Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mitochondrial Genomic Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Wild Rapeseed Rorippa indica

1 Department of Biological Technology, Nanchang Normal University, Nanchang, 330032, China

2 Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Poultry Genetic Improvement, Nanchang Normal University, Nanchang, 330032, China

* Corresponding Author: Wentao Sheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Organelles Comparative Genomics and DNA Systematics)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 2015-2031. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.066232

Received 02 April 2025; Accepted 04 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Rorippa indica is a wild oilseed crop of Brassicaceae with good environmental adaptability and strong stress resistance. This plant has become an important wild relative species for rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) and is used to improve its agronomic traits, with important development and utilization value. However, the research of R. indica genetics is still lacking. And no mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) in the genus Rorippa has been expounded. To analyze the structural characteristics of the R. indica mitogenome, second-generation and third-generation sequencing techniques were made to assemble its mitogenome. The results showed that its mitogenome is composed of a single master circle DNA molecule, with 59 genes (33 protein-coding, 23 tRNA, and 3 ribosomal RNA genes) annotated. The length of the circular genome is 219,775 bp, with a GC content of 45.24%. The mitochondrial genome contains 55 SSRs, 17 tandem repeats, and 252 scattered repeat sequences, with scattered repeat sequences accounting for 77.78%. The top two codons with the highest expression levels are TTT and AUU. Moreover, 377 RNA editing sites were forecasted in the R. indica mitogenome. And 22 collinear gene fragments were discriminated in the R. indica chloroplast and mitogenomes, with a total 13,153 bp length, accounting for 4.08% of the mitogenome sequence. The longest gene migration fragment is 2186 bp, and the shortest fragment is 42 bp. Furthermore, 12 genes undergo complete migration between the two genomes, and 10 genes undergo partial migration. Systematic evolutionary analysis shows that R. indica and Brassica napus are grouped, indicating a close genetic relationship between the two. Herein, the R. indica mitogenome was sequenced and annotated, and it was compared with other Brassicaceae mitogenomes. A genomic data foundation was supplied for elucidating the R. indica origin and evolution.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileMitochondria are the energy powerhouses of plant cells and are semi-autonomous organelles coming of prokaryotes through endosymbiosis, containing the genetic material necessary for cellular functions [1,2]. Unlike the dual lineage inheritance of the nuclear genome, mitochondrial genome DNA (mtDNA) is typically inherited through the maternal lineage, hence it is also known as the cytoplasmic genome [3]. Due to the genetic diversity and the restriction of biparental inheritance limiting cross-recombination, the plant cytoplasmic genome has served as an important material in plant systematic studies, crop domestication tracing, plant breeding, and plant genetic engineering [4–6]. Mitochondria are the primary site of respiration in living organisms, and mtDNA is a double-stranded DNA molecule, mainly in a closed circular structure [7]. To date, the mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) of over 1,595,364 animals have been registered, but only 309,132 complete plant mitogenome sequences and 314,312 entire fungi mitogenome sequences have been reported (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse#!/organelles/, accessed on 25 March 2025). Among these, the animal mitogenome size ranges from 14 to 39 kb, fungal mitogenomes from 17 to 176 kb, while plant mitochondrial genomes mainly range from 200 to 2500 kb, exhibiting greater complexity [8,9]. As an extranuclear genetic system, the mtDNA genome is characterized by polymorphism, semi-autonomy, and possessing a unique expression system, but it contains relatively few genes and has a limited variety of synthesized proteins, thus requiring coordination with nuclear genes to participate in normal biological functions [10]. Organelle DNA is primarily maternally inherited, and most higher plant chloroplast genomes owned little homologous recombination, showing conservation in gene number, order, and composition [11]. In contrast, mitogenomes show a high degree of conservation in gene composition, are relatively larger than chloroplast genomes, exhibit significant structural variation, and contain abundant repeat sequences, providing extensive phylogenetic information and addressing classification and identification issues among closely related species [12,13].

In rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) and many vegetables belonging to the Brassicaceae family, a wealth of genetic resources with many advantageous traits are available for crop genetic improvement, such as disease and pest resistance, salt and alkali tolerance, drought resistance, moisture tolerance, and high oil content, making it a valuable gene pool that is significant for the genetic improvement and germplasm innovation of Brassicaceae crops like rapeseed [14]. Rorippa indica (L.) Hiern is a biennial herbaceous plant belonging to the genus Rorippa in Brassicaceae, commonly known as wild rapeseed, which possesses excellent traits such as good resistance and a high seed set rate, with an average of over 70 seeds per pod, significantly higher than that of ordinary rapeseed varieties, marking it as a highly valuable genetic resource [15,16]. R. indica also exhibits high resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary, a significant disease that restricts global rapeseed production, particularly severe in China’s main winter rapeseed production areas [17,18]. Many researchers have introduced the excellent traits of R. indica into rapeseed through distant hybridization and protoplast fusion, creating new germplasm resources, aiming to provide intermediate materials for the genetic improvement of rapeseed varieties, which not only benefits the yield and stability of rapeseed but also holds significance for ensuring the secure supply of plant oils [19,20]. However, the R. indica mitogenome has not been reported, and the mechanisms, evolutionary characteristics, and genetic diversity of its superior traits remain unclear. Thus, the aims of this study were to: (1) supply newly sequenced complete mitogenomes for the genus Rorippa and understand their overall genome structures; (2) compare these reported mitogenomes and identify highly divergent regions for the genus Rorippa; (3) reconstruct phylogeny using the mitogenome protein-coding gene (PCG) sequences in the Brassicaceae family.

Samples were obtained from R. indica on the campus of Nanchang Normal University, Changbei Campus (81°17′56.52″ E, 40°32′36.90″ N). One gram of healthy and tender leaves from the upper middle part of ten individual plants was selected, preserved in liquid nitrogen, and its genomic DNA was extracted.

2.2 Construction and Sequencing of Genomic Libraries

The Covaris ultrasonic disruptor was used to fragment the qualified DNA, and magnetic beads were used to enrich and purify the large fragment DNA. Damaged DNA was repaired and underwent end repair. The ends of the sequence were linked to stem loops, and unacceptable sequences were removed using exonucleases. The constructed library was sequenced with Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (San Diego, CA, USA) and Oxford Nanopore PromethION (Oxford, UK).

2.3 Mitochondrial Genome Assembly

A combination of Illumina and Nanopore strategies was used to assemble the mitogenome. Specifically, loRDEC was first used to correct errors in Nanopore sequencing data using Illumina data [21]. Then, GetOrganelle was used to extract the chloroplast genome from Illumina sequencing data as a reference chloroplast genome [22]. Next, Minimap2 was made to align Nanopore data to the chloroplast genome, and the matching parts were removed to exclude interference from the chloroplast genome during assembly [23]. Finally, using rapeseed as the mitochondrial reference genome (NC_008285.1), the aligned parts were extracted. The extracted data were assembled into the mitogenome using GetOrganelle [22], Canu [24], and Spades [25]. The second-generation data in Spades came from GetOrganelle [22], and the third-generation data were the mitochondrial parts aligned with Minimap2 [23]. Geneious was used for alignment analysis to check overlaps and fill gaps [26].

2.4 Mitochondrial Gene Annotation

MitoFinder (https://github.com/RemiAllio/MitoFinder, accessed on 25 March 2025) were used for annotation with default settings, employing tRNA scan-SE to annotate tRNA (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/, accessed on 25 March 2025). Geneious was utilized to manually correct annotation issues [26] and OGDRAW (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/OGDraw.html, accessed on 25 March 2025) was made to draw genomic maps [27].

Microsatellite repeats were discriminated with MISAv2.1 (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/index.php?action=1, accessed on 25 March 2025) with parameters ‘1-10 2-5 3-4 4-3 5-3 6-3’. Tandem repeat sequences were checked using TRF with parameters: ‘2 7 7 80 10 50 500 -f -d -m’ [28]. Dispersed repeats were checked with REPute (https://bibiserv.ebitec.uni-biele-feld.de/recorter/, accessed on 25 March 2025) using hamming distance, 3; maximum computed repeats, 5000; minimal repeat size, 30; e-value 1e−4 [29]. Finally, the repeats were visualized with the Circos2D software implemented in TBtools [30,31].

2.6 Mitochondrial PCGs Selection Pressure Analysis

The value of non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitutions is significant for reconstructing the phylogeny and understanding the PCGs dynamics among closely related species [32]. To analyze the Ks and Ka substitution rates in the R. indica mitogenome PCGs and other higher plants (Arabidopsis thaliana, OW119601.1; Brassica napus, NC_008285.1; Cardamine chenopodiifolia, OZ000492.1; Draba incana, OY755218.1; Hirschfeldia incana, CM048459.1; Lepidium didymium, OY986989.1; Raphanus sativus, NC_018551.1; and Sinapis arvensis, NC_031896.1) were selected as references. The corresponding PCGs from the R. indica mitogenome and these references were extracted and aligned using Clustal W [33]. The PCG substitution rates were calculated in DnaSP v5 [34].

2.7 Codon Usage Preference and Mitochondrial RNA Editing Analysis

Codon usage preference analysis was conducted using the Sequence Manipulation Suite online tool (http://wheatomics.sdau.edu.cn/sms2/about.html, accessed on 25 March 2025), and the output results were stored as tables for statistical analysis in Excel. RNA editing is a post-transcriptional modification that transforms the genetic information of mRNA [35]. Mitochondrial RNA editing sites were estimated with an online tool (http://www.prepact.de/prepact-main.php, accessed on 25 March 2025).

2.8 Horizontal Gene Transfer between Organelles in R. indica

The sequence similarity between the chloroplast and mitogenome was utilized to appraise homologous sequences. BLASTN was applied with an e-value cutoff of 1e−5 [36]. The homology was visualized with the Circos software in TBtools [31]. The homology sequences between the chloroplast and mitochondria were searched with Blast, with similarity set to 70% and E-value to 1e−5 [36]. To represent homologous segments between the chloroplast and mitogenomes, Circos v0.69-5 was used for visualization (https://circos.ca/software/download/, accessed on 25 March 2025).

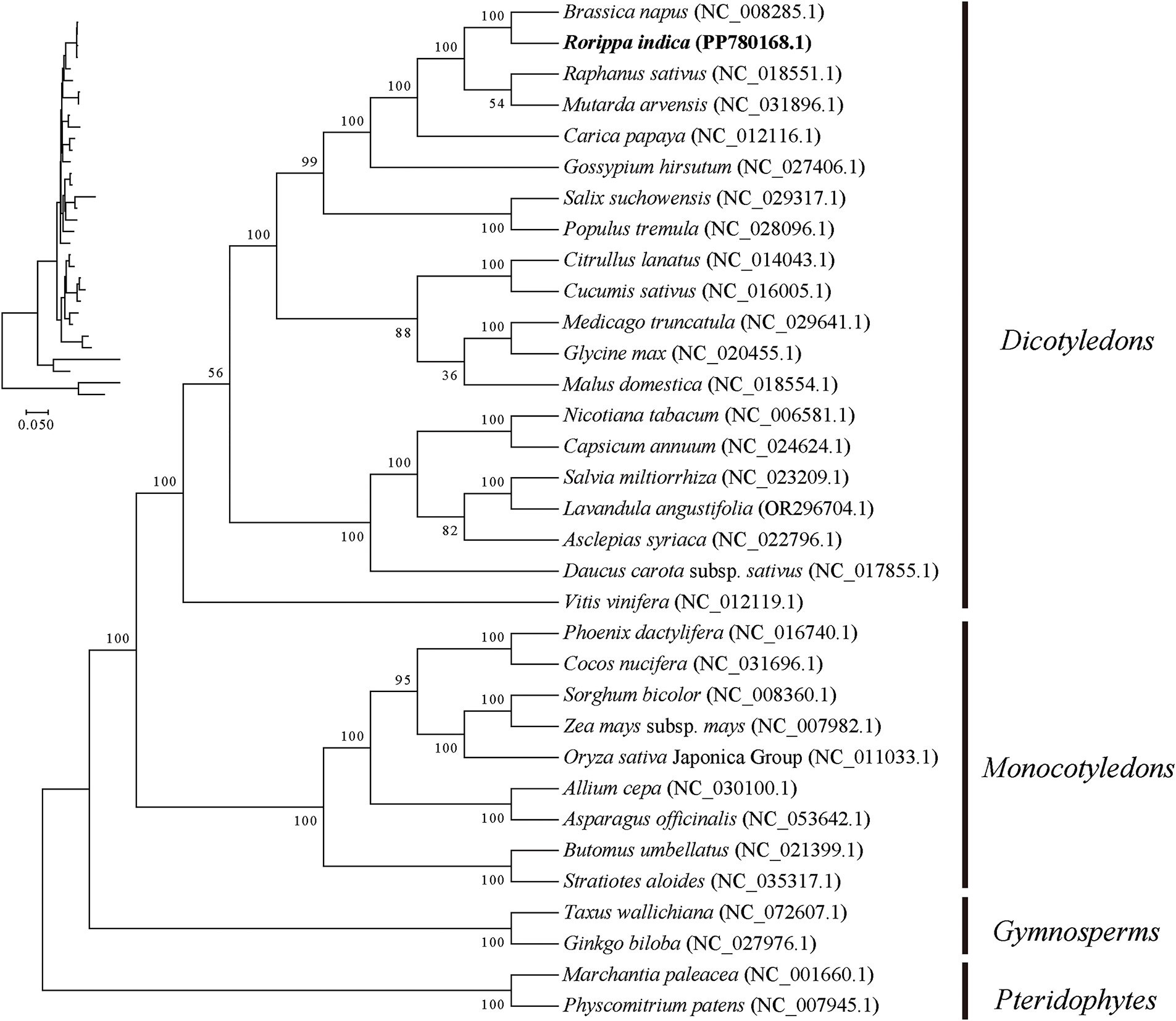

2.9 Phylogenetic Analysis Based on Mitogenome Sequences

In this study, 30 mitochondrial PCGs were extracted from the 33 species mitogenomes for analysis. MAFFT was used for alignment [37], trimAL for trimming [38], and concatenate sequence for concatenated alignment. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree was built with the coding genes (CDS), with interspecies sequences aligned using MAFFT software, then concatenated and trimmed. The model was estimated with jmodeltest-2.1.10 software, determining it to be of GTR type [39], and then RAxML v8.2.10 software was made to construct the ML evolutionary tree [40].

3.1 R. indica Mitogenome Basic Characteristics

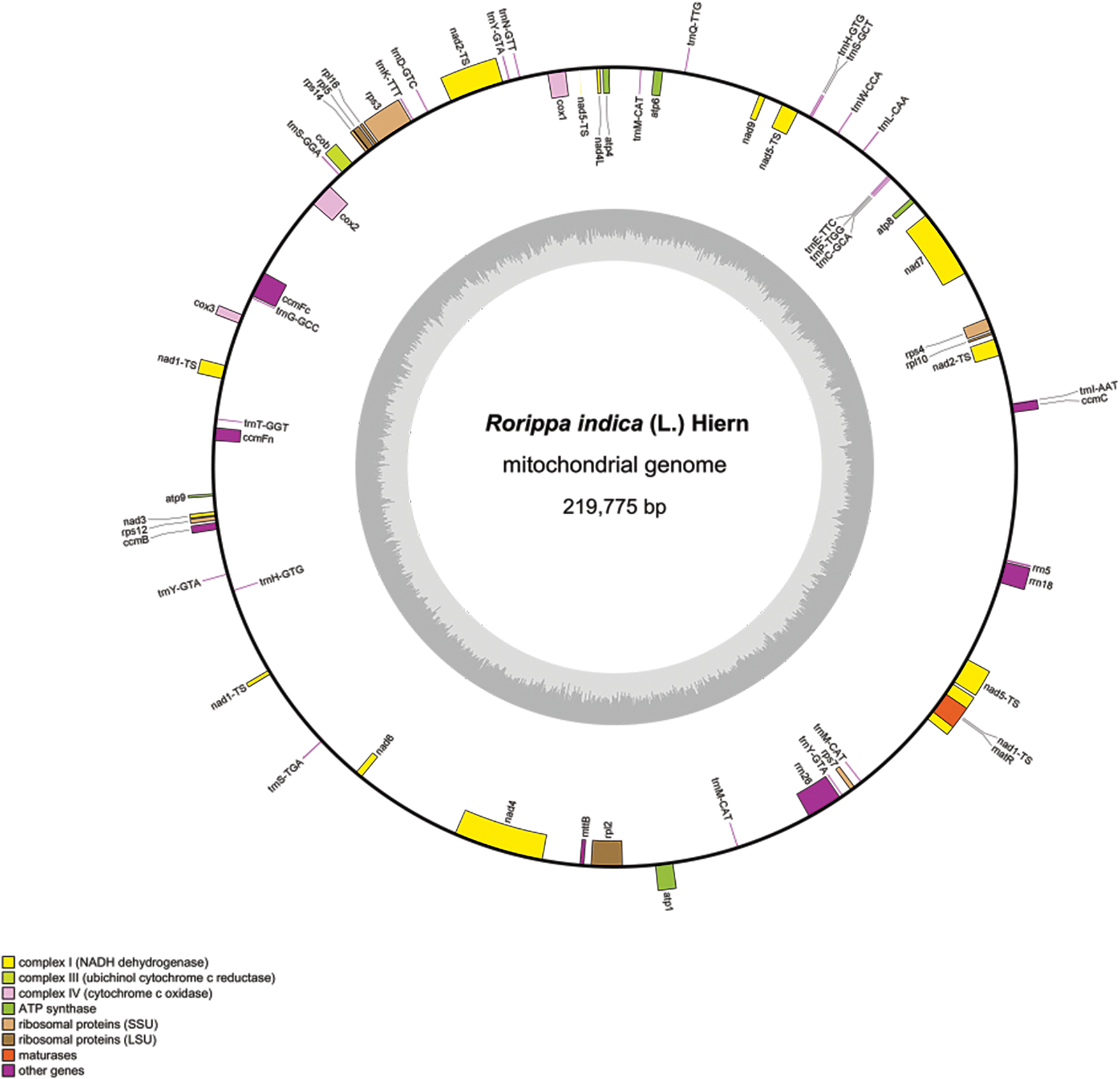

The results indicate that the R. indica mitogenome is assembled into a typical single circular molecule, with a 219,775 bp length and a NCBI accession number of PP780168.1 (Fig. 1). The mitogenome contains 59 functional genes, mostly composing of inter-genic regions, and the gene sequences occupying only a small proportion. The mitogenome comprises three rRNA genes (0.26%) and 21 tRNA genes (0.84%), along with 33 PCGs (7.89%). And no succinate dehydrogenase (sdh3 and sdh4) genes were found. Based on their functions, the 33 PCGs can be classified into 10 categories. Most genes in the mitogenome are single-copy genes, with three tRNA genes (trnH-GTG, trnM-CAT and trnY-GTA), having multiple copies. Moreover, 11 genes contain introns. Rps3, rpl2, cox2, ccmFc, trnI-AAT, and trnT-GGT had one intron. Meanwhile, nad1, nad2, nad4, nad5, and nad7 owned four introns (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, the longest PCG is NADH dehydrogenase gene (nad5) with a 2010 bp length, the second longest PCG is Maturases (matR) with a 1974 bp length, and the shortest PCGs are ATP synthase gene (atp9) and ribosomal protein gene (rpl10) with a length of 225 bp each (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1: Rorippa indica mitogenome map

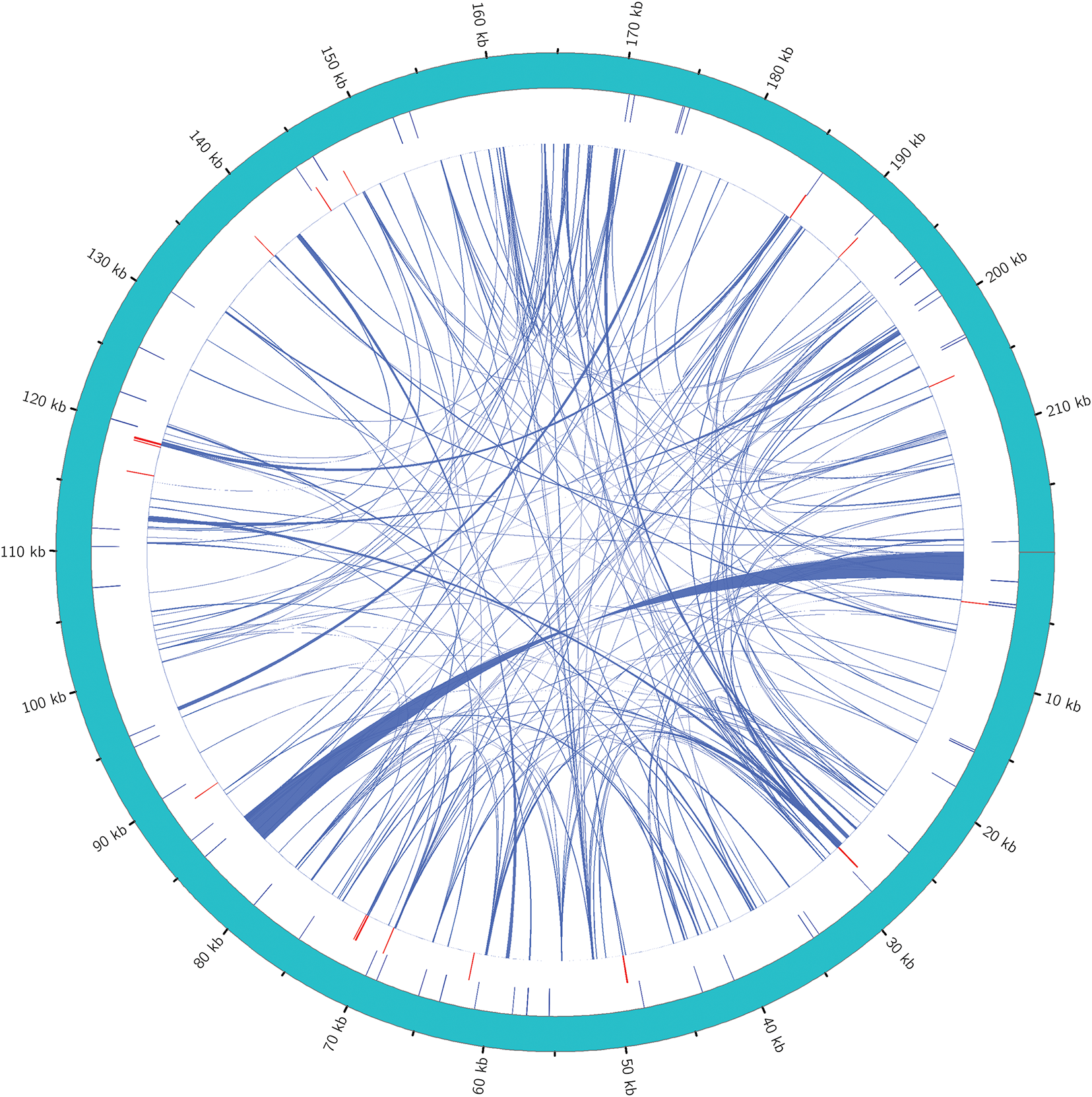

The total simple sequence repeats (SSRs) number in the R. indica mitogenome is 55, while the total SSR number in the chloroplast genome is 315 (PP780169.1). Compared to the chloroplast, mitochondrial SSR loci are relatively few. According to the statistics of repeat types, the most common type is the mononucleotide repeat type, with a total of 20, accounting for 36.36% of all repeat sequences, among which the A base repeat is the most abundant, with 12 occurrences. And 18 mononucleotide repeats are combinations of A or T, and only two is a combination of C. The next most common type is the tetranucleotide repeat type, with a total of 18, accounting for 32.72% of all repeat sequences. The least frequent is the pentanucleotide repeat type, with only one occurrence, and no hexanucleotides were detected. Tandem repeats exist in the DNA of all sequenced organisms. These sequences consist of multiple contiguous repeat units, and due to their tendency to gain or lose repeat units, showing extremely high mutation rates [41]. In this study, 17 repeated sequences were found across the mitogenome (Supplementary Table S3), with tandem repeat sequences ranging in size from 3 to 39 bp and a repetition range from 1.9 to 8.3 times. In the mitogenome, 253 dispersed repeat sequences were identified, including 108 forward repeat sequences and 144 palindromic repeat sequences. They account for 42.85% and 57.15% of all dispersed repeats, respectively. The lengths of dispersed repeats range from 29 to 2427 bp, with only 20 sequences longer than 100 bp (Supplementary Table S4), indicating that most of the repeats in the R. indica mitogenome are small fragments. In summary, 55 SSRs, 17 tandem repeats, and 253 dispersed repeats were checked in the R. indica mitogenome (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Repeat sequence distribution in Rorippa indica mitogenome

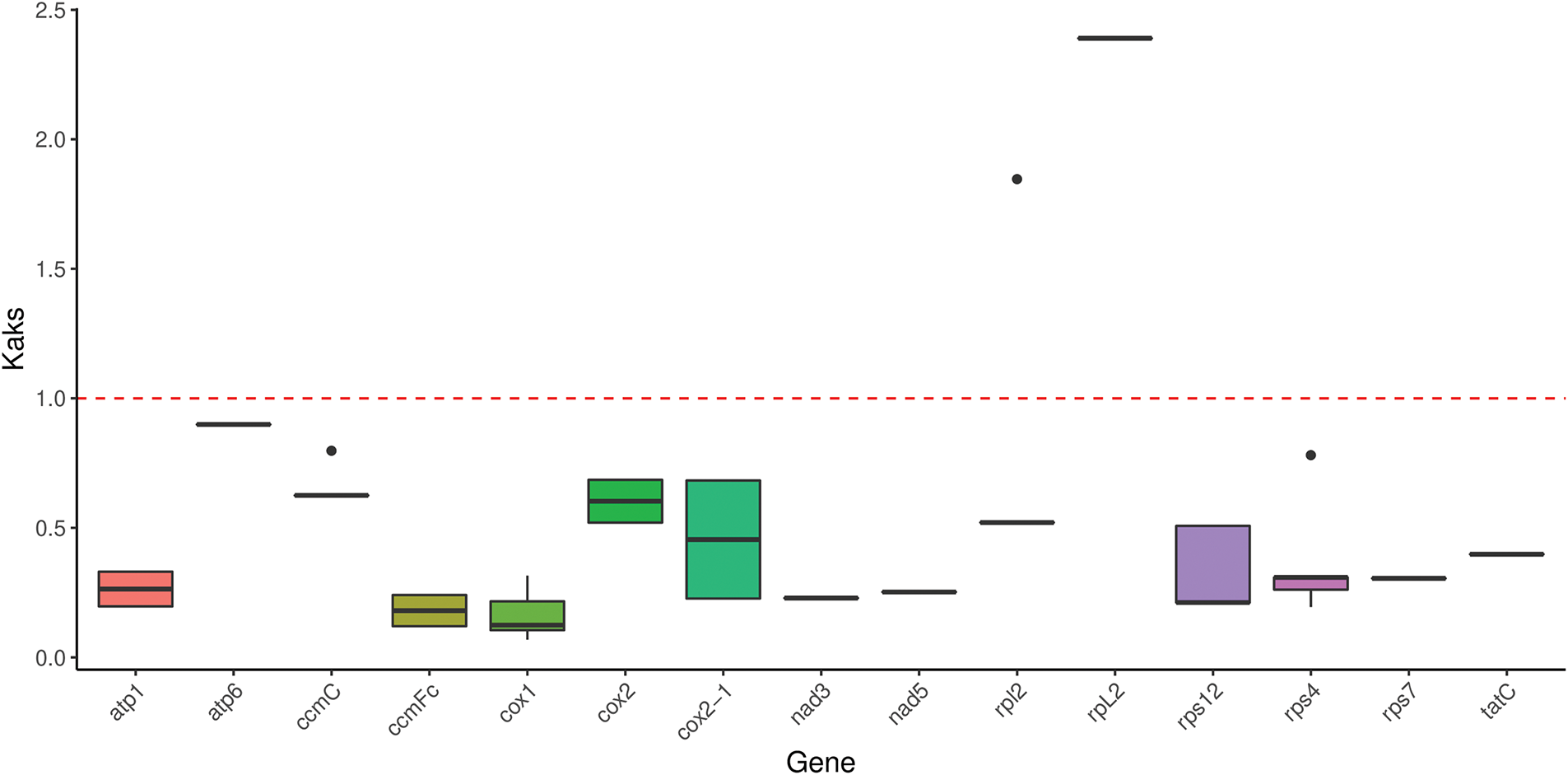

3.3 Selection Pressure on Mitochondrial PCGs

In genetics, the rates of Ka and Ks are significant for understanding the PCGs evolutionary dynamics. It is well known that when Ka/Ks equals one, indicating neutral evolution; when Ka/Ks is greater than one, showing positive selection; and when Ka/Ks is less than one, demonstrating negative selection [42]. In this study, 15 PCGs from the mitogenomes were used to count the substitution rates of Ka and Ks for the R. indica mitogenome. As shown in Fig. 3, the ratio of Ka/Ks in most PCGs is significantly less than one, indicating negative selection during evolution. In conclusion, this study concludes that mitochondrial genes are highly conserved in Brassicaceae.

Figure 3: Ka/Ks value in Rorippa indica mitogenome

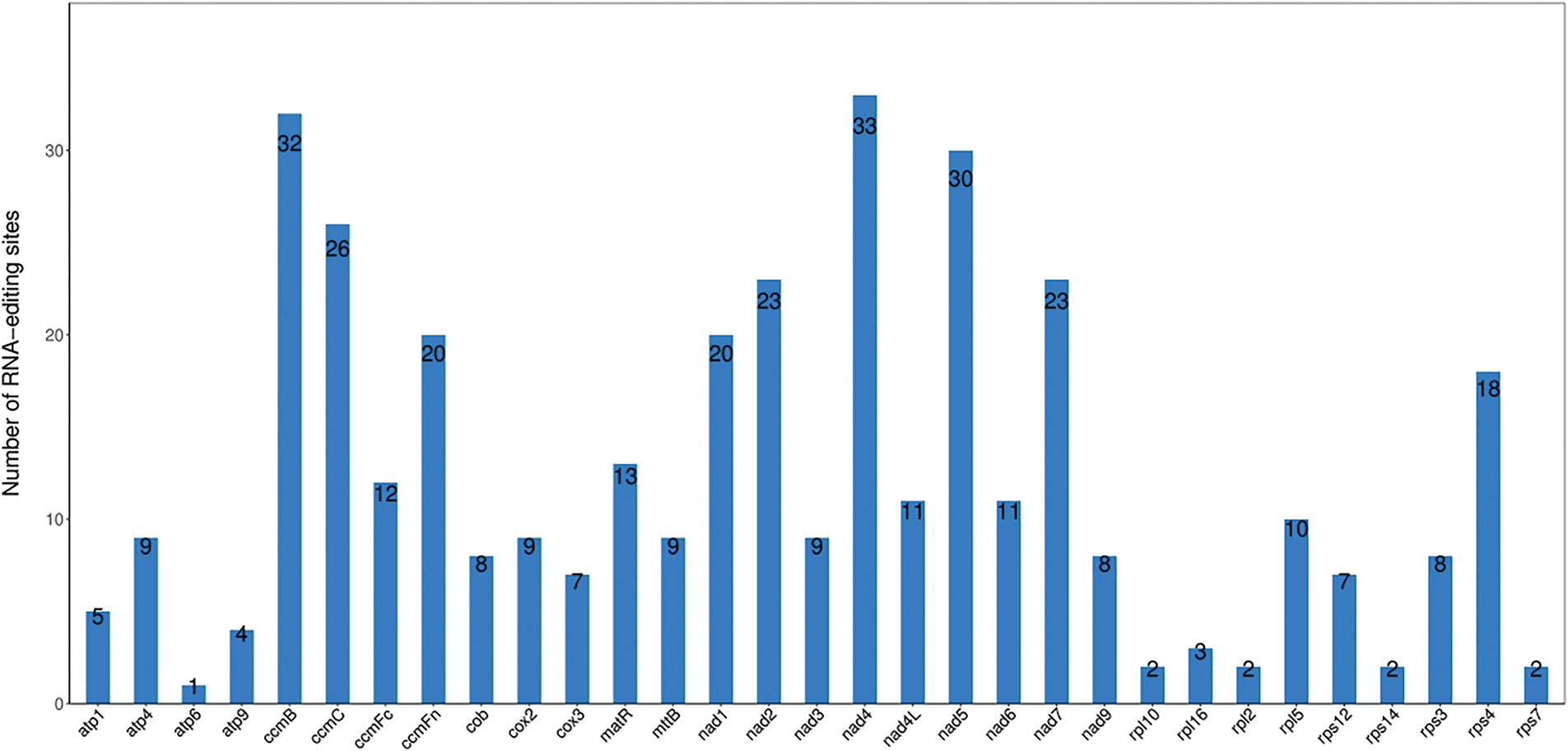

3.4 Mitochondrial RNA Editing Analysis

RNA editing is commonly present in the activities of animals, plants, and microorganisms, and occurs commonly among the three genomes (mitogenome, chloroplast genome, nuclear genome) [43]. A significant difference existed in the RNA editing site number between mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes; although they share similar editing patterns, the editing site number in chloroplasts is far fewer than in plant mitochondria [44]. RNA editing was predicted in the R. indica mitogenome, and 377 RNA editing sites were checked in 31 PCGs, while no editing sites were predicted in the remaining two PCGs (atp8 and cox1) (Fig. 4). Among these editing sites, 60.21% (227) are positioned at the first codon base, 35.54% (134) occur at the second codon base. Meanwhile, two bases were co-changing, containing six CCC (P) → TTC (F) and ten CCT (P) → TTT (F). In the R. indica mitogenome, 21.48% of amino acids maintain their hydrophobicity after RNA editing, whereas 78.25% of amino acids will change from hydrophilicity to hydrophobicity (Supplementary Table S5). Additionally, RNA editing may lead to PCG premature termination.

Figure 4: RNA editing site in Rorippa indica mitogenome

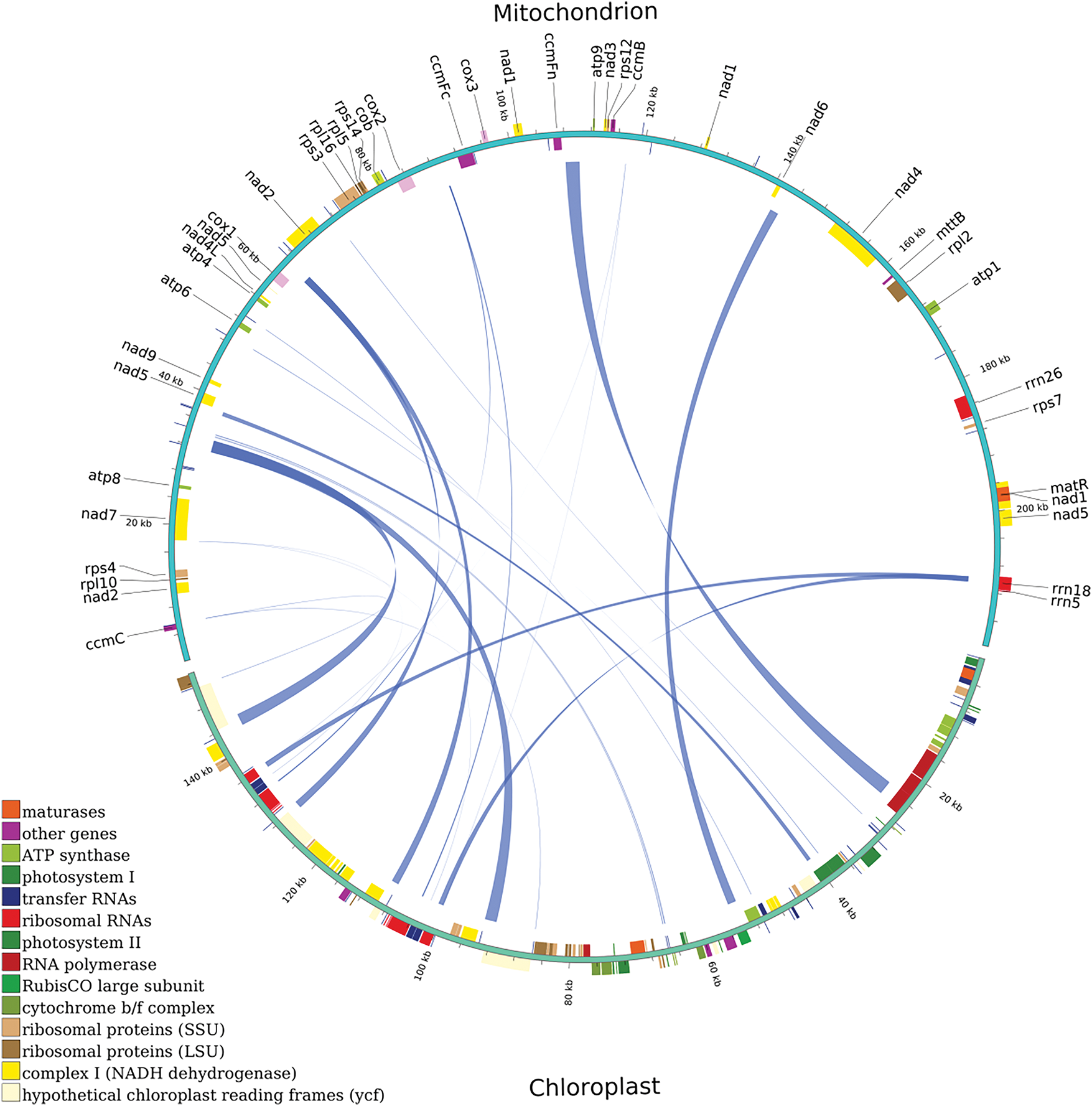

The transfer of mitochondria and chloroplast DNA to the nucleus is regarded part of ongoing genomic evolution and affects the eukaryote evolution. This process occurs not only between organelles and the nucleus but also between chloroplast and mitochondrial DNA [45,46]. For example, during the angiosperm evolution, the chloroplast gene rbcL has been transferred multiple times into the mitogenome [47]. To examine whether chloroplast DNA has been transferred into its mitogenome, this study used BLASTN to recognize potential homologous sequences between chloroplast and mitogenomes, with a critical e-value of 1e−05. And 22 DNA fragments were sought out between the two organellar genomes. The total length is 13,153 bp, making up 8.57% of the entire chloroplast genome and 4.08% of the entire mitogenome. And the longest mitogenome fragment is 2186 bp, while the shortest fragment is 42 bp. The positions of the 22 homologous fragments between the mitogenome and chloroplast genome are unveiled in Fig. 5. Furthermore, 12 annotated genes were displayed on these genomic fragments, and all of which are tRNA genes: trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnN-GUU, trnD-GUC, trnW-CCA, trnL-CAA, trnM-CAU, trnW-CCA, trnN-GTT, trnM-CAT, trnD-GTC, and trnI-AAT. Other transferred sequences were partially gene fragments (Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 5: DNA transfer between Rorippa indica chloroplast genome and mitogenome

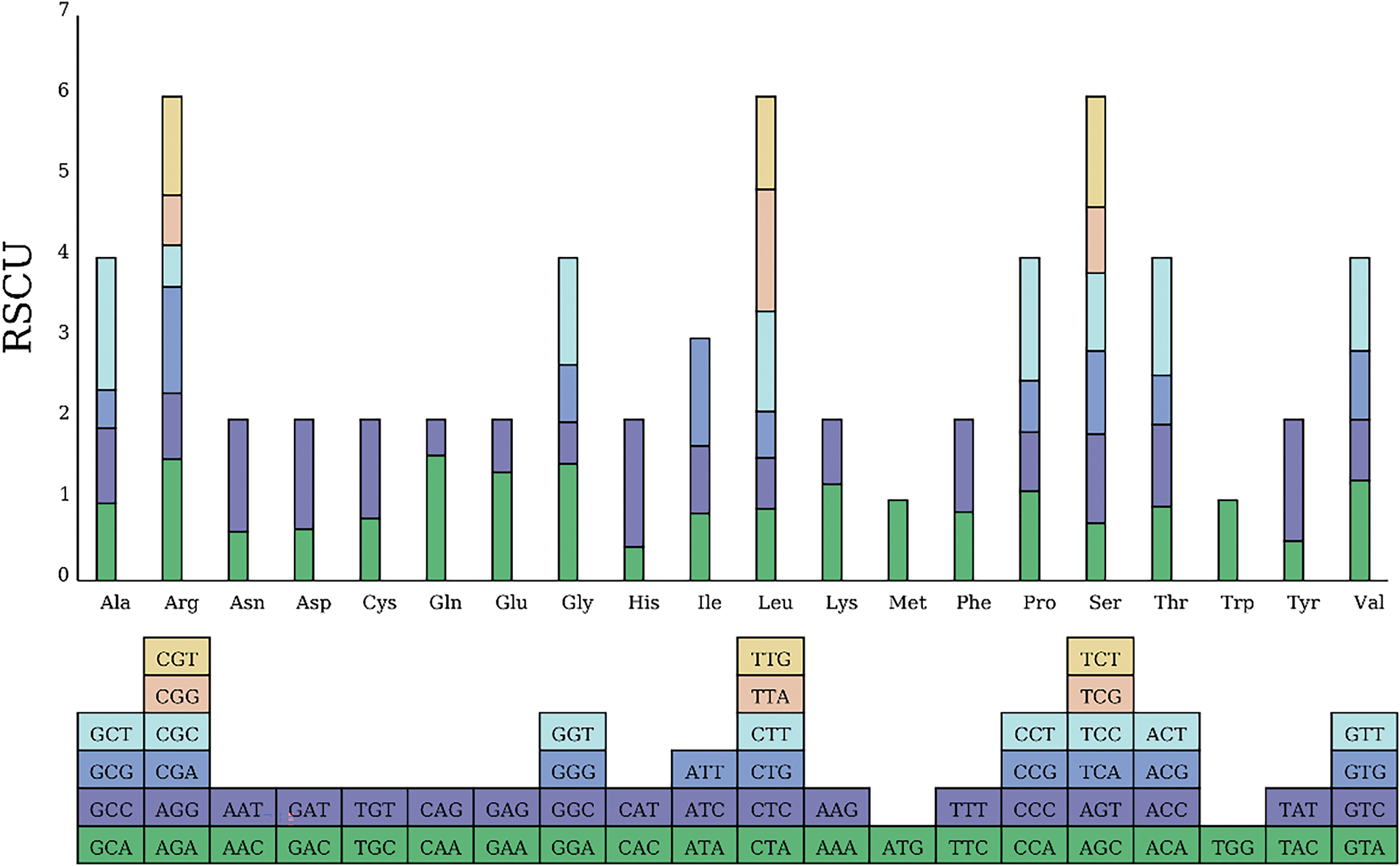

The codon preference analysis results for the R. indica mitochondrial genes are displayed in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table S7. The 33 mitochondrial coding genes used a total of 9685 codons, with the most preferred codon being phenylalanine (Phe-TTT), encoding a total of 380. The next are isoleucine (Ile-AUU) and methionine (Met-AUG), encoding 328 and 270, respectively. The least preferred is cysteine (Cys-UGC and Cys-UGU), encoding only 137. Among all codons, those ending with A or T total 6023, accounting for 61.31%, indicating a certain preference for A/T bases.

Figure 6: RSCU value in Rorippa indica mitogenome

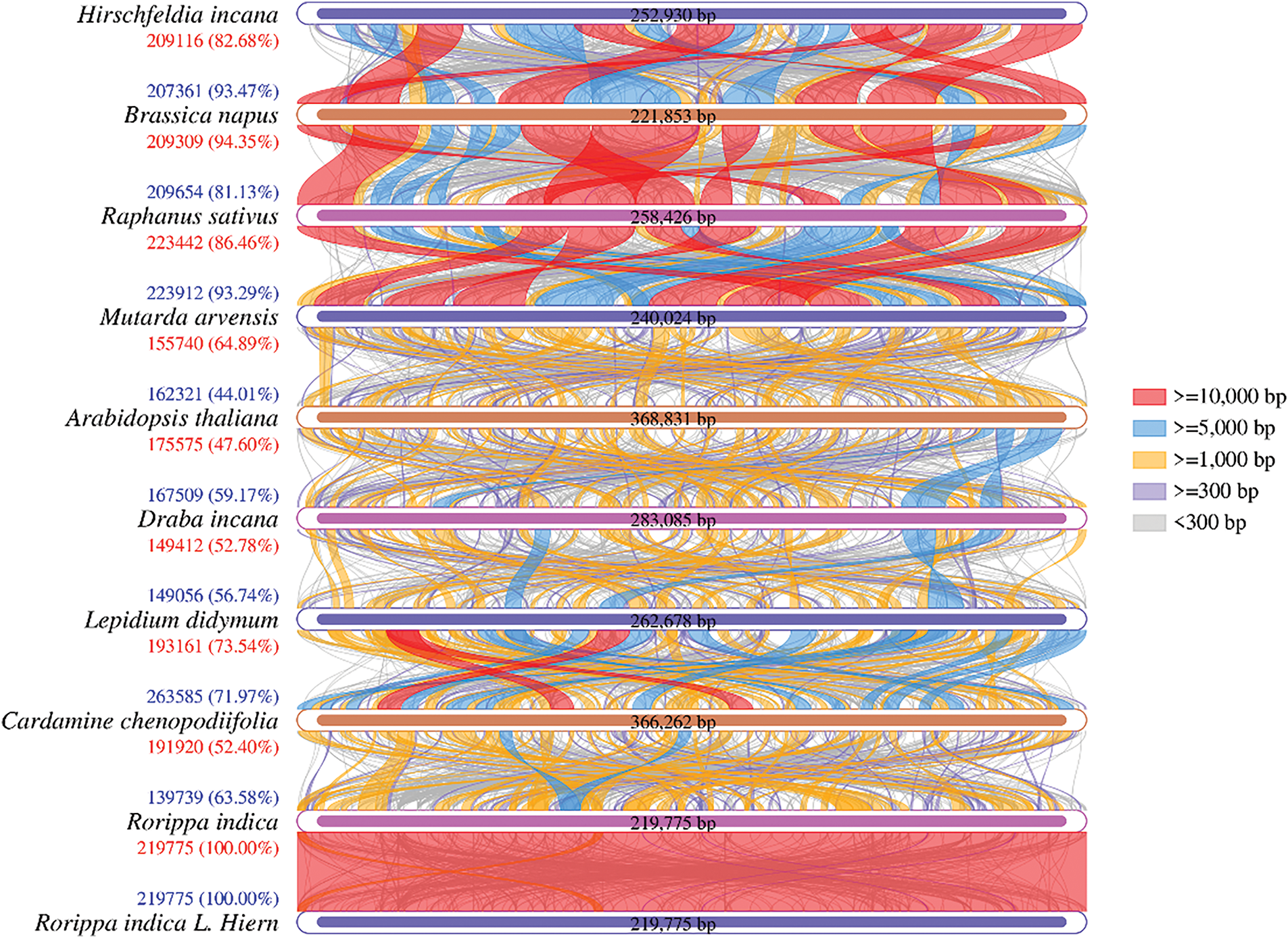

3.7 Mitochondrial Sequence Collinearity

Using the nucmer software (4.0.0beta2) (https://taylorreiter.github.io/2019-05-11-Visualizing-NUCmer-Output/, accessed on 25 March 2025), genomic comparisons were made between R. indica mitogenome and selected Brassicaceae sequences, generating a Dot-plot graph. As shown in Fig. 7, no significant conserved collinear blocks were observed among R. indica and other eight cruciferous plants, which may be related to the extensive recombination experienced by the R. indica genome. Conserved collinear regions are only sparsely distributed across different regions of the genome, most of which are where the conserved mitochondrial gene sequences are located, suggesting that a large number of non-coding regions are specific to R. indica. The non-coding regions in R. indica may be caused by redundancy from a large of repeat sequences and exogenous sequences, among which the R. indica chloroplast genome may be a major contributor to the exogenous sequences.

Figure 7: Collinearity mitogenome arrangement between Rorippa indica and other Cruciferae plants

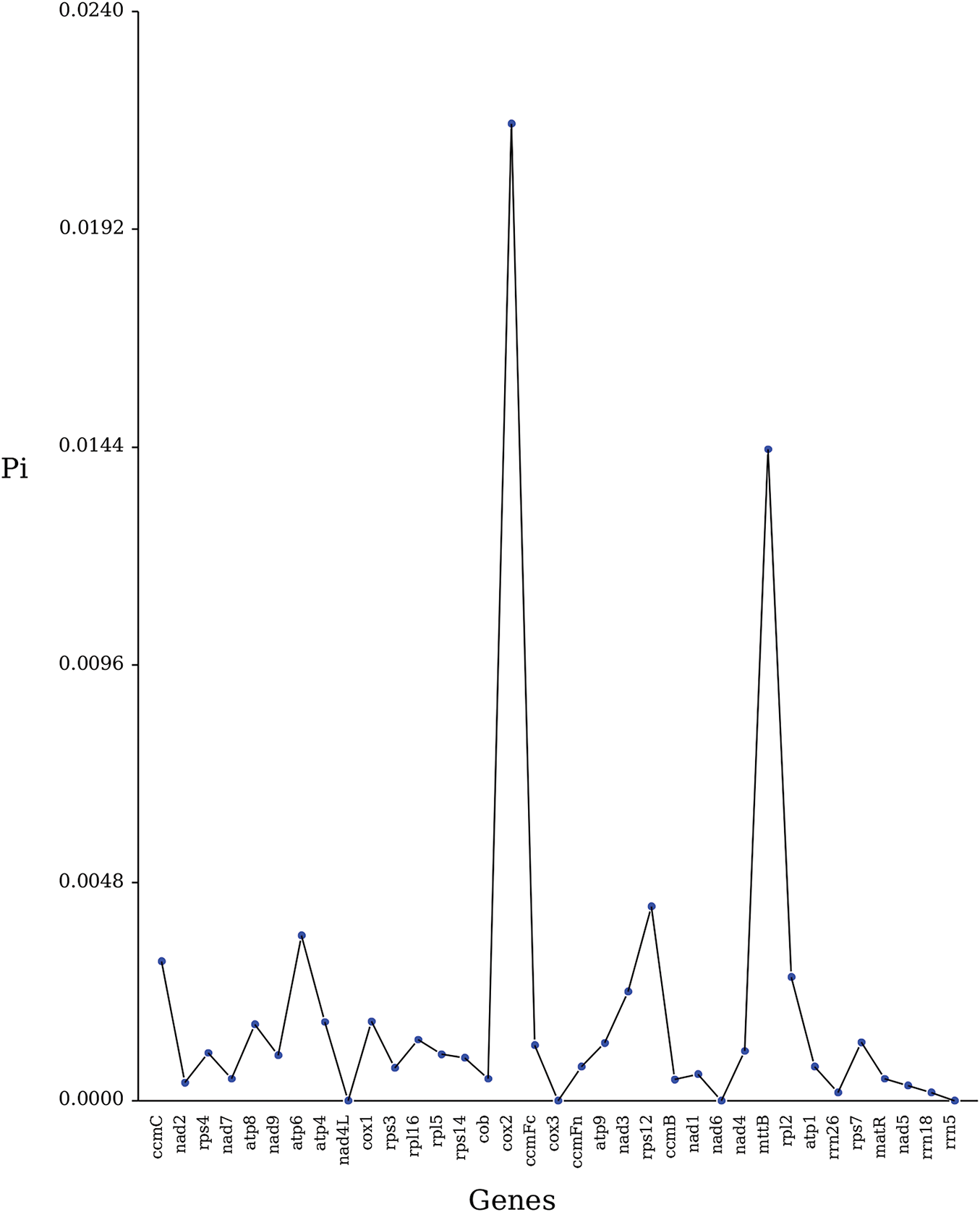

3.8 Nucleotide Diversity Analysis

Nucleotide diversity (Pi) value indicates the extent of nucleotide sequence variation, with highly variable regions potentially regarding as genetic molecular markers [48]. Using the MAFFT software (v7.427, –auto mode) (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/, accessed on 25 March 2025), a global homologous gene sequence alignment among different species was performed, and the Pi values were calculated using Dnasp v5 [34]. We compared the mitogenomes of R. indica and nine cruciferous plants, and statistics were made on the genes with nucleotide sequence variations. As shown in Fig. 8, 33 genes were found to have nucleotide sequence variations in R. indica, with Pi values ranging from 0.00018 to 0.02153, most of which are below 0.002, with the highest being 0.02153 for the cox2 gene. Moreover, the Pi values of these genes (cox3, nad6, rrn5, and nad4L) are all 0 (Supplementary Table S8). These diversity sites can be used for further analysis of the evolutionary process of mitogenomes in the genus Rorippa.

Figure 8: Pi value in Rorippa indica mitogenome

A phylogenetic tree was built with the ML method based on PCGs in this research (Fig. 9). And Physcomitrella patens (NC_007945.1) and Marchantia paleacea (NC_001660) were used as the outgroup. It was found that among the 20 nodes constructed in the phylogenetic tree of the mitogenome, 17 nodes had values exceeding 82%, and 15 nodes had values of 100%. The phylogenetic tree built from the mitogenome strongly supports the divergence of R. indica from other Brassicaceae plants. In this phylogenetic tree, the 33 species were first separated into four major branches: one branch consisting of 20 dicotyledonous plants, one branch of nine monocotyledonous plants, one branch of two gymnosperm plants, and one branch of two bryophyte plant. The phylogenetic tree strongly stands up for the dividing of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants, with a support rate of 100%, as well as the separation of angiosperms and gymnosperms (100%). Additionally, according to the ML tree, R. indica and Brassica napus are most closely related, with a support rate of 100%.

Figure 9: Phylogenetic tree constructed from Rorippa indica and other Cruciferae plant mitogenomes

The plant mitogenome has complex combinations, diverse structures, highly recombinant repetitive sequences, and fluctuating non-coding sequences, making it difficult to study plant mitochondria [46,49]. This is based on the fact that the plant organelle copy number is much higher than its nuclear genomes, and the second-generation Illumina and third-generation Nanopore sequencing technology were utilized to fulfil the assembly of the R. indica mitogenome. The results indicate that the mitogenome (219,775 bp, GC content: 45.24%) is similar in size and GC value to the mitogenomes of other Brassicaceae plants, such as Brassica napus (221,853 bp, GC content: 45%, NC_008285.1), Sinapis arvensis (240,024 bp, GC content: 44.78%, NC_031896.1), Raphanus sativus (258,426 bp, GC content: 44.82%, NC_018551.1), and Lepidium didymium (262,678 bp, OY986989.1, 45.18%). The R. indica mitogenomes and Brassica napus are structurally the most similar, both exhibiting a circular shape structure. In addition, this study identified 59 genes, constituting 23 PCGs, 23 tRNA, and 3 rRNA genes. The type and number of genes were consistent with most of the terrestrial plant circular mitogenome [50]. More than 80% of the R. indica mitogenome comprised non-coding regions, with coding regions accounting for only 8.99% of its total length. This may be due to the gradual increase of repetitive sequences and insertion of exogenous fragments in the mitochondrial genome [51].

SSRs (typically one to six bp in length) are abundant in higher plant genomes and show rich polymorphism. Thus, SSRs are often treated as genetic markers for distinguishing similar species [52]. SSRs can be categorized into mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats based on their primary repeating unit length. This study differentiated 315 SSRs in chloroplast sequences and 55 SSRs in mitochondrial sequences. The most abundant SSR in the chloroplast is mononucleotide SSRs, accounting for 79.61%. However, the SSRs in the R. indica mitogenome are mainly composed of tetranucleotide polymers, accounting for 36.36%. The SSR type in the mitogenome are distributed more evenly than those in the chloroplast. Tandem repeats occur in the DNA of all sequenced organisms. These sequences make up multiple contiguous repeat units and own high mutation rates in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes due to their tendency to repeat unit change [53]. This study checks out 125 tandem repeats in the chloroplast and 17 tandem repeats in the R. indica mitogenome. The applicability of repeat sequences as DNA fingerprint markers can be further tested. Additionally, this study identified 68 dispersed repeats in the chloroplast and 252 dispersed repeats in the mitogenome. In most PCGs, the ratio of Ka/Ks is significantly less than one, indicating negative selection during evolution. Mitochondrial genes are highly conserved in the evolutionary process, which is similar to findings in other species of the same family [54].

Compared to other herbaceous and shrub plants in Brassicaceae, R. indica grows in harsh environments, requiring mitochondria to provide a large amount of energy to survive in adverse conditions. Studies have found significant differences in the types of codon transfer in mitochondrial RNA editing between flowering plants (monocots and dicots) and other plant groups, with a marked increase in codon conversion types among flowering plants [55]. Mitochondrial RNA editing can affect plant growth and development, the pentatricopeptide repeat gene in Oryza sativa can regulate the RNA editing of mitochondrial genes, influencing the energy metabolism of cultivated rice under drought stress [56]. In cotton, RNA editing of the mitochondrial atp1 gene is related to fiber growth and development, regulating the development of epidermal hairs and roots [57]. This study indicated that after RNA editing, the codon pattern of amino acids tends towards leucine and favors hydrophobic amino acids. It is speculated that hydrophobic residues are generally located inside proteins, but if hydrophilic mutations increase within the protein, it may lead to structural instability and failure to fold [58].

A phylogenetic tree was established using 30 PCGs from the mitogenome, revealing that at larger taxonomic ranks, mitogenome data can distinguish different groups, including the separation of mosses, gymnosperms and angiosperms, as well as the separation of Brassicaceae plants and other angiosperms, confirming the application value of mitogenome data at higher taxonomic levels. The phylogenetic tree also shows that R. indica is closely related to Brassica napus, which aligns with traditional classification results. Meanwhile, 22 homologous fragments are determined between the chloroplast genome and its mitogenome. Among these fragments, there are 12 annotated genes, all of which are tRNA genes. The data from this study also indicate that some chloroplast PCGs, namely atpB, rrn16S, and atpA, have transferred from the chloroplast to the mitochondria. Although most of them have lost integrity, only partial sequences can currently be found in the mitogenome. The atpA gene is involved in abiotic stress; studies have shown that in high salinity environments, atpA may promote ATP synthesis to meet energy consumption under stress conditions, and its expression begins to increase under low-temperature stress. AtpA is also related to plant salt tolerance and disease resistance [59–61]. R. indica grows in barren and damp conditions, and over a long period of adaptation to the environment, some genes related to poor land environment tolerance and disease resistance may have gradually transferred from the chloroplast to the mitogenome. Although only partial gene sequences are found in the mitochondria, it cannot be ruled out that they may completely transfer to the mitochondria during long-term evolution. It is speculated that these genes may gradually migrate from the chloroplast to the mitochondria, potentially enhancing the resistance of R. indica to external stress. The different destinations of transferred PCGs and tRNA genes indicate that they are more conserved than the mitogenome PCGs, suggesting that they may take an indispensable role in the mitogenome [62].

In conclusion, we reported the mitochondrial genome of R. indica. This study also verified that the coding sequences in the mitochondrial genome can distinguish classification systems above the family level. A data foundation was provided for the genomic research of R. indica.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Jiangxi Province Higher Education Teaching Research Project (JXJG-22-23-3, NSJG-21-25), and Jiangxi Province Key Laboratory of Oil Crops Biology (YLKFKT202203).

Availability of Data and Materials: The genome sequences are available in GenBank under the accession number PP780168.1 (mitochondrial genome) and PP780169.1 (chloroplast genome). The associated BioProject, SRA, and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA1110342, SRP507074, and SAMN41343559.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.066232/s1.

References

1. Lane N, Martin W. The energetics of genome complexity. Nature. 2010;467:929–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Ghiselli F, Milani L. Linking the mitochondrial genotype to phenotype: a complex endeavour. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2020;375:20190169. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Daniell H, Lin CS, Yu M, Chang WJ. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):134. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wambugu PW, Brozynska M, Furtado A, Waters DL, Henry RJ. Relationships of wild and domesticated rices (Oryza AA genome species) based upon whole chloroplast genome sequences. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):13957. doi:10.1038/srep13957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Gu ZL, Zhu Z, Li Z, Zhan QL, Feng Q, Zhou CC, et al. Cytoplasmic and nuclear genome variations of rice hybrids and their parents inform the trajectory and strategy of hybrid rice breeding. Mol Plant. 2021;14(12):2056–71. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2021.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gao Y, Thiele W, Saleh O, Scossa F, Arabi F, Zhang H, et al. Chloroplast translational regulation uncovers nonessential photosynthesis genes as key players in plant cold acclimation. Plant Cell. 2022;34(5):2056–79. doi:10.1093/plcell/koac056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Christensen AC. Plant Mitochondria are a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an Enigma. J Mol Evol. 2021;89(3):151–6. doi:10.1007/s00239-020-09980-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Knoop V, Rudinger M. DYW-type PPR proteins in a heterolobosean protist: plant RNA editing factors involved in an ancient horizontal gene transfer. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(20):4287–91. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sheng WT, Kuang Q, Zhang QF, Chai XW, Zhang Y. The characteristic analysis of 560 plant mitogenome registered in NCBI Data. Mol Plant Breed. 2023. (In Chinese). [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/46.1068.S.20231016.1819.043. [Google Scholar]

10. Wu ZQ, Liao XZ, Zhang XN, Tembrock LR, Broz A. Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria—a review of multichromosomal structuring. J Syst Evol. 2022;60(1):160–8. doi:10.1111/jse.12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Møller IM, Rasmusson AG, Aken OV. Plant mitochondria—past, present and future. Plant J. 2021;108(4):912–59. doi:10.1111/tpj.15495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Janouškovec J, Liu SL, Martone PT, Carré W, Leblanc C, Collén J, et al. Evolution of red algal plastid genomes: ancient architectures, introns, horizontal gene transfer, and taxonomic utility of plastid markers. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59001. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kan SL, Shen TT, Ran JH, Wang XQ. Both Conifer II and Gnetales are characterized by a high frequency of ancient mitochondrial gene transfer to the nuclear genome. BMC Biol. 2021;19(1):146. doi:10.1186/s12915-021-01096-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wu J, Liang JL, Lin RM, Cai X, Zhang L, Guo XL, et al. Investigation of Brassica and its relative genomes in the post-genomics era. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhac182. doi:10.1093/hr/uhac182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sasidharan R, Mustroph A, Boonman A, Akman M, Ammerlaan AMH, Breit T, et al. Root transcript profiling of two Rorippa species reveals gene clusters associated with extreme submergence tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(3):1277–92. doi:10.1104/pp.113.222588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tu WF, Zhang Y, Tang J, Tu YQ, Xin JJ, Ji HL, et al. Comparison of taxonomic morphological characteristics between Rorippa indica and R. dubia. Biodivers Sci. 2019;27(2):168–76. doi:10.17520/biods. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tu YQ, Dai XL, Tu WF, Tang J. Identification of resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and drought resistance, waterlogging tolerance of Rorippa indica seedling. J Plant Resour Environ. 2011;20(3):9–15. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

18. Prakash S, Bhat SR, Quiros CF, Kirti PB, Chopra VL. Brassica and its close allies: cytogenetics and evolution. Plant Breed Rev. 2009;31:21–187. doi:10.1002/9780470593783.ch2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dai XL, Cheng CM, Song LQ, Tang J, Xiong RX, Zhang T, et al. Germplasm enhancement through wide crosses of Brassica napus × India rorippa. J Plant Genet Resour. 2005;6(2):242–4. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

20. Bandopadhyay L, Basu D, Ranjan SS. De novo transcriptome assembly and global analysis of differential gene expression of aphid tolerant wild mustard Rorippa indica (L.) Hiern infested by mustard aphid Lipaphis Erysimi (L.) Kaltenbach. Funct Integr Genom. 2024;24(2):43. doi:10.1007/s10142-024-01323-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Salmela ER. LoRDEC: accurate and efficient long read error correction. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(24):3506–14. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jin JJ, Yu WB, Yang JB, Song Y, dePamphilis CW, Yi TS, et al. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):241. doi:10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Li H. Minimap and miniasm: fast mapping and de novo assembly for noisy long sequences. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(14):2103–10. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btw152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):722–36. doi:10.1101/071282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Prjibelski A, Antipov D, Meleshko D, Lapidus A, Korobeynikov A. Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2020;70(1):e102. doi:10.1002/cpbi.102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–9. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R. Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W59–64. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acid Res. 1999;27(2):573–80. doi:10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acid Res. 2001;29(22):4633–42. doi:10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen CJ, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He YH, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang H, Meltzer P, Davis S. RCircos: an R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14(1):244. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-14-244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Fay JC, Wu CI. Sequencing divergence, functional constraint, and selection in protein evolution. Annu Rev Genom Hum G. 2003;4(1):213. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.4.020303.162528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Sievers F, Higgins DG. The clustal omega multiple alignment package. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2231(1):3–16. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-1036-7_1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–62. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Small ID, Schallenberg-Rudinger M, Takenaka M, Mireau H, Ostersetzer-Biran O. Plant organellar RNA editing: what 30 years of research has revealed. Plant J. 2020;101(5):1040–56. doi:10.1111/tpj.14578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chen Y, Ye WC, Zhang YD, Xu YS. High speed BLASTN: an accelerated Mega BLAST search tool. Nucleic Acid Res. 2015;43(16):7762–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–80. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1972–3. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):772. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Cole LW, Guo W, Mower JP, Palmer JD. High and variable rates of repeat-mediated mitochondrial genome rearrangement in a genus of plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(11):2773–85. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bi CW, Paterson AH, Wang XL, Yu YQ, Wu DY, Qu YS, et al. Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii by comparative genomics approaches. BioMed Res Int. 2016;1:5040598. doi:10.1155/2019/9691253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Li S, Chang L, Zhang J. Advancing organelle genome transformation and editing for crop improvement. Plant Comm. 2021;2(2):100141. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2021.100141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Barreto P, Koltun A, Nonato J, Yassitepe J, Maia IDG, Arruda P. Metabolism and signaling of plant mitochondria in adaptation to environmental stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11176. doi:10.3390/ijms231911176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Kim YK, Jo S, Cheon SH, Hong JR, Kim KJ. Ancient horizontal gene transfers from plastome to mitogenome of a nonphotosynthetic orchid, Gastrodia pubilabiata (Epidendroideae, Orchidaceae). Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:11448. doi:10.3390/ijms-241411448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Niu Y, Lu Y, Song W, He X, Liu Z, Zheng C, et al. Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of three Macadamia species (M. integrifolia, M. Ternifolia and M. Tetraphylla). PLoS One. 2022;17(5):e0263545. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang Y, Zhang A, Li X, Lu C. The role of chloroplast gene expression in plant responses to environmental stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):6082. doi:10.3390/ijms21176082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Liu AZ, John MB. Patterns of nucleotide diversity in wild and cultivated sunflower. Genetics. 2006;173(1):321–30. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.051110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang J, Kan SL, Liao XZ, Zhou JW, Tembrock LR, Daniell H, et al. Plant organellar genomes: much done, much more to do. Trends Plant Sci. 2024;29(7):754–69. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2023.12.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wang SY, Qiu J, Sun N, Han FC, Wang ZF, Bi CW. Characterization and comparative analysis of the first mitochondrial genome of Michelia (Magnoliaceae). Genom Commun. 2025;2(1):e001. doi:10.48130/gcomm-0025-0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kim SC, Kang ES, Kim TH, Choi YR, Kim HJ. Report on the complete organelle genomes of Orobanche Filicicola Nakai ex Hyun, YS Lim & HC Shin (Orobanchaceaeinsights from comparison with Orobanchaceae plant genomes. BMC Genom. 2025;26(1):157. doi:10.1186/s12864-025-11298-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Song QJ, Shi JR, Singh S, Fickus EW, Costa JM, Lewis J, et al. Development and mapping of microsatellite (SSR) markers in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;110(3):550–60. doi:10.1007/s00122-004-1871-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Victoria FC, da Maia LC, de Oliveira AC. In silico comparative analysis of SSR markers in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11(1):15. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-11-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Robles P, Quesada V. Organelle genetics in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):2104. doi:10.3390/ijms22042104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wan P. Evolution of RNA editing in land plant mitochondria. Biotechnol Bull. 2013;251(6):99–103. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

56. Maldonado M, Abe KM, Letts JA. A structural perspective on the RNA editing of plant respiratory complexes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):684. doi:10.3390/ijms23020684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Kong JL, Wang J, Nie LY, Tembrock LR, Zou CS, Kan SL, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of mitochondrial genomes and intracellular transfers among diploid and allopolyploid cotton species. BMC Biol. 2025;23(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12915-025-02115-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Jiang Y, Fan SL, Song MZ, Yu JN, Yu SX. Identification and analysis of RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts of Gossypium hirsutum. Chin Bull Bot. 2011;46(4):386–95. doi:10.3724/sp.j.1259.2011.00386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Asrar H, Hussain T, Hadi S, Nielsenb BL, Khana MA. Salinity induced changes in light harvesting and carbon assimilating complexes of Desmostachya bipinnata (L.) Staph. Env Exp Bot. 2016;135(8):86–95. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.12.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Spence AK, Boddu J, Wang DF, James B, Swaminathan K, Moose SP, et al. Transcriptional responses indicate maintenance of photosynthetic proteins as key to the exceptional chilling tolerance of C4 photosynthesis in Miscanthus × giganteus. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(13):3737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

61. Suda Y, Yoshikawa T, Okuda Y, Tsunemoto M, Matsuda Y, Tanaka S, et al. Comparative analysis of a CFo-ATP synthase subunit II homologue derived from marine and fresh-water algae. J Biosci Bioeng. 2009;108(5):365–8. doi:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.05.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Ye N, Wang XL, Li J, Bi CW, Xu YQ, Wu DY, et al. Assembly and comparative analysis of complete mitogenome sequence of an economic plant Salix suchowensis. PeerJ. 2017;5(1):e3148. doi:10.7717/peerj.3148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools