Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Tools against Infectious Diseases

Microbiology Ph.D. Program, Department of Biological Sciences, Alabama State University, Montgomery, AL 36104, USA

* Corresponding Author: QIANA L. MATTHEWS. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Mechanism and Theranostic Potential of Extracellular RNAs in Current Medicine)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1605-1629. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065474

Received 13 March 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) have arisen as potential therapeutic tools in managing infectious diseases because EVs can regulate cell-to-cell signaling, function as drug transport mechanisms, and influence immune reactions. They are obtained from a myriad of sources, such as plants, humans, and animal cells. EVs like exosomes and ectosomes can be utilized in their native form as therapeutics or engineered to encompass antimicrobials, vaccines, and oligonucleotides of interest with a targeted delivery strategy. An in-depth understanding of host-pathogen dynamics provides a solid foundation for exploiting its full potential in therapeutics against infectious diseases. This review mainly offers an extensive summary of EVs, comprising their various origins, formations, and pathogen relationships. It further provides insights into the various techniques utilized in isolating and engineering these vesicles to target infectious diseases and how challenges involving large-scale production and cargo loading efficiency should be addressed for clinical application. Finally, preclinical and clinical implementations of EVs derived from animals, plants, and microorganisms are elucidated, stressing their promise for designing innovative antimicrobial approaches.Keywords

Infectious diseases caused by viral, bacterial, and parasitic microorganisms remain a worldwide health challenge that has led to elevated morbidity and mortality rates globally [1]. Traditional therapeutic approaches against these diseases consist of antibacterial, antiviral, and antiparasitic agents. However, these agents have encountered constraints such as drug resistance, inability to travel across some biological barriers, and reduced effectiveness, especially in recently emerging diseases such as COVID-19 and Ebola [2]. Lately, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have appeared to serve as innovative therapeutic tools that can regulate immunological reactions, transport therapeutic contents, and also simulate pathogen-originated cues to regulate disease advancement [3].

EVs are small, membrane-bound structures released by cells into the external environment [4–7]. They are lipid-bound vesicles that encompass an assortment of cell-derived components consisting of lipids, proteins, genetic material such as DNA, messenger RNAs (mRNAs), microRNAs, and other biologically active molecules [7,8]. Depending on their cellular formation, dimension, and role, they are categorized into various primary subtypes: exosomes, microvesicles (MVs), and apoptotic bodies [7,9,10]. They have emerged as vital facilitators in cell-to-cell signaling and possess considerable potential as therapeutic tools in combating infectious diseases [8]. EVs are engaged in diverse physiological and pathological processes comprising immune defense, inflammation, cellular stress, and the modulation of disease mechanisms in conditions like cancer and nervous system disorders [11,12]. Modern innovations have notably improved the purification and characterization of EVs, enabling a profound insight into their functions in health and illness [13].

EVs serve as modulators of both innate and adaptive immune reactions [14,15]. The therapeutic possibilities of EVs are extensive, with their use in vaccine formation, immune-regulating strategies, and transport of antimicrobial compounds [16,17]. The clinical capacity of EVs can be improved by modifying them to alter their exterior composition or packaging with the desired cargo [10,18]. These vesicles can also serve therapeutic purposes as it has been suggested to be used in sheathing adenovirus used in gene therapy and drug delivery strategies [19]. An in-depth understanding of the roles EVs play in disease progression and spread lays a foundation for their utilization as therapeutic interventions. Studies on viral host interaction have shown exosomes to be involved in the entry and spread of Coronavirus (CoV) via the exosomal protein transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) [20]. HIV, Ebola, Epstein-Barr Virus, and Hepatitis Virus were shown to exploit the host endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) and miRNA machineries vital in exosomal biogenesis and formation. This exploitation has facilitated viral spread [21].

Current research has emphasized the complex functions of EVs in infectious illnesses, such as virus-bacteria concurrent infections, immune regulation, and immunization. For example, EVs enable cross-kingdom nutrient transport, increasing microorganism persistence during viral-bacteria co-infections [22]. Bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) are currently acknowledged as crucial agents in host-microbe interaction and have prospects in detection and treatment approaches [23]. Protein-related examination of the outer membrane vesicle-based vaccine VA-MENGOC-BC® showed a complex composition that is effective against Neisseria meningitidis strains B and C [24]. Moreover, the immune-activating ability of meningococcal external membrane vesicles is strongly reliant on their biochemical structure, affecting their capacity to stimulate innate immune reactions [25].

This review mainly intends to offer an extensive overview of the diverse functions of EVs in infectious diseases. It will address the origins of EVs, their formation and content, innovations in the isolation process, and characterization. Additionally, this review covers the EVs’ role in host-pathogen dynamics while also addressing their function as therapeutic tools and modification for improved effectiveness in infectious diseases. The investigation of EVs serving as therapeutic tools in contagious illnesses indicates a rapidly developing discipline with substantial effects on future treatment approaches [16].

2 Biogenesis and Composition of Extracellular Vesicles

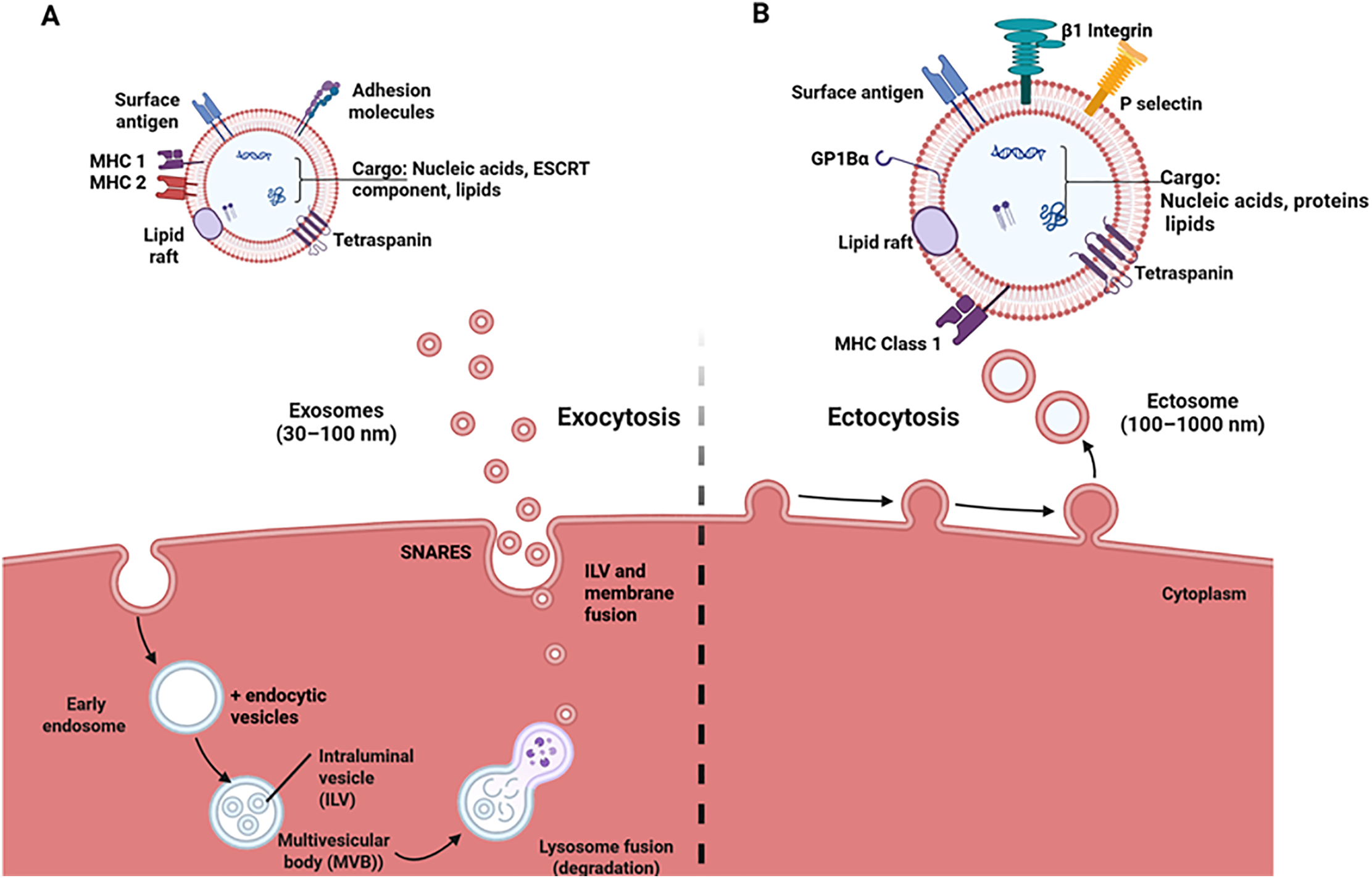

In 1983, studies reported that vesicles from endosomes were used by mature reticulocytes to transport transferrin receptors [26,27], leading to the discovery of exosomes. Exosomes are formed from endosomal systems via endocytosis and successive multivesicular body (MVB) formation. It starts with the plasma membrane budding inwards and forming endosomes that contain cell surface proteins and extracellular macromolecules [28]. These early endosomes mature into late endosomes by changing their intracellular location, replacing some endosomal membrane proteins and lipids, such as sphingomyelin and RAB5, with ceramides and RAB11, respectively, and forming MVBs [29]. Within the MVBs are intraluminal vesicles (ILV) produced by the invagination of the endosomal membrane via an ESCRT-dependent or independent pathway [30]. These vesicles contain specific lipids, proteins, nucleic acids, and cytosolic molecules. MVBs have more than one fate after production; some fuse with lysosomes, and the cargo contained in the ILV is degraded, while the rest are transported along the microtubule network and fuse with the plasma membrane. The ILVs are exocytosed into the extracellular matrix as exosomes (Fig. 1) [28,29]. Small GTPases like RAB 2B, 5, 7, 9A, 11, 27A, 27B, and 35 mediate ILV formation by promoting the transport of MVB along microtubules and membrane fusion, while RAB 31 hinders the fusion of MVB and lysosome fusion [31,32].

Figure 1: This depiction shows the biogenesis and composition of exosomes and ectosomes. (A) Exosome formation begins with the invagination of the plasma membrane. The endocytic vesicles fuse with the early endosomes to form the MVB, which contains intraluminal vesicles formed after the invagination of the early endosomes. MVBs fuse with lysosomes and are degraded, releasing the ILVs. These ILVs fuse with the plasma membrane and are exocytosed as exosomes comprising tetraspanins, ESCRT components (Alix, TSG101), and MHC 1 & 2, depending on the cell origin. (B) Ectosomes are formed via outward budding of the plasma membrane through a process called ectocytosis. These vesicles comprise tetraspanins, glycoprotein 1Bα (GP1Bα), β1 integrin, and MHC 1, depending on the cell origin. This image was created utilizing Bio Render

Ectosomes, also called microvesicles (MVs), are membrane-bound vesicles that evaginate from the plasma membrane of cells via exocytosis after a well-regulated pinching and scission event (Fig. 1). This formation origin/mechanism is the basis for differentiating these vesicles from exosomes. The series of events leading to the formation of ectosomes involves the reorganization of the cellular membrane’s phospholipid mediated by scramblases and flippases due to an increase in cytosolic calcium level and pinching off vesicles regulated by the actomyosin contractile machinery [33–36]. According to Muralidharan-Chari et al., ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) of the small GTP-binding proteins mediates the release of ectosomes into surrounding environments [37]. This study delved into its mechanism of action and reported that the phosphorylation of myosin II light chain (MLC) at Thr18/Ser19 generates the force needed for the scission of microvesicles via an actomyosin-based contraction at the vesicles’ neck. Li et al. showed that a Rho A-dependent pathway is involved in the biogenesis of ectosomes [38]. The study discovered that through a series of events ending with phosphorylation of cofilin on ser3, actomyosin contracts leading to ectosome biogenesis.

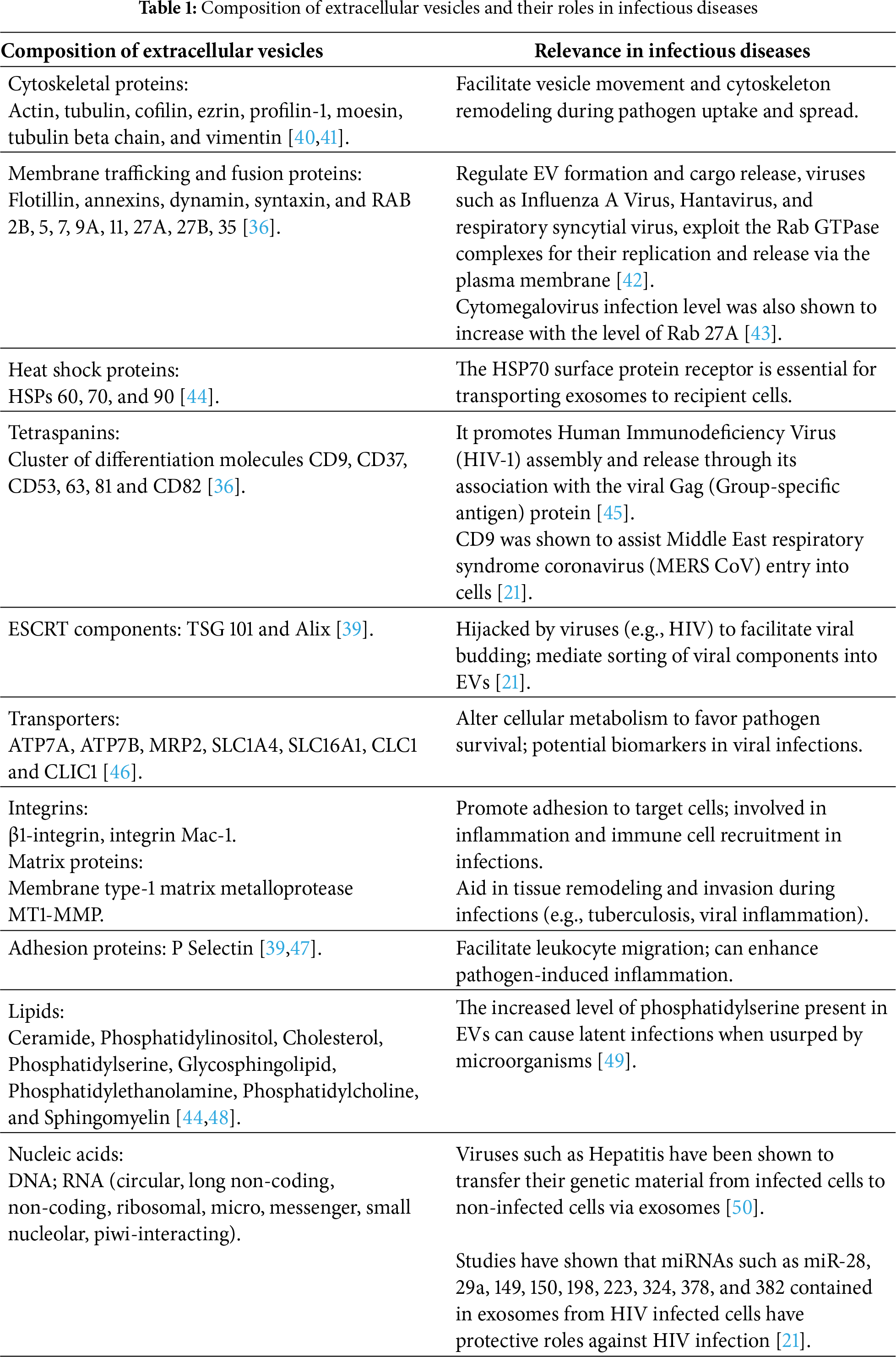

Molecular Make-Up of Extracellular Vesicles

Extracellular vesicles have been reported to carry a wide array of molecular cargoes, which can be influenced by the cellular origin and formation pathway of the vesicles [39]. They comprise genetic materials, lipids, and proteins, and these cargoes often play important roles in the progression of infectious diseases and their treatment (Table 1).

3 Extracellular Vesicles in Infectious Disease Progression

The interplay between hosts and pathogens is an intricate and active mechanism, and EVs serve as essential contributors [51]. Importantly, comprehension of the process of host and pathogen interplay via EVs plays a significant role in utilizing EVs as a therapeutic approach to contagious diseases [52]. EVs function as crucial intermediaries in the signaling between infectious agents and host organisms. Hence, they assist in the transfer of cellular messages, which can affect the result of diseases [53]. The host and pathogen interplay forms a complex relationship between infectious microbes, including viruses, fungi, bacteria, and parasites [54,55]. Such interactions happen within multiple stages, including cell-level, organismal, and biochemical processes. They are defined via the ongoing struggle between the host’s immune responses and the microbe’s approaches to avoid and utilize such safeguards [54,55].

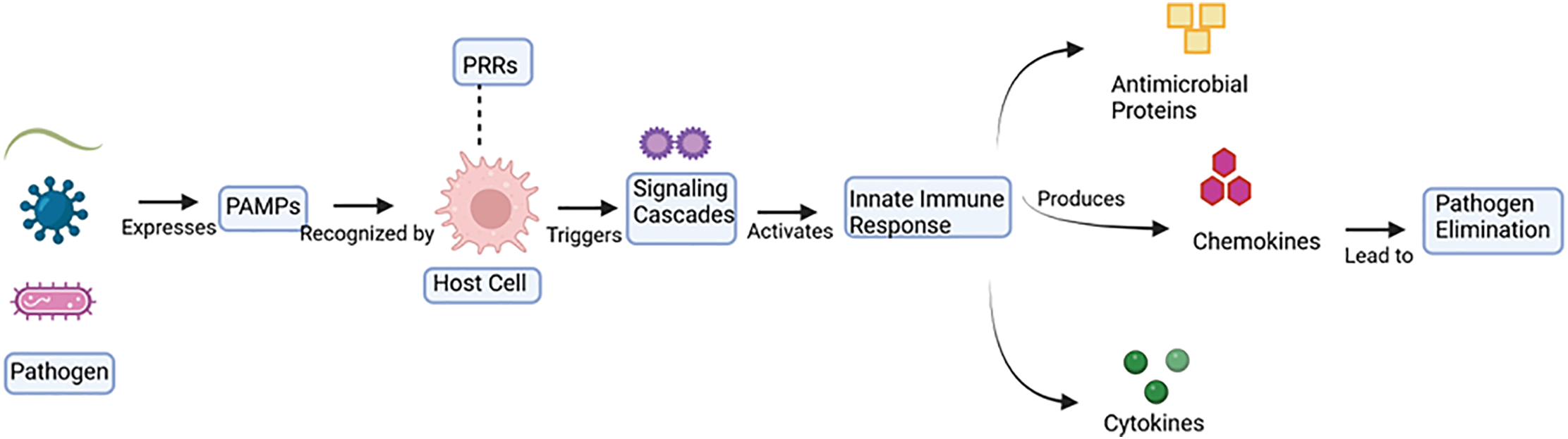

Fig. 2 indicates that once an infectious agent invades a host, the pathogen needs to maneuver the immune barrier network [56]. On entry, pathogens produce unique molecular signals called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are detected using pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) at the outer layer of target cells [57]. Hence, initiating signal transduction cascades that stimulate the innate defense system [58]. Also, the interplay between the PAMPs and PRRs can initiate the intercellular signaling routes [58]. Such routes engage the gathering of numerous modulatory proteins and various activator signaling components. These eventually result in triggering immune responses, which are intended to remove the infectious agents [58–60]. However, pathogens possess diverse approaches to avoid the host defense responses [61,62].

Figure 2: Schematic depiction of microorganism identification and innate defense mechanism initiation. This figure demonstrates the infectious agent recognition process and the innate immune defense initiation. Microorganisms produce Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) that are detected via Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) on the exterior of target cells. Then, this action detection stimulates inside the cell signaling cascades, initiating the innate defense response. This stimulated defensive reaction leads to the synthesis of antimicrobial proteins, chemokines, and cytokines. Together, these immune regulators assist in the removal of microorganisms. Image created utilizing Bio Render

Pathogens such as fungi, parasites, and bacteria emit EVs that encompass diverse biological molecules, such as DNA, RNA, and proteins [63]. These EVs can transfer pathogenic factors and regulatory genetic materials into the target cells, thereby regulating the immune defenses of hosts and assisting in microbe persistence and spread [64]. However, EVs originating from host cells such as macrophages serve a vital function in modulating immunological reactions and countering infections caused by viruses, bacteria, and parasites [65].

The external membrane particles derived from gram-negative bacteria are capable of delivering catalysts and harmful substances, which play a significant role in disease development as well as immune resistance [66]. Additionally, bacteria-derived EVs can trigger immune-inflammatory reactions via engaging with pathogen-sensing receptors like Toll-like receptors on host cells. This could result in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines. For instance, EVs originating from pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus that invaded vascular lining cells have the potential to trigger a pro-inflammatory reaction within the host cells via transferring pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as supplementary immune stimulators [17,67]. In the Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, EVs from infected cells can promote the disease progression by causing the recruitment of more macrophages and naïve T cells through stimulating chemokine release from non-infected macrophages. It was also shown in mouse models that administration of EVs from M. tuberculosis and M. bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) caused accelerated tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and Interleukin 12 (IL-12) production and migration of uninfected target macrophages, causing disease progression [68]. Bacterial EVs assist infectious agents in escaping the organism’s immune reaction by transporting compounds that suppress complement-driven cell rupture and additional immune systems [66]. EVs derived from bacteria also transport infection-sourced elements and can act as durable indicators of disease presence, providing a promising detection tool [69]. Such EVs remain highly persistent in the bloodstream relative to dissolvable components and can be employed for observing the process of advancement of pathological conditions [68].

In viral infections, EVs transmit viral components such as proteins, genetic molecules, and receptors from infected cells to healthy cells, increasing susceptibility to infection. Research has found a crucial receptor in the fusion of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles with the host cell membrane, Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), in EVs generated by some cells; this suggests that these vesicles play a role in promoting CoV infection [70]. As an alternative, coronaviruses (CoVs) can enter cells through the endocytic route that is dependent on caveolin-1, since caveolin-1 is a component of EVs and a crucial regulator of EV biogenesis. It has been proposed that EVs expressing caveolin-1 may aid in the propagation of SARS-CoV-2 [71]. Moreover, exosomal microRNAs like miR-145 and miR-885 are involved in the modulation of blood clot formation in CoV patients, corresponding with the D-dimer concentrations and causing endothelial impairment [72]. Research on lipid biochemical processes obtained from plasma small EVs in COVID-19 recovering patients has shown ongoing changes, suggesting prolonged metabolic effects due to the disease [73]. Endothelial EVs loaded with microRNA-34a are recognized as indicators of recently diagnosed diabetes in COVID-19 patients, providing knowledge of metabolic sequelae linked with the infection [74]. Additionally, the investigation of canine and feline CoVs and Crandell-Rees Feline Kidney cells and Canine fibrosarcoma cells (A-72) emphasizes the significance of comprehending the modification of EV production and its content after viral infection. Therefore, suggesting approaches to prevent future CoVs from companion animals [6,7,75–77].

EVs propagate HIV by transferring proteins to target cells, rendering them susceptible to infection. HIV protein Nef is sorted into EVs [78,79]. When these EVs are supplied to latent HIV-1 cells, they become activated and more susceptible to HIV infection. HIV-infected cells were also shown to produce EVs with trans activation response element (TAR) RNA that interacts with Tat protein and upregulates viral RNA production. The interaction results in resistance to apoptosis and sustenance of viral release [80]. Hepatitis C virus was initially assumed to collect in the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum (ER); however, a study has shown that this virus is encapsulated into MVBs/exosomes and released via the exosomal secretory pathway, dependent on hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HRS) [81]. Infection with cytomegalovirus has been shown to produce EVs containing lectin and DC-SIGN that are proviral while subsequently impairing the host’s antiviral response [82]. Epstein-Barr virus utilizes EVs to enhance host defense evasion in throat cancer via loading programmed death-ligand 1 into small EVs through the LMP1-ALIX axis, as a result suppressing CD8+ T cell activity [83].

MVs from the fungus C. neoformans were the first studied before vesicles from other fungi were explored. This organism causes cryptococcosis, especially in immunosuppressed individuals. Within these EVs is the polysaccharide glucuronoxylomannan (a virulence factor) which confers protection against phagocytosis and prevents leukocyte migration [84]. These events promote fungal persistence and spread. Infections by Candida albicans cause the host to produce EVs rich in transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1), which causes an increase in fungal immune tolerance and reduces host immune response, subsequently causing the organism to thrive in the host [85]. Also, EVs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae were shown to contain Sup35p prions in their infectious aggregated state [86]. These infectious prions were reported by Liu et al. to be taken up by recipient mammalian cells [87].

EVs are also produced from pathogens that can inhibit their host defense reaction by transporting substances capable of blocking complement-driven lysis and other defense pathways [15,88–90]. For example, EVs derived from Trypanosoma cruzi can suppress complement-driven parasitic lysis and facilitate microbial avoidance [91]. Furthermore, EVs enable inter-kingdom RNA transfer, in which microRNAs originating in infectious agents are transferred into host cells. This mechanism can control genetic activity and adjust the immunological mechanism [61]. This process is detected in diseases caused by parasites, whereby vesicles carry RNA variants homologous to the host microRNAs, hence resulting in immune regulation [64]. EVs derived from parasitic organisms such as Trypanosoma cruzi and Echinococcus granulosus carry microRNAs and additional non-coding RNAs, which can modulate the host defense mechanisms as well as enhance disease development [92]. An infection of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum releases EVs with functioning 20S proteasome complexes that change the mechanical characteristics of healthy red blood cells, subsequently increasing their vulnerability to infection. Also, high levels of the cytokine CXCL10 have caused these EVs to terminate the cytokine synthesis, thereby encouraging the thriving and survival of P. falciparum and malaria disease [92]. Additionally, cellular hosts secrete EVs due to pathogen invasion, which can influence immune defense and impact the infectious agents’ capacity to invade and reproduce [62].

Finally, the function of EVs in host-pathogen relationships is complex and essential in facilitating the progress of EV-based treatment approaches in contagious diseases [68]. Through grasping and exploiting these relationships, investigators can develop novel treatments that regulate the immune reaction, convey treatment agents, as well as fight diseases with greater efficiency [93].

4 Technological Advances in Extracellular Vesicle Isolation and Characterization

The extraction of EVs is an essential phase in their research and application, especially within the scope of therapeutic tools for contagious illnesses [8,94]. EVs are mostly isolated using the differential ultracentrifugation method, commonly known as the gold standard for EV extraction [95]. It is lengthy, necessitates large sample quantities, and might not distinguish various categories of EVs, such as exosomes, MVs, apoptotic bodies, autophagic EVs, stressed EVs, matrix vesicles, and oncosomes effectively [96,97]. However, density gradient centrifugation enables enhanced purification [98–100]. Additionally, ultrafiltration employs membrane filters with distinct pore sizes to isolate EVs [101]. It is more efficient and does not necessitate costly equipment, but it can result in vesicle blockage and trapping within the filter [101,102].

Moreover, the immune affinity isolation method plays a significant role in the EV isolation process [94]. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) also isolates EVs according to their dimension and molecular mass, thereby generating EVs with higher stability and unaltered vesicle characteristics [94]. It is especially effective for separating EVs from small specimen quantities and is also capable of being expanded and automated [103]. Importantly, the SEC can maintain the physical-biological and functional characteristics of purified EVs [104]. Furthermore, asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) is an advanced technique that isolates components according to their diffusion rate [105,106]. It needs a lesser volume of an initial substance than standard chromatography and isolates EV samples of elevated quality [107]. Another technique is precipitation, which involves utilizing polymers or salt to isolate EVs from the specimen [108]. The miRCURY, like commercial kits, employs sedimentation to separate EVs, which is rapid and simple [109]. However, this technique commonly leads to reduced purity and increased contamination with dissolvable peptides [103].

Characterizing EVs is crucial to comprehending EVs’ dimensions, concentration, content, and functional attributes [94]. Various analytical techniques are utilized for this purpose. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measures EV size distribution by analyzing photon scattering caused by Brownian motion [110–112] while nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) tracks individual particles in real time to assess their dimensions and density; however requires careful dilution to avoid interference [113,114]. Flow cytometry enables the identification and classification of functional EVs based on membrane markers and other features, subsequently offering a detailed profiling of EV subsets [115–117]. Electron microscopy (EM and Cryo-EM) is also employed in observing the morphology and dimensions of EVs at high resolution [118,119] as it offers significant details on EVs’ dimensions and structure. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) scans EV surfaces with a fine probe, yielding detailed images of their surface topography and dimensional range [120–122]. Furthermore, tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) quantifies EV dimension and concentration by detecting variations in electrical impedance while particles travel across a pore [94,123], offering high sensitivity [124]. Immunoblotting assays like ELISA, western, and dot blot are utilized to examine the protein composition of EVs [125]. Additionally, optical techniques such as super-resolution microscopy [126] help evaluate the dimension, chemical makeup, morphology, and cellular source of individual EVs [127], offering comprehensive insight into the heterogeneity of EV preparations [128,129]. All these methods provide a comprehensive insight into EVs, which is crucial for advancing their application as therapeutic agents in infectious diseases.

5 Modes of Anti-Pathogen Action by Extracellular Vesicles

EVs are pivotal in modulating host-pathogen interactions via several means. Their mode of action against infectious organisms is highly dependent on their composition, cell of origin, and target specificity. These means are widely divided into two major groups, which are the natural cargo effectors that possess the fundamental biological action of the vesicles and the engineered cargo effectors that involve the alteration of EVs to deliver therapeutic payloads. These two groups of vesicles act on the pathogen or stimulate immunomodulatory effects that enhance pathogen clearance and reduce the pathological manifestation of the infection. The naturally released EVs contain PAMPs that stimulate PRRs and MHC class I and II molecules that lead to cytokine production and antigen-specific T-cell activation, respectively [130]. Furthermore, EVs are modified by loading their interior or surface with RNAs, CRISPR-Cas components, proteins, lipids, and antimicrobial compounds [131,132]. The surfaces of these EVs have targeted ligands, aptamers, and antibodies attached to them for targeted delivery [133].

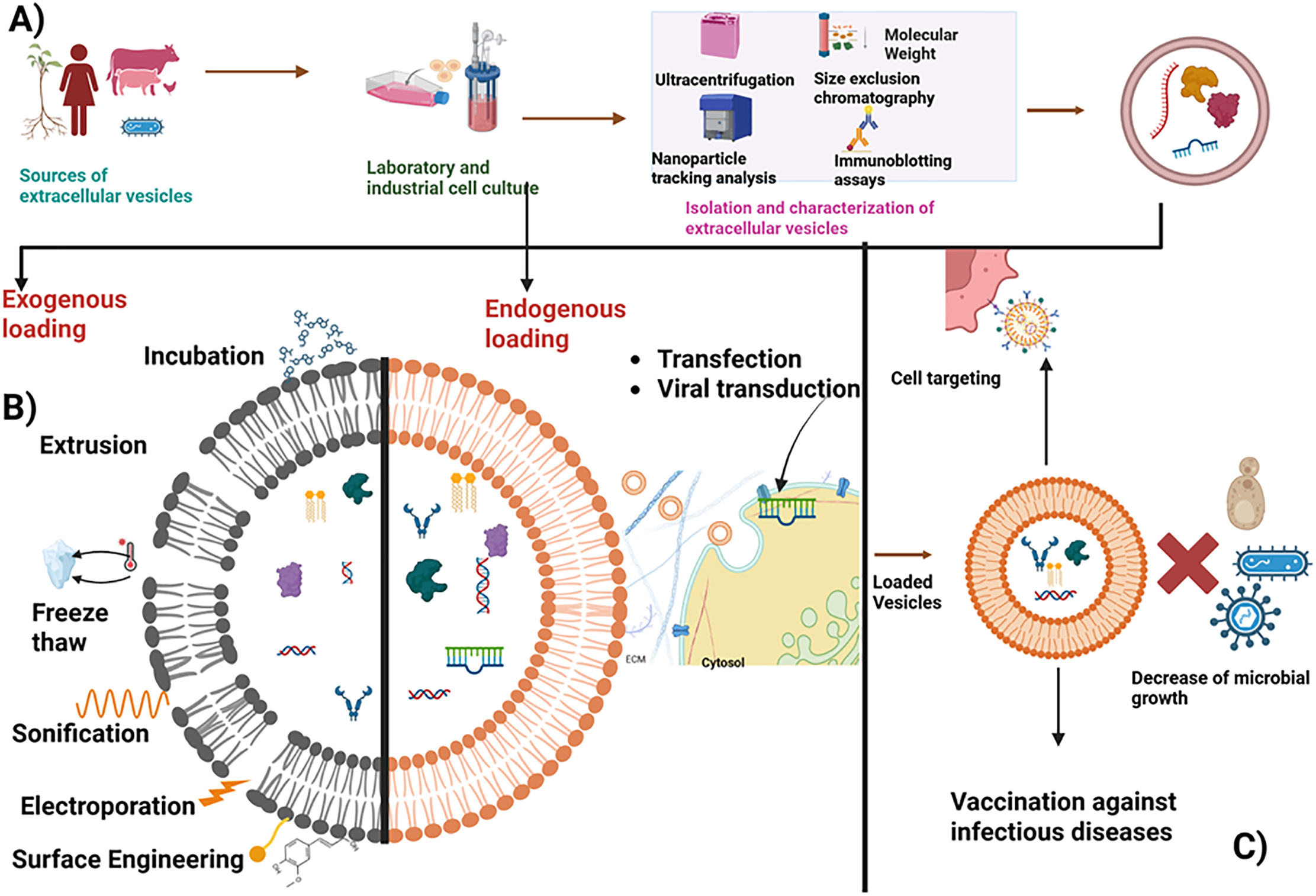

Engineering Extracellular Vesicles for Therapeutic Purposes

EVs can be loaded endogenously by introducing functional oligonucleotides into parent cells to modulate gene expression. These oligonucleotides are packaged within the EVs and the EVs are released with the required therapeutic advantage during EV biogenesis [134]. In addition to endogenous loading, vesicles can also be exogenously loaded post-isolation by directly modifying the EVs. The incubation method is often considered a passive strategy that involves the direct incubation of drugs with EVs. It depends on the drug’s hydrophobic nature, which allows it to interact with the lipid layer of the vesicle’s membrane (Fig. 3B,C). It is a simple and affordable technique that does not involve high-throughput technology to transport hydrophobic cargoes only. Electroporation is the most common method. It was introduced for the loading of water-soluble drugs (Fig. 3B). It is also used to load small hydrophilic cytotoxin molecules like doxorubicin. This technique is referred to as advantageous because it produces an average loading efficiency compared to other substitutes, and it is done without additives. A higher field strength is applied to increase the membrane permeabilization when working with EVs [135], but this strong field causes damage to the vesicles and their cargo.

Figure 3: Presents a schematic illustration of the process of obtaining extracellular vesicles (EVs) and loading them with therapeutic payloads. (A) First, EVs are sourced from a variety of biological materials, including plants, cells, human and animal body fluids, and microorganisms. These cells can be cultured either in the laboratory or industrially. (B) The vesicles can be loaded with therapeutics through two methods: endogenous or exogenous loading. For endogenous loading, cells are transfected or virally transduced with the oligonucleotide of interest, after which the vesicles are released and isolated, carrying the therapeutic molecules. In exogenous loading, vesicles are first isolated and characterized using techniques such as ultracentrifugation, size exclusion chromatography, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and immunoblotting assays. Subsequently, the vesicles are loaded with the therapeutic payload via passive incubation or active methods that modify the phospholipid bilayer, such as electroporation, sonication, freeze-thawing, and extrusion. (C) These engineered vesicles enhance specific targeting of cells, microbial killing, and the delivery of vaccines for infectious diseases. Image created utilizing Bio Render

Sonication involves using sound waves to produce calm shearing forces that aid in disrupting the lipid bilayer and subsequently incorporating the desired molecule within the EVs (Fig. 3B). However, certain challenges, such as alteration of zeta potential [136], loss of exosomal protein, heat generation during the sonication cycle, and membrane disruption, are some drawbacks involved with this technique. During extrusion, the lipid bilayer membrane is disrupted through a small-sized polycarbonate porous membrane, and the molecules of interest are loaded within the vesicles (Fig. 3B). However, this strategy can increase EV toxicity by initiating mechanical stress that changes its membrane arrangement and zeta potential [136]. Freeze-thaw methods comprise an ephemeral induction of pores on the vesicles’ membrane after freezing at −80°C and then thawing at 37°C multiple times to aid the entry of the desired molecules into these EVs (Fig. 3B). The membrane’s integrity is preserved due to the reduced external force required [137]. However, incessant freeze-thaw cycles clump these vesicles, inactivate the protein, and increase their size. Therefore, it should be carried out with optimum care to ensure the integrity is intact [138].

6 Pre-Clinical and Clinical Application of Extracellular Vesicles

6.1 EV-Mediated Antiviral Strategies

Viral diseases have taken countless lives throughout the ages, often eradicating significant segments of the global population, as demonstrated by the 1918 influenza epidemic and the devastating COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2019, the deadly SARS-CoV-2 virus has been responsible for over 6 million fatalities and 766 million illnesses [139]. These events have reechoed the importance of developing effective strategies for the treatment and prevention of viral infection.

Current studies have emphasized complex functions of EVs in viral disease development, such as COVID-19, and their application in the treatment. Animal-derived EVs, mainly from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), exhibit the possibility of treating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) through regulating immune responses and decreasing inflammation [140]. The safety profile of nebulized exosomes obtained from allogenic adipose tissue mesenchymal stromal cells in treating COVID-19-associated pneumonia was assessed in a phase 2 pilot clinical trial conducted in Wuhan, China. After 5 days of consecutively inhaling these vesicles, the patients’ conditions were alleviated, which was characterized by decreased lung inflammation and lack of adverse events [141]. However, the study was challenged by the small number of patients enrolled. Additionally, treatment with nebulized EVs employing umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes demonstrated potential in managing COVID-19 lung infection, along with findings supporting improved lung damage absorption and a decrease in patient care duration [142]. Also, it was reported that exosomes from COVID-19 patients had ACE2 receptors on their surface. Through competition with the binding site of cellular ACE2, these vesicles can prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in humanized ACE2 (hACE2) transgenic mice [143].

Recent studies have shown the therapeutic effect of oral administered extracellular vesicles from Lactobacillus reuteri (LrEVs) against influenza A virus (IAV) infections. The administration of the LrEVs in vivo was effective against IAV through its modulation of the immunological response of IL-17-producing cells in the intestine and gut. This involved inhibiting Th-17 cell development and transportation. It also contained miR-4239, which controlled the production of IL-17a, thereby suggesting its potential in IAV treatment [144].

Plant-derived extracellular vesicles (PDEV) have also been isolated [131,145–147]. PDEVs are utilized in therapeutics due to their inherent bioactive properties and their ability to withstand digestive enzymes without inducing inflammatory responses [148,149]. Exosomes from epithelial cells infected with SARS-COV-2 (exosomesNsp12Nsp13) were shown by Teng et al. to have induced lung inflammation in mice, while Ginger exosome-like nanoparticles (GELN) were utilized in the inhibition of the SARS-COV-2 gene via its inherent miRNA without causing side effects [150]. The GELN microRNA (miRNA aly-miR396a-5p) and rlcv-miR-rL1-28-3p bound to multiple sites on the viral genome and inhibited spike gene and Nsp 12 expression. This miRNA and the host miRNA do not share homology in their sequence, therefore supporting the unlikeliness of side effects occurring. Plant-based exosomal microRNAs were discovered to suppress pulmonary inflammation caused by exosomes, including SARS-CoV-2 Nsp12, indicating a possible cross-kingdom medical approach [150].

Additionally, MSC-originated EVs have also shown potential as an anti-inflammatory agent and improved healing during severe pulmonary damage induced by the influenza virus [52,96]. Zou et al. utilized exosomes in delivering anti-HIV agents to infected cells and induced cell death [151]. This is important because of the adverse drug events faced after the treatment of HIV [152,153]. This was done by transfecting HEK293 cells with plasmids containing single chain variable fragment (scFv) of a high-affinity HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibody, 10E8, and subsequently loading the exosomes expressing scFv from these transfected cells (10E8scFv-exos) with curcumin (a molecule that destroys HIV infected cells) or miR-143 (an apoptosis-inducing mRNA) [151]. MSC-derived EVs suppressed viral duplication within Hepatitis C virus-exposed cells via the function belonging to particular microRNAs such as miR-145, miR-199, miR-221, and let-7f [154]. In another study by Chen et al., exosomes from CRISPR/CAS9-expressing cells were endogenously loaded with Cas9 and human papillomavirus (HPV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) specific single guide RNA (sgRNA). These vesicles were able to destroy transfected HPV and HBV genomes in the human cervical cancer cell line (HeLa) and the human liver cancer cell line (HUH7), respectively. However, the full-length Cas9 mRNA protein was not expressed in the exosome, which was suspected to have contributed to the weak gene editing activity. Also, this strategy could increase the off-target effect, thereby affecting the safe profile of the CRISPR/CAS 9 system via the intracellular communication of the vesicles with neighboring cells and tissues. Finally, no exosome distinctive isolation technique was utilized in this study, so microvesicles/ectosomes could have been involved in the delivery [132].

Anticoli et al. fused antigens from Influenza Virus NP, Hepatitis C Virus NS3, Ebola Virus VP24, NP and VP40, Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever NP, and West Nile Virus NS3 with a HIV Nef protein. For every studied viral protein, mouse intramuscular vaccinations produced a strong and targeted cytotoxic CD8(+) T cell response. This vaccine platform maintains EVs’ high biosafety profile while improving their low cytotoxic T lymphocyte immunogenicity [155]. To enhance the effectiveness of the therapeutic when loaded endogenously, the mRNA of interest is fused to an RNA binding domain (RBD) that encodes an EV sorting protein. Zickler et al. integrated the target mRNA expression cassette into the genome of the EV producer cell with CD63 fused to an optimized version of the designer Pumilio and Fem-3 mRNA-Binding Factor from Caenorhabditis elegans (FBF) homology domain. This prevented the carryover of the mRNA-encoding plasmid and subsequently increased assay robustness [156].

Additionally, exosomal miRNA from honeysuckle was shown to be highly stable and target a myriad number of influenza viruses, including H7N9, H5N1, and H1N1. It caused a significant reduction in the expression of H1N-encoded NS1 and PB2 proteins [157]. Also, this microRNA was reported by Huang et al. to impair varicella-zoster virus replication through its target of the gene IE62 [158]. PDEV has not been extensively studied against viral diseases compared to its animal counterparts, so its studies are still at the laboratory phase. Pre-clinical investigations have indicated encouraging outcomes, and clinical studies remain essential to completely assess the safety and effectiveness of EVs in humans [159]. The application of EVs as treatment methods necessitates precise uniformity related to their extraction and identification [160]. Finally, guaranteeing the protection and effectiveness of these EVs in therapeutic applications is essential. Since they may transport toxic compounds [161].

6.2 EV-Mediated Antibacterial Strategies

EVs have shown promise as therapeutics against bacterial infections in their native or modified form by loading cargoes (Fig. 3A,B). In a study by Imparato et al., nontoxic, biocompatible EVs were obtained from mature biofilm formed by Candida albicans. When tested in vitro, it showed an antagonistic effect against K. pneumoniae, affecting its ability to form biofilms and inhibiting its attachment to mammalian cells [162]. A study by Gao et al. isolated cell membrane nanovesicles endogenously engineered to contain ceftazidime (CEF) and expressed Resolvin D1 (RvD1) on their surface via incubation. Co-delivery of ceftazidime and Resolvin D1 in a mouse model decreased bacterium-induced peritonitis [163]. However, this technique tends to offer lower encapsulation efficiencies [164]. Li et al. compared passive and active (electroporation and sonication) loading of LEV with Doxorubicin and assessed its effect against Staphylococcus species. L. plantarum WCFS1-derived extracellular vesicles (LDEVs) loaded passively showed lesser efficacy than actively loading, where the two approaches had similar efficacy. Also, doxorubicin loaded in LDEV showed increased antimicrobial activity compared to free Doxorubicin [165]. Yang et al. utilized exosomes for a targeted treatment of intracellular methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in macrophages. They loaded the mannosylated exosome with vancomycin or lysostaphin via mild sonication. This drug delivery system showed a better intracellular accumulation of the drug and inhibitory action against MRSA [166].

Gao et al. also coated PLGA NP loaded with vancomycin and rifampicin with BMV from S. aureus (NP@EV). This delivery platform showed improved targeting ability and alleviated S. aureus infection in vitro and in vivo [167]. Also, bacterial membrane vesicles (BMV) obtained from E. coli were used to modify the surface of a citrate-stabilized 30 nm gold (Au) nanoparticle (NP) [168]. The final BM-coated AuNP obtained was more stable in a biological environment than the BMV only. Furthermore, intravenous injection of this coated Np caused an increased and longer-lasting cellular and antibody response, showing its promise as an effective antibacterial vaccine. Animal-sourced EVs also possess demonstrated capability in managing pulmonary infections such as E. coli-caused severe lung damage and bloodstream and gastrointestinal infections, mainly through regulating immune responses, boosting bacterial elimination, and facilitating cellular regeneration [169].

Ginger exosome-like nanoparticles (GELN) impacted the entry, adhesion, multiplication, and survival of Porphyromonas gingivalis in a phosphatidic acid-dependent manner when administered orally in a mouse model with periodontitis. This occurred due to the interaction of GELN with hemin-binding protein 35 (HBP35) on P. gingivalis [170]. However, more studies need to be carried out to assess the effect of GELN on polymicrobial biofilms. Ginger-derived EVs were further shown by Qiao et al. in a synergistic combination with a biomimetic nanoplatform (Pd-Pt nanosheets) to eradicate Staphylococcus aureus and its biofilm. The EVs in this nanoplatform ensured biocompatibility and sustained circulation in the blood and accumulation of the platform at the infection site, while the nanosheet provided electro-influenced catalytic and photothermal activity [171]. Apis mellifera honey-derived EVs were reported by Leiva-Sabadini et al. to possess antibacterial and anti-biofilm effects against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis. The vesicle’s cargo was assessed to understand the mechanism associated with this effect, and defensin-1, major royal jelly protein-1 (MRJP1), and jellein-3 were identified. These molecules have an antibacterial effect, which is expressed through the formation of pores, cell membrane disruption, and lysis [172].

Broadening the field related to EV-derived vaccines has uncovered their potential to function as both antigen transporters and immunological regulators in infectious illnesses. Outer membrane vesicle (OMV)-derived vaccines, such as VA-MENGOC-BC®, have effectively proven defensive against Neisseria meningitides [24]. Its immune-activating ability is based significantly on their structure [25]. Moreover, investigation and advancement in this field might improve our comprehension of EVs in the role of versatile tools intended for upcoming vaccine approaches [23].

Creating approaches that focus on the targeted transport of EVs to locations inside the body is important to optimize EVs’ therapeutic capability (Fig. 3C) while at the same time reducing non-specific impacts [173]. Additionally, approaches aimed at suppressing secretion and activity involving bacterial-derived EVs have the potential to be investigated as a method for interrupting the pathogenicity of infectious agents [174].

6.3 EV-Mediated Antifungal Strategies

New approaches are desperately needed to prevent and treat fungal infections, which kill over 1.5 million people each year and impact over a billion people globally [175]. Furthermore, it is critical to stress that emerging fungal infections and their resistance to antifungals pose global health security risks, especially in immunocompromised individuals [176]. In contrast to other infectious illnesses, fungal infections have received much less research funding despite this public health burden [175]. In this regard, efforts to treat fungal infections, such as those utilizing EVs, can be advantageous.

EVs derived from Aspergillus fumigatus (AF), a prominent causative agent of fungal keratitis (FK), were assessed against A. fumigatus to understand their protective role in the disease in vivo and in vitro [177]. It was shown that A. fumigatus fungal keratitis was much less severe in mice who had EV injections beforehand, as evidenced by decreased fungus burden, inflammatory manifestations, and clinical ratings. The study highlights AF-derived EVs as a future in therapeutic development against FK.

The commensal microbe Candida albicans persists in the mucosal surfaces of healthy individuals. However, its overgrowth can be detrimental because it is the most common agent isolated from patients with extreme presentations of fungal infections [176]. Human oral mucosal epithelial cell line-derived EVs (Leuk-1 cells) were investigated against oral candidiasis in a mouse model. Results from this analysis showed enhanced responses of oral mucosal epithelial cells to C. albicans defense, detrimental changes structurally and morphologically, and reduced hyphal invasion into mucosal epithelium, thereby impairing fungal growth.

Moreover, the mold Aspergillus fumigatus poses a great challenge due to the difficulty encountered during its diagnosis, its resistance to antifungals, and inadequate, nuanced therapeutic interventions. However, EVs released from polymorphonuclear cells after infection with wild-type and the melanin-deficient pksP mutant conidia from A. fumigatus showed an effect on hyphal growth after coincubation with conidia in a concentration-dependent manner. The authors attributed the antifungal ability to the cathepsin G and azurocidin present in the EVs and damage caused by the physical interaction of the EVs and the hyphae, leading to mitochondria fragmentation and changes and invaginations on the cellular surface [178].

An article published by Xiao et al. explained how Cryptococcus neoformans-derived EVs carry disease agents such as laccase, melanin, urease, as well as the Ssa1 gene, enabling fungal disease-causing potential and immune system resistance. Therefore, these findings emphasize that EVs have the potential for therapeutic goals for novel antifungal treatments against cryptococcosis [179].

In addition, EVs from plants (PDEVs) have also shown prospects as therapeutics and delivery vehicles for treating fungal infections. EVs obtained from the sunflower seedlings Helianthus annuus contained a huge amount of defense proteins, so Regente et al. assessed the effect of these vesicles on phytopathogenic Sclerotinia sclerotiorum ascospores [180]. These EVs were internalized by the fungus, and they impaired spore growth and development, subsequently causing fungal death. PDEVs from Arabidopsis have also shown effects against the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea by transferring small RNAs (sRNA) into fungal cells to silence virulence-related genes [131]. Cumulatively, these findings pinpoint the need for extended and intense exploration of the therapeutic potential of EVs against fungal infections.

6.4 EV-Mediated Antiparasitic Strategies

The substantial burden of illness and mortality caused by protozoan and helminthic diseases globally, particularly in tropical countries, makes them important public health concerns. Approximately one in four people worldwide are infected with gastrointestinal parasites. Infections with soil-transmitted helminths (STH), such as Trichuris trichiura, usually cause stunted growth, anaemia, and delayed cognitive development [181,182]. However, existing drugs used in combating this parasite have reduced efficacy and are ineffective against recurrence, showing the need for better treatments and a vaccine [183]. According to an investigation by Shears et al., in a mouse model, administration of EVs garnered from the soluble material of Trichuris muris was protective against re-infection. The results showed an increase in IgG2a/c and IgG1 levels, thereby presenting these vesicles as strongly immunogenic. However, further studies should be carried out combining this strategy with adjuvants to better exploit its potential [183].

In Chagas disease, investigative studies showed that a parasite virulence factor (MASP) coated with T. cruzi-derived EVs coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin induced higher survival rates and lower parasite loads in the heart, liver, and spleen post-infection. It subsequently showed an increase in the levels of neutralizing antibodies and protective cytokine expression, indicating the suitability of this vaccine candidate [184].

The potentially fatal illness, malaria, is caused by parasites belonging to the genus Plasmodium. The parasite has been shown to utilize EVs to transfer antigenic materials to host cells, contributing to the parasite and infection spread. On the contrary, these EVs have been shown by research as an effective strategy against Plasmodium falciparum. In a study by Borgheti-Cardoso et al., tafenoquine and atovaquone, encompassed within EVs from plasmodium-infected red blood cells, impaired the growth of the parasite better than the drugs alone, thereby showing a stronger efficiency of hydrophobic drugs after sheathing with EVs [185].

Toxoplasma gondii is an apicomplexan parasite that causes toxoplasmosis [186]. This disease is a heavy challenge that can induce stillbirth and abortion in livestock [186]. The main treatments for toxoplasmosis have had failure rates, therefore stating the importance of alternative strategies and exploration of novel vaccine candidates [186,187]. Tawfeek et al. explored exosomes from human hepatoblastoma cell lines infected with T. gondii as potential immunizing agents. The strategy in this study involved conjugating exosomes to alum (an adjuvant) and comparing its efficacy to excretory secretory antigens (ESAs), the most superior vaccine candidates. The EV-alum candidate presented a more robust cellular and humoral immune response and higher protection against T. gondii challenge [187]. Leishmania species obtained EVs that decreased parasite levels and regulated immunological reactions, demonstrating therapeutic potential [52]. EVs extracted from schistosomes influence host defense mechanisms and have the potential to assist in creating medical interventions treating schistosomiasis [52]. These studies, in general, have provided a new direction for the development of therapeutics to combat Toxoplasma infections.

While ongoing research emphasizes the potential function of EVs from varied origins in fighting infectious illnesses, multiple crucial aspects require additional investigations to transition from basic discovery to clinical implementation. Collaborative efforts should be put into bridging the gap in diagnostic sensitivity, therapeutic specificity, and regulatory guidelines. Of high importance is the development of sensitive, high-throughput techniques that can analyze single EVs for applications in infectious disease control. Despite promising in vitro findings, challenges in standardized isolation methods, cargo loading, and large-scale production need to be surpassed to fully exploit the clinical application of this therapy in infectious diseases. Future studies should focus more on understanding EV biodistribution, improving the bioengineering of EVs, and ensuring their safety and application in human trials to combat infectious diseases. A synergistic utilization of EVs as delivery vehicles and nuance technology should be employed to achieve “Precision Medicine” and tailored medication therapy. Furthermore, as gene therapy and non-cellular treatment advance, the use of EVs will also play a vital role in these therapeutic approaches. Thus, EV-based drug delivery systems provide a future in the medical industry.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the National Science Foundation grant (IOS-1900377), received by QLM and EPSCoR GRSP Round 19 grant received by SVTW.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Chioma C. Ezeuko and Sandani V. T. Wijerathne; draft manuscript preparation: Chioma C. Ezeuko and Sandani V. T. Wijerathne; review and editing: Qiana L. Matthews; visualization: Chioma C. Ezeuko and Sandani V. T. Wijerathne; supervision: Qiana L. Matthews. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Antabe R, Ziegler BR. Diseases, emerging and infectious. In: Kobayashi A, editor. International encyclopedia of human geography. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 389–91. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102295-5.10439-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm Ther. 2015;40(4):277–83. [Google Scholar]

3. El Andaloussi S, Mäger I, Breakefield XO, Wood MJA. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(5):347–57. doi:10.1038/nrd3978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Rafieezadeh D, Rafieezadeh A. Extracellular vesicles and their therapeutic applications: a review article (part1). Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2024;16(1):1–9. doi:10.62347/QPAG5693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu YJ, Wang C. A review of the regulatory mechanisms of extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):77. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01103-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wijerathne SVT, Pandit R, Ezeuko CC, Matthews QL. Comparative examination of feline coronavirus and canine coronavirus effects on extracellular vesicles acquired from A-72 canine fibrosarcoma cell line. Vet Sci. 2025;12(5):477. doi:10.3390/vetsci12050477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wijerathne SVT, Pandit R, Ipinmoroti AO, Crenshaw BJ, Matthews QL. Feline coronavirus influences the biogenesis and composition of extracellular vesicles derived from CRFK cells. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1388438. doi:10.3389/fvets.2024.1388438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar MA, Baba SK, Sadida HQ, Marzooqi SA, Jerobin J, Altemani FH, et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):27. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01735-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Doyle LM, Wang MZ. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells. 2019;8(7):727. doi:10.3390/cells8070727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Abels ER, Breakefield XO. Introduction to extracellular vesicles: biogenesis, RNA cargo selection, content, release, and uptake. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36(3):301–12. doi:10.1007/s10571-016-0366-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4(1):27066. doi:10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Amin S, Massoumi H, Tewari D, Roy A, Chaudhuri M, Jazayerli C, et al. Cell type-specific extracellular vesicles and their impact on health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(5):2730. doi:10.3390/ijms25052730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wu Q, Kan J, Fu C, Liu X, Cui Z, Wang S, et al. Insights into the unique roles of extracellular vesicles for gut health modulation: mechanisms, challenges, and perspectives. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2024;7(1):100301. doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2024.100301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Möbs C, Jung AL. Extracellular vesicles: messengers of allergic immune responses and novel therapeutic strategy. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54(5):e2350392. doi:10.1002/eji.202350392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen Z, Larregina AT, Morelli AE. Impact of extracellular vesicles on innate immunity. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2019;24(6):670–8. doi:10.1097/MOT.0000000000000701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Liu S, Wu X, Chandra S, Lyon C, Ning B, Jiang L, et al. Extracellular vesicles: emerging tools as therapeutic agent carriers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(10):3822–42. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2022.05.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Buzas EI. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23(4):236–50. doi:10.1038/s41577-022-00763-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. René CA, Parks RJ. Bioengineering extracellular vesicle cargo for optimal therapeutic efficiency. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2024;32(2):101259. doi:10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ezeuko CC, Efa BB, Matthews QL. Chapter 10—methods to mitigate immune response. In: Curiel DT, Parker AL, editors. Adenoviral vectors for gene therapy. 3rd ed. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press; 2025. p. 275–308. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-89821-8.00005-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–80. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chaudhari P, Ghate V, Nampoothiri M, Lewis S. Multifunctional role of exosomes in viral diseases: from transmission to diagnosis and therapy. Cell Signal. 2022;94(1):110325. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2022.110325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Hendricks MR, Lane S, Melvin JA, Ouyang Y, Stolz DB, Williams JV, et al. Extracellular vesicles promote transkingdom nutrient transfer during viral-bacterial co-infection. Cell Rep. 2021;34(4):108672. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wen M, Wang J, Ou Z, Nie G, Chen Y, Li M, et al. Bacterial extracellular vesicles: a position paper by the microbial vesicles task force of the Chinese society for extracellular vesicles. Interdiscip Med. 2023;1(3):e20230017. doi:10.1002/INMD.20230017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Masforrol Y, Gil J, García D, Noda J, Ramos Y, Betancourt L, et al. A deeper mining on the protein composition of VA-MENGOC-BC®: an OMV-based vaccine against N. meningitidis serogroup B and C. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2548–60. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1356961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zariri A, Beskers J, van de Waterbeemd B, Hamstra HJ, Bindels THE, van Riet E, et al. Meningococcal outer membrane vesicle composition-dependent activation of the innate immune response. Infect Immun. 2016;84(10):3024–33. doi:10.1128/IAI.00635-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Pan BT, Johnstone RM. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 1983;33(3):967–78. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97(2):329–39. doi:10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Kang T, Atukorala I, Mathivanan S. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles. Subcell Biochem. 2021;97(3):19–43. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-67171-6_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Krylova SV, Feng D. The machinery of exosomes: biogenesis, release, and uptake. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1337. doi:10.3390/ijms24021337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu H, Tang WH. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019;9(1):19. doi:10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fan Q, Yang L, Zhang X, Peng X, Wei S, Su D, et al. The emerging role of exosome-derived non-coding RNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Lett. 2018;414:107–15. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wei D, Zhan W, Gao Y, Huang L, Gong R, Wang W, et al. RAB31 marks and controls an ESCRT-independent exosome pathway. Cell Res. 2021;31(2):157–77. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-00409-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Shkair L, Garanina EE, Stott RJ, Foster TL, Rizvanov AA, Khaiboullina SF. Membrane microvesicles as potential vaccine candidates. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1142. doi:10.3390/ijms22031142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Tricarico C, Clancy J, D’Souza-Schorey C. Biology and biogenesis of shed microvesicles. Small GTPases. 2017;8(4):220–32. doi:10.1080/21541248.2016.1215283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sędzik M, Rakoczy K, Sleziak J, Kisiel M, Kraska K, Rubin J, et al. Comparative analysis of exosomes and extracellular microvesicles in healing pathways: insights for advancing regenerative therapies. Molecules. 2024;29(15):3681. doi:10.3390/molecules29153681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Savcı D, Işık G, Hızlıok S, Erbaş O. Exosomes and Microvesicles. J Exp Basic Med Sci. 2024;5(1):19–32. doi:10.5606/jebms.2024.1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Muralidharan-Chari V, Clancy J, Plou C, Romao M, Chavrier P, Raposo G, et al. ARF6-regulated shedding of tumor cell-derived plasma membrane microvesicles. Curr Biol. 2009;19(22):1875–85. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li B, Antonyak MA, Zhang J, Cerione RA. RhoA triggers a specific signaling pathway that generates transforming microvesicles in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31(45):4740–9. doi:10.1038/onc.2011.636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Clancy JW, Schmidtmann M, D’Souza-Schorey C. The ins and outs of microvesicles. FASEB Bioadv. 2021;3(6):399–406. doi:10.1096/fba.2020-00127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gurung S, Perocheau D, Touramanidou L, Baruteau J. The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12964-021-00730-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Brás IC, Khani MH, Riedel D, Parfentev I, Gerhardt E, van Riesen C, et al. Ectosomes and exosomes modulate neuronal spontaneous activity. J Proteomics. 2022;269(8):104721. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2022.104721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Gonçalves D, Pinto SN, Fernandes F. Extracellular vesicles and infection: from hijacked machinery to therapeutic tools. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(6):1738. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15061738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Fraile-Ramos A, Cepeda V, Elstak E, van der Sluijs P. Rab27a is required for human cytomegalovirus assembly. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Rech J, Getinger-Panek A, Gałka S, Bednarek I. Origin and composition of exosomes as crucial factors in designing drug delivery systems. Appl Sci. 2022;12(23):12259. doi:10.3390/app122312259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Cheruiyot C, Pataki Z, Ramratnam B, Li M. Proteomic analysis of exosomes and its application in HIV-1 infection. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2018;12(5):e1700142. doi:10.1002/prca.201700142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Li J, Zan J, Xu Z, Yang C, Han X, Huang S, et al. Exosomes as novel nanocarriers for cancer therapy. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024;101:106262. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2024.106262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Meldolesi J. Exosomes and ectosomes in intercellular communication. Curr Biol. 2018;28(8):R435–44. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Skotland T, Sandvig K, Llorente A. Lipids in exosomes: current knowledge and the way forward. Prog Lipid Res. 2017;66:30–41. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2017.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Bevers EM, Williamson PL. Getting to the outer leaflet: physiology of phosphatidylserine exposure at the plasma membrane. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(2):605–45. doi:10.1152/physrev.00020.2015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ramakrishnaiah V, Thumann C, Fofana I, Habersetzer F, Pan Q, de Ruiter PE, et al. Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(32):13109–13. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221899110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zou C, Zhang Y, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhou X. Extracellular vesicles: recent insights into the interaction between host and pathogenic bacteria. Front Immunol. 2022;13:840550. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.840550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Regev-Rudzki N, Michaeli S, Torrecilhas AC. Editorial: extracellular vesicles in infectious diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:697919. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.697919. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Stotz HU, Brotherton D, Inal J. Communication is key: extracellular vesicles as mediators of infection and defence during host-microbe interactions in animals and plants. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2022;46(1):fuab044. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuab044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Rana A, Ahmed M, Rub A, Akhter Y. A tug-of-war between the host and the pathogen generates strategic hotspots for the development of novel therapeutic interventions against infectious diseases. Virulence. 2015;6(6):566–80. doi:10.1080/21505594.2015.1062211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Host-pathogen interactions: basic concepts of microbial commensalism, colonization, infection, and disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68(12):6511–8. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.12.6511-6518.2000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Kaufmann SH, Walker BD. Host-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(4):371–3. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30(1):16–34. doi:10.3109/08830185.2010.529976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):240–73. doi:10.1128/CMR.00046-08. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Li D, Wu M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):291. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00687-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Amarante-Mendes GP, Adjemian S, Branco LM, Zanetti LC, Weinlich R, Bortoluci KR. Pattern recognition receptors and the host cell death molecular machinery. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2379. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Cai Q, He B, Weiberg A, Buck AH, Jin H. Small RNAs and extracellular vesicles: new mechanisms of cross-species communication and innovative tools for disease control. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(12):e1008090. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Kumar A, Kodidela S, Tadrous E, Cory TJ, Walker CM, Smith AM, et al. Extracellular vesicles in viral replication and pathogenesis and their potential role in therapeutic intervention. Viruses. 2020;12(8):887. doi:10.3390/v12080887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Alvarado-Ocampo J, Abrahams-Sandí E, Retana-Moreira L. Overview of extracellular vesicles in pathogens with special focus on human extracellular protozoan parasites. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2024;119(11):e240073. doi:10.1590/0074-02760240073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Schemiko Almeida K, Rossi SA, Alves LR. RNA-containing extracellular vesicles in infection. RNA Biol. 2024;21(1):37–51. doi:10.1080/15476286.2024.2431781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Arteaga-Blanco LA, Bou-Habib DC. The role of extracellular vesicles from human macrophages on host-pathogen interaction. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10262. doi:10.3390/ijms221910262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Magaña G, Harvey C, Taggart CC, Rodgers AM. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles: role in pathogenesis and host-cell interactions. Antibiotics. 2023;13(1):32. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13010032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Kim J, Bin BH, Choi EJ, Lee HG, Lee TR, Cho EG. Staphylococcus aureus-derived extracellular vesicles induce monocyte recruitment by activating human dermal microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(1):68–81. doi:10.1111/cea.13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Rodrigues M, Fan J, Lyon C, Wan M, Hu Y. Role of extracellular vesicles in viral and bacterial infections: pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Theranostics. 2018;8(10):2709–21. doi:10.7150/thno.20576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Effah CY, Ding X, Drokow EK, Li X, Tong R, Sun T. Bacteria-derived extracellular vesicles: endogenous roles, therapeutic potentials and their biomimetics for the treatment and prevention of sepsis. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1296061. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1296061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Wang J, Chen S, Bihl J. Exosome-mediated transfer of ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) from endothelial progenitor cells promotes survival and function of endothelial cell. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020(1):4213541–11. doi:10.1155/2020/4213541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Tahyra ASC, Calado RT, Almeida F. The role of extracellular vesicles in COVID-19 pathology. Cells. 2022;11(16):2496. doi:10.3390/cells11162496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Gambardella J, Kansakar U, Sardu C, Messina V, Jankauskas SS, Marfella R, et al. Exosomal miR-145 and miR-885 regulate thrombosis in COVID-19. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2023;384(1):109–15. doi:10.1124/jpet.122.001209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Xiao W, Huang Q, Luo P, Tan X, Xia H, Wang S, et al. Lipid metabolism of plasma-derived small extracellular vesicles in COVID-19 convalescent patients. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16642. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-43189-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Mone P, Jankauskas SS, Manzi MV, Gambardella J, Coppola A, Kansakar U, et al. Endothelial extracellular vesicles enriched in microRNA-34a predict new-onset diabetes in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: novel insights for long COVID metabolic sequelae. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2024;389(1):34–9. doi:10.1124/jpet.122.001253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Pandit R, Ipinmoroti AO, Crenshaw BJ, Li T, Matthews QL. Canine coronavirus infection modulates the biogenesis and composition of cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):976. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11030976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Sharma HN, Latimore COD, Matthews QL. Biology and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2: understandings for therapeutic developments against COVID-19. Pathogens. 2021;10(9):1218. doi:10.3390/pathogens10091218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Pandit R, Matthews QL. A SARS-CoV-2: companion animal transmission and variants classification. Pathogens. 2023;12(6):775. doi:10.3390/pathogens12060775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Ali SA, Huang MB, Campbell PE, Roth WW, Campbell T, Khan M, et al. Genetic characterization of HIV type 1 Nef-induced vesicle secretion. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(2):173–92. doi:10.1089/aid.2009.0068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Raymond AD, Campbell-Sims TC, Khan M, Lang M, Huang MB, Bond VC, et al. HIV Type 1 Nef is released from infected cells in CD45+ microvesicles and is present in the plasma of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27(2):167–78. doi:10.1089/aid.2009.0170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Narayanan A, Iordanskiy S, Das R, Van Duyne R, Santos S, Jaworski E, et al. Exosomes derived from HIV-1-infected cells contain trans-activation response element RNA. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(27):20014–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.438895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Tamai K, Shiina M, Tanaka N, Nakano T, Yamamoto A, Kondo Y, et al. Regulation of hepatitis C virus secretion by the Hrs-dependent exosomal pathway. Virology. 2012;422(2):377–85. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Plazolles N, Humbert JM, Vachot L, Verrier B, Hocke C, Halary F. Pivotal advance: the promotion of soluble DC-SIGN release by inflammatory signals and its enhancement of cytomegalovirus-mediated Cis-infection of myeloid dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(3):329–42. doi:10.1189/jlb.0710386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Gong Z, Cheng C, Sun C, Cheng X. Harnessing engineered extracellular vesicles for enhanced therapeutic efficacy: advancements in cancer immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44(1):138. doi:10.1186/s13046-025-03403-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Ellerbroek PM, Lefeber DJ, van Veghel R, Scharringa J, Brouwer E, Gerwig GJ, et al. O-acetylation of cryptococcal capsular glucuronoxylomannan is essential for interference with neutrophil migration. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7513–20. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Halder LD, Jo EAH, Hasan MZ, Ferreira-Gomes M, Krüger T, Westermann M, et al. Immune modulation by complement receptor 3-dependent human monocyte TGF-β1-transporting vesicles. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2331. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16241-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Kabani M, Melki R. Sup35p in its soluble and prion states is packaged inside extracellular vesicles. mBio. 2015;6(4):e01017–15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01017-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Liu S, Hossinger A, Hofmann JP, Denner P, Vorberg IM. Horizontal transmission of cytosolic Sup35 prions by extracellular vesicles. mBio. 2016;7(4):e00915–16. doi:10.1128/mBio.00915-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Crenshaw BJ, Jones LB, Bell CR, Kumar S, Matthews QL. Perspective on adenoviruses: epidemiology, pathogenicity, and gene therapy. Biomedicines. 2019;7(3):61. doi:10.3390/biomedicines7030061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Jones LB, Bell CR, Bibb KE, Gu L, Coats MT, Matthews QL. Pathogens and their effect on exosome biogenesis and composition. Biomedicines. 2018;6(3):79. doi:10.3390/biomedicines6030079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Jones LB, Kumar S, Bell CR, Crenshaw BJ, Coats MT, Sims B, et al. Lipopolysaccharide administration alters extracellular vesicles in cell lines and mice. Curr Microbiol. 2021;78(3):920–31. doi:10.1007/s00284-021-02348-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Dantas-Pereira L, Menna-Barreto R, Lannes-Vieira J. Extracellular vesicles: potential role in remote signaling and inflammation in Trypanosoma cruzi-triggered disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:798054. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.798054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Pinheiro AAS, Torrecilhas AC, Souza BSF, Cruz FF, Guedes HLM, Ramos TD, et al. Potential of extracellular vesicles in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy for parasitic diseases. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024;13(8):e12496. doi:10.1002/jev2.12496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Thomas CJ, Delgado K, Sawant K, Roy J, Gupta U, Song CS, et al. Harnessing bacterial agents to modulate the tumor microenvironment and enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2024;16(22):3810. doi:10.3390/cancers16223810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. De Sousa KP, Rossi I, Abdullahi M, Ramirez MI, Stratton D, Inal JM. Isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles and future directions in diagnosis and therapy. Wires Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2023;15(1):e1835. doi:10.1002/wnan.1835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Zhang Q, Jeppesen DK, Higginbotham JN, Franklin JL, Coffey RJ. Comprehensive isolation of extracellular vesicles and nanoparticles. Nat Protoc. 2023;18(5):1462–87. doi:10.1038/s41596-023-00811-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Manzoor T, Saleem A, Farooq N, Dar LA, Nazir J, Saleem S, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells—a novel therapeutic tool in infectious diseases. Inflamm Regen. 2023;43(1):17. doi:10.1186/s41232-023-00266-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Payandeh Z, Tangruksa B, Synnergren J, Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Nordin JZ, Andaloussi SE, et al. Extracellular vesicles transport RNA between cells: unraveling their dual role in diagnostics and therapeutics. Mol Aspects Med. 2024;99:101302. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2024.101302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Sims B, Farrow AL, Williams SD, Bansal A, Krendelchtchikov A, Matthews QL. Tetraspanin blockage reduces exosome-mediated HIV-1 entry. Arch Virol. 2018;163(6):1683–9. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-3737-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Gao J, Dong X, Wang Z. Generation, purification and engineering of extracellular vesicles and their biomedical applications. Methods. 2020;177(8):114–25. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Konoshenko MY, Lekchnov EA, Vlassov AV, Laktionov PP. Isolation of extracellular vesicles: general methodologies and latest trends. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8545347. doi:10.1155/2018/8545347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Akbar A, Malekian F, Baghban N, Kodam SP, Ullah M. Methodologies to isolate and purify clinical grade extracellular vesicles for medical applications. Cells. 2022;11(2):186. doi:10.3390/cells11020186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Li P, Kaslan M, Lee SH, Yao J, Gao Z. Progress in exosome isolation techniques. Theranostics. 2017;7(3):789–804. doi:10.7150/thno.18133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Jia Y, Yu L, Ma T, Xu W, Qian H, Sun Y, et al. Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation: current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications. Theranostics. 2022;12(15):6548–75. doi:10.7150/thno.74305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Kaddour H, Tranquille M, Okeoma CM. The past, the present, and the future of the size exclusion chromatography in extracellular vesicles separation. Viruses. 2021;13(11):2272. doi:10.3390/v13112272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Quattrini F, Berrecoso G, Crecente-Campo J, Alonso MJ. Asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation as a multifunctional technique for the characterization of polymeric nanocarriers. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021;11(2):373–95. doi:10.1007/s13346-021-00918-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Eskelin K, Poranen MM, Oksanen HM. Asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation on virus and virus-like particle applications. Microorganisms. 2019;7(11):555. doi:10.3390/microorganisms7110555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Zhang H, Lyden D. Asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation technology for exomere and small extracellular vesicle separation and characterization. Nat Protoc. 2019;14(4):1027–53. doi:10.1038/s41596-019-0126-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Kırbaş OK, Bozkurt BT, Asutay AB, Mat B, Ozdemir B, Öztürkoğlu D, et al. Optimized isolation of extracellular vesicles from various organic sources using aqueous two-phase system. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19159. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55477-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Zhao Z, Wijerathne H, Godwin AK, Soper SA. Isolation and analysis methods of extracellular vesicles (EVs). Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucl Acids. 2021;2(1):80–103. doi:10.20517/evcna.2021.07. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Ross Hallett F. Scattering and particle sizing, applications. In: Lindon JC, editor. Encyclopedia of spectroscopy and spectrometry. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 1999. p. 2067–74. doi:10.1006/rwsp.2000.0273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Stetefeld J, McKenna SA, Patel TR. Dynamic light scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences. Biophys Rev. 2016;8(4):409–27. doi:10.1007/s12551-016-0218-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Wishard A, Gibb BC. Dynamic Light Scattering—an all-purpose guide for the supramolecular chemist. Supramol Chem. 2019;31(9):608–15. doi:10.1080/10610278.2019.1629438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]