Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Transcriptomics Provides New Insights into Resistance Mechanisms in Wheat Infected with Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici

1 Huaibei Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement and Efficient Green Safe Production, Anhui Key Laboratory of Plant Resources and Biology, School of Life Science, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, 235000, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas, NWAFU, Yangling, 712100, China

* Corresponding Authors: Gensheng Zhang. Email: ; Guiping Li. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Plant Breeding and Genetic Improvement: Leveraging Molecular Markers and Novel Genetic Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2701-2718. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070017

Received 06 July 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Wheat stripe rust, a devastating disease caused by the fungal pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), poses a significant threat to global wheat production. Growing resistant cultivars is a crucial strategy for wheat stripe rust management. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of wheat resistance to Pst remain incompletely understood. To unravel these mechanisms, we employed high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to analyze the transcriptome of the resistant wheat cultivar Mianmai 46 (MM46) at different time points (24, 48, and 96 h) post-inoculation with the Pst race CYR33. The analysis revealed that Pst infection significantly altered the expression of genes involved in photosynthesis and energy metabolism, suggesting a disruption of host cellular processes. Conversely, the expression of several resistance genes was upregulated, indicating activation of defense responses. Further analysis identified transcription factors (TFs), pathogen-related (PR) proteins, and chitinase-encoding genes as key players in wheat resistance to Pst. These genes likely contribute to the activation of defense pathways, such as the oxidative burst, which involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The activities of antioxidant enzymes, including peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT), were also upregulated, suggesting a role in mitigating oxidative damage caused by ROS. Our findings provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying wheat resistance to Pst. By identifying key genes and pathways involved in this complex interaction, we can develop more effective strategies for breeding resistant wheat cultivars and managing this destructive disease.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileWheat (Triticum aestivum L.), a globally cultivated food crop, accounts for over 20% of human energy needs [1]. However, wheat cultivation is threatened by various fungal diseases, including powdery mildew, Fusarium head blight, wheat rust, and sheath blight. Wheat stripe rust (Chinese yellow rust, CYR), caused by Puccinia Striiformis f. sp. Tritici (Pst), is a global airborne fungal disease that severely reduces wheat yield and quality [2]. The high mutation rate of Pst has enabled the rapid evolution of new races with altered virulence profiles. These new races can evade host plant defense mechanisms, leading to disease outbreaks and yield losses in wheat [2]. Since 1950, China has endured eight epidemic outbreaks of wheat stripe rust in 1950, 1964, 1990, 2002, 2017, 2019, 2021, and 2022. The first four outbreaks were particularly devastating, leading to a 13.8 million ton decrease in wheat production [3]. To date, 34 physiological races have been officially named in China (CYR1–CYR34). Among them, CYR32 and CYR33 had the highest occurrence frequencies in the field physiological races from 1997 to 2009 and became the dominant races [4]. Subsequently, the G22 pathotype physiologic race, which was first discovered in Sichuan Province, China, in 2009, gradually increased in frequency in the wheat-growing regions of Northwest and Southwest of China, and gradually became the dominant physiologic race. It was officially named as CYR34 in 2016 [5,6]. Highly effective fungicides, such as tebuconazole and propiconazole, can be utilized to control wheat stripe rust, and their application can increase production costs and contribute to environmental pollution [7]. However, the most sustainable and effective measure for managing wheat stripe rust is the breeding and cultivation of resistant wheat cultivars [2,3,8].

Plants employ multifaceted defense systems to combat pathogenic infections. Physical barriers, including cell walls, provide the first line of defense [9]. In addition, plants have complex immune systems that help them recognize and fight pathogens, preventing infections from spreading. In plants, pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) represent two distinct yet interconnected layers of pathogen-host plant interactions [10–12]. PAMPs induce immunity by specifically recognizing pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the surface of host cells. ETI can protect PTI-mediated signaling pathways. However, many effectors can target and inhibit PRRs signaling pathways [13]. To counteract these attacks, plants have evolved nucleotide-binding domains and leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins that protect PRR signaling components from effector recognition, thus enabling the detection of pathogen-induced ETI in plant cells [9]. PTI and ETI are interdependent and rely on multiple signaling components to elicit effective immune responses. These components include Ca2+ influx, reactive oxygen species (ROS) bursts, activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades, production of plant cytokines and defense hormones, and expression of a large number of related immune genes [9,14]. The PTI and ETI exhibit mutually reinforcing relationships. ETI promotes PTI by upregulating the transcription of PTI signaling components, whereas PTI ensures normal development of the complete resistance function of ETI through MAPK and NADPH signaling. In the process of plant immunity, PTI induced by flg22 (flagellin 22) or nlp20 [necrosis- and ethylene-inducing peptide 1 (Nep1)-like protein 20] promotes the expression of related TNL (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor-nucleotide binding site-leucine rich repeat) genes and the hypersensitive response (HR) [15–17]. Therefore, studying the complex immune system that works together with pathogens in plants is important for the prevention and management of fungal diseases.

In recent years, the rapid development of biotechnology, particularly transcriptomics, has enabled comprehensive analysis of gene expression patterns in plants under pathogen attack. This has led to significant advances in the understanding of plant resistance mechanisms. Li et al. analyzed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in two barley cultivars in response to Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei (Bgh) infection using transcriptome sequencing [18]. Their analysis revealed the involvement of the MAPK pathway, plant hormone signal transduction, and six candidate genes (PR13, glutaredoxin, alcohol dehydrogenase, and cytochrome P450) that potentially contributed to the ability of the Feng 7 cultivar to mediate resistance to Bgh. These findings provide important information for understanding the defense of barley against Bgh infection and the molecular mechanisms underlying the differences in genetic resistance to powdery mildew. Using transcriptomic sequencing, Tao et al. revealed that phosphatase 2C10 and LRR receptor-like serine/threonine protein kinases are positively regulated in plants with higher-temperature seedling-plant resistance, possibly through interactions with different resistance proteins, leading to an HR [19]. Therefore, it is feasible to reveal the gene expression patterns and molecular mechanisms of wheat defense against stripe rust infestation using transcriptome sequencing technology. However, the gene regulatory networks, molecular mechanisms, and changes in the physicochemical properties of resistant wheat under specific Pst race infestations have not been elucidated.

Hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) has a complex and large genome that is difficult to transform. Pst is a biotrophic fungus that is binuclear and highly heterozygous [20,21]. The main objective of this study was to analyze the mechanisms underlying resistance to Pst-wheat interactions. Transcriptomes of the resistant cultivar Mianmai 46 (MM46) inoculated with Pst-CYR33 were sequenced at 24, 48, and 96 h post-inoculation (hpi). We identified DEGs and characterized their associated pathways using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses. ROS levels and antioxidant enzyme activity were measured. These findings provide novel insights into the complex mechanisms underlying wheat resistance to stripe rust and will aid in the development of durable resistant cultivars.

2.1 Wheat Planting and Pst-CYR33 Inoculation

The wheat cultivar Mianmai 46, which is resistant to the currently most prevalent race, CYR33, was selected for this study as one of the major cultivars in China. Among them, MM46 is provided by Nanjing Agricultural University, and CYR33 is provided by Northwest A&F University. Thirteen seeds were sown in plastic flower pots (7 cm × 7 cm × 7 cm). The samples were transferred to iron trays and watered. The wheat plants were grown in an artificial climate incubator at 18 ± 2°C for 16 h of light (8000 to 10,000 μmol∙m−2∙s−1) and 8 h of darkness. At the two-leaf stage, the seedlings were inoculated with the prevalent Chinese Pst race CYR33. The uredospores of Pst were mixed with an electronic fluorinated liquid at a ratio of 1:20 (v/v) to prepare a uredospore suspension. Subsequently, 10 μL of the uredospore suspension was evenly inoculated onto wheat leaves using a pipette, and the inoculation sites were marked with a pencil. Wheat plants were divided into four groups with a total of 12 pots, and one group was inoculated with sterile water as a control group. After inoculation, the seedlings were maintained at 100% humidity and 10°C in the dark for 24 h [22]. Leaves inoculated with Pst were collected at 0, 24, 48, and 96 hpi, MM46 leaves were used as controls at 0 h after inoculation, and the 24, 48, and 96 hpi samples as the experimental groups, with two biological replicates conducted at each time point. After collection, the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C immediately.

2.2 RNA Isolation and cDNA Library Construction

Total RNA was extracted from eight biological samples using the TRIzol reagent (Shanghai Sangon, 15596018CN, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Q32866, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis (Beijing Liuyi, 122-3146, Beijing, China), respectively. The mRNA samples were enriched, purified, and fragmented. First- and second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (YEASEN, Shanghai, China). The double-stranded cDNA was purified using Hieff NGSTM DNA Selection Beads and subjected to end repair, poly-A tailing, and adaptor ligation. The resulting cDNA library was amplified using PCR (BIO-RAD, 186109, Shanghai, China) and visualized on an agarose gel. Eight high-quality cDNA libraries were sequenced on an MGISEQ-2000 platform (Shanghai Sangong Bioengineering Co., Shanghai, China) to generate 150 bp paired-end reads.

2.3 Sequencing Data Quality Control and Reference Genome Comparison

Raw sequencing data from eight samples were subjected to quality control using Trimmomatic (Version: 0.36) to remove low-quality reads, including sequences with poly-N, adapter sequences, low-quality bases (Q < 20), and short reads, thereby obtaining clean reads for subsequent bioinformatics analyses and minimizing the negative impact of low-quality sequences on the analyses. The quality of the sequencing libraries was assessed using FastQC (Version: 0.11.2) to evaluate parameters, such as base quality (Q30), base content distribution (GC content), and repeat correlation (r2). Clean reads were aligned to the IWGSC RefSeq v1.0, wheat (Chinese Spring) genome using HISAT2 (Version: 2.1.0), and the mapping quality was assessed using RSeQC (Version: 2.6.1) [23]. Transcripts were reassembled using StringTie (Version: 1.3.3b) to identify novel transcripts, and redundant genes were removed using the appropriate filtering criteria [24].

2.4 Statistical Analysis of Gene Expression Levels

The level of gene expression was positively correlated with the abundance of transcripts. In RNA-seq analysis, the level of gene expression was mapped by the number of sequences (reads) localized to genomic regions or exonic regions. Additionally, read counts were positively correlated with gene length and depth. The transcripts per million (TPM) values indicate the proportion of a given transcript in the total RNA pool. The TPM value accounts for the effect of both sequencing depth and gene length on the number of reads and is commonly used to estimate gene expression levels [25]. The formula is as follows:

DESeq (Version: 1.26.0) was used to analyze the DEGs, and the criteria for determining significant differences in gene expression were Q-value < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1.

2.5 GO Term and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analyses

Functional enrichment analysis of the DEGs was performed using the GO database (http://www.geneontology.org), and metabolic pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs was performed using the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp). Genes were analyzed for enrichment using the hypergeometric distribution test, and significant enrichment was considered when the corrected Q-value was <0.05.

2.6 Measurement of Physiological and Biochemical Indicators

Leaves were sampled at 0, 24, 48, and 96 hpi posttreatment, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. The contents of H2O2, superoxide anion (O2•−), and malondialdehyde (MDA) were determined using spectrophotometric methods. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT) were measured according to the methods described by Zainy et al. and Liu et al. [26,27]. Three biological replicates were analyzed at each time point.

Total RNA was extracted from MM46 leaves at 0, 24, 48, and 96 hpi post-inoculation to observe dynamic gene expression in response to Pst-CYR33 over time. Three biological replicates were used at each time point. RNA extraction was performed using the aforementioned method. Gene-specific primer sequences were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software, as listed in Table S1. qRT–PCR was performed on a Light Cycler®96 (Roche, 05815916001, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines with TB Green® Premix EX Taq™ II (TaKaRa, No. CN830A, Wuhan, China). Each qRT–PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μL, which included 10 μL of TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (TaKaRa, No. RR820A, Wuhan, China), 0.8 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 μM), 2 μL of cDNA, and ddH2O (6.4 μL). The expression of the ACTIN (TaEF) gene was measured as a negative control, and each reaction was repeated three times. Three biological replicates were performed at each time point. The 2−ΔΔCT relative quantification method was used to analyze the experimental results.

3.1 Transcriptome Data Quality

To clarify the molecular response mechanisms underlying the resistance of MM46 to Pst infection at the seedling stage, total RNA was extracted from each sample, and cDNA libraries were constructed. RNA-seq analysis was performed to clarify gene expression patterns at the transcriptome level. Approximately 220.80 Gb of raw reads with a paired-end length of 150 bp were obtained. After excluding the connector and low-quality sequences (Q < 20), 311.641 million clean reads were screened from the 365.255 million raw total reads, accounting for 85.321% of the total reads. Clean reads were mapped to the genome of the wheat cultivar Chinese Spring (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0), and the alignment efficiency ranged from 91.09% to 92.66%, indicating that the majority of the expressed genes were captured by sequencing. The proportion of Q30 in each library was between 91.26% and 92.71%, and the proportion of GC content ranged from 54.26% to 57.19%, indicating that the transcriptome data of each sample were suitable for DEG analysis (Table S2).

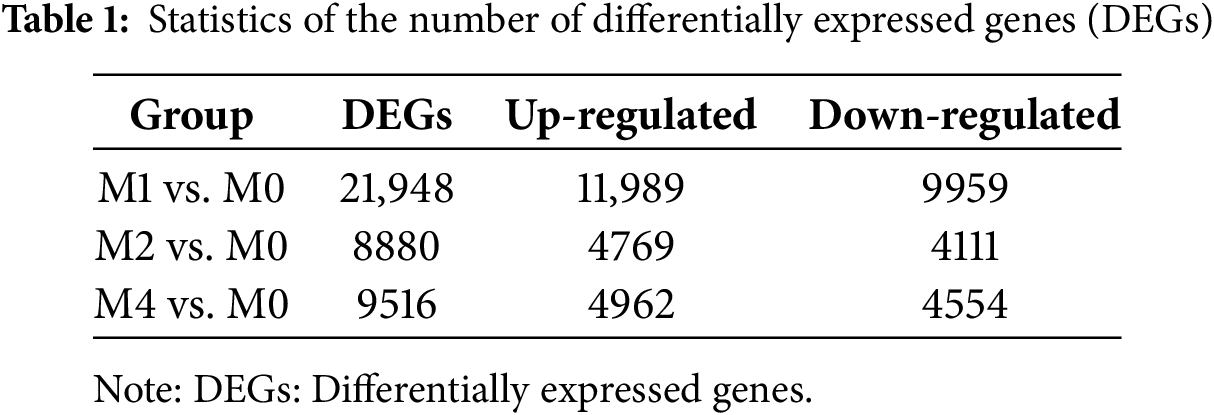

To identify significant DEGs, the filter thresholds were set to a Q-value < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1. The wheat cultivar MM46 was inoculated with Pst-CYR33 and examined at 0 hpi as a control (M0) and at 24 hpi (M1), 48 hpi (M2), and 96 hpi (M4) in the experimental groups. The experimental groups were compared to the control group. As shown in Table 1, compared to plants inoculated with Pst-CYR33 at 0 h, the number of DEGs in the resistant wheat cultivars 24 h after Pst inoculation was significantly greater.

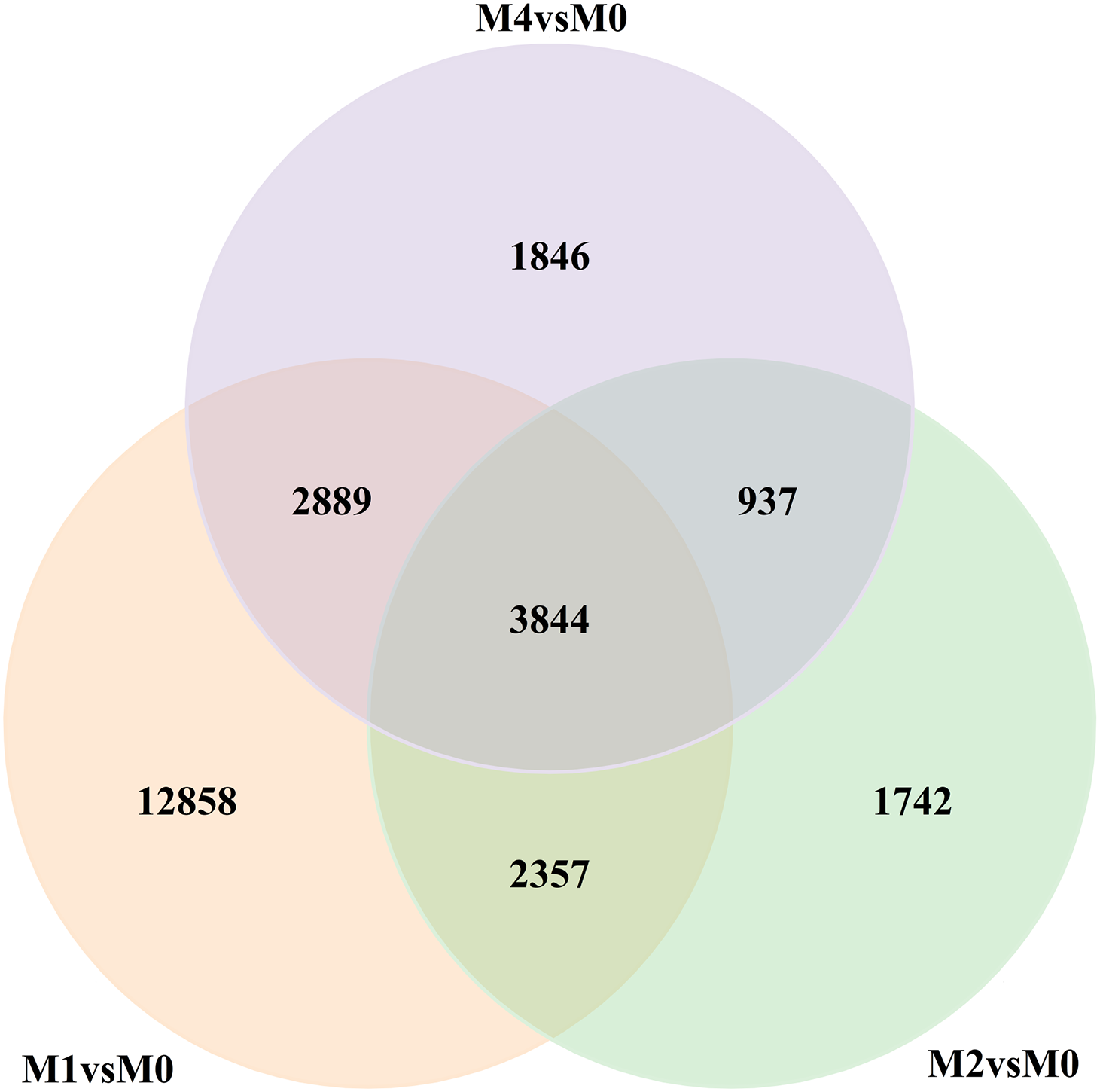

The Venn diagram illustrates the overlapping and unique sets of DEGs identified at different time points during the Pst-wheat interaction. A total of 3844 DEGs were co-expressed across all four time points (0, 24, 48, and 96 hpi), with 1972 upregulated genes and 1872 downregulated genes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at different time points after MM46 is inoculated with Pst-CYR33. M0: Control group, M1, M2, and M4 represent 24, 48, and 96 h after MM46 inoculation with Pst-CYR33

3.3 GO Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

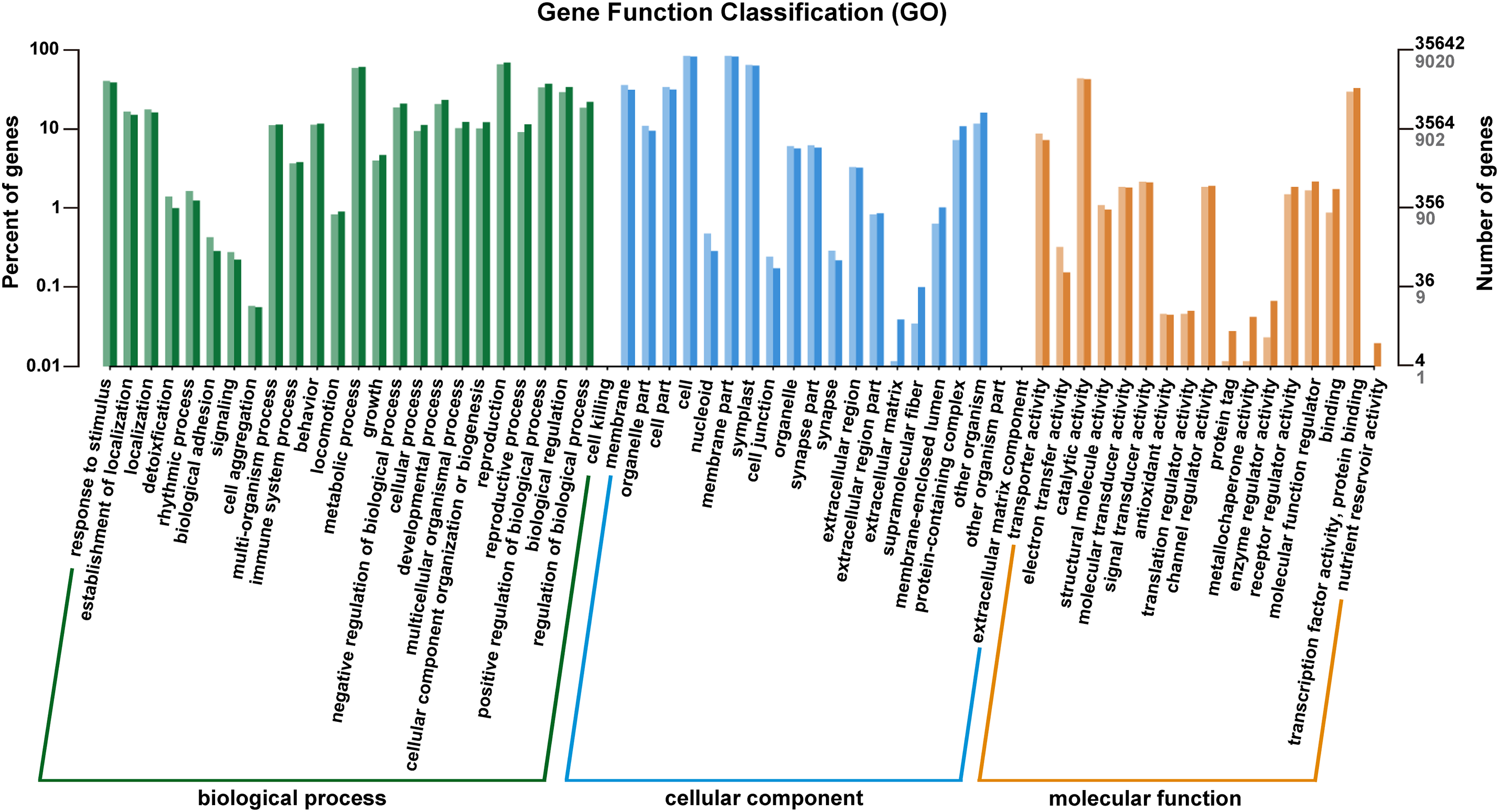

GO enrichment analysis was performed using the GO.db 3.3.0 package to identify the biological functions and molecular mechanisms associated with the DEGs. The DEGs were analyzed using three GO categories: biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions. The results indicated that the most significantly enriched terms in the biological process category were responses to stimuli, cellular processes, metabolic processes, and biological regulation. Membranes, cellular components, and organelles were the predominant terms in the cellular component category. Finally, the most likely terms were catalytic activity, binding, antioxidant activity, and transport activity (Fig. 2). The above GO enrichment results suggest that the key pathways enriched by differentially expressed genes are closely related to the activation of the plant immune system, signal transduction, and defense metabolism.

Figure 2: Bar chart of Gene Ontology annotation classification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The horizontal axis is the functional classification, and the vertical axis is the number of genes in this classification (right) and the percentage of the total number of genes annotated (left). Different colors represent different classifications. In the bar chart and on the coordinate axes, the light color represents differentially expressed genes, and the dark color represents all genes

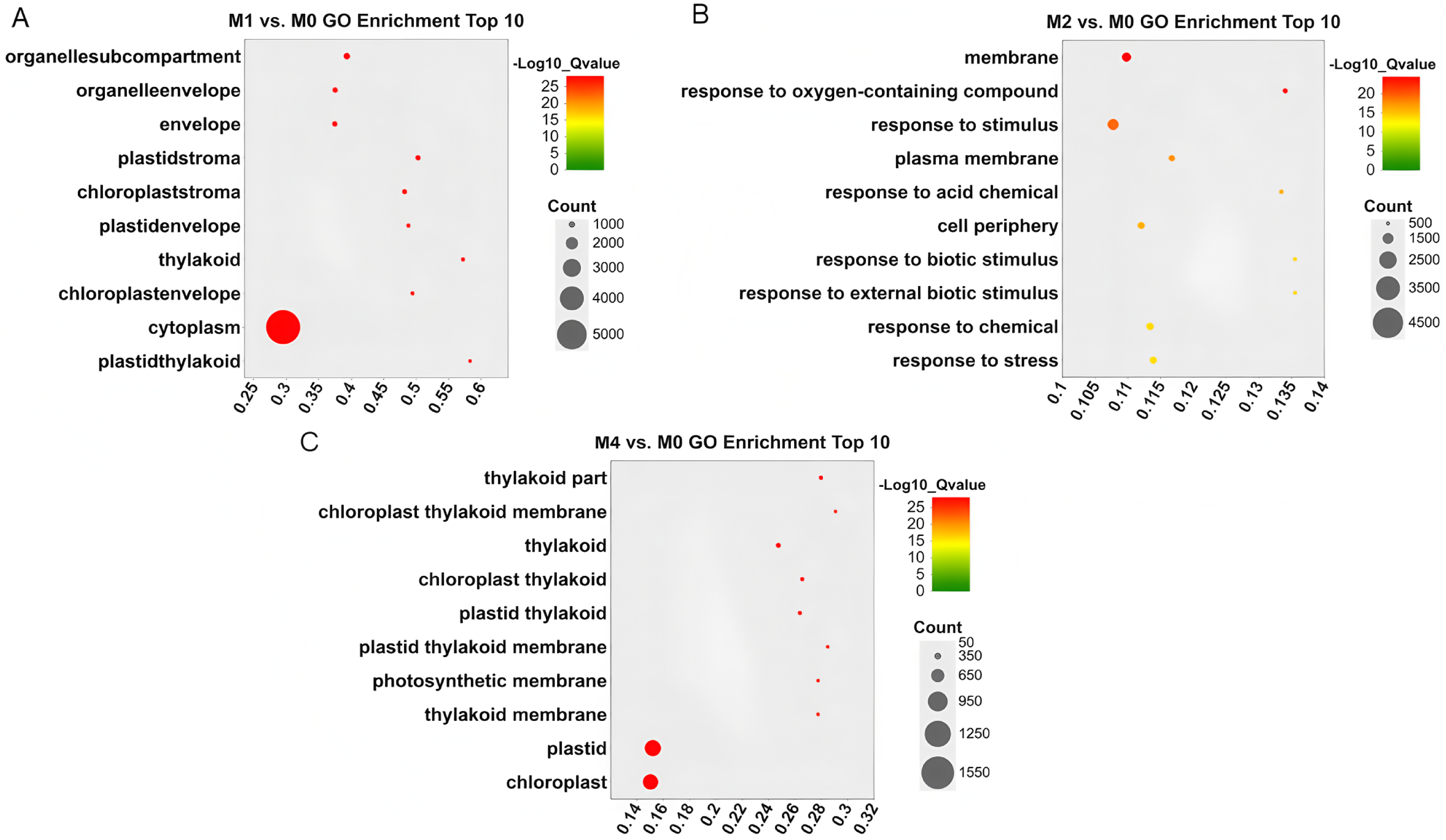

To further understand the functional categories that were significantly enriched during Pst infection, the 30 most significant GO terms were selected based on the criteria count > 10 and Q-value < 0.05. For the MM46-Pst interaction, only the membrane (GO: 0016020) was consistently enriched in both the M1 vs. M0 and M2 vs. M0 comparisons. Altogether, five terms were co-enriched in the M1 vs. M0 and M4 vs. M0 comparisons: membranes (GO: 0016020), thylakoids (GO: 0009579), plastids (GO: 0009536), photosynthesis (GO: 0015979), and chloroplasts (GO: 0009507). Finally, seven terms, including stress response (GO: 0006950), response to stimulus (GO: 0050896), response to chemical (GO: 0042221), response to acid chemical (GO: 0001101), response to abiotic stimulus (GO: 0009628), membrane (GO: 0016020), and response to oxygen-containing compound (GO: 1901700), were significantly enriched in both M2 vs. M0 and M4 vs. M0 comparisons. Notably, the membrane (GO: 0016020) was the only term co-enriched at all three time points (Fig. 3A–C, Table S3). These results indicate that photosynthesis, energy metabolism, small molecule synthesis, and transporter activity play essential roles in wheat defense against Pst.

Figure 3: Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (A) to (C) represent 24, 48, and 96 h after MM46 is inoculated with Pst-CYR33, respectively. The size of the circle represents the number of genes annotated under this GO term. The color represents the significance level (Q-value < 0.001). The horizontal coordinate (GeneRatio) represents the ratio of the number of genes annotated under this GO term to all differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Only the top 10 are shown

3.4 KEGG Pathway Analysis of DEGs

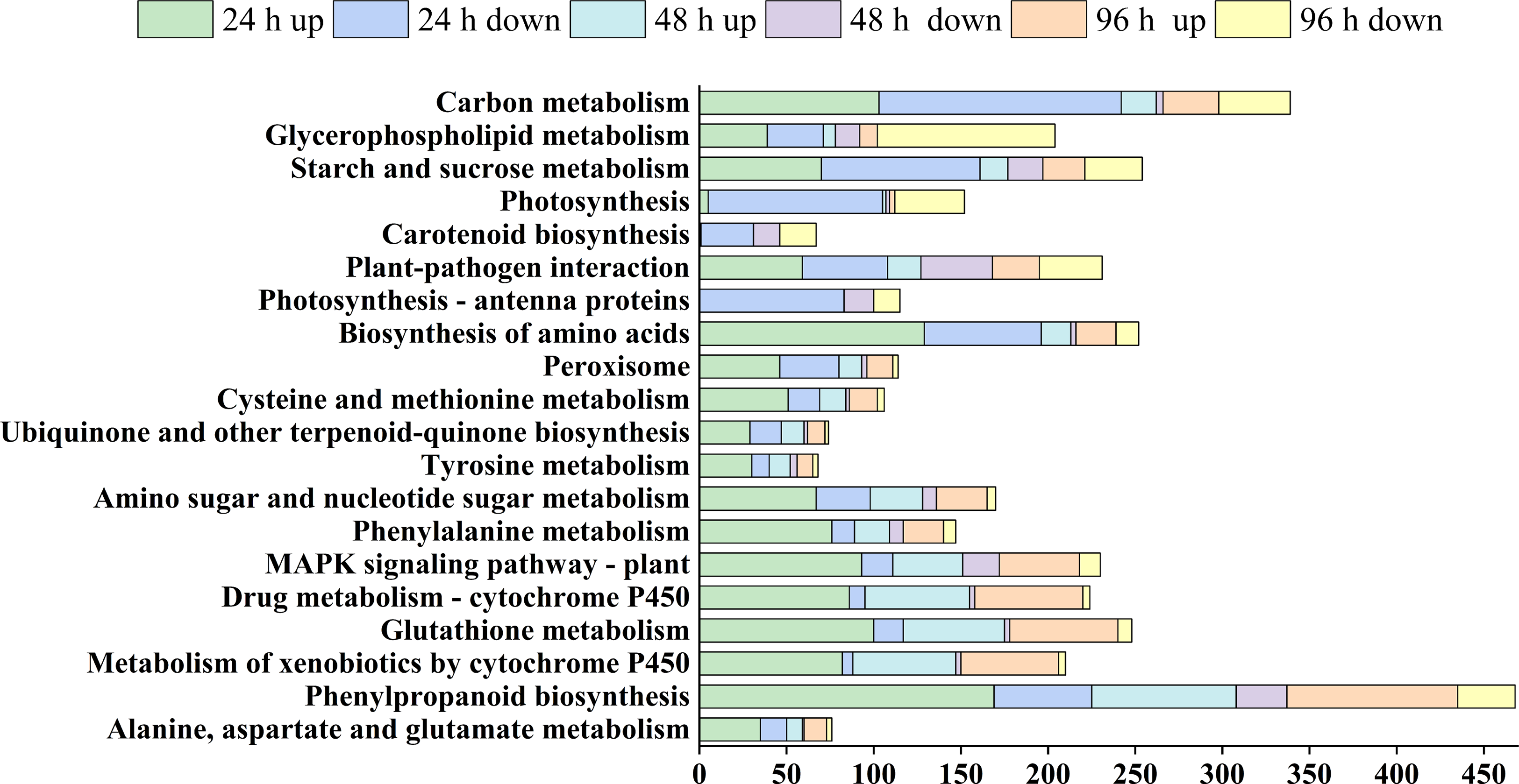

To further investigate the metabolic pathways in which the DEGs identified in each comparison group were involved, KEGG database annotation enrichment analysis was performed. Using a Q-value < 0.05 as the screening threshold, this analysis revealed 136 (24 hpi), 53 (48 hpi), and 61 (96 hpi) significantly enriched pathways for the upregulated DEGs and 37 (24 hpi), 19 (48 hpi), and 26 (96 hpi) significantly enriched pathways for the downregulated DEGs in MM46 plants inoculated with Pst-CYR33. We conducted an intersection analysis of significantly annotated pathways across different time points to investigate the metabolic pathways involved in stripe rust infection. The analysis identified 24 co-enriched pathways with upregulated DEGs and six co-enriched pathways with downregulated DEGs at 24, 48, and 96 hpi in MM46 plants infected with Pst.

DEGs were selected based on KEGG pathway enrichment, with screening criteria set at |log2FoldChange| ≥ 2 and Q-value < 0.001. Although some potentially interesting genes were excluded by these criteria, this approach helped to identify disease resistance-related target genes more accurately (Table S4). Pathways such as phenylalanine biosynthesis (KO00940), cytochrome P450 exogenous substance metabolism (KO00980 and KO00982), glutathione metabolism (KO00480), MAPK signaling, amino acid biosynthesis (KO04016), and peroxidase activity (KO00030) were upregulated following infection with Pst (Fig. 4 and Table S5). Conversely, the pathways related to energy metabolism (photosynthesis and sugar metabolism), carotenoid synthesis, and linoleic acid metabolism showed an increase in the number of downregulated DEGs after Pst infection. Among them, the phenylpropanoid-glutathione-MAPK signaling pathway, which is continuously activated during disease resistance, is closely related to core aspects of plant immunity, such as pathogen recognition and signal transduction.

Figure 4: KEGG co-enrichment pathway and gene screening. The horizontal coordinate represents the number of genes in this pathway. The vertical coordinate shows the top 20 metabolic pathways, up: Upregulated, down: Downregulated

3.5 DEGs in the Plant–Pathogen Interaction Pathway

The KEGG pathway revealed 59, 19, and 27 upregulated DEGs and 49, 41, and 36 downregulated DEGs involved in the plant–pathogen interaction pathway in MM46 at 24, 48, and 96 hpi with Pst-CYR33, respectively (|log2FoldChange| ≥ 2 and Q-value < 0.001). These DEGs were associated with various biological processes, including the HR, apoptosis, stomatal closure, and induction of defense-related genes. A comparative analysis of DEG expression patterns at 24, 48, and 96 hpi highlighted 24 hpi as the most critical time point, with a notably higher number of DEGs involved in wheat defense regulation than at other time points (Table S5). Wheat initiates multiple defense pathways to defend against Pst, including the PTI and ETI pathways.

At 24 hpi, key genes such as flagellin-sensitive 2 (FLS2), respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH), and calmodulin/calmodulin-like (CaM/CML) were significantly upregulated, although some CaM/CML genes were downregulated. Overall, most genes were upregulated in MM46 after Pst infection, indicating that MM46 triggers PTI by mediating the activation of HR via ROS and nitric oxide (NO) signaling pathways. Moreover, the assay revealed that the expression of genes such as MKK1/2 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase), WRKY25/33, and WRKY22/29 was markedly upregulated at 24 hpi, suggesting the involvement of the MAPK signaling cascade in defense. In addition, the genes NHO1 (non-host 1) and PR1 (pathogenesis-related protein) were significantly upregulated, contributing to wheat defense mechanisms. However, genes related to the CNGC (cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel) proteins were notably downregulated at 24 hpi, potentially mitigating excessive apoptosis caused by prolonged Ca2+ influx. By 48 hpi, only genes encoding MKK1/2, NHO1, and PR1 remained upregulated, whereas FLS2 and CaM/CML were downregulated (Table S6). At 96 hpi, only NHO1 and PR1 were upregulated, whereas CDPK (calcium-dependent protein kinase), RHOB, and FLS2 were significantly downregulated, affecting the ROS and NO signaling pathways.

In addition, fungal cell wall chitin significantly activated wheat chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1(CERK1) at 24 hpi. Genes such as RIN4, SGT1 (a suppressor of the G2 allele of SKP1), and RAR1 (required for Mla12 resistance) were also activated and upregulated, whereas HSP90 (encoding a heat shock protein) was moderately upregulated. However, the number of downregulated genes exceeded that of upregulated genes. Thus, ETI was activated by the combined action of RIN4, SGT1, RAR1, and HSP90. However, nearly all ETI-related genes had ceased expression by 48 hpi, with the exception of HSP90, which continued to exhibit downregulated expression until 96 hpi (Fig. S1).

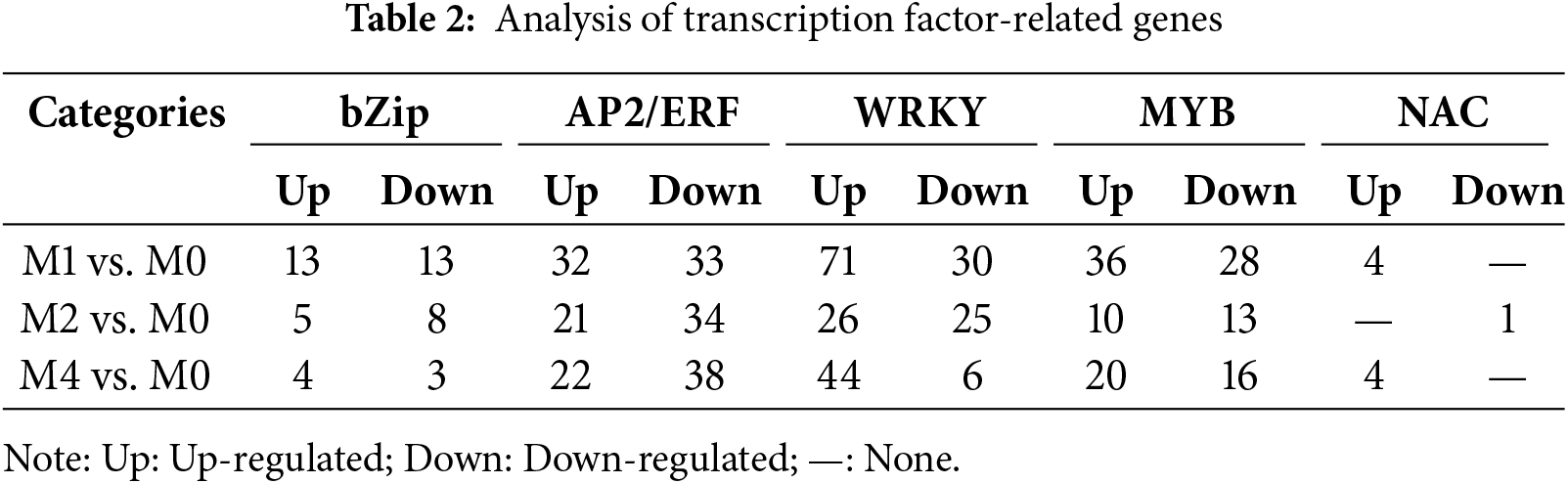

3.6 Transcription Factor (TF)-Related Genes

Transcription factors (TFs) play important roles in regulating plant disease resistance and defense responses at the transcriptional level. Functional annotation and statistical analysis of DEG-encoding transcription factors (criteria: |log2FoldChange| > 1 and Q-value < 0.05) showed that the key TFs involved in the defense response included WRKY, MYB, bZIP, AP2/ERF, and NAC (Table 2). DEGs encoding the five types of TFs showed a positive response to wheat defense regulation against Pst-CYR33 at 24 hpi, with a higher number of DEGs observed at 24 hpi than at 48 and 96 hpi. DEGs encoding WRKY TFs were the most abundant, with the number of upregulated genes exceeding those downregulated by more than two-fold. Moreover, the genes encoding AP2/ERF, MYB, and NAC were significantly upregulated in response to Pst infection. At 48 and 96 hpi, the number of genes encoding AP2/ERF, WRKY, and MYB TFs decreased slightly but maintained high expression levels. Interestingly, the number of upregulated AP2/ERF TFs genes was consistently lower than that of the downregulated genes from 24 to 96 hpi, suggesting that these genes may play a role in the negative regulatory response of wheat.

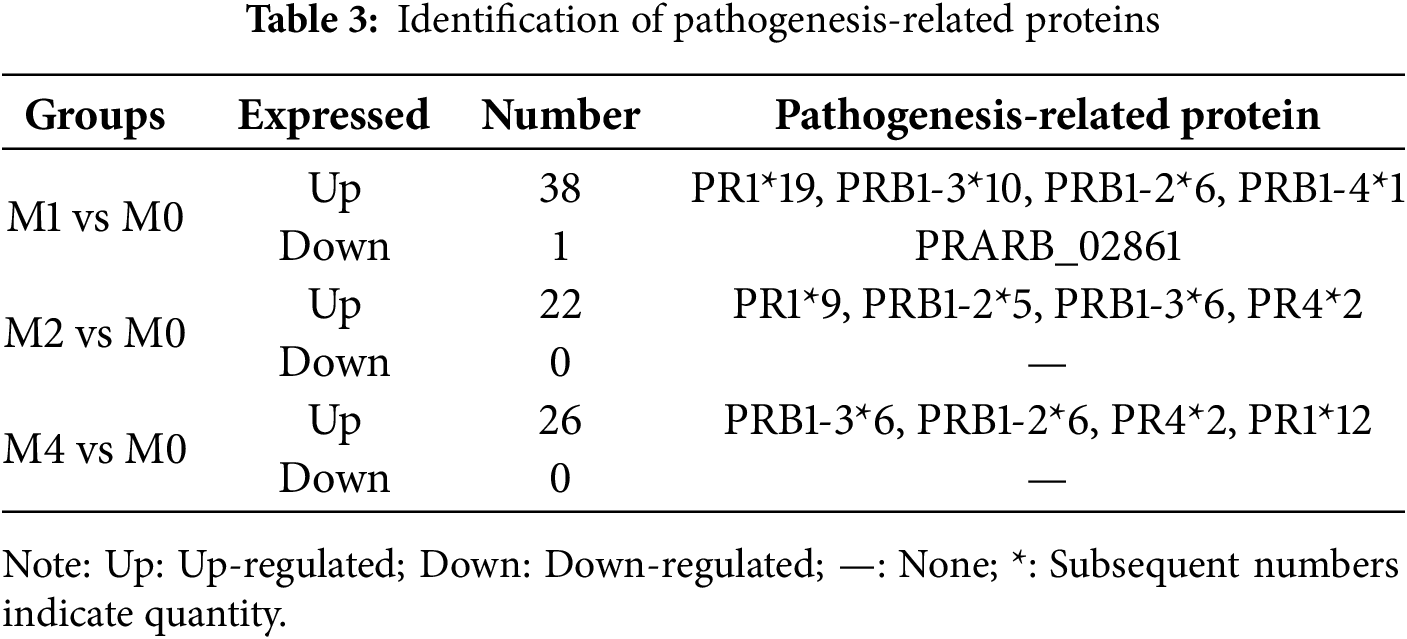

3.7 Pathogenesis-Related Protein-Encoding Genes

Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins are essential defense proteins produced by plants in response to pathogen attacks. Analysis of the DEGs encoding PR proteins revealed 37, 22, and 26 upregulated DEGs in MM46 leaves inoculated with Pst-CYR33 at 24, 48, and 96 hpi, respectively, and only one downregulated DEG at 24 hpi. The identified PR proteins were primarily PR1, PRB1-3, PRB1-2, and PR4 (Table 3).

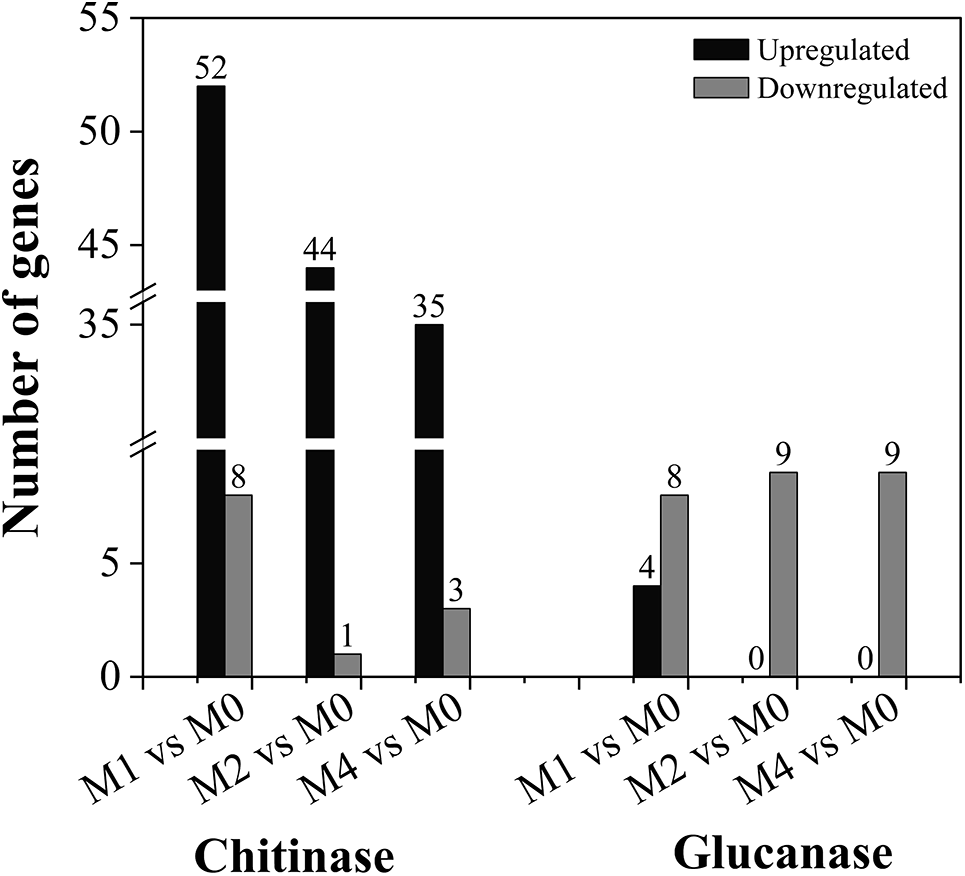

3.8 Chitinase and Glucanase Genes

Chitin and glucan are major components of fungal cell walls and are recognized by plants as typical fungal PAMPs that activate downstream immune responses. Therefore, chitinases and glucanases are likely to play crucial roles in wheat defense against stripe rust infection. Analysis of DEGs encoding chitinases and glucanases revealed that genes encoding chitinases were significantly upregulated, whereas those encoding glucanases were downregulated at different time points (24, 48, and 96 hpi) after inoculation with Pst-CYR33 in MM46 compared to the control (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Statistics on the number of genes encoding chitinase (left) and glucanase (right) in MM46 during Pst-CYR33 infection

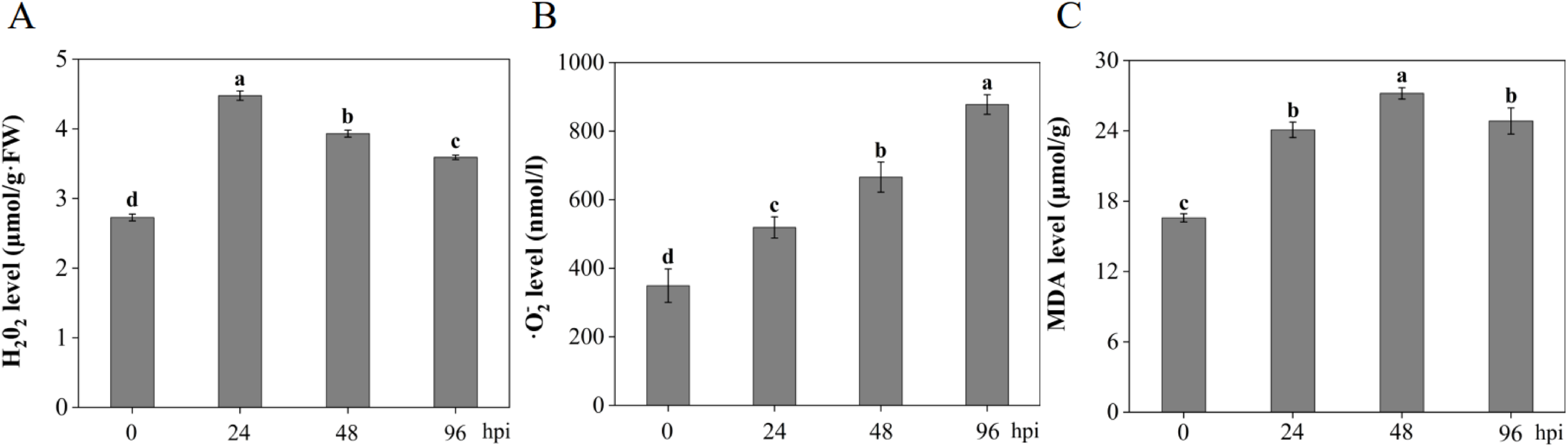

3.9 Analysis of Reactive Oxygen Species Content

Based on the GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway enrichment results, the accumulation of ROS may play a crucial role in wheat response to Pst, and MDA serves as an important indicator of membrane lipid peroxidation in plants under stress conditions. Therefore, the levels of H2O2, O2•−, and MDA were determined at different time points after infection with Pst-CYR33 (Fig. 6). The results showed significant changes in the levels of these substances in MM46 plants as Pst-CYR33 infection progressed. First, the level of H2O2, a representative ROS, was consistently higher in MM46 plants than in control plants (0 hpi) throughout the infection period. The H2O2 content increased sharply (approximately 1.5-fold) at the onset of infection (24 hpi) and then gradually decreased. Second, the level of O2•−, another major ROS component, initially increased in MM46 plants, peaked at 96 hpi at approximately 2.2 times the level in uninoculated plants, and then began to decline. Finally, compared to the uninoculated MM46 plants, the MDA content peaked at 48 hpi and subsequently declined.

Figure 6: Changes in the content of some substances in MM46 at different times during Pst-CYR33 infection. (A) Hydrogen peroxide, H2O2; (B) Superoxide anion, O2•−; (C) Malondialdehyde, MDA; Hpi: Hours post inoculation. The different letters ‘a–d’ in the figure indicate significant differences between treatment times for the same variety, as determined by the Duncan test, with p < 0.05

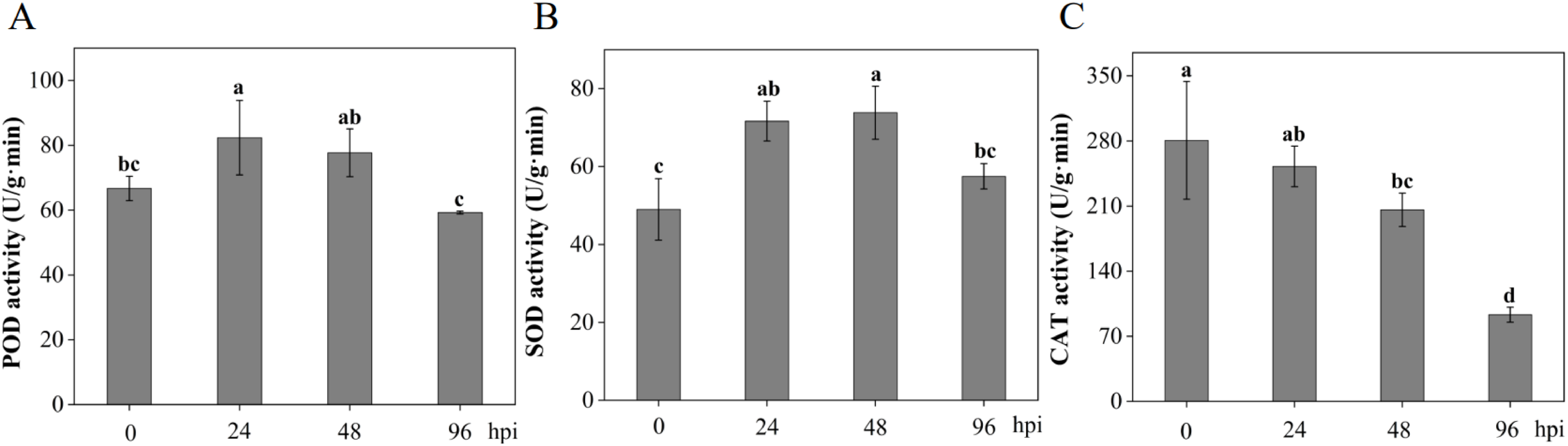

3.10 Analysis of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

POD, SOD, and CAT are the major antioxidant enzymes in plants, and the antioxidant enzyme system helps prevent excessive accumulation of ROS, which can cause serious damage to plants. In MM46 plants inoculated with Pst-CYR33, POD and SOD activities initially increased and then decreased compared to those in uninoculated plants. POD activity peaked on the first day, whereas SOD activity peaked on the second day. In contrast, CAT activity (reaching 12.5% of control by 96 hpi) may sustain H2O2 accumulation to potentiate hypersensitive response (HR), representing a trade-off between ROS signaling and oxidative damage control (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Changes in antioxidant enzyme activities in MM46 at different times during Pst-CYR33 infection. (A) Peroxidase, POD; (B) Superoxide dismutase, SOD; (C) Catalase, CAT; Hpi: Hours post-inoculation. The different letters ‘a–d’ in the figure indicate significant differences between treatment times for the same variety, as determined by the Duncan test, with p < 0.05

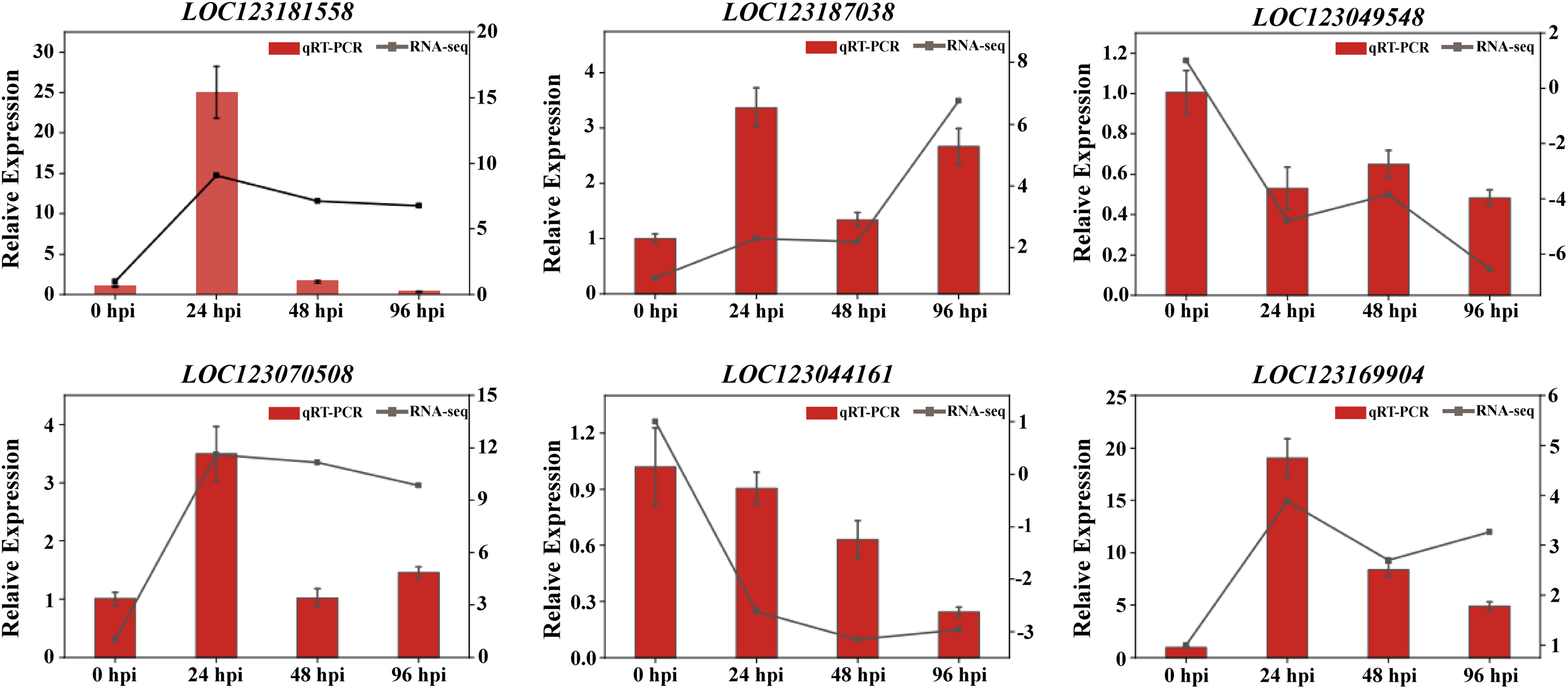

To verify the accuracy and confidence of the transcriptomic data, six candidate DEGs whose expression changed significantly were selected for qRT–PCR, and the ACTIN gene was used as the internal reference gene. Based on gene function annotation analysis, these six genes were shown to be chitinase 8-like (LOC123181558), basic endochitinase A-like (LOC123187038, LOC123070508), pathogenesis-related protein PRB1-3-like (LOC123169904), serine/threonine-protein kinase SAPK2-like (LOC123044161), probable calcium-binding protein CML22 (LOC123049548). The correlations between the RNA-Seq and qRT–PCR results are shown in Fig. 8. The trends of the qRT–PCR results and RNA–Seq data for the six genes were basically consistent; however, the upregulation and downregulation trends of the related genes remained the same in all periods, although the fold change factor varied. Therefore, the reliability of the transcriptomic data was confirmed.

Figure 8: Relative expression level changes of DEGs in MM46 inoculated with CYR33 by RNA-seq and qRT-PCR. TPM values from RNA-seq (blue) are scaled on the right vertical axis, with qRT-PCR relative expression levels (red) on the left vertical axis

Wheat stripe rust is the most destructive fungal disease in wheat and seriously affects the safety of wheat production. RNA-seq analysis is one of the fastest and most effective methods for unraveling plant-pathogen interactions at the transcriptional level, such as those of genes, regulatory networks, and TFs [28]. In the present study, RNA-seq analysis was performed on the resistant cultivar MM46 after inoculation with Pst-CYR33. The wheat cultivar MM46 is widely planted in China. Conducting RNA-seq analysis on this cultivar is helpful for understanding the activation and expression patterns of genes related to stress resistance in wheat plants and for analyzing the molecular mechanisms that can protect plants from biotic and abiotic stresses.

During wheat infection by Pst, the expression of a large number of wheat defense genes is induced. In this study, following the inoculation of MM46 with CYR33, the number of DEGs at 24 hpi was more than double that at 48 and 96 hpi. These results indicated that the expression of a large number of genes was immediately activated after wheat was infected with Pst, which is a critical period for the wheat plant to defend itself against Pst infection. This finding has also been confirmed in transcriptome analyses of varieties with all-stage resistance (SM126, Zhong 4) and varieties with adult plant resistance (XZ9104, XY6) [19,24,29,30]. Some studies have shown that this phenomenon might be related to host invasion through the formation of haustoria in Pst [13,30].

GO enrichment showed that after CYR33 infection, the DEGs in MM46 were mainly grouped into four modules: photosynthesis, small-molecule metabolism, transmembrane transport, and energy metabolism. Among these, lignin metabolism genes were markedly up-regulated, whereas the synthesis of the chlorophyll precursor uroporphyrin III was down-regulated. This suggests that wheat first thickens its cell wall to physically block the pathogen [31], and then restricts the carbon supply by suppressing photosynthesis, thereby limiting pathogen expansion [32,33].

Corresponding KEGG pathway enrichment further supports these findings. The phenylpropanoid–phenylalanine biosynthesis pathway (KO00940) was activated at all three post-inoculation time points, promoting the synthesis of the secondary metabolite lignin [29,34]. Meanwhile, the photosynthesis pathway (KO00195) was significantly inhibited, indicating that photosynthesis not only serves energy metabolism but also plays an important role in immune regulation induced during the plant’s response to pathogen infection [35].

Plants have developed robust immune responses to resist pathogens through long-term natural selection and coevolution [36]. At 24 hpi, the fungal Pst-CYR33 PAMPs are first perceived by the pattern-recognition receptors CERK1 and FLS2; the interaction between the two receptors enhances wheat resistance. Although FLS2 is traditionally regarded as a receptor for bacterial flagellin [37], our study and the reports by Zhang and Yuan both confirm that it can also be induced under fungal stress, indicating that FLS2 has cross-kingdom PAMP-recognition capability. Subsequently, FLS2 activates WRKY25/33 through the MEKK1–MKK1/2–MAPK cascade, directly up-regulating the expression of the defense genes PR1 and NHO1 [24,38,39].

Meanwhile, CDPK is activated by calcium signals and regulates the accumulation of extracellular ROS, cell-wall thickening, and stomatal closure, laying both an oxidative and a physical barrier for later defense. Bacterial flagellin and fungal PAMPs together trigger a rapid ROS burst that further amplifies the immune signal [40].

Plant resistance involves the coordinated expression of various defense genes, with TFs playing a significant regulatory role. In this study, five major transcription factors, namely bZIP, MYB, AP2/ERF, WRKY, and NAC, were identified. In MM46 plants infected by CYR33, WRKY TFs upregulation enhanced wheat stripe rust resistance. Previous studies have shown that TaWRKY49 enhances high-temperature seedling resistance to stripe rust in wheat by regulating the SA, JA, and ET signaling pathways [23]. In addition, MYB TFs contribute to systemic acquired resistance, a positive regulator of wheat disease resistance, by enhancing SA and ROS accumulation [41–43]. MYB-related genes played a positive role in the interactions between wheat and Pst. NAC TFs are induced to regulate wheat’s immune response upon Pst infection, although some NAC TFs, like TaNAC30 and TaNAC1, are negative regulators, with silencing TaNAC30 inhibiting Pst colonization [44] and overexpression of TaNAC1 suppressing SA and JA signaling pathways, thereby reducing disease resistance [45]. Additionally, AP2/ERF and bZIP TFs have been confirmed to be positive regulators of wheat stripe rust resistance [46–48], although bZIP-related gene expression was slightly lower than that of other TFs, optimizing energy use in wheat plants. In this study, the number of downregulated genes of the transcription factor AP2/ERF at 48 and 96 hpi was higher than that of the upregulated genes, showing a greater tendency towards negative regulation. In a study on the molecular mechanism of wild winter wheat resistance to stripe rust, Ren indicated that the transcription factors WRKY and AP2/ERF play decisive roles in the early stage of infection (24 hpi), whereas in the later stage of infection (72 hpi), they rely on MYB, NAC, and bZIP. In this study, although the expression of the transcription factor NAC was irregular, the other four transcription factors all played key roles in the early stages of infection. WRKY, AP2/ERF, and MYB actively respond to wheat disease resistance [49].

PR proteins are essential for plant defense against pathogen invasion [50]. In this study, DEGs encoding PR proteins were identified, and 24 h after the inoculation of MM46 with CYR33, all PR genes were upregulated, except for the gene encoding the PRARB gene, which was downregulated. The PR proteins implicated in defense included PR1, PRB1-2, PRB1-3, PRB1-4, and PR4 (Table S6); Pst infection significantly upregulated PR protein-encoding genes, suggesting that PR proteins play a positive role in wheat defense against stripe rust.

Chitin and glucan, crucial fungal cell wall components, are recognized by chitinase and glucanase, respectively, during Pst infection in wheat. These antibacterial hydrolytic enzymes degrade fungal cell walls and contribute to plant defense mechanisms [51]. In the present study, chitinase genes were highly activated in the resistant MM46 plants following Pst infection, thereby enhancing the ability of wheat to withstand fungal pathogens.

During pathogen invasion or abiotic stress, plants generate substantial reactive oxygen species (ROS), activating defense responses; however, excessive ROS accumulation is detrimental. As key ROS components, elevated hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion (O2•−) oxidize cellular membranes and proteins, damage DNA, and ultimately trigger programmed cell death [52]. In this study, inoculation with Pst-CYR33 induced a significant increase in H2O2 content in MM46 wheat leaves by 24 h post-inoculation (hpi), followed by a significant rise in O2•− levels by 96 hpi, with early ROS accumulation contributing to enhanced stripe rust resistance. Malondialdehyde (MDA), a byproduct of ROS formed either enzymatically via lipoxygenase (LOX) activity or non-enzymatically during oxidative stress [53], serves as an indicator of stress-induced damage. Reduced MDA accumulation in Pst-CYR33-infected MM46 suggests an attenuation of the biomembrane system damage, potentially aiding resistance.

Stress-induced ROS accumulation prompts plants to synthesize antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD) to scavenge ROS [54]. SOD and POD constitute a crucial defense system. Here, both POD and SOD activities were rapidly induced early during Pst-CYR33 infection. POD activity peaked at 24 hpi, likely responding immediately to reduce ROS by decomposing H2O2 [55], while SOD activity peaked at 48 hpi, catalyzing the dismutation of O2 •− into H2O2 and O2, thereby mitigating its toxicity and providing substrate for POD [26]. This synergistic action helps maintain ROS homeostasis, preventing oxidative damage and enhancing resistance [52]. Surprisingly, CAT activity, also involved in H2O2 decomposition [56,57], continuously decreased post-inoculation, plummeting to one-eighth of control levels by 96 hpi. This indicates that MM46 prioritizes POD and SOD mobilization for ROS scavenging, potentially at the expense of CAT function, or suggests pathogen interference with antioxidant enzyme regulation [13]. Supporting this, TaCAT3 overexpression reduces stripe rust resistance [58]. Nevertheless, the observed CAT decline may not be entirely detrimental, as it could facilitate H2O2 accumulation, potentially triggering the hypersensitive response or activating other defenses.

SOD is generally regarded as the first line of defense in the plant antioxidant response, with CAT subsequently responsible for decomposing the resulting H2O2. However, this study found that in wheat leaves inoculated with the stripe rust pathogen CYR33, CAT activity was higher than SOD at 0 and 24 h post-inoculation. This observation aligns with findings in salt-stressed soybean mutant ko-2 during the germination stage, where CAT activity was also significantly higher than SOD [59]. These results suggest that CAT may play a more efficient role in scavenging hydrogen peroxide at early stages, thereby protecting cells from oxidative damage. Such differences could be closely associated with the plant’s physiological state, environmental conditions, and the regulation of gene expression.

Alterations in ROS levels and enzyme activity were consistent with the gene expression profiles obtained from transcriptome sequencing (Table S7). Thus, a significant link likely exists between the dynamic changes in H2O2 content and disease resistance in wheat, with H2O2 homeostasis requiring the involvement of multiple enzymes.

Overall, MM46 establishes an early Pst barrier by reinforcing cell walls with lignin while activating POD/SOD and repressing CAT. In the present survey, the transcriptome also revealed a significant response from numerous immune-related genes. This finding aligns with Hossein Sabouri’s conclusions regarding multi-disease resistance genes [60]. In subsequent research, further exploration through molecular markers can be conducted, providing new insights into the mechanisms of stripe rust.

In summary, MM46 employs a biphasic defense strategy. At 24 hpi, rapid initiation of the FLS2/CERK1-MAPK-PR1 signaling cascade occurs concurrently with upregulated lignin biosynthesis and ROS-mediated signaling, establishing early-phase cell wall fortification. Transcriptomics analysis further reveals that the defense network is coordinately amplified through the synergistic action of WRKY/MYB transcription factors, PR proteins, and chitinases, enabling swift containment of the pathogen. Concurrently, significant surges in peroxidase and superoxide dismutase activities, coupled with selective suppression of catalase, collectively maintain ROS homeostasis; this balance effectively curbs Pst proliferation while minimizing oxidative damage to host tissues.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all the members of the laboratory for their sound and constructive advice on the completion of this experiment, and the supervisor for her support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32502517), the Open Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas (SKLCSRHPKF20), Collaborative Innovation Project of Department of Education of Anhui Provincial (GXXT-2019-033), Horizontal project-Breeding of high yield and multi resistant wheat varieties (2021122401).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Guiping Li. Methodology: Shenglong Wang, Jiawei Yuan. Software: Shenglong Wang, Jing Zhang. Formal analysis: Shenglong Wang, Jing Zhang, Jiawei Yuan. Investigation: Jing Zhang, Qingsong Ba, Huifen Qiao. Date curation: Shenglong Wang, Jiawei Yuan. Writing–original draft preparation: Guiping Li, Gensheng Zhang. Writing–review and editing: Guiping Li, Gensheng Zhang. Supervision: Guiping Li, Qingsong Ba, Gensheng Zhang. Project administration: Guiping Li, Gensheng Zhang. Funding acquisition: Guiping Li, Gensheng Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are accessible through the BioProject accession number PRJNA1193700 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1193700, accessed on 04 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.070017/s1.

References

1. Ma K, Li X, Li Y, Wang Z, Zhao B, Wang B, et al. Disease resistance and genes in 146 wheat cultivars (lines) from the Huang-Huai-Hai Region of China. Agronomy. 2021;11(6):1025. doi:10.3390/agronomy11061025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen X. Pathogens which threaten food security: Puccinia striiformis, the wheat stripe rust pathogen. Food Secur. 2020;12(2):239–51. doi:10.1007/s12571-020-01016-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao J, Kang Z. Fighting wheat rusts in China: a look back and into the future. Phytopathol Res. 2023;5(1):6. doi:10.1186/s42483-023-00159-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen W, Zhang Z, Tian Y, Kang Z, Zhao J. Race composition and genetic diversity of a Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici population from Yunnan and Guizhou epidemiological regions in China in 2018. J Plant Pathol. 2023;105(1):253–67. doi:10.1007/s42161-022-01273-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Huang L, Xiao XZ, Liu B, Gao L, Gong GS, Chen WQ, et al. Identification of stripe rust resistance genes in common wheat cultivars from the Huang-Huai-Hai Region of China. Plant Dis. 2020;104(6):1763–70. doi:10.1094/PDIS-10-19-2119-RE. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang M, Zeng M, Tian B, Liu Q, Li G, Gao H, et al. Evaluation of resistance and molecular detection of resistance genes to wheat stripe rust of 82 wheat cultivars in Xinjiang. China Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):31308. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-82772-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Carmona M, Sautua F, Pérez-Hérnandez O, Reis EM. Role of fungicide applications on the integrated management of wheat stripe rust. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:733. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chen W, Wellings C, Chen X, Kang Z, Liu T. Wheat stripe (yellow) rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Mol Plant Pathol. 2014;15(5):433–46. doi:10.1111/mpp.12116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ngou BPM, Ding P, Jones JDG. Thirty years of resistance: zig-zag through the plant immune system. Plant Cell. 2022;34(5):1447–78. doi:10.1093/plcell/koac041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yuan M, Ngou BPM, Ding P, Xin XF. PTI-ETI crosstalk: an integrative view of plant immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2021;62:102030. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Chang M, Chen H, Liu F, Fu ZQ. PTI and ETI: convergent pathways with diverse elicitors. Trends Plant Sci. 2022;27(2):113–5. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2021.11.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jones JDG, Staskawicz BJ, Dangl JL. The plant immune system: from discovery to deployment. Cell. 2024;187(9):2095–116. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shu W, Yuan J, Zhang J, Wang S, Ba Q, Li G, et al. The stripe rust effector Pst3180.3 inhibits the transcriptional activity of TaMYB4L to modulate wheat immunity and analyzes the key active sites of the interaction conformation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;280(Pt 2):135584. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang R, He F, Ning Y, Wang GL. Fine-tuning of RBOH-mediated ROS signaling in plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25(11):1060–2. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2020.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wan WL, Zhang L, Pruitt R, Zaidem M, Brugman R, Ma X, et al. Comparing Arabidopsis receptor kinase and receptor protein-mediated immune signaling reveals BIK1-dependent differences. New Phytol. 2019;221(4):2080–95. doi:10.1111/nph.15497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yuan M, Jiang Z, Bi G, Nomura K, Liu M, Wang Y, et al. Pattern-recognition receptors are required for NLR-mediated plant immunity. Nature. 2021;592(7852):105–9. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03316-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bjornson M, Pimprikar P, Nürnberger T, Zipfel C. The transcriptional landscape of Arabidopsis thaliana pattern-triggered immunity. Nat Plants. 2021;7(5):579–86. doi:10.1038/s41477-021-00874-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Li Y, Guo G, Zhou L, Chen Y, Zong Y, Huang J, et al. Transcriptome analysis identifies candidate genes and functional pathways controlling the response of two contrasting barley varieties to powdery mildew infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21(1):151. doi:10.3390/ijms21010151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Tao F, Wang J, Guo Z, Hu J, Xu X, Yang J, et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveal the molecular mechanisms of wheat higher-temperature seedling-plant resistance to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. Tritici Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:240. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yin C, Hulbert S. Prospects for functional analysis of effectors from cereal rust fungi. Euphytica. 2011;179(1):57–67. doi:10.1007/s10681-010-0285-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Aime MC, McTaggart AR. A higher-rank classification for rust fungi, with notes on Genera. Fungal Syst Evol. 2021;7(1):21–47. doi:10.3114/fuse.2021.07.02. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang H, Wang C, Cheng Y, Chen X, Han Q, Huang L, et al. Histological and cytological characterization of adult plant resistance to wheat stripe rust. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31(12):2121–37. doi:10.1007/s00299-012-1322-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ahmad Mir Z, Chauhan D, Pradhan AK, Srivastava V, Sharma D, Budhlakoti N, et al. Comparative transcriptome profiling of near isogenic lines PBW343 and FLW29 to unravel defense related genes and pathways contributing to stripe rust resistance in wheat. Funct Integr Genomics. 2023;23(2):169. doi:10.1007/s10142-023-01104-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang Y, Huang L, Luo W, Jin Y, Gong F, He J, et al. Transcriptome analysis provides insights into the mechanisms underlying wheat cultivar Shumai126 responding to stripe rust. Gene. 2021;768(10):145290. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2020.145290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wagner GP, Kin K, Lynch VJ. A model based criterion for gene expression calls using RNA-seq data. Theory Biosci. 2013;132(3):159–64. doi:10.1007/s12064-013-0178-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zainy Z, Fayyaz M, Yasmin T, Hyder MZ, Haider W, Farrakh S. Antioxidant enzymes activity and gene expression in wheat-stripe rust interaction at seedling stage. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2023;124(12):101960. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2023.101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu R, Lv X, Wang X, Yang L, Cao J, Dai Y, et al. Integrative analysis of the multi-omics reveals the stripe rust fungus resistance mechanism of the TaPAL in wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1174450. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1174450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Nagalakshmi U, Waern K, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a method for comprehensive transcriptome analysis. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010;89(1):4–11. doi:10.1002/0471142727.mb0411s89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hao Y, Wang T, Wang K, Wang X, Fu Y, Huang L, et al. Transcriptome analysis provides insights into the mechanisms underlying wheat plant resistance to stripe rust at the adult plant stage. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150717. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lv X, Deng J, Zhou C, Abdullah A, Yang Z, Wang Z, et al. Comparative transcriptomic insights into molecular mechanisms of the susceptibility wheat variety MX169 response to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst) infection. Infection Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12(8):e0377423. doi:10.1128/spectrum.03774-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Wan J, He M, Hou Q, Zou L, Yang Y, Wei Y, et al. Cell wall associated immunity in plants. Stress Biol. 2021;1(1):3. doi:10.1007/s44154-021-00003-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu R, Lu J, Zhang L, Wu Y. Transcriptomic insights into the molecular mechanism of wheat response to stripe rust fungus. Heliyon. 2022;8(10):e10951. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Garai S, Tripathy BC. Alleviation of nitrogen and sulfur deficiency and enhancement of photosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana by overexpression of uroporphyrinogen III methyltransferase (UPM1). Front Plant Sci. 2018;8:2265. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.02265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Weisshaar B, Jenkins GI. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and its regulation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1(3):251–7. doi:10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80113-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Kangasjärvi S, Neukermans J, Li S, Aro EM, Noctor G. Photosynthesis, photorespiration, and light signalling in defence responses. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(4):1619–36. doi:10.1093/jxb/err402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124(4):803–14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Gómez-Gómez L, Boller T. FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell. 2000;5(6):1003–11. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80265-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang H, Yang Y, Wang C, Liu M, Li H, Fu Y, et al. Large-scale transcriptome comparison reveals distinct gene activations in wheat responding to stripe rust and powdery mildew. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):898. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yuan C, Miao Y, Zhang H, Liu S, Wang Y. Comparison of gene expression changes in two wheat varieties with different phenotype to strip rust using RNA-Seq analysis. Plant Prot Sci. 2023;59(2):134–44. doi:10.17221/125/2022-pps. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang N, Fan X, He M, Hu Z, Tang C, Zhang S, et al. Transcriptional repression of TaNOX10 by TaWRKY19 compromises ROS generation and enhances wheat susceptibility to stripe rust. Plant Cell. 2022;34(5):1784–803. doi:10.1093/plcell/koac001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang Z, Chen J, Su Y, Liu H, Chen Y, Luo P, et al. TaLHY, a 1R-MYB transcription factor, plays an important role in disease resistance against stripe rust fungus and ear heading in wheat. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127723. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang F, Lin R, Li Y, Wang P, Feng J, Chen W, et al. TabZIP74 acts as a positive regulator in wheat stripe rust resistance and involves root development by mRNA splicing. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1551. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhu X, Li X, He Q, Guo D, Liu C, Cao J, et al. TaMYB29: a novel R2R3-MYB transcription factor involved in wheat defense against stripe rust. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:783388. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.783388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang B, Wei J, Song N, Wang N, Zhao J, Kang Z. A novel wheat NAC transcription factor, TaNAC30, negatively regulates resistance of wheat to stripe rust. J Integr Plant Biol. 2018;60(5):432–43. doi:10.1111/jipb.12627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Wang F, Lin R, Feng J, Chen W, Qiu D, Xu S. TaNAC1 acts as a negative regulator of stripe rust resistance in wheat, enhances susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringae, and promotes lateral root development in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6(302):108. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kim NY, Jang YJ, Park OK. AP2/ERF family transcription factors ORA59 and RAP2.3 interact in the nucleus and function together in ethylene responses. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1675. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ng DW, Abeysinghe JK, Kamali M. Regulating the regulators: the control of transcription factors in plant defense signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3737. doi:10.3390/ijms19123737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yang YN, Kim Y, Kim H, Kim SJ, Cho KM, Kim Y, et al. The transcription factor ORA59 exhibits dual DNA binding specificity that differentially regulates ethylene- and jasmonic acid-induced genes in plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2021;187(4):2763–84. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiab437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ren J, Chen L, Liu J, Zhou B, Sha Y, Hu G, et al. Transcriptomic insights into the molecular mechanism for response of wild emmer wheat to stripe rust fungus. Front Plant Sci. 2024;14:1320976. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1320976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Dos Santos C, Franco OL. Pathogenesis-related proteins (PRs) with enzyme activity activating plant defense responses. Plants. 2023;12(11):2226. doi:10.3390/plants12112226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ferreira RB, Monteiro S, Freitas R, Santos CN, Chen Z, Batista LM, et al. The role of plant defence proteins in fungal pathogenesis. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8(5):677–700. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00419.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Mittler R, Zandalinas SI, Fichman Y, Van Breusegem F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(10):663–79. doi:10.1038/s41580-022-00499-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Morales M, Munné-Bosch S. Malondialdehyde: facts and artifacts. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(3):1246–50. doi:10.1104/pp.19.00405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Rabilloud T, Heller M, Rigobello MP, Bindoli A, Aebersold R, Lunardi J. The mitochondrial antioxidant defence system and its response to oxidative stress. Proteomics. 2001;1(9):1105–10. doi:10.1002/1615-9861(200109)1:9<1105::AID-PROT1105>3.0.CO;2-M. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wang P, Liu WC, Han C, Wang S, Bai MY, Song CP. Reactive oxygen species: multidimensional regulators of plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J Integr Plant Biol. 2024;66(3):330–67. doi:10.1111/jipb.13601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ighodaro OM, Akinloye OA. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SODcatalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPXtheir fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex J Med. 2018;54(4):287–93. doi:10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Baker A, Lin CC, Lett C, Karpinska B, Wright MH, Foyer CH. Catalase: a critical node in the regulation of cell fate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;199(33):56–66. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wei X, Liu N, Yang W, Hou W, Hou Y, Kang Z, et al. Stripe rust effector Pst9653 interferes with subcellular distributions of catalase TaCAT3 to facilitate susceptibility-involved ROS scavenging in wheat. New Phytol. 2025;247(6):2885–902. doi:10.1111/nph.70341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Yang R, Ma Y, Yang Z, Pu Y, Liu M, Du J, et al. Knockdown of β-conglycinin α’ and α subunits alters seed protein composition and improves salt tolerance in soybean. Plant J. 2024;120(4):1488–507. doi:10.1111/tpj.17062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Sabouri H, Kazerani B, Ali Fallahi H, Ali Dehghan M, Alegh SM, Dadras AR, et al. Association analysis of yellow rust, fusarium head blight, tan spot, powdery mildew, and brown rust horizontal resistance genes in wheat. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2022;118(3):101808. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2022.101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools