Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Reactive Depression Following Psychological Distress among Iraqi Students

1 School of Education for Humanities, Department of Educational and Psychological Sciences, University of Anbar, Ramadi, 20, Iraq

2 School of Basic Education, Department of Psychological Counseling and Educational Guidance, University of Diala, Diala, 25, Iraq

3 Department of Psychiatry, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

* Corresponding Author: Fuaad Mohammed Freh. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Depression Across the Lifespan: Perspectives on Prevention, Intervention, and Holistic Care)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1117-1131. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.065203

Received 06 March 2025; Accepted 23 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: The world is now experiencing many crises and adversities of great impact that pose serious threats to both physical and mental health. Threats to mental health include major depressive disorder, which can be severe and disabling. The current study aimed to identify the prevalence of one type of depressive disorder, reactive depression (RD), and its relationship to demographic and psychological variables. Methods: For this study, RD is defined as an abnormal emotional response to traumatic situations involving mood difficulties. This study created an online self-report reactive depression questionnaire consisting of 23 items distributed across three subscales: 1) bad feelings and life attitudes, 2) loss of hope and loneliness, and 3) feeling sad and loss of confidence. The questionnaire was administered to a volunteer sample of 362 male and female Iraqi university students. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), t-tests, and one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to investigate exploratory and confirmatory factor structures of the questionnaire. Results: Evidence of reactive depression was found in 18.2% of the students. Female students had significantly higher levels of reactive depression than males (female N = 205, mean = 85.00, SD = 11.30; male N = 157, mean = 76.46, SD = 11.51). The high levels of reactive depression identified in these students demonstrate the value of assessing reactive depression in university students. Conclusion: The study underscores that the loss of emotional and psychological security, particularly in the face of traumatic and permanent events such as the death of a loved one, may contribute to the onset and progression of depressive symptoms. Future research should explore the role of specific cultural factors and further validate the reactive depression questionnaire in broader populations. Additionally, there is a need for improved mental health support in Iraqi universities, particularly for female students, who may face unique challenges.Keywords

Serious crises and adversities prevalent in today’s world pose serious threats to both physical and mental health. Especially since the beginning of 2020, numerous major natural disasters (earthquakes, floods, forest fires, hurricanes) have been recorded, associated with extensive loss of life and property. In 2021, 15 earthquakes struck in China, affecting more than 1.4 million people [1]. Sudden floods, forest fires, and storms occurred in Australia, killing 33 people and more than a billion animals and destroying 11 million hectares of land and thousands of homes. The scientific literature has established that critical incidents and adversities of various types are associated with psychological and social problems, notably including fear, panic, helplessness, sleep problems, mood disorders, and low self-efficacy, often precipitating psychological crises [2,3].

Mamun and Ullah [4] found that the psychological stressors associated with fear of being infected with coronavirus (COVID-19 contagion anxiety) led to emotional responses of panic, loneliness, and phobias, especially among people with underlying health problems. With serious cognitive and behavioral consequences. A study by Quadros et al. [3] reported that 18%–45% of population members expressed morbid fear of COVID-19 infection. The World Health Organization (WHO) found an increased prevalence of depression by at least 7% in association with the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing, and other protective restrictions imposed by some countries. These stressors, coupled with the unprecedented pandemic-related stressors of social isolation and insufficient psychosocial support, appeared to further increase risks for the development of reactive depression [5]. Research has demonstrated that constant exposure to psychological crises and adversities such as the COVID-19 pandemic may contribute to the development of deep frustration, sadness, and grief, which, in turn, may lead to self-harm behaviors and suicidality [6].

In recent years, the population of Iraq has suffered serious ongoing adversities and crises, creating substantial personal challenges and life-threatening dangers. One of the greatest potential consequences of these hardships is to the mental health of the civilian population [7,8]. Given these circumstances, the prevalence of psychological and emotional instability and mental disorders has increased in Iraq over this period, especially in children and young adults. Studies have also reported that as many as 47% of Iraqi people may have been exposed to a major traumatic event [9], reflecting the volatile and violent environments of their existence. One study estimated that as many as one out of three adults in Iraq may have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and/or depressive disorder, and 14% of Iraqi children may have posttraumatic or depressive symptoms [9,10].

Knowledge about reactive depression among Iraqi students is of critical importance in terms of the five main considerations. The first involves an appreciation of the widespread presence of socio-political and economic stressors. Iraq has experienced prolonged periods of conflict, economic instability, and political turmoil, which contribute to high levels of stress, anxiety, and risk for reactive depression [11]. The second revolves around comprehension of the negative effects of reactive depression on academic performance and prospects. Depression is well known to impair cognitive functions such as concentration, memory, and problem-solving, promoting problems of academic performance and educational dropout. Gaining knowledge about these problems can help stimulate the development and implementation of interventions to support students in achieving their educational goals. The third encompasses a better understanding of methods of coping and fostering resilience. Learning how Iraqi students cope with stressors can provide insights into effective resilience-building strategies and stimulate the development and implementation of culturally appropriate interventions. The fourth pertains to long-term psychological and social consequences. Unaddressed reactive depression can progress to chronic mental health problems, social withdrawal, and even suicidality, which can be prevented by early intervention [12]. The fifth supports policy and educational reforms. Understanding the prevalence and causes of reactive depression can help policymakers, educators, and mental health professionals implement policies to promote student well-being and academic success.

Based on the foregoing, the current study represents a step in investigating the psychological, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social sequelae associated with reactive depressive symptoms during personal crises and hardships, including terrorist incidents. This study addresses important gaps in the scientific literature on the effects on students of exposure to death or other loss of a relative or loved one, which are vital to responding to these students’ needs.

The current study specifically aimed to 1) create a questionnaire for reactive depression during stressful events among university students, 2) investigate the detection of reactive depression about stressful events among these students, 3) identify variables associated with reactive depression among them, including gender, age, marital status, and aspects of the psychological distress response, and 4) assess the independent associations of each of these variables (gender, age, marital status, and features of the psychological distress response) with reactive depression.

Theoretical Framework

Experimental research has long attempted to explain the occurrence of depression. This research has demonstrated extensive contradictions and generated a set of theoretical frameworks to model cognitive, social, and psychological constructs of depressive symptoms, distinguishing their development in stress-exposed compared to non-exposed individuals [13]. The major classical theories about reactive depression are structured around three influential models: psychoanalytic, cognitive, and behavioral.

Psychoanalytic theory emphasizes the importance of the loss of central sources of love and emotional security as preliminary to the onset of reactive depression. These losses presumably lead to a variety of endogenous consequences that culminate in various states of depression. With the advent of psychoanalytic theory about depression in general, the focus shifted from the loss of external narcissistic gratification to the loss of internal sources of security, such as self-esteem, accompanied by intense and irrational self-criticism. Freud assumed that after exposure to a traumatic event, part of the ego arising within the individual is subconsciously directed against others, judges them critically, and tries to avoid them. To explain extreme self-criticism, Freud assumed that self-blame is not directed at the ego only, but is directed at the lost object resulting from exposure to the traumatic event. Explicit hostility may thus be directed toward others and lead to many additional psychological consequences, including feelings of guilt, representing the individual’s anger directed toward the self. Thus, reactive depression is conceptualized as a product of directing the hostile side of contradictory feelings towards oneself and others [14].

From the cognitive perspective, the learned helplessness model of reactive depression has been highly influenced by the cognitive theory of depression [15]. According to Beck, reactive depression occurs because of a negative cognitive scheme or group of schemes constructed regarding oneself, the future, and the world, the so-called “depression triad.” These developments predispose the individual to reactive depression after exposure to stressful, traumatic events. Beck suggested that individual exposures to stressful life events or losses activate these schemes and result in the distortion of the individual’s organized thoughts and perceptions. For example, Beck observed that individuals with reactive depression tend to exaggerate arbitrary inferences (drawing conclusions based on a small part of one piece of information without consideration of the complete information), which are especially prone to selective abstraction (drawing conclusions based on a small part of one piece of information in isolation). Additionally, individuals with reactive depression may tend to exaggerate through a process of overgeneralization (drawing comprehensive and general conclusions from limited individual perceptions about the event) and through complementary amplification and minimization (respectively overemphasizing the importance of negative events and devaluing the importance of positive events). In the same vein, Kuiper et al. [16] postulated that the self-schema of reactive depression exerts a negative impact on a wide range of activities and cognitive processes, including memory, reasoning, and perception. This self-depressive schema is thought to arise gradually along with the development and increasing severity of a reactive depression episode. Non-depressed individuals possess positive self-schemas, in contrast to individuals with reactive depression who are inclined to confuse positive and negative schemas. In other words, as reactive depression deepens, the self-schema becomes increasingly negative. Kuiper et al. [16] concluded that individuals without reactive depression were more efficient and positive in processing information compared to individuals with severe and moderate reactive depression.

The behavioral perspective substantially diverges from psychoanalytic and cognitive approaches, emphasizing decreased activity as a main feature of reactive depression. This position is supported by psychological studies: Freh [17] found that activity levels decrease in the face of low levels of positive reinforcement, and, according to the behavioral orientation, this relates to personal characteristics such as age, gender, attractiveness, or even a deficit of appropriate skills. These low levels of positive reinforcement lead to a vicious cycle of low activity, leaving the individual isolated and further vulnerable to reactive depression tendencies. In other words, when family members, relatives, and close friends do not display empathy or interest, the individual becomes increasingly isolated and prone to depressive moods. This, in turn, generates further negative responses from others and a self-perpetuating cycle of reactive depression.

A descriptive-correlational approach was adopted to achieve the aims of the current study. This approach allows systematic observation, documentation, and analysis of reactive depression as it occurs in real-life settings. It can enable the ascertainment of how widespread this condition is among specific populations, such as Iraqi students, and provide a clear picture of its characteristics.

2.1 Sampling and Ethical Approval

Data were collected from a volunteer sample of Iraqi university students recruited by internet invitation to participate in an online questionnaire via the University platform (the portal of the university). Inclusion criteria were: 1) undergraduate students; 2) >age 18; 3) were engaged in morning study (who were more representative than students of evening studies of the study’s age inclusion criteria); 4) with no prior history of major depressive symptoms (MDD); and 5) not selected for any recent traumatic or stressful event. A total of 362 unique responses from participants meeting study criteria were received. Before completing the online questionnaire, all participants were informed online about the purpose and procedures of this study and then provided online written informed consent. Participants were informed that the study data would be anonymous without collecting personally identifying information. Although participants were informed that involvement in the study might be a demanding emotional experience, the study was considered to entail no more than minimal risk to participants’ well-being. Participants had to complete all items before submitting their answers to avoid resubmitting their responses. The participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 24 years; 205 (56.63%) were males and 157 (43.37%) were females.

Ethical clearance was obtained by approval of the University of Anbar/Ethical Committee (UoAEC) (reference number: A303/5/4). This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline [18].

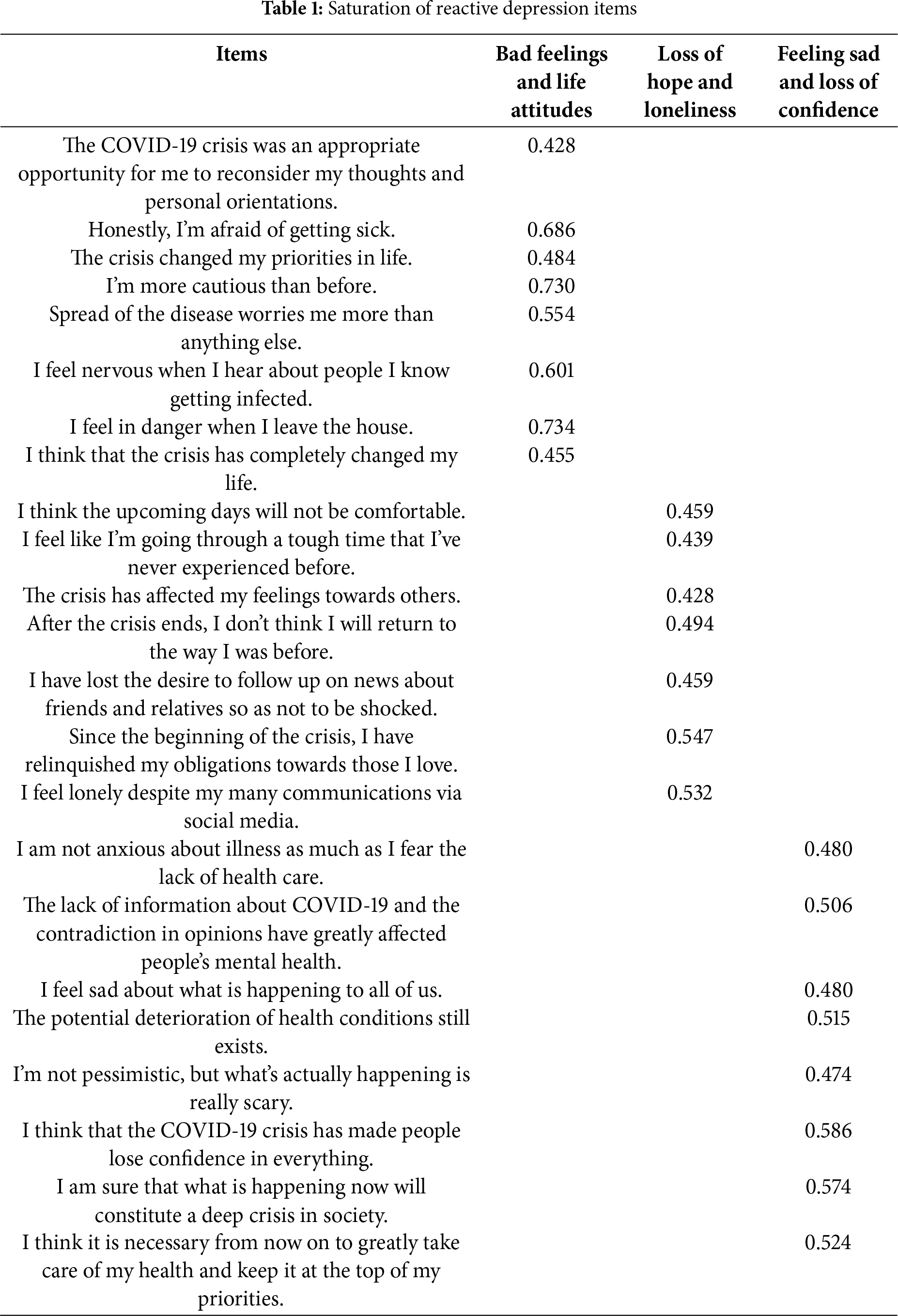

The researchers created a self-report questionnaire to measure reactive depression among University students, based on Gary’s [19] definition of reactive depression as stated above. Participants reported the extent of feelings related to exposure to stressful events such as losing a family member, close friend, and/or relatives, through 23 items (see items in Table 1). The responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = “completely agree” to 5 = “completely disagree”). Higher scores indicate higher levels, and lower scores indicate lower levels of reactive depression.

Following extensive data checking, SPSS 21 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to conduct univariate and bivariate analyses. t-tests for one sample were used to measure Reactive Depression. t-tests for two independent samples were also used to examine the associations of demographic variables with reactive depression. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to extract factors from the reactive depression questionnaire. Data from 362 participants were subjected to analysis. After checking the adequacy of the analysis sample, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin showed (KMO = 0.835, Bartlet’s = 2440.923, df = 465, p < 0.001). The exploratory factor analysis findings presented in Table 1 reveal three factors of reactive depression, accounting for 60.05% of the total variation, and the saturation of items ranged from 0.428 to 0.734. The resulting factors are:

First factor: This factor was saturated with eight items, accounting for 19.32% of the total variance, revolving around perceived stress and exhaustion from the traumatic event. This factor is labeled “Bad Feelings and Life Attitudes.”

Second factor: This factor was saturated with seven items, accounting for 25.46% of the total variance, reflecting a lack of hope and desire in life, feelings of negativity, and lack of communication with others. This factor is labeled “Loss of Hope and Loneliness.”

Third factor: This factor was saturated with eight items, accounting for 31.42% of the total variance, revolving around feelings of sadness, lack of self-esteem, lack of effectiveness, and negative evaluation of personal achievements as part of the inability to adapt to the stressors. This factor is labeled “Feeling Sad and Loss of Confidence.”

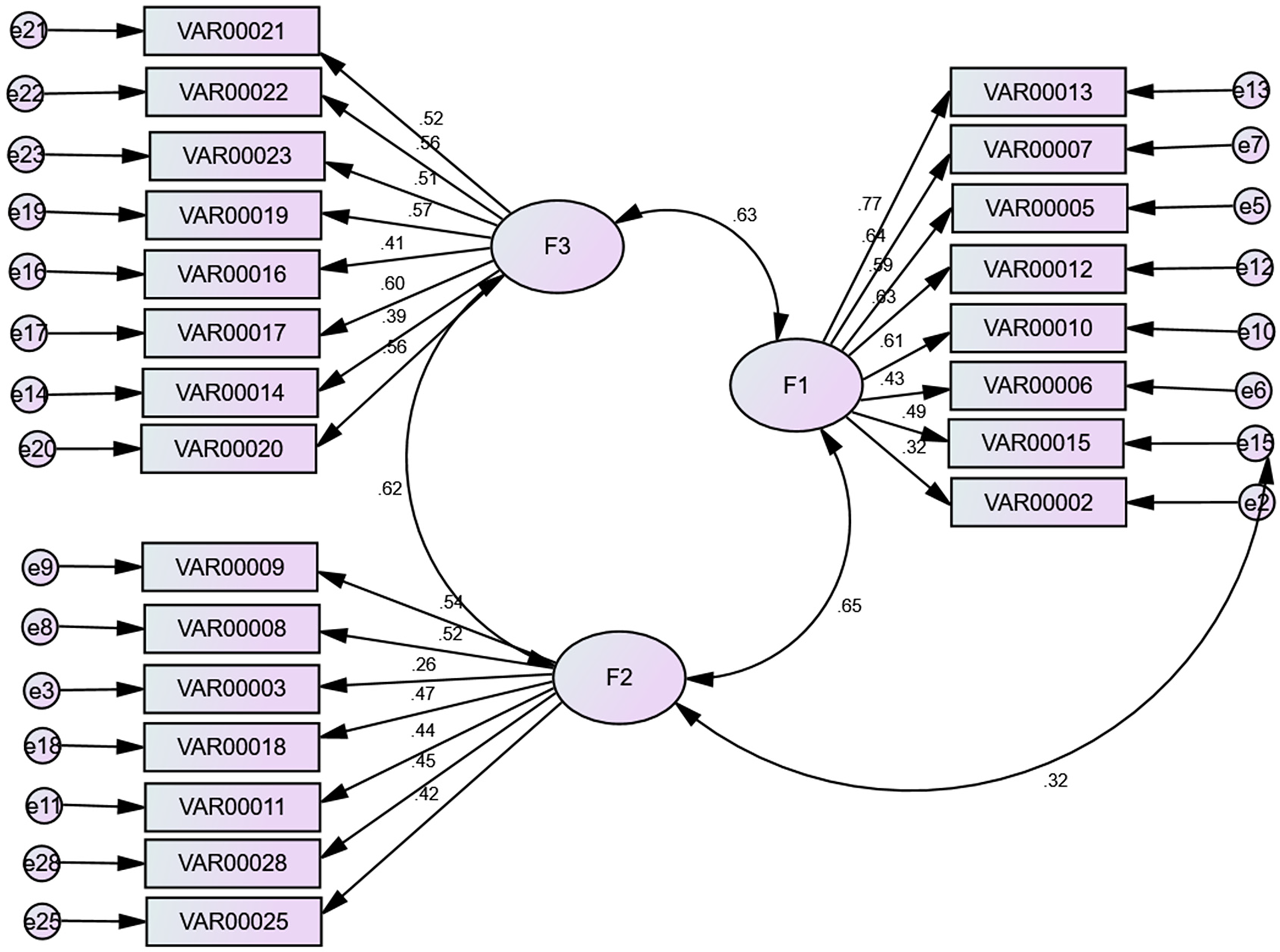

Second-order confirmatory factor analysis was used to verify the goodness of fit of the data of the study sample against the proposed theoretical model of reactive depression, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

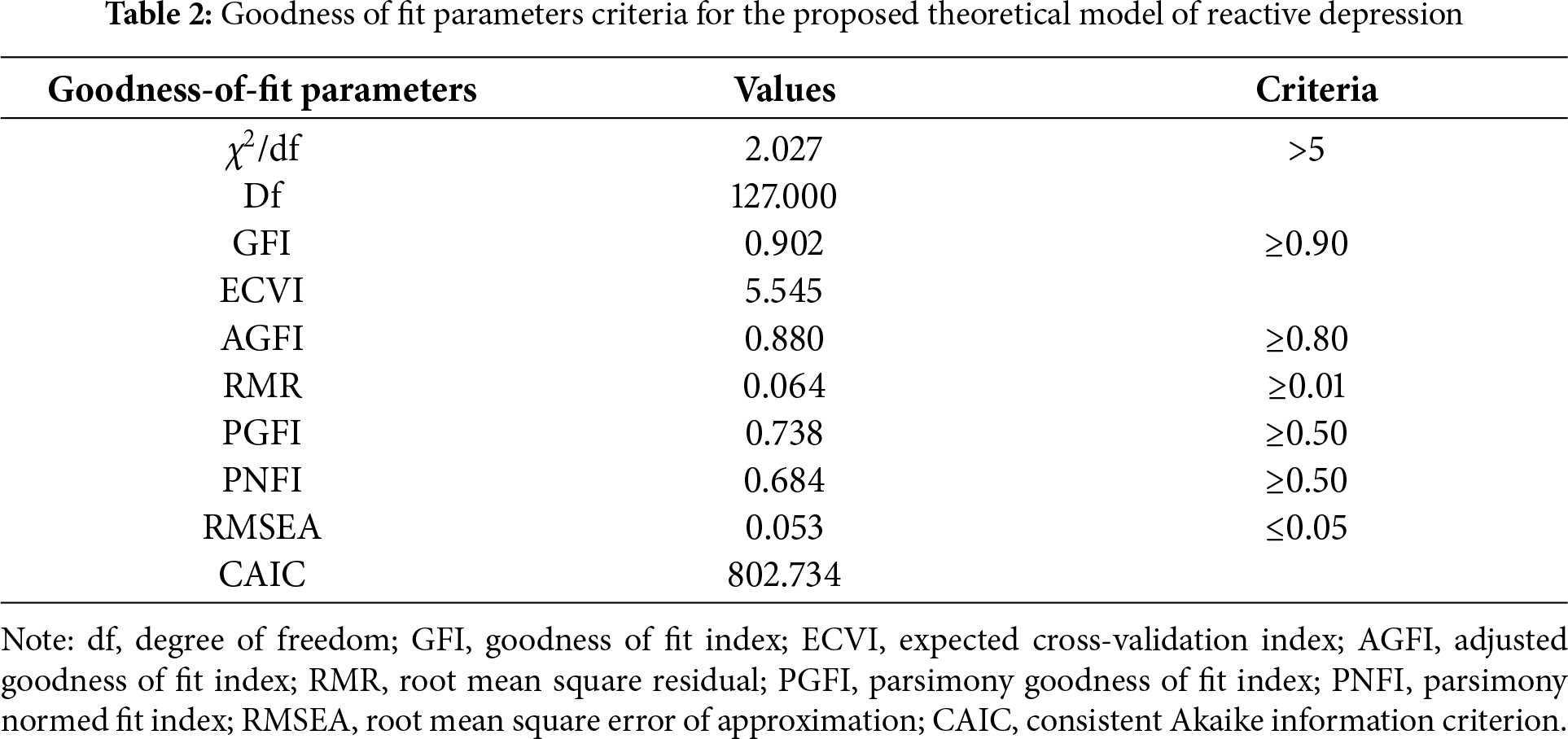

Table 2 demonstrates that a three-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model provided goodness of fit of the model (χ2/df = 2.027; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.902; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.053).

2.4 Reliability and Validity of the Reactive Depression (RD) Measure

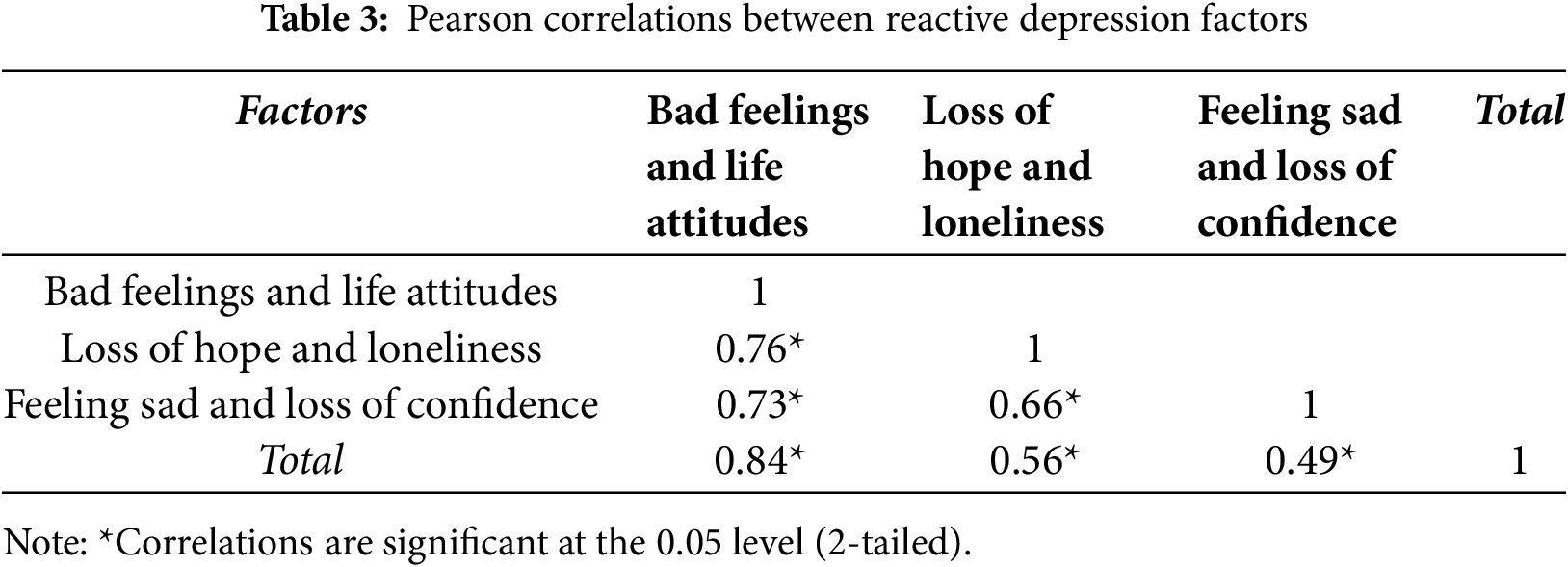

Internal Consistency. Correlation coefficients were calculated between the three factors within reactive depression. Table 3 presents relationships between reactive depression factors among students as found in the structural model and the structural equation. The correlation coefficients between reactive depression and three factors were significant at the level of p = 0.05. The correlations between reactive depression and Bad Feelings and Life Attitudes, Loss of Hope and Loneliness, and Feeling Sad and Loss of Confidence were 0.84, 0.56, and 0.49, respectively.

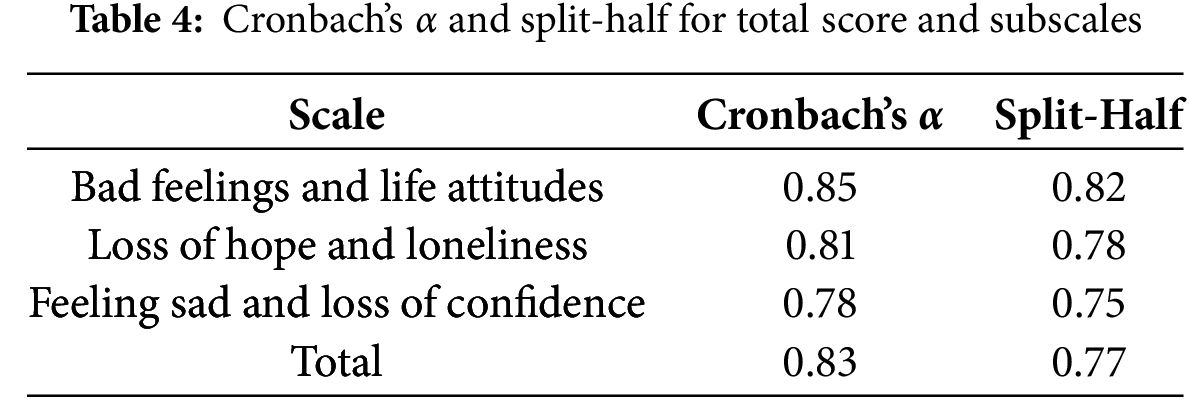

Reliability. To verify the reliability of the reactive depression total score and subscales, Cronbach’s α and split-half were used. The reliability findings shown in Table 4 demonstrate acceptable results. Cronbach’s α values for the subscales were 0.85, 0.81, and 0.78, and for the total score was 0.83. Higher scores in this questionnaire reflect higher levels of reactive depression.

Criterion Validity Assessment (CVA). The reactive depression (RD) questionnaire has been found to have concurrent validity, represented by significant correlations with clinical diagnosis of adjustment disorder with depressed mood according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) [20] and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision (ICD-11) [21], made with structured clinical interviews, e.g., the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, (SCID-5) and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) [22]. It has also been found to have high concurrent validity with established self-report depression scales, e.g., the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [23], the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [24], and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [25].

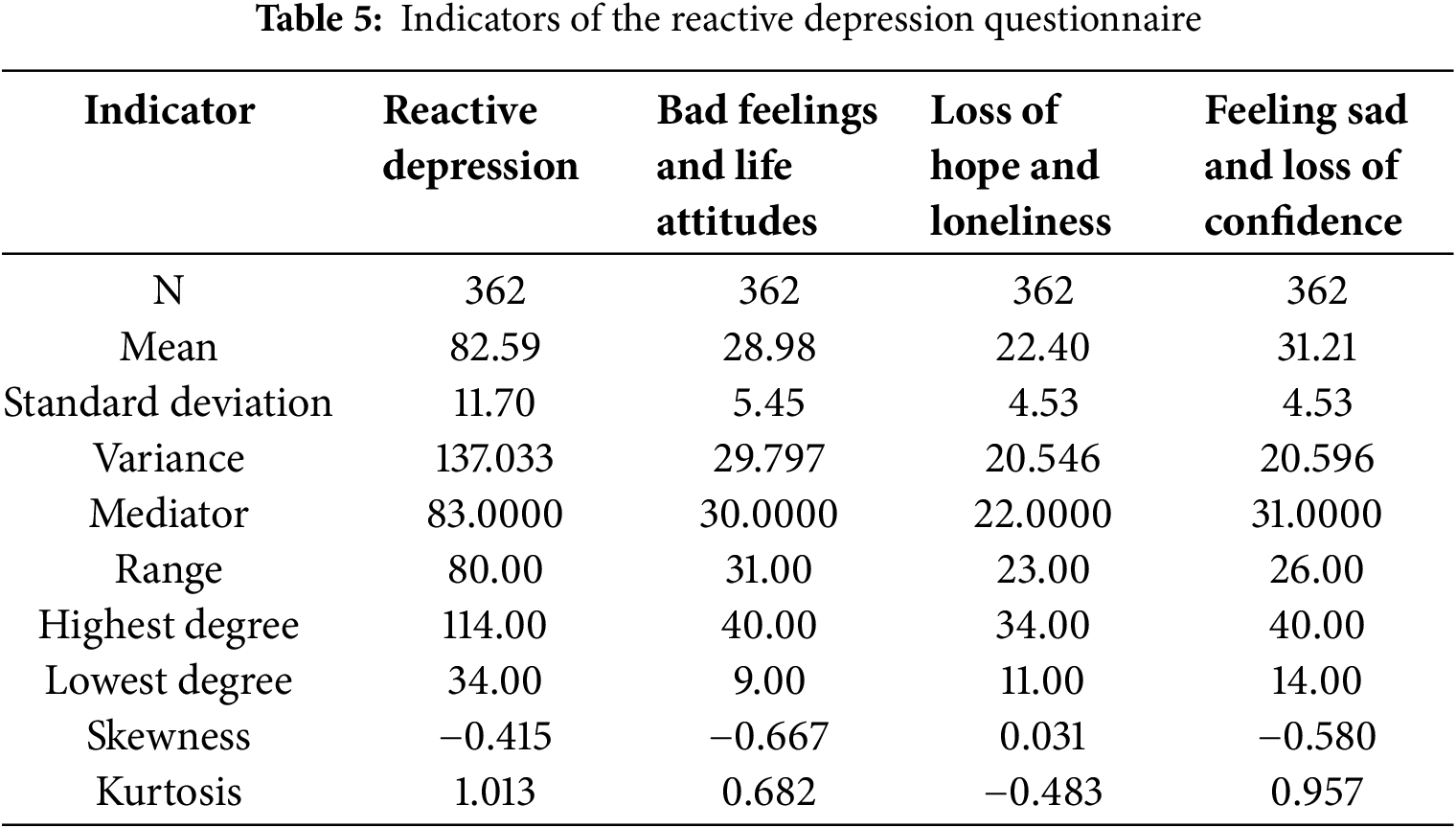

Accuracy of the RD Questionnaire. Accuracy of the RD questionnaire was further evaluated using 1) sensitivity for identification of students with reactive depression; 2) specificity for identification of students without reactive depression; 3) positive predictive value (PPV) for determining the probability that students who test positive have reactive depression, and 4) negative predictive value (NPV) for determining the probability that students who test negative truly do not have reactive depression. Because the psychological and educational literature has confirmed that psychological and social phenomena should be distributed normally to permit generalization of research findings, extracting the statistical indicators of the questionnaire provided preliminary indications about the normal distribution. There was convergence between the questionnaire’s indicators of the mean, median, and decreased standard error as well as skewness and kurtosis in the distribution of values, providing acceptable indications that the distribution of this sample’s data is close to normal distributions and representative of the population of interest. The indicators were obtained using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and their values are displayed in Table 5.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis (Enter Method) was conducted to determine the influence of individual demographic variables on reactive depression.

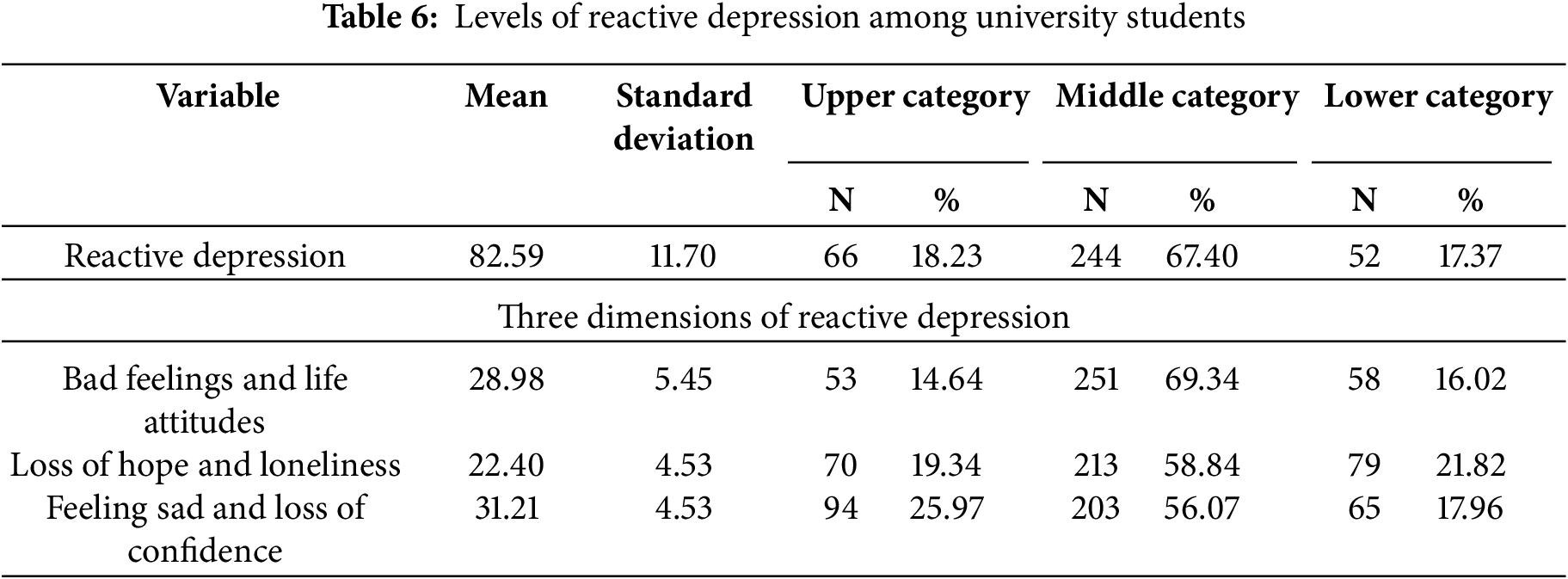

The current study aimed to investigate levels of reactive depression among Iraqi university students. Quantitative estimates of reactive depression levels were based on questionnaire scores comprised of counts of positive responses. A score mean +1 standard deviation (SD) was adopted as defining a valid category of high reactive depression. Mean –1 SD was used to define a category of low reactive depression. A third, intermediate category was defined as scores falling between these two aforementioned categories. Using ANOVA, no significant differences were identified between these three groups (upper, middle, and lower) of questionnaire scores as a single or three-dimensional factor, as shown in Table 6. A mean/SD method was used to categorize levels of reactive depression to indicate that if a person’s score is 1 SD above the mean, it suggests it is significantly above average (score < mean: normal, with low levels of depressive symptoms; score between mean and +1 SD above mean: mild symptoms; score > 1 SD above mean: clinically significant, moderate to severe depression).

Table 6 shows that 18.23% of the students had high levels of depressive symptoms related to exposure to stressful events. Specifically, 14.64% reported bad feelings and life attitudes, 19.34% reported loss of hope and a sense of loneliness, and 25.97% reported feelings of sadness and loss of confidence.

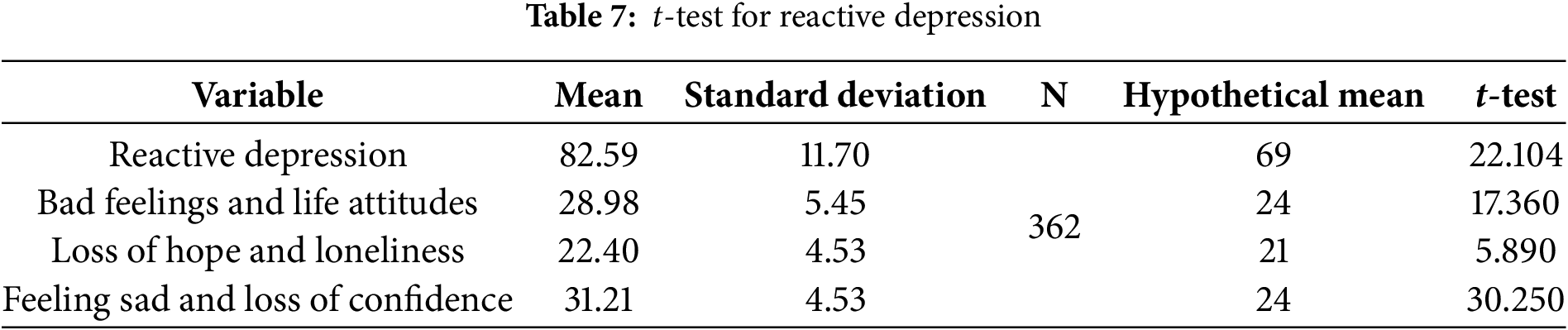

Reactive depression was examined as a general factor and a three-dimensional factor. Significant differences were identified between observed and hypothetical means. Table 7 demonstrates high levels of reactive depressive symptoms in all dimensions reported by these students.

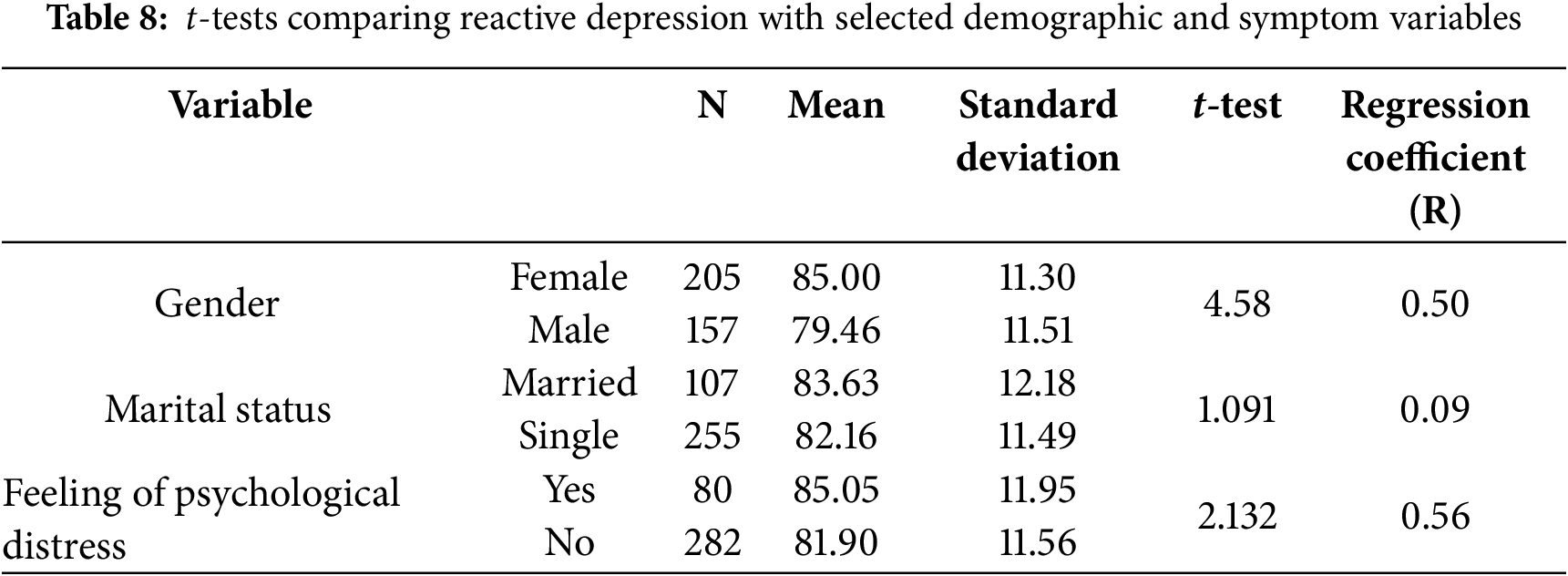

t-tests for one sample were defined as statistically significant at the level of significance of p ≤ 0.05. Associations of demographic variables with reactive depression were examined using t-tests for two independent samples, comparing mean reactive depression scores for demographic variables. Table 8 demonstrates that reactive depression scores were significantly higher for females than for males. Additionally, perceived psychological distress related to the loss of a family member was significantly associated with a higher level of reactive depression. There were no significant differences in comparisons on the marital status variable.

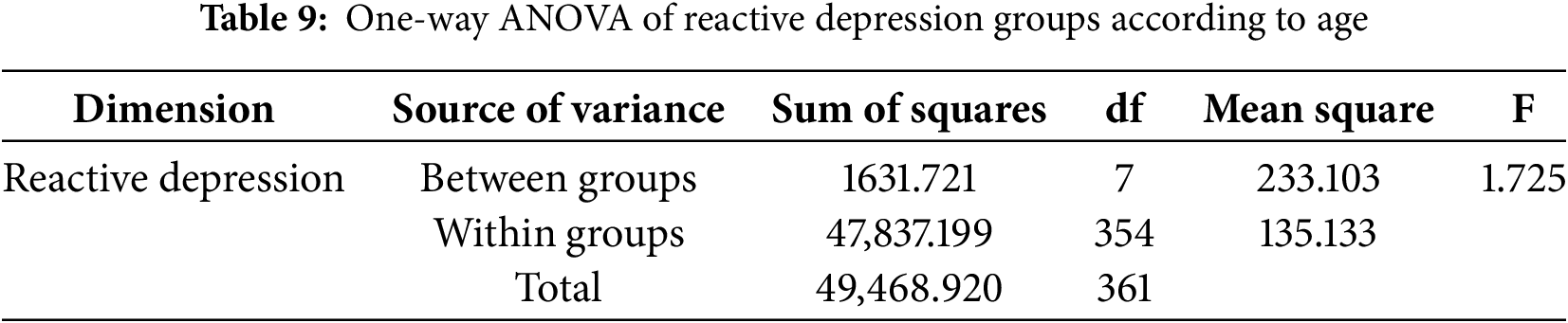

Results of one-way ANOVA analysis presented in Table 9 did not find age to be associated with reactive depression; i.e., reactive depression can occur at any age.

Finally, hierarchical multiple regression analysis to examine the independent contributions of gender, age, marital status, and belief in the seriousness of the crisis incorporated within a single model provided a model capable of predicting reactive depression. In this model, belief in the severity of the crisis and gender both significantly predicted reactive depression (0.424 and 0.222, respectively). None of the other variables significantly predicted reactive depression.

This study had two main scientific aims. The first was to investigate levels of reactive depression among university students. The second was to identify associations of reactive depression scores with demographic variables (gender, marital status, and age).

4.1 Summary and Interpretation of Findings

The main overall finding was that 18.23% of the students had developed high levels of depressive symptoms related to exposure to stressful events. A possible interpretation of this finding is that the loss of emotional and psychological security among Iraqi university students may confer vulnerability to the onset and further development of reactive depression. According to psychological constructs of depressive symptoms, inability to cope with stressful events may have led to further deterioration in mental health and risk for reactive depression. Luke et al. [26] investigated the relationship between Emotional Intelligence (EI) and a clinical diagnosis of depression among 62 patients (59.70% female) with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of a major affective disorder and 39 age-matched controls (56.40% female) who completed self-report instruments assessing EI and depression. This study found significant associations between the severity of depression and the EI dimensions of Emotional Management (r = –0.56) and Emotional Control (r = –0.62).

In the current study, exposure to stressful events was significantly associated with reactive depression. This is consistent with cognitive theory that holds that depressive symptoms that are preceded by a recent loss, such as failure in school, marriage, love, or work, and especially with events that occur suddenly and are permanent, such as the death of a family member, are the most severe. In these situations, individuals adopt negative perspectives about themselves, the world, and the future. Distorted ideas may develop about the loss and lead to negative cognitions and processes that contribute to the formation of negative self-depressive schemas that gradually increase in parallel with the increasing severity of reactive depression [27]. The specific contextual factors in Iraq, such as socio-political instability, economic hardship, and/or cultural stigma surrounding mental health, likely exacerbated stress and depressive symptoms. All the above possibilities likely played a role in the development of reactive depression among these Iraqi university students.

These interpretations are consistent with findings of prior research [17] indicating that crises of greatest severity, especially those involving the loss of a family member, are associated with the highest likelihood of development of mental disorders, in particular reactive depression. This association can also be interpreted through the behavioral perspective, which holds that interactions with close people in our lives represent a source of positive reinforcement and support. The loss of a loved one deprives the individual of positive reinforcements and, in turn, leads to isolation in a process of self-perpetuating conditional reinforcement of reactive depression. The learned helplessness model further invokes cognitive processes in which people experiencing the loss of a loved one adopt negative views of the source of their loss, followed by feelings of inability to control their circumstances. In other words, the surrounding environment affects them and not the other way around, leading them to believe that there is no point in trying to change the circumstances. Thus, passivity, feelings of sadness, and depression result, according to Beck, from negative interpretations of perceptions with the adoption of depressive cognitive mindsets [28].

In the current study, reactive depression was more prevalent in female than male students. This finding can be considered to be consistent with the inherent nature of biological and psychological characteristics between them. Additionally, women in Iraq face uniquely disproportionate social, psychological, and academic pressures in the form of restrictive social norms, academic challenges, and limited psychological support. These cumulative pressures may contribute to heightened levels of psychological distress and a greater risk of developing depression. Aside from these vulnerabilities specific to women that confer risk for depression, it is well established in epidemiologic research that the prevalence of mood, anxiety, and stress-related disorders is far more prevalent in women than in men [29–32]. These gender disparities may arise from biological differences, cultural effects, differential exposure to stressors, and reporting differences.

In the current study, age and marital status had no significant role in predicting reactive depression. This finding can be assumed to indicate that reactive depression may affect all individuals regardless of age or marital status, especially given that they all live in difficult psychological and social circumstances. Additionally, the cultural, social, and political pressures and exposures to stressors that disproportionally affect women may overwhelm the effects of age and marital status. No other variables significantly predicted reactive depression. The origins of many mental disorders, including depression, are not sufficiently understood. It may be difficult to determine whether depression arises as a primary or secondary process, or could result from organic disease that mimics depression [33].

4.2 Study Strengths and Limitations

Srengths of this study included the relatively large size of the sample of Iraqi university students, the development and successful application of a new online self-report questionnaire to identify evidence of reactive depression, the high questionnaire completion rate among students meeting study inclusion criteria, the statistical power of the factor analysis through both exploratory and confirmatory analysis, successful identification of meaningful factors based on analysis of the questionnaire items, and ability to anchor the interpretation of the results in accepted theory. An important limitation of the study was the inability of the reactive depression questionnaire to provide a psychiatric diagnosis using established criteria. High scores on the reactive depression questionnaire need diagnostic evaluation by a clinician to inform treatment decisions. Another limitation was the volunteer nature of the sample, with unknown proportions of participating respondents among the existing population of Iraqi university students, introducing potential for sampling bias and nonrepresentativeness of the sample. Additionally, because this study’s sample was limited to Iraqi university students, the findings may not apply to other age groups or other sociodemographic groups or populations of other countries.

This study was not designed to examine the effects of specific cultural factors on mental health, and it did not examine demographic variables other than gender, age, and marital status; thus, research is needed to explore these issues. Further research is needed to further validate and characterize the psychometric properties of the new reactive depression questionnaire. This instrument also needs to be tested more broadly on other populations in other locations. Additionally, exploration of the potential for ongoing surveillance of social media/text messages to identify risk for reactive depression may open new directions for early identification and intervention.

4.4 Implications for Practice and Policy

The current study’s findings suggest a need for activation of psychological counseling units in Iraqi universities to address the mental health of students exposed to stressful events. Additionally, the findings point to a need for the provision of psychoeducation and support to help these students face the difficult circumstances of their existence in Iraq. The high prevalence of reactive depression identified by the reactive depression questionnaire in this sample indicates that its adoption may help detect risk for reactive depression in university students. Its application could facilitate the linkage of students with needs to appropriate treatment, and even possibly contribute to the prevention of this important outcome of severe adversity faced by these students. This study’s specific findings of greater reactive depression in female compared to male students indicate the critical importance of assisting female students. The findings that age and marital status were not predictive of reactive depression further suggest that students of all ages and marital statuses deserve adequate attention to their needs.

It can be concluded that Iraqi university students exhibite high levels of depressive symptoms linked to exposure to stressful events, highlighting the vulnerability of this population to reactive depression. Notably, female students were more likely to experience reactive depression than their male counterparts, potentially due to gender-specific social, psychological, and academic pressures. The study underscores that the loss of emotional and psychological security, particularly in the face of traumatic and permanent events such as the death of a loved one, may contribute to the onset and progression of depressive symptoms. Although no significant associations were found between age, marital status, and reactive depression, it is important to recognize that the shared cultural, social, and political stressors in Iraq likely contribute to the uniformity of these effects across various demographic groups. Future research should explore the role of specific cultural factors and further validate the reactive depression questionnaire in broader populations. Additionally, there is a need for improved mental health support in Iraqi universities, particularly for female students, who may face unique challenges.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all the participants who gave their valuable time and experience to take part in this study, to the University of Anbar and Uniersity of Diala for their help with recruiting participants.

Funding Statement: This study received no funding.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fuaad Mohammed Freh, Muhand Mohammed Abdulsattar ALNuaimy; data collection: Fuaad Mohammed Freh; analysis and interpretation of results: Fuaad Mohammed Freh, Muhand Mohammed Abdulsattar ALNuaimy, Carol S. North; draft manuscript preparation: Muhand Mohammed Abdulsattar ALNuaimy, Carol S. North. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Fuaad Mohammed Freh, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical clearance was obtained by approval of the University of Anbar/Ethical Committee (UoAEC) (reference number: A303/5/4). This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. All participants were informed online about the purpose and procedures of this study and then provided online written informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lu B, Zeng W, Li Z, Wen J. Risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder 10 years after Wenchuan earthquake: a population-based case-control study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e25. doi:10.1017/S2045796021000123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ashraf MU, Raza S, Ashraf A, Mehmood W, Patwary AK. Silent cries behind closed doors: an online empirical assessment of fear of COVID-19, situational depression, and quality of life among Pakistani citizens. J Republic Affairs. 2021;21(4):1–12. doi:10.1002/pa.2716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Quadros S, Garg S, Ranjan R, Vijayasarathi G, Mamun MA. Fear of COVID-19 infection across different cohorts: a scoping review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:708430. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.708430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mamun MA, Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty?—the forthcoming economic challenges for developing country. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87(7):163–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–20. doi:10.1177/0020764020915212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Shi W, Hall BJ. What can we do for people exposed to multiple traumatic events during the coronavirus pandemic? Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51(10):102065. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bolton P. Mental health in Iraq: issues and challenges. Lancet. 2013;381(9870):879–81. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60637-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmed DR. The psychological profile of Iraq: a nation haunted by decades of suffering. Open Health. 2024;5(1):20230024. doi:10.1515/ohe-2023-0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Freh FM, Cheung CM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and death anxiety among Iraqi civilians exposed to a suicide car bombing: the role of religious coping and attachment. J Ment Health. 2021;30(6):743–50. doi:10.1080/09638237.2021.1952954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Freh FM, Chung MC, Dallos R. In the shadow of terror: posttraumatic stress and psychiatric co-morbidity following bombing in Iraq: the role of shattered world assumptions and altered self-capacities. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):215–25. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.10.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Al Shawi AF, Sarhan YT, Altaha MA. Adverse childhood experiences and their relationship to gender and depression among young adults in Iraq: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1687. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7957-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Chen P. Understanding and addressing youth depression: risk factors, resources, and promoting mental health and well-being. Psychol. 2023;14(8):1189–202. doi:10.4236/psych.2023.148065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J. Self-regulatory perseveration and the depressive self-focusing style: a self-awareness theory of reactive depression. Psychol Bull. 1987;102(1):122–38. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.1.122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Norouzi E, Rezaie L, Bender AM, Khazaie H. Mindfulness plus physical activity reduces emotion dysregulation and insomnia severity among people with major depression. Behav Sleep Med. 2024;22(1):1–13. doi:10.1080/15402002.2023.2176853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY, USA: International Universities Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

16. Kuiper NA, Derry PA, MacDonald MR. Self-reference and person perception in depression: a social cognition perspective. In: Weary G, Mirels H, editors. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1982. p. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

17. Freh FM. PTSD, depression, and anxiety among young people in Iraq one decade after the American invasion. Traumatology. 2016;22(1):56–62. doi:10.1037/trm0000062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Gary RV. Dictionary of psychology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

20. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

21. World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. 11th revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

22. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Janavs J, Baker R. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(97)83296-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX, USA: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Obeid S, Azzi V, Hallit S. Validation and psychometric properties of the Arabic version of Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 7 items (HAMD-7) among non-clinical and clinical samples of Lebanese adults. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285665. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0285665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Luke A, Downey P, Karen H, Rechal S, Con S, Virginia T, et al. Relationship between emotion intelligence and depression in a clinical sample. Eur J Psychiatry. 2008;22:93–8. [Google Scholar]

27. Shan G, Zhou L, Zhang D. What reveals about depression level? The role of multimodal features at the level of interview questions. Inf Manag. 2020;57(7):103349. doi:10.1016/j.im.2020.103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gawronski I, Privette G. Empathy and reactive depression. Psychol Rep. 1997;80(3):1043–9. doi:10.2466/pr0.1997.80.3.1043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bland RC. Psychiatric disorders in America: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1992;17(1):34–6. [Google Scholar]

30. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–60. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105. doi:10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chung MC, Freh FM. The trajectory of bombing-related posttraumatic stress disorder among Iraqi civilians: shattered world assumptions and altered self-capacities as mediators; attachment and crisis support as moderators. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273(8):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools