Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Death Ligand Signaling Involving the COX/PKC/MLKL Axis Mediates Erythrocyte Death by HDAC/DNMT Inhibitor, Parthenolide, through ROS Generation and Calcium Mobilization

Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 12372, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Mohammad A. Alfhili. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellular Senescence in Health and Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2167-2180. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071827

Received 13 August 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Targeting epigenetic modifications in anticancer therapy is a promising approach to overcoming cancer cell chemoresistance. The histone deacetylase/DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, parthenolide (PTL), has antitumor activity, but contrasting findings exist on its effect in normal cells. This study aims to examine the non-genomic toxic mechanisms of PTL in human erythrocytes. Methods: Cell death as stimulated by 20–200 μM of PTL for 24 h at 37°C was assessed using fluorescence-assorted cell sorting and spectrophotometric assays. Canonical markers of cell death, including membrane scrambling, oxidative stress, and Ca2+ mobilization, were captured by annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, and Fluo4/AM labeling, respectively. Rescue experiments using a wide array of inhibitors were also conducted. Results: PTL stimulated significant membrane scrambling and blebbing, and showed potent hemolytic activity coupled with significant elevations in dichlorofluorescein and Fluo4 fluorescence. While hemolysis was ameliorated by glutathione, caffeine, acetylsalicylic acid, staurosporin, necrosulfonamide, guanosine, and Ca2+ deprivation, it was rather exacerbated by necrostatin-2, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) or Fas ligand (FasL) neutralization, and concurrent Ca2+ deprivation and membrane depolarization. In contrast, eryptosis was attenuated by N-acetyl-cysteine, TNFα, or FasL blockade, and simultaneous Ca2+ elimination and KCl enrichment; and augmented by necrostatin-2, necrosulfonamide, and adenosine triphosphate. Interestingly, loss of volume was only prevented by melatonin, acetylsalicylic acid, and N(gamma)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. Conclusion: PTL stimulates oxidative hemolysis and eryptosis through Ca2+ mobilization and death ligand signaling involving the cyclooxygenase/protein kinase C/mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase axis. This research highlights the non-genomic toxic mechanisms of PTL and presents potential pharmacological targets for mitigating its adverse off-target effects.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileParthenolide (PTL) is a germacrane sesquiterpene lactone isolated from the plants Tanacetum parthenium and Tanacetum vulgare. It exerts epigenetic modifications by inhibiting histone deacetylase 1 [1] and DNA methyltransferase [2] enzyme activities, and demonstrates anti-inflammatory, redox-modulating, antihypertensive, neuroprotective, and hepatoprotective properties [3–5]. The anticancer properties of PTL have been reported in colorectal [6,7], cholangiocarcinoma [8], multiple myeloma [9], glioblastoma [10], pancreatic [11,12], bladder [13], Burkitt lymphoma [14], liver [15–17], lung [18–20], ovarian [21], breast [22], oral [23], cervical [24], gastric [25], lymphoma [26], melanoma [27], thyroid [28], lymphoid [29] and gallbladder [30] cells. Several intracellular targets related to apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress have been identified in the aformentioned studies including caspases, Fas ligand (FasL), death receptor 5 (DR5), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), cyclins, p53, p21, Bax, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xL), BH3 interacting-domain death agonist (Bid), Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death (Bim), survivin, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). However, PTL has also been known to inhibit apoptosis, primarily by acting as an antioxidant, as demonstrated in normal cells such as lens epithelial cells [31,32], osteoblasts [33], mouse myeloblasts [34], and intestinal epithelial cells [35] and in neuroblastoma cells [36].

In the circulation, red blood cells (RBCs) are continuously being exposed to numerous inflammatory mediators, toxins, and metabolites, and rely on their antioxidant defense mechanisms to counteract these challenges. When overwhelmed by mechanical, chemical, or biological stress, RBCs either remain intact but display biochemical signs of cell death or undergo accidental or programmed lysis. Intact but dead cells activate a unique pathway similar to apoptosis that occurs in nucleated cells known as eryptosis, which is thus far one of the two known programmed cell death pathways that exist in RBCs, in addition to necroptosis [37]. Previous studies have unequivocally shown that RBC death underlies the cytotoxicity of many anticancer drugs, which exacerbates chemotherapy-related anemia [38]. Specifically, hemolysis releases oxidative hemoglobin leading to anemia, hemoglobinuria, and acute kidney injury, whereas eryptosis depletes circulating RBCs and increases their adherence to endothelial cells, which contributes to vascular inflammation and thrombosis [39].

The main driver of eryptosis is Ca2+ influx through nonspecific cation channels. Accumulation of Ca2+ inside the cell influences scramblase activity, which perturbs the orientation of phospholipids on the plasma membrane in favor of phosphatidylserine (PS) translocation. Another effect of Ca2+ accumulation involves the activation of K+ channels, which is responsible for eryptotic loss of volume due to membrane hyperpolarization and KCl and water leakage. Additional mechanisms implicated in RBC death include calpain stimulation, which results in the appearance of membrane blebs and several other enzymes such as caspases, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), p38 MAPK, cyclooxygenase (COX), phospholipase A2, protein kinase C (PKC), receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), and mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL) [37]. Formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is also a major mechanism underlying eryptosis and hemolysis through cytoskeletal and membrane oxidation as well as Ca2+ accumulation [40].

PTL, being an electrophilic compound, generates ROS [3], and RBCs, being particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress, depend on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and reduced glutathione (GSH) to maintain homeostasis. PTL also modulates intracellular Ca2+ levels [6], which are central to RBC survival. Importantly, like many anticancer compounds, PTL may precipitate chemotherapy-related anemia by triggering RBC death. As such, erythrocytes serve as a cost-effective and sensitive cellular model of drug toxicity [41].

This research examines the potential cytotoxicity of PTL in human RBCs independent of genomic influence, which informs formulation strategies that aim to mitigate its nonspecific toxicity and minimize off-target adverse effects. The study specifically aims to test the hypothesis that PTL toxicity is nonspecific to cancer cells and may extend to normal cells through canonical death mechanisms without invoking epigenetic modifications.

All chemicals were procured from Solarbio (Beijing, China) unless otherwise noted. Ethical approval was obtained from King Saud University IRB Committee (E-23-7685). All participants provided informed consent in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. All experiments were designed and conducted in accordance with the latest recommendations of the Eryptosis Study Consortium [37]. Blood was drawn in EDTA from twelve healthy adults, seven males and five females, aged 24–39 years. Inclusion criteria were being healthy adults with normal complete blood count results and without acute or chronic conditions influencing RBC health. Exclusion criteria were being at the extremes of age and the diagnosis of conditions known to modulate RBC survival or function. A 40 mM stock solution of PTL (CAS #20554-84-1), equivalent to 10 mg/mL, was prepared and stored in aliquots at –80°C. Cells were isolated using Sorvall ST 8R benchtop centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 1500× g for 15 min, and suspensions of freshly drawn erythrocytes were incubated in Ringer buffers for 24 h at 37°C to be examined for cell death with and without 20–200 μM of PTL. This range corresponds to the anticancer concentrations previously reported for PTL in various cancer cells [5,42]. Contamination of cultures with Mycoplasma was ruled out using the Hoechst exclusion test [43], which showed no fluorescence.

Detection of OD405 was used to measure the hemolytic rate using a microplate reader (LMPR-A14, Labtron, Surrey, UK). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and aspartate transaminase (AST) activities were assayed using the BS240-pro analyzer (Mindray, Shenzhen, China) [44]. After treatment, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000× g for 1 min to collect the supernatants, which were immediately assayed for hemolysis, LDH, and AST.

Cytofluorimetry was utilized to study eryptosis using a Northern Lights flow cytometer (Cytek, Fremont, CA, USA), and all markers were detected in 10,000 events. Oxidative stress and Ca2+ levels were evaluated using 10 µM of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) and 5 µM of Fluo4/AM, respectively [45]. To prepare cells for examination, 50 µL of live cell suspensions were incubated in 150 µL of the staining solution for 30 min at 37°C, wrapped in foil. Samples were subsequently washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4) to remove excess unbound stain and then analyzed at Ex/Em of 480/520 nm for both dyes. PS externalization was identified using annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Briefly, 50 µL of live cells were incubated with a 1% working solution of annexin V-FITC for 10 min at room temperature away from light. FITC was then excited by the blue laser at 488 nm, and the emitted green light was captured at 520 nm. Since Fluo4/AM and annexin V-FITC require Ca2+ to bind to their respective targets, the staining solution for all three dyes consisted of PBS supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2. Cell size was simultaneously measured by the forward scatter signal.

Cellular architecture was visualized by scanning electron microscope (JSM-7610F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) [46]. In brief, cells were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde, stained with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a series of ethanol concentrations (30%–100%), and dried. Samples were then mounted, coated, and imaged.

Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with and without 160 μM of PTL in the presence and absence of several antioxidants, enzyme inhibitors, channel blockers, energy substrates, and antibodies. These included N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC; #SA5830; purity: >98%; 5 mM), reduced glutathione (GSH; #G8180; purity: >98%; 20 μM), melatonin (#M8600; purity: >99%; 50 μM), N(gamma)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; #IL0320; purity: >98%; 20 μM), acetylsalicylic acid (#IA0550; purity: >98%; 50 μM), staurosporine (#IS0470; purity: >98%; 1 μM), necrostatin-2 (#IN0360; purity: >98%; 100 μM), necrosulfonamide (#IN4150; purity: >98%; 0.5 μM), Z-VAD-FMK (#IZ0810; purity: >98%; 100 μM), SB203580 (#IS0460; purity: >98%; 100 μM), D4476 (#ID0550; purity: >98%; 20 μM), NSC23766 (#IN0720; purity: >98%; 100 μM), myriocin (#IM3130; purity: >98%; 10 μM), caffeine (#C0750; purity: >98%, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA; 0.5 mM), 2-[N-[2-(acetyloxymethoxy)-2-oxoethyl]-2-[2-[2-[bis[2-(acetyloxymethoxy)-2-oxoethyl]amino]phenoxy]ethoxy]anilino]acetic acid acetyloxymethyl ester (BAPTA-AM; #IB1370; purity: >95%; 10 μM), glucose, (#G8150, purity: >99.8%; 25 mM), guanosine (#SG9310, purity: >98%; 2 mM), adenine (#SA8710; purity: >98%; 2 mM), adenosine triphosphate (ATP; #A9130; purity: >95%; 0.5 mM), monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNFα; #K011377M; 1 μg/mL), and monocloncal antibody against FasL (anti-FasL; #K011376M; 1 μg/mL) [37].

Data are reported as mean + SEM and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s correction using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Prism Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

3.1 PTL Triggers Hemolysis and Eryptosis

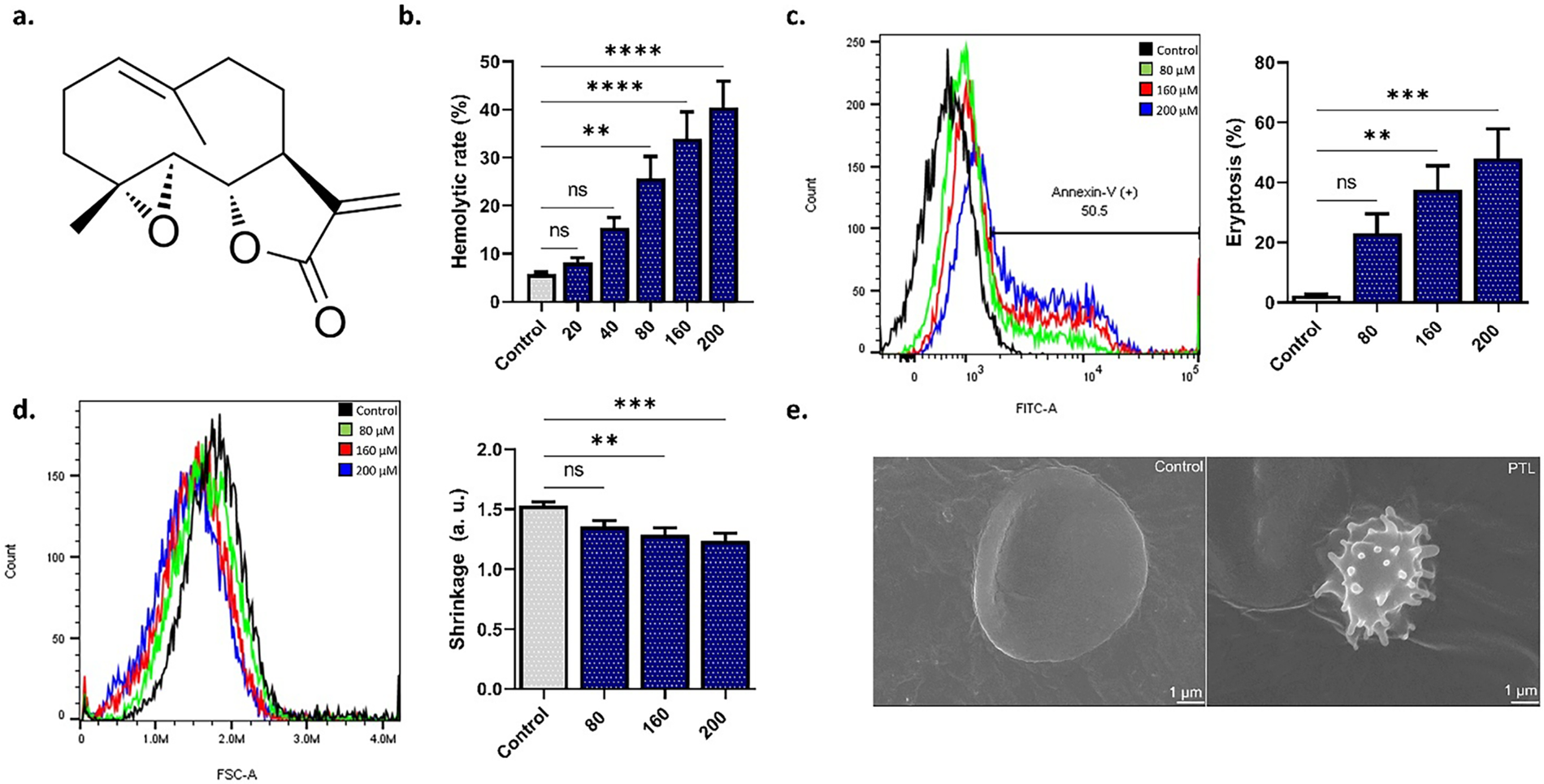

Fig. 1a depicts the molecular structure of PTL. To establish the type of cell death triggered by PTL, we assessed hemoglobin release and PS externalization as surrogate markers of hemolysis and eryptosis, respectively. As seen in Fig. 1b, treatment with PTL resulted in significant hemolysis (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001) at 80–200 μM. Concurrently, significant membrane scrambling (Fig. 1c) and loss of volume (Fig. 1d) were detected at 160 μM (p < 0.01) and 200 μM (p < 0.001). Furthermore, Fig. 1e confirms eryptosis induction as evidenced by shrinkage and membrane blebs.

Figure 1: Parthenolide (PTL) activates both hemolysis and eryptosis. (a) PTL structure. (b) Hemolytic rate as measured by hemoglobin release. (c) Eryptosis as measured by PS translocation. (d) Cell size as measured by forward scatter. (e) Electron microscopy images. Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test) is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

3.2 PTL Elicits Oxidative Stress

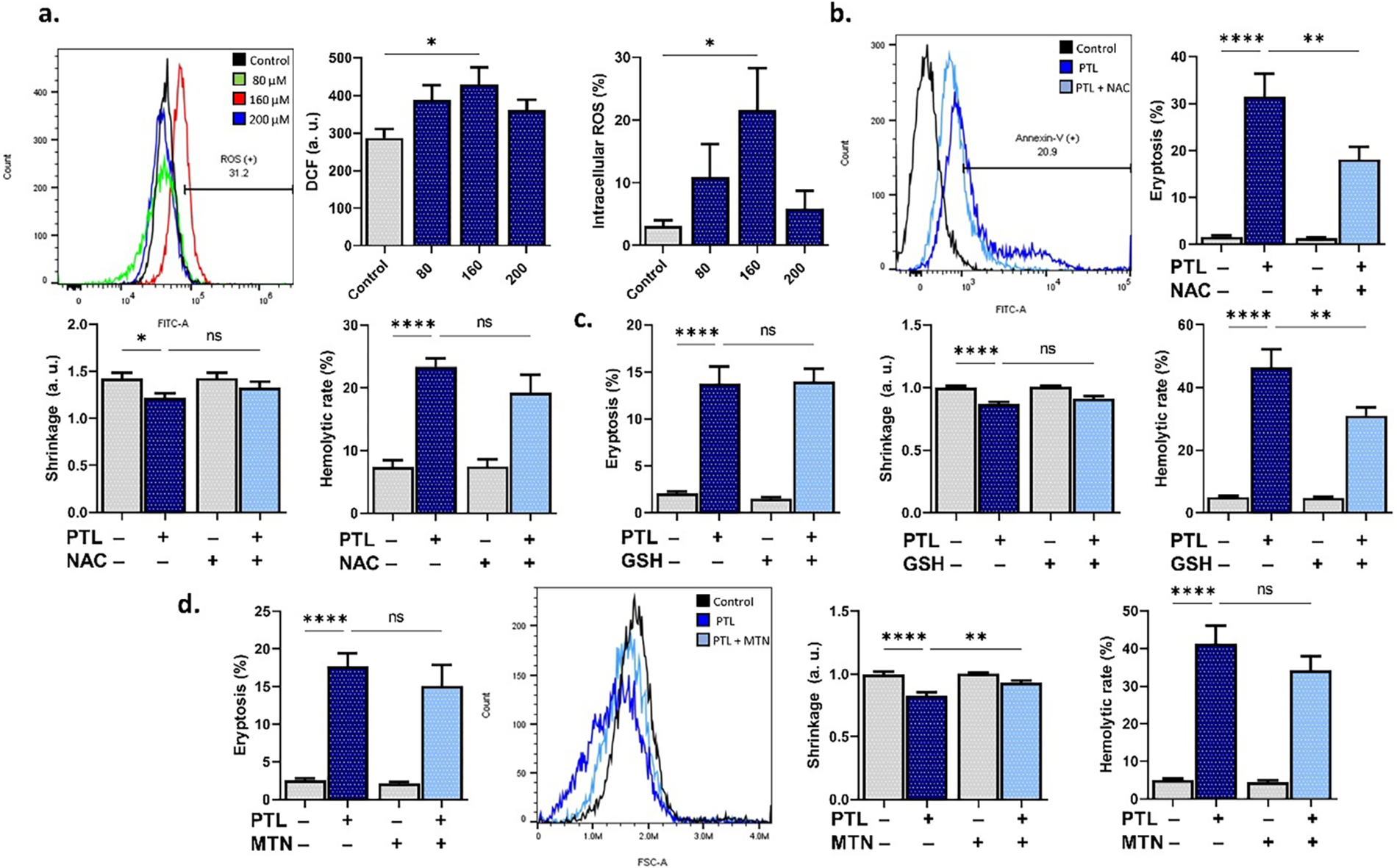

To examine the role of oxidative stress in PTL-induced RBC death, we measured intracellular ROS and the mitigating potential of antioxidants. Fig. 2a shows that PTL significantly elevates DCF fluorescence at 160 μM (p < 0.05). Notably, while NAC (Fig. 2b) did not prevent hemolysis, GSH (Fig. 2c) significantly mitigated the hemolytic activity of PTL. Melatonin (Fig. 2d) only abrogated the loss of volume (p < 0.01).

Figure 2: Parthenolide (PTL) increases oxidative stress. (a) Dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence (arbitrary units and percentages) as a measure of reactive oxygen species. (b) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC). (c) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without reduced glutathione (GSH). (d) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without melatonin (MTN). Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test) is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001

3.3 PTL Stimulates Ca2+ Mobilization

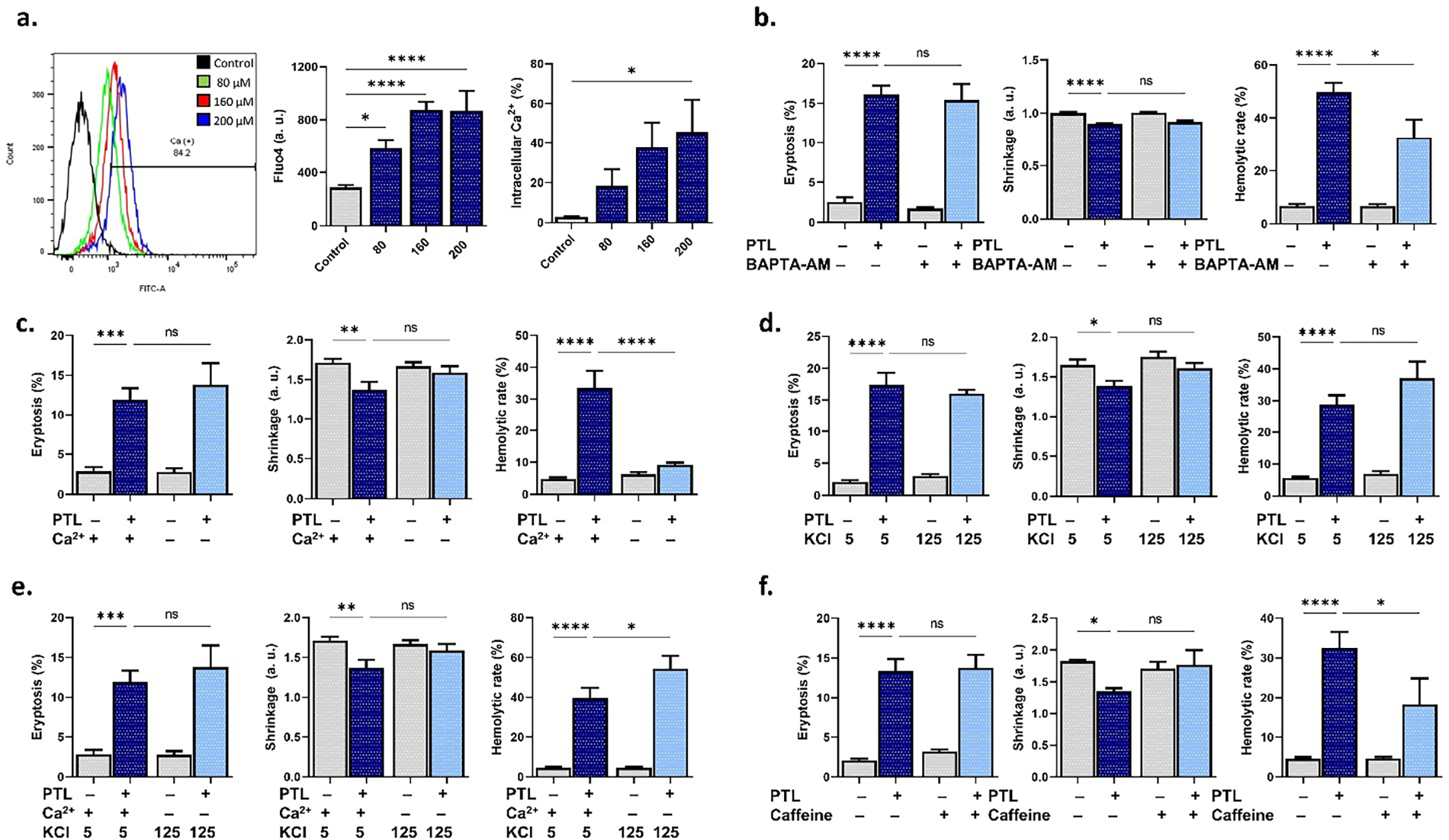

In addition, experiments were set up to modify the extracellular space Ca2+ and ion trafficking. Fig. 3a shows Fluo4 fluorescence and percentage of cells with increased Ca2+, which indicates that PTL indeed significantly increased intracellular Ca2+ levels at 80 μM (p < 0.05), 160 μM, and 200 μM (p < 0.0001). Additionally, the cell-permeable Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA-AM, significantly (p < 0.05) ameliorated hemolysis (Fig. 3b) as did (p < 0.0001) extracellular Ca2+ depletion (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, increasing extracellular KCl from 5 mM to 125 mM KCl to impede cellular KCl loss (Fig. 3d) was ineffective, but the combination of Ca2+ depletion and KCl enrichment (Fig. 3e) rather exacerbated PTL-induced hemolysis (p < 0.05). Caffeine (Fig. 3f), an inhibitor of Ca2+ entry in RBCs, was found to be anti-hemolytic (p < 0.05).

Figure 3: Effect of Ca2+ modulation on parthenolide cytotoxicity. (a) Fluo4 fluorescence (arbitrary units and percentages) as a measure of intracellular Ca2+. (b) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without 2-[N-[2-(acetyloxymethoxy)-2-oxoethyl]-2-[2-[2-[bis[2-(acetyloxymethoxy)-2-oxoethyl]amino]phenoxy]ethoxy]anilino]acetic acid acetyloxymethyl ester (BAPTA-AM). (c) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without extracellular Ca2+ deprivation. (d) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without membrane depolarization (KCl). (e) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without simultaneous extracellular Ca2+ deprivation and membrane depolarization (KCl). (f) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without caffeine. Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test) is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

3.4 PTL Activates COX/PKC/MLKL Signaling

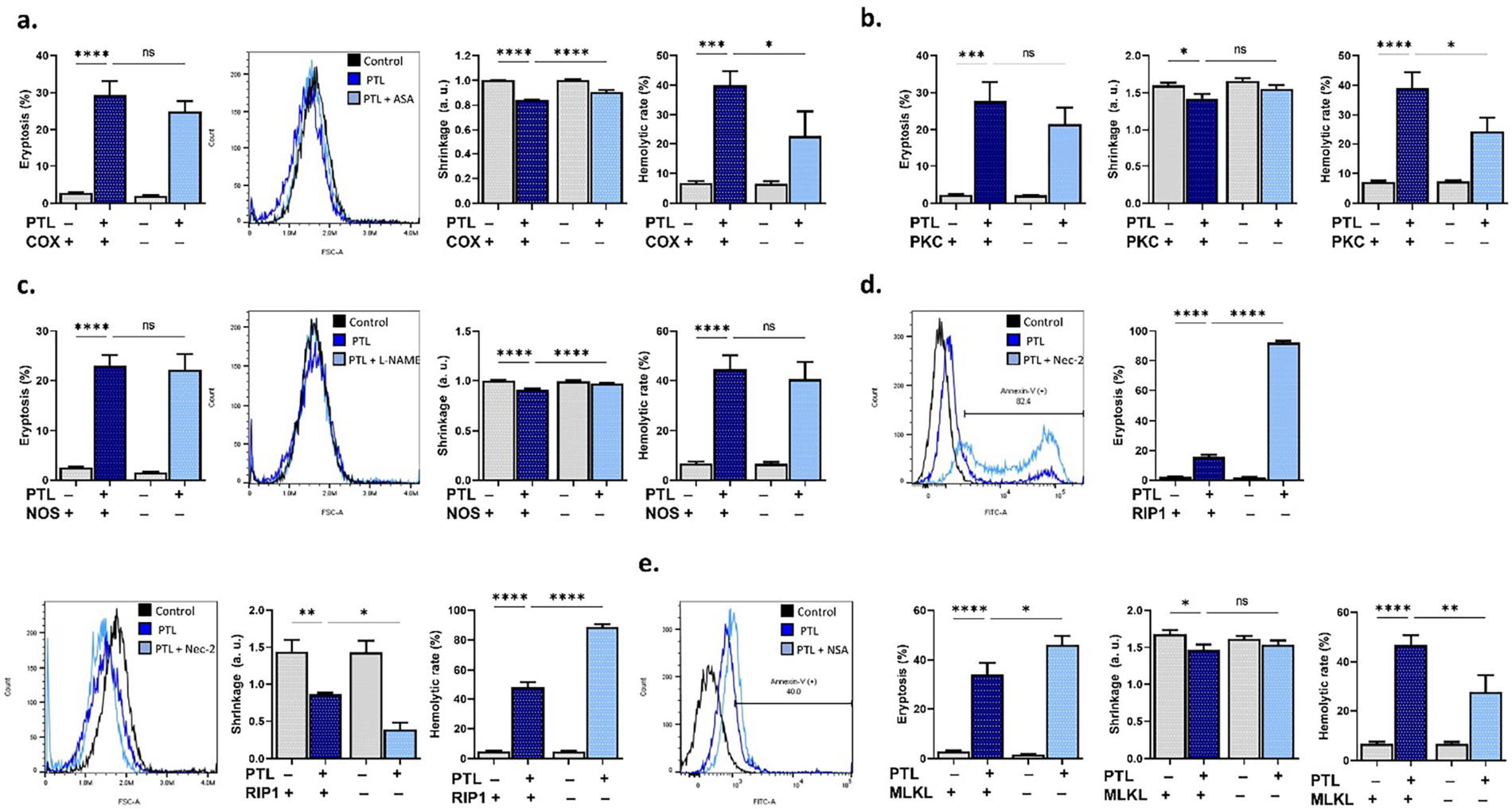

Next, we used small-molecule inhibitors to block key signaling enzymes, including COX, PKC, NOS, RIP1, and MLKL, and then observed the resulting toxic phenotype. Fig. 4a shows that acetylsalicylic acid (COX-inhibitor) significantly attenuated the loss of volume (p < 0.0001) and hemolysis (p < 0.05), whereas staurosporin (PKC-inhibitor) (Fig. 4b) only prevented the latter (p < 0.05). In Fig. 4c, cell shrinkage was the only toxic endpoint that was reversed by L-NAME (NOS inhibitor), similar to the effect of melatonin. Interestingly, the RIP1 inhibitor, necrostatin-2 (Fig. 4d), exacerbated membrane scrambling (p < 0.0001), shrinkage (p < 0.05), and hemolysis (p < 0.0001), while necrosulfonamide (Fig. 4e), a MLKL inhibitor, had contrasting effects by increasing scrambling (p < 0.05) and attenuating hemolysis (p < 0.01). Moreover, Z-VAD-FMK (caspase inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), D4476 (casein kinase 1α inhibitor), NSC23776 (Rac1 inhibitor), and myriocin (serine palmitoyltransferase inhibitor) did not influence PTL toxicity (supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 4: Pathways involved in parthenolide (PTL) cytotoxicity. (a) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition (acetylsalicylic acid). (b) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without protein kinase C (PKC) inhibition (staurosporin). (c) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibition (N(gamma)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester). (d) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) inhibition (necrostatin-2). (e) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL) inhibition (necrosulfonamide). Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test) is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

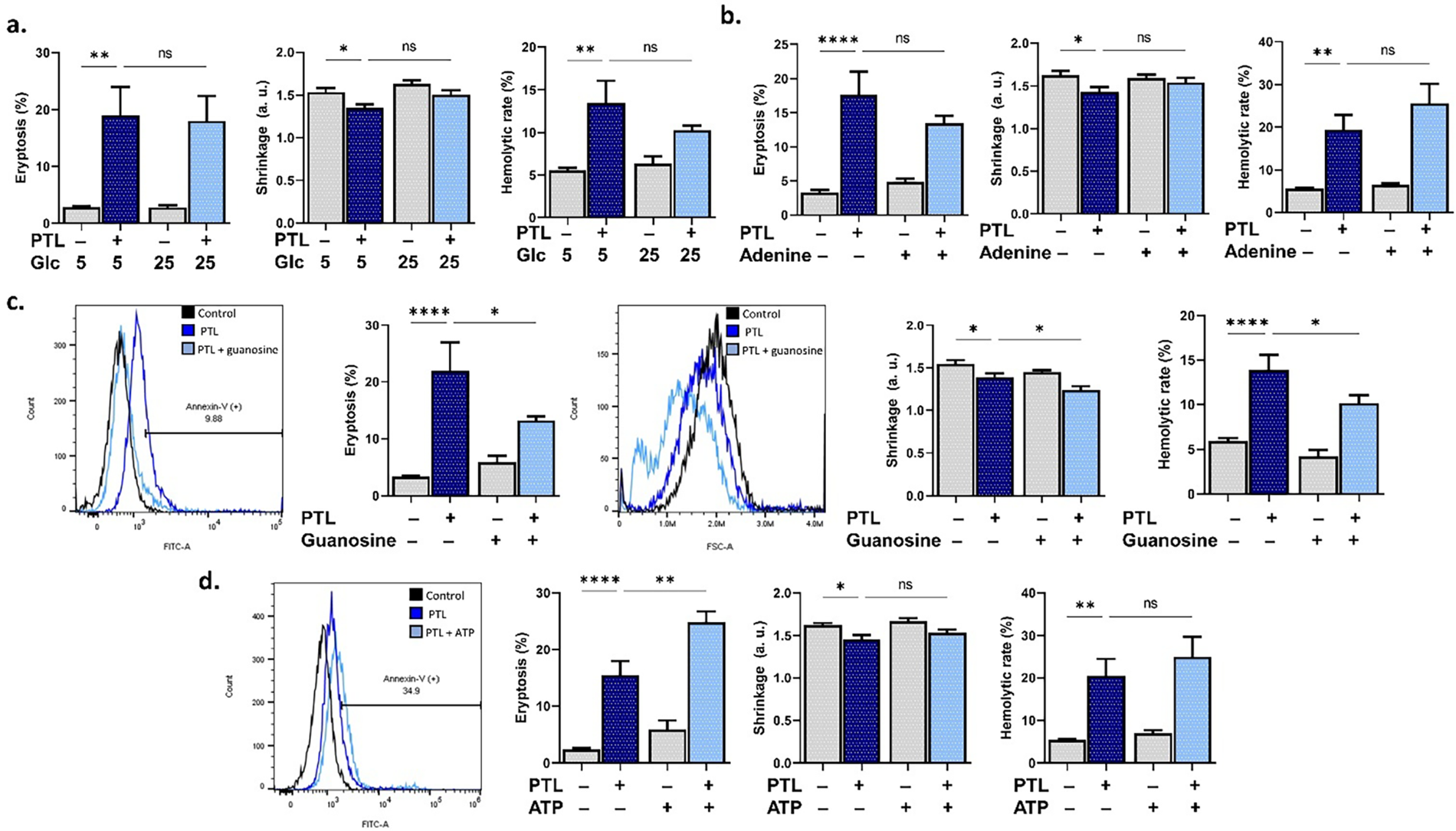

3.5 Differential Effects of Energy Substrates on PTL Toxicity

The potential of energy replenishment to rescue from cell death was also interrogated. It was revealed that neither glucose (Fig. 5a) nor adenine (Fig. 5b) supplementation rescued RBCs from PTL toxicity. However, guanosine (Fig. 5c), while paradoxically reversing scrambling (p < 0.05) and exacerbating the loss of volume, significantly inhibited hemolysis (p < 0.05). ATP (Fig. 5d), on the other hand, aggravated PTL-induced PS translocation (p < 0.01).

Figure 5: Effect of energy replenishment on parthenolide cytotoxicity. (a) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with 5 mM or 25 mM glucose (Glc). (b) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without adenine. (c) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without guanosine. (d) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test) is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001

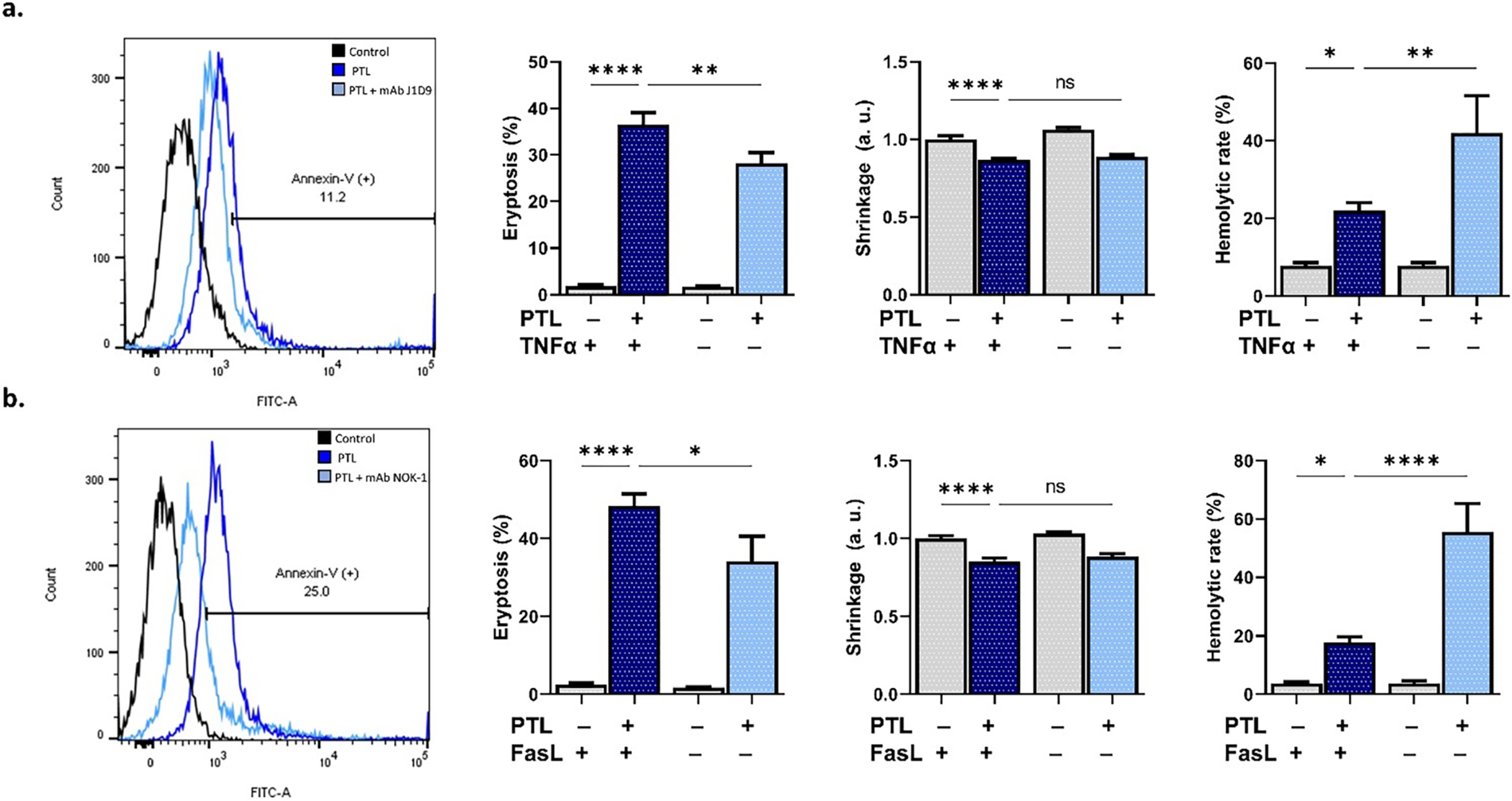

3.6 Contrasting Roles of Death Ligands in PTL-Induced RBC Death

Finally, cell death receptors were investigated using antibodies against TNFα and FasL. Blocking TNFα (Fig. 6a) significantly reversed membrane scrambling while increasing hemolysis (p < 0.01), which was also the case with anti-FasL (Fig. 6b), as it inhibited eryptosis (p < 0.05) but augmented hemolysis (p < 0.0001).

Figure 6: Involvement of death ligands in parthenolide cytotoxicity. (a) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without neutralization of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) using anti-TNFα. (b) Eryptosis, shrinkage, and hemolytic rate with and without blocking Fas ligand (FasL) using anti-FasL. Statistical significance (one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test) is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001

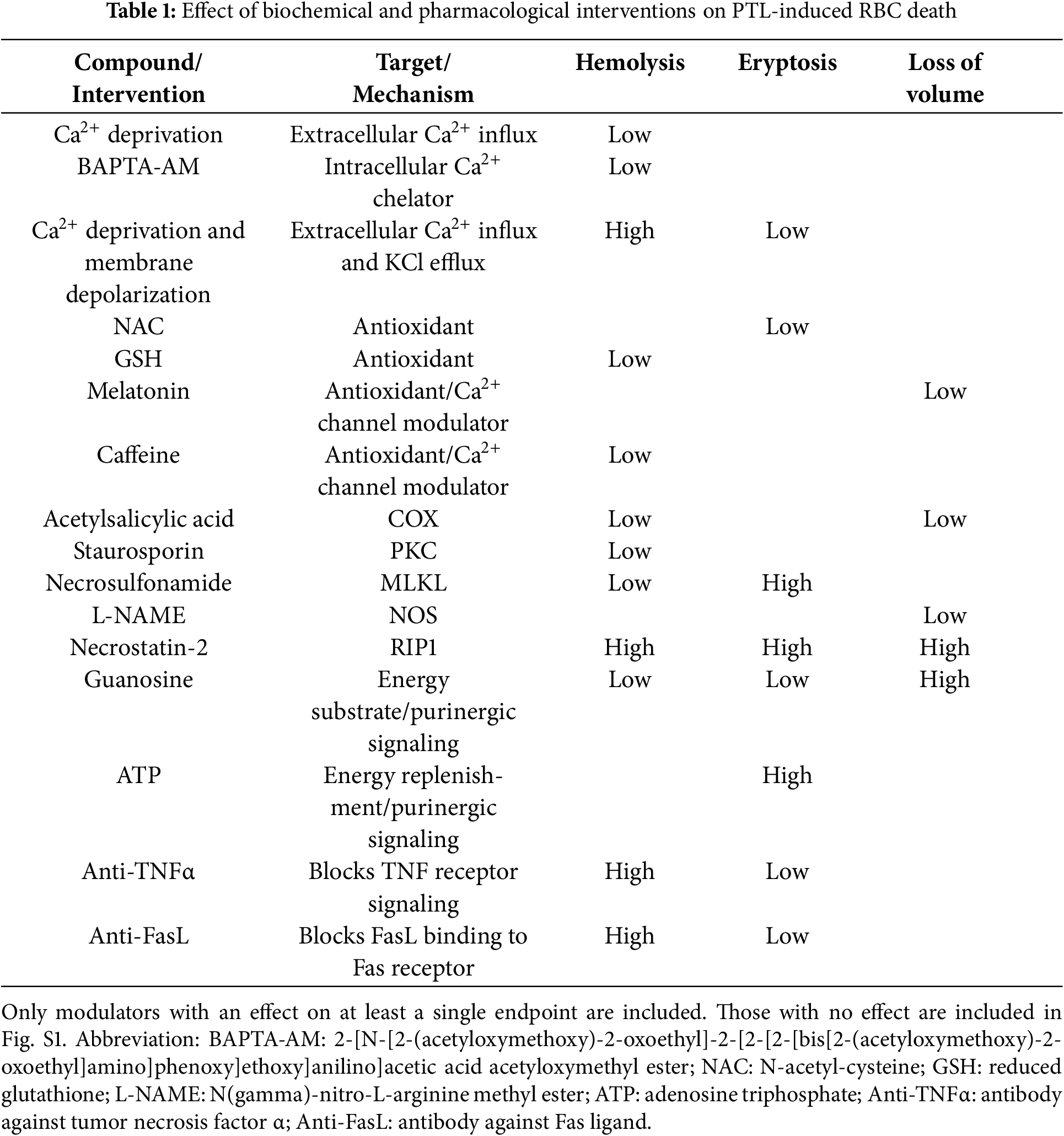

A strong line of evidence conclusively establishes PTL as an anticancer agent with great clinical prospects. However, the nonspecific toxicity of PTL, especially to RBCs, has largely been overlooked. This research highlights the non-genomic toxic mechanisms of PTL and suggests that its anticancer potential can be enhanced by attenuating its cytotoxic effects on RBCs through the identified pathways.

This study revealed for the first time the hemolytic properties of PTL (Fig. 1), which is in line with its reported effect on the cytoskeleton. Specifically, PTL has been shown to prevent microtubule detyrosination by inhibiting tubulin carboxypeptidase and to bind multiple tubulin isoforms [3]. Since cytoskeletal breakdown contributes to hemolysis, examination of the abundance of specific proteins such as spectrin, actin, and ankyrin will likely reveal the structural targets of PTL in RBCs. Furthermore, the current observations implicate ROS (Fig. 2) and Ca2+ signaling (Fig. 3), which act synergistically, leading to oxidative membrane destabilization as well as activation of calpains and phospholipases. Congruently, the hemolytic activity of PTL was ameliorated in cells replenished with GSH (Fig. 2), identifying redox imbalance as a key mechanism. Indeed, PTL has been reported to deplete GSH and other thiols by inhibiting its synthesis through protein alkylation and NADPH modification [3]. Likewise, inhibition of Ca2+ overload, either by Ca2+ deprivation or by BAPTA-AM, reversed PTL-induced hemolysis (Fig. 3), suggesting the restoration of physiological Ca2+ channel activity along with Ca2+-dependent enzymatic and ionic regulation.

Of note, volume regulation was partially restored when Ca2+ entry was blocked and under membrane depolarization conditions (Fig. 3), indicating that residual KCl efflux is sufficient to induce significant cell shrinkage as triggered by PTL. However, only when Ca2+ was eliminated and the K+ gradient collapsed was PTL-induced hemolysis augmented, which argues for the presence of alternative mechanisms that likely dominate when canonical mediators are absent. With regard to eryptotic volume loss, our results show that PTL requires oxidative stress and COX and NOS activities. Melatonin likely attenuates ROS accumulation and subsequent activation of Ca2+ and K+ channels [47]. COX inhibition reduces inflammatory signals mediated by prostaglandin E2 and phospholipase A2, which are implicated in eryptosis through cation channels [48]. Beyond ROS, NOS-dependent nitric oxide signaling has also been shown to modulate ion channel activity, which seems to be essential for PTL toxicity. Caffeine, which was anti-hemolytic (Fig. 3), has been demonstrated to act as an antioxidant [49], to have a concentration-dependent dual effect on Ca2+ influx [50], and to enhance RBC survival by blocking Ca2+ entry [51]. Altogether, this further implies the involvement of Ca2+ influx and oxidative insult in the hemolytic and eryptotic activities of PTL.

Importantly, these mechanisms seem to be downstream of a signaling axis comprising COX, PKC, and MLKL (Fig. 4). COX mediates the synthesis of prostaglandin E2, which activates nonspecific Ca2+ channels in erythrocytes, and its blockade with acetylsalicylic acid has previously been shown to attenuate cell death [52]. However, caution must be exercised in its use in vulnerable patients such as those with G6PD deficiency [53]. Similarly, PKC is activated by intracellular Ca2+ nucleation and leads to changes in the membrane, including further Ca2+ entry and PS externalization, especially as induced by glucose depletion [37]. This is supported by the protective effect of guanosine against PTL-induced eryptosis and hemolysis (Fig. 5), which argues for the role of PKC in sensing energy turnover and cell survival regulation.

PTL also seems to trigger membrane perforation by MLKL, a key effector in necroptosis. MLKL could be triggered by ROS or Ca2+ and is reported to engage following exposure to bacterial toxins, hyperglycemia, and prolonged storage of RBCs [37]. Nevertheless, the current findings must be complemented by a demonstration of the necroptosome assembly, preferably beside Syk and Src phosphorylation, to confirm the activation of erythronecroptosis. Interestingly, MLKL blockade sensitized the cells to PTL-induced PS externalization (Fig. 4) and appears to redirect the stress response to readily available mediators, most notably Ca2+ or ROS. In contrast, RIP1 inhibition augmented all toxic endpoints, suggesting that this kinase may act as a negative regulator that shapes the trajectory of PTL-induced RBC death by maintaining threshold control over MLKL activation.

Among all metabolic substrates used, guanosine offered protection against PS translocation and hemolysis (Fig. 5), identifying the depletion of nucleotide pools as an essential mechanism in PTL-induced RBC death. Guanosine replenishes intracellular GTP pools, which support ion trafficking, membrane integrity, and energy turnover [54]. Exogenous ATP, on the other hand, augmented eryptosis likely through purinergic receptors [55], which could potentially promote Ca2+ influx.

Eryptosis by PTL depends on death signals mediated by TNFα and FasL (Fig. 6), which trigger signaling cascades that promote PS translocation. The blunted phenotype upon neutralization of these ligands indicates that PTL either stimulates signaling pathways downstream of TNFα/FasL or sensitizes TNF/Fas receptors, possibly through ROS, which promotes receptor clustering. This is in congruence with previous reports implicating these ligands in erythronecroptosis induced by bacterial toxins [56]. In the absence of this ligand outlet, the stress response is diverted toward membrane rupture, likely as a compensatory mechanism with an amplified outcome, which highlights the plasticity of RBC death pathways.

Limitations of the current study include the absence of in vivo examination, which precludes the assessment of long-term and systemic effects, the uncertain pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic relevance of the concentrations used, and the untested potential applicability of PTL in combination therapy often required in anticancer regimens.

In conclusion, this report shows for the first time the non-genomic cytotoxicity of PTL and highlights the divergent pathways employed to elicit eryptosis and hemolysis (Table 1). Importantly, the findings lend support to the incorporation of antioxidants, Ca2+ chelators or channel blockers, enzyme inhibitors, energy substrates, and neutralizing antibodies in PTL-based treatment regimens to alleviate its nonspecific toxicity. Toxicological profiling of PTL-derived compounds with better bioavailability [4,5] is similarly urgently needed.

Acknowledgement: The authors are thankful to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-554) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding Program at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia through grant number ORF-2025-554.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mohammad A. Alfhili; data collection: Sara Y. Aldeghaither; analysis and interpretation of results: Sara Y. Aldeghaither, Jawaher Alsughayyir, Sabiha Fatima, Mohammad A. Alfhili; draft manuscript preparation: Sara Y. Aldeghaither, Jawaher Alsughayyir, Sabiha Fatima, Mohammad A. Alfhili. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Mohammad A. Alfhili, upon reasonable request and with permission from King Saud University.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from King Saud University IRB Committee (E-23-7685).

Informed Consent: All participants provided informed consent in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.071827/s1. Figure S1: Modulators with no effect on PTL-induced RBC death. Eryptosis, cell shrinkage, and hemolysis in the presence of PTL with and without (a) Z-VAD-FMK, (b) SB203580, (c) D4476, (d) NSC23776, and (e) myriocin. SPT, serine palmitoyltransferase. Statistical comparisons were carried out using one-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test. ns no significance; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

References

1. Vashisht Gopal YN, Arora TS, Van Dyke MW. Parthenolide specifically depletes histone deacetylase 1 protein and induces cell death through ataxia telangiectasia mutated. Chem Biol. 2007;14(7):813–23. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Liu Z, Liu S, Xie Z, Pavlovicz RE, Wu J, Chen P, et al. Modulation of DNA methylation by a sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329(2):505–14. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.147934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Freund RRA, Gobrecht P, Fischer D, Arndt HD. Advances in chemistry and bioactivity of parthenolide. Nat Prod Rep. 2020;37(4):541–65. doi:10.1039/c9np00049f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Liu X, Wang X. Recent advances on the structural modification of parthenolide and its derivatives as anticancer agents. Chin J Nat Med. 2022;20(11):814–29. doi:10.1016/S1875-5364(22)60238-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu J, Cui M, Wang Y, Wang J. Trends in parthenolide research over the past two decades: a bibliometric analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(7):e17843. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang S, Ong CN, Shen HM. Critical roles of intracellular thiols and calcium in parthenolide-induced apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2004;208(2):143–53. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2003.11.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Gehren AS, de Souza WF, Sousa-Squiavinato ACM, Ramos DAA, Pires BRB, Abdelhay ESFW, et al. Parthenolide inhibits proliferation and invasion, promotes apoptosis, and reverts the cell-cell adhesion loss through downregulation of NF-κB pathway TNF-α-activated in colorectal cancer cells. Cell Biol Int. 2023;47(9):1638–49. doi:10.1002/cbin.12060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kim JH, Liu L, Lee SO, Kim YT, You KR, Kim DG. Susceptibility of cholangiocarcinoma cells to parthenolide-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6312–20. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wang W, Adachi M, Kawamura R, Sakamoto H, Hayashi T, Ishida T, et al. Parthenolide-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells involves reactive oxygen species generation and cell sensitivity depends on catalase activity. Apoptosis. 2006;11(12):2225–35. doi:10.1007/s10495-006-0287-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Anderson KN, Bejcek BE. Parthenolide induces apoptosis in glioblastomas without affecting NF-κB. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106(2):318–20. doi:10.1254/jphs.sc0060164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Liu JW, Cai MX, Xin Y, Wu QS, Ma J, Yang P, et al. Parthenolide induces proliferation inhibition and apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29(1):108. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-29-108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Liu W, Wang X, Sun J, Yang Y, Li W, Song J. Parthenolide suppresses pancreatic cell growth by autophagy-mediated apoptosis. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:453–61. doi:10.2147/OTT.S117250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng G, Xie L. Parthenolide induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest of human 5637 bladder cancer cells in vitro. Molecules. 2011;16(8):6758–68. doi:10.3390/molecules16086758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Li Y, Zhang Y, Fu M, Yao Q, Zhuo H, Lu Q, et al. Parthenolide induces apoptosis and lytic cytotoxicity in Epstein-Barr virus-positive Burkitt lymphoma. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6(3):477–82. doi:10.3892/mmr.2012.959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sun J, Zhang C, Bao YL, Wu Y, Chen ZL, Yu CL, et al. Parthenolide-induced apoptosis, autophagy and suppression of proliferation in HepG2 cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4897–902. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.12.4897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yi J, Gong X, Yin XY, Wang L, Hou JX, Chen J, et al. Parthenolide and arsenic trioxide co-trigger autophagy-accompanied apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Front Oncol. 2022;12:988528. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.988528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Z, Qiao Y, Sun Q, Peng L, Sun L. A novel SLC25A1 inhibitor, parthenolide, suppresses the growth and stemness of liver cancer stem cells with metabolic vulnerability. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):350. doi:10.1038/s41420-023-01640-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao X, Liu X, Su L. Parthenolide induces apoptosis via TNFRSF10B and PMAIP1 pathways in human lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33(1):3. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-33-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Talib WH, Al Kury LT. Parthenolide inhibits tumor-promoting effects of nicotine in lung cancer by inducing P53—dependent apoptosis and inhibiting VEGF expression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;107(12):1488–95. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li X, Huang R, Li M, Zhu Z, Chen Z, Cui L, et al. Parthenolide inhibits the growth of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20(1):561. doi:10.1186/s12935-020-01658-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kwak SW, Park ES, Lee CS. Parthenolide induces apoptosis by activating the mitochondrial and death receptor pathways and inhibits FAK-mediated cell invasion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;385(1–2):133–44. doi:10.1007/s11010-013-1822-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lu C, Wang W, Jia Y, Liu X, Tong Z, Li B. Inhibition of AMPK/autophagy potentiates parthenolide-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(8):1458–66. doi:10.1002/jcb.24808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yu HJ, Jung JY, Jeong JH, Cho SD, Lee JS. Induction of apoptosis by parthenolide in human oral cancer cell lines and tumor xenografts. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(6):602–9. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Jeyamohan S, Moorthy RK, Kannan MK, Arockiam AJV. Parthenolide induces apoptosis and autophagy through the suppression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in cervical cancer. Biotechnol Lett. 2016;38(8):1251–60. doi:10.1007/s10529-016-2102-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li H, Lu H, Lv M, Wang Q, Sun Y. Parthenolide facilitates apoptosis and reverses drug-resistance of human gastric carcinoma cells by inhibiting the STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(3):3572–9. doi:10.3892/ol.2018.7739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Karam L, Abou Staiteieh S, Chaaban R, Hayar B, Ismail B, Neipel F, et al. Anticancer activities of parthenolide in primary effusion lymphoma preclinical models. Mol Carcinog. 2021;60(8):567–81. doi:10.1002/mc.23324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Che ST, Bie L, Li X, Qi H, Yu P, Zuo L. Parthenolide inhibits the proliferation and induces the apoptosis of human uveal melanoma cells. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(10):1531–8. doi:10.18240/ijo.2019.10.03. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Cui M, Wang Z, Huang LT, Wang JH. Parthenolide leads to proteomic differences in thyroid cancer cells and promotes apoptosis. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):99. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03579-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Jorge J, Neves J, Alves R, Geraldes C, Gonçalves AC, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB. Parthenolide induces ROS-mediated apoptosis in lymphoid malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9167. doi:10.3390/ijms24119167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Obulkasim H, Aji G, Abudoula A, Liu Y, Duan S. Parthenolide induces gallbladder cancer cell apoptosis via MAPK signalling. Ann Med Surg. 2024;86(4):1956–66. doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000001828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Yao H, Tang X, Shao X, Feng L, Wu N, Yao K. Parthenolide protects human lens epithelial cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via inhibition of activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9. Cell Res. 2007;17(6):565–71. doi:10.1038/cr.2007.6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Shentu XC, Ping XY, Cheng YL, Zhang X, Tang YL, Tang XJ. Hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis of human lens epithelial cells is inhibited by parthenolide. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(1):12–7. doi:10.18240/ijo.2018.01.03. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mao W, Zhu Z. Parthenolide inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced osteoblast apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(6):8369–76. doi:10.3892/mmr.2018.8908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ren Y, Li Y, Lv J, Guo X, Zhang J, Zhou D, et al. Parthenolide regulates oxidative stress-induced mitophagy and suppresses apoptosis through p53 signaling pathway in C2C12 myoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(9):15695–708. doi:10.1002/jcb.28839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Guo NK, She H, Tan L, Zhou YQ, Tang CQ, Peng XY, et al. Nano parthenolide improves intestinal barrier function of sepsis by inhibiting apoptosis and ROS via 5-HTR2A. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:693–709. doi:10.2147/IJN.S394544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Arslan ME, Türkez H, Sevim Y, Selvitopi H, Kadi A, Öner S, et al. Costunolide and parthenolide ameliorate MPP+ induced apoptosis in the cellular Parkinson’s disease model. Cells. 2023;12(7):992. doi:10.3390/cells12070992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Tkachenko A, Alfhili MA, Alsughayyir J, Attanzio A, Al Mamun Bhuyan A, Bukowska B, et al. Current understanding of eryptosis: mechanisms, physiological functions, role in disease, pharmacological applications, and nomenclature recommendations. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):467. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07784-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Lang E, Bissinger R, Qadri SM, Lang F. Suicidal death of erythrocytes in cancer and its chemotherapy: a potential target in the treatment of tumor-associated Anemia. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(8):1522–8. doi:10.1002/ijc.30800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Abed M, Towhid ST, Mia S, Pakladok T, Alesutan I, Borst O, et al. Sphingomyelinase-induced adhesion of eryptotic erythrocytes to endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303(9):C991–9. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00239.2012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Bissinger R, Al Mamun Bhuyan A, Qadri SM, Lang F. Oxidative stress, eryptosis and anemia: a pivotal mechanistic nexus in systemic diseases. FEBS J. 2019;286(5):826–54. doi:10.1111/febs.14606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Tkachenko A. Hemocompatibility studies in nanotoxicology: hemolysis or eryptosis? (a review). Toxicol In Vitro. 2024;98(Suppl. 2):105814. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2024.105814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Sztiller-Sikorska M, Czyz M. Parthenolide as cooperating agent for anti-cancer treatment of various malignancies. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13(8):194. doi:10.3390/ph13080194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ligasová A, Vydržalová M, Buriánová R, Brůčková L, Večeřová R, Janošťáková A, et al. A new sensitive method for the detection of mycoplasmas using fluorescence microscopy. Cells. 2019;8(12):1510. doi:10.3390/cells8121510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Liu A, Jacobs-McFarlane C, Sebastiani P, Glassberg J, McCuskee S, Curtis S. Plasma free hemoglobin is associated with LDH, AST, total bilirubin, reticulocyte count, and the hemolysis score in patients with sickle cell anemia. Ann Hematol. 2025;104(4):2221–8. doi:10.1007/s00277-025-06253-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Jemaà M, Fezai M, Bissinger R, Lang F. Methods employed in cytofluorometric assessment of eryptosis, the suicidal erythrocyte death. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43(2):431–44. doi:10.1159/000480469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Cahalan SM, Lukacs V, Ranade SS, Shu C, Bandell M, Patapoutian A. Piezo1 links mechanical forces to red blood cell volume. eLife. 2015;4:e07370. doi:10.7554/eLife.07370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan DX, Sainz RM, Alatorre-Jimenez M, Qin L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res. 2016;61(3):253–78. doi:10.1111/jpi.12360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Hernández G, Villanueva-Ibarra CA, Maldonado-Vega M, López-Vanegas NC, Ruiz-Cascante CE, Calderón-Salinas JV. Participation of phospholipase-A2 and sphingomyelinase in the molecular pathways to eryptosis induced by oxidative stress in lead-exposed workers. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;371(2):12–9. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2019.03.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ősz BE, Jîtcă G, Ştefănescu RE, Puşcaş A, Tero-Vescan A, Vari CE. Caffeine and its antioxidant properties–it is all about dose and source. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(21):13074. doi:10.3390/ijms232113074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Karhapää L, Törnquist K. Effects of caffeine on the influx of extracellular calcium in GH4C1 pituitary cells. J Cell Physiol. 1997;171(1):52–60. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199704)171:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Floride E, Föller M, Ritter M, Lang F. Caffeine inhibits suicidal erythrocyte death. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22(1–4):253–60. doi:10.1159/000149803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Shumilina E, Kiedaisch V, Akkel A, Lang P, Hermle T, Kempe DS, et al. Stimulation of suicidal erythrocyte death by lipoxygenase inhibitor Bay-Y5884. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2006;18(4–5):233–42. doi:10.1159/000097670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Li J, Chen Y, Ou Z, Ouyang F, Liang J, Jiang Z, et al. Aspirin therapy in cardiovascular disease with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, safe or not? Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2021;21(4):377–82. doi:10.1007/s40256-020-00460-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Armstrong MC, Weiß YR, Hoachlander-Hobby LE, Roy AA, Visco I, Moe A, et al. The biochemical mechanism of Rho GTPase membrane binding, activation and retention in activity patterning. EMBO J. 2025;44(9):2620–57. doi:10.1038/s44318-025-00418-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Huang Z, Xie N, Illes P, Di Virgilio F, Ulrich H, Semyanov A, et al. From purines to purinergic signalling: molecular functions and human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):162. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00553-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. LaRocca TJ, Stivison EA, Hod EA, Spitalnik SL, Cowan PJ, Randis TM, et al. Human-specific bacterial pore-forming toxins induce programmed necrosis in erythrocytes. mBio. 2014;5(5):e01251–14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01251-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools