Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HPLC-DAD Profiling and Diuretic Effect of Solanum elaeagnifolium (Cav.) Aqueous Extract: A Combined Experimental and Computational Approach

1 Laboratory of Biotechnology, Conservation and Valorisation of Bioresources (BCVB), Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, 30000, Morocco

2 Biomedical and Translational Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Fez, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, 30000, Morocco

3 Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Fez, 30000, Morocco

4 Department of Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, 110062, India

5 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, Qassim, 51452, Saudi Arabia

6 Department of Medical Laboratories, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Qassim University, Buraydah, 51452, Saudi Arabia

7 Laboratoire d’Amélioration des Productions Agricoles, Biotechnologie et Environnement (LAPABE), Faculté des Sciences, Université Mohammed Premier, Oujda, 60000, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Amine Elbouzidi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Strategies in Medicinal Plant Biotechnology: From Traditional Knowledge to Modern Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1505-1518. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063896

Received 27 January 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

The Solanum genus is known for its diverse bioactive compounds, yet its diuretic potential remains understudied. This research commenced with an analysis of polyphenol and flavonoid content in Solanum elaeagnifolium leaf extract (SEFE) using colorimetric techniques, followed by HPLC-DAD to delineate its chemical composition. The aqueous extract revealed prominent constituents: naringin (12.38%), quercetin 3-O-B-D-Glucoside (27.25%), and flavone (15.26%). A 15-day study on normal rats investigated the diuretic potential of SEFE at repeated doses. SEFE significantly increased urine volume and urinary sodium/potassium levels without inducing hypokalaemia, contrasting with furosemide, a standard diuretic that induced hypokalaemia. Conversely, furosemide, a standard diuretic, increased urinary sodium and potassium while inducing hypokalaemia. It was evident that the diuretic effect of S. elaeagnifolium is dose-dependent, with a dosage of 500 mg/kg body weight exerting a more potent diuretic effect compared to furosemide. The diuretic activity of this plant was supported by an in silico study of the diuretic effect. The findings demonstrate how S. elaeagnifolium leaves have a potent diuretic impact on rats. However, more in-depth studies are needed to examine the following aspects: identifying the specific molecules responsible for the diuretic effect, understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying this activity, and assessing the long-term safety and clinical efficacy of this plant in different contexts.Keywords

Kidneys and their problems are becoming increasingly common as a result of lifestyle changes, industrialization, and nutritional deficiency [1]. Chronic renal failure is a progressive disease that affects one in every ten people worldwide, or more than 800 million people. Chronic kidney disease has risen to become one of the world’s leading causes of death [2]. Diuretics increase the elimination by the kidneys of water, sodium, and chloride ions by increasing urine production [3]. These substances may be beneficial in the treatment of a variety of potentially fatal conditions, including congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, hypertension, nephritic syndrome, preeclampsia, and renal failure [4]. Unfortunately, most conventional diuretics, such as thiazides, loop diuretics, and potassium-sparing diuretics, come with numerous adverse effects, including electrolyte imbalances, metabolic disturbances, impotence, fatigue, and weakness [5–7]. Hence, there is a need to seek newer and safer therapeutic diuretics in plants. Herbal medicines have gained importance and popularity in recent years due to their effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and safety. Medicinal plants, therefore, serve as alternative sources for the development of novel diuretics due to the presence of specific chemical compounds that confer pharmacological activities [8–10].

The genus Solanum, widely acknowledged for its diverse pharmacological potential, stands as a treasure trove in the realm of medicinal substances. Comprising a spectrum of chemical compounds, Solanum species encompass an array of bioactive molecules, including saponins, steroids, alkaloids, sterols, terpenes, lignans, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and coumarins. These chemical constituents, discovered within the Solanum genus, have captured the keen interest of pharmaceutical researchers due to their immense therapeutic promise and potential applications [11].

Amid the vast species diversity within Solanum, these compounds have been a subject of extensive exploration, drawing attention due to their multifaceted pharmacological effects and diverse potential applications. This genus exhibits an extensive range of pharmacological activities, making it a focal point of interest in medicinal research and drug development. Various studies have demonstrated the cytotoxicity of Solanum species against different types of cancers, such as prostate, breast, and colorectal cancer [12–15]. Such promising anticancer properties underline the potential for Solanum compounds to serve as valuable leads in the development of novel cancer treatments [16].

One notable species within the Solanum genus, S. elaeagnifolium, has emerged as a subject of particular interest due to its multifunctional pharmacological profile. This species showcases an impressive array of pharmacological attributes, including analgesic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and insecticidal properties. Notably, S. elaeagnifolium has been recognized for its hepatoprotective and anticancer potential, making it a promising candidate for further pharmaceutical exploration [17–19].

Solanum elaeagnifolium presents several mechanisms contributing to its diuretic effects. Its bioactive compounds, such as alkaloids and flavonoids [20], influence the metabolism of body fluids and kidney function by promoting the excretion of sodium and water [10,21]. Additionally, the antioxidants present in the plant reduce renal oxidative stress, thus improving kidney function [22]. It also regulates electrolyte balance and possesses anti-inflammatory properties that optimize the diuretic effect. Some extracts may modulate the action of the antidiuretic hormone (ADH), contributing to water elimination [23].

Given the extensive range of pharmacological effects exhibited by Solanum species, particularly the diversified attributes of S. elaeagnifolium, there exists a need for in-depth investigation to unravel its therapeutic potential. This serves as the foundation for the current study, which is designed to delve into the effects of S. elaeagnifolium leaf extracts on various physiological parameters, focusing particularly on urine volume, plasma electrolytes, creatinine, urea, and electrolyte excretion in normal rats. The study further aims to compare the effects of S. elaeagnifolium leaf extracts at different doses and subchronic oral administrations to a standard diuretic, furosemide.

The specific focus of this research is to uncover the impact of S. elaeagnifolium leaf extracts on urinary parameters and electrolyte balance in rats, drawing comparisons to the effects induced by furosemide. By investigating the diuretic potential of S. elaeagnifolium, this study seeks to ascertain its effectiveness in inducing diuresis, its impact on urinary constituents, and its potential as an alternative or supplementary therapeutic agent compared to standard diuretics.

The significant diversity of pharmacological effects displayed by Solanum genus compounds, coupled with the multifunctional attributes of S. elaeagnifolium, underscores the necessity for in-depth scientific exploration. Understanding the mechanisms behind the diuretic effects of S. elaeagnifolium and evaluating its impact on urinary and plasma parameters in animal models can pave the way for novel therapeutic avenues. Such research endeavors are pivotal in advancing our knowledge of potential medicinal applications and fostering the development of safer and more effective therapeutic agents.

S. elaeagnifolium samples were obtained from Fez city in Morocco and preserved in the herbarium of the Faculty of Sciences, Dhar El Mehraz, Fez, Morocco, with voucher number (E17/14054). The leaves of S. elaeagnifolium were meticulously cleaned and left to air dry for 15 days before being finely ground into a powder. The process of extraction was carried out by combining 50 g of powder with 500 mL of water and boiling it for 30 min at 100°C. The resulting solution was then filtered using a Whatman filter paper no. 1 and concentrated in a rotary evaporator (Model R-200, Büchi labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) at 40°C under reduced pressure, resulting in a solid residue. This residue was subsequently dissolved in distilled water to achieve the desired concentrations, which were selected for use in vivo experiments.

For the analysis of S. elaeagnifolium leaves extract (SEFE), reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used. For the analysis, a MOS-1 HYPERSIL 250 mm × 4.6 mm SS Exsil ODS analytical column (5 μm) fitted to a Thermo Scientific HPLC system was utilized. The following elution gradient was used for the gradient mode separation: 80% A, 20% C for 1 min; 60% A, 40% C for 2.5 min; and 80% A, 20% C for 4 min. The solvents used were A (water) and C (acetonitrile). The injection volume was 5 μL, and the flow rate was set at 1 mL/min. The aqueous leaf extract was prepared at 50 mg/mL and filtered through 0.45 micro-filters. Spectrophotometric detection was done at 340 nm, and the separation was conducted at a constant temperature of 40°C. Thermo Fisher Scientific’s TSQ Endura triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, which was in negative mode, was outfitted with a heated-electrospray ionization (H-ESI) source. The compounds were recognized by contrasting their UV spectra and retention periods with those of reliable standards [19,24].

This experiment was conducted using normal male Albino rats, each weighing between 180–250 g. These animals come from the animal house of the Faculty of Science at Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah University in FES, Morocco. The rats were housed under standard controlled conditions at the animal facility of the Faculty of Science, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez. They were acclimatized to a controlled environment set at 25 ± 1°C, with a 12-h light/dark cycle. The rats had unrestricted access to both tap water and food ad libitum. All relevant international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were strictly adhered to. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Science, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (L.20. USMBA-SNAMOPEQ 2023-03.).

Each rat was kept in a metabolic cage for 48 h before the experiment. Four groups of three rats each were formed: The first group received distilled water (10 mL/kg body weight), the second group oral furosemide (10 mg/kg body weight), the third group 250 mg/kg body weight SEFE, and the fourth group 500 mg/kg body weight SEFE for 15 days. The choice of the two test doses was based on a study of the acute toxicity of the leaf extract of the plant studied, which showed that the toxic doses of this plant exceeded 2000 mg/kg [25].

2.3.3 Urine Collection and Examination

To assess liquid excretion, urine samples were collected in graduated cylinders on days 0, 7, and 15 of the treatment period. Following that, the levels of sodium, potassium, creatinine, and urea in the urine were measured and stored at 20°C.

Blood samples were collected at the end of the treatment using a retro-orbital puncture under mild ketamine anesthesia on slightly asleep animals [26]. The plasma was subsequently separated by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min before being preserved at 20°C for sodium, potassium, creatinine, and urea analysis [27].

In the area of computational analysis, we evaluated the diuretic action that targets carbonic anhydrase II in silico. Carbonic anhydrase II is an enzyme involved in maintaining the acid-base balance and regulating renal function processes, making it a relevant target for our study. We employed compounds identified by HPLC/DAD from S. elaeagnifolium (Cav.) leaves to create the ligand. Molecular structures were sourced from the PUBCHEM website and imported into the Schrödinger Maestro 11.5 workspace. Subsequently, the LigPrep tool, employing the OPLS3 force field, facilitated their preparation. This process involved generating a maximum of 32 stereoisomers and selecting ionization states at pH 7.0 ± 2.0 [28]. In terms of protein preparation, carbonic anhydrase II (PDB ID: 1Z9Y) was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. PyMOL was utilized for visualizing these structures and predicting active site residues [8,29]. The Schrödinger Maestro’s protein preparation wizard refined the structures, assigning charges and bond orders, adding hydrogens to heavy atoms, converting selenomethionines to methionines, and eliminating water molecules. Notably, the OPLS3 force field was employed for structure minimization, with the RMSD value of heavy atoms set to 3.0. Finally, the receptor grid generation tool defined the protein’s binding pocket with a volumetric spacing of 20 × 20 × 20 [30]. Conducting Glide Standard Precision (SP) Ligand Docking, flexible ligand docking in Schrödinger-Maestro (v11.5), utilized standard precision (SP). Penalties were imposed for non-cis/trans amide bonds, and the van der Waals scaling factor and partial charge cutoff of ligand atoms were set to 0.80 and 0.15, respectively. The final scoring relied on energy-minimized poses, employing the Glide score for evaluation. The top-docked pose with the lowest Glide score value was identified and recorded for each ligand [29].

GraphPad Prism® (version 8.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to compare results. When evaluating data from only two groups, a student’s t-test was used. Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used in cases involving three or more groups in comparison to a control group. Data were represented as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

3.1 Phytochemical Analysis of the Extract

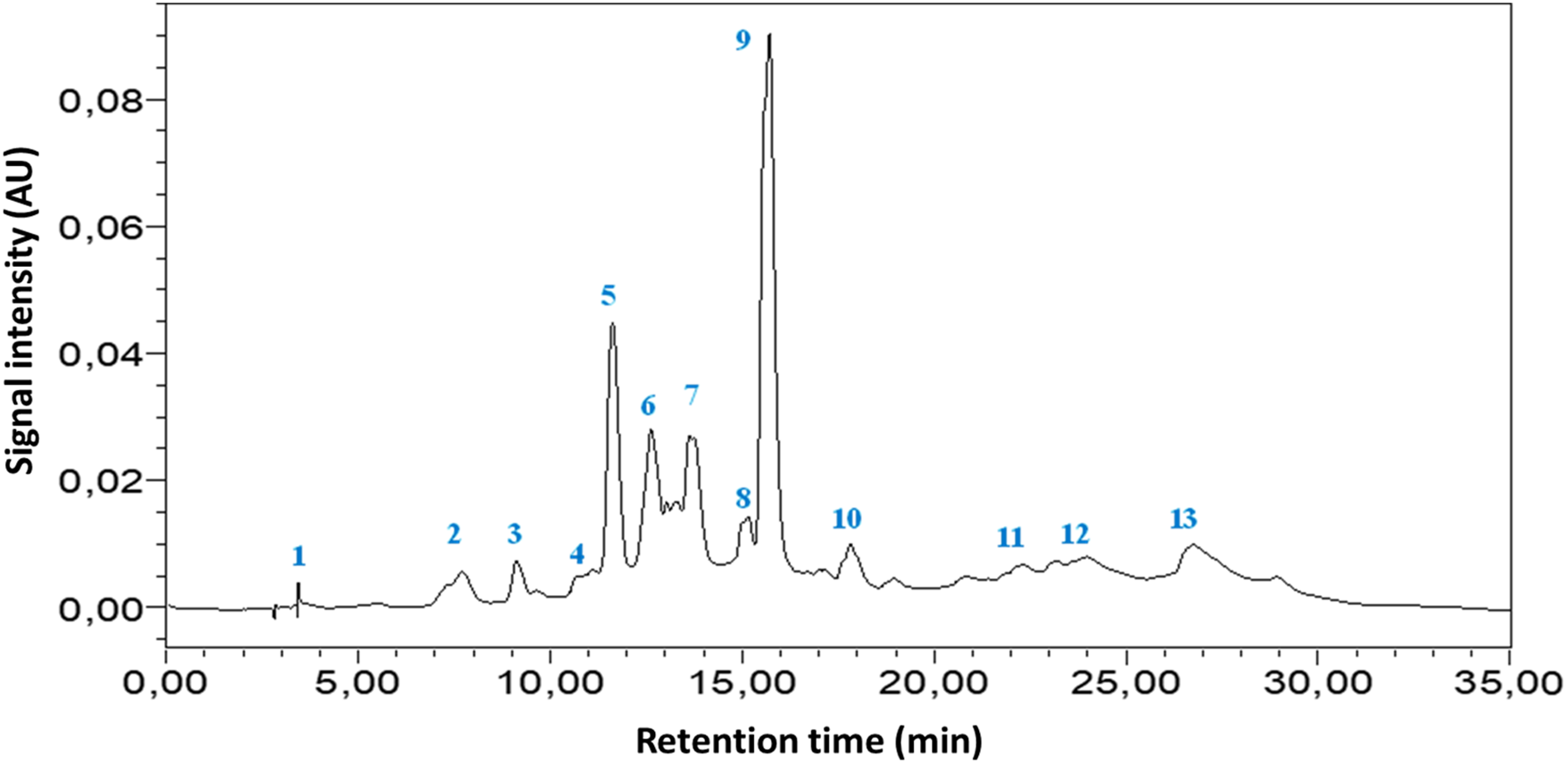

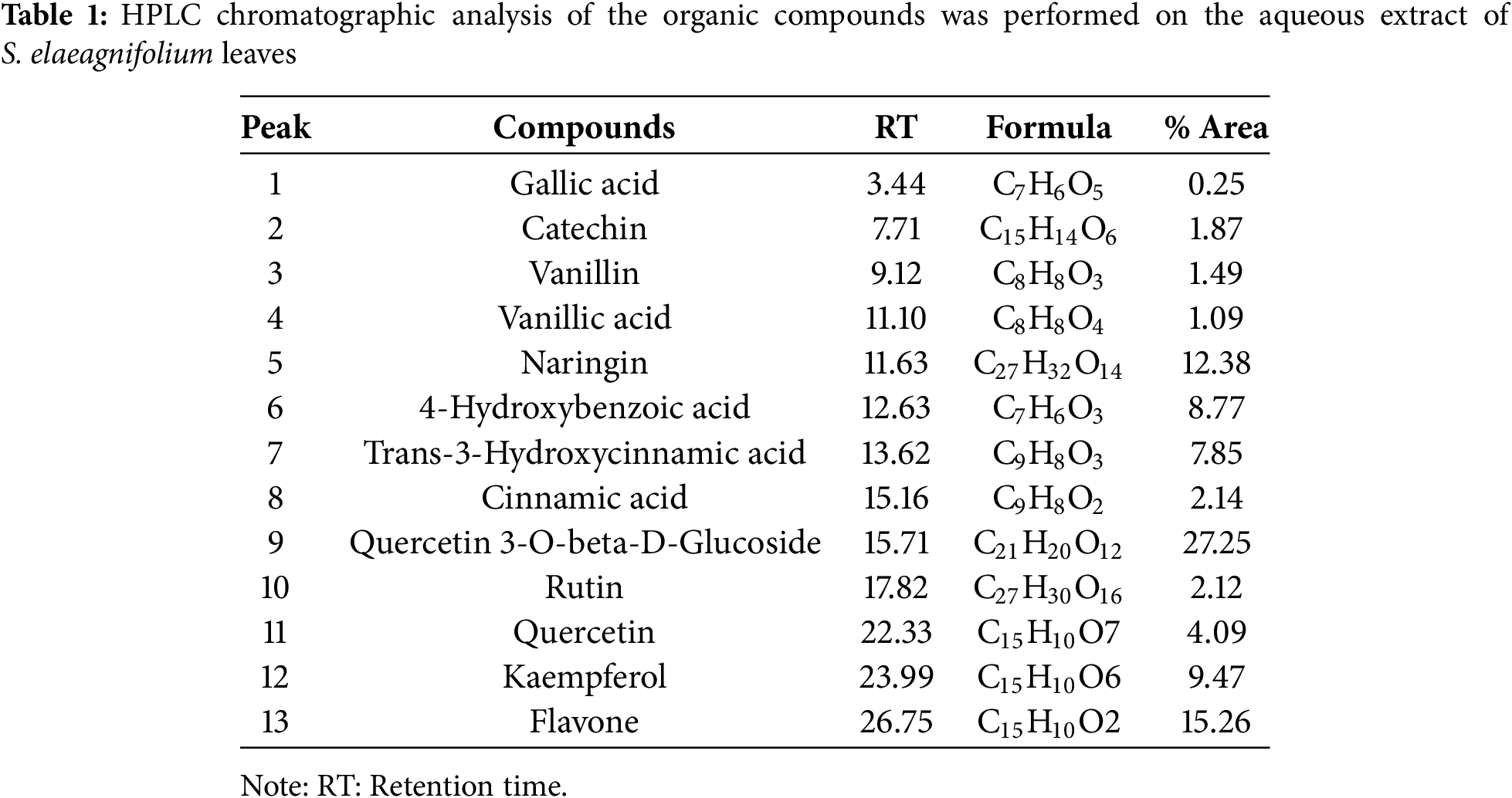

HPLC DAD was used to analyze the extract under investigation. The analysis revealed the presence of 13 phenolic compounds in aqueous extract (SEFE) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Gallic acid, Catechin, Vanillin, Vanilic acid, Naringin, 4-Hydroxy Benzoic acid, Trans-3-Hydroxycinnamic Acid, Cinnamic Acid, Quercetin 3-O-B-D-Glucoside, Rutin, Quercetin, Kaempferol, and Flavone were found in the aqueous extract of S. elaeagnifolium leaves. Naringin (12.38%), Quercetin 3-O-B-D-Glucoside (27.25%), and Flavone (15.26%) were the most abundant elements in this plant’s aqueous extract.

Figure 1: HPLC-DAD chromatogram of S. elaeagnifolium aqueous extract leaves and standards at 340 nm

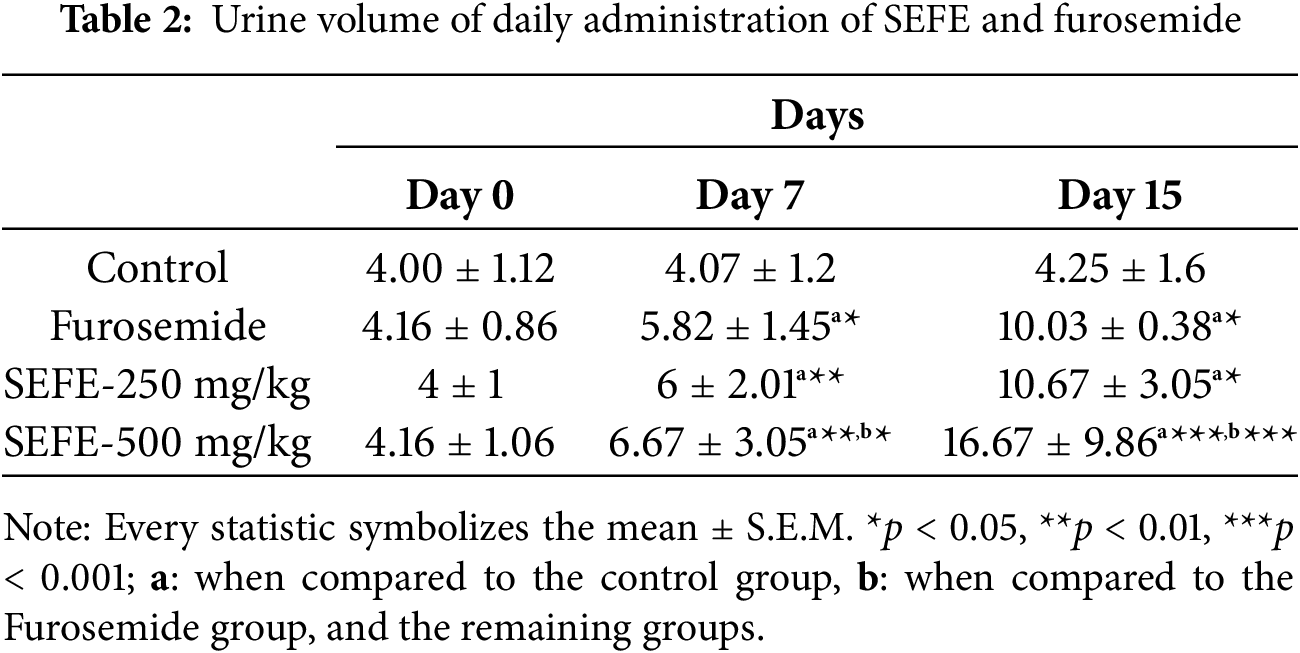

3.2.1 Effect of SEFE’s on Urine Volume

The elimination of urine was measured on the first, seventh, and fifteenth days of treatment. The results shown in Table 2 show that urine production was not affected significantly after treatment with distilled water. The findings of this study offer an in-depth assessment of the diuretic effects of SEFE (at doses of 250 and 500 mg/kg) and furosemide over a 15-day period. Throughout the experiment, it is clear that SEFE and furosemide induced substantial increases in urine volume, a clear indication of their diuretic properties compared with the control group. The performance of SEFE-500 mg/kg, which showed the greatest diuretic effect, with a remarkable increase in urine volume, particularly visible on day 15, was particularly significant (p < 0.001).

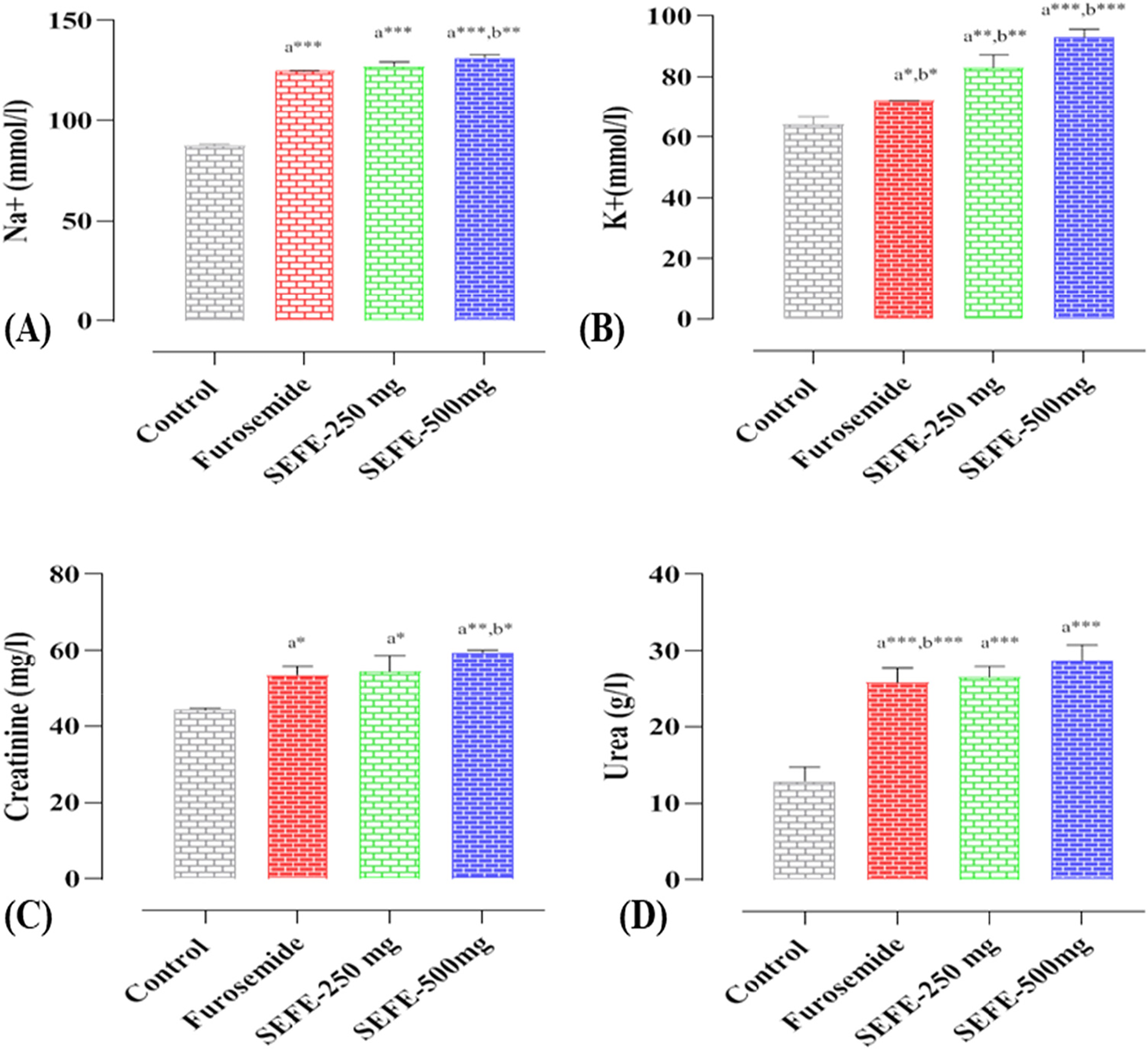

3.2.2 Impact of SEFE’s on Urine Electrolyte, Creatinine, and Urea

The results of the effects of SEFE and furosemide on creatinine, urea, Na+, and K+ are shown in Fig. 2. When compared to the negative control, furosemide and both doses of SEFE increased the urinary clearance of sodium, potassium, creatinine, and urea significantly (p < 0.001). The sodium excretion was dose-dependent, with values ranging from 127.30 ± 2.12 mmol/L for the dose (250 mg/kg body weight) to 131.54 ± 1.44 mmol/L for the dose (500 mg/kg body weight). The increase in furosemide was 124.8 ± 0.28 mmol/L.

Figure 2: Effect of the interventions on (A) urine Na+, (B) urine K+, (C) creatinine, and (D) urea on day 15. Every statistic symbolizes the mean ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; a when compared to the control group, b when compared to the Furosemide group, and the remaining

Potassium concentration was dose-dependent, with values ranging from 83.07 ± 4.23 mmol/L for the dose (250 mg/kg body weight) to 93.08 ± 2.64 mmol/L for the dose (500 mg/kg body weight). Both doses have been demonstrated to provide more potassium than Furosemide (p < 0.01). SEFE, like Furosemide, caused a significant (p < 0.01) increase in creatinine and urea in the urine when compared to the negative control. These findings suggest that SEFE is an effective diuretic, with SEFE at 500 mg showing the most potent diuretic activity in this particular study.

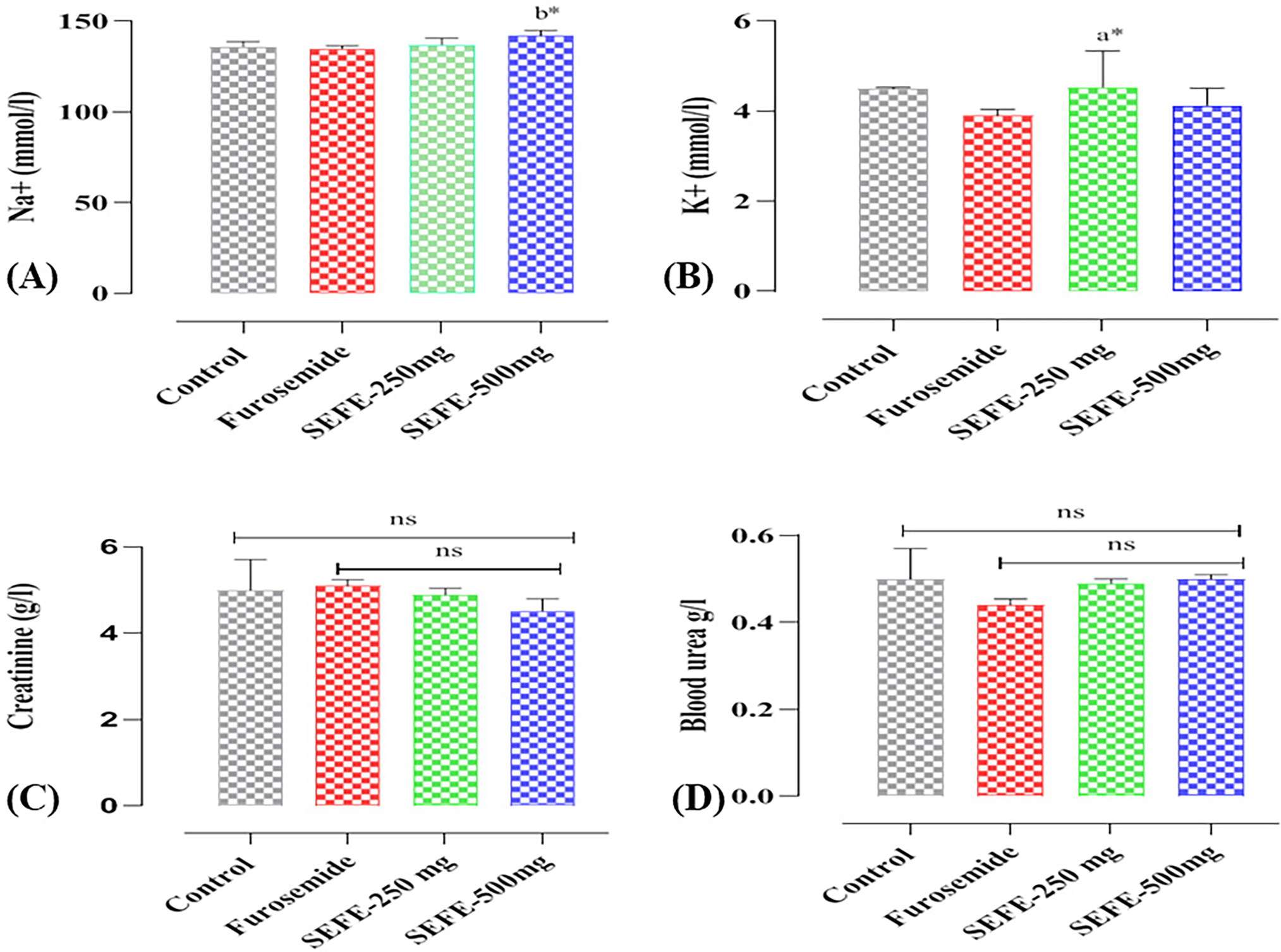

3.2.3 Impact of SEFE’s on Serum Electrolyte, Creatinine, and Urea

The plasma electrolyte, urea, and creatinine levels of the treatment of rats with leaf extracts (SEFE) at both doses and Furosemide for 15 days are presented in Fig. 3. When compared to the negative control, furosemide and the two doses of SEFE had no effect on plasma electrolytes, urea, or creatinine.

Figure 3: Effect of the interventions on (A) blood level of Na+, (B) blood level of K+, (C) creatinine, and (D) urea on day 15. Every statistic symbolizes the mean ± S.E.M. ns: non-significant; *p < 0.05; a when compared to the control group, b when compared to the Furosemide group, and the remaining

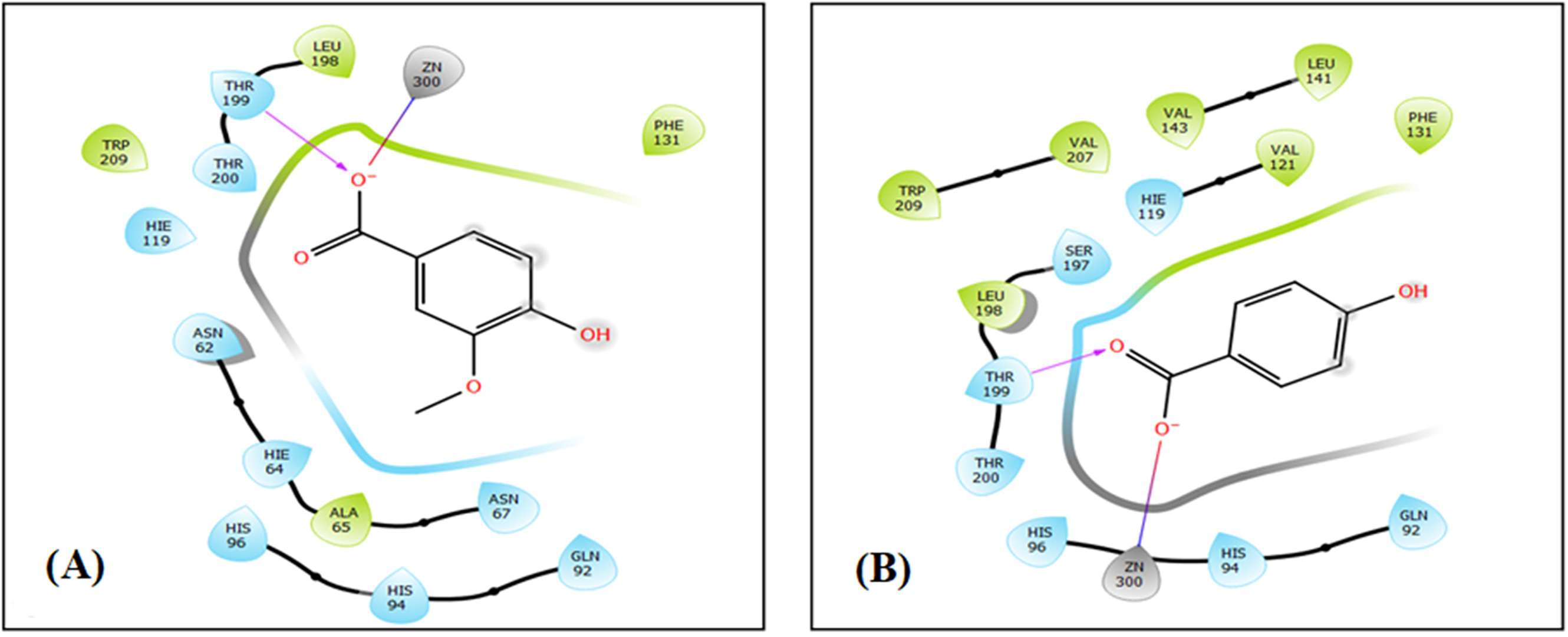

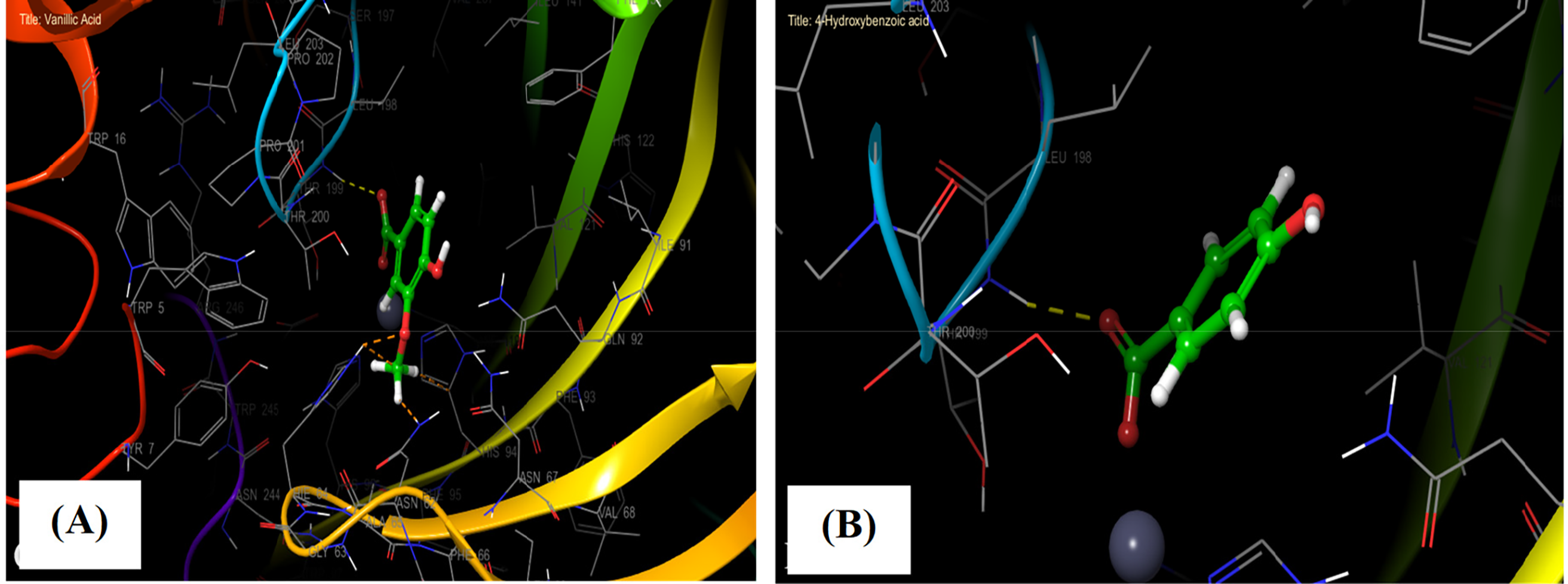

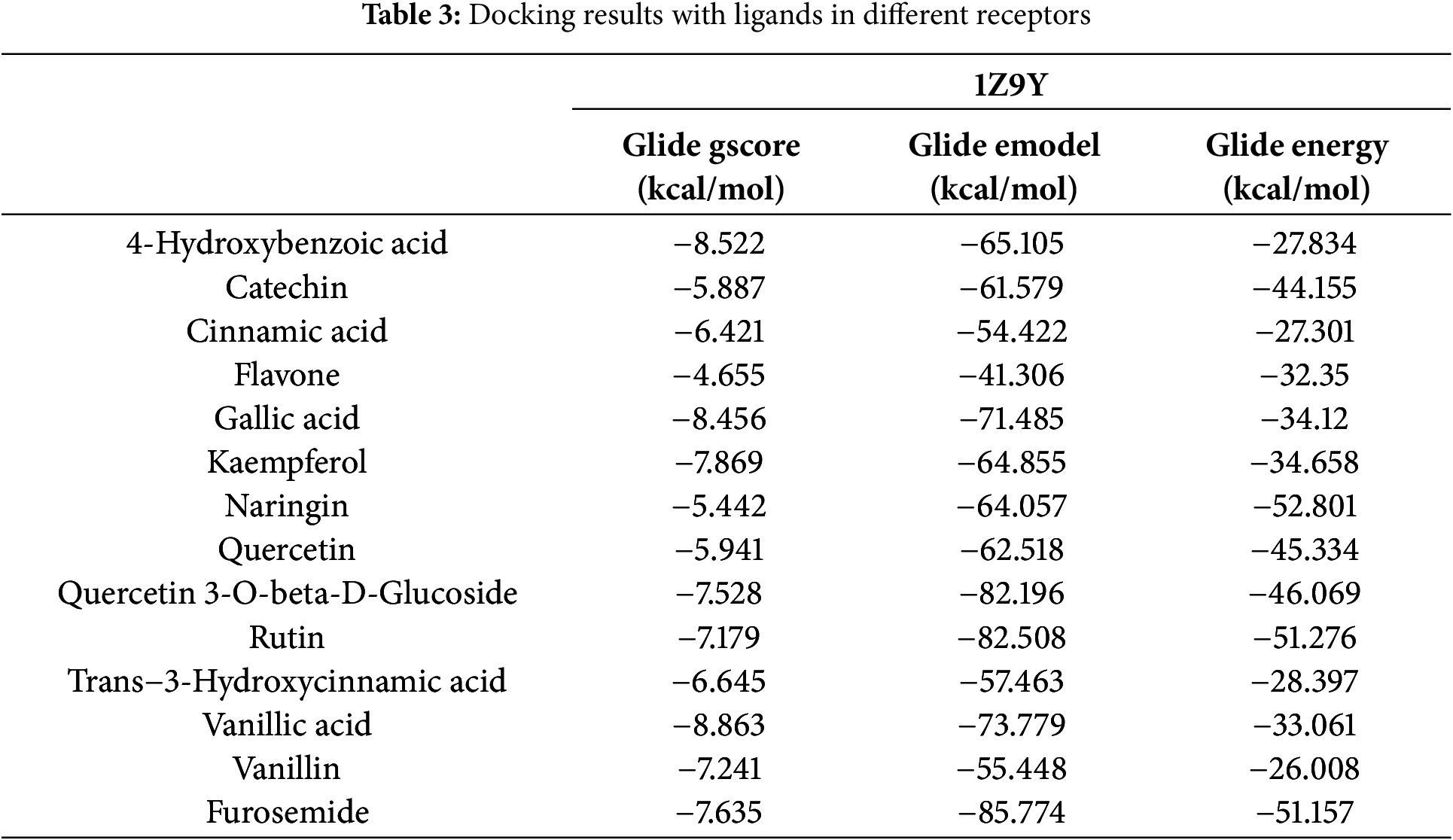

Docking studies were performed on the phenolic compounds and the target protein of the CA-II enzyme co-complexed with furosemide (PDB ID: 1Z9Y) on the one hand, and docking studies were performed on the phenolic compounds. Figs. 4 and 5 show the detailed results of the interactions, and Table 3 shows the score obtained by these natural compounds.

Figure 4: The 2D viewer of ligand interactions with the active site. (A and B) Vanillic Acid, and 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid interactions with the active site of carbonic anhydrase II

Figure 5: The 3D viewer of ligand interactions with the active site. (A and B) Vanillic Acid, and 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid interactions with the active site of carbonic anhydrase II

In the carbonic anhydrase II active site, Vanillic Acid established one hydrogen bond with residue THR 199 and a single salt bridge with residue ZN 300. Whereas 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid established one hydrogen bond with residue THR 199 and a single salt bridge with residue ZN 300 in the same active site (Figs. 4A,B, and 5A,B).

Diuretic medications promote urine formation by the kidneys. They assist the body in eliminating excess fluids, salts, and toxic substances by increasing urine production. Diuretics function in two primary ways: first, they reduce water reabsorption in the nephrons of the kidneys, and second, they alter the osmotic balance, leading to increased water loss [31]. Numerous plant preparations are utilized as diuretics. Several studies have been conducted to support the diuretic effects of various traditional herbal medicines [9]. The Solanum genus includes several species found in tropical and subtropical regions, commonly known as ‘yubeba’ because of the prickles on their stems [11]. These plants are used in folk medicine and dietary supplements. Among these species, S. elaeagnifolium (Cav.) is called silverleaf nightshade, and it’s considered particularly important ethnobotanically due to its traditional use in healthcare for treating various ailments. The leaves and bitter berries of S. elaeagnifolium have been traditionally utilized for the treatment of sore throats as an antiseptic agent, toothaches, and gastrointestinal disorders [32]. Currently, there is no scientific report detailing the diuretic activity of the leaf extract from S. elaeagnifolium. Given this gap in research, the present study aimed to analyze the phytochemical composition and pharmacological characteristics of the diuretic effects of the crude aqueous extract of S. elaeagnifolium leaves (SEFE), utilizing two different doses (250 and 500 mg/kg of body weight).

The Phytochemical analysis of SEFE revealed a rich composition of bioactive molecules that have been reported to possess medicinal properties [19,24,33]. Kaempferol is a major flavonoid aglycone found in many plants and displays several promising biological activities, such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, antitumor, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, and antidiabetic effects [20,34,35]. It has also been reported to have a diuretic effect. Additionally, the extract (SEFE) contains high quantities of several compounds, including quercetin, rutin, cinnamic acid, and vanillin, which exhibit numerous biologically significant functions. These functions include protection against oxidative stress and degenerative diseases [36]. A study conducted by Yang et al. (2018) highlights that these polyphenols can effectively inhibit the formation of calcium oxalate urinary stones, the most common type of renal stone [37]. This inhibition is associated with their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and diuretic properties, and their ability to inhibit angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) [38]. In the same context, Naringin is one of the molecules that compose SEFE, and it has been shown that treating rats with naringin improves kidney function significantly [39].

When discussing diuretic activity, it’s important to note that diuretics are designed to promote the elimination of water and salt through urine. This process helps reduce fluid retention and can lead to lower blood pressure. The clinical use of diuretics often focuses on regulating sodium (Na+) excretion, which is essential in controlling extracellular fluid volume. For example, furosemide works by inhibiting the Na+/K+/2Cl− symporter, which disrupts the absorption of sodium, potassium, and chloride ions [40]. Our study found that two doses (250 and 500 mg/kg body weight) of SEFE significantly increased urinary volume (10.67 ± 3.05 mL/24 h and 16.67 ± 9.86 mL/24 h, respectively) and improved urinary electrolyte parameters over 15 days of treatment compared to the control group. The SEFE did not demonstrate a decrease in plasma potassium levels compared to furosemide, which caused hypokalemia. Furosemide was selected as a standard drug in this study because loop diuretics like it are known to significantly enhance the urinary flow rate and electrolyte excretion. Additionally, furosemide is one of the most commonly prescribed diuretics for various medical conditions [31].

The precise mechanism and active principle responsible for the diuretic and natriuretic activities of the aqueous extract of S. elaeagnifolium remain unclear. However, there is a possibility that it may exhibit a similar impact to loop diuretics, as it has shown an increase in the excretion of potassium and sodium, akin to the effects of furosemide [41,42]. The phytochemical screening of SEFE revealed the presence of flavonoids and polyphenols (Table 3). It is reasonable to suggest that these secondary metabolites may act individually or synergistically to produce the observed diuretic and natriuretic activities of S. elaeagnifolium [31,43]. In a study involving the administration of Solanum xanthocarpum (AESX) at doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg, a significant increase in urine volume was observed after 5 and 24 h. Furthermore, when AESX was administered at doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg, there was a substantial increase in the urinary excretion of sodium, potassium, and chloride, with effects similar in potency to hydrochlorothiazide (HTZ), a recognized diuretic [10]. This indicates that Solanum xanthocarpum may possess diuretic properties comparable to HTZ [44]. In another study, it was confirmed that the aqueous methanolic extract of Solanum surattense induced a significant, dose-dependent increase in urine output in rats, akin to the effects of the standard diuretic drug, furosemide [21].

Additionally, as urine volume increased, the extract also enhanced the excretion of sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and calcium (Ca2+) in urine, demonstrating a similar effect to that triggered by furosemide in comparison to the control group [21]. Carbonic anhydrase is an enzyme that catalyzes the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to form bicarbonate and protons. There are different isoforms of carbonic anhydrase, and one of them is carbonic anhydrase II (CA II), which is found in various tissues, including the kidneys. The role of carbonic anhydrase in diuretic activity is associated with its involvement in the reabsorption of bicarbonate in the renal tubules. The kidneys play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of electrolytes and water in the body by selectively reabsorbing substances from the urine. Bicarbonate is an important ion involved in acid-base balance [45]. The inhibition of carbonic anhydrase disrupts the normal exchange of ions and water in the renal tubules, resulting in increased urine production. This diuretic effect can be beneficial in various medical conditions, such as glaucoma, where reducing intraocular pressure is important, and in the prevention and treatment of altitude sickness [45]. Vanillic Acid, 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, and Gallic Acid exhibited the highest anti-carbonic anhydrase II activity with a glide gscore of −8.863, −8.522, and −8.456 kcal/mol. These three molecules also presented an inhibitory activity greater than that of Furosemide (−7635 kcal/mol). The use of carbonic anhydrase II inhibitors as diuretics has been clinically proven [46]. Similar to other previously published research on the docking of phytomolecules for inhibition of the enzyme carbonic anhydrase II, our work likewise showed successful docking of the ligands indicated [8].

This study provides strong evidence for the diuretic potential of S. elaeagnifolium leaves, which can increase urine volume and electrolyte excretion without causing hypokalemia. Although the specific active ingredients have not been identified, the presence of phenolics, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds suggests that its diuretic effects may be synergistic. The extract exhibited diuretic effects comparable to furosemide while maintaining electrolyte balance, highlighting its potential as a safer alternative. These findings open new avenues for future research to elucidate its precise mechanism of action and therapeutic applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Bouslamti Mohammed and Nouioura Ghizlane; methodology, Tbatou Widad and Mohamed Chebaibi; software, Najoua Soulo; validation, Tbatou Widad, Mohamed Chebaibi and Abdulsalam Alhalmi; formal analysis, Bouslamti Mohammed; investigation, Bouslamti Mohammed; resources, Nouioura Ghizlane; data curation, Nouioura Ghizlane; writing—original draft preparation Bouslamti Mohammed; writing—review and editing, Bouslamti Mohammed, Sulaiman Mohammed Alnasser and Fahad M Alshabrmi; visualization, Amine Elbouzidi; supervision, Lyoussi Badiaa and Benjelloun Ahmed Samir; project administration, Amine Elbouzidi; funding acquisition, Sulaiman Mohammed Alnasser and Fahad M Alshabrmi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, M.B., upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Science, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (L.20. USMBA-SNAMOPEQ 2023-03).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Noureddine B, Mostafa E, Mandal SC. Ethnobotanical, pharmacological, phytochemical, and clinical investigations on Moroccan medicinal plants traditionally used for the management of renal dysfunctions. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;292:115178. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2022;12(1):7–11. doi:10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yakubu MT, Oyagoke AM, Quadri LA, Agboola AO, Oloyede HOB. Diuretic activity of ethanol extract of Mirabilis jalapa (Linn.) leaf in normal male Wistar rats. J Med Plants Econ Dev. 2019;3(1):1–7. doi:10.4102/jomped.v3i1.70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Agunu A, Abdurahman EM, Andrew GO, Muhammed Z. Diuretic activity of the stem-bark extracts of Steganotaenia araliacea hochst [Apiaceae]. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96(3):471–5. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. DeFalco AP, Ray SD. Side effects of diuretics. In: Side effects of drugs annual. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. Vol. 45, p. 209–15. doi:10.1016/bs.seda.2023.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Guo L, Fu B, Liu Y, Hao N, Ji Y, Yang H. Diuretic resistance in patients with kidney disease: challenges and opportunities. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;157(4):114058. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Arioglu-Inan E, Kayki-Mutlu G. Diuretic agents. In: Comprehensive pharmacology. Amsterdam, The Netherland: Elsevier; 2022. p. 634–55. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-820472-6.00162-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sharma S, Kumar G, Kumar N, Sethiya NK, Bisht D. Diuretic activity of ethanol extract of Piper attenuatum leaves might be due to the inhibition of carbonic anhydrase enzyme: an in vivo and in silico investigation. Clin Complementary Med Pharmacol. 2024;4(1):100117. doi:10.1016/j.ccmp.2023.100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Melka AE, Makonnen E, Debella A, Fekadu N, Geleta B. Diuretic activity of the aqueous crude extract and solvent fractions of the leaves of Thymus serrulatus in mice. J Exp Pharmacol. 2016;8:61–7. doi:10.2147/JEP.S121133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ranka D, Aswar M, Aswar U, Bodhankar S. Diuretic potential of aqueous extract of roots of Solanum xanthocarpum Schrad & Wendl, a preliminary study. Indian J Exp Biol. 2013;51(10):833–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Kaunda JS, Zhang YJ. The genus Solanum: an ethnopharmacological, phytochemical and biological properties review. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2019;9(2):77–137. doi:10.1007/s13659-019-0201-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Pandey G, Prajapati KK, Shukla L, Vartika Pandey VN, Pandey R. Anticancer activity and new drug discovery in Solanum species: a review. Int J Plant Environ. 2024;10(3):48–58. doi:10.18811/ijpen.v10i03.05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Oluremi BB, Oloche JJ, Adeniji AJ. Anticancer and antibacterial activities of Solanum aethiopicum L., Solanum macrocarpon L. and Garcinia kola heckel. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2021;5(5):938–42. doi:10.26538/tjnpr/v5i5.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Okokon J, Udo N, Nyong E, Amazu L. Analgesic activity of ethanolic leaf extract of Solanum anomalum. Afr J Pharmacol Ther. 2020;9(1):22–6. [Google Scholar]

15. Jahanabadi S, Ahmad B, Nikoui V, Khan G, Khan MI. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of Solanum melongena. Phytopharmacological Com. 2022;2(1):21–32. doi:10.55627/ppc.002.01.0049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Radwan MM, Badawy A, Zayed R, Hassanin H, ElSohly MA, Ahmed SA. Cytotoxic flavone glycosides from Solanum elaeagnifolium. Med Chem Res. 2015;24(3):1326–30. doi:10.1007/s00044-014-1219-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hawas UW, Soliman GM, Abou El-Kassem LT, Farrag ARH, Mahmoud K, León F. A new flavonoid C-glycoside from Solanum elaeagnifolium with hepatoprotective and curative activities against paracetamol-induced liver injury in mice. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2013;68(1–2):19–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Bouslamti M, Metouekel A, Chelouati T, El Moussaoui A, Barnossi AE, Chebaibi M, et al. Solanum elaeagnifolium var. Obtusifolium (dunal) dunal: antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal activities of polyphenol-rich extracts chemically characterized by use of in vitro and in silico approaches. Molecules. 2022;27(24):8688. doi:10.3390/molecules27248688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Bouslamti M, Loukili EH, Elrherabi A, El Moussaoui A, Chebaibi M, Bencheikh N, et al. Phenolic profile, inhibition of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase enzymes, and antioxidant properties of Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. (Solanaceaein vitro and in silico investigations. Processes. 2023;11:1384. doi:10.3390/pr11051384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Feki H, Koubaa I, Jabeur H, Makni J, Mohamed D. Characteristics and chemical composition of Solanum elaeagnifolium seed oil. ARPN J Eng Appl Sci. 2013;8(9):708–12. [Google Scholar]

21. Ahmed MM, Andleeb S, Saqib F, Hussain M, Khatun MN, Ch BA, et al. Diuretic and serum electrolyte regulation potential of aqueous methanolic extract of Solanum surattense fruit validates its folkloric use in dysuria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):166. doi:10.1186/s12906-016-1148-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Adefola ET, John AA, Sunday ES. Effects of lutein on the body weights, hepato-renal DNA and antioxidant capacity following paraquat-induced toxicity in wistar rats. South Asian Res J App Med Sci. 2024;6(5):132–40. doi:10.36346/sarjams.2024.v06i05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kusumarathna K, Jayathilaka P, Rathnayake B, Wijesinghe A, Priyalath N, Gunarathna I, et al. Advances in understanding and management of antidiuretic hormone disorders: a comprehensive review. Charlottesville, VA, USA: Uva Clinical Lab; 2024. Retrieved from advances in understanding and management of antidiuretic hormone disorders: a comprehensive review. [Google Scholar]

24. Bouslamti M, Elrherabi A, Loukili EH, Noman OM, Mothana RA, Ibrahim MN, et al. Phytochemical profile, antilipase, hemoglobin antiglycation, antihyperglycemic, and anti-inflammatory activities of Solanum elaeagnifolium cav. Appl Sci. 2023;13(20):11519. doi:10.3390/app132011519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bouslamti M, Nouioura G, Kandsi F, El Hachlafi N, Elrherabi A, Lyoussi B, et al. Phytochemical analysis and acute toxicity of Solanum elaeagnifolium extract in Swiss albino mice. Sci Afr. 2024;24(Suppl 1):e02212. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2024.e02212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. El-Desoky AH, Abdel-Rahman RF, Ahmed OK, El-Beltagi HS, Hattori M. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of naringin isolated from Carissa carandas L.: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Phytomedicine. 2018;42(8):126–34. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ghouizi AE, Menyiy NE, Falcão SI, Vilas-Boas M, Lyoussi B. Chemical composition, antioxidant activity, and diuretic effect of Moroccan fresh bee pollen in rats. Vet World. 2020;13(7):1251–61. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2020.1251-1261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Aboul-Soud MAM, Ennaji H, Kumar A, Alfhili MA, Bari A, Ahamed M, et al. Antioxidant, anti-proliferative activity and chemical fingerprinting of Centaurea calcitrapa against breast cancer cells and molecular docking of caspase-3. Antioxidants. 2022;11(8):1514. doi:10.3390/antiox11081514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Amrati FE, Slighoua M, Mssillou I, Chebaibi M, Galvão de Azevedo R, Boukhira S, et al. Lipids fraction from Caralluma europaea (guss.microtof and HPLC analyses and exploration of its antioxidant, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and wound healing effects. Separations. 2023;10(3):172. doi:10.3390/separations10030172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ban T, Ohue M, Akiyama Y. Multiple grid arrangement improves ligand docking with unknown binding sites: application to the inverse docking problem. Comput Biol Chem. 2018;73(8):139–46. doi:10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.02.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Tbatou W, Aboulghazi A, Ghouizi A, El-Yagoubi K, Soulo N, Ouaritini Z, et al. Phenolic screening, antioxidant activity and diuretic effect of Moroccan pinus pinaster bark extract. Avicenna J Phytomedicine. doi:10.22038/ajp.2024.25198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chidambaram K, Alqahtani T, Alghazwani Y, Aldahish A, Annadurai S, Venkatesan K, et al. Medicinal plants of Solanum species: the promising sources of Phyto-insecticidal compounds. J Trop Med. 2022;2022(1):4952221. doi:10.1155/2022/4952221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Bouslamti M, El Barnossi A, Kara M, Alotaibi BS, Al Kamaly O, Assouguem A, et al. Total polyphenols content, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leaves of Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. from Morocco. Molecules. 2022;27(13):4322. doi:10.3390/molecules27134322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Houda M, Derbré S, Jedy A, Tlili N, Legault J, Richomme P, et al. Combined anti-ages and antioxidant activities of different solvent extracts of Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav (Solanacea) fruits during ripening and related to their phytochemical compositions. EXCLI J. 2014;13:1029–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

35. Al-hamaideh K, Dmour I, El-Elimat T, Afifi F. UPLC-MS profile and anti-proliferative activity of the berries of an aggressive wild-growing weed: Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. (solanaceae). Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2020;4(12):1131–8. doi:10.26538/tjnpr/v4i12.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Arulselvi P, Kavya KR, Kesavapriya M. Dietary polyphenols: recent trends in its biological significance. In: Science and engineering of polyphenols: fundamentals and industrial scale applications. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2024. p. 489–507. doi:10.1002/9781394203932.ch20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yang Y, Huang J, Ma X, Xie H, Xie L, Liu C. Bidirectional impact of varying severity of acute kidney injury on calcium oxalate stone formation. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2024;49(1):946–60. doi:10.1159/000542077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Qidwai T, Prasad S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition properties and antioxidant effects of plants and their bioactive compounds as cardioprotective agent. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2023;20(4):457–68. doi:10.2174/1570180819666220513115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Amini N, Maleki M, Badavi M. Nephroprotective activity of naringin against chemical-induced toxicity and renal ischemia/reperfusion injury: a review. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2022;12(4):357–70. doi:10.22038/AJP.2022.19620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wargo KA, Banta WM. A comprehensive review of the loop diuretics: should furosemide be first line? Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(11):1836–47. doi:10.1345/aph.1M177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ilenwabor BP, Asowata EO, Obika LF. Circadian potassium excretion is unaffected following furosemide induced increase in sodium delivery to the distal nephron. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2017;32(1):1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

42. Rao VS, Ivey-Miranda JB, Cox ZL, Moreno-Villagomez J, Ramos-Mastache D, Neville D, et al. Serial direct sodium removal in patients with heart failure and diuretic resistance. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26(5):1215–30. doi:10.1002/ejhf.3196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kurkin VA, Pravdivtseva OE, Zaitseva EN, Dubishchev AV, Tsibina AS, Kurkina AV, et al. Terpenoids and phenolic compounds as biologically active compounds of medicinal plants with diuretic effect. Farm Farmakol. 2024;11(6):446–60. doi:10.19163/2307-9266-2023-11-6-446-460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Deshmukh MT, Shete RV, Deshmukh VT, Borate SR, Deshmukh SV. Preclinical evaluation of diuretic activity of aqueous extract of Solanum xanthocarpum leaves in experimental animals. J Curr Pharma Res. 2013;3(4):1023–6. doi:10.33786/JCPR.2013.v03i04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kumar S, Rulhania S, Jaswal S, Monga V. Recent advances in the medicinal chemistry of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;209:112923. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sethi KK, Abha Mishra KM, Verma SM, Vullo D, Carta F, Supuran CT. Synthesis and human carbonic anhydrase I, II, IX, and XII inhibition studies of sulphonamides incorporating mono-, Bi- and tricyclic imide moieties. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(7):693. doi:10.3390/ph14070693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools