Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Malignant Transformation of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: Pathophysiology, Molecular Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications

1 College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

2 Department of Translational Research, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

* Corresponding Author: Vikrant Rai. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Understanding Cellular Mechanisms in Wound Healing During Therapeutic Interventions)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1887-1911. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067207

Received 27 April 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are a serious complication of diabetes mellitus and are associated with high morbidity, risk of amputation, and increased mortality. Although DFUs typically remain a chronic, non-healing wound, a small portion of DFUs may undergo malignant transformation. The subsequent malignancies are skin cancers such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma. Understanding the pathophysiology of DFUs and the molecular and clinical determinants that contribute to their potential malignant transformation if crucial for clinical management. Chronic inflammation, dysregulation of cytokine signaling, faulty immune surveillance, and impaired wound healing all play a role in creating a tumor-permissive environment for the diabetic foot. This review highlights molecular mechanisms driving this transformation, including, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) pathway dysregulation, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) mediated angiogenic signaling, chronic osteomyelitis, and oxidative stress, which can collectively promote progression to malignancies, most notably cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Classic examples like Marjolin’s ulcer demonstrate how chronic injury can drive carcinogenesis, reinforcing the importance of vigilant DFU management. Connecting findings across clinical reports and mechanistic studies reveals that understanding DFU carcinogenesis is essential for earlier detection, informed targeted treatment, and improved patient outcomes.Keywords

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a chronic metabolic disorder, arises from the body’s inability to produce or effectively use insulin, resulting in elevated blood glucose levels [1]. Diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are a serious complication of poorly controlled DM, with a lifetime risk of 19% to 34% in diabetic patients [2]. DFU is the most common reason for hospitalization of diabetic patients, due to its high prevalence and increased mortality and morbidity rates [3]. They are characterized by an open wound, often resulting from peripheral neuropathy, hyperglycemia, peripheral vascular disease, ischemia, or immune dysregulation. DFUs typically localize to areas of high pressure and are commonly caused by a combination of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and neuropathy [4]. They are typically classified by depth, size, ischemia, and presence of infection. In severe cases, treatment requires surgical interventions or limb amputation [3]. Unfortunately, with the projected rise in global diabetes prevalence, the incidence of DFUs is also likely to follow the trend [5].

Chronic DFUs can severely impact patients’ quality of life and are associated with a high risk of amputation and recurrence. Late-stage DFUs usually present with decreased limb sensation and motor function, leading to unsteadiness and an increased risk of falls [6]. Today, DFUs are the leading cause of non-traumatic amputation, subjecting patients to increased hospitalization rates and mortality. A recent meta-analysis reported mortality rates of 13.1% within 1 year, 49.1% within 5 years, and 76.9% within 10 years following a DFU diagnosis [7]. Additionally, amputation or other surgical procedures can impose a heavy economic burden on patients and significantly impact their quality of life [8]. Diabetes-related lower extremity amputations have an estimated 5-year mortality rate of 52% following minor amputations and 69% following major amputations [9]. DFUs also have significant recurrence rates, including 37.39% in males and 32.18% in females, with certain lifestyle and pathological factors increasing risk in some individuals [10].

In addition to these complications, DFUs are now being increasingly recognized for their potential role in malignant transformation. While overall, malignant transformation of DFUs is not highly common, there have been numerous case studies reporting carcinogenesis within DFUs [4,11,12]. Furthermore, DFUs are increasingly recognized as a risk factor for the development of skin tumors. Repeated diabetic ulcers have the potential to undergo malignant transformations, most commonly developing into cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) [11]. Though SCC is the predominant malignancy in chronic wounds and burn scars, there have also been cases involving basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, sarcoma, and other neoplasms [13]. Malignancies developing from chronic wounds have been shown to develop over the span of 4 weeks to 75 years [14]. These malignant transformations are believed to be the result of chronic inflammatory responses altering the local microenvironment in ways that can promote subsequent tumor growth. In some cases, melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers have been misdiagnosed as DFU, leading to delayed treatment and worse clinical outcomes [13]. Most notably, delayed treatment increases the risk of metastasis. A recent study discovered 30% to 40% of chronic wound malignancies metastasize, leading to poorer prognoses [13,15]. These observations underscore the importance of continuous assessment and histopathological analysis of chronic DFUs to differentiate them from malignant transformations or adjacent neoplasms.

To effectively address and treat DFU-derived malignancies, we must first understand the underlying molecular mechanisms that promote their malignant transformation. Analyzing these mechanisms may help distinguish transformed malignancies from adjacent or coexisting neoplasms, reducing misdiagnoses and allowing earlier and more targeted interventions. This is especially important as DFUs and malignancies often share similar clinical presentations. In some cases, chronic ulcers can obscure the detection of neoplasms [16]. As a result, histopathological analysis is one of the only reliable methods for accurate differentiation and is thus considered the gold standard [4,17]. By delineating the exact pathways and molecules involved in their carcinogenesis, we could provide more insight into the development of chemotherapies or adjuvants specific to DFU-derived cancer cells. With the global rise in diabetes, the risk of DFUs and, by extension, DFU-associated malignancies is expected to increase [18]. As a result, early detection and treatment of malignant, DFU-derived ulcers is becoming increasingly relevant. Identifying the molecular basis of this transformation could help discern biomarkers for early screening in high-risk patients. This review aims to synthesize current evidence on the malignant transformation of DFUs and explore the proposed molecular mechanisms driving their progression, with the ultimate goal of improving early detection and informing therapeutic development.

2 Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Pathophysiology and Clinical Course

DFUs are full-thickness wounds extending through the dermis, typically occurring in weight-bearing or pressure-prone areas. DFU development typically results from peripheral neuropathy, hyperglycemia, peripheral vascular disease, ischemia, or immune dysregulation [4]. Neuropathy, trauma, and vascular insufficiency are a well-documented critical triad underlying the pathogenesis of DFU development [19].

Sensory neuropathy occurs as a result of hyperglycemia and accumulation of glucose derivatives, disrupting nerve cell synthesis and conduction [19,20]. Consequently, sensory loss occurs, often beginning at the lower extremities, and results in a loss of protective sensation, leading to an increased risk of trauma [21]. Further complications arise from diabetes-induced neuronal autonomic dysfunction, which can impair sweat production, leading to dryness and skin fissuring [22]. Additionally, motor neuron dysfunction contributes to muscle wasting and foot deformities, increasing localized pressure and predisposing to ulceration [20].

Repetitive minor trauma is also a key factor in ulcer development and is seen in most cases of DFUs. Factors such as elevated pressure at weight-bearing sites, increased friction or shearing, gait abnormalities, or unrecognized injuries to an insensate foot can all contribute to ulcer development [23,24]. Thus, the triad of neuropathy, foot deformity, and repetitive trauma without noticing it due to decreased sensation contributes significantly to the development of DFUs in diabetic patients.

Vascular insufficiency also plays an important role in the pathophysiology behind DFU development. Approximately 50% of people with DM and a DFU also suffer from peripheral artery disease (PAD), which can significantly increase adverse effects in limbs [25]. PAD results in damage to blood vessels and is associated with atherosclerotic blockages, arteriolar wall hardening, and thickening of capillary basement membranes, resulting in restricted blood flow and decreased systemic circulation [23,26]. Poor circulation tends to affect extremities first, making the feet particularly vulnerable in diabetic patients with PAD. Vascular insufficiency plays a key role in delayed wound healing and can increase the risk of infection and subsequent amputation at the site of the ulcer [27,28]. Together, the critical triad interacts synergistically, compounding their individual effects while driving the progression of chronic, non-healing ulcers.

On a molecular level, oxidative stress from nitric oxide (NO), pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, IL-8, chemokines, and pathogenic microorganisms contribute to DFU pathogenesis [29,30]. An increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, is associated with nonhealing DFUs, contributing to the chronic inflammation and impaired healing process. While anti-inflammatory cytokines during the resolving phase promote wound healing. Thus, an imbalance between pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines during the inflammatory phase, with a predominance of pro-inflammatory cytokines, plays a critical role in sustaining the inflammatory phase of wound healing without progressing it to the resolving phase and contribute to chronicity if nonhealing ulcers [29,30]. Alongside this, DFUs are associated with a chronic wound environment, characterized by diminished expression of growth factors, angiogenic factors, and cytokines necessary for wound healing. Both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are characterized by an imbalance in the release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, leading to impairments in tissue repair and humoral immune defense [31,32]. For example, the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α not only increase matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) production but also decrease their inhibitors namely tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs). This leads to ECM degradation while cell migration, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen synthesis are reduced [33].

Oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) also contribute to DFU pathogenesis. A key contributor to cytotoxicity in the diabetic wound environment is the disproportionate generation of ROS, which works in tandem with inflammatory effectors to promote accumulation of glycoxidation end-products (AGEs) [34]. Subsequently, in vivo experiments on mice found AGEs also activate pro-survival and anti-apoptotic peptides, further encouraging tumorigenic processes [35,36]. AGEs also increase ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which can further damage local tissue [37].

The interplay between diabetes and nitric oxide (NO) is more complex. A recent study investigated the role of a portable NO jet healing device (NJHD) on diabetic wounds in mice and found that the treatment can promote wound healing by modulating the extracellular matrix (ECM), increasing collagen I deposition, and decreasing MMP-9 levels. However, while mouse studies showed promise, researchers acknowledged potential clinical difficulties with maintaining optimal NO concentrations at the wound site [38]. On the other hand, older studies have shown a dichotomous role of NO in wound healing. Soneja et al. [39] reported that high levels of NO can promote angiogenesis as well as endothelial cell remodeling and proliferation. However, in the oxidative environment of a DFU, NO can react with superoxide (O2−) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH). These reactive nitrogen species (RNS) trigger a cascade of oxidative stress, leading to the production of damaging radicals, including carbonate (CO3−), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•). These species impose significant oxidative damage and impair the wound healing process [39]. Further indicating the complex role of NO in wound healing, low levels of NO have been shown to delay wound healing by decreasing blood supply to the site of the wound [33].

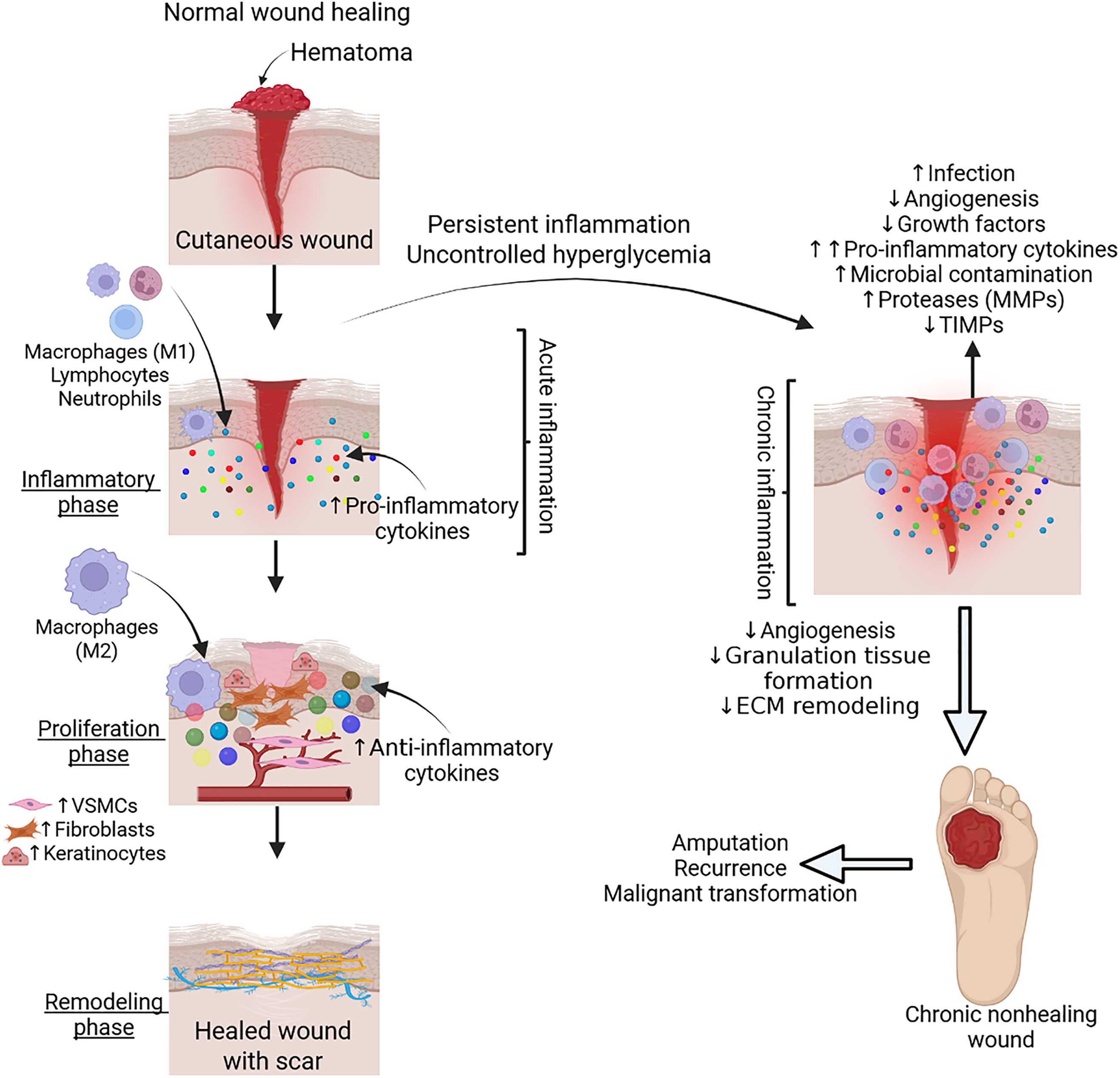

Delayed wound healing has also been linked to microvascular dysfunction [40]. The role of phenotypic change of fibroblasts, chronic inflammation, imbalance between pro-and anti-angiogenic factors, interaction between immune cells and cells contributing wound healing, such as endothelial cells, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts, and non-coding RNAs in DFU pathogenesis and nonhealing has also been discussed [41–45]. Typical wound healing is characterized by the progression of 3 stages: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. However, in chronic wounds, such as DFUs, the process is halted in the initial inflammatory state [46] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Normal physiological wound healing and pathophysiology of nonhealing chronic diabetic wound. Acute inflammation with infiltration of immune cells secreting cytokines plays a critical role in wound healing. However, uncontrolled hyperglycemia and persistent inflammation contribute to increased infection, microbial contamination, decreased growth factors, angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation, and altered extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, leading to a chronic nonhealing diabetic wound. VSMCs-vascular smooth muscle cells, MMPs- matrix metalloproteinases, TIMPs- tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases. Figure created with BioRender.com

During chronic wound healing, there is an imbalance of regeneration and generation of the ECM. Specifically in diabetics, granulocytic dysfunction and improper release of growth factors result in a faulty microenvironment that perpetuates the degradation of the ECM. DFUs have been shown to have low levels of platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) and elevated levels of MMPs [4]. This is relevant because proteins like PDGF and tumor necrosis factors (TNF) α and β, typically increase the work rate of mitosis and ECM production, stimulating wound healing. On the other hand, elevated levels of MMPs, such as MMP-9, lead to poor wound healing, wound chronicity, and a prolonged inflammatory state [47] (Fig. 1).

PDGF plays an important role in wound healing and inadequate amounts result in an array of deleterious effects leading to wound chronicity. For example, the PDGF receptor, PDGFR-β, is capable of activating the Akt/mTORC1 signaling pathway promoting expression of type I collagen. However, in DFUs decreased levels of PDGF result in diminished downstream effects from PDGFR. This leads to decreased production of collagen I, a critical component in dermal ECM [48]. PDGF is also involved in the recruitment of phagocytes to the wound, meaning deficiencies are associated with decreased macrophage recruitment and increased risk of bacterial contamination. PDGF was also found to aid in the reparations of diabetic ulcer damage by increasing fibroblasts and capillaries in diabetic mouse models [49,50]. As a result, deficiencies in PDGF are associated with impaired reparations.

Increased levels of bacterial endotoxins, ECM fragments, and cellular detritus at the site of DFUs result in granulocyte homing and secretion of cytokines and growth factors, such as TNFα and IL-1β, which can also lead to sustained chronic inflammation [51,52]. Unnoticed, recurring tissue trauma also impedes the process of wound healing [53] (Fig. 1).

Understanding the clinical progression of DFUs is critical, particularly given their prevalence and serious health consequences. DFUs affect approximately 15% of patients with DM and are the leading cause of diabetes-related hospitalizations. They are often associated with poor prognosis, preceding 80% of lower extremity amputations in diabetic patients, and correlating with increased risk of death [54]. Additionally, DFUs have been linked to malignant transformations resulting in cancerous ulcers [4].

DFU severity has been classified by various systems that base their scoring criteria on wound characteristics such as size, depth, ischemia, and infection. Though there is no universal grading scale, the Wagner system has been commonly used and shown to be one of the better classification systems for DFUs [3]. The Wagner system divides DFUs pathological progression into 6 gradings: Grade 0, a normal or at-risk foot; Grade 1, a superficial ulcer; Grade 2, a deep ulcer extending to tendon, capsule, or bone; Grade 3, a deep ulcer with abscess, osteomyelitis or joint sepsis; Grade 4, localized gangrene; and Grade 5, full-foot gangrene. A Grade 3 wound, or the development of DFUs, marks a pivotal point in the spectrum of diabetic foot disease and calls for more urgent and aggressive treatment and management. Grade 3 ulcers can be categorized by the type of foot they develop on, delineating DFUs by the complications and comorbidities they occur with [55]. In neuropathic feet, ulcers are associated with neglected callus and high plantar pressure and are typically located on the plantar surface of the foot and toes. In contrast, neuroischaemic foot ulcers are associated with trauma or improper shoes and typically develop on the apices of the toes or back of the heel [56].

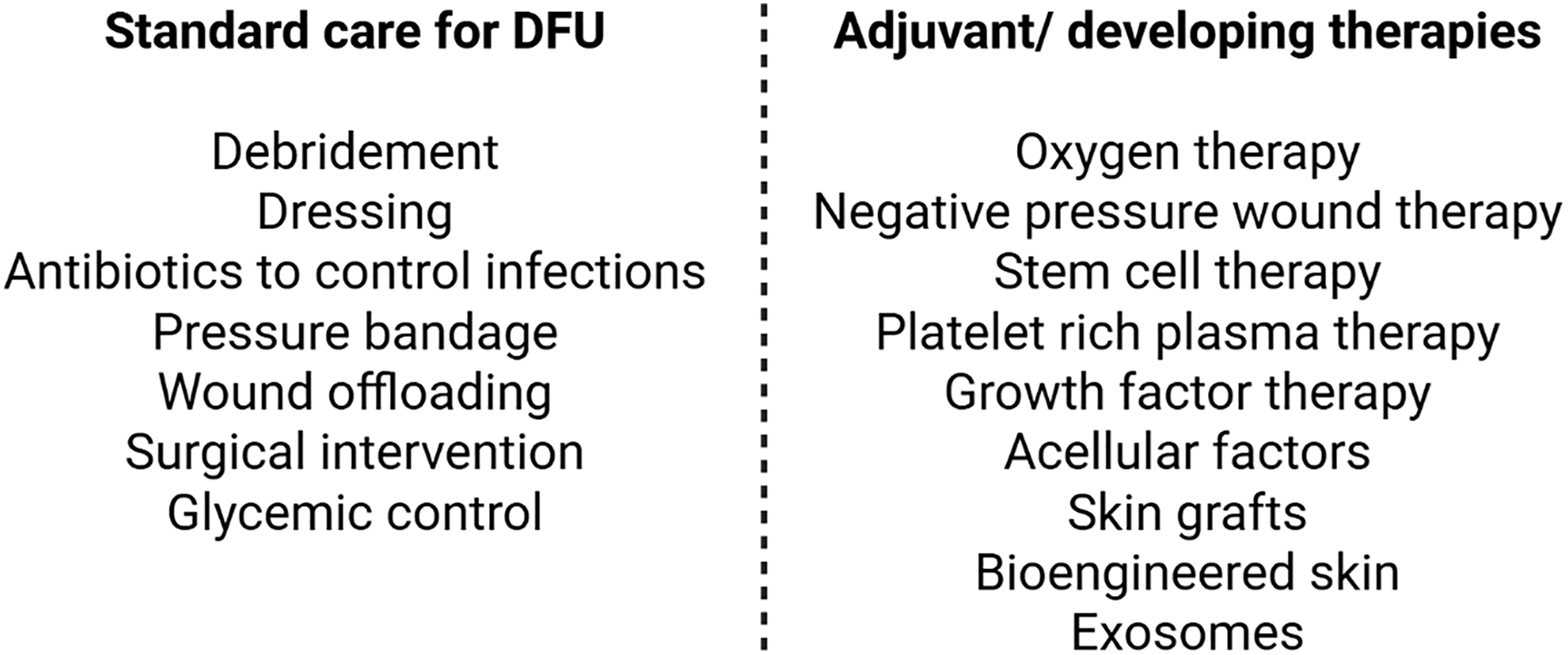

DFU care involves standardized procedures of debridement, dressing, wound off-loading, vascular assessment, infection control, and glycemic control (Fig. 2). Each of these components plays a unique role in promoting wound healing. For instance, debridement removes the necrotic tissue and aids in re-epithelialization and infection control, while appropriate dressings help maintain a moist environment and help manage exudate. Additionally, wound off-loading plays a crucial role in reducing plantar pressure and shear stress, both of which are essential to promote healing and prevent DFU recurrence [57]. Vascular status must also be evaluated, as it helps identify comorbidities such as PAD, which are associated with delayed healing, increased risk of amputation, and higher mortality [58]. Prompt recognition and treatment of active infections are critical, as reducing bacterial burden and inflammation is vital for optimal health outcomes [59]. Moreover, maintaining glycemic control has been consistently linked to improved wound healing and it is widely recommended to limit the adverse effects of infections [60,61]. Effective DFU treatment typically requires a multidisciplinary team, which depending on the severity, may include a surgeon, podiatrist, diabetes specialist, physical therapist, and wound care nurse. Adjuvant therapies have also been introduced to complement these core interventions. Some of these agents include the use of oxygen therapies, negative pressure wound therapy, acellular bioproducts, human growth factors, platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, exosomes, skin grafts, and bioengineered skin [57,62–64] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Current, adjuvant, and developing therapeutics for diabetic foot ulcers (DFU). Figure created with BioRender.com

4 Increased Skin Cancer Risk in Patients with Diabetic Foot Disease

DM and cancer are two of the most impactful and relevant major public health concerns, drawing increased interest in their potential interconnection. Diabetic foot disease (DFD), a complication of diabetes, stands out for its potential for subsequent comorbidities, such as malignancies. Specifically, foot ulcers, a hallmark of DFD, may be an indicator of malignancy considering the increased risk of skin cancer development in individuals with DM [14,65].

A recent retrospective analysis analyzed 700 patients and calculated the prevalence of different cancers between diabetic foot syndrome (DFS) patients, non-DFS patients and non-diabetic patients. They discovered the cancer prevalence in the DFS+ cohort was significantly higher than DFS- (p = 0.008) and the controls (p = 0.031). Skin cancer was the most common malignancy in the DFS+ group consisting of 26.1% [66]. Another study found that the risk of cancer was doubled in patients with DFD when compared to diabetic patients without DFD. Additionally, 15.87% of the new cancers observed throughout this study were categorized as either SCC or other cutaneous malignancies [67]. Interestingly, the incidence of skin cancer in diabetic individuals is higher in patients above 60 years, with males being more likely to develop both non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and melanoma [68].

Although malignant transformation of DFUs is rare, it poses a significant threat to patient well-being and quality of life. Current data on transformation rate remains limited, though a 2025 case report examining chronic leg ulcer transformations into SCC reported a 1.7% carcinogenesis rate [69]. This data highlights a key area for future investigation, specifically examining DFU transformation rates and outcomes.

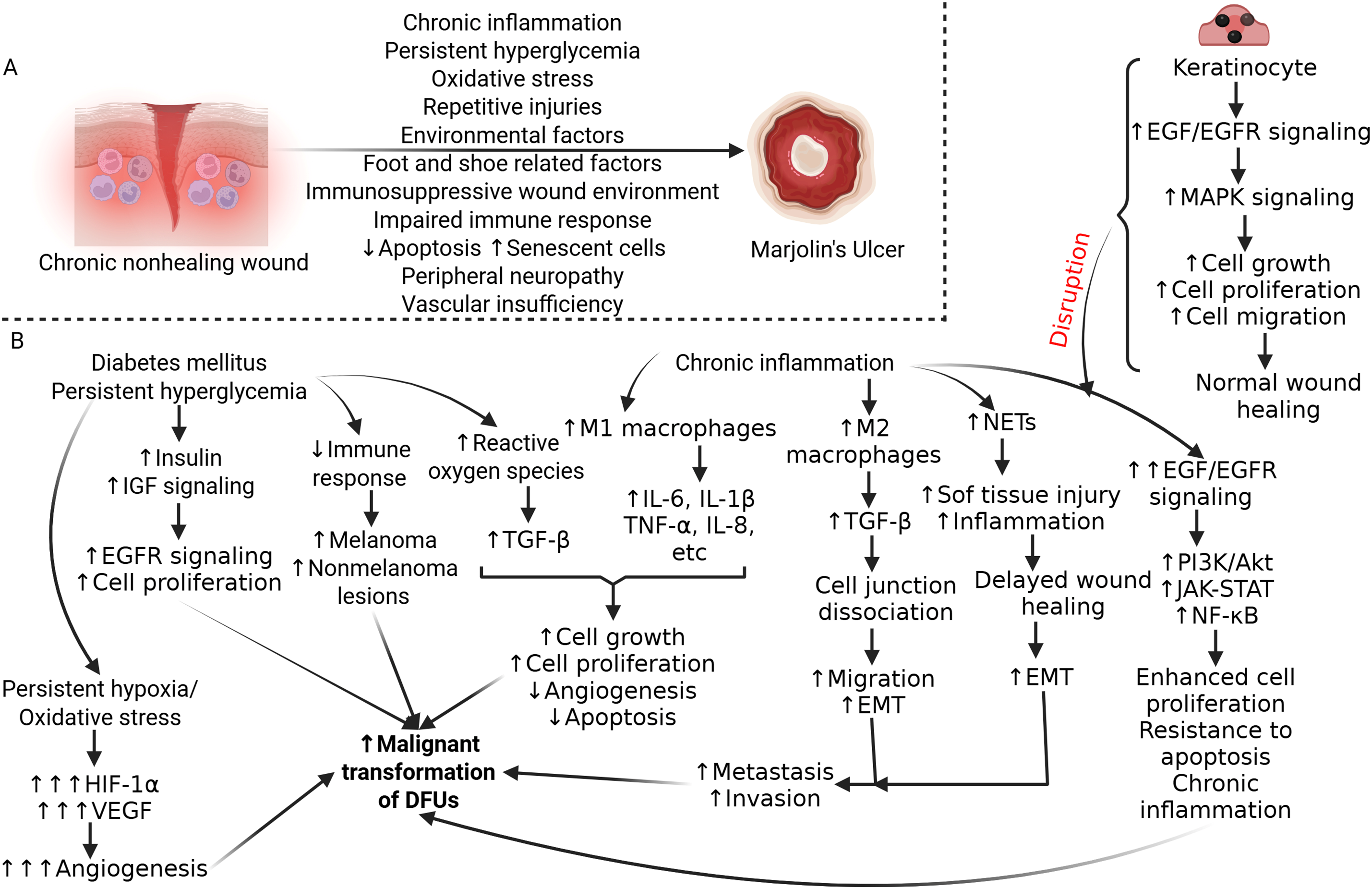

With the increasing interconnection of cancer and diabetes, it is important to understand the risk factors and mechanisms involved in their relationship. Factors including hyperglycemia, low-grade chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and environmental influences have been associated with both skin cancer and DM (Fig. 3A). Diabetes and its related complications have also been shown to impact the appropriate management of cutaneous malignancies [65].

Figure 3: Molecular mechanism and signaling cascade involved in transformation of diabetic foot ulcer to malignancy. (A) Molecular mechanisms involved in malignant transformation of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Chronic inflammation, persistent hyperglycemia, hypoxic microenvironment, decreased immune response, immunosuppression, repetitive injury, and environmental factors play a critical role in the malignant transformation of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). (B) The presence of persistent hyperglycemia increased reactive oxygen species, chronic inflammation, and signaling involved and activated in these pathologies will contribute to malignant transformation of DFU. These signaling involves various cytokines, growth factors, growth factor receptors, and immune cells affecting angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling, cell proliferation and survival, and metastasis of cancer cells. IGF- insulin-like growth factor, EGFR- epidermal growth factor receptor, HIF-1α- hypoxia-induced factor 1 alpha, VEGF- vascular endothelial growth factor, TGFβ- transforming growth factor beta, IL- interleukin, TNFα- tumor necrosis factor-alpha, EMT- epithelial-mesenchymal transition, NETs- neutrophil extracellular traps, MAPK- mitogen-activated protein kinase, PI3K- phosphoinositide 3-kinase, JAK-STAT- Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription, NF-κB- nuclear factor kappa beta. Figure created with BioRender.com

An important risk factor is poor glycemic control. Abnormal glucose homeostasis has been linked to increased tumor progression [70,71]. Hyperglycemia can promote malignant transformations both directly and indirectly by inducing diabetes related oxidative stress and DNA damage that may facilitate malignant transformation [71,72]. Hyperglycemia directly favors proliferation, induces mutations, and amplifies invasion and migration in tumor cells. On the other hand, the indirect effect is mediated through organs that produce growth factors or inflammatory cytokines, promoting a malignant environment [65]. Diabetes and hyperglycemia can also be associated with a state of oxidative stress resulting in consequential DNA damage and potentially leading to the transformation of oncogenes and the development of cancers [73,74]. Additionally, increased insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling in diabetic patients has been shown to upregulate cell proliferation and carcinogenic epidermal growth factor receptors, ultimately increasing mitogenic activity and promoting malignant transformation [75] (Fig. 3B).

Persistent, uncontrolled diabetes also weakens immune function, increasing the risk for non-melanoma skin cancer and melanoma development [76] (Fig. 3B). Diabetes patients have secondary immunodeficiencies due to their bodies’ disrupted immune response. Diabetes-related neuropathy increases the risk of natural barrier damage, while cellular effects from hyperglycemia & insulin deficiency lead to suppression of cytokine production, defects in phagocytosis, and dysfunction of immune cells [76–78].

Emerging evidence supports a possible link between DFD and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC). Recent studies have established DM, and subsequent pathological changes, as a risk factor for several malignancies, with worse prognoses commonly observed in diabetic populations [79]. cSCC, in particular, has been linked to sites of chronic inflammation, repeated injury, and impaired immune surveillance, all of which are factors commonly present in patients with DFD [79,80]. Chronicity of this disease state in the diabetic foot can promote subsequent pathologic changes.

For example, in advanced stages of DFUs, soft tissue infections may spread to the bone, resulting in diabetic foot osteomyelitis (DFO) [81]. During DFO, tissue and bones are eroded forming sinus tracts that allow for infected material to drain from the bone to the skin. This can further promote epithelial irritation resulting in SCC as a secondary complication [82] (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, chronic osteomyelitis, is one of the most critical risk factors associated with malignant transformation, particularly into SCC [83]. A 2023 retrospective study found 30% of DFUs progressed to DFO over a 6 year period, averaging an annual incidence of approximately 5% [84]. Chronic osteomyelitis has been associated with a latency period of 20–50 years before transformation, which overlaps with the 30–35 year latency period seen in Marjolin ulcers, a specific type of malignant ulcer developing from chronic wounds [85,86].

Beyond the increased risk of skin cancer, diabetic foot complications themselves carry a mortality risk that rivals or even exceeds that of several common cancers. The five-year mortality rate following of minor and major lower extremity amputations were 52% an 69%, respectively [9]. Despite this, DFD often lacks the same clinical urgency or public health recognition. This stark overlap in outcomes supports the growing perspective that chronic, non-healing diabetic foot ulcers deserve the same level of early intervention, surveillance, and aggressive management typically reserved for malignancies.

5 Marjolin’s Ulcers and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

To better understand the mechanisms involved in the malignant transformations of DFUs, we must first understand what malignant transformation is and its history in chronic wounds. Malignant transformation of chronic wounds refers to the process by which non-cancerous tissues, such as DFUs, evolve into cancerous lesions, most commonly cSCC. The general mechanism involves chronic wounds creating a hostile environment characterized by elevated proinflammatory cytokines, ROS, proteases, and senescent cells [87] (Fig. 3A). While the exact mechanisms of carcinogenesis in these inflammatory environments are still being researched, in general, the longer the inflammation persists, the higher the risk of cancer development [88,89].

A common pathology associated with the malignant transformation of chronic ulcers is Marjolin’s ulcer (MU). MU is a rare, aggressive skin cancer known to develop in skin areas of previous damage or chronic inflammation. Historically, MUs were associated with SCC, developing specifically from burn scars, as noted by Jean-Nicolas Marjolin in the 19th century [4]. However, the modern-day classification of MUs has broadened to include all neoplasms arising from chronic wounds, regardless of their origin [90]. Marjolin’s ulcer, a malignant transformation of chronic wounds, is strongly associated with SCC. While Marjolin’s ulcers can develop in various chronic wound settings, the most common type of malignancy associated with them is SCC. This malignant transformation can occur in a variety of chronic wounds, including those associated with burns, osteomyelitis, venous ulcers, and DFUs [13,90]. This means that when a DFU undergoes malignant transformation and becomes SCC, it would be classified as a type of Marjolin’s ulcer under the modern definition (Fig. 3A). Importantly, patients with impaired immune systems, such as those with DM, have an increased risk of malignant transformation in their wounds, explaining why they may have an increased risk of developing a MU [91]. It is also notable that lower extremities are the most common site of incidence for Marjolin’s ulcers, and SCC is the most common malignancy within the ulcer [92]. Dorr et. al investigated clinical transformations of DFUs into MUs and reported an annual incidence of 0.6% [4]. Though these transformations are not frequent, they can lead to the development of aggressive skin cancers, and with the increasing incidence of DM and its subsequent complications, we must understand the pathophysiology involved.

One way to do this is by emphasizing recognition of SCC and the DFU risk factors that may make development more likely. SCC is the second most common skin cancer and the most frequent carcinoma associated with scars and chronic wounds. SCC is defined as a malignant tumor of keratinocytes, located in the epidermis, and characterized by invasive growth and frequent metastasis to adjacent lymph nodes. SCC occurring in chronic wounds has more aggressive attributes, and it was found that upon initial diagnosis of malignant ulceration, 32% of patients were already experiencing some form of metastasis [4].

Past case studies investigating the malignant transformation of diabetic foot ulcers into SCC identified that initial signs of carcinogenesis may be the appearance of a small scaly bump or plaque, progressing to a hard, protruding callus-like lesion [79,93]. Upon initial recognition of the neoplasm, proper staging and grading based on the SCC’s size, depth, and metastases are necessary to appropriately address the pathology. Grading of the tumor measures the percentage of differentiated cells in a sample. G1 represents >75% differentiated cells, G2 25%–75%, and G3 < 25% differentiated cells [4]. It has been noted that the majority of Marjolin’s ulcers present with well-differentiated SCC [94].

The risk factors associated with the development of SCC from DFUs can be complex and multifaceted. As previously mentioned, chronic osteomyelitis (OM) incurs a risk of SCC development [95,96]. This is relevant because osteomyelitis is a common complication of DFUs, meaning clinicians should also consider potential comorbidities such as OM when they are assessing the chance of carcinogenesis in DFUs. Studies have also shown that women were affected by the MUs twice as frequently as men [13]. Other risk factors include DM-associated peripheral neuropathy, which is associated with an absence of pain recognition, resulting in loss of protective sensation [4]. This may result in further irritation as continuous pressure on the ulcerative site further delays healing and encourages inflammation, increasing the risk of carcinogenesis [4] (Fig. 3A).

6 Underlying Molecular Mechanisms of Malignant Transformation of DFUs

6.1 Chronic Inflammation and Cytokine Dysregulation

One of the primary drivers of carcinogenesis in DFUs is the persistent state of inflammation, characterized by the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. In DFUs, secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β from M1 macrophages is upregulated [4]. In addition, DM is strongly associated with a chronic inflammatory state and is known to contribute to the release of ROS, IL-1, IL-6, and tumor growth factor beta (TGF-β). Together, these factors, along with TNFα, have been indicated in the promotion of some cancers’ development by inducing cellular growth, proliferation, angiogenesis, and inhibition of cellular apoptosis (Fig. 3B).

M2 macrophages, at the site of DFUs, also secrete TGF-β, which plays a complex role in wound healing. While TGF-β is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that typically contributes to tissue regeneration and fibrosis resolution, its persistent activation in chronic wounds may also lead to abnormal tissue remodeling and has been implicated in pro-tumorigenic signaling in other epithelial contexts [52,97]. For example, epidermal overexpression of TGF-β1 has been shown to cause excess inflammation [97]. TGF-β exposure has also been linked to the dissociation of keratinocyte cell-cell junctions, typically promoting migration necessary for wound healing. However, these same mechanisms may also induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process implicated in cellular invasion and metastasis [98] (Fig. 3B). In a 2024 study, researchers analyzed human samples of DFUs and found elevated levels of TGF-β1 and TGF-β1R. TGF-β1 was also described as a cytokine that plays a role in cancer and fibrosis, and was proposed to be critical in DFU development [99].

Chronic wound sites also home granulocytes, such as neutrophils, fighting infections in the wound. Neutrophils in diabetic ulcers produce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which further lead to increased tissue damage, increased inflammation, and poor healing of DFUs [100,101] (Fig. 3B). In cancer biology, NETs have been associated with altering the environment to be favorable for the settlement and growth of cancer cells, making it more favorable for tumor development. NETs can interfere with the immune system’s ability to recognize and fight cancer cells, creating a tumor-friendly environment. NETs can increase metastasis by increasing the vascular permeability and invasion by increasing EMT [102–104]. A recent study investigated the role of NETs in promoting peritoneal metastasis in a diabetic host. Neutrophils were isolated from the bone marrow and peritoneal cavity of C57BL/JhamSlc-ob/ob (T2D model) and wild-type mice and stimulated to analyze NET formation [105]. However, this trial has not yet been validated in clinical trials, and the complex interplay between NETs and DM in promoting malignant transformation is still not completely understood. Overall, DFUs have many mechanisms promoting a pro-inflammatory microenvironment, which are a key driver in the development of cancer in chronic wounds [106,107].

6.2 Imbalance of Growth Factors and Proteases

The chronic wound environment of DFUs disrupts the normal balance of growth factors and proteases essential for tissue repair. This is partially the result of ulcer sites exhibiting impaired granulocyte functions, leading to disruptions in the expression of growth factors necessary for proper wound healing. For example, levels of PDGF and TIMPs decrease, while MMP levels increase [4]. Persistent high levels of MMPs lead to wound chronicity and prolonged inflammation in DFUs that can be further exacerbated by bacterial contamination and tissue damage. Specifically, increased MMP-9 and MMP-9: TIMP-1 ratios have been found in DFU wound fluids and are associated with slower wound healing rates [47]. The sustained elevation of endopeptidase MMPs in DFUs may contribute to a feed-forward inflammatory loop, in which excessive MMP-9 production by infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages further exacerbates ECM degradation and growth factor dysregulation. This contributes to the pro-inflammatory environment and consequently elevates the risk of malignant transformation [108–110] (Fig. 3B).

A subsequent in vitro study analyzing reactions of biopsied human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) from diabetic patients and cultured them in normal glucose (8 mM) and high glucose (30 mM) media. Then, skin tissue was analyzed via Masson’s trichrome stain and western blot and RNA-Seq was performed to analyze MMP-2/TIMP-2 and MMP-9/TMIP-1 ratios. Interestingly, the conditions with increased glucose, simulating diabetes, had disordered collagen and increased rations of MMP-2/TIMP-2 and MMP-9/TIMP-1, indicating the role of MMP-2 and MMP-9s as collagenases that regulate the synthesis and decomposition of collagen. These proteins specifically regulate type I collagen, the primary collagen type in dermal extracellular membrane, leading to significant alterations in the stability of skin collagen [111]. Other MMPs are capable of cleaving a variety of ECM components, including elastin, laminin, fibronectin, proteoglycans and cell adhesion proteins [112]. This is significant not only due to ECM disruption at the site of ulceration but also because MMPs can form complexes with TIMPs and CD44 to negatively influence cell-cell adhesion and cell-ECM adhesion which has been shown to promote invasion of cancer cells in some cases [113,114].

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) plays an imperative role in wound healing but can also lead to potential malignancies if dysregulated. During the process of wound healing, keratinocytes, the primary cells of the epidermis, play a crucial role in re-epithelialization. Keratinocytes migrate to the wound edges and begin proliferating to slowly cover the affected site, upregulating the expression of EGF to promote healing. Puccinelli et al. performed in vitro experiments on immortalized human keratinocytes to deduce EGF/EGFR reactions. Typically, EGF binds EGFR, a transmembrane receptor, and induces activation of the mitogen-associated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, resulting in cell proliferation and cellular migration [115]. However, in chronic wounds, EGFR signaling is often disrupted due to cytoplasmic retention or degradation by wound-associated proteases, further hindering proper healing [52]. Additionally, EGF itself can promote MMP expression and when exposed to unfavorable environments, trigger uncontrolled protease activity, contributing to pathological outcomes such as SCC metastasis [116,117] (Fig. 3B). Abnormalities in the gene or amount of EGF can also result in hyperproliferative and neoplastic epithelium as EGF plays a role in cellular proliferation, epidermal thickness, keratinocyte differentiation and migration and cell survival and apoptosis resistance [118,119].

EGFR has also been implicated in multiple other pathways involving malignant progression. Specifically in SCC development, EGFR is frequently overexpressed or dysregulated, suggesting a shift in signaling behavior during malignant progression. While the exact mechanism of EGFR in DFU malignant transformation is unknown, the transmembrane protein has been shown to activate oncogenic pathways including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K-Akt), Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT), and nuclear factor—kappa beta (NF-kB) [120,121]. These pathways contribute to enhanced cell survival, resistance to apoptosis, chronic inflammation, and tumor progression (Fig. 3B). The PI3K-AKT pathways can be activated by ligands interacting with receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), such as EGFR, VEGF, and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) [122]. These interactions lead to the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 then recruits oncogenic signaling proteins, such as Akt. Akt activation results in the phosphorylation of numerous substrates, such as mTOR, that promote tumor cell survival, proliferation and metabolism through downstream effectors [123]. This pathway activates many growth factors, such as VEGF, which can cause a positive feedback loop within this system [124]. The JAK/STAT pathway works similarly, as JAK activation leads to STAT phosphorylation, resulting in downstream effects mediating cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis [125]. This pathway also results in overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, and TNF-α, which can create oncogenic conditions and inhibit apoptosis [126–129].

DFUs are hypoxic environments, which is a key trigger for angiogenesis, another mechanism involved in the transformation to malignancy [130]. Reduced partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) at the DFU stimulates the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α), stimulating the production of the pro-angiogenic factor, VEGF. Typically, VEGF and HIF-1α transcripts are only expressed briefly at the site of a wound and return to baseline levels after re-epithelialization. However, in chronic wounds, these factors remain elevated, creating a sustained tumor-permissive environment [52]. This abnormal angiogenic signaling parallels vascular remodeling observed in tumors and may facilitate malignant transformation in chronic DFUs (Fig. 3B). However, it should be noted that, as of now, the role of enhanced angiogenesis, which plays a critical role in tumor progression, in the malignant transformation of chronic ulcers has not been established.

Sustained HIF-1α and VEGF activity in chronic wounds not only perpetuates angiogenesis but may also induce tumor-like vascular abnormalities that contribute to malignancy risk. DFU are hypoxic environments that can lead to hypoxia-driven HIF-1α stabilization and the activation of genes promoting endothelial proliferation, migration, and permeability, leading to leaky, disorganized vasculature [131,132]. The dysfunctional vessels limit tissue perfusion and facilitate tumor cell escape and dissemination [133]. Additionally, prolonged VEGF signaling under hypoxic conditions has been linked to immunosuppressive effects, including inhibitors of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) mediated tumor killing and enhancement of regulatory T cell (Treg) activity [134,135]. These findings suggest that the chronic hypoxic-angiogenic environment of DFUs could promote not only abnormal vascular remodeling but also localized immune tolerance, further fostering a microenvironment more susceptible to malignant transformation.

Taken together, it is likely that a cumulation of chronic inflammation, abnormal protein expression, EMT, and sustained angiogenesis all contribute to the unique microenvironment mandating the malignant transformation of DFUs.

Recent investigations have also highlighted the role of miR193b-3p as a tumor suppressor of SCC development in DFUs. In a 2022 study, Marjanovic et al. used human organotypic (ex vivo), murine in vivo wound models, and diabetic murine in vivo wounds to investigate the role of miR193b-3p in DFU carcinogenesis. They discovered that miR193b-3p is a master gene expression regulator that plays an imperative role in tumor suppression as it is believed to contribute to the low incidence of malignancies in DFUs [136]. Subsequently, they hypothesized mutations or suppression of miR193b-3p may play a key role in the pathogenesis of cancerous ulcers derived from DFUs. miR193b-3p is a dominant inhibitor of epithelialization and decreases cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis through inhibition of keratinocyte motility. It is thought that miR193b-3p inhibits migration by disrupting stress fiber formation by decreasing the activity of GTPase RhoA, a molecule involved in tumor progression and metastasis [136,137]. DFUs have been found to express high levels of miR193b-3p, contributing to decreased keratinocyte motility and slower healing, while also explaining the low incidence of malignant transformations at these wound sites [136]. Interestingly, diabetes can lead to changes in DNA methylation, which could be a potential mechanism for silencing the miR193b-3p transcript [138,139]. Though more research is required to understand the exact mechanism, epigenetic modifications provide a potential explanation for the inactivation of the gene expression regulator.

While these findings highlight a tumor-suppressive role of miR193b-3p in wound repair, they were derived from preclinical models. The use of human organotypic skin (ex vivo), non-diabetic and diabetic murine in vivo models provide valuable insight, but clinical studies confirming miR193b-3p’s relevance in human DFUs are currently lacking. Additionally, limitations in translating these results to patients should be acknowledged, as ex vivo and murine models may not fully represent the complexity of human chronic wounds.

Environmental factors can contribute to the progression of DFUs toward malignancy, often called Marjolin’s ulcer. The presence of chronic inflammation and persistent tissue damage in chronic nonhealing wounds contributes to malignant transformation. Foot and shoe-related factors such as poorly fitted shoes or inadequate footwear or foot deformities (claw toes or high arches), peripheral neuropathy which causes a loss of protective sensation, and vasculopathy/vascular insufficiency can lead to undetected injuries and ulcer formation. These factors contribute to repetitive damage to the tissue causing chronic irritation and may promote malignant growth. Poor foot hygiene can also contribute to infection and further damage. Increased foot temperature, excessive temperature changes, and humidity further compromise tissue integrity and increase the risk of infection and ulcer progression. Metabolic derangements impairing tissue viability and wound healing increase the risk of ulcer progression and malignant transformation. In summary, chronic inflammation, pressure, repetitive trauma, and other environmental factors can push DFUs toward malignancy [4,140–143].

6.6 Theories of Cancer Ulcer Development

While there has been some research on malignant transformations from chronic wounds, much of the proposed literature is theory. In reality, the exact molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of cancerous ulcers are likely a combination of many propositions. For example, the chronic irritation theory aligns with many of the mechanisms explored earlier. Other explanations include the toxins theory which proposes the chronic release of toxins from adjacent damaged tissues stimulating cellular mutations. The inheritance theory also proposes a hereditary predisposition in which certain individuals may have inherited genetics such as the human leukocyte antigen DL4 (HLA DL4) gene, an abnormal p53 gene, or mutations in the Fas receptor which have been correlated with Marjolin’s ulcers [95].

7 Diagnostic Challenges and Recommendations

7.1 Differentiating Chronic DFUs and Malignant Skin Ulcers

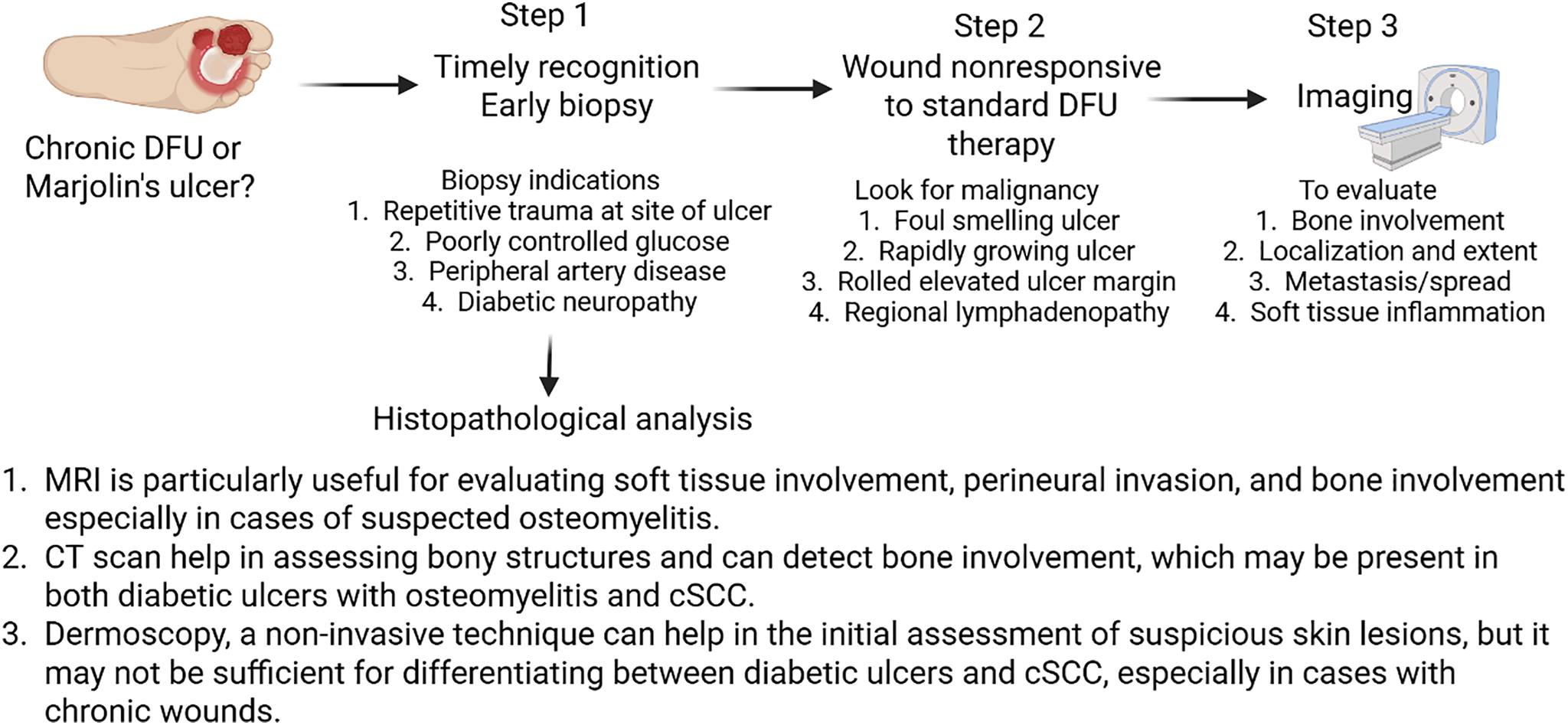

Though malignant transformations of DFUs are rare, initial diagnosis is an ongoing challenge, due to the clinical similarities between chronic ulcers and neoplastic lesions. The resulting malignancy often mimics typical non-healing DFU, making it difficult to distinguish without histopathological evaluation. Features such as persistent ulceration, abnormal granulation, or bleeding may be attributed to the DFU, resulting in delayed cancer diagnosis [4,91]. Given this overlap, timely recognition and early biopsy are critical for effective treatment. This section outlines key diagnostic challenges and current recommendations to improve early detection of malignancy in patients with DFUs.

Lyundup et al. [14] conducted a systematic review analyzing the misdiagnoses of different malignancies as DFUs and found an increased risk (odds ratio (OR): 2.452; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.132–5.312; p-value = 0.019) of misdiagnosis in elderly patients (age ≥ 65). Interestingly, they found an array of different cancers were misdiagnosed, including melanoma (68% of the cases), Kaposi’s sarcoma (14%), SCC (11%), mantle cell lymphoma, and diffuse B-cell lymphoma (both by 4%) [14]. Sondermann et al. also conducted a retrospective observational study where nearly one-third of patients with melanoma foot lesions were incorrectly diagnosed at their first medical visit, with DFU as one of the most frequent initial misdiagnoses [144]. This is an especially urgent issue because, at the same time, it is well-known that misdiagnoses and diagnostic delays of malignancies can result in worse prognosis and disease outcomes [145].

Due to the potential for malignant mimicry of DFUs, early biopsies of non-healing suspected DFUs are imperative. Biopsies for histological diagnoses are recommended when chronic ulcers have been open continuously without signs of healing for 3 months or when DFUs have been unresponsive to treatment for 6 weeks [146]. Clinicians should consider biopsies, particularly in patients with high-risk profiles such as trauma to the site, poorly controlled glucose, PAD, and diabetic neuropathy [147] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Flow chart for clinical assessment and early detection of diabetic foot ulcer changing to squamous cell carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan, diabetic foot ulcer (DFU), cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC). Created using BioRender.com

Wounds that show little response to standard DFU therapies such as off-loading or negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) should also be further investigated for potential malignancies. Visually, malignant ulcers are often ulcerative, foul-smelling, and rapidly growing with rolled elevated margins and regional lymphadenopathy [91,148] (Fig. 4). Reports note the latency period for malignant transformation can range from 4 weeks to 75 years, with immunocompromised patients at higher risk [91,149]. A recent case report of an elderly man with melanoma misdiagnosed as multiple diabetic foot ulcers proposed that assessing glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels may aid in differentiating cancerous ulcers from diabetic ones, though further research is needed to validate this approach [150]. While HbA1c testing may help identify non-diabetic etiologies in patients with atypical ulcers, it is unlikely to distinguish malignant transformation within a chronic diabetic foot ulcer. This is not an isolated case of misdiagnosis, which further underscores the importance of early, accurate screening and the need for greater awareness of both malignant transformations and cancerous lesions that mimic diabetic ulcers [14].

Biopsy remains the cornerstone of diagnosis for distinguishing cancerous ulcers and DFUs. When assessing malignant transformations of chronic DFUs to MUs, clinicians will often be dealing with SCC, making it imperative that they are familiar with the histopathology associated with the malignancy [151] (Fig. 4). First, the standardized procedure when performing a biopsy on a MU involves excising tissue specimens from various locations of the ulcer, including the margins and deeper portions to minimize false negatives [95]. Histologically, malignant transformations to MUs are typically characterized by well-differentiated SCC [94]. These lesions may lack solar elastosis, typically found in conventional SCC, and instead be accompanied by an ulcer or scar. Other histological characteristics may include an atrophic lesion, with an ulcerative center and dense scarring associated with invading strands of tumor cells spanning the epidermis or ulcer edge [152]. The notion of an early biopsy for the diagnosis of malignant transformation is supported by the report of Park et al. [153] that untreated ulcers may undergo a malignant transformation. The study reported 54-year-old women with malignant transformation of a diabetic ulcer, which remained untreated. The study concluded that an early biopsy for DFUs failing to heal with acute treatment can enable an earlier diagnosis [153]. This may help in treatment without amputation, a better quality of life, and decreased chance of malignant transformation of DFUs. Following diagnoses, imaging is recommended to assess the progression of malignancy.

Imaging plays a vital role in the diagnostic workup of suspected malignant transformation in DFUs. While histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis, imaging can help assess localization, bone involvement, and metastasis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is particularly useful in evaluating soft tissue inflammation and identifying bone destruction, making it the preferred method for assessing suspected osteomyelitis or tumor infiltration. Computed tomography (CT) provides detailed anatomical information and can reveal tumor infiltration into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Additionally, ultrasound may be used to assess regional lymph node involvement and metastasis [4] (Fig. 4).

Imaging may not only help in early detection but also in treatment planning the appropriate surgical or other treatment strategies for both diabetic ulcers and cSCC, and monitoring the response to treatment and detecting any recurrence or progression of disease.

8 Therapeutic Considerations and Future Perspectives

Surgical management is the primary treatment for MUs and SCC arising from DFUs. The standard procedure emphasizes complete excision, with 2 cm margins of normal appearing tissue, to reduce the risk of recurrence and metastasis. In cases where proper margins cannot be safely achieved, amputation may be necessary [4]. The standardized procedure is Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), which involves excision and histologic examination of thin layers of skin from the site of the lesion. This process has favorable outcomes, with a reported 5-year cure rate of 90%, compared to 76% with traditional surgical excision. In advanced malignancies where lymph nodes are involved, lymphadenectomies are often warranted [151]. When primary closure of surgical wounds is not feasible, split-thickness skin grafts or soft tissue flaps are recommended to prevent the recurrence of malignancy [4].

For patients who are not surgical candidates, treatments include topical and systemic chemotherapeutics, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. Topical agents such as 5-fluorouracil have been involved in MU treatment, while methotrexate and platinum-based therapies can be used as systemic chemotherapeutics [151]. Adjuvant radiotherapy also offers a non-surgical treatment for regional lymph node metastasis, high-grade lesions (Grade 3+), or lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter [154]. Radiation can also be considered preoperatively to shrink tumors or postoperatively to reduce recurrence rates [155].

In cases of advanced disease, where bones or joints are involved, amputation becomes a treatment consideration. MRIs offer a useful tool to determine the extent of bone involvement. Ogawa et. al recommended amputation for Grade 2 or 3 lesions, reserving wide excision for smaller, less invasive (Grade 1) lesions [156]. Prognosis worsens with increased lesion depth and metastasis. Studies have shown that amputations associated with DFUs have significant mortality rates. Within 5 years, minor and major amputations correlate to 46.2% and 56.5% mortality rates, respectively [157]. This highlights the importance of early, aggressive, and appropriate management of malignant transformations in DFUs.

There is a growing interest in the use of targeted therapies and immunotherapy to treat SCC, with early findings suggesting potential applications for MUs. Though data is limited, anti-PD-1 therapies suggest a potential treatment associated with disease control and improved survival [158]. Specifically, cemiplimab may offer clinical benefits to DFU-derived SCCs, as it was recently approved for treatment in advanced and metastatic cSCC [159]. Other potential treatments have been tied to miR193b-3p. Marjanovic et al. propose miR193b-3p levels as a potential biomarker for predicted malignant transformation in DFUs. Their research also indicated that increased expression of the miR193b-3p had a tumor-protective role in DFUs, which could make it a potential therapeutic target to help prevent or reverse malignant transformations [136].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and telemedicine are also novel options that can aid in preventative care and screening. As previously mentioned, early detection is an essential step in preventative care of DFU malignant transformation. Telemedicine-assisted foot examinations have been an up-and-coming service that has already been shown to be as effective as in-person exams at detecting early lesions, while also saving time and cost for patients [160,161]. Other recent technologies include DFUCare, a deep learning platform, for DFU detection, analysis, and monitoring. This platform is capable of conducing comparative macroscopic wound analyses addressing wound size, tissue color, and texture to predict infections and ischemia [162]. A 2025 systematic review analyzing AI approaches to DFU care concluded that AI-based techniques aid clinicians in establishing higher diagnostic accuracy, while increasing levels of personalized care, even in resource-limited settings. Predictive models can already forecast outcomes such as likelihood of DFU healing or risk of amputation, so it seems plausible that within the next few years they will also be able to predict carcinogenesis risk [163]. At this point, the primary barrier is the lack of research and general awareness about malignant DFUs, rather than limitations in technology. AI models can also be used to assist pathologists in detecting abnormalities in histopathology. Whole slide scanners can digitize histopathology processes to help ease work load and assist in diagnoses in regards to segmentation, quantification, and classification [164,165]. These novel AI and technological advancements are being increasingly recommended as integrated components of diagnostic teams in healthcare, in hopes that they will increase diagnostic accuracy and enhance patient care [166].

Overall, prevention and early detection remain critical for improving prognosis. Early biopsy of non-healing ulcers and enhanced screening methods can facilitate the detection of malignant transformation before it develops into invasive cancer. Advancing treatment research will require a multidisciplinary approach, merging surgical skills with imaging technologies and molecular tools alongside new therapeutic strategies to enhance patient outcomes.

The malignant transformation of DFUs, while relatively rare, is a serious and often underdiagnosed complication of DFD. DFUs continue to pose a serious threat to healthcare systems due to their high rates of recurrence, amputation, and mortality. Underlying malignancies, particularly cSCC, are associated with significantly worse prognoses and cannot be overlooked. Chronic inflammation, dysregulation of cytokine signaling, faulty immune surveillance, and impaired wound healing all play a role in creating a tumor-permissive environment for the diabetic foot. Some malignancies, such as Marjolin’s ulcers, are classic instances of such transformation, particularly in the context of chronic or recurrent ulcers. Delayed suspicion and misdiagnosis may result in poor survival and prognosis. Therefore, early suspicion, timely biopsies, and integration of imaging and histopathology should be employed for accurate and effective treatment. A deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving the carcinogenesis of DFUs may enable earlier detection and more targeted treatment, ultimately improving patients’ prognosis. Identification of key regulators and more accurate biomarkers may help in early diagnosis and designing targeted therapies to treat these malignancies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sophia Strukel and Vikrant Rai; draft manuscript preparation: Sophia Strukel; review and editing: Vikrant Rai; visualization: Vikrant Rai; supervision: Vikrant Rai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BCC | Basal cell carcinoma |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| cSCC | Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma |

| DFD | Diabetic foot disease |

| DFS | Diabetic foot syndrome |

| DFU | Diabetic foot ulcer |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| FGFR | Fibroblast growth factor receptor |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha |

| IL | Interleukin |

| JAK-STAT | Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MMS | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MU | Marjolin’s ulcer |

| NETs | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa beta |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NPWT | Negative pressure wound therapy |

| PAD | Peripheral arterial disease |

| PDGF | Platelet derived growth factor |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

1. Lotti V, de Siena G, Bacci S. Effects of Exendin-4 on diabetic wounds: direct action on proliferative phase of wound healing. BIOCELL. 2024;48(12):1751–9. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.057904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Akkus G, Sert M. Diabetic foot ulcers: a devastating complication of diabetes mellitus continues non-stop in spite of new medical treatment modalities. World J Diabetes. 2022;13(12):1106–21. doi:10.4239/wjd.v13.i12.1106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wang X, Yuan CX, Xu B, Yu Z. Diabetic foot ulcers: classification, risk factors and management. World J Diabetes. 2022;13(12):1049–65. doi:10.4239/wjd.v13.i12.1049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dorr S, Lucke-Paulig L, Vollmer C, Lobmann R. Malignant transformation in diabetic foot ulcers-case reports and review of the literature. Geriatrics. 2019;4(4):62. doi:10.3390/geriatrics4040062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ogbeide OA, Okeleke SI, Okorie JC, Mandong J, Ajiboye A, Olawale OO, et al. Evolving trends in the management of diabetic foot ulcers: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16(7):e65095. doi:10.7759/cureus.65095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Brown SJ, Handsaker JC, Bowling FL, Boulton AJ, Reeves ND. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy compromises balance during daily activities. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):1116–22. doi:10.2337/dc14-1982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJ, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(1):209–21. doi:10.2337/dci22-0043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dalla Paola L, Faglia E. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcer: an overview strategies for clinical approach. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2(4):431–47. doi:10.2174/1573399810602040431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lauwers P, Wouters K, Vanoverloop J, Avalosse H, Hendriks JMH, Nobels F, et al. The impact of diabetes on mortality rates after lower extremity amputation. Diabet Med. 2024;41(1):e15152. doi:10.1111/dme.15152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lin C, Tian J, Zhang Z, Zheng C, Liu J. Risk factors associated with the recurrence of diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2025;20(2):e0318216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0318216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Luo Y, Li CY, Wang YQ, Xiang SM, Zhao C. Diabetic ulcer with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. World J Clin Oncol. 2024;15(12):1514–9. doi:10.5306/wjco.v15.i12.1514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Huang BL, Tan M, Li ML, Teng YY, Zhou M, Wang M. Case report: type 2 diabetes mellitus with plantar malignant melanoma: report of two cases. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1089578. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1089578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Marietta M, Crane JS. Marjolin ulcer. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar]

14. Lyundup AV, Balyasin MV, Maksimova NV, Kovina MV, Krasheninnikov ME, Dyuzheva TG, et al. Misdiagnosis of diabetic foot ulcer in patients with undiagnosed skin malignancies. Int Wound J. 2022;19(4):871–87. doi:10.1111/iwj.13688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Mitra S, Panda S, Sikka K, Mallick S, Thakar A. Multimodality management of locoregionally extensive Marjolin ulcer: a case report and review of the literature. Wounds. 2024;36(5):166–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. de Gennaro G, Baronti W, Sambuco L, Trapani E, Rizzo L. Non-healing foot ulcers in diabetes mellitus and role of biopsy: a report of two cases. J Wound Manag. 2024;25(3):103–6. doi:10.35279/jowm2024.25.03.02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lauri C, Noriega-Alvarez E, Chakravartty RM, Gheysens O, Glaudemans A, Slart R, et al. Diagnostic imaging of the diabetic foot: an EANM evidence-based guidance. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2024;51(8):2229–46. doi:10.1007/s00259-024-06693-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes Atlas. 9th ed. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Raja JM, Maturana MA, Kayali S, Khouzam A, Efeovbokhan N. Diabetic foot ulcer: a comprehensive review of pathophysiology and management modalities. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(8):1684–93. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tesfaye S. Recent advances in the management of diabetic distal symmetrical polyneuropathy. J Diabetes Investig. 2011;2(1):33–42. doi:10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00083.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Feldman EL, Callaghan BC, Pop-Busui R, Zochodne DW, Wright DE, Bennett DL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):42. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0092-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, Stensel V, Forsberg RC, Davignon DR, Smith DG. A prospective study of risk factors for diabetic foot ulcer. Seattle Diabet Foot Study—Diabetes Care. 1999;22(7):1036–42. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.7.1036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Martin JK, Davis BL. Diabetic foot considerations related to plantar pressures and shear. Foot Ankle Clin. 2023;28(1):13–25. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2022.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Boulton AJ. The pathway to foot ulceration in diabetes. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97(5):775–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Fitridge R, Chuter V, Mills J, Hinchliffe R, Azuma N, Behrendt CA, et al. The intersocietal IWGDF, ESVS, SVS guidelines on peripheral artery disease in people with diabetes mellitus and a foot ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2023;78(5):1101–31. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2023.07.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, Cissell MA, Eberhardt MS, Meigs JB, et al, editors. Diabetes in America. 3rd ed. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US); 2018. [Google Scholar]

27. Sinai M. Peripheral arterial disease: an overlooked cause of poor wound healing [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://health.mountsinai.org/blog/peripheral-arterial-disease-pad-an-overlooked-cause-of-poor-wound-healing. [Google Scholar]

28. Elghazaly H, Howard T, Sanjay S, Mohamed OG, Sounderajah V, Mehar Z, et al. Evaluating the prognostic performance of bedside tests used for peripheral arterial disease diagnosis in the prediction of diabetic foot ulcer healing. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(2):NCT04058626. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2022-003110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Patel M, Patel V, Shah U, Patel A. Molecular pathology and therapeutics of the diabetic foot ulcer; comprehensive reviews. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2024;130(5):591–8. doi:10.1080/13813455.2023.2219863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Rai V, Moellmer R, Agrawal DK. The role of CXCL8 in chronic nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers and phenotypic changes in fibroblasts: a molecular perspective. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(2):1565–72. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07144-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fisman EZ, Adler Y, Tenenbaum A. Biomarkers in cardiovascular diabetology: interleukins and matrixins. Adv Cardiol. 2008;45:44–64. doi:10.1159/000115187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hatanaka E, Monteagudo PT, Marrocos MS, Campa A. Neutrophils and monocytes as potentially important sources of proinflammatory cytokines in diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146(3):443–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03229.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Schilrreff P, Alexiev U. Chronic inflammation in non-healing skin wounds and promising natural bioactive compounds treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4928. doi:10.3390/ijms23094928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Nyanhongo GS, Sygmund C, Ludwig R, Prasetyo EN, Guebitz GM. An antioxidant regenerating system for continuous quenching of free radicals in chronic wounds. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;83(3):396–404. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.10.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Twarda-Clapa A, Olczak A, Bialkowska AM, Koziolkiewicz M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEsformation, chemistry, classification, receptors, and diseases related to AGEs. Cells. 2022;11(8):1312. doi:10.3390/cells11081312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Malik P, Chaudhry N, Mittal R, Mukherjee TK. Role of receptor for advanced glycation end products in the complication and progression of various types of cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850(9):1898–904. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.05.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Malone-Povolny MJ, Maloney SE, Schoenfisch MH. Nitric Oxide therapy for diabetic wound healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(12):e1801210. doi:10.1002/adhm.201801210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bian H, Wang J, Shan X, Li X, Wang Y, Sun R, et al. A portable on-demand therapeutic nitric oxide generation apparatus: new strategy for diabetic foot ulcers. Chem Eng J. 2024;480(6122):148088. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.148088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Soneja A, Drews M, Malinski T. Role of nitric oxide, nitroxidative and oxidative stress in wound healing. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

40. Burgess JL, Wyant WA, Abdo Abujamra B, Kirsner RS, Jozic I. Diabetic wound-healing science. Medicina. 2021;57(10):1072. doi:10.3390/medicina57101072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Littig JPB, Moellmer R, Estes AM, Agrawal DK, Rai V. Increased population of CD40+ fibroblasts is associated with impaired wound healing and chronic inflammation in diabetic foot Ulcers. J Clin Med. 2022;11(21):6335. doi:10.3390/jcm11216335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Rai V. Transcriptomics revealed differentially expressed transcription factors and microRNAs in human diabetic foot ulcers. Proteomes. 2024;12(4):32. doi:10.3390/proteomes12040032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Rai V, Le H, Agrawal DK. Novel mediators regulating angiogenesis in diabetic foot ulcer healing. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2023;101(10):488–501. doi:10.1139/cjpp-2023-0193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Rai V, Moellmer R, Agrawal DK. Role of fibroblast plasticity and heterogeneity in modulating angiogenesis and healing in the diabetic foot ulcer. Mol Biol Rep. 2023;50(2):1913–29. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-08107-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Smith J, Rai V. Novel factors regulating proliferation, migration, and differentiation of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells during wound healing. Biomedicines. 2024;12(9):1939. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12091939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Dinh T, Elder S, Veves A. Delayed wound healing in diabetes: considering future treatments. Diabetes Manag. 2011;1(5):509. [Google Scholar]

47. Liu Y, Min D, Bolton T, Nube V, Twigg SM, Yue DK, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 predicts poor wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):117–9. doi:10.2337/dc08-0763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Cao Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Leng P. Research progress on the role of PDGF/PDGFR in type 2 diabetes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164(14):114983. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Li H, Fu X, Zhang L, Huang Q, Wu Z, Sun T. Research of PDGF-BB gel on the wound healing of diabetic rats and its pharmacodynamics. J Surg Res. 2008;145(1):41–8. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Greenhalgh DG, Sprugel KH, Murray MJ, Ross R. PDGF and FGF stimulate wound healing in the genetically diabetic mouse. Am J Pathol. 1990;136(6):1235–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

51. Mast BA, Schultz GS. Interactions of cytokines, growth factors, and proteases in acute and chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 1996;4(4):411–20. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475x.1996.40404.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Sundaram GM, Quah S, Sampath P. Cancer: the dark side of wound healing. FEBS J. 2018;285(24):4516–34. doi:10.1111/febs.14586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Lobmann R. Diabetic foot syndrome. Internist. 2011;52(5):539–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

54. Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Review of diabetic foot Ulcers-Reply. JAMA. 2023;330(17):1695–6. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.17194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Meloni M, Izzo V, Giurato L, Lázaro-Martínez JL, Uccioli L. Prevalence, clinical aspects and outcomes in a large cohort of persons with diabetic foot disease: comparison between neuropathic and Ischemic Ulcers. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1780. doi:10.3390/jcm9061780. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Edmonds M. Diabetic foot ulcers: practical treatment recommendations. Drugs. 2006;66(7):913–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

57. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411(1):153–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

58. Prompers L, Schaper N, Apelqvist J, Edmonds M, Jude E, Mauricio D, et al. Prediction of outcome in individuals with diabetic foot ulcers: focus on the differences between individuals with and without peripheral arterial disease. The EURODIALE study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(5):747–55. doi:10.1007/s00125-008-0940-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Abbas M, Uçkay I, Lipsky BA. In diabetic foot infections antibiotics are to treat infection, not to heal wounds. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(6):821–32. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1021780. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Braun L, Kim PJ, Margolis D, Peters EJ, Lavery LA, Wound Healing S. What’s new in the literature: an update of new research since the original WHS diabetic foot ulcer guidelines in 2006. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22(5):594–604. doi:10.1111/wrr.12220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Fernando ME, Seneviratne RM, Tan YM, Lazzarini PA, Sangla KS, Cunningham M, et al. Intensive versus conventional glycaemic control for treating diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(1):CD010764. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010764.pub2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Littig JPB, Moellmer R, Agrawal DK, Rai V. Future applications of exosomes delivering resolvins and cytokines in facilitating diabetic foot ulcer healing. World J Diabetes. 2023;14(1):35–47. doi:10.4239/wjd.v14.i1.35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Rai V, Moellmer R, Agrawal DK. Stem cells and angiogenesis: implications and limitations in enhancing chronic diabetic foot ulcer healing. Cells. 2022;11(15):2287. doi:10.3390/cells11152287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Smith J, Rai V. Platelet-Rich plasma in diabetic foot ulcer healing: contemplating the facts. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):12864. doi:10.3390/ijms252312864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Dobrica EC, Banciu ML, Kipkorir V, Khazeei Tabari MA, Cox MJ, Simhachalam Kutikuppala LV, et al. Diabetes and skin cancers: risk factors, molecular mechanisms and impact on prognosis. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(31):11214–25. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Goretti C, Prete A, Brocchi A, Iacopi E, Pieruzzi L, Piaggesi A. Higher prevalence of cancer in patients with diabetic foot syndrome. J Clin Med. 2024;13(5):1448. doi:10.3390/jcm13051448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Alkhami F, Borderie G, Foussard N, Larroumet A, Blanco L, Barbet-Massin MA, et al. More new cancers in type 2 diabetes with diabetic foot disease: a longitudinal observational study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2023;17(10):102859. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2023.102859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Juwita TA, Siregar IS. The analysis study of association of type 2 diabetes mellitus and skin cancer: a comprehensive systematic review. J Adv Res Med Health Sci. 2024;10(6):113–21. doi:10.61841/xdw7fm80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Rustamova T, Plate S. From chronic leg ulcer to squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Eur J Med Health Sci. 2025;7(2):32–4. doi:10.24018/ejmed.2025.7.2.2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Tang Q, Wu S, Zhao B, Li Z, Zhou Q, Yu Y, et al. Reprogramming of glucose metabolism: the hallmark of malignant transformation and target for advanced diagnostics and treatments. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;178:117257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]