Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Chemical Characterization of Jarilla caudata Seeds from Mexico

1 Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad de Guadalajara, Camino Padilla Sánchez No. 2100, Zapopan, Jalisco, 45101, México

2 Instituto de la Grasa (C.S.I.C.), Campus Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Carretera de Utrera km 1, Sevilla, 41089, España

* Corresponding Author: Juan Francisco Zamora Natera. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Chemistry and Environmental Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1533-1544. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064966

Received 28 February 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

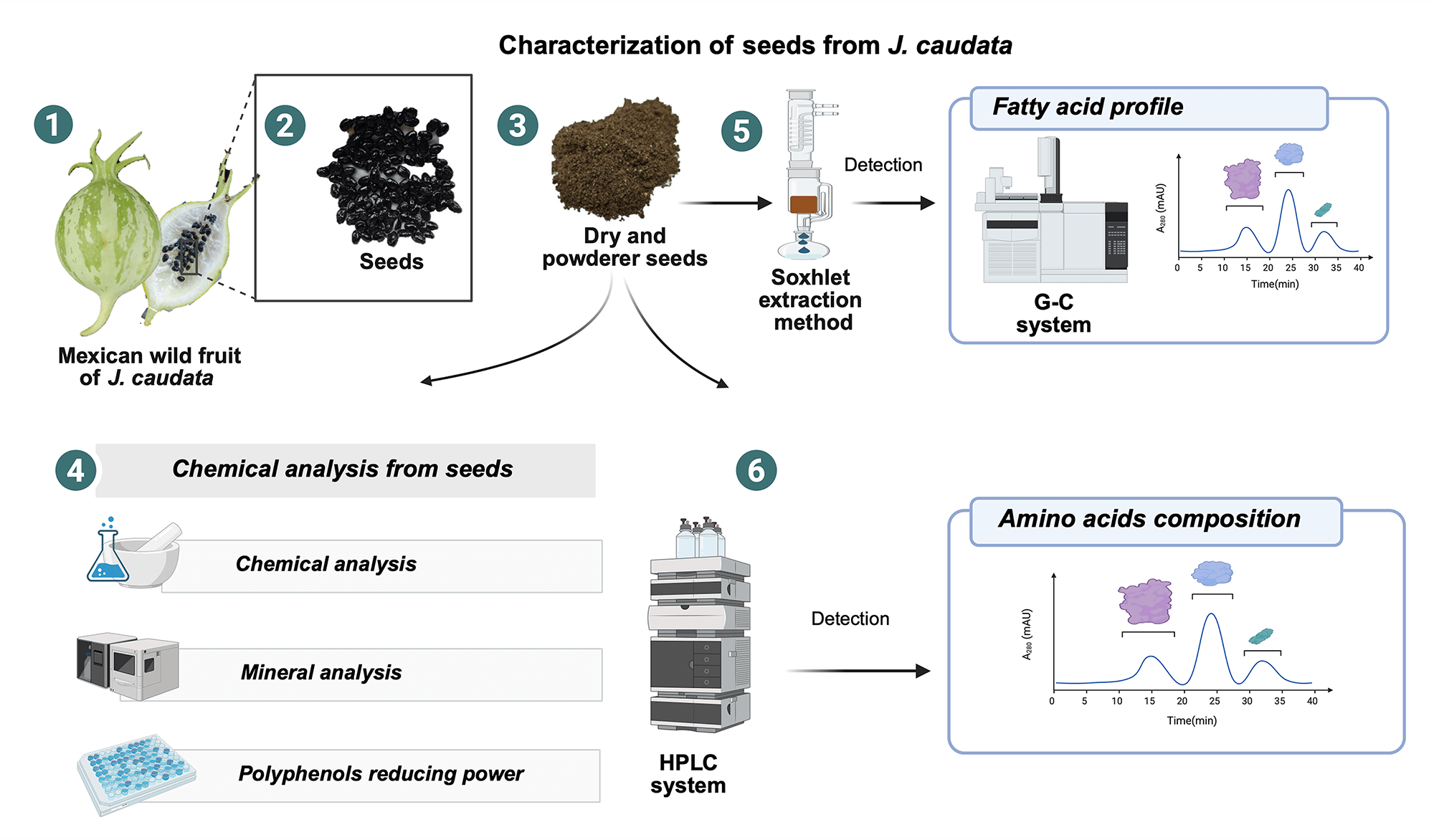

Jarilla caudata Standl. (Caricaceae) is a wild herbaceous plant native to Mexico recognized for its edible fruits. It is considered to be the closest taxonomically species to Carica papaya L. (Caricaceae), whose seeds have good nutritional and functional properties. This study analyzes and compares the seed chemical compositions of J. caudata and C. papaya to study the nutritional and functional potential of J. caudata seeds. The analysis of the proximate composition was based on standard methods. High-performance liquid chromatography was used to determine the free amino acid profile, gas chromatography to quantify the fatty acid content, and inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry to measure minerals. Both J. caudata and C. papaya seeds have high protein (24.03% to 26.94%) and lipid (21.32% to 25.07%) content. The mineral study indicated high potassium, calcium, iron, and zinc content. Minor functional compounds present, with similar contents in J. caudata and C. papaya seeds, were soluble sugars, phytic acid, polyphenols, and pectin. The main fatty acid in seed oil was oleic acid (C18:1), with 61.4% in J. caudata seeds and 72.6% in C. papaya seeds. Among free amino acids, leucine with 6.9/100 g free amino acids and phenylalanine with 13.6/100 g free amino acids were the most abundant in the seeds of J. caudata and C. papaya, respectively. Polyphenols of J. caudata and C. papaya seeds showed similar antioxidant activity. J. caudata seeds may represent a useful source of nutritional compounds for food and feeding, and functional compounds with antioxidant activity.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

There is growing interest in using plant seeds as sources of nutrients to meet the increasing demand for food and also as a source of functional compounds [1]. There is abundant information regarding the chemical composition of commonly cultivated crops, including legumes, cereals, and oilseeds [2]. Seeds from local cultures and/or wild fruit are also of interest as sources of nutritional and functional compounds [3]. For instance, protein, oil, carbohydrate, and mineral constituents of fruit seeds from wild plants have been considered suitable for food formulations [4,5], and as a source of functional compounds, flavonoids, phenolic acids, carotenoids, alkaloids, and glucosinolates, with health-promoting properties [6,7].

Jarilla caudata is an herbaceous perennial plant belonging to the family Caricaceae. This plant is close taxonomically to Carica papaya. The fruit of C. papaya is widely consumed and recognized for its nutritional and health-promoting properties [8]. Molecular data support the relationship of C. papaya to a Mexican/Guatemalan clade of the genus Jarilla [9]. This clade includes three herbaceous Jarilla species (J. heterophylla, J. chocola, and J. caudata) that grow in the northwest of Mexico. These three species are all appreciated for their edible fruits. However, J. caudata is the most popular one in local communities, and its fruit is collected from the wild and locally consumed as immature as fresh snacks with salt and lemon.

The green fruit of J. caudata has been chemically characterized and is rich in proteins, macrominerals, and carbohydrates [10]. The chemical composition of C. papaya seeds and fruits has been analyzed showing good nutritional and pharmacological properties [11,12]. However, studies on J. caudata seeds are lacking. Hence, due to the close taxonomic relationship with C. papaya, J. caudata seeds may be as well rich a source of nutritional and functional compounds as C. papaya seeds. The objective of this work was to analyze and compare the chemical composition of J. caudata and C. papaya seeds in terms of their proximal composition, fatty acids, mineral content, free amino acids, and antioxidant activity.

Mature fruits of J. caudata plants were collected in November 2023 from several populations in Tizapan (Jalisco, Mexico), (N20°072′77.2′′; W103°03′21′′) and 1546 m above sea level. Seeds were manually recovered from the ripe fruits, washed with water to eliminate pulp residues, and dehydrated in a forced air oven at 45°C until constant weight. Seeds were ground with a hammer mill with a size 60 sieve, packaged in polyethylene bags, and stored at 5°C until analysis. Plants were identified and a voucher specimen of J. caudata (No. 221029) was deposited at Luz Maria Villarreal de Puga herbarium, located at Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias belonging to the University of Guadalajara (Guadalajara, Jalisco, México). C. papaya seeds were taken from fruits obtained in a local market and processed as described for J. caudata seeds.

Moisture, ash, lipid, and protein (%N × 6.25) content were determined according to approved standard methods of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists: methods 925.09, 923.03, 920.85, and 920.87, respectively [13]. Acid and alkaline digestion were used to determine crude fiber, while total carbohydrates were estimated by difference according to the following equation:

Total carbohydrate (%) = 100 − (% Ash + % Moisture + % Protein + % Fat + % Fiber).

The energy value was calculated according to FAO [14] following the equation:

kcal/100 g = (% available carbohydrates × 4) + (% proteins × 4) + (% fats × 9).

Additionally, soluble sugars were determined according to the Dubois method [15]. Pythic acid was determined following a colorimetric method [16]. Pectins were determined as galacturonic acid equivalents [17], and total polyphenol contents were measured with the Folin-Ciocalteu method [18].

Seed flours (0.5 g) were digested with 4 mL of 7 M HNO3 and 4 mL of 30% (w/w) H2O2 in a microwave oven at 600 W power for 1 h. After digestion, the solution was diluted with ultrapure water to 25 mL in a volumetric flask [10]. Minerals were determined by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) with an Optima 4300 DV (Perkin Elmer) spectrometer. Operating conditions were as follows: power, 1200 W; plasma flow gas, 14 L/min; auxiliary gas flow, 0.2 L/min; nebulizer gas flow, 0.9 L/min.

Seed flours were extracted with hexane in a Soxhlet for 8 h. The oil extract was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the solvent was evaporated using a vacuum rotary evaporator. Oil content was determined gravimetrically. Fatty acids were analyzed by gas chromatography as their methyl esters [19]. A standard mixture of olive, rapeseed, and sunflower oils was used for identification and quantification, by the internal normalization method.

Free amino acids were analyzed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography after their extraction with ethanol (60%) and derivatization using diethyl ethoxymethylenemalonate [20].

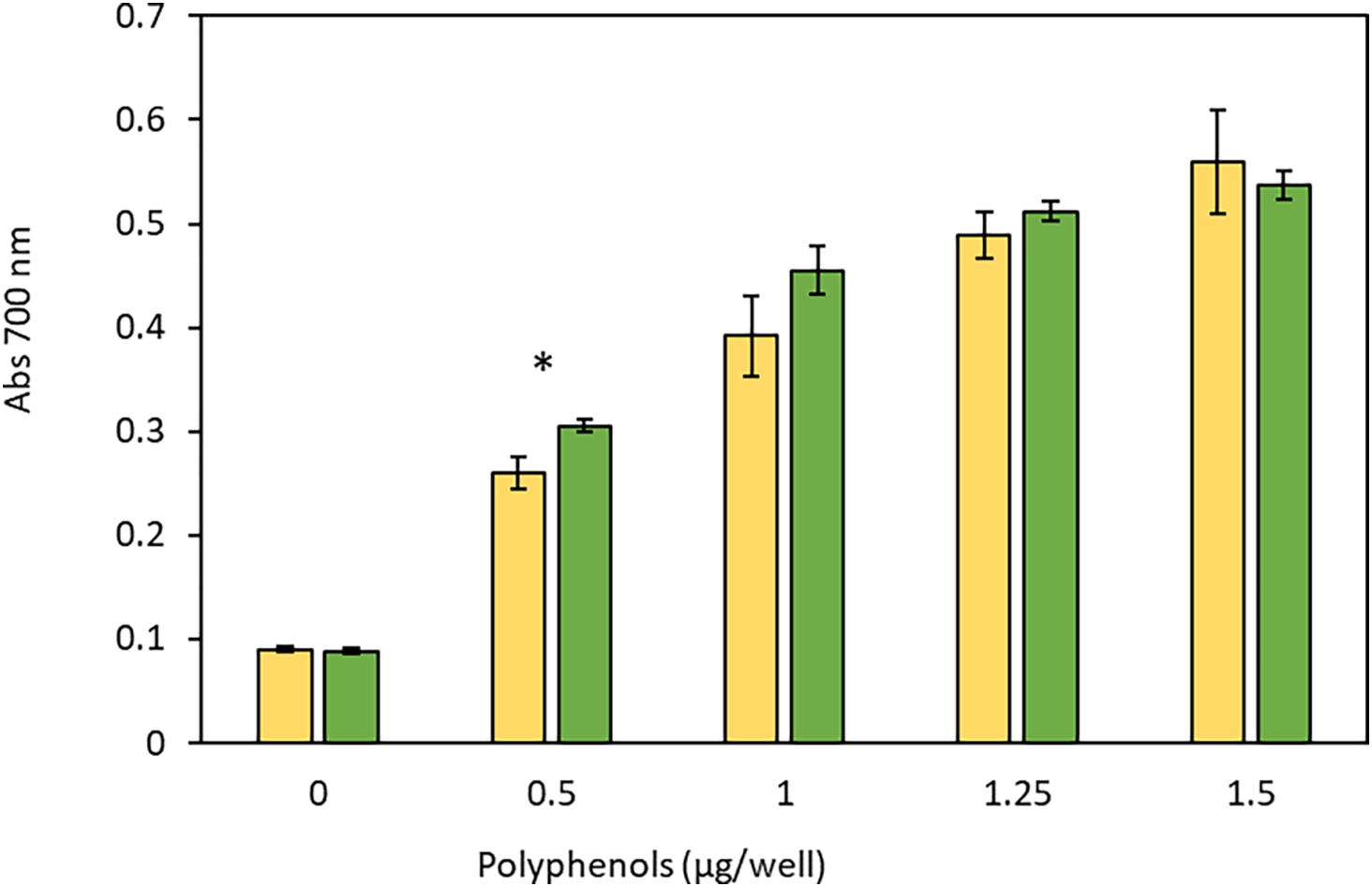

2.6 Polyphenols Reducing Power

The reducing power of J. caudata and C. papaya seed flour polyphenols was determined according to Oyaizu [21]. In microplates, 0, 0.5 1, 1.25, and 1.5 μg polyphenols/well were evaluated. Reducing power was measured at 700 nm in a microplate reader (Scientific Multiskan GO Spectrophotometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Increases in the reaction mixture’s absorbance indicate higher reducing capacity.

Student t-test was used to analyze and compare data means between the groups (two different seed types) at 0.05 probability, using Minitab Statistical Software.

3.1 Chemical Composition of J. caudata Seeds

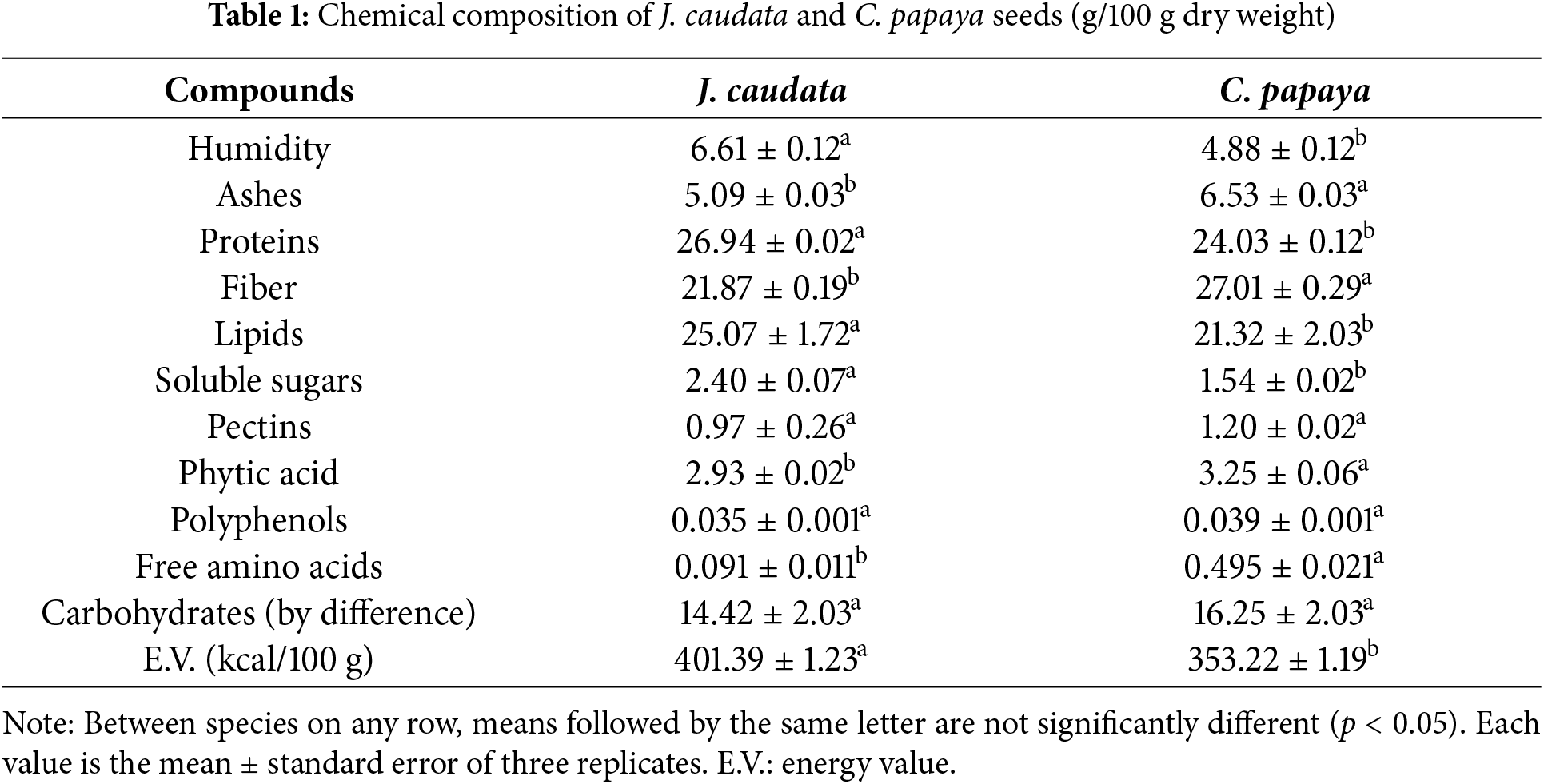

Chemical composition of J. caudata and C. papaya seeds is shown in Table 1. Protein and lipids were the main components in both J. caudata and C. papaya seeds, although significative higher in J. caudata than in C. papaya (26.94% vs. 24.03%, and 25.07% vs. 21.32%, respectively).

On the contrary, C. papaya seeds were richer in fiber (27.01% vs. 21.87%) and carbohydrates (16.25% vs. 14.42%) than J. caudata seeds, while ashes content were similar in both plants (6.53% and 5.09%, respectively). Other compounds present in minor amounts were soluble sugars, phytic acid, pectins, and polyphenols. Only soluble sugars contents differed significantly between J. caudata and C. papaya seeds (2.40% and 1.54%, respectively). Energy values differed significantly between the two samples, with 401.39 kcal/100 g for J. caudata seeds and 353.22 kcal/100 g for C. papaya seeds. Seeds with 400 to 600 kcal/100 g E.V. are considered an appropiate source of energy for human nutrition.

3.2 Mineral Composition of J. caudata Seeds

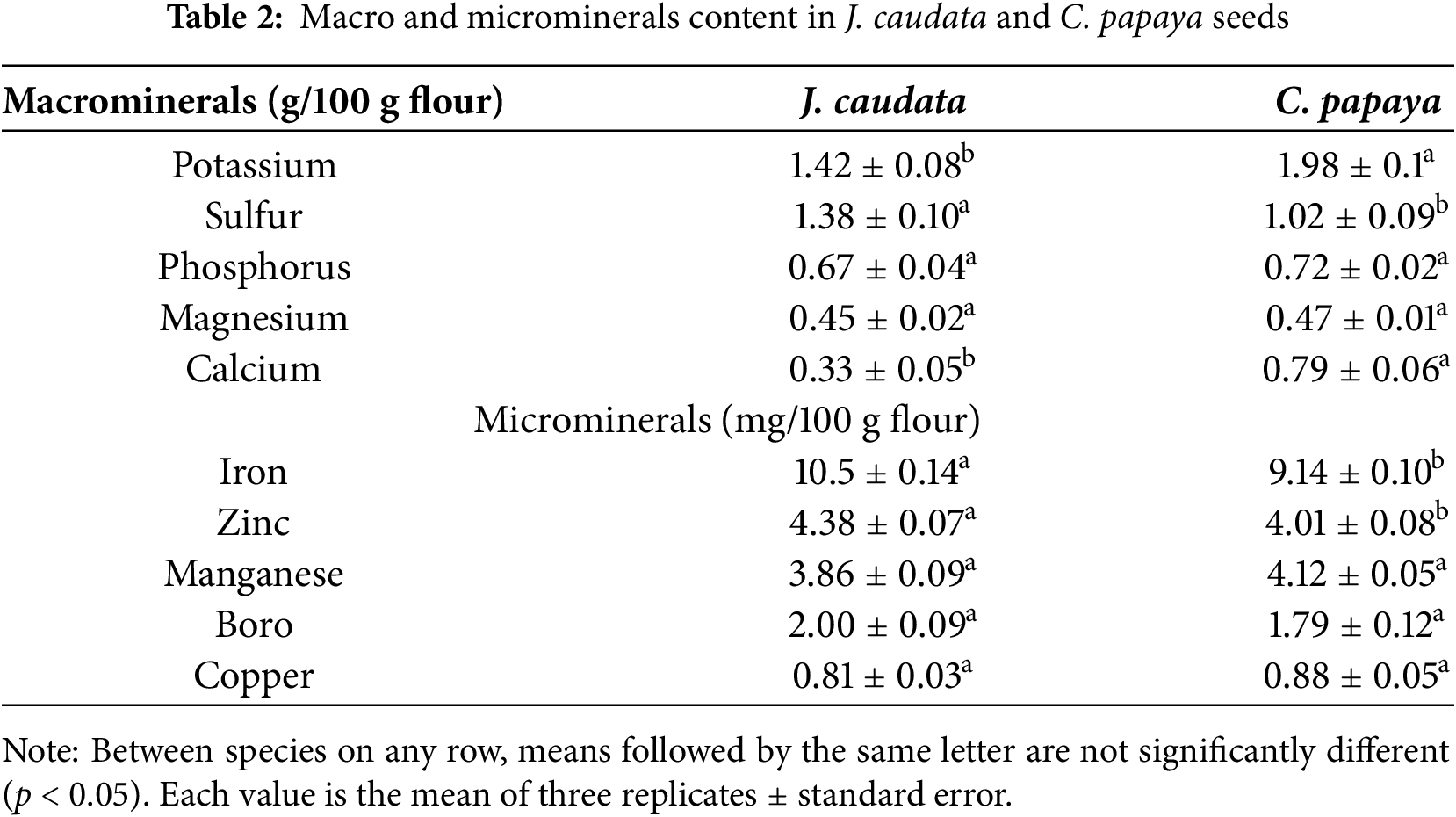

Mineral composition of J. caudata and C. papaya seeds is shown in Table 2. In both plants, potassium was the most abundant macromineral, followed by sulfur, phosphorus, magnesium, and calcium. Only potassium and calcium contents differed significantly between the two seeds.

Potassium contents were significantly higher in C. papaya than in J. caudata seeds (1.43/100 g vs. 1.98/100 g). Also, calcium contents were 100% higher in C. papaya than in J. caudata seeds (0.79/100 g vs. 0.33/100 g). Among microminerals, iron was the most abundant in both seeds, followed by zinc, manganese, and boro. Zinc and iron values were higher in J. caudata than in C. papaya seeds, although these differences were not significative different. Copper contents were low in both species, with values of 0.81 mg/100 g in J. caudata and 0.88 mg/100 g in C. papaya. Sodium was not detected in the two seeds.

3.3 Fatty Acids Composition of J. caudata Seed Oil

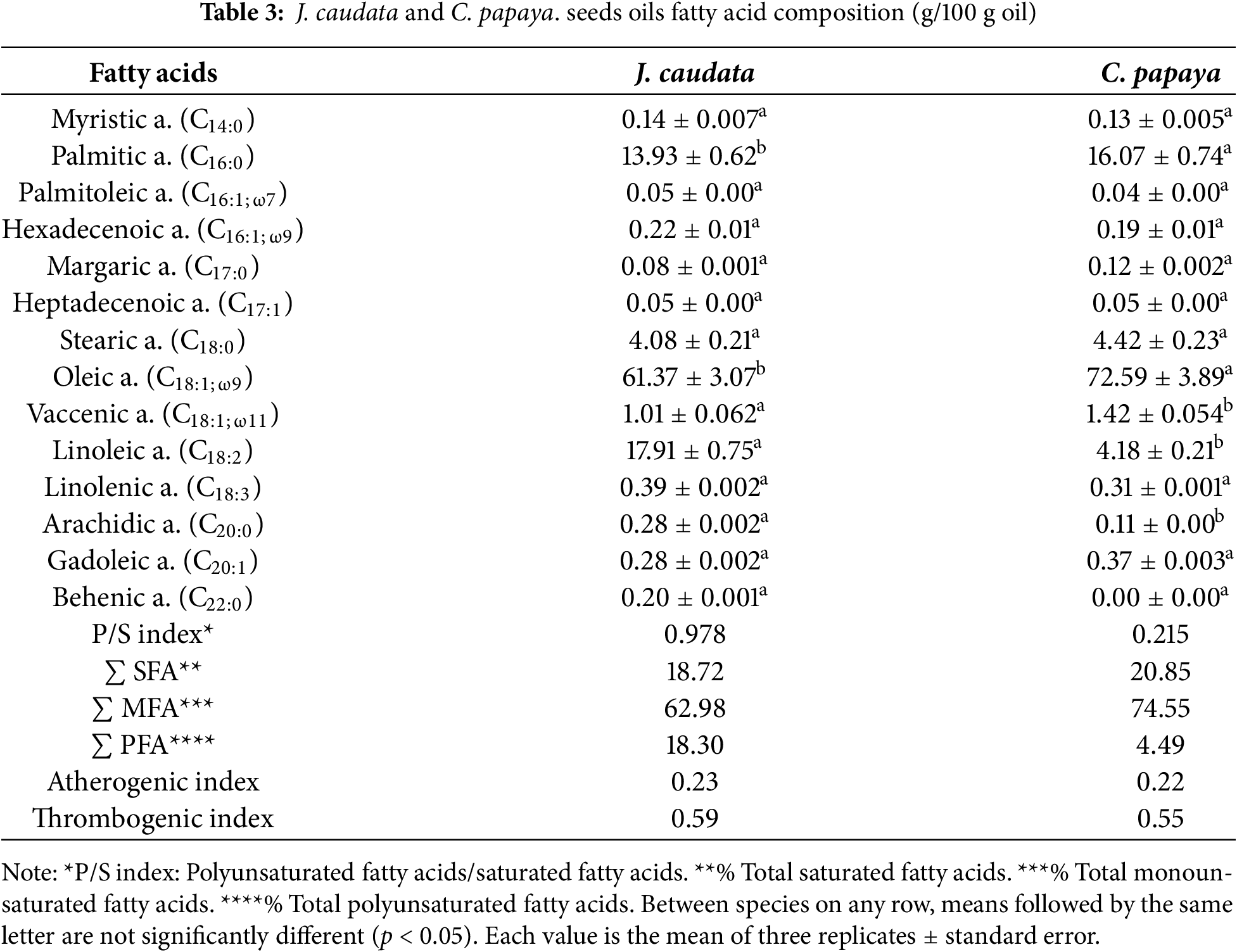

Seed oil fatty acid composition is shown in Table 3. Unsaturated fatty acids represented 81.29% and 79.15% of the seed oil in J. caudata and C. papaya seeds, respectively. Oleic acid was the majoritary fatty acid in J. caudata (61.37%) and C. papaya (72.59%) seed oil. Other fatty acids in minor amounts were palmitic and linoleic acid.

Hence, palmitic acid was the most abundant saturated fatty acid in both plants, followed by stearic acid. Other fatty acids such as palmitoleic, gadoleic, and linolenic acid were found in low percentages (<1%). The P/S index was higher in J. caudata seeds than in C. papaya seeds (0.978% vs. 0.215%). The atherogenic index and thrombogenic index values were similar in the two oil samples (Table 3).

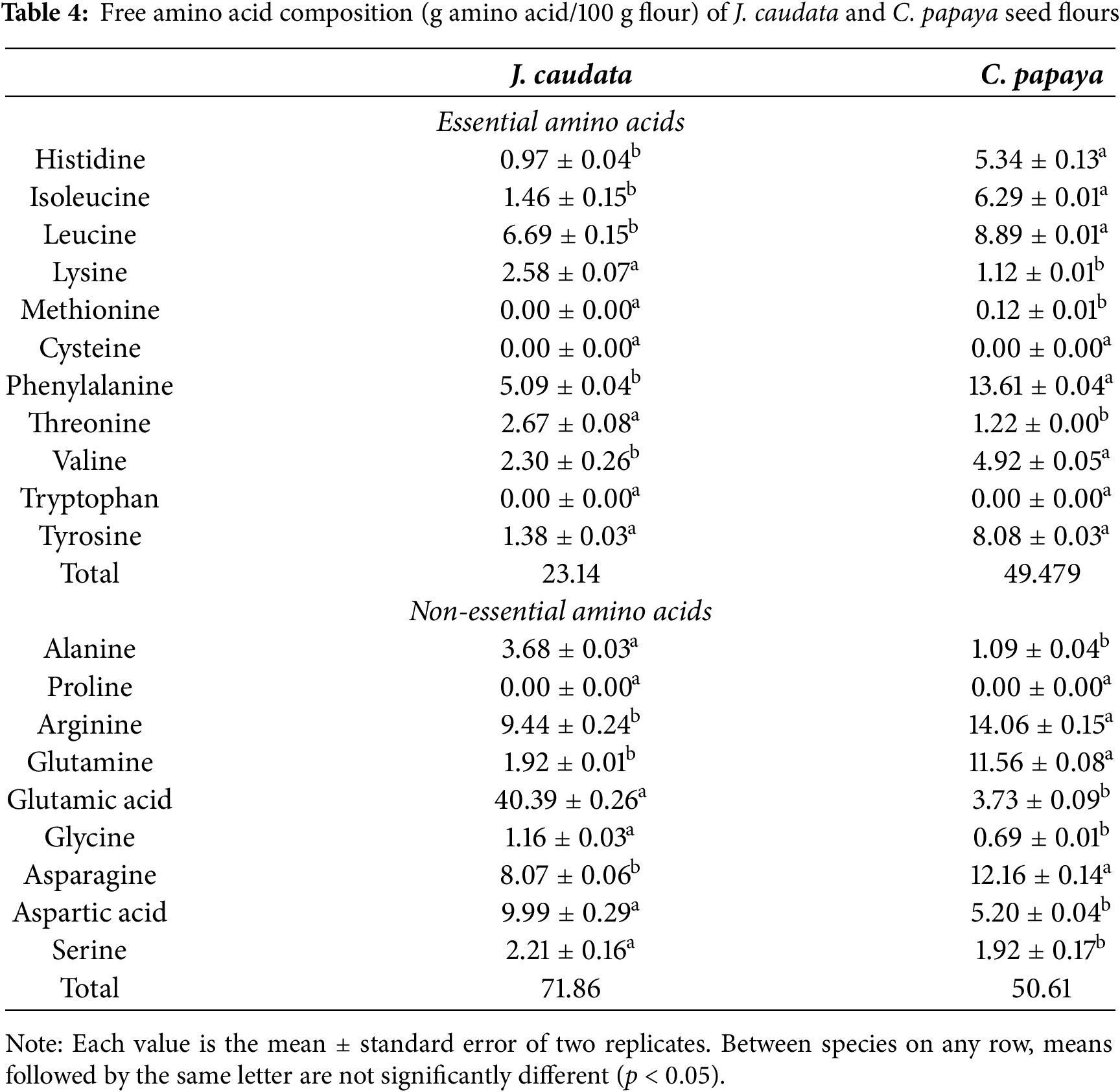

3.4 Free Amino Acid Composition

Free amino acid composition of J. caudata and C. papaya seed flour is shown in Table 4. The essential free amino acid content of J. caudata seeds was 23.14/100 g, while in C. papaya seeds was 49.47/100 g. The nonessential amino acid contents of J. caudata seeds and C. papaya seeds were 73.24/100 g and 58.69/100 g, respectively.

All essential amino acids except leucine and threonine were present at significantly higher levels in C. papaya than in J. caudata seeds. Methionine and tryptophan were not detected in J. caudata seeds. Methionine was found in low quantities (0.12/100 g) and tryptophan was not detected in C. papaya seeds. Among non essential amino acids, alanine, aspartic acid, and serine contents were higher in J. caudata than in C. papaya seeds. The opposite was observed with tyrosine, arginine, glutamine, asparagine, and valine contents, which were higher in C. papaya than in J. caudata seeds. Glutamic acid, glycine, proline, and tryptophan were not detected in either of the two seed samples.

3.5 Antioxidant Activity of J. caudata Seed Polyphenols

The reducing power of J. caudata and C. papaya seed polyphenols at increasing concentrations is shown in Fig. 1. Both extracts showed increasing reducing activity with the increment in concentration from 0 to 1.5 μg/well. The reducing power of the two polyphenol extracts was similar, and was significantly higher only for J. caudata polyphenols at 0.5 μg/well.

Figure 1: Reducing power of J. caudata (green bars) and C. papaya (yellow bars) seed polyphenol extracts. Results are the mean ± standard deviation of three determinations. *Significant difference in activity between J. caudata and C. papaya at the same extract concentration (p < 0.05)

J. caudata fruit seeds show good nutritional properties, with high contents of macronutrients such as proteins and lipids. Hence, J. caudata seeds showed protein contents similar to protein-rich seeds such as legumes [22]. J. caudata seeds also contain more protein than do seeds of other consumed wild species, such as Okenia hypogaea (Nyctaginaceae), Opuntia joconostle (Cactaceae), and Ditaxis heterantha (Euphorbiaceae). Their lipid contents were also high although lower than the reported for seeds of Mexican plants such as Jatropha curcas (Euphorbiaceae) and Ricinus communis (Euphorbiaceae) [23–26]. It also showed higher protein contents than seeds of other plant species used as food [27,28]. Protein, lipid, and carbohydrate contents were similar to those of C. papaya seeds [29]. Hence, J. caudata seeds are highly nutritious, with protein and oil contents similar to those reported for oilseeds such as rapeseed and sunflower seeds [30,31]. As has been reported for C. papaya seed proteins, J. caudata seed proteins could be exploited as an alternative feed ingredient for poultry and might become a source of proteins and lipids for human nutrition [32]. J. caudata seeds are low in sugars in comparison with other seeds. Hence, from the perspective of consumers, they could also be suitable for people with special needs, such as diabetics, and on special diets [33]. It is known that high levels of sugar in seeds not only provide calories as energy to the human body but can also improve cooking quality [34]. Phytic acid contents were slightly higher in C. papaya than in J. caudata seeds (3.25% and 2.93%, respectively). These values are higher than the reported for other seeds of wild and cultivated species (from 0.87% to 1.70%). Phytic acid is often considered an antinutritional compound because it can bind minerals and proteins, thus decreasing their bioavailability. However, its chelating property may also be positive as an antioxidant and an anticancer agent [35]. The pectin content in C. papaya seeds was slightly higher than in J. caudata seeds (1.20% vs. 0.97%, respectively). A value of 2.05% pectin in C. papaya grown in India has been reported [36]. Polyphenol contents were low in comparison with those from seeds of different C. papaya varieties (0.12/100 to 1.43/100 g) [37].

Macro and micro minerals are of great importance in the human diet, although they comprise only 4.6% of human body weight [38]. The mineral composition of fruit pulp has been reported for several species, but there are few studies on seeds mineral contents. Regarding the Caricaceae family, the mineral composition of the fruit of Jacaratia spinosa, J. caudata, Vasconcellea quercifolia, and C. papaya have been reported [10,39,40]. However, studies on seeds are limited to C. papaya and have been designed to understand their potential as a functional feedstuff and some of their functional properties [32]. The macro and micromineral composition of J. caudata and C. papaya seeds were similar except for potassium, calcium, and zinc. Potassium, phosphorus, and calcium contents were higher than those of other oilseeds such as peanuts, almonds, corn, and sunflower [2]. However, studies to determine the bioavailability of these minerals in J. caudata seeds are needed.

Lipids are among the most important nutrients for humans. As with most plant seed oils [41], J. caudata and C. papaya seed oil showed a predominance of unsaturated fatty acids, with oleic acid being the main one. Thus, the fatty acid profile observed in J. caudata seed oil is similar to that reported for edible oils such as canola, sunflower, and olive in terms of the high percentage of unsaturated fatty acids. In addition, the oleic acid content was very high in both species, and similar to that reported for olive oil, the edible oil with the highest oleic acid percentages [42]. Other fatty acids in high amounts in the seeds of J. caudata were linoleic and palmitic acids. The contents of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids were similar for J. caudata and C. papaya seeds. The main difference between both species was observed in the content of linoleic acid, which was higher in J. caudata seed oil, resulting in a higher polyunsaturated/saturated fatty acid ratio in J. caudata seed oil. In C. papaya, the second most abundant fatty acid was palmitic acid, as has been reported elsewhere [43,44]. In related taxa such as Vasconcellea quercifolia, oleic acid was also the main fatty acid representing 58.2% of the total, and palmitic acid was also the second most abundant acid, as reported for C. papaya seed oil [39]. Atherogenic and thrombogenic indexes were similar for both species. These indexes were lower than those reported for animal fats and plant oils such as palm and coconut oil, and closer to plant oils such as olive oil [45]. Hence, from a nutritional point of view, the seeds of J. caudata may be an interesting source of good quality oil due to its high content of oleic acid and unsaturated fatty acids. Because of the similar fatty acid composition of J. caudata seed oil, it is also a potential biomass source for renewable energy production that could be used to diversify and promote the bioenergy sector [46].

Plants are a rich source of amino acids, and the abundance of individual amino acids in plants is of great importance, especially in terms of food. Free amino acids are important biologically active compounds. There is no report on the content of free amino acids in seeds of wild Caricaceae species, but our results indicate that the free amino acids profile of J. caudata seeds is similar to that of C. papaya seeds. A total of 16 free amino acids were detected in J. caudata seeds and 17 in C. papaya seeds. These data agree with those reported in the literature [36]. Individual free amino acid contents differed in their abundance among the seeds studied. For example, phenylalanine and leucine were the essential amino acids most abundant in both seeds (13.61 vs. 5.09 and 8.89 vs. 6.69 g/protein, respectively); although their contents were higher in C. papaya. All essential amino acids, except threonine and lysine, were more abundant in C. papaya seeds than in J. caudata seeds. Arginine and asparagine were the most abundant nonessential amino acids in C. papaya seeds, while glutamic acid, arginine, and aspartic acid were the most abundant in J. caudata seeds. This agrees with previous reports that the most abundant amino acids in plants are glutamic acid and aspartic acid [47]. Differences in the individual concentrations of free amino acids between J. caudata and C. papaya seeds may be due to the more limiting growing conditions of J. caudata in the wild where the soil fertility is low. In contrast, C. papaya, being a cultivated species, is cultivated in favorable growth conditions with water and nutrient supply. Hence, fertilizers play an important role in fruit quality, including sugar and amino acid content [48]. A study on pear trees reported that the concentrations of both essential and non-essential amino acids increased significantly when N supply increased [49].

Polyphenols are among secondary compounds observed in plant seeds. Polyphenols are considered bioactive compounds with health-promoting properties, being antioxidants and antiproliferatives. Our results here indicate that J. caudata and C. papaya seed extracts have moderate antioxidant effects compared with those of seed extracts from other wild species [50]. Although polyphenols with recognized antioxidant activity, such as p-hydroxybenzoic and vanillic acid have been reported in C. papaya seeds [51].

In conclusion, J. caudata fruit seeds constitute an interesting source of nutritional and functional compounds. The chemical composition of J. caudata seeds is similar to that of C. papaya seeds. The main compounds showed acceptable properties for their exploitation in human nutrition, the oil was very rich in unsaturated fatty acids. J. caudata and C. papaya polyphenols showed similar antioxidant activity. These results show that J. caudata seeds may be of interest for their application for food or feeding. This plant is consumed for its green fruit in salads. The mature fruit is also used to make juices and sweet beverages and the seeds are discarded. However, these seeds could be employed as a source of proteins and oils in human and animal nutrition. Further work to study the organoleptic properties and nutrient bioavailability of J. caudata seeds is needed.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financed with an I-COOP project (ref. COOPA 20469) funded by C.S.I.C. To National Council Humanities for Science and Technology (CONAHCYT, Mexico) by the postgraduate scholarship granted to Mario Felipe Gonzalez Gonzalez (No. 001073088).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Juan Francisco Zamora Natera and Mario Felipe González González; methodology, Manuel Alaiz; Validation, Javier Vioque and Julio Girón-Calle; formal analysis, Juan Francisco Zamora Natera and Mario Felipe González González; writing of the original draft preparation; Juan Francisco Zamora Natera and Javier Vioque; writing–review and editing, Manuel Alaiz and Julio Girón-Calle; supervicion, Juan Francisco Zamora Natera. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Juan Francisco Zamora Natera, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the present study.

References

1. Sahu PK, Cervera-Mata A, Chakradhari S, Singh Patel K, Towett EK, Quesada-Granados JJ, et al. Seeds as potential sources of phenolic compounds and minerals for the Indian population. Molecules. 2022;27(10):3184. doi:10.3390/molecules27103184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Musa Özcan M. Determination of the mineral compositions of some selected oil-bearing seeds and kernels using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES). Grasas Aceites. 2006;57(2):211–8. doi:10.3989/gya.2006.v57.i2.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Eromosele CO, Paschal NH. Characterization and viscosity parameters of seed oils from wild plants. Bioresour Technol. 2003;86(2):203–5. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00147-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Eromosele IC, Eromosele CO. Studies on the chemical composition and physico-chemical properties of seeds of some wild plants. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1993;43(3):251–8. doi:10.1007/BF01886227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Vadivel V, Janardhanan K. Nutritional and antinutritional characteristics of seven South Indian wild legumes. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2005;60(2):69–75. doi:10.1007/s11130-005-5102-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Chidewe CK, Chirukamare P, Nyanga LK, Zvidzai CJ, Chitindingu K. Phytochemical constituents and the effect of processing on antioxidant properties of seeds of an underutilized wild legume Bauhinia Petersiana. J Food Biochem. 2016;40(3):326–34. doi:10.1111/jfbc.12221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kanjana K, Krishnapriya K. Proximal and phytochemical analysis of wild jack fruit seeds (Artocarpus hirsutus Lam.anti-diabetic and anti-microbial properties and formulation of food products. J Res Siddha Med. 2019;2(2):88. doi:10.4103/2582-1954.327521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Alara OR, Abdurahman NH, Alara JA. Carica papaya: comprehensive overview of the nutritional values, phytochemicals and pharmacological activities. Adv Tradit Med. 2022;22(1):17–47. doi:10.1007/s13596-020-00481-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Carvalho FA, Renner SS. A dated phylogeny of the Papaya family (Caricaceae) reveals the crop’s closest relatives and the family’s biogeographic history. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;65(1):46–53. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.05.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. González González MF, Zamora Natera JF, Vioque Peña J, Zañudo Hernández J, Ruiz López MA, Ramírez López CB. Caracterización químico nutricional y análisis fitoquímico de frutos de Jarilla caudata (Caricaceae) de Jalisco, México. Acta Bot Mex. 2022;(129):e2100. doi:10.21829/abm129.2022.2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yanty NAM, Marikkar JMN, Nusantoro BP, Long K, Ghazali HM. Physico-chemical characteristics of Papaya (Carica papaya L.) seed oil of the Hong Kong/Sekaki variety. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63(9):885–92. doi:10.5650/jos.ess13221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Marfo EK, Oke OL, Afolabi OA. Chemical composition of Papaya (Carica papaya) seeds. Food Chem. 1986;22(4):259–66. doi:10.1016/0308-8146(86)90084-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. AOAC. Official methods of analysis. 17th ed. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: The association of official analytical chemists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

14. FAO. Food energy-methods of analysis and conversion factors [Report]. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2003. [Google Scholar]

15. DuBois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28(3):350–6. doi:10.1021/ac60111a017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gao Y, Shang C, Saghai Maroof MA, Biyashev RM, Grabau EA, Kwanyuen P, et al. A modified colorimetric method for phytic acid analysis in soybean. Crop Sci. 2007;47(5):1797–803. doi:10.2135/cropsci2007.03.0122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Blumenkrantz N, Asboe-Hansen G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal Biochem. 1973;54(2):484–9. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(73)90377-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventós RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Meth Enzymol. 1999;299(10):152–78. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Martín MJ, Pablos F, González AG, Valdenebro MS, León-Camacho M. Fatty acid profiles as discriminant parameters for coffee varieties differentiation. Talanta. 2001;54(2):291–7. doi:10.1016/S0039-9140(00)00647-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Alaiz M, Navarro JL, Girón J, Vioque E. Amino acid analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography after derivatization with diethyl ethoxymethylenemalonate. J Chromatogr. 1992;591(1–2):181–6. doi:10.1016/0021-9673(92)80236-N. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Oyaizu M. Studies of products of browning reaction: antioxidative activity of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr Diet. 1986;44(6):307–15. doi:10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Elamine Y, Alaiz M, Girón-Calle J, Guiné RPF, Vioque J. Nutritional characteristics of the seed protein in 23 Mediterranean legumes. Agronomy. 2022;12(2):400. doi:10.3390/agronomy12020400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bello-Pérez LA, Solorza-Feria J, Arenas-Ocampo ML, Jiménez-Aparicio A, Velázquez del Valle M. Composición química de la semilla de okenia hypogaea (Schl. & cham). Agrociencia. 2001;35:459–68. (In Spain). [Google Scholar]

24. Méndez-Robles MD, Flores-Chavira C, Jaramillo-Flores ME, Orozco-Ávila I, Lugo-Cervantes E. Chemical composition and current distribution of “Azafr’an de Bolita” (Ditaxis Heterantha Zucc; Euphorbiaceaea food pigment producing plant. Econ Bot. 2004;58(4):530–5. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2004)058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Morales P, Ramírez-Moreno E, de Cortes Sanchez-Mata M, Carvalho AM, Ferreira ICFR. Nutritional and antioxidant properties of pulp and seeds of two xoconostle cultivars (Opuntia joconostle F.A.C. Weber ex Diguet and Opuntia matudae Scheinvar) of high consumption in Mexico. Food Res Int. 2012;46(1):279–85. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2011.12.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Vasco-Leal JF, Hernández-Rios I, Méndez-Gallegos SDJ, Ventura-Ramos EJr, Cuellar-Núñez ML, Mosquera-Artamonov JD. Relation between the chemical composition of the seed and oil quality of twelve accessions of Ricinus communis L. Rev Mex De Cienc Agrícolas. 2017;8(6):1343–56. [Google Scholar]

27. Kibar B, Kibar H. Determination of the nutritional and seed properties of some wild edible plants consumed as vegetable in the Middle Black Sea Region of Turkey. S Afr N J Bot. 2017;108:117–25. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2016.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Adesuyi AO, Ipinmoroti KO. The nutritional and functional properties of the seed flour of three varieties of Carica papaya. Curr Res Chem. 2010;3(1):70–5. doi:10.3923/crc.2011.70.75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Moses MO, Olanrewaju MJ. Proximate and selected mineral composition of ripe pawpaw (Carica papaya) seeds and skin. J Sci Innov Res. 2018;7(3):75–7. doi:10.31254/jsir.2018.7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gonçalves N, Vioque J, Clemente A, Sánchez Vioque R, Bautista-Gallego J, Millán F. Obtención y caracterización de aislados proteicos de colza. Grasas y Aceites. 1997;48:282–9. (In Spain). doi:10.3989/gya.1997.v48.i5.804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Villanueva A, Clemente A, Bautista J, Millán F. Production of an extensive sunflower protein hydrolysate by sequential hydrolysis with endo- and exo-proteases. Grasas Aceites. 1999;50(6):472–6. doi:10.3989/gya.1999.v50.i6.697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sugiharto S. Papaya (Carica papaya L.) seed as a potent functional feedstuff for poultry—a review. Vet World. 2020;13(8):1613–9. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2020.1613-1619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Weng Y, Ravelombola WS, Yang W, Qin J, Zhou W, Wang YJ, et al. Screening of seed soluble sugar content in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) walp). Am J Plant Sci. 2018;9(7):1455–66. doi:10.4236/ajps.2018.97106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kazankaya A, Balta MF, Yörük IH, Balta F, Battal P. Analysis of sugar composition in nut crops. Asian J Chem. 2008;20(2):1519–25. [Google Scholar]

35. Kumar A, Dash GK, Sahoo SK, Lal MK, Sahoo U, Sah RP, et al. Phytic acid: a reservoir of phosphorus in seeds plays a dynamic role in plant and animal metabolism. Phytochem Rev. 2023;22(5):1281–304. doi:10.1007/s11101-023-09868-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Begum M, Anil B. Estimation of polyphenol and antioxidant content from Papaya (Carica papaya) and mango (Mangifera indica) seed, peel and leaves. Int J Curr Sci Res Rev. 2024;7(8):6460–5. doi:10.47191/ijcsrr/v7-i8-58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Winarti W, Yudiarti T, Widiastuti E, Wahuni H, Sartoro TA, Sugiharto S. Nutritional value and antioxidant activity of sprouts from seeds of Carica papaya—their benefits for broiler nutrition. Bulg J Agri Sci. 2024;30(1):107–14. [Google Scholar]

38. Magaia T, Uamusse A, Sjöholm I, Skog K. Dietary fiber, organic acids and minerals in selected wild edible fruits of Mozambique. SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1):88. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. de Fátima Ferreira da Silva L, Rodrigues KF, Ethur EM, Hoehne L, de Souza CFV, Bonemann DH, et al. Nutritional potential of Vasconcellea quercifolia A. St.-Hil. green fruit flour. Braz J Food Technol. 2022;25(11):e2021080. doi:10.1590/1981-6723.08021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Prospero ETP, da Silva PPM, Spoto MHF. Caracterização físico-química, nutricional e de compostos voláteis de frutos de Jacaratia spinosa provenientes de três regiões do estado de são Paulo-Brasil. Rev Bras De Tecnologia Agroindustrial. 2016;10(1):2095–111. doi:10.3895/rbta.v10n1.2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kostik V, Memeti S, Bauer B. Fatty acid composition of edible oils and fats. J Hyg Eng Des. 2013;4:112–6. [Google Scholar]

42. Di Serio MG, Di Giacinto L, Di Loreto G, Giansante L, Pellegrino M, Vito R, et al. Chemical and sensory characteristics of Italian virgin olive oils from Grossa di Gerace cv. Euro J Lipid Sci Tech. 2016;118(2):288–98. doi:10.1002/ejlt.201400622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Malacrida CR, Kimura M, Jorge N. Characterization of a high oleic oil extracted from Papaya (Carica papaya L.) seeds. Ciênc Tecnol Aliment. 2011;31(4):929–34. doi:10.1590/s0101-20612011000400016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Senrayan J, Venkatachalam S. Solvent-assisted extraction of oil from Papaya (Carica papaya L.) seeds: evaluation of its physiochemical properties and fatty-acid composition. Sep Sci Technol. 2018;53(17):2852–9. doi:10.1080/01496395.2018.1480632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ulbricht TLV, Southgate DAT. Coronary heart disease: seven dietary factors. Lancet. 1991;338(8773):985–92. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)91846-M. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Tagarda EBP, Deloso LE, Oclarit LJZ, Lungay GS, Mabayo VIF, Arazo RO. Utilizing Carica papaya seeds as a promising source for bio-oil production: optimization and characterization. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(20):25093–102. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04471-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kumar V, Sharma A, Kaur R, Thukral AK, Bhardwaj R, Ahmad P. Differential distribution of amino acids in plants. Amino Acids. 2017;49(5):821–69. doi:10.1007/s00726-017-2401-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kim YX, Son SY, Lee S, Lee Y, Sung J, Lee CH. Effects of limited water supply on metabolite composition in tomato fruits (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in two soils with different nutrient conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:983725. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.983725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Qin Z, Ge Y, Jia W, Zhang L, Feng M, Huang X, et al. Nitrogen fertilization enhances growth and development of Cacopsylla chinensis by modifying production of ferulic acid and amino acids in pears. J Pest Sci. 2024;97(3):1417–31. doi:10.1007/s10340-023-01708-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Soong YY, Barlow PJ. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of selected fruit seeds. Food Chem. 2004;88(3):411–7. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhou K, Wang H, Mei W, Li X, Luo Y, Dai H. Antioxidant activity of Papaya seed extracts. Molecules. 2011;16(8):6179–92. doi:10.3390/molecules16086179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools