Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mycorrhizal Fertilizer Enhances Lettuce Growth and Vitamin C in Semi-Arid Conditions

Department of Plant and Animal Production, Adıyaman University Kahta Vocational School, Adıyaman, 02400, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Ceren Ayşe Bayram. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Plant Nutrition-Mechanisms, Regulation, and Sustainable Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3283-3295. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073047

Received 09 September 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

In semi-arid regions where climatic limitations hinder open-field vegetable production, greenhouse-based lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivation plays a vital role in ensuring off-season supply. In this study, the potential of sustainable input combinations was evaluated to enhance lettuce productivity, quality, and profitability under unheated greenhouse conditions in Southeastern Türkiye. Treatments included farmer practice and a mycorrhizal biofertilizer (ERS, a water-soluble arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus product) applied alone or in combination with organic-based biostimulants (IS and NM). Evaluated parameters were plant height, leaf pigmentation (a*, h°), SPAD values, vitamin C, nitrogen and phosphorus content, and gross margin. The ERS2+IS&NM treatment significantly enhanced plant height (32.5 cm), vitamin C content (28.63 mg 100 g−1 FW), and gross margin ($616.09 da−1), along with improved nutrient uptake and leaf coloration. These findings highlight the synergistic benefits of integrating mycorrhizal inoculants with organic-based biostimulants in greenhouse-grown lettuce systems. The results contribute to the development of eco-friendly, climate-resilient production strategies for protected cultivation in semi-arid environments.Keywords

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is among the most widely cultivated leafy vegetables in Türkiye, largely due to its short growing cycle, high consumer demand, and adaptability to both open-field and protected cultivation systems [1,2]. As a cool-season crop, it is particularly suited for early spring and autumn production and is often grown in greenhouses to meet off-season market demands. Due to its rapid physiological response to environmental and nutritional changes, lettuce is commonly used as a model crop in studies evaluating fertilization strategies, irrigation regimes, and plant biostimulants [3].

In semi-arid regions such as Southeastern Anatolia, year-round open-field vegetable production is severely limited by climatic constraints, including drought, temperature extremes, and variable precipitation patterns. In this context, greenhouse-based lettuce cultivation represents a high-value alternative that supports sustainable intensification in horticulture [4,5]. The province of Adıyaman, located in Southeastern Türkiye, is characterized by hot, dry summers and cold, wet winters, necessitating the use of protected cultivation systems to ensure early and off-season vegetable supply. Recent natural disasters, such as the extreme snowfall event in 2022 and the devastating earthquake in 2023, have significantly damaged greenhouse infrastructure and disrupted local agricultural practices. However, with the aid of government recovery programs, greenhouse vegetable production has rebounded by 2024, highlighting the growing importance of protected agriculture in the region [6,7,8].

Abiotic stressors such as drought, salinity, and temperature extremes increasingly threaten vegetable production under climate change. Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi play a crucial role in enhancing plant resistance to abiotic stresses such as drought. This effect occurs through a series of physiological and biochemical mechanisms, including improved water and nutrient uptake, strengthened antioxidant defense systems, and regulation of osmotic balance in plants. Specifically, AM fungi have been shown to increase water use efficiency, thereby supporting plant adaptation under drought conditions [9]. (AM) fungi also reduce dependence on chemical fertilizers and improve nutrient uptake, offering an eco-friendly tool for sustainable vegetable production [10]. Similarly, organic fertilizers—such as vermicompost and compost—contribute to soil health, support microbial activity, and positively influence yield and quality attributes of leafy vegetables [11,12,13].

Research shows that the combined application of (AM) fungi and organic-based biostimulants can improve lettuce morphological traits, such as plant height, leaf area, and biomass, while enhancing nutritional parameters like vitamin C and mineral content [14,15,16]. These practices align with global efforts to promote climate-resilient and low-input farming systems, particularly in resource-limited and semi-arid regions [17,18].

Given this background, the present study was conducted under semi-arid greenhouse conditions in Adıyaman, Türkiye. The objective was to evaluate the effects of mycorrhizal biofertilizer (ERS) and organic-based biostimulants (IS and NM), compared with conventional farmer practices, on lettuce growth performance, yield, nutritional quality, and economic return. Agronomic traits (plant height, SPAD values, leaf pigmentation), yield, vitamin C, and mineral contents (N and P) were assessed to determine the physiological and functional responses of lettuce. Special attention was given to the potential of mycorrhizal biofertilizer as a sustainable input under environmentally constrained conditions.

This study provides novel insights into the integrated use of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi and organic biostimulants in lettuce cultivation under semi-arid greenhouse conditions, a setting that is increasingly relevant due to climate change and water scarcity in Türkiye. To date, integrated applications of AM fungi and organic biostimulants under such conditions in Türkiye have been rarely investigated, highlighting the novelty of this study. While previous studies have examined mycorrhizal inoculation or biostimulant application individually, this research uniquely combines these approaches and evaluates their combined effects on both physiological traits, such as vitamin C content, and economic parameters, including gross margin. The simultaneous assessment of plant quality and economic returns distinguishes this work from prior national and international studies. By demonstrating how integrated biostimulant management can enhance both nutritional value and profitability, this study offers practical insights for sustainable vegetable production and the adoption of advanced agricultural practices among progressive farmers in semi-arid regions.

This study was conducted under semi-arid climatic conditions in a greenhouse covered with non-heated polyethylene film in Adıyaman, Türkiye (37°37′46″ N–38°17′46″ E), to evaluate the effects of a mycorrhizal-based organic fertilizer on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L., cv. ‘Cosprina’) growth, yield, vitamin C content, and economic return, in comparison with conventional farmer practices. This cultivar is widely cultivated in Türkiye, with a vegetation period of 50–70 days, and is suitable for both greenhouse and open-field production due to its strong foliage and compact head structure.

Seedlings were supplied by a commercial nursery and transplanted on 05 December 2024. Harvest was conducted on 12 March 2025, following standard greenhouse management without supplemental heating.

The experimental design for this study was structured using a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD), incorporating different fertilizer treatments and a single lettuce variety. The experimental design included four replications for each fertilizer treatment, ensuring the reliability of the results. Each replication consisted of 32 plants, with measurements taken for plant growth, biomass, yield, and nutritional parameters, including vitamin C content. This design allowed for a robust evaluation of the effects of different fertilization strategies on the performance of lettuce in a semi-arid greenhouse environment. The use of four replications per treatment ensured that variations due to environmental factors were minimized, providing more accurate assessments of fertilizer efficacy in improving both crop yield and quality. In the farmer’s practices, Isabion and NutriMin fertilizers were applied as foliar treatments. In addition to these applications, Endo Roots Soluble (ERS) was also applied by drip irrigation. The biostimulant products used in this experiment were obtained from different commercial sources. ERS Bioglobal Inc. (Antalya, Türkiye) supplied the ERS-based formulation, Nutrimin (JH Biotech, Ventura, CA, USA) provided the micronutrient complex, and Isobion (Syngenta, Basel, Switzerland) was used as an amino acid-based biostimulant. The guaranteed content of the product includes a total of 23.5% live organisms, consisting of Glomus intraradices (21%), Glomus aggregatum (20%), Glomus mosseae (20%), Glomus clarum (1%), Glomus monosporus (1%), Glomus deserticola (1%), Glomus brasilianum (1%), Glomus etunicatum (1%), and Gigaspora margarita (1%). Isabion is a liquid organic fertilizer derived from animal origin, containing free amino acids and both long and short-chain peptides in an optimal and well-balanced ratio, making it a highly selected product for enhancing plant growth. NutriMin 534 is a unique foliar fertilizer formulated with high-quality trace elements and secondary elements chelated with glycine, selected for its superior nutritional content and its ability to promote healthy plant development.

Mycorrhizal fungi, such as those used in ERS, enhance the plant’s ability to absorb more water and nutrients from the soil through colonization of root surfaces, tissues, and intercellular spaces, forming dense networks of hyphae that extend beyond the root zone [15]. This mutually beneficial symbiosis improves nutrient uptake and water acquisition, particularly in nutrient-poor or drought-prone soils. ERS (Mycorrhizal Fungi) is a water-soluble powder formulation that is certified for organic use and suitable for under-cover vegetable production. When applied during the transplanting of vegetable seedlings, ERS helps to increase the establishment rate of the plants, particularly in challenging environmental conditions, such as drought, cold, or adverse soil conditions where the efficacy of mycorrhizal fungi is significantly enhanced. This product was selected due to its superior performance under these stress conditions, improving seedling survival and overall plant health.

Isabion was applied once or twice per week at a dosage of 10–20 L ha−1, and NutriMin 534 was applied six times at a rate of 0.5–1.5 kg ha−1, diluted in 100–200 L of water. In addition, ERS (Endo Roots Soluble) was applied twice at a concentration of 2–3 g L−1. The selection of Nutrimin 534 and Isabion as biostimulant products was based on their well-documented efficacy in enhancing plant growth, nutrient uptake, and quality attributes in leafy vegetables. Although these products are not universally applied in local farming, they are increasingly used by progressive and informed farmers seeking to optimize productivity and crop quality. ERS was selected due to its superior performance under stress conditions, improving seedling establishment and overall plant health. The inclusion of these biostimulants in this study also aimed to evaluate their potential to directly contribute to local agricultural development and promote sustainable production practices through university-led research initiatives.

The soil characteristics were measured at two depths, 0–30 cm and 30–60 cm, and are presented in Table 1. Salt content was not measured in the 30–60 cm layer, focusing only on the 0–30 cm root zone.

Table 1: Soil characteristics of experimental area.

| Soil Parameter | 0–30 cm Depth | 30–60 cm Depth |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.39 | 6.99 |

| Total Salt Content | 13.29 dS m−1 | - |

| Lime Content | 43.24% | 13.71% |

| Texture | Clay | Heavy Clay |

| Organic Matter | 2.00% | 1.06% |

| Phosphorus (P) | 0.60 kg da−1 | 2.15 kg da−1 |

| Potassium (K) | 29.0 kg da−1 | 11.41 kg da−1 |

| Iron (Fe) | 5.28 mg kg−1 | 1.35 mg kg−1 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 0.83 mg kg−1 | 1.01 mg kg−1 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 12.44 mg kg−1 | 5.26 mg kg−1 |

| Copper (Cu) | 3.02 mg kg−1 | 0.25 mg kg−1 |

2.1 Plant Growth and Quality Parameters

Morphological measurements such as plant height (cm), head diameter (cm), leaf length and width (cm), and stem diameter (mm) were conducted using a digital caliper and ruler at harvest time. The number of total leaves, number of usable (marketable) leaves, and number of discarded leaves per plant were manually counted. Head weight, leaf weight, root weight, dry plant weight, and dry root weight were measured using a precision digital scale. Fresh weights were recorded immediately after harvest, whereas dry weights were obtained after oven-drying the samples at 65°C until constant weight was achieved.

Yield per decare (kg/da) was calculated by multiplying the average head weight per plant. Root length (cm) was measured from the stem base to the tip of the longest root using a ruler. Chlorophyll content was estimated using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Japan), and values were expressed in SPAD units. Vitamin C content was measured by the 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol titrimetric method, and the results were expressed as mg 100 g−1 FW. Total nitrogen (N%) content of leaves was determined by the Kjeldahl method [19] after acid digestion. Phosphorus content (P%) was measured calorimetrically using the molybdenum blue assay, with absorbance readings taken at 880 nm via a spectrophotometer [20]. The results were expressed as a percentage of dry matter.

The color characteristics of the samples were quantified using a WR18/4–8 FRU colorimeter, measuring parameters L*, a*, and b*. The L* value indicates the brightness level, ranging from 0 (complete black) to 100 (complete white). The a* and b* coordinates represent color dimensions orthogonal to the L* axis, where the neutral point (a* = 0, b* = 0) corresponds to a neutral gray tone.

Positive values of a* correspond to red shades, while negative values indicate green. Similarly, positive b* values correspond to yellow hues, and negative b* values indicate blue tones (Fig. 1).

To better describe color attributes, hue angle (h°) and chroma (C*) were derived from the a* and b* values using the formulas below [21]. Hue angle reflects the dominant wavelength or basic color tone, with 0° representing red-pink, 90° yellow, 180° green, and 270° blue. Chroma quantifies the intensity or purity of the color.

Figure 1: Formula of colour parameters.

The economic efficiency of the applied treatments was evaluated through the calculation of gross margin. Gross margin (GM) was defined as the difference between gross revenue and total variable costs (VC) associated with each treatment. Total variable costs included all production costs that vary with the level of output, such as costs of fertilizers, pesticides, labor, irrigation, and other inputs directly related to production. This calculation was used to compare the economic performance of different treatments and identify the most profitable management practices. For economic analysis, lettuce market prices were based on actual wholesale or local sales prices recorded at each harvest, and input costs for mycorrhizal products and farmer practices were obtained from real purchase invoices, ensuring realistic and reliable evaluation of gross margins.

Gross revenue (GR) (expressed in currency per unit area) was calculated by multiplying the yield (kg per unit area) by the market price of the product (currency per kg): GR = Yield (kg area−1) × Product Price (currency/kg). The gross margin was calculated using the following formula: GM = GR − VC [22].

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the MSS statistical software (data file: CRNMRL25). The experimental design was a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with one factor (treatment) and four replications. Differences among treatments were tested at the 0.05 level of significance using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test to separate treatment means. All measurements were conducted in four replicates per treatment. The experimental model applied was “Model 7: One Factor Randomized Complete Block Design”, and the analysis included 24 data points across six treatments and four replications.

Only one lettuce cultivar, ‘Cosprina’, was used in this study, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other varieties. Cosprina was selected due to its widespread cultivation and consumer preference in the region, reflecting both market demand and typical consumption habits. The soil used in this experiment exhibited unusually high lime content (43.24%) and electrical conductivity (13.29 dS m−1), which are higher than typical greenhouse soils. These conditions may have influenced lettuce growth and the plant’s response to fertilizers and biostimulants, as high lime can affect nutrient availability and high salinity can impose osmotic stress. Therefore, the observed effects of mycorrhizal fungi and organic biostimulants should be interpreted within this specific soil and varietal context. Despite these challenging conditions, the treatments enhanced plant growth, vitamin C content, and economic returns, highlighting the potential of integrated biostimulant management even under stress-prone environments.

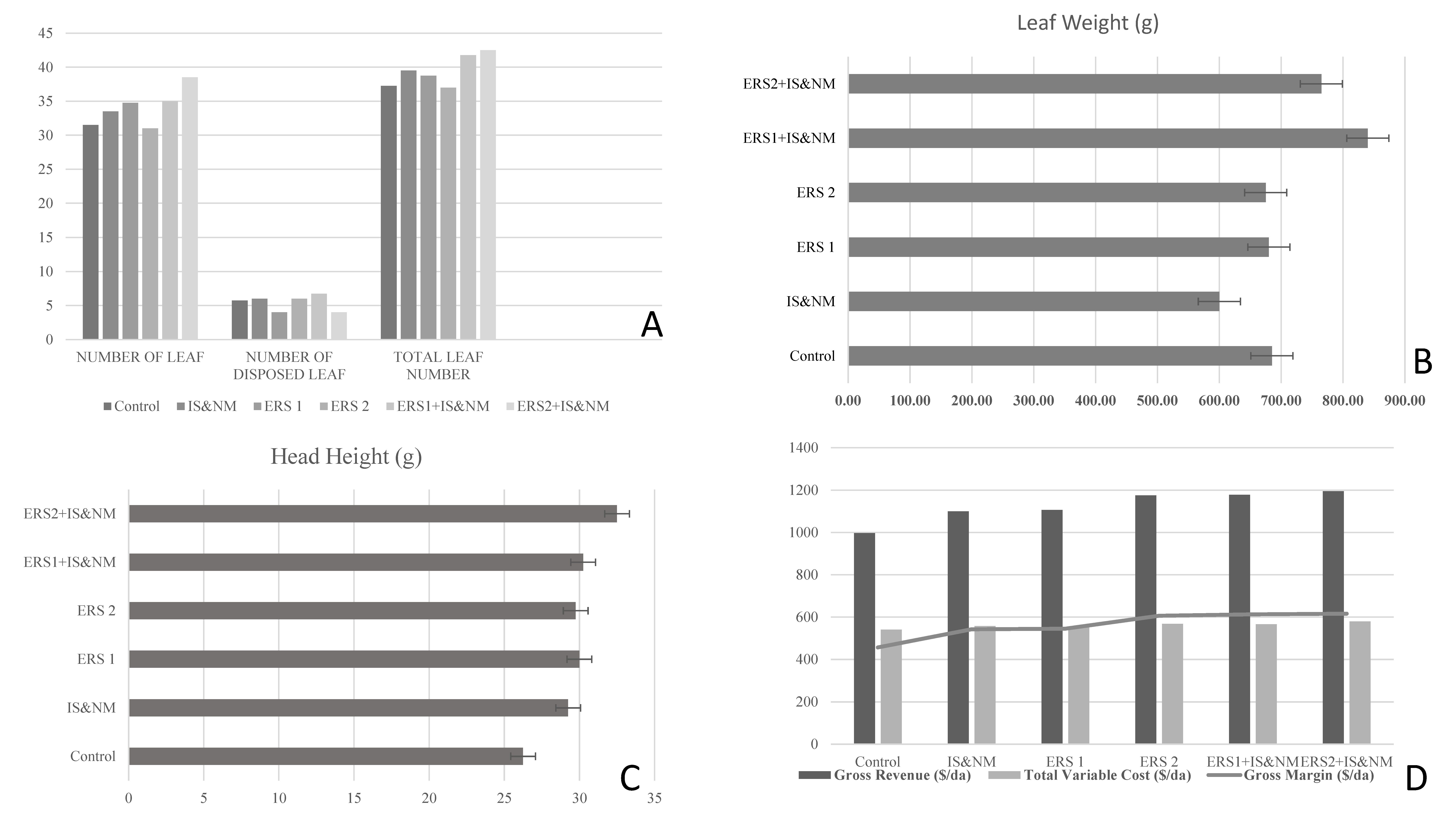

The experimental results demonstrated that mycorrhizal and organic fertilizer treatments significantly influenced various morphological, physiological, and nutritional traits of lettuce grown under semi-arid greenhouse conditions, although not all parameters responded significantly to the applications (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Among the morphological traits, head height showed a statistically significant increase (p ≤ 0.01) with the ERS2+IS&NM treatment producing the tallest plants (32.50 cm), followed by ERS1+IS&NM (30.25 cm) and ERS1 (30.00 cm), whereas the control had the lowest height (26.25 cm). This increase in plant height may be attributed to improved nutrient and water uptake. Other morphological parameters such as head diameter, leaf width and length, total leaf number, root length, and stem diameter did not differ significantly, although numerical differences were observed. Notably, the number of disposed leaves was significantly lower (p ≤ 0.05) in combined treatments (ERS+IS&NM) compared to single treatments and control. Chlorophyll content, as indicated by SPAD values (ranging from 41.13 to 48.88), and total soluble solids (TSS) showed no significant differences among treatments. However, significant changes were detected in leaf color parameters, especially the a* (red-green) and hue angle (h°), with ERS2+IS&NM increasing red pigmentation significantly (p ≤ 0.05). Vitamin C content varied significantly among treatments (p ≤ 0.01), with ERS2+IS&NM yielding the highest concentration (28.63 mg 100 g−1 FW), followed by ERS1+IS&NM (26.50 mg/100 g FW), while the control had the lowest value (16.29 mg 100 g−1 FW). Leaf phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations were significantly affected by treatments (p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively), with the highest levels found in ERS2+IS&NM. Although fresh biomass and yield values improved with all fertilization strategies compared to control, only leaf weight showed a statistically significant increase (p ≤ 0.05), with ERS1+IS&NM producing the highest leaf weight (840 g/plant). Marketable yield was numerically higher in mycorrhizal treatments (up to 35 tones ha−1) compared to the control (29.2 tones ha−1), although these differences were not statistically significant. Economic analysis revealed significant differences in gross margin among treatments (p ≤ 0.0063), with ERS2, ERS1+IS&NM, and ERS2+IS&NM achieving the highest gross margins (~6.07–6.16 $ da−1), significantly higher than the control and other single treatments (Fig. 2). These results highlight the positive effects of integrated mycorrhizal and organic nutrient management on lettuce growth and economic returns under semi-arid greenhouse conditions.

Table 2: Morphological parameters of lettuce under different treatments.

| Parameters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head Height (cm) | Head Diameter (cm) | Leaf Width (cm) | Leaf Length (cm) | Number of Leaf | Number of Disposed Leaf | Total Number of Leaf | Root Length (cm) | Stem Diameter (mm) | ||

| Applications | 1 | 26.25c | 29.00 | 13.13 | 24.00 | 31.50 | 5.75ab | 37.25 | 13.50 | 31.81 |

| 2 | 29.25b | 30.25 | 14.63 | 26.00 | 33.50 | 6.00a | 39.50 | 13.75 | 30.38 | |

| 3 | 30.00ab | 30.50 | 13.50 | 25.75 | 34.75 | 4.00b | 38.75 | 13.75 | 31.88 | |

| 4 | 29.75ab | 32.50 | 13.75 | 27.25 | 31.00 | 6.00a | 37.00 | 17.25 | 29.02 | |

| 5 | 30.25ab | 29.25 | 13.38 | 26.25 | 35.00 | 6.75a | 41.75 | 15.75 | 31.03 | |

| 6 | 32.50a | 30.50 | 14.75 | 26.03 | 38.50 | 4.00b | 41.42 | 15.75 | 30.48 | |

| 0.0084** | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.0381* | NS | NS | NS | ||

Table 3: Colorimetric and quality parameters of lettuce leaves under different Treatments.

| Parameters | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | a | b | H° | Choroma | TSS | Vitamin C (mg 100 g−1 FW) | SPAD | % N | % P | ||

| Applications | 1 | 36.97 | −10.30ab | 26.47a | 111.36cd | 28.41a | 1.98 | 16.29f | 41.13 | 4.08a | 40.55 |

| 2 | 34.58 | −9.44bc | 25.63a | 110.15d | 27.32a | 2.60 | 16.89e | 43.15 | 4.05a | 46.25 | |

| 3 | 42.86 | −7.68c | 17.93b | 113.32ab | 19.51b | 2.53 | 18.05d | 45.58 | 3.95a | 55.25 | |

| 4 | 36.93 | −9.26bc | 22.75ab | 112.24bc | 24.57ab | 2.98 | 20.85c | 48.10 | 3.75b | 63.25 | |

| 5 | 43.80 | −10.83ab | 24.60a | 113.78ab | 26.88a | 3.13 | 26.50b | 44.55 | 3.45c | 74.75 | |

| 6 | 40.99 | −11.99a | 26.27a | 114.56a | 28.88a | 3.10 | 28.63a | 48.88 | 3.58c | 88.75 | |

| NS | 0.0084** | 0.0361* | 0.0009** | 0.0329* | NS | 0.0000** | NS | 0.0000** | NS | ||

Table 4: Yield and economic analysis of lettuce under different treatments.

| Parameters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf Weight (g) | Dry Leaf Weight (g) | Root Weight (g) | Dry Root Weight (g) | Head Weight (g) | Yield Tones ha−1 | Gross Revenue ($ da−1) | Total Variable Cost ($ da−1) | Gross Margin ($ da−1) | ||

| Applications | 1 | 685.00bc | 44.98 | 64.68 | 35.63 | 730.00 | 29.2 | 9.973 | 5.407 | 4.566b |

| 2 | 600.00c | 53.79 | 78.35 | 40.89 | 800.00 | 32.0 | 10.997 | 5.577 | 5.421b | |

| 3 | 680.00bc | 55.13 | 81.78 | 39.09 | 805.00 | 32.2 | 11.063 | 5.544 | 5.454b | |

| 4 | 675.00bc | 53.05 | 71.76 | 29.88 | 860.00 | 34.4 | 11.749 | 5.680 | 6.068a | |

| 5 | 840.00a | 46.50 | 66.32 | 33.38 | 862.50 | 34.5 | 11.783 | 5.656 | 6.127a | |

| 6 | 765.00ab | 53.05 | 76.02 | 41.42 | 875.00 | 35.0 | 11.954 | 5.793 | 6.161a | |

| 0.0407* | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.0063 | ||||

Figure 2: (A) Effects of Treatments on Leaf Parameters of Lettuce; (B) Effects of Treatments on Leaf Weight (g) of Lettuce; (C) Effects of Treatments Head Height (cm) of Lettuce; (D) Effects of Treatments on Gross Margin ($ da−1).

The application of mycorrhizal fertilizer combined with other fertilization strategies significantly improved selected morphological, physiological, and nutritional parameters of lettuce grown under semi-arid greenhouse conditions [23]. The observed reduction in leaf senescence may be attributed to enhanced plant vigor resulting from the applied fertilizers and organic nutrients [8]. Among all measured traits, plant height exhibited a statistically significant increase in treatments integrating mycorrhizal fungi with organic inputs, with the tallest plants recorded in the ERS2+IS&NM group (32.5 cm), demonstrating a synergistic effect of these treatments. This aligns with findings by [24], who reported that biostimulants promote shoot elongation through increased nutrient uptake and hormone-like activity. Similarly, Ref. [25] documented significantly higher biomass and yield in lettuce grown in vertical farming systems compared to conventional soil-based cultivation. Although vertical farming was not employed in this study, yield levels up to 3.5 t ha−1 under organic-biological input regimes suggest that conventional systems supplemented with mycorrhizal fertilizers and biostimulants can compete with more advanced technologies. Further supporting this, Ref. [26] observed significant differences in vegetative growth traits among lettuce cultivars during autumn cultivation, highlighting the positive role of mycorrhizal and organic fertilization. Despite varietal influences on growth, biofertilizer integration remains an effective approach to enhance off-season production.

While other morphological parameters such as leaf width, head diameter, and stem diameter did not differ significantly, numerical increases were observed in most mycorrhizal treatments. This selective enhancement of vertical growth over radial growth may result from improved water and nutrient uptake, consistent with [8], who demonstrated that organic amendments promote root-shoot development in leafy vegetables. Ref. [27] reported that humic acid applications (500–2000 ppm) significantly increased lettuce plant height, fresh and dry weight, root collar diameter, and leaf number under greenhouse conditions. These findings parallel our observations, where ERS2+IS&NM treatments enhanced plant height, root length, and vitamin C content. Kibar’s study found optimal effects at 500 ppm humic acid, indicating that moderate doses can substantially improve morpho-physiological traits. These results support integrating humic substances with mycorrhizal and organic inputs to maximize agronomic and quality outcomes in resource-limited greenhouse environments.

In related research, Ref. [28] showed that boron fertilizer slightly increased root length and yield in curly lettuce but reduced leaf number, while humic acid improved leaf length and overall growth but reduced root length. These findings partially align with our study, where the combined mycorrhizal and organic fertilizer application (ERS2+IS&NM) enhanced plant height, root length, and vitamin C content, though yield improvements were not statistically significant. Several studies on curly lettuce have reported considerable variation in vitamin C content depending on cultivation methods and environmental conditions. For example, Ref. [29] found vitamin C levels between 19.30 and 22.39 mg 100 g−1 FW fresh weight in soilless culture, while Ref. [25] reported values ranging narrowly between 22.82 and 22.87 mg 100 g−1 FW. Another study [30] observed a wider range from 6.08 to 29.13 mg 100 g−1 FW, and [31] found vitamin C levels of 11.15 to 11.57 mg 100 g−1 FW following oxalic acid treatments. These variations indicate that vitamin C content in lettuce is highly influenced by input type, cultivation method, and environmental stress. Therefore, integrating mycorrhizal fertilizers with organic amendments appears promising for enhancing plant health and nutritional quality in protected cultivation, consistent with previous reports demonstrating the positive effect of organic fertilization on vitamin C content in leafy vegetables [32,33].

Regarding leaf color, Chroma (C*) and b* values did not differ significantly, indicating stable lightness and yellowness across treatments. However, variations in a* (red-green axis) and hue angle (H°) were significant; ERS2+IS&NM treatment showed increased red pigmentation, suggesting elevated anthocyanin and antioxidant levels, which can improve both visual appeal and market value. This aligns with [25], who documented enhanced chlorophyll content and total antioxidant capacity in tower-grown lettuce, supporting the notion that optimized growth conditions can boost pigment development and antioxidant profiles in leafy vegetables.

Total soluble solids (TSS) levels were consistent among treatments, corroborating findings by [34,35], who reported no significant differences in TSS across organic, conventional, or hydroponic cultivation methods. Thus, under semi-arid greenhouse conditions, fertilization strategies did not significantly affect lettuce leaf soluble solids concentration.

Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations were significantly higher in the ERS2+IS&NM treatment, indicating improved nutrient acquisition. These results corroborate earlier studies demonstrating arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi mediated phosphorus uptake [36] and align with [25], who observed enhanced nutrient accumulation in advanced production systems. Such findings confirm the beneficial role of mycorrhizal fungi in nutrient uptake enhancement.

Although total yield differences were not statistically significant, ERS1+IS&NM treatment produced the highest leaf weight (840 g/plant), an important factor for marketable yield. This concurs with [37], who emphasized the impact of substrate and nutrient solution interactions on yield performance, reinforcing that biological inputs provide a viable alternative in conventional soil-based systems, especially where vertical farming is not economically feasible.

Economic analysis revealed the highest gross margins in ERS2+IS&NM and ERS1+IS&NM treatments, reflecting strong economic performance. While vertical farming may offer yield and quality advantages [25], its high-cost limits accessibility for many growers. Thus, integrating mycorrhizal fertilizer into low-technology greenhouses represents a practical strategy to improve economic returns under semi-arid conditions. These findings underscore the potential for increased marketable biomass through integrated fertilization [38].

Biostimulants enhance vegetable productivity by improving photosynthesis, activating antioxidant defenses, mimicking auxin activity, and promoting nutrient uptake [39]. In this study, mycorrhizal fungi and organic nutrients significantly improved lettuce growth and vitamin C content under stress-prone semi-arid greenhouse conditions. These results highlight the necessity of site-specific evaluation of biostimulants, taking into account crop type, soil conditions, and microbial populations. The observed increase in vitamin C content in mycorrhizal treatments can be attributed to several physiological mechanisms [40]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi enhance nutrient uptake, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, which in turn supports photosynthesis and carbon metabolism, leading to higher vitamin C synthesis. Additionally, mycorrhizal colonization improves plant stress tolerance and stimulates antioxidant metabolism, further contributing to elevated vitamin C levels [41]. These effects may also be mediated by hormonal regulation and enhanced enzymatic antioxidant activity, as reported in recent studies [42].

In summary, the combination of mycorrhizal fungi with organic nutrients and biostimulants substantially improved morphological traits, vitamin C content, nutrient uptake, and economic outcomes. These findings align with previous literature and provide valuable insights for sustainable vegetable production in Southeastern Türkiye. Future research should investigate long-term soil health effects and the molecular mechanisms underlying these improvements.

This study demonstrated that the combined application of mycorrhizal fertilizer and a locally developed organic nutrient regimen significantly enhanced the growth performance and vitamin C content of lettuce under semi-arid greenhouse conditions. These treatments resulted in taller plants with improved leaf nutrient status, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, highlighting the efficacy of natural biofertilizers in promoting plant health. Moreover, economic analysis confirmed the potential for increased profitability with integrated fertilization approaches. These strategies could be scaled up for commercial semi-arid greenhouse production in Türkiye, potentially reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers and contributing to environmentally sustainable vegetable cultivation. Future research should aim to optimize biofertilizer application protocols tailored to diverse soil types and climatic conditions, explore underlying molecular mechanisms, and conduct multi-season validations to further advance sustainable vegetable production.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Original data will be made available by the author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ermiş S. Varieties and characteristics of lettuce/salad (Lactuca sativa L.) recorded in Türkiye. In: Proceedings of the Balkan Agricultural Congress; 2022 Aug 31–Sep 2; Edirne, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

2. Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu (TÜİK). Bitkisel Üretim İstatistikleri. Ankara, Türkiye: Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu; 2023. [Google Scholar]

3. Clément J, Delisle-Houde M, Nguyen TTA, Dorais M, Tweddell RJ. Effect of biostimulants on leafy vegetables (baby leaf lettuce and Batavia lettuce) exposed to abiotic or biotic stress under two different growing systems. Agronomy. 2023;13(3):879. doi:10.3390/agronomy13030879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Engindeniz S, Tuzel Y. Economic analysis of organic greenhouse lettuce production in Turkey. Sci Agric. 2006;63(3):285–90. doi:10.1590/s0103-90162006000300012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tüzel Y, Öztekin GB. Recent developments of vegetables protected cultivation in Turkey. In: VI Balkan Symposium on Vegetables and Potatoes; 2014 Sep 29–Oct 2; Zagreb, Croatia. Leuven, Belgium: ISHS; 2014. p. 435–42. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2016.1142.66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mysore S. Transforming horticulture for sustainable development: research and policy options. Indian J Agric Econ. 2025;80(1):38–58. doi:10.63040/25827510.2025.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tonini P. Mitigating food loss and waste in the vegetable sector: exploring the feasibility and prospects of locally implemented strategies 2024. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10803/691688. [Google Scholar]

8. Siankwilimba E, Hiddlestone-Mumford J, Hoque ME, Hang’ombe BM, Mumba C, Hasimuna OJ, et al. Effects of systemic challenges on agricultural development systems: a systematic review of perspectives. Cogent Food Agric. 2025;11(1):2480266. doi:10.1080/23311932.2025.2480266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Boorboori MR, Lackóová L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and salinity stress mitigation in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2025;15:1504970. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1504970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Durak A, Altuntaş Ö, Kutsal İK, Işık R, Karaat FE. The effects of vermicompost on yield and some growth parameters of lettuce. Turk JAF Sci Tech. 2017;5(12):1566–70. doi:10.24925/turjaf.v5i12.1566-1570.1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Colla G, Rouphael Y. Biostimulants in horticulture. Sci Hortic. 2015;196:1–2. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.10.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Abd-Elrahman SH, Saudy HS, El-Fattah DAA, Hashem FA. Effect of irrigation water and organic fertilizer on reducing nitrate accumulation and boosting lettuce productivity. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22(2):2144–55. doi:10.1007/s42729-022-00799-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Oyege I, Balaji Bhaskar MS. Effects of vermicompost on soil and plant health and promoting sustainable agriculture. Soil Syst. 2023;7(4):101. doi:10.3390/soilsystems7040101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. FAO. The state of food and agriculture—making agrifood systems more resilient to shocks and stresses. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2021. doi:10.4060/cb4476en. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kheyrodin H. Plant and soil relationship between fungi. Int J Res Stud Biosci. 2014;2(9):42–9. [Google Scholar]

16. Demir H, Sönmez İ, Uçan U, Akgün İH. Biofertilizers improve the plant growth, yield, and mineral concentration of lettuce and broccoli. Agronomy. 2023;13(8):2031. doi:10.3390/agronomy13082031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dasgan HY, Yilmaz D, Zikaria K, Ikiz B, Gruda NS. Enhancing the yield, quality and antioxidant content of lettuce through innovative and eco-friendly biofertilizer practices in hydroponics. Horticulturae. 2023;9(12):1274. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9121274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. FAO. The state of the world’s biodiversity for food and agriculture. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

19. Jackson ML. Soil chemical analysis: advanced course; a manual of methods useful for instruction and research in soil chemistry, physical chemistry of soils, soil fertility, and soil genesis. Madison, WI, USA: UW-Madison Libraries Parallel Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

20. Murphy J, Riley JP. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal Chim Acta. 1962;27:31–6. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. McGuire RG. Reporting of objective color measurements. HortScience. 1992;27(12):1254–5. doi:10.21273/hortsci.27.12.1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kay RD, Edwards WM. Farm management. 4th ed. Boston, MA, USA: McGraw Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

23. Abdelkader M, Suliman AA, Salem SS, Assiya A, Voronina L, Puchkov M, et al. Studying the combined impact of salinity and drought stress-simulated conditions on physio-biochemical characteristics of lettuce plant. Horticulturae. 2024;10(11):1186. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10111186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zrig A, Alsherif EA, Aloufi AS, Korany SM, Selim S, Almuhayawi MS, et al. The biomass and health-enhancing qualities of lettuce are amplified through the inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. BMC Plant Biol. 2025;25(1):521. doi:10.1186/s12870-025-06317-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Demirel M, Aktaş H. Dikey tarım (Kule) sisteminde ve toprak koşullarında yetiştirilen kıvırcık salata (Lactuca sativa var. crisp a) türünün verim ve kalite bakımından karşılaştırılması. Ziraat Fak Derg. 2023;18(2):123–33. doi:10.54975/isubuzfd.1366809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Şahin GT, Kandemir D, Balkaya A, Karaağaç O, Sarıbaş Ş. Sonbahar dönemi yetiştiriciliğinde kıvırcık (Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa) ve yedikule (Lactuca sativa L. var. longifolia) tipi marul çeşitlerinin vejetatif büyüme düzeylerinin incelenmesi. Bahçe. 2022;51(1):1–10. doi:10.53471/bahce.1067643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kibar B. Effects of humic acid applications at different doses on plant growth and quality in green onion and lettuce. Int J Agric Wildl Sci. 2022;8(1):12–24. doi:10.24180/ijaws.1020237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kurt Ö, Uğur A. Effect of boron fertilizer and humic acid applications on some plant characteristics of curly lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa). Turk J Agric Eng Res. 2022;3(1):1–14. doi:10.46592/turkager.998431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Çakmak P. Farklı dikim zamanları ve organik gübrelerin topraksız tarım koşullarında kıvırcık yapraklı salata (Lactuca sativa var. crispa) yetiştiriciliğinde verim ve kalite özelliklerine etkisi [master’s thesis]. Tokat, Türkiye: Gaziosmanpaşa Üniversitesi; 2011. 55 p. [Google Scholar]

30. Yildirim E, Kul R, Turan M, Ekinci M, Alak G, Atamanalp M. Effect of nitrogen and fish manure fertilization on growth and chemical composition of lettuce. AIP Conf Proc. 2016;1726:020021. doi:10.1063/1.4945847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sonkaya B. Oksalik asit uygulamalarının marulda verim ve kalite üzerine etkileri [master’s thesis]. Isparta, Türkiye: Isparta Uygulamalı Bilimler Üniversitesi; 2022. [Google Scholar]

32. Citak S, Sonmez S. Effects of conventional and organic fertilization on spinach (Spinacea oleracea L.) growth, yield, vitamin C and nitrate concentration during two successive seasons. Sci Hortic. 2010;126(4):415–20. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2010.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Verruma-Bernardi MR, Pimenta DM, Levrero GR, Forti VA, de Medeiros SD, Ceccato-Antonini SR, et al. Yield and quality of curly kale grown using organic fertilizers. Hortic Bras. 2021;39(1):112–21. doi:10.1590/s0102-0536-20210116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. da Silva EMN, Ferreira RLF, de Araújo Neto SE, Tavella LB, Solino AJ. Qualidade de alface crespa cultivada em sistema orgânico, convencional e hidropônico. Hortic Bras. 2011;29(2):242–5. doi:10.1590/s0102-05362011000200019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Fontana L, Rossi CA, Hubinger SZ, Ferreira MD, Spoto MHF, Sala FC, et al. Physicochemical characterization and sensory evaluation of lettuce cultivated in three growing systems. Hortic Bras. 2018;36(1):20–6. doi:10.1590/s0102-053620180104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jansa J, Mozafar A, Kuhn G, Anken T, Ruh R, Sanders IR, et al. Soil tillage affects the community structure of mycorrhizal fungi in maize roots. Ecol Appl. 2003;13(4):1164–76. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2003)13[1164:STATCS]2.0.CO;2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kowalska B, Szczech M. Differences in microbiological quality of leafy green vegetables. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2022;29(2):238–45. doi:10.26444/aaem/149963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Barickman TC, Sublett WL, Miles C, Crow D, Scheenstra E. Lettuce biomass accumulation and phytonutrient concentrations are influenced by genotype, N application rate and location. Horticulturae. 2018;4(3):12. doi:10.3390/horticulturae4030012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Şensoy S. The role of biostimulants in enhancing yield, quality, and stress tolerance in sustainable vegetable production. In: Innovations in sustainable agriculture and aquatic sciences. Ankara, Türkiye: Akademisyen Kitabevi; 2024. p. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

40. Boutasknit A, Ait-El-Mokhtar M, Fassih B, Ben-Laouane R, Wahbi S, Meddich A. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rock phosphate on growth, physiology, and biochemistry of carob under water stress and after rehydration in vermicompost-amended soil. Metabolites. 2024;14(4):202. doi:10.3390/metabo14040202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shalaby OA, Ramadan ME. Mycorrhizal colonization and calcium spraying modulate physiological and antioxidant responses to improve pepper growth and yield under salinity stress. Rhizosphere. 2024;29:100852. doi:10.1016/j.rhisph.2024.100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Baslam M, Garmendia I, Goicoechea N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) improved growth and nutritional quality of greenhouse-grown lettuce. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(10):5504–15. doi:10.1021/jf200501c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools