Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Antioxidant Potential of Different Plant Part of Allium roseum L. from Montenegro

1 University of Priština in Kosovska Mitrovica, Faculty of Agriculture, Lešak, 38219, Serbia

2 University of Niš, Faculty of Technology, Bulevar Oslobodenja 124, Leskovac, 16000, Serbia

3 University of Novi Sad, Institute of Food Technology, Bulevar Cara Lazara 2, Novi Sad, 21000, Serbia

* Corresponding Author: Zoran S. Ilić. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Phytochemical and Medicinal Values of Plants)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2515-2527. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069082

Received 14 June 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

This study aims to determine the phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity (AA) of different plant parts (bulbs, stalk, leaves and flowers) of wild rosy garlic (Allium roseum) from Montenegro. The flower exhibited the highest concentration of total phenols (55.7 GAE/g d.e.), followed by the leaf (25.6 mg GAE/g d.e.). The leaf displayed the highest concentration of total flavonoids (41.48 mg RE/g d.e.), followed by the flower (36.26 mg RE/g d.e.) and top part of the stalk (26.80 mg RE/g d.e.). The AA of different parts of A. roseum after 60 min of incubation decreased in the following order: flower (0.15 mg/cm3) > upper stalk (0.32 mg/cm3) > leaf (0.36 mg/cm3) > basal stalk (0.80 mg/cm3) > bulb (1.53 mg/cm3). The flowers exhibited the lowest EC50 values, indicating the highest antioxidant potential throughout the entire incubation period. Among all plant parts analyzed, the flowers demonstrated the highest ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), reaching 24.99 mg Fe2+/g, thereby indicating their superior antioxidant potential. Given their edibility, pleasant flavor, and high nutritional value, A. roseum flowers may be considered a promising natural additive for functional food products or culinary applications, including dish enhancement and decoration.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe largest and most significant genus from Liliaceae family’s is Allium, with over 500 different species. Allium cultivated and wild species contain secondary metabolites with diverse bioactivities, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory effects, which are closely related to their chemical structure and functional groups [1]. Plant species from this genus are characterized by a high content of organosulfur compounds, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, exhibit distinct effects on cancer cells [2,3]. Allium roseum L. is a species with a typical Mediterranean distribution and includes different intraspecific taxa, varieties and subvarietes. A. roseum, commonly known as rosy garlic, is wild vegetable plants from the Liliaceae family, which spontaneously grows in Adriatic sea cost, thriving on nutrient-poor soil, widely used in the diet of the local population as fresh salads, or additional in the food industry because of their antimicrobial activity [4], and folk medicine for the treatment of headaches, stomachaches and rheumatism.

A. roseum is primarily used fresh during the developmental phases up to flowering, and later in the year, it can be used dried or frozen. The entire plant is edible, including both its above-ground and underground parts, rich in nutrients and mineralsorgano-sulfur compounds and flavonoids, especially kaempherol [5], while polysaccharide compounds exhibited promising antioxidant properties with significant anti-inflammatory effects in vitro and in vivo and anticancer activity both on U87 and IGROV-1 cancer cell growth [6]. It is well established that the distribution of secondary metabolites in plants is not uniform and often varies among different organs, such as leaves, flowers, stems, and bulbs. For example, in other Allium species, the bulb is typically considered the most valuable part due to its high concentration of bioactive compounds. However, preliminary evidence suggests that this may not be the case for A. roseum, where other parts of the plant, such as the flower or leaf, might contribute more significantly to its antioxidant potential. To gain a better understanding of the bioactivity of different plant parts of A. roseum, a thorough evaluation of phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity is essential.

Therefore, the aim of the present work was to study the chemical composition of different plant part (bulbs, stalks, leaves, flowers) of A. roseum from Montenegro in order to evidence a new specific chemotype according to the region location, adapted to climatic and soil conditions. The ethanolic extract antioxidant activity of this species was investigated.

Allium roseum subsp. roseum L. (Amaryllidaceae) is found in the Mediterranean region and is a perennial plant that grows on rocky habitats, as well as in grasslands and shrublands. The bulbs are deeply embedded in the soil, making them difficult to extract. The bulb is small, composed of several cloves, and often has small bulbils “offspring” attached to the main bulb. The leaves are lanceolate, few in number, long and narrow, 5–10 mm wide. Rose garlic usually develops a single flowering stem that ends in an inflorescence. The inflorescence is beautiful and loose, with a large number of individual flowers in white and pink colors, with a typical structure characteristic of the Alliaceae family. A. roseum was collected from the monastery Podlastva (Grbalj), Montenegro seaside area (with coordinates of 42°29′33″ N 18°41′26″ E) during the vegetation period in 2024, identified by Prof. Dr. Zoran Ilić of the University of Priština in Kosovska Mitrovica. A voucher specimen has been deposited at the Herbarium of the Department of Biology in the Faculty of Agriculture. The samples when inflorescent with flowers reached full flowering stage (see Figs. S1 and S2 in Supplementary Materials). The samples of A. roseum leaves, stems (two various parts), flowers and bulbs, were collected in beginning of May. Samples were collected from over 100 individual plants with three biological replicates per plant organ.

Chemical reagents, H2SO4, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), AlCl3, ascorbic acid, gallic acid, Na2CO3, ethanol were obtained by Breckland ScientificTM, UK. NaOH, C6N6FeK3, HgO, K2SO4, Na2S2O3, CH3CO2K, and Zn granules were obtained from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany.

After harvest, the rosy garlic samples were cleaned well with tap water followed by distilled water to remove dust, mud, and other possible impurities. The edible parts of the samples; stem and leaves, were air dried at room temperature under shade, to remove excess water. Then dried in a hot air oven (Biotechnologies Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA) at 45°C to obtain a constant weight and ground to fine powder. They were stored under 4°C for further chemical analysis.

The ground and homogenized plant material (stem 1, stem 2, leaf, bulb, and flower ofrosygarlic) (1 g) was weighed into erlenmeyer flasks and subsequently extracted with 70% v/v ethanol (20 cm3) for 24 h at 25°C to obtain the total extractive matter (TEM) (solid-to-solvent ratio was 1:20 m/v). All extraction procedures were independently performed in triplicate (n = 3). After extraction, the yield of TEM was determined by gravimetric analysis and expressed as g TEM/100 g of plant material.

2.4.2 Determination of Total Phenols Content

The content of total phenols in the rosy garlic extracts (stem 1, stem 2, leaf, bulb, and flower of wild garlic) was determined spectrophotometrically (Cole Parmer spectrophotometer, Cole-Parmer, Chicago, IL, USA) according to the Folin-Ciocalteu method descibed by Milenković et al. [7] with some modifications. About 0.5 mL of the sample extract and 0.1 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (0.5 N) were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Then 2.5 mL 7.5% Na2CO3 was added to the mixture and further incubated for 2 h in the dark at room temperature and then the absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). The concentration of total phenols was expressed as gallic acid equivalents per g dry weight (mg GAE/g dw) of the sample. The gallic acid was used as a standard (the concentration range was: 0.00625–0.2 mg/cm3). The absorbance of galic acid at 765 nm was expressed in equation:

2.4.3 Determination of Total Flavonoids Content (TFC)

The TFC of the extracts was determined by the aluminium chloride colorimetric assay [8], with certain modifications. About 2 mL of rosy garlic extracts (stem 1, stem 2, leaf, bulb, and flower) was mixed with, 0.1 mL of 10% AlCl3, 0.1 mL of 1 M CH3CO2K, and 2.8 mL distilled water and incubated at room temperature for 40 min. The absorbance was measured at 415 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Finland). The total flavonoid content was expressed as milligrams of rutin equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg RE/g d.e.), based on the following equation:

2.4.4 Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using DPPH Test

A series of different concentrations of ethanolic extracts of rosy garlic extracts were made (a concentration range of 0.0078–0.5 mg/cm3 was chosen for all extracts, except the bulb extract, where the concentration range was 0.010–0.66 mg/cm3). The ethanolic solution of DPPH radical (1 cm3, 3 × 10−4 mol/dm3) was added to 2.5 cm3 of extract solutions of different concentrations. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature, in the dark, for 20–60 min. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Finland). The percentage inhibition of the radicals due to the antioxidant activity was calculated using the following formula (As-absorbance of the sample, Ac-absorbance of the control).

2.4.5 Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using FRAP Test

Antioxidant activity of rosy garlic ethanolic extracts using the FRAP test was determined according to the method of Benzie and Strain [9] with certain modifications [10]. The procedure for determining the antioxidant activity of the extracts was the same as for the standard solutions, where the extracts were added instead of the standard solutions. The concentration (mmol/dm3) of Fe2+ equivalents in each sample was read directly from the calibration curve (y = 0.00495 + 0.65746 × c) and converted to dry extract mass (mg Fe2+/g d.e., or mmol Fe2+/g d.e.). This value is called the FRAP value. The higher this value, the better the antioxidant activity.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA to assess the effect of plant part organ, while on selected chemicals parameters principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. For both analysis TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA (2020). Data Science Workbench, version 14. (http://tibco.com) was used.

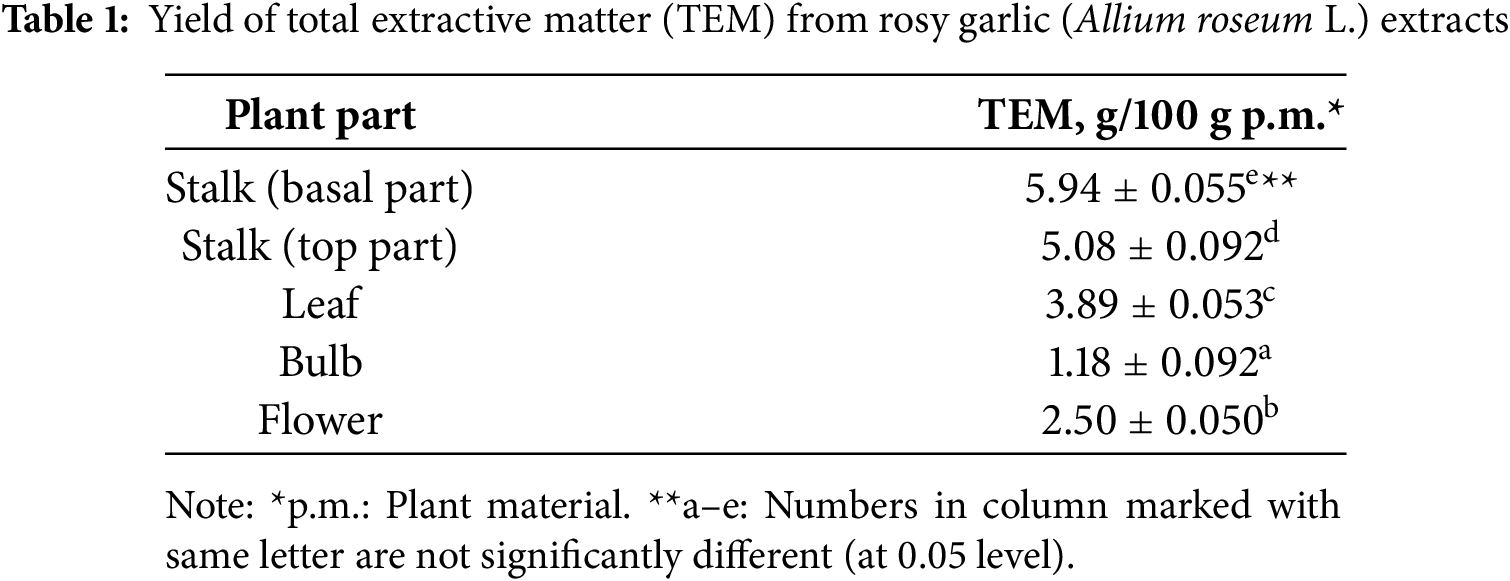

The yield of total extractive matter (TEM) expressed in grams of dry extract per 100 g of plant material (g/100 g) wild rosy garlic (Allium roseum L.) extracts from different plant organs during the process of maceration (hydromodule 1:20 m/V, 70% EtOH during 24 h) was presented in Table 1.

The basal part of the stalk exhibited the highest TEM yield (5.94 ± 0.055 g/100 g p.m.), followed by the top part of the stalk (5.08 ± 0.092 g/100 g p.m.), suggesting that the stalk is a rich source of extractable compounds in this species. In contrast, the bulb, often considered a primary edible and bioactive component in other Allium species, demonstrated the lowest TEM yield (1.18 ± 0.092 g/100 g p.m.), indicating it may not be the most optimal part for extracting bioactive antioxidants in A. roseum. The intermediate yields observed in the leaf (3.89 ± 0.053 g/100 g p.m.) and flower (2.50 ± 0.050 g/100 g p.m.) suggest these parts could also contribute to the overall antioxidant potential, though to a lesser extent than the stalk. Bulbs typically have very high water content (70%–90%), which makes the tissue extremely soft and difficult to handle. During dehydration and resin embedding, this can lead to cell collapse, shrinkage, and poor infiltration, resulting in damaged or unusable ultrathin sections for TEM. Bulb cells contain fewer membrane-bound organelles (like chloroplasts, ER, mitochondria) compared to leaves or active root tissues. Since TEM contrast heavily depends on membranes and organelles, bulb tissues may show less structural detail and lower contrast, affecting the interpretability of sections.

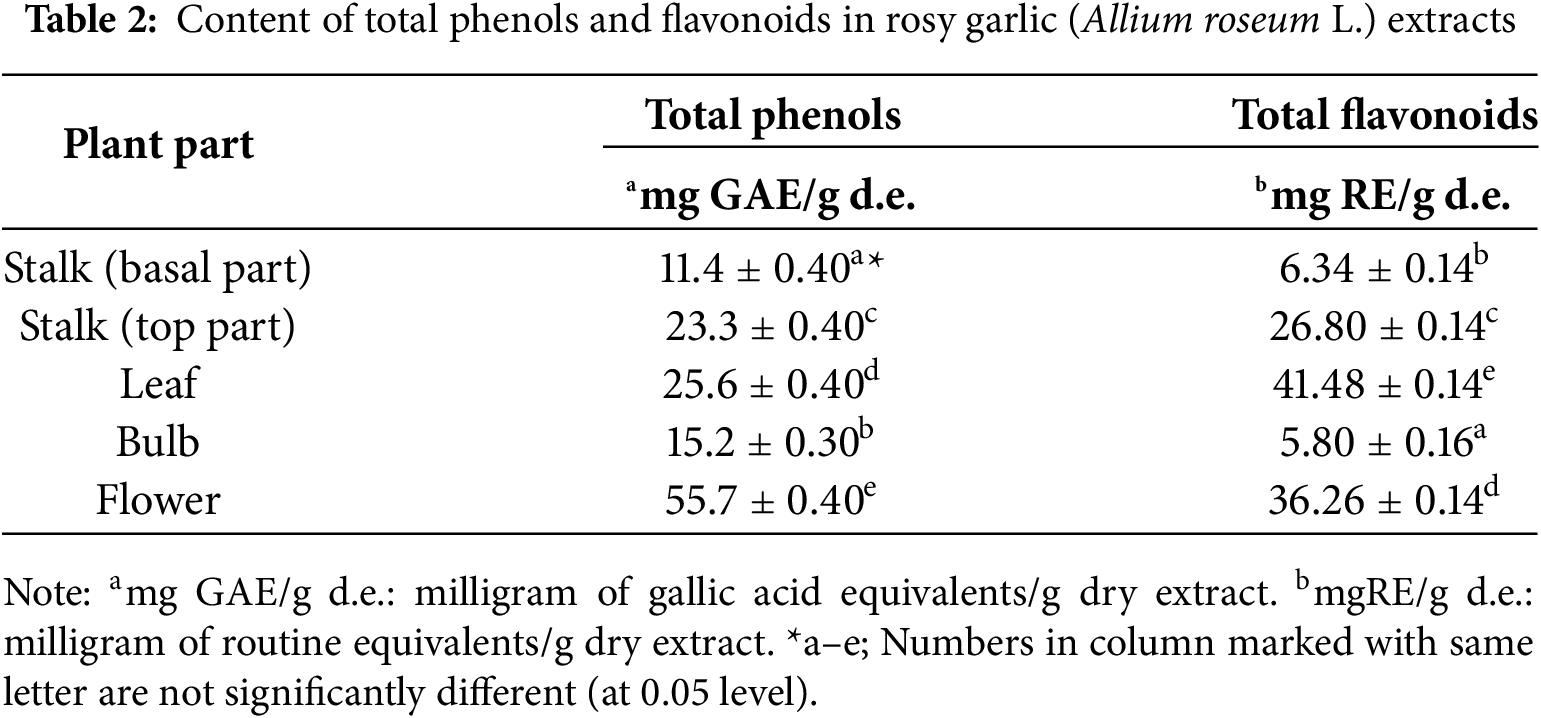

The content of total phenols and flavonoids in Allium roseum L. extracts, as shown in Table 2, reveals a distinct distribution of these bioactive compounds across different plant parts, which may significantly influence the antioxidant potential of the species. The flower exhibited the highest concentration of total phenols (55.7 ± 0.40 mg GAE/g d.e.), followed by the leaf (25.6 ± 0.40 mg GAE/g d.e.) and top part of the stalk (23.3 ± 0.40 mg GAE/g d.e.), indicating that these parts are rich sources of phenolic compounds. In contrast, the basal part of the stalk and bulb contained lower levels of total phenols (11.4 ± 0.40 and 15.2 ± 0.30 mg GAE/g d.e., respectively). Similarly, the leaf displayed the highest concentration of total flavonoids (41.48 ± 0.14 mg RE/g d.e.), followed by the flower (36.26 ± 0.14 mg RE/g d.e.) and top part of the stalk (26.80 ± 0.14 mg RE/g d.e.), while the basal part of the stalk and bulb had markedly lower flavonoid contents (6.34 ± 0.14 and 5.80 ± 0.16 mg RE/g d.e., respectively). These findings suggest that the flower and leaf are the most promising parts for exploiting the antioxidant properties of A. roseum, as they contain the highest levels of both phenolic compounds and flavonoids, which are known to contribute significantly to antioxidant activity.

Flowers typically accumulate anthocyanins, carotenoids, and specific phenolicacids that have very strong antioxidant activities. Leaves may have more flavonoids quantitatively, but not necessarily the most active ones in terms of scavenging free radicals. Flowers often contain a diverse combination of pigments (anthocyanins, betalains, carotenoids) and phenolics. These compounds can act synergistically, enhancing the overall antioxidant capacity beyond what would be predicted by flavonoid content alone. Leaves primarily accumulate flavonoids for UV protection, defense, and signaling. Flowers, on the other hand, accumulate pigments and antioxidants to attract pollinators and protect delicate reproductive tissues from oxidative stress. Because flowers are short-lived and exposed, they may rely on a burst of highly potent antioxidants to protect against damage during their brief but critical life phase. Most antioxidant assays (DPPH, FRAP, ABTS) measure functional activity, not total flavonoid content. Flowers might contain fewer total flavonoids but more reactive antioxidants that perform better in these assays. For example, anthocyanins in flowers show strong radical scavenging, often outperforming more abundant but less reactive flavonoids in leaves.

Conversely, the bulb and basal part of the stalk appear to be less favorable in terms of their phenolic and flavonoid content, despite the bulb’s traditional culinary relevance in other Allium species. This variability in secondary metabolite distribution underscores the importance of selecting specific plant parts for optimizing the extraction of antioxidants from A. roseum.

The highest total phenolic content (TPC) was recorded in the leaf and flower extracts. This observation is consistent with the fact that aerial parts of the plant are more exposed to solar radiation, which stimulates the enhanced biosynthesis of phenolic compounds known to function as natural photoprotective agents against UV-B radiation.

Above-ground plant organs have a higher content of phenols and flavonoids compared to the underground parts of the plant. In similar studies, Snoussi and colleagues [5] reported that the leaves of A. roseum from Tunisia are the richest in phenol content (84.39 mg GAE/g d.e.), while the flowers (5.88 mg CE/g d.e.) contain the highest levels of flavonoids.

The observed differences in bioactive constituents between A. roseum from Tunisia and the local A. roseum populations from Montenegro are likely attributable to the genetic specificity of regional chemotypes, as well as their adaptation to distinct environmental conditions, including climate and soil characteristics of the respective habitats. Furthermore, discrepancies in certain phytochemical profiles may also arise from methodological differences, particularly in the choice of extraction solvents and analytical techniques. Specifically, the Montenegrin samples were extracted using ethanol, whereas methanol was used for the Tunisian samples. The ethanol extraction method employed is widely recognized for its efficacy in recovering both polar and moderately non-polar phytochemicals, particularly phenolic compounds and flavonoids. Nevertheless, it should be noted that extraction efficiency may be influenced by factors such as plant matrix complexity, solvent polarity, and potential volatilization or degradation of thermolabile constituents during concentration and drying steps. Such potential losses, although minimized by controlled temperature and reduced pressure, are inherent to the extraction process and must be considered when interpreting yield data.

Rosy garlic is distinguished by a higher total phenolic content compared to both garlic and onion [11]. The TPC content varies depending on the solvent used. Specifically, the methanol and acetone extracts showed higher TPC compared to the water extract. This indicates that the water extract of rosy garlic is primarily composed of non-polar phenolic compounds [11]. Similar to our findings, the results from Dziri et al. [12] show that the flowers and leaves have the highest TPC, TFC content, and antioxidant activity.

While the Folin-Ciocalteu and aluminum chloride methods are widely used for the determination of total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC), respectively, each method has inherent limitations that must be considered when interpreting results. These limitations highlight the importance of complementing colorimetric assays with more specific analytical techniques, such as HPLC or LC-MS, when precise quantification and characterization of phenolic and flavonoid compounds are required. Nonetheless, despite their limitations, the Folin-Ciocalteu and aluminum chloride methods remain useful for comparative studies and preliminary screenings due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and rapid execution.

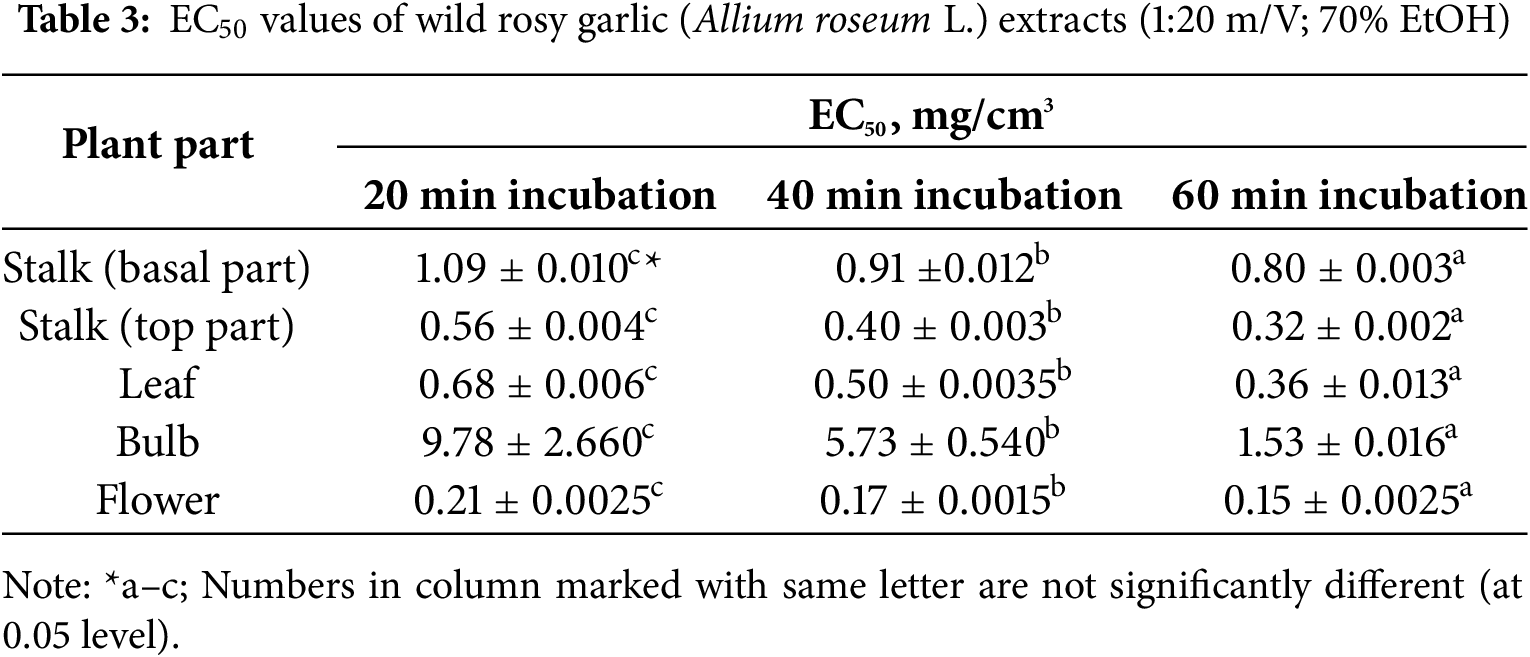

The degree of DPPH radical neutralization increased across an incubation time from 20 to 60 min. The leaves of rosy garlic demonstrate superior antioxidant activity compared to the other parts of the plant. The antioxidant activity from the different plant parts of the A. roseum during the incubation time of 60 min decreased in a sequence: flowers (0.15 mg/cm3) > stalk (top part) (0.32 mg/cm3) > leaf (0.36 mg/cm3) > stalk (basal part) (0.80 mg/cm3) > bulb (1.53 mg/cm3), Table 3.

Similar results were reported by Snoussi et al. [5] with A. roseum var. odoratissimum (rosy garlic) cultivated in Tunisia, where leaf and flower extracts exhibited the highest antioxidant capacity, with TPC content (84.39 mg gallic acid equivalents/g plant material) and TFC contents (5.88 mg (+)-catechin equivalents/g plant material), respectively.

Similarly, the anti-DPPH radical activity of the flowers, stems, and leaves—reflected in IC50 values of 137.00, 131.66, and 162.33 μg/mL, respectively—demonstrated the greatest capacity for neutralizing this free radical. In contrast, the bulb extract showed the weakest activity, with a significantly higher EC50 value of 920 μg/mL [5]. These findings are consistent with the literature cited by Nencini et al. [13] who reported that the flowers and leaves of Allium neapolitanum and Allium roseum L. exhibit the strongest anti-DPPH radical activity, while bulbs and young shoots display considerably weaker effects.

The EC50 values presented in Table 3 provide a quantitative measure of the antioxidant activity of A. roseum extracts from different plant parts, assessed at varying incubation times (20, 40, and 60 min). The EC50 values observed in antioxidant assays vary with incubation time, indicating that the antioxidant capacity of a compound is not a fixed parameter but rather depends on the duration of its interaction with reactive species. This variability may result from multiple factors, including the temporal stability of the antioxidant compound, the kinetics of its radical-scavenging reactions, and the potential for secondary reactions or compound degradation occurring during the assay. Lower EC50 values indicate higher antioxidant potency, as they represent the concentration required to neutralize 50% of free radicals. The flower exhibited the lowest EC50 values across all incubation times (0.21 ± 0.0025 mg/cm3 at 20 min, 0.17 ± 0.0015 mg/cm3 at 40 min, and 0.15 ± 0.0025 mg/cm3 at 60 min), underscoring its exceptional antioxidant capacity. The top part of the stalk and the leaf also demonstrated relatively low EC50 values, with a decreasing trend observed as incubation time increased, indicating enhanced antioxidant activity over time. Notably, the bulb showed significantly higher EC50 values compared to other parts, particularly at shorter incubation times (9.78 ± 2.660 mg/cm3 at 20 min), though its efficacy improved markedly after 60 min (1.53 ± 0.016 mg/cm3). The basal part of the stalk exhibited intermediate EC50 values, suggesting moderate antioxidant activity. These findings align with the trends observed in Tables 2 and 3, where the flower and leaf were identified as rich sources of phenolic compounds and flavonoids, which likely contribute to their potent antioxidant activity. Conversely, the bulb’s lower bioactive compound content correlates with its reduced antioxidant efficacy, especially at shorter incubation periods. Overall, these results highlight the flower as the most effective part for antioxidant applications, followed by the leaf and top part of the stalk, while the bulb demonstrates delayed but still notable antioxidant potential. This variability in EC50 values underscores the importance of considering both plant part and incubation time when evaluating the antioxidant properties of A. roseum.

Leaves and flowers, as aerial plant organs, exhibit higher DPPH and ABTS values compared to underground organs (7 to 14.5-fold higher, using the DPPH method) [14] which has also been confirmed in numerous studies by various authors. The higher EC50 values (indicating lower antioxidant activity) observed in wild garlic bulbs compared to leaves and flowers are likely due to differences in the concentration and types of antioxidant compounds present. Bulbs generally have a higher concentration of sulfur-containing compounds, like allicin, which are known for their antioxidant properties. However, leaves and flowers tend to contain higher levels of other antioxidants, such as polyphenols, which contribute to their stronger antioxidant activity.

A similar trend was observed in the content of vitamin C. The highest concentration was found in the flowers of A. roseum (1.94 μmol/g fresh weight), while in the bulbs it was 0.28 μmol/g fresh weight. In addition, the leaves (1.25 μmol/g fresh weight), inflorescences (0.79 μmol/g fresh weight), and bulblets (0.45 μmol/g fresh weight) of A. roseum also contain higher amounts of ascorbic acid compared to the same plant parts of Allium sativum [14].

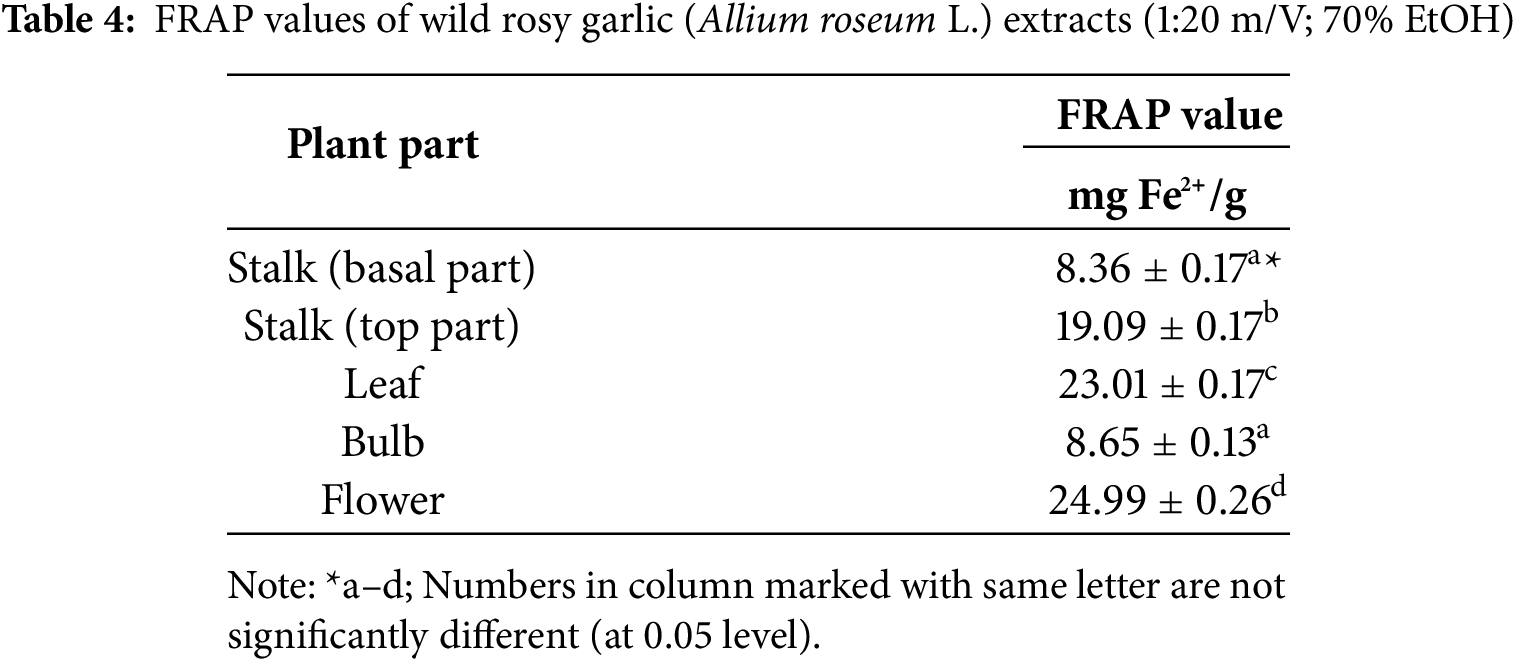

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) values of A. roseum extracts, presented in Table 4, provide insight into the antioxidant capacity of different plant parts, expressed both as mg Fe2+/g. The flower exhibited the highest FRAP value (24.99 ± 0.26 mg Fe2+/g) indicating its superior ferric ion-reducing ability compared to other parts of the plant. This was closely followed by the leaf (23.01 ± 0.17 mg Fe2+/g) and the top part of the stalk (19.09 ± 0.17 mg Fe2+/g), which also demonstrated relatively high antioxidant capacities. In contrast, the basal part of the stalk and the bulb had significantly lower FRAP values (8.36 ± 0.17 and 8.65 ± 0.13 mg Fe2+/g, respectively), suggesting that these parts contribute less to the overall antioxidant potential of the plant. These results are consistent with the trends observed for total phenols and flavonoids in Table 2, where the flower and leaf were identified as the richest sources of these bioactive compounds. Collectively, these findings emphasize the flower and leaf as the most potent carrier to the AA of rosy garlic, while the bulb and basal part of the stalk appear to play a lesser role in this context. This highlights the importance of selecting specific plant parts when evaluating or utilizing the antioxidant properties of A. roseum. Rosy garlic exhibits antioxidant capabilities in all its fresh organs. The greatest content of thiosulfinates is present in the flowers bulblets, while the levels of ascorbic acid, quercetin and rutin are greater in the flowers. The bulbs, bulblets, flowers bulblets, leaves and flowers are a good source of important bioactive compounds [14].

AA of rosy garlic leaves was also confirmed by the FRAP method in exploration of Stajner et al. [15] were the highest antioxidant content was recorded in the leaves (6.46 μmol Fe2+), followed by the stems (3.11 μmol Fe2+), while the lowest content was found in the bulbs (2.62 μmol Fe2+), which is significantly lower compared to our research. Therefore, it can be concluded that the ecotype from Montenegro is very rich in antioxidants in all plant parts, especially in the flowers, which can have various applications, including use as edible flowers. The high antioxidant activity in flowers represents a key adaptation to UV-B radiation, safeguarding both the plant’s reproductive success and potentially influencing pollinator behavior. This interdependence between UV-B exposure, antioxidant production, and reproductive strategies highlights the complexity of evolutionary plant responses to diverse ecological conditions.

In A. roseum, elevated antioxidant activity in flowers is associated with adaptation to UV-B radiation and the preservation of reproductive function. Flavonoids and other antioxidants protect sensitive floral structures, particularly pollen, from oxidative stress caused by UV-B, thereby ensuring successful fertilization. This protective mechanism is especially prominent in plants growing under increased UV-B exposure, indicating an evolutionary adaptation.

The leaves of A. roseum are particularly rich in phytochemicals known for their strong antioxidant properties. This characteristic positions them as promising natural preservatives with antioxidant potential for use in food preservation within the food industry. Fresh or dried, Allium roseum leaves can be considered as a natural preservative, antibacterial and flavoring agent in double cream cheese [16].

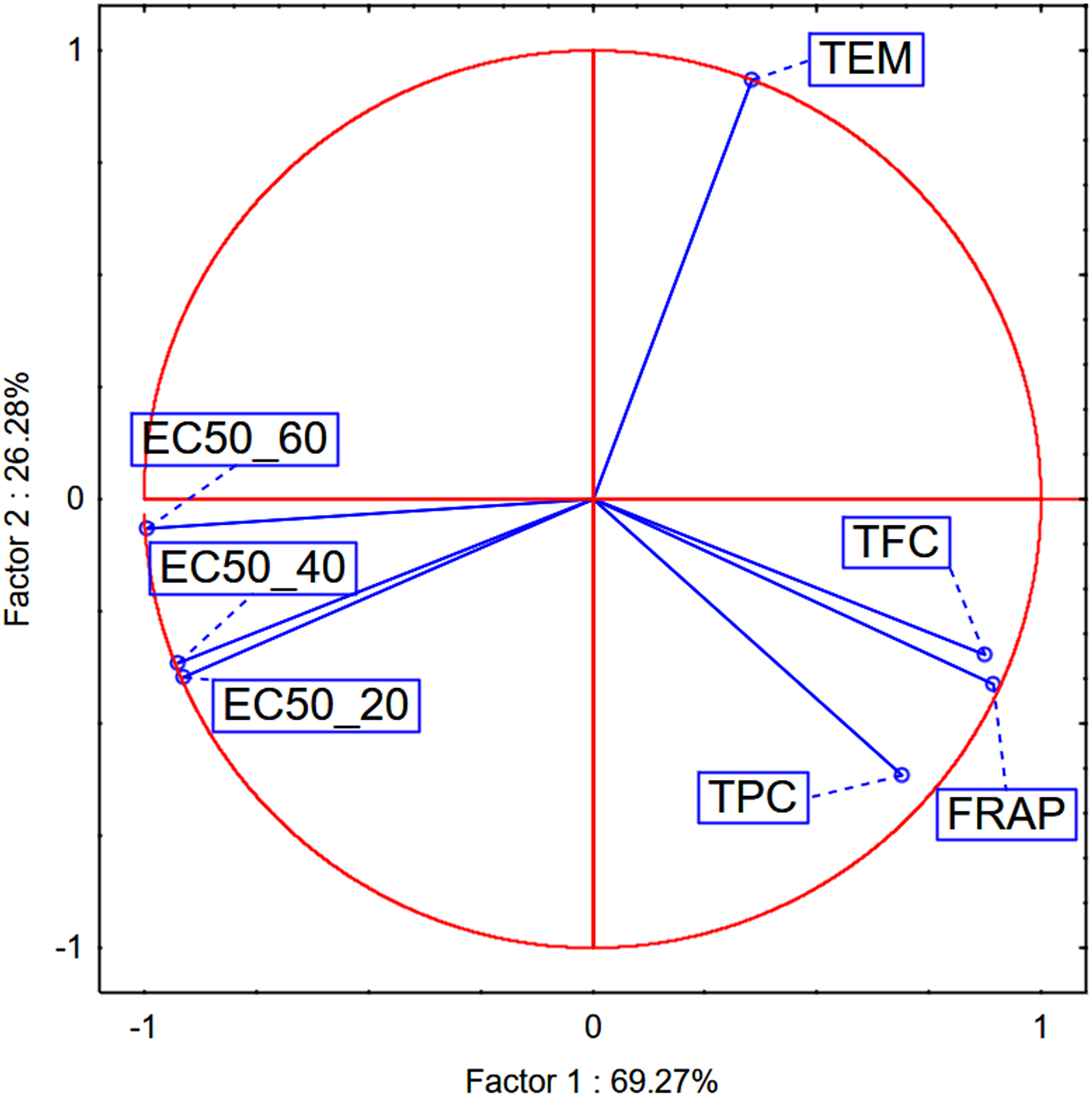

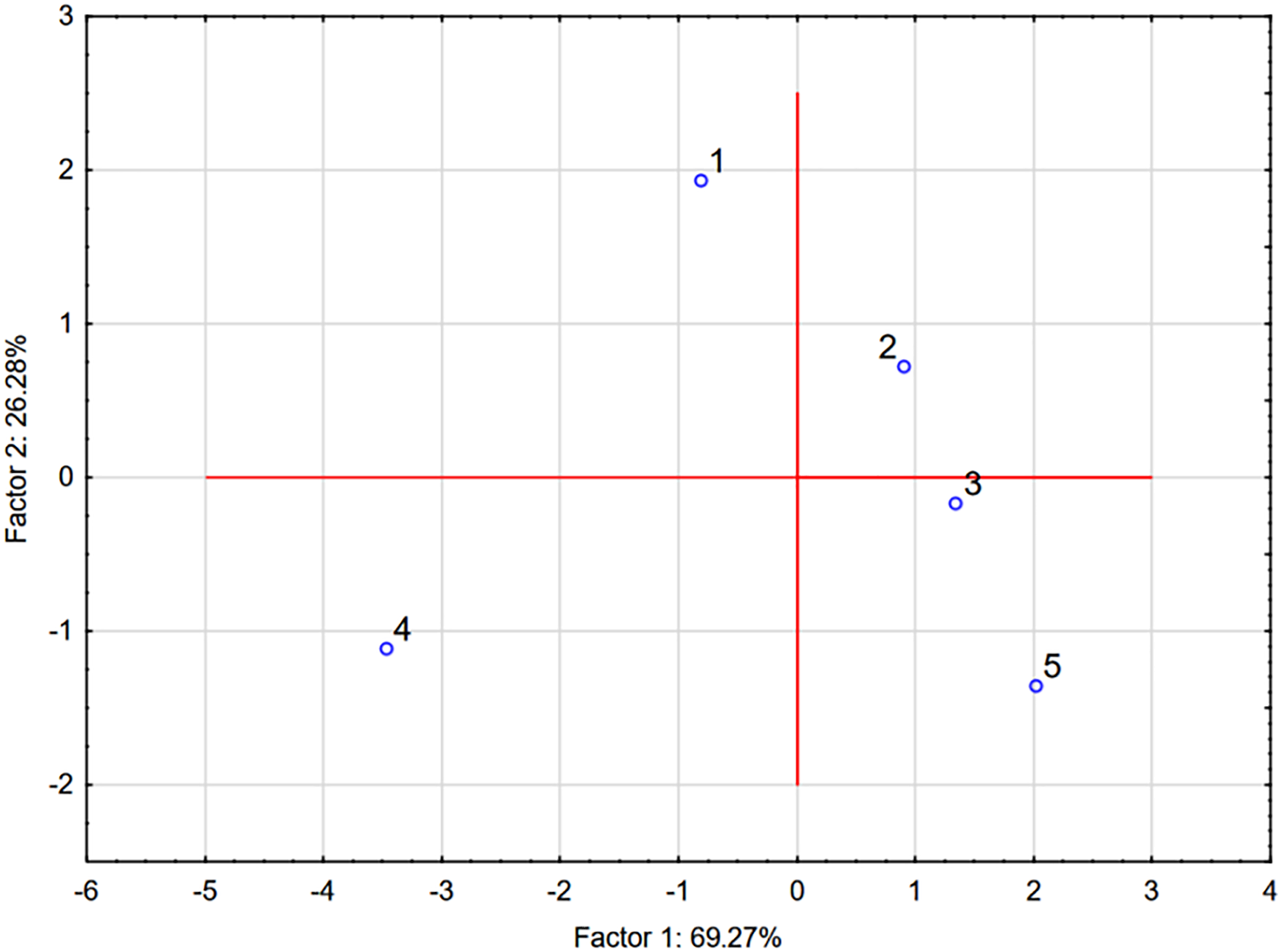

The principal component analysis (PCA) of the antioxidant-related parameters in A. roseum L. provides a comprehensive overview of the relationships and variability among the measured variables (Fig. 1). The eigenvalues of the correlation matrix indicate that the first two principal components (Factor 1 and Factor 2) explain 69.27% and 26.28% of the total variance, respectively, cumulatively accounting for 95.54% of the data variability. This suggests that these two factors capture the majority of the information contained in the dataset (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Projection of the variables on the factor-plane. TEM—total extractive matter; TPC—total phenol content; TFC—total flavonoids content; FRAP—antioxidant activity; EC50_20—EC50 value after 20 min of incubation; EC50_40—EC50 value after 40 min of incubation; EC50_60—EC50 value after 60 min of incubation

Figure 2: Projection of the cases on the factor-plane. 1—Stalk (basal part); 2—Stalk (top part); 3—Leaf; 4—Bulb; 5—Flower

In terms of variable contributions, Factor 1 is strongly influenced by EC50 values (EC50 20: −0.912, EC50 40: −0.926, EC50 60: −0.995), which load negatively on this factor, indicating that lower EC50 values (higher antioxidant activity) are associated with positive scores on Factor 1. Conversely, total flavonoids (0.876) and FRAP values (0.894) also contribute significantly to Factor 1 but with positive loadings, suggesting a strong positive correlation between these variables and antioxidant potential. Factor 2 is primarily characterized by an opposition between TEM (0.356, positively loaded) and total phenols (−0.616) and flavonoids (−0.347), implying that the yield of extractable matter may not be directly correlated with the concentration of specific bioactive compounds.

The factor coordinates of cases further elucidate the relationships among the plant parts. The flower (Case 5) exhibits the highest positive score on Factor 1 (2.019), reflecting its superior antioxidant capacity due to high levels of flavonoids, phenols, and FRAP values, as well as low EC50 values. The leaf (Case 3) and top part of the stalk (Case 2) also show relatively high scores on Factor 1, consistent with their moderate-to-high antioxidant activities. In contrast, the bulb (Case 4) has the most negative score on Factor 1 (−3.467), indicating its inferior antioxidant properties, which aligns with the previously observed low yields of phenols, flavonoids, and FRAP values, as well as higher EC50 values. The basal part of the stalk (Case 1) occupies an intermediate position, reflecting its moderate contribution to the overall antioxidant potential.

The PCA results confirm that the flower is the most potent source of antioxidants in A. roseum, followed by the leaf and top part of the stalk, while the bulb contributes the least. These findings reinforce the importance of selecting specific plant parts for optimizing the extraction of bioactive compounds and maximizing the antioxidant properties of A. roseum. Additionally, the PCA highlights the complex interplay between different parameters, emphasizing the need for a multifaceted approach when evaluating the antioxidant potential of plant materials.

Local populations from Montenegro represent promising candidates for domestication due to their abundant leaf biomass, large inflorescences, and compact bulbs—traits associated with high-yielding varieties—thus providing a valuable foundation for future breeding and selection programs.

A. roseum has significance in nutrition during emergency situations, warfare, survival in nature, scarce food supply for local populations, etc. It is also important for the preservation of genetic resources, categorization, evaluation, conservation, and the protection of biodiversity and genetic resources of wild vegetables. The result presented herein showed the high potential of A. roseum as antioxidant agents. This implies their possible application for different purposes, such as natural preservative agents, and may be used as alternatives to replace synthetic antioxidants in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industry.

All plant parts of Allium roseum, including both underground and aerial organs, are suitable for consumption due to their high antioxidant content. The inflorescence with flowers of A. roseumis the plant organ characterized by the highest phytochemical potential. The antioxidant activity of A. roseum flowers plays an adaptive role in mitigating UV-B stress and maintaining reproductive viability under challenging environmental conditions. The flowers of A. roseum represent a culinary ingredient of emerging interest, offering mild Allium flavors, characterized by mild garlic notes with subtle sweet and floral undertones, suitable for both traditional and modern gastronomy. The aromatic compounds present are markedly less pungent than those found in the bulbs or leaves, rendering the flowers suitable for applications where a gentle Allium flavor is desired. In addition to use in fresh form, several culinary techniques (air-drying or lyophilization, fermentation) preserve or enhance the sensory properties of A. roseum flowers or may be candied for integration into applications where floral-sweet profiles are desired. A. roseum contains sulfur-containing secondary metabolites, including thiosulfinates and related compounds. While hypersensitivity reactions to the flowers are rarely documented compared to the bulbs, potential exists for contact dermatitis and oral allergy syndrome or mild gastrointestinal reactions upon ingestion. Concurrently, their ecological role in sustaining pollinator health through antioxidant provision reinforces their value in sustainable agriculture and biodiversity conservation. A. roseum is characterized by a significant content of health-promoting phytochemicals and has great potential to serve as a basis for the development of new pharmaceutical products through biochemical and pharmacological research.

Methodological limitations such as the only one location for plant collection sites, as well as the absence of certain analyses related to sensory characteristics, taste evaluation, and potential allergenic effects, represent limiting factors of this study.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Ministry of Education Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia with grant numbers 451-03-47/2025-01/200133 and 451-344 03-47/2025-01/200189.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Zoran S. Ilić; Data collection: Lidija Milenković, Ljubomir Šunić, Dragana Lalević; Analysis and interpretation of results: Ljiljana Stanojević, Aleksandra Milenković; Draft manuscript preparation: Zoran S. Ilić, Žarko Kevrešan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.069082/s1.

Abbreviations

| AlCl3 | Aluminum chloride |

| CH3CO2K | Potassium acetate |

| Na2CO3 | Sodium carbonate |

| (DPPH) | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric ion reducing antioxidant potential |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| RE | Routine equivalents |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

1. Kurnia D, Ajiati D, Heliawati L, Sumiarsa D. Antioxidant properties and structure-antioxidant activity relationship of Allium species leaves. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7175. doi:10.3390/molecules26237175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Rocchetti G, Zhang L, Bocchi S, Giuberti G, Ak G, Elbasan F, et al. The functional potential of nine Allium species related to their untargeted phytochemical characterization, antioxidant capacity and enzyme inhibitory ability. Food Chem. 2022;368(5):130782. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Talib WH, Atawneh S, Shakhatreh AN, Shakhatreh GN, aljarrah Rasheed IS, Ali Hamed R, et al. Anticancer potential of garlic bioactive constituents: allicin, Z-ajoene, and organosulfur compounds. Pharmacia. 2024;71(1):1–23. doi:10.3897/pharmacia.71.e114556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Teka N, Alminderej FM, Souid G, El-Ghoul Y, Le Cerf D, Majdoub H. Characterization of polysaccharides sequentially extracted from Allium roseum leaves and their hepatoprotective effects against cadmium induced toxicity in mouse liver. Antioxidants. 2022;11(10):1866. doi:10.3390/antiox11101866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Snoussi M, Trabelsi N, Dehmeni A, Benzekri R, Bouslama L, Hajlaoui B, et al. Phytochemical analysis, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Allium roseum var. odoratissimum (Desf.) Coss extracts. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;89(1):533–42. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.05.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kherroubi S, Morjen M, Teka N, Mraihi F, Srairi-Abid N, Le Cerf D, et al. Chemical characterization and pharmacological properties of polysaccharides from Allium roseum leaves: in vitro and in vivo assays. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;277(Pt 3):134302. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Milenković A, Stanojević J, Stojanović-Radić Z, Pejčić M, Cvetković D, Zvezdanović J, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidative and antimicrobial activity of allspice (Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr.) essential oil and extract. Adv Techol. 2020;9(1):27–36. doi:10.5937/savteh2001027m. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lin JY, Tang CY. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid contents in selected fruits and vegetables, as well as their stimulatory effects on mouse splenocyte proliferation. Food Chem. 2007;101(1):140–7. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–6. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Milenković A, Aleksovski S, Miteva K, Milenković L, Stanojević J, Nikolić G, et al. The effect of extraction technique on the yield, extraction kinetics and antioxidant activity of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) ethanolic extracts. Horticulturae. 2025;11(2):125. doi:10.3390/horticulturae11020125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Najjaa H, Zerria K, Fattouch S, Ammar E, Neffati M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Allium roseum L. lazoul, a wild edible endemic species in north Africa. Int J Food Prop. 2011;14(2):371–80. doi:10.1080/10942910903203164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dziri S, Hassen I, Fatnassi S, Mrabet Y, Casabianca H, Hanchi B, et al. Phenolic constituents, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of rosy garlic (Allium roseum var. odoratissimum). J Funct Foods. 2012;4(2):423–32. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2012.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nencini C, Menchiari A, Franchi GG, Micheli L. In vitro antioxidant activity of aged extracts of some Italian Allium species. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2011;66(1):11–6. doi:10.1007/s11130-010-0204-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fiaschi AI, Moltoni L, Menchiari A, Micheli L. Determination of ascorbic acid, rutin and antioxidant capacities of wild Allium roseum from Italy. Pharmacol Pharm. 2019;10(5):271–82. doi:10.4236/pp.2019.105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Stajner D, Popovic BM, Canadanović-Brunet J, Igić RS. Antioxidant and free-radical scavenging activities of Allium roseum and Allium subhirsutum. Phytother Res. 2008;22(11):1469–71. doi:10.1002/ptr.2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gliguem H, Ben Hassine D, Ben Haj Said L, Ben Tekaya I, Rahmani R, Bellagha S. Supplementation of double cream cheese with Allium roseum: effects on quality improvement and shelf-life extension. Foods. 2021;10(6):1276. doi:10.3390/foods10061276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools