Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Biostimulatory Influence of Commercial Seaweed Extract on Seed Emergence, Seedling Growth, and Vigor of Winter Rice

1 Department of Agronomy, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, 2202, Bangladesh

2 Department of Agricultural Chemistry, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, 2202, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Md. Parvez Anwar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Utilization of Biostimulants in Plant Growth and Health)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 19 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.075524

Received 03 November 2025; Accepted 26 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Seaweed extract contains plant growth regulators and bio-stimulants that enhance plant growth and development. In Bangladesh, winter rice (Boro rice) in the nursery bed often shows poor seed emergence and weak seedling growth due to low temperature. This problem can be addressed by using seaweed extract as a seed priming agent and bio-stimulant. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of seaweed extract (Crop Plus) on seed emergence, seedling growth, and vigor of winter rice in the nursery. Two experiments were conducted at Bangladesh Agricultural University using BRRI dhan89. The laboratory experiment consisted of 17 treatments combining three concentrations of Crop Plus (5000, 10,000 and 15,000 ppm) and four priming durations (6, 12, 18, and 24 h), along with hydro-priming and a no priming as control. Seed priming with 15,000 ppm for 24 h produced the highest germination percentage and superior seedling growth traits. The nursery bed experiment comprised 11 treatments combining two doses (1 mL m−2 and 2 mL m−2) of Crop Plus and five different foliar application schedules, along with a control. All treatments outperformed the control, with the best results from Crop Plus @2 mL m−2 applied at 20 and 30 days after sowing (DAS). Overall, the treatment involving seed priming with 15,000 ppm seaweed extract for 24 h, followed by nursery application at 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS, resulted in higher germination and improved early growth of winter rice. However, further validation across multiple locations, seasons, and rice cultivars is recommended.Keywords

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a vital staple food for billions of people worldwide. In Bangladesh, as well as in many other tropical and sub-tropical countries, rice is cultivated either through direct sowing or transplanting, depending on the climate and farming practices. However, rice production often faces challenges due to low-temperature stress during the early growth stages. Chilling conditions can significantly reduce germination, hinder seedling establishment, and cause yellowing, stunted growth, and lower tiller production [1]. In northern Bangladesh, temperatures below 10°C can lead to seedling mortality rates as high as 90% [2]. These chilling conditions are commonly encountered in winter rice, especially in nursery beds when seeds are planted early or during seedling establishment in the main field when transplanting is delayed, resulting in serious yield losses [3].

Seed priming has emerged as a simple yet effective strategy to mitigate these challenges. This pre-sowing technique involves partially hydrating seeds and then drying them before the radicle emerges [4]. Priming triggers early metabolic activity, preparing the seeds for rapid germination once sown [5]. Studies have demonstrated that primed seeds germinate faster, produce stronger seedlings, and ultimately lead to higher yields [6,7,8,9]. This is due to enhanced enzyme activity, increased RNA and DNA synthesis, improved ATP production, and more robust mitochondrial function [10]. Priming also reduces seed dormancy, accelerates seedling emergence, and fosters stronger, more vigorous seedlings [11,12]. Consequently, crops often show faster growth, earlier flowering, and improved yields [13,14]. In rice, seed priming has been shown to improve germination and vigor, enhance tolerance to abiotic stresses like chilling, high temperature, salinity and drought stresses [7,15,16,17,18], and improve competitiveness against weeds [17,19]. Seaweed extracts have also demonstrated broad effectiveness across numerous crop species other than rice. In cereals such as maize, seaweed extracts from Ecklonia maxima and Sargassum spp. enhanced germination more effectively than humic substances, and combined seed soaking plus foliar application or repeated foliar sprays significantly increased chlorophyll content and shoot and root growth [20]. Legumes like soybean also respond positively, exhibiting improved nutrient uptake, higher pod and seed weight, and greater drought tolerance [21]. In horticultural crops, seaweed extracts consistently promote growth and resilience. For instance, long-term use of brown-algae extracts derived from Ascophyllum nodosum and Durvillaea potatorum has been shown to enhance the performance of tomato by increasing yield traits, fruit number and quality, and improving both root and shoot biomass [22]. Similar growth and yield enhancing effects have been reported in cucumber [23], spinach [24], and strawberry [25], where seaweed treatments improve biomass accumulation, nutrient status, stress resistance, yield, and overall quality. Even perennial fruit crops such as apples and oranges benefit from seaweed applications, demonstrating improved fruit set, yield, nutrient composition, post-harvest characteristics, and resistance to pests and diseases [26,27].

Seaweed extract offers another promising, natural approach to improving plant performance. Seaweeds, marine algae typically found in coastal ecosystems, are categorized into brown, red, and green types. Among these, brown seaweeds, including species such as Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus, Laminaria, Sargassum, and Turbinaria, are most commonly utilized in agriculture as sustainable alternatives to chemical fertilizers [28,29]. Seaweed extracts are widely used in agriculture for their plant growth-promoting effects and their ability to improve crop tolerance to various abiotic stresses, such as salinity, extreme temperatures, nutrient deficiencies, and drought. These extracts contain a variety of chemical constituents, including complex polysaccharides, fatty acids, vitamins, phytohormones, and essential mineral nutrients. The presence of these bioactive compounds helps enhance plant resilience and overall growth, making seaweed extracts a valuable natural resource in sustainable farming practices [30]. Additionally, bioactive compounds like alginic acids and polyphenols found in seaweed extracts support plant growth and improve tolerance to both biotic and abiotic stresses. Unlike synthetic chemicals, seaweed-based products are biodegradable, non-toxic, and environmentally friendly. Numerous studies have reported the positive effects of seaweed extracts on crop performance, where these natural growth regulators enhance metabolism and increase yield [31]. While seaweed extract is widely used to improve plant tolerance to various stress conditions, its application under normal growing conditions, particularly for winter rice, remains limited. It’s therefore hypothesized that seaweed extract might enhance faster and higher germination, seedling growth, and vigor of winter rice.

This study aims to explore the potential of seaweed extract as a priming agent in improving seed germination and seedling vigor under laboratory conditions, and as a bio-stimulant in enhancing seedling growth of winter rice in a nursery bed.

The laboratory experiment was conducted at the Agro Innovation Laboratory, Department of Agronomy, Bangladesh Agricultural University, in November 2023. The experimental site is located at 23°77′ N latitude and 90°33′ E longitude, at an altitude of 18.6 m above sea level, under a sub-tropical climate.

Seaweed extract (Crop Plus): Crop Plus is a seaweed-based bio-stimulant that enhances plant growth, yield, and stress tolerance in crops. It contains 18% seaweed extract as the main active ingredient, supported by 2% alginic acid and 0.1% amino acids that stimulate root development and improve stress resistance. The formulation also provides essential macronutrients including 8.0% total nitrogen, 2.0% phosphate (P2O5), and 4.0% potash (K2O), along with secondary nutrients such as magnesium (0.1%), calcium (0.8%), and iodine (0.004%). To enhance nutrient absorption, Crop Plus is enriched with chelated micronutrients: iron (Fe-EDTA) and manganese (Mn-EDTA) each at 1.56%, copper (Cu-EDTA) at 0.68%, and zinc (Zn-EDTA) at 0.2%. This balanced formulation not only nourishes plants but also strengthens their resilience against environmental stress, making it a sustainable solution for crop production.

Rice variety BRRI dhan89: BRRI dhan89 is a high-yielding winter rice variety released by the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) in 2018. It was developed by crossing BRRI dhan29 with the wild rice Oryza rufipogon through soma clonal variation. The variety matures in about 154–158 days and yields 8.0–9.7 t per hectare, with harvest typically from mid-April to early May. BRRI dhan89 is moderately tolerant to medium wilt disease, grows to about 106 cm in height, and produces medium-sized, slender grains with a thousand-grain weight of 24.4 g.

2.1.4 Experimental Treatments and Design

The laboratory experiment consisted of a full factorial combination of Crop Plus concentration (0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5% w/v; equivalent to 0, 5000, 10,000, and 15,000 ppm) and priming duration (6, 12, 18, and 24 h), along with a non-primed control. The 0% treatment represented hydropriming with distilled water. Crop Plus solutions were prepared by dissolving 5, 10, and 15 g of Crop Plus in 1 L of distilled water to obtain 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5% w/v (5000, 10,000, and 15,000 ppm) solutions, respectively.

The study followed a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with four replications for each treatment to ensure reliability and statistical accuracy.

2.1.5 Seed Priming and Germination Procedure

Rice seeds were primed according to the designated treatments by soaking them in solutions of different concentrations prepared with distilled water. Soaking durations were 6, 12, 18, and 24 h at room temperature (25 ± 2°C) under natural light, with ambient relative humidity, maintaining a seed-to-solution ratio of 1:5 (g L−1). After soaking, the seeds were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove any residual priming solution. They were then dried with forced air for 48–60 h at 28 ± 2°C until the moisture content returned close to the original level (9.5%, determined by the oven-dry method). Once dried, the seeds were stored in sealed polythene bags at 5 ± 1°C for seven days before germination. The control treatment consisted of unprimed seeds. During the entire process, no incidents of fungal contamination were observed.

For germination, sterilized sand was used as the growing medium, and plastic Petri dishes (90 mm diameter × 15 mm depth) served as containers. Sand moisture was maintained at about 80% of field capacity by adding distilled water each morning. For each priming treatment, 400 rice seeds were used in four replicates. In each Petri dish, 100 seeds were sown at a depth of 0.5 cm in the moist sand. The dishes were then placed on laboratory benches at room temperature (25 ± 2°C) under ambient conditions for germination.

2.1.6 Data Collection and Recorded Parameters

Observations were made on germination pattern, germination percentage, seedling growth, and vigor-related traits. The measured parameters included germination percentage (GP), days to 50% germination (T50), mean germination time (MGT), seedling vigor index (SVI), and germination index (GI), which were calculated using standard formulas.

The number of germinated seeds were counted every morning. Appearance of plumule over sand layer was considered as germination. Germination percentages (GP) was calculated as follows:

Time to 50% germination:

Time to fifty percent germination is calculated as follows:

Mean germination time (MGT):

After 14 days of seed placement for germination, 10 seedlings from each replicate were randomly selected. Root and shoot lengths were measured, and then oven dried at 70°C for 72 h to record root and shoot dry weight of seedlings. Seedling vigor index (SVI) was calculated as follows:

Germination index (GI):

2.1.9 Measurement of Seedling Growth Parameters

Seedling growth was evaluated by measuring both length and weight. Root length was measured from the base to the tip of the longest root and shoot length from the base to the tip of the longest leaf. The sum of root and shoot length was considered as total seedling length. For dry weight, ten seedlings were oven-dried at 60°C for 72 h, after which root, shoot, and total seedling dry weights were recorded. The balance between root and shoot growth was expressed as the root-to-shoot ratio.

2.2.1 Experimental Duration and Site

The study was carried out during the Winter season from 10 December 2023 to 22 January 2024 at the Agronomy Field Laboratory, Department of Agronomy, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh (90°50′ E and 24°75′ N latitude, 18 m above sea level). The experimental site belongs to the non-calcareous dark grey floodplain soil under the Old Brahmaputra Floodplain Agro-Ecological Zone (AEZ-9). The land was well-drained, medium-high, with silt-loam texture. The soil was nearly neutral (pH 6.8), low in organic matter (1.27%), and had low fertility (1.1% total N, 25 ppm available P, and 0.16 meq% exchangeable K). The area is characterized by a subtropical monsoon climate with a humid environment. During the study period, maximum, minimum, and average temperatures were 28.6°C, 11.2°C, and 18.92°C, respectively; relative humidity ranged from 40% to 100% with an average of 85.6%. Total rainfall was 0.0 mm, and total sunshine hrs was 203.5 h.

2.2.2 Experimental Treatments and Design

The experiment consisted of eleven treatments as follows:

- (i)Control (no Crop Plus)

- (ii)Crop Plus @ 1 mL m−2 at 15 DAS

- (iii)Crop Plus @ 1 mL m−2 at 20 DAS

- (iv)Crop Plus @ 1 mL m−2 at 30 DAS

- (v)Crop Plus @ 1 mL m−2 at 15 DAS and 30 DAS

- (vi)Crop Plus @ 1 mL m−2 at 20 DAS and 30 DAS

- (vii)Crop Plus @ 2 mL m−2 at 15 DAS

- (viii)Crop Plus @ 2 mL m−2 at 20 DAS

- (ix)Crop Plus @ 2 mL m−2 at 30 DAS

- (x)Crop Plus @ 2 mL m−2 at 15 DAS and 30 DAS

- (xi)Crop Plus @ 2 mL m−2 at 20 DAS and 30 DAS

The nursery bed experiment consisted of a factorial combination of Crop Plus foliar application rate (1 and 2 mL m−2) and application timing (15, 20, and 30 DAS, alone or in combination), along with an untreated control. The experiment was laid out in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with three replications. The unit plot size was 1.0 m × 1.0 m.

2.2.3 Experimental and Plant Materials Used

The plant material and experimental management were the same as those described in the laboratory experiment.

Seeds of BRRI dhan89 were collected from the Agronomy Field Laboratory, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh. They were soaked in water for 24 h and wrapped in moist gunny bags in a warm condition to enhance seed sprouting. Germination started within 48 h, and sprouted seeds were ready for sowing after 72 h.

Nursery beds (1.0 m × 1.0 m) were prepared on 10 December 2023 by puddling through repeated ploughing and laddering, followed by removal of weeds, stubbles, and crop residues. After leveling, the sprouted seeds were sown in raised wet beds according to the experimental design. No manures or fertilizers were applied, but proper water management and drainage channels were maintained. The beds were protected from birds up to 7 DAS. Seedlings were regularly monitored to ensure healthy growth. During the nursery period, seedlings grew well, remained green, and showed no lodging. Insect attacks were absent, disease pressure was minimal, and only one manual weeding was needed at 30 DAS.

2.2.5 Application of Seaweed Extract, Sampling, and Harvesting

Liquid seaweed extract (Crop Plus) was applied as a foliar spray at 1 mL m−2 or 2 mL m−2, diluted with water according to treatments. Spray volume was maintained at 250 mL m−2, while control plots received no application.

Seedlings were harvested at 40 DAS (22 January 2024). To minimize injury during uprooting, nursery beds were moistened with water in the morning and evening before sampling. Ten seedlings were randomly selected from each bed, carefully uprooted, and taken to the laboratory for measurement. Seedlings from each bed were bundled separately, properly tagged, and transported for further analysis.

2.2.6 Data Collection and Recorded Parameters

Seedling growth and vigor were assessed by measuring root length (cm), shoot length (cm), total seedling length (cm), root dry weight (mg), shoot dry weight (mg), total seedling dry weight (mg), and root-to-shoot ratio (weight basis).

2.2.7 Statistical Analysis of Laboratory and Nursery Experiments

The recorded data was compiled and tabulated for statistical analysis. Data normality was initially checked using histogram plots. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was then performed using the Statistix 10 software. Mean differences among treatments were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a significance level of p < 0.01.

3.1.1 Seed Germination and Seedling Vigor

Seed germination and seedling vigor were strongly influenced by the concentration of seaweed extract (Crop Plus) and the duration of seed priming. Priming with 5000 ppm for 24 h produced the highest germination percentage. Treatments with 15,000 ppm for 24 and 18 h, 10,000 ppm for 24 h, and hydropriming for 24 h showed statistically similar results, while the control consistently produced the lowest germination percentage (Table 1).

The time required for 50% germination was reduced by seed priming. In particular, 15,000 ppm for 24 h and hydropriming for 24 h were the most effective, resulting in faster germination compared to the control (Table 1).

Priming had a notable impact on mean germination time as well. Seeds treated with 10,000 ppm Crop Plus for 24 h germinated the quickest, requiring only 3.5 days compared to 5.7 days in the control. Across all treatments, primed seeds germinated faster than unprimed ones (Table 1).

Seedling vigor, measured through vigor index, also improved significantly with priming. The strongest seedlings were obtained with 15,000 ppm for 24 h, followed closely by 10,000 ppm and 5000 ppm for 24 h. By contrast, the control treatment produced the weakest seedlings (Table 1).

Table 1: Combined effect of priming agent (Crop Plus) concentration and priming duration on winter rice seedling germination.

| Treatments | Germination Percentage | Time to 50% Germination | Mean Germination Time | Seedling Vigor Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control-no priming | 84.12 (1.46) f | 4.42 (0.36) a | 5.70 (0.36) a | 14.64 (1.29) f |

| Hydro priming for 6 h | 88.82 (3.01) ef | 3.70 (0.37) b | 4.52 (0.21) b | 18.33 (1.53) e |

| Hydro priming for 12 h | 91.10 (1.81) b–e | 3.47 (0.17) b | 4.00 (0.69) bcd | 19.46 (0.49) cde |

| Hydro priming for 18 h | 94.80 (0.91) abc | 3.27 (0.31) b | 3.90 (0.29) bcd | 20.78 (1.18) a–e |

| Hydro priming for 24 h | 96.12 (1.03) ab | 3.22 (0.22) b | 3.72 (0.21) cd | 21.07 (1.32) a–d |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 6 h | 88.37 (2.53) ef | 3.75 (0.21) ab | 4.42 (0.17) bc | 19.06 (0.80) de |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 12 h | 91.75 (2.09) b–e | 3.42 (0.17) b | 3.85 (0.26) bcd | 19.93 (0.67) b–e |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 18 h | 94.20 (1.92) a–d | 3.37 (0.17) b | 3.70 (0.22) cd | 21.36 (0.89) a–d |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 24 h | 97.12 (1.72) a | 3.35 (0.47) b | 3.60 (0.29) d | 22.74 (0.46) a |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 6 h | 89.82 (2.00) cde | 3.57 (0.25) b | 4.52 (0.34) b | 19.69 (0.40) cde |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 12 h | 90.87 (2.96) b–e | 3.30 (0.33) b | 4.07 (0.25) bcd | 20.23 (0.58) b–e |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 18 h | 92.80 (2.72) a–e | 3.32 (0.37) b | 3.65 (0.13) d | 21.42 (0.78) a–d |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 24 h | 95.80 (1.19) ab | 3.20 (0.22) b | 3.55 (0.21) d | 22.72 (0.65) a |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 6 h | 89.22 (2.18) def | 3.67 (0.17) b | 4.42 (0.25) bc | 20.16 (1.60) b–e |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 12 h | 92.92 (3.13) a–e | 3.57 (0.17) b | 4.25 (0.21) bcd | 21.52 (0.46) abc |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 18 h | 96.10 (1.33) ab | 3.40 (0.22) b | 3.85 (0.29) bcd | 22.31 (1.26) ab |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 24 h | 96.00 (1.34) ab | 3.22 (0.17) b | 3.77 (0.17) bcd | 23.11 (0.49) a |

| Sx | 1.47 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.68 |

| Level of significance | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| CV (%) | 2.25 | 7.77 | 7.17 | 4.67 |

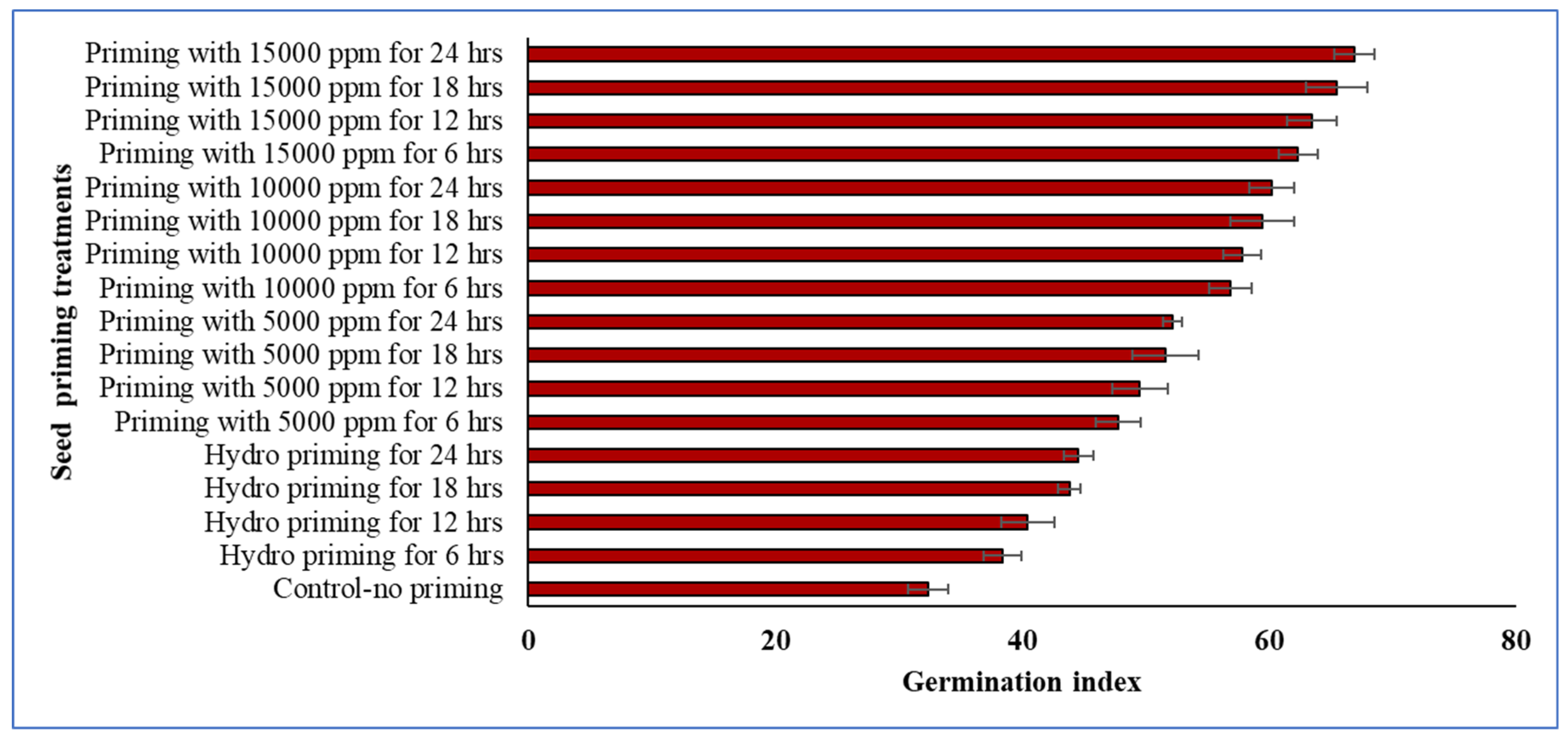

Among the treatments, seeds primed with 15,000 ppm Crop Plus for 24 h and 18 h showed the highest germination index, indicating enhanced seed vigor and more uniform germination (Fig. 1). In contrast, hydropriming did not provide any noticeable improvement in the germination index. The control treatment, without priming, recorded the lowest germination index.

Figure 1: Combined effect of priming agent (Crop Plus) concentration and priming duration on the germination index of winter rice. Vertical lines on the bars represent the standard deviation of four replications.

3.1.3 Seedling Growth and Biomass

The combined effects of Crop Plus concentration and priming duration had a significant impact on the growth and biomass of winter rice seedlings. Root length was notably improved by all priming treatments compared to the control, with no significant differences among the primed seeds. The control seedlings consistently showed the shortest roots (Table 2).

Shoot length was similarly influenced by priming. The tallest shoots (8.02 cm) were recorded in seeds primed with 15,000 ppm Crop Plus for 24 h, whereas unprimed seeds produced the shortest shoots (5.68 cm). Total seedling length followed the same pattern: seeds primed with 15,000 ppm, 10,000 ppm, and 5000 ppm for 24 h produced the longest seedlings, while control seedlings were significantly shorter, averaging 17.41 cm (Table 2).

Seedling biomass also benefited from priming. The highest root dry weight (41.91 mg) was observed in seeds primed with 15,000 ppm for 24 h, whereas hydropriming for 6 h resulted in the lowest root dry weight (32.45 mg). Shoot dry weight showed a similar trend, with the maximum value (23.27 mg) in 15,000 ppm–primed seeds and the lowest (17.02 mg) in the control (Table 2).

Despite these improvements in growth and biomass, the root-to-shoot ratio was not significantly affected by any of the treatments, indicating a balanced allocation of biomass between roots and shoots. Overall, these results demonstrate that priming winter rice seeds with 15,000 ppm Crop Plus for 24 h enhances both seedling growth and biomass accumulation, supporting healthier and more vigorous early seedling development (Table 2).

Table 2: Combined effect of priming agent (Crop Plus) concentration and priming duration on seedling vigor of winter rice.

| Treatments | Root Length (cm) | Shoot Length (cm) | Seedling Length (cm) | Root Dry Weight (mg) | Shoot Dry Weight (mg) | Root: Shoot (Weight) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control-no priming | 11.72 (1.16) b | 5.68 (0.37) c | 17.41 (1.53) c | 36.46 (2.12) bc | 17.02 (1.06) c | 1.90 (0.02) |

| Hydro priming for 6 h | 13.82 (1.30) ab | 6.80 (0.29) bc | 20.63 (1.45) b | 32.45 (2.00) c | 19.79 (0.70) bc | 1.84 (0.16) |

| Hydro priming for 12 h | 14.35 (1.27) a | 7.02 (0.33) ab | 21.37 (0.95) ab | 37.51 (1.16) abc | 20.57 (1.24) ab | 1.83 (0.16) |

| Hydro priming for 18 h | 14.62 (0.70) a | 7.29 (0.59) ab | 21.92 (1.28) ab | 38.48 (0.78) ab | 21.16 (1.75) ab | 1.82 (0.11) |

| Hydro priming for 24 h | 14.72 (1.12) a | 7.20 (0.29) ab | 21.92 (1.41) ab | 38.65 (2.10) ab | 21.02 (1.06) ab | 1.84 (0.17) |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 6 h | 14.47 (1.58) a | 7.12 (0.49) ab | 21.60 (1.49) ab | 37.67 (1.75) ab | 20.75 (1.56) ab | 1.82 (0.23) |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 12 h | 14.62 (0.54) a | 7.10 (0.65) ab | 21.73 (0.67) ab | 38.46 (0.45) ab | 20.46 (1.72) ab | 1.89 (0.18) |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 18 h | 15.27 (0.94) a | 7.42 (0.66) ab | 22.70 (1.33) ab | 39.67 (1.93) ab | 21.35 (1.55) ab | 1.86 (0.21) |

| Priming with 5000 ppm for 24 h | 15.60 (0.50) a | 7.82 (0.22) ab | 23.42 (0.53) a | 40.91 (2.45) ab | 23.00 (1.19) ab | 1.78 (0.18) |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 6 h | 14.70 (0.71) a | 7.24 (0.34) ab | 21.94 (0.90) ab | 38.51 (2.39) ab | 20.89 (0.99) ab | 1.85 (0.20) |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 12 h | 14.85 (0.93) a | 7.45 (0.37) ab | 22.30 (1.29) ab | 38.93 (0.76) ab | 21.62 (0.86) ab | 1.80 (0.06) |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 18 h | 15.47 (0.49) a | 7.61 (0.46) ab | 23.09 (0.50) ab | 40.51 (2.33) ab | 22.29 (1.25) ab | 1.81 (0.01) |

| Priming with 10,000 ppm for 24 h | 15.87 (0.46) a | 7.84 (0.24) ab | 23.71 (0.68) a | 41.35 (2.17) ab | 22.80 (1.76) ab | 1.81 (0.05) |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 6 h | 15.02 (0.98) a | 7.55 (0.49) ab | 22.57 (1.27) ab | 39.41 (1.19) ab | 21.67 (0.24) ab | 1.81 (0.04) |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 12 h | 15.42 (0.42) a | 7.75 (0.56) ab | 23.17 (0.29) ab | 40.22 (3.19) ab | 22.55 (1.43) ab | 1.79 (0.24) |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 18 h | 15.57 (0.78) a | 7.63 (0.58) ab | 23.21 (1.07) ab | 40.87 (2.57) ab | 22.23 (0.92) ab | 1.84 (0.19) |

| Priming with 15,000 ppm for 24 h | 16.05 (0.29) a | 8.02 (0.43) a | 24.07 (0.26) a | 41.91 (2.09) a | 23.27 (1.32) a | 1.80 (0.10) |

| Sx | 0.64 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 1.40 | 0.90 | 0.11 |

| Level of significance | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | NS |

| CV (%) | 6.11 | 6.20 | 4.86 | 5.09 | 5.97 | 8.41 |

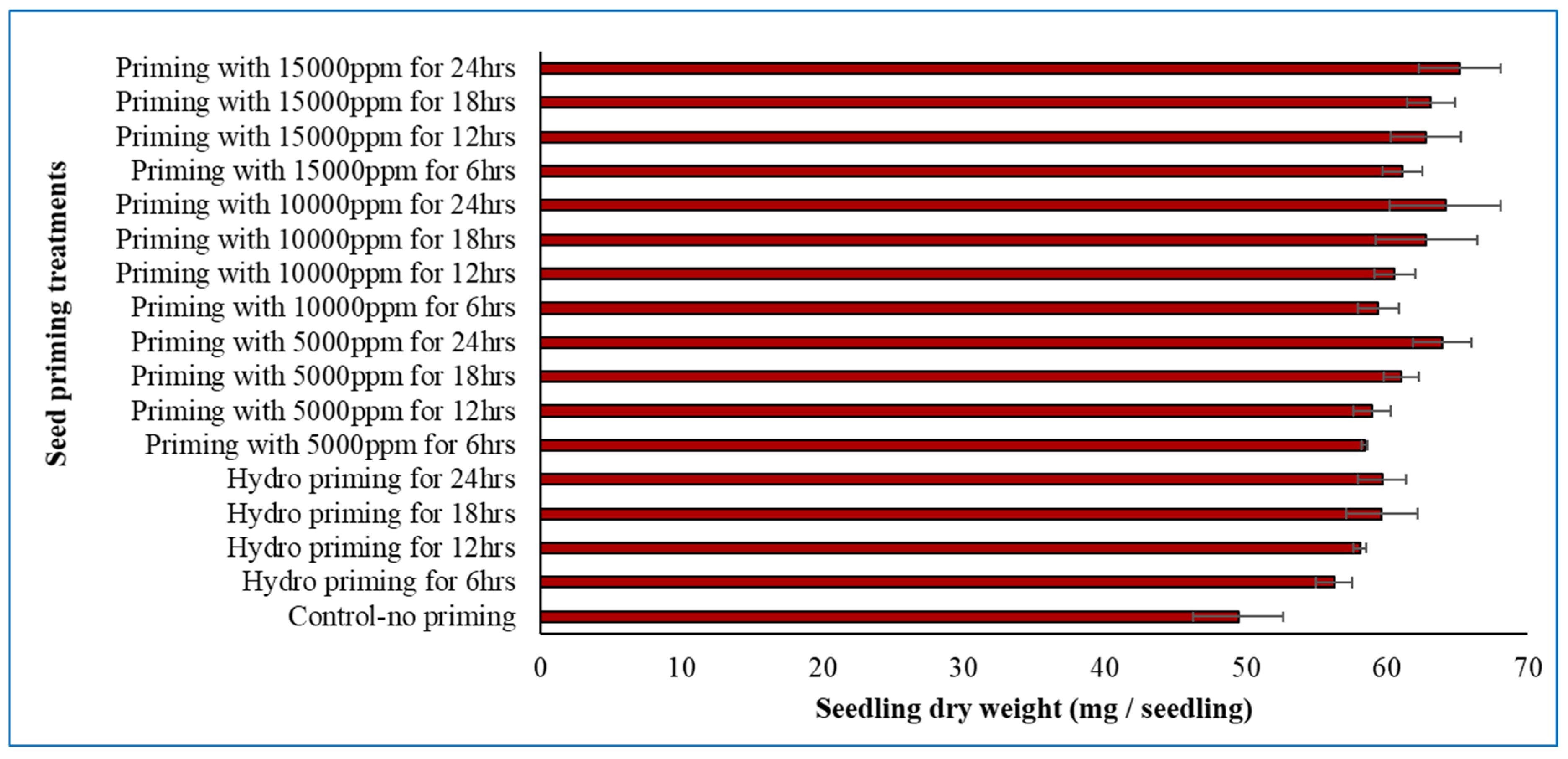

The concentration of the seed priming agent (Crop Plus) and the duration of priming had a significant effect on winter rice seedling dry weight. The highest seedling dry weight was observed in seeds primed with 15,000 ppm for 24 h, whereas the lowest dry weight was recorded in the control (unprimed) seeds (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Combined effect of priming agent (Crop Plus) concentration and priming duration on seedling dry weight of winter rice in the laboratory. Vertical lines on the bars represent the standard deviation of four replications.

3.2.1 Seedling Growth and Biomass

Foliar sprays of seaweed extract (Crop Plus) did not significantly affect the root length of winter rice seedlings, suggesting that root elongation was relatively unaffected by the treatments. However, shoot growth responded positively to the sprays. The tallest shoots (11.53 cm) were observed in seedlings treated with 1 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS, 2 mL m−2 at 15 and 30 DAS, and 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS, while the control seedlings, which received no Crop Plus, had the shortest shoots (9.70 cm) (Table 3).

Total seedling length also increased significantly with foliar applications. The longest seedlings (21.03 cm) were recorded in treatments receiving 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS and 2 mL m−2 at 15 and 30 DAS, whereas control seedlings remained shortest (18.60 cm). Root dry weight followed a similar pattern. The highest root dry weight was found in seedlings treated with 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS, 2 mL m−2 at 15 and 30 DAS, 2 mL m−2 at 30 DAS, and 1 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS, while control seedlings had the lowest root dry weight (156.73 mg) (Table 3).

Shoot dry weight was also highest in seedlings treated with 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS and 2 mL m−2 at 15 and 30 DAS, and lowest in the control treatment. The root-to-shoot weight ratio was significantly influenced by the sprays, with the highest ratio observed in seedlings treated with 1 mL m−2 at 15 DAS, while the other treatments showed similar ratios, indicating a balanced allocation of biomass between roots and shoots (Table 3).

Table 3: Effect of seaweed extract (Crop Plus) doses and foliar spray schedule on Winter rice seedling growth.

| Treatments | Root Length (cm) | Shoot Length (cm) | Seedling Length (cm) | Root Dry Weight (mg) | Shoot Dry Weight (mg) | Root: Shoot (Weight) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control or no Crop plus | 8.90 (0.60) | 9.70 (1.65) c | 18.60 (2.25) e | 156.73 (20.42) b | 230.00 (14.86) f | 0.669 (0.11) ab |

| 1 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 15 DAS | 8.93 (0.85) | 10.16 (0.55) bc | 19.10 (0.30) de | 179.50 (18.15) ab | 256.76 (18.18) ef | 0.713 (0.05) a |

| 1 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 20 DAS | 9.03 (0.75) | 10.36 (1.60) abc | 19.40 (0.85) cde | 185.53 (8.40) ab | 268.53 (9.10) def | 0.683 (0.04) ab |

| 1 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 30 DAS | 9.33 (1.35) | 10.73 (0.80) abc | 20.06 (2.15) a–d | 193.03 (17.16) ab | 282.12 (14.45) de | 0.695 (0.08) ab |

| 1 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 15 DAS + 30 DAS | 9.70 (0.66) | 11.00 (0.60) ab | 20.70 (1.25) ab | 196.43 (6.90) a | 286.90 (15.30) cde | 0.673 (0.04) ab |

| 1 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 20 DAS + 30 DAS | 9.60 (0.30) | 11.40 (1.65) a | 21.00 (1.35) ab | 203.10 (8.21) a | 298.78 (10.40) bcd | 0.671 (0.02) ab |

| 2 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 15 DAS | 8.96 (0.75) | 10.46 (1.20) abc | 19.43 (0.45) cde | 189.60 (9.65) ab | 302.07 (13.95) bcd | 0.617 (0.02) b |

| 2 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 20 DAS | 9.10 (0.40) | 10.70 (1.20) abc | 19.80 (0.80) bc | 203.30 (8.10) a | 326.95 (8.25) abc | 0.627 (0.03) ab |

| 2 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 30 DAS | 9.30 (0.66) | 11.20 (0.56) ab | 20.50 (1.21) abc | 209.10 (13.56) a | 338.09 (13.30) ab | 0.613 (0.05) b |

| 2 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 15 DAS + 30 DAS | 9.50 (0.40) | 11.53 (0.45) a | 21.03 (0.85) a | 211.73 (7.60) a | 342.61 (14.10) a | 0.609 (0.01) b |

| 2 mL m−2 Crop Plus at 20 DAS + 30 DAS | 9.60 (0.70) | 11.53 (0.85) a | 21.13 (1.55) a | 216.70 (13.20) a | 350.93 (12.55) a | 0.625 (0.03) b |

| Sx | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 10.71 | 11.11 | 0.02 |

| Level of significance | NS | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| CV (%) | 8.00 | 3.71 | 2.08 | 6.73 | 4.56 | 4.50 |

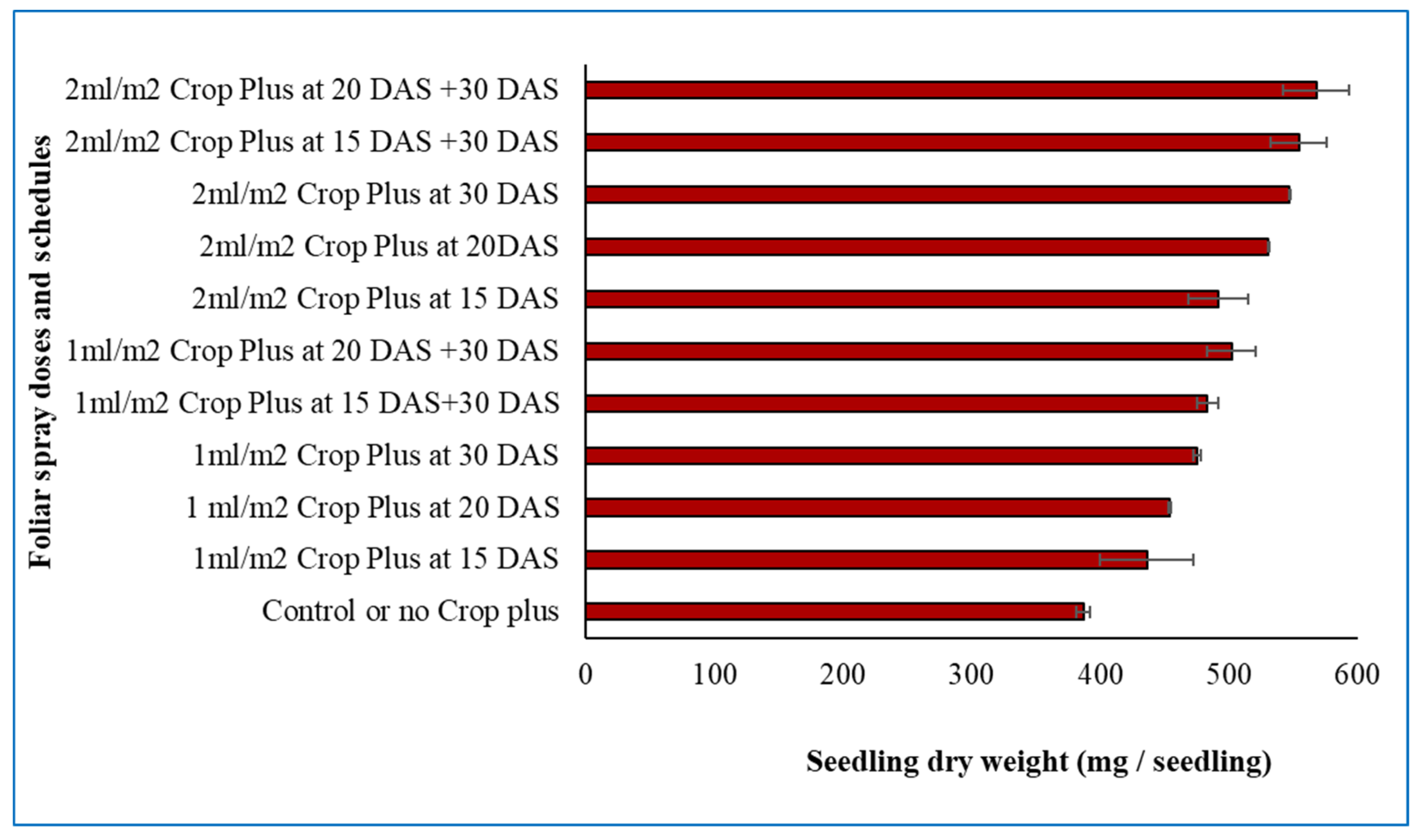

Seedlings treated with 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS recorded the highest dry weight (567.63 mg), indicating that this treatment effectively enhanced biomass accumulation during the early growth stage. In contrast, the control seedlings, which did not receive any Crop Plus, produced the lowest dry weight (386.73 mg), highlighting the positive role of seaweed extract in promoting seedling overall growth (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Effect of seaweed extract (Crop Plus) doses and foliar spray schedules on seedling dry weight of winter rice in nursery bed. Vertical lines on the bars represent the standard deviation of four replications.

This study demonstrates that seaweed extract (Crop Plus) can play a vital role in improving the germination, vigor, and early growth of winter rice. Both laboratory and nursery experiments confirmed that seed priming and foliar application enhanced seedling performance compared to untreated controls. Priming with 15,000 ppm for 24 h produced the best results across different parameters compared to untreated seeds. Lower concentrations such as 10,000 ppm and 5000 ppm were also beneficial, while unprimed seeds consistently performed the poorest. Foliar sprays of seaweed extract also improved seedling development, particularly shoot length and biomass, with the strongest effects observed in most cases when 2 mL m−2 was applied at 20 and 30 DAS, although the results varied across different parameters.

The positive role of seaweed extracts in early plant development is well established. They are widely recognized as natural bio stimulants, supplying plant growth regulators such as auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins [32], along with essential micronutrients [33]. These compounds improve germination percentage, enhance root and shoot elongation, and strengthen seedling vigor. Importantly, the effects are concentration-dependent, while optimal levels stimulate germination and growth, excessively high doses may suppress performance due to salt stress. The optimal concentration for promoting germination varies by seaweed species and crop sensitivity to specific bioactive compounds. For example, a 15% concentration of Kappaphycus or Gracilaria sap significantly improved wheat germination [34]. On the other hand, Ghaderiardakani et al. [35] found that Ulva extract concentrations above 0.1% inhibit Arabidopsis germination and root growth.

Earlier studies [36,37] have supported the role of seed priming with different agents as natural enhancers of germination and vigor. Bright et al. [38] similarly showed that priming rice seeds with a cyanobacterial–bacterial biofilm extract (CBB) at 100–200 mL kg−1 significantly increased germination and seedling length, further supporting the effectiveness of biological priming agents in enhancing early seedling vigor. In our study, priming seeds with a 15,000-ppm seaweed extract for 24 h increased germination by 14.12% and boosted the vigor index by 57.85%. Similar trends have been observed in other crops, where seed priming not only boosts the germination rate but also improves uniformity and seedling vigor [16]. For example, A 20% seaweed liquid extract from Sargassum wightii increased the seed germination of Triticum aestivum var. Pusa Gold by 11% compared to the control [39]. Similary, in maize [20], and groundnut [40] priming with seaweed extract increased seed germination. This may be because seaweed sap provides essential nutrients and plant growth regulators like IAA, gibberellins, cytokinins, choline chloride, and glycine betaine, all of which support positive physiological responses [41]. Additionally, in our study, priming with seaweed extract reduced the mean germination time (3.5 days for 10,000 ppm compared to 5.7 days in the control), showing that primed seeds germinate more quickly and uniformly. Faster germination and improved vigor are likely due to enhanced water uptake during priming, which activates metabolic processes and strengthens seed membranes, preparing the seeds for rapid growth [7].

Furthermore, in our subsequent nursery experiments, root elongation was less affected, yet overall seedling size and dry weight improved significantly. Compared with Castro et al. [42], who has observed a 20% increase in rice root length using a 2% Kappaphycus alvarezii extract, the smaller root response in our study may be due to BRRI dhan89’s varietal traits or differences in extract composition. However, the increase in total seedling biomass is consistent with international findings, which similarly report steady stimulation of shoot growth across diverse environments. For example, Elamparithi et al. [43] reported that, foliar spray of seaweed extract combined with seed presoaking in Sargassum myricocystum methanol extract under field conditions increased rice dry matter production by 31.27%, which is comparable to our observed 31.9% increase in seedling dry weight under nursery conditions. This indicates that even in controlled environments, seaweed extracts can induce growth enhancements similar in magnitude to those observed in field trials. These growth-promoting effects are largely attributed to the diverse bioactive compounds present in seaweed extracts. Auxins stimulate cell elongation and root initiation, cytokinins enhance shoot development, leaf expansion, and nutrient mobilization, and gibberellins promote stem elongation and seed germination. Polysaccharides such as alginates and laminarins act as signaling molecules that activate defense pathways and improve stress tolerance, while betaine and polyphenols function as osmoprotectants and antioxidants, reducing oxidative damage under stress conditions [44,45].

The benefits of seaweed extracts extend beyond germination to overall plant growth and nutrient acquisition. Previous studies have shown that plants treated with Ascophyllum nodosum extract demonstrate enhanced uptake of nitrogen and sulfur, linked to the activation of genes encoding root transporters for nitrate (BnNRT1.1, BnNRT2.1) and sulfate (BnSultr4.1, BnSultr4.2) [46,47,48,49]. Such gene-level responses provide a mechanistic explanation for the improved growth observed in our study. Several studies have reported that combining seaweed extracts increases plant height, leaf area, dry weight, and overall biomass [50,51]. This effect is likely because seaweed extracts supply growth-promoting substances while also stimulating soil biological activity. Together, these factors enhance the plant’s ability to produce more dry matter and reach its full growth potential [52].

Furthermore, seaweed extract contains natural chelating agents like alginates and mannitol, which bind to micronutrients such as iron, zinc, and manganese, making them more accessible for rice plants. This improved nutrient availability enhances absorption and utilization, resulting in healthier and more productive crops. In addition, seaweed extract functions as a natural bio stimulant by supporting beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere. A healthier soil ecosystem, in turn, ensures better nutrient uptake and overall crop performance [53]. For instance, a study from China reported that foliar application of seaweed extracts significantly modified the rhizosphere bacterial community at both tillering and heading stages, increasing bacterial diversity and nutrient availability, particularly nitrate, phosphorus, and potassium [54]. However, soil biological activity was not measured in our study, and this explanation remains hypothetical. Although nutrient uptake in rice seedlings is limited, it is essential for establishing healthy plants. Enhanced plant growth following seaweed extract application has also been reported in rice [55,56], and okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) [57].

Foliar application provides a faster way to deliver mineral nutrients to plants compared to traditional soil application methods [58,59]. This efficiency is largely because nutrients are actively absorbed through stomata rather than slowly diffusing through the leaf cuticle [60,61]. The nursery experiment further reinforced these results, showing that foliar sprays of seaweed extract significantly improved seedling height, length, and biomass. These improvements are consistent with previous reports where foliar application of seaweed extracts enhanced plant height, dry weight, and growth rate in several crops [34,62]. The observed increase in seedling dry weight and balanced root-to-shoot ratio suggests that foliar applications improve nutrient mobilization and biomass partitioning, leading to healthier seedlings. Similarly, Devi and Mani [63] reported increases in plant height, leaf area index, and crop growth rate of rice at all growth stages due to foliar application of seaweed saps (Kappaphycus alvarezii and Gracilaria). These physiological responses were attributed to enhanced nutrient mobilization and partitioning, which promoted greater leaf area, dry matter accumulation, and overall crop growth.

Moreover, seaweed extracts also enhance the synthesis of bioactive molecules. Different seaweed species contain unique bioactive compounds, which means their extracts can influence plant growth in different ways. Interestingly, these active substances are effective even when applied in very small amounts [64]. For instance, spinach treated with A. nodosum extract showed significant increases in biomass, chlorophyll, carotenoids, proteins, phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity, improvements that were linked to upregulation of the GS1 gene involved in nitrogen assimilation [65]. Such responses highlight the dual role of seaweed extracts in strengthening plant nutrition. This could also explain the observed effect on rice seedlings. It is important to note that, in our study, improvements in nutrient mobilization or hormone activity were not measured. Therefore, these interpretations should be considered potential rather than confirmed mechanisms.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the positive outcomes, this study has several limitations. The results were obtained under controlled laboratory and nursery conditions, and no field trials were conducted, which restricts the ability to predict responses under variable environmental conditions. The short duration of the experiment limits insight into longer-term physiological effects. Additionally, only a single seaweed extract product was tested, and no comparisons were made with other biostimulants or conventional fertilizers. These limitations indicate that the present findings should be interpreted as preliminary.

Future research should include multi-season field evaluations, comparisons with microbial inoculants and standard fertilization regimes, and detailed biochemical analyses of seaweed extracts to identify the active compounds responsible for the observed responses. Additional physiological measurements, including nutrient profiling, hormone analysis, and root system architecture studies, would help clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Taken together, our results indicate that Crop Plus has promising potential as a natural bio-stimulant capable of enhancing seed germination, accelerating early seedling growth and vigor, and improving biomass accumulation in winter rice. The combined use of seed priming and foliar applications suggests that seaweed extracts may offer a sustainable approach to strengthening crop establishment and productivity. Among the treatments evaluated, priming rice seeds with 15,000 ppm seaweed extract for 24 h, followed by nursery application at 2 mL m−2 at 20 and 30 DAS, produced the higher germination, better seedling growth, and greater vigor of winter rice. These findings show that seaweed extract can serve as an effective tool for improving seedling performance in winter rice; however, broader field validation and multi-season evaluations are needed before definitive agronomic recommendations can be made.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System (BAURES) through the Project No. 2024/48/BAU.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Md. Parvez Anwar and Afroza Sultana; investigation: Zakia Akter and Sumona Akter Jannat; writing—original draft preparation: Zakia Akter, Sumona Akter Jannat, Sheikh Md. Shibly, Amdadul Hoque Amran and Joairia Hossain Faria; writing-review and editing: Md. Parvez Anwar, Sabina Yeasmin and Afroza Sultana; supervision: Md. Parvez Anwar and Sabina Yeasmin; funding acquisition: Md. Parvez Anwar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ahmed S , Humphreys E , Chauhan BS . Optimum sowing date and cultivar duration of dry-seeded boro on the High Ganges River Floodplain of Bangladesh. Field Crops Res. 2016; 190: 91– 102. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2015.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rashid MM , Yasmeen R . Cold injury and flash flood damage in boro rice cultivation in Bangladesh: a review. Bangladesh Rice J. 2018; 21( 1): 13– 25. doi:10.3329/brj.v21i1.37360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Anwar MP , Jahan R , Rahman MR , Islam AM , Uddin FJ . Seed priming for increased seed germination and enhanced seedling vigor of winter rice. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021; 756( 1): 012047. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/756/1/012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Farooq M , Basra SMA , Ahmad N . Improving the performance of transplanted rice by seed priming. Plant Growth Regul. 2007; 51( 2): 129– 37. doi:10.1007/s10725-006-9155-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Paparella S , Araújo SS , Rossi G , Wijayasinghe M , Carbonera D , Balestrazzi A . Seed priming: state of the art and new perspectives. Plant Cell Rep. 2015; 34( 8): 1281– 93. doi:10.1007/s00299-015-1784-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. MacDonald MT , Mohan VR . Chemical seed priming: molecules and mechanisms for enhancing plant germination, growth, and stress tolerance. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025; 47( 3): 177. doi:10.3390/cimb47030177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Anwar MP , Khalid MAI , Mominul Islam AKM , Yeasmin S , Ahmed S , Hadifa A , et al. Potentiality of different seed priming agents to mitigate cold stress of winter rice seedling. Phyton. 2021; 90( 5): 1491– 506. doi:10.32604/phyton.2021.015822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mim T , Anwar M , Ahmed M , Sriti N , Moni E , Hasan A , et al. Competence of different priming agents for increasing seed germination, seedling growth and vigor of wheat. Fundam Appl Agric. 2022; 6( 4): 444– 59. doi:10.5455/faa.46026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Anwar MP , Akhter M , Aktar S , Kheya SA , Islam AKMM , Yeasmin S , et al. Relationship between seed priming mediated seedling vigor and yield performance of spring wheat. Phyton. 2024; 93( 6): 1159– 77. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.049073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Afzal I , Basra SM , Ahmad NA , Warraich EA , Khaliq A . Effect of priming and growth regulator treatments on emergence and seedling growth of hybrid maize (Zea mays L.). Int J Agric Biol. 2002; 4( 2): 303– 6. [Google Scholar]

11. Yang J , Zhang W , Wang T , Xu J , Wang J , Huang J , et al. Enhancing sweet sorghum emergence and stress resilience in saline-alkaline soils through ABA seed priming: insights into hormonal and metabolic reprogramming. BMC Genom. 2025; 26( 1): 241. doi:10.1186/s12864-025-11420-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Anwar MP , Juraimi AS , Puteh A , Selamat A , Rahman MM , Samedani B . Seed priming influences weed competitiveness and productivity of aerobic rice. Acta Agric Scand Sect B. 2012; 62( 6): 499– 509. doi:10.1080/09064710.2012.662244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kaur S , Gupta AK , Kaur N . Seed priming increases crop yield possibly by modulating enzymes of sucrose metabolism in chickpea. J Agron Crop Sci. 2005; 191( 2): 81– 7. doi:10.1111/j.1439-037X.2004.00140.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Asadujjaman M , Anwar MP , Hossain A , Kheya SA , Hasan AK , Yeasmin S , et al. Augmenting spring wheat productivity through seed priming under late-sown condition in Bangladesh. Ataturk Univ J Agric Fac. 2023; 54( 2): 57– 67. doi:10.5152/auaf.2023.23112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Qian J , Mo X , Wang Y , Li Q . Seed priming with 2,4-epibrassionolide enhances seed germination and heat tolerance in rice by regulating the antioxidant system and plant hormone signaling pathways. Antioxidants. 2025; 14( 2): 242. doi:10.3390/antiox14020242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zheng M , Tao Y , Hussain S , Jiang Q , Peng S , Huang J , et al. Seed priming in dry direct-seeded rice: consequences for emergence, seedling growth and associated metabolic events under drought stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2016; 78( 2): 167– 78. doi:10.1007/s10725-015-0083-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Miah M , Anwar M , Uddin F , Sultana A , Islam A , Yeasmin S . Seed priming influence on high temperature tolerance and weed suppressive ability of late sown dry direct seeded winter rice. J Bangladesh Agril Univ. 2022; 20( 4): 383– 92. doi:10.5455/jbau.112372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sahin NK . Evaluation of seaweeds as stimulators to alleviate salinity-induced stress on some agronomic traits of different peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivars. Phyton. 2025; 94( 8): 2399– 421. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.067880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Anwar MP , Ahmed MK , Islam AM , Hossain MD , Uddin FJ . Improvement of weed competitiveness and yield performance of dry direct-seeded rice through seed priming. Turk J Sci. 2020; 23( 1): 15– 23. [Google Scholar]

20. Matysiak K , Kaczmarek S , Krawczyk R . Influence of seaweed extracts and mixture of humic and fluvic acids on germination and growth of Zea mays L. Acta Sci Pol Agric. 2011; 10( 1): 33– 45. [Google Scholar]

21. Shukla PS , Shotton K , Norman E , Neily W , Critchley AT , Prithiviraj B . Seaweed extract improve drought tolerance of soybean by regulating stress-response genes. AoB Plants. 2017; 10( 1): plx051. doi:10.1093/aobpla/plx051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hussain HI , Kasinadhuni N , Arioli T . The effect of seaweed extract on tomato plant growth, productivity and soil. J Appl Phycol. 2021; 33( 2): 1305– 14. doi:10.1007/s10811-021-02387-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jayaraman J , Norrie J , Punja ZK . Commercial extract from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum reduces fungal diseases in greenhouse cucumber. J Appl Phycol. 2011; 23( 3): 353– 61. doi:10.1007/s10811-010-9547-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rouphael Y , Giordano M , Cardarelli M , Cozzolino E , Mori M , Kyriacou M , et al. Plant- and seaweed-based extracts increase yield but differentially modulate nutritional quality of greenhouse spinach through biostimulant action. Agronomy. 2018; 8( 7): 126. doi:10.3390/agronomy8070126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mattner SW , Milinkovic M , Arioli T . Increased growth response of strawberry roots to a commercial extract from Durvillaea potatorum and Ascophyllum nodosum. J Appl Phycol. 2018; 30( 5): 2943– 51. doi:10.1007/s10811-017-1387-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Spinelli F , Fiori G , Noferini M , Sprocatti M , Costa G . Perspectives on the use of a seaweed extract to moderate the negative effects of alternate bearing in apple trees. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2009; 84( 6): 131– 7. doi:10.1080/14620316.2009.11512610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Arioli T , Mattner SW , Winberg PC . Applications of seaweed extracts in Australian agriculture: past, present and future. J Appl Phycol. 2015; 27( 5): 2007– 15. doi:10.1007/s10811-015-0574-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hong DD , Hien HM , Son PN . Seaweeds from Vietnam used for functional food, medicine and biofertilizer. J Appl Phycol. 2007; 19( 6): 817– 26. doi:10.1007/s10811-007-9228-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ugarte RA , Sharp G , Moore B . Changes in the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) le jol. plant morphology and biomass produced by cutter rake harvests in southern new Brunswick, Canada. J Appl Phycol. 2006; 18( 3): 351– 9. doi:10.1007/s10811-006-9044-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Battacharyya D , Babgohari MZ , Rathor P , Prithiviraj B . Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci Hortic. 2015; 196: 39– 48. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang W , Peng S , Chen Q , Mei J , Dong H , Nie L . Effects of pre-sowing seed treatments on establishment of dry direct-seeded early rice under chilling stress. AoB Plants. 2017; 8: plw074. doi:10.1093/aobpla/plw074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sivasankari S , Venkatesalu V , Anantharaj M , Chandrasekaran M . Effect of seaweed extracts on the growth and biochemical constituents of Vigna sinensis. Bioresour Technol. 2006; 97( 14): 1745– 51. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2005.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Layek J , Das A , Ramkrushna GI , Ghosh A , Panwar AS , Krishnappa R , et al. Effect of seaweed sap on germination, growth and productivity of maize (Zea mays) in North Eastern Himalayas. Indian J Agron. 2016; 61( 3): 354– 9. doi:10.59797/ija.v61i3.4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Basavaraja SDPK , Yogendra Arup Ghosh ND . Influence of seaweed saps on germination, growth and yield of hybrid maize under Cauvery command of Karnataka, india. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017; 6( 9): 1047– 56. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2017.609.126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ghaderiardakani F , Collas E , Damiano DK , Tagg K , Graham NS , Coates JC . Effects of green seaweed extract on Arabidopsis early development suggest roles for hormone signalling in plant responses to algal fertilisers. Sci Rep. 2019; 9( 1): 1983. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-38093-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mamun AA , Naher UA , Ali MY . Effect of seed priming on seed germination and seedling growth of modern rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties. Agriculturists. 2018; 16( 1): 34– 43. doi:10.3329/agric.v16i1.37532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Abdul Shukor Juraimi AS , Md. Parvez Anwar MP , Ahmad Selamat AS , Adam Puteh AP , Azmi Man AM . The influence of seed priming on weed suppression in aerobic rice. Weed Sci. 2012; 18: 257– 64. [Google Scholar]

38. Bright JP , Maheshwari HS , Thangappan S , Perveen K , Bukhari NA , Mitra D , et al. Biofilmed-PGPR: next-generation bioinoculant for plant growth promotion in rice under changing climate. Rice Sci. 2025; 32( 1): 94– 106. doi:10.1016/j.rsci.2024.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kumar G , Sahoo D . Effect of seaweed liquid extract on growth and yield of Triticum aestivum var. Pusa Gold. J Appl Phycol. 2011; 23( 2): 251– 5. doi:10.1007/s10811-011-9660-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sivritepe N , Organic priming with seaweed extract (Ascophyllum nodosum) affects viability of pepper seeds. Asian J Chem. 2008; 20( 7): 5689– 94. [Google Scholar]

41. Layek J , Das A , Idapuganti RG , Sarkar D , Ghosh A , Zodape ST , et al. Seaweed extract as organic bio-stimulant improves productivity and quality of rice in eastern Himalayas. J Appl Phycol. 2018; 30( 1): 547– 58. doi:10.1007/s10811-017-1225-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. van Tol de Castro TA , Tavares OCH , de Oliveira Torchia DF , Pereira EG , Rodrigues NF , Santos LA , et al. Regulation of growth and stress metabolism in rice plants through foliar and root application of seaweed extract from Kappaphycus alvarezii (Rhodophyta). J Appl Phycol. 2024; 36( 4): 2295– 310. doi:10.1007/s10811-024-03216-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Elamparithi R , Sujatha K , Alex Albert V , Sivakumar T , Gurusamy A , Mini ML . Synergistic effects of seaweed extract presoaking and foliar spray on the performance of paddy improved kavuni (CO 57). Plant Sci Today. 2025; 12( 1): 2348– 1900. doi:10.14719/pst.6412 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Khan A , Khalil SK , Khan AZ , Marwat KB , Afzal A . The role of seed priming in semi-arid area for mungbean phenology and yield. Pak J Bot. 2008; 40( 6): 2471– 80. [Google Scholar]

45. Stirk WA , Novák O , Strnad M , van Staden J . Cytokinins in macroalgae. Plant Growth Regul. 2003; 41( 1): 13– 24. doi:10.1023/A:1027376507197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Nanda S , Kumar G , Hussain S . Utilization of seaweed-based biostimulants in improving plant and soil health: current updates and future prospective. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2022; 19( 12): 12839– 52. doi:10.1007/s13762-021-03568-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Jannin L , Arkoun M , Etienne P , Laîné P , Goux D , Garnica M , et al. Brassica napus growth is promoted by Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) le jol. seaweed extract: microarray analysis and physiological characterization of N, C, and S metabolisms. J Plant Growth Regul. 2013; 32( 1): 31– 52. doi:10.1007/s00344-012-9273-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ali O , Ramsubhag A , Jayaraman J . Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants. 2021; 10( 3): 531. doi:10.3390/plants10030531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Billard V , Etienne P , Jannin L , Garnica M , Cruz F , Garcia-Mina JM , et al. Two biostimulants derived from algae or humic acid induce similar responses in the mineral content and gene expression of winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). J Plant Growth Regul. 2014; 33( 2): 305– 16. doi:10.1007/s00344-013-9372-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kaniyassery A , Thorat SA , Shanthi N , Tantry S , Sudhakar MP , Arunkumar K , et al. In vitro plant growth promoting effect of fucoidan fractions of Turbinaria decurrens for seed germination, organogenesis, and adventitious root formation in finger millet and eggplant. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024; 43( 1): 283– 98. doi:10.1007/s00344-023-11084-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kumari R , Kaur I , Bhatnagar AK . Effect of aqueous extract of Sargassum johnstonii Setchell & Gardner on growth, yield and quality of Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. J Appl Phycol. 2011; 23( 3): 623– 33. doi:10.1007/s10811-011-9651-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Karanja BK , Isutsa DK , Aguyoh JN . Climate change adaptation of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.): influence of Biozyme® rate on potato yield, quality, and mineral nutrient uptake. J Chem Biol Phy Sci. 2013; 3( 3): 2019– 31. [Google Scholar]

53. Chanthini KM , Senthil-Nathan S , Pavithra GS , Malarvizhi P , Murugan P , Deva-Andrews A , et al. Aqueous seaweed extract alleviates salinity-induced toxicities in rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) by modulating their physiology and biochemistry. Agriculture. 2022; 12( 12): 2049. doi:10.3390/agriculture12122049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Chen CL , Song WL , Sun L , Qin S , Ren CG , Yang JC , et al. Effect of seaweed extract supplement on rice rhizosphere bacterial community in tillering and heading stages. Agronomy. 2022; 12( 2): 342. doi:10.3390/agronomy12020342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Patel VP , Deshmukh S , Patel A , Ghosh A . Increasing productivity of paddy (Oryza sativa L.) through use of seaweed sap. Trends Biosci. 2015; 8( 1): 201– 5. [Google Scholar]

56. Singh SK , Thakur R , Singh MK , Singh CS , Pal SK . Effect of fertilizer level and seaweed sap on productivity and profitability of rice (Oryza sativa). Indian J Agron. 2015; 60( 3): 420– 5. doi:10.59797/ija.v60i3.4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zodape ST , Kawarkhe VJ , Patolia JS , Warade AD . Effect of liquid seaweed fertilizer on yield and quality of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.). J Sci Ind Res. 2008; 67( 12): 1115– 17. [Google Scholar]

58. Shah MT , Zodape ST , Chaudhary DR , Eswaran K , Chikara J . Seaweed sap as an alternative liquid fertilizer for yield and quality improvement of wheat. J Plant Nutr. 2013; 36( 2): 192– 200. doi:10.1080/01904167.2012.737886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Nedumaran T , Arulbalachandran D . Seaweeds: a promising source for sustainable development. In: Environmental sustainability. New Delhi, India: Springer; 2014. p. 65– 88. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2056-5_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Marschner H . Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

61. Fernández V , Brown PH . From plant surface to plant metabolism: the uncertain fate of foliar-applied nutrients. Front Plant Sci. 2013; 4: 289. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Biswajit P , Koushik B , Arup G . Effect of seaweed saps on growth and yield improvement of green gram. Afr J Agric Res. 2013; 8( 13): 1180– 6. doi:10.5897/ajar12.1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Leindah Devi N , Mani S . Effect of seaweed saps Kappaphycus alvarezii and Gracilaria on growth, yield and quality of rice. Indian J Sci Technol. 2015; 8( 19): 47610. doi:10.17485/ijst/2015/v8i19/47610 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Khan W , Rayirath UP , Subramanian S , Jithesh MN , Rayorath P , Hodges DM , et al. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants of plant growth and development. J Plant Growth Regul. 2009; 28( 4): 386– 99. doi:10.1007/s00344-009-9103-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Abd Tahar SZ , How SE , Lum MS , Surugau N . Seaweed extracts as bio-stimulants for rice plant (Oryza sativa)—a review. Preprints. 2022. doi:10.20944/preprints202210.0387.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools