Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Citrus Viroids: A New Frontier in Virus and Virus-Like Pathogens in the Citrus Growing Areas

1 Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, 40100, Pakistan

2 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Selangor, Malaysia

3 Laboratory of Sustainable Agronomy and Crop Protection, Institute of Plantation Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Selangor, Malaysia

4 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Technology, Sivas University of Science and Technology, Sivas, 58140, Türkiye

5 Department of Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of the Punjab, Lahore, 54590, Pakistan

6 Department of Biology, College of Science, King Khalid University, Abha, 61413, Saudi Arabia

7 Prince Sultan Bin Abdelaziz for Environmental Research and Natural Resources Sustainability Center, King Khalid University, Abha, 61421, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Yasir Iftikhar. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3827-3843. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071555

Received 07 August 2025; Accepted 19 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Citrus viroids are small non-coding RNA pathogens that pose a significant threat to global citrus production by reducing fruit yield, quality, and tree longevity. Several viroids, including Citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd), Hop stunt viroid (HSVd), Citrus bent leaf viroid (CBLVd), and newly identified members such as Citrus Viroid VI (CVd-VI) and Citrus Viroid VII (CVd-VII) have been reported from diverse citrus-growing regions. These pathogens are transmitted mainly through vegetative propagation, contaminated tools, and occasionally via seed or pollen, making their management complex. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the biology, structural diversity, transmission, symptomatology, detection, and economic impact of citrus viroids. In addition to compiling existing findings, it emphasizes critical challenges such as understanding host–pathogen molecular interactions, the implications of viroid infections under climate change, and the limited availability of resistant rootstocks. Recent advances in diagnostic tools, including Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR), Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR), High-throughput sequencing (HTS), and in silico approaches, are evaluated alongside practical constraints in low-resource settings. Furthermore, the review highlights management strategies focused on certified planting material, sanitation, resistant genotypes, and integration into global citrus certification programs. By consolidating existing information while outlining key knowledge gaps and future directions, this work provides a foundation for developing sustainable strategies to mitigate the impact of viroids on the citrus industry.Keywords

1.1 Citrus Viroids, Isolates, Etiology, and Geographical Distribution

Citrus is one of the most widely cultivated fruit crops globally, but its production is threatened by several viruses and virus-like pathogens, including viroids, which represent a unique group of sub-viral agents. Citrus viroids are tiny pathogens that lack coding ability and consist of circular RNA genomes, but can severely affect citrus crops by affecting the fruit yields and quality [1]. The genome size of viroids ranges from 246 to 401 nucleotides and depends entirely on the cellular machinery of the host for replication [2]. Some of the most significant citrus viroids include Citrus exocortis viroid [CEVd], Citrus bent leaf viroid (CBLVd), Hop stunt viroid (HSVd), Citrus bark cracking viroid (CBCVd), Citrus dwarfing viroid (CDVd), and Citrus viroids V [3] and VI (CVd-V, CVd-VI) [4]. Citrus viroids are categorized into two different families, Pospiviroidae and Avsunviroidae (Table 1). There is a central conserved region (CCR) in Pospiviroidae, while Avsunviroidae lacks a CCR but utilizes hammerhead ribozymes for self-cleavage, respectively [5].

Citrus viroids exhibit different symptoms, like CEVd, which causes bark scaling, stunted growth, and reduced yield [6], while CBLVd causes leaf deformation and poor fruit quality [7]. HSVd infects multiple citrus species and causes symptoms like leaf chlorosis and stunting in trees [8]. Nursery rootstocks get infected by Citrus bark cracking viroid, which causes bark cracking and plant death [9]. CDVd produces symptoms like tree dwarfing, which can be beneficial for high-density planting, but still requires careful management [10]. Viroids often present in mixed infections, and this synergy can intensify disease severity while the diagnosis of the disease becomes more challenging [11].

Transmission mainly occurs through infected plant materials such as budwood and grafts, as well as via contaminated tools [12]. Unlike viruses, viroids lack insect vectors, which makes human-mediated movement the primary mode of spread [13]. They can remain latent for long periods, creating hurdles in early detection. Symptoms include stunting, chlorosis, bark cracking, and poor fruit development, which ultimately reduce economic viability [6]. A study of the distribution and prevalence of citrus viroids is necessary for the evaluation of their impact on citrus production. Reports show that citrus viroids, e.g., CEVd, CVd-III, CVd-IV, HSVd, and CVd-V, are widespread in geographical locations including Greece, Palestine, Japan, and Pakistan. Major citrus viroids have been reported to be found worldwide, but there is less knowledge present for viroids like CVd-VI and CVd-VII [14,15].

Viroids, including CEVd, CBLVd, HSVd, CVd-III, CVd-IV, and CVd-V, have been reported in Africa with cases in Sudan [16] and in the Middle East [17]. These have been found in the Turkey and Palestine region. Reports from Europe confirm the presence of citrus viroids in Italy and in South America; they have been found in Uruguay and Costa Rica areas [18,19]. CEVd has also been identified even in ornamental plants and weeds which are associated with citrus orchards and highlight the broader ecological impact of this viroid [20]. HSVd co-occurring with CEVd and CDVd in mixed viroid infections and found in Greece, etc., is another main cause to intensify disease severity, and this synergy makes management more challenging [21]. HSVd was identified in Japan and reported [22]. CVd-V has been reported in Asia and Punjab, Pakistan, by [15]. CVd-VII has been identified in Japan and North Africa, and recently reported its first case of CVd-V [23] along with CVd-V in China and Australia, which shows the global prevalence of citrus viroids across various geographies [24].

Effective management of viroid disease of citrus depends on accurate diagnostics strategies, and the infection can be avoided to enter into new locations by using viroid-free planting materials and strict budwood certification programs. Quarantine regulations are very important to restrict the movement of infected plant material. Genetic resistance and cross-protection techniques can be a long-term solution for managing these infections. A deeper understanding of viroid diversity and viroid-host interactions is necessary to develop sustainable management strategies for citrus viroid disease management. Although scattered information on different citrus viroids is available, it is limited to molecular detection and characterization. Therefore, this review consolidates current information on the biology, detection, epidemiology, and management of citrus viroids for sustainable fruit production. Critical gaps in knowledge, such as the need for resistant rootstocks and adaptation strategies under climate change, have also been identified. This perspective distinguishes it from earlier information, reviews, and highlights directions for future research.

Table 1: Citrus viroids infecting different citrus varieties.

| Viroid | Previous Name | Isolates | Family | Genus | Distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd) | Citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd) | V1, OP925746 | Pospiviroidae | Pospiviroid | Mediterranean basin, USA, South America, Central America, Caribbean, Asia, Africa, Middle East | [6,17,25,26,27] |

| Hop stunt viroid (HSVd) | Citrus cachexia viroid/Citrus viroid II (CVd-II) | Plum-type, hop-type, and citrus-type | Pospiviroidae | Hostuviroid | Slovenia, China (Xinjiang), Japan, Australia (grapevines), Germany, Finland (cucumbers), Netherlands, Trinidad, Tobago, Venezuela | [28,29] |

| Citrus bent leaf viroid (CBLVd) Isolates: CVd-Ia, CVd-Ib, CVd-I-LSS | Citrus viroid I (CVd-I) | CVd-Ia, CVd-Ib, CVd-I-LSS. (CVd-I-LSS Pakistan variant) | Pospiviroidae | Apscaviroid | UAE, Italy, Israel, Pakistan, China, Cambodia, Australia, Malaysia, Iran, Japan, Argentina, Crete (Greece). CVd-I-LSS is prominent in Pakistan and China. | [27,30,31] |

| Citrus viroid-III | Citrus dwarfing viroid (CDVd) | CVd-III-PS-1, CVd-III-PS-2, OP902248, OP902249 | Pospiviroidae | Apscaviroid | Greece (Argolida, Chania, Heraklio, Rethimno, Arta) | [9,17,32] |

| Citrus bark cracking viroid | Citrus viroid-IV (CVd-IV) | CBCVd-LSS, OP902247 | Pospiviroidae | Cocadviroid | Argolida, Chania, Heraklio, Rethimno | [17,27,33] |

| Citrus viroid-V (CVd-V) | CVd-VCA, CVd-VST, CVd-VNE | Pospiviroidae | Apscaviroid | Oman, California (USA), Spain, Nepal, Spain (Valencia) | [34,35] | |

| Citrus viroid-VI (CVd-VI) | CVd-OS | Pospiviroidae | Apscaviroid | Japan (origin), China, Pakistan | [22,31,36,37] |

1.2 Economic Impact on Citrus Production and Trade

Citrus viroids have an impact on citrus production and trade. These viroid diseases can reduce yield and increase management costs, ultimately creating market and economic challenges. Infected citrus orchards show lower fruit quality, which leads to decreased yields. Research on CEVd reported that infected citrus produce fewer large fruits than healthy ones and cause financial losses over multiple growing seasons [38,39]. Management of viroid infections requires additional labor and resources to monitor regular symptoms, infected tree removal, and careful measures during pruning or grafting, which ultimately increase the costs [27,40]. Infected fruits often suffer from malformations due to viroid-induced stress, which reduce their marketability and consumer appeal [17,39]. Quarantine measures or restrictions imposed on trade can increase the economic burden on citrus-exporting countries, which reduces their profitability [27]. The presence of viroid infection significantly influences rootstock selection, compelling growers to invest in resistant varieties or less susceptible rootstocks that impose additional costs for obtaining such materials [39,41]. Citrus viroids pose a significant threat to the sustainability of citrus production, and if not correctly managed, this disease can destroy the productivity of citrus globally [27,40].

2 Structural Differences of Citrus Viroids

2.1 Citrus Exocortis Viroid (CEVd)

Citrus Exocortis Viroid (CEVd) is a viroid having circular and single-stranded RNA viroid with a genome size in the range of 368 to 375 nucleotides (nt), while a few variants of CEVd can have a size up to 463–467 nucleotides [20]. CEVd was first identified in 1948 by Fawcett and Klotz, and later it was recognized as the pathogen causing citrus exocortis disease [42]. It has the ability to from a highly base-paired rod-like conformation, which is necessary and helpful for its infectivity [43]. The variability domain of CEVd shows significant genetic diversity due to frequent insertions and deletions in the genome, while its pathogenicity domain is responsible for inducing bark scaling and stunted growth in infected citrus trees [6].

2.2 Citrus Hop Stunt Viroid (HSVd)

Citrus Hop Stunt Viroid (HSVd) was detected for the first time in hops (Humulus lupulus) in 1977 [44] and later found associated with citrus species [45]. Genome size of HSVd is approximately 298–303 nt and is present in a stable rod-like RNA conformation [46]. The variability domain of HSVd demonstrates the moderate sequence diversity while its pathogenicity domain causes the severe stunting and fruit deformation in infected citrus cultivars [45].

2.3 Citrus Bent Leaf Viroid (CBLVd)

Citrus Bent Leaf Viroid (CBLVd) was known as Citrus Variable Viroid (CVaV) previously and was first studied in 1977 for the first time [47]. It belongs to the Apscaviroid genus with a genome size of 315–330 bp [7]. Its structure is a circular RNA forming a rod-like secondary conformation (Chebli & Afechtal, 2018). The variability domain is present as the three recognized variants of CBLVd, which are CVd-Ia, CVd-Ib, CVd-I-LSS [48], while the pathogenicity domain is responsible for the infections and symptoms formation, like leaf bending and potential yield reductions [49].

2.4 Citrus Viroid III (CVd-III)—Citrus Dwarfing Viroid (CDVd)

Citrus Viroid III (CVd-III) was previously named Citrus Dwarfing Viroid (CDVd), and it is a member of the Apscaviroid genus. It has a genome size of approximately 294–300 nt [47], and it was identified in citrus trees first. CDVd has a rod-like RNA structure [9]. The variability domain shows close resemblance to the Citrus Exocortis Viroid, while its pathogenicity domain causes dwarfing and reduced fruit production effects in infected plants [50].

2.5 Citrus Viroid IV (CVd-IV)—Citrus Bark Cracking Viroid (CBCVd)

Citrus Viroid IV (CVd-IV) is also known as Citrus Bark Cracking Viroid (CBCVd), and it was first identified in citron, while later its association with severe bark cracking symptoms in trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata) was identified [51]. It has a genome size of 284–288 bp and belongs to the Cocadviroid genus [52]. The circular RNA structure of CVd-IV forms a rod-like conformation [10], which has the variability domain that helps in strain diversity, while the pathogenicity domain causes the severe bark scaling and cracking symptoms [53,54].

Citrus Viroid V (CVd-V) was first reported in the early 2000s [3], and it has a genome size of 293–294 nt bp, which forms an RNA structure in rod shape with a GC-rich sequence (68.7% paired nucleotides) [34]. The variability domain of CVd-V consists of minimal sequence deviation, and the pathogenicity domain interacts with other viroids and creates a synergistic effect that ultimately influences disease severity [3,55].

Citrus Viroid VI (CVd-VI) had the name Citrus Viroid-D (CVd-OS) previously, and it was first reported in Japan from the citrus cultivar Shiranui [22]. Its genome size ranges from 326 to 331 nt and has a rod-like circular RNA structure [56,57]. The variability domain has a similar conserved region with other Apscaviroid members, but the sequence similarity with other viroids is only 68% [58]. The pathogenicity domain remains unclear and less studied, but is suspected to cause different citrus growth abnormalities [59].

2.8 Citrus Viroid VII (CVd-VII)

Citrus Viroid VII (CVd-VII) is a recently discovered viroid and is categorized in the Apscaviroid genus (Table 2). It has been identified in research stations in Dareton, New South Wales, Australia [4], while its Chinese variant has been reported as well, and the genome size is 326 to 331 nt [58]. It has a rod-like RNA conformation [32] while its Pathogenicity (P) Domain is associated with the ability to cause disease symptoms in host plants [60]. Mutations here can alter symptom severity. The Variability domain contributes to the adaptability and host range [10].

Table 2: Comparative citrus viroids.

| Viroid | Genome Size (nt) | Structure | Variability Domain | Pathogenicity Domain | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEVd | 369–394 | Circular, rod-like | High genetic variation (insertions/deletions) | Bark scaling, stunted growth | [6,20,42,43] |

| HSVd | 246–401 | Circular, rod-like | Moderate sequence diversity | Stunting, fruit deformation | [8,44,46] |

| CBLVd | 330–340 | Circular, rod-like | Three variants (CVd-Ia, CVd-Ib, CVd-I-LSS) | Leaf bending, yield reduction | [7] |

| CVd-III (CDVd) | 291–296 | Circular, rod-like | Similar to CEVd | Dwarfing, reduced fruit production | [9,47] |

| CVd-IV (CBCVd) | 275 | Circular, rod-like | Strain diversity | Severe bark scaling and cracking | [10,54] |

| CVd-V | 293–294 | Circular, rod-like | Minimal sequence variation | Interacts with other viroids, modifying severity | [3,35,61] |

| CVd-VI | 328–331 | Circular, rod-like | 68% sequence similarity with other viroids | Minor citrus abnormalities | [22,56,57,58,59] |

| CVd-VII | 369–394 | Circular, rod-like | High sequence variability | Mild slight stunting or leaf epinasty and still not studied extensively | [4,24,32] |

3 Transmission and Host Range of Citrus Viroids

Citrus viroids exhibit various symptoms, host specificity, and transmission pathways that influence their spread and impact citrus production (Table 3). CEVd [32] affects multiple citrus species and spreads primarily through contaminated tools, grafting, and mechanical means with no known insect vectors [31]. CBLVd is associated with reduced fruit yield and detected in sweet oranges and some hybrid citrus varieties, and is transmitted through grafting and mechanical means, though seed transmission remains uncertain [60]. HSVd infects citrus, hops, and other woody hosts species, which leads to reduced tree vigor, smaller fruit size, and occasional leaf yellowing [62]. It is primarily spread through contaminated tools, grafting material, and possibly by pollen or seeds [63]. CVd-III induces symptoms like gumming, leaf epinasty, and vein necrosis, particularly in sweet oranges, mandarins, and lemon cultivars [17]. This viroid is transmitted mechanically, and through infected propagation material [32]. CVd-IV causes bark cracking and gumming and reduces tree longevity [64]. It primarily infects oranges, mandarins, and grapefruit. At the same time, it spreads through mechanical means, grafting and seed transmission [65] CVd, CVD-VI, and CVd-VII often result in latent infections, but can take part in tree decline when occurring alongside other viroids [4]. These viroids have been infecting various citrus species and are transmitted through mechanical means or grafting [32]. While the possibility of seed transmission has been reported but remains controversial. The presence and transmission of Citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd) through seeds in ornamentals like Impatiens and Verbena, with infection rates as high as 66% in fresh seedlings but declining to 26% after two years of storage [66]. However, conclusive evidence in citrus remains scarce, and the epidemiological significance of this pathway is still debated.

Table 3: Symptoms, host range, and transmission methods of citrus viroids.

| Viroid | Symptoms | Host Range | Transmission Modes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus Exocortis Viroid (CEVd) | Stunted growth, bark scaling, cracking | Multiple citrus species, especially trifoliate orange | Contaminated tools, grafting, mechanical means, no insect vectors | [6,25] |

| Hop Stunt Viroid (HSVd) | Reduced tree vigor, smaller fruit, leaf yellowing | Citrus, hops, and other woody hosts | Contaminated tools, grafting, possibly by pollen or seeds | [8] |

| Citrus Bent Leaf Viroid (CBLVd) | Mild leaf bending, delayed growth, reduced yield | Sweet oranges, hybrid citrus varieties | Grafting, mechanical transmission, uncertain seed transmission | [17,30] |

| Citrus Viroid III (CVd-III) | Gumming, leaf epinasty, vein necrosis | Sweet oranges, mandarins, lemons | Mechanical transmission, infected propagation material | [9,67] |

| Citrus Viroid IV (CVd-IV) | Bark cracking, gumming, reduced tree longevity | Oranges, mandarins, grapefruit | Mechanical means, grafting, possibly seed transmission | [17,33] |

| Citrus Viroid V (CVd-V) | Latent infection contributes to tree decline | Various citrus species | Mechanical transmission, grafting, unclear seed transmission | [34,68] |

| Citrus Viroid VI (CVd-VI) | Often latent but may weaken trees | Sour orange | Mechanical transmission, grafting | [17,22] |

3.1 Detection of Citrus Viroids

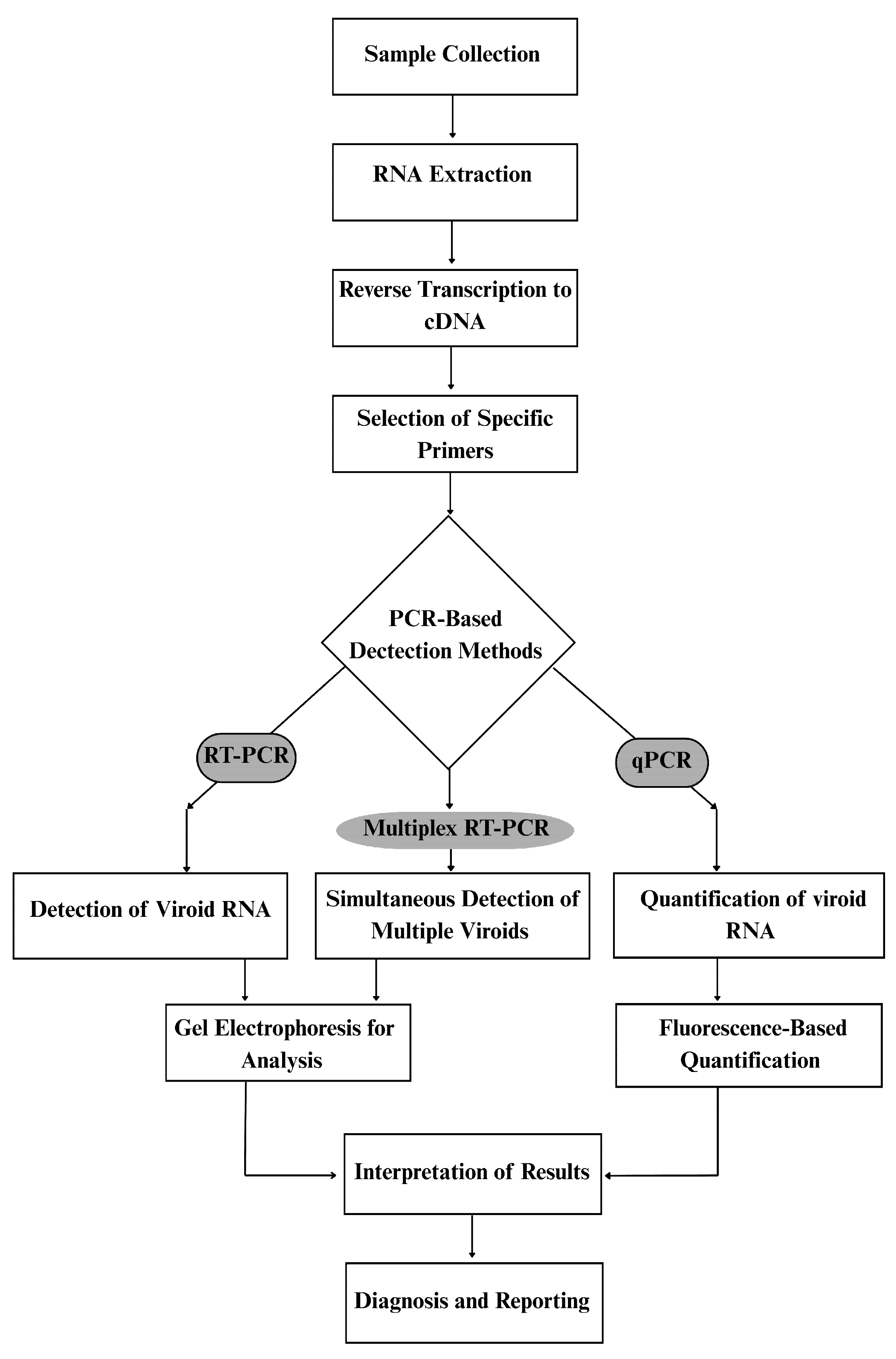

Citrus viroids are essential pathogens that affect the health and productivity of citrus plants. Their detection is crucial for effective management and disease control. Various methods, from biological observations to advanced molecular techniques, have been developed for citrus viroid detection (Table 4, Fig. 1). Visual inspection remains the most basic approach, where symptoms such as leaf curling, stunted growth, and bark cracking may indicate viroid infections. However, these symptoms are not definitive since they can be caused by other factors, including environmental stress and other pathogens [68]. Molecular methods such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are widely used to achieve accurate diagnosis. RT-PCR enables the amplification of viroid RNA from plant tissues, offering high sensitivity and specificity in detecting viroid infections [69,70]. Multiplex RT-PCR further enhances diagnostic efficiency by allowing the simultaneous detection of multiple viroids in a single reaction, making it particularly useful for large-scale testing [36,71]. However, implementation of these advanced molecular techniques can be challenging in low-resource regions due to high costs, specialized equipment and technical expertise requirements. Another significant technique is real-time RT-PCR (qPCR), which confirms the presence of viroids and quantifies their levels in infected tissues, providing insights into disease severity and progression [72,73].

Table 4: Methods for detecting citrus viroids and their salient features.

| Detection Method | Salient Features | References |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | Observes symptoms like leaf curling and bark cracking but lacks specificity | [68] |

| RT-PCR | Highly sensitive and specific; detects low viroid loads | [70,74] |

| Multiplex RT-PCR | Simultaneously detects multiple viroids; useful for large-scale screening. | [36,71] |

| Real-Time RT-PCR (qPCR) | Provides quantitative data on viroid abundance, aiding disease monitoring | [72,73] |

| Dot-Blot Hybridization | Uses labeled probes for detection; useful as a confirmatory method | [72,74] |

| High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) | Identifies known and novel viroids; useful for viroid discovery. | [75,76] |

| In Silico Detection | Analyzes sequencing data for viroid identification. | [77] |

| Lateral Flow Devices | Rapid field-based detection using antibodies or nucleic acid probes. | [71] |

Besides PCR-based methods, hybridization techniques like dot-blot hybridization are also employed. This method involves transferring RNA onto a membrane and hybridizing it with labeled probes specific to the target viroid [72,74]. Although it is less common than PCR-based approaches, dot-blot hybridization remains useful for confirming viroid presence. High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has emerged as a powerful tool for detecting known and novel viroids. HTS enables direct RNA sequencing from plant tissues, allowing comprehensive analysis of viroid populations and discovery of new variants [75,76]. Additionally, in silico detection tools have been developed to analyze sequencing data and identify viroid-specific sequences, improving diagnostic accuracy [77]. Rapid diagnostic tests, such as lateral flow devices, are also being developed for field-based detection. These devices utilize antibodies or nucleic acid probes to deliver fast results, making them highly beneficial for real-time monitoring [72]. Despite advancements, viroid detection faces challenges such as asymptomatic infections, mixed infections, and the need for cost-effective diagnostic solutions. Many infected citrus trees do not exhibit symptoms until significant damage has occurred, complicating early detection efforts [32,78]. Mixed infections involving multiple viroid species further obscure diagnosis, as overlapping symptoms can lead to misidentification [79]. Moreover, molecular techniques require specialized equipment and trained personnel, challenging accessibility in resource-limited regions [80]. Standardization of diagnostic protocols across laboratories is also necessary to ensure consistency in results [81]. Future advancements in citrus viroid detection will likely focus on developing cost-effective, rapid, and field-deployable diagnostic assays, integrating molecular and serological methods, and improving bioinformatics tools to enhance viroid identification and monitoring [82]. While these molecular techniques offer high sensitivity and specificity, their application in low-resource countries presents practical challenges. The high cost of reagents, the need for specialized equipment, and limited technical expertise often restrict widespread use [11]. In many citrus-growing regions, laboratories may lack infrastructure for qPCR or HTS, leading to reliance on conventional RT-PCR or biological indexing. Capacity building, affordable diagnostic kits, and decentralized testing facilities are critical for ensuring reliable surveillance in such contexts [43].

Figure 1: Workflow of molecular characterization techniques for citrus viroids, including RNA extraction, reverse transcription, PCR amplification, and sequencing steps.

3.2 Control and Management Strategies for Citrus Viroids

Currently, there are no direct chemical controls available for citrus viroids. Therefore, management must rely on preventive and integrated approaches. Certified disease-free planting material remains the cornerstone of viroid management. Strict sanitation practices, including disinfecting tools and avoiding contaminated propagation sources are equally essential. The use of resistant or tolerant rootstocks, where available, can mitigate symptom severity and improve orchard productivity. Cross-protection, using mild strains of certain viroids, has been explored in some cases though it requires careful monitoring to prevent unintended spread of more aggressive variants.

Quarantine regulations are fundamental in preventing the introduction and spread of citrus viroids across regions and countries. Import regulations mandate rigorous inspection and testing of citrus plants before entry into a country, ensuring that only disease-free material is transported [83]. The USDA, for instance, enforces strict protocols for testing citrus plants for viroids such as Citrus Exocortis Viroid (CEVd) and Hop Stunt Viroid (HSVd) before import [84]. Regular monitoring programs further aid in the early detection and containment of viroid outbreaks. In Spain, national surveillance programs routinely inspect citrus orchards for viroid infections, enforcing phytosanitary standards [60]. Infected trees are often subjected to eradication protocols, which involve removing diseased plants and replacing them with certified, disease-free stock [85]. Additionally, public awareness campaigns educate growers on the risks of viroid infections and the importance of compliance with quarantine measures [86,87].

3.2.2 Citrus Certification and Registered Nurseries

Sanitary measures play a crucial role in minimizing the spread of citrus viroids. Certification programs ensure that nursery stock is tested and verified to be viroid-free before distribution [85]. For instance, the California Certified Nursery Stock (CCNS) program mandates testing of nursery stock for CEVd and other pathogens before approval for sale [88]. Clean stock programs further reinforce the use of disease-free planting material, regularly testing mother plants for viroid infections to maintain healthy propagation sources [60,83]. Proper sanitation during orchard management practices, such as disinfecting pruning tools with sodium hypochlorite or alcohol, reduces the mechanical transmission of viroids [89]. Training initiatives also educate citrus growers on recognizing viroid symptoms and implementing effective sanitation protocols [87].

3.2.3 Chemical and Biological Methods

While there are no direct chemical treatments for viroids, proper fertilization and pest management can enhance tree resilience against infections [90]. Some studies suggest that biostimulants may improve plant health, indirectly reducing the effects of viroid infections [32]. Biological control strategies are an emerging area of research. Beneficial microorganisms such as endophytic fungi show promise in enhancing plant defenses and outcompeting pathogens, though further studies are needed to establish their efficacy [91,92]. Integrated pest management (IPM) strategies, which focus on controlling aphid populations that may contribute to viroid transmission, are also considered effective [93].

3.2.4 Genetic Resistance and Breeding Strategies

Developing viroid-resistant citrus cultivars remains a long-term solution. Some citrus rootstocks, such as trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), exhibit tolerance to CEVd and are being explored for commercial use [94]. Advances in molecular biology have enabled marker-assisted selection, allowing breeders to identify genetic markers associated with resistance traits [95]. Genetic engineering is also being explored as a potential tool, although commercial application remains in its early stages [96]. Field trials assessing the performance of resistant hybrids in natural conditions provide valuable insights for breeding programs [97].

3.3 Mechanism of Infection by Citrus Viroids

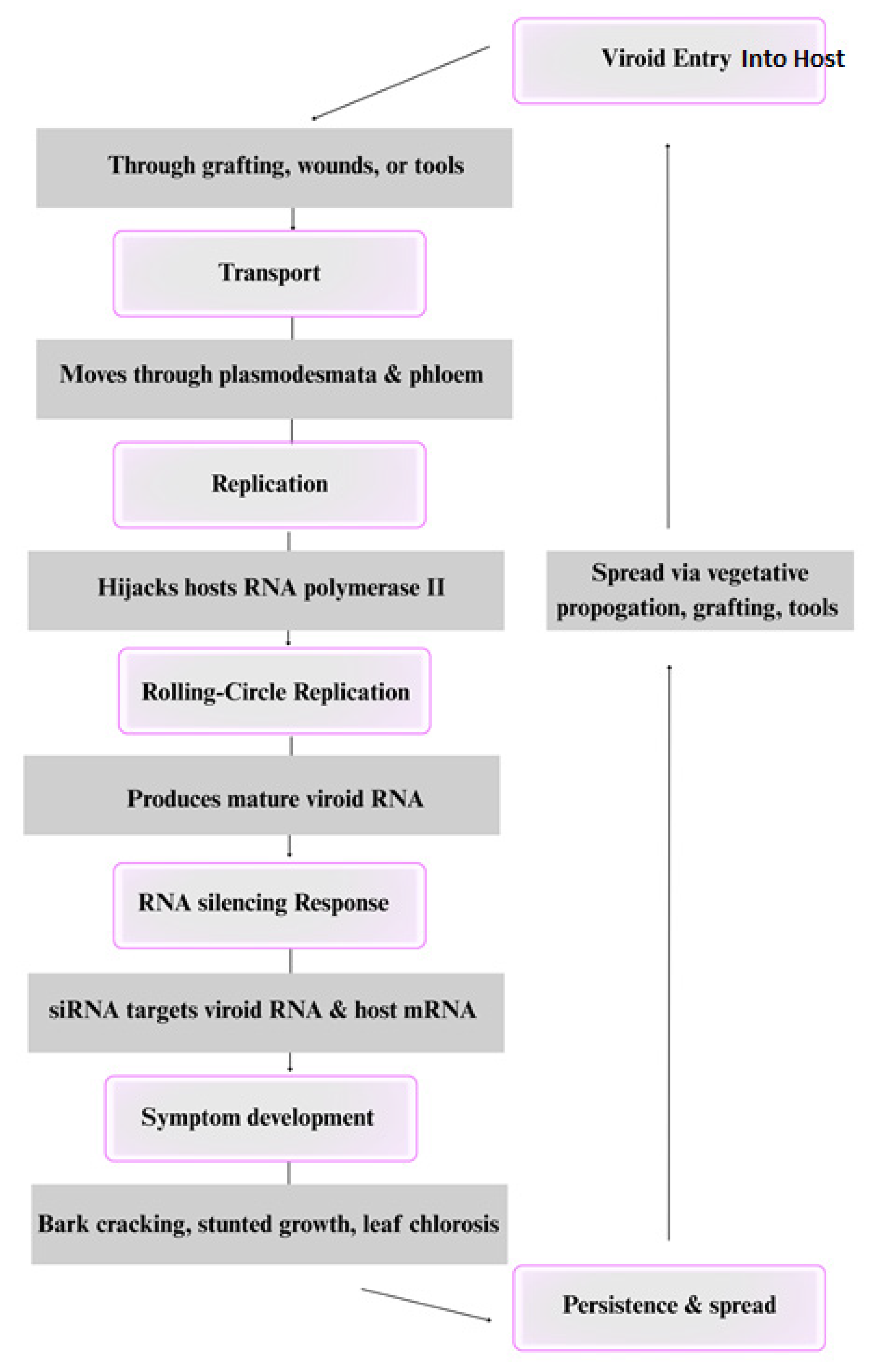

Citrus viroids infect host plants through a non-coding RNA-based mechanism, relying entirely on the host’s cellular machinery for replication and systemic movement (Fig. 2). The primary mode of viroid entry into citrus plants is through grafting, mechanical wounds, or vegetative propagation, although seed transmission has been observed in some cases [98]. Once inside the plant, viroids move through plasmodesmata, the microscopic channels connecting plant cells, and are further transported via the phloem network, enabling systemic infection [99]. Unlike viruses, viroids do not encode proteins; instead, they replicate autonomously through a rolling-circle mechanism. This replication process is mediated by host DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II, which the viroid hijacks to transcribe its RNA genome [52]. The replication cycle involves circular or linear RNA intermediates that undergo cleavage and ligation to generate mature viroid RNA molecules capable of further infection [100].

Figure 2: Transmission and infection cycle of viroids in the citrus host.

Once viroids accumulate in host cells, they trigger the plant’s RNA silencing defense mechanisms, producing small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that target both viroid RNA and, in some cases, host mRNA [84]. These siRNAs serve a dual function: on the one hand, they contribute to plant defense by degrading viroid RNA; on the other, they can inadvertently silence host genes, leading to symptoms such as bark cracking, leaf chlorosis, and stunted growth [61]. The severity of these symptoms is influenced by viroid strain, host genotype, and environmental factors [26]. In cases of co-infection, viroids can interact in synergistic or antagonistic ways, altering disease severity. Some mild viroid strains, such as mild CEVd, can offer cross-protection against more severe strains by pre-activating host defenses through siRNA pathways, thereby reducing symptom severity [99,100]. Conversely, certain viroid combinations, such as CBLVd with CVd-IV or CDVd, have been observed to exacerbate symptoms, leading to increased bark cracking and growth reduction [11]. Citrus viroids persist as systemic infections and are efficiently transmitted through vegetative propagation, grafting, and contaminated tools, making them a major concern for citrus production worldwide [101]. Given their significant impact on citrus health, understanding their infection mechanisms is crucial for developing viroid management strategies, including breeding for resistant cultivars and employing cross-protection techniques [102].

3.4 Importance of Continued Research and Collaboration to Address Citrus Viroid Challenges

The ongoing threat posed by citrus viroids necessitates continued research efforts to deepen our understanding of these pathogens and their interactions with host plants. Key areas for future research include:

3.4.1 Viroid-Host Interactions

Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying viroid-host interactions can provide insights into how these pathogens manipulate host cellular processes [102]. Understanding RNA silencing mechanisms and the role of viroid-derived small interfering RNAs (vd-siRNAs) in symptom expression will be critical for developing targeted management strategies [103].

3.4.2 Development of New Diagnostic Tools

As new strains or variants of citrus viroids emerge, there is a need for the development of advanced diagnostic tools that can rapidly identify these pathogens in diverse environments. Innovations in portable diagnostic devices could facilitate early detection in the field [77].

3.4.3 Novel Management Strategies

Exploring genetic engineering approaches to develop resistant citrus varieties could offer long-term solutions to combat viroid infections. Additionally, integrating biological control methods with traditional management practices may enhance effectiveness in controlling viroid spread [104].

3.4.4 Collaboration across Disciplines

Addressing the challenges of citrus viroids requires collaboration among researchers, extension services, growers, and regulatory agencies. Sharing knowledge about best practices for detection, management strategies, and emerging research findings will be essential for developing comprehensive solutions [21].

3.4.5 Global Monitoring Programs

Establishing international monitoring programs for citrus viroids can help track their spread across regions and inform regulatory measures to prevent outbreaks. Collaboration among countries can facilitate data sharing and improve response strategies to mitigate risks associated with these pathogens [105]. Several international initiatives provide strong examples of such cooperation. The International Organization of Citrus Virologists (IOCV) facilitates global expertise and diagnostic standards exchange. The European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) coordinates regional surveillance, sets phytosanitary guidelines and supports certification schemes. Similarly, national programs, such as those led by the USDA Citrus Health Response Program in the United States and the Citrus Certification Program in India provide frameworks for systematic viroid testing and certified propagation material. These initiatives underscore the importance of harmonized surveillance systems in minimizing the spread of citrus viroids across borders. In conclusion, while significant progress has been made in understanding citrus viroids and their impact on citrus production, ongoing research and collaboration are vital for effectively addressing the challenges. By leveraging advances in molecular biology, diagnostics, and integrated pest management strategies, stakeholders in the citrus industry can enhance their ability to combat these persistent pathogens while ensuring sustainable production practices.

Citrus viroids threaten global citrus production by compromising plant vigour, yield, and overall orchard sustainability. While progress has been made in unravelling viroid–host interactions and advancing diagnostic technologies, substantial gaps remain in management and long-term control. Future research should priorities the development of viroid-resistant citrus cultivars, integrating bioinformatics and molecular surveillance tools for early detection, and further exploring viroid–virus synergism to understand its role in disease severity better. Strengthening these areas will be critical for designing more effective, sustainable, and globally applicable management strategies.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: original draft manuscript preparation: Mustansar Mubeen, supervision: Yasir Iftikhar, study conception; Ganesan Vadamalai, validation: Muhammad Aasim and Muhammad Faiq, Formal analysis: Uthman Balgith Algopishi and Ahmed Ezzat Ahmed. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Agrios GN . Plant pathology. 5th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

2. Gas ME , Molina-Serrano D , Hernández C , Flores R , Daròs JA . Monomeric linear RNA of Citrus exocortis viroid resulting from processing in vivo has 5′-phosphomonoester and 3′-hydroxyl termini: implications for the RNase and RNA ligase involved in replication. J Virol. 2008; 82( 20): 10321– 5. doi:10.1128/JVI.01229-08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cao M , Atta S , Su H , Wang X , Wu Q , Li Z , et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Citrus viroid V isolates from Pakistan. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2013; 135( 1): 11– 21. doi:10.1007/s10658-012-0034-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chambers GA , Geering ADW , Bogema DR , Holford P , Vidalakis G , Donovan NJ . Characterisation of the genetic diversity of Citrus viroid VII using amplicon sequencing. Arch Virol. 2024; 170( 1): 12. doi:10.1007/s00705-024-06191-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gandía M , Rubio L , Palacio A , Duran-Vila N . Genetic variation and population structure of an isolate of Citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd) and of the progenies of two infectious sequence variants. Arch Virol. 2005; 150( 10): 1945– 57. doi:10.1007/s00705-005-0570-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khallou A , Belabess Z , Boualam Y , Mohsini S , Lahlali R . Assessing the prevalence of viral and virus-like diseases in citrus orchards of northeast Morocco: a contribution to orchard health. Afr Mediterr Agric J Al Awamia. 2024; 145: 141– 52. doi:10.1007/s00705-024-06191-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khoo YW , Iftikhar Y , Kong LL , Vadamalai G . Citrus bent leaf viroid. Pertanika J Sch Res Rev. 2017; 3( 3): 31– 40. doi:10.1079/cabicompendium.119766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Marquez-Molins J , Gomez G , Pallas V . Hop stunt viroid: a polyphagous pathogenic RNA that has shed light on viroid-host interactions. Mol Plant Pathol. 2021; 22( 2): 153– 62. doi:10.1111/mpp.13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Vernière C , Perrier X , Dubois C , Dubois A , Botella L , Chabrier C , et al. Interactions between Citrus viroids affect symptom expression and field performance of clementine trees grafted on trifoliate orange. Phytopathology. 2006; 96( 4): 356– 68. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-96-0356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sano T . Progress in 50 years of viroid research-Molecular structure, pathogenicity, and host adaptation. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2021; 97( 7): 371– 401. doi:10.2183/pjab.97.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Falaki F . Citrus virus and viroid diseases. In: Citrus research—horticultural and human health aspects. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2023. p. 1– 20. doi:10.5772/intechopen.108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Matsushita Y , Tsuda S . Seed transmission of potato spindle Tuber viroid, tomato chlorotic dwarf viroid, tomato apical stunt viroid, and Columnea latent viroid in horticultural plants. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2016; 145( 4): 1007– 11. doi:10.1007/s10658-016-0868-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Di Serio F , Flores R , Verhoeven JTJ , Li SF , Pallás V , Randles JW , et al. Current status of viroid taxonomy. Arch Virol. 2014; 159( 12): 3467– 78. doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2200-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Narayanasamy P . Cultural practices influencing biological management of crop diseases. In: Biological management of diseases of crops. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013. p. 9– 56. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6377-7_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ali A , Umar UUD , Akhtar S , Shakeel MT , Rehman AU , Tahir MN , et al. Identification and primary distribution of Citrus viroid V in Citrus in Punjab, Pakistan. Mol Biol Rep. 2022; 49( 12): 11433– 41. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07677-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mohamed M , Hashemian SB , Dafalla G , Bové J , Duran-Vila N . Occurrence and identification of citrus viroids from Sudan. J Plant Pathol. 2009; 91( 1): 185– 90. doi:10.4454/jpp.v91i1.640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abualrob A , Alabdallah O , Abou Kubaa R , Naser SM , Alkowni R . Molecular detection of Citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd), Citrus viroid-III (CVd-III), and Citrus viroid-IV (CVd-IV) in Palestine. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 423. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50271-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pagliano G , Orlando L , Gravina A . Detección y caracterización del complejo de viroides de los cítricos en Uruguay. Agrociencia. 1998; 2( 1): 74– 83. (In Spanish). doi:10.31285/agro.02.1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Villalobos W , Rivera C , Hammond RW . Occurrence of Citrus viroids in Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop. 1997; 45( 3): 983– 7. [Google Scholar]

20. Hull R . Plant virology. 5th ed. London, UK: Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

21. Hadidi A , Sun L , Randles JW . Modes of viroid transmission. Cells. 2022; 11( 4): 719. doi:10.3390/cells11040719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ito T , Ieki H , Ozaki K , Ito T . Characterization of a new Citrus viroid species tentatively termed Citrus viroid OS. Arch Virol. 2001; 146( 5): 975– 82. doi:10.1007/s007050170129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hamdi I , Elleuch A , Bessaies N , Grubb CD , Fakhfakh H . First report of Citrus viroid V in north Africa. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2015; 81( 1): 87– 91. doi:10.1007/s10327-014-0556-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chambers GA , Donovan NJ , Bodaghi S , Jelinek SM , Vidalakis G . A novel Citrus viroid found in Australia, tentatively named Citrus viroid VII. Arch Virol. 2018; 163( 1): 215– 8. doi:10.1007/s00705-017-3591-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Roistacher CN , Pehrson JE , Semancik JS . Effect of Citrus viroids and the influence of rootstocks on field performance of navel orange. Int Organ Citrus Virol Conf Proc (1957–2010). 1991; 11( 11): 234– 9. doi:10.5070/c589b2q748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Vernière C , Perrier X , Dubois C , Dubois A , Botella L , Chabrier C , et al. Citrus Viroids: symptom expression and effect on vegetative growth and yield of clementine trees grafted on trifoliate orange. Plant Dis. 2004; 88( 11): 1189– 97. doi:10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.11.1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mathioudakis MM , Tektonidis N , Karagianni A , Mikalef L , Gómez P , Hasiów-Jaroszewska B . Incidence and epidemiology of Citrus Viroids in Greece: role of host and cultivar in epidemiological characteristics. Viruses. 2023; 15( 3): 605. doi:10.3390/v15030605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Parkinson N , Reed P . Rapid Pest Risk Analysis for Hop Stunt Viroid [Internet]. Edinburgh, UK: The Food and Environment Research Agency (FERA); 2013 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://secure.fera.defra.gov.uk/phiw/riskRegister/downloadExternalPra.cfm. [Google Scholar]

29. Bar-Joseph M . On the trail of viroids a return to phytosanitary awareness. Pathogens. 2025; 14( 6): 545. doi:10.3390/pathogens14060545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Semancik JS , Rakowski AG , Bash JA , Gumpf DJ . Application of selected viroids for dwarfing and enhancement of production of ‘Valencia’ orange. J Hortic Sci. 1997; 72( 4): 563– 70. doi:10.1080/14620316.1997.11515544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ali A , Umar UUD , Naqvi SAH , Shakeel MT , Tahir MN , Khan MF , et al. Molecular characterization of divergent isolates of Citrus bent leaf viroid (CBLVd) from Citrus cultivars of Punjab, Pakistan. Front Genet. 2023; 13: 1104635. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.1104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang Y , Shi Y , Li H , Chang J . Understanding Citrus Viroid interactions: experience and prospects. Viruses. 2024; 16( 4): 577. doi:10.3390/v16040577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Cao MJ , Liu YQ , Wang XF , Yang FY , Zhou CY . First Report of Citrus bark cracking viroid and Citrus viroid V infecting Citrus in China. Plant Dis. 2010; 94( 7): 922. doi:10.1094/PDIS-94-7-0922C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Serra P , Eiras M , Bani-Hashemian SM , Murcia N , Kitajima EW , Daròs JA , et al. Citrus viroid V: occurrence, host range, diagnosis, and identification of new variants. Phytopathology. 2008; 98( 11): 1199– 204. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-98-11-1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Serra P , Pina JA , Duran-Vila N . Identification and characterization of a variant of Citrus viroid V (CVd-V) in Seminole tangelo. Int Organ Citrus Virol Conf Proc (1957–2010). 2010; 17( 17): 150– 7. doi:10.5070/c534m1b2xq. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ito T , Ieki H , Ozaki K , Iwanami T , Nakahara K , Hataya T , et al. Multiple Citrus viroids in Citrus from Japan and their ability to produce exocortis-like symptoms in citron. Phytopathology. 2002; 92( 5): 542– 7. doi:10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.5.542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Iwanami T . Citrus viroids and minor Citrus viruses in Japan. Jpn Agric Res Q JARQ. 2023; 57( 3): 195– 204. doi:10.6090/jarq.57.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Davis TJ , Gómez MI , Harper SJ , Twomey M . The economic impact of hop stunt viroid and certified clean planting materials. HortScience. 2021; 56( 12): 1471– 5. doi:10.21273/hortsci15975-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Venkataraman S , Shahgolzari M , Hefferon K , Atri E , De Steur H . Economic Impacts of Viroids [Internet]. Preprints.org; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202405.2134/v1. [Google Scholar]

40. Randles J . Economic Impact of Viroid Diseases [Internet]. CABI Digital Library; 2003 [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20033106033. [Google Scholar]

41. Madhavan S , Sakthivel K , Dantuluri RVS , Tadigiri S , Moturu US , Muniyappa L , et al. Characterization of Fusarium falciforme inciting wilt in peace lily (Spathiphyllum wallisii). Sci Hortic. 2025; 339: 113834. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Abdelbaset T , Sakr K , Al Shorbagy A , Elsisi A . Combination of cold therapy and chemotherapy for eradication of Citrus exocortis viroid. J Plant Prot Pathol. 2023; 14( 6): 187– 94. doi:10.21608/jppp.2023.208009.1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Steger G , Wüsthoff KP , Matoušek J , Riesner D . Viroids: non-coding circular RNAs are tiny pathogens provoking a broad response in host plants. In: RNA structure and function. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2023. p. 295– 309. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-36390-0_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kofalvi SA , Marcos JF , Cañizares MC , Pallás V , Candresse T . Hop stunt viroid (HSVd) sequence variants from Prunus species: evidence for recombination between HSVd isolates. J Gen Virol. 1997; 78( 12): 3177– 86. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Marquez-Molins J . Uncovered diversity of infectious circular RNAs: a new paradigm for the minimal parasites? NPJ Viruses. 2024; 2( 1): 13. doi:10.1038/s44298-024-00023-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Afechtal M , Friha AA . Molecular Characterization of Hop Stunt Viroid (HSVd) Infecting Citrus Orchards in Morocco [Internet]. CABI Digital Library; 2018 [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20203478369. [Google Scholar]

47. Lavagi-Craddock I , Dang T , Comstock S , Osman F , Bodaghi S , Vidalakis G . Transcriptome analysis of Citrus dwarfing viroid induced dwarfing phenotype of sweet orange on trifoliate orange rootstock. Microorganisms. 2022; 10( 6): 1144. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10061144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bernad L , Duran-Vila N . A novel RT-PCR approach for detection and characterization of Citrus viroids. Mol Cell Probes. 2006; 20( 2): 105– 13. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2005.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Alcántara-Mendoza S , Vergara-Pineda S , García-Rubio O , Cambrón-Sandoval VH , Colmenares-Aragón D , Nava-Díaz C . Caracterización del Viroide exocortis de los cítricos en diferentes condiciones de indexado. Rev Mex De Fitopatología Mex J Phytopathol. 2017; 35( 2): 284– 303. (In Spanish). doi:10.18781/r.mex.fit.1701-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Thangaraj P , Balamurali AS , Seethapathy P . Citrus Exocortis viroid. In: Compendium of phytopathogenic microbes in agro-ecology. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 443– 51. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-81884-4_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Jagani S , Born U , Winterhagen P , Schrader G , Hagemann MH . Detection and persistence of Citrus bark cracking viroid and other viroids in Citrus peel oils for agricultural applications. J Plant Pathol. 2025; 1–12. doi:10.1007/s42161-025-01953-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang Y , Atta S , Wang X , Yang F , Zhou C , Cao M . Transcriptome sequencing reveals novel Citrus bark cracking viroid (CBCVd) variants from Citrus and their molecular characterization. PLoS One. 2018; 13( 6): e0198022. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Barbosa CJ , Pina JA , Pérez-Panadés J , Bernad L , Serra P , Navarro L , et al. Mechanical transmission of Citrus Viroids. Plant Dis. 2005; 89( 7): 749– 54. doi:10.1094/pd-89-0749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. EPPO . Cocadviroid rimocitri [Internet]. European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/CBCVD0/datasheet. [Google Scholar]

55. Cao MJ , Atta S , Liu YQ , Wang XF , Zhou CY , Mustafa A , et al. First Report of Citrus bent leaf viroid and Citrus dwarfing viroid from Citrus in Punjab, Pakistan. Plant Dis. 2009; 93( 8): 840. doi:10.1094/PDIS-93-8-0840C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Flores R , Di Serio F , Hernández C . Viroids: the noncoding genomes. Semin Virol. 1997; 8( 1): 65– 73. doi:10.1006/smvy.1997.0107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Flores R , Randles JW , Bar-Joseph M , Diener TO . A proposed scheme for viroid classification and nomenclature. Arch Virol. 1998; 143( 3): 623– 9. doi:10.1007/s007050050318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Cao M , Wu Q , Yang F , Wang X , Li R , Zhou C , et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Citrus viroid VI variants from Citrus in China. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2017; 149( 4): 885– 93. doi:10.1007/s10658-017-1236-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Nakaune R , Nakano M . Identification of a new Apscaviroid from Japanese persimmon. Arch Virol. 2008; 153( 5): 969– 72. doi:10.1007/s00705-008-0073-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Najar A , Hamdi I , Mahmoud KB . Citrus viroids: characterization, prevalence, distribution and struggle methods. J New Sci. 2018; 50: 3129– 37. [Google Scholar]

61. Serra P , Barbosa CJ , Daròs JA , Flores R , Duran-Vila N . Citrus viroid V: molecular characterization and synergistic interactions with other members of the genus Apscaviroid. Virology. 2008; 370( 1): 102– 12. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Stackhouse T , Waliullah S , Oliver JE , Williams-Woodward JL , Ali ME . First report of hop stunt viroid infecting Citrus trees in Georgia, USA. Plant Dis. 2021; 105( 2): 515. doi:10.1094/pdis-07-20-1537-pdn. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Radisek S , Majer A , Jakse J , Javornik B , Matoušek J . First report of hop stunt viroid infecting hop in Slovenia. Plant Dis. 2012; 96( 4): 592. doi:10.1094/PDIS-08-11-0640-PDN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Vernière C , Botella L , Dubois A , Chabrier C , Duran-Vila N . Properties of Citrus viroids: symptom expression and dwarfing. Int Organ Citrus Virol Conf Proc (1957–2010). 2002; 15( 15): 240– 8. doi:10.5070/c5121096qg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Najar A , Hamdi I , Varsani A , Duran-Vila N . Citrus viroids in Tunisia: prevalence and molecular characterization. J Plant Pathol. 2017; 99( 3): 787– 92. [Google Scholar]

66. Singh RP , Dilworth AD , Ao X , Singh M , Baranwal VK . Citrus exocortis viroid transmission through commercially-distributed seeds of Impatiens and Verbena plants. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2009; 124( 4): 691– 4. doi:10.1007/s10658-009-9440-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Baig KS , Ahmad F , Asghar U , Khan WA . Biosorption studies on arsenic (III) removal from industrial wastewater by using fixed and fluidized bed operation. Mehran Univ Res J Eng Technol. 2024; 43( 1): 154. doi:10.22581/muet1982.2401.2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Ali A , Umar UU , Akthar S , Rehman AU , Shakeel MT , Tahir MN , et al. Prevalence, symptomology, detection and molecular characterization of citrus viroid V infecting new citrus cultivars in Pakistan. Preprint. 2022. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1310164/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Rizza S , Nobile G , Tessitori M , Catara A , Conte E . Real time RT-PCR assay for quantitative detection of Citrus viroid III in plant tissues. Plant Pathol. 2009; 58( 1): 181– 5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2008.01941.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Vidalakis G , Wang J , inventors; University of California San Diego UCSD , assignee. Molecular method for universal detection of citrus viroids. United States patent US 9,574,244 B2. 2017 Feb 21. [Google Scholar]

71. Yao SM , Wu ML , Hung TH . Development of multiplex RT-PCR assay for the simultaneous detection of four systemic diseases infecting Citrus. Agriculture. 2023; 13( 6): 1227. doi:10.3390/agriculture13061227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Umaña R , Pritsch C , Arbiza JR , Rivas F , Pagliano G . Evaluation of four viroid RNA extraction methods for the molecular diagnosis of CEVd in Citrus limon using RT-PCR, Dot blot and Northern blot. Biotecnol Apl. 2013; 30( 2): 125– 36. [Google Scholar]

73. Bernad L , Duran-Vila N . An improved protocol for extraction and RT-PCR detection of Citrus viroids. Int Organ Citrus Virol Conf Proc (1957–2010). 2005; 16( 16): 452– 5. doi:10.5070/c50b19s756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Bagherian S , Amid-Motlagh MH , Izadpanah K . A new sensitive method for detection of viroids. Iran J Virol. 2009; 3( 1): 7– 11. doi:10.21859/isv.3.1.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Bester R , Steyn C , Breytenbach JHJ , de Bruyn R , Cook G , Maree HJ . Reproducibility and sensitivity of high-throughput sequencing (HTS)-based detection of Citrus tristeza virus and three Citrus viroids. Plants. 2022; 11( 15): 1939. doi:10.3390/plants11151939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Dang T , Espindola A , Vidalakis G , Cardwell K . An in silico detection of a Citrus Viroid from raw high-throughput sequencing data. Methods Mol Biol. 2022; 2316: 275– 83. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-1464-8_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Vidalakis G , Wang J , Dang T , Rucker T , Bodaghi S , Tan SH , et al. SYBR® green RT-qPCR for the universal detection of Citrus Viroids. Methods Mol Biol. 2022; 2316: 211– 7. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-1464-8_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Wang YM , Ostendorf B , Gautam D , Habili N , Pagay V . Plant viral disease detection: from molecular diagnosis to optical sensing technology—a multidisciplinary review. Remote Sens. 2022; 14( 7): 1542. doi:10.3390/rs14071542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Pallás V , Sánchez-Navarro JA , James D . Recent advances on the multiplex molecular detection of plant viruses and viroids. Front Microbiol. 2018; 9: 2087. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Mehetre GT , Leo VV , Singh G , Sorokan A , Maksimov I , Yadav MK , et al. Current developments and challenges in plant viral diagnostics: a systematic review. Viruses. 2021; 13( 3): 412. doi:10.3390/v13030412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Kanapiya A , Amanbayeva U , Tulegenova Z , Abash A , Zhangazin S , Dyussembayev K , et al. Recent advances and challenges in plant viral diagnostics. Front Plant Sci. 2024; 15: 1451790. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1451790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Gucek T , Trdan S , Jakse J , Javornik B , Matousek J , Radisek S . Diagnostic techniques for viroids. Plant Pathol. 2017; 66( 3): 339– 58. doi:10.1111/ppa.12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Abubaker M , Elhassan S . Survey and molecular detection of two Citrus viroids affecting commercial Citrus orchards in the Northern part of Sudan. Agric Biol J N Am. 2010; 1( 5): 930– 7. doi:10.5251/abjna.2010.1.5.930.937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Zhang P , Zhang X , Mohamed AM , Wang L , Daròs JA , Li S , et al. RNA silencing response in chloroplast-replicating viroid siRNA biogenesis in plants. Phytopathol Res. 2025; 7( 1): 62. doi:10.1186/s42483-025-00351-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Belabess Z , Radouane N , Sagouti T , Tahiri A , Lahlali R . A current overview of two viroids prevailing in Citrus orchards: Citrus exocortis viroid and hop stunt viroid. In: Citrus—research, development and biotechnology. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2021. doi:10.5772/intechopen.95914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Malfitano M , Barone M , Duran-Vila N , Alioto D . Indexing of viroids in Citrus orchards of Campania, southern Italy. J Plant Pathol. 2005; 87( 2): 115– 21. [Google Scholar]

87. Ramin AA , Alirezanezhad A . Effects of Citrus rootstocks on fruit yield and quality of Ruby Red and Marsh grapefruit. Fruits. 2005; 60( 5): 311– 7. doi:10.1051/fruits:2005037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Turan M , Mammadov R . Overview of Characteristics of the Citrus Genus [Internet]. In: Overview on horticulture. Ankara, Turkey: IKSAD; 2021 [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Murat-Turan-5/publication/356105416_Overview_of_Characteristics_of_the_Citrus_Genus/links/622097edadd1b367ae107126/Overview-of-Characteristics-of-the-Citrus-Genus.pdf. [Google Scholar]

89. Kapari-Isaia T , Kyriakou A , Papayiannis L , Tsaltas D , Gregoriou S , Psaltis I . Rapid in vitro microindexing of viroids in Citrus. Plant Pathol. 2008; 57( 2): 348– 53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2007.01774.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Nicoletti R . Endophytic fungi of Citrus plants. Agriculture. 2019; 9( 12): 247. doi:10.3390/agriculture9120247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Lü Y , Wu WJ , Zhu MY , Rong ZY , Zhang TZ , Tan XP , et al. Comparative response of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi versus endophytic fungi in tangor Citrus: photosynthetic efficiency and P-acquisition traits. Horticulturae. 2024; 10( 2): 145. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10020145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Mubeen M , Bakhtawar F , Iftikhar Y , Shakeel Q , Sajid A , Iqbal R , et al. Biological and molecular characterization of Citrus bent leaf viroid. Heliyon. 2024; 10( 7): e28209. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Mestre PF , Asíns MJ , Carbonell EA , Navarro L . New gene(s) involved in the resistance of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. to Citrus tristeza virus. Theor Appl Genet. 1997; 95( 4): 691– 5. doi:10.1007/s001220050613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Arlotta C , Ciacciulli A , Strano MC , Cafaro V , Salonia F , Caruso P , et al. Disease resistant Citrus breeding using newly developed high resolution melting and CAPS protocols for Alternaria brown spot marker assisted selection. Agronomy. 2020; 10( 9): 1368. doi:10.3390/agronomy10091368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Ahmar S , Ballesta P , Ali M , Mora-Poblete F . Achievements and challenges of genomics-assisted breeding in forest trees: from marker-assisted selection to genome editing. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22( 19): 10583. doi:10.3390/ijms221910583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Alves MN , Lopes SA , Raiol-Junior LL , Wulff NA , Girardi EA , Ollitrault P , et al. Resistance to ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus,’ the huanglongbing associated bacterium, in sexually and/or graft-compatible Citrus relatives. Front Plant Sci. 2021; 11: 617664. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.617664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Vidalakis G , Pagliaccia D , Bash JA , Afunian M , Semancik JS . Citrus dwarfing viroid: effects on tree size and scion performance specific to Poncirus trifoliata rootstock for high-density planting. Ann Appl Biol. 2011; 158( 2): 204– 17. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2010.00454.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Flores R , Delgado S , Gas ME , Carbonell A , Molina D , Gago S , et al. Viroids: the minimal non-coding RNAs with autonomous replication. FEBS Lett. 2004; 567( 1): 42– 8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Owens RA , Hammond RW . Viroid pathogenicity: one process, many faces. Viruses. 2009; 1( 2): 298– 316. doi:10.3390/v1020298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Jakše J , Wang Y , Matoušek J . Transcriptomic analyses provide insights into plant-viroid interactions. Fundam Viroid Biol. 2024: 255– 74. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-99688-4.00010-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Dang T , Lavagi-Craddock I , Bodaghi S , Vidalakis G . Next-generation sequencing identification and characterization of microRNAs in dwarfed Citrus trees infected with Citrus dwarfing viroid in high-density plantings. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12: 646273. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.646273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Zhang Y , Nie Y , Wang L , Wu J . Viroid replication, movement, and the host factors involved. Microorganisms. 2024; 12( 3): 565. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12030565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Ramesh SV , Yogindran S , Gnanasekaran P , Chakraborty S , Winter S , Pappu HR . Virus and viroid-derived small RNAs as modulators of host gene expression: molecular insights into pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2021; 11: 614231. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.614231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Sun L , Ke F , Nie Z , Wang P , Xu J . Citrus genetic engineering for disease resistance: past, present and future. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20( 21): 5256. doi:10.3390/ijms20215256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. de León CEP , Castellanos AIF , Figueroa J , Stein B . Comparison of different diagnostic methods for detection of hop stunt viroid and citrus exocortis viroid in citrus. Int Organ Citrus Virol Conf Proc (1957–2010). 2011; 18( 18): 4. doi:10.5070/c57zf5v3q6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools