Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Synergistic Regulation of Light Intensity and Calcium Nutrition in PFAL-Grown Lettuce by Optimizing Morphogenesis and Nutrient Homeostasis

1 College of Agricultural Engineering, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, 212013, China

2 College of Resources and Environmental Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 100083, China

* Corresponding Author: Jinxiu Song. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Plant Nutrition-Mechanisms, Regulation, and Sustainable Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3611-3632. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070680

Received 21 July 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

In plant factory with artificial lighting, precise regulation of environmental and nutritional factors is essential to optimize both growth and quality of leafy vegetables. This study systematically evaluated the combined effects of light intensity (150, 200, 250 μmol/(m2·s)) and calcium supply in the nutrient solution (0.5, 1.0, 1.5 mmol/L) on lettuce morphology, photosynthesis, quality indices, and tipburn incidence. Elevating light from 150 to 200 μmol/(m2·s) significantly enhanced leaf number, area, photosynthetic rate, biomass, and foliar calcium. These gains plateaued at 250 μmol/(m2·s), where tipburn incidence surged to 76.5%. Photosynthetic pigments progressively rose with light intensity. Calcium supply showed limited morphological influence but proved critical under high light (250 μmol/(m2·s)): increasing calcium to 1.5 mmol/L significantly boosted vitamin C and soluble sugars while reducing nitrate accumulation and suppressing tipburn to 12.8%. Elevated calcium also partially compensated for growth and quality limitations under low light through compensatory effects. Results demonstrated light intensity as the dominant factor governing morphogenesis and photosynthetic capacity, these findings establish that coordinated optimization of light and calcium inputs is crucial for simultaneously improving lettuce yield, nutritional quality, and marketability in controlled environments. This study provides both theoretical insights and practical guidance for efficient and safe leafy vegetable cultivation in controlled environments.Keywords

As an advanced and highly intensive production system in protected agriculture, the plant factories with artificial lighting (PFALs) have become an important solution for achieving stable, high-yield crop production and consistent quality through precise environmental control [1,2]. Among the key environmental factors, light management plays a critical role. In PFALs, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) have emerged as the dominant artificial lighting source for both seedling propagation and leafy vegetable cultivation, due to their high energy efficiency, tunable spectral properties, and low thermal output [3,4]. Nevertheless, artificial lighting accounts for approximately 60%–80% of the total energy consumption in PFALs, representing a major barrier to their widespread adoption and commercial scalability [5]. Several studies have shown that increasing the daily light integral (DLI)—the cumulative product of light intensity and photoperiod—from 10.80 mol/(m2·d) to 12.96 mol/(m2·d) significantly boosts the biomass accumulation of tomato seedlings, while reducing the electric energy consumed per unit of dry mass [6]. However, higher DLI levels also elevate the internal thermal load, which in turn reduces the system’s overall energy use efficiency due to increased cooling demands [7]. These findings underscore the dual challenge faced by PFALs: optimizing light parameters to improve productivity and crop quality, while simultaneously minimizing energy inputs. As such, the development of energy-efficient lighting strategies and environment-responsive light control systems has become a central focus in recent research on PFAL sustainability and performance enhancement [8].

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is among the most widely cultivated leafy vegetables in PFALs, owing to its short growth cycle, high nutritional value, and strong responsiveness to environmental cues [9]. Numerous studies have confirmed that light intensity is a key factor affecting lettuce growth, morphogenesis, and quality formation in controlled environments [10]. When the photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) is maintained within the range of 200–250 μmol/(m2·s), both photosynthetic rate and chlorophyll content in lettuce leaves are significantly improved, contributing to enhanced dry matter accumulation [11]. However, exposure to light levels exceeding the photoinhibition threshold can induce photoinhibition and lead to growth stagnation [12]. Moderate optimization of the light environment has thus been demonstrated to effectively enhance lettuce productivity in PFALs [13]. Nevertheless, accelerated growth induced by high light intensity may also increase the incidence of physiological disorders such as tipburn, particularly during the later stages of development [14]. These findings underscore the necessity of precise light management strategies in PFALs to balance growth promotion and quality maintenance in lettuce production.

Tipburn in lettuce is a common physiological disorder, primarily manifested as chlorosis of emerging leaves, wrinkling along leaf margins, and browning at the tips, which may progress to tissue necrosis and eventual decay under severe conditions [15]. The primary cause of tipburn is the mismatch between the rapid growth of young leaf tissues and the insufficient calcium supply to meet their elevated demand [16]. This imbalance disrupts the formation of the cell wall and middle lamella in expanding cells, resulting in weakened tissue structure [17]. Moreover, calcium serves as a crucial secondary messenger in cellular signaling and is essential for proper chromosome segregation during mitosis. Calcium deficiency can impair this process, leading to mitotic abnormalities and reduced cell proliferation in developing tissues [18]. In parallel, inadequate calcium supply can exacerbate membrane lipid peroxidation, evidenced by elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) accumulation, which compromises cell membrane integrity and contributes to the characteristic browning and desiccation symptoms associated with tipburn [19].

In recent years, the incidence of tipburn in leafy vegetables grown in plant factories has markedly increased, often exceeding that observed under open-field or greenhouse conditions. To better understand the etiology of tipburn in lettuce cultivated under fully enclosed artificial lighting systems, extensive studies have been conducted both domestically and internationally, focusing on factors such as cultivar susceptibility [20,21], mineral nutrition [22,23], airflow dynamics [24,25], and foliar fertilization [26,27]. While multiple environmental and physiological factors contribute to tipburn in plant factories, the primary cause is widely attributed to accelerated shoot growth that results in internal calcium deficiency [28]. Enhancing calcium accumulation in leaf tissue is therefore critical for mitigating tipburn in leafy vegetable production. It is generally accepted that increasing transpiration can alleviate calcium deficiency-related disorders, and strategies such as reducing relative humidity (increasing vapor pressure deficit, VPD) [29], enhancing air circulation [30], and moderating growth rate [31] have been proposed. However, these approaches are often constrained in plant factory environments due to inherently high humidity, low air velocity (typically <0.5 m/s), and rapid plant growth rates [32], all of which suppress transpiration and limit calcium transport. Consequently, solely relying on increased transpiration is insufficient to prevent tipburn under these conditions.

Previous research has demonstrated that moderate increases in light intensity can significantly promote biomass accumulation in lettuce [33,34], but may also exacerbate calcium depletion in leaf tissue [35]. In contrast, increasing calcium concentrations in the nutrient solution offers a more direct and effective approach to enhance calcium uptake. Elevated calcium content not only reduce tipburn incidence but also improve lettuce quality by increasing vitamin C and soluble protein content [36]. Nutrient solution regulation has become a preferred strategy for tipburn mitigation due to its controllability and cost-effectiveness [37]. Nevertheless, limited research has addressed the interactive effects of light intensity and calcium supply on biomass production and tipburn control in plant factories. Therefore, the present study investigates the interactive effects of light intensity and calcium supply in nutrient solution, aiming to balance the trade-off between yield and quality in lettuce cultivation. This research seeks to identify optimal light-calcium combinations that promote biomass production while concurrently mitigating the risk of tipburn under high-light conditions, thereby providing a scientific basis for the efficient and high-quality production of lettuce in plant factories with artificial lighting.

The lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivar used in this study was ‘U.S. Great Rapid’, provided by the Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The experiment was conducted from March to May 2024 in a plant factory equipped with artificial lighting, located at the Key Laboratory of Modern Agricultural Equipment and Technology, Ministry of Education, Jiangsu University.

Prior to sowing, seeds underwent warm water treatment and pre-germination, and were then sown in 72-cell plug trays filled with a substrate composed of peat, vermiculite, and perlite in a volumetric ratio of 3:1:1. Seedlings were grown under controlled environmental conditions: daytime/nighttime temperatures of (22 ± 1)°C/(18 ± 1)°C, relative humidity of (70 ± 5)%/(60 ± 5)%, and a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 200 μmol/(m2·s). The photoperiod was maintained at 12 h per day (08:00–20:00), with illumination provided by LED fixtures (WR-LED-T5-16W, Beijing Shengyanggu Technology Co., Beijing, China) emitting a red-to-blue light ratio (R:B) of 1.2 and a photosynthetic photon efficacy of 2.8 μmol/(s·W). During the light period, the CO2 concentration inside the PFAL was maintained at 500 μmol/mol by supplying CO2 from a liquid CO2 cylinder equipped with a feedback control valve. During the dark period, no supplemental CO2 was supplied, as plant respiration typically caused the CO2 concentration to remain at or even exceed 500 μmol/mol.

Five days after sowing, seedlings were irrigated with a half-strength Yamazaki nutrient solution (Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 236 mg/L; KNO3, 404 mg/L; MgSO4·7H2O, 123 mg/L; NH4H2PO4, 57 mg/L; Na2Fe-EDTA, 15.38 mg/L; H3BO3, 1.127 mg/L; MnSO4·H2O, 0.615 mg/L; ZnSO4·5H2O, 0.088 mg/L; CuSO4·5H2O, 0.039 mg/L; (NH4)6Mo7O2·4H2O, 0.013 mg/L). From the seventh day after sowing onward, a full-strength nutrient solution of the same formulation was applied.

Once the lettuce seedlings had developed four true leaves, uniformly vigorous individuals were selected for transplantation. After gently removing the root substrate and rinsing the roots with water, the seedlings were transplanted into plastic pots (15 cm in diameter, 14 cm in height) filled with a mixed growing medium composed of peat, vermiculite, and perlite in a volumetric ratio of 3:1:1. Each treatment comprised no fewer than 18 plants. During the vegetative growth stage of lettuce, the environmental conditions—including temperature, relative humidity, CO2 concentration, and nutrient solution composition—were kept consistent with those applied during the seedling stage. At this stage, the leaf-level VPD in plant factory with artificial lighting was maintained at 1.06 kPa during the daytime and 0.62 kPa at night, aligning well with the optimal VPD range for commercial lettuce production [38].

During the cultivation period, light cycles were regulated using an automated timer set to maintain a photoperiod of 12 h per day (08:00–20:00). Illumination was provided by LED light sources with a R:B of 1.2, and light intensity were set to 150, 200, and 250 μmol/(m2·s) (named P1, P2 and P3). The nutrient solution was formulated to adjust Ca2+ concentration to 0.5× (C1), 1.0× (C2, standard), and 1.5× (C3) of the standard level, while maintaining the concentrations of other essential ions unchanged. In the C1 treatment, halving Ca(NO3)2 reduced both Ca2+ and NO3−; therefore, the missing NO3− was compensated by adding NaNO3. In the C3 treatment, additional Ca2+ was provided as CaCl2, so that nitrate concentration remained identical to that of C2. As a result, differences among treatments mainly reflect Ca2+ availability. The use of Na+ and Cl− as balancing ions did not substantially affect lettuce growth, as supported by previous studies, and the EC values among the three nutrient solutions remained similar. A full-factorial experimental design was implemented, comprising two factors—light intensity and calcium supply in nutrient solution—each with three levels, resulting in a total of nine treatment combinations.

2.3.1 Measurement of Morphological Growth

At 28 days after transplanting, eight lettuce plants were randomly selected from each treatment to evaluate morphological growth parameters. The leaf number was recorded as the total count of fully expanded leaves per plant. Leaf length and width were measured using a ruler, corresponding to the longest and widest dimensions of the largest leaf, respectively. Total leaf area was determined by scanning all leaves using a flatbed scanner (LiDE-110, Canon, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam), and the scanned images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop to calculate the cumulative leaf area per plant. The methodology for leaf area determination was based on the protocol described by Song et al. [39].

2.3.2 Measurement of Photosynthetic Characteristics

Six leaves were randomly collected from the same relative position on different lettuce plants within each treatment to determine pigment concentrations. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents were measured using the 80% acetone extraction method. Total chlorophyll content and the chlorophyll a/b ratio were subsequently calculated following the protocol described by Ali Lakhiar et al. [40].

In addition, eight lettuce plants were randomly selected from each treatment to assess photosynthetic parameters. A portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400XT, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) equipped with a 6400-02B standard light source leaf chamber (2 × 3 cm2) was used to measure the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and transpiration rate of the largest fully expanded leaf between 09:00 and 11:00. Measurement procedures were conducted in accordance with the method described by Hussain Tunio et al. [41]. The conditions inside the leaf chamber were maintained as follows: photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 200 μmol/(m2·s), reference CO2 concentration of 500 μmol/mol, airflow rate of 500 μmol/s, and a leaf chamber temperature of 20°C.

2.3.3 Measurement of Biomass Accumulation

Six intact lettuce plants were randomly selected from each treatment for biomass analysis. The shoots and roots of each plant were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water, and residual surface moisture was gently blotted using absorbent paper. Fresh weights of the aboveground and belowground parts were then measured separately using an electronic balance (ME204E, Mettler Toledo Technology Co., Ltd., Greifensee, Switzerland). Subsequently, the shoot and root tissues were placed in separate kraft paper envelopes and subjected to an initial drying at 105°C for 2 h to inactivate enzymatic activity. This was followed by oven-drying at 85°C until a constant weight was reached. After cooling to room temperature in a desiccator, the dry weights of the shoot and root were determined using the same electronic balance. Total fresh weight, total dry weight, and root to shoot ratio were calculated accordingly. The calculation procedures followed the method outlined by Dou et al. [42].

2.3.4 Determination of Nutrient Quality

In each treatment, six lettuce leaves were randomly selected from different plants at identical leaf positions to serve as samples for biochemical analysis. Following collection, the leaves were rinsed with distilled water and gently wiped to remove surface moisture. The cleaned samples were then immediately flash-frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen to produce a homogeneous tissue powder for subsequent analyses.

Nitrate nitrogen content was quantified using the sulfosalicylic acid colorimetric method, following the procedure described by Zhan et al. [43]. Vitamin C concentration was determined via titration with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol, in accordance with the protocol of Shyamala and Jamuna [44]. Soluble sugar content was measured using the sulfuric acid–anthrone colorimetric method, as outlined by Song et al. [23]. Soluble protein concentration was assessed using the Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 dye-binding assay, based on the method reported by Tunio et al. [45].

2.3.5 Assessment of Tipburn Incidence and Calcium Content in Lettuce Leaves

At the time of harvest, the occurrence of tipburn was investigated in all lettuce plants across treatments. Plants exhibiting necrotic lesions or brownish spots larger than 2 mm in diameter on any leaf were identified as having tipburn. The number of affected plants and the incidence rate of tipburn were then calculated. For calcium content analysis, six representative plants were randomly selected from each treatment. From each plant, the first to second innermost leaf layers were collected, inactivated at 105°C for 2 h, and subsequently dried at 80°C to a constant weight. The dried samples were ground into a fine powder, and 0.2 g of powder was digested with nitric acid. The calcium content of the leaves was then determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (UV-2800A, Unico (Shanghai, China) Instrument Co., Ltd.), following the procedure described by Jahan et al. [46].

2.4 Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data organization and preliminary figure preparation were performed using Microsoft Excel 2019. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. All measured variables were subjected to two-way ANOVA to evaluate the effects of light intensity, calcium supply, and their interaction. Multiple comparisons were conducted using the Waller–Duncan method (p < 0.05), with significant differences denoted by asterisk (*) and non-significant differences by “NS” in figures and tables. When a significant interaction was detected, simple effects analysis was performed. Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out using Origin2021 to visualize the integrated effects of light and calcium on multivariate lettuce traits. Data were standardized prior to analysis, and principal components with eigenvalues >1 were interpreted.

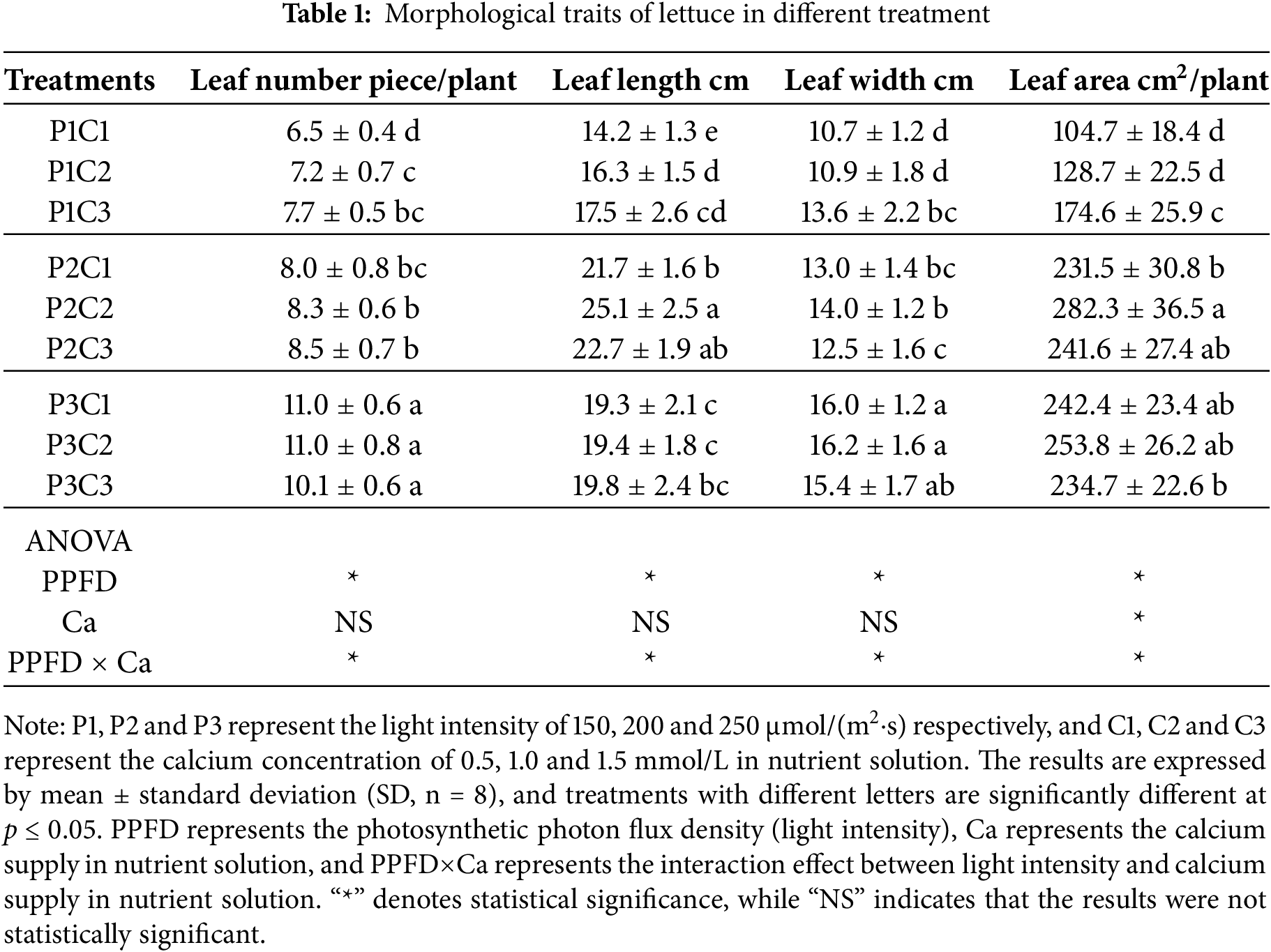

3.1 Effects of Light Intensity and Calcium Supply on Leaf Morphological Traits of Lettuce

As shown in Table 1, both light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution significantly affected the morphological development of lettuce leaves. An increase in light intensity led to a significant rise in leaf number and total leaf area across all treatment combinations. At calcium supply of 0.5 and 1.0 mmol/L, leaf width progressively increased with higher light intensity, while leaf length exhibited an initial increase followed by a slight decline. At a light intensity of 150 μmol/(m2·s), the leaf number, leaf length, leaf width, and total leaf area all increased with higher calcium supply in nutrient solution. However, at 200 and 250 μmol/(m2·s), no significant differences in these morphological parameters were observed among the calcium treatments. Analysis of variance revealed that light intensity and its interaction with calcium supply had significant effects on leaf morphological characteristics, whereas calcium supply did not exert a statistically significant effect.

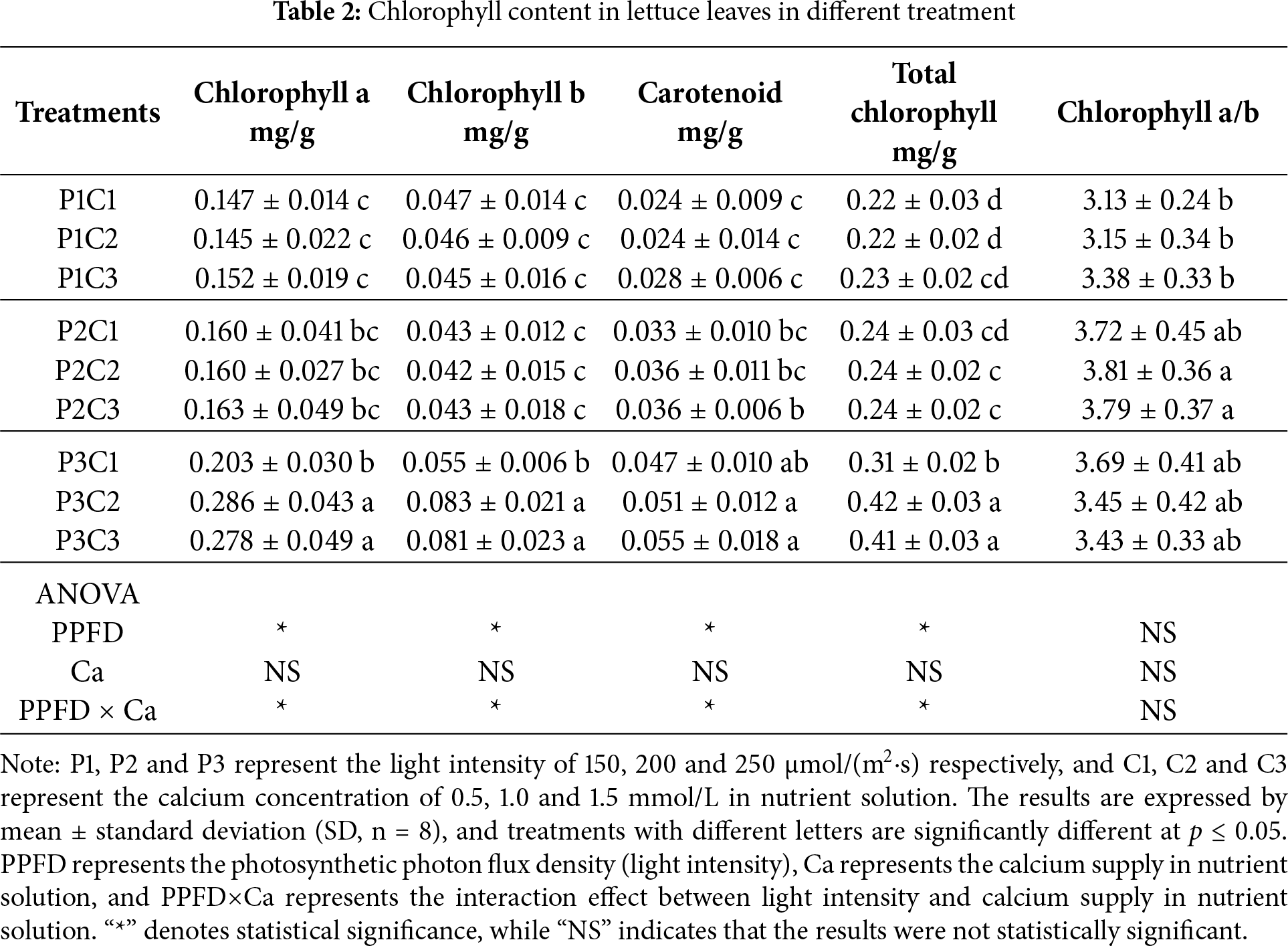

3.2 Photosynthetic Performance of Lettuce in Response to Light Intensity and Calcium Supply

Light intensity had a significant effect on chlorophyll content in lettuce leaves (Table 2). As the light intensity increased, the contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, carotenoids, and total chlorophyll in the leaves showed an overall increasing trend. However, no significant differences were observed in chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, or carotenoid contents between the treatments with light intensity of 150 and 200 μmol/(m2·s). Except under the light intensity of 250 μmol/(m2·s), the calcium supply in the nutrient solution did not significantly affect chlorophyll accumulation. At 250 μmol/(m2·s), the contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were significantly lower in lettuce treated with the calcium supply of 0.5 μmol/L than in the other treatments, whereas no significant differences were found between the treatment with the calcium supply of 1.0 and 1.5 μmol/L. According to the results of the analysis of variance, the interaction between light intensity and calcium supply had a significant impact on all measured chlorophyll parameters except for the chlorophyll a/b.

As shown in Table 3, under the same calcium supply in the nutrient solution, the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate of lettuce leaves increased progressively with increasing light intensity, while the intercellular CO2 concentration gradually decreased. However, no significant differences were observed between the treatments with the light intensity of 200 and 250 μmol/(m2·s). Under the same light intensity, calcium supply in the nutrient solution had no significant effect on net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, or transpiration rate, except for stomatal conductance at 150 μmol/(m2·s). According to the analysis of variance, light intensity and the interaction between light intensity and calcium supply had significant effects on the net photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance of lettuce leaves, whereas calcium supply alone had no significant influence on any of the measured photosynthetic parameters.

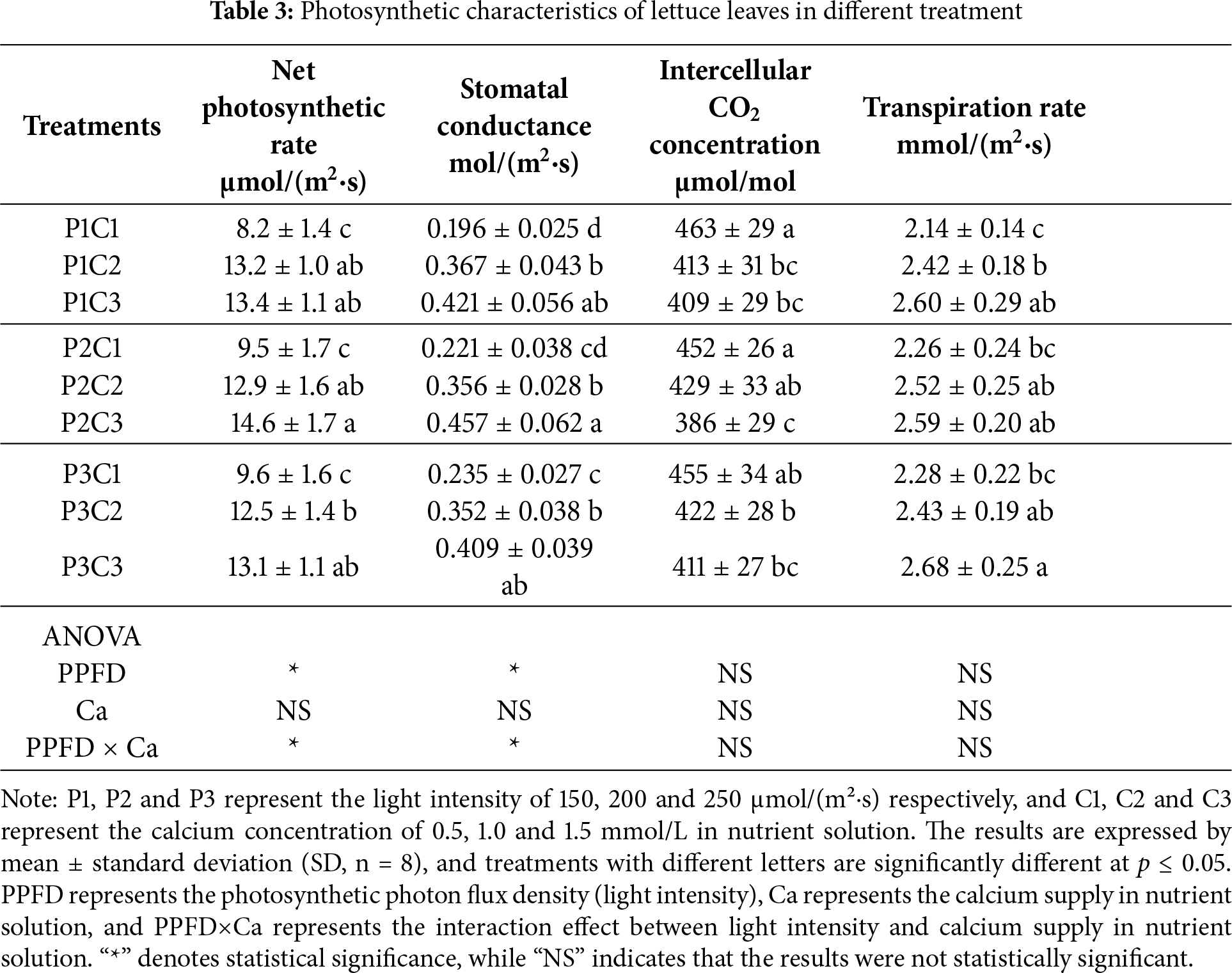

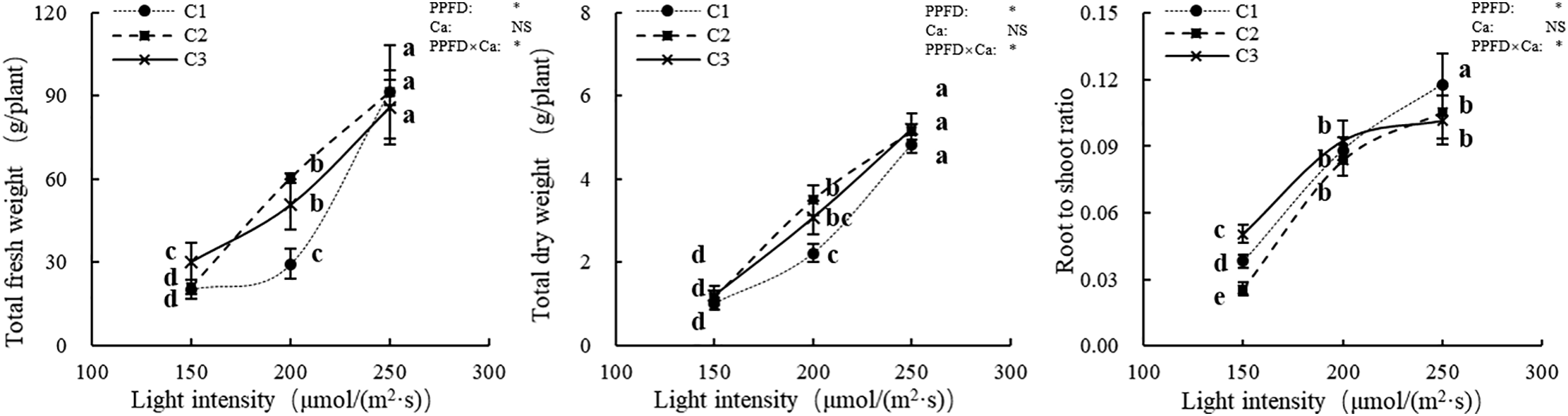

3.3 Effects of Light Intensity and Calcium Supply on Biomass Accumulation of Lettuce

Light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution had significant effects on the biomass accumulation of lettuce plants (Fig. 1). Under same calcium supply in the nutrient solution, the fresh and dry weights of both shoots and roots increased with increasing light intensity. Specifically, at a light intensity of 250 μmol/(m2·s), the shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, shoot dry weight, and root dry weight were 45.3%, 106.7%, 44.0%, and 81.5% higher, respectively, than those observed under 200 μmol/(m2·s). At a light intensity of 200 μmol/(m2·s), shoot and root fresh and dry weights increased progressively with rising calcium supply in the nutrient solution. However, no significant differences were observed among calcium treatments under 250 μmol/(m2·s), indicating that light intensity was the dominant factor in promoting biomass accumulation under higher irradiance conditions. According to the ANOVA results, both light intensity and the interaction between light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution significantly affected the biomass accumulation of the shoot and root in lettuce, whereas the effect of calcium supply in the nutrient solution alone on the dry matter accumulation of both shoot and root was not significant.

Figure 1: Biomass accumulation of lettuce plants. Note: P1, P2 and P3 represent the light intensity of 150, 200 and 250 μmol/(m2·s) respectively, and C1, C2 and C3 represent the calcium concentration of 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mmol/L in nutrient solution. The vertical bars above the histograms indicate standard deviation (SD, n = 6). The treatments with different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. PPFD represents the photosynthetic photon flux density (light intensity), Ca represents the calcium supply in nutrient solution, and PPFD×Ca represents the interaction effect between light intensity and calcium supply in nutrient solution. “*” denotes statistical significance, while “NS” indicates that the results were not statistically significant

The total fresh and dry weights of lettuce plants exhibited trends consistent with those observed in the shoot and root fresh and dry weights. As shown in Fig. 2, under the same calcium supply in the nutrient solution, both total fresh weight, total dry weight, and the root to shoot ratio of lettuce plants significantly increased with rising light intensity. At a light intensity of 150 μmol/(m2·s), total fresh weight increased markedly with higher calcium supply, and a similar trend was observed for total dry weight at 200 μmol/(m2·s). However, under a light intensity of 250 μmol/(m2·s), neither total fresh nor dry weight was significantly affected by the calcium supply in the nutrient solution. Additionally, under identical light intensities, the root to shoot ratio did not follow a consistent pattern across calcium treatments. Therefore, light intensity and its interaction with calcium supply significantly influenced the root to shoot ratio of lettuce plants, whereas the main effect of calcium supply alone was not statistically significant.

Figure 2: Root to shoot ratio of lettuce plants. Note: P1, P2 and P3 represent the light intensity of 150, 200 and 250 μmol/(m2·s) respectively, and C1, C2 and C3 represent the calcium concentration of 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mmol/L in nutrient solution. The vertical bars above the histograms indicate standard deviation (SD, n = 6). The treatments with different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. PPFD represents the photosynthetic photon flux density (light intensity), Ca represents the calcium supply in nutrient solution, and PPFD×Ca represents the interaction effect between light intensity and calcium supply in nutrient solution. “*” denotes statistical significance, while “NS” indicates that the results were not statistically significant

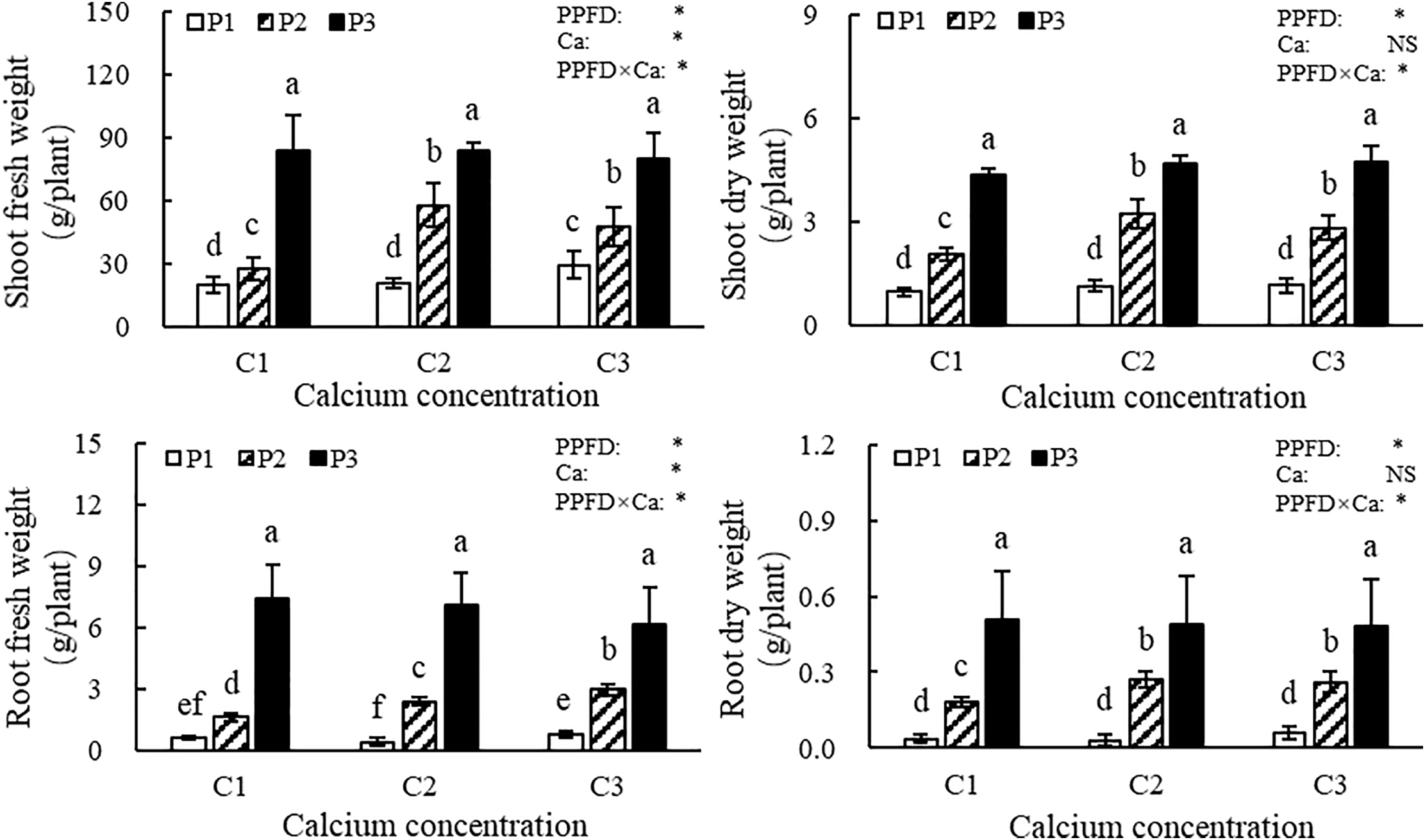

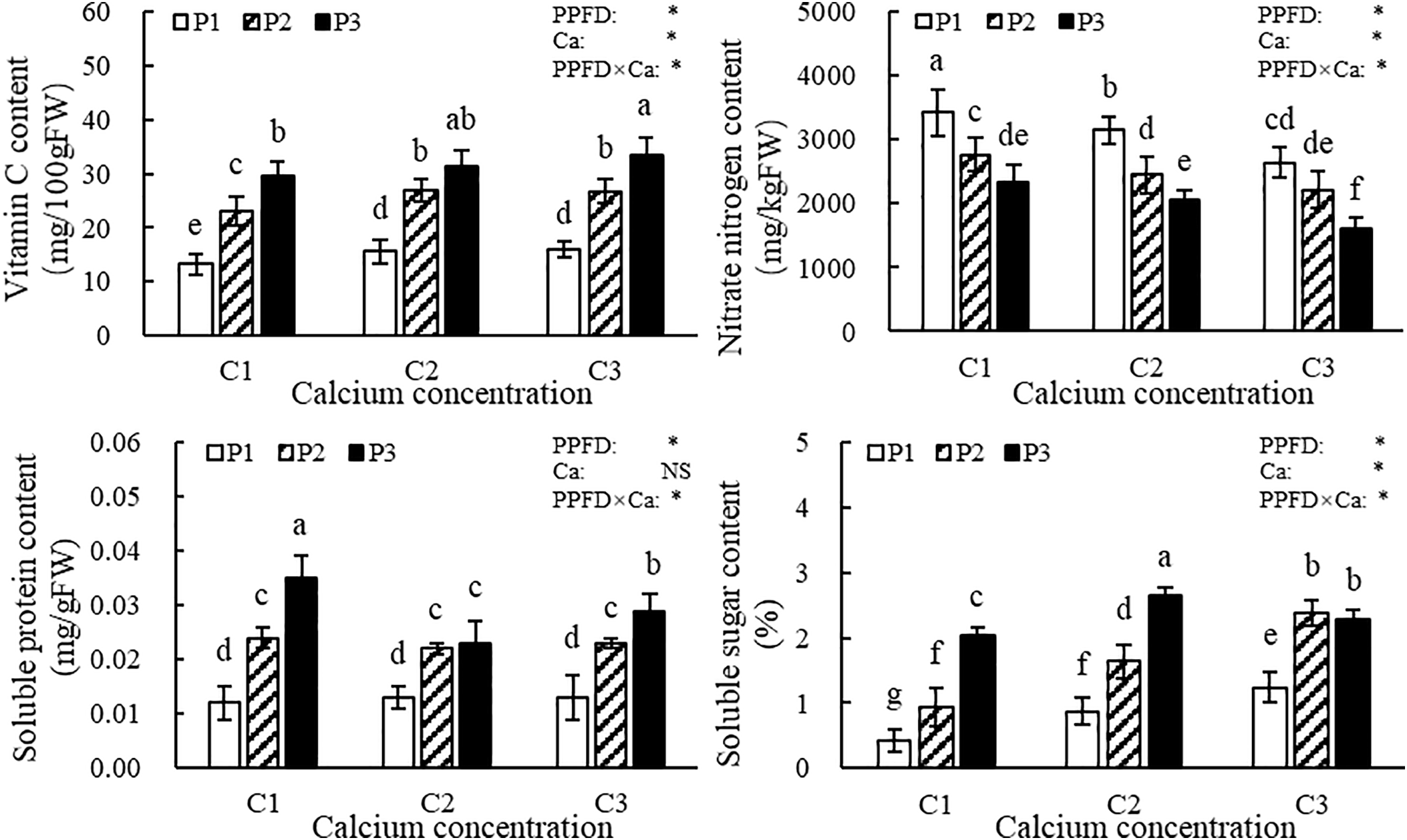

3.4 Effects of Light Intensity and Calcium Supply on Nutritional Quality of Lettuce

As shown in Fig. 3, both light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution significantly affected the nutritional quality of lettuce leaves. Under the same calcium supply, the contents of vitamin C, soluble proteins, and soluble sugars in the leaves increased with rising light intensity, while nitrate content showed a decreasing trend. Under constant light intensity, vitamin C and soluble sugar contents increased with higher calcium supply, and nitrate content decreased accordingly. However, no consistent pattern was observed in the soluble protein content in response to varying calcium supply. According to the ANOVA results, both light intensity and the interaction between light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution significantly influenced the nutritional quality of lettuce leaves. Except for soluble protein content, the calcium supply in the nutrient solution exerted significant effects on the vitamin C content, nitrate nitrogen content, and soluble sugar content of lettuce leaves.

Figure 3: Nutritional quality of lettuce leaves. Note: The vertical bars above the histograms indicate standard deviation (SD, n = 8). PPFD represents the photosynthetic photon flux density (light intensity), Ca represents the calcium supply in nutrient solution, and PPFD×Ca represents the interaction effect between light intensity and calcium supply in nutrient solution. “*” denotes statistical significance, while “NS” indicates that the results were not statistically significant

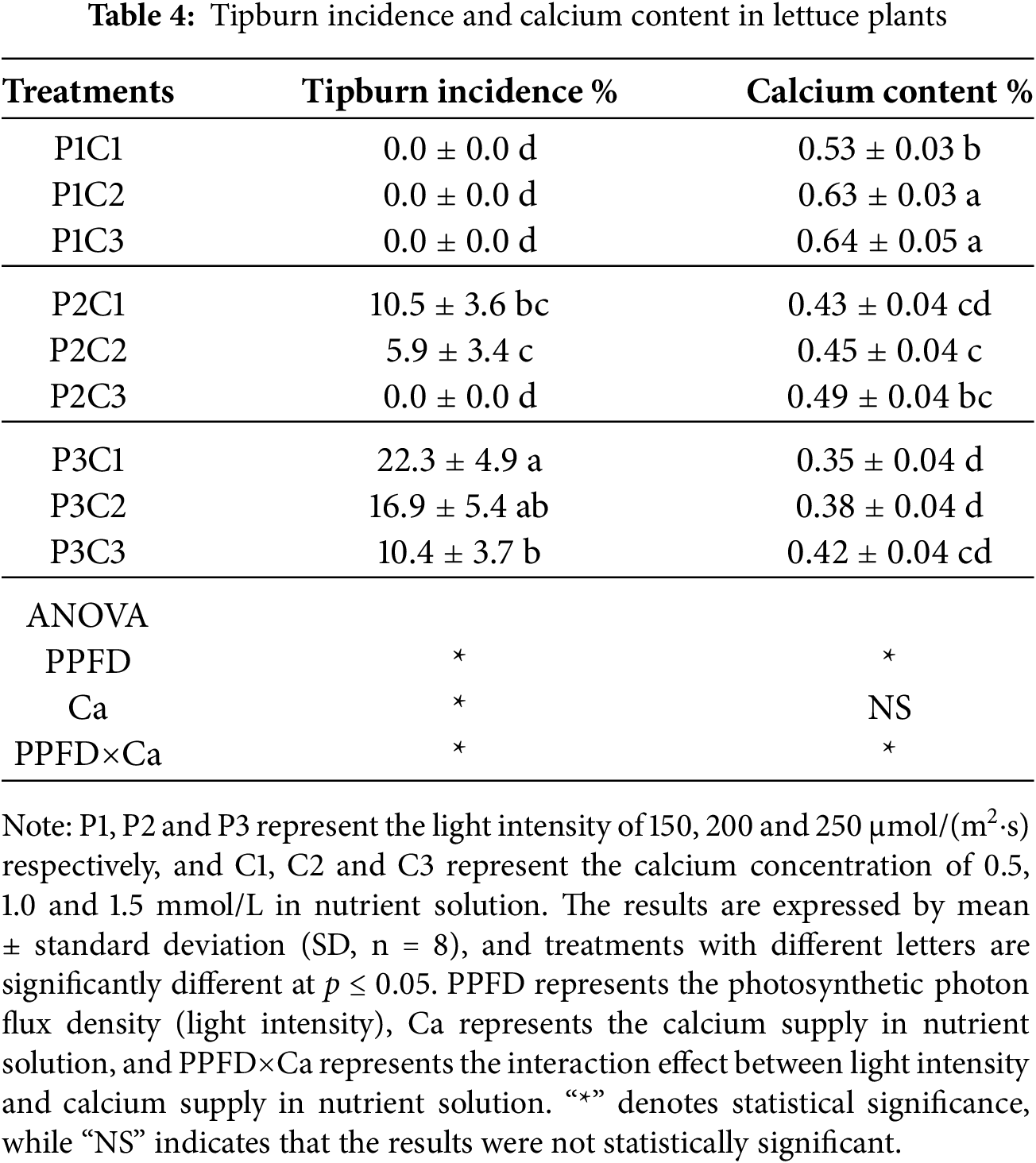

Under the combined influence of light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution, certain treatments led to the occurrence of pronounced tipburn symptoms in lettuce plants (Table 4). At a light intensity of 150 μmol/(m2·s), no tipburn symptoms were observed in any treatment. When the light intensity was increased to 200 μmol/(m2·s), tipburn occurred in plants supplied with 0.5 μmol/L and 1.0 μmol/L calcium, although the incidence rate did not differ significantly between these treatments. At a light intensity of 250 μmol/(m2·s), all lettuce plants exhibited tipburn symptoms, with the incidence rate decreasing as the calcium supply increased. Under the light intensity of 150 μmol/(m2·s), leaf calcium content increased with higher calcium supply in the nutrient solution, whereas at higher light intensities, no significant changes in leaf calcium content were observed in response to calcium supply in nutrient solution. Regardless of calcium concentration, leaf calcium content showed a clear downward trend with increasing light intensity.

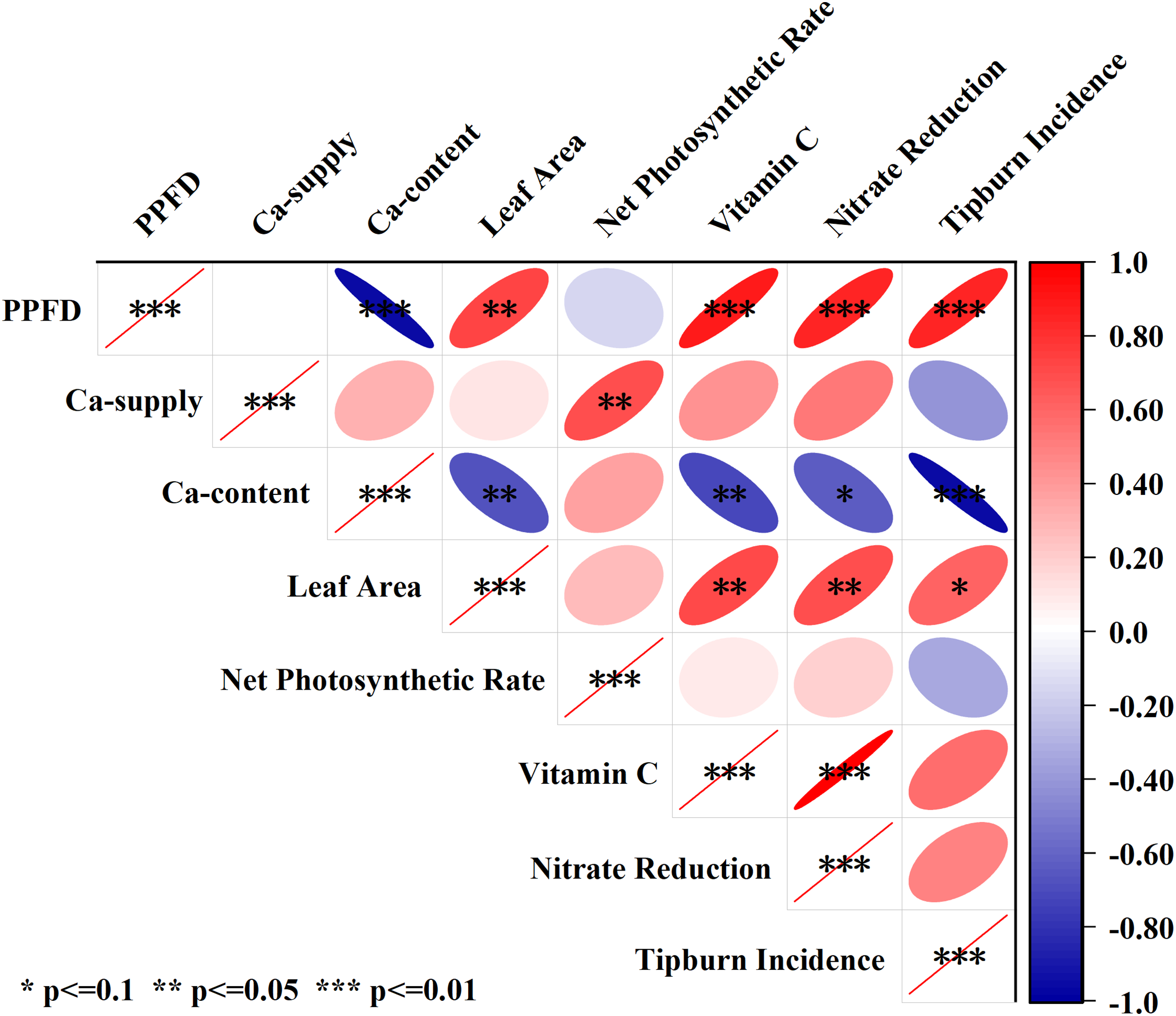

3.5 Correlations among Indicators and with Light Intensity and Calcium Supply

To clarify the interrelationships among the indicators themselves and with light intensity and calcium supply concentration, this study conducted a correlation analysis on the primary indicators: light intensity, calcium supply concentration, Calcium content, leaf area, net photosynthetic rate, vitamin C content, nitrate reduction rate, and tipburn incidence. The results are presented in Fig. 4. As shown in the figure and consistent with previous descriptions, while light intensity showed significant positive correlations with leaf area (r = 0.74, p < 0.01), vitamin C content (r = 0.90, p < 0.01), and nitrate reduction rate (r = 0.840, p < 0.01), it also exhibited a highly significant positive correlation with tipburn incidence (r = 0.85, p < 0.001). This indicates that high light intensity can compromise lettuce quality to some extent. Although calcium supply showed no significant correlation with leaf area (r = 0.11, p ≥ 0.05), it demonstrated a significant negative correlation with tipburn incidence (r = −0.41, p < 0.05). Calcium content showed a negative correlation with tipburn incidence (r = −0.63, p < 0.1), significant negative correlations with leaf area (r = −0.67, p < 0.05) and vitamin C content (r = −0.72, p < 0.05), and a highly significant negative correlation with nitrate reduction rate (r = −0.94, p < 0.01). Increasing calcium supply can effectively reduce tipburn incidence.Notably, while leaf area itself showed a significant positive correlation with tipburn incidence (r = 0.61, p < 0.05), it was also positively correlated with vitamin C content (r = 0.72, p < 0.05) and nitrate reduction rate (r = 0.70, p < 0.01). These findings highlight the complexity of how light intensity and calcium supply regulate lettuce growth and quality.

Figure 4: The correlation among main indicators

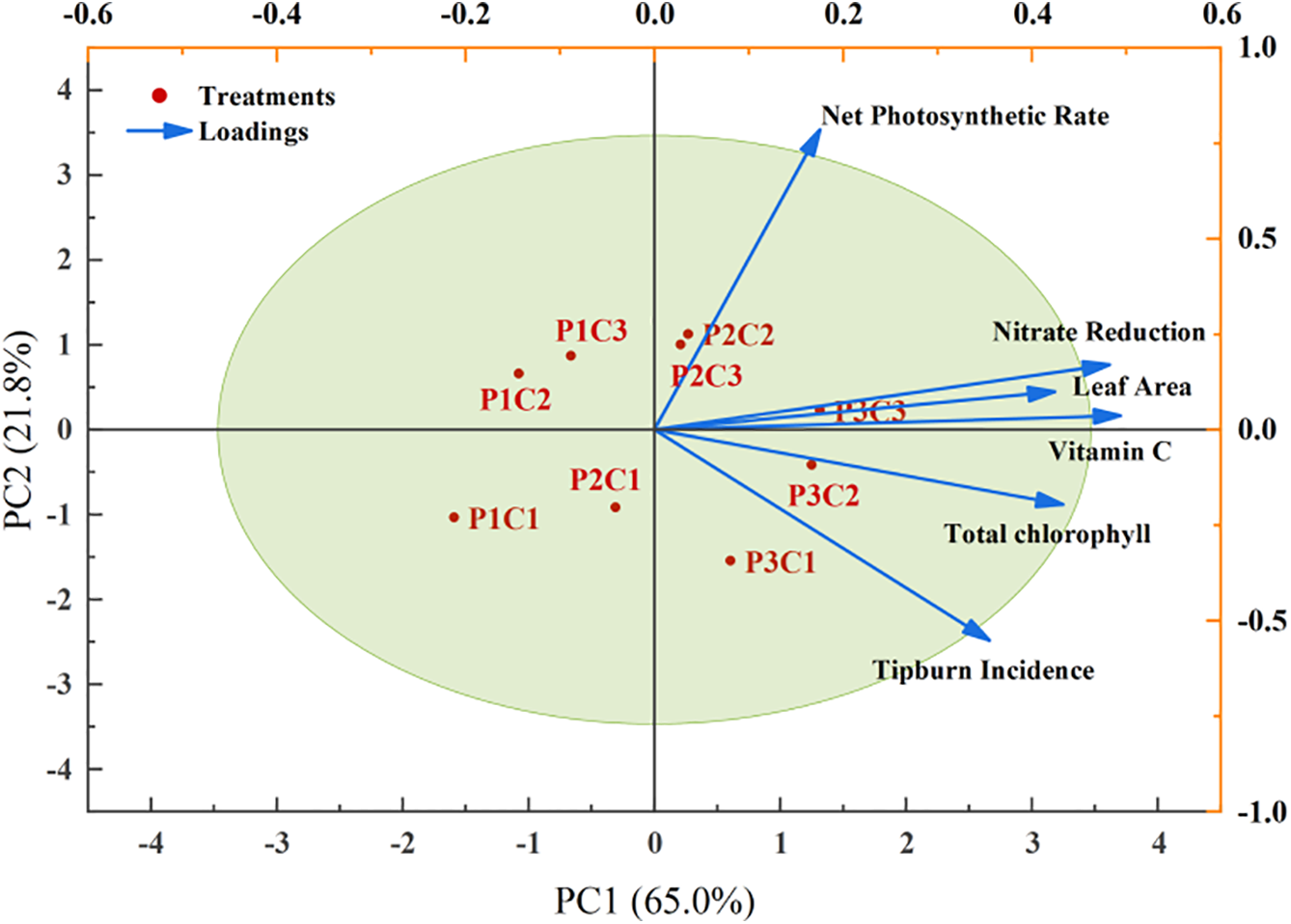

To further elucidate the effects of light intensity and calcium supply on lettuce, this study conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) on six key indicators encompassing growth and morphogenesis, photosynthetic capacity, and nutritional and metabolic quality: leaf area, net photosynthetic rate, vitamin C content, nitrate reduction rate, tipburn incidence, and total chlorophyll content, with results presented in Fig. 5. The first two principal components (PCs) accounted for over 80% of the total variance, with PC1 explaining 65.0% and PC2 explaining 21.8%; therefore, the variation among indicators was analyzed based on the distribution within these first two PCs. PC1 (Growth-Quality Axis) was primarily positively driven by leaf area (loading = 0.424), vitamin C content (loading = 0.493), and nitrate reduction rate (loading = 0.482), reflecting the synergistic effect between plant growth and nutritional quality, while PC2 (Photosynthesis-Health Axis) was mainly characterized by a positive contribution from net photosynthetic rate (loading = 0.785) and a negative constraint from tipburn incidence (loading = −0.552), representing the functional health status of the leaves. The distribution of treatment groups within the PCA space revealed distinct patterns: the P2C2 treatment was positioned near the balance point of PC1 and PC2; compared to P2C2, the P3C3 treatment reached its peak on PC1 (score = 1.31) but was constrained by its lower PC2 score (0.23); and the P3C1 treatment scored lowest on PC2. Comprehensive analysis indicated that the P2C2 treatment was the most favorable for enhancing lettuce growth and quality among all treatments. Furthermore, high-light intensity treatment groups (P3) showed significant rightward shifts along the PC1 axis, and high-calcium treatments (C3) consistently shifted upwards along the PC2 axis. Specifically, the low-light/high-calcium treatment (P1C3) performed notably well on PC2 (score = 0.87), while the low-light/low-calcium treatment (P1C1) scored −1.03 on PC2; thus, the P1C3 treatment surpassed P1C1 by a significant margin of 1.9 units on PC2. Collectively, these results suggest that light intensity remains the primary driver for lettuce growth and quality enhancement, while increasing calcium supply can improve photosynthetic performance under low-light conditions.

Figure 5: Principal component analysis among core indicators

3.6 Enhancing Effect of High Calcium Supply on Lettuce Growth under Low Light Intensity

Key Translation Choices Explained

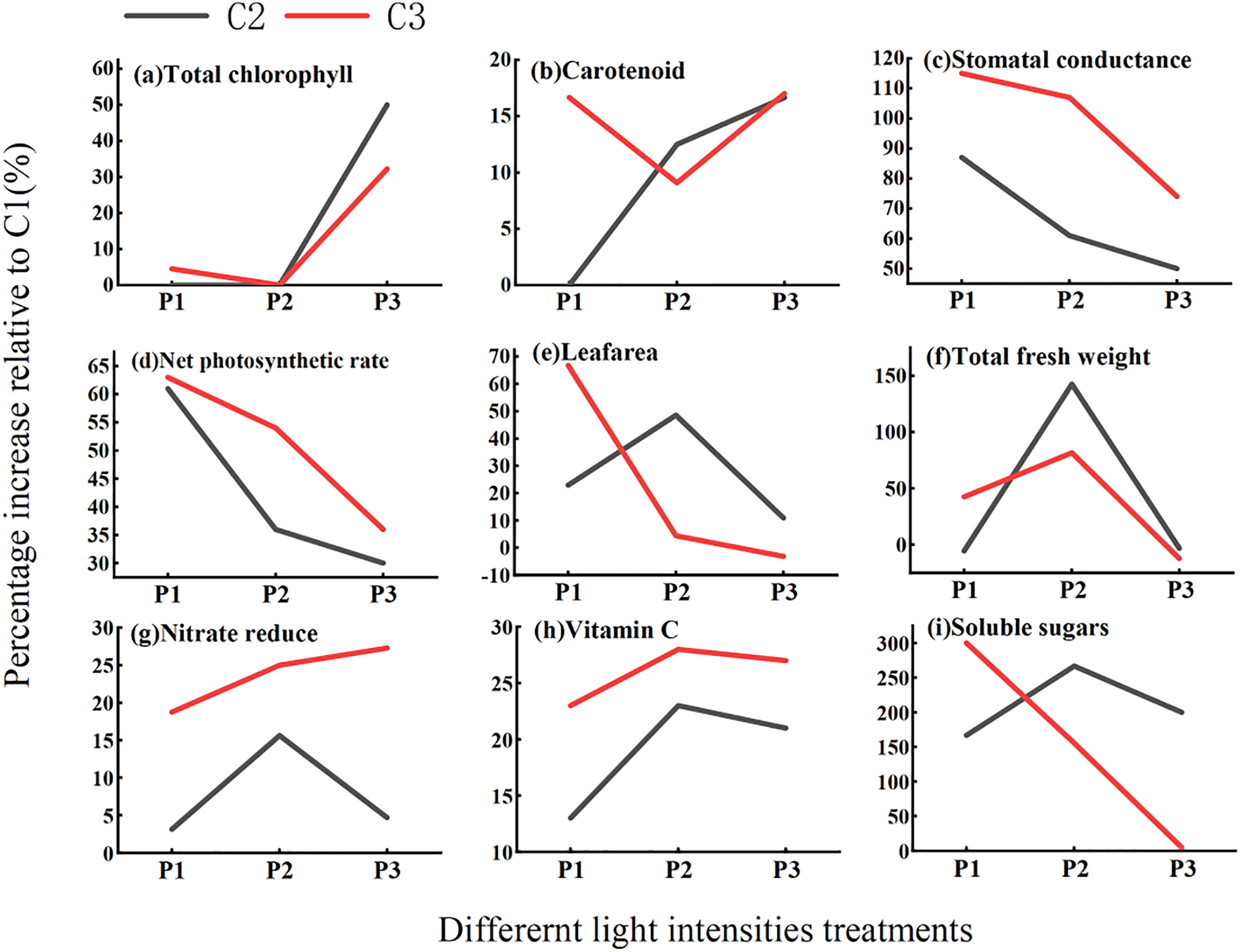

Given the aforementioned results, this study further analyzed the increase rates of nine key indicators: total chlorophyll content, carotenoid content, net photosynthetic rate, leaf area, total fresh weight, nitrate reduction rate, vitamin C content, and soluble sugar content—in the high-calcium treatments C2 and C3 relative to C1, across the light intensity gradient. The results are presented in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Enhancement effects of calcium concentration

Regarding photosynthetic pigments and photosynthetic capacity, total chlorophyll content (Fig. 6a) under P1 light showed a slight increase of 3.4% in C3 compared to C1, while C2 decreased by 1.36%. Under P2 light, C3 and C2 increased by 9.09% and 12.50%, respectively. This indicates that chlorophyll content changes under P1 conditions are primarily dominated by light intensity, with the enhancement effect of high calcium being relatively weak. Carotenoid content (Fig. 6b) under P1 light increased by 16.7% only in C3, with no difference in C2. Under P2 light, C3 increased by 9.1% and C2 by 12.50%, demonstrating a positive response of carotenoid accumulation to the C3 calcium concentration under low light (P1). Stomatal conductance (Fig. 6c) under P1 light increased substantially by 115% in C3 and 87% in C2; under P2 light, increases were 107% in C3 and 61% in C2, indicating a strong enhancement of stomatal opening with increasing calcium concentration. Net photosynthetic rate (Fig. 6d) under P1 light increased by 61% in C2 and 63% in C3; under P2 light, increases were 36% in C3 and 30% in C2. This demonstrates that calcium supply exceeding the C2 level can significantly enhance photosynthetic rate under low light, with the C3 treatment consistently showing a higher increase rate than C2, potentially linked to the observed improvement in stomatal conductance.

In terms of morphogenesis and biomass, leaf area (Fig. 6e) under P1 light exhibited a high increase rate of 66.8% for C3, surpassing the 22.9% increase in C2, suggesting that leaf area expansion under P1 light intensifies with higher calcium concentration. Under P2 light, the increase rate for C3 dropped to 4.46%, while that for C2 rose to 48.52%, indicating that the promotive effect of the C3 treatment on leaf area is sensitive to light intensity; the trend of increase rates for C3 and C2 under P2 light paralleled that of leaf area itself. Total fresh weight (Fig. 6f) under P1 light showed a 42.6% yield increase for C3 compared to C1, while C2 resulted in a 5.6% reduction, highlighting the high sensitivity of biomass accumulation to calcium concentration under low light. Conversely, under P2 light, C3 showed a 12.29% yield reduction and C2 a 3.24% reduction compared to C1, demonstrating that the yield-increasing effect of high calcium supply (C3) is also significantly influenced by light intensity.

Regarding physiological metabolism and quality indicators, the nitrate reduction rate (Fig. 6g) under P1 light was 18.75% higher in C3 than C1, approximately six times the reduction achieved by C2. Under P2 light, C3 achieved a 27% nitrate reduction, about 23% higher than the reduction by C2, indicating superior regulation of nitrate reduction by the C3 calcium concentration. Vitamin C content (Fig. 6h) under P1 light was 123% higher in C3 than C1, exceeding the C2 level by 110%. Under P2 light, C3 was 28% higher than C1 and C2 was 23% higher, showing a more pronounced promotion of vitamin C accumulation by the C3 calcium supply. Soluble sugar content (Fig. 6i) under P1 light was significantly increased by 300% in C3, markedly higher than the 166% increase in C2. Under P2 conditions, the increase rate for C3 decreased to 155%, while that for C2 rose to 266%, reflecting the positive effect of the C3 calcium concentration on sugar accumulation in lettuce under low light (P1).

4.1 Light Intensity as the Dominant Factor Influencing Lettuce Morphogenesis

This study systematically investigated the effects of combined regulation of light intensity and calcium supply in nutrient solution on leaf morphology, biomass accumulation, nutritional quality, and the incidence of tipburn in lettuce grown in a plant factory artificial lighting. The aim was to identify optimal light intensity–calcium supply coupling parameters to improve yield, enhance quality, and mitigate the risk of tipburn.

Our findings demonstrate that light intensity is the primary factor governing lettuce leaf morphogenesis under controlled plant factory conditions [47]. With increasing light intensity, both the number of leaves and total leaf area showed significant enhancement, aligning with the results reported by Miao et al. [48] and Kang et al. [49], who observed increased leaf area index in spinach and lettuce under high light conditions. Although calcium supply in the nutrient solution did not exhibit a statistically significant main effect on leaf morphology, a notable interaction between light intensity and calcium supply was detected. This interaction is likely attributable to the role of calcium in stabilizing cell walls and its involvement in coordinating light-regulated processes such as cell division and expansion [50]. These results are consistent with the findings of Luo et al. [51], who also reported an interactive effect of light intensity and calcium concentration on the morphological development of lettuce.

4.2 Enhanced Photosynthetic Capacity through Light Intensity and Light–Calcium Interaction

Elevated light intensity significantly increased chlorophyll content and enhanced key photosynthetic parameters in lettuce leaves. As light intensity increased, net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate also increased, whereas intercellular CO2 concentration decreased. These patterns indicate that an appropriate level of light intensity effectively improves photosynthetic photon efficacy in lettuce leaves [52]. This trend is consistent with the findings of Hesham et al. [10], who reported enhanced photosynthetic performance in vegetable crops under higher light intensities. Although calcium supply in the nutrient solution had no statistically significant effect on photosynthetic traits when analyzed independently, its influence became evident under high light conditions (250 μmol/(m²·s)). Under such conditions, calcium deficiency inhibited chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduced Photosystem II activity, indicating a typical stress response in calcium-starved lettuce leaves [53]. These observations underscore the essential role of calcium as a stabilizing factor in the antioxidant defense system, particularly under high light conditions, where its contribution to photoprotection becomes critical [54].

4.3 Light–Calcium Regulation Promotes Biomass Accumulation with a Saturation Effect

Under identical calcium supply in the nutrient solution, increasing light intensity significantly enhanced both shoot and root fresh and dry weights of lettuce plants. These trends are consistent with the observed improvements in leaf morphology and photosynthetic performance, confirming that light intensity serves as a primary driver of photosynthetic carbon assimilation and biomass accumulation in lettuce [55]. Notably, the promotive effect of light intensity on biomass accumulation was more pronounced under conditions below 200 μmol/(m2·s), aligning with the findings of Loconsole et al. [56]. However, when light intensity increased from 200 to 250 μmol/(m2·s), the incremental gains in several biomass-related indices became marginal or statistically insignificant. This suggests the existence of a “light saturation point” beyond which plants exhibit limited capacity to utilize additional LED light energy [11]. In this study, the saturation threshold for lettuce biomass accumulation occurred at relatively low light intensities, possibly due to the high proportion of blue light in the employed LED spectrum.

Under a light intensity of 200 μmol/(m2·s), increasing calcium supply in the nutrient solution significantly promoted biomass accumulation in lettuce plants, consistent with previous findings [57]. At 250 μmol/(m2·s), overall biomass was higher than at 200 μmol/(m2·s) across all treatments, reflecting the increased daily light integral and total carbon assimilation. However, differences in calcium supply did not result in statistically significant differences in biomass at this PPFD, although C1 consistently exhibited lower net photosynthetic rate compared with C2 and C3. The relative pattern of net photosynthetic rate among treatments was in agreement with the relative pattern of biomass, suggesting that calcium primarily affected photosynthetic capacity rather than biomass accumulation being limited by photooxidative stress [58].

4.4 Light–Calcium Regulation Enhances Lettuce Quality and Reduces the Incidence of Tipburn

The contents of vitamin C, soluble sugars, and soluble proteins in lettuce leaves increased significantly with elevated light intensity, consistent with findings reported by Dai et al. [59] and Min et al. [60]. Additionally, the nitrate content of lettuce leaves exhibited a decreasing trend as light intensity increased, in agreement with the results of Zhou et al. [61] and Fu et al. [52]. The highest nitrate content in this study was observed in the combination treatment of low light intensity (150 μmol/(m²·s)) and low calcium supply (0.5 mmol/L). Notably, even under these conditions, this content remains well below the limit specified for greenhouse-grown lettuce (≤4500 mg/kg) by the European Union standard (EC No. 1258/2011), while all other treatments were lower than the safety threshold for nitrate in leafy vegetables (≤3000 mg/kg) established by the Chinese national standard (GB 19338-2003).This may be attributed to the promotion of photosynthetic activity under higher light intensity, which accelerates the conversion of inorganic nitrogen into amino acids and proteins, thereby reducing nitrate accumulation in leaf tissues [62,63]. Moreover, elevated light intensity can enhance nitrate reductase activity, further promoting nitrate assimilation [11]. These results suggest that moderate increases in light intensity can improve lettuce leaf quality while suppressing nitrate accumulation. Simultaneously, increasing calcium supply in the nutrient solution within an appropriate range also significantly enhanced the contents of vitamin C and soluble sugars, while reducing nitrate levels. This supports the role of calcium in improving plant quality by modulating metabolic activity and maintaining ion homeostasis [64].

Importantly, this study found that the incidence of tipburn in lettuce leaves exhibited a positive correlation with light intensity but a negative correlation with calcium supply in the nutrient solution. At a light intensity of 250 μmol/(m2·s), tipburn symptoms were observed across all treatments, indicating that excessive light intensity may drive rapid shoot growth beyond the capacity of calcium supply [65]. However, increasing calcium supply in the nutrient solution effectively reduced the incidence of tipburn, corroborating the findings of Miao et al. [48], and confirming the suppressive effect of calcium on tipburn development in lettuce [26]. These findings are consistent with the study by Gilliham et al. [66], which associated calcium transport limitations with chlorosis and tipburn in leaf tissues. Furthermore, under high light intensity, a reduction in leaf calcium content was observed in the present study. Although elevated transpiration can enhance calcium mass flow, our results showed that high light intensity (250 μmol/(m2·s)) did not significantly increase the transpiration rate. Instead, the reduced calcium content under high light is likely attributable to a dilution effect caused by accelerated biomass accumulation, which may have outpaced calcium uptake and translocation [62]. Additionally, high light may induce photooxidative stress that could impair root uptake or vascular transport of calcium. This resultant insufficiency of calcium supply to rapidly developing tissues ultimately contributes to the observed tipburn symptoms [67], which is consistent with the incidence reported in this study.

4.5 Light–Calcium Synergy Improves Nutritional Quality and Mitigates Low-Light Stress

Current research indicates that the regulation of lettuce growth and quality by light intensity and calcium supply is complex. This complexity primarily manifests in their synergistic effects on lettuce physiological functions [23,68]. The study by Jiang et al. [69] found that, under 200 μmol/(m2·s) light, foliar spraying of loose-leaf lettuce ‘Lvya’ with a 0.5% calcium nutrient solution, compared to no calcium application, significantly increased plant height and leaf width (+29%), fresh weight (+13.7%), root fresh weight (+50.6%), root activity (+13.9%), soluble protein (+43.6%), soluble sugar (+19.1%), and vitamin C content (+14.9%), while simultaneously significantly reducing tipburn incidence (−81.6%). However, nitrate content significantly increased by 22.3%. In contrast, our study observed a 123% increase in vitamin C content, a 300% increase in soluble sugar content, and an 18.8% decrease in nitrate content in high-calcium treatments compared to the low-calcium group. This discrepancy may be related to factors such as calcium application method and concentration thresholds.

The complexity of light-calcium synergy is further evident in the ability of high calcium supply to partially compensate for the adverse effects of low light intensity on lettuce growth and quality. Research by Luo et al. [51] demonstrated that for the temperate lettuce variety ‘Baby Butter’ cultivated in the tropics, while high calcium supplementation under low light could not fully eliminate yield reduction, it increased yield by 161%, significantly enhanced chlorophyll concentration by 22.2%, significantly raised the shoot/root calcium content ratio by 30.3%, and resulted in a slightly higher Fv/Fm (the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II) ratio (0.813) compared to the low-light/low-calcium group (0.802). Collectively, these results suggest that high calcium under low light cannot completely reverse the growth limitations caused by insufficient light intensity. However, it can significantly enhance lettuce’s physiological resilience under low-light stress by boosting chlorophyll synthesis, maintaining photosystem stability, and promoting the effective allocation of calcium to functional leaves, thereby providing a pathway for quality improvement. Our study found that under low light intensity (150 μmol/(m2·s)), the 1.5 mmol/L high-calcium treatment significantly promoted stomatal conductance (increase of ~115%) and net photosynthetic rate (increase of 63%) in lettuce. This implies that high calcium supply may maintain stomatal function by activating Ca2+-ATPase channels, thereby improving CO2 supply and ultimately alleviating the limitation of low-light stress on carbon assimilation rate [70], supporting the view that calcium nutrition helps mitigate low-light deficits and maintain leaf health functionality. However, the biomass enhancement effect of high calcium supply under low light in our study was relatively limited; for instance, the fresh weight increase was 42.6%, significantly lower than the biomass increase (161%) observed in Luo et al.’s study. This difference may be related to factors such as the lettuce varieties tested. On the other hand, the high-calcium treatment in our study demonstrated superior improvement effects on several key quality indicators, such as a 123% increase in vitamin C content, a 300% increase in soluble sugar content, and an 18.8% decrease in nitrate content. These results further suggest that calcium supplementation measures may hold greater practical potential for alleviating the negative impact of low light on lettuce nutritional quality, particularly concerning sugar accumulation and antioxidant compound synthesis.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that a high calcium supply (1.0–1.5 mmol/L) can partially compensate for the adverse effects of low light intensity (150–200 μmol/(m2·s)) on photosynthesis and quality in lettuce. This compensatory mechanism is likely achieved through the stabilization of Photosystem II and the optimization of stomatal function, providing a novel strategy for high-quality lettuce production under light-limiting conditions.

It is essential to note that the conclusions drawn in this study are derived from preliminary data obtained in an exploratory cultivation experiment. Notably, the responses observed across the various indicators exhibited asynchrony. The precise calcium saturation threshold requires further validation through dedicated dose-response experiments. Additionally, the magnitude of improvement for some indicators was relatively limited. While the findings presented here serve as exploratory evidence, practical application necessitates further in-depth research. This should include constructing a light-calcium interaction model and conducting multi-variety validation across different lettuce cultivars.

This study systematically evaluated the interactive effects of light intensity and calcium supply in the nutrient solution on lettuce yield and quality. The results elucidate the synergistic mechanisms between light environment and mineral nutrition in regulating crop performance. Light intensity emerged as the dominant factor influencing leaf morphological development, photosynthetic performance, and biomass accumulation. Moderate increases in light intensity significantly enhanced photosynthetic activity, nutrient accumulation, and overall yield. However, when the light intensity exceeded 250 μmol/(m²·s), the increase in biomass plateaued, and the risk of physiological disorders such as tipburn markedly increased. Although calcium supply had a limited impact on leaf morphology and photosynthetic traits under low to moderate light conditions, it significantly improved nutritional quality, reduced nitrate accumulation, and alleviated tipburn symptoms under high light intensity. A significant interaction between light and calcium factors was observed, indicating that an optimal combination of light intensity and calcium supply is essential for the coordinated enhancement of both yield and quality in lettuce. These findings provide theoretical guidance and practical insights for the efficient and safe production of leafy vegetables in artificially lit plant factory systems.

Acknowledgement: Not Applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42307428); the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD-2023-87); the Key Laboratory of Desert–Oasis Crop Physiology, Ecology and Cultivation, MOARAF, (project no. xjnkywdzc-2025002-01-03); the National Key Laboratory of Wheat Improvement of China (KFKT202507); the Key Laboratory for Crop Production and Smart Agriculture of Yunnan Province (project no. 2024ZHNY03); the Key Laboratory of Spectroscopy Sensing, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, China (project no. 2024ZJUGP002).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jie Jin, Tianci Wang and Jinxiu Song; methodology, Jie Jin and Jinxiu Song; validation, Jie Jin, Tianci Wang, Yaning Wang and Jingqi Yao; formal analysis, Jie Jin and Jinxiu Song; investigation, Jie Jin, Tianci Wang and Yaning Wang; data curation, Jie Jin,Tianci Wang,Yaning Wang, Jingqi Yao and Jinxiu Song; writing—original draft preparation, Jie Jin, Jingqi Yao and Jinxiu Song; writing—review and editing, Jie Jin and Jinxiu Song; visualization, Tianci Wang, Yaning Wang and Jingqi Yao; supervision, Jinxiu Song; project administration, Jinxiu Song; funding acquisition, Jinxiu Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yu H, Yu H, Zhang B, Chen M, Liu Y, Sui Y. Quantitative perturbation analysis of plant factory LED heat dissipation on crop microclimate. Horticulturae. 2023;9(6):660. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9060660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen X, Hou T, Liu S, Guo Y, Hu J, Xu G, et al. Design of a micro-plant factory using a validated CFD model. Agriculture. 2024;14(12):2227. doi:10.3390/agriculture14122227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang X, Zhang M, Xu B, Mujumdar AS, Guo Z. Light-emitting diodes (below 700 nmimproving the preservation of fresh foods during postharvest handling, storage, and transportation. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2022;21(1):106–26. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Si C, Lin Y, Luo S, Yu Y, Liu R, Naz M, et al. Effects of LED light quality combinations on growth and leaf colour of tissue culture-generated plantlets in Sedum rubrotinctum. Hortic Sci Technol. 2024;42(1):53–67. doi:10.7235/hort.20240005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Song J, Fan Y, Li X, Li Y, Mao H, Zuo Z, et al. Effects of daily light integral on toma to (Solanum lycopersicon L.) grafting and quality in a controlled environment. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2022;15(6):44–50. doi:10.25165/j.ijabe.20221506.7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xu X, Yang F, Song J, Zhang R, Cai W. Does the daily light integral influence the sowing density of tomato plug seedlings in a controlled environment? Horticulturae. 2024;10(7):730. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10070730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hang T, Lu N, Takagaki M, Mao H. Leaf area model based on thermal effectiveness and photosynthetically active radiation in lettuce grown in mini-plant factories under different light cycles. Sci Hortic. 2019;252(5734):113–20. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.03.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Song J, Zhang R, Yang F, Wang J, Cai W, Zhang Y. Nocturnal LED supplemental lighting improves quality of tomato seedlings by increasing biomass accumulation in a controlled environment. Agronomy. 2024;14(9):1888. doi:10.3390/agronomy14091888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Saito Y, Shimizu H, Nakashima H, Miyasaka J, Ohdoi K. The effect of light quality on growth of lettuce. IFAC Proc Vol. 2010;43(26):294–8. doi:10.3182/20101206-3-jp-3009.00052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ahmed HA, Tong YX, Yang QC. Optimal control of environmental conditions affecting lettuce plant growth in a controlled environment with artificial lighting: a review. S Afr N J Bot. 2020;130(2):75–89. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang X, He D, Niu G, Yan Z, Song J. Effects of environment lighting on the growth, photosynthesis, and quality of hydroponic lettuce in a plant factory. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2018;11(2):33–40. doi:10.25165/j.ijabe.20181102.3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shimizu H, Saito Y, Nakashima H, Miyasaka J, Ohdoi K. Light environment optimization for lettuce growth in plant factory. IFAC Proc Vol. 2011;44(1):605–9. doi:10.3182/20110828-6-it-1002.02683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhou J, Li P, Wang J. Effects of light intensity and temperature on the photosynthesis characteristics and yield of lettuce. Horticulturae. 2022;8(2):178. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8020178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sun J, Ge X, Wu X, Dai C, Yang N. Identification of pesticide residues in lettuce leaves based on near infrared transmission spectroscopy. J Food Process Eng. 2018;41(6):e12816. doi:10.1111/jfpe.12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Y, Kacira M, An L. A CFD study on improving air flow uniformity in indoor plant factory system. Biosyst Eng. 2016;147(1):193–205. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2016.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tadashi I, Fan SX. Effects of calcium on nutrient absorption and growth and development of Lactuca sativa var. longifolia Lam. in nutrient film technique culture. Acta Hortic Sin. 2002;29(2):149–52. [Google Scholar]

17. Ahmed HA, Tong YX, Yang QC. Lettuce plant growth and tipburn occurrence as affected by airflow using a multi-fan system in a plant factory with artificial light. J Therm Biol. 2020;88(2):102496. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.102496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Cox EF, McKee JMT, Dearman AS. The effect of growth rate on tipburn occurrence in lettuce. J Hortic Sci. 1976;51(3):297–309. doi:10.1080/00221589.1976.11514693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou J, Wang JZ, Hang T, Li PP. Photosynthetic characteristics and growth performance of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) under different light/dark cycles in mini plant factories. Photosynthetica. 2020;58(3):740–7. doi:10.32615/ps.2020.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Beacham AM, Hand P, Teakle GR, Barker GC, Pink DAC, Monaghan JM. Tipburn resilience in lettuce (Lactuca spp.)—the importance of germplasm resources and production system-specific assays. J Sci Food Agric. 2023;103(9):4481–8. doi:10.1002/jsfa.12523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Uno Y, Okubo H, Itoh H, Koyama R. Reduction of leaf lettuce tipburn using an indicator cultivar. Sci Hortic. 2016;210:14–8. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2016.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Olle M, Bender I. Causes and control of calcium deficiency disorders in vegetables: a review. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2009;84(6):577–84. doi:10.1080/14620316.2009.11512568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Song J, Huang H, Hao Y, Song S, Zhang Y, Su W, et al. Nutritional quality, mineral and antioxidant content in lettuce affected by interaction of light intensity and nutrient solution concentration. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2796. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-59574-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lee JG, Choi CS, Jang YA, Jang SW, Lee SG, Um YC. Effects of air temperature and air flow rate control on the tipburn occurrence of leaf lettuce in a closed-type plant factory system. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2013;54(4):303–10. doi:10.1007/s13580-013-0031-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yu H, Wang P, Zhu L, Liu Y, Chen M, Zhang S, et al. Optimizing light intensity and airflow for improved lettuce growth and reduced tip burn disease in a plant factory. Sci Hortic. 2024;338:113693. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Samarakoon U, Palmer J, Ling P, Altland J. Effects of electrical conductivity, pH, and foliar application of calcium chloride on yield and tipburn of Lactuca sativa grown using the nutrient-film technique. HortScience. 2020;55(8):1265–71. doi:10.21273/hortsci15070-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Raza H, Sharif H, Zaaboul F, Shoaib M, Aboshora W, Ali B, et al. Effect of chickpeas (Cicerarietinum) germination under minerals stress on the content of isoflavones and functional properties. Res Portal Den. 2020;57(2):591–8. doi:10.21162/PAKJAS/19.844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Qian Y, Wu Z, Liu N, Wang B, Tong J. Identification of the ACA/ECA gene family and preliminary verification of their functional in calcium transport in lettuce. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):20370. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-08671-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Elbeltagi A, Srivastava A, Deng J, Li Z, Raza A, Khadke L, et al. Forecasting vapor pressure deficit for agricultural water management using machine learning in semi-arid environments. Agric Water Manag. 2023;283(2):108302. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang Y, Hao GD, Ge MM, Chang Y, Tan J, Wang J, et al. Function and application of calcium in plant growth and development. Acta Agronom Sin. 2024;50(4):793–807. doi:10.3724/sp.j.1006.2024.34145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fan ZT, Liu H, Huang Y, Ma MB, Li LX, Wei F, et al. Research progress on effects of calcium ions on growth and accumulation of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Mod Chin Med. 2023;25(8):1789–98. (In Chinese). doi:10.13313/j.issn.1673-4890.20221009001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kuronuma T, Kinoshita N, Ando M, Watanabe H. Difference of Ca distribution before and after the onset of tipburn in Lisianthus [Eustoma grandiflorum (Raf.) Shinn.] cultivars. Sci Hortic. 2020;261(10):108911. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mao H, Hang T, Zhang X, Lu N. Both multi-segment light intensity and extended photoperiod lighting strategies, with the same daily light integral, promoted Lactuca sativa L. growth and Photosynthesis. Agronomy. 2019;9(12):857. doi:10.3390/agronomy9120857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhou J, Li P, Wang J, Fu W. Growth, photosynthesis, and nutrient uptake at different light intensities and temperatures in lettuce. HortScience. 2019;54(11):1925–33. doi:10.21273/hortsci14161-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sago Y. Effects of light intensity and growth rate on tipburn development and leaf calcium concentration in butterhead lettuce. HortScience. 2016;51(9):1087–91. doi:10.21273/hortsci10668-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kubota C, Papio G, Ertle J. Technological overview of tipburn management for lettuce (Lactuca sativa) in vertical farming conditions. Acta Hortic. 2023;88(1369):65–74. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2023.1369.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Inthichack P, Nishimura Y, Fukumoto Y. Effect of potassium sources and rates on plant growth, mineral absorption, and the incidence of tip burn in cabbage, celery, and lettuce. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2012;53(2):135–42. doi:10.1007/s13580-012-0126-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Huang S, Yan H, Zhang C, Wang G, Acquah SJ, Yu J, et al. Modeling evapotranspiration for cucumber plants based on the Shuttleworth-Wallace model in a Venlo-type greenhouse. Agric Water Manag. 2020;228(4):105861. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2019.105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Song J, Meng Q, Du W, He D. Effects of light quality on growth and development of cucumber seedlings in controlled environment. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2017;10(3):312–8. doi:10.3965/j.ijabe.20171003.2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ali Lakhiar I, Gao J, Xu X, Syed TN, Ali Chandio F, Jing Z, et al. Effects of various aeroponic atomizers (droplet sizes) on growth, polyphenol content, and antioxidant activity of leaf lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Trans ASABE. 2019;62(6):1475–87. doi:10.13031/trans.13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hussain Tunio M, Gao J, Ahmed Qureshi W, Ali Sheikh S, Chen J, Ali Chandio F, et al. Effects of droplet size and spray interval on root-to-shoot ratio, photosynthesis efficiency, and nutritional quality of aeroponically grown butterhead lettuce. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2022;15(1):79–88. doi:10.25165/j.ijabe.20221501.6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dou H, Li X, Li Z, Song J, Yang Y, Yan Z. Supplementary far-red light for photosynthetic active radiation differentially influences the photochemical efficiency and biomass accumulation in greenhouse-grown lettuce. Plants. 2024;13(15):2169. doi:10.3390/plants13152169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhan L, Hu J, Ai Z, Pang L, Li Y, Zhu M. Light exposure during storage preserving soluble sugar and l-ascorbic acid content of minimally processed romaine lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. longifolia). Food Chem. 2013;136(1):273–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Shyamala BNJr, Jamuna P. Nutritional content and antioxidant properties of pulp waste from Daucus carota and beta vulgaris. Malays J Nutr. 2010;16(3):397–408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

45. Tunio MH, Gao J, Mohamed TMK, Ahmad F, Abbas I, Ali Shaikh S. Comparison of nutrient use efficiency, antioxidant assay, and nutritional quality of butter-head lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) in five cultivation systems. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2023;16(1):95–103. doi:10.25165/j.ijabe.20231601.6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jahan MS, Guo S, Baloch AR, Sun J, Shu S, Wang Y, et al. Melatonin alleviates nickel phytotoxicity by improving photosynthesis, secondary metabolism and oxidative stress tolerance in toma to seedlings. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;197:110593. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Kozai T. Resource use efficiency of closed plant production system with artificial light: concept, estimation and application to plant factory. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2013;89(10):447–61. doi:10.2183/pjab.89.447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Miao C, Yang S, Xu J, Wang H, Zhang Y, Cui J, et al. Effects of light intensity on growth and quality of lettuce and spinach cultivars in a plant factory. Plants. 2023;12(18):3337. doi:10.3390/plants12183337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kang JH, KrishnaKumar S, Atulba SLS, Jeong BR, Hwang SJ. Light intensity and photoperiod influence the growth and development of hydroponically grown leaf lettuce in a closed-type plant factory system. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2013;54(6):501–9. doi:10.1007/s13580-013-0109-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Sutulienė R, Laužikė K, Pukas T, Samuolienė G. Effect of light intensity on the growth and antioxidant activity of sweet basil and lettuce. Plants. 2022;11(13):1709. doi:10.3390/plants11131709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Luo HY, He J, Lee SK. Interaction between calcium concentration and growth irradiance on photosynthesis and growth of temperate lettuce in the tropics. J Plant Nutr. 2009;32(12):2062–79. doi:10.1080/01904160903308150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Fu Y, Li H, Yu J, Liu H, Cao Z, Manukovsky NS, et al. Interaction effects of light intensity and nitrogen concentration on growth, photosynthetic characteristics and quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. Var. Youmaicai). Sci Hortic. 2017;214(93):51–7. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2016.11.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yan W, Wang Q, Yang L. Distribution of lanthanum in Spinach chloroplasts and its effect on photosynthesis. Chin Sci Bull. 2005;50(12):1195–200. doi:10.1360/csb2005-50-12-1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Feng J, Liu R, Luo H. Effect of different calcium levels on growth, yield and fruit quality of tomatoes in substrate culture. Agric Sci Technol. 2015;16(8):1704–8. doi:10.16175/j.cnki.1009-4229.2015.08.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Lauwers S, Coussement JR, Steppe K. Interlinked temperature and light effects on lettuce photosynthesis and transpiration: insights from a dynamic whole-plant gas exchange system. Agronomy. 2025;15(9):2180. doi:10.3390/agronomy15092180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Loconsole D, Cocetta G, Santoro P, Ferrante A. Optimization of LED lighting and quality evaluation of romaine lettuce grown in an innovative indoor cultivation system. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):841. doi:10.3390/su11030841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. de Bang TC, Husted S, Laursen KH, Persson DP, Schjoerring JK. The molecular-physiological functions of mineral macronutrients and their consequences for deficiency symptoms in plants. New Phytol. 2021;229(5):2446–69. doi:10.1111/nph.17074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Kuang D, Romand S, Zvereva AS, Marchesano BMO, Grenzi M, Buratti S, et al. The burning glass effect of water droplets triggers a high light-induced calcium response in the chloroplast stroma. Curr Biol. 2025;35(11):2642–58.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2025.04.065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Dai M, Tan X, Ye Z, Ren J, Chen X, Kong D. Optimal light intensity for lettuce growth, quality, and photosynthesis in plant factories. Plants. 2024;13(18):2616. doi:10.3390/plants13182616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Min Q, Marcelis LFM, Nicole CCS, Woltering EJ. High light intensity applied shortly before harvest improves lettuce nutritional quality and extends the shelf life. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:615355. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.615355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhou WL, Liu WK, Wen J, Yang QC. Changes in and correlation analysis of quality indices of hydroponic lettuce under short-term continuous light. Chin J Eco Agric. 2011;19(6):1319–23. doi:10.3724/sp.j.1011.2011.01319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Bian ZH, Yang QC, Liu WK. Effects of light quality on the accumulation of phytochemicals in vegetables produced in controlled environments: a review. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;95(5):869–77. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Wu Y, Zhu J, Li Y, Li M. Effect of high-voltage electrostatic field on inorganic nitrogen uptake by cucumber plants. Trans ASABE. 2016;59(1):25–9. doi:10.13031/trans.59.11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Zhou X, Sun J, Mao H, Wu X, Zhang X, Yang N. Visualization research of moisture content in leaf lettuce leaves based on WT-PLSR and hyperspectral imaging technology. J Food Process Eng. 2018;41(2):e12647. doi:10.1111/jfpe.12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Cui S, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Nie S. Genome-wide identification of BrCAX genes and functional analysis of BrCAX1 involved in Ca2+ transport and Ca2+ deficiency-induced tip-burn in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Genes. 2023;14(9):1810. doi:10.3390/genes14091810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Gilliham M, Dayod M, Hocking BJ, Xu B, Conn SJ, Kaiser BN, et al. Calcium delivery and storage in plant leaves: exploring the link with water flow. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(7):2233–50. doi:10.1093/jxb/err111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Li H, Lian HF, Liu SQ, Yu XH, Sun YL, Guo HP. Effect of cadmium stress on physiological characteristics of garlic seedlings and the alleviation effects of exogenous calcium. Chin J Appl Ecol. 2015;26(4):1193–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.13287/j.1001-9332.2015.0032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Zhang Y, Luo ZR, Li NY, Ma YH, Huang Z, Yang YQ, et al. Effect of light intensity on the physiological indexes of senxibeier and jiminuo Lactuca sativa. Agric Technol Equip, 2025;2025(1):168–70,176. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

69. Jiang Y, Jing D, Wang L. Effects of calcium chloride solution on quality and tipburn of lettuce in plant factories. North Hortic. 2018;5:46–52. (In Chinese). doi:10.14083/j.issn.1001-4942.2024.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Tan YQ, Yang Y, Shen X, Zhu M, Shen J, Zhang W, et al. Multiple cyclic nucleotide-gated channels function as ABA-activated Ca2+ channels required for ABA-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2023;35(1):239–59. doi:10.1093/plcell/koac274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools