Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Application and Prospects of CRISPR/Cas Gene Editing Technology in Major Crop Molecular Breeding and Improving

1 College of Life Science, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, 130118, China

2 Jilin Biological Research Institute, Changchun, 130012, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaoyu Lu. Email: ; Huijing Liu. Email:

# Co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Enhancing Grain Yield: From Molecular Mechanisms to Sustainable Agriculture)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1669-1694. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064344

Received 12 February 2025; Accepted 26 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat sequences (CRISPR) and their accompanying proteins (Cas), commonly presenting in bacteria and archaea, make up the CRISPR/Cas system. As one of the fundamental sources of nutrition for humans, edible crops play a crucial role in ensuring global food security. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has been applied to improve many crop traits, such as increasing nitrogen utilization efficiency, creating male sterile germplasm, and regulating tiller and spikelet formation. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of the use of CRISPR/Cas gene editing technology in crop genomes, covering the targeted genes, the types of editing that take place, the mechanism of action. Finally, we also discussed the efficiency of gene editing and pointed the future direction on how to speed up crop molecular breeding, increase breeding effectiveness, and produce more new crop varieties with high qualities.Keywords

Although global food production has increased at par with population growth over the last four decades, about 1 billion people, mostly residing in developing nations, are still malnourished [1–3]. To fulfill the demands of the growing global population, rising wages, and increasing consumption, the global food production has been estimated to be increased by 70% by 2050 [4–6]. To achieve this, it is important to produce new crop varieties with high yields, quality, and resistance to natural disasters owing to the decline in arable land and unpredictable weather patterns. Breeding new crop varieties plays a crucial role in enhancing agricultural productivity. Humans have been selectively breeding economically beneficial crops and taking advantage of natural genetic changes in crops since the dawn of agriculture. Owing to advancements in breeding techniques, radiation and chemical mutagenesis have been used to artificially increase mutations and produce new crop varieties with superior features more rapidly and efficiently. However, the creation of mutations, whether natural or artificial, is unpredictable and necessitates a protracted and laborious selection process to produce stable new crop varieties. Furthermore, developing a new variety may take more than a decade or even several decades of continuous effort [7,8].

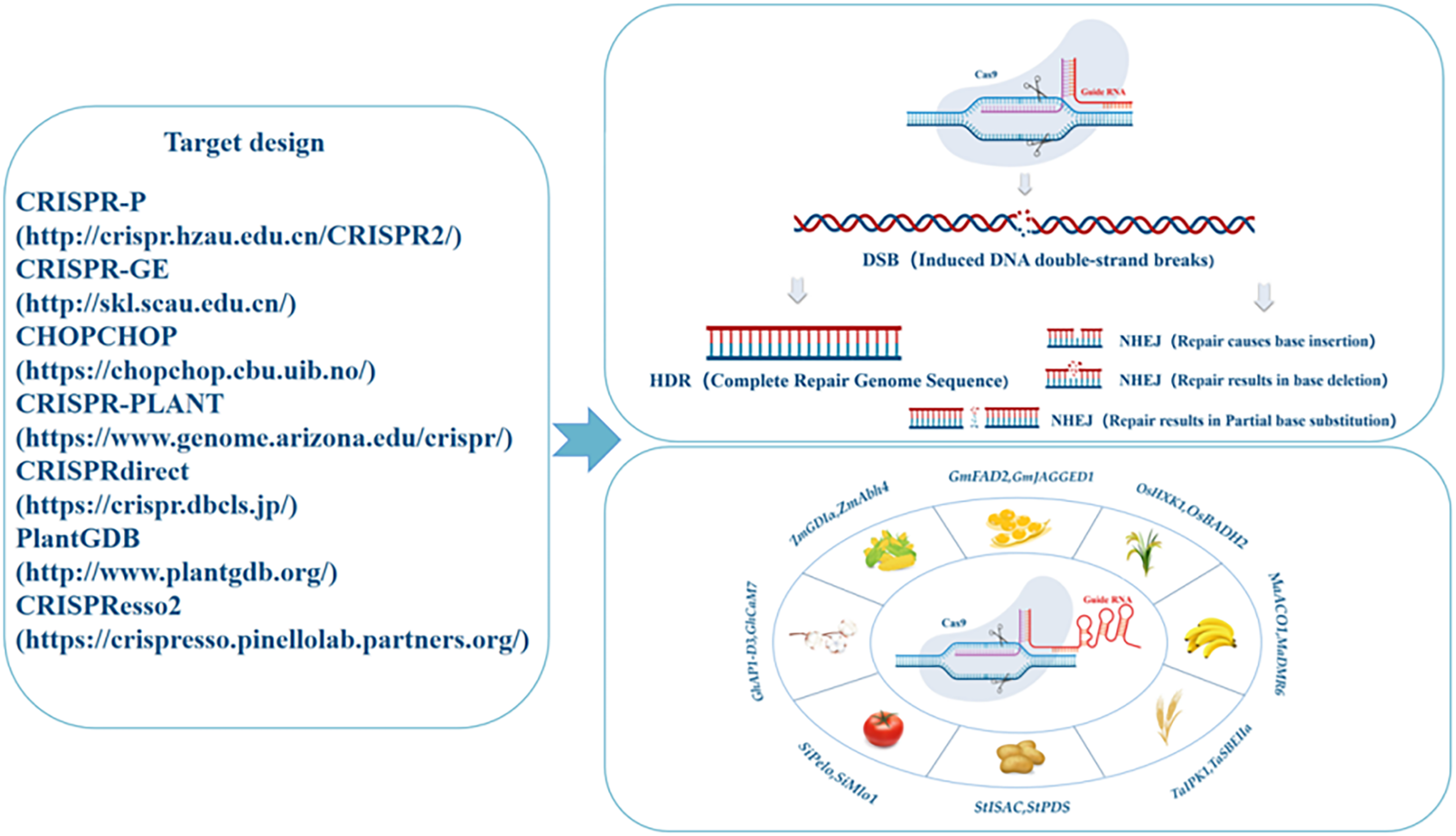

In recent years, the emergence of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) gene editing technologies have advanced plant molecular breeding. Unlike conventional mutagenesis, CRISPR/Cas9 can rapidly edit genes at any location in the target genome [9–11]. This system was originally discovered in bacteria and archaea, where in it acts as a defense mechanism against foreign viruses and phages by targeting, binding to, and degrading exogenous DNA. These loci containing spaced repeat sequences are termed as CRISPR and are found in the genomes of microorganisms [12–14]. Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN), transcription activator–like effector nucleases (TALEN), and CRISPR comprise the three basic types of gene editing techniques. ZFN and TALEN have limited use in crop breeding owing to their laborious technical procedures and high costs. However, CRISPR technology has been extensively used in crop breeding as it offers a high editing efficiency, good specificity, ease of operation, relatively low cost, and low off-target rate (Fig. 1) [15–19].

Figure 1: Working mechanism of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. Cas9 nuclease induces DNA to undergo double-strand breaks, and its main repair mechanisms are homologous recombination (HDR) and nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ), where HDR results in base fragment substitutions, and NHEJ results in base insertions, substitutions, and deletions

This review aims to generate ideas for the future development of breeding techniques via crop genome editing. This study primarily includes the applications of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology in molecular breeding, its role in improving crop traits, and a brief introduction of the practical application of this technology by breeders in recent years.

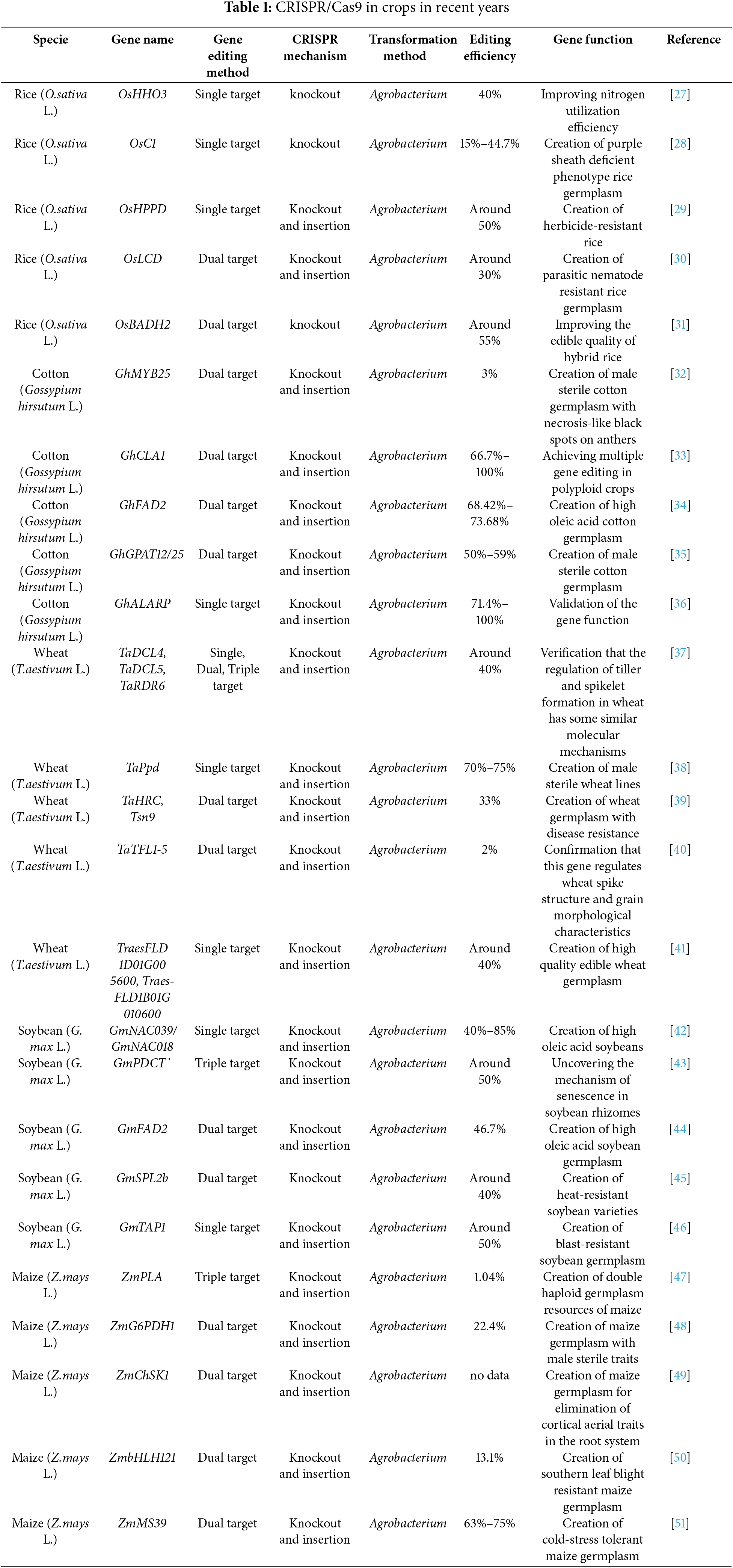

2 Multiple Uses of CRISPR/Cas9 in Crop Breeding

In 2013, CRISPR/Cas9 successfully edited the genomes of the model plants Arabidopsis thaliana and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) [20–22]. Since then, the technology has gained widespread acceptance and has been used in various crops, including rice, soybean, maize, and barley [23]. CRISPR/Cas9 has been rapidly developed in recent years to produce crops with better features and ensure the safety and security of the human food supply (Table 1) [24–26].

2.1 Achieving Increased Crop Yields

Food security is a global goal; however, the food security situation worldwide currently is not optimistic, especially owing to the onslaught of the New Crown Epidemic, which has left the global food system showing unprecedented vulnerability. Ensuring a steady increase in food production for 8 billion people is a top priority [52–54]. With the rapid development of molecular breeding, improving crop yield has become crucial. Traditional breeding techniques, such as hybridization, have been successful in varietal improvement and crop development; however, they cannot ensure food security and maximize food production. The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology acts on the functional genomes or transcription factors of major crops such as rice, soybean, and corn, becoming the most popular tool for increasing crop yield. This technology eliminates the drawbacks of traditional breeding, including cumbersome operation and long cycle time, and accelerates the breeding process [55–57].

In rice, transcription factors and master genes that can regulate multiple traits are the focus of research by breeders. For example, the AH2 gene encodes a MYB structural domain protein involved in rice hull and grain development. Ren et al. [58] knocked out the rice AH2 gene using CRISPR/Cas9; mutations in the AH2 gene produced smaller grains and thus higher rice yields and altered grain quality, including lowering the content of straight-chain starch and gel consistency and increasing protein content. AH2 is an allele of SLL1, and the AH2 mutant has the same leafroll phenotype as SLL1; however, it also alters epidermal cell characteristics, grain size, and mass. The AH2 mutant is characterized by a single base C to T mutation in the exon, while the SLL1 mutant features a G to A base substitution in the intron. These mutations can serve as a basis for the further exploration of the regulatory functions of this transcription factor using base editors. Dong et al. [59] introduced loss-of-function mutations into OsPDCD11 using CRISPR/Cas9 in five rice varieties. OsPDCD5-targeted mutagenesis increased seed yield and improved plant architecture by increasing plant height and optimizing spike and grain shape. Furthermore, Wang et al. [60] knocked out the miR396 gene in rice and showed an increase in grain size and yield as well as an increase in grain aspect ratio in the mutant. Wang et al. [61] constructed a knockout mutant of the rice OsUBC45 gene, which was found to produce phenotypes such as short stems, reduced number of grains in a spike, and lower grain weight through agronomic trait analysis. They ultimately reduced the yield by more than 50% and were found to significantly attenuate rice resistance to rice blast, confirming that it exerts a positive regulatory function. Plant height (PH) is an important agronomic characteristic that directly affects rice yield, and Yan et al. [62] introduced a loss-of-function mutation into OsPAGN1 using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The resulting OsPAGN1 mutant plants showed higher seed yield compared to control plants due to increased PH, number of tillers per spike, and number of grains per spike, and resolved the molecular mechanism by which OsPAGN1 regulates the PH of rice spikes, number of tillers, and number of grains per spike. The molecular mechanism of OsPAGN1-regulating PH and tiller and grain number in rice spike was analyzed. Altering the structure of the rice root system can be avoided to affect rice yield under saline conditions; Kitomi et al. [63] found by editing the rice qSOR1 gene that in saline soils, near-allelic lines carrying the qSOR1 loss-of-function allele have a soil surface root (SOR), which enables the rice to avoid the reductive stress of saline soils and thus increase yields compared to the parental cultivar without the SOR. Redundancy of functional gene families still exists in the rice genome. Gao et al. [64] used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to target eight rice FWL genes, resulting in significantly higher yields and tillers in multigene mutants than in the wild type. Zeng et al. [65] edited three rice genes simultaneously: OsPIN5b (Spike length gene), GS3 (Grain size gene), and OsMYB30 (Cold tolerance gene), resulting in mutants with increased spike length, grain size, and cold tolerance, respectively. The multigene editing strategy can suppress the negative effects of functional redundancy of gene families and ensure the effectiveness of gene editing for breeding, but multiple assemblies of guide RNAs will inhibit each other from functioning and affect editing efficiency.

The primary goal of soybean gene editing breeding is to increase yield. Cai et al. [66] achieved this by using CRISPR/Cas9 multigene editing technology to edit GmJAG in a low-latitude spring soybean variety called Huachun 6. In another study, Liu et al. [67] found that the SHSP26 gene in soybean can enhance drought resistance and yield by comparing overexpression and gene-edited lines of the gene. In the future, precise regulatory modes will be developed to realize soybean yield increase. In maize, Shi et al. [68] edited ARGOS8, a negative regulator of ethylene response in maize, and by knock-in ARGOS8 variants, they were able to detect higher levels of ARGOS8 transcripts in all tissues tested, and the mutant agronomic traits showed elevated yield. Liu et al. [69] used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to engineer mutations in maize yield-related traits by creating a weak promoter allele of the CLE gene and a newly discovered null allele of the partially redundant compensatory CLE gene, and these strategies increased a wide range of maize grain yields.

The study of PH and branching-related functional genes in oilseed rape is a popular topic in breeding. Zheng et al. [70] found that by knocking down all four BnaMAX1 alleles in oilseed rape, the plant takes on a semidwarf and branching-increased phenotype. This leads to more accessory inflorescences and an increase in yield per plant unit compared to the wild type. For the sorghum genome, where the phenotypes of polygenic mutants are even more pronounced, Brant et al. [71] utilized CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutation of the sorghum LG1 gene, resulting in haploid and diploid. The phenotypic changes in the single and double allele LG1 mutants were more pronounced in the T1 progeny plants with the double allele mutation in LG1, which completely lacked the ligule and had a more severe reduction in the angle of inclination of the leaf blade compared to the single allele mutant. Zhang et al. [72] edited the wheat TaARE1 gene using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. The mutant tolerates a lack of nitrogen and shows delayed senescence and substantially higher yield.

Improving grain yield is a complex process with various factors at play. One major approach to boost yield is by regulating cytokinin homeostasis. Future research aims to use CRISPR/Cas9 to uncover the molecular mechanisms of the primary effector genes and transcription factors involved in cytokinin homeostasis regulation.

2.2 Optimizing Crop Agronomic Traits

Crop traits are affected by many factors, such as climate and environmental conditions, and the use of genome editing technology to improve crop agronomic traits has garnered the attention of breeders in recent years. Different crops have different characteristics, and the direction of improvement is also distinct [73–75]. In rice, PH is one of the most important agronomic traits, as it directly affects yield potential and resistance to failure. Han et al. [76] knocked out the rice OsGA20ox2 gene, and the mutant lines exhibited reduced gibberellin levels and PH at maturity, reduced flag leaf length, and increased yields per plant. However, they did not affect other agronomic traits. Regulation of the number of organelles in rice cells facilitates the regulation of agronomic traits of rice growth. Zhu et al. [77] used CRISPR/Cas9 to knock down the rice LW5 gene. Loss of LW5 function results in an increase in photosynthesis rate, vascular bundles, and chlorophyll content but a significant decrease in the stover ratio and grouting rate. Furthermore, mutants are suitable materials for studying the molecular mechanisms of rice fertility regulation and are potential germplasm for producing hybrid seeds. Xu et al. [78] used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to edit the OsROS9 gene and explore how the gene regulates pollen and embryo sac defects in rice. Tillering is one of the most important traits that regulate rice yield. Cui et al. [79] used CRISPR/Cas9 to knocked out the Os1900 gene, which is homologous to MAX1 in Arabidopsis. A detailed analysis of a series of Os1900 promoter deletion mutations showed that fertilization is controlling the number of tillers in rice through the transcriptional regulation of Os1900 and that a few promoter mutations alone increase tiller number and grain yield even under conditions of small amounts of fertilizer application, while under normal fertilization conditions, a single defective Os1900 mutation does not increase tillering. Besides, grain size is one of the most important agronomic traits determining rice yield, and the knockdown of regulatory genes regulating grain size using the CRISPR/Cas9 system is an important means to resolve its molecular mechanism and regulatory network. Qing et al. [80] knocked down the OsMKK3 gene using CRISPR/Cas9 and explored that OsMKK3 controls grain size by regulating the cellular protein content.

The number of nodes on the main diameter of the plant and the number of branches are major agronomic traits in soybeans. Bao et al. [81] used CRISPR/Cas9 to mutate four genes encoding the SQUAMOSA promoter-binding protein-like transcription factor in the SPL9 family of soybeans and found that higher-order mutant plants carrying various combinations of the mutations exhibit an increase in the number of nodes and branches on the main stem, thereby increasing the total number of nodes per plant to varying degrees. Cheng et al. [82] mutated four late elongated hypocotyl (LHY) genes in soybeans with four gRNAs, and phenotypic analyses revealed that the quadruple mutant plants of GmLHY show reduced PH and shortened internodes. Additionally, Zhong et al. [83] edited the soybean GmHdz4 gene, and the total root length, root surface area, and number of root tips were significantly higher in the pure mutant lines than in the overexpression mutant lines. Mu et al. [84] used CRISPR/Cas9 to target six GmBIC genes in soybeans and found that single, double, and quadruple mutations in the GmBIC gene result in an increased dwarf phenotype.

PH and stalk strength in maize are the primary factors for improving jade agronomic traits. Zhang et al. [85] edited the maize GA20ox3 gene using CRISPR/Cas9 technology and obtained semidwarf maize plants. Due to the disruption of GA20 oxidase, the mutants had elevated levels of GA12 and GA53 and reduced levels of other GA precursors (GA15, GA9, GA44, and GA20), as well as reduced accumulation of biologically active GA1 and GA4, which resulted in a semidwarf phenotype. Zhang et al. [86] edited the allele of stiff1, which is a gene at the major quantitative trait locus of maize stalk strength, by the CRISPR/Cas9 system and found that the plants had thicker stalks than the control that was not edited. Qiang et al. [87] used CRISPR/ Cas9 to knock out the ZmMYB18 gene in maize, and the mutant showed thicker cell walls and higher lignin content without any visible growth defects.

In wheat crops, Liu et al. [88] edited the gene encoding caffeic acid O-methyltransferase, HvCOMT1, in barley, and the mutant showed a 14% reduction in total lignin content and a 34% increase in fermentable glucose recovery, providing improved quality lignocellulosic feedstock for the efficient production of lignocellulosic biofuels. Gupta et al. [89] edited the recognition element of TaSPL12 and generated 13 mutations in three homologous genes, which resulted in an approximately twofold increase in TaSPL13 mutant transcripts, and phenotypic evaluation showed that the MRE mutation in TaSPL13 resulted in a decrease in flowering time, tiller number, and PH, with a concomitant increase in grain size and number of grains. The functional genes that regulate the quality traits of wheat are often associated with yield and other traits. The effects of gene editing breeding obtained by editing multiple different genes for polyploid crops are also different [87–89]. Furthermore, Karunarathne et al. [90] edited the gene encoding the cytokinin-responsive repressor, HvARE1, to improve barley nitrogen use efficiency. Cheng et al. [91] edited the gene encoding gibberellin oxidase, HvGA3ox1, in barley to increase embryo sheath length by an average of 8.2 mm, which may provide the necessary adaptation to maintain yield under climate change.

Li et al. [92] knocked down lncRNA1459 in tomatoes by CRISPR/Cas9, and the lncRNA1459 mutant significantly inhibited the ripening process in tomatoes compared to wild-type fruit. Ethylene production and lycopene accumulation were largely suppressed in the lncRNA1459 mutant. Gomez et al. [93] created CRISPR-mediated novel capsule-binding protein1 (NCBP1) and NCBP2 genes in cassava. Shao et al. [94] obtained new germplasm resources expressing semidwarf traits by editing the banana MaGA20ox2 gene. Hu et al. [95] created several MaACO9 genes in banana using the CRISPR/Cas9 system with different editing MaACO9 genes with different editing modes in bananas, which extended their shelf life. Shen et al. [96] used CRISPR/Cas9 to knockdown the PdHXK1 gene in poplar, and the agronomic traits of the mutant showed an increase in stomatal aperture and water loss and a decrease in drought tolerance. Brant et al. [71] used CRISPR/Cas9 to create several genes with different editing modes in sorghum, editing the LIGULELESS-1 (LG1) gene to create a double allele mutant with a reduced leaf inclination angle. Furthermore, Fan et al. [97] edited two canola BnaBP genes using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and showed that individual knockout of the BnaA03.BP gene results in semidwarf and compact plant structures without any other inferior traits. Tef (Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter) is a staple food and a valuable cash crop for millions in Ethiopia. Beyene et al. [98] used CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce a knockout mutation in the tef direct homolog of the rice SEMIDWARF-1 (SD1) gene to confer semidwarfism and ultimately produce resistance to stunting. An et al. [99] verified that the gene regulates photosynthesis and reduces leaf angle in lettuce by comparing knockout and overexpression of the LsNRL2 gene. While using CRISPR/Cas9 to target and regulate the functional genes or transcription factors of crop agronomic traits, some studies have found that it will produce some other trait alterations affecting the normal growth pattern of plants. Thus, the future scope of gene editing and breeding is to improve the targeting and specificity and realize more precise trait regulation.

2.3 Improvement of Crop Quality

Crop quality plays a key role in determining the market value of a crop, which is determined by extrinsic and intrinsic traits [100–102]. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated crop quality improvement focuses on physical appearance, food quality, fruit texture, and nutritional value. Extrinsic quality attributes include appearance and aesthetic features such as color, texture, and aroma. By contrast, intrinsic quality is more important, which includes nutrients such as proteins, starch, and lipids and bioactive compounds such as carotenoids, lycopene, γ-aminobutyric acid, and flavonoids [103,104].

Edible quality and nutrient content are important quality traits of rice. Zhang et al. edited the Waxy gene in two widely cultivated varieties of fine japonica rice and showed that mutations in the Waxy gene reduce straight-chain starch content and convert rice to glutinous rice without affecting its other desirable agronomic traits [104]. Additionally, Tang et al. edited the gene encoding betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase, OsBADH2, to enhance the aroma of the indica rice variety R317 by knocking down OsBADH2 to promote the natural aroma substance 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) [105]. Wang et al. [106] took advantage of the use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate a new gene in three high-yielding japonica rice varieties and a japonica rice line to generate OsAAP10 and OsAAP6 knockout mutants, which reduce the high grain protein content in rice and thereby improve the eating and cooking quality of the rice. Huang et al. [107] found six new Wx allele promoters by editing the region near the TATA box, which in turn downregulate Wx expression and fine-tune the content of rectilinear starch. SBE-resistant starch (RS) is not readily digested and absorbed in the stomach or small intestine but is passed directly to the large intestine. RS-rich grains may be beneficial for improving human health and reducing the risk of diet-related chronic diseases. Biswas et al. [108] created a new high starch-resistant rice germplasm resource by editing four key enzyme-encoding genes in the family of genes encoding the starch-branching enzyme SBE. Hui et al. [31] showed that by editing the Wx and OsBADH2 genes in rice, the mutants had low straight-chain starch content and significantly higher 2-acetyl-1-pyrrolidinium aroma. Furthermore, Tian et al. [109] showed that by editing the Rc gene in weed rice germplasm, not only could weed rice be removed for its deleterious seed coat characteristics, but also improved drought tolerance in seed germination.

Fatty acid content and protein content are important quality traits in soybeans. Li et al. [110] edited soybean seed storage protein genes Glyma.20g148400, Glyma.03g163500, and Glyma.19g164900 using the hairy root transformation technique to provide ideas for creating high-protein soybean seeds. Zhang et al. [111] found that the mutant had higher oil content and germination rate than wild-type seeds under high temperature and humidity by knocking out the soybean phospholipase D1 (PLD1KD) gene. Additionally, Qu et al. [112] found that overexpression of the transgenic strain reduces the oleic acid content of the soybean Gm15G117700 gene by 3.94%, and the gene-edited strain increase it by 3.49% by comparing the oleic acid content of the edited and overexpressed soybean Gm15G117700 genes. Zhou et al. [44] edited five key enzyme genes in the soybean GmFAD2 family and comparing the effects of different editing modes on soybean lipid synthesis, it was found that editing of the GmFAD2-1A gene increase soybean oleic acid content by 91.49%.

Among other crops, celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered in genetically susceptible individuals by the ingestion of gluten proteins from wheat, barley, and rye. Sánchez-León et al. [113] created low-gluten, transgene-free wheat germplasm by editing a conserved region adjacent to the 33-mer coding sequence in the α-wheat glycolysin gene using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. Li et al. [114] successfully altered the starch composition, structure, and properties of winter and spring wheat varieties and obtained transgene-free high straight-chain amylose wheat by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of TaSBEIIa. Raffan et al. [115] edited the wheat asparagine synthase gene, TaASN2, to reduce free asparagine accumulation in wheat and improve its edible quality.

Important quality traits can differ from crop to crop. For instance, in rice, grains with low levels of straight-chain amylose are considered to have better cooking and eating qualities. Similarly, in oilseed crops, breeders focus on creating germplasm that is high in oleic acid.

2.4 Resistance to Abiotic Stresses

Abiotic stresses, including drought, temperature extremes, salinity, and waterlogging, are significant constraints to crop production. Abiotic stress is the adverse effect of any abiotic factor on a plant in a given environment that affects its growth and development, and plants have evolved mechanisms to sense these environmental challenges and adjust their growth processes for survival and reproduction [116–118]. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology has emerged as a promising tool for editing the genome of a plant to obtain desirable traits, and breeders have used CRISPR/Cas9 to create a variety of crop varieties that can tolerate abiotic stresses [119–121].

Tian et al. [122] identified GW5-Like, a homolog of the GW5 gene in rice, as a negative regulator of seed size and salt stress tolerance by editing it and providing breeding ideas to improve yield and salt stress tolerance. Santosh Kumar et al. [123] targeted editing of indica rice CV.MTU1010 in the OsDST gene. The mutant had wider leaves with reduced stomatal density and, therefore, enhanced leaf water retention under dehydration stress and showed moderate tolerance to osmotic stress and higher intensity tolerance to salt stress at the seedling stage. Li et al. [124] found that OsADR3 knockdown in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated rice increase its sensitivity to drought and oxidative stress. Besides, Zhou et al. [125] showed a significant increase in the sensitivity of rice to drought and oxidative stress by editing four loci in rice circRNAs: Os02circ25329, Os06circ02797, Os03circ00204, and Os05circ02465; the mutant phenotypes showed salt tolerance as well as fertility shortening phenotypes. Alam et al. [126] edited the rice OsbHLH024 gene and the mutant showed a significant increase in shoot weight, total chlorophyll content, and chlorophyll fluorescence. In addition, high antioxidant activity coincided with less reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stabilized MDA levels in A91. Using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis, Zhang et al. [127] showed that the mutant of rice OsbHLH57 gene is more sensitive to cold conditions and has reduced trehalose content. Meanwhile, OsbHLH57 may regulate ROS metabolism and CBFs/DREBs-dependent pathways in response to cold stress.

Du et al. [128] inhibited the expression of stress-related genes by knocking down the soybean transcription factor GmMYB118, which exhibited lower drought and salt tolerance compared with overexpressed lines. Zhou et al. [129] negatively regulated drought tolerance in soybeans by editing miR398c, and the mutant increased the expression of GmCSD1a/b, GmCSD2a/b/c, and GmCCS compared to overexpressed lines, which enhanced the ability to remove O2−. Xiao et al. [130] identified a total of 112 GmPLA family genes in the soybean genome, and knocked down two paralogous genes, GmpPLA-II epsilon and GmpPLA-II zeta, by CRISPR/Cas9, and found that single or simultaneous knockdown of both genes interferes with the root response to the phosphorus-deficient environment, and some of the mutant lines are more resistant to flooding and drought compared with the control. Niu et al. [131] knocked out lncRNA77580 in soybean and found that deletion and overexpression of lncRNA77580 altered the expression of several neighboring protein-encoding genes associated with the genes of salt stress response, and the longer the missing DNA fragment in lncRNA77580, the greater the effect on the expression of lncRNA77580 and neighboring genes. Wang et al. [132] successfully created Cas9-free GmAITR36 double mutants and GmAITR23456 quintet mutants by targeting six GmAITR simultaneously using CRISPR/Cas9 and found that mutations in the GmAITR gene result in enhanced salt tolerance in soybeans, and that higher-order mutants had more pronounced salt tolerance traits. Yang et al. [133] edited GmNAC12 transcription factor in soybean, resulting in at least a 12% decrease in survival under drought stress for transgenic plants with the correct editing event. The study concluded that GmNAC12 is a key gene that positively regulates drought stress tolerance in soybean.

Feng et al. [134] knocked down the maize ZmLBD5 gene by CRISPR/Cas9, and the mutant seedlings were dwarf but drought-tolerant, confirming ZmLBD5 as a negative regulator of drought tolerance in maize. Zhu et al. [135] found that the sensitivity to saline conditions is enhanced by two CRISPR/Cas9 knockdown lines of ZmEREB9 in maize, and overexpression of ZmEREB57 increases salt tolerance in maize and Arabidopsis.

2.5 Enhancement of Crop Disease Resistance

Protection of food crops from viral pathogens is a priority in crop breeding. However, in the context of the current climate change scenario, rapidly evolving plant viruses have led to the loss of host resistance mechanisms. Genome editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, have been recognized as the most promising tools for creating germplasm possessing resistance to plant viruses. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9-based resistance to plant viruses has already been successfully achieved through gene targeting and cleavage of the viral genome or alteration of the plant genome to enhance the innate immunity of plants [136–139].

Macovei et al. [140] conferred natural resistance to the rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV) by editing the translation initiation factor 4γ gene (eIF4G) in the RTSV-sensitive variety IR4. Li et al. [141] inhibited the expression of Xa13 in leaves by knocking out the gene without affecting its expression and function in anthers, and improved the broad-spectrum resistance of rice. Kim et al. [142] concluded by comparing the phenotypic analysis of gene-edited and overexpressed lines. They concluded that tissue-specific activation of DOF11 in rice promotes resistance to sheath blight and increases seed weight through activation of SWEET14 by comparing the phenotypic analyses of gene-edited and overexpressed lines. Tao et al. [143] used CRISPR/Cas9 to create loss-of-function mutants with the rice broad-spectrum resistance genes Pi21 and Bsr-d1, and the resulting mutants showed increased resistance to Aspergillus oryzae. We also generated a knockout mutant of the S gene Xa5, which showed increased resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae. Zhou et al. [144] edited three rice broad-spectrum resistance genes, Bsr-d922, Pi638 and ERF638, and all single mutants and triple mutants showed enhanced resistance to rice blast. Wang et al. [145] compared knockout and overexpressed lines of the rice gene HEXOKINASE 1 and showed that knockout of this gene increases the susceptibility of rice to rice black-streaked dwarf virus infection. Lu et al. [146] used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate a knockout mutant of OsV-ATPase d in rice. The mutation did not have any adverse effects on plant growth and yield and significantly increased the biosynthesis of JA and ABA and resistance to southern SRBSDV but decreased the resistance to rice stripe virus compared to the wild type. Liu et al. [147] created rice varieties with broad-spectrum disease resistance abilities by editing the rice OsS5H gene.

Ma et al. [148] demonstrated that defects in GmLMM2 reduce chlorophyll content by disrupting tetrapyrrole biosynthesis and enhance resistance to Phytophthora sojae leading to necrotic spots in developing leaves of CRISPR/Cas9-edited mutants. Liu et al. [149] not only improved soybean resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa but also simultaneously affected soybean growth and fatty acid metabolism processes by editing the genes encoding for soybean PHYSODRAFT_522340 (PsFACL) and PHYSODRAFT_344464 (PsCPT). By editing PsSu(z)12, a gene encoding the core subunit of the H3K27me3 methyltransferase complex, and obtaining three deletion mutants, Wang et al. [150] found that the mutants loses the ability to evade immune recognition in soybean carrying Rps1b. Zhang et al. [151] used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiple gene editing to simultaneously target GmF3H1, GmF3H2, and GmFNSII-1 in soybean hairy roots and plants, and found a significant increase in isoflavonoid content and a one-third decrease in soybean mosaic virus (SMV) coat protein content in the mutants, indicating that the increase in isoflavone content enhanced leaf resistance to SMV. Gu et al. [152] created target gene site-specific knockout and knock-in mutants to explore the mechanism and function by which the soybean pathogen Mycobacterium smegmatis can pass through its corresponding effector gene, Avr1b-1, and all of the selected knockout transformants gained virulence on Rps1b plants, whereas infection was not impaired in plants lacking Rps1b. When the sgRNA-resistant version of Avr1b-1 was reintroduced into the Avr1b-1 locus of the knockout Avr1b transformant, the knock-in transformant with a well-transcribed Avr1b-1 gene was unable to infect Rps1b-containing soybeans. Yu et al. [153] edited the soybean GmDRR1 gene, which was significantly reduced compared to the RNAi overexpressed strains, knockdown of the GmDRR1 gene resulted in a significant reduction in soybean resistance to Mycobacterium abscessus infection compared to the overexpressed strains. Fan et al. [154] obtained a mutant with a 2-bp deletion in the coding region of the soybean transcription factor GmTCP19L and created soybean germplasm resources with a significant increase in susceptibility to Blastomyces. The resistance to Phytophthora ramorum (Rps) gene in plants is characterized by the recognition of a specific effector of the pathogen, which is encoded by the avirulence (Avr) gene. New soybean varieties carrying Rps8 resistance were created by knocking out the Avr45a gene by Arsenault-Labrecque et al. [155].

The bacterium Erwinia amylovora is the causal agent of fire blight in apples (Malus homea), triggering its infection through a DspA/E effector that interacts with the apple susceptibility protein MdDIPM4. Pompili et al. [156] edited the MdDIPM4 gene to reduce the susceptibility of apples to fire blight. Kis et al. [157] enhanced resistance to wheat dwarf virus in barley by editing its genome sequence. Cao et al. [158] reduced the ratio of S/G lignin composition by knockdown of the F5H gene to improve mycobacterial resistance in Brassica napus. Tripathi et al. [159] enhanced resistance to Botrytis cinerea wilt (BCW) by editing the direct homolog of the DMR6 gene in bananas. Shi et al. [160] enhanced the broad-spectrum resistance of rice by editing the OsFd1 gene without affecting growth and yield. He et al. [161] generated wheat TaCIPK14 mutant plants by simultaneously editing three homologous genes using CRISPR/Cas9. The TaCIPK14 mutant lines showed broad-spectrum resistance to the fungus Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), but the yield of the mutants was affected. Liu et al. [162] edited two target genes produced by ZmGDIα by CRISPR/Cas9, and the resulting mutant showed increased resistance to maize stubby dwarf disease compared to the natural ZmGDIα-hel allele without affecting other traits. Liu et al. [163] edited the ZmFER1 gene, a homolog of the wheat TaHRC gene, in maize, and the mutant showed improved resistance to Fusarium wilt, and the same gene editing event did not alter other agronomic traits. Noureen et al. [164] edited the eIF4E conserved region in the potato cultivar Kruda, and the mutant showed increased resistance to potato virus Y (PVY). Zhou et al. [165] knocked out the SLdml2-3, SLdml2-4, and SLdml2-5 genes in tomatoes to create triple-pure and mutants, and the phenotypes showed that the leaves of the mutants are smaller, shorter in length and width, and weighed lower than the wild-type leaves. These results revealed the functional diversity of SlDML2 in regulating multiple developmental processes in tomatoes.

Disrupting susceptibility genes to produce pathogen-specific germplasm can have unintended effects, such as reduced growth, programmed cell death, low fertility, and loss of tolerance to other stresses. Research is focusing on enhancing plant disease resistance without impacting other traits to mitigate these pleiotropic effects.

2.6 Participation in Photoperiod Regulation

In response to changing seasons, plants precisely control the timing of flowering at the right time of the year to ensure reproductive success. Flowering time affects the reproductive success of plants and has a significant impact on the yield of cereal crops. Flowering time is regulated by various environmental factors, with light duration often playing an important role. Crops can be categorized into different types based on their photoperiodic requirements for flowering. For example, long daylight crops include wheat, barley, and peas; short-daylight crops include rice, soybean, and corn. As a widely used genome editing tool, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology is essential for understanding the molecular regulation of flowering and its genotypic variation for molecular breeding and crop improvement [166–168].

Song et al. [169] generated three OsMFT1 knockout mutants in rice using CRISPR/Cas9 and all of them had significantly reduced tasseling stage and spikelet number, and the number of primary and secondary meristems was significantly reduced compared with the wild type. Li et al. [170] used CRISPR/Cas9 to create double-knockout mutants of maize ZmPHYC1 and ZmPHYC2, which exhibited a moderately early-flowering phenotype under long daylight conditions. Additionally, ZmPHYC2 overexpressing plants showed moderately reduced plant and spike heights. Li et al. [171] used CRISPR/Cas9 to design three single guide RNAs to edit four LNK2 genes and obtained a LNK2 gene–free transgenic pure four mutants. The flowering time of the quadruple mutant was significantly earlier than that of the wild type and the transcript level of the quadruple mutant LNK2 was significantly lower than that of the wild type under long daylight conditions. Zhao et al. [172] created single or combination mutants targeting either GmPHYA or GmPHYB genes using CRISPR/Cas9. Phenotypic analysis of the mutants showed that GmPHYB1 predominantly mediated sunlight-induced photomorphogenesis, followed by GmPHYA2 and GmPHYA3 that had redundant and additive function of GhAP1-D3s in mediating the seedling sunlight response. Wang et al. [173] found that the mutant line generated by genome editing flowered significantly later than the wild type. Wolabu et al. [174] used CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the MsFTa1 gene in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), and the mutant showed delayed flowering traits and created many superior traits, which indirectly improved alfalfa forage biomass production and quality. Wan et al. [175] used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of the E1 gene of Tianlong 1, a soybean cultivar that carries a dominant E1, to study its precise function in photoperiodic regulation, and four types of mutations were produced in the coding region of E1, and a pure mutant was obtained. The E1 mutant showed significant structural changes, including the onset of terminal flowering, definitive stem formation, and reduced number of branches. Zhou et al. [176] developed a novel high-efficiency multiplex promoter-targeting strategy based on CRISPR/Cas9, which edits the promoter region of rice tasseling master genes, realizes the continuous variation of rice tasseling under the same genetic background, and can regulate the tasseling period of existing excellent varieties.

2.7 Creation of New Male Sterile Germplasm

Male sterility is an essential factor for the growth of crops, particularly those that reproduce sexually and the seed production of hybrids. Using male sterile lines to create hybrids can significantly reduce the production costs of hybrid seeds, enhance the quality of hybrids, and broaden their use. However, the current limitation to commercializing this crop advantage is the unavailability of appropriate male sterile lines. The use of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology can solve this problem and has significant application significance [177–179].

Chen et al. [180] transformed the maize MS8 gene into a CRISPR/Cas9 vector, and phenotypic analysis revealed that the MS8 gene mutation and the male sterility phenotype could be stably inherited in a Mendelian manner to the next generation. Okada et al. [181] edited the wheat MS1 gene to create new wheat varieties Fielder and Gladius with completely new male sterile germplasm. Tang et al. [182] edited the MS2 gene in dwarf male sterile wheat germplasm and restored its fertility. Li et al. [183] used the CRISPR/Cas9 system optimized for different promoters for editing three homozygous alleles of TaNP1, a triple purity mutation in the TaNP1 gene that results in complete male sterility in maize. Zhang et al. [184] targeted editing of LpDMC1 and LpCENH3 genes in ryegrass (Lolium spp.) and the mutants were completely male sterile. Jiang et al. [185] utilized CRISPR/Cas9 to create ZmTGA9-2/-3/-3 triple mutant and ZmMYB1-2/-10 double mutant, phenotypically showing complete male sterility. Chen et al. [186] used CRISPR/Cas9 to target edit AMS homologs in soybeans to produce stable male sterile lines. Targeted editing of GmAMS1 was found to result in a male sterile phenotype, whereas editing of GmAMS2 failed to produce male sterile lines. GmAMS1 plays a role not only in the formation of pollen walls, but also in controlling the degradation of soybean tapeworms. Jiang et al. [187] used CRISPR/Cas9 to edit Glyma.13G114200, and the phenotypes of pure plants from the two edited lines replicated the male sterility trait of MS1 mutant plants. Zhang et al. [41] edited the wheat TaDCL4, TaDCL5, and TaRDR6 genes, and succeeded in the creation of male sterile germplasm.

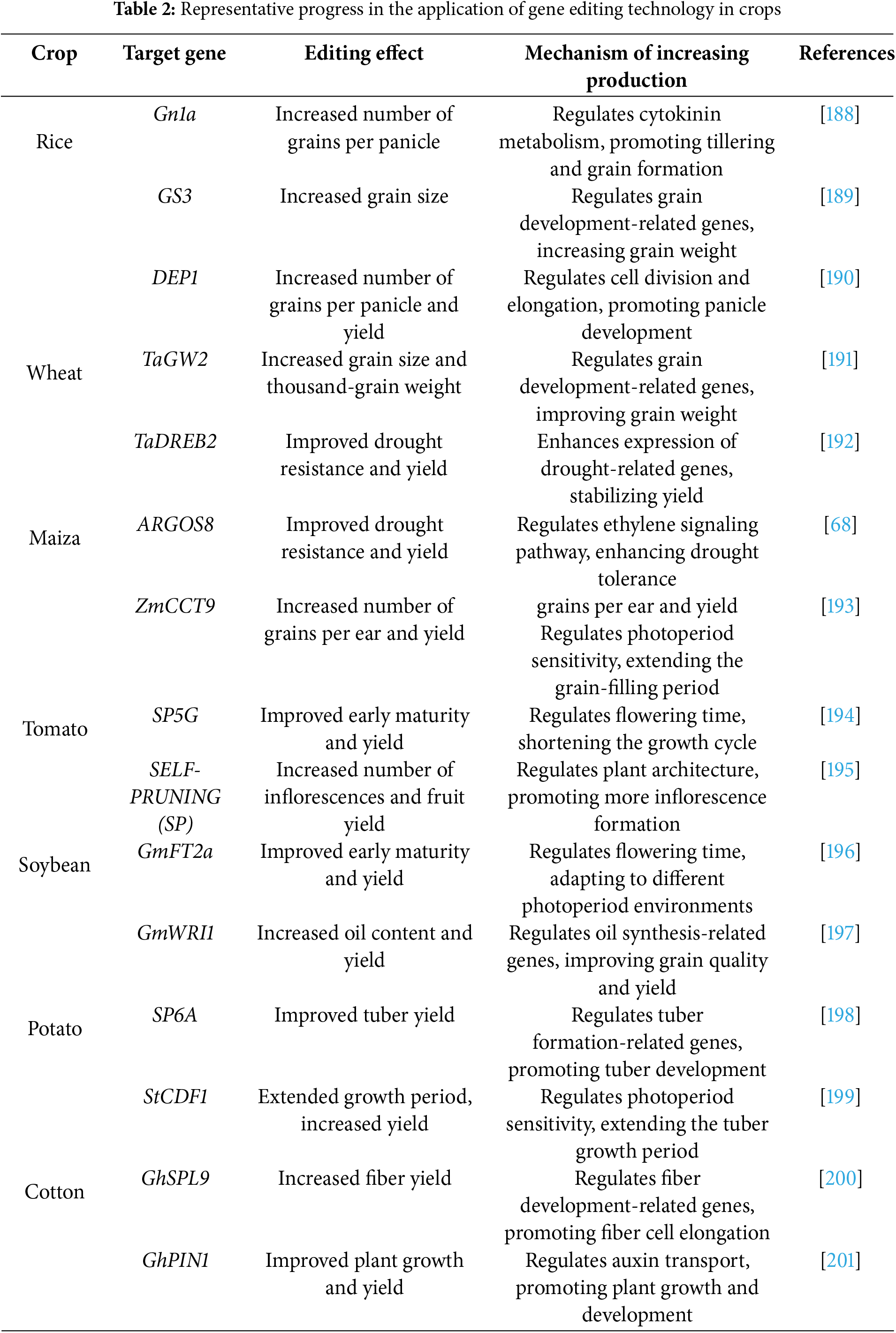

Hybridization advantage has been widely used in agricultural breeding to improve yield and quality. However, for commercial production of hybrid seeds, the self-pollination of the parent must be avoided to eliminate purebred seeds. Establishing male sterile lines in the parent line is the most efficient and practical method. Although many male sterile lines have been documented in different crops, converting male sterile lines to other genetic backgrounds is usually time-consuming and laborious. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology rapidly establishes male sterility in transformable lines—creating new male sterile germplasm by targeting multiple male sterility master genes (Table 2).

3 Conclusions and Future Directions

3.1 Development of Gene Editing Tool Delivery

The main advantages of CRISPR/Cas9 technology are low cost, simple design, high specificity, high efficiency, and the ability to edit a single gene multilocus or multiple genes simultaneously.

Since its introduction, CRISPR/Cas9 technology has gained immense popularity among researchers in the biological field. This technology has been successfully applied to improve various crops, including rice, soybean, corn, barley, and potato. It has been widely used to increase crop yield, improve crop quality, and enhance crop resistance to abiotic stresses [40,42,43].

Notably, researchers have made significant progress in developing more precise base editing and guide editing technologies based on Cas9 technology, in addition to the traditional CRISPR/Cas9 technology based on DNA double-strand breaks. These advancements have led to successful editing in crop genomes, although there are still challenges to overcome, such as the low efficiency of gene editing and a limited range of mutations. Nevertheless, as base editing continues to improve, it has the potential to create even more remarkable crop traits in the future. However, the delivery of genome editing tools to crops remains a challenge in the development of CRISPR/Cas9 technology for genome editing in crops.

Cao et al. [202] developed an extremely simple cut-dip-bud delivery system, which uses Agrobacterium rhizogenes to inoculate the explant to produce transformed roots, which then absorb nutrients to form transformed buds. The method is capable of efficient transformation or gene editing under nonsterile conditions using a very simple exosome impregnation protocol without the need for tissue culture.

3.2 Development and Application of Novel Gene Editing Tools

In crop genome families, when multiple genes have similar functions, it can be challenging to edit them accurately and efficiently. Additionally, editing multiple traits using multigene editing is a complex process. However, a study by Liu et al. suggests that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated tandem duplication knockdowns can help solve this problem. The study found that up to 80% of CRISPR-mediated TAG knockout alleles produced double alleles (deletion-inversion or delinver), which can lead to misinterpretation of experimental data and the production of genetically heterogeneous offspring. These delinver mutations are not limited to gene tandem duplications and can occur at nontandem duplication loci. The study also proposed a modified three-step polymerase chain reaction identification scheme to effectively identify delinver mutations [46–48].

To further improve the gene editing efficiency of base editing and guide editing, Zhang et al. [203] developed a multiple orthogonal base editor (MoBE) and a random multiple sgRNA assembly strategy to maximize gene diversity. MoBE efficiently induced orthogonal ABE editing (<36.6%), CBE editing (<36.0%), and ABE&CBE (<37.6%), while the sgRNA assembly strategy randomized base editing on different targets. Single or linked mutations for stronger herbicide resistance were obtained in the forward and reverse strands of exon 34 of rice acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (OsACC) at 130 and 84 target sites, respectively, and targeted evolution of OsACC was performed in rice using MoBE and randomized dual sgRNA libraries. These strategies are useful for the in situ–directed evolution of functional genes and may accelerate the process of trait improvement in rice. The key to expanding the use and development of base editing and guide editing in plant genomes is to improve their gene editing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects. Although CRISPR/Cas9 has shown promising results in crop breeding, there are still significant challenges that must be addressed before it can be widely adopted.

3.3 Future Development Direction of Gene Editing in Crop Molecular Breeding

When using gene editing tools, different crops show different editing effects due to differences in genome complexity, regeneration ability, genetic background and biological characteristics. For example, monocotyledonous plants such as rice and wheat often have high conversion efficiency and regenerative capacity, making tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 efficient for editing target genes; Dicotyledonous plants such as tomato and potato have strong regenerative ability, but their polyploid characteristics or complex metabolic pathways may cause the phenotypic changes after editing are not obvious. In addition, the application of gene editing in woody plants (such as fruit trees) is limited due to the difficulty of regeneration and long growth cycle. Therefore, editing tools, delivery methods and experimental conditions need to be optimized for the characteristics of different crops to achieve accurate and efficient gene editing.

The application of gene editing technology in crop molecular breeding faces multiple challenges, including off-target effects and low editing efficiency at the technical level, unclear policies and intellectual property disputes at the regulatory level, public acceptance and ecological risk concerns at the ethical and social level, and high research and development costs and market acceptance issues at the economic level. In addition, the complexity of polygene editing and the influence of genetic background also increase the difficulty of the application of the technology, while gene drift and long-term biosafety issues still need to be further studied and evaluated. These factors together restrict the wide application of gene editing technology in crop breeding. The future development direction of gene editing technology in crop molecular breeding will focus on improving editing accuracy and efficiency, and developing more advanced tools such as CRISPR/ Cas9 variants to reduce off-target effects; At the same time, the research on multi-gene editing and regulation of complex traits will be promoted to achieve an overall improvement in crop yield, stress resistance and nutritional quality. In addition, strengthen international cooperation and policy coordination, develop a clear regulatory framework, enhance public acceptance, and explore ecological risk assessment methods for gene-edited crops to ensure their safety and sustainability, and ultimately promote the widespread application and commercialization of gene editing technology in agriculture.

Acknowledgement: The National Engineering Research Center for Major Food Crops is thanked for its technical and instrumental support for this study.

Funding Statement: This study was financially supported by Jilin Provincial Department of Education (JJKH20230394KJ).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dao Yao and Junming Zhou; methodology, Yashuo Wang; software, Yuxin Li; validation, Junming Zhou; formal analysis, Xiaoyu Lu; investigation, Wenge Cheng; resources, Huijing Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Huijing Liu; writing—review and editing, Junming Zhou; supervision, Dao Yao; project administration, Huijing Liu; funding acquisition, Xiaoyu Lu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li F, Ma S, Liu X. Changing multi-scale spatiotemporal patterns in food security risk in China. J Clean Prod. 2023;384(6):135618. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao S, Li T, Wang G. Agricultural food system transformation on China’s food security. Foods. 2023;12(15):2906. doi:10.3390/foods12152906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Birhanu MY, Osei-Amponsah R, Yeboah Obese F, Dessie T. Smallholder poultry production in the context of increasing global food prices: roles in poverty reduction and food security. Anim Front. 2023;13(1):17–25. doi:10.1093/af/vfac069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tyczewska A, Twardowski T, Woźniak-Gientka E. Agricultural biotechnology for sustainable food security. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41(3):331–41. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.12.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Legendre M, Demirer GS. Improving crop genetic transformation to feed the world. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41(3):264–6. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.12.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Seay-Fleming C. Feed the futureland: an actor-based approach to studying food security projects. Agric Hum Values. 2023;40(4):1623–37. doi:10.1007/s10460-023-10460-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Snowdon RJ, Wittkop B, Chen TW, Stahl A. Crop adaptation to climate change as a consequence of long-term breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2021;134(6):1613–23. doi:10.1007/s00122-020-03729-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Godwin ID, Rutkoski J, Varshney RK, Hickey LT. Technological perspectives for plant breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132(3):555–7. doi:10.1007/s00122-019-03321-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu H, Zhang B. Virus-based CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in plants. Trends Genet. 2020;36(11):810–3. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2020.08.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ma X, Zhu Q, Chen Y, Liu YG. CRISPR/Cas9 platforms for genome editing in plants: developments and applications. Mol Plant. 2016;9(7):961–74. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2016.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li Y, Li W, Li J. The CRISPR/Cas9 revolution continues: from base editing to prime editing in plant science. J Genet Genomics. 2021;48(8):661–70. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2021.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Yin K, Gao C, Qiu JL. Progress and prospects in plant genome editing. Nat Plants. 2017;3(8):17107. doi:10.1038/nplants.2017.107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Qi Q, Hu B, Jiang W, Wang Y, Yan J, Ma F, et al. Advances in plant epigenome editing research and its application in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3442. doi:10.3390/ijms24043442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Gan WC, Ling APK. CRISPR/Cas9 in plant biotechnology: applications and challenges. BioTechnologia. 2022;103(1):81–93. doi:10.5114/bta.2022.113919. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao G, Pu J, Tang B. Applications of ZFN TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 techniques in disease modeling and gene therapy. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2016;33(6):857–62. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2016.06.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang H, Zhang J, Lang Z, Botella JR, Zhu JK. Genome editing—principles and applications for functional genomics research and crop improvement. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2017;36(4):291–309. doi:10.1080/07352689.2017.1402989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wani F, Rashid S, Wani S, Saleem Bhat S, Bhat S, Tufekci ED, et al. Applications of genome editing in plant virus disease management: crispr/Cas9 plays a central role. Can J Plant Pathol. 2023;45(5–6):463–74. doi:10.1080/07060661.2023.2215212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alok A, Sandhya D, Jogam P, Rodrigues V, Bhati KK, Sharma H, et al. The rise of the CRISPR/Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:264. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Jaganathan D, Ramasamy K, Sellamuthu G, Jayabalan S, Venkataraman G. CRISPR for crop improvement: an update review. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:985. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li JF, Norville JE, Aach J, McCormack M, Zhang D, Bush J, et al. Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):688–91. doi:10.1038/nbt.2654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Nekrasov V, Staskawicz B, Weigel D, Jones JDG, Kamoun S. Targeted mutagenesis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana using Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):691–3. doi:10.1038/nbt.2655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Shan Q, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Chen K, Liang Z, et al. Targeted genome modification of crop plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):686–8. doi:10.1038/nbt.2650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jacobs TB, LaFayette PR, Schmitz RJ, Parrott WA. Targeted genome modifications in soybean with CRISPR/Cas9. BMC Biotechnol. 2015;15(1):16. doi:10.1186/s12896-015-0131-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sha G, Sun P, Kong X, Han X, Sun Q, Fouillen L, et al. Genome editing of a rice CDP-DAG synthase confers multipathogen resistance. Nature. 2023;618(7967):1017–23. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06205-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li S, Lin D, Zhang Y, Deng M, Chen Y, Lv B, et al. Genome-edited powdery mildew resistance in wheat without growth penalties. Nature. 2022;602(7897):455–60. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04395-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Khanna K, Ohri P, Bhardwaj R. Nanotechnology and CRISPR/Cas9 system for sustainable agriculture. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(56):118049–64. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-26482-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Liu K, Sakuraba Y, Ohtsuki N, Yang M, Ueda Y, Yanagisawa S. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated elimination of OsHHO3, a transcriptional repressor of three AMMONIUM TRANSPORTER1 genes, improves nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(11):2169–72. doi:10.1111/pbi.14167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Chin HS, Wu YP, Hour AL, Hong CY, Lin YR. Genetic and evolutionary analysis of purple leaf sheath in rice. Rice. 2016;9(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12284-016-0080-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wu Y, Xiao N, Cai Y, Yang Q, Yu L, Chen Z, et al. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing of the OsHPPD 3' UTR confers enhanced resistance to HPPD-inhibiting herbicides in rice. Plant Commun. 2023;4(5):100605. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen H, Ye R, Liang Y, Zhang S, Liu X, Sun C, et al. Generation of low-cadmium rice germplasms via knockout of OsLCD using CRISPR/Cas9. J Environ Sci (China). 2023;126(3):138–52. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2022.05.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hui S, Li H, Mawia AM, Zhou L, Cai J, Ahmad S, et al. Production of aromatic three-line hybrid rice using novel alleles of BADH2. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20(1):59–74. doi:10.1111/pbi.13695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang J, Wu P, Li N, Xu X, Wang S, Chang S, et al. A male-sterile mutant with necrosis-like dark spots on anthers was generated in cotton. Front Plant Sci. 2023;13:1102196. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1102196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Gao X, Wheeler T, Li Z, Kenerley CM, He P, Shan L. Silencing GhNDR1 and GhMKK2 compromises cotton resistance to Verticillium wilt. Plant J. 2011;66(2):293–305. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04491.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Chen Y, Fu M, Li H, Wang L, Liu R, Liu Z, et al. High-oleic acid content, nontransgenic allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) generated by knockout of GhFAD2 genes with CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(3):424–6. doi:10.1111/pbi.13507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang M, Wei H, Hao P, Wu A, Ma Q, Zhang J, et al. GhGPAT12/25 are essential for the formation of anther cuticle and pollen exine in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:667739. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.667739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhu S, Yu X, Li Y, Sun Y, Zhu Q, Sun J. Highly efficient targeted gene editing in upland cotton using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3000. doi:10.3390/ijms19103000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Liu D, Yang H, Zhang Z, Chen Q, Guo W, Rossi V, et al. An elite γ-gliadin allele improves end-use quality in wheat. New Phytol. 2023;239(1):87–101. doi:10.1111/nph.18722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Errum A, Rehman N, Uzair M, Inam S, Ali GM, Khan MR. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of wheat Ppd-1 gene homoeologs alters spike architecture and grain morphometric traits. Funct Integr Genomics. 2023;23(1):66. doi:10.1007/s10142-023-00989-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Karmacharya A, Li D, Leng Y, Shi G, Liu Z, Yang S, et al. Targeting disease susceptibility genes in wheat through wide hybridization with maize expressing Cas9 and guide RNA. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2023;36(9):554–7. doi:10.1094/MPMI-01-23-0004-SC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Sun J, Bie XM, Chu XL, Wang N, Zhang XS, Gao XQ. Genome-edited TaTFL1-5 mutation decreases tiller and spikelet numbers in common wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1142779. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1142779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang R, Zhang S, Li J, Gao J, Song G, Li W, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of TaDCL4, TaDCL5 and TaRDR6 induces male sterility in common wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(4):839–53. doi:10.1111/pbi.14000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Yu H, Xiao A, Wu J, Li H, Duan Y, Chen Q, et al. GmNAC039 and GmNAC018 activate the expression of cysteine protease genes to promote soybean nodule senescence. Plant Cell. 2023;35(8):2929–51. doi:10.1093/plcell/koad129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Li H, Zhou R, Liu P, Yang M, Xin D, Liu C, et al. Design of high-monounsaturated fatty acid soybean seed oil using GmPDCTs knockout via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(7):1317–9. doi:10.1111/pbi.14060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zhou J, Li Z, Li Y, Zhao Q, Luan X, Wang L, et al. Effects of different gene editing modes of CRISPR/Cas9 on soybean fatty acid anabolic metabolism based on GmFAD2 family. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4769. doi:10.3390/ijms24054769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ding X, Guo J, Lv M, Wang H, Sheng Y, Liu Y, et al. The miR156b-GmSPL2b module mediates male fertility regulation of cytoplasmic male sterility-based restorer line under high-temperature stress in soybean. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(8):1542–59. doi:10.1111/pbi.14056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Liu T, Ji J, Cheng Y, Zhang S, Wang Z, Duan K, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of GmTAP1 confers enhanced resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. J Integr Plant Biol. 2023;65(7):1609–12. doi:10.1111/jipb.13476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Rangari SK, Kaur Sudha M, Kaur H, Uppal N, Singh G, Vikal Y, et al. DNA-free genome editing for ZmPLA1 gene via targeting immature embryos in tropical maize. GM Crops Food. 2023;14(1):1–7. doi:10.1080/21645698.2023.2197303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Li X, Cai Q, Yu T, Li S, Li S, Li Y, et al. ZmG6PDH1 in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase family enhances cold stress tolerance in maize. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1116237. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1116237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Chen C, Zhao Y, Tabor G, Nian H, Phillips J, Wolters P, et al. A leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase gene confers quantitative susceptibility to maize southern leaf blight. New Phytol. 2023;238(3):1182–97. doi:10.1111/nph.18781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Schneider HM, Lor VS, Zhang X, Saengwilai P, Hanlon MT, Klein SP, et al. Transcription factor bHLH121 regulates root cortical aerenchyma formation in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(12):e2219668120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2219668120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Niu Q, Shi Z, Zhang P, Su S, Jiang B, Liu X, et al. ZmMS39 encodes a callose synthase essential for male fertility in maize (Zea mays L.). Crop J. 2023;11(2):394–404. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2022.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wahner M. Genetic engineering in the food industry—contributions to global food security and importance for the value chain. Zuchtungskunde. 2023;95(2):130. [Google Scholar]

53. Kuizinaitė J, Morkūnas M, Volkov A. Assessment of the most appropriate measures for mitigation of risks in the agri-food supply chain. Sustainability. 2023;15(12):9378. doi:10.3390/su15129378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Arcese G, Fortuna F, Pasca MG. The sustainability assessments of the supply chain of agri-food products: the integration of socio-economic metrics. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2023;40:100782. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2023.100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Haque E, Taniguchi H, Hassan MM, Bhowmik P, Karim MR, Śmiech M, et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology for the improvement of crops cultivated in tropical climates: recent progress, prospects, and challenges. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:617. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Chen G, Zhou Y, Kishchenko O, Stepanenko A, Jatayev S, Zhang D, et al. Gene editing to facilitate hybrid crop production. Biotechnol Adv. 2021;46:107676. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zlobin NE, Lebedeva MV, Taranov VV. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing through in planta transformation. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020;40(2):153–68. doi:10.1080/07388551.2019.1709795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Ren D, Cui Y, Hu H, Xu Q, Rao Y, Yu X, et al. AH2 encodes a MYB domain protein that determines hull fate and affects grain yield and quality in rice. Plant J. 2019;100(4):813–24. doi:10.1111/tpj.14481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Dong S, Dong X, Han X, Zhang F, Zhu Y, Xin X, et al. OsPDCD5 negatively regulates plant architecture and grain yield in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(29):e2018799118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2018799118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Wang W, Wang W, Pan Y, Tan C, Li H, Chen Y, et al. A new gain-of-function OsGS2/GRF4 allele generated by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing increases rice grain size and yield. Crop J. 2022;10(4):1207–12. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2022.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Wang Y, Yue J, Yang N, Zheng C, Zheng Y, Wu X, et al. An ERAD-related ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme boosts broad-spectrum disease resistance and yield in rice. Nat Food. 2023;4(9):774–87. doi:10.1038/s43016-023-00820-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Yan P, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Ma F, Lan D, Niu F, et al. A new RING finger protein, PLANT ARCHITECTURE and GRAIN NUMBER 1, affects plant architecture and grain yield in rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):824. doi:10.3390/ijms23020824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Kitomi Y, Hanzawa E, Kuya N, Inoue H, Hara N, Kawai S, et al. Root angle modifications by the DRO1 homolog improve rice yields in saline paddy fields. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21242–50. doi:10.1073/pnas.2005911117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Gao Q, Li G, Sun H, Xu M, Wang H, Ji J, et al. Targeted mutagenesis of the rice FW 2.2-like gene family using the CRISPR/Cas9 system reveals OsFWL4 as a regulator of tiller number and plant yield in rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):809. doi:10.3390/ijms21030809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Zeng Y, Wen J, Zhao W, Wang Q, Huang W. Rational improvement of rice yield and cold tolerance by editing the three genes OsPIN5b, GS3, and OsMYB30 with the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Front Plant Sci. 2020;10:1663. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Cai Z, Xian P, Cheng Y, Ma Q, Lian T, Nian H, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing of GmJAGGED1 increased yield in the low-latitude soybean variety Huachun 6. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(10):1898–900. doi:10.1111/pbi.13673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Liu S, Liu J, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Hu S, Shi A, et al. Cloning of the soybean sHSP26 gene and analysis of its drought resistance. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2022;91(7):1465–82. doi:10.32604/phyton.2022.018836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Shi J, Gao H, Wang H, Lafitte HR, Archibald RL, Yang M, et al. ARGOS8 variants generated by CRISPR-Cas9 improve maize grain yield under field drought stress conditions. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(2):207–16. doi:10.1111/pbi.12603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Liu L, Gallagher J, Arevalo ED, Chen R, Skopelitis T, Wu Q, et al. Enhancing grain-yield-related traits by CRISPR-Cas9 promoter editing of maize CLE genes. Nat Plants. 2021;7(3):287–94. doi:10.1038/s41477-021-00858-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zheng M, Zhang L, Tang M, Liu J, Liu H, Yang H, et al. Knockout of two BnaMAX1 homologs by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis improves plant architecture and increases yield in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(3):644–54. doi:10.1111/pbi.13228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Brant EJ, Baloglu MC, Parikh A, Altpeter F. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated targeted mutagenesis of LIGULELESS-1 in sorghum provides a rapidly scorable phenotype by altering leaf inclination angle. Biotechnol J. 2021;16(11):e2100237. doi:10.1002/biot.202100237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zhang J, Zhang H, Li S, Li J, Yan L, Xia L. Increasing yield potential through manipulating of an ARE1 ortholog related to nitrogen use efficiency in wheat by CRISPR/Cas9. J Integr Plant Biol. 2021;63(9):1649–63. doi:10.1111/jipb.13151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Dahleen LS, Stuthman DD, Rines HW. Agronomic trait variation in oat lines derived from tissue culture. Crop Sci. 1991;31(1):90–4. doi:10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100010023x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Davies JP, Christensen CA. Developing transgenic agronomic traits for crops: targets, methods, and challenges. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1864(11):343–65. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-8778-8_22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Nguyen KL, Grondin A, Courtois B, Gantet P. Next-generation sequencing accelerates crop gene discovery. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24(3):263–74. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2018.11.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Han Y, Teng K, Nawaz G, Feng X, Usman B, Wang X, et al. Generation of semi-dwarf rice (Oryza sativa L.) lines by CRISPR/Cas9-directed mutagenesis of OsGA20ox2 and proteomic analysis of unveiled changes caused by mutations. 3 Biotech. 2019;9(11):387. doi:10.1007/s13205-019-1919-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Zhu Y, Li T, Xu J, Wang J, Wang L, Zou W, et al. Leaf width gene LW5/D1 affects plant architecture and yield in rice by regulating nitrogen utilization efficiency. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;157(11):359–69. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.10.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Xu Y, Wang F, Chen Z, Wang J, Li W, Fan F, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the OsROS1 gene induces pollen and embryo sac defects in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(10):1999–2001. doi:10.1111/pbi.13388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Cui J, Nishide N, Mashiguchi K, Kuroha K, Miya M, Sugimoto K, et al. Fertilization controls tiller numbers via transcriptional regulation of a MAX1-like gene in rice cultivation. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3191. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38670-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Qing D, Chen W, Huang S, Li J, Pan Y, Zhou W, et al. Editing of rice (Oryza sativa L.) OsMKK3 gene using CRISPR/Cas9 decreases grain length by modulating the expression of photosystem components. Proteomics. 2023;23(18):e2200538. doi:10.1002/pmic.202200538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Bao A, Chen H, Chen L, Chen S, Hao Q, Guo W, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of GmSPL9 genes alters plant architecture in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):131. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-1746-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Cheng Q, Dong L, Su T, Li T, Gan Z, Nan H, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of GmLHY genes alters plant height and internode length in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):562. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-2145-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Zhong X, Hong W, Shu Y, Li J, Liu L, Chen X, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene-editing of GmHdz4 transcription factor enhances drought tolerance in soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:988505. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.988505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Mu R, Lyu X, Ji R, Liu J, Zhao T, Li H, et al. GmBICs modulate low blue light-induced stem elongation in soybean. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:803122. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.803122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Zhang J, Zhang X, Chen R, Yang L, Fan K, Liu Y, et al. Generation of transgene-free semidwarf maize plants by gene editing of Gibberellin-Oxidase20-3 using CRISPR/Cas9. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1048. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.01048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Zhang Z, Zhang X, Lin Z, Wang J, Liu H, Zhou L, et al. A large transposon insertion in the stiff1 promoter increases stalk strength in maize. Plant Cell. 2020;32(1):152–65. doi:10.1105/tpc.19.00486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Qiang Z, Sun H, Ge F, Li W, Li C, Wang S, et al. The transcription factor ZmMYB69 represses lignin biosynthesis by activating ZmMYB31/42 expression in maize. Plant Physiol. 2022;189(4):1916–9. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiac233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Liu X, Zhang S, Jiang Y, Yan T, Fang C, Hou Q, et al. Use of CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing to simultaneously mutate multiple homologous genes required for pollen development and male fertility in maize. Cells. 2022;11(3):439. doi:10.3390/cells11030439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Gupta A, Hua L, Zhang Z, Yang B, Li W. CRISPR-induced miRNA156-recognition element mutations in TaSPL13 improve multiple agronomic traits in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(3):536–48. doi:10.1111/pbi.13969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Karunarathne SD, Han Y, Zhang XQ, Li C. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and natural variation analysis demonstrate the potential for HvARE1 in improvement of nitrogen use efficiency in barley. J Integr Plant Biol. 2022;64(3):756–70. doi:10.1111/jipb.13214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Cheng J, Hill C, Han Y, He T, Ye X, Shabala S, et al. New semi-dwarfing alleles with increased coleoptile length by gene editing of gibberellin 3-oxidase 1 using CRISPR-Cas9 in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(4):806–18. doi:10.1111/pbi.13998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Li R, Fu D, Zhu B, Luo Y, Zhu H. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of lncRNA1459 alters tomato fruit ripening. Plant J. 2018;94(3):513–24. doi:10.1111/tpj.13872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Gomez MA, Lin ZD, Moll T, Chauhan RD, Hayden L, Renninger K, et al. Simultaneous CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of cassava eIF4E isoforms nCBP-1 and nCBP-2 reduces cassava brown streak disease symptom severity and incidence. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17(2):421–34. doi:10.1111/pbi.12987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Shao X, Wu S, Dou T, Zhu H, Hu C, Huo H, et al. Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system to create MaGA20ox2 gene-modified semi-dwarf banana. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(1):17–9. doi:10.1111/pbi.13216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Hu C, Sheng O, Deng G, He W, Dong T, Yang Q, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of MaACO1 (aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 1) promotes the shelf life of banana fruit. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(4):654–6. doi:10.1111/pbi.13534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Shen C, Zhang Y, Li Q, Liu S, He F, An Y, et al. PdGNC confers drought tolerance by mediating stomatal closure resulting from NO and H2 O2 production via the direct regulation of PdHXK1 expression in Populus. New Phytol. 2021;230(5):1868–82. doi:10.1111/nph.17301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Fan S, Zhang L, Tang M, Cai Y, Liu J, Liu H, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the BnaA03.BP gene confers semi-dwarf and compact architecture to rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(12):2383–5. doi:10.1111/pbi.13703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Beyene G, Chauhan RD, Villmer J, Husic N, Wang N, Gebre E, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Tetra-allelic mutation of the ‘Green Revolution’ SEMIDWARF-1 (SD-1) gene confers lodging resistance in tef (Eragrostis tef). Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20(9):1716–29. doi:10.1111/pbi.13842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. An G, Qi Y, Zhang W, Gao H, Qian J, Larkin RM, et al. LsNRL4 enhances photosynthesis and decreases leaf angles in lettuce. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20(10):1956–67. doi:10.1111/pbi.13878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. He Q, Zhou G, Liu J. Progress in studies of climatic suitability of crop quality and resistance mechanisms in the context of climate warming. Agronomy. 2022;12(12):3183. doi:10.3390/agronomy12123183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Yang Y, Xu C, Shen Z, Yan C. Crop quality improvement through genome editing strategy. Front Genome Ed. 2021;3:819687. doi:10.3389/fgeed.2021.819687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Liu Q, Yang F, Zhang J, Liu H, Rahman S, Islam S, et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in crop quality improvement. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):4206. doi:10.3390/ijms22084206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Rillig MC, Lehmann A. Exploring the agricultural parameter space for crop yield and sustainability. New Phytol. 2019;223(2):517–9. doi:10.1111/nph.15744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Zhang J, Zhang H, Botella JR, Zhu JK. Generation of new glutinous rice by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the Waxy gene in elite rice varieties. J Integr Plant Biol. 2018;60(5):369–75. doi:10.1111/jipb.12620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Tang Y, Abdelrahman M, Li J, Wang F, Ji Z, Qi H, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 induces exon skipping that facilitates development of fragrant rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(4):642–4. doi:10.1111/pbi.13514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Wang S, Yang Y, Guo M, Zhong C, Yan C, Sun S. Targeted mutagenesis of amino acid transporter genes for rice quality improvement using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Crop J. 2020;8(3):457–64. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2020.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Huang L, Li Q, Zhang C, Chu R, Gu Z, Tan H, et al. Creating novel Wx alleles with fine-tuned amylose levels and improved grain quality in rice by promoter editing using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(11):2164–6. doi:10.1111/pbi.13391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Biswas S, Ibarra O, Shaphek M, Molina-Risco M, Faion-Molina M, Bellinatti-Della Gracia M, et al. Increasing the level of resistant starch in ‘Presidio’ rice through multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing of starch branching enzyme genes. Plant Genome. 2023;16(2):e20225. doi:10.1002/tpg2.20225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Tian Y, Zhou Y, Gao G, Zhang Q, Li Y, Lou G, et al. Creation of two-line fragrant glutinous hybrid rice by editing the Wx and OsBADH2 genes via the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(1):849. doi:10.3390/ijms24010849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Li C, Nguyen V, Liu J, Fu W, Chen C, Yu K, et al. Mutagenesis of seed storage protein genes in Soybean using CRISPR/Cas9. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):176. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4207-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Zhang G, Bahn SC, Wang G, Zhang Y, Chen B, Zhang Y, et al. PLDα1-knockdown soybean seeds display higher unsaturated glycerolipid contents and seed vigor in high temperature and humidity environments. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13068-018-1340-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]