Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Advances in Grapevine Breeding: Integrating Traditional Selection, Genomic Tools, and Gene Editing Technologies

1 Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas y Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Km 2.5 Carretera a Rosales, Campus Delicias, Delicias, C.P. 33000, Chihuahua, Mexico

2 Facultad de Posgrado, Universidad Técnica de Manabí, Portoviejo, 130105, Ecuador

3 Instituto Politécnico Nacional, CIIDIR Unidad Sinaloa, Blvd. Juan de Dios Bátiz-Paredes 250, San Joachín, Guasave, C.P. 81101, Sinaloa, Mexico

4 Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo (CIAD), Unidad Delicias, Av. Cuarta Sur 3828, Fracc. Vencedores del Desierto, Delicias, C.P. 33089, Chihuahua, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Sandra Pérez-Álvarez. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adaptation Mechanisms of Grapevines to Growing Environments and Agricultural Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3749-3803. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072135

Received 20 August 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

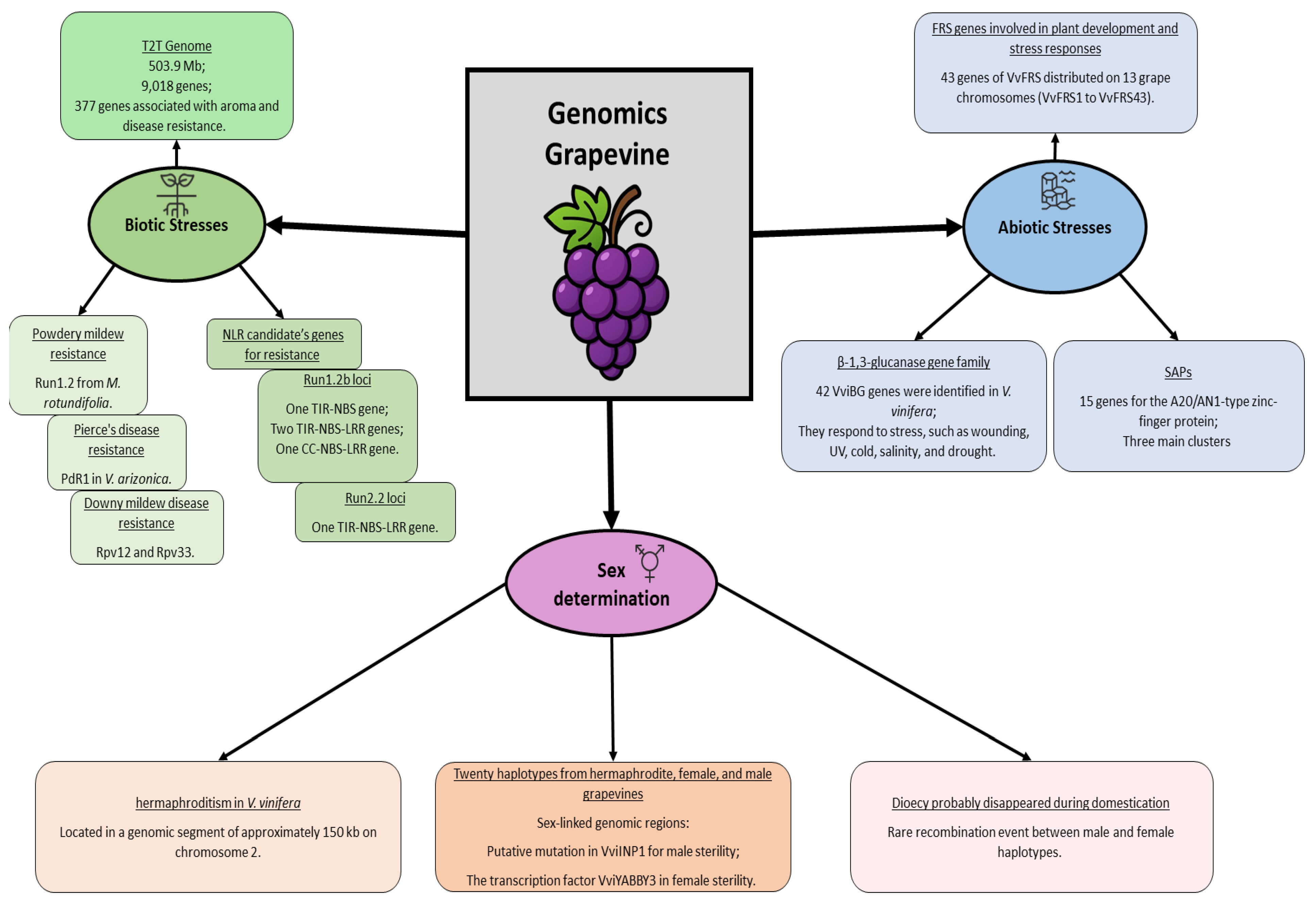

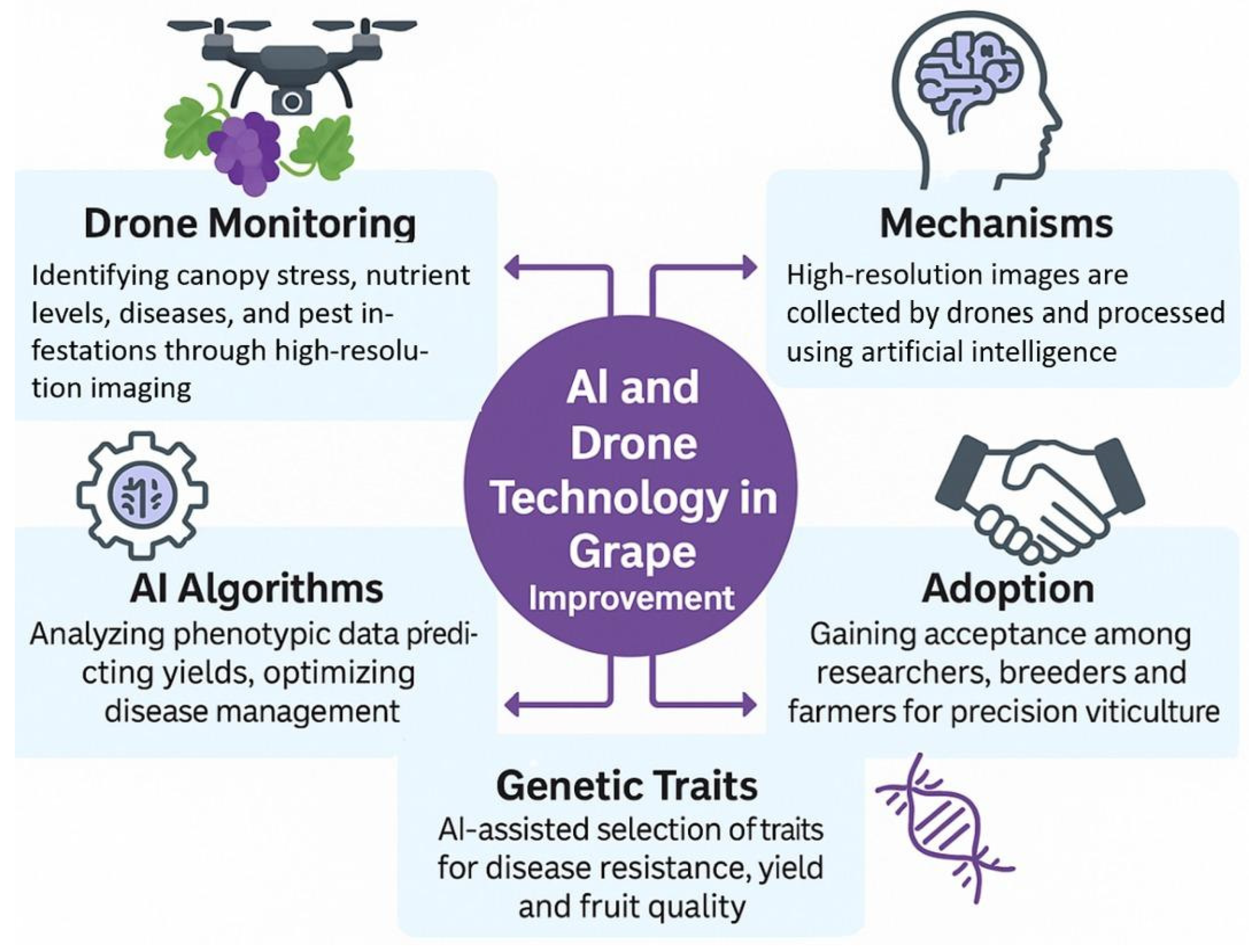

Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivation has progressed from early domestication and clonal propagation to modern, data-driven breeding that is reshaping viticulture and wine quality. Yet climatic and biotic constraints still impose heavy losses—downy mildew can reduce yields by ≈75% in humid regions and gray mold by 20–50%—sustaining the need for resistant cultivars. Producer selection, interspecific crossing, and formal improvement programs have generated ~10,000 varieties, although only a few dozen dominate global acreage. Conventional breeding has delivered fungus-resistant “PIWI” cultivars that retain ≥85% of the V. vinifera genome; in Austria, national PIWI varieties are gaining acceptance for combined resistance to downy and powdery mildew and strong enological quality, while in Brazil, using ‘BRS Isis’ as a male parent produced a high proportion of seedless progeny. Over the past two decades, mapping studies have identified >30 resistance loci to Plasmopara viticola (Rpv) and 15 to Erysiphe necator (Ren/Run), enabling MAS and locus pyramiding; widely deployed loci include Rpv1, Rpv3 haplotypes, Rpv10, Rpv12, Run1, Ren1, Ren3, and Ren9. Gene editing further expands options: CRISPR knockout of VvMLO3 confers powdery-mildew resistance, whereas VvPR4b knockout increases susceptibility to P. viticola, highlighting both opportunity and gene-specific risk. To date, no consolidated program- or country-level percentages exist for MAS/CRISPR adoption in grape. Instead, proxy indicators—MAS screening throughput, the number of programs employing MAS, and CRISPR’s laboratory/pilot status with no commercial releases—suggest broad operational MAS and early-stage CRISPR implementation; for example, Germany reported >23 disease-resistant grapevine varieties developed with MAS and the loci above by 2022. Finally, this review analyzes the future of grapevine breeding, with a particular emphasis on the adoption of novel approaches to multi-omics, AI in breeding models, and sustainability for improving breeding schemes. An interdisciplinary effort will be required to find future solutions, as viticulture has entered a precision breeding revolution to address the challenges posed by the industry and the fight for long-term sustainability of grape production.Keywords

The grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) originated in the Caucasus region, from where it spread to the Mediterranean, the rest of Europe, and later to other parts of the world. Its domestication began at least around 6000 years ago, and its uses include the production of wine, vinegar, and juice, as well as consumption as fresh fruit or dried as raisins. Grapevine is the fruit that occupies the largest cultivated area on the planet, with more than 7 million hectares [1].

It is estimated that there are around 10,000 grape varieties worldwide [2], resulting from traditional selection by winemakers and scientific breeding efforts that began in the 19th century. This has led to a remarkable diversity in the physiological and agronomic characteristics of grapevines, as well as in the organoleptic properties of their fruits. However, large-scale commercial production has resulted in only a few dozen varieties—such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, and Merlot—occupying the largest cultivated areas. Consequently, the actual genetic base of global viticulture has eroded [3], reducing the adaptability of varieties to new challenges.

Among the main contemporary threats to viticulture are bacterial diseases such as Pierce’s disease, caused by Xylella fastidiosa [4], and fungal diseases such as gray mold (Botrytis cinerea), downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola), and powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) [1]. Climate change events are altering plant growth patterns and their yield [5] as well as wine quality [6]. In addition, the intensification of extreme conditions caused by climate change exacerbates the effects of water deficit susceptibility in grapevine varieties [7] and increases the damage caused by pathogenic microorganisms.

Genetic improvement offers a medium- and long-term solution to overcome these challenges, and encompasses a wide range of techniques and approaches. Hybridization among V. vinifera varieties has mainly aimed to increase yield and obtain wines with specific properties, while interspecific hybridization is of great interest to breeders because germplasm from other Vitis species can provide genes for resistance to biotic and abiotic factors [8]. Clonal selection of outstanding genotypes has focused on obtaining individuals distinguished by their enological qualities and/or their tolerance to different types of stress [9,10]. The use of rootstocks, although not considered by some authors as a genetic improvement technique per se, enhances fruit production and wine quality and contributes to pest and disease management [11].

The conservation and recovery of wild Vitis varieties and related taxa are contributing both to the development of genotypes tolerant to biotic and abiotic stress factors and to their use as parents in breeding programs, owing to the valuable genes they contribute to the progeny [8,12].

Recent advances in molecular biology have been increasingly applied to support genetic improvement. Genomic studies [13], research on genetic variability using molecular markers [3], genome editing with CRISPR/cas9 [14], and the identification of genes for resistance to fungal diseases [1] are some examples of the contribution of molecular biology to the development of promising genotypes.

This article reviews the progress achieved in the genetic improvement of Vitis vinifera L. through conventional breeding methods, traditional propagation, and in vitro culture techniques, as well as advances in the use of marker-assisted selection, genome modification, and gene editing. Particular emphasis is placed on the application of multi-omics technologies in breeding, and the recent introduction of artificial intelligence for this purpose. In this way, an integrated overview is provided of the achievements in grapevine improvement and its future prospects.

2 Traditional Breeding Methods

The beginning of genetic improvement in V. vinifera can be traced back to the late 19th century. The introduction of varieties from North America to Europe brought with it a dangerous insect (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae), commonly known as phylloxera, capable of destroying entire vineyards. Its appearance in 1863 in France and Great Britain was followed by a rapid spread across Europe, Australia, and American countries. The immediate solution was the use of North American Vitis species, resistant to phylloxera, as rootstocks, primarily V. berlandieri Planch, V. riparia Michx., and V. rupestris Scheele [15].

Grafting is not considered, in itself, a genetic improvement technique, since there is no genetic exchange between the rootstock and the scion, nor is a hybrid progeny obtained. However, several authors include this practice in discussions of genetic improvement for the following reasons:

- ➣It has been shown that in grafted plants, the genetic characteristics of the rootstock are expressed, such as enhanced absorption of nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, among others [16,17], which improves performance and leads to higher yields.

- ➣Grafting modifies the expression of genes associated with stress resistance [18,19], resulting in better plant behavior against biotic and abiotic factors.

- ➣The vascular connection between rootstock and scion enables communication through chemical and hormonal signals, which in turn modifies the scion’s transcriptome [20]. Consequently, although no genetic changes occur in the scion, the expression of rootstock-derived genes can be detected in it.

Rootstocks commonly used belong to species of the Vitis genus, primarily distinguished by their tolerance to biotic and abiotic factors. In Brazil, the rootstocks IAC 313 and IAC 572, developed through hybridization at the Instituto Agronômico de Campinas between 1950 and 1970, are regarded as the cornerstone of tropical viticulture in that country [21]. Their introduction enabled grapevine cultivation under Brazil’s warm and humid climate, to which other European rootstocks were poorly adapted.

Species such as V. labrusca, V. aestivalis, V. rupestris, V. smalliana, V. caribaea, V. shuttleworthii, and V. berlandieri have been, and continue to be, used as rootstocks to confer on the scion desirable traits such as resistance to viruses, nematodes, soil acidity, drought, and salinity, among other biotic and abiotic stresses [22]. In China, the rootstocks LDP-191 and LDP-294 (V. piasezkii Maxim. var. pagnucii) have provided cold tolerance to the table grape cultivars ‘Fujiminori’ and ‘Red Globe’ [23]. In Florida, grafting onto Vitis vulpina L. has enhanced resistance to nematodes, whereas Vitis champinii Planch. is known as a rootstock resistant to Pierce’s disease, drought, and nematodes [24].

Other Vitis species, such as V. rotundifolia, V. coignetiae, and V. thunbergii, although recognized for their strong resistance to fungal pathogens, nematodes, and temperature extremes [25], cannot be employed as rootstocks for V. vinifera due to graft incompatibility. Nevertheless, the success of grafting V. vinifera cultivars onto other compatible rootstocks led, by the 1980s, to the widespread replacement of own-rooted vineyards with grafted vines [26]. An interesting breeding strategy involves interspecific hybridization between Euvitis and Muscadinia, aimed at developing rootstocks with enhanced adaptive traits [27], although the progeny from such crosses generally exhibits low viability because of chromosomal and vascular incompatibilities.

In order to obtain rootstocks that confer desired characteristics to the scion, hybridization programs between Vitis species have been developed, and outstanding hybrids have been selected, for both direct use as rootstocks and as parents [22,23,26,27,28,29].

In traditional breeding through hybridization, the main objectives, either separately or together, have been those examined below.

Disease Resistance

In general, commercial varieties of Vitis vinifera are, to a greater or lesser extent, susceptible to diseases such as downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) and powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator). The strategy for improvement has been the hybridization of European commercial varieties with North American Vitis species. Based on the studies conducted so far, the use of V. rotundifolia and V. piasezkii in crossing confers complete resistance to the progeny [30].

The varieties obtained through this method are called “PIWI”, a term derived from the German “Pilzwiderstandsfähig” (fungus-resistant). The acceptance of these new varieties is growing, as it has been demonstrated that they retain at least 85% of the original V. vinifera genome. Among these varieties are the German “Regent” and “Solaris”, which combine proven resistance with the production of wines of adequate quality [31]. A detailed list of PIWI varieties is publicly available and can be consulted at the International Piwi organization (https://piwi-international.org).

In Brazil [32] resistance to P. viticola in three PIWI varieties obtained in Germany was significantly higher than that of the susceptible control. Ten PIWI varieties evaluated in Italy showed an average 93% reduction in P. viticola infection compared to the susceptible control variety “Pinot Grigio” [33]. In Austria, three national PIWI varieties are gaining great acceptance for their resistance to both diseases and their high enological quality [34]. In La Rioja, Spain, the introduction of five white PIWI varieties and four red ones has also yielded good results [35].

Climate Adaptation and Tolerance to Abiotic Stress

Among the challenges already faced by this crop are spring frosts, which occur beyond the winter season, and excessive heat at the beginning of autumn. Frosts can damage the shoots, preventing the plant from forming grape clusters, whereas excessively high temperatures lead to over-ripening, producing musts with excessive sugar and consequently high alcohol content. The solution lies in the search for varieties with late budding and ripening, to prevent these phenological phases from coinciding with frosts and off-season heat [36].

Fortunately, there is considerable diversity in traits related to climate change adaptation, such as polyphenol content in fruits [37] and drought tolerance [38]. It has also been observed that there is a positive correlation between fruit size at maturity and malic acid content, and a negative correlation with tartaric acid content in a set of 33 genotypes [39]. The study of these traits and their expression under adverse conditions can contribute to the development of breeding programs to address climate change.

Traits such as cold tolerance are also of interest for genetic improvement. Selection in the progeny of crosses between V. vinifera and other species has led to the development of varieties suited to the harsh winter conditions of northern states in the U.S. [40]. Since 2011, North Dakota State University has conducted a hybridization program with this goal, and recently, genetic-molecular tools have been incorporated into the research [41].

An interesting result was obtained [42] when investigating daytime and nighttime transpiration of two varieties (“Syrah” and “Grenache”) and 186 descendants from their cross. A negative correlation was observed between nighttime transpiration (resulting from poor stomatal closure) and plant growth, both under normal water supply and under water deficit conditions. However, more basic studies are needed to better understand the mechanisms associated with tolerance. For instance, it is known that the response of grapevine varieties to drought involves both abscisic acid-dependent and -independent mechanisms, but the role of each and their interaction remain unclear, as does, the genetic regulation of root system performance, xylem, and other factors contributing to tolerance [43]. Nonetheless, some recent studies have reported success in breeding for drought stress [44], salinity [45] and heat tolerance [46,47].

Agronomic Characteristics and Agricultural Yield

Today, yield is not a priority for breeding; the most pressing issue has been solving other problems previously mentioned, such as disease resistance and adaptation to abiotic stress. Of course, obtaining varieties with these characteristics implies maintaining adequate yield and commercial quality, so evaluating these parameters is essential for achieving crop sustainability [48].

Grafting, used as a practice to improve resistance or tolerance to biotic and abiotic factors, indirectly influences agricultural yield, as it provides the scion with benefits such as more efficient nutrient absorption [16,17] and enhanced defense mechanisms against stress [18,19]. Additionally, grafting has been observed to directly impact yield: scions of Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay grafted onto 15 different rootstocks increased their yield by approximately 50%, due to higher fruit weight [49]. The authors suggest that this effect likely results from rootstocks enhancing water absorption by the plants.

A review of research conducted in countries with a long tradition of grapevine genetic improvement reveals that the main breeding efforts have historically focused on other primary objectives [50]. While yield remains an essential trait that must be maintained in newly developed varieties, the focus has expanded to encompass crop sustainability through the management of multiple factors.

Fruit Quality and Chemical Composition

Among the parameters considered to evaluate quality are sugars, which determine the alcohol content in the wine; polyphenols, which provide body and color to the must; organic acids, which influence acidity; cations, which affect pH; and other compounds related to aroma and flavor. Although the exact ways in which temperature and other factors affect the composition of the fruit are not yet fully understood [51], genetic improvement considers this one of its main objectives.

Not all crosses aimed at improving tolerance to adverse climatic conditions result in fruits capable of producing wines of adequate quality. For example, the progeny of V. vinifera × V. riparia, while producing descendants able to withstand the low temperatures of the northern states of the U.S., fails to meet the quality standards required by viticulturists [40,52]. Crosses of V. vinifera × V. amurensis to obtain cold-tolerant progeny in China have also produced some varieties [53], though their enological quality remains low.

It seems that hybridization of V. vinifera with other species, while tending to produce individuals with some environmental plasticity, often reduces wine quality. In contrast, crosses among V. vinifera varieties known for their enological quality can yield new varieties whose properties match or even surpass those of their parents. The hybridization of the varieties “Graciano” and “Tempranillo” generated several offspring producing grapes with high polyphenol content, adequate acidity, intense color, and excellent aroma [54].

As in any hybridization strategy, combining parents in grapevine faces issues related to pollen fertility and offspring viability. These variables were studied in six V. vinifera varieties and their progeny during 2020 and 2021 [55]. “Ecolly” was the variety with the highest pollen fertility, suggesting its use as a male parent. Conversely, the variety “Marselan” exhibited a self-fertilization index between 0.88 and 0.93, indicating that its use as a female parent may be challenging.

Seedless Grapes

The absence of seeds is a highly valued trait in table grapes and raisins [56], and breeding programs have been developed with this goal in mind.

In Brazil, 200 descendants from 38 combinations were evaluated over six seasons between 2018 and 2021 [57]. The crosses involved 30 cultivars of V. vinifera and interspecific hybrids. The fruits of the progenies were classified as seedless, soft-seeded, and seeded fruits. Around 20% of the hybrids produced seedless fruits; the use of the Brazilian variety “BRS Isis” as a male parent resulted in a high proportion of seedless descendants.

In Turkey, one of the world’s leading producers of table grapes, hybridization programs have also been developed to continue improving fruit quality. For this purpose, seedless V. vinifera varieties, either Turkish or American, have been used as male parents, while both V. vinifera and V. labrusca varieties have served as female parents [58]. The progeny has been characterized, and several outstanding cultivars have been recommended for evaluation in different regions of the country.

It is known that inheritance of this trait is determined by three independent recessive genes controlled by the dominant gene SdI [59]. This knowledge has enabled the use of more precise biotechnological tools for the development of seedless grape varieties, such as embryo rescue and marker-assisted selection [56].

3 Clonal Propagation and Selection

Traditional Cloning

Grapevine cloning dates back thousands of years [60], and according to Walter [61] a clone is defined as the offspring of a crop, in this case grapevine, selected for its varietal purity, phenotypic characteristics and health status.

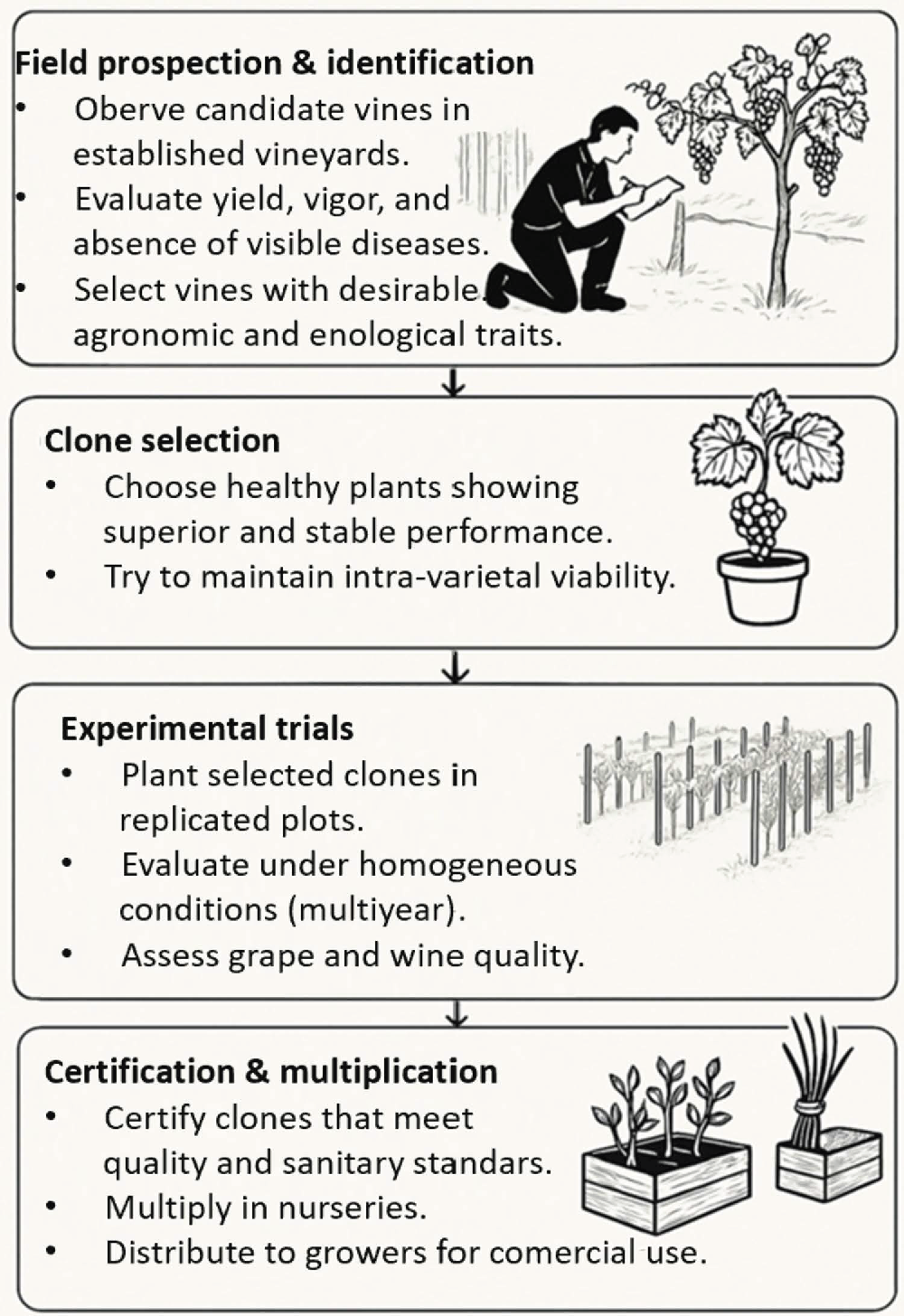

Since the 1960s, the focus of clonal selection in grapevines has been on developing high-yield, virus-free clones that have higher sugar content in the fruit. However, the quality potential of these certified clones can differ based on the grape variety. While clonal selection is generally embraced for its benefits, it does come with two main downsides: first, the limited qualitative impact of clonal selection in certain varieties like Cabernet Franc and Sémillon, as well as many secondary varieties such as Carmenère, Malbec, Petit Verdot or Cot; and second, the significant loss of genetic diversity within grapevine populations when clonal selection is the only method used to enhance plant material [62,63]. Fig. 1 shows the clonal selection process for grapevine cultivation.

Figure 1: Traditional clonal selection workflow for grapevine cultivation.

According to Fig. 1 the clonal selection process for grapevine cultivation begins with the identification of promising clones, which involves detailed assessments of agronomic traits (such as yield, vigor, and growth habit) and enological characteristics (including sugar content, acidity, and flavor profile) to determine their potential for high-quality grape and wine production; secondly, the selection of the clone process involves two main stages that are genetic and sanitary selection, which together consider genetic diversity while maintaining varietal purity prevent the propagation of virus-infected or disease-prone plants and mitigates the negative effects of mutations in future vineyards [64,65]; thirdly, only the healthiest and most promising clones are chosen to ensure long-term sustainability. These clones are tested under uniform conditions to determine their capacity for producing high-quality grapes and to support their certification and availability to growers [66]. Finally, the certification of a grapevine clone involves a thorough evaluation to ensure it meets strict standards for genetic identity, agronomic performance, and phytosanitary status (e.g., free from viruses and other diseases). Once certified, the clone is approved for commercial propagation and can be distributed to nurseries and growers for large-scale cultivation, ensuring consistency in vine quality and performance across vineyards [67].

A major disadvantage of cloning is that all offspring will have the same characteristics as the mother plant, so any biotic or abiotic factor that affects that vineyard will cause all plants to suffer the same consequences. Therefore, it is important to have a large number of selected clones to obtain a good response to the pressure of natural selection (new pests, droughts, excessive rainfall, salinity, climate changes, etc.), improve the quality of the wines and not affect the genetic variability of the cultivars. The best technique to achieve this is to use old vineyards for preselection, taking into account first of all the number of vineyards and not the number of plants per vineyard, thus being able to have greater variability in the selected phenotypes [62]. Nevertheless, once clones propagate the line, they accumulate somatic mutations. Some of these mutations have become a new resource for genetic improvement [68,69]. Fig. 2 presents the benefits and risks of grape propagation by clones, aspects that are analyzed in this section theoretically or through case studies.

Figure 2: Benefits and risks of clonal propagation in grapevine.

By the 20th century, these somatic changes became the foundation for clonal selection in viticulture. Through clonal propagation for over nine centuries, a number of variants of Pinot Noir have emerged via spontaneous bud mutation mechanisms, such as Pinot Meunier, Pinot Grigio, Pinot Blanc, and Pinot Gris [70]. The first reference genome for grapevines was built using PN40024, a highly homozygous line derived from PN [71].

The Institute for Grapevine Breeding at Geilweilerhof (JKI) in Germany has demonstrated the significant impact of genetic disease resistance on sustainable grape production through its breeding programs. A prime example is the ‘Regent’ cultivar, released in 1994, which possesses genetic resistance to downy mildew and powdery mildew. Despite moderate resistance levels now due to evolving pathogens, ‘Regent’ vines in 2021 trials still showed a 50% reduction in fungicide applications compared to susceptible cultivars, even under intense downy mildew pressure. This highlights the long-term potential of resistance breeding for environmentally friendly and economically viable viticulture. The JKI’s work underscores the importance of investing in grapevine breeding for durable disease resistance to reduce environmental impact, ensure economic viability for growers, promote biodiversity, and safeguard consumer health [72].

Complementing resistance breeding, traditional clonal selection has been pivotal for shaping regional wine styles and ensuring consistency. In Champagne (region in northeastern France), clonal breeding is the basis of grape growing in order to achieve wine style and varietal expression. Over decades of the clonal selection of Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, and Chardonnay vineyards, uniformity of yields has been attained, along with performance consistency, thus assisting in sustaining the world fame of the appellation. At the same time, clonal preservation of less-used cultivars—Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Arbane, Petit Meslier—is now proving strategic: recent research indicates these minor varieties may ripen more appropriately in warmer vintages, and their reintroduction into blends could help maintain freshness and acidity under climate change [73]. Hence, clonal selection ensures varietal identity while simultaneously widening the adaptive range of the grower.

Extending the evidence base, the long-term trials in the Carpathian Basin highlighted the quantitative gains obtainable through clonal selection in multiple cultivars. For Welsch Riesling, the Vojvodina clone SK. 54 and Hungarian B. 20 outperformed unselected populations over 13–14 years, the traits being improved at a level of ~10% and yields were 30% more. Previously undisclosed cases obtained similar results for Pinot Gris: for yield-related traits, clones B. 10 (Hungary) and Gm. 2-54 (Germany) ranged from being 22 to 62% superior. These differences in yield-related traits further extended to large differences between clone effects seen in Chardonnay-French 75 being 83% greater in cluster yield and 57% greater in cluster size compared with Italian VCR. 4, whereas for White Riesling, clone Gm. 2-54 yielded 55% more than local unselected vines. Thus, these results prove that clonal selection may increase productivity and agronomic performance while maintaining varietal typicity [74].

Thus, after the clonal lines have been fixed, sanitation can improve final performance by sanitizing the viral constraints. Removing Grapevine leafroll virus (GLRaV-1, GLRaV-3) in clones already in use has been shown to promote vine vigor and better physiological functioning so as to improve grape and wine qualities, whereas in some cases, a virus-free clone of the same genotype offers better results despite likely not showing an increase in yield [75]. In summary, combining resistance breeding together with clonal selections and sanitation could create a coherent pathway toward a sustainable pool of viticulture, high quality, and lower-input.

In addition to winemaking, table grape cultivation has become a key source of agricultural income for communities in various parts of the world. Despite a general decline in global vineyard areas, grape production has risen, largely due to expanded table grape plantations and the improved productivity of newer cultivars [76]. Countries such as Morocco, Egypt, India, and China have seen notable growth in table grape production areas. Recently, the popularity of seedless grapes has driven market trends, with nearly all new grape varieties being seedless [77]. In response to evolving consumer preferences, numerous nations have launched breeding programs aimed at producing new grape varieties. These programs focus on developing seedless grapes with larger berries, unique flavors, and resistance or tolerance to various stress factors [78].

The clonal propagation efficiency was evaluated in a newly developed microvine variety for the production of seedless table grapes, considering two factors: (a) position of the cutting on the shoot and (b) length of the misting period (between 3 and 7 weeks). Some of the rooted cuttings were subsequently transferred to the hydroponic system under controlled conditions and monitored for establishment, initial growth, flowering, and fruit development. After 3 weeks, 83.7% of the cuttings rooted, regardless of which part of the shoot they came from or the duration of misting; 16.7% of the cuttings did not survive. After transplanting to the hydroponic system, 100% of the rooted cuttings were successfully established, and the fruit yield and quality did not vary among the cutting sources. The whole production cycle has a duration of 208 days, with 63 days in seedling development and 145 days from transplanting until the first harvest. Flowering occurred at about 33.9 days, while veraison started after around 116 days. Under these conditions, fruits complied with the sugar content requirements for the Australian market [79].

Developed by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation-like agency, the table grape breeding program in Australia focuses on cultivars customized to consumer needs. Seedlessness, large-size berries, good texture, and flavor are major attributes under consideration, along with resistance to the more common diseases. Varieties assessing early and late ripening are also included to increase the harvest window. It has been important, as well, to develop grapes that can live longer on the shelf, thus being stored and exported to faraway markets. As an example, being the first CSIRO variety offered to market, Marroo Seedless was born of a cross between Ruby Seedless and Carolina Blackrose, and it is a very productive large berries: seedless, crisp, black, sweet-flavored, downy mildew tolerant, but powdery mildew susceptible. In the US, it became an important variety with over 1.3 million boxes produced in the 1990s. Similarly, in selecting high-yielding Sultana clones that represented more than half of Australia’s total grape crop in the 1970s for wine and raisin production, the CSIRO played a pivotal role [76].

Anamaria et al. [80] conducted a study in which four varieties of table grapes—Moldova, Bican Roz, Victoria, and Centennial Seedless—were tested. In the first year, 10 clonal selections were made for each variety; in the years that followed, five elite clones per variety were selected. Clones derived from this selection exhibited normal development and showed a greater grape weight than those of non-selected clones. The clonal selections of Moldova and Bican Roz were well suited for transport and storage; in contrast, Victoria and Centennial Seedless were much better suited for fresh consumption. Additional uses of Centennial Seedless included raisining.

The clonal selection controls viral diseases and allows the targeted selection of genotypes with regard to agronomic, viticultural, or enological traits. On the other hand, while clonal selection may provide uniformity and stability, obtaining asexual clones also limits recombination, thus generating cases of genetic erosion. Genetic erosion in clonally propagated grapevines arises when reliance on a narrow set of elite genotypes limits recombination and gradually narrows the adaptive pool. Although vegetative propagation confers relative genetic stability, somatic mutations still occur [81]. On the positive side, such mutations can yield superior attributes or distinctive characters—occasionally giving rise to sports or new cultivars—but they may also disrupt key quality traits [82]. Crucially, asexual propagation fixes these mutations, so vineyards accumulate intra-varietal diversity over time, generating multiple clonal lines with distinct phenotypes within the same named variety [83]. This duality—stability with drift—means that, without deliberate conservation (massal selection, broader clonal portfolios, and genomic monitoring), clonal agriculture can erode genetic breadth even as it preserves typicity, ultimately reducing resilience to new pathogens and climate stresses. Studies have shown that excessive reliance on clonal reproduction may reduce the genetic resources available for biotic and abiotic stress adaptation. For example, Vondras et al. [84] also showed that long-term propagation of Zinfandel clones had led to thousands of somatic mutations accumulating, representing both the possibilities for divergence within the variety and the narrowing of genetic options through time. It was concluded in the study that intergenic repetition is a key factor in the genomic diversification of clones, as well as the accumulation of presumably deleterious mutations.

Case studies highlight the menace of erosion that arises with decades of vegetative propagation of grape cultivars. Strioto et al. [85] documented for the popular table grape, ‘Italia’ how extensive clonal propagation gave somatic variation that destabilized key agronomic traits like berry size and fertility. This shows how a long-term reliance on a few selected clones possibly can undermine the same uniformity it attempts to protect while simultaneously diminishing genetic receptivity to new viticultural challenges.

According to Roby et al. [86], the preservation of grapevine genetic resources requires more than just institutional clonal selection. Authors highlight the importance of combining clonal-type practices with those of massal selection in order to conserve intra-varietal diversity. Further, Pelsy [87] studied another paradox of clonality: it maintains desirable traits but limits wider levels of genetic exchange, potentially reducing adaptive ability. This tension implies that viticulture must walk a fine line between safeguarding clonal stability on the one hand and fostering diversity in the long run on the other. Taken together, the research stresses that the future of viticulture can be saved only by engaging in a deliberate act of balancing the positives of clonal propagation with strategies against genetic erosion induced by climate change and new disease pressures.

in vitro Cloning

Grapes, like all crops, are under various conditions of biotic and abiotic stress that affect their yield and fruit quality, and also demand has increased not only for fresh and dried fruit, but also for wines (increase in wine-producing industries) [88]. The issues mentioned above are generally addressed by generating and providing healthy propagation material, along with implementing genetic enhancement and introducing genotypes—such as exclusive varieties—that offer resistance or tolerance to pests, diseases, and varying soil and climate conditions [89,90,91].

In vitro culture, grounded in the theory of totipotency—the concept that complete plants can be regenerated from somatic cells [91]—enables the mass propagation of plants without requiring sexual reproduction (cloning). This method also yields plant material with superior phytosanitary quality compared to conventional propagation techniques. Among various biotechnological tools, in vitro culture stands out as a key technique for the propagation, conservation, and genetic improvement of plant species [92].

Genetic improvement programs for perennial species like grapevines are inherently slow and complex due to their extended life cycle [93]. As a result, more than 80% of grapevines have historically been propagated through vegetative means, a practice sustained for centuries to preserve desirable traits [94].

Some authors claim that depending on the table and wine grape cultivars, standardized culture media and their optimal conditions for in vitro propagation should be set up [95]. The major factors that can influence their propagation response include the cultivar type [96], the pruning method [97], genotype and the culture medium used [98], and the inappropriate or correct use of plant growth regulators [99].

As part of the breeding program at the Kazakh Scientific Research Institute of Fruit Growing and Viticulture, an in vitro collection was established to safely preserve grapevine hybrids, while also evaluating their resistance to Plasmopara viticola through the presence of the Rpv3 and Rpv12 loci. For in vitro initiation, plant material (18 selected hybrids of grapevines) consisted of either shoots collected directly from field-grown vines or budwood cuttings forced to sprout indoors. Disinfection of field-harvested shoots was most effective with a treatment of 0.1% mercuric chloride (HgCl2) for 5–7 min, achieving a moderate viability rate, with 17–21% of explants establishing successfully across all tested genotypes. The optimal growth medium was Murashige and Skoog (MS) [100] basal medium supplemented with 1 mg L−1 BAP, 0.1 mg L−1 IBA, and 0.1 mg L−1 gibberellic acid (GA) at pH 5.7, resulting in 4 to 4.4 shoots per explant. When using shoots from budwood cuttings sprouted in the laboratory, establishment was less effective. Although contamination rates decreased with longer HgCl2 exposure (from 65% at 5 min to 6% at 10 min), viability also declined, with high rates of necrosis (10% at 5 min and 87% at 10 min) and poor regeneration. Ultimately, 16 grapevine accessions were identified as possessing P. viticola resistance associated with the Rpv3 and Rpv12 loci [101].

Another in vitro way to improve grape cultivation and also to conserve resources is somatic embryogenesis (SE). In this process, somatic cells are stimulated to generate cells with embryogenic potential, which produce structures that give rise to a complete plant [102,103].

In short, SE using floral-origin explants is a fantastic way to regenerate healthy grapevine plants that are free from a host of viruses. While SE is a bit more complex and takes more time than the usual virus-cleaning methods [104], it has shown to be incredibly effective for grapevines. For chimeric grapevine cultivars, viruses can be removed through traditional techniques like meristem tip culture paired with thermotherapy, or by using cryotherapy, often requiring a mix of these methods [105,106].

Alongside traditional clonal selection in the vineyard, in vitro approaches have been instrumental in generating enhanced grapevine varieties, whether through sanitation, somaclonal variation, embryo rescue, or induced mutagenesis. Early studies illustrate the potential of these methods: the first establishment of somatic embryogenesis from cultured anthers was achieved in the 1970s [107,108], with germinable embryos later recorded in the interspecific hybrid Gloryvine. By 1977, vines derived from somatic embryos of cv. Seyval were already being planted commercially in Maryland [109], and in 1985 a U.S. patent formalized a grape SE protocol [110].

Sanitation via in vitro regeneration has also been reported. For example, embryos and plantlets obtained from ovaries of V. vinifera cv. Roobernet infected with Grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) tested negative for all leafroll-associated viruses, indicating successful elimination. However, when the same technique was applied to anthers of infected V. rupestris cv. Rupestris du Lot, regenerated plants remained infected [111], highlighting both the potential and the limitations of in vitro sanitation.

In parallel, embryo rescue has become a cornerstone of modern grapevine breeding. Over the past five years, nearly 60% of newly released seedless cultivars have been obtained through this technique, which recovers otherwise abortive embryos. Landmark achievements include the first stenospermocarpic, seedless hybrid between V. vinifera and V. rotundifolia [112]. More recently, programs combining stenospermocarpic female parents with seeded, cold-tolerant male parents produced cold-resistant seedless grapes, with 91 progenies showing seedlessness and 18 carrying cold tolerance [113].

Finally, induced mutagenesis has further expanded the scope of in vitro breeding strategies. Defined as the generation of new cultivars through novel genetic variation induced by physical or chemical agents [114], this technique has been tested in several grapevine cultivars. Munir et al. [115] reported that gamma irradiation enhanced plant height more effectively than chemical mutagens in V. vinifera cvs. Desi, Sundar Khani, and Chinese grape, with sodium azide being effective only at low concentrations (0.1%), while higher doses caused explant browning. Similarly, Kuksova et al. [116] demonstrated in V. vinifera cv. Podarok Magaracha that somaclonal variation and in vitro mutagenesis produced notable genetic diversity: 2.5% of regenerants were spontaneous tetraploids, gamma irradiation (5–100 Gy) increased tetraploid frequency to about 7% and induced some aneuploids, whereas colchicine failed to induce tetraploids. Subsequent field evaluations confirmed additional phenotypic variability among regenerants, underlining the capacity of in vitro mutagenesis to generate agronomically useful diversity.

Finally, a comparative summary of the main features of grape traditional breeding, traditional cloning and in vitro cloning is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative summary of grapevine improvement strategies: traditional breeding, traditional cloning, and in vitro cloning.

| Grapevine Breeding Method | Definition | Positive Aspects | Negative Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional breeding | Hybridizes existing grape varieties to combine desirable traits. | Can introduce new desired traits like seedlessness or disease resistance. | Slow due to the long-life cycle of grapes; difficult to create new seedless varieties using traditional methods, as embryos are often lost; grape varieties often lack resistance to diseases and environmental stresses; relies on existing genetic variability within the V. vinifera genus; high genetic variability; low propagation efficiency. |

| Traditional cloning | This is the offspring of a crop, in this case grapevine, selected for its varietal purity, phenotypic characteristics and health status. | Maintains the desirable characteristics of a specific cultivar; can be used to select for improved yield, resistance, or quality; very low genetic variability; moderate to high propagation efficiency. | The limited qualitative impact of clonal selection in certain varieties; the significant loss of genetic diversity within grapevine populations. |

| In vitro cloning | Complete plants can be regenerated from somatic cells. | The mass propagation of plants without requiring sexual reproduction; plant material with superior phytosanitary quality; rapid multiplication of desired genotypes; very low genetic variability; high propagation efficiency. | Can induce somaclonal variations or mutations, potentially altering the genetic makeup of the regenerated plants; the induction of somatic embryogenesis can be low and highly dependent on genotype. |

These approaches, taken together, illustrate the continuum of strategies found in grapevine breeding: from producing new cultivars to improving already existing cultivars and finally to applying biotechnological tools that more quickly cone propagation and adaptation.

Plant breeding has evolved parallelly with human populations, since the beginning of civilization when the human began to culture its own food, they started to select plants with desired characters, based on observations of individual plant phenotypes in order to produce offspring with desired traits [117]. Targeting plant breeding began implementing morphological markers, not only to visually distinguish and select desired characters, such as fruit, seed, flower and stem related traits, but also perceptible important agronomic traits, such as flavor and nutritional and sugar content. Additionally, main concerns in commercial and intensive grapevine production have focused on selecting characters related to improve yields and enhance biotic and abiotic stress resistance [118]. Morphological markers have consistently proven to be a valuable and readily available tool in plant cultivation, facilitating plant breeding initiatives without necessitating specialized expertise, methodologies, or equipment. Despite their utility, these markers present certain drawbacks, including the requirement for considerable, sustained effort and the potential for ambiguity. A primary concern with conventional plant breeding methods is their lack of specificity, as phenotypic traits can be influenced more by environmental factors than by genotype.

Advances in biotechnology and molecular tools have transformed plant breeding to molecular plant breeding, turning traits selection by genotype rather than phenotype-based tools, giving place to Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS). In MAS morphological/phenotypical traits are selected based on the genotype or molecular markers. A molecular marker is a small fragment of DNA sequence that acts as sign or flag closely related with changes in specific genes. These changes in DNA are majorly controlling gene expression of a particular gene that results in improved agronomic traits [119]. Once the molecular markers have been proven, this information is valuable to be used not only for targeting plant breeding but also to plant transformation by incorporating desirable agronomic traits either from other species or from wild-related species by introgression. Many of the agronomic traits are polygenic, which means that more than one gene/marker should be analyzed to increase the accuracy of the association. The advent of new technologies for massive DNA sequencing released the opportunity to analyze multiple molecular markers in parallel. This advance in DNA sequencing technology has revolutionized MAS by reducing time and efforts, enhancing targeting plant breeding efficiency [120].

With the advent of Next generation sequencing (NGS), a bunch of DNA molecular markers have been developed and are available to be successfully implemented in MAS for many crops and for genetic conservation of wild populations [121]. Application of MAS began around the 1980s but it was accelerated a decade later due to the emergence of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Before NGS, most of research on MAS lied to a single gene amplified by PCR; variations in amplified DNA sequence were not only located in specific chromosome locations but also related to changes in agronomic traits, this technique was known as quantitative trait loci (QTLs) [117]. The number of publications with the terms QTL and MAS increased tremendously at least during the next two decades [120]. Despite the vast number of available molecular markers for plant breeding, choosing the right molecular marker is fundamental to have better results, the more polymorphic, the more informative to identify useful variations in the nucleotide sequences of DNA, enabling to identify alleles, either in the nucleotide composition or in the longitude of the sequence. Polymorphisms in DNA sequences are revealed by electrophoresis and molecular techniques such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), random amplified DNA polymorphism (RAPD), simple sequence repeats (SSRs), single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), among others. NGS enhance tremendously the genotyping technologies making possible to analyze hundreds of thousands of SNP markers by genotyping technologies such as genotyping by sequencing (GBS), restriction site associated DNA sequencing (RADSeq) diversity arrays technology (DArT) and others [122], allowing differentiation among individuals or populations more efficiently.

Since the huge pallet of molecular markers available, choosing the appropriate marker technique must respond to the research question. However, sometimes the choice of the molecular techniques is based on the previous knowledge of the species, such as genome size, genetic diversity, frequency of repetitive DNA in the genome, among others. Furthermore, considerations regarding technical know-how, infrastructure, funding research, are also crucial to choose the right markers to be working with [123]. MAS might be performed directly or indirectly by identifying polymorphisms in DNA sequences that are closely linked to underlying genes. When the association is robust, the polymorphisms serve as practical flags that signal the gene or surrounding gene associated with agronomical traits independently if the gene is known or not [124]. Advances on NGS technologies have revolutionized the way of genotyping and massive SNP marker analysis. Plant genome sequencing is now available for many crop species, which represents unprecedented advances for MAS and generation of elite varieties for many crops. This advance in knowledge and technical capability might enhance the way to identify specific and nonspecific genes, and molecular markers associated with desirable agronomical traits. MAS is a powerful tool that enables plant breeders to make more accurate selection as early as first stages of plant development, enhancing tremendously the efficiency to develop elite varieties, especially in long-life and woody perennial plants such as grapevine. Whole genome sequencing has enhanced the understanding of structural and functional genomics, stating valuable knowledge on the genetic architecture of plants. This knowledge makes it possible to develop complex statistical models for genomic selection that can be very informative for predicting the performance of a given molecular marker for plant breeding [118]. One of the most known techniques for association markers is the Genome-wide association study (GWAS), which is an approach that involves scanning markers across the genomes of many plants/cultivars and integrates statistical models to help plant breeders to find genetic variations such as SNP markers associated with desired agronomical traits. Though GWAS and other association marker studies such as QTLs enable identifying associated SNP markers or QTL statistically linked to traits, these regions are not always causative. It has been reported that SNP markers identified by GWAS techniques as highly associated to traits, often are not causal one but they are in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with main causative genes [125,126]. LD is referred to the non-random association of gene polymorphisms at different genetic loci in a population, meaning certain alleles appear together often and this is due to the physical proximity of these alleles on a chromosome rather than real association between the genotype with the phenotype.

The advances in high-throughput genotyping technologies and statistical models have tremendously enhanced the accuracy of GWAS in plant breeding research. However, the more complexity of data, the more resources and bioinformatics expertise resources are needed for analysis and biological interpretation. Models on GWAS have increased the accuracy to identify SNP markers, QTL or other DNA variations that are strongly associated with desirable agronomic traits by analyzing and comparing genomes of more diverse species or breeding populations [127,128]. Recent evidence suggests that a huge number of desirable traits for plant breeding, including disease or pest resistance have been identified through GWAS, including complex traits enriched near genes or polygenic trait-associated genetic variants [129]. Hence, trait-associated gene discovery can be empowered by elucidating the aggregated effect of a set of variants not only within but also around a gene, where transcriptional factors play fundamental roles through gene regulation. For polygenic traits as seedlessness in grapevine varieties, conducting gene-based association mapping should be integrated by analyzing GWAS information, Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) and molecular QTL data, complemented by populations genetics and comparative genomics from a reference sample [127,129,130].

Grapevines (Vitis vinifera) is an important fruit crop; it has been a source of food and wine since their domestication. Due to its economic importance, grapevines have been highly studied, becoming a model organism for studying perennial fruit crops. The whole genome sequence of V. vinifera was one the pioneers in fruit crops, the first draft genome sequence was released in 2007 by “The French–Italian Public Consortium for Grapevine Genome Characterization”, PN40024 [71]; since then, it has been used as genome reference for thousands of GWAS, trait-gene related and transcriptomic studies. A new, more complete reference genome, developed with advanced long-read sequencing, offers unprecedented detail and accuracy, overcoming limitations of previous techniques in repetitive and complex regions [131]. This resource is expected to significantly impact various fields, including research into biotic and abiotic stress in grapevine cultivars [132]. Gene annotation in grapevines has been in continuous evolution for both structural and functional genomics, however, a high complexity of the genome makes it difficult to fully understand the grapevine genome [133]. Now, technologies of massive sequencing and bioinformatics are fastly evolving [134]. V. vinifera has shown a very high genetic diversity with a high number of commercial cultivars, some of them have already genome assembled [135,136,137]. The genomes of most commercial grapevine varieties are available on a web portal for grape research (https://www.grapegenomics.com/index.php). However, it is still a challenge to understand complex traits, such as disease and pest-resistance, berry metabolites, morphology, seeds related traits and other oenological characteristics. Genomic regions associated with these traits have been widely identified through GWAS, LD studies and QTL analyses. However, most of the traits of interest for grapevine breeding are polygenic and show a complex quantitative trait-association [138,139] making MAS for grapevines a difficult and laborious process.

The integration of MAS with advances in agriculture of precision have increased the development of new cultivars adapted to climate change, higher yield and other desirable traits. Grapevine cultivars serve various purposes, either by consumption in fresh or processed in different products such as wine, raisins, juice and other applications. The development of products obtained from grapevine has become increasingly diversified, nowadays there are a high number of commercial cultivars that are product-specific, growing in different regions. However industrial production demands for new cultivars of even more productive and high-value products, promoting the development of new strategies for grapevine breeding [139]. Genetic mapping for QTL detection has been one of the widely used and preferred methods for MAS in grapevines. The high-density genotyping and genetic mapping have tremendously increased with the advent of massive sequencing, giving place to Association Mapping (AM) studies. However, as stated before, strategies for dissecting and selecting complex and polygenic traits should be integrative, including tools such as LD, GWAS, QTL and AM [140]. AM studies consider a big and diverse collection of germplasm, which might include commercial cultivars, inbreeding lines and/or wild populations. This set of diverse genotypes comprise an association mapping for discriminating new QTLs for targeting breeding, increasing the number of alleles available at each locus for a selected trait [138]. However, AM studies must be taken cautiously since the mix of geographically distinct genotypes with different pedigree might result in false-positive marker trait association by confounding effects of population structure [141]. Fortunately, many statistical methods such as estimation of false discovery rate (FDR), and Bonferroni correction have been developed to reduce and correct the false-positive associated traits in AM studies [142].

AM provides higher resolution compared to inaccurate QTL methods, especially in germplasm with high genetic diversity and low LD such as grapevines [140]. Thus, AM has been considered as the most widely accepted path to disentangle the right association between genotype and phenotype diversity for a high number of crops [142]. In grapevines, AM studies have been a useful tool to explain the genetic basis for complex traits of agronomic interest, such as yield, disease and pest resistance [143], cold tolerance [144], berry metabolites, berry morphology, phenology, vegetative traits, seed related traits [129], cluster related traits and abiotic stress to enhance resilience facing global warming [142]. Despite the limitations, the process of developing new grapevine cultivars through AM studies have shown very effective results by reducing the time of dissecting meaningful genetic markers effectively linked to the phenotype. Integrative approaches have shown better and more accurate results in plant breeding research. Technical advances in knowledge, technologies and the generation of more specific models to reduce the error rate enables new approaches to resolve previous QTL limitations in grapevine research.

Recent strategies have focused on identifying genetic markers associated with advantageous agricultural characteristics. Genomic Selection (GS) and Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) are both standard methodologies utilized in plant breeding for the identification of genetic markers associated with agronomic traits. While both serve this purpose, they differ significantly in their approaches, primarily concerning the number of markers utilized per trait. MAS, an older and more established technique, employs a considerably smaller number of markers. This makes it effective for simple traits controlled by a limited number of QTL markers. In contrast, GS is a more recent and powerful tool. It considers a large set of markers distributed across the entire genome, offering a statistically more robust approach for identifying loci associated with desired characteristics. Consequently, while MAS is efficient for simple traits, GS demonstrates a superior success rate for complex traits that are controlled by multiple QTLs.

The publication of the V. vinifera pangenome represents a significant advancement for viticultural research and breeding [145]. This comprehensive genetic resource encapsulates most of the genetic diversity of Vitis spp. furnishing a powerful instrument for comprehending characteristics such as disease resistance, fruit quality, and climate adaptability. In contrast to preceding single reference genomes, the pangenome offers a more exhaustive genomic perspective, thereby enabling breeders to identify and leverage a broader spectrum of advantageous alleles. This augmented genetic understanding is projected to accelerate the development of novel grapevine cultivars that exhibit greater resilience to environmental exigencies, necessitate reduced chemical interventions, and produce superior quality fruit, ultimately benefiting the global wine and grape industries.

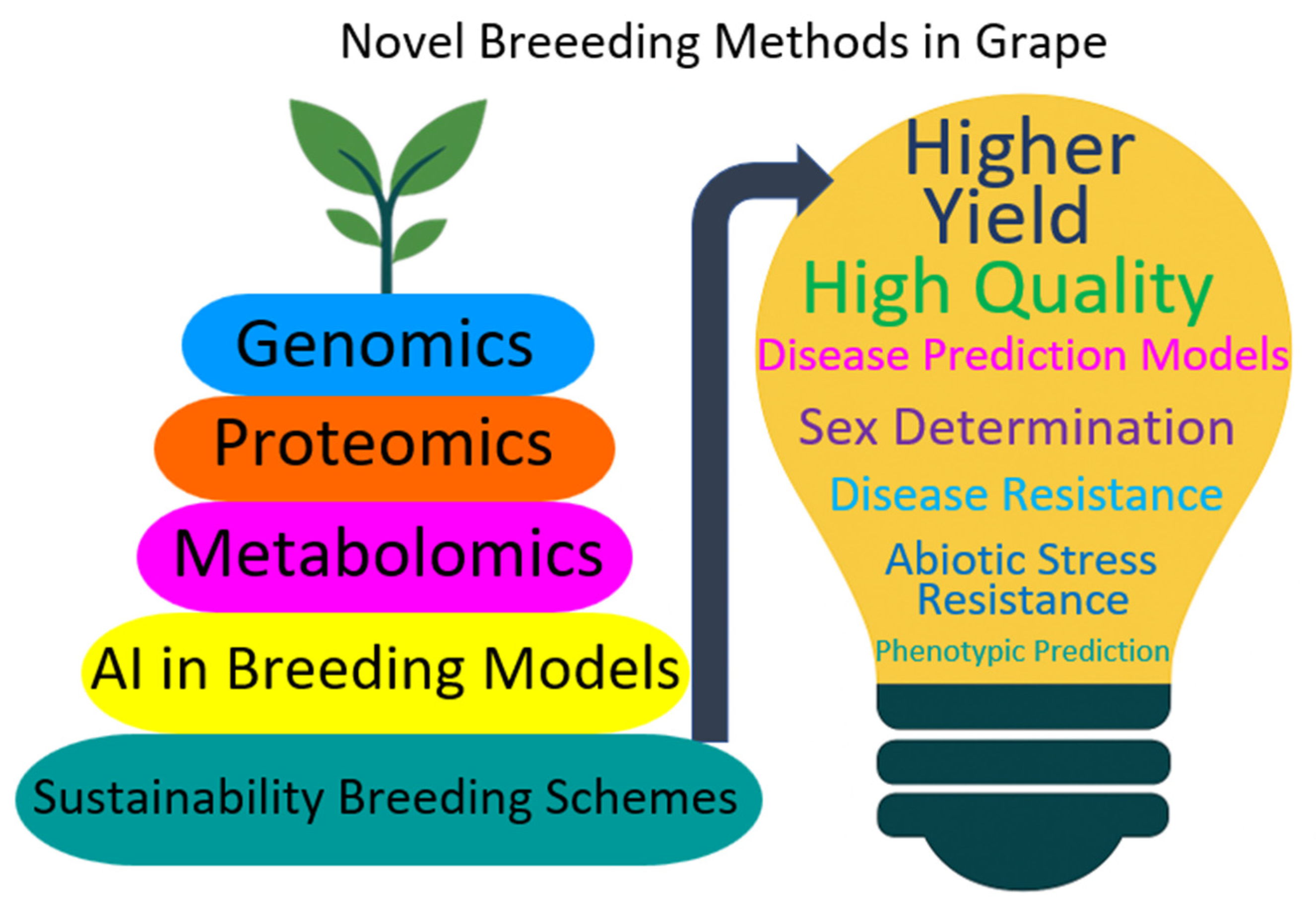

In conclusion, grapevine breeding research has experienced remarkable advancements in recent years, primarily driven by the synergy of NGS and bioinformatics, alongside the comprehensive integration of various omics approaches. These include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, all of which contribute to a holistic understanding of grapevine biology. The availability of high-quality and integrative genomic information is pivotal. It not only enhances the resolution and precision of MAS but also provides novel frameworks for unraveling the intricate mechanisms of phenotype-genotype interactions. Understanding how specific genetic variations translate into observable traits is crucial for targeted breeding efforts.

Moreover, it is essential to analyze the results from MAS, GS, and AM in conjunction with data generated through integrative genomics. This combined approach allows for a more profound comprehension of the functional metabolic pathways that underpin complex traits in grapevines. By correlating genetic markers and genomic regions with expression patterns, protein profiles, metabolic fluxes, and epigenetic modifications, researchers can identify key regulatory elements and biological processes influencing desired characteristics such as disease resistance, fruit quality, and climate adaptability. This comprehensive integration of diverse data types is critical for developing more resilient and productive grapevine varieties, ultimately contributing to the sustainability and advancement of viticulture.

Despite the advances in plant breeding technologies, food security is still insufficient due to the increasing worldwide population. Advances in biotechnology and MAS have boosted crop yield by not only identifying and selecting but also by incorporating new traits into plants. The emergence of recombinant DNA techniques in the 1970s marked the birth of genetically modified (GM) crops, which claimed the ability of improved pest/disease resistance, yield and nutritional value [146]. GM crops are plants whose DNA has been genetically engineered and utilized in agriculture. The Plant DNA of these plants is manipulated by insertions of specific segments of foreign DNA into the host plant genome, mediated either by Agrobacterium tumefaciens or by direct gene transfer through recombinant technology. The genes inserted into the genome of the host plant can be naturally present in the same or related species (cisgenesis) or different species (transgenesis). Cisgenesis involves no foreign DNA, thus might not be considered as a strict plant transformation since genes are or were already present in the same or closely related species, conserving genetic diversity naturally present [147]. Transgenesis, on the other hand, is more controversial since it involves modification on the DNA by the introducing foreign genes from non-related species, which often implies ecological and biosafety concerns. Despite advances in knowledge, GM technology is still questionable, main concerns are over potential environmental and health impacts that avoids the complete acceptance and difficult its regulation [148].

Notwithstanding the concerns about using GM crops, the adoption of GM technology is quickly increasing. The pioneer GM crops were mostly herbicide and/or pesticide-resistant in the early 1990s, stating the beginning of the “Gene revolution” era. First commercially available GM crops were introduced to the USA in 1994. By 2014, the USA had become the largest producer of GM crops, first cultivated transgenic crops in the USA were represented by maize (Zea mays L.), soybean (Glycine max), and cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) plants, representing more than 90% of its production. GM crops were also worldwide accepted, representing an increase from only 1.7 million ha cultivated in 1996 to 190.4 million ha by 2019 [148]. For grapevine, first efforts in GM were mainly focused on incorporating resistance genes for susceptibility to fungus attack. Resistant genes were isolated from Trichoderma spp. and Arabidopsis thaliana to be incorporated by using double gene constructs engineering grapevine, which conferred resistance to powdery mildew fungus in Vitis spp. [149]. Despite the controversy, using transgenic crops has tremendously boosted world agricultural profits, a global meta-analysis of the impact of GM crop adoption has estimated that transgenic technology has increased farmer profits by 68%. Furthermore, GM crops have reduced chemical pesticide use by 37% and increased crop yields by 22%. This information expands the knowledge of GM technologies by giving valuable information about ecological and economic benefits that GM crops have provided since they emerged [150]. Advances in biotechnology and MAS have provided a huge amount of tools for GM crops development, more effort have been applied to develop GM crops tolerant to herbicides such as glyphosate, however pest/disease resistance, abiotic stress tolerance and nutritional enhancement are also important traits to be working with [150,151].

Initially, genetic modification strategies were based on a single trait [152]. Advances in technology of recombinant DNA and whole genome sequencing make it now possible to easily introduce multiple traits within the same GM plant by gene stacking [153]. Gene stacking is a promissory tool in grapevine aiming to increase breeding efficiency for resistance to downy mildew and powdery mildew since it takes advantage of already known resistance genes or QTLs which have previously isolated and validated. Using gene stacking for grapevine breeding allowed it to have resistance genes on many varieties of Vitis spp. worldwide cultured [149]. Stacked plants increased tremendously in their planted area from 2000 until 2020 about 2 to 90% in corn and from 30 to 95% in cotton [150]. More commercialized GM crops are maize, cotton, potato, soybean, brinjal, rice, poplar, tomato, sugarcane, beans, canola, carnation, sugar beet, wheat, safflower, papaya, squash, plum and sweet pepper. Aiming to dismiss public concerns and uncertainties surrounding transgenic technology have led to a search for alternative approaches, such as cisgenesis, intragenesis and genome editing. With these techniques, in spite of a genetic modification being involved during its development, the end products are free of any foreign gene (transgene). Therefore, crop plants developed by those approaches are not genetically different from plants developed by way of plant breeding, thus, they will be more easily accepted by the society compared to the transgenic crops and would be approved by worldwide legislation in a shorter time [154].

These new technologies for genetically modified plants represent promising advances for genetic plant breeding and the development of new improved commercial cultivars; however, these techniques present biological limitations in certain woody and fruit plants, such as grapevines. These limitations include the incidence of somaclonal variation and recalcitrance to regeneration, which hinder the full progression of these approaches [155]. Moreover, the application of cisgenesis in grape breeding is currently limited by the lack of effective and robust promoters for Vitis species. Promoters are essential for controlling gene expression, and without efficient ones, the potential of cisgenesis to introduce desirable traits like disease resistance or improved fruit quality remains unfulfilled. Identifying and characterizing native Vitis promoters with strong and reliable activity is therefore crucial for advancing cisgenic approaches in grape biotechnology [149].

Regeneration is the process by which plants reestablish not only their cells but also their organs and tissues after an injury. A reduced number of crop species have the capacity of natural regeneration, however, lots of them can regenerate plantlets in vitro if explants are cultivated on a nutrient-enriched medium supplemented with auxin and cytokinin [156]. Tissue culture is a very useful technique for clonal propagation of many crop species, plant regeneration might start from various types of source organs, such as stem, roots, leaves, and sexual organs. Thus, regeneration is fully exploited to transmit the desired genetic modification to new cultivars, starting from different sources of explants [155]. Understanding the complex molecular processes that control plant regeneration in grapevines is extremely important. This knowledge is crucial for understanding cell and developmental biology, and has significant implications for viticulture and agricultural biotechnology. The investigation of genetic and biochemical pathways in grapevine regeneration provides valuable insights into plant developmental plasticity, the regulation of meristematic activity, and cellular reprogramming signals. This knowledge has the potential to facilitate improved propagation methods, the development of disease-resistant varieties, and the enhancement of desirable traits in Vitis spp. [156].

Genomic design is a cutting-edge approach in grapevine breeding involving high-throughput sequencing, genomic selection, and a predictive model for speeding up the design of superior cultivars. It measures genome-wide markers along with phenotypic traits to identify favorable combinations of alleles for complex traits such as resistance to disease, fruit quality, and climate resilience [157,158]. Genomic design in grapevines, which has a long juvenile phase and a high degree of heterozygosity, brings transformation possibilities to overcome traditional limitations imposed by breeding efficiency and to enhance genetic gain [159].

The Vitis genus (2n = 38) accommodates vast genetic diversity comprising wild subspecies, hybrids, and cultivated varieties [160,161]. This diversity has remained due to its mode of asexual propagation through cloning [162]. Also, commercially up to 1200 grapevine cultivars have found their origin through crossing of domesticated varieties with wild Vitis species [163]. Hence, the grapevine germplasm comprises some 15,000 named cultivars, many of which are either synonyms and are genetically the same but called by different names, or homonyms having the same name but are genetically different [164].

Whole-genome resequencing (WGR) as a whole-genome resequencing (WGR) application became popular in grapevine research after in 2007 the first draft genome (8X) of V. vinifera, derived from a highly homozygous (PN40024) and heterozygous (ENTAV115) Pinot Noir accession, came out [131,165]. This resource was later developed with more refined versions (12X.v0 and 12X.v2) that allowed serious studies on genetic variation within and between species of grapevines [166,167]. WGR also allows genotyping of extremely high resolution at a clonal level that cannot be achieved through traditional markers such as SSRs and SNPs [168,169]. Using second-generation sequencing technologies like Illumina and Roche 454, many works have been applied in grapevine studies and stand as the best choice for DNA variation identification, with respective powers of generating millions of sequences simultaneously. Carrier et al. [170] for instance, with the 454 sequencing, studied three Pinot Noir clones, identifying transposable elements as the most noteworthy source of somatic mutations. Carbonell-Bejerano et al. [171] were instead interested in a structural rearrangement causing white berries in Tempranillo using Illumina sequencing, while Gambino et al. [172] re-sequenced three highly divergent Nebbiolo clones and identified thousands of clone-specific SNVs.

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) allowed for the use of genomic methods to genetically explore complex phenotypes through different approaches, such as GWAS or GS. Disappointingly, methods like GWAS and GS that leverage markers across the genome to predict phenotypes are not easy to apply in highly heterozygous species like grapevine [173], however there are a few examples of GS application for grapevine breeding. In this case Fodor et al. [173] assessed the ability of GWAS-GS approaches to predict structured traits using four grapevine training populations comprising 1000 individuals each. Results demonstrated that the combined GWAS-GS model gave the highest prediction accuracy, reaching as much as 0.9. On the basis of these results, the authors suggest utilizing this integrated prediction model with the core collection as the training population to further grapevine breeding or breeding programs of other economically important crops bearing similar traits.

Evidence from another study indicates that in order to enhance the understanding of the genomic variation of agronomic traits in table grape populations for future MAS and GS needs, a molecular marker set associated with variation in genes was used to detect several Quantitative Trait Loci (QTLs), whereas the QTL method is imprecise and must yield to a more powerful lookup of the genetic architectures of the studied population done using an alternative genomic analysis known as Bayesian Lasso (BLasso, Bayesian Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator), which is a statistical method used in GS for predicting complex and polygenic traits, such as grapevine breeding, reducing the many minor effects of markers and thus inferring more efficient utility for the acceleration of selection for agronomic trait studies in table grapes as compared with QTL analyses [174]. In an additional study focused on genomic prediction and QTL detection for drought-related traits in grapevine, penalized regression methods applied on data collected from biparental progeny of 14 traits under two irrigation environments showed high predictive accuracy within populations (with a maximum of 0.68), leading to the detection of new QTL and candidate genes and thus establishing the promise of genomic prediction in grapevine breeding [175].

A related study assessed the genomic prediction accuracy for 15 key traits in grapevine, covering phenology, yield, vigor, and berry composition, at both cross and individual levels, while uncovering that whereas prediction accuracy for cross means averaged 0.6 (up to 0.7), and for individual values averaged 0.26. Results emphasize the importance of genetic distance, heritability, and cross effects on predictive power, which provide a great insight toward optimizing training sets and implementing genomic selection in breeding programs [176]. Another point discussed by Flutre et al. [177], is that a genetic diversity panel with 279 V. vinifera cultivars assessed between numerous years for 127 traits over 5 vineyard blocks was genotyped for about 63,000 SNPs from combined microarray and sequencing data. They detected 489 robust and novel QTLs-many of these previously undetected in bipolar studies-with average prediction accuracies above 0.42 for half of the traits studied and provided valuable insights regarding the genomic architecture of complex agro-economic and quality traits.

The advent of third-generation sequencing (TGS) technology allows the generation of long reads, from tens to hundreds of kilobases, for the overspilling analysis of structural variation (SV). Hence, they are equipped with more theoretical possibilities for in-depth SV analyses. In 2016, Chin et al. [135] created a new reference for the heterozygous cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon, stitching together SMRT sequencing with the FALCON assembler into a much more contiguous assembly (contig N50 = 2.17 Mb) compared to the previous PN40024 genome (contig N50 = 102.7 kbp) and releasing the first haplotype-phased sequence of the diploid V. vinifera genome. Recently, Vondras et al. [84] exercised whole-genome PacBio sequencing on 15 Zinfandel clones and found evidence that clonal propagation incites the accumulation of deleterious mutations, mostly in non-coding regions such as introns and intergenic regions. Besides long-read sequencing are more useful in complex genomes with highly repetitive gene cluster regions, allowing higher resolution among predicted alleles [178], TGS platforms have two major drawbacks for large-scale genotyping: they cost more than short-read sequencing and are prone to even more errors, ranging from 10% to 20% in PacBio and Nanopore technologies, compared to up to 0.1% in Illumina, limiting their usefulness for the detection of small variants, especially in repetitive regions of the genome [136].

Recent advancements in DNA sequencing technologies, genomics, transcriptomics and bioinformatics have substantially enhanced our comprehension of the genetic foundations of various crucial traits in grapevines, including stress tolerance, fruit quality, and overall yield. These technological progressions present an unparalleled opportunity to investigate the molecular mechanisms governing these intricate characteristics. The strategic integration of these modern technologies with traditional physiological and biochemical resources, alongside established conventional breeding methodologies, holds considerable promise for the future trajectory of grapevine research and development. This synergistic approach facilitates a more comprehensive and efficient pathway towards the development of improved grapevine varieties. A particularly compelling avenue within this integrated framework is the utilization of cutting-edge CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology. This revolutionary tool offers the capability for precise and targeted modification of pivotal genes directly associated with grapevine stress resilience. By accurately editing these specific genes, researchers can potentially augment the natural defenses of Vitis spp. against a broad spectrum of environmental stressors, such as drought, extreme temperatures, and various pathogens. This precision gene-editing approach creates opportunities for developing grapevines that are not only more robust and adaptable to changing climatic conditions but also maintain or enhance desirable fruit quality and yield, ultimately contributing to more sustainable viticulture practices globally.

Genome editing technologies have been developed as powerful tools to improve traits in grapevines, with more precision and efficiency than traditional breeding methods. Among others, CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to edit mutated genes for resistance against diseases, fruit quality, and tolerance against stresses [179]. Due to the complexity in the genome and a long generation time of the grapevine Vitis vinifera L., these given techniques represent an attractive alternative to speeding up genetic improvement to meet challenges of climate change and new pathogens [14,180].