Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hydroalcoholic Extracts of Achillea spp. from Greece: A Study on Phenolic Content and Their Biological Activities

1 Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece

2 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Kragujevac, Radoja Domanovića 12, Kragujevac, 34000, Serbia

3 Department of Science, Institute for Information Technologies, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, 34000, Serbia

4 Department of Chemistry, University of Crete, Voutes, Heraklion, 71003, Greece

* Corresponding Author: Olga S. Tsiftsoglou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses and Adaptations to Environmental Stresses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.075566

Received 04 November 2025; Accepted 26 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

Achillea species are known for their healing properties since ancient times. There is extensive literature on their pharmacological action due to their bioactive compounds. The present study aimed to investigate the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of hydroalcoholic extracts from the inflorescences and leaves of the species Achillea crithmifolia Waldst. and Kit., A. grandifolia Friv. and A. millefolium L. The phytochemical profiles of all extracts were evaluated both by NMR spectroscopy and LC-MS analysis, and the results were consistent with the spectrophotometrically determined total phenolic (TP: 125.42–191.98 mg/g) and total flavonoid (TF: 47.34–180.02 mg/g) contents. All the extracts were tested for their antioxidant activity using DPPH and ABTS•+ radical scavenging assay, as well as ferrous ion chelating ability and reducing power tests. All the extracts showed moderate antioxidant activity, compared to the reference substance BHT. Additionally, the antibacterial activity of the extracts was evaluated against major food-borne pathogens, showing moderate antimicrobial effects.Keywords

Plants are the source of specialty materials such as biocides, colorants, dyes, essential oils, medications, and cosmetics. The majority of medicinal and aromatic plant (MAP) species are still harvested from the wild, while many are grown for such industrial purposes. Farmers have the possibility to grow these crops because of the requirement for sustainable industrial product sources and the preservation of plant biodiversity [1]. The usage of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) is expanding across industries, from cosmetics to medicine, thus influencing a variety of market trends. By carefully evaluating these parameters, potential producers can identify promising MAPs for cultivation that support sustainable practices and contribute to the expansion of the specialty industrial materials sector [2]. Based on a variety of species and a broad range of potencies, the Asteraceae (Compositae) family is the largest blooming family of traditional Mediterranean herbal medicines. Named for the Greek hero Achilles, who reportedly employed the plant to treat battle wounds, Achillea ranks among the most biologically active genera in the Asteraceae family. There are about a hundred species in the genus Achillea that are found growing all over the world [3]. In Greece, according to the website “Flora of Greece”, genus Achillea counts 29 different species [4].

In the food, beverage, and pharmaceutical sectors, bioactive plant extracts are used for various purposes, such as producing functional foods and supplements or extending the shelf life of products, thereby supporting low costs and high consumer acceptance in terms of chemical and microbiological safety [5]. Achillea millefolium L. (common yarrow) is one of the oldest widely used medicinal herbs not only in European traditional medicine but worldwide [6]. The aerial parts of the above-mentioned plant are mostly used to heal wounds, gastrointestinal issues, skin conditions, liver conditions, and are mild sedatives, among other things. In Germany, Poland, and Spain, products containing substances for the herbal tea of A. millefolium have been on the market for more than thirty years, according to EMA [7]. Preclinical research suggests that yarrow has hepatoprotective, antipathogenic, and anxiolytic properties, and has the potential to re well-tolerated [8]. According to the recent study, yarrow infusions and yarrow subcritical water extracts have been successfully used as substrate for fermentation of Kombucha in order to produce the famous beverage in an alternative way [9].

Recent years have seen a rise in research on the dermatological qualities of Achillea species, with A. millefolium being the most extensively researched and utilized member of the genus. Strong scientific evidence suggests that other yarrow species may also be abundant sources of compounds significant for cosmetic application, including anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, skin-calming and rejuvenating qualities.

Although A. millefolium extracts remain the most prominent yarrow components in cosmetic products, accumulating evidence indicates that other Achillea species also demonstrate valuable biological properties for dermatological and cosmetic use. Given the widespread global distribution of these plants, extracts from various Achillea species may be readily accessible and serve as valuable active ingredients in cosmetics and medicinal ointments for acne treatment [10,11].

Building upon the existing scientific literature on Achillea spp., the present study investigates the antioxidant capacity and antimicrobial efficacy of extracts derived from three distinct species, alongside a comprehensive characterization of their chemical constituents. This multifaceted approach aims to evaluate the potential of these extracts for integration into various industrial applications, particularly within cosmetology, functional foods, and natural product formulations, where safe and effective bioactive ingredients are increasingly in demand.

As A. millefolium is already well-established in global medicinal, food, and cosmetic markets due to its broad spectrum of biological activities, it serves as an important benchmark. Conducting a comparative assessment of A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia against this widely utilized species provides meaningful insight into their relative strengths, unique phytochemical signatures, and potential functional advantages. Through this comparison, the study seeks not only to broaden the understanding of chemical diversity within the genus but also to identify promising alternative species that could diversify raw material sources, support sustainable harvesting strategies, and expand the portfolio of Achillea-based ingredients available for industrial exploitation.

In the present study, the aerial parts of wild populations of Achillea crithmifolia Waldst. & Kit. (ACFW and ACLW), A. grandifolia (AGFW and AGLW), and A. millefolium L. (AMLW) were collected from Mount Menoikio (Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, Greece) during the summer of 2015. All plant specimens were taxonomically identified, and the material was separated into leaves and inflorescences before drying. A voucher specimen has been deposited at the School of Pharmacy, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece) under Nos. Lazari D. 7512, Lazari D. 7513 and Lazari D. 7514. The cultivated plant material of Achillea millefolium L. was obtained from the culture of two different locations, one from Agio Pnevma Serres (Central Macedonia, Greece) [AMFC] and the other from Heraklion (Crete, Greece) [AMLC].

2.2 Preparation of the Extracts

For each species, three separate extractions were performed, each using 1 g of plant material. In each extraction, the sample was treated with 50 mL of a methanol–water solvent mixture (70:30 v/v) at room temperature. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction was carried out in a controlled bath for 30 min for each of the three extraction cycles.

2.3 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

The 1H NMR spectra were recorded on an Agilent DD2 500 spectrometer operating at 500.1 MHz. For each sample, approximately 0.7 mL of methanol-d4 (CD3OD) was used as the NMR solvent to ensure complete dissolution of the analyte and to provide a stable deuterium lock. Chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm) relative to TMS (3.31 ppm for CD3OD).

2.4 HPLC-PDA-MS Analysis of the Samples

The analytical measurements were conducted using an LC-PDA-MS Thermo Finnigan system, consisting of an LC Pump Plus, Autosampler, and Surveyor PDA Plus Detector, interfaced with an ESI MSQ Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, MA, USA) and operated via Xcalibur software. The mass spectrometer was operated in negative ionization mode over an m/z range of 100–1000. The gas temperature was set to 350°C, with a nitrogen flow rate of 10 L/min, and the capillary voltage was maintained at 3000 V. The cone voltage was set at 75 V. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Thermo Hypersil Gold RP-C18 column (5 μm, 100 mm × 4.6 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) maintained at 30°C. The mobile phase consisted of H2O containing 0.05% formic acid (pH 2.8–3.0) (A) and acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Sample analysis was performed using the following gradien: 0–8 min, 87% A; 8–40 min, 40–45 min, to 87% A and 45–50 min, 87% A. A volume of 10 μL was injected. The UV–vis spectra were obtained across the 220–600 nm range, while chromatographic detection was carried out at 280 nm [12].

All solvents (methanol, ethanol, DMSO), compounds (gallic acid, rutin, NaHCO3, AlCl3, FeSO4, FeCl3, K4[Fe(CN)6]), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, butylated hydroxytoluene, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), ferrozine, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, trichloroacetic acid, erythromycin, nystatin, and resazurin) and reagents Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, used for the determination of the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of extracts were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Sterilized 96-well micro test plates U-bottom were purchased from Ratiolab, Dreieich, Germany. Nutrient mediums for the cultivation of microorganisms and performing antimicrobial tests were obtained from the Institute “Torlak”, Belgrade, Serbia. Spectrophotometric measurements were performed on a UV/Vis double beam spectrophotometer Halo DB-20S (Dynamica GmbH, Dietikon, Switzerland).

2.6 Determination of Total Phenolic Content

The method outlined by Singleton et al. [13] was used to determine the total phenolic content in extracts. To prepare the reaction mixture, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (2.5 mL; diluted 10-fold) and NaHCO3 (1 mL, 7.5%) were added to 0.5 mL of the extracts’ solutions in methanol (0.5 mg/mL). The absorbance was measured at 765 nm after a 15-min incubation period at 45°C. The total phenol content was calculated using the mean of three separate analyses and reported as mg of gallic acid equivalents per g of extract (mg GAE/g extract).

2.7 Determination of Flavonoid Content

The method described by Brighente et al. [14] was used to determine the total flavonoid content. After incubating 1 mL of 2% AlCl3 solution in methanol and the same volume of a plant extract solution in methanol (0.5 mg/mL) for an hour at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 415 nm. The total flavonoid content was reported as the mean value of three separate analyses and expressed in mg of rutin equivalents per g extract (mg RUE/g extract).

2.8 Determination of DPPH Free-Radical Scavenging Activity

To determine the extracts’ capacity to scavenge DPPH radicals, 1 mL of DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) solution (80 μg/mL) prepared in methanol was added to 1 mL of different concentrations of extract solution in methanol. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm after 30 min of mixture incubation at room temperature [15]. As a reference antioxidant, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) was employed. Three separate analyses of every sample were conducted. The percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity of extracts and BHT was calculated using the following equation:

The absorbance of the control solution is Ac (without extracts or standard solutions), while the absorbance of the extract solution with DPPH is As. The sigmoidal dose-response curve plotting the percentage of scavenging against the extract concentration (mg/mL) allowed for the calculation of the concentration of extracts that provided 50% scavenging (IC50).

For the determination of ABTS•+ scavenging activity of extracts, 16 h before experiments, ABTS radical cation (ABTS•+) solution was prepared. For that purpose, equal volumes of 7 mM ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) ethanol solution and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate aqueous solution were mixed and left to stand at room temperature protected from light. After 16 h, the solution of generated ABTS•+ was diluted with ethanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.005 at 734 nm. In a series of double dilutions of the extracts (0.2 mL) and BHT as a standard compound, ABTS•+ solution (1.8 mL) was added and allowed to react for 30 min at room temperature [16]. After measuring the absorbance at 734 nm, the radical scavenging activity was calculated using the equation described in the DPPH method and displayed as an IC50 value.

2.10 Measurement of Ferrous Ion Chelating Ability

The method for determining the capacity of extracts to chelate Fe2+ ions was based on monitoring the decrease of the formation complex of Fe2+ ions with ferrozine, which manifests as a decrease in absorbance at 562 nm. In this reaction, 1 mL of 0.125 mM FeSO4 was added to 1 mL of various concentrations of methanolic solutions of extracts or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA) solutions, followed by the addition of 1.0 mL of 0.3125 mM ferrozine solution and left for 10 min prior to the measurement of absorbance at 562 nm [17]. The percentage of chelating capacity of extracts and corresponding IC50 values for extracts and EDTA were determined in comparison to the control (without test sample). The sample’s capacity to chelate ferrous ions was determined in the same way as described for the DPPH method.

2.11 Measurement of Reducing Power

Different extract concentrations (2.5 mL) made in distilled water were combined with the same amount of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 1% potassium ferricyanide solution. After 20 min of incubation at 50°C, the mixture was treated with 2.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (w/v). The samples were then centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 8 min, and the top layer (5 mL) was combined with 1 mL of FeCl3 (0.1%) solution [18]. Following that, the absorbance at 700 nm was measured, and the results were displayed as mg of ascorbic acid per gram of extract.

2.12 Determination of Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The minimal concentrations of Achillea hydroalcoholic extracts that inhibit (MIC) the growth of different bacterial and fungal species were determined according to the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [19,20,21]. The antimicrobial potential of extracts was tested on three gram-positive (G+) bacteria (Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, and Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633), four gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 10145, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 70063), the yeast Candida albicans ATCC 10231, and molds Aspergillus brasiliensis ATCC 16404, Fusarium oxysporum FSB 91, Alternaria alternata FSB 51, Doratomyces stemonitis FSB 41, Trichoderma longibrachiatum FSB 13, Trichoderma harzianum FSB 12, Penicillium canescens FSB 24, Penicillium chrysogenum FSB 22. The fungal species with FSB numbers are isolated from biological samples and obtained from the Laboratory for Microbiology, Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, University of Kragujevac, Serbia. All microorganisms used in the experiments for the determination of MIC were freshly cultured 24–48 h before the experiment.

For the determination of MIC for extract samples, the microdilution assay was employed using sterile 96-well microtiter plates. The used extracts concentrations were from 5 to 0.039 mg/mL while standards (erythromycin and nystatin) concentrations were from 40 to 0.3125 μg/mL microorganism inocula were adjusted to a concentration of roughly 1.0 × 106 CFU/mL for bacteria [20] and yeast [19] and 1.0 × 104 CFU/mL for fungi [21]. The lowest concentration of extract at which there was no bacterial growth after 24 h at 37°C, or fungal growth after 48 h at 28°C, represented MIC. Resazurin color change was an indicator of bacterial growth, while fungal growth was observed visually.

The results are presented as the mean of three independent measurements ± standard deviation. The OriginPro8 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) was used for the calculation of the IC50 value, the concentration of the extract that reduces the concentration of free radicals by 50%, in the determination of the antioxidant activity of samples. Statistical analysis was performed using OriginPro 8 software. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, and differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons were carried out by comparing the obtained values among samples within the same experimental set.

3.1 Phenolic Content of Achillea spp. Extract

3.1.1 Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content of Achillea spp. Extracts

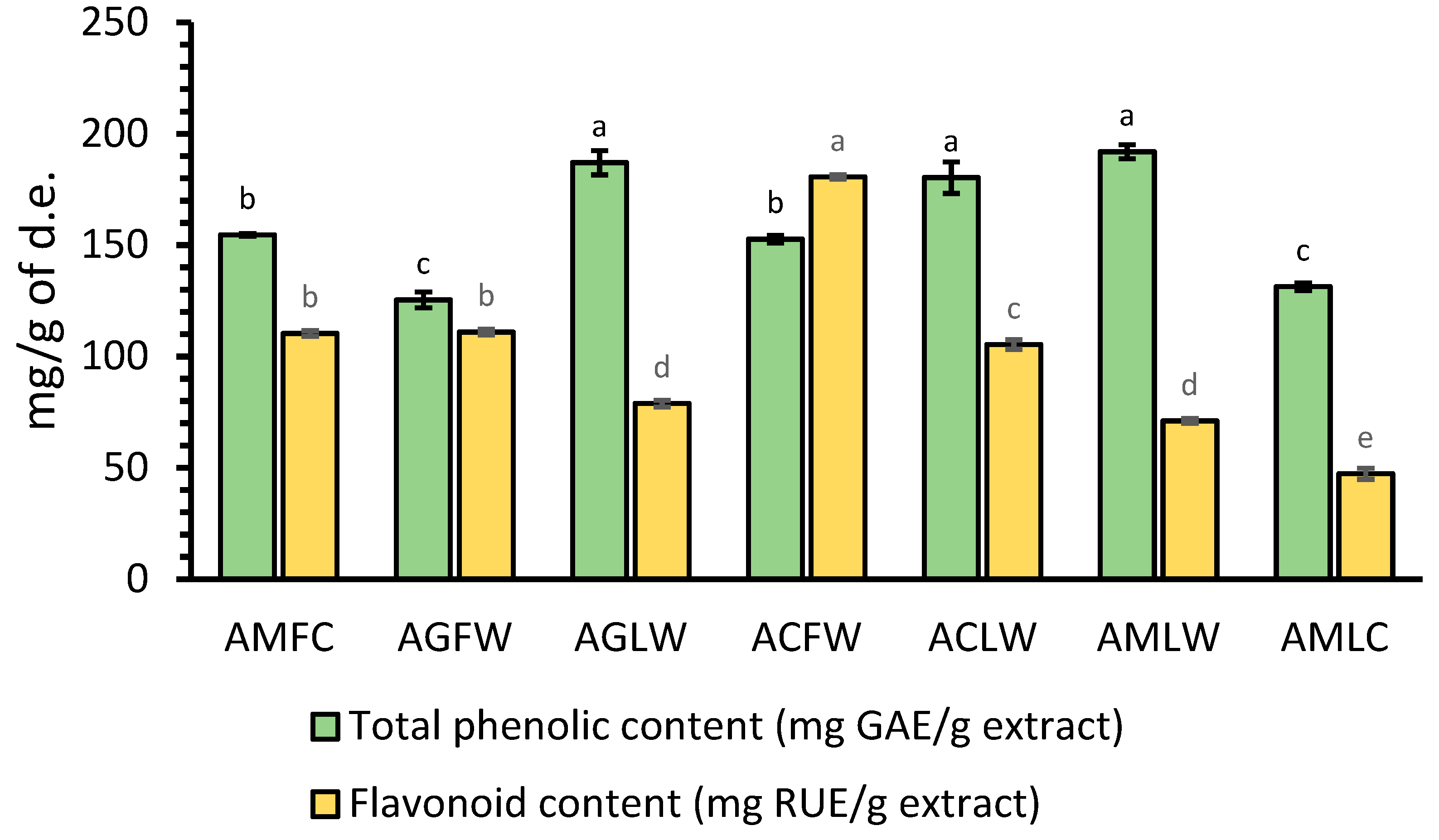

Achillea species are well known as plants rich in phenolic compounds, especially distinguished by their high content of flavonoids [22,23]. Fig. 1 showed that all studied Achillea spp. possess high total phenolic content (TPC) between 125.42 and 191.98 mg of GAE per gram of dry extract. Also, the results showed that most of the measured amount of phenolics consists of flavonoids (Fig. 1). The extracts obtained from plant leaves contained higher total phenolic content in comparison with inflorescence extracts, while the inflorescence extracts were richer in total flavonoid content (TFC) in comparison with leaves extracts. Among the studied extracts, wild A. milefolium, A. grandifolia, and A. crithmifolia leaves extracts contained the highest total phenolic content (191.98, 187.08, and 180.34 mg GAE/g extract, respectively). The highest total flavonoid content was recorded in wild A. crithmifolia inflorescences (ACFW) extract (180.62 mg RUE/g extract). The extract of cultivated A. milefolium leaves (AMLC) possessed lower TPC and TFC in comparison with the extract from wild-growing A. milefolium (AMLW). However, the extract obtained from cultivated A. millefolium inflorescences (AMFC) was richer in TPC content compared with the extract of wild-growing A. grandifolia, while the TFC was almost the same in these two extracts (110.31 and 110.99 RUE/g extract, respectively).

Figure 1: Total phenolic and flavonoid contents of cultivated A. milefoliun inflorescences (AMFC), wild A. grandifolia inflorescences (AGFW), wild A. grandifolia leaves (AGLW), wild A. crithmifolia inflorescences (ACFW), wild A. crithmifolia leaves (ACLW), wild A. milefolium leaves (AMLW), and cultivated A. milefolium leaves (AMLC) extract. GAE—gallic acid equivalents; RUE—rutin equivalents; d.e.—dry extract; Results are mean values ± SD from three experiments. Values for the same group of compounds with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

3.1.2 NMR Analysis of Phenolics and Flavonoids Achillea spp. Extract

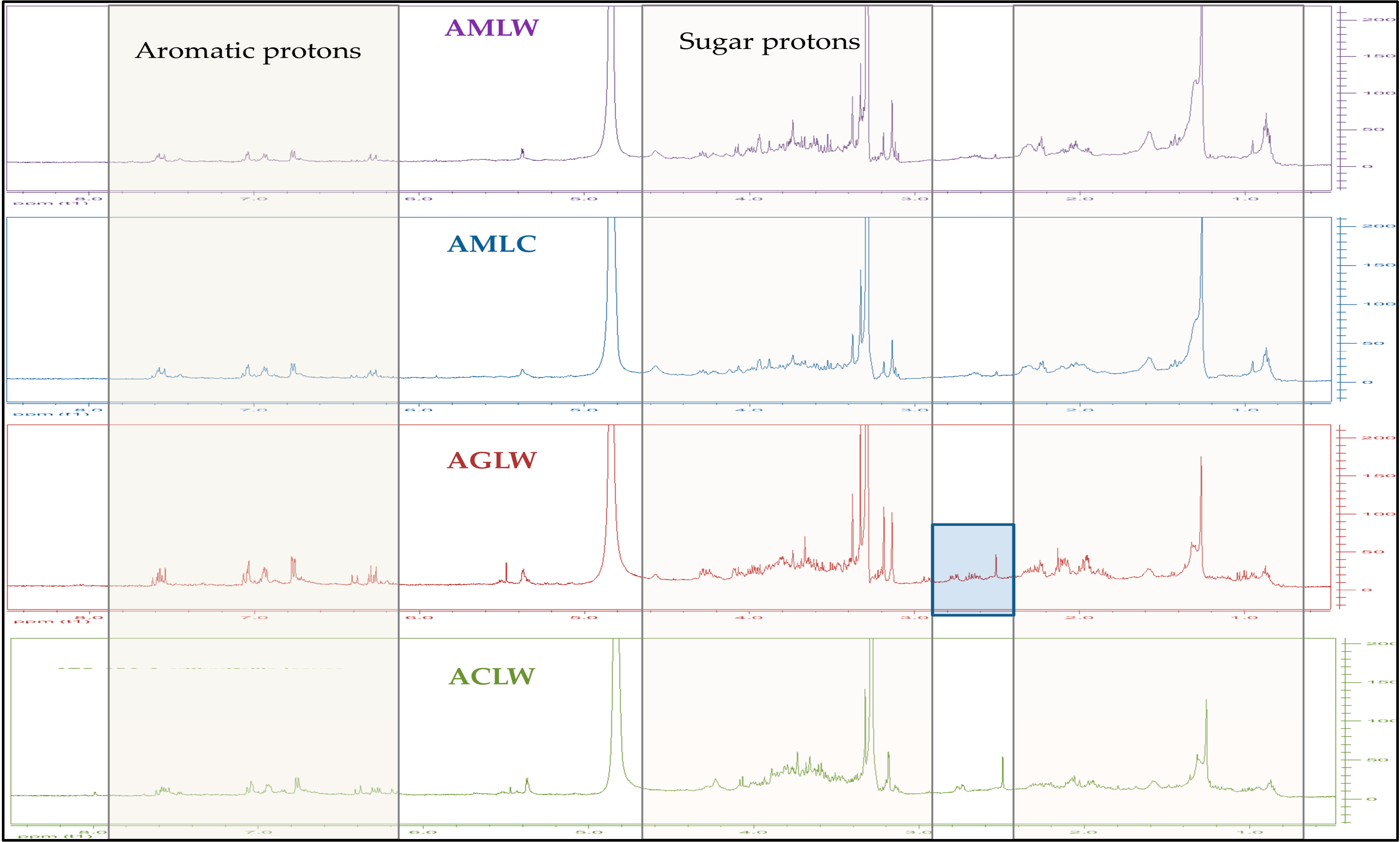

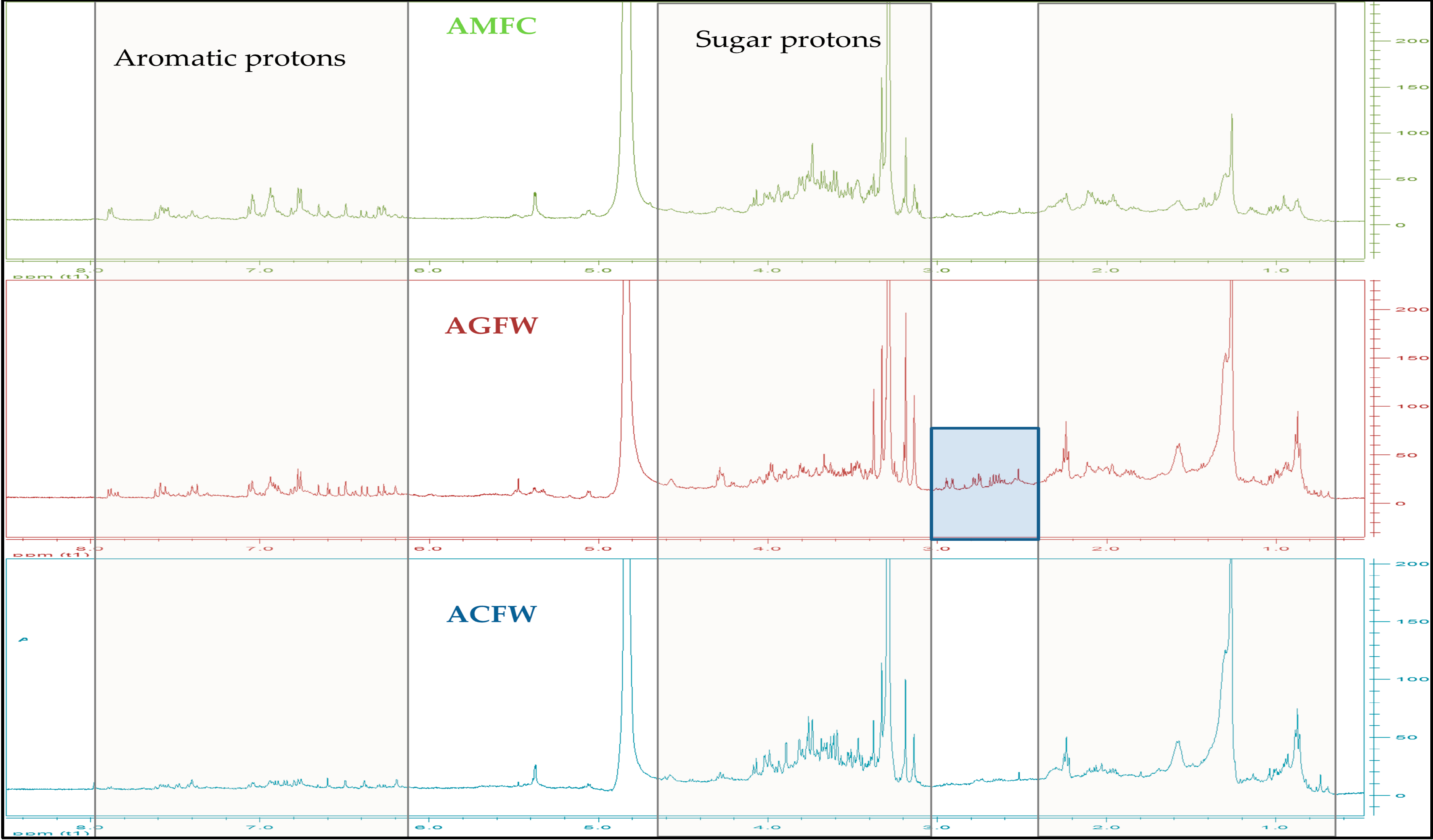

The 1H-NMR spectra of all extracts Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, revealed a complex phenolic profile, as all extracts were found to contain both glycosylated and non-glycosylated forms of phenolic acids and flavonoids: trans-caffeic acid and its derivatives were identified by the presence of a characteristic pair of trans-olefinic proton signals at 7.57 and 6.30 ppm (d, J = 16.0 Hz), whereas signals that corresponded to ABX systems and other aromatic protons (at 7.66–6.19 ppm) indicated the presence of other phenolic acids and flavonoids. Signals between 5.55 and 3.15 ppm were assigned to sugar protons. The study of the 1H-NMR spectra also revealed differences between the species. The main difference is between A. grandifolia (both for inflorescense and leaves) and all the other samples in δ region 2.40–3.00 ppm (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Figure 2: 1H-NMR spectra of all the hydroalcoholic extracts derived from the leaves of Achillea spp. X axis ppm, Y axis intention 0–200 (CD3OD, 500 MHz).

Figure 3: 1H-NMR spectra of all the hydroalcoholic extracts derived from the inflorescence of Achillea spp. X axis ppm, Y axis intention 0–200 (CD3OD, 500 MHz).

3.1.3 LC-MS on Achillea spp. Extract

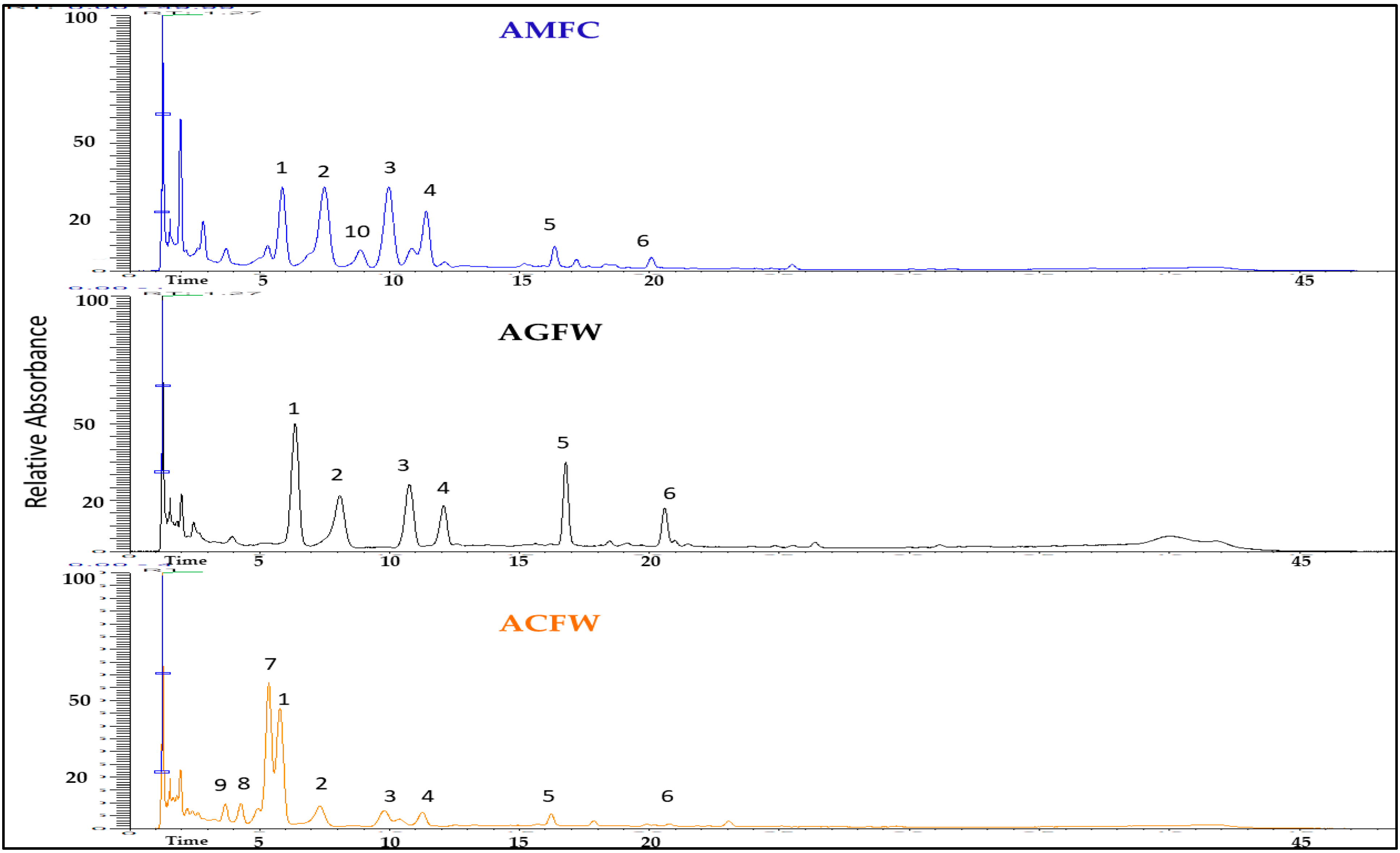

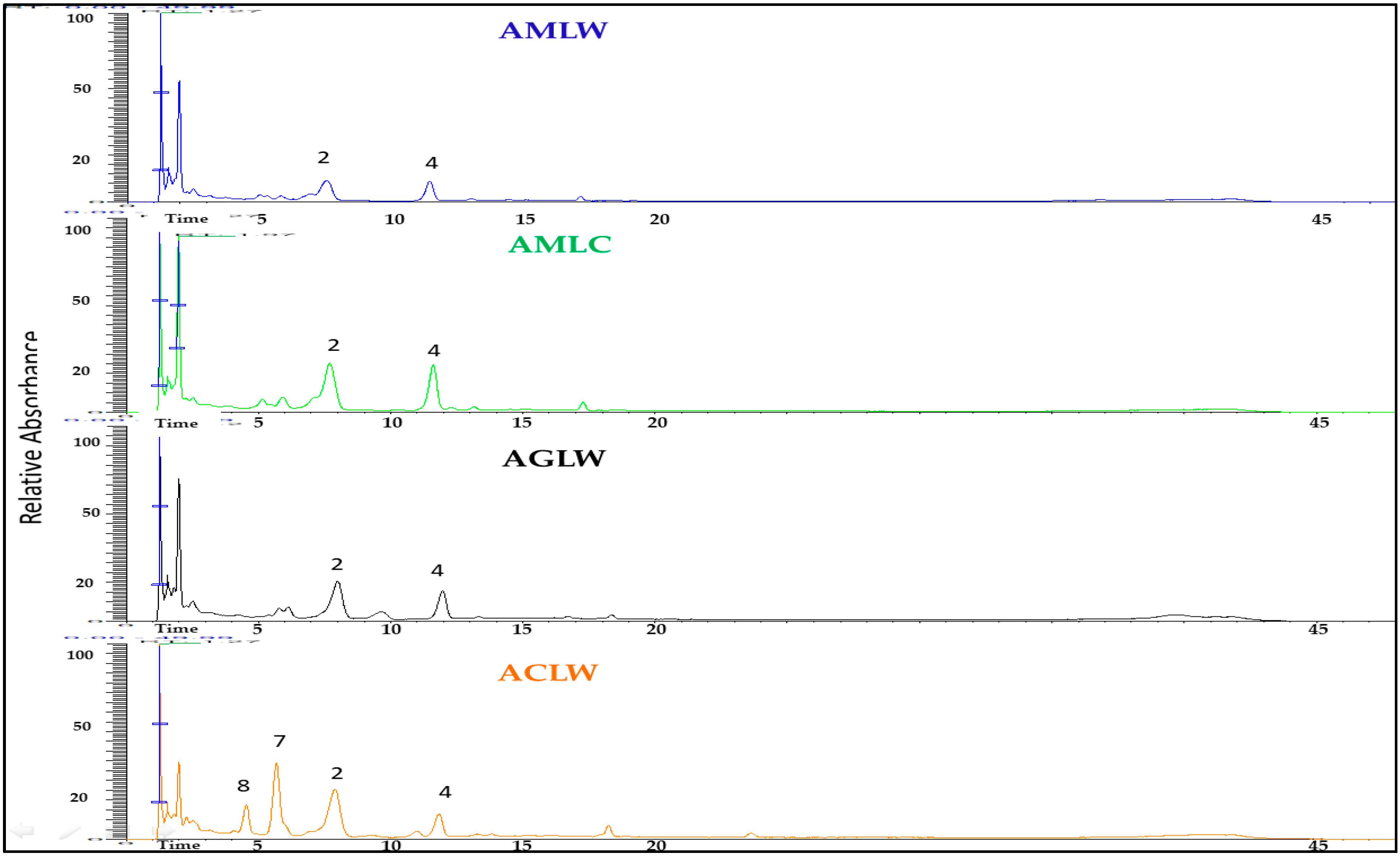

The results of qualitative analysis of dried hydroalcoholic extracts of the examined plant material from the leaves and inflorescence of Achillea spp. are presented in Table 1, and the LC-MS chromatograms are shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5. Based on the fragmentation patterns and retention times, two acyl quinic acids and eight flavonoids were the most predominant identified compounds in the examined extracts.

One peak at m/z 515 [M-H]− afforded prominent ions at m/z 353 and m/z 191, indicating the subsequent losses of caffeoyl moiety reveal the presence of a dicaffeoyl quinic acid. Another peak with a retention time tR = 7.34 min gave [M-H]− ion at m/z 353 (C16H17O9) [caffeoylquinic acid –H]− with product ions m/z 191. (C7H11O6) [quinic acid-H]− and m/z 135 (C8H7O2) [caffeic acid –H–CO2]− indicate the presence of 3-caffeoyl quinic acid [24].

In the negative ion mode, flavonoids deprotonate readily to provide the ion [M-H]−. Moreover, by breaking glycosidic bonds, flavone O-glycoside mostly loses the sugar group. Flavonoids’ parent nucleus loses the CO group and it is also vulnerable to RDA cracking [25]. So luteolin was identified with a molecular ion peak at m/z 285, which fragmented to an ion at m/z 133 and apigenin with a molecular ion peak at m/z 269, which is fragmented to an ion at m/z 117. Luteolin glucoside, having 162 amu higher molecular weight than luteolin, demonstrated [M-H]− value at m/z 447 and the product ion at m/z 285 representing luteolin aglycone through the absence of a glucoside moiety [26]. In the chromatograms, ions can be observed that indicate the presence of two apigenin O-glycosylated compounds in the examined extracts, along with the apigenin aglycone. The apigenin-7-O-glycoside, with a molecular ion at m/z 431 and a fragment ion at m/z 269 resulting from the loss of a hexose moiety [27], and an apigenin diglycoside (rhamnoside–hexoside) with a molecular ion at m/z 577 and a fragment ion at m/z 269, suggest that the two sugar residues (rhamnose and hexose) are linked to each other through the same oxygen atom.

Peaks 7, 8 and 9 (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) were identified as quercetin derivatives owing to the product ion observed at around m/z 301 and UV spectra (λmax around 350–357 nm) [28]. Peaks 8 and 9 (m/z 609.1 [M-H]−) were identified as two di-O-glycosyl isomers. Compound 8 is identified as a quercetin rutinoside due to the absence of the daughter ion with m/z 462.95, which appears in the case of compound 9. The presence of this ion in compound 9 indicates that the two glycosides (rhamnose and hexose) are attached to different oxygen atoms.

Table 1: Predominant secondary metabolites in the studied Achillea extracts by HPLC-PDA-MS.

| Retention Time (min) | m/z | Fragments | Identification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.69 | 608.99 | 462.95, 300.84, 158.87, 137.00 | Quercetin-Ox-hexoside-Oy rhamnoside | [28] |

| 4.28 | 609.02 | 301.00, 179.06, 137.04 | Quercetin O-rutinoside | [28] |

| 5.36 | 476.94 | 300.99, 179.05, 150.98, 120.47 | Quercetin glucuronide | [29] |

| 6.44 | 446.96 | 284.97, 158.90, 133.04 | Luteolin 7 O-glucoside | [26] |

| 8.78 | 353.07 | 191.08, 179.0, 160.0, 135.0 | Chlorogenic acid | [26] |

| 8.87 | 577.04 | 269.01, 137.00 | Apigenin O-rutinoside | [30] |

| 10.88 | 431.00 | 267.93 | Apigenin 7 O-glucoside | [26] |

| 12.14 | 514.98 | 353.09, 191.07, 179.08 | Dicaffeoyl quinic | [26] |

| 16.85 | 285.01 | 133.05 | Luteolin | [26] |

| 20.69 | 268.99 | 117.00 | Apigenin | [26] |

Figure 4: Base peak chromatogram of the inflorescences’ extracts from Achillea spp. in the negative mode (1: luteolin-O-hexoside, 2: chlorogenic acid, 3: apigenin-O-hexoside, 4: dicaffeoylquinid acid, 5: luteolin, 6: apigenin, 7: quercetin-O-glucuronide, 8: quercetin Ox-rhamnoside-Oy-hexoside, 9: quercetin O-rutinoside, 10: apigenin-O-(rhamnoside-hexoside).

Figure 5: Base peak chromatogram of the leaves’ extracts from Achillea spp. in the negative mode (2: chlorogenic acid, 4: dicaffeoylquinid acid, 7: quercetin-O-glucuronide, 8: quercetin Ox-rhamnoside-Oy-hexoside).

3.2 Antioxidant Activity of Achillea spp. Extracts

All studied Achillea hydroalcoholic extracts showed strong antioxidant activity across different assays. (Table 2). In the neutralization of DPPH radicals, all extracts were effective to scavenge 50% of free radicals a concentration below 100 μg/mL, while IC50 values for extracts in ABTS•+ scavenging activity were between 81.24 to 132.85 μg/mL. IC50 values for the synthetic antioxidant in these two methods were about 20 μg/mL. The highest DPPH scavenging activity (IC50 44.93 g/mL) was demonstrated by wild A. milefolium leaves [extract with the highest TPC] followed by wild A. crithmifolia leaves, cultivated A. milefolium inflorescences, and cultivated A. milefolium leaves extracts. Regarding the ABTS•+ method, the highest potential to neutralize free radicals was shown by wild A. crithmifolia leaves and wild A. milefolium leaves extracts with similar IC50 values (81.24 and 85.57 μg/mL, respectively). Although the IC50 values of the examined extracts were significantly higher compared to BHT, these extracts may be considered as natural antioxidants with high scavenging potential, suggesting that they contain various compounds with strong antioxidant activity.

The metal chelating activity assay was used to determine the capacity of Achillea spp. hydroalcoholic extracts to bind and thus disable the pro-oxidant metal ions from participating in reactions that may generate free radicals, such as hydroxy radicals [31,32]. The results showed that almost all studied extracts may chelate 50% of Fe2+ in concentrations below 1 mg/mL, except wild A. grandifolia leaves extract, where no IC50 value below 2 mg/mL was recorded (Table 2). The results for chelating ability suggest that these extracts have high metal chelating properties, considering that EDTA, used as one of the most powerful chelating agents, had IC50 24.65 μg/mL. Contrary, wild A. grandifolia inflorescences and wild A. crithmifolia inflorescences extracts possessed IC50 values of 119.69 and 131.51 μg/mL, respectively. Also, the highest metal chelating activity was shown by extracts with the highest TFC. According to Craft et al. [33], among phytochemicals, flavonoids and their derivatives possess the most powerful metal chelating properties. The ability of extracts to reduce, donating an electron, some oxidants such as free radicals and metal ions was also determined. Both wild A. grandifolia and A. milefolium inflorescences extracts showed the highest reducing power, indicating that 1 g of AGFW and AMFC extracts possess reducing power similar to 244.18 and 232.76 mg of ascorbic acid, respectively (Table 2). These results demonstrated that Achillea extracts, with the highest potential to reduce the Fe3+, had approximately 25% of the reducing power of ascorbic acid.

Table 2: Antioxidant potential of Achillea spp. hydroalcoholic extracts.

| Samples | IC50 μg/mL | Reducing Power (mg AA/g) Extracts) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH• | ABTS•+ | Metal Chelating | ||

| AMFC | 65.82 ± 3.39b | 126.07 ± 5.41a | 232.86 ± 36.00d | 232.76 ± 5.75a |

| AGFW | 86.88 ± 2.89a | 132.85 ± 2.39a | 119.69 ± 8.55e | 244.18 ± 12.59a |

| AGLW | 80.88 ± 1.96a | 111.37 ± 6.70b | >2000a | 172.45 ± 6.35b |

| ACFW | 86.78 ± 2.15a | 107.81 ± 5.93b | 131.51 ± 1.57e | 126.86 ± 6.63c |

| ACLW | 63.19 ± 2.27b | 81.24 ± 4.35c | 258.76 ± 0.60d | 90.36 ± 2.45d |

| AMLW | 44.93 ± 1.31c | 85.57 ± 0.41c | 593.46 ± 28.38b | 106.92 ± 0.54c |

| AMLC | 77.41 ± 0.21a | 122.76 ± 8.52a | 349.71 ± 34.28c | 81.02 ± 2.78d |

| Standards | ||||

| BHT | 19.49 ± 1.36d | 20.27 ± 1.83d | - | - |

| EDTA | - | - | 24.65 ± 2.31f | - |

3.3 Antimicrobial Activity of Achillea spp. Hydroalcoholic Extracts

Scientific research on the antimicrobial potential of Achillea plants has been mainly focused on their essential oils; therefore, scarce information is available concerning the antimicrobial activity of their extracts. Based on the results shown in Table 3, it is observed that different extracts of A. grandifolia, A. crithmifolia, and A. milefolium did not show inhibitory activity against most of the used bacteria and fungi in concentrations up to 5 mg/mL. The activity of the AGLW extract against E. faecalis, S. typhimurium, and the fungus T. harzianum, with MIC values of 1.25 mg/mL may be highlighted. As well as the activity of AMLW extract against the fungi T. lougibrachiatum, T. harzianum, and P. chrysogenum (MIC 1.25 mg/mL). Interestingly, T. harzianum was susceptible to almost all tested extracts (MIC 1.25 mg/mL) except the ACFW extract, which showed more prominent activity against T. lougibrachiatum. In general, both Trichoderma species showed the highest sensitivity to all tested extracts. All obtained MIC values for the studied extracts may suggest that wild A. grandifolia leaves extract possesses a slightly higher antimicrobial potential with MIC values > 5 mg/mL for the highest number of microorganisms compared with other studied extracts.

Table 3: Antimicrobial potential of Achillea spp. hydroalcoholic extracts.

| Microorganisms | MIC (mg/mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMFC | AGFW | AGLW | ACFW | ACLW | AMLW | AMLC | Antibiotica/Antimycoticb | |

| E. faecalis | >5 | 5 | 1.25 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 2.5 |

| B. subtilis | >5 | >5 | 2.5 | 5 | >5 | >5 | 5 | 2.5 |

| S. aureus | 2.5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | >5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 0.625 |

| P. aeruginosa | >5 | >5 | >5 | 5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >40 |

| S. typhimurium | 5 | 5 | 1.25 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 0.625 |

| E. coli | 5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | >5 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 0.625 |

| K. pneumoniae | >5 | 5 | 5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | <0.3125 |

| C. albicans | >5 | >5 | 5 | >5 | 5 | >5 | 5 | 2.5 |

| A. brasiliensis | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 10 |

| F. oxysporum | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 5 |

| A. alternata | 5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 5 |

| D. stemonitis | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 5 |

| T. lougibrachiatum | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 |

| T. harzianum | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 5 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 5 |

| P. canescens | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| P. chrysogenum | 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 |

Numerous investigations have focused on the phytochemical screening of certain categories of secondary metabolites in various species of the genus Achillea [34,35,36,37]. The obtained results from the quantification of phenolic compounds in hydroalcoholic extracts suggest that all three wild Achillea species possess very similar total phenolic content in their leaves. Inflorescence extracts are scarce in total phenolic content compared with the corresponding leaves extracts but contain significantly higher flavonoid amounts. As it concerns the flowers of A. grandifolia these results are in contrast to those presented by Taşkın et al. [38] in which the flower extract contains the highest amount of phenolic compounds. Although similar values for phenolic and flavonoid content in the methanolic extract of wild A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia were obtained by Stanković et al. [39]. However, in that study, A. crithmifolia possessed higher TPC in the above-ground part compared with A. grandifolia, while both plants’ extracts from our study contained similar TFC. These distinctions in phenolic content may be conditioned by the different methods of extraction and the different localities where plants grow. A study conducted with Achillea species from Turkey showed that A. milefolium flower infusion had the highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents compared with A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia infusions [40]. According to a study published by Radušiene et al. [41], phenolic acids and flavonoids are the most abundant phenolic compounds in 70% methanol extracts of inflorescences and leaves of A. milefolium populations from Turkey and Lithuania. They concluded that A. milefolium inflorescences and leaves contain high quantities of chlorogenic acid and 3,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid, with the highest content of these compounds in leaves. Meanwhile, the highest amount of different flavonoids was observed in A. milefolium inflorescences with luteolin, apigenin, and their derivatives as dominant compounds [41].

Previous research also showed the high antioxidant potential of Achillea species [42]. The methanolic extract of A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia from Serbia showed similar antioxidant activity in different methods, but A. crithmifolia possessed slightly higher potential to neutralize DPPH and ABTS•+ radicals, as well as reducing power [38]. In our study antioxidant activity of these two species was similar; however, in some methods, A. grandifolia demonstrated higher antioxidant potential compared with A. crithmifolia. The IC50 value for the methanolic extract of A. milefolium leaves collected in Pakistan [43] was 72.33 μg/mL for DPPH scavenging activity, which is similar to the IC50 values for cultivated A. milefolium leaves extract from our study, while the extract of wild A. milefolium leaves demonstrated significantly higher antioxidant potential (IC50 44.93 μg/mL). According to Konyalioglu and Karamenderes [40], among Achillea species from Turkey, A. milefolium infusion possessed the highest free radical scavenging activity, while A. grandifolia infusion had slightly lower activity, followed by A. crithmifolia, which is in accordance with the results obtained in our research. Considering the results obtained for phenolic quantification in the extracts and their antioxidant potential, the extracts with the highest TPC exhibited the greatest radical scavenging activity, while those with the highest TFC demonstrated the strongest metal chelating ability. According to Craft et al. [33], among phytochemicals, flavonoids and their derivatives possess the most potent metal chelating properties.

The antibacterial properties of Achillea species and their associated extracts have been extensively evaluated over the last two decades [44,45]. The extracts of A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia in our study showed higher antibacterial activity compared with the antimicrobial activities of methanolic extracts of the aerial parts of the same plants published by Stanković et al. [39]. The mentioned study showed that the extract of A. grandifolia was the most effective against P. aeruginosa (isolated from sputum) and E. coli (isolated from the wound) with MIC values from 12.5 to 50 mg/mL [39]. The studies conducted by Frey & Meyers46] confirmed the antibacterial activity of the aqueous extract of A. millefolium against S. typhimurium and S. aureus, with a higher zone of inhibition recorded against gram-positive S. aureus (9.6 mm) [46]. A recent study about the antimicrobial potential of A. millefolium showed that its 80% ethanolic and methanolic extracts displayed antimicrobial activity against some pathogenic bacterial species and C. albicans with MIC values in the range of 2.4 to 1.6 mg/mL [47].

This study has several limitations. Because the analysis focused mainly on phenolic compounds, it does not capture the full metabolomic diversity of the samples and was not intended to provide an integrated view of biochemical–antioxidant relationships. Environmental and seasonal factors were not systematically controlled, and reliance on a single analytical method further narrows the scope. Finally, the limited sample size may reduce the generalizability of the findings.

The preliminary phytochemical characterization of the extracts from the studied Achillea species revealed variability in their composition and bioactivity. Total phenolic and flavonoid compounds were found to be present in significant amounts in all extracts. According to the results of phenolic component measurements in the hydroalcoholic extracts, the total phenolic content in the leaves of all three wild Achillea species was very similar. In comparison with the corresponding leaf extracts, the inflorescence extracts showed lower total phenolic content but substantially higher flavonoid levels. Overall, no significant differences were observed among the examined Achillea species regarding their phytochemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and antimicrobial activity. The bioactivity profiles of A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia closely paralleled those recorded for the widely used A. millefolium, a species well recognized for its therapeutic and industrial applications. The close similarity across these metrics underscores the potential of A. grandifolia and A. crithmifolia as valuable alternative sources of bioactive compounds. Consequently, these species may be considered promising candidates for broader utilization in international food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries—particularly in formulations where A. millefolium is traditionally employed. Their comparable phytochemical richness, coupled with potential advantages related to availability, cultivation, or regional biodiversity management, further highlights their relevance for future biotechnological and commercial exploitation.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the Serbian Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development (Agreements No. 451–03-136/2025–03/200122 and 451-03-136/2025-03/200378).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou and Diamanto Lazari; methodology, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou, Kyriakos Michail Dimitriadis, Vladimir Mihailovic and Nikola Sreckovic; software, Michalis K. Stefanakis; validation, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou, Vladimir Mihailovic and Diamanto Lazari; formal analysis, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou, Vladimir Mihailovic and Nikola Sreckovic; investigation, Kyriakos Michail Dimitriadis, Nikola Sreckovic and Jelena S. Katanic Stankovic; resources, Diamanto Lazari; data curation, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou; writing—original draft preparation, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou and Michalis K. Stefanakis; writing—review and editing, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou and Vladimir Mihailovic; visualization, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou; supervision, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou and Diamanto Lazrai; project administration, Olga S. Tsiftsoglou. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Lubbe A , Verpoorte R . Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Ind Crops Prod. 2011; 34( 1): 785– 801. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.01.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Singh S , Singh VP , Nainwal RC , Singh D , Tewari SK . Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. In: Kumar L , Bharadvaja N , Singh R , Anand R , editors. Medicinal and aromatic plants. Sustainable landscape planning and natural resources management. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 231– 41. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-64601-0_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kbaydet O , Abou-Ela M , Raafat K . Achillea extracts elicit anti-diabetic neuropathic pain by modulating inflammatory cytokines. J Tradit Complement Med. 2024; 15( 4): 388– 403. doi:10.1016/j.jtcme.2024.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. The Flora of Greece web. [cited 2025 May 9]. Available from: https://portal.cybertaxonomy.org/flora-greece/cdm_dataportal/taxon/992c9854-e2af-456a-90cf-a7d88b1129f6. [Google Scholar]

5. Mannila E , Marti-Quijal FJ , Selma-Royo M , Calatayud M , Falcó I , de la Fuente B , et al. In vitro bioactivities of food grade extracts from yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.) and stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.) leaves. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2023; 78( 1): 132– 8. doi:10.1007/s11130-022-01020-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Benedek B , Kopp B . Achillea millefolium L. s.l. revisited: recent findings confirm the traditional use. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2007; 157( 13–14): 312– 4. doi:10.1007/s10354-007-0431-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. European Medicines Agency . Assessment report on Achillea millefolium L., herba. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: European Medicines Agency; 2009. Report No.: EMA/HMPC/290309/2009. [Google Scholar]

8. Ritika , Rizwana , Tripathi AD , Agarwal A . Achillea millefolium L., common yarrow. In: Sharma A , Nayik GA , editors. Immunity boosting medicinal plants of the western Himalayas. Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 29– 57. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-9501-9_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Vitas JS , Cvetanović AD , Mašković PZ , Švarc-Gajić JV , Malbaša RV . Chemical composition and biological activity of novel types of kombucha beverages with yarrow. J Funct Foods. 2018; 44: 95– 102. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2018.02.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Strzępek-Gomółka M , Gaweł-Bęben K , Kukula-Koch W . Achillea species as sources of active phytochemicals for dermatological and cosmetic applications. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021; 2021: 6643827. doi:10.1155/2021/6643827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shah R , Peethambaran B . Anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial properties of Achillea millefolium in acne treatment. In: Chatterjee S , Jungraithmayr W , Bagchi D , editors. Immunity and inflammation in health and disease. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2018. p. 241– 8. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-805417-8.00019-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Paloukopoulou C , Karioti A . A validated method for the determination of carnosic acid and carnosol in the fresh foliage of Salvia rosmarinus and Salvia officinalis from Greece. Plants. 2022; 11( 22): 3106. doi:10.3390/plants11223106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Singleton VL , Orthofer R , Lamuela-Raventós RM . Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1998; 299: 152– 78. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99017-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Brighente IMC , Dias M , Verdi LG , Pizzolatti MG . Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of some Brazilian species. Pharm Biol. 2007; 45( 2): 156– 61. doi:10.1080/13880200601113131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kumarasamy Y , Byres M , Cox PJ , Jaspars M , Nahar L , Sarker SD . Screening seeds of some Scottish plants for free radical scavenging activity. Phytother Res. 2007; 21( 7): 615– 21. doi:10.1002/ptr.2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Re R , Pellegrini N , Proteggente A , Pannala A , Yang M , Rice-Evans C . Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999; 26( 9–10): 1231– 7. doi:10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lim YY , Lim TT , Tee JJ . Antioxidant properties of guava fruit: comparison with some local fruits. Sunway Acad J. 2006; 3: 9– 20. [Google Scholar]

18. Oyaizu M . Studies on products of browning reaction prepared from glucose amine. JPN J Nutr. 1986; 44: 307– 14. [Google Scholar]

19. CLSI M27-A3. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 3rd ed. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

20. CLSI M38-A2. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

21. CLSI M07-A9. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 9th ed. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

22. Tsiftsoglou OS , Krigas N , Gounaris C , Papitsa C , Nanouli M , Vartholomatos E , et al. Isolation of secondary metabolites from Achillea grandifolia friv. (Asteraceae) and main compounds’ effects on a glioblastoma cellular model. Pharmaceutics. 2023; 15( 5): 1383. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15051383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Konyalioglu S , Karamenderes C . The protective effects of Achillea L. species native in Turkey against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in human erythrocytes and leucocytes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005; 102( 2): 221– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang J , Yao L , Gong K , Li K , Sun L , Cai W . Identification and quantification of chlorogenic acids from the root bark of Acanthopanax gracilistylus by UHPLC-Q-exactive orbitrap mass spectrometry. ACS Omega. 2022; 7( 29): 25675– 85. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c02899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ding Y , Chen S , Wang H , Li S , Ma C , Wang J , et al. Identification of secondary metabolites in Flammulina velutipes by UPLC-Q-exactive-orbitrap MS. J Food Qual. 2021; 2021: 4103952. doi:10.1155/2021/4103952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gevrenova R , Zengin G , Sinan KI , Yıldıztugay E , Zheleva-Dimitrova D , Picot-Allain C , et al. UHPLC-MS characterization and biological insights of different solvent extracts of two Achillea species (A. aleppica and A. santolinoides) from Turkey. Antioxidants. 2021; 10( 8): 1180. doi:10.3390/antiox10081180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Abd-El-Aziz NM , Hifnawy MS , Lotfy RA , Younis IY . LC/MS/MS and GC/MS/MS metabolic profiling of Leontodon hispidulus, in vitro and in silico anticancer activity evaluation targeting hexokinase 2 enzyme. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 6872. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-57288-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sobral F , Calhelha RC , Barros L , Dueñas M , Tomás A , Santos-Buelga C , et al. Flavonoid composition and antitumor activity of bee bread collected in northeast Portugal. Molecules. 2017; 22( 2): 248. doi:10.3390/molecules22020248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ncube EN , Steenkamp PA , Madala NE , Dubery IA . Metabolite profiling of the undifferentiated cultured cells and differentiated leaf tissues of Centella asiatica. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017; 129( 3): 431– 43. doi:10.1007/s11240-017-1189-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cvetković S , Ignjatijević A , Kukić-Marković J , Vuletić S , Ušjak L , Milutinović V , et al. Further insights into antimicrobial and cytotoxic potential of Achillea millefolium herb methanol and dichloromethane extracts. Ind Crops Prod. 2025; 225: 120553. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.120553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mihailović V , Katanić Stanković JS , Jurić T , Srećković N , Mišić D , Šiler B , et al. Blackstonia perfoliata (L.) Huds. (Gentianaceae): a promising source of useful bioactive compounds. Ind Crops Prod. 2020; 145: 111974. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Valko M , Leibfritz D , Moncol J , Cronin MTD , Mazur M , Telser J . Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007; 39( 1): 44– 84. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Craft BD , Kerrihard AL , Amarowicz R , Pegg RB . Phenol-based antioxidants and the in vitro methods used for their assessment. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2012; 11( 2): 148– 73. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00173.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Villalva M , Silvan JM , Alarcón-Cavero T , Villanueva-Bermejo D , Jaime L , Santoyo S , et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties of an Achillea millefolium L. extract and its fractions obtained by supercritical anti-solvent fractionation against Helicobacter pylori. Antioxidants. 2022; 11( 10): 1849. doi:10.3390/antiox11101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Raudone L , Radušiene J , Seyis F , Yayla F , Vilkickyte G , Marksa M , et al. Distribution of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in plant parts and populations of seven underutilized wild Achillea species. Plants. 2022; 11( 3): 447. doi:10.3390/plants11030447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tsiftsoglou OS , Atskakani ME , Krigas N , Stefanakis MK , Gounaris C , Hadjipavlou-Litina D , et al. Exploring the medicinal potential of Achillea grandifolia in Greek wild-growing populations: characterization of volatile compounds, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of leaves and inflorescences. Plants. 2023; 12( 3): 613. doi:10.3390/plants12030613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Apel L , Lorenz P , Urban S , Sauer S , Spring O , Stintzing FC , et al. Phytochemical characterization of different yarrow species (Achillea sp.) and investigations into their antimicrobial activity. Z Für Naturforsch C. 2020; 76( 1–2): 55– 65. doi:10.1515/znc-2020-0149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Taşkın D , Alkaya DB , Dölen E . Evaluation of antioxidant capacity and analysis of major phenolic compounds in Achillea grandifolia by HPLC-DAD with Q-TOF LC/MS confirmation. Chiang Mai J Sci. 2018; 45( 1): 287– 98. [Google Scholar]

39. Stanković N , Mihajilov-Krstev T , Zlatković B , Stankov-Jovanović V , Mitić V , Jović J , et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of traditional medicinal plants from the Balkan peninsula. NJAS Wagening J Life Sci. 2016; 78( 1): 21– 8. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2015.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Konyalioglu S , Karamenderes C . Screening of total flavonoid, phenol contents and antioxidant capacities of some Achillea L. species growing in Turkey. Acta Pharm Turc. 2004; 46( 3): 163– 70. [Google Scholar]

41. Radušienė J , Karpavičienė B , Raudone L , Vilkickyte G , Çırak C , Seyis F , et al. Trends in phenolic profiles of Achillea millefolium from different geographical gradients. Plants. 2023; 12( 4): 746. doi:10.3390/plants12040746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mohammadhosseini M , Sarker SD , Akbarzadeh A . Chemical composition of the essential oils and extracts of Achillea species and their biological activities: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017; 199: 257– 315. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2017.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mehmood A , Javid S , Khan MF , Ahmad KS , Mustafa A . In vitro total phenolics, total flavonoids, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of selected medicinal plants using different solvent systems. BMC Chem. 2022; 16( 1): 64. doi:10.1186/s13065-022-00858-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Salehi B , Selamoglu Z , Sevindik M , Fahmy NM , Al-Sayed E , El-Shazly M , et al. Achillea spp. a comprehensive review on its ethnobotany, phytochemistry, phytopharmacology and industrial applications. Cell Mol Biol. 2020; 66( 4): 78– 103. doi:10.14715/cmb/2020.66.4.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Grigore A , Colceru-Mihul S , Bazdoaca C , Yuksel R , Ionita C , Glava L . Antimicrobial activity of an Achillea millefolium L. Proceedings. 2020; 57( 1): 34. doi:10.3390/proceedings2020057034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Frey FM , Meyers R . Antibacterial activity of traditional medicinal plants used by Haudenosaunee peoples of New York State. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010; 10: 64. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-10-64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ivanović M , Grujić D , Cerar J , Islamčević Razboršek M , Topalić-Trivunović L , Savić A , et al. Extraction of bioactive metabolites from Achillea millefolium L. with choline chloride based natural deep eutectic solvents: a study of the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Antioxidants. 2022; 11( 4): 724. doi:10.3390/antiox11040724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools