Open Access

Open Access

MINI REVIEW

Role of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Therapy in Heart Failure

Department of Medicine, Cardiology Division, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 040039-032, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Andrey Jorge Serra. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Stem Cells Therapy in Health and Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1873-1885. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067186

Received 26 April 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) therapy has emerged as a promising strategy for treating degenerative, inflammatory, and cardiometabolic diseases. In addition to their higher bioavailability in adipose tissue, ADSCs demonstrate superior activity in producing specific immune modulators and growth factors when compared to other stem cell types. The detrimental impact of heart failure (HF)—a condition that still lacks a fully effective therapy—has driven significant interest in the therapeutic potential of ADSCs. This interest is supported by robust evidence from experimental studies employing HF animal models. Accordingly, this review aims to explore the cardioprotective mechanisms through which ADSCs may exert beneficial effects in the context of HF.Keywords

Reports on stem cell therapy date back to the 1960s [1–3], and data have highlighted its capacity to stimulate and regulate mechanisms that treat diseases rather than merely alleviating symptoms [4]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are the most commonly used adult stem cells and are found in various niches, including bone marrow, umbilical cord, and adipose tissue [5]. MSCs exhibit immunosuppressive properties, significantly reducing the incidence and severity of graft-vs.-host disease [6]. Moreover, MSCs suppress T-cell activity through both direct contact and the release of soluble molecules, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), prostaglandin E2, nitric oxide (NO), and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G5, which safeguard MSCs from lysis mediated by natural killer cells [6–8].

Adipose MSCs (ADSCs) have garnered considerable attention due to their versatility across a range of applications, including metabolic [9,10], musculoskeletal [11,12], and cardiovascular diseases [13–17], as well as their reproducible and minimally invasive isolation process. ADSCs can differentiate into various cell lineages, making them suitable for both allogeneic and autologous therapies [18–20]. ADSCs also exhibit immunomodulatory effects, primarily attributed to their ability to secrete interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TGF-β1. Additionally, the absence of HLA-DR expression further underscores their immunological versatility [21,22]. Clinical studies have explored transplantation strategies using stromal vascular fraction—a component of adipose tissue isolated prior to cell culture—as well as ADSCs, ADSC sheets, and ADSC-derived exosomes, to investigate various bioactive molecules involved in tissue regeneration [23,24].

The heart is a key target for ADSCs therapy, given its limited regenerative capacity [25]. Evidence suggests that ADSCs possess the potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells [26–28]. These properties have supported the application of ADSCs in treating both ischemic and non-ischemic HF. Accordingly, this review will delve into the molecular mechanisms underlying the cardioprotective effects of ADSCs in HF.

2 Mechanisms of ADSCs Action in the Myocardium

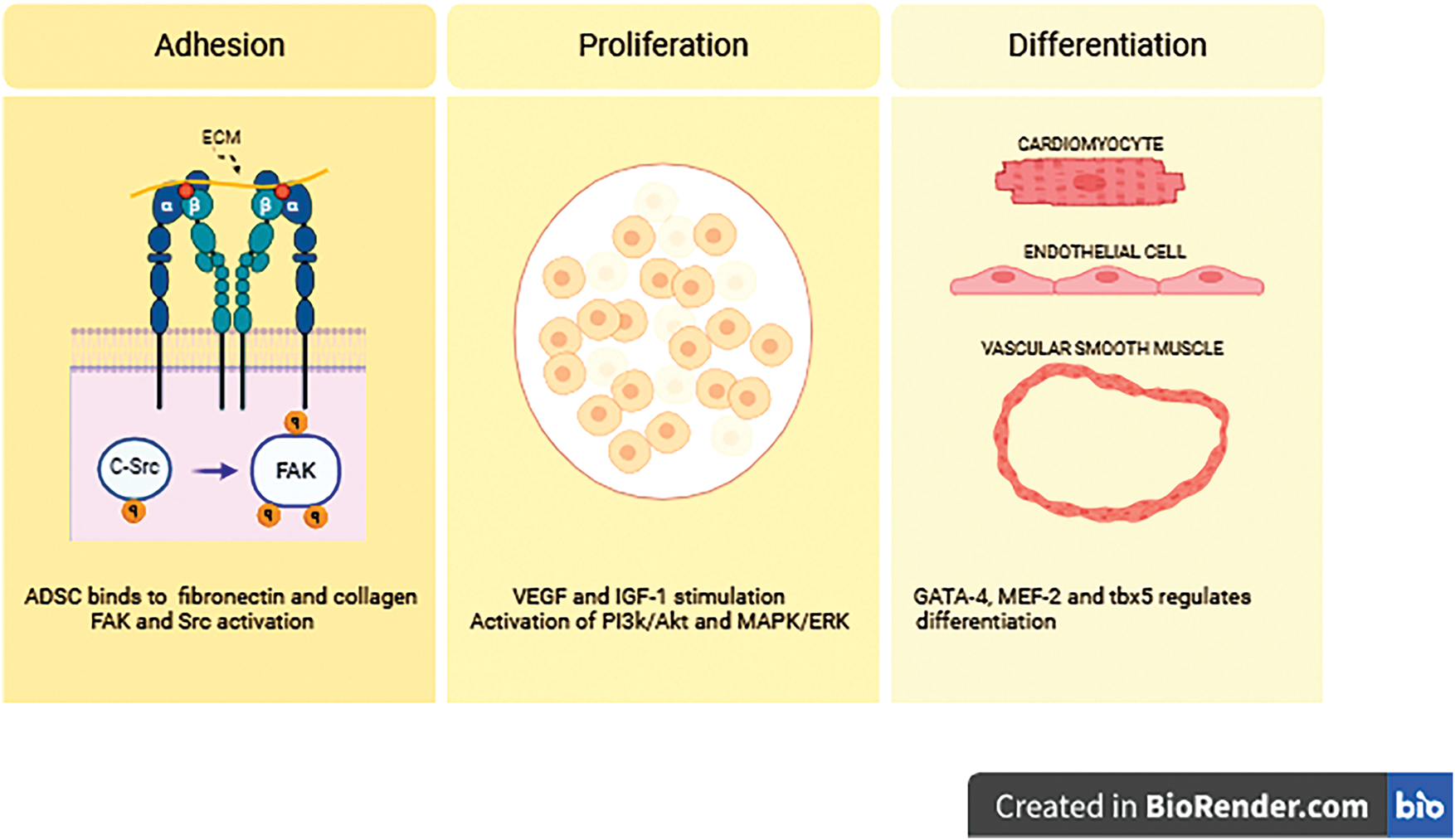

ADSCs can be isolated from subcutaneous lipoaspirates to establish a rich cell culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium [29]. These cells express surface markers, such as CD90, CD29, CD44, and CD105, while lacking markers associated with hematopoietic lineage. In culture, ADSCs display a fibroblast-like morphology [30,31] and play a beneficial role in injured tissue by promoting adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [32]. Following cardiac injury, chemotactic signaling stimulates stem cell migration via regulation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) axis [33]. Notably, integrin α5β1—a key cellular receptor—facilitates the binding of ADSCs to fibronectin and collagen in injured myocardial tissue, which in turn promotes tissue regeneration [34]. Thereby, extracellular matrix (ECM) changes in a way that promotes the interaction of ADSCs and their exosomes with specific ECM components, particularly fibronectin, tenascin-C, and type III collagen. This process activates intracellular signaling pathways, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and steroid receptor coactivator (Src), promoting cell survival and anchorage [35,36]. Growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), activate signaling pathways such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK). This activation leads to enhanced clonal expansion of ADSCs, potentially contributing to improved cardiac function [37,38]. The differentiation of ADSCs into cardiomyocytes or endothelial cells is regulated by transcription factors, such as GATA-4, MEF-2, and Tbx5. These factors modulate the expression of specific genes, including α-actinin and cardiac troponin (Fig. 1) [39,40].

Figure 1: The adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) are orchestrated by various signaling pathways and growth factors. Initiates with adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM), and prominent molecules involved in these processes include focal adhesion kinase (FAK), steroid receptor coactivator (Src), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (Akt), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Integrin α and β denote subunits of integrin receptors, such as α5β1, which mediate ADSC binding to ECM components like fibronectin and collagen. The symbol “q” refers to Gαq, a subunit of G-proteins involved in intracellular signaling cascades related to ADSC-mediated cardioprotection

A myocardial microenvironment rich in cytokines and paracrine factors drives the differentiation of ADSCs [29,41]. Common strategies to induce cardiomyocyte differentiation include the use of growth factor-enriched culture media, dimethyl agents, and cardiomyocyte co-cultures [42]. However, preserving the functional capacity of harvested cardiac cells remains a significant challenge. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)-based cultures have demonstrated a synergistic effect with VEGF and are hypothesized to generate endothelial cells from ADSCs by modulating miRNA/mRNA interactions [43,44]. Moreover, Rangappa et al. [45] reported that ADSCs can differentiate into cardiomyocytes when incubated with 5-azacytidine (9 μmol/L for 24 h), a cytidine analogue that promotes CpG (cytosine followed by a guanine) base-pair demethylation, expressing sarcomere protein markers such as α-actinin, myosin heavy chain, and troponin I.

A pivotal mechanism underlying ADSC therapy is their paracrine effect, which modulates the cardiac microenvironment. ADSCs have been demonstrated to support regeneration in ischemic disease by secreting VEGF and IGF-1 [44]. ADSCs also stimulate the upregulation of endothelial cell-specific molecule-1 (Esm1) and stanniocalcin-1 (Stc1) mRNA expression [46]. This process enhances the binding of VEGF to its receptor VEGFR2, thereby amplifying VEGF signaling and promoting angiogenesis [46–48]. The pro-angiogenic potential of ADSCs appears to persist even when collected from elderly individuals. Additionally, ADSCs have been shown to reduce tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) protein secretion by type 1 (M1) macrophages. These findings suggest that ADSCs may offer protection against atherosclerosis by targeting M1 macrophage foam cells through the regulation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)/TNF-α signaling pathway [49].

ADSC-derived exosomes have been shown to mitigate cardiac injury in infarcted mice by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting angiogenesis through the miRNA-205 signaling pathway [50]. These exosomes contain miRNAs such as miRNA-21 and miRNA-210, along with their associated proteins. miRNA-21 plays a crucial role in suppressing apoptosis and enhancing cell survival, while miRNA-210 facilitates angiogenesis and strengthens the cardiac response to hypoxia [51,52]. Exomes derived from ADSCs also facilitate macrophage M2 polarization and contribute to the attenuation of post-infarct myocardial (IM) injury by activating the sphingosine-1-phosphate/sphingosine kinase-1/sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1P/SK1/S1PR1) signaling pathway. These exosomes have been shown to downregulate the expression of fibrotic proteins, including collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA [53].

Despite their therapeutic potential, the efficacy of ADSCs can be constrained by limited viability and differentiation following transplantation. This challenge has driven research into strategies aimed at enhancing ADSCs resilience. One promising approach involves platelet-derived extracellular vesicles, which have been shown to augment the pro-angiogenic properties of ADSCs. This enhancement leads to improved vascularization, increased blood flow, and greater capillary density, while also mitigating tissue degeneration in ischemic environments [35]. Moreover photobiomodulation has been shown to enhance the metabolic activity and paracrine signaling of ADSCs, while also increasing their resistance to doxorubicin-induced toxicity [14,54–56].

HF remains a significant global disease burden [57–59]. Several experimental studies have demonstrated that ADSCs can enhance cardiac function, mitigate fibrosis, and stimulate angiogenesis [60]. Yan et al. [61] found that ADSCs overexpressing N-cadherin exhibited improved myocardial retention, increased cardiomyocyte proliferation and angiogenesis, reduced fibrosis, and enhanced left ventricular systolic performance. ADSCs have been observed to persist at the infarct site for at least two weeks, secreting angiogenic factors such as Esm1 and Stc1, which contribute to cardioprotection and neovascularization [46]. Furthermore, even under hypoxic conditions, the upregulation of α1-adrenergic receptors and VEGF enhanced new vessel formation and reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in ADSC sheet-based therapy following myocardial infarction (MI). Notably, the α1-adrenergic antagonist doxazosin abolished this regenerative effect, highlighting the critical role of α1-adrenergic receptors in promoting angiogenesis in ADSC-based post-MI therapy [62].

Wang et al. [63] examined the therapeutic potential of ADSC-derived exosomes in a rat model of doxorubicin-induced HF. The exosomes boosted ATP synthesis and reduced myocardial apoptosis, culminating in improved cardiac performance. Furthermore, ADSCs were found to regulate key apoptosis-related proteins, including Bax, caspase-3, and p53. In humans, the SCIENCE study demonstrated that ADSCs therapy had no significant impact on cardiac function or myocardial miRNA expression, as assessed by extracellular vesicle analysis. The only observed change was a slight increase in miRNA-126 expression. These findings suggest that, while ADSCs are safe, they did not confer substantial clinical benefit in patients with ischemic HF [64].

ADSCs therapy in ischemic and non-ischemic HF exhibits a consistent safety profile, although clinical efficacy outcomes remain heterogeneous. The SCIENCE II trial showed that intramyocardial injections of allogeneic ADSCs in patients with non-ischemic HF significantly reduced left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) and improved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and quality of life, suggesting clinical benefit [65]. In contrast, the Danish trial involving patients with ischemic HF found that ADSCs did not induce significant improvements in cardiac parameters or clinical symptoms, despite being well tolerated [66]. Complementary studies, such as that by Kawamura et al. [67], which applied ADSCs in spray form during coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), demonstrated enhanced ventricular function and alleviation of HF symptoms, possibly due to angiogenesis induction and microvascular regeneration.

Kastrup et al. [68] further evaluated intramyocardial ADSCs delivery in ischemic HF patients, reinforcing the safety use of ADSCs and reporting a trend toward improved LVEF and functional capacity. Although no relevant immunological reactions were observed, four patients developed donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies without clinical manifestations. The absence of significant adverse effects supports clinical feasibility, in which ADSCs benefits appears more consistent in patients with active inflammation and less irreversible structural damage. However, the discrepant outcomes across HF phenotypes underscore the need to better identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit, as well as to standardize dosing, delivery methods, and clinical response criteria.

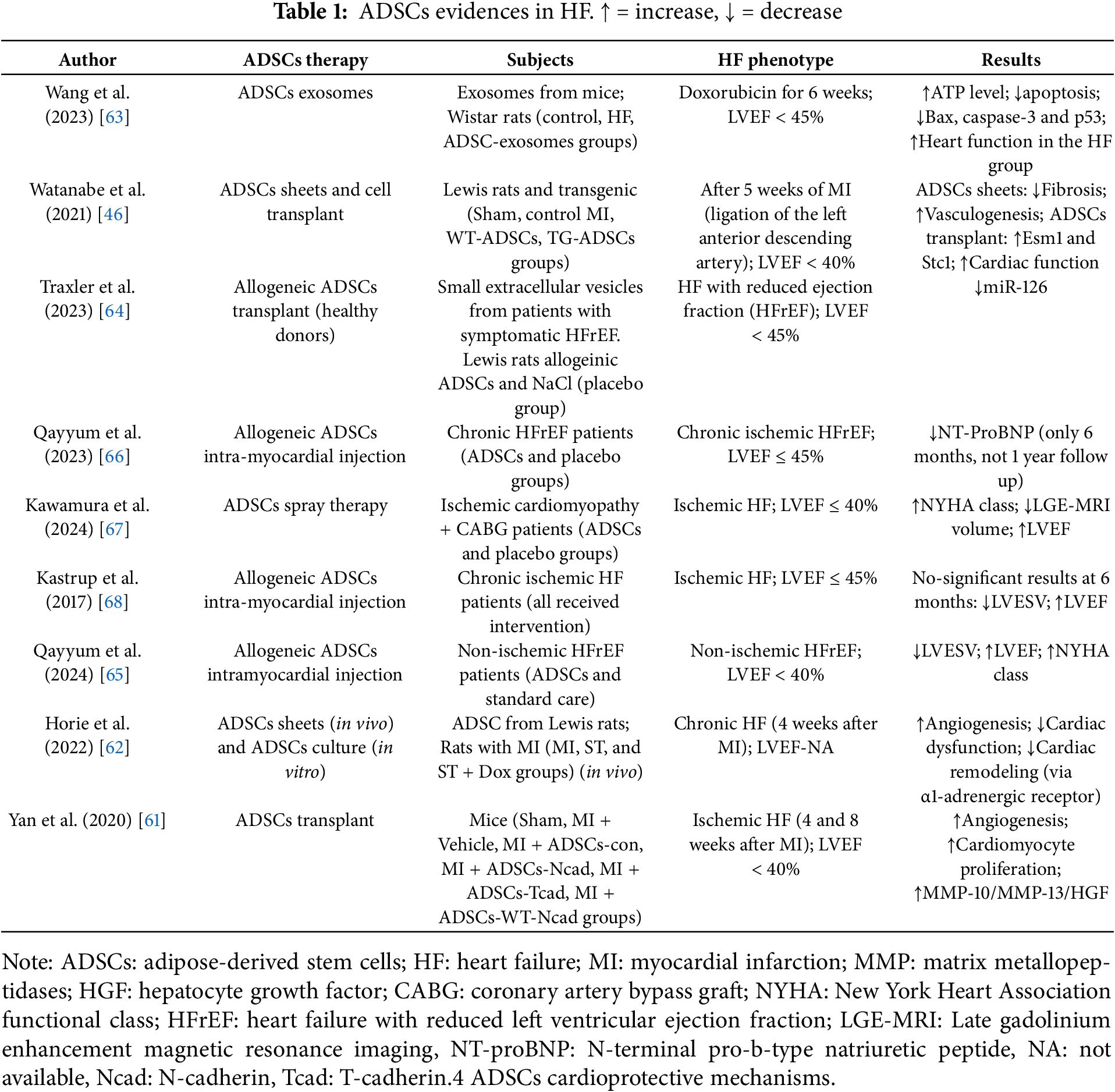

Evidence suggests that ADSCs promote regeneration and neovascularization, mitigate fibrosis, and regulate apoptosis, potentially making them a viable alternative to conventional HF treatments. However, no single molecular mechanism has been identified as responsible for their protective effects (Table 1) [69]. Moreover, according to clinicaltrials.gov, only ten ongoing clinical trials are currently evaluating the safety and efficacy of ADSCs (clinical trial IDs: NCT02387723; NCT03092284; NCT06840275; NCT01502514; NCT02673164; NCT01502501; NCT03797092; NCT03746938; NCT02052427; NCT01556022).

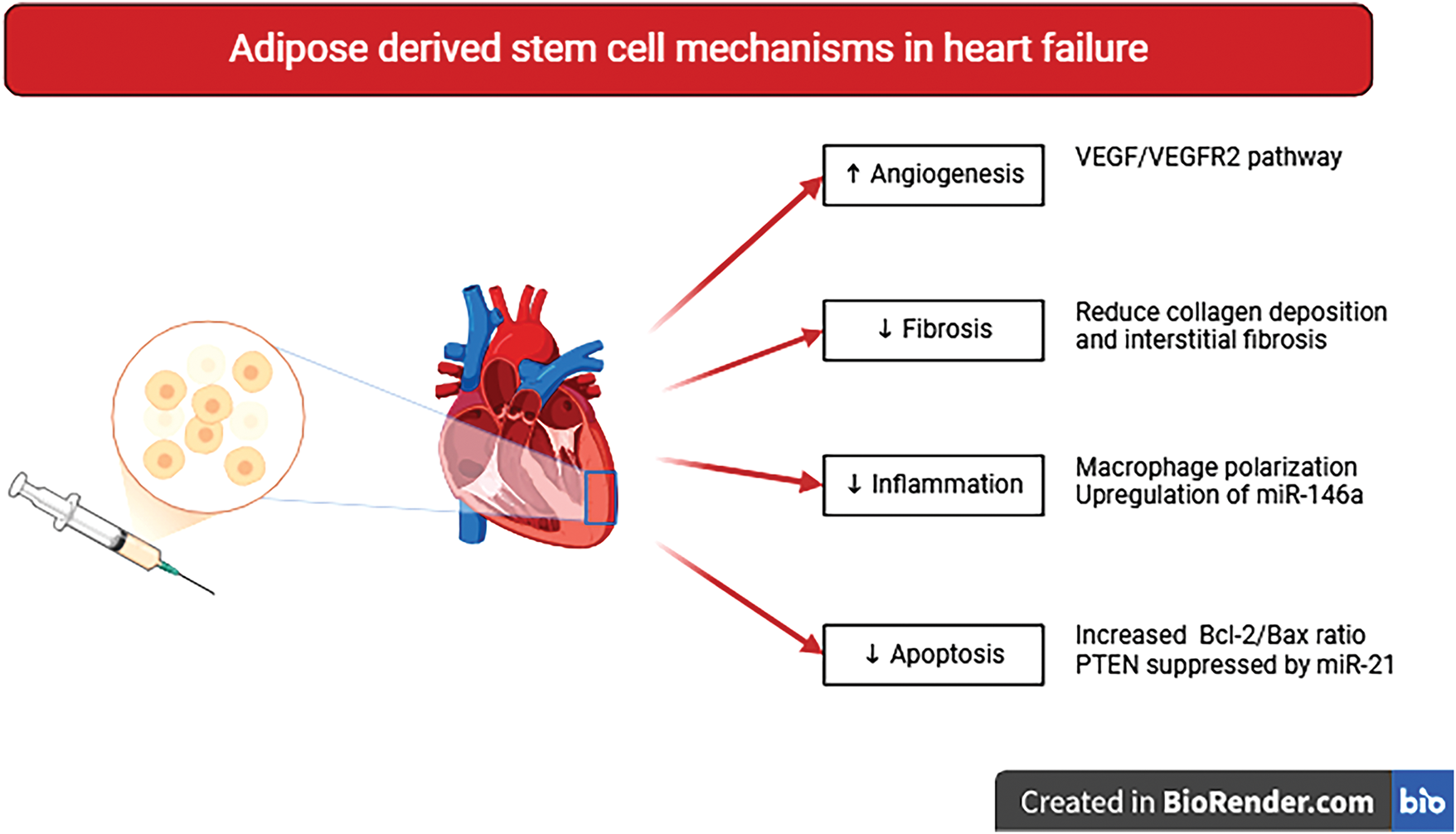

Multiple mechanisms have been implicated in the cardioprotective effects of ADSCs (Fig. 2). Angiogenic factors, including Esm1 and Stc1, activate the VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway, enhancing endothelial cell migration and survival [46]. ADSC-derived exosomes contain regulatory miRNAs, such as miR-126 and miR-210, that enhance the angiogenic response by suppressing pathways antagonistic to VEGF signaling [70]. ADSCs regulate apoptosis by increasing the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, suppressing caspase activation, and inhibiting the intrinsic apoptotic pathway [63]. An increased Bcl-2/Bax ratio, combined with miRNA-21 in ADSC-derived exosomes, suppresses the expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a negative regulator of the PI3K/Akt pathway. PTEN inhibition triggers Akt activation, subsequently promoting cell proliferation and survival [71,72].

Figure 2: Putative molecular mechanisms underlying ADSCs therapy are based on paracrine effects. The key therapeutic outcomes include pro-angiogenic, antifibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic cardioprotective actions

Myocardial fibrosis is a common consequence of HF, contributing to impaired contractility and myocardial relaxation. ADSCs have been shown to reduce collagen deposition and interstitial fibrosis [46]. Our previous studies demonstrated that ADSCs inhibited myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis while improving inflammatory cytokine levels in infarcted rats [16]. These findings were linked to enhanced myocardial contractility as well as capillary density, and reduced apoptosis [73]. In H9c2 cardiomyocytes co-cultured with ADSCs, there was a decrease in fibrosis markers (e.g., MMP-2 and MMP-9) alongside the suppression of apoptotic markers (t-Bid and caspase-3) and hypertrophic markers (NFAT3, ANP, and BNP) [74].

ADSCs plays a central role in post-MI immune modulation by promoting the polarization of macrophages from M1 to the M2 phenotype, contributing to tissue regeneration. ADSC-derived exosomes activate the S1P/SK1/S1PR1 pathway, promoting this phenotypic transition and attenuating myocardial damage [53]. Furthermore, in diabetes wound model, these exosomes carry miRNA-146a, which inhibits the NF-κB inflammatory pathway [75]. This may contribute to attenuating local inflammation and fostering a more favorable microenvironment in the injured myocardium, however, more evidence is needed to understand this mechanism in HF.

Allogeneic clinical ADSCs transplant is safe in HF, and may the therapeutic effects be mediated by paracrine mechanisms, such as immunomodulation, pro-angiogenic signaling, antiapoptotic effects, and antifibrotic remodeling. These molecular mechanisms align with clinical observations and represent possible pathways for improving heart function. The upregulation of VEGF pathways and reduction of fibrosis markers could be related to reported improvements in LVEF [65]. Similarly, the immunomodulatory effects, including macrophage polarization and NF-κB inhibition, may contribute to improved functional status, as reflected in improvement of NYHA class [67]. Therefore, while current clinical trials support the therapeutic potential of ADSCs in HF, particularly through their molecular actions, further studies are needed to standardize protocols and better define patient subgroups most likely to benefit from this regenerative strategy.

Taken together, microRNAs such as miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-205 represent promising mediators of ADSC-induced cardioprotection. However, their roles appear context-dependent and variably validated across different HF etiologies. Ischemic HF is marked by a robust acute inflammatory response, making miR-21 especially relevant due to its regulation of ERK/MAPK signaling and targets like Sprouty Homolog 1 (Spry-1) and Programmed Cell Death 4 (PDCD4), which contribute to remodeling and fibrosis [76,77]. Although preclinical studies support its therapeutic potential, clinical validation remains limited [78]. In non-cardiac models, miR-146a exhibits anti-inflammatory effects via NF-κB pathway suppression, though evidence in HF-specific contexts is scarce [79]. Conversely, recent studies demonstrated that miR-205-enriched ADSC-derived exosomes promote angiogenesis and reduce apoptosis in acute MI models, improving cardiac function and attenuating fibrosis [50]. Moreover, a sub-analysis of the SCIENCE trial showed that ADSC therapy modestly reduced miR-126 expression in ischemic HF patients. However, these effects were not assessed in chronic HF, underscoring translational challenges [64]. Thus, while miR-21 appears most relevant in ischemic remodeling, miR-146a and miR-205 show context-dependent promise. Further studies comparing their roles in ischemic vs. non-ischemic HF are needed to optimize ADSC-based therapies.

4 Conclusions and Perspectives

This review explores the therapeutic potential of ADSCs and their derivatives in the treatment of heart failure (HF). Through the secretion of angiogenic factors, modulation of apoptosis, reduction of fibrosis, and immunomodulatory effects, ADSCs contribute to favorable cardiac remodeling. Emerging evidence suggests improvements in cardiac function, reduced end-systolic volume, enhanced exercise tolerance, and alleviation of HF symptoms.

Although clinical trials have demonstrated the feasibility and safety of ADSC-based therapies in patients with HF, several challenges remain. Not all clinical trial outcomes have achieved statistical significance, underscoring the need for further investigation. Critical issues, including optimal methods for stem cell isolation and expansion, as well as determining appropriate dosage and administration routes, must be addressed in future experimental and clinical investigations. Developing strategies to enhance the survival, engraftment, and therapeutic efficacy of ADSCs could represent a groundbreaking advancement, offering new hope for individuals living with HF.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP (2023/17028-7; 2024/09328-3; 2023/17028-7) and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq (grants: 300199/2025-2; 306385/2020-1). The funding sources were not involved in the study design; the data collection, analysis or interpretation; the writing of the article; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: review conception: Andrey Jorge Serra, Gabriel Matheus da Silva Batista; search methodology and figures: Gabriel Matheus da Silva Batista; writing—review and editing: Andrey Jorge Serra, Gabriel Matheus da Silva Batista, Lucas Pina Rodrigues. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ADSC | Adipose-derived stem cell |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| bFGF | Basic fibroblast growth factor |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass graft |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| Esm1 | Endothelial cell-specific molecule-1 |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| Gαq | G-protein alpha q subunit |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LGE-MRI | Late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| M1 | Macrophage type 1 phenotype |

| M2 | Macrophage type 2 phenotype |

| MMP | Matrix metallopeptidases |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| Ncad | N-cadherin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| PDCD4 | Programmed Cell Death 4 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| S1P | Sphingosine-1-phosphate |

| S1PR1 | Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor |

| SK1 | Sphingosine kinase-1 |

| Spry-1 | Sprouty Homolog 1 |

| Src | Steroid receptor coactivator |

| Stc1 | Stanniocalcin-1 |

| t-Bid | Truncated BH3 interacting-domain death agonist |

| Tcad | T-cadherin |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 |

| α5β1 | Integrin alpha-5 beta-1 |

References

1. Blau CA. E. Donnall Thomas, M.D. (1920–2012). Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(2):81–2. doi:10.5966/sctm.2013-0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Atala A. STEM CELLS translational medicine: a decade of evolution to a vibrant stem cell and regenerative medicine global community. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10(2):157–9. doi:10.1002/sctm.21-0016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu G, David BT, Trawczynski M, Fessler RG. Advances in pluripotent stem cells: history, mechanisms, technologies, and applications. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16(1):3–32. doi:10.1007/s12015-019-09935-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. O’Brien T, Barry FP. Stem cell therapy and regenerative medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(10):859–61. doi:10.4065/84.10.859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mannino G, Russo C, Maugeri G, Musumeci G, Vicario N, Tibullo D, et al. Adult stem cell niches for tissue homeostasis. J Cell Physiol. 2022;237(1):239–57. doi:10.1002/jcp.30562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Machado CD, Telles PD, Nascimento ILO. Immunological characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2013;35(1):62–7. doi:10.5581/1516-8484.20130017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Dulak J, Szade K, Szade A, Nowak W, Józkowicz A. Adult stem cells: hopes and hypes of regenerative medicine. Acta Biochim Pol. 2015;62(3):329–37. doi:10.18388/abp.2015_1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Jacobs SA, Roobrouck VD, Verfaillie CM, Van Gool SW. Immunological characteristics of human mesenchymal stem cells and multipotent adult progenitor cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91(1):32–9. doi:10.1038/icb.2012.64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Hu LR, Pan J. Adipose-derived stem cell therapy shows promising results for secondary lymphedema. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12(7):612–20. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v12.i7.612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mikłosz A, Chabowski A. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells therapy as a new treatment option for diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(8):1889–97. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Tevlin R, desJardins-Park H, Huber J, DiIorio SE, Longaker MT, Wan DC. Musculoskeletal tissue engineering: adipose derived stromal cell implementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2022;286:121544. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Biazzo A, D’Ambrosi R, Masia F, Izzo V, Verde F. Autologous adipose stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis: where are we now? Phys Sportsmed. 2020;48(4):392–9. doi:10.1080/00913847.2020.1758001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. de Souza Vieira S, de Melo BL, Dos Santos LF, Cummings CO, Tucci PJF, Serra AJ. Exercise training in boosting post-mi mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021;17(6):2361–3. doi:10.1007/s12015-021-10274-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. de Lima RDN, Vieira SS, Antonio EL, de Carvalho PTC, de Paula Vieira R, Mansano BSDM, et al. Low-level laser therapy alleviates the deleterious effect of doxorubicin on rat adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;196:111512. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Seibt LE, Antonio EL, AzevedoTeixeira IL, de Oliveira HA, Dias ARL, Neves Dos Santos LF, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells increase resistance against ventricular arrhythmias provoked in rats with myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(8):2293–302. doi:10.1007/s12015-024-10773-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Vieira SS, Antonio EL, de Melo BL, Dos Santos LFN, Santana ET, Feliciano R, et al. Increased myocardial retention of mesenchymal stem cells post-MI by pre-conditioning exercise training. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16(4):730–41. doi:10.1007/s12015-020-09970-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Alzghoul Y, Issa HJB, Sanajleh AK, Alabduh T, Rababah F, Al-Shdaifat M, et al. Therapeutic and regenerative potential of different sources of mesenchymal stem cells for cardiovascular diseases. BIOCELL. 2024;48(4):559–69. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.048056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mazini L, Rochette L, Admou B, Amal S, Malka G. Hopes and limits of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1306. doi:10.3390/ijms21041306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mazini L, Rochette L, Amine M, Malka G. Regenerative capacity of adipose derived stem cells (ADSCscomparison with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2523. doi:10.3390/ijms20102523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Czerwiec K, Zawrzykraj M, Deptuła M, Skoniecka A, Tymińska A, Zieliński J, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in basic research and clinical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3888. doi:10.3390/ijms24043888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Al-Ghadban S, Bunnell BA. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells: immunomodulatory effects and therapeutic potential. Physiology. 2020;35(2):125–33. doi:10.1152/physiol.00021.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Melief SM, Zwaginga JJ, Fibbe WE, Roelofs H. Adipose tissue-derived multipotent stromal cells have a higher immunomodulatory capacity than their bone marrow-derived counterparts. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(6):455–63. doi:10.5966/sctm.2012-0184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Bunnell BA. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cells. 2021;10(12):3433. doi:10.3390/cells10123433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Bacakova L, Zarubova J, Travnickova M, Musilkova J, Pajorova J, Slepicka P, et al. Stem cells: their source, potency and use in regenerative therapies with focus on adipose-derived stem cells—a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36(4):1111–26. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.03.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Nguyen PD, de Bakker DEM, Bakkers J. Cardiac regenerative capacity: an evolutionary after thought? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(12):5107–22. doi:10.1007/s00018-021-03831-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang D, Yu K, Hu X, Jiang A. Uniformly-aligned gelatin/polycaprolactone fibers promote proliferation in adipose-derived stem cells and have distinct effects on cardiac cell differentiation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2021;14(6):680–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Zhang J, Liu Y, Chen Y, Yuan L, Liu H, Wang J, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells: current applications and future directions in the regeneration of multiple tissues. Stem Cells Int. 2020;2020:8810813. doi:10.1155/2020/8810813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Panina YA, Yakimov AS, Komleva YK, Morgun AV, Lopatina OL, Malinovskaya NA, et al. Plasticity of adipose tissue-derived stem cells and regulation of angiogenesis. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1656. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Suzuki E, Fujita D, Takahashi M, Oba S, Nishimatsu H. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells as a therapeutic tool for cardiovascular disease. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(8):454–65. doi:10.4330/wjc.v7.i8.454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Mitchell JB, McIntosh K, Zvonic S, Garrett S, Floyd ZE, Kloster A, et al. Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells. 2006;24(2):376–85. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, Krause DS, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–7. doi:10.1080/14653240600855905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yamazaki M, Sugimoto K, Mabuchi Y, Yamashita R, Ichikawa-Tomikawa N, Kaneko T, et al. Soluble JAM-C ectodomain serves as the niche for adipose-derived stromal/stem cells. Biomedicines. 2021;9(3):278. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9030278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Penn MS, Pastore J, Miller T, Aras R. SDF-1 in myocardial repair. Gene Ther. 2012;19(6):583–7. doi:10.1038/gt.2012.32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Sedlář A, Trávníčková M, Bojarová P, Vlachová M, Slámová K, Křen V, et al. Interaction between galectin-3 and integrins mediates cell-matrix adhesion in endothelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(10):5144. doi:10.3390/ijms22105144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Tang Y, Li J, Wang W, Chen B, Chen J, Shen Z, et al. Platelet extracellular vesicles enhance the proangiogenic potential of adipose-derived stem cells in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):497. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02561-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang W, Shen Z, Tang Y, Chen B, Chen J, Hou J, et al. Astragaloside IV promotes the angiogenic capacity of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a hindlimb ischemia model by FAK phosphorylation via CXCR2. Phytomedicine. 2022;96:153908. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Bagno LL, Carvalho D, Mesquita F, Louzada RA, Andrade B, Kasai-Brunswick TH, et al. Sustained IGF-1 secretion by adipose-derived stem cells improves infarcted heart function. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(9):1609–22. doi:10.3727/096368915X690215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Liu H, Shi M, Li X, Lu W, Zhang M, Zhang T, et al. Adipose mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes prevent testicular torsion injury via activating PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:8065771. doi:10.1155/2022/8065771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Isomi M, Sadahiro T, Yamakawa H, Fujita R, Yamada Y, Abe Y, et al. Overexpression of Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 generates induced cardiomyocytes via direct reprogramming and rare fusion in the heart. Circulation. 2021;143(21):2123–5. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wystrychowski W, Patlolla B, Zhuge Y, Neofytou E, Robbins RC, Beygui RE. Multipotency and cardiomyogenic potential of human adipose-derived stem cells from epicardium, pericardium, and omentum. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):84. doi:10.1186/s13287-016-0343-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ma T, Sun J, Zhao Z, Lei W, Chen Y, Wang X, et al. A brief review: adipose-derived stem cells and their therapeutic potential in cardiovascular diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):124. doi:10.1186/s13287-017-0585-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Carvalho PH, Daibert APF, Monteiro BS, Okano BS, Carvalho JL, Cunha DN, et al. Differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;100(1):82–9. doi:10.1590/s0066-782x2012005000114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Arderiu G, Civit-Urgell A, Díez-Caballero A, Moscatiello F, Ballesta C, Badimon L. Differentiation of adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells into endothelial cells depends on fat depot conditions: regulation by miRNA. Cells. 2024;13(6):513. doi:10.3390/cells13060513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Arderiu G, Peña E, Aledo R, Juan-Babot O, Crespo J, Vilahur G, et al. MicroRNA-145 regulates the differentiation of adipose stem cells toward microvascular endothelial cells and promotes angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2019;125(1):74–89. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Rangappa S, Fen C, Lee EH, Bongso A, Sim EKW. Transformation of adult mesenchymal stem cells isolated from the fatty tissue into cardiomyocytes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(3):775–9. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04568-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Watanabe M, Horie H, Kurata Y, Inoue Y, Notsu T, Wakimizu T, et al. Esm1 and Stc1 as angiogenic factors responsible for protective actions of adipose-derived stem cell sheets on chronic heart failure after rat myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2021;85(5):657–66. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-20-0877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zhou J, Zhou P, Wang J, Song J. Roles of endothelial cell specific molecule-1 in tumor angiogenesis (review). Oncol Lett. 2024;27(3):137. doi:10.3892/ol.2024.14270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Nguyen VTT, Pham KD, Cao HTQ, Pham PV. Mesenchymal stem cells and the angiogenic regulatory network with potential incorporation and modification for therapeutic development. BIOCELL. 2024;48(2):173–89. doi:10.32604/biocell.2023.043664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zubkova ES, Beloglazova IB, Makarevich PI, Boldyreva MA, Sukhareva OY, Shestakova MV, et al. Regulation of adipose tissue stem cells angiogenic potential by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(1):180–96. doi:10.1002/jcb.25263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wang T, Li T, Niu X, Hu L, Cheng J, Guo D, et al. ADSC-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial infarction injury by promoting miR-205-mediated cardiac angiogenesis. Biol Direct. 2023;18(1):6. doi:10.1186/s13062-023-00361-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Shen NN, Wang JL, Fu YP. The microRNA expression profiling in heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:856358. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.856358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Han M, Toli J, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs in the cardiovascular system. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26(3):181–9. doi:10.1097/HCO.0b013e328345983d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Deng S, Zhou X, Ge Z, Song Y, Wang H, Liu X, et al. Exosomes from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cardiac damage after myocardial infarction by activating S1P/SK1/S1PR1 signaling and promoting macrophage M2 polarization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;114:105564. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2019.105564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Mansano BSDM, da Rocha VP, Teixeira ILA, de Oliveira HA, Vieira SS, Antonio EL, et al. Light-emitting diode can enhance the metabolism and paracrine action of mesenchymal stem cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2023;99(6):1420–8. doi:10.1111/php.13794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Mansano BSDM, da Rocha VP, Antonio EL, Peron DF, do Nascimento de Lima R, Tucci PJF, et al. Enhancing the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells with light-emitting diode: implications and molecular mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:6663539. doi:10.1155/2021/6663539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. da Rocha VP, Mansano BSDM, Dos Santos CFC, Teixeira ILA, de Oliveira HA, Vieira SS, et al. How long does the biological effect of a red light-emitting diode last on adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells? Photochem Photobiol. 2025;101(1):206–14. doi:10.1111/php.13983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118(17):3272–87. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvac013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Yan T, Zhu S, Yin X, Xie C, Xue J, Zhu M, et al. Burden, trends, and inequalities of heart failure globally, 1990 to 2019: a secondary analysis based on the global burden of disease 2019 study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(6):e027852. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.027852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Khan MS, Shahid I, Bennis A, Rakisheva A, Metra M, Butler J. Global epidemiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21(10):717–34. doi:10.1038/s41569-024-01046-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Bakinowska E, Kiełbowski K, Boboryko D, Bratborska AW, Olejnik-Wojciechowska J, Rusiński M, et al. The role of stem cells in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3901. doi:10.3390/ijms25073901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Yan W, Lin C, Guo Y, Chen Y, Du Y, Lau WB, et al. N-cadherin overexpression mobilizes the protective effects of mesenchymal stromal cells against ischemic heart injury through a β-catenin-dependent manner. Circ Res. 2020;126(7):857–74. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Horie H, Hisatome I, Kurata Y, Yamamoto Y, Notsu T, Adachi M, et al. α1-Adrenergic receptor mediates adipose-derived stem cell sheet-induced protection against chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction in rats. Hypertens Res. 2022;45(2):283–91. doi:10.1038/s41440-021-00802-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Wang L, Zhang JJ, Wang SS, Li L. Mechanism of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell exosomes in the treatment of heart failure. World J Stem Cells. 2023;15(9):897–907. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v15.i9.897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Traxler D, Dannenberg V, Zlabinger K, Gugerell A, Mester-Tonczar J, Lukovic D, et al. Plasma small extracellular vesicle cardiac miRNA expression in patients with ischemic heart failure, randomized to percutaneous intramyocardial treatment of adipose derived stem cells or placebo: subanalysis of the SCIENCE study. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10647. doi:10.3390/ijms241310647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Qayyum AA, Frljak S, Juhl M, Poglajen G, Zemljičl G, Cerar A, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells to treat patients with non-ischaemic heart failure: results from SCIENCE II pilot study. ESC Heart Fail. 2024;11(6):3882–91. doi:10.1002/ehf2.14925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Qayyum AA, Mouridsen M, Nilsson B, Gustafsson I, Schou M, Nielsen OW, et al. Danish phase II trial using adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stromal cells for patients with ischaemic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2023;10(2):1170–83. doi:10.1002/ehf2.14281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Kawamura T, Yoshioka D, Kawamura A, Misumi Y, Taguchi T, Mori D, et al. Safety and therapeutic potential of allogeneic adipose-derived stem cell spray transplantation in ischemic cardiomyopathy: a phase I clinical trial. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):1091. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05816-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Kastrup J, Haack-Sørensen M, Juhl M, Harary Søndergaard R, Follin B, Drozd Lund L, et al. Cryopreserved off-the-shelf allogeneic adipose-derived stromal cells for therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease and heart failure-a safety study. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(11):1963–71. doi:10.1002/sctm.17-0040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Przybyt E, Harmsen MC. Mesenchymal stem cells: promising for myocardial regeneration? Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;8(4):270–7. doi:10.2174/1574888x11308040002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zhang Y, Xu Y, Zhou K, Kao G, Xiao J. MicroRNA-126 and VEGF enhance the function of endothelial progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(2):142. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.11065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Zhou H, Liu H, Jiang M, Zhang S, Chen J, Fan X. Targeting microRNA-21 suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation and migration via PTEN/Akt signaling axis. Cell Transplant. 2019;28(3):306–17. doi:10.1177/0963689719825573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zhang J, Liu X, Li H, Chen C, Hu B, Niu X, et al. Exosomes/tricalcium phosphate combination scaffolds can enhance bone regeneration by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):136. doi:10.1186/s13287-016-0391-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. de Souza Vieira S, Antonio EL, de Melo BL, Portes LA, Montemor J, Oliveira HA, et al. Exercise training potentiates the cardioprotective effects of stem cells post-infarction. Heart Lung Circ. 2019;28(2):263–71. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2017.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Chen TS, Kuo CH, Battsengel S, Pan LF, Day CH, Shen CY, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells decrease cardiomyocyte damage induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis endotoxin through suppressing hypertrophy, apoptosis, fibrosis, and MAPK markers. Environ Toxicol. 2018;33(4):508–13. doi:10.1002/tox.22536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Che D, Xiang X, Xie J, Chen Z, Bao Q, Cao D. Exosomes derived from adipose stem cells enhance angiogenesis in diabetic wound via miR-146a-5p/JAZF1 axis. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(4):1026–39. doi:10.1007/s12015-024-10685-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456(7224):980–4. doi:10.1038/nature07511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Gu J, Chen X, Luo Z, Li R, Xu Q, Liu M, et al. Cardiomyocyte-derived exosomes promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and neonatal heart regeneration. FASEB J. 2024;38(22):e70186. doi:10.1096/fj.202400737RR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. He F, Guan W. The role of miR-21 as a biomarker and therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2025;574:120304. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2025.120304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Chen G, Wu Y, Zou L, Zeng Y. Effect of microRNA-146a modified adipose-derived stem cell exosomes on rat back wound healing. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2023;22(4):704–12. doi:10.1177/15347346211038092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools