intensity increases, the levels of melatonin in the water hyacinth appear to rise as well [10]. Plant melatonin undergoes hydroxylation by M2H and M3H to form two hydroxylated metabolites, namely 2-hydroxymelatonin (2-OHM) and cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin (C3-OHM) [11]. 2-hydroxymelatonin (2-OHM) is derived from the hydroxylation of M2H, among which M2H is one of the most important metabolic pathways. The gene of melatonin hydroxylation metabolite C3-OHM was cloned in rice and expressed in the cytoplasm, catalyzed by the M3H enzyme [12]. To better understand the biological function of melatonin, it is critical to further reveal its metabolism.

3 Effect of Melatonin on Plant Growth and Development

3.1 Melatonin Stimulates Plant Growth

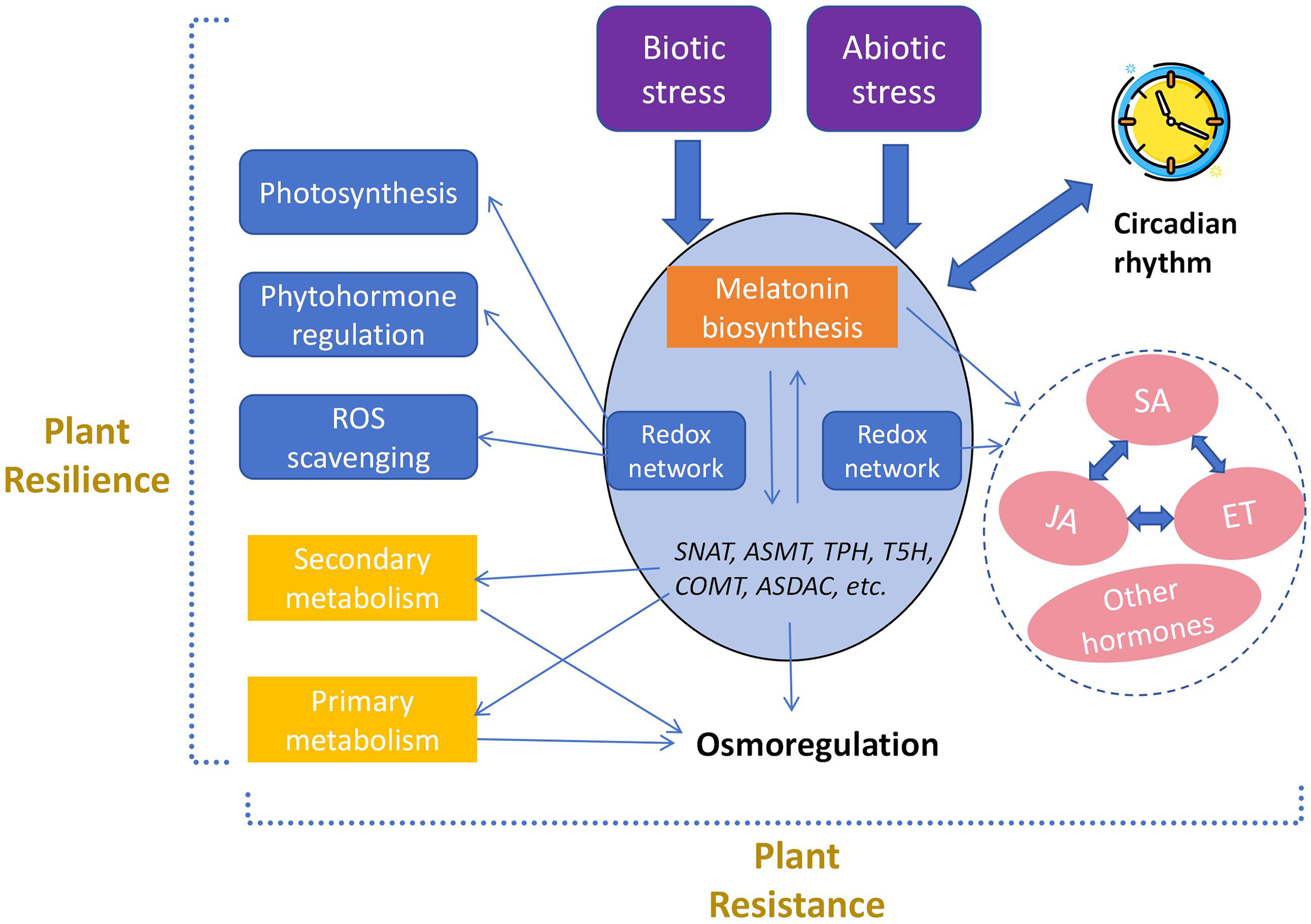

Exogenous melatonin can increase the fresh weight and root number of plant growth. For instance, the spraying of exogenous melatonin has been demonstrated to be a highly efficacious method to promote the growth parameters of wheat seedlings, including root length, root number, fresh weight, and dry weight [13]. Additionally, it was demonstrated that the addition of various concentrations of melatonin to pineapples and tomatoes significantly enhances plant rooting. This effect is somewhat reminiscent of the effects of the growth hormone IAA [14]. The effects of varying concentrations of melatonin on plant root growth and development are entirely divergent. Melatonin does exhibit significant dose-dependent effects in its application: low concentrations may promote growth, while high concentrations may have the opposite effect. High concentrations of melatonin inhibit the growth and development of roots while slowing their accumulation of beneficial compounds. Conversely, low concentrations of melatonin significantly boost nutrient accumulation in plants, thereby enhancing their stress resistance and growth potential [15]. This paradoxical effect stems from the fact that melatonin triggers multiple distinct signaling pathways, each with different activation thresholds and ultimate effects at different concentrations [16,17]. Low concentrations of melatonin directly scavenge ROS and upregulate endogenous antioxidant enzyme systems, whereas extremely high concentrations of melatonin molecules may react with certain metal ions, unexpectedly generating small amounts of ROS with signaling functions. ROS signaling may inhibit the expression of genes associated with cell division and elongation, leading to growth arrest [18]. Furthermore, melatonin-induced reactions require significant energy expenditure. High concentrations of melatonin strongly activate systemic defense responses like systemic acquired resistance, consuming significant energy and carbon skeleton resources [19]. After 24 h of treatment, melatonin promotes the growth of Arabidopsis roots, stems, and leaves. This effect is efficient, further demonstrating the significance of melatonin in root growth and development [20]. Moreover, varying concentrations of melatonin influence the elongation of rice tiller buds. The application of appropriate concentrations of melatonin can not only encourage the elongation of rice tiller buds but also mitigate the inhibition of bud elongation caused by high concentrations of basic amino acids [21]. Melatonin not only influences root growth but also impacts the photoperiod and flowering of plants. It has been demonstrated that the exogenous addition of melatonin can ameliorate photoperiod disorders and promote the flowering of Arabidopsis plants when subjected to a 12-h light cycle. The transcription levels of flowering genes FT, SOC1, and LFY increase significantly, thereby enhancing the flowering process [22]. Therefore, melatonin can serve as a small-molecule active substance to regulate plant physiological processes, such as cell expansion and root growth, with varying concentrations producing different effects (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The role of melatonin in regulating stress responses through the mediation of redox networks

Melatonin enhances plant resilience by improving photosynthetic efficiency, regulating the synthesis of other plant hormones, promoting the accumulation of primary and secondary metabolites, and scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS). It combats oxidative stress caused by various biotic and abiotic stresses by regulating the synthesis of key enzymes within the redox network.

3.2 Melatonin Inhibits Leaf Senescence

Leaf senescence, an important organ of plant photosynthesis, is directly related to crop yield [23]. A proteomic analysis of apple trees subjected to prolonged melatonin root irrigation indicated that it can inhibit the activity of hydrolases associated with photosynthesis and redox responses in apple leaf plastids, thereby effectively delaying the senescence of apple leaves [24]. Furthermore, melatonin administration to the roots of grapevines led to a reduction in the extent of photosynthetic activity inhibition caused by NaCl, while simultaneously enhancing the maximum fluorescence and maximum photochemical efficiency of leaves under light conditions. Therefore, the root application of melatonin mitigates the injury to the photosynthetic process of grape leaves under NaCl stress [25]. Moreover, melatonin delays plant leaf senescence primarily by boosting the activity of antioxidant enzymes, maintaining the activity of leaf photosynthetic enzymes, improving the efficiency of photosystem II, and decelerating the degradation rate of chlorophyll. It also prevents protein degradation by regulating sugar and nitrogen metabolism [26]. First, melatonin directly scavenges ROS by upregulating certain antioxidant enzyme genes and enhancing the endogenous antioxidant system, maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and thereby delaying the onset of leaf senescence [27]. Melatonin strongly inhibits the expression of the NYE1/SGR1 genes, thereby blocking the chlorophyll degradation pathway at its source and maintaining photosynthetic capacity [28]. Melatonin also regulates the senescence-associated transcription factor network. ORE1 is a NAC family transcription factor that positively regulates aging. By inhibiting the expression of ORE1, melatonin abrogates its activation of numerous downstream senescence-associated genes (SAGs) [29]. ANAC016, another pro-aging NAC transcription factor, is also inhibited by melatonin [30]. Certain WRKY family members, such as WRKY6, also promote senescence, and melatonin inhibits their expression [31]. Melatonin has been shown to upregulate the expression of core autophagy-related genes (ATGs). Some studies suggest that moderate and orderly autophagy is beneficial for delaying aging, and melatonin-induced autophagy tends to be a type of “maintenance autophagy,” promptly removing damaged mitochondria and misfolded proteins [32]. Therefore, melatonin does not act through a single gene but rather as a system regulator that works together at multiple levels to delay leaf senescence.

3.3 Interaction between Melatonin and Other Phytohormones

Melatonin and ABA have antagonistic effects in regulating leaf senescence, yet the specific mechanism of action remains unclear. Exogenous melatonin can delay the senescence of mature melon leaves under ABA stress and protect the functionality of photosystem II. Under high concentrations of ABA stress, melatonin induced the expression of the respiratory burst oxidase homolog D (CmRBOHD) gene in melon and promoted the accumulation of H2O2 [33]. Moreover, melatonin has been demonstrated to regulate the synthesis and metabolism of the plant growth hormone (IAA), thereby exerting a significant influence on the growth, development, and physiological metabolism of plants. In an experiment where melatonin and IAA interacted to regulate the growth of Arabidopsis taproots, melatonin inhibited the expression of key genes in the cytokinin signaling pathway (AHK4, AHP, ARR15), consequently affecting the regulatory role of cytokinin on root growth. Therefore, the similar effects of melatonin and IAA may stem from their regulatory influences on plant growth hormones rather than merely acting as substitutes for them [20].

GA is a plant hormone that plays a pivotal role in various processes, including plant growth and development. It has been demonstrated that under conditions of salt stress, melatonin is capable of upregulating the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of GA, specifically, CsGA20ox and CsGA3ox, in cucumber seeds. In addition to this, melatonin appears to enhance the synthesis of GA, particularly the hydroxy-GA (HA) form, whilst concomitantly mitigating the inhibitory effects of NaCl–induced stress on seed germination. Melatonin interacts with GA to mediate plant growth by regulating its biosynthesis, transport, and signal transduction [34]. Ethylene is involved in the control of various physiological processes, including plant growth, development, and responses to adversity. The application of exogenous melatonin was found to inhibit ethylene release in pear fruit to a significant extent. It was also demonstrated to reduce peel colour change, as well as to delay the decline in titratable acid in the fruit. Furthermore, chlorophyll content was observed to be increased by the treatment. Melatonin can impact plant nutrient absorption, fruit ripening, and stress resistance by regulating ethylene synthesis and release [35].

The crosstalk between ABA and melatonin constitutes a key hub in the finely regulated growth-defense trade-off in plants. In many circumstances, ABA and melatonin exhibit antagonistic physiological effects, including on processes such as stomatal closure, seed germination, and leaf senescence. However, this antagonism is not simply a cancellation but rather involves complex interactions at multiple levels of the signaling pathway. In the presence of melatonin, it scavenges or attenuates ROS generated in the ABA signaling pathway, thereby interrupting or weakening ABA downstream signaling outputs, such as stomatal closure [27]. ABA and melatonin both activate the MAPK pathway, but they may activate different members or induce distinct phosphorylation patterns, ultimately activating different transcription factors and leading to opposing gene expression [36]. At the transcriptional level, ABA activates the expression of ABRE-binding genes and upregulates senescence-related transcription factors, while melatonin inhibits the expression of these ABA-induced senescence and stress-related genes [37]. Furthermore, exogenous ABA treatment downregulated the expression of genes (T5H and ASMT) involved in melatonin biosynthesis, leading to reduced endogenous melatonin levels [38]. Therefore, ABA and melatonin have a relationship similar to the “brake and accelerator” in plant growth and stress. In summary, melatonin coordinates with various plant hormones during growth and development, regulating plant growth, development, and responses to adversity by modulating hormone synthesis, transport, and signal transduction.

4 Roles of Melatonin in Plant Abiotic Stress

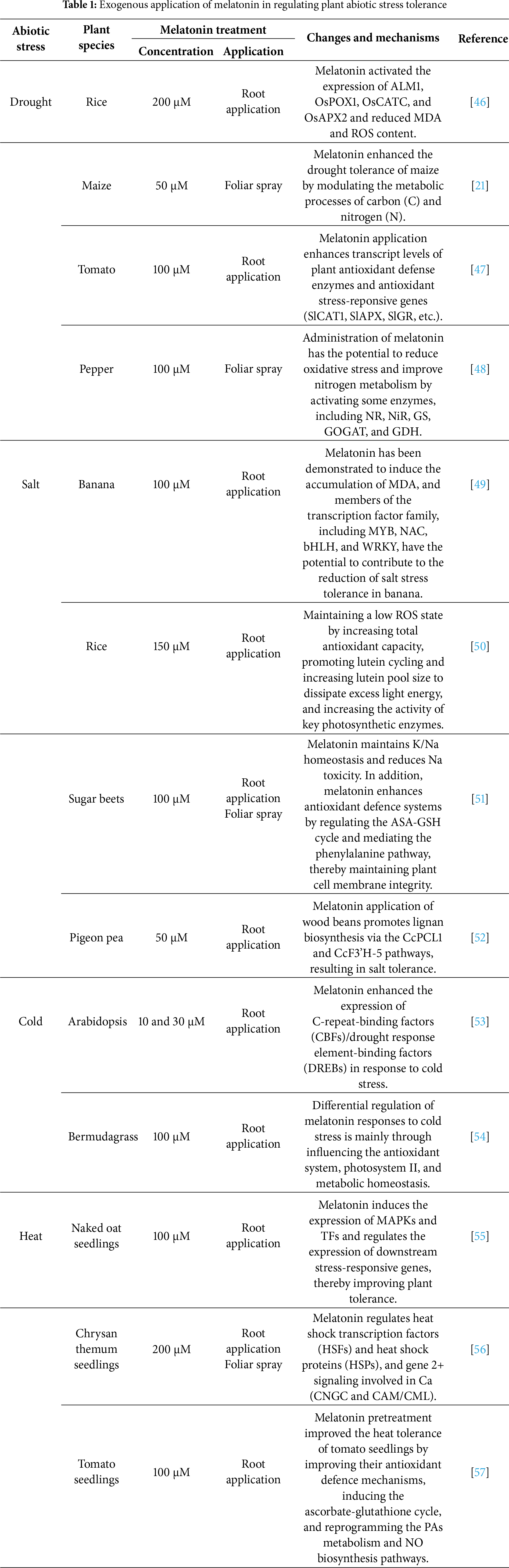

In light of the recognised function of melatonin in mitigating abiotic stress in plants, researchers have initiated studies on the administration of exogenous melatonin prior to stress events to enhance plant tolerance. Some studies suggested that exogenous administration of melatonin to plant seeds or the most vulnerable stages of plant growth and development, either through soaking, irrigation, or foliar spraying, can attenuate adverse impacts associated with abiotic stresses such as cold, heat, heavy metals, drought, waterlogging, and salt stress (Table 1). The current frontier and critical focus of plant melatonin studies is exploring the variations in melatonin efficacy across different stress types and plant species. It indicates that the efficacy of melatonin exhibits significant ‘stress-species’ specificity [39]. This variation primarily stems from two mechanisms. Firstly, different abiotic stresses (such as drought, salinity, heavy metals, and extreme temperatures) cause primary damage and secondary oxidative stress through distinct pathways [40,41]. Meanwhile, melatonin’s core function lies in its role as a potent antioxidant and regulator of oxidative stress signalling. Thus, for stress types where oxidative bursts constitute primary secondary damage (e.g., drought, salt, and heavy metal stress), the application of exogenous melatonin typically exhibits higher protective efficacy by directly scavenging ROS and upregulating endogenous antioxidant enzyme systems [42]. Conversely, for stresses causing direct physical damage, their effects may be weaker and more indirect. Additionally, inherent variations in melatonin sensitivity exist among different plant species and even cultivars. These variations are closely linked to baseline endogenous melatonin levels, metabolic rates, receptor protein affinities, and the completeness of downstream signalling pathways [43]. For example, species with lower endogenous melatonin levels may exhibit heightened sensitivity and more pronounced responses to exogenous supplementation [44]. Conversely, certain species may possess more efficient melatonin synthesis pathways or signalling networks, enabling the rapid amplification of exogenous melatonin signals to coordinate a series of physiological stress responses, such as stomatal closure, the induction of stress-resistant gene expression, and the regulation of ion homeostasis [45]. The species that are inherently vulnerable to specific stresses, or that have limited endogenous antioxidant capacity, often benefit more from melatonin supplementation.

4.1 Application of Melatonin under Drought Stress

Drought is a factor that seriously affects crop growth. Plants can replenish water in dry root systems during drought conditions through hydraulic redistribution, which increases the water potential of the root systems and helps maintain normal physiological functions [58]. Under drought stress, an imbalance between the generation and removal of ROS in plant cells has been shown to result in damage to the membrane system. The application of antioxidants can maintain the balance of reactive oxygen species in cells [59]. As a natural antioxidant, melatonin can increase the content and activity of antioxidant substances in plants, thereby alleviating the effects of drought stress on plants. The optimal growth temperature for pepper is 25–30°C; however, temperatures below 15°C negatively impact seed development. The application of 5 μM melatonin to the roots of plants such as Capsicum peppers has various positive effects, including an increase in seed biomass, improvements in photosynthesis and antioxidant activity, and a reduction in membrane permeability, MDA, hydrogen peroxide, and other indicators. Melatonin pretreatment can also double the early yield of pepper under cold stress [31]. Studies have shown that foliar spraying with melatonin reduces oxidative damage and enhances net photosynthesis in plants under cold stress [60]. The administration of melatonin has been shown to protect photosynthetic pigments, counteract the impact of drought stress on Amorpha fruticosa seedlings, and increase antioxidant enzyme activity [61]. The application of melatonin to Psoralea corylifolia and sweet sorghum can enhance their drought tolerance, decrease lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, facilitate the recovery of leaf structure and function, boost photosynthetic pigment levels, and increase antioxidant enzyme activity [62,63]. Thus, exogenous melatonin can reduce drought-stressed crops’ damage. When the ambient temperature exceeds the optimal temperature of the plant, heat stress occurs. Festuca arundinacea is sensitive to high temperatures during the seedling stage. Eight-day-old tall fescue seedlings exhibited improved tolerance to elevated temperatures when 20 μM melatonin was added to their growth medium. Treatment with melatonin increased the fresh weight, plant height, chlorophyll content, and protein levels of the seedlings. It also enhanced the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, POD, and CAT, and reduced electrolyte leakage, MDA, and hydrogen peroxide levels. Additionally, melatonin treatment upregulated several genes associated with heat response, while downregulating other genes such as FaF-box, FaHSFA6B, and FaCYP710A. These results indicate that the application of melatonin can enhance the adaptability of tall fescue to heat stress [64]. Drought negatively impacts crop growth and yield, but variations in melatonin-treated crops and their mechanisms of adaptation determine their sensitivity to drought and their ability to withstand adverse conditions.

4.2 Application of Melatonin in Salt Stress

Salinisation is a significant threat to the ecological environment and agricultural production, ranking among the most prevalent abiotic stresses affecting global agriculture. Salt stress has a negative impact on plant growth and development. The damage caused by excessive salt mainly includes osmotic stress, ion toxicity, and oxidative stress [65]. Exogenous melatonin can enhance the antioxidant and osmotic regulation capabilities of rice, remove a large amount of accumulated ROS, alleviate the oxidative damage, and improve the salt tolerance of seedlings [46]. The application of melatonin can reduce the harm of salt stress to plants and promote plant growth and development. Cotton seedlings showed growth inhibition under salt stress. The levels of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions in the plant increased, while the levels of osmotic regulators in the leaves decreased. This data indicates that the seedlings produced excessive ROS, and the cell membrane was damaged. The application of exogenous melatonin to cotton seedlings inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), enhances the activity of the antioxidant enzyme system, and increases the levels of substances that regulate osmosis. It also reduces membrane lipid peroxidation and protects the integrity of the lipid membrane under salt stress. These actions mitigate the damage caused by salt stress to seedlings and effectively reduce its negative impact on their growth [66]. Under salt stress conditions, wheat seedlings treated with melatonin showed a certain degree of growth recovery. Dry weight, IAA content, leaf photosynthesis rate, maximum photochemical efficiency of photosystem II, and chlorophyll content were all higher than in the salt stress control group. However, they remained lower than in the blank control group under normal conditions. Melatonin alleviated the inhibitory effect of salt stress on the growth of the whole wheat plant to a certain extent. It significantly alleviated salt-induced oxidative damage to upland cotton, which was achieved by increasing the accumulation of osmotic-regulating substances and activating the activity of antioxidant enzymes [67]. In addition, melatonin also enhances the tolerance of upland cotton to salt stress by regulating the expression of stress response genes and ion channel genes [68]. Salt stress negatively affects the expression patterns of melatonin biosynthetic enzymes and increases endogenous melatonin levels. Overexpressing SNAT significantly increases plant salt tolerance. For instance, Arabidopsis plants overexpressing VvSNAT1 exhibited greener leaves, more vigorous growth, and higher germination rates in response to salt stress than wild-type lines [69].

Melatonin fundamentally helps maintain ion balance to combat salt stress. For example, the application of melatonin increased the accumulation of potassium ion, decreased the absorption of sodium ion, and maintained a high K+/Na+ ratio, thereby enhancing the salt tolerance of corn seedlings. Melatonin positively influences the response of plants to salt stress. It can regulate the growth and development of plants, boost their antioxidant capacity, and mitigate the oxidative damage caused by salt stress. It can also increase their tolerance to these conditions [70]. Melatonin upregulates and enhances the activity of SOS1, SOS2, and SOS3 proteins, which regulate the functionality of the entire SOS pathway by driving the SOS1 protein to actively pump excess sodium out of the cytoplasm. This process utilizes the proton gradient established by the plasma membrane H+-ATPase, which directly contributes to the reduction of intracellular sodium concentrations [71,72]. Melatonin significantly upregulates the expression and protein activity of sodium/hydrogen transporters such as NHX1. It also enhances the activity of the tonoplast H+pump, providing a stronger driving force for sodium compartmentalization [73]. Under salt stress, high sodium concentrations inhibit potassium absorption channels. Melatonin, through its potent antioxidant properties, reduces oxidative damage to potassium channels, such as AKT1, caused by ROS generated by salt stress [74,75]. Melatonin also reduces potassium leakage by maintaining membrane integrity. However, the effects of melatonin can vary between different plant species and varieties. Further studies are needed to uncover how it works and how it can be used.

4.3 Application of Melatonin in Cold Response

Low-temperature environments will affect the fluidity and enzyme activity of plant cell membranes, inhibiting photosynthesis and nutrient transport, causing damage to the plant body, and leading to a reduction in crop yield [76]. Melatonin improves rice’s tolerance of low-temperature stress by regulating the activity of enzymes in the antioxidant system, the levels of osmotic substances and chlorophyll, the levels of plant hormones, and the expression of genes that confer cold resistance in rice [77]. Spraying melatonin can promote the growth of cucumber seedlings in low temperatures, enhance the osmotic regulation capability of the leaves, maintain the balance of plant hormones, and thus improve the cold resistance of cucumber seedlings [78]. By adding appropriate concentrations of exogenous melatonin, the growth of seedlings can be enhanced while reducing the levels of MDA and H2O2 in the leaves and increasing the content of AsA and GSH, which helps mitigate the damage caused by low-temperature stress to potato seedlings, thereby improving their resistance to low-temperature stress to varying degrees [79]. Exogenous melatonin has also been used to enhance the growth of highland barley seedlings under cold stress. The results showed that exogenous melatonin could restore circadian oscillations in the clock genes HvCCA1 and HvTOC1. These genes had lost their circadian phenotype due to environmental cold stress [80]. These studies have demonstrated the potential of exogenous melatonin in enhancing plant tolerance to low-temperature stress. Spraying exogenous melatonin can promote the growth of plant seedlings, increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the capability of osmotic regulation, and maintain the balance of plant hormones. This increases the resistance of plants to low-temperature stress. Furthermore, exogenous melatonin can regulate plant clock genes and restore circadian oscillations, thereby mitigating the effects of low temperatures on plants. Using exogenous melatonin to improve crop resistance to low-temperature stress provides a theoretical basis and practical guidance.

4.4 Application of Melatonin in Heat Stress

High temperatures cause plant stomata to close, affect photosynthesis, and interfere with water balance and mineral metabolism. It can also cause antioxidant system disorders and increase oxidative damage. These changes have a significant impact on plant growth and reproduction, resulting in lower crop yields [81]. In Arabidopsis, melatonin-mediated heat tolerance has been found to be associated with the increased expression of HSFA2, HSA32, HSP90, and HSP101. Furthermore, Hsp40 interacts with SNAT to regulate melatonin biosynthesis, thereby enhancing heat tolerance by stabilising the Rubisco enzyme during periods of heat stress [82]. The administration of exogenous melatonin can inhibit the upregulation of genes involved in pyruvate synthesis and the downregulation of genes related to pyruvate consumption in celery. This prevents pyruvate accumulation from rapidly increasing the expression of peroxidase genes and enhancing peroxidase activity. Physiologically, the application of exogenous melatonin in celery significantly enhanced the plant’s ability to remove ROS under heat stress and improved the plant’s heat tolerance [83]. Exogenous melatonin alleviated the heat damage to plants by improving antioxidant capacity, reducing ROS accumulation, and upregulating the transcription of HSF7, HSP70.1, and HSP70.11. Specifically, the heat damage symptoms were mild, and the heat damage index was reduced. Applying melatonin improves a plant’s resistance to high temperatures. This enhancement occurs through several mechanisms, including increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes APx and GR, boosting the antioxidant compound levels of AsA and GSH, inhibiting ROS production, safeguarding cell membrane stability, and enhancing the plant’s ability to endure high temperatures [45].

Endogenous melatonin increases significantly under high-temperature stress, which may reflect a response mechanism for plants to resist such stress. This enhancement occurs as it can induce the expression of HSFA1a, HSFA1b, HSFA1d, and HSFA1e genes, thereby activating downstream heat shock protein genes and improving the tolerance to high temperatures. Thus, both high temperature and melatonin can jointly induce the expression of the HSFA1 gene; however, melatonin does not enhance the resistance of HSFA1 mutant plants to high temperatures. Additionally, exogenous melatonin inhibits the expression of downstream heat shock protein genes that are activated by HSFA1 [84]. Both high temperature and exogenous melatonin induce the expression of the HSFA1 gene, enhance the expression of HSP, and improve plant tolerance to high-temperature stress. The results suggest that melatonin plays a significant regulatory role in how plants respond to high-temperature stress. Using exogenous melatonin can increase a plant’s antioxidant capacity, maintain the stability of its cell membranes, and regulate the expression of heat shock transcription factors and heat shock protein genes. This ultimately enhances a plant’s tolerance to elevated temperatures.

The first melatonin study demonstrated its consistent action across plants, animals, and humans. For instance, melatonin may play a role in life phenomena such as light morphogenesis by acting as a time regulator. Since plant melatonin shares structural similarities with IAA, a previous study sought to determine whether melatonin exhibits similar physiological functions as IAA, such as promoting growth, root development, and seed germination. Both the methoxy group in the fifth position of the indole ring of melatonin and the N-acetyl group in the side chain of melatonin are crucial for its ability to scavenge ROS. Consequently, the antioxidant effects of melatonin in plants have also become a focal point of research, encompassing resistance to adversity and responses to both biological and abiotic stresses, as well as aging and apoptosis related to ROS. Recently, the primary focus has shifted toward verifying the hypotheses from earlier studies and expanding to include all aspects of melatonin. These include different plant organs, cultivated and wild species, plant-derived products, the molecular mechanisms of melatonin, and metabolic pathways. Despite advances in plant melatonin research, some scientific issues remain. First, while numerous studies have examined the synthesis pathway of plant melatonin, fewer have investigated plant melatonin receptors. An attractive and challenging direction for future research is exploring whether melatonin has additional receptors by leveraging existing research, along with advanced facilities and technologies. What role does exogenous plant melatonin play in the core clock-phytomelatonin-redox network? The signaling pathway of plant melatonin is not fully understood. The synergistic effects of plant melatonin and other plant hormones in regulating physiological processes remain unclear. In addition, the role of melatonin signaling at the interface between soil microorganisms and roots in relation to plant growth, ion transport, and nutrient distribution requires further exploration.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (202410376009), Anhui Province College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (S202310376057, S202510376030), Quality Engineering Project of West Anhui University (wxxy2024011), Quality Engineering Project of Anhui Province (2024zybj032), and Development of Big Data Integration and Analysis Platform for Traditional Chinese Medicine Genomics (0045025050).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiaomei He, Xiaoting Wan, Cheng Song; data collection: Xiaoting Wan; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiaomei He, Xiaoting Wan; draft manuscript preparation: Xiaomei He, Xiaoting Wan, Ziyang Hu, Haiyu Wang, Muhammad Arif, Muhammad Aamir Manzoor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lerner AB, Case JD, Takahashi Y. Isolation of melatonin and 5-methoxyindole-3-acetic acid from bovine pineal glands. J Biol Chem. 1960;235(7):1992–7. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)69351-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Claustrat B, Leston J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie. 2015;61(2–3):77–84. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan DX, Sainz RM, Alatorre-Jimenez M, Qin L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res. 2016;61(3):253–78. doi:10.1111/jpi.12360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Melatonin and its relationship to plant hormones. Ann Bot. 2018;121(2):195–207. doi:10.1093/aob/mcx114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Hassan MU, Mahmood A, Awan MI, Maqbool R, Aamer M, Alhaithloul HAS, et al. Melatonin-induced protection against plant abiotic stress: mechanisms and prospects. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:902694. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.902694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liao L, Zhou Y, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Liu X, Liu B, et al. Structural and molecular dynamics analysis of plant serotonin n-acetyltransferase reveal an acid/base-assisted catalysis in melatonin biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(21):12020–6. doi:10.1002/anie.202100992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Back K, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin biosynthesis in plants: multiple pathways catalyze tryptophan to melatonin in the cytoplasm or chloroplasts. J Pineal Res. 2016;61(4):426–37. doi:10.1111/jpi.12364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Mishra A, Mishra KB, Höermiller II, Heyer AG, Nedbal L. Chlorophyll fluorescence emission as a reporter on cold tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6(2):301–10. doi:10.4161/psb.6.2.15278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Esteban-Zubero E, Zhou Z, Reiter RJ. Melatonin as a potent and inducible endogenous antioxidant: synth metabol. Molecules. 2015;20(10):18886–906. doi:10.3390/molecules201018886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Di Mascio P, Martinez GR, Prado FM, Reiter RJ. Novel rhythms of N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine and its precursor melatonin in water hyacinth: importance for phytoremediation. FASEB J. 2007;21(8):1724–9. doi:10.1096/fj.06-7745com. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Byeon Y, Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Back K. Predominance of 2-hydroxymelatonin over melatonin in plants. J Pineal Res. 2015;59(4):448–54. doi:10.1111/jpi.12274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Byeon Y, Back K. Molecular cloning of melatonin 2-hydroxylase responsible for 2-hydroxymelatonin production in rice (Oryza sativa). J Pineal Res. 2015;58(3):343–51. doi:10.1111/jpi.12220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wang J, Lv P, Yan D, Zhang Z, Xu X, Wang T, et al. Exogenous melatonin improves seed germination of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8436. doi:10.3390/ijms23158436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xie Q, Zhang Y, Cheng Y, Tian Y, Luo J, Hu Z, et al. The role of melatonin in tomato stress response, growth and development. Plant Cell Rep. 2022;41(8):1631–50. doi:10.1007/s00299-022-02876-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jahan MS, Guo S, Sun J, Shu S, Wang Y, El-Yazied AA, et al. Melatonin-mediated photosynthetic performance of tomato seedlings under high-temperature stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;167(6):309–20. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.08.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Givler D, Givler A, Luther PM, Wenger DM, Ahmadzadeh S, Shekoohi S, et al. Chronic administration of melatonin: physiological and clinical considerations. Neurol Int. 2023;15(1):518–33. doi:10.3390/neurolint15010031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kocyigit A, Guler EM, Karatas E, Caglar H, Bulut H. Dose-dependent proliferative and cytotoxic effects of melatonin on human epidermoid carcinoma and normal skin fibroblast cells. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2018;829-830(11):50–60. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Loren P, Sánchez R, Arias ME, Felmer R, Risopatrón J, Cheuquemán C. Melatonin scavenger properties against oxidative and nitrosative stress: impact on gamete handling and in vitro embryo production in humans and other mammals. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1119. doi:10.3390/ijms18061119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Owino S, Buonfiglio DDC, Tchio C, Tosini G. Melatonin signaling a key regulator of glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:488. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yang L, You J, Li J, Wang Y, Chan Z. Melatonin promotes Arabidopsis primary root growth in an IAA-dependent manner. J Exp Bot. 2021;72(15):5599–611. doi:10.1093/jxb/erab196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Ren J, Yang X, Ma C, Wang Y, Zhao J. Melatonin enhances drought stress tolerance in maize through coordinated regulation of carbon and nitrogen assimilation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;167:958–69. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Yang SJ, Huang B, Zhao YQ, Hu D, Chen T, Ding CB, et al. Melatonin enhanced the tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana to high light through improving anti-oxidative system and photosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:752584. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.752584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Back K. Melatonin metabolism, signaling and possible roles in plants. Plant J. 2021;105(2):376–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Verde A, Míguez JM, Gallardo M. Role of melatonin in apple fruit during growth and ripening: possible interaction with ethylene. Plants. 2022;11(5):688. doi:10.3390/plants11050688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li Z, Zhang S, Xue J, Mu B, Song H, Liu Y. Exogenous melatonin treatment induces disease resistance against botrytis cinerea on post-harvest grapes by activating defence responses. Foods. 2022;11(15):2231. doi:10.3390/foods11152231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Han QH, Huang B, Ding CB, Zhang ZW, Chen YE, Hu C, et al. Effects of melatonin on anti-oxidative systems and photosystem ii in cold-stressed rice seedlings. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:785. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ahammed GJ, Li Z, Chen J, Dong Y, Qu K, Guo T, et al. Reactive oxygen species signaling in melatonin-mediated plant stress response. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024;207:108398. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. An W, Wang G, Dou J, Zhang Y, Yang Q, He Y, et al. Protective mechanisms of exogenous melatonin on chlorophyll metabolism and photosynthesis in tomato seedlings under heat stress. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1519950. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1519950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ma L, Liu Q, Tian M, Tian X, Gao L. Mechanisms of melatonin in anti-aging and its regulation effects in radiation-induced premature senescence. Radiat Med Prot. 2021;2(1):33–7. doi:10.1016/j.radmp.2021.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Eysholdt-Derzsó E, Renziehausen T, Frings S, Frohn S, Von Bongartz K, Igisch CP, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-bound ANAC013 factor is cleaved by RHOMBOID-LIKE 2 during the initial response to hypoxia in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(11):e2221308120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2221308120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Robatzek S, Somssich IE. Targets of At WRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 2002;16(9):1139–49. doi:10.1101/gad.222702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhu C-Z, Li G-Z, Lyu H-F, Lu Y-Y, Li Y, Zhang X-N. Modulation of autophagy by melatonin and its receptors: implications in brain disorders. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2025;46(3):525–38. doi:10.1038/s41401-024-01398-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Guo Y, Zhu J, Liu J, Xue Y, Chang J, Zhang Y, et al. Melatonin delays ABA-induced leaf senescence via H2O2 -dependent calcium signalling. Plant Cell Environ. 2023;46(1):171–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

34. Zhang H, Zhang N, Yang R, Wang L, Sun Q, Li D, et al. Melatonin promotes seed germination under high salinity by regulating antioxidant systems, ABA and GA4 interaction in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J Pineal Res. 2014;57(3):269–79. doi:10.1111/jpi.12167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Melatonin against environmental plant stressors: a review. Curr Protein Pept Sc. 2021;22(5):413–29. doi:10.2174/1389203721999210101235422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bychkov I, Kudryakova N, Pojidaeva ES, Doroshenko A, Shitikova V, Kusnetsov V. ABA and melatonin: players on the same field? Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(22):12266. doi:10.3390/ijms252212266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Aerts N, Hickman R, Van Dijken AJH, Kaufmann M, Snoek BL, Pieterse CMJ, et al. Architecture and dynamics of the abscisic acid gene regulatory network. Plant J. 2024;119(5):2538–63. doi:10.1111/tpj.16899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mansouri S, Koushesh Saba M, Sarikhani H. Exogenous melatonin delays strawberry fruit ripening by suppressing endogenous ABA signaling. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):14209. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-41311-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Choi K, Lee YJ, Park S, Je NK, Suh HS. Efficacy of melatonin for chronic insomnia: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;66(1):101692. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, Xu J, Li R, Ge Y, Li Y, Li R. Plants’ response to abiotic stress: mechanisms and strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10915. doi:10.3390/ijms241310915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang Q-H, Chen Y-Q, Li Z-B, Tan X-T, Xin G-R, He C-T. Defense guard: strategies of plants in the fight against Cadmium stress. Adv Biotechnol. 2024;2(4):44. doi:10.1007/s44307-024-00052-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kesawat MS, Satheesh N, Kherawat BS, Kumar A, Kim HU, Chung SM, et al. Regulation of reactive oxygen species during salt stress in plants and their crosstalk with other signaling molecules—current perspectives and future directions. Plants. 2023;12(4):864. doi:10.3390/plants12040864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hardeland R. Melatonin in plants–diversity of levels and multiplicity of functions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:198. [cited 2025 Sep 14]. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/Article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00198/abstract. [Google Scholar]

44. Bargunam S, Roy R, Shetty D, H AS, VS S, Babu VS. Melatonin-governed growth and metabolome divergence: circadian and stress responses in key plant species. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025;221(22):109635. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Tan D, Hardeland R, Back K, Manchester LC, Alatorre-Jimenez MA, Reiter RJ. On the significance of an alternate pathway of melatonin synthesis via 5-methoxytryptamine: comparisons across species. J Pineal Res. 2016;61(1):27–40. doi:10.1111/jpi.12336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Luo C, Min W, Akhtar M, Lu X, Bai X, Zhang Y, et al. Melatonin enhances drought tolerance in rice seedlings by modulating antioxidant systems, osmoregulation, and corresponding gene expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20):12075. doi:10.3390/ijms232012075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Mushtaq N, Iqbal S, Hayat F, Raziq A, Ayaz A, Zaman W. Melatonin in micro-tom tomato: improved drought tolerance via the regulation of the photosynthetic apparatus, membrane stability, osmoprotectants, and root system. 2022;12(11):1922. doi:10.3390/life12111922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kaya C, Shabala S. Melatonin improves drought stress tolerance of pepper (Capsicum annuum) plants via upregulating nitrogen metabolism. Funct Plant Biol. 2023;51(1):FP23060. doi:10.1071/FP23060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wei J, Liang J, Liu D, Liu Y, Liu G, Wei S. Melatonin-induced physiology and transcriptome changes in banana seedlings under salt stress conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:938262. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.938262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Yan F, Zhang J, Li W, Ding Y, Zhong Q, Xu X, et al. Exogenous melatonin alleviates salt stress by improving leaf photosynthesis in rice seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;163:367–75. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang P, Liu L, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang H, Chen J, et al. Beneficial effects of exogenous melatonin on overcoming salt stress in sugar beets (Beta vulgaris L.). Plants. 2021;10(5):886. doi:10.3390/plants10050886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Song Z, Yang Q, Dong B, Li N, Wang M, Du T, et al. Melatonin enhances stress tolerance in pigeon pea by promoting flavonoid enrichment, particularly luteolin in response to salt stress. J Exp Botany. 2022;73(17):5992–6008. doi:10.1093/jxb/erac276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Bajwa VS, Shukla MR, Sherif SM, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. Role of melatonin in alleviating cold stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Pineal Res. 2014;56(3):238–45. doi:10.1111/jpi.12115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Hu Z, Fan J, Xie Y, Amombo E, Liu A, Gitau MM, et al. Comparative photosynthetic and metabolic analyses reveal mechanism of improved cold stress tolerance in bermudagrass by exogenous melatonin. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;100:94–104. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Gao W, Zhang Y, Feng Z, Bai Q, He J, Wang Y. Effects of melatonin on antioxidant capacity in naked oat seedlings under drought stress. Molecules. 2018;23(7):1580. doi:10.3390/molecules23071580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Xing X, Ding Y, Jin J, Song A, Chen S, Chen F, et al. Physiological and transcripts analyses reveal the mechanism by which melatonin alleviates heat stress in chrysanthemum seedlings. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:673236. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.673236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Jahan MS, Shu S, Wang Y, Chen Z, He M, Tao M, et al. Melatonin alleviates heat-induced damage of tomato seedlings by balancing redox homeostasis and modulating polyamine and nitric oxide biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):414. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-1992-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Sha S, Cai G, Liu S, Ahmed MA. Roots to the rescue: how plants harness hydraulic redistribution to survive drought across contrasting soil textures. Adv Biotechnol. 2024;2(4):43. doi:10.1007/s44307-024-00050-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Melatonin as a regulatory hub of plant hormone levels and action in stress situations. Plant Biol J. 2021;23:7–19. doi:10.1111/plb.13202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Li X, Wei JP, Scott E, Liu JW, Guo S, Li Y, et al. Exogenous melatonin alleviates cold stress by promoting antioxidant defense and redox homeostasis in Camellia sinensis L. Molecules. 2018;23(1):165. doi:10.3390/molecules23010165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang J, Gao X, Wang X, Song W, Wang Q, Wang X, et al. Exogenous melatonin ameliorates drought stress in Agropyron mongolicum by regulating flavonoid biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1051165. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1051165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Wan X, Zhang Y, Wang G, Liao R, Pan H, Chen C, et al. Melatonin affects peucedanum praeruptorum vegetative growth and coumarin synthesis by modulating the antioxidant system, photosynthesis, and endogenous hormones. J Pineal Res. 2024;76(8):e70018. doi:10.1111/jpi.70018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Song C, Manzoor MA, Mao D, Ren X, Zhang W, Zhang Y. Photosynthetic machinery and antioxidant enzymes system regulation confers cadmium stress tolerance to tomato seedlings pretreated with melatonin. Sci Hortic. 2024;323(8):112550. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Liang D, Gao F, Ni Z, Lin L, Deng Q, Tang Y, et al. Melatonin improves heat tolerance in kiwifruit seedlings through promoting antioxidant enzymatic activity and glutathione s-transferase transcription. Molecules. 2018;23(3):584. doi:10.3390/molecules23030584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Zhao S, Zhang Q, Liu M, Zhou H, Ma C, Wang P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

66. Jiang D, Lu B, Liu L, Duan W, Chen L, Li J, et al. Exogenous melatonin improves salt stress adaptation of cotton seedlings by regulating active oxygen metabolism. PeerJ. 2020;8(2):e10486. doi:10.7717/peerj.10486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Ke Q, Ye J, Wang B, Ren J, Yin L, Deng X, et al. Melatonin mitigates salt stress in wheat seedlings by modulating polyamine metabolism. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:914. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Shen J, Chen D, Zhang X, Song L, Dong J, Xu Q, et al. Mitigation of salt stress response in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) by exogenous melatonin. J Plant Res. 2021;134(4):857–71. doi:10.1007/s10265-021-01284-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Wu Y, Fan X, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Sun L, Rahman FU, et al. VvSNAT1 overexpression enhances melatonin production and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;166:485–94. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Li C, Wang P, Wei Z, Liang D, Liu C, Yin L, et al. The mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin on salinity-induced stress in Malus hupehensis. J Pineal Res. 2012 Oct;53(3):298–306. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079x.2012.00999.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Ji H, Pardo JM, Batelli G, Van Oosten MJ, Bressan RA, Li X. The salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway: established and emerging roles. Mol Plant. 2013;6(2):275–86. doi:10.1093/mp/sst017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Quintero FJ, Martinez-Atienza J, Villalta I, Jiang X, Kim WY, Ali Z, et al. Activation of the plasma membrane Na/H antiporter Salt-Overly-Sensitive 1 (SOS1) by phosphorylation of an auto-inhibitory C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(6):2611–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018921108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Li J, Yuan F, Liu Y, Zhang M, Liu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Exogenous melatonin enhances salt secretion from salt glands by upregulating the expression of ion transporter and vesicle transport genes in Limonium bicolor. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):493. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-02703-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Assaha DVM, Ueda A, Saneoka H, Al-Yahyai R, Yaish MW. The role of Na+ and K+ transporters in salt stress adaptation in glycophytes. Front Physiol. 2017;8:509. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Wu H. Plant salt tolerance and Na+ sensing and transport. Crop J. 2018;6(3):215–25. [Google Scholar]

76. Kidokoro S, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory network of plant cold-stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2022;27(9):922–35. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2022.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Byeon Y, Back K. Melatonin synthesis in rice seedlings in vivo is enhanced at high temperatures and under dark conditions due to increased serotonin N-acetyltransferase and N-acetylserotonin methyltransferase activities. J Pineal Res. 2014;56(2):189–95. doi:10.1111/jpi.12111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhao H, Zhang K, Zhou X, Xi L, Wang Y, Xu H, et al. Melatonin alleviates chilling stress in cucumber seedlings by up-regulation of CsZat12 and modulation of polyamine and abscisic acid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4998. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05267-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Tiwari RK, Lal MK, Kumar R, Mangal V, Altaf MA, Sharma S, et al. Insight into melatonin-mediated response and signaling in the regulation of plant defense under biotic stress. Plant Mol Biol. 2022;109(4–5):385–99. doi:10.1007/s11103-021-01202-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Chang T, Zhao Y, He H, Xi Q, Fu J, Zhao Y. Exogenous melatonin improves growth in hulless barley seedlings under cold stress by influencing the expression rhythms of circadian clock genes. PeerJ. 2021;9(1):e10740. doi:10.7717/peerj.10740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Ohama N, Sato H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory network of plant heat stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22(1):53–65. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Wang X, Zhang H, Xie Q, Liu Y, Lv H, Bai R, et al. SlSNAT interacts with HSP40, a molecular chaperone, to regulate melatonin biosynthesis and promote thermotolerance in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020;61(5):909–21. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcaa018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Li M, Zhou J, Du J, Li X, Sun Y, Wang Z, et al. Comparative physiological and transcriptomic analyses of improved heat stress tolerance in celery (Apium Graveolens L.) caused by exogenous melatonin. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11382. doi:10.3390/ijms231911382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Shi H, Tan D, Reiter RJ, Ye T, Yang F, Chan Z. Melatonin induces class A1 heat-shock factors (HSFA1s) and their possible involvement of thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. J Pineal Res. 2015;58(3):335–42. doi:10.1111/jpi.12219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools