Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Research Progress on Bio-Based Biodegradable Barrier Materials

1 New Energy College, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

2 School of Materials and Chemical Engineering, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaojing Zhang. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(12), 2309-2353. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0108

Received 29 May 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The current global shortage of oil resources and the pollution problems caused by traditional barrier materials urgently require the search for new substitutes. Biodegradable bio-based barrier materials possess the characteristics of being renewable, environmentally friendly, and having excellent barrier properties. They have become an important choice in fields such as food packaging, agricultural film covering, and medical protection. This review systematically analyzes the design and research of this type of material, classifying biobased and biodegradable barrier materials based on the sources of raw materials and synthesis pathways. It also provides a detailed introduction to the latest research progress of biobased and biodegradable barrier materials, discussing the synthesis methods and improvement measures of their barrier properties. Subsequently, it analyzes the related technologies for enhancing the barrier properties of biobased and biodegradable barrier materials, and finally looks forward to the directions that future research should focus on, promoting the transition of biobased and biodegradable barrier materials from the laboratory to industrial applications.Keywords

Barrier materials constitute a core branch of functional materials. They can effectively prevent the penetration of environmental factors such as gases and water vapor. This characteristic enables them to provide a comprehensive protective barrier for products. However, the high barrier materials are mainly composed of non-degradable materials currently [1]. Although these materials have excellent barrier properties, their main synthetic raw materials come from traditional fossil resources. However, approximately 97% of the world’s oil was discovered in the 20th century. In the past decade, the global production of alternative crude oil has been less than 50%. This data highlights the significant challenges faced globally in seeking new oil resources to replace the increasingly depleted existing reserves [2,3]. As time goes by, traditional synthetic petroleum-based materials continue to accumulate in landfill sites, oceans, and other habitats, posing a threat to ecosystems and wildlife and becoming a long-standing environmental burden [4–6]. Facing the dual pressures of increasingly scarce resources and prominent environmental risks in modern society, accelerating the research and application of green high-barrier materials has become an inevitable choice to break through the bottleneck of industrial development and achieve sustainable development [7].

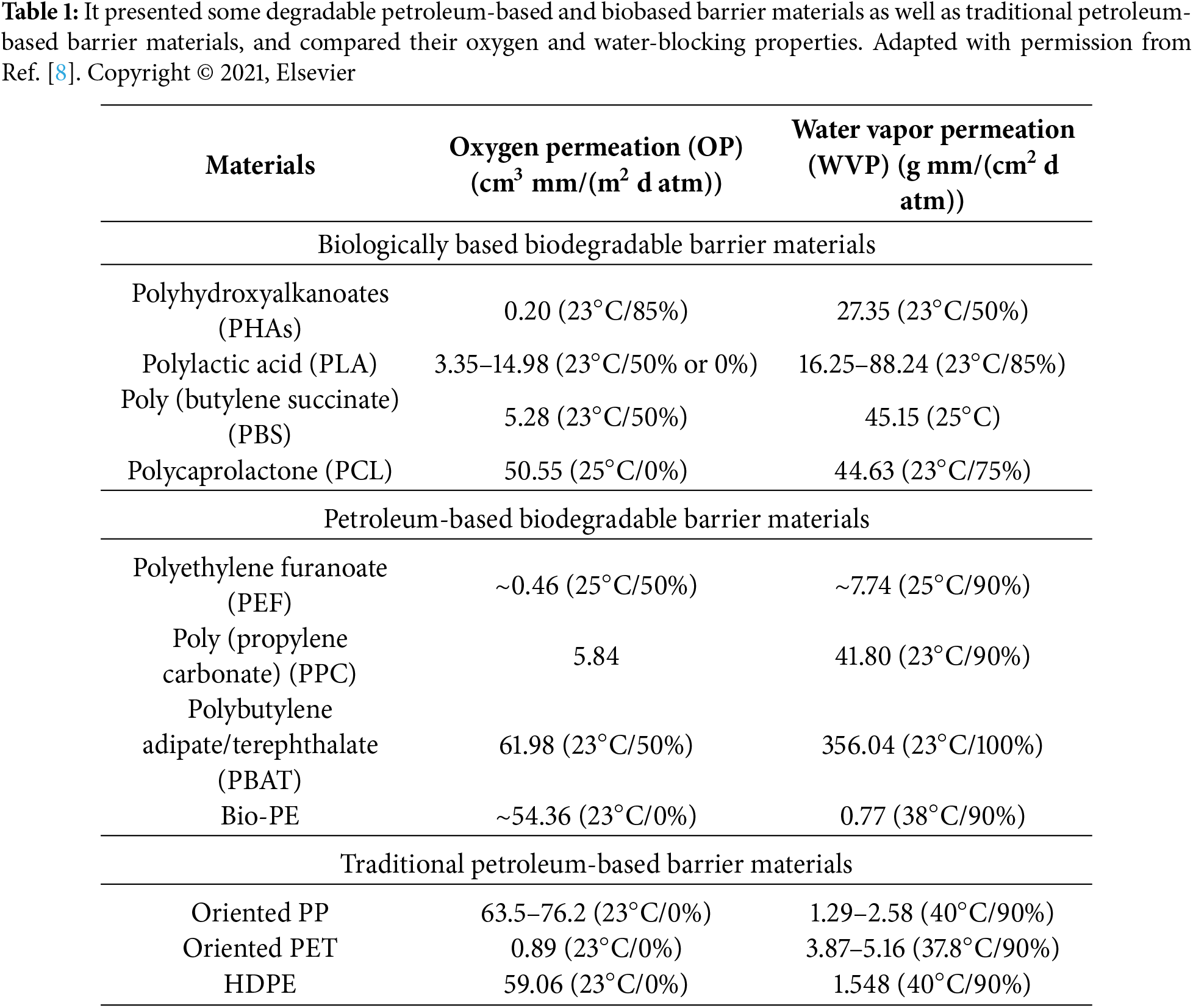

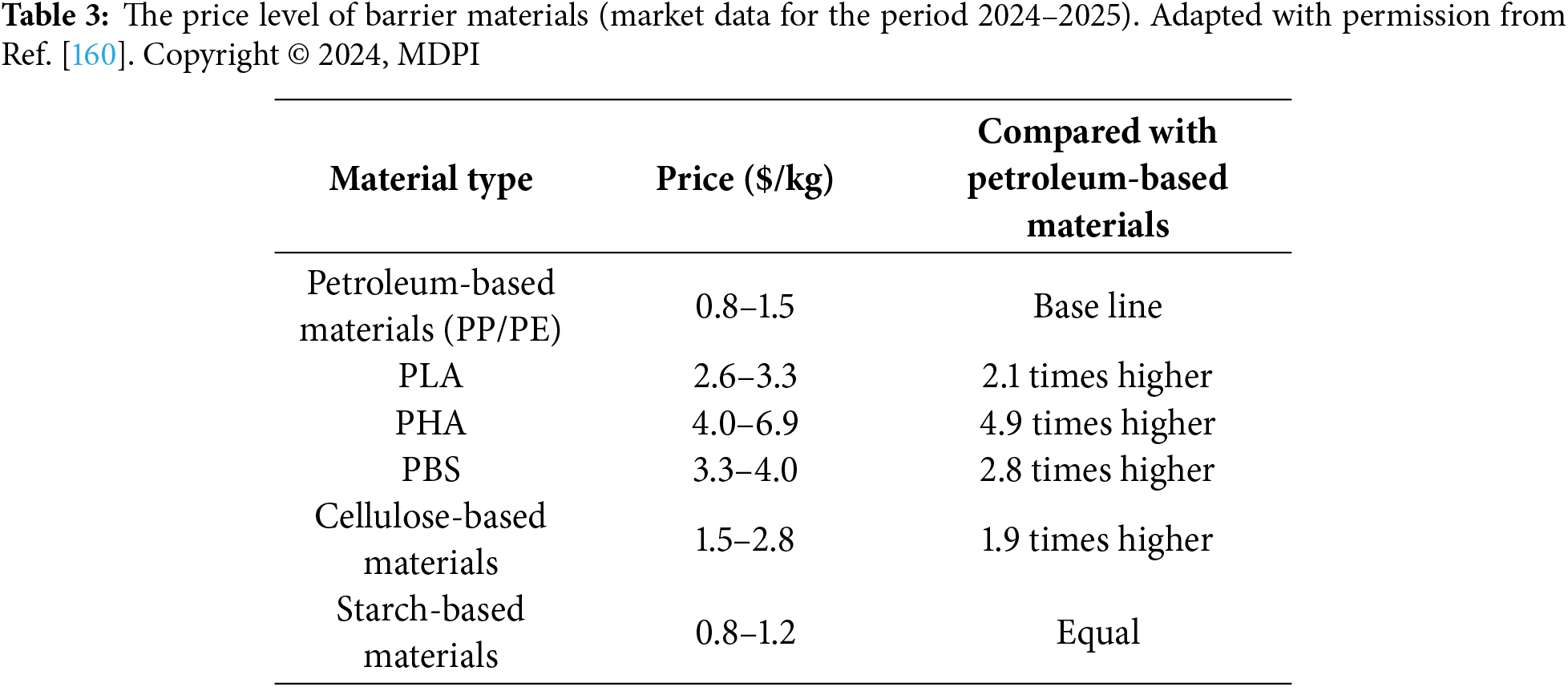

Biodegradable barrier materials are regarded as an important alternative to traditional (non-biodegradable) petroleum-based barrier materials due to their characteristic of being decomposable by microorganisms under specific conditions. It is necessary to clearly point out that, based on the source of the raw materials, these materials can be divided into two major categories. Petroleum-based biodegradable barrier materials: The raw materials required for their synthesis mainly come from non-renewable resources. Therefore, their production process is highly dependent on oil extraction and chemical processing technologies, and has the characteristic of being non-renewable. The acquisition of raw materials and the production process (such as oil extraction, transportation, refining, and related chemical processes) inevitably bring about carbon emissions, potential pollution, and other environmental burdens. Biobased biodegradable barrier materials: their synthetic raw materials mainly come from renewable substances (such as polysaccharides, proteins, special polymers, etc.). From this, it can be seen that although both can eventually be biodegraded, there are significant differences in their raw material sources and environmental impacts. Petroleum-based biodegradable materials essentially still rely on non-renewable resources and carry the ecological footprint of the fossil energy industry chain. Table 1 presents some degradable petroleum-based and biobased barrier materials as well as traditional petroleum-based barrier materials, and compares their oxygen-blocking/water-blocking properties [8]. Therefore, the search for new materials that possess both high barrier properties and biodegradability is currently a research hotspot [9,10].

This article systematically reviews the latest research progress of bio-based biodegradable barrier materials. The core contents include: (a) classification of material properties and application overview; (b) barrier characteristics and modification strategies of representative materials (such as starch, cellulose, PLA, PHA) based on their sources (biomass extraction, chemical synthesis, microbial synthesis); (c) key modification techniques for enhancing barrier performance (such as blending, multilayer extrusion, etc.). Finally, it looks forward to the challenges and opportunities in performance optimization and large-scale production in this field, aiming to provide research guidance for the development of sustainable high-performance barrier materials.

2 Introduction to Bio-Based Biodegradable Barrier Materials

2.1 Introduction to Bio-Based Biodegradable Materials

Biobased degradable materials refer to those materials whose raw materials come from renewable resources and are synthesized through biological or chemical methods. This type of substance can undergo gradual decomposition and mineralization under certain reaction conditions. The ideal complete biodegradation process ultimately mainly converts into simple small molecules such as carbon dioxide, water, or methane (CH4), as well as microbial biomass. However, in actual (especially non-controlled) conditions, the degradation process often produces intermediate products. Only when mineralization is completed under suitable environmental conditions and sufficient time can these materials ultimately be transformed into harmless substances (main products being CO2 and H2O), and partially participate in the carbon cycle of nature. The ideal bio-based biodegradable material should possess excellent mechanical properties (such as strength and flexibility) as well as a controllable degradation rate to meet the demands of various application scenarios [11].

2.2 Introduction to Barrier Materials

Barrier materials are a type of functional material with the function of selectively isolating permeating substances. Their core value lies in maintaining the stability of the internal environment of the protected system through the physical barrier effect. For packaging, this type of material can form an excellent barrier, protecting against multiple threats such as oxygen and water vapor. This not only effectively prevents the oxidation, moisture absorption, deterioration, and degradation caused by light of the internal products, but also ensures the freshness, taste, and efficacy of the products, and is the key to significantly extending the shelf life. With the development of materials science, the application of barrier materials has expanded from traditional food packaging to multiple fields such as electronic device packaging, separators for new energy batteries, self-cleaning coatings, and medical protection. Their advantages are reflected in dimensions such as high barrier efficiency, processing adaptability, mechanical strength, and environmental friendliness [12,13].

2.2.1 Properties of Barrier Materials

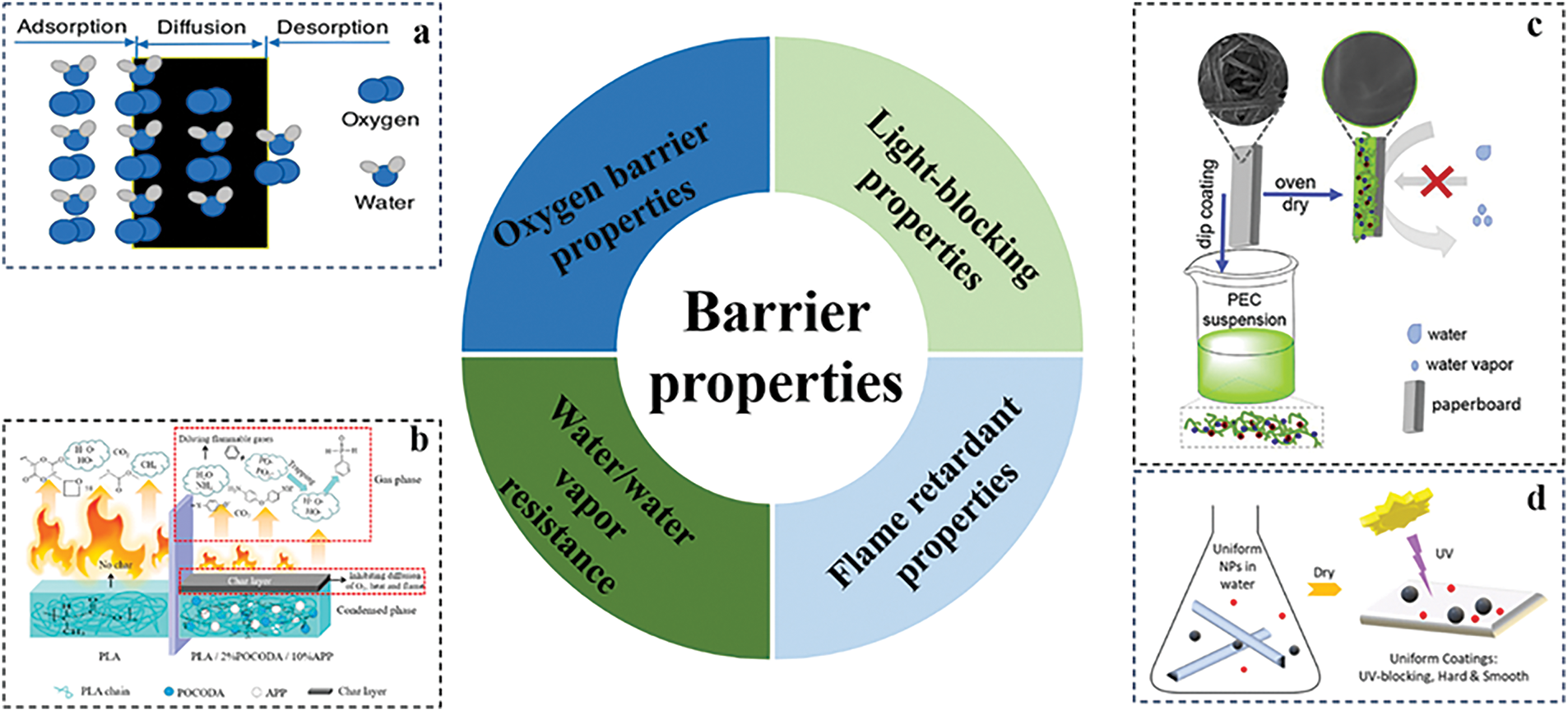

The barrier property measures how effectively a material can act as a barrier to slow down or prevent the penetration rate of substances (such as oxygen, fragrance) driven by concentration differences. The barrier properties of materials mainly include (Fig. 1) oxygen barrier performance, water barrier performance, light barrier performance, and flame retardant performance [14].

Figure 1: Classification of barrier properties and schematic diagrams of different barrier properties; (a) The permeation process of oxygen/water vapor. Adapted with permission from Ref. [15]. Copyright © 2021 Taylor & Francis; (b) Flame retardant performance of PLA/2%POCODA/10%APP composites. Adapted with permission from Ref. [16]. Copyright © 2021, Elsevier; (c) Starch-based starch complex barrier coatings against water and water vapor. Adapted with permission from Ref. [17]. Copyright © 2020, Elsevier; (d) The ultraviolet (UV) blocking performance of the coating. Adapted with permission from Ref. [18]. Copyright © 2020, American Chemical Society

Oxygen Barrier Performance

Excellent oxygen barrier properties are one of the core functional attributes of packaging materials. When there is a difference in oxygen concentration inside and outside the package, oxidation reactions will cause quality deterioration and a decline in service life, thereby significantly affecting the market value of the products. At present, it has become a consensus in the industry to extend the shelf life by using high-performance barrier materials, and its mechanism of action is mainly achieved by blocking the penetration path of oxygen molecules. The penetration process of oxygen molecules in barrier materials mainly consists of four steps: (1) Adsorption of oxygen molecules on the surface of barrier materials; (2) Dissolution; (3) Diffusion; (4) Desorption occurs on the other surface of the barrier material [19,20]. Generally speaking, the first and fourth steps of oxygen molecules on the surface of the isolation material are much faster compared to the entire process. Therefore, it is usually believed that the permeability of oxygen depends on the solubility and diffusivity of gas molecules in the barrier material [21]. However, during the barrier formation process, the role of diffusivity in enhancing the barrier performance is greater than that of solubility [22]. Therefore, most of the research in this field focuses on enhancing the barrier properties by increasing the complexity of the diffusion pathways and inhibiting the movement of oxygen molecules.

Water Vapor/Water Resistance Performance

The barrier properties of materials against water can be divided into two phases: liquid water and water vapor. There are essential differences between the two in terms of molecular size, thermodynamic behavior, and permeation mechanism. Water vapor molecules, due to their smaller size and lower cohesion, impose higher barrier requirements on materials [23]. The water vapor barrier property is an important material barrier characteristic, ranking alongside the oxygen barrier property. Both of these are the most common and crucial indicators for measuring the gas barrier performance of materials. The penetration process of water vapor in materials generally follows the four steps of oxygen penetration. Therefore, by designing and extending the migration path of water vapor molecules within the material, it is possible to effectively inhibit its diffusion rate, thereby significantly enhancing the barrier performance of the material. Furthermore, if the material’s waterproof vapor resistance is poor, this could cause the material to be affected by water vapor, and it would also reduce its barrier properties against oxygen and other gases.

Meanwhile, the liquid water barrier performance is also an important property required for barrier materials, reducing water penetration to avoid the influence of moisture. The key factors influencing the penetration of liquid water include the material structure and environmental parameters. From nanoscale pore wetting to macroscopic pressure driving, the process involves multiple mechanisms such as diffusion, adsorption, and capillary action. The water molecule permeation behavior of different materials is greatly influenced by their structure, composition, and environmental conditions. The existing studies usually achieve this by conducting hydrophobic modification to reduce the adsorption and capillary action of the material towards water molecules, thereby improving its barrier properties. Moreover, hydrophobic modification can also enhance the water vapor resistance performance of materials to a certain extent [24].

Oil Barrier Performance

Nowadays, oil substances are widely present in various industries, and their potential leakage risks pose a significant threat to product integrity and environmental safety. Therefore, there is an urgent need for materials to have good oil barrier properties. The methods to enhance oil barrier performance mainly include: (1) Improving the oil barrier performance of materials by reducing their surface tension, such as adding or coating oil repellents; (2) The compactness of packaging materials can be enhanced by adding fillers or covering them with coatings. The dense structure makes it less likely for oil to penetrate, thereby achieving an effective oil-blocking effect. At present, many studies have been dedicated to developing composite materials with excellent oil barrier properties [25,26].

Light-Blocking Performance

For light-blocking performance, the main function is to block the irradiation of ultraviolet rays. Ultraviolet radiation is an important environmental factor that causes deterioration of various materials and living organisms. Especially for emerging technologies such as organic photovoltaics and organic light-emitting diodes, where environmental stability is of vital importance, the light-blocking ability is particularly crucial [27,28]. For example, in the field of food packaging, the UV blocking property is crucial for preventing the loss of nutritional value and the color change of food [29]. Ultraviolet blocking mainly shields ultraviolet rays through physical reflection or scattering, chemical absorption, etc., protecting materials from solar radiation and slowing down their photoaging [30,31].

Flame Retardant Performance

Flame-retardant performance is also one of the important types of barrier performance. In daily life, the combustion of materials releases a large amount of heat and is accompanied by molten droplets, which can easily cause large-scale fires and pose a serious threat to the lives and property of the country and its people. Therefore, the use of flame-retardant materials is of vital importance [32].

At present, the flame-retardant performance of materials is mainly endowed through two methods: physical blending of flame retardants and coating surface treatment. The barrier mechanisms include: Flame-retardant materials form a protective film during combustion to isolate air and heat transfer to achieve flame retardancy; they decompose and release inert gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapor to dilute flammable gases such as oxygen to achieve flame retardancy; they absorb and consume the heat generated during combustion through decomposition reactions to achieve flame retardancy; and multiple flame-retardant substances work together to achieve flame retardancy [33].

2.3 Application of Bio-Based Biodegradable Barrier Materials

Bio-based biodegradable barrier materials, as innovative alternatives to traditional composite materials, have demonstrated transformative potential for sustainable development in fields such as food packaging, agriculture, and healthcare, thanks to their environmentally friendly characteristics and multi-dimensional performance advantages. This type of material not only realizes the green substitution of petroleum-based materials but also meets the advanced requirements for material performance in different scenarios through functional design, providing an innovative path for achieving sustainable development goals.

Regarding food packaging, the core performance indicators of biodegradable barrier materials cover two major dimensions: barrier performance and mechanical strength [34]. The ideal barrier performance requires the synergistic blocking ability of gases (O2/CO2), water vapor, and UV simultaneously. Amaregouda’s [35] team modified the interface of chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) composite films through anthocyanin-ZnO nanoparticles. The chitosan/PVA composite film has been successfully endowed with excellent mechanical properties, barrier capabilities, and significantly enhanced antioxidant and antibacterial functions.

In the agricultural sector, the extensive use of biodegradable barrier materials has increased yields, enabled earlier harvests, reduced reliance on herbicides and pesticides, better maintained soil temperature, and more effectively retained water and fertilizers. Therefore, plastic films are widely applied due to their excellent performance. However, the pollution burden caused by plastic films is inevitable. Therefore, the introduction of bio-based biodegradable materials to synthesize mulching films is a very promising alternative. Bio-based biodegradable mulching films, such as starch and PVA films and thermoplastic starch (TPS) materials based on renewable resources, are currently the main raw materials for most commercial biodegradable mulching film coverings [36]. In addition to the use of agricultural mulch films for protection, the utilization of fertilizers required by plants can also be further enhanced through encapsulation. For example, chitosan forms complexes with other compounds in the presence of amino acids and enters the vascular system of plants to activate the metabolic and physiological pathways of plants. In this way, chitosan can be combined with fertilizers or other nutrient elements to provide the necessary nutrients for plants, and it can also help improve soil texture [37].

In biomedical applications, biodegradable barrier materials have been widely used in fields such as bone and soft tissue regeneration engineering, cell therapy vector construction, and drug-controlled-release systems due to their excellent mechanical properties, superior biocompatibility, controllable degradation performance, and non-toxic metabolites [38]. The combination of biodegradable barrier materials (such as TPS) and bioactive ceramics significantly enhances the performance of bone repair materials. For example, the TPS composite material doped with 10% β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) nanoparticles [39] not only significantly improved mechanical properties, but also exhibited excellent biocompatibility. Particularly noteworthy is that it has good cell compatibility in bone tissue engineering applications, and no signs of cytotoxicity were observed. In the field of drug-controlled-release systems, some researchers have taken advantage of the pH-sensitive property of chitosan as a starting point to use it to create intelligent and efficient drug delivery systems. The sensitivity of chitosan to pH changes is due to the amine functional groups of chitosan being easily protonated in acidic pH conditions. Therefore, based on the unique pH value in the target environment, the drug molecules are released through swelling [40].

Bio-based biodegradable materials have permeated core fields such as packaging, agriculture, and healthcare, and are demonstrating potential in emerging directions such as construction and electronics. For example, bio-based composites based on wood and mycelium have been used in the construction field. This innovative insulation material has a thermal conductivity as low as 0.04 W/(m K) [41]. PLA/nanocellulose composites can be used to manufacture biodegradable capacitive touch sensors, and the electromagnetic shielding efficacy of PLA films containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes reaches 40 dB [42]. A dense silica coating is constructed on the surface of PLA products by a splash deposition process, which enhances the surface barrier property. The oxygen barrier property is increased by more than 10 times, and it is suitable for the packaging of degradable electronic components.

3 Classification of Bio-Based Biodegradable Barrier Materials

Bio-based biodegradable barrier materials refer to materials made from natural renewable resources (such as plant fibers, starch, proteins, etc.), which have excellent biodegradability and barrier performance. They can be decomposed by microorganisms into water and carbon dioxide in the natural environment, while effectively preventing the penetration of substances such as water vapor and oxygen.

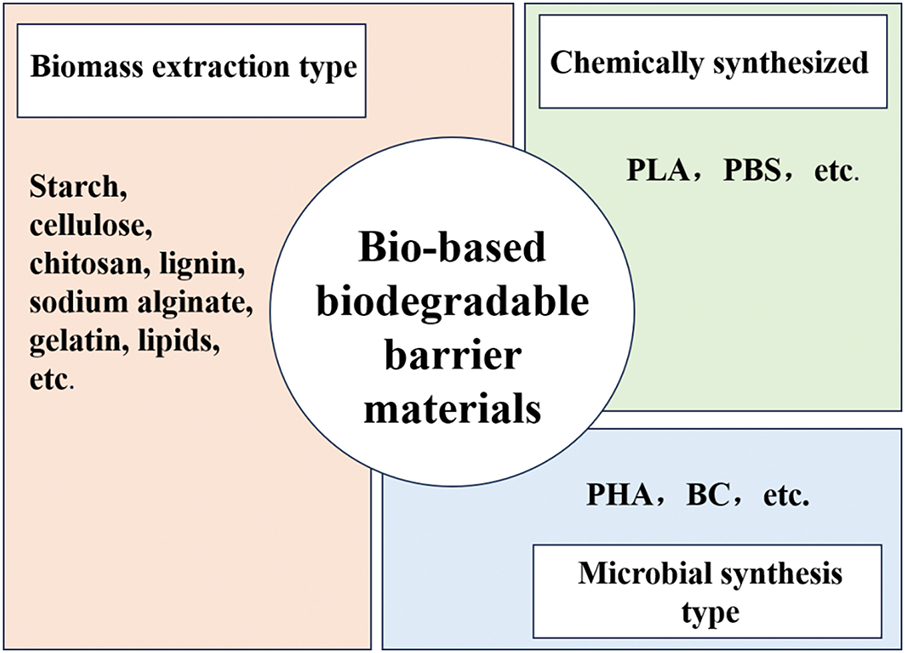

Bio-based barrier materials, as green alternatives to petroleum-based barrier materials, have shown great potential in the barrier fields of packaging, medicine, agriculture, etc., due to their biodegradable properties and renewable advantages. According to the source and synthetic route, bio-based biodegradable barrier materials can be classified into three major categories (Fig. 2): (1) Biomass extraction type [43]; (2) Chemical synthesis molding; (3) Microbial synthesis. These three types of materials have significant differences in structural characteristics, processing performance, and degradation behavior, and their functions need to be optimized through modification techniques to meet the requirements of practical applications.

Figure 2: Classification of bio-based biodegradable barrier materials

3.1 Biomass Extraction Type Barrier Materials

Biomass extraction type biodegradable barrier materials are materials made from biodegradable natural polymers as the base material. Such degradable materials have abundant raw material sources, can be completely biodegraded, and the products are safe and non-toxic. The main natural polymer materials in nature include: polysaccharides (such as starch, cellulose, chitosan, sodium alginate and pectin, etc.), proteins (gelatin, whey protein, soy protein, corn protein and silk protein, etc.), lipids (wax, glyceryl acetate and emulsifiers, etc.) and special polymers (lignin, shellac and natural rubber, etc.).

3.1.1 Starch-Based Barrier Materials

Starch is a natural high-molecular polysaccharide formed by the polymerization of α-glucose units through glycosidic bonds. It is commonly stored in the form of granules in plants. The molecular chain of starch contains a large number of reactive hydroxyl functional groups. Coupled with its inherent good biocompatibility and film-forming ability, it is easy to regulate its properties through chemical modification or enzymatic treatment. Therefore, it has become a highly promising biodegradable natural high-molecular material [44,45]. Starch is widely available and can be sourced from commercial-scale production of such crops as corn, potatoes, and cassava. Its price is significantly lower than that of petroleum-based polymers [46]. For instance, the cost of cassava starch is only 0.99 €/L, while that of synthetic gelling agents is as high as 5.98 €/L. Moreover, the production cost of starch-based films is approximately 1.18 €/kg (including the costs of recycling/combustion treatment), while the cost of petroleum-based PE materials is 1.56–2.25 €/kg. By blending and modifying (such as combining with PBAT and PVA), the cost can be further reduced [47,48]. For instance, in PBAT/TPS (thermoplastic starch) composites, the starch content reaches 30%, resulting in a 20%–30% reduction in total cost [49].

Starch has two structures: amylose and amylopectin. The ratio of linear/branched starch is one of the key factors regulating the mechanical and barrier abilities of starch-based materials. Changes in this ratio can be used to purposefully adjust the rigidity and toughness of the material, as well as its barrier effect against gases and water vapor. A high content of amylose can enhance tensile strength and barrier properties. In the study of Zhao et al. [50], potato starch and wheat starch were respectively mixed with chitosan solution in a volume ratio of 1:1, and glycerol was used as the plasticizer to cast and form films. The research results reveal that there are significant differences in the properties among different starch-based composite films. The quality fraction of linear amylose in potato starch is 14%. The prepared composite film has the best tensile elongation and permeability. The tensile elongation can reach 55.65% (much lower than that of petroleum-based barrier materials), and the OP is slightly higher than that of PET at 3.47 cm3 mm/(m2 day atm). The branched amylose quality fraction in wheat starch is 27%. The prepared composite film has the best tensile strength and barrier performance. The tensile strength can reach 14.04 MPa (lower than 55 MPa of PET), and the OP is 0.13 cm3 mm/(m2 day atm), while WVP is comparable to PP at 1.03 g mm/(m2 day atm). The composite films are all hydrophilic materials, and the various film-forming substances have good compatibility with each other. Although the WVP of the starch film is comparable to that of traditional petroleum-based barrier materials, the tensile elongation and tensile strength of a single starch film are far lower than those of materials such as PP and PE.

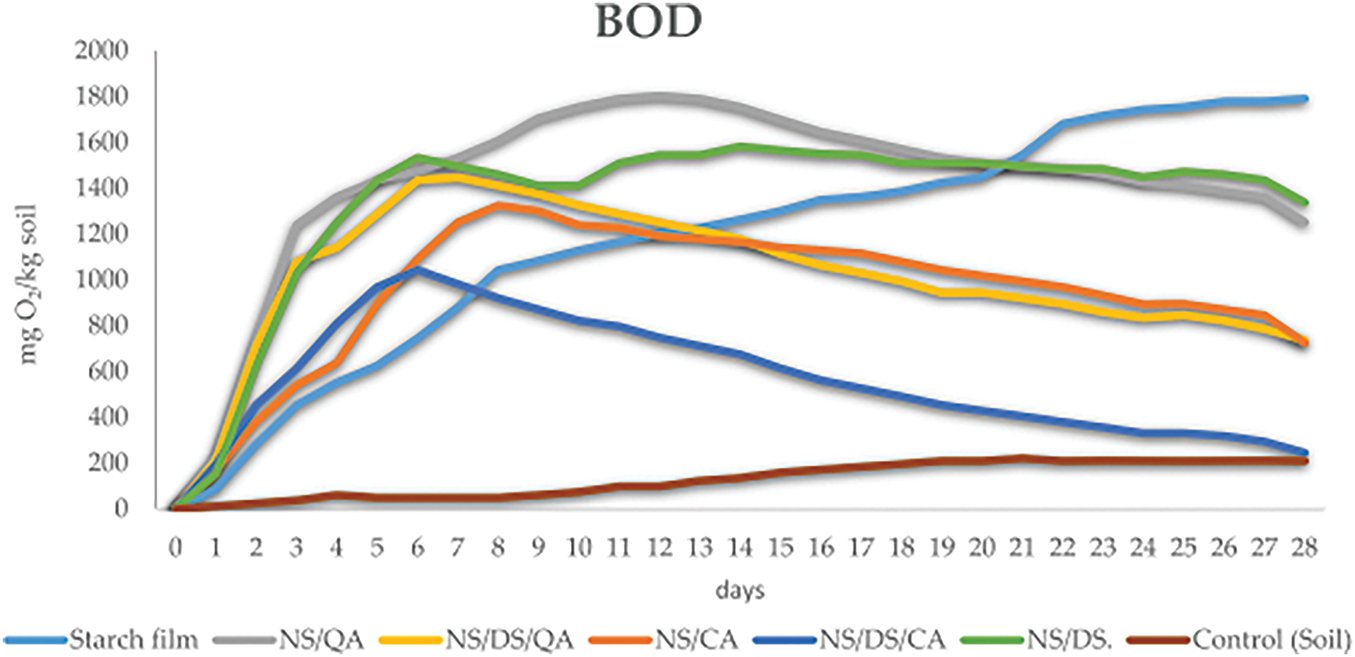

To address the shortcomings of natural starch films, such as low tensile strength, low elongation at break, and poor water resistance, their properties can be improved through physical (gelatinization, blending) or chemical (polymerization, cross-linking) modification methods [51]. Research shows that after starch is blended with PVA, the mechanical strength (tensile strength up to 27.57 MPa) and waterproofing ability of the material can be markedly enhanced through cross-linking reaction, and the degradation rate of soil burial within 60 days exceeds 65% [52]. Furthermore, the team of Bajer [53] innovatively used potato starch (PS) as the matrix, constructed a molecular network through a dialdehyde starch (DS) crosslinking agent, and synergistically introduced natural phenolic compounds such as caffeic acid (CA)/quinic acid (QA). A new type of food packaging material with high barrier properties, mechanical reinforcement, and antioxidant synergistic effects has been successfully developed. Studies have shown that the aldehyde group of DS forms covalent cross-linking with the hydroxyl group of starch, effectively regulating the proportion of crystallization-amorphous regions of starch. By increasing the entanglement density of the molecular chain, the tensile strength is enhanced by 38%. The catechol structure in CA/QA endows the material with a significant DPPH radical scavenging ability (with a scavenging rate of 92% ± 3%), and its antioxidant efficacy is 5–7 times higher than that of unmodified starch. To evaluate the biodegradability of the barrier membrane, this study verified it by measuring the microbial biological oxygen demand (BOD) in the soil environment (results shown in Fig. 3). The data indicated that the biodegradation rates of all materials were closely related to their chemical compositions. The BOD values of all starch-based samples were significantly higher than those of the control group, confirming that they were more easily utilized by microorganisms. Notably, the biodegradation kinetics of the modified starch membrane exhibited typical two-stage characteristics: the initial degradation was rapid (most significant from the 12th day), and then the rate gradually slowed down.

Figure 3: BOD data of the biodegradation process of starch films in the soil environment. Adapted with permission from Ref. [53]. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier

In the research on starch-based composites. Zhang et al. [54] used activated starch as the substrate and introduced a stable citrus essential oil pickering emulsion (PLCPE) based on pectin-nanocellulose to develop a composite membrane. Through experiments, it was verified that the PLCPE could be well compatible with the starch substrate, fill the intermolecular gaps, and enhance cross-linking through hydrogen bonds, significantly improving the mechanical properties of the pure starch membrane. As the amount of PLCPE increased (1%–10%), the film tensile strength gradually increased, reaching up to 2.5 times that of the pure starch membrane; the trend of the elongation at break was consistent with the tensile strength, also increasing with the increase in PLCPE addition amount. Only when the PLCPE addition amount reached 25%, due to the disruption of the starch matrix continuity caused by emulsion aggregation, did the tensile strength decrease. The research has found that when PLCPE forms new hydrogen bonds with starch, it hinders the hydrogen bond interaction between starch and water molecules. Moreover, due to the hydrophobicity of the nanocellulose in PLCPE and its uniform dispersion in the starch matrix, a dense network structure is formed. This not only enhances the hydrophobicity of the film surface (when the PLCPE addition amount increases, the film WCA shows a concentration-dependent increase, reaching up to 90.75°, while the water contact angle of the pure starch membrane is only 69.00°), but also significantly reduces the WVP and OP of the PLCPE-starch composite membrane. The composite membrane material is derived from natural plants, is biologically safe and degradable, providing a new solution for replacing petroleum-based plastics and reducing food waste. It can also be utilized for the development of edible films and medicinal capsules [55]. Ilyas et al. [56] used agricultural waste as the raw material and adopted the solid-state casting method to prepare biocomposite materials (with plasticized sugar palm starch (PSPS) of proportion from 0.1 wt.% to 1.0 wt.%). The focus was on investigating their thermal properties, water barrier properties, and soil biodegradability. The results showed that the constituents of high compatibility and strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds between PSPS and sugar palm nano-fibrillated celluloses (SP-NFCs), as the content of SP-NFCs increased, the thermal stability of the composite materials (such as TMax increasing from 305.14°C to 315.81°C) improved. The uniformly dispersed SP-NFCs formed tortuous permeation paths in the composite materials, and the hydrogen bond between SP-NFCs and PSPS reduced the number of hydroxyl groups in PSPS, thereby improving the water barrier properties of the composite materials (WVP decreasing from 9.58 × 10−10 to 1.21 × 10−10 g/smPa). Because the interface interaction between SP-NFCs and PSPS enhanced the structural stability of the material and slowed down the erosion rate of microorganisms on the substrate, the degradation of the composite materials was slower, but they could still be completely degraded. This material can be applied in short-term life cycle environmentally friendly products such as plastic packaging and food containers, providing a green alternative to petroleum-based materials.

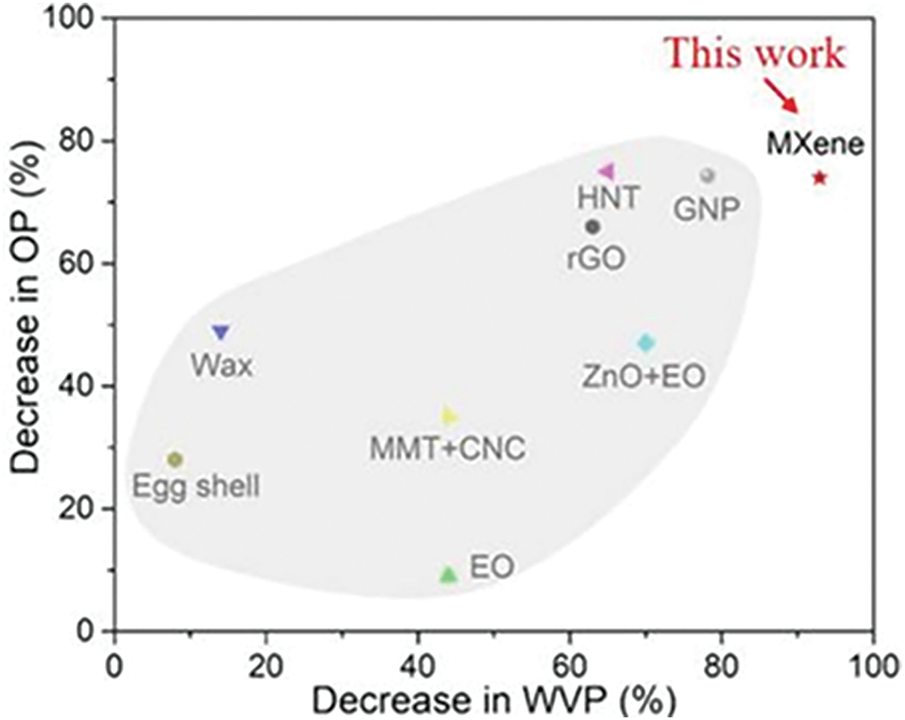

There are also studies that, by compounding with nano-fillers, improve the inherent defects of starch, enhance its mechanical properties and barrier performance, and even the prepared composite films can be rapidly degraded in the soil. In the study of Dong et al. [57], MXene nanosheets were used to overcome the limitations of starch itself. Adding 10% MXene enables a significant leap in the performance of the starch film: the mechanical strength is greatly enhanced (with a modulus of 1923 MPa and a strength of 19 MPa), and at the same time, the barrier properties are excellent (water vapor barrier improves by 92.9%, oxygen barrier improves by 74%). This high-performance starch-based film is expected to replace traditional plastics and be applied in various high-end packaging scenarios. Fig. 4 shows that MXene nanosheets, as fillers, can significantly enhance the oxygen barrier and WVP of starch films compared with other fillers. In addition, these films retain their biodegradability and decompose in the soil after six weeks. These outstanding performances fully demonstrate its great potential in the field of sustainable applications, especially in the packaging industry. The excellent moisture and gas barrier properties are the key to achieving long-term product quality preservation. The successful introduction of montmorillonite nanosheets into the starch matrix marks an important progress in enhancing the functionality of biopolymers without sacrificing biodegradability, providing a feasible solution that combines high performance and environmental benefits to replace traditional non-degradable materials.

Figure 4: The relationship between the WVP and OP values of starch films and different fillers. Adapted with permission from Ref. [57]. Copyright © 2024, American Chemical Society

3.1.2 Cellulose-Based Barrier Materials

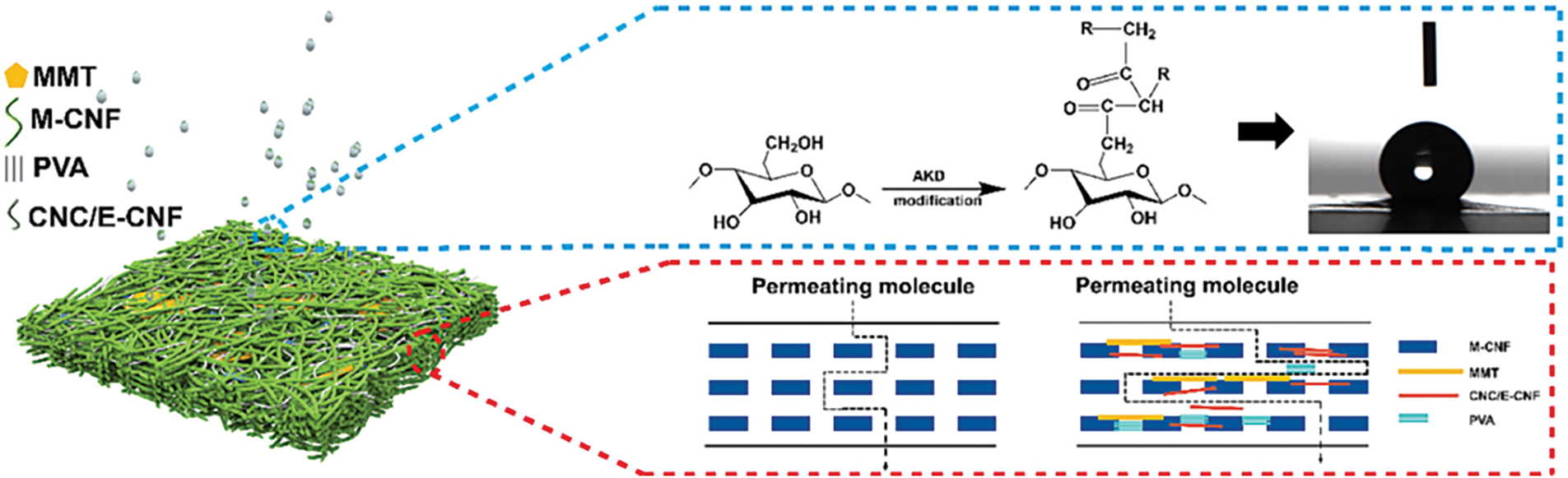

Cellulose is a natural polymer composed of D-glucose units linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds. It is the most abundant renewable polysaccharide resource in nature. Its derivatives have excellent physical and chemical properties, such as high strength, high modulus, good toughness, and gas barrier performance. Therefore, they have extensive applications in many fields [58]. Cellulose performs well in terms of oxygen barrier and biodegradability, but its strong hydrophilicity limits its application in food packaging. Cellulose nanofilaments (CNF) can be prepared through enzyme pretreatment combined with mechanical pretreatment and compounded with materials such as montmorillonite (MMT) to effectively improve their barrier performance [59]. For instance, Zeng et al. [60] successfully constructed a multi-scale enhanced composite film by introducing two-dimensional (2D) montmorillonite (MMT) nanosheets and one-dimensional (1D) cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) into a three-dimensional (3D) cellulose nanofiber (CNF) network structure. In this study, PVA was further used as the adhesive, and hydrophobic modification was carried out using diethylene ketone (AKD). Eventually, an M-CNF/CNC composite film with excellent barrier properties was prepared. Based on this, this research systematically explored the influence of laws of different dimensional and size ratios of nanocellulose combinations on the microscopic densification degree, mechanical properties, and barrier behavior of the film. Through the innovative design of the membrane structure, this material exhibits outstanding comprehensive performance: its tensile strength reaches as high as 209.37 MPa, and it possesses excellent flexibility, capable of withstanding 6849 repeated folds without breaking. In terms of barrier properties, the composite membrane shows an extremely low gas permeability, with the water vapor permeability being only 0.062 cm3 mm/(m2 day atm), and the oxygen permeability being as low as 0.193 g mm/(m2 day atm). These characteristics indicate that this material has significant application value in the high-end packaging field. In addition, the composite membrane has excellent water and oil resistance and remains impermeable throughout the 10-h soaking process. Based on this, researchers believe that modifying nanocellulose with AKD reduces the solubility of water vapor on the surface. Meanwhile, the structure within the nanocellulose membrane extends the diffusion path of water vapor molecules, both of which enhance the water vapor barrier performance of the film. Fig. 5 shows a schematic diagram of the M-CNF/CNC membrane structure and the added diffusion path within the nanocellulose membrane. In another study, Meng et al. [61] compounded cellulose nanofibers (TOCNFs) with natural rubber latex (NRL) to prepare a composite membrane. The WVP and OP of this membrane were as low as 6.07 × 10−13 g/(m2 s Pa) and 3.11 × 10−15 cm3 cm/(cm2 s Pa), respectively. This composite membrane exhibits excellent water resistance. Its wet tensile strength can reach 15.87 MPa, which is equivalent to 71.69% of its dry strength. Meanwhile, the high ductility of NRL significantly enhances the toughness of the composite membrane. Its elongation at break is approximately three times that of other nanocellulose-based membranes, demonstrating excellent fracture resistance.

Figure 5: Schematic diagram of the M-CNF/CNC membrane structure and the added diffusion paths within the nanocellulose membrane. Adapted with permission from Ref. [60]. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier

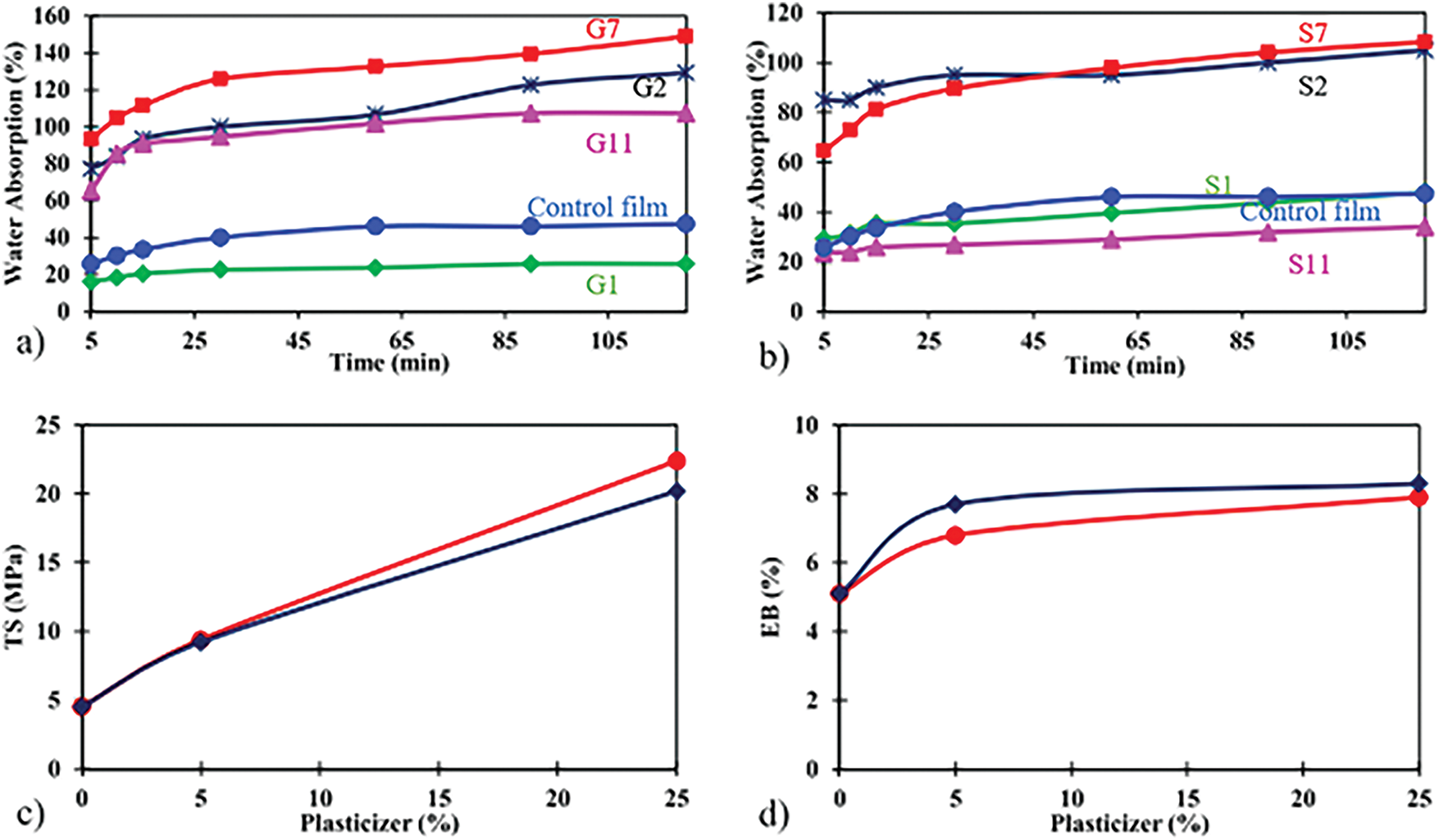

Some studies have also revealed the influence mechanism of plasticizer types on the performance of cellulose-based films, laying the foundation for the development of controllable degradable packaging materials [62]. For example, the Paudel et al. team [63] adopted the Box-Behnken experimental design to optimize the preparation process of microcrystalline cellulose films and systematically compared the action mechanisms of glycerol and sorbitol plasticizers. Experiments show that the glycerol system has a water vapor transmission rate 1.8 times higher than that of the sorbitol system due to its strong hydrophilicity. However, both exhibit excellent biodegradability (degradation rate >80% within 30 days) in soil degradation experiments. Fig. 6 elaborately demonstrates the influence of introducing different contents of glycerol and sorbitol on the water absorption rate, elongation at break, and tensile strength of cellulose films. Furthermore, combining with other biodegradable materials (such as PLA and starch) can significantly enhance the mechanical properties of the cellulose membrane [64]. For instance, cellulose nanofilaments can increase the creep resistance of starch films by 15%–20%, while the strength of starch films reinforced by 7% cellulose nanocrystals is close to that of polyolefins [65,66].

Figure 6: Effects of glycerol and sorbitol on the water absorption rate of the film (a, b) and the tensile strength (c) and elongation at break (d) of the film. Adapted with permission from Ref. [63]. Copyright © 2023, Elsevier

To address the issues of high-water absorption and poor barrier performance of cellulose nanofibers (CNF) in packaging applications under humid conditions. A research team drew inspiration from the cell walls of plants in nature and utilized the catalytic oxidation effect of laccase to polymerize lignin in the aqueous dispersion of carbon nanofibers, thereby preparing a carbon nanofiber/polymerized lignin coating that is entirely composed of bio-composites. When using isopropanol as the lignin component with a loading of 15 wt.% and an enzymatic polymerization time of 6 h, the coating performance was the best—the film water contact angle reached approximately 120°, and the Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) of the coated cardboard decreased by 54%, the oxygen transmission rate (OTR) decreased by 52 times, and the lipid barrier performance reached KIT level 12. Adding carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) can improve the coating’s rheological properties and uniformity [67]. Compared to traditional petroleum-based plastic coatings (such as polyethylene PE) and other biobased coatings (such as chitosan, starch-based), the advantages are: 1. The fully biobased components (CNF, lignin, CMC) are biodegradable, avoiding the environmental accumulation problem of petroleum-based plastics; 2. Excellent barrier properties against water vapor, oxygen, and lipids (WVTR decreased by 54%, OTR decreased by 52 times, KIT = 12), while chitosan coatings typically only reduce WVTR by 30%–40%, and starch-based coatings are prone to absorbing moisture, resulting in unstable barriers; 3. Strong affinity with paper/cardboard substrates, and does not affect the original mechanical properties of the substrate. Although the fully biobased CNF/polymerized lignin has many advantages, its hydrophobicity still has room for improvement, and the long-term barrier stability under high humidity has not been clearly defined. At the same time, since the preparation of CNF requires high-pressure homogenization, the cost is high, and the difficulty of large-scale production is relatively high.

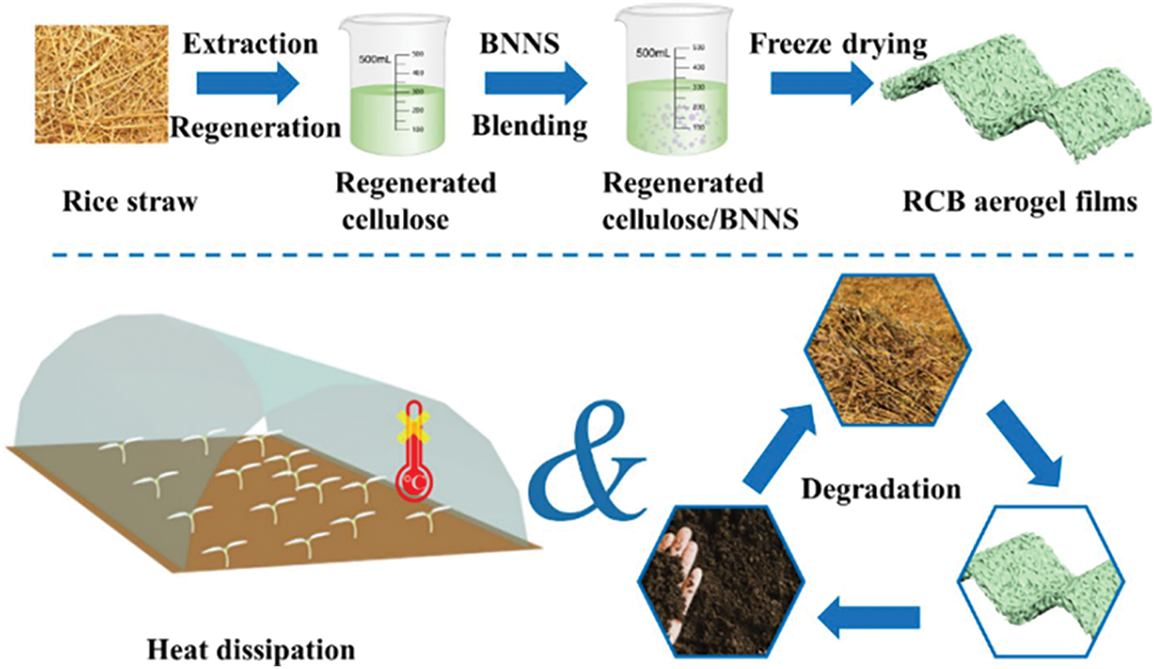

To address the problem of traditional agricultural film pollution, Chen’s et al. team [68] combined regenerated cellulose/boron nitrogen nanosheets (BNNS) through multi-scale structural design, and processed them into regenerated cellulose/BNNS aerogel films (RCB aerogel films) through dissolution, regeneration, and freeze-drying. Fig. 7 is a detailed flowchart for the preparation of RCB films. Using waste straw as raw material, a three-dimensional interpenetrating network was constructed through dissolution-regeneration-freeze-drying. Among them, BNNS and cellulose formed a dense interface through hydrogen bonds (with a binding energy of −28.6 kJ/mol), increasing the tensile stress to 27.46 MPa, which was 16.85 times stronger than that of pure cellulose aerogel. In terms of thermal management performance, RCB aerogel shows a high thermal conductivity of 4.023 W/(m K). In the simulated sunlight experiment, it can reduce the temperature inside the film by 6°C compared with the traditional ground film, which is due to the rapid heat conduction channels established by BNNS. The degradation experiment showed that it was completely mineralized within 25 days, while the weight loss rate of polyethylene mulching film during the same period was less than 5%, demonstrating significant environmental protection advantages [69].

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of the preparation process of biodegradable cellulose-based aerogel heat dissipation film for agriculture. Adapted with permission from Ref. [68]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature

Chitosan (CS) is a kind of polysaccharide made from the shells of shrimps and crabs, etc. It has a large stock among many bio-based materials and is a non-toxic and inexpensive polysaccharide. It has the advantages of good biodegradability, biocompatibility, and antibacterial properties, and is a material of great concern to many researchers. Among them, CS-based films are one of the research directions. Besides the above advantages, they also have excellent mechanical properties [70]. However, as a biodegradable barrier material, CS still has several inherent drawbacks. For instance, the hydroxyl structures present in the molecular chains of CS result in relatively low hydrophobicity. Therefore, its barrier properties, mechanical strength and antibacterial activity can be enhanced through chemical modification (mainly including carboxymethylation, graft copolymerization and cross-linking, etc.) or in combination with other bio-based materials (cellulose, starch, chitin), plant/animal proteins (corn alcohol-soluble protein, whey protein, gelatin), beeswax and minerals (montmorillonite and graphene), etc.

Liu et al. [71] conducted research on CS and beeswax in improving the gas-blocking ability of paper-based materials, and explored the effects of the addition amount of beeswax and its compounding method with chitosan (blending and stratification) on the barrier abilities of paper-based materials and the thermal stability of the coating. The results show that the WVP of the coated paper decreases with the increase in the amount of beeswax. When the addition amount of beeswax is 15%, under the condition of 50% RH, the WVP of the layered coated paper and the blended coated paper decreases to 21.87 and 24.13 g mm/(m2 d atm), respectively. Compared with the pure chitosan-coated paper, it was reduced by 80.3% and 78.2%, respectively. There was no significant difference in water vapor transmission between layer-coated paper and blended coated paper. Under 75% RH conditions, the WVP of layer-coated paper (163.69 g/(m2 d atm)) and blended coated paper (242.24 g/(m2 d atm)) decreased by 79.4% and 69.5%, respectively, compared with pure chitosan coated paper, while compared with blended coated paper, the WVP of layer-coated paper decreased by 32%. The oxygen transmission rates of blended coated paper and layered coated paper increased with the increase of beeswax addition. When the beeswax addition rate was 15%, the oxygen transmission rates of layered coated paper and blended coated paper were still as low as 70.19 and 101.75 cm3/(m2 d atm), respectively. The final results revealed that the chitosan/beeswax composite method also had a significant impact on the gas barrier performance of paper-based materials.

Lignin is the second most abundant natural polymer material in nature. Globally, over 50 million tons of industrial lignin are produced annually through papermaking and bioethanol processes. However, due to the complexity of the structure of lignin itself and the insolubility of most lignin, approximately 98% of lignin is used as fuel each year, and only about 2% of lignin is effectively utilized [72,73]. Lignin is a renewable resource rich in repeating benzene ring structural units and has advantages such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, and excellent processability. Moreover, lignin has unique properties such as hydrophobicity, flame retardancy, UV blocking, and antioxidant properties, and can be developed as a functional component of barrier materials [74].

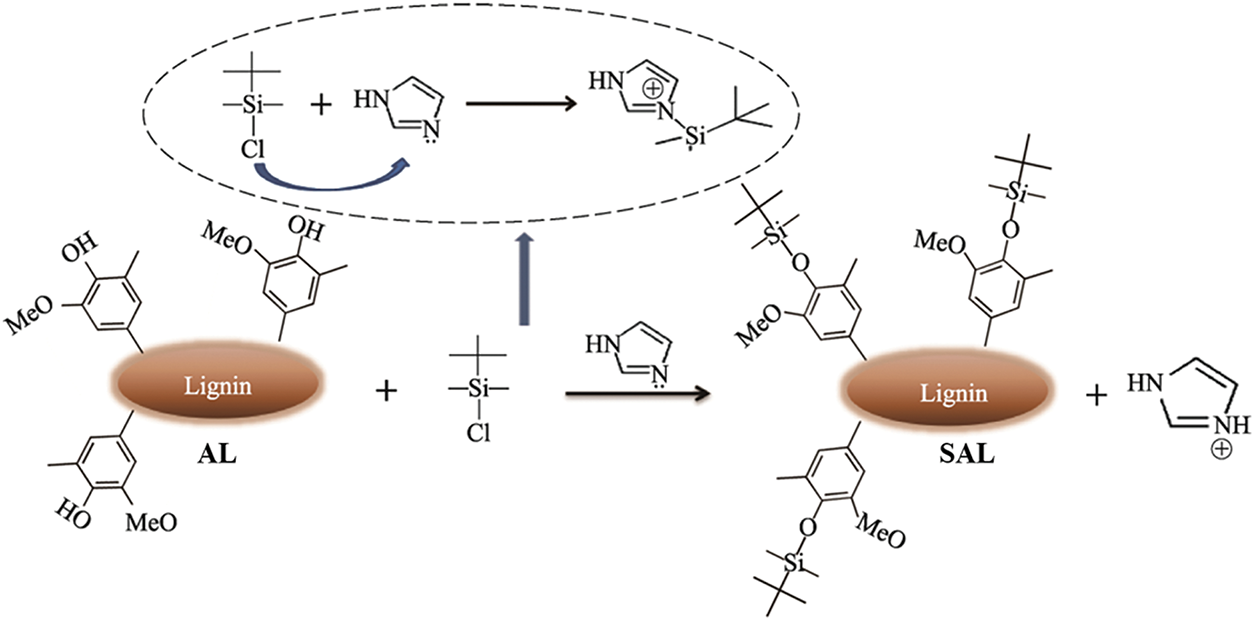

The reticular dense structure of lignin molecules and their filling effect on fiber pores endow them with better performance in inhibiting oxygen permeation. Meanwhile, as most lignin itself has a relatively high hydrophobic property, the structure of the composite material is less likely to be damaged by water vapor and swell under high humidity conditions, which is more conducive to maintaining a high oxygen barrier performance. Therefore, lignin has significant research value in the development of oxygen barrier materials. For instance, some researchers blended silicified lignin (SAL, the silaneation process is shown in Fig. 8) with PBAT to prepare SAL/PBAT composite membranes with better performance. Compared with the pure PBAT membrane, the mechanical and barrier properties of the SAL/PBAT composite membrane have been significantly improved. The tensile strength increased by 31.0%, but the elongation at break decreased by 37.4%. At the same time, its barrier properties were significantly enhanced, with the oxygen permeability and water vapor permeability reducing by 39.4% and 42.4%, respectively. These results indicate that the synergistic enhancement effect between the modified lignin (SAL) and the PBAT matrix has effectively optimized the comprehensive performance of the composite material. The modified membrane can extend the application of starch-based materials in various industries by creating a more effective barrier. Moreover, due to the hydrogen bonds between lignin molecules causing aggregation, nano-crystallization will increase its specific surface area and improve its compatibility with the polymer matrix. In addition, lignin is transformed into nanoparticles through chemical pathways. Nanoscale lignin materials have many advantages, such as mono-dispersion and high specific surface area, and have been used as barrier enhancers on cardboard and paper packaging [75]. In addition, there are also research reports on the preparation of nano-lignin particle/sodium alginate composite films by the casting method. The addition of nano-lignin particles endows the composite film with excellent ultraviolet and gas barrier properties, which can be used for the preservation of agricultural products such as fruits and vegetables. With the increase of the extent of nano-lignin particles in the composite film, its thermal stability and ultraviolet absorbance improve, while the equilibrium moisture content and water vapor transmission rate decrease significantly. After 24 h, its water vapor transmission rate is only 1/3 of that of the control group.

Figure 8: Schematic diagram of lignin silanization modification

Sodium alginate (SA) is a common linear polysaccharide substance. Alginates have many advantages, such as strong film-forming ability, non-toxicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility, making alginates one of the most promising and deeply studied bio-based materials. Furthermore, its structure contains a large number of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, which enable it to easily mix with various substances in water, thereby preparing composite films. However, sodium alginate films have defects such as poor mechanical properties, strong brittleness, and low barrier performance, which limit their application in food packaging [76]. To improve the barrier property of sodium alginate membranes, researchers have attempted to enhance the barrier performance of the membranes by combining them with substances such as cellulose, PVA, or nanoparticles.

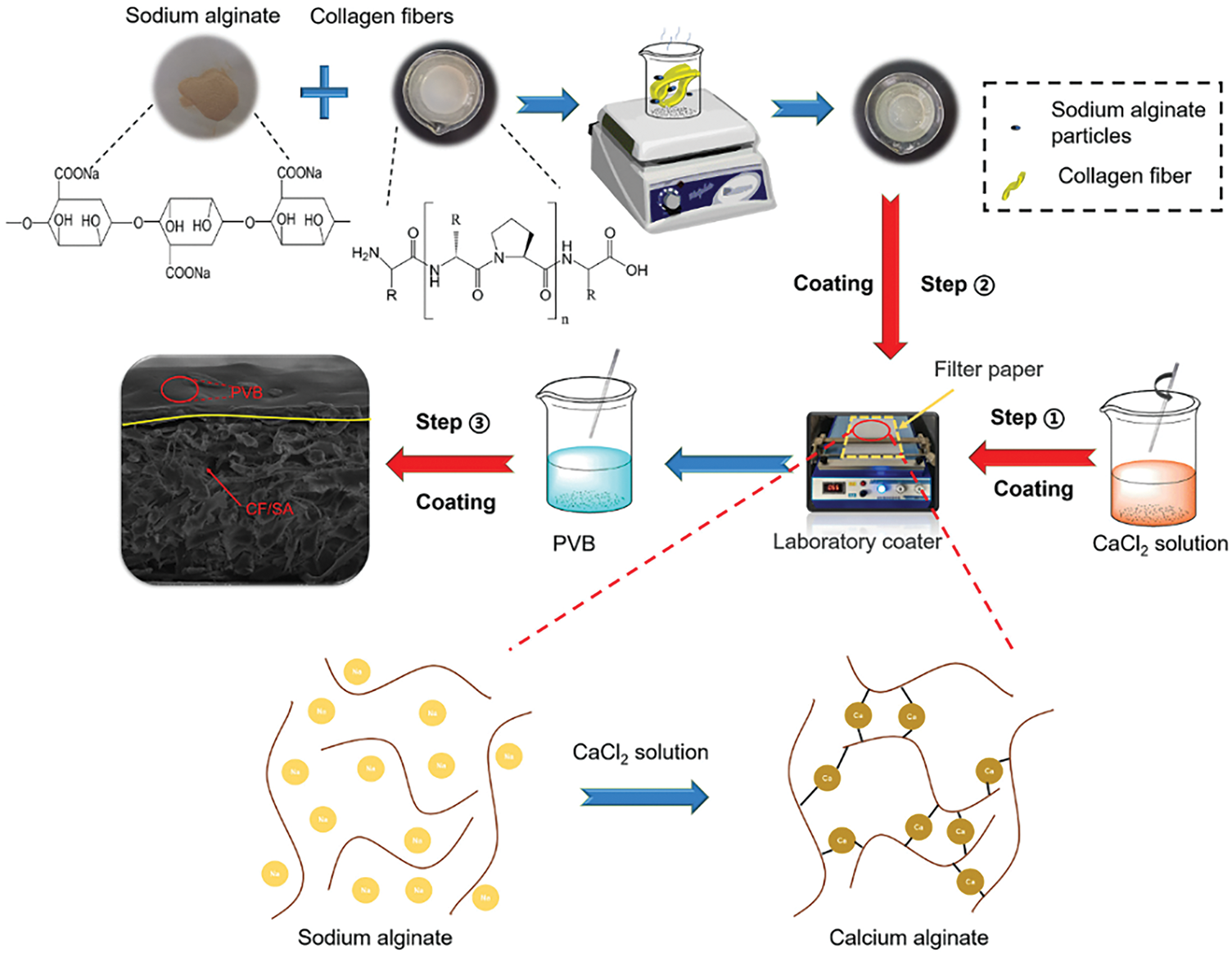

Sodium alginate, due to its excellent antibacterial and antioxidant properties, has been used in the design of functional paper-based packaging materials. It can be prepared by coating paper with a mixture of sodium alginate and carboxymethyl cellulose. Depending on the combination of coating materials, the water barrier performance is significantly enhanced. Jing et al. [77] successfully prepared a composite coating using SA aqueous solution, collagen fibers (CF), and polyvinyl alcohol butyraldehyde (PVB) as raw materials. Firstly, CF was mixed with different mass fractions of SA solution, and after thorough stirring to achieve uniformity, it was applied onto the surface of the paper substrate that had been pre-treated with CaCl2 to induce ionic cross-linking reaction. Subsequently, PVB solution was applied onto this substrate again to form a composite barrier coating. Fig. 9 shows the specific process of preparing the CF/SA/PVB-coated paper. This composite coated paper has excellent interface properties, with the water and oil contact angles reaching 51° and 48°, respectively. During the testing process, the material shows significant contact angle stability with a low attenuation rate. Performance analysis indicates that the hydrophobic/hydrophilic property of the coated paper is positively correlated with the SA addition amount, and reaches saturation at a concentration of 2.8%, at which point the optimal comprehensive barrier performance can be achieved. In addition, after coating with sodium alginate and collagen fibers, the WVP significantly decreased (725 g/(m2 day atm)), while that of uncoated paper was 975 g/(m2 day atm), and after adding PVB coating, the WVP further reduced to approximately 48 g/(m2 day atm).

Figure 9: The preparation flowchart of the CF/SA/PVB composite material. Adapted with permission from Ref. [77]. Copyright © 2021, Elsevier

3.1.6 Gelatin Barrier Material

Gelatin is a partial degradation product of collagen in animal connective tissue. It is mainly composed of amino acids such as glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline, and also contains aromatic amino acids, which can endow gelatin materials with certain ultraviolet shielding ability. Gelatin, with properties such as water solubility, foaming, and emulsification, is a highly popular natural polymer material. It is widely applied in such fields as medicine, food, and packaging [78]. In the field of food packaging, gelatin has become a research hotspot due to its excellent film-forming property, gas barrier property, and biodegradability. However, the water resistance performance property of pure gelatin film deteriorates with the increase in humidity. But by compounding with chitosan, its synergistic effect can reduce the WVP by 30% while maintaining a tensile strength of approximately 25 MPa [79]. Liu et al. [80] addressed the performance limitations of gelatin films and innovatively introduced three natural bioactive materials (red yeast rice pigment (MR), algal blue protein (PH), and safflower yellow (SY)) that possess coloring, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. These materials were combined with gelatin/chitosan to prepare functional films. The experiment revealed that there were hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions between the three bioactive materials and gelatin/chitosan, forming a dense structure. The introduction of all three active materials effectively enhanced the tensile strength of the composite films. Additionally, the composite film exhibited a reduced transmittance of 300–800 nm, significantly increased opacity, effectively blocked ultraviolet rays, prevented food oxidation and spoilage, and due to the formation of a dense structure, significantly reduced the oxygen permeability to a minimum of 9.14 × 10−14 cm3 cm/(cm2 s Pa).

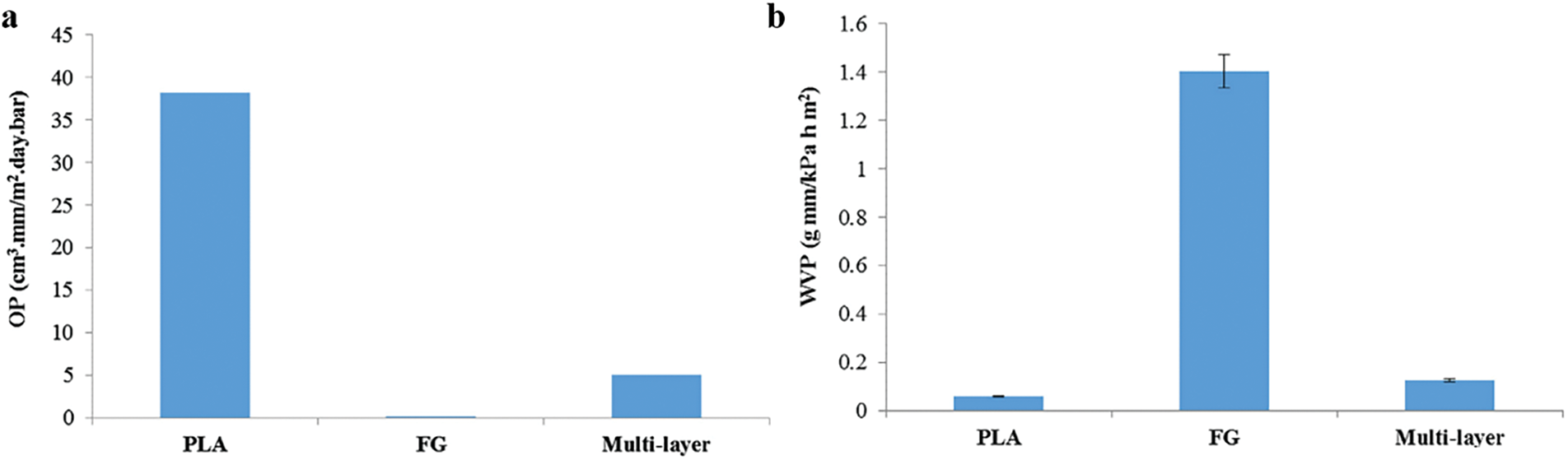

Moreover, Hosseini et al. [81] prepared fish gelatin (FG)/PLA multilayer film structures by the solvent casting method, aiming to prepare biofilms with low oxygen permeability. Scanning electron microscope images show that the outer PLA layer and the inner FG layer are closely combined to form a continuous film. Fig. 10a shows the OP of a single film and its multilayer structure. It is found that the OP value (5.02 cm3/ (m2 day atm)) of the prepared multilayer film was more than 8 times lower than that of the PLA. Fig. 10b shows the WVP of a single film and its multilayer structure. It can be obtained from the figure that the WVP (0.125 g mm/(m2 kPa h)) of the multilayer film is also 11 times lower than that of the FG. The composite with PLA greatly enhanced the water resistance of the pure bright rubber film. The tensile strength of the three-layer film (25 ± 2.13 MPa) is higher than that of the fiberglass composite film (7.48 ± 1.70 MPa). Meanwhile, the obtained film maintains high optical transparency.

Figure 10: (a) (OP) of a single membrane and its multilayer structure; (b) WVP of a single membrane and its multilayer structure. Adapted with permission from Ref. [81]. Copyright © 2016, Elsevier

Although gelatin films have made progress in chemical and mechanical property research as well as in the exploration of food packaging applications, the core challenge is their poor water vapor barrier performance. The existing improvement strategies include: adding fatty acids, preparing composite blends with inorganic/organic additives, using emulsion systems, adjusting the content of plasticizers, and laminating with other polymer films. To achieve the substitution of traditional plastics by gelatin and other biological polymer films, the problem of insufficient water vapor barrier performance still needs to be solved [78].

Lipids are natural oils derived from the bodies of animals and plants. Generally speaking, lipids are classified into three main categories: simple, derived, and complex lipids. Lipid materials are regarded as promising alternatives to petroleum-based barrier materials due to their characteristics, such as sustainability, biodegradability, and environmental friendliness. Natural oils and fats from animals or plants (fatty acids, monoglycerides, diglycerides, triglycerides), etc., have a key impact on barrier performance due to the differences in lipid chain length, saturation, and crystal arrangement (such as orthorhombic crystal system). Long-chain saturated lipids can further reduce water vapor permeability due to their closely stacked molecules [82,83]. Oils such as paraffin and beeswax, due to their inherent low polarity, are considered to be able to effectively and efficiently block the transfer of moisture. Lipid materials have good water-blocking performance. As the concentration of the hydrophobic (lipid) phase in the material increases, its water vapor permeability decreases. However, its low mechanical strength severely limits its application. It can be used as a coating to be compounded with other materials to improve the functionality of the membrane [84]. For instance, Rastogi and Samyn [85] developed a bio-based hydrophobic coating for packaging paper by combining the deposition of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) particles with nano-fiberized NFC and plant wax. Firstly, polyhydroxybutyrate micro-particles (PHB-MP) and submicron-particles (PHB-SP) were synthesized through a synthesis process, and they were coated onto filter paper to be used as coating materials. Then, comparative experiments were conducted through two methods: simple dip coating and sizing with plant wax solution. The inherent hydrophobicity of PHB-MP coated paper increases, and the static contact Angle is 105°–122°. The thickened coating on the PHB-MP-coated paper significantly improved the contact angle (increasing from 129° to 144°), indicating that it has the potential for hydrophobic modification. In the PHB-SP/NFC coated paper, the contact angle of the wax coating increased from 112° to 152°, showing a positive correlation with the NFC content (0–7 wt.%). Subsequently, the researchers conducted further analysis and discovered that the crystallinity of PHB-SP was higher than that of PHB-MP. This was due to the chemical interaction between the PHB-MP particles and the paper fibers. This reaction was identified as an esterification reaction, and the morphology of the NFC fiber network also played a crucial adhesive role. The PHB-SP with a higher crystallinity is retained on the surface of the paper, thus helping to improve hydrophobicity.

In recent years, bio-based materials from organic sources have made remarkable progress in the preparation of biodegradable barrier materials. Combinations of different types of proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids have been widely used in the preparation of binary and ternary membranes as well as coatings. Butt et al. [86] incorporated different concentrations (0.5%, 1.0%, and 1.5%) of Carnauba wax into sodium alginate and whey protein-based composite films to further enhance their water-blocking performance and mechanical strength. The addition of Carnauba wax can improve the moisture-proof performance and water solubility of the film. At a wax concentration of 1.5%, the water vapor pressure (3.12 ± 0.31 g mm/(m2 kPa h)) and water vapor saturation (26.76 ± 1.01%) of the film are the lowest. In another report, Chevalier et al. [87] prepared protein/lipid composite films by twin-screw extrusion, which combines the lipid’s water/vapor barrier property with the excellent oxygen barrier property of proteins. In this experiment, researchers added the organic acid potassium sorbate (KS) to the prepared protein/lipid composite films. The study showed that even at low concentrations, the presence of KS significantly inhibited Escherichia coli. Additionally, when 10% of KS was added, the mechanical abilities and water resistance of the composite films were significantly improved. For water vapor permeability, among the waxes introduced into sheet materials, only beeswax can effectively reduce WVP (20%).

3.2 Chemically Synthesized Barrier Materials

Chemically synthesized biodegradable barrier materials refer to biodegradable materials synthesized and manufactured by chemical methods. Most of these polymer materials are aliphatic (co-) polyesters with ester group structures introduced into their molecular structures. In nature, ester groups are easily decomposed by microorganisms or enzymes. At present, it has been confirmed that biodegradable barrier materials that can be completely synthesized chemically from bio-based raw materials include PLA and polybutylene succinate (PBS).

PLA is a biodegradable material prepared by the polymerization of lactic acid monomers and derived from renewable resources. Its degradation products are CO2 and H2O, making it an alternative to many traditional petroleum-based barrier materials. PLA has excellent properties, such as outstanding mechanical strength, high modulus, biodegradability, and biocompatibility. Meanwhile, PLA is a semi-crystalline material. Its crystallinity determines the barrier performance of the film. When the crystallinity is low, the barrier performance is poor. The key point restricting the further development of PLA is the barrier performance. Its OP is approximately 480 cm3/(m2 day atm), and the WVP is 130 g/(m2 day atm). None of them meets the requirements of a high barrier. The performance can be improved by compounding with other materials. For instance, the blending modification of PLA with other barrier materials (such as PBAT, PHB, etc.) is an important method to enhance the barrier performance. The PLA/PBAT composite film significantly improves the water vapor barrier property through hydrophobic coating and surface modification. The blending of PLA with PHB with a higher crystallinity significantly improved the oxygen barrier performance [88].

To address the inherent brittleness (elongation at break <5%) of PLA and the insufficient gas barrier performance. Some researchers synthesized poly (butylene glycol diacid-synthetic-pyran maleic acid) (PBDF), which possesses excellent flexibility (elongation at break 450%–780%) and high gas barrier properties. They melted this material with PLA and introduced a multifunctional epoxy compatibilizer to enhance compatibility. PBDF exists as a dispersed phase in the PLA matrix and acts as a “stress concentration point”, inducing shear yield in the PLA matrix and absorbing a large amount of energy, thereby alleviating brittle fracture. Data show that the elongation at break of PLA/PBDF20 increased from 4.3% of pure PLA to 176.7%, an increase of over 40 times. Moreover, the PBDF molecular structure contains a furan ring, and its asymmetric geometric structure and the high dipole moment of the furan epoxy atoms can hinder the penetration paths of gas molecules (O2, CO2, H2O); at the same time, PBDF is uniformly dispersed in the PLA matrix (especially after adding ADR), forming a “physical barrier”, further reducing the gas permeability [89]. Compared with existing toughening schemes (such as PBAT blending), it has the following advantages: 1. The incorporation of PBAT can enhance the toughness of PLA; 2. PBDF itself has both high flexibility (elongation at break 450%–780%) and excellent gas barrier properties (CO2/O2 barrier ratio is 6.0–107.9/7.4–77.3 times that of PBAT), and the O2/CO2/H2O permeability of PLA/PBDF20 after blending with PBDF is reduced by 21.3%, 50.8%, and 46.3% respectively compared to pure PLA; 3. Although the existing schemes with PBAT blending can toughen, PBAT is non-biodegradable; while PBDF is a biodegradable polyester, PLA/PBDF20 loses weight by 19.0% after 5 weeks of composting (pure PLA only 2.7%), and is completely biodegradable 4. The process of mixing PBDF and PLA by means of melt blending (at a temperature of 185°C for 6 min) is simple and more suitable for industrial production.

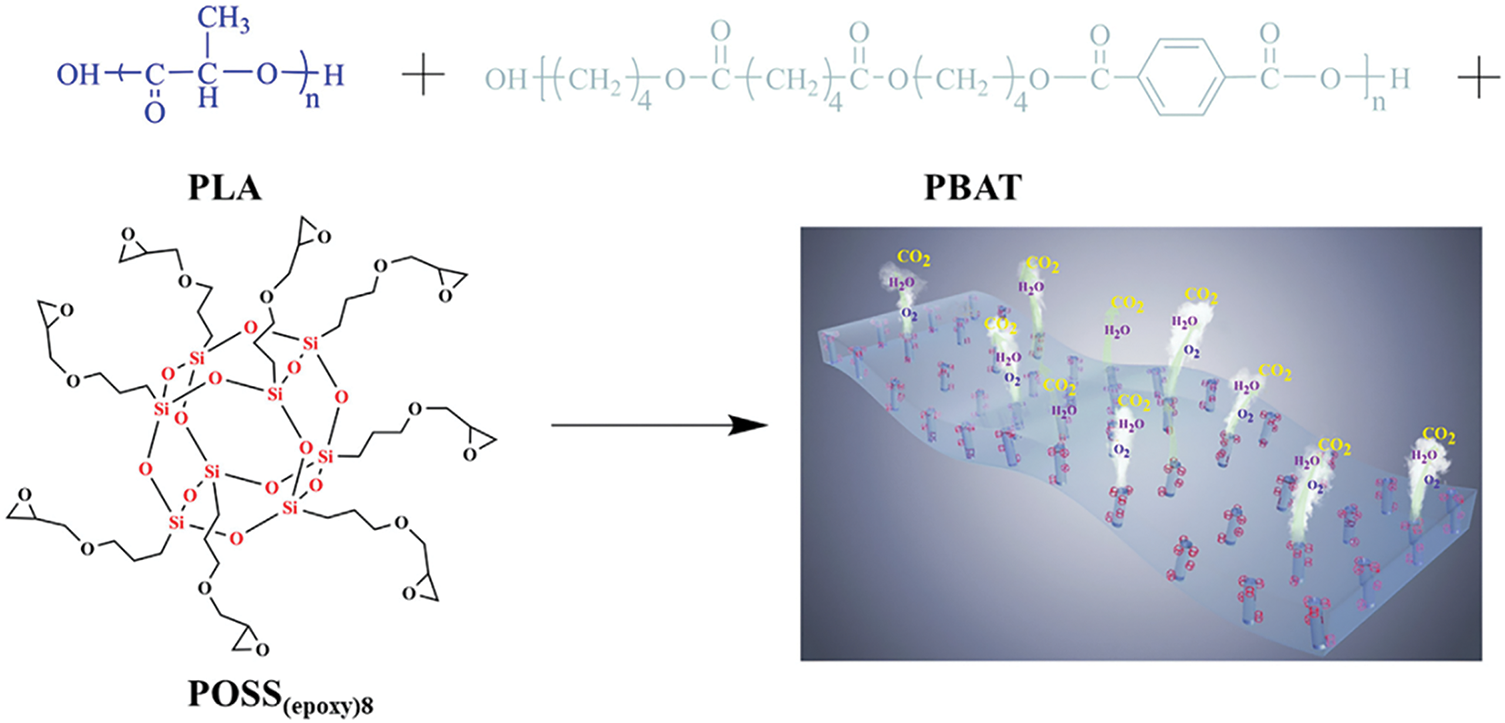

To address the issues of poor flexibility and poor gas proofness of PLA as a biobased degradable material. Qiu et al. [90] used nano-polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS(epoxy)8) as a plasticizer. The PLA/PBAT biodegradable composite film was prepared by the melt method, and its properties were measured. POSS(epoxy)8 reacted with the interfacial phase of PLA/PBAT through the ring-opening reaction of epoxy rings and formed a chemical bond. Moreover, the introduction of POSS(epoxy)8 enhanced the interfacial bonding strength between PLA and PBAT matrices. This is because POSS is uniformly dispersed in the matrix and interacts with the interface. It plays a role in plasticizing the composite film, thereby improving the tensile strength and toughness of the composite film. When the content of POSS(epoxy)8 is 1 wt.%, the tensile strength, tear strength, and longitudinal tensile elongation of the composite film are the best, and the difference between the transverse and longitudinal values is the smallest. Moreover, after adding POSS(epoxy)8, the WVP of the composite film was significantly improved (the WVP of POSS-5 wt.% increased by 45% and 71% respectively, compared with POSS-0 wt.% and POSS-1 wt.%). Fig. 11 simulates the process of gas molecules passing through the composite membrane. Furthermore, researchers have optimized the properties of polylactic acid-based films by adding poly-fructose, chain extenders (ADR4468), and synthetic biobased plasticizer octyl isosorbide dioctate (SDO). The addition of SDO significantly improved the toughness of the film. At 15 wt.% SDO, it reached the balance point for mechanical properties (elongation at break of 79.7%, tensile strength of 30.6 MPa). At 20 wt.% SDO, although the toughness was higher, the strength loss was too significant. Moreover, it was found that 20 wt.% SDO reduced the water vapor permeability (WVP) by 12.7% (to 2.95 × 10−14 kg m/(m2·s·Pa)) and the oxygen permeability (OP) by 20.6% (to 1.95 × 10−3 cm3·m/(m2·d·Pa)). The reason is that the long-chain alkyl group of SDO can isolate the PLA molecular chains and improve the film density, thereby reducing WVP and OP. This research fills the research gap of PLA mixed with Pullulan, expanding the application scenarios of biobased plasticizers [91].

Figure 11: Flowchart of gas molecule penetration through the composite film. Adapted with permission from Ref. [90]. Copyright © 2020, Elsevier

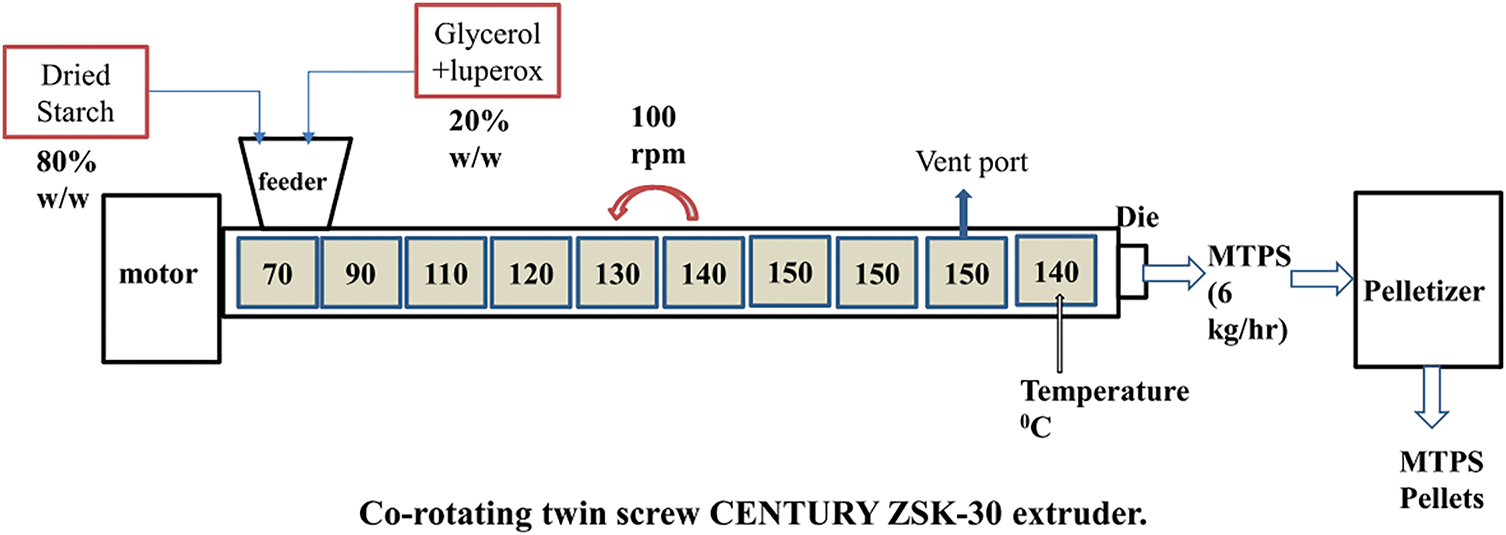

Moreover, Priyadarsini et al. [92] prepared guar gel /PLA/PBAT composite films through a two-step extrusion process. The research results show that after adding guar gum to the composite film, the tensile strength can be increased to 153.06% while retaining its biodegradability. The developed composite film exhibited good hydrophobicity, with a contact angle of 89.55°. When the PLA content increased, the water vapor permeability also decreased by 26.49 g/mm. Moreover, this composite film also exhibits higher thermal stability at temperatures as high as 200°C. Kulkarni and Narayan [93] prepared composite films of PLA and modified thermoplastic starch (MTPS, the preparation process is shown in Fig. 12) by using a twin-screw extruder. It was determined by the acetone-soluble extract method that 80% of the glycerol had been grafted onto the starch during the preparation of MTPS. When the content of MTPS is 5%, the crystallinity of PLA is significantly enhanced, reaching 28.6% (from 7.7%), and the total crystallinity of the blend after annealing treatment even reaches 50.6%. From the SEM results, it can be seen that there is good interfacial adhesion and wettability between MTPS and PLA. When 5% and 1% of MTPS were added respectively to PLA, the OP of the composite films decreased by 33% and 27%, respectively. The researchers believed that this was caused by the increase in the crystallinity of PLA. The highly crystalline regions in the PLA structure form impermeable areas, which create tortuous paths for the diffusion of the permeating substances, thereby reducing the permeability. Furthermore, the high oxygen-blocking ability of starch also helps to reduce the oxygen permeability of the composite membrane. The addition of MA may react with water to form acidic groups. This can promote the chain breakage of PLA, thereby accelerating its biodegradation rate. Further biodegradation tests in a composting environment are needed to verify this assumption.

Figure 12: It shows the process of preparing thermoplastic starch with maleic anhydride by reaction extrusion. Adapted with permission from Ref. [93]. Copyright © 2021, Elsevier

3.2.2 Polybutylene Succinate (PBS)

PBS is a kind of aliphatic polyester biodegradable material, which can be synthesized through polycondensation reaction from petroleum-based Succinic Acid and butylene glycol (1, 4-butanediol). Fully bio-based PBS can also be prepared from furfural produced from inedible agricultural cellulose waste [94]. PBS has good processing conditions and mechanical properties. Compared with PLA, it also shows similar barrier properties, but its gas barrier property is poor. Its performance can be optimized through copolymerization or blending [95].

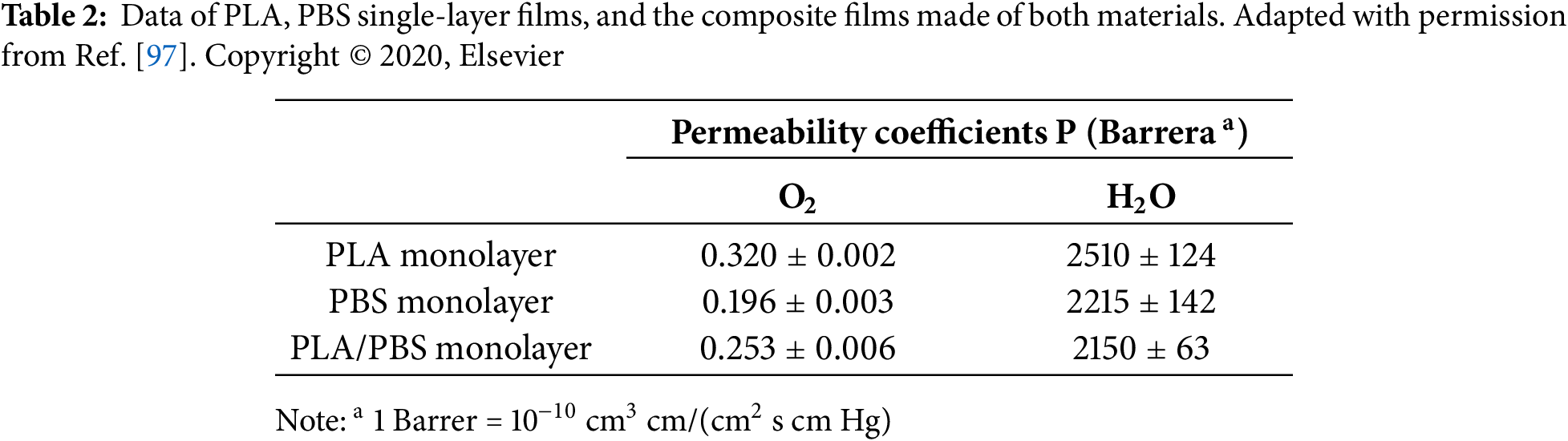

When PBS and Polyglycolic acid (PGA) are blended to prepare a composite film, their compatibility is poor, and the melting points differ significantly. To address this issue, the team of Ma [96] synthesized a bio-based compatibilizer, epoxidized soybean oil branched cardanol ether (ESOn-ECD), through a two-step reaction method. ESOn-ECD can undergo in-situ branching and chain extension reactions with the carboxyl/hydroxyl groups at the ends of PBS and PGA, significantly improving the compatibility, mechanical properties, and barrier properties of the two materials. After adding 0.7 phr ESO3-ECD, the mechanical properties of the blend significantly improved, with the tensile strength increasing from 15.3 to 19.4 MPa, and the elongation at break increasing from 244.5% to 449.0%. After adding the compatibilizer, the crystallinity of the composite film decreased, and ESO3-ECD made PGA more uniformly dispersed, forming a dense barrier structure that hindered the diffusion of water molecules. The WVTR of the film without the compatibilizer was 287.6 g/(m2 day), and the WVP was 2.74 × 10−14 g cm/(cm2 s Pa). After adding 0.7 phr ESO3-ECD, the WVTR decreased to 202.3 g/(m2 day), and the WVP decreased to 1.97 × 10−14 g cm/(cm2 s Pa). Messin et al. [97] successfully prepared polyester multilayer films with alternating layers of PLA and PBS exceeding 2000 layers on a multi-component device through nano-layer co-extrusion technology. The research structure shows that the multi-layer PLA/PBS film does not stratify when the two materials are immiscible compared with pure PLA and PBS, and improves the barrier performance of gas and water. The nanolayer film prepared by 80% PLA and 20% PBS has a 30% higher barrier performance against O2, a 39% higher barrier performance against H2O, and a 70% higher barrier performance against CO2 compared with the pure PBS film. The specific data can be found in Table 2.

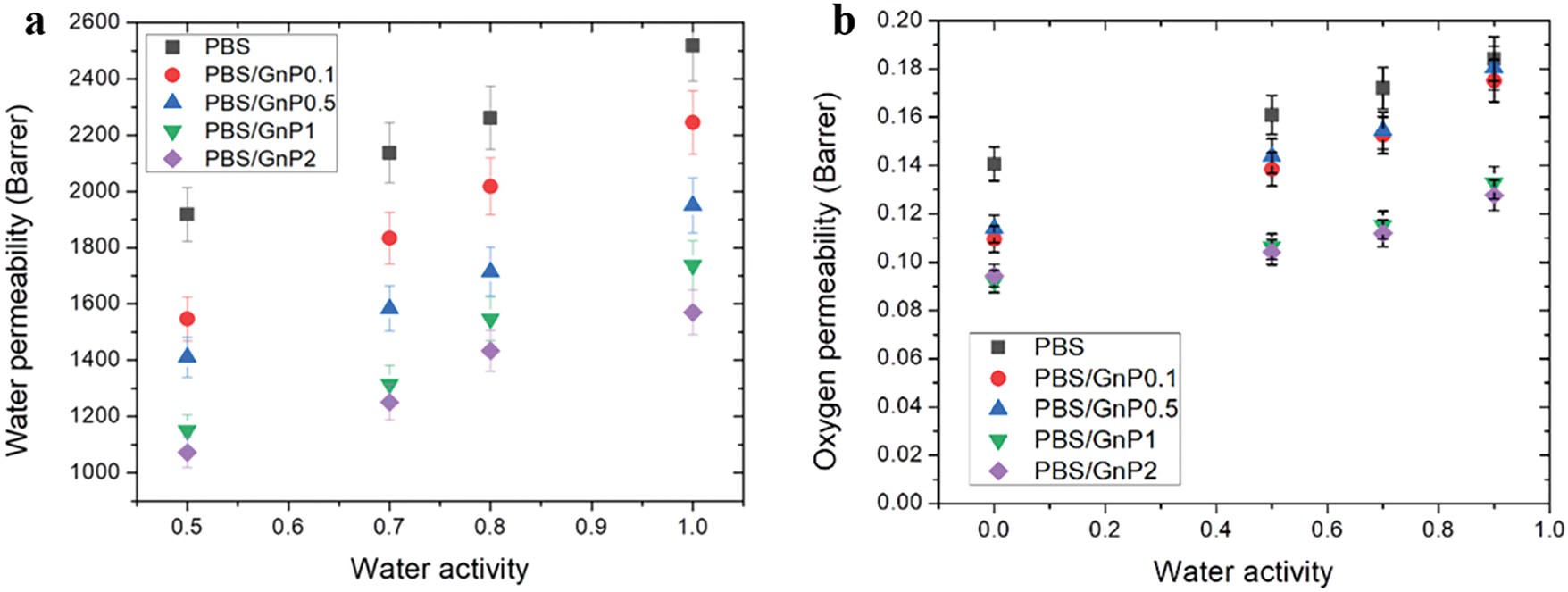

Some studies have also shown that the introduction of nano-clay and graphene nanosheets can further enhance the barrier stability of PBS, promoting its commercialization in the field of agricultural mulching films [98]. Charlon et al. [99] successfully fabricated two composite films of PBS loaded with 5 wt.% natural (CNa) or organo-modified (C30B) montmorillonite using a new water-assisted extrusion process. The introduction of nano-fillers can increase the diffusion path, and also form water clusters on the clay surface, thus the oxygen/water permeability of the PBS/CNa composite film decreased by approximately 24% and 14% respectively, while that of the PBS/C30B composite film decreased by approximately 14% and 35% respectively. In addition, Cosquer et al. [100] successfully prepared PBS/ Graphene nanoplatelets (GnP) nanocomposite membranes by adding GnP to the PBS matrix. Researchers conducted water permeability measurements within the water activity range of 0.5 to 1 at 25°C. When the water activity was 1, the water permeability coefficient value obtained from the pure PBS matrix was 2518 Barrer. With the increase of GNP in the PBS matrix, the water permeability gradually decreased (the water permeability coefficient of the nanocomposite membrane containing 2 wt.% GnP was approximately 1550 Barrer. For detailed data, see Fig. 13a). At 25°C, the oxygen permeability of pure PBS matrix and different nanocomposites was measured. The water activity ranged from 0 to 0.9. The oxygen molecule permeability coefficient of pure PBS in the anhydrous state was equal to 0.135 Barrer. After adding GnP, the permeability coefficient of oxygen molecules decreased significantly (the permeability coefficients of oxygen molecules of different composite films were within the range of 0.09–0.12 Barrer. For detailed data, see Fig. 13b). The introduction of GNP improved the barrier performance of PBS. This improvement was attributed to the pure geometric effect of increasing tortuosity, and the barrier performance of water and molecular oxygen permeability increased by 38% and 35%, respectively.

Figure 13: (a) The relationship between water permeability and water activity; (b) The relationship between the permeability coefficient of oxygen molecules and the activity of water. Adapted with permission from Ref. [100]. Copyright © 2021, MDPI

3.3 Microbial Synthetic Barrier Materials

Microbial synthetic biodegradable barrier materials refer to biodegradable materials obtained through microbial fermentation using organic matter as the carbon source, mainly including microbial polyester and microbial polysaccharides. The material is mainly carbon-containing. Once it enters the environment, microorganisms can decompose, digest, and absorb it as their own nutrients. Through fermentation, they can synthesize high-molecular-weight polyester and store it in granular form within the bacteria. At present, the common biosynthetic and biodegradable materials include biodegradable polyester and bacterial cellulose (BC).

3.3.1 Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)

PHA is a type of biodegradable polyester synthesized by microorganisms. Its barrier properties vary depending on the composition of the monomers and the degree of crystallinity. For example, short-chain PHA (such as PHB) has moderate barrier properties against oxygen (OTR 10–15 cm3 mmm−2 day−1atm−1) and water vapor (WVTR 10–20 g/m2 day atm) due to its high crystallinity (60%–80%), but there are problems such as brittleness and thermal sensitivity [101]. The research was conducted through copolymerization modification (such as introducing HV units into PHBV to balance barrier and flexibility) [102], nanocomposites (adding 5% nano-clay to reduce the OTR of PHB by 40%) [103], multi-layer coatings (PHA/chitosan bilayer structure to reduce OTR by 50%), and chemical cross-linking (OTR decreased by 50% after DCP cross-linking PHB) [104]. Adding a crosslinking agent to the starch/PHA mixture can significantly improve the mechanical capacity of the film and significantly improve the compatibility between the starch and PHA molecules [105], and has been successfully applied in fields such as food packaging and drug-controlled release.

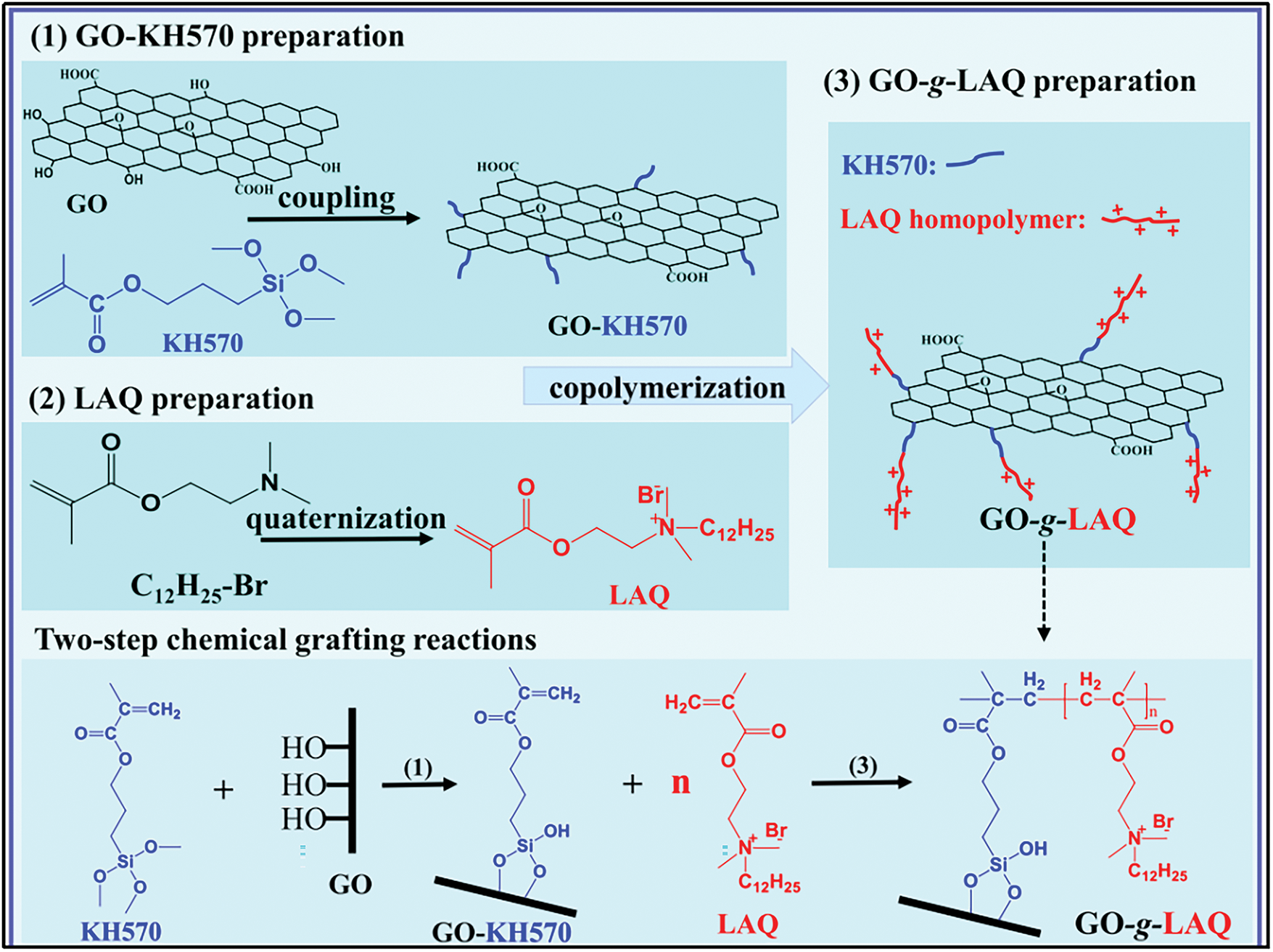

In addition, there are other research reports. For instance, Xu et al. [106] first prepared GO-KH 750 by coupling graphene oxide (GO) with 3-methylacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (KH-570), and prepared long alkyl chain quaternary ammonium salt (LAQ) through quaternization reaction. Then, through the vinyl bond of LAQ, free radical polymerization was carried out on the surface of GO-KH 75. Fig. 14 shows the synthesis process flow. Finally, the composite film of PHA/GO-g-LAQ was successfully prepared by the solvent casting method. The addition of GO-g-GLA improves the cohesion at the interface between GO and the PHA matrix, increases the crystallinity of GO, and thereby significantly enhances the crystallization behavior of PHA. Introducing GO molecules with long alkyl chains into the composite membrane can significantly improve the antibacterial performance, gas barrier ability, and tensile strength of PHA. After adding 5 wt.% of GO-g-LAQ, the OP value of the PHA membrane decreased by 86%, while the tensile strength (at room temperature) and storage modulus (at 100°C) of the PHA membrane increased to 40 MPa (from 25 MPa) and 285 MPa (from 40 MPa), respectively. Meanwhile, the antibacterial activity of the prepared composite membrane was 99.9%, and no antibacterial agent leaked out. In addition, the Melendez-Rodriguez et al.'s team [107] innovatively adopted cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) as the interlayer material. The PHA-based multilayer film prepared by blending PBAT exhibited an ultra-high oxygen barrier performance of 8.2 × 10−12 kg/(m2 Pa s). When the thickness of the CNC interlayer is optimized to 1 μm, its barrier efficiency reaches the maximum value, which is attributed to the synergistic effect between the dense physical barrier formed by nanocellulose and the barrier material matrix [108,109].

Figure 14: Schematic diagram of the synthesis of GO-g-LAQ nanohybrids: (1) Preparation of GO-KH 570 through the coupling reaction between GO and KH 570, (2) Preparation of LAQ through the quaternization reaction, (3) GO-g-LAQ Preparation Process. Adapted with permission from Ref. [106]. Copyright © 2019, Elsevier

In the design of PHA-based composites, the introduction of inorganic nano-fillers (such as nano-clay or layered boron nitride) can significantly enhance the barrier performance by increasing the bending effect of the gas diffusion path [110]. Pal et al. [111] investigated the effects of the content of organically modified nano-clay on the PHBV/PBAT mixture. The barrier properties of PHBV/PBAT nanocomposite films extruded by casting have been improved compared with those formed by compression. The results show that in the cast PHBV/PBAT composite membrane, after adding 1.2 wt.% of nano-clay, the permeability of OP and WVP significantly increased by approximately 79% and 70%, respectively, indicating the good dispersibility and strong barrier property of nano-clay. Taking boron nitride (BN) as an example, Öner et al.'s team [112] prepared PHBV/BN nanocomposites by compounding PHBV with the silanized type BN (sheet OSFBN and hexagonal disc-shaped OSBN). Experiments show that adding 2 wt.% OSFBN can reduce the oxygen permeability from 1.32 cm3 mm/(m2 day atm) of pure PHBV to 0.84 cm3 mm/(m2 day atm), which is attributed to the uniform dispersion of BN under low filler content to form a dense barrier network. However, when the content is high, the dispersion will deteriorate, thereby limiting the improvement in performance. Another study shows that silanization treatment raised the initial thermal decomposition temperature of PHBV/OSFBN to 252.7°C. Moreover, as the BN content increased, the maximum weight loss temperature significantly rose from 275.08°C to 295.50°C. Meanwhile, the Young’s modulus of the composite film containing 1 wt.% OSFBN increased by 19% compared with pure PHBV [113].

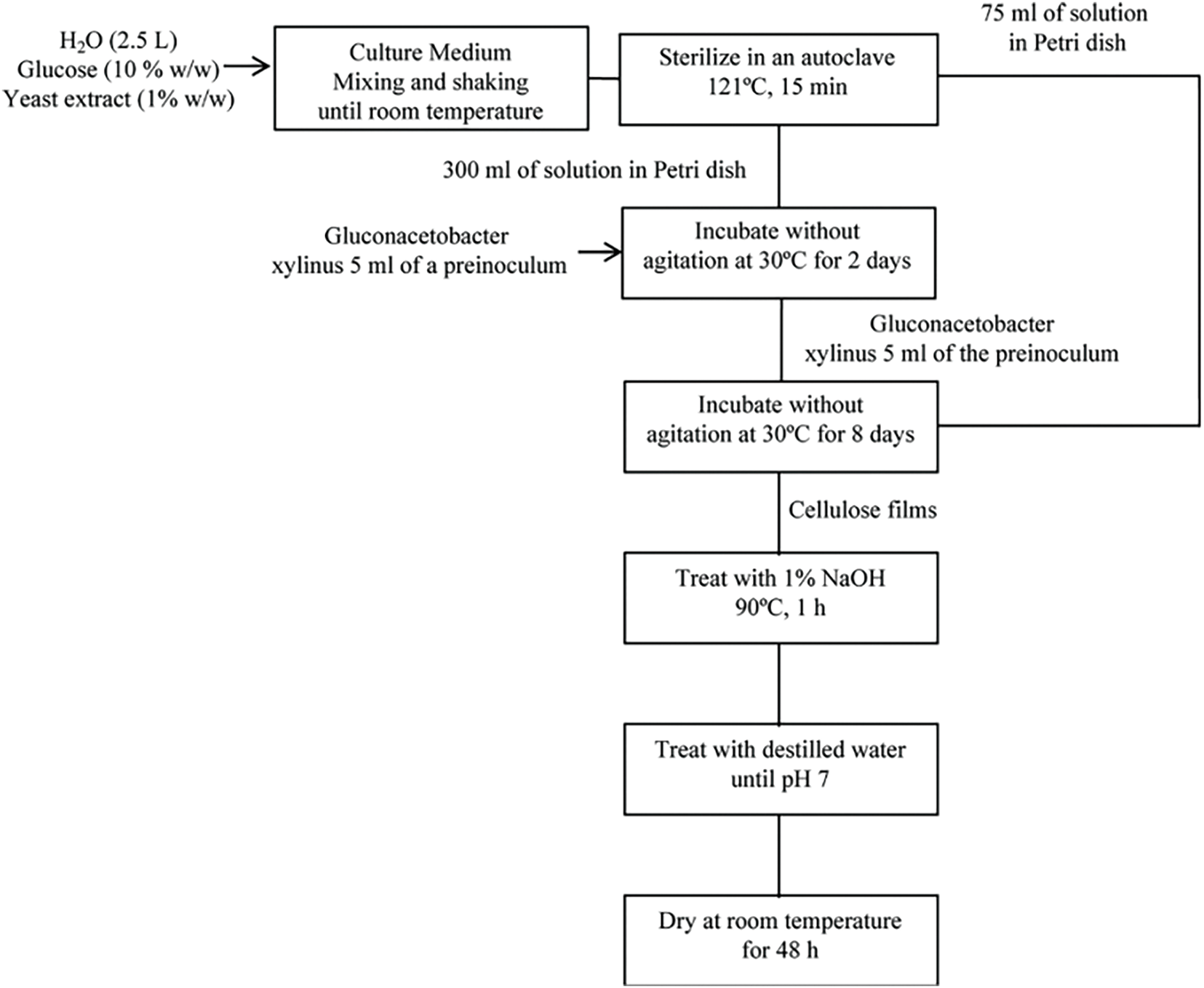

3.3.2 Bacterial Cellulose (BC)

BC refers to the general term for cellulose synthesized by certain types of bacteria under specific conditions. Firstly, bacterial cellulose can be produced by Acetobacter [114,115], and it can also be produced by some Gram-negative bacteria, such as Acetobacter, rhizobia, Agrobacterium, nitrogen-fixing bacteria, Pseudomonas, Salmonella, and Gram-positive bacteria such as Streptococcus gastric [116]. There is a β-1, 4 bond between the two glucose molecules of BC. Although this structure is the same as that found in plant cellulose, it differs from the chemical and physical properties of these cellulose substances [117]. Compared with plant cellulose, BC does not contain lignin, hemicellulose, or extracts, and has the characteristic of high purity. In recent years, the most frequently studied approach is to use BC nanofibers or nanocrystals as reinforcing agents and incorporate these BC nanocomponents into the matrix of bio-based barrier materials to alter the properties of composite membranes such as starch, polylactic acid, gelatin, and other bio-based barrier materials.