Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of Supplementation Time and Selenium Chemical Form on the Efficiency of Dandelion Biofortification

1 Federal Scientific Vegetable Center, Selectsionnaya 14, VNIISSOK, Odintsovo District, Moscow, 143072, Russia

2 Medical Faculty, Department of General and Clinical Pharmacology, Penza State University, Penza, 440026, Russia

3 Institute of Living Systems, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Kaliningrad, 236040, Russia

4 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Biotechnology and Horticulture, University of Agriculture, Krakow, 31-120, Poland

5 Department of Food Technologies, ‘Ion Ionescu de la Brad’ Iasi University of Life Sciences, Iasi, 700490, Romania

6 Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Portici, Naples, 80055, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Nadezhda Golubkina. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3861-3877. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070988

Received 29 July 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

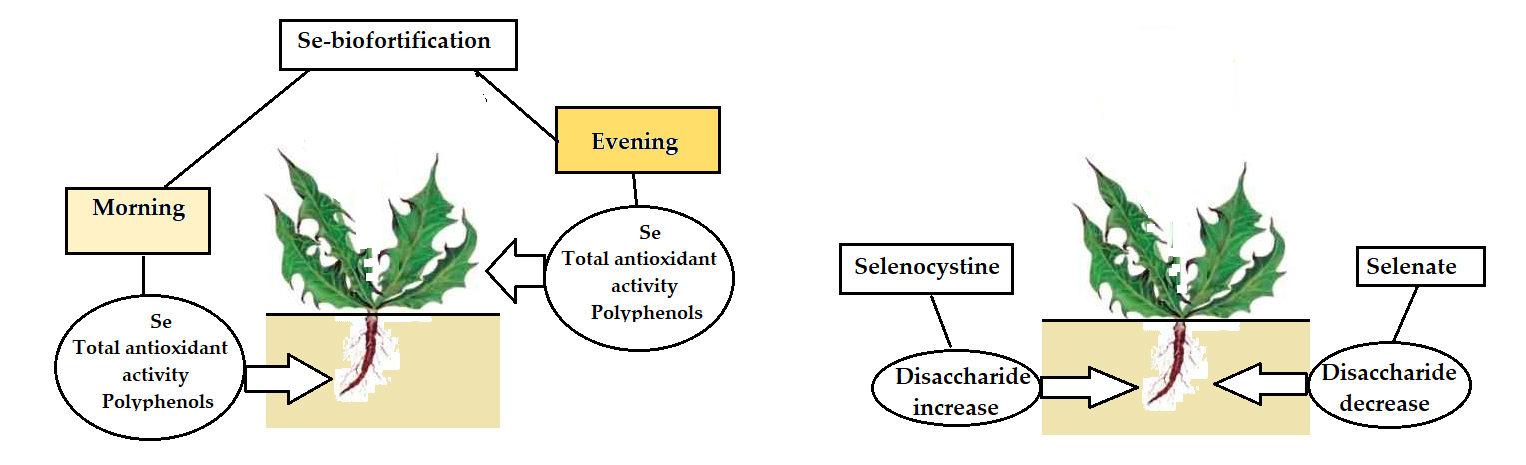

Circadian biorhythms are fundamental in plant adaptability and development. To reveal the effect of organic and inorganic forms of Se, foliar treatments of dandelion with 0.26 mM Se solutions were practiced in two contrasting day times: in the morning with the highest levels of leaf Se and polyphenol (TP) and the lowest dry matter, and in the evening with the opposite characteristics. Compared to the control, the morning Se supply demonstrated a higher increase of root biomass (1.27–1.37 times), Se (1.82–2.85 times), TP content (1.42–1.44 times), and antioxidant activity (AOA) (1.47–1.48 times) than the evening treatment. The latter did not affect root biomass and TP levels, but increased Se (1.38–2.57 times) and AOA (1.47–1.48 times). Contrary, compared to control, the evening Se supply improved leaf parameters more significantly than the morning treatment: AOA (1.22–1.25 vs. 1.12–1.17), TP (1.29–1.33 vs. 1.10–1.25), and Se (7.03–8.58 vs. 5.32–7.19). Similar photosynthetic pigment increase was recorded under organic and inorganic Se supply and between morning and evening treatments. Contrasting trends in root disaccharide accumulation under Se supply were recorded between morning and evening treatments, with a significant decrease of the mentioned parameter in the former case (1.27–1.15 times) and an increase in the latter (1.11–1.31 times). Contrary to other dandelion characteristics, only disaccharide root levels demonstrated higher changes under selenocystine supply, compared to selenate. The revealed phenomenon indicates the differences in root/leaf biochemical profile response to the time of Se supplementation and may become the basis of targeted production of functional food products with improved yield and nutritional value.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Circadian biorhythms of various biochemical processes represent the basis of plant growth, development, and the adaptation efficiency to the environmental factors, optimizing hormonal and antioxidant status, photosynthesis, and plant productivity [1,2]. The biosynthesis regulation of various phytohormones, such as ethylene, salicylic, jasmonic, indol-3-acetic, and abscisic acids, gibberellins, cytokinin, and brassinosteroids, via special circadian genes participation provides the daily rhythms in hormone activities, optimizes nutrient assimilation, and the protection of plants against biotic and abiotic stresses [3,4]. In their turn, phytohormones modulate the biosynthesis of many biologically active compounds, including polyphenols [5,6], terpenoids [7], sterols [8], vitamins [9], etc. According to literature reports, low selenium dose supply may affect gene expression, phytohormone and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, improving yield and the accumulation of natural antioxidants, stimulating photosynthesis, and increasing protein and carbohydrate content [10,11].

Investigations of Se circadian biorhythms of several Allium species, trees, and bushes revealed significant circadian oscillations of the element concentrations supposedly linked to the involvement of the volatile methyl selenide formation [12]. The detected phenomenon and the ability of small Se doses to stimulate antioxidant biosynthesis in plants indicate the possibility of the circadian biorhythm effect on the efficiency of plant biofortification with Se. The latter may become of high importance in the production of functional food with high levels of Se suitable for the optimization of the human Se status. Uneven distribution of Se in the world causes the abundance of Se deficiency among the population of many countries [13], inducing decreased resistance to viral, oncological, and cardiovascular diseases [14,15], optimizing the immunity and providing the beneficial conditions of the iodine metabolism [16].

Up to date, the common recommendations of plant biofortification with Se include foliar Se supply in the morning or evening to diminish the possibility of plant sunburn [17]. Several investigations indicate higher prospects of the evening Se supply, due to low leaf temperature and stomatal closure preventing Se loss through transpiration and enhancing plant absorption [18].

Foliar Se treatment was proven to be more beneficial than soil application due to the exclusion of the irreversible soil absorption of the element [19]. Accumulation of Se by leaves occurs through the stomata, cuticle, stigmata, hydathodes, and trichomes with the subsequent transfer of the microelement to chloroplasts and the formation of seleno-amino acids: selenocysteine and selenomethionine [20,21]. Selenate is the prevailing chemical form of Se used for biofortification, characterized by high mobility and accessibility. Utilization of organic chemical forms (selenomethionine, selenocystine) results in higher levels of the most bioavailable Se amino acids for humans, but it is not so popular due to the high costs of Se-amino acid synthesis. In this respect, the new method of low-cost selenocystine production [22] opens high prospects of its utilization in plant biofortification with Se.

Taking into account that no investigations of the circadian biorhythms' effect on plant Se biofortification have been documented so far, the present research aimed to evaluate the efficiency of the morning/evening foliar Se supply, both in the forms of selenate and selenocystine, on dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) growth and biochemical parameters. Dandelion (Asteraceae family) has been the object of investigation and is known for its high adaptability, fast growth, high nutritional and medicinal value [23,24], and suitability for Se biofortification [25].

2.1 Experimental Protocol and Growing Conditions

Research was carried out on wild dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) grown in Moscow region (55°48′00″ N; 37°56′00″ E) in clay-loam soil with pH 6.8, 1.8% organic matter, and 230 μg kg−1 d.w. Se content.

To elicit the dandelion circadian biorhythms of Se and polyphenols, leaf samples were gathered from 4 to 22 h in 3 random sunny days around mid-May in 2024 and 2025 every two hours, cutting leaves from 5–6 plants to compose a mixed sample. Probes were kept in the refrigerator at +10°C up to the next day and transferred to the laboratory. The samples were dried at 70°C, homogenized, and subjected to the determination of Se, AOA, and TP.

The experimental protocol was based on the factorial combination between two foliar selenium biofortification treatments (sodium selenate and selenocystine) and two application times (8.00 in the morning and 20.00 in the evening), plus an untreated control. The Se treatments were practiced twice on 10 and 12 May 2025, spraying plants with 0.26 mM solutions (100 mL per 10 plants) of sodium selenate (Sigma-Aldrich, SigmaUltra, St. Louis, MO, USA) or selenocystine (synthesized in Penza University, according to Poluboyarinov et al. [22]). The chosen concentration of Se is most often used for agricultural crop biofortification due to low toxicity and high efficiency of Se accumulation.

Mean day/night temperature during the experiment is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Mean day, night temperatures during the experiment.

A randomized complete block design was used for the treatment distribution in the field, with three replicates, and each experimental unit covered a 10 m2 surface area. Plants were harvested in the evening on 1 June. After transferring to the laboratory, roots and leaves were separated, washed with the tip water, and dried using a filter paper. After measuring the biometrical parameters and weight, leaves were homogenized, and the ascorbic acid and photosynthetic pigments were analyzed. The residue was dried at 70°C to constant weight and homogenized to obtain a fine powder for determining AOA, TP, carbohydrates, and Se.

The dry residue was assessed gravimetrically by drying the samples in an oven at 70°C until constant weight. The calculation of dry matter content was performed according to the formula: D.M. (%) = (M1:M2) × 100, where M1 and M2 are the sample biomass after and before drying, respectively.

Chlorophyll a, b, and carotene (in mg g−1 f.w.) were determined spectrophotometrically using the absorption level of leaf ethanolic extracts at 664, 649, and 407 nm on Unico 2804 UV spectrophotometer (Suite E, Dayton, Newark, NJ, USA) and the appropriate equations [26]: Chl a = 13.36A664 − 5.19A649; Chl b = 27.43A649 − 8.12A664; Car = (1000A470 − 2.13Chl a − 97.63Chl b)/209 where A = light absorption, Chl-a: chlorophyll a, Chl-b: chlorophyll b, Car: carotene.

The concentration of the ascorbic acid was determined according to the AOAC titrimetric method based on Tillman’s reagent utilization [27] and using 6% trichloracetic acid for vitamin C extraction. The sensitivity of visual titration is equal to 5 μg mL−1. The results were expressed in mg 100 g−1 f.w.

2.2.4 Preparation of Ethanolic Extracts

The antioxidant activity and TP content were analyzed in 70% ethanol extracts of dry homogenized dandelion root and leaf power. Utilization of dry homogenized material of dandelion roots and leaves provides the opportunity to use representative probes, which is extremely important due to low sampling weight. One gram of dry dandelion root and half a gram of leaf powder were extracted with 20 mL of 70% ethanol (7:3, v/v) at 80°C for 1 h. The mixture was cooled and quantitatively transferred to a volumetric flask, and the volume was adjusted to 25 mL. The obtained extracts after filtration were used for the determination of TP and AOA.

Polyphenol content was assessed spectrophotometrically based on the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method [28]. One mL of ethanolic extract prepared as described in Section 2.2.4 was transferred to a 25 mL volumetric flask, to which 2.5 mL of saturated sodium carbonate solution and 0.25 mL of diluted (1:1, v/v) Folin–Ciocalteu reagent were added. After adjusting the volume to 25 mL with distilled water and keeping the mixture at room temperature for 1 h, the absorption of the reaction mixture at 730 nm was read, and the TP concentration was calculated using the gallic acid solution as an external standard. The TP content was expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per g (mg GAE g−1 d.w.).

2.2.6 Antioxidant Activity (AOA)

The total antioxidant activity of dandelion leaves and roots was assessed via titration of 1 mL 0.01 N potassium permanganate solution in 8 mL of distilled water and 1 mL of 20% sulfuric acid with ethanolic extracts, produced as described in Section 2.2.4 [28], with the formation of colorless Mn2+. As an external standard, 0.02% gallic acid was used. The AOA values were expressed as mg GAE g−1 d.w.

The monosaccharides in dry dandelion roots were determined using the ferricyanide colorimetric method, based on the reaction of sugar with potassium ferricyanide K3Fe(CN)6 in the presence of an alkaline, with the formation of potassium ferrocyanide K4Fe(CN)6 [29]. Sugar extraction was achieved by distilled water at 80°C in half an hour. After precipitation of proteins with a saturated solution of lead acetate and removal of lead acetate excess using 10% sodium sulfate solution, the extract was filtered through a filter paper and used for the titration of 1% potassium ferricyanide solution in the presence of 1% sodium hydroxide and a drop of 1% methylene blue as an internal indicator. The endpoint of the titration was represented by the full discoloration of the solution. The total sugar content was analogically determined after acidic hydrolysis of water extracts with 20% hydrochloric acid, and the disaccharide concentration was calculated as a difference between the above-mentioned parameters. Fructose was used as an external standard, and all the determinations were performed in triplicate. The results were expressed in % per d.w.

2.2.8 Crude Polysaccharides [30]

One g of dried homogenized dandelion root powder was mixed with 15 mL of water and extracted using intensive agitation for 3 h at 80°C. The mixture was centrifuged at 8000 r min−1 for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was separated and mixed with a four times higher volume of 85% ethanol to form a precipitate. The latter was separated via centrifugation at 10,000 r min−1 for 20 min at 4°C and dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water. The amount of polysaccharide content was determined gravimetrically after protein removal and polysaccharide precipitation with ethanol.

Selenium was analyzed using the microfluorometric method [31] based on sample digestion with a mixture of nitric-perchloric acids, reduction of selenate (Se6+) to selenite (Se4+) via interaction with 6 N HCl, and the formation of a complex (piazoselenol) between Se4+ and 2,3-diaminonaphtalene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The Se concentration (in μg kg−1 d.w.) was calculated by recording the piazoselenol fluorescence value in hexane at 519 nm λ emission and 376 nm λ excitation with fluorimeter Fluorate 02–5M (Lumex, Saint Petersburg, Russia). The precision of the results was verified using in each determination two reference standards: Se-fortified mitsuba stem powder and lyophilized cabbage powder, with Se concentrations of 1865 μg kg−1 and 150 μg kg−1, respectively (Federal Scientific Vegetable Center, Moscow, Russia). The concentration of Se was determined using a calibration curve (R2 = 0.996) built with 5 different Se concentrations of sodium selenate (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 nM Se). The Se concentration was calculated according to the formula: Se (μg kg−1 d.w.) = 79 × C:a, where C—the Se content in a probe, determined from a calibration curve, in nM; 79—the Se atomic mass; a—the sample weight, in g.

All the analyses were performed in triplicate. All data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test at a significance level of p < 0.05. The results confirmed that all parameters followed a normal distribution. Subsequently, the data were subjected to analysis of variance, and mean separations were performed through Duncan’s multiple range test, with reference to a 0.05 probability level, using SPSS software version 29 (Armonk, NY, USA). Data expressed as percentages were subjected to angular transformation before processing.

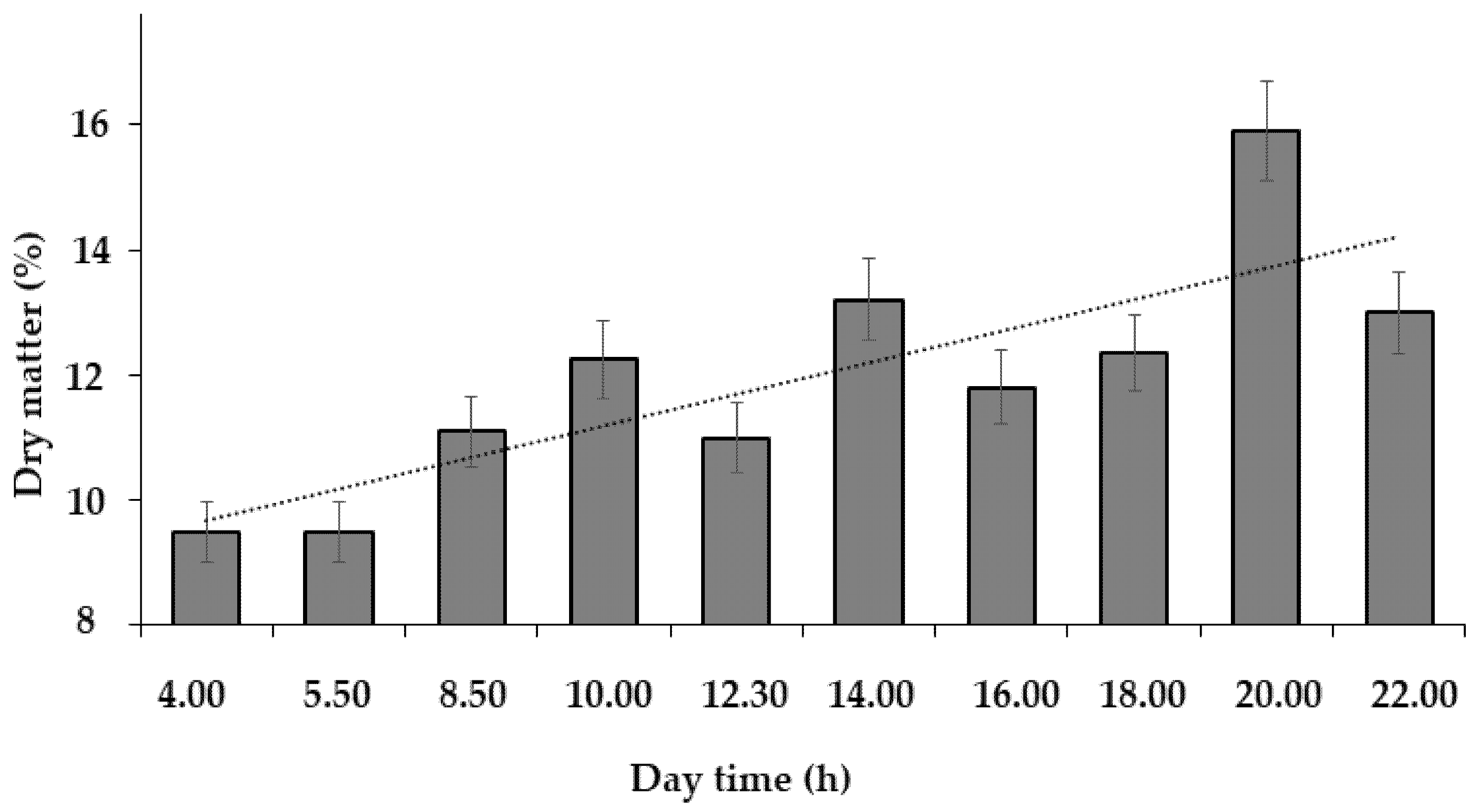

The evaluation of circadian fluctuations of the dandelion leaf chemical composition demonstrated a gradual increase in the leaf dry matter content during the daytime (Fig. 2), which was related to the intensive evaporation. Lack of precipitation during the period investigated makes it consider the dew as the main water source for dandelion development, and the main differences in water availability in the morning and evening.

Figure 2: Dynamics of the dandelion leaf dry matter content (mean values for 3 tested days).

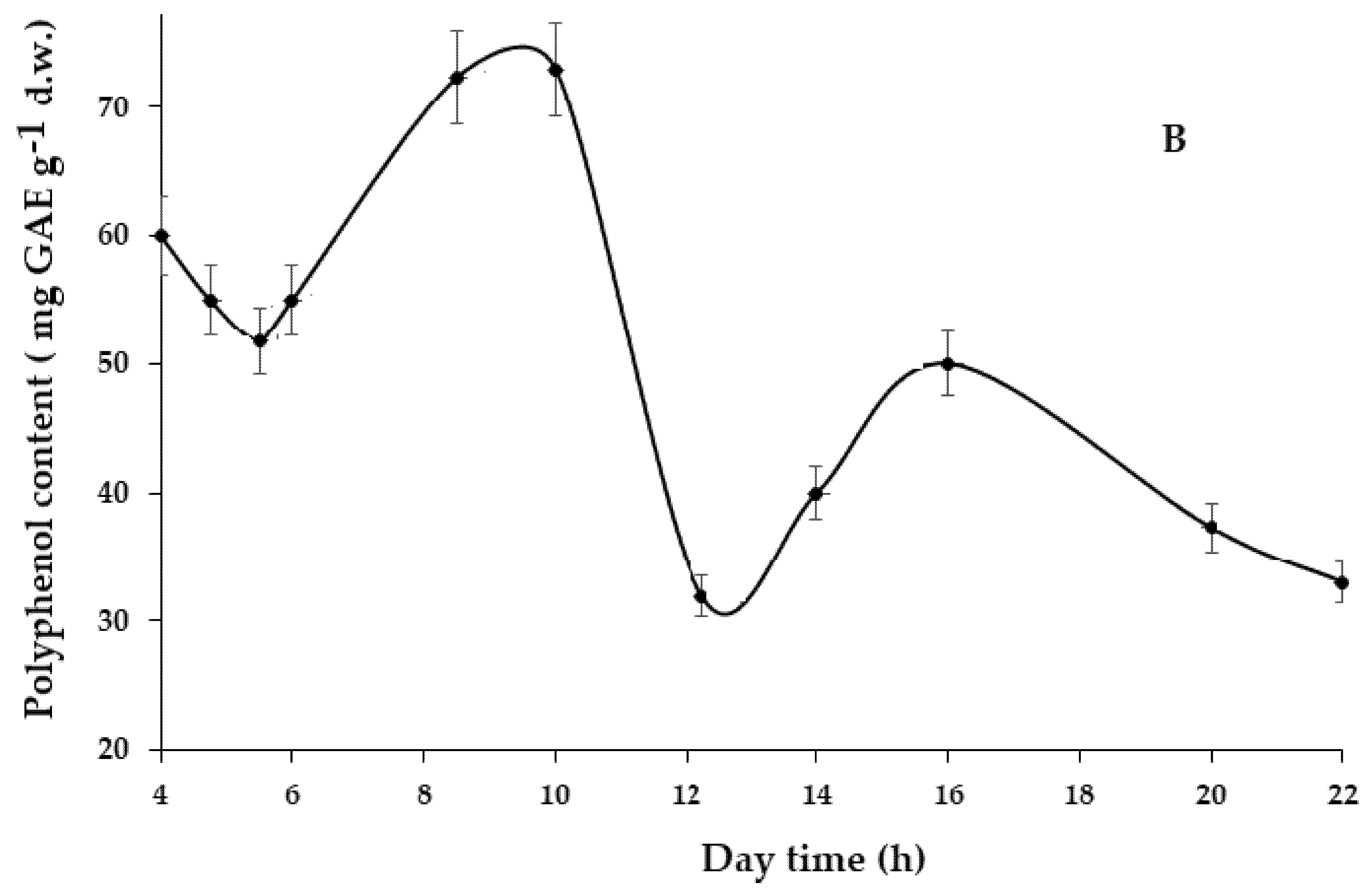

During this period, significant fluctuations were recorded both for leaf Se (Fig. 3A) and TP content (Fig. 3B). In both cases, the peaks of Se and TP concentrations were recorded with an interval of 8–10 h in the morning, with a much lower intensity of these parameters at 4 p.m. (16 h). The two lowest values were recorded in the early morning (5.30) and at noon (12.00), with the latter point corresponding to the highest intensity of sunlight and temperature.

Similar circadian fluctuations of Se in Allium leaves, corresponding to (8–10 h) and (15–16 h) peaks, along with the noon minimum, were previously reported [12]. Taking into account the ability of plants to synthesize volatile methyl selenides [32,33], the present results make it suppose the participation of the latter compounds in plant Se status regulation, not only in conditions of excess environmental Se, but also in the dynamics of physiological processes during the daytime.

Figure 3: Circadian biorhythms of Se (A) and total polyphenols (B) in dandelion leaves.

Up to date, Se methylation process has been discussed only as a promising way of Se phytoremediation [33]. Multiplicity of the environmental factor effects makes it difficult to predict the behavior of the appropriate parameters for other plant species, though Se day fluctuations have been previously recorded in leaves of chives (A. schoenoprasum), garlic (A. sativum), strawberry (Fragaria viridis), apple-tree (Malus domestica), and blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) [12].

A close relationship between Se and phytohormones may at least partially explain Se fluctuations being the effect of Se-ethylene [34], Se-gibberellins [18,35], Se-salicylic acid [36], and Se-cytokinin [37] interactions. Nevertheless, the possible relationship between circadian phytohormone fluctuations [38,39] and Se concentration levels needs further investigation.

As far as polyphenol oscillations are concerned, literature reports confirm the existence of the morning peak in the TP accumulation in plant leaves associated with high UV radiation in the first light hours of the day [40]. Other investigations indicate species-dependent TP biorhythms with possible variations of the TP component composition [5].

Furthermore, the synchronous fluctuations of Se and polyphenol content during daytime indicate a high positive correlation between these parameters (r = 0.800; p < 0.001; n = 11). The results are in accordance with the literature reports about Se biostimulation of antioxidants in plants [41,42].

Taking into account the significant variations between morning and evening, in terms of plant physiological parameters remarkably differing in the dry matter content and antioxidant status including the AOA, TP, and Se levels, plants were sprayed with a solution of sodium selenate and selenocystine in two opposite day times: (1) 8 a.m. (low dry matter; high Se and polyphenol content) and (2) 8 p.m. (high dry matter; low Se and polyphenol content).

The biometrical parameters showed a significant increase in plant biomass as well as leaf length, width, and surface under Se supply (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1: Plant biomass and dry matter content in dandelion under organic and inorganic Se supply.

| Parameter | Se Form and Time of Application | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf biomass (g) | Control | 17.9 ± 1.7 d |

| Selenate-morning | 39.2 ± 3.2 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 34.9 ± 3.1 ab | |

| Selenate-evening | 31.7 ± 4.0 bc | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 27.4 ± 2.6 c | |

| Root biomass (g) | Control | 9.9 ± 0.9 b |

| Selenate-morning | 13.6 ± 1.3 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 12.2 ± 1.1 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 9.8 ± 0.7 b | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 9.4 ± 0.8 b | |

| Leaf dry matter (%) | Control | 12.8 ± 1.1 a |

| Selenate-morning | 13.0 ± 1.2 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 13.8 ± 1.3 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 12.5 ± 1.2 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 12.4 ± 1.2 a | |

| Root dry matter (%) | Control | 25.3 ± 2.1 a |

| Selenate-morning | 26.0 ± 2.2 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 25.4 ± 2.2 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 25.1 ± 2.1 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 24.4 ± 2.1 a |

Indeed, selenate treatment increased leaf biomass by 2.2–2.3 times, compared to control, independently of the treatment time, while selenocystine was less effective, augmenting leaf biomass by 1.5–1.9 times. Contrary, root biomass did not change significantly after evening Se supply of both selenate and selenocystine, whereas the morning treatment enhanced root biomass by 1.23–1.37 times (Table 1).

No significant changes in the dry matter content in leaves and roots were recorded as a result of Se supplementation. Dandelion leaf surface and width under morning Se supply showed significant increase by 1.62–1.75 and 1.29–1.43 times, respectively, with no significant effect in the evening (Table 2). Leaf length changed by 1.03–1.17 times.

Table 2: Leaf morphological parameters of dandelion under Se supply.

| Parameter | Se Form and Time of Application | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf length (cm) | Control | 33.0 ± 3.0 a |

| Selenate-morning | 37.0 ± 4.3 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 38.7 ± 3.3 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 34.0 ± 3.1 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 38.5 ± 3.2 a | |

| Leaf surface (mm2) | Control | 117.9 ± 11.2 b |

| Selenate-morning | 206.8 ± 20.0 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 190.7 ± 16.0 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 113.1 ± 11 b | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 95.3 ± 9.2 b | |

| Leaf width (cm) | Control | 70.0 ± 6.8 c |

| Selenate-morning | 90.0 ± 8.9 ab | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 100.0 ± 10.0 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 70.0 ±7.1 c | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 80.0 ± 7.9 bc |

The recorded growth stimulation effect of Se described in other plants [11,43] was in agreement with the significant increase of photosynthetic pigment accumulation in dandelion leaves (Table 3). Indeed, Se supply improved chlorophyll a content by 1.3–1.5 times, chlorophyll b—by 1.3–1.4 times, and carotene—by 1.2–1.4 times. A similar encouragement of photosynthetic pigment biosynthesis occurred in other plants treated with different forms of Se [11,41,43]. No significant differences between morning and evening values of the measured parameters were recorded for carotene and total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a/b, and chlorophyll/carotene ratios. The chemical form of Se also did not significantly affect the efficiency of photosynthesis activation, and, based on the obtained results, there was only a tendency of lower selenocystine effect (Fig. 4).

Table 3: Photosynthetic pigments of dandelion leaves.

| Parameter | Se Form and Time of Application | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll a (mg g−1 f.w.) | Control | 0.153 ± 0.012 b |

| Selenate-morning | 0.217 ± 0.020 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 0.206 ± 0.020 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 0.225 ± 0.020 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 0.200 ± 0.018 a | |

| Chlorophyll b (mg g−1 f.w.) | Control | 0.090 ± 0.006 c |

| Selenate-morning | 0.126 ± 0.010 b | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 0.121 ± 0.010 b | |

| Selenate-evening | 0.125 ± 0.100 b | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 0.125 ± 0.100 b | |

| Carotene (mg g−1 f.w.) | Control | 0.026 ± 0.002 b |

| Selenate-morning | 0.037 ± 0.003 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 0.035 ± 0.003 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 0.036 ± 0.003 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 0.032 ± 0.003 a | |

| Total chlorophyll (mg g−1 f.w.) | Control | 0.162 ± 0.012 b |

| Selenate-morning | 0.343 ± 0.031 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 0.327 ± 0.030 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 0.330 ± 0.031 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 0.325 ± 0.030 a | |

| Chlorophyll a/b ratio | Control | 1.70 ± 0.11 a |

| Selenate-morning | 1.72 ± 0.11 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 1.70 ± 0.10 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 1.64 ± 0.10 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 1.60 ± 0.10 a | |

| Total Chlorophyll/Carotene ratio | Control | 6.23 ± 0.61 b |

| Selenate-morning | 9.27 ± 0.62 a | |

| Selenocystine-morning | 9.34 ± 0.63 a | |

| Selenate-evening | 9.70 ± 0.64 a | |

| Selenocystine-evening | 10.09 ± 0.97 a |

Figure 4: Effect of circadian fluctuations and chemical form of Se on accumulation of photosynthetic pigments in dandelion leaves.

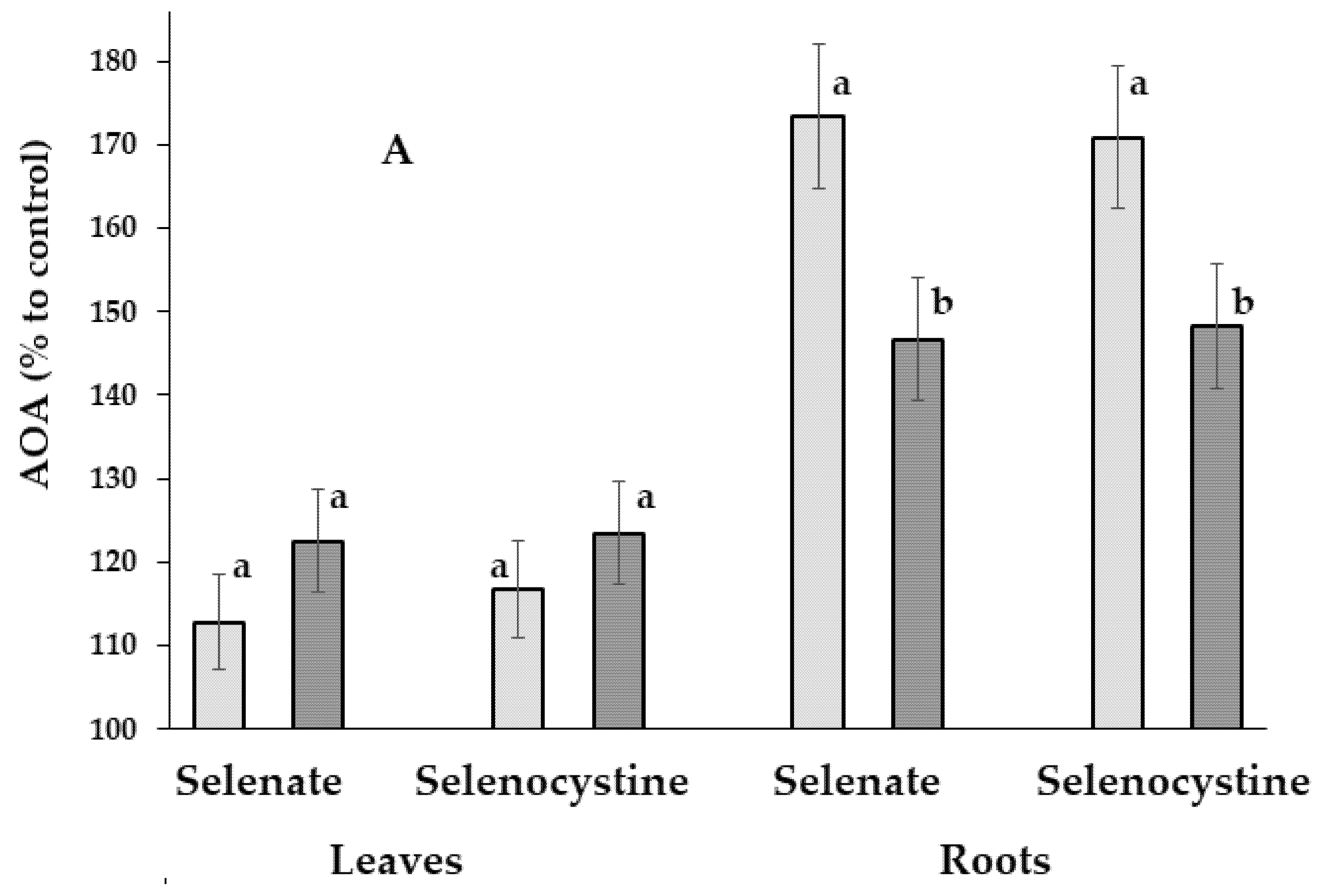

3.2.3 Effect of Se on the Antioxidant Status of Plants

Being a natural antioxidant, Se improves membrane stability, antioxidant enzyme biosynthesis via gene regulation, and stimulates the accumulation of secondary metabolites, including ascorbic acid and TP, especially in stress conditions [41]. Indeed, Se supplementation increased the ascorbic acid content in dandelion leaves by 1.28–1.45 times, compared to the control plants, with slightly lower effect under the selenocystine supply (Table 4). Similar beneficial effect of Se was recorded previously in other agricultural crops [43,44].

Table 4: Antioxidant status of dandelion under Se supply.

| Se Form and Time of Application | AOA (mg GAE g−1 d.w.) | TP (mg GAE g−1 d.w.) | AA (mg 100 g−1 f.w.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Roots | Leaves | Roots | ||

| Control | 28.5 ± 2.0 a | 12.0 ± 1.0 b | 25.5 ± 2.1 c | 13.0 ± 1.0 b | 26.0 ± 2.1 b |

| Selenate-morning | 32.0 ± 2.9 ab | 20.8 ± 1.8 a | 28.0 ± 2.4 bc | 18.7 ± 1.4 a | 37.8 ± 3.3 a |

| Selenocystine-morning | 33.3 ± 3.0 ab | 20.5 ± 1.8 a | 31.9 ± 2.9 ab | 18.5 ± 1.4 a | 33.3 ± 3.0 a |

| Selenate-evening | 34.9 ± 3.0 a | 17.6 ± 1.2 a | 32.8 ± 3.0 ab | 13.8 ± 1.1 b | 37.2 ± 3.3 a |

| Selenocystine-evening | 35.2 ± 3.1 a | 17.8 ±1.3 a | 34.0 ± 3.1 a | 14.3 ± 1.2 b | 35.5 ±3.2 a |

The obtained data indicated that the effect of treatment time was not significant on the ascorbic acid content. Contrary, the corresponding effect of treatment time and Se chemical form on the AOA and TP was more specific, especially in plant roots (Table 4, Fig. 5).

Interestingly, despite the known significantly higher TP and AOA levels in leaves compared to the corresponding root parameters [45], Se beneficial effect was more pronounced in roots (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Effect of Se biofortification, day time, and chemical form on the total antioxidant activity (A) and the polyphenol content (B) of dandelion leaves and roots. AOA: total antioxidant activity; TP: polyphenol content. Within each organ, values with the same letters ‘a–b’ do not differ significantly according to the Duncan test at p < 0.05.

Indeed, differences in AOA/TP levels between the morning and evening Se-treated plants were much more pronounced compared to the corresponding data related to the ascorbic acid and photosynthetic pigment accumulation. Furthermore, changes in AOA/TP parameters as a result of morning/evening Se supply predominated in roots, compared to leaves (Fig. 5), eliciting an increase of root AOA by 1.7 times when plants were treated in the morning and by 1.45 times under the evening Se supply. Total root polyphenol content increased by 1.43 times compared to the control data only under morning treatment, with no significant effect in the evening.

In general, the morning Se treatment resulted in higher AOA levels in roots, compared to the evening supply, while the opposite trend was recorded in leaves (Fig. 5); the same pattern was observed for the TP content. The results suggest that the evening Se biofortification of leafy vegetables should provide higher leaf quality, while morning Se supply is more beneficial in root vegetable production. The existence of a certain mechanism of the equilibrium maintenance between the antioxidant status of roots and leaves has also arisen: the predominance of leaf antioxidant status improvement in conditions of TP and Se deficiency in the evening, and the predominance of root quality improvement in conditions of high leaf antioxidant status in the morning.

Notably, Se supply provided in leaves the highest increase of water-soluble antioxidant, and ascorbic acid (by 1.28–1.45 times), while lower changes were recorded for ethanolic extract parameters, i.e., the AOA (by 1.12–1.24 times) and TP (by 1.10–1.33 times) levels. The observed relationships may relate to the known interactions between these compounds and phytohormones: AA—with ethylene and gibberelins [46], TP—with auxins and cytokinins [47], Se—with ethylene, gibberelins, auxins, and abscisic acid [12,41].

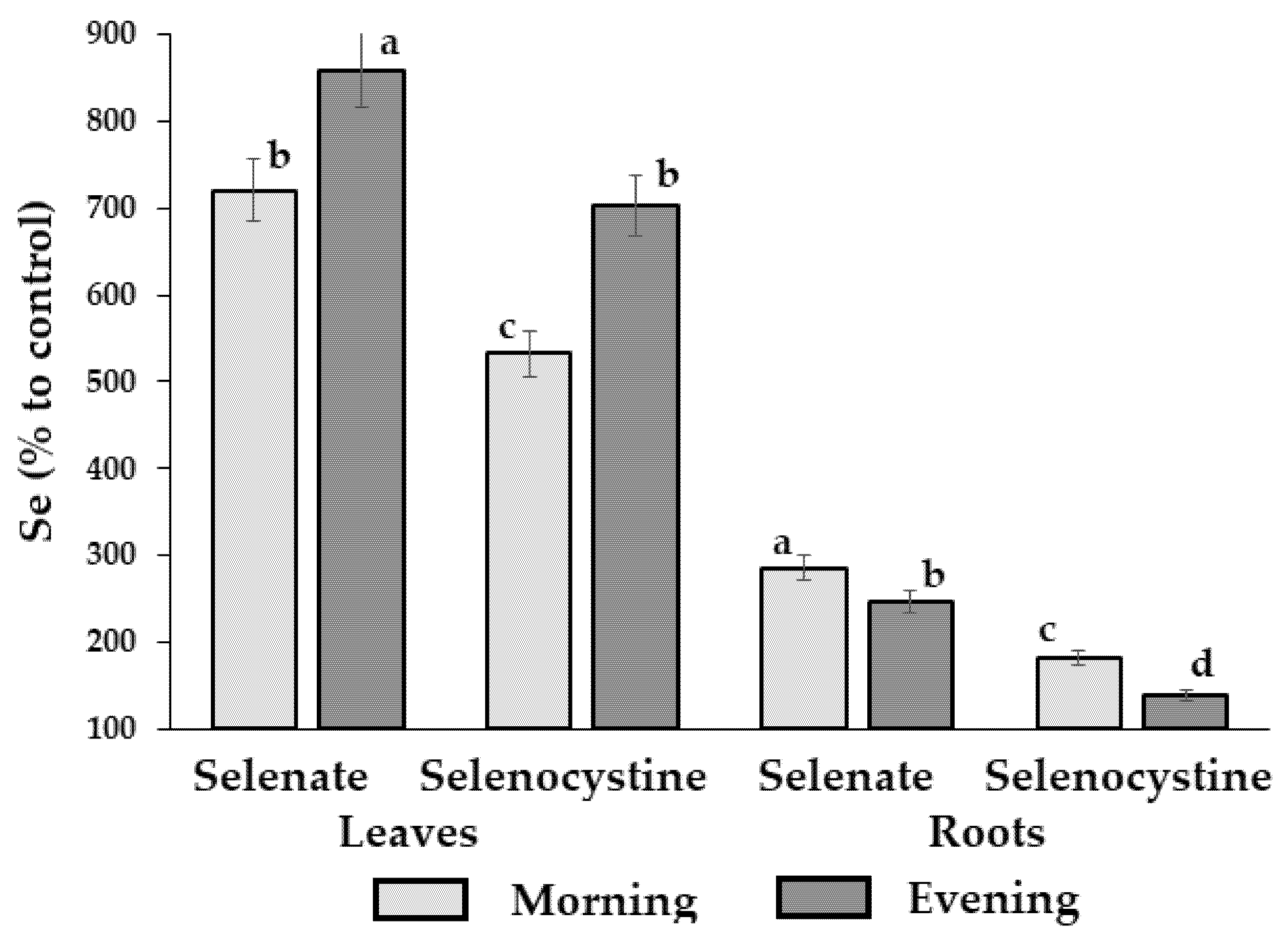

A similar phenomenon regarding the effect of Se supplementation time was revealed for the peculiarities of Se biofortification levels (Table 5, Fig. 6).

Table 5: Se content in dandelion leaves and roots before and after Se biofortification (μg kg−1 d.w.).

| Se Form and Time of Application | Leaves | Roots | Leaf/Root Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 74.1 ± 2.1 d | 50.6 ± 1.0 e | 1.46 |

| Selenate-morning | 533.0 ± 15.0 b | 144.0 ± 10.0 a | 3.70 |

| Selenocystine-morning | 394.0 ± 22.0 c | 92.0 ± 6.0 c | 4.28 |

| Selenate-evening | 636.0 ± 44.0 a | 125.0 ± 8.0 b | 5.09 |

| Selenocystine-evening | 521.0 ± 42.0 b | 70.4 ± 3.0 d | 7.40 |

Figure 6: Effect of Se supplementation time on the efficiency of dandelion biofortification with Se. Within each organ, values with the same letters ‘a–d’ do not differ statistically according to the Duncan test at p < 0.05.

Indeed, in conditions of low Se in sod-podzolic soil, the evening Se supply elicited a higher biofortification of leaves but lower of roots, whereas control plants accumulated only 74.1 and 50.1 μg Se per kg of dry dandelion leaves and roots, respectively. Notably, sodium selenate supply resulted in higher Se accumulation in roots than selenocystine, possibly due to the higher mobility of the Se6+. Furthermore, the results are in accordance with the reports of higher biofortification levels of plants with lower Se content [48] and differences between selenate and selenocystine effects on beetroot [49].

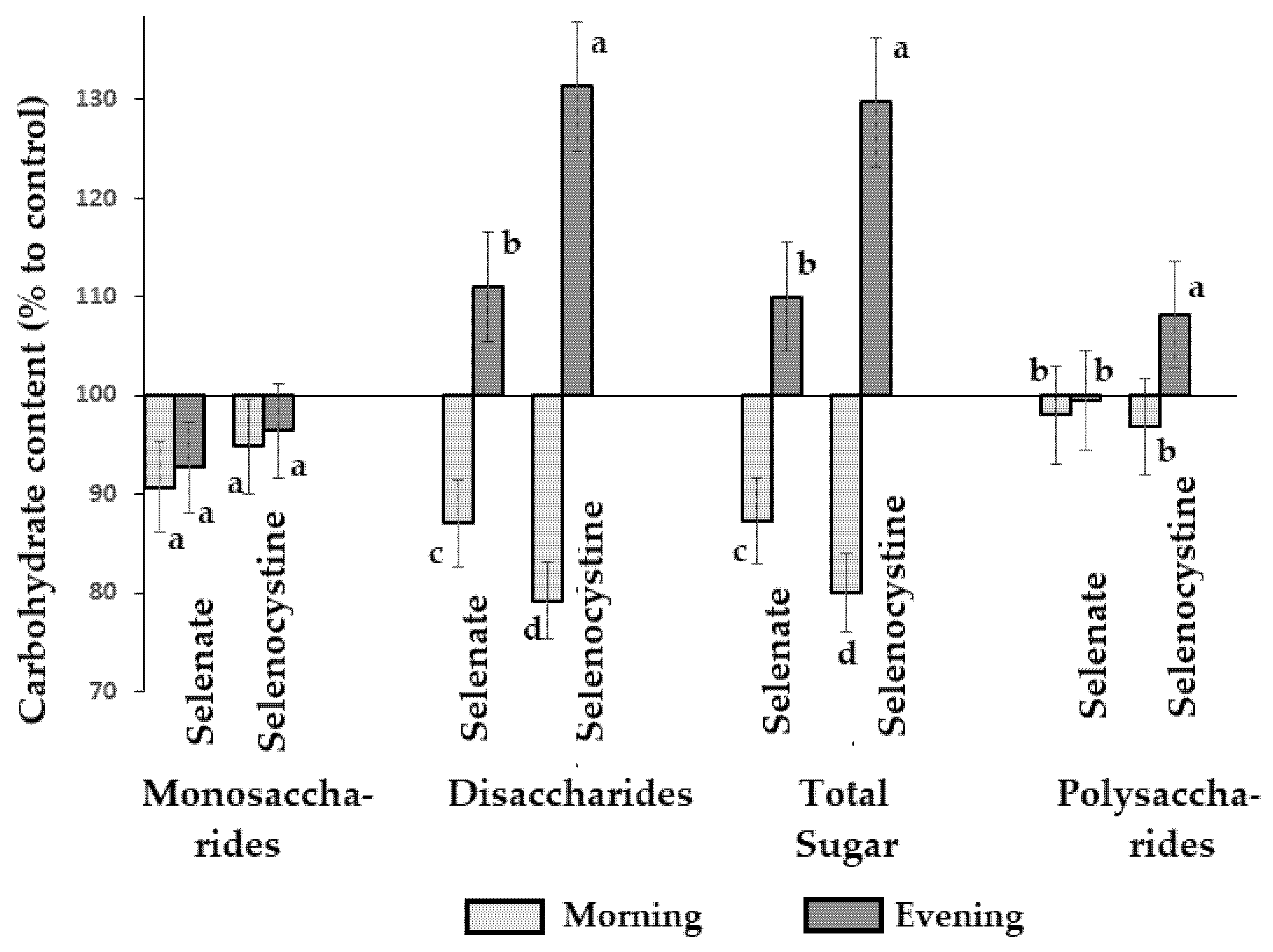

3.2.5 Mono-, Di-, and Polysaccharide Content

Dandelion roots are famous due to their polysaccharides showing immune regulation, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-aggregation properties [50]. The content of the mentioned compounds in dandelion roots may exceed 40% of d.w. in autumn, while it is about 20% in spring [51,52]. Lack of significant changes in polysaccharide accumulation is presumably connected with the short crop cycle of dandelion in spring, when polysaccharide content did not exceed 20%. The continuous accumulation of mono-, di-, and polysaccharides in dandelion roots during summer emphasizes the significance of low molecular weight carbohydrates at the beginning of vegetation. In the present investigation, the content of polysaccharides in dandelion roots did not exceed 20%, while the di-saccharides prevailed over the mono-saccharides, attaining 35–58% of root dry weight (Table 6, Fig. 7).

Table 6: Sugar content in dandelion roots as affected by Se supply (% of d.w.).

| Se Form and Time of Application | Monosaccharides | Disaccharides | Total | Crude Polysaccharides |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.5 ± 0.2 a | 44.3 ± 4.1 b | 46.7 ± 4.0 b | 19.4 ± 1.2 a |

| Selenate-morning | 2.3 ± 0.2 a | 38.5 ± 4.0 c | 40.8 ± 3.8 bc | 19.0 ± 1.2 a |

| Selenocystine-morning | 2.4 ± 0.2 a | 35.0 ± 3.2 c | 37.4 ± 3.4 c | 18.4 ± 1.2 a |

| Selenate-evening | 2.3 ± 0.2 a | 49.1 ± 4.3 ab | 51.4 ± 4.8 ab | 19.0 ± 1.2 a |

| Selenocystine-evening | 2.4 ± 0.2 a | 58.1 ± 5.1 a | 60.5 ± 5.8 a | 20.8 ± 1.3 a |

Figure 7: Effect of time of Se foliar supply on mono-, di-, and polysaccharide content in dandelion roots. Within each parameter values with the same letters ‘a–d’ do not differ statistically according to the Duncan test at p < 0.05.

Fig. 7 emphasizes the most significant changes due to Se supply, which take place in disaccharides whose amount differs greatly between the two chemical forms of Se applied and the two times of Se supplementation. In both cases, the variations were more remarkable under selenocystine supply than under selenate application. Furthermore, the morning and evening treatments produced the opposite effects on disaccharide accumulation in dandelion roots; the morning Se supply reduced disaccharide content; conversely, the evening application of Se led to the enhancement of disaccharide levels by 111% and 131%, under selenate and selenocystine, respectively. The possibility of water-soluble saccharide decrease as a result of Se biofortification has been previously reported in beetroot [53], but the contrasting differences in the morning/evening effect were recorded in the present work for the first time.

The present knowledge of Se’s effect on disaccharide content in plant roots and tubers reveals significant complexity of Se-carbohydrate interaction. It makes it hypothesizes an indirect Se effect via modulation of plant hormones participating in root development (cytokinins, in particular) [37], changes in the plant antioxidant system playing a significant role in disaccharide accumulation [54], stimulating the biosynthesis of monosaccharide precursors of disaccharides, and affecting gene expression. Indeed, the present results indicate significant changes in the root antioxidant system under the Se supply, and make it suppose the existence of different relationships between organic and inorganic Se forms with carbohydrates of dandelion roots.

It is known that at low concentrations, Se may affect genes involved in the biosynthesis of phytohormones, such as ethylene, auxin, abscisic acid, and hormones associated with the antioxidant defense [41]. At the same time, enhanced carbohydrate content under the evening Se supply may be connected with the ability of Se to downregulate auxin biosynthesis, affecting root growth and architecture [55,56].

The existence of Se circadian biorhythms in dandelion influences the efficiency of Se biofortification, changes root-leaf antioxidant status, and root sugar accumulation, depending on the morning/evening time of foliar Se supply. Both organic and inorganic forms of Se demonstrated strong growth stimulation effects and similar behavior changes depending on the time of Se supply, with a higher beneficial effect of selenate on all parameters tested. Compared to the evening treatment, the morning Se supply was more beneficial for root development with increased levels of root biomass, Se, and AOA/TP content, but decreased disaccharide levels. Contrary, the evening Se treatment stimulated leaf development with a greater increase of leaf Se, AOA, TP, and root disaccharide content, but did not affect root biomass and polyphenols. Further investigations are necessary to confirm the ubiquitous nature of the revealed phenomenon and develop a specific strategy for the optimization of root and leafy vegetable biofortification with selenium.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Nadezhda Golubkina and Gianluca Caruso; investigation: Nadezhda Golubkina and Pavel Poluboyarinov; methodology and formal analysis: Lyubov Skrypnik, Agnieszka Sękara, and Otilia Cristina Murariu; validation: Pavel Poluboyarinov, Otilia Cristina Murariu, and Gianluca Caruso; writing original draft: Nadezhda Golubkina and Agnieszka Sękara; writing, review, and editing: Nadezhda Golubkina, Lyubov Skrypnik, and Gianluca Caruso. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ascorbic acid | |

| total antioxidant activity | |

| Carotene | |

| Chlorophyll | |

| dry matter | |

| gallic acid equivalent | |

| Selenium | |

| total polyphenols |

References

1. Venkat A , Muneer S . Role of circadian rhythms in major plant metabolic and signaling pathways. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 836244. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.836244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jang J , Lee S , Kim JI , Lee S , Kim JA . The roles of circadian clock genes in plant temperature stress responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25( 2): 918. doi:10.3390/ijms25020918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Aaron N , Fei-He L , Hameed S , Jin L , Shuai L The circadian rhythms: role of biological clock in plants growth and development. Int J Micro Biol Genet Monocular Biol Res. 2021; 5( 1): 17– 32. doi:10.37745/ijmgmr.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Srivastava D , Shamim M , Kumar M , Mishra A , Maurya R , Sharma D , et al. Role of circadian rhythm in plant system: an update from development to stress response. Environ Exp Bot. 2019; 162: 256– 71. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.02.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Soengas P , Cartea ME , Velasco P , Francisco M . Endogenous circadian rhythms in polyphenolic composition induce changes in antioxidant properties in Brassica cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2018; 66( 24): 5984– 91. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ávila-Román J , Soliz-Rueda JR , Bravo FI , Aragonès G , Suárez M , Arola-Arnal A , et al. Phenolic compounds and biological rhythms: who takes the lead? Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021; 113: 77– 85. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.04.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Basallo O , Lucido A , Sorribas A , Marin-Sanguino A , Vilaprinyo E , Martinez E , et al. Modeling the effect of daytime duration on the biosynthesis of terpenoid precursors. Front Plant Sci. 2024; 15: 1465030. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1465030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hatori M , Hirota T , Iitsuka M , Kurabayashi N , Haraguchi S , Kokame K , et al. Light-dependent and circadian clock-regulated activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein, X-box-binding protein 1, and heat shock factor pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108( 12): 4864– 9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015959108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang L , Strobbe S , Van Der Straeten D , Zhang C . Regulation of plant vitamin metabolism: backbone of biofortification for the alleviation of hidden hunger. Mol Plant. 2021; 14( 1): 40– 60. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2020.11.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bandehagh A , Dehghanian Z , Gougerdchi V , Anwar Hossain M . Selenium: a game changer in plant development, growth, and stress tolerance, via the modulation in gene expression and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Phyton. 2023; 92( 8): 2301– 24. doi:10.32604/phyton.2023.028586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Skrypnik L , Feduraev P , Golovin A , Maslennikov P , Styran T , Antipina M , et al. The integral boosting effect of selenium on the secondary metabolism of higher plants. Plants. 2022; 11( 24): 3432. doi:10.3390/plants11243432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Golubkina N . Circadian biorhythms of selenium and hormonal regulation. In: Aomori C , Hokkaido M , editors. Selenium: sources, functions and health effects. Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers Inc.; 2012. p. 33– 75. [Google Scholar]

13. Bai S , Zhang M , Tang S , Li M , Wu R , Wan S , et al. Effects and impact of selenium on human health, a review. Molecules. 2025; 30( 1): 50. doi:10.3390/molecules30010050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rataan AO , Geary SM , Zakharia Y , Rustum YM , Salem AK . Potential role of selenium in the treatment of cancer and viral infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 4): 2215. doi:10.3390/ijms23042215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Leszto K , Biskup L , Korona K , Marcinkowska W , Możdżan M , Węgiel A , et al. Selenium as a modulator of redox reactions in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants. 2024; 13( 6): 688. doi:10.3390/antiox13060688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Golubkina N , Moldovan A , Kekina H , Kharchenko V , Sekara A , Vasileva V , et al. Joint biofortification of plants with selenium and iodine: new field of discoveries. Plants. 2021; 10( 7): 1352. doi:10.3390/plants10071352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mrština T , Praus L , Száková J , Kaplan L , Tlustoš P . Foliar selenium biofortification of soybean: the potential for transformation of mineral selenium into organic forms. Front Plant Sci. 2024; 15: 1379877. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1379877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ikram S , Yang L , Chai L , Yi D , Wang H , Qiang L , et al. Selenium in plants: a nexus of growth, antioxidants, and phytohormones. J Plant Physiol. 2024; 296: 154237. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2024.154237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Danso OP , Asante-Badu B , Zhang Z , Song J , Wang Z , Yin X , et al. Selenium biofortification: strategies, progress and challenges. Agriculture. 2023; 13( 2): 416. doi:10.3390/agriculture13020416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lidon FC , Oliveira K , Galhano C , Guerra M , Ribeiro MM , Pelica J , et al. Selenium biofortification of rice through foliar application with selenite and selenate. Exp Agric. 2019; 55( 4): 528– 42. doi:10.1017/s0014479718000157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang M , Ali F , Wang M , Dinh QT , Zhou F , Bañuelos GS , et al. Understanding boosting selenium accumulation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) following foliar selenium application at different stages, forms, and doses. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020; 27( 1): 717– 28. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06914-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Poluboyarinov PA , Moiseeva IJ , Mikulyak NI , Golubkina NA , Kaplun AP . A new synthesis of cystine and selenocystine enanthiomers and their derivatives. Chem Chem Technol. 2022; 65( 2): 19– 29. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

23. Gruszecki R , Walasek-Janusz M , Caruso G , Pokluda R , Tallarita AV , Golubkina N , et al. Multilateral use of dandelion in folk medicine of central-eastern Europe. Plants. 2024; 14( 1): 84. doi:10.3390/plants14010084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tanasa Acretei MV , Negreanu-Pirjol T , Olariu L , Negreanu-Pirjol BS , Lepadatu AC , Anghel Cireasa L , et al. Bioactive compounds from vegetal organs of Taraxacum species (dandelion) with biomedical applications: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025; 26( 2): 450. doi:10.3390/ijms26020450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mazej D , Osvald J , Stibilj V . Selenium species in leaves of chicory, dandelion, lamb’s lettuce and parsley. Food Chem. 2008; 107( 1): 75– 83. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.07.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lichtenthaler HK . Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In: Plant cell membranes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1987. p. 350– 82. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. AOAC International . Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. 22nd ed. Rockville, MD, USA: AOAC International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

28. Golubkina NA , Kekina HG , Molchanova AV , Antoshkina MS , Nadezhkin SM , Soldatenko AV . Plant antioxidants and methods of their determination. Moscow, Russia: Infra-M; 2020. [Google Scholar]

29. Swamy PM . Laboratory manual on biotechnology. Meerut, India: Rastogi Publications; 2008. 617 p. [Google Scholar]

30. Qiao Q , Song X , Zhang C , Jiang C , Jiang R . Structure and immunostimulating activity of polysaccharides derived from the roots and leaves of dandelion. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2024; 11( 1): 51. doi:10.1186/s40538-024-00568-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Alfthan G . A micromethod for the determination of selenium in tissues and biological fluids by single-test-tube fluorimetry. Anal Chim Acta. 1984; 165: 187– 94. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(00)85199-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang F , Zhang J , Xu L , Ma A , Zhuang G , Huo S , et al. Selenium volatilization in plants, microalgae, and microorganisms. Heliyon. 2024; 10( 4): e26023. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Somagattu P , Chinnannan K , Yammanuru H , Reddy UK , Nimmakayala P . Selenium dynamics in plants: uptake, transport, toxicity, and sustainable management strategies. Sci Total Environ. 2024; 949: 175033. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Costa LC , Luz LM , Nascimento VL , Araujo FF , Santos MNS , de F M França C , et al. Selenium-ethylene interplay in postharvest life of cut flowers. Front Plant Sci. 2020; 11: 584698. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.584698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xu Y , Zhang L , Wang J , Liang D , Xia H , Lv X , et al. Gibberellic acid promotes selenium accumulation in Cyphomandra betacea under selenium stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 968768. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.968768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bai Y , Wang X , Wang X , Dai Q , Zhan X , Gong H , et al. Effects of combined application of selenium and various plant hormones on the cold stress tolerance of tomato plants. Plant Soil. 2024; 501( 1): 471– 89. doi:10.1007/s11104-024-06534-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Teixeira LS , Mota TAL , Lopez DJC , Amorim VA , Almeida CS , Souza GA , et al. Cytokinin biosynthesis is affected by selenium and nitrate availabilities to regulate shoot and root growth in rice seedlings. Nitrogen. 2024; 5( 1): 191– 201. doi:10.3390/nitrogen5010013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Fraser OJP , Cargill SJ , Spoel SH , van Ooijen G . Crosstalk between salicylic acid signalling and the circadian clock promotes an effective immune response in plants. npj Biol Timing Sleep. 2024; 1: 6. doi:10.1038/s44323-024-00006-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Thain SC , Vandenbussche F , Laarhoven LJJ , Dowson-Day MJ , Wang ZY , Tobin EM , et al. Circadian rhythms of ethylene emission in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004; 136( 3): 3751– 61. doi:10.1104/pp.104.042523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zagoskina NV , Zubova MY , Nechaeva TL , Kazantseva VV , Goncharuk EA , Katanskaya VM , et al. Polyphenols in plants: structure, biosynthesis, abiotic stress regulation, and practical applications (review). Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24( 18): 13874. doi:10.3390/ijms241813874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu H , Xiao C , Qiu T , Deng J , Cheng H , Cong X , et al. Selenium regulates antioxidant, photosynthesis, and cell permeability in plants under various abiotic stresses: a review. Plants. 2022; 12( 1): 44. doi:10.3390/plants12010044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhou Y , Nie K , Geng L , Wang Y , Li L , Cheng H . Selenium’s role in plant secondary metabolism: regulation and mechanistic insights. Agronomy. 2025; 15( 1): 54. doi:10.3390/agronomy15010054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tallarita AV , Golubkina N , De Pascale S , Sękara A , Pokluda R , Murariu OC , et al. Effects of selenium/iodine foliar application and seasonal conditions on yield and quality of perennial wall rocket. Horticulturae. 2025; 11( 2): 211. doi:10.3390/horticulturae11020211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Skrypnik L , Styran T , Savina T , Golubkina N . Effect of selenium application and growth stage at harvest on hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in lamb’s lettuce (Valerianella locusta L. laterr.). Plants. 2021; 10( 12): 2733. doi:10.3390/plants10122733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yan Q , Xing Q , Liu Z , Zou Y , Liu X , Xia H . The phytochemical and pharmacological profile of dandelion. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024; 179: 117334. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wang C , García-Caparros P , Li Z , Chen F . A comprehensive review on plant ascorbic acid. Trop Plants. 2024; 3( 1): e042. doi:10.48130/tp-0024-0042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yadav A , Singh S . Effect of exogenous phytohormone treatment on antioxidant activity, enzyme activity and phenolic content in wheat sprouts and identification of metabolites of control and treated samples by UHPLC-MS analysis. Food Res Int. 2023; 169: 112811. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Antoshkina M , Golubkina N , Sekara A , Tallarita A , Caruso G . Effects of selenium application on biochemical characteristics and biofortification level of kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea L. var. gongylodes) produce. Front Biosci. 2021; 26( 9): 533– 42. doi:10.52586/4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Golubkina N , Zayachkovsky V , Poluboyarinov P , Amagova Z , Sękara A , Murariu OC , et al. Beneficial effect of organic and inorganic forms of selenium on yield and nutritional characteristics of beetroot. Acta Agric Slov. 2025; 121( 1): 1– 10. doi:10.14720/aas.2025.121.1.19926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhou S , Wang Z , Hao Y , An P , Luo J , Luo Y . Dandelion polysaccharides ameliorate high-fat-diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities. Nutrients. 2023; 15( 19): 4120. doi:10.3390/nu15194120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wilson RG , Kachman SD , Martin AR . Seasonal changes in glucose, fructose, sucrose, and fructans in the roots of dandelion. Weed Sci. 2001; 49( 2): 150– 5. doi:10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0150:scigfs]2.0.co;2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Du G , Liu Y , Zhang J , Fang S , Wang C . Microwave-assisted extraction of dandelion root polysaccharides: extraction process optimization, purification, structural characterization, and analysis of antioxidant activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025; 299: 139732. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.139732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Šlosár M , Mezeyová I , Mezey J . The effect of selenium application on root yield and nutritional quality of fresh and pasteurized beetroot (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris var. conditiva Alef. Helm.) juice. J Agric Food Res. 2025; 21: 101969. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2025.101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Mroczek-Zdyrska M , Wójcik M . The influence of selenium on root growth and oxidative stress induced by lead in Vicia faba L. minor plants. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012; 147( 1): 320– 8. doi:10.1007/s12011-011-9292-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Covington MF , Harmer SL . The circadian clock regulates auxin signaling and responses in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2007; 5( 8): e222. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Malheiros RSP , Costa LC , Ávila RT , Pimenta TM , Teixeira LS , Brito FAL , et al. Selenium downregulates auxin and ethylene biosynthesis in rice seedlings to modify primary metabolism and root architecture. Planta. 2019; 250( 1): 333– 45. doi:10.1007/s00425-019-03175-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools