Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Immune Mechanisms of the Comorbid Course of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Tuberculosis

1 Department of Nursing, Ryazan State Medical University, Ryazan, 390026, Russia

2 Department of Infectious Diseases and Phthisiology, Ryazan State Medical University, Ryazan, 390026, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Stanislav Kotlyarov. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mechanisms Driving COPD, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Innovations)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1631-1661. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066675

Received 14 April 2025; Accepted 17 July 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and respiratory tuberculosis are important respiratory problems. Meeting together, these diseases can mutually worsen the severity of clinical manifestations and negatively affect prognosis. COPD and tuberculosis share a number of common risk factors and pathogenetic mechanisms involving various immune and non-immune cells. Inflammation, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and lung tissue remodeling play an important role in the comorbid course of COPD and respiratory tuberculosis. These mechanisms are of diagnostic interest and are promising therapeutic targets. Thus, the aim of the current review is to discuss the mechanisms of the comorbid course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and respiratory tuberculosis.Keywords

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and respiratory tuberculosis (TB) are serious diseases that pose significant challenges to modern medicine, especially when comorbid [1–5]. COPD, characterized by irreversible airflow limitation and chronic airway inflammation, ranks among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [6–9]. Global estimates show that in people over 40 years of age, the prevalence of COPD is as high as 12.64% (according to GOLD criteria), with a global prevalence of 2512.86 cases per 100,000 people in 2021 [10,11]. Projections indicate that the number of COPD cases worldwide will approach 600 million by 2050 [12]. Regarding mortality, the global mortality rate in 2021 was 45.22 deaths per 100,000 people [10]. Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains a key global health problem, especially in regions with high prevalence of infection [13,14]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2023, 10.8 million new cases of tuberculosis were registered, and mortality from this disease was 1.25 million people, making it one of the leading causes of death from infectious diseases in the world [15,16]. The combined presence of these severe diseases in one patient significantly complicates the clinical picture, intensifies pathological processes, and worsens the prognosis, which emphasizes the importance of studying their interaction [17,18]. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies (36,641 with COPD and 491,538 without COPD), the mean prevalence of COPD among TB survivors was found to be 21% (95% confidence interval (CI) 16%–25%) [19]. In a multivariate model, pulmonary TB and TB in general were associated with a 2.57-fold [95% CI, 2.31–2.87)] and 1.67-fold (95% CI, 1.48–1.90) increase in COPD risk, respectively [20]. In the population-based PLATINO study (Latin America), GOLD obstruction was reported in 30.7% of individuals with a history of TB and 13.8% of those without a history of TB (odds ratio (OR) 2.6) [21]. A large population-based cohort study in the Republic of Korea (≈700,000 people) also found a 63% higher risk of COPD in patients with tuberculosis (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 1.63; 95% CI 1.54–1.73) [22]. Conversely, COPD in turn increases susceptibility to TB: a study based on data from a Swedish registry of 115,867 patients found a threefold increased risk of TB in COPD patients (HR 3.0; 95% CI 2.4–4.0) [23]. Computer modeling also confirms that comorbidity doubles overall mortality compared with isolated TB or COPD [24]. With the number of new TB cases exceeding 10 million annually and the proportion of COPD among TB survivors ranging from 20%–30%, it is estimated that at least 2–3 million people worldwide are added to the cohort of patients with COPD and TB comorbidity each year. Clinically, the combination of diseases is associated with more frequent hospitalizations, poorer quality of life, and increased mortality, emphasizing the need for two-way screening—early detection of COPD in TB patients and active search for TB in COPD patients [25]. Thus, the relevance of the study of COPD and respiratory tuberculosis is due to several factors at once. First, the prevalence of COPD is steadily increasing due to the increasing number of smokers, environmental pollution, and an aging population. Second, as mentioned above, tuberculosis continues to claim millions of lives each year, remaining one of the leading causes of death from infectious diseases despite efforts to control it. Comorbidity of these conditions is common in clinical practice, especially in immunocompromised patients or in regions with a high prevalence of tuberculosis. Understanding the mechanisms of their interaction is essential to improve diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, making this topic a priority for medical science [26–29].

The challenges facing researchers of immunologic aspects of COPD and TB comorbidity are also quite multifaceted. The first is to examine how the chronic inflammation and oxidative stress characteristic of COPD affect the immune response in tuberculosis, including the body’s ability to combat M. tuberculosis [30]. The second is to determine how tuberculosis infection exacerbates the course of COPD by promoting the progression of lung tissue destruction and fibrosis [31,32]. The third is to identify key molecular and cellular mechanisms, such as hyperproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), imbalance of proteases and antiproteases, and activation of metalloproteinases, which may become targets for novel therapeutic approaches [33]. All these studies aim to unravel the complex pathogenetic links between diseases. The practical applications of the knowledge gained from such studies have great potential.

Thus, this review undertakes a critical examination of the pathophysiological pathways that drive the comorbid progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary tuberculosis.

2 Immunology of Inflammation in the Comorbid Course of COPD and Respiratory Tuberculosis

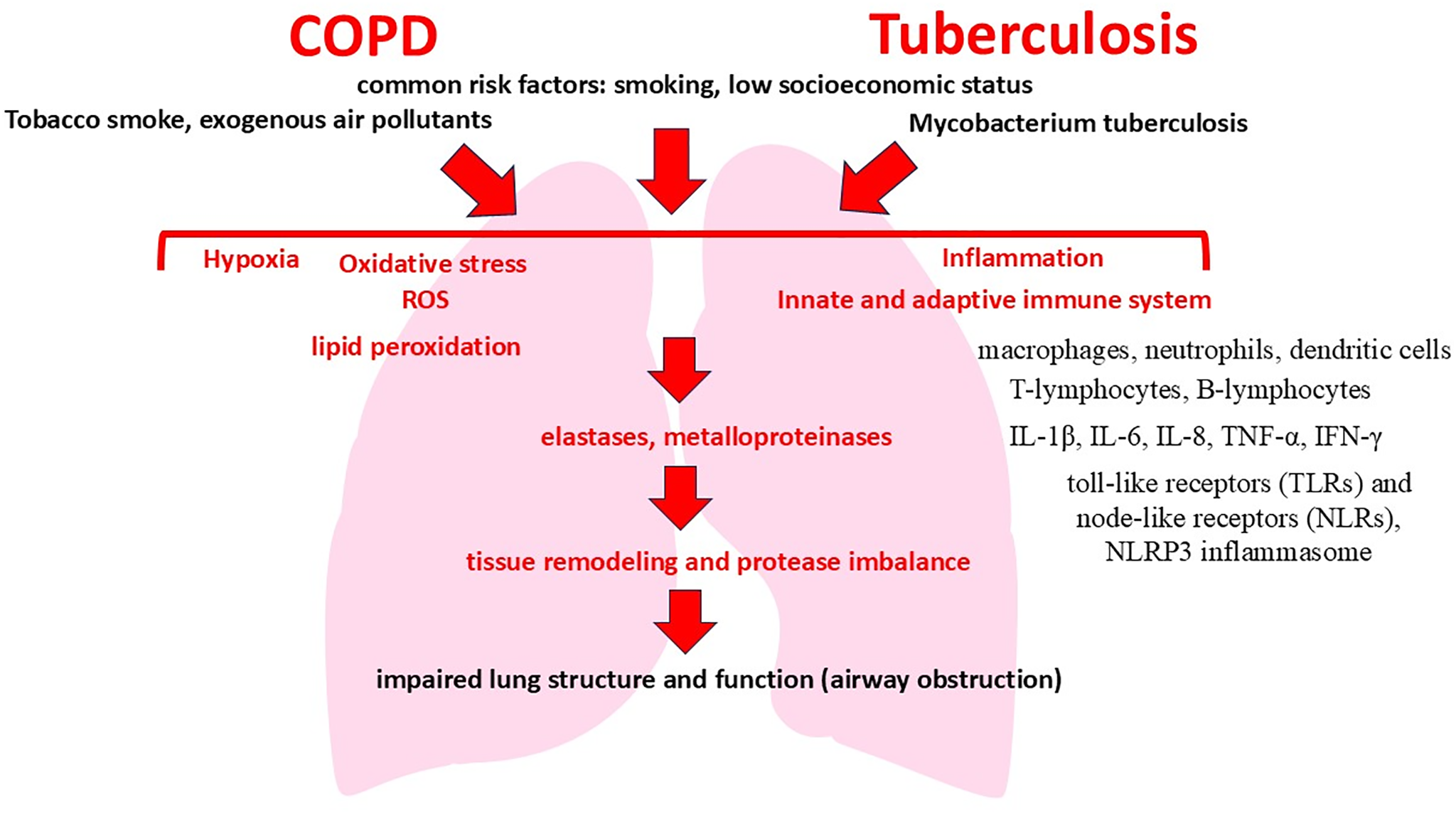

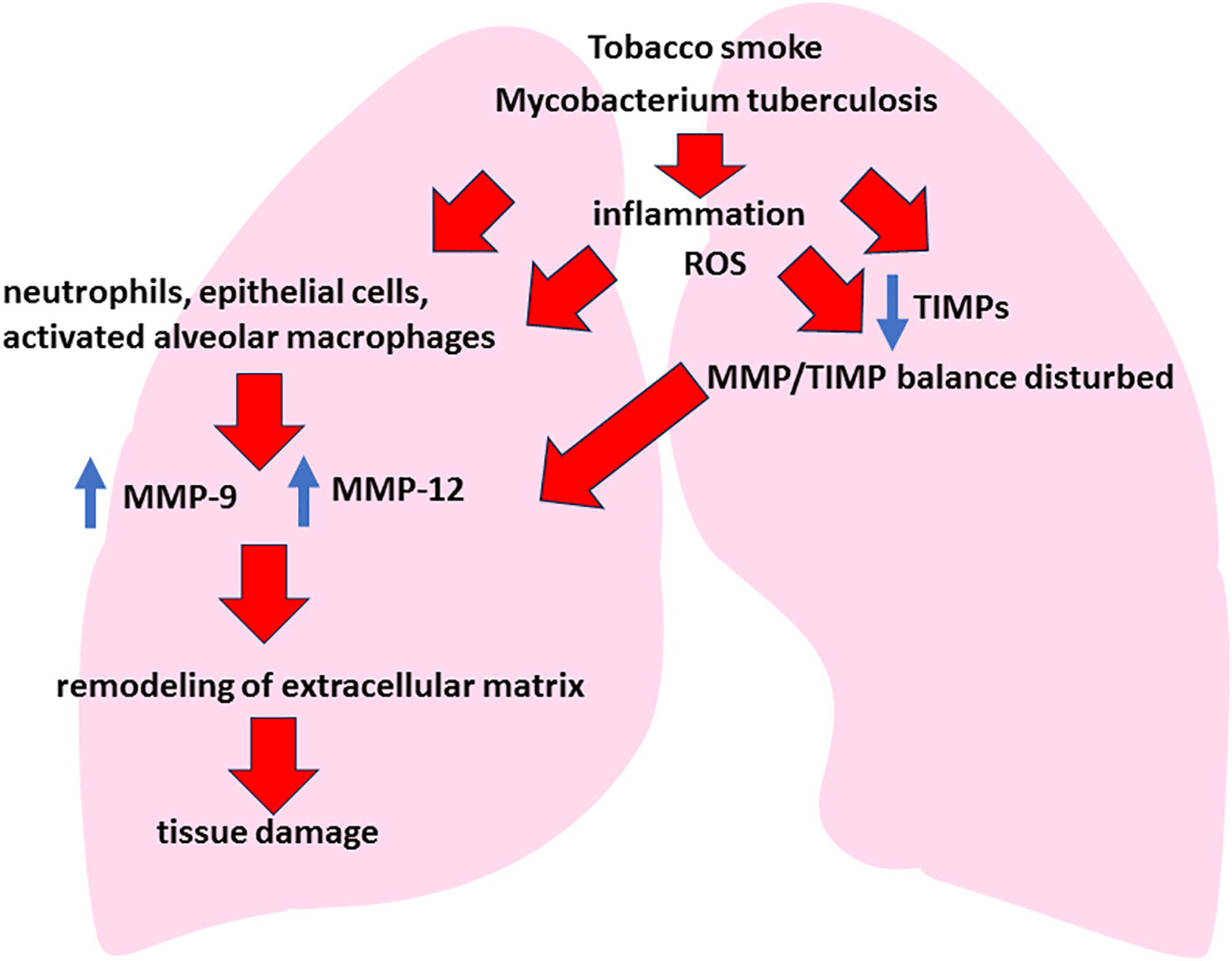

COPD and pulmonary tuberculosis are primarily inflammatory diseases. Comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis is characterized by quite specific immunopathological mechanisms that increase inflammation and damage to lung tissue (Fig. 1). The pathological process is based on a complex interaction between cells of innate and adaptive immunity, which is mediated by the production of cytokines and chemokines that support chronic inflammation in tissues [34–37]. Co-exposure to tobacco smoke and M. tuberculosis results in activation of innate immunity receptors (Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2)), stimulating cascades of intracellular signaling pathways (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [38–41]. This in turn leads to the release of proinflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and IL-8 that promote the migration and activation of macrophages and neutrophils in lung tissue [42–45].

Figure 1: Mechanisms of the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis

Alveolar macrophages play a special role in this case, which acquire a hyperactivated phenotype in comorbidity, producing TNF-α and IL-1β in large quantities. Hyperproduction of these interleukins enhances local inflammation and promotes the formation of persistent neutrophil infiltration characteristic of both diseases [46]. In parallel, neutrophil activation is accompanied by the secretion of neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9, MMP-12), which destroy the extracellular matrix, causing emphysema and bronchiectasis [47–51]. Simultaneously, adaptive immunity is activated with an increase in the number of CD4+ T-lymphocytes, mainly Th1 and Th17 subpopulations. Th1 cells produce IFN-γ, which enhances antitubercular immune response, but also maintains chronic inflammation of lung tissue. In turn, Th17 cells secrete IL-17, further promoting neutrophil recruitment and enhancing secretion of metalloproteinases [52,53]. As a result, a vicious circle of chronic inflammation and lung tissue damage is formed, in which inflammation, supported by neutrophils and T cells, aggravates lung tissue destruction and maintains the activity of infection. An important factor influencing the described immunopathologic mechanisms and significantly aggravating the inflammatory process is oxidative stress [54,55].

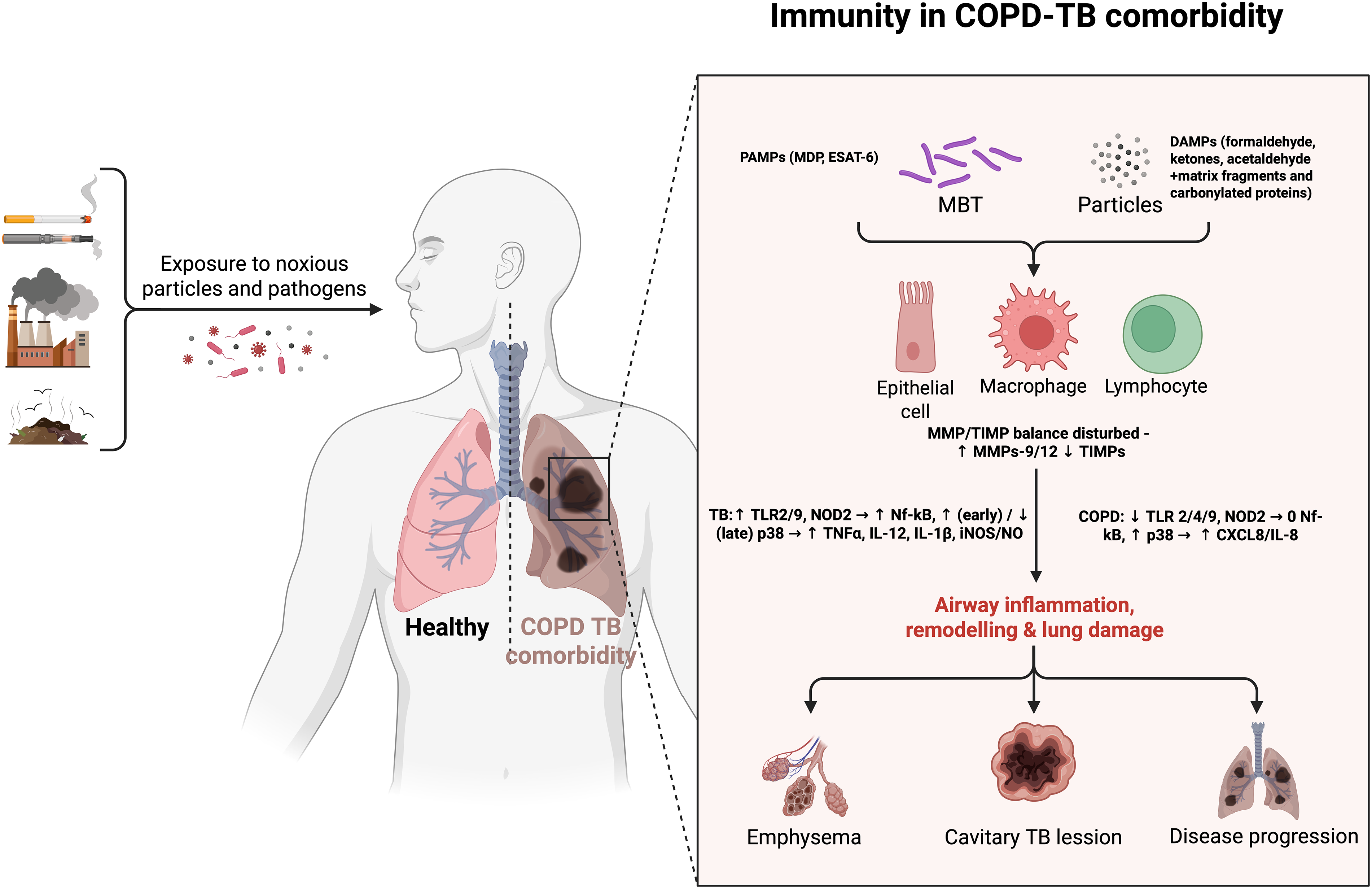

Increased production of ROS in COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity also activates signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK, increasing the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2) [56,57]. ROS causes lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, damage to proteins and DNA, and promotes apoptosis and necrosis of pulmonary parenchyma cells. This leads to increased release of endogenous damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMPs), which further activate receptors of innate immunity and maintain chronic inflammation [58,59].

Figure 2: Immune mechanisms of the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis. Exposure to noxious particles or Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MBT) bacilli activates pattern-recognition receptors—Toll-like receptors (TLR 2/4/9) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2)—on airway epithelial cells, macrophages and lymphocytes. Differential downstream signalling modulates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK), leading to increased secretion of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8/Interleukin-8 (CXCL8/IL-8) in COPD and of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-12 (IL-12) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) during TB. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as muramyl dipeptide (MDP) and early secreted antigenic target-6 kDa (ESAT-6), together with damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), further skew the inflammatory milieu, disturb the balance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9/-12) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), and enhance inducible nitric-oxide-synthase (iNOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO) production—collectively accelerating airway remodeling, emphysema, cavitation and overall disease progression. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/dih5c8d (accessed on 01 January 2025)

Analysis of the signaling pathways of innate immunity shows that in tuberculosis, the NOD2 receptor is a key element of antimicrobial defense. NOD2 plays a key role in the innate immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is expressed in alveolar macrophages and, upon recognition of muramyl dipeptide (MDP), induces the production of cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, as well as the antimicrobial peptide LL37, which enhances intracellular control of M. tuberculosis [60]. NOD2 also affects adaptive immunity. Nod2-deficient mice have decreased production of type 1 cytokines and reduced recruitment of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, resulting in impaired adaptive antimycobacterial immunity and increased bacterial infection [61–63].

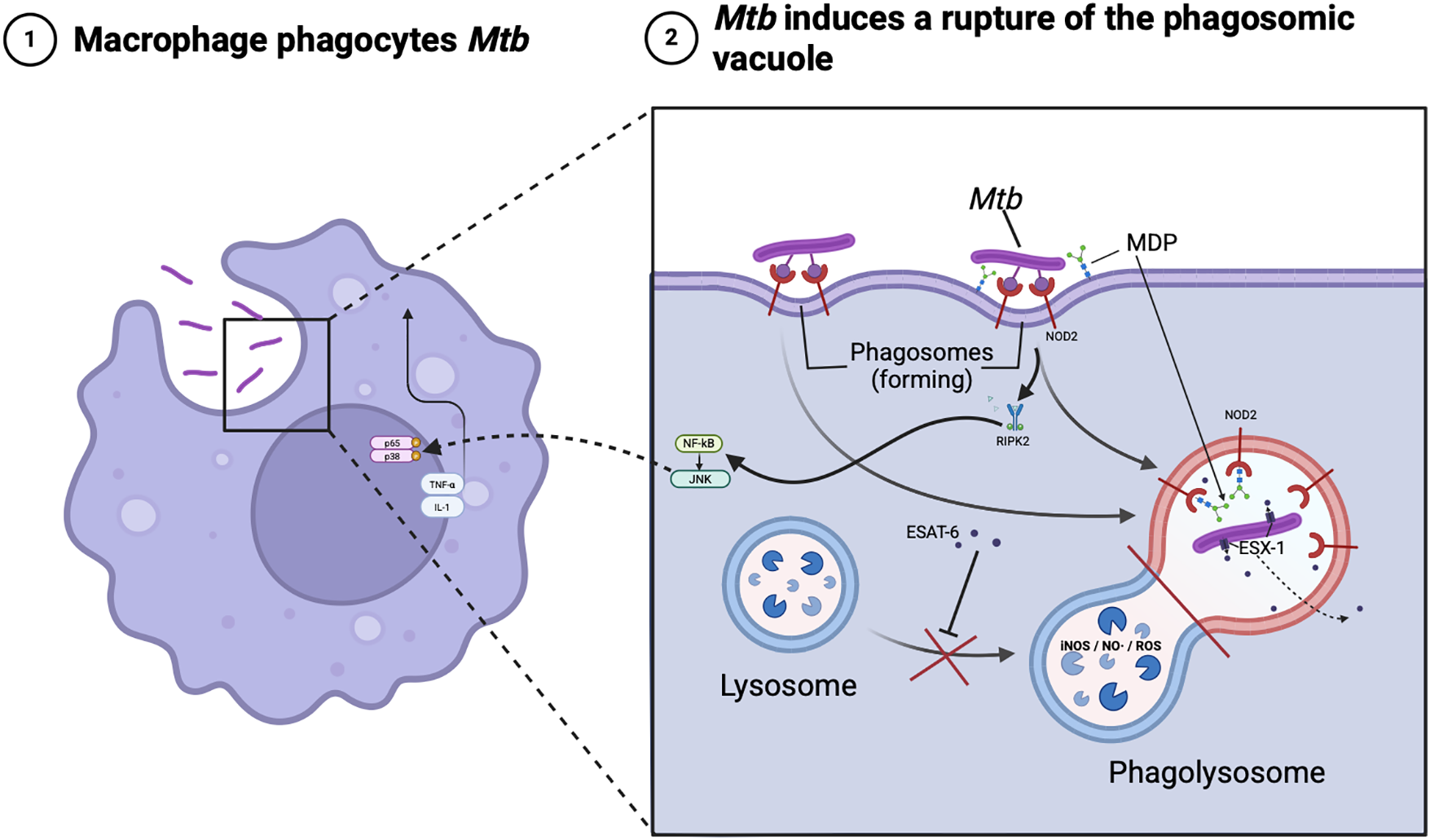

This receptor modulates iNOS-dependent antimicrobial pathways that help to restrict intracellular multiplication of mycobacteria in macrophages [64]. It is the binding of NOD2 receptor to muramyl dipeptide of M. tuberculosis that triggers the receptor-interacting protein kinase 2 (RIP2) → NF-κB/JNK/p38 cascade, which leads to an increase in the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, activates MMP-9/iNOS and forms a full macrophage response at early stages of the disease [65–67]. According to literature data, experimental inactivation of NOD2 receptor by siRNA leads to an increase in intracellular M. tuberculosis population by ≈85%, and Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (M. bovis BCG)—more than doubled, within the first 24 h, while the process of mycobacterial cell uptake (phagocytosis) by macrophage itself is not altered, indicating a defect in subsequent phagosome maturation and M. tuberculosis lysis rather than impaired capture [68]. Inhibition of the NOD2 receptor leads to decreased phosphorylation of RIP2 and decreased production of TNF-α and IL-1β. And accordingly, the saturation of phagosome with active forms of nitrogen and oxygen is reduced, which disrupts autophagy mechanisms in macrophage (no complete phagolysosome is formed) (Fig. 3) [60,69]. In the absence of full-fledged NOD2-signaling, M. tuberculosis more easily blocks the fusion of the phagosome with the lysosome, maintain a slightly acidic environment, and remain viable in the so-called “incomplete” phagosome [70,71]. Moreover, the high porosity of the membrane of such a vacuole and the ability of M. tuberculosis to translocate secretory proteins such as ESX-1 allow a part of bacterial antigens to enter the cytosol and additionally suppress antimicrobial cascades [72]. Thus, full activation of NOD2 is critical for the inhibition of pathogen spread and proper formation of tuberculous granuloma. NOD2 blockade leads to the formation of widespread, poorly organized granulomas with an increased tendency to decay and subsequent cavity formation [73–75].

Figure 3: Intracellular traffic of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Note: The schematic illustrates how a macrophage engulfed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mbt) recognizes bacterial muramyl dipeptide (MDP) via the NOD2 receptor on the phagosome membrane, activating the RIP2 adaptor kinase and NF-κB/JNK pathways. This leads to TNF-α/IL-1 release and NO/ROS accumulation in the phagolysosome, while the ESAT-6 protein and the ESX-1 secretory system of MBT disrupts phagolysosome formation and helps the pathogen to evade immunity. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/qsh5tkv (accessed on 01 January 2025)

In comorbidity in the lungs of smokers with COPD, chronic exposure to cigarette smoke and endogenous DAMPs reduces the expression of TLR2/4 and especially NOD2 on macrophages, putting them in a state of relative tolerance [76–78]. At the same time, the basal level of p65 NF-κB in the nucleus remains elevated, but additional stimulation with muramyl dipeptide hardly enhances TNF-α/IL-8 release [79].

Comparative analysis of innate immunity cascades shows that the TLR/NOD2 receptor circuit, as well as the downstream NF-κB and MAPK pathways are activated differently in TB and COPD. In alveolar macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, TLR2/TLR9 ligation and especially NOD2-dependent recognition of muramyl dipeptide lead to rapid RIP2 receptor phosphorylation, degradation of inhibitor of κB alpha (IκBα), and translocation of the p65 NF-κB subunit to the nucleus, accompanied by simultaneous release of the proinflammatory interleukins TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12; a parallel signaling pathway via p38- and JNK-MAPK receptors that enhances the expression of MMP-9 and iNOS required for granuloma formation. Although M. tuberculosis virulence factors (e.g., ESAT-6) can subsequently suppress p38 activation, the potent primary activation of NF-κB/MAPK remains a key factor in the development of caseous necrotic inflammation. In turn, in the lungs of smokers with COPD, chronic exposure to cigarette smoke and endogenous DAMPs generates a different distribution of pattern-recognizing receptors: TLR2/4 expression on macrophages is reduced and signaling output via NOD2 is attenuated, as evidenced by reduced IL-8 and TNF-α production upon stimulation with Pam3Cys or muramyl dipeptide ex vivo [80–83].

Thus, TB-associated COPD is characterized by hypertrophy along the NOD2-NF-κB/JNK/p38 axis with further matrix destruction and fibrosis, whereas chronic p38 activation and partial TLR/NOD2-tolerance predominate in non-TB COPD, causing prolonged neutrophilic inflammation without granulomatous component. Thus, immunopathological mechanisms of inflammation in the comorbidity of COPD and respiratory tuberculosis are characterized by dysregulation of the immune response, hyperproduction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, increased activity of neutrophils and macrophages, and an imbalance between different subpopulations of T-lymphocytes. These processes, in combination with oxidative stress, support chronic inflammation and contribute to irreversible damage to lung tissue, determining a severe course with frequent relapses and unfavorable prognosis in the comorbid course of these diseases.

3 Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of COPD and Respiratory Tuberculosis Comorbidity

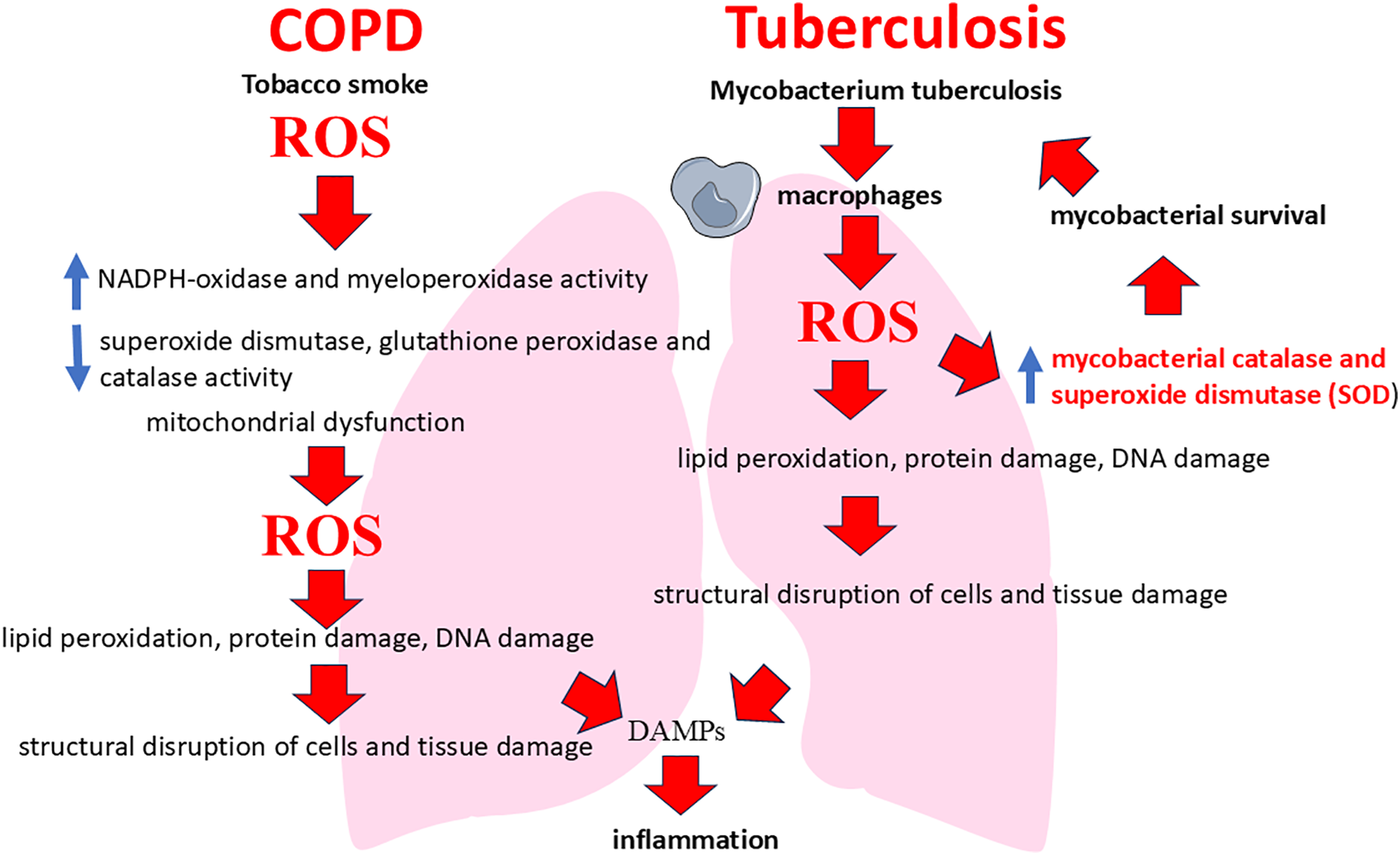

ROS formation is a key link in the pathogenesis of COPD [84–87]. In this disease, the main cause of enhanced ROS production is exposure to tobacco smoke, which contains many free radicals and other prooxidants [88–90]. Prooxidants in turn trigger inflammatory signaling pathways and activate immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, leading to oxidative stress and lung tissue damage [91–93]. Tobacco smoke triggers the activation of pro-oxidant enzymes such as NADPH-oxidase and myeloperoxidase, enhancing the generation of superoxide (O2-) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [94–96]. At the same time, increased ROS production suppresses the body’s antioxidant defense, including decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activity, leading to cell membrane damage, protein inactivation, and DNA fragmentation [97,98]. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes significantly to ROS production in COPD. Under conditions of chronic inflammation and exposure to tobacco smoke, mitochondria in airway cells begin to produce excessive amounts of ROS, which additionally damages lipids, proteins, and DNA [99]. These processes lead to the destruction of alveolar walls and fibrosis characteristic of COPD [100,101].

In pulmonary tuberculosis, ROS are formed predominantly in response to the infection of macrophages with M. tuberculosis [102–106]. Infection activates the NADPH-oxidase complex, leading to the generation of superoxide and other radicals necessary to kill the intracellularly proliferating pathogen [107,108]. However, M. tuberculosis have the ability to evade this defense mechanism, through the production of antioxidant enzymes (mycobacterial catalase and SOD), leading to chronic activation of macrophages and overproduction of ROS [109,110]. Thus, chronic inflammation in tuberculosis increases oxidative stress, which damages lung tissue and promotes the formation of lung tissue decay sites. Several studies show that neutrophils also play an important role in this process, increasing ROS production and exacerbating tissue damage [111–113].

In COPD and respiratory tuberculosis comorbidity, there is a mutual enhancement of ROS formation. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress caused by tobacco smoke in COPD create favorable conditions for M. tuberculosis persistence [114–116]. In turn, infection increases the activation of immune cells, which leads to even greater ROS production [117]. At the same time, increased ROS content causes even greater damage to membrane lipids, disruption of protein structure and function, and DNA fragmentation, contributing to apoptosis and necrosis of pulmonary parenchyma cells [118]. In comorbid conditions, ROS actively stimulate pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, enhance neutrophil and macrophage infiltration and pulmonary fibrosis formation, which ultimately exacerbates the destruction of alveolar architecture and the progression of respiratory failure [119].

ROS trigger lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, which leads to the formation of highly reactive aldehydes such as malonic dialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal [120]. In turn, the products of lipid peroxidation damage the structure of membranes, increase their permeability, and disrupt cellular homeostasis, leading to the death of alveolocytes and airway epithelial cells [121]. Also, the action of ROS causes irreversible structural changes in proteins such as carbonylation, oxidation of amino acid residues (cysteine, tyrosine, methionine) and formation of aggregates [122,123]. Oxidized proteins lose their biological activity, leading to dysfunction of cellular enzymes, receptors, and transport proteins [124–126]. As a result, intracellular signaling pathways, mitochondrial energy production, and impaired repair of damaged tissues are impaired, which worsens the functional status of the lungs [127]. At the same time, ROS directly interact with DNA molecules, causing oxidative damage [128]. The most typical damage is the formation of 8-oxoguanine. This disrupts replication and transcription of genetic material, leading to mutations, cell death, and activation of pathological apoptosis. Also, increased oxidative stress activates caspase-dependent pathways of apoptosis, and this in turn leads to massive death of alveolocytes and bronchial epithelium, exacerbating emphysematous changes and bronchial obstruction in COPD and tuberculosis [129,130]. Damaged lipids, proteins, and DNA act as endogenous DAMPs, activating innate immunity receptors (TLR, NLRP3-inflammasome) [131]. This induces and maintains chronic inflammation accompanied by neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), further exacerbating lung tissue damage [132,133]. Continuous hyperproduction of ROS leads to depletion of essential antioxidant substances and enzymes such as reduced glutathione, SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. A decrease in their activity reduces the ability of cells to neutralize free radicals, as a result of which tissue damage increases and becomes chronic [134]. This significantly reduces the ability of lung tissue to repair, slows epithelial regeneration and healing of lesions, contributing to the progression of fibrosis, emphysema, and bronchiectasis. It should be clarified that SOD catalyzes the conversion of superoxide anion radical (O2-) to the less active molecule hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). But under conditions of chronic oxidative stress in COPD and tuberculosis, SOD activity decreases due to ROS damage to its active center and oxidative modification of its cofactors (copper, zinc, manganese) [135]. And as a result, the accumulation of superoxide radicals increases, increasing the damage to cellular structures [136]. In turn, catalase neutralizes H2O2 formed by the action of SOD, converting it into water and oxygen. Under prolonged oxidative stress, catalase activity is significantly reduced due to direct oxidative damage to the enzyme and suppression of CAT gene expression in lung epithelial cells [137,138]. Deficiency of catalase promotes the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, which is a potent oxidant and damages membranes, proteins, and DNA of lung tissue cells [139]. Glutathione peroxidase uses reduced glutathione to neutralize peroxides (including H2O2 and lipid peroxides), converting them to water and the corresponding alcohols. In chronic oxidative stress, the level of reduced glutathione decreases, and glutathione peroxidase activity falls due to substrate deficiency. Glutathione peroxidase deficiency also leads to the accumulation of organic peroxides and hydrogen peroxide, greatly increasing the risk of irreversible cellular damage, which also contributes to the progression of pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis [140,141].

Oxidative stress also directly alters the activity of receptors and growth factors (vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)), which are necessary for lung epithelial barrier repair [142]. By disrupting their production and signaling activity, oxidative stress slows down the formation of new blood vessels in the focus of damage, tissue nutrition and oxygenation deteriorate, which significantly slows down the restoration of pulmonary structure and aggravates chronic hypoxia [143–145]. This slows down the proliferation and migration of epithelial cells, reduces the regenerative capacity of the epithelium, increases inflammation and the formation of scar tissue instead of functional epithelium. ROS also inhibit the functional activity of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and pulmonary fibroblasts. MSCs lose the ability to differentiate into mature cells and produce growth factors, and fibroblasts acquire a profibrotic phenotype, contributing to the formation of pathological pulmonary fibrosis [146,147]. Excessive production of ROS and activation of metalloproteinases (MMP-9, MMP-12) lead to uncontrolled degradation of elastin and collagen of the extracellular matrix. This disruption of lung tissue structure also interferes with normal regeneration and supports the progression of emphysema, fibrosis, and bronchiectasis [148].

Thus, oxidative stress significantly reduces reparative capabilities of lung tissue, increasing chronic inflammation, destruction and fibrosis in COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity. In summary, ROS accumulation in COPD and tuberculosis is one of the key pathologic processes due to tobacco smoke exposure and M. tuberculosis persistence, respectively, and understanding its mechanisms holds promise for the development of treatments aimed at reducing oxidative stress, such as the use of antioxidants to control these diseases.

Summarizing these data, it should be noted that in COPD ROS come from outside with smoke and are generated endogenously by inflammatory cells reactive to the stimulus. Their role is predominantly pathogenetic—direct tissue damage and maintenance of chronic inflammation [149–151]. In tuberculosis, ROS (and reactive nitrogen species (RNS)) are generated endogenously by immune cells (primarily macrophages) in response to infection as part of the defense mechanism. However, their excessive or uncontrolled production leads to significant damage to host tissues, forming the characteristic pathology of TB (Fig. 4) [152,153]. Thus, ROS in TB have a dual nature: protective and damaging.

Figure 4: ROS involvement in the pathogenesis of COPD and tuberculosis

4 Tissue Remodeling and Protease Imbalance in COPD and Respiratory Tuberculosis Comorbidity

Tissue remodeling is a process of tissue structure change, which in COPD and respiratory tuberculosis is associated with destruction of the extracellular matrix (ECM). ECM is a network of structural proteins (collagen, elastin, etc.) that support lung architectonics [154,155]. Degradation of ECM against the background of oxidative stress occurs under the action of MMPs, which are activated by ROS and proinflammatory cytokines. In normal conditions, the activity of MMPs is restrained by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), but in chronic inflammation in conditions of comorbidity this balance is disturbed, which leads to excessive destruction of ECM (Fig. 5) [156,157]. The destruction of ECM has two key consequences: physical tissue destruction (in COPD and tuberculosis, proteolytic destruction of alveolar septa causes emphysema and fibrosis, impairing gas exchange) and the release of matrix fragments, in which case these fragments act as chemoattractants, attracting additional immune cells to the site of damage. It is the second aspect—the release of ECM/fragments—that plays a critical role in increasing inflammation and, consequently, oxidative stress. MMPs themselves are zinc-dependent enzymes involved in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix and play a key role in the pathogenesis of lung damage in COPD and tuberculosis [158–161]. In the comorbid course of these diseases there is an increased activation of MMPs due to chronic inflammation and pronounced oxidative stress. The main metalloproteinases that change their activity in comorbidity are MMP-9 (gelatinase B) and MMP-12 (macrophage elastase) [162,163]. MMP-9 is activated mainly by neutrophils, epithelial cells and to a lesser extent by alveolar macrophages. In doing so, it efficiently degrades extracellular matrix components such as type IV collagen and elastin, damaging the basal membranes of the airways and alveoli [164]. In turn, MMP-12 is secreted predominantly by activated macrophages, which is particularly potent under the influence of tobacco smoke and mycobacterial infection. It is MMP-12 that plays a key role in the degradation of elastin and other structural proteins of the pulmonary matrix, causing loss of elasticity and emphysematous changes in the lung [165]. The main mechanism of MMPs activation in COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity is a significant increase in the production of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17) under the combined influence of tobacco smoke and M. tuberculosis, which activates the production of MMPs by cells of inflammatory infiltrate and tuberculous granulomas (neutrophils and macrophages) [166]. Additionally, ROS directly promote the activation of metalloproteinases by oxidizing and inactivating their TIMPs, enhancing the MMP/TIMP imbalance and contributing to uncontrolled pulmonary matrix damage [167,168].

Figure 5: Tissue remodeling and protease imbalance in COPD and respiratory tuberculosis comorbidity. Note: In COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity, chronic exposure to air pollutants (tobacco smoke, industrial emissions) and pathogen-associated Mbt molecules (muramyl dipeptide, ESAT-6) initially activates innate immunity mechanisms for respiratory defense. The pathogenetic processes of both diseases overlap with MMP-9/-12 ↔ TIMP imbalance leading to chronic inflammation, remodeling of the extracellular matrix and progressive lung damage (emphysema, cavernous lesions, impaired gas exchange)

Increased activity of MMP-12 and MMP-9 first for all causes of degradation of elastin fibers, which leads to loss of elasticity and development of emphysematous cavities. As a consequence, irreversible respiratory failure and pulmonary hyperinflation, characteristic of the severe course of COPD, are formed [169,170]. Activation of MMP-9 in the focus of tuberculous inflammation leads to the destruction of the basal membrane of alveoli and vessels, facilitating the spread of mycobacteria and increasing tissue destruction. This increases the risk of cavernous formation and chronic lung failure [171]. Chronic inflammation and increased activity of MMPs disrupt the balance of pulmonary tissue remodeling, promoting pathologic fibrosis. The prevalence of extracellular matrix degradation activates fibroblasts and provokes uncontrolled synthesis of pathologic collagen, contributing to scar tissue formation, impaired gas exchange, and progression of pulmonary insufficiency [172]. The consequence of the described processes is the loss of structural support of lung tissue and development of marked emphysema, formation of bronchiectasis due to destruction of airway walls and progression of pulmonary fibrosis, leading to impaired diffusion capacity of the lungs and development of chronic respiratory failure and rapid formation of cavernous forms of tuberculosis, complicating the course of both diseases [173]. Thus, MMPs activation in COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity is an important factor of pathological remodeling of lung tissue, leading to its structural destruction and persistent decrease in lung function.

As mentioned above, TIMPs are natural regulators of metalloproteinase activity [174]. In the comorbidity of COPD and tuberculosis, the MMP/TIMP balance is disturbed, also leading to progressive lung tissue damage. The most important TIMPs in lung tissue are TIMP-1, TIMP-2 and TIMP-3: TIMP-1 inhibits the activity of most MMPs, especially described MMP-9 and MMP-12, preventing excessive degradation of collagen and elastin, and TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 actively regulate the processes of remodeling of extracellular matrix and suppress apoptosis of epithelial cells, providing tissue homeostasis and stability of alveolar structure [175–177]. Oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and mycobacterial infection are also causes of decreased TIMPs activity in COPD and tuberculosis. High levels of ROS cause oxidative damage to TIMPs molecules, leading to a decrease in their functional activity and reduced ability to bind and neutralize MMPs. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) suppress the expression of TIMPs while enhancing the expression of MMPs, thereby disrupting the balance between them. And M. tuberculosis induce the production of MMPs by macrophages and neutrophils, while suppressing the production of TIMPs in granulomas, exacerbating the destruction of lung tissue and the spread of infection. The consequence of disruption of the TIMPs/MMPs balance in lung tissue is an increase in its destruction. Decreased activity of TIMPs leads to an unlimited increase in the activity of MMP-9 and MMP-12, which increases the destruction of elastin and collagen in the alveolar wall, contributes to the development of emphysema, bronchiectasis and cavernous formation in tuberculosis [178]. Disturbance of TIMP/MMP balance also stimulates pathological remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Insufficient regulation of MMPs activity activates fibroblasts, increases pathologic collagen production and forms scar tissue, leading to the development of irreversible pulmonary fibrosis and impaired gas exchange. Decreased levels of TIMPs lead to the release of matrix fragments (e.g., elastin) that act as DAMPs. This causes persistent activation of innate immunity, increasing chronic inflammation and progression of lung damage [179]. TIMPs are involved not only in the inhibition of proteolytic enzymes, but also in the regulation of cell migration and differentiation necessary for lung tissue regeneration. Decreased activity of TIMPs leads to slower epithelial repair processes, impairment of lung tissue regeneration, and prevents effective healing of areas of destruction [180,181].

According to literature data in the bronchoalveolar lavage of smokers of patients with respiratory tuberculosis (comorbid patients with COPD and TB), MMP-9 and MMP-12 concentrations were 2–3 times higher in comparison with the groups of smokers without TB and nonsmokers with TB, while TIMP-1 levels remained similar in all these groups; therefore, the MMP/TIMP ratio was significantly higher in comorbidity. A similar profile of metalloproteases was reproduced in an experiment in mice exposed to cigarette smoke and infected with M. bovis BCG, in which MMP-9/-12 concentrations in lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) increased in the absence of compensatory induction of TIMP-1, indicating a sustained protease shift due to the combined effects of smoking and mycobacterial infection [152]. When protease profiles of patients with tuberculosis-associated obstructive pulmonary disease (TOPD) were analyzed, it was also found that MMP-1 and MMP-9 concentrations were elevated in BAL in this cohort, which correlates with the volume of fibrotic cavernous changes on respiratory computed tomography (CT) [178]. However, there is no evidence of a significant increase in TIMP-1, which also emphasizes the imbalance towards proteases. For comparison, in classical COPD in smokers, the increase in MMP-9 is usually accompanied by a parallel increase in TIMP-1; the MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio increases quite moderately and is less associated with the presence of emphysematous changes in the lungs [177].

Thus, decreased activity of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity disturbs the MMP/TIMP balance, increasing lung tissue destruction, chronic inflammation and fibrosis, leading to rapid deterioration of pulmonary function and unfavorable clinical outcome. The expression of MMPs in COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity is also actively influenced by pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β). TNF-α is a potent inducer of metalloproteinase expression (especially MMP-9 and MMP-12). Acting through TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors, TNF-α activates NF-κB and MAP-kinase (ERK1/2, p38) signaling pathways, it stimulates transcription of metalloproteinase genes [50]. This leads to enhanced release of MMPs by macrophages and neutrophils, dramatically accelerating the degradation of elastin and collagen in the extracellular matrix of lung tissue [182]. In turn, IL-1β produced by activated macrophages and neutrophils during chronic inflammation also significantly increases the expression of MMPs. IL-1β binds to its receptor IL-1R, activating intracellular NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways. This stimulates the production of MMP-9, which promotes damage to the basal membrane of the alveoli, and enhances the migration of immune cells into lung tissue, further increasing the severity of inflammation [183].

Thus, pulmonary tissue remodeling plays an important role in the pathogenesis of the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis, which has clinical significance.

5 Interaction of Epithelial and Immune Cells in Comorbidity of COPD and Respiratory Tuberculosis

Epithelial cells of the respiratory tract and alveoli are the first to respond to pathogens (including M. tuberculosis) and harmful factors (tobacco smoke, air pollution particles) by producing a wide range of cytokines and chemokines [184]. These molecules trigger and maintain the inflammatory response, playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of COPD and tuberculosis. Epithelial cells are activated by: components of tobacco smoke (oxidants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), products of M. tuberculosis metabolism and cell wall (lipomannan, lipoarabinomannan) and DAMPs produced by tissue damage [185]. Through innate immunity receptors (TLR2, TLR4, NOD2 and others), epitheliocytes activate NF-κB and MAP kinase (ERK, p38) signaling pathways, inducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [186]. The key cytokines secreted by epithelial cells are IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α and TGF-β. The epithelium secretes IL-1β in response to ROS injury, pathogens, and irritants, activating local immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils) and enhancing the inflammatory response [187]. IL-1β maintains chronic inflammation, stimulates the production of other cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), and, as previously described, metalloproteinases [188].

In turn, the effects of IL-8 include attracting neutrophils to the lung tissue and maintaining their chronic infiltration leading to tissue damage through the release of proteases (neutrophil elastase) and ROS, increased expression and activation of MMP-9 and MMP-12, contributing to the destruction of extracellular matrix and the development of emphysema and bronchiectasis [189]. Epithelial cells can also produce TNF-α, which stimulates inflammatory cell activation and secretion of other proinflammatory mediators. TNF-α enhances the inflammatory response, increases oxidative stress, and stimulates the production of MMPs, leading to lung tissue destruction [190].

Also during chronic injury and oxidative stress, the alveolar and bronchial epithelium secrete TGF-β. TGF-β is the most important mediator of pathological tissue remodeling, promoting activation and proliferation of fibroblasts with the development of pulmonary fibrosis; stimulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, leading to loss of epithelial characteristics and pathological pulmonary fibrosis; and suppression of epithelial reparative capacity, which prevents normal regeneration of lung tissue and accelerates the formation of scar tissue [191–193].

Thus, lung epithelial cells under simultaneous exposure to tobacco smoke and M. tuberculosis acquire a pronounced proinflammatory and profibrotic phenotype, secreting IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α and TGF-β. These cytokines and chemokines form a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation with degradation of extracellular matrix, increased destruction and pathologic remodeling of lung tissue, which contributes to irreversible damage and progression of lung failure in COPD and TB comorbidity [192].

From the moment proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1) are secreted by airway epithelial cells and alveoli, activation and recruitment of immune cells begins, leading to their marked migration into lung tissue and maintenance of chronic inflammation [194,195]. In this case, IL-8 (CXCL8) in response to exposure to tobacco smoke and M. tuberculosis products acts through CXCR1 and CXCR2 neutrophil receptors, promoting neutrophil chemotaxis from blood vessels to lung tissue; activation of neutrophils, leading to their release of ROS, proteases (elastase, MMP-9), which increases damage to alveolar walls and basal membranes; formation of persistent neutrophilic inflammation, leading to the development of bronchial obstruction and emphysema [196]. The cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β also activate resident alveolar macrophages, inducing their migration and activation.

Activated macrophages secrete metalloproteinases (especially MMP-9, MMP-12), which destroy the extracellular matrix of lung tissue and contribute to the development of emphysema, caverns and bronchiectasis. Macrophages produce additional cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6), increasing inflammation and stimulating the migration of new immune cells (neutrophils, T lymphocytes) [197]. The production of ROS by macrophages further increases inflammation and lung tissue damage. TNF-α and IL-1β produced by macrophages and epithelial cells enhance T-lymphocyte activation and contribute to the adaptive immune response in tuberculosis and COPD [198]. There is activation of CD4+ T-lymphocytes and differentiation into Th1 and Th17 type T-helper cells. There is an increase in the production of IFN-γ, IL-17, which stimulate the production of metalloproteinases and neutrophilic inflammation. In turn, TGF-β, secreted by epithelial cells and macrophages, promotes attraction and activation of fibroblasts with the development of pathologic pulmonary fibrosis and other processes described above. Thus, the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by epithelial cells in the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis induces a persistent inflammatory process, attracting neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes [199]. This significantly exacerbates lung tissue damage and leads to rapid progression of respiratory failure.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway plays one of the important roles in the regulation of the immune response in tuberculosis. This pathway controls the metabolism and function of immune cells, such as macrophages and T lymphocytes, which are necessary to fight infection [200]. In TB, mTOR activation can inhibit autophagy, the process through which macrophages destroy bacteria within themselves [201]. This reduces the effectiveness of the immune response because M. tuberculosis is able to survive and multiply in macrophages. At the same time, mTOR promotes the polarization of macrophages to the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, which is important for early control of infection [202]. With respect to T lymphocytes, mTOR also plays an important role in their differentiation and affects the function of different T helper populations. Activation of mTOR promotes differentiation of CD4+ T-lymphocytes into pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 subpopulations characterized by the production of IFN-γ and IL-17, respectively [203,204]. These cytokines enhance macrophage and neutrophilic inflammatory response in lung tissue, which is essential for the control of tuberculosis infection.

Thus, mTOR acts in a dual manner: it supports the inflammation necessary to fight infection, but at the same time weakens defense mechanisms, which may complicate the course of TB [205]. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in COPD increase the activity of this pathway. This leads to suppression of autophagy in macrophages, reducing their ability to destroy M. tuberculosis. The immune cell dysfunction seen in COPD also exacerbates the situation. As a result, chronic inflammation caused by COPD disrupts mTOR regulation, increasing inflammation but weakening defense mechanisms. The immune response against TB becomes less effective, which contributes to the progression of infection and worsens the course of the disease.

6 Effect of Hypoxia on Oxidative Stress in COPD and Respiratory Tuberculosis Comorbidity

Hypoxia, which develops during progressive lung tissue damage in patients with COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity, plays a critical role in enhancing chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [206]. In this case, a central part of the cellular response to reduced oxygen tension is the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a key transcription factor that regulates the cellular response to hypoxia [207–210]. Under normal tissue oxygenation, HIF-1α is continuously degraded under the influence of prolyl hydroxylases [211]. However, under conditions of chronic hypoxia, characteristic of patients with severe COPD and pulmonary tuberculosis, HIF-1α degradation is inhibited and it accumulates in lung tissue cells. Under these conditions, stabilized HIF-1α translocates to the nucleus and dimerizes with the constitutively expressed nuclear subunit HIF-1β, forming the transcriptionally active HIF-1 complex that drives expression of numerous genes required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia [212,213]. Also, one of the important functions of HIF-1α under hypoxia conditions is the activation of proinflammatory and prooxidant pathways that enhance oxidative stress and chronic inflammation in lung tissue [214]. For example, HIF-1α directly stimulates the transcription of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α), promoting additional recruitment and activation of neutrophils and macrophages in foci of inflammation [215,216]. These immune cells produce significant amounts of ROS and proteases, which exacerbates lung tissue destruction, forming a vicious cycle of damage. In addition to stimulating inflammatory pathways, HIF-1α also directly enhances ROS generation [217]. Specifically, under conditions of chronic hypoxia, it affects the induction of expression of NADPH-oxidase, a key enzyme in superoxide anion radical production, which further increases the level of oxidative stress [217,218]. In addition, HIF-1α activation enhances VEGF expression, causing pathologic angiogenesis, which does not lead to effective tissue repair, but instead promotes the formation of abnormal vessels with increased permeability [219,220]. This aggravates pulmonary edema and further impairs gas exchange. Also, HIF-1α activates the production of TGF-β, which promotes pulmonary fibrosis by activating fibroblasts and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [221]. Thus, chronic hypoxia through activation of hypoxia-induced factor HIF-1α significantly aggravates inflammatory and oxidative reactions, accelerates lung tissue damage, promotes the formation of a vicious circle of inflammation, tissue remodelling and oxidative stress, leading to rapid progression of severe respiratory failure in patients with comorbidity of COPD and tuberculosis.

Deletion of HIF-1α from the myeloid lineage in mice renders them dramatically sensitive to M. tuberculosis: intrapulmonary bacterial load increases 10–12-fold, the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines decreases, and the animals die significantly earlier than the control group [222,223]. Also besides its direct effect on microbicidality, HIF-1α is very important for the preservation of granuloma architecture: In vivo inactivation of HIF-1α in macrophages accelerates its breakdown, facilitating mycobacterial dissemination and disease progression to disseminated rapidly progressive forms [224]. In turn, M. tuberculosis has adapted to this defence mechanism by producing the effector protein Rv0927c, which triggers VHL-dependent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α, while blocking its nuclear translocation through the NF-κB/cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 pathway; HIF-1α suppression reduces glycolytic flux in macrophages and significantly increases intracellular bacterial survival [225]. Thus, HIF-1α has a dual but predominantly protective function. HIF-1α enhances IFN-γ-dependent macrophage anti-tuberculosis defence mechanisms and limits M. tuberculosis growth; it preserves granuloma integrity and prevents its premature disintegration, thereby reducing bacterial dissemination.

7 Clinical Significance of Studying the Mechanisms of COPD and Tuberculosis Comorbidity

COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity is a complex clinical condition in which the pathogenetic mechanisms of these diseases are intertwined, reinforcing each other and significantly worsening the prognosis of patients. And the development of targeted therapies for such cases requires a deep understanding of the molecular and cellular processes underlying their interactions. Major research directions should focus on key aspects of comorbidity development, such as oxidative stress, tissue remodelling and immune dysregulation, which play a central role in the progression of both diseases.

As both diseases are associated with chronic inflammation and impaired immune response in the lungs, making targeting approaches promising. These include biologic drugs such as monoclonal antibodies to cytokines (IL-5, IL-13, IL-33, IL-25, Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)) and IL-17 inhibitors aimed at reducing eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation in COPD, as well as NLRP3-inflammasome inhibitors and more selective phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors to reduce chronic inflammation [226–229]. For tuberculosis, therapeutic vaccines that enhance the immune response against M. tuberculosis, modulators of granulomatous inflammation that regulate TNF-α balance, and inhibitors of immune checkpoints (PD-1, CTLA-4) are being developed, as well as host-directed therapy using mTOR inhibitors and immunomodulators such as corticosteroids to control infection and inflammation [230–232]. Common targets include modulation of macrophage and neutrophil function, inhibition of the NF-κB pathway, and use of antioxidants to reduce oxidative stress. These approaches require further clinical studies to confirm their efficacy and safety, given the complexity of the diseases and the risks of immunomodulation.

Given the presence of oxidative stress in the combination of COPD and tuberculosis, the most important therapeutic task is to restore antioxidant defence [233]. Promising directions are the use of direct-acting antioxidants, activation of antioxidant enzymes and transcription factors, and restoration of glutathione levels and activity [234–236]. Activation of antioxidant enzymes and transcription factors is possible through activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor that triggers the expression of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) [237,238]. Drugs that activate Nrf2 (sulforaphane, curcumin) enhance the antioxidant response by restoring the level of enzymatic defence in the lungs [239,240]. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (roflumilast), which reduce oxidative stress by increasing the activity of endogenous antioxidants, also have potential for use [241,242]. Additionally, NADPH-oxidase inhibitors, which are able to interrupt excessive ROS production, represent another potential target for research [243–245]. In turn, the use of drugs that increase intracellular glutathione levels (N-acetylcysteine, carbocysteine, S-adenosylmethionine) can restore antioxidant capacity of the lungs, suppress inflammation and accelerate tissue repair [246,247]. The use of micronutrients can also be considered as one of the directions of adjuvant therapy. These are zinc, selenium, manganese and copper, which are cofactors of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, glutathione peroxidase). Micronutrient supplementation increases the activity of these enzymes, improving the protection of lung tissue cells from ROS-induced damages [248,249]. And naturally limiting exposure to pro-oxidants—stopping smoking and eliminating other sources of oxidative damage reduces ROS formation, preventing depletion of antioxidant systems and reducing the extent of lung damage [250–252]. In parallel with oxidative stress, tissue remodelling caused by an imbalance between MMPs and their inhibitors (TIMPs) plays a significant role in the development of comorbidity [253,254]. Therefore, the development of selective inhibitors of MMPs or enhancers of TIMPs activity becomes a promising area of research here [255].

For example, synthetic inhibitors such as aderamastat, already being studied in asthma and COPD, could be adapted to treat COPD and tuberculosis comorbidity to slow lung tissue degradation and improve lung structural integrity [256,257]. Immune dysregulation complements this pathological cycle by maintaining chronic inflammation in comorbidity, creating a vicious cycle that needs to be interrupted. An important area of focus is the development of immunomodulators that can mitigate the excessive immune response without suppressing antimicrobial defences. For example, TNF-α inhibitors such as infliximab can reduce inflammation, but their use requires caution due to the risk of activating TB infection [258–260]. Alternatively, research may focus on modulating TGF-β or IL-8 activity to reduce the recruitment of inflammatory cells without compromising immune control of M. tuberculosis [261]. These approaches represent a promising area of research in the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis, requiring further investigation to determine their optimal clinical efficacy and safety

Thus, in the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis, a complex, self-sustaining, pathological mechanism known as the “vicious circle” of oxidative stress and lung tissue remodeling forms. This process is driven by the constant hyperproduction of ROS, which is induced by chronic exposure to tobacco smoke and prolonged mycobacterial infection. Initial exposure to pathogens and toxic substances activates bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, which increases the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8. These cytokines, primarily IL-8, cause the infiltration of large numbers of neutrophils and macrophages into lung tissue. Neutrophil activation is accompanied by the release of serine proteases, such as neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3. These proteases degrade the elastin and collagen of the alveolar wall, resulting in emphysema and the structural collapse of the lung. Additionally, neutrophils secrete large amounts of ROS, which increases oxidative stress, damaging epithelial cells and closing the first part of the vicious circle. At the same time, alveolar macrophages, which are activated by mycobacterial cell wall components and products of extracellular matrix degradation, produce metalloproteinases (MMP-9 and MMP-12), which destroy the structural elements of the lungs, particularly elastin. This tissue degradation leads to an increase in biologically active matrix fragments (elastin and collagen peptides), which act as DAMPs. These fragments are recognized by innate immunity receptors (TLR2, TLR4, and NLRP3 inflammasome) on epithelial cells and macrophages, which causes additional activation of the pro-inflammatory pathways NF-κB and MAPK [262]. Consequently, the production of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8) and growth factors (TGF-β) increases, which activates a subsequent wave of immune cell migration and activation. This process maintains chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. Prolonged inflammation is accompanied by the activation of MMP-9 and MMP-12 metalloproteinases, which increase the degradation of the extracellular matrix and accelerate the formation of emphysema, bronchiectasis, and pathological lung tissue fibrosis. Progressive tissue degradation disrupts alveolar architecture, deteriorates gas exchange, and develops chronic hypoxia. Hypoxia increases oxidative stress and inflammation by activating HIF-1α, which increases ROS production in the mitochondria of lung tissue cells and enhances proinflammatory cytokine expression.

The known data suggest that the comorbidity of tuberculosis and COPD causes a unique pathophysiological phenotype characterized by granulomatosis, cavitations, fibrosis and persistent MMP activation, which fundamentally distinguishes it from the pathogenesis of virus-induced COPD exacerbations and requires the development of specific diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Although the efficacy of standard six-month courses of treatment with the main TB drugs (isoniazid–rifampicin–pyrazinamide–ethambutol) for drug-sensitive TB currently reaches >85%–90%, and the efficacy of short nine-month regimens for multidrug-resistant/rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/RR-TB) already exceeds 80% [263], the clinical prognosis in patients with combined COPD and TB remains less favourable. This is primarily due to the fact that modern COPD treatment was developed without taking into account the specific immunopathology of tuberculosis [264,265]. Secondly, the combined use of standard regimens for the treatment of tuberculosis and COPD is accompanied by significant pharmacokinetic limitations: for example, rifampicin induces CYP3A4 and reduces the total anti-inflammatory activity of roflumilast by about 60%, making long-term PDE-4 therapy unpromising in the intensive phase of antituberculosis chemotherapy [266]. Inhaled glucocorticosteroids are metabolized by the same isoenzymes and, in addition to the risk of reduced duration of action, increase the probability of tuberculosis reactivation (relative risk ≈ 2.0) in patients with posttuberculous changes [267], which also fundamentally limits their long-term use. At the same time, standard chemotherapy of tuberculosis with first-line drugs does not affect chronic hyperproduction of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1/-9), which, as already mentioned, trigger the breakdown of lung tissue and its subsequent remodelling, but at the same time in an experimental model of bone tuberculosis in rabbits the addition of doxycycline (which is an MMP inhibitor) significantly reduced the destruction of parenchyma and accelerated microbiological sterilization of tuberculosis foci [268]. Like metalloprotease activity, oxidative stress, which is a common manifestation of COPD and active or surviving TB, is poorly controlled by basic chemotherapy regimens. Current patient-centered pathogenetic approaches to immunocorrection in TB (using statins, metformin, mTOR inhibitors, PPAR-γ agonists, autophagy modulators, and targeted antimicrobial peptides), which are at the stage of clinical and preclinical studies, have shown the ability to simultaneously increase the efficacy of antituberculosis drugs, suppress cytokine “storm” and limit the remodelling of pulmonary parenchyma [269].

Thus, the literature indicates that simple summarization of existing standard TB and COPD treatment regimens is only a tactical solution, while the full management of patients with comorbidity requires the development of multifactorial strategies, including patient-oriented immunocorrective and antifibrotic drugs to control tissue remodelling and fibrosis in particular, specific MMP inhibitors, personalized use of inhaled corticosteroids taking into account the risk of tuberculosis reactivation, antioxidant agents and Nrf2 inducers aimed at correction of redox imbalance and modified regimens using bronchodilators without clinically significant metabolic interaction with rifampicin. Only such a multimodal, pathogenetically based approach can reduce residual inflammatory-fibrotic burden and improve long-term prognosis in this category of patients.

Thus, in the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis, there is a complex, self-sustaining mechanism in which ROS initiate tissue damage and chronic inflammation. Additionally, lung tissue degradation products enhance the immune response and ROS generation. This forms a vicious circle that becomes the main factor of irreversible lung tissue damage in the comorbid course of COPD and tuberculosis, leading to the progression of emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis, and respiratory failure.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Stanislav Kotlyarov; methodology, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; software, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; validation, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; formal analysis, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; investigation, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; resources, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; data curation, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; writing—original draft preparation, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; writing—review and editing, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; visualization, Stanislav Kotlyarov and Dmitry Oskin; supervision, Stanislav Kotlyarov; project administration, Stanislav Kotlyarov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| aHR | Adjusted Hazard Ratio |

| BAL | Broncho-alveolar lavage |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette Guérin vaccine |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COPD | Сhronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| COX-2 | Cyclo-Oxygenase-2 |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8/Interleukin-8 |

| CXCR1/2 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptors 1 and 2 |

| CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| ESAT-6 | Early Secreted Antigenic Target-6 kDa |

| ESX-1 | ESAT-6 secretion system 1 (type VII secretion) |

| GOLD | Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LL-37 | Cathelicidin LL-37 (antimicrobial peptide) |

| M. tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| M1, M2 | Classically activated M1 macrophages (M1), alternatively activated M2 macrophages (M2) |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDR/RR-TB | Multidrug-/Rifampicin-Resistant Tuberculosis |

| MDP | Muramyl Dipeptide |

| MCP | Monocyte chemoattractant protein |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NADPH-oxidase | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NOD | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| O2- | Superoxide |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| p38 | A group of mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| PDE4 | Phosphodiesterase-4 |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PLATINO | Latin American Project for the Investigation of Obstructive Lung Disease |

| RIP2 | Receptor-Interacting Protein Kinase 2 |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| Th | T helper lymphocyte |

| TIMPs | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TNFR | Tumor necrosis factor receptor |

| TOPD | Tuberculosis-Associated Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| TSLP | Thymic stromal lymphopoietin |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VHL | Von Hippel-Lindau protein |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

1. Lange C, Bothamley G, Günther G, Guglielmetti L, Kontsevaya I, Kuksa L, et al. A year in review on tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacteria disease: a 2025 update for clinicians and scientists. Pathog Immun. 2025;10(2):1–45. doi:10.20411/pai.v10i2.791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Katicheva AV, Brazhenko NA, Brazhenko ON, Zheleznyak SG, Tsygan NV. Respiratory tuberculosis associated with chronic obstructive lung disease—actual problem of modern phthisiology. Bull Russ Mil Med Acad. 2020;22(1):185–90. doi:10.17816/brmma25990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jain N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tuberculosis. Lung India. 2017;34(5):468. doi:10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_183_17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Boers E, Allen A, Barrett M, Benjafield AV, Rice MB, Wedzicha JA, et al. Forecasting the global economic and health burden of COPD from 2025 through 2050. Chest. 2025. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2025.03.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zafari Z, Li S, Eakin MN, Bellanger M, Reed RM. Projecting long-term health and economic burden of COPD in the United States. Chest. 2021;159(4):1400–10. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lange P, Ahmed E, Lahmar ZM, Martinez FJ, Bourdin A. Natural history and mechanisms of COPD. Respirology. 2021;26(4):298–321. doi:10.1111/resp.14007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Snoeck-Stroband JB, Postma DS, Lapperre TS, Gosman MM, Thiadens HA, Kauffman HF, et al. Airway inflammation contributes to health status in COPD: a cross-sectional study. Respir Res. 2006;7(1):140. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-7-140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Agarwal AK, Raja A, Brown BD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Beach, FL, USA: Fort Myers; 2025. [Google Scholar]

9. Momtazmanesh S, Moghaddam SS, Ghamari S-H, Rad EM, Rezaei N, Shobeiri P, et al. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: an update from the global burden of disease study 2019. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;59(10258):101936. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wang Z, Lin J, Liang L, Huang F, Yao X, Peng K, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Respir Res. 2025;26(1):2. doi:10.1186/s12931-024-03051-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Al Wachami N, Guennouni M, Iderdar Y, Boumendil K, Arraji M, Mourajid Y, et al. Estimating the global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPDa systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):297. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-17686-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Boers E, Barrett M, Su JG, Benjafield AV, Sinha S, Kaye L, et al. Global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease through 2050. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2346598. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.46598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bai W, Ameyaw EK. Global, regional and national trends in tuberculosis incidence and main risk factors: a study using data from 2000 to 2021. BMC Pub Health. 2024;24(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-17495-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Yang H, Ruan X, Li W, Xiong J, Zheng Y. Global, regional, and national burden of tuberculosis and attributable risk factors for 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases 2021 study. BMC Pub Health. 2024;24(1):3111. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20664-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Tuberculosis (TB). [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. [Google Scholar]

16. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024. [Google Scholar]

17. Sarno Filho MV, Soares LN, Lima Costa Neves MC. Clinical-epidemiological profile of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated at the pneumology outpatient clinic of a Brazilian University Hospital. Cureus. 2024;16:e75451. doi:10.7759/cureus.75451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang Z, Dai Y, Chang J, Xiang P, Liang Z, Yin Y, et al. The clinical characteristics, treatment and prognosis of tuberculosis-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a protocol for a multicenter prospective cohort study in China. Int J Chron Obs Pulmon Dis. 2024;19:2097–107. doi:10.2147/COPD.S475451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Fan H, Wu F, Liu J, Zeng W, Zheng S, Tian H, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis as a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(5):390. doi:10.21037/atm-20-4576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang J, Yu L, Yang Z, Shen P, Sun Y, Shui L, et al. Development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after a tuberculosis episode in a large, population-based cohort from Eastern China. Int J Epidemiol. 2025;54(2):dyae174. doi:10.1093/ije/dyae174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gai X, Allwood B, Sun Y. Advances in the awareness of tuberculosis-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med. 2024;2(4):250–6. doi:10.1016/j.pccm.2024.08.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kim T, Choi H, Kim SH, Yang B, Han K, Jung J-H, et al. Increased risk of incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related hospitalizations in tuberculosis survivors: a population-based matched cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2024;39(11):e105. doi:10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zavala MJ, Becker GL, Blount RJ. Interrelationships between tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2023;29(2):104–11. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sershen CL, Salim T, May EE. Investigating the comorbidity of COPD and tuberculosis, a computational study. Front Syst Biol. 2023;3:940097. doi:10.3389/fsysb.2023.940097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Choi JY. Pathophysiology, clinical manifestation, and treatment of tuberculosis-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a narrative review. Ewha Med J. 2025;48(2):e24. doi:10.12771/emj.2025.00059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kamenar K, Hossen S, Gupte AN, Siddharthan T, Pollard S, Chowdhury M, et al. Previous tuberculosis disease as a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional analysis of multicountry, population-based studies. Thorax. 2022;77(11):1088–97. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mordyk A, Bagisheva N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tuberculosis: phenotypes options. Eur Respir J Nd. 2020;56:481. doi:10.1183/13993003.congress-2020.481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Boutbagha N, Farhat S, Ikrou H, Essaid Y, Khannous A, Imzil A, et al. COPD and tuberculosis: friends or foes? Eur Respir J. 2023;62(suppl 67):PA2412. doi:10.1183/13993003.congress-2023.PA2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gai X, Allwood B, Sun Y. Post-tuberculosis lung disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J. 2023;136(16):1923–8. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000002771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Guzmán-Beltrán S, Carreto-Binaghi LE, Carranza C, Torres M, Gonzalez Y, Muñoz-Torrico M, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators in exhaled breath condensate of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: a pilot study with a biomarker perspective. Antioxidants. 2021;10(10):1572. doi:10.3390/antiox10101572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Allwood BW, Byrne A, Meghji J, Rachow A, van der Zalm MM, Schoch OD. Post-tuberculosis lung disease: clinical review of an under-recognised global challenge. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2021;100(8):751–63. doi:10.1159/000512531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ravimohan S, Kornfeld H, Weissman D, Bisson GP. Tuberculosis and lung damage: from epidemiology to pathophysiology. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(147):170077. doi:10.1183/16000617.0077-2017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Jena AB, Samal RR, Bhol NK, Duttaroy AK. Cellular Red-Ox system in health and disease: the latest update. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162(5):114606. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Chavda VP, Bezbaruah R, Ahmed N, Alom S, Bhattacharjee B, Nalla LV, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines in chronic respiratory diseases and their management. Cells. 2025;14(6):400. doi:10.3390/cells14060400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Katicheva AV, Brazhenko NA, Brazhenko ON, Chuikova AG, Zheleznyak SG, Tsygan NV. Features of the course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with respiratory tuberculosis in modern conditions. Bull Russ Mil Med Acad. 2020;22(2):106–9. doi:10.17816/brmma50054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kotlyarov S, Oskin D. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of comorbidity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(6):2378. doi:10.3390/ijms26062378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Caramori G, Casolari P, Barczyk A, Durham AL, Di Stefano A, Adcock I. COPD immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38(4):497–515. doi:10.1007/s00281-016-0561-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Basu J, Shin D-M, Jo E-K. Mycobacterial signaling through toll-like receptors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:145. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Carroll SL, Pasare C, Barton GM. Control of adaptive immunity by pattern recognition receptors. Immunity. 2024;57(4):632–48. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2024.03.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Li Z, Shang D. NOD1 and NOD2: essential monitoring partners in the innate immune system. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(9):9463–79. doi:10.3390/cimb46090561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Kim J-S, Kim Y-R, Yang C-S. Latest comprehensive knowledge of the crosstalk between TLR signaling and mycobacteria and the antigens driving the process. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;29(10):1506–21. doi:10.4014/jmb.1908.08057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Mosser DM, Hamidzadeh K, Goncalves R. Macrophages and the maintenance of homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(3):579–87. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-00541-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang F, Xia Y, Su J, Quan F, Zhou H, Li Q, et al. Neutrophil diversity and function in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):343. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-02049-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Manoj H, Gomes SM, Thimmappa PY, Nagareddy PR, Jamora C, Joshi MB. Cytokine signalling in formation of neutrophil extracellular traps: implications for health and diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025;81:27–39. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2024.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2014;5(11):491. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Lee J-W, Chun W, Lee HJ, Min J-H, Kim S-M, Seo J-Y, et al. The role of macrophages in the development of acute and chronic inflammatory lung diseases. Cells. 2021;10(4):897. doi:10.3390/cells10040897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Bezerra FS, Lanzetti M, Nesi RT, Nagato AC, Silva CP, Kennedy-Feitosa E, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in acute and chronic lung injuries. Antioxidants. 2023;12(3):548. doi:10.3390/antiox12030548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. McGarry Houghton A. Matrix metalloproteinases in destructive lung disease. Matrix Biol. 2015;44–46:167–74. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2015.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Garratt LW, Sutanto EN, Ling K-M, Looi K, Iosifidis T, Martinovich KM, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activation by free neutrophil elastase contributes to bronchiectasis progression in early cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(2):384–94. doi:10.1183/09031936.00212114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Sabir N, Hussain T, Mangi MH, Zhao D, Zhou X. Matrix metalloproteinases: expression, regulation and role in the immunopathology of tuberculosis. Cell Prolif. 2019;52(4):e12649. doi:10.1111/cpr.12649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Chalmers JD, Metersky M, Aliberti S, Morgan L, Fucile S, Lauterio M, et al. Neutrophilic inflammation in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir Rev. 2025;34(176):240179. doi:10.1183/16000617.0179-2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Sun L, Su Y, Jiao A, Wang X, Zhang B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):235. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01471-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Flynn JL, Chan J. Immune cell interactions in tuberculosis. Cell. 2022;185(25):4682–702. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Shastri MD, Shukla SD, Chong WC, Dua K, Peterson GM, Patel RP, et al. Role of oxidative stress in the pathology and management of human tuberculosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018(1):7695364. doi:10.1155/2018/7695364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Soomro S. Oxidative stress and inflammation. Open J Immunol. 2019;9(1):1–20. doi:10.4236/oji.2019.91001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Rodrigues SDO, Cunha CMCD, Soares GMV, Silva PL, Silva AR, Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque CF. Mechanisms, pathophysiology and currently proposed treatments of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(10):979. doi:10.3390/ph14100979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Yao H, Rahman I. Current concepts on oxidative/carbonyl stress, inflammation and epigenetics in patho-genesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;254(2):72–85. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2009.10.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Clemen R, Bekeschus S. Oxidatively modified proteins: cause and control of diseases. Appl Sci. 2020;10(18):6419. doi:10.3390/app10186419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]