Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of PEO (Polyethylene Oxide) Assisted Electrospinning of Chitosan: Innovation, Production, and Application

1 Department of Textile Engineering, Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology, 141 & 142, Love Road, Tejgaon Industrial Area, Dhaka, 1208, Bangladesh

2 Department of Textile Engineering, Northern University Bangladesh, 111/2, Ashkona, Dakshinkhan, Dhaka, 1230, Bangladesh

3 Department of Textile Engineering, Port City International University, Chattogram, 4225, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Mohammad Tajul Islam. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 677-711. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.068356

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Electrospinning has gained significant importance across various fields, including biomedicine, filtration, and packaging due to the control it provides over the properties of the resulting materials, such as fiber diameter and membrane thickness. Chitosan is a biopolymer that can be utilized with both natural and synthetic copolymers, owing to its therapeutic potential, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. However, producing electrospun chitosan is challenging due to its high solution viscosity, which often results in the formation of beads instead of uniform fibers. To address this issue, the spinnability of chitosan is significantly enhanced, and the production of continuous nanofibers is facilitated by combining it with polymers such as polyethylene oxide (PEO) in suitable ratios. These chitosan–PEO nanofibers are primarily used in biomedical applications, including wound healing, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering scaffolds. Additionally, they have shown promise in water treatment, filtration membranes, and packaging. Among all the nanofiber mats, chitosan/PEO-AC had the smallest fiber diameter (83 ± 12.5 nm), chitosan/PEO_45S5 had the highest tensile strength (1611 ± 678 MPa). This comprehensive review highlights recent advancements, ongoing challenges, and future directions in the electrospinning of chitosan-based fibers assisted by PEO.Keywords

Electrospinning is a widely adopted fiber fabrication technique that has found applications in various fields such as biomedicine [1], filtration [2,3], separation [4], packaging [5], and many emerging fields (Fig. 1) [6]. Its key advantages include the ability to finely control fiber diameter and membrane thickness, along with the production of highly porous structures with large surface areas. Nanofibrous membranes created through electrospinning mimic the architecture of the natural extracellular matrix, supporting cell adhesion, growth, and differentiation. Additionally, electrospun fibers can be tailored in terms of pore size and drug release behavior [7–11], making them particularly suitable for wound healing [1,8,11–13] and tissue engineering [14–17] applications. Over recent years, electrospinning has played a significant role in enhancing the usability of chitosan in wound care products. Chitosan-based nanofibers are now commonly used in the treatment of infected wounds [18,19], burns [20], and as scaffolds for tissue engineering [21]. Apart from conventional usage, chitosan is also used in enzyme detection [22], ion detection [6,23], food packaging [5], and water treatment [4]. The electrospinning process allows for the generation of fibers from micron to nanometer scales [19].

Figure 1: A schematic of electrospinning of Chitosan/PEO solution to produce nanofiber (NFs) for various advanced applications

Chitosan, a biopolymer derived from chitin, is abundantly found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans. It is recognized for being biodegradable, biocompatible, antibacterial, and non-toxic, with an oral LD50 above 16 g/kg in mice [6,7]. However, chitosan alone presents challenges in electrospinning due to its poor solution properties, the creation of strong hydrogen bonds, and the restricted free motion of the polymeric chains exposed to the electrical field. These factors may be the reasons for the limited electrospinning of pure chitosan, which results in jet break-up. During jet stretching, bending, and whipping, repulsion between ionic groups is expected to hinder the chain entanglement necessary for continuous nanofiber formation. As a result, nanobeads are primarily formed instead of nanofibers. Additionally, the high viscosity of its aqueous solution prevents the electrospinning of chitosan [10]. Blending it with a copolymer, e.g., poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO), a water-soluble and non-toxic polymer, improves its spinnability and mechanical integrity [14]. While PEO itself has limited mechanical strength, its combination with chitosan and other polymers yields more durable nanofibrous scaffolds suitable for biomedical applications [6]. Chitosan forms a viscous solution due to hydrogen bonding between its amino (-NH2) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups. However, viscosity decreases when mixed with polyethylene oxide (PEO) as PEO disrupts hydrogen bond formation.

In a study by Abd El Hady et al., it was found that a pure chitosan solution, i.e., a solution of 5% (w/v) chitosan in 70% (v/v) acetic acid, had a viscosity exceeding 2800 cP when it was used alone. But when PEO (2.5% w/v PEO in a 70% v/v acetic acid solution) was added in different ratios, i.e., 9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 6:4 and 5:5, the viscosity gradually decreased, reaching its lowest value of around 1300 cP for a 5:5 ratio. Electrospinning of a pure chitosan solution (chitosan solution in acetic acid) doesn’t form fibers but deposits into bead formation due to its high viscosity, which hinders continuous flow through the syringe nozzle. Apart from chitosan’s high viscosity, its polycationic nature in acidic aqueous solutions, along with numerous amino groups along its backbone, make electrospinning challenging. To date, solutions of chitosan prepared in 90 wt% aqueous acetic acid or solvents like trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), dichloromethane (DCM), or formic acid have been successfully used to produce nanofibers. However, residual solvents or toxic organic acids from these systems pose safety concerns, especially if fibers come into contact with human skin or damaged tissue. To address this, biodegradable synthetic polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene oxide (PEO), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), polylactic acid (PLA), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polycaprolactone (PCL) have been employed to facilitate electrospinning of chitosan and to create nanofiber mats. Incorporating PVA, PLA, PCL, PEO, PET, and PVP significantly enhances the mechanical strength, biocompatibility, antibacterial properties, and overall performance of chitosan-based nanofibers [10,24].

Several reviews have discussed the overall electrospinning process, parameters, and outputs of nanofibers made from different polymer solutions, such as PVA, PVP, PEO, chitosan, etc., as a whole [24–27] but no literature has focused explicitly on developing nanofibers using the chitosan/PEO system or examined its feasibility and challenges. This comprehensive review reports the electrospinning of PEO-assisted chitosan nanofibers, their process parameters, application, limitations, and future directions.

Chitosan is a polysaccharide obtained from chitin, the shell of sea animals, mostly of the Arthropoda group, such as shrimp and crab through alkali processing [28]. Chitosan is used in different applications, such as packaging, coloration [29] as they are non-toxic, environment-friendly, and durable [28]. Chitosan exhibits excellent biocompatibility, making it an ideal candidate for use in medical textiles. Moreover, it possesses outstanding physical and chemical properties, rendering it suitable for a wide range of applications. Additionally, chitosan shows hydrophilicity in blends with different polymers, making it suitable for any modification [30]. Chitosan is electrospun with PEO to increase the yield of chitosan [31]. Chitosan and PEO show compatibility while electrospinning due to the molecular interaction between the functional groups of chitosan and PEO. Amine and hydroxyl groups from chitosan can create a linkage with PEO’s ether groups through hydrogen bonds; which tends to better solubility during electrospinning resulting in a sustainable mat [32]. Additionally, chitosan has stability in the solid state due to a well-organized H-bond network, providing good mechanical properties in different applications [31]. Besides specific biomedical applications, chitosan blended composites can actively participate in wastewater treatment [33]. Due to the polycationic nature of chitosan, chitosan-based composites can be used as flocculants in water and effluent treatment plants. It is also used as a heavy metal scavenger and chelating agent [34]. Chitosan composites are used for oil and chemical separation [35]. Sometimes cellulose nanocrystals can be added with chitosan to impart better uniformity in the nanofiber structure [36].

Chitosan is integrated with Polyethylene oxide (PEO) using the electrospinning method, which can be used in many applications. Primarily focusing on wound dressing, tissue engineering, and multifarious biomedical applications [30,37–40]. Besides, it can be used as antifungal and antibacterial applications [41,42], drug delivery system [43–45].

A common polymer in biomedical and biomimetics applications, PEO is hydrophilic, water soluble, non-toxic, and biocompatible. For almost four decades, PEO’s phase separation behavior and solubility properties in aqueous solutions have piqued the curiosity of both industry and academia. Because PEO is biocompatible and soluble in various aqueous solvents, it is a more desirable polymer to blend with chitosan. Since any phase separation that takes place during the forming processes, like film casting, fiber spinning, and solution electro-spraying, significantly alters the morphology and physico-mechanical properties of the finished products, it is imperative to comprehend the phase behavior and miscibility of aqueous acidic solutions of chitosan and PEO and their blends [46].

The addition of PEO to the chitosan solution may lead to the formation of nanofibers with a more porous structure. This increased porosity provides a larger surface area, resulting in more active sites for interactions. This improvement is critical for wound dressing applications because it promotes better fluid absorption and cell interaction. PEO enhances the electrospinnability of the polymer solution, facilitating the creation of smoother fibers. Its presence aids in producing homogeneous nanofibers with the desired shape [47]. When added to the composite, PEO helps the nanofibrous films’ mechanical elasticity and flexibility, allowing them to resemble human skin’s mechanical characteristics. Its presence in the composite modulates water vapor permeability, ensuring proper breathability and preventing wound desiccation or maceration [48]. During electrospinning, PEO increases the spinnability of natural polymers such as chitosan, creating continuous, bead-free nanofibers. Better fiber stability and homogeneity result from its inclusion. PEO helped maintain low surface tension (~26.4–27.9 mN/m), facilitating bead-free fiber formation in the needle-free electrospinning [49]. PEO is a carrier matrix that facilitates the incorporation and uniform distribution of bioactive glass particles within the fibers, enhancing the composite’s bioactivity [50]. PEO was used as a sacrificial fiber during electrospinning to enhance scaffold porosity. The removal process effectively increased porosity, particularly at higher PEO contents (up to 60%) [51].

An established technique that can reliably create fibers in the sub-micron range is electrospinning [52]. It is a straightforward technique for creating composites, primarily fibers, with a diameter of micro to nano using an electrically charged jet of polymeric solutions. One of the most notable characteristics of electrospun fibers for creating composites is their high surface area to volume ratio. Additionally, the technique necessitates moderate temperature conditions, which are ideal for encapsulating bioactive compounds [53,54]. Using a wide range of food-grade, biodegradable, and biocompatible polymers as wall materials to encapsulate bioactive chemicals is made possible by electrospinning [55]. Electrostatic forces pull melts or solutions of polymers into thin filaments.

4.1 Mechanism of Electrospinning

The electrospinning process (Fig. 2) can be broken down into several stages:

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the electrospinning process, reprinted from [56] with permission under the creative commons attribution (CC BY) license

Charging the Polymer Solution: Fiber formation in electrospinning begins by applying a high-voltage electric field to a polymer solution. This electric field generates electrostatic forces that overcome the droplet’s surface tension at the needle tip. As the field strength increases, electrostatic repulsion among surface charges deforms the droplet into a cone-like shape known as the Taylor cone. Once the electrostatic force exceeds surface tension, a charged jet is ejected. The electrical conductivity and charge density of the polymer solution play a crucial role in this process, as they significantly influence the stability of the Taylor cone and the successful initiation of uniform fiber formation [57,58].

Formation of the Taylor Cone: When exposed to an electric field, a polymer solution changes from a pendant droplet to a continuous jet. A polymer solution gets highly electrified when a high voltage is applied, which results in Coulombic attraction from the external electric field and repulsion between surface charges. The electric field is concentrated at the pointed tip of the cone, causing a stress imbalance that causes the liquid to elongate into a tiny jet. Properties of the solution, such as conductivity and viscosity, affect the stability of the Taylor Cone. The stability of the cone determines jet elongation and thinning phases, and effective electrospinning depends on ideal conditions [56,57,59].

Jet Ejection and Thinning: Ultrafine polymer fibers are formed in this stage. When a high voltage is applied, the droplet gets deformed into a Taylor cone by electrostatic forces. A charged polymer jet is released once the electric field overcomes surface tension, traveling through intricate instabilities. Polymer chains solidify into continuous nanofibers when the jet’s diameter shrinks as it thins and elongates. Producing homogeneous, flawless nanofibers with the required mechanical and functional qualities requires carefully managed jet thinning [57,59].

Fiber Deposition: To create a nonwoven nanofibrous mat, a charged polymer jet is deposited onto a grounded or charged collector on this stage. Fiber orientation and porosity are affected by the collector’s design, including patterned electrodes, moving drums, or static flat plates. While ideal drying conditions provide uniform deposition, environmental factors like temperature and humidity can impact fiber shape. Important factors include motion refinement of fiber alignment and packing density, electric field distribution, and collector conductivity [57,59].

Nonetheless, post-deposition procedures enhance mechanical stability and fiber bonding, enabling smooth control of mat characteristics such as mechanical strength, surface area, and pore size—all are essential for practical nanofibrous materials [60].

4.2 Parameters Affecting Electrospinning

Three important aspects affect the electrospinning process: environmental variables, processing conditions, and solution characteristics. Properties of the solution, such as conductivity and polymer content, influence the form of the fiber. The solvent selection influences evaporation rates, and reliable jet formation requires optimization of processing parameters such as voltage and flow rate. Defects in hygroscopic polymers may be introduced by environmental variables such as temperature and humidity, which can affect solvent evaporation and fiber drying [59]. Optimization of processing parameters can provide fault-free nanofibrous electrospun mats [61].

4.3 Specialized Electrospinning Methods

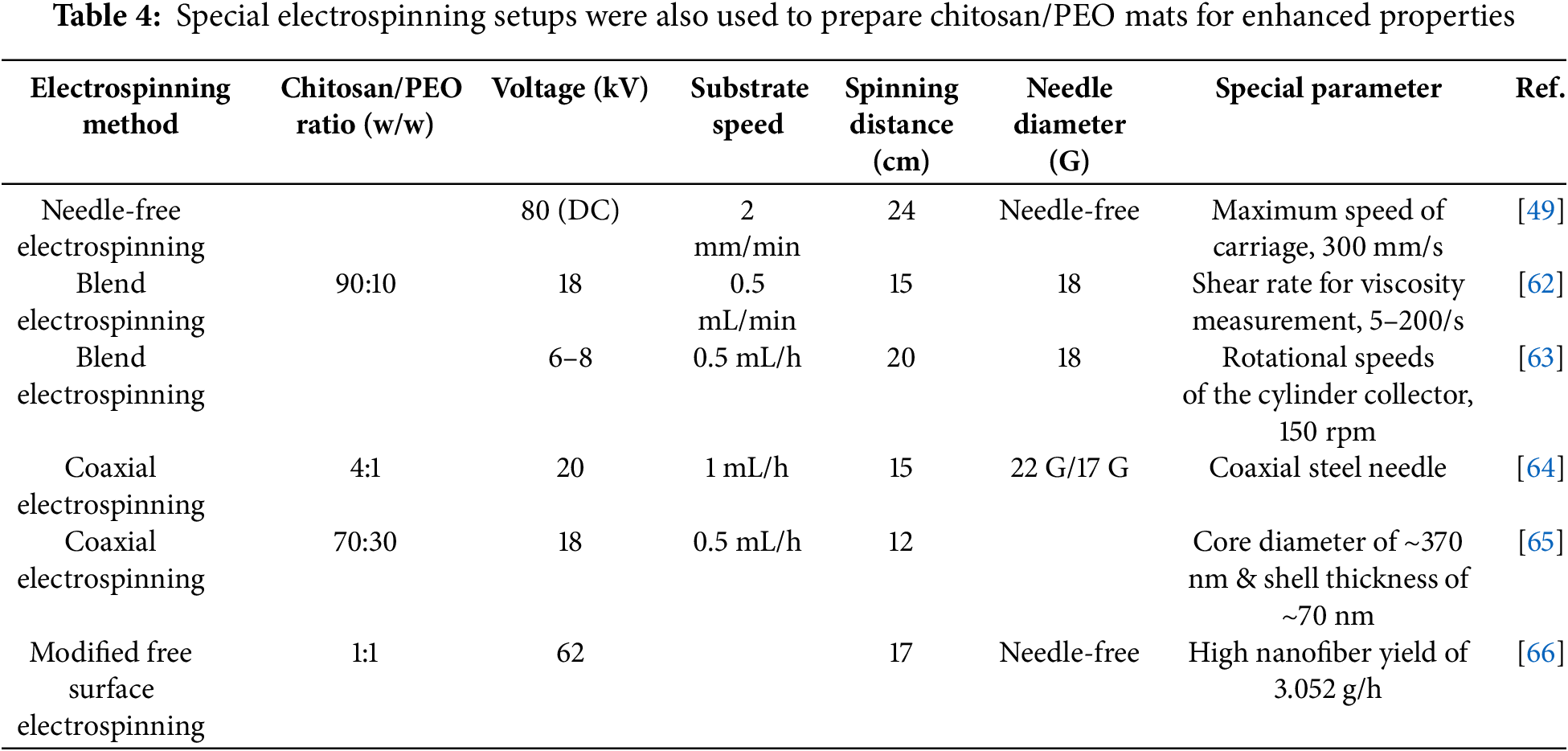

Traditional electrospinning setups have been modified, and specialized techniques have been developed to address specific application requirements. They offer improved functionalities and scalability due to different fiber formation processes, spinneret designs, and material management approaches. An overview of such electrospinning techniques is presented in Table 1, along with an explanation of their advantages and typical uses.

4.3.1 Needle-Free Electrospinning

The needle-free electrospinning process eliminates spinnerets by generating multiple jets directly from the surface of the polymer solution. This is typically achieved through mechanical or electrostatic forces. In this way, multiple nanofibers can be produced simultaneously without clogging the nozzle, thereby increasing production capacity. Additionally, it ensures a more uniform electric field, resulting in consistently high-quality fibers. This method has the advantage of being scalable and efficient, making it ideal for bulk nanofiber production, which can be utilized in various applications, including wound dressings, filtration systems, and scaffolds, among others [49].

To produce composite nanofibers, blend electrospinning combines two or more polymers in a solvent before electrospinning the mixture. Using this technique, properties such as improved mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and hydrophilicity can be combined synergistically. In particular, it has proven effective for integrating functional biopolymers, such as chitosan, with carrier polymers like PEO or PVA. The simplicity of blend electrospinning and the ability to tailor fiber characteristics make it a popular method for fabricating biomedical scaffolds, filtration membranes, and protective textiles [21].

Coaxial electrospinning uses a spinneret with concentric inner and outer nozzles to electrospun two different polymer solutions simultaneously to form fibers with a core-shell structure. The technique is particularly useful for encapsulating bioactive agents, controlling their release rate, or protecting sensitive materials inside the core. The process allows the production of multifunctional nanofibers with improved surface and bulk properties, which can be used in drug delivery, biosensors, and regenerative medicine [64].

4.3.4 Modified Free Surface Electrospinning (MFSE)

MFSE is a type of free surface electrospinning that uses adjustments like rotating drums, bubble creation, or tilted surfaces to improve how jets start and fiber consistency. With MFSE, solution-air interfaces are optimized, and multiple jets without needles are allowed, resulting in more uniform fibers and increased production efficiency. Nanofibers with controlled shapes can be generated on a large scale using this approach, with potential applications in textile coatings, environmental filtration, and catalysis [66].

5 Electrospinning Parameters and Process Variations for Chitosan/PEO Nanofiber Fabrication

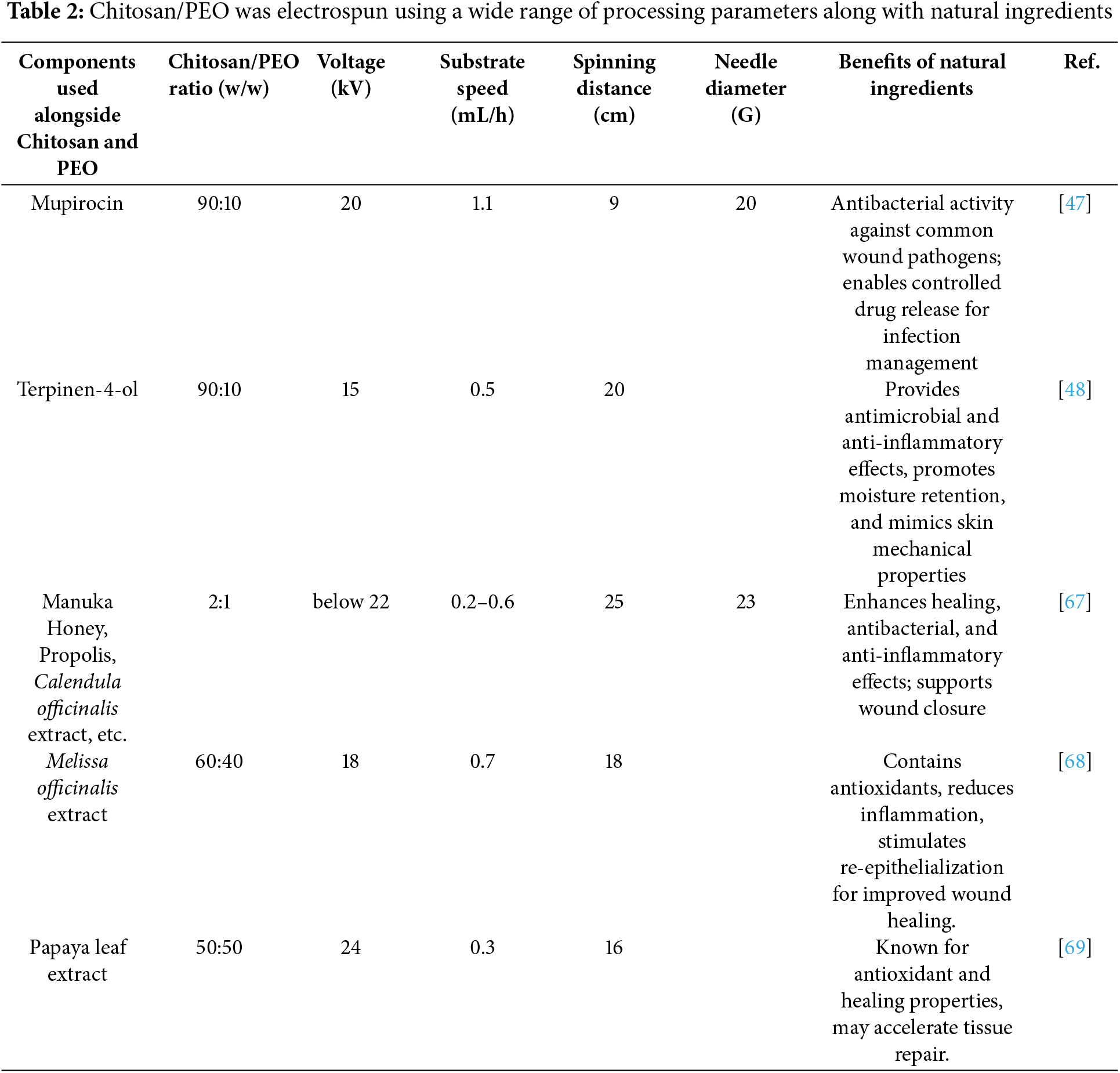

A range of operational parameters of conventional electrospinning (Tables 2 and 3) affects the fiber morphology, diameter, and functional performance of conventional electrospinning of chitosan blended with PEO. A chitosan/PEO ratio of 90:10 to 60:40 (w/w) is typically used, with 12 to 30 kV voltages and flow rates of 0.2 to 1.1 mL/h. Most spinning distances range between 9 and 25 cm, with needle gauges ranging from 18 to 23 G.

Natural additives such as mupirocin, terpinen-4-ol, and calendula extract are often incorporated to enhance antimicrobial, antioxidant, or wound healing properties. They allow controlled drug release and enhance biological properties. For example, they reduce fiber diameter, increase porosity, and modulate fiber characteristics. Meanwhile, synthetic additives and nanoparticles, such as PCL, THPC, Ag, and CeONPs, enhance conductivity, bioactivity, and mechanical robustness. A multifunctional agent, such as quaternary ammonium chitosan or carbon dots, can provide antimicrobial activity in addition to pH sensitivity.

Conventional electrospinning allows tailored chitosan/PEO nanofibers to be produced by adjusting composition and operating parameters, especially for biomedical applications like wound dressings, scaffolds, or drug carriers.

The needle diameter greatly influences the stability and flow rate of the electrospinning jet, which in turn determines the uniformity and structure of the fibers. Smaller needle diameters, associated with higher gauge numbers, generally produce finer and more uniform fibers due to lower flow rates and improved jet control. However, very small diameters can cause blockages when working with viscous liquids or bioactive compounds. The adjustments in needle sizes, from 20 to 23 G (Table 2) and from 18 to 25 G (Table 4), reflect efforts to accommodate different solution viscosities and desired fiber characteristics. For example, smaller needles, such as 25 G, were used with hydrochloric acid and potassium hydroxide to enhance jet precision. Conversely, mupirocin and terpinen-4-ol were applied with a 20 G needle, likely to balance flow stability and maintain steady jet formation.

Longer tip-to-collector distances offer more time in flight, which promotes elongation and solvent evaporation, producing finer and more uniform fibers. Due to insufficient stretching and rapid deposition, shorter distances may result in larger fibers or bead formation. Formulations based on natural ingredients, such as propolis and extracts from Calendula officinalis, were electrospun over longer distances (20–25 cm). However, because of their shorter jet elongation time, Mupirocin, which is electrospun at a shorter distance, can generate thicker or less uniform fibers. The range of distances for formulations with synthetic ingredients, such as CeONPs, Bioactive Glass Particles, PCL & THPC, and Titanium-coated membranes, is broader, ranging from 10 to 24 cm. Interrelated factors, such as voltage, solution viscosity, and environmental conditions, all influence optimal fiber production.

Most of the paper discusses using aluminum foil to capture electrospun fibers and form a mat structure without mentioning the collector design. This method maintains the integrity and uniformity of the fiber mat while collecting the fibers.

Various electrospinning techniques, including needle-free, blend, coaxial, and modified free surface electrospinning (MFSE), are being explored to overcome the limitations of conventional single-needle systems and produce functionally enhanced chitosan/PEO nanofibers.

Using needle-free systems, high voltages (80 kV DC) and high-speed carriages (300 mm/s) can produce large quantities of nanofibers with improved productivity. By blending chitosan/PEO with bioactives such as vancomycin, curcumin, or collagen, electrospinning produces hydrophilic fibrous mats that are mechanically strong and promote wound healing. A core-shell fiber created with coaxial electrospinning can deliver drugs like thymol and rosuvastatin with controlled release, improving stability and drug loading capacity. As an alternative, the MFSE process uses high voltage (up to 62 kV) and optimized acetic acid concentrations to produce uniform, fine fibers that are highly productive (up to 3.05 g per hour).

Chitosan/PEO nanofibers can be used in a wide range of applications, and these advanced methods provide increased control over fiber structure, scalability, and multifunctionality, especially useful for clinical, environmental, and food packaging applications.

Schulte-Werning et al. used needle-free electrospinning process to produce multifunctional nanofibrous for wound dressings. The approach enhanced mechanical strength, tensile strength, and elongation at break in nanofibers. The incorporation of active biopolymers such as beta-glucan and chloramphenicol produced multifunctional nanofibers exhibiting improved antibacterial and anti-inflammatory characteristics. The unique electrospinning method enhanced drug release profiles and swelling capability, essential for wound healing applications [49].

Kalalinia et al. used the blend-electrospinning technique to fabricate vancomycin-encapsulated CH/PEO nanofibers for wound healing applications. The procedure generates nanofibers with consistent shape and nanometer-scale diameters. The nanofibers enhanced mechanical strength, tensile strength, and antibacterial effectiveness. They demonstrated prolonged drug release patterns, excellent biocompatibility, and notable antibacterial efficiency [62].

Jirofti et al. developed curcumin-encapsulated chitosan/polyethylene oxide/collagen nanofibers for wound healing applications using the blend-electrospinning technique. The nanofibers exhibited superior mechanical capabilities, better biocompatibility, and prolonged drug release over a three days period. They exhibited elevated porosity, enhanced water absorption capacity, and expedited wound healing. These results emphasize the effective incorporation of curcumin into electrospun nanofibers, augmenting their therapeutic effectiveness in wound healing. In vitro and in vivo investigations demonstrated a considerable improvement in wound healing rates and closure [63].

Zhu et al. reported that the coaxial spinning coupled with in-situ etching crosslinking results in a more uniform, defect-free core-shell nanofibers with enhanced mechanical strength, elasticity, and rigidity, due to the covalent bond with genipin, which restricted the mobility of the polymer chain. Furthermore, the produced films showed increased water resistance, and maintained about 30% weight after immersion rather being completely soluble like typically produced film from conventional electrospinning. Additionally, thermal stability was improved due to covalent bonds, and the encapsulated active compounds, such as thymol, demonstrated sustained release, maintaining antioxidative and antibacterial efficacy [64].

Ghasemvand et al. used a coaxial electrospinning method to fabricate CH and PEO/polycaprolactone as core/shell nanofibrous mats including RSV for prolonged drug release. The nanofibers were optimized for smoothness, and plasma treatment enhanced wettability and drug release properties. The mats exhibited regulated, prolonged RSV release over a period of 90 days, characterized by diminished initial burst release. They also improved the osteogenic development of human mesenchymal stem cells, indicating promise for applications in bone tissue engineering [65].

Ahmed et al. developed a modified free surface electrospinning (MFSE) technique to produce high-throughput CS/PEO nanofibers. This technology employs a titanium/polyamide solution reservoir and an ideal voltage of 62 kV to generate homogenous, high-quality nanofibers. The researchers determined that elevated acetic acid concentrations and a CS/PEO mixture of 4 wt% produced the finest nanofibers, averaging 100 ± 4.18 nm in diameter. The MFSE process yielded improved quality and greater outputs than conventional electrospinning methods, with a maximum yield of 3.052 g/h, so rendering it appropriate for industrial-scale nanofiber manufacturing [66].

6 Chitosan/PEO Electrospinning in Conventional Electrospinning Setup

The adaptability of electrospinning encompasses a broad range of polymers that can be used, including synthetic types that can be aided by natural chemicals and natural types that are antibacterial and environmentally friendly. Furthermore, it permits the use of composite materials, such as glass and nanoparticles, which can improve conductivity and mechanical robustness.

6.1 Naturally Derived Ingredients Assisted Electrospinning

Mupirocin is a natural antibiotic effective against various bacteria, including those commonly involved in burn wound infections such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. When mupirocin was added to the Chitosan/PEO/PVA, the electrospun mats produced showed notable fiber characteristics like reduced fiber diameter and increased porosity. Higher chitosan content in the solution lowered viscosity, decreased fiber diameter, and boosted the porosity of the nanofiber mats. The inclusion of PEO resulted in larger pores in chitosan/PVA membranes, potentially increasing micro-void density by up to 5%. These mats also demonstrated superior antibacterial activity. They offer improved wettability and hydrophilicity; however, as the chitosan concentration increased, the PVA content decreased, making the blended polymers more hydrophobic and less hydrophilic. Adding PEO to the nanofiber mats can create additional active sites, further enhancing the scaffolds’ wettability and hydrophilicity. Incorporating mupirocin into the scaffolds increased their porosity, enabling them to absorb more water than drug-free versions. [47].

It is the main component of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil. It possesses bactericidal and anti-inflammatory effects, making it effective against various pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It was incorporated into chitosan dressings to enhance antimicrobial activity and promote wound healing. The mats exhibited excellent moisture retention properties. The water vapor transmission rate and the simulated tissue fluid absorption of films were optimized to attain 2193 g m−2 d−1 and 1676%, respectively. The Young’s modulus and elongation at break of the films were 114.69 kPa and 72.04%, respectively, in the wet state, resulting in mechanical properties akin to human skin. Additionally, a smooth and beadless structure was obtained. [48].

6.1.3 Manuka Honey, Propolis, Calendula Officinalis Extract, Insulin and L-Arginine

Manuka honey is renowned for its trophic (nutritional) and antimicrobial properties; its inherent antibacterial qualities promote wound healing and provide resistance against infections. Propolis, rich in flavonoids and phenolic acids, is a resinous substance produced by bees that has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant qualities. Because it encourages healing and reduces inflammation, it helps treat wounds. Calendula officinalis extract is used for its antioxidant effects and to stimulate reepithelialization. It possesses compounds that help reduce inflammation and promote skin healing. Insulin is a peptide hormone that regulates blood glucose levels and acts as a growth factor to accelerate wound healing, promoting tissue regeneration and re-epithelialization. L-Arginine is a natural amino acid that acts as a precursor to nitric oxide (NO), which plays a significant role in collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and immune response regulation at the wound site.

A chitosan/PEO nanofibrous mat was functionalized with manuka honey, propolis, Calendula officinalis extract, insulin, and L-arginine. The mats showed reduced zero-shear viscosity. Adding various active compounds to the chitosan/PEO solution decreased the zero-shear viscosity. The original chitosan/PEO solution had a high zero-shear viscosity of around 2.10 Pa⋅s. After adding active compounds, the zero-shear viscosity ranged from 0.36 to 1.58 Pa⋅s. A smooth, bead-free structure was obtained. The nanofibers demonstrated good biodegradability, with significant weight loss (up to 60% in phosphate-buffered saline), and exhibited good swelling in phosphate-buffered saline and physiological extracellular fluid, along with increased hemocompatibility. The hemolytic index was less than 4% (below 5% is considered safe and hemocompatible).

All the mats exhibited reduced cytotoxicity, with a cell viability exceeding 90%, and showed notable antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. The chitosan/PEO nanofiber mats containing propolis and Calendula officinalis extract were the most suitable for wound care, demonstrating non-toxic properties with cell viability above 97%. They also showed strong radical scavenging ability, with DPPH inhibition exceeding 65%. Additionally, these mats had enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial effects, especially against the strain of S. aureus [67].

6.1.4 Melissa Officinalis Extract

Rich in phenolic compounds and flavonoids, which provide antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, it reduces the need for artificial preservatives or additives in food packaging. The prepared chitosan/PEO/Melissa officinalis extract nanofiber mats had homogeneous and bead-free structure. Water vapor permeability values for the as-spun and cross-linked chitosan/PEO/Melissa officinalis extract nanofibers were 39.34 ± 0.77 and 22.26 ± 1.25 g mm/kPa·h·m2, respectively. Both as-spun and crosslinked chitosan/PEO/Melissa officinalis extract nanofibers showed inhibition halos of 11.7 ± 0.9 and 11.7 ± 1.2 mm, respectively [68].

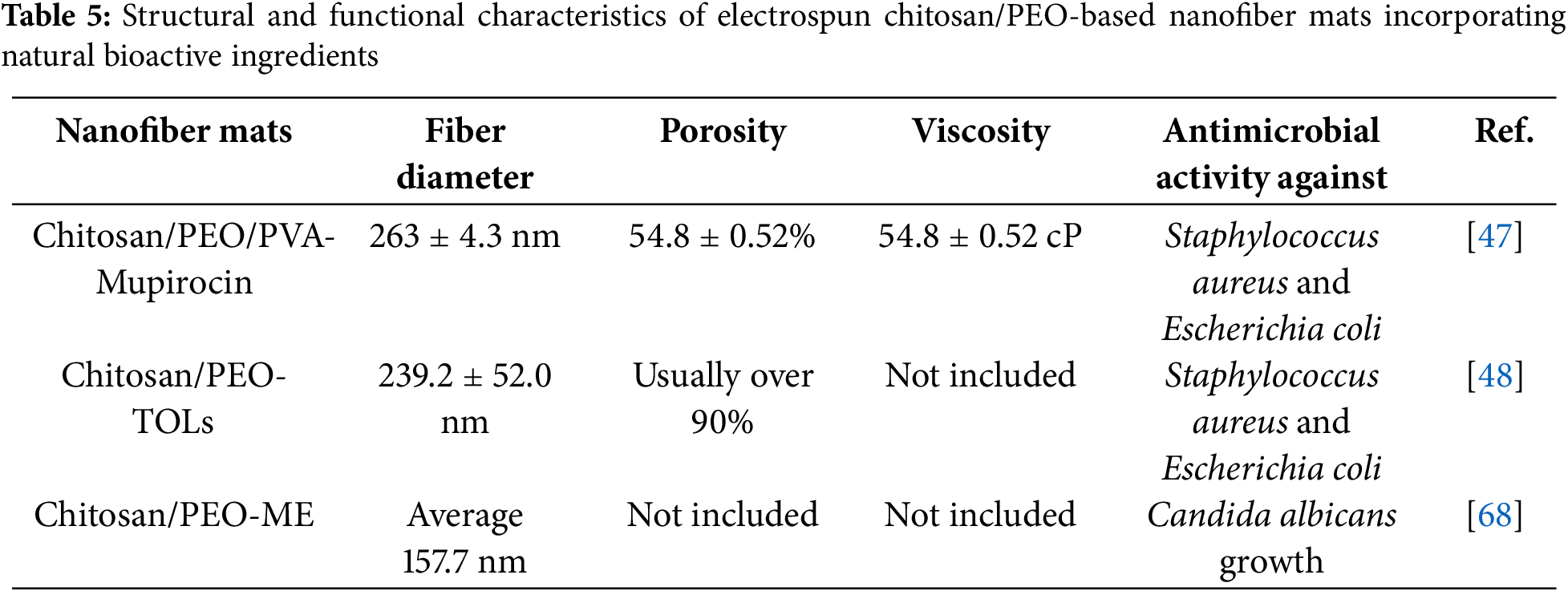

Table 5 summarizes and compares key parameters of chitosan/PEO-based nanofiber mats aided by various naturally derived ingredients discussed in Sections 6.1.1 through 6.1.4. It highlights differences in fiber diameter, porosity, viscosity, and antimicrobial activity. Using mupirocin in chitosan/PEO/PVA mats produced relatively thick fibers (~263 nm) and moderate porosity (~55%), while still providing effective antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. However, terpinen-4-ol (TOLs) produced fine fibers (225 nm) with relatively high porosity (>90%), which helps retain moisture. The Melissa officinalis extract generated the finest fibers (157 nm) and showed antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Chitosan/PEO electrospun mats exhibit a broad range of antimicrobial properties when functionalized with natural bioactive agents, making them a promising material for wound care, biomedical applications, and even food packaging.

6.2 Synthetic Chemicals and Nanoparticles Assisted Electrospinning

A biodegradable polyester, can be used as a scaffold material due to its biocompatibility and mechanical properties. It is appropriate for tissue engineering applications because it promotes cell proliferation and attachment.

Arnebia euchroma (A. euchroma) extract

It is a herbal extract that has therapeutic qualities, especially in wound care. It contains bioactive substances that have antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and therapeutic properties.

Two-nozzle electrospinning was used to fabricate multilayered nanofibrous scaffolds. This technique produced a uniform, porous, and biomimetic mat. A. euchroma slightly reduced the mechanical strength but stayed within acceptable limits for skin scaffolds. Water vapor permeability ranged from 20–23 g/m2/day, supporting a moist environment conducive to wound healing while allowing excess exudate to escape—crucial for preventing infection and promoting tissue regeneration. The mats demonstrated controlled biodegradability. Over 28 days, the scaffolds gradually degraded in PBS with lysozyme. Higher A. euchroma concentrations sped up the breakdown, aligning with the goal for transient skin scaffolds that resorb gradually as new tissue forms. Additionally, A. euchroma brought significant antibacterial effects, with inhibition rates against bacteria like E. coli reaching up to 57.5%. It also enhanced fibroblast proliferation and was non-toxic [70].

6.2.2 2-Formylphenylboronic Acid

It was employed in the imination reaction to functionalize the chitosan fibers, introducing antimicrobial properties by forming imine bonds.

Lysozyme

It was used to improve biodegradability in wound settings. This enzyme plays a role in the natural biodegradation during wound healing and can break down chitosan.

The average diameter of the mats containing 2-Formylphenylboronic acid and lysozyme was 137 ± 21 nm for the initial chitosan/PEO fibers, which increased to 176 ± 33 nm after PEO removal due to swelling. The mats showed enhanced hydrophilicity because imination, imino-chitosan, resulted in increased water loss compared to neat chitosan. The pore sizes were less than 2 nm, demonstrating microporosity, which benefits biological fluid interaction and water sorption [71].

Short amino acids called RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) peptides imitate extracellular matrix proteins like fibronectin and laminin and bind to integrin receptors to promote cell adhesion.

PLGA-PEG membranes

A combination of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG), PLGA-PEG membranes formed a biodegradable, porous scaffold that provided mechanical strength, structural support, and controlled degradation, making them ideal for tissue engineering applications.

The fibers had a uniform, smooth shape and were ideal for nerve regeneration, with an average diameter of 287.6 ± 76.3 nm. High-speed rotary electrospinning (2600 RPM) produced precisely aligned fibers, which served as directional signals for targeted axonal growth. Inflammation was prevented by buffering the acidic breakdown of PLGA-PEG with β-TCP [72].

6.2.4 Titanium-Coated Track-Etched Membranes

Specialized filtering materials known as titanium-coated track-etched membranes were created by exposing polymer sheets to heavy ion radiation. A thin titanium layer was applied to improve their mechanical stability, adhesion, corrosion resistance, electrical conductivity, and biocompatibility. Nanofibers that were consistent, smooth, and bead-free were produced, with an average fiber diameter of 156.55 nm. Glutaraldehyde vapor crosslinked the material, increasing its resistance to disintegration at different pH levels. They show low toxicity to Daphnia magna, indicating suitability for biological and environmental applications. Their high stability under extreme pH conditions resulted in swelling capacities of 85.72% in acidic, 76.47% in neutral, and 69.23% in alkaline environments [73].

6.2.5 Quaternary Ammonium Chitosan

It is a chemically altered chitosan derivative that has quaternary ammonium groups (-NR3+) in place of the amino groups (-NH2). Its improved antimicrobial activity, biocompatibility, and antibacterial qualities make it perfect for tissue regeneration, wound dressings, and biomedical applications.

Carbon Dots

Ultrasmall, fluorescent nanoparticles with little toxicity, superior biocompatibility, and adjustable optical characteristics, carbon dots (or CDs) are perfect for antibacterial activity and real-time wound monitoring.

The prepared chitosan/PEO-CDs nanofiber mats produced uniform, bead-free nanofibers. They formed a three-dimensional, porous network that mimicked the extracellular matrix (ECM) for cell attachment. It also showed a linear relationship between pH and RGB values [74].

6.2.6 Tetrakis (Hydroxymethyl) Phosphonium Chloride (THPC)

It is a reducing agent used in the in situ synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) on the scaffolds. AuNPs improved the scaffolds’ electrical conductivity, which is advantageous for nerve regeneration.

The mat produced by triple-jet electrospinning created uniform fibrous mats with interconnected porosity. The mats exhibited high porosity, reaching up to 75%–80% at 40% PEO content. They showed improved Schwann cell adhesion, spreading, and proliferation. The mats also had enhanced electrical conductivity. Using reducing agents like THPC alone or with formaldehyde improved conductivity, achieving 3.125 ± 0.75 S/m for THPC and 4.44 ± 0.83 S/m for THPC + formaldehyde [51].

Triton X-100 is a surfactant added to reduce surface tension during nanofiber production and can aid in developing uniform fibers. Glacial acetic acid was used as a solvent to prepare chitosan solutions for electrospinning, enabling the formation of nanofibers capable of adsorbing contaminants. The nanofibers’ high surface area-to-volume ratio increased their potential for use in water cleanup and adsorption, and they were free of defects or beaded structures. The removal of ibuprofen depended on the concentration of the nanofiber mat; the higher the concentration, the more ibuprofen was removed from wastewater (70% of the 100-ppm solution removed) [34].

Activated carbon from rice husk is rich in carbon, making it suitable for carbonization and activation to produce high-surface-area activated carbon with efficient adsorption properties. Potassium hydroxide was used as an activating agent in the chemical activation process, and hydrochloric acid was used to wash the activated carbon to remove residual chemicals and impurities. The mats have demonstrated improved adsorption due to integration of activated carbon. Carbon activation reduced the fiber diameter, improving uniformity and contact area. Activated carbon enhanced the viscosity of fiber mat from 233 ± 4 to 441 ± 6, which provided better conductivity and resistance to surface tension. Compared with the other nanofiber mat blends, it was found that chitosan/PEO-AC nanofibrous membrane showed better adsorption capacity in terms of all metal ions [75].

6.2.9 Doxycycline Hyclate (DOXH)

DOXH, an antibiotic, was integrated into the nanofibers for its antibacterial action against periodontal pathogens. Silver nanoparticles (Ag) were also added due to their potent antibacterial properties. Silver has a long history of use in medical applications because of its effectiveness against a wide range of microorganisms. Hydroxyapatite (HA), a naturally occurring mineral form of calcium apatite, was included to enhance the bioactivity and biocompatibility of the chitosan/PEO-DOXH-Ag/HA/Si nanocomposite. Silica was incorporated to improve mechanical properties. The characteristics of the prepared chitosan/PEO-DOXH-Ag/HA/Si nanocomposite mats were analyzed. The mats were produced using a horizontal electrospinning setup. Uniform, bead-free nanofiber mats were generated. The inclusion of Ag/HA/Si reduced the drug release rate and enhanced morphological integrity during degradation. With the lowest level of DOXH, the electrospun nanofibers exhibited improved antibacterial activity against strains of Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli [76].

6.2.10 Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles (CeONPs)

CeONPs was added to the chitosan/PEO blend to enhance the scaffolds’ mechanical properties and bioactivity. These particles provide antioxidant properties. The nanofiber mats showed increased mechanical strength with the incorporation of CeONPs (from 455 MPa in chitosan/PEO to 689 MPa in chitosan/PEO-CeONP). Additionally, increased stiffness was observed (from 6.2% to 5.4%). The addition of CeONPs improved swelling in water and saline solutions, which is beneficial for exudate absorption in wound healing applications. Chitosan/PEO-CeONP mats degraded more slowly than chitosan/PEO mats, retaining most of their structure after 90 days. There were no signs of toxicity, infection, or adverse inflammation. The presence of CeONPs contributed to a moderated inflammatory response and supported the formation of new vascular tissue [77].

6.2.11 Bioactive Glass Particles (e.g., 45S5, BGMS10, BGMS_2Zn)

These glasses were used to bond with bone and promote tissue regeneration. They release ions that can stimulate cellular activity and enhance the composite mats’ bioactivity. The Chitosan/PEO_45S5 composite mat showed the best mechanical properties among the tested samples (1611 ± 678 MPa) but had the lowest tensile strain at break (16% ± 2%), indicating it is stiff with good mechanical strength. Meanwhile, the chitosan/PEO_BGMS_2Zn mat displayed the highest tensile strain at break (52% ± 23%), suggesting better flexibility and elongation before failure. The bioactive glass particles (BGMS10 and BGMS_2Zn) are designed to release beneficial ions (e.g., Si, Ca, Mg, Zn) that can enhance cellular activities and promote healing. These particles may boost the potential for bone regeneration by improving osteoconductivity and aiding in the formation of hydroxycarbonate apatite (HCA), which is essential for bone bonding [50].

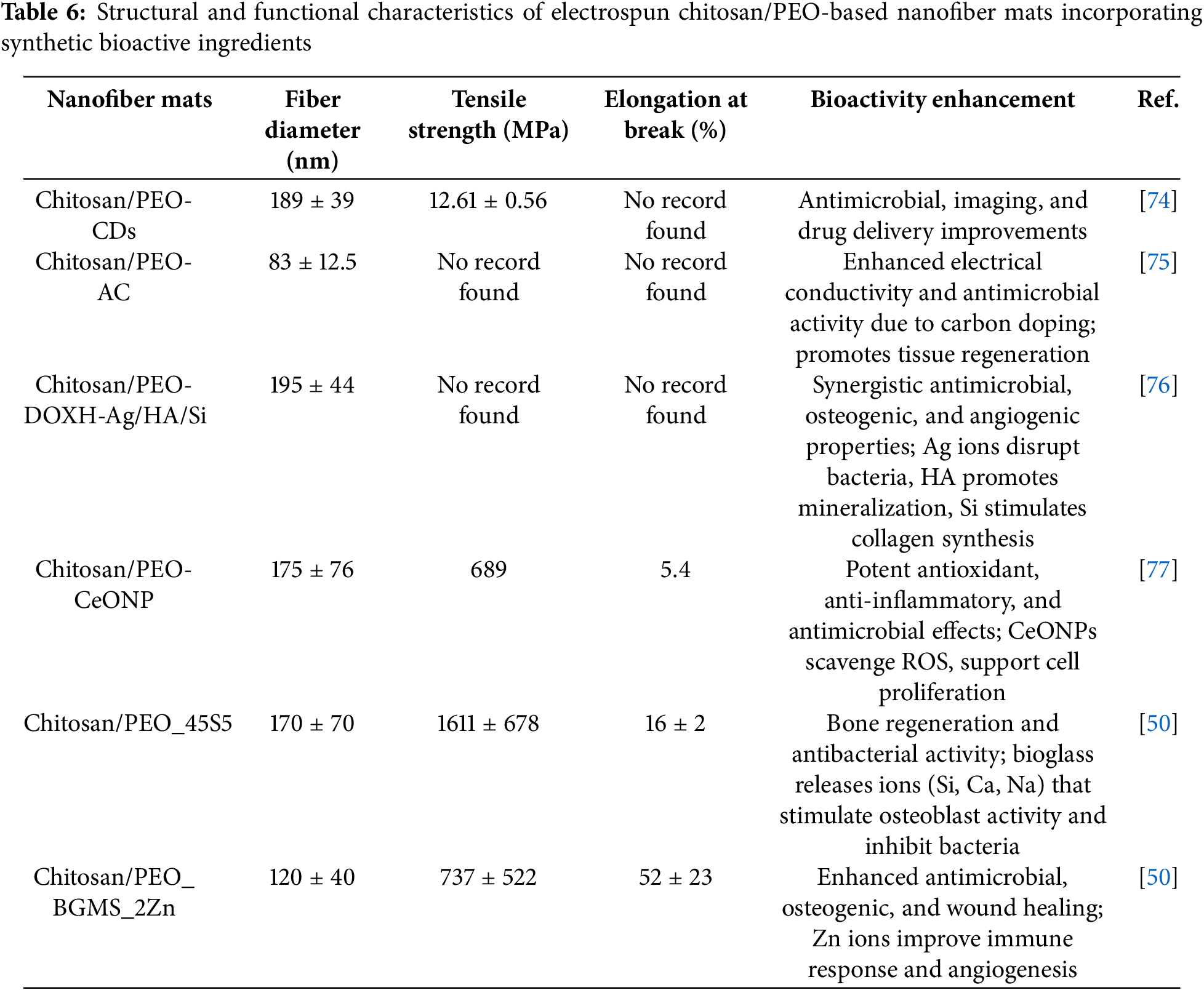

Table 6 summarizes the structural and mechanical properties of nanofiber mats enhanced with synthetic chemicals and nanoparticles. Different additives, including carbon dots (CDs), activated carbon (AC), cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeONP), and different bioactive glasses, influenced fiber diameters from 83 to 195 nm. The chitosan/PEO_45S5 composite demonstrated the highest tensile strength, at 1611 MPa, as well as an elongation at break of 16%, indicating excellent mechanical properties. Furthermore, the BGMS_2Zn-reinforced system demonstrated remarkable flexibility and toughness with a significant 52% elongation. The results of several studies, however, did not provide complete mechanical data, highlighting inconsistencies between methods of reporting and testing. The bioactivity improvements from synthetic bioactive ingredients were varied and significant. For example, CDs and AC enhanced antimicrobial properties and improved imaging or electrical conductivity, respectively. The DOXH-Ag/HA/Si system provided a synergistic effect that combined antimicrobial, osteogenic, and angiogenic abilities. CeONPs showed strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects by removing reactive oxygen species (ROS). Adding bioactive glasses like 45S5 and BGMS_2Zn boosted bone regeneration, antibacterial action, and wound healing, mainly through ion release (e.g., Si, Ca, Zn) that promoted osteoblast activity and immune responses. These results indicated that choosing the proper functional additives was crucial for adjusting the mechanical performance and therapeutic potential of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds.

7 Chitosan/PEO Electrospinning in Modified Electrospinning Setup

The employment of multiple nozzles, needle-free, and complex setups to produce fibers with unique characteristics. It allows for the production of core-shell and composite fibers that offer enhanced versatility and the ability to create multifunctional materials.

7.1 Needle-Free Electrospinning

Chloramphenicol is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used to treat various bacterial infections, and beta-glucan is a natural polysaccharide known for its immunomodulatory and wound-healing properties, which were electrospun using a needle-free electrospinning technique. The average mat thickness ranged from 35 to 86 μm. The elongation at break varied from 3.5% to 8.9%, and they had smoother surfaces. The nanofibers with chloramphenicol showed a high absorption capacity and a burst release of chloramphenicol. While preserving chloramphenicol’s antimicrobial activity, nanofibers containing all three active ingredients (beta-glucan, chitosan, and chloramphenicol) exhibited concentration-dependent anti-inflammatory properties [49].

Vancomycin (VCM) is a naturally occurring antibiotic derived from the Amycolatopsis orientalis bacteria. It effectively combats Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a Gram-positive bacterium, and is specifically used in wound care to prevent and treat serious infections. Glutaraldehyde is a dialdehyde compound utilized as a crosslinking agent, enhancing nanofibers’ stability and mechanical properties. Additionally, it is recognized for its antimicrobial properties, making it beneficial for medical applications. Vancomycin and glutaraldehyde were combined to produce a nanofibrous mat. VMC increased the fiber diameter. The average fiber diameters were 360 nm for chitosan/PEO, 428 nm for chitosan/PEO/VCM 2.5%, and 823 nm for chitosan/PEO/VCM 5%. Therefore, 2.5% VMC formulation is considered optimal. Additionally, the 2.5% VCM formulation demonstrated superior mechanical properties, faster wound healing, enhanced antibacterial effects, and a more controlled release profile. It outperformed traditional treatments like silver sulfadiazine. Crosslinking with glutaraldehyde vapor improved the nanofibers’ stability in aqueous environments, preventing rapid dissolution of the hydrophilic fibers [62].

Curcumin (Cur) is derived from Curcuma longa. It exhibits strong anti-inflammatory, anti-infective, and antioxidant properties, which help in wound healing and reducing inflammation. Collagen (Col), the most abundant extracellular matrix protein in natural tissues, is widely used in biomedical applications because of its biodegradability and biocompatibility, allowing it to integrate with the human biological system. Curcumin and collagen were combined to produce an electrospun mat. The resulting chitosan/PEO/Col and chitosan/PEO/Col/Cur mats contain smooth, uniform, and bead-free nanofibers. These mats demonstrate good porosity and high hydrophilicity. The porosity varies with the Cur loading: chitosan/PEO (without Cur) was 89.35%, chitosan/PEO/Col (without Cur) was 78.02%, chitosan/PEO/Col/Cur 10% was 61.01%, and chitosan/PEO/Col/Cur 15% was 80.66%. The chitosan/PEO/Col/Cur 15% mat showed water uptake ability of up to 827%, indicating high hydrophilicity and absorption capacity suitable for wound exudate absorption. Additionally, nanofibers with higher Cur concentration (15%) displayed slow-release characteristics over extended [63].

Thymol, a component of thyme essential oil (Thymus vulgaris), exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against molds, yeasts, fungi, and bacteria. Therefore, it is useful for preventing microbial growth in food and potentially in medical settings. The prepared nanofiber mats of chitosan/PEO with encapsulated Thymol via coaxial electrospinning are smooth and free from beads or defects. Thymol was encapsulated in the core, with the chitosan/PEO forming the shell, enabling controlled release. The average fiber diameter ranged from approximately 117 to 130 nm. Crosslinked nanofibers demonstrated improved tensile strength and elasticity, making them durable for handling and packaging applications. The core-shell design allows slow, sustained release of Thymol, extending antibacterial effects over time. The nanofiber mats successfully inhibited the growth of E. coli and S. aureus, confirming their potential for antimicrobial packaging. Crosslinking with genipin increased hydrophobicity (higher contact angles), which enhances water resistance and stability in humid environments [64].

Rosuvastatin is mainly used to promote bone regeneration by encouraging stem cell differentiation. Polycaprolactone is a biodegradable, biocompatible polyester with excellent mechanical properties. It functions as the shell material in core/shell fibers, providing structural support while affecting degradation and drug release profiles. Rosuvastatin was incorporated into the core with polycaprolactone forming the shell using a coaxial electrospinning technique. The resulting chitosan/PEO-Rosuvastatin nanofiber mats produced through coaxial electrospinning are uniform and free of beads. The core diameter was about 370 nm, and the shell thickness was approximately 70 nm. Thermogravimetric analysis showed the fibers had good thermal stability, with degradation behaviors related to their polymers and the incorporated drug. Plasma treatment increased the hydrophilicity of the mats, improving cell adhesion and water absorption. It can sustain drug release for up to 90 days [65].

7.4 Modified Free Surface Electrospinning (MFSE)

Higher solution conductivity and lower viscosity produced the finest nanofibers, with an average diameter of 100 ± 4.18 nm, at 40 wt% acetic acid and 6 wt% chitosan/PEO concentration. A high nanofiber yield of 3.052 g/h at 62 kV was achieved using the modified free surface electrospinning (MFSE) technique with optimal solution conditions of 60 wt% acetic acid and 4 wt% chitosan/PEO. The maximum radial electric field intensity (Emax) from MFSE was 2.87 × 10^6 V/m, while the axial Emax was 5.05 × 10^6 V/m. The average values were 9.64 × 10^5 V/m (radial) and 8.37 × 10^5 V/m (axial). MFSE exhibited a more uniform electric field distribution, indicating superior ordering characteristics of the prepared nanofiber [66].

Chitosan/PEO nanocomposite mats are versatile materials with a wide range of applications across biomedical, environmental, and commercial fields. They have quite a few unique properties, such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, antibacterial, and antimicrobial activity, which make them particularly valuable in advancing technologies in wound healing, tissue engineering, controlled drug delivery (Fig. 3), active food packaging, filtration, and more. Tables 7 and 8 below list the potential applications of chitosan/PEO nanofibrous mats.

Figure 3: Biomedical applications of the electrospun chitosan/PEO nanofibers

9 Limitations and Future Directions

Chitosan/PEO composites electrospun for biomedical and environmental applications show promise, however there are a number of drawbacks that require more research and development. Fig. 4 shows a schematic illustration of these challenges and future prospects.

Figure 4: Challenges and future directions of chitosan/PEO electrospinning and developed nanofibers

The interaction between the electrospun nanofibers and functional components is one of the main issues. Additives may weaken the nanofibrous structure by altering the viscosity, spinnability, or surface energy, even though they are often used to improve biological or chemical performance. For instance, adding natural additives like lawsone may significantly lower the nanofiber mats’ surface angle, which may prevent cells from adhering. The surface angle for nanofiber materials drastically decreased to 37° for nanofibrous mats containing 10%wt/V lawsone, which is inappropriate for cell adhesion. The uniformity and quality of the fibers, which are necessary to guarantee their stability and usefulness in a variety of applications, may also be diminished by the inclusion of these additives. These interactions show that in order to preserve the integrity of the electrospun fibers, additive amounts must be carefully optimized. Additionally, the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria were still not completely under control after eight hours, and the number of their colonies continued to decline. Moreover, the analysis in vitro, as opposed to in-vivo limits the understanding of real-world challenges [13].

Crosslinking chemicals like glutaraldehyde provide new difficulties even if they are helpful in maintaining the chitosan/PEO nanofibers. The cytocompatibility of the nanofibers may be impacted by these crosslinkers, resulting in a trade-off between cellular toxicity and structural integrity. Even though chitosan/PEO electrospun mats are usually regarded as safe for clinical usage, little is known about their long-term consequences, particularly with regard to material degradation and human skin contact. It will be necessary to create less toxic crosslinking chemicals or alternative stabilizing approaches in order to strike a compromise between maintaining structural strength and lowering toxicity. This will guarantee the nanofibers’ long-term safety and efficacy in biological applications. Nonetheless, prior research indicates that chitosan/PEO electrospun patches have been documented as safe for use in clinical settings. It has not been discussed how it affects human skin or how long it lasts (>15) [80].

The effectiveness of medication encapsulation, especially with cationic medicinal agents, is another significant drawback of the chitosan/PEO electrospinning technique. The effectiveness of encapsulation may be hampered by the electrostatic interactions between charged drug molecules and the polymer matrix, particularly for positively charged medicines. For instance, electrostatic repulsion between the drug and chitosan was shown to result in decreased encapsulation efficacy in the case of teicoplanin-loaded nanofibers. This restriction hinders the wider use of chitosan-based drug delivery systems and reduces their adaptability. Advanced drug-loading strategies that might reduce electrostatic interactions and increase drug loading capacity, including core-shell fiber designs or surface immobilization techniques, would be needed to overcome this obstacle [81].

Certain natural additives can reduce fiber quality and mat uniformity, especially when their concentrations are not optimized. An increase in nanofiber diameter was observed with lanolin addition, but this effect was diminished with smaller amounts of lanolin. The chitosan/PEO solution exhibited poor spinnability and low productivity, yielding a mat weight of approximately 7.0 g/m2. The chitosan/PEO/lanolin composite, however, produced a much thinner mat, weighing only 1.88 g/m2, with insufficient thickness and inadequate absorbency due to PEO dissolution [82].

The scalability of the electrospinning process is often constrained by the intrinsic viscosity of chitosan, especially in high molecular weight forms with significant degrees of deacetylation. Low productivity, frequent drying at the needle tip, and trouble pumping are all consequences of high viscosity caused by chitosan’s medium molecular weight and 75%–85% deacetylation degree. The process’s capacity to be scaled up for industrial purposes is greatly impacted by these issues. Future studies should look at methods to improve the formulations of chitosan/PEO solutions and examine the usage of various grades of chitosan that may increase spinnability without sacrificing the fibers’ mechanical and functional qualities. This might result in electrospinning procedures that are more effective and fruitful, increasing the viability of producing chitosan/PEO nanofibers for large-scale uses [82].

Many of the successful in vitro outcomes of chitosan/PEO nanofibers have not been confirmed in vivo, especially when it comes to the long-term impacts on tissue regeneration, immunological responses, and biodegradation. Studies using IMD-embedded chitosan nanofibers, for example, have shown early-stage wound healing but have not adequately addressed problems like immunological responses, scarring, or chronic wound closure. Furthermore, nothing is known about the rates of biodegradation and the possibility of leftover pieces at the wound site that might lead to irritation or slowed healing. Additionally, while the structure of the IMD was mentioned, its in-vivo or PBS-based degradation behavior was not thoroughly investigated. It remains unclear how long the dressing persists at the wound site or whether it leaves residual fragments that could cause inflammation or delayed healing. To fully comprehend the long-term functionality of chitosan/PEO nanofibers and their therapeutic significance, especially in the areas of tissue regeneration and chronic wound care, more thorough in vivo research is needed [18].

Investigating the addition of laccase to gluten networks to enhance the functional and sensory qualities of baked goods is a viable avenue for further study. To further improve the quality and stability of fruit juices, the immobilized form of laccase may also be used in fruit juice processing to stop the production of protein–polyphenol haze. To preserve a targeted scientific approach, these developments should be investigated in specialized research, apart from other uses such as electrospinning [82,83].

The biocompatibility of chitosan/PEO nanofibers is another area that needs further research, particularly when functional additives like lanolin are included. Certain compounds enhance the properties of fibers, but it is unknown how they impact cell survival, tissue contact, and immune responses. It will be crucial to investigate the long-term effects of these additives to ensure that chitosan/PEO nanofibers are safe for clinical use in tissue engineering and wound healing applications. This will include assessing their potential toxicity, immunological response, and overall biocompatibility in increasingly complex biological systems. Enhancing encapsulation efficiency is a major area of attention for future approaches. Advanced drug-loading strategies such core-shell fiber topologies or other polymers may be used to overcome the electrostatic repulsion between drug molecules and the polymer matrix. The development of non-toxic crosslinkers or other stabilizing techniques will also be essential to reduce toxicity while maintaining the structural integrity of the nanofibers. It is crucial to validate the long-term performance of the nanofibers in vivo. Research should focus on wound healing, tissue regeneration, immunological response, and biodegradation to ensure therapeutic usefulness of the materials. Additionally, improving the electrospinning process would be vital for industrial applications in order to boost reproducibility and scalability. Coaxial and needle-free electrospinning are two new electrospinning methods that could be able to overcome current limitations and improve the quality and quantity of fiber produced. Investigating the incorporation of extra functional additives that enhance fiber properties without compromising spinnability or uniformity is an intriguing avenue for further research. Chitosan/PEO nanofibers may be further enhanced for usage in a variety of biomedical and environmental applications by tackling these biological and technological obstacles.

Lastly, in addition to increasing functionality, future studies should concentrate on boosting system stability, drug release control, and repeatability in a variety of biological models. In future studies, the development of Ti3C2Tx/polymer composites will be pursued for applications beyond catalysis, including adsorbents, biomedical scaffolds, and wearable dressing materials [84]. To address the burst release observed in teicoplanin-loaded fibers, alternative polymers may be employed, and advanced drug-loading methods such as surface immobilization or core–shell fiber architectures will be considered. The biocompatibility of lanolin-incorporated CA and TPU nanofibers will be assessed using L929 fibroblasts and HS2 epithelial cells [81]. Additionally, porosity, air and water vapor permeability, and the effects of lanolin concentration and deposition time will be evaluated.

Electrospinning, a powerful technique to fabricate nanofibrous materials with high surface area, tunable porosity, and structural similarity to the natural extracellular matrix. Incorporating biocomaterials such as chitosan in electrospinning to produce nanofibers, is both biocompatible and biodegradable. Developing materials from biodiversity for use in biomedicine (tissue engineering, wound care, medication administration) and environmental protection (food packaging, water and air filters) represents a promising field. However, electrospinning of chitosan without any other coagent is very challenging, due to high viscosity, strong hydrogen bonding, and limited solubility, which is why they often results in bead formation. To counter these problems, the most common technique for electrospinning clean chitosan fibers involves blending with a co-spinning agent, such as poly (ethylene oxide), which provides complementary properties for specific applications and facilitates easier electrospinning. The resulting chitosan/PEO nanofibers showed improved mechanical integrity, controlled porosity, and favorable interactions with biological tissues, making them excellent candidates in medical applications. It was found that, nanoparticles and glass particle-assisted electrospun mats have higher mechanical strength than others. whereas, synthetic chemical assisted electrospun mats have lower fiber diameters than natural ingredient assisted electrospun mats.

There are also significant drawbacks that need more research despite these benefits. The addition of functional additives or bioactive substances may harm mechanical performance, spinnability, or fiber homogeneity. Large-scale deployment and clinical translation are hampered by issues including poor scalability, inconsistent fiber homogeneity, low encapsulation efficiency, and insufficient in vivo validation, despite advancements in electrospinning. Glutaraldehyde and other crosslinkers may be cytotoxic, and leftover solvents can make medical usage unsafe. The necessity for thorough optimization is further highlighted by the possibility that some additives could impair cytocompatibility or cell adhesion. Furthermore, because chitosan is polycationic and electrostatically repels positively charged pharmaceuticals, encapsulation efficiency is still a bottleneck. Looking forward, future research should focus on developing biocompatible and non-toxic crosslinkers, improving drug encapsulation techniques (e.g., core–shell fibers or surface immobilization), and refining process parameters to enhance reproducibility and scalability. Coaxial and needle-free electrospinning methods may offer promising avenues to increase yield and fiber quality. Additionally, incorporating functional materials like Ti3C2Tx or cellulose nanocrystals could further extend the utility of chitosan/PEO nanofibers across biomedical, environmental, and industrial domains.

In summary, while electrospun chitosan/PEO nanofibers present exciting possibilities across multiple sectors, addressing their current limitations through advanced formulations, improved process engineering, and in-depth biological validation will be essential to realize their full potential in real-world applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Mohammad Tajul Islam; Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, and Writing—original draft: Md. Tanvir Raihan, Md. Himel Mahmud, Badhon Chandra Mazumder, and Md. Nazif Hasan Chowdhury; Supervision, and Writing—review & editing: Mohammad Tajul Islam. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Moghaddam A, Nejaddehbashi F, Orazizadeh M. Resveratrol-coated chitosan mats promote angiogenesis for enhanced wound healing in animal model. Artif Organs. 2024;48(9):961–76. doi:10.1111/aor.14759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Pan W, Wang JP, Sun XB, Wang XX, Jiang JY, Zhang ZG, et al. Ultra uniform metal−organic framework-5 loading along electrospun chitosan/polyethylene oxide membrane fibers for efficient PM2.5 removal. J Clean Prod. 2021;291(15):125270. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Risch P, Adlhart C. A chitosan nanofiber sponge for oyster-inspired filtration of microplastics. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2021;3(9):4685–94. doi:10.1021/acsapm.1c00799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cárdenas Bates II, Loranger Éric, Mathew AP, Chabot B. Cellulose reinforced electrospun chitosan nanofibers bio-based composite sorbent for water treatment applications. Cellulose. 2021;28(8):4865–85. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-03828-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Duan M, Sun J, Yu S, Zhi Z, Pang J, Wu C. Insights into electrospun pullulan-carboxymethyl chitosan/PEO core-shell nanofibers loaded with nanogels for food antibacterial packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;233:123433. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang X, Wang Y, Huang L, Li B, Yan X, Huang Z, et al. Sensitive Cu2+ detection by reversible on-off fluorescence using Eu3+ complexes in SiO2, in chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibers. Mater Des. 2021;205(37):109708. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fouad SA, Ismail AM, Abdel Rafea M, Abu Saied MA, El-Dissouky A. Preparation and characterization of chitosan nanofiber: kinetic studies and enhancement of insulin delivery system. Nanomater. 2024;14(11):952. doi:10.3390/nano14110952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Huang Y, Wang L, Liu Y, Li T, Xin B. Drug-loaded PLCL/PEO-SA bilayer nanofibrous membrane for controlled release. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2021;32(18):2331–48. doi:10.1080/09205063.2021.1970881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Chen CK, Liao MG, Wu YL, Fang ZY, Chen JA. Preparation of highly swelling/antibacterial cross-linked N-maleoyl-functional chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofiber meshes for controlled antibiotic release. Mol Pharm. 2020;17(9):3461–76. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Abd El Hady WE, Soliman OAE, El Sabbagh HM, Mohamed EA. Glutaraldehyde-crosslinked chitosan-polyethylene oxide nanofibers as a potential gastroretentive delivery system of nizatidine for augmented gastroprotective activity. Drug Deliv. 2021;28(1):1795–809. doi:10.1080/10717544.2021.1971796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Islam MT, Ali A, McConnell M, Laing R, Wilson C. Mechanisms and kinetics of silver nanoparticle release from polyvinyl alcohol/keratin/chitosan electrospun nanofibrous scaffold. In: AUTEX2019-19th World Textile Conference on Textiles at the Crossroads; 2019 Jun 11–15; Ghent, Belgium. p. 11–5. [Google Scholar]

12. Ho YS, Al Sharmin A, Islam MT, Halim AF. Future direction of wound dressing research: evidence From the bibliometric analysis. J Ind Text. 2022;52:15280837221130518. doi:10.1177/15280837221130518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abadehie FS, Dehkordi AH, Zafari M, Bagheri M, Yousefiasl S, Pourmotabed S, et al. Lawsone-encapsulated chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibrous mat as a potential antibacterial biobased wound dressing. Eng Regen. 2021;2(4):219–26. doi:10.1016/j.engreg.2022.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Singh YP, Mishra B, Gupta MK, Mishra NC, Dasgupta S. Enhancing physicochemical, mechanical, and bioactive performances of monetite nanoparticles reinforced chitosan-PEO electrospun scaffold for bone tissue engineering. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022;139(40):e52844. doi:10.1002/app.52844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Garcia Garcia CE, Bossard F, Lardy B, Rinaudo M. Electrospun chitosan nanofibers used for chondrocyte development: influence of the structure of fibrillar support. NanoWorld J. 2022;8(2):66–72. doi:10.17756/nwj.2022-101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tamburaci S, Tihminlioglu F. Development of Si doped nano hydroxyapatite reinforced bilayer chitosan nanocomposite barrier membranes for guided bone regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;128:112298. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2021.112298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Yang Q, Guo J, Zhang S, Guan F, Yu Y, Feng S, et al. Development of cell adhesive and inherently antibacterial polyvinyl alcohol/polyethylene oxide nanofiber scaffolds via incorporating chitosan for tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;236:124004. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Fang L, Hu Y, Lin Z, Ren Y, Liu X, Gong J. Instant mucus dressing of PEO reinforced by chitosan nanofiber scaffold for open wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;263(2016):130512. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li X, Jiang F, Duan Y, Li Q, Qu Y, Zhao S, et al. Chitosan electrospun nanofibers derived from Periplaneta americana residue for promoting infected wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;229(6):654–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Khan F, Bairagi B, Mondal B, Mandal D, Nath D. In vivo biocompatibility of electrospun chitosan/PEO nanofiber as potential wound dressing material for diabetic burn wound injury of mice. Chem Pap. 2024;78(16):8833–47. doi:10.1007/s11696-024-03714-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Islam MT, Laing RM, Wilson CA, McConnell M, Ali MA. Fabrication and characterization of 3-dimensional electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol)/keratin/chitosan nanofibrous scaffold. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;275(3):118682. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kinyua CK, Owino AO, Kaur K, Das D, Karuri NW, Müller M, et al. Impact of surface area on sensitivity in autonomously reporting sensing hydrogel nanomaterials for the detection of bacterial enzymes. Chemosensors. 2022;10(8):299. doi:10.3390/chemosensors10080299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Huang Z, Wang Y, Yan X, Mao X, Gao Z, Kipper MJ, et al. Stable chitosan fluorescent nanofiber sensor containing Eu3+ complexes for detection of copper ion. Opt Mater. 2023;135:113245. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2022.113245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shoueir KR, El-Desouky N, Rashad MM, Ahmed MK, Janowska I, El-Kemary M. Chitosan based-nanoparticles and nanocapsules: overview, physicochemical features, applications of a nanofibrous scaffold, and bioprinting. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;167(2):1176–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kakoria A, Sinha-Ray S. A review on biopolymer-based fibers via electrospinning and solution blowing and their applications. Fibers. 2018;6(3):45. doi:10.3390/fib6030045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Masillamani A, Sabarinathan KG, Gomathy M, Kumutha K, Prasanthrajan M, Kannan J, et al. Sustainable encapsulation of bio-active agents and microorganisms in electrospun nanofibers: a comprehensive review. Plant Sci Today. 2024;11(sp4):1–14. doi:10.14719/pst.5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jabur A, Al-Tuhafi R. Preparation and characterization of NiTi/PVA nanofibers by electrospinning. Eng Technol J. 2021;39(11):1674–80. doi:10.30684/etj.v39i11.2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kuntzler SG, Costa JAV, de Morais MG. Development of electrospun nanofibers containing chitosan/PEO blend and phenolic compounds with antibacterial activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;117:800–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Mahbub MA, Mahmud MH, Ahona MJ, Ahmed T,Ashraf SM,Sultana JA,et al. Chitosan as a cationizing agent in pigment dyeing of cotton fabric. Carbohydr Polym Tech Appl. 2024;7:100502. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2024.100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Asadian M, Onyshchenko I, Thukkaram M, Esbah Tabaei PS, Van Guyse J, Cools P, et al. Effects of a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) treatment on chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibers and their cellular interactions. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;201(3):402–15. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.08.092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Mengistu Lemma S, Bossard F, Rinaudo M. Preparation of pure and stable chitosan nanofibers by electrospinning in the presence of poly(ethylene oxide). Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(11):1790. doi:10.3390/ijms17111790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Al-Harbi N. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanocomposite films with different concentrations of zirconia nanocomposites. Polym Test. 2023;128:108204. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Min LL, Zhong LB, Zheng YM, Liu Q, Yuan ZH, Yang LM. Functionalized chitosan electrospun nanofiber for effective removal of trace arsenate from water. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):32480. doi:10.1038/srep32480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Paradis-Tanguay L, Camiré A, Renaud M, Chabot B, Lajeunesse A. Sorption capacities of chitosan/polyethylene oxide (PEO) electrospun nanofibers used to remove ibuprofen in water. J Polym Eng. 2019;39(3):207–15. doi:10.1515/polyeng-2018-0224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mokhena TC, Luyt AS. Development of multifunctional nano/ultrafiltration membrane based on a chitosan thin film on alginate electrospun nanofibres. J Clean Prod. 2017;156:470–9. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ridolfi DM, Lemes AP, de Oliveira S, Justo GZ, Palladino MV, Durán N. Electrospun poly(ethylene oxide)/chitosan nanofibers with cellulose nanocrystals as support for cell culture of 3T3 fibroblasts. Cellulose. 2017;24(8):3353–65. doi:10.1007/s10570-017-1362-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Rahimi M, Seyyed Tabaei SJ, Ali Ziai S, Sadri M. Anti-leishmanial effects of chitosan-polyethylene oxide nanofibers containing berberine: an applied model for leishmanial wound dressing. Iran J Med Sci. 2020;45(4):286–97. doi:10.30476/IJMS.2019.45784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Vigani B, Rossi S, Sandri G, Bonferoni MC, Rui M, Collina S, et al. Dual-functioning scaffolds for the treatment of spinal cord injury: alginate nanofibers loaded with the sigma 1 receptor (S1R) agonist RC-33 in chitosan films. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(1):21. doi:10.3390/md18010021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Singh YP, Dasgupta S, Nayar S, Bhaskar R. Optimization of electrospinning process & parameters for producing defect-free chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibers for bone tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2020;31(6):781–803. doi:10.1080/09205063.2020.1718824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Kuo TY, Lin CM, Hung SC, Hsien TY, Wang DM, Hsieh HJ. Incorporation and selective removal of space-forming nanofibers to enhance the permeability of cytocompatible nanofiber membranes for better cell growth. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2018;91:146–54. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2018.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Karimi S, Moradipour P, Azandaryani AH, Arkan E. Amphotericin-B and vancomycin-loaded chitosan nanofiber for antifungal and antibacterial application. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2019;55(25):e17115. doi:10.1590/s2175-97902019000117115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Arkoun M, Daigle F, Heuzey MC, Ajji A. Mechanism of action of electrospun chitosan-based nanofibers against meat spoilage and pathogenic bacteria. Molecules. 2017;22(4):585. doi:10.3390/molecules22040585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hakkarainen E, Kõrkjas A, Laidmäe I, Lust A, Semjonov K, Kogermann K, et al. Comparison of traditional and ultrasound-enhanced electrospinning in fabricating nanofibrous drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(10):495. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11100495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lancina MGIII, Shankar RK, Yang H. Chitosan nanofibers for transbuccal insulin delivery. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2017;105(5):1252–9. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Guo H, Tan S, Gao J, Wang L. Sequential release of drugs form a dual-delivery system based on pH-responsive nanofibrous mats towards wound care. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(8):1759–70. doi:10.1039/c9tb02522g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Pakravan M, Heuzey MC, Ajji A. A fundamental study of chitosan/PEO electrospinning. Polymer. 2011;52(21):4813–24. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2011.08.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]