Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design and Research of Eco-Friendly Biodegradable Composites Based on Renewable Biopolymer Materials, Reed, and Hemp Waste

1 The Department of Plastics and Biologically Active Polymers Technology, National Technical University (Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute), Kharkiv, 61002, Ukraine

2 Department of Oil, Gas and Solid Fuel Refining Technologies, National Technical University (Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute), Kharkiv, 61002, Ukraine

3 Coal Department, The Ukrainian Research Coal-Chemistry Institute, Kharkiv, 61023, Ukraine

4 Department of Industrial and Biomedical Electronics, National Technical University (Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute), Kharkiv, 61002, Ukraine

5 Department of Engineering Technology and Cutting Machines, National Technical University (Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute), Kharkiv, 61002, Ukraine

6 Department of Chemical Technology of Oil and Gas Processing, Lviv Polytechnic National University, Lviv, 79013, Ukraine

* Corresponding Author: Serhiy Pyshyev. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(8), 1645-1660. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0049

Received 03 March 2025; Accepted 13 May 2025; Issue published 22 August 2025

Abstract

Nowadays, the development of effective bioplastics aims to combine traditional plastics’ functionality with environmentally friendly properties. The most effective and durable modern bioplastics are made from the edible part of crops. This forces bioplastics to compete with food production because the crops that produce bioplastics can also be used for human nutrition. That is why the article’s main focus is on creating bioplastics using renewable, non-food raw materials (cellulose, lignin, etc.). Eco-friendly composites based on a renewable bioplastic blend of polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate, corn starch, and poly(lactic acid) with reed and hemp waste as a filler. The physic-chemical features of the structure and surface, as well as the technological characteristics of reed and hemp waste as the organic fillers for renewable bioplastic blend of polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate, corn starch, and poly(lactic acid), were studied. The effect of the fractional composition analysis, morphology, and nature of reed and hemp waste on the quality of the design of eco-friendly biodegradable composites and their ability to disperse in the matrix of renewable bioplastic blend of polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate, corn starch and poly(lactic acid) was carried out. The influence of different content and morphology of reed and hemp waste on the composite characteristics was investigated. It is shown that the most optimal direction for obtaining strong eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on a renewable bioplastic blend of polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate, corn starch, and poly(lactic acid) is associated with the use of waste reed stalks, with its optimal content at the level of 50 wt.%.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Today, with the increase in the production and use of plastic, the amount of waste that pollutes the environment is also increasing [1] since traditional synthetic plastics are non-biodegradable materials [2]. Synthetic polymers are currently a source of environmental pollution, which is already leading to an ecological disaster, and also require the use of raw materials based on hydrocarbons, the content of which in the earth’s crust is significantly decreasing [3–6]. The production of eco-plastics is a pressing problem worldwide [7]. Production of products from environmentally friendly, natural raw materials has recently attracted increasing attention from the public. This area is currently relevant due to the constantly increasing production volumes of polymers and polymer products, including biodegradable plastic, which creates many problems: it requires special disposal conditions; it may contain metal compounds that are not dangerous in themselves, but ultimately harm nature; it requires specific environmental conditions for decomposition; it is not recyclable; its production leads to an increase in capital investment; a by-product of its decomposition is methane; and, ultimately, it does not solve the problem of environmental pollution.

At present, eco-plastics are confidently replacing classical materials from traditional areas of use (household products, appliance housings, building materials, furniture, vehicle interior parts), as they allow solving several urgent problems related to weight reduction, increasing environmental safety, and expanding the raw material base [8]. The intensive introduction of eco-plastic materials based on polymers and fillers of natural origin solves ecological problems associated with using renewable resources and components that are part of the natural environment [9]. Improving the technologies for forming and enhancing the properties of eco-plastic materials will ensure the intensive use of products based on components of natural origin. It will lead to a partial or complete abandonment of the use of synthetic polymers in favor of eco-plastics. Such approaches determine the relevance of research in developing new composites based on biopolymers and natural fillers, as they require studying the processes of forming eco-plastic products and the properties and structure of the developed eco-plastic materials [10]. Typically, the technology of forming polymer composite materials is determined by the properties of the synthetic or biopolymer binder and the type and content of modifiers and fillers. The development of polymer composites of a new chemical composition requires studying the structure and properties of composites depending on the influence of technological factors, which will allow the formation of defect-free products, taking into account the features of phase transformations under the influence of external physical fields.

Using a biopolymer matrix involves press equipment and an elevated temperature for forming products containing wood floor as a filler [11]. The prepared composition is subjected to pressing and heat treatment, the mode of which is determined by the content and chemical composition of the fillers, which requires studying the features of structural transformations of the biopolymer matrix and studying the processes of interaction of the components with each other [12]. The expansion of the range of products based on eco-plastic materials containing natural components from renewable sources is proliferating, which is due to the urgent need to develop the direction of environmentally sustainable technologies and the limitation of raw materials used for the manufacture of synthetic polymer fibers or matrices [13]. In many cases, biomaterials with natural fibers have many advantages over synthetic ones, as they provide a reduction in the weight of the product due to the low density of the material, satisfactory specific strength, additional functionality (damping, shock absorption) [14,15], increased occupational safety through the use of environmentally friendly technologies, activation of nature restoration processes as a result of carbon dioxide biosequestration and the ability to biodegrade.

The main development direction of the economy’s manufacturing sector is developing and applying various environmentally friendly composite materials based on renewable raw materials [16]. The development, design, and further application of environmentally friendly composite materials based on renewable raw materials using plant products not characterized by food value has gained particular development [17]. This industry is characterized by obtaining a broad raw material base in a minimum period. At the same time, the main advantages are the unpretentiousness of plant products and a high yield of fibrous material [18]. A promising direction in obtaining environmentally friendly composite materials is hemp and reed plant fibers [19]. Western scientists use hemp fibers to create biocomposite materials for various applications [20]. Biocomposite materials are being developed entirely from organic materials and using fillers in the form of hemp and reed plant fibers [21].

Analysis of literature sources [19,20,22] showed that the main components of environmentally safe composite materials based on plant waste are a biodegradable polymer matrix, an organic filler, and various functional additives are also used: antiseptics, flame retardants, compatibilizers, etc. For example, a joint study by scientists from Canada and the UK allowed the creation of new biocomposite materials from hemp waste using a silica matrix. Such composites are water-resistant and show good mechanical characteristics, which made it possible to develop new thermal insulation building materials based on them. In the study, composites based on hemp firewood were manufactured using silica sol as a binder, which gave the composite multifunctionality [21]. Slovenian company Movichem specializes in producing chemical materials that allow the modification of hemp waste for further use as a filler in building boards and other materials resistant to fire and moisture. One of the leading products is Retacell FLR-A1—a fire-resistant and environmentally friendly polymer gel [22]. Using ecological additives (flax fibers, hemp, bonfire, etc.) as a filler, you can get biodegradable plastics with different properties. NCA Renewable Technologies, a manufacturer of composites from natural fibers, has developed hemp-based INCA panels. The undoubted advantage of such panels is that they will reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 76%, waste production by 89%, and water consumption by 82% compared to plywood from the Lauan rainforest, which is currently used in the automotive, leisure, furniture, and film industries [23]. A characteristic feature of manufacturing practical and durable structures and products from environmentally friendly composite materials is optimizing their component composition depending on the application areas [24]. Therefore, the current direction is developing biodegradable composite materials with high-strength characteristics while maintaining the ability to biodegrade [25,26].

In our past scientific works [24,27], environmentally friendly polymer composites were obtained based on polylactide and polyester biodegradable polymer matrices using a wide range of organic waste and functional modifiers [28]. Almost always, the high quality and durability of products and structures from the studied environmentally friendly composite materials are due to the combination of the correct choice of the component composition of the material and the selection of the most influential production method.

Therefore, it is essential to produce eco-friendly composites based on a renewable bioplastic blend of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate), corn starch, and poly(lactic acid) (PBAT/PLA composites), adding reed and hemp waste as a filler with different fractional compositions and shapes with particle sizes.

The work aimed to create eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials and reed-hemp waste studying and designing.

To achieve this aim in the work, it was necessary to perform the following tasks:

- To study the reed and hemp waste impact on the eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer material’s physical and mechanical properties complex;

- To determine the optimal content and type of reed and hemp wastes in the PBAT/PLA composites to obtain highly effective, eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials.

In this work, we used such objects as:

- Renewable bioplastic blend of 40 wt.% poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate), 20 wt.%, corn starch, and 40 wt.%, poly(lactic acid), grade OK HOME (Weifang Huawei New Materials Technology Co., Ltd., Weifang, China);

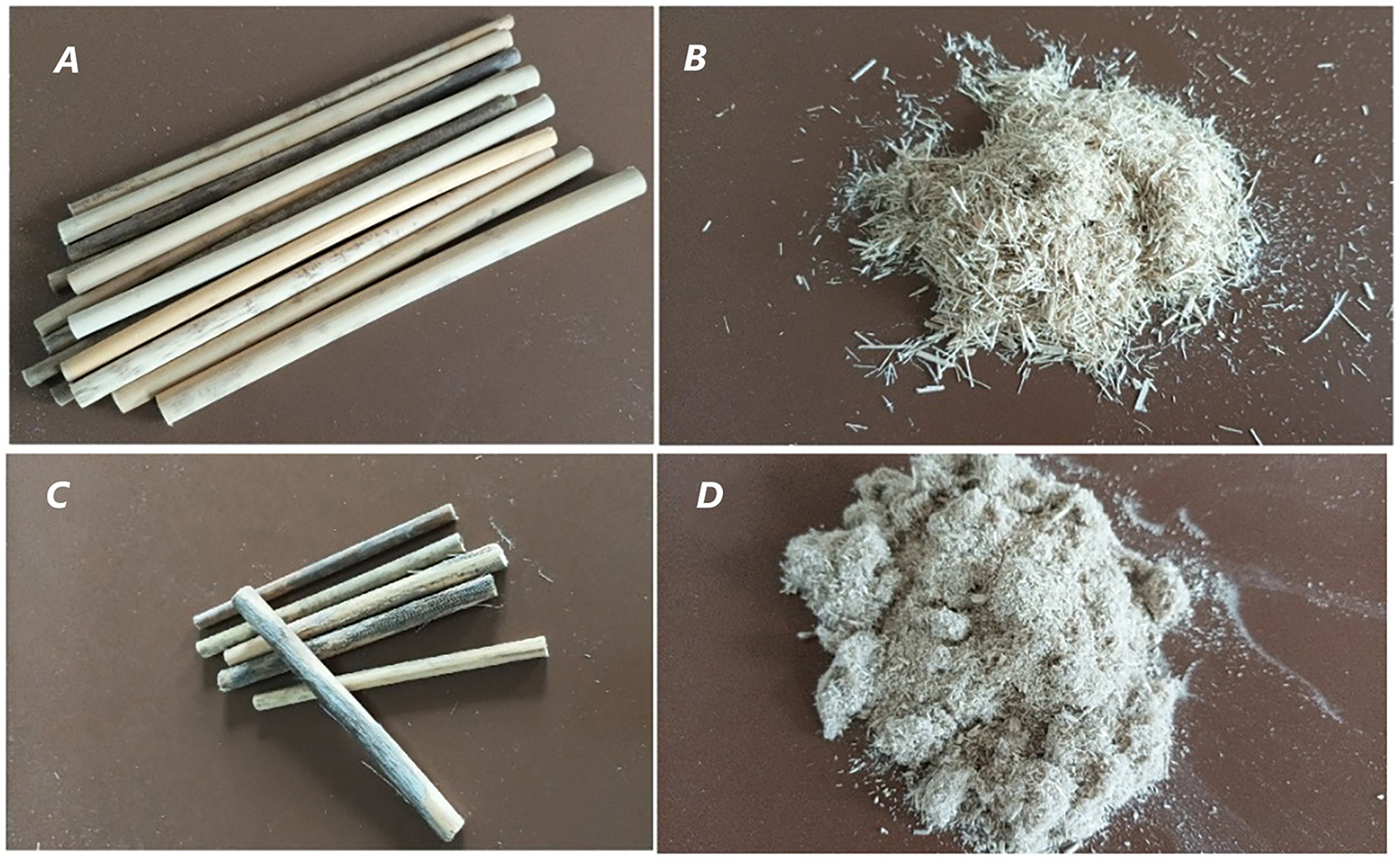

- Waste of marsh reed stems, which were collected in the Kharkiv region and crushed in a Braun blender to a size of 0.5–6 mm (Fig. 1). Waste of reed stems contains up to 45% cellulose, 25% lignin, 22% hemicellulose, about 9% protein, and mineral components. As in most plants, in the hard part of the reed stem, cellulose fibers are collected in long bundles, surrounded and intertwined with hemicelluloses [29]. Cellulose is an almost crystalline substance; hemicellulose is amorphous. All this interweaving is filled with lignin—a solid polyphenol resin. This structure of the plant determines its vertical orientation and strength.

- Waste of hemp stems, collected in the Kharkiv region and crushed in a Braun blender to a size of 0.5–6 mm. Structurally, the outer stem tissue (bark) consists of polyhedral cells (Fig. 1). Behind it are the parenchyma with a ring of bast bundles and the core. The length of the elementary hemp fibers is 4–5 cm or more. Bast fibers are intertwined and glued together with lignopectin. In the hemp stem, as a result of the action of the cambium, a second inner ring of bast bundles is formed, and behind it, the third and fourth often appear [25]. Secondary bast fibers are unevenly placed in the stem. The lower part of the stem is the richest in them; in the upper part, only primary fibers are found. Deficiencies contain 20–25% of the fiber and the material—15–20%.

Figure 1: Photos: (A): reed stem waste, (B): crushed reed stem waste, (C): hemp stem waste, (D): crushed hemp stem waste

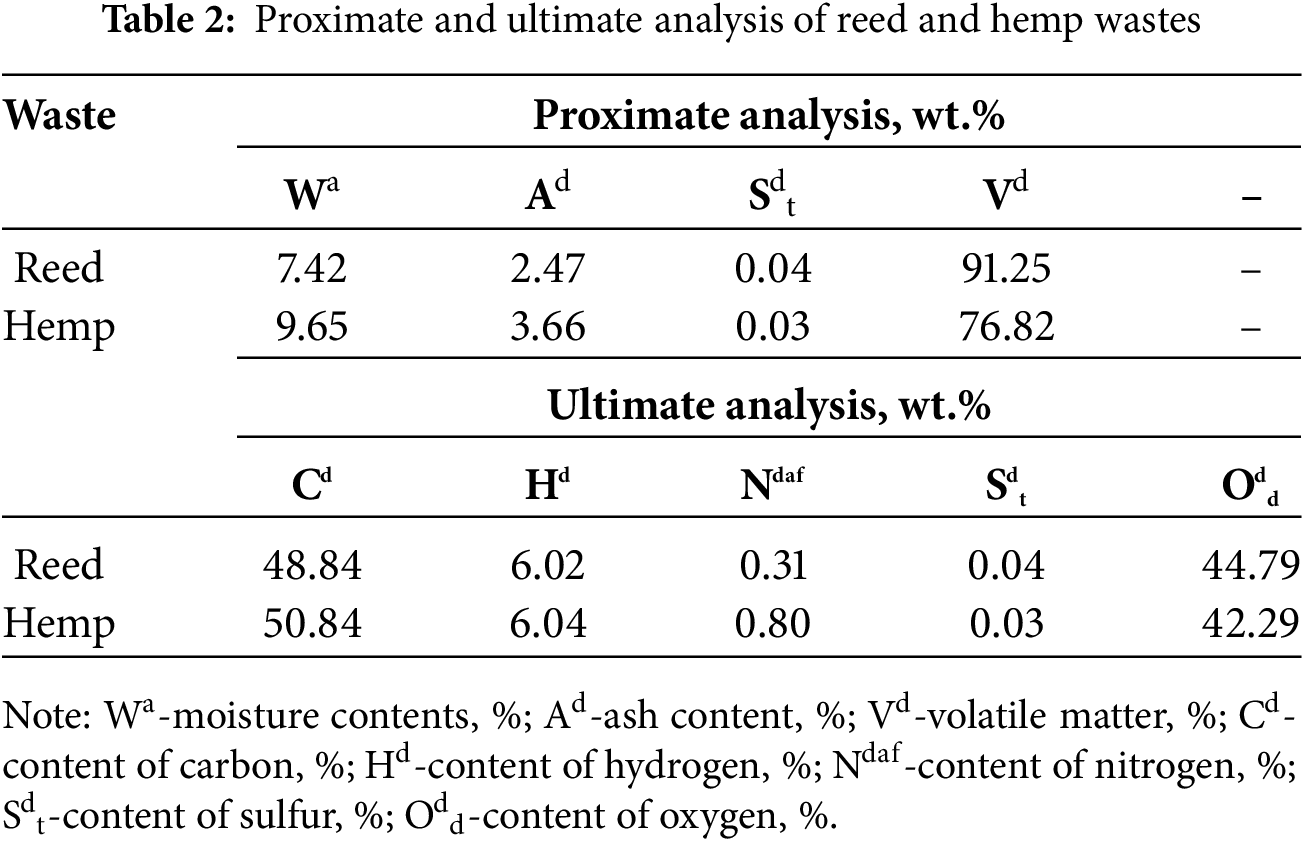

2.2 Preparation of Eco-Friendly Biodegradable Composites

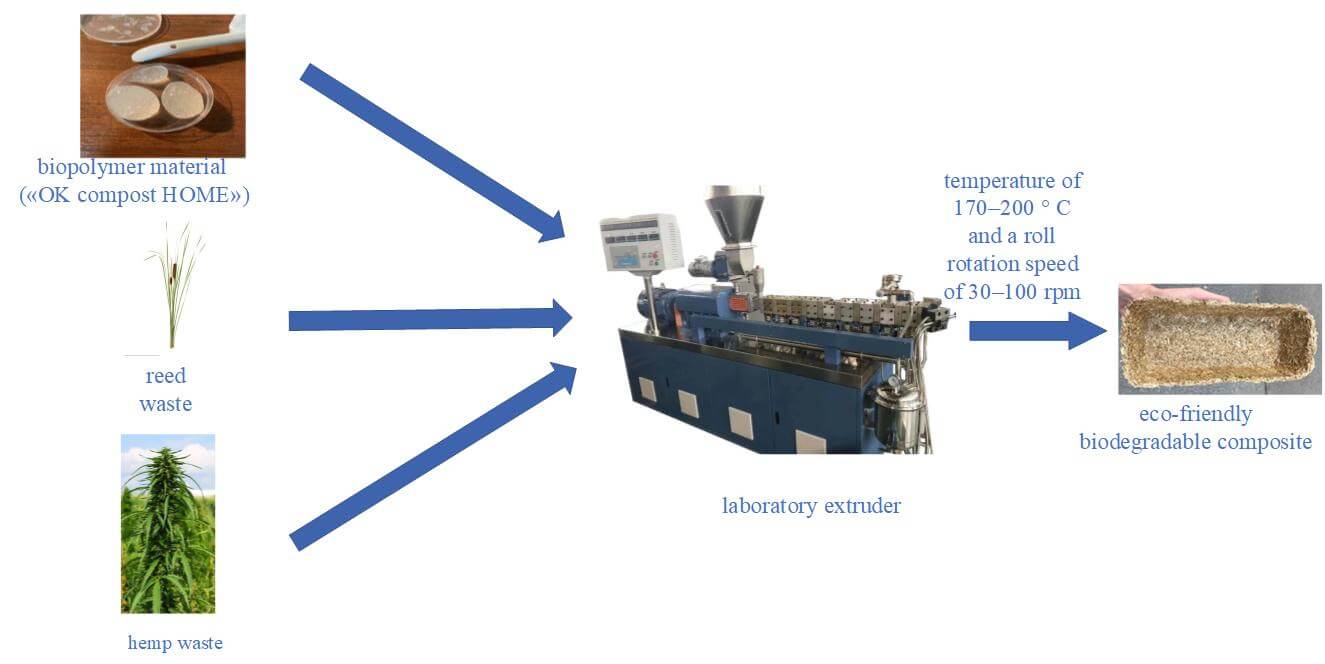

The eco-friendly biodegradable composites (Table 1) were obtained by extruding pre-prepared raw materials in a single-screw laboratory extruder Sinbak (Zhangjiagang Sinbak Machinery Co., Ltd., Zhangjiagang, China) at a temperature of 170–200°C and a roll rotation speed of 30–100 rpm, torque 80 Nm, pressure 20 MPa, energy input 2.4 kW.

The L/D ratio of the extruder is 25, with the die-head in a ring form with a 20 mm diameter to increase the uniformity of dispersed pant waste distribution like crushed reed stem waste and crushed hemp stem waste in PBAT/PLA blend; two mass passes were used to obtain finished samples. Initially, PBAT/PLA composite granules were mixed with crushed plant waste in a 1-L ceramic container, and the resulting mixture was loaded into the extruder’s feed compartment. There were 20 parallel experiments for each composition; statistical processing was made using characteristics such as arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and variation coefficient.

The study of impact strength and breaking stress during bending of the eco-friendly biodegradable composites without notching at a temperature of 20°C was carried out on a pendulum head according to ISO 180 and ISO 178, respectively, on samples conditioned under standard controlled temperature and humidity for those standards. The size of the test specimen was: sample width at its middle 10 mm, sample thickness at its middle 5 mm, sample height at its middle 15 mm. The test specimens were obtained by pressing eco-friendly biodegradable composites heated on an extruder to a temperature of 180°C into brass molds of the appropriate size. Impact strength and breaking stress during bending were performed on a pendulum impact tester XJU-2.75 (Time Group Inc., Beijing, China). According to the Izod method, the impact strength of notched specimens is the impact energy expended on the fracture of the notched specimen, referred to as the original cross-sectional area of the specimen at the notch. During testing, the specimen is vertically clamped at one end in the impact tester device. The determination of breaking stress during bending consists of determining the ultimate stress during bending of the specimen and its deflection at the moment of failure under the bending stress at a given deflection value equal to (20.0 ± 0.2) mm.

Shore A hardness, according to ISO 868, was measured with a Novotest TSh-C digital hardness tester (NOVOTEST, Samar, Ukraine). The method is based on the use of a type A durometer, which is based on measuring the initial indentation depth, the indentation depth after specified periods of time, or both.

Microscope studying was done using an electronic microscope Digital Microscope HD color CMOS Sensor (China) and petrographic complex LECO (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The petrographic complex includes an Olympus BX51/BX52 research microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with magnification in the reflected light of 100–500× and U = ±0.04%, an automatic image analyzer with a high-quality digital camera, updated Lucia Vitrinite 7.13 software and an automatic press for hot pressing of samples [26].

Sieve analysis was used on sieves with woven metal cloth with cell sizes 1.25, 1, 0.315, 0.14, 0.09, 0.063, and 0.05 mm.

Thermal stability of the eco-friendly biodegradable composites in terms of melting and destruction temperature ranges was determined according to ISO 3146 on a laboratory brass disk with a diameter of 50 mm and a thickness of 19 mm with a side hole for a thermometer with a diameter of 9 mm.

Water barrier properties of the eco-friendly biodegradable composites were determined by the rate of water absorption of samples in cold water for 1 day according to ISO 62:2008.

Each eco-friendly biodegradable composites experiment was repeated three times, and the average value was calculated. Experiments on the impact strength, breaking stress during bending, thermal stability, and water barrier properties were performed in three replicates to ensure reproducibility. The obtained data were presented as average values and standard deviations. Data normality was assessed for statistical analysis using Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test using ANOVA. The parameters used in the ANOVA analysis had a significance value of p < 0.05 at the 95% confidence level. In this work, primary methods of statistical processing of experimental data are used to obtain individual indicators of the properties of eco-friendly biodegradable composites, which objectively reflect the results of experimental measurements [11]. Within the framework of parallel experiments, a sample eco-friendly biodegradable composite average value was used, which is calculated by the formula of the following form [11]:

where xi is the value of the indicator of the i-sample; n is the number of eco-friendly biodegradable composite samples. Data normality and reduction of variability were achieved by producing 20 parallel samples using the principle of removing the largest and smallest research results.

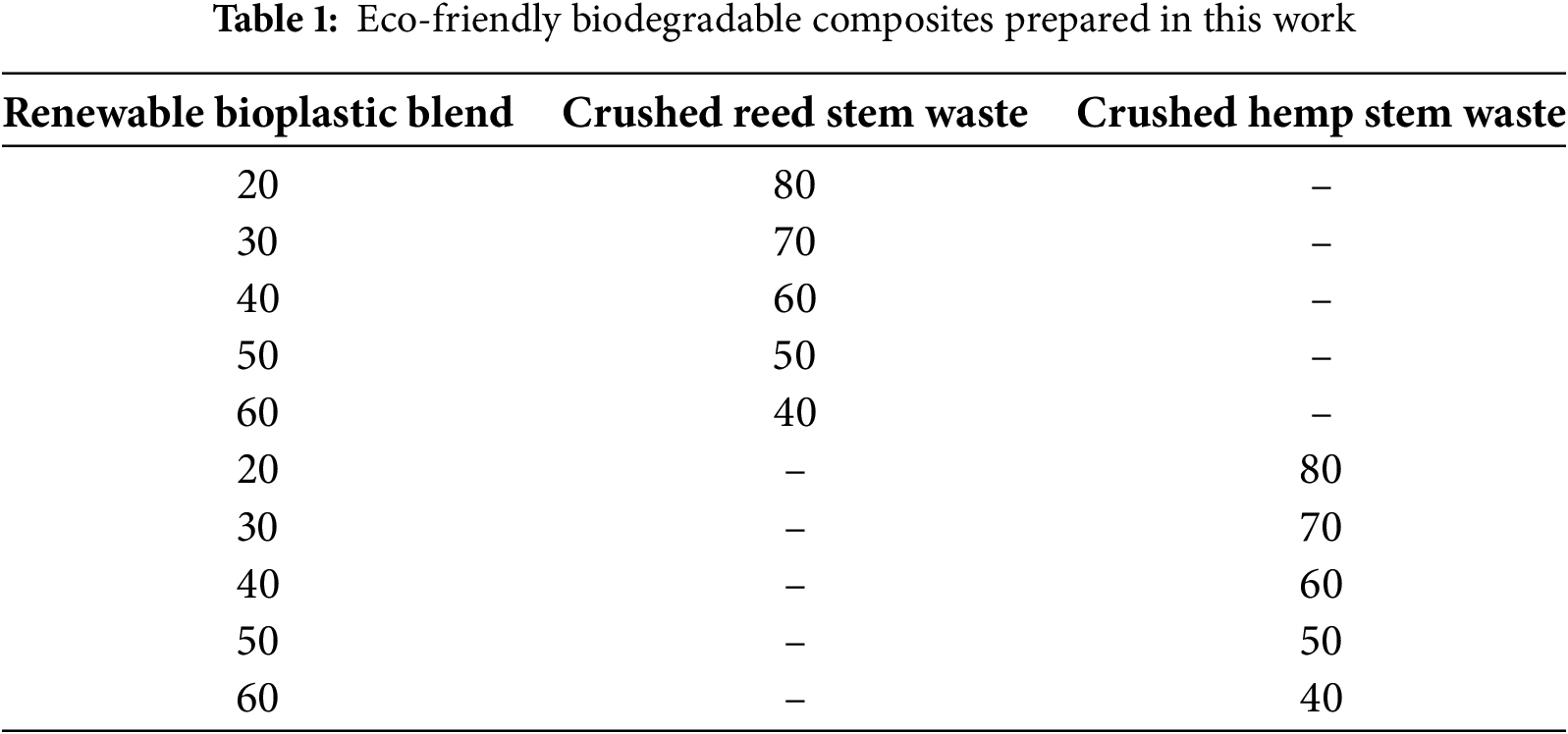

Primary studies aimed to determine the most important physicochemical characteristics of renewable reed and hemp wastes. The proximate and ultimate analysis of reed and hemp wastes are given in Table 2.

From the results of qualitative and elemental analysis of reed and hemp waste, it is clear that these substances are very similar in content and ratio of essential elements; they have practically the same level of hydrogen, sulfur, carbon, and oxygen. At the same time, reed is characterized by an increased content of volatile substances and a reduced moisture content compared to hemp.

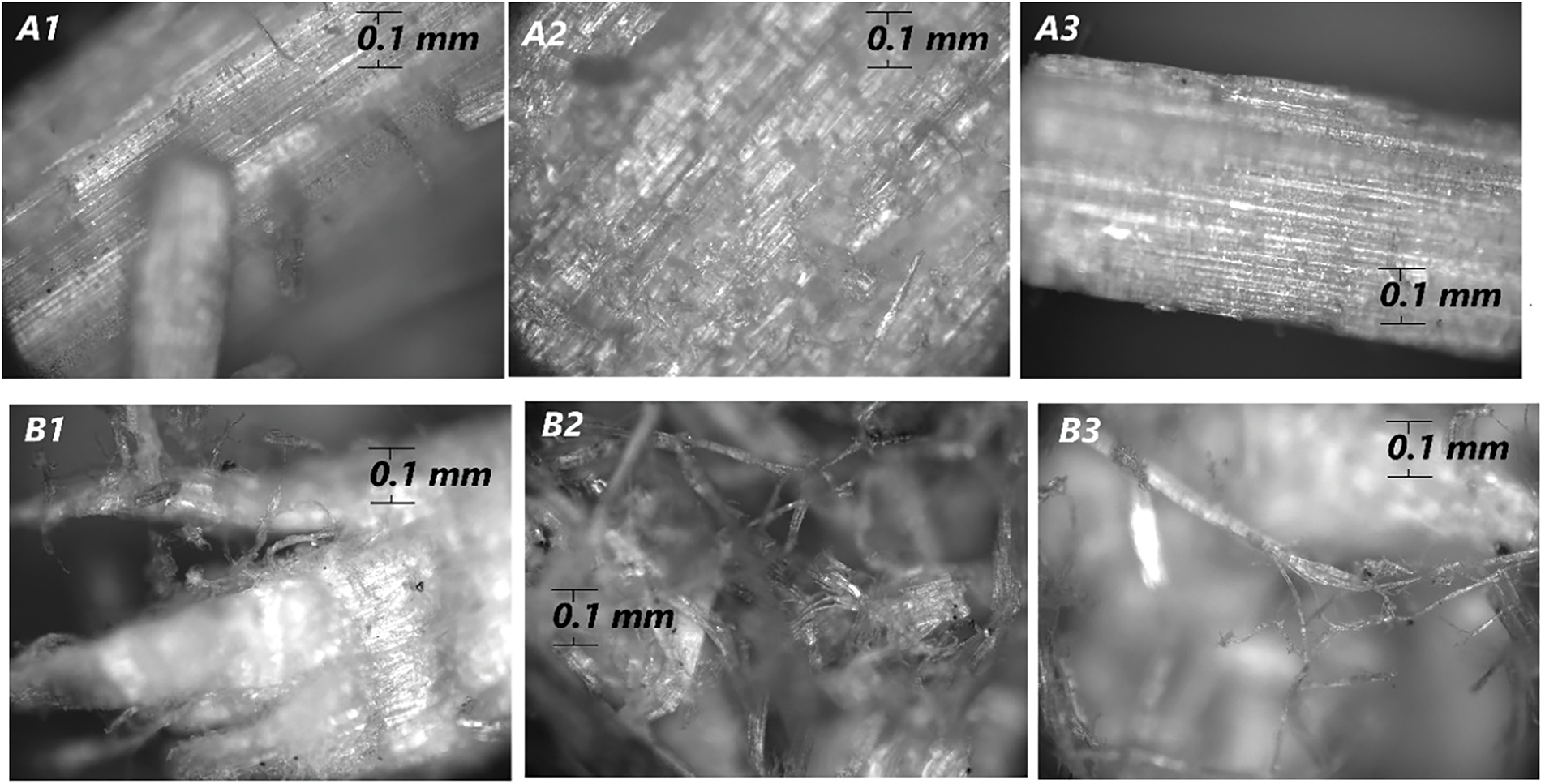

Microscopic studies were conducted to determine the morphology of crushed reed and hemp stalk waste, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Microscopic research: (A1–A3): crushed reed stem waste, (B1–B3): crushed hemp stem waste

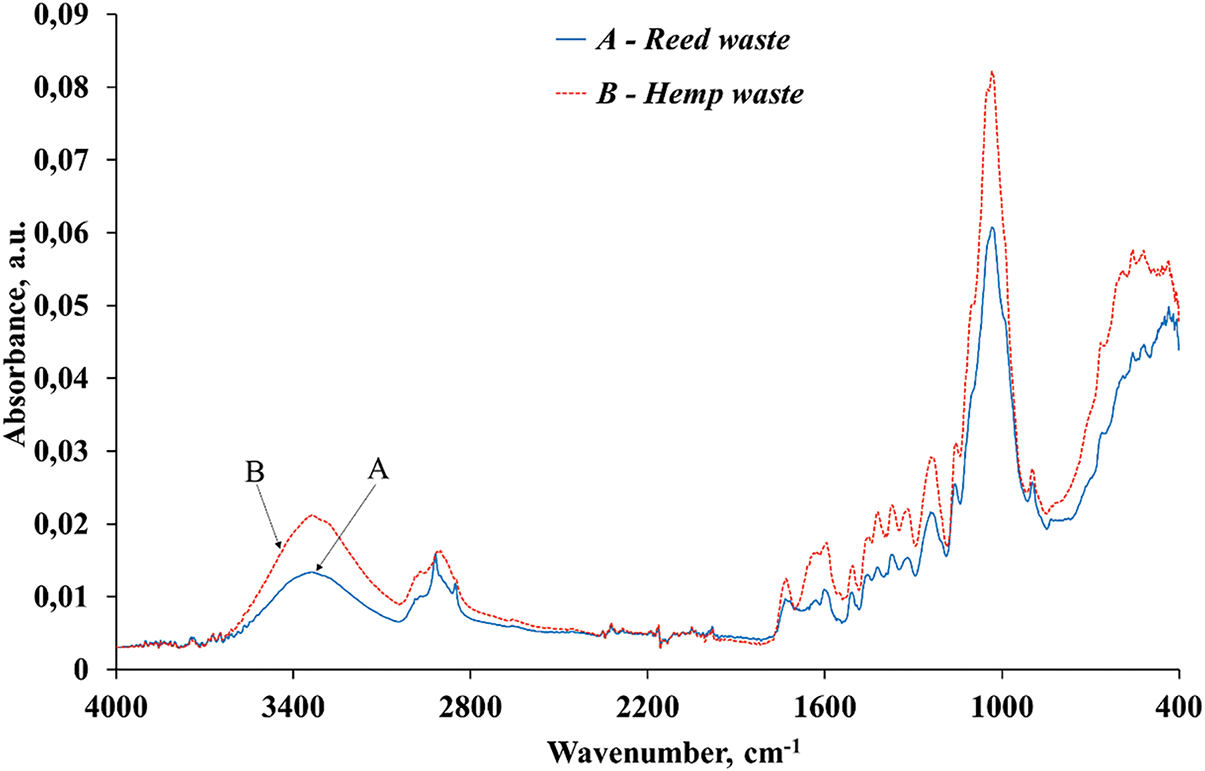

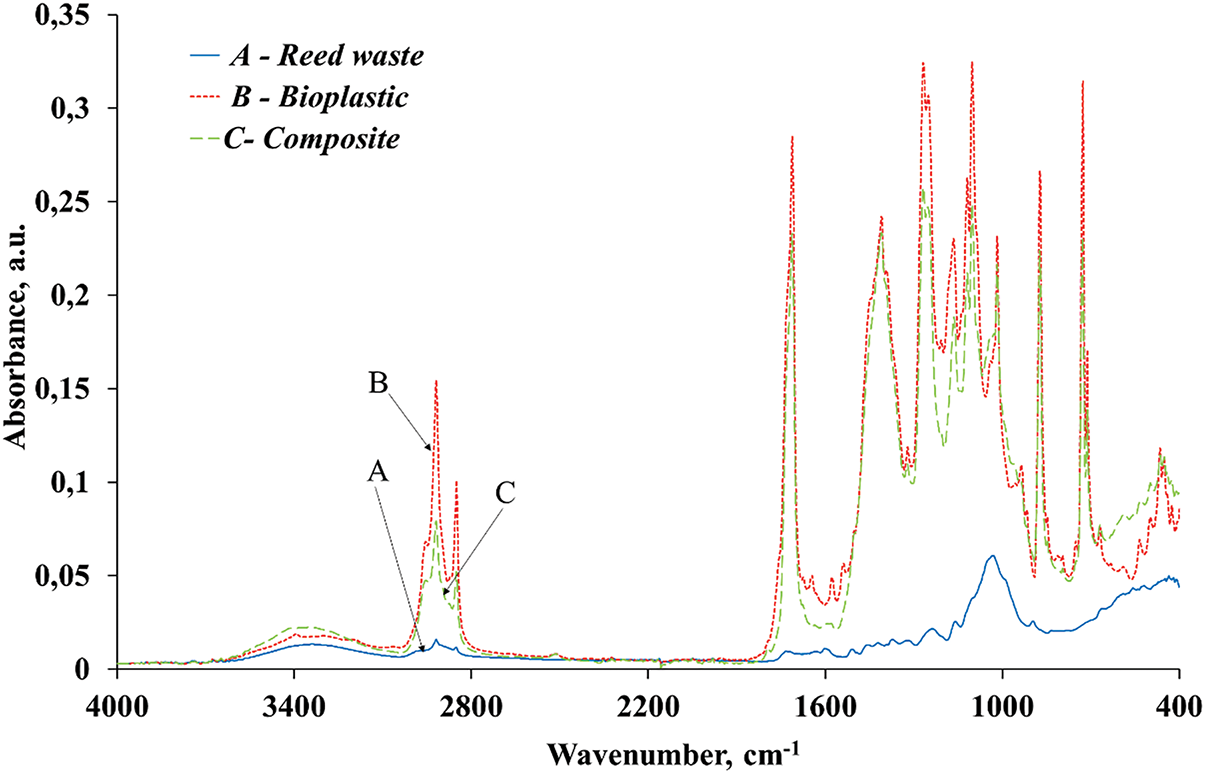

Their results show that lamellar particles with a sufficiently hard surface are formed when grinding reed stalk waste, while a fibrous structure with a small proportion of lamellar particles characterizes crushed hemp stalk waste. In general, it is essential to note the physical characteristics of crushed reed and hemp stem waste. It is necessary to note the former’s increased hardness and significant hydrophobicity compared to hemp material. It was determined that hemp stalks have a surface hardness of 20–22 Shore A, while for cane waste, this indicator was 55–60 Shore A. Crushed hemp stem waste is a fluffy, fibrous cotton-like mass with a very low bulk density compared to crushed reed stem waste, characterized by an appearance similar to sawdust of varying sizes. Also, the different filler particle morphology is associated with a higher cellulose content (up to 75 wt.%) and a lower lignin content (3.5–5 wt.%) in reed waste compared to hemp waste (50 wt.% cellulose and up to 8.5–10 wt.% lignin). At the same time, from the results of the IR spectra analysis (Fig. 3), it is clear that these organic wastes are practically identical in terms of their chemical composition.

Figure 3: IR-spectra of crushed reed stem waste (A) and crushed hemp stem waste (B)

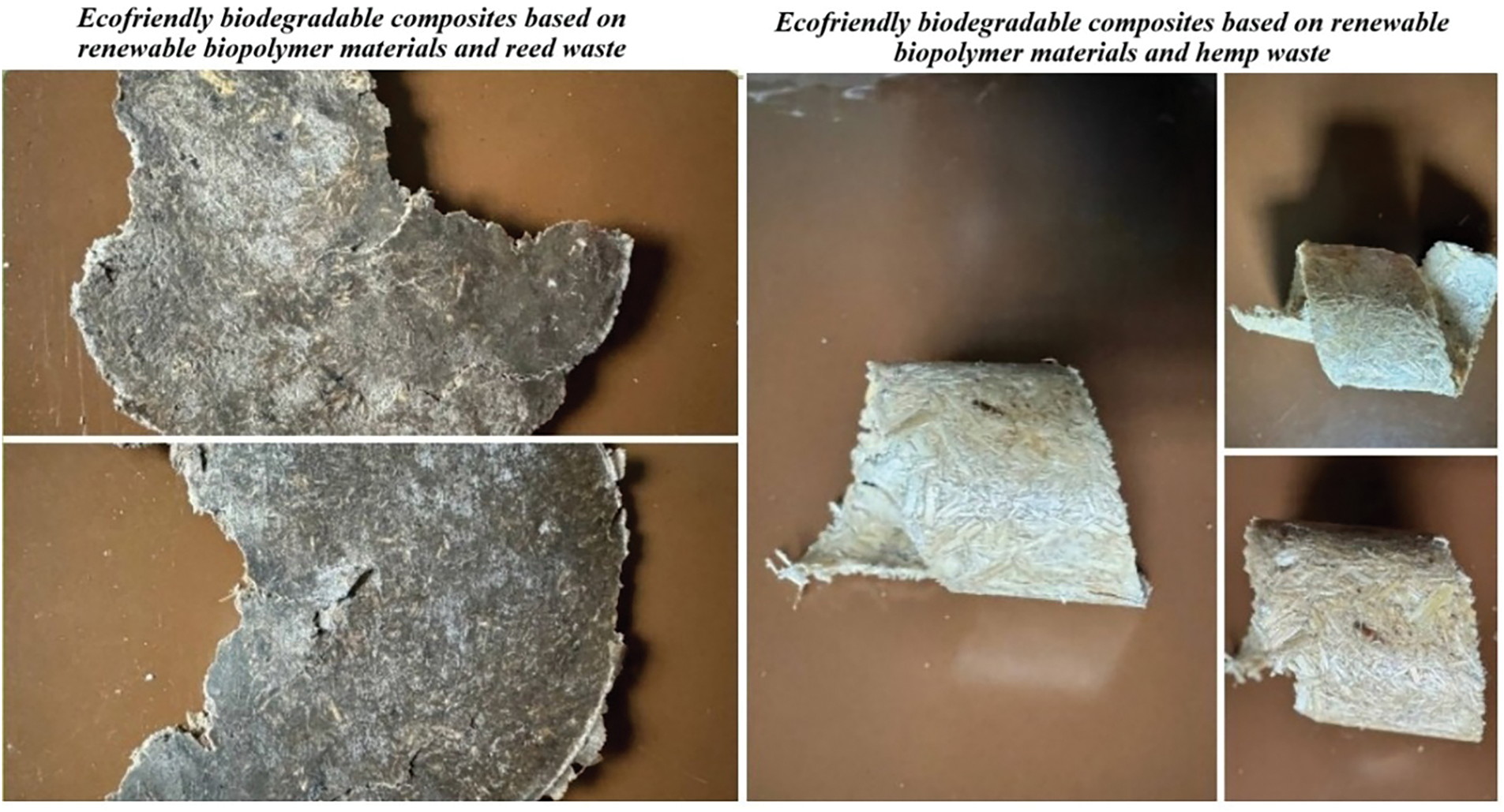

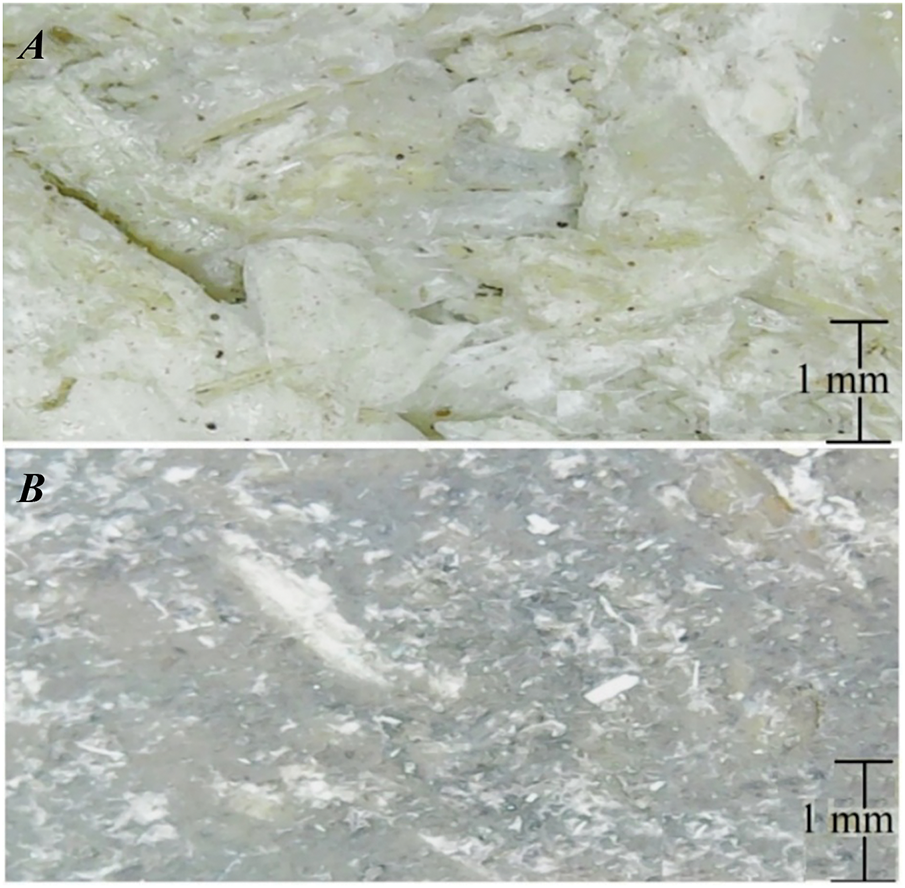

Further studies aimed to obtain PBAT/PLA composites with reed-hemp waste by extrusion method with composite mass production with different component compositions to study their strength characteristics further. Fig. 4 shows PBAT/PLA composites with reed-hemp waste with an organic waste content of 50 wt.%, while Fig. 5 shows their surface micrographs.

Figure 4: Photo of PBAT/PLA composites with reed-hemp waste

Figure 5: Microscopic research: (A): PBAT/PLA composites with reed stem waste, (B): PBAT/PLA composites with hemp stem waste

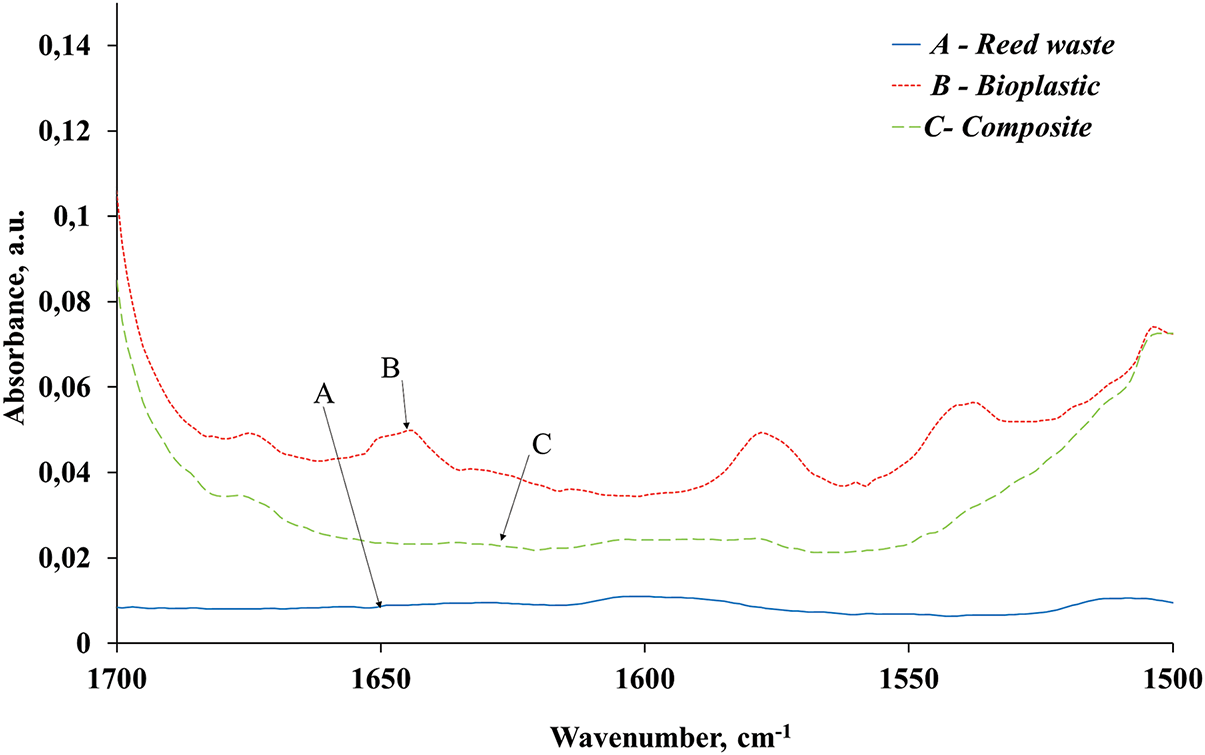

From the visual and microscopic analysis of the surfaces of the obtained PBAT/PLA composites with reed-hemp waste, it is seen that the compositions with reed are characterized by a more heterogeneous surface with the presence of plate-like structures due to large particles. In contrast, the compositions with hemp have a more homogeneous fibrous surface structure. At the same time, the polylactide component in PBAT/PLA composites acts as a heat-resistant and durable matrix. It is also worth noting that when obtaining PBAT/PLA composites with reed waste, a chemical interaction is observed between the amino acid residues of starch bioplastics, which in groups correspond to C=N groups at 1644 cm−1, N-H groups at 1578 cm−1 and C=O groups at 1538 cm−1 with the corresponding groups of the organic filler, which is visible in the IR spectra in Figs. 6 and 7.

Figure 6: IR-spectra of reed stem waste (A), renewable bioplastic PBAT/PLA (B), eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials and reed stem waste (C)

Figure 7: IR-spectra in the range 1700–1500 cm−1 of reed stem waste (A), renewable bioplastic PBAT/PLA (B), eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials, and reed stem waste (C)

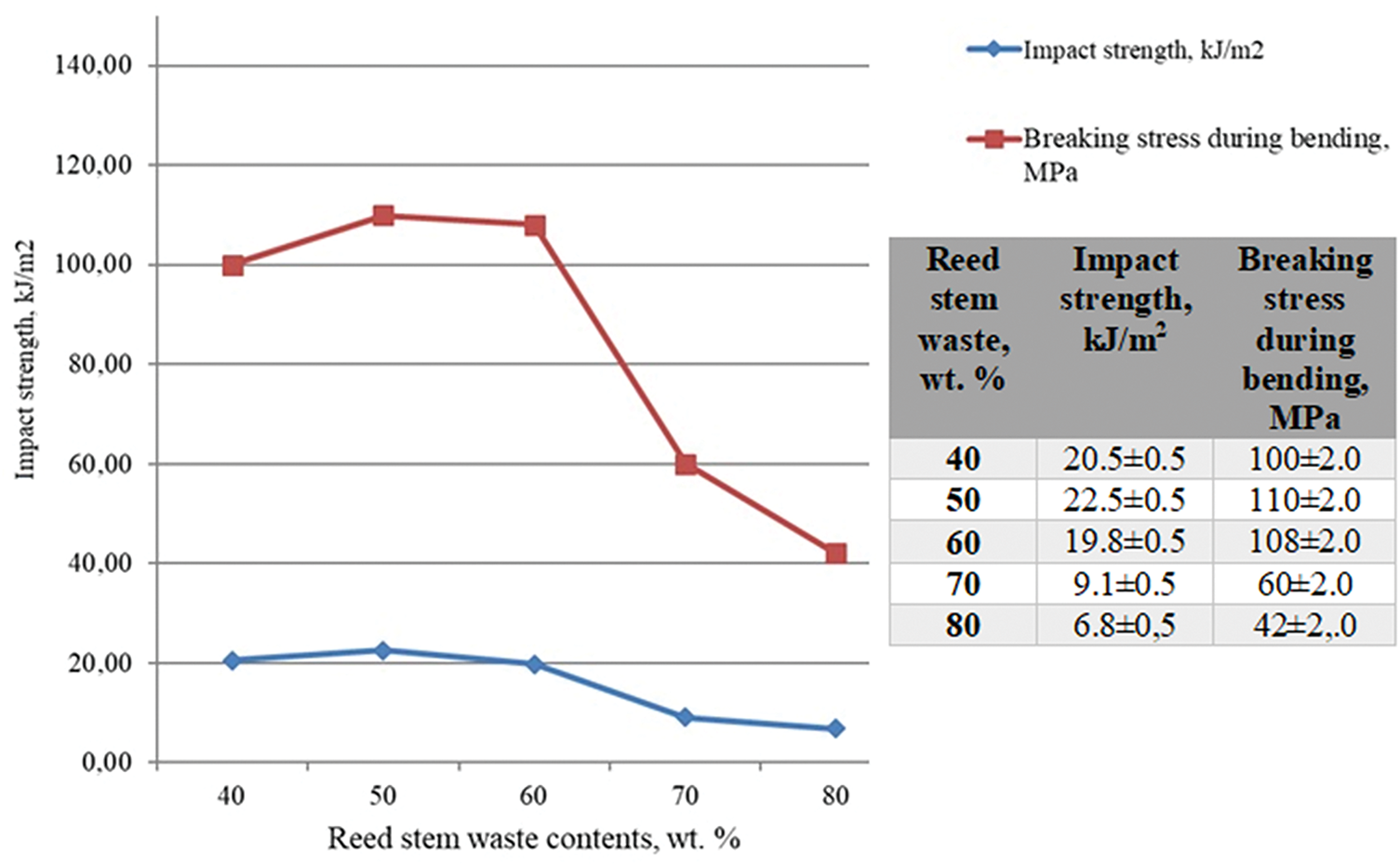

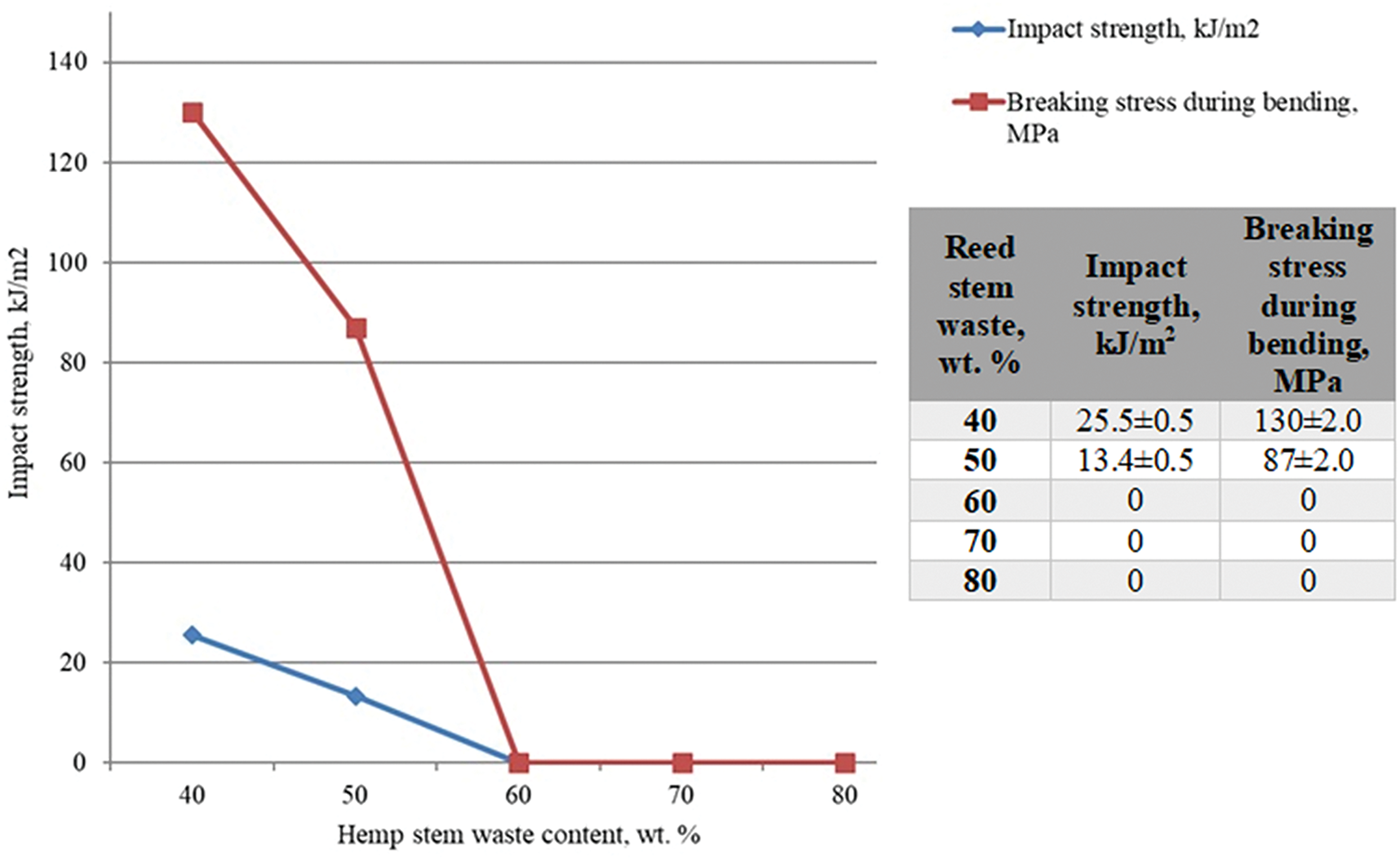

The influence of the content of reed and hemp stem waste on the complex strength characteristics of PBAT/PLA composites with reed-hemp waste was investigated: impact strength and tensile stress during bending (Figs. 8 and 9).

Figure 8: Reed stem waste content impact on the physical and mechanical properties level for PBAT/PLA composites

Figure 9: Hemp stem waste content impact on the physical and mechanical properties level for PBAT/PLA composites

When introduced into the composition of PBAT/PLA composites, there is an increase in the impact strength and ultimate bending stress for both investigated fillers reed and hemp stem waste: from 18 to 20 kJ/m2 and from 80 to 100 MPa, respectively. The results of the study of the data from Figs. 8 and 9 show that the most optimal direction for obtaining high-strength properties of PBAT/PLA composites is associated with waste reed stalks, with their optimal content at 50 wt.%. At the same time, PBAT/PLA composites with waste hemp stalks are characterized by fragile strength characteristics at 40–50 wt content. %, with its increase in the range of 60–80 wt.%, the resulting compositions become brittle and practically do not hold their shape. Also, the different PBAT/PLA composite’s strength and stability are associated with a higher cellulose content (up to 75 wt.%) and a lower lignin content (3.5–5 wt.%) in reed waste compared to hemp waste (50 wt.% cellulose and up to 8.5–10 wt.% lignin). Discussing the results of introducing different amounts of crushed reed and hemp stem waste into PBAT/PLA composites, it can be noted that stable shape and strength characteristics were characteristic of 40–50 wt.% organic waste.

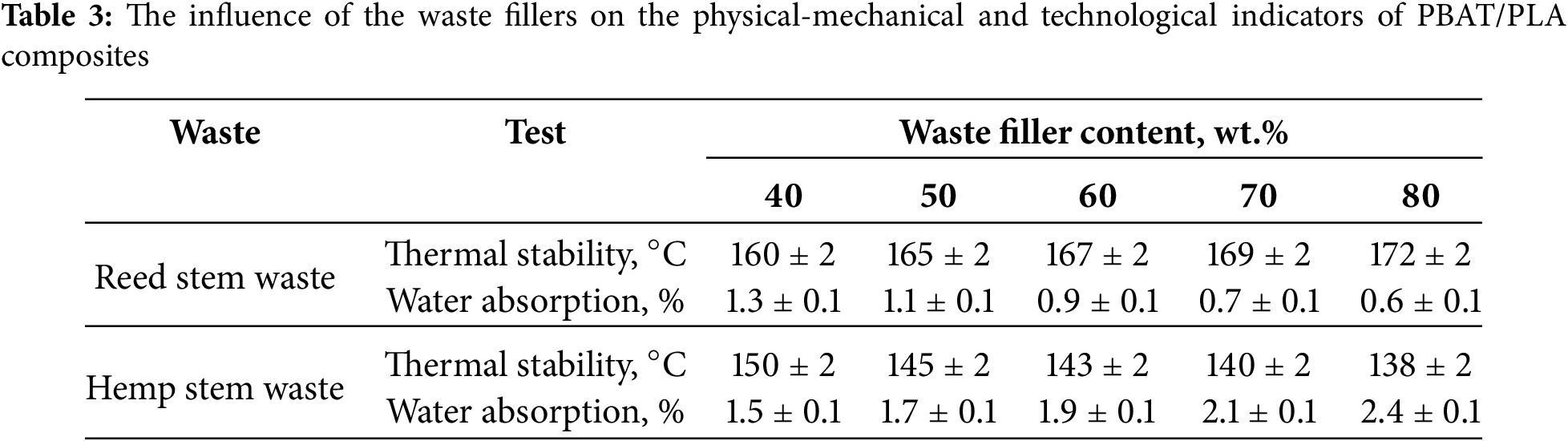

Table 3 presents the results of studies of the thermal stability and water barrier properties of PBAT/PLA composites with reed stem waste and hemp stem waste, depending on the content of the filler.

From the data in Table 1, it is clear that hemp and reed waste have opposite effects on the level of heat resistance and water absorption of PBAT/PLA composites. Thus, there was an increase in the content of reed waste from 40 to 80 wt.%, the level of heat resistance and water absorption of PBAT/PLA composites increases from 160 to 172°C and from 1.3 to 0.6 wt.%, respectively. At the same time, with an increase in the content of hemp waste from 40 to 80 wt.% the level of heat resistance and water absorption of PBAT/PLA composites decreases from 150 to 138°C and from 1.5 to 2.4 wt.%, respectively. It can be stated that the design of PBAT/PLA composites with 50 wt.% of reed straw waste are high-strength, heat-resistant, and water-resistant materials optimal for manufacturing ecological containers and packaging of various functional orientations. Also, the different PBAT/PLA composite’s strength and stability are associated with a higher cellulose content (up to 75 wt.%) and a lower lignin content (3.5–5 wt.%) in reed waste compared to hemp waste (50 wt.% cellulose and up to 8.5–10 wt.% lignin). In general, strength and performance properties correspond to the best commercial biocomposites based on related components [30,31].

Currently, there is a wide range of products for various functional purposes made from eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials filled with organic crushed waste, which implies the presence of many technological methods and techniques for their production [1], taking into account the size and purpose of the products [32], production volumes and operating conditions [33], product configuration [34], qualifications and equipment of the manufacturer [35], etc. The influence of organic fillers on the properties of a composite depends mainly on the properties of the filler itself. Therefore, for the appropriate and scientifically sound creation of composites by reinforcement, it is necessary to know the characteristics of the fillers. Qualitative analysis of fillers consists of assessing the granularity, shape, and nature of the distribution of particles by size. The shape and size of the particles determine the density of the filler packing, the uniformity of the particle distribution, the area of contact with the binder, rheological, physical-mechanical, and other properties [2]. In our case, PBAT/PLA composites filled with crushed reed stem waste is a fibrous-filled composite material consisting of a dispersed phase represented by fibrous particles of crushed reed stem waste and PBAT/PLA composites, between which there is a phase boundary and adhesive interaction. According to this definition, fibrous composite materials are a matrix reinforced with a mechanical frame in the form of fibers, which gives the material high strength at a relatively low density [1]. On this basis, the product was designed using eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials. The PBAT/PLA composites were filled with crushed reed stem waste. It is important to note that from the point of view of creating finished products and parts from PBAT/PLA composites with crushed waste of reed and hemp stems—these are composite materials consisting of an organic phase in the form of a polymer and a dispersed bioactive phase. At the same time, it is essential to consider the features of the technology for manufacturing products from PBAT/PLA composites with the crushed waste of reed and hemp stems as two-phase systems, which is somewhat different from the flow of pure polymers. Two types of two-phase flow are based on the degree of phase separation. One type is a two-phase flow of a dispersed system, in which one component exists as a dispersed phase, dispersed in another element, forming a continuous phase. The other type is layered, in which both components form continuous phases with a constant interface. When filled to 50%, the polymer flows according to the first type and obeys the statistical flow law. The studied flow curves in processing PBAT/PLA composites with the crushed waste of reed and hemp stems with different percentages of waste showed that when filled to 50%, the material is viscous. In the Newtonian flow region, the shear stress increases proportionately to the shear rate. The dilatancy effect inherent in highly concentrated two-phase systems does not appear. It is also worth emphasizing that the higher strength and performance characteristics of PBAT/PLA composites with reed waste are associated, in our opinion, with the lamellar morphology of solid particles of these materials and the prevalence of particle size at the level of 0.315–1 mm in the fractional composition, while hemp waste is characterized by a loose fibrous morphology with the highest content of the 1.25 mm fraction with a softer surface. An equally important factor in the higher strength and performance characteristics of PBAT/PLA composites with reed waste is higher cellulose content (up to 75 wt.%) and a lower lignin content (3.5–5 wt.%) in reed waste compared to hemp waste (50 wt.% cellulose and up to 8.5–10 wt.% lignin).

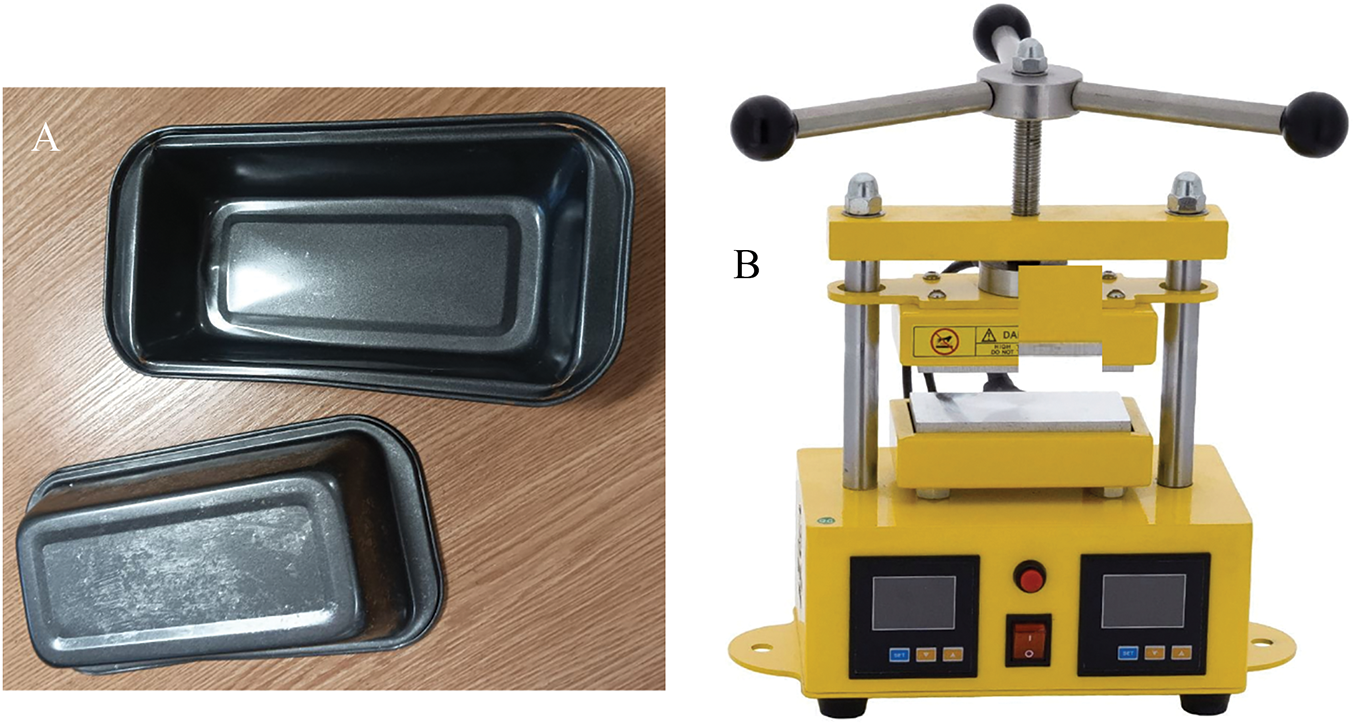

For the composition of PBAT/PLA composites with a content of 50 wt.% of crushed reed stem waste, as the most optimal in terms of strength characteristics and dimensional stability, samples of eco-containers in the form of a tray for packaging and storing food products in the form of fruits, vegetables, and berries were obtained, the appearance of which is presented in Fig. 10. To get the above tray samples, the extruded mass of PBAT/PLA composites with a content of 50 wt.% of crushed reed stem waste was additionally heated to a melting temperature of 165–170°C, placed in a two-component metal mold for pressing rectangular trays (Fig. 11A), and pressed on a hand press at a pressure of 1 t with heating to 140–150°C (Fig. 11B).

Figure 10: PBAT/PLA composites with 50 wt.% hemp stem waste tray for packaging and storing food products in the form of fruits, vegetables, and berries

Figure 11: Two-component metal mold for pressing rectangular trays (A) and hand press (B) for PBAT/PLA composites with 50 wt.% hemp stem waste tray for packaging and storing food products in the form of fruits, vegetables, and berries

So, the designed eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials and reed waste can be used to produce biodegradable containers, packaging, and tableware. It was found that the thermal stability and water barrier properties for such compositions are about 140°C and 0.5 wt.%, respectively, which makes it possible to recommend them for producing heat-resistant and water-resistant containers and packaging.

Herein, we present innovative PBAT/PLA composites with reed and hemp waste as a filler with different fractional compositions and shapes with particle sizes from 0.5 to 6 mm were obtained and studied.

Optimization studies were conducted to determine the most effective composition of the eco-friendly biodegradable composites based on renewable biopolymer materials and reed and hemp waste. It is shown that the most optimal direction for obtaining strong, PBAT/PLA composites is associated with waste reed stalks, with its optimal content at 50 wt.%. The PBAT/PLA composites with reed waste can be used to produce biodegradable containers, packaging, and tableware with increased heat and water resistance. For the composition of PBAT/PLA composites with a content of 50 wt.% of crushed reed stem waste, as the most optimal in terms of strength characteristics and dimensional stability, samples of eco-containers in the form of a tray for packaging and storing food products in the form of fruits, vegetables, and berries were obtained.

The next step in our research will be to investigate the most critical performance characteristics of the developed products in terms of heat resistance, water resistance, and service life in various external conditions.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: : The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Denis Miroshnichenko, Vladimir Lebedev, Serhiy Pyshyev; software: Magomediemin Gasanov, Yevgen Sokol, Yuriy Lutsenko; validation: Denis Miroshnichenko, Vladimir Lebedev, Serhiy Pyshyev; formal analysis: Anna Cherkashina; investigation: Artem Kariev, Vladimir Lebedev; resources: Artem Kariev; data curation: Magomediemin Gasanov, Yevgen Sokol, Yuriy Lutsenko; writing—original draft preparation: Denis Miroshnichenko, Vladimir Lebedev; writing—review and editing: Magomediemin Gasanov, Yevgen Sokol, Serhiy Pyshyev; visualization: Anna Cherkashina, Yevgen Sokol. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kaur G, Uisan K, Ong KL, Ki Lin CS. Recent trends in green and sustainable chemistry & waste valorisation: rethinking plastics in a circular economy. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2018;9:30–9. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2017.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cecchini C. Bioplastics made from upcycled food waste. Prospects for their use in the field of design. Des J. 2017;20(sup1):S1596–610. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1352684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cabrera FC. Eco-friendly polymer composites: a review of suitable methods for waste management. Polym Compos. 2021;42(6):2653–77. doi:10.1002/pc.26033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pyshyev S, Lypko Y, Demchuk Y, Kukhar O, Korchak B, Pochapska I, et al. Characteristics and applications of waste tire pyrolysis products: a review. Chem Chem Technol. 2024;18(2):244–57. doi:10.23939/chcht18.02.244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hrynyshyn K, Chervinskyy T, Helzhynskyy I, Skorokhoda V. Study on regularities of polyethylene waste low-temperature pyrolysis. Chem Chem Technol. 2023;17(4):923–8. doi:10.23939/chcht17.04.923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jana SK, Pattanayak S, Bhausaheb MS, Ruidas BC, Pal DB. Pyrolysis of waste plastic to fuel conversion for utilization in internal combustion engine. Chem Chem Technol. 2023;17(2):438–49. doi:10.23939/chcht17.02.438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Maraz KM, Karmaker N, Meem RA, Khan RA. Development of biodegradable packaging materials from bio-based raw materials. J Res Updates Polym Sci. 2019;8:66–84. doi:10.6000/1929-5995.2019.08.09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Q, Jia P, Luo Y, Liu Y. Renewable biomass as a platform for preparing green chemistry. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(2):325–28. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.044083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Banea MD. Natural fibre composites and their mechanical behaviour. Polymers. 2023;15(5):1185. doi:10.3390/polym15051185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Jagadeesh D, Kanny K, Prashantha K. A review on research and development of green composites from plant protein-based polymers. Polym Compos. 2017;38(8):1504–18. doi:10.1002/pc.23718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lebedev V, Miroshnichenko D, Savchenko D, Bilets D, Mysiak V, Tykhomyrova T. Computer modeling of chemical composition of hybrid biodegradable composites. In: Proceedings of the Information Technology for Education, Science, and Technics 2022; 2022 Jun 23–25; Cherkasy, Ukraine. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-35467-0_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Temesgen S, Großmann L, Tesfaye T, Kuehnert I, Smolka N, Nase M. Rheological, structural and melt spinnability study on thermo-plastic starch/PLA blend biopolymers and tensile, thermal and structural characteristics of melt spun fibers. J Res Updates Polym Sci. 2024;13:187–209. doi:10.6000/1929-5995.2024.13.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Boughanmi O, Allegue L, Marouani H, Koubaa A, Fouad Y. Repetitive recycling effects on mechanical characteristics of poly-lactic acid and PLA/spent coffee grounds composite used for 3D printing filament. Polym Eng Sci. 2024;64(11):5613–26. doi:10.1002/pen.26938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lebedev V, Miroshnichenko D, Vytrykush N, Pyshyev S, Masikevych A, Filenko O, et al. Novel biodegradable polymers modified by humic acids. Mater Chem Phys. 2024;313(2):128778. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.128778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Thyavihalli Girijappa YG, Mavinkere Rangappa S, Parameswaranpillai J, Siengchin S. Natural fibers as sustainable and renewable resource for development of eco-friendly composites: a comprehensive review. Front Mater. 2019;6:226. doi:10.3389/fmats.2019.00226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Huang Y, Yin Z, Liu M, Li M, Zuo Y, Qing Y, et al. Effect of multi-hydroxyl polymer-treated MUF resin on the mechanical properties of particleboard manufactured with reed straw. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(9):3417–31. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.028511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Raj Mahendran A, Wuzella G, Pichler S, Lammer H. Properties of different chemically treated woven hemp fabric reinforced bio-composites. J Renew Mater. 2022;10(6):1505–16. doi:10.32604/jrm.2022.017835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Talla AFS, Erchiqui F, Kocaefe D, Kaddami H. Effect of hemp fiber on PET/hemp composites. J Renew Mater. 2014;2(4):285–90. doi:10.7569/JRM.2014.634122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ezzahra El Abbassi F, Assarar M, Ayad R, Sabhi H, Buet S, Lamdouar N. Effect of recycling cycles on the mechanical and damping properties of short Alfa fibre reinforced polypropylene composite. J Renew Mater. 2019;7(3):253–67. doi:10.32604/jrm.2019.01759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hussain A, Calabria-Holley J, Lawrence M, Ansell MP, Jiang Y, Schorr D, et al. Development of novel building composites based on hemp and multi-functional silica matrix. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;156:266–73. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.08.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ahmad MR, Chen B, Yousefi Oderji S, Mohsan M. Development of a new bio-composite for building insulation and structural purpose using corn stalk and magnesium phosphate cement. Energy Build. 2018;173(2):719–33. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Prasad V, Alliyankal Vijayakumar A, Jose T, George SC. A comprehensive review of sustainability in natural-fiber-reinforced polymers. Sustainability. 2024;16(3):1223. doi:10.3390/su16031223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kar E, Maity S, Kar A, Sen S. Agricultural waste rice husk/poly(vinylidene fluoride) composite: a wearable triboelectric energy harvester for real-time smart IoT applications. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2024;7(3):87. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-00896-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lebedev V, Miroshnichenko D, Pyshyev S, Kohut A. Study of hybrid humic acids modification of environmentally safe biodegradable films based on hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose. Chem Chem Technol. 2023;17(2):357–64. doi:10.23939/chcht17.02.357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pecoraro MT, Mellinas C, Piccolella S, Garrigos MC, Pacifico S. Hemp stem epidermis and cuticle: from waste to starter in bio-based material development. Polymers. 2022;14(14):2816. doi:10.3390/polym14142816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Miroshnichenko D, Lebedeva K, Cherkashina A, Lebedev V, Tsereniuk O, Krygina N. Study of hybrid modification with humic acids of environmentally safe biodegradable hydrogel films based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose. C-J Carbon Res. 2022;8(4):71. doi:10.3390/c8040071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lebedev V, Miroshnichenko D, Bilets D, Mysiak V. Investigation of hybrid modification of eco-friendly polymers by humic substances. Solid State Phenom. 2022;334(2):154–61. doi:10.4028/p-gv30w7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lebedev V, Miroshnichenko D, Zhang X, Pyshyev S, Dmytro S, Nikolaichuk Y. Use of humic acids from low-grade metamorphism coal for the modification of biofilms based on polyvinyl alcohol. Petrol Coal. 2021;63(4):953–62. [Google Scholar]

29. Linderbäck P, Gebrehiwot S, Montin L, Björkvall R, Suarez L, Theis J, et al. Common reed as a novel biosource for composite production. In: Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Composite Materials ECCM21; 2024 Jul 2–5; Nantes, France. doi:10.60691/yj56-np80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xie L, Huang J, Xu H, Feng C, Na H, Liu F, et al. Effect of large sized reed fillers on properties and degradability of PBAT composites. Polym Compos. 2023;44(3):1752–61. doi:10.1002/pc.27202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xu J, Feng K, Li Y, Xie J, Wang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Enhanced biodegradation rate of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites using reed fiber. Polymers. 2024;16(3):411. doi:10.3390/polym16030411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Chen X, Manshaii F, Tioran K, Wang S, Zhou Y, Zhao J, et al. Wearable biosensors for cardiovascular monitoring leveraging nanomaterials. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2024;7(3):97. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-00906-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Scaffaro R, Gulino EF, Citarrella MC. Multifunctional 3D-printed composites based on biopolymeric matrices and tomato plant (Solanum lycopersicum) waste for contextual fertilizer release and Cu(II) ions removal. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2024;7(3):95. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-00908-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gao S, Huang K, Lan C, Xu J, Yao H, Zhang Z, et al. Terahertz biosensor for amino acids upon all-dielectric metasurfaces with high-quality factor. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2024;7(3):85. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-00901-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tamjid E, Najafi P, Khalili MA, Shokouhnejad N, Karimi M, Sepahdoost N. Review of sustainable, eco-friendly, and conductive polymer nanocomposites for electronic and thermal applications: current status and future prospects. Discov Nano. 2024;19(1):29. doi:10.1186/s11671-024-03965-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools