Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of Phenological Stage on the Volatile Content and Biological Properties of Origanum elongatum Essential Oil

1 Laboratory of Applied Organic Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Imouzzer Road, Fez, Morocco

2 Plant Protection Research Unit, National Institute of Agronomic Research, Regional Center of Agronomic Research of Meknes INRA-CRRA, Meknes, Morocco

3 Laboratory of Microbial Biotechnology and Bioactive Molecules, Faculty of Sciences and Technologies Faculty, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, P.O. Box 2202, Imouzzer Road, Fez, Morocco

4 Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

5 Laboratory of Drug Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy, and Dental Medicine of Fez, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco

6 Department of Medical Laboratories, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Qassim University, Buraydah, Saudi Arabia

7 King Fahad Armed Forced Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

8 Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Guelmim, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Naoufal El Hachlafi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Strategies in Medicinal Plant Biotechnology: From Traditional Knowledge to Modern Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 12 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.072398

Received 26 August 2025; Accepted 14 January 2026; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Origanum elongatum (OE) is an aromatic, medicinal plant endemic to Morocco that is widely used in traditional medicine due to its biological properties. This study aimed to elucidate the chemical composition of the essential oil (EO) obtained from O. elongatum (OEEO) at three stages of its life cycle, including vegetative stage (OEEO-VS), flowering stage (OEEO-FS), and post-flowering (OEEO-PFS), as well as to evaluate its biological and antiradical characteristics. The chemical analysis of the essential oil was conducted using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The antibacterial activity was evaluated in vitro through distinct methodologies, namely, disc diffusion and microatmosphere assay; subsequently, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was then determined. The antioxidant potential was also measured by using the DPPH and FRAP assays. The GC-MS revealed the predominant of p-cymene (26.83%_31.45%), γ-terpinene (8.46%_26.95%), thymol (13%_29.54%), and carvacrol (20.25%_37.26%), in all three samples, with notable variations according to the phenological stage of the samples. The EOs extracted at three phenological stages demonstrated notable antibacterial efficacy against all the phytopathogen tested. The MICs for Erwinia amylovora exhibited a range of 6.25 and 250 µg/mL. However, for Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 and Allorhizobium vitis S4, the MICs spanned 125 and 250 µg/mL. In the DPPH test, the IC50 values were 168.25 ± 1.14, 147.01 ± 0.78, and 132.01 ± 2.06 µg/mL for EOs derived from the vegetative, flowering, and post-flowering period, respectively. In the FRAP test, the EC50 values were 164.22 ± 1.04, 215.73 ± 1.48, and 184.06 ± 0.95 µg/mL for the same stages. The findings offer promising prospects for the phytochemical development, demonstrating how the phenological stage significantly influences the therapeutic and biotechnological potential of O. elongatum. This has the potential to open up new avenues of research in the pharmaceutical, agronomic, and environmental fields.Keywords

Northern Morocco, with its Mediterranean climate, is very rich in aromatic and medicinal plants, some of which are endemic. Among these, we found Origanum species that are used worldwide in conventional therapy for the treatment of a certain range of diseases, including respiratory problems [1], digestive troubles, poisoning, dandruff [2], diabetes [3], and inflammation [4]. Extensive in vitro testing has revealed a vast array of pharmacological properties related to these plants, notably antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antiviral properties [5,6,7,8,9].

Numerous research studies have reported that the Origanum genus essential oils contain a diverse range of terpenoids and phenolic compounds, including carvacrol, thymol, γ-terpinene, and p-cymene [10,11,12]. This chemical composition is affected by many factors, such as altitude [13] and the phenological stage [14,15].

Origanum elongatum is an endemic aromatic and medicinal plant of the Lamiaceae family, a perennial herb of the Origanum genus [16]. Its distribution in the wild is limited to the northeast (NE) of Morocco and extends from the Middle Atlas to the Rif mountain [17], in open forests, rocky outcrops and mountain matorrals, on siliceous substrates and deep, well-drained soils, and characterized by bioclimatic plasticity since it is able to grow under different climatic conditions, including semi-arid, sub-humid, humid and per-humid [18]. O. elongatum develops easily in temperate continental climates and grows rapidly [19]. O. elongatum is therefore characterized by chemical polymorphism with appreciable inter- and intrapopulation variability. In this context, a phytochemical study of 168 samples of O. elongatum from different regions reported that the most dominant compound was carvacrol, followed by thymol and p-cymene. Limonene, α-terpineol, thymoquinone, carvacrylic methyl oxide, and caryophyllene oxide (rare compounds in Origanum taxa) [17]. Other studies too have shown the richness of Origanum elongatum by several classes of bioactive compounds, including terpenoids, flavonoids, oxygenated compounds, hydrocarbon compounds, and phenolic compounds [5,18,20,21].

O. elongatum grows naturally in the Moroccan Rif and is of great importance as a plant of ethnopharmacological value to the local population [17]. Certain individuals prefer the plant’s preparation at specific stages, with some favoring the flowering stage while others prefer the post-flowering stage [22].

The aim of this study was to determine for the first time the optimal harvesting period with the richest concentration of bioactive compounds, and to evaluate the variation of chemical compounds in O. elongatum essential oil at three different phenological stages, including vegetative, flowering, and post-flowering stages. In addition, the antibacterial, antioxidant, and OEEO activities of different phenological stages were evaluated to establish possible correlations between biological activity and the chemical composition of the oils.

2.1 Plant Material and Essential Oils Extraction

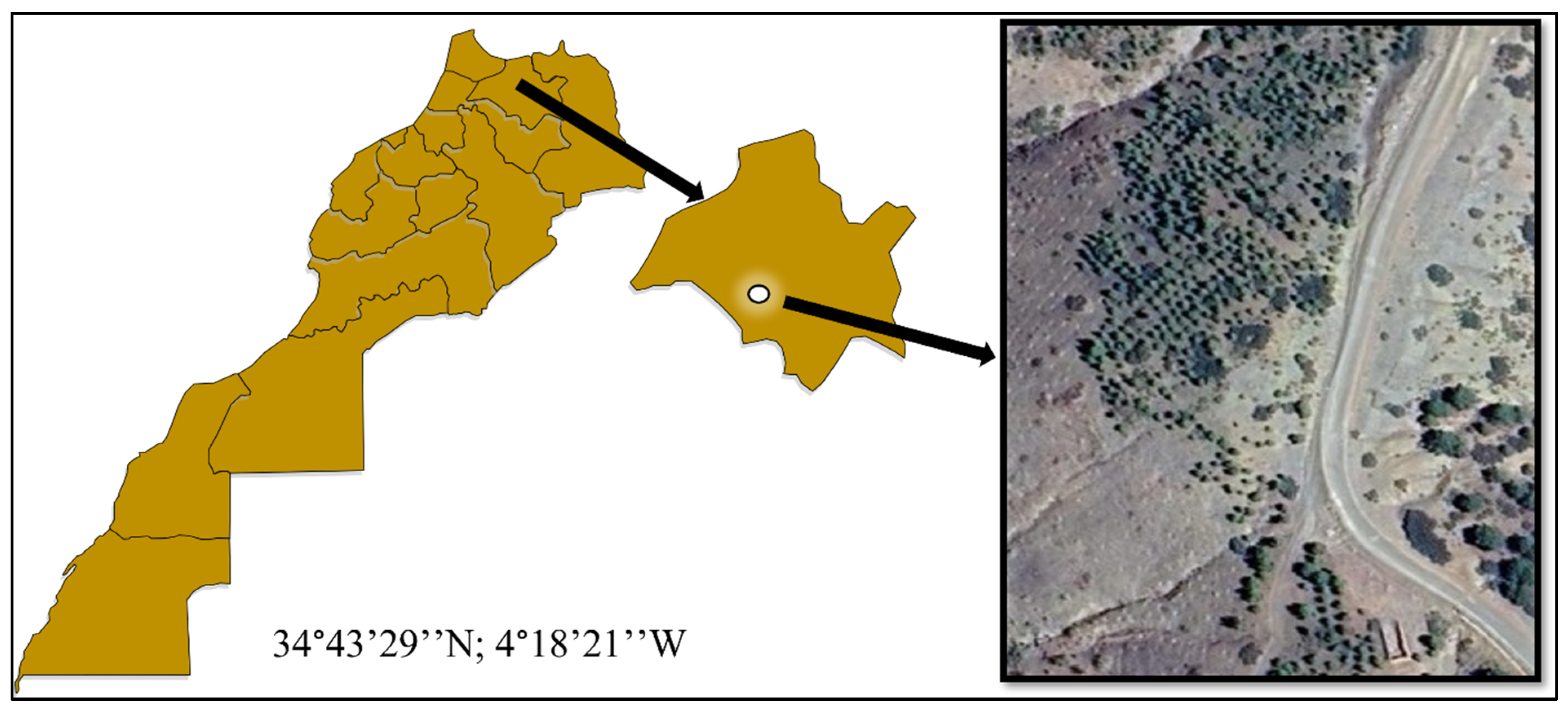

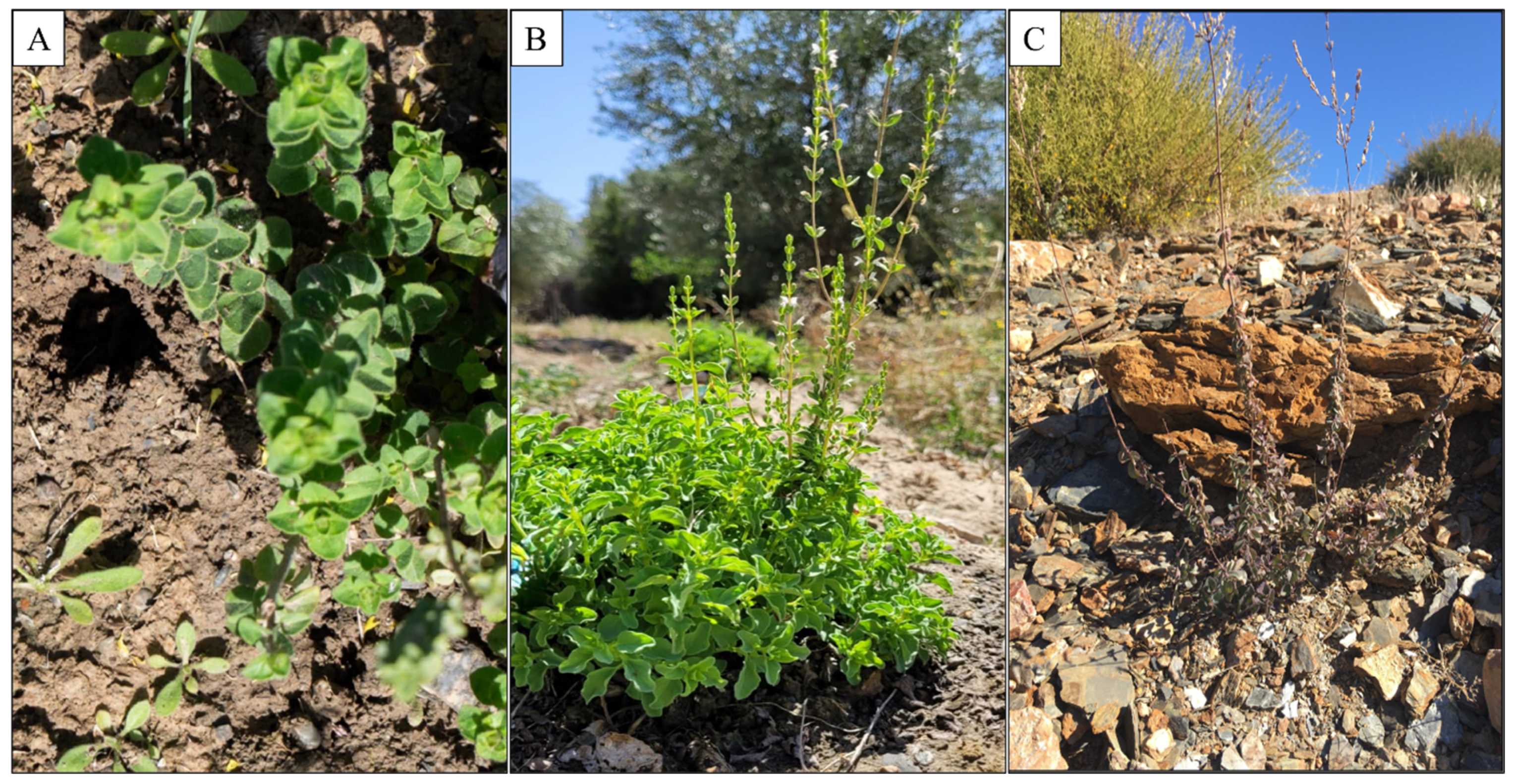

As part of our study, we collected areal part of O. elongatum in the Targuist region (34°43′29″ N; 4°18′21″ W) (Fig. 1). The samples were collected aerial plant part at three key points in the OE life cycle: the vegetative period (April 2023), the flowering period (June 2023) and the post-flowering period in August 2023 (Fig. 2). From these samples, we were able to carry out chemical and biological analyses of EO in the early, middle and late stages of their development. The plant material was dried in the shade and subjected to hydrodistillation using a Clevenger apparatus. The obtained EO was stores at 4°C until use.

Figure 1: Mapping of Origanum elongatum collection point at various development stage.

Figure 2: Origanum elongatum in its natural state in three stages of development: (A) O. elongatum at Vegetative stage; (B): O. elongatum at flowering stage; (C): O. elongatum at post flowering stage.

2.2 Study Area and Climate Condition

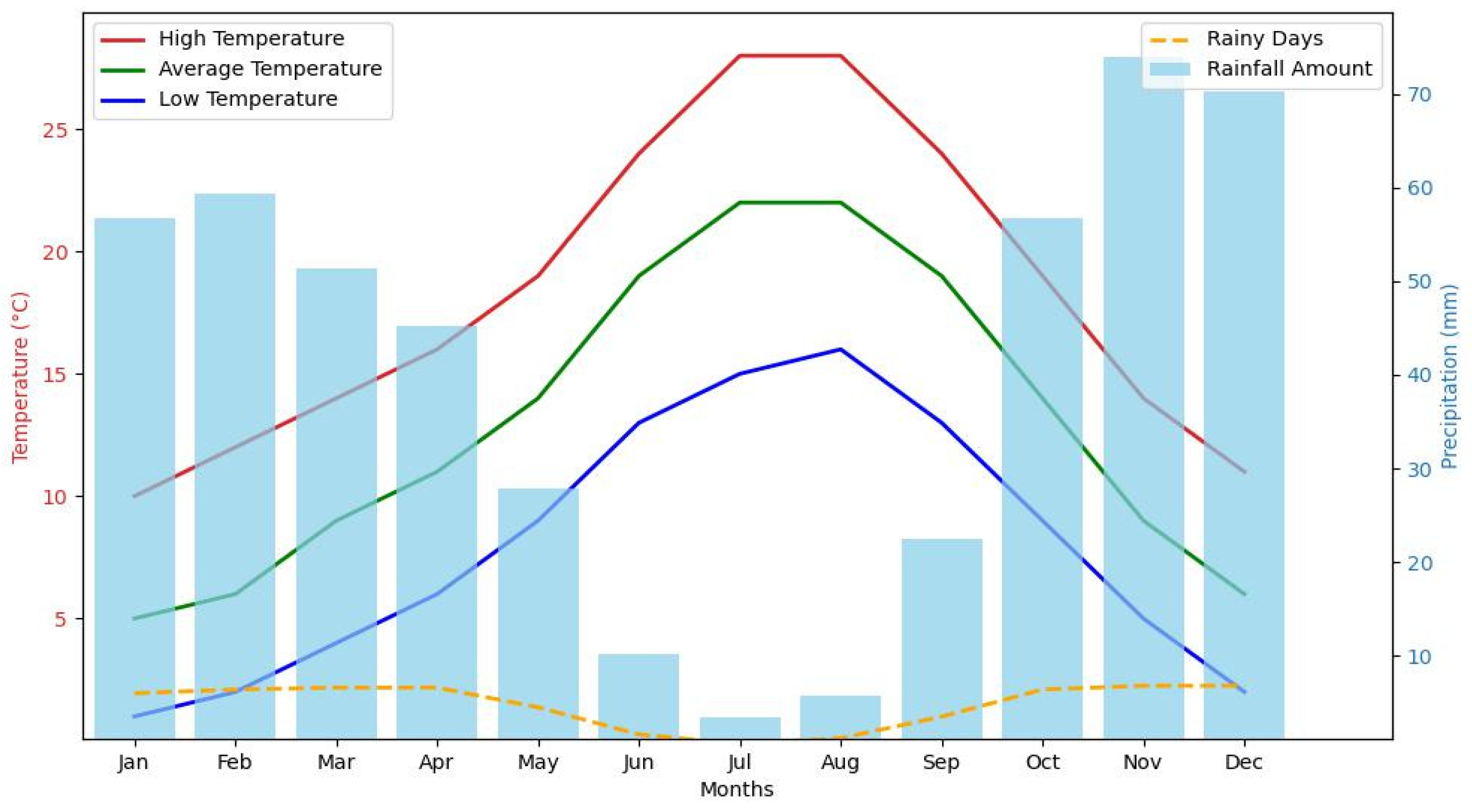

The climate of the region varies considerably during the months that are most important for the development of the plants. In April, during the vegetative stage, the average temperature is around 11°C, providing relatively mild conditions for plant growth. The plants start growing vigorously, with maximum temperatures reaching 16°C. However, the number of rainy days (a day on which measurable rainfall occurs, which is commonly defined as ≥1 mm of precipitation) in April was 6.6 days, with a total rainfall of 45.2 mm. This may affect the health and growth of the crop. In June, when the plants are flowering, the climate warms considerably, with an average temperature of 19°C and a maximum up to 24°C. This increase in temperature promotes flower blooming. In addition, the number of rainy days drops dramatically to an average of only 1.6 days with an average rainfall of 10.2 mm. In August, during the post-flowering period, temperatures remained warm with an average of 22°C, although the maximum and minimum values did not differ much from those of June (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the number of rainy days remained low, with an average of only 0.6 days and a minimum rainfall of 3.4 mm.

Figure 3: Rainfall and temperature distribution in study area.

2.3 Identification of Volatile Components

The GC-MS analyses were carried out on three samples of OEEO corresponding to three phenological stages (vegetative, flowering, and post-flowering). The gas chromatography-mass spectrometry was performed using a GC-MS-TQ8040 NX (Shimadzu) equipped with a triple quadrupole detector. The compounds were isolated on a non-polar RTxi-5 Sil MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 µm). Helium was used as the carrier gas. The injection volume was set at 1 µL in splitless mode, with the split being opened after 4 min. The injection temperature was set at 250°C, with a pressure of 37.1 kPa. The temperature program started at 50°C/min (held for 2 min), followed by two ramps: 5°C/min to 160°C (held for 2 min), then 5°C/min to 280°C (held for 2 min), for a total analysis time of 50 min. The ion source and interface temperatures were 200°C and 280°C, respectively. The acquisition was performed in full scan mode, and the compounds were identified using the NIST library version 2019, and Hexane was used as a dilution solvent for the samples. To obtain the percentage of relative peak area for the EOs, firstly, we add up all the areas of all the peaks. Then we divided the area of each peak by the total area and multiplied the results by 100 to obtain the percentage of each EO component [17]. The GC-MS analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility.

2.4.1 Bacteria Strains and Growth Conditions

Three phytopathogens, including Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58, Allorhizobium Vitis S4, and Erwinia amylovora, were used to study the antibacterial potential of OEEO at three phenological stages. All the bacterial strains used in this work were obtained from the Laboratory of Phytopathology of the Regional Centre for Agronomic Research (INRA-CRRA) in Meknes. The preparation of the bacterial suspension followed a precise protocol. However, separate colonies from a fresh culture on LB agar medium were carefully selected. These colonies were then transferred to a sterile sodium chloride (0.9% NaCl) solution. The bacterial concentration was adjusted to approximately 106 CFU/mL. The optical density of the suspension was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer at 625 nm and standardized according to the 0.5 McFarland standard.

The antibacterial efficacy of each phenological stage of OEEO was estimated using the disc diffusion technique. This method was adapted from a published method with minor changes [15]. The previously prepared bacterial working suspensions, adjusted to 106 CFU/mL, were spread homogeneously on LB agar plates. A sterile filter disc of 6 mm diameter, soaked with 10 μL of OEEO of each phenological stage, was carefully positioned on the inoculated plates. Streptomycin 15 μg/disc was used as a positive control, and the diameter of the inhibition zone around each disc was measured in millimeters after incubation at 37°C for 24 h.

2.4.3 The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The antibacterial activity of OEEO at three phenological stages (OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS, and OEEO-PFS) was evaluated using a 96-well microplate dilution method [15]. Each well contained 95 µL of double-strength LB broth, to which serial dilutions of EO (in 4% DMSO) were added, yielding final concentrations ranging from 1000 to 7.8 µg/mL. Streptomycin was used as a positive control, and 4% DMSO alone served as a negative control. Then, 10 µL of bacterial suspension (≈ 106 CFU/mL) was added to each well. Microplate was incubated at 35°C for 24 h. Bacterial growth was assessed by adding 20 µL of resazurin solution; a color change from blue to pink indicated metabolic activity. The MIC was defined as the lowest OEEO concentration at which no color change was observed

The free radical scavenging properties of OEEO during the vegetative (OEEO-VS), flowering (OEEO-FS), and post-flowering (OEEO-PFS) stages were evaluated using the 2,2-diphenyl 1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. This method, which has been previously documented in a published paper, was used with a slight modification to determine the free radical scavenging potential of each OEEO phenological stage [23]. Briefly, 90 µL of EO at different concentrations were mixed with 600 µL of 0.04% ethanolic DPPH solution. After incubation for 30 min in the dark, the absorbance was measured at 530 nm using a spectrophotometer. Negative controls were prepared by mixing 90 µL of ethanol with 600 µL of DPPH solution, without EOs, to correct for background absorbance. However, positive controls included BHT (Butylated hydroxytoluene) and ascorbic acid. All assays were performed in triplicate, and the IC50 was calculated as the concentration of EOs required to inhibit 50% of DPPH free radicals.

The ferric reducing antioxidant capacity of each sample of OEEO phenological stage was studied as reported by [24] with some slight changes.

Briefly, a reaction mixture was prepared by combining 0.5 mL of each EO at various concentrations with 1.25 mL of phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH = 6.6) and 1.25 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide. The resulting mixture was incubated at 50°C for 25 min. After incubation, 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to precipitate the proteins, and centrifugation was performed at 5000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant obtained (1.25 mL) was diluted with 1.25 mL of distilled water, and 250 µL of 0.1% ferric chloride (FeCl3) was added. However, negative controls were prepared by replacing the EO with ethanol only to correct for background absorbance. Positive controls included BHT and ascorbic acid. The EC50, defined as the concentration of OEEO required to achieve an absorbance of 0.5, was then calculated.

All assays were conducted in triplicate, and the data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad version 9. Mean differences were evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, with significance accepted at p < 0.05.

3.1 Chemical Profile of the Three OEEO Phenological Stage Samples.

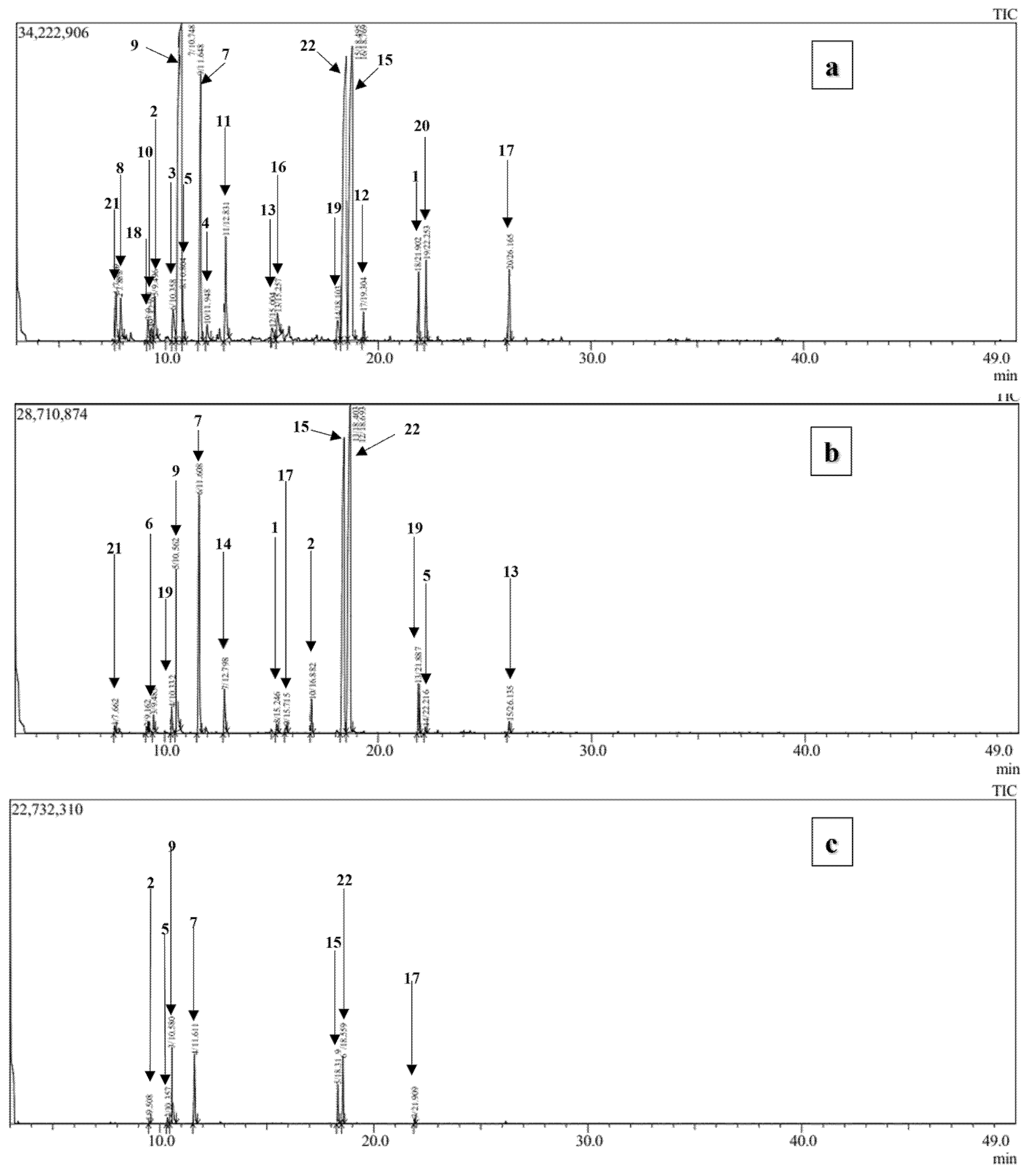

The GC-MS analysis of the essential oils of O. elongatum from three different phenological stages, including vegetative, flowering, and post-flowering (Fig. 4 and Table 1), revealed a diverse range of chemical composition (22 compounds), with monoterpenes representing the dominant class of compounds. The extraction yields were found to be 4.9%, 5% and 2.1% for OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS, and OEEO-PFS, respectively. The predominant compounds identified in all three samples were p-cymene (26.83%_31.45%), γ-terpinene (8.46%_26.95%), thymol (13%_29.54%), and carvacrol (20.25%_37.26%), with notable variations according to the phenological stage of the samples. The predominant chemical group was oxygenated monoterpenes, representing 49.22%, 69.29% and 62.76% of the total composition, respectively, for OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS, and OEEO-PFS. This was followed by hydrocarbon monoterpenes, which constituted 41.92%, 25.16% and 34.63% of the total composition, respectively. The presence of sesquiterpenes was observed in minimal quantities in OEEO-VS (4.11%) and OEEO-FS (2.62%), whereas no such compounds were identified in OEEO-PFS (Table 2). However, OEEO-FS was characterized by particularly high levels of carvacrol (37.26%) and thymol (29.54%), while OEEO-PFS had the highest concentration of γ-terpinene (26.95%) and p-cymene (31.45%). These results highlight the significant influence of the phenological stage on the chemical composition of OEEO.

The chemical composition of OEEO is comparable to that of other species within the Origanum genus, yet it possesses distinctive characteristics. In their studies of O. compactum, Bouyahya and colleagues observed that oxygenated monoterpenes (49.4–62.975%) and hydrocarbon monoterpenes (31.815–43.632%) constituted the main chemical groups, with carvacrol, thymol, p-cymene, and γ-terpinene identified as the major compounds. The proportions of carvacrol and thymol exhibited notable variation across the three phenological stages, at the vegetative stage, they constituted 27.71% and 15.32%, respectively. In contrast, at the flowering stage, carvacrol increased to 43.58%, while thymol decreased to 10.33%. At the post-flowering stage, this trend was reversed, with 38% thymol and 6.4% carvacrol being the predominant compounds [14,25]. A similar trend was observed in O. vulgare in a previous study, which reported that carvacrol was the predominant compound at all stages (61.08–83.37%), followed by p-cymene (3.02–9.87%) and γ-terpinene (4.13–6.34%) [22]. Morshedloo and colleagues additionally observed the preponderance of carvacrol (18.1–79.2%) in the EO vulgare subsp. gracile, with elevated concentrations in the flowers (79.2%), roots (70%), and early vegetative stage (67.34%) [26]. A further study revealed that thymol constituted the principal compound (46.90–62.26%) in O. vulgare EO at all stage of development, with γ-terpinene (1.11–11.75%) and p-cymene (3.11–5.32%) ranking as the next most abundant components [27]. However, Moradi and colleagues reported that the EO content was highest at the post-flowering stage (1.87%) and the lowest at the pre-flowering stage (1.01%) in O. vulgare, with carvacrol, p-cymene, and γ-terpinene as the main components [28].

It is of great importance to highlight that the chemical composition of EO is subject to variation due to a multitude of factors that influence the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. The geographical origin of the plant, its exposure, the altitude of its habitat, climatic conditions, in particular temperature, the genotype of the plant, and edaphic factors linked to the soil are among the factors that contribute to the variation in chemical composition observed in EOs [29]. The aforementioned diversity of parameters provides an explanation for the observed variations in the chemical composition of our study in comparison with other oregano species analyzed in the scientific literature.

Table 1: Chemical profile of OEEO at three phenological stage.

| N° | Compounds | Formula | RI1 | LRT2 | OEEO-VS3 (%) | OEEO-FS4 (%) | OEEO-PFS5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-thujene | C10H16 | 902 | 921 | 1.48 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | _ |

| 2 | δ-carene | C10H16 | 919 | 929 | 1.46 ± 0.08 | 1.29 ± 0.04 | 2.36 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | α-pinene | C10H16 | 948 | 943 | 1.27 ± 0.14 | _ | _ |

| 4 | 3-octanonere | C8H16O | 952 | 969 | 0.42 ± 0.1 | _ | _ |

| 5 | β-myrcene | C10H16 | 958 | 990 | 1.31 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.21 | 0.81 ± 0.11 |

| 6 | morillol | C8H16O | 969 | 1009 | _ | 0.28 ± 0.01 | _ |

| 7 | γ-terpinene | C10H16 | 998 | 1017 | 8.46 ± 0.43 | 13.60 ± 1.57 | 26.95 ± 0.28 |

| 8 | D-limonene | C10H16 | 1018 | 1031 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | _ | _ |

| 9 | p-cymene | C10H14 | 1023 | 1024 | 26.83 ± 1.05 | 9.13 ± 0.26 | 31.45 ± 1.46 |

| 10 | Trans-sabinene hydrate | C10H18O | 1041 | 1042 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | _ | _ |

| 11 | linalool | C10H18O | 1082 | 1082 | 2.24 ± 0.13 | _ | _ |

| 12 | L-4-terpineol | C10H18O | 1137 | 1177 | 1.20 ± 0.03 | _ | _ |

| 13 | endo-borneol | C10H18O | 1138 | 1140 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | _ |

| 14 | isothymol methyl ether | C11H16O | 1231 | 1235 | _ | 1.40 ± 0.06 | _ |

| 15 | thymol | C10H14O | 1262 | 1294 | 24.39 ± 0.27 | 29.54 ± 0.73 | 13.00 ± 0.21 |

| 16 | tropolone | C10H12O2 | 1311 | 1313 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | _ | _ |

| 17 | p-ethylguaiacol | C 10H14O2 | 1416 | 1430 | 1.80 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 1.63 ± 0.17 |

| 18 | farnesyl acetate | C15H26O | 1479 | 1470 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | _ | _ |

| 19 | caryophyllene | C15H24 | 1494 | 1448 | 1.43 ± 0.01 | 2.62 ± 0.03 | _ |

| 20 | caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O | 1507 | 1578 | 1.96 ± 0.04 | _ | _ |

| 21 | thiofenchone | C10H18O | 1575 | 1555 | _ | 0.52 ± 0.01 | _ |

| 22 | carvacrol | C10H14O | 1665 | 1590 | 20.25 ± 0.36 | 37.26 ± 0.55 | 21.81 ± 0.6 |

| TOTAL (%) | 98.02 | 97.62 | 99.01 | ||||

| YIELD (%) | 4.9 | 5 | 2.1 | ||||

Table 2: Chemical groups of OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS and OEEO-PFS.

| Chemical Groups | OEEO-VS1 (%) | OEEO-FS2 (%) | OEEO-PFS3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 41.92 | 25.16 | 34.62 |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 49.22 | 69.29 | 62.76 |

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 1.43 | 2.62 | _ |

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 2.68 | _ | _ |

| Other | 2.77 | 0.55 | 1.63 |

Figure 4: GC-MS profiles of O. elongatum EOs. (a) the vegetative stage, (b) flowering stage, and (c) postflowering stages.

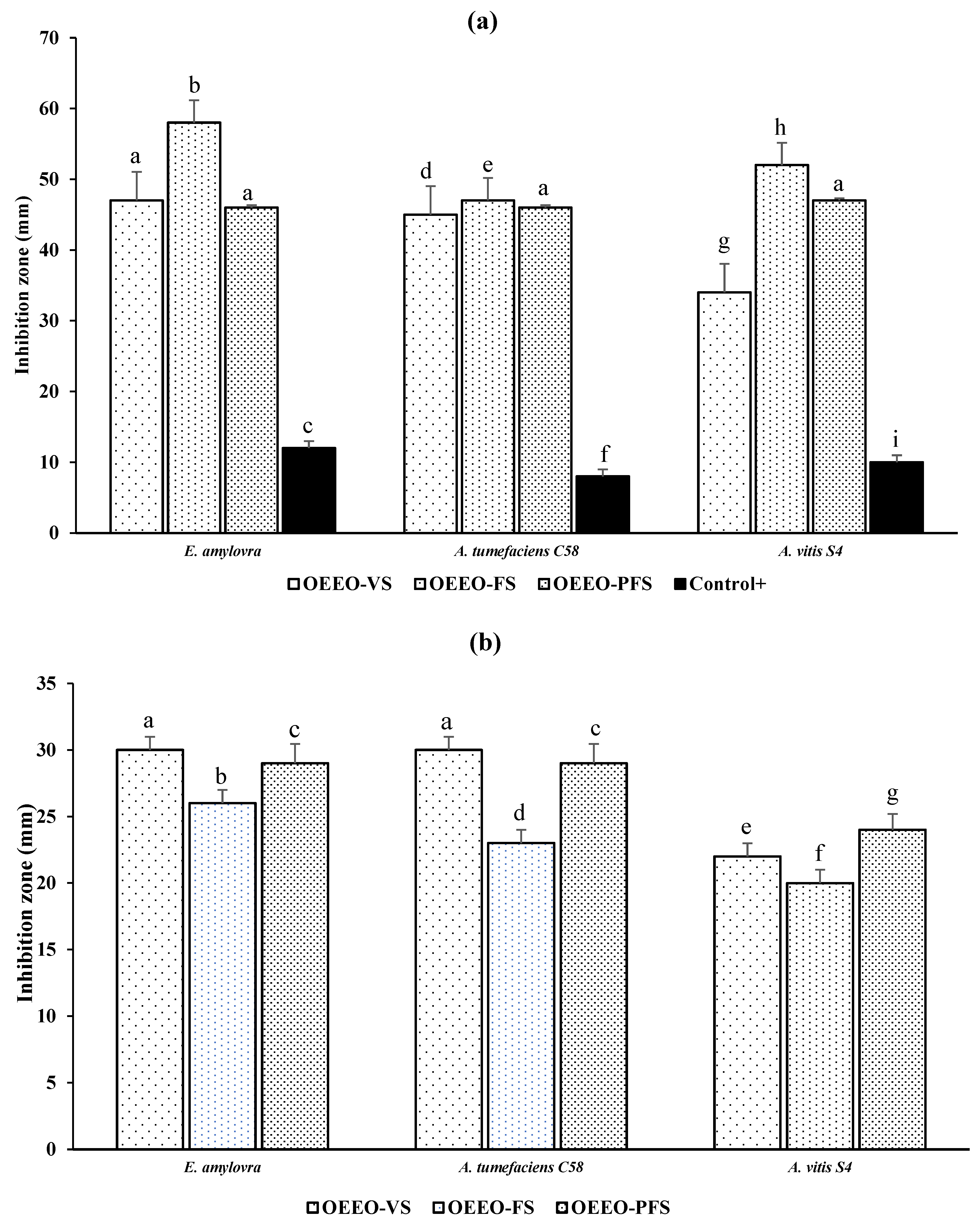

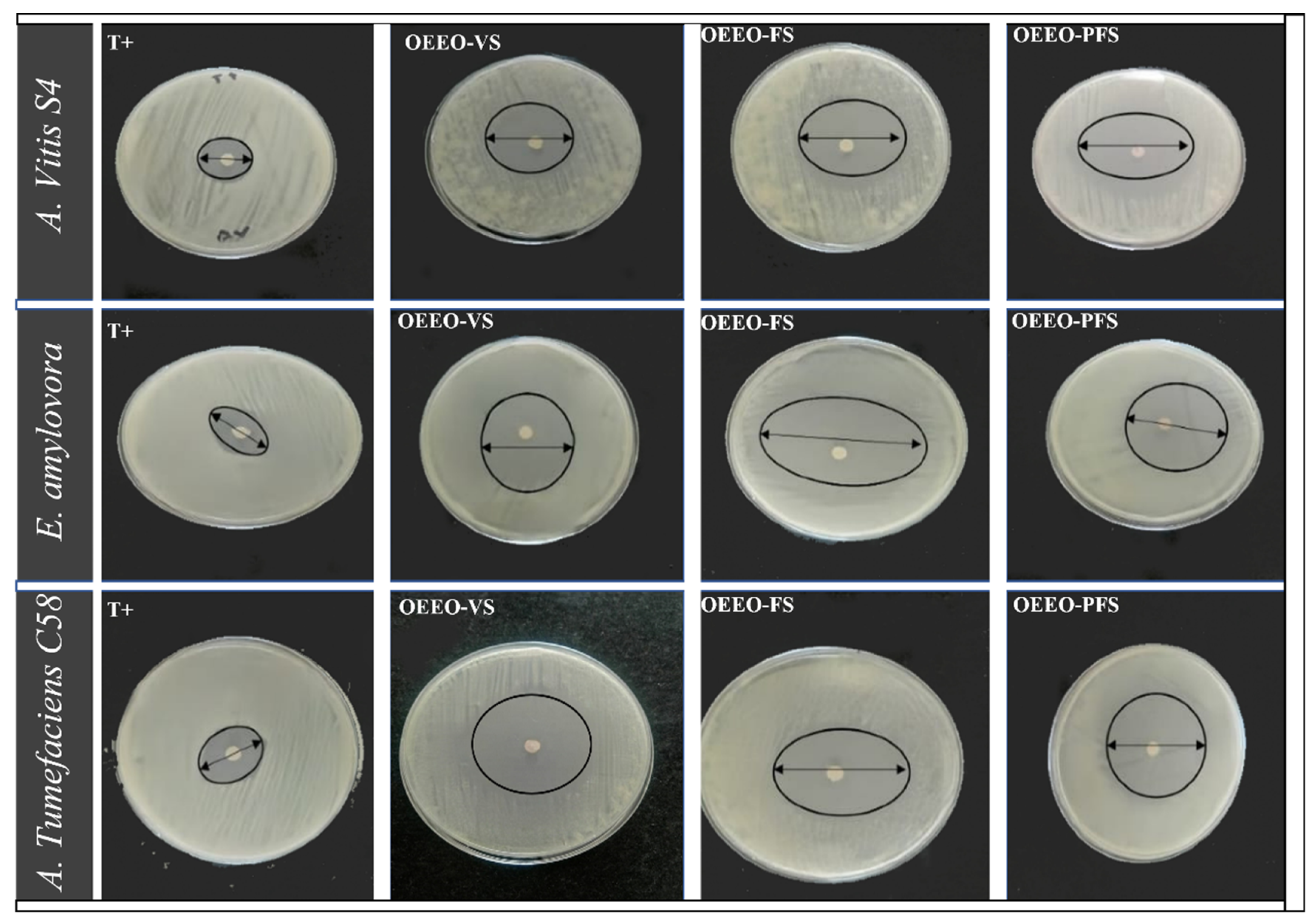

The results of the evolution of the antibacterial activity of OEEO as a function of its stage of development, using the disc diffusion method, show notable variations in antibacterial efficacy for the three phytopathogenic bacteria tested (Fig. 5a). The inhibition zones measured for E. amylovora were 47 ± 3.1 mm for OEEO-VS, 58 ± 2.01 mm for OEEO-FS, and 46 ± 1.13 mm for OEEO-PFS. When subjected to OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS, and OEEO-PFS, A. tumefaciens C58 exhibited inhibition zones of 45 ± 1.12, 47 ± 1.45, and 46 ± 1.32 mm, respectively. However, A. vitis S4 displayed inhibition zones of 34 ± 2.4, 52 ± 2.21, and 47 ± 3.32 mm for OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS, and OEEO-PFS, respectively. The findings showed that the OEEO-FS was the most effective, with the largest inhibition zones for the three phytopathogen tested, and the most sensitive to the essential oils tested was E. amylovora (Fig. 6). In the case of microatmospher assay, the inhibition zone caused by the volatile compounds present in OEEO are presented in Fig. 5b. With the OEEO-VS, E. amylovora and A. tumefaciens C58 displayed the most extensive zone of inhibition, measuring 30 ± 2.1 and 30 ± 3.2 mm, respectively. Additionally, E. amylovora reported a 26 ± 3.2 mm zone of inhibition for OEEO-FS. In summary, the biggest zone of inhibition for E. amylovora and A. tumefaciens C58 was 29 ± 1.07 and 29 ± 2.5 mm in the present of OEEO-PFS. On the other hand, the results of MIC demonstrate that OEEO exhibits antibacterial activity towards the three phytopathogen strains tested, including E. amylovora, A. tumefaciens C58, and A. vitis S4. However, the degree of sensitivity exhibited varies according to the phenological stage of OEEO (Table 3). Overall, OEEO-FS demonstrated the greatest efficacy, particularly against E. amylovora, exhibiting an MIC of 62.5 µg/mL, lower than that of the positive control. For A. vitis oils from vegetative and flowering stages exhibited equivalent activity (125 µg/mL), which was twice as potent as that observed in the post OEEO-PFS (250 µg/mL). A similar trend was observed for A. tumefaciens, with the OEEO-VS and OEEO-FS exhibiting more pronounced activity (140 µg/mL). In contrast, OEEO-PFS demonstrate reduced efficacy (300 µg/mL). In fact, a study has shown that O. elongatum EOs fractions obtained between 141 and 160 min of hydrodistillation exhibited the highest activity, with MICs ranging from 0.0312 to 0.125%(v/v) and MBCs ranging from 0.0312 to 0.25% (v/v) [30]. Furthermore, another study on the antibacterial efficacy of O. elongatum reported MICs ranging from 2 to 8 µL/mL against several bacterial strains, except for Staphylococcus aureus (MIC = 32 µL/mL) [5]

The aforementioned studies irrefutably demonstrate that the EOs of assorted medicinal plants exhibit pronounced antibacterial activity, with discernible variations contingent on the phenological phase. The analysis of Origanum vulgare subsp. glandulosum revealed zone of inhibition ranging from 9 to 36 mm and the MICs of 125 to 600 µg/mL. against Bacillus subtilis [22]. However, the efficacy of the vegetative and flowering stages of Origanum compactum against Staphylococcus aureus was also confirmed, with remarkable inhibition diameters of 47 mm and best bactericidal action (MIC = MBC = 0.0312%(v/v)) [23]. In a separate study, the researchers investigated the antibacterial activity of Thymus daenensis and Thymus fedtschenkoi EOs against diverse range of pathogenic bacteria. They observed that the plant exhibited notable antibacterial efficacy at various phenological stages, with MICs values ranging from 1 to 16 mg/mL and 2 to 32 mg/mL, respectively [31]. Nevertheless, a comprehensive examination of Salvia officinalis at all three developmental stages revealed a consistent and pronounced antibacterial efficacy. The most sensitive bacteria were Listeria monocytogenes, followed by Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, and salmonella typhimurium, with slight superiority at the flowering stage [32]. This trend towards optimum efficacy at the flowering stage was also observed in Pelargonium graveolens against different bacterial strains, with zones of inhibition ranging from 11 to 17.30 and MICs of 0.25 to 2% (v/v) [33]. Notably, Thymus maroccanus yield particularly impressive results, demonstrating maximum activity against both Gram positive (21–48 mm and Gram negative (9.7–23.7 mm) bacteria, and the MICs (0.13 to 0.95 mg/mL at different stages of development [34].

Figure 5: Inhibition zone of OEEO at three phenological stage against E. amylovora, A. tumefaciens C58 and A. vitis S4. (a): disc diffusion assay; (b) microatmospher assay. OEEO-VS: O. elongatum EO—vegetative stage; OEEO-FS: O. elongatum EO—flowering stage; OEEO-PFS: O. elongatum EO—post flowering stage and control+: streptomycin. Data with the same letter in the same test present non-significant difference by Tukey’s multiple range test (ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Figure 6: Inhibition zones of OEEO-VS, OEEO-FS and OEEO-PFS against three phytopathogens. OEEO-VS: O. elongatum EO—vegetative stage; OEEO-FS: O. elongatum EO—flowering stage; OEEO-PFS: O. elongatum EO—post flowering stage and T+: streptomycin (positive control).

Table 3: Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of OEEO at different stages.

| Bacterial Strains | MIC (µg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEEO-VS1 | OEEO-FS2 | OEEO-PFS3 | Control+4 | |

| A. vitis S4 | 125 | 125 | 250 | 65 |

| A. tumefaciens C58 | 150 | 150 | 300 | 130 |

| E. amylovra | 125 | 62.5 | 125 | 130 |

The antioxidant potential of OEEO was evaluated using DPPH and FRAP tests, which yielded distinct activity profiling according to phenological stage (Table 4). This suggests an intriguing variation in antioxidant power. The DPPH test results demonstrated that the OEEO-PFS exhibited the most potent antioxidant effect, with an IC50 value of 132.01 ± 2.06 µg/mL. This was followed by OEEO-VS (IC50 = 147.01 ± 0.78 µg/mL), whereas OEEO-FS displayed the lowest activity with an IC50 of 168.25 ± 1.14 µg/mL. However, although these results are promising, they are still less effective than the reference antioxidant BHT (IC50 = 63.21 ± 0.03 µg/mL) and ascorbic acid (IC50 = 41.32 ± 0.08 µg/mL). While the results of the FRAP test demonstrated a notable variation in the antioxidant activity of OEEO across the different phenological stages of the plant. The most pronounced antioxidant effect was observed in OEEO-FS, with an EC50 of 164.22 ± 1.04 µg/mL, followed by OEEO-PFS (184.06 ± 0.95 µg/mL). In contrast, the OEEO-VS showed the lowest activity, with an EC50 of 215.73 ± 1.48 µg/mL. While these values indicate an intriguing antioxidant potential, they remain inferior to that of BHT (89.44 ± 0.13 µg/mL), which serves as reference antioxidant.

Table 4: Antioxidant activity of OEEO at three phenological stage.

| Samples | Positive Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEEO-FS1 | OEEO-VS2 | OEEO-PFS3 | BHT4 | Ascorbic Acid | |

| FRAP (EC50 (µg/mL)) | 164.22 ± 1.04b | 215.73 ± 1.48d | 184.06 ± 0.95c | 89.44 ± 0.13a | - |

| DPPH (IC50 (µg/mL)) | 168.25 ± 1.14e | 147.01 ± 0.78d | 132.01 ± 2.06c | 63.21 ± 0.03b | 41.32 ± 0.08a |

A comparison of our results with those of previous studies revealed both similarities and differences in the antioxidant ability of our OEEO, depending on the phenological stage. However, for Origanum vulgare subsp. gracile, Morshedloo, and colleagues observed maximum antioxidant activity in the flowering stage (EC50 = 0.86 mL/mL), while the vegetative and fruiting stages showed lower activity [26]. Conversely, another study demonstrated a progressive increase in antioxidant activity for Origanum compactum, with antioxidant capacity rising from EC50 = 94.18 to 53.28 µg/mL and IC50 values falling from 320 to 172.87 µg/mL, between the vegetative flowering and post flowering stages of growth [23]. In contrast, Origanum majorana exhibited higher antioxidant activity at the late vegetative stage (IC50 = 40–50 µg/mL) compared to the early vegetative and flowering period [35]. However, a study demonstrated that the antioxidant activity of Origanum vulgare ssp. Hirtum reaches its peak during the full flowering stage (7.711 ± 0.253 µmol/g), subsequently declining significantly at the post flowering phase [36]. Nevertheless, an investigation on Origanum vulgare L fined that the potential antioxidant of his EOs at various stages of growth range between EC50 = 7.91 and 8.59 mg/mL [37]. Additionally, the anti-radical activity expressed by IC50 of Origanum vulgare subsp glandulosum (Desf.) Ietswaart was varied from 59.2 mg/L to 226.19 mg/L [38]. In another work on the effect of the development stage of Rosmarinus officinalis L. var. typicus Batt, find a high of ability of EOs to trap the free radicals of DPPH (IC50 = 17.3 µg/mL for vegetative EO and IC50 = 8.59 mg/mL for fruiting stage) [39]. The observed variations in antioxidant activity at different phenological growth stages may be ascribed to alterations in the chemical structure of the EOs occurring during the plant’s development. This hypothesis is supported by the findings of supplementary studies, including [37]. Geographical origin, exposure to sunlight, altitude, soil climate, and plant genetics can also modify the chemical content and therefore the antioxidant capacity of the plant [25,40,41].

This study highlighted, for the first time, the decisive impact of the phenological stage on the chemical composition and biological properties of O. elongatum EO. GC-MS analysis confirmed that the major compounds (p-cymene, γ-terpinene, thymol, and carvacrol) are present at all stages, but in varying proportions. The flowering stage (OEEO-FS) was characterized by maximum carvacrol (37.36%) and thymol (29.54%) content, while the post-flowering stage (OEEO-PFS) revealed higher levels of γ-terpinene (26.95%) and p-cymene (31.45%). These chemical fluctuations resulted in notable differences at the biological level. The EO produced during the flowering stage exhibited the most pronounced antibacterial activity, particularly against E. amylovra with an MIC of 62.5 µg/mL, confirming its value as a natural biocontrol agent. At the same time, the EO from the post-flowering stage demonstrated greater effectiveness in trapping free radicals FPPH, while that from the flowering stage performed better in the FRAP test. Overall, these results highlight the crucial importance of choosing the right harvest stage to optimize therapeutic and biotechnological use of O. elongatum EO. The flowering stage appears to be the most appropriate for antibacterial actions, while the post-flowering stage could be valued for its antioxidant properties. These findings pave the way for better utilization of this endemic Moroccan species, with promising prospects in the pharmaceutical, agronomic, and environmental fields.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Amine Batbat, Khaoula Habbadi and Naoufal El Hachlafi; data acquisition: Samiah Hamad Al-Mijalli, Fahad M. Alshabrmi, Naif Hesham Moursi, Hanae Naceiri Mrabti and Mohamed Jeddi; methodology: Hassane Greche and Naoufal El Hachlafi; software: Fahad M Alshabrmi, Mohamed Jeddi and Naif Hesham Moursi; analysis and interpretation of data: Amine Batbat, Khaoula Habbadi Hassane Greche and Mohamed Jeddi; drafting of the manuscript: Naoufal El Hachlafi, Amine Batbat and Mohamed Jeddi; critical revision of the manuscript: Khaoula Habbadi and Hanae Naceiri Mrabti; supervision: Khaoula Habbadi and Naoufal El Hachlafi. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Piasecki B , Balázs VL , Kieltyka-Dadasiewicz A , Szabó P , Kocsis B , Horváth G , et al. Microbiological studies on the influence of essential oils from several Origanum species on respiratory pathogens. Molecules. 2023; 28( 7): 3044. doi:10.3390/molecules28073044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. El Yaagoubi W , El Ghadraoui L , Soussi M , Ezrari S , Belmalha S . Large-scale ethnomedicinal inventory and therapeutic applications of medicinal and aromatic plants used extensively in folk medicine by the local population in the middle atlas and the plain of Saiss, Morocco. Ethnobot Res App. 2023; 25: 1– 29. doi:10.32859/era.25.1.1-29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Güllü İB , Albayrak S , Kaymak E , Yay A . Antidiabetic and antioxidant effect of Origanum minutiflorum O. Schwarz & P. H. Davis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Hacettepe J Biol Chem. 2023; 51( 3): 259– 70. doi:10.15671/hjbc.1239345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Youbi A , Ouahidi I , Mansouri L , Daoudi A , Bousta D . Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for immunological diseases in four regions of Morocco. Eur J Med Plants. 2016; 13( 1): 1– 24. doi:10.9734/EJMP/2016/12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tagnaout I , Zerkani H , Bencheikh N , Amalich S , Bouhrim M , Mothana RA , et al. Chemical composition, antioxidants, antibacterial, and insecticidal activities of Origanum elongatum (bonnet) emberger & maire aerial part essential oil from Morocco. Antibiotics. 2023; 12( 1): 174. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12010174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Taha M , Elazab ST , Abdelbagi O , Saati AA , Babateen O , Baokbah TAS , et al. Phytochemical analysis of Origanum majorana L. extract and investigation of its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects against experimentally induced colitis downregulating Th17 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023; 317: 116826. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2023.116826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yarlılar ŞG , Yabalak E , Yetkin D , Gizir AM , Mazmancı B . Anticancer potential of Origanum munzurense extract against MCF-7 breast cancer cell. Int J Environ Health Res. 2023; 33( 6): 600– 8. doi:10.1080/09603123.2022.2042495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zulu L , Gao H , Zhu Y , Wu H , Xie Y , Liu X , et al. Antifungal effects of seven plant essential oils against Penicillium digitatum. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2023; 10( 1): 82. doi:10.1186/s40538-023-00434-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Marrelli M , Statti GA , Conforti F . Origanum spp.: An update of their chemical and biological profiles. Phytochem Rev. 2018; 17( 4): 873– 88. doi:10.1007/s11101-018-9566-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Machado AM , Lopes V , Barata AM , Póvoa O , Farinha N , Figueiredo AC . Essential oils from Origanum vulgare subsp. virens (hoffmanns. & link) ietsw. grown in Portugal: chemical diversity and relevance of chemical descriptors. Plants. 2023; 12( 3): 621. doi:10.3390/plants12030621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Petrakis EA , Mikropoulou EV , Mitakou S , Halabalaki M , Kalpoutzakis E . A GC-MS and LC-HRMS perspective on the chemotaxonomic investigation of the natural hybrid Origanum × Lirium and its parents, O. vulgare subsp. hirtum and O. scabrum. Phytochem Anal. 2023; 34( 3): 289– 300. doi:10.1002/pca.3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Nurzyńska-Wierdak R , Walasek-Janusz M . Chemical composition, biological activity, and potential uses of oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) and oregano essential oil. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18( 2): 267. doi:10.3390/ph18020267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Karaca Öner E , Yeşil M . Effects of different altitudes on essential oil composition of Origanum majorana species. Biology. 2023. doi:10.20944/preprints202303.0134.v1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bouyahya A , Dakka N , Talbaoui A , Et-Touys A , El-Boury H , Abrini J , et al. Correlation between phenological changes, chemical composition and biological activities of the essential oil from Moroccan endemic Oregano (Origanum compactum Benth). Ind Crops Prod. 2017; 108: 729– 37. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.07.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Stefanakis MK , Touloupakis E , Anastasopoulos E , Ghanotakis D , Katerinopoulos HE , Makridis P . Antibacterial activity of essential oils from plants of the genus Origanum. Food Control. 2013; 34( 2): 539– 46. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.05.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rankou H , Culham A , Jury SL , Christenhusz MJM . The endemic flora of Morocco. Phytotaxa. 2013; 78( 1): 1– 69. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.78.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bakha M , El Mtili N , Machon N , Aboukhalid K , Amchra FZ , Khiraoui A , et al. Intraspecific chemical variability of the essential oils of Moroccan endemic Origanum elongatum L. (Lamiaceae) from its whole natural habitats. Arab J Chem. 2020; 13( 1): 3070– 81. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abdelaali B , El Menyiy N , El Omari N , Benali T , Guaouguaou FE , Salhi N , et al. Phytochemistry, toxicology, and pharmacological properties of Origanum elongatum. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2021; 2021: 6658593. doi:10.1155/2021/6658593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Figuérédo G , Cabassu P , Chalchat JC , Pasquier B . Studies of Mediterranean oregano populations. VIII—chemical composition of essential oils of oreganos of various origins. Flavour Fragr J. 2006; 21( 1): 134– 9. doi:10.1002/ffj.1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rchid H , Oualili H , Nmila R , Chibi F , Lasky M , Mricha A . Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Origanum elongatum essential oil. Phcog Res. 2019; 11( 3): 283. doi:10.4103/pr.pr_157_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hari A , Echchgadda G , Darkaoui FA , Taarji N , Sahri N , Sobeh M , et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant properties, and antifungal activity of wild Origanum elongatum extracts against Phytophthora infestans. Front Plant Sci. 2024; 15: 1278538. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1278538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Béjaoui A , Chaabane H , Jemli M , Boulila A , Boussaid M . Essential oil composition and antibacterial activity of Origanum vulgare subsp. glandulosum Desf. at different phenological stages. J Med Food. 2013; 16( 12): 1115– 20. doi:10.1089/jmf.2013.0079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ouzakar S , Senhaji NS , Harsal AE , Abrini J . Synergistic interaction between Chlorella vulgaris extract and Origanum elongatum essential oil against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int Microbiol. 2025; 28( 4): 691– 701. doi:10.1007/s10123-024-00576-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. El Hachlafi N , Elbouzidi A , Batbat A , Taibi M , Jeddi M , Addi M , et al. Chemical composition and assessment of the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, cytotoxic and skin enzyme inhibitory activities of Citrus sinensis (L.) osbeck essential oil and its major compound limonene. Pharmaceuticals. 2024; 17( 12): 1652. doi:10.3390/ph17121652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bouyahya A , Dakka N , Lagrouh F , Abrini J , Bakri Y . Anti-dermatophytes activity of Origanum compactum essential oil at three developmental stages. Phytothérapie. 2018; 17( 4): 201– 5. doi:10.3166/phyto-2018-0063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Morshedloo MR , Mumivand H , Craker LE , Maggi F . Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils in Origanum vulgare subsp. gracile at different phenological stages and plant parts. J Food Process Preserv. 2018; 42( 2): e13516. doi:10.1111/jfpp.13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chauhan NK , Singh S , Haider SZ , Lohani H . Influence of phenological stages on yield and quality of oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) under the agroclimatic condition of doon valley (uttarakhand). Indian J Pharm Sci. 2013; 75( 4): 489– 93. doi:10.4103/0250-474X.119824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Moradi M , Hassani A , Sefidkon F , Maroofi H . Qualitative and quantitative changes in the essential oil of Origanum vulgare ssp. gracile as affected by different harvesting times. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology. J Agric Sci Technol. 2021; 23: 179– 86. [Google Scholar]

29. Chen L , Liao P . Current insights into plant volatile organic compound biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2025; 85: 102708. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2025.102708 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. El Harsal A , Ibn Mansour A , Skali Senhaji N , Ouardy Khay EL , Bouhdid S , Amajoud N , et al. Influence of extraction time on the yield, chemical composition, and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Origanum elongatum (E. & M.) harvested at northern Morocco. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2018; 21( 6): 1460– 74. doi:10.1080/0972060X.2019.1572545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mumivand H , Shayganfar A , Hasanvand F , Maggi F , Alizadeh A , Darvishnia M . Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of essential oil from Thymus daenensis and Thymus fedtschenkoi during phenological stages. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2021; 24( 3): 469– 79. doi:10.1080/0972060X.2021.1947898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Paudel PN , Satyal P , Satyal R , Setzer WN , Gyawali R . Chemical composition, enantiomeric distribution, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Origanum majorana L. essential oil from Nepal. Molecules. 2022; 27( 18): 6136. doi:10.3390/molecules27186136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hmidouche O , Bouftini k , Sabir I , Lasky M , Mricha A , Rchid H , et al. Bioactive potential of Origanum elongatum extracts: focus on phytochemical composition and antioxidant properties of different fractions. Not Sci Biol. 2025; 17( 3): 12417. doi:10.55779/nsb17312417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Jamali CA , Kasrati A , Bekkouche K , Hassani L , Wohlmuth H , Leach D , et al. Phenological changes to the chemical composition and biological activity of the essential oil from Moroccan endemic thyme (Thymus maroccanus Ball). Ind Crops Prod. 2013; 49: 366– 72. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.05.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Baâtour O , Tarchoun I , Nasri N , Kaddour R , Harrathi J , Drawi E , et al. Effect of growth stages on phenolics content and antioxidant activities of shoots in sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) varieties under salt stress. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012; 11: 16486– 93. [Google Scholar]

36. Król B , Kołodziej B , Kędzia B , Hołderna-Kędzia E , Sugier D , Luchowska K . Date of harvesting affects yields and quality of Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum (Link) Ietswaart. J Sci Food Agric. 2019; 99( 12): 5432– 43. doi:10.1002/jsfa.9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ilić Z , Stanojević L , Milenković L , Šunić L , Milenković A , Stanojević J , et al. The yield, chemical composition, and antioxidant activities of essential oils from different plant parts of the wild and cultivated oregano (Origanum vulgare L.). Horticulturae. 2022; 8( 11): 1042. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8111042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mechergui K , Coelho JA , Serra MC , Lamine SB , Boukhchina S , Khouja ML . Essential oils of Origanum vulgare L. subsp. glandulosum (Desf.) Ietswaart from Tunisia: chemical composition and antioxidant activity. J Sci Food Agric. 2010; 90( 10): 1745– 9. doi:10.1002/jsfa.4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yosr Z , Hnia C , Rim T , Mohamed B . Changes in essential oil composition and phenolic fraction in Rosmarinus officinalis L. var. typicus Batt. organs during growth and incidence on the antioxidant activity. Ind Crops Prod. 2013; 43: 412– 9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.07.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Boukhira S , Bousta F , Moularat S , Abdellaoui A , Ouaritini ZB , Bousta D . Evaluation of the preservative properties of Origanum elongatum essential oil in a topically applied formulation under a challenge test. Phytothérapie. 2018; 18( 2): 92– 8. doi:10.3166/phyto-2018-0067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Merghni A , Belmamoun AR , Urcan AC , Bobiş O , Ali Lassoued M . 1, 8-cineol (eucalyptol) disrupts membrane integrity and induces oxidative stress in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antioxidants. 2023; 12( 7): 1388. doi:10.3390/antiox12071388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools