Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Species Number of Invasive Plants Negatively Regulates Carbon Contents, Enzyme Activities, and Bacterial Alpha Diversity in Soil

1 School of Environment and Safety Engineering, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, 212013, China

2 School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China

3 Weed Research Laboratory, College of Life Sciences, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 210095, China

4 Key Laboratory of Ocean Space Resource Management Technology, Marine Academy of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, 310012, China

5 Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Technology and Material of Water Treatment, Suzhou University of Science and Technology, Suzhou, 215009, China

* Corresponding Authors: Congyan Wang. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses and Adaptations to Environmental Stresses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2873-2891. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065970

Received 26 March 2025; Accepted 29 May 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The leaves of multiple invasive plants can coexist and intermingle within the same environment. As species number of invasive plants increases, variations may occur in decomposition processes of invasive plants, soil nutrient contents, soil enzyme activities, and soil microbial community structure. Existing progress have predominantly focused on the ecological effects of one species of invasive plant compared to native species, with limited attention paid to the ecological effects of multiple invasive plants compared to one species of invasive plant. This study aimed to determine the differences in the effects of mono- and co-decomposition of four Asteraceae invasive plants, horseweed (Erigeron canadensis (L.) Cronq.), Guernsey fleabane (E. sumatrensis Retz.), daisy fleabane (E. annuus (L.) Pers.), and Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis L.), on litter decomposition responses, soil carbon contents, soil enzyme activities, and soil bacterial community structure. Species number of invasive plants did not significantly affect on the decomposition rate of mixed leaves or mixed-effect intensity of co-decomposition. Soil pH and electrical conductivity enhanced as species number of invasive plants increased. Soil carbon contents (including soluble organic carbon content and microbial carbon content), soil enzyme (including polyphenol oxidase, FDA hydrolase, and sucrase) activities, soil bacterial alpha diversity (including the OTU species, Chao1 richness, ACE richness, and Phylogenetic diversity indexes), and the number of pathways of most functional genes of soil bacterial communities closely related to decomposition processes declined as species number of invasive plants increased. Hence, soil pH and electrical conductivity significantly increased with increasing species number of invasive plants, but soil carbon contents, soil enzyme activities, soil bacterial alpha diversity, and the number of pathways of most functional genes of soil bacterial communities closely related to decomposition processes significantly reduced with growing species number of invasive plants.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe ecological security issues triggered by biological invasions facilitated by invasive plants (IPS) have emerged as a prominent concern among ecologists currently [1–4]. The species number of IPS (SIPS) presently existing in China is 515 [5]. The SIPS of the Asteraceae family (92 species) is the greatest at the family level in China [5]. It is, therefore, imperative to clarify the foremost mechanisms underpinning the successful colonization of IPS [2,4,6,7], especially of Asteraceae IPS [2,8–10].

One of the chief factors contributing to the success of IPS invasion is its capacity to interact with soil microbes through decomposition processes. This permits IPS to release numerous nutrients, thereby fluctuating soil nutrient profile (e.g., carbon) and the metabolic activity and diversity of soil microbes, which can generate a soil microenvironment that is more conducive to their further invasion [11–14]. In particular, the decomposition rate, soil carbon content, soil microbial carbon content, soil ammonium content, soil nitrate content, and soil microbial nitrogen content exhibited 116.80%, 6.86%, 34.12%, 29.68%, 16.58%, and 25.81% increase in IPS compared to native plants, respectively [15].

The successful colonization of one IPS has been demonstrated to cause fluctuations in nutrient contents, enzyme activities, and microbial community structure in soil. This, in turn, has been shown to increase the possibility of the successful colonization of other IPS in a given environment [7,16–18]. Accordingly, the co-invasion of multiple IPS is a prevalent phenomenon [11,19–21]. In particular, Asteraceae IPS can typically coexist in the same environment in Jiangsu, China, which has been shown to result in noteworthy variations in both plant community structure and soil bacterial community structure (SBC) [20,22,23]. Therefore, leaves of multiple Asteraceae IPS can coexist and intermingle in the same environment [12,23–25].

During decomposition processes, plants can release numerous components (especially carbon-containing substances). These substances have the capacity to influence soil nutrient (e.g., carbon) contents, soil enzyme activities, and SBC. Nevertheless, soil nutrient content, soil enzyme activities, and SBC, in turn, affect the decomposition processes of plants [14,23,26,27]. In particular, SBC is one of the vital regulators of decomposition rate, especially SBC plays a vital role in the initial stages of decomposition processes of plants [28–31]. Thus, decomposition processes of IPS, soil nutrient contents, soil enzyme activities, and SBC may be affected by the increase in SIPS due to altered leaf quantity and quality in invaded environments following the establishment of co-invasion [24,32–34]. Thus, further research is required to examine the relationship between SIPS and decomposition processes of multiple IPS, soil nutrient (e.g., carbon) contents, soil enzyme activities, as well as SBC. This can facilitate the illumination of the main mechanisms underlying the co-invasion facilitated by multiple IPS, especially with a gradient of SIPS. However, extant research has predominantly concentrated on the ecological effects of one species of invasive plant in comparison to native species, with limited attention paid to the ecological effects of multiple invasive plants in comparison to one species of IPS. Additionally, there is presently a paucity of research progress in determining the relationship between SIPS and decomposition processes of multiple IPS, soil nutrient (e.g., carbon) contents, soil enzyme activities, as well as SBC, especially with regard to decomposition processes.

The present study was conducted with the objective of illuminating the differences in the effects of mono- and co-decomposition of four IPS, horseweed (Erigeron canadensis (L.) Cronq.), Guernsey fleabane (E. sumatrensis Retz.), daisy fleabane (E. annuus (L.) Pers.), and Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis L.), on litter decomposition responses, soil carbon contents, soil enzyme activities, and SBC. This study was completed via a polyethylene-litterbag experiment with a six-month period.

We hypothesize that the decomposition rate of multiple IPS, soil carbon contents, soil enzyme activities, SBC alpha diversity, and the number of functional gene pathways of SBC closely related to decomposition processes (No-FGP) will increase as SIPS increases during decomposition processes.

Four IPS were selected for investigation: horseweed, Guernsey fleabane, daisy fleabane, and Canada goldenrod (Figs. S1–S4). Intact and mature leaves from the adult individuals of the four IPS (more than ten individuals) were randomly collected in Zhenjiang (32.163–32.209° N, 119.456–119.529° E), Jiangsu, China, in May 2022. All of these IPS belong to the Asteraceae family, and SIPS of Asteraceae family is the greatest at the family level in China [5]. The four IPS originate from America, and SIPS originating from America is higher than those originating from other areas [5]. The four IPS have comparable growth patterns, with the peak growth season occurring between April and August in Jiangsu, China. They also exhibit analogous life styles, with erect herbs being a common trait. They are also found in alike environments, including wastelands, agroecosystems, and both sides of the main roads in Jiangsu, China. The four IPS have the ability to form extensive monodominant communities when they invade independently, which can decrease biodiversity in native communities [35–38]. Thus, they have been designated as harmful IPS in China. The four IPS can coexist in the same environment (Figs. S5–S15).

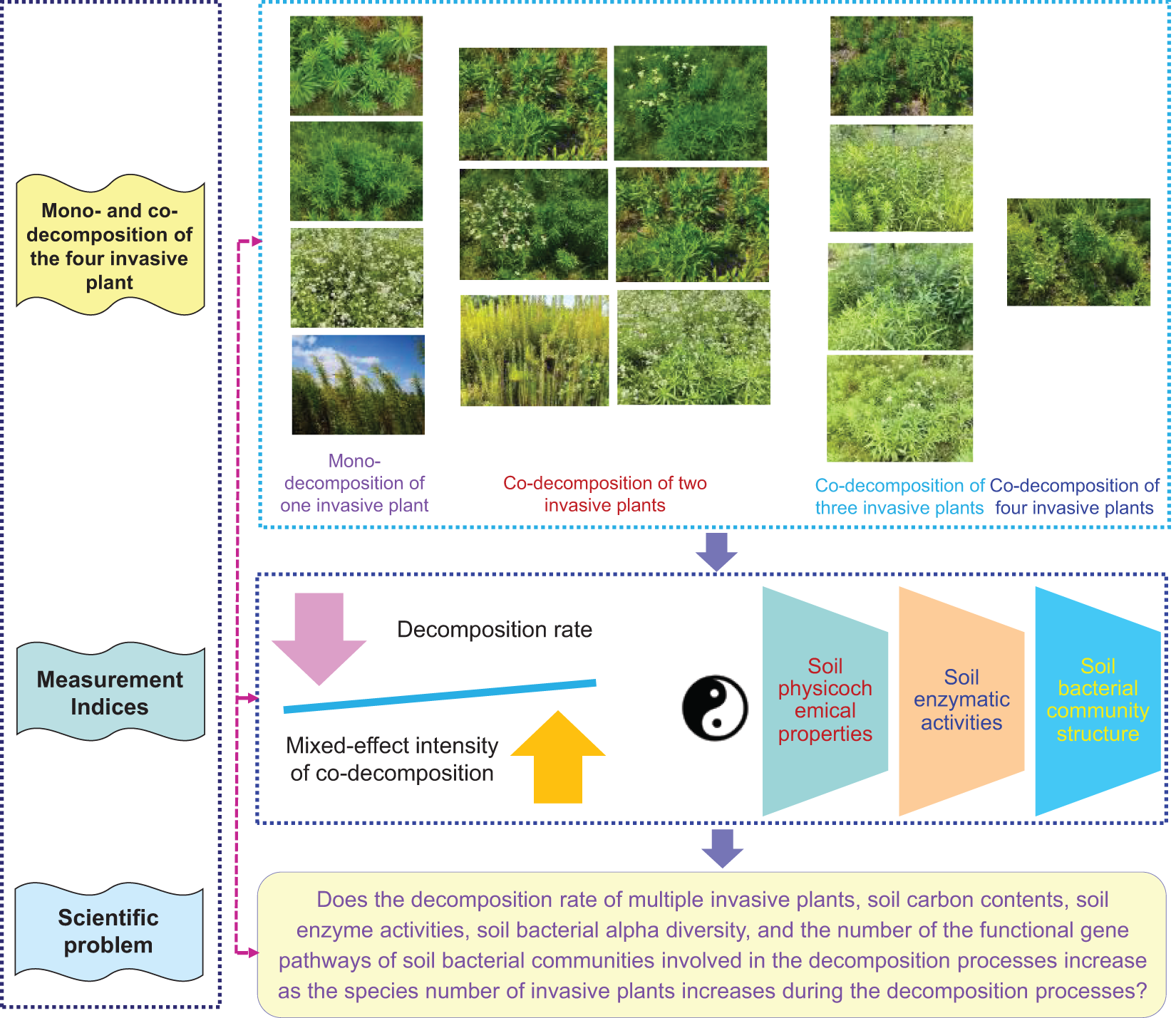

Decomposition processes of the four IPS was replicated in a polyethylene-litterbag experiment conducted from 01 June 2022 to 02 December 2022 (~184 d) in a greenhouse at Zhenjiang (32.2061° N, 119.5128° E) at room temperature. The air-dried leaves from the four IPS were positioned in the polyethylene-litterbags (mesh size: ~0.425 mm; dimensions: 10 × 15 cm). The leaves from the four IPS were scheduled in one of the next fifteen types per polyethylene-litterbag: (1) 6 g leaves from one species of the four IPS (four types); (2) 6 g equally mixed leaves from two species of the four IPS (six types); (3) 6 g equally mixed leaves from three species of the four IPS (four types); (4) 6 g equally mixed leaves from all of the four IPS (one type). Treatments without any leaves from the four IPS were used as control. Three replicates were performed per treatment. Polyethylene-litterbags were placed into store-bought pasture soil (pH: ~6.29; organic matter content: ~324 g kg−1; Shenzhibei Agr. Technol. Co., Ltd., Baishan, China) at a ~2 cm depth in planting pots (height: 16.5 cm; top diameter: 25 cm; bottom diameter: 13.4 cm; one polyethylene-litterbag per planting pot). The rationale for the application of pasture soil as culture medium is to weaken the potential for invasion experience of IPS as much as possible to become established in natural soils. Pasture soil was homogenised before the experiments were carried out. Pasture soil was not disinfected, to confirm normal existence of soil microbes. Water was applied weekly during decomposition experiment to simulate normal precipitation as well as soil moisture status in nature. The level of water application was based on the amount of precipitation in Zhenjiang. The experimental design is exemplified in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The chart of the experiment design

According to experimental period of some studies [27,39–41], decomposition processes in this study lasted for about six months. All polyethylene-litterbags were collected after ~184 d of experimental treatment. Leaves from the four IPS in polyethylene-litterbags were slightly washed and completely air-dried to estimate decomposition variables. Soil samples were recalled at a depth of ~1 cm from polyethylene-litterbags and passed via a 2 mm-sieve to determine soil variables and SBC.

2.3 Determination of Decomposition Variables

The decomposition coefficient (k) of leaves of the four IPS, expected k of mixed leaves of the four IPS, and mixed-effect intensity of co-decomposition of leaves of the four IPS were surveyed.

The determination methods for analyzed variables closely related to decomposition processes are defined in Table S1.

2.4 Determination of Soil Variables

The pH, moisture, electrical conductivity, and the contents of total organic carbon, soluble organic carbon, and microbial carbon in soil was examined.

The activities of several enzymes closely related to soil carbon cycle were studied, including polyphenol oxidase, FDA hydrolase, cellulase, β-glucosidase, β-xylosidase, and sucrase.

The determination methods for examined soil variables are defined in Table S1.

2.5 Determination of Alpha Diversity, Beta Diversity, and Species Composition of SBC, and No-FGP

The alpha diversity, beta diversity, and species composition of SBC, and No-FGP was assayed by Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, Guangdong, China via the application of Illumina PE250 at GENE DENOVO. The primers 341F and 806R was used to amplify the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA genes of SBC [42,43].

The sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of ≥97% similarity using the UPARSE pipeline [44,45]. The KEGG pathway analysis of the OTUs was inferred using the Tax4Fun [46].

Soil bacterial alpha diversity was calculated using the following indices: OUT species index, Shannon diversity index [47], Simpson dominance index [48], Pielou evenness index [49], Chao1 richness index [50], ACE richness index [51], and Phylogenetic diversity index [52]. The good’s coverage index was also evaluated to indicate the coverage level of the sample library [53].

Correlations in soil bacterial beta diversity were appraised using the weighted UniFrac algorithm [52] through principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) [54] and nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) [55].

Statistical analysis of differences in the values of measured variables between various treatments was conducted using the Tukey multiple comparison test. Correlation between the values of measured variables and SIPS was estimated using the correlation analysis judged by the Pearson’s coefficient. The path analysis was employed to estimate the influences of the values of measured variables on the decomposition coefficient as well as the influences of SIPS on the values of measured variables judged by the path coefficient (i.e., the standardized regression coefficient). Significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were made using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0.

3.1 Differences in Decomposition Variables

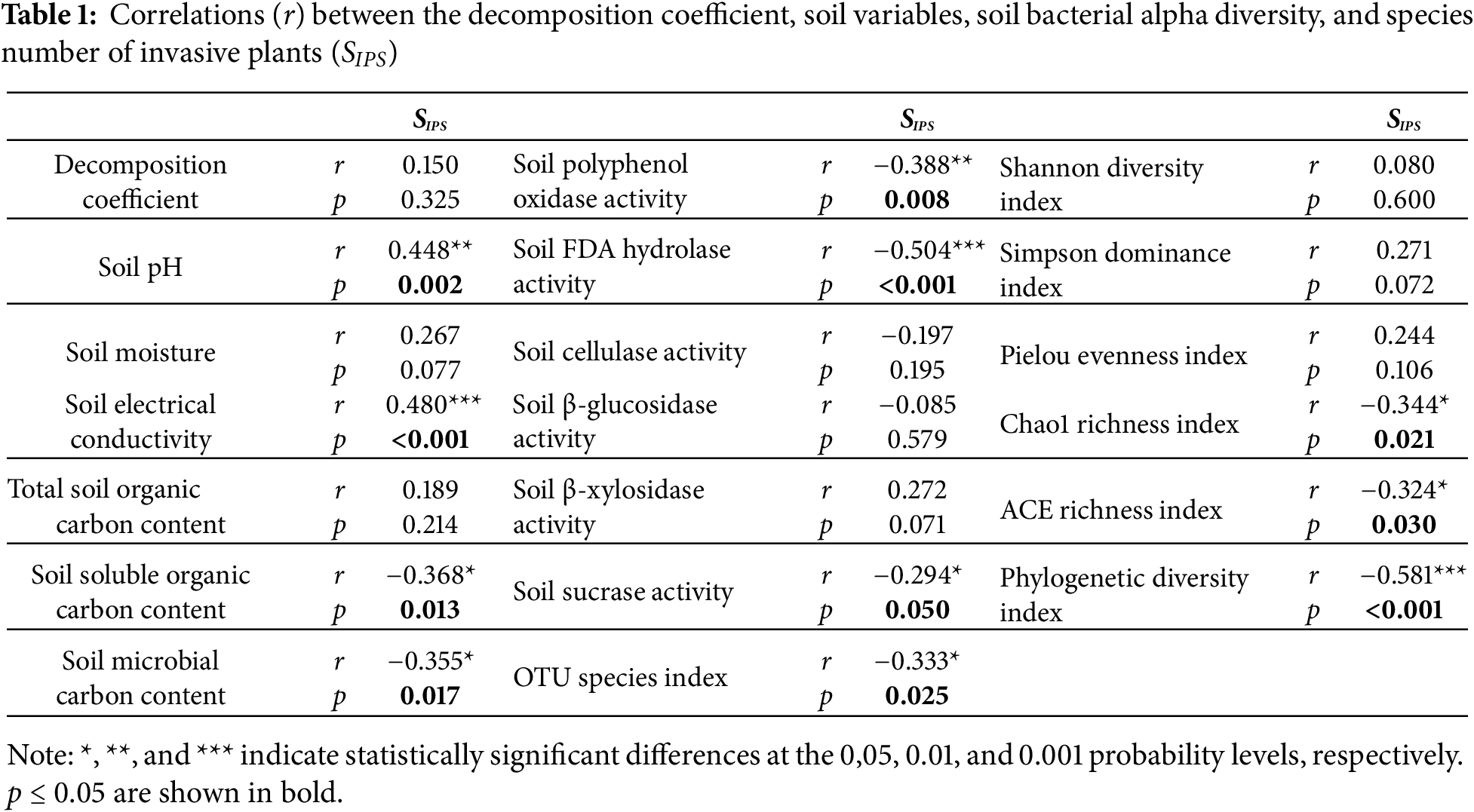

There were no differences between the decomposition coefficients between any of the mixes of plant litter from a single species to the four mixed species (p > 0.05) (data not shown). No close correlations were detected between the decomposition coefficient of the four IPS and SIPS (p = 0.325; Table 1).

The observed decomposition coefficient was similar to the expected decomposition coefficient for co-decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS (p > 0.05) (data not shown). There were no significant differences in mixed-effect intensity of co-decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS (p > 0.05) (data not shown). The mixed-effect intensity of co-decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS was slightly greater than zero (data not shown).

3.2 Differences in Soil Variables

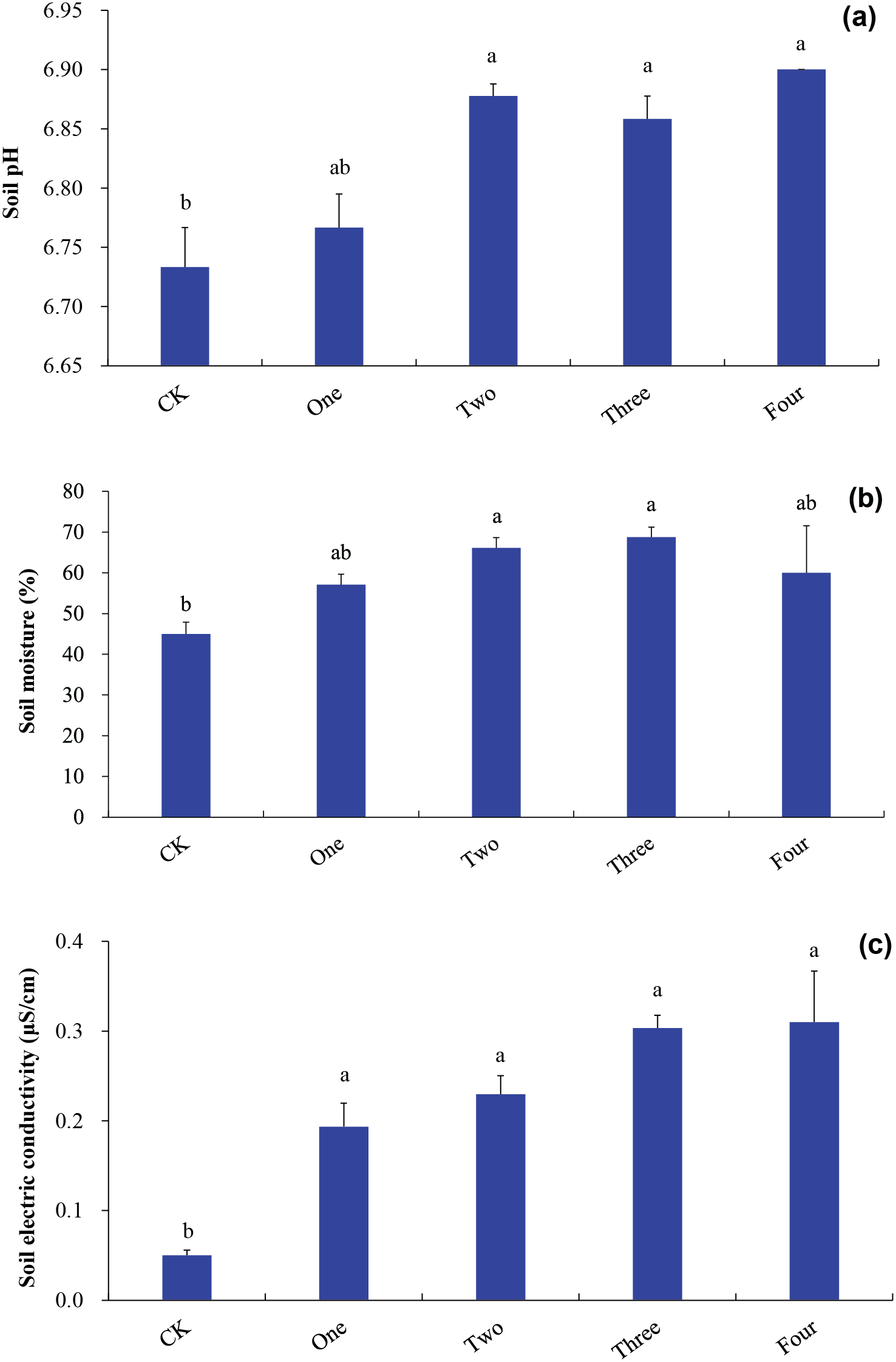

Soil pH under co-decomposition of two IPS, co-decomposition of three IPS, and co-decomposition of four IPS was greater than that under control (p < 0.05; Fig. 2a). Soil pH was positively related to SIPS (p = 0.002; Table 1).

Figure 2: Soil physicochemical properties ((a), soil pH; (b), soil moisture; (c), soil electrical conductivity). Bars (means and SE) with different letters indicate statistically significant differences at 0.05 probability (p < 0.05). Abbreviation: CK, control (n = 3); One, mono-decomposition of one invasive plant (n = 12); Two, co-decomposition of two invasive plants (n = 18); Three, co-decomposition of three invasive plants (n = 12); Four, co-decomposition of four invasive plants (n = 3)

Soil moisture under co-decomposition of two IPS and co-decomposition of three IPS was superior than that under control (p < 0.05; Fig. 2b). No strong correlations were found between soil moisture and SIPS (p = 0.077; Table 1).

The decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS increased soil electrical conductivity compared to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 2c). Soil electrical conductivity was positively related to SIPS (p < 0.001; Table 1).

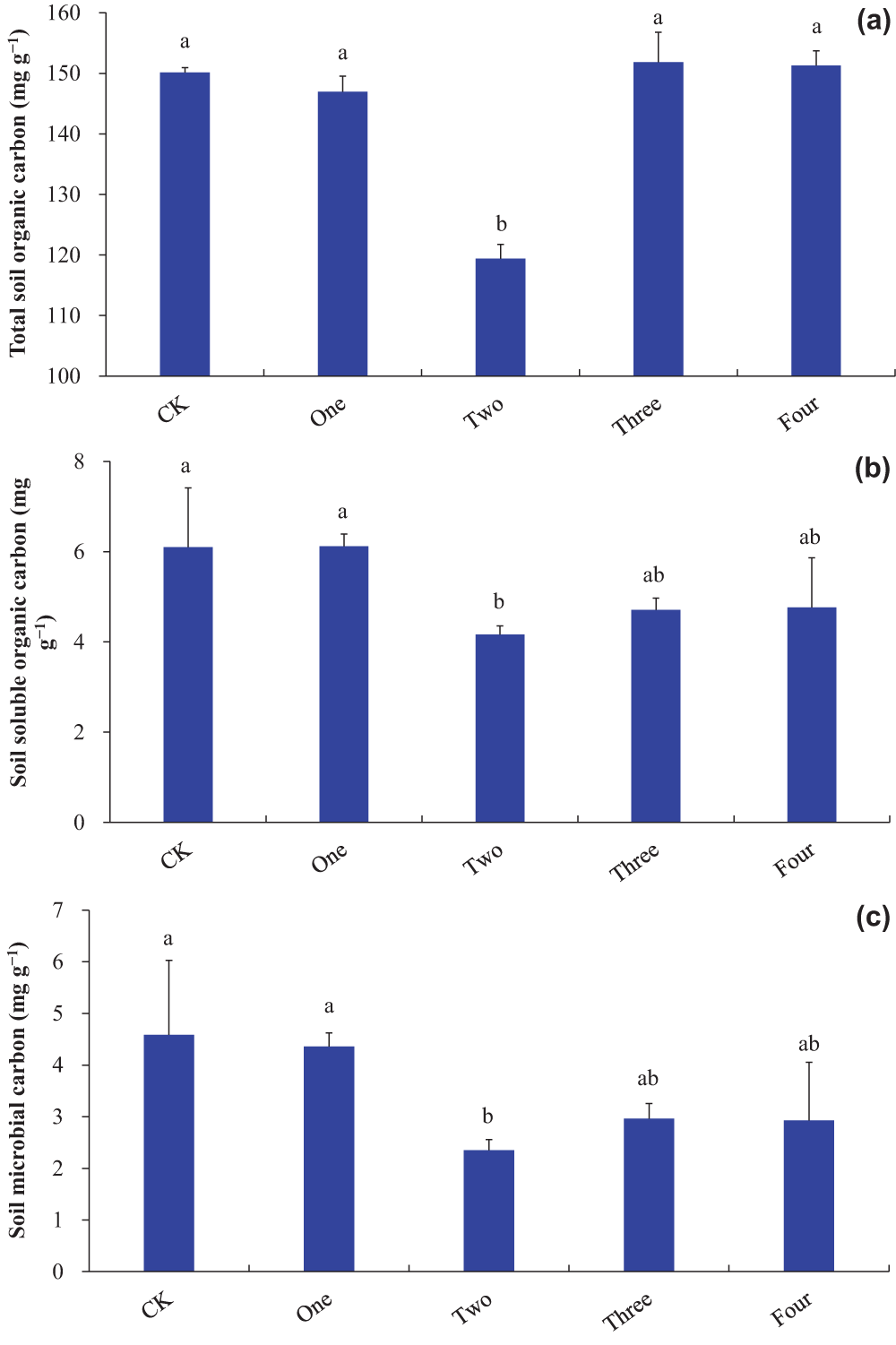

Co-decomposition of two IPS decreased the contents of total organic carbon, soluble organic carbon, and microbial carbon in soil compared to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 3a–c). Total soil organic carbon content under co-decomposition of two IPS was less than that under mono-decomposition of one IPS, co-decomposition of three IPS, and co-decomposition of the four IPS (p < 0.05; Fig. 3a). The contents of soluble organic carbon and microbial carbon in soil under the co-decomposition of two IPS were lesser than those under the mono-decomposition of one IPS (p < 0.05; Fig. 3b,c). No strong correlations were detected between total soil organic carbon content and SIPS (p = 0.214; Table 1). The contents of soluble organic carbon (p = 0.013) and microbial carbon (p = 0.017) in soil were negatively related to SIPS (Table 1).

Figure 3: Soil carbon contents ((a), total soil organic carbon; (b), soil soluble organic carbon; (c), soil microbial carbon). Bars (means and SE) with different letters indicate statistically significant differences at 0.05 probability (p < 0.05). Abbreviations have the same meanings as presented in Fig. 2

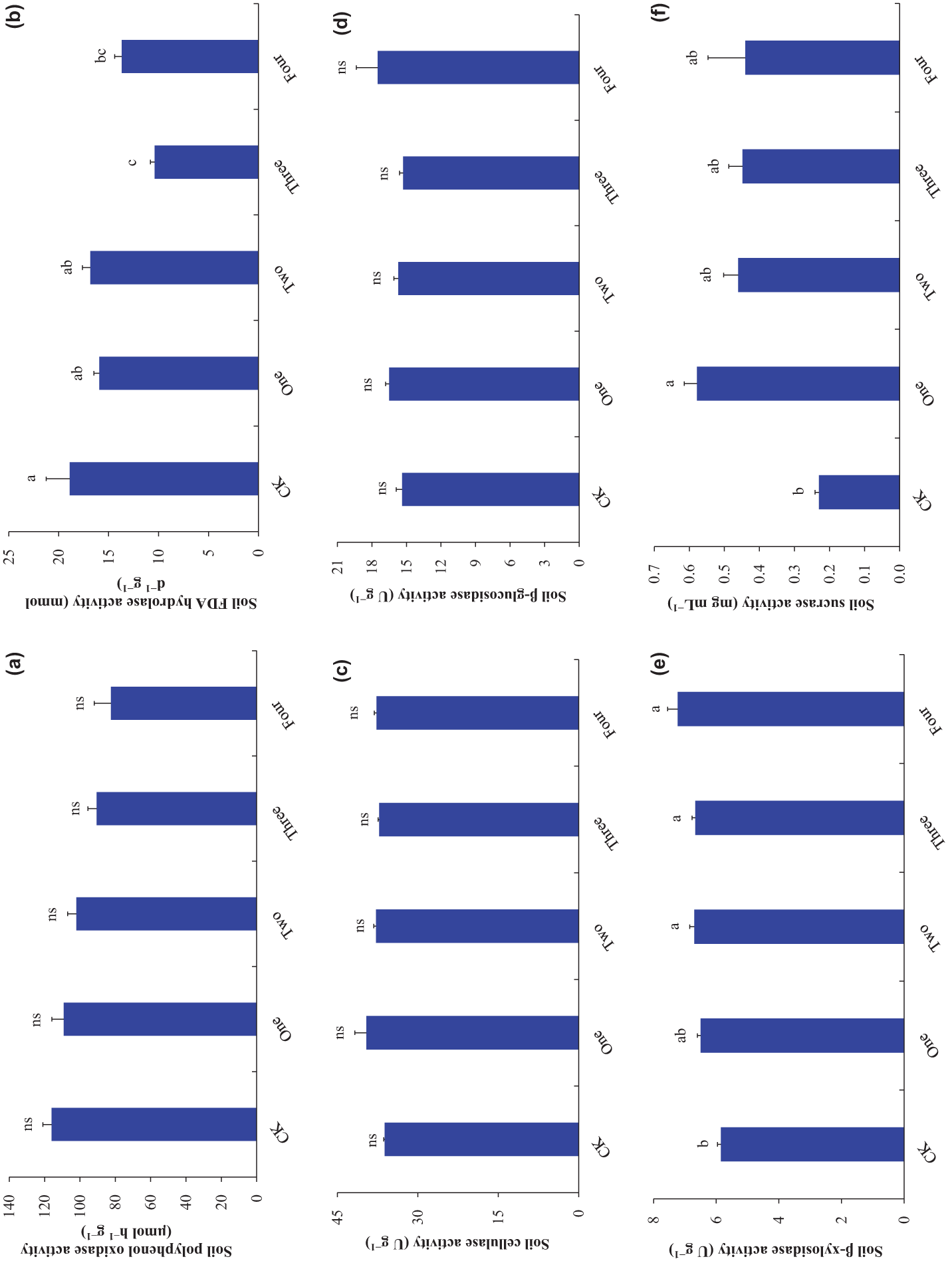

Co-decomposition of three IPS and co-decomposition of the four IPS decreased soil FDA hydrolase activity compared to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 4b). Soil FDA hydrolase activity under the co-decomposition of three IPS was lesser than that under the mono-decomposition of one IPS and co-decomposition of two IPS (p < 0.05; Fig. 4b). Soil FDA hydrolase activity was negatively related to SIPS (p < 0.001; Table 1).

Figure 4: Soil enzyme activities ((a), soil polyphenol oxidase activity; (b), soil FDA hydrolase activity; (c), soil cellulase activity; (d), soil β-glucosidase activity; (e), soil β-xylosidase activity; (f), soil sucrase activity). Bars (means and SE) with different letters indicate statistically significant differences at 0.05 probability (p < 0.05). “ns” indicate no statistically significant differences at 0.05 probability (p > 0.05). Abbreviations have the same meanings as presented in Fig. 2

Co-decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS increased soil β-xylosidase activity compared to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 4e). No robust correlations were found between soil β-xylosidase activity and SIPS (p = 0.071; Table 1).

Mono-decomposition of one IPS increased soil sucrase activity compared to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 4f). Soil sucrase activity was negatively related to SIPS (p = 0.05; Table 1).

The decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS did not significantly affect soil polyphenol oxidase activity, soil cellulase activity, and soil β-glucosidase activity compared to control (p > 0.05; Fig. 4a,c,d). Soil polyphenol oxidase activity was negatively related to SIPS (p = 0.008; Table 1). No strong correlations were observed between soil cellulase activity (p = 0.195), soil β-glucosidase activity (p = 0.579), and SIPS (Table 1).

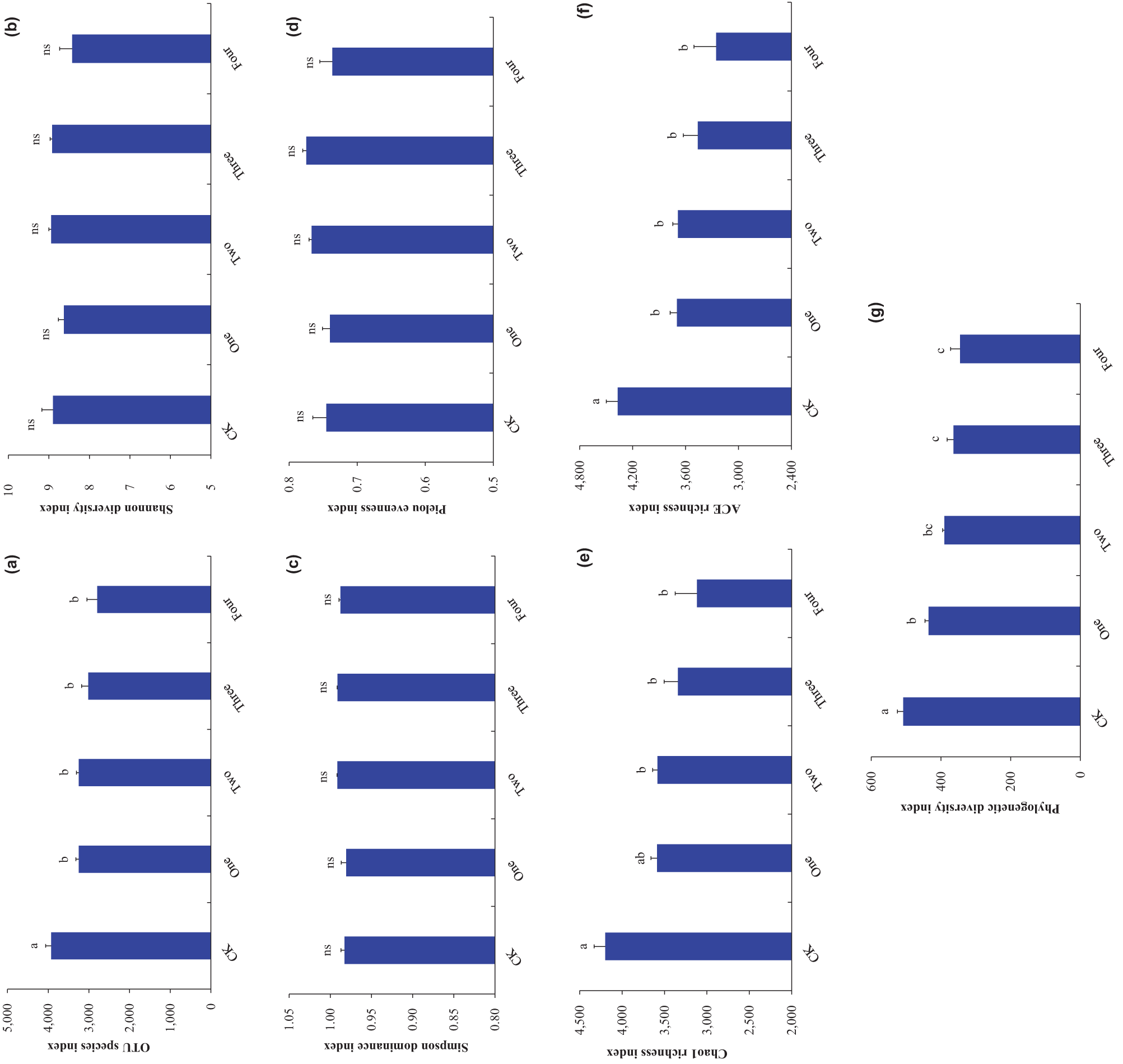

3.3 Differences in SBC Alpha Diversity

The decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS decreased the OTU species, ACE richness, and Phylogenetic diversity indexes of SBC compared to control (p < 0.05; Fig. 5a,f,g). Co-decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS decreased the Chao1 richness index of SBC compared with control (p < 0.05; Fig. 5e). The OTU species (p = 0.025), Chao1 richness (p = 0.021), ACE richness (p = 0.030), and Phylogenetic diversity (p < 0.001) indexes of SBC were negatively related to SIPS (Table 1).

Figure 5: Soil bacterial alpha diversity ((a), OTU species index; (b), Shannon diversity index; (c), Simpson dominance index; (d), Pielou evenness index; (e), Chao1 richness index; (f), ACE richness index; (g), Phylogenetic diversity index). Bars (means and SE) with different letters indicate statistically significant differences at 0.05 probability (p < 0.05). “ns” indicates no statistically significant differences at 0.05 probability (p > 0.05). Abbreviations have the same meanings as presented in Fig. 2

The decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS did not significantly affect the Shannon diversity (p = 0.600), Simpson dominance (p = 0.072), and Pielou evenness (p = 0.106) indexes of SBC compared to control (p > 0.05; Fig. 5b–d). No robust correlations were observed between the Shannon diversity (p = 0.600), Simpson dominance (p = 0.271), and Pielou evenness (p = 0.244) indexes of SBC and SIPS (Table 1).

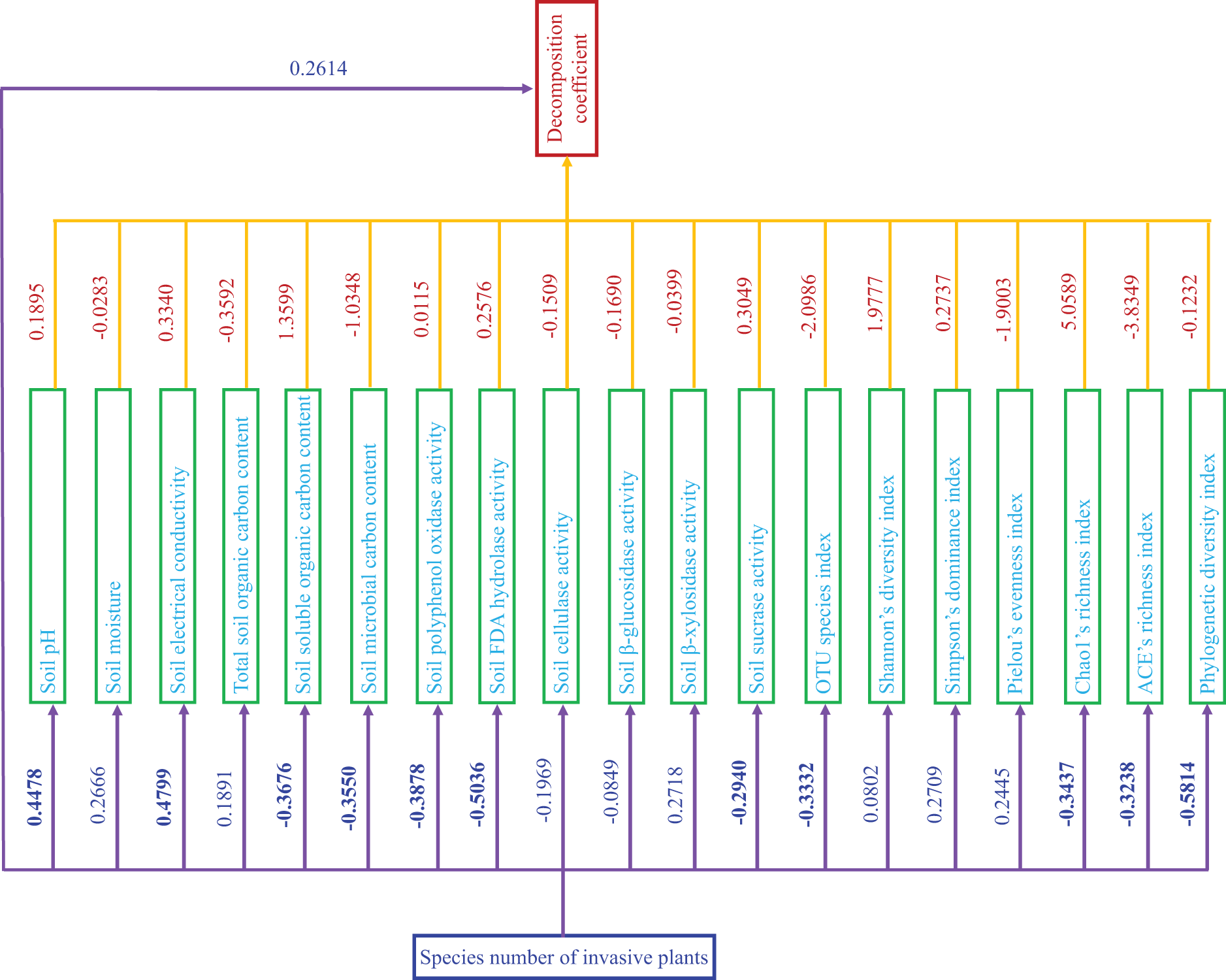

3.4 Influences of Soil Variables and SBC Alpha Diversity on the Decomposition Coefficient and Influences of SIPS on the Decomposition Coefficient, Soil Variables, and SBC Alpha Diversity

The SIPS posed significantly positive influences on soil pH and electrical conductivity (p < 0.05; Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Schematic diagram of path analysis. Blue numbers represent influences of species number of invasive plants on the decomposition coefficient, soil variables, and soil bacterial alpha diversity. Fuchsia numbers represent influences of soil variables and soil bacterial alpha diversity on the decomposition coefficient. Positive values indicate positive influences, while negative values indicate negative influences. The stronger the influence, the greater the deviation from 0; and vice versa. p ≤ 0.05 are shown in bold

The SIPS caused significantly negative influences on soluble organic carbon content, microbial carbon content, polyphenol oxidase activity, FDA hydrolase activity, and sucrase activity in soil, and the OTU species, Chao1 richness, ACE richness, and Phylogenetic diversity indexes of SBC (p < 0.05; Fig. 6).

The mean value of the good coverage indices of SBC across all samples was ~0.988. The SBC beta diversity under the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS showed obvious differences with control based on weighted UniFrac distances (Figs. S16 and S17). There were marked differences in SBC beta diversity between mono-decomposition of one IPS and the co-decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS based on weighted UniFrac distances (Figs. S16 and S17).

At the class level, the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS improved the relative abundance of Alphaproteobacteria and Actinobacteria, but apparently failed the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria compared to control (Fig. S18). At the order level, the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS increased the relative abundance of Sphingomonadales, Cytophagales, Propionibacteriales, Gemmatimonadales, and Saccharimonadales compared to control (Fig. S19). At the family level, the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS increased the relative abundance of Sphingomonadaceae, Microscillaceae, Sphingobacteriaceae, Nocardioidaceae, and Gemmatimonadaceae, but declined the relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae compared to control (Fig. S20).

At the class level, the prevalence of Blastocatellia, Acidobacteriae, and Gammaproteobacteria was declined, but the prevalence of Planctomycetes, Saccharimonadia, Gemmatimonadetes, Actinobacteria, and Alphaproteobacteria was enhanced under the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS compared to control (Fig. S21). At the order level, the prevalence of Burkholderiales and Xanthomonadales was decreased, but the prevalence of Micrococcales, Saccharimonadales, Gemmatimonadales, Propionibacteriales, Cytophagales, and Sphingomonadales was improved under the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS compared to control (Fig. S22). At the family level, the prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae was decreased, but the prevalence of Pseudonocardiaceae, Nocardioidaceae, Microscillaceae, and Sphingomonadaceae was increased under the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS compared to control (Fig. S23).

There were sixty-two No-FGP that reached significant levels between different treatments in this study (Table S2).

The number of pathways of most functional genes of SBC closely related to decomposition processes reduced with increasing SIPS (Table S2).

Correlations between No-FGP and SIPS that reached significant levels were all negatively related (p < 0.05; Table S3).

Multiple IPS can cooccur in the same environment [11,19,22,36]. Thus, leaves of multiple IPS can coexist in the same environment and then be degraded collectively. Hence, it is expected that the decomposition rate may be influenced by the differing characteristics of mixed leaves from multiple IPS, primarily due to the divergent quantities of exuded materials and the major components. However, there is currently no consensus on the relationship between the decomposition rate of mixed leaves from multiple IPS and SIPS. Earlier studies have revealed that co-decomposition of two or more IPS can result in either a synergistic effect [12,56–58] or an antagonistic effect [23,59–61], depending largely on the nature of interspecific facilitation or interspecific interference. In this study, the neutral effects of co-decomposition of the four IPS on the decomposition rate of mixed leaves or mixed-effect intensity of co-decomposition may be qualified to the comparable percentage of soluble substances and recalcitrant substances in the leaves from the four IPS. In other words, the quality of the leaves from the four IPS may be comparable. This phenomenon may be ascribed to the fact that they are all Asteraceae species [5], which originate from America [5], and have very similar growth patterns, lifestyles, and environments. Thus, the proportion of soluble substances and recalcitrant substances in the leaves of one IPS and mixed leaves from the four IPS was comparable. This finding may also be qualified to the moderately short period of time in this study, during which the differences in the decomposition rate of the leaves from a single IPS and mixed leaves from the four IPS have not yet manifested themselves. This result validates the earlier findings that the co-decomposition of multiple plants results in a neutral effect [23,57,62,63]. Thus, contrary to expectations, SIPS does not appear to be a significant factor influencing the decomposition rate of mixed leaves or the mixed-effect intensity of co-decomposition.

In general, IPS can change soil physicochemical properties through the exudation of secondary compounds during decomposition processes [9,64–66]. In this study, the positive regulatory effects of SIPS on soil pH may be attributed to the secretion of alkaline components or other components that may have an alkaline effect, e.g., anions, during decomposition processes [64,65,67,68]. The enhanced soil alkalization with increasing SIPS may be attributed that there may a negative relationship between soil pH and organic carbon content [69,70]. Similarly, the positive regulatory effects of SIPS on soil electrical conductivity can be ascribed to elevated ion contents in soil resulting from decomposition processes of the four IPS [71–74].

Usually, IPS may modify soil carbon contents through the exudation of carbonaceous materials during decomposition processes. In general, IPS has the potential to increase soil carbon contents by growing the input of carbon into ecosystems. This process, known as soil carbon sequestration, can be facilitated by IPS [67,75–77]. Contrary to the expected result, the negative regulatory effects of SIPS on the contents of soluble organic carbon and microbial carbon in soil may be attributed to accelerated carbon metabolism of soil microorganisms as SIPS increased. The negative regulatory effects of SIPS on the contents of soluble organic carbon and microbial carbon in soil may also be attributed to increased soil pH and conductivity, which can lead to ion competition and therefore inhibit microbial activity [69,70]. Thus, as SIPS increases, the probability of carbon being released from soil to atmosphere also increases probably. This proposes that IPS may play a more significant role in carbon emission than was formerly thought, rather than functioning as a carbon sink. Thus, the co-invasion facilitated by multiple IPS (particularly the co-invasion facilitated by two IPS) may contribute to climate change by reducing the contents of soluble organic carbon and microbial carbon in soil via decomposition processes. It is, therefore, imperative to minimize the co-invasion recruited by multiple IPS as early as possible to lessen or even prevent further carbon release from the soil through invasion process mediated by IPS. It should be noted that IPS affect carbon cycle in ways other than through decomposition processes, including growth. It is, therefore, evident that further comprehensive analysis is required to gain a more comprehensive explanation for the overall impacts of IPS on the carbon cycle.

Additionally, IPS has been detected to affect soil enzyme activities [78–81] and SBC alpha diversity [82–85] through the release of nutrients (particularly nitrogenous substances) during decomposition processes. Contrary to the expected result, the negative regulatory effects of SIPS on soil polyphenol oxidase capability, FDA hydrolytic capability, and sucros hydrolytic capability may be qualified to a decrease in nutrient availability level in soil and/or an increased metabolic rate of microbes during decomposition processes of the four IPS. In addition, it is expected that mixed leaves from multiple IPS will deliver a greater variety and more complex amount of organic matter to the soil subsystem through decomposition processes. This will result in greater biochemical diversity and the increased niches of available substrates, which will typically support the growth of a wider variety of SBC [26,86–88]. However, there may be a negative regulatory effect of SIPS on SBC alpha diversity, especially the OTU species, Chao1 richness, ACE richness, and Phylogenetic diversity. This finding has already been detected in other studies [82–84,89]. Similarly, there may be a negative regulatory effect of SIPS on the number of pathways of the majority of functional genes of SBC closely related to decomposition processes. Thus, the alpha diversity and No-FGP are largely influenced by the identity rather than the diversity of IPS [23,32,88,90]. The observed decrease in the alpha diversity and No-FGP with increasing SIPS may be attributed to concomitant increases in soil pH and electrical conductivity. However, soil pH [91–93] and electrical conductivity [91] are thought to have significant (typically negative) effects on SBC diversity and abundance, largely by altering absorption and use of resources metabolized by SBC. Therefore, it is imperative to control the co-invasion mediated by multiple IPS as early as possible, especially in agroecosystems, wastelands, and both sides of the main roads, to alleviate or even prevent a decline in soil enzyme activities, SBC alpha diversity, and the number of pathways of functional genes of SBC closely related to decomposition processes.

It has been shown that IPS can create a favorable soil microenvironment by altering SBC, which can accelerate the subsequent invasion process via plant-soil feedback [27,94–96]. The decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS can significantly influence SBC beta diversity and the relative abundance of specific SBC’ taxa as well as lead to the emergence of numerous dominant SBC. Thus, the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS can significantly alter SBC by altering specific SBC’ taxa. The altered relative abundance of specific SBC’ taxa, in addition to the up-regulated predominant SBC and other down-regulated predominant SBC may be attributed to the selective facilitation or suppression of selection induced by the altered quantity, type, and complexity of organic matter in soil [23,66] under the decomposition of the four IPS independent of SIPS, particularly decomposition processes of mixed leaves from multiple IPS.

However, the experimental design operated in this study has a few insufficiencies. For instance, the composition, especially the contents of recalcitrant components (those that decomposed slower) and soluble components (those that decomposed faster), in the leaves from multiple IPS were not subjected to investigation. Furthermore, decomposition processes of the native plants did not evaluate in this study. The mesh size of the used polyethylene litterbags may affect the access of decomposers (especially microbes) as well as their metabolic activity, which in turn may affect the results. Thus, the experimental design needs to be further enhanced. Precisely, future studies still need to be executed to determine the composition in leaves from multiple IPS as well as the differences in litter decomposition responses, soil physicochemical properties, soil enzyme activities, and SBC between native plants and mono- and co-decomposition of multiple IPS. This can facilitate the acquisition of more comprehensive data on the effects of mono- and co-decomposition of multiple IPS with a gradient of species number on the litter mass loss, soil carbon contents, soil enzyme activities, and SBC.

This study has examined the effects of mono- and co-decomposition of four Asteraceae invasive plants on soil carbon contents, soil enzyme activities, and SBC. Specifically, SIPS recruits a negative influence on soil carbon contents (including soluble organic carbon content and microbial carbon content), soil enzyme activities (including polyphenol oxidase activity, FDA hydrolase activity, and sucrase activity), SBC alpha diversity (including the OTU species, Chao1 richness, ACE richness, and Phylogenetic diversity indexes), and the number of pathways of most functional genes of SBC involved in decomposition processes.

Acknowledgement: We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for the insightful and constructive comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by Open Science Research Fund of Key Laboratory of Ocean Space Resource Management Technology, Marine Academy of Zhejiang Province, China (KF-2024-112), Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Technology and Material of Water Treatment (no grant number), and Research Project on the Application of Invasive Plants in Soil Ecological Restoration in Jiangsu (20240110).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Congyan Wang; data collection: Qi Chen, Yizhuo Du, Yingsheng Liu, Yue Li, Chuang Li, Zhelun Xu; analysis and interpretation of results: Qi Chen, Yizhuo Du, Yingsheng Liu, Yue Li, Chuang Li, Zhelun Xu; draft manuscript preparation: Congyan Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.065970/s1.

References

1. Souza-Alonso P, Guisande-Collazo A, Lechuga-Lago Y, González L. Changes in decomposition dynamics, soil community function and the growth of native seedlings under the leaf litter of two invasive plants. Biol Invasions. 2024;26(11):3695–714. doi:10.1007/s10530-024-03405-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lu YJ, Wang YF, Wu BD, Wang S, Wei M, Du DL, et al. Allelopathy of three Compositae invasive alien species on indigenous Lactuca sativa L. enhanced under Cu and Pb pollution. Sci Hortic. 2020;267(3):109323. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Adomako MO, Ning L, Tang M, Du DL, van Kleunen M, Yu FH. Diversity- and density-mediated allelopathic effects of resident plant communities on invasion by an exotic plant. Plant Soil. 2019;440(1–2):581–92. doi:10.1007/s11104-019-04123-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xu ZL, Zhong SS, Yu YL, Wang YY, Cheng HY, Du DL, et al. Rhus typhina L. triggered greater allelopathic effects than Koelreuteria paniculata Laxm under ammonium fertilization. Sci Hortic. 2023;309:111703. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yan XL, Liu QR, Shou HY, Zeng XF, Zhang Y, Chen L, et al. The categorization and analysis on the geographic distribution patterns of Chinese alien invasive plants. Biodivers Sci. 2014;22:667–76. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1003.2014.14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Erckie L, Adedoja O, Geerts S, van Wyk E, Boatwright JS. Impacts of an invasive alien Proteaceae on native plant species richness and vegetation structure. S Afr J Bot. 2022;144(40166):332–8. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2021.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Beshai RA, Truong DA, Henry AK, Sorte CJB. Biotic resistance or invasional meltdown? Diversity reduces invasibility but not exotic dominance in southern California epibenthic communities. Biol Invasions. 2023;25:533–49. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-980025/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fang YQ, Zhang XH, Wei HY, Wang DJ, Chen RD, Wang LK, et al. Predicting the invasive trend of exotic plants in China based on the ensemble model under climate change: a case for three invasive plants of Asteraceae. Sci Total Environ. 2021;756(6):143841. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ahmad Dar M, Ahmad M, Singh R, Kumar Kohli R, Singh HP, Batish DR. Invasive plants alter soil properties and nutrient dynamics: a case study of Anthemis cotula invasion in Kashmir Himalaya. CATENA. 2023;226(5):107069. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2023.107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang S, Wei M, Wu BD, Cheng HY, Wang CY. Combined nitrogen deposition and Cd stress antagonistically affect the allelopathy of invasive alien species Canada goldenrod on the cultivated crop lettuce. Sci Hortic. 2020;261(3):108955. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rastogi R, Qureshi Q, Shrivastava A, Jhala YV. Multiple invasions exert combined magnified effects on native plants, soil nutrients and alters the plant-herbivore interaction in dry tropical forest. For Ecol Manage. 2023;531(10):120781. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen L, Wang MQ, Shi Y, Ma PP, Xiao YL, Yu HW, et al. Soil phosphorus form affects the advantages that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi confer on the invasive plant species, Solidago canadensis, over its congener. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1160631. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1160631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kumar M, Kumar S, Verma AK, Joshi RK, Garkoti SC. Invasion of Lantana camara and Ageratina adenophora alters the soil physico-chemical characteristics and microbial biomass of chir pine forests in the central Himalaya. India CATENA. 2021;207(3):105624. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2021.105624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pereira A, Ferreira V. Increasing inputs of invasive N-fixing Acacia litter decrease litter decomposition and associated microbial activity in streams. Freshwater Biol. 2021;67(2):13841. doi:10.1111/fwb.13841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liao CZ, Peng RH, Luo YQ, Zhou XH, Wu XW, Fang CM, et al. Altered ecosystem carbon and nitrogen cycles by plant invasion: a meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2008;177(3):706–14. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02290.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. De La Cruz HJ, Salgado-Luarte C, Stotz GC, Gianoli E. An exotic plant species indirectly facilitates a secondary exotic plant through increased soil salinity. Biol Invasions. 2023;25(8):2599–611. doi:10.1007/s10530-023-03061-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin D, Meiners SJ, Ni M, Ye Q, He F, Cadotte MW. Positive interactions of native species melt invasional meltdown over long-term plant succession. Ecol Lett. 2022;25(12):2584–96. doi:10.1111/ele.14127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Collins RJ, Copenheaver CA, Barney JN, Radtke PJ. Using invasional meltdown theory to understand patterns of invasive richness and abundance in forests of the Northeastern USA. Nat Area J. 2020;40:336–44 doi:10.3375/043.040.0406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Vujanović D, Losapio G, Milić S, Milić D. The impact of multiple species invasion on soil and plant communities increases with invasive species co-occurrence. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:875824. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.875824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Guo YJ, Shao MN, Guan P, Yu MY, Geng L, Gao Y, et al. Co-invasion of congeneric invasive plants adopts different strategies depending on their origins. Plants. 2024;13:1807. doi:10.3390/plants13131807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kama R, Javed Q, Liu Y, Li ZY, Iqbal B, Diatta S, et al. Effect of soil type on native Pterocypsela laciniata performance under single invasion and co-invasion. Life. 2022;12(11):1898. doi:10.3390/life12111898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wang CY, Yu YL, Cheng HY, Du DL. Which factor contributes most to the invasion resistance of native plant communities under the co-invasion of two invasive plant species? Sci Total Environ. 2022;813:152628. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhong SS, Xu ZL, Yu YL, Cheng HY, Wang S, Wei M, et al. Acid deposition at higher acidity weakens the antagonistic responses during the co-decomposition of two Asteraceae invasive plants. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;243:114012. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hu X, Arif M, Ding DD, Li JJ, He XR, Li CX. Invasive plants and species richness impact litter decomposition in Riparian Zones. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:955656. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.955656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kaur A, Sharma A, Kaur S, Siddiqui MH, Alamri S, Ahmad M, et al. Role of plant functional traits in the invasion success: analysis of nine species of Asteraceae. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):784. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05498-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chapman SK, Newman GS, Hart SC, Schweitzer JA, Koch GW. Leaf litter mixtures alter microbial community development: mechanisms for non-additive effects in litter decomposition. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62671. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sun JF, Rutherford S, Ullah MS, Ullah I, Javed Q, Rasool G, et al. Plant-soil feedback during biological invasions: effect of litter decomposition from an invasive plant (Sphagneticola trilobata) on its native congener (S. calendulacea). J Plant Ecol. 2022;15(3):610–24. doi:10.1093/jpe/rtab095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Oraegbunam CJ, Kimura A, Yamamoto T, Madegwa YM, Obalum SE, Tatsumi C, et al. Bacterial communities and soil properties influencing dung decomposition and gas emissions among Japanese Dairy Farms. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2023;23(3):3343–8. doi:10.1007/s42729-023-01250-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu GD, Sun JF, Xie P, Guo C, Li MQ, Tian K. Mechanism of bacterial communities regulating litter decomposition under climate warming in temperate wetlands. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(21):60663–77. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-26843-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yuan HL, Zheng TT, Min KK, Deng YX, Lin JM, Xie HT, et al. Deciphering agricultural and forest litter decomposition: stage dependence of home-field advantage as affected by plant residue chemistry and bacterial community. Plant Soil. 2024;510:997–1012. doi:10.1007/s11104-11024-06973-11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xue ZJ, Qu TT, Li XY, Chen Q, Zhou ZC, Wang BR, et al. Different contributing processes in bacterial vs. fungal necromass affect soil carbon fractions during plant residue transformation. Plant Soil. 2024;494:301–19. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2689283/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Barantal S, Roy J, Fromin N, Schimann H, Hättenschwiler S. Long-term presence of tree species but not chemical diversity affect litter mixture effects on decomposition in a neotropical rainforest. Oecologia. 2011;167(1):241–52. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-1966-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hoorens B, Aerts R, Stroetenga M. Does initial litter chemistry explain litter mixture effects on decomposition. Oecologia. 2003;137(4):578–86. doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1365-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ahmad R, Lone SA, Rashid I, Khuroo AA. A global synthesis of the ecological effects of co-invasions. J Ecol. 2025;113:570–81. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.14475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang CY, Cheng HY, Wang S, Wei M, Du DL. Plant community and the influence of plant taxonomic diversity on community stability and invasibility: a case study based on Solidago canadensis L. Sci Total Environ. 2021;768:144518. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang CY, Wei M, Wang S, Wu BD, Cheng HY. Erigeron annuus (L.) Pers. and Solidago canadensis L. antagonistically affect community stability and community invasibility under the co-invasion condition. Sci Total Environ. 2020;716:137128. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Rezacova V, Rezac M, Gryndler M, Hrselova H, Gryndlerova H, Michalova T. Plant invasion alters community structure and decreases diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Appl Soil Ecol. 2021;167(4):104039. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang KM, Gu RY, Yang YB, Yan J, Ma YP, Shen Y. Recent distribution changes of invasive Asteraceae species in China: a five-year analysis (2016–2020). J Environ Manage. 2025;376:124445. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.124445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. He YD, Xing YJ, Yan GY, Liu GC, Liu T, Wang QG. Long-term nitrogen addition could modify degradation of soil organic matter through changes in soil enzymatic activity in a natural secondary forest. Forests. 2023;14:2049. doi:10.3390/f14102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kouadio HK, Koné AW, Touré G-PT, Konan LN, Yapo GR, Abobi HDA. Litter decomposition in the mixed Chromolaena odorata (Asteraceae, herbaceous)-Cajanus cajan (Fabaceae, ligneous) fallow: synergistic or antagonistic mixing effect? Agrofor Syst. 2023;97(8):1525–39. doi:10.1007/s10457-023-00874-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. McBride SG, Levi EM, Nelson JA, Archer SR, Barnes PW, Throop HL, et al. Soil-litter mixing mediates drivers of dryland decomposition along a continuum of biotic and abiotic factors. Ecosystems. 2023;26(6):1349–66. doi:10.1007/s10021-023-00837-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(1):e1. doi:10.1093/nar/gks808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wear EK, Wilbanks EG, Nelson CE, Carlson CA. Primer selection impacts specific population abundances but not community dynamics in a monthly time-series 16S rRNA gene amplicon analysis of coastal marine bacterioplankton. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20(8):2709–26. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):996–8. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10(1):57–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Aßhauer KP, Wemheuer B, Daniel R, Meinicke P. Tax4Fun: predicting functional profiles from metagenomic 16S rRNA data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(17):2882–4. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Shannon CE, Weaver W. The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL, USA: University of Illinois Press; 1949. p. 1–117. [Google Scholar]

48. Simpson EH. Measurement of diversity. Nature. 1949;163:688. doi:10.1038/163688a0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Pielou EC. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J Theor Biol. 1966;13:131–44. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(66)90013-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Chao A, Chazdon RL, Colwell RK, Shen TJ. A new statistical approach for assessing similarity of species composition with incidence and abundance data. Ecol Lett. 2005;8(2):148–59. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00707.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Hughes JB, Hellmann JJ, Ricketts TH, Bohannan BJM. Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(10):4399–406. doi:10.1128/aem.67.10.4399-4406.2001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hamady M, Lozupone C, Knight R. Fast UniFrac: facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and PhyloChip data. ISME J. 2009;4(1):17–27. doi:10.1038/ismej.2009.97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Rodrigues VD, Torres TT, Ottoboni LMM. Bacterial diversity assessment in soil of an active Brazilian copper mine using high-throughput sequencing of 16S rDNA amplicons. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106(5):879–90. doi:10.1007/s10482-014-0257-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Jiang XT, Peng X, Deng GH, Sheng HF, Wang Y, Zhou HW, et al. Illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA tag revealed spatial variations of bacterial communities in a mangrove wetland. Microb Ecol. 2013;66(1):96–104. doi:10.1007/s00248-013-0238-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Magali NR, Burton OT, Wise P, Zhang YQ, Hobson SA, Maria GL, et al. A microbiota signature associated with experimental food allergy promotes allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(1):201–12. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Hoorens B, Stroetenga M, Aerts R. Litter mixture interactions at the level of plant functional types are additive. Ecosystems. 2010;13(1):90–8. doi:10.1007/s10021-009-9301-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Gogo S, Laggoun-Défarge F, Merzouki F, Mounier S, Guirimand-Dufour A, Jozja N, et al. In situ and laboratory non-additive litter mixture effect on C dynamics of Sphagnum rubellum and Molinia caerulea litters. J Soil Sediment. 2016;16(1):13–27. doi:10.1007/s11368-015-1178-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Gogo S, Leroy F, Zocatelli R, Jacotot A, Laggoun-Défarge F. Determinism of nonadditive litter mixture effect on decomposition: role of the moisture content of litters. Ecol Evol. 2021;11(14):9530–42. doi:10.1002/ece3.7771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zhang L, Zhang YJ, Zou JW, Siemann E. Decomposition of Phragmites australis litter retarded by invasive Solidago canadensis in mixtures: an antagonistic non-additive effect. Sci Rep. 2014;4(1):5488. doi:10.1038/srep05488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Zhou S, Butenschoen O, Barantal S, Handa IT, Makkonen M, Vos V, et al. Decomposition of leaf litter mixtures across biomes: the role of litter identity, diversity and soil fauna. J Ecol. 2020;108(6):2283–97. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Hickman JE, Ashton IW, Howe KM, Lerdau MT. The native-invasive balance: implications for nutrient cycling in ecosystems. Oecologia. 2013;173(1):319–28. doi:10.1007/s00442-013-2607-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Chen BM, Peng SL, D’Antonio CM, Li DJ, Ren W-T. Non-additive effects on decomposition from mixing litter of the invasive Mikania micrantha H.B.K. with native plants. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66289. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Chen Y, Ma S, Sun J, Wang X, Cheng G, Lu X. Chemical diversity and incubation time affect non-additive responses of soil carbon and nitrogen cycling to litter mixtures from an alpine steppe soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;109:124–34. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Guo X, Xu ZW, Li MY, Ren XH, Liu J, Guo WH. Increased soil moisture aggravated the competitive effects of the invasive tree Rhus typhina on the native tree Cotinus coggygria. BMC Ecol. 2020;20:17. doi:10.21203/rs.2.13831/v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Fröhlich B, Niemetz R, Gross GG. Gallotannin biosynthesis: two new galloyltransferases from Rhus typhina leaves preferentially acylating hexa- and heptagalloylglucoses. Planta. 2002;216(1):168–72. doi:10.1007/s00425-002-0877-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Liu YS, Du YZ, Li Y, Li C, Zhong SS, Xu ZL, et al. Does Bidens pilosa L. affect carbon and nitrogen contents, enzymatic activities, and bacterial communities in soil treated with different forms of nitrogen deposition? Microorganisms. 2024;12(8):1624. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12081624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Stefanowicz AM, Zubek S, Stanek M, Grzes LM, Rozej-Pabijan E, Blaszkowski J, et al. Invasion of Rosa rugosa induced changes in soil nutrients and microbial communities of coastal sand dunes. Sci Total Environ. 2019;677:340–9. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Li WH, Zhang CB, Jiang HB, Xin GR, Yang ZY. Changes in soil microbial community associated with invasion of the exotic weed, Mikania micrantha H.B.K. Plant Soil. 2006;281(1–2):309–24. doi:10.1007/s11104-005-9641-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Conser C, Connor EF. Assessing the residual effects of Carpobrotus edulis invasion, implications for restoration. Biol Invasions. 2009;11(2):349–58. doi:10.1007/s10530-008-9252-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Vilà M, Tessier M, Suehs CM, Brundu G, Carta L, Galanidis A, et al. Local and regional assessments of the impacts of plant invaders on vegetation structure and soil properties of Mediterranean islands. J Biogeogr. 2006;33(5):853–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01430.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Liu SL, Maimaitiaili B, Joergensen RG, Feng G. Response of soil microorganisms after converting a saline desert to arable land in central Asia. Appl Soil Ecol. 2016;98:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.08.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Chang CL, Fu XP, Zhou XG, Guo MY, Wu FZ. Effects of seven different companion plants on cucumber productivity, soil chemical characteristics and Pseudomonas community. J Integr Agric. 2017;16(10):2206–14. doi:10.1016/s2095-3119(17)61698-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Wu X, Wu H, Ye JY, Zhong B. Study on the release routes of allelochemicals from Pistia stratiotes Linn., and its anti-cyanobacteria mechanisms on Microcystis aeruginosa. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(23):18994–9001. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5104-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Uddin MN, Robinson RW. Can nutrient enrichment influence the invasion of Phragmites australis? Sci Total Environ. 2018;613(6):1449–59. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Ahmad R, Khuroo AA, Hamid M, Rashid I. Plant invasion alters the physico-chemical dynamics of soil system: insights from invasive Leucanthemum vulgare in the Indian Himalaya. Environ Monit Assess. 2020;191(S3):792. doi:10.1007/s10661-019-7683-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Zhang G, Bai J, Wang W, Jia J, Huang L, Kong F, et al. Plant invasion reshapes the latitudinal pattern of soil microbial necromass and its contribution to soil organic carbon in coastal wetlands. Catena. 2023;222:106859. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2022.106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Li GL, Xu SX, Tang Y, Wang YJ, Lou JB, Zhang QY, et al. Spartina alterniflora invasion altered soil greenhouse gas emissions via affecting labile organic carbon in a coastal wetland. Appl Soil Ecol. 2024;203(5):105615. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Ge YY, Wang QL, Wang L, Liu WX, Liu XY, Huang YJ, et al. Response of soil enzymes and microbial communities to root extracts of the alien Alternanthera philoxeroides. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2018;64(5):708–17. doi:10.1080/03650340.2017.1373186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Stefanowicz AM, Frąc M, Oszust K, Stanek M. Contrasting effects of extracts from invasive Reynoutria japonica on soil microbial biomass, activity, and community structure. Biol Invasions. 2022;24(10):3233–47. doi:10.1007/s10530-022-02842-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Kapagianni PD, Topalis I, Gwynn-Jones D, Menkissoglu-Spiroudi U, Stamou GP, Papatheodorou EM. Effects of plant invaders on rhizosphere microbial attributes depend on plant identity and growth stage. Soil Res. 2021;59(3):225–38. doi:10.1071/sr20138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Allison SD, Nielsen C, Hughes RF. Elevated enzyme activities in soils under the invasive nitrogen-fixing tree Falcataria moluccana. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38(7):1537–44. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Lazzaro L, Giuliani C, Fabiani A, Agnelli AE, Pastorelli R, Lagomarsino A, et al. Soil and plant changing after invasion: the case of Acacia dealbata in a Mediterranean ecosystem. Sci Total Environ. 2014;497–498(2):491–8. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.08.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Slabbert E, Jacobs SM, Jacobs K. The soil bacterial communities of South African fynbos riparian ecosystems invaded by Australian Acacia species. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86560. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Yang W, Jeelani N, Zhu Z, Luo Y, Cheng X, An S. Alterations in soil bacterial community in relation to Spartina alterniflora Loisel. invasion chronosequence in the eastern Chinese coastal wetlands. Appl Soil Ecol. 2019;135:38–43. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Torres N, Herrera I, Fajardo L, Bustamante RO. Meta-analysis of the impact of plant invasions on soil microbial communities. BMC Ecol Evol. 2021;21(1):172. doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01899-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Hättenschwiler S, Fromin N, Barantal S. Functional diversity of terrestrial microbial decomposers and their substrates. C R Biol. 2011;334(5–6):393–402. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2011.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Brunel C, Gros R, Ziarelli F, Farnet Da Silva AM. Additive or non-additive effect of mixing oak in pine stands on soil properties depends on the tree species in Mediterranean forests. Sci Total Environ. 2017;590–591:676–85. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Santonja M, Rancon A, Fromin N, Baldy V, Hättenschwiler S, Fernandez C, et al. Plant litter diversity increases microbial abundance, fungal diversity, and carbon and nitrogen cycling in a Mediterranean shrubland. Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;111:124–34. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Zhu P, Wei W, Bai XF, Wu N, Hou YP. Effects of invasive Rhus typhina L. on bacterial diversity and community composition in soil. Ecoscience. 2020;27(3):177–84. doi:10.1080/11956860.2020.1753312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Santonja M, Baldy V, Fernandez C, Balesdent J, Gauquelin T. Potential shift in plant communities with climate change in a Mediterranean Oak forest: consequence on nutrients and secondary metabolites release during litter decomposition. Ecosystems. 2015;18(7):1253–68. doi:10.1007/s10021-015-9896-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Shen WS, Gao N, Min J, Shi WM, He XH, Lin XG. Influences of past application rates of nitrogen and a catch crop on soil microbial communities between an intensive rotation. Acta Agr Scand B–Soil Plant Sci. 2016;66(2):97–106. doi:10.1080/09064710.2015.1072234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Rousk J, Bååth E, Brookes PC, Lauber CL, Lozupone C, Caporaso JG, et al. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010;4(10):1340–51. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Liu X, Zhang B, Zhao WR, Wang L, Xie DJ, Huo WT, et al. Comparative effects of sulfuric and nitric acid rain on litter decomposition and soil microbial community in subtropical plantation of Yangtze River Delta region. Sci Total Environ. 2017;601–602:669–78. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Uddin MN, Asaeda T, Sarkar A, Ranawakage VP, Robinson RW. Conspecific and heterospecific plant-soil biota interactions of Lonicera japonica in its native and introduced range: implications for invasion success. Plant Ecol. 2021;222(12):1313–24. doi:10.1007/s11258-021-01180-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Coughlin EM, Shefferson RP, Clark SL, Wurzburger N. Plant-soil feedbacks and the introduction of Castanea (chestnut) hybrids to eastern North American forests. Restor Ecol. 2021;29(3):e13326. doi:10.1111/rec.13326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Chen D, van Kleunen M. Negative conspecific plant-soil feedback on alien plants co-growing with natives is partly mitigated by another alien. Plant Soil. 2024;505:733–45. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3894431/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools