Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genomic and Functional Characterization of Thermophilic Paenibacillus sp. VCA1: A Biocontrol Agent Isolated from El Chichón Volcano Crater Lake

1 Laboratorio de Biología Molecular, Tecnológico Nacional de México/Instituto Tecnológico de Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Carretera Panamericana km 1080, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, CP 29050, México

2 Departamento de Bioquímica, Instituto Nacional de Cardiología, Juan Badiano #1, Colonia Sección XVI, Tlalpan, Mexico City, CP 14080, México

3 Departamento de Microbiología y Parasitología, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, CP 04510, México

4 Department of Biological Functions Engineering, Kyushu Institute of Technology, 2-4 Wakamatsu-ku, Kita-kushu, 808-0196, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Víctor Manuel Ruíz-Valdiviezo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Enhancing Grain Yield: From Molecular Mechanisms to Sustainable Agriculture)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2729-2743. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068176

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Species of the genus Paenibacillus, especially those from extreme environments that have been reported, are known for producing bioactive compounds with agricultural and biotechnological applications. In this study, we investigated the genomic and biochemical potential of Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 strain isolated from a thermophilic environment. Taxonomic identification was performed using whole genome similarity analysis, TETRA four-nucleotide frequency of occurrence analysis, ANI average nucleotide identity analysis, and gene distance analysis using digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH). Functional analysis of the strain VCA1 was performed by detecting genes, enzymes, and genome subsystems involved in biocontrol and plant growth promotion, which was carried out using the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology), the seed server and antiSAMSH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell). Genetic analyses showed the existence of 11 fatty acid and isoprenoid production genes, 56 motility and chemotaxis genes, 29 N-acetylglucosamine genes, and five siderophore genes. Finally, the antifungal and emulsifying activities demonstrated that strain VCA1 has activity against Fusarium oxysporum strain 45ta using integrated genomic and experimental validation, and the antifungal properties of the Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 has suggested potential use as a biocontrol agent against phytopathogenic fungi, and its continuous study can have beneficial applications in sustainable agriculture and biotechnology.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileExtreme environments are known to be distributed over large portions of the Earth. These environments are characterized by different physicochemical, chemical, and biological conditions, such as extremely high or low temperatures, high concentrations of heavy metals, very pronounced pH ranges, etc. [1]. This environment includes hydrothermal and volcanic sites, which have been found on the Earth’s surface and the deep sea [2].

Various microorganisms capable of adapting to geothermal ecosystems have been identified. These include bacteria [3], fungi [4], algae [5], and cyanobacteria [6]. These capabilities are related to survival under these hostile conditions. Classification of these microorganisms is based on the physicochemical conditions in which they can adapt and develop extensively [7]. For example, those that live in high temperature conditions are considered thermophiles (45°C to 60°C) and hyperthermophiles (>80°C), whereas those developing and reproducing at low temperatures are referred to as psychrophiles (<10°C). Microorganisms that tolerate high salt concentrations are referred to as halophiles. Finally, those that tolerate various pH ranges are divided into three groups: acidophiles (living in a pH range of 0 to 5), alkalines (tolerating a pH range of 5 to 8), and alkalophiles (those surviving at a pH above 8) [8,9].

The genus Paenibacillus predominates in this category [10]. These Gram-positive, spore-forming bacteria exhibit facultative anaerobic metabolism and belong to the phylum Firmicutes [11]. Bacteria belonging to this genus have been identified in different extreme ecosystems, one of them is the active volcano El Chichón, which is located northwest of the State of Chiapas, Mexico, with a crater lake formed after its eruption in 1982. This complex is considered a highly hydrodynamic system due to the geochemical composition, variations in temperature and pH of the lake, and geothermal activity due to the presence of minerals, heavy metals and sulfur, which gives the lake acid-thermal characteristics [12]. Due to the hostile qualities of the crater lake, microbial life is limited; however, there are reports where different microbial strains have been identified that can produce phytohormones, solubilize phosphates, fix nitrogen, and synthesize siderophores [13]. In summary, Paenibacillus bacteria play an essential role in soil ecology and agriculture, and their continued study may have beneficial applications in sustainable agriculture and biotechnology.

Biosurfactants are surface metabolites produced by microbes [14]. According to reports, the genera Acinetobacter, Arthrobacter, Pseudomonas, Halomonas, Bacillus, Rhodococcus, and Enterobacter, as well as some Paenibacillus species such as P. polymyxa, P. macerans, P. dendritiformis, etc., can produce these metabolites [15,16]. Most biosurfactants are produced by metabolic activities, where the metabolic substrates are lipids, alkanes, and sugars. These compounds are classified according to their molecular structure, where categories such as glycolipids, phospholipids, neutral lipids, and lipopeptides can be found [17]. Lipopeptides are defined as low molecular weight compounds with a peptide chain variation between 6 and 13 amino acids and several variations along the fatty acid chain [18]. They can form pores in phytopathogens while possessing siderophore activity, biofilm inhibition, and detachment activity. Lastly, they can prevent colonization by phytopathogens [19].

The use of microorganisms and their secreted metabolites for the suppression of phytopathogenic fungi and promotion of plant growth has numerous advantages [20]. The degradation of these metabolites is easy and environmentally friendly, and they can even become part of the cycles of natural elements, which is in stark contrast with the chemical products used nowadays. However, a critical scientific problem lies in the understanding of the genetic and metabolic mechanisms involved in the biosynthesis of antifungal compounds in thermophilic bacteria. This knowledge gap hinders the development of new biotechnological strategies for the control of phytopathogens and the promotion of plant growth. Based on this, we hypothesize that Paenibacillus strain VCA1 presents unique genomic and metabolic characteristics as a biocontrol agent and plant growth promoter. Therefore, this work aimed to evaluate the antifungal and genomic potential, along with the biosurfactant activity of the Paenibacillus sp. strain VCA1 isolated from the crater lake of El Chichón volcano, thus attempting to provide scientific evidence for its application as a next-generation microbial biocontrol agent in sustainable agriculture.

Paenibacillus sp. strain VCA1 was isolated from volcanic sediments using a series of culture and isolation techniques at high temperatures, as reported by [21].

2.2 Functional Genome Annotation and Identification of Biosynthetic Genes Related to Biocontrol and Plant Growth Promotion

Genomic DNA from strain VCA1 was extracted and sequenced, as was reported by [21]. In this study, functional genome annotation was performed with the RAST-The Seed Server web server in conjunction with PROKKA v.1.15.5. In addition, annotation and identification of biosynthetic genes that are involved in biocontrol were performed with antiSMASH v.7.0.1 under predetermined parameters [22].

Taxonomic classification was conducted using a combination of genome-based metrics: tetranucleotide similarity analysis (TETRA), average nucleotide identity (ANIb and ANIm) using the Jspecies tool, and DNA-DNA hybridization using the genome-genome distance calculator (GGDC) method with the DSMZ (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen) server [21].

2.3 Extraction of Lipopeptide Compounds by Acid Precipitation from Paenibacillus sp. Strain VCA1

A total of 10 mL of VCA1 was inoculated into 1000 mL of LB medium with trace elements contained in an Erlenmeyer flask containing MgSO4·7H2O 0.5 g/L; (NH4)2HPO4 0.2 g/L; ZnSO4·7H2O 0.2 g/L; MnSO4·4H2O 0.08 g/L; Na2MoO4·2H2O 0.08 g/L; CoCl2·6H2O 0.0016 g/L; CuSO4·5H2O 0.008 g/L; H3BO4 0.006 g/L [22]. The cultures were incubated at a temperature of 45°C for a time of 72 h. After the incubation time had elapsed, the cultures were centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 40 min at 4°C to perform cell separation. After separation, 6M HCl was added to the cell-free supernatant until pH 2 was reached and refrigerated overnight at 4°C [22]. After the cooling time, the acid precipitates were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min at a temperature of 4°C. Once the precipitates were centrifuged, they were washed three times with acidic water (pH 2), discarding the acidic water and neutralizing the precipitates with NaOH 6M.

Subsequently, methanol was added to the obtained precipitates and allowed to stand for 5 h at a temperature of 4°C. Once the standing time passed, the insoluble impurities were removed by centrifuging at 4000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, repeating this whole procedure in duplicate [23]. Traces of methanol in the samples were removed with the help of a rotary evaporator at 56°C, 45 rpm, and a pressure of 270 hPa until it was completely removed. To dry the samples completely, they were taken to an oven at 40°C for 48 h.

2.4 Analysis of the Lipopeptide Structures of Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 Extracts

For the analysis of the lipopeptides present in the VCA1 samples, first the functional groups were analyzed with the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) technique with 32 scans, a resolution of 4, spacing of 0.482 cm−1 in a Transmittance format, the results were analyzed with the web server Spectroscopic Tools; while to determine the molecular structure and the chemical composition of the samples was performed with the technique of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMR) where nuclear magnetic spectra of 1H and 13C at 298 K were obtained in a 600 MHz spectrometer with a magnetic field of 1.14 T, the results were analyzed with the MestReNova 5.1.1 program [24].

2.5 In Vitro Experimental Validation of Biocontrol Potential by Strain VCA1

2.5.1 Antifungal Activity Assay

The phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum 45ta strain was used to evaluate the antifungal activity of VCA1. Fungal cultures were incubated at 28°C for 7 days. Dual culture assays were performed on PDA plates by placing 0.6 mm diameter fungal plugs 15 mm from the plate’s edge. The VCA1 strain was seeded 35 mm away from the fungal disk position. The confrontations were also incubated at 28°C for 7 days. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The inhibition rate was determined by Eq. (1).

where Rc is the radial growth of the fungal control, and Rt is the radial growth of the fungfungusfronted with the VCA1 strain [25].

2.5.2 Emulsifying Activity Assay

Metabolite extraction was performed according to the methodology described by [26,27]. Briefly described, 0.5 mL of metabolite extract was added into a 13 mm × 100 mm test tube, followed by the addition of 7.5 mL of a buffer containing Tris-HCl [20 mM] and MgSO4 [10 mM], after which the pH was adjusted to ±7 with HCl 1 M and 0.1 mL of olive oil and 0.1 mL of soybean oil for each experiment. Samples were whirled for 1 min on a Vortex-Genie II Mixer SI-0236 (Scientific Industries, Bohemia, NY, USA) and incubated at 30°C for one h. The emulsifying activity was determined by measuring the mixture’s absorbance for each tube, which was performed at a wavelength of 540 nm with a VE 5600 UV-A11807003 spectrophotometer (VELAB®, Pharr, TX, USA). All assays were performed in triplicate, including the control, which contained 0.5 mL of uninoculated liquid LB medium supplemented with 7.5 mL of the previously mentioned buffer [27].

The dual confrontation and emulsification data were studied in a statistical analysis where the values are presented as the mean value and standard deviation. To compare the differences in means, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using Tukey’s test with the help of Statgraphics Centurion XVII.II-X64 software (Statgraphics Technologies Inc., Virgin, UT, USA), with 95% reliability and statistical difference significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3.1 Genome Analysis of Strain VCA1

According to the data obtained from the sequencing of the genome of strain VCA1, genome size was found to be 6.69 Mb, and the GC content was 51.8%, with an N50 value of 483,213, and an L50 of 6, a total of 450 subsystems and 6312 coding regions, as was announced previously by [21].

3.2 Taxonomic Assignment and Comparison of Strain VCA1

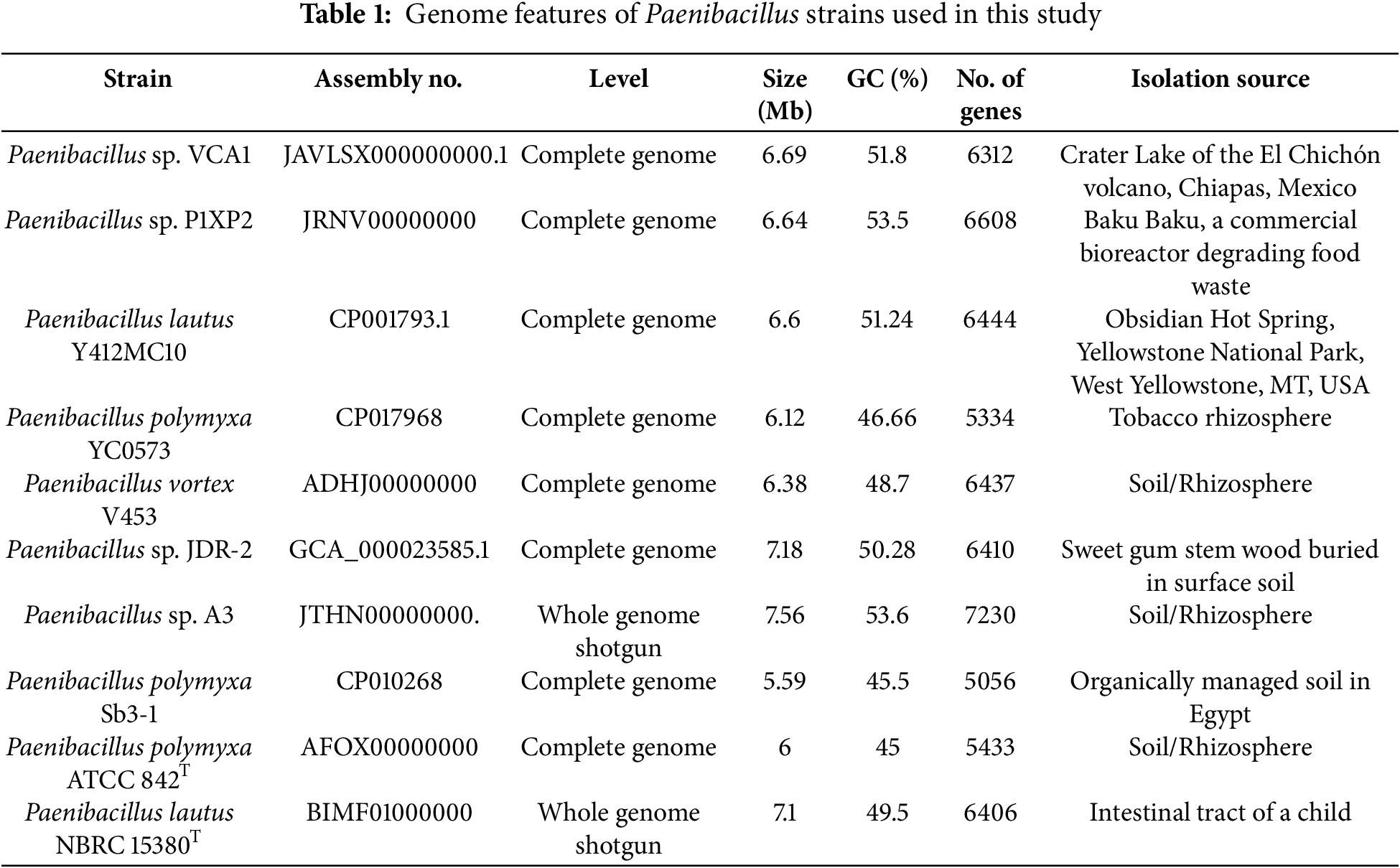

Different genomic studies were performed to assign a taxonomic classification to the VCA1 strain. These provided a guideline that would allow us to find degrees of similarity between the genome of strain VCA1 and others that had been previously reported. It was found that some Paenibacillus genomes were very similar to our microorganism and were of interest to our strain (Table 1).

As seen in Table 1, the first strain compared was Paenibacillus sp. P1XP2 [28] was isolated from a food waste bioreactor at a temperature of 45°C, where the sequenced genome size was 6.64 Mb and the GC content was 53.5%. Similarly, Paenibacillus lautus strain Y412MC10 [29], isolated from Yellowstone National Park at 50°C, contained a genome size of 6.6 Mb and GC content of 51.24%. Also, Paenibacillus polymyxa YC0573 was isolated from agricultural soil and classified within the plant growth-promoting bacteria group with the ability to inhibit activity in plant pathogens. This strain presented a genome size of 6.12 Mb and a noticeably lower GC content of 46.66% [30].

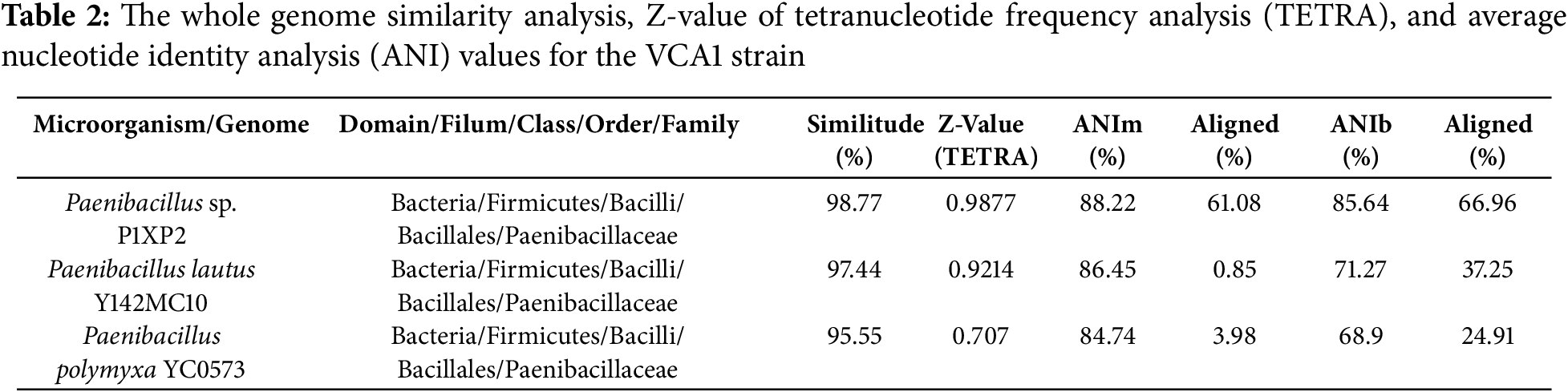

The comparison between the genomes mentioned above and the one sequenced in this work was carried out using the method of genome similarity analysis, which is shown in Table 2. Herein, the percentage of genome similarity of the VCA1 strain with Paenibacillus sp. P1XP2 (98.77% similarity), Paenibacillus lautus Y412MC10 (97.44% similarity), and Paenibacillus polymyxa YC0573 (95.55% similarity) have been determined. According to ANIm, ANIb, and DNA-DNA hybridization analysis values, it is suggested the VCA1 strain be classified as a new subspecies.

3.3 Functional Analysis of the VCA1 Genome

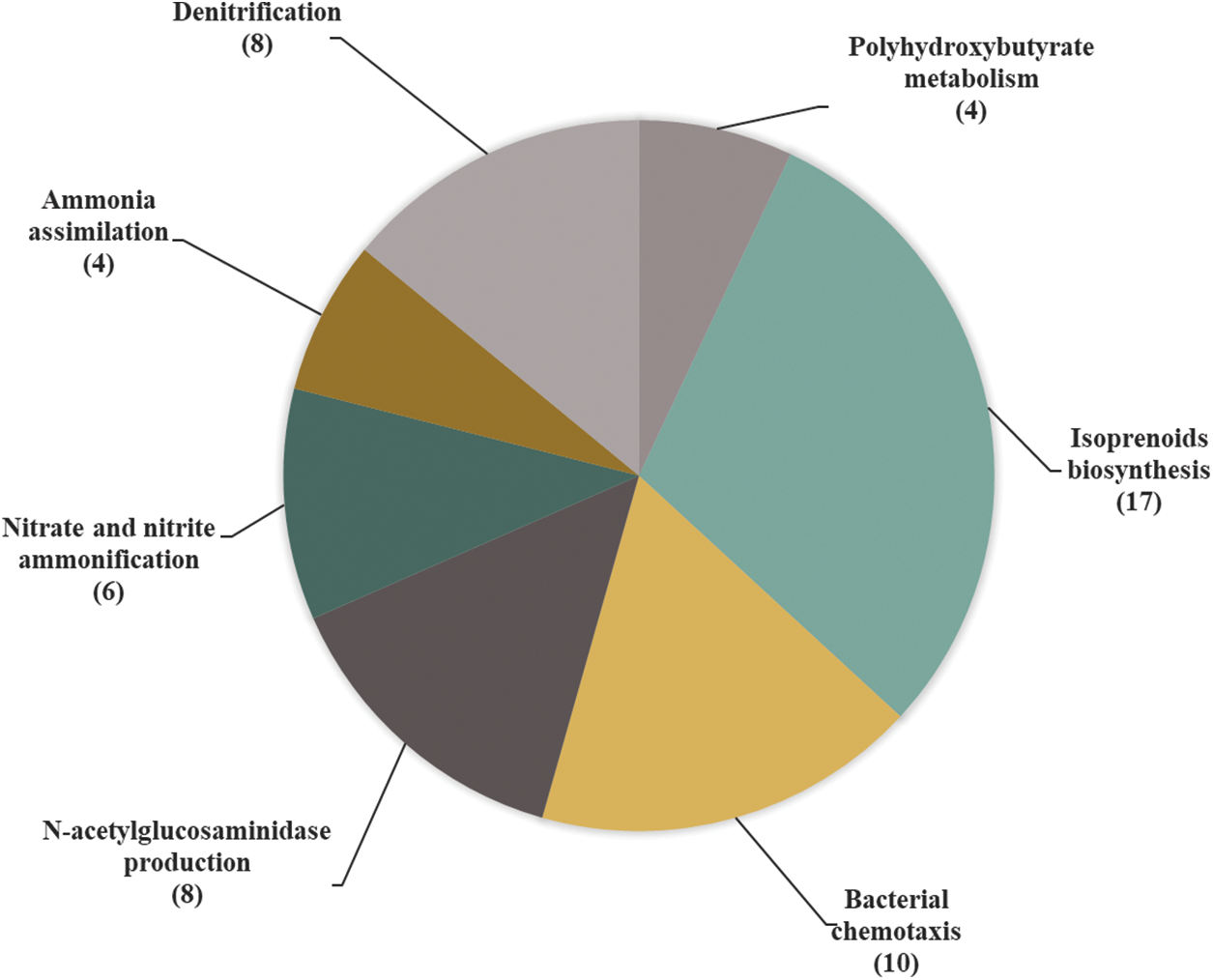

After taxonomic assignment, the functional analysis of the strain was carried out, which consisted of characterizing and structuring the genome’s categories and functions (Supplementary Material Fig. S1). To achieve detailed explanations, the subsystems investigation was carried out at the function level, which is shown in Fig. 1. This figure shows the number of genes and functions involved in plant growth promotion and the biocontrol of the phytopathogens. Strain VCA1 was found to have the ability to produce isoprenoids, also known as terpenoids. Another function of great interest that was identified within the genome of strain VCA1 is the production of siderophores, which was found in the subsystem corresponding to iron metabolism (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Classification of functions involved in biocontrol and plant growth promotion in the complete genome of VCA1 strain

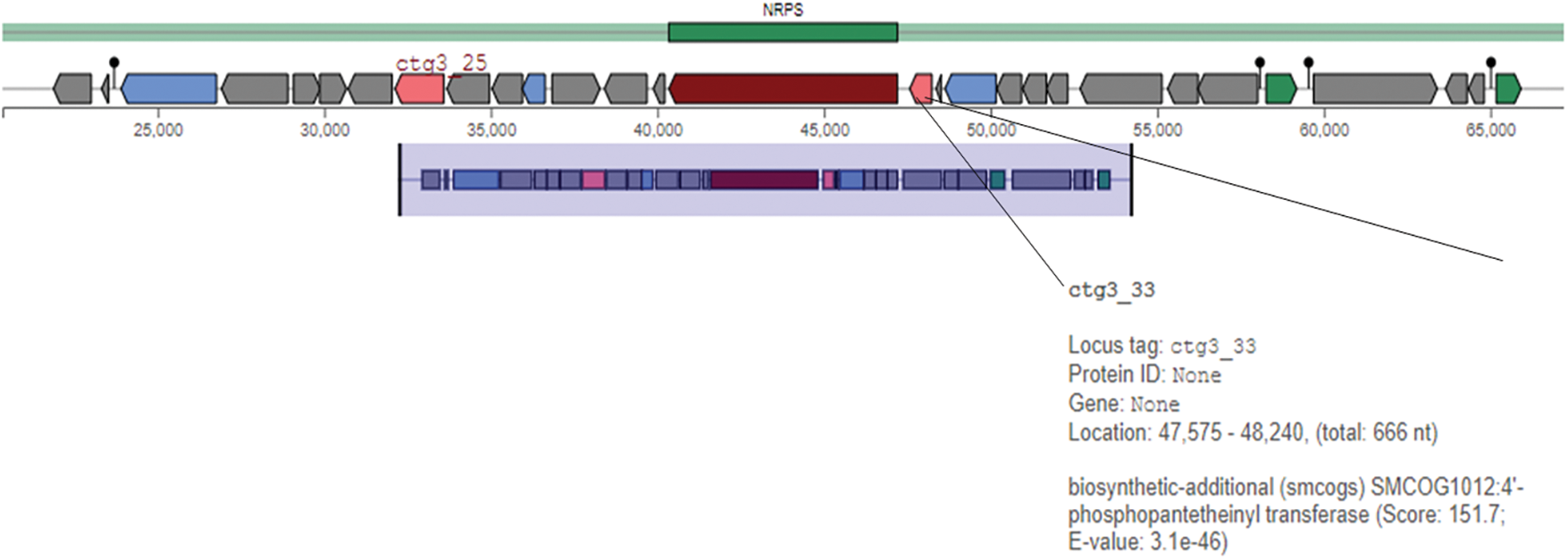

3.4 Analysis of Biosynthetic Genes for Secondary Metabolites Involved in Biocontrol

A genome analysis was also performed to determine biosynthetic gene clusters (BGC) involved in the biocontrol of phytopathogens. These results revealed the identification of 7 putative BGCs, one of which was involved in synthesizing non-ribosomal peptides (NRPS). Fig. 2 shows region 3.1 of the complete genome of strain VCA1. A biosynthetic gene for the enzyme 4-phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) was identified in this region.

Figure 2: Bioinformatic identification of clusters for the biosynthesis of biological control-related genes. Analysis was performed using the antiSMASH v.7.0.1 platform

3.5 Analysis of Functional Groups of the Surfactant Compound by FTIR-ATR

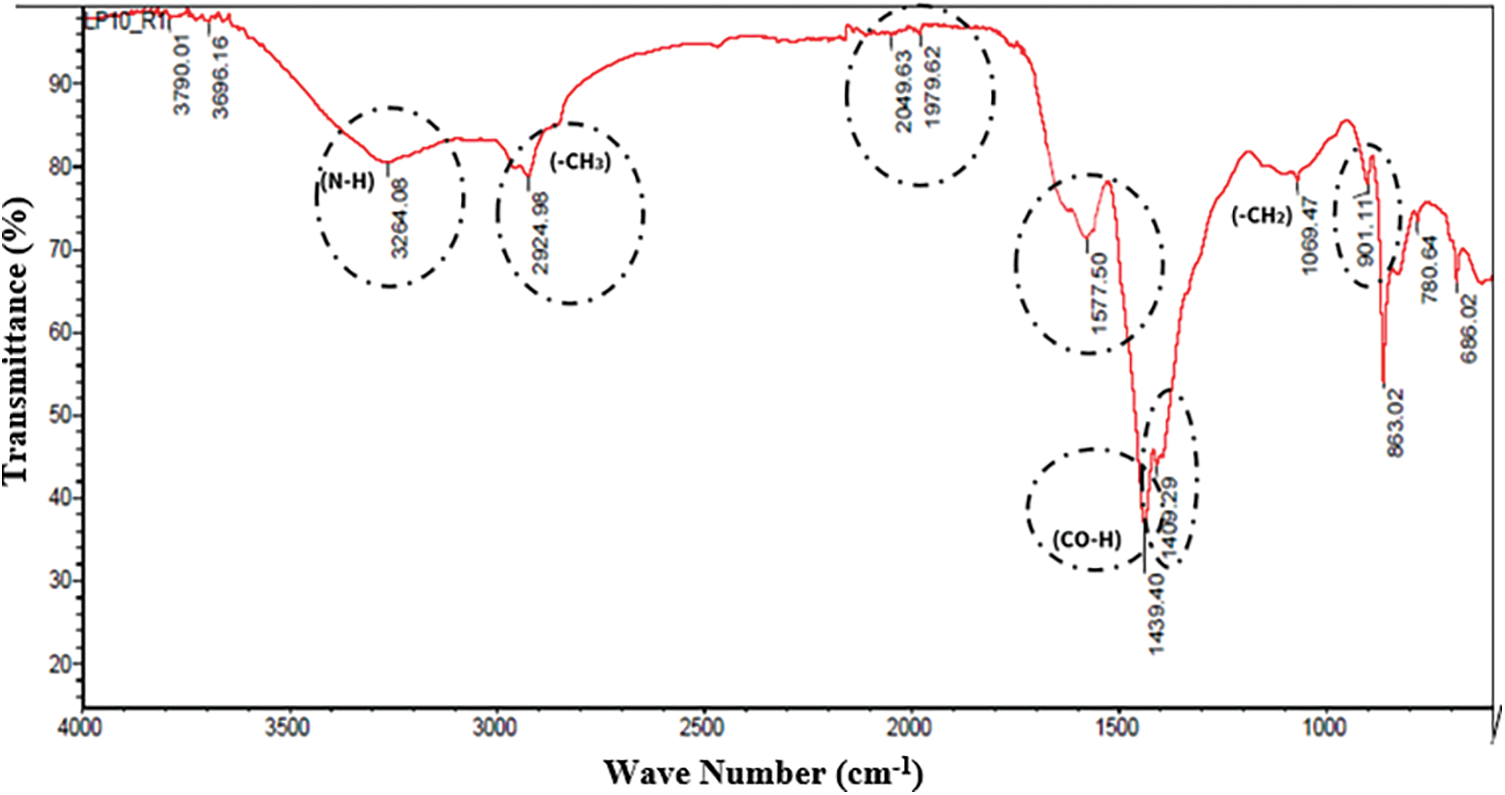

For further analysis to determine which lipopeptide was present in the sample of the acidic extract of the VCA1 strain, the analysis of the functional groups was performed by FTIR-ATR (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: IR spectrum of acid precipitation extracts of strain VCA1

According to the signals of the spectra obtained, it was found that at 3264 cm−1 there is an N-H stretching, a high signal was obtained by hydrogen bridge with overtone pattern at 2924 cm−1, a signal at 2094 and 1979 demonstrated the presence of the N=C=S double bonds characteristic of isothiocyanate, a signal at 1577 cm−1 for primary amine (NH2) bending vibrations, an aromatic ring system demonstrated its presence by a strong signal at 1439 cm−1, a C=O stretching at 1409 cm−1 gives evidence of a protein COO-bond and a deformation of the terminal C=C bond at 901 cm−1. All these results are characteristic of the presence of lipid and peptide functional groups; these results are like those reported by [24] as the signals generated in the infrared spectrum give a hint to the presence of lipopeptides.

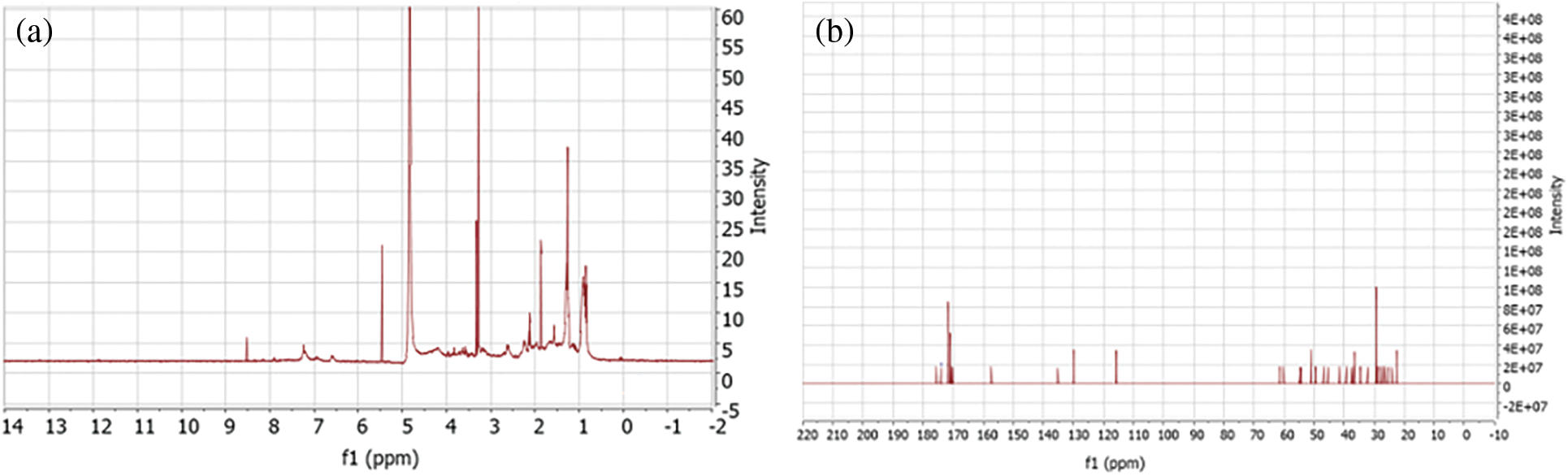

3.6 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) of the Surfactant Compound

After the functional groups present in the sample were identified, nuclear magnetic resonance was performed (Fig. 3), according to the peaks of the spectrum at positions 0.89, 0.93, 0. 94, 1.4, 1.8 2.3, 5.5 and 8.6 of the 1H proton and peaks 23.3, 29.9, 32.5, 38.7, 40.2, 50.1 115.6, 130 and 173.8 of the C13 spectrum, the identified compound belongs to the ITURINE C family (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Resonance spectra of the: (a) 1H and (b) 13C proton resonance of the acid extract of strain VCA1

3.7 Biocontrol Capabilities of Strain VCA1

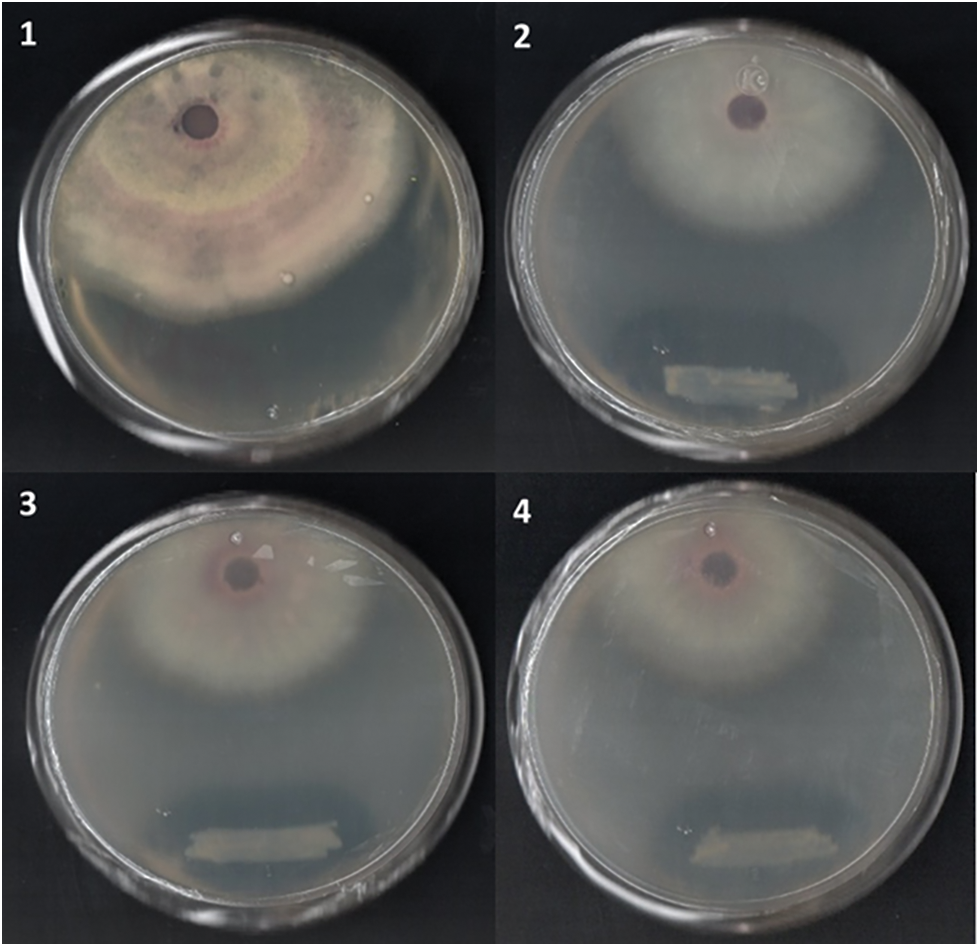

In vitro, analyses were performed to confirm the strain’s ability and efficacy to inhibit phytopathogenic fungi of agricultural interest. The antifungal activity was evaluated by measuring the inhibition rate and fungal growth diameter, which can be seen in Supplementary Material Table S1. An inhibition of 49.4% was obtained against Fusarium oxysporum 45ta, as seen in Fig. 5. This value was compared with the control fungus, where a statistically significant difference was observed.

Figure 5: Dual confrontation of Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 against Fusarium oxysporum 45ta. (1) Fusarium oxysporum 45ta control, (2–4) Fusarium oxysporum 45ta + VCA1

On the other hand, biocontrol by Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 was corroborated by the emulsification activity of metabolic extracts produced by strain VCA1. The emulsification analysis of these metabolites showed that the obtained values are lower than those of the control (Supplementary Material Table S2). The absorbance related to this activity suggests a reduction in the oil content in the samples containing the extracts of the metabolites. These results were compared with those reported by [27], who obtained absorbance values of 0.040, 0.0002, and 0.075 when emulsifying corn oil, olive oil, and soybean oil when producing biosurfactants from Bacillus subtilis Bs-Cach.

Bioinformatics techniques based on whole genome information and used for taxonomic assignment of microorganisms help us broadly delimit the comparison between related species [31]. According to data obtained for strain P1XP2, it had higher TETRA, ANIb, and ANIm values than those shown for strains Y412MC10 and YC0573, as seen in Table 2. Although there are insufficient reports for the identification of Paenibacillus species by use of TETRA, it has proved to be effective in identifying several species in a genus, such as Thioalkalivibrio [29], Paraburkholderia [32] and Salinimomas [33], as different authors have reported that a Z value closer to a value of 1.0 indicates similarity between them at the species level. On the other hand, it has been stated that the cutoff level between the compared genomes must be above the 95%–96% similarity range to assert that they are the same species, according to the ANIb and ANIm analysis [34]. However, although data for percentage similarity and TETRA analysis generated species-level matches with the P1XP2 strain, ANIn, and ANIb analysis determined that it is a new species, according to the recommended cutoff level. However, [35] demonstrated that if ANI values are below 95% but within an 80%–90% range, it is still the same species and is a new subspecies instead. These results were demonstrated via DNA-DNA hybridization analysis (Supplementary Material Table S3) with the GGDC method, which helped determine the genomic relationship between microorganisms. This technique is based on the combination of two single DNA strands, which give way to a double-stranded molecule by base pairing. When the percentage of this pairing is above 70%, it is concluded that it is a new subspecies. The percentage of hybridization similarity was 84.5% with Paenibacillus sp. P1XP2, meaning there is high similarity between strain VCA1 and P1XP2. However, it could be a new subspecies. The identification of new thermophilic isolates is desirable for research expansion in the biotechnology and agriculture fields. Also, this information is highly useful for visualizing the genomic similarities and differences between different species and subspecies within the same bacterial genus [36]. The ecological niche of strain VCA1 is markedly distinct from that of mesophilic P. polymyxa strains commonly isolated from soil environments (Table 1). Strain VCA1, isolated from the geothermal environment of El Chichón volcano, occupies a thermophilic niche that contrasts sharply with mesophilic soil-derived P. polymyxa strains, which typically grow optimally around 30°C–32°C (soil isolates; Optima ~30°C–32°C) (Grady et al., 2016). The adaptation of VCA1 to high-temperature environments is supported by the presence of thermotolerance-related genes, such as Hsp20 and Hsp70, which are well-documented in thermophilic bacteria as key factors for protein stabilization under thermal stress [30].

On the other hand, according to the genomic functionality data from strain VCA1, a diversity of subsystems in the genome was found. One of the most important functions for living things is the ability to metabolize carbohydrates, as this allows them to produce the energy needed to live and reproduce [37]. Although this function is essential among bacteria, small differences can be observed between the metabolic pathways of existing genera, which then provide information on how each microorganism adapts to the surrounding environment [38]. Other notable functions in the genome of strain VCA1 include the ability to metabolize iron, sulfur metabolism, amino acid and fatty acid metabolism, motility, and chemotaxis. It is worth mentioning that sulfur metabolism is of the utmost importance, as strain VCA1 was isolated from an ecosystem in which several sulfur-containing species are present [39].

Likewise, when analyzing the subsystems found in the complete genome of strain VCA1, it was found that several functions are involved in biocontrol and plant growth promotion. One of these functions is the synthesis of isoprenoids, whose type of metabolite is classified under secondary metabolites, meaning they are involved in the defense against phytopathogens that cause damage and subsequent death to the plant [38]. Likewise, it was observed that it has flagellar motility capabilities, whereby a certain number of genes are involved in the motility that benefits bacteria, as they can move to colonize plant roots and carry out their promoter and biocontrol functions [40]. On the other hand, the function involved in bacterial chemotaxis, which allows microorganisms to have the ability to move according to the different chemical gradients that exist in their environment, also allows them to adapt and is in addition to flagellar mobility [41]. This mechanism belongs to the signal translation system, which controls the movement of bacteria. This implies that it oversees converting an extracellular stimulus into an intracellular signal, creating a response that will establish guidelines to approach or move away from the existing chemical gradient [42]. These extracellular stimuli can come from the environment or a neighboring cell. Another function observed was responsible for the production of N-acetylglucosaminidase. This enzyme is involved in the degradation of chitin, which can weaken cell structure and decrease the ability to infect [43]. The degradation of this polymer is of utmost importance for biological control because, as the fungal cell wall degrades, fungal cells become exposed and are more vulnerable to various molecules produced by bacteria, which are responsible for inhibiting phytopathogenic functions [44]. Finally, the role of the production of siderophores is iron-chelating compounds secreted by microorganisms [45]. It has been reported that iron tends to limit agricultural productivity in various environments. Therefore, chelating compounds are of extreme importance for iron assimilation and utilization in plants, as they can create a mechanism that promotes plant growth [46].

All the above can be compared with the study by [38], where different genes and functions were reported for the Paenibacillus pasadensis R16 strain, which was isolated from the rhizosphere in agricultural soils. This strain was capable of controlling phytopathogens such as Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium graminearum, and Aspergillus niger. Likewise, it has been reported that the Paenibacillus genus could biocontrol other genera, such as Alternaria and Chrysosporum [47], and serves as a plant growth promoter. Belonging to the same bacterial genus, strain VCA1 presents this functional similarity.

Regarding the analysis used to determine biosynthetic gene clusters (BGC), genes involved in cyclic lipopeptide biosynthesis are assembled as large gene groups that encode multifunctional enzyme complexes (NRPS), which have a structure with multiple domains that affect activation and recognition for amino acid ordering, this system functions as an enzymatic assembly line where each domain incorporates an amino acid to the peptide of interest. For the synthesis of iturin, 4 domains are necessary: (1) Domain A (Adelination), which recognizes and activates the amino acids necessary for the formation of lipopeptides, where each free amino acid is activated with ATP to form an aminoacyl-AMP; (2) Domain T (Thioester), which oversees transporting the activated amino acids. This domain contains a phosphopantetheine group that binds to the activated amino acid using a thioester bond; (3) C domain (condensation), this domain forms the peptide bonds between the new amino acid and the previous one, in this way the reaction is catalyzed between the amino group and the carboxyl group of the previous amino acid giving way to the binding of a new residue to the peptide in formation; (4) TE domain (Thioesterase), this domain is in charge of releasing the peptide complex [48].

Upon further analysis, it was found that the production of the 4-phosphopantetheinyl transferase enzyme is occurring within the analyzed region. It has been reported that this enzyme can perform post-translational modification for the active functionality of NRPS [49]. This enzyme is encoded by the sfp gene, which plays an essential role in priming some synthases and NRPS, such as cyclic lipopeptides and, more specifically, surfactins, iturins, and fengycins [21].

All these results indicate that Paenibacillus sp. strain VCA1 can inhibit disease-causing phytopathogens in various plants of agricultural and commercial interest, which could contribute to reducing crop losses and improving productivity. It is essential to mention that the VCA1 strain isolated from the extreme environment of El Chichón Volcano has some advantages for agricultural applications, as it can withstand temperatures ranging from 28°C to 65°C and pH ranges from 3 to 5.

In this study, the antagonistic activity of Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 against the fungal pathogen Fusarium oxysporum 45ta had an inhibition of 49.4%, a result comparable to that reported by [50], where Paenibacillus polymyxa SK1 obtained an inhibition of 55.5% against the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Similarly, [51] reported 59.2% inhibition with Paenibacillus peoriae CFCC and 46.9% inhibition with Paenibacillus enshidis CCTCCAB when they tested the antifungal activity against the plant pathogen Fusarium graminearum. A similar result to that obtained with VCA1 was reported by [52], where the Paenibacillus kribbensis T-9 strain showed broad antifungal activity against several phytopathogens such as Phytophthora capsici, Botrytis cinerea and Colletrotrichum acutatum, which are mainly transmitted through soil. Although the inhibition rate of VCA1 is slightly lower than some of the reported values, this variation can be attributed to several factors, including differences in experimental conditions (e.g., medium composition, temperature, pH, and incubation time), the specificity of interactions between the bacterial strain and the phytopathogen tested, and the quantity and diversity of antifungal metabolites produced. Furthermore, the extreme environment from which VCA1 was isolated (the crater lake of El Chichón volcano) may have shaped unique metabolic adaptations that limit the optimal production of bioactive compounds under conventional laboratory conditions. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing culture parameters to enhance the synthesis of antifungal secondary metabolites (Ngo et al., 2025) and exploring alternative strategies, such as co-cultivation or metabolic engineering, to improve its efficacy as a biocontrol agent.

Thus, it is worth mentioning that not only hydrolytic enzymes could function as antifungals, but some biosurfactants (lipopeptides) are associated with this activity and have been reported to inhibit the growth of phytopathogenic fungi [53]. These biotensoactive compounds not only reduce the surface tension of water but also play a direct role in biocontrol mechanisms against phytopathogenic diseases. The mechanism by which they reduce the surface tension of the fungal membrane is through the degradation of phospholipids [54]. Finally, they also offer advantages for ecological purposes, as they have low toxicity, are easily degradable, have good environmental compatibility, and are highly selective in extreme environments [55].

According to the genomic analyses performed, DNA-DNA digital hybridization (dDDH) showed 84.5% similarity with the compared genomes, suggesting that Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 may represent a new subspecies of this genus. Functional genome annotation revealed the presence of genes associated with plant growth promotion, biocontrol mechanisms, and biosynthesis of antifungal and antimicrobial lipopeptides applicable to agriculture. Since the bacterium produces compounds that have biocontrol activity, the VCA1 strain could inhibit the growth of phytopathogenic fungi isolated from tomato plants. This antagonistic effect is likely mediated by the production of bioactive compounds capable of degrading fungal cell walls and membranes. Therefore, in this work, the use of Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 strain isolated from the lake crater of El Chichón Volcano was elucidated for the first time against a phytopathogenic fungus that causes significant losses of crops. Consequently, it’s important to carry out field experiments to understand the behavior of the bacterial strain in the presence of crops, specifically tomato crops with symptoms of diseases caused by phytopathogens and its possible action as a plant growth promoter, in addition to the implications of working with a thermophilic bacterium, since there are challenges such as the viability and stability of crops, the formulation and production at scale of these microorganisms, which are little explored, is of interest in the scientific and technological field for the development of new bioinoculants.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Tecnológico Nacional de México/IT de Tuxtla Gutiérrez with project number 22847.25-P. Funding came from the “Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías” (CONAHCYT, México), with Project No. 320299.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Betsy Anaid Peña-Ocaña, Rodolfo García-Contreras and Víctor Manuel Ruíz-Valdiviezo; data curation, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Betsy Anaid Peña-Ocaña, Toshinari Maeda, Reiner Rincón-Rosales and Federico Antonio Gutiérrez-Miceli; investigation, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Toshinari Maeda, Reiner Rincón-Rosales and Federico Antonio Gutiérrez-Miceli; formal analysis, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Rodolfo García-Contreras, Toshinari Maeda, Reiner Rincón-Rosales and Federico Antonio Gutiérrez-Miceli; methodology, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Betsy Anaid Peña-Ocaña and Víctor Manuel Ruíz-Valdiviezo; funding acquisition and resources, Víctor Manuel Ruíz-Valdiviezo; software, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Betsy Anaid Peña-Ocaña and Toshinari Maeda; validation, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Betsy Anaid Peña-Ocaña, Rodolfo García-Contreras, Toshinari Maeda, Reiner Rincón-Rosales, Federico Antonio Gutiérrez-Miceli and Víctor Manuel Ruíz-Valdiviezo; writing—original draft, Nancy Abril Martínez-López; writing—review and editing, Nancy Abril Martínez-López, Rodolfo García-Contreras and Víctor Manuel Ruíz-Valdiviezo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this article. The whole-genome shotgun project for VCA1 has been deposited at GenBank under the accession number JAVLSX000000000.1. The sequenced genome is publicly available under SRA, BioProject, and BioSample numbers, which are SRR25304438, PRJNA993667, and SAMN33190539, respectively.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.068176/s1.

References

1. Giordano D. Bioactive molecules from extreme environments II. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(11):642. doi:10.3390/md19110642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Schultz J, Rosado AS. Extreme environments: a source of biosurfactants for biotechnological applications. Extremophiles. 2020;24(2):189–206. doi:10.1007/s00792-019-01151-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Fariq A, Yasmin A, Blazier JC, Jannat S. Identification of bacterial communities in extreme sites of Pakistan using high throughput barcoded amplicon sequencing. Biodivers Data J. 2021;9:e68929. doi:10.3897/BDJ.9.e68929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zain Ul Arifeen M, Ma YN, Xue YR, Liu CH. Deep-sea fungi could be the new arsenal for bioactive molecules. Mar Drugs. 2019;18(1):9. doi:10.3390/md18010009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang X, Cvetkovska M, Morgan-Kiss R, Hüner NPA, Smith DR. Draft genome sequence of the Antarctic green alga Chlamydomonas sp. UWO241. iScience. 2021;24(2):102084. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Shaw C, Brooke C, Hawley E, Connolly MP, Garcia JA, Harmon-Smith M, et al. Phototrophic co-cultures from extreme environments: community structure and potential value for fundamental and applied research. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:572131. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.572131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Burket A, Douglas TA, Waldrop MP, Mackelprang R. Changes in the active, dead and dormant microbial chronosequence. Appl Env Microbiol. 2019;7:1–16. [Google Scholar]

8. Cabrera MÁ, Blamey JM. Biotechnological applications of archaeal enzymes from extreme environments. Biol Res. 2018;51(1):37. doi:10.1186/s40659-018-0186-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Schiraldi C, Rosa MD, Histology M. Encyclopedia of membranes; 2020. [Google Scholar]

10. Lebedeva J, Jukneviciute G, Čepaitė R, Vickackaite V, Pranckutė R, Kuisiene N. Genome mining and characterization of biosynthetic gene clusters in two cave strains of Paenibacillus sp. Front Microbiol. 2021;11:612483. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.612483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Liu X, Li Q, Li Y, Guan G, Chen S. Paenibacillus strains with nitrogen fixation and multiple beneficial properties for promoting plant growth. PeerJ. 2019;7(1):e7445. doi:10.7717/peerj.7445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Peña-Ocaña BA, Ovando-Ovando CI, Puente-Sánchez F, Tamames J, Servín-Garcidueñas LE, González-Toril E, et al. Metagenomic and metabolic analyses of poly-extreme microbiome from an active crater volcano lake. Environ Res. 2022;203(2):111862. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Rincón-Molina CI, Martínez-Romero E, Ruiz-Valdiviezo VM, Velázquez E, Ruiz-Lau N, Rogel-Hernández MA, et al. Plant growth-promoting potential of bacteria associated to pioneer plants from an active volcanic site of Chiapas (Mexico). Appl Soil Ecol. 2020;146(4):103390. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.103390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sharma J, Sundar D, Srivastava P. Biosurfactants: potential agents for controlling cellular communication, motility, and antagonism. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:727070. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.727070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Patiño AD, Montoya-Giraldo M, Quintero M, López-Parra LL, Blandón LM, Gómez-León J. Dereplication of antimicrobial biosurfactants from marine bacteria using molecular networking. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16286. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95788-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rani M, Weadge JT, Jabaji S. Isolation and characterization of biosurfactant-producing bacteria from oil well batteries with antimicrobial activities against food-borne and plant pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:64. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bjerk TR, Severino P, Jain S, Marques C, Silva AM, Pashirova T, et al. Biosurfactants: properties and applications in drug delivery, biotechnology and ecotoxicology. Bioengineering. 2021;8(8):115. doi:10.3390/bioengineering8080115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Mülner P, Schwarz E, Dietel K, Herfort S, Jähne J, Lasch P, et al. Fusaricidins, polymyxins and volatiles produced by Paenibacillus polymyxa strains DSM 32871 and M1. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):1485. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Malviya D, Sahu PK, Singh UB, Paul S, Gupta A, Gupta AR, et al. Lesson from ecotoxicity: revisiting the microbial lipopeptides for the management of emerging diseases for crop protection. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1434. doi:10.3390/ijerph17041434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chávez-Ramírez B, Rodríguez-Velázquez ND, Mondragón-Talonia CM, Avendaño-Arrazate CH, Martínez-Bolaños M, Vásquez-Murrieta MS, et al. Paenibacillus polymyxa NMA1017 as a potential biocontrol agent of Phytophthora tropicalis, causal agent of cacao black pod rot in Chiapas. Mexico Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2021;114(1):55–68. doi:10.1007/s10482-020-01498-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Martínez-López NA, Peña-Ocaña BA, García-Contreras R, Maeda T, Rincón-Rosales R, Cazares A, et al. Complete genome sequence of Paenibacillus sp. VCA1 isolated from crater lake of the El Chichón Volcano. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2023;12(11):e0058323. doi:10.1128/MRA.00583-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Sarwar A, Brader G, Corretto E, Aleti G, Ullah MA, Sessitsch A, et al. Qualitative analysis of biosurfactants from Bacillus species exhibiting antifungal activity. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198107. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Xu BH, Lu YQ, Ye ZW, Zheng QW, Wei T, Lin JF, et al. Genomics-guided discovery and structure identification of cyclic lipopeptides from the Bacillus siamensis JFL15. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202893. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0202893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Prakash J, Arora NK. Novel metabolites from Bacillus safensis and their antifungal property against Alternaria alternata. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2021;114(8):1245–58. doi:10.1007/s10482-021-01598-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Valenzuela Ruiz V, Santoyo G, Gómez Godínez LJ, Cira Chávez LA, Parra Cota FI, de los Santos Villalobos S. Complete genome sequencing of Bacillus cabrialesii TE3T: a plant growth-promoting and biological control agent isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui valley. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2023;4(w1):100193. doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2023.100193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kim J, Le KD, Yu NH, Kim JI, Kim JC, Lee CW. Structure and antifungal activity of pelgipeptins from Paenibacillus elgii against phytopathogenic fungi. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2020;163:154–63. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.11.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Méndez-Trujillo V, Carrillo-Beltrán, Valdez-Salas B, Gonzalez-Mendoza D. Bacteria with capacities of production of biosurfactants isolated from native plants of Baja California, México. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2016;85(1):225–30. doi:10.32604/phyton.2016.85.225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Adelskov J, Patel BKC. Draft genome sequence of Paenibacillus strain P1XP2, a polysaccharide-degrading, thermophilic, facultative anaerobic bacterium isolated from a commercial bioreactor degrading food waste. Genome Announc. 2015;3(1):e01484–14. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01484-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Mead DA, Lucas S, Copeland A, Lapidus A, Cheng JF, Bruce DC, et al. Complete genome sequence of Paenibacillus strain Y4.12MC10, a novel Paenibacillus lautus strain isolated from obsidian hot spring in Yellowstone national park. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6(3):381–400. doi:10.4056/sigs.2605792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Liu H, Wang C, Li Y, Liu K, Hou Q, Xu W, et al. Complete genome sequence of Paenibacillus polymyxa YC0573, a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium with antimicrobial activity. Genome Announc. 2017;5(6):e01636–16. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01636-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ahn AC, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Overmars L, Richter M, Woyke T, Sorokin DY, et al. Genomic diversity within the haloalkaliphilic genus Thioalkalivibrio. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173517. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Pratama AA, Jiménez DJ, Chen Q, Bunk B, Spröer C, Overmann J, et al. Delineation of a subgroup of the genus Paraburkholderia, including P. terrae DSM 17804T, P. hospita DSM 17164T, and four soil-isolated fungiphiles, reveals remarkable genomic and ecological features-proposal for the definition of a P. hospita species cluster. Genome Biol Evol. 2020;12(4):325–44. doi:10.1093/gbe/evaa031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Cao J, Lai Q, Liu P, Wei Y, Wang L, Liu R, et al. Salinimonas sediminis sp. nov., a piezophilic bacterium isolated from a deep-sea sediment sample from the New Britain Trench. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68(12):3766–71. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.003055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Palmer M, Steenkamp ET, Blom J, Hedlund BP, Venter SN. All ANIs are not created equal: implications for prokaryotic species boundaries and integration of ANIs into polyphasic taxonomy. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70(4):2937–48. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gomila M, Peña A, Mulet M, Lalucat J, García-Valdés E. Phylogenomics and systematics in Pseudomonas. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:214. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Balk M, Heilig HGHJ, van Eekert MHA, Stams AJM, Rijpstra IC, Sinninghe-Damsté JS, et al. Isolation and characterization of a new CO-utilizing strain, Thermoanaerobacter thermohydrosulfuricus subsp. carboxydovorans, isolated from a geothermal spring in Turkey. Extremophiles. 2009;13(6):885–94. doi:10.1007/s00792-009-0276-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Lee Y, Balaraju K, Kim SY, Jeon Y. Occurrence of phenotypic variation in Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 associated with sporulation and carbohydrate metabolism. Biotechnol Rep. 2022;34:e00719. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2022.e00719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Passera A, Marcolungo L, Casati P, Brasca M, Quaglino F, Cantaloni C, et al. Hybrid genome assembly and annotation of Paenibacillus pasadenensis strain R16 reveals insights on endophytic life style and antifungal activity. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189993. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ovando-Ovando CI, Feregrino-Mondragón RD, Rincón-Rosales R, Jasso-Chávez R, Ruíz-Valdiviezo VM. Isolation and identification of arsenic-resistant extremophilic bacteria from the crater-lake volcano El Chichon. Mexico Curr Microbiol. 2023;80(8):257. doi:10.1007/s00284-023-03327-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Jeong A, Suazo KF, Wood WG, Distefano MD, Li L. Isoprenoids and protein prenylation: implications in the pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention of Alzheimer’s disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;53(3):279–310. doi:10.1080/10409238.2018.1458070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Matilla MA, Krell T. The effect of bacterial chemotaxis on host infection and pathogenicity. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42(1):fux052. doi:10.1093/femsre/fux052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Galicia Jimenez MM, Sandoval-Castro C, Herrera Rojas R, Magaña Sevilla H. Bacterial chemotaxis and flavonoids: prospects for the use of probiotics. Trop Subtrop Agroecosyst. 2011;14(3):891–900. doi:10.56369/tsaes.1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Gaderer R, Seidl-Seiboth V, de Vries RP, Seiboth B, Kappel L. N-acetylglucosamine, the building block of chitin, inhibits growth of Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol. 2017;107:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2017.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Kavanat Beerahassan R, Vadavanath Prabhakaran V, Pillai D. Formulation of an exoskeleton degrading bacterial consortium from seafood processing effluent for the biocontrol of crustacean parasite Alitropus typus. Vet Parasitol. 2021;290:109348. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.109348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Mitter B, Petric A, Shin MW, Chain PSG, Hauberg-Lotte L, Reinhold-Hurek B, et al. Comparative genome analysis of Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN reveals a wide spectrum of endophytic lifestyles based on interaction strategies with host plants. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:120. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Årstøl E, Hohmann-Marriott MF. Cyanobacterial siderophores-physiology, structure, biosynthesis, and applications. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(5):281. doi:10.3390/md17050281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Soni R, Rawal K, Keharia H. Genomics assisted functional characterization of Paenibacillus polymyxa HK4 as a biocontrol and plant growth promoting bacterium. Microbiol Res. 2021;248(12):126734. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2021.126734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Jin P, Wang H, Liu W, Miao W. Characterization of lpaH2 gene corresponding to lipopeptide synthesis in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens HAB-2. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):227. doi:10.1186/s12866-017-1134-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Contreras-Cornejo HA, Macías-Rodríguez L, Herrera-Estrella A, López-Bucio J. The 4-phosphopantetheinyl transferase of Trichoderma virens plays a role in plant protection against Botrytis cinerea through volatile organic compound emission. Plant Soil. 2014;379(1):261–74. doi:10.1007/s11104-014-2069-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Khan MS, Gao J, Zhang M, Chen X, Moe TS, Du Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria Bacillus stratosphericus LW-03 from Lilium wardii. 3 Biotech. 2020;10(7):305. doi:10.1007/s13205-020-02294-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ali MA, Lou Y, Hafeez R, Li X, Hossain A, Xie T, et al. Functional analysis and genome mining reveal high potential of biocontrol and plant growth promotion in nodule-inhabiting bacteria within Paenibacillus polymyxa complex. Front Microbiol. 2021;11:618601. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.618601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Xu SJ, Hong SJ, Choi W, Kim BS. Antifungal activity of Paenibacillus kribbensis strain T-9 isolated from soils against several plant pathogenic fungi. Plant Pathol J. 2014;30(1):102–8. doi:10.5423/PPJ.OA.05.2013.0052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Pacwa-Płociniczak M, Płociniczak T, Iwan J, Żarska M, Chorążewski M, Dzida M, et al. Isolation of hydrocarbon-degrading and biosurfactant-producing bacteria and assessment their plant growth-promoting traits. J Environ Manage. 2016;168:175–84. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.11.058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Liang TW, Wu CC, Cheng WT, Chen YC, Wang CL, Wang IL, et al. Exopolysaccharides and antimicrobial biosurfactants produced by Paenibacillus macerans TKU029. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172(2):933–50. doi:10.1007/s12010-013-0568-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Fenibo EO, Ijoma GN, Selvarajan R, Chikere CB. Microbial surfactants: the next generation multifunctional biomolecules for applications in the petroleum industry and its associated environmental remediation. Microorganisms. 2019;7(11):581. doi:10.3390/microorganisms7110581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools