Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Viticulture: History, Breeding Systems and Recent Developments

1 Plant Developmental Genetics, Institute of Biophysics v.v.i, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Královopolská 135, Brno, 61265, Czech Republic

2 Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiología de Salamanca (IRNASA)—Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Cordel de Merinas, 40, Salamanca, 37008, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Emilio Cervantes. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adaptation Mechanisms of Grapevines to Growing Environments and Agricultural Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2649-2667. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068936

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Grapevine is unique among crops because its domestication resulted not only in new morphological characteristics, but also in altered reproductive mechanisms. Viticulture involves a change from a dioecious to a hermaphroditic mating system, which makes the reproductive system more efficient. In consequence and the fact that it is one of the oldest and most economically important cultivated plants, Vitis vinifera could be defined as an over-domesticated species. Here we review some key aspects in viticulture. The main areas of interest have remained consistent throughout history, including the origin and characterisation of cultivars, resistance to environmental conditions, pests and pathogens, and berry quality. Advances in genomic analysis and epigenetics shed new light on these aspects. Although the vine has a long and complex life cycle, recent haplotype sequencing techniques allow genomic characteristics related to different reproduction processes to be identified. Recent work on haplotype sequencing reveals genomic changes accompanying each reproductive type, providing improved detail about the sex-determining region (SDR). Meanwhile, the application of epigenetic analysis offers new tools for defining varietal characteristics and their responses to changing environmental conditions. However, critical issues, such as differentiating between sylvestris and feral cultivars, remain unclear. Understanding the molecular basis of morphological differences and investigating the epigenetic regulation of gene expression and genome dynamics in response to breeding and environmental factors in this species will be crucial. Seed morphology could help to resolve how to differentiate between wild and feral plants.Keywords

Gabriel Alonso de Herrera (Talavera de la Reina, Toledo, 1470–1539) wrote his Agricultura general (General Agriculture) at the request of Cardinal Cisneros [1]. First published in Alcalá de Henares in 1530 by the Imprenta de Brocar, the work went through several editions and was translated into Latin, Italian and French. Spanning 230 pages, it is dedicated to viticulture and describes the main characteristics of several varieties cultivated in Castile in the 15th century that are still grown today, including Torrontés, Moscatel, Cigüente, Jaén and Hebén. Hebén is described as a white grape variety producing large, sparse bunches of grapes with large seeds. Possibly originating in North Africa, the Hebén variety is female and, through crosses with other varieties between the 9th and 12th centuries, has produced many descendants, representing the genetic contribution of the Iberian Peninsula to modern Vitis cultivars [2–4].

In The Gardeners’ Dictionary (1752) [5], Philip Miller (1691–1771) mentions several varieties of Vitis, in addition to V. sylvestris Labrusca, including V. praecox columellae, V. corinthiaca, V. laciniatis foliis and V. subhirsuta. Some of these varieties correspond to actual cultivars; for example, V. uva perampla corresponds to Chasselas Blanc, a cultivar of unknown origin [6] that gives the wines of Valais in Switzerland.

The Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid conserves the ampelographic material (leaves and shoots) collected and preserved by Simón de Rojas Clemente y Rubio (Titaguas, Valencia, 1777-Madrid, 1827), the author of Variedades de la vid común que vegetan en Andalucía (Varieties of the common vine that grow in Andalusia) [7]. His herbarium, the oldest vine herbarium in existence, is still used for studies of phenotypic and genetic diversity, molecular characterisation and wine history, providing a unique insight into vine cultivation in the early 19th century (the pre-phylloxera era). Due to his herbarium and writings, which were translated into French, Simón de Rojas Clemente is often regarded as the father of modern ampelography.

Modern clonal selection began around 1876. The first registered “grapevine clone” was of V. vinifera cv. Silvaner variety [8]. Hermann Müller (1850–1927), who worked at the Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute, created the Müller-Thurgau grape variety (a cross between Riesling and Madeleine Royale) and reported the inheritance of traits such as early ripening and yield using phenotypic selection [9].

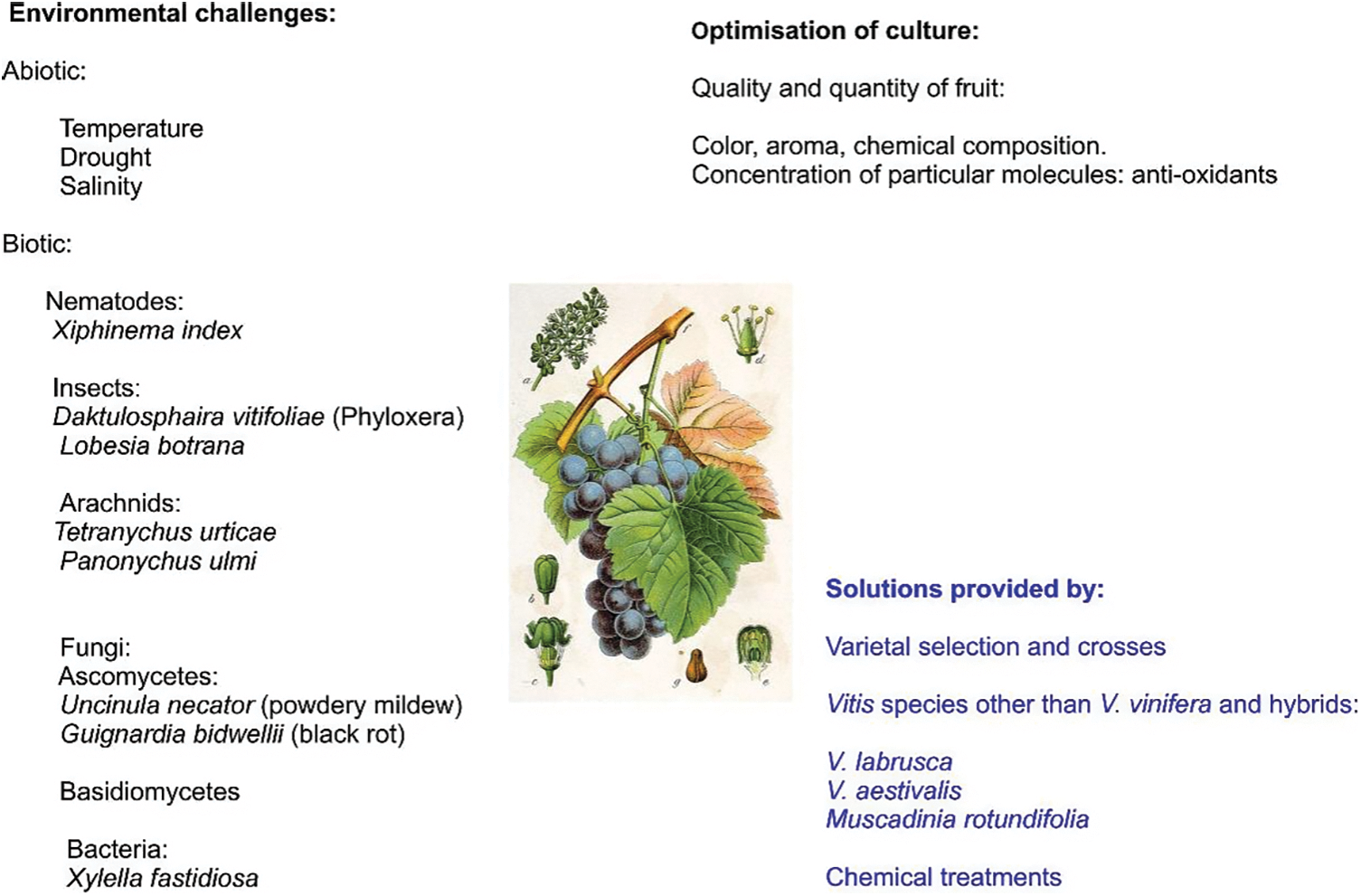

The Grapes of New York (Hedrick, 1870–1951; [10]) describes the ampelographic characteristics of Vitis cultivars and species, and in the article entitled A Century of American Viticulture, Read and Gu [11] outlined the key topics covered in articles published over the course of a century in the journal Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., including chromosome counts, self-fertility, parthenocarpy and seed abortion, fruiting habit, and disease resistance. Preliminary breeding results were reported, and examples of trait inheritance, including sex determination, fruit colors, resistance to pathogens, and dioecy and dimorphism, were given [12–21]. For centuries, the main objectives of viticulture have been related with adaptation to changing environmental conditions, including biotic (salinity, temperature, drought, …), and abiotic (pests and pathogens) factors, as well as the optimization of biochemical characters (quality) and yield (Fig. 1). This review summarises how recent developments can affect our understanding of, and improvements to, these aspects. Optimising viticultural possibilities requires knowledge of the genetic composition of Vitis species and cultivars. While some varieties are reported to be direct selections from wild types (e.g., Traminer, [22,23]), others are known to be crosses between existing cultivated varieties (e.g., Cabernet Sauvignon, which is a cross between Sauvignon Blanc and Cabernet Franc, [24]). Crosses between wild types and varieties also exist: Riesling, for example, is a cross between Gouais and a Traminer × V. silvestris hybrid [22,25,26]. Similar to Hebén in Spain and Heunisch in Germany, Gouais is the parent of dozens of cultivars [6].

Figure 1: The main objectives in viticulture are related with adaptation to changing environmental conditions, including biotic (salinity, temperature, drought, …), and abiotic (pests and pathogens) factors, as well as the optimization of biochemical characters (quality) and yield. Optimizing the possibilities of viticulture requires a knowledge of the genetic composition of Vitis species and cultivars

Classical genetic maps were based on phenotypic markers. The inheritance of traits was observed in the progeny (F1, F2 or backcross generations) and linkage was estimated by calculating the frequencies of recombination between traits. To include genes in maps, the traits had to follow a Mendelian pattern and be controlled by single genes with clear dominant/recessive characteristics. This classical analysis, which was based on phenotypic observations, controlled crosses and Mendelian principles, was first developed in Drosophila [27] and worked well in other small organisms with rapid life cycles, such as Arabidopsis [28]. However, this approach encountered difficulties in Vitis, an organism with a long generation time, high heterozygosity and a complex genome comprising 19 chromosomes (2n = 38). These characteristics made linkage analysis of observable traits challenging. Thanks to the development of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and the application of molecular markers, the prospect changed at the end of the 20th century. Usage of Microsatellites [29] and other PCR-based markers, such as amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLPs) [30], greatly reduced the time required to create genetic linkage maps. These DNA markers are useful for germplasm characterisation, marker-assisted selection, marker-assisted introgression and genomic selection. Vezzulli et al. and Tympakianakis et al. [31,32] review genetic markers and the development of genetic maps in grapes.

Lodhi et al. [33] used a two-way pseudo testcross between Cayuga White and Aurora to cover 1176 and 1477 cM, respectively, using 422 RAPD markers and 16 AFLP and isozyme markers. Further research by different groups expanded the range of available markers. Findings on co-dominant microsatellite-based markers provided good coverage of the Vitis genome. Doligez et al. mapped 1002 cM using 250 AFLP and 44 SSR markers [34], while Grando et al. developed 1639 cM using 338 AFLP microsatellite markers for the wine cultivar Moscato Bianco (Vitis vinifera L.), defining the 19 linkage groups of the Vitis riparia Michx. paternal map with 429 loci covering 1518 cM [35]. Doligez et al. used Carthagene to map 1647 cM Kosambi with 502 SSRs and 13 other types of PCR-based markers in Vitis vinifera L. [34]. Recognition of the importance of these maps came with the establishment of the Vitis Microsatellite Consortium (VMC) to develop a map based on a set of 371 microsatellite (SSR) markers [36,37]. Maps in Vitis rupestris and Vitis arizonica were developed to identify the loci responsible for the resistance to infections caused by the nematode Xiphinema index and the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa [38].

Wang et al. reviewed the advances in the field of Vitis genomics and its applications [39]. The first two Vitis genomes were published in 2007: one was a Pinot Noir clone (ENTAV115), which is grown in various soils for producing red and sparkling wines and is not self-pollinating [40]; the other was a highly homozygous V. vinifera genotype (PN40024) [41]. The PN40024 originated from the Helfensteiner genotype, resulting from a cross between Pinot Noir and Schiava Grossa in 1931. It was then bred to almost full homozygosity through successive self-pollinations [42]. A 474 Mb sequence revealed evidence of an ancient hexaploidization event and contained a set of 30,434 protein-coding genes across 19 chromosomes, with an average of 372 codons and five exons per gene. This number was significantly lower than the one observed in poplar (Populus trichocarpa Torr. & A.Gray ex Hook.), which has a similar genome size of 485 Mb, or rice (Oryza sativa L.), with a smaller genome size of 389 Mb [43,44]. However, Vitis showed a number of 3000 protein-coding genes more than the reported for Arabidopsis thaliana, despite its genome size being 3.5 times smaller at 135 Mb [45]. A summary of advances in Vitis genomics is shown in Table 1.

Different approaches revealed an average of 41.4% repetitive DNA/transposable elements in the grapevine genome. This is a slightly higher proportion than that identified in the rice genome (33%–38%). New genomic sequences of PN40024 demonstrated that this cultivar resulted from nine selfings of cv. ‘Helfensteiner’ (a cross between ‘Pinot noir’ and ‘Schiava grossa’), rather than a single ‘Pinot noir’ cultivar. This data led to an improved version of the reference sequence called PN40024.v4 [42]. Updates to the genome include rootstocks from crosses between V. vinifera, V. riparia, V. rupestris, and V. berlandieri, as well as alternative spliced isoforms [68]. A gap-free, telomere-to-telomere reference genome for the PN40024 cultivar was published in 2023 [66]. This genome is 69 Mb longer than previous versions and contains 67% repetitive sequences, 19 centromeres, 36 telomeres, and 9018 additional genes. A summary of the published grape genomes consists of 16 for V. vinifera subsp. vinifera, 21 for wild Vitis species and nine for interspecific hybrids [39].

Additional data from the Amur grape (Vitis amurensis Rupr.), V. riparia and V. labrusca [53,57,63] as well as from cultivars such as Chardonnay, Shiraz, Shine and Muscat [50,60,64] has improved our understanding of plant-pathogen interactions, cold resistance and the influence of domestication on sex determination as well as the metabolism of phenols. For example, salt-tolerant loci were identified using a pangenomic-GWAS approach based on methods of pairwise whole-genome alignment [61]. Studies on the genomics of berry related traits and other quality aspects involve those of Guo et al. [61] and others.

The genomes of modern cultivars are insufficient for investigating changes during domestication. To this end, the genome of Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris has been analysed in several studies [51,69,70]. Contrasting results from these studies led to a new project involving the analysis of 3186 new sequences [3]. This work provides new insights into the origins and relationships between Vitis sylvestris and cultivars, supporting the theory of a dual origin of V. vinifera. The study defines six groups of pure or nearly pure ancestries among cultivated vines: Western Asian table grapevines (CG1); Caucasian wine grapevines (CG2); muscat grapevines (CG3); Balkan wine grapevines (CG4); Iberian wine grapevines (CG5); and Western European wine grapevines (CG6), and describes selective sweep genes in 132 regions for CG1 and 887 genes in 137 regions for CG2. CG5 is well represented by Hebén, a female cultivar that is the progenitor of many other cultivars in Spain and Portugal [2–4].

Traditional genomic sequences are linear representations of an organism’s DNA, usually assembled as a reference genome from a consensus of multiple individuals or sequencing reads. In diploid organisms, the two homologous chromosomes—each inherited from one parent—are typically collapsed into a single composite sequence. While this simplification facilitates general analyses, it masks the physical linkage of variants and fails to capture how alleles are inherited together. In contrast, haplotype-resolved sequences provide a more accurate picture by distinguishing between the two chromosome copies, enabling the identification of how specific alleles are linked across loci. This approach is particularly important for studying highly heterozygous species and genomic regions with reduced recombination. Haplotype research identifies genetic variations within populations that can be linked to functional traits like cold tolerance, berry size, or sugar composition.

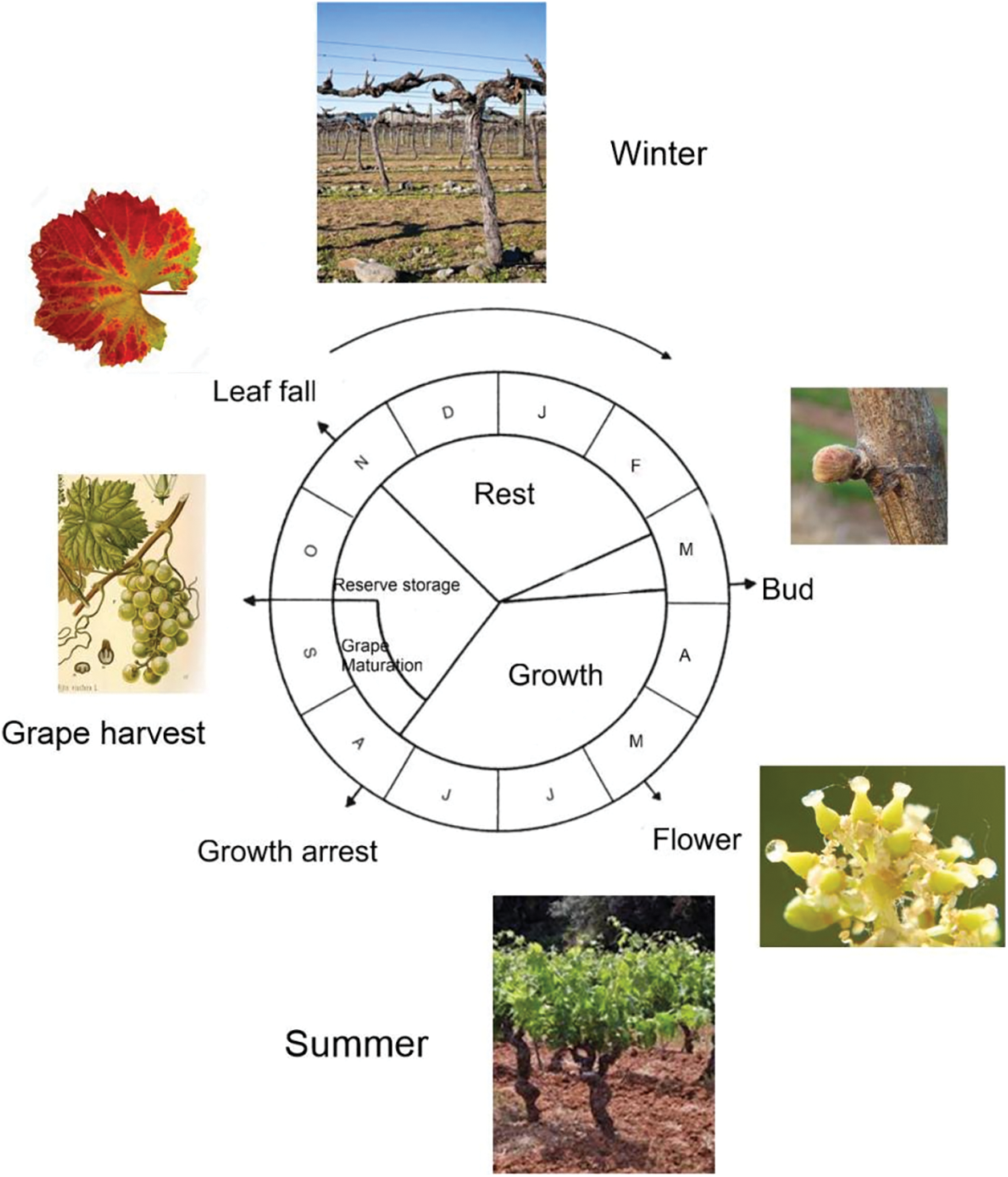

In clonally propagated plants such as grapevine (Fig. 2), somatic mutations accumulate over time, further increasing intra-varietal diversity. Studies have shown transposable elements significant contribution to somatic polymorphism in Vitis [71], and such mutations occur more frequently in intergenic regions than in coding sequences [55]. As a result, different clonal lines of the same cultivar can carry varying levels of heterozygous structural variants (SVs). Many horticultural species, including Vitis, are outbreeding and consequently exhibit high levels of heterozygosity. For instance, SNP-level heterozygosity has been estimated at 1.02% in pear (Pyrus communis L.) [72] and 2.27% in lychee (Litchi chinensis) [73], while in Vitis, it ranges from as low as 0.01% in the inbred PN40024 line to 0.20%–0.40% in more diverse genotypes [74]. These high levels of heterozygosity and structural variation complicate genome assembly and gene mapping, requiring haplotype-resolved diploid genomes for precise allele identification and QTL analysis. Thanks to recent advances in long-read sequencing and assembly technologies [75,76], fully phased diploid genomes have been generated in multiple species [77], including several Vitis cultivars [50,52,70,75,78–80].

Figure 2: Vitis plants are propagated vegetatively. Each vine plant takes between 3 and 5 years to start producing grapes suitable for winemaking and may be active typically between 30–40 years of age, with peak quality and yield often occurring between 10 and 20 years. In the first year, the vine develops strong roots, and the second year is dedicated to growing and strengthening. The first bunches may appear in the third year, but the most abundant and highest quality harvests usually come from the fourth or fifth year onwards. The flowers, hermaphrodite in the wild, are dioecious in cultivated plants. Seeds are produced, but under vegetative regime they are usually discarded. In cultivated Vitis, sexual reproduction is exceptionally used only in crosses

Reproductive strategies in Vitis play a crucial role in shaping genome structure. While wild Vitis species are typically dioecious and outcrossing, domesticated grapes have predominantly vegetative propagation, with occasional hybridization events. Each reproduction mode—outcrossing, selfing, or clonal propagation—has distinct genomic consequences. Clonal propagation leads to the accumulation of somatic mutations and increased heterozygosity [74]; in contrast, self-fertilization reduces heterozygosity, purging deleterious alleles and increasing homozygosity. Cross-breeding and clonal propagation, on the other hand, tend to mask such mutations. To understand the genomic consequences of these reproductive modes, researchers compared a haplotype-resolved genome of PN40024 with two haplotypes (PN1 and PN2) derived from a different Pinot Noir clone. This comparison revealed extensive haplotypic diversity, including unique gene families and structural variations [74]. Resequencing data from 38 Vitis vinifera samples—comprising 18 PN clones, 20 wild grapevines, and 3 muscadine grapes as outgroups—further enabled the detection of selection signatures in PN clones, particularly in chromosomes 1, 3, 4, 5, and 18, and introgression signals from European populations in chromosomes 1, 2, 3, and 19.

Admixture analysis clarified the genetic relationships among clones. PN40024 clones showed genetic independence compared to other genotypes such as HE (Helfensteiner), GB (Gouais Blanc), and CD (Chardonnay), which retained mixed genotypes from their parentals. For example, HE derives from PN and SG (Schiava Grossa), while CD and GN (Gamay Noir) originate from crosses between PN and GB. Among these, the PN40024 clones exhibited the lowest levels of nucleotide diversity and heterozygosity, consistent with the effects of prolonged self-fertilization. To further explore how recombination affects genetic load, researchers used SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant) to identify deleterious SNPs (dSNPs). Clonal groups (PN, SG, GB, CD, GN, HE) exhibited a significant higher genetic burden than wild outcrossing groups from Europe (EU) and the Middle East (ME). Notably, selfed PN40024 carried the highest recessive burden and the lowest heterozygous burden. Across 167 examined combinations, the genotypes were often heterozygous in PN, SG, or HE, but homozygous in PN40024, illustrating how selfing unmasks deleterious variants. Interestingly, in the GB sub-lineage—including GB, CD, and GN—many mutations remained in a heterozygous state due to close linkage of deleterious and structural variants in repulsion, which can maintain heterozygosity even after successive selfings [74].

Overall, these findings underscore how breeding practices and reproductive modes in grapevine—whether clonal propagation, selfing, or crossing—profoundly shape genome heterozygosity, structural variation, and the accumulation of deleterious mutations. Haplotype-resolved genomic analysis emerges as an indispensable tool for unraveling these complex patterns in grapevine evolution and improvement.

5 Sex Determining Region (SDR)

Dioecy, the condition in which male and female reproductive structures are found on separate individuals, is relatively rare, affecting only about 6%–8% of angiosperms. It is often associated with traits such as monoecy, wind pollination, and climbing growth [81], and occurs in a number of agronomically important species, including Carica papaya L., Actinidia chinensis Planch., Fragaria vesca L. [82–84], and various species of Silene and Rumex [85–89]. Within the Vitaceae family, dioecy is observed in Vitis and Tetrastigma, and has been the focus of comparative studies across these genera [90]. During grapevine domestication, a significant reproductive shift occurred—from dioecy to hermaphroditism—enabling self-pollination and increased breeding control.

Early genetic models attempted to explain this transition. Oberle [91] proposed a two-gene system, with dominant alleles So and Sp controlling ovule suppression and pollen development, respectively; males were heterozygous at both loci, while females were homozygous recessive. Recombination between these genes could yield hermaphrodites. Levadoux [92] later suggested a single locus with three alleles (M > H > F) controlling the development of male, hermaphrodite, and female flowers. These hypotheses laid the groundwork for later studies that mapped sex determination to a ~150-kb region on chromosome 2, now known as the Sex Determining Region (SDR) [93,94].

Detailed molecular analysis of the SDR has uncovered a suite of candidate genes implicated in floral sex determination. Fechter et al. [93] identified genes involved in cytokinin metabolism (e.g., a flavin-containing monooxygenase and an adenine phosphoribosyltransferase) as well as markers capable of distinguishing between male, female, and hermaphrodite plants. Experimental work supported these roles; for instance, Negi and Olmo [95] demonstrated that exogenous application of cytokinins could induce hermaphroditic flowers from male plants. Additional candidate genes—such as trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (TPP), WRKY transcription factors, and ETO1, involved in ethylene metabolism—have also been proposed [56,96].

This ~400-kb SDR, extending from 4.90 to 5.33 Mb on chromosome 2, marks a region of strong divergence between wild and cultivated grapevines [97]. Allele frequency analyses revealed two peaks of divergence, with 13 and 32 genes, respectively. In one peak, six genes were significantly overexpressed in female (F) versus male (M) and hermaphrodite (H) flowers, including VviFSEX, a candidate male sterility gene. Male individuals are typically heterozygous (M/f), females homozygous recessive (f/f), and recombination in this region is nearly absent, preserving sex haplotypes. Genome-wide resequencing of 556 accessions from Europe, East Asia, and North America confirmed that the SDR and its boundaries are conserved across the Vitis genus [97]. Strong linkage disequilibrium is observed in wild species, while recombination patterns along the H haplotypes of cultivated accessions revealed two distinct forms: H1 and H2.

Subsequent studies have narrowed the genetic elements of the SDR. Coito et al. [98] identified VviAPRT3 as a key gene associated with male fertility and found ten genes carrying female-specific SNPs, including INAPERTURATE POLLEN 1 (INP1), a strong candidate for male promotion. Badouin et al. [99] compared SDR haplotypes (X, Y, Yh) between wild and cultivated Vitis, revealing that the Yh haplotype derives from Y, and carries more transposable elements. They further identified a conserved 93-kb segment essential for the male phenotype, present as either XYh or YhYh in the 5′ part of the locus, and never as YhYh in the 3′ end. Among 13 cultivars examined, six showed recombinant haplotypes, suggesting structural rearrangements within the SDR are common. Massonnet et al. [56], analyzing twenty haplotypes, confirmed sex-linked regions, identified a candidate male sterility mutation in VviINP1, and proposed that VviYABBY3 may underlie female sterility. Their findings support the hypothesis that domesticated grapevines became hermaphroditic due to a rare recombination between male and female SDR haplotypes.

Finally, recent transcriptomic data add another layer of complexity. Nunhes-Ramos et al. [100] analyzed three developmental stages across all three flower types in Vitis, uncovering transcriptional activity in intergenic and unannotated regions, hinting at the presence of novel sex-related genes. These findings suggest that even after extensive mapping, important components of the SDR may remain unidentified.

Together, these genetic, genomic, and transcriptomic studies provide a comprehensive picture of how sex determination in Vitis is controlled and how its evolution during domestication led to the stable hermaphroditism observed in modern cultivars. The SDR stands as a key locus of both fundamental biological interest and practical relevance in grapevine breeding.

Epigenetic modifications—such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—play essential roles in regulating gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications are modulated by environmental conditions and the changes are inherited. In plants, DNA methylation in promoters typically represses gene activity, whereas gene body methylation may influence processes like alternative splicing [101]. In grapevine (Vitis vinifera), these mechanisms are crucial for development, stress responses, and environmental adaptation, particularly in the context of vegetative propagation [102,103].

Domesticated grapevines exhibit higher levels of DNA methylation compared to wild relatives, especially at genes related to stress responses, hormone signaling, and secondary metabolism [104]. Methylation divergence has been associated with selection during domestication and adaptation to clonal propagation. Vineyard populations show terroir-driven epigenetic structuring, with methylation patterns clustering geographically even when genetic diversity is low [103]. Moreover, somatic stress memory may persist over seasons: Tan et al. [105] found that drought/heat-primed vines retained altered DNA methylation and stronger transcriptional responses to stress even a year after priming, suggesting long-term epigenetic memory in perennials. Histone modifications offer additional regulatory complexity. Wang et al. [106] identified 117 histone-modifying genes in grapevine, with functions in seed development, powdery mildew resistance, and hormonal responses. Zuo et al. [107] identified three H3K27 methyltransferase genes—VvH3K27-1/2/3—which were downregulated during berry development and repressed under H2O2 treatment, linking histone methylation to ripening control. Similarly, Zhu et al. [108] showed dynamic H3K27me3 redistribution in response to cold stress, suggesting transient chromatin regulation under abiotic stress. The application of iron oxide nanoparticles has also been linked to changes in antioxidant profiles and gene expression patterns related to stress responses, potentially involving epigenetic mechanisms [109].

Postharvest quality and metabolic stability in grape berries can be significantly altered by organic treatments and nutrient supplementation, with evidence pointing to underlying epigenetic regulation of phenolic biosynthesis. Recent studies have highlighted the relevance of epigenetic regulation postharvest. Jia et al. [110] demonstrated that treatment with 5-azacytidine (a DNA demethylating agent) and trichostatin A (a histone deacetylase inhibitor) altered sugar, acid, and aroma profiles in ‘Shine Muscat’ berries. Notably, VvHDA15 emerged as a key histone deacetylase regulating postharvest quality traits, connecting acetylation to VOC composition and flavour. At the proteomic level, Pei et al. [111] mapped 822 lysine methylation sites in ripening berries, implicating epigenetic marks in energy metabolism and fruit quality. Similarly, Battilana et al. [112] found histone mark differences at the VvOMT3 locus between skin and flesh tissues, showing epigenetic control of methoxypyrazine production. Methoxypyrazines are chemical compounds in wine that produce herbaceous or vegetal aromas and they are particularly prominent in grape varieties such as Sauvignon Blanc and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Plant-pathogen interaction represents the third major focus for epigenetic analysis. Pereira et al. [113] reviewed the multifaceted epigenetic landscape in grapevine–pathogen interactions, underscoring the importance of chromatin remodeling and small RNAs in defence priming.

Altogether, the expanding field of grapevine epigenetics points to a multilayered regulatory network that modulates traits from development to postharvest quality [114]. These mechanisms provide a promising frontier for biotechnology and breeding aimed at improving grapevine resilience, yield, and wine quality under global climate challenges.

7 Future Perspectives and Critical Aspects

Traditional viticultural objectives include controlling the effects of environmental factors (abiotic and biotic) and optimising cultural conditions to produce fruits that satisfy consumer demand [115]. While pests and pathogens are often controlled by chemical treatment, both the control of pathogens and plant resistance to abiotic factors are traditionally achieved through the selection of resistant varieties or species and cross-breeding. These strategies are informed by knowledge of Vitis cultivars and species other than V. vinifera. In the 19th century, the American species V. labrusca and V. aestivalis were used as rootstocks in the fight against phylloxera, and today, other species such as Vitis rotundifolia are used as sources of pathogen resistance in breeding programmes [116, 117]. Genes for resistance to down mildew and powdery mildew were introduced by introgression from V. rotundifolia and other Vitis species [116]. An important contribution to this task is the identification of minority cultivars with desired properties able to confront climate change conditions [118].

Traditional viticulture is highly demanding on agrochemicals and new trends involve those related to organic management. Studies on soil tillage and organic fertilizers are important trends in this area [119,120]. Soil management and organic fertilization strategies have been shown to modulate the grape berry metabolome, offering further insights into genotype × environment × management interactions in viticulture.

Grapes are known to be an important source of antioxidants and aminoacids. The identification and selection of cultivars rich in these compounds is an area of active research in viticulture. Recent studies show differences in berry quality traits in different developmental stages and growth conditions, underscoring the role of genetic background in trait regulation [121]. The optimisation of these cultivars also involves a selection of other grape varieties as pollinators. Research on Bozcaada Çavuşu and other local cultivars has demonstrated that pollinator variety significantly influences berry composition, hormonal regulation, and sugar accumulation, further emphasizing the importance of haplotype interactions and clonal diversity [122,123]. Other innovative approaches aimed at improving the quality and efficiency of grape and wine production are related with the utilization of nanoparticles in numerous applications including disease control, nutrient management, and wine quality improvement [124].

The distinction between sylvestris and feral plants, i.e., grapes that were once cultivated but escaped human control and, later, grew in the wild, is still a matter of debate and it is possible that plants considered once sylvestris were indeed feral, thus, affecting the results in studies of introgression or local interactions between sylvestris and cultivated grapes. It has been suggested that approximately 5%–10% of cultivars in the grapevine collections of germplasm may not be correctly annotated [125], and this is a particularly delicate question in the case of plants maintained in collections as sylvestris that may correspond to feral cultivars. The identification of nucleotide sequences specific of sylvestris varieties has been reported for several nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms and frame shifts caused by insertions and deletions in Portuguese sylvestris lines [71], or in the differentiation of subspecies in European [126] and Tunisian accessions [127]. The genomic analysis of Marrano et al. identified signatures associated with cultivars [128].

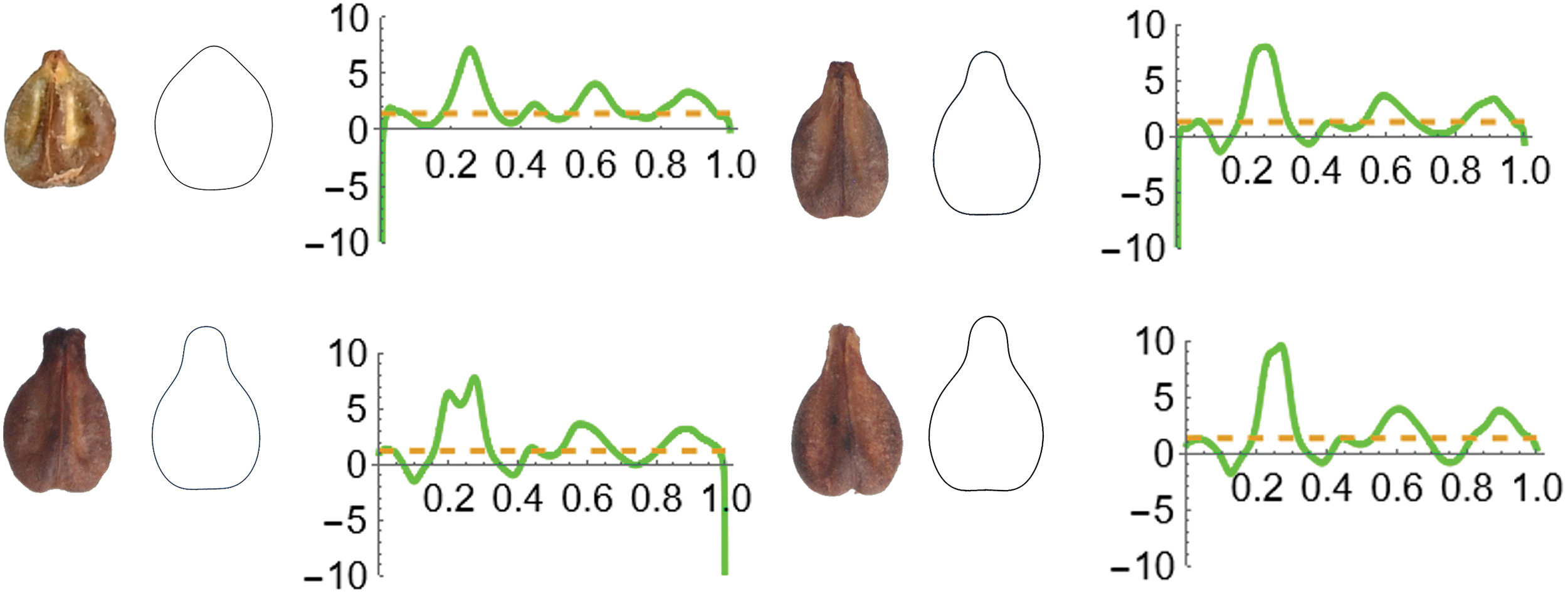

In addition to SNPs or other types of sequence analysis, the quantitative analysis of seed shape may be an interesting method to differentiate between Vitis sylvestris and ferals. While in most Vitis species the seeds are compact with high solidity [129], in contrast, the seeds of cultivated varieties present much higher diversity and in general have more sinuous contours with lower solidity and differences in curvature values [130,131]; (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Curvature analysis. Above: seeds of V. amurensis (left) and V. vinifera cv. Hebén (right). Below: V. vinifera cv. Tempranillo (left) and V. vinifera cv. Regina dei Vignetti (right). Each panel contains: image of a representative seed. Image of the average contour corresponding to the EFT representation (7 harmonics) of 20 seeds of the corresponding genotype and graph of curvature analysis. The corresponding values of curvature in this order are: Average curvatures: 1.1, 1.4, 1.5 and 1. 6. Máximum curvature (in the apex): 7.2, 8.2, 8.0, 10. Minimum curvature (absolute value): 0, 2, 2 and 2. Solidity values (average of 20 seeds for each genotype) are: 0.974 (V. amurensis), 0.960 (Hebén), 0.941 (Tempranillo) and 0.941 (Regina dei Vignetti)

Different seed morphologies are associated with diverse genotypes, and it is possible to investigate the dominance relations between them by means of crosses [132]. The phenotypes can be quantitatively defined by different measurements including J-index (Percent similarity to a model), solidity, and curvature values [2,130,131], and the corresponding QTLs may be associated with different chromosomal markers, similar to what has been done for QTLs associated with other seed properties [133,134].

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, José Luis Rodríguez-Lorenzo, Bohuslav Janoušek and Emilio Cervantes; methodology, not applicable; validation, José Luis Rodríguez-Lorenzo, Bohuslav Janoušek and Emilio Cervantes; formal analysis, not applicable; investigation, JoséLuis Rodríguez-Lorenzo, Bohuslav Janoušek and Emilio Cervantes; resources, not applicable; data curation, Emilio Cervantes; writing, José Luis Rodríguez-Lorenzo, Bohuslav Janoušek and Emilio Cervantes; writing—review and editing, José Luis Rodríguez-Lorenzo, Bohuslav Janoušek and Emilio Cervantes; visualization, Emilio Cervantes; supervision, not applicable; project administration, not applicable; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature/abbreviations

| Divergence (Dxy) | Dxy measures the absolute genetic divergence between two populations by calculating the average number of nucleotide differences (or substitutions) per site between pairs of sequences from the two groups. |

| fd statistic | A population genetics measurement used to measure introgression—the transfer of genetic material between populations or species via hybridization followed by backcrossing. It’s an extension of the broader family of (f)-statistics introduced by Pickrell et al. in 2012 [135] to study population relationships and gene flow. Specifically, fd measures the excess sharing of derived alleles between a target population and a potential donor population, beyond what would be expected under a simple tree-like model of divergence without gene flow. |

| FST (Fixation Index) | FST is a measure of population differentiation based on the variation in allele frequencies between subpopulations. It essentially tells how much genetic variation is explained by differences between groups rather than within them. |

| GERP (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling) | A measure used in comparative genomics to quantify the level of evolutionary constraint at specific sites in a genome. It indicates how conserved a nucleotide position is across multiple species, with the underlying assumption that highly conserved sites are likely functionally important and under purifying selection (i.e., mutations at these sites are deleterious and removed over time). GERP values are widely used to prioritize variants in studies of disease, adaptation, or functional genomics. |

| PBS (Population Branch Statistic) scan | Genome-wide analysis used to detect signatures of recent, population-specific positive selection by systematically calculating the PBS metric across many genetic loci (typically SNPs) in a target population. |

| SIFT | SIFT, or Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant, is a computational tool used to predict the potential impact of an amino acid substitution (caused by a nucleotide change) on a protein’s function |

| Site Frequency Spectrum (SFS) | Also known as the allele frequency spectrum, is a fundamental concept in population genetics that summarizes the distribution of allele frequencies across polymorphic sites (e.g., SNPs) in a sample of individuals from a population. The SFS is typically represented as a histogram or vector, where each bin or entry corresponds to the number of sites with a specific frequency of the minor (or derived) allele. |

| Solidity | Solidity is an important property of closed-plane curves. It is related to convexity and expresses the ratio of two areas: the area of an object to the area of its convex Hull [136]. Solidity is the most conserved morphological property in seeds of many species belonging to diverse families of plants [137–141]. |

References

1. Herrera A. Agricultura general. Madrid, Spain: Imprenta Real; 1818. [Google Scholar]

2. Cervantes E, Martín-Gómez JJ, Rodríguez-Lorenzo JL, del Pozo DG, Cabello Sáenz de Santamaría F, Muñoz-Organero G, et al. Seed morphology in Vitis cultivars related to Hebén. AgriEngineering. 2025;7(3):62. doi:10.3390/agriengineering7030062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dong Y, Duan S, Xia Q, Liang Z, Dong X, Margaryan K, et al. Dual domestications and origin of traits in grapevine evolution. Science. 2023;379(6635):892–901. doi:10.1126/science.add865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zinelabidine LH, Cunha J, Eiras-Dias JE, Cabello F, Martínez-Zapater JM, Ibáñez J. Pedigree analysis of the Spanish grapevine cultivar ‘Hebén’. Vitis. 2015;54:81–6. [Google Scholar]

5. Miller P. Gardeners dictionary. 6th ed. London, UK: John and James Rivington, at the Bible and Crown in St. Paul’s Church-Yard; 1752. [Google Scholar]

6. Röckel E, Töpfer R, Röckel F, Brühl U, Hundemer M, Mahler-Ries A. Vitis international variety catalogue; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 15]. Available from: www.vivc.de. [Google Scholar]

7. Clemente y Rubio SdR. Ensayo sobre las variedades de la vid común que vegetan en Andalucía. Vol. 64. Madrid, Spain: Imprenta Perojo, calle de Mendizábal; 1879. [Google Scholar]

8. Froelich GA. Zur hybridisation der reben und der auswahl der zuchtreben. Weinbau Weinhandel. 1900;18:230–1. [Google Scholar]

9. Dettweiler E, Jung A, Zyprian E, Toepfer R. Grapevine cultivar Müller-Thurgau and its true to type descent. Vitis-Geilweilerhof. 2000;39(2):63–5. [Google Scholar]

10. Hedrick UP. The grapes of New York. Albany, NY, USA: J.B. Lyon Company; 1908. [Google Scholar]

11. Read PE, Gu S. A century of American viticulture. HortScience. 2003;38(5):943–51. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.38.5.943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sax K. Chromosome counts in Vitis and related genera. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1929;26:32–3. [Google Scholar]

13. Dearing C. The production of self-fertile Muscadine grapes. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1917;14:30–4. [Google Scholar]

14. Olmo HP. Bud mutation in the vinifera grape. I. Parthenocarpic Sultanina. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1934;31:119–21. [Google Scholar]

15. Pearson. Parthenocarpy and seed abortion in Vitis vinifera. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1932;29:169–75. [Google Scholar]

16. Partridge NL. Further observations on the fruiting habit of the Concord grape. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1922;19:180–3. [Google Scholar]

17. Pickett WF. Further study on the fruiting habit of the grape. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1927;24:151–4. [Google Scholar]

18. Demarée JB, Dix IW, Magoon CA. Observations on the resistance of grape varieties to black rot and downmildew. Proc Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1937;35:451–60. [Google Scholar]

19. Barrett HC. Sex determination in a progeny of a self pollinated staminate clone of Vitis. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1966;88:338–40. [Google Scholar]

20. Barritt BH, Einset J. The inheritance of three major fruit colors in grapes. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1969;94(2):87–9. doi:10.21273/JASHS.94.2.87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Negi SS, Olmo HP. Conversion and determination of sex in Vitis vinifera L. (sylvestris). Vitis. 1971;9:265–79. doi:10.5073/vitis.1970.9.265-279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Forneck A, Benjak A, Rühl E. Grapevine (Vitis ssp.example of clonal reproduction in agricultural important plants. In: Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P, editors. Lost sex: the evolutionary biology of parthenogenesis. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2009. p. 581–98 doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Regner F. Die genetische analyse von Rebsorten. In: Deutsches weinbau-jahrbuch 2000 (51 Jahrgang). Waldkirch, Germany: Waldkircher Verlag; 1999. p. 125–32. [Google Scholar]

24. Bowers JE, Meredith CP. The parentage of a classic wine grape, Cabernet Sauvignon. Nat Genet. 1997;16(1):84–7. doi:10.1038/ng0597-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Boursiquot JM, Lacombe T, Bowers J, Meredith C. Le Gouais, un cépage clé du patrimoine viticole européen. Bull De L’OIV. 2004;77:5–19. [Google Scholar]

26. Regner F, Stadlhuber A, Eisenheld C, Kaserer H. Considerations about the evolution of grapevine and the role of Traminer. Acta Hortic. 2000;528:179–84. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2000.528.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sturtevant AH. The linear arrangement of six sex-linked factors in Drosophila, as shown by their mode of association. J Exp Zool. 1913;14(1):43–59. doi:10.1002/jez.1400140104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Koornneef M, van Eden J, Hanhart CJ, Stam P, Braaksma FJ, Feenstra WJ. Linkage map of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Hered. 1983;74(4):265–72. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Thomas MR, Scott NS. Microsatellite repeats in grapevine reveal DNA polymorphisms when analysed as sequence-tagged sites (STSs). Theor App Genet. 1993;86(8):985–90. doi:10.1007/BF00211051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, Tvd Lee, Hornes M, et al. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(21):4407–14. doi:10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Vezzulli S, Doligez A, Bellin D. Molecular mapping of grapevine genes. In: Cantu D, Walker MA, editors. The grape genome. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 103–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18601-2_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tympakianakis S, Trantas E, Avramidou EV, Ververidis F. Vitis vinifera genotyping toolbox to highlight diversity and germplasm identification. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1139647. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1139647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lodhi MA, Ye GN, Weeden NF, Reisch BI, Daly MJ. A molecular marker based linkage map of Vitis. Genome. 1995;38(4):786–94. doi:10.1139/g95-100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Doligez A, Adam-Blondon AF, Cipriani G, Di Gaspero G, Laucou V, Merdinoglu D, et al. An integrated SSR map of grapevine based on five mapping populations. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;113(3):369–82. doi:10.1007/s00122-006-0295-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Grando MS, Bellin D, Edwards KJ, Pozzi C, Stefanini M, Velasco R. Molecular linkage maps of Vitis vinifera L. and Vitis riparia Mchx. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106(7):1213–24. doi:10.1007/s00122-002-1170-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Adam-Blondon AF, Roux C, Claux D, Butterlin G, Merdinoglu D, This P. Mapping 245 SSR markers on the Vitis vinifera genome: a tool for grape genetics. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109(5):1017–27. doi:10.1007/s00122-004-1704-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Riaz S, Dangl GS, Edwards KJ, Meredith CP. A microsatellite marker based framework linkage map of Vitis vinifera L. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108(5):864–72. doi:10.1007/s00122-003-1488-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Doucleff M, Jin Y, Gao F, Riaz S, Krivanek AF, Walker MA. A genetic linkage map of grape, utilizing Vitis rupestris and Vitis arizonica. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109(6):1178–87. doi:10.1007/s00122-004-1728-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Y, Ding K, Li H, Kuang Y, Liang Z. Biography of Vitis genomics: recent advances and prospective. Hort Res. 2024;11(7):uhae128. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Jaillon O, Aury J-M, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C, Casagrande A, et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449(7161):463–7. doi:10.1038/nature06148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Velasco R, Zharkikh A, Troggio M, Cartwright DA, Cestaro A, Pruss D, et al. A high quality draft consensus sequence of the genome of a heterozygous grapevine variety. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1326. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Velt A, Frommer B, Blanc S, Holtgräwe D, Duchêne É, Dumas V, et al. An improved reference of the grapevine genome reasserts the origin of the PN40024 highly homozygous genotype. G3. 2023;13(5):jkad067. doi:10.1093/g3journal/jkad067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–604. doi:10.1126/science.1128691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436(7052):793–800. doi:10.1038/nature03895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Arabidopsis Genome I. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408(6814):796–815. doi:10.1038/35048692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Da Silva C, Zamperin G, Ferrarini A, Minio A, Dal Molin A, Venturini L, et al. The high polyphenol content of grapevine cultivar Tannat berries is conferred primarily by genes that are not shared with the reference genome. Plant Cell. 2013;25(12):4777–88. doi:10.1105/tpc.113.118810.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Di Genova A, Almeida AM, Muñoz-Espinoza C, Vizoso P, Travisany D, Moraga C, et al. Whole genome comparison between table and wine grapes reveals a comprehensive catalog of structural variants. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):7. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-14-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Chin CS, Peluso P, Sedlazeck FJ, Nattestad M, Concepcion GT, Clum A, et al. Phased diploid genome assembly with single-molecule real-time sequencing. Nat Methods. 2016;13(12):1050–4. doi:10.1038/nmeth.4035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Patel S, Lu Z, Jin X, Swaminathan P, Zeng E, Fennell AY. Comparison of three assembly strategies for a heterozygous seedless grapevine genome assembly. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):57. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4434-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Roach MJ, Johnson DL, Bohlmann J, van Vuuren HJJ, Jones SJM, Pretorius IS, et al. Population sequencing reveals clonal diversity and ancestral inbreeding in the grapevine cultivar Chardonnay. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(11):e1007807. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liang Z, Duan S, Sheng J, Zhu S, Ni X, Shao J, et al. Whole-genome resequencing of 472 Vitis accessions for grapevine diversity and demographic history analyses. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1190. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09135-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Minio A, Massonnet M, Figueroa-Balderas R, Castro A, Cantu D. Diploid genome assembly of the wine grape Carménère. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2019;9(5):1331–7. doi:10.1534/g3.119.400030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Patel S, Robben M, Fennell A, Londo JP, Alahakoon D, Villegas-Diaz R, et al. Draft genome of the Native American cold hardy grapevine Vitis riparia Michx. ‘Manitoba 37’. Hort Res. 2020;7(1):92. doi:10.1038/s41438-020-0316-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Vondras AM, Minio A, Blanco-Ulate B, Figueroa-Balderas R, Penn MA, Zhou Y, et al. The genomic diversification of grapevine clones. BMC Genom. 2019;20(1):972. doi:10.1186/s12864-019-6211-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zhou Y, Minio A, Massonnet M, Solares E, Lv Y, Beridze T, et al. The population genetics of structural variants in grapevine domestication. Nat Plants. 2019;5(9):965–79. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0507-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Massonnet M, Cochetel N, Minio A, Vondras AM, Lin J, Muyle A, et al. The genetic basis of sex determination in grapes. Nature Comm. 2020;11(1):2902. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16700-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Wang Y, Xin H, Fan P, Zhang J, Liu Y, Dong Y, et al. The genome of Shanputao (Vitis amurensis) provides a new insight into cold tolerance of grapevine. Plant J. 2021;105(6):1495–506. doi:10.1111/tpj.15127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Minio A, Cochetel N, Massonnet M, Figueroa-Balderas R, Cantu D. HiFi chromosome-scale diploid assemblies of the grape rootstocks 110R, Kober 5BB, and 101-14 Mgt. Sci Data. 2022;9(1):660. doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01753-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Shirasawa K, Hirakawa H, Azuma A, Taniguchi F, Yamamoto T, Sato A, et al. De novo whole-genome assembly in an interspecific hybrid table grape “Shine Muscat”. DNA Res. 2022;29(6):dsac040. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsac040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Cochetel N, Minio A, Guarracino A, Garcia JF, Figueroa-Balderas R, Massonnet M, et al. A super-pangenome of the North American wild grape species. Genome Biol. 2023;24(1):290. doi:10.1186/s13059-023-03133-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Guo DL, Zhao HL, Li Q, Zhang G, Jiang J, Liu C, et al. Genome-wide association study of berry-related traits in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) based on genotyping-by-sequencing markers. Hortic. 2019;6(1):11. doi:10.1038/s41438-018-0089-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Li B, Gschwend AR. Vitis labrusca genome assembly reveals diversification between wild and cultivated grapevine genomes. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1234130. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1234130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Onetto CA, Ward CM, Borneman AR. The genome assembly of Vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz Aust J Grape Wine R. 2023;2023. doi:10.1155/2023/6686706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Patel S, Harris ZN, Londo JP, Miller A, Fennell A. Genome assembly of the hybrid grapevine Vitis ‘Chambourcin’. GigaByte. 2023;2023:gigabyte84. doi:10.46471/gigabyte.84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Shi X, Cao S, Wang X, Huang S, Wang Y, Liu Z, et al. The complete reference genome for grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) genetics and breeding. Hort Res. 2023;10(5):uhad061. doi:10.1093/hr/uhad061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang KK, Du M, Zhang H, Zhang X, Cao S, Wang X, et al. The haplotype-resolved T2T genome of teinturier cultivar Yan73 reveals the genetic basis of anthocyanin biosynthesis in grapes. Hortic Res. 2023;10(11):uhad205. doi:10.1093/hr/uhad205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Wang X, Tu M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Yin W, Fang J, et al. Telomere-to-telomere and gap-free genome assembly of a susceptible grape vine species (Thompson Seedless) to facilitate grape functional genomics. Hortic Res. 2024;11(1):uhad260. doi:10.1093/hr/uhad260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Vitulo N, Forcato C, Carpinelli EC, Telatin A, Campagna D, D’Angelo M, et al. A deep survey of alternative splicing in grape reveals changes in the splicing machinery related to tissue, stress condition and genotype. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):99. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-14-99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Magris G, Jurman I, Fornasiero A, Paparelli E, Schwope R, Marroni F, et al. The genomes of 204 Vitis vinifera accessions reveal the origin of European wine grapes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):7240. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27487-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Ramos MJN, Coito JL, Faísca-Silva D, Cunha J, Costa MMR, Amâncio S, et al. Portuguese wild grapevine genome re-sequencing (Vitis vinifera sylvestris). Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18993. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-76012-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Carrier G, Le Cunff L, Dereeper A, Legrand D, Sabot F, Bouchez O, et al. Transposable elements are a major cause of somatic polymorphism in Vitis vinifera L. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32973. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032973. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Wu J, Wang Z, Shi Z, Zhang S, Ming R, Zhu S, et al. The genome of the pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Genome Res. 2013;23(2):396–408. doi:10.1101/gr.144311.112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Hu G, Feng J, Xiang X, Wang J, Salojärvi J, Liu C, et al. Two divergent haplotypes from a highly heterozygous lychee genome suggest independent domestication events for early and late-maturing cultivars. Nat Genet. 2022;54(1):73–83. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00971-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Xiao H, Wang Y, Liu W, Shi X, Huang S, Cao S, et al. Impacts of reproductive systems on grapevine genome and breeding. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2031. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-56817-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Cheng H, Concepcion GT, Feng X, Zhang H, Li H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods. 2021;18(2):170–5. doi:10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Nurk S, Walenz BP, Rhie A, Vollger MR, Logsdon GA, Grothe R. Accurate assembly of segmental duplications, satellites, and allelic variants from high-fidelity long reads. Genome Res. 2020;30(9):1291–305. doi:10.1101/gr.263566.120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Garg S, Fungtammasan A, Carroll A, Chou M, Schmitt A, Zhou X, et al. Chromosome-scale, haplotype-resolved assembly of human genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39(3):309–12. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0711-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Calderón L, Carbonell-Bejerano P, Muñoz C, Bree L, Sola C, Bergamin D, et al. Diploid genome assembly of the Malbec grapevine cultivar enables haplotype-aware analysis of transcriptomic differences underlying clonal phenotypic variation. Hort Res. 2024;11(5):uhae080. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Guo L, Wang X, Ayhan DH, Rhaman MS, Yan M, Jiang J, et al. Super pangenome of Vitis empowers identification of downy mildew resistance genes for grapevine improvement. Nat Genet. 2025;57(3):741–53. doi:10.1038/s41588-025-02111-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Zou C, Sapkota S, Figueroa-Balderas R, Glaubitz J, Cantu D, Kingham BF, et al. A multitiered haplotype strategy to enhance phased assembly and fine mapping of a disease resistance locus. Plant Physiol. 2023;193(4):2321–36. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiad494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Renner SS, Ricklefs RE. Dioecy and its correlates in the flowering plants. Am J Bot. 1995;82(5):596–606. doi:10.2307/2445418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Akagi T, Pilkington SM, Varkonyi-Gasic E, Henry IM, Sugano SS, Sonoda M, et al. Two Y-chromosome-encoded genes determine sex in kiwifruit. Nat Plants. 2019;5(8):801–9. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0489-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Spigler RB, Lewers KS, Main DS, Ashman TL. Genetic mapping of sex determination in a wild strawberry, Fragaria virginiana, reveals earliest form of sex chromosome. Heredity. 2008;101(6):507–17. doi:10.1038/hdy.2008.100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Wang J, Na J-K, Yu Q, Gschwend AR, Han J, Zeng F, et al. Sequencing papaya X and Y chromosomes reveals molecular basis of incipient sex chromosome evolution. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2012;109(34):13710–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1207833109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Balounova V, Gogela R, Cegan R, Cangren P, Zluvova J, Safar J, et al. Evolution of sex determination and heterogamety changes in section Otites of the genus Silene. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1045. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37412-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Fujita N, Torii C, Ishii K, Aonuma W, Shimizu Y, Kazama Y, et al. Narrowing down the mapping of plant sex-determination regions using new Y-Chromosome-specific markers and heavy-ion beam irradiation-induced Y-deletion mutants in Silene latifolia. G3. 2012;2(2):271–8. doi:10.1534/g3.111.001420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Martin H, Carpentier F, Gallina S, Godé C, Schmitt E, Muyle A, et al. Evolution of young sex chromosomes in two dioecious sister plant species with distinct sex determination systems. Genome Biol Evol. 2019;11(2):350–61. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Hough J, Hollister JD, Wang W, Barrett SCH, Wright SI. Genetic degeneration of old and young Y chromosomes in the flowering plant Rumex hastatulus. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2014;111(21):7713–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319227111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Sacchi B, Humphries Z, Kružlicová J, Bodláková M, Pyne C, Choudhury BI, et al. Phased assembly of neo-sex chromosomes reveals extensive Y degeneration and rapid genome evolution in Rumex hastatulus. Mol Biol Evol. 2024;41(4):msae074. doi:10.1093/molbev/msae074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Gerrath J, Posluszny U, Melville L. Reproductive features of the vitaceae. In: Gerrath J, Posluszny U, Melville L, editors. Taming the wild grape: botany and horticulture in the vitaceae. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 45–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24352-8_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Oberle GD. A genetic study of variations in floral morphology and function in cultivated forms of Vitis. New York State Agr Expt Sta Tech Bul. 1938;250:1–63. [Google Scholar]

92. Levadoux L. Study of the flower and sexuality in grapes. Annales De L’École Nationale D’Agriculture De Montpellier. 1946;27:1–89. [Google Scholar]

93. Fechter I, Hausmann L, Daum M, Rosleff Sörensen T, Viehöver P, Weisshaar B, et al. Candidate genes within a 143 kb region of the flower sex locus in Vitis. Mol Genet Genom. 2012;287(3):247–59. doi:10.1007/s00438-012-0674-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Picq S, Santoni S, Lacombe T, Latreille M, Weber A, Ardisson M, et al. A small XY chromosomal region explains sex determination in wild dioecious V. vinifera and the reversal to hermaphroditism in domesticated grapevines. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0229-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Negi SS, Olmo HP. Sex conversion in a male Vitis vinifera L. by a kinin. Science. 1966;152(3729):1624–5. doi:10.1126/science.152.3729.1624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Zou C, Massonnet M, Minio A, Patel S, Llaca V, Karn A, et al. Multiple independent recombinations led to hermaphroditism in grapevine. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2021;118(15):e2023548118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2023548118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Zhou Y, Massonnet M, Sanjak JS, Cantu D, Gaut BS. Evolutionary genomics of grape (Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera) domestication. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2017;114(44):11715–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.1709257114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Coito JL, Ramos MJN, Cunha J, Silva HG, Amâncio S, Costa MMR, et al. VviAPRT3 and VviFSEX: two tenes involved in sex specification able to distinguish different flower types in Vitis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(229):98. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Badouin H, Velt A, Gindraud F, Flutre T, Dumas V, Vautrin S, et al. The wild grape genome sequence provides insights into the transition from dioecy to hermaphroditism during grape domestication. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):223. doi:10.1186/s13059-020-02131-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Nunhes-Ramos MJ, Coito JL, Fino J, Cunha J, Silva P, Gomes de Almeida P. Deep analysis of wild Vitis flower transcriptome reveals unexplored genome regions associated with sex specification. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;93(1-2):151–70. doi:10.1007/s11103-016-0553-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Zhang H, Lang Z, Zhu J-K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(8):489–506. doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0016-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Venios X, Gkizi D, Nisiotou A, Korkas E, Tjamos SE, Zamioudis C, et al. Emerging roles of epigenetics in grapevine and winegrowing. Plants. 2024;13(4):515. doi:10.3390/plants13040515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Xie H, Konate M, Sai N, Tesfamicael KG, Cavagnaro T, Gilliham M, et al. Environmental conditions and agronomic practices induce consistent global changes in DNA methylation patterns in grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv Shiraz). bioRxiv. 2017;55:207. doi:10.1101/127977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Kong J, Berger M, Colling A, Stammitti L, Teyssier E, Gallusci P. Epigenetic regulation in fleshy fruit: perspective for grape berry development and ripening. In: Cantu D, Walker MA, editors. The grape genome. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 167–97 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-18601-2_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Tan JW, Tesfamicael K, Hu Y, Shinde H, Edwards EJ, Tricker P, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals long-term somatic memory of stress in the woody perennial crop, grapevine Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. bioRxiv. 2024;31:47. doi:10.1101/2024.04.06.588326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Wang L, Ahmad B, Liang C, Shi X, Sun R, Zhang S, et al. Bioinformatics and expression analysis of histone modification genes in grapevine predict their involvement in seed development, powdery mildew resistance, and hormonal signaling. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):412. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-02618-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Zuo D-D, Sun H-T, Yang L, Shang F-H-Z, Guo D-L. Identification of grape H3K27 methyltransferase genes and their expression profiles during grape fruit ripening. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;52(1):21. doi:10.1007/s11033-024-10117-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Zhu Z, Li Q, Gichuki DK, Hou Y, Liu Y, Zhou H, et al. Genome-wide profiling of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation and its modification in response to chilling stress in grapevine leaves. Hortic Plant J. 2023;9(3):496–508. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2023.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Daler S, Kaya O, Kaplan D. Nanotechnology in viticulture: alleviating lime stress in 1103 Paulsen Rootstock with iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NPs). Acta Physiol Plant. 2025;47:59. doi:10.1007/s11738-025-03739-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Jia H, Su Z, Ren Y, Pei D, Yu K, Dong T, et al. Exploration of 5-Azacytidine and Trichostatin A in the modulation of postharvest quality of ‘Shine Muscat’ grape berries. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2024;209(1):112719. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2023.112719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Pei MS, Liu HN, Wei TL, Guo DL. Proteome-wide identification of non-histone lysine methylation during grape berry ripening. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(31):12140–52. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c03144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Battilana J, Dunlevy JD, Boss PK. Histone modifications at the grapevine VvOMT3 locus, which encodes an enzyme responsible for methoxypyrazine production in the berry. Funct Plant Biol. 2017;44(7):655–64. doi:10.1071/FP16434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Pereira JP, Bevilacqua I, Santos RB, Varotto S, Chitarra W, Nerva L, et al. Epigenetic regulation and beyond in grapevine-pathogen interactions: a biotechnological perspective. Phys Plant. 2025;177(2):e70216. doi:10.1111/ppl.70216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Cantu D, Massonnet M, Cochetel N. The wild side of grape genomics. Trends Genet. 2024;40(7):601–12. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2024.04.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Atak A. Vitis species for stress tolerance/resistance. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2025;72(2):2425–44. doi:10.1007/s10722-024-02106-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

116. Barker CL, Donald T, Pauquet J, Ratnaparkhe MB, Bouquet A, Adam-Blondon AF, et al. Genetic and physical mapping of the grapevine powdery mildew resistance gene, Run1, using a bacterial artificial chromosome library. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111(2):370–7. doi:10.1007/s00122-005-2030-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Possamai T, Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S. Phenotyping for QTL identification: a case study of resistance to Plasmopara viticola and Erysiphe necator in grapevine. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:930954. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.930954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Muñoz-Organero G, Espinosa FE, Cabello F, Zamorano JP, Urbanos MA, Puertas B, et al. Phenological study of 53 Spanish minority grape varieties to search for adaptation of vitiviniculture to climate change conditions. Horticulturae. 2022;8(11):984. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8110984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

119. Maltas A, Charles R, Jeangros B, Sinaj S. Effect of organic fertilizers and reduced-tillage on soil properties, crop nitrogen response and crop yield: results of a 12-year experiment in Changins. Switzerland Soil Tillage Res. 2013;126(4):11–8. doi:10.1016/j.still.2012.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

120. Kaya O, Yilmaz T, Ates F, Kustutan F, Hatterman-Valenti H, Hajizadeh HS, et al. Improving organic grape production: the effects of soil management and organic fertilizers on biogenic amine levels in Vitis vinifera cv., ‘Royal’ grapes. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2024;11(1):38. doi:10.1186/s40538-024-00564-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

121. Savoi S, Wong DC, Arapitsas P, Miculan M, Bucchetti B, Peterlunger E, et al. Transcriptome and metabolite profiling reveals that prolonged drought modulates the phenylpropanoid and terpenoid pathway in white grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16(1):67. doi:10.1186/s12870-016-0760-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Kaya O. Harmony in the vineyard: exploring the eco-chemical interplay of Bozcaada Çavuşu (Vitis vinifera L.) grape cultivar and pollinator varieties on some phytochemicals. Eur Food Res Technol. 2024;250(5):1327–39. doi:10.1007/s00217-024-04470-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

123. Fotiric M, Mulitinovic M, Nikolic D, Rakonjac V. Pollinizer influence on berry and seed properties in grapevine cultivar ‘Bagrina’ (Vitis vinifera L.). Acta Hortic. 2003;603(603):775–7. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.603.110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

124. Mierczynska-Vasilev A. The role of nanoparticles in wine science: innovations and applications. Nanomater. 2025;15(3):175. doi:10.3390/nano15030175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Dettweiler E. The grapevine herbarium as an aid to grapevine identification—first results. Vitis. 1992;31:117–20. [Google Scholar]

126. Péros J-P, Launay A, Peyrière A, Berger G, Roux C, Lacombe T, et al. Species relationships within the genus Vitis based on molecular and morphological data. PLoS One. 2023;18(7):e0283324. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0283324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Ghaffari S, Hasnaoui N, Zinelabidine LH, Ferchichi A, Martínez-Zapater JM, Ibáñez J. Genetic diversity and parentage of Tunisian wild and cultivated grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.) as revealed by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. Tree Genet Genom. 2014;10(4):1103–12. doi:10.1007/S11295-014-0746-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

128. Marrano A, Micheletti D, Lorenzi S, Neale D, Grando MS. Genomic signatures of different adaptations to environmental stimuli between wild and cultivated Vitis vinifera L. Hort Res. 2018;5(1):34. doi:10.1038/s41438-018-0041-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Martín-Gómez JJ, Rodríguez-Lorenzo JL, Gutiérrez del Pozo D, Cabello Sáez de Santamaría F, Muñoz-Organero G, Tocino Á, et al. Seed morphological analysis in species of Vitis and relatives. Horticulturae. 2024;10(3):285. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10030285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

130. Cervantes E, Martín-Gómez JJ, Espinosa-Roldán FE, Muñoz-Organero G, Tocino Á, Cabello-Sáenz de Santamaría F. Seed morphology in key spanish grapevine cultivars. Agronomy. 2021;11(4):734. doi:10.3390/agronomy11040734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

131. Martín-Gómez JJ, Rodríguez-Lorenzo JL, Espinosa-Roldán FE, de Santamaría FCS, Muñoz-Organero G, Tocino Á, et al. Seed morphometry reveals two major groups in Spanish grapevine cultivars. Plants. 2025;14(10):1522. doi:10.3390/plants14101522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Tello J, Ibáñez J. Review: status and prospects of association mapping in grapevine. Plant Sci. 2023;327(10):111539. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Cabezas JA, Cervera MT, Ruiz-García L, Carreño J, Martínez-Zapater JM. A genetic analysis of seed and berry weight in grapevine. Genome. 2006;49(12):1572–85. doi:10.1139/g06-122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Doligez A, Bertrand Y, Farnos M, Grolier M, Romieu C, Esnault F, et al. New stable QTLs for berry weight do not colocalize with QTLs for seed traits in cultivated grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13(1):217. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-13-217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Pickrell JK, Patterson N, Barbieri C, Berthold F, Gerlach L, Güldemann T, et al. The genetic prehistory of southern Africa. Nature Comm. 2012;3(1):1143. doi:10.1038/ncomms2140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

136. Abbena E, Salamon S, Gray A. Modern differential geometry of curves and surfaces with mathematica. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

137. Cervantes E, Martín-Gómez JJ, del Pozo DG, Tocino Á. Curvature analysis of seed silhouettes in the Euphorbiaceae. Seeds. 2024;3(4):608–38. doi:10.3390/seeds3040041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

138. Gutiérrez del Pozo D, Martín-Gómez JJ, Reyes Tomala NI, Tocino Á, Cervantes E. Seed geometry in species of the Nepetoideae (Lamiaceae). Horticulturae. 2025;11(3):315. doi:10.3390/horticulturae11030315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

139. Gyulai G, Rovner I, Vinogradov S, Kerti B, Emödi A, Csákvári E, et al. Digital seed morphometry of dioecious wild and crop plants; development and usefulness of the seed diversity index. Seed Sci Technol. 2015;43(3):492–506. doi:10.15258/sst.2015.43.3.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

140. Jannah RM, Ratnawati S, Suwarno WB, Ardie SW. Digital phenotyping for robust seeds variability assessment in Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. J Seed Sci. 2024;46(1):e202446012. doi:10.1590/2317-1545v46281586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

141. Martín-Gómez JJ, Gutiérrez del Pozo D, Rodríguez-Lorenzo JL, Tocino Á, Cervantes E. Geometric analysis of seed shape diversity in the Cucurbitaceae. Seeds. 2024;3(1):40–55. doi:10.3390/seeds3010004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools