Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Ferroptosis Mediates Zinc Toxicity: Implications for Cancer Therapy

BIOCEV, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Průmyslová 595, Vestec, 252 50, Czech Republic

* Corresponding Author: Anton Tkachenko. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(5), 721-741. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.063301

Received 10 January 2025; Accepted 03 March 2025; Issue published 27 May 2025

Abstract

Ferroptosis is an iron-driven, phospholipid hydroperoxide-mediated cell death, which has recently emerged as an attractive tool in cancer research due to its ability to govern the anti-tumor immune response. A growing research interest in ferroptosis biology has revealed the contribution of this regulated cell death to multiple diseases. In addition to iron, ferroptosis has been reported to be triggered by multiple heavy metals, which sheds light on the novel aspects of heavy metals-induced cytotoxicity. In this review, the ability of zinc, an essential biogenic element with a wide array of biological functions, to modulate ferroptosis in normal and malignant cells has been summarized. Accumulating evidence suggests that zinc-induced biological effects can be mediated by ferroptosis induction or attenuation. In addition, the anti-cancer effects of zinc can be at least partly attributed to ferroptosis induction. The signaling pathways governing zinc-regulated ferroptosis are highlighted. It has been underscored that zinc-mediated modulation of ferroptosis is dependent on alterations of redox homeostasis, antioxidant defense (in particular, the SLC7A11/GSH/GPX4 axis), and iron metabolism. Additionally, data on ferroptosis induction by zinc oxide nanoparticles are summarized to emphasize the potential of these nanomaterials as a promising therapeutic choice in anti-cancer treatment.Keywords

Over the past few decades, our understanding of key signaling pathways involved in cell death regulation has been considerably expanded, which has resulted in the identification of multiple unique regulated cell death (RCD) modalities, i.e., distinct cell death types that require the distinctive, specialized genetically programmed machinery [1]. Nowadays there are over 25 identified and described lethal subroutines. Although these RCDs are unique, signaling pathways frequently overlap forming the all-encompassing network [2]. Extensive studies demonstrate that some of the RCDs offer novel therapeutic opportunities, especially in the field of cancer research, since cancer is characterized primarily by dysregulated cell death [3–5]. It is important to note that cell death-targeted therapy can not only enable cancer cells to die inexorably but also adjust the immune response due to the diverse immunogenic effects of different cell death pathways [6,7]. In particular, ample evidence suggests that ferroptosis, which is an iron (Fe)-dependent RCD associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated accelerated phospholipid peroxidation and depletion of the antioxidant system, is a feasible target in cancer [8,9]. A growing body of evidence indicates that ferroptosis induction is of value for ensuring cell death of apoptosis-resistant cancer cells. In addition, this strategy can be used in cancer immunotherapy and to overcome drug resistance [10,11].

At the molecular level, ferroptosis is primarily driven by Fe overload and phospholipid peroxidation. Fe triggers a Fenton reaction resulting in the accumulation of ROS, which in turn drives phospholipid peroxidation [12]. ROS-induced phospholipid peroxidation generates toxic phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOH), which play a pivotal role in the execution of ferroptosis [13]. Ferroptosis sensitivity is dictated by multiple pathways. In particular, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), a lipid metabolism enzyme, facilitates ferroptosis by regulating the fatty acid composition of phospholipids in cell membranes, smoothing the way for induction and execution of ferroptosis [14,15]. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) is another lipid metabolism-associated enzyme critical for ferroptosis [16]. Similar to ACSL4, LPCAT3 adjusts the phospholipid composition of cell membranes, regulating the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis [17]. Along with Fe overload and ROS-induced PLOOH formation, altered antioxidant signaling pathways are essential conditions for ferroptosis execution [12]. For instance, the system Xc−/reduced glutathione (GSH)/glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis is a critical well-characterized regulator of ferroptosis [18]. GPX4 is a selenium-containing GSH-dependent antioxidant enzyme involved in the detoxification of ferroptosis-driving PLOOHs, and GSH for its action is primarily supplied by the system Xc− containing solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11). SLC7A11 is an essential component of the system Xc− that determines its role as a glutamate/cysteine antiporter. SLC7A11 ensures the uptake of cystine by cells, which is further converted to cysteine, an amino acid that acts as a source of the thiol group crucially important for the antioxidant activity of GSH [19,20]. GPX4 depletion determines the high sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis [21].

Ferroptosis dysregulation has been widely linked to pathogenesis of multiple diseases [22,23]. Abundant evidence clearly states that ferroptosis has been implicated in a broad array of pulmonary, hepatic, renal, pancreatic, gastrointestinal, dermal, autoimmune, neurodegenerative, endocrine, metabolic, and cardiovascular diseases [24]. Moreover, ferroptosis induction has been reported as a cytotoxic mechanism for several heavy metals. For instance, hexavalent chromium induces ferroptosis mainly by promoting oxidative stress and Fe accumulation [25]. Mercury (Hg) was shown to trigger ferroptosis in renal cells depleting GPX4 due to the antagonistic effects of Hg2+ to selenium, which is a structural component of GPX4 [26]. Xu et al. reported that the neurotoxicity of methylmercury was mediated by ferroptosis induction associated with Fe overload and inhibition of GPX4 and SLC7A11 [27]. Likewise, SLC7A11 downregulation regulated by MiR-378a-3p was demonstrated to mediate ferroptosis in lead (Pb)-mediated neurotoxicity [28]. In addition, the contribution of Pb-induced ferroptosis to neuroinflammation was shown by Guo et al. in an animal-based model [29]. In this case, Pb-induced ferroptosis was dependent on oxidative stress and the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/GPX4 pathway [29]. He et al. revealed that cadmium (Cd)-induced ferroptosis mediated liver dysfunction and was regulated by the protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK)/eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α)/activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)/CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) signaling pathway [30]. Moreover, Cd-induced damage to pancreatic β-cells was attributed to inflammation mediated by ferroptosis regulated through the GPX4/Ager/p65 signaling pathway [31]. Wang et al. showed that Cd-induced neurotoxicity was associated with ferroptosis driven by the mitochondrial ROS (mitROS)/ferritinophagy pathway [32]. Although copper (Cu) is capable of triggering a distinct RCD termed “cuproptosis” [33], Cu triggers ferroptosis as well. In particular, Cu-induced ferroptosis is mediated by autophagic degradation of GPX4 [34]. In C. elegans, the neurotoxicity of Cu is at least partly attributed to the mitROS/ferritinophagy axis [32]. Additionally, Yang et al. demonstrated that nickel (Ni)-triggered nephrotoxicity relied on ferroptosis associated with autophagy-dependent ferritin degradation and subsequent iron accumulation [35]. Like in the case of other heavy metals discussed above, Ni-associated neurotoxicity is associated with its ability to induce ferroptosis [36]. Ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis contributed to liver damage caused by arsenic (As) exposure [37]. Furthermore, induced lung damage via ferroptosis mediated by the mitROS-triggered endoplasmic reticulum membrane dysfunction [38].

The studies outlined above emphasize the role of ferroptosis in mediating the toxicity of heavy metals, especially in relation to its immunogenic consequences, indicating that ferroptosis inhibition might be a tempting strategy to reduce the toxicity of heavy metals. Moreover, ferroptosis induction by materials containing heavy metals, e.g., metal-based nanomaterials, seems to be promising for cancer treatment. To our knowledge, the links between zinc (Zn) and ferroptosis have not been yet summarized. Thus, in this review, the currently available relevant data on the ability of zinc to induce ferroptosis is summarized with a focus on the molecular signaling pathways involved and Zn-based nanoparticles as anti-cancer inducers of ferroptosis.

2 Zinc and Its Biological Effects: Possible Links to Ferroptosis

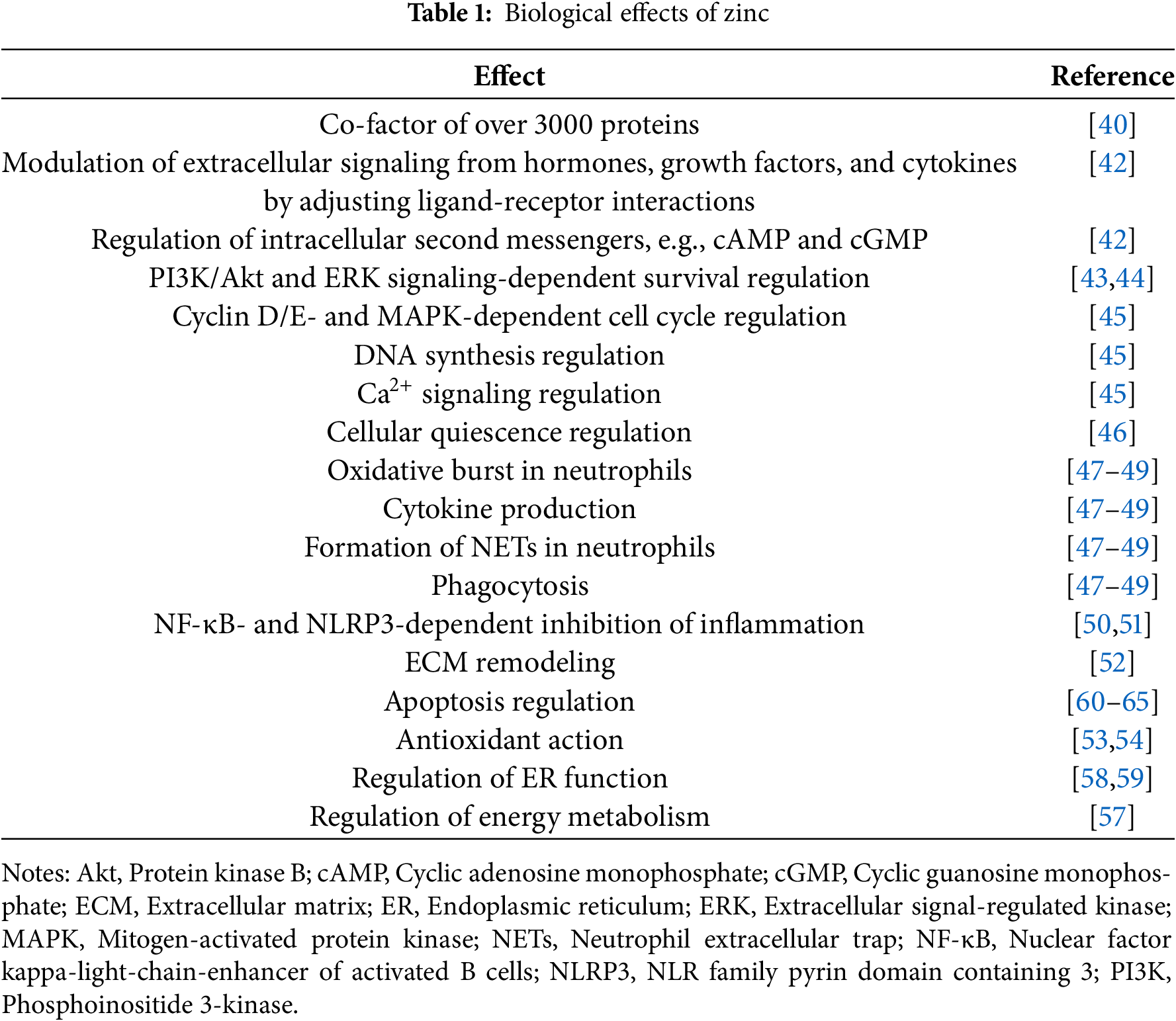

Zn is an essential biological trace element with a variety of important biological functions [39]. The diversity of Zn effects is associated with the fact that this metal is able to bind over 3000 various proteins comprising approximately 1/10 of the proteome. Additionally, Zn-coordinating Zn-finger domains are found in about 3% of proteins [40]. Zn modulates the activity of signaling pathways, transcription factors, and second messenger systems regulating mitosis and differentiation of cells [41]. Zn affects the intracellular content of second messengers, including cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Furthermore, it increases the affinity of certain ligands to receptors, modulating in this way extracellular signaling from hormones, cytokines, growth factors, etc. [42]. Zn promotes the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling [43,44]. Notably, Zn is involved in the regulation of the cell cycle at multiple levels, including via managing cyclin D/E, Ca2+ signaling, MAPK activity, and DNA synthesis [45]. On top of that, cellular quiescence is triggered by Zn deficiency [46].

Compelling evidence demonstrates that Zn is crucial for immunity by participating in oxidative burst, cytokine production, neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and phagocytosis [47–49]. Physiologically, Zn inhibits inflammation by suppressing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [50]. Furthermore, inhibition of inflammation by Zn is mediated by NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome inhibition [51]. Additionally, as a cofactor of a wide array of enzymes, Zn promotes wound healing, modulating extracellular matrix remodeling via regulating matrix metalloproteinases [52]. Converging lines of evidence suggest that Zn elicits indirect antioxidant effects by suppressing inflammation-induced ROS generation, as a co-factor of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), by upregulation of ROS-scavenging metallothionein, and through protection of -SH groups in proteins [53,54]. Zn deficiency is associated with DNA damage, indicating its involvement in DNA repair [55]. Due to the involvement of Zn in mediating neurotransmitter/receptor interactions, it maintains the transmission of nerve impulses contributing to supporting cognitive functions [56]. Furthermore, Zn can normalize the altered energy metabolism and ATP synthesis in stress conditions [57]. Ample evidence indicates that Zn is known to alleviate endoplasmic reticulum stress [58,59].

Abundant evidence indicates that Zn is involved in the regulation of cell death. Indeed, Zn is both pro- and anti-apoptotic. Furthermore, Zn induces apoptosis via ROS generation [60,61] and through the external Fas-mediated pathway [61]. Moreover, high levels of Zn were demonstrated to activate caspase-3, a key executioner of apoptosis [62]. At the same time, Zn might inhibit the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway by blocking Bax/Bak-mediated cytochrome c release [63]. Zn directly binds and inhibits caspases, proteases critically essential for the execution of apoptosis [64]. Moreover, caspase activation in cells might be triggered by Zn deficiency in cells suggesting a protective anti-apoptotic role of Zn [65]. Thus, the impact of Zn on apoptosis might be context-dependent and requires the crosstalk with other pro- and anti-apoptotic stimuli. Moreover, accumulating evidence indicates that Zn-mediated effects on apoptosis are cell type- and concentration-dependent [42].

The diversity of Zn-associated biological effects, its abundance in the human proteome, and its contribution to the regulation of cell death has resulted in a hypothesis that Zn overload can trigger a unique RCD termed “zincoptosis” by analogy with Cu-driven cuproptosis and Fe-driven ferroptosis [66].

High Zn intake results in its toxicity, promoting Zn-induced Cu deficiency and neurological disorders. However, toxic levels of Zn can hardly be achieved via oral intake [67]. Thus, the issues of Zn toxicity are poorly studied compared to its deficiency. At the molecular level, Zn-induced toxicity is mediated by a variety of molecular mechanisms. The effects observed as a result of Zn overload are frequently opposite to those reported for physiological concentrations of this metal. In general, excessive Zn-associated toxicity is linked to oxidative stress, mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction, DNA damage, modification of gene transcription and DNA methylation profiles, induction of apoptosis, regulation of the inflammatory response, and modulation of cell death pathways.

Zn-induced excitotoxicity is mediated by activation of protein kinase C with downstream recruitment of NADPH oxidase (NOX) that promotes ROS production [68]. Furthermore, oxidative stress in neurons can be aggravated due to excessive peroxynitrite formation associated with neuronal NO synthase activation [68]. Furthermore, Zn induces ROS generation, and depletes NADPH, and GSH-dependent links of the antioxidant system, e.g., glutathione reductase, in astrocytes [69]. In line with the data outlined above, Zn triggers NOX-dependent ROS generation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion [70]. In addition to NOX-derived ROS, Zn toxicity is mediated by mitROS whose production is upregulated as a result of Zn-triggered mitochondrial dysfunction [71–73]. Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by exposure to excessive Zn levels leads to a decline in ATP synthesis promoting energy deficit [74]. Notably, mitochondrial dysfunction in excessive Zn-exposed cells is associated with lysosomal dysfunction, suggesting the involvement of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis in Zn-mediated cytotoxicity [75]. Yang et al. revealed that cathepsin D was essential for activation of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis and Zn-induced apoptosis mediated by recruitment of this axis [75].

Although Zn prevents DNA damage at physiological concentrations, Zn overload promotes DNA damage in cancer cells, reinforcing genomic instability [76,77]. Excessive Zn exposure is associated with epigenetic changes, including DNA hypomethylation and therefore dysregulation of gene expression [78].

Accumulating evidence suggests that excessive Zn alters the inflammatory response. In particular, high Zn levels downregulate NF-κB-dependent secretion of interleukin 2 (IL-2), interleukin-2 receptor alpha (IL-2Rα), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in Th0 cells [79]. Conversely, exposure to supraphysiological Zn concentrations triggered NF-κB-dependent generation of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in THP-1 monocytes [80]. In general, a limited number of studies have focused on the impact of Zn exposure at high levels on immune functions.

Zn is widely studied as an inducer of apoptosis in cancer cells. Feng et al. showed that Zn triggered apoptosis in prostate cancer cells upregulating Bax [81]. In melanoma cells, Zn triggers ROS- and FAS-dependent apoptosis [60,61]. Zn triggers apoptosis activating caspase-3, upregulating Bax, and downregulating Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in malignant epithelial cells [82]. Moreover, Zn potentiates the action of anti-cancer drugs, e.g., docetaxel, in non-small-cell lung cancer in an oxidative stress-mediated fashion [83]. Thus, Zn-associated anti-cancer effects might be linked to apoptosis induction.

To sum up, Zn is an essential trace element, which is crucial for the proper functioning of a wide array of biological processes (Table 1). Its deficiency is well-documented. On the other hand, Zn overload is associated with toxicity, which is poorly studied. The current analysis suggests that cell death, in particular, apoptosis, is implicated in Zn toxicity. Moreover, the contribution of ROS production and mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction to Zn-mediated cytotoxicity indicates that Zn might elicit its toxicity via ferroptosis induction.

This review highlights the features of Zn-induced ferroptosis and summarizes studies focusing on the molecular pathways involved in ferroptosis regulated by Zn and Zn-containing compounds. Elucidation of Zn-induced ferroptosis features might provide insight into novel mechanisms of Zn-based cancer treatment to expand its potential clinical applications.

3 Ferroptosis Is Regulated by Zinc in a Context-Dependent Manner

Notably, the ability of Zn to regulate ferroptosis is built on a simple premise that Zn is tightly linked with Fe, a key inducer of ferroptosis, even at the organismal level. Indeed, there is extensive evidence supporting the interplay between Zn and Fe metabolism. In particular, Zn influences Fe intestinal absorption, and hence its bioavailability upregulates divalent metal iron transporter-1 (DMT1) and ferroportin (FPN1) [84]. Conversely, Zn was shown to reduce Fe absorption due to the competition between both ions for the intestinal transport systems [85]. Further research demonstrated that Zn contributed to whole-body Fe homeostasis by regulating circulating ferritin levels and the intracellular Fe pool [86]. Thus, Zn might regulate the bioavailability of Fe at the organismal level and its intracellular pool, which might contribute to the regulation of ferroptosis. In general, the impact of the whole-body Zn status on ferroptosis might widen our understanding of the crosstalk between biogenic elements (Zn and Fe) and provide novel insight into inflammation-related effects of Zn, since ferroptosis is known to be immunogenic cell death that emits multiple inflammation-regulating signals [87].

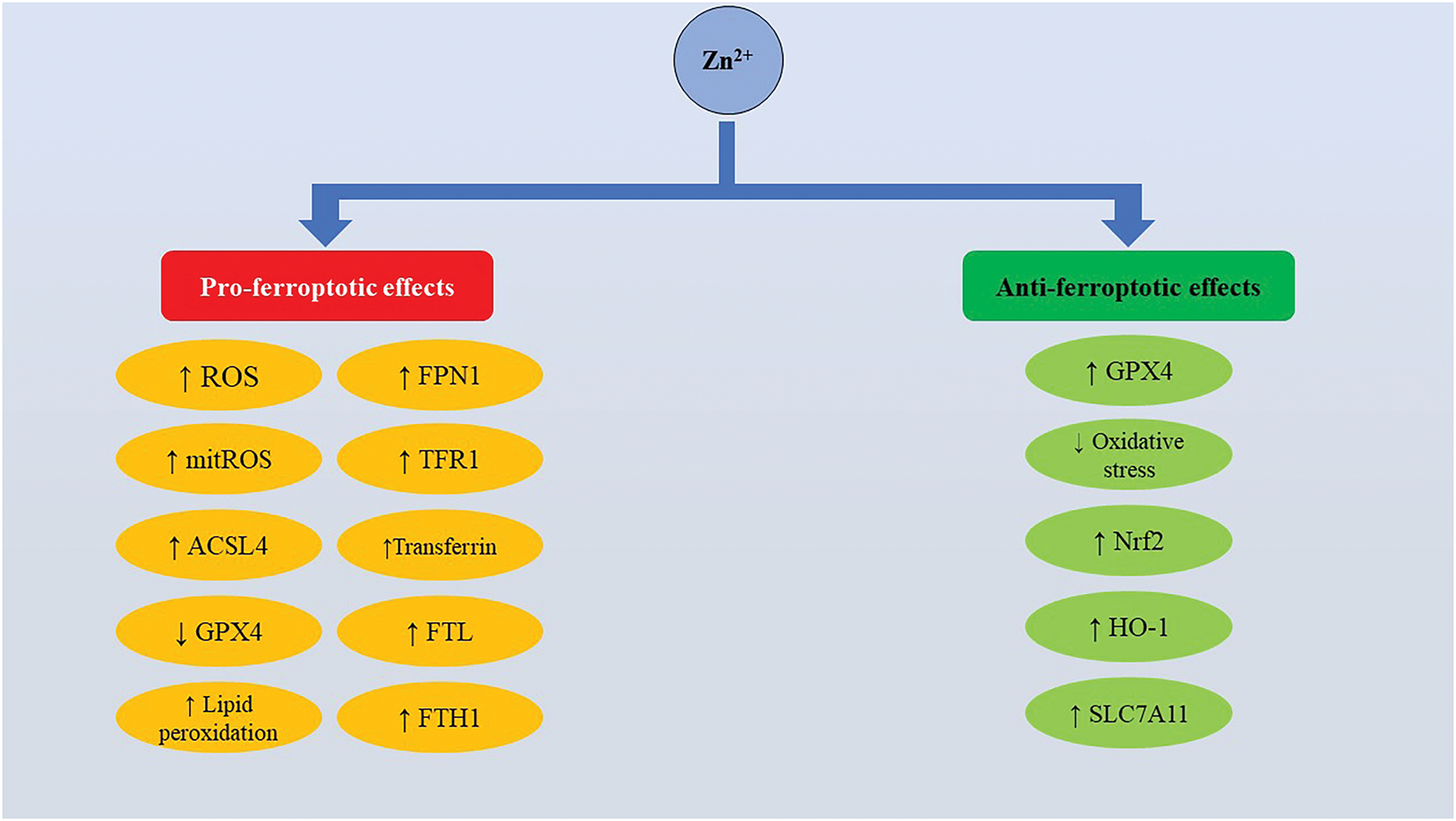

As illustrated in Fig. 1, our analysis reveals that Zn might be pro- and anti-ferroptotic depending on the context and cell types., In non-tumor cells, the effects of Zn on ferroptosis are cell type-dependent. Zn-mediated regulation of ferroptosis has been shown to ensure neuroprotection, as well as nephroprotection. At the same time, Zn-mediated toxicity can be attributed to the induction of ferroptosis. In particular, Zn-induced ferroptosis has been implicated in neurotoxicity [88]. In HT-22 murine hippocampal neuronal cells, combined exposure to Zn, Cu, and Fe triggered ROS-dependent ferroptosis associated with upregulation of iron-metabolism-associated proteins TFR1, FPN1, FTL, and FTH1, as well as ACSL4, and downregulation of GPX4. Notably, in the same experiment, Zn alone induced ferroptosis promoting lipid peroxidation downregulating GPX4, as well as upregulating TFR1, FPN1, and FTH1. Of note, the effect of the metal mixture was much more pronounced compared to individual metals, suggesting a certain level of additivity [88]. However, Zn was shown to be neuroprotective inhibiting oxidative stress-induced ferroptosis by promoting overexpression of GPX4, Nrf2, and HO-1 [89]. Apparently, the context-dependent neuroprotective or neurotoxic effects of Zn are mediated by its impact on redox signaling. Converging lines of evidence suggest that the impact of Zn on redox metabolism is not straightforward and Zn may be pro- or antioxidant, depending on the cellular microenvironment [54]. Thus, it can be assumed that the influence of Zn on ferroptosis in the nervous tissue is dependent on the balance between its prooxidant and antioxidant activities. This hypothesis is in line with the key role played by oxidative stress in Zn-mediated ferroptosis-associated neurotoxicity and alleviation of ferroptosis following Zn-induced mitigation of oxidative stress.

Figure 1: Physiologically, zinc regulates ferroptosis in a cell type- and context-dependent manner. Zinc modulates ferroptosis by regulating ROS production, antioxidant enzymes, and iron metabolism-regulating proteins. Abbreviations: ACSL4, Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; FPN1, Ferroportin 1; FTH1, Ferritin heavy chain 1; FTL, Ferritin light chain; GPX4, Glutathione peroxidase 4; HO-1, Heme oxygenase 1; mitROS, Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; Nfr2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; SLC7A11, Solute carrier family 7 member 11; TFR1, Transferrin receptor 1

In swine testicular cells, Zn-induced ferroptosis promotes mitROS generation, lipid peroxidation, ferritin and GPX4 downregulation, upregulation of TFR1, transferrin, and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) [90]. At the same time, Zn was shown to protect renal tubular cells from contrast media-induced ferroptosis [91]. Additionally, Zn ameliorated As-induced ferroptosis in carp kidney cells upregulating GPX4 and SLC7A11 and reducing oxidative damage [92].

Regrettably, there is a dearth of research focusing on Zn-induced ferroptosis. However, it has become clear that Zn can be either pro- or anti-ferroptotic. Among the factors that determine the response of cells to Zn, oxidative stress is of significant importance.

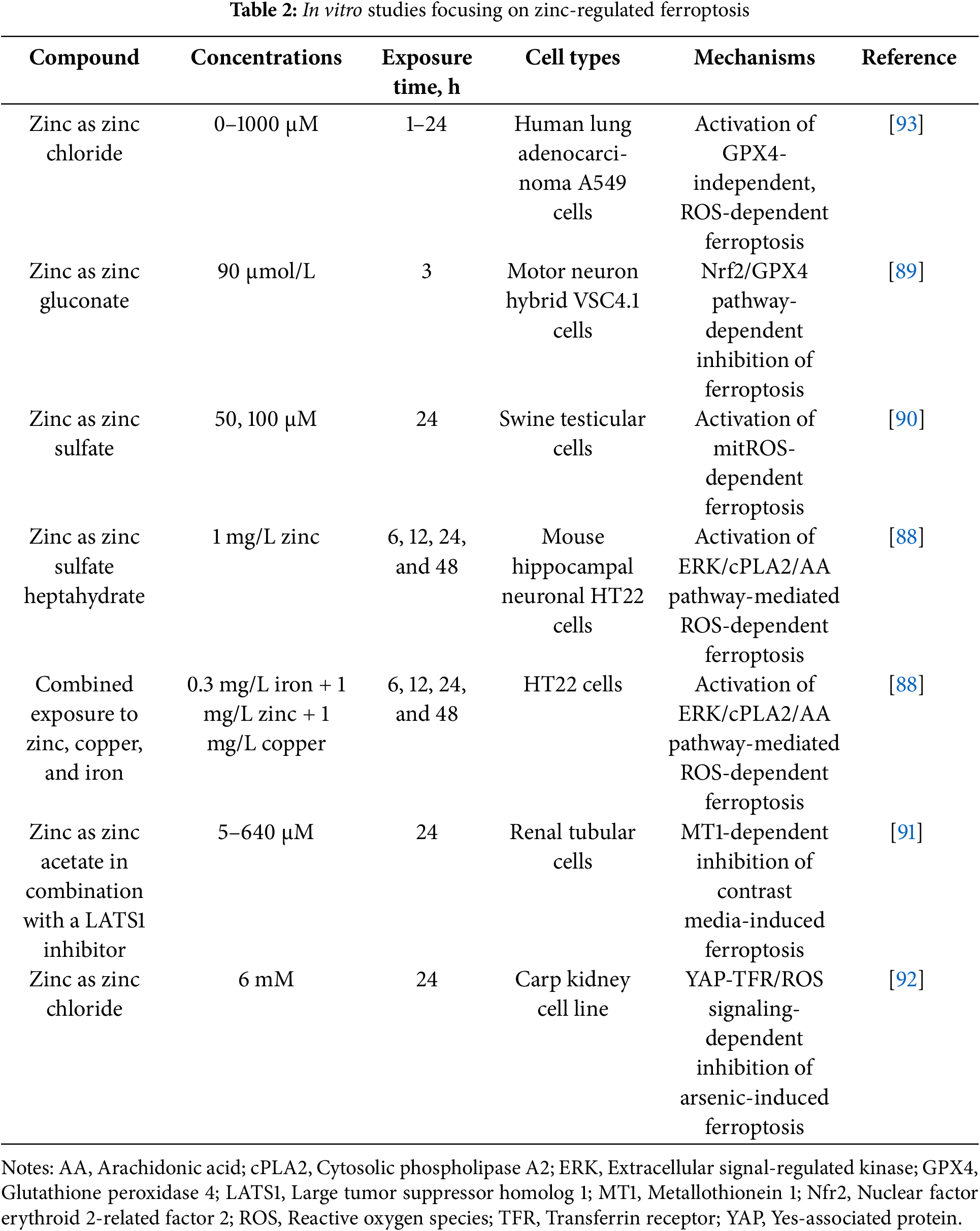

Unsurprisingly, a variety of studies have focused on Zn-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells to investigate the potential implications of Zn-based anti-cancer therapy (Table 2). In A549 human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines, Zn induced ferroptosis, which was clearly distinct from necrotic cell death and apoptosis at the proteomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic levels [93]. Ferroptosis was associated with lipid peroxidation, deactivation of the system xc− and GSH depletion, upregulation of glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1), which is an important regulator of redox metabolism and ferroptosis [93]. Furthermore, Zn deficiency inhibited ferroptosis of EC109 esophageal squamous carcinoma cells by adjusting lactate production [94].

It has become clear that Zn can regulate ferroptosis in normal and malignant cells. The paucity of currently available data about the factors that might determine the response of the ferroptosis machinery to Zn suggests that there is still a long way to complete elucidation of Zn-ferroptosis interactions. Apparently, the ferroptosis pathway machinery represents an important target for Zn in both non-malignant and malignant cells, indicating that Zn regulation of ferroptosis has physiological and pathophysiological implications. Nevertheless, more studies are required to provide a deeper insight into the potential clinical applications of ferroptosis targeting by Zn for cancer therapy.

4 Diverse Signaling Pathways Govern Ferroptosis Modulated by Zinc

Signaling pathways involved in Zn-induced ferroptosis are far from being elucidated at the moment. The impact of Zn on ferroptosis can be also modulated through the zinc transporter SLC39A7 (ZIP7), which is shown to regulate ferroptosis by supporting endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis [95]. Further studies demonstrated the involvement of another Zn regulator, ZRT/IRT-like protein 14 (ZIP14), in ferroptosis through modulation of Fe bioavailability [96].

It is clear that Zn might influence ferroptosis by affecting the prooxidant/antioxidant balance. The SLC7A11/GSH/GPX4 axis plays a key role in the regulation of susceptibility to ferroptosis and is well-documented to be affected by Zn. It is interesting to note that Zn can induce ferroptosis without downregulation of GPX4 [93]. However, GPX4 depletion-associated ferroptosis has been reported and seems to be important [90]. At the same time, protective inhibitory effects of Zn on ferroptosis are associated with GPX4 overexpression [89]. Thus, in cells exposed to Zn, GPX4 expression might be downregulated, unaffected, or upregulated, which contributes to determination of the cell fate by counteracting pro-ferroptotic effects of ROS and PLOOH. Little is known about the precise molecular interactions between zinc and key ferroptosis regulators. Protective effects of Zn against ferroptosis are attributed to NRF2/HO-1-dependent GPX4 upregulation [89]. Importantly, the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway is activated in response to oxidative stress to upregulate antioxidant enzymes and alleviate oxidative damage [97]. At the same time, it is clear that Zn2+ overload-induced ROS production might deplete GSH [98], which increases susceptibility to ferroptosis. Thus, it can be suggested that the degree of redox imbalance triggered by Zn can be decisive for modulating the regulation of antioxidant ferroptosis-related enzymes. Additionally, Zn is known to stimulate autophagy [99] and autophagy-dependent degradation of GPX4 is frequently associated with heavy metals-induced ferroptosis [100]. However, this hypothesis has not yet been verified experimentally. Notably, the SLC7A11 acetylation status has been shown to affect susceptibility to Zn-induced ferroptosis [101]. Obviously, more efforts are required to elucidate how the anti-ferroptotic machinery is influenced by Zn.

Mitochondria play an important role in modulating ferroptosis-associated effects of Zn. Zn-induced ferroptosis is mediated by mitophagy [90]. Furthermore, mitochondrial Zn2+ influx is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in activation of ferroptosis [102]. Oxidative stress essential for ferroptosis induction is also worsened by Zn through induction of mitROS generation, suggesting that mitROS production is an important mechanism for Zn-induced ferroptosis [90].

Apart from the redox pathways, it has been shown that the ERK/cPLA2 (cytosolic phospholipase A2)/AA (arachidonic acid) signaling pathway is activated to mediate ferroptosis induced by co-exposure to Zn, Cu, and Fe [88]. Additionally, activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway is involved in ferroptosis inhibition by Zn [89].

Notably, the cell’s exposure to toxic concentrations of Zn aims to adapt by upregulation of cysteine-rich Zn-chelating metallothioneins (MTs), including MT1F, MT1X, and MT2A [93]. Interestingly, Zn-induced upregulation of MT1 protects cells from contrast media-induced ferroptosis [91]. Furthermore, the protective anti-ferroptosis effects of Zn have been associated with the modulation of the YAP/TFR pathway [92].

Thus, Zn affects various ferroptosis-regulating signaling axes, both driving and inhibiting them. These pathways regulate redox homeostasis, antioxidant defense, and iron metabolism. The abundance of the signaling pathways associated with the regulation of Zn-induced ferroptosis underscores the complexity of this phenomenon. Importantly, initiating mechanisms that launch the entire ferroptosis machinery under the influence of Zn remains unexplored. Novel studies focusing on the elucidation of the signaling pathways orchestrating Zn-regulated ferroptosis might shed light on the mechanisms of Zn toxicity and identify novel conditions for Zn-based therapeutic interventions.

5 Ferroptosis Induction by ZnO Nanoparticles Is a Promising Approach for Anti-Cancer Immunotherapy

Given a variety of functions and processes affected by Zn, Zn supplementation is considered to have therapeutic potential [42]. In this study, it has been emphasized that the therapeutic effectiveness of Zn can be at least partly attributed to ferroptosis modulation. At the same time, Zn itself is probably not suitable for ferroptosis-modulating therapy due to its multifaceted nature in the human body and lack of selectivity. Nonetheless, Zn-based nanomaterials are promising versatile candidates for therapeutic agents that can overcome the shortcomings of Zn. They can be investigated as ferroptosis modulators and are adjustable to ensure the possibility of further modification of their properties to fine-tune the therapeutic effects.

ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) are well-characterized nanomaterials with a good safety profile and a broad range of potential biomedical applications, including for bioimaging and drug delivery, as antibacterial, anti-cancer, antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, hepatoprotective and wound healing agents [103]. It is important to note that ZnO NPs are declared by the Food and Drug Administration among quite a few metal-containing nanomaterials as generally recognized as safe [104]. The biocompatibility of ZnO NPs supports further research aimed at delineation of their medical applications. Anti-cancer effects of ZnO NPs are under scrutinous investigation and can be potentially applied for in vivo tumor imaging, as anti-cancer agents, for targeted drug delivery and diagnostic purposes [105]. In general, the anti-cancer effects of ZnO NPs are attributed to oxidative stress, Zn2+ release, apoptosis induction, induction of mitochondrial dysfunction, and lysosomal membrane destabilization [105–108]. However, modern data have revealed that cancer cells are vulnerable to ferroptosis, which can be exploited for cancer therapy [109]. Cancer susceptibility to ferroptosis has fueled research dealing with the search for novel nanotechnology-based ferroptosis-triggering anti-cancer agents. In this review, the currently available data on the pro-ferroptotic effects of ZnO NPs and other Zn-containing nanomaterials are summarized.

ZnO NPs have been shown to trigger ferroptosis in normal cell lines, including human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [110,111], EA.hy926 human endothelial cells [111], and GC-2 spd murine spermatocytes [112]. Furthermore, ZnO NPs induced ferroptosis in Mycobacterium-infected RAW264.7 macrophages, evidenced by ACSL4 upregulation and GPX4 downregulation [113]. This study sheds light on the possible application of ZnO NPs as ferroptosis-targeting antibacterial agents.

In HUVECs or EA.hy926 cells, ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis was associated with the depletion of the antioxidant system (GSH and GPX4 depletion), and ROS overproduction-induced lipid peroxidation [110,111]. However, it is important to note that ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis in HUVECs or EA.hy926 cells is not associated with abnormal expression of ACSL4 or SLC7A11 [111]. In murine spermatocytes, ferroptosis was linked to ROS overproduction, lipid peroxidation, GSH depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction, and downregulation of NCOA4, FTH1, SLC7A11 and GPX4 [112]. Notably, ferroptosis induction by ZnO NPs in HUVECs and EA.hy926 cells critically depends on NCOA4 (nuclear receptor coactivator 4)-dependent ferritinophagy, which increases Fe availability inside the cells by autophagic degradation of ferritin involved in iron storage [111]. Another mechanism involved in ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis includes miR-342-5p-dependent ERC1 (ELKS/RAB6-Interacting/CAST Family Member 1) inactivation and NF-κB recruitment [112]. Pro-ferroptotic SLC7A11 downregulation induced by ZnO NPs in HUVECs was found to be p53-dependent, which is another insight into the regulation of ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis [110]. It is worth mentioning that Zn ions at least partly contribute to ferroptosis induced by ZnO NPs, since their accumulation in ZnO NPs-treated normal cells has been shown [113].

Selective induction of ferroptosis in cancer cells without affecting non-tumor cells remains one of the severe limitations of ferroptosis induction in cancer therapy [114]. This review clearly shows that ZnO NPs can induce ferroptosis in a broad array of normal cell lines, suggesting that further efforts should be put into investigating the improvements that can be applied to increase selectivity.

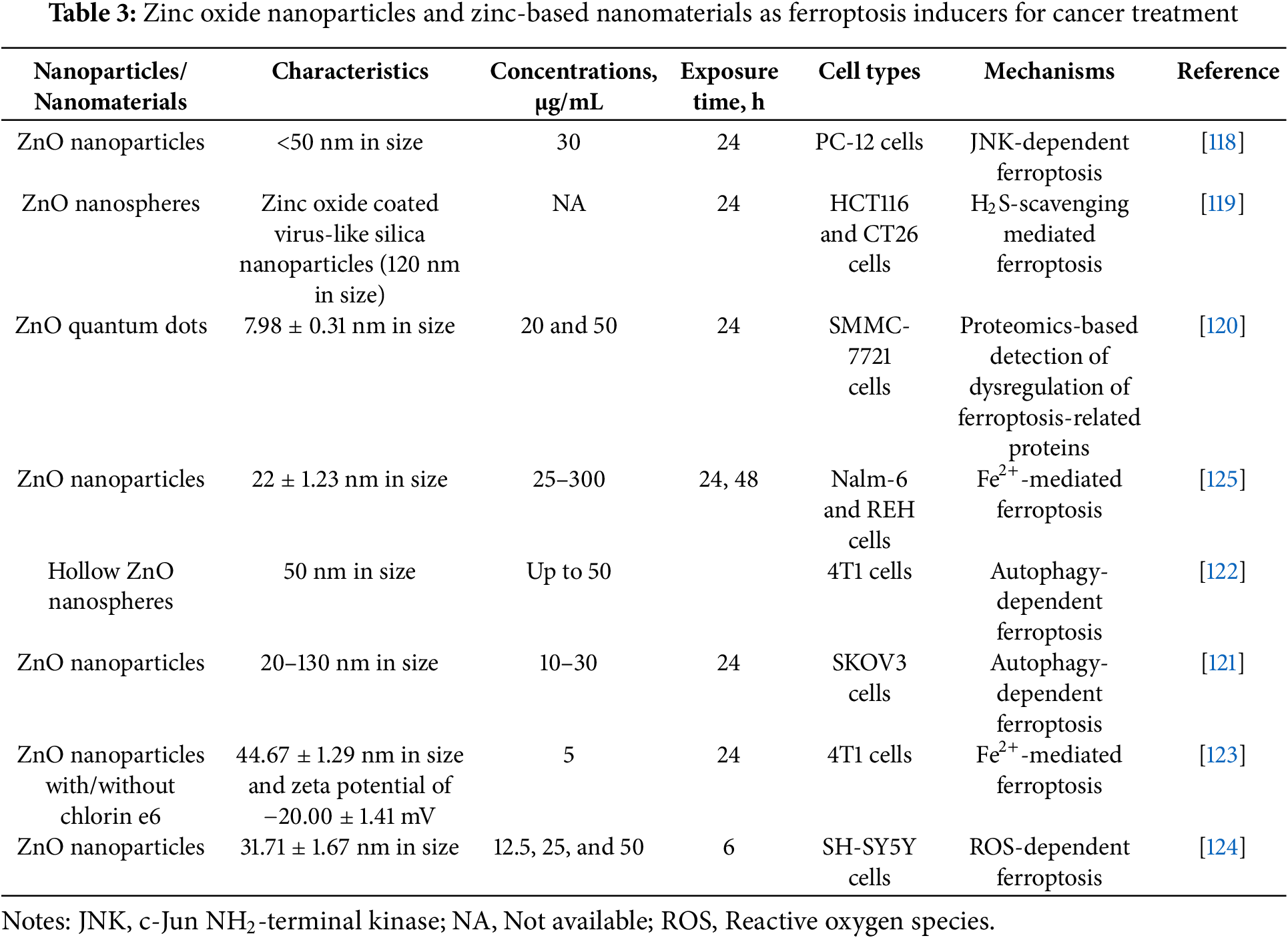

In multiple studies, iron doping is widely used to enhance ROS-generating and pro-ferroptotic action of ZnO NPs [115,116]. Indeed, iron doping is a common strategy used for ferroptosis-inducing nanomaterials in cancer treatment [117]. However, in this study, the effects of exclusively non-doped Zn-based nanomaterials are summarized to delineate their ferroptosis-inducing potential. ZnO NPs trigger ferroptosis in cancer cell lines, including rat pheochromocytoma PC-12 cells [118], HCT116 and CT26 colon carcinoma cell lines [119], SMMC-7721 human hepatocarcinoma cells [120], SKOV3 ovarian adenocarcinoma cells [121], murine breast cancer 4T1 cell line [122,123], SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells [124], and pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia Nalm-6 and REH cells [125]. In SMMC-7721 cells exposed to ZnO quantum dots, proteomic analysis revealed altered expression of ferroptosis-associated proteins, but no further verification of ferroptosis induction was performed [120]. In other studies, ferroptosis was demonstrated by using ferroptosis inhibitors or via the detection of ferroptosis markers.

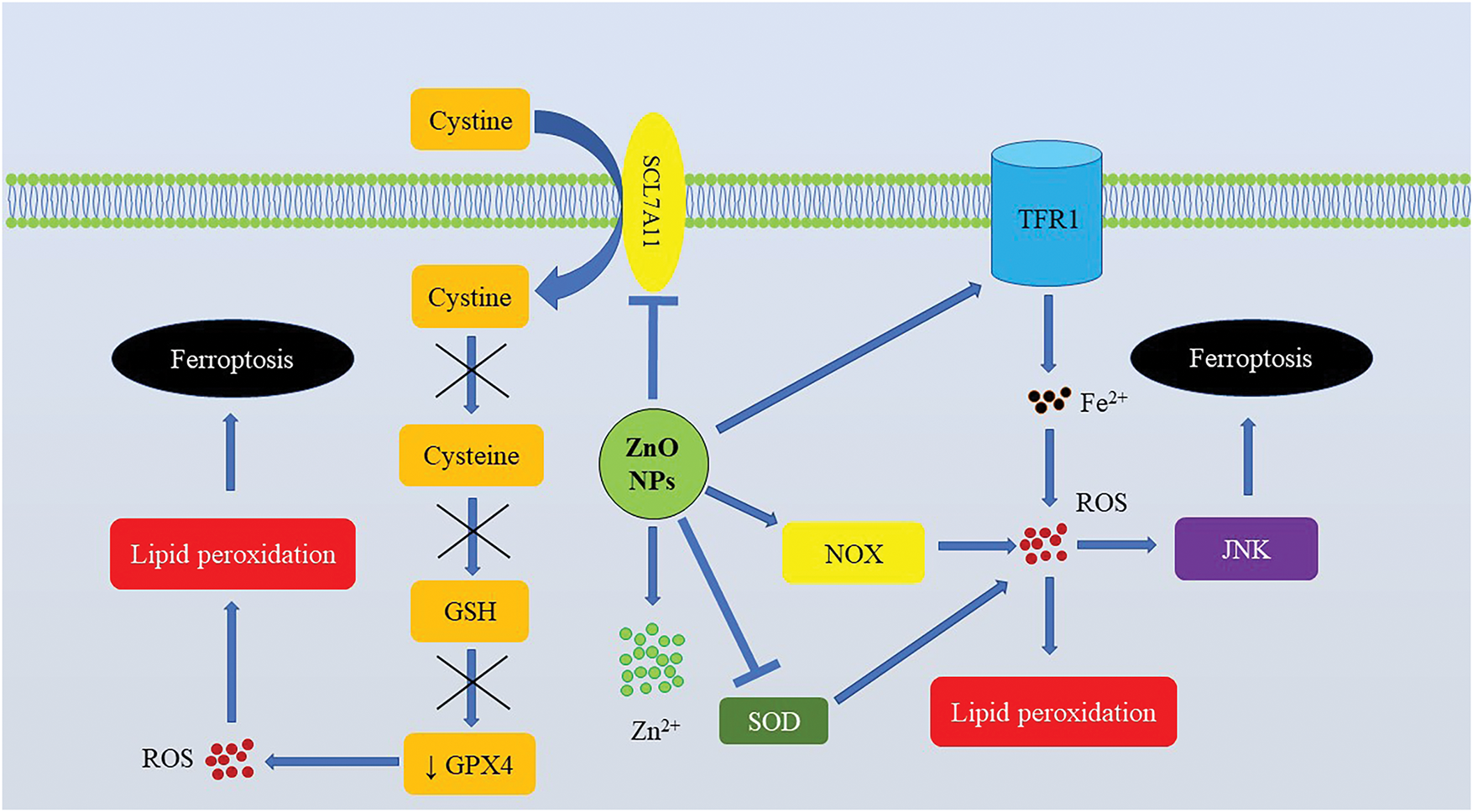

As illustrated in Fig. 2, GPX4 and SCL7A11 downregulation was a hallmark of ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis [118,119,123–125]. In HCT116 and CT26 cells, ZnO nanospheres-induced ferroptosis was associated with ROS overproduction and upregulation of NOX1, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), and TFR1 [119]. In SKOV3 cells, ZnO NPs promoted oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, downregulation of SOD and GPX4, and upregulation of TFR1 and ACSL4 [121]. In the 4T1 cell line, ZnO NPs induced ferroptosis associated with depletion of GSH, SLC7A11, GPX4, and ALOX15 upregulation [122,123]. ZnO NPs-triggered ferroptosis of SH-SY5Y cells was linked to the downregulation of GPX4, FTL, and SLC7A11, as well as the development of oxidative stress [124]. In Nalm-6 and REH cells, ferroptosis was associated with lipid peroxidation, Fe overload, upregulation of ACSL4, ALOX15, and p53, GSH depletion, and downregulation of SLC7A11 and GPX4 [125] (Table 3).

Figure 2: Zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. In cancer cells, ZnO NPs induce oxidative stress by promoting ROS generation and causing GSH depletion by inhibiting the system Xc−. Abbreviations: GPX4, Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, Reduced glutathione; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; NOX, NADPH oxidase; NPs, Nanoparticles; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; SLC7A11, Solute carrier family 7 member 11; SOD, Superoxidase dismutase; TFR1, Transferrin receptor 1

Comparative analysis of the studies focusing on ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells reveals the importance of targeting the SLC7A11/GSH/GPX4 axis, depleting the antioxidant capacity of cells to ensure ROS-mediated damage to cells for further lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis induction. Additionally, Fe overload is an important upstream mechanism that triggers ROS production and ferroptosis under the action of ZnO NPs [123]. ROS generation is also of paramount importance [124]. Of note, in rat pheochromocytoma PC-12 cells, ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis was JNK-dependent [118]. Activation of the JNK pathway was triggered by ROS and amplified pro-ferroptotic signals via Fe accumulation [126]. Of note, the crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy has been shown to mediate tumor cell-killing effects of ZnO NPs. In particular, ferroptosis induced by ZnO NPs in ovarian adenocarcinoma cells was autophagy-dependent and required autophagy protein 5 (ATG5) recruitment [121]. Furthermore, autophagy was reported to promote ferroptosis in cancer cells by reducing GPX4 [122]. Of note, like in the case of normal cells, Zn2+ release from ZnO NPs is required for ferroptosis induction [124].

It is important to note that in some studies the selectivity of ferroptosis-inducing effects of ZnO NPs towards cancer cells compared with the non-tumor cells has been demonstrated [125]. To sum up, ZnO NPs can be considered promising candidates for applying as anti-cancer agents. This review clearly demonstrates that ferroptosis induction is an important weapon in the arsenal of ZnO NPs.

Collectively, ferroptosis targeting by ZnO NPs is under investigation in antibacterial and anti-cancer therapy. Ample evidence suggests that ZnO NPs-mediated ferroptosis induction is a feasible anti-cancer strategy. ZnO NPs primarily induce ferroptosis by boosting ROS production and depleting the antioxidant machinery protective against ferroptosis. It remains largely underexplored whether the depletion of ferroptosis-related antioxidant enzymes is indirect and associated with ROS overproduction or is directly affected by NPs. Moreover, the field definitely lacks studies revealing the impact of ZnO NPs-induced ferroptosis on anti-cancer immunity. This issue is of crucial importance since ferroptosis-mediated anti-cancer effects are primarily attributed to the immunogenic properties of this cell death.

Zn is an essential biological element performing a wide range of biological functions. This review provides evidence that ferroptosis, an oxidative stress-associated, iron-driven RCD, is involved in the pathological effects of both Zn deficiency and toxicity. Although scarce data on the links between Zn and ferroptosis are currently available, it has already become clear that Zn-associated effects on ferroptosis are cell type- and context-dependent. However, factors that might influence susceptibility to Zn-induced ferroptosis or conditions in which Zn-induced ferroptosis might be activated are poorly explored. In addition, Zn might regulate inflammation by adjusting ferroptosis levels. In particular, in spinal cord injury, alleviation of ferroptosis by Zn downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines to reduce inflammation [89]. At the same time, the induction of ferroptosis by Zn can boost inflammation, since ferroptosis alters inflammatory pathways [127].

Much remains to be understood in the circumstances and ways of ferroptosis-associated Zn-induced cytotoxicity. A great variety of challenges and unknown issues harness the development of the field. Currently, it has become clear that ferroptosis sensitivity is different in various cells and is subject to regulation by intracellular signaling and metabolic networks [128], which determines the context-dependent character of ferroptosis regulation. Although we are far from an in-depth understanding of this process, apparently, this susceptibility is shaped by changes in the expression of ferroptosis-related genes [14]. This explains why Zn can be pro- or anti-ferroptotic in different cells. It can be assumed that the impact of Zn on the cells is imposed upon the integrated ferroptosis genetic suppressor network and the pro-ferroptotic PLOOH-forming system and the interplay of these inputs determines the output (ferroptosis). This hypothesis is supported by the fact outlined in this review that Zn-induced ferroptosis might occur when GPX4 is not dysregulated or even upregulated.

Recent findings indicate that pro-ferroptotic signaling converges upon an execution mechanism [128]. Indeed, in the current study, Zn has been shown to affect ferroptosis by regulation of ROS production, as well as iron and GSH availability. At the moment, it seems challenging to detect initiating factors and mechanisms contributing to ferroptosis induction by Zn. Reasonably, the complex interaction between these links rather determines the cell fact. In particular, ROS are known as one of the major regulators of survival/cell death that can also ensure a switch between different lethal subroutines acting as a rheostat [129]. Likewise, GSH depletion is an essential signaling hallmark of multiple RCDs [130].

Regulation of Zn availability has been already suggested as a promising strategy for cancer treatment [131]. Over recent years, ferroptosis has become a hotspot in cancer research due to its cancer cell-killing and immunogenic effects [132]. In this review, the hypothesis that ferroptosis modulation might be involved in the anticancer effects of Zn is supported. In addition, converging lines of evidence suggest that ZnO NPs are potential ferroptosis-inducing anticancer agents. In this review, the GSH/GPX4 status is shown to be an important hub in the modulation of ferroptosis by Zn and ZnO NPs. This is consistent with other data supporting the role of GSH in determining the cell fate in Zn-exposed cells [133]. In addition, although Zn is of limited redox activity, ROS production plays a pivotal role in its pro-ferroptotic effects. Importantly, there is some evidence that tumor cells are more vulnerable to Zn-induced ferroptosis in comparison with non-cancer cells, which indicates the prospective for the search for novel Zn-based anti-cancer drugs. At the same time, Zn-associated ferroptosis induction in cancer therapy might be associated with adverse effects. Immunogenic effects of Zn-induced ferroptosis [134] should be tightly monitored to avoid excessive, long-term activation of inflammation that might promote tumor growth instead of boosting anti-tumor immunity.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Funding was provided by an EHA Ukraine Bridge Funding awarded by the European Hematology Association.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATF4 | Activating transcription factor 4 |

| ATG5 | Autophagy protein 5 |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| cPLA2 | Cytosolic phospholipase A2 |

| CHOP | CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein |

| COX2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| DMT1 | Divalent metal iron transporter-1 |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FPN1 | Ferroportin 1 |

| FTH1 | Ferritin heavy chain 1 |

| FTL | Ferritin light chain |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| HUVECs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-2Rα | Interleukin-2 receptor alpha |

| JNK | c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase |

| LATS1 | Large tumor suppressor homolog 1 |

| LPCAT3 | Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 |

| mitROS | Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species |

| MT1 | Metallothionein 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PERK | Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PLOOH | Phospholipid hydroperoxides |

| RCD | Regulated cell death |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TFR | Transferrin receptor |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

References

1. Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, et al. Essential versus accessory aspects of cell death: recommendations of the NCCD 2015. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(1):58–73. doi:10.1038/cdd.2014.137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Snyder AG, Oberst A. The antisocial network: cross talk between cell death programs in host defense. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39(1):77–101. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-112019-072301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Peng F, Liao M, Qin R, Zhu S, Peng C, Fu L, et al. Regulated cell death (RCD) in cancer: key pathways and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):286. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01110-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gong L, Huang D, Shi Y, Liang Z, Bu H. Regulated cell death in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. Chin Med J. 2023;136(6):653–65. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000002239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Damiescu R, Efferth T, Dawood M. Dysregulation of different modes of programmed cell death by epigenetic modifications and their role in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024;584:216623. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hänggi K, Ruffell B. Cell death, therapeutics, and the immune response in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2023;9(5):381–96. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2023.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Meier P, Legrand AJ, Adam D, Silke J. Immunogenic cell death in cancer: targeting necroptosis to induce antitumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024;24(5):299–315. doi:10.1038/s41568-024-00674-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Dixon SJ, Olzmann JA. The cell biology of ferroptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(6):424–42. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00703-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ma L, Shao W, Zhu W. Exploring the molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies of ferroptosis in ovarian cancer. BIOCELL. 2024;48(3):379–86. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.047812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nie Z, Chen M, Gao Y, Huang D, Cao H, Peng Y, et al. Ferroptosis and tumor drug resistance: current status and major challenges. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879317. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.879317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y, Guo R. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01530-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Chen Y, Fang Z-M, Yi X, Wei X, Jiang D-S. The interaction between ferroptosis and inflammatory signaling pathways. Cell Death Disease. 2023;14(3):205. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-05716-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Chen X, Kang R, Tang D. Ferroptosis by lipid peroxidation: the tip of the iceberg? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:646890. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.646890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91–8. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jia B, Li J, Song Y, Luo C. ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis and its potential role in central nervous system diseases and injuries. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(12):10021. doi:10.3390/ijms241210021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kim JW, Lee JY, Oh M, Lee EW. An integrated view of lipid metabolism in ferroptosis revisited via lipidomic analysis. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(8):1620–31. doi:10.1038/s12276-023-01077-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Hao J, Wang T, Cao C, Li X, Li H, Gao H et al. LPCAT3 exacerbates early brain injury and ferroptosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res. 2024;1832:148864. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2024.148864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Li FJ, Long HZ, Zhou ZW, Luo HY, Xu SG, Gao LC. System Xc−/GSH/GPX4 axis: an important antioxidant system for the ferroptosis in drug-resistant solid tumor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:910292. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.910292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ma T, Du J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang B, Zhang T. GPX4-independent ferroptosis—a new strategy in disease’s therapy. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):434. doi:10.1038/s41420-022-01212-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sun S, Shen J, Jiang J, Wang F, Min J. Targeting ferroptosis opens new avenues for the development of novel therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):372. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01606-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021;31(2):107–25. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi AA, et al. Ferroptosis: mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):49. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00428-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chen F, Kang R, Tang D, Liu J. Ferroptosis: principles and significance in health and disease. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1):41. doi:10.1186/s13045-024-01564-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kurmangaliyeva S, Baktikulova K, Tkachenko V, Seitkhanova B, Shapambayev N, Rakhimzhanova F et al. An overview of hexavalent chromium-induced necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2024;10(24):1149720. doi:10.1007/s12011-024-04376-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen J, Ma M, Wang R, Gao M, Hu L, Liu S, et al. Roles of glutathione peroxidase 4 on the mercury-triggered ferroptosis in renal cells: implications for the antagonism between selenium and mercury. Metallomics. 2023;15(3):mfad014. doi:10.1093/mtomcs/mfad014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Xu X, Wang SS, Zhang L, Lu AX, Lin Y, Liu JX, et al. Methylmercury induced ferroptosis by interference of iron homeostasis and glutathione metabolism in CTX cells. Environ Pollut. 2023;335:122278. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wang W, Shi F, Cui J, Pang S, Zheng G, Zhang Y. MiR-378a-3p/SLC7A11 regulate ferroptosis in nerve injury induced by lead exposure. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;239:113639. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Guo JT, Cheng C, Shi JX, Zhang WT, Sun H, Liu CM. Avicularin attenuated lead-induced ferroptosis, neuroinflammation, and memory impairment in mice. Antioxidants. 2024;13(8):1024. doi:10.3390/antiox13081024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. He Z, Shen P, Feng L, Hao H, He Y, Fan G, et al. Cadmium induces liver dysfunction and ferroptosis through the endoplasmic stress-ferritinophagy axis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;245(3):114123. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hong H, Lin X, Xu Y, Tong T, Zhang J, He H, et al. Cadmium induces ferroptosis mediated inflammation by activating Gpx4/Ager/p65 axis in pancreatic β-cells. Sci Total Environ. 2022;849(5):157819. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang D, Wu Y, Zhou X, Liang C, Ma Y, Yuan Q, et al. Cadmium exposure induced neuronal ferroptosis and cognitive deficits via the mtROS-ferritinophagy pathway. Environ Pollut. 2024;349:123958. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 2022;375(6586):1254–61. doi:10.1126/science.abf0529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Xue Q, Yan D, Chen X, Li X, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, et al. Copper-dependent autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy. 2023;19(7):1982–96. doi:10.1080/15548627.2023.2165323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yang Q, Zuo Z, Zeng Y, Ouyang Y, Cui H, Deng H, et al. Autophagy-mediated ferroptosis involved in nickel-induced nephrotoxicity in the mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023;259:115049. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Z, Li K, Xu Y, Song Z, Lan X, Pan C, et al. Ferroptosis contributes to nickel-induced developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish. Sci Total Environ. 2023;858(3):160078. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yu L, Lv Z, Li S, Jiang H, Han B, Zheng X, et al. Chronic arsenic exposure induces ferroptosis via enhancing ferritinophagy in chicken livers. Sci Total Environ. 2023;890:164172. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li MD, Fu L, Lv BB, Xiang Y, Xiang HX, Xu DX, et al. Arsenic induces ferroptosis and acute lung injury through mtROS-mediated mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane dysfunction. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;238(1):113595. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Dean MC, Garrevoet J, Van Malderen SJM, Santos F, Mirazón Lahr M, Foley R, et al. The distribution and biogenic origins of zinc in the mineralised tooth tissues of modern and fossil hominoids: implications for life history, diet and taphonomy. Biology. 2023;12(12):1455. doi:10.3390/biology12121455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Chen B, Yu P, Chan WN, Xie F, Zhang Y, Liang L, et al. Cellular zinc metabolism and zinc signaling: from biological functions to diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):6. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01679-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Beyersmann D, Haase H. Functions of zinc in signaling, proliferation and differentiation of mammalian cells. Biometals. 2001;14(3–4):331–41. doi:10.1023/a:1012905406548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Costa MI, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, Gonçalves AC. Zinc: from biological functions to therapeutic potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4822. doi:10.3390/ijms24054822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ohashi K, Nagata Y, Wada E, Zammit PS, Shiozuka M, Matsuda R. Zinc promotes proliferation and activation of myogenic cells via the PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling cascade. Exp Cell Res. 2015;333(2):228–37. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Anson KJ, Corbet GA, Palmer AE. Zn2+ influx activates ERK and Akt signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(11):e2015786118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2015786118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang X, Hou Y, Huang Y, Chen W, Zhang H. Interplay between zinc and cell proliferation and implications for the growth of livestock. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2023;107(6):1402–18. doi:10.1111/jpn.13851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Lo MN, Damon LJ, Wei Tay J, Jia S, Palmer AE. Single cell analysis reveals multiple requirements for zinc in the mammalian cell cycle. eLife. 2020;9:e51107. doi:10.7554/eLife.51107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Shankar AH, Prasad AS. Zinc and immune function: the biological basis of altered resistance to infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(2):447s–63s. doi:10.1093/ajcn/68.2.447S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Mayer LS, Uciechowski P, Meyer S, Schwerdtle T, Rink L, Haase H. Differential impact of zinc deficiency on phagocytosis, oxidative burst, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by human monocytes. Metallomics. 2014;6(7):1288–95. doi:10.1039/c4mt00051j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Poli V, Pui-Yan Ma V, Di Gioia M, Broggi A, Benamar M, Chen Q et al. Zinc-dependent histone deacetylases drive neutrophil extracellular trap formation and potentiate local and systemic inflammation. iScience. 2021;24(11):103256. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Prasad AS, Bao B, Beck FWJ, Sarkar FH. Zinc-suppressed inflammatory cytokines by induction of A20-mediated inhibition of nuclear factor-κB. Nutrition. 2011;27(7):816–23. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2010.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Lin J-Q, Tian H, Zhao XG, Lin S, Li DY, Liu YY et al. Zinc provides neuroprotection by regulating NLRP3 inflammasome through autophagy and ubiquitination in a spinal contusion injury model. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(4):413–25. doi:10.1111/cns.13460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Lin PH, Sermersheim M, Li H, Lee PHU, Steinberg SM, Ma J. Zinc in wound healing modulation. Nutrients. 2017;10(1):16. doi:10.3390/nu10010016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Marreiro DD, Cruz KJ, Morais JB, Beserra JB, Severo JS, de Oliveira AR. Zinc and oxidative stress: current mechanisms. Antioxidants. 2017;6(2):24. doi:10.3390/antiox6020024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Lee SR. Critical role of zinc as either an antioxidant or a prooxidant in cellular systems. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018(1):9156285. doi:10.1155/2018/9156285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Song Y, Leonard SW, Traber MG, Ho E. Zinc deficiency affects DNA damage, oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and DNA repair in rats. J Nutr. 2009;139(9):1626–31. doi:10.3945/jn.109.106369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Kiouri DP, Tsoupra E, Peana M, Perlepes SP, Stefanidou ME, Chasapis CT. Multifunctional role of zinc in human health: an update. EXCLI J. 2023;22:809–27. doi:10.17179/excli2023-6335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Yang X, Wang H, Huang C, He X, Xu W, Luo Y et al. Zinc enhances the cellular energy supply to improve cell motility and restore impaired energetic metabolism in a toxic environment induced by OTA. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14669. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14868-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Nguyen TS, Kohno K, Kimata Y. Zinc depletion activates the endoplasmic reticulum-stress sensor Ire1 via pleiotropic mechanisms. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77(6):1337–9. doi:10.1271/bbb.130130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Bodiga VL, Vemuri PK, Nimmagadda G, Bodiga S. Zinc-dependent changes in oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress during cardiomyocyte hypoxia/reoxygenation. Biol Chem. 2020;401(11):1257–71. doi:10.1515/hsz-2020-0167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Provinciali M, Donnini A, Argentati K, Di Stasio G, Bartozzi B, Bernardini G. Reactive oxygen species modulate Zn2+-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32(5):431–45. doi:10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00830-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Provinciali M, Pierpaoli E, Bartozzi B, Bernardini G. Zinc induces apoptosis of human melanoma cells, increasing reactive oxygen species, p53 and FAS ligand. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(10):5309–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

62. Wood JPM, Osborne NN. The influence of zinc on caspase-3 and DNA breakdown in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(1):81–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

63. Ganju N, Eastman A. Zinc inhibits Bax and Bak activation and cytochrome c release induced by chemical inducers of apoptosis but not by death-receptor-initiated pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10(6):652–61. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Eron SJ, MacPherson DJ, Dagbay KB, Hardy JA. Multiple mechanisms of zinc-mediated inhibition for the apoptotic caspases-3, -6, -7, and -8. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13(5):1279–90. doi:10.1021/acschembio.8b00064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Truong-Tran AQ, Carter J, Ruffin RE, Zalewski PD. The role of zinc in caspase activation and apoptotic cell death. Biometals. 2001;14(3–4):315–30. doi:10.1023/A:1012993017026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Tkachenko A, Onishchenko A. Zincoptosis: does it exist? Apoptosis. 2023;28(5–6):681–2. doi:10.1007/s10495-023-01836-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Schoofs H, Schmit J, Rink L. Zinc toxicity: understanding the limits. Molecules. 2024;29(13):3130. doi:10.3390/molecules29133130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Kim YH, Eom JW, Koh JY. Mechanism of zinc excitotoxicity: a focus on AMPK. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:577958. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.577958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Bishop GM, Dringen R, Robinson SR. Zinc stimulates the production of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inhibits glutathione reductase in astrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(8):1222–30. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zhao Y, Yan F, Yin J, Pan R, Shi W, Qi Z, et al. Synergistic interaction between zinc and reactive oxygen species amplifies ischemic brain injury in rats. Stroke. 2018;49(9):2200–10. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Pan R, Liu KJ, Qi Z. Zinc causes the death of hypoxic astrocytes by inducing ROS production through mitochondria dysfunction. Biophys Rep. 2019;5(4):209–17. doi:10.1007/s41048-019-00098-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Bagshaw ORM, Alva R, Goldman J, Drelich JW, Stuart JA. 33—mitochondrial zinc toxicity. In: de Oliveira MR, editor. Mitochondrial intoxication. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2023. p. 723–44. [Google Scholar]

73. Yang Y, Wang P, Guo J, Ma T, Hu Y, Huang L, et al. Zinc overload induces damage to H9c2 cardiomyocyte through mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS-mediated mitophagy. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2023;23(11–12):388–405. doi:10.1007/s12012-023-09811-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Lemire J, Mailloux R, Appanna VD. Zinc toxicity alters mitochondrial metabolism and leads to decreased ATP production in hepatocytes. J Appl Toxicol. 2008;28(2):175–82. doi:10.1002/jat.1263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Yang Q, Fang Y, Zhang C, Liu X, Wu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Exposure to zinc induces lysosomal-mitochondrial axis-mediated apoptosis in PK-15 cells. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;241(1):113716. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Sliwinski T, Czechowska A, Kolodziejczak M, Jajte J, Wisniewska-Jarosinska M, Blasiak J. Zinc salts differentially modulate DNA damage in normal and cancer cells. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33(4):542–7. doi:10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.02.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Wedler N, Matthäus T, Strauch B, Dilger E, Waterstraat M, Mangerich A, et al. Impact of the cellular zinc status on PARP-1 activity and genomic stability in HeLa S3 cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2021;34(3):839–48. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Vandegehuchte MB, De Coninck D, Vandenbrouck T, De Coen WM, Janssen CR. Gene transcription profiles, global DNA methylation and potential transgenerational epigenetic effects related to Zn exposure history in Daphnia magna. Environ Pollut. 2010;158(10):3323–9. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2010.07.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Bao B, Prasad A, Beck FWJ, Suneja A, Sarkar F. Toxic effect of zinc on NF-κB, IL-2, IL-2 receptor α, and TNF-α in HUT-78 (Th0) cells. Toxicol Lett. 2006;166(3):222–8. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.07.306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Freitas M, Fernandes E. Zinc, cadmium and nickel increase the activation of NF-κB and the release of cytokines from THP-1 monocytic cells. Metallomics. 2011;3(11):1238–43. doi:10.1039/c1mt00050k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Feng P, Li T, Guan Z, Franklin RB, Costello LC. The involvement of Bax in zinc-induced mitochondrial apoptogenesis in malignant prostate cells. Mol Cancer. 2008;7(1):25. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-7-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Bae SN, Lee YS, Kim MY, Kim JD, Park LO. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of zinc-citrate compound (CIZAR

83. Kocdor H, Ates H, Aydin S, Cehreli R, Soyarat F, Kemanli P, et al. Zinc supplementation induces apoptosis and enhances antitumor efficacy of docetaxel in non-small-cell lung cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3899–909. doi:10.2147/DDDT. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Kondaiah P, Yaduvanshi PS, Sharp PA, Pullakhandam R. Iron and zinc homeostasis and interactions: does enteric zinc excretion cross-talk with intestinal iron absorption? Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1885. doi:10.3390/nu11081885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Olivares M, Pizarro F, Ruz M, de Romaña DL. Acute inhibition of iron bioavailability by zinc: studies in humans. Biometals. 2012;25(4):657–64. doi:10.1007/s10534-012-9524-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Kondaiah P, Palika R, Mashurabad P, Singh Yaduvanshi P, Sharp P, Pullakhandam R. Effect of zinc depletion/repletion on intestinal iron absorption and iron status in rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2021;97:108800. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Dang Q, Sun Z, Wang Y, Wang L, Liu Z, Han X. Ferroptosis: a double-edged sword mediating immune tolerance of cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(11):925. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-05384-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Shi W, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Lu L, Zhou Q, Wang Y et al. Co-exposure to Fe, Zn, and Cu induced neuronal ferroptosis with associated lipid metabolism disorder via the ERK/cPLA2/AA pathway. Environ Pollut. 2023;336:122438. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Ge MH, Tian H, Mao L, Li DY, Lin JQ, Hu HS et al. Zinc attenuates ferroptosis and promotes functional recovery in contusion spinal cord injury by activating Nrf2/GPX4 defense pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(9):1023–40. doi:10.1111/cns.13657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Li Q, Yang Q, Guo P, Feng Y, Wang S, Guo J et al. Mitophagy contributes to zinc-induced ferroptosis in porcine testis cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023;179:113950. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2023.113950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Dai B, Liu X, Du M, Xie S, Dou L, Mi X et al. LATS1 inhibitor and zinc supplement synergistically ameliorates contrast-induced acute kidney injury: induction of Metallothionein-1 and suppression of tubular ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;223:42–52. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.07.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Lu H, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang R, Guo T, Wang Q et al. New insights into zinc alleviating renal toxicity of arsenic-exposed carp (Cyprinus carpio) through YAP-TFR/ROS signaling pathway. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2024;205:106153. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2024.106153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Palmer LD, Jordan AT, Maloney KN, Farrow MA, Gutierrez DB, Gant-Branum R, et al. Zinc intoxication induces ferroptosis in A549 human lung cells. Metallomics. 2019;11(5):982–93. doi:10.1039/c8mt00360b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Yang P, Li H, Sun M, Guo X, Liao Y, Hu M, et al. Zinc deficiency drives ferroptosis resistance by lactate production in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;213:512–22. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.01.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Chen PH, Wu J, Xu Y, Ding CC, Mestre AA, Lin CC, et al. Zinc transporter ZIP7 is a novel determinant of ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(2):198. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-03482-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Wu K, Fei L, Wang X, Lei Y, Yu L, Xu W, et al. ZIP14 is involved in iron deposition and triggers ferroptosis in diabetic nephropathy. Metallomics. 2022;14(7):mfac034. doi:10.1093/mtomcs/mfac034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Upadhayay S, Mehan S. Targeting Nrf2/HO-1 anti-oxidant signaling pathway in the progression of multiple sclerosis and influences on neurological dysfunctions. Brain Disord. 2021;3(21):100019. doi:10.1016/j.dscb.2021.100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Steiger MG, Patzschke A, Holz C, Lang C, Causon T, Hann S et al. Impact of glutathione metabolism on zinc homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017;17(4):fox028. doi:10.1093/femsyr/fox028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Liuzzi JP, Pazos R. Interplay between autophagy and zinc. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2020;62:126636. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Yu S, Li Z, Zhang Q, Wang R, Zhao Z, Ding W et al. GPX4 degradation via chaperone-mediated autophagy contributes to antimony-triggered neuronal ferroptosis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;234:113413. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Xu YC, Zheng H, Tan XY, Hogstrand C, Zhao T, Wei XL et al. Differential effects of two Zn sources (ZnO nanoparticles and ZnSO4) on lipid metabolism via the ferroptosis pathway and SLC7A11K23 acetylation by HDAC8 and HDAC6 in a freshwater teleost. Environ Sci Nano. 2024;11(10):4240–54. doi:10.1039/D4EN00239C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Tang J, Zhuo Y, Li Y. Effects of iron and zinc on mitochondria: potential mechanisms of glaucomatous injury. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:720288. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.720288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Dey S, Mohanty DI, Divya N, Bakshi V, Mohanty A, Rath D, et al. A critical review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, properties and biomedical applications. Intell Pharm. 2014;3(1):53–70. [Google Scholar]

104. Bilensoy E, Varan C. Is there a niche for zinc oxide nanoparticles in future drug discovery? Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2023;18(9):943–5. doi:10.1080/17460441.2023.2230152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Anjum S, Hashim M, Malik SA, Khan M, Lorenzo JM, Abbasi BH et al. Recent advances in zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) for cancer diagnosis, target drug delivery, and treatment. Cancers. 2021;13(18):4570. doi:10.3390/cancers13184570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Bisht G, Rayamajhi S. ZnO nanoparticles: a promising anticancer agent. Nanobiomedicine. 2016;3:9. doi:10.5772/63437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Patrón-Romero L, Luque-Morales PA, Loera-Castañeda V, Lares-Asseff I, Leal-Ávila MÁ, Alvelais-Palacios JA, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by zinc oxide nanoparticles. Crystals. 2022;12(8):1089. doi:10.3390/cryst12081089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Sadanandan B, Murali Krishna P, Kumari M, Vijayalakshmi V, Nagabhushana BM, Vangala S et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles exhibit anti-cancer activity against human cell lines. J Mol Struct. 2024;1305:137723. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.137723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381–96. doi:10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Zhang C, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Ma L, Song E, Song Y. “Iron free” zinc oxide nanoparticles with ion-leaking properties disrupt intracellular ROS and iron homeostasis to induce ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(3):183. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2384-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Qin X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xu G, Yang X, Zou Z, et al. Ferritinophagy is involved in the zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced ferroptosis of vascular endothelial cells. Autophagy. 2021;17(12):4266–85. doi:10.1080/15548627.2021.1911016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Liu G, Lv J, Wang Y, Sun K, Gao H, Li Y, et al. ZnO NPs induce miR-342-5p mediated ferroptosis of spermatocytes through the NF-κB pathway in mice. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22(1):390. doi:10.1186/s12951-024-02672-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Geng S, Hao P, Wang D, Zhong P, Tian F, Zhang R, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles have biphasic roles on Mycobacterium-induced inflammation by activating autophagy and ferroptosis mechanisms in infected macrophages. Microb Pathog. 2023;180(5):106132. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2023.106132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(6):830–49. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2019.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Hu Z, Song X, Ding L, Cai Y, Yu L, Zhang L, et al. Engineering Fe/Mn-doped zinc oxide nanosonosensitizers for ultrasound-activated and multiple ferroptosis-augmented nanodynamic tumor suppression. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16(3):100452. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Yu J, Zhu F, Yang Y, Zhang P, Zheng Y, Chen H, et al. Ultrasmall iron-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles for ferroptosis assisted sono-chemodynamic cancer therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2023;232:113606. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Ensoy M, Ozturk BI, Cansaran-Duman D, Yilmazer A. Inducing ferroptosis via nanomaterials: a novel and effective route in cancer therapy. J Phys Mater. 2024;7(3):032003. doi:10.1088/2515-7639/ad4d1e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

118. Qin X, Tang Q, Jiang X, Zhang J, Wang B, Liu X et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce ferroptotic neuronal cell death in vitro and in vivo. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:5299–315. doi:10.2147/IJN.S250367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Pan X, Qi Y, Du Z, He J, Yao S, Lu W et al. Zinc oxide nanosphere for hydrogen sulfide scavenging and ferroptosis of colorectal cancer. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):392. doi:10.1186/s12951-021-01069-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Yang Y, Wang X, Song Z, Zheng Y, Ji S. Proteomics and metabolomics analysis reveals the toxicity of ZnO quantum dots on human SMMC-7721 cells. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:277–91. doi:10.2147/IJN.S389535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Gu W, Yang C. Zinc oxide nanoparticles mitigate the malignant progression of ovarian cancer by mediating autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150(12):513. doi:10.1007/s00432-024-06029-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Cai L, Sun T, Han F, Zhang H, Zhao J, Hu Q et al. Degradable and piezoelectric hollow ZnO heterostructures for sonodynamic therapy and pro-death autophagy. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(49):34188–98. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c14489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Wang J, Liu M, Wang J, Li Z, Feng Z, Xu M, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles with catalase-like nanozyme activity and near-infrared light response: a combination of effective photodynamic therapy, autophagy, ferroptosis, and antitumor immunity. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14(10):4493–508. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2024.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Yan Y, Huang W, Lu X, Chen X, Shan Y, Luo X, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induces cell death and consequently leading to incomplete neural tube closure through oxidative stress during embryogenesis. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2024;40(1):51. doi:10.1007/s10565-024-09894-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Ashoub MH, Amiri M, Fatemi A, Farsinejad A. Evaluation of ferroptosis-based anti-leukemic activities of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by a green route against Pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (Nalm-6 and REH). Heliyon. 2024;10(17):e36608. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Zakaria S, Ibrahim N, Abdo WE, El-Sisi A. JNK inhibitor and ferroptosis modulator as possible therapeutic modalities in Alzheimer disease (AD). Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23293. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-73596-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Wickert A, Schwantes A, Fuhrmann DC, Brüne B. Inflammation in a ferroptotic environment. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1474285. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1474285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Magtanong L, Mueller GD, Williams KJ, Billmann M, Chan K, Armenta DA, et al. Context-dependent regulation of ferroptosis sensitivity. Cell Chem Biol. 2022;29(9):1409–18.e6. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.06.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Maryanovich M, Gross A. A ROS rheostat for cell fate regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23(3):129–34. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2012.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Franco R, Cidlowski JA. Glutathione efflux and cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17(12):1694–713. doi:10.1089/ars.2012.4553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Claudio-Ares O, Luciano-Rodríguez J, Del Valle-González YL, Schiavone-Chamorro SL, Pastor AJ, Rivera-Reyes JO, et al. Exploring the use of intracellular chelation and non-iron metals to program ferroptosis for anticancer application. Inorganics. 2024;12(1):26. doi:10.3390/inorganics12010026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y, et al. Ferroptosis in cancer: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):55. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01769-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Li T, Yu C. Metal-dependent cell death in renal fibrosis: now and in the future. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(24):13279. doi:10.3390/ijms252413279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Demuynck R, Efimova I, Naessens F, Krysko DV. Immunogenic ferroptosis and where to find it? J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(12):e003430. doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-003430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools