Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LncRNA CRYBG3 Regulates Adaptive Radioresistance in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells through the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 Axis

1 State Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine and Protection, School of Radiation Medicine and Protection, Collaborative Innovation Center of Radiological Medicine of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, Soochow University, Suzhou, 215123, China

2 Department of Radiotherapy, The Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Nantong University, Nantong, 226361, China

* Corresponding Author: Anqing Wu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mitochondrial Dynamics and Oxidative Stress in Disease: Cellular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1929-1946. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066935

Received 21 April 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Fractionated radiotherapy represents a standardized and widely adopted treatment modality for cancer management, with approximately 40% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients receiving it. However, repeated irradiation may induce radioresistance in cancer cells, reducing treatment effectiveness and raising recurrence risk. The long noncoding RNA CRYBG3 (lncRNA CRYBG3), which is upregulated in lung cancer cells after X-ray irradiation, contributes to the radioresistance of NSCLC cells by promoting wild-type p53 protein degradation. This study aims to elucidate the mechanism of fractionated irradiation-induced radioresistance, in which lncRNA CRYBG3 regulates radiation-induced mitochondrial damage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation through the p53 downstream signaling pathway. Methods: To investigate the critical roles of lncRNA CRYBG3 in mediating radioresistance induced by fractionated irradiation in NSCLC, we established radioresistant NSCLC cells by irradiating the A549 and H460 cell lines with 60 Gy of X-rays in 12 fractions, and named the radioresistant cells A549R and H460R, respectively. Lentiviral vectors were used to deliver short hairpin RNA (shRNA) into cells to knock down lncRNA CRYBG3, thereby investigating its contribution to adaptive radioresistance in A549R and H460R cells. All cells were irradiated with 4 Gy of X-rays, and subsequent analyses were conducted to evaluate mitochondrial damage, ROS generation, apoptosis, and the expression of oxidative stress-related proteins. Results: Increased expression levels of lncRNA CRYBG3 were positively associated with the acquisition of radioresistance in NSCLC cells. Additionally, suppressing lncRNA CRYBG3 increased mitochondrial damage and promoted radiation-induced apoptosis in radioresistant NSCLC cells. Mechanistically, the downregulation of lncRNA CRYBG3 led to increased p53 levels, resulting in decreased expression of heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 (TRAP1), as well as enhanced radiation-induced mitochondrial oxidative damage and apoptosis. Conclusion: The results indicate that lncRNA CRYBG3 plays a regulatory role in adaptive radioresistance in NSCLC cells through the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 axis. Therefore, targeting lncRNA CRYBG3 could potentially improve the efficacy of fractionated radiotherapy in NSCLC.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCurrently, lung cancer is still the primary cause of cancer-related mortality among both males and females, resulting in millions of deaths globally each year. Radiotherapy is an effective modality used for the treatment of lung cancer [1,2]. Radiotherapy can induce tumor cell death by causing direct or indirect damage, such as the breakage of covalent bonds and the accumulation of ROS within cells [3]. During radiotherapy, the presence of oxygen enhances radiation-induced damage by facilitating peroxide formation, which further damages DNA and other cellular components. Therefore, hyperbaric oxygen inhalation and oxygen-carrying agents are often used in clinical practice to improve the hypoxic environment of tumors, thereby enhancing tumor radiosensitivity and improving the efficacy of radiotherapy [4]. However, the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as NRF2, HO-1, and GSTA2, in response to radiation-induced ROS may potentially reduce treatment efficacy [5–7]. Fractionated irradiation, which delivers multiple smaller doses over time, more effectively stimulates the antioxidant response than a single high dose, and thus may potentially increase radioresistance [8]. Therefore, elucidating the signaling pathways associated with radiation-induced resistance may provide insights into developing effective strategies to overcome radioresistance in fractionated radiotherapy.

Radioresistance refers to the tumor’s adaptive response to radiation-induced injury, involving modifications in various cellular mechanisms that sustain tumor progression. These include DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, changes in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, modulation of autophagy, tumor metabolic adjustments, and variations in ROS levels [9]. The majority of ROS in mammalian cells is generated through the mitochondrial oxidative respiratory chain [10]. Multiple fractionated radiotherapy can induce mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage, thereby impairing mitochondrial function and resulting in persistent ROS production. This may trigger the expression of antioxidant proteins, leading to radioresistance in some cancer cells that survive ionizing radiation. The modifications in mitochondrial function and ROS generation caused by ionizing radiation are crucial for governing apoptosis avoidance and radioresistance. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be further explored.

Numerous studies show that in response to DNA damage, wild-type p53 activates pro-oxidant genes and suppresses anti-oxidant genes, thereby increasing intracellular ROS generation and leading to cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis [11,12]. Current knowledge suggests that p53 can determine a specific cellular outcome by specifically modulating its target genes. The specific activation of p53 target genes is modulated by diverse signaling molecules, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), leading to different cellular outcomes [13]. LncRNAs are a class of linear RNA molecules that lack transcriptional activity and protein-coding capability, and have been proven to play important regulatory roles in cellular gene expression, genomic stability, and tumorigenesis [14,15]. It has been demonstrated that the abnormal expression of lncRNAs is related to alterations in energy metabolism, cancer progression, and resistance to treatments [16,17]. lncRNA CRYBG3 is a newly identified lncRNA that functions as a regulator of diverse cellular processes, with particular relevance in cancer biology [18–20]. It has been shown to be upregulated in response to ionizing radiation and is implicated in tumor growth, metastasis, and cellular mechanics [21,22]. Our previous study suggested that the expression of lncRNA CRYBG3 was enhanced by X-ray exposure, and that knockdown of lncRNA CRYBG3 can enhance the radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells with wild-type p53, but not in those with mutant p53. However, the mechanism through which lncRNA CRYBG3 regulates radiosensitivity in lung cancer cells via the p53 downstream pathway remains unclear.

The latest study has revealed that increased p53 levels promote the degradation of heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) in Huntington’s disease [23]. In addition, p53 is capable of inhibiting HSF1 expression by binding to the repressor elements located in the HSF1 promoter region [24]. HSF1 is a canonical transcription factor responsible for mediating cellular stress responses and inducing the expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs), such as HSP27, HSP40, HSP90, HSP70, and TRAP1 [25–29]. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 (TRAP1), a member of the HSP90 chaperone family that is primarily localized in the mitochondrial matrix, functions as a critical mitochondrial chaperone. TRAP1 plays an essential role in maintaining mitochondrial integrity and function, and its antioxidant properties are vital for safeguarding cells against radiation-induced oxidative stress [30–32]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the upregulation of TRAP1 can reduce ROS production, thereby preventing mitochondrial damage and cell death caused by excessive ROS [33,34]. However, limited research has been conducted on the regulatory role of TRAP1 in radiation-induced mitochondrial injury. This study hypothesized that radiation-induced lncRNA CRYBG3 acts as an upstream signaling molecule of TRAP1, thereby modulating radiation-induced mitochondrial damage and contributing to the development of adaptive radioresistance through the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 signaling pathway.

2.1 Cell Culture and Irradiation

A549 and H460 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). These cell lines and their corresponding radioresistant cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, R8758, St. Louis, MO, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A5256701, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10378016). The culture conditions were set at 37°C within a humidified incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, BB15) that contained 5% CO2. Mycoplasma contamination was eradicated using a Mycoplasma Removal Agent (Beyotime, C0288S, Shanghai, China). The cells were irradiated using an X-ray machine (Rad Source, RS2000, Atlanta, GA, USA) at a constant dose rate of 1.16 Gy/min.

2.2 Establishment of Radioresistant NSCLC Cell Lines

A549 and H460 cells were grown in 100 mm dishes with a density of 1 × 106 cells per dish. Following a 24-h incubation, the cells were subjected to fractionated X-ray doses of 2, 2, 4, 4, 4, 4, 6, 6, 6, 6, 8, and 8 Gy [35]. After each radiation treatment session, the cells were given a recovery period lasting 3–7 days to subsequent irradiation. Upon completion of the final irradiation session, it was evident that the cells had acquired significantly enhanced resistance to radiation relative to their initial state. These newly resistant cell lines were designated as A549R and H460R, while their parent cell lines (A549 and H460) were referred to as the radiosensitive counterparts. The radioresistant cells used in subsequent experiments were maintained between the 4th and 10th passages after their establishment.

Cells were seeded in 35 mm culture dishes at densities of 150, 150, 200, 400, and 600 cells per dish, corresponding to irradiation doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy, respectively. After a 24-h culture period, the cells were irradiated with X-rays and then cultured for an additional 14 days to allow for colony formation. Subsequently, the colonies were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 70% ethanol. Staining was done with a 0.1% crystal violet solution (Beyotime, Y268091). A viable colony was defined as one containing more than 50 cells, which were counted using a light microscope (Olympus, IX73, Tokyo, Japan). The survival curves were analyzed using the single-hit multitarget model in GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, version 8.3.0, San Diego, CA, USA), based on the equation

Intracellular ROS levels were determined using a ROS Assay Kit (Beyotime, S0033M), which includes the 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescent probe (Excitation: 488 nm; Emission: 530 nm). For the experiment, cells were plated in 6-well plates at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells per well. Following exposure to 4 Gy of X-ray irradiation for 2 h, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS and subsequently incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS. Fluorescence was analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, FACSVerse, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The fluorescence intensity, indicating the level of ROS generation, was recorded. Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) were measured using the MitoSOX Red mitochondrial superoxide detection kit (Beyotime, S0061S). Cells were inoculated into a 96-well plate (5 × 103 cells per well) and cultured for 24 h before being exposed to X-rays. Two hours after irradiation, the cells were incubated with MitoSOX Red (5 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was then analyzed using a fluorescence microplate reader (Agilent, Synergy NEO, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Following 24 h of irradiation, the cells were rinsed twice with PBS. Next, 1 mL of JC-1 staining solution (Beyotime, C2005) was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. After being washed twice with JC-1 buffer solution, the cells were resuspended in fresh culture medium and captured using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, IX73). Fluorescence imaging was conducted using red (585/590 nm) and green (500/525 nm) excitation/emission filters. For each sample, five fields of view were captured, and quantitative analysis of the fluorescence images was performed using ImageJ software (Media Cybernetics, 1.8.0, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Consequently, mitochondrial depolarization is indicated by a decrease in the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio.

2.6 Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15596026CN). The extracted RNA was then converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, RR037, Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out utilizing PowerUp™ SYBR® Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A25918) on a Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ViiA 7). The primers used for lncRNA CRYBG3 were as follows: forward, GAAGAGTGGAAGTGCGAAGGA; reverse, GGCAATGACCCCATTAGCTC. The primers for GAPDH were as follows: forward, GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC; reverse, TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA. GAPDH was used as a normalization control. The relative gene expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

2.7 Gene Silencing and Overexpression

The A549R and H460R cells were infected with lentiviral particles carrying short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting lncRNA CRYBG3 (Sangon, Shanghai, China) for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to selection with 2 μg/mL puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A1113803), and their knockdown efficiency was further validated by qRT-PCR as described previously. Stable cell lines demonstrating reduced expression of lncRNA CRYBG3 were maintained in culture with 1 μg/mL puromycin for subsequent experiments. To investigate the relationship between lncRNA CRYBG3 and the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 pathway, siRNAs targeting p53 or HSF1 were introduced into H460R and H460R-shCRYBG3 cells to specifically inhibit the expression of these proteins. HSF1 siRNA (siHSF1): Sense, 5′-ACAGCUUCCACGUGUUCGGTT3′; Antisense, 5′-UCGAACACGUGGAAGCUGUTT3′. p53 siRNA (sip53): Sense, 5′-CUACUUCCUGAAAACAACGTT3′; Antisense, 5′-CGUUGUUUUCAGGAAGUAGTT3′. Negative control siRNA (siNC) sequences: Sense, 5′-CGUACGCGGAAUACUUCGCTT3′; Antisense, 5′-UCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACGTT-3. Additionally, adenovirus particles (Sangon, Shanghai, China) containing lncRNA CRYBG3 were transfected into H460R-shCRYBG3 cells to restore the expression of lncRNA CRYBG3. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with HSF1 siRNA for another 24 h and then exposed to 4 Gy of X-rays.

Total proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, P0013B), and the protein concentration was determined using a DC Protein Assay Kit I (Bio-Rad, 500-0111, Hercules, CA, USA). All protein samples were denatured at 99°C for 5 min. Equal amounts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were soaked in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature to block non-specific binding, then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After three washes with PBST (Phosphate-Buffered Saline containing 0.1% Tween 20), the membranes were treated with a horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, 7074, Boston, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were identified using an ECL kit (Millipore, WBKLS0500) and recorded with a polychromatic fluorescence and chemiluminescence imaging analysis system (ProteinSample, FluorChem E, San Francisco, CA, USA). The protein blot relative densitometry values were evaluated utilizing the ImageJ software (Media Cybernetics, 1.8.0). The following antibodies were utilized for western blot analysis: p53 (1∶1000, Abcam, ab32049, Cambridge, UK), HSF1 (1∶1000, Abcam, ab242138), and GAPDH (1∶2500, Abcam, ab9485); Bax (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 5023), β-actin (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 4970), Cleaved-Caspase-3 (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9664), Bcl-2 (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 3498), PGC-1α (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 2178), Cytochrome c (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 11940), and TRAP1 (1∶1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 92345).

The cells under investigation were harvested 24 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-rays. Subsequently, flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, FACSVerse) and the Annexin V-PE/7-AAD Apoptosis Detection Kit (Univ, abs50007, Shanghai, China) were used to quantify apoptotic cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The cells were grown on glass coverslips in a 24-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. 2 h after irradiation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime, P0099) for 15 min and then rinsed three times with PBS. Next, they were permeabilized at room temperature for 15 min using 0.2% Triton X-100 (Beyotime, P0096). To block non-specific binding, the cells were incubated in 5% BSA (Beyotime, ST2254) for 1 h. Finally, an overnight incubation at 4°C was conducted with γ-H2AX antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, 9718). After being washed three times with PBST, the samples were incubated with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor-594 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 8889) for 1 h. Subsequently, another round of washing with PBST was performed three times before the samples were mounted using an anti-quenching reagent containing DAPI (Beyotime, P0131). Foci of γ-H2AX were quantified from no fewer than six randomly selected fields under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, FV1200).

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, version 8.3.0). All experiments were independently repeated at least three times, and all data were represented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

3.1 lncRNA CRYBG3 Was Highly Expressed in Radioresistant NSCLC Cells

To establish radioresistant NSCLC cell lines, A549 and H460 cells were irradiated with gradually increasing doses of X-rays (Fig. 1A). The radioresistant cell lines were designated as A549R and H460R. The radioresistance of A549R and H460R cells was assessed using a colony formation assay following X-ray irradiation at doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy. The survival curves obtained from the colony formation assay demonstrated that both A549R and H460R cells exhibited significantly increased resistance to radiation compared to their parental A549 and H460 cell lines, respectively (Fig. 1B,C). Analogously, the radiobiological parameters D0, Dq, and SF2 were higher in radioresistant cells than in their parental cells, indicating that the radioresistant cells exhibited greater tolerance to radiation (Table S1). Representative colony formation images were shown in Fig. S1. Furthermore, H460R and A549R cells exhibited a significantly reduced apoptotic response after irradiation with 4 Gy of X-rays compared to H460 and A549 cells (Fig. 1D–G). Moreover, lncRNA CRYBG3 expression was analyzed in the aforementioned cells to evaluate its potential association with the radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells. Results showed that lncRNA CRYBG3 was upregulated in A549R and H460R cells compared to their parental counterparts (Fig. 1H). The findings suggest that radiation-induced upregulation of lncRNA CRYBG3 may facilitate the enhancement of radioresistance in NSCLC cells.

Figure 1: lncRNA CRYBG3 was highly expressed in radioresistant NSCLC cells. (A) The schematic diagram illustrated the process of inducing radiation-resistant cells; (B,C) The clonogenic assay was performed to evaluate the radioresistance of A549R and H460R cells, which were subjected to X-ray irradiation at doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy; (D–G) The rate of apoptosis was determined by flow cytometer in A549R (D,F) and H460R (E,G) cells, both in the presence and absence of 4 Gy of X-ray treatment (n = 5, data are represented as means ± SD). (H) The expression of lncRNA CRYBG3 was assessed in the parental NSCLC cells (A549 and H460) and the radioresistant NSCLC cells (A549R and H460R) using qRT-PCR analysis (n = 3, means ± SD)

3.2 Suppression of lncRNA CRYBG3 Enhanced Radiation-Triggered Production of ROS and Apoptosis in Radioresistant NSCLC Cells

To further elucidate the role of lncRNA CRYBG3 in facilitating adaptive radioresistance in NSCLC cells, we used lentiviral vectors carrying short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to effectively inhibit its expression in A549R and H460R cells (Fig. S2). Radiation-induced ROS generation can cause intracellular oxidative stress, which may lead to permanent cellular damage. Therefore, the levels of intracellular ROS were monitored in A549R and H460R cells 2 h after irradiation. It was verified that the downregulation of lncRNA CRYBG3 increased the radiation-induced generation of ROS in radioresistant NSCLC cells (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, γH2AX foci were analyzed to assess the impact of lncRNA CRYBG3 on the DNA repair ability of radioresistant NSCLC cells 2 h after irradiation. It was found that γH2AX foci were increased in lncRNA CRYBG3 knockdown cells compared to those in shNC cells (Fig. 2C–F). In addition, radiation-triggered apoptosis was significantly enhanced in radioresistant NSCLC cells with lncRNA CRYBG3 knockdown (Fig. 3A–D). Meanwhile, inhibition of lncRNA CRYBG3 significantly promoted the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Cleaved Caspase-3, while suppressing the level of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in A549R and H460R cells after radiation (Fig. 3E,F). Collectively, these results demonstrate that lncRNA CRYBG3 downregulation significantly decreases the radioresistance of A549R and H460R cells.

Figure 2: Inhibition of lncRNA CRYBG3 increased radiation-induced ROS and DNA damage in radioresistant NSCLC cells. (A,B) ROS levels were measured in radioresistant cells (A549R and H460R) transfected with shCRYBG3 or shNC at 2 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-rays (n = 5, data are represented as means ± SD); (C,E) Images illustrating the formation of γ-H2AX foci were captured in A549R and H460R cells transfected with shCRYBG3 or shNC at 2 h after 4 Gy of X-ray irradiation. Red fluorescence indicates γ-H2AX foci. Scale bar: 10 μm; (D,F) The quantification of γ-H2AX foci formation was performed by normalizing the foci count in each group to that of the shNC cells at 0 Gy (n = 3, means ± SD). shCRYBG3: lncRNA CRYBG3 shRNA; shNC: Negative control shRNA

Figure 3: Suppression of lncRNA CRYBG3 enhanced radiation-triggered apoptosis in radioresistant NSCLC cells. (A–D) The rate of apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry in A549R (A,B) and H460R (C,D) cells transfected with shCRYBG3 or shNC at 48 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-rays (n = 5; data are represented as means ± SD). (E,F) Western blot analyses were performed to examine proteins associated with apoptosis at 48 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-rays. The histogram presented the quantitative analysis of the protein bands (n = 3, means ± SD). shCRYBG3: lncRNA CRYBG3 shRNA; shNC: Negative control shRNA

3.3 Suppression of lncRNA CRYBG3 Increased Mitochondrial Damage in Radioresistant NSCLC Cells after Radiation

A large number of studies have shown that the overproduction of ROS within cells, triggered by radiation, is linked to mitochondrial impairment, which can lead to severe cellular damage and apoptosis. The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) serves as a marker of mitochondrial health, and a reduction in this potential indicates mitochondrial injury. To determine the role of lncRNA CRYBG3 in radiation-induced mitochondrial damage, JC-1 staining was utilized to assess the MMP. Red fluorescence corresponds to a higher MMP, while green fluorescence indicates a lower MMP. In unirradiated cells, stronger red fluorescence indicated a higher MMP under normal physiological conditions. After being exposed to 4 Gy of X-rays, shCRYBG3 cells exhibited diminished red fluorescence and enhanced green fluorescence in comparison to shNC cells, indicating that more mitochondrial injury occurs in radioresistant NSCLC cells with downregulated lncRNA CRYBG3 after radiation (Fig. 4A–D). The production of mitochondrial ROS was examined, and the results demonstrated that in irradiated cells with lncRNA CRYBG3 knockdown, the level of mitochondrial ROS was significantly increased (Fig. S3). The release of cytochrome c (Cyt c) from mitochondria, a critical event in apoptosis, triggers the activation of procaspase-9 and subsequently the downstream caspases, thereby amplifying the apoptotic signaling cascade. PGC-1α serves as a critical regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Its downregulation suppresses the expression of functional proteins within mitochondria, resulting in impaired mitochondrial function [37]. The results demonstrated a rise in the release of Cyt c and a downregulation of PGC-1α in shCRYBG3 cells irradiated with 4 Gy of X-rays, compared to shNC cells (Fig. 4E,F). These findings suggest that lncRNA CRYBG3 downregulation exacerbated radiation-induced damage to mitochondrial function, thereby exerting a more pronounced effect on inhibiting radioresistance in A549R and H460R cells.

Figure 4: Inhibition of lncRNA CRYBG3 increased mitochondrial damage in radioresistant NSCLC cells. (A,C) Representative immunofluorescence images of JC-1 staining; the red fluorescence represents JC-1 aggregates, while the green fluorescence corresponds to JC-1 monomers. Scale bar: 100 μm; (B,D) The red/green fluorescence ratio was analyzed to assess mitochondrial membrane potential (n = 5, data are represented as means ± SD); (E,F) Western blot analyses were performed to evaluate the expression levels of PGC-1α and Cyt c at 24 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-rays. Histograms presented the quantitative analysis of the protein bands (n = 3, means ± SD). shCRYBG3: lncRNA CRYBG3 shRNA; shNC: Negative control shRNA

3.4 lncRNA CRYBG3 Regulated the Radioresistance of NSCLC Cells by Modulating the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 Signaling Pathway

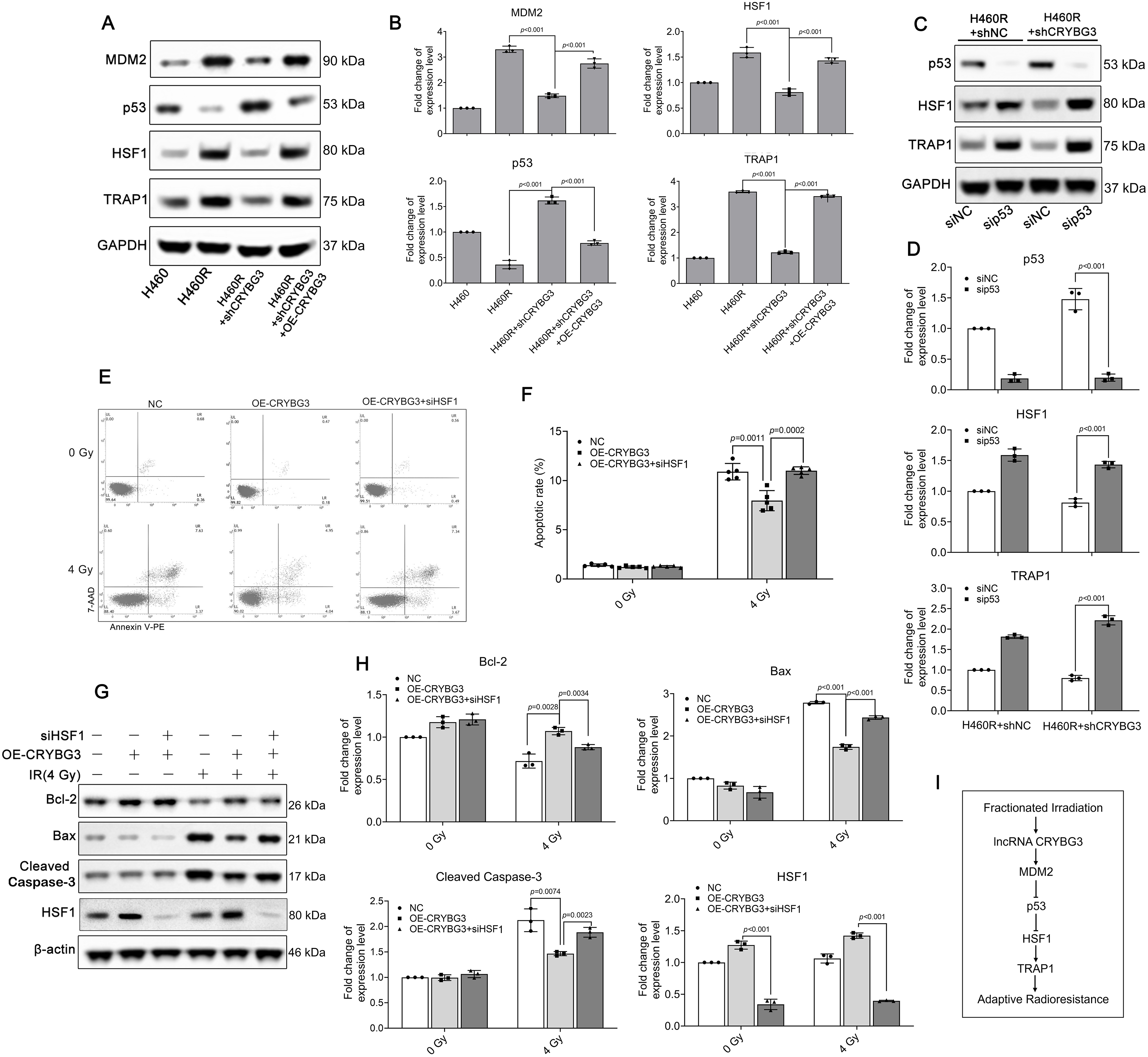

In our previous study, we demonstrated that lncRNA CRYBG3 exerts a suppressive effect on the expression of wild-type p53 by upregulating E3 ligase MDM2 levels, thereby facilitating p53 ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. Recent studies have revealed that p53 can suppress HSF1 expression during certain stress responses [38]. To investigate whether lncRNA CRYBG3 regulates HSF1 through the p53 signaling pathway, we restored the expression of lncRNA CRYBG3 in H460R-shCRYBG3 cells by transfecting them with an adenoviral vector designed to overexpress lncRNA CRYBG3 (Fig. S4). Subsequently, we evaluated HSF1 and TRAP1 expression levels in H460 and H460R cell lines under different lncRNA CRYBG3 expression conditions. Suppression of lncRNA CRYBG3 led to a significant downregulation of both HSF1 and TRAP1 expression in H460R cells. Conversely, the reduced levels of HSF1 and TRAP1 in H460R-shCRYBG3 cells were markedly restored upon re-expression of lncRNA CRYBG3 (Fig. 5A,B). However, further results demonstrated that the HSF1 downregulation induced by lncRNA CRYBG3 knockdown was significantly attenuated in H460R-shCRYBG3 cells transfected with p53 siRNA (Fig. 5C,D). To explore the regulatory function of lncRNA CRYBG3 in radiation-induced cell damage via the HSF1/TRAP1 pathway, we employed siRNA-mediated knockdown to reduce HSF1 expression in cells with lncRNA CRYBG3 overexpression. The apoptosis assay revealed that restoring lncRNA CRYBG3 significantly reduced apoptosis in H460R-shCRYBG3 cells exposed to X-rays. Nevertheless, this attenuation of apoptosis induced by lncRNA CRYBG3 restoration was not evident when HSF1 expression was downregulated (Fig. 5E–H). The acquired data demonstrated that fractionated irradiation induces an increase in the level of lncRNA CRYBG3, which subsequently promotes p53 degradation by upregulating MDM2 expression. This process attenuates the suppressive effect of p53 on HSF1 and enhances HSF1-induced TRAP1 expression, ultimately improving the antioxidant capacity of cells and augmenting radioresistance (Fig. 5I).

Figure 5: lncRNA CRYBG3 regulates radiation-induced cell damage through the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 signaling pathway. (A,B) Western blot analyses were conducted to evaluate the expression levels of MDM2, p53, HSF1, and TRAP1 in H460R cells with either lncRNA CRYBG3 knockdown or overexpression. The histogram presented the quantitative analysis of the protein bands (n = 3, data are represented as means ± SD); (C,D) The expression levels of p53, HSF1, and TRAP1 were measured by means of western blot analysis in H460R + shNC and H460R + shCRYBG3 cells transfected with p53 siRNA. The histogram presented the quantitative analysis of the protein bands (n = 3, means ± SD); (E,F) The apoptosis rate was estimated using flow cytometry at 48 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-ray irradiation in H460R + shCRYBG3 cells with lncRNA CRYBG3 restoration and HSF1 knockdown (n = 5, means ± SD); (G,H) Western blot analyses of proteins related to apoptosis at 48 h after 4 Gy of X-ray irradiation. The histogram presented the quantitative analysis of the protein bands (n = 3, means ± SD); (I) Schematic drawing of the signal transduction pathway of lncRNA CRYBG3-induced radioresistance. shCRYBG3: lncRNA CRYBG3 shRNA; shNC: Negative control shRNA; OE: Overexpression; NC: Negative control; sip53: p53 siRNA; siHSF1: HSF1 siRNA

At present, more effective treatment strategies for curing lung cancer have not yet been identified, and the utilization rate of radiotherapy in the management of NSCLC generally remains at approximately 40% [39]. However, radioresistance presents a significant obstacle to the effectiveness of radiotherapy in treating NSCLC. A thorough insight into the molecular processes that govern radioresistance in NSCLC is imperative to optimize lung cancer radiotherapy. Currently, there is a notable scarcity of efficient biological targets aimed at enhancing radiosensitivity. Nevertheless, a growing body of evidence in recent years has demonstrated that lncRNAs play significant roles in tumor progression through diverse pathways. LncRNA CRYBG3 has been demonstrated to play crucial regulatory roles in NSCLC tumorigenesis and development, including the disturbance of the cell cycle, triggering aneuploidy, modulating glycolysis, and facilitating metastasis. Importantly, lncRNA CRYBG3 directly interacts with G-actin, lactate dehydrogenase A, and eEF1A1 during these physiological processes. Our recent studies have demonstrated that reducing lncRNA CRYBG3 enhances radiosensitivity in NSCLC cells expressing wild-type p53 by downregulating MDM2 expression and inhibiting MDM2-mediated degradation of p53. Therefore, we hypothesized that the enhanced radioresistance observed in lung cancer cells with high expression levels of lncRNA CRYBG3 could be attributed to the modulation of p53 signaling mediated by this lncRNA.

We further investigated the role of lncRNA CRYBG3 in enhancing radioresistance in NSCLC cells and its interaction with the p53 signaling pathway. We established radioresistant NSCLC cells by irradiating A549 and H460 cell lines with 60 Gy of X-rays in 12 fractions to generate radioresistant NSCLC cell lines, designated A549R and H460R. Interestingly, lncRNA CRYBG3 upregulation was observed concurrently with the development of radioresistance in A549R and H460R cells. Furthermore, silencing lncRNA CRYBG3 significantly inhibited the radioresistance of A549R and H460R cells. Additionally, the results demonstrated a significant increase in radiation-induced DNA damage and apoptosis in A549R and H460R cells with lncRNA CRYBG3 knockdown. It is widely acknowledged that cancer cells exhibit elevated levels of ROS compared to normal cells, and that ROS play a crucial role in sustaining the cancer phenotype [40]. However, radiation can induce excessive production of ROS, which are implicated in DNA breaks and chromosomal aberrations induced by IR. Mitochondria serve as the main sites for oxygen utilization within cells, with one side serving as the predominant source of ROS, primarily derived from complexes I and III of the respiratory chain [41]. Consequently, the other side also becomes a major target for ROS in vivo, leading to alterations in mitochondrial morphology and functional impairments. Radiation exposure can elicit mitochondrial oxidative stress by inducing an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants due to excessive ROS generation during irradiation. The accumulation of ROS can overwhelm the antioxidant defense mechanisms in mitochondria, leading to damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA molecules within these organelles. To mitigate cellular damage, mitochondria exhibit antioxidant activity through both enzymatic and non-enzymatic pathways. This stress response is closely associated with various mitochondrial antioxidant stress factors. Based on these findings, the damage to and repair of mitochondria following irradiation may play a crucial role in the development of radiation resistance in cancer cells [42]. In this study, we observed that the inhibition of lncRNA CRYBG3 resulted in increased ROS production and worsened mitochondrial damage in radioresistant NSCLC cells after exposure to X-rays, suggesting the potential involvement of lncRNA CRYBG3 in modulating the mitochondrial stress response to radiation. The inhibition of lncRNA CRYBG3 may diminish the mitochondrial self-repair capability, consequently reducing the mitochondrial contribution to the development of radiation resistance.

In previous studies, we reported that lncRNA CRYBG3 regulates the radiosensitivity of lung cancer cells by influencing MDM2 expression, which in turn affects the degradation of wild-type p53. Therefore, we hypothesized that the modulation of lncRNA CRYBG3 on radiation-induced mitochondrial damage may be intricately linked to the p53 pathway. The latest study revealed the regulatory role of p53 in mediating HSF1 protein degradation in Huntington’s disease. We also observed in this study that p53 downregulation resulted in reduced degradation of HSF1 in lung cancer cells harboring wild-type p53. The transcription factor HSF1 serves as a key regulator in the expression of stress-induced chaperones, including HSP90, HSP70, and HSP40, and acts as the core element in the heat-shock stress response (HSR). HSP90 is a highly abundant molecular chaperone that facilitates the maturation and activation of its client proteins. Many of these client proteins are integral components of signaling pathways associated with cancer cells and play essential roles in promoting unrestricted cancer development and conferring resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy [43,44]. TRAP1, which belongs to the HSP90 family, is essential for maintaining mitochondrial function under oxidative stress by inhibiting ROS production, promoting the refolding of denatured proteins, and preventing damaged proteins from aggregation or further denaturation [45,46]. Furthermore, TRAP1 plays a role in modulating mitochondrial apoptosis and the permeability transition pore, as well as in folding and stabilizing key client proteins, including cyclophilin D [47]. Studies have demonstrated that TRAP1 protects mitochondria from oxidative damage caused by excessive ROS and also plays a crucial regulatory role in diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, such as neurodegenerative diseases, myocardial infarction, stroke, and cancer [48]. HSF1 has been identified as a constitutive binding factor to the promoters of mitochondrial chaperone genes, such as HSP60, HSP10, and TRAP1. Mitochondrial chaperones are essential proteins that are crucial for maintaining the correct folding and assembly of mitochondrial proteins. Consequently, the regulation mediated by HSF1 is vital for ensuring the efficient functioning and integrity of the mitochondria. In this study, after knocking down lncRNA CRYBG3, we observed an upregulation of p53, which subsequently led to a downregulation of HSF1. As a result, the expression of TRAP1 was reduced, thereby decreasing the cellular antioxidant capacity in radioresistant NSCLC cells. In addition, it has been reported that TRAP1 stabilizes HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha) by increasing intracellular succinate levels, thereby promoting tumor growth under hypoxic conditions. Consequently, reducing TRAP1 expression levels may effectively suppress tumor progression under various conditions [49,50]. Numerous inhibitors have been clinically used to target the HSP90 family in order to inhibit tumor growth. Geldanamycin (GDM) is considered the earliest inhibitor of HSP90, exerting its inhibitory effects by interacting with the N-terminal ATP/ADP binding site of HSP90 and effectively suppressing its ATPase activity, thereby significantly impacting tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Telatinib is currently one of the most extensively used HSP90 inhibitors in anti-tumor research, exhibiting significant inhibitory effects on various malignant solid neoplasms, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma, and colon cancer, as demonstrated in phase I clinical trials [51]. In the current study, we demonstrated that elevated levels of lncRNA CRYBG3 in NSCLC cells enhance radioresistance by promoting TRAP1 expression. Therefore, combining lncRNA CRYBG3 inhibition with TRAP1 inhibitors and radiotherapy holds promise for enhancing therapeutic efficacy.

The latest research demonstrates that radiotherapy upregulates the expression of the EGFR ligand amphiregulin in tumor cells, thereby enhancing the immune escape capability of tumor cells and facilitating their distant metastasis [52]. Our present study is committed to mitigating the side effects of radiotherapy, diminishing tumor radiation resistance, and augmenting radiation-induced oxidative damage to induce cell death. The investigations into lncRNA CRYBG3 have demonstrated that its downregulation in NSCLC cells not only inhibits their invasive and metastatic capabilities but also reduces their resistance to radiotherapy. Unfortunately, our present study has certain limitations. Specifically, it did not in-depth investigate the impact of lncRNA CRYBG3 on other pathways downstream of p53 during fractionated radiotherapy. In addition, our current conclusions require further validation using clinical samples. However, we will continue to conduct more in-depth investigations into the regulation of the biological effects induced by radiation through lncRNA CRYBG3. We propose that inhibiting lncRNA CRYBG3 may serve as a promising therapeutic approach to improve the efficacy of fractionated radiotherapy, particularly when combined with oxygen enhancers in the treatment of NSCLC.

In conclusion, we report that repetitive irradiation can induce the development of radioresistance in NSCLC cells, accompanied by a concomitant upregulation of lncRNA CRYBG3 expression. Additionally, inhibition of lncRNA CRYBG3 attenuates adaptive radioresistance in NSCLC cells by modulating the p53/HSF1/TRAP1 axis. Therefore, the development of inhibitors targeting lncRNA CRYBG3 is expected to provide a novel approach for enhancing the radiosensitivity of NSCLC in radiotherapy.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank all the staff of the Key Laboratory of Radiation Damage and Treatment of Jiangsu Provincial Universities and colleges for expert technical assistance and administrative support. We sincerely thank Professor Dong Yu for providing experimental site.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12205215), Suzhou Fundamental Research Project (No. SJC2023001), Basic Research Program of Nantong Science and Technology Bureau (No. JC12022103), College Student Innovation Training Program Project of Soochow University (No. 202410285101Z), and a Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Anqing Wu, Yangyang Ge, Ying Xu; data collection: Xiangyu Yan, Yusheng Jin, Yan Yuan, Xubaihe Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiangyu Yan, Yusheng Jin, Jiayi Li; draft manuscript preparation: Xiangyu Yan, Yusheng Jin, Anqing Wu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Figure S1: Representative colony formation images. Figure S2: qRT-PCRs were performed to evaluate the expression levels of lncRNA CRYBG3 in cells transfected with either shRNA targeting CRYBG3 (shCRYBG3) or a control shRNA (shNC). Figure S3: Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) were measured in radioresistant cells (A549R and H460R) transfected with shCRYBG3 or shNC at 2 h after exposure to 4 Gy of X-rays. Figure S4: Adenovirus particles containing lncRNA CRYBG3 (OE-CRYBG3) were transfected into H460R-shCRYBG3 cells to restore CRYBG3 expression, which was subsequently evaluated by qRT-PCR analysis 24 h post-transfection. Table S1: Radiobiological parameters in different groups. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.066935/s1.

Abbreviations

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| IR | Ionizing radiation |

| MDM2 | Murine double minute 2 |

| HSF1 | Heat shock factor 1 |

| TRAP1 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha coactivator 1α |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| GSTA2 | Glutathione S-transferase alpha 2 |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bax | BCL2-associated X protein |

| lncRNA | long non-coding RNA |

| shRNA | short hairpin RNA |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| DCFH-DA | 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial ROS |

| PE | Plating efficiency |

| SE | Survival efficiency |

| D0 | Mean lethal dose |

| Dq | Quasi-threshold Dose |

| SF2 | Survival fraction at 2 Gy |

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. doi:10.3322/caac.21763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Vinod SK, Hau E. Radiotherapy treatment for lung cancer: current status and future directions. Respirology. 2020;25(Suppl 2):61–71. doi:10.1111/resp.13870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Borrego-Soto G, Ortiz-López R, Rojas-Martínez A. Ionizing radiation-induced DNA injury and damage detection in patients with breast cancer. Genet Mol Biol. 2015;38(4):420–32. doi:10.1590/S1415-475738420150019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang R, Shen Y, Zhou X, Li J, Zhao H, Zhang Z, et al. Hypoxia-tropic delivery of nanozymes targeting transferrin receptor 1 for nasopharyngeal carcinoma radiotherapy sensitization. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):890. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-56134-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. McDonald JT, Kim K, Norris AJ, Vlashi E, Phillips TM, Lagadec C, et al. Ionizing radiation activates the Nrf2 antioxidant response. Cancer Res. 2010;70(21):8886–95. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Reinema FV, Kaanders JHAM, Peeters WJM, Adema GJ, Sweep FCGJ, Bussink J, et al. Radiotherapy induces an increase in serum antioxidant capacity reflecting tumor response. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2024;45(Pt 1):100726. doi:10.1016/j.ctro.2024.100726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Woo Y, Lee HJ, Jung YM, Jung YJ. mTOR-mediated antioxidant activation in solid tumor radioresistance. J Oncol. 2019;2019(7):5956867. doi:10.1155/2019/5956867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ghaderi N, Jung J, Brüningk SC, Subramanian A, Nassour L, Peacock J. A century of fractionated radiotherapy: how mathematical oncology can break the rules. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1316. doi:10.3390/ijms23031316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. McCann E, O’Sullivan J, Marcone S. Targeting cancer-cell mitochondria and metabolism to improve radiotherapy response. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(1):100905. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhao RZ, Jiang S, Zhang L, Yu ZB. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2019;44(1):3–15. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2019.4188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Song YC, Kuo CC, Liu CT, Wu TC, Kuo YT, Yen HR. Combined effects of tanshinone IIA and an autophagy inhibitor on the apoptosis of leukemia cells via p53, apoptosis-related proteins and oxidative stress pathways. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022;21:15347354221117776. doi:10.1177/15347354221117776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Srinivas US, Tan BWQ, Vellayappan BA, Jeyasekharan AD. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 2019;25(12):101084. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2018.101084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Liu B, Chen Y, St Clair DK. ROS and p53: a versatile partnership. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(8):1529–35. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Napoli S. LncRNAs and available databases. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2348(7414):3–26. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-1581-2_1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Bridges MC, Daulagala AC, Kourtidis A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. J Cell Biol. 2021;220(2):e202009045. doi:10.1083/jcb.202009045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Roh J, Im M, Chae Y, Kang J, Kim W. The involvement of long non-coding RNAs in glutamine-metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):14808. doi:10.3390/ijms232314808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Tang H, Liu S, Yan X, Jin Y, He X, Huang H, et al. Inhibition of LNC EBLN3P enhances radiation-induced mitochondrial damage in lung cancer cells by targeting the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 axis. Biology. 2023;12(9):1208. doi:10.3390/biology12091208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chen H, Pei H, Hu W, Ma J, Zhang J, Mao W, et al. Long non-coding RNA CRYBG3 regulates glycolysis of lung cancer cells by interacting with lactate dehydrogenase A. J Cancer. 2018;9(14):2580–8. doi:10.7150/jca.24896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mao W, Guo Z, Dai Y, Nie J, Li B, Pei H, et al. LNC CRYBG3 inhibits tumor growth by inducing M phase arrest. J Cancer. 2019;10(12):2764–70. doi:10.7150/jca.31703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wu A, Tang J, Guo Z, Dai Y, Nie J, Hu W, et al. Long non-coding RNA CRYBG3 promotes lung cancer metastasis via activating the eEF1A1/MDM2/MTBP axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3211. doi:10.3390/ijms22063211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wu A, Tang J, Dai Y, Huang H, Nie J, Hu W, et al. Downregulation of long noncoding RNA CRYBG3 enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer depending on p53 status. Radiat Res. 2022;198(3):297–305. doi:10.1667/RADE-21-00197.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zheng L, Luo C, Yang N, Pei H, Ji M, Shu Y, et al. Ionizing radiation-induced long noncoding RNA CRYBG3 regulates YAP/TAZ through mechanotransduction. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(3):209. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-04650-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Mansky RH, Greguske EA, Yu D, Zarate N, Intihar TA, Tsai W, et al. Tumor suppressor p53 regulates heat shock factor 1 protein degradation in Huntington’s disease. Cell Rep. 2023;42(3):112198. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gong L, Zhang Q, Pan X, Chen S, Yang L, Liu B, et al. p53 protects cells from death at the heatstroke threshold temperature. Cell Rep. 2019;29(11):3693–707.e5. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Park HK, Yoon NG, Lee JE, Hu S, Yoon S, Kim SY, et al. Unleashing the full potential of Hsp90 inhibitors as cancer therapeutics through simultaneous inactivation of Hsp90, Grp94, and TRAP1. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(1):79–91. doi:10.1038/s12276-019-0360-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Dekker FA, Rüdiger SGD. The mitochondrial Hsp90 TRAP1 and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:697913. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.697913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gandhapudi SK, Murapa P, Threlkeld ZD, Ward M, Sarge KD, Snow C, et al. Heat shock transcription factor 1 is activated as a consequence of lymphocyte activation and regulates a major proteostasis network in T cells critical for cell division during stress. J Immunol. 2013;191(8):4068–79. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1202831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Katiyar A, Fujimoto M, Tan K, Kurashima A, Srivastava P, Okada M, et al. HSF1 is required for induction of mitochondrial chaperones during the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. FEBS Open Bio. 2020;10(6):1135–48. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Prodromou C. Mechanisms of Hsp90 regulation. Biochem J. 2016;473(16):2439–52. doi:10.1042/BCJ20160005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang P, Lu Y, Yu D, Zhang D, Hu W. TRAP1 provides protection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(5):2072–82. doi:10.1159/000430174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Xie S, Wang X, Gan S, Tang X, Kang X, Zhu S. The mitochondrial chaperone TRAP1 as a candidate target of oncotherapy. Front Oncol. 2020;10:585047. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.585047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Jeong H, Kang BH, Lee C. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of Trap1 complexed with Hsp90 inhibitors. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2014;70(Pt 12):1683–7. doi:10.1107/S2053230X14024959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ramos Rego I, Silvério D, Eufrásio MI, Pinhanços SS, da Costa B L, Teixeira J, et al. TRAP1 is expressed in human retinal pigment epithelial cells and is required to maintain their energetic status. Antioxidants. 2023;12(2):381. doi:10.3390/antiox12020381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Clarke BE, Kalmar B, Greensmith L. Enhanced expression of TRAP1 protects mitochondrial function in motor neurons under conditions of oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1789. doi:10.3390/ijms23031789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zhu L, Chen Q, Zhang L, Hu S, Zheng W, Wang C, et al. CLIC4 regulates radioresistance of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by iNOS after γ-rays but not carbon ions irradiation. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10(5):1400–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Zhang Y, Yang H, Wang L, Zhou H, Zhang G, Xiao Z, et al. TOP2A correlates with poor prognosis and affects radioresistance of medulloblastoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:918959. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.918959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Halling JF, Pilegaard H. PGC-1α-mediated regulation of mitochondrial function and physiological implications. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45(9):927–36. doi:10.1139/apnm-2020-0005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Isermann T, Şener ÖÇ, Stender A, Klemke L, Winkler N, Neesse A, et al. Suppression of HSF1 activity by wildtype p53 creates a driving force for p53 loss-of-heterozygosity. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4019. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24064-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. MacKenzie P, Vajdic C, Delaney G, Comans T, Morris L, Agar M, et al. Radiotherapy utilisation rates for patients with cancer as a function of age: a systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14(3):101387. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2022.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gibellini L, Pinti M, Nasi M, De Biasi S, Roat E, Bertoncelli L, et al. Interfering with ROS metabolism in cancer cells: the potential role of quercetin. Cancers. 2010;2(2):1288–311. doi:10.3390/cancers2021288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Siebels I, Dröse S. Q-site inhibitor induced ROS production of mitochondrial complex II is attenuated by TCA cycle dicarboxylates. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(10):1156–64. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ding Y, Jing W, Kang Z, Yang Z. Exploring the role and application of mitochondria in radiation therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2025;1871(3):167623. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Orth M, Albrecht V, Seidl K, Kinzel L, Unger K, Hess J, et al. Inhibition of HSP90 as a strategy to radiosensitize glioblastoma: targeting the DNA damage response and beyond. Front Oncol. 2021;11:612354. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.612354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Song Q, Wen J, Li W, Xue J, Zhang Y, Liu H, et al. HSP90 promotes radioresistance of cervical cancer cells via reducing FBXO6-mediated CD147 polyubiquitination. Cancer Sci. 2022;113(4):1463–74. doi:10.1111/cas.15269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li XT, Li YS, Shi ZY, Guo XL. New insights into molecular chaperone TRAP1 as a feasible target for future cancer treatments. Life Sci. 2020;254(12):117737. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang X, Dong Y, Gao M, Hao M, Ren H, Guo L, et al. Knockdown of TRAP1 promotes cisplatin-induced apoptosis by promoting the ROS-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction in lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476(2):1075–82. doi:10.1007/s11010-020-03973-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang L, Liu L, Li X, Zhang X, Zhao J, Luo Y, et al. TRAP1 attenuates H9C2 myocardial cell injury induced by extracellular acidification via the inhibition of MPTP opening. Int J Mol Med. 2020;46(2):663–74. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2020.4631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Rai SN, Singh SS, Birla H, Zahra W, Rathore AS, Singh P, et al. Commentary: metformin reverses TRAP1 mutation-associated alterations in mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:221. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Chen Y, Lu Z, Qi C, Yu C, Li Y, Huan W, et al. N6-methyladenosine-modified TRAF1 promotes sunitinib resistance by regulating apoptosis and angiogenesis in a METTL14-dependent manner in renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):111. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01549-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Sciacovelli M, Guzzo G, Morello V, Frezza C, Zheng L, Nannini N, et al. The mitochondrial chaperone TRAP1 promotes neoplastic growth by inhibiting succinate dehydrogenase. Cell Metab. 2013;17(6):988–99. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Baird L, Suzuki T, Takahashi Y, Hishinuma E, Saigusa D, Yamamoto M. Geldanamycin-derived HSP90 inhibitors are synthetic lethal with NRF2. Mol Cell Biol. 2020;40(22):428. doi:10.1128/MCB.00377-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Piffkó A, Yang K, Panda A, Heide J, Tesak K, Wen C, et al. Radiation-induced amphiregulin drives tumour metastasis. Nature. 2025;643(8072):810–9. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08994-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools