Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

ROS Regulation by Natural Products: A Promising Therapeutic Approach for Breast Cancer

1 State Key Laboratory of Southwestern Chinese Medicine Resources, School of Pharmacy, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, 611137, China

2 College of Life Sciences, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, 235000, China

* Corresponding Authors: HUI AO. Email: ; HONG ZHANG. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Phytochemicals and Bioactive Monomers from Herbal Medicine: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2299-2333. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071569

Received 07 August 2025; Accepted 18 September 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Breast cancer ranks first among cancer-related fatalities and is the most frequent cancer in women globally. ROS plays an important role in controlling the occurrence and progression of breast cancer. Increasing reports suggest that natural products and their derivatives are beneficial for the management of breast cancer via the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). A summary of the known patterns of natural products that modulate ROS against breast cancer will contribute to the discovery of more natural medicines for clinical applications and the development of new drugs. In this review, the pharmacological effects of more than 40 natural compounds and extracts on the regulation of ROS were evaluated, and these natural products were categorized based on their mechanisms of action. The functional characteristics and primary patterns of action were outlined for natural products as ROS modulators in breast cancer treatment. Natural products can reverse breast cancer progression through the regulation of ROS levels, which is achieved by multiple mechanisms. Targeting ROS regulation with natural products remains a promising therapeutic approach for breast cancer.Keywords

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent malignant tumors worldwide, with the second highest incidence (11.6%), after lung cancer (12.4%), and the fourth highest mortality (6.9%) [1]. It is predicted that the incidence and mortality of breast cancer in China will continue to rise by 2030 with growth rates of 36.27% and 54.01%, respectively [2]. The current treatment strategies include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [3], many of which can lead to toxic side effects and adverse reactions. Therefore, search for new treatments and the creation of drugs that are safer and more effective have become the current top priority.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a class of complex containing oxygen, including peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radicals, singlet oxygen, α-oxygen, etc. Due to the presence of unpaired electrons, it exhibits high chemical reactivity. Cells can emanate ROS through various mechanisms, but the primary sources of endogenous ROS are mitochondrial metabolism, peroxisomes, and the active responses of the transmembrane Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen (NADPH) oxidases (NOXs) family [4,5]. Under normal circumstances, ROS is maintained at an appropriate low concentration level to sustain normal cellular function and a relative balance between the oxidative and antioxidant systems. Many tumor-promoting events, involving triggering of oncogenes, deprivation of tumor suppressive capability, altered activity of mitochondria, augmentation of hypoxia, and changes in matrix interactions, can encourage the emergence of ROS. The accumulation and removal of ROS are dynamically balanced within normal cells [6]. Clearance of ROS is associated with the following pathways: (i) Cells have a variety of antioxidant systems such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase and glutathione peroxidases (GPXs); (ii) Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) can be restricted by the autophagic procedure, which eliminates damaged mitochondria producing ROS by targeting autophagy; (iii) Spatial regulation: Multiple mechanisms exist to control the localization of ROS within the cell, determining the subcellular localization of ROS-producing and degrading systems answer to specific stimulate, allowing for localized and selective responses.

ROS has a bidirectional effect on tumors. Increased ROS caused by carcinogenic disturbance may be a necessary condition for carcinogenesis [7], which can facilitate tumor progression through various pathways, including DNA damage and the acquisition of genomic instability, causing the accumulation of oncogenic changes [8,9]. Epigenetic regulation may also boost carcinogenic transformation for ROS response in gene expression by altering the activity of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) or histone deacetylases (HDACs) [10]. On the flip side, the destructive effect of excessive ROS is not conducive to the survival of cancer cells. Tumor cells with higher oxidative pressure are more sensitive to ROS. Increased oxidative damage and ROS-dependent death signaling are also powerful in preventing certain stages of tumorigenesis. Accumulation of ROS can elicit various forms of cell death. Ferroptosis has become a popular research issue in oncology as a form of cell death triggered by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation caused by membrane ROS and mtROS [11]. Elevated levels of ROS lead to apoptosis of tumor cells by increasing oxidative stress beyond the tolerable threshold [12]. Therefore, targeted regulation of ROS is commonly used in the development of anticancer drugs, which has promising prospects in tumor therapy [13–15].

Although numerous natural products with anti-breast cancer effects through ROS modulation have been reported, the relevant literature remains fragmented. The lack of a systematic review that analyzes natural products based on their mechanisms of action and chemical structural types may hinder researchers’ ability to quickly grasp the knowledge framework of this field and prioritize lead compounds, thereby impeding the translation of basic research into clinical applications. This review aims to systematically summarize and classify these natural products, provide an in-depth analysis of their molecular mechanisms, and explore their dual role in ROS regulation as well as their potential applications in precision therapy for breast cancer. We anticipate that this work can offer a clear roadmap for researchers, not only deepening the understanding of targeting ROS therapies but also accelerating the development of natural product-based drugs for breast cancer treatment.

2 Application of Natural Products for Treating Breast Cancer

As one of the predominant traditional remedies for human diseases, natural products have been used for thousands of years. Natural products are a principal source of anti-tumor drugs currently, and 61% of the small molecule anti-tumor drugs used in clinical practice originate from natural products, including plants, fungi, microorganisms, etc. [16]. Natural products not only have potential anticancer effects, but also have such advantages as high efficiency, low toxicity, and multiple targets. This has prompted researchers to further search for and develop new anticancer drugs of natural origin [17,18]. On the other hand, the mechanism by which some natural drugs exert anti-cancer effects is not yet clear, which will affect their further rational research and clinical application. It is crucial to study the targets and mechanisms of natural products to better develop new drugs. Increasing evidence has suggested that numerous natural products, including extracts and monomers, are beneficial for the management of breast cancers, such as andrographolide, isoglycyrrhizin, gallic acid, alpinetin, and hyperoside.

Furthermore, the regulation of ROS is considered one of the most important mechanisms for natural products to treat breast cancer. Inducing excessive production of ROS in cancer cells is called oxidative therapy, which can trigger the death reaction of breast cancer cells, causing apoptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis, etc. To be specific, natural products can induce endogenous apoptosis in the mitochondrial pathway of cancer cells through inducing ROS generation. Elevated ROS can induce apoptosis by modulating the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signaling pathway, inactivating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, disrupting the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, and activating apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)/c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway. ROS also triggers apoptosis through mediating oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress. ROS participates in the formation and degradation of autophagosomes, inducing mutual regulation between autophagy and apoptosis. Excessive production of ROS can cause lipid peroxidation, which disrupts the normal structure and operation of mitochondria, eventually eliciting ferroptosis. Accumulation of ROS can increase the levels of cleaved caspase-3, which causes the cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD), releasing the pore-forming N-terminal fragment of GSDMD (GSDMDNT). It is translocated to the cytoplasmic membrane, forming an inserted pore-like structure, through which cells secrete a large amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately causing pyroptosis.

3 Inducing the Death of Breast Cancer Cells via Increasing ROS

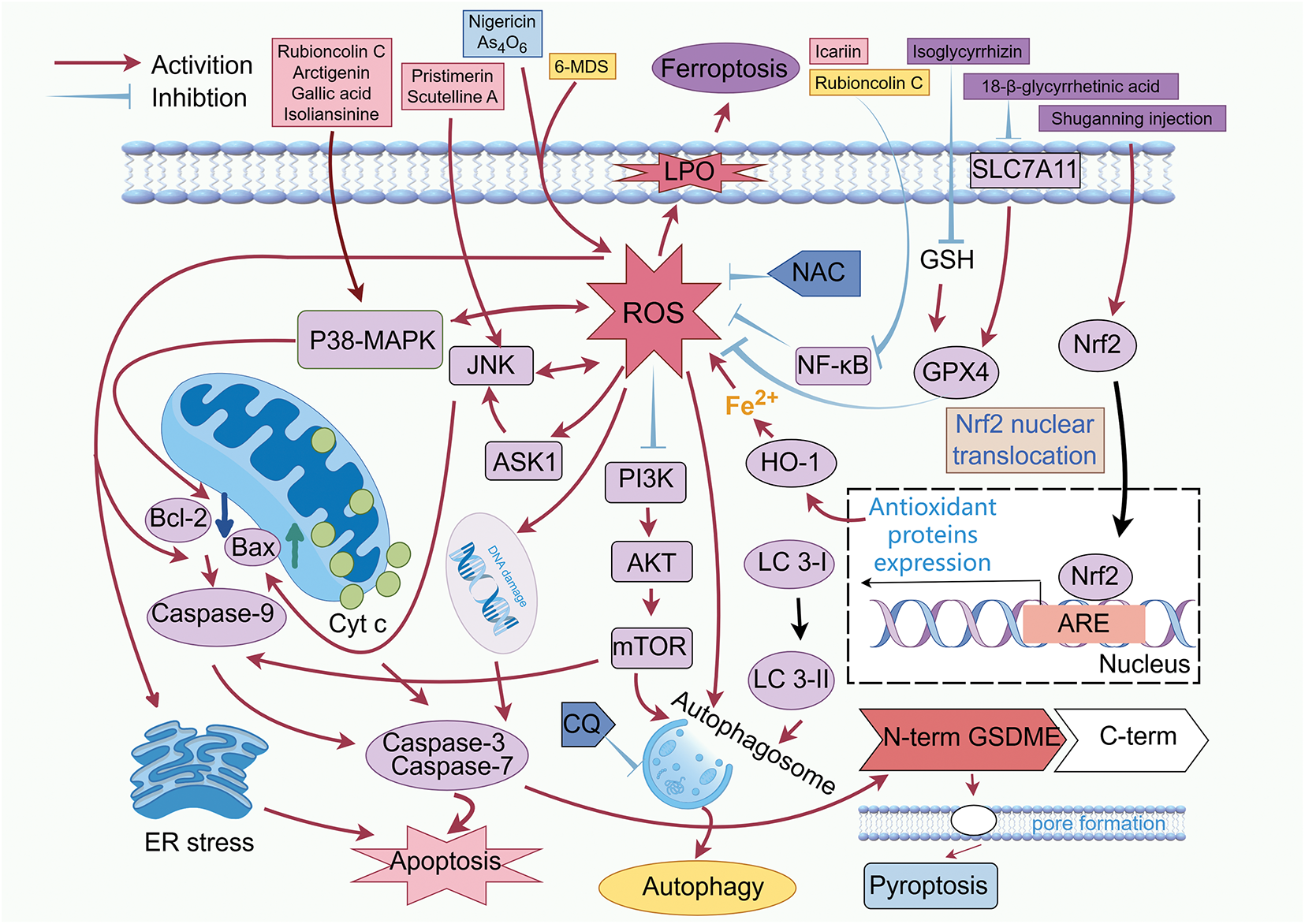

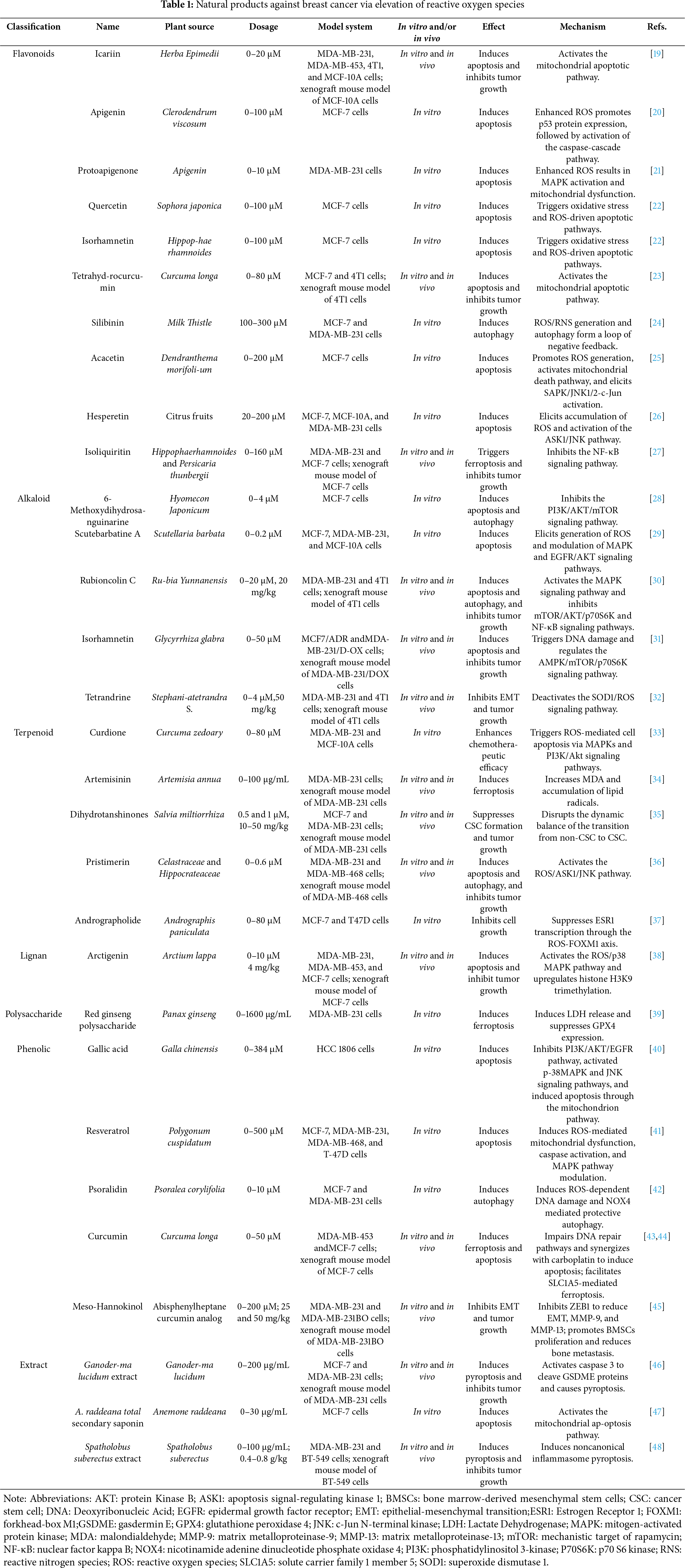

Table 1 lists the major natural products inducing the death of breast cancer cells via increasing ROS levels, and the mechanisms of action involved are summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Induction of breast cancer cell death by increasing ROS levels. Abbreviations: AKT: protein kinase B; ARE: antioxidant response element; ASK1: apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; Bax: Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; Caspase-3: cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 3; Caspase-7: cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 7; Caspase-9: cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 9; CQ: chloroquine; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; GPX4: glutathione per-oxidase 4; GSDME: gasdermin E; GSH: glutathione; HO-1: heme oxygenase-1; LC-I: microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-I; LC-II: microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-II; LPO: lipid peroxidation; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; NAC: N-acetylcysteine; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B: Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; 6-MDS: 6-methox-ydihydrosanguine. (Created with the assistance of Figdraw. https://www.figdraw.com/static/index.html, accessed on 01 January 2025)

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death (type I programmed cell death), primarily mediated by the mitochondrial-dependent endogenous cytochrome c/caspase-9 pathway and caspase-8-related exogenous death receptor pathway [49,50]. When cells are under stress, ROS signaling alters the balance between pro-apoptotic (e.g., Bax/Bak) and anti-apoptotic (e.g., Bcl-2) proteins. This disruption reduces mitochondrial membrane permeability, leading to cytochrome c leakage into the cytoplasm. The released cytochrome c then triggers the caspase cascade, ultimately resulting in mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. It has been proven that bitter melon-derived vesicle extract (BMVE) can induce apoptosis of 4T1 cells by stimulating the production of ROS and destroying the function of mitochondria [51]. ROS mediates MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells apoptosis induced by (-)-Epicatechin [52]. Ligands bind to cell surface death receptors and then activate the exogenous death pathway via caspase 8. The activation and accumulation of ROS are key factors in cell apoptosis [53]. Meanwhile, apoptosis is connected to the interplay between ROS and death signaling pathways, as well as ROS-mediated oxidative stress.

MAPKs signaling pathway regulates exogenous and endogenous apoptotic pathways, in which p38 MAPK, extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK), and JNK are prominent signaling mediators [54]. p38 MAPK and JNK pathways play critical roles in apoptotic signaling in tumor cells, which can be activated by genotoxic drugs and cytokine-mediated stress responses, leading to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis [55]. ROS is an important regulator of MAPK pathway signaling [56]. Many anticancer compounds induce the formation of ROS and regulate the MAPK pathway, ultimately leading to cancer cell apoptosis [57]. Chrysophanol selectively induces apoptosis of BT-474 and MCF-7 cells by inducing ROS production and endoplasmic reticulum stress via AKT and MAPK signal pathways [58].

As a natural naphthohydroquinone dimer isolated from the roots and rhizomes of Rubia yunnanensis Diels, rubioncolin C reduces the expression of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) protein, interrupts the permeability of mitochondrial membrane, and enhances the liberation of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, as well as inducing ROS production through activating the p38-MAPK pathway. This promotes the expression of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9, and induces apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells [30]. Arctigenin, a lignan from Arctium lappa L., is well-known for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor effects. It activates p38-MAPK signaling through interaction with p22phox. This interaction stimulates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 1 (NOX1), attenuates glutathione (GSH)-mediated ROS consumption, and ultimately induces ROS accumulation. The activation of p38 MAPK elicits mitochondria-independent apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells by downregulating Bcl-2 and releasing apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and mitochondrial nucleic acid endonuclease G (EndoG) [38]. Gallic acid is a polyphenolic substance with multiple biological properties. Treatment of HCC 1806 cells with gallic acid results in a marked elevation of ROS levels, a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), and a decrease in Bcl-2 expression. In contrast, the expression levels of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-9, Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), and p53 are up-regulated. These results indicate that gallic acid induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. In the meantime, the rise in ROS induced by gallic acid inhibits the PI3K/AKT/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway, activates the p38 MAPK and JNK signaling pathways, suggesting that the ROS-regulated signaling pathway plays a critical role in gallic acid-induced apoptosis [40]. Isoliansinine is one of the main alkaloids in lotus embryos. Pre-treatment with the inhibitor of p38 MAPK (SB 203580) or transfection of p38-specific siRNA markedly reduces the elevation of ROS caused by isoliansinine. At the same time, activated p38 MAPK and JNK are partially inhibited by N-acetylcysteine (NAC, ROS inhibitor), indicating that the p38 MAPK pathway and production of ROS reinforce isoliansinine caused apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells [27].

Resveratrol (RES), a natural polyphenol, exhibits an anti-proliferative activity in breast cancer cells. Salinomycin, a monocarboxylic polyether ionophore, is recognized for selectively targeting breast cancer.

Stem cells (BCSC). The combination of salinomycin and RES synergistically induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells through ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction, caspase activation, and MAPK pathway modulation. But the extremely low toxicity is exhibited in MCF-10A cells [41]. RES also enhances sorafenib-mediated apoptosis in MCF-7 cells through ROS, cell cycle inhibition, caspase 3, and PARP cleavage [59]. Apigenin, a naturally occurring flavonoid isolated from Clerodendrum viscosum leaves, has been demonstrated to trigger intracellular ROS generation in MCF-7 cells. ROS induction mediates G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and promotes apoptosis through the modulation of p53 and caspase cascade signaling pathways [20]. Protoapigenone, a natural structural derivative of apigenin, demonstrates approximately ten times greater potency in inducing cell death in MDA-MB-231 cells compared to apigenin. Following protoapigenone treatment, cells exhibited increased ROS generation, reduced intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels, and sustained activation of MAPK signaling pathways. These changes were accompanied by hyperphosphorylation of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, as well as a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Notably, the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) significantly suppressed protoapigenone-induced MAPK activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis [21]. Docetaxel, a clinical first-line anti-tumor chemotherapy drug, is mainly used for the treatment of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer. Curdione is one of the main components of Curcuma zedoary. Compared with monotherapy, the combination therapy of curcumin and docetaxel significantly induces the accumulation of ROS in MDA-MB-468 cells. The pro-apoptosis markers, including Bax, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer (Bak), apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (apaf-1), and cytochrome c, increase. The co-treatment also enhances phosphorylated p38 and decreases phosphorylation of Akt and Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1/2(CDK 1/2), accompanied by the expression decline of NF-κB and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2). NAC reverses these effects [33].

3.1.2 PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a complex intracellular pathway leading to cell growth and tumor proliferation [60]. ROS, as an oxidation-reduction signaling molecule, plays an important role in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [61]. Accumulation of excessive ROS can inhibit the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, resulting in apoptosis [62]. In the year 2022, 6-methoxydihydrosanguine (6-MDS), a benzophenanthroline alkaloid, was isolated from the Hyomecon japonicum (Thunb.) Prantl. The production of ROS triggered by 6-MDS inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, reinforces cleaved caspase-7 and cleaved Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP), as well as the expression of Bax protein, and reduces the expression of Bcl-2 protein. Subsequently, the mitochondrial signaling pathway is stimulated to trigger apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. But the antioxidant NAC reverses the inhibitory effects [28]. (6aS, 10S, 11aR, 11bR, 11cS)210-Methylamino-dodecahydro-3a, 7a-diaza-benzo(de)anthracene-8-thione (MASM), an effective derivative of matrine, enhances apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells through PI3K/AKT/mTOR and ERK/P38 signaling pathways mediated by elevated ROS levels. Autophagic inhibitor Chloroquine (CQ) increases MASM-induced apoptosis in cancer cells, and NAC rescues this effect [63]. The rhizome of Anemone raddeana Regel (A. raddeana), a famous traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), possesses the efficacy of dispelling wind and dampness, and eliminating carbuncle and swelling. Total secondary saponins (TSS) and total saponins of A. raddeana (ATS) could suppress the growth of MDA-MB-231, SKBR-3, and particularly MCF-7 cells. TSS induces endogenous apoptosis in MCF-7 cells via increasing ROS, down-regulating the ratio of p-PI3K/PI3K, p-AKT/AKT, and p-mTOR/mTOR, up-regulating the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, decreasing MMP, and activating caspase-3/9. Inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway further promotes activity of the mitochondrial apoptotic route [47]. RES, a multi-target antioxidant with anticancer properties, is capable of inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) through regulation of PI3K/AKT and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways [64]. However, its clinical translation is hindered by poor bioavailability. To overcome this limitation, a zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8)-based nano-delivery system co-encapsulating cellulose enzyme and resveratrol (RES)—denoted as ZIF-8@CL&Resv—is developed. This system exhibits enhanced cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 cells, with an IC50 value of 17.18 μg/mL, and induces 61.81% cell death through ROS accumulation and mitochondrial depolarization, ultimately resulting in apoptosis [65]. In addition, a combined treatment of electric pulses and RES is shown to significantly increase ROS generation, promote apoptosis, and markedly reduce the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells [66]. Glabridin, a natural isoflavone, demonstrates estrogen receptor agonist activity and modulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. It markedly suppresses the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells by reducing MMP and increasing intracellular ROS levels, resulting in caspase cascade activation and apoptosis. Furthermore, glabridin enhances the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of tamoxifen on MDA-MB-231 cells, further supporting its role in targeting the PI3K pathway [67].

Cellular antioxidant mechanisms exhibit vitalization or inactivation in response to oxidative stress environments [68]. For example, transient oxidative stress can induce detoxification reaction of ROS by activating superoxide dismutase (SOD) or catalase (CAT), while sustained oxidative stress induces death of cancer cells and early apoptosis by impairing mitochondrial function [69]. Excessive production of ROS can trigger oxidative stress by destroying t44he equilibrium of enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems, which is essential to sustain the redox state in all oxygen-demanding cells [70]. Elevated oxidative stress can impair DNA, proteins, and lipids, ultimately leading to apoptosis or necrosis [71]. For chemotherapy, anti-cancer drugs that modulate oxidative stress usually produce higher levels of oxidative stress, which exceeds the tolerance threshold of ROS and curbs the progression of cancer cells.

Compared to the normal breast M10 cell line, Withanolide C (WHC) had more potent antiproliferative effects on SKBR3, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells. WHC triggers the production of ROS and mitochondrial superoxide (MitoSOX) and the exhaustion of glutathione. In addition, the ATP consumption of SKBR3 and MCF7 cells induced by WHC is higher than that of normal breast cells. WHC inhibits the proliferation of cells through oxidative stress-mediated alterations of the cell cycle, apoptosis, and DNA damage. Pre-treatment with NAC reduces oxidative stress-mediated ATP depletion, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, ROS/MitoSOX generation, and DNA damage [72]. Physapruin A (PHA) is a compound isolated from Physalis peruviana L. In MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, PHA induces ATP depletion and triggers oxidative stress, including overexpression of ROS and MitoSOX, depolarization of MMP, and enhancement of GSR mRNA, leading to apoptosis and DNA damage. Pre-treatment with NAC reverses the PHA-induced suppression of cell proliferation, as well as oxidative stress, apoptosis, and DNA damage, suggesting that the cell-killing mechanism operates in an oxidative stress-dependent manner [73]. Zerumbone (15 μM), in combination with paclitaxel (1 μM), significantly enhances ROS levels and promotes apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. The pro-oxidative properties of zerumbone may increase the sensitivity of MCF-7 cells to paclitaxel by enhancing intracellular ROS-mediated oxidative stress [74].

Quercetin (Que), a prominent flavonoid, along with its water-soluble metabolites isorhamnetin (IS) and isorhamnetin-3-glucuronide (I3G), exhibits dose-dependent cytotoxic effects in MCF-7 cells. Treatment with 25 μM of each compound for 48 h induced apoptosis in 36.6%, 35.3%, and 16.8% of the cells, respectively. Furthermore, all three compounds elevate ROS levels and promote apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating that their cytotoxicity is mediated through oxidative stress and ROS-driven apoptotic pathways [22]. Furthermore, the treatment with Anoectochilus roxburghii extracts (AREs) enhances the effects of doxorubicin (Dox) chemotherapy in the 4T1 breast cancer cells by promoting cell morphology damage, oxidative stress, and ROS generation [75]. The extracts of Krameria lappacea (Dombey) Burdet and B.B. Simpson induce MCF-7 cell death through elevating ROS levels and promoting oxidative stress, leading to mitochondrial membrane dysfunction and caspase activation, ultimately resulting in caspase-dependent apoptosis [76]. The extract of Nepenthes thorellii x elicits GSH depletion, triggering rapid accumulation of ROS. This results in oxidative stress, which subsequently leads to oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in MCF7 and SKBR3 cells. ROS inhibitors reverse these changes [77].

In addition to the signaling pathways previously addressed, ROS can also induce apoptosis in cancer cells via activating the ASK1/JNK and stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/JNK 1/2-c-Jun pathways, suppressing NF-κB signaling, and triggering endoplasmic reticulum stress. The activation of the ASK1/JNK pathway may represent another mechanism through which natural products promote ROS-mediated apoptosis. Pristimerin, a natural triterpenoid compound derived from various species of Celastraceae and Cruciferae, has been shown to markedly elevate ROS levels. Treatment of breast cancer cells with 0.4 μM pristimerin results in an approximately 10-fold increase in ROS production compared with untreated controls. Thioredoxin-1(Trx-1) is a major redox protein in the cytoplasm. Under physiological conditions, the reduced form of Trx-1 binds to the N-terminal domain of ASK 1, thereby inhibiting its kinase activity. Upon dissociation from Trx-1, ASK1 becomes activated and triggers the oxidation of Trx-1. This activation leads to the phosphorylation and activation of JNK and p38 MAPK pathways, ultimately promoting cell death. Pristimerin facilitates the release of ASK1 from Trx-1, causing phosphorylation of ASK1 at Threonine 845(Thr 845). NAC suppresses pristimerin-triggered vitalization of ASK1 and completely blocks apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells [36]. Hesperidin, a flavonoid glycoside compound found mainly in citrus fruits with extensive biological activities, shows significant cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells but does not impact the activity of HMEC and MCF-10A normal cells. Hesperidin activates the ASK1/JNK signaling cascade by inducing the production of ROS, leading to an increase in the ratio of Bax: Bcl2, a loss of MMP, and the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol. This subsequently activates caspase-9 and caspase-7, and induces PARP cleavage, thereby initiating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and ultimately resulting in apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Pre-treatment with NAC or glutathione markedly abolishes hesperidin-induced apoptosis, which is also significantly reversed by JNK inhibitor SP600125. These results indicate that ROS accumulation and activation of the ASK 1/JNK pathway play a key role in apoptosis induced by hesperidin [26]. Acacetin induces ROS production, resulting in MMP collapse, Bcl-2 reduction, and an elevated ratio of Bax and Bcl-2. Subsequently, caspases 8, 9, and 7 are activated, while cytochrome c and AIF are released into the cytoplasm, collectively enhancing MCF-7 cell apoptosis [25].

Targeting the NF-κB pathway may represent a promising strategy for inducing apoptosis. Icariin, a natural flavanol glycoside, elicits ROS production by inhibiting the tricarboxylic acid cycle through disrupting the NF-κB pathway. This effect increases cleaved caspase 3 and Bax expression, accompanied by marked downregulation of Bcl-2, leading to a significantly increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. These findings suggest that icariin-induced apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells is mediated through a mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway triggered by ROS [19]. In response to ROS-mediated oxidative stress, the accumulation of unfolded proteins can trigger endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as an adaptive mechanism to alleviate proteotoxic pressure and restore ER homeostasis. However, under sustained stress conditions, the ER stress response can also activate apoptotic signaling, eliciting cell death in various cancer cell types [78]. Scutelline A (SBT-A), a diterpenoid alkaloid, induces a significant increase in ROS and superoxide levels, causing DNA damage and cell cycle arrest. In the meantime, ROS activation upregulates the ER stress-related protein C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), which regulates the expression of apoptosis-related genes in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. The SBT-A-induced expression of CHOP is significantly reversed by NAC, suggesting that SBT-A-activated ER stress depends on ROS. In addition, SBT-A raises the phosphorylation of JNK and P38 MAPK, represses the phosphorylation of ERK, and decreases EGFR expression and the phosphorylation of Akt and p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K), thereby inhibiting the EGFR signaling pathway and promoting apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. However, the relationship between ROS and these pathways requires further investigation [29]. Withaferin A (WA), a natural bioactive compound derived from Withania somnifera, has significant anti-tumor activity. It enhances the antitumor effect of sorafenib by suppressing thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR 1) activity, resulting in ROS accumulation, DNA damage, ER stress pathway activation, ultimately leading to apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Pre-treatment with the antioxidant NAC reverses these changes [79].

Curcumin, a natural polyphenol derived from turmeric rhizomes, exhibits potent antitumor activity. It overcomes carboplatin resistance in CAL-51-R and MDA-MB-231 cells through ROS-mediated mechanisms. By elevating ROS levels, curcumin downregulates RAD51 expression, upregulates γH2AX, and impairs DNA repair pathways, thereby synergizing with carboplatin to induce apoptosis. This synergistic effect can be reversed by the ROS scavenger NAC [43].

Autophagy and apoptosis can jointly regulate cell death. Under certain conditions, autophagy promotes cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis; however, it can also induce cell death or serve as an alternative cell death mechanism when apoptosis is impaired. Thus, the two processes are closely interrelated and mutually restrictive. Autophagy exhibits a dual role in tumor biology: it can either support tumor progression or contribute to tumor cell death. ROS participates in the formation and degradation of autophagosomes. Some natural compounds induce autophagic tumor cell death by increasing ROS.

Daucosterol, an orally active natural sterol, induces autophagy in MCF-7 cells to inhibit cancer cell proliferation in a ROS-dependent manner. Treatment with ROS scavengers GSH or NAC, as well as the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA), counteracts these effects [80]. 6-MDS, a natural benzophenanthridine alkaloid isolated from Hylomecon japonica (Thunb.) Prantl markedly elevates the number of autophagosomes in MCF-7 cells compared with the control group. Autophagy-related protein 5 (Atg5) is a component of the lipid kinase complex essential for autophagosome formation during autophagy initiation. During this process, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-I (LC 3-I) is converted to LC 3-II. The detection of LC3 (an autophagy marker) and Atg5 protein levels serves as a reliable method for monitoring autophagy activation. The ratio of LC 3 II/LC 3 I and the expression of ATG 5 protein are evidently increased after 6-MDS treatment. Silencing ATG 5 dramatically enhances the reduction in MCF-7 cell viability induced by 6-MDS. Furthermore, autophagy induction by 6-MDS is promoted by the PI3K inhibitor LY 294002, while pre-treatment with the antioxidant NAC reverses the enhanced autophagy and inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. These results indicate that 6-MDS regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and increases ROS accumulation, thereby inhibiting autophagy in MCF-7 cells [28].

Rubioncolin C, a natural naphthohydroquinone dimer isolated from the roots and rhizomes of Rubia yunnanensis Diels, significantly enhances the production of hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anions, and mitochondrial superoxide anions in MDA-MB-231 cells. It also increases the expression of LC3 and promotes the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II. The antioxidant agents NAC and GSH rescue cell viability by scavenging ROS and inhibiting RC-induced cleavage of PARP and LC3. Both chloroquine (CQ, a late-phase autophagy inhibitor) and 3-methyladenine (3-MA, an early-phase autophagy inhibitor) attenuate RC-caused cell death. RC also triggers autophagic death in MDA-MB-231 cells through ROS-mediated inhibition of the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K and NF-κB signaling pathways [30].

Psoralidin (PSO), a phenolic coumarin isolated from psoralidin, significantly induces autophagy in MCF-7 cells, as indicated by the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and changes in LC3-I expression. Co-treatment with CQ enhances PSO-induced cell death. PSO induces ROS generation, while pretreatment with NAC or the NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) reverses ROS accumulation, DNA damage, and autophagy. In addition, PSO significantly enhances NOX 4 expression, and NOX 4 knockdown inhibits ROS production, DNA damage, and autophagy activation. These results demonstrate that PSO triggers DNA damage and protective autophagy in MCF-7 cells through a ROS-dependent mechanism mediated by NOX 4 [42]. Euterpe oleracea Mart. (açai), a native Amazon palm species, yields seed extract that exhibits high cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells. It may induce autophagy by increasing ROS production [81].

In 2012, the term “ferroptosis” was introduced to describe a form of regulated cell death characterized by its dependence on iron and lipid ROS [82]. The labile iron pool (LIP) plays a central role in promoting ferroptosis [83]. Through the Fenton reaction, LIP catalyzes lipid ROS formation, which drives ferroptotic cell death [84]. Meanwhile, excessive ROS production can result in lipid peroxidation, disrupting mitochondrial integrity and function, further contributing to ferroptosis. At the molecular level, the key mechanisms implicated in ferroptosis include: (a) suppression of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4); (b) reduction of the cystine glutamate transporter receptor (system xc-); and (c) inhibition of cysteine uptake via reduced expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), a critical subunit of system Xc−, thereby enhancing celluar sensitivity to ferroptosis. Given that many cancer cells resistant to other forms of regulated cell death (RCD) are still sensitive to ferroptosis, targeting this pathway has garnered significant interest as a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment [85]. Isoglycyrrhizin (ISO), a flavonoid glycoside isolated from Glycyrrhiza glabra, concentration- and time-dependently reduces the vitality of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. In MDA-MB-231 cells, ISO significantly increases the levels of Fe2+, ROS, and MDA, while decreasing GSH levels and downregulating the protein expression of GPX4 and SLC7A-11. GPX4 inhibits lipid peroxidation by reducing small molecule peroxides and lipid peroxides. However, ISO promotes ferroptosis through enhancing ROS accumulation and restraining both GSH synthesis and GPX4 expression [31]. Levistilide (LA), an active compound extracted from Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort., elevates intracellular iron by upregulating heme oxygenase-1 and its upstream molecule Nrf2. Excessive iron disrupts intracellular redox homeostasis, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS accumulation, which in turn elicits lipid peroxidation. In MDA-MB-231 cells, LA markedly suppresses GPX4 expression, leading to compensatory upregulation of mRNA related to GSH synthesis-limiting enzymes, enhanced ROS production, and ultimately ferroptosis [86]. 18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (GA), an active compound from licorice root, promotes the generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) by downregulating system xc-subunit SLC7A11 and reducing the activities of GSH and GPX. This process is mediated through activation of NADPH oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), exacerbating lipid peroxidation and eliciting ferroptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells [87].

Besides promoting apoptosis, curcumin can also induce ferroptosis. This process is mediated through solute carrier family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5), and involves enhanced accumulation of lipid ROS, increased production of malondialdehyde (MDA), and elevated intracellular Fe2+ levels. As a result, curcumin suppresses the viability of MDA-MB-453 and MCF-7 cells and inhibits tumor growth in vivo [44]. Red ginseng polysaccharide (RGP), an active ingredient from the traditional Chinese medicine Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer (Araliaceae), induces significant accumulation of lipid ROS in MDA-MB231 cells. Overexpression of GPX4 eliminates the anti-viability effects of RGP. Similarly, overexpression of GPX4 reduces the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the absence of RGP and attenuates the LDH release induced by RGP, concurrently reversing the accumulation of ROS. RGP likely triggers ferroptosis by inducing ROS production to downregulate GPX4 [39]. Artemisinin (ART) and its derivatives have been investigated as potential anticancer agents for the treatment of highly aggressive cancers due to their ability to induce ferroptosis through iron-mediated cleavage of the endoperoxide bridge. However, their clinical application is limited by poor water solubility and insufficient intracellular iron availability. To overcome these challenges, a zeolitic imidazolate framework-based nanocarrier coordinated with tannic acid and ferrous iron (TA-Fe/ART@ZIF) is developed. This system synergizes Fe2+-triggered ART activation with the Fenton reaction to markedly elevate ROS levels in MDA-MB-231 cells, resulting in a 2.5-fold increase in MDA, accumulation of lipid radicals, and potent ferroptosis-mediated suppression of MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumor growth [34]. Shuganning injection (SGNI), a traditional Chinese patent medicine, enhances ROS generation in MDA-MB-231 cells through inducing oxidative stress. This process promotes the activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which translocates into the nucleus and binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), thereby upregulating the transcription of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and facilitating the accumulation of LIPs through a feedback mechanism. Subsequent degradation of HO-1 leads to increased cytoplasmic Fe2+ levels, which induce lipid peroxidation and disrupt cell membrane integrity, ultimately causing ferroptosis in MD-MB 231 cells [88].

Pyroptosis, also known as inflammatory necrosis of cells, is a programmed cell death characterized by continuous swelling of cells until the cell membrane ruptures, resulting in the release of intracellular contents and the initiation of an intense inflammatory response. As a crucial innate immune mechanism, pyroptosis is essential in inhibiting cancer growth. This process is mainly mediated by gasdermin family proteins, especially GSDMD. In the classical pyroptosis pathway, activating stimuli promote inflammasome assembly, which in turn triggers inflammatory caspases that cleave GSDMD. The resulting N-terminal fragment of GSDMD (GSDMDNT) translocates to the cytoplasmic membrane, where it undergoes conformational changes and oligomerizes to form pore-like structures. Through these pores, cells release a large amount of pro-inflammatory factors, triggering an intense inflammatory response and inducing an anti-tumor immune response. ROS can directly regulate caspase activity related to inflammasomes, influence GSDMD cleavage or pore-forming function, and ultimately lead to membrane rupture and necrotic cell death.

Nigericin, an antibiotic derived from Streptomyces species, induces ROS accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction by promoting potassium efflux in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells. These effects cause an increase in cleaved caspase-3 and activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Meanwhile, mitochondrion impairment elicits activation of the caspase-1/GSDMD cascade, resulting in pyroptosis. This further enhances the infiltration and anti-tumor immune response of cluster of differentiation 4 positive (CD4+) and cluster of differentiation 8 positive (CD8+) T cells [89]. Tetraarsenic hexoxide has been proven to fight cancer by inducing apoptosis. Recent studies have shown that it also inhibits the proliferation of the murine mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells and human MDA-MB-231 cells by triggering pyroptosis. Mechanistically, tetraarsenic hexoxide promotes apoptosis in these cells by inhibiting the phosphorylation of mitochondrial signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), increasing mitochondrial ROS production, and subsequently activating caspase-3. At the same time, cleaved caspase-3 mediates GSDMD cleavage, releasing its N-terminal fragment GSDMDNT. This fragment translocates to the cytoplasmic membrane, where it oligomerizes and forms pore-like structures. These pores facilitate the extensive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately causing pyroptosis in 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells [90].

Ganoderma lucidum extract (GLE), a traditional Chinese herb known for its excellent antitumor activity, significantly increases ROS levels in MCF-7 cells and activates caspase 3 at concentrations ranging from 50–200 μg/mL. This leads to the cleavage of GSDME proteins, ultimately causing pyroptosis [46]. Similarly, Spatholobus suberectus Dunn has remarkable anticancer efficacy. Treatment with Spatholobus soil percolate (SSP) alone promotes ROS generation and activates caspase-4 and caspase-9 in TNBC cells. The N-terminal fragment of GSDME forms pores in the plasma membrane, leading to pyroptosis in BT 549 and MDA-MB-231 cells. This process occurs independently of canonical inflammasome complexes and is considered to operate through a nonclassical inflammasome pyroptosis signaling pathway. The antioxidant GSH attenuates ROS production and reverses SSP induced pyroptosis [48].

Metastasis is a hallmark of cancer and a primary cause of cancer-related mortality. About 30%–40% of breast cancer patients have already displayed metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, understanding the metastatic mechanism of breast cancer and developing effective strategies are crucial for improving patient survival. Breast cancer metastasis is mainly related to such factors as epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), extracellular matrix (ECM) attachment, blood circulation, and tumor microenvironment. In addition, cancer stem cells (CSC) contribute to metastasis and recurrence. Natural products can inhibit breast cancer metastasis through regulating these processes by ROS modulation.

Dihydrotanshinones (DHTS), a natural compound isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, shows cytotoxicity to various tumor cells. In breast spheroids, DHTS induces ROS generation by increasing NOX5 expression through calcium-mediated signaling. This decreases the nuclear phosphorylation of Stat3 and the secretion of IL-6. Consequently, DHTS suppresses CSC formation and relieves the dynamic balance between non-CSC and CSC transition. Ultimately, DHTS increases CSC death by ROS accumulation and deregulation of the Stat3/IL-6 pathway [35]. Meso-Hannokinol (HA), a diphenylheptane analogue of curcumin, increases the levels of ROS in a dose dependent manner and activates JNK phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 cells, which are reversed by the antioxidant NAC. MMP-9 and MMP-13 are vital activators of bone metastasis and zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1(ZEB1) is the promoter of EMT. HA inhibits ZEB1 expression by inducing ROS accumulation to reduce the expression of EMT markers, MMP9 and MMP13 in MDA-MB-231 cells. HA promotes the proliferation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) and reduces bone metastasis of MDA-MB-231 cells [45].

Tetrandrine (TET), a natural plant alkaloid isolated from the dried roots of Stephania tetrandra S. Moore, induces the production of ROS through down-regulating superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and catalase. This causes a reduction in breast cancer stem cells, impairment of EMT properties, and suppression of cell stemness. The inhibitory effects of TET on MDA-MB-231 cells are reversed by either SOD1 overexpression or NAC. Consistent with this, in vivo experiments show that cells overexpressing SOD1 and BCSC-enriched populations are less sensitive to TET treatment compared with vector control cells. These findings demonstrate that TET effectively inhibits BCSC properties and the EMT process via the SOD 1/ROS signaling pathway [32].

Around 70% of newly diagnosed breast tumors express the estrogen receptor (ER)-α. Although targeted therapies such as fulvestrant can effectively reduce ER activity, their clinical utility is often limited by the development of anti-estrogen resistance. In breast cancer cells, knockdown of ER-α can promote autophagy and enhance ROS-triggered cell death [91]. Andrographolide (AD), an active ingredient from Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees markedly suppresses the proliferation of ER-positive breast cancer cells. It acts through hindering ER-α transcription and inducing ROS generation, thereby downregulating the forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1)-ER-α axis and enhancing the efficacy of fulvestrant [37]. In addition, andrographolide induces apoptosis in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells via inducing inactivation of the ER-α receptor and suppression of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [92].

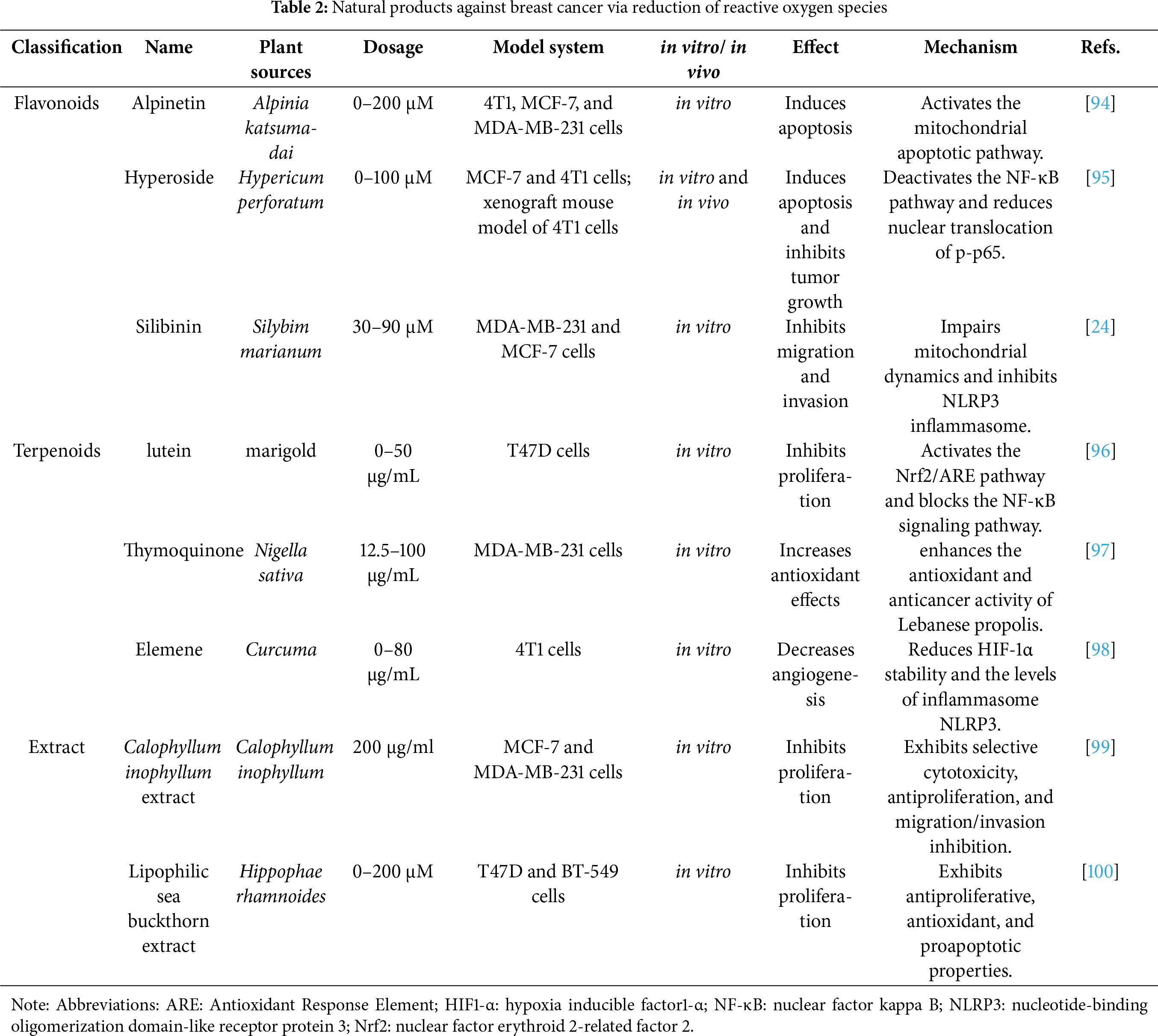

4 Suppressing the Development of Breast Cancer by Reducing ROS

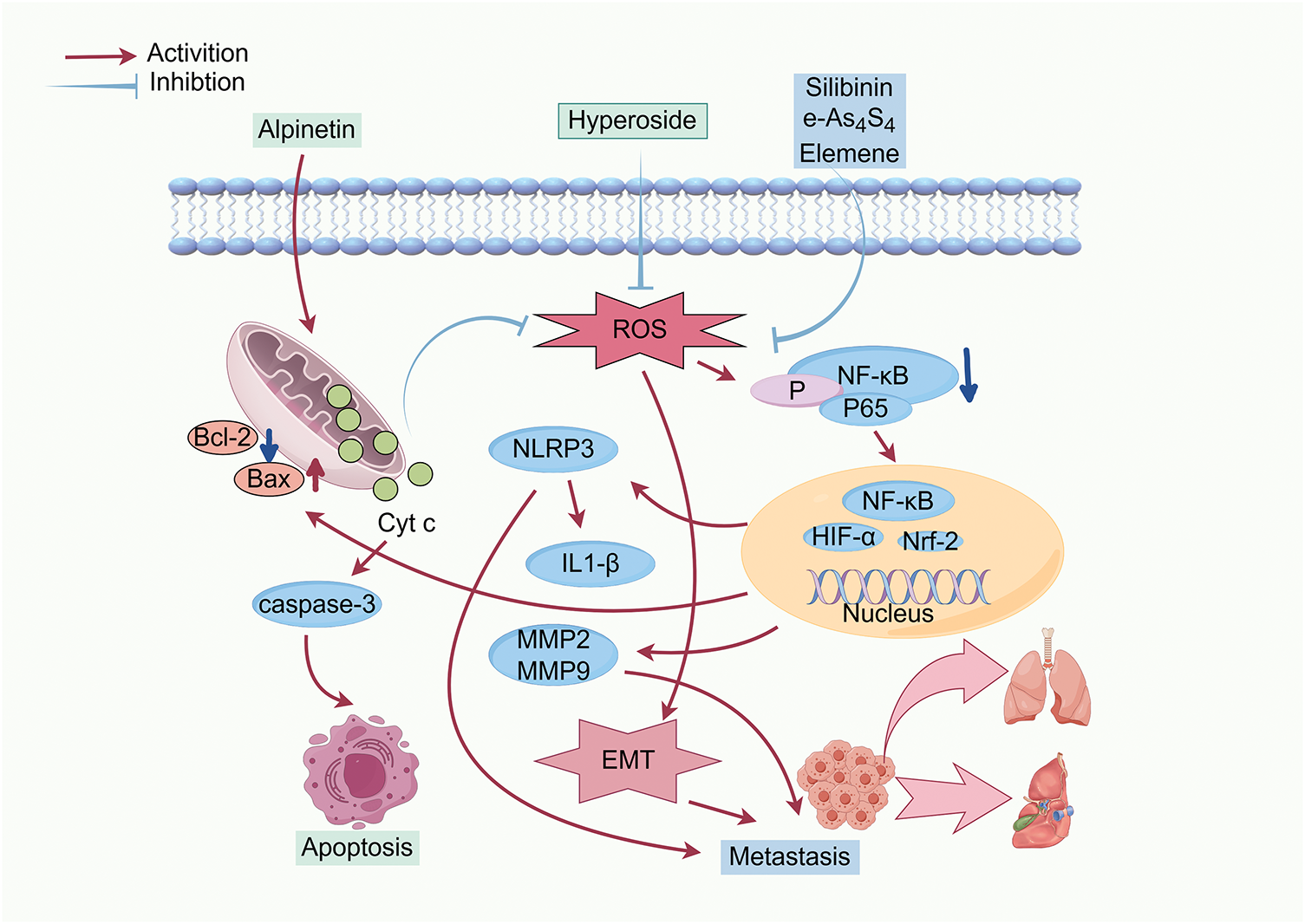

In cancer cells, ROS levels exceeding the redox balance threshold can effectively trigger self-destruction mechanisms. Conversely, when ROS levels remain below this threshold, they can inhibit tumor progression by slowing the proliferation rate, suppressing metastatic potential, and inducing apoptosis [93]. The application of antioxidants offers a promising strategy to reduce intracellular ROS, potentially improving treatment outcomes for metastatic solid tumors dependent on ROS signaling. This approach has achieved remarkable efficacy across various in vitro and in vivo models, providing useful insights for future anticancer strategies [73]. Many studies have explored the mechanisms through which natural products fight breast cancer by reducing ROS, particularly in subtypes exhibiting high ROS dependency. As summarized in Table 2, the major natural products impede the progression of breast cancer through decreasing ROS levels, and their mechanisms of action are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Inhibition of breast cancer progression by reducing ROS levels. Abbreviations: Bax: Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; caspase-3: cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 3; Cyt c: cytochrome c; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; HIF-α: hypoxia inducible factor-α; IL1-β: Interleukin-1 β; MMP2: matrix metalloproteinase-2; MMP9: matrix metalloproteinase-9; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; NLRP3: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3; Nrf-2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Created with the assistance of Figdraw. https://www.figdraw.com/static/index.html, accessed on 01 January 2025)

4.1 Induction of Apoptosis or Inhibition of Proliferation

Nrf2 is a basic zipper (bZIP) transcription element involved in the regulation of oxidative damage and cellular protection against carcinogens. Overexpression of Nrf2 has been linked to enhanced cancer proliferation. The imbalance between Nrf2 and NF-κB is implicated in many diseases, especially cancer. Many natural products exert anti-breast cancer effects through modulation of Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways. Alpinetin, a major active ingredient derived from Alpinia Katsumadai Hayata, promotes apoptosis in 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 cells through elevating the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2. This leads to the release of cyto-c from mitochondria into the cytoplasm. Meanwhile, alpinetin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction decreases intracellular production of ROS, subsequently repressing NF-κB pathway activation and reducing the transcription of hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α). The downregulation of HIF-1α, mediated by impaired NF-κB signaling, inhibits numerous oncogenic target genes, ultimately restraining the migration of cancer cells [94]. Hyperoside, one of the flavonoid glycosides, has anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, and anti-cancer effects. In 4T1 cells, hypericin suppresses NF-κB pathway activation and reduces the nuclear translocation of p-p65 by decreasing ROS generation. The inhibition of NF-κB down-regulates the transcription of anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl-2 and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), while promoting the accumulation of Bax. These changes result in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis through caspase-3 activation [95]. Lutein, an oxygenated carotenoid widely present in nature, significantly promotes the production of antioxidants and improves the ability of anti-oxidative stress in human breast cancer T47D cells. Meanwhile, it reduces intracellular ROS levels and attenuates oxidative damage. The decline in ROS blocks NF-κB pathway activation and decreases the levels of NF-κB p65. Subsequently, Nrf2 is activated and translocated to the nucleus, where it upregulates the downstream genes encoding cellular antioxidant enzymes, ultimately inhibiting the proliferation of breast cancer cells [96].

4.2 Suppression of Migration and Invasion

Tumor metastasis is the main cause of cancer progression and mortality, driven by complex interactions within the tumor microenvironment. A key mechanism facilitating metastasis is EMT, through which cancer cells acquire invasive and migratory capabilities. ROS can promote EMT progression, thereby accelerating metastatic behavior [101]. Additionally, chronic inflammation is closely associated with the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer [102]. Inflammatory mediators in the tumor microenvironment, including ROS and RNS, contribute to the development of inflammation-related cancers [103]. Natural products can counteract these processes by reducing ROS levels through mitochondrial fusion, thereby inhibiting EMT and inflammasome NLRP3 activation. The suppression of intracellular ROS also downregulates migration-related proteins such as MMP-2 and MMP-9, further reducing metastasis in various cancers.

Silibinin, a natural polyphenol flavone isolated from Silybum marianum, exhibits potential activity against breast cancer. It disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and suppresses the migration of MDA-MB-231 cells by elevating mitochondrial fusion, decreasing the generation of ROS, and inhibiting the activation of inflammatory vesicle NLRP3. Additionally, silibinin downregulates the expression of migration-related proteins MMP-2 and MMP-9. Conversely, treatment with tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP), an exogenous donor of ROS, increases the levels of MMP2 and MMP9, decreases E-cadherin expression, and increases N-cadherin and the EMT-related marker vimentin. This treatment also reverses the anti-migratory effects induced by silibinin [24].

As4S4 is an orally administered mineral drug with poor solubility in its raw form (r-As4S4). For the enhancement of its bioavailability, a hydrophilic nanoparticle formulation of As4S4 (e-As4S4) is developed. When applied to breast cancer cells in both normal and hormonally stimulated mice, e-As4S4 exhibits greater cytotoxicity and more strongly inhibits the proliferation of 4T1 cells than r-As4S4. HIF signaling acts as a major regulator of breast cancer metastasis by activating the transcription of genes encoding proteins involved in this process. Oral administration of e-As4S4 significantly increases the accumulation of arsenic within tumor tissue, effectively scavenging ROS. This reduction in ROS levels leads to the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and suppression of HIF-1α expression. Consequently, angiogenesis and metastasis to the lungs and liver are markedly reduced, ultimately prolonging the survival of the tumor-bearing mice [104].

Calophyllum inophyllum L., commonly known as Laurelwood, is a tropical evergreen tree whose various parts, including leaves, flowers, and stem bark, possess medicinal properties. The extracts derived from different parts of the plant are rich in antioxidants, such as polyphenols, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals with antioxidant structures. These compounds contribute to the extract’s anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anti-cancer activities [105,106]. The extract of Calophyllum inophyllum L. is shown to attenuate intracellular ROS production, eliciting the downregulation of NRF2 and HIF-1α. This results in reduced expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, inhibition of EMT, and consequent suppression of migration and invasion in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Notably, these effects occur without significant toxicity to normal cells [99]. Elemene, a sesquiterpenoid compound isolated from the rhizomes of Curcuma species, also exhibits anti-metastatic properties. Its nanoemulsion formulation could effectively scavenge ROS and reduce the stability of HIF-1α in vivo and in vitro. These effects lead to diminished angiogenesis within the tumor microenvironment, reduce activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and decrease levels of the key pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Ultimately, elemene nanoemulsion markedly inhibits the metastasis of 4T1 cells to the lungs and liver [98].

4.3 Enhancement of Antioxidant Potential

Oxidative stress, mediated by ROS, is implicated in the pathogenesis of diverse diseases. Scavenging excess ROS by supplementation with exogenous antioxidants has been recognized as a potential strategy for disease prevention. Many natural products possess excellent antioxidant activities and are useful in the treatment of breast cancer and other conditions. Nevertheless, given the chemical and biochemical diversity of ROS and the different mechanisms of antioxidants, combination approaches may yield greater efficacy than single-agent treatments [107].

Propolis, a resinous mixture produced by bees, has shown protective effects against oxidative stress. Bioactive compounds in Lebanese propolis, in particular, are effective in scavenging free radicals. Thymoquinone (TQ), another natural compound, is a potent ROS scavenger and inhibitor of non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation. When half concentrations of Lebanese propolis and TQ are combined, the treatment is more effective than either agent alone. This combination enhances antioxidant and anticancer activities, improving DPPH radical scavenging capacity and protecting red blood cells from H2O2-induced hemolysis. Moreover, TQ enhances the repressive effects of propolis extract on the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells [97]. These findings suggest that combining natural products can synergistically increase antioxidant effects, offering valuable insights for future research [108]. Furthermore, natural antioxidants may also be combined with conventional chemotherapeutic agents to enhance clinical outcomes.

As the most common malignant tumor in women, the prevention and treatment of breast cancer is still a major problem. Through early diagnosis and mammography screening, as well as improvement of treatments, the rate of increase in breast cancer mortality has slowed, but still accounts for nearly one quarter of all female cancer cases and one sixth of all female cancer deaths globally, making it the leading cause of cancer deaths among women worldwide [1]. Although the pathogenesis of breast cancer is better recognized, the progression in treatment remains slow [109,110]. The priority is to discover more powerful treatment approaches. Recently, natural products have received more and more attention and become an important source of drugs against cancer due to their wide sources, diverse structures, strong biological activities, low toxicity and side effects, wide range of targets, and unique mechanisms of action [111]. ROS is involved in various biological processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, and invasion of tumor cells, and plays an essential role in the progression of cancer [112,113]. Given the significance of natural products and the crucial role of ROS in cancer progression, this review summarizes the mechanisms by which various types of natural products exert anti-breast cancer effects through regulating ROS levels.

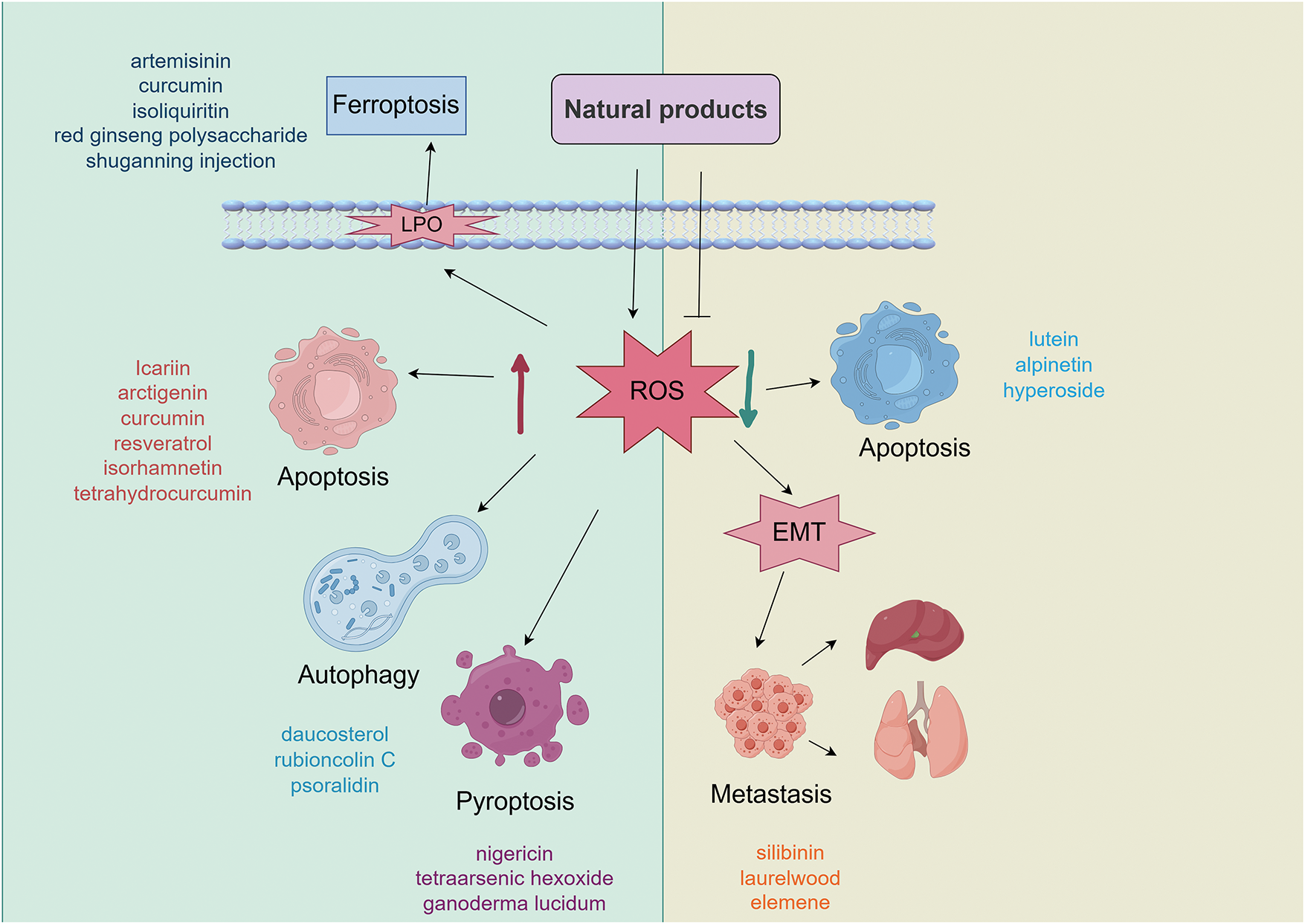

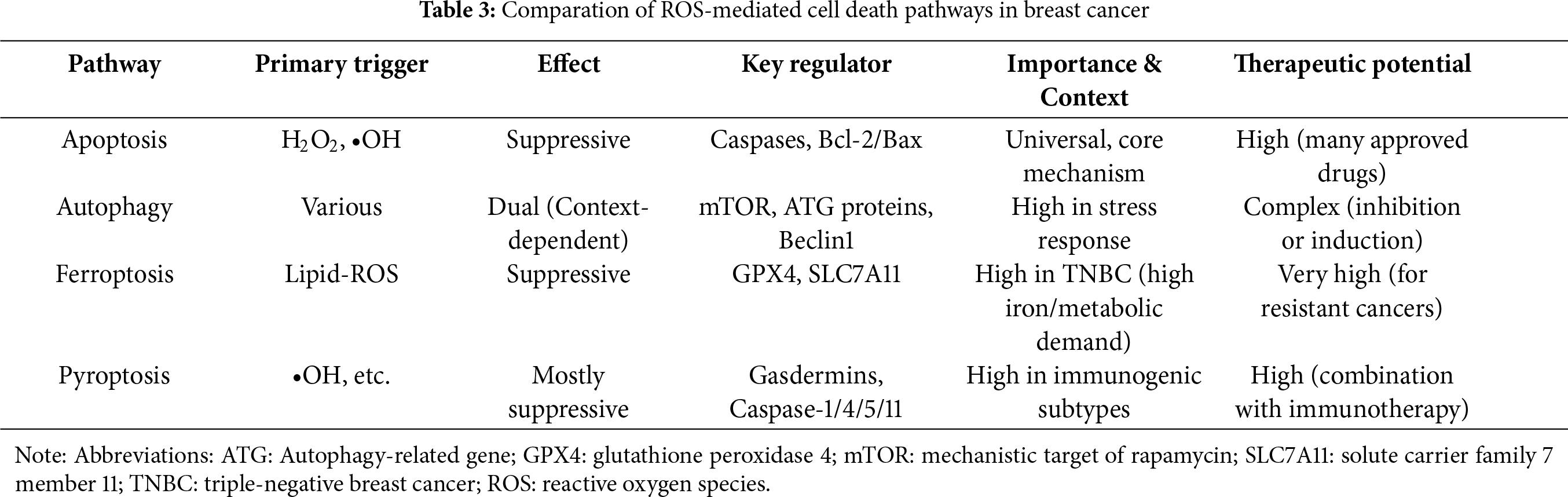

Natural products can induce various forms of cell death in breast cancer through ROS-mediated mechanisms, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagy (Fig. 3). Among these, apoptosis induction remains the most classical and prevalent ROS-dependent antitumor mechanism, though it may lead to drug resistance. Due to its strong dependence on lipid metabolism and iron ions, ferroptosis may play a particularly important role in treating highly metabolic subtypes such as TNBC. Inducing ferroptosis may represent a novel strategy to overcome apoptosis-resistant TNBC. Pyroptosis is likely more relevant to immunogenic subtypes (e.g., TNBC), as it can activate antitumor immunity and may synergize with immunotherapy, potentially enhancing the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Autophagy plays a dual role in cancer. Although the cell death can be elicited under some specific conditions, autophagy often functions as a critical survival mechanism under nutrient-deprived conditions in the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, inducing autophagy is generally not a preferred therapeutic strategy. Notably, these cell death pathways may be simultaneously activated by ROS. The comparative summary of ROS-mediated cell death pathways in breast cancer is provided in Table 3.

Figure 3: ROS-mediated pathways of natural product-induced cell death in breast cancer. Abbreviations: LPO: lipid peroxidation; ROS: reactive oxygen species; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Created with the assistance of Figdraw. https://www.figdraw.com/static/index.html, accessed on 01 January 2025)

In terms of breast cancer cell death caused by natural products increasing ROS levels, promoting apoptosis plays a major role. Natural products induce the production of ROS to trigger apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway and unidirectional or bidirectional interactions with ROS-dependent death signaling pathways. In addition, estrogen is also involved in ROS-mediated cancer cell death. Knockdown of ER-α induces autophagy and inhibits anti-estrogen-mediated activation of the unfolded protein response, promoting ROS-induced death of breast cancer cells. In addition to directly causing the death of cancer cells, natural products can also affect the metabolic pathway of cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP450), activate NOX5 to induce the production of ROS, and reduce the levels of nuclear phosphorylation of STAT3 and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). This impedes CSC formation, inhibits the characteristics of BCSC and the EMT process, subsequently inhibiting the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells.

Reduction of ROS levels by natural products also exerts anti-breast cancer effects. Decreased ROS suppresses the NF-κB signaling pathway, increases the levels of cytochrome c and the activity of caspase-3, and inhibits the transcription of HIF-1α, thereby eliciting cell apoptosis to restrain the progression of breast cancer. Reduced ROS also hinders the EMT process and formation of the inflammasome NLRP3 to prevent metastasis. The combination of natural products enhances the potential of antioxidants, reduces drug side effects when used in combination with chemotherapeutic agents. This improves tissue structure by reducing oxidative stress and increasing the expression of the tumor suppressor gene. The activity of antioxidants is related to the reduction and clearance of free radical formation. Phenolics and flavonoids exhibit strong free radical-scavenging capabilities, attributable to their hydroxyl groups, which make them highly effective antioxidants [100]. The anticancer effects of these natural products are often associated with their ability to reduce intracellular ROS levels, underscoring the role of antioxidant activity in their mechanisms of action. This suggests that potent natural antioxidants represent a promising source for the development of novel antitumor drugs.

Although modulating ROS has emerged as a potential strategy for breast cancer treatment, an inherent contradiction exists in balancing pro-oxidant and antioxidant interventions. Excessive elevation of ROS may damage normal tissues and accelerate tumor evolution, whereas excessive suppression of ROS could undermine endogenous tumor-suppressive mechanisms. Although natural products display anti-breast cancer potential, their clinical application requires precise consideration of the tumor biological context. For example, TNBC with high baseline ROS levels may be more vulnerable to pro-oxidants that exceed the oxidative stress threshold to induce cell death. In contrast, luminal breast cancer with its estrogen pathway-mediated ROS generation may be more sensitive to antioxidants. In the early stage of breast cancer, the immune microenvironment is more active, and pro-pyroptosis could stimulate antitumor immunity. Conversely, in advanced/metastatic settings, antioxidant interventions may be more appropriate for inhibiting ROS-driven migration.

In terms of the chemical structures of these natural products, the most common are flavonoids and alkaloids. Unlike other tumors, estrogen and ER are intimately associated with the progression and treatment of breast cancer. Exposure to excess endogenous estrogen or elevated levels of environmental estrogenic chemicals is an important risk factor for breast cancer. The metabolites and ROS produced during estrogen metabolism play an essential role in estrogen-induced carcinogenesis. Estrogen induces breast cancer cell proliferation by ROS-dependent regulation of genes and epigenetic reprogramming of histones [114]. Furthermore, depletion of Erβ induces the accumulation of ROS and reverses the resistance of ositinib in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in vitro and in vivo [115]. Due to their structural similarity to estrogen, flavonoids can exert estrogen-like effects to regulate ER and influence downstream signaling pathways. Therefore, targeting ER may be another effective pathway for flavonoids to regulate ROS. These characteristics make flavonoids promising candidates for the treatment of breast cancer. However, TNBC, defined by the absence of ER, progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) expression, is insensitive to conventional endocrine and targeted therapies. This subtype is associated with early recurrence, a high risk of metastasis, and poor prognosis. Although icariin, quercetin, and isorhamnetin belong to the flavonoid family, many studies have demonstrated that these compounds significantly suppress TNBC growth by increasing ROS levels. This suggests that their antitumor effects may be independent of the estrogen signaling pathway and highlights the promising potential for clinical translation.

The antitumor effects of alkaloids are related to the developmental stage of tumor cells. Alkaloids can inhibit the division process of abnormally proliferating cells, thus decreasing the proliferation of tumor cells, but do not obviously affect non-proliferative cells. In addition, alkaloids can exert anti-tumor effects through various mechanisms such as interfering with cell cycle and signaling and regulating the apoptosis-related genes. For example, paclitaxel can prevent microtubule aggregation that triggers apoptosis during the M phase of the cell cycle. Alkaloids can also suppress TNBC growth by elevating ROS levels, such as tetrandrine. Other types of compounds, such as artemisinin (sesquiterpene), arctigenin (lignan), curcumin (polyphenol), and resveratrol (polyphenol), have also significant anti-TNBC effects both in vitro and in vivo, indicating their promising translation potential.

ROS play a crucial role in the progression of breast cancer. The regulation of ROS can either promote or inhibit tumor development at different stages [6]. However, the mechanisms through which natural products modulate ROS levels, including their direct targets and downstream signaling pathways, remain incompletely understood. Further in-depth research is essential to elucidate these targeting mechanisms. Only with a clearer understanding can natural products with diverse mechanisms be rationally combined to achieve synergistic effects, reduce toxicity, and facilitate the development of multi-target therapies against breast cancer. For traditional Chinese medicines and natural medicines, the synergistic therapeutic effects of multi-component combinations represent a key characteristic and major advantage. Although several natural products are already in clinical use, their combinations with conventional antitumor drugs, as well as with other natural products, require further systematic investigation.

ROS plays a vital role in breast cancer progression. Natural products can reverse breast cancer progression by modulating ROS levels to elicit tumor cell death, inhibit metastasis, and enhance chemotherapy sensitivity. Increasing or decreasing ROS levels depend on the specific biological context of the tumor. This review summarizes the effects and mechanisms of various types of natural products against breast cancer through regulating ROS levels. Despite promising preclinical findings, the clinical translation of ROS-modulating natural products faces several challenges. Major issues include pathway crosstalk, precise target identification, synergistic strategies with conventional therapies, nanoparticle delivery systems, bioavailability, safety profiles, and clinical validation of efficacy. Nevertheless, due to their multi-target capabilities and favorable toxicity profiles, natural products that modulate ROS levels represent a promising therapeutic strategy for breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82174023), Anhui Higher Education Science Research Project (2023AH040055), and Anhui Natural Science Foundation Project (2308085MC79).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Hong Zhang and Hui Ao; Formal analysis: Yang-Yang Shuai; Funding acquisition: Hong Zhang and Hai-Jun Zhang; Investigation and Methodology: Yang-Yang Shuai and Hong Zhang; Supervision: Hong Zhang, Hai-Jun Zhang and Hui Ao; Visualization: Yang-Yang Shuai and Pei-Pei Wang; Writing—original draft: Yang-Yang Shuai; Writing—review & editing: Wei Peng and Hong Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AD | Andrographolide |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| Atg 5 | Autophagy-related protein 5 |

| apaf-1 | Apoptotic protease activating factor-1 |

| ASK1 | Apoptosis Signal-regulating Kinase 1 |

| ATS | Total saponin of A. raddeana |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bak | Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BCSC | Breast cancer stem cells |

| BMSCs | Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| Bzip | Basic (region leucine) zipper |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CDK1/2 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1/2 |

| CD4+ | Cells Cluster of differentiation 4 positive cells |

| CD8+ | Cells Cluster of differentiation 8 positive cells |

| CHOP | C/EBP-homologous protein |

| CQ | Chloroquine |

| CSC | Cancer stem cells |

| CYP450 | Cytochrome P450 enzyme |

| DHTS | Dihydrotanshinones |

| DNMTS | DNA methyl-transferases |

| DPI | Diphenyleneiodonium |

| e-As4S4 | As4S4 nanoparticle |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EMT | Eepithelial mesenchymal transition |

| EndoG | Endonuclease G |

| ER | Eendoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 |

| ER-α | Eestrogen receptor-α |

| ESR1 | Eestrogen receptor 1 |

| FOXM1 | Forkhead box protein M1 |

| GA | 18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid |

| GLE | Gganoderma lucidum extract |

| GPX4 | Gglutathione per-oxidase 4 |

| GPXs | Glutathione peroxidases |

| GSDMD | Gasdermin D |

| GSDMDNT | N-terminal fragment of GSDMD |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HA | Meso-hannokinol |

| HDACS | Histone deacetylases |

| HER-2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia inducible factor-1α |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| ISO | Isoglycyrrhizin |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| AIF | Apoptosis-inducing factor |

| LA | Levistilide |

| LC3-I | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-I |

| LC3-II | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-II |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LIPs | Labile iron pools |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MASM | [(6aS, 10S, 11aR, 11bR, 11cS)210-Methylamino-dodecahydro-3a, 7a-diaza-benzo (de)anthracene-8-thione] |

| MitoSOX | Mitochondrial superoxide |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| mTOR | mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| MtROS | Mitochondrial ROS |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NOXs | NADPH oxidases |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase |

| PHA | Physapruin A |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PRDX | Peroxidase |

| PSO | Psoralidin |

| P70S6K | p70 Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase |

| (r-As4s4) | raw As4S4 |

| RCD | Regulated cell death |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SAPK | Stress-Activated Protein Kinase |

| SBT-A | Scutelline A |

| SGNI | Shuganning injection |

| SLC7A-11 | Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| SSP | Spatholobus soil percolate |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| SystemXC | Cystine/glutamate transporter receptor |

| tBHP | tert-Butyl hydroperoxide |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| TET | Tetrandrine |

| Thr845 | Threonine 845 |

| TNBC | triple negative breast cancer |

| TQ | Thymoquinone |

| Trx-1 | Thioredoxin-1 |

| TrxR 1 | Thioredoxin Reductase 1 |

| TSS | Total secondary saponins |

| WA | Withaferin A |

| WHC | Withanolide C |

| XIAP | X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein |

| ZEB1 | Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 1 |

| 3-MA | 3-methyladenine |

| 6-MDS | 6-methox-ydihydrosanguine |

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Lei S, Zheng R, Zhang S, Chen R, Wang S, Sun K, et al. Breast cancer incidence and mortality in women in China: temporal trends and projections to 2030. Cancer Biol Med. 2021;18(3):900–9. doi:10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(3):288–300. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Humpton TJ, Alagesan B, DeNicola GM, Lu D, Yordanov GN, Leonhardt CS, et al. Oncogenic KRAS induces NIX-mediated mitophagy to promote pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(9):1268–87. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Pak VV, Ezeriņa D, Lyublinskaya OG, Pedre Bán, Tyurin-Kuzmin PA, Mishina NM, et al. Ultrasensitive genetically encoded indicator for hydrogen peroxide identifies roles for the oxidant in cell migration and mitochondrial function. Cell Metab. 2020;31(3):642–53. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2020.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cheung EC, Vousden KH. The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(5):280–97. doi:10.1038/s41568-021-00435-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, Weinberg S, Joseph J, Lopez M, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(19):8788–93. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003428107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Fouzat A, Hussein OJ, Gupta I, Al-Farsi HF, Khalil A, Al Moustafa AE. Elaeagnus angustifolia plant extract induces apoptosis via P53 and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathways in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Front Nutr. 2022;9:871667. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.871667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nieborowska-Skorska M, Kopinski PK, Ray R, Hoser G, Ngaba D, Flis S, et al. Rac2-MRC-cIII-generated ROS cause genomic instability in chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells and primitive progenitors. Blood. 2012;119(18):4253–63. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-385658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. O’Hagan HM, Wang W, Sen S, Destefano Shields C, Lee SS, Zhang YW, et al. Oxidative damage targets complexes containing DNA methyltransferases, SIRT1, and polycomb members to promoter CpG Islands. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):606–19. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–82. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;80:50–64. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lee JC, Hou MF, Huang HW, Chang FR, Yeh CC, Tang JY, et al. Marine algal natural products with anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13(1):55. doi:10.1186/1475-2867-13-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tang JY, Ou-Yang F, Hou MF, Huang HW, Wang HR, Li KT, et al. Oxidative stress-modulating drugs have preferential anticancer effects-involving the regulation of apoptosis, DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, metabolism, and migration. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;58:109–17. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Widodo N, Priyandoko D, Shah N, Wadhwa R, Kaul SC. Selective killing of cancer cells by Ashwagandha leaf extract and its component Withanone involves ROS signaling. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13536. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Sznarkowska A, Kostecka A, Meller K, Bielawski KP. Inhibition of cancer antioxidant defense by natural compounds. Oncotarget. 2017;8(9):15996–6016. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.13723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Yadav JP, Arya V, Yadav S, Panghal M, Kumar S, Dhankhar S. Cassia occidentalis L.: a review on its ethnobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(4):223–30. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.09.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Rastogi N, Gara RK, Trivedi R, Singh A, Dixit P, Maurya R, et al. Corrigendum to “(6)-Gingerol induced myeloid leukemia cell death is initiated by reactive oxygen species and activation of miR-27b expression” [Free Radic. Biol. Med. 68 (2014) 288–301]. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;146:404. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.08.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Song L, Chen X, Mi L, Liu C, Zhu S, Yang T, et al. Icariin-induced inhibition of SIRT6/NF-κB triggers redox mediated apoptosis and enhances anti-tumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(11):4242–56. doi:10.1111/cas.14648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Shendge AK, Chaudhuri D, Basu T, Mandal N. A natural flavonoid, apigenin isolated from Clerodendrum viscosum leaves, induces G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MCF-7 cells through the regulation of p53 and caspase-cascade pathway. Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(4):718–30. doi:10.1007/s12094-020-02461-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chen WY, Hsieh YA, Tsai CI, Kang YF, Chang FR, Wu YC, et al. Protoapigenone, a natural derivative of apigenin, induces mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells associated with induction of oxidative stress and inhibition of glutathione S-transferase π. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29(6):1347–59. doi:10.1007/s10637-010-9497-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wu Q, Kroon PA, Shao H, Needs PW, Yang X. Differential effects of quercetin and two of its derivatives, isorhamnetin and isorhamnetin-3-glucuronide, in inhibiting the proliferation of human breast-cancer MCF-7 cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(27):7181–9. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zeng A, Yu X, Chen B, Hao L, Chen P, Chen X, et al. Tetrahydrocurcumin regulates the tumor immune microenvironment to inhibit breast cancer proliferation and metastasis via the CYP1A1/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12935-023-02850-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Si L, Fu J, Liu W, Hayashi T, Nie Y, Mizuno K, et al. Silibinin inhibits migration and invasion of breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells through induction of mitochondrial fusion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;463(1–2):189–201. doi:10.1007/s11010-019-03640-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Shim HY, Park JH, Paik HD, Nah SY, Kim DSHL, Han YS. Acacetin-induced apoptosis of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells involves caspase cascade, mitochondria-mediated death signaling and SAPK/JNK1/2-c-Jun activation. Mol Cells. 2007;24(1):95–104. doi:10.1016/s1016-8478(23)10760-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Palit S, Kar S, Sharma G, Das PK. Hesperetin induces apoptosis in breast carcinoma by triggering accumulation of ROS and activation of ASK1/JNK pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(8):1729–39. doi:10.1002/jcp.24818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang X, Wang X, Wu T, Li B, Liu T, Wang R, et al. Isoliensinine induces apoptosis in triple-negative human breast cancer cells through ROS generation and p38 MAPK/JNK activation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12579. doi:10.1038/srep12579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]