Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

BMP-2 Inhibits the Inflammatory Response and Promotes Bone Formation in Rats with Femoral Fracture by Activating the AMPK Signaling Pathway

1 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Qing Hai University Affiliated Hospital, 29 Tongren Street, Chengxi District, Xining, 810001, China

2 Department of Orthopedics, Second People’s Hospital of Jiangyou City, 31 Juhui Street, Jiangyou, Mianyang, 621700, China

* Corresponding Author: Chungui Huang. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2195-2216. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072716

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Objective: Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are important cells in bone tissue engineering. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) effectively treats bone defects and nonunion. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether BMP-2 promotes bone formation and femoral fracture healing by inhibiting inflammation and promoting osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, in order to provide an experimental basis for developing more efficient fracture treatment strategies. Methods: Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs) were isolated from rats and treated with OE-BMP-2, the 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signal agonist 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR), and the inhibitor Compound C. Osteogenic differentiation was evaluated through an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) kit, Western blot, and Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining. A rat model of femoral fracture was constructed, and fracture healing in the rats was detected by X-ray, microcomputed tomography (CT), and pathological staining. The AMPK signaling pathway and inflammation levels in the BMSCs and fracture model rats were measured by Western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. Results: After BMP-2 overexpression, the ALP activity in osteogenic BMSCs was significantly increased (increased to 253.64%), the levels of osteogenic differentiation proteins (Osterix and osteocalcin) and p-AMPK Thr172 protein were significantly increased, and the concentrations of inflammatory factors were decreased. In rat fracture tissues, BMP-2 overexpression promoted the expression of p-AMPK Thr172 protein and bone callus formation, increased bone volume (increased to 22.22%), reduced the number of fibrous components in the cartilage matrix, increased the numbers of osteoblasts and chondrocytes, increased the expression of osteogenic differentiation proteins, and reduced the content of inflammatory factors in the serum. After AICAR intervention, ALP activity and the expression of osteogenic differentiation proteins in BMSCs and fracture tissues further increased, and the level of inflammation decreased. However, the changes in osteogenic differentiation and inflammation levels were significantly reversed after Compound C intervention. Conclusion: BMP-2 activated the AMPK signaling pathway, inhibited the inflammatory response, and effectively promoted the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and femoral fracture healing in rats.Keywords

Highlights:

• Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) promotes osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs).

• BMP-2 inhibits the inflammatory response of BMSCs through the AMPK signaling pathway.

• BMP-2 promotes osteogenic differentiation through the AMPK signaling pathway.

• BMP-2 supports femoral fracture healing in rats through the AMPK signaling pathway.

Bones have many daily functions in the body, such as maintaining stability and balancing the mineral structure. A damaged bone can have a serious impact on the body’s motor function. As a common clinical disease, the main symptoms of a fracture are pain, swelling, and limited limb movement. Fracture healing involves an array of histological and biochemical changes that are coordinated by a variety of different factors [1]. Previous studies indicate that although fracture injuries can heal normally after surgery or conservative treatment in most cases, approximately 15% of patients will experience a disruption to the healing process. The clinical manifestations are delayed fracture healing or delayed union, even nonunion [2,3], and the lifetime incidence rate is high. Fractures can also have a serious impact on the patient’s future daily life [4]. Therefore, actively studying and developing treatment strategies that promote osteogenesis has become an important direction of basic research in orthopedics.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)-based therapies have shown great advantages for restoring the structure of damaged bones. Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs) are isolated from bone progenitor cells of the bone marrow. They are a kind of MSCs with strong proliferation ability, multidirectional differentiation potential, and low immunogenicity. Under certain conditions, these cells can differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes. These cells are important seed cells for promoting fracture repair and bone regeneration and play a vital role in bone repair and reconstruction [5,6]. Moreover, BMSCs have abundant sources, convenient sampling methods, and a variety of differentiation capabilities. In addition, they also have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. These characteristics are conducive to regeneration and have been widely used in a variety of regenerative medicine and tissue repair strategies. In completed clinical trials, BMSCs have been shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of a variety of diseases, including tissue regeneration, bone damage repair, and myocardial injury repair [7–9]. A decrease in BMSCs proliferation ability further decreases the activity of osteoblasts and inhibits their ability to undergo osteogenic differentiation [10]. Therefore, BMSCs have important clinical importance for bone defect repair [11]. Currently, improving the osteogenic differentiation capacity of BMSCs is a research hotspot for treating fractures.

Bone wound healing is often accompanied by synergistic effects of various biochemical factors, biophysiological factors, and mechanical factors. The speed of bone wound healing can be adjusted by changing the local factor components in the bone wound area. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are unique extracellular multifunctional signaling cytokines synthesized by osteoblasts. BMPs have a variety of biological activities and are crucial for the growth, reconstruction, and repair of bone and cartilage. BMPs can promote cell proliferation by inducing BMSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts [12]. Among the BMP family members, bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) promotes fracture healing most strongly, and the absence of BMP-2 leads to severe damage to bone formation. BMP-2 is not only vital for the development of fat but also participates in the growth of bone when the human body is in the early stages of embryonic development [13]. The decrease in the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs may be related to many factors, such as the inflammatory response. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 are key inflammatory markers involved in many pathological states and are crucial for the inflammatory response [14,15]. BMP-2 can promote bone cell differentiation and bone tissue growth, is vital for fracture healing, and can mediate the occurrence and development of bone defects, nonunion, osteoporosis, and other diseases [16]. Therefore, BMP-2 may be a target for fracture therapy.

5′-Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a heterotrimeric protein composed of catalytic subunit α and regulatory subunits β and γ. AMPK is responsible for maintaining the balance between adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and consumption in cells. It is considered to be a metabolic stress-sensing enzyme and plays an important role in regulating cellular and systemic energy homeostasis. Previous studies have shown that the AMPK signaling pathway is a therapeutic target for metabolic diseases, cancer, and atherosclerosis, and plays an important role in anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antiaging, and other treatments [17,18]. Recent studies have shown that the AMPK signaling pathway can regulate osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Ren et al. reported that in rat BMSCs, the activated AMPK signaling pathway was involved in metformin-induced bone formation [19]. AMPK activation can also regulate bone formation and bone mass in vitro and in vivo, and is vital for osteoblast differentiation and bone development by regulating BMP-2 levels [20,21]. Therefore, the AMPK signaling pathway is thought to play a key role in bone regeneration.

In this study, BMSCs were isolated from rats, and the influence of BMP-2 on osteogenic differentiation and the inflammatory response was studied. By constructing a rat model of femoral fracture and interfering with BMP-2 expression, the effects of BMP-2 on the inflammatory response, femoral fracture healing, and bone regeneration in rats were investigated, and the role of the AMPK signaling pathway was explored. This study aimed to elucidate the effect of BMP-2 on bone regeneration in rats to provide a valuable experimental basis for the clinical treatment of fractures.

2.1 Isolation and Culture of Rat Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs)

In this study, 8 3-month-old SPF female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, weighing 270 ± 20 g, were obtained from Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). During the experiment, all the animals were raised under the same conditions (room temperature, 20°C–22°C; relative humidity, 40%–60%), fed freely with standard feed, and provided with sufficient drinking water. This experiment was approved by the Qing Hai University Affiliated Hospital’s ethics review board (batch no. P-SL-202204) and followed the principles of ethical animal experimentation.

After the end of the adaptation period, 8 rats were randomly selected by a researcher who was not involved in the follow-up experiment. The rats were injected intraperitoneally with 3% pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg). After anesthesia, the rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and immersed in 75% alcohol for 60 s. The femurs and tibias of the rats were removed from the surrounding soft tissue, placed in a 6 cm culture dish, and washed with medium. The bone marrow was cut into small pieces and washed with Minimum Essential Medium (a-MEM, Servicebio, G4559, Wuhan, China) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, G8003, Servicebio) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin sulfate (Beyotime, ST488S, Shanghai, China) until the solution became clear. The collected cell suspension was centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, and an appropriate amount of medium was added gently to allow the cell precipitate to resuspend into a single-cell state. The cells were transferred into a Petri dish and cultured in a 5% CO2, 37°C incubator (Thermo Scientific, 8000, Waltham, MA, USA). After 2 days of static culture, half of the medium was changed to ensure the stable survival of the cells while excluding a certain number of suspended blood cells [22]. The cell state was observed, and the medium was completely changed for 2–3 days. The nonadherent cells were gradually removed, and the BMSCs were purified. When 70%–90% of the BMSCs were passaged, the third generation of BMSCs was used for experiments.

Third-generation BMSCs were inoculated into culture flasks. When the cells reached approximately 80% confluence, they were digested with 0.25% trypsin (G4001, Servicebio) and centrifuged. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in a centrifuge tube containing 2% FBS. The cells were incubated with 10 μL of CD29 (BioLegend, 102215, San Diego, CA, USA), CD34 (Abcam, ab316277, Cambridge, UK), CD44 (Abcam, ab316123), CD45 (BioLegend, 202203), CD73 (FineTest, FNab05878, Wuhan, China) or human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR, Ruiqi, Rs-1198R, Shanghai, China) at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. After incubation, the cells were resuspended in 500 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and filtered through a 200-mesh sieve. BMSCs were identified by flow cytometry (BD, FACSAria II, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA) [23,24]. The mycoplasma detection kit (Solarbio, CA1080, Beijing, China) was used to detect the mycoplasma contamination of the extracted BMSCs to ensure that the cells used in the subsequent experiments were free of mycoplasma contamination.

BMSCs with a confluence rate of approximately 80% were collected, the medium was discarded, the cells were digested with trypsin for 3 min, and the cell density was adjusted to 2 × 103 cells/cm2. Two milliliters of a-MEM was added to each well of a 6-well plate. When the cell confluence reached 100%, the medium was replaced with the adipogenic differentiation medium of rat BMSCs (Solarbio, D3512, Beijing, China) for adipogenic differentiation, and the medium was changed every 3 days. After 14 days of culture, oil red O staining was performed when sufficient lipid droplets were observed under a microscope. The medium was discarded, the samples were rinsed with PBS twice, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (covering the cell surface) for 20 min, rinsed with PBS twice, and stained with 1 mL of oil red O working solution (Servicebio, G1015) for 30 min. The staining solution was discarded, and the background magazine was washed clean. The induction and staining effects were observed under a microscope (Olympus, Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan) [23].

2.3 Osteogenic Induction and Cell Transfection

Osteogenic differentiation was performed using a rat BMSCs osteogenic differentiation kit (Oricell, RAXMX-90021, Guangzhou, China). Third-generation BMSCs (5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates. 2 mL of osteogenic differentiation medium (50 μmol/L vitamin C, 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate) was added to each well, and the medium was changed every other day. Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining was used to identify whether osteogenic induction was successful [23].

The recombinant adenovirus vectors containing the BMP-2 gene coding sequence (reference sequence: NM_017178.2) (Ad-OE-BMP-2) and the rat BMP-2 gene (Ad-sh-BMP-2) were prepared by He Bei Technology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). The sequence used to target the BMP-2 shRNA: #1: 5′-GCATCTTGTTCTTTCTTAACTCGAGTTAAGAAAGAACAAGATGCTTTTTT-3′, #2: 5′-CCUAUAUGCUCGACCUGUACTCGAGUACAGGUCGAGCAUAUAGGTTTTTT-3′, #3: 5′-GCACAGCAAGAATAAATAACTCGAGTTATTTATTCTTGCTGTGCTTTTTT-3′; and the sh-NC sequence was 5′-GUAUCACUAGGCUAUACUGTCGAGCAGUAUAGCCUAGUGAUACTTTTTT-3′. HEK293T cells were seeded in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with control (Ad-GFP), BMP-2-knockdown (Ad-sh-BMP-2), or BMP-2-overexpressing (Ad-OE-BMP-2) adenovirus. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was 50. After 8 h of transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM for 72 h. The cells were collected and centrifuged. The supernatant containing the adenovirus extract was removed and transfected into the BMSCs. Two milliliters of third-generation BMSCs (0.5 × 105 cells/mL) were cultured for 24 h, and the corresponding recombinant adenovirus was added for transfection. There were three transfection groups: the sh-BMP-2 group, the OE-BMP-2 group, and the Ad-GFP (sh-NC and OE-NC) groups. After 30 h of culture, the knockdown or overexpression effects were assessed by Western blot.

After OE-BMP-2 was transfected into rat BMSCs for 48 h, the BMSCs were treated with the AMPK signal agonist AICAR (1 mM; Beyotime, S1515) and the inhibitor Compound C (10 μM; Selleck.cn, S7840, Shanghai, China) for 12 h.

2.4 Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Kit

The BMSCs were collected on the 7th and 14th days of osteogenic differentiation, and the osteogenic ability of the BMSCs was analyzed through an ALP activity kit (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, A059-1, Nanjing, China) [24]. After the cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Servicebio, G2002), the resulting cell supernatant was centrifuged for 10 min (4°C, 2000× g) using a centrifuge (Eppendorf SE, Eppendorf 5424 R, Hamburg, Germany). ALP detection kits were used to detect optical density (OD) values at 520 nm with a microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Cytation5, Burlington, VT, USA).

On the 7th day of osteogenic induction culture, the 6-well plates were removed from the incubator and placed on an ultraclean bench. After the original medium in each well was removed, the samples were washed with PBS three times. Each well was fixed for 30 min with 4% paraformaldehyde solution. In accordance with the ALP staining kit instructions (Solarbio, G1481), the corresponding amounts of ALP incubation solution, Co solution, and sulfide solution were added to the wells and incubated at room temperature. After completion, the dye solution in the wells was removed by a suction gun. Finally, the PBS in each well was removed, and the insoluble gray–blue precipitate was observed and photographed under a microscope (NIKON, Ts2, Tokyo, Japan) [25].

The BMSCs were cultured on Day 14 of osteogenic induction, and the bone mineralization of the osteoblasts was evaluated [24,26]. The BMSCs were removed from the incubator and rinsed with PBS 3 times. In each well, 4% paraformaldehyde solution was added to fix for 15 min. PBS rinsing was performed to remove the organic components in the fixative and prevent the organic components from polluting the sample, so that the results of the sample analysis were more accurate and reliable. After rinsing, 500 μL of alizarin red staining working solution (Servicebio, G1038) was carefully added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min in the dark. After incubation, PBS was added, the samples were washed three times, and photos were taken under a microscope (NIKON, Ts2, Tokyo, Japan). To quantify the relative content of calcium, 400 μL of 10% cetylpyridinium chloride and 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate solution were added, and the absorbance value was determined with a microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Cytation5, Burlington, CT, USA) at a wavelength of 570 nm.

2.7 Rat Femoral Fracture Model

30 3-month-old SPF female SD rats, weighing 270 ± 20 g, were obtained from Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). During the experiment, all the animals were raised under the same conditions, fed freely with standard feed, and provided with sufficient drinking water. This experiment was approved by the Qing Hai University Affiliated Hospital’s ethics review board (batch no. P-SL-202204) and followed the principles of ethical animal experimentation.

This study used a completely randomized design. After the end of the adaptation period, 30 SD rats were randomly assigned to the Sham group (n = 5) and the femoral fracture model (Model) group (n = 25) by a researcher who was not involved in the follow-up experiment using a computer random number generator (www.randomizer.org) (accessed on 27 September 2025). A femoral fracture model was established according to a previous study [26]. The rats were fasted for 8 h before modeling, and water was withheld. After intraperitoneal anesthesia with 1% pentobarbital sodium (1 mL/kg), the left prone position was taken, the left hip and lateral thigh hairs were removed, and the left hind limb skin was prepared. After disinfection, the left lateral femoral incision (1.5–2.5 cm) was made, the lateral femoral muscle was separated, the femur was fully exposed, the femur was cut in the middle of the femur (the integrity of the fracture end was ensured when cutting), and the distance between the broken ends was less than 1 mm. A Kirschner wire with a diameter of 1 mm was retrogradely inserted into the proximal end of the femoral shaft from the fracture end and passed through the greater trochanter of the femur to reset the two fracture ends, and the Kirschner wire was anterogradely passed back after reduction. The knee joint of the operated side of the rat was activated to confirm that the Kirschner wire was not inserted into the knee joint and was fixed firmly, and the excess Kirschner wire was cut off. The incision was rinsed with an appropriate amount of normal saline, the muscle and skin were sutured, and the rats were then fed normally. After successful modeling, an independent researcher who was not involved in subsequent experimental operations and data analysis used an online randomization tool to generate a random distribution sequence, and assigned the animal number to the Model group, Model + OE-NC group, Model + OE-BMP-2 group, Model + OE-BMP-2 + AICAR group, and Model + OE-BMP-2 + Compound C group, with 5 rats in each group. The grouping information was sealed in an opaque envelope, sorted by number, until the data analysis was completed. The rats in the OE-NC and OE-BMP-2 groups were then intraperitoneally injected with 40 nmol/μL OE-NC or OE-BMP-2, respectively, once every 3 days. The rats in the AICAR and Compound C groups were intraperitoneally injected with 200 mg/kg AICAR and 0.2 mg/kg Compound C 1 h before modeling. For the rats in the Sham group, only the femoral shaft was exposed, and the femur was not cut. In the 4th week, X-rays (Jiaxin Huixiong Technology Co., Ltd., HX-100P, Beijing, China) were used to irradiate the femoral fractures of the rats to evaluate fracture healing [26]. Two days after the end of treatment, 2 mL of abdominal aortic blood was collected and centrifuged for 15 min (4°C, 3000× g) using a centrifuge (Eppendorf SE, Eppendorf 5424 R, Hamburg, Germany), and the serum was stored at −80°C. Then, the rats were sacrificed, and the cartilage tissue around the fracture was separated. At the same time, the corpus callosum tissue at the femoral fracture site was removed for measurement. In order to reduce subjective bias, this study blinded intervention implementers and outcome evaluators. The researcher A, who was responsible for daily administration, only knew the cage number and individual number of the animal and did not know its grouping (all syringes and feeds were prepared and numbered by another person in advance). Researcher B, who was responsible for analyzing tissue sections, was completely unaware of the grouping information. Data collection and analysis personnel were blinded to the grouping information during the grouping period, and the grouping information was only uncovered after all data analysis was completed.

2.8 Microcomputed Tomography (CT)

In the 4th week of femoral fracture in the rats, the right femur was removed, and the muscles and soft tissues around the femur were removed. The fracture area morphology and callus shape were observed by a micro-CT scanner (Pingsheng, PINGSENG, Kunshan, China) [26]. The parameter settings used were as follows: continuous scanning, tube voltage 90 kV, tube current 50 μA, 20 frame numbers per second, and DSD 415 mm. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the image was performed using NRecon 2.0 software (Bruker Micro-CT, Bielelika, MA, USA) to analyze the bone volume (BV, mm3).

Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining: Tissues 5 mm above and below the femoral fracture were removed from the rats and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing, they were soaked in 14% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Servicebio, GC202001) solution for decalcification. After gradient alcohol dehydration, xylene transparency, paraffin embedding, and continuous sectioning, 5 μm thick sections were prepared. Hematoxylin staining (Servicebio, GC307020) was performed for 5 min, a 1% hydrochloric acid treatment was performed, followed by eosin (Servicebio, G1002) restaining and neutral gum sealing. Pathological changes in femoral tissue were observed by microscopy, and images were collected [26]. The main observation indexes included trabecular bone, the number of osteoblasts, bone healing tissue, and inflammatory infiltration. The test was completed by the researchers within 3 weeks of sampling.

Safranin O-fast green staining (Solarbio, G1371): Paraffin sections of bone tissue were stained with Weigert staining solution for 5 min, rinsed with 1% acetic acid solution, stained with solid green staining solution for 5 min, stained with safranin O staining solution for 5 min, washed with anhydrous ethanol to remove excess staining solution, cleared with xylene, sealed with neutral gum, and observed under a microscope [26]. The main observation indexes included: fiber composition in cartilage matrix and the number of chondrocytes. The test was completed by the researchers within 3 weeks of sampling.

The femoral fracture tissues of the rats were fixed and decalcified, embedded with optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) embedding agent (Servicebio, G6059), and cut into frozen sections with a thickness of approximately 5 μm. The sections were dehydrated with gradient alcohol and cleared with xylene. Then, 10% goat serum (G1208, Servicebio) was added dropwise, and the samples were blocked at room temperature for 50 min. An anti-OPN antibody (Abcam, ab11503, 1:100) was added to the slices, which were subsequently incubated at 4°C overnight. The next day, the slices were removed, rewarmed at room temperature, washed with PBS, incubated with an Alexa Fluor 594-labeled fluorescent secondary antibody (Servicebio, GB28303, 1:500), and stained in a wet box at room temperature for 2 h. Afterward, the samples were washed with PBS, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added, and the samples were then placed in a wet box for 10 min. An antifluorescence quenching sealing agent was used to seal the tablets. The stained sections were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Laikuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Odyssey, Beijing, China), and images were collected. The relative fluorescence intensity of OPN was analyzed by ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.8.0, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) [26]. The test was completed by the researchers within 3 weeks of sampling.

2.11 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

BMSCs were collected on the 14th day of osteogenic differentiation, and the serum of the rats in each group was collected as samples for testing. The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and ALP were detected by ELISA kits (mlbio, ml064292, ml002859, ml003057, ml003360, Shanghai, China) [27]. The absorbance was measured by a microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Cytation5, Burlington, CT, USA), and the concentration was calculated according to the standard curve. The test was completed by the researchers within 1 week of sampling.

BMSCs were collected on the 14th day of osteogenic differentiation, and RIPA lysis buffer (Servicebio, G2002) was added for cell lysis and protein extraction after they were incubated on ice for 15 min. The callosal tissue from the rat femoral fracture was supplemented with homogenate beads and RIPA lysis buffer; the mixture was lysed on ice for 30 min, and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentrations of the samples were determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Servicebio, G2026). After the protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Servicebio, G6047) and blocked with 5% skim milk powder for 2 h, after which diluted primary antibodies were added. The mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed three times with TBST (Servicebio, G2150), and IgG-HRP-labeled secondary antibody (Abcam, ab6734, 1:5000) was added and incubated for 1 h. The PVDF membrane was placed on a chemiluminescence instrument, and the target band was developed and exposed by the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method. The original image of Western blot was shown in the supplementary materials. The gray value of each group of bands was analyzed by ImageJ software.

The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: osteocalcin (OCN, Abcam, ab93876, 1:1000), BMP-2 (Abcam, ab284387, 1:1000), Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2, Abcam, ab192256, 1:2000), Osterix (Abcam, ab209484, 1:1000), OPN (Abcam, ab11503, 1:1000), AMPK (Abcam, ab105028, 1:1000), p-AMPK Thr172 (Abcam, ab314032, 1:5000), and GAPDH (Abcam, ab181603, 1:10,000).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) software. All the data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test were used for comparisons between groups. The data from each group are expressed as the means ± standard deviations. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 Identification of Primary BMSCs Isolated from Rats

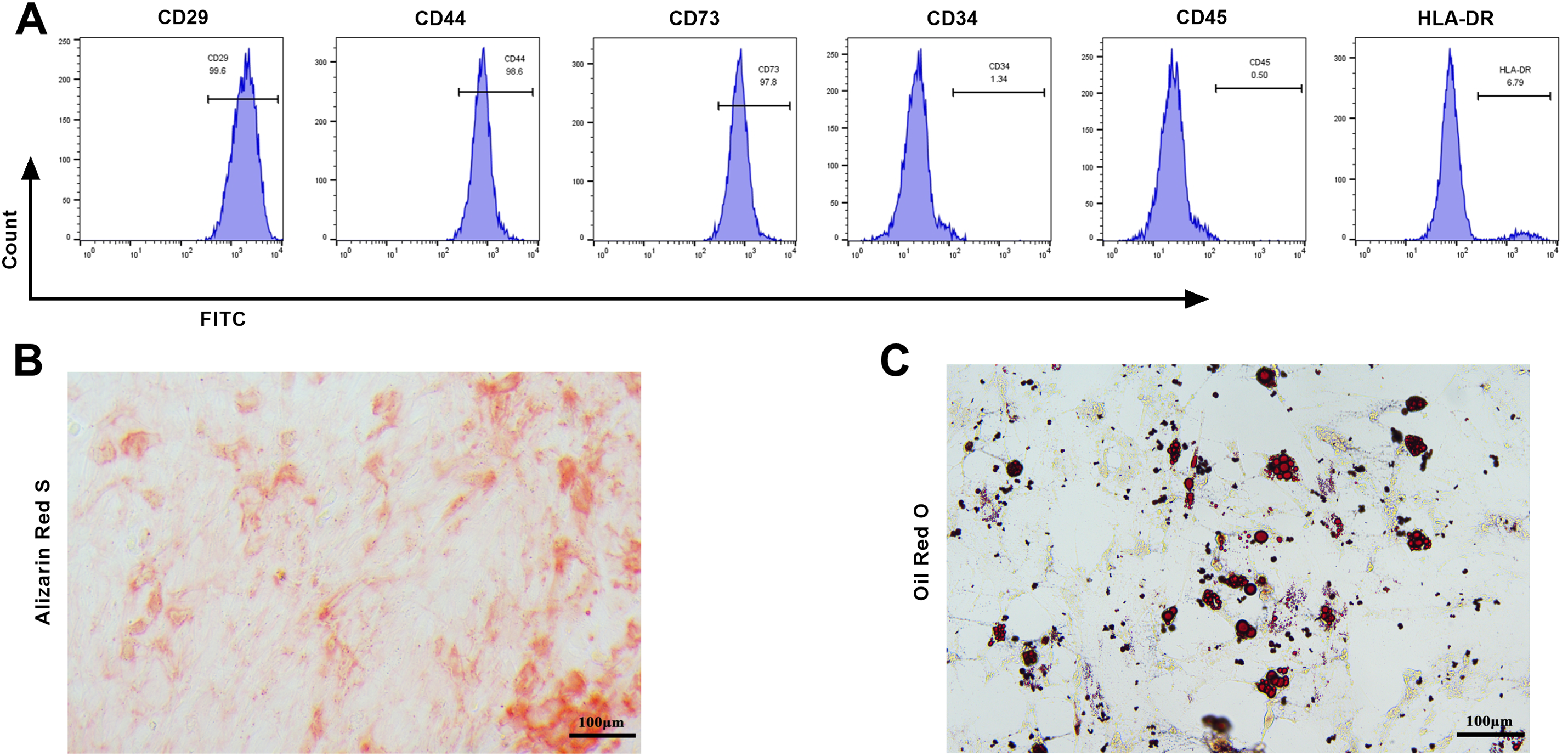

Primary BMSCs were isolated and extracted under normal culture conditions. After the first change of culture medium, the cells were round and evenly covered the bottom of the bottle. After 72 h of culture, the rat BMSCs extended pseudopodia, most of the cells were spindle shaped, and a small number of cells grew into polygonal colonies and merged into a single-cell layer. The surface markers of the BMSCs (CD29, CD44, and CD73) were positive for the third-generation BMSCs surface antigen, and the percents of expression were 99.6%, 98.6%, and 97.8%, respectively; the hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR) were negative, and the percentages of expression were 1.34%, 0.50%, and 6.79%, respectively (Fig. 1A). These results indicated that the extracted cells were rat BMSCs. Osteogenic differentiation was an important characteristic of BMSCs. When BMSCs were exposed to osteogenic induction medium, they could differentiate into osteoblasts. ARS could form purple or red complexes with calcium ions, which could be used to evaluate the osteogenic effect [28]. ARS staining revealed that osteogenic differentiation induced more red-stained calcified nodules in the BMSCs (Fig. 1B). After the adipogenic induction of BMSCs, red lipid droplets stained with oil red O working solution were observed (Fig. 1C), indicating that the BMSCs were induced into adipocytes.

Figure 1: Identification of original bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs). (A) Flow cytometry was used to detect BMSCs’ surface markers CD29, CD44, CD73, and hematopoietic surface markers CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR. The BMSCs’ surface markers of the third generation of BMSCs were positive, and the hematopoietic surface markers were negative; (B) The osteogenic differentiation ability was evaluated by Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining, and red-stained calcified nodules were observed (×20, 100 μm); (C) The adipogenic differentiation capacity in BMSCs was evaluated by oil red O staining, and red lipid droplets were observed (×20, 100 μm). n = 3

3.2 BMP-2 Promoted the Osteogenic Differentiation of BMSCs

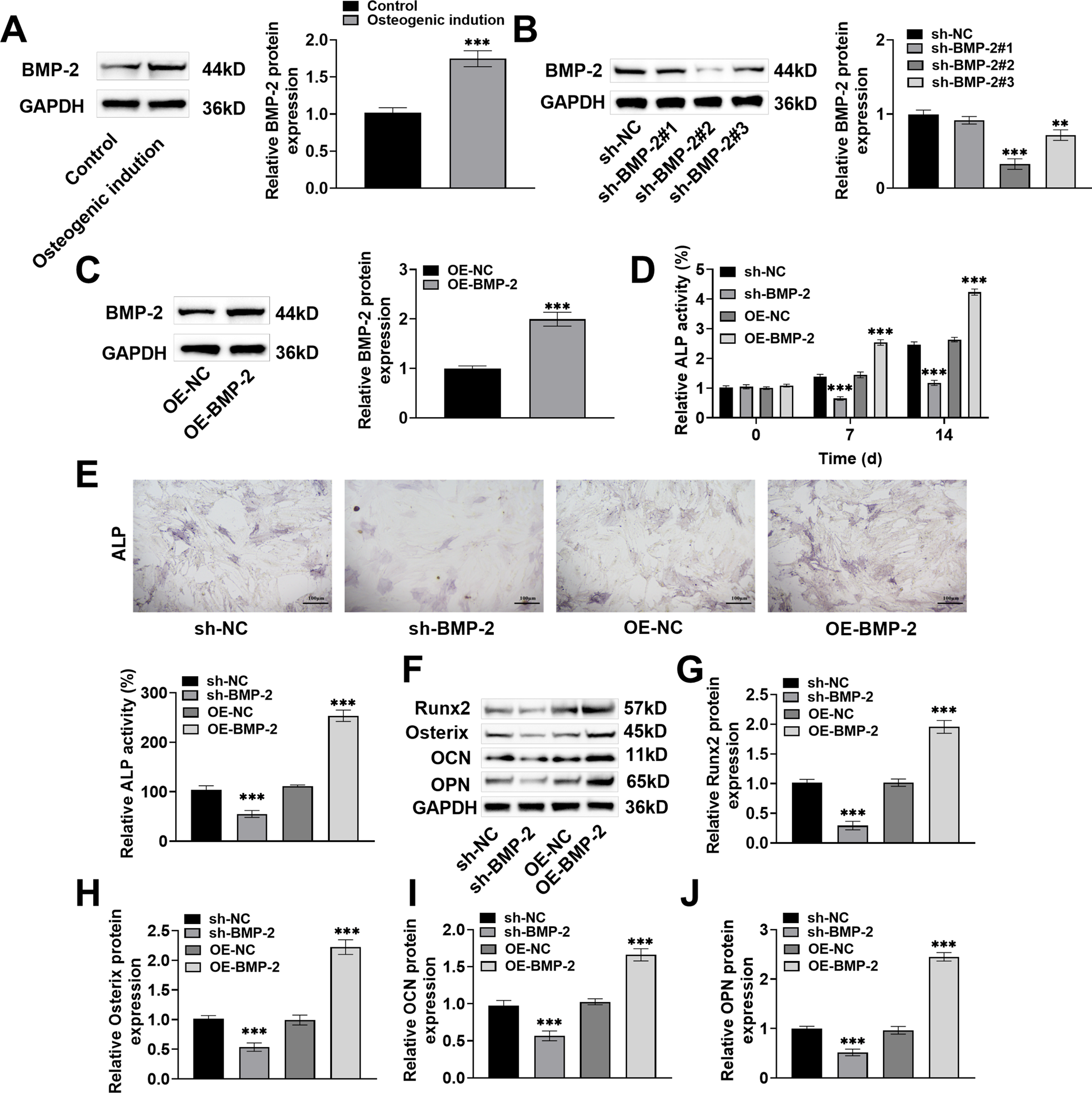

The expression of BMP-2 protein increased markedly after osteogenic induction (increased by 1.75 times, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A), suggesting that BMP-2 might have a regulatory effect on the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Next, sh-BMP-2 and OE-BMP-2 were transfected into BMSCs. sh-BMP-2#2 and #3 markedly decreased the BMP-2 level in the BMSCs, whereas OE-BMP-2 significantly increased the BMP-2 level in the BMSCs (Fig. 2B,C), indicating that BMP-2 was successfully knocked down and overexpressed. The knockdown effect of sh-BMP-2#2 was the greatest; therefore, this plasmid was selected for subsequent knockdown experiments. In addition, ALP was a marker of the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. In BMSCs cultured for 7 days or 14 days, ALP activity decreased significantly after BMP-2 knockdown (7 day: decreased to 0.65%, 14 day: decreased to 1.18%, p < 0.001) and increased significantly after BMP-2 overexpression (7 day: increased to 2.54%, 14 day: increased to 4.24%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2D). After 7 days of osteogenic induction, quantitative analysis of ALP-stained areas revealed that blue–black particles and the expression and activity of ALP in BMSCs were significantly reduced after BMP-2 knockdown (decreased to 55.19%, p < 0.001) and significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression (increased to 253.64%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2E). Finally, the Western blot results revealed that the expressions of Runx2, Osterix, OCN, and OPN decreased significantly after BMP-2 knockdown (p < 0.001) and increased significantly after BMP-2 overexpression (p < 0.001) in the BMSCs on Day 14 of osteogenic induction culture (Fig. 2F–J). These increased expressions of bone formation markers indicated that BMP-2 increased the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs.

Figure 2: Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) promoted osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. (A) BMP-2 protein in osteogenic induced BMSCs was discovered with Western blot, and it was markedly increased; (B,C) The sh-BMP-2 and OE-BMP-2 were transfected into BMSCs by adenovirus vector, and the efficiencies of BMP-2 knockdown and overexpression were detected by Western blot. BMP-2 was successfully knocked down and overexpressed; (D) The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity kit was used to detect the ALP activity after 7 and 14 days of osteogenic differentiation. BMP-2 overexpression significantly increased ALP activity; (E) ALP activity after 7 days of osteogenic differentiation was tested by ALP staining. BMP-2 overexpression significantly increased ALP activity (×20, 100 μm); (F) Western blot was performed to measure osteogenic differentiation marker proteins in BMSCs after 14 days of osteogenic induction; (G) Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2); (H) Osterix; (I) Osteocalcin (OCN), and (J) Osteopontin (OPN) expressions were significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression. n = 3, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

3.3 BMP-2 Inhibited the BMSCs Inflammatory Response through the AMPK Signaling Pathway

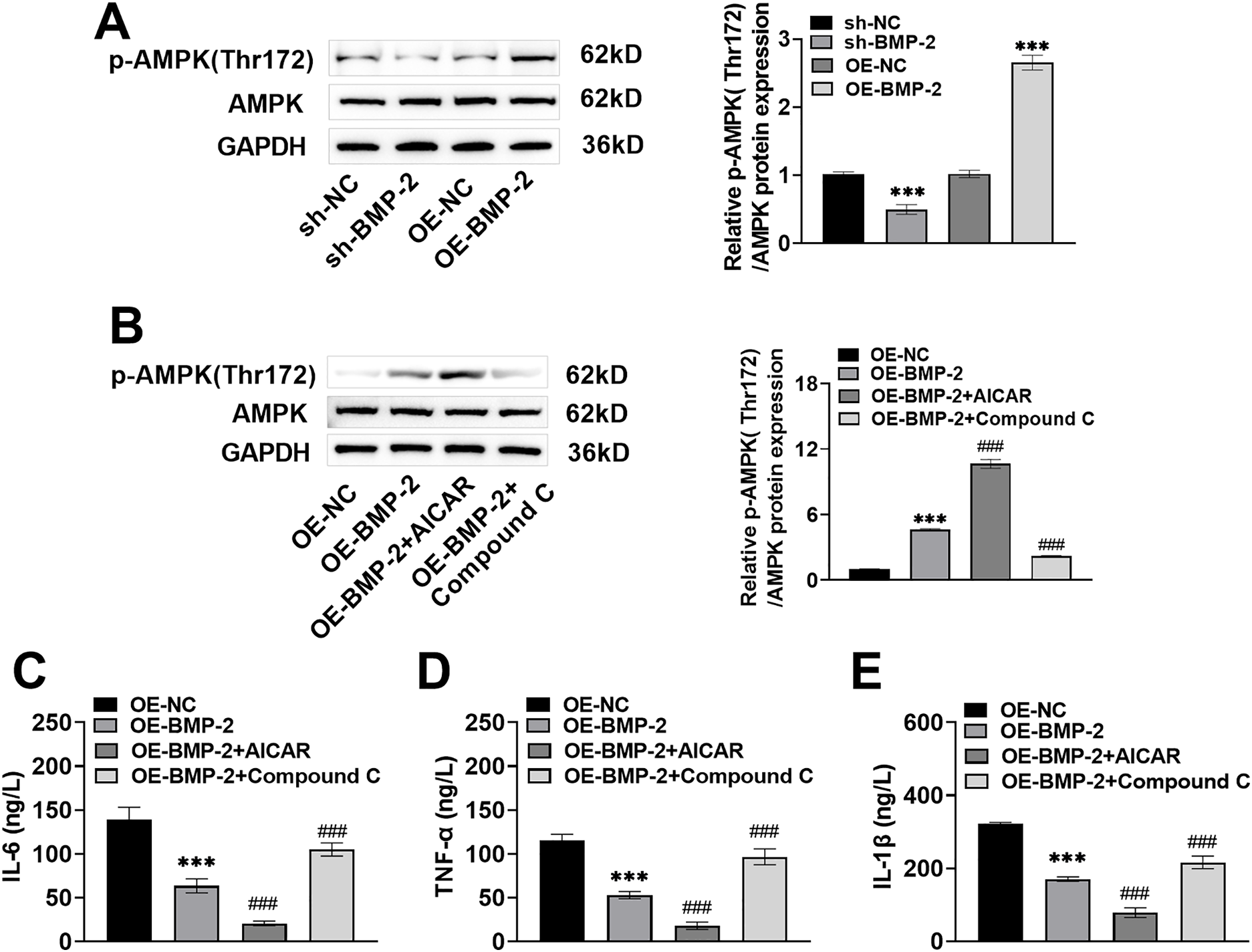

Activation of the AMPK signaling pathway promoted the differentiation of osteoblasts [29,30]. In this study, after 14 days of osteogenic induction of BMSCs, the p-AMPK Thr172 protein level decreased significantly after BMP-2 knockdown and increased significantly after BMP-2 overexpression (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the AMPK signaling pathway might play a regulatory role in the ability of BMP-2 to promote the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. After 48 h of OE-BMP-2 transfection, the BMSCs were treated with the AMPK signaling agonist AICAR and the inhibitor Compound C. Compared with BMP-2 overexpression, AICAR increased the expression of p-AMPK Thr172 protein, and Compound C decreased the expression of p-AMPK Thr172 protein (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). These findings indicated that BMP-2 activated the AMPK signaling pathway. The AMPK signaling pathway regulates inflammation and immunity, contributing to cell differentiation [31]. After 14 days of osteogenic differentiation, the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in the BMSCs were significantly decreased after BMP-2 overexpression. Compared with those in BMP-2-overexpressing cells, the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were significantly lower after AICAR intervention and significantly greater after Compound C intervention (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3C–E). These findings indicated that BMP-2 inhibited the inflammatory response of BMSCs through the AMPK signaling pathway.

Figure 3: BMP-2 inhibited BMSCs inflammatory response through the AMPK signaling pathway. (A) The AMPK signaling pathway proteins in BMSCs, when 14 days of osteogenic differentiation were measured by Western blot, the expression of p-AMPK Thr172 was significantly raised after BMP-2 overexpression. (B) After 48 h of OE-BMP-2 transfection, BMSCs were treated with AMPK signal agonist 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) and inhibitor Compound C for 12 h. The AMPK signaling pathway proteins were detected by Western blot. p-AMPK Thr172 level increased significantly after AICAR intervention and decreased significantly after Compound C intervention. (C–E) The contents of inflammatory factors in BMSCs when 14 days of osteogenic differentiation, were detected by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β contents were markedly lowered after BMP-2 overexpression. n = 3, ***p < 0.001 vs. OE-NC/sh-NC group; ###p < 0.001 vs. OE-BMP-2 group

3.4 BMP-2 Promoted the Osteogenic Differentiation of MSCs through the AMPK Signaling Pathway

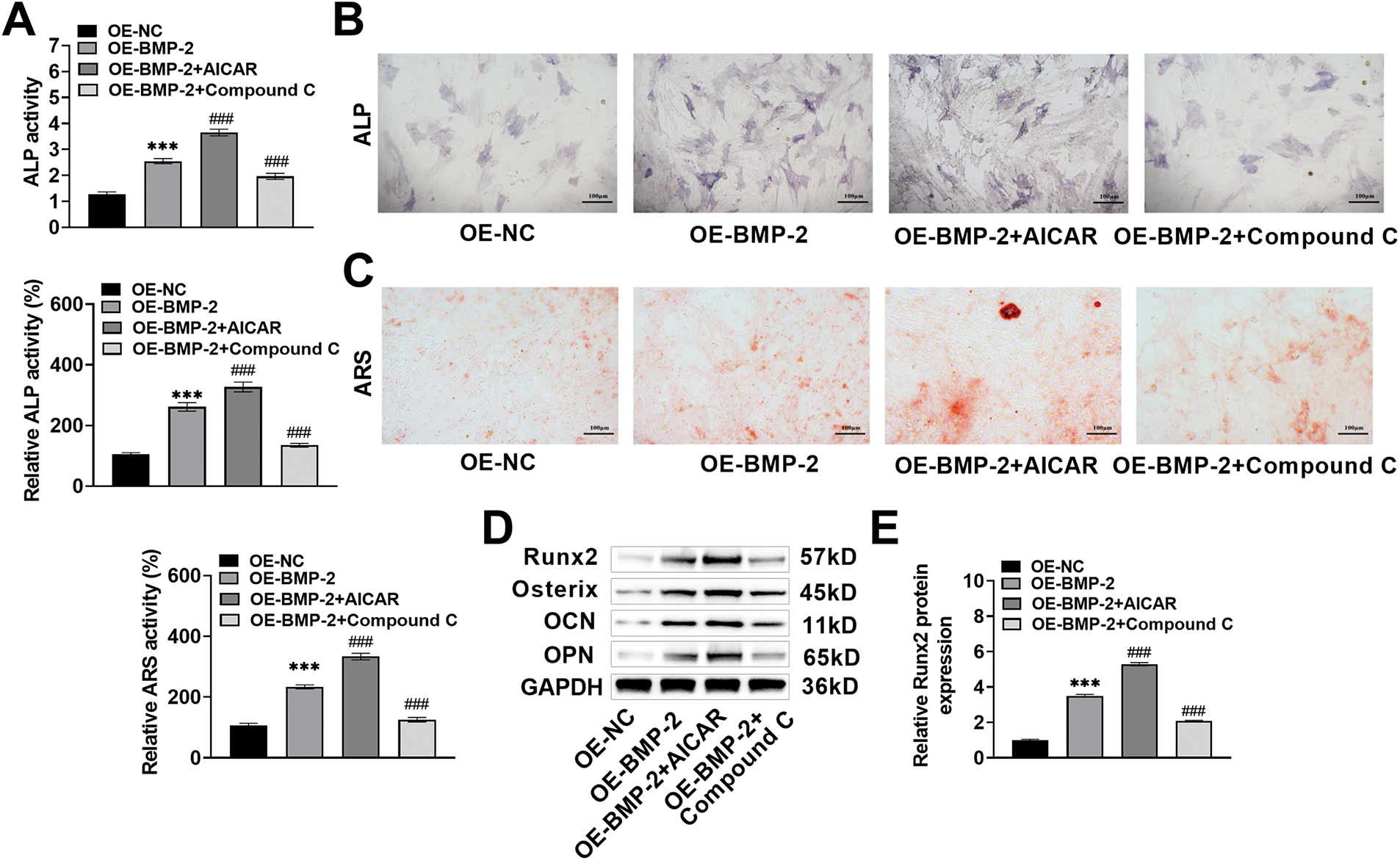

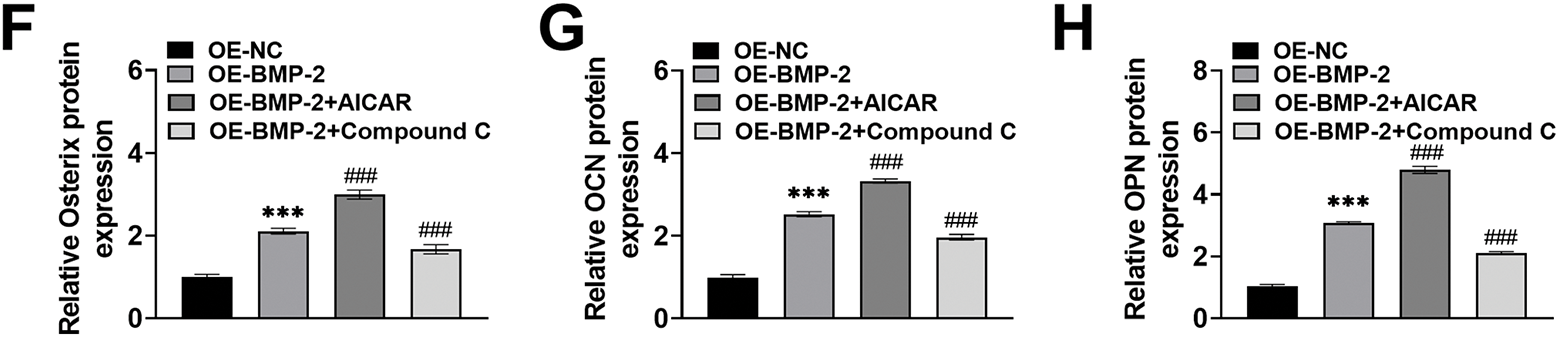

Compared with those in the BMP-2-overexpressing BMSCs, gray–blue granules and the expression and activity of ALP in the BMSCs increased significantly after AICAR intervention (increased to 3.65% and 326.98%, p < 0.001) and decreased significantly after Compound C intervention (decreased to 1.96% and 134.85%, p < 0.001) and osteogenic induction for 7 days (Fig. 4A,B). ARS staining revealed that after AICAR treatment, there were more ARS-specific red-stained calcified nodules, the degree of staining was greater, the red-stained plaque area was greater, the area increased to 333.56%, and the calcified nodule formation ability was greater. After Compound C treatment, fewer red-stained calcified nodules were observed, the red-stained plaque area was smaller, which was reduced to 125.49%, and the ability to form calcified nodules was weaker (Fig. 4C), indicating that BMP-2 promoted mineralized nodule formation in BMSCs. Finally, the expressions of Runx2, Osterix, OCN, and OPN in the BMSCs on Day 14 of osteogenic differentiation culture were notably increased after AICAR intervention and significantly decreased after Compound C intervention (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4D–H). These results indicated that BMP-2 improved the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs through the AMPK signaling pathway.

Figure 4: BMP-2 enhanced osteogenic differentiation in MSCs through the AMPK signaling pathway. (A,B) ALP activity in BMSCs when osteogenic differentiation for 7 days was tested by ALP kit and staining, which increased significantly after AICAR intervention and decreased significantly after Compound C intervention (×20, 100 μm). (C) The mineralization of BMSCs after 14 days of osteogenic induction was measured by ARS staining. AICAR enhanced the ability to form calcified nodules, and Compound C attenuated this ability (×20, 100 μm). (D–H) The osteogenic differentiation marker proteins of BMSCs when 14 days of osteogenic differentiation were detected by Western blot. The expressions of Runx2, Osterix, OCN, and OPN increased significantly after AICAR intervention, and decreased significantly after Compound C intervention. n = 3, ***p < 0.001 vs. OE-NC group; ###p < 0.001 vs. OE-BMP-2 group

3.5 BMP-2 Promoted the Activation of the AMPK Signaling Pathway in the Bone Tissue of Rats with Femoral Fracture and Inhibited the Inflammatory Response

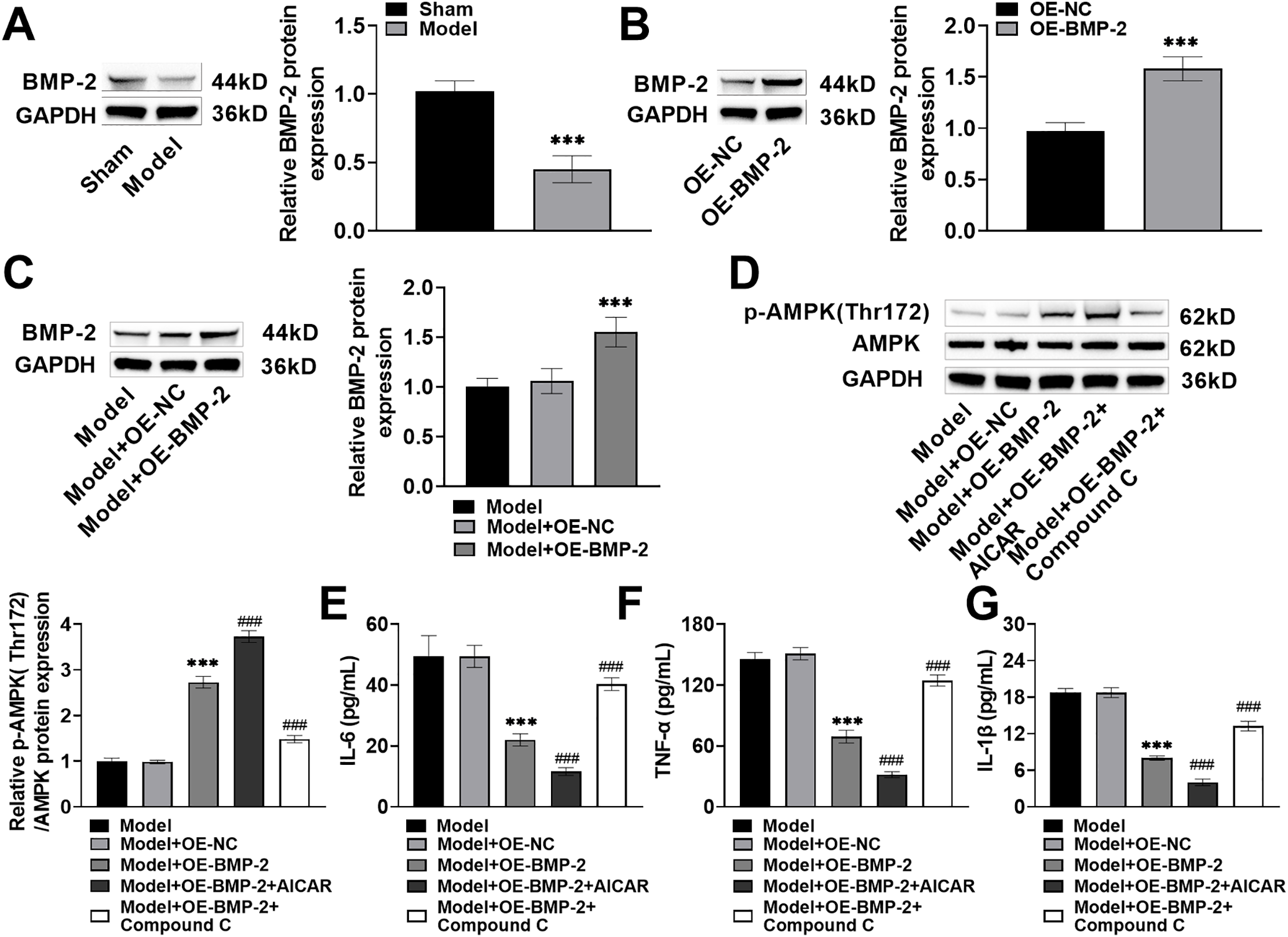

A fracture model was established in rats. AICAR and Compound C were injected intraperitoneally 1 h before modeling, and OE-BMP-2 was injected intraperitoneally for 42 days. The rats were sacrificed, and callosal tissue was collected. The expression of BMP-2 protein was markedly decreased (decreased by 54%, p < 0.001) in rats with femoral fractures (Fig. 5A). After the injection of OE-BMP-2, the expression of BMP-2 in the corpus callosum was significantly increased (increased by 1.58 times, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5B), indicating that BMP-2 was effectively overexpressed in the rats. Compared with those in fractured rats, the expressions of BMP-2 and p-AMPK Thr172 in the corpus callosum were significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression (Fig. 5C,D). Compared with that in BMP-2-overexpressing rats, the p-AMPK Thr172 protein level in the corpus callosum was notably increased after AICAR intervention and significantly decreased after Compound C intervention (Fig. 5D), suggesting that BMP-2 promoted the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway within the bone tissue of rats with femoral fractures. Finally, the IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β contents in rat serum were markedly decreased after BMP-2 overexpression (IL-6: decreased to 22.01 pg/mL; TNF-α: decreased to 69.23 pg/mL; IL-1β: decreased to 8.02 pg/mL, p < 0.001), decreased again after AICAR intervention (IL-6: decreased to 11.58 pg/mL; TNF-α: decreased to 31.73 pg/mL; IL-1β: decreased to 4.02 pg/mL, p < 0.001), and significantly increased after Compound C intervention (IL-6: increased to 40.32 pg/mL; TNF-α: increased to 124.55 pg/mL; IL-1β: increased to 13.26 pg/mL, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5E–G). These results indicated that BMP-2 activated the AMPK signaling pathway in vivo and inhibited the inflammatory response in rats with femoral fractures.

Figure 5: BMP-2 promoted the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway in the bone tissue of rats with femoral fracture and inhibited the inflammatory response. (A) The rat model of femoral fracture was established, and BMP-2 protein in the corpus callosum was detected by Western blot, which was significantly reduced. (B) Rats were intraperitoneally injected with OE-BMP-2 once every 3 days for 42 days. The overexpression efficiency of BMP-2 in the corpus callosum was detected by Western blot. (C) BMP-2 protein in the corpus callosum of rat femoral fracture was detected by Western blot, which was significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression. (D) The AMPK signaling pathway proteins in the corpus callosum of rat femoral fracture were detected by Western blot, and p-AMPK Thr172 level was significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression. (E–G) The contents of inflammatory factors in the serum of rats were detected by an ELISA kit. The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were significantly decreased after BMP-2 overexpression. n = 5, ***p < 0.001 vs. Sham/OE-NC/Model + OE-NC group; ###p < 0.001 vs. Model + OE-BMP-2 group

3.6 BMP-2 Promoted Femoral Fracture Healing and Bone Regeneration in Rats through the AMPK Signaling Pathway

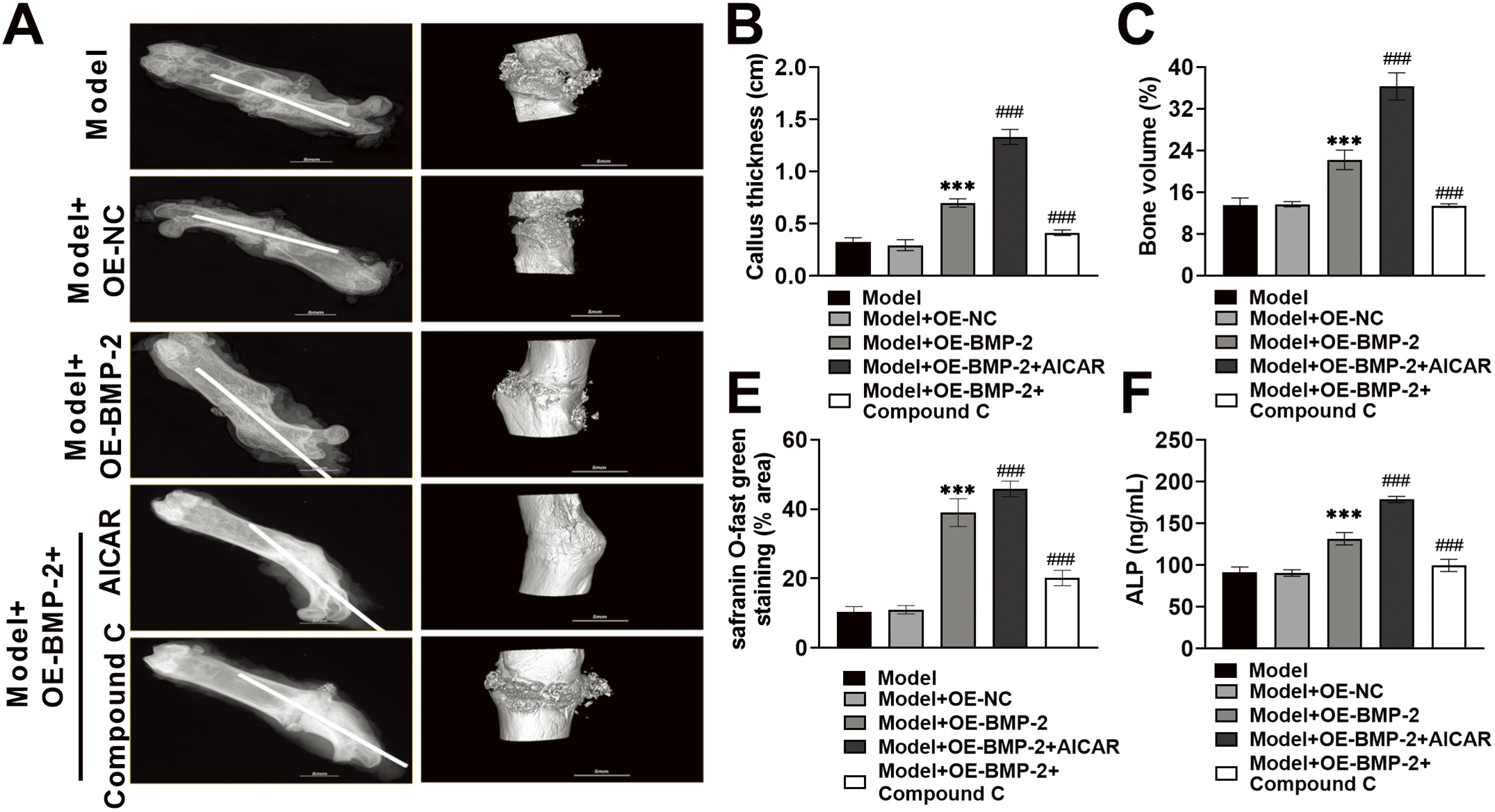

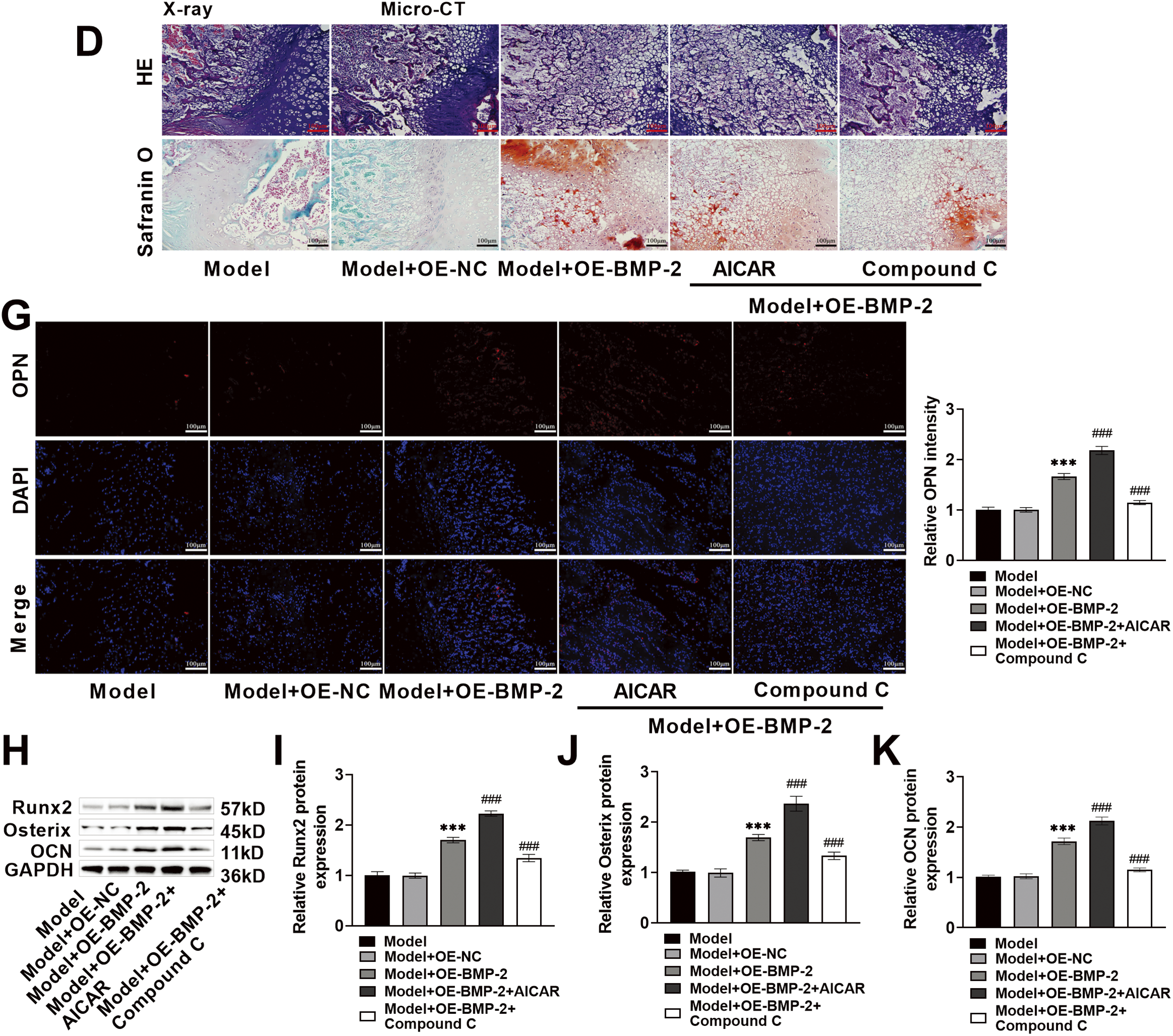

To assess the role of BMP-2 in bone formation through regulation of the AMPK signaling pathway, a rat femoral fracture model was prepared. OE-BMP-2, AICAR, and Compound C were used for intervention, and fracture healing was observed. The results of the X-ray imaging system revealed a very clear fracture line in the rats in the Model group. After BMP-2 overexpression, the fracture line of the rats was blurred, and the thickness of the newly formed callus increased to 0.70 cm. After AICAR intervention, the fracture line of the rats almost disappeared, and the thickness of the callus increased significantly to 1.33 cm. After the Compound C intervention, the fracture line of the rats appeared again, and the thickness of the callus decreased significantly to 0.41 cm (Fig. 6A,B). Micro-CT 3D reconstruction revealed that the mineralization of the femoral fracture end in the Model group was separated, and no callus formation was observed. BMP-2 overexpression promoted callus formation, significantly increasing BV to 22.22%, indicating the presence of newly formed bones. After AICAR intervention, the mineralization of the rat callus was continuous, a callus formed, and the BV further increased to 36.31%, suggesting that there were more newly formed bones; however, after Compound C treatment, callus mineralization and BV decreased in the rats, and BV decreased to 13.42% (Fig. 6A,C). HE staining revealed that the trabecular bone of the femur tissue of the Model group was relatively small, with fewer osteoblasts and a large number of fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. After BMP-2 overexpression, the bone morphology slightly improved, the trabecular bone thickened, the number of osteoblasts increased, and bone healing tissue formed, but inflammatory cell invasion was still present. AICAR significantly improved the arrangement of trabecular bone, and bone regeneration was more active. Compound C weakened the formation of calli (Fig. 6D). Most fractures were repaired by periosteal ossification and endochondral ossification. Therefore, Safranin O-fast green staining was performed. In the Model group, the number of fibrous components in the cartilage matrix increased, the number of membrane-like structures on the cartilage surface significantly decreased, and the number of chondrocytes decreased. The fibrous components in the cartilage matrix of the Model + OE-BMP-2 group and the Model + OE-BMP-2 + AICAR group were reduced, the number of chondrocytes was significantly increased, and the red staining area was significantly increased to 39.04% and 45.84%, and those in the Model + OE-BMP-2 + AICAR group were greater. However, in the Model + OE-BMP-2 + Compound C group, the cartilage fiber composition increased, the number of chondrocytes and the area of red staining decreased, and the area decreased to 20.17% (Fig. 6D,E). These results indicated that BMP-2 improved the structure of trabecular bone, positively affected BV, and promoted bone formation in vivo through the AMPK signaling pathway. In addition, the serum ALP content was significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression (increased to 131.88 ng/mL, p < 0.001) and AICAR intervention (increased to 178.83 ng/mL, p < 0.001), but significantly decreased after Compound C treatment (decreased to 99.89 ng/mL, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6F). The fluorescence intensity of OPN in rat fracture tissue increased significantly after BMP-2 overexpression. However, AICAR significantly increased the fluorescence intensity of OPN, and Compound C significantly reduced the fluorescence intensity of OPN (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6G). The trend in Runx2, Osterix, and OCN protein levels was consistent with the trend in OPN expression (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6H–K). In conclusion, BMP-2 activated the AMPK signaling pathway in vivo, stimulated the expression of osteogenic factors, and promoted the healing of femoral fractures in rats.

Figure 6: BMP-2 promoted femoral fracture healing and bone regeneration in rats through the AMPK signaling pathway. (A,B) The newly formed bones in the fourth week of fracture in rats were photographed by an X-ray imaging system. BMP-2 overexpression blurred the fracture line of rats and increased the thickness of the newly formed callus. (A,C) Micro-CT recorded BV at the 4th week of fracture in rats, and BMP-2 overexpression significantly increased BV. (D,E) The conditions of the fracture site were observed by Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. After BMP-2 overexpression, the number of osteoblasts increased, and bone healing tissue was formed. The cartilage at the fracture site was observed by Safranin O-fast green staining. After BMP-2 overexpression, the fibrous components in the cartilage matrix decreased, and the number of chondrocytes increased significantly (×20, 100 μm). (F) ALP content was detected by ELISA, which was significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression. (G) The expression of OPN in the corpus callosum of rat femoral fracture was detected by immunofluorescence, and the fluorescence intensity of OPN was significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression (×20, 100 μm). (H–K) The expressions of Runx2, Osterix, and OCN proteins in the corpus callosum of rat femoral fracture were detected by Western blot. They increased significantly after BMP-2 overexpression. n = 5, ***p < 0.001 vs. Model + OE-NC group; ###p < 0.001 vs. Model + OE-BMP-2 group

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have suggested that stem cell transplantation is a new method for bone defect therapy. BMSCs have become an important tool for studying the role of pathways in osteoblast differentiation [32,33]. The fate of BMSCs in the direction of osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation significantly affects bone health [34]. Osteoblasts produce extracellular protein combinations that constitute the main components of bone [35]. Elucidating the detailed mechanism regulating osteoblast differentiation and function is highly important for the clinical application of bone defect treatment. In this study, BMSCs were isolated from rat bone marrow, and their cell types were identified by surface marker determination and induced differentiation. The results revealed that the BMSC’ surface markers (CD29, CD44, and CD73) of the third-generation cells were positive, whereas the hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR) were negative, indicating high purity and good osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation potential, suggesting that the BMSCs were successfully isolated. It has been reported that appropriately induced BMSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts and release a variety of osteogenic active factors that have potential efficacy in the treatment of bone defects [36]. Thus, exploring the potential molecular mechanisms regulating BMSCs osteogenic differentiation is vital for improving the treatment of bone diseases.

The osteogenic process of BMSCs is affected by many factors, such as drugs, hormones, and cytokines. Therefore, the regulation of the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by related factors can provide novel strategies for fracture treatment. ALP is a functional enzyme of osteoblasts that can be used to reflect bone cell activity and bone turnover [37]. ALP activity and the formation of mineralized nodules are markers of osteoblast differentiation and are also important indicators of the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Runx2 is a member of the Runt transcription factor homologous family, which is highly important for regulating osteoblast differentiation [38]. Runx2 activates ALP, OPN, and OCN expression and promotes bone formation [39]. The upregulation of its expression marks the beginning of osteogenic differentiation and guides BMSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts [40]. Moreover, Osterix is vital for the regulation of the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Osterix combines with osteogenic markers such as OPN and OCN through acetylation and acts on downstream targets to regulate the differentiation and maturation of osteoblasts; on the other hand, Osterix inhibits bone resorption to maintain bone homeostasis by participating in the regulation of osteoclast differentiation [41]. In addition, OPN is a common osteogenic differentiation-related protein that is usually expressed during the process of bone formation in mature osteoblasts. It can stimulate the adhesion, proliferation, and calcification of osteoblasts [42]. OPN is widely distributed in tissues and cells. It is one of the predictors of bone formation and development. It is also a marker of specific expression in osteoblasts and is usually used as a marker of bone formation [43,44].

In recent years, the use of gene-modified cell transplantation therapy has made significant progress in promoting bone cell growth and stimulating bone regeneration, providing a promising treatment option for patients with bone lesions. Recent studies have shown that BMPs are key factors in regulating osteoblast differentiation. In particular, BMP-2 can significantly increase the expression of ALP and OCN in cells [45]. BMP-2 is the main bone morphogenetic protein in the body and can stimulate DNA synthesis and cell replication, promote the differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts, expand osteoblast proliferation, induce cartilage and bone formation in the body, and participate in the fracture healing process [46]. Therefore, long-term induction of the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by BMP-2 and subsequent reconstruction of bone defects may constitute an effective method for bone defect repair. In this study, BMP-2 was significantly highly expressed in osteogenic-induced BMSCs. After BMP-2 overexpression, the activity of ALP and the expressions of Runx2, Osterix, OCN, and OPN in BMSCs increased significantly, suggesting that BMP-2 promoted the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs. Therefore, BMP-2 could be an effective target for bone defect therapy.

AMPK is an energy sensor that maintains the intracellular energy balance. AMPK is key to promote bone formation and bone differentiation [19]. The AMPK signaling pathway participates in regulating the osteogenic differentiation process in BMSCs [47]. When it is inactivated, it causes the downregulation of ALP and osteocalcin expression and bone formation disorders [48]. Metformin has been reported to activate the AMPK signaling pathway in a dose-dependent manner, increasing osteoblast activity, mineralization, ALP and OCN secretion, and BMP-2 expression [19]. Therefore, this study further detected the expression of the AMPK signaling pathway in BMSCs and revealed that the p-AMPK Thr172 protein level significantly decreased after BMP-2 knockdown and significantly increased after BMP-2 overexpression. Therefore, the ability of BMP-2 to promote the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs might be achieved by activating the AMPK signaling pathway. The osteogenic ability of the BMSCs was assessed by ALP staining. The number of calcium nodules was measured by ARS staining. These two staining methods indicated that the AMPK signal agonist AICAR increased ALP activity and bone mineralization and promoted the expressions of osteogenic differentiation marker proteins. Therefore, the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway promoted the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. The AMPK signal inhibitor Compound C had a certain inhibitory effect on the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Therefore, these findings demonstrate that BMP-2 promotes the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs through the AMPK signaling pathway.

The decrease in the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs may be related to the inflammatory response. TNF-α and IL-6 have been shown to inhibit the differentiation of MSCs into osteoblasts and contribute to the pathogenesis of various bone diseases by disrupting the balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts [49,50]. EVs derived from rat BMSCs can reduce IL-6 and TNF-α levels in an inflammatory environment [51]. Moreover, IL-1β inhibits the expressions of Runx2 and collagen in BMSCs and inhibits mouse BMSCs differentiation. By binding to the α subunit of AMPK, Compound C interferes with the phosphorylation process of AMPK, thereby inhibiting AMPK. Previous studies have shown that Compound C can play a proinflammatory role. Li et al. reported that Compound C promoted the secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β induced by LPS [52]. In this study, the IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β contents were notably decreased when BMP-2 was overexpressed. However, with AICAR, the concentrations of inflammatory factors were further reduced, and Compound C increased the concentrations of inflammatory factors. In summary, these findings demonstrate that BMP-2 inhibits the inflammatory response of BMSCs by activating the AMPK signaling pathway.

Fracture healing can be roughly divided into three stages: the hematoma inflammation stage, the callus formation stage, and the bone plate formation molding stage. During the inflammation stage, symptoms such as pain, tissue swelling, and dysfunction occur, and severe bone cracks develop. Therefore, eliminating hematoma inflammation and promoting callus formation are important factors that promote fracture healing. Inflammatory stimulation can lead to bone tissue deposition, continuous proliferation of fibroblasts, and thickening of the vascular wall of the tissue, affecting the differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts and resulting in delayed fracture healing. In this study, we established a rat model of femoral fracture and found that the expression of BMP-2 was significantly reduced in fracture tissue. When BMP-2 was overexpressed, the p-AMPK Thr172 level increased significantly, and the concentrations of inflammatory factors decreased significantly. In this study, an animal X-ray imaging system and micro-CT revealed that BMP-2 promoted the healing of femoral fractures. BMP-2 overexpression increased the thickness of newly formed calli and significantly increased the BV. Staining for pathology revealed that the fibroblasts and inflammatory cells at the broken end of the femur in the Model group were significantly aggregated, the number of osteoblasts was lower, the number of fibrous components in the cartilage matrix was greater, the number of membrane-like structures on the cartilage surface was significantly destroyed, and the number of chondrocytes was lower. After BMP-2 overexpression, the number of inflammatory cells decreased, bone trabecula formation increased, and the number of fibrous components in the cartilage matrix decreased, indicating that BMP-2 promoted the formation of calli and accelerated fracture healing. Bone formation was the final stage of fracture healing. In this study, after BMP-2 overexpression, the content of ALP in the serum and the protein expressions of Runx2, Osterix, OPN, and OCN in the fractured corpus callosum were significantly increased, indicating that bone formation was ongoing, which was consistent with the characteristics of osteogenesis, suggesting that BMP-2 promoted fracture healing. AICAR enhanced the fracture healing promoted by BMP-2, whereas Compound C inhibited it. These results indicate that BMP-2 inhibits the inflammatory response through the AMPK signaling pathway and promotes femoral fracture healing in rats.

However, this study also has several limitations. Only BMSCs were used as targets of BMP-2 after osteoblast differentiation in vitro. The differentiation of osteoclasts and chondrocytes is lacking. Moreover, these experiments focused on the detection of osteogenic-related indicators, and research on related phenotypes, such as bone resorption and adipogenic differentiation, was not explored in depth. Future experiments should further explore the molecular mechanisms of other phenotypes on this basis. Although the expression of BMP-2 in rat bone tissue and related indices of inflammation and bone regeneration were assessed in this study, whether BMP-2 could specifically target BMSCs in vivo remains to be verified. In subsequent experiments, BMP-2 will be modulated by direct transplantation or an adeno-associated virus carrying a BMSC-specific gene promoter, which will directly act on the local fracture tissue. In addition, the pathogenesis of fracture involves complex and diverse key proteins and signaling pathways. In the future, the interactions between related molecular pathways in the treatment of fractures by BMP-2 should be further clarified to provide a more comprehensive scientific basis for fracture treatment.

In summary, this study revealed that BMP-2 improved the ability of BMSCs to undergo osteogenic differentiation, stimulated the expression of osteogenic factors, inhibited the inflammatory response, and promoted the healing of femoral fractures in rats. The underlying mechanism involved the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway. It lays an experimental foundation for the clinical treatment of fractures. Therefore, BMP-2 may be a candidate target for fracture therapy.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Qinghai Province Natural Science Foundation Youth Project Grant No. 2022-ZJ-968Q.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Yong Huang, Xiandeng Li; data collection: Qingling Jing, Qin Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Yong Huang, Chungui Huang; draft manuscript preparation: Yong Huang, Chungui Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved from Qing Hai University Affiliated Hospital’s ethics review board (P-SL-202204).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| AMPK | 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| ARS | Alizarin Red S |

| BMP-2 | Bone morphogenetic protein-2 |

| BMPs | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| BMSCs | Bonemarrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| BV | Bone volume |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| HLA-DR | Human leukocyte antigen-DR |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| Runx2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

1. Hellwinkel JE, Working ZM, Certain L, García AJ, Wenke JC, Bahney CS. The intersection of fracture healing and infection: orthopaedics research society workshop 2021. J Orthop Res. 2022;40(3):541–52. doi:10.1002/jor.25261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Panteli M, Vun JSH, Pountos I, Howard AJ, Jones E, Giannoudis PV. Biological and molecular profile of fracture non-union tissue: a systematic review and an update on current insights. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26(3):601–23. doi:10.1111/jcmm.17096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. ElHawary H, Baradaran A, Abi-Rafeh J, Vorstenbosch J, Xu L, Efanov JI. Bone healing and inflammation: principles of fracture and repair. Semin Plast Surg. 2021;35(3):198–203. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1732334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Murphy SC, Murphy B, O’Loughlin P. Syndesmotic injury with ankle fracture: a systematic review of screw vs. dynamic fixation. Ir J Med Sci. 2024;193(3):1323–30. doi:10.1007/s11845-024-03619-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Purwaningrum M, Jamilah NS, Purbantoro SD, Sawangmake C, Nantavisai S. Comparative characteristic study from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Vet Sci. 2021;22(6):e74. doi:10.4142/jvs.2021.22.e74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang W, Chen Q, Ye Y, Zou B, Liu Y, Cheng L, et al. AntagomiR-199a enhances the liver protective effect of hypoxia-preconditioned BM-MSCs in a rat model of reduced-size liver transplantation. Transplant. 2020;104(1):61–71. doi:10.1097/tp.0000000000002928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wang J, Liu S, Li J, Zhao S, Yi Z. Roles for miRNAs in osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):197. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1309-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sun Q, Zhang C, Hu G, Zhu K, Zheng S. Albiflorin improves osteoporotic bone regeneration by promoting osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2025;754:151551. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2025.151551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Nazir S, Maqbool T, Savas S. Cardiac repair and mesenchymal stem cells: exploring new frontiers in regenerative medicine. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2025. doi:10.2174/011573403x376065250728094646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lin Z, He H, Wang M, Liang J. MicroRNA-130a controls bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards the osteoblastic and adipogenic fate. Cell Prolif. 2019;52(6):e12688. doi:10.1111/cpr.12688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Song W, Bo X, Ma X, Hou K, Li D, Geng W, et al. Craniomaxillofacial derived bone marrow mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (BMSCs) for craniomaxillofacial bone tissue engineering: a literature review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;123(6):e650–9. doi:10.1016/j.jormas.2022.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sun K, Lin H, Tang Y, Xiang S, Xue J, Yin W, et al. Injectable BMP-2 gene-activated scaffold for the repair of cranial bone defect in mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020;9(12):1631–42. doi:10.1002/sctm.19-0315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kostiv RE, Matveeva NY, Kalinichenko SG. Localization of VEGF, TGF-β1, BMP-2, and apoptosis factors in hypertrophic nonunion of human tubular bones. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2022;173(1):160–8. doi:10.1007/s10517-022-05513-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Du J, Sun J, Wen Z, Wu Z, Li Q, Xia Y, et al. Serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels are correlated with disease severity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Lab Med. 2022;53(2):149–55. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmab029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao WB, Lin KR, Xu QF. Correlation of serum IL-6, TNF-α levels and disease activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2024;28(1):80–9. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202401_34893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ingwersen LC, Frank M, Naujokat H, Loger K, Bader R, Jonitz-Heincke A. BMP-2 long-term stimulation of human pre-osteoblasts induces osteogenic differentiation and promotes transdifferentiation and bone remodeling processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6):3077. doi:10.3390/ijms23063077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Cui Y, Chen J, Zhang Z, Shi H, Sun W, Yi Q. The role of AMPK in macrophage metabolism, function and polarisation. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):892. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04772-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Li RZ, Guan XX, Wang XR, Bao W-Q, Lian L-R, Choi SW, et al. Sinomenine hydrochloride bidirectionally inhibits progression of tumor and autoimmune diseases by regulating AMPK pathway. Phytomedicine. 2023;114:154751. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ren C, Hao X, Wang L, Hu Y, Meng L, Zheng S, et al. Metformin carbon dots for promoting periodontal bone regeneration via activation of ERK/AMPK pathway. Adv Heal Mater. 2021;10(12):e2100196. doi:10.1002/adhm.202100196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Shao H, Wu R, Cao L, Gu H, Chai F. Trelagliptin stimulates osteoblastic differentiation by increasing runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2a therapeutic implication in osteoporosis. Bioeng. 2021;12(1):960–8. doi:10.1080/21655979.2021.1900633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kanazawa I, Takeno A, Tanaka KI, Notsu M, Sugimoto T. Osteoblast AMP-activated protein kinase regulates postnatal skeletal development in male mice. Endocrinol. 2018;159(2):597–608. doi:10.1210/en.2017-00357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Han Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Han Y, Chang F, Ding J. Mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine. Cells. 2019;8(8):886. doi:10.3390/cells8080886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang C, Wang X, Cheng H, Fang J. MiR-22-3p facilitates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell osteogenesis and fracture healing through the SOSTDC1-PI3K/AKT pathway. Int J Exp Pathol. 2024;105(2):52–63. doi:10.1111/iep.12500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Li Y, Fu G, Gong Y, Li B, Li W, Liu D, et al. BMP-2 promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by enhancing mitochondrial activity. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2022;22(1):123–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Wang N, Wang L, Yang J, Wang Z, Cheng L. Quercetin promotes osteogenic differentiation and antioxidant responses of mouse bone mesenchymal stem cells through activation of the AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 2021;35(5):2639–50. doi:10.1002/ptr.7010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Pan FF, Shao J, Shi CJ, Li ZP, Fu WM, Zhang JF. Apigenin promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and accelerates bone fracture healing via activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021;320(4):E760–71. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00543.2019 d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Shin MR, Kim HY, Choi HY, Park KS, Choi HJ, Roh SS. Boswellia serrata extract, 5-loxin®, prevents joint pain and cartilage degeneration in a rat model of osteoarthritis through inhibition of inflammatory responses and restoration of matrix homeostasis. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2022;2022(1):3067526. doi:10.1155/2022/3067526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Qu G, Li Y, Chen L, Chen Q, Zou D, Yang C, et al. Comparison of osteogenic differentiation potential of human dental-derived stem cells isolated from dental pulp, periodontal ligament, dental follicle, and alveolar bone. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021(1):6631905. doi:10.1155/2021/6631905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Fu S, Yan M, Fan Q, Xu J. Salidroside promotes osteoblast proliferation and differentiation via the activation of AMPK to inhibit bone resorption of knee osteoarthritis mice. Tissue Cell. 2022;79:101917. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2022.101917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou L, Sun S, Zhang T, Yu Y, Xu L, Li H, et al. ATP-binding cassette g1 regulates osteogenesis via Wnt/β-catenin and AMPK signaling pathways. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(10):7439–49. doi:10.1007/s11033-020-05800-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Tong X, Ganta RR, Liu Z. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates autophagy, inflammation and immunity and contributes to osteoclast differentiation and functionabs. Biol Cell. 2020;112(9):251–64. doi:10.1111/boc.202000008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hu M, Xing L, Zhang L, Liu F, Wang S, Xie Y, et al. NAP1L2 drives mesenchymal stem cell senescence and suppresses osteogenic differentiation. Aging Cell. 2022;21(2):e13551. doi:10.1111/acel.13551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Gholami Farashah MS, Mohammadi A, Javadi M, Soleimani Rad J, Shakouri SK, Meshgi S, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells’ osteogenic potential: superiority or non-superiority to other sources of mesenchymal stem cells? Cell Tissue Bank. 2023;24(3):663–81. doi:10.1007/s10561-022-10066-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. He M, Lei H, He X, Liu Y, Wang A, Ren Z, et al. METTL14 regulates osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via inducing autophagy through m6A/IGF2BPs/Beclin-1 signal Axis. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2022;11(9):987–1001. doi:10.1093/stcltm/szac049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zujur D, Kanke K, Onodera S, Tani S, Lai J, Azuma T, et al. Stepwise strategy for generating osteoblasts from human pluripotent stem cells under fully defined xeno-free conditions with small-molecule inducers. Regen Ther. 2020;14:19–31. doi:10.1016/j.reth.2019.12.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yu H, Cheng J, Shi W, Ren B, Zhao F, Shi Y, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote tendon regeneration by facilitating the proliferation and migration of endogenous tendon stem/progenitor cells. Acta Biomater. 2020;106:328–41. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2020.01.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. He L, Zhou Q, Zhang H, Zhao N, Liao L. PF127 hydrogel-based delivery of exosomal ctnnb1 from mesenchymal stem cells induces osteogenic differentiation during the repair of alveolar bone defects. Nanomater. 2023;13(6):1083. doi:10.3390/nano13061083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Amri R, Chelly A, Ayedi M, Rebaii MA, Aifa S, Masmoudi S, et al. RANKL, OPG, and RUNX2 expression and epigenetic modifications in giant cell tumour of bone in 32 patients. Bone Jt Res. 2024;13(2):83–90. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.132.Bjr-2023-0023.R2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Hiew VV, Teoh PL. Collagen modulates the biological characteristics of WJ-MSCs in basal and osteoinduced conditions. Stem Cells Int. 2022;2022(1):2116367. doi:10.1155/2022/2116367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Xu C, Wang A, Zhang L, Yang C, Gao Y, Dong Z, et al. Epithelium-Specific Runx2 knockout mice display junctional epithelium and alveolar bone defects. Oral Dis. 2021;27(5):1292–9. doi:10.1111/odi.13647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu Q, Li M, Wang S, Xiao Z, Xiong Y, Wang G. Recent advances of osterix transcription factor in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:601224. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.601224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bai RJ, Li YS, Zhang FJ. Osteopontin, a bridge links osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1012508. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.1012508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Luo W, Lin Z, Yuan Y, Wu Z, Zhong W, Liu Q. Osteopontin (OPN) alleviates the progression of osteoarthritis by promoting the anabolism of chondrocytes. Genes Dis. 2023;10(4):1714–25. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2022.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Garbe A, Graef F, Appelt J, Schmidt-Bleek K, Jahn D, Lünnemann T, et al. Leptin mediated pathways stabilize posttraumatic insulin and osteocalcin patterns after long bone fracture and concomitant traumatic brain injury and thus influence fracture healing in a combined murine trauma model. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):9144. doi:10.3390/ijms21239144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Liu DD, Zhang CY, Liu Y, Li J, Wang YX, Zheng SG. RUNX2 regulates osteoblast differentiation via the BMP4 signaling pathway. J Dent Res. 2022;101(10):1227–37. doi:10.1177/00220345221093518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Shoji S, Uchida K, Satio W, Sekiguchi H, Inoue G, Miyagi M, et al. Acceleration of bone union by in situ-formed hydrogel containing bone morphogenetic protein-2 in a mouse refractory fracture model. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):426. doi:10.1186/s13018-020-01953-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Yue H, Leng Z, Bo Y, Tian Y, Yan Z, Xue C, et al. Novel peptides from sea cucumber intestinal enzyme hydrolysates promote osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells via phosphorylation of PPARγ at serine 112. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2023;67(9):e2200451. doi:10.1002/mnfr.202200451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. He H, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Xu J, Yang Y, et al. Folic acid attenuates high-fat diet-induced osteoporosis through the AMPK signaling pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:791880. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.791880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Tang J, Wang X, Lin X, Wu C. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: a regulator and carrier for targeting bone-related diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):212. doi:10.1038/s41420-024-01973-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhou B, Chen Q, Zhang Q, Tian W, Chen T, Liu Z. Therapeutic potential of adipose-derived stem cell extracellular vesicles: from inflammation regulation to tissue repair. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15(1):249. doi:10.1186/s13287-024-03863-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Lu X, Xu G, Lin Z, Zou F, Liu S, Zhang Y, et al. Engineered exosomes enriched in netrin-1 modRNA promote axonal growth in spinal cord injury by attenuating inflammation and pyroptosis. Biomater Res. 2023;27(1):3. doi:10.1186/s40824-023-00339-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Li X, Jamal M, Guo P, Jin Z, Zheng F, Song X, et al. Irisin alleviates pulmonary epithelial barrier dysfunction in sepsis-induced acute lung injury via activation of AMPK/SIRT1 pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:109363. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools