Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Differential Gene Expression and Metabolic Changes in Soybean Leaves Triggered by Caterpillar Chewing Sound Signals

1 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), BIOAGRO/INCT-IPP, Viçosa, 36570-900, MG, Brazil

2 Department of General Biology, Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), Viçosa, 36570-900, MG, Brazil

3 Center for Biomolecules Analysis, NuBioMol, Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), Viçosa, 36570-900, MG, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Humberto Josué de Oliveira Ramos. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant and Environments)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1787-1810. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064068

Received 04 February 2025; Accepted 19 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

Sound contains mechanical signals that can promote physiological and biochemical changes in plants. Insects produce different sounds in the environment, which may be relevant to plant behavior. Thus, we evaluated whether signaling cascades are regulated differently by ecological sounds and whether they trigger molecular responses following those produced by herbivorous insects. Soybean plants were treated with two different sounds: chewing herbivore and forest ambient. The responses were markedly distinct, indicating that sound signals may also trigger specific cascades. Enzymes involved in oxidative metabolism were responsive to both sounds, while salicylic acid (SA) was responsive only to the chewing sound. In contrast, lipoxygenase (LOX) activity and jasmonic acid (JA) did not change. Soybean Kunitz trypsin inhibitor gene (SKTI) and Bowman-Birk (BBI) genes, encoding for protease inhibitors, were induced by chewing sound. Chewing sound-induced high expression of the pathogenesis-related protein (PR1) gene, confirming the activation of SA-dependent cascades. In contrast, the sound treatments promoted modifications in different branches of the phenylpropanoid pathway, highlighting a tendency for increased flavonols for plants under chewing sounds. Accordingly, chewing sounds induced pathogenesis-related protein (PR10/Bet v-1) and gmFLS1 flavonol synthase (FLS1) genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis and flavonols. Finally, our results propose that plants may recognize herbivores by their chewing sound and that different ecological sounds can trigger distinct signaling cascades.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCommunication is a ubiquitous natural phenomenon characteristic of all living organisms. The ecosystems have several forms of communication, which convey important information for the adaptation and evolution of species [1]. Sound vibrations (SVs) are wave phenomena of mechanical origin, one of nature’s sources of communication. They are used by various organisms to alert a danger, to allow a relationship between organisms from the same or different species, and to help establish the complex network of interaction between the individual and the environment [2,3].

In nature, the niches occupied by plants are not free from sounds and other vibrational signals of mechanical origin. These environments evolved with sound vibrations encompassing a spectrum of frequencies and amplitudes from different physical and biological sources. Sounds are acoustic energies acting as pressure waves that propagate through gas, liquids, and solids. Thus, plants likely present biological mechanisms adapted to the perception of sound vibrations within a spectrum of frequencies and amplitudes to facilitate understanding the numerous signs of ecological relevance [3,4].

Several studies with the application of sounds in plants have shown that can affect plant development and growth. Different sounds are activated to activate calcium- and reactive oxygen species-dependent signal transduction cascades [5], alter the secondary structure of membrane proteins, and increase the fluidity of the physical state of membranes [4–6]. Alteration in the expression gene [7,8] and an increase in the levels of amino acids and soluble sugars and polyamines [7,9,10] were also reported. Therefore, it is likely that sound vibration can serve as a long-range stimulus that triggers molecular signaling mechanisms, promoting alterations in the cellular metabolic flow and affecting the plant-environment interactions [4,11,12]. However, the molecular mechanisms involved in sound perception, processing, and its ecological importance for the environment-plant interactions remain inconclusive due to the difficulties in mapping the perception and signal transduction pathways.

Although plants do not have an organ specialized in perceiving sound vibrations, sophisticated molecular mechanisms can be responsible for this phenomenon. Ghosh and Mishra, investigating transcriptional alterations in Arabidopsis thaliana treated with sound and touch, observed that both mechanical stimuli induce the expression of ion channel genes [5,8,13]. However, differences in gene expression profiles between mechanical stimuli were enough to show that the processing of these signals occurs by different biological mechanisms. These observations have indicated that the mechanism of sound vibration perception in plants may involve mechanosensitive proteins and ion channel-forming proteins [4,8,13].

Research on plant bioacoustics does not necessarily seek to answer whether plants are sensitive to acoustic vibrations or not. Applied efforts mainly aim to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in perception and to verify the ability of plants to differentiate the sounds present in nature (sounds of ecological relevance) [11,14,15]. In a study investigating whether plants can recognize herbivore-feeding sounds Appel and Cocroft reported that vibrations caused by insect feeding can trigger chemical defenses [16]. Another study showed that bee hums also induced the opening of anthers for pollen release only at a particular acoustic frequency produced by the pollinator bee [17]. These results demonstrate the importance of sound perception as an adaptive and evolutionary tool and plant capability to differentiate and elaborate specific metabolic responses toward each type of sound of ecological relevance.

Although several studies indicated plant responses to treatment with sound waves, little is known about the molecular mechanisms involved in signaling and metabolic adjustment. Due to this gap in knowledge of how plants process environmental sound signals, this study aimed to investigate metabolic changes in soybean plants treated with different environmental sounds.

We also determine whether the molecular and biochemical responses are specific and follow the information from the acoustic waves. First, we verified the similarities and differences in the metabolic and molecular responses between plants treated with chewing sound and forest. We then investigated whether the responses found in the chewing sound resembled the response observed for the caterpillar attack. Soybean plants were treated with two ecological sounds: herbivore chewing and forest sound. Key enzymatic activities, gene expression, and metabolites, including hormones, amino acids, polyamines, and flavonoids, were evaluated. Finally, the metabolic and molecular profiles generated from the chewing and forest sound treatments were compared with those commonly observed during the caterpillar attack.

Glycine max (Embrapa 48) seeds were supplied by the Plant Molecular Biology Laboratory from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of the Federal University of Viçosa/UFV, Brazil. Seeds were germinated in 40 polyethylene pots (3.5 L) containing a mixture of substrates for growing seedlings (Tropstrato) and latosol soil in a 2:1 ratio. After germination, we kept three seedlings per pot. Plants were kept in greenhouse conditions for 45 days (V7) before starting the sound treatments in the acoustic treatment boxes.

The forest sound was recorded in “Mata da Biologia” on a spring morning. Mata da Biologia is located within the Federal University of Viçosa—UFV, in Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. A digital file containing chewing sounds was downloaded from https://www.zapsplat.com/page (accessed on 18 May 2025). These sounds contain the frequencies of a non-specific soybean caterpillar chewing a plant leaf. The downloaded audio file was edited, mixed, and mastered using the package Reaper. The sounds were reproduced in the acoustic treatment boxes at an intensity (volume) of 70 decibels (dB). To evaluate whether there was differentiation in the biochemical response of the plants to treatments with two different types of ecological sounds (distinct spectra of sound frequencies, see Fig. S1), sound intensity (dB) was standardized to 70 dB. The intensity of 70 dB was chosen because it represents the average value of the ambient sound of the forest where the audio was recorded. The chewing sound was played as well at 70 dB to prevent the measured response from being a consequence of the difference between the intensities of the two ecological sounds.

Chewing and forest sounds exhibit distinct acoustic properties regarding their origin and specific parameters (Fig. S1B). Chewing sounds are characterized by frequency ranges concentrated in the mid to high frequencies, roughly from 1 to 5 kHz. Transient impulses during chewing present distinct peaks within a limited frequency band, indicating short bursts or impulses. The temporal dynamics show that the sound is intermittent, with pauses between each chewing event. The spectral content reveals that energy is less spread out over time.

In contrast, forest sounds typically cover a broader range, from low frequencies (e.g., wind, distant water flows) below 500 Hz to high frequencies (e.g., bird calls, insect chirps) extending up to 10–12 kHz or even higher. Various sound sources contribute to different frequency bands, creating a complex, layered acoustic environment. Unlike the discrete transients in chewing sounds, the waveform of forest sounds is more continuous, with overlapping, irregular fluctuations in amplitude. The signal does not have clearly defined onsets or decay times, as many sounds blend into one another. In the forest sound profile, there is continuous variation in sound intensity, reflecting the dynamic and ever-changing natural environment. A spectrogram of forest sounds would typically reveal a rich tapestry of frequencies, with different elements (such as rustling leaves, distant animal calls, and ambient wind noise) appearing and fading at different times.

The sound treatments were conducted in specially designed acoustic chambers equipped with integrated sound and lighting systems to reproduce ecological sounds (Fig. S1). The chambers were constructed from 10-mm thick plywood, with external dimensions of 62 × 62 × 86 cm (width × length × height) and internal dimensions of 45 × 45 × 76 cm. The interior was lined with fiberglass insulation (Fig. S1). LED lights and speakers were mounted on the wooden ceiling panel, with all connections sealed using acoustic rubber.

Two plant pods, each containing three plants, were placed inside the chambers and exposed to sound treatments for 48 h over three consecutive days (Fig. S2). Daily treatment consisted of a 6-h session divided into six cycles, each comprising 1 h of sound exposure followed by 15 min of rest. Sessions occurred between 8:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. Following each session, plants were removed from the chambers and maintained in the greenhouse under ambient sound conditions until the next treatment session (Fig. S2). The 15-min rest periods served to prevent CO2 accumulation and allowed rotation of biological replicates between chambers to avoid positional bias. Chambers remained hermetically sealed throughout to prevent external sound interference and internal sound leakage.

Plants were maintained in the acoustic chambers under standardized environmental conditions. This experimental design isolated sound as the sole variable of interest, controlling for potential confounding factors including ambient light, greenhouse noise, and air currents.

The acoustic chambers were installed adjacent to greenhouse benches (Fig. S1). The study employed a split-block design with five biological replicates per treatment: one experimental block for chewing sounds and another for forest sounds (Fig. S2). Five chambers were allocated for sound treatments and five for silent controls. Control plants were maintained in identical chambers with all conditions matched except for sound exposure.

The first experiment evaluated forest sounds with two treatment conditions (sound exposure vs. silent control) and two exposure durations (12 and 18 h). Five chambers served as biological replicates for sound treatments, with an additional five for silent controls. Each chamber contained two pots (three plants per pot)—one for 12-h exposure and another for 18-h exposure (Fig. S2).

The second experiment followed identical protocols but used chewing sounds and a separate plant cohort. Thus, two independent experiments were performed.

Both experiments included two sound treatments differentiated by exposure duration (12 vs. 18 h). These time points were selected based on preliminary studies testing shorter exposures (2 and 6 h), where intermediate durations (12–18 h) demonstrated the most biologically significant responses in herbivory-related defense pathways, as evidenced by gene expression and metabolite profiling.

2.4 RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

Pulverized leaves (50 mg) were processed to extract total RNA from the control and sound treatments with CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) reagent, following the protocol established by [18], with some modifications. RNA quality was examined in 1.0% (m v-1) denatured agarose gels stained with 0.1 μg/mL ethidium bromide (EtBr) and quantified using a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A total of 2 μg of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression levels were obtained using an ABI7500 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) and Fast Master SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The amplification reactions were carried out using the following parameters: 20 s at 95°C, 45 cycles at 95°C for 5 s; 30 s at 60°C and final denaturation at 95°C for 25 s, followed by a melting curve. Primers were designed using Primer-BLAST software, with a melt temperature (T) of 58°C to 62°C, a length of 18 to 28 bp, and an amplifier product size of 130 to 160 bp, for 40% to 60% GC content. Two technical replicates were performed for each one of the five biological replicates. Gene expression was quantified using the ΔCT method and the expression levels were calculated as 2−ΔCT [19]. Primers used for qRT-PCR are described in Table S1. The reference gene used for normalization was the UNK-2 [20].

2.5 Determination of Lipoxygenases, PPO and CAT Activity and Protease Inhibitors

For evaluation of the lipoxygenase (LOX), polyphenol oxidase (PPO), and catalase (CAT) activities, 100 mg soybean leaf powder was homogenized with 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1% polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in the ratio of 100 mg of leaf per 1 mL of buffer.

Linoleic acid was used as a substrate for the lipoxygenase (LOX) activity was monitored at 234 nm [21]. Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity was obtained by measuring the increased absorbance rate at 420 nm when 20 μL of leaf extract was mixed with 60 μL of substrate buffer (100 mM Potassium Phosphate Buffer and catechol, pH 7). Catalase (CAT) activity was assayed by measuring the rate of decrease in absorbance at 240 nm in the presence of 60 μL of substrate buffer (100 mM Potassium Phosphate Buffer and 12.5 mM hydrogen peroxide, pH 7) [22].

The protease inhibitors were determined by measuring the inhibition of purified trypsin with 120 mg soybean leaf powder using 1.2 mM L-BApNA as substrate. Two controls were used to determine the total inhibitor activity: trypsin control (20 μL of trypsin 4.7 × 10−5 M, 90 μL of the substrate, and 100 μL of extraction buffer) and the substrate control (90 μL of the substrate and 120 μL of extraction buffer). Samples with 10 μL of trypsin, 10 μL of plant extract, and 100 μL of extraction buffer were incubated at ambient temperature for 5 min. Then, 90 μL of the substrate was added, and the change in absorbance (Absf-Absi) at 410 nm was measured after 3 min (one absorbance collection point every 20 s).

2.6 Phytohormone and Metabolite Profiling Analysis by LC/MS

Phytohormones and metabolites extractions were performed from soybean leaves as described by Lima and Coutinho with some modifications [23,24].

Aliquots of 180 mg fresh weight were extracted using 500 μL of extraction solution (methanol, isopropanol, and acetic acid 20:79:1 (v/v/v)). About 500 μL of the extracts were placed in vials, and 5.0 μL were injected into the LC/MS system, using a column Eclipse Plus, RRHD, 1.8 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with the continuous flow (Φ = 0.3 mL/min) and coupled to a mass spectrometer QqQ triple quadrupole (Agilent) from NuBioMol (Center for Biomolecules Analysis/UFV, Viçosa, Brazil).

LC/MS profiles were obtained in alternating negative/positive modes according to each metabolite by MRM method (multiple reaction monitoring) for detecting some phytohormones and target metabolites (Tables S2–S4). Metabolic profiles were obtained from five biological replicates for each treatment. The mass spectra were processed using the Skyline software according to the methods described by [24]. The XIC area values by MRM were used to determine the relative abundance of the phytohormones in the Metaboanalyst platform (Tables S5 and S6).

2.7 Bioinformatic Analysis: Characterization of Sound Response

As two experiments were carried out independently, one for the chewing sounds and the other for the forest sounds, the results of each experiment were analyzed separately. Thus, a statistical contrast was not performed between the forest and chewing sound data. The comparison occurred only within each type of sound, between soundless control and sound treatment. However, the statistical significance for the metabolite profiles was used to compare the response to the chewing sound and the forest sound.

Metabo Analyst was used to perform the following statistical analyses of the metabolomics data: heatmap, random forest, test t (α < 0.05) and pathway analysis. The data were normalized according to their type of distribution (normalization by the sum of the peaks or median). Moreover, the data were transformed using the Pareto scaling method. The Pathway analysis combines a robust enrichment analysis with pathway topology analysis, aiming to identify the most relevant pathways. This approach usually refers to quantitative enrichment analysis directly using the compound concentration values, comparing with compound lists used by over-representation analysis. Thus, the main pathways affected by the sound treatment were classified for mapping the phenolic compounds and flavonoids.

Thus, it is more sensitive and has the potential to identify changes in compounds involved in the same biological pathway [25,26]. The pathway topology analysis uses two well-established node centrality measures to estimate node importance—degree centrality and betweenness centrality. The node importance measure selected for topological analysis was the betweenness centrality. The betweenness centrality measures the number of shortest paths going through the node. The degree centrality measure focuses more on local connectivity, while the betweenness centrality measure focuses more on global network topology [27].

The JMP Statistical Discovery software was used to analyze the expression gene and enzyme activity data. Student t-test (normal distribution and homogeneous variance) and Welch t-test (normal distribution and heterogeneous variance) were performed to identify the significant variables (α < 0.05) of each sound treatment.

3.1 Soybean Plants under Different Ecological Sound Signals Showed Distinct Phytohormonal Profiles

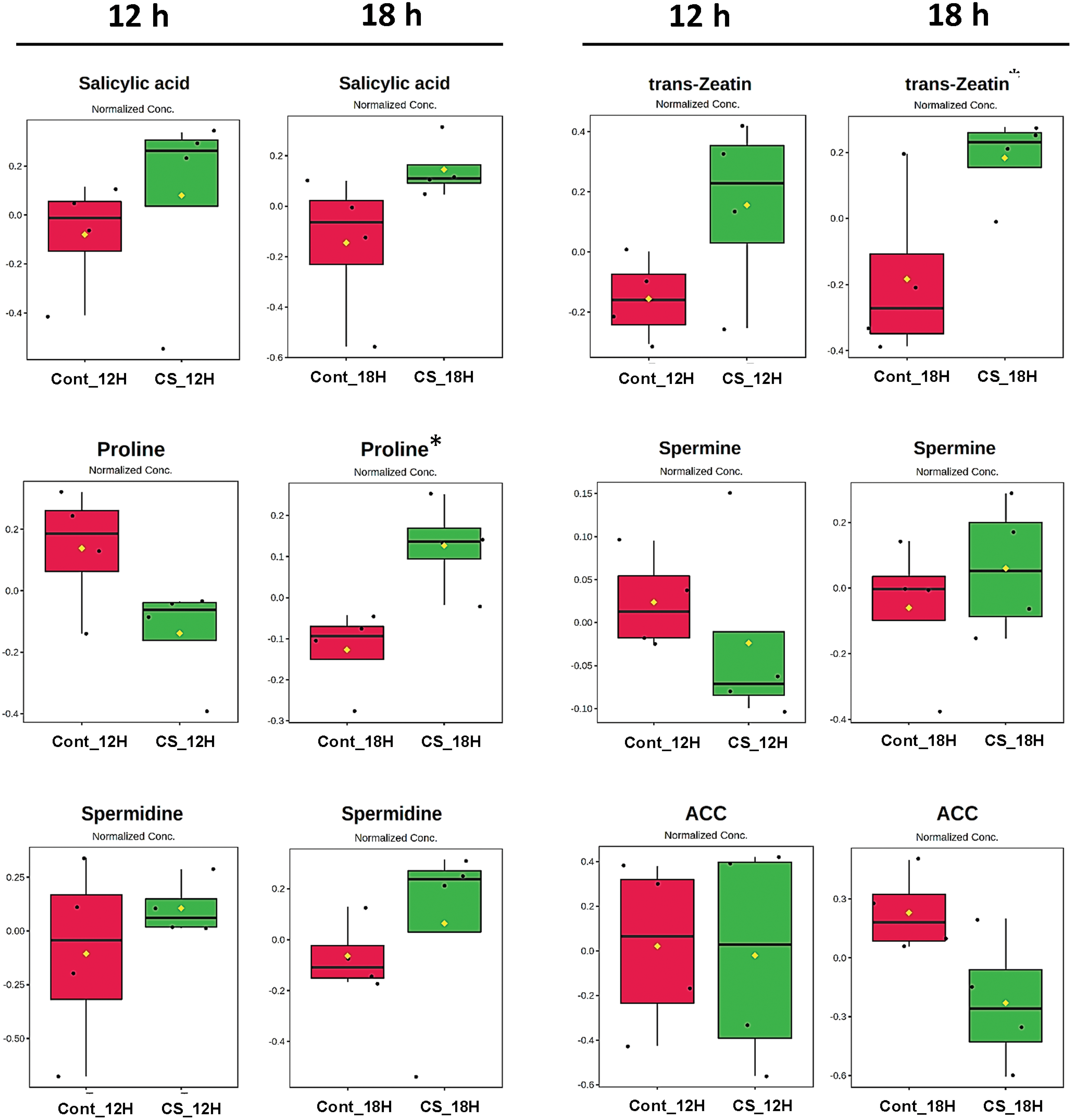

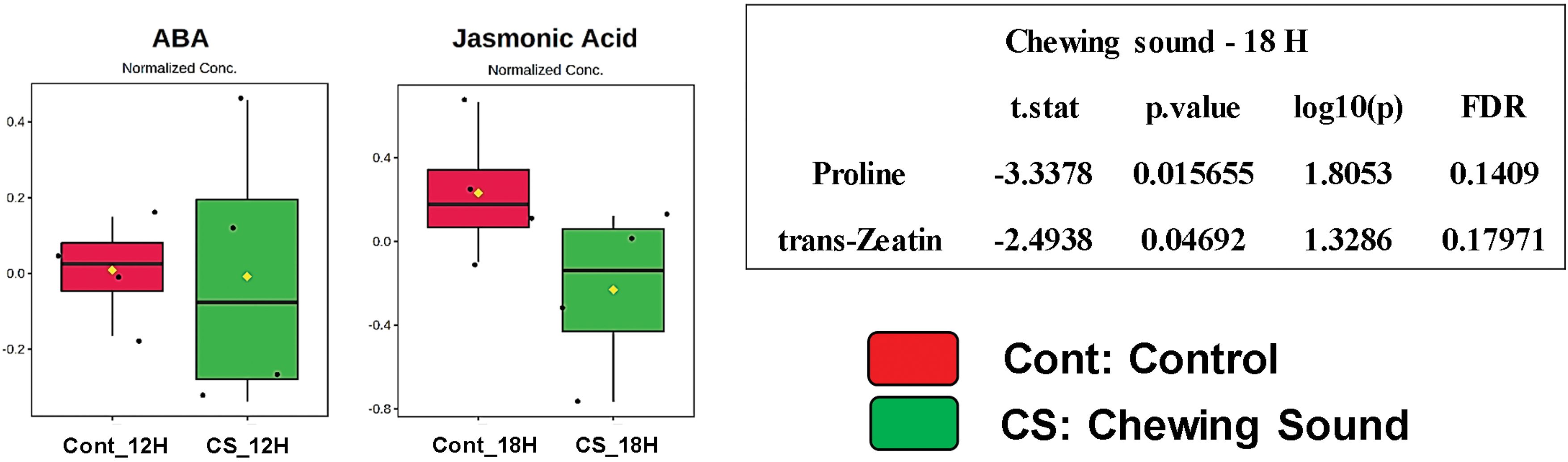

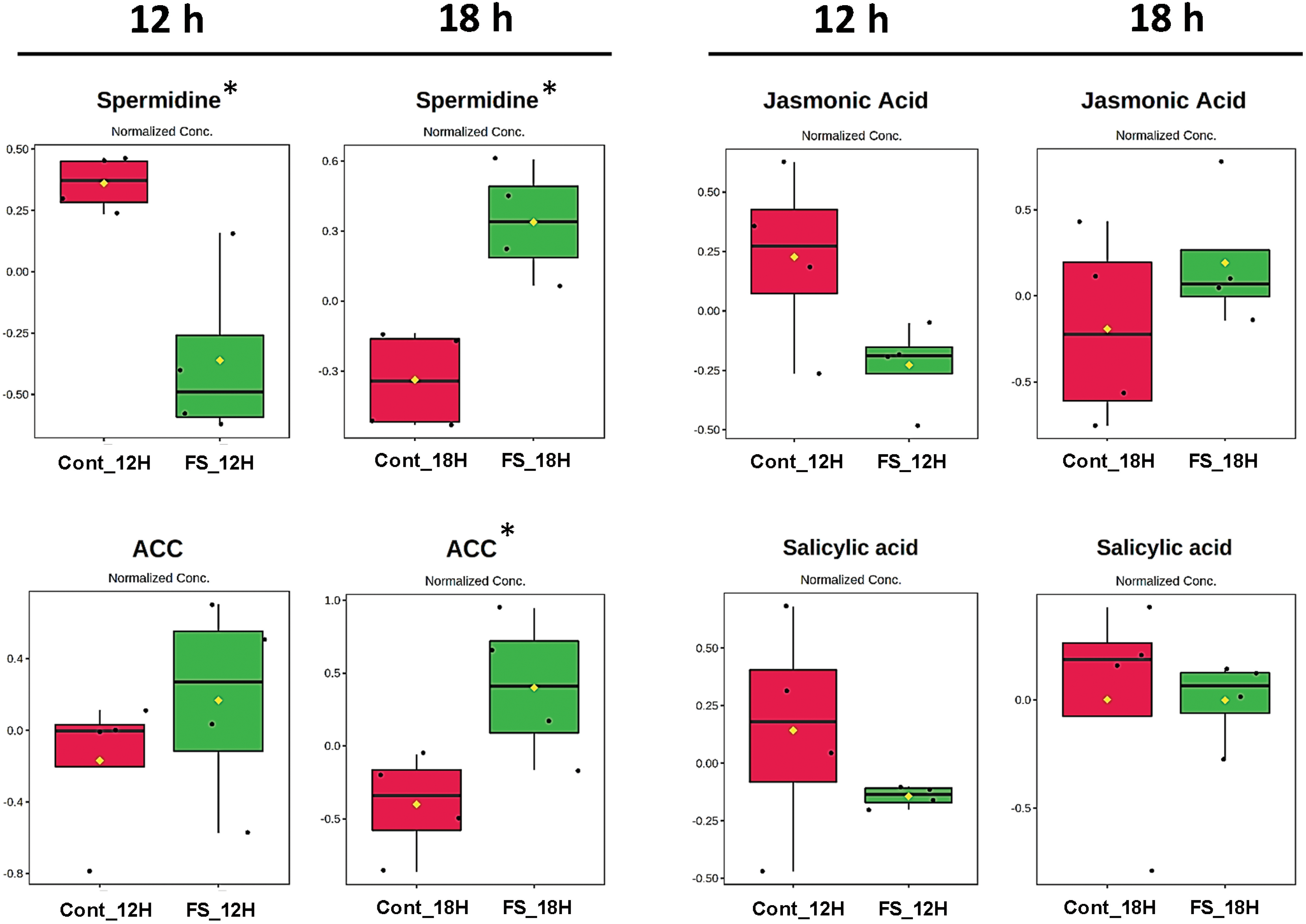

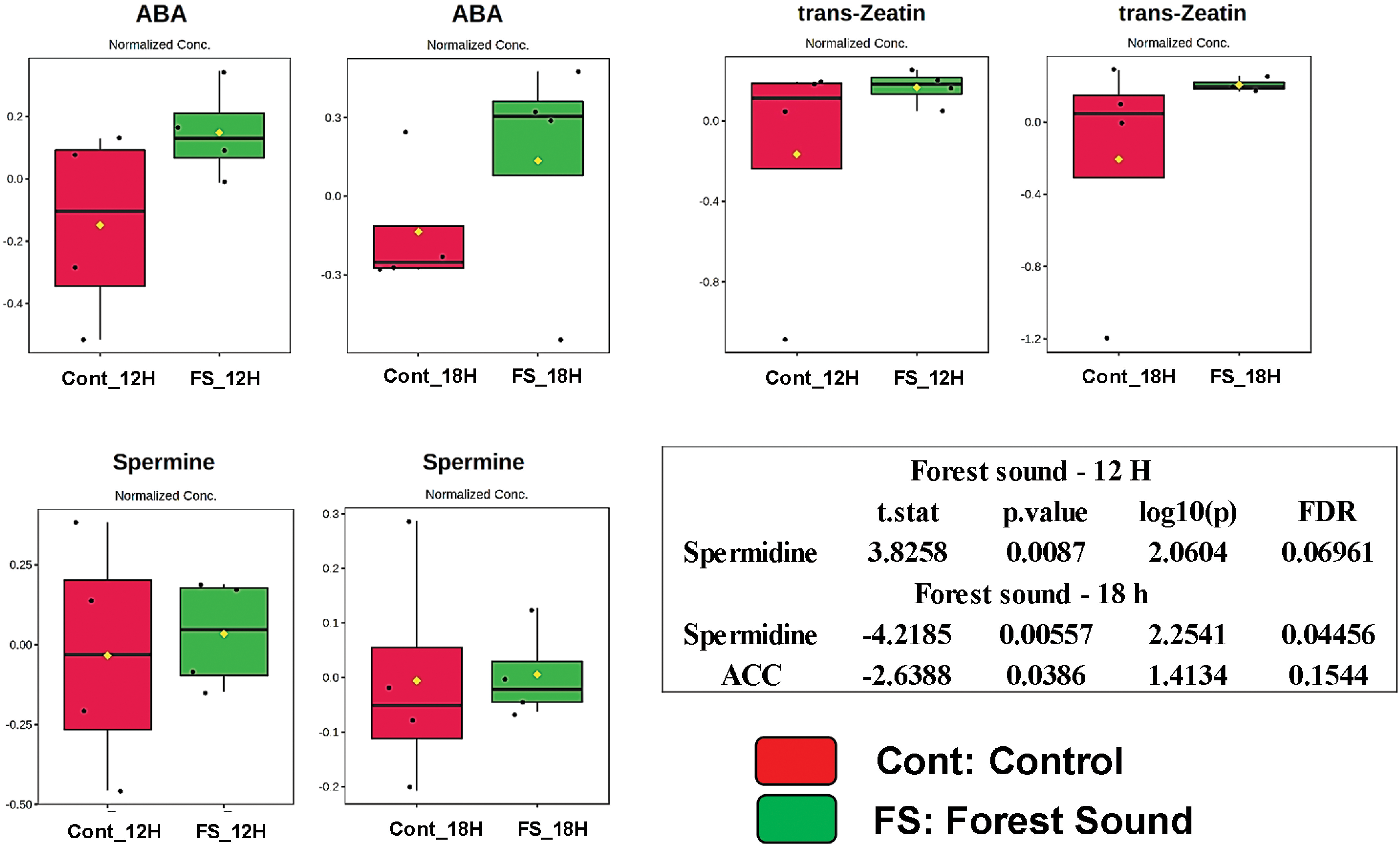

Plant responses against herbivorous insects involve the biosynthesis of chemical defenses and protease inhibitors (PIs) which depend on signal perception and phytohormone biosynthesis [28–30]. Thus, phytohormone and stress-responsive metabolite concentrations were evaluated by LC/MS QqQ (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Box plots showing normalized relative concentrations of the phytohormones, polyamines and proline from soybean leaves by LC/MS after 12 and 18 h under chewing sound treatments. Cont_12H and Cont_18H indicate plants in the absence of sound treatment. CS_12H and CS_18H indicate plants in the presence of chewing sound. t. stat: Negative values indicate greater relative abundance for the Sound Treatment and positive values greater abundance for the Soundless Control. The higher the |t. stat|, the greater the variable significance. p-value: Important features selected by t-tests with a threshold of 0.05. Note the p-values are transformed by −log10 so that the more significant features (with smaller p-values) will be plotted higher on the graph. FDR: False Discovery Rate. *Significant features (α < 0.05)

Figure 2: Box plots showing normalized relative concentrations of the phytohormones, polyamines and proline from soybean leaves by LC/MS after 12 and 18 h under forest sound treatments. Cont_12H and Cont_18H indicate plants in the absence of sound. FS_12H and FS_18H indicate plants in the presence of forest sound. t. stat: Negative values indicate greater relative abundance for the Sound Treatment and positive values greater abundance for the Soundless Control. The higher the |t. stat|, the greater the variable significance. p-value: Important features selected by t-tests with a threshold of 0.05. Note the p-values are transformed by −log10 so that the more significant features (with smaller p-values) will be plotted higher on the graph. FDR: False Discovery Rate. *Significant features (α < 0.05)

Jasmonic acid (JA) is the most responsive phytohormone in plant-insect interactions [31,32]. Moreover, its level depends on activating the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway. The JA levels showed no change after 12 and 18 h in plants elicited by sounds produced during caterpillar chewing (Fig. 1). However, other phytohormones responsive to insect attacks, such as salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene precursor (ACC), changed under chewing sound treatment. SA levels increased after 12 and 18 h, while the ACC levels decreased, although they are not statistically significant. SA acts positively during plant-insect interactions, while ACC negatively. Zeatin (ZA) levels were also responsive to chewing sound, and they increased after 18 h (p < 0.05). Thus, phytohormone profiles indicated that chewing sound did not trigger JA cascades. However, cascades activated by ZA and SA may have been activated.

Sound treatments changed the abundance of the stress-responsive metabolites (Figs. 1 and 2). Proline and spermidine increased significantly after 18 h of treatment with chewing and forest sounds, respectively. To determine whether the phytohormonal responses were specific for the chewing sound frequencies, we evaluated the phytohormone profiles under treatment of forest sound, containing different frequencies (Fig. 2). Forest sounds also induced changes in some phytohormones.

Abscisic acid (ABA) and ACC levels increased after 18 h while SA showed no change under forest sound (Fig. 2). In contrast, JA levels showed a trend of reduction after 12 h. Proline and spermidine increased significantly after 18 h of treatment with chewing and forest sounds, respectively. Interstingling, these responses were similar to those observed for chewing sounds (Fig. 1).

The concentration data from all phytohormone and stress-responsive metabolites (Figs. 1 and 2) were also used for clustering analysis by heatmap, aiming to visualize the overall tendencies of the metabolites related to response to sound treatments (Fig. S3A,B). These results also indicated that sounds with different frequencies promoted different responses.

After 18 h, both sound signals increased the proline and spermidine abundance (Fig. S3B). For phytohormones, the profiles indicated antagonistic tendencies, except for ZA, which showed an increase after 12- and 18-h treatment for both sounds (Fig. S3B). A random forest test (mean decrease accuracy as a rank parameter) was applied to classify the most responsive variables to sound treatments (Fig. S4). For chewing sounds, SA showed higher abundance alterations for both 12- and 18-h treatment (Fig. S4), while for the forest sounds spermidine was the most responsive. Thus, we conclude that the different ecological sounds may trigger distinct signaling cascades.

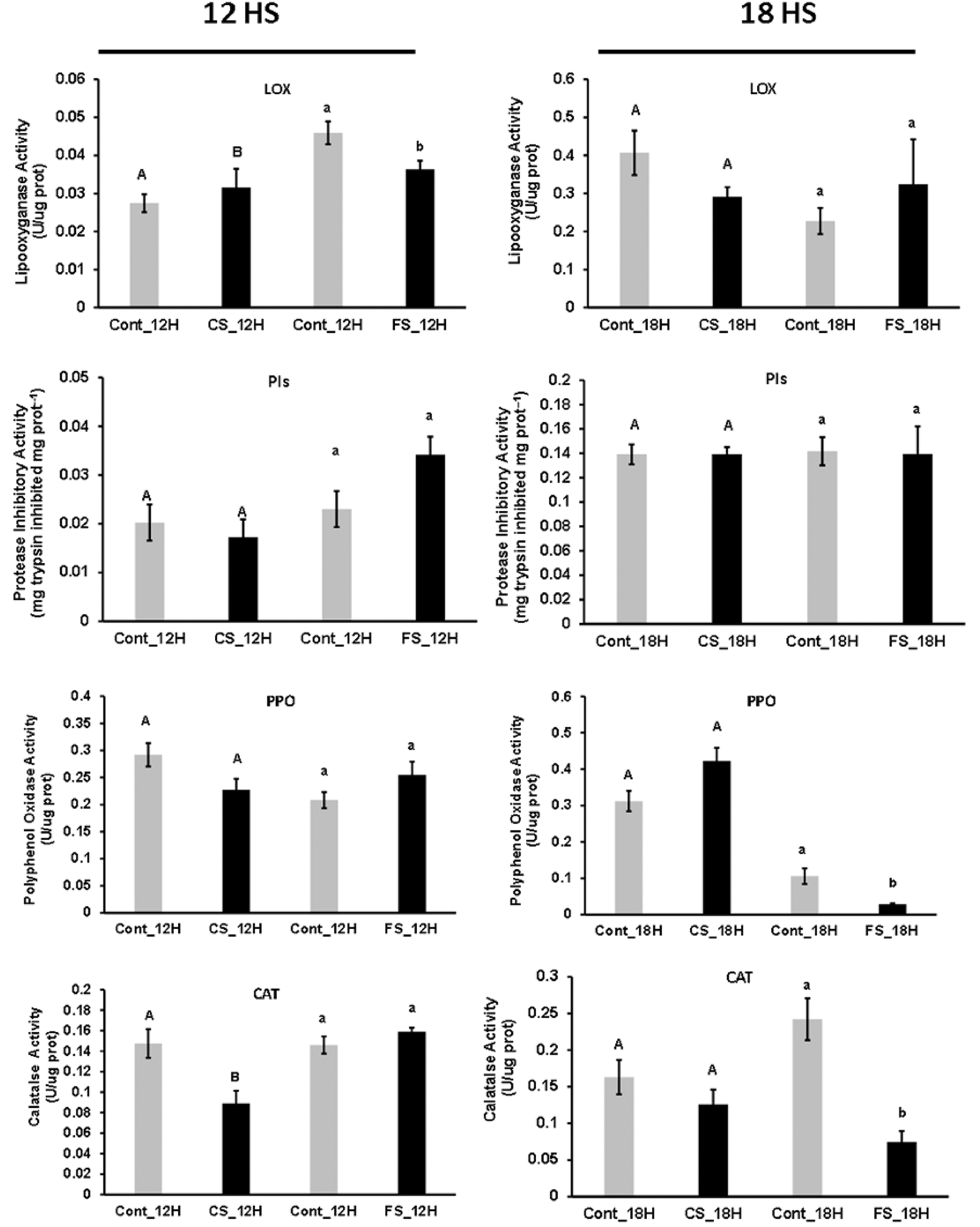

3.2 PPO and CAT Enzymatic Activities from Soybean Leaves Exhibited Changes under Sound Treatments

The activity of some plants’ oxidative metabolism enzymes commonly changes in response to environmental stresses. Thus, we evaluated lipoxygenases (LOX), polyphenol oxidases (PPO), and catalase (CAT) activities. Protease inhibition activity was also evaluated because it is a typical response to insect attacks (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Bar graph for the mean values of relative enzymatic activity in the 12- and 18-h sound treatments. Significant variables (p < 0.05) are represented by different letters, and non-significant variables by the same letters. As the experiments are independent, the comparisons occurred within each sound treatment. Uppercase letters are for comparisons within the chewing sound and lowercase letters from the forest sound. For variables with heterogeneous variance, the Welch’s t-test was applied

LOX activities were not affected by sound signals, despite an increase after 12 h under forest sound treatment (Fig. 3). These results for LOX activities correlated with JA levels (Figs. 1 and 2). JA has triggered PIs synthesis from soybean plants under insect attack [33]. However, PI activities showed no change under chewing and forest sounds (Fig. 3). Thus, the plant responses to sound treatment did not involve LOX and JA cascades, at least for the evaluated exposure time.

After 12 h, PPO activities were decreased under chewing sound (24%, p = 0.0715) and increased under forest sound (22%, p = 0.154). In both cases, the variations were insignificant, but there was a trend increasing the PPO activity. After 18 h, PPO activities were more contrasting, increasing 35% in response to chewing sound (p = 0.051) and decreasing 56% (p = 0.035) in forest sound, being more responsive to the forest sound (Fig. 3).

Chewing sound did not stimulate the JA- and LOX-dependent herbivory signaling pathway. However, a significant increase in PPO activity under the 18-h chewing sound may indicate a possible activation of other herbivory signaling cascades. The plant defense against herbivorous insects induces the oxidation of phenols catalyzed by PPO. Products, such as quinones, bind covalently to leaf proteins and inhibit protein digestion in herbivores [34,35].

CAT activities were also changed in response to sound treatments, showing a decrease in response to both sound signals, especially after 12 h of chewing sounds (p = 0.02) and after 18 h of forest sound treatments (p = 0.021). Although both treatments caused a decrease in the CAT activity, responses were faster for chewing sounds (Fig. 3).

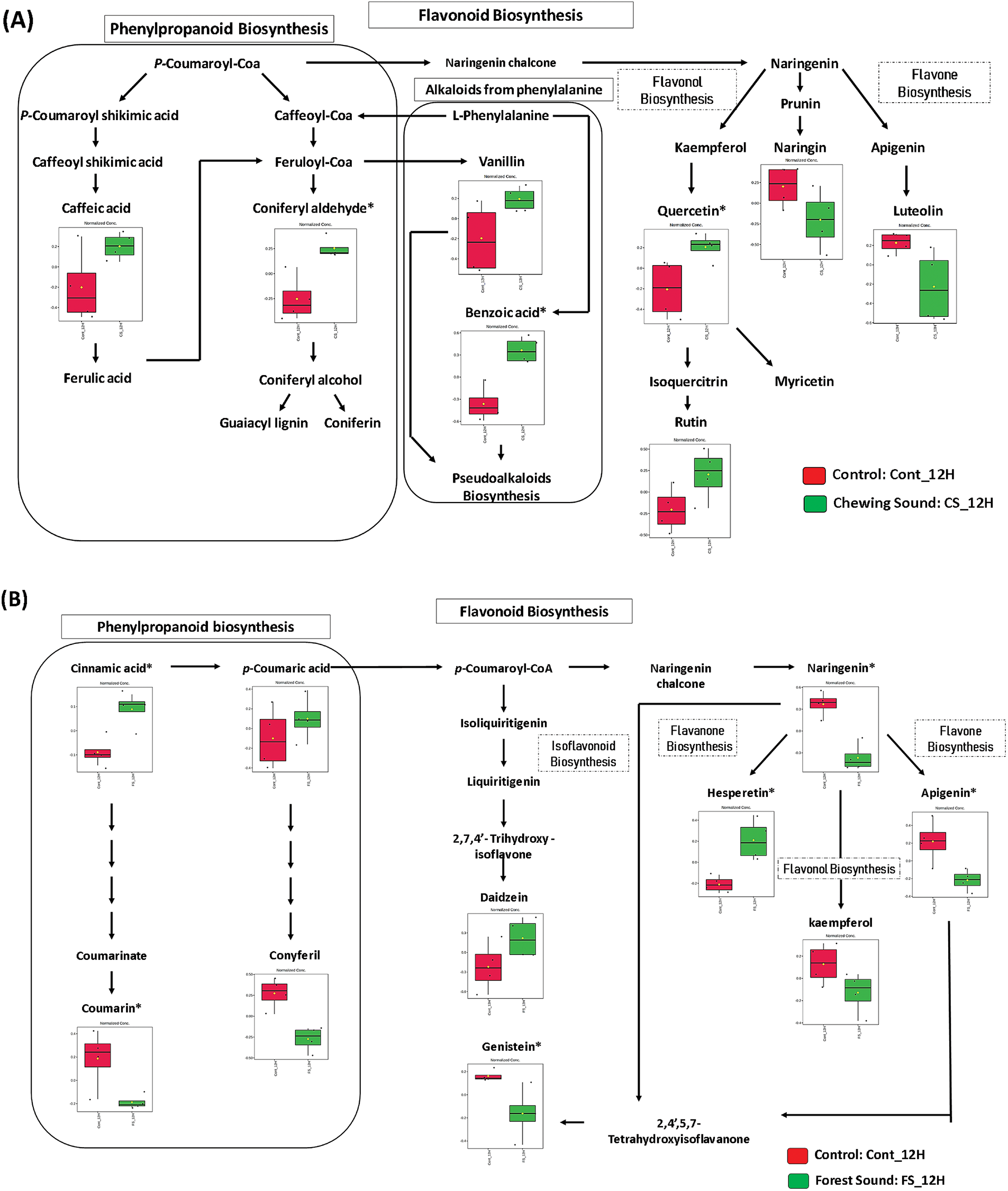

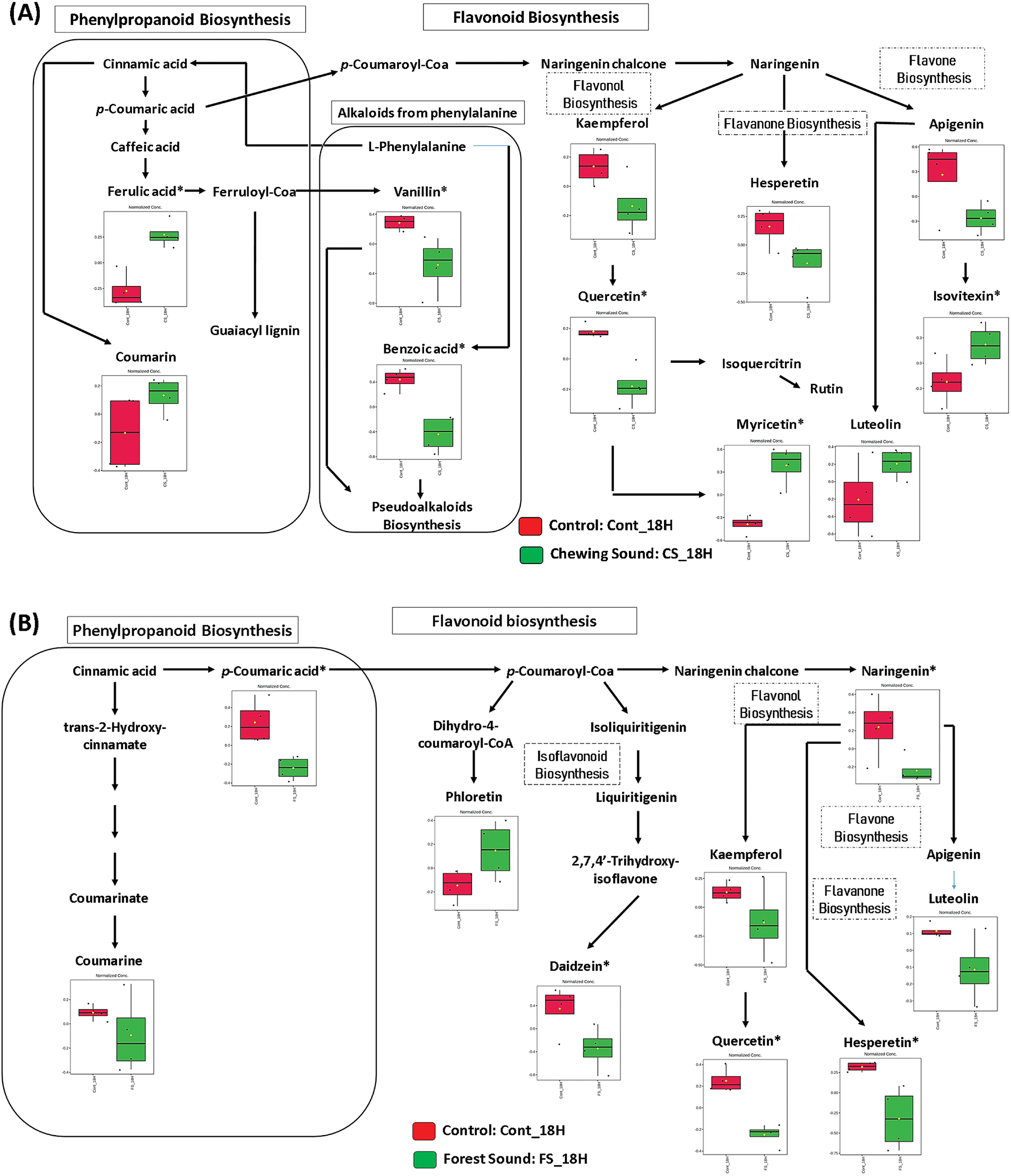

3.3 Flavones and Flavonol Biosynthesis Were the Most Impacted Pathway by the Sound Signals

Secondary metabolites are responsive to biotic and abiotic environmental stresses. In plant-insect interactions, phenolic compounds may reduce the palatability of the tissues, acting as repellents or reducing insect survival. Some classes, such as flavonoid, have been detected in higher concentrations in the soybean genotypes during infestations by A. gemmatalis [33,36].

Thus, we evaluated the abundance of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in response to ecological sounds and the most affected pathways. Enrichment analysis ranked the most responsive and significative metabolites (α < 0.05), and a pathway topology analysis indicated the most significant and impacted pathways. The significance of the pathway is related to the level and abundance of significant metabolites mapped in the pathway. The impact is also related to the metabolite distribution and proximity within the pathway.

As observed for the phytohormones, the phenolic compound and flavonoid profiles were distinct for soybean under chewing and forest sound after 12 and 18 h treatments (Fig. S5). Likewise, the number and specifically dysregulated compounds were also different for each sound type, as well as the significantly responsive metabolites (Table S7).

In the analysis of the pathways after 12-h chewing sound treatment, the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway was the only one significantly affected (α < 0.05). The sound treatment also impacted the flavone and flavonol biosynthesis pathways, but it was insignificant (α > 0.05). While the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway changed with the lowest significance (Table S8). In the 12-h forest sound treatment, all three pathways most affected by ecological sounds were significant. The flavonoid biosynthesis pathway was the most significant and the second most impacted by the sound (Table S9). In the treatment with the 18-h chewing sound, the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway was the only one not showing statistical significance. However, it was the second most impacted, and the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway was the most significant and the least impacted. The flavone and flavonol biosynthesis pathways were the second most significant and the most impacted by sound (Table S10). In the 18-h forest sound treatment, the sound significantly affected the three pathways classified as most important. The flavonoid biosynthesis pathway was the most significant and the second most impacted. The phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway was the second most significant and least impacted, and the flavone and flavonol biosynthesis pathway was the least significant and most impacted by sound (Table S11).

3.4 The Mapping of the Most Responsive Metabolic Pathways Indicates Relevant Differences in the Biosynthesis of Flavones and Flavonols for the Ecological Sounds

Changes in the abundance of the phenolic compounds were also examined in their respective metabolic pathways, aiming to indicate those specifically responsive to sound treatments (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Mapping the most responsive metabolites to 12-h sound treatments. (A) Chewing sound and (B) Forest sound. *Significant features

Figure 5: Mapping the most responsive metabolites to 18-h sound treatments. (A) Chewing sound and (B) Forest sound. *Significant features

Pathway topology analysis indicated the most significant and impacted pathways. However, it does not provide a detailed dynamic of the metabolic adjustment regions where the changes occurred (Fig. S5). Thus, mapping the metabolites in the pathways was carried out to verify fluctuations of the pathways most affected by sounds in more detail. The biosynthesis pathways for flavonoids, flavones, flavonols, and phenylpropanoids were mapped to the responsible metabolites using the KEGG platform (Figs. 4 and 5). This mapping provided substantial evidence that different types of ecological sounds can drive distinct patterns of metabolic responses. The mapping of responsive metabolites also provided strong evidence that for each type of ecological sound, the plant adopted a specific behavior in metabolic reprogramming. Although the flavone and flavonol biosynthesis pathway was the most impacted by ecological sounds, the mapping showed that the metabolic adjustment in this pathway was specific for each type of sound.

Exposition to chewing sound during 12 h significantly changed the accumulation of caffeic acid, coniferyl aldehyde, and benzoic acid. This treatment also affected the metabolites quercetin and rutin, which belong to the flavonol pathway (Fig. 4A). In contrast, different metabolites changed after 12 h of forest sound treatment: cinnamic acid (UP), coumarin (down), naringenin (down), apigenin (down), hesperetin (UP), and genistein (Down) (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the chewing sound-induced the flavonol pathway, while the forest sound-induced the isoflavonoid and flavanone pathways. Accordingly, increased levels of quercetin and rutin (flavonol class) were observed in response to chewing sounds. The flavonol biosynthesis was down-regulated in the 12-h forest sound treatment (low abundance for kaempferol and no adjustments for the other flavonols).

After 18 h of sound treatments, the phenolic compound and flavonoid profiles were distinct from 12 h (Fig. 5) due to a decrease in the quercetin levels and a concomitant increase in the myricetin flavonol by chewing sounds. This signal also changes isovitexin and luteolin levels. Likewise, ferulic acid, vanillin, and benzoic acid levels were statistically modified (Fig. 5A). The reductions in the benzoic acid levels may be related to the increased levels of SA (Figs. 1 and 2) because benzoic acid can be converted to SA [37].

Chewing sound also induced flavonol biosynthesis after 18 h, increasing the myricetin (Fig. 5). This treatment also affected flavone biosynthesis because isovitexin and luteolin abundances increased. Sound treatment responses were distinct from chewing sounds. We highlight decreased p-coumaric acid, naringenin, daidzein, quercetin, and hesperetin. Phloretin was the only compound to be up-regulated. Forest sounds down-regulated the flavonol biosynthesis (Fig. 5B).

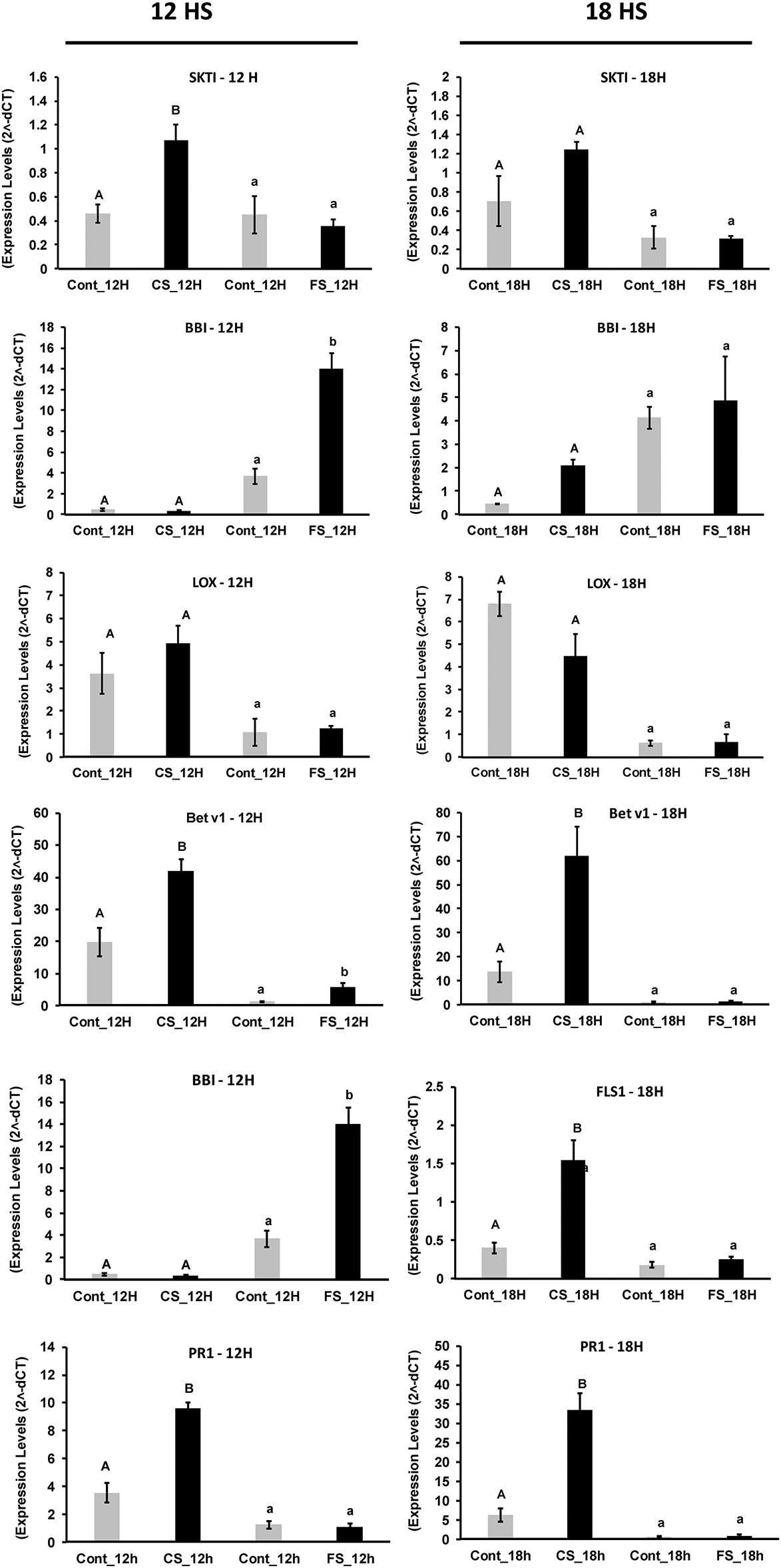

3.5 Genes Involved in the Flavonol Biosynthesis Were Responsive to Chewing Sound

As the previous experiments indicated that chewing sounds differently triggered cascades, we evaluated the expression of some genes involved in the insect-plant interactions by qRT-PCR. The results also showed that the chewing sound might induce the herbivory-responsive cascades (Fig. 6). In contrast, forest sound appeared not to influence the cascades associated with herbivory attack.

Figure 6: Gene expression levels from soybean plants under 12- and 18-h sound treatments. Significant variables (p-value < 0.05) are represented by different letters and non-significant variables by the same letters. As the experiments are independent, the comparisons occurred within each sound treatment. Uppercase letters are for comparisons within the chewing sound and lowercase letters from the forest sound. For variables with heterogeneous variance, the Welch’s t-test was applied

LOX expression and activity are critical in the herbivory signaling cascade. However, both the chewing sound and forest sounds did not promote significant changes in its expression levels, by the JA levels (Figs. 1 and 2) and LOX activity (Fig. 3). Thus, reinforcing the hypothesis that the chewing sound was not able to activate the JA-dependent defense pathway. However, the expression of PI genes, which usually are induced by JA, was significantly responsive to chewing.

The expression of the SKTI, encoding protease inhibitor responsive to herbivore infestation, also increased significantly (p = 0.0151) after 12-h chewing sound treatment (Fig. 6). Although not statistically significant (p = 0.1204), the SKTI transcript level remained higher after 18-h chewing sound treatment compared with the control. SKTI and BBI expression levels showed no change significantly in response to forest sound treatments. Although BBI and SKTI genes were responsive to the chewing sound, the protease inhibition activities did not alter (Fig. 3), at least for the evaluated periods.

As the flavone and flavonol biosynthesis pathways were the most impacted by sound treatments, we also evaluated some A. gemmatalis-responsive genes [38]. FLS1 expression has been induced under attack by herbivores in soybeans [33]. FLS1 encodes flavonol synthase (FLS), a key enzyme in flavonol biosynthesis that catalyzes the conversion of dihydroflavonols to flavonols such as kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin. The FLS1 expression profiles at 12 and 18 h after the chewing sound treatment (Fig. 6) were distinct from those of the forest sound. After 12 h of the chewing sound, the FLS1 expression level for the sound treatment was significantly lower than the control (p = 0.039).

However, after 18 h of the chewing sound, the FLS1 expression levels were highly induced in response to the chewing sound (p = 0.0129). In contrast, the expression levels of the FLS1 gene were not responsive to forest sound (Fig. 6). These results are due to the changes in the flavonol biosynthesis in response to the chewing sound (Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, the increases in the myricetin abundances verified after 18 h of chewing sound treatment appeared to be due to the increased expression of the FLS1 gene (Fig. 5A).

PR10/Bet v1 is involved in synthesizing phenolic compounds and regulating flavonol biosynthesis [39]. Furthermore, PR10/Bet v1 was highly responsive to infestations in A. gemmatalis in soybean leaves [38]. After 12 h of the chewing sound treatment, Bet v-1 expression was significantly (p = 0.0173) induced (Fig. 6) and remained higher than the control plants even after 18 h (p = 0.0752). These results are interesting because they are related to the greater abundance of flavonols in plants treated with the chewing sound (Figs. 4 and 5). In contrast, flavonol biosynthesis was down-regulated after 12 and 18 h of the forest sound treatments (Figs. 4 and 5). These results were consistent with the expression levels of Bet v-1 and FLS1 genes (Fig. 6), which did not alter under forest sound.

Phytohormone profiles indicated that SA was responsive to chewing sounds for 12- and 18-h treatment. Thus, we also evaluated the expression of the PR1 gene, which is frequently used as a marker for SA-dependent cascades. Interestingly, the PR1 gene was highly up-regulated in soybean plants after 12 and 18 h of chewing sound treatment (Fig. 6). These results reinforce the hypothesis that plants recognize and trigger a specific signaling response to sound from different ecological sources, such as from chewing sounds. Accordingly, PR1 genes were not induced in soybean plants by forest sound treatments (Fig. 6).

Recent evidences have indicated that sound vibrations (SVs) contribute to plant robustness. Thus, acting beyond the chemical triggers may improve plant health by enhancing plant growth and resistance [4,10]. Otherwise, plant membranes have many mechanosensitive channels that appear to be responsive to mechanical vibrations [4,5,8]. Therefore, we investigated whether soybean plants can recognize chewing sounds as signals that specifically trigger cascades involved in plant-insect interactions. For this, gene expression and metabolic profiles were compared in response to treatment with sound signals containing distinct frequencies from chewing and forest.

One of the first responses of the soybean plants to insect attack is the increase of the JA levels due to the LOX pathway activation [33] after recognizing the chemical signals from insects. These signaling cascades are often triggered within just a few hours. However, the JA levels, LOX expression, and activities showed no change after the evaluated times of the chewing sound treatment. In contrast, the SA levels increased after 12-and 18-h chewing sound treatments, while the ACC levels decreased under the same conditions.

While JA and LOX activation are considered canonical markers of herbivore defense, studies have shown that soybean plants may engage SA-dependent or JA-independent pathways when responding to specific biotic cues [33,40,41]. Our results indicate that chewing sounds selectively activate SA-regulated responses, including PR1 expression, PPO activity, and flavonol biosynthesis. This may represent an alternative or complementary signaling route that mimics herbivory through non-classical mechanisms. Thus, the absence of JA does not negate an herbivore-like response but suggests that vibrational cues may elicit a distinct, SA-centered signaling network.

Although SA levels did not reach statistical significance at all time points, the consistent trend of increase, together with the strong activation of SA-regulated genes (PR1, PR10/Bet v-1) and metabolic pathways (flavonol biosynthesis), supports the activation of an SA-dependent signaling cascade. Notably, signaling molecules such as SA often act at low and transient concentrations, yet are capable of triggering amplified downstream responses [42–44]. Additionally, the observed reduction in ACC levels—although modest—may further contribute to this response, as SA and ethylene often act antagonistically in regulating defense mechanisms [45–47]. Thus, a decrease in ACC may facilitate the SA response, reinforcing its role in chewing sound-induced signaling.

Ghosh and collaborators also investigated the global gene expression and phytohormonal changes in Arabidopsis thaliana upon treatment with sound vibrations of 500 Hz treatment during 6, 24 and 48 h. These authors observed changes for all the phytohormones except ABA, while JA levels increased only after 48 h. In addition, salicylic acid (SA) levels remained consistently higher at all evaluated time points under sound treatment conditions [5]. Thus, JA levels changed within the first few hours of treatments, returning to basal levels after 12 h. Alternatively, the duration of the sound signal treatment times was not sufficient to induce a change JA levels in our conditions

As also observed in our profiles, sound treatments produced changes in phytohormonal profiles. However, these modulations may depend on the applied time and frequencies [5,11]. Moreover, we observed distinct phytohormonal profiles after 12 and 18 h, specifically for SA levels under chewing sound. Furthermore, some stress-responsive metabolites, such as proline, 12 and 18 h after chewing sound treatment, and spermidine upon the forest sound, were also different.

Environmental stresses stimulate photosynthesis photoinhibition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and antioxidant defense. Several enzymes indicate oxidative status and are involved in plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses, including catalase (CAT) and polyphenol oxidase (PPO). Sound treatments changed the enzymatic activities of both CAT and PPO. CAT activity significantly decreased after 12 h of chewing sound treatment (p = 0.0201) and 18 h of forest sound treatment (p = 0.0021). On the other hand, within 18 h of treatment, PPO showed an increased activity by the chewing sound (p = 0.051) and reduced by the forest sound (0.0351) (Fig. 3).

This responsiveness to sound treatments may be due to these enzymes activated by several environmental stresses that produce ROS, thus indicating that sound treatments may act as general or specific stress. Thus, plants under both treatments exhibited some similar responses, indicating that sounds induce general stress on membrane systems. However, the chewing and forest sounds have different frequency spectra, justifying the specific responses of the plants for each sound treatment.

Thus, the forest sound and chewing sound may trigger different signaling cascades. The increase in the PPO activity may also be a specific response to the chewing sound treatment because it is also highly responsive to insect attack [35,48] (Fig. 3). This hypothesis is consistent with our results and those observed by Ghosh for phytohormone profiles [5].

Another typical plant response to environmental signals is the activation of the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathways, which have an essential role in plant adaptation to different conditions [49,50], predominantly to the biotic stresses [51]. Both chewing and forest sound induced significant changes in the abundance of phenolic compounds and flavonoids. However, the dysregulated branches of the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathways were remarkably distinct (Figs. 4 and 5). These specific changes in the plant secondary metabolisms also are consistent with the hypothesis that sound with different frequencies may act as a general or specific signal. For example, a tendency to activate the flovonol (12- and 18-h treatments) and flavone (18-h treatment) biosynthesis was observed in response to the chewing sound, whereas isoflavonoid and flavanone biosynthesis (12-h treatment) were changed in response to forest sounds.

Chewing sound treatment increased the rutin, quercetin, and myricetin levels, while the forest sound-induced reductions in the flavonol pathway. These results suggest that the chewing sound triggered signaling cascades, up-regulating the flavonol pathway. Accordingly, the aglycone substrate was funneled to produce active glycosylated forms. Reference [52] also observed alterations in flavonoid contents (25%–88% increase) of the sprouts of radish, lettuce, and cabbage in response to acoustic waves, which also vary according to the sound frequency, exposure time, and species. Likewise, A. thaliana rosettes pre-treated with the sound vibrations caused by caterpillar feeding showed higher levels of glucosinolate and anthocyanin, when subsequently fed by Pieris rapae caterpillars than untreated plants. These plants also discriminated between the vibrations caused by chewing and those caused by wind or insect song [16]. Other evidence for a possible specific regulatory cascade activated by the chewing sounds was an increase of the benzoic acid levels after 12 h of the treatment (Fig. 4A), which acts as a substrate for increasing the SA levels (Figs. 1 and 2).

Expression gene regulations also were activated specifically for the chewing sound. During the response to the insect attack, the soybean plants produce molecules and toxins that interact directly with the insects, causing damage to their development [33,53]. These include Kunitz family protease inhibitors (SKTI) and Bowman-Birk (BBI) serine protease inhibitors, which are JA-induced trypsin inhibitors (PI), which reduce the absorption of amino acids in the insect gut. Accordingly, both BBI and SKTI genes were responsive specifically to chewing sound (Fig. 6). However, the variation in the BBI and SKTI expression did not relate to the JA levels.

JA levels increase under insect attack. However, resistant and susceptible soybean genotypes display similar JA levels in response to infestation, indicating that the insect resistance may be JA-independent [33]. Despite this observation, the BBI gene was highly up-regulated in the genotype IAC 17, which indicated that induction of PI biosynthesis might also be controlled by other phytohormones such as SA and ET [28]. SA involvement is not very evident in the regulatory cascades of plant defense against insect attack. However, some studies highlighted its importance [54,55]. The absence of changes in the LOX and protease inhibition activities and JA levels in the soybean leaves under chewing sounds may be attributed to the reduced exposure times. Ghosh and collaborators observed that the levels of JA from A. thaliana leaves were increased only after 48 h of sound treatment [5].

Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins are plant proteins induced during pathogen infection and in response to abiotic stresses, including wounding, drought, and high salinity. PR10/Bet v 1-like proteins are involved in producing plant phenolics, including flavonoids, which were related as a determinant of the soybean resistance to insect attack [33,56,57]. Accordingly, gmPR10/Bet v-1 gene expression increased significantly in soybean plants under chewing sound. Takeuchi and collaborators reported a complex regulatory cascade controlling the expression of gmPR10/Bet v-1, involving the signaling pathways of JA, ET, and salicylic acid SA [58]. SA and ACC were the most responsive phytohormones in the soybean leaves under chewing sound treatment. Accordingly, studies indicated that SA-dependent signaling pathways are involved in the tomato systemic defense responses to herbivores [42], which culminated in the induction of the PR1 gene expression. We observed that chewing sounds for soybean plants also triggered a signaling cascade that increased SA levels and induced PR1 up-regulation. In plants under forest sound treatment, the expression levels did not alter. Thus, plants recognize and trigger a specific signaling response to sounds from different ecological sources, such as chewing sounds.

Flavonol Synthase (FLS1), methyltransferase (SOMT-9), and Flavonol 3-O-methyltransferase (3-OMT) proteins participate in the glycoconjugate flavonol biosynthesis. These genes were highly induced by insect attacks [52]. These authors also verified higher levels of flavonol glycosylated in resistant genotypes, indicating that FLS activity can intensely regulate the metabolic flow toward flavonols or anthocyanin biosynthesis. Expression levels of the gmFLS1 gene were highly induced in response to chewing sound. They were not responsive to forest sound (Fig. 6). Thus, these results are consistent with the metabolomic data, suggesting that chewing sounds trigger specific signaling cascades, leading to distinct activation of the flavone and flavonol biosynthetic pathways. Consequently, the observed metabolic changes in the plant may be specific to the frequencies applied.

Furthermore, we observed that physiological and metabolic responses were specific to the environmental signals generated by the sound waves. Under chewing sound, soybean plants showed responses similar to the caterpillar attack. As the cascades responsive to chewing sounds appear did not involve LOX and JA. Thus, an alternative pathway connected chewing sound with insect attack cascades. The overlapping between biotic and abiotic signaling cascades has been potentialized, producing similar responses of the plants to environmental stresses [41,59], such as drought and herbivory. In agreement, some physiological responses were similar to a general stress response. However, the gene expression and metabolic changes align with plant defense against insect attack. The regulatory cascades triggered by the chewing sound appeared to be SA-dependent.

The decision to place all plants, including controls, inside identical acoustic boxes was deliberate to minimize environmental variability and isolate sound as the only experimental variable. However, we acknowledge that the acoustic enclosure itself may have introduced some level of mechanical or environmental stress. While this design enhances internal consistency, future studies may benefit from complementary controls outside the boxes to assess baseline physiological responses under standard greenhouse conditions.

Previous studies have shown that plants can respond to mechanical vibrations or specific frequencies associated with biotic threats. For instance, Apel and Cocroft demonstrated rapid transcriptional responses in Arabidopsis exposed to chewing sounds [16]. However, such studies typically focus on early signaling markers within short time frames and do not address longer-term biochemical or hormonal changes. In contrast, our findings suggest that extended exposure to complex, ecologically relevant soundscapes can modulate defense-related metabolic and gene expression pathways. While our results do not directly prove that plants “recognize” chewing sounds, they indicate that specific sound profiles can induce distinct molecular responses, possibly through mechanosensitive or frequency-specific perception systems. This reinforces the emerging view that plants integrate acoustic cues in a context-dependent manner.

Because of the positive effects on several growth parameters of plants, sound treatments have been used in biotechnology and agriculture [13,60,61]. In the present study, we also verified significative changes in the relative abundances of phenolic compounds, including flavonoids, when the plants were grown under both chewing and forest sound treatment. Flavonoids are an important class of antioxidants that play a crucial role in eliminating toxic ROS and protecting both animal and plant cells [61–63]. Kim and collaborators considered the increase in flavonoid levels observed in over 88% of the sprouts as an additional advantage since the enhancement of these antioxidant compounds is expected to improve the overall antioxidative capacity of plants used for food consumption [52].

Our findings suggest that acoustic treatments may modulate specific defense-related and metabolic pathways in soybean plants. In agricultural settings, such sound-based stimuli could be explored as a non-invasive strategy to prime plants for enhanced resilience against biotic stress, potentially reducing reliance on chemical pesticides. Moreover, the increase in antioxidant flavonoids indicates a potential for improving nutritional or nutraceutical quality in edible plants. However, practical implementation requires overcoming challenges such as identifying optimal sound frequencies and durations for different crops, ensuring uniform sound exposure in large-scale environments, and developing cost-effective delivery systems. Further research is needed to translate these findings into scalable technologies that align with precision agriculture practices.

Studies that decipher the ecological relevance of responses triggered by sound vibrations have recently made some advances [13,64,65]. De Luca and collaborators suggested that buzz pollination may have evolved as a strategy enabling plants to distinguish between pollen thieves and true pollinators, based on the specific buzz frequencies produced by bees [17]. Plants can respond to the chewing sound by producing some molecules similar to when plants are attacked by herbivores [16]. Therefore, the divergences in metabolic and gene expression adjustments between chewing sound and forest sound treatments, along with the consistency of the chewing sound response with herbivore attack stimuli, reinforce the hypothesis that ecological sounds can induce specific signaling pathways used by plants to process information from the environment.

Finally, we propose that acoustic chewing signals may act as a first line of defense against herbivory. Although the chewing sound and the forest sound shared similarities in the expression of molecules responsive to biotic and abiotic stresses, the differences in metabolic adjustments between the two sound signals were more striking and accentuated. These observations are consistent with the proposition that the type of SV-triggered signaling cascade depends on the frequencies that characterize the sound. Moreover, we demonstrated that the chewing sound-induced regulatory cascades similar to those triggered by an herbivore: SA-dependent herbivory signaling pathway, increase in the PPO activity, up-regulation in the biosynthesis of flavonols and genes involved in the biosynthesis and regulation of flavonoids and flavonols. In contrast, these metabolic adjustments were not induced by the forest sound, showing that ecological sounds can serve as an important long-range signal capable of transmitting alerts and habitat information. However, studies on the acoustics of plant-herbivore interactions need to be expanded to other plant-insect systems to reveal their broad applicability, magnitude, and ecological relevance.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank to NuBioMol (Center of Analyses of Biomolecules-UFV, Brazil) for the infrastructure and technical assistance. This study was supported by National Institute of Science and Technology in Plant-Pest Interaction (INCT-IPP), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Lucas Leal Lima; Analice Martins Duarte; Filipe Schitini Salgado: performed greenhouse experiments. Lucas Leal Lima; Angélica Souza Gouveia; Iana Pedro da Silva Quadros: performed qRT-PCR assays. Lucas Leal Lima; Angélica Souza Gouveia; Nathália Silva Oliveira, Monique da Silva Bonjour: performed enzymatic assays. Lucas Leal Lima; Flavia Maria Silva Carmo: designed the study. Lucas Leal Lima; Humberto Josué de Oliveira Ramos: performed and analyzed mass spectrometry. Lucas Leal Lima; Elizabeth Pacheco Batista Fontes; Humberto Josué de Oliveira Ramos: performed data integration. Lucas Leal Lima; Monique da Silva Bonjour; Maria Goreti Almeida Oliveira; Elizabeth Pacheco Batista Fontes; Humberto Josué de Oliveira Ramos: wrote the paper with input from all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All authors are in accordance with the publication of all data and figures.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.064068/s1.

References

1. Gagliano M, Renton M, Duvdevani N, Timmins M, Mancuso S. Out of sight but not out of mind: alternative means of communication in plants. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37382. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Godfrey-Smith P. Sender-receiver systems within and between organisms. Philos Sci. 2014;81(5):866–78. doi:10.1086/677686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Del Stabile F, Marsili V, Forti L, Arru L. Is there a role for sound in plants? Plants. 2022;11(18):2391. doi:10.3390/plants11182391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Demey ML, Mishra RC, Van Der Straeten D. Sound perception in plants: from ecological significance to molecular understanding. Trends Plant Sci. 2023;28(7):825–40. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2023.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ghosh R, Mishra RC, Choi B, Kwon YS, Bae DW, Park SC, et al. Exposure to sound vibrations lead to transcriptomic, proteomic and hormonal changes in Arabidopsis. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):33370. doi:10.1038/srep33370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jia Y, Wang B, Wang X, Wang D, Duan C, Toyama Y, et al. Effect of sound wave on the metabolism of Chrysanthemum roots. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2003;29(2–3):115–8. doi:10.1016/S0927-7765(02)00155-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kim JY, Ahn HR, Kim ST, Min CW, Lee SI, Kim JA, et al. Sound wave affects the expression of ethylene biosynthesis-related genes through control of transcription factors RIN and HB-1. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2016;10(6):437–45. doi:10.1007/s11816-016-0419-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ghosh R, Gururani MA, Ponpandian LN, Mishra RC, Park SC, Jeong MJ, et al. Expression analysis of sound vibration-regulated genes by touch treatment in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:100. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Qin YC, Lee WC, Choi YC, Kim TW. Biochemical and physiological changes in plants as a result of different sonic exposures. Ultrasonics. 2003;41(5):407–11. doi:10.1016/s0041-624x(03)00103-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Bhandawat A, Jayaswall K. Biological relevance of sound in plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2022;200:104919. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2022.104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tyagi A, Ali S, Park S, Bae H. Assessing the effect of sound vibrations on plant neurotransmitters in Arabidopsis. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(8):5216–23. doi:10.1007/s00344-023-10918-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fernandez-Jaramillo AA, Duarte-Galvan C, Garcia-Mier L, Jimenez-Garcia SN, Contreras-Medina LM. Effects of acoustic waves on plants: an agricultural, ecological, molecular and biochemical perspective. Sci Hortic. 2018;235:340–8. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2018.02.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mishra RC, Ghosh R, Bae H. Plant acoustics: in the search of a sound mechanism for sound signaling in plants. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(15):4483–94. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Chowdhury MEK, Lim HS, Bae H. Update on the effects of sound wave on plants. Res Plant Dis. 2014;20(1):1–7. doi:10.5423/rpd.2014.20.1.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. de Melo HC. Plants detect and respond to sounds. Planta. 2023;257(3):55. doi:10.1007/s00425-023-04088-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Appel HM, Cocroft RB. Plants respond to leaf vibrations caused by insect herbivore chewing. Oecologia. 2014;175(4):1257–66. doi:10.1007/s00442-014-2995-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. De Luca PA, Vallejo-Marín M. What’s the ‘buzz’ about? The ecology and evolutionary significance of buzz-pollination. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16(4):429–35. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2013.05.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Guertler P, Harwardt A, Eichelinger A, Muschler P, Goerlich O, Busch U. Development of a CTAB buffer-based automated gDNA extraction method for the surveillance of GMO in seed. Eur Food Res Technol. 2013;236(4):599–606. doi:10.1007/s00217-013-1916-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi:10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Melo BP, Fraga OT, Silva JCF, Ferreira DO, Brustolini OJB, Carpinetti PA, et al. Revisiting the soybean GmNAC superfamily. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1864. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Axelrod B, Cheesbrough TM, Laakso S. Lipoxygenase from soybeans: EC 1.13.11.12 Linoleate: oxygen oxidoreductase. In: Lowenstein JM, editor. Methods in enzymology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1981. p. 441–51. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(81)71055-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. de Araújo NO, de Sousa Santos MN, de Araujo FF, Véras MLM, de Jesus Tello JP, da Silva Arruda R, et al. Balance between oxidative stress and the antioxidant system is associated with the level of cold tolerance in sweet potato roots. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2021;172(6):111359. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2020.111359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lima LL, Balbi BP, Mesquita RO, Cleydson J, Coutinho FS, Maria F, et al. Proteomic and metabolomic analysis of a drought tolerant soybean cultivar from Brazilian savanna. Crop Breed Genet Genom. 2019;1:e190022. doi:10.20900/cbgg2019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Coutinho FS, Dos Santos DS, Lima LL, Vital CE, Santos LA, Pimenta MR, et al. Mechanism of the drought tolerance of a transgenic soybean overexpressing the molecular chaperone BiP. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2019;25(2):457–72. doi:10.1007/s12298-019-00643-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hummel M, Meister R, Mansmann U. GlobalANCOVA: exploration and assessment of gene group effects. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(1):78–85. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Goeman JJ, Bühlmann P. Analyzing gene expression data in terms of gene sets: methodological issues. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(8):980–7. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Aittokallio T, Schwikowski B. Graph-based methods for analysing networks in cell biology. Brief Bioinform. 2006;7(3):243–55. doi:10.1093/bib/bbl022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Nguyen D, Rieu I, Mariani C, van Dam NM. How plants handle multiple stresses: hormonal interactions underlying responses to abiotic stress and insect herbivory. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;91(6):727–40. doi:10.1007/s11103-016-0481-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Divekar PA, Rani V, Majumder S, Karkute SG, Molla KA, Pandey KK, et al. Protease inhibitors: an induced plant defense mechanism against herbivores. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(10):6057–73. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10767-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kumar DM. Plant protease inhibitors: a defense mechanism against phytophagous insects. J Res Appl Sci Biotechnol. 2024;3(1):70–3. doi:10.55544/jrasb.3.1.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang J, Duan G, Li C, Liu L, Han G, Zhang Y, et al. The crosstalks between jasmonic acid and other plant hormone signaling highlight the involvement of jasmonic acid as a core component in plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1349. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang Y, Mostafa S, Zeng W, Jin B. Function and mechanism of jasmonic acid in plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8568. doi:10.3390/ijms22168568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Gómez JD, Pinheiro VJM, Silva JC, Romero JV, Meriño-Cabrera Y, Coutinho FS, et al. Leaf metabolic profiles of two soybean genotypes differentially affect the survival and the digestibility of Anticarsia gemmatalis caterpillars. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;155(4):196–212. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.07.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kaur H, Salh PK, Singh B. Role of defense enzymes and phenolics in resistance of wheat crop (Triticum aestivum L.) towards aphid complex. J Plant Interact. 2017;12(1):304–11. doi:10.1080/17429145.2017.1353653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang J, Sun X. Recent advances in polyphenol oxidase-mediated plant stress responses. Phytochemistry. 2021;181:112588. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Gómez JD, Vital CE, Oliveira MGA, Ramos HJO. Broad range flavonoid profiling by LC/MS of soybean genotypes contrasting for resistance to Anticarsia gemmatalis (Lepidoptera: noctuidae). PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0205010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Lefevere H, Bauters L, Gheysen G. Salicylic acid biosynthesis in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:338. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Pinheiro VJM, Gómez JD, Gouveia AS, Coutinho FS, Teixeira RM, Loriato VAP, et al. Gene expression, proteomic, and metabolic profiles of Brazilian soybean genotypes reveal a possible mechanism of resistance to the velvet bean caterpillar Anticarsia gemmatalis. Arthropod Plant Interact. 2024;18(1):15–32. doi:10.1007/s11829-023-10030-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Dastmalchi M. Elusive partners: a review of the auxiliary proteins guiding metabolic flux in flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2021;108(2):314–29. doi:10.1111/tpj.15446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Erb M, Reymond P. Molecular interactions between plants and insect herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2019;70(1):527–57. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-095910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Faustino VA, de Souza Gouveia A, Coutinho FS, da Silva NRJr, de Almeida Barros R, Meriño Cabrera Y, et al. Soybean plants under simultaneous signals of drought and Anticarsia gemmatalis herbivory trigger gene expression and metabolic pathways reducing larval survival. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;190(11):104594. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Peng Y, Yang J, Li X, Zhang Y. Salicylic acid: biosynthesis and signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2021;72(1):761–91. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-081320-092855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Roychowdhury R, Mishra S, Anand G, Dalal D, Gupta R, Kumar A, et al. Decoding the molecular mechanism underlying salicylic acid (SA)-mediated plant immunity: an integrated overview from its biosynthesis to the mode of action. Physiol Plant. 2024;176(3):e14399. doi:10.1111/ppl.14399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lukan T, Coll A. Intertwined roles of reactive oxygen species and salicylic acid signaling are crucial for the plant response to biotic stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5568. doi:10.3390/ijms23105568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li N, Han X, Feng D, Yuan D, Huang LJ. Signaling crosstalk between salicylic acid and ethylene/jasmonate in plant defense: do we understand what they are whispering? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):671. doi:10.3390/ijms20030671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kunkel BN, Brooks DM. Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5(4):325–31. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00275-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zander M, Camera SL, Lamotte O, Métraux JP, Gatz C. Arabidopsis thaliana class-II TGA transcription factors are essential activators of jasmonic acid/ethylene-induced defense responses. Plant J. 2010;61(2):200–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04044.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Bhonwong A, Stout MJ, Attajarusit J, Tantasawat P. Defensive role of tomato polyphenol oxidases against cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) and beet armyworm (Spodoptera exigua). J Chem Ecol. 2009;35(1):28–38. doi:10.1007/s10886-008-9571-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ramaroson ML, Koutouan C, Helesbeux JJ, Le Clerc V, Hamama L, Geoffriau E, et al. Role of phenylpropanoids and flavonoids in plant resistance to pests and diseases. Molecules. 2022;27(23):8371. doi:10.3390/molecules27238371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Pratyusha DS, Sarada DVL. MYB transcription factors-master regulators of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and diverse developmental and stress responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2022;41(12):2245–60. doi:10.1007/s00299-022-02927-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Gutiérrez-Albanchez E, Gradillas A, García A, García-Villaraco A, Gutierrez-Mañero FJ, Ramos-Solano B. Elicitation with Bacillus QV15 reveals a pivotal role of F3H on flavonoid metabolism improving adaptation to biotic stress in blackberry. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232626. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Kim JY, Lee SI, Kim JA, Muthusamy M, Jeong MJ. Specific audible sound waves improve flavonoid contents and antioxidative properties of sprouts. Sci Hortic. 2021;276(4):109746. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Aljbory Z, Chen MS. Indirect plant defense against insect herbivores: a review. Insect Sci. 2018;25(1):2–23. doi:10.1111/1744-7917.12436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ali J, Tonğa A, Islam T, Mir S, Mukarram M, Konôpková AS, et al. Defense strategies and associated phytohormonal regulation in Brassica plants in response to chewing and sap-sucking insects. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1376917. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1376917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Liu YX, Han WH, Wang JX, Zhang FB, Ji SX, Zhong YW, et al. Differential induction of JA/SA determines plant defense against successive leaf-chewing and phloem-feeding insects. J Pest Sci. 2025;98(2):1085–100. doi:10.1007/s10340-024-01821-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Aglas L, Soh WT, Kraiem A, Wenger M, Brandstetter H, Ferreira F. Ligand binding of PR-10 proteins with a particular focus on the bet v 1 allergen family. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20(7):25. doi:10.1007/s11882-020-00918-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Morris JS, Caldo KMP, Liang S, Facchini PJ. PR10/bet v1-like proteins as novel contributors to plant biochemical diversity. Chembiochem. 2021;22(2):264–87. doi:10.1002/cbic.202000354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Takeuchi K, Gyohda A, Tominaga M, Kawakatsu M, Hatakeyama A, Ishii N, et al. RSOsPR10 expression in response to environmental stresses is regulated antagonistically by jasmonate/ethylene and salicylic acid signaling pathways in rice roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52(9):1686–96. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcr105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. de Melo BP, Lourenço-Tessutti IT, Paixão JFR, Noriega DD, Silva MCM, de Almeida-Engler J, et al. Transcriptional modulation of AREB-1 by CRISPRa improves plant physiological performance under severe water deficit. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16231. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-72464-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Hassanien RH, Hou TZ, Li YF, Li BM. Advances in effects of sound waves on plants. J Integr Agric. 2014;13(2):335–48. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60492-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. García-Caparrós P, De Filippis L, Gul A, Hasanuzzaman M, Ozturk M, Altay V, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: a review. Bot Rev. 2021;87(4):421–66. doi:10.1007/s12229-020-09231-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Vicente O, Boscaiu M. Flavonoids: antioxidant compounds for plant defence.. and for a healthy human diet. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2017;46(1):14–21. doi:10.15835/nbha46110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Dias MC, Pinto DCGA, Silva AMS. Plant flavonoids: chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules. 2021;26(17):5377. doi:10.3390/molecules26175377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Robinson JM, Annells A, Cando-Dumancela C, Breed MF. Sonic restoration: acoustic stimulation enhances plant growth-promoting fungi activity. Biol Lett. 2024;20(10):20240295. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2024.0295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Jung J, Kim SK, Kim JY, Jeong MJ, Ryu CM. Beyond chemical triggers: evidence for sound-evoked physiological reactions in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:25. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools